INTELLECTUAL

PROPERTY

Assessing Factors

That Affect Patent

Infringement

Litigation Could Help

Improve Patent

Quality

Report to Congressional Committees

August 2013

GAO-13-465

United States Government Accountability Office

United States Government Accountability Office

Highlights of GAO-13-465, a report to

congressional committees

August 2013

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

Assessing Factors That Affect Patent Infringement

Litigation Could Help Improve Patent Quality

Why GAO Did This Study

Legal commentators, technology

companies, Congress, and others have

raised questions about patent

infringement lawsuits by entities that

own patents but do not make products.

Such entities may include universities

licensing patents developed by

university research, companies

focused on licensing patents they

developed, or companies that buy

patents from others for the purposes of

asserting the patents for profit.

Section 34 of AIA mandated that GAO

conduct a study on the consequences

of patent litigation by NPEs. This report

examines (1) the volume and

characteristics of recent patent

litigation activity; (2) views of

stakeholders knowledgeable in patent

litigation on key factors that have

contributed to recent patent litigation;

(3) what developments in the judicial

system may affect patent litigation; and

(4) what actions, if any, PTO has

recently taken that may affect patent

litigation in the future. GAO reviewed

relevant laws, analyzed patent

infringement litigation data from 2000

to 2011, and interviewed officials from

PTO and knowledgeable stakeholders,

including representatives of companies

involved in patent litigation.

What GAO Recommends

GAO recommends that PTO consider

examining trends in patent

infringement litigation and consider

linking this information to internal

patent examination data to improve

patent quality and examination. PTO

commented on a draft of this report

and agreed with key findings and this

recommendation.

What GAO Found

From 2000 to 2010, the number of patent infringement lawsuits in the federal

courts fluctuated slightly, and from 2010 to 2011, the number of such lawsuits

increased by about a third. Some stakeholders GAO interviewed said that the

increase in 2011 was most likely influenced by the anticipation of changes in the

2011 Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), which made several significant

changes to the U.S. patent system, including limiting the number of defendants in

a lawsuit, causing some plaintiffs that would have previously filed a single lawsuit

with multiple defendants to break the lawsuit into multiple lawsuits. In addition,

GAO’s detailed analysis of a representative sample of 500 lawsuits from 2007 to

2011 shows that the number of overall defendants in patent infringement lawsuits

increased by about 129 percent over this period. These data also show that

companies that make products brought most of the lawsuits and that

nonpracticing entities (NPE) brought about a fifth of all lawsuits. GAO’s analysis

of these data also found that lawsuits involving software-related patents

accounted for about 89 percent of the increase in defendants over this period.

Stakeholders knowledgeable in patent litigation identified three key factors that

likely contributed to many recent patent infringement lawsuits. First, several

stakeholders GAO interviewed said that many such lawsuits are related to the

prevalence of patents with unclear property rights; for example, several of these

stakeholders noted that software-related patents often had overly broad or

unclear claims or both. Second, some stakeholders said that the potential for

large monetary awards from the courts, even for ideas that make only small

contributions to a product, can be an incentive for patent owners to file

infringement lawsuits. Third, several stakeholders said that the recognition by

companies that patents are a more valuable asset than once assumed may have

contributed to recent patent infringement lawsuits.

The judicial system is implementing new initiatives to improve the handling of

patent cases in the federal courts, including (1) a patent pilot program, to

encourage the enhancement of expertise in patent cases among district court

judges, and (2) new rules in some federal court districts that are designed to

reduce the time and expense of patent infringement litigation. Recent court

decisions may also affect how monetary awards are calculated, among other

things. Several stakeholders said that it is too early to tell what effect these

initiatives will have on patent litigation.

The U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (PTO) has taken several recent actions

that are likely to affect patent quality and litigation in the future, including agency

initiatives and changes required by AIA. For example, in November 2011, PTO

began working with the software industry to develop more uniform terminology

for software-related patents. PTO officials said that they generally try to adapt to

developments in patent law and industry to improve patent quality. However, the

agency does not currently use information on patent litigation in initiating such

actions; some PTO staff said that the types of patents involved in infringement

litigation could be linked to PTO's internal data on the patent examination

process, and a 2003 National Academies study showed that such analysis could

be used to improve patent quality and examination by exposing patterns in the

examination of patents that end up in court.

View GAO-13-465. For more information,

contact Frank Rusco at (202) 512-3841 or

Page i GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

Letter 1

Background 7

Number of Patent Infringement Lawsuits Increased Significantly in

2011 and the Number of Defendants Increased between 2007 and

2011 14

Stakeholders Identified Three Key Factors Contributing to Many

Recent Patent Infringement Lawsuits 28

New Initiatives in the Courts May Affect Patent Litigation 36

PTO Has Taken Actions to Improve Patent Quality and Implement

New AIA Proceedings That May Affect Patent Litigation in the

Future 39

Conclusions 45

Recommendation for Executive Action 46

Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 46

Appendix I Objectives, Scope, and Methodology 48

Appendix II Comments from the Patent and Trademark Office 55

Appendix III GAO Contact and Staff Acknowledgments 56

Table

Table 1: Evidence or Information Used to Review Lex Machina’s

Plaintiff Classifications 52

Figures

Figure 1: Number of Software-Related Patents Granted per Year by

PTO, 1991 to 2011 12

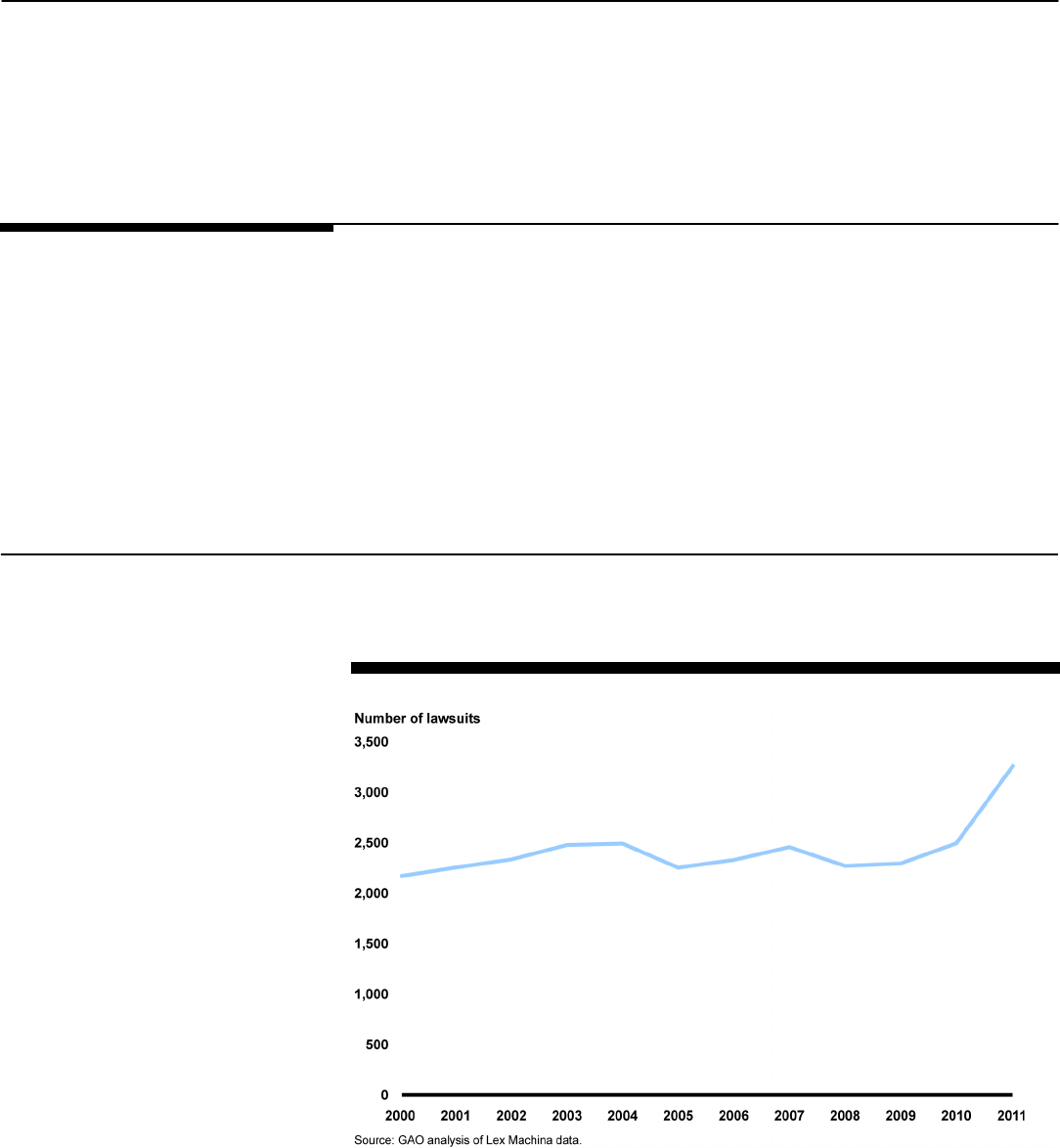

Figure 2: Patent Infringement Lawsuits, 2000 to 2011 14

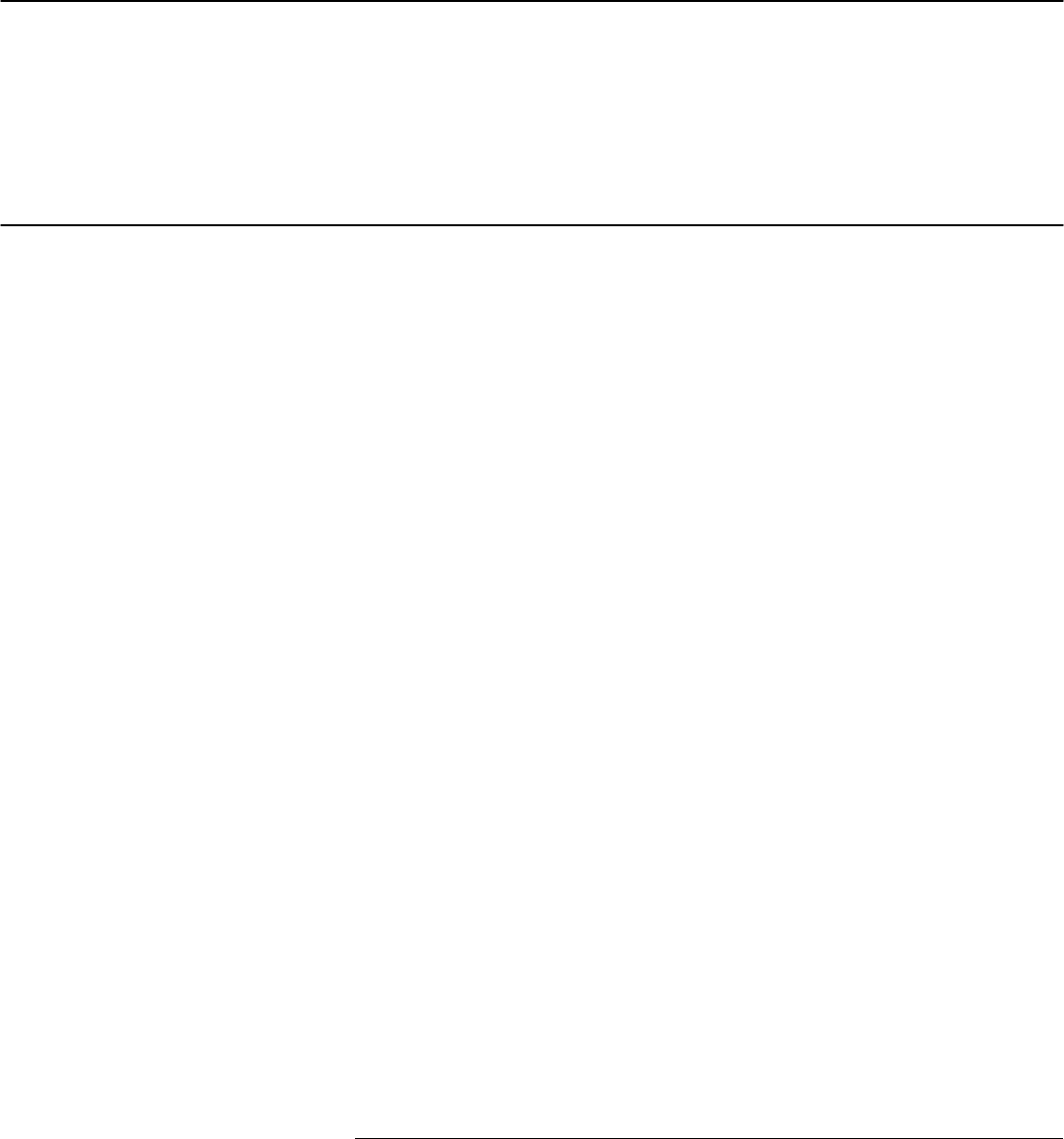

Figure 3: Estimated Number of Defendants in Patent Infringement

Lawsuits, 2007 to 2011 16

Figure 4: Estimated Patent Infringement Lawsuits by Type of

Plaintiff, 2007 to 2011 18

Contents

Page ii GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

Figure 5: Estimated Number of Patent Infringement Lawsuits and

Defendants Associated with Software-Related Patents,

2007 to 2011 21

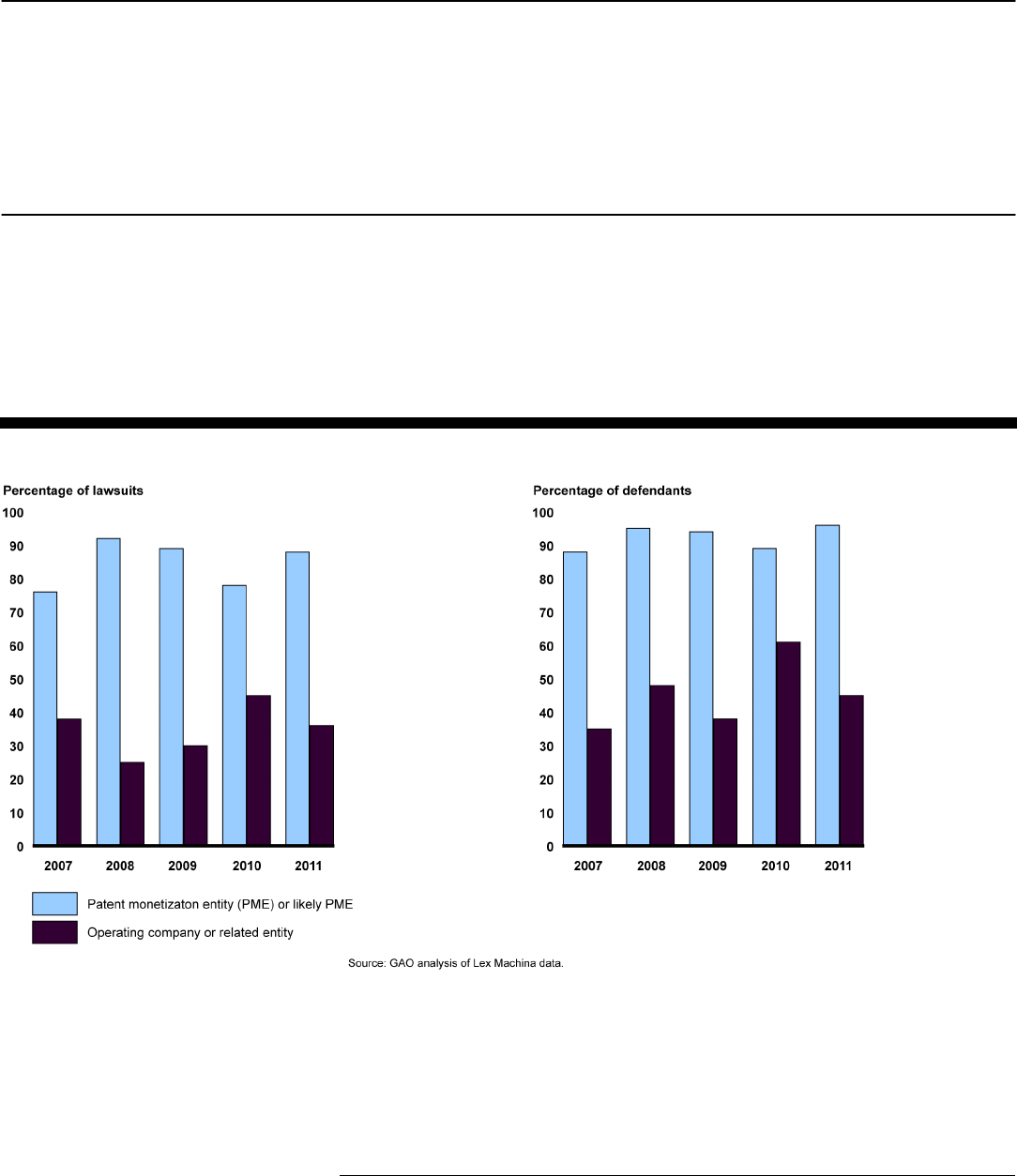

Figure 6: Estimated Percentage of PME and Operating Company

Lawsuits and Defendants Associated with Software-

Related Patents, 2007 to 2011 22

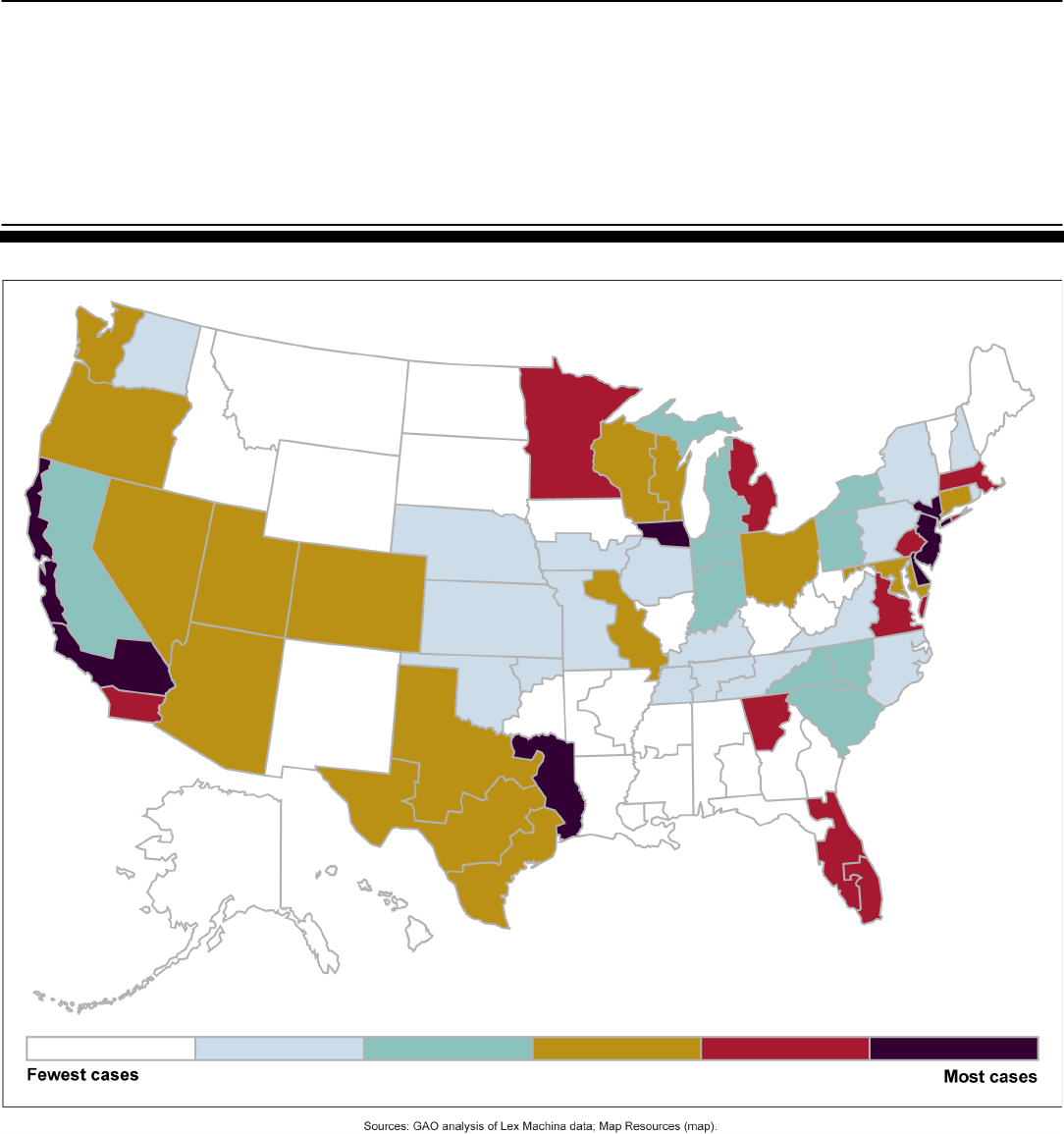

Figure 7: Distribution of Total Patent Infringement Lawsuits across

U.S. District Courts from 2000 to 2011 24

Abbreviations

AIA Leahy-Smith America Invents Act

AIPLA American Intellectual Property Law Association

AOUSC Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts

CPC Cooperative Patent Classification

EPO European Patent Office

FTC Federal Trade Commission

ITC International Trade Commission

NPE nonpracticing entities

PAE patent assertion entities

PME patent monetization entities

PTO Patent and Trademark Office

R&D research and development

SEC Securities and Exchange Commission

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. The published product may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety

without further permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain

copyrighted images or other material, permission from the copyright holder may be

necessary if you wish to reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

441 G St. N.W.

Washington, DC 20548

August 22, 2013

Congressional Committees

History is filled with examples of successful inventors who did not develop

products based on the technologies they patented. For example, Elias

Howe patented a key component of the sewing machine––a mechanism

for making a lockstitch––but it was Isaac Singer who most successfully

brought these machines into the homes of thousands of Americans by

obtaining crucial patents of his own and paying Howe and other inventors

to license the technology described in their patents.

1

In the United States,

the party that owns a patent––the patent owner––is not required to put

the patent to use in order to profit from it; he can also license others to

use it.

2

In some instances, patent owners may need to actively assert

their patents in an adversarial context if another firm’s product infringes

their patents.

3

For example, Singer initially refused to obtain a license to

Howe’s patent, but when Howe sued Singer for infringing his patent, the

two parties ultimately entered a licensing agreement.

4

1

A patent is an exclusive right granted for a fixed period of time to someone who invents

or discovers (1) a new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of

matter or (2) any new and useful improvement of such items.

2

In this report, when we use the term “patent owner,” it includes the real party in interest

when that party is not the patent owner. A real party in interest may be, among other

things, an entity that has a legal right to enforce the patent, such as a parent entity or

exclusive licensee.

3

Anyone who makes, sells, offers to sell, uses, or imports the patented invention during

the term of the patent without the patent owner’s permission infringes the patent. Patent

infringement is a strict liability offense—the alleged infringer’s intent to copy or act of

copying the patented invention are not relevant to the outcome of an infringement

lawsuit—so an individual who independently develops an invention that falls within the

scope of a patent may infringe the patent. A patent owner can grant permission to use a

patented invention by licensing others to use, make, sell, or import the patented invention.

Patent owners can also transfer title to their patents by assigning their patent rights to

others.

4

For more information on the dispute between Howe and Singer, see: Adam Mossof, The

Rise and Fall of the First American Patent Thicket: The Sewing Machine War of the

1850s, 53 Ariz. L. Rev.165 (2011). See also Ryan L. Lampe & Petra Moser, Do Patent

Pools Encourage Innovation? Evidence from the 19th-Century Sewing Machine Industry,

NBER Working Paper No. 15061 (June 2009).

Page 2 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

According to economists who have studied these issues, the U.S. patent

system—authorized by the U.S. Constitution—aims to promote innovation

by making it more profitable.

5

In addition to individual inventors who may choose not to develop

products based on their patents, there are other types of “nonpracticing”

patent owners, or nonpracticing entities (NPE). For example, some

universities are NPEs, as they develop technologies in campus

laboratories, and rather than producing and selling products that

incorporate these technologies, they license their patents on these

technologies to companies who use them in their products. In addition,

some private firms are NPEs as they specialize in R&D, and rather than

selling products, they license the patents for those products to fund

further research. Some NPEs simply buy patents from others for the

purpose of asserting them for profit; these NPEs are known as patent

monetization entities (PME).

For example, a patent owner can generally

exclude others from making, using, selling, or importing the patented

technology for 20 years from the date on which the application for the

patent was filed. By restricting competition, patents can allow their owners

to earn greater profits on their patented technologies than they could earn

if these technologies could be imitated freely. Due to the exclusive rights

provided by patents, patents can help their owners recoup the costs of

the research and development (R&D) of new technologies. On the other

hand, any limiting effects on competition caused by the exclusive nature

of patents may result in higher prices for products having patented

technologies. The patent system, therefore, gives rise to complex trade-

offs involving innovation and competition. These trade-offs can be

affected by decisions made by the United States Patent and Trademark

Office (PTO), which issues patents; the federal courts, which decide

patent infringement lawsuits; and the International Trade Commission

(ITC), which can order imports that infringe U.S. patents to be excluded

from entering the country.

6

5

The Constitution grants to Congress the power “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and

useful Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the exclusive Right to

their respective Writings and Discoveries.” U.S. Const., art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

Other PMEs include companies that

produced products at one time and still own patents on the technologies

6

The Federal Trade Commission uses the related term “patent assertion entities” to focus

on entities whose business model solely focuses on asserting typically purchased patents.

As such, the PME term also encompasses entities that might use third-party NPEs to

assert patents for them.

Page 3 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

for those products. Experts agree that NPEs have a variety of business

models, which makes it difficult to fit them neatly into any one of these

categories. For example, even companies that produce products related

to their patents—known as practicing patent owners, or operating

companies—sometimes assert patents that they own but that are not

related to the products they produce, which further complicates defining

an NPE.

Some legal commentators, technology companies, the Federal Trade

Commission (FTC),

7

and Congress, among others, have raised concerns

that patent infringement litigation by NPEs is increasing and that this

litigation, in some cases, has imposed high costs on firms that are

actually developing and manufacturing products, especially in the

software and technology sectors. Among the concerns of some

technology companies and legal commentators is that because NPEs

generally face lower litigation costs than those they are accusing of

infringement, NPEs are likely to use the threat of imposing these costs as

leverage in seeking infringement compensation.

8

The Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), signed into law September

16, 2011, made several significant changes to the U.S. patent system.

Section 34 of the AIA

These technology

companies and legal commentators also have noted that NPEs often

claim that their patent covers an entire technology when in fact it may

cover just a small improvement in an existing technology, and that it can

be difficult for judges and juries to determine the patent’s scope when

complex technologies are involved.

9

7

FTC’s mission includes prevention of and enforcement against anticompetitive, unfair, or

deceptive business practices including, potentially, patent assertion activities.

mandates that GAO conduct a study on the

8

This is not unique to patent infringement litigation. As discussed later in the report, in civil

lawsuits, the parties must exchange certain information relevant to the litigation, a process

known as discovery. Discovery costs in complex litigation, including patent infringement

litigation, can run into the millions of dollars. Because NPEs do not make products, they

generally have less information to disclose and thus have lower discovery costs. They

also cannot be countersued for patent infringement. This asymmetry in litigation costs

(which exists in other types of complex litigation) can give NPEs leverage in seeking

financial compensation from operating companies.

9

Pub. L. No.112-29 § 34 (2011).

Page 4 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

consequences of patent litigation by NPEs.

10

To address all four objectives, we reviewed relevant laws, including the

AIA, and interviewed officials from PTO, FTC, ITC, and 44 stakeholders

knowledgeable about patent litigation. These included representatives

from companies and industry groups that were recently sued for patent

infringement, PMEs, judges, various legal commentators (including law

professors and patent litigators representing operating companies and

PMEs), economists, representatives from research universities that

license patents, patent brokers who help others buy and sell patents,

venture capitalists, and individual inventors.

Our objectives in conducting

this study were to determine: (1) what is known about the volume and

characteristics of recent patent litigation activity; (2) the views of

stakeholders knowledgeable in patent litigation on what is known about

the key factors that have contributed to recent patent litigation; (3) what

developments in the judicial system may affect patent litigation; and (4)

what actions, if any, has PTO recently taken that may affect patent

litigation in the future.

11

10

As noted in a September 7, 2011, letter from the Comptroller General to the chairs and

ranking members of the congressional committees with jurisdiction over patents, the bill

being considered at that time would have required a GAO study involving several

questions for which reliable data were not available or could not be obtained. The bill was

enacted without change, but the Chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, responding to

these concerns, stated that GAO should note data and methodology limitations in its

report prepared in response to the mandate. 157 CONG. REC. S 5402, S5441 (daily ed.

Sept. 8, 2011) (statement of Sen. Leahy). Consequently, we developed report objectives

consistent with these limitations, and we have noted specific data limitations in appendix I

and throughout this report, as appropriate.

To describe what is known

about the volume and characteristics of recent patent litigation activity for

2007 to 2011, we analyzed patent infringement litigation data from Lex

Machina, a firm that collects and analyzes data on patent litigation. Lex

Machina provided data for all patent infringement lawsuits filed in federal

district court from 2000 to 2011. From these data, Lex Machina selected a

random, generalizable sample of 500 lawsuits (100 per year from 2007 to

2011), which allows us to estimate percentages with a margin of error of

11

We identified some of these stakeholders from patent infringement litigation data from

2000 through 2011 that we reviewed. Representatives of companies and PMEs we talked

with had regularly been sued or had regularly sued others over the past decade. Other

stakeholders we identified through our review of academic literature on patent litigation

and the patent system and were knowledgeable in the issues we were asked to study.

Because stakeholders varied in their expertise with various topics, not every stakeholder

provided an opinion on every topic.

Page 5 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

no more than plus or minus 5 percentage points over all these years and

no more than plus or minus 10 percentage points for any particular year.

12

Lex Machina used a variety of characteristics from court records, U.S.

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings, and corporate

websites to categorize litigants, including as an operating company or

likely operating company, PME or likely PME, university, or an individual

or trust.

13

A limitation of this categorization is that litigants were not

contacted to verify their identity, so there is some uncertainty about the

accuracy of the category in which Lex Machina placed them. We also

obtained patent infringement data from RPX, another firm that collects

data on patent infringement lawsuits, in an effort to verify Lex Machina’s

litigant categorizations.

14

12

This sample allowed us to draw conclusions about the broader population of patent

infringement lawsuits for each of these years and is therefore generalizable to all patent

infringement lawsuits filed in federal district court from 2007 to 2011. However, as noted,

estimates from the Lex Machina sample are subject to a 5 percent margin of error. This

means that an estimate of 50 percent, for example, based on all years of data, would have

a 95 percent confidence interval of between 45 percent and 55 percent. The margin of

error is 10 percent when looking at individual years, which means that an estimate of 50

percent, for example, looking at an individual year, would have a 95 percent confidence

interval of between 40 percent and 60 percent. Because Lex Machina followed a

probability procedure based on random selections, the sample is only one of a large

number of samples that might have been drawn. Since each sample could have provided

different estimates, we express our confidence in the precision of our particular sample’s

results as a 95 percent confidence interval. This is the interval that would contain the

actual population value for 95 percent of the samples that could have been drawn. Unless

otherwise noted, the margin of error associated with the confidence intervals of our survey

estimates is no more than plus or minus 10 percentage points at the 95 percent level of

confidence.

Also to describe what is known about the

volume and characteristics of recent patent litigation activity, we reported

data collected by the American Intellectual Property Law Association

13

Definitions of these categories are discussed below and detailed in appendix I. We

found that it was difficult to reliably identify the type of NPEs through analysis of data from

court records because, among other things, firms do not identify themselves as such in

these records. Lex Machina did not include patent owners that primarily seek to develop

and transfer technology, such as universities and research firms, as PMEs. See appendix

I for more detail on Lex Machina’s categorizations and our review of them.

14

RPX also purchases patents itself, to prevent them from being asserted against its

members. RPX provided us with summary data on the number of patent infringement

lawsuits filed in federal district court since January 2005. RPX’s data identified NPEs and

other types of plaintiffs in these lawsuits by using a variety of factors, such as whether

there was evidence that an entity sells or develops products. RPX representatives said

that they used professional judgment to some extent in making these determinations. We

were not able to fully assess the reliability of the judgments RPX used in making these

classifications.

Page 6 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

(AIPLA) on the costs of patent litigation.

15

In addition to the steps we took to address all four objectives, in order to

describe views of stakeholders on what is known about the key factors

that contribute to recent patent litigation trends, we reviewed academic

literature on the patent and judicial systems and the benefits and costs of

patent assertion, including economic and legal studies. To describe

developments in the judicial system that may affect patent litigation, we

interviewed officials and judges from the U.S. District Courts for the

District of Delaware and for the Eastern District of Texas. We selected

these district courts because they had high levels of patent infringement

lawsuits according to Lex Machina data. We also interviewed judges with

the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Federal Circuit) in

Washington, D.C., which hears appeals of patent cases decided in

federal district courts, as well as officials from the Administrative Office of

the U.S. Courts (AOUSC) and the Federal Judicial Center––organizations

that provide broad administrative, legal, and technological services and

support to the judicial branch. We also reviewed documents and data

from the courts, as well as economic and legal studies. To describe what

actions, if any, PTO has recently taken that may affect patent litigation in

the future, we conducted interviews with officials from PTO and reviewed

documents and data from the agency, as well as economic and legal

studies. Appendix I provides more details on our scope and methodology.

We also reviewed academic

literature on patent litigation and the patent system in general and

assessed the methodology of the studies we reported on for soundness.

To assess the reliability of data from Lex Machina, we met with Lex

Machina staff, examined documentation, and tested and reviewed the

data provided for completeness and accuracy. To assess the reliability of

data from PTO, AIPLA, and RPX, we conducted interviews and reviewed

relevant methodology documentation. We found these data to be

sufficiently reliable for purposes of this report.

We conducted this performance audit from November 2011 to August

2013 in accordance with generally accepted government auditing

standards. Those standards require that we plan and perform the audit to

15

AIPLA is a national, voluntary bar association constituted primarily of patent lawyers in

private and corporate practice, in government service, and in the academic community.

See AIPLA, Report of the Economic Survey 2011 (Arlington, Va.: July 2011). AIPLA

surveyed its members during 2011 and asked them to estimate legal costs for typical

patent infringement cases. AIPLA’s findings are based on an 18 percent response rate.

Page 7 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

obtain sufficient, appropriate evidence to provide a reasonable basis for

our findings and conclusions based on our audit objectives. We believe

that the evidence obtained provides a reasonable basis for our findings

and conclusions based on our audit objectives.

When PTO receives a patent application, it assigns it to a team of patent

examiners with relevant technology expertise. PTO does not begin

examining patent applications upon receiving them and PTO’s data

shows that, as of June 2013, the average time between filing and an

examiner’s initial decision on the application was about 18 months.

16

The focus of patent examination is determining whether the patent

application satisfies the statutory requirements for a patent, including: (1)

novelty, (2) nonobviousness, (3) utility, and (4) patentable subject

matter.

On

average, it takes 30 months for PTO to issue a patent once an application

is submitted.

17

Generally, other patents, publications, and publicly disclosed but

unpatented inventions that pre-date the patent application’s filing date are

known as prior art. During patent examination, the examiner, among other

things, compares an application’s claims to the prior art to determine

whether the claimed invention is novel and nonobvious.

18

U.S. patents include the specification and the claims:

The examiner

then decides to reject or grant the claims in the application and deny the

application or grant a patent.

16

PTO’s data show that the current inventory of new applications that have not yet

received an initial decision was around 600,000 applications. PTO refers to these initial

decisions as a “first action on the merits.”

17

To be patentable subject matter, the invention must be a (1) process; (2) machine; (3)

manufacture; (4) composition of matter; or (5) improvement of a process, machine,

manufacture, or composition of matter. To be nonobvious, the claimed invention’s

improvements to the prior art must be more than the predictable use of prior art elements

according to their established functions. Specifically, at the time of the invention, the

differences between the scope and content of claimed invention and the prior art cannot

render the claimed invention as a whole obvious to a person having ordinary skill in the

art.

18

During the patent examination, the applicant and the examiner communicate about the

application, including aspects that might be deficient. For example, the examiner may

inform the applicant that one of the claims is not novel because of prior art, and the

applicant might revise the claim to distinguish it from the prior art the examiner found.

Background

Page 8 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

• The specification is a written description of the invention that, among

other things, sufficiently discloses the invention and the manner and

process of making and using it. The specification must be written in

full, clear, concise, and exact terms so as to enable any person skilled

in the art to make and use the invention. As an example, an excerpt

from the specification for a cardboard coffee cup and insulator

invention describes “corrugated containers and container holders

which can be made from existing cellulosic materials, such as paper.”

• The claims define the scope of the invention for which protection is

granted and must be definite. There are often a dozen or more claims

per patent, and they can often be difficult for a layperson to

understand, according to legal commentators. For example, one claim

for the cardboard coffee cup insulator begins by referring to “a

recyclable, insulating beverage container holder, comprising a

corrugated tubular member comprising cellulosic material and at least

a first opening therein for receiving and retaining a beverage

container.” A patent’s claims can be written broadly or be more

narrowly defined, according to legal commentators, and applicants

can change the wording of claims—which can affect their scope—

during examination based on examiner feedback. Patents are a

property right and—like land—their claims define their boundaries.

When a property right is not clearly defined, it can lead to boundary

disputes, although to some extent uncertainty is inherent.

Consequently, legal commentators define high-quality patents as

those whose claims clearly define and provide clear notice of their

boundaries.

Once issued by PTO, a patent is presumed to be valid. However, the

patentability of its claims can be challenged in administrative proceedings

before PTO or its Patent Trial and Appeal Board and its validity can be

challenged in federal court. For example, the AIA established three new

administrative proceedings for entities to challenge the patentability of a

patent’s claims:

• Inter partes review.

19

19

Inter partes is Latin for “between the parties.”

This proceeding allows anyone who is not the

patent owner to request review of an issued patent by presenting prior

art to PTO—either patents or other publications—to challenge the

claimed invention’s patentability as obvious or not novel. This review

proceeding became available on September 16, 2012, 1 year after the

enactment of the AIA, but entities cannot request this review until the

Page 9 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

later of (1) 9 months after a patent is granted or (2) completion of

post-grant review, if such a proceeding is held.

• Post-grant review. This proceeding allows anyone who is not the

patent owner to request a review of an issued patent that challenges

at least one of the claims’ patentability in more circumstances than

inter partes review—such as the invention not being useful—and not

solely based on prior art. This proceeding is available for patents

issued from patent applications with a filing date of March 16, 2013, or

later and requests must be filed within 9 months of the patent’s

issuance.

• Transitional program for covered business method patents.

20

In addition, a patent’s validity can be challenged in the 94 federal district

courts throughout the country by, for example, presenting additional prior

art that PTO may have been unaware of when it granted the patent.

Challenges to a patent’s validity are often brought by an accused infringer

who has been sued for infringing the patent.

This

proceeding allows anyone who is sued or charged with infringing a

covered business method patent to request a review of the patent to

challenge a claim’s patentability in generally the same circumstances

as post-grant review. This review proceeding became available on

September 16, 2012, and requests must be filed within 9 months of

the patent’s issuance.

21

20

A covered business method patent is a patent that claims a method or corresponding

apparatus for performing data processing or other operations used in the practice,

administration, or management of a financial product or service but does not include

patents for technological inventions. This transitional program is subject to a sunset

provision that will repeal the program on September 16, 2020.

Patent owners can bring

infringement lawsuits against anyone who uses, makes, sells, offers to

sell, or imports the patented invention without authorization because a

patent is a right to exclude others from practicing the invention. Exactly

what a patent covers and whether another product infringes the patent’s

claims are rarely easy questions to resolve in litigation, according to legal

commentators. As noted, appeals of district court decisions in

infringement cases are heard in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal

Circuit in Washington D.C.

21

In patent infringement lawsuits, the accused infringer often challenges the patent’s

validity as an “affirmative defense,” meaning that even if the infringement allegations are

true, the would-be infringer is not liable because the patent is invalid. A party accused of

infringement can also file a lawsuit to obtain a court decision on whether they are

infringing or whether the patent is valid, which is known as a declaratory judgment action.

Page 10 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

If a patent infringement lawsuit is not dismissed in the initial stages, it

proceeds to discovery (a process that exists in all federal civil litigation)

and claim construction. Discovery requires the accused infringer to

produce documents or other information that shows, among other things,

how the allegedly infringing product is made and operates to help the

patent owner establish infringement. Similarly, the patent owner must

produce documents or other information that the accused infringer can

use to challenge the patent’s validity, among other things. However,

parties that do not offer products or services using the patents at issue

often have far fewer documents to disclose—because they do not have

any documents related to their products or services—than patent owners

or accused infringers who do offer products or services.

22

With this information the patent owner specifies which patent claims

allegedly are infringed and the alleged infringer responds by explaining

why the allegedly infringing product is not covered by the patent’s claims.

This identifies the patent claims the court needs to interpret. Known as

claim construction, this is a fundamental issue in patent cases, and each

party tries to persuade the court to interpret the patent claims in its favor.

The court has broad discretion in how it goes about this process, which

can involve a hearing with testimony from witnesses, according to legal

commentators.

23

Once the judge interprets the claims, the claims are then applied to the

allegedly infringing product, to determine infringement, and to the prior

art, to determine the patent’s validity if it is challenged. If the patent is

found to be both valid and infringed, the court can award the patent owner

monetary damages, issue an injunction to prohibit further infringement, or

both. The court is required to award damages adequate to compensate

In addition, if the patent’s validity is being challenged,

the alleged infringer specifies why the patent allegedly is not valid,

including any prior art.

22

As noted, asymmetrical discovery demands, burdens, and costs are not unique to NPE

patent infringement litigation. For example, parties in class actions and antitrust litigation

typically face the same asymmetry. See, e.g.,Thorogood v. Sears, Roebuck & Co., 624

F.3d 842, 849-50 (7

th

Cir. 2010) (class action discovery); Bell Atlantic Corp. v. Twombly,

550 U.S. 544, 558-559 (2007) (antitrust discovery).

23

This hearing is often referred to as a Markman hearing after the Supreme Court’s

decision in Markman v. Westview Instruments, Inc., 517 U.S. 370 (1996).

Page 11 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

for the infringement that are at least what a reasonable royalty would be

for the use made of the invention by the infringer.

24

In addition to being enforced in the federal courts, patents can also be

enforced at ITC, which handles investigations into allegations of certain

unfair practices in import trade. Specifically, certain patent owners can file

a complaint with ITC if imported goods infringe their patent or are made

by a process covered by the patent’s claims.

25

If ITC determines after an

investigation that an imported good infringes a patent, the agency can

issue an exclusion order barring the products at issue from entry into the

United States, which the President can disapprove for policy reasons. ITC

decisions can be appealed to the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal

Circuit. Legal commentators have reported that a 2006 Supreme Court

decision led to increased complaints alleging imported goods infringed

U.S. patents being filed with ITC, and recent ITC data show that the

number of investigations instituted by ITC increased from 32 in 2006 to 37

in 2012.

26

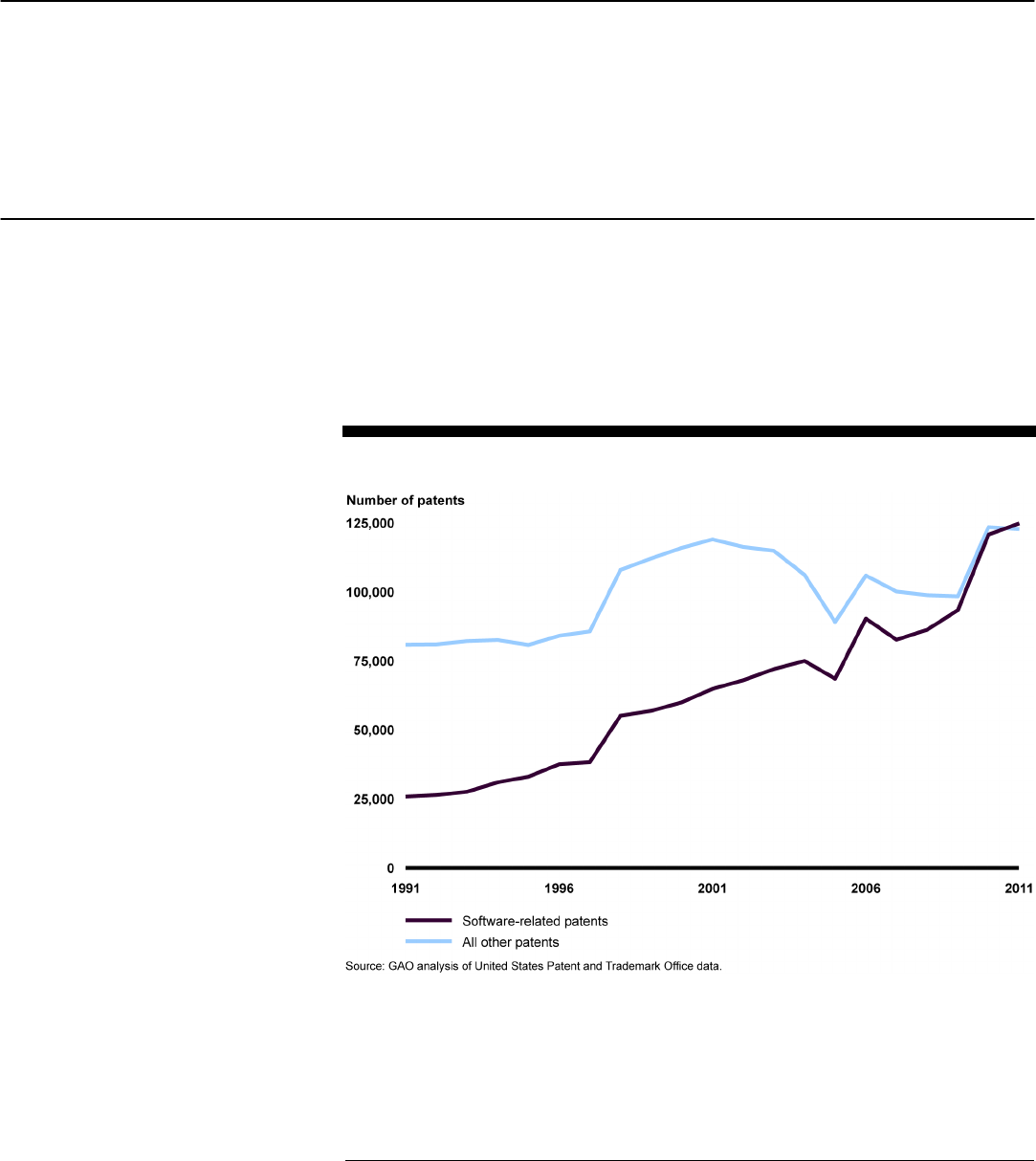

According to PTO data, applications for all types of patents have

increased in recent years, and patents granted for software-related

technologies have seen dramatic increases over the past 2 decades (see

24

The judge has the authority to increase damages up to three times the amount initially

awarded, called treble damages, for cases of willful infringement. In “exceptional cases”

the court is authorized to award the prevailing party reasonable attorney fees.

25

In order for ITC to have jurisdiction to hear the complaint, there must be an industry in

the United States in existence or in the process of being established that relates to the

articles protected by the patent concerned. An industry in the United States is considered

to exist if there is in the country, with respect to the articles protected by the patent: (1) a

significant investment in plant and equipment; (2) significant employment of labor or

capital; or (3) substantial investment in its exploitation, including engineering, research

and development, or licensing. This is known as the domestic industry requirement.

26

Prior to this 2006 Supreme Court case, the Federal Circuit’s general rule was for district

court judges to issue injunctions in patent cases once validity and infringement had been

determined except in unusual cases under exceptional circumstances and in rare

instances to protect public interest. In the 2006 eBay decision, the Supreme Court ruled

that district courts should not assume an injunction was automatically needed in patent

infringement cases and instead should use the same test used in other cases to

determine whether to award the plaintiff an injunction. eBay, Inc. v. MercExchange, L.L.C.,

547 U.S. 388 (2006). According to several legal commentators we spoke with, this

decision has generally made it more difficult for NPEs to obtain injunctions in the courts

and has led them to pursue exclusion orders at ITC—although there may have been other

reasons for the increase in filings, including the relative speed of proceedings at ITC.

Page 12 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

fig. 1).

27

Figure 1: Number of Software-Related Patents Granted per Year by PTO, 1991 to

2011

Software-related patents occur in a variety of technologies

containing at least some element of software, and cover things like

sending messages or conducting business over the Internet (e.g. e-

commerce). Patents related to software can, but do not generally, detail

computer software programming code in the specification, but often

provide a more general description of the invention, which can be

programmed in a variety of ways.

Note: Software-related patents include a number of patent classes that are most likely to include

patents with software-related claims, and this includes business method patents.

According to legal commentators, the number of software-related patents

grew as computers were integrated into a greater expanse of everyday

27

Although PTO does not have a specific “software-related” patent class, we combined a

number of entire patent classes that PTO economists have said are most likely to include

patents with software-related claims, and this includes business method patents. For the

list of these classes, see S. Graham, , and S. Vishnubhakat, Of Smart Phone Wars and

Software Patents, Journal of Economic Perspectives, v. 27 no.1 (2013), pp. 67-86.

Page 13 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

products. By 2011 patents related to software made up more than half of

all issued patents. Software was not always patentable, and Supreme

Court decisions in the 1970s found mathematical formulas used by

computers were not patentable subject matter.

28

However, a 1981

Supreme Court decision overturned PTO’s denial of a patent application

for a mathematical formula and a programmed digital computer because,

as a process, it was patentable subject matter.

29

Subsequently, in 1998,

the Federal Circuit ruled that a mathematical formula in the form of a

computer program is patentable if it is applied in a useful way.

30

According to PTO officials, the agency interpreted these cases as limiting

their ability to reject patent applications for computer processes. Legal

commentators also said that after these decisions, particularly the 1998

Federal Circuit decision, software-related patenting grew as many

technology companies made the conscious effort to generate more

patents for offensive or defensive purposes—that is, to use them to sue

or countersue competitors in infringement lawsuits, rather than use them

to recoup R&D costs. As recently as 2010, the Supreme Court has noted

that the patent statute acknowledges that business methods are

patentable subject matter.

31

28

Gottschalk v. Benson, 409 U.S. 63 (1972) (finding a mathematical formula that had no

substantial practical application except in connection with a digital computer was not

patentable because it is like a law of nature, which cannot be the subject of a patent);

Parker v. Flook, 437 U.S. 584 (1978) (finding a method for updating alarm limits through

computerized calculations was not patentable because the alarm limit is a number and the

patent application was for a formula to compute it).

29

Diamond v. Diehr, 450 U.S. 175 (1981) (finding a patent claim containing a

mathematical formula that implements or applies that formula in a structure or process,

which, when considered as a whole, is performing a function which the patent laws were

designed to protect, to be patentable).

30

State Street Bank & Trust Co. v. Signature Financial Group, Inc., 149 F.3d 1368 (Fed.

Cir. 1998).

31

Bilski v. Kappos, __ U.S. __, 130 S. Ct. 3218 (2010).

Page 14 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

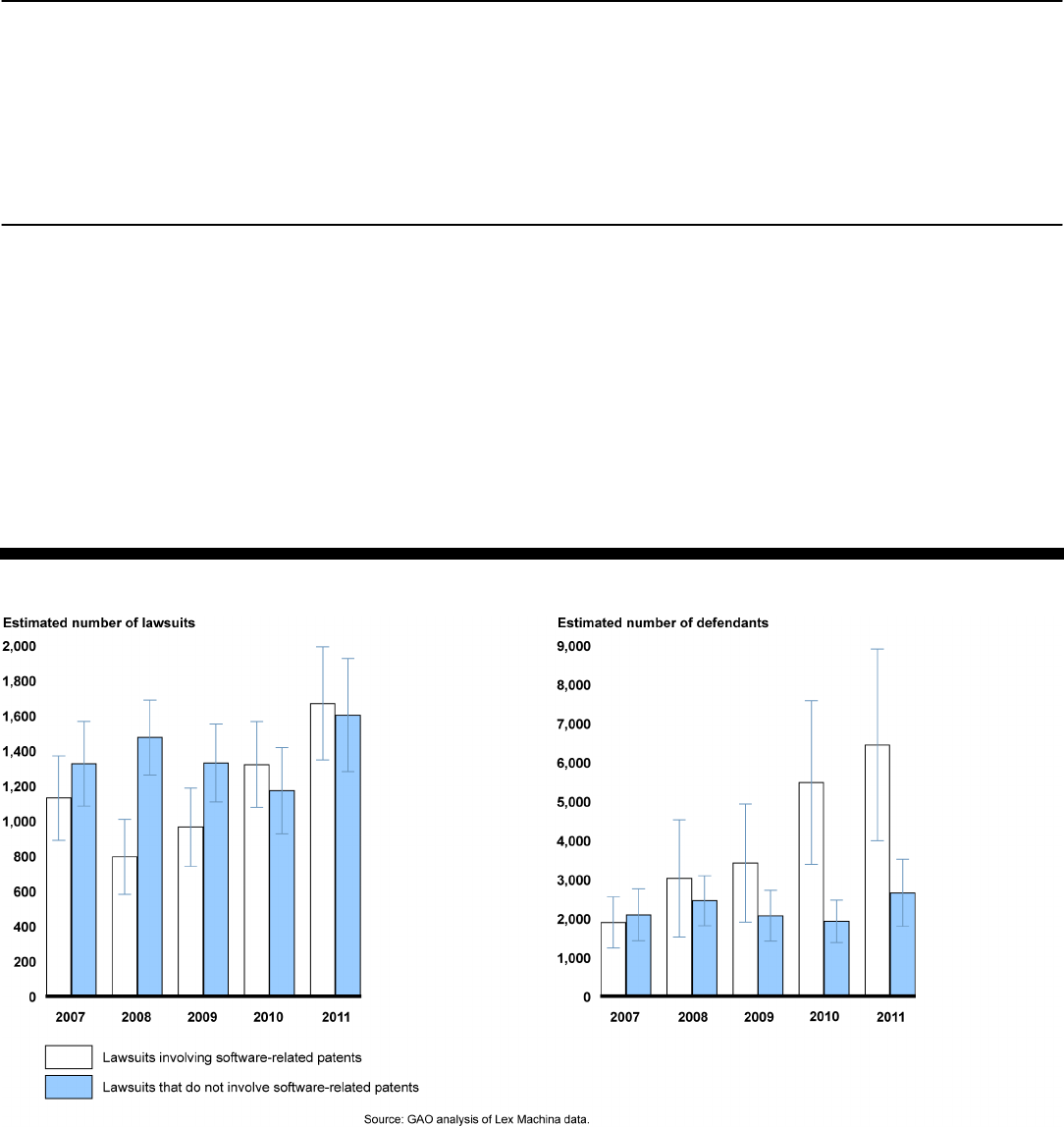

From 2000 to 2010, the number of patent infringement lawsuits fluctuated

slightly, and from 2010 to 2011, the number increased about 31 percent.

Our more detailed analysis of a generalizable sample of 500 lawsuits

estimates that the overall number of defendants in these cases increased

from 2007 to 2011 by about 129 percent over the 5-year period. This

analysis also shows that operating companies brought most of these

lawsuits and that lawsuits involving software-related patents accounted

for about 89 percent of the increase in defendants during this period.

Some stakeholders we interviewed said that they experienced a

substantial amount of patent assertion without firms ever filing lawsuits

against them.

From 2000 to 2011, about 29,000 patent infringement lawsuits were filed

in U.S. district courts. The number of these lawsuits fluctuated slightly

until 2011, when there was a 31 percent increase (see fig. 2).

Figure 2: Patent Infringement Lawsuits, 2000 to 2011

Specifically, about 900 more lawsuits were filed in 2011 than the average

number of lawsuits filed in each of the previous years. Some stakeholders

Number of Patent

Infringement Lawsuits

Increased

Significantly in 2011

and the Number of

Defendants Increased

between 2007 and

2011

Number of Patent

Infringement Lawsuits

Fluctuated Slightly before

Increasing in 2011, but

Number of Defendants

Increased from 2007 to

2011

Page 15 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

we interviewed generally attributed the increase in 2011 to patent owners’

anticipation of the passage of AIA, which restricts the number of accused

infringers who can be joined in a single lawsuit.

32

Prior to the enactment

of AIA, plaintiffs could sue numerous defendants in a single lawsuit. AIA

restricts this practice by prohibiting joining unrelated defendants into a

single lawsuit based solely on allegations that they have infringed the

same patent. According to the legislative history of AIA, this provision was

designed to address problems created by plaintiffs joining defendants,

sometimes numbering in the dozens.

33

32

Pub. L. No. 112-29, § 19(d)(1) (2011). Specifically, accused infringers may be joined, or

have their actions consolidated for trial, only if (1) questions of fact common to all will arise

in the action; and (2) any right to relief is asserted against the parties jointly and severally

or with respect to or arising out of the same transaction, occurrence, or series of

transactions or occurrences relating to the same accused product or process. AIA Section

19(d)(1), however, allows an accused infringer to waive these restrictions.

As a result, some stakeholders we

interviewed generally agreed that the increase in 2011 was due to the fact

that plaintiffs had to file more lawsuits at the end of 2011 after AIA’s

enactment in order to sue the same number of defendants or anticipated

this change and rushed to file lawsuits against multiple defendants before

it was enacted. In addition, our analysis of a generalizable sample of data

from 2007 through 2011 estimates that the number of overall defendants

in patent infringement suits increased by about 129 percent over the 5-

year period (see fig. 3).

33

H. Rep. No. 112-98, at 54 (2011).

Page 16 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

Figure 3: Estimated Number of Defendants in Patent Infringement Lawsuits, 2007 to

2011

Note: Defendant estimates are representative of all patent infringement lawsuits and error bars

display 95 percent confidence intervals.

Representatives of several operating companies that we interviewed said

they are being sued more often since the mid-2000s. For example, one

former official at a large technology company told us that, in 2002, the

company was a defendant in five patent infringement lawsuits, but in

2011, it was a defendant in more than 50. However, a few legal

commentators we interviewed said that such increases are common

during periods of rapid technological change—new industries lead to

more patents and the number of patent infringement lawsuits also

increases because there are more patents to be enforced. Similarly, one

researcher working on these issues told us that, historically, major

technological developments—such as the development of automobiles,

airplanes, and radio—have also led to temporary, dramatic increases in

patent infringement lawsuits.

Page 17 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

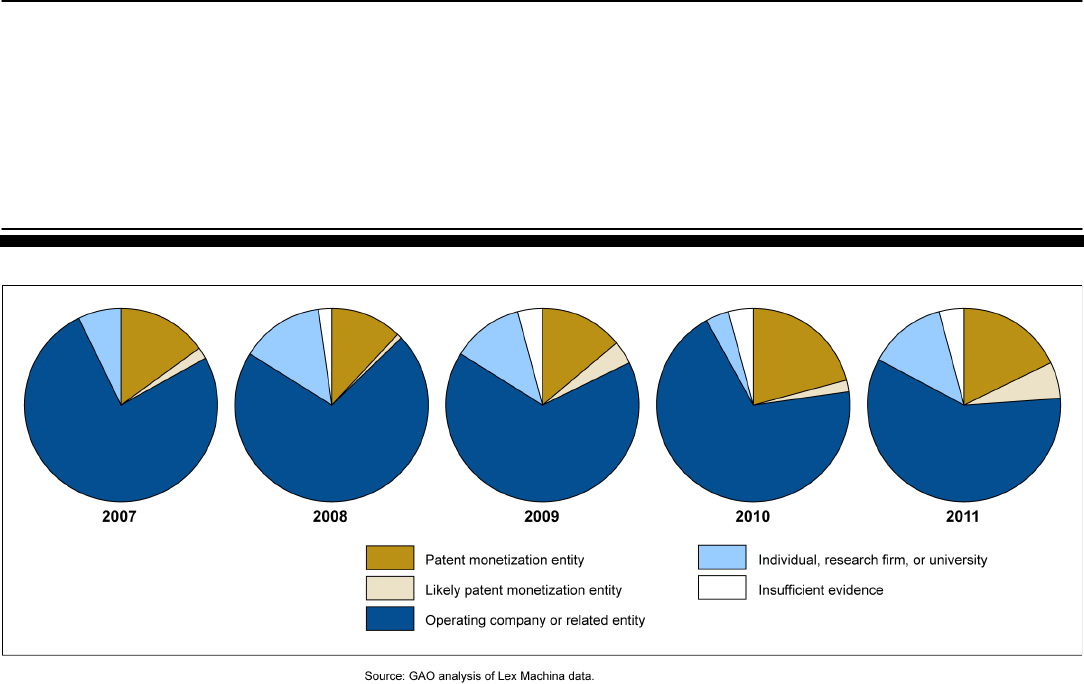

Operating companies brought most of the patent infringement lawsuits

from 2007 to 2011. According to our analysis of data for this period,

operating companies and related entities brought an estimated 68 percent

of all lawsuits.

34

PMEs and likely PMEs brought 19 percent of the

lawsuits.

35

PMEs and likely PMEs brought 17 percent of all lawsuits in

2007 and 24 percent in 2011, although this increase was not statistically

significant. In contrast, operating companies and related entities filed 76

percent of the lawsuits in 2007 and 59 percent in 2011, a statistically

significant decrease.

36

34

The evidence that Lex Machina used to classify an entity as an operating company and

that we then used to review Lex Machina’s classifications is described in appendix I.

Related entities included subsidiaries of operating companies—see appendix I for more

information. We did not verify whether the companies practiced the patents at issue in the

lawsuit.

Individual inventors brought about 8 percent of the

lawsuits, and research firms and universities brought less than 3 percent

over the 5 year span. In about 3 percent of the lawsuits there was

insufficient evidence to determine the type of plaintiff (see fig. 4).

35

The evidence that Lex Machina used to classify an entity as a PME or likely PME and

that we then used to review Lex Machina’s classifications is described in appendix I.

Another paper using data from Lex Machina presented different proportions of patent

monetizing plaintiffs, and these differences may be due to differences in methodology. For

example, this study included other plaintiff groups as patent monetizers, including

individuals and trusts. See Robin Feldman, Tom Ewing, and Sara Jeruss, The AIA 500

Expanded: The Effects of Patent Monetization Entities, UCLA Journal of Law &

Technology (forthcoming).

36

Our analysis of litigation data from RPX showed similar results. Specifically, RPX’s

classification of all infringement suits from 2007 to 2011 shows that operating companies

brought 69 percent of lawsuits, and firms that RPX classified as patent assertion entities

(PAE) brought 25 percent. RPX’s PAE category excluded universities and individual

inventors acting as NPEs, making it similar to Lex Machina’s PME category. Individual

inventors brought about 6 percent of the lawsuits, and universities brought less than 1

percent. Operating companies litigating patents that do not relate to the technology of their

primary business sector—classified as noncompeting entities by RPX—brought less than

1 percent of all lawsuits. Additionally, lawsuits filed by PAEs increased by about a third

from 2007 to 2010 and, in 2011, doubled over the previous year, and lawsuits brought by

operating companies decreased by about 6 percent from 2007 to 2010 and, in 2011,

increased by about 3 percent over the previous year.

Characteristics of

Plaintiffs in Recent Patent

Litigation

Page 18 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

Figure 4: Estimated Patent Infringement Lawsuits by Type of Plaintiff, 2007 to 2011

Note: Lawsuit estimates are subject to a margin of error of up to plus or minus 10 percentage points.

Our analysis of the data from 2007 through 2011 shows that PMEs

tended to sue more defendants per suit than operating companies. For

this period, there were about 1.9 defendants on average for suits filed by

operating companies, and about 4.1 defendants on average for suits filed

by PMEs. In addition, a disproportionate share of PMEs sued a relatively

large number of defendants. For example, about 12 percent of PMEs

sued 10 defendants or more in a single lawsuit, compared to about 3

percent of operating companies, a statistically significant difference. Thus,

even with bringing about a fifth of all patent infringement lawsuits from

2007 to 2011, PMEs sued close to one-third of the overall defendants,

accounting for about half of the overall increase in defendants.

Additionally, the estimated total number of defendants sued by PMEs

more than tripled from 834 in 2007 to 3,401 in 2011, while the increase in

Page 19 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

the total number of defendants sued by operating companies was not

statistically significant.

37

To further explore the characteristics of PMEs and other NPEs, we

interviewed stakeholders knowledgeable about patent infringement

lawsuits. According to some stakeholders we interviewed, NPEs have

many different characteristics and there are a spectrum of NPE business

models and behaviors, including operating companies that partner with

NPEs to file infringement suits.

38

• PMEs and likely PMEs. PMEs we spoke with did not develop

technology or sell products but, instead, derived most of their revenue

from asserting patents against operating companies. Some of these

PMEs told us that they acquired patents from a variety of sellers, such

as universities, individual inventors, failed companies, or operating

companies. A few of these PMEs told us they were able to get patents

on their own even with minimal R&D investments, especially for

software-related processes. Some PMEs we spoke with said that they

formerly produced patented products and now simply assert those

patents, and others said that they sued on behalf of individual

inventors who did not have the resources to enforce patents on their

own.

These different types of NPEs include

the following:

• Entities Related to Operating Companies. Our analysis of patent

infringement lawsuit data shows that some entities were subsidiaries

of or had other corporate relationships with operating companies,

although they did not produce products themselves. In addition, some

stakeholders we interviewed said that operating companies

sometimes partner with PMEs to monetize patents. In some cases,

these partnerships may allow an operating company to sue its

competitors with less risk of countersuits. A few operating companies

we spoke with acknowledged that they are aware of such

partnerships, although none said they engaged in this practice. The

two patent brokers we interviewed told us that they have structured

37

Our analysis of RPX data showed similar results. Specifically, RPX’s data show that

from 2007 to 2011 operating companies sued about 51 percent of all defendants and that

firms RPX classified as PAEs sued about 42 percent of all defendants. Additionally,

defendants sued by these firms almost tripled, while defendants sued by operating

companies decreased by about 20 percent. RPX identified more than 200 NPEs that sued

more than 20 defendants since 2005, suing 12 defendants per suit on average.

38

Often both the NPE and operating company appear as plaintiffs in the same suit.

Page 20 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

agreements where they transfer patents from an operating company

to a PME, and one legal commentator who also structured such deals

told us that operating companies often retain an interest in the gains

from any lawsuits the PME files. This commentator also said that

there are many PME lawsuits in which the identity of interested

operating companies is intentionally hidden; our review of court

records indicates that corporate relationships may not be easily

deciphered. In some cases, business relationships were easily

identifiable from court records and in other cases the links were more

difficult to identify.

39

Further, some operating companies, like PMEs,

also assert patents not related to products they produce, according to

some stakeholders.

40

• Research firms. Representatives from a few of the companies we

interviewed said that they invested heavily in R&D and made efforts to

share their technology with other companies and to help them develop

new products. Specifically, these representatives told us that their

companies did not focus on producing products but, rather, mainly

developed new technologies and then licensed them to operating

companies to pay for continued R&D.

41

• Universities. Many universities license their patented technologies to

companies who use them in their products, according to a

representative from each of two large research universities we spoke

with, although they said that the licensing revenue is generally small

in relation to other sources of university revenue. They also noted that

licensing at many universities is mostly driven by life sciences

research and that, sometimes before research begins, universities

develop partnerships with private sector firms, such as

These representatives also

said that they provided technical support to the firms they license

patents to helping them to make the best use of their patented

technologies, which distinguishes them from PMEs.

39

For example, some operating companies owned patent monetization subsidiaries that

shared their name, and others were linked to outside monetization entities with different

names.

40

RPX collects data on these types of lawsuits and, according to RPX’s data, these

lawsuits accounted for less than 1 percent of lawsuits in RPX’s database from 2007 to

2011.

41

These research firms told us that they file patent infringement lawsuits if their patented

technologies are used without or in violation of licensing agreements. Economic literature

suggests that this division of labor is valuable because companies that specialize in R&D

can often innovate more nimbly and create new, innovative technologies that other

companies can then incorporate into products they manufacture.

Page 21 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

pharmaceutical companies, who have the first right to bring patented

ideas into the marketplace.

Our analysis of patent infringement lawsuit data from 2007 to 2011 shows

that on average about 46 percent of the lawsuits involved software-

related patents. Between 2007 to 2011, 64 percent of defendants were

sued over software-related patents, and these patents were at issue in

the lawsuits that accounted for about 89 percent of the increase in

defendants over this period (see fig. 5). About 49 percent of the patents in

our sample were asserted within 5 years of being granted, and there was

no statistically significant difference between software-related patents and

other patents in this regard.

Figure 5: Estimated Number of Patent Infringement Lawsuits and Defendants Associated with Software-Related Patents, 2007

to 2011

Notes: Lawsuit and defendant estimates are representative of all patent infringement lawsuits and

error bars display 95 percent confidence intervals. Software-related patents include a number of

patent classes that are most likely to include patents with software-related claims, and this includes

business method patents.

Our analysis of patent infringement lawsuit data from 2007 to 2011 shows

that operating companies and PMEs both asserted software-related

patents, although PME lawsuits involved these patents to a much greater

Types of Patents Involved in

Recent Patent Infringement

Litigation

Page 22 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

extent. Specifically, about 84 percent of PME lawsuits from 2007 to 2011

involved software-related patents, while about 35 percent of operating

company lawsuits did. However, operating companies brought a greater

number of lawsuits involving software-related patents, given that they filed

more lawsuits overall.

42

Figure 6: Estimated Percentage of PME and Operating Company Lawsuits and Defendants Associated with Software-Related

Patents, 2007 to 2011

By defendant, software-related patents were used

to sue 93 percent of the defendants in PME suits and 46 percent of the

defendants in operating company suits (see fig. 6).

Note: Percentage of lawsuit and defendant estimates are subject to a margin of error of up to plus or

minus 10 percentage points. Software-related patents include a number of patent classes that are

most likely to include patents with software-related claims, and this includes business method

patents. PMEs focus solely on asserting typically purchased patents.

Technology-related operating companies were not the only companies

sued for infringing software-related patents; other sectors were also sued

42

We estimate that, from 2007 to 2011, operating companies and related entities brought

3,037 lawsuits involving software-related patents, while PMEs and likely PMEs brought

2,093 such lawsuits.

Page 23 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

for infringing such patents, including retail companies and local

governments. We estimate that 39 percent of suits involving software-

related patents were against firms in nontechnology sectors, according to

our analysis of 2007 to 2011 data. One representative from a retail

company noted that historically, all of the patent infringement lawsuits

brought against the company used to be related to products they sold.

However, as of mid-2012, the representative said that half of the lawsuits

against the company were related to e-commerce software that the

company uses for its shopping website—such as software that allows

customers to locate their stores on the website—and were brought by

PMEs. Representatives of retail and pharmaceutical companies told us

they also defend lawsuits brought by PMEs related to features on their

websites––typically software that outside vendors provide to them, rather

than something they developed. Additionally, city public transit agencies

have been sued for allegedly infringing patents by using software for real-

time public transit arrival notifications, according to a few stakeholders we

interviewed.

For 2007 to 2011, an estimated 32 percent of patent infringement lawsuits

were filed in 3 of the 94 federal district courts: the Eastern District of

Texas, the District of Delaware, and the Central District of California.

These districts also had the most lawsuits filed for the period of 2000 to

2011 (see fig. 7).

Common Venues of Recent

Patent Litigation

Page 24 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

Figure 7: Distribution of Total Patent Infringement Lawsuits across U.S. District Courts from 2000 to 2011

In addition, our review of 2007 to 2011 litigation data shows that PMEs

filed more lawsuits in the Eastern District of Texas than other types of

plaintiffs. Specifically, from 2007 to 2011, 39 percent of PME and likely

PME lawsuits were filed in the Eastern District of Texas, compared to

about 8 percent of lawsuits filed by all other plaintiffs. Some stakeholders

Page 25 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

we interviewed said that in their view this occurs because juries in this

district favor patent owners over alleged infringers.

43

In addition, one

study we reviewed that looked at all decisions for all patent lawsuits from

1995 to 2011, showed that the Eastern District of Texas, the Eastern

District of Virginia, and the District of Delaware were among the top

districts for quicker trials, higher success rates, and higher damage

awards for patent owners.

44

An estimated 21 percent of patent infringement cases from 2007 to 2011

were still ongoing. Of the remaining cases, our analysis shows that about

86 percent either ended or likely ended in a settlement. This occurred

because both parties agreed to a judgment that the judge sanctioned,

both parties agreed to end the lawsuit, or the plaintiff, who had brought

the lawsuit, asked for it to be dismissed.

45

Lawsuits brought by both

operating companies and PMEs settled or likely settled at similar rates.

46

We were not able to determine litigation cost information from our sample

data, and we found very little information on the costs of patent

Less than 3 percent of the cases that were not ongoing ended in a trial

and judgment, or were on appeal, which was consistent with what some

representatives of operating companies told us—very few of their lawsuits

go to trial because they settle quickly to avoid high litigation costs.

43

Defendants can request that the district court transfer the case to another court in

certain circumstances. If the district court denies the defendant’s request, the defendant

can ask the Federal Circuit to order the district court to transfer the lawsuit. For example,

in 2008, the Federal Circuit ordered the Eastern District of Texas to transfer a case

because none of the parties had an office and no witnesses or evidence were located in

the district. In re: TS Tech, 551 F.3d 1315 (Fed. Cir. 2008). According to one legal

commentator, the precedent in this case and other Federal Circuit transfers likely resulted

in fewer lawsuits being filed in the Eastern District of Texas.

44

PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2012 Patent Litigation Study: Litigation continues to rise amid

growing awareness of patent value. www.pwc.com/us/en/forensic-

services/publications/2012-patent-litigation-study.jhtml. Pricewaterhouse looked at

decisions identified through the WestLaw database.

45

We estimate that 46 percent of all patent infringement lawsuits filed between 2007 and

2011 ended or likely ended in a settlement within 1 year of being filed.

46

Of the lawsuits that were not ongoing, 86 percent of PME suits and 87 percent of

operating company suits settled, which was not a statistically significant difference.

However, our analysis showed a statistically significant difference between suits involving

software-related patents, of which 82 percent settled compared with 89 percent of suits

that did not involve software-related patents.

Outcomes and Costs of Recent

Patent Litigation

Page 26 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

infringement lawsuits in court records. Further, as one stakeholder we

interviewed noted, all litigation is expensive, not just patent infringement

litigation. According to a 2011 nongeneralizable survey of patent lawyers

by AIPLA, the cost of defending one patent infringement lawsuit, which

excludes any damages awarded, was from $650,000 to $5 million in

2011, depending on how much was at risk.

47

As for damages awarded, a

2012 study that looked at all district court patent decisions that proceeded

through trial from 1995 to 2011 found that the median damage award was

over $5 million dollars and that damage awards in NPE cases were

higher than in other types of suits.

48

The authors of a 2012 paper who

collected data from a nonrandom, nongeneralizable set of 82 operating

companies noted that total litigation costs for NPE suits, including

damages awarded and legal fees, were around $300,000 for small and

medium companies and $600,000 for large companies.

49

The author of

another 2012 paper sought to examine the impacts of NPE litigation on

small companies and collected data from a nonrandom, nongeneralizable

set of 223 small technology companies.

50

Of the 79 companies that

indicated that they had received a patent demand, 31 reported that the

demand affected the company in various ways, including reduced hiring

or a reduced value of their company—which the author collectively

described as “significant operational impacts.”

In addition to lawsuits, patent assertion occurs without firms ever filing

lawsuits, but the extent of this practice is unclear because we were not

able to find reliable data on patent assertion outside of the court system.

According to representatives of some operating companies we spoke

with, they often get letters from patent owners offering licenses for the

47

For the 18 percent of those lawyers that responded, AIPLA reports that the median legal

cost for one patent infringement lawsuit was $650,000 when less than $1 million was at

risk for damages; $2.5 million when between $1 million and $25 million was at risk for

damages; and $5 million when more than $25 million was at risk for damages. These

costs include legal fees and exclude damage awards.

48

PricewaterhouseCoopers, 2012 Patent Litigation Study: Litigation continues to rise amid

growing awareness of patent value. Pricewaterhouse looked at decisions identified

through the WestLaw database.

49

James E. Bessen and Michael J. Meurer, The Direct Costs from NPE Disputes, Law and

Economics Research Paper No. 12-34 (Boston University School of Law: June 28, 2012).

50

Colleen Chien, Startups and Patent Trolls, Santa Clara Univ. Legal Studies Research

Paper No. 09-12 (Sept. 28, 2012).

Stakeholders Reported

That Patent Assertion

Occurs Without Firms

Ever Filing Lawsuits

Page 27 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

use of their patents. They said that these letters, which they refer to as

“demand letters,” sometimes threaten lawsuits if the parties do not reach

a licensing agreement. These company representatives told us that for

every patent infringement lawsuit filed against them, they might receive

many times more letters notifying them of potential infringement and

offering licenses.

51

However, a few PME representatives told us that operating companies

generally ignore their letters, thus leading the PMEs to sue the companies

first to get their attention. A few of these PMEs also told us that they are

more likely to sue without sending a demand letter after a 2007 Supreme

Court decision expanded accused infringers’ ability to file preemptive

declaratory judgment lawsuits seeking determinations that the patent is

invalid, unenforceable, or not being infringed.

Representatives from a few operating companies we

spoke with said that these letters can sometimes help to resolve issues

without litigation, but that at times the letters can be so vague that they do

not reference the patents at issue or what products the operating

company sells that may be infringing these patents.

52

Because licenses or payments resulting from out-of-court patent

assertions are almost always confidential, it is difficult to know the cost of

these settlements. The authors of the 2012 study noted above of a

nonrandom, nongeneralizable set of 82 operating companies attempted

to identify this cost. The 46 companies that provided data on costs

reported that they spent an average of about $30 million on NPE suits,

including both legal fees and settlements, which were settled without

litigation from 2005 to 2011.

The threat of a declaratory

judgment lawsuit can derail patent owners’ attempts to reach a licensing

agreement, according to a few PMEs we spoke with.

51

The author of a 2012 study of a nonrandom, nongeneralizable set of 223 small

technology companies noted above found that about two-thirds of the 79 companies that

reported that they had received a demand from an NPE were not sued.

52

MedImmune Inc. v. Genentech, 549 U.S. 118 (2007).

Page 28 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

Stakeholders we spoke with identified three key factors that likely

contributed to many recent patent infringement lawsuits: (1) unclear and

overly broad patents, (2) the potential for disproportionately large damage

awards, and (3) the increasing recognition that patents are a valuable

asset.

Several of the stakeholders we spoke with, including representatives from

PMEs, operating companies, and legal commentators, said that many

recent patent infringement lawsuits are related to the prevalence of low-

quality patents; that is, patents with unclear property rights, overly broad

claims, or both. Although there is some inherent uncertainty associated

with all patent claims, several of the stakeholders with this opinion noted

that claims in software-related patents are often overly broad, unclear or

both. Unclear and overly broad patents do not provide notice about their

boundaries and the uncertainty of a patent’s scope then usually needs to

be resolved in court, according to some stakeholders we spoke with.

Stakeholders we interviewed identified several reasons why patents may

be overly broad, unclear, or vague:

• Some stakeholders representing different interests, including

operating companies, PMEs, and legal commentators, said the use of

unclear terminology in patents can lead to a lack of understanding of

patent claims and, therefore, what constitutes infringement, which

needs to be resolved in court. For example, two of these stakeholders

said the computer software industry does not have clear terminology

or common vocabularies for describing concepts, innovations, and

ideas. Language describing emerging technologies, such as software,

may be inherently imprecise because these technologies are

constantly evolving. In contrast, pharmaceutical drug patents are

relatively clear because they use standardized scientific terminology,

according to a few stakeholders.

• Some stakeholders, including operating companies and legal

commentators, emphasized that claims in software patents

sometimes define the scope of the invention by encompassing an

Stakeholders

Identified Three Key

Factors Contributing

to Many Recent

Patent Infringement

Lawsuits

Stakeholders Said That

Some Patents Have

Unclear Property Rights

and Make Overly Broad

Claims

Page 29 GAO-13-465 Patent Litigation

entire function––like sending an e-mail––rather than the specific

means of performing that function.

53