how to bring about

social-ecological transformation

DEGROWTH & STRATEGY

Edited by

Nathan Barlow, Livia Regen, Noémie Cadiou, Ekaterina Chertkovskaya,

Max Hollweg, Christina Plank, Merle Schulken and Verena Wolf

D

EGR

O

WT

H

STRATE

GY

&

how to bring about social-ecological

transformation

Degrowth is a research area and a social movement that has the

ambitious aim of transforming society towards social and ecological

justice. But how do we get there? That is the question this book

addresses. Adhering to the multiplicity of degrowth whilst also arguing

that strategic prioritisation and coordination are key, Degrowth

& Strategy advances the debate on strategy for social-ecological

transformation. It explores what strategising means, identifies key

directions for the degrowth movement, and scrutinises strategies

that aim to realise a degrowth society. Bringing together voices from

degrowth and related movements, this book creates a polyphony for

change that goes beyond the sum of its parts.

" This book is the perfect gateway to strategy and action for our time. "

Julia Steinberger

" This is a book everyone in the degrowth community has been waiting for.

"

Giorgos Kallis

" This is a true gift, not only to degrowthers, but to all those who

understand the need for radical change. "

Stefania Barca

" Above all, Degrowth & Strategy is a work of revolutionary optimism. "

Jamie Tyberg

www.mayflybooks.org

how to bring about social-ecological

transformation

degrowth

s t r a t e g y

&

may f l y

Published by Mayy Books. Available in paperpack

and free online at www.mayybooks.org in 2022.

© Authors remain the holders of the copyright of their own texts. ey may

republish their own texts in dierent contexts, including modied versions of

the texts under the condition that proper attribution is given to Degrowth &

Strategy.

ISBN (Print) 978-1-906948-60-3

ISBN (PDF) 978-1-906948-61-0

ISBN (ebook)978-1-906948-62-7

is work is licensed under the Creative Commons

Attribution-Non commercial-No Derivatives 4.0

International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0).

To view a copy of this license, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0

Cover art work by Dana Rausch who retains the image copyright.

Layout by Mihkali Pennanen.

Edited by Nathan Barlow, Livia Regen, Noémie Cadiou,

Ekaterina Chertkovskaya, Max Hollweg,

Christina Plank, Merle Schulken and Verena Wolf

how to bring about social-ecological

transformation

degrowth

s t r a t e g y

&

vii

Praise for this book

“is book is what the degrowth movement needed the most: a well-reasoned and

empirically grounded compendium of strategic thinking and praxis for systemic

transformations. is is a true gift, not only to degrowthers, but to allthose who

understand the need for radical change.In an era of unprecedented challenges as the

one we are living through, this book should become essential reading in every higher-

education course across the social sciences and humanities.”

Stefania Barca, University of Santiago de Compostela, author of Forces of

Reproduction – Notes for a Counterhegemonic Anthropocene

“Emerging amidst the ruins of the destroyed (some call it developed) world, degrowth

is a powerful call for transformation towards justice and sustainability. is book takes

degrowth’s ideological basis towards strategy and practice, relates it to other movements,

and shows pathways that are crucial for the Global North to take if life on earth has to

ourish again.”

Ashish Kothari, co-author of Pluriverse: A Post-Development Dictionary

“e book is an exciting source of hope for degrowth futures. It is a thoroughly readable

and ambitious book that sets out what degrowth wants to do and what it is actually

achieving. It contains many inspiring examples of new ways of living together, illustrating

how to share resources, create caring institutions, fair infrastructures, and new ways of

relating to humans and more-than-humans.”

Wendy Harcourt,International Institute of Social Studies of Erasmus University

Rotterdam

“In contrast to previous works on the topic the focus is rmly placed on the challenge

of how to achieve social-ecological transformation in the face of economic structures

and powerful vested interests committed to a utopian vision of sustaining economic

growth without end; a vision that pretends to be concerned for the poor while exploiting

them and destroying Nature. An alternative multi-faceted vision is outlined in the

most comprehensive exploration of the topic available, including addressing the role of

money, mobility, energy, food, technology, housing, and most importantly how to change

modernity’s various growth–obsessed social–economic systems.”

Clive Spash, Vienna University of Economics and Business, editor of Handbook of

Ecological Economics: Nature & Society

“We live in times of great despair and danger, but also great promise. is book is the

perfect gateway to strategy and action for our time, written by some of the very top

thinkers in the degrowth movement. It will help you create possibilities to transform our

world for the better.”

Julia Steinberger, University of Lausanne

“is is a book everyone in the degrowth community has been waiting for. Moving beyond

the diagnosis about the costs and limits of growth, this volume asks the question of what is to

be done and puts forward an ambitious political program of how we go from here to there.

e authors present a coherent vision of how dierent mobilisations at dierent scales can

come together and steer societies to what now seems politically impossible – degrowth.”

Giorgos Kallis, ICREA Professor, ICTA-UAB, author of Limits and e Case for

Degrowth

viii

“What is to be done about the Global North? Young economists of the degrowth

generation share strategies on food, housing, energy, transport, technology, and money.

Practical, stimulating, and provocative.”

Ariel Salleh,author of Eco-Suciency & Global Justice

“How do we go from here to there? Read this book and you will nd how societies can

undertake a transformation towards degrowth.”

Federico Demaria, University of Barcelona, co-author of

e Case for Degrowth

“Above all, Degrowth & Strategy is a work of revolutionary optimism. e range of visions

oered in this text teaches us that we are better o nding a common ground in our

strategies and tactics than dwelling on our dierences, so that we may step into the future

together.With this text, the degrowth movement shifts its central focus from the what

and the why to the how. Be warned: this is for those to whom degrowth is an everyday

commitment and not a mere thought exercise!”

Jamie Tyberg, co-founder and member of DegrowNYC

“Degrowth & Strategyis an important collection of essays on a subject of the

greatest signicance and urgency. Particularly impressive is the emphasis on public

communication, workable political strategies and practical solutions.”

Amitav Ghosh, author of e Great Derangement: Climate Change and the

Unthinkable

“e most critical challenge isimplementingdegrowth – to ensure that production and

consumption meet basic needs, neither more (waste) nor less (poverty). is collection

confrontsstrategyhead-on, with a singular unity of purpose and a rich variety of

approaches. A must-read for all concerned about our uncertain future.”

Anitra Nelson, University of Melbourne (Australia), co-author ofExploring

Degrowth, and co-editor of

Food for DegrowthandHousing for Degrowth

“is book makes a timely and essential contribution to a number of intersecting

debates regarding the how of social-ecological transformation. Expertly edited, the book’s

emphasis on philosophies, strugglesand strategiesin more ‘in principle’

terms complements very eectively the consideration of concrete practices across a wide

range of societal sites and sectors. A must-read for scholars and activists alike.”

Ian Bru, University of Manchester

“at we need to moveto a degrowth economyis becoming ever more obvious. How

we go about achieving it has hitherto been less clear, and less discussed in degrowth

literature. is comprehensive and astute survey oftransformativestrategies, both those

already in train and those that need to come into force, provides an essential guide.”

Kate Soper, London Metropolitan University

ix

“Nothing grows forever, and the same is true of economies. In this urgently needed book,

an impressive group of academics and activists consider how we get to an economic

system that operates within natural limits and with regard to social justice. Illustrated

with inspiring case studies, the authors focus on the how, because the planet and our

natural world are already showing us the why.”

Martin Parker, Bristol University, author of Shut Down the Business School

“e structural, cultural and ideational barriers to degrowth have long been recognised

by its advocates. Contributors to this collection respond to the challenges positively and

creatively by thinking about strategy and how this concept can be harnessed by diverse

social movements to initiate, inspire and institute bottom-up social-ecological change.”

Ruth Kinna, Loughborough University

“We need to go beyond envisioning degrowth but identify pathways towards it. is is

the rst book that provides a comprehensive and in-depth engagement with strategies for

degrowth, denitely leading us closer to a degrowth future. Required reading for anyone

who aims to realise degrowth.”

Jin Xue, Norwegian University of Life Sciences

“e Western growth model becomes increasingly untenable as a societal project, thereby

urging communities, researchers, and decision-makers to nd alternative pathways. To

guide us through these turbulent times and towards a future beyond growth, the authors of

Degrowth & Strategy provide a much-needed map – unprecedented in detail but also aware

of the yet unknown.”

Benedikt Schmid, University of Freiburg, author of Making Transformative

Geographies

“How can we better organise to achieve social and ecological justice in a nite world? is

is a big question with no easy answer. In an honest and thoughtful way, this book brings

multiple voices expressing diverse pathways to pursue social-ecological transformation.

What emerges from the presentation of dierent perspectives and strategies is not the

suggestion of one right way to bring about change but a healthy, pluralistic, thought-

provoking and respectful dialogue that can lead us in new and promising directions.”

Ana Maria Peredo, Professor of Social and Inclusive Entrepreneurship, University of

Ottawa & Professor of Political Ecology, University of Victoria

“In my classes, students keep circling back to the question – how do we move from

the current world driven by the logic of capital, endless growth, needless production

and consumption to a world that centres on justice, care, and living well in a way that

amplies life? is book provides what so many of us are craving for – thought-provoking

engagement with the issue of strategies for materialising social-ecological transformation.

e book oers theoretical frameworks, pathways, and practical examples of diverse

strategies for social-ecological transformations at work.It is a must-read for academics,

activists, practitioners, and ordinary people striving for an equitable and sustainable

world. I am grateful to the editors and authors for creating this excellent resource for

thinking and acting to facilitate a ‘strategic assemblage for degrowth’.”

Neera Singh, Geography & Planning, University of Toronto

x

Table of Contents

Forewords by Brototi Roy and Carola Rackete &

Introduction: Strategy for the multiplicity of degrowth by Merle Schulken,

Nathan Barlow, Noémie Cadiou, Ekaterina Chertkovskaya,

Max Hollweg, Christina Plank, Livia Regen and Verena Wolf

Part I: Strategy in degrowth research and activism

e importance of strategy for thinking about transformation

Chapter Radical emancipatory social-ecological transformations: degrowth

and the role of strategy by Ulrich Brand

Chapter A strategic canvas for degrowth: in dialogue with Erik Olin Wright

by Ekaterina Chertkovskaya

Chapter Taking stock: degrowth and strategy so far by Nathan Barlow

Degrowth movement(s): strategising and plurality

Chapter Strategising within diversity: the challenge of structuring

by Viviana Asara

Chapter Degrowth actors and their strategies: towards a Degrowth International

by Andro Rilović, Constanza Hepp,

Joëlle Saey-Volckrick, Joe Herbert and Carol Bardi

Chapter Who shut shit down? What degrowth can learn from other

social-ecological movements by Corinna Burkhart, Tonny Nowshin,

Matthias Schmelzer and Nina Treu

Strategising with our eyes wide open

Chapter Social equity is the foundation of degrowth by Samantha Mailhot

and Patricia E. Perkins

Chapter Evaluating strategies for emancipatory degrowth transformations

by Panos Petridis

Chapter Rethinking state-civil society relations by Max Koch

Chapter Strategic entanglements by Susan Paulson

Part II: Strategies in practice

Provisioning sectors

Chapter Food

Overview by Christina Plank

Case: e movement for food sovereignty by Julianna Fehlinger, Elisabeth Jost

and Lisa Francesca Rail

Chapter Urban housing

Overview by Gabu Heindl

Case: Deutsche Wohnen & Co. Enteignen by Ian Clotworthy and Ania Spatzier

Chapter Digital technologies

Overview & Case: Low-Tech Magazine and Decidim by Nicolas Guenot

and Andrea Vetter

Chapter Energy

Overview by Mario Díaz Muñoz

Case: e struggle against energy extractivism in Southern Chile

by Gabriela Cabaña

Chapter Mobility and transport

Overview by John Szabo, omas SJ Smith and Leon Leuser

Case: e Autolib’ car-sharing platform by Marion Drut

Economic and political reorganisation

Chapter Care

Overview by Corinna Dengler, Miriam Lang and Lisa M. Seebacher

Case: e Health Centre Cecosesola by Georg Rath

Chapter Paid work

Overview & Case: Just Transition in the aviation sector by Halliki Kreinin

and Tahir Latif

Chapter Money and nance

Overview & Case: e Austrian Cooperative for the Common Good

by Ernest Aigner, Christina Buczko, Louison Cahen-Fourot and Colleen Schneider

Chapter Trade and decolonisation

Overview by Gabriel Trettel Silva

Case: Litigation as a tool for resistance and mobilisation in Nigeria

by Godwin Uyi Ojo

About the Authors

About the Editors

Acknowledgements

Forewords

By Brototi Roy, co-president of Research and Degrowth (R&D)

and co-founder of the Degrowth India Initiative

I rst came across the term degrowth in while I was a

master’s student in economics in New Delhi, India. I was in my

third semester and decided to take an elective course called “Key

concepts in Ecological Economics.” is course was the start of

my engagement with the term, the movement and the academic

scholarship on degrowth. With my friend and co-conspirator Arpita,

I started the Degrowth India Initiative to have discussions and

conversations on degrowth. Why, you ask? Because I was frustrated

with the way a lot of people in Delhi had embraced the “imperial

mode of living.” And although I didn’t know it at that time,

the Degrowth India Initiative was a strategy to link the research

carried out by the students in the university on sustainability and

environmental justice with ideas about degrowth, with the hope of

repoliticising the debate on social-ecological justice and equity in the

Indian context.

Fast forward to October , when I was in a public debate

on degrowth in Antwerp, Belgium. One of the questions asked

about the non-feasibility of degrowth was “What about the poor

garment workers in Bangladesh? Will you ask them to degrow?”

In the audience, there were quite a few of us who have been a part

of various degrowth initiatives and actions over the years, and we

shared our frustrations about this, and many other similar questions

often being asked about degrowth and how it harms the poor in the

Global South. Some go so far as to claim that people in the Global

North should continue consuming fast fashion because of these

garment workers, who are being done a favour and are kept in jobs

because of this.

But has anyone asked the garment workers if this is what they

really want, instead of just assuming and speaking on their behalf?

Is this their idea of meaningful employment? What led them to

work in these exploitative positions? And what would they consider

a meaningful transformation of their lives and livelihoods? For me,

a radical social-ecological transformation can only be achieved when

it is anti-colonial and feminist. A degrowth strategy for me is to

allow for the garment workers to speak their truths, collectively nd

solutions together, and never assume we know better.

is public event, despite being one of the most frustrating ones

in terms of misrepresenting degrowth, did help in bringing a bunch

of people together and has led to the creation of a degrowth group

in Belgium. Would the group be able to engage with the colonial

history of the country and strategise about what degrowth in the

Belgian context means? I remain hopeful about it.

Both the Indian and the Belgian initiatives were born out of

frustration with the current system and the need for social-ecological

transformation, due to the exploitative patterns of capitalism, based

on oppression and exploitation of marginalised communities and

nature by some sections of the world and society. Both initiatives

found degrowth ideas could help inform strategy while being critical

and self-reective.

From these two small anecdotes, I now turn to this edited volume.

In the last couple of decades, degrowth has ourished as an academic

sub-discipline and movement, with multiple books, articles, special

issues, conferences, talks, and debates being organised around the

topic. Yet not enough has been written on how one can go about

creating long-lasting changes towards justice and equity.

is is precisely what the book does. It is a very important and

impressive collection of strategies, which might or might not have

stemmed from similar frustrations as mentioned above, experienced

by the editors and authors, but which will denitely help, in the

years to come, others who are trying to nd solutions for social-

ecological transformation in their own contexts.

By looking at the dierent strategies for a degrowth pathway

and focusing on dierent aspects of the globalised world economy,

this book provides concrete proposals for social-ecological

transformations – albeit with a focus on the Global North. At the

same time, the book also engages with critical ideas of feminist and

decolonial degrowth in tangible ways – such as through the case of

global trade or considerations around the organisation of care. e

degrowth movement has been criticised for paying lip service to

feminist and decolonial ideas; this book shows that once we move

from the “why “question to the “how” question, one can’t ignore the

need for a holistic framework that is serious about its feminist and

decolonial views.

All in all, the book is a step forward in thinking together with

dierent degrowth initiatives and actors about how radical social-

ecological transformation can be realised. By bringing degrowth in

conversation with dierent other actors and movements ghting

for social-ecological justice and equity, such as the climate justice

movement, and providing concrete ways of engagement, I hope

to see this book create ripples for change towards radical societal

transformation towards justice and equity.

By Carola Rackete, Sea-Watch captain, and social and

environmental justice activist

I am staring at my tomatoes. I didn’t grow them, I rescued them

from a trash bin where they were suocating in plastic. I wonder

what happened to them before I found them, how they were shipped

from far away, who planted, harvested and processed them. I am sure

they were dreaming of a better place. Me too.

I am dreaming of agriculture that regenerates the soil instead of

depleting it. at sustains life for future generations and non-

humans alike. at provides people with meaningful work and

collective ownership of the land. A place where care for the

community of life is valued more than its destruction. I am

dreaming of a world where the tomatoes in my hands have come to

me in a completely dierent way.

It’s easy to imagine that better world once I start thinking about it.

But how do we transition from one tomato to the other? How do we

make that better tomato a reality? If degrowth is to have a part in our

future we need to draw a map for how to move on from one place

to the other. We need to dene not only the destination at the end

of that path, but also be able to share with other people how to nd

the trailhead and get started in a very practical way. is pathway of

transformation must be as credible and real as the tomatoes in front

of me.

is book is about these pathways of transformation – about

mapping what is ahead, how to nd the trailhead, what to bring

on the journey, how to get from one trail marker to the next, and

how to overcome expected obstacles. It is not only about ecological

transformation – which is how I got connected to the degrowth

movement – but about pathways towards better housing, care,

mobility and energy, and global social justice. All these pathways

intersect and lead us into the same direction of a future based on

justice, decolonialism and care for one another, based on the choice

of limiting economic and social practices that are set up to destroy

everyone.

If we can envision not only where we want to get to, but

also how we are going to get there, others might feel safe and

condent enough to join us on that journey. At rst, that path of

transformation may only be taken by those who already share our

vision of a just social-ecological future and who feel they have the

skills, motivation and opportunity to make a start. But one of our

most important challenges will be to practically demonstrate how

walking that path of transformation will be benecial for everyone in

our societies beyond those already engaged.

erefore, this book about degrowth transformation and strategy

is important as a tool to prepare for getting underway towards the

world of better tomatoes.

Introduction

Strategy for the multiplicity of degrowth

By Merle Schulken, Nathan Barlow, Noémie Cadiou, Ekaterina

Chertkovskaya, Max Hollweg, Christina Plank, Livia Regen and

Verena Wolf

We live in troubled times: climate emergency, rising inequality and

the COVID- pandemic are just some of the grand challenges we

are faced with. ese are not unfortunate coincidences caused by

humanity as a whole but the outcomes of a system oriented toward

perpetual economic growth and capital accumulation. It is a system

characterised by brutal injustices within and across societies – based

on class, gender and racial divisions, and uneven relations between

the Global North and the Global South. Addressing the current

multifaceted ecological, social and economic crisis requires not just

incremental but systemic change, which in this book we refer to as

social-ecological transformation (see Chapter for a denition).

Institutional responses to this crisis from those in power are not

enough to meet the scale of the social-ecological transformation

required. When it comes to climate change, for example, we are

well into the third decade of high-prole UN Climate Change

Conferences, where member states negotiate how to reduce global

greenhouse gas emissions. Meanwhile, emissions are only rising.

With states and corporations joining hands as the threat of climate

change becomes increasingly real, false solutions are being proposed,

including dangerous technologies and further nancialisation to keep

the economic engine running at full speed. ese supposed solutions

are wrapped into creative accounting to make them appear eective

and are communicated using elusive terminologies, such as “net-

zero” or “climate neutrality”, which create a sense of change while

continuing business as usual.

Parallel to this, many social movements have risen and keep rising

to oppose the current state of things. From anti-austerity, Black

Lives Matter, climate and environmental justice movements, to

autonomous, feminist, indigenous and peasant movements, people

across the world are boldly protesting against injustices, resisting

entrenched structures of domination and building alternatives. is

book emerged from discussions on degrowth, a burgeoning research

area and an emerging social movement that critiques the pursuit of

economic growth and capital accumulation and strives to reorganise

societies to make them both ecologically sustainable and socially just.

e degrowth vision of social-ecological transformation connects

with a mosaic of progressive bottom-up movements across the world

(Akbulut et al. , Burkhart et al. ). Together, we see these

movements as key agents of an urgently needed social-ecological

transformation.

In order to be eective, social movements have to confront the

agendas driven by corporate and state actors, who have the power

to ignore, water down, co-opt and criminalise transformative

eorts. Social movements often lack time and energy, capacities and

resources, and it is easy to run out of steam and feel that eorts to

bring change are futile. But there is no time for despair! What we

need to do is to organise better within and across the movements we

are a part of and to develop a more clear-eyed perspective on how to

confront the powerful interests and structures standing in the way of

systemic change. is is why the question of strategy is so important

for anyone engaged in eorts for social-ecological transformation.

is book aims to tackle the question of how systemic change can be

fostered despite the constraints we face.

Degrowth & Strategy: how to bring about social-ecological

transformation builds on existing research on degrowth and its vision

for a society with ecological sustainability and social justice at the

core. But it also takes this research further to dig more deeply into

the question of strategy. e book oers a conceptual discussion of

strategy and its relation to degrowth and social movements more

generally and investigates strategies in practice, drawing on a variety

of examples. In doing this, it brings together multiple voices from

degrowth and related movements, to create a polyphony that reects

the multiplicity of degrowth. is discussion, we hope, will help

the readers reect on questions of strategy and empower them to

apply this thinking in practice, contributing to more eective and

concerted eorts for social-ecological transformation.

e remainder of this introduction will be structured as follows.

We start by outlining a degrowth vision for social-ecological

transformation. Second, we trace the existing discussion on strategy

in the degrowth movement and explain why it is important to think

about strategy. ird, we turn to conceptualising how we understand

strategy in this book, which builds on and is closely aligned with our

understanding of degrowth. Finally, we introduce the book and its

structure, followed by a conclusion.

What is degrowth, and why does it need strategy?

We understand degrowth as a democratically deliberated absolute

reduction of material and energy throughput, which ensures

well-being for all within planetary boundaries. Contrary to

perpetuating economies driven by growth and prot, degrowth

oers an alternative vision for societies, centred on life-making,

ecological sustainability and social justice. Since degrowth is based

on the principles of autonomy, solidarity and direct democracy,

bottom-up organising is seen as key to making an equitable and

just transformation happen (Asara et al. ). Crucially, degrowth

also acknowledges the historical inequities of colonialism and neo-

colonialism, and therefore demands that the Global North reverse

the social and ecological burdens it imposes on the Global South.

Degrowth is a concept that comes from the European context,

but it connects to a pluriverse of ideas from around the world that

advocate for a good life beyond economic growth, capitalism, and

development (Kothari et al. ), where living well also means not

living at anyone else’s expense (Brand et al. ).

e term degrowth was coined in as décroissance by André

Gorz, a French philosopher whose thought has been an important

source of inspiration for those working on degrowth (Kallis et al.

, Leonardi ). In the early s, it was mobilised as an

activist slogan in France, Italy (decrescita), Catalonia (decreixement)

and Spain (decrecimiento), and décroissance as a social movement

emerged in Lyon and spread across France (Demaria et al. ). In

, the rst International Degrowth Conference for Ecological

Sustainability and Social Equity took place in Paris, which is also

when the term was translated into English. Since then, degrowth

has gained further traction in academic and (some) activist circles.

International degrowth conferences serve as key spaces for academic-

activist discussion and have been hosted from multiple locations

(Barcelona, Venice, Montreal, Leipzig, Budapest, Malmö, Mexico

City, Vienna, Manchester, e Hague).

Within the academic realm, degrowth today is a burgeoning

area of interdisciplinary research with the publication of hundreds

of articles and a growing number of books on the topic in the last

decade (Kallis et al. , Weiss and Cattaneo ). Multiplicity is

a key characteristic and arguably a strength of degrowth research,

as it draws from dierent theoretical perspectives and currents of

thought, and there is an acknowledgement that degrowth is not a

unied scientic paradigm (Paulson ). is allows degrowth

to be an inclusive conversation and a space for multiple voices that

share the basic premise that the growth imperative must be overcome

to ensure a good life for all (Barca et al. ). ere are also some

asymmetries and blind spots in the degrowth discussion. Critiques

from, for example, decolonial, ecosocialist and feminist perspectives

have pointed some of these out and have put forward paths for acting

upon them (e.g. Andreucci and Engel-Di Mauro , Dengler and

Seebacher , Gregoratti and Raphael , Nirmal and Rocheleau

). In this volume, we embrace the multiplicity of degrowth,

which, as the readers will notice, means that contributing authors will

sometimes take dierent stances on degrowth’s diverse manifestations.

Besides being a eld of interdisciplinary research, degrowth has also

been described as an emerging international social movement with

close connections to other social-ecological movements (Chapter ,

Chapter ; see also Akbulut et al. , Demaria et al. ). Others

prefer to describe degrowth as a community of activist scholars, or

a network of networks. Whatever one’s take on how to characterise

the institutional set-up of degrowth, we can see that multiple

international and regional groups have emerged and stabilised as

relevant actors within degrowth activism, albeit mostly in Europe.

International groups include, for example, degrowth.info (a web

platform for information related to degrowth), the Support Group (a

team supporting degrowth conferences) and Research & Degrowth (a

group of degrowth researchers). Many regional groups, in turn, have

organised themselves around research and activist communities, and

some of these have also hosted international degrowth conferences

or even formed a political party. However, groups and organisations

coming together around degrowth ideas have not yet found concerted

ways to collectively act together.

In this book, we argue that it is time to seriously address the

question of strategy for degrowth, whilst respecting its multiplicity.

is is not an easy path. It will involve a lot of negotiation and

deliberation and is likely to come with dierent and contradictory

views on how to bring about social-ecological transformation.

Without seriously addressing the question of strategy for degrowth,

the eorts of degrowthers and others fostering compatible visions

around the world risk remaining marginal and fragmented, staying in

the realm of ideas and fragile oases of alternatives. Or, when entering

spaces beyond the movement, they risk being co-opted or engaged

with in a one-sided way by actors opposed to systemic change.

Concerted actions and coordination would help to amplify the eorts

for social-ecological transformation and create more powerful ways to

act collectively. us, we believe that only a rigorous discussion on

strategy can help avoid this fragmentation or co-optation.

Degrowth and strategy so far

e lack of engagement with questions related to strategy by, for,

and within the degrowth movement rst became apparent during

the Malmö Degrowth Conference. A more or less coherent

degrowth vision of social-ecological transformation had, by then,

emerged. is vision covers dierent spheres of life, exemplied by

multiple existing small-scale initiatives and ideas for institutional and

policy interventions that would help them ourish. However, the

dicult question of how to foster degrowth –i.e., the question of

strategy – was conspicuously missing from this debate. In October

, a new generation of academic activists in the degrowth

movement vocalised this gap by publishing a piece entitled “Beyond

visions and projects: the need for a debate on strategy in the

degrowth movement” (Ambach et al. ) on the blog of degrowth.

info. e authors argued that the degrowth community of academics

and activists should critically reect on degrowth researchers’ then

predominant and implicit approach to strategy, which the authors

described as strategic indeterminism. To further this discussion,

degrowth.info launched a ten-part series on degrowth and strategy

(see Chapter ). Finally, a group of young activists and academics

– today known as Degrowth Vienna –decided to organise the rst

degrowth conference that had an explicit focus on strategies for

social-ecological transformation. e objective of this conference was

two-fold: rst, to create a space that would allow for an exchange on,

analysis of, and critical discussion about the role of strategy for the

degrowth movement and research; second, to strategically advance

degrowth as a concept within Austrian media, institutions, and

organisations.

e Degrowth Vienna 2020 Conference: Strategies for Social-

Ecological Transformation took place from May to June

. It explored obstacles, pathways, and limitations of ongoing

and past transformations. e conference drew on the city of

Vienna’s intellectual history, from Red Vienna in the s and

the legacy of Karl Polanyi to the vibrant discussion of social-

ecological transformation taking place in the city today. Conference

contributions were grounded in the work of many academic

and activist groups in and around Vienna and supported by an

interdisciplinary body of knowledge. e conference opened up

a virtual space for an exchange on functioning, abandoned and

promising strategies for social-ecological transformation. ese,

the conference revealed, must include reections on the degrowth

movement’s own internal organisation and strategic orientation, as

well as alliance-building with other social-ecological movements, in

addition to the continuous work of decolonising the degrowth vision

and its praxis (Asara ).

By switching, relatively quickly, to an online format due to the

COVID- pandemic, the Degrowth Vienna organising team

widened the imagination of how the degrowth movement could

gather as a community. Moreover, despite the challenges of the

pandemic, the shift to an online conference allowed the discussion

around strategy to be more inclusive than an in-person format would

have allowed, with over , participants from both the Global

North and the Global South joining the conversation.

e editorial team of this book was initiated by some of the

organisers of the Degrowth Vienna conference and then joined

by fellow degrowth researchers interested in the issue of strategy.

Together, we concluded that the degrowth.info series and the Vienna

conference were only the rst steps for addressing strategy in relation

to degrowth and that much more discussion was still needed. We

drew on contributions to the blog series and the conference as a

point of departure for selecting key issues that we thought could

be deepened. e result was an -month process of coming to a

shared understanding of the selected issues, contacting authors,

reviewing drafts, asking for feedback, scrutinising our understanding

of strategy, revising our timeline (several times), and learning from

the diversity of perspectives and knowledge present in the degrowth

movement and the social-ecological movements that degrowth is

aligned with. In this sense, our book does not oer a comprehensive

survey of the existing literature on degrowth and strategy, but rather

puts forward our approach to selecting, framing and advancing key

debates.

Conceptualising strategy for social-ecological transformation

In order to bring about social-ecological transformation in the

face of powerful actors who employ various strategies of their own

to oppose change, we believe that an honest and critical discussion

about strategies must take place. In this section, we present the

understanding of the term “strategy” that we have developed for

and adopted throughout this book. at said, the conceptualisation

proposed here should not be misinterpreted as an attempt to close

the debate about what strategy is and what it should be about

in the context of degrowth. Quite to the contrary, we hope that

our contribution will be one helpful reference point that can

sharpen future engagement with strategy. Before we introduce our

conceptualisation, however, it is important to acknowledge that by

engaging with strategy we are dealing with a contested concept.

Dealing with a contested concept

Applying the concept of strategy to degrowth thinking and activism

is not a straightforward endeavour. In the history of Western

thought, engagement with strategy started in the modern era in

the context of eorts to apply rational methods of organisation to

warfare (Freedman ). From the s onwards, metaphors and

concepts surrounding strategy travelled from military thought to the

realms of business and management (Ibid.). Until today, strategy is

primarily associated with the military or the corporate world, and

hierarchical chains of command – contexts and characteristics that

are alien to the degrowth vision.

e source we have just cited, Sir Lawrence Freedman, is also not

your usual scholar to be quoted in a degrowth book. Freedman is

most known for his writings about and political involvement in

military matters. He has contributed to justifying powerful imperial

forces that we – as degrowth scholars and activists – condemn

and oppose. At the same time, he is the author of one of the most

comprehensive books on strategy in English, which is hard to miss

or ignore if one is trying to dig into the concept. In that book, he

also proposes the most encompassing and elaborated denition of

strategy we could nd, which we engage with later in this section.

We are aware that a progressive movement like degrowth needs

to be careful when dealing with the concept of strategy, and

referencing sources engaging with it, so as not to reproduce what we

advocate against. Examples of potential dangers of an unreective

application of strategy to degrowth thinking might include creating

a vanguard group concerned exclusively with strategising that

stands in hierarchical relation to the rest of the movement, thereby

stiing attempts to build more horizontal forms of governance

and potentially depriving the strategising process of feedback and

creativity. Talking about change in terms of strategy might also

invoke the notion that social-ecological transformation is only an

antagonistic process and downplay the importance of deliberative

practices or cultural change.

at said, within the debates on degrowth, the term strategy

already appears now and again, especially more recently given the

rising attention to the issue of strategy (e.g. Asara et al. , Koch

, Nelson ). So far, however, the term is rarely clearly

dened, is often used as a metaphor, and has not yet been subject

to conceptual and critical scrutiny (see Chapter ). Meanwhile,

attempts to engage with strategy for a bottom-up transformation

are by no means conned to the degrowth movement. Scholars

and activists in a variety of contexts have been tackling or at least

touching upon this uneasy terrain, trying to reclaim and rethink

strategy for progressive social change (e.g., Maeckelbergh ,

Maney et al. , Mueller , Parker ). e question of

strategy has also been raised in relation to various allied social

movements, ranging from agroecology, through the climate and

environmental movements, to Occupy and the Zapatista (e.g.,

Smucker , Staggenborg , Stahler-Sholk , Val et al.

).

Despite the challenging roots of the concept, strategy is thus de

facto an ongoing concern for progressive movements, including

degrowth. Grappling with the concept in a clearly dened manner,

we argue, can foster already existing discussions and organising, with

cautious engagement being better than shying away from the topic

due to its challenges. In working with strategy, we want to oer a

conceptualisation of it that avoids the problematic aspects we have

highlighted and is also in tune with degrowth while preserving the

important and at times challenging insights it brings.

Strategy – a thought construct and a exible mental map

We understand strategy as a thought construct that details how one

or several actors intend to bring about systemic change towards a

desired end state. When applied in practice, a strategy serves as

a exible mental map that links an analysis of the status quo to a

vision of a desirable end state by detailing dierent ways of achieving

(intermediate) goals on the journey towards that envisioned future

as well as certain means to potentially be employed along these ways

(Freedman ). Ways refer to dierent pathways through which

the transformation from the status quo to the desired end-state

may come about. ese pathways can be distinguished from one

another, among other things, by the relations they envision between

the strategising actor and other actors or between the actor and

the structures they intend to change. Means, in turn, are concrete

actions that actors may undertake when pursuing a strategy. Strategy

may encompass antagonistic and consensual processes, where actors

involved in strategising engage with adversaries or allies, anticipating

their actions and responding to the opportunities or obstacles these

create (Maney et al. ).

We are aware that, especially in progressive social movements

and organisations, strategies are not always explicitly discussed.

Instead, the ways and means pursued by an organisation in their

everyday activities always at least partly emerge organically out of

past experiences of their members and the narratives created by them

(de Moor and Wahlström ). Research that looks at strategies-as-

practice highlights the diverse and sometimes unconscious processes

out of which strategies emerge in real-world organisations (Golsorkhi

et al. ). For example, peasant-to-peasant processes can be seen as

key to La Via Campesina’s strategy for spreading peasant agroecology

(Val et al. ). Furthermore, the very participation in building

alternatives has a strategic element as “the creation of new political

structures [i]s intended to replace existing political structures”

(Maeckelbergh , ).

While we acknowledge such an understanding of strategies,

in this book we argue for thinking about strategies analytically

as well as deliberately and then applying this thinking in practice.

Conceptualising strategies as thought constructs allows us to engage in

analytical discussions about opportunities and challenges presented

by a given context, to organise ourselves internally and with potential

allies, and to evaluate dierent strategies for their ex-ante desirability

and their ex-post ecacy.

By understanding strategy as a exible mental map, in turn, we

highlight that a strategy in practice is necessarily context-specic and

dynamic. A strategy in practice, while still being a thought construct,

is always dened in relation to the circumstances of the strategising

actor. is includes their goals, their (limited) resources, how they

are situated within broader social structures and processes, as well

as what they anticipate other actors (allies and opponents) will do.

Crucially, a strategy is thereby more than a mere plan. While a plan

outlines a concrete list of steps an actor intends to take to reach a

goal, a strategy comprises a set of considerations for how one might

bring about change more generally, the details of which may later

change. Indeed, the ways, the means and even intermediate goals

foreseen in a strategy may need to be adapted as a strategy plays out

and one must react to the actions of allies and opponents and to

changing circumstances more broadly.

To add yet another layer of complexity to the discussion of strategy

as a exible mental map, strategies over time must also be able to

reect changes in the strategising actor’s understanding of their

surroundings. Indeed, how an actor analyses the status quo and the

levers and mechanisms available to enact change is never complete

and must thus be updated over time (Wright ). Strategies for

degrowth at any one point in time can only ever reect an informed

guess about how transformation may come about. Working towards

social-ecological transformation thus requires us to acknowledge

uncertainty, complexity, and possible unintended consequences

when strategising, and to create institutions for reecting on and

responding to these issues (Barca et al. ).

inking analytically and deliberately about strategy

inking analytically and deliberately about strategy, we argue,

can enhance organising and action towards social-ecological

transformation. To foster such thinking, it is necessary to

dierentiate distinct ways from means and means from ends.

Separating dierent ways from the means employed along those

ways allows dierent strategies to be sorted and grouped, and their

distinctions to be discussed analytically. e vocabulary of Erik

Olin Wright is particularly helpful for thinking of dierent waysin

which an actor may choose to work toward transformation. Wright

(, ) discerns three “modes of transformation” within anti-

capitalist movements – interstitial, ruptural and symbiotic. ese

are each accompanied by respective “strategic logics” (Wright ).

e popularity that Wright’s framework enjoys within and beyond

degrowth for thinking about dierent ways of bringing about

progressive change is one reason why we – at times also critically –

engage with it in our book, hoping to create continuity with broader

debates. Another reason for building on Wright’s framework is that

it highlights synergies between distinct modes of transformation and

thus potentially facilitates collaboration between distinct political

factions within degrowth and allied movements. We engage with

Wright’s work at greater length later in the book, by setting out a

strategic canvas that degrowthers and allies can engage with to

identify and coordinate strategic priorities and tensions between

dierent groups, and to think about how to avoid co-optation

(see Chapter ). We have also asked authors, especially in chapters

dealing with strategies in practice (Chapters to ), to deliberately

reect on strategies employed in their elds and organisations by

drawing on the analytical vocabulary of Wright or the way we have

furthered (and diverged from) it in this book.

Separating means from ends in our denition of strategy creates

space for debating about which means (and intermediate ends)

should be considered conducive to social-ecological transformation,

and which should not. is analytical process of separating means

from ends is not a common approach within degrowth, but one

which we think would be benecial. Crucially, we do not wish

to imply that the desirable end of reaching a socially just and

ecologically sustainable society justies using all possible means

available to degrowth actors. As mentioned in the previous section,

given the complexity of social change, it is impossible to foresee with

certainty which means would lead to what ends. Calling for brutal

means to achieve a peaceful end, for example, would ignore the great

uncertainty attached to whether that end will come about because

of these means. Instead, undesirable means may become ends in

themselves (Parker ). erefore, we maintain that it is vital that

the strategising process itself as well as the ways and means discussed

in degrowth strategies are guided by degrowth values like autonomy,

care, conviviality, democracy, and equity even as their applicability in

a specic context might be challenged.

Simply conating means and ends when discussing and evaluating

strategies is also problematic. Even for practices where means and

ends seem to be in concert – sometimes referred to as pregurative

strategies – this is never completely the case. For example, a local

bicycle repair cooperative engaged in pregurative organising might

still be using bicycle parts from factories that suppress organised

labour or that use metals gained in exploitative extraction processes

(see also Parker ). An open discussion about means and ends is

thus needed to argue why a particular practice might nevertheless be

considered part of a degrowth strategy.

Another reason for making a conceptual distinction between

means and ends is that conating them limits our thinking about

how social-ecological transformation can be achieved. To drive

the kind of change pregured by running a bicycle repair coop at

a systemic level, a broader set of strategic actions would be needed

–such as cooperation with other initiatives for alternative transport,

pushing for favourable regulation and redistribution, blocking

unsustainable forms of transport, and supporting international

workers’ movements (Maney et al. , Parker , drawing on

Boggs ). Analytically separating means and ends may also

help in thinking about framing and communication, which are

important elements of strategy in social movements (Smucker

, Staggenborg ). As Smucker (, –) points out,

when framed only in moral terms that reect the ends, rather

than, for example, showing how a particular action has a believable

chance of making a dierence, communication may fail to mobilise

those sympathetic to the cause but struggling to see how it can be

achieved. In other words, many strategic actions are primarily means

to a greater end and may not always already embody the structures

and processes characterising the end. ey may nevertheless be

important for driving social-ecological transformation and are thus

not to be omitted from our thinking about strategies.

Strategy through organisation

Social-ecological transformation must be informed by a multiplicity

of dierent knowledges and practices and involve many people

– most of them not self-proclaimed proponents of degrowth and

potentially not even self-proclaimed progressives (see Chapter ).

Strategies for social-ecological transformation are bottom-up and

focused on building counter-power to dominant actors who focus

on reproducing business as usual (see also Mueller ). Rather

than trying to wield power for a single vision of a coordinated

transformation, they primarily deal with dismantling existing power

relations and organising alternatives.

By including multiple actorsin the denition of strategy adopted

in this book, we foreground the organisational capacities required

for the strategising process (Staggenborg ). In other words,

the creation and execution of strategies depend on the existence of

collective actors (e.g. activist groups, social movements, economic

organisations) that engage in organising. us, a key element of

strategy is “building organisation in order to achieve major structural

changes in the political, economic and social orders” (Breines ,

). In tune with degrowth principles, organisation “needs to be able

to take forms other than hierarchical and xed” (Maeckelbergh ,

), whilst acknowledging the necessity of action on a global scale

(Parker ). is involves both “developing new social practices

and autonomous structures of authority”, like the Zapatista (Stahler-

Sholk , ), and applying movement pressure to reshape the

existing institutions that constrain the spectrum of what is possible,

whether international organisations or the state (see Chapter ). e

question of how to organise can thus be seen as both the foundation

for and a deliberate part of a successful strategy (Maney et al. ,

Parker ).

We admit that there is a risk of creating hierarchies and closures

when strategising, slipping into the problematic aspects of strategy

that we started this section with. For example, this can happen

through the emergence of “elite” groups or individual actors within

a movement, specialised in strategising, and their separation from

the rest of the movement. Such alienation could be mitigated by

continued attention being paid to degrowth values like autonomy,

care, conviviality and direct democracy in the strategising process,

reecting and acting upon any closures as they arise (Barca et al.

). Moreover, the necessity of embedding the strategising process

in specic contexts and practices involves drawing on the experiences

of members and allies already engaged in various elds of practice

(Smith et al. ). An open and analytical exchange about strategies

can thereby potentially help build coherence within dierent strands

of the movement and beyond by forming narratives and enabling

storytelling (de Moor and Wahlström ). However, the usefulness

of clearly dening and discussing strategies in fostering movement

participation and coordination rather than leading to alienation

always hinges on how these dialogues are conducted. For degrowth,

with strategic action becoming more important, good organisation

and coordination are thus key to mitigating risks of developing

distant leadership and misguided solutions.

Beyond its focus on bringing about “external transformation”, a

signicant part of the book focuses on “internal movement building”

(Maney et al. ) – in other words, the strategic coordination

among degrowth actors, and with allied movements. e term

“strategic assemblage” (see Chapter ) points to three areas for

deliberate coordination in relation to degrowth and strategy that

are discussed in this book. First, while strategic plurality is essential

for degrowth, plurality is not strategic in itself, but can become

strategic through coordinated eorts of multiple actors involved in

the degrowth movement and beyond. Explicitly denoting dierent

strategic considerations will render the plurality of approaches that

necessarily make up struggles for social-ecological transformation

more eective, by highlighting synergies and acknowledging

incompatibilities. Second, internal coordination within the

degrowth movement, and an open discussion about it, may

facilitate participation of more people in the movement, help build

relations and create shared denitions, and avoid the reproduction

of hierarchies(see Chapter ). Finally, and crucially, actors who self-

identify with degrowth only play a humble role in fostering social-

ecological transformation and are meaningful only as part of larger

joint eorts with allied movements. us, coordination of degrowth

actors with a mosaic of connected movements is needed (see Chapter

).

To sum up, thinking about strategy analytically and deliberately,

we argue, can enhance bottom-up organising and action towards

social-ecological transformation. Explicitly discussing and

categorising strategies allows us to deliberate about their desirability,

mutual compatibility, or incompatibility. Further, it enables us to

analyse their ecacy and to coordinate and communicate our vision

for how to achieve transformation with others – inside and outside

of degrowth. To be aligned with the multiplicity of degrowth,

strategies need to be dynamic and plural, based on degrowth values

and sensitive to power relations. Strategies are to be fostered through

organising and coordination, within the degrowth movement itself

and as part of larger eorts of allied groups and social movements.

e book can be seen as a collective quest for building strategies that

are in tune with the multiplicity of degrowth, and it is now time to

introduce its content.

Summary of the book

is book presents the rst comprehensive attempt at grappling

with the intersection of degrowth and strategy while confronting

the underlying challenges of such an endeavour. It scrutinises

strategy theoretically, identies key strategic directions for degrowth,

and explores strategies that are already being practised to realise a

degrowth society. Its main argument is that to bring about social-

ecological transformation, an intentional mix of strategies needs to

be collectively deliberated and critically reected on, making sure

that it is (re-)aligned with degrowth values and contributes to the

ensemble of broader eorts for social-ecological transformation.

In line with this argument, it was crucial to us that the making

of the book itself was a collective process, assembling many voices.

At the same time, we wanted the book to be carefully crafted to not

be just an edited volume on the topic of strategy, but a coherent

whole, where each contribution has its specic role and space. us,

when contacting authors for writing dierent chapters, we asked

them to address a specic sub-topic that we as the editorial team

had identied as important to cover and that we thought they could

contribute to. e dierent chapters of the book were written by

academics, activists, and practitioners from the degrowth movement

as well as allied groups and disciplines.

Part I of this volume explores the meaning of strategy for

degrowth as both a research area and an emerging international

social movement with its own agency. It presents the rst collective

eort of degrowth scholars to engage with the questions of strategy

explicitly and in-depth. e chapters within this part of the book

are in productive dialogue with each other, not shying away from

disagreement while building upon a common foundation and

charting various paths forward.

Part II provides an analysis of strategies in practice and oers

insights from various actors involved in strategies for social-

ecological transformation. First, it covers degrowth strategies

in relation to provisioning systems, focusing on food, housing,

technology, energy and mobility. Second, it addresses strategies for

re-organising economic and political systems, covering care, work

and labour, money and nance, and trade and decolonisation.

is selection is not exhaustive but rather illustrative, illuminating

strategies within concrete areas of practice.

To ensure coherence across the book, we followed three key steps.

First, we shared the terminology on strategy used within the book,

the key elements of which have been elaborated on earlier in this

chapter. Second, we dedicated one chapter of the book (Chapter )

to mapping out an analytical framework for engaging with strategy,

which builds on the helpful vocabulary of Erik Olin Wright, but

also diverges from it, in line with degrowth thinking. We then asked

the authors of Part II to engage with the framework developed in

the book, or the original terminology of Wright, in their chapters.

ird, in asking the authors to engage with the book’s vocabulary

and framework, we strived for consistency across the book whilst

allowing room for interpretation and exibility by the authors. We

hope that these steps have made it possible for multiple voices to

come together into a polyphony, making the book a coherent whole.

Part I: Strategy in degrowth research and activism

Part I consists of three sections, each dealing with a specic aspect

of degrowth and strategy. e rst section highlights the importance

of strategy for thinking about social-ecological transformation.

Chapter positions degrowth within the broader discourse on

social-ecological transformation and argues why it is important

for degrowth to discuss the issue of strategy. Chapter outlines a

framework for thinking about strategy in degrowth and other social

movements through a critical dialogue with Erik Olin Wright.

It is this framework, or the ideas of Wright directly, that we asked

authors in Part II to engage with. Chapter summarises how strategy

has been discussed in the degrowth movement and suggests a new

term to advance the discussion of strategy in degrowth – a strategic

assemblage for degrowth.

e second section focuses on degrowth as a movement. Chapter

discusses the challenges of devising a common strategy within

degrowth given its plurality, drawing on social movement studies.

Chapter provides an overview of the degrowth movement, its

history, loose organisational structure and processes, reecting on

its agency and possible strategic ways forward. Chapter situates

degrowth vis a vis other social-ecological movements; it both explores

how degrowth actors could position themselves and highlights what

the degrowth movement can learn from other movements.

e nal section in Part I highlights the diversity of how strategy

is thought about in a degrowth context. Chapter makes the case

that, to overcome current asymmetric power relations underpinning

capitalist growth, social equity needs to be a core element of

strategising for social-ecological transformation. Chapter suggests

emancipatory potential as a useful guiding criterion for degrowth

strategies. Chapter sheds light on how the state can be understood

and engaged with from a degrowth perspective and uses such a

conceptualisation to rethink how state-society relations could be

transformed. Chapter concludes the section by reconciling, on

the one hand, the insights on the diversity in degrowth, and, on the

other, the voices arguing for strategic action within the degrowth

movement.

Part II: Strategies in practice

Part II consists of two sections, where the rst section focuses on

strategies for transforming provisioning sectors and the second

focuses on strategies for economic and political reorganisation.

Each chapter in Part II is divided into two sub-chapters, starting

with an overview of degrowth strategies in an area of practice and

followed by a concrete case in that eld. e overview provides

background information on the interdependencies of degrowth and

the eld studied as well as insights on strategies that have already

been practised, discussed in the literature, or could be promising.

Following the overview, each case delves into concrete examples and

discusses their strategic challenges and potential in detail.

e two sub-chapters for each eld have dierent authors:

for most chapters, the overview is written by an author with an

academic background, while the case sub-chapter is written by an

activist or practitioner who constructively reects on a degrowth

strategy in their eld – a campaign, an action, a project and so

on – of which they have rst-hand experience. In some chapters,

academics and activists have collaborated, resulting in a single,

integrated chapter that fulls both purposes.

In Section I of Part II, Chapter reviews literature on food and

degrowth and argues that apart from building local food alternatives,

the inclusion of other strategies and learning from, for example,

the food sovereignty movement are necessary for social-ecological

transformation. e case explores the strategies implemented by

the Nyéléni food sovereignty movement at dierent administrative

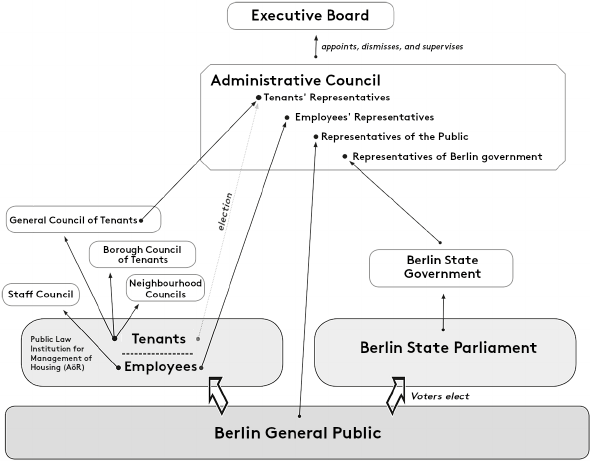

scales. Chapter focuses on housing and zooms into a series of

strategies at the national and regional levels. e Berlin-based

campaign against private speculation in the housing market,

Deutsche Wohnen & CO Enteignen, is the case in focus. Chapter

challenges the role of digital technologies in our lives and questions

our social imaginary toward technology. Highlighting potential

strategies to challenge this relationship, it proposes low-tech digital

tools and platforms like Decidim as a promising pathway for action.

Chapter on energy portrays various strategies that have been used

to oppose big fossil fuel and renewable energy schemes, including

the divestment movement and the use of legal instruments. e

case looks into strategic alliances in resistance to mega-energy

projects in Chile. Finally, Chapter tackles questions of degrowth

strategy in relation to mobility. It investigates dierent approaches to

transforming the mobility sector, from technology-based scenarios

to others that question mobility itself. A Paris-based case is analysed

to assess the extent to which car-sharing may represent a satisfactory

degrowth strategy.

Moving on to Section II, Chapter introduces care as an essential

underpinning for all social relations and provisioning, presenting

strategies to strengthen care and avoid exploitative structures. e

Integral Health Centre Cecosesola in Venezuela is an example of

how care work can be organised dierently based on rethinking

its meaning and value in society. In Chapter , strategies for the

reorganisation of paid work are discussed. e chapter delves

specically into the transformation of work in the aviation sector

and explores the potential of alliances between unions and activists

as well as local institutions for bringing about transformative

change. Chapter reviews various strategies for transforming the

monetary and nancial system. e example of the Cooperative for

the Common Good in Austria points to the struggle of transforming

the nancial system from below. e section closes with Chapter

on trade and decolonisation, which illustrates that strategies in the

Global North can only be considered against the background of

colonial structures. e case presents the use of litigation to ght

fossil corporate power in Nigeria.

Conclusion

Despite the urgent need for systemic change and the many strong

voices that call for it, we see very little consequential action, while

many demands are simply being watered down by governments and

corporate actors. Even as their discussion is often rather sophisticated

– with talks about climate emergency, circular economy, and

various governance frameworks to address the multifaceted crisis –

we cannot expect change at the scale required to come from those

in power. Instead, the degrowth movement and allied groups need

to think about how to organise strategically within and across their

movements to shape the bottom-up social-ecological transformation

that would bring an equitable, ecologically sustainable and thriving

world for all.

e interrelations between theory and practice are at the core

of the book, as no theory prepares us suciently for the creativity

needed for building strategy, and strategy without theoretically

informed considerations risks being reduced to short-term objectives

without a vision. While Part I oers a nuanced and cogent view for

building transformative strategies, Part II shows how strategies are

embodied in ongoing practices that are already enacted by multiple

actors striving for social-ecological transformation.

is book oers a solid ground for thinking about strategy in

degrowth and related social movements and will inform action and

research for social-ecological transformation. We expect that this

volume – the outcome of a truly collective eort – will be of interest

to academics, activists, practitioners and anyone else striving for an

equitable and ecologically sustainable world, where everyone lives

well, not at anyone else’s expense and within planetary boundaries

(Brand et al. ). is volume addresses strategy in a way that

lives up to the multiplicity of degrowth on the one hand, and the

need for well-coordinated and ambitious action for social-ecological

transformation on the other. It points to many open questions

in relation to strategy and challenges to address by the degrowth

movement and its allies. We hope that this book will only be the

beginning of a wider debate about how to collectively build strategies

for systemic change. May many ideas and eorts that illuminate and

strengthen the how of social-ecological transformation ourish!

References

Akbulut,Bengi,FedericoDemaria,Julien-FrançoisGerber, andJoanMartínez Alier.

. “Who Promotes Sustainability? Five eses on the Relationships between

the Degrowth and the Environmental Justice Movements.” Ecological Econom-

ics (November),.

Ambach, Christoph, Nathan Barlow, Pietro Cigna, Joe Herbert, and Iris Frey. .

“Beyond Visions and Projects: e Need for a Debate on Strategy in the De-

growth Movement.” Degrowth.info (blog), October , . https://degrowth.

info/blog/beyond-visions-and-projects-the-need-for-a-debate-on-strategy-in-the-

degrowth-movement.

Andreucci, Diego, and Salvatore Engel-Di Mauro. .“Capitalism, Socialism and

the Challenge of Degrowth: Introduction to the Symposium.” Capitalism Nature

Socialism , no. :–.

Asara, Viviana, Emanuele Profumi, and Giorgos Kallis. . “Degrowth, Democra-

cy and Autonomy.” Environmental Values , no. : –.

Asara, Viviana, Iago Otero, Federico Demaria, and Esteve Corbera. . “Socially

Sustainable Degrowth as a Social-Ecological Transformation: Repoliticizing Sus-

tainability.” Sustainability Science , no. : –.

Asara, Viviana. . “Degrowth Vienna : Reections upon the Conference

and How to Move Forward – Part II.” Degrowth.info (blog), https://degrowth.

info/en/blog/degrowth-vienna--reections-upon-the-conference-and-how-

to-move-forward-part-ii.

Barca, Stefania, Ekaterina Chertkovskaya, and Alexander Paulsson. . “e End

of Growth as We Know It: From Growth Realism to Nomadic Utopianism.” In

Towards a Political Economy of Degrowth, edited by Ekaterina Chertkovskaya, Al-

exander Paulsson and Stefania Barca, –. London: Rowman & Littleeld.

Brand, Ulrich, Barbara Muraca, Éric Pineault, Marlyne Sahakian, Anke Schaartz-

ik, Andreas Novy, Christoph Streissler, Helmut Haberl, Viviana Asara, Kristina

Dietz, Miriam Lang, Ashish Kothari, Tone Smith, Clive Spash, Alina Brad, Mel-

anie Pichler, Christina Plank, Giorgos Velegrakis, omas Jahn, Angela Carter,

Qingzhi Huan, Giorgos Kallis, Joan Martínez Alier, Gabriel Riva, Vishwas Satgar,

Emiliano Teran Mantovani, Michelle Williams, Markus Wissen and Christoph

Görg..“From Planetary to Societal Boundaries: An Argument for Collec-

tively Dened Self-Limitation.”Sustainability: Science, Practice and Policy,, no.

:–.

Boggs, Carl. . “Marxism, Pregurative Communism, and the Problem of Work-

ers’ Control.” Radical America , no. : –. https://libcom.org/library/mar-

xism-pregurative-communism-problem-workers-control-carl-boggs.

Breines, Wini . Community and Organisation in the New Left 1962–1968: e

Great Refusal. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Burkhart, Corinna, Matthias Schmelzer, and Nina Treu. .

Degrowth in Movement(s): Exploring Pathways for Transformation. Winchester:

Zero Books.

De Moor, Joost, and Mattias Wahlström. . “Narrating Political Opportunities:

Explaining Strategic Adaptation in the Climate Movement.” eory and Soci-

ety48, no. : –.

Demaria, Federico, François Schneider, Filka Sekulova, and Joan Martinez–Alier.

. “What Is Degrowth? From an Activist Slogan to a Social Movement.” Envi-

ronmental Values , no. : –.

Dengler, Corinna and Lisa M. Seebacher. . “What about the Global South?

Towards a Feminist Decolonial Degrowth Approach.” Ecological Economics :

–.

Freedman, Lawrence. .Strategy: A History. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Gregoratti, Catia and Riya Raphael. . “e Historical Roots of a Feminist ‘De-

growth’: Maria Mies’s and Marylin Waring’s Critiques of Growth.” In Towards

a Political Economy of Degrowth, edited by Ekaterina Chertkovskaya, Alexander

Paulsson, and Stefania Barca. London: Rowman & Littleeld, –.

Golsorkhi, Damon, Linda Rouleau, David Seidl, and Eero Vaara. . “What is

Strategy-as-Practice?” InCambridge Handbook of Strategy as Practice, edited by

Damon Golsorkhi, Linda Rouleau, David Seidl, and Eero Vaara, –. Cam-

bridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kallis, Giorgos, Federico Demaria, and Giacomo D’Alisa. . “Introduction: De-

growth.” In Degrowth: A Vocabulary for a New Era, edited by Giacomo D’Alisa,

Federico Demaria, and Giorgos Kallis. London: Routledge, –.

Kallis, Giorgos, Vasilis Kostakis, Steen Lange, Barbara Muraca, Susan Paulson, and

Matthias Schmelzer. . “Research on Degrowth.” Annual Review of Environ-

ment and Resources : –.

Koch, Max. . “State-Civil Society Relations in Gramsci, Poulantzas and Bour-

dieu: Strategic Implications for the Degrowth Movement.” Ecological Economics