The California Academy of Sciences

This San Francisco museum designed an iconic, sustainable building to attract visitors and

deepen their connection with the natural world.

CASE

STUDY

2

Organization

The California Academy of Sciences

Location

San Francisco, California, USA

Construction Type

New construction

Opening Date

2008

Project Area

410,000 sqaure feet

Project Cost

$488 million

S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation Investment

$2.5 million

Executive Summary

United States of

America

e California Academy of Sciences (the Academy) is a scientic

and educational institution in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park.

Founded in 1853, the Academy conducts research and operates

a museum that educates visitors about the natural world. Over

decades, a series of ad hoc additions to the original facility created

physical separation between museum departments and exhibitions,

inhibiting cross-disciplinary research and preventing visitors from

experiencing the full breadth of the Academy’s oerings. Following

years of waning attendance and the eects of a devastating 1989

earthquake, the Academy launched an eort to renovate its damaged

aquarium. However, strong support from its local community and

private donors encouraged the Academy to think bigger—leading to a

decision to reconstruct the entire facility.

e Academy recognized that this capital project held potential

to amplify the organization’s mission and establish it as a leader in

environmental sustainability. By developing an environmentally-

friendly building and interactive exhibits, the Academy sought to

respond to contemporary conservation issues while inviting visitors to

explore, learn about, and protect the natural world.

e project team chose Renzo Piano, a world-renowned architect,

to design an iconic facility that would be a symbol of sustainability.

e signature element of Piano’s concept was a living roof with

undulating hills echoing the landscape surrounding the museum. A

pair of impressive three-story domes, each 90 feet in diameter, would

contain the museum’s rainforest exhibit and planetarium. While

this ambitious project vision contributed to dramatically increased

construction and overall project costs, the innovative green design

also attracted donors who supported the expanded scope.

Today, the Academy houses an aquarium, planetarium, and natural

history museum, as well as scientic research and education programs

under one roof. It is the world’s rst LEED

i

Double Platinum

museum, and the largest Double Platinum building on the planet.

Visitor attendance has nearly doubled since the building opened,

with guests of all ages beneting from engaging learning experiences.

e new facility has also enabled better collaboration across sta

departments, and inspired the Academy to focus its research on

critical environmental concerns. is project inuenced the Academy

to evolve its mission, from “explore and explain the natural world” to

“explore, explain, and sustain life on Earth.”

is case study is based on research conducted by MASS Design

Group in November 2015. Funded by the S. D. Bechtel, Jr.

Foundation, this case illustrates how a capital project can require a

balance between an organization’s internal sta needs and external

aspirations—and how a visionary design can bring both benets and

risks. It also demonstrates how a temporary space can help leaders

advance operations and program changes prior to moving to a new

building.

i LEED, or Leadership in Energy & Environmental Design, is a

globally recognized symbol of excellence in green building. Source: http://

www.usgbc.org/articles/about-leed.

3

Capital projects often bring lasting benets to nonprot organizations and the people they serve.

Given this opportunity, foundations grant more than $3 billion annually to construct or improve

buildings in the United States alone.

ii

Each capital project aects an organization’s ability to

achieve its mission—signaling its values, shaping interaction with its constituents, inuencing its

work processes and culture, and creating new nancial realities. While many projects succeed in

fullling their purpose, others fall short of their potential. In most instances, organizations fail to

capture and share lessons learned that can improve practice.

To help funders and their nonprot partners make the most of capital projects, e Atlantic

Philanthropies and the S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation commissioned Purpose Built—a multi-

faceted study by MASS Design Group, a nonprot architecture and research rm. In 2015 and

2016, MASS conducted interviews, reviewed literature, and examined a diverse set of completed

projects around the world; each project was supported by one of the above funders.

e study generated a set of core principles as well as tools for those considering or conducting

capital projects:

See the full Purpose Built series online at www.massdesigngroup.org/purposebuilt.

ii Foundation Center, Foundation Maps data based on grants made in the United States, 2006-2015.

Purpose Built Series

Introducing the Purpose Built Series is an overview of the study and its core

principles.

Purpose Built Case Studies report on 15 projects to illustrate a range of

intents, approaches, and outcomes.

Charting Capital Results is a step-by-step guide for those evaluating

completed projects.

Planning for Impact is a practical, comprehensive tool for those initiating

capital projects.

Making Capital Projects Work more fully describes the Purpose Built

principles, illustrating each with examples.

4

Introduction

A STORIED HISTORY AND CONNECTION TO COMMUNITY

e California Academy of Natural Sciences was established in

San Francisco in 1853 during the Gold Rush years. Its stated aim

was to systematically survey the new state of California and collect

“rare and rich” natural specimens.

1

Two decades later, the renamed

California Academy of Sciences (the Academy) opened as the city’s

rst public museum.

2

Since the end of the 19

th

century, the Academy

has conducted scientic research while also operating a museum to

educate visitors about the natural world.

After the Great Quake of 1906 destroyed the Academy’s original

structure in downtown San Francisco, the museum moved to Golden

Gate Park—opening there in 1916. With funding from the estate of a

prominent local banker, Steinhart Aquarium was added to the facility

in 1923.

3

During this era, an important and enduring relationship

between the City of San Francisco and the Academy took shape, with

the City providing land and contributing to maintenance of facilities

constructed by the Academy and its donors. Over decades, the

Academy expanded to include North American Hall, Simson African

Hall, Science Hall, Morrison Planetarium, and other components.

4

Featuring accessible content, low-cost admission, and a prominent

location, the museum catered to children and families throughout

the 20

th

century, reecting an egalitarian quality lacking in many peer

cultural institutions. As one respondent said, during this era, “almost

every child” in San Francisco experienced the Academy.

IMPLICATIONS OF GROWTH AND FINANCIAL CHALLENGES

Over many decades, the museum constructed a dozen additions

to its Golden Gate Park facility. en Director of Exhibit Design

and Production Scott Moran described these additions as “very

much separate buildings connected by hallways and doorways.”

is growth took place without a master plan, and physical distance

created departmental silos that made collaboration among researchers

dicult. e lack of a cohesive work culture slowed the Academy in

advancing its research and museum programs.

e public perception of the Academy reected the disjointed nature

of the institution. Although visitors valued the museum as a beloved

cultural institution, individually they were often unaware of the

Academy’s full range of oerings. As Moran explained, “Many people

didn’t know of the Academy as the California Academy of Sciences—

they knew of it as the Steinhart Aquarium [or the] Morrison

Planetarium.” e separation of exhibitions and the buildings’ lack of

exibility also inhibited the Academy’s ability to address marketplace

“A lot of natural history

museums are good at

telling what was, but [we

were] trying to shift to

telling what could be or

what should be.”

—Staff member,

California Academy

of Sciences

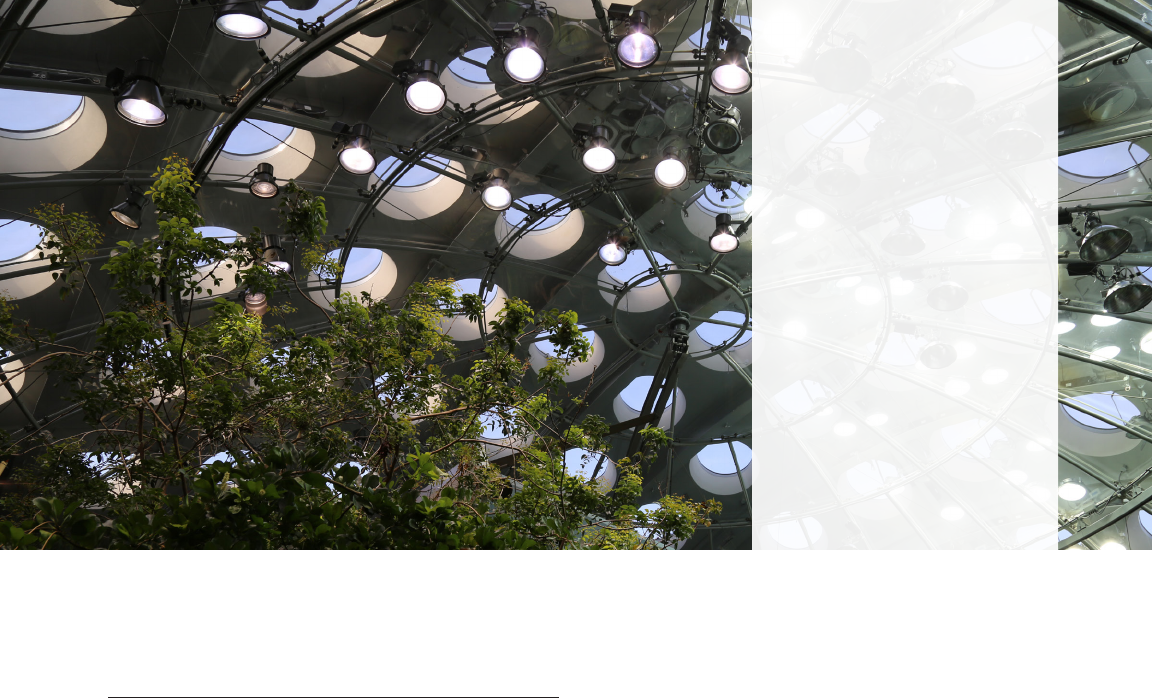

Above. Circular skylights in the museum’s living roof provide

natural light to the rainforest exhibit.

Cover. The museum’s stunning living roof mimics the seven hills

of San Francisco.

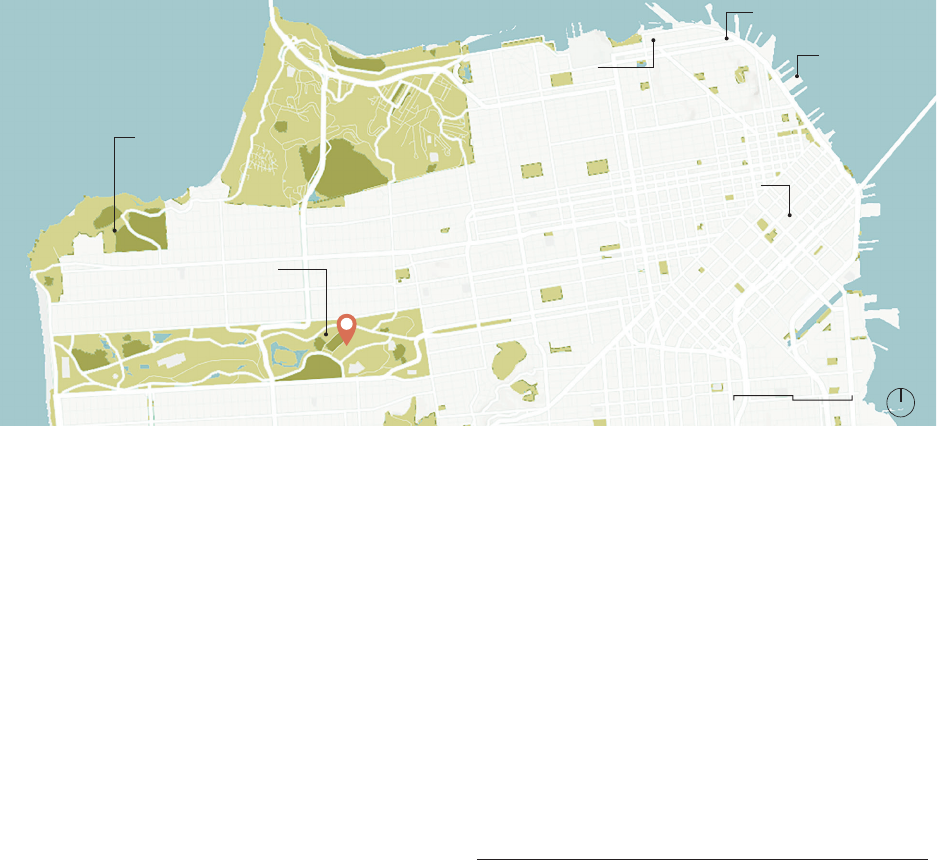

N

0 0.5 1 mi

5

The Exploratorium

Museum of

Modern Art

Fisherman’s Wharf

The Presidio

The Legion

of Honor

de Young

Museum

California

Academy of

Sciences

Aquarium of the Bay

Golden Gate Park

changes and respond to heightened visitor expectations for museum

experiences that were entertaining, interactive, and relevant.

Sta reported that attendance was dropping by about 4 percent

annually in the 1990s, and admission income alone was far from

sucient to meet the museum’s nancial needs. As one sta member

explained, the Academy “didn’t have enough money, no matter what

the attendance was. . . . [ere was an ongoing need to] cut and cut

to work within the existing budgets.”

A DEVASTATING EARTHQUAKE LEADS TO A NEW START

In 1989, the 6.9-magnitude Loma Prieta earthquake

5

shook San

Francisco, causing irrevocable damage to the Steinhart Aquarium and

forcing Bird Hall to close.

6

e Academy’s useable exhibit space was

reduced by about 25,000 square feet, and the safety and function of

some facilities were severely compromised. One sta member recalled

that conditions were so poor that employees had to wear hard hats

in some oce areas due to concrete falling from the ceiling. e

extensive damage made it clear that the Academy would need to

nd funding for massive infrastructure improvements. In 1995, the

Academy approached San Francisco voters with a bond measure for

$29.2 million to rehabilitate the aquarium. e measure passed with

the required two-thirds majority vote.

7

While these funds would cover the aquarium’s pressing structural

problems, they would not help the Academy address its broader

needs for improved exhibit spaces and greater internal cohesion across

departments. e strong support of residents expressed through

the bond vote encouraged the Academy to expand its vision and

consider the potential for a larger capital project that would advance

the institution in a more holistic way. With an intent to replace

and rebuild the museum completely, the Academy returned to San

Francisco voters in 2000 with an additional request for $87.4 million.

e community also approved this measure.

8

e bond measures provided the Academy with the capital needed to

begin a large-scale project, and gave the organization’s board members

condence that the new building would be nancially viable. In the

words of one board member, “the bonds meant that we could aord

to dream. ere was a belief that, if we’re going to do this, we have to

do it big and grand.”

Project Mission

e Academy approached this capital project as an opportunity to

examine and elevate its organizational mission. While the museum’s

role had historically been to educate visitors about the past, the

Academy now hoped to teach people about the future. As one sta

member explained, “A lot of natural history museums are good at

telling what was, but [we were] trying to shift to telling what could be

or what should be.”

In particular, the Academy felt it could play a valuable role at a

Above. Located in Golden Gate Park, the Academy is near several other

attractions within San Francisco.

6

time of increasing international attention on climate change and

conservation. In preparing for this capital project, the Academy

expanded its organizational mission—its historic focus on exploring

and explaining the natural world would now include an emphasis

on protecting life on Earth. Project leaders aimed to create an

environmentally sustainable building that would serve as an attraction

for visitors, drawing them to the museum, creating a stronger revenue

stream for the institution, and educating new generations about

contemporary global issues. ey also set out to achieve a unied

design that would connect the Academy’s research sta, enhancing

their collaboration and improving their quantity and quality of

scientic outputs.

Process

ENGAGING PROJECT LEADERS AND CITIZEN ADVISORS

e capital project would be instrumental to the future of the

Academy and called for strong leadership from its board of trustees.

Board members were engaged throughout the process; several had

expertise that was directly relevant to the project. Wall Street nancier

Dick Bingham served as board chair for the duration of the eort to

plan and construct the facility. e Academy also beneted from the

experience of board member Bill Wilson, a local developer and owner

of a construction company.

Since the City of San Francisco was a signicant investor through its

bond measures, the Academy formed a Community Advisory Group

of about 15 individuals from neighborhoods and interest groups.

Interactions with these advisors helped the Academy gain critical

feedback and anticipate community concerns. It also nurtured buy-

in—through the Advisory Group, the Academy built relationships

with residents who would become advocates for the project at City

hearings and in their neighborhoods.

SEEKING AND SELECTING A RENOWNED ARCHITECT

e Academy board wanted an architect whose stature would reect

the project’s ambitious vision. e museum hired a former executive

director of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, the eld’s most prestigious

award, to conduct the search. Out of six nalists, the board ultimately

selected Renzo Piano Building Workshop after an interview with the

rm’s founder that became legendary at the Academy. While many of

the prospective architects presented polished models and renderings

of their proposed buildings, Renzo Piano brought only a notepad and

rearranged chairs in the interview room to form a circle. Rather than

presenting an idea for the building’s design, he opened the interview

by asking the board about the Academy’s mission and institutional

goals. On the spot, Piano sketched out a design in response to the

board members’ answers. As one sta member recalled, this interview

was “one of the [primary] reasons they selected him—because it was

a conversation.”

DESIGNING A SUSTAINABLE, ACCESSIBLE BUILDING

e selection of Renzo Piano fueled the Academy’s high aspirations

for the museum’s architecture and solidied its commitment to

creating a sustainable building. Piano’s design began with a living

roof concept, which he described as “[lifting] up a piece of the park

and [putting] a building underneath.”

9

e roof would feature a eld

and seven rolling hills to mimic San Francisco’s landscape. e roof

would be visible from the Music Concourse, an open-air plaza within

Golden Gate Park.

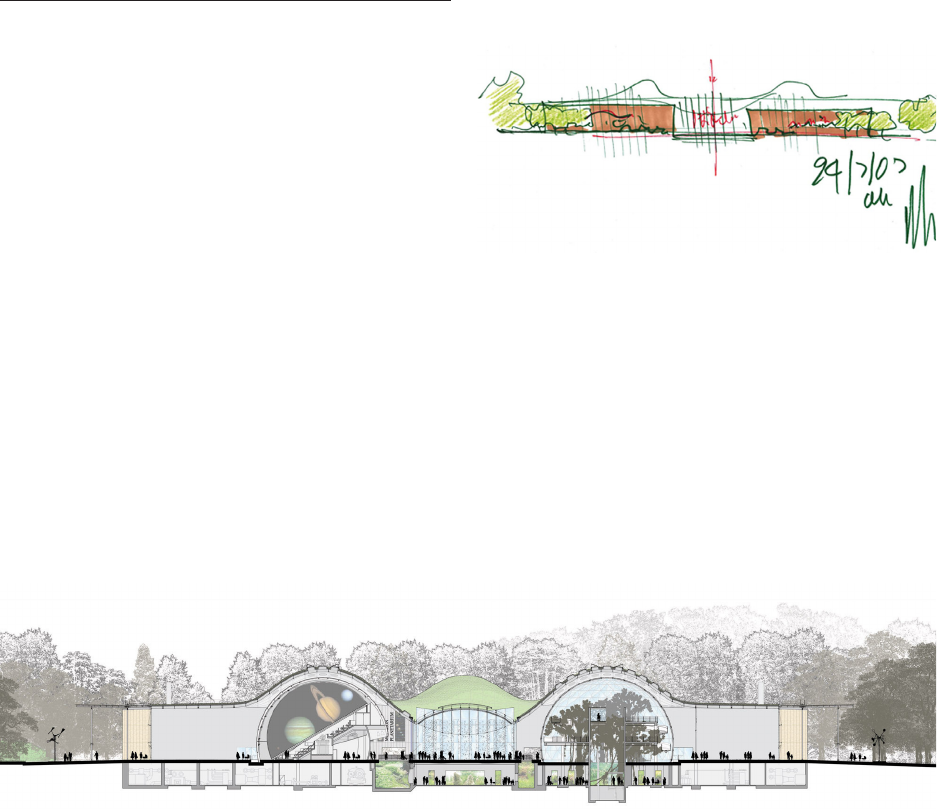

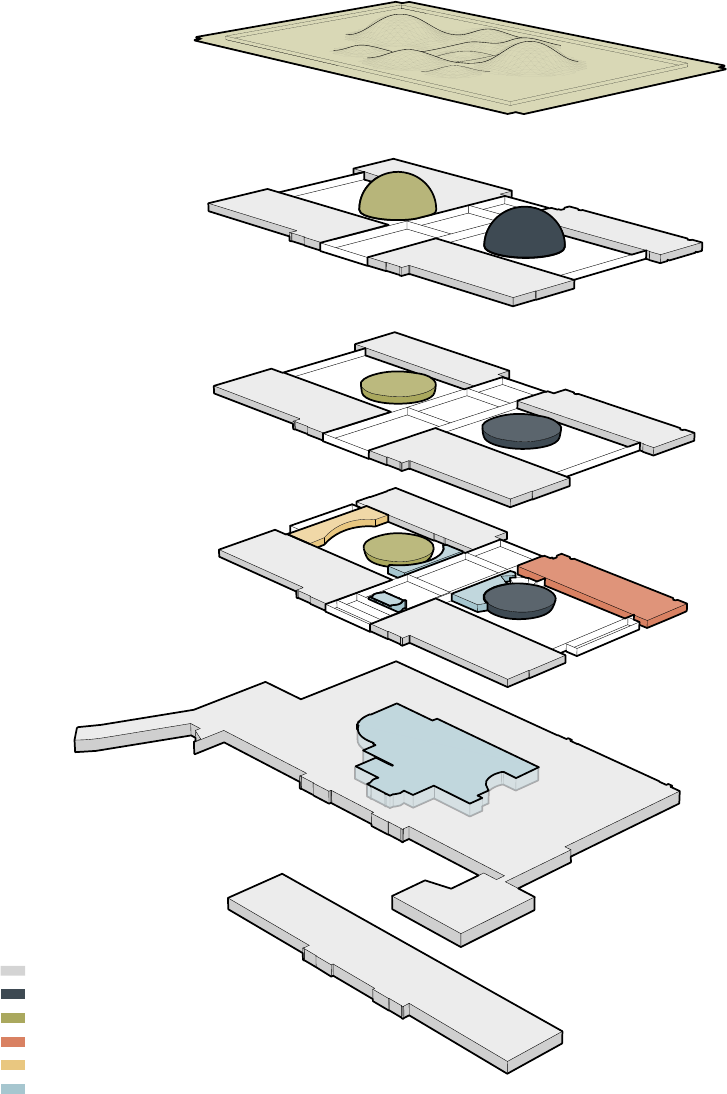

Below. Domes on each end of the museum house the planetarium and rainforest

exhibits.

Above. Piano’s design represented a bold vision for the Academy that

resonated with many donors.

Right. The building

consolidates several

exhibits under one roof;

these offerings were

formerly distributed

across multiple

structures.

Office Space

Planetarium

Aquarium + Swamp

African Hall

Earthquake!

Rainforest

Basement

Lower Level

Level One

Level Two

Level Three

Living Roof

7

8

To make the museum more welcoming and transparent, glass exterior

walls would visually connect visitors inside the Academy to the

surrounding park. Piano described the approach as a reaction to the

prior Academy and its solid walls; that structure was “in the middle of

Golden Gate Park, one of the most beautiful places in the world . . .

[yet visitors] had no sense of what was there.”

10

Under two of the hills on either end of the museum, 90-foot diameter

domes rising three stories would anchor the Academy’s entrance

oor. Separated by a central piazza, these impressive domes would

house a rainforest exhibit and planetarium, with the aquarium

located on the oor beneath. is design would provide visitors on

the rst oor with sightlines of these three signature aspects of the

Academy. e aquarium tanks would be seen from many angles—a

contrast from the one-sided views in the original Steinhart facility.

Nonlinear, interactive exhibits would encourage visitors to engage

with educational materials rather than tour the museum as passive

onlookers. Overall, the design intended to spark visitors’ curiosity

through an exploratory environment and bring them into contact

with science and important environmental issues. To improve internal

operations, including research collaborations, all sta would be

consolidated in open-plan oces at the rear of the museum.

As the design developed, LEED certication was gaining national

notice and many donors were attracted to the Academy’s LEED

Double Platinum ambitions. e building would reect the

Academy’s commitment to sustainability through features including

its living roof, ENERGY STAR® appliances, clean energy sources, and

low-emission and ozone-friendly heating systems, ventilation, and air

conditioning. e living roof and an accompanying “Building Green”

exhibit would educate visitors and highlight the building’s sustainable

features. Weather stations on the roof would monitor wind, rain, and

changes in temperature so that the building’s automated systems and

retractable skylights could respond accordingly. e roof’s hills would

be edged by solar panels and lined with 50,000 porous, biodegradable

vegetation trays, and native plants would provide a habitat for a

variety of wildlife.

11

CREATING A LARGE PROJECT TEAM—AND TENSIONS

Working with Europe-based Renzo Piano required the project team

to engage a local architect of record, and Stantec Architecture was

selected for this role. Along with several exhibit design rms, Stantec

developed the building’s nal design with input from the Academy’s

sta, board, and local community members.

To address the complexities of working with a large project team and

myriad stakeholders, the Academy hired Don Young & Associates to

manage the overall eort. Young acted as a liaison between the various

design consultants and the board. Communications were centralized

through Young to help streamline the overall process. However, this

approach limited direct communication between project players and

created gaps in coordination. Designers described situations in which

critical exhibit components, such as drains in the aquariums, had not

been included in the architect’s plans—requiring last-minute changes

during construction.

Some exhibit designers felt that the Academy’s prioritization of the

building’s living roof overshadowed their perspectives, forcing them

to adapt to Piano’s vision in ways that compromised other parts of the

building and its exhibits. ey pointed to the exhibits at either end

of the building as creating a “somewhat disjointed visitor experience.”

One expressed concern that the Academy had “[fallen] too madly in

love with the building as an icon” during the design process.

ESCALATING COSTS, FUNDRAISING, AND FINANCING

Piano's design came at a high price. Eventually totaling $488

million, the construction of the new Academy was signicantly more

costly than other major capital projects in the region. For instance,

the reconstruction of the de Young Museum cost $202 million in

2005 following the Loma Prieta earthquake.

12, 13

e Monterey Bay

Aquarium was constructed or renovated in phases from 1984 to 2005

and cost $133 million.

14

Factors unique to the Academy project contributed to the colossal

price tag. Some expenses were driven by the Academy’s aim to

become a visible symbol of sustainability—for example, the project’s

living roof cost about $30 per square foot, whereas a standard green

roof is about $18 per square foot.

15

Other costs stemmed from

the nature of the nal design—for instance, the sloping roof and

glass domes called for custom glass and metal structures, and their

Above. Visitors travel on a ramp through the rainforest exhibit.

9

construction requirements led to costly rearrangement of typical

building phases. Still other expenses resulted from unanticipated

external forces —the price of steel and concrete on the global market

spiked

16

in 2001 following the September 11 attacks and again in

2004 after Hurricane Katrina.

Between 2001 and 2005, the Academy increased the project budget

by more than 25 percent, from $388 to $488 million, even as it

modied plans to reduce the building’s size to decrease costs.

17

Increases came on seven occasions, and the project process was

paused at points due to nancial concerns. e nal gure included

all design and management fees as well as public engagement, site

development, building construction, and exhibit and sta transition

costs—including the expense of operating a temporary space for four

years.

18

While the ambitious project vision brought a signicantly higher

price tag, it also attracted donors. eir support allowed the Academy

to increase the project’s budget rather than abandon its design vision

or LEED certication goals. Each of these elements had its own

proponents. Director of Foundation and Government Relations

Katharine Greenbaum explained, “Renzo captured people’s attention,

especially people who liked art more than science.” Drawings and

renderings of the building were essential to its fundraising appeal,

and the Academy regularly highlighted Piano in communications,

including featuring him on the rst page of the building’s post-

completion report. e facility’s sustainable elements drew the notice

of donors interested in the museum’s contributions to environmental

conservation or science education, and some sta members believed

that the Academy’s ambition to be the greenest museum in the

world had a greater impact on the team’s ability to fundraise than the

glamorous draw of a “starchitect.”

In addition to securing private donations and municipal bond

revenue, the Academy was able to take advantage of bond nancing

through the California Infrastructure and Economic Development

Bank. e bank provides low-cost, tax-exempt nancing to nonprot

organizations for acquisitions and/or improvements of facilities

and capital assets. is resource allowed the Academy to access an

additional $281 million in July 2008, which was used to refund

previously issued bonds and to nance construction.

19

MAKING THE MOST OF THE TRANSITION PROCESS

While construction was underway, the Academy housed its exhibits

in a facility on Howard Street in downtown San Francisco. A move to

this space was in itself an accomplishment, as it required transferring

the marine life in the Steinhart Aquarium as well as other museum

collections. e team treated this temporary site as an opportunity

to test exhibit designs and programs and prepare sta for the coming

transition to a major new building. rough its four years on Howard

Street, the Academy succeeded in keeping the public involved and

invested in its work, while setting the stage for greater success in

its future home. According to Bart Shepherd, the director of the

Steinhart Aquarium, “We invested in [the temporary] building

heavily, because we knew it would be an important learning space.”

At the temporary site, scientists constructed a mock-up coral reef tank

to assess sunlight levels and procedures for divers. Sta built scale

models of the penguin exhibit and a tide pool touch tank that would

be installed in the new building. ey piloted programs to engage

visitors who were in their 20s and 30s—an underserved demographic

for the Academy. A weekly “NightLife” event brought these young

adults into the Academy; each evening featured food, drinks, and a

special theme. is series has continued and become a popular feature

in the new Academy space.

To prepare for smooth operations in the new building, leaders tested

open-plan oce congurations and helped sta adjust to new ways

of working. In a 2008 interview, Moran explained, “By modeling the

temporary facility as much as possible on what was being proposed

for the new building, we were able to help people overcome their

initial resistance to some ideas.”

20

Operating the temporary site

required fewer sta members; the Academy downsized its operations

for these interim years. Positions were then added as the new

facility opened, with the institution hiring to match its expanded

opportunities and future needs.

Above. Glass walls create a visual connection to the surrounding Golden

Gate Park, helping the Academy feel open, welcoming, and connected to its

surroundings.

10

Impact

INCREASING THE NUMBER OF VISITORS AND MEMBERS

On September 27, 2008, the new Academy had a huge opening day.

21

According to a sta member, a line of 16,000 visitors stretched for

more than a mile outside the entrance, with trac managers placed

at the door to limit crowd size in the facility. Chief of Sta Alison

Brown lamented the opening day lines, saying, “Probably the greatest

challenge that we still have [is that] people think we’re too crowded to

come visit.” Nevertheless, Brown said the rebuilt Academy welcomed

over two million guests during its rst year.

As of fall 2015, annual attendance had settled at 1.4 million visitors,

almost double the gure in the prior facility. Sta members view

the increase in visitors and household memberships as the largest

indicators of success for the project. One sta member stated, “We

have 55,000 member households, which is huge for an institution

our size. And I think that’s reective [of] people’s love for the place;

they just love coming here.” In addition to better marketing, an

enhanced visitor experience, and expanded programming, some of

the attendance gains can be attributed to the Academy’s new building,

with surveys suggesting that as many as 20 percent of guests come to

the museum to see the building itself.

As trac grew, the museum shifted toward a business model driven

by admission revenue and made the decision to increase its ticket

prices. While the higher cost of admission makes the Academy

less economically accessible to some potential visitors, many sta

members strongly defended this change. ey pointed out that the

Academy’s increased annual operating budget allows the institution

to provide more free admission days and reduced-price educational

programs, helping it serve more people overall. Additionally, one

sta member reected on the business model for the institution,

saying:

If [the Academy] is all going to be paid for by public

funds—like many of the European museums—then it

should be free, but it's not. . . . We’re a private nonprot

and we get some money from the City of San Francisco . . .

but the rest of it is all private funds and admission.

RESPONDING TO NEW ECONOMIC REALITIES

Shifts in the Academy’s business model have had mixed results to

date. On the one hand, the museum now benets from a signicantly

higher and more sustainable source of earned income: annual revenue

from admissions and membership fees. is combined income source

was under $2 million annually prior to opening the new Academy in

2008. at amount skyrocketed to $28 million in the new facility’s

rst year, and has remained above $23 million annually since (see

g. 1). One board member explained, “We were all aware that if you

don’t bring the public in, if you don’t have an attraction, you can’t

support the science.”

Above. Visitors experience the coral reef aquarium from many angles; the new

facility includes views from within as well as above the exhibit.

11

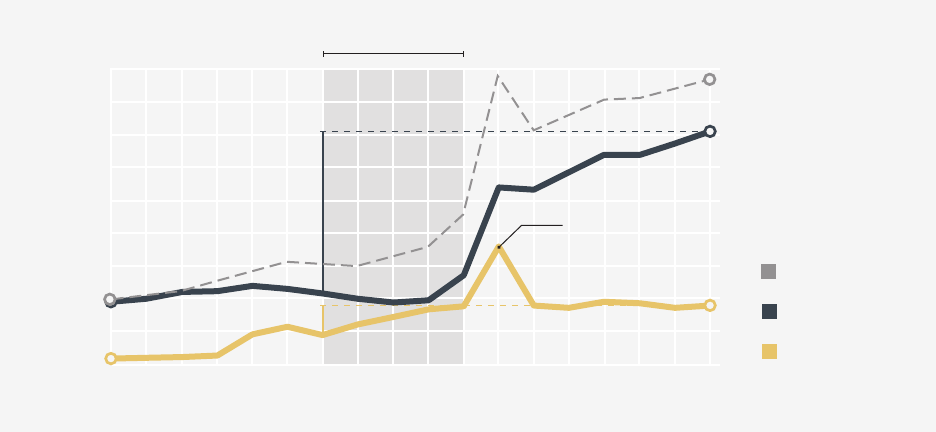

However, admission and membership revenue has not been able

to keep pace with substantial expense increases in the new facility.

Between 1998 and 2008, the Academy’s total annual expenses

remained at or below $44 million, while the total since the move

has uctuated between $70 and $90 million per year (see g. 2).

Between 2004 and 2015, as the institution planned and implemented

its expansive vision in the new space, operating expenses (sta and

program) increased threefold, accounting for 80 percent of total

expenses in 2015. Meanwhile, annual facility costs doubled.

e Academy secured bond nancing from San Francisco and

California to support the project, and chose to invest a portion of the

bond revenue with the hope that it could generate returns and extend

use of these funds. According to Moran, the capital project “created

a foundation for new ways of thinking. We completely reinvented

ourselves . . . and tried to use a for-prot approach to a nonprot.”

While this strategy provided additional revenue (investments resulted

in net gains of about $20 million or more in 2007, 2011, and 2014),

it introduced greater economic volatility as well by making the

Academy’s annual income subject to uctuations in nancial markets.

e Academy incurred net investment losses greater than $10M in

2008, 2009, and 2012 (see g. 1).

ADVANCING THE ORGANIZATION’S MISSION

Prior to beginning this capital project, the Academy’s mission

was to “explore and explain the natural world.” As it examined the

opportunities inherent in creating a new facility—in the context of

increasing global concern regarding the environment—in 2005, the

institution changed its mission to “explore, explain, and protect the

natural world.” In 2013, ve years after occupying its new facility, the

mission further evolved to “explore, explain, and sustain life on Earth.”

Executive Director Jonathan Foley said he hopes the Academy will be

known as “the rst sustainability museum.” ough the Academy’s

expanded mission statement was not solely the product of the capital

project, many sta members believe that the building played a

signicant role in the mission’s evolution. Foley remarked that “the

building made it an entirely new Academy.”

e new building also facilitated the organizational and cultural

changes its leaders sought, co-locating the Academy’s research

departments to focus on critical conservation issues. Sta members

now work across disciplines, and this integrated approach is reected

in exhibits that connect visitors to the interrelated challenges facing

the natural world. Open-plan oces along the southeast of the

building foster a more collaborative workplace, while the new, iconic

architecture of the Academy helps attract scientic talent.

e building is a symbol of the Academy’s values. As the world’s rst

LEED Double Platinum museum and the largest Double Platinum

building in the world, the Academy is known for its commitment

to environmental sustainability.

22

e roof alone is a remarkable

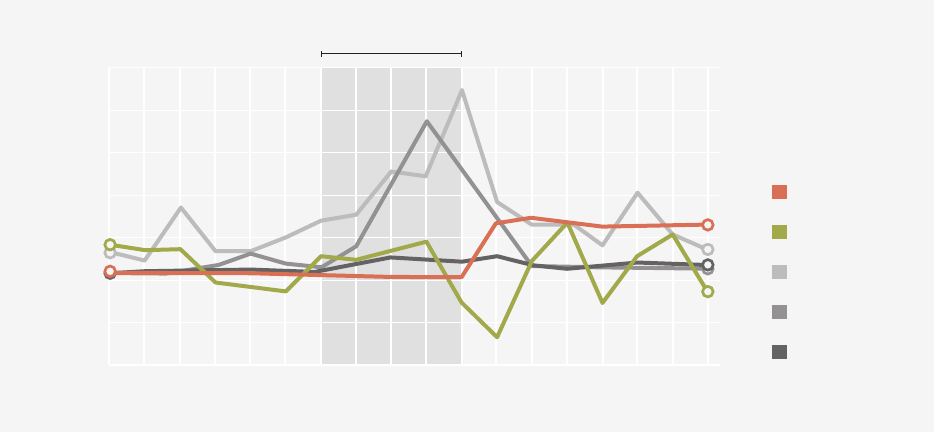

Figure 1. California Academy of Sciences Revenue Mix

Temporary Facility

($40)

($20)

$0

$20

$40

$60

$80

$100

Millions (USD)

Admissions &

Memberships

Contributions

Net Investment

Income

Government

Grants

Net Investment

Gains/Losses

2000 2005 2010 2015

Fiscal Year Ending June 30

“e building made it an entirely

new Academy.”

12

achievement: it prevents the release of 405,000 pounds of greenhouse

gases per year, keeps the museum’s interior temperature 10 degrees

cooler than a standard roof system would, and absorbs enough

rainwater to prevent 95 percent of potential storm water runo.

23

DELIVERING MEANINGFUL LEARNING EXPERIENCES

e new building is home to a deeper and richer set of experiences

for visitors. In addition to engaging exhibit designs, the Academy has

added docents and scientists in public spaces. One visitor noted, “It

was obvious when we came to the building that the Academy wanted

to provide a dierent service to people.” A school teacher commented

on the changed educational style, saying, “Previously, the Academy

was more teacher-directed because it wasn’t as interactive.”

Citing the impact of the facility on visitors, one sta member

explained:

[e building] helps you understand the world better.

Being able to go up into the rainforest, then come down in

a rainstorm and end up under the Amazon, you look and

see how things are distributed. It ows like an ecosystem.

at is new, and I think that is a wonderful way that the

new Academy helps people learn about the environment.

Sta members indicated that the interactive quality of the Academy

has increased visitor satisfaction and compelled guests to stay longer.

Data collected via a self-administered kiosk survey revealed that

visitor satisfaction increased from 64 percent in 2004 to 73 percent in

2014. Academy sta reported that visitors are staying at the museum

for three and a half to four hours, compared to one to two hours

in the prior facility. ey commented that this increased time has

positively aected visitors’ learning experiences, although it has also

posed some challenges in crowd management.

Community members described the Academy as an essential resource

for local education, and some suggested that the museum has

improved the quality of STEM (science, technology, engineering, and

math) education in the San Francisco Unied School District.

STRENGTHENING A CITY’S IDENTITY

For many in San Francisco, the Academy reects the city’s ambition

to be sophisticated, worldly, and environmentally conscious. One

local teacher explained, “ere is a sense of pride in the community

that we have a building like this—that this is our museum.” Because

San Francisco residents were instrumental in nancing the project

(local bond revenue made up about 25 percent of the project’s total

funding), the museum strove specically to deliver on the impact

it had promised to the community. Sta members said that the

Academy’s increased volume of visitors and memberships indicates that

this goal has been achieved and conveys residents’ “love for the place.”

“ere is a sense of pride in the community

that we have a building like this—that this

is our museum.”

Figure 2. California Academy of Sciences Expense Mix

Total Expenses

Temporary Facility

Millions (USD)

$0

$10

$20

$30

$40

$50

$60

$70

$80

2000 2005 2010 2015

3x

2x

Operating Expenses

Facility Expenses

$90

Costs associated with

transitioning to the new

building caused a

temporary spike in

facility expenses.

Fiscal Year Ending June 30

13

Conclusion

When structural damage from an earthquake precipitated the need

for a new building, the California Academy of Sciences embraced this

challenge to increase its visibility, dramatically grow its attendance

and memberships, expand and enrich its programs, and demonstrate

its leadership in sustainability. ese changes were accompanied by

an evolution in mission that moved the Academy beyond a historical

focus on exploring and explaining the natural world to an expressed

intent to help sustain life on Earth as well. Guided by the inspiring

design of a world-renowned architect, Academy leaders and donors

were emboldened to pursue an elevated vision and scale of programs

for the institution, and to nance capital project cost increases that

brought an already large $388 million budget to an eventual total of

$488 million.

Important elements of the project process included knowledgeable

board leadership, active connections to the local community, and

purposeful use of four years in a temporary facility to test approaches

and prepare for success at the new Academy. Public support was

evident in the passage of two bonds that helped initiate and nance

the project, and in community participation and pride in the new

facility.

In addition to cost increases that hampered project progress, the

number of project participants and division of roles created tensions

and some missteps during the design and construction process. Once

completed, the design and programs of the new facility generated

dramatic growth in admission fees and memberships, boosting the

Academy’s earned income. However, new revenues are still falling

short of increased expenses in the new facility. While economic

challenges persist, and the organization carries signicant debt related

to project nancing, the new Academy continues to garner support

and serve its stakeholders. In the words of Scott Moran, director of

exhibit design and production, this ambitious capital project created

“a new era for the California Academy of Sciences that will also help

change many other museums and institutions.”

Videos

For additional information on this case study, see the following videos

available at www.massdesigngroup.org/purposebuilt:

Finding the Right Architect

Raising the Museum’s Prole

e Mission of the Building

Below. Hills on the living roof mimic the seven hills in San Francisco.

14

Commit to planning to set the right scope.

Visionary design carries reward and risk: Due to costs inherent in aspects of the nal

design, unexpected changes in material costs, and other factors, the Academy expanded the

budget for its new building by more than $100 million over the course of the project. When

faced with escalating costs, leaders opted to increase the project’s budget, rather than eliminate

major elements of the design.

Donors were attracted to the project. ey responded to the boldness of the architect’s vision

and the inspiring approach to environmental sustainability reected in the building concept,

despite the costs involved. Not all capital projects can achieve this level of deep and expansive

donor commitment. Every project must weigh nancial and design considerations; in this

case the trade-os were largely manageable.

Still, the ambitions of this project created debt for the Academy, as well as signicantly

increased operating and facility costs. With advantages including a supportive donor base,

large numbers of visitors and members, and building maintenance contributions from

the City of San Francisco, the Academy may be able to oset these costs and achieve solid

nancial footing for the long term.

Combine inside knowledge with outside expertise.

Big ideas call for coordination, balance: e visually stunning and environmentally

innovative work of a “starchitect” brought high visibility and attracted nancial support

to this project. Renzo Piano’s design, as well as his European location, also contributed

complexity to this large, multifaceted eort. e project team included a San Francisco

architect and many local designers to complete key aspects of the new facility. A construction

project management rm was put in charge of coordinating communications between all

design consultants and the Academy’s sta and board.

is structure streamlined project implementation, but created gaps in needed coordination

between project players. Some felt that the overall commitment to Renzo Piano’s vision

compromised the design of some exhibits, with exhibits needing to t the overall architectural

approach rather than vice versa. In addition, essential alignment between designers was missed

at points—including missteps related to aquarium drains that had to be corrected in the

construction phase of the project.

Lessons from the California Academy

of Sciences

15

Be ready for organizational change.

Interim space is a place to prepare: When the Academy began the process of replacing its

museum, it had to move exhibits into a temporary o-site space to remain open to the public.

Unlike many natural history museums, the Academy featured living marine exhibits, which

made the move logistically complex.

e Academy not only handled the transition smoothly, it used the temporary space as

a learning laboratory to test many ideas for its new facility. Sta members constructed

mock-ups of the coral reef tank and tested sunlight levels and dive-show procedures, built

scale models of penguin exhibits and touch tanks, and grew their collection in preparation

for expanded exhibits and operations. e Academy also piloted NightLife, a program that

continued following the move as a means to bring younger adults into the institution.

In addition, Academy leaders used the move to temporary space, which required fewer sta

to operate, as a time to rethink their operating structure. Sta reduction for the four-year

interval was followed by adding positions in the new facility that matched the organization’s

evolved mission and future intent. At the same time, more collaborative, cross-disciplinary

approaches to research, and to public programs, were introduced in the temporary space and

carried over into the new Academy.

is approach to the interim years allowed the Academy to open the new facility in ways that

reected its ambitions, and that avoided many of the change-management issues that often

accompany the move to new physical environments.

Lessons from the California Academy

of Sciences

16

End Notes

1. California Academy of Sciences. “About Us.” http://www.

calacademy.org/about-us.

2. Ibid.

3. Wels, S. & Piano, R. California Academy of Sciences: Architecture

in Harmony with Nature. Chronicle Books. 2008.

4. California Academy of Sciences. “Our History.” http://www.

calacademy.org/our-history.

5. Nakata, John K. et al. “e October 17, 1989, Loma Prieta,

California, Earthquake—Selected Photographs.” United States

Geological Survey. 1999. http://pubs.usgs.gov/dds/dds-29/.

6. “Our History,” op. cit.

7. Wels, S. & Piano, R., op. cit., p. 38.

8. Roberts, Katherine. “Prop. B Seeks Funds to Repair Academy

of Sciences / Con / Cost to S.F. Residents Too High.”

SFGate. February 17, 2000. http://www.sfgate.com/opinion/

openforum/article/PROP-B-SEEKS-FUNDS-TO-REPAIR-

ACADEMY-OF-SCIENCES-2775455.php.

9. Milvy, Erika. “Natural Wonder.” Los Angeles Times. September

28, 2008. http://articles.latimes.com/2008/sep/28/travel/tr-

academy28.

10. Wels, S. & Piano, R., op. cit., p. 53.

11. California Academy of Sciences. “Living Roof.” http://www.

calacademy.org/exhibits/living-roof.

12. de Young. “Architecture and Grounds.” https://deyoung.famsf.

org/about/architecture-and-grounds.

13. “de Young Museum, San Francisco, CA, United States of

America.” designbuild-network.com. http://www.designbuild-

network.com/projects/de_young/.

14. Monterey Bay Aquarium. “Monterey Bay Aquarium Overview

– 2000.” 2011. http://storage.montereybayaquarium.org/

storage/pressroom/presskit/pdf/2011%20monterey%20bay%20

aquarium%20overview.pdf.

15. Green, Jared. “ree Years Later: San Francisco’s Academy of

Sciences Living Roof Also Educates the Design Community.”

e Dirt. October 13, 2011. https://dirt.asla.org/2011/10/13/

three-years-later-san-francisco’s-california-academy-of-sciences-

living-roof-also-educates-the-design-community/.

16. Coté, John. “Rebuilding Academy of Sciences No Walk in the

Park.” SFGate. September 21, 2008. http://www.sfgate.com/

science/article/Rebuilding-Academy-of-Sciences-no-walk-in-

park-3268556.php.

17. California Academy of Sciences. “Building Budget

Comparisons.” December 2015.

18. California Academy of Sciences. “Rebuilding Project Fact

Sheet.” https://www.calacademy.org/press/releases/rebuilding-

project-fact-sheet.

19. California Academy of Sciences. “Audited Financials.” 2015.

20. ArchNewsNow. “A Bridge Between: California Academy

of Sciences and Steinhart Aquarium Transition Facility by

Melander Architects.” ArchNewsNow.com. February 5, 2008.

http://www.archnewsnow.com/features/Feature245.htm.

21. Perlman, David. “Mile-long line for Academy of Sciences

opening.” SFGate. September 28, 2008. http://www.sfgate.

com/bayarea/article/Mile-long-line-for-Academy-of-Sciences-

opening-3267874.php.

22. “Cal Academy of Sciences Receives Second LEED Platinum

Rating from USGBC.” USGBC Northern California.

September 27, 2011. http://www.usgbc-ncc.org/resources/

blog/11-green-building-news/624-cal-academy-of-sciences-

receives-second-leed-platium-rating-from-usgbc.

23. Green, op. cit.

Image Credits

Cover courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Accessed online: www.

commons.wikimedia.org. “Building Exterior.”

p. 6 Image taken from Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Accessed

online: www.rpbw.com. “Concept Sketch.”

p. 6 Image taken from Renzo Piano Building Workshop. Accessed

online: www.rpbw.com. “Building Section.”

All other images courtesy of MASS Design Group.