Walden University

ScholarWorks

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies

Collection

2019

Accounts Receivable Management Strategies to

Ensure Timely Payments in Rural Clinics

Anthony N. Medel

Walden University

Follow this and additional works at: h)ps://scholarworks.waldenu.edu/dissertations

Part of the Finance Commons

(is Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies Collection at ScholarWorks. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Walden Dissertations and Doctoral Studies by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks. For more information, please

contact ScholarW[email protected].

Walden University

College of Management and Technology

This is to certify that the doctoral study by

Anthony Natividad Medel

has been found to be complete and satisfactory in all respects,

and that any and all revisions required by

the review committee have been made.

Review Committee

Dr. Roger Mayer, Committee Chairperson, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. Warren Lesser, Committee Member, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Dr. Judith Blando, University Reviewer, Doctor of Business Administration Faculty

Chief Academic Officer

Eric Riedel, Ph.D.

Walden University

2019

Abstract

Accounts Receivable Management Strategies to Ensure Timely Payments in Rural

Clinics

by

Anthony Natividad Medel

MBA, University of Phoenix, 2005

BSHS, University of Phoenix, 2003

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

April 2019

Abstract

Healthcare business leaders in a rural clinic setting can enhance profitability by

implementing strategies to ensure timely payments. The purpose of this multiple case

study was to examine strategies applied by healthcare leaders in rural clinics to improve

profitability. The population included 10 rural clinic managers and billing staff from 5

rural clinics in the southwestern region of the United States. The conceptual framework

for this study was Wernerfelt’s resource-based value theory. Implementing Yin’s

multiple-step data analysis process, data from semistructured interviews were transcribed,

coded, and analyzed to identify strategies used by rural clinic managers and billing staff

to enhance profitability. Four primary themes emerged regarding revenue cycle

management that could increase profitability, including developing effective

communication between medical providers and billing staff, implementing payment plan

strategies, ensuring accuracy of billing claims, and consistently reviewing open

receivable accounts. The implications of this study for positive social change include

insights for clinic managers in the development of strategies to increase cash from

accounts receivables, which may contribute to the financial stability of the clinic and

improve the provision of healthcare for citizens of the southwestern region of the United

States.

Accounts Receivable Management Strategies to Ensure Timely Payments in Rural

Clinics

by

Anthony Natividad Medel

MBA, University of Phoenix, 2005

BSHS, University of Phoenix, 2003

Doctoral Study Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements for the Degree of

Doctor of Business Administration

Walden University

April 2019

Dedication

I dedicate my study to my wife, Karen. You have been with me through every

step of this process, and I could never thank you enough for standing by side in this

process. I love you very much, and I look forward to sharing the rest of my life with you.

To my children, Cheryl, Andrew, Kaitlan, and Alexander, for all of the times that I

missed your activities. To my brothers and sister Steve, Manuel, Rene, and Christina, as

the family is everything. Also, I dedicate this doctoral study to the memory of my parents

Manuel Young and Clementina Natividad Medel for instilling in me a strong work ethic

and a faith in God that can never be broken.

Acknowledgments

First, I thank God the Father Almighty for his guidance, and granting me the

strength, patience, and perseverance to complete this educational journey. With God, all

things are possible and I would not have made it without the strength and faith that His

presence in my life.

I thank my family, friends, and coworkers for their support, encouragement, and

listening to me throughout this process and providing uplifting words during the most

difficult times in this process. Thank you to my maternal Aunts and Uncles as we have

had some pass away during this time, but I have kept them all in my heart and blessed

that they were a part of my life. Thank you to Dr. David E. Bealer (1955-2016), for a

meeting we had back in 2016 and providing words of wisdom, encouragement, and

support, your memory will not be forgotten.

Finally, I thank my Chair, Dr. Roger Mayer. You have worked with and assisted

many doctoral graduates by providing your time, encouragement, and most of all support.

Thank you for everything that you have done to help students reach their educational

goals, and you came into my life at a time when I needed direction and you far exceeded

this task. Also, thank you to my committee members Dr. Warren Lesser, Dr. Robert

Hockin (1950-2019), Dr. Jill Murray, and Dr. Judith Blando for your feedback and

dedication to help students place an emphasis on the quality of work produced. This has

been an unforgettable journey, and I will be eternally grateful for all those who have been

there for me along the way.

i

Table of Contents

Section 1: Foundation of the Study ......................................................................................1

Background of the Problem ...........................................................................................1

Problem Statement .........................................................................................................2

Purpose Statement ..........................................................................................................2

Nature of the Study ........................................................................................................3

Research Question .........................................................................................................4

Interview Questions .......................................................................................................4

Conceptual Framework ..................................................................................................5

Operational Definitions ..................................................................................................6

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations ................................................................7

Assumptions ............................................................................................................ 7

Limitations .............................................................................................................. 8

Delimitations ........................................................................................................... 8

Significance of the Study ...............................................................................................8

Contribution to Business Practice ........................................................................... 9

Implications for Social Change ............................................................................... 9

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature ..............................................10

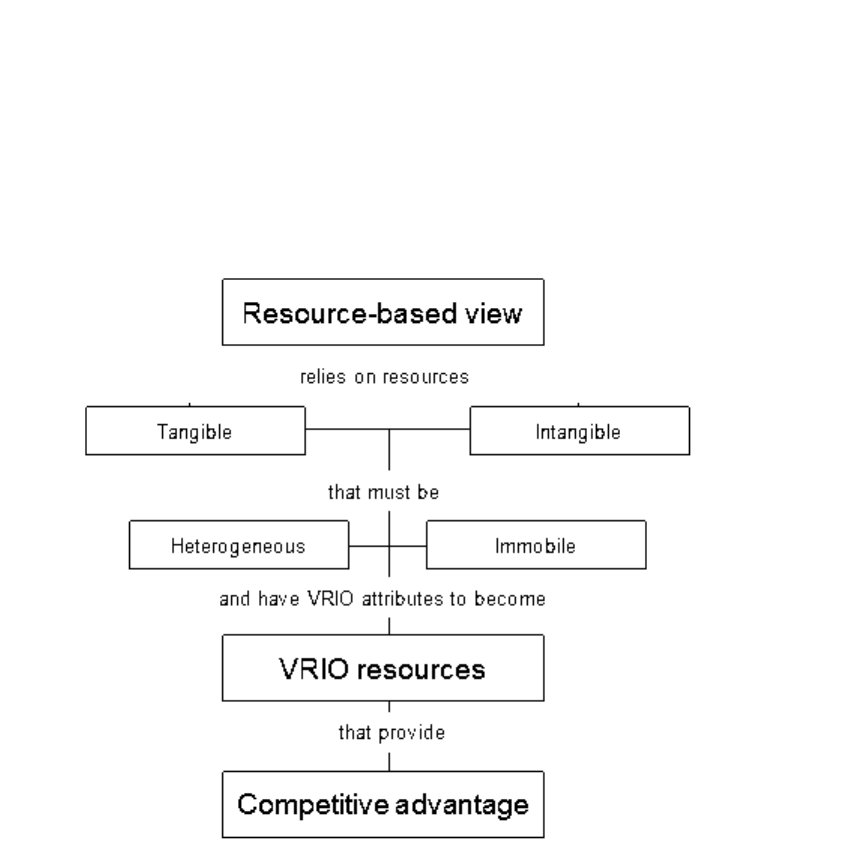

Resource-Based Value Theory ............................................................................. 12

Alternative Theories.............................................................................................. 19

Historical Involvement by Government in the Health Care System..................... 22

Health Care Financial Options and Medical Care ................................................ 26

ii

Fee-For-Service (FFS) vs. Value-Based Purchasing (VBP) ................................. 31

Accounts Receivable Management and Health Care ............................................ 38

Transition .....................................................................................................................41

Section 2: The Project ........................................................................................................42

Purpose Statement ........................................................................................................42

Role of the Researcher .................................................................................................42

Participants ...................................................................................................................45

Research Method and Design ......................................................................................47

Research Method .................................................................................................. 47

Research Design.................................................................................................... 48

Population and Sampling .............................................................................................50

Ethical Research...........................................................................................................52

Data Collection Instruments ........................................................................................54

Data Collection Technique ..........................................................................................57

Data Organization Technique ......................................................................................59

Data Analysis ...............................................................................................................61

Reliability and Validity ................................................................................................63

Reliability .............................................................................................................. 64

Validity ................................................................................................................. 65

Transition and Summary ..............................................................................................67

Section 3: Application to Professional Practice and Implications for Change ..................68

Introduction ..................................................................................................................68

iii

Presentation of the Findings.........................................................................................68

Theme 1: Communication Between Medical Providers and Billing Staff ........... 70

Theme 2: Payment Plan Setup .............................................................................. 73

Theme 3: Accuracy of Billing Claims .................................................................. 77

Theme 4: Consistent Accounts Receivable Reviews ............................................ 79

Overall Findings Applied to the Conceptual Framework ..................................... 83

Applications to Professional Practice ..........................................................................84

Implications for Social Change ....................................................................................85

Recommendations for Action ......................................................................................86

Recommendations for Further Research ......................................................................87

Reflections ...................................................................................................................88

Conclusion ...................................................................................................................88

References ..........................................................................................................................90

Appendix A: Interview Protocol ......................................................................................136

Appendix B: Interview Questions ....................................................................................137

iv

List of Figures

Figure 1. The resource-based view ....................................................................................16

1

Section 1: Foundation of the Study

Effective revenue cycle management in rural clinics is essential to their economic

sustainability (Lubberink, Blok, van Ophem, & Omta, 2017). In the initial phase of a

revenue cycle strategy, a healthcare organization summarizes potential revenue outlets

based on the volume of patients and mix of insurance payers (Johnson & Garvin, 2017).

Revenue, in the form of accounts receivable collection processes, of healthcare

organizations are unlike most with other industries (Mindel & Mathiassen, 2015).

Healthcare providers must deal with multiple payers and unique rules such as bundled

payments, case-based payments, copayers, and contractual allowances (Hernandez,

2017). Healthcare managers must deal with payment delays, challenges by payers for

services provided and unreimbursed services (Cascardo, 2015). Thus, healthcare clinic

managers must develop strategies to address these revenue cycle challenges in order to

obtain timely payments from patients and their insurance payers.

Background of the Problem

Developing an effective means to collect payment for health services rendered

during a routine visit is a challenging task in the health care industry. Rural clinics that

serve a high number of indigent patients would close without adequate reimbursement.

The goal of the Medicaid program enacted in 1965 was to provide medical services to

lower income individuals and families (Leemon, 2014). The passage of the Affordable

Care Act (ACA) in 2010 became another form of health coverage introduced to the

public. It provides health insurance to the uninsured, which constitutes approximately

27.3 million individuals or 8.6% of the population (United States Census Bureau, 2016).

2

Other forms of coverage or payment can include private pay insurance plans, direct

payment, and a sliding fee scale based on one’s ability to pay (Barbaresco,

Courtemanche, & Qi, 2015). Clinic managers and financial support staff will benefit from

successful strategies to obtain timely payment for medical services from patients, which

relate to strategies for collecting accounts receivables.

Problem Statement

Rural clinic managers struggle to generate cash flow from unpaid patient accounts

(Lail, Laird, McCall, Naretto, & York, 2016). Healthcare organizations spend roughly

$26 billion on revenue cycle management addressing reimbursement and collection

processes (Hayes, Subhan, & Lakatos, 2015). The general business problem was that

healthcare leaders do not develop effective revenue cycle strategies and cash flow

shortfalls may threaten the survival of the organization. The specific business problem

was that some rural clinic managers lack strategies to obtain timely payments from

patients and insurance payers.

Purpose Statement

The purpose of this qualitative multiple case study was to explore strategies rural

clinic managers use to obtain timely payment from patients and insurance payers. Study

subjects included clinic managers from five rural clinics in southwestern region of the

United States who have incorporated strategies to obtain timely payment from patients

and insurance payers. The implication for positive social change could come from

insights for clinic managers when they develop strategies to increase cash from accounts

3

receivables, which may improve the financial stability of the clinic and increase the

wellbeing of individuals in southwestern region of the United States.

Nature of the Study

The three research methods are qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods

(Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). Qualitative researchers gather in-depth data, discover the

meaning of the unknown, and reconstruct stories of participants on a conceptual level

(Guba & Lincoln, 1994). I have selected the qualitative methodology to recognize

multifaceted comprehensive medical services performed in rural clinics. A quantitative

researcher focuses on empirical evidence by using statistical processes (Petrescu &

Lauer, 2017). A quantitative methodology was not an appropriate method, because I was

not examining numeric data with statistical processes. The mixed methods methodology

incorporates both quantitative and qualitative components (Polit & Beck, 2010). This was

not a suitable choice, as I do not intend to incorporate statistical methods to explore my

research question.

I considered four qualitative research designs, including (a) phenomenology, (b)

ethnography, (c) narrative design, and (d) case study. Phenomenology researchers

emphasize the meaning of participants’ lived experiences (Moustakas, 1994). The

phenomenology design was not appropriate for this study because my goal was not to

explain the meaning of the participants’ lived experiences. Ethnography researchers

emphasize the meaning of the participants’ expression of culture (Symons & Maggio,

2014). I do not propose to explore a participant’s individual customs or culture and an

ethnography design was not appropriate for this study. A narrative design provides the

4

researcher the opportunity to focus on the lives of individuals as told through their own

stories (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011). I did not intend to focus on the lives of the participants

through their own stories and rejected a narrative design for this study. I used a case

study design to explore the research question as the case study approach allows the

researcher to view the issue in a natural setting.

Research Question

What strategies do rural clinic managers use to obtain timely payments from

patients and insurance payers?

Interview Questions

1. What strategies do you use to obtain timely payments from your patients and

insurance payers?

2. What strategies do you use to collect from uninsured and underinsured

patients?

3. What strategies do you use to manage doubtful accounts and bad debt?

4. What strategies does your organization use to ensure staff complete billing

forms correctly with no errors that delay payments?

5. What techniques does your office staff use to collect copayment either before

or after the patient visit?

6. How does the organization provide training to the billing staff to ensure they

are able to meet the organization’s standard for timely collections?

7. How does the organization ensure that the billing staff has the current training

or professional development regarding health information technology?

5

8. What billing techniques does the organization use that would be a

competitive advantage over other similar organizations?

9. What are the necessary attributes and abilities of a biller to ensure continued

profitability and sustainability for the organization?

10. What additional information can you make available that accounts receivable

strategies ensure timely payment from patients and insurance payers?

Conceptual Framework

The resource-based value theory (RBV) served as the foundation for this

qualitative multiple case study. Wernerfelt (1984) provided an approach in finding a

balance between manipulation of existing resources and the expansion of resources to an

organization’s firm strategic management design to yield increased profits. The RBV

indicates a correlation between profitability and resources as well as managing

organizations’ resources for the long term (Wernerfelt, 1984). RBV theorists and

strategists are contributors in the RBV development.

The healthcare industry exemplifies the RBV within the internal organizational

resources to include attributes, abilities, organizational procedures, and expertise

formulated at the administrative level of an organization (Patidar, Gupta, Azbik, &

Weech-Maldonado, 2016). RBV theorists Warnerfelt (1984) and Barney (1991),

proposed to improve an organization’s efficiency and effectiveness with an increase in

profitability and sustainability. The prevalence of internal resources to maintain a

competitive advantage over rival competitors can be found using RBV. A turbulent

period for the healthcare industry is transpiring due to competition, an adjustment in

6

reimbursement for services rendered, and struggles in keeping current with health

information technology and electronic medical records (Angeli & Norwood, 2017). The

RBV combines superior resources and competencies to achieve increased financial

earnings. The RBV perspective emphasizes the development of dynamic capabilities and

useful resources as possible foundations for a definite competitive advantage (Kash,

Spaulding, Gamm, & Johnson, 2014).

Operational Definitions

Arizona Health Care Cost Containment System (AHCCCS): A version of the

Medicaid system in the state of Arizona that provides medical benefits to those with

lower to moderate incomes (Langellier, de Zapien, Rosales, Ingram, & Carvajal, 2014).

Contractual adjustments: The difference between healthcare organizations’ fully

charged amounts for services and payments received (Chen et al., 2015).

Contractual allowances: The financial difference between what the healthcare

organization bills and the agreement entered into financial conditions with a third party

payer (Rosolio, 2016).

Customary allowable rate: The rate of reimbursement intended to mirror the

value of the services provided by the provider (Panning, 2014).

Government-funded health plans: A provision as part of social wellbeing to

provide healthcare services to lower income individuals (i.e., disabled, children, and the

elderly; Bradbury, 2015).

7

Multifaceted health care organization: Healthcare organization with many

different elements or combinations of services or roles provided to customers/patients

(Prowle & Harradine, 2014).

Reimbursement rate (normal/customary): The fee or charge associated based on

the volume of services provided to a customer or patient during an encounter with a

medical provider (Jones & Ku, 2015).

Timely payments: A reimbursement for services rendered by the health care

provider within a payment timeframe defined by the payor (Fitzpatrick, Butler,

Pitsikoulis, Smith, & Walden, 2014).

Assumptions, Limitations, and Delimitations

Assumptions, limitations, and delimitations can limit the methods and

examination of the research within the study. Assumptions and limitations are outside the

scope of the researcher’s control. Delimitations are essential within the context of the

research managed by the researcher. Furthermore, these concepts are integral in outlining

methodology within the context of the research detailed as part of the study.

Assumptions

The rural clinic acknowledged a responsibility to provide the patient with quality

healthcare services regardless of the volume of ailments during an encounter with the

assumption the clinic would be paid. Another assumption was the accounts receivable

management strategies in collecting co-payments or deductibles imposed by

organizational leadership was determinate in the collection of timely payments from the

patient. Second, an essential assumption was specific strategies and methods pertaining to

8

the collection process were abided by according to company financial policy (Grant,

2014). The last assumption was that implemented revenue management strategies

developed by clinic managers would positively affect payments from patients and

insurance payers.

Limitations

Marshall and Rossman (2016) defined limitations as elements of the study outside

the control of the researcher. A significant limitation of this study was that payment

information could not be gathered from patients or insurance providers. One of the

limitations of this study was that participants potentially could withdraw at any time in

the study thereby skewing the data due to the small sample size. The participants’

interview responses are subject to their personal presumptions (Yin, 2017).

Delimitations

Delimitations define the scope of the research study determined by the researcher

(Yazan, 2015). This study included 10 clinic managers from southwestern region of the

United States to include South County and East County. This study included clinic

managers who reside in Arizona and live in southwestern region of the United States and

who confirmed insurance payers for treated patients.

Significance of the Study

Rural clinic managers and individuals residing in southwestern region of the

United States could benefit from the outcomes of this study. The healthcare industry

prevails as a change agent for reducing costs and improving patient outcomes. Reducing

costs, lowering or bundling healthcare services, and establishing strategic processes in

9

obtaining payments from insurance payers may result in a higher volume of patients. An

examination of the accounts receivable management processes may provide awareness to

rural clinic managers regarding attaining payment from patients and insurance payers.

Contribution to Business Practice

Rural clinic managers could benefit from this study by understanding their role as

it relates to reimbursement practices. Healthcare leaders must demonstrate strategic

business practices interpreting the development of volume and scale of insurance payors

in conjunction with the business model (Kemperman et al., 2016). The healthcare

business model requires transparency in the reimbursement process of services rendered.

. Ideally, a healthcare organization must provide patients with a high quality of care at

affordable prices to form an organizational culture of accountability (Mkanta, Katta,

Basireddy, English, & de Grubb, 2016). Rural clinic business leaders may gain awareness

of strategies to increase cash flow, which could increase resources necessary to provide

quality services.

Implications for Social Change

Organizational leadership, hospitals, and physician-based groups considering

collaboration could benefit from the results of this study on rural clinics while

influencing the quality of care. The healthcare business model of requiring payment in

advance of services has demonstrated ineffective in the inability to provide adequate

healthcare to underserved communities (LeFevre, Shillcutt, Broomhead, Labrique, &

Jones, 2017). Patients decide their healthcare needs based on the qualities and expertise

of the medical provider (Reddy & Mythri, 2016). Effective cash collection strategies that

10

allow for payments of co-pays, deductibles and uninsured payments may increase the

likelihood of health care services to residents in underserved communities, which will

impact the patients’ well-being.

A Review of the Professional and Academic Literature

Reviewing prior published research is a strategy researchers use to gain a more in-

depth understanding of a research topic. Lubberink et al. (2017) stated that the literature

review is an essential component of the research because it provides systemic, activities-

based approach to reported context. The purpose of this qualitative multiple case study

coincides with research related to evolving changes in reimbursement. Included in this

section is a review of the academic and professional literature on the RBV theory as used

by other researchers to investigate related research topics. I examined literature from

other scholars who deliberated regarding rural clinic managers’ strategies to obtain timely

payments from patients and insurance payers and my findings aim to help managers

reduce the interruption or delay in receiving payment from patients and insurance payers

for medical services rendered.

The information gathered from this study came from a multitude of sources

including ABI/INFORM Global, ProQuest, SAGE Publications, Google scholar, Wiley

Online, Academic Search Complete, Emerald Insight, MEDLINE, Proquest Central,

Proquest Health and Medical Collection, Proquest Nursing & Allied Health Source, and

EBSCOHost. The keyword search terms for this research included: health care, health

care industry, business model, government involvement, financial options, medical care,

11

Medicaid, ACA, fee-for-service, value-based purchasing, Resource Base Value, and total

quality management. .

The financial health care models in the literature illustrate how healthcare services

can be efficient and which methods are cost-effective. The reimbursement models

indicate the delivery of healthcare services, efficiency of effective billing procedures, and

exhibit cost-effective methods to develop the success of a healthcare operation. I

presented the value-based purchasing model, which was the defining standard for

healthcare operations’ performance. The core business values of this model consist of

cost control, financial stability, and sustainability of healthcare operations. Consistency

of adequate reimbursement of healthcare organizations maintains sustainability. With this

intention, healthcare organizations determine adequate reimbursement fee schedules

concerning payment for the businesses to remain flexible for future success.

The U.S. healthcare sector has changed as health insurance plans provide an array

of healthcare services. The clinic manager is responsible for reimbursement and assessing

strategic business models for obtaining timely payment within the clinic. The continuity

of care diminishes when patients are required to choose their provider solely based on

insurance coverage. The delivery of healthcare is a focal point for patients who can be

loyal to a medical provider or turn to a competitor for the same services based on

insurance (Hegwer, 2014). The value-based purchasing model holds medical providers

accountable for the cost and quality of care. Healthcare organizations using a value-based

purchasing model focused on cost containment accompanied by quality care, presuming

patients will choose quality. The literature review consists of 299 references from peer-

12

reviewed journals, government reports, and books with at least 94% of the sources

published between 2013 and 2018, or within 5 years of my expected graduation.

Resource-Based Value Theory

The RBV is a relevant framework for service-based industries where there is a

requirement of trust. The organization’s ability to gain the patient’s trust will increase its

competitive advantage and improve its financial performance (Lin, Chang, & Dang,

2015). The central tenet of RBV theory is that healthcare leaders should focus on

efficient and strategic uses of resources to remain viable (Ozuru & Igwe, 2016). The

profitability of an organization stems from the implementation of strategies based on

resources identified by organizational leaders (Liu, Zhu, & Seuring, 2017). The RBV

model concentrates on the service-concept methodology and is dependent on the

performance of individuals executing roles within the organization. It becomes necessary

to apply resources to provide medical services that benefit the patient. An organization

must consider the implementation of services and equipment, specialty amenities, and

quality improvement for their patients as assets and strengths.

Only recently have researchers and business leaders applied RBV to the

healthcare field. It is a relevant framework because it claims product-based endeavors are

part of a grand business strategy. RBV indicates resources are scarce and unique in

stature; these strategic resources are necessary to maintain a competitive advantage in a

healthcare market (Gerber & Hess, 2017). The financial and operational well-being of the

organization hinges on internal resources within the business (Neghina, Bloemer, van

Birgelen, & Caniëls, 2017). Managers can use RBV to develop a strategic plan for using

13

internal resources to enhance financial success and sustainability.

Managers in the healthcare industry face difficulties in implementing

RBV strategies when the business is at an early stage of development (Voss, Perks,

Sousa, Witell, & Wünderlich, 2016). Healthcare leaders can base organizational policies

on the RBV theory to specify assets that support the delivery of medical care to patients

(Wilden & Gudergan, 2017). In the healthcare industry, the roles of patients, healthcare

organizations, and medical providers are still evolving. The RBV framework includes a

service delivery model emphasizing employee skills and knowledge expertise which is a

foundational piece of financial success (Ozuru & Igwe, 2016). As healthcare systems

develop towards financial prosperity, the connection with RBV amplifies.

The RBV framework includes strategies to remain competitive. RBV when

applied as a business strategy exposes possible disadvantages involving profitability and

reputation to the organization (Jain & Singal, 2014). The RBV as a strategic business

model proposes using internal resources to outperform competitors. The healthcare

organization used resources to strategically coordinate with the medical practice to secure

a competitive advantage (Abidemi, Halim, & Alshuaibi, 2017), and key resources are

employees, who all need to be included in the strategy (Pinto, 2017). Rural clinics leaders

also consider the revenue cycle process to guarantee payment, a resource that

organizational leaders need to manage. Business leaders manage internal resources in

order to keep revenue consistent with the long-term financial growth of the organization.

In rural clinics, the focal point is services provided to patients (check-up, follow-

up care, or consultation). The healthcare industry is a service-model based exchange, and

14

with the flow of internal resources and potential employees’ capabilities, a creation of

value will develop over time indicating innovation as the focal theme (Schneider &

Sachs, 2017). RBV within a healthcare organization improves patient outcomes through

the use of internal resources within the healthcare organization towards continuity of care

(Szymaniec-Mlicka, 2016) and guides business strategies towards competitiveness in the

marketplace (Li, Jiang, Pei, & Jiang, 2017). The healthcare industry has integrated RBV

into its business models to drive potential success, economic prosperity, and strategic

preparation.

RBV in the management environment. The methodology of RBV strategy in a

management setting focuses on internal business resources. The healthcare industry is

service-based and must ensure approaches are successful and services provided exceed

those of competitors (Jali, Abas, & Ariffin, 2016). The indicators regarding internal

resources needs rethinking with the managerial emphasis placed on varying differences

and unique characteristics of health care services (Neghina et al., 2017). Successes stem

from creating new and innovative ways to deliver services by reducing costs and passing

on the value to the patients.

Rural health clinics need to develop new and innovative ways to build their

patient base and management’s ability to expound, implement, and reintroduce strategic

resources. The healthcare industry must adapt to healthcare reform and seek innovative

processes regarding internal resources to attain a competitive advantage (Lillis,

Szwejczewski, & Goffin, 2015). The control over strategic resources gives businesses a

unique competitive advantage that creates barriers to entry (Ferlie et al., 2015). Managers

15

following RBV concentrate on their most valuable assets to achieve continued

sustainability. The progression of the RBV is achievable, but a path towards

organizational development follows a period of increased growth to meet an

organization’s financial goals (Maurer & Ryan, 2016). The objective of rural clinics is to

enable access to medical providers, establish growth, become more productive, and

maintain a consistent and sustainable profit margin.

RBV within rural clinics emphasizes using internal resources to improve the

quality of care for patients, stressing improvements toward operational goals and

objectives. The operational and performance goals of a healthcare organization include

balancing healthcare services, reducing costs, and improving patient outcomes

(Adebanjo, Laosirihongthong, & Samaranayake, 2016). Thus, essential characteristics

surrounding RBV within the healthcare environment include producing positive results

while managing revenue collections to provide long-term fiscal sustainability. Healthcare

leaders must continue to focus on the improvement of patient care while ensuring the

financial growth of the medical practice.

RBV methods can contribute to a medical practice’s success by building its

strategic resources and hence improving its competitive advantage (Maurer & Ryan,

2016). Corporate social responsibility also builds organizational goodwill by improving

reputation (Sheikh, 2017). Some medical practices focus on collecting payments from

insurance payers without any impediment or delay in payment (Lai & Gelb, 2015).

Increasing the timeliness of payments is a strategy that increases the competitive

advantage of a clinic.

16

An organization’s resources align with RBV based upon the value to the

organization (Lin et al., 2015). The service-based model is grounded on an ecosystem of

multiple variables as internal resources become tangible for the strategic betterment of

the organization (Voss et al., 2016). The service-based model goes through a shift where

the focus is on tangible resources creating capabilities for future strategic planning

(Wilden & Gudergan, 2017).

Figure 1. The resource-based view.

RBV in the healthcare setting. RBV principles emphasize the importance of the

delivery of services and resources for rural clinics to set themselves apart from

competitors. Healthcare organizations allocate resources efficiently to give legitimacy to

management and leadership in the decision-making process of RBV (Angelis, Kanavos,

17

& Montibeller, 2017). Business leaders consider the healthcare organization’s resources

to be valuable assets. The healthcare organization is poised to use all available internal

resources to provide consistency and continuity of care to patients. The internal resources

available to the healthcare organization are well thought-out, have identifiable

characteristics, and designated as VRIO (valuable, rare, inimitable, and organized; Lin et

al., 2015). The VIRO characteristics selected are the foundation for RBV.

The connection between products and services are intertwined and generate

combinations of resources (Benedettini, Neely, & Swink, 2015). The resulting resources

are significant to the rural clinic advantage over competitors, but are not sustainable and

will not benefit the healthcare organization over the course of time (Mweru & dan Muya,

2015). Rural clinic managers use RBV strategies to recognize and implement approaches

to make improvements in efficiency and effectiveness (Teece, 2017). Rural clinics

incorporate resources into their strategic planning for the purposes of financial

achievement (Patidar et al., 2016). Healthcare organizations value internal resources,

which are components of their competitive advantage (Helmig, Hinz, & Ingerfurth,

2014). Their competitive positions regarding administration efficiency influence potential

operational development of competitive strategies (Krzakiewicz & Cyfert, 2017). The

rural clinics’ used for this doctoral study have strategic approaches in line with RBV, as

cost and organizational performance are devices providing the business with

sustainability and competitive advantage for years to come (Abidemi et al., 2017).

Through strategic planning, an organization can establish a competitive

dominance over its rivals (Kash et al., 2014). RBV is becoming a strategic management

18

model trending towards organizational management, and developing applicability of

external resources within the healthcare industry (Hitt, Xu, & Carnes, 2016). The RBV

framework in the healthcare industry is an innovative approach within the confines of the

management structure and all internal resources within the organization has not been

sufficient to establish RBV within healthcare strategic planning. However, healthcare

organizations are willing to be a part of this rapidly growing model. The U.S. healthcare

sector follows and identifies common strategic initiatives put into practice by hospitals,

community health centers, and urgent care facilities. Accordingly, a broader view of

RBV includes internal viable resources, adding to increased capabilities, employees and

staff, and financial assets (Wilden & Gudergan, 2017).

The healthcare industry consists of operational and clinical professionals and their

collaboration within the health care environment is essential. Business leaders consider

VIRO attributes to be valuable, inimitable, rare, and organized difficult to replace that

lead towards a competitive advantage for the health care organization. The health care

organization’s administration explores competitive advantages coming from within the

firm’s specific resources and limitations, depending on the location (Yang, 2014). The

healthcare profession has organizations that can strategically manage resources to

improve their performance (Evans, Brown, & Baker 2015). RBV’s place within rural

clinics in combination with strategic resource planning remains driven by healthcare

professionals whose objective is quality care.

RBV methods put into place the needed resources to provide patients with the

continuum of care and offer a strategy to sustain competitive advantage (Popli, Ladkani,

19

& Gaur, 2017). The strategic business model is a representation of the view of a health

care organization reflecting potential sustainability and viability (Goyal, Sergi, &

Kapoor, 2014). The RBV approach, a health care business implementation, is the

building block of competitiveness not only in the present but in the future and reinforces

sustainable benefits for the long-term (Teece, 2017). Rural clinic managers can use RBV

as a reliable business model to properly use internal resources to facilitate sustainment.

The financial results were referencing accounts receivable segments of the business focus

on the strategies implemented by leaders within the establishment. A rural clinic manager

uses RBV in conjunction with its business model to develop financially and clinically to

build the community’s trust.

Alternative Theories

RBV addresses the roles or control of one’s resources as a primary method to

create a strategic advantage over competitors (Popli et al., 2017). Critics indicate the

RBV approach is limited because it focuses on the user of the resource (Gerber & Hess,

2017). The utilization of internal organizational resources becomes part of the landscape,

and the user of the resource takes on a far lesser role in the overall encounter. The

potential for the business to sustain its resources over an extended period will prolong a

fierce competitive advantage during specific phases of time (Lee, 2017). Resource

dependence theory (RDT) has similarities to RBV with the role of the RDT taking on

external environmental linkages within the organization (Shaukat, Qiu, & Trojanowski,

2016). I used both RDT and TQM as analytical frameworks to explore health care

20

organization management strategies. Wernerfelt (1984) details RBV as a means to use

internal resources and includes components to separate businesses from its competitors.

Resource dependence theory. In 1978, Pfeffer and Salancik addressed resource

dependencies and indicated the effect external resources had on the role of an

organization. Pfeffer and Salancik (2003) detailed that health care organizations are

providers of significant resources, and like other organizations, they need to make

changes to fulfill positive outcomes. RDT indicates organizations require resources from

competing organizations within a similar market to innovate, resulting in distinctive

qualities within competing organizations (Van den Broek, Boselie, & Paauwe, 2017).

Pfeffer and Salancik (2003) stated that organizations have more power drawing from the

interdependence of others and the need for their positions in the marketplace. RDT

describes dependent players in the organization as having a weaker position within the

competitive market to offset structures to collaborate (Christensen, 2016). From the

organizational aspect, minimal information in the form of external constraints affecting

management decisions ought yet to be determined (Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003). RDT has

three specific factors: the significance of the resource to the organization, scarceness of

the resource, and the level of internal organization competition (Selviaridis, Matopoulos,

Thomas-Szamosi, & Psychogios, 2016). Business leaders manage potential constraints

and uncertainties potentially resulting in the acquisition of external resources (Pfeffer &

Salancik, 2003).

The viability of the health care organization is contingent on RDT in which a

strategy may alter a power-dependent relational dynamic (Doyle, Kelly, & O’Donohoe,

21

2016). Management sets the strategy, and these individuals play a crucial role in the

process and scheming of resource dependencies. Any organization can build resources

both internally and externally to assemble competencies to enter and leave the market and

to take a competitive advantage (Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003). RDT researchers focus on the

use and outcomes of resources utilization (Coupet & McWilliams, 2017). An

organization’s management may devise a scheme to ensure resources remain supported

and seek a clear competitive advantage over market rivals (Pfeffer & Salancik, 2003).

Total quality management. In 1985, Deming addressed the Western style of

management called total quality management (TQM), which introduces organizational

attempts to deliver quality products and services. TQM emphasizes planning and

introducing methods to improve an organization’s products and services to decrease costs

(Deming, 1985). The focus of enhancing quality concentrates on the customer (Deming,

2000), which is supervised by management. Health care managers introduced TQM into

the field in the late 1980s, intending to increase patient satisfaction, reduce costs, and

increase productivity at all levels within the organization (Chiarini & Vagnoni, 2017).

Management is fully responsible for creating processes, ensuring stability, and

establishing strategies for the success of the organization (Deming, 2000).

Deming’s approach centered on process improvement (Matthews & Marzec,

2017). Deming (2000) provides a thorough concept showing that any considerable

improvement must come from actions introduced by operations management. TQM

methodology has in the past focused on the supply side of operations, but now has a

presence in an organization’s services sector (Iqbal et al., 2017). The service-based

22

industries such as health care apply various TQM improvement practices by enhancing

services and reducing costs for patients during a routine encounter (Deming, 2000). The

implementation of TQM within a health care organization has led to improved processes

in the quality of patient care, patient satisfaction, and increased financial prosperity

(Mosadeghrad, 2015). RBV is the best choice for this study, as the theoretical lens

focuses on quality improvement organizational concepts.

Historical Involvement by Government in the Health Care System

Governmental involvement in the health care system has gone through an

evolutionary process since the initial phase in the early 1900s. The U.S. government

implemented health care services emphasizing the health and welfare of its citizens. The

first model of health care reform began with the Sheppard-Towner Act of 1921, one of

the catalysts in the health care reform movement (Haeder & Weimer, 2015). In

subsequent years following the Sheppard-Towner Act, President Harry S. Truman

tendered a plan for universal health care, a measure unable to pass through the

government (Manchikanti, Helm, Benyamin, & Hirsch, 2017). Haeder and Weimer

(2015) stated that federal health care programs aimed to expand health care services to

influence care reimbursement and financial outcomes, with an overarching goal of

universal health care.

As the movement towards universal health care continued, the health concern

continued into the Great Depression. The Social Security Act of 1935 provided stability

in the health care system and identified residents who were either elderly or disabled to

receive health care through Medicare and Medicaid (Haeder & Weimer, 2015). Federal

23

and state governments were delivering health services and sharing the cost provided

stability for U.S. citizens and medical providers taking care of the sick and infirm.

Welfare state policies became part of society with the combination of health care

insurance and retirement funding for the public (Mayhew, 2015).

The enactment of Medicare and Medicaid as health care programs did not appeal

to both the federal and state governments and not all states participated initially (Haeder

& Weimer, 2015; Leemon, 2014). The health care recipients in those states receiving

government-funded health care plans have to use either of these health care plans based

on income and age requirements. Individuals who are apathetic regarding health care

dwell on the ineffectiveness of programs established by government leaders. The

individuals receiving health care assistance viewed government intervention in a negative

context by the lack of transparency of the government regarding cost, quality of care, and

treatment outcomes (Maurer et al., 2017).

The principles of health care were to ensure services of value and quality is

accessible to individuals with moderate to lower incomes. The design of health care

reform existed as a social and societal norm, and economic instability has occurred in the

form of a conservative fiscal approach or terms of limited government intervention for

health care services (Schimmel, 2013). Reforming the health care system based on an

economic point of view will provide health care to all citizens as a cheaper and more

efficient alternative (Pineda & Hermes, 2015). In addition, the scope of health care

expansion is to ensure all citizens have access to health care services (i.e., hospitals,

public clinics, and health centers). The health care claim is that individuals pay from their

24

income if they do not need health care services. However, people should receive health

care services based on need, not income (Nardin, Zallman, Sayah, & McCormick 2016).

Government’s role in health care is not the solution and may hinder positive

advancements in health care reform (Manchikanti et al., 2017). Approximately 45 million

Americans are without health care coverage and millions more deal with lapses in their

health care insurance and are considered to be underinsured (Schimmel, 2013). The

concern with health care reform continues to come from the involvement of the

government, and the government has only marginally controlled health care costs

(Howrigon, 2016). There is market demand for health care services for the millions of

individuals without health care insurance. The health care industry is in a phase of

fluctuation, and the challenge ahead for rural clinics is to identify proactively potential

changes in health care reform.

The reform of health care insurance does not follow in the footsteps of socialized

medicine, as services remain vulnerable now and in the upcoming future. The idea

concerning health care as an inalienable right would regulate and conflict with other’s

rights and freedoms, as coordinating health care services is not the primary focus

(Roberts, 2012). The marketplace is a determinant regarding financial control in health

care with the emphasis placed on profitability and not necessarily on treating the illness

(Darrow, 2015). The concern of state or federal government officials is not to engage in

the agreement of social, economic, or even cultural rights between citizens but to play a

role in the scope of health care reform. Early health care reform had a lasting effect on

legislation in the United States (Durenberger, 2015). There is controversy about

25

government involvement in health care today, and without consensus, reform cannot take

place. The debate over universal health care is prevalent and divisive, but the right to

have health care remains unsettled with the advent of the ACA.

During the past 50 years, much of the health care system remains pieced together

ensuring individuals have access to hospitals, clinics, doctors, and medical supplies

(Farnsworth, 2015). Business leaders seeking for-profit benefits focus financially on

volume while spending less time providing adequate care (Joynt, Orav, & Jha, 2014). The

extension of health care benefits aimed to ensure those who were uninsured received

sufficient health care assistance, though a segment of the population is still without health

care insurance or is underinsured because of cost control means put in place by the

government (Schimmel, 2013).

The progression of health care services within the American health care system

results from the efforts of the public, private, government, businesses, and other

industries to create a universal health system. The evolutionary process of the American

health care system from a historical perspective exists in addressing enhanced

accessibility to services, upgrading the quality of care, and cost-effectiveness, or control

(Farnsworth, 2015). The U.S. health care system remains segmented into three groups:

government-assisted insurance, private insurance, and no insurance (Marshall et al.,

2016). There are differences between public and private health care, and evidence shows

that private health care according to US standards remains the best option (Nardin et al.,

2016). The idea persists that each citizen is responsible for his or her health care services

26

and may need to seek health care by any means possible through state-funded, federally

based, or private options.

The American legislature has different methodologies regarding health care

reform, and hence nothing has emerged as a clear means for all citizens to have adequate

health care. The past 50 years of government involvement has led from

Medicare/Medicaid to the ACA with no affordable options to all citizens (Durenberger,

2015). The selection of health care reform models comes from a form of compensation

for health care organizations who can deliver skilled and superior care (Barinaga et al.,

2017). The decision for health care reform comes from the government, which can

fluctuate between liberal and conservative perspectives, but operational or business

functions must address the financial stability of the organizations (Noh, 2016). The

selection of different reimbursement methods, such as fee-for-service (FFS) or value-

based purchasing (VBP) determines the economic outcome of a health care organization

and will be the catalyst for creating a cost-effective health care system (Schneider & Hall,

2017).

Health Care Financial Options and Medical Care

Health insurance representatives base their coverage decisions on factors such as

cost, effectiveness, and outcomes of care. A misunderstanding is to base a model of

health insurance with the resulting cost of delivering care. The government related

options available to U.S. citizens are minimal regarding health care, as they are referred

to as “safety nets.” The fail-safe system set up by the federal government to ensure

necessary care exists for individuals with lower to moderate income (Chokshi, Chang, &

27

Wilson, 2016). Thirty-one million Americans are without health care coverage, and

health care organizations need possible financial outcomes to provide coverage and care

(Hall & Lord, 2014). The rural clinic manager’s goal is viability in providing a public

health commodity and service (Reddy & Mythri, 2016). Medicaid and the ACA provide

stability of health care services, but individuals at or below the poverty level will use one

model or another irrelevant of the cost (Durenberger, 2015). The number of Americans

without health care coverage is a determining factor regarding reimbursement progress

affecting health care organizations (Kessell et al., 2015).

The quality of health care is a crucial financial consideration in addressing

adequate health care. The viability of health care concerning Medicaid and the ACA was

due to the expansion of Medicaid support to the states ensuring health insurance would be

accessible to low-income adults (Nguyen & Sommers, 2016). The premise towards the

expansion of Medicaid services was not only to meet the growing need for new patients,

but a determinant of the ACA to deliver quality care (Franz, Skinner, & Murphy, 2016).

Patients choose their health care services based on their health insurance and the

necessity of medical treatment or service. Uninsured individuals may experience lower

quality health care in comparison to those with private health care insurance (Nardin et

al., 2016). A rural clinic should implement services and treatment models following

private health care insurance.

The fiscal model for private insurance may not be adequate for all health care

organizations, as there are regional differences in access to appropriate health care. Thus,

if the area does not have a medical specialist, Medicaid and ACA patients, who depend

28

on the safety-net providers such as community-based health care services, will visit

primary care providers (Nguyen & Sommers, 2016). The advantage of health care

organizations is in facilitating and examining costs to the health care facility, while in

turn ensuring the quality of health care services promoting positive patient outcomes

(Shortell et al., 2015). Rural clinics build a kinship with patients in their regions with an

undertaking that medical services are available in each community. Ultimately, the care

and treatment is available for individuals who are in federal or state health care plans

regardless of the ailment or sickness, and the medical practice will build an assortment of

various payer sources.

The financial barriers associated with the ACA originated from the Massachusetts

Health Reform of 2006. The proposal is to expand Medicaid in a provision to decrease

the number of uninsured individuals. The financial obligation has been the ability of

health care organizations to provide affordable health care insurance to individuals with

moderate to low incomes (Nardin et al., 2016). The quality of health care in the United

States has languished over the past several years; however, costs have soared caused by

the reimbursement process (Choi, Lai, &Lai, 2016). Since the introduction of the ACA in

2010, the number of insured persons has increased by around 20 million, which has

reduced the number of persons not insured (Oberlander, 2017). The rural clinic benefits

with growth in the number of insured but the provision of quality health care is also

essential.

Limitations of both Medicaid and the ACA are a focus of legislators (Nardin et

al., 2016). The changes to the delivery of health care to Medicaid or ACA should not

29

affect the utilization of health care services or deny needed care (Nardin et al., 2016).

Health care organizations benefit from ACA because providers can generate high net

revenues from the increase in expanded coverage (Glied & Jackson, 2017). The quality of

care given a patient does not affect the amount of reimbursement (Glied & Jackson,

2017).

There is a movement towards personalized health care to hold patients

accountable for their lifestyles and tailored treatments. The principle of customized health

care has a dual purpose of enhancing the quality of health care services while lowering

costs (Teng, 2015). The rural clinic must ensure accountability for the total costs and

move away from past FFS beliefs towards risk-sharing measures (Blumenthal, 2016).

Similarly, the idea of personalized health care and price do not associate with each other,

but there are segments of the health care system to indicate care and treatment are

universal (Teng, 2015). The evidence-based information shows personalized health care

is a cost-effective approach to health care in the United States (Kuramoto, 2014). Overall,

implementing personalized care will bring focus on patient-centered care, but other

aspects are involved such as cost-effectiveness and containment.

The cost savings to the rural clinic does not appear to be evidence indicating

improved patient satisfaction. Personalized health care can educate, teach, and encourage

patient care, leading to financially supportive reimbursement arrangements (Teng, 2015).

Health economics plays an essential role in the identification of a payment system, but

the assurance of quality care will come at a significant cost (Chen & Goldman, 2016).

Preventative care is a necessary part of the quality goals of health care reform. Such an

30

incentive-based health care policy will enable cost-effective health care for all citizens:

the right care at the right time for the appropriate individuals (Kuramoto, 2014).

Health care reform potentially harms insurance profitability over time due to

shifts in reimbursement payments (Teng, 2015). Health care insurance existed before the

ACA in the form of private insurance, government funded, subsidized, regulated health

care, as Medicaid and Medicare coverage was primarily for the poor and elderly. The

objective was to have health care reform much like Canada, a single-payer system

emulating universal health care (Hall & Lord, 2014). The concept of a universal health

care system exceeds the financial accountability of Medicaid, and expanding Medicaid

would ease the financial burden on the states (Langellier et al., 2014). The concept of a

temporary health care system is universal and far exceeds financial accountability based

on poverty. Expanding Medicaid to ease the financial burden on the states to cover

medical services for individuals who remain uninsured is a temporary solution

(Langellier et al., 2014).

The correlation between financial preferences and health care is a crucial way to

solve the problems that overwhelm state and federal governments. The payment

structures for receiving medical care historically centered on FFS (fee-for-service) and

the capitation rate structure (predetermined rate to reimburse medical providers or

capitated rate or managed care) (Leemon, 2014). Health care organizations are

developing an infrastructure to move from previous ways of thinking about payment

modalities and creating revenue (Conrad, Vaughn, Grembowski, & Marcus-Smith, 2016).

Consequently, risk/reward plays a factor in financial preferences and the delivery of

31

services to the patient. The customary allowable rates are a risky proposition for rural

clinics due to the flat rate becoming a point of contention for the rural clinic depending

on the negotiation of the signed contract. Health care reform in Medicaid and ACA has

benefits for most Americans, regardless of the patient’s ability to pay. The objective of

health care reform is to provide adequate health care to the patient at a reasonable cost.

The challenges are facing health care financing options and medical care rest on

the patient’s ability to pay. Rural health care facilities face increased challenges in

comparison to urban areas due to differences in levels of income of patients (Allen,

Davis, Hu, & Owusu-Amankwah, 2015). The U.S. government offers rural health clinic

services through Medicare and Medicaid to the needy (Ortiz, Meemon, Zhou, & Wan,

2013). The rural health hospitals in smaller communities are financially unstable, but they

become viable substitutes for the patient in search of health care (Allen et al., 2015). The

mission of rural health clinics is to provide medical services to an underserved population

due to financial and operational issues. The rural clinic managers must contend with the

increased patient flow while managing costs and quality.

Fee-For-Service (FFS) vs. Value-Based Purchasing (VBP)

The duality of rural clinics is to serve the patients who walk through their doors

and manage the financial well-being of the operation. Reimbursements to health care

organizations are important considerations within the health care reform framework

(Oberlander, 2017). Business leaders will need to address reimbursement approaches in

preparing a profitable business model for the future (Gurganious, 2016). With health care

costs rising, reducing costs will lead to a decline in accessibility or value of the American

32

health care industry (Rudnicki et al., 2016). Thus, changes in coverage for patients to

visit hospitals, health care facilities, and providers will have a profound impact on the

operational bottom line.

Rural clinics link prospective payment for medical services to either FFS or VBP,

which encompasses payment through improved performance and reduced cost. This form

of payment holds health care providers responsible for the costs and quality of their care

and attempts to reduce and identify and reward inappropriate care (Kessell et al., 2015).

In order to establish continuity, rural clinics need a strategy for collecting reimbursement

and payment. FFS or VBP are important financial choices to a health care organization

and for the provider of medical services (Feldman, 2015). The future of health care

reform centers on price and value, and less on status, with the emphasis on conventional

health care economics (Gerben, 2016). Operations management makes decisions

regarding the volume or value of these payment options. Overall, rural clinics select the

most common and reliable payment types to establish consistency in the changing

landscape of health care reform.

The modes of payment for health care services have reached critical levels as

proponents of both sides view each system with flaws. The FFS model places

accountability for costs on medical providers (Feldman, 2015). The majority of health

care leadership analyzes payment reform as an approach to motivate medical providers to

incorporate the delivery of services (Murphy, Ko, Kizer, & Bindman, 2015). However,

the objective is to maximize profits, and the number of services and potential outcomes is

difficult for rural clinics to predict. The rural clinic distinguishes the best possible

33

payment opportunity for the business to create increased volume. Many contend having

one payment source and a financial plan to address lengthy payment delays is better for

the health care organization (Cascardo, 2015).

Health care reform interests should bring about restrictions on the way rural

clinics decide to accept or deny revenue streams. Health care providers recognize the FFS

model, but in some areas, the bundled payment is part of VBP and is standard for medical

generalists (Kuramoto, 2014). Business leaders determine the soundest payment structure

to ensure medical providers and the business receive compensation while still

emphasizing quality and efficiency (Ojeifo & Berkowitz, 2015). A mode of collection is

not to isolate specialists from accepting one form of payment for services (Palinkas et al.,

2015). Rural clinics comprise of a mixture of general practitioners and specialists.

Health care organizations must anticipate changes in health care reform as cost

conflicts could take place among medical providers regarding lower reimbursement rates.

The perception of clinical equity is something an organization must confront due to cost-

effectiveness or the anticipation of high-quality care and treatment (Kuramoto, 2014).

The health care system has gone through changes in the language of policy and

inconsistency with the delivery of medical services, leading to gaps in coverage,

conflicting outcomes, and inexcusable costs (Larkin, Swanson, Fuller, & Cortese, 2016).

The perspective of the business is to follow any advantage obtained or accept one payer

source over another, focusing on the overall value of the provided services. Rural clinics

address possible changes in the reimbursement fee schedule while identifying potential

opportunities to expand business and cost-effectiveness (Abidemi et al., 2017). Finally,

34

business leaders establish strategies to separate themselves from competitors and limit the

need for unnecessary risk-taking.

The U.S. health care system has migrated away from an FFS option regarding

reimbursement and is trending towards VBP as a financial alternative. Health care

clinicians are progressing towards VBP for services rendered (Joynt et al., 2017). The

transformation of the reimbursement revenue cycle has caused business leaders to assess

operational infrastructure with the limited resources available in the selection of a

payment model (Granata & Hamilton, 2015). Additionally, enrollment of individuals in

the ACA or Medicaid remains scripted as these plans continue for persons with lower to

moderate incomes (Durenberger, 2015). Business leaders will initiate a plan for accepting

either reimbursement arrangement (FFS or VBP), and the economic impact of the

decision-making process may result in financial implications for days, weeks, months,

and years.

The financial impact of health care reform on health care organizations is not

entirely clear. The FFS model remains monetarily centered on one particular service-

taking place for the patient (Leemon, 2014). Conversely, the VBP payment modality

provides a consistent financial revenue flow for the health care organization, along with

the element of increased quality of care and higher health outcomes for patients (Joynt et

al., 2017). Health care organizations seek revenue streams that provide an incentive base

for the business and do not discourage utilizing capitation rates (Doran, Maurer, & Ryan,

2017). Overall, payment modalities have a financial impact on the organization, and

sustainability is the groundwork for success.

35

Rural clinics need to focus on the delivery of services to address prospective

payment reimbursement concerns to ensure a consistent source of revenue. This analysis

should emphasize the elements of risk and reward to incentivize to include expectations

on treatment expenses, value, and results (Halfon et al., 2014). Higher expectations fuel

increasing health care costs, as health care organizations plan to improve patient

satisfaction and reduce costs (Moraros, Lemstra, & Nwankwo, 2016). While the U.S.

health care system is meant to provide affordable services, they are often ineffective and

high priced. The business strategies implied by an association with an FFS model serves

as a volume-driven entity, while the modality of VBP promotes costs and quality of care

(Noether & May, 2017). Rural clinics identify a recurring payer source as suitable for

financial growth while providing patients viable health care solutions.

The reimbursement process considers aspects such as improvement in the quality

of care, managed spending, and a patient’s access to health care services. The

involvement of federal and state governments regarding health care is a primary source,

and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is presently in the middle

(Haeder & Weimer, 2015). The directive is to initiate replacing the reimbursement model

of FFS with the model of VBP (Schneider & Hall, 2017). CMS established an enhanced

version of paying for the quality of care (Cassel, Kerr, Kalman, & Smith, 2015). The

justification for change stems from the quality and quantity of the medical services

provided to the patient by the medical provider. Overall, the financial risk implied with

this VBP process emphasizes the value of health care services provided to patients.

36

The concern about health care exchanges with Medicaid and the ACA focuses on

inducements that reduce health care costs and provide improved service quality. The

research regarding FFS and VBP or bundling of services has lasting fiscal effects on

federal and state governments (Noh, 2016). The budgetary durability of our health care

system rests with federal and state governments determining a balance between cost

containment and quality care (Landers et al., 2016). Accordingly, federal and state

governments have addressed changes regarding health care reform and considered

reducing funds due to sustained debt at federal and state levels (Maurer et al., 2017). The

financial implications of health care reform with the implementation of the ACA remain

a temporary solution with the revamping of health care, as it currently exists.

Medicaid and ACA address cost, utilization of services, and trends in the health

care system. The forecasting of federal and state budgets regarding health care services is

a complex task; roughly, 20% of a state’s budget consists of health care funds, second

only to education (Gerstorff & Gibson, 2016). Health care spending is a national issue

and reforms can result in increased health care expenses (Duijmelinck & van de Ven,

2016). Data collection is important because the resulting reports illustrate the cost

efficiency of programs relative to the type of reimbursement model used (Eggbeer &

Bowers, 2014). Financial and operational strategies that result from data collection

prioritize cost containment, and health care outcomes are essential for the operation to be

successful.

Many individuals affected by health care reform and who are covered by

Medicaid (AHCCHS-Arizona) or the ACA reside in rural communities. Most of these

37

areas are underserved locations or populations that have other forms of payment for

medical services, including deductibles or co-pays or, for patients with lower to moderate

income, a sliding fee scale payment (Gao, Nocon, Sharma, & Huang, 2017). The

reduction in health care costs may become pivotal to enhance our current health care