Messiah University Messiah University

Mosaic Mosaic

Graduate Education Student Scholarship Education

Spring 2018

Adapted Art Curriculum: A Guide for Teachers of Students With Adapted Art Curriculum: A Guide for Teachers of Students With

Disabilities Disabilities

Genevieve Yoder

Messiah College

www.Messiah.edu One University Ave. | Mechanicsburg PA 17055

Follow this and additional works at: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/gredu_st

Part of the Art Education Commons, Curriculum and Instruction Commons, and the Disability and

Equity in Education Commons

Permanent URL: https://mosaic.messiah.edu/gredu_st/1

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Yoder, Genevieve, "Adapted Art Curriculum: A Guide for Teachers of Students With Disabilities" (2018).

Graduate Education Student Scholarship

. 1.

https://mosaic.messiah.edu/gredu_st/1

Sharpening Intellect | Deepening Christian Faith | Inspiring Action

Messiah University is a Christian university of the liberal and applied arts and sciences. Our mission is to educate

men and women toward maturity of intellect, character and Christian faith in preparation for lives of service,

leadership and reconciliation in church and society.

Runninghead:ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

Adapted Art Curriculum: A Guide for Teachers of Students With Disabilities

Genevieve Yoder

Messiah College

Curriculum and Instruction Research Project

Dr. Janet DeRosa

Spring 2018

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

2

Abstract

Due to the changes in the educational system since the 1997 Individuals with Disabilities Act,

few resources have been created to assist art teachers in adapting curriculum and art tools for

students with disabilities. This research project explores studies in art and disabilities, as well as

curriculum adaptations. The literature review offers an extensive view at current literature on

four major themes: a need for curriculum, general education curriculum adaptations, adapted arts

curriculum, and the impact of arts education in the lives of people with disabilities. Based on this

research, a project was developed to incorporate aspects of these themes into a usable curriculum

map, with accommodation considerations provided. This product also includes three unit plans

on three types of media found successful with students of disabilities: digital art, two-

dimensional media, and three-dimensional media. Each is elaborated on its usefulness for

students with varying need. This adapted curriculum map provides a solution to the research

problem because it plans for diversity of needs from the onset, and allows for flexibility. Lastly,

the researcher discusses the possible implications of this research project.

Key words: disability, curriculum, adapted arts, arts education, special education, special

needs

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

3

Table of Contents

Chapter 1: Introduction…………………………………………………………………..…..5

Narrative……………………………………………………………………..…….....5

Contextualizing the Problem…………………………………………………..……..7

Purpose of the Project Study…………………………………………………..……...8

Methodology……………………………………………………………………..…...9

Definition of Terms……………………………………………………………..……10

Chapter 2: Literature Review……………….…………………………………………….......11

A Need For Curriculum..……………………………………………………………..11

General Education Curriculum Adaptations………………………………………….12

Adapted Arts Curriculum.………………………………………………………….....17

Impact of Arts Education……………..……………………………………………....27

Chapter 3: Adapted Arts Curriculum Plan………………………………..…………………..32

Art for Grades K-5…………………………………………...……..……..……..…...34

Unit Plans……………………………………………………………………………..41

Digital Technology..…………………………………………………………..41

Two-Dimensional Arts…..………………………………..…………………..46

Three-Dimensional Arts.………………………..…………………………….51

Accommodations Template.………………………….……………………….51

Chapter 4: Discussion………………………………………..……………………………......56

Implications…………………………………………………………………………...56

Epilogue………………………………………………………………………………58

References………………………………………………………………………….....60

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

4

Chapter 1: Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of a research study that explores adaptations for

individuals with disabilities. It includes an adapted art curriculum map for students with

disabilities. The curriculum plan includes three unit plans complete with adaptations,

accommodations, art tools, standards, and rubrics appropriate for students with disabilities of

elementary age-range and ability. This curriculum plan will be based on research of people with

disabilities. In this chapter, I will describe my journey through art and education in relation to

special needs and my Christian faith. I also describe the background to the problem and provide

a brief overview of the literature on adaptations for individuals with disabilities. I then discuss

the study’s purpose, the methods for collecting and organizing data, and the definitions of key

terms in this study.

Narrative

Art has always been my passion. Since I was a little girl, I have always known that the act

of creating art would play an important role in my life and bring me joy. The joy of teaching

came later in life. I began to think about my gifts and talents given to me by God. One of these

talents was my ability and desire to help others. Taken together, my amiable nature and my

passion for creating art developed into the field of art education. In praying and searching for a

path to start my career, God placed me in a school for students with severe disabilities. I had

taken undergraduate courses pertaining to students with special needs, but I was not prepared for

the level of need for those with severe and multiple disabilities. My lack of experience at the

time pressured me to become more knowledgeable and fight for ways to achieve success and

participation on behalf of my students. I took additional classes in graduate school on special

education, I met and talked with special education teachers in my building for ideas, and I

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

5

listened to and watched the paraprofessionals work with the students. Coming out of college I

was prepared to challenge students’ abilities and raise the bar of what it meant for arts education

to be a part of schools. However, when I found out that many of my students could not hold a

pencil, I wondered, “How can I challenge these students?” The challenge looks different, but it is

still possible. Part of my experience has taught me that success looks different for everyone. For

many students, it is gripping an item such as a spoon or a paintbrush for longer periods of time.

For others, it is tolerating hand-over-hand movements or tolerating certain textures. For some, it

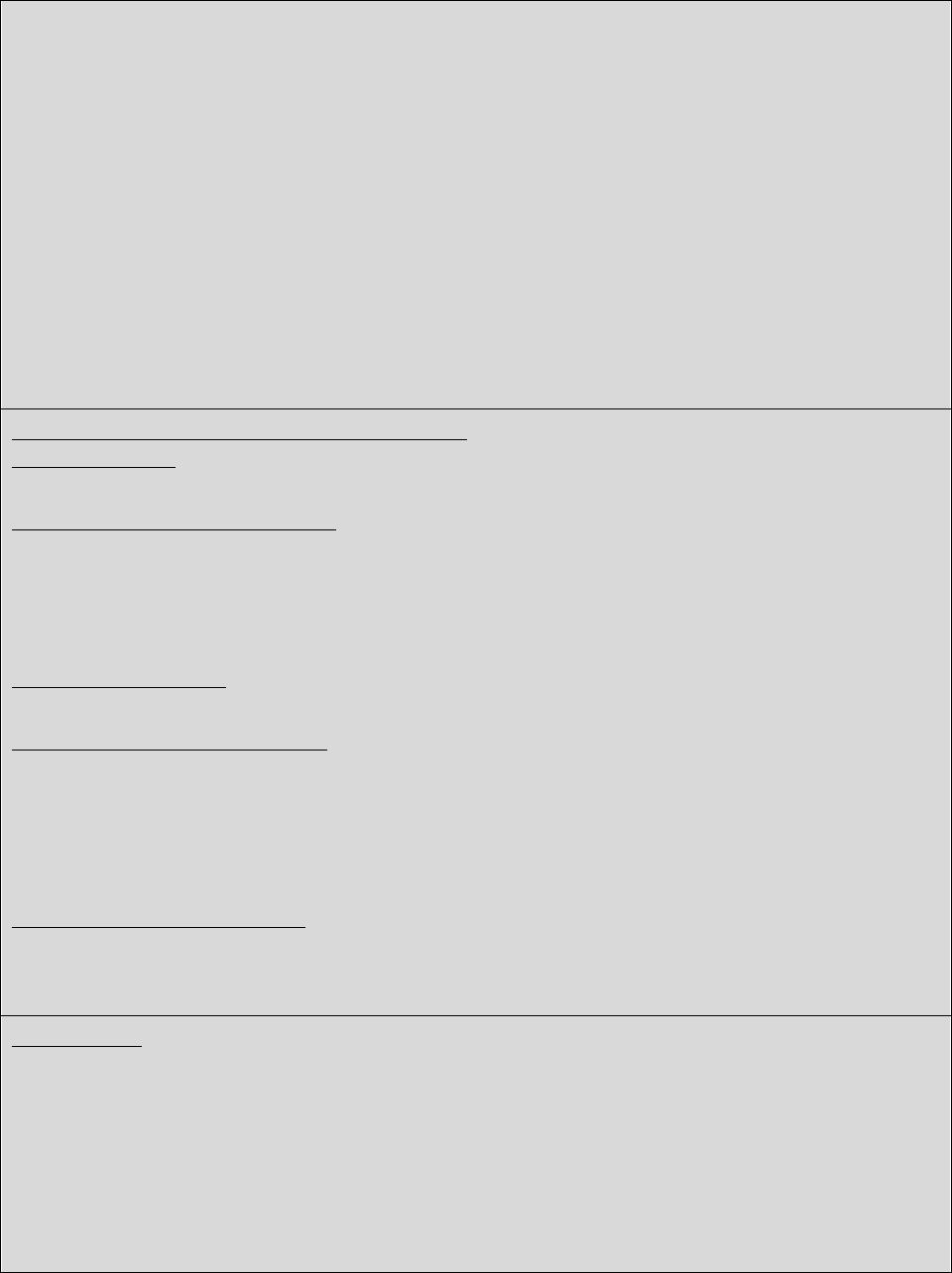

is learning about cause and effect when they push a switch button and electric scissors turn on. In

creating this curriculum, I acknowledged that every child is unique and has their own set of

successes and challenges. Loesl (2012) stated,

The lives of students who have experienced adaptive art making have been changed in

ways that others may not understand. As with most students, the experience of art making

is very personal. And, like the other student artists, their work may never hang in an art

gallery…The work that is created comes from the very essence of who they are.

In essence, these individuals benefit greatly from artistic expression, and it is my desire to make

this possible for every child. Art is a method in which to express one’s self. For some

individuals, art is a part of their identity and they choose to fulfill that inner desire, despite any

physical or mental disabilities that try to hold them back. It is my aspiration that other teachers

can use this curriculum and research practices to provide opportunities to open the doors to art

tools, media, and techniques for individuals with differing abilities regardless of age.

Contextualizing the Problem

According to the American Community Survey approximately 12.6% of the U.S.

population was diagnosed with a disability in 2015 (Kraus, 2017). A total public school

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

6

enrollment survey taken in the same year measured children enrolled under the Individuals with

Disabilities Act (IDEA) and concluded that 6.6 million students were in need of free and

appropriate education (National Center for Education Statistics, 2017). Despite higher education

programs promoting the instruction of students with special needs, many non-special education

teachers feel unprepared for teaching students with disabilities. There is a vast need for school-

age curriculum designed specifically for these individuals, especially in the special subjects of

art, physical education, and music.

A search of many education journals and articles for research on “adaptive art” produces

few results. The immense lack of relevant or current literature on the subject is troubling. With

growing numbers of students in need, scholars can no longer ignore the necessity of adaptive

curriculum and tools for educators to use within their art studies (Cramer, Coleman, Park, Bell,

& Coles, 2015; Derby, 2016; Guay, 1994; Mason, Thormann, & Steedly, 2004). As an educator,

I have experienced the lack of resources available in adaptive art for individuals with autism,

emotional and behavioral needs, life skills, multiple disabilities, blind/visually impaired, and

deaf/hard of hearing. Not only are special tools needed for these students to participate and

access their materials, but existing curriculum needs to be modified to the individuals as well.

A lack of curriculum for adaptive art poses many issues for the inexperienced teacher.

Teachers of individuals with disabilities, especially severe disabilities, have no pre-established

goals or objectives to aim for or draw from without an adapted curriculum. With no objectives, it

is difficult to assess the students’ abilities and understanding of the content. The educator does

not know where to start, what they are to accomplish, or how to know they have arrived at a

finishing point. The students also do not know their end goal, what it means to achieve mastery,

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

7

or what it means to have any sense of continuity within the course. Both teacher and student

should aim to build on their skills each week as they progress through any curriculum.

Students with disabilities are required under IDEA to have equal access to materials.

Why then, are there so few resources available to special subject teachers in the way of

curriculum and tools? Mason et al. (2004) listed implementation of a specific arts curriculum as

one of six ways future researchers could measure academic achievement and cognition through

the arts. Individuals with disabilities have often been marginalized in our society and in

education (Coleman, Cramer, Park, & Bell, 2015). Educators and researchers are the pioneers for

giving these students an opportunity to be successful. Art curricula found in schools K-12 today

assumes that a child has the use of their hands, including fine motor skills. This is not the case

for many individuals in special education, and special tools must be used for these students to

participate. A curriculum that addresses this issue best suits the needs of these individuals and

provides equal opportunity for learning (Coleman et al., 2015; Erim & Caferoğlu, 2017;

MacLean, 2008).

Purpose of the Project Study

The purpose of this study is to investigate methods of teaching and adapting art materials

and concepts to students with one or more disabilities. The research guided the researcher to

create a curriculum plan with select lesson examples that breaks down the steps and provides a

comprehensive walkthrough of options and considerations for teachers working with these

students. Even though there are multiple traits and variations of disabilities, the curriculum

provides some guidance for altering lessons so that students with disabilities can be successful in

the art classroom. Creators of curriculum in core subjects, who have these students in mind, have

also discovered underlying theories, ideologies, and practices that can be transferred to the field

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

8

of art education for those with disabilities. As many general-education teachers do not have

experience with severe disabilities, this curriculum plan based on existing research will be a

useful resource for this field.

Methodology

To address the study’s problem, peer-reviewed research was gathered on the topics of

adaptive art, special needs, art curriculum, special education theories, adaptations, and

occupational tools. Relevant studies were used to source additional resources from the reference

sections of each article. Not only did this ensure that the articles shared a similar theme, but the

reference sections allowed me to see what authors are most prominent in this field of study. Data

collected from these academic journals were collected, examined, and organized according to

common themes. A grid was used to collect specific examples of adaptations used in general

education and art education. For art education, information was collected on three art categories:

digital art, two-dimensional media, and three-dimensional media. These criteria are standard

elements of an art curriculum and will be useful for art teachers to see specific examples in

literature. As the themes were recorded and sorted, I was able to see the needs, solutions, and

evidence-based theories to implement or consider in planning an adaptive art curriculum plan.

Definition of Terms

The following key terms are used throughout this research study:

Accommodation: A type of adaptation to the curriculum content, teaching strategies,

location, timing, schedule, student response, environment, or other aspects of learning that

increases access for a student with a disability to participate without lowering the expectations or

standards of the course content (Wright, 2003).

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

9

Adapted art: Artwork created by students with disabilities that is changed or modified to

allow the student to create and experience art methods as independently as possible.

Assistive technology (AT): A device or piece of equipment that allows a child with a

disability to improve, maintain, or increase their speech or physical experiences and capabilities.

Curriculum: A set of lessons or courses focused on one overarching subject that builds on

concepts over a period of time. Curricula are planned experiences often taking place within

educational institutions.

Severe disabilities: An individual with greatly impacted physical or mental capacities.

These impairments may greatly limit the individual’s mobility, communication, self-care, self-

direction, interpersonal skills, and work skills and may include a hearing, visual, or health

impairment.

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

10

Chapter 2: Literature Review

This literature review presents research from general education programs that provide

adaptations and modifications to curriculum for students with disabilities. It will then consider

what past literature has found in regards to what should be included in adaptive art curricula

through the use of different art mediums, assistive technology, independence, and instruction.

Finally, it will address what literature says about why arts education is valuable in the lives of

students and people with disabilities in multiple facets.

A Need for Curriculum

On November 29, 1975, the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (Public Law

94-142) was passed providing access for students with disabilities to general education at public

schools (U.S. Department of Education, n.d.). Today, this is known as the Individuals with

Disabilities Education Act (IDEA). Since this law was passed, many education programs in

universities and colleges have required at least one special education course for students in

teacher education programs. However, large numbers of teachers still feel unprepared for

teaching students with special needs, especially severe disabilities (Cramer, Coleman, Park,

Bell, & Coles, 2015; Derby, 2016; Guay, 1994).

In a study of preservice preparation to teach art to students with disabilities, Guay (1994)

found that the teachers she interviewed relayed that they lacked preparation and had to learn

from their students, or by working closely with a special education teacher, through trial and

error, returning to graduate school, or through workshops. Not much research has been done on

the subject since Guay’s 1994 study, so it is often used as a reference in other researchers’ work

(Coleman et al., 2015).

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

11

In interviewing educator’s perceptions of teaching students with disabilities, Mason et al.

(2004) wrote, “Comments from teachers across the country support the value of the arts for

students with disabilities” (p. 39). Coleman, et al. (2015) similarly found that 96% of teachers

agreed or strongly agreed that it is important for students with significant disabilities to

participate in art making. This underlines the problem of this study. If teachers are open to the

idea, then why are there so few curricula and tool resources available to art teachers in order to

prepare them for the increasing number of students with disabilities in public schools?

General Education Curriculum Adaptations

In researching curricular needs and accommodations for people with disabilities, findings

suggest there is a need for more universal design for learning, normalization, higher order

thinking skills, and adaptations. The following sections will address each of these methods.

Universal Design for Learning

In Robinson’s (2013) study of the quality of arts integration research, she noticed that

universal design for learning (UDL) principles were being used in many school districts, such as

New York City. UDL is an interdisciplinary approach that provides students with multiple means

of engaging, expressing, and representing their ideas and learning. It is also a backwards design

that allows for essential concepts to connect to big ideas. Pugach and Warger (2001) also

mention UDL as a “goal yet to be fully realized in most contemporary classrooms” (p. 196),

especially when it comes to the textbooks chosen within the curriculum. The special education

teachers interviewed by Ponder and Kissinger (2009) felt that “the arts might play a role in

differentiated teaching strategies that could address the various learning styles and dominant

multiple intelligences of their students in order to meet educational and behavioral goals” (p. 41).

While students that need multiple means of learning and acquiring information might benefit

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

12

from UDL and the use of multiple intelligences, some authors suggest curriculum needs to be

chronological, age-appropriate, and teach functional skills that are representative of non-school

environments (Baumgart et al., 1982). On the other hand, the teachers interviewed by Ruppar

Ruppar, Roberts, and Olson (2017) noted the importance of teaching life skills, but also

emphasized the importance of persistence in teaching academic skills to those with severe

disabilities. The teachers did make an effort to make sure their curriculum was age appropriate

with a sense of equity to what other students were doing in the school building. Guay (1993b)

refers to this as normalization.

Normalization

Guay (1993b) describes “normalization” as an ideology that is “a combination of beliefs,

attitudes, and interpretations of reality, that derives from one’s experiences, one’s knowledge of

what one presumes to be fact, and above all, one’s values” (p. 59). Normalization is about

keeping classroom topics, student interests, social interactions, and other needs similar to that of

students with disabilities peers. For Guay (1993b), “Normalization focuses on the classroom

system. It does not seek to provide simplified art or in any way to separate or segregate students,

but rather makes instructional provisions that accommodate the diversity” (p. 62). Broderick,

Mehta-Parekh, and Reid (2005) agree that inclusive education should resist students being

excluded and marginalized, but they differ in their approach from Guay. They wrote, “Offering

the same lesson to all makes no sense when every indication is that U.S. classrooms are

inherently diverse” (Broderick et al., 2005, p. 196). They describe differentiated instruction (DI),

which allows teachers to address diversity by “planning and delivering rigorous and relevant, yet

flexible and responsive, instruction” (Broderick et al., 2005, p. 196) in general-education

classrooms.

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

13

Higher Order Thinking

When it comes to curriculum, many authors expressed the need for higher order thinking

skills to be addressed (Ponder & Kissinger, 2009; Pugach & Warger, 2001; Robinson, 2013;

Ruppar et al., 2017). Pugach and Warger (2001) express the curriculum issue of complex content

that requires deeper understanding, when many students with disabilities lack basic skills that

could inhibit them from reaching these deeper concepts. They wrote: “The underlying

assumption has always been that content requiring higher-order cognition was beyond the reach

of most students with disabilities” (p. 196). Instead of offering a watered-down curriculum or

only focusing effort on basic skills, these authors point out research that states, “Students with

disabilities are capable of achieving far higher levels of understanding of complex material than

many special educators previously believed was possible” (Pugach & Warger, 2001, p. 196).

In a study by Ruppar et al. (2017), they interviewed 11 teachers of students with severe

disabilities and were identified as expert teachers in this field. One theme that came up in this

study was high expectations. One teacher said, “You really have to believe that every single

student is capable of learning anything that you’re teaching” (Ruppar et al., 2017, p. 128).

Presuming competence is something that Broderick et al. (2005) address:

One is left in the position of having to make decisions about a student’s curriculum and

instruction based on assumptions, rather than certainty. One is thus faced with a choice:

(a) assume that the student is probably not able to comprehend and elect to provide that

student with more limited learning opportunities, focusing on intensive remedial

coverage of very basic concepts; or (b) assume that the student is able to comprehend

beyond his or her ability to demonstrate that comprehension and elect to provide that

student with more rich and varied learning opportunities, while continuing to seek a more

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

14

reliable means for that student to demonstrate comprehension through differentiate

process and products. (pp. 198-199)

Ruppar et al. (2017) wrote, “High expectations for students are reflected in teachers’ advocacy,

systematic instruction, curricular decisions (i.e., academics), and collegial relationships” (p.

128). All of these authors feel that curriculum for those with disabilities can and should include

higher order thinking skills. These skills are made possible through the use of adaptations.

Adaptations

Adaptations for general education curriculum may include many things. Some authors

offer specific examples (Broderick et al., 2005; Guay, 1993a; Ruppar et al., 2017). In Ruppar et

al.’s (2017) study, expert teachers thoroughly individualized their instruction. They also used

adaptations that were specific to the students and customized their learning. Knowledge of these

adaptations was key. For instance, these expert teachers used multiple ways to present materials,

such as visual, tactile, and kinesthetic information, providing schedules, using manipulatives, and

using technology. Teachers also noted that having a deep knowledge of the student allowed for

more individualized instruction and allowed them to choose adaptations based on the students’

strengths. Just as the teachers in Ruppar et al.’s study did not believe that one size fit all,

Broderick et al. (2005) also discovered that people with disabilities are not all the same:

Disability does not play out for all students in the same way, even when they carry the

same label. . . . The intersectionality of all personal and social characteristics determines

how disability will be experienced. Thinking about disabilities as absolute categories of

difference also causes trouble because it emphasizes students’ common deficits . . . rather

than their uniqueness and competence. If teachers are to provide access to the general

education curriculum, as the 1997 . . . IDEA . . . mandate, they must identify and build on

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

15

all students’ strengths, talents, and prior knowledge. Only through building on their

strengths and acknowledging their experiences can teachers engage students in

appropriately challenging classroom activities. (p. 196)

Regardless of their label, many students with disabilities are unable to read at the expected grade

level. Broderick et al. (2005) suggested using a reading buddy, assigning parts ahead of time,

allowing them to decide what they read, bypassing reading altogether, providing an alternative

text, placing visual aids within the text, or supporting the text with graphic organizers. Teachers

must be aware of and practiced in using adaptations in all subjects. Regardless of the adaptation,

it is the teacher that must problem-solve and remain flexible to adapt, but not water down the

material (Broderick et al., 2005; Coleman et al., 2015).

Adapted Arts Curriculum

Is there a need for specialized arts curricula? In kindergarten through 12th grade,

respondents reported that “66.7% taught students with disabilities only in integrated

classes, 30.9% taught a combination of integrated and segregated classes, and 2.4% taught

students with disabilities only in segregated classes” (Guay, 1994, p. 46). This is part of the

change brought on by IDEA. Guay (1994) goes on to say that, “Consequently, all art teachers

must be prepared to teach students with disabilities in integrated classes and to respond to the

social, instructional, and curricular needs of students with a broad range of ability” (p. 44). Many

teachers are not prepared for this, however; and therefore points to a need for adapted

curriculum.

While art educators may be provided with a typical standards-aligned curriculum, it may

not be appropriate for many of the students that are included in their classrooms. For Zederayko

and Ward (1999) a rigorous visual arts program contains “a range of elements including art

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

16

study, two-dimensional and three-dimensional work. Thus, the student in a wheelchair who is

unable to make any marks on a two-dimensional surface will be able to experience only a portion

of a full art education experience” (p. 18). MacLean (2008) puts it this way: “The goal of

inclusion is not uniformity, true inclusion means offering each student the opportunity to learn in

a style and environment that maximizes his/her ability to fully develop as a human being”

(p. 95).

Art educators do not have to work alone. In collaboration with universities, art educators

could provide knowledge of tools and adaptive materials for review. Another form of

collaboration takes place within the school building: “Art teachers often serve students with

significant disabilities for limited amounts of time and have limited disability-specific

knowledge while special education teachers understand individual students’ needs but have little

knowledge about the art curriculum” (Coleman et al., 2015, p. 639). Both special educators and

art educators must rely on each other for support and the exchange of knowledge.

Artistic Media

Digital technology. In an art-based study conducted by Darewych, Carlton, and Farrugie

(2015), digital technology was explored as a possible art medium for adults with developmental

disabilities in art therapy. It was found successful, especially by those on the Autism spectrum

with touch, tactile, or smell sensitivity (Darewych et al., 2015). The authors found that

“participants with tactile sensitivity favoured creating art on the texture-free touchscreen devices

because of its compact, mess-free therapeutic environment. Such results support . . . that certain

individuals may interact more effectively with low kinetic sensory or mess-free digital device

than with traditional messy art materials” (p. 99). Taylor (2005) also investigated ways in which

the arts curriculum could be made accessible to young disabled people through digital

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

17

technology. Although many disabled students have difficulties with manipulative skills that keep

them from techniques such as drawing, she argued that “digital technology if managed

appropriately, has the power to obviate the requirement for high levels of manipulative skills and

physical dexterity in the production of visual images” (Taylor, 2005, p. 327). Digital technology

is just one artistic medium available to students with disabilities. Next, literature on two-

dimensional art will be explored.

Two-dimensional arts. Painting, printmaking, collage, and drawing are all techniques

found in art curricula. As mentioned previously, drawing can be a particularly difficult technique

for students with severe disabilities to accomplish (Taylor, 2005). Zederayko and Ward (1999)

have also seen this struggle in two-dimensional works: “The student who is physically unable to

hold a pencil or paintbrush, for example, is bound to have difficulties with a lesson on painting

or drawing” (p. 18). In Guay’s (1993a) study of effective art programs, she noticed that “teachers

emphasized assignments that did not require realistic drawing. Printmaking and ceramics were

the most frequently observed studio activities” (p. 228). The teachers in Guay’s study often

chose art media and processes for whole class success. For painting, LaMore and Nelson (1993)

found that “adults with mental disabilities painted significantly more if they were given options

and the opportunity for choice than if they were not given options” (p. 400). Although many

students struggle to hold a pencil or paintbrush, Zederayko and Ward (1999) constructed

assistive technology, which was designed to address this issue. This technology will be discussed

in a later section of this review.

Three-dimensional arts. Art also consists of the three-dimensional arts including

sculpture and ceramics. Timmons and MacDonald (2008) conducted a study on the experience of

using clay for people with chronic illness and disability. They wrote, “Occupational therapists

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

18

have reported that clay offers an opportunity for creativity, imagination and expression, whilst at

the same time requiring dexterity and strength, making it useful for improving fine motor control

and coordination (Breines, 1995)” (pp. 86-87). Not only did the clay provide opportunities for

fine motor skills, but “the diversity of techniques and the essence of clay as a sculptural medium

enabled the participants to create pleasing work despite physical limitations” (Timmons &

MacDonald, 2008, p. 91). Similarly, clay stood out as an artistic medium because no tools were

needed and the participants enjoyed the feeling of the clay. For those that do not like the feel of

clay, gloves could be worn as protection.

Curricular Content

Some authors lamented that current art curricula lack in value and effectiveness for

individuals with disabilities. Having a curriculum that was meaningful was important to multiple

researchers (Broderick et al., 2005; Ponder & Kissinger, 2009; Pugach & Warger, 2001). In

addition, Eisenhauer (2007) advocated for “the inclusion of disabled people doing art in art

curriculum,” which “placed an emphasis upon the representation of difference through a

curriculum of admiration and appreciation in which individual artists are admired for their ability

to create work similar to other able-bodied artists” (p. 9). Lastly, Schiller (1994) and Guay

(1993a) both mention the discipline-based arts education (DBAE) as a recommended focus for

art education goals. For example, Schiller (1994) writes, “Art lessons that are content-rich, in

that they include concepts in art history, criticism and aesthetics, can promote the use of oral and

written language, as well as addressing specific art learning” (p. 12). Looking at these studies, a

combination of meaningful art lessons, the inclusion of disabled artists, and DBAE would give

an art educator focus for a well-rounded art education curriculum.

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

19

Accommodations and Adaptations

When looking at accommodations or adaptations to the curriculum, some researchers

consider teachers being proactive to be the best approach (Cramer et al., 2015; Pugach &

Warger, 2001; Wexler & Luethi-Garrecht, 2015). Cramer et al. (2015) believe that “students

require teachers to be proactive in creating art experiences that are meaningful by being fluent in

various accommodations and modifications that allow them to participate fully in the preK-12 art

classroom” (p. 7). Pugach and Warger (2001) feel that being proactive is not only important in

understanding accommodations, but in redeveloping the way curriculum is approached. They

shared:

. . . Bart Pisha and Peggy Coyne, are among those who are taking a proactive approach to

“hardwiring” curriculum materials from the outset so that they naturally accommodate a

far greater range of students and motivate them as well. In this way, they are attempting

to relieve an unreasonable burden for teachers and make curriculum materials flexible

enough from the start to meet typical differing needs. This in turn, can free up specialists

to work on very complex needs. (Pugach & Warger, 2001, p. 196)

When a teacher is proactive in their approach to inclusive curricula, they consider the

environment, any need for assistive technology, opportunities for independence, and their

instructional methods.

Environment: bringing out the best in students.

The environment, and even the layout of the art room can have an impact on whether or

not a student with a disability feels welcomed and included. Wexler and Luethi-Garrecht (2015)

found that the physical arrangement of the art room was more of an obstruction to collaboration,

independence, empathy, and dialogue than the lack of communication itself. MacLean (2008) put

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

20

it this way: “Because she is in charge of creating an environment that is conducive to learning,

the teacher has many decisions to make including how she will physically set up the space, what

materials she will make available, and the best way to plan” (pp. 93-94). Broderick et al. (2005)

suggested:

To accommodate disabled students, aisles should be clear and wide enough to be

wheelchair accessible and students should be able to choose the specific environment in

which they prefer to work. . . . Materials should be accessible, charts and bulletin boards

at eye-level. (p. 198)

Not only does the physical environment play a role, but the teacher’s perception and

attitude toward diverse individuals. Broderick et al. (2005) seems to also make this point,

“Students tend to take cues from the teacher, and so the teacher’s attitudes toward disability will

greatly influence how students treat difference. Thus, teaching about diversity . . . should be an

integral part of the curriculum in inclusive classrooms” (p. 198). Teachers can take care to set up

their room to accommodate different needs, as well as check their own engagement with students

with disabilities in the classroom. Next, assistive technology will be discussed in relation to

participation in the art room.

Assistive technology: the sky’s the limit.

Assistive technology (AT) is a device or piece of equipment that allows a child with a

disability to improve, maintain, or increase their speech or physical experiences and capabilities.

Finding the most effective combinations of adaptations and teaching strategies for

students with physical, visual, severe, or multiple disabilities access to the general

curriculum can be especially difficult for teachers. Though true for all-inclusive

environments, this especially applies for art classrooms where curriculum access relies

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

21

heavily on physical, visual, and abstract problem solving abilities. (Coleman & Cramer,

2015, p. 638)

The results of Coleman et al.’s (2015) study showed that over half of surveyed teachers rarely or

never used assistive technology. In contrast, the experienced teachers in Cramer et al.’s (2015)

study often used more than one type of assistive device to help students with disabilities. Taylor

(2005) asserted that students with disabilities are subject to the lottery principal when it comes to

teachers that are trained to use assistive technology. She writes, “They may or may not encounter

the teachers and technicians who can equip them with the adaptations to the computer, its

hardware and software that they require, and they may or may not encounter a teacher who is

committed to the creative use of [Information Communication Technology] in the arts” (Taylor,

2005, p. 331). It is because of this that teachers must become more knowledgeable of current

technology, tools, and adaptations for these students.

Zederayko and Ward (1999) suggest varieties of adaptive strategies such as adjustable

tables, elevated lapboards, or tools to modify art materials, such as larger crayons, for the student

to be able to grasp them more easily. These are not just tools; they are opportunities for children

to experience art as their peers do. After creating an adaptive tool for a student to use, Zederayko

and Ward (1999) wrote:

At last Craig was making his own drawings. Craig felt intense personal achievement with

his accomplishments and felt ownership for his drawing. He was so engrossed that he

refused to give up his activity long enough to allow his aide to switch pen colors in the

drawing tool. In the past Craig permitted his aide to complete most of his art projects for

him as he sat placidly watching the process. (p. 21)

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

22

This incredible transformation would not have been possible without assistive technology. In

Guay’s (1993a) study, “traditional art media and processes were found viable for all students,

although adaptations of tools and alternative methods for working with materials were observed”

(p. 230). She also found that a student’s physical needs could require media to be chosen or

adapted in order to provide independence. For example, “Oak tag and chunky crayons helped

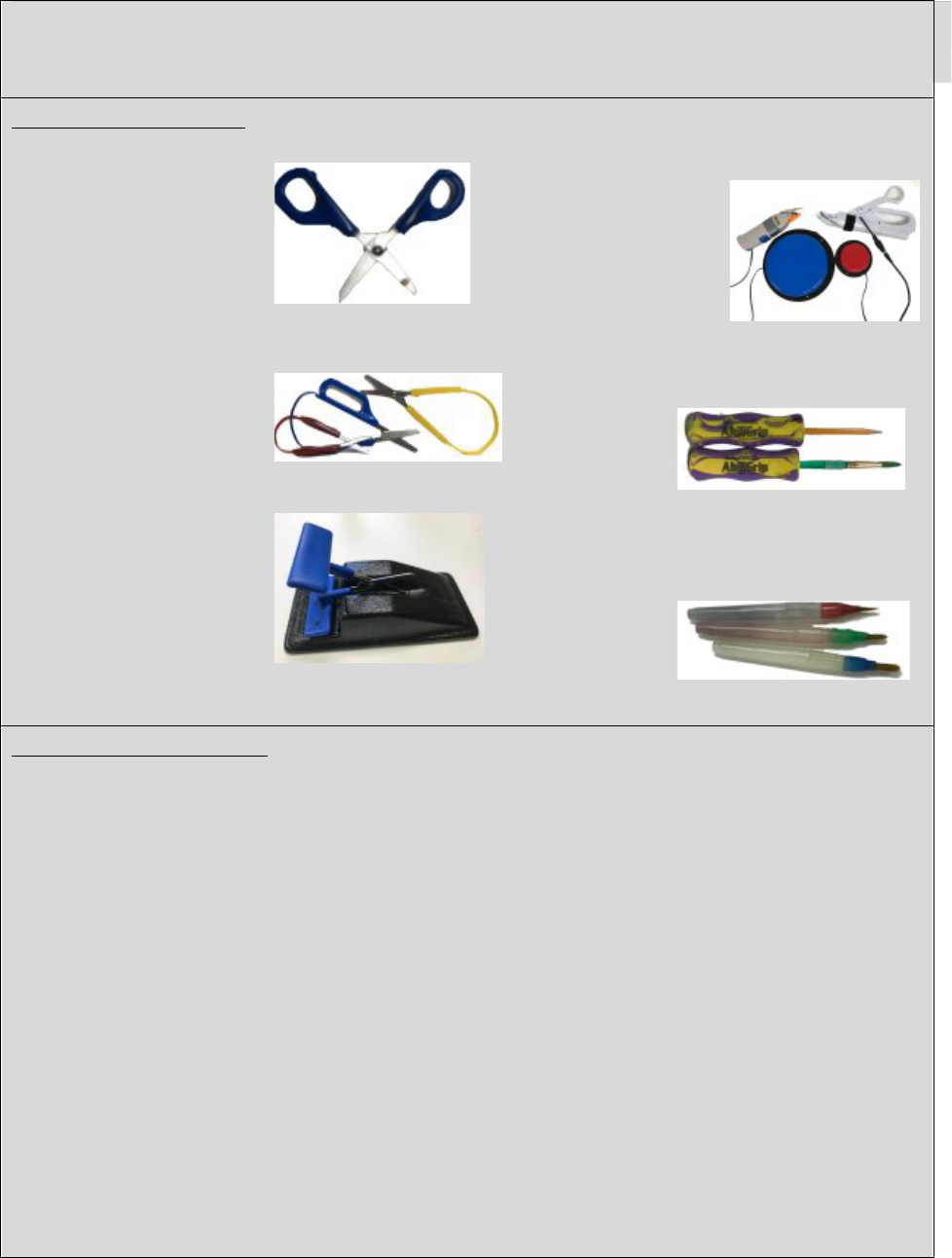

when hands were awkward. One used a turntable when students had limited reach . . . five styles

of scissors were found in classrooms along with teacher-invented paper and scissor holding

devices” (Guay, 1993a, p. 229). Taylor (2005) also made a suggestion about adapting art

materials: “There are a range of both sophisticated and simple technological solutions that

facilitate students’ learning in the arts. These can be as simple as a crayon attached to a long

stick or a moulded splint that supports or effects grasping a drawing implement” (p. 326). AT

does not have to stretch the budget or be store bought.

Baumgart, Brown, and Pumpian (1982) list five ways to create individualized

adaptations. These include: (a) utilizing/creating materials and devices, (b) utilizing personal

assistance, (c) adapting skill sequences, (d) adapting rules, and (e) using social/attitudinal

adaptations. However, many solutions should be attempted before an adaptation is decided upon.

An expert teacher would have multiple adaptations of tools prepared for each lesson to

individualize the technology to each student. As seen in Coleman et al.’s (2015) study, teachers

need to be more active and conscientious of creating adaptations through the use of assistive

technology. Assistive technology is used to increase skills in many areas but with a common goal

to increase independence.

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

23

Independence: the artist in me.

Independence is something that individuals without disabilities may take for granted.

When students with disabilities are provided with aides or lack AT, their voices may not come

through in their artwork (Taylor, 2005; Zederayko & Ward, 1999). Taylor (2005) believes that

“The enabler’s role should be to build confidence in independent thought and recognition that

difference is valid and worthy of aesthetic consideration. A significant part of this creative

process is to learn by making mistakes or by taking advantage of the ‘happy accident’” (p. 330).

The art classroom is an ideal place to allow for independence, as there are multiple ways to

interpret art, and children with or without disabilities should not be pressured to conform. Ruppar

et al. (2007) also felt that the teacher played an important role in creating student independence.

They wrote, “An expert teacher takes responsibility for equipping students for independence and

recognizes that part of the job of teaching is to find opportunities for students to build on their

strengths” (Ruppar et al., 2007, p. 128).

In the reviewing studies focused on adapting art for people with disabilities,

independence was always seen as a positive. For example, Ponder and Kissinger (2009) shared

that during multiple projects taught by a special education teacher, a teaching artist, and an arts

specialist, “the students learned to work independently and to meet the challenge of producing

finished objects to certain specifications, and they have successfully sold their works at

gardening shows” (p. 42). With some students with disabilities being segregated in different

schools, it was important for Guay (1993a) to see that a “normalized art curriculum” was still

being used to promote independence and provide the students with “classroom responsibilities

similar to those at non-segregated sites” (p. 230). Through the use of computers, Darewych et al.

(2015) found that there was an improvement in independence of digital art over traditional art:

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

24

Due to the multimedia design of touchscreen devices and the proximity of the digital

canvas right at one’s fingertips, as sessions progressed, participants were able to

independently choose their preferred art tools, blend their desired colours, and transfer

images from the Internet onto digital collage work. The participants often require

assistance with mixing colours and operating tools such as scissors when creating

traditional art. (Darewych et al., 2015, p. 98)

LaMore and Nelson’s (1993) study shows that “choice making within parameters set by the

therapist can enhance performance. In addition, choice making is a developmental achievement

in its right that should be encouraged” (p. 400). This is one method for creating independence so

that the child has a voice.

Instructional methods: initiating student artistic success.

In addition to the environment and assistive technology, a teacher’s instructional methods

can be adapted to accommodate or modify a student’s access to learning. In the pilot project

initiated by Ponder and Kissinger (2009), the arts specialists learned that “they needed to give

directions in a very linear way, that they might have to repeat themselves more often, and that

they had to give directions in smaller ‘chunks,’ step by step” (p. 43). The arts specialists also

learned “how to structure activities so that students with a variety of abilities could be successful.

They learned how to differentiate teaching in classes where students have various dominant

learning styles and multiple intelligences” (Ponder & Kissinger, 2009, p. 43).

For further instructional adaptations, Guay (1993a) lists “one-one-one directness,

repetition, example, and modeling” (p. 228). One might think that repetition might decrease the

likelihood of creativity, but she found that “students experiencing developmental disabilities

gained in art knowledge and art skills while creating original designs” (p. 223). Similarly, Arem

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

25

and Zimmerman (1976) found that “modeling art behaviors, demonstrating techniques, and

showing completed examples of art products did not stifle creativity but rather enhanced it” (as

cited in Guay, 1993a, p. 223). Task analysis, a strategy found useful by Guay (1993a, 1993b) is

an approach used to reduce specific skills into small sequential steps. In her study, Guay (1993a)

also breaks instruction down into different categories. For students needing academic assistance,

she recorded that “teachers used a cue hierarchy, verbal cuing, and additional demonstration

preceding hand-over-hand assistance if needed” (Guay, 1993a, p. 229). For students with

attention and behavioral disabilities, Guay found that teachers allowed them to work in the media

of their choice, instructed in small increments, provided effective tools, and tried to keep

frustration levels down.

Zederayko and Ward (1999) suggested an approach to lessons that move away from

“appropriate” activities and instead focuses on skills needed for the lesson, such as holding and

using a pencil. For Broderick et al. (2005), “Students need many and varied smaller opportunities

throughout the course of study and having multiple opportunities for rehearsal and practice of

assessment activities typically supports students’ successful performance” (pp. 199-200). They

also stated that “goals and procedures are clearly articulated; the instruction is relevant,

accessible, and responsive; and the tasks are interesting and challenging, but reachable with

effort. Disabled students benefit from good instruction, just as all students do” (Broderick et al.,

2005, p. 200). It is clear that there are many techniques a teacher must consider as they instruct

individuals with disabilities to promote success.

Impact of Arts Integration

If you are wondering why arts education is important in the lives of children with

disabilities, the literature so far discussed so far has found many benefits to not only teacher

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

26

perceptions, but to the individual student’s perceptions of themselves and their disability (Derby,

2016; Guay, 1994; Mason et al., 2004). Some of these benefits include: (a) a greater range of

communication possibilities through visuals (Coleman et. al, 2015; Mason et al., 2004;

Zederayko & Ward, 1999); (b) developed literacy, writing, and numeracy skills; (c) improving

motivation and comprehension; and (d) opportunities to find success, build confidence, social

skills, fine motor skills, problem solving, and participation (Erim & Caferoğlu, 2017; Mason et

al., 2004). Given these benefits, “to deny students access to art is to deny them the opportunity to

develop themselves” (Zederayko & Ward, 1999, p. 19). According to Ponder and Kissinger

(2009), students with disabilities gain many additional benefits through the arts:

Students are “given a voice,” are allowed to solve problems in different ways, and are

inspired to ask more questions and make their own choices, improving communication

skills. Students are proud of their work and their self-esteem “blooms” when they get to

show it to visitors. Some commented on how the arts encourage practice in skills such as

fine motor control, following instructions, and seeing a project through to the end, and

how they provide direct connections to academic subjects (i.e., arrangements of colors,

shapes, and patterns connect to mathematical abilities). (p. 45)

Some of the most significant benefits will be discussed in the final sections of this review.

Motor Skills Development

Because the arts allow for more than one solution to a problem, they encourage students

to problem-solve in new and creative ways, differing from the structured path of academic core

subjects (Guay, 1993b; MacLean, 2008). The arts also provide opportunities for fine motor skills

to be developed. Erim and Cafeogu (2017) found that “most of the special education teachers

have agreed that using art education for the education of mentally retarded children has a

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

27

positive effect on the motor skills development of the children” (p. 1306). Motor skills are not

the only benefit to arts education, but communication skills are also found to increase with time

spent in the arts for those with disabilities.

Communication: Art as a Voice

Another common theme of previous research was the ability to communicate through, or

because of, the arts (Coleman et al., 2015; Kissinger & Ponder, 2009; MacLean, 2008; Schiller,

1994; Taylor, 2005; Zederayko & Ward, 1999). Schiller (1994) believes that “the link between

language development and art should be highlighted as an important aspect of lesson objectives”

(p. 13). In Give Students With Special Needs Something to Talk About, Schiller interviewed a

speech pathologist, Dora, to get her perspective on art and communication. Dora said, “By doing

art projects, I can see, coming from a language perspective, how advantageous it is to do these

kinds of activities” (Schiller, 1994, p. 13). Zederayko and Ward (1999) found that “art study also

provides the student with a greater range of communication possibilities because it provides

students with access to the language of the visual" (p. 19). Taylor (2005) expresses that although

augmentative communication may be used, teachers and assistants may also look for eye

direction, facial expression, gesture and sound as communication for choices and art criticism.

Students may also find ways to communicate or collaborate in the arts through the social

interaction of class. “One special education teacher reported discovering that her students learned

‘so much more than art’ in the project: vocabulary, social skills, cognitive skills, planning, and

pride in their work” (Ponder & Kissinger, 2009, p. 43). Art is interdisciplinary in nature, but does

lend itself to other opportunities outside of traditional art making. Robinson (2013) felt that “arts

integration is naturally engaging, as it offers students many opportunities for individual choice,

autonomy, and self-regulation through collaborative learning experiences with peers” (p. 192).

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

28

Likewise, Coleman et al. (2015) wrote, “Students of all ages and ability levels can benefit from

expressing their thoughts, ideas, and emotions through the multiple modes of learning (intuitive,

kinesthetic, etc.), creative processes, graphic narratives, and social experiences of an art

classroom (e.g., working with shared materials, learning how to critique constructively,

participating in group art projects)” (p. 638). All of these authors have found that art provides

opportunity for growth in multiple areas of their learning, and should not be discounted.

Self-Esteem and Expression

Self-empowerment, enjoyment, confidence, and expression through art making were

common themes in the literature (Darewych et al., 2015; Erim & Cafeogu, 2017; Mason et al.,

2004; Ponder & Kissinger, 2009; Schiller, 1994; Timmons & MacDonald, 2008). In exploring in

digital technology, Darewych et al. (2015) found that, “through the creative process, participants

gained a sense of empowerment and utilized their talents and imaginative thinking abilities” (p.

100). In the evaluation of clay for people with disabilities, Timmons and MacDonald (2008)

wrote, “Whether it was through the process of making or the end product, all the participants

gained a sense of enjoyment and satisfaction from creating works in clay” (p. 89). Erim and

Cafeogu (2017) found the exploration of art materials to create expression despite physical

developmental delays:

Art materials result in beneficial outcomes for mentally retarded children in terms of

coordinated use of their hands and eyes simultaneously. Different materials and methods

affect the developmental processes of children and increase their interest for art lessons.

Since techniques and methods taught by working with different materials help children

link their physical and personal features, children find opportunities to express

themselves in a better way. (p. 1302)

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

29

Not only did students’ self-perception change positively after engaging in the arts, but the

teachers’ perceptions of the students’ capabilities and strengths also changed in positive ways.

Teacher Expectations and Perceptions

Many researchers found that teacher perceptions of success reflected the expectations that

were set (Broderick et al., 2005; Guay, 1993b; Mason et al., 2004; Ponder & Kissinger, 2009;

Wexler & Luethi-Garrecht, 2015). In one study that conducted focus groups with teachers,

Mason et al. (2004) found that they reported being thrilled when students demonstrated artistic

talents or abilities in their classroom, and were encouraged when they observed students engaged

in the artistic process. These authors state, “Many teachers truly believed that students with and

without disabilities who experience success with the arts and have experiences with the arts, tend

to learn more and be more successful academically” (Mason et al., 2004, p. 27).

Ponder and Kissinger (2009) also saw similar results: “[Special education teachers] also

reported learning that their students were capable of creating in the arts beyond the levels they

had imagined at the beginning of the project” (p. 43). In these authors’ pilot program, “Parents

were very pleased with the works of art their children created, were surprised they were so

successful, and were very proud” (Ponder & Kissinger, 2009, p. 44). In addition, Guay (1993b)

found that “many art teachers have shared their belief that disabled students seem to rise to

expectations, often surprising other teachers and parents” (p. 59).

According to Valle and Connor (2011), “What teachers believe about disability

determines how students with disabilities are really educated” (p. 13). This means that teachers

must be prepared and educated on disabilities and more resources are needed to demonstrate to

these teachers how to believe in these students’ strengths. How does one raise teacher

expectations of learning for those with disabilities? Broderick et al. (2005) state “Educators must

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

30

presume, first and foremost, that their students are competent individuals who are ready for and

capable of benefitting from academic curricular content, and then must create the necessary

instructional package to ensure students’ access to that content” (p. 199). Teachers must presume

competence, and set high expectations of learning for these individuals to be welcomed and

included in education.

Conclusion

Throughout this chapter it has been clear that there is a need for individualized

curriculum. Peterson (1995) warns that it “does little good to include a student only to have the

group or program exclude the individual beyond observation of activities” (p. 6). This literature

review has pointed to past research indicating that arts integration for students with special needs

is important (Derby, 2016; Erim & Caferoğlu, 2017; Guay, 1994; Mason et al, 2004) and yet

lacking (Coleman et al., 2015; Cramer et al., 2015; Guay, 1994; Mason et al., 2004; Zederayko

& Ward, 1999). This review considered the accommodations and adaptations of both general

education curriculum and arts education curriculum and instruction. It also included multiple

studies on the benefits of arts education in the lives of individuals with disabilities and the

changed perception of their teachers. With a look into past and current literature, it is still

apparent that even with the enactment of IDEA, there is still a need of specific art-related

knowledge for art educators including instructional adaptation, curriculum, and tools.

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

31

Chapter 3

Adapted Arts Curriculum

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

32

Adapted

ArtCurriculum

Grades K-5

GenevieveYoder

May2018

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

33

Table of contents

Introduction……………………………………………………………………………………...35

Art for Grades K-5…….………………………………………………………………………...35

The Goal of the Curriculum Map…….…………………………………..……………………...36

The Unit Plans …….……………………………………………………………………..……...37

Digital Technology…….………………………………………………………………...37

Two-Dimensional Arts…….………………………………………………………...…..43

Three-Dimensional Arts…….…………………………………………………………...48

Accommodations Template…….………………………………………………………..53

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

34

Introduction

This curriculum produces the application and response to the meta-analysis research

found in the Adapted Art Curriculum thesis project by Genevieve Yoder. First, the following

curriculum will cover the application and background of the curriculum plan. This curriculum

will include three in-depth unit plans that demonstrate the three art media sections mentioned in

the research meta-analysis: Digital Technology, Two-Dimensional Arts, and Three-dimensional

Arts. Each unit plan will incorporate accommodations and modifications for successful art

making for students of all abilities. After that, there will be a separate table for an

Accommodations Template to help teachers plan for accommodations that can be made for

presentation, response, and setting. The full curriculum plan will be shown as a map for

overarching topics to be covered for the entire year for elementary students levels K-5. This map

can be viewed as a supplemental document.

Art for Grades K-5

The curriculum map is designed to be age appropriate, rigorous, and relevant, while still

allowing flexibility for individualization (Broderick et al., 2005; Guay, 1993b). There are

columns, or sections, to the curriculum map for each grade K-5: Units, Media, Art Production,

Cultural History, Art Criticism, Aesthetic Standards, and Modifications. Art Production, Cultural

History, Art Criticism, and Aesthetic Standards are all established on the Disciplined-Based Arts

Education (DBAE) principle, suggested earlier by Schiller (1994) and Guay (1993a).

“Art lessons that are content-rich, in that they include concepts in art history, criticism and

aesthetics, can promote the use of oral and written language, as well as addressing specific art

learning” (Schiller, 1994, p. 12). These four areas of learning are also reflected in the

Pennsylvania Academic Standards for the Arts and Humanities. Because of this, the

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

35

Pennsylvania (PA) standards were applied to each category according to the unit topics being

covered. For the individual unit plans, the National Core Art Standards were included in addition

to the PA standards.

The Goal of the Curriculum Map

The goal of the curriculum map* was to make sure that:

1. Learning was tiered, becoming more complex with each grade level

2. Each academic standard was accomplished within a student’s elementary educational

experience

3. There was some form of proactive adaptation or modification ‘hardwired’ in the

curriculum from the start (Pugach and Warger, 2001).

*The curriculum map is available for reference in a supplemental document created for

these units.

These modifications were made directly from the research above, including specific items

under three categories: Environment, Instruction, and Materials. A teacher with one or more

students with disabilities will need to be proactive in accomplishing or preparing many of these

items. This is why it is important to have it listed in the curriculum plan, so that it is in the

forefront of the teacher’s mind. They must plan with purpose to allow for the most success.

Many items, such as AT communication devices may require collaborating with speech

therapists in order to understand what words the child has access to, or how to assist the student

in using the device if it is new to them. As far as artistic tools, teachers may need to purchase

these before the need arises so that they are prepared to swap out materials at any moment.

The Elements, Principles, Artists, and Cultures are intended to be closely related and

overlap to an extent, activating prior knowledge. For instance, in 5

th

grade, students will learn

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

36

about artists Diego Rivera and Frida Kahlo. In order to learn about these artists appropriately, the

culture of Mexico would also be taught. A lesson on the Dias de los Muertos (Day of the Dead)

may include symmetrical skeletons of Diego and Frida (Cortes, n.d.). During the lesson students

will learn about art elements and principles such as shape, pattern, balance and unity. These

elements and principles of design would be discussed and learned prior to this lesson, which

incorporates a merging of artist, culture, and design. This repetition will be helpful to typical

students, as well as students with disabilities. Each district has differing amounts of time spent in

the arts, so the number of lessons that include the art elements and principles, artists, and cultures

would be flexible according to the needs of each teacher.

The Unit Plans

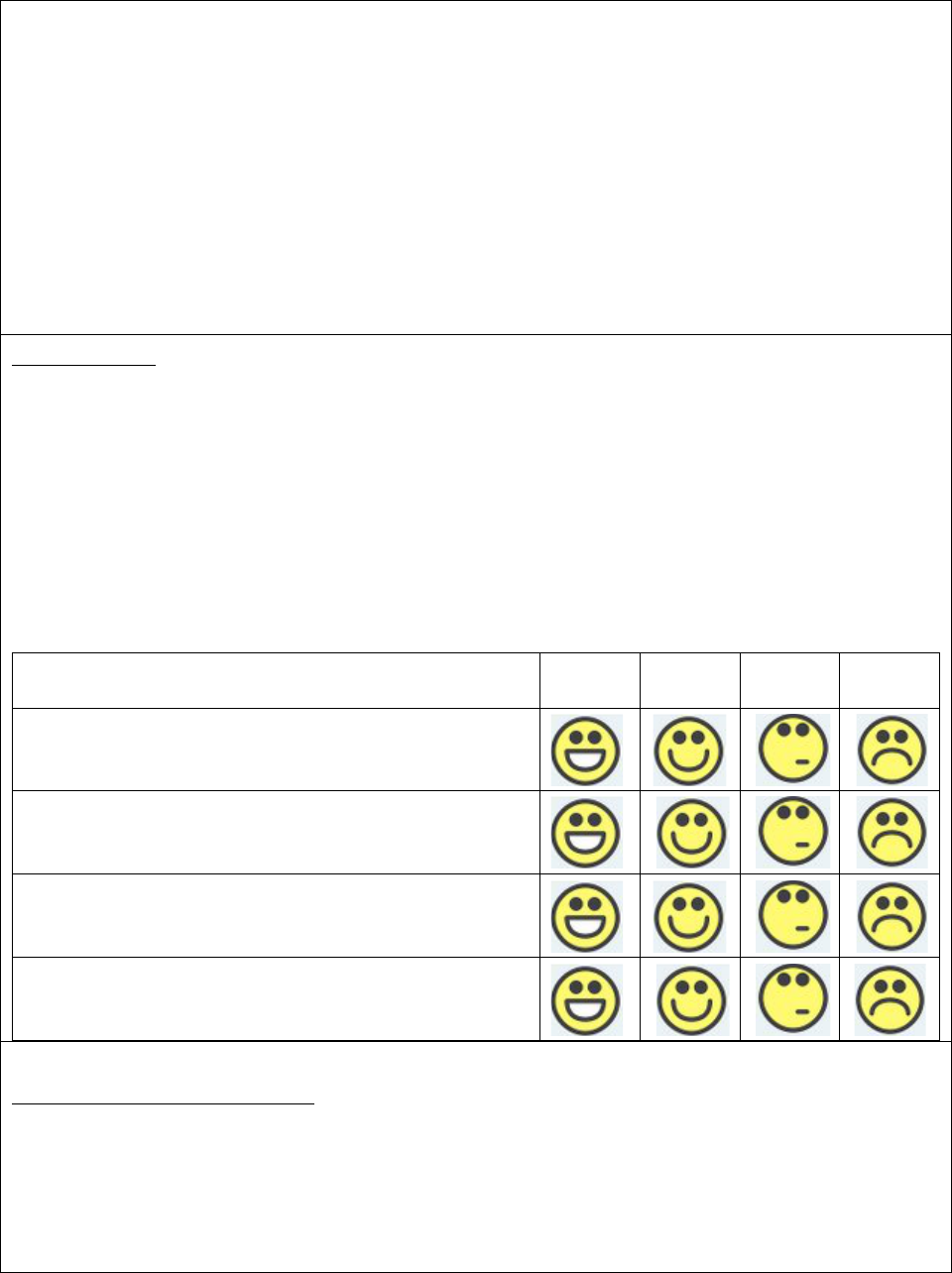

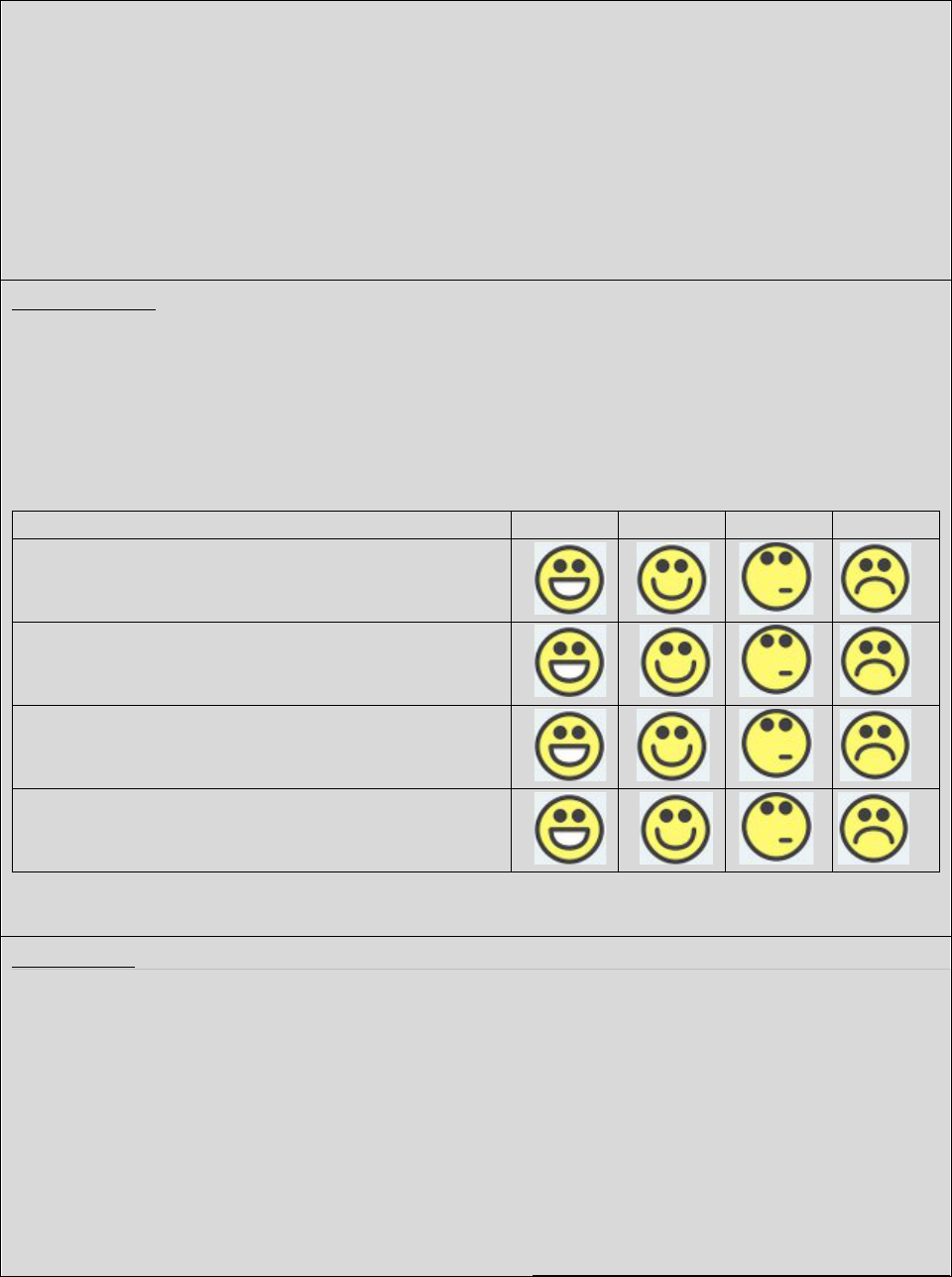

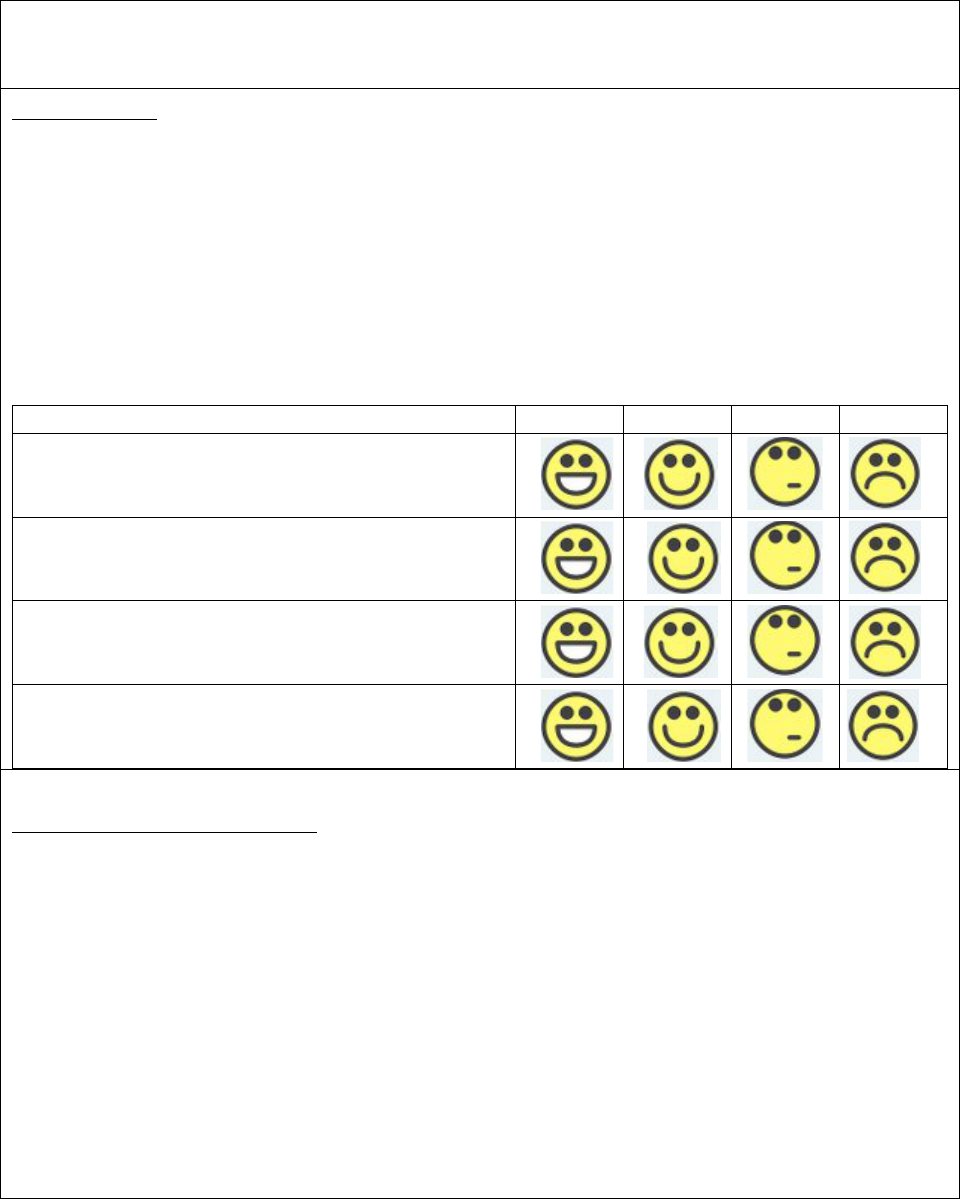

Each unit plan includes a description, essential questions, learning objectives, curriculum

standards, assessments, materials, instructional activities, accommodations, and resources. The

description is important for the teacher, administrator, or substitute teacher to familiarize

themselves with the overarching concepts and goals of the unit. The essential questions and

vocabulary focus the teacher to address the learning so that the students will be able to answer

the questions by the end of each lesson or unit. The summative assessments included in the unit

plans are geared towards elementary-aged students. The rubrics are visual, allowing for

understanding for students with English as a second language, students with disabilities, and

typical students alike. The materials, resources, accommodations, and instructional activities are

all structured in a way that will lead back to the instructional objectives. This creates a

backwards, universal design where students have multiple means to represent and express their

learning (Robinson, 2013).

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

37

Digital Technology

In Chapter two, it was expressed that Darewych et al. (2015) found that digital

technology benefitted those with touch and smell sensitivity because it is texture-free and mess-

free. Using technology in the art room provides engagement different from the traditional tools

that may also be used for creation. For this unit, students will be creating an artistic image using

an iPad application (app) called Pic Collage. It is a free application, and with instruction, is easy

to learn and use. Many children are already exposed to this technology by this age, but it is

important for the teacher to go over the basic functions of the device before beginning the lesson.

Not only does this unit incorporate technology skills, but it also provides interdisciplinary

avenues through the use of literature.

Through the use of a digital surface, an accommodation is already being made for whole

class success. Since the iPad is the only art media being used, there are not an abundance of

adaptive materials to worry about. However, there may be students with severe disabilities who

lack fine motor capabilities that may find the screen too small for their arm movements. In this

case, under the Modifications/Accommodation section of the unit plan, a suggestion was

included to have the student(s) use the interactive classroom board, whether it is a Smartboard,

Promethean, IPEVO, or other interactive instructional device. If the digital pen is too short, it can

be attached to a yardstick and wielded hand-over-hand if necessary. For students are visually

impaired and would not be able to engage with the device by touch, it was suggested to modify

the assignment by having the student use three-dimensional materials such as foam, so that they

can feel the shapes they are producing and arranging. While these adaptations or modifications

do not address every possible scenario, they demonstrate the flexibility in the lesson and the

possibilities to create success for individual learners.

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

38

Unit: Eric Carle iPad Collages Grade Level: 1st Grade

Description: Students will use the app Pic Collage on their iPads to create an Eric Carle

inspired digital collage. As a class, we will complete an author study by reading multiple books

by Eric Carle. We will compare them and look at how each shape is made up of smaller shapes.

We will watch a short video to see Eric Carle painting and creating the textures, then cutting

them out. Students will learn how to use tools in Pic Collage such as web search, clip tools, and

creating shapes. They will search for Eric Carle backgrounds, add them to their Pic Collage

gallery, and then cut shapes from the textures using their finger. They will then use these shapes

to create an image that illustrates a part of a fable found in one of the books on Epic! Students

will be assessed on this final design.

Essential Learning/Instructional Outcomes: (Identify the important concepts and

skills that students are expected to learn)

Students will be able to:

• Identify similarities between books illustrated by Eric Carle

• Illustrate for another book using Eric Carle’s style and textures

• Create a unique image using shapes, texture, and color on the iPad

Essential Questions:

• How can I illustrate a book using implied textures?

• How can I use technology to create a digital collage?

Vocabulary:

• Eric Carle

• Illustration

• Implied Texture

• Shape

• Collage

Curriculum Standard:

PA Academic Standards:

9.1.3.A: Know and use the elements and principles of each art form to create works in the arts

and humanities

9.1.3.B: Recognize, know, use and demonstrate a variety of appropriate arts elements and

principles to produce, review and revise original works in the arts.

9.1.3.C: Recognize and use fundamental vocabulary within each of the arts forms.

9.1.3.E: Demonstrate the ability to define objects, express emotions, illustrate an action, or relate

an experience through creation of works in the arts.

9.1.3.J: Know and use traditional and contemporary technologies for producing, performing, and

exhibiting works in the arts or the works of others.

9.2.3.L: Identify, explain, and analyze common themes, forms, and techniques from works in the

arts.

9.3.3.A: Recognize critical processes used in the examination of works in the arts and humanities

(compare and contrast)

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

39

National Core Arts Standards:

Va:Cr1.2.1a: Use observation and investigation in preparation for making a work of art

Va:Cr2.1.1a: Explore uses of materials and tools to create works of art or design

ELA Standards:

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.7

Explain how specific aspects of a text’s illustrations contribute to what is conveyed by

the words in a story (e.g., create mood, emphasize aspects of a character or setting)

CCSS.ELA-LITERACY.RL.3.9

Compare and contrast the themes, settings, and plots of stories written by the same

author about the same or similar characters (e.g., in books from a series)

Assessment: (Identify the formative or summative assessments you will use to determine

student progress toward achieving that instructional outcomes of the lesson)

Formative:

• Whole class discussion- “What is similar about the way these books are illustrated by

Eric Carle?”

• Whole class discussion- reading comprehension of books

• Ticket in/out the door on the artist

Summative:

• Students will be graded according to this rubric:

4

points

3

points

2

points

1

points

Image fills the entire screen

Collage has two or more shapes and two or more

textures

Collage illustrates part of a fable

Creativity- the image created is unique and complex

Materials and Resources: (Identify major resources/materials needed for the lesson)

LESSON 1: Reading; Drawing

• Eric Carle books

• Epic! reading site

• Pencils*

• White copy paper

• Pic Collage app on iPads*

• Drawing from previous week

LESSON 3: Create Illustration

• Pic Collage app on iPads

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

40

LESSON 2: Collect textures

• Eric Carle books*

• Epic! reading site

• Drawing from first week

*Denotes something that may require an adaptation

Instruction/Activities:

1. Whole class author study of Eric Carle

2. Compare and contrast books illustrated by Eric Carle and determine how the images are

made

3. Watch a short video to see Eric Carle painting and creating the textures, then cutting them

out

4. Whole class discussion on fables- Look at fable stories on Epic!

5. Choose a fable and brainstorm ideas and do a preliminary sketch on copy paper before

designing on the iPad

6. Use tools in Pic Collage such as web search, clip tools, and creating shapes to search for

Eric Carle backgrounds, add them to their Pic Collage gallery, and then cut shapes from

the textures using their finger

7. Create an image made of smaller shapes using Eric Carle’s textures on a digital device

Anticipatory Sets

• Read a selection of books illustrated by Eric Carle

• Discussion on common themes

• Discussion on fables

• Video(s) on Eric Carle’s process spaced out over the course of the unit

Technology Integration

• PowerPoint Presentation on artist

• iPad app (Pic Collage) to create final product

Modeling/Guided Practice

• How to use the Pic Collage app

o Web search through app- “Eric Carle Backgrounds”

o Select and add to library

o Add background image(s)

o Shapes- use existing and create your own using your finger

o Continue creating and moving around shapes to create a larger image

o Mistake? - How to change a shape once it has been clipped

Adjustments/Modifications/Grouping:

Hard of Hearing- face student during presentations; sign language and visual cues for each step

Students with Physical Disability- Hand over hand creation; use wheelchair trays or elevated

board to support the iPad; wheelchair tray or clipboard to support paper during preliminary

drawing; in small class sizes, they could create on the app using a large interactive white board,

instead of creating directly on the iPad. Student may need the digital marker to be attached to a

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

41

yard stick for additional length

Students with Autism- Few transitions; visual cues for steps

Students with Visual Impairment- puffy paint, glue lines, or braille for book images/text; text to

speech option for Epic! books; black background when presenting visuals; screen brightness

turned up, preferred seating close to the board

*A student whom is fully blind would create the shape collage using paper or foam sheets to be

able to manipulate tactilely

Non-communicative students- AT options (such as Big Mack button or LAMP communication

device) for participation/assessment; eye gaze for color/texture choices, sign language for

instructions/prompting

Resources:

Manipulatives:

• iPads

• Pic Collage App

• Epic! Reading site

• Eric Carle books

o Very Hungry Caterpillar

o Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See?

o Polar Bear, Polar Bear, What Do You Hear?

o From Head to Toe

o 10 Little Rubber Ducks

Instruction:

• PowerPoint Presentation

• Videos on Eric Carle

o 40 Years- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vYG1tLt5GCQ#t=119

o Brown Bear Series- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QbCOteqvdII#t=84

• Eric Carle’s Process: http://eric-carle.com/photogallery.html

• Lesson: http://www.erintegration.com/2016/12/21/eric-carle-style-digital-collages-on-

pic-collage/

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

42

Two-Dimensional Art Lesson

In art, there are many two-dimensional media. As mentioned above, in a study conducted

by Guay (1993a) she found that teachers relied most on printmaking and ceramics when fine

motor skills were compromised. For this reason, printmaking was not selected as the model unit,

but instead a paper collage was chosen as a demonstration of adaptations for materials, such as

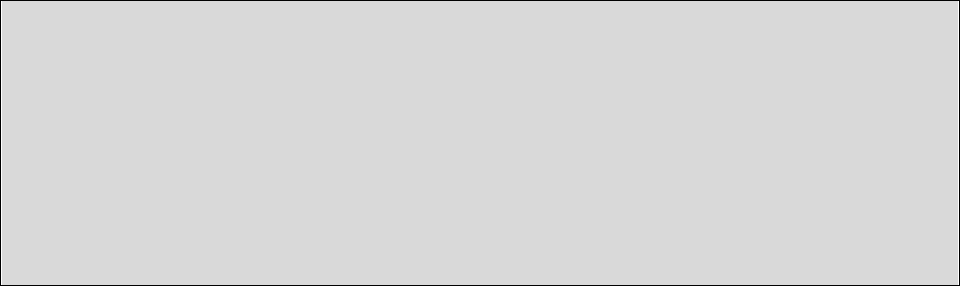

scissors. There are four examples of differentiated scissors for a range of capabilities. A short

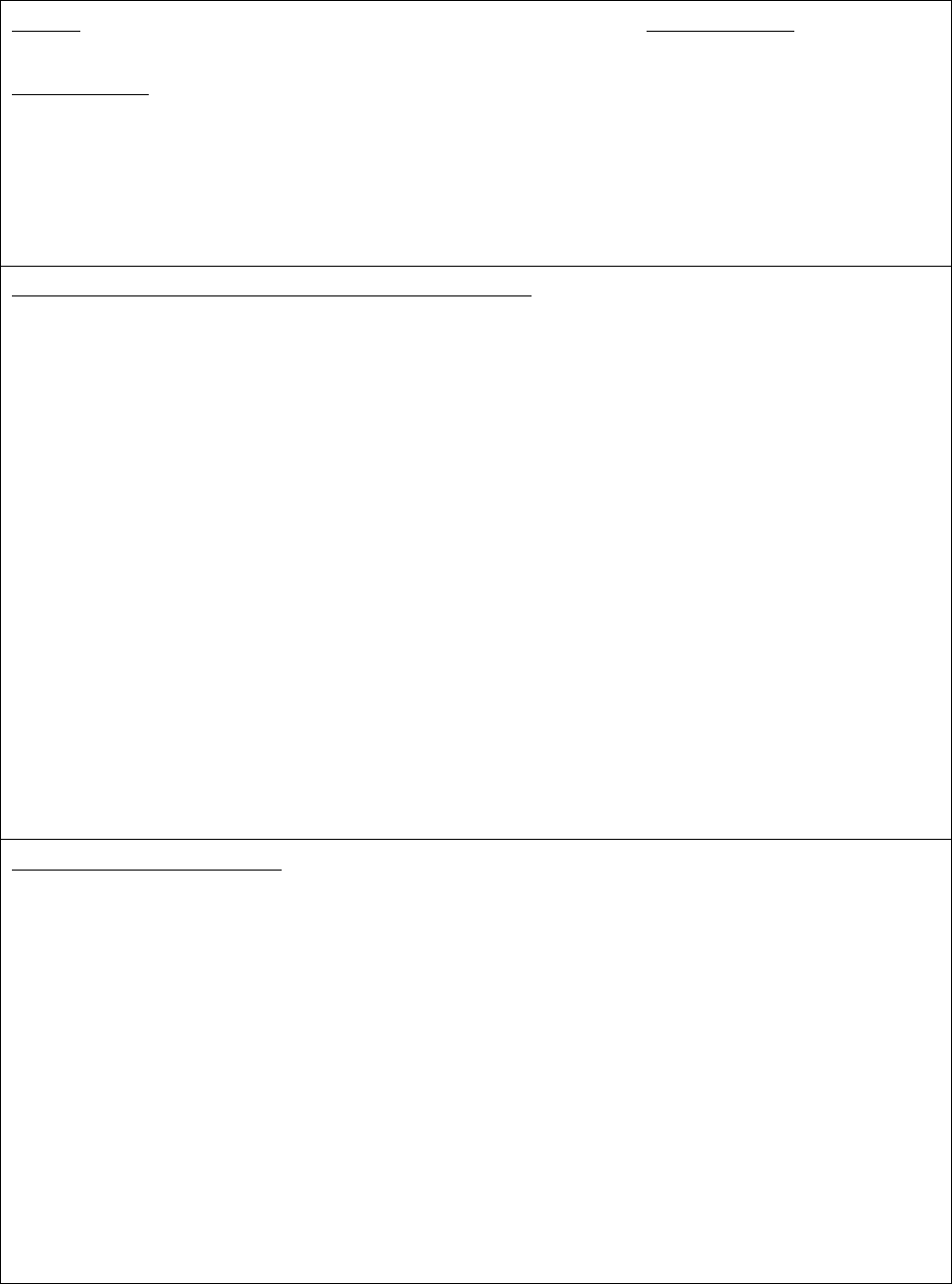

description is included. There is also a handgrip option for a larger grasp for items such as

paintbrushes, pencils, crayons, and other straight materials. Lastly, another option for watercolor

painting is included, called the Aqua-flo brush. These come in three brush sizes and can be filled

with water or ink to allow for more continuous painting with no fear of knocking over cups of

water.

In addition to the added section of adapted materials, this unit was selected because of the

opportunity to promote people with disabilities or restrictions as artists. In the literature review, it

was advocated that disabled people doing art in art curriculum would place “…an emphasis upon

the representation of difference through a curriculum of admiration and appreciation in which

individual artists are admired for their ability to create work similar to other able-bodied artists”

(Eisenhauer, 2007, p. 9). Although Henri Matisse was not born disabled, he experienced

difficulty in creating art from a wheelchair, needing help to accomplish his visions. This is one

example of representation within the art curriculum so that people with disabilities are not

continually marginalized.

ADAPTEDARTCURRICULUM

43

Unit: Matisse Paper Collage Grade Level: 3rd Grade

Description: Students will learn about the French artist Henri Matisse and his unique

decoupage style that began later in his life due to external factors. After surgery for severe

intestinal disease, Matisse was confined to his bed or to a wheelchair and needed create

differently than he had in the past, due to his restricted movement. Instead of painting, Matisse

began to “draw with scissors.” An assistant helped Matisse arrange his cut shapes onto a large

surface until he was content with it. After watching short videos of Matisse and participating in

read aloud stories on Matisse, students will discuss disabilities and art.

For their project, they will create multiple geometric and organic shapes and use both the