Digital

technologies

for a new future

ECLAC

Publications

Thank you for your interest in

this ECLAC publication

Please register if you would like to receive information on our editorial

products and activities. When you register, you may specify your particular

areas of interest and you will gain access to our products in other formats.

www.cepal.org/en/publications

Publicaciones

www.cepal.org/apps

Register

facebook.com/publicacionesdelacepal

Digital technologies

for a new future

Digital Agenda for Latin America and the Caribbean

Work on this document was coordinated by Sebastián Rovira, Economic Affairs Officer of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC),

in collaboration with Wilson Peres and Nunzia Saporito. The drafting committee also comprised Valeria Jordán, Georgina Núñez, Alejandro Patiño, Laura Poveda,

Fernando Rojas and Joaquín Vargas, of the Division of Production, Productivity and Management, and Rodrigo Martínez, Amalia Palma and Daniela Trucco, of the

Social Development Division. The chapters were prepared with input from the consultants Sebastián Cabello and Nicolás Grossman.

The document also included valuable contributions deriving from the seventh Ministerial Conference on the Information Society in Latin America and the Caribbean,

and from the comments and contributions of the official delegations that participated in the meeting.

The boundaries and names shown on the maps included in this publication do not imply official endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

United Nations publication

LC/TS.2021/43

Distribution: L

Copyright © United Nations, 2021

All rights reserved

Printed at United Nations, Santiago

S.20-00960

This publication should be cited as: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Digital technologies for a new future (LC/TS.2021/43), Santiago, 2021.

Applications for authorization to reproduce this work in whole or in part should be sent to the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), Documents

and Publications Division, [email protected]. Member States and their governmental institutions may reproduce this work without prior authorization, but are

requested to mention the source and to inform ECLAC of such reproduction.

3

Foreword 5

I. Towards a sustainable digital society 9

A. The systemic impact of digital disruption 11

B. The difficult balance between digitalization and sustainability 13

C. The roll-out of 5G networks: essential to the new models of industrial production and organization 16

D. The mass take-up of new technologies requires more infrastructure investment 18

1. Telecommunications are moving to the cloud: the transformation of the sector 18

2. The digital transformation driven by 5G networks will have a significant

economic impact but require large investments 20

Bibliography 24

II. Digitalization for social welfare and inclusion 25

A. Divides in broadband access 27

B. The use and take-up of digital technologies 32

1. Distance learning: essential but inaccessible for many 32

2. Digital health care in the pandemic emergency 34

3. Digitalization, the labour market and employment 36

4. Financial inclusion: the advance of financial technology (fintech) 38

5. Smart cities: a hub of inclusive and sustainable development 41

C. Universalizing access 43

Bibliography 45

III. Digitalization for productive development 47

A. Digitalization and productivity 49

1. Productivity dynamics in Latin America and the Caribbean 49

2. Digital technologies and productivity 51

B. The digitalization of production chains 54

1. The potential of disruptive technologies to dynamize theregion’s sectors 54

2. Agro-industry 56

3. Manufacturing 58

4. Retail 60

C. The digital ecosystem and the main barriers todigitalization of production 61

1. The digitalization of production processes in the region 61

2. Factors that enable and constrain the digitalization ofproduction 64

D. Digital policies for recovery and the transformation ofproduction methods 66

Bibliography 69

IV. Digital governance, institutions and agendas 71

A. Digital agendas: empowerment and cross-sectoral policies 73

B. Competition, privacy and data security at the heart ofdigital agendas 79

C. Fifteen years on from the first regional digital agenda: strengthening competition 82

D. The regional digital market at the heart of subregional integration mechanisms 84

Bibliography 86

Annex IV.A1 87

Contents

Índice

Prólogo

Tecnologías digitales para un nuevo futuro

5

Foreword

7

In the two years since the sixth Ministerial Conference on the Information Society in Latin America and

theCaribbean, held in Cartagena de Indias (Colombia) in April 2018, issues in the digital sphere that were

then considered to be emerging or incipient have come to occupy centre stage. Meanwhile, the coronavirus

(COVID-19) pandemic has had an unprecedented economic and social impact on Latin America and the

Caribbean. It is estimated that the region’s GDP has contracted by about 7.7%, that the value of exports has

fallen by 13% and that reduced demand and the slowdown of supply have led to the closure of over 2.7 million

businesses, resulting in more than 18 million unemployed. All these dynamics will have major effects on the

level of inequality and poverty in the region, and it is estimated that the number of people living in poverty

will increase by more than 45 million.

In respect of digitalization, 15 years on from the approval of the first Digital Agenda for Latin America and

the Caribbean, the region is facing a new world and a challenging context. Some of the expectations of that

time have been fulfilled, but others have not.

Digital technologies have grown exponentially, and their use has globalized. Ubiquitous and continuous

connectivity has reached much of humanity thanks to the mass take-up of smartphones and the consequent

access to information, social networks and audiovisual entertainment. The acceleration of technical progress in

the digital realm has made the use of devices and applications employing cloud computing, big data analysis,

blockchains or artificial intelligence routine. The technological revolution has combined with a change in the

strategies of the companies at the forefront of digital technology use to greatly increase the role of global

platforms, the result being that excessive economic and political power is wielded by no more than twenty or

so corporations based in two or three world powers, an all too small group of firms with market capitalizations

of close to or more than a trillion dollars.

Technological progress has gone along with socially negative outcomes, such as the exclusion of a large

proportion of the world’s people from the benefits of digitalization, essentially because their incomes are

too low for them to have meaningful connectivity (i.e., high-quality access), access to devices, fixed home

connections and the ability to use these day to day. A large demand gap has thus opened up, as coverage

is adequate but is not reflected in connections and usage. Other problems have also worsened, such as the

proliferation of fake news and cyber attacks, the growing risk to privacy and personal data security, and the

large-scale production of electronic waste.

The global backdrop to the unresolved balance between the benefits and costs of digitalization is more

adverse than was anticipated 15 years ago. Geopolitical struggles, often centred on digital patents, standards

and production, have markedly weakened multilateral decision-making and action. The environmental crisis has

escalated into an environmental emergency or, according to some analysts, an environmental catastrophe.

The increase in inequality in many countries and the exclusion of vulnerable population groups is making it

even more difficult to build social and political systems capable of adequately steering digital development.

The COVID-19 pandemic has accentuated all these problems and driven the world into the worst economic

crisis since the Second World War, with all the attendant negative effects on jobs, wages and the struggle

against poverty and inequality. Digital technologies have played a key role in addressing the effects of the

pandemic. However, the benefits from their use are limited by structural factors, such as limits on connectivity

(access, use and speed), social inequalities, productive heterogeneity and low competitiveness, and restricted

access to data and information management, among other factors.

Thus, new opportunities and new challenges are opening up for the countries of Latin America and the

Caribbean. The region will be the hardest hit by the crisis and will have to confront long-standing problems

from a position of greater structural weakness. In particular, it will have to surmount the slow economic growth

of the last seven years, with falling investment and stagnant productivity, while at the same time vigorously

recommitting itself to the struggle against poverty and inequality. To overcome these problems, it will have to

embark on a big push for economic, social and environmental sustainability leading to progressive structural

change based on the vigorous creation and incorporation of technology to diversify the production system.

Foreword

Eco

nomic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

8

Against this background, the present document seeks to contribute to the debate and to the deployment

and use of digital technologies at national and regional level in support of development. Its contents have

been organized into four sections. The first section discusses the need to move towards a sustainable digital

society within the framework of the systemic impact of digital disruption. The second analyses the effects of

digitalization on social welfare and equality, posits the need to universalize access to these technologies and

assesses the cost of doing so. The third examines the relationship between digitalization and productivity

and the impact on agricultural, manufacturing and services production chains, and looks at some policies for

post-pandemic recovery involving economic transformation. Lastly, the fourth section analyses the state of

digital agendas in the region, in particular with regard to data management, and presents recommendations to

strengthen regional cooperation and the move towards a regional digital market. It also summarizes the main

conclusions of the working meetings and panels of the seventh Ministerial Conference on the Information

Society in Latin America and the Caribbean, which was held virtually in November 2020 and chaired by Ecuador.

The proposals put forward in the document, once discussed and further developed at the Conference, will

open the way for more inclusive and sustainable digitalization, i.e., digitalization that creates the conditions

not only for faster recovery from the current crisis but for a more productive and efficient use of these digital

technologies and for greater productivity, better jobs and higher wages, helping to reduce the high levels of

inequality in Latin America and the Caribbean. In short, the digitalization that is needed for a new future and

for progress towards a digital welfare State.

Alicia Bárcena

E

xecutive Secretary

Economic Commission for

Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

9

Towards a sustainable

digital society

A. The systemic impact of digital disruption

B. The difficult balance between digitalization and sustainability

C. The roll-out of 5G networks: essential to the new models

of industrial production and organization

D. The mass take-up of new technologies requires

more infrastructure investment

Bibliography

CHAPTER

I

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

11

A. The systemic impact of digital disruption

Since the late 1980s, the digital revolution has transformed the economy and society. First came the

development of a connected economy, characterized by mass take-up of the Internet and the roll-out of

broadband networks. This was followed by the development of a digital economy via the increasing use of

digital platforms as business models for the supply of goods and services. Now the movement is towards

a digitalized economy whose production and consumption models are based on the incorporation of digital

technologies in all economic, social and environmental dimensions.

The adoption and integration of advanced digital technologies (fifth-generation (5G) mobile networks,

the Internet of things (IoT), cloud computing, artificial intelligence, big data analysis, robotics, etc.) means

that we are moving from a hyperconnected world to one of digitalized economies and societies. It is a world

in which the traditional economy, with its organizational, productive and governance systems, overlaps or

merges with the digital economy, with its innovative features in terms of business models, production,

business organization and governance. This results in a new, digitally interwoven system in which models from

both spheres interact, giving rise to more complex ecosystems that are currently undergoing organizational,

institutional and regulatory transformation (ECLAC, 2018).

These dimensions of digital development are constantly evolving, in a synergistic process that affects

activities at the level of society, the production apparatus and the State (see diagram I.1). This makes the

digital transformation process highly dynamic and complex, and thus challenging for public policies insofar

as it requires constant adaptation and a systemic approach to national development. Within this framework,

5Gnetworks will make the convergence of telecommunications and information technologies viable, changing

the structure and dynamics of the sector, while the adoption of digital technologies and artificial intelligence

(as general purpose technologies) marks a new stage, that of the digitalized economy.

At the societal level, digital disruption leads to changes in communication, interaction and consumption

models that are reflected in greater demand for devices, software with more functionalities, cloud computing

and data traffic services and the basic digital skills needed to use the associated technologies. In turn, the digital

economy represents an opportunity for consumers to access information and knowledge of all kinds in various

formats, goods and services, and more streamlined forms of remote consumption. The move towards the

digital economy should mean that consumers’ needs can be met with smart products, often associated with

advanced services that are highly customized. All this means an increase in consumer welfare, accompanied

by a reconfiguration of the digital skills needed for more advanced digital consumption and for the new labour

requirements resulting from the new production models. At the same time, the new forms of consumption

are associated with potential benefits from reduced material use and more sustainable environmental choices,

insofar as these are based on more and better information (about the environmental footprint of a product,

for example) or reward more environmentally friendly practices.

1

The development of the digital economy has radically changed the value proposition of goods and services

via the reduction of transaction and intermediation costs and the exploitation of information from data generated

and shared on digital platforms. These digitally enabled models facilitate the generation and capture of data which,

when processed and analysed with smart tools, can be used to improve decision-making and optimize supply.

This results in more streamlined operating processes, in market segmentation and in product customization

and transformation. Data and digitalized knowledge become a strategic production factor (ECLAC,2016). All

this entails a need for regulatory changes in a variety of areas ranging from telecommunications to trade,

taking in competition and data protection and cybersecurity policies on the way.

1

For example, the fintech company Ant Group, an affiliate of Alibaba, implemented an application on its payment platform that has engaged over 500 million Chinese

citizens in carbon-saving consumption activities, thus bringing about a change in citizen behaviour. When its users perform some activity that has a positive impact

in the form of reduced carbon emissions, such as paying bills online or walking to work, they receive “green energy” points. Once users accumulate enough points

virtually, a real tree is planted. Since its launch in August 2016, Ant Forest and its NGO partners have planted around 122 million trees in some of China’s driest

areas (UNEP, 2019).

Chapter I

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

12

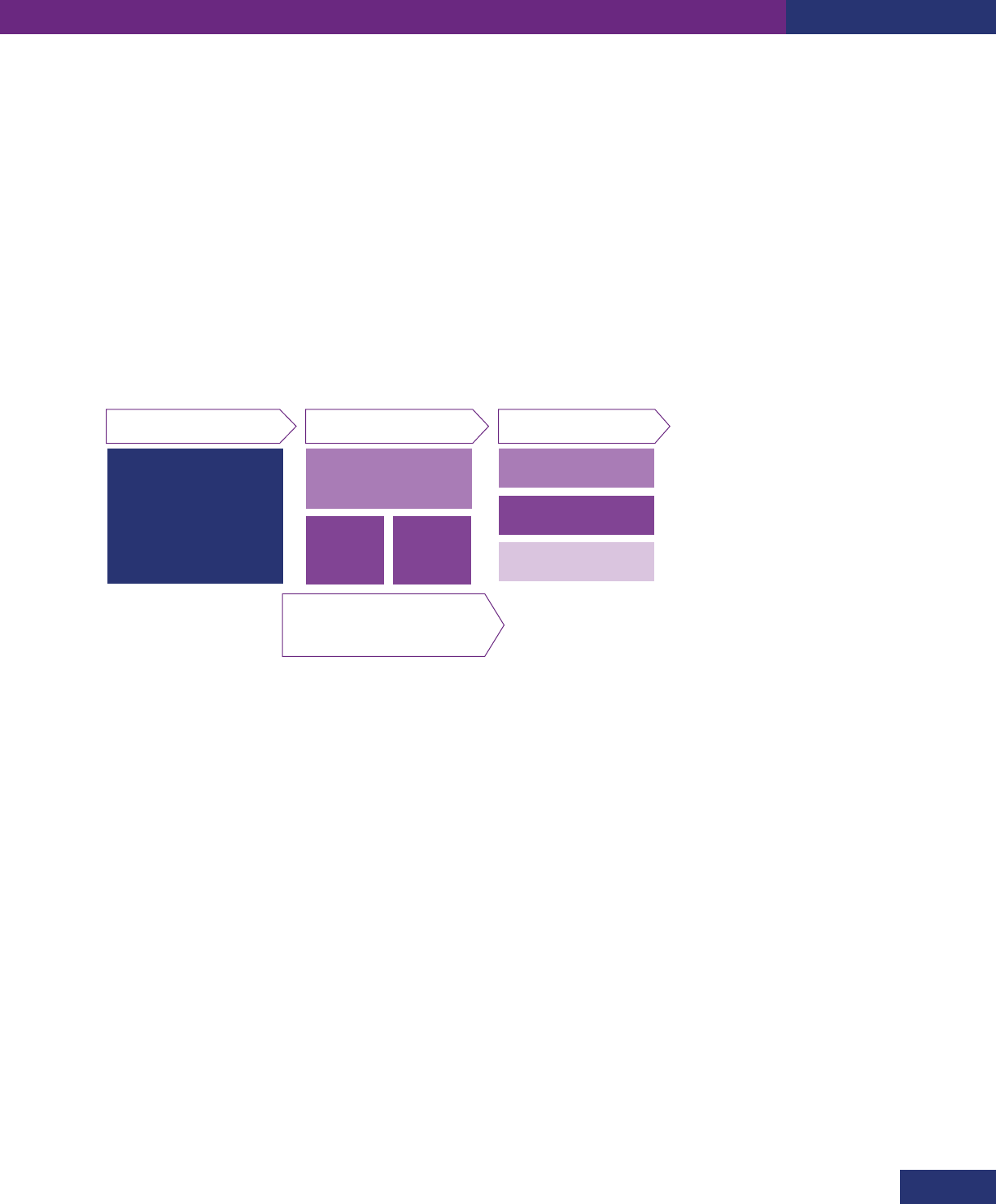

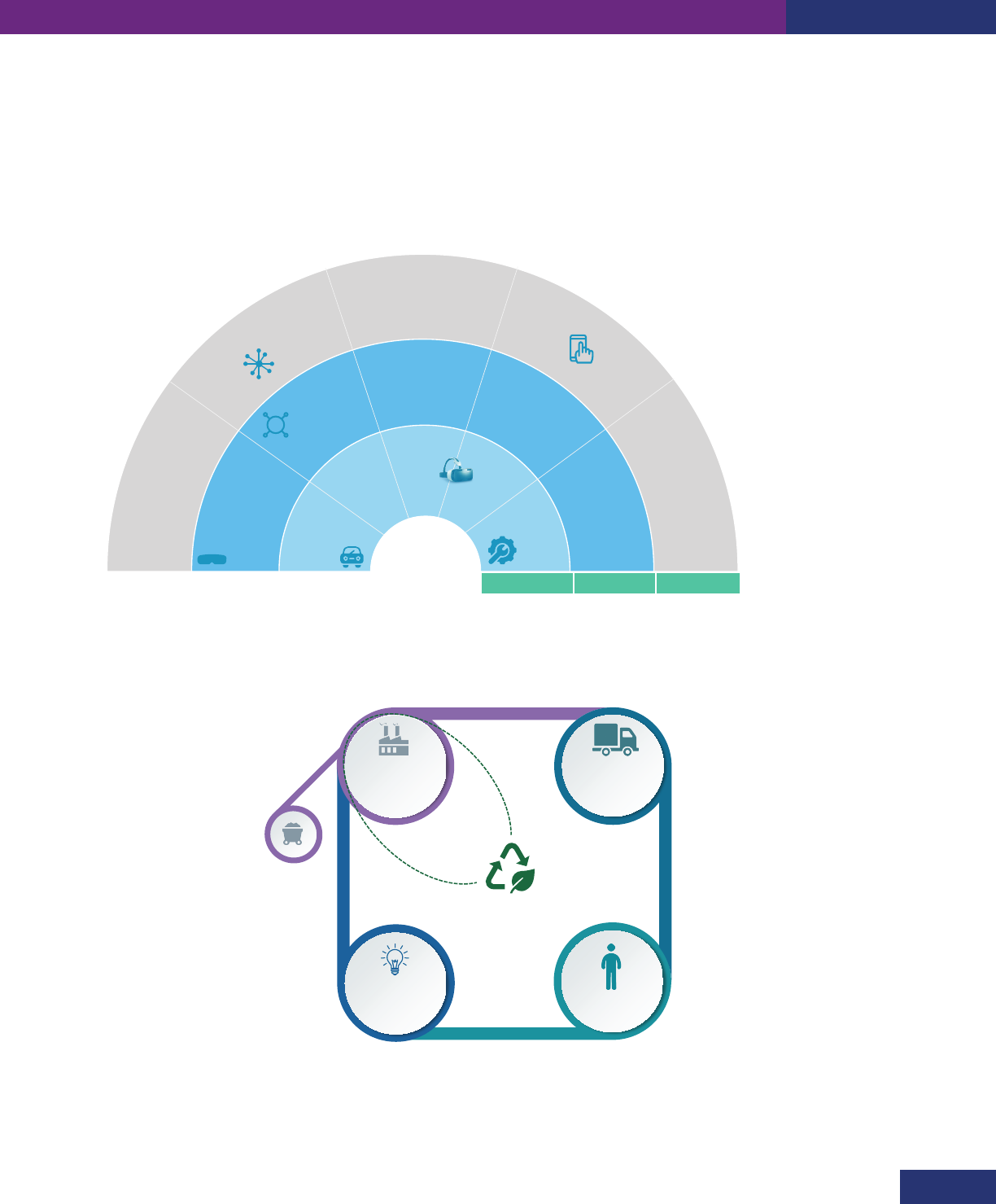

Diagram I.1

Dimensions of digital development and the effects on society, the production sector and the State

Risks

Greater inequality

Reduced competitiveness

Economic concentration

Institutional crisis

Geopolitical polarization

Telecommunications and

information technology pillar

Digital infrastructure

Telecommunications services

Software and systems

Information technology services

Multifunctional devices

Digital economy

Digital goods and services

Applications and digital platforms:

marketplaces, social networks,

video streaming

Digital content and media

Sharing economy

The digitalized economy

E-business

E-commerce

Industry 4.0

Agricultural technology

(agritech), financial technology

(fintech), automotive technology

(autotech), etc.

The smart economy

Production sector

New management models

New business models

New production models

Industrial restructuring

Society

New models of communication

and interaction

New models of consumption

State

Digital government

Citizen participation

Network and service coverage

High data transmission speeds and low latency

Access to information technology services and software

Affordability of devices and services

Welfare and

sustainability

Productivity and

sustainability

Efficiency, effectiveness

and sustainability

Information and knowledge

Online goods and services

Access to public services

Consumption on demand

and customization

Data privacy and security

New jobs, new skills

Smart products

Products as services

Informed and customized

consumption

Premium on responsible

consumption

Data privacy and security

New jobs, new skills

Innovation and entrepreneurship

Market access

Efficiency in management,

marketing and distribution

Data as a strategic asset

Cybersecurity and data privacy

Industrial reconfiguration

Automation and robotics

Sophisticated production

Digital transformation

of production (data-based

productivity)

Cybersecurity and data privacy

Digital government

Digital innovation in the State

Digital tax efficiency

Digital citizenship and

citizen participation

Open data and transparency

Cybersecurity and data privacy

State digital innovation

Governance of public services

(education, health,

justice, security)

Governance for digital

transformation (cybersecurity,

competition, tax, trade, etc.)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

The digital transformation of the production sector is taking the form of new management, business and

production models that are facilitating innovation and the introduction of new markets and disrupting traditional

industries. The expansion of the industrial Internet, smart systems, virtual value chains and artificial intelligence

in production processes is speeding up innovation and generating productivity gains, with positive effects on

economic growth. In addition, all this is driving the transformation of traditional industries through automotive

technology (autotech), agricultural technology (agritech) and financial technology (fintech), among others.

In particular, smart production models can bring increased competitiveness with a smaller environmental

footprint, as companies are using digital tools to map and reduce their footprint in order to assess their impact

on climate change and modify their production processes.

A similar process ought to take place in the public management models of State bodies, in order to meet

citizens’ demands and improve government action. The adoption of these technologies by such institutions

would increase the efficiency and effectiveness of provision for services such as health care, education

and transport. It would also improve citizen participation in democratic processes, increase transparency

in government operations and facilitate more sustainable practices. In particular, smart city solutions are

transformative because of their potential social, economic and environmental impact, especially in a region

where 80% of the population is concentrated in cities.

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

13

Despite all this potential, however, digital development that is not governed by principles of inclusiveness

and sustainability can reinforce patterns of social exclusion, as well as unsustainable exploitation and production

practices. Although digitalization can make a major contribution to the three dimensions of sustainable

development (growth, equality and sustainability), its net impact will depend on the extent to which it is

adopted and on its system of governance.

In the current situation, the economic and social crisis generated by the COVID-19 pandemic and physical

distancing measures have precipitated many of the changes discussed, as preference has been given to

online channels in an attempt to maintain a certain level of activity (see diagram I.2). This acceleration of digital

transformation in production and consumption seems irreversible. The pandemic has created a greater need

to reduce digital divides and has shown the importance of these technologies, for example, in contact tracing

applications. To carry forward the recovery, digital technologies must be used to build a new future through

economic growth, job creation, the reduction of inequality and greater sustainability. This is the way to achieve

the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and meet the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

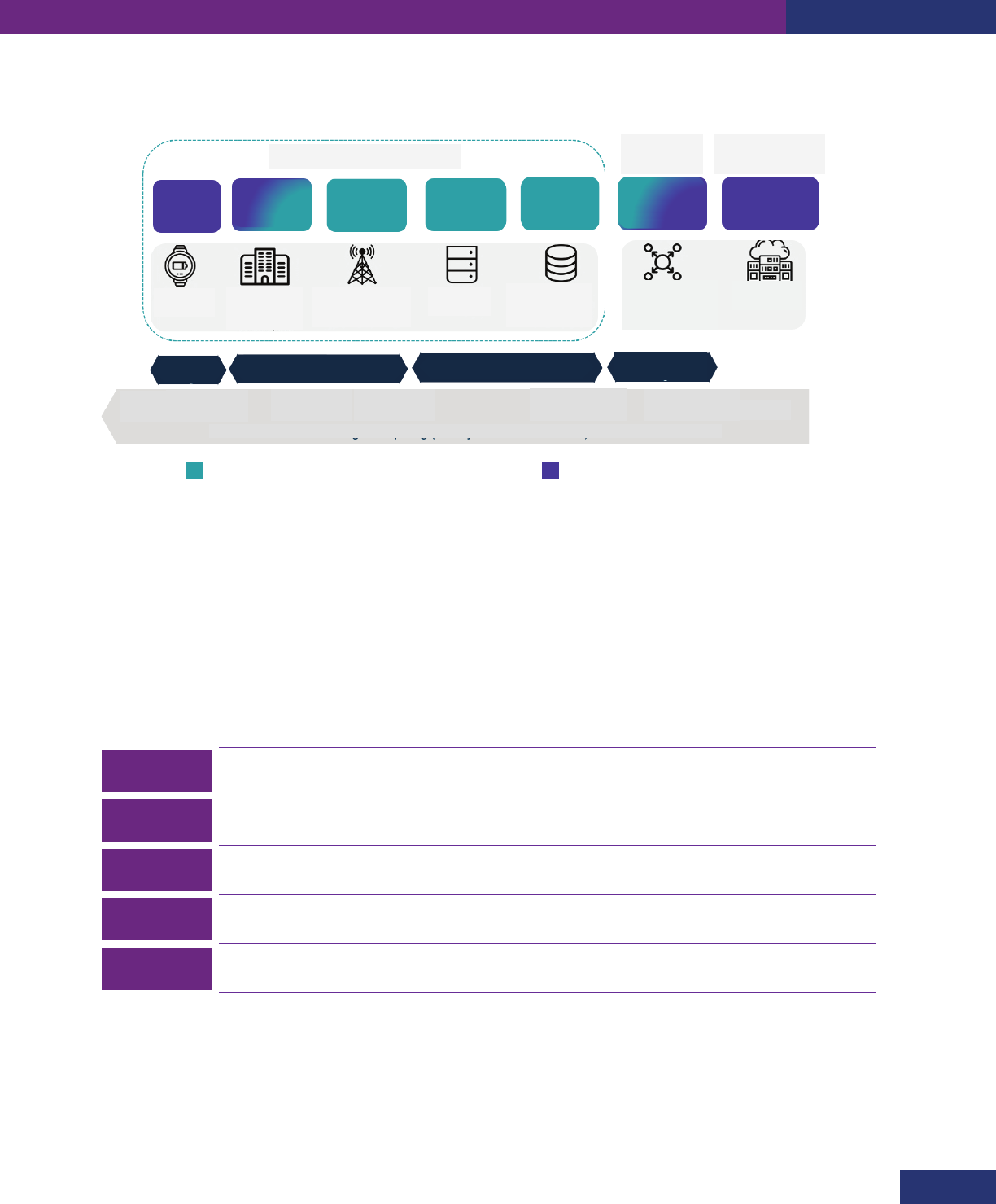

Diagram I.2

Latin America and the Caribbean: towards reactivation, 2020

Digital transformation

(5G networks, cloud computing,

Internet of things, artificial

intelligence, robots)

New realityEconomic crisis Priorities

Digitalized economyConnected economy

Online

business

models

Smart

production

models

-7.7%

GDP

Exports -23%

Firms -2.7 million

Unemployed +18 million

Poor +45.4 million

Online consumption models

Social welfare

Resilient production

Sustainability

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

B. The difficult balance between digitalization

and sustainability

Digital technologies foster ecological innovations that contribute to sustainable development by reducing

environmental impacts and optimizing resource use. As these technologies evolve and converge with

biotechnology and nanotechnology, they could generate exponential innovations that contribute to a sustainable

future. Digitalization has both positive and negative impacts on the environment. On the one hand, it can

dematerialize the economy by facilitating the supply of the digital goods and services that represent an

increasingly large part of the economy and exports; an increase in the importance of digitally supplied services

reduces movements and thence emissions. A more profound change in consumption is expected with the

development of the product as a service (PaaS) model, which makes it possible to compare the desired

outcome of using a product without purchasing it. Mobility as a service (MaaS) uses this model to combine

transport services from public and private providers through a unified gateway that creates and manages

journeys. This reduces carbon emissions and optimizes the space occupied by vehicles, helping progress

towards more sustainable cities.

At the same time, new business models such as the gig economy are optimizing the use of existing

resources by multiplying the opportunities for employing capital goods. Thus, for example, the supply of

accommodation services can expand without the need for new hotel construction, or the supply of urban

Chapter I

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

14

mobility services can be increased by making use of vehicle downtime: the demand for units does not rise,

and there are consequently savings in materials and energy. Urban navigation applications, meanwhile,

reduce journey times and emissions. In the production sector, the incorporation of artificial intelligence into

decision-making optimizes resource management and reduces the environmental footprint in areas such as

the exploitation of natural resources, manufacturing, logistics and transport, and consumption. Digitalization

also makes it possible to disintermediate activities, reducing transaction costs and links in value chains, with

the consequent savings in energy and inputs.

The Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI) study #SMARTer2030 estimated that by implementing digital

solutions in different sectors of the economy, total global carbon dioxide equivalent (CO

2

e) emissions could be

reduced by 12 gigatons (Gt) by 2030, providing a path to sustainable growth. The most significant contribution

to this reduction would be made by mobility solutions, followed by applications in the manufacturing and

agricultural sectors (see figure I.1). Real-time traffic information, smart logistics and lighting and other digitally

enabled solutions could reduce CO

2

e by 3.6 Gt, including savings in emissions from journeys forgone. Smart

manufacturing, including virtual manufacturing, customer-centred production, circular supply chains and smart

services could save 2.7 Gt of CO

2

e. Besides lower carbon emissions, benefits would include a 30% increase

in agricultural crop yields, savings of more than 300 trillion litres of water, a reduction of 25 billion barrels per

year in oil demand and a decrease of 135 million vehicles in the global vehicle fleet (GeSI, 2015).

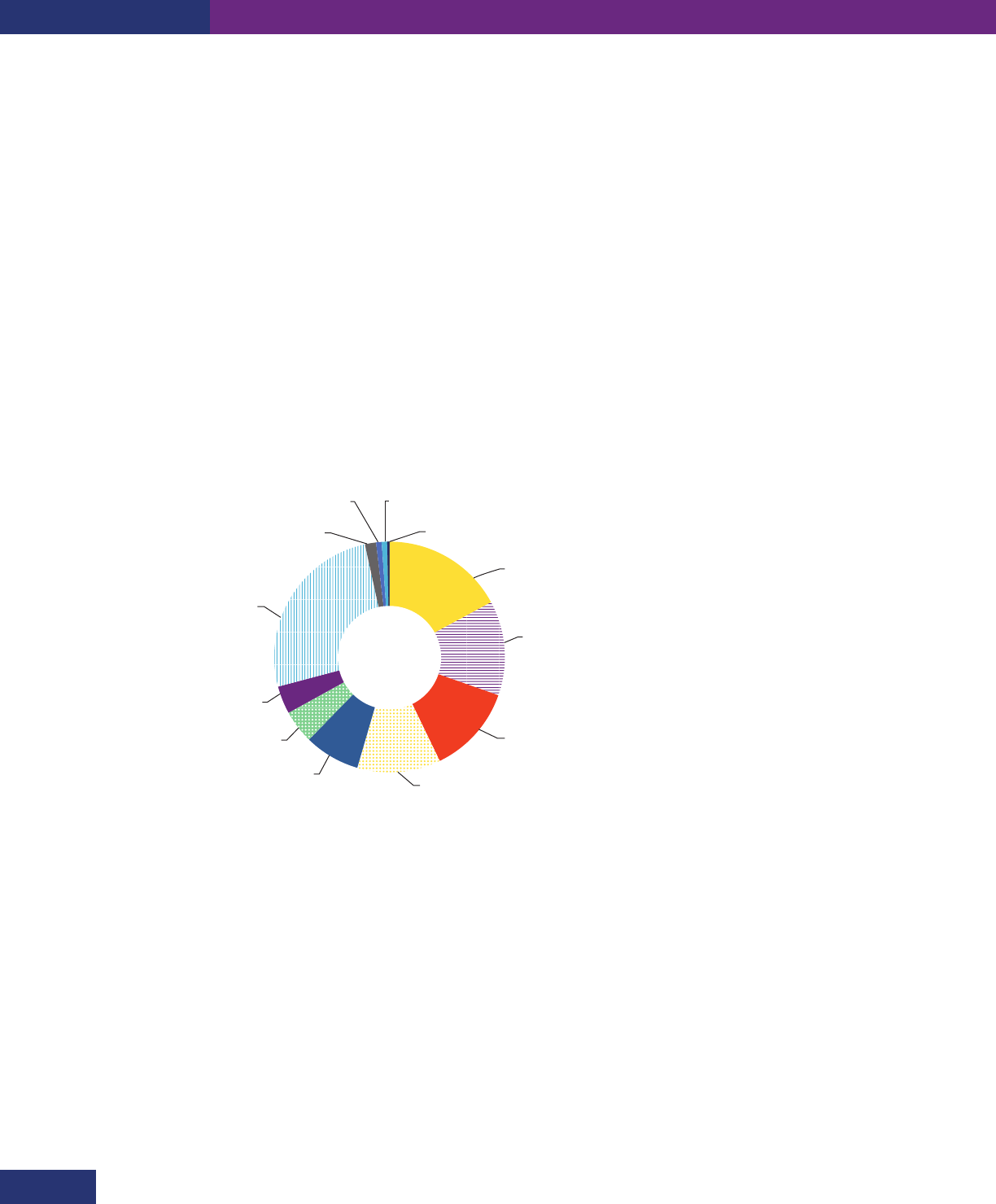

Figure I.1

Potential for reducing carbon dioxide (CO

2

) by 2030, by type of digital solution

Smart manufacturing

(22)

Smart agriculture

(17)

Smart buildings

(16)

Smart energy

(15)

Smart logistics

(10)

Optimized traffic control

(6)

Connected private transport

(5)

E-working

(33)

E-commerce

(2)

E-health

(1)

E-learning

(1)

E-banking

(0)

Source: Global e-Sustainability Initiative (GeSI), #SMARTer2030: ICT Solutions for 21st Century Challenges, Brussels, 2015 [online] https://smarter2030.gesi.org/

downloads/Full_report.pdf.

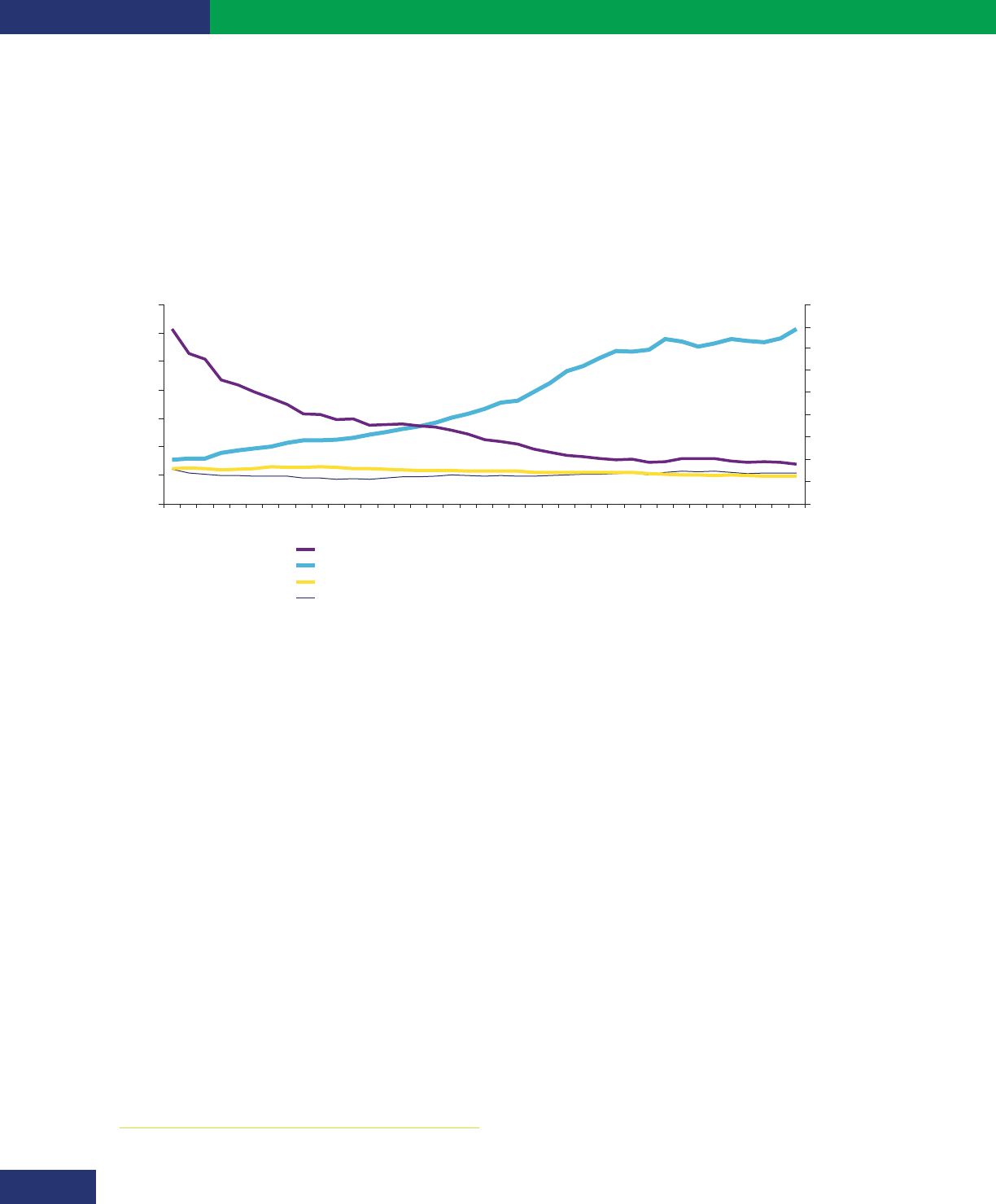

On the other hand, increased digital development generates negative effects associated with energy

consumption (data centres and networks), polluting hardware (screen) production processes, and business

models that encourage the rapid replacement of devices. Likewise, the increased use of audio and video

solutions and of data in general tends to result in a continuing rise in energy consumption. However, while

electricity consumption and the carbon footprint of the information and communications technology (ICT) sector

increased between 2007 and 2015, the rate of increase slowed down considerably despite strong growth in

subscriptions and data traffic. Intensity indicators show that substantial progress has been made with energy

consumption and carbon footprint generation, as each subscription or each GB transmitted has a decreasing

impact (81 kg CO

2

e/subscription in 2015 compared to 134 kg CO

2

e/subscription in 2007, and0.8 kg CO

2

e/GB

in 2015 compared to 7 kg CO

2

e/GB in 2007) (Malmodin and Lunden, 2018) (see figure I.2).

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

15

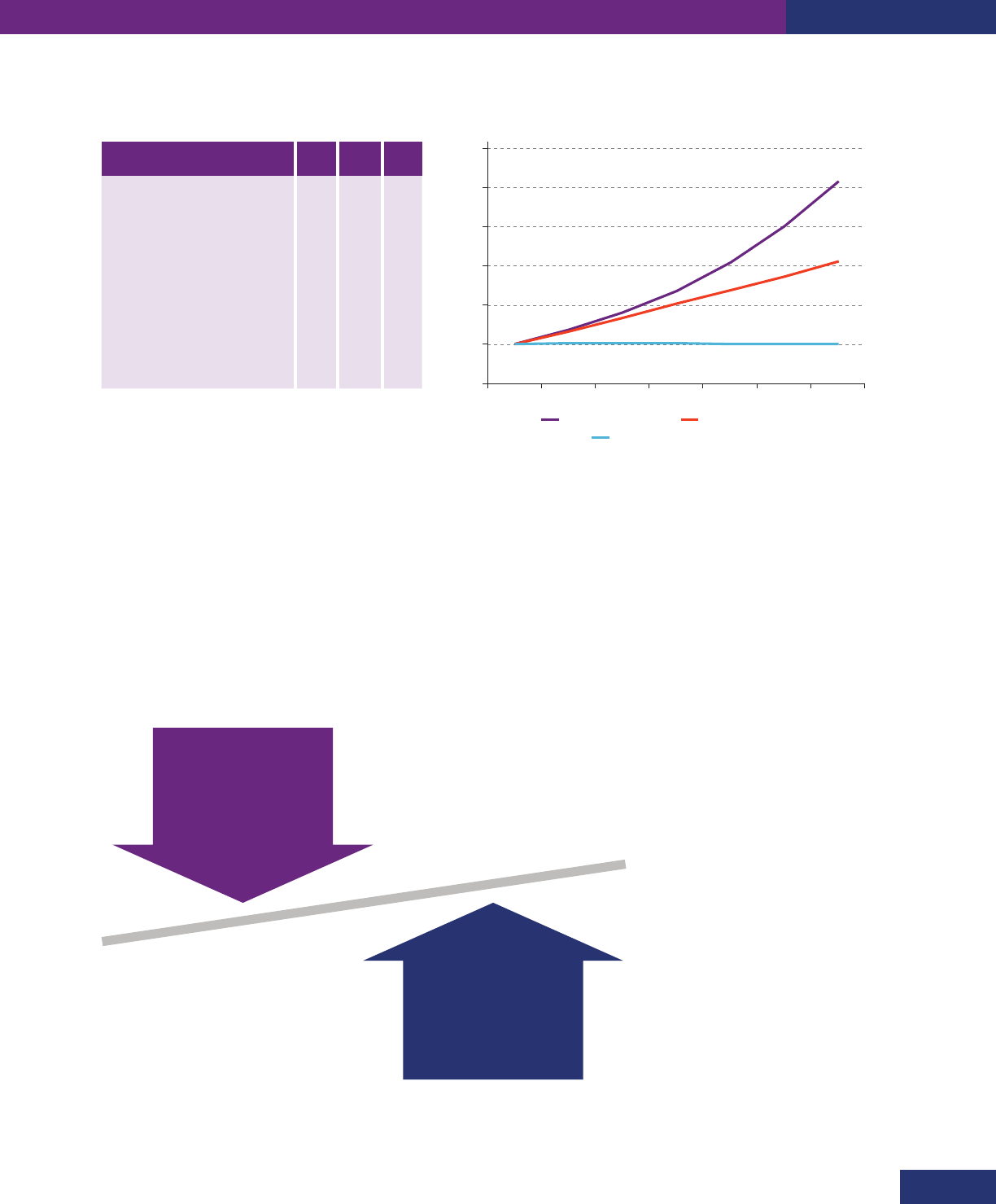

Figure I.2

The carbon and energy footprint of information and communications technologies (ICTs)

and trends in Internet traffic and data centre workloads

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

2015 2016 2017 2018 2019 2020 2021

Index (2015=100)

Internet traffic

Data centre workloads

Data centre energy consumption

2007 2010 2015

Carbon footprint of the ICT

sector (tMCO

2

)

620 720 730

Operational electricity consumption

of the ICT sector (TWh)

710 800 805

Carbon footprint per ICT subscription

(kg CO

2

/subs)

134 107 81

Carbon footprint per GB in networks

(kg CO

2

/GB)

7 3 0,8

Operational electricity consumption

per subscription (kWh/subs)

153 119 89

Operational electricity consumption

per GB in networks (kWh/GB)

7.6 3.3 0.88

Source: J. Malmodin and D. Lunden, “The energy and carbon footprint of the global ICT and E&M sectors 2010–2015”, Sustainability, vol. 10, No. 9, Basel, Multidisciplinary

Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), 2018; International Energy Agency (IEA), Digitalization and Energy, Paris, 2017.

In addition, the development of advanced technologies such as 5G, the Internet of things and artificial

intelligence should help reduce global carbon emissions by up to 15%, or almost a third of the 50% reduction

proposed for 2030, via the development of solutions for the energy, manufacturing, agriculture and natural

resource extraction, construction, services, transport and traffic management sectors (Ekholm and Rockström,

2019). This can offset some of the negative effects of the production and use of these technologies, which

involve high energy consumption (1.4% of the world total), massive generation of e-waste and extraction of

natural resources such as copper and lithium (see diagram I.3) (Malmodin and Lunden, 2018).

Diagram I.3

The effects of digitalization on sustainability

• Energy consumption

•

•

2015

3.6%

1.4%

49.8

-15%

Global carbon emissions

in 2030

•

Dematerialization

•

Disintermediation

•

Resource management

optimization in

manufacturing, logistics

•

Conscious consumption

of global energy consumption

million tons of electronic waste

of CO

2

emissions

Polluting hardware

production processes

Devices with short

replacement cycles

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of B. Ekholm and J. Rockström, “Digital technology can cut global emissions

by 15%. Here’s how”, Cologny, World Economic Forum (WEF), 2019 [online] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/why-digitalization-is-the-key-to-

exponential-climate-action/; J. Malmodin and D. Lunden, “The energy and carbon footprint of the global ICT and E&M sectors 2010–2015”, Sustainability,

vol. 10, No. 9, Basel, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), 2018.

Chapter I

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

16

C. The roll-out of 5G networks: essential to the new

models of industrial production and organization

The fifth generation of mobile networks (5G) will be disruptive to industrial organization and production

models because of its technical characteristics (higher transmission speeds, of up to 20 Gbps), ultra-reliable

low latency (less than a millisecond), increased network security, massive machine type communications and

enhanced device energy efficiency. Thus, the roll-out of these networks will make it possible to extend wireless

broadband services beyond the mobile Internet to complex Internet of things systems, with the low latency

and high level of reliability needed to support critical applications in all economic sectors (see diagram I.4).

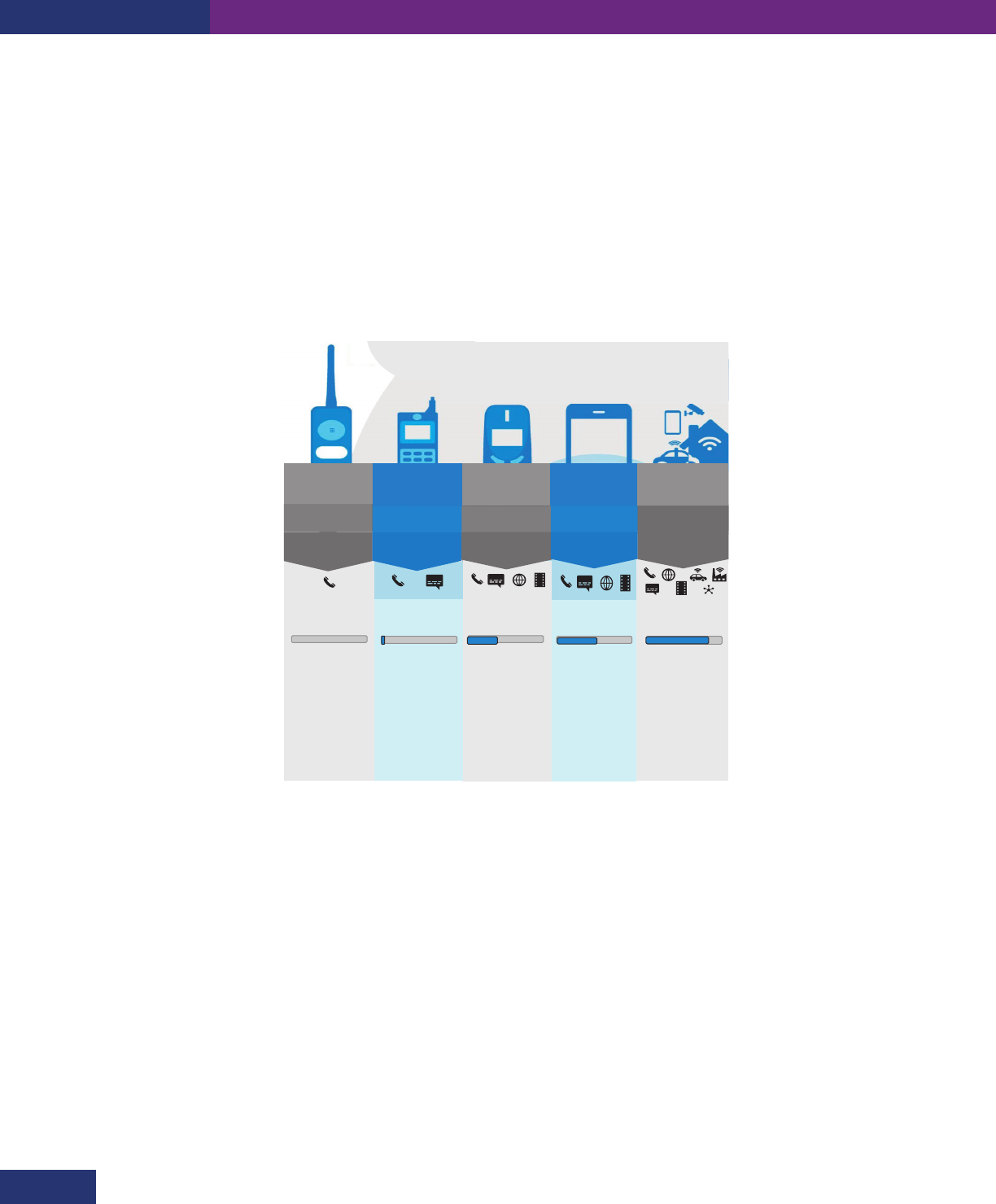

Diagram I.4

The evolution of mobile networks and their technical characteristics

3G

2001

2G

1991

4G

2010

5G

2020

HD

HD

Data transmission

0

Up to 40 kbps

Up to 20 Mbps

Up to 1 Gbps

Up to 20 Gbps

1G

1980

Impact on industry Impact on industry Impact on industry Impact on industry Impact on industry

• No impact

on industrial

applications

• Text messages

from and to

remote machines

• Video monitoring

•

Remote access

to machines

(teleservice)

•

Remote

conditioning

monitoring

• Mobile technical

services

• Services via

smartphones

•

Wireless

environment

networks

• Autonomous

logistics

•

Assisted work

• Robots and

autonomous

machines

•

Wireless backhaul

•

Real-time data

analytics

•

Carbon footprint

management

Latency N/A 300-1 000 ms 100-500 ms < 25 ms < 1 ms

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of Micron Technology, “5G, AI, and the Coming Mobile Revolution”, Boise,

2020 [online] https://www.micron.com/insight/5g-ai-and-the-coming-mobile-revolution; Siemens, “Industrial 5G: for the industry of tomorrow”, Munich, 2020

[online] https://new.siemens.com/global/en/products/automation/industrial-communication/5g.html.

5G mobile networks will support innovative uses in virtually all industries. Enhanced broadband experiences,

the large-scale Internet of things and mission-critical services will provide a basis for innovative uses offering

segmented levels of latency (see diagram I.5). Although edge computing can be used in a 4G environment,

the combination of this with 5G networks and artificial intelligence (AI) is expected to open up new uses

in vertical industries and speed up the adoption of Industry 4.0 models, yielding gains in productivity and

competitiveness and improvements in sustainability.

5G networks make it possible to build smart factories and take advantage of technologies such as automation

and robotics, artificial intelligence, augmented reality and the Internet of things at different stages of the value

chain (see diagram I.6). Having real-time access to information for decision-making along an entire value chain is

a key competitive advantage when it comes to making efficient use of resources and better meeting demand.

Cloud-based solutions make it possible to better integrate the different stages of the chain. The same software

can be used for the design, simulation and implementation of configurations and instructions for running physical

production lines, thus improving the quality and flexibility of operations. This type of solution replaces traditional

assembly processes and provides greater flexibility to reconfigure production plants in the event of changes

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

17

in the product or in demand. They serve to streamline processes and cut costs, as well as reducing delivery

times, improving logistics management and capturing the attention of consumers. Other particularly important

uses include industrial automation and control systems, planning and design systems, and field devices that

provide information for complete process optimization. In addition, the incorporation of artificial intelligence

into decision-making allows resource management to be optimized with a view to reducing the environmental

footprint in areas such as natural resource exploitation, manufacturing, logistics and transport, and consumption.

Diagram I.5

Applications of sectoral 5G networks depending on the levels of latency required

Big data for

real-time

decision-making

ControlledUltra-low Medium

Augmented reality

with landmarks

Autonomous

transport

Industrial

automation

Virtual

reality

High-quality

video

Real-time

collaboration

Robotics

Man-machine

interaction

Gaming

Household

sensors

Contextual

recommendations

Contextual

content

Remote

surgery

Telemedicine

Sensorized clothing

Latency

requirements

A

u

t

o

m

o

t

i

v

e

I

n

d

u

s

t

r

y

H

e

a

l

t

h

L

i

f

e

a

n

d

w

o

r

k

S

m

a

r

t

c

i

t

i

e

s

Source: Detecon International, “5G campus networks: an industry survey”, Cologne, 2019 [online] https://www.detecon.com/drupal/sites/default/files/2019-10/kor%20

190613_5G_Market_Survey_final_0.pdf.

Diagram I.6

Digital transformation of the production chain

Internet of things

Internet of things

5G

Consum

•

Geolocation (drones, machinery

and other assets)

Meteorological information systems

(Internet of things)

Performance monitoring

(Internet of things or drones)

Smart management (irrigation,

fertilization, machinery)

Predictive maintenance (Internet of things,

big data, articial intelligence)

•

•

•

•

• Fast prototyping (3D)

Business-to-consumer platforms

for product design cooperation

•

•

Electric vehicles

Product traceability

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

• Product-as-a-service

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

In addition to driving sustainable industrialization, digital transformation can provide social and environmental

value through the development of education, health, transport, city and teleworking applications, as discussed

in chapter II.

Chapter I

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

18

D. The mass take-up of new technologies requires

more infrastructure investment

1. Telecommunications are moving to the cloud:

the transformation of the sector

Telecommunications service operators (TSOs) need to become more competitive (reduce their capital and

operating expenditure) and make their services more responsive. 5G technology creates an opportunity for

them because it allows network functions to be virtualized with lower operating costs. It also allows processes

to be automated and made more flexible, with all the consequent scalability and greater dynamism in network

management. Network operators will become digital service providers, disrupting the sector’s business model.

4G technology marked the beginning of a path towards network virtualization that will be consolidated

with 5G technology. Network virtualization allows resource managers to integrate fixed and mobile services,

separating them into layers so as to provide each business or individual user with the services they require.

Thus, innovative uses requiring different levels of latency can be explored in industry, health services, education,

transport, work and home life and cities.

Cloud computing is one of the drivers and enablers for the processing of the large amounts of data

generated by the ever-increasing connectivity of things. As this connectivity increases, a crucial factor will be

the use of artificial intelligence and the ability of cloud computing to achieve the low latency times required by

autonomous vehicles, virtual or augmented reality and certain industrial automation services. Edge computing

will supplement cloud computing, which will be provided in a decentralized or distributed manner according

to the requirements of the different services (the network gateway, the customer’s installations or peripheral

devices), as in so-called hyperscale computing (higher latency). These new needs converge with a parallel

process in the universe of telecommunications operators, which are resorting to “cloudification” to cut network

costs and increase the responsiveness, security and analytical capacity of the data they carry.

These needs and trends are leading to a new convergence between the world of telecommunications

and the information technology sector, which provides public cloud services. Telecommunications service

operators see that hyperscale public cloud providers could become competitors in the provision of connectivity

services. Globally, traditional telecommunications providers such as AT&T and Verizon are working with cloud

service providers such as Microsoft and Amazon to add network edge computing to network centres in order

to implement 5G technology (see diagram I.7). The two will need each other to achieve an infrastructure capable

of providing connectivity and computing capacity to businesses and devices. It is therefore to be expected that

more and more partnerships will arise between these actors in order to develop the new supply of integrated

services that will make access to the technologies of the fourth industrial revolution viable.

One indication of the transformation in the sector is the tendency to sell off or split up the business, with

one part operating the infrastructure network and the other operating the service itself. Just over a decade

ago, operators controlled all the passive and active components of the telecommunications infrastructure.

Today, telecommunications operators are choosing to split vertically, forming companies that specialize in

managing their property assets or selling their towers and sites to new infrastructure network operators. By

the end of the first quarter of 2019, over 50% of all towers in Latin America and the Caribbean were in the

hands of specialized companies and not these operators (Euromoney Global Limited, 2019). The separation of

network management from service provision is motivated by considerations of specialization and the need for

sufficient scale to provide services efficiently. This is why some operators have chosen to divest themselves

of their data centres. In January 2021, for example, Telefónica signed an agreement with American Tower

Corporation to sell its telecommunication towers division in Europe (Germany and Spain) and Latin America

(Argentina, Brazil, Chile and Peru) (Telefónica, 2021).

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

19

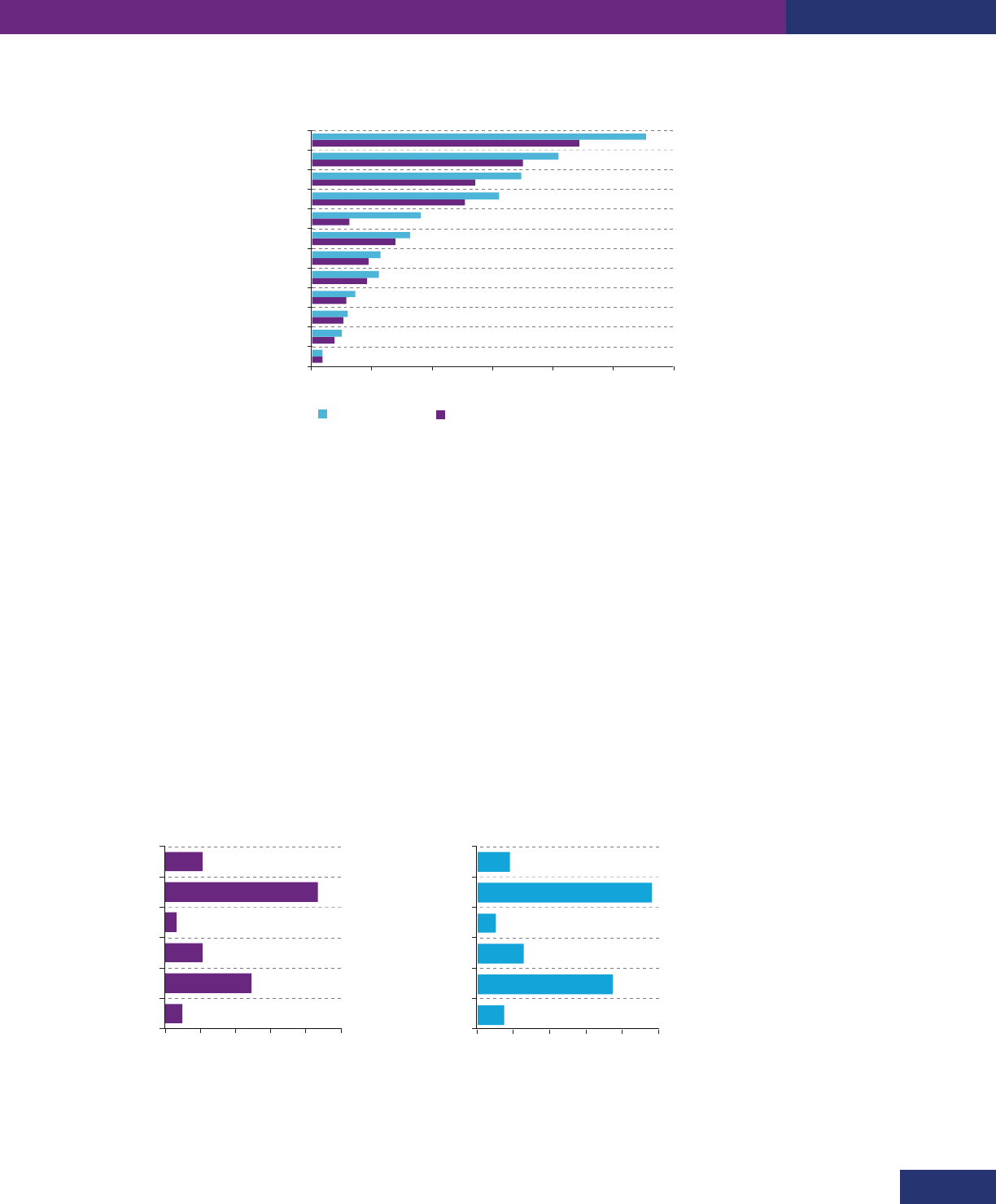

Diagram I.7

Convergence between telecommunications operators and information technology:

network virtualization, cloud distribution and network edge computing

Strengths of telecommunications operator Strengths of cloud provider

Devices Firm

Access

point

Network

aggregation

points

Core

network

Internet

exchange

Hyperscale/

private cloud

National

backbone

International

backbone

End devices

Customer premises:

households, offices,

factories, etc.

Mobile telephony towers,

street distributors

(fixed or mobile)

C-RAN exchange Central offices,

central data centres

and exchange centres

Interconnection points,

Internet exchange,

placement

Data centres

Device

Network/multiple access

Regional

Latency 2 ms <5 ms ~20 ms 20-25 ms 25-50 ms 30-75 ms

Access network

Edge computing (reductions in latency to the left)

Customer premises

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

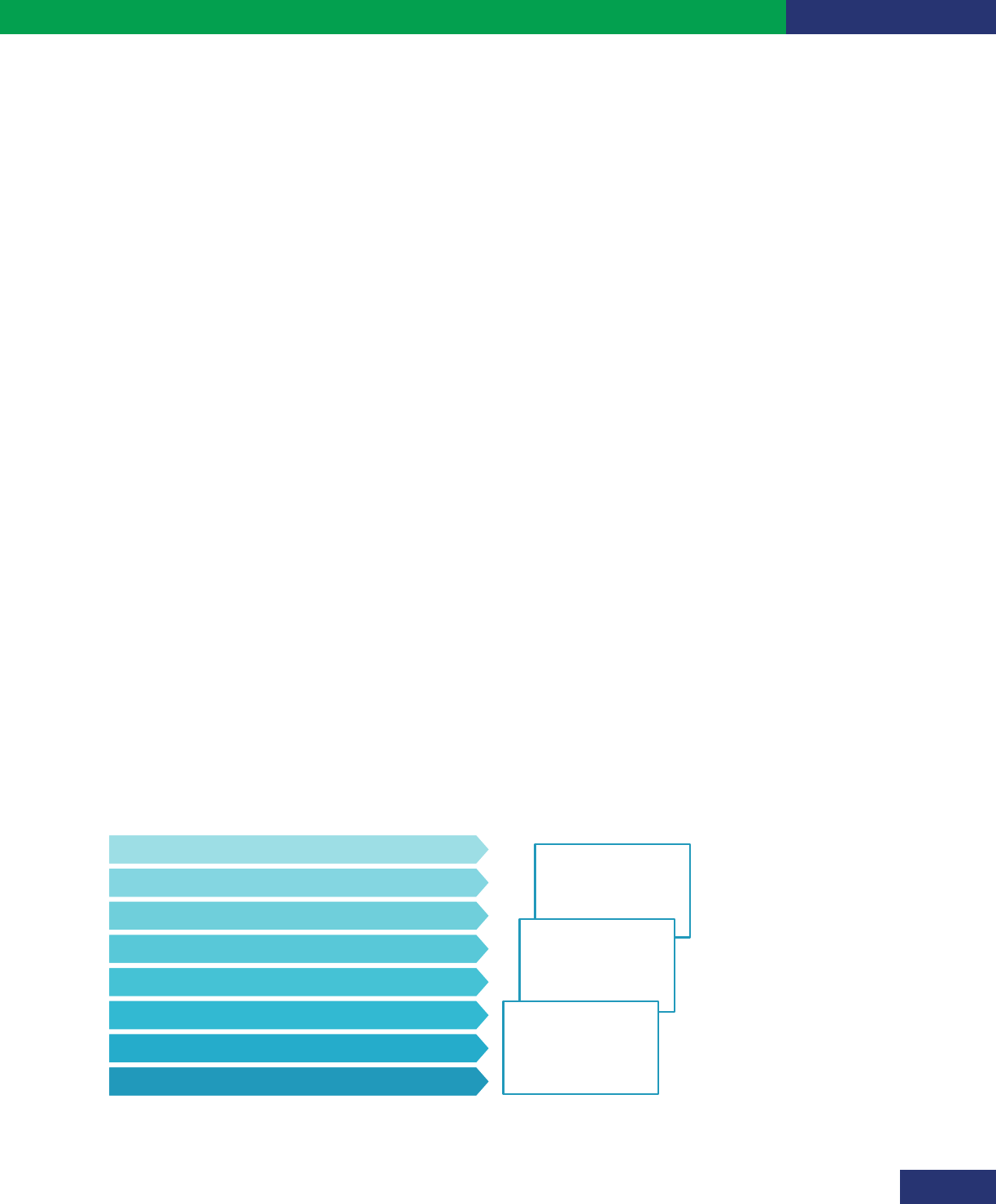

Changes in business models are transforming the industry (see table I.1). The virtualization of networks and

the need to process large amounts of data are leading to convergence with the information technology sector that

is encouraging the entry of new players. Maximizing the benefits of technological innovation requires a clear vision

of these challenges and a regulatory framework designed to encourage the development of new value chains.

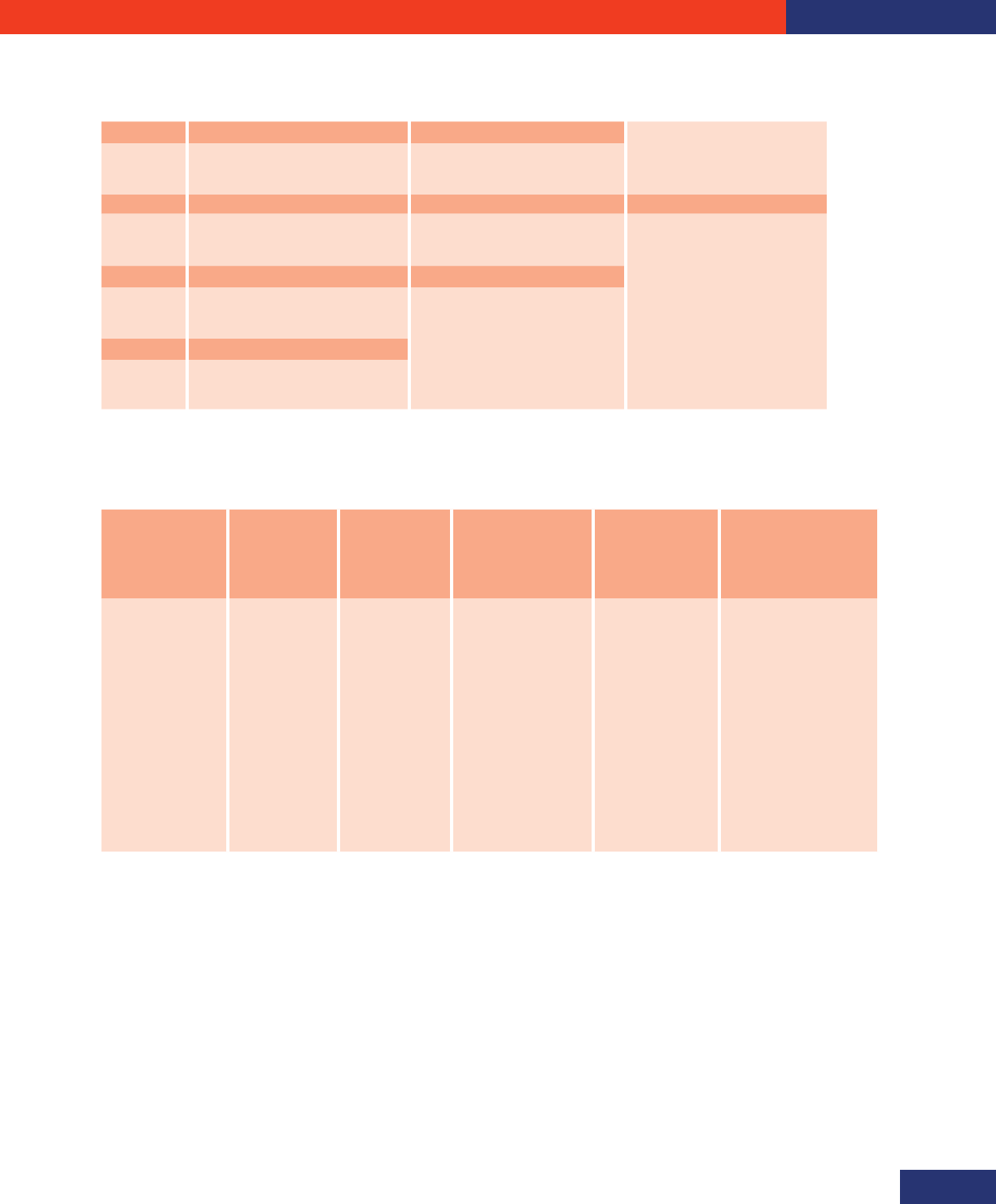

Table I.1

The new dynamics of interaction between new and traditional actors and disruptive developments

Passive

infrastructure

Devices

Operators

Traditional players

Active/network

infrastructure

Disruptive developments

New players

Over-the-top

(OTT) services

AMX, TEF, MIC, TECO

Ericsson, Huawei, Nokia,

Samsung, ZTE

Samsung, Apple, Xiami,

Huawei, Oppo, LG

AMX, TEF, MIC, TECO

Service and content platforms

Unbundling, management specialization,

asset sweating, sharing

Virtualization, consolidation, sharing,

cybersecurity, trade war

Scale, operating systems, Internet of things,

wearables, sensorization

Consolidation, heavy regulation, spectrum cost,

unlicensed use (Wi-Fi)

Softwarization, network slicing, business-to-business

(B2B) services, vertical industry services, content,

cloud/big data, artificial intelligence

American Tower, SBA, Phoenix,

Cellnex, Telxius, Telesites

OpenRAN (Parallel Wireless, Altiostar)

CloudCos (AWS, Azure, Google)

Internet of things players, 5G

Internet service providers (ISPs) offering

dynamic IP addresses, private networks,

wholesalers, satellite/HAPS

Heavy fragmentation by niche

Cloud (infrastructure as a service, platform

as a service, software as a service)

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC).

Chapter I

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

20

2. The digital transformation driven by 5G networks will have a

significant economic impact but require large investments

The transition to 5G technology began in late 2018 in the United States, China and the Republic of Korea, and

it is expected to start being deployed more systematically in Latin America and the Caribbean during 2021.

At the same time, the development of high-performance satellites, coupled with new models for the use of

unlicensed radio spectrum such as Wi-Fi, will be drivers of innovation aimed at increasing connectivity options

and improving coverage.

Implementing the procedures for moving from 4G to 5G technology could increase Latin America’s GDP

by between US$229 billion and US$293 billion by 2030 (Katz and Cabello, 2019). This finding is based on

two scenarios. The first is a baseline scenario of urban-suburban deployment centring on first- and second-tier

metropolitan centres, with network speeds and capacities remaining consistently lower in rural areas. The

second is a national maximum scenario, with a service speed and quality experience that is more uniform in

the areas where 95% of the population lives. This measurement is based on consideration of three areas of

impact for mobile expansion:

1.

The impact on digital transformation: benefits in the form of connectivity, digitalization of households

and the production system, growth of digital industries.

2.

The impact on GDP growth: the effect of the level of digitalization on GDP, partly because of investment

in network roll-out, but mainly as a result of spillover effects (positive externalities) on the economy

as a whole.

3.

The impact on the GDP of certain industrial sectors: the spillover effects from increased operational

efficiency and improved productivity in certain industrial sectors.

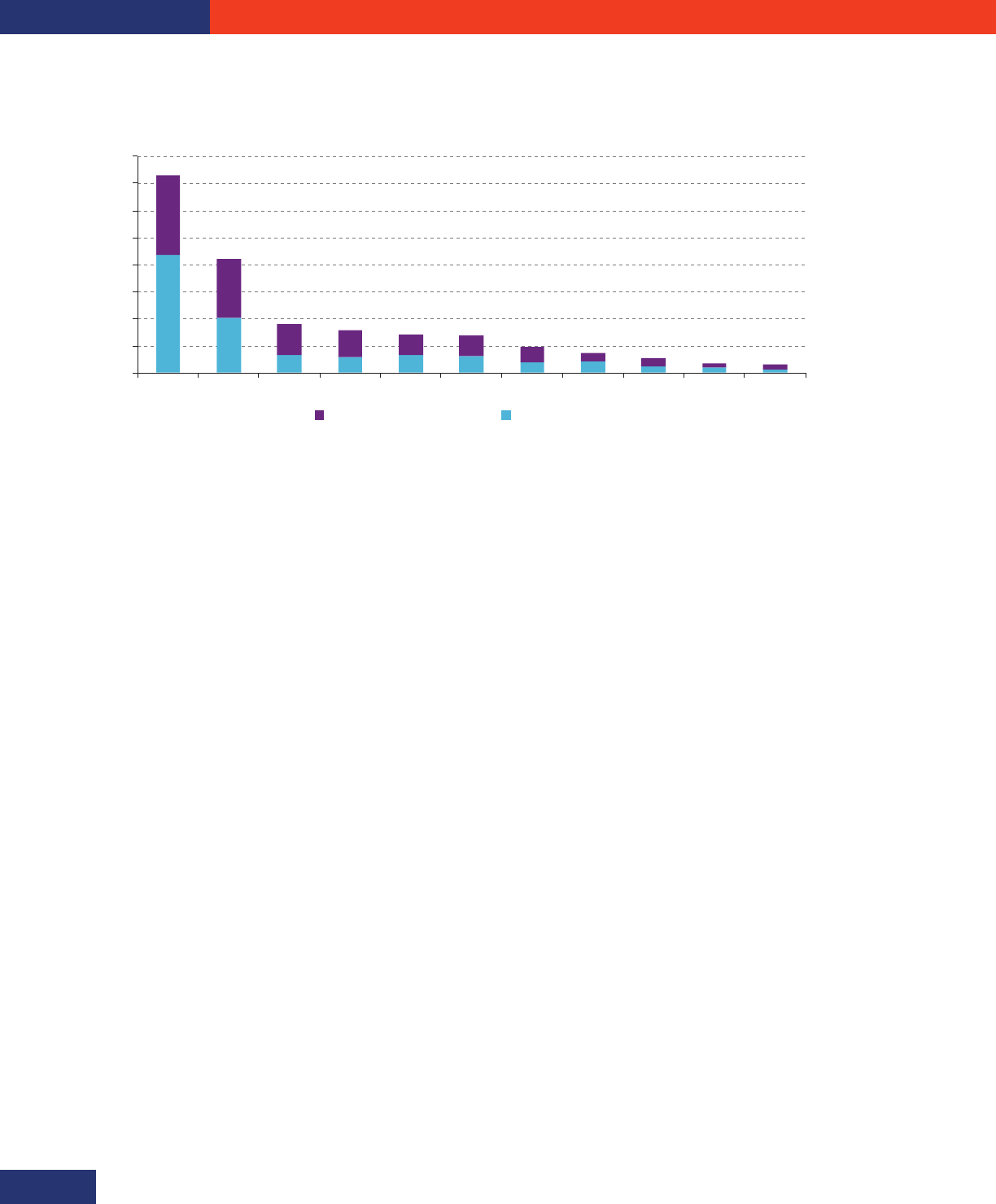

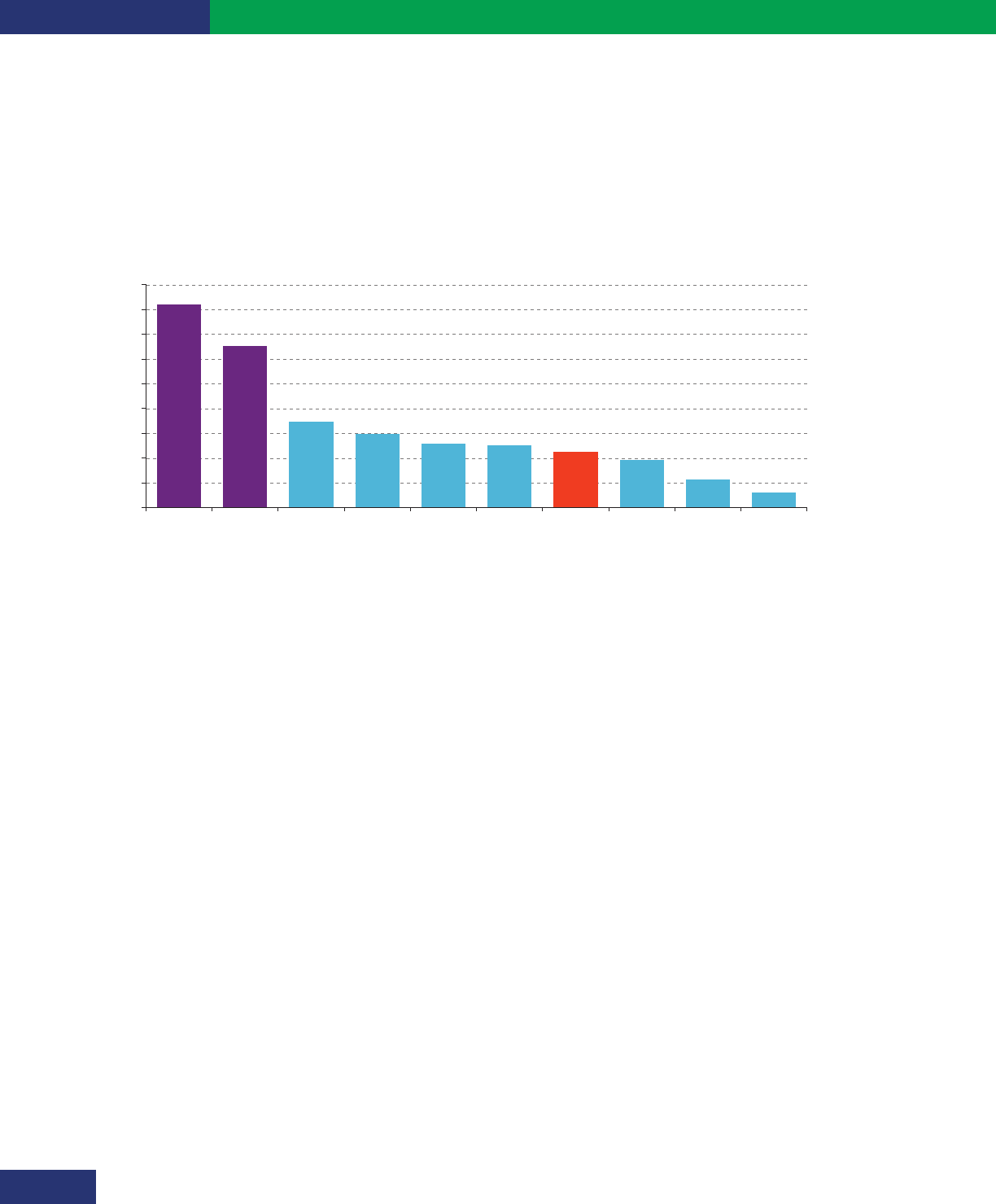

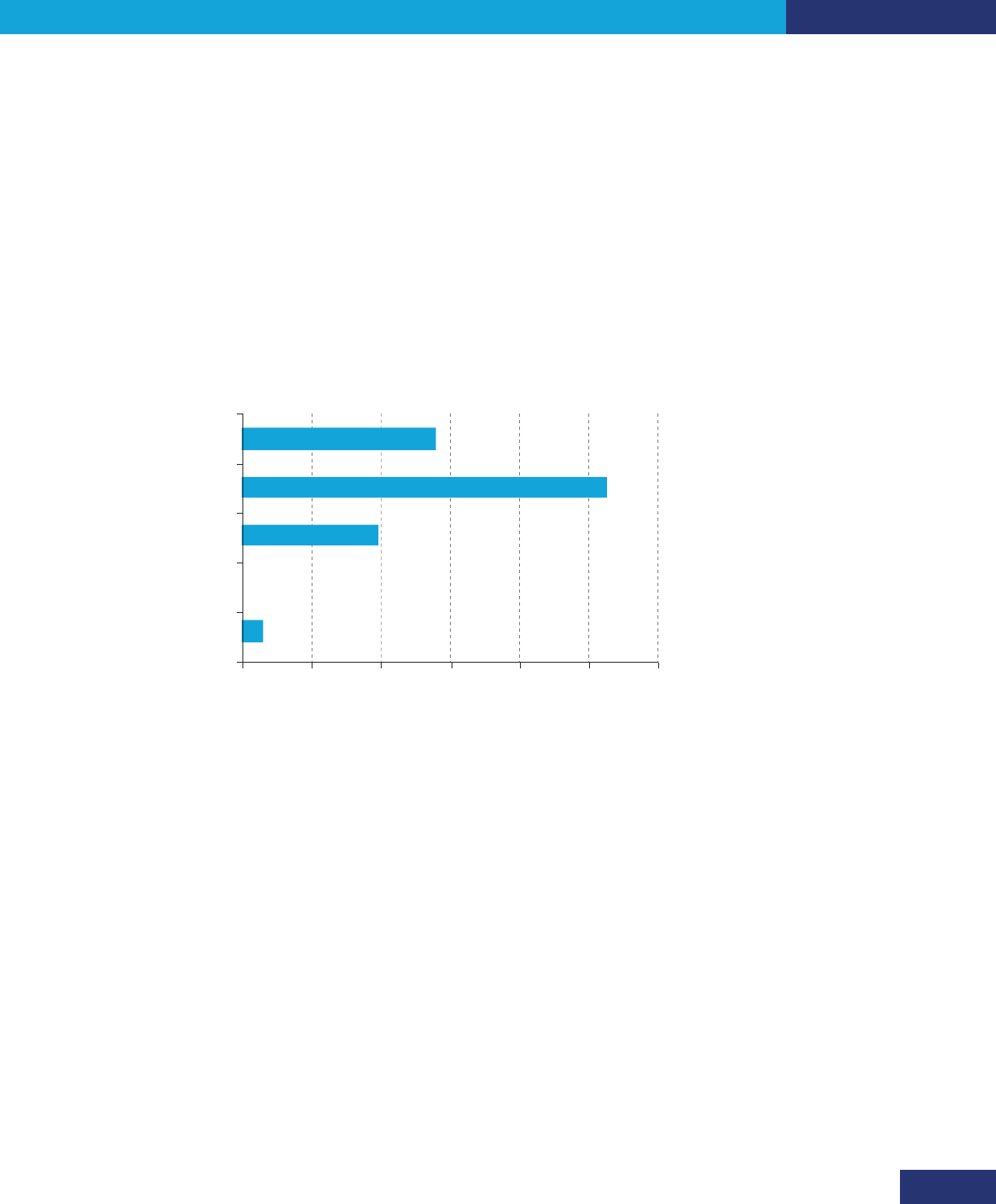

Figure I.3 shows the impact of improved connectivity on GDP in the six countries analysed, ranging from

US$104 billion for Brazil to US$15 billion for Peru, and attributable to direct and indirect effects in a high-impact

scenario. The adoption of use cases facilitated by the technological leap could have a combined impact on the

efficiency of companies and the public sector, as well as on the scope and coverage of services. At the sectoral

level, it is estimated that the greatest benefits from the substantial improvement in quality and efficiency

will come in public services (health care, education and security, including smart city services such as traffic

management). A considerable increase in value is also expected in professional services, manufacturing and

logistics, commerce and services, and agroindustry.

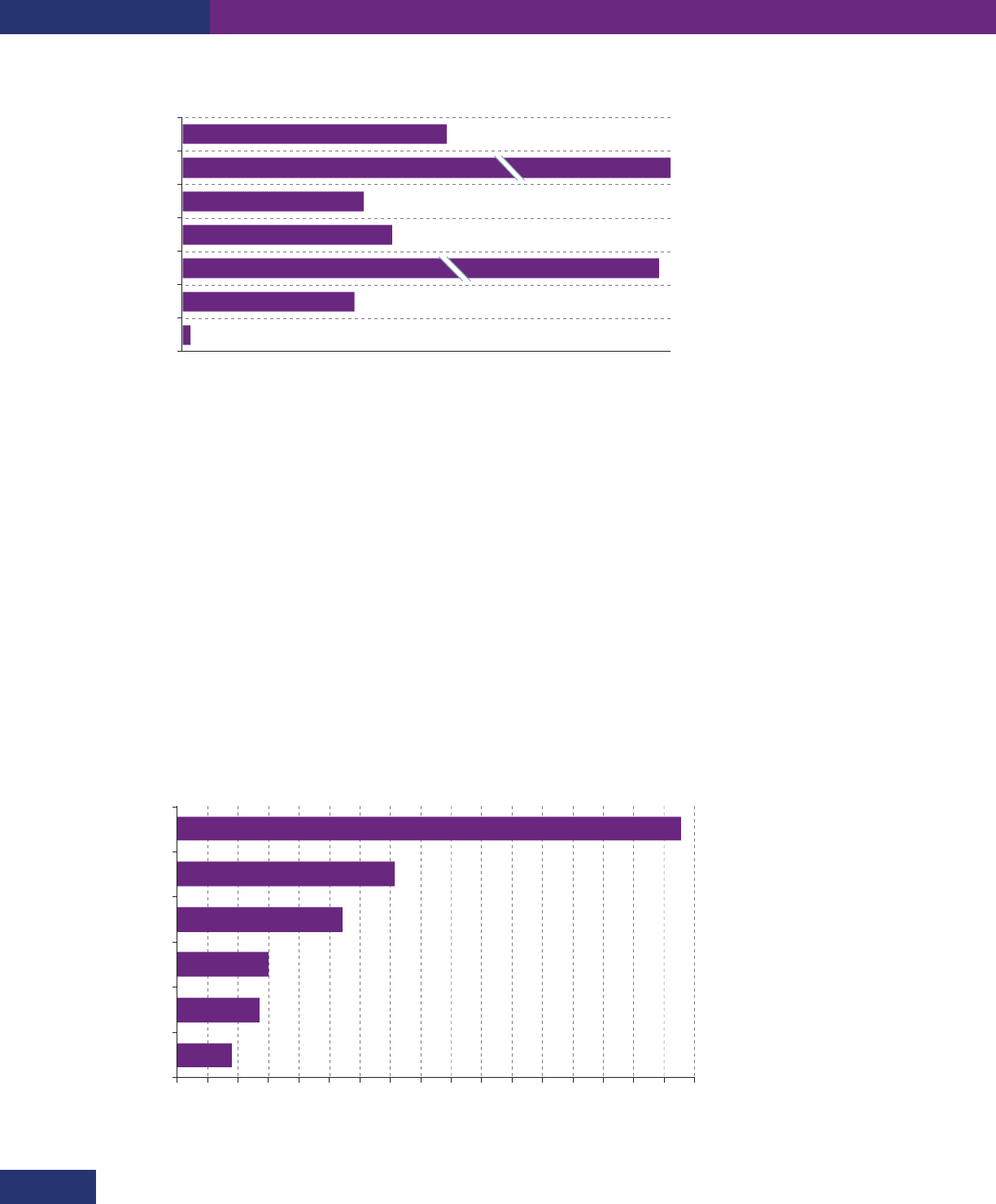

Figure I.3

Latin America (6 countries): the impact of mobile expansion on GDP and by economic sector to 2030

Argentina

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Peru

Mexico

Argentina

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Peru

Mexico

10.6

48.5

13.9

12.3

85.9

25.0

15.4

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110

68.4

17.4

14.8

103.9

30.0

+0.40%

+0.48%

+0.40%

+0.49%

+0.44%

+0.53%

+0.42%

+0.53%

+0.40%

+0.56%

+0.67%

US$ 229.97 billion US$ 292.81 billion

+0.46%

Billions of dollars

Baseline scenario: urban and suburban coverage Maximum scenario: national coverage III

Annual growth

Billions of dollars

Annual growth

A. GDP impact

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90

Latin American

total

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

21

2

4

5

6

9

9

14

6

25

27

35

44

2

5

6

7

11

11

16

18

31

34

41

55

0 10 20 30 40 50 60

Maximum scenario

Baseline scenario

B. Impact by economic sector

Billions of dollars

Public services (health, education,

security, smart cities)

Professional services

Manufacturing

a

Commerce

Agribusiness

Financial services

Entertainment

Transport

Mining

Real estate

Construction

Basic services (water, electricity, etc.)

Source: R. Katz and S. Cabello, The Value of Digital Transformation through Expansive Mobile in Latin America, New York, Telecom Advisory Services, 2019.

a

Includes all production subsectors except food processing.

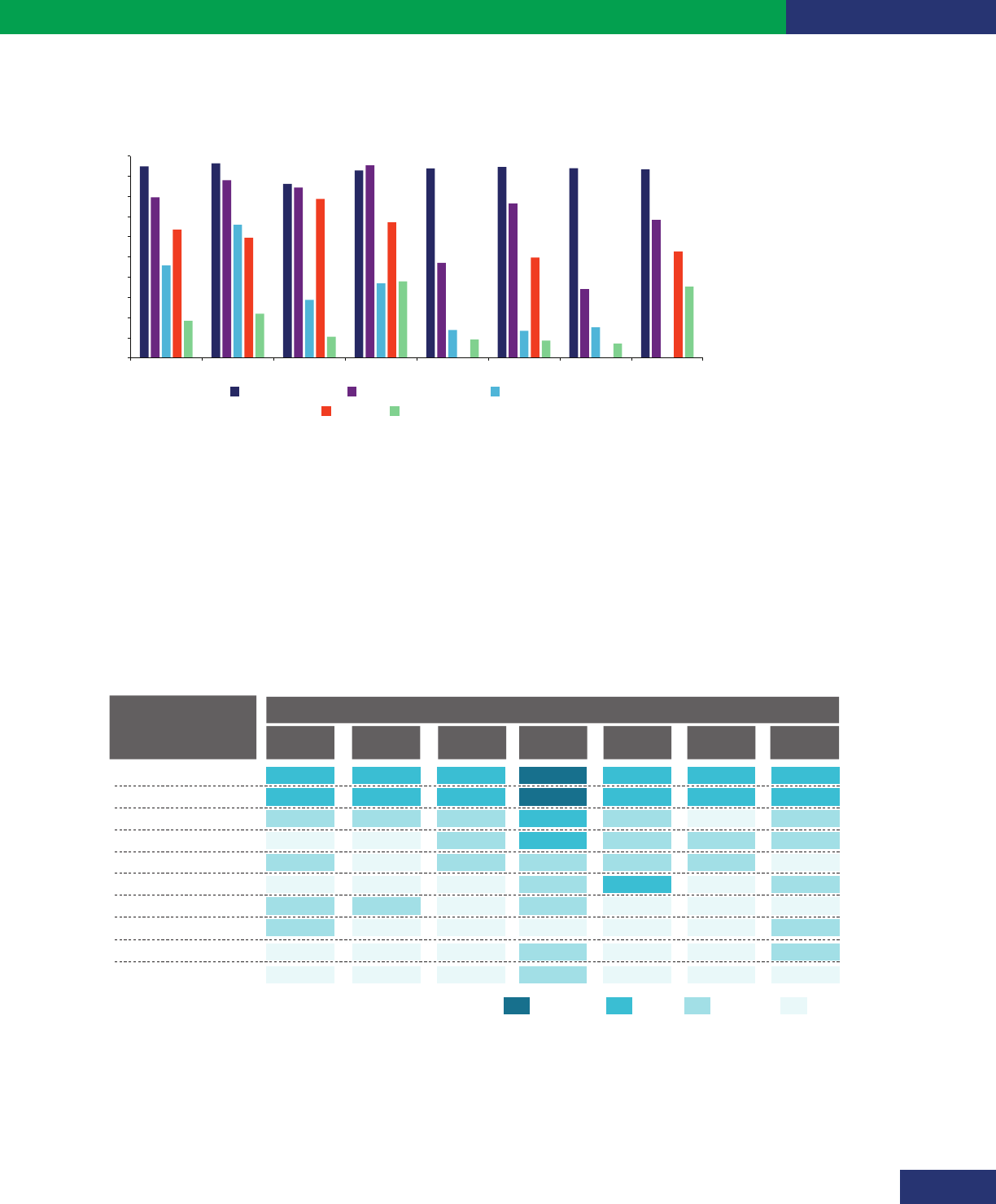

The investment in capital goods required to roll out these networks in the six countries considered

ranges from US$50.8 billion in the urban-suburban scenario to US$ 120.07 billion in national scenario III

(maximumimpact). This implies that telecommunications service operators would have to increase their annual

capital expenditures by between 10% (baseline scenario) and 40% (maximum scenario) from their current

values. The deployment of 5G technology requires the installation of a denser network with greater capillarity.

In addition to telephone antennas and other components, small cells must be installed to extend coverage and

fibre optics to connect the installations. The use of small cells and new multiple-input multiple-output (MIMO)

antenna techniques is a key factor in this cost, since it will mean acquiring and maintaining two to three times

more sites by 2030 than the industry had accumulated in those countries by the end of 2018, assuming that

the number of base stations needs to grow three- or fourfold (see figure I.4).

Figure I.4

Latin America (selected countries): estimated total and annual investment required for mobile

expansion in the next seven years and projected growth in sites needed by 2030

A. Investment needed over seven years

0 5 10 15 20 25 0 10 20 30 40 50

7.4

37.4

12.6

5.2

48.4

9.1

2.6

12.9

5.4

1.7

22.7

5.5

$ 0.79

$ 3.24

$ 0.24

$ 0.78

$ 1.84

$ 0.37

Argentina

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Peru

Mexico

Argentina

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Peru

Mexico

Billions of dollars

Baseline scenario: urban and suburban coverage

Maximum scenario: national coverage III

50.8 billion dollars 120.1 billion dollarsTotal:

$ 1.30

$ 6.92

$ 0.74

$ 1.80

$ 5.34

$ 1.05

Billions of dollars

Figure I.3 (concluded)

Chapter I

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

22

B. Projected growth in sites needed by 2030

1 326

28 183

78 125

34 364

29 776

43 341

168 416

2.1

2.5

2.2

2.6

2.5

2.8

0.5

2030 v. 2018

Argentina

Brazil

Chile

Colombia

Peru

Mexico

Costa Rica

Number of sites

Source: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), on the basis of R. Katz and S. Cabello, The Value of Digital Transformation through

Expansive Mobile in Latin America, New York, Telecom Advisory Services, 2019.

Note: The numbers adjoining the bars are the amount of annual investment (in billions of dollars) required for mobile expansion, assuming an investment horizon of

seven years. The capital spending figures do not include spectrum expenditure.

Infrastructure sharing can be a way to cope with this level of investment. However, it poses challenges for

regulation, as the more infrastructure is shared, the greater the risk of anti-competitive behaviour. Regulatory

attention will need to increase as the number of operators and wholesale networks consolidates and as

sharing needs increase.

In addition to transmission networks, the region needs to be equipped with more information technology

infrastructure to support the exponential growth of data and the provision of new cloud services. According to

the Datacenter Technologies Cooling Market Map Thompson and Wentworth (2019), there are 151 data centres

in the region, located in 24 countries: 118 in South America and 33 in Central America and the Caribbean. The

region has invested very little in data centres in relation to its population (Thompson and Wentworth, 2019)

(see figure I.5). For example, Argentina, with a population of 44 million people, has 30,000 square metres in

operation, the same space as Austin, Texas, with 1.9 million.

Figure I.5

Latin America (6 countries): operational floor area of data centres, multiple operators, 2019

(Thousands of square metres)

18

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110 120 130 140 150 160 170

27

30

54

71

165

Colombia

Peru

Argentina

Chile

Mexico

Brazil

Source: D. Thompson and E. Wentworth, “Buenos Aires: multitenant datacenter market”, Datacenter Technologies Cooling Market Map, New York, 451 Research, 2019.

Figure I.4 (concluded)

Chapter I

Digital technologies for a new future

23

Cloud services have become dominant as drivers of the digital transformation. The cloud provides flexible

information technology resources that create the conditions for transformed business models and service

provision, nimble marketing processes and easy experimentation with new services without the need for new

information technology resources, as well as offering greater cybersecurity. Governments and companies have

slowly adopted the cloud in their operations, but this trend has been accelerated by physical distancing measures.

Teleworking, telemedicine, tele-education, video-conferencing, video on demand, e-commerce, e-banking and

online official procedures are now carried out on a large scale and have become part of everyday life.

The most widely used application is software as a service, with solutions such as email, video conferencing,

office applications, customer relationship management, resource planning, workflow automation and security.

In addition, it enables the use of e-commerce support tools, such as chatbots and messaging, which expand

communication channels with customers. In 2019, software as a service uses constituted almost 50% of the

cloud market in Latin America and the Caribbean, followed by infrastructure as a service uses, with 46%, and

platform as a service uses, with 4.3% (GlobalData, 2020). The region accounts for 8% of global cloud traffic,

and this traffic is expected to grow by 22% on average per year up to 2023.

Internet exchange points (IXPs) are crucial to the digital infrastructure. There are 101 IXPs in Latin America and

the Caribbean, of which 60% are in Argentina and Brazil. In February 2020, the aggregate traffic of all IXPs in the

region averaged 9 terabits per second (Tbps), a figure that increased significantly during lockdowns. In Brazil, it

peaked at 8.79 Tbps in mid-March, as compared to an average of 4.89 Tbps. In Chile, total average traffic increased

from 732 gigabits per second (Gbps) to 1.96 Tbps and has settled at around 1 Tbps (Graham-Cumming, 2020).

There are still very few data centres belonging to content distribution networks (CDNs), although the main

ones have their own points of presence in many Latin American and Caribbean countries, in addition to hundreds

of caches installed at IXPs and in the networks of Internet service providers (ISPs). This is fundamental, since

in the last decade content has been located closer to the user. Some 90% of the content searched for by users

is located two jumps or less (in topological terms) from the user’s ISP. Therefore, although underwater cables

are still essential, it is very important to promote the growth of infrastructure that allows content to be stored

close to the user in order to make access more efficient (IXPs, data centres and caches) (Echeberría, 2020).

Many data centres in the region were built and designed to meet business demand. But now there is

demand for more powerful services, and investment in data centres needs to be increased. Some of the

content distribution network operators are coming up against limits in the data centre market when they try

to set up more points of presence. In the short term, more data centres will be needed to meet demand from

companies as they continue moving their services to the cloud and to respond to higher power requirements.

In sum, the impacts of the digital revolution have become more visible and intensified with the pandemic,

reinforcing long-term trends. As will be seen in the following chapter, applications linked to the remote provision

of education, health and shopping services, as well as those used for teleworking and social connections, have

grown and permeated large areas of society, although digital divides are preventing the universalization of

their use and impact. At the same time, despite the positive effects of dematerialization, digital development

has sustained or even exacerbated growth patterns that are intensive in energy and raw materials, increasing

the generation of greenhouse gases and waste. The positive effects are present and palpable, but so are the

negative effects. Taking advantage of the former while reducing the latter means changing the pattern of digital

progress and setting it on a path of inclusiveness and sustainability. This process is not automatic and involves

all economic and social sectors. The digital revolution must be integrated into a big push for sustainability

by means of a progressive structural change that develops the digital sector in the region through large

investments, that encourages the take-up of these technologies in the production apparatus and governments,

and that universalizes access and develops the capacities required for full use to be made of them. The final

outcome will depend on the implementation of strategies, policies and actions that are timely and capable of

repurposing digitalization in pursuit of sustainable development.

Chapter I

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

24

Bibliography

Accenture (2019), “Buy and own? That’s so yesterday’s model”, Dublin.

Belkhir, L. and A. Elmeligi (2018), “Assessing ICT global emissions footprint: trends to 2040 & recommendations”, Journal

of Cleaner Production, vol. 177, Amsterdam, Elsevier, March.

ECLAC (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean) (2020), Building a New Future: Transformative

Recovery with Equality and Sustainability (LC/SES.38/3-P/Rev.1), Santiago, October.

(2018), Data, Algorithms and Policies: Redefining the Digital World (LC/CMSI.6/4), Santiago, April.

(2016), The new digital revolution: From the consumer Internet to the industrial Internet (LC/L.4029(CMSI.5/4)/Rev.1),

Santiago, August.

ECLAC/CAF (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean/Development Bank of Latin America) (2020),

Las oportunidades de la digitalización en América Latina frente al COVID-19, Santiago, April.

Ekholm, B. and J. Rockström (2019), “Digital technology can cut global emissions by 15%. Here’s how”, Cologny, World

Economic Forum (WEF), 15 January [online] https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/why-digitalization-is-the-key-

to-exponential-climate-action/.

Echeberría, R. (2020), “Infraestructura de Internet en América Latina: puntos de intercambio de tráfico, redes de distribución

de contenido, cables submarinos y centros de datos”, Productive Development series, No. 226 (LC/TS.2020/120),

Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), November.

Euromoney Global Limited (2019), TowerXchange Americas Dossier 2019, London.

GeSI (Global e-Sustainability Initiative) (2015), #SMARTer2030: ICT Solutions for 21st Century Challenges, Brussels, June

[online] https://smarter2030.gesi.org/downloads/Full_report.pdf.

GlobalData (2020), “Demand for hybrid cloud solutions drives 22.4% CAGR increase in Latin America’s cloud computing

services market from 2019 to 2023”, London, 4 February [online] https://www.globaldata.com/demand-for-hybrid-cloud-

solutions-drives-22-4-cagr-increase-in-latin-americas-cloud-computing-services-market-from-2019-to-2023/.

Graham-Cumming, J. (2020), “Internet performance during the COVID-19 emergency”, San Francisco, Cloudflare, 23 April

[online] https://blog.cloudflare.com/recent-trends-in-internet-traffic/.

IEA (International Energy Agency) (2017), Digitalization and Energy, Paris.

Katz, R. and S. Cabello (2019), The Value of Digital Transformation through Expansive Mobile in Latin America, New York,

Telecom Advisory Services.

Malmodin, J. and D. Lunden (2018), “The energy and carbon footprint of the global ICT and E&M sectors 2010–2015”,

Sustainability, vol. 10, No. 9, Basel, Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute (MDPI), August.

Micron Technology (2020), “5G, AI, and the Coming Mobile Revolution”, Boise [online] https://www.micron.com/insight/5g-

ai-and-the-coming-mobile-revolution.

OECD (Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development) (2020), Latin American Economic Outlook 2020: Digital

Transformation for Building Back Better, Paris.

Putkonen, R. and U. Tikkanen (2019), “MaaS, EVs and AVs: how Helsinki became a transport trendsetter”, Kent, Intelligent

Transport, 21 August [online] https://www.intelligenttransport.com/transport-articles/86384/maas-ev-av-helsinki-trendsetter/.

Siemens (2020), “Industrial 5G: for the industry of tomorrow”, Munich [online] https://new.siemens.com/global/en/products/

automation/industrial-communication/5g.html.

Thompson, D. and E. Wentworth (2019), “Buenos Aires: multitenant datacenter market”, Datacenter Technologies Cooling

Market Map, New York, 451 Research.

UNEP (United Nations Environment Programme) (2019), “Chinese initiative Ant Forest wins UN Champions of the Earth

award”, Nairobi, 19 September [online] http://www.unenvironment.org/news-and-stories/press-release/chinese-initiative-

ant-forest-wins-un-champions-earth-award.

Chapter II

Digital technologies for a new future

25

Digitalization for social

welfare and inclusion

A. Divides in broadband access

B. The use and take-up of digital technologies

C. Universalizing access

Bibliography

CHAPTER

II

Chapter II

Digital technologies for a new future

27

A. Divides in broadband access

The digital revolution has changed and will continue to change consumption, production and business models. In

addition to increasing the productivity and well-being of users, these changes can fit well with objectives of growth,

employment, inclusion and environmental sustainability (ECLAC, 2020c).

However, this does not happen automatically; rather, the development and adoption of digital solutions are

strongly influenced by structural factors. In countries where production structures are excessively heterogeneous

and undiversified in product terms and where there are highly informal and insecure labour markets and

socioeconomic constraints on access and connectivity, a large part of society is unable to appropriate the value

generated by digital technologies. In particular, connectivity, understood as adequately fast broadband and

ownership of access devices, affects the exercise of the rights to health, education and work, and the lack of it

can lead to increased socioeconomic inequalities.

Digital development that does not respect human rights in the digital environment (digital rights) and that is

not based on principles of inclusion and sustainability can reinforce patterns of social exclusion and unsustainable

methods of resource exploitation and production, as well as exacerbating their negative environmental impacts.

In this case, the net effect will depend on the way in which business strategies tie in with policy actions aimed

at steering digitalization towards development with equality and sustainability.

Inclusion, as a way of being in or belonging to a society, is affected by the digital revolution and the ability

of individuals, society, markets and States to adapt and respond. Moreover, the pandemic and compulsory

lockdowns have created a need to find new ways of sustaining social and civil practices through digital platforms.

It is thus urgently necessary to strengthen digital citizenship associated with the way people participate in the

digital society and economy. It is also necessary to understand the new forms of power and the new public

sphere emerging from the digital realm, dominated as this is by a few global companies. Although the digital

space could be thought of as a continuation of the analogue space, it also involves new tools and forms of

participation (ECLAC, 2016; Claro and others, 2020).

Digital citizenship requires people to have new capabilities and skills if they are to be part of this new way of

being a citizen. Digital transformation in Latin America and the Caribbean is taking place in a context of structural

inequality which influences the different fields of action and results. This will prevent many people from taking

advantage of the opportunities offered by new technologies unless action is taken to make these opportunities

visible and equalize access to them. Thus, public policies have an increasing role to play in ensuring that the changes

resulting from the digital transformation pave the way for faster progress with inclusive social development and

do not widen gaps in a region with high levels of inequality in several dimensions of development.

As of 2019, 66.7% of the inhabitants of Latin America and the Caribbean used the Internet. This is remarkable

in terms of the speed and extent of the spread of a technology in the region, and was possible because the

incorporation of technological progress has been combined with strategies of vigorous competition by private

or public companies (depending on the country) and with the implementation of support and regulatory policies

for the sector. Despite this great progress, one in three inhabitants of the region has limited or no access to

digital technologies because of their economic and social situation, with the main variables being income, age

and place of residence.

The context of the pandemic has highlighted the benefits of using digital technologies in different economic

and social spheres. However, it has also shown that these benefits are not within the reach of everyone, owing

to the different dimensions of the divides in access to and use of these technologies. Divides in access, in

uses and skills and in opportunities for inclusion in an increasingly digitalized world are reproduced along the

main lines of the region’s social inequality matrix, which includes socioeconomic status, stage in the life cycle,

geographical location, ethnic or racial origin and gender inequalities, among other dimensions (ECLAC, 2016).

One of the main determinants of access is income. The lowest-income quintiles are those with the most

individuals and households excluded from Internet access (see figure II.1). Despite the increase in access

between 2010 and 2018, income-related gaps remain. There are also major differences in the situations of the

region’s countries. For example, Costa Rica has a higher proportion of households with Internet access in the

first quintile (the poorest) than the Plurinational State of Bolivia has in the fifth quintile (the richest).

Chapter II

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

28

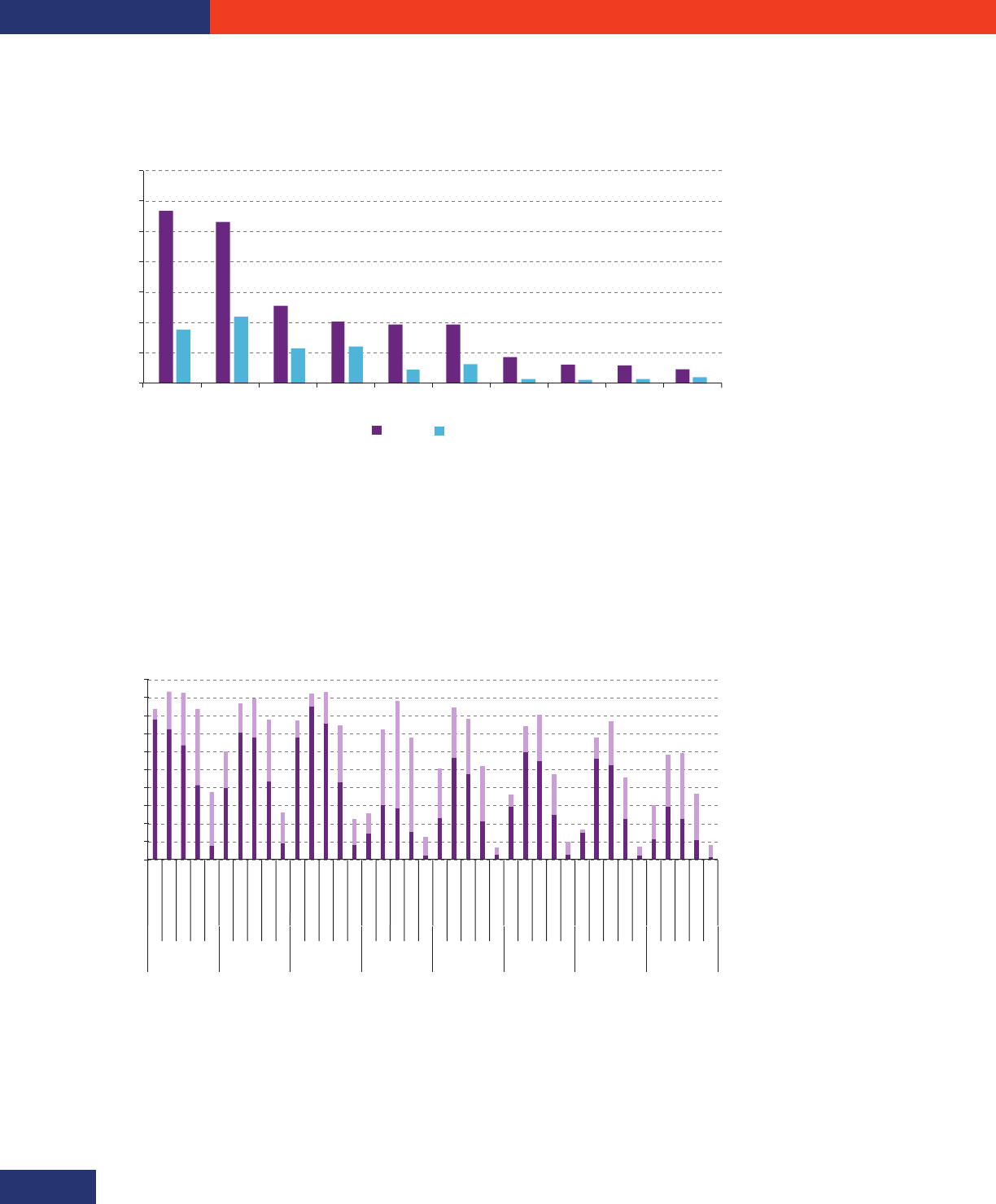

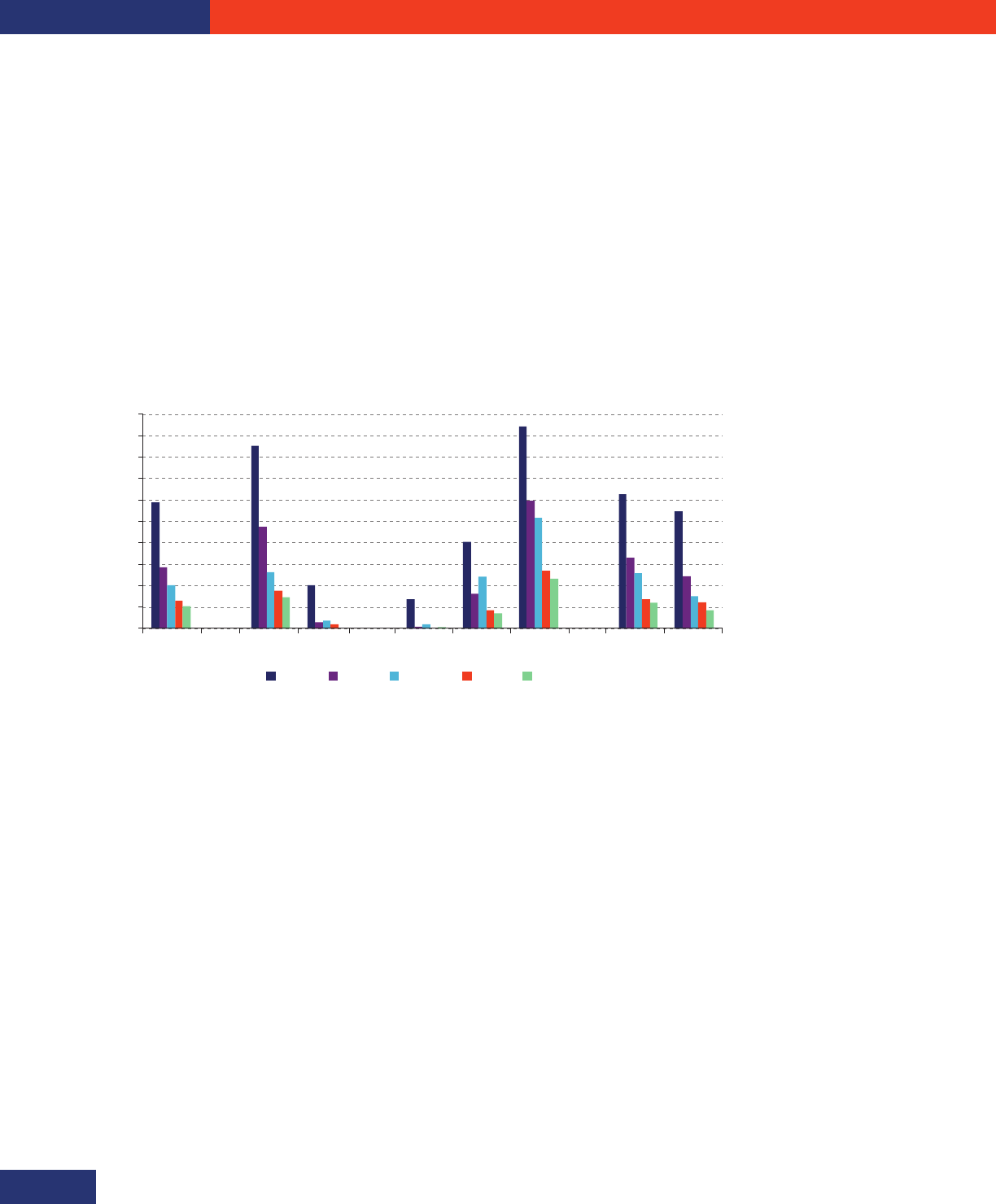

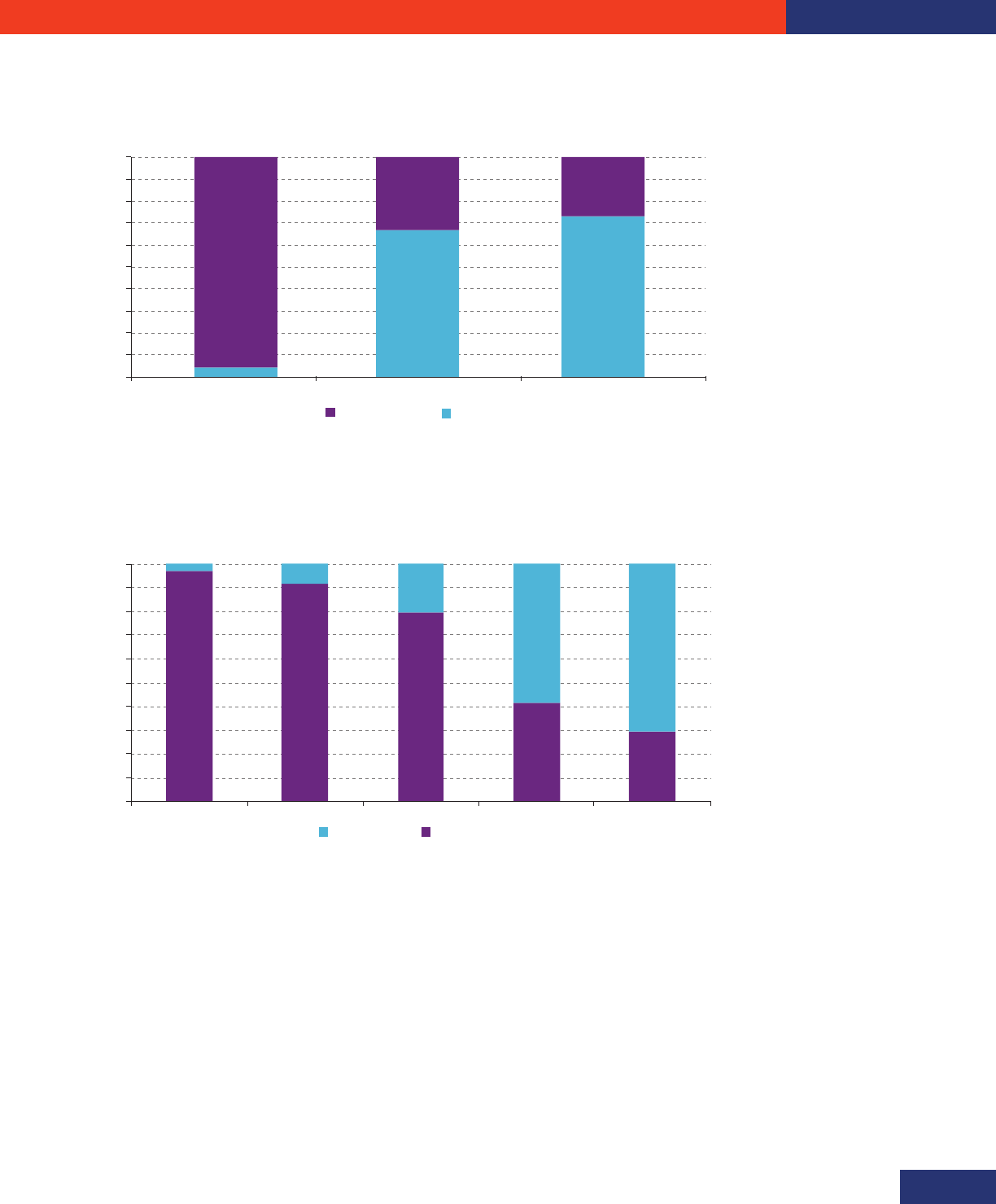

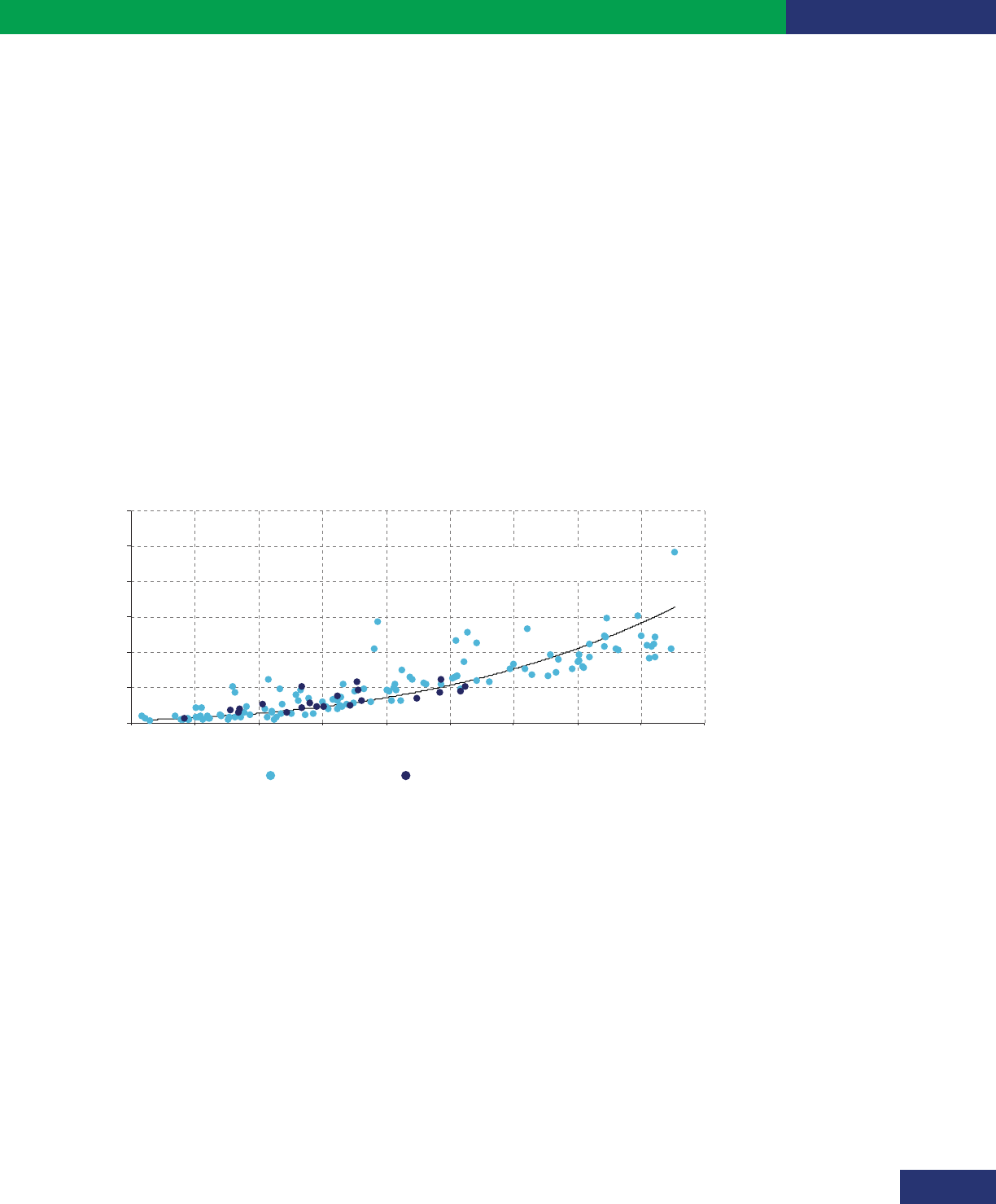

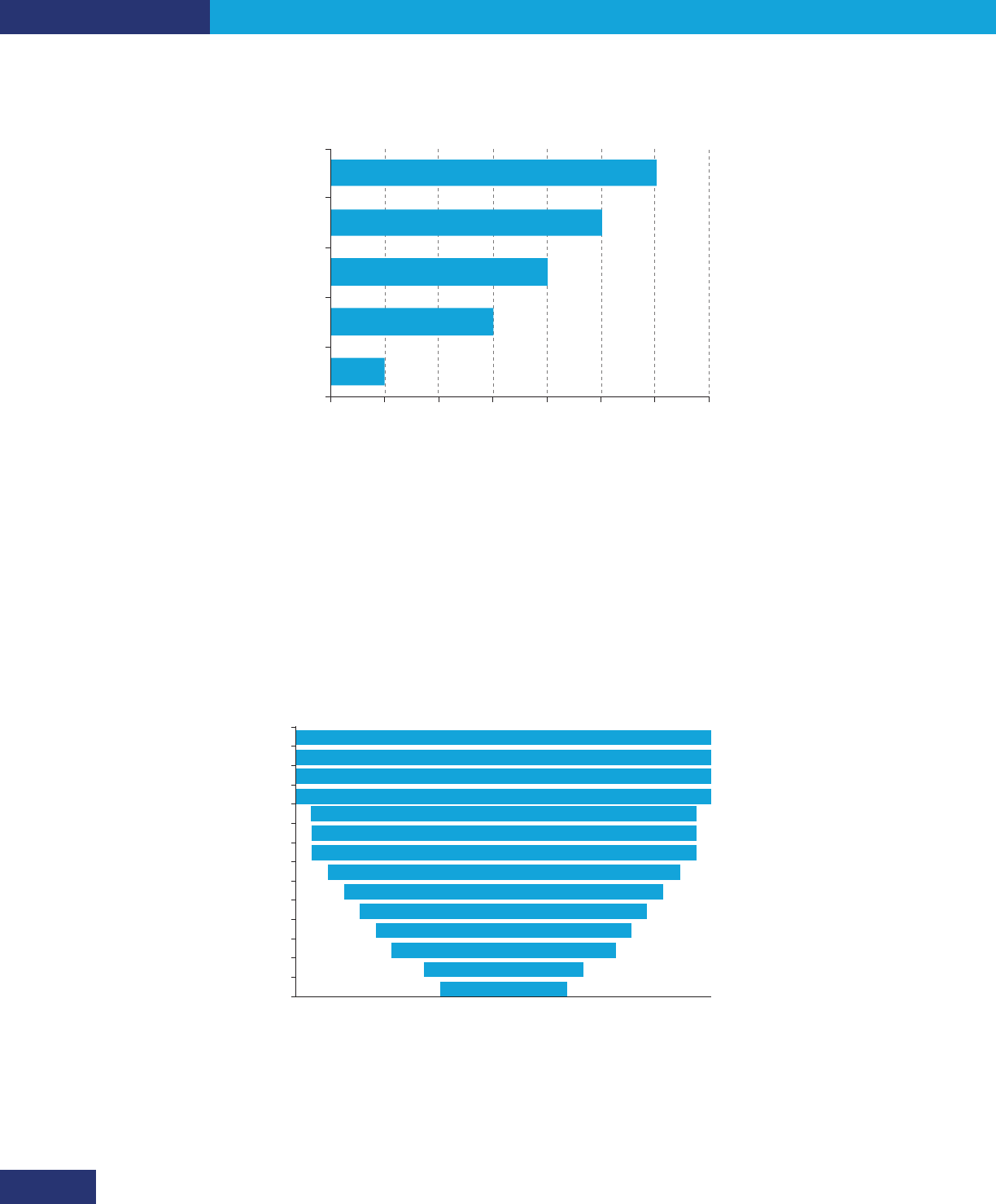

Figure II.1

Latin America (10 countries): ratios between the number of households with Internet access

in the top and bottom income quintiles, 2010 and 2018

(Multiples)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Peru Paraguay

Bolivia

(Plur. State of)

El Salvador Ecuador Mexico Costa Rica Chile Brazil Uruguay

2010 2018

Source: Regional Broadband Observatory, on the basis of Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

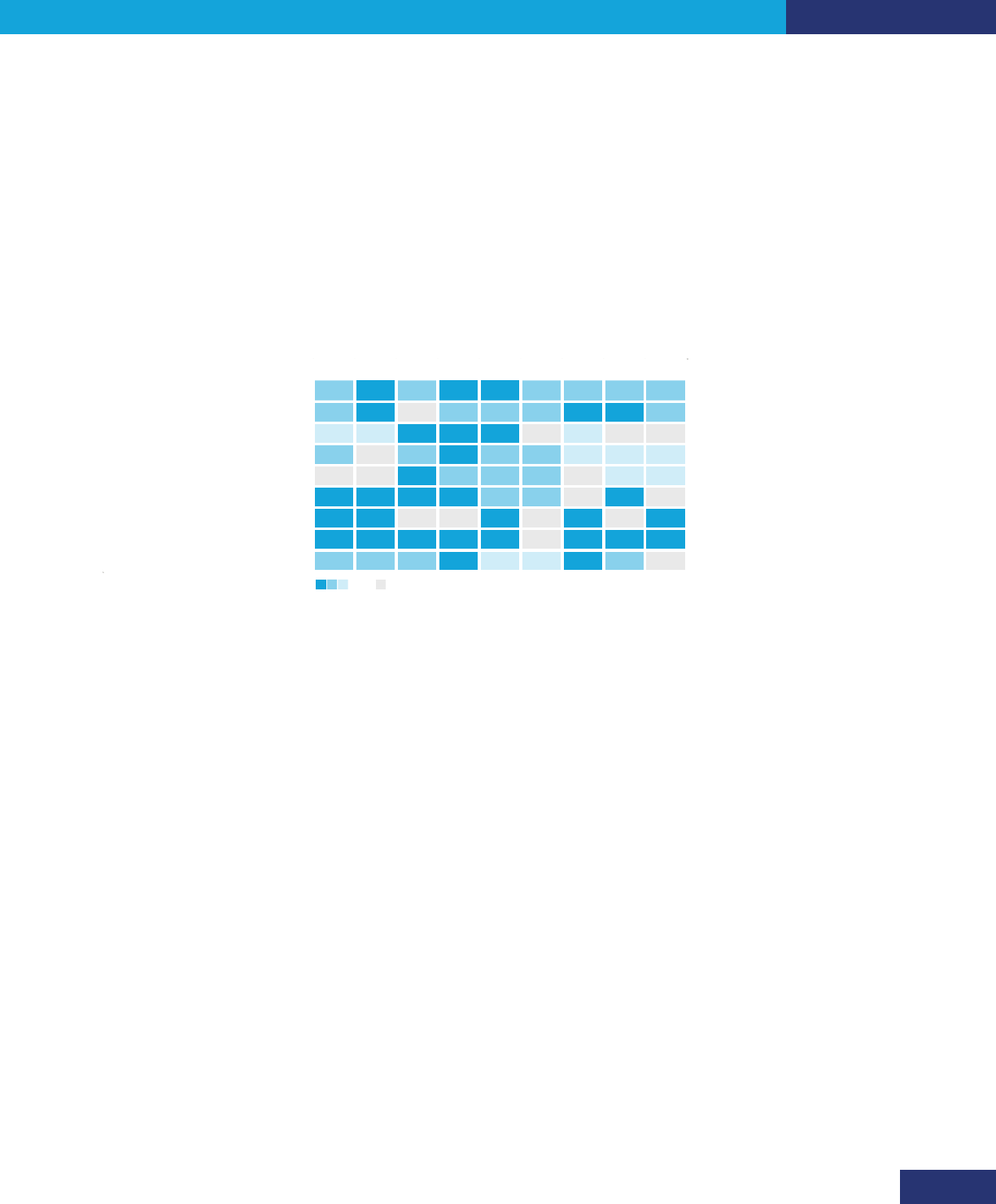

The age groups with the lowest proportions of Internet users are children aged 5 to 12 and adults over 66,

except in Uruguay and Chile (see figure II.2). This situation has remained fairly stable over time despite the increase

in usage in all countries. As early as 2010, Internet use was already high among children aged 5to12 and young

people aged 13 to 20 in Uruguay, possibly as a result of the implementation of the CeibalPlan, created in 2007.

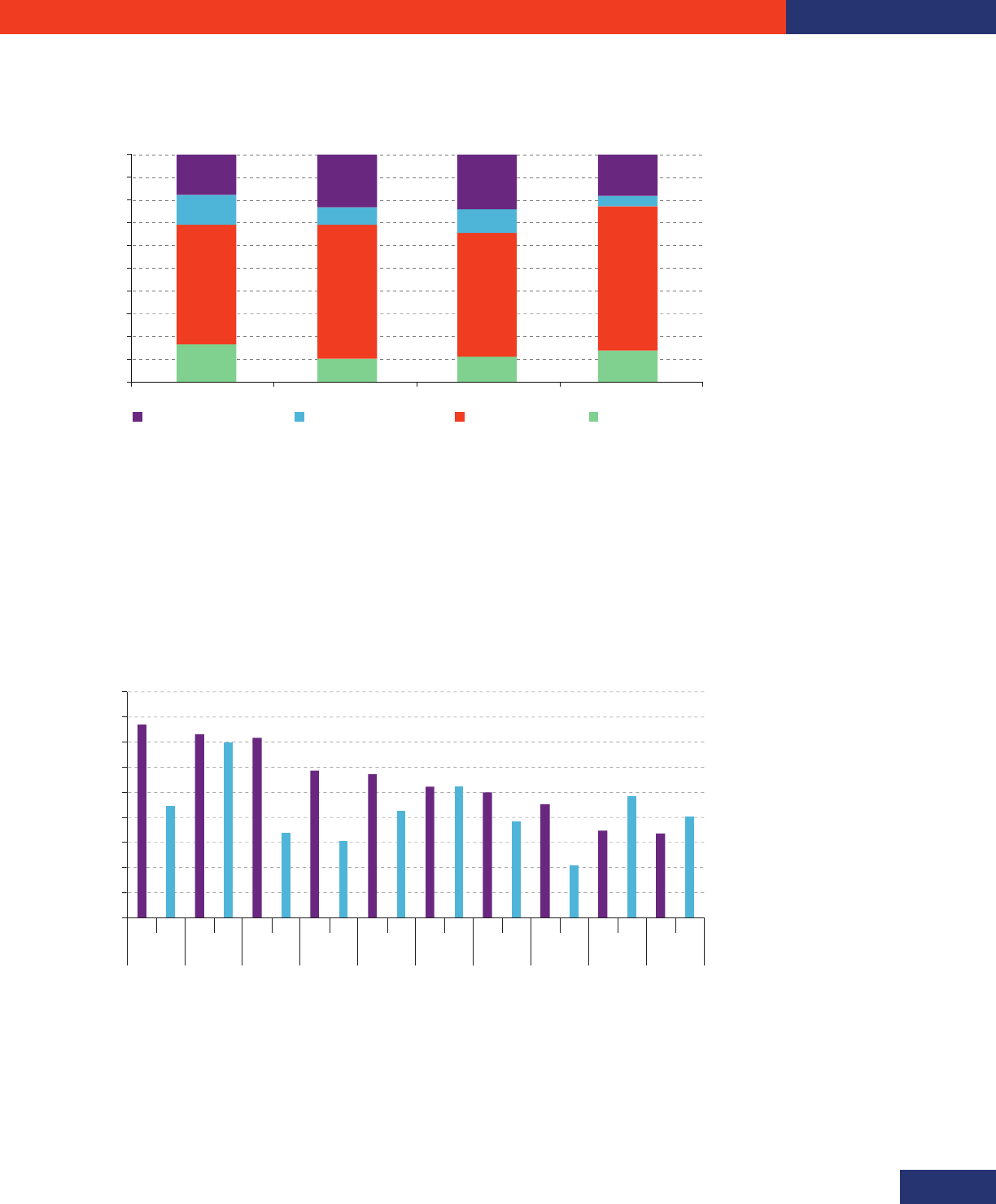

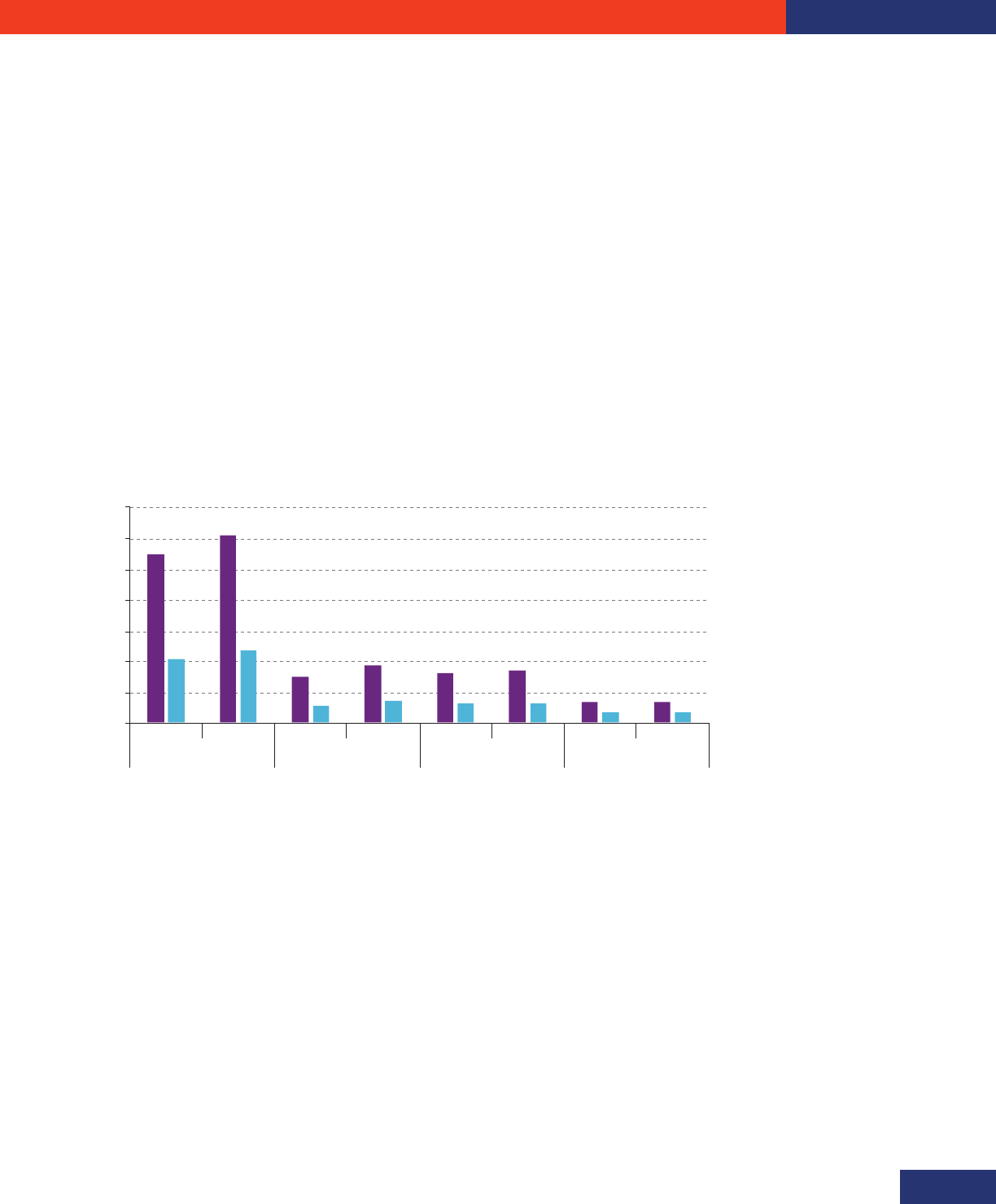

Figure II.2

Latin America (8 countries): Internet users by age group, 2010 and 2018

(Percentages)

Uruguay Costa Rica Chile Paraguay Ecuador Peru Bolivia

(Plur. State of)

El Salvador

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

5–12

13–20

21–25

26–65

66 years and over

Source: Regional Broadband Observatory, on the basis of Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

Note: Dark colours show the situation in 2010 and the sum of dark and light colours that in 2018.

The type of device and the ability to stay connected in different places substantially affect the development

of children’s and adolescents’ digital skills. The predominant form of access is from a mobile phone at home,

and the least common is ubiquitous multi-device access, i.e., access from several places using different

devices, which can be associated with more highly developed digital skills (see figure II.3).

Chapter II

Digital technologies for a new future

29

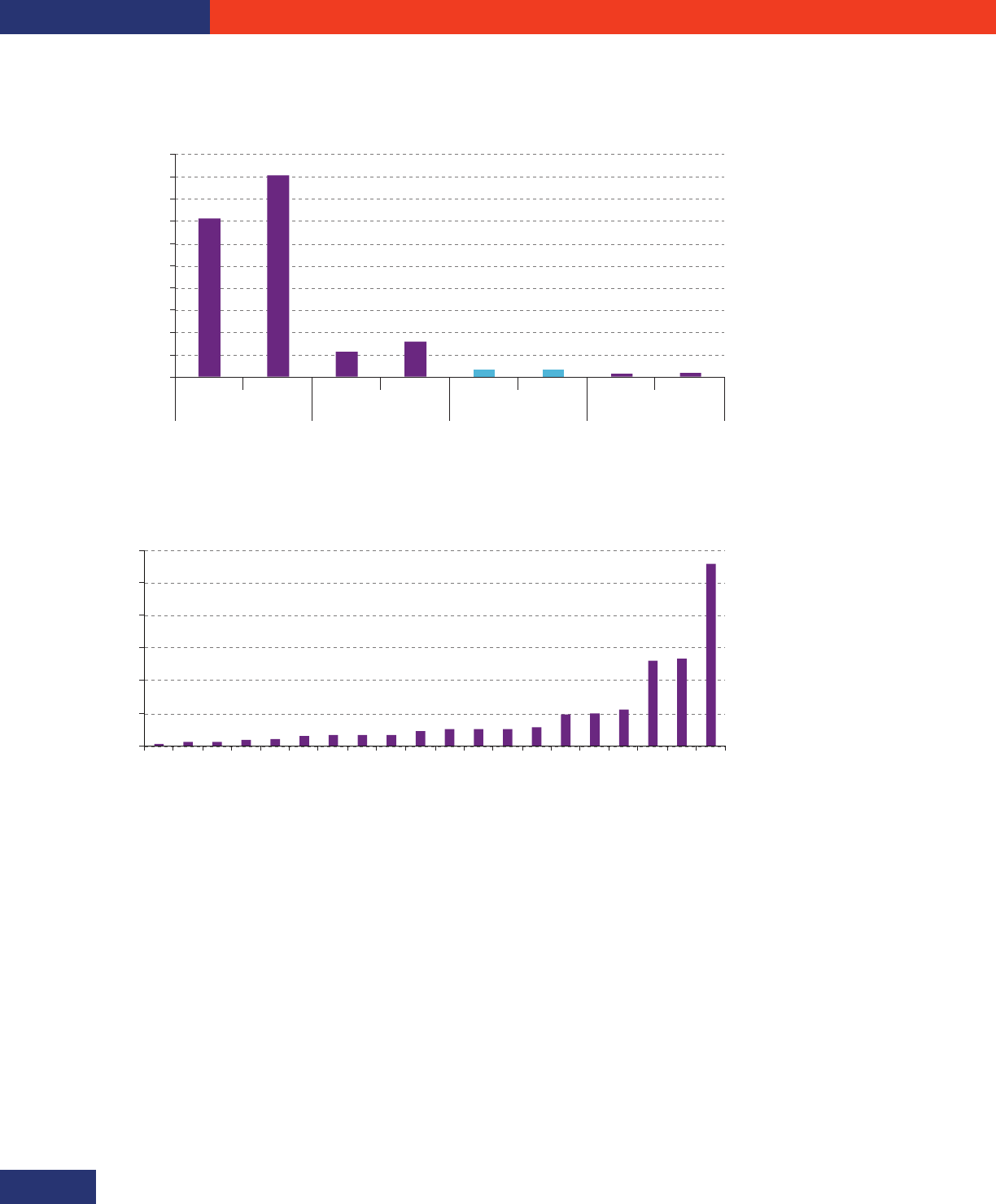

Figure II.3

Latin America (4 countries): methods of physical access employed by child and adolescent Internet users, 2016-2018

(Percentages)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

16.6

10.3

11.1

13.9

52.5

59.1

54.4

63.4

13.3

7.5

10.5

4.8

17.6

23.1

24.0

17.9

Brazil Chile Costa Rica Uruguay

Home (multi-device)Home (mobile phone)Everywhere (multi-device)Everywhere (mobile phone)

Source: D. Trucco and A. Palma (eds.), “Infancia y adolescencia en la era digital: un informe comparativo de los estudios de Kids Online del Brasil, Chile, Costa Rica y

el Uruguay”, Project Documents (LC/TS.2020/18/Rev.1), Santiago, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2020.

Note: There are limitations on the comparability of the four countries’ data, mainly due to differences in sample designs and the inclusion of different variables for

ascertaining key dimensions, such as the socioeconomic level of the population surveyed.

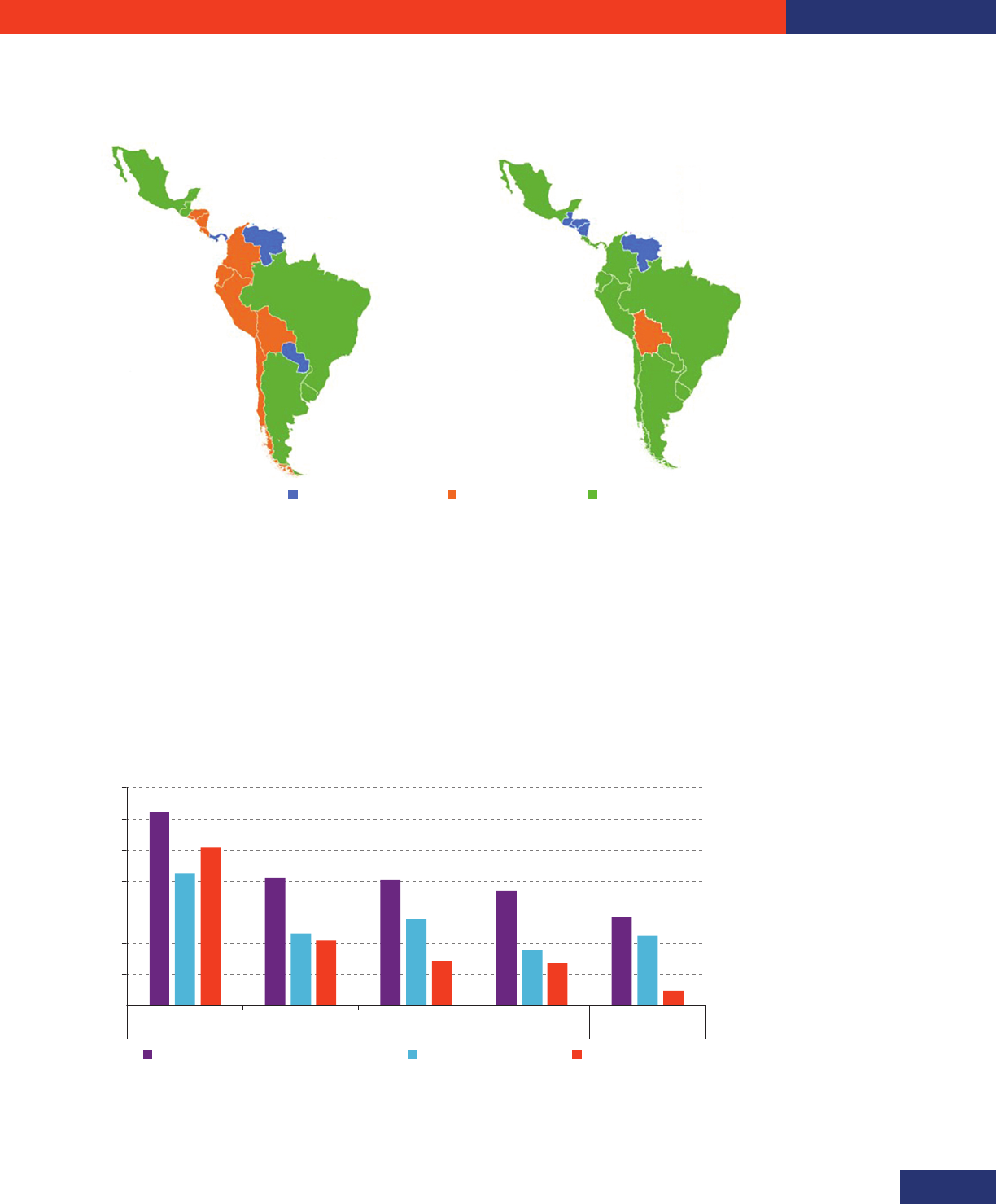

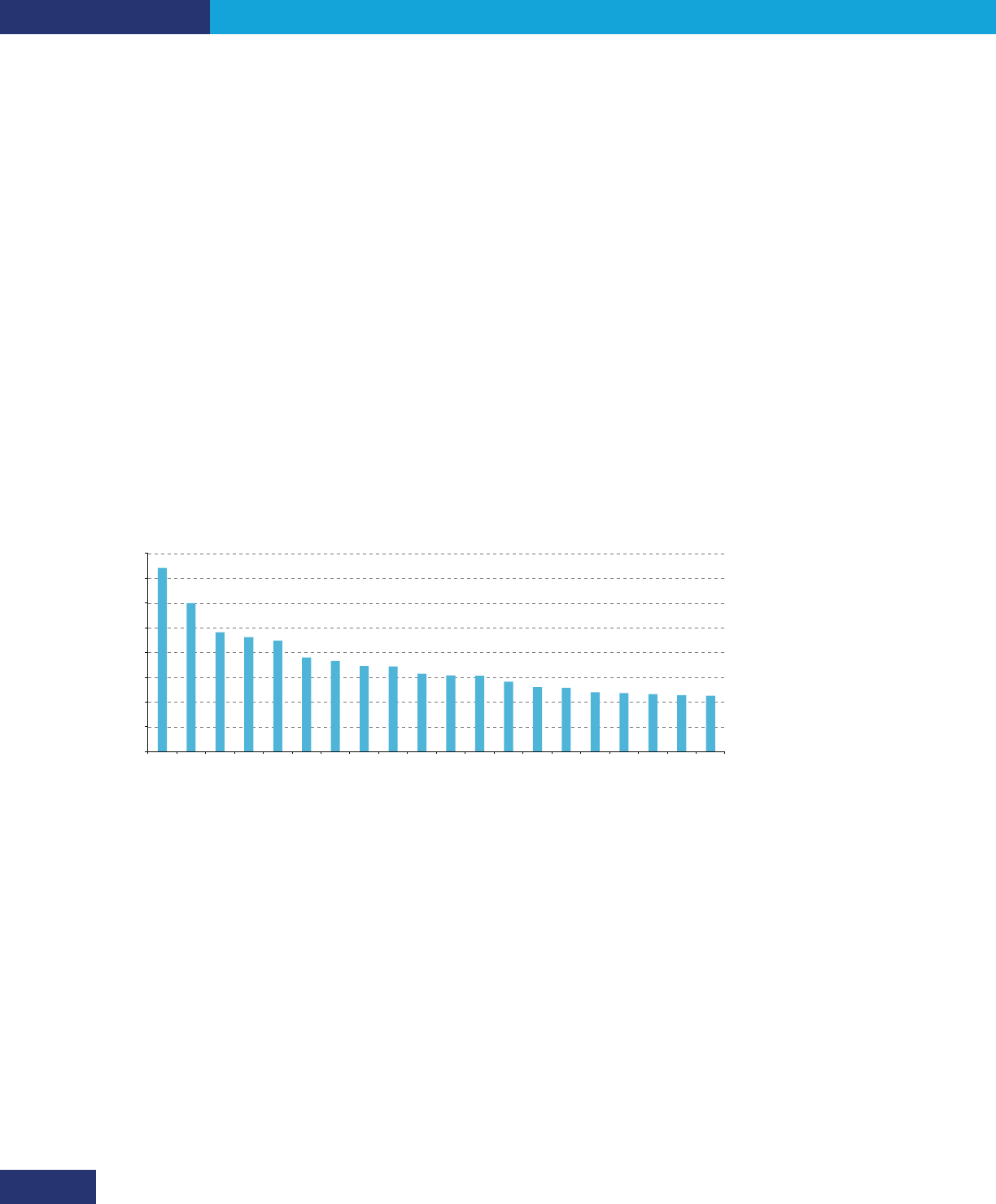

In the countries included in figure II.4, with the exceptions of Uruguay and Costa Rica, the gap between

urban and rural households increased during the period from 2010 to 2018, in some cases even doubling. This

increase was generally due to faster growth in the number of users in urban areas.

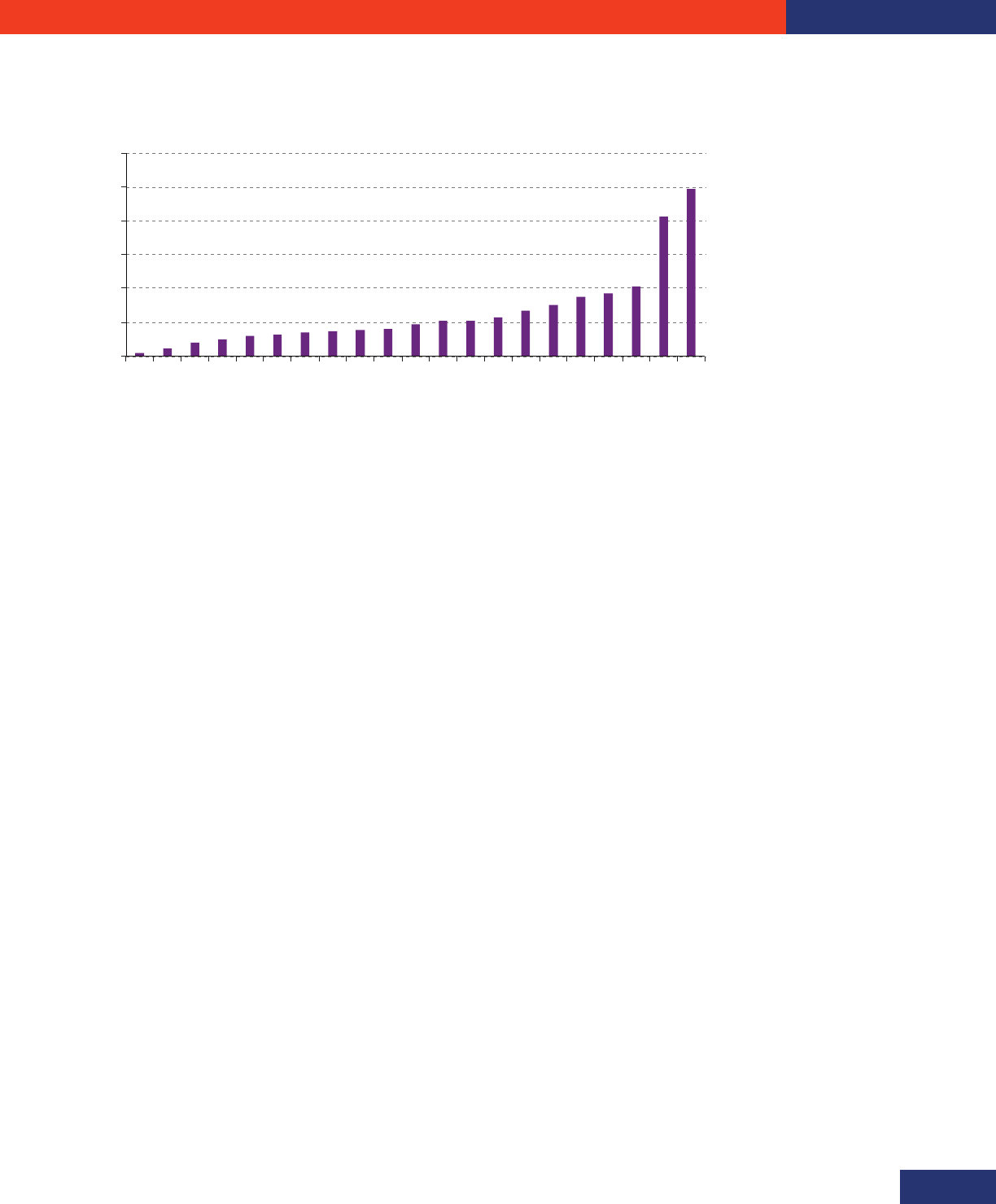

Figure II.4

Latin America (10 countries): access divides between urban and rural households, 2010 and 2018

(Percentage points)

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

40

45

2018 2010 2018 2011 2018 2010 2017 2010 2018 2013 2017 2009 2018 2010 2018 2011 2018 2011 2018 2010

Mexico Brazil Peru Ecuador El Salvador Chile Paraguay

Bolivia

(Plur. State of)

Costa Rica Uruguay

Source: Regional Broadband Observatory, on the basis of Household Survey Data Bank (BADEHOG).

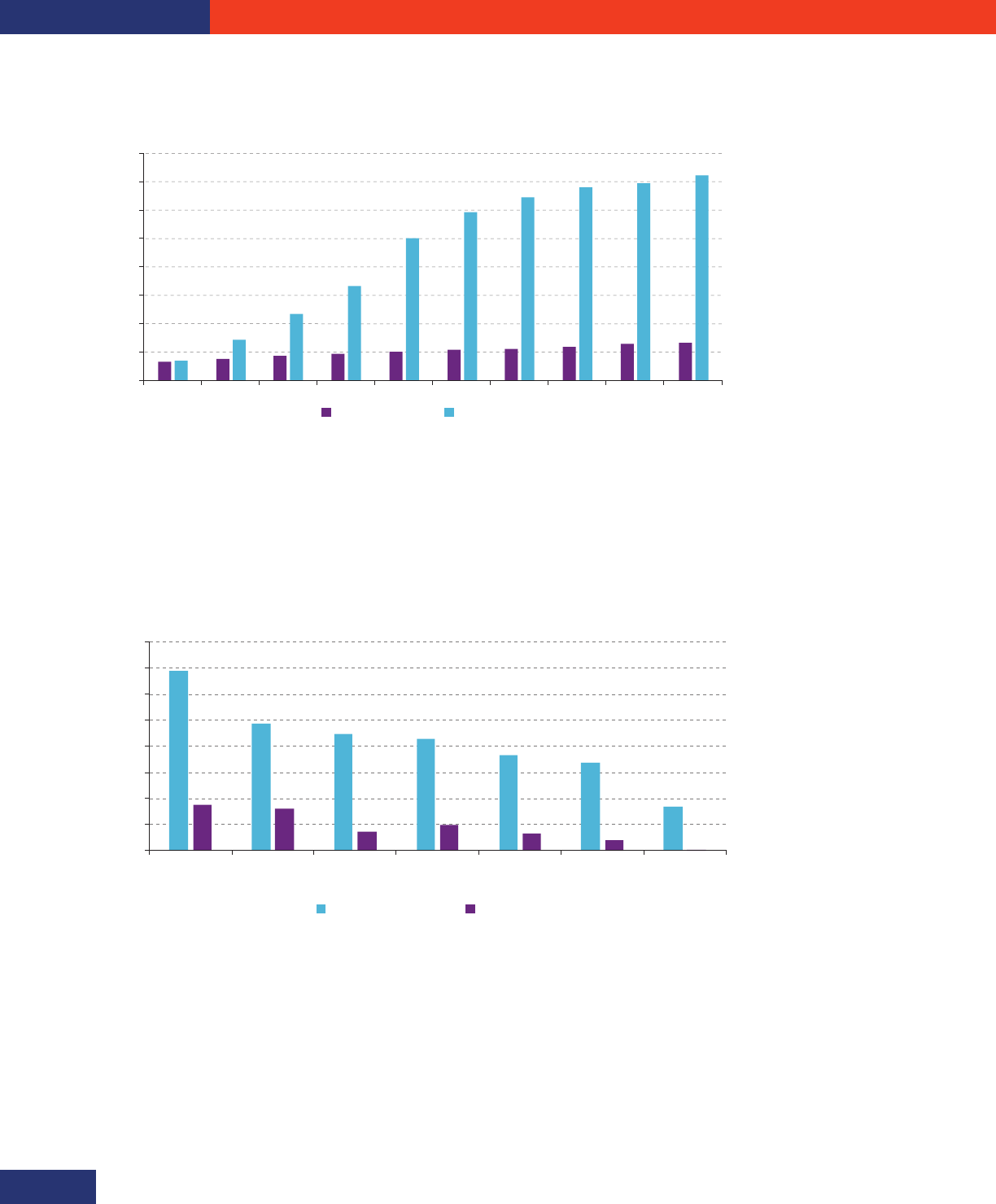

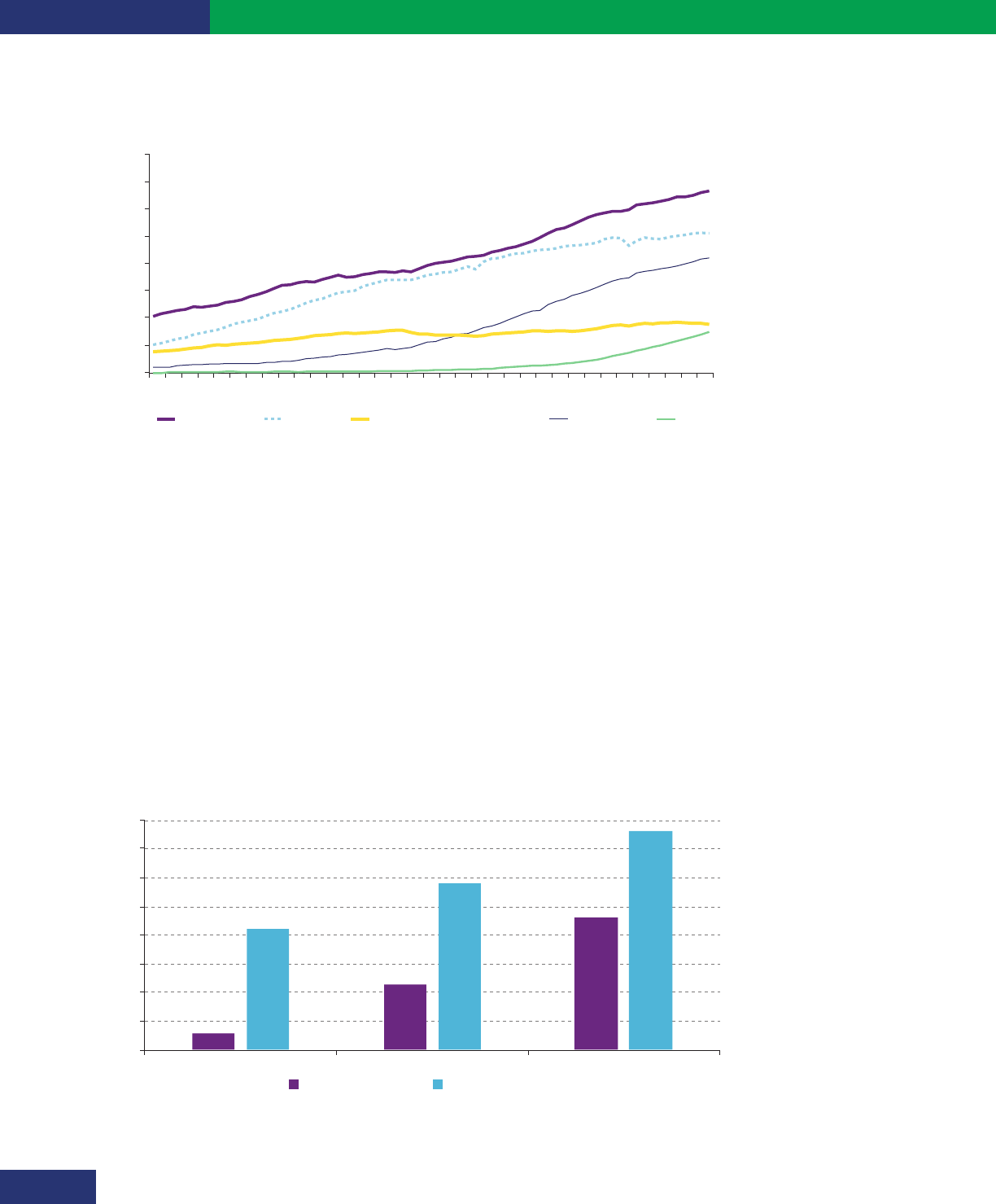

The percentage of the population with a mobile broadband subscription increased tenfold from 2010 to 2018,

rising from about 7% to 73%. In contrast, growth in fixed broadband access was much lower, rising from

6.6% to 13.3% over the same period (see figure II.5).

Chapter II

Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC)

30

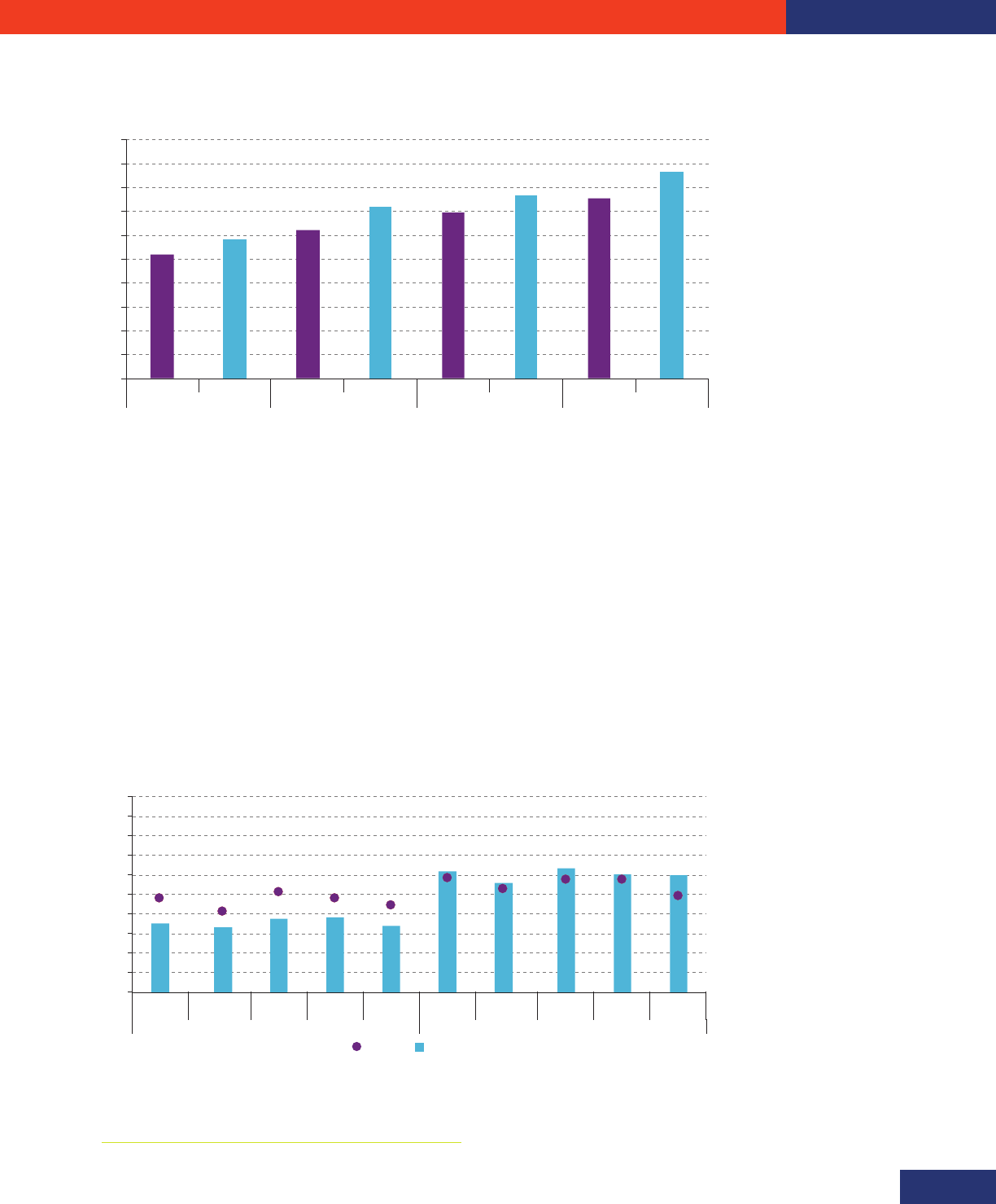

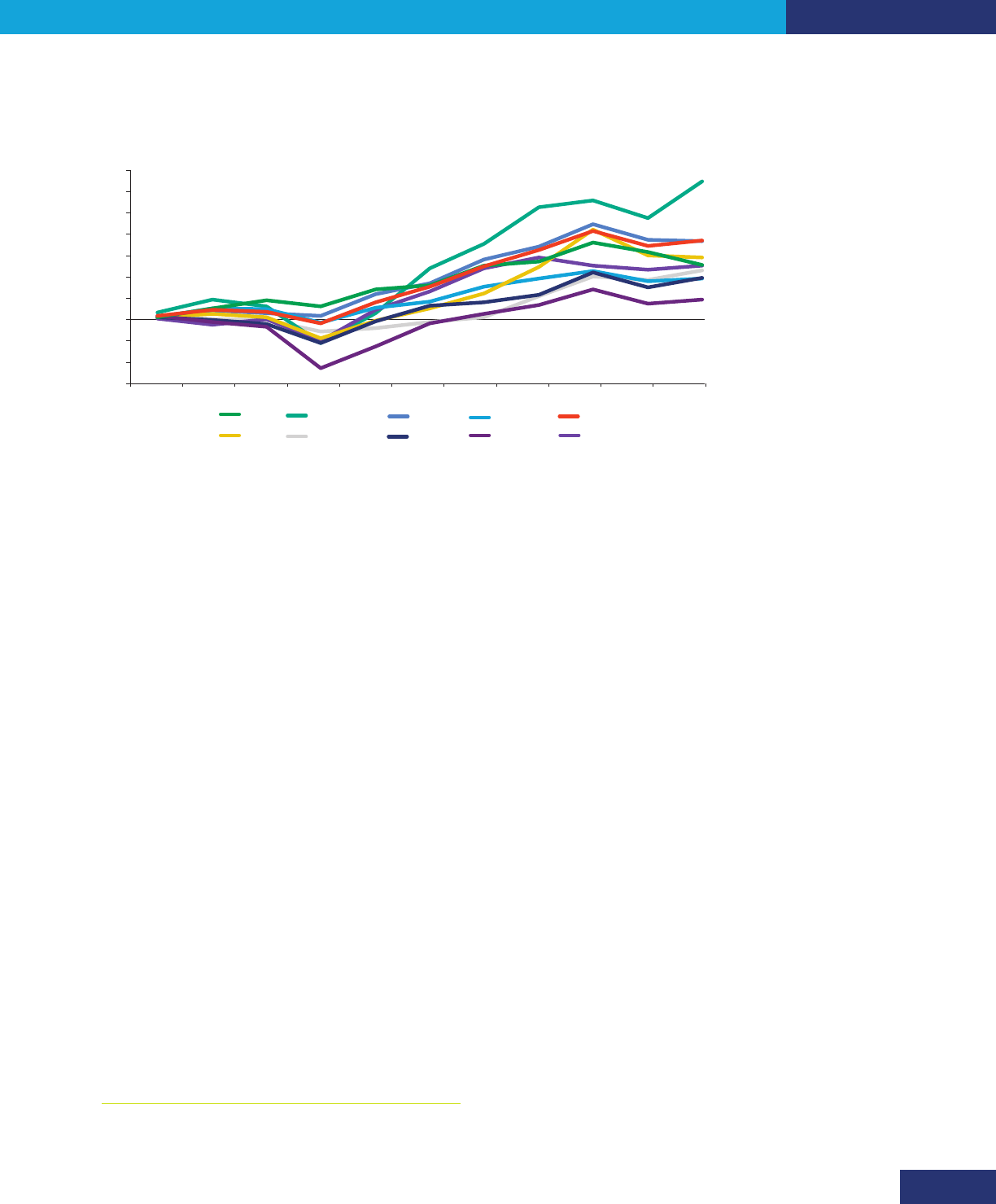

Figure II.5

Latin America and the Caribbean: fixed and mobile broadband subscriptions, 2010-2019

(Percentages of the total population)

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019

Fixed broadband

Mobile broadband

Source: Regional Broadband Observatory.

Latin America and the Caribbean lags behind other regions of the world in the percentage of the population

with mobile and fixed broadband subscriptions. In both cases, the region is ahead of only the Arab and African

countries (see figure II.6).

Figure II.6

Fixed and mobile broadband subscriptions, 2019

(Percentages of the population)

137.6

97.4

89.0

85.4