Truth and Reconciliation

Commission of Canada:

Interim Report

Truth and Reconciliation

Commission of Canada:

Interim Report

is report is in the public domain. Anyone may, without charge or request for

permission, reproduce all or part of this report.

2012

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada, 2012

1500–360 Main Street

Winnipeg, Manitoba

R3C 3Z3

Telephone: (204) 984-5885

Toll Free: 1-888-872-5554 (1-888-TRC-5554)

Fax: (204) 984-5915

E-mail: [email protected]a

Website: www.trc.ca

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada interim report.

Issued also in French under title: Commission de vérité et réconciliation

du Canada, rapport intérimaire.

Includes bibliographical references.

Electronic monograph in PDF format.

Issued also in printed form.

ISBN 978-1-100-19994-8

Cat. no.: IR4-3/1-2012E-PDF

1. Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada--Management.

2. Native peoples--Canada--Residential schools. 3. Native peoples-- Reparations--

Canada. 4. Native peoples--Civil rights--Canada. 5. Truth

commissions--Canada--Management. 6. Native peoples--Canada--Government

relations. 7. Transitional justice--Canada. I. Title.

E96.5 T78 2012 352.8’80971 C2012-980019-8

Table of Contents

Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Purpose . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

Background ..................................................................................... 1

Mission Statement ............................................................................ 2

Vision Statement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Setting Up the Commission: Governance and Operational Framework . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2

Head and Regional Oces . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3

Inuit Sub-Commission ........................................................................ 3

Stang . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .3

Commissioner Activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 4

What People Told the Commission ................................................................ 4

Education . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Languages and Traditional Knowledge . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Parenting Skills ............................................................................... 7

Extension and Enhancement of Health Support Services ......................................... 8

Exclusions from Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 8

Impact and Reach of Apology from Canada ..................................................... 9

Establishing a Framework for Reconciliation .................................................... 9

e Aboriginal Healing Foundation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

e International Context . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10

Commission Activities . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 12

Statement Gathering: Truth Sharing .............................................................. 12

Document Collection . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 13

Lack of Cooperation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Cost-related issues . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

Research and Report Preparation . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Missing Children and Unmarked Graves ....................................................... 17

A National Research Centre: Establishing a National Memory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

Commemoration: Creating a Lasting Legacy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

National Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

e Winnipeg National Event, June 16–19, 2010 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 18

e Northern National Event, Inuvik, Northwest Territories, June 28–July 1, 2011 . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 19

Community Events . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 21

Review of Past Reports . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Residential-School Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 22

Reconciliation Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 23

Conclusions . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 25

Recommendations . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 28

Works Cited ....................................................................................... 30

1

“e road we travel is equal in importance to the destination we seek.

ere are no shortcuts. When it comes to truth and reconciliation,

we are all forced to go the distance.”

-Justice Murray Sinclair,

Chair of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada,

to the Canadian Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples,

September 28, 2010

Introduction

Purpose

is interim report covers the activities of the Truth and

Reconciliation Commission of Canada since the appointment

of the current three Commissioners on July 1, 2009. e report

summarizes:

the activities of the Commissioners•

the messages presented to the Commission at hearings •

and National Events

the activities of the Commission with relation to its •

mandate

the Commission’s interim ndings•

the Commission’s recommendations. •

Background

Up until the 1990s, the Canadian government, in part-

nership with a number of Christian churches, operated a

residential school system for Aboriginal children. ese gov-

ernment-funded, usually church-run schools and residences

were set up to assimilate Aboriginal people forcibly into the

Canadian mainstream by eliminating parental and commu-

nity involvement in the intellectual, cultural, and spiritual

development of Aboriginal children.

More than 150,000 First Nations, Inuit, and Métis chil-

dren were placed in what were known as Indian residential

schools. As a matter of policy, the children commonly were

forbidden to speak their own language or engage in their

own cultural and spiritual practices. Generations of children

were traumatized by the experience. e lack of parental and

family involvement in the upbringing of their own children

also denied those same children the ability to develop par-

enting skills. ere are an estimated 80,000 former students

still living today. Because residential schools operated for well

more than a century, their impact has been transmitted from

grandparents to parents to children. is legacy from one gen-

eration to the next has contributed to social problems, poor

health, and low educational success rates in Aboriginal com-

munities today.

e 1996 Canadian Royal Commission on Aboriginal

Peoples and various other reports and inquiries have docu-

mented the emotional, physical, and sexual abuse that many

children experienced during their school years. Beginning in

the mid-1990s, thousands of former students took legal action

against the churches that ran the schools and the federal gov-

ernment that funded them. ese civil lawsuits sought com-

pensation for the injuries that individuals had sustained, and

for loss of language and culture. ey were the basis of several

large class-action suits that were resolved in 2007 with the

implementation of the Indian Residential Schools Settlement

Agreement, the largest class-action settlement in Canadian

history. e Agreement, which is being implemented under

court supervision, is intended to begin repairing the harm

caused by the residential school system.

In addition to providing compensation to former students,

the Agreement established the Truth and Reconciliation

Commission of Canada with a budget of $60-million and a

ve-year term.

e Commission’s overarching purposes are to:

reveal to Canadians the complex truth about the history •

and the ongoing legacy of the church-run residential

schools, in a manner that fully documents the indi-

vidual and collective harms perpetrated against Aborig-

inal peoples, and honours the resiliency and courage of

former students, their families, and communities; and

guide and inspire a process of truth and healing, leading •

toward reconciliation within Aboriginal families, and

between Aboriginal peoples and non-Aboriginal com-

munities, churches, governments, and Canadians gen-

2 | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

erally. e process will work to renew relationships on a

basis of inclusion, mutual understanding, and respect.

To guide its work, the Commission has developed a stra-

tegic plan with the following mission and vision statements.

Mission Statement

e Truth and Reconciliation Commission -

will reveal the complete story of Canada’s

residential school system, and lead the way

to respect through reconciliation … for the

child taken, for the parent left behind.

Vision Statement

We will reveal the truth about residential -

schools, and establish a renewed sense of

Canada that is inclusive and respectful,

and that enables reconciliation.

Setting Up the Commission: Governance

and Operational Framework

e Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

(TRC) was established by Order-in-Council in June 2008. e

initial Commission consisted of Justice Harry LaForme as

chair, Claudette Dumont-Smith, and Jane Brewin Morley. Jus-

tice LaForme resigned in October 2008, stating that the Com-

mission’s independence had been compromised by political

interference, and that conict with the other two Commis-

sioners regarding his authority made the Commission unwork-

able. Commissioners Dumont-Smith and Brewin Morley

resigned in January 2009, stating that the best way forward for

a successful Truth and Reconciliation Commission process

would be with a new slate of Commissioners.

e parties to the Settlement Agreement then selected

three new Commissioners: Justice Murray Sinclair as chair,

Chief Wilton Littlechild, and Marie Wilson. eir appoint-

ments took eect on July 1, 2009. A ten-member Indian

Residential School Survivor Committee, made up of former

residential school students, also was appointed to serve as an

advisory body to the Commissioners.

e resignation of the initial Commissioners led to a loss

of time and momentum. By the time the new Commissioners

took oce, a full year of the Commission’s original ve-year

mandate had passed. From the moment they took oce, the

new Commissioners faced the challenge of restarting the

Commission and restoring its credibility with survivors and

the Canadian public.

e decision by the parties to the Settlement Agreement

to establish the Commission as a federal government depart-

ment—as opposed to a commission under the Inquiries

Act—was made prior to the appointment of the current Com-

missioners, and is not one with which they would have con-

curred. at decision has created additional challenges for the

Commission. e rules and regulations that govern large, well-

established, permanent federal government departments have

proven onerous and highly problematic for a small, newly cre-

ated organization with a time-limited mandate.

Departmental stang and other processes normally do

not apply to federal commissions or special investigations.

e requirement that the Truth and Reconciliation Commis-

sion comply with provisions that apply to the operations of a

federal department has led to signicant delays that will have

an impact on the Commission’s ability to meet its deadlines.

e Commission is required to create an entirely new federal

department, subject to, and accountable for, the complete

range of federal government statutes, regulations, policies,

directives, and guidelines. It has to do this with a compara-

tively small sta and budget. Meeting these requirements has

hampered the Commission’s ability to carry out its mandate

to implement a statement-gathering process, hold National

Events and community hearings, and establish processes for

document collection and research activities.

One of the consequences of the resignation of the original

Commissioners and the designation of the Commission as a

department of government is the discrepancy between the

original federal Treasury Board approval of the Commission

budget in 2008 and the orders-in-council appointing the cur-

rent Commissioners in 2009. e Commission expects its nal

public event to be held close to July 1, 2014. However, its cur-

rent budget authority will have expired before then, and it is

clear there will be a period of time after July 1, 2014, required

to transfer records to the National Research Centre and to

make nal decisions concerning the Commission’s nancial

records, personnel resources, and physical assets. A period of

time after July 1, 2014 also may be required for translation and

production of the Commission’s nal report. e Commission

will require orders-in-council and funding authorities to be

modied to expire at the end of the 2014–15 scal year.

R

1) e Commission recommends that the Government

of Canada issue the necessary orders-in-council and

funding authorities to ensure that the end date of

the Commission and Commissioners’ appointments

coincide, including the necessary wind-down period

after the Commission’s last public event.

Interim Report | 3

July 1, 2011, the Commission employed seventy-ve people,

including forty-eight Aboriginal employees who work at all

levels of the organization.

2) e Commission recommends that the Government

of Canada work with the Commission to ensure the

Commission has adequate funds to complete its

mandate on time.

3) e Commission recommends that the Government

of Canada ensure that Health Canada, in conjunction

with appropriate provincial, territorial, and traditional

health care partners, has the resources needed to

provide for the safe completion of the Truth and

Reconciliation Commission’s full mandate, and to

provide for continuous, high-quality mental health and

cultural support services for all those involved in Truth

and Reconciliation and other Indian Residential Schools

Settlement Agreement activities, through to completion

of these activities.

Despite these challenges, the Commission developed a

strategic framework to guide its work, established a multi-year

budget, and set about making and implementing several key

operational decisions in its rst year.

Head and Regional Oces

While the residential school system operated across

Canada, the majority of schools were located in the West and

the North. For this reason, the Commission established its

head oce in Winnipeg, Manitoba. It retained a small Ottawa

oce, and opened satellite oces in Hobbema, Alberta, and

Yellowknife, Northwest Territories. To extend the Commis-

sion’s reach into smaller centres and communities and as

required by the Settlement Agreement, seven regional liaison

workers have been hired to work in Quebec and Atlantic

Canada, Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta, British

Columbia, and the Yukon and Northwest Territories.

Inuit Sub-Commission

In recognition of the unique cultures of the Inuit, and the

experiences and impacts of residential schools on them, the

Truth and Reconciliation Commission also established an

Inuit Sub-Commission. It is charged with ensuring that the

Commission addresses the challenges to statement gathering

and record collection in remote, isolated Inuit communities,

and among Inuit throughout Canada. e Inuit Sub-Com-

mission provides the environment and supports necessary to

earn the trust of Inuit survivors.

Stang

e Commission sta is drawn from the public service,

private sector, and non-governmental organizations. As of

4

Commissioner Activities

From the moment of their appointment, the Commis-

sioners made it a priority to meet with former residential

school students and sta. When the Commissioners took

oce, they initially travelled to events already organized

by former students. is took them to such places as Oro-

mocto, New Brunswick; Spanish, Ontario; Kamloops, British

Columbia; and Cut Knife, Saskatchewan. e Commissioners

and Commission sta also have visited hundreds of Aborig-

inal communities to talk about the Commission, the residen-

tial school legacy, and reconciliation.

In their public education work, the Commissioners have

attended numerous conferences of Aboriginal organizations

and churches, and have appeared as speakers at over 200 con-

ferences and events organized by universities, governments,

and churches, as well as by various professional and social

organizations. Initially, presentations dealt with the Com-

mission and its mandate, and the history of the residential

schools. Dialogue now has moved towards engaging Cana-

dians in discussions about the importance and meaning of

reconciliation.

Early in their mandate, the Commissioners received the

generous support of Governor General Michaëlle Jean in

raising awareness of the Commission and the residential

school legacy. e Governor General’s primary interest was in

engaging youth. In 2009, with the Commissioners, she hosted

a special event, Witnessing the Future, at Rideau Hall. In 2010

she invited the Commissioners to help engage hundreds of

Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal youth at a forum in Vancouver

immediately prior to the Vancouver Olympics. Later in the

year, she attended the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s

rst National Event in Winnipeg, where, as the Commission’s

rst Honourary Witness, she participated in a Sharing Circle

with Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal young people to discuss

the legacy of the schools.

e Commissioners also have been active in discussions

with regional and federal leaders. In July 2009, they attended

and addressed the Annual General Assembly of the Assembly

of First Nations. In January 2010, they met with the board of

the Métis National Council. In July 2010, they met with the

board of the Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami. In September 2010, the

Commissioners made a formal presentation to the Canadian

Senate Standing Committee on Aboriginal Peoples as part of

the Committee’s review of Canada’s progress since the fed-

eral government’s formal apology to residential school sur-

vivors in 2008. e Commissioners also have had meetings

with various federal ministers, and provincial and territorial

premiers.

In addition, the Commissioners have been involved in

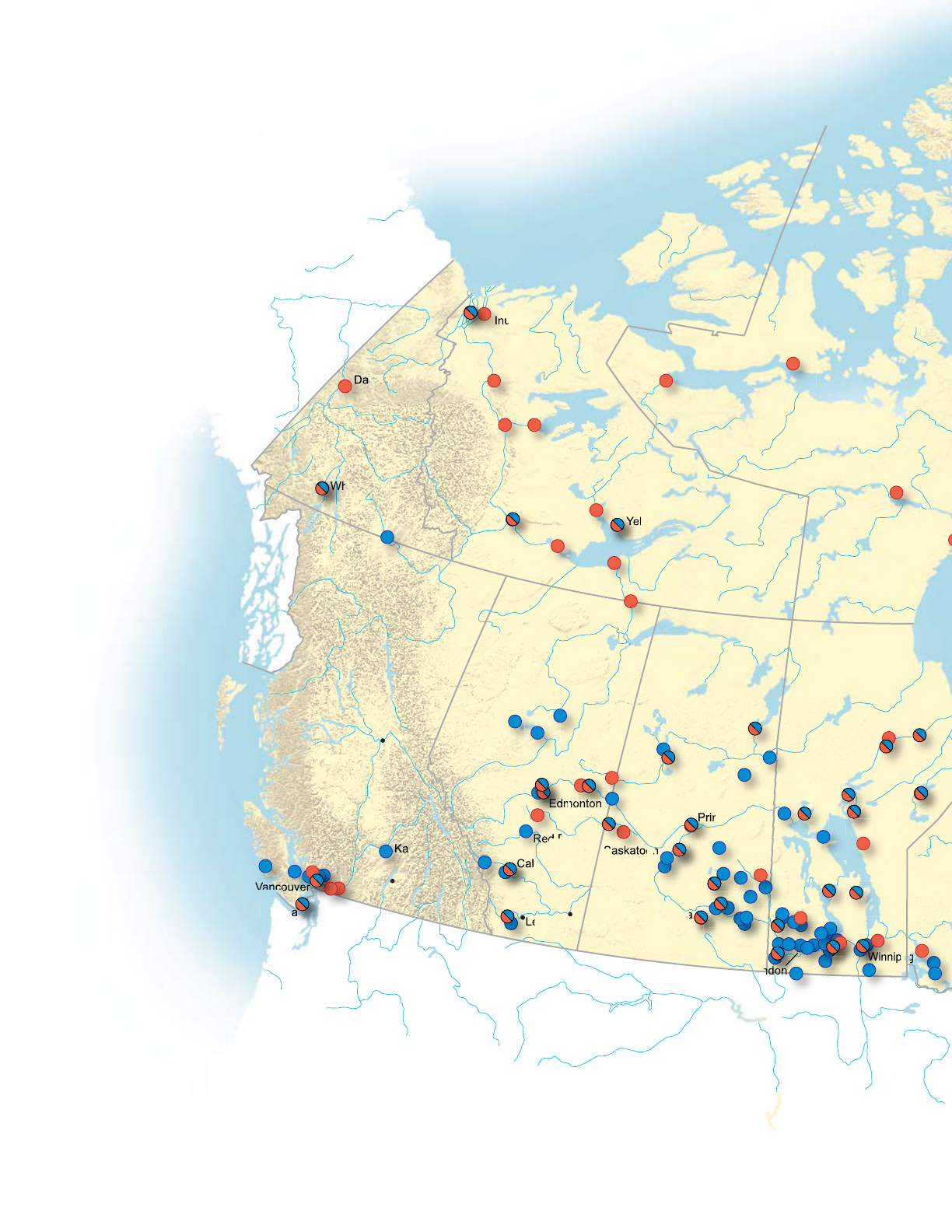

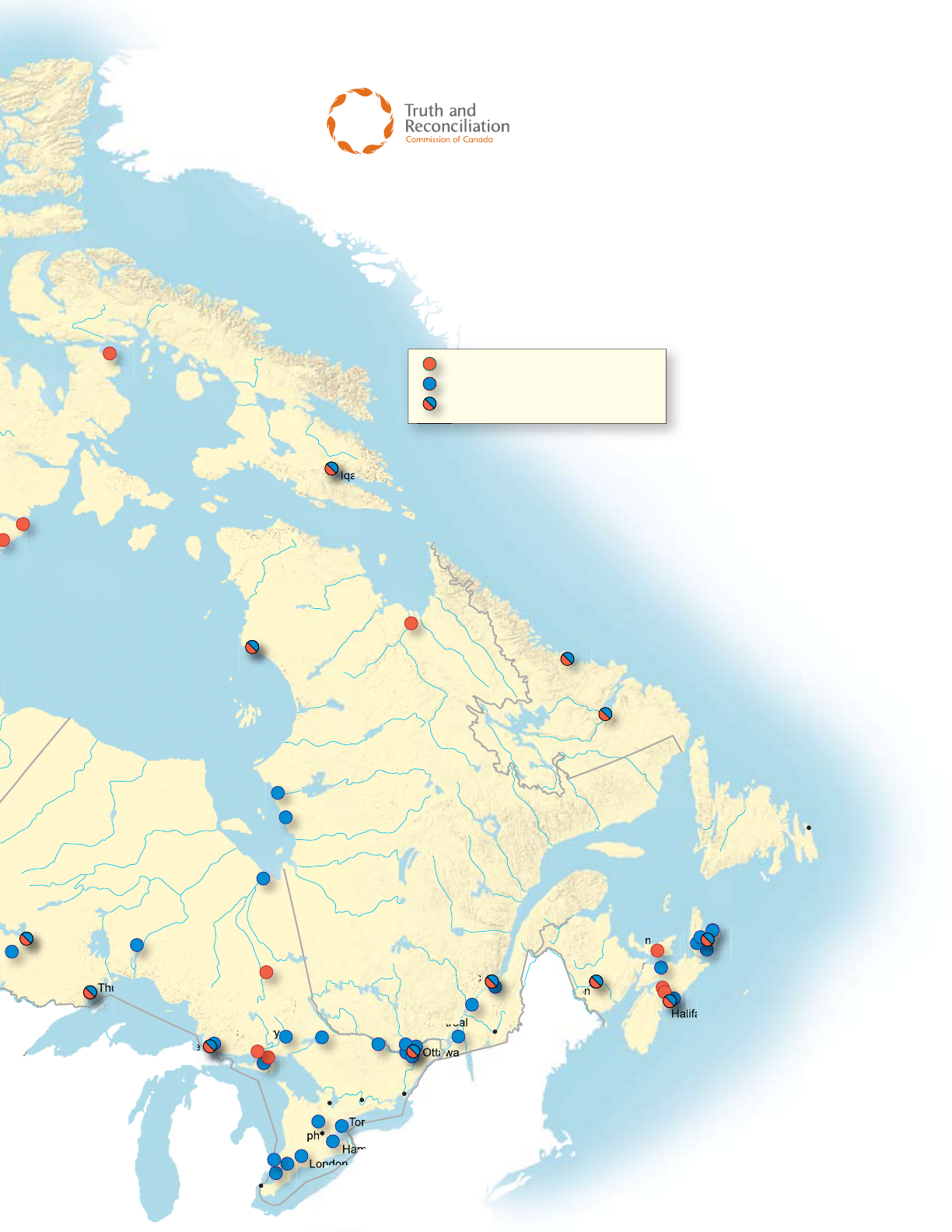

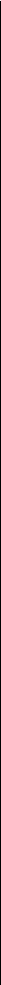

the activities that are outlined further in this report. Map 1

provides an overview of where the Commission has been

in the rst two years after the appointment of the current

Commissioners.

By the end of September 2011, the Commissioners had

met with former residential school students in every province

and territory in the country.

What People Told the Commission

Over the past two years, the Commission has made it a pri-

ority to take every opportunity to hear directly from the people

most aected by the residential school system: the students

and sta who worked in the schools. In this interim report,

it is not possible to summarize all that the Commission was

told. But, for a variety of reasons, including the advanced age

of many of the former students, the Commissioners believe

certain messages must be relayed to Canadians now.

People have come before the Commission to speak of tragic

loss and heroic recovery. eir message is powerful because

Interim Report | 5

it touches the lives of parents and children. It is important

because it connects our nation’s past and future. It is inspiring

because those who were oppressed, victimized, and silenced

have struggled to heal themselves and regain their voice.

At event after event, people spoke of parents having to send

children o to residential school against their will. ey spoke

of tearful farewells at train stations, shorelines, and in school

parlours, of children crying throughout the entire ight to

school, and of cold and impersonal receptions given to chil-

dren on arrival.

People told the Commission of being sent to school hun-

dreds and even thousands of kilometres from their homes.

Once they were there, it was impossible for their parents to

visit them. In many schools, children stayed in school over

the Christmas holidays, and, in some cases, they stayed over

the summer as well. Some did not return home for years at a

time.

People spoke of the immediate losses they experienced

at school. Traditional, and often highly valued, clothing and

footwear, handmade by loving mothers and grandmothers,

were taken from them and never seen again. Long hair, often

in traditional braids that reected sacred beliefs, was sheared

o. Many people had bitter memories of being deloused with

lye or chemicals, regardless of whether they had lice. Children

lost their identity as their names were changed—or simply

replaced with a number. e Commission has heard of how

students lost their individuality, were forced to wear uniforms,

to march in lines, to wash in communal showers—treated,

as several former students said, like they were animals in a

herd. In the words of countless students, it was a frightening,

degrading, and humiliating experience.

Former students described how they came from loving

families and were cast into loveless institutions. ey spoke

of tremendous loneliness, and of young children crying them-

selves to sleep for months. Brothers and sisters were separated

from each other within the schools, and often were punished

for hugging or simply waving at one another.

Food was strange, spoiled and rotten in many cases, poorly

prepared, and often in short supply. Many people recalled

being punished for being unable to clean their plates. Others

recalled that they were always hungry, and were punished for

taking food from the kitchen or the garden.

For many, little in the classroom related to their lives. e

only Aboriginal people they could recall from their history

books were savages and heathen, responsible for the deaths

of priests. ey told the Commission of how the spiritual

practices of their parents and ancestors were belittled and

ridiculed.

Children were separated from families to get an educa-

tion, but many of them spoke of how they spent much of

their school days doing manual labour to support the school.

Children who had lived traditional lifeways told us that after a

decade of education, they did not have the skills they needed

to survive when they returned home.

Many people came with stories of harsh discipline, of class-

room errors corrected with a crack of a ruler, a sharp tug of the

ear, hair pulling, or severe and frequent strappings. e Com-

mission heard of discipline crossing into abuse: of boys being

beaten like men, of girls being whipped for running away.

People spoke of children being forced to beat other children,

sometimes their own brothers and sisters. e Commission

was told of runaways being placed in solitary connement

with bread-and-water diets and shaven heads.

People spoke of being sexually abused within days of

arriving at residential school. In some cases, they were abused

by sta; in others, by older students. Reports of abuse have

come from all parts of the country and all types of schools.

e students felt they had no one to turn to for help. If they did

speak up, often it was impossible to nd anyone who would

believe them. ose who ran away from abuse said that in

some cases, this only made their situation worse. ose who

raised complaints often had the same experience. Many com-

pared the schools to jail (in some cases, complete with barbed

wire), and fantasized about being able to return home. ose

who ran away could nd themselves in trouble at home, at

school, and with the police.

e Commission was told of children who died of disease,

of children who killed themselves, of mysterious and unex-

plained deaths.

Many students who came to school speaking no English

lost the right to express themselves. Students repeatedly told

the Commission of being punished for speaking their tradi-

tional languages. People were made to feel ashamed of their

language—even if they could speak it, they would not, and

they did not teach it to their children.

It was made clear that not only language was lost: it was

voice. People said their mouths had been padlocked. At

school, boys and girls could not speak to each other, meaning

that brothers and sisters were cut o from one another.

If they were abused, the only people they could complain

to were the abusers. Later, as adults and parents, former stu-

dents did not want to talk about their experiences to their chil-

dren; husbands and wives did not wish to speak to one another

about their residential school experiences. Some who were

not abused or beaten said they had survived by trying to be as

inconspicuous as possible. To stay out of trouble, they trained

themselves to be silent and invisible. Students who witnessed

violence and abuse spoke of how it left them traumatized.

e Commission heard about the hopes that some

teachers had had when they started teaching in residential

6 | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

schools. It heard from teachers who fought on behalf of stu-

dents. Teachers spoke of how they came to question their own

work: to wonder about the lack of resources and the wisdom

of attempting to change a people’s culture.

Church representatives spoke about the dicult expe-

rience of learning such distressing truths about their own

church’s past. ey are struggling to rethink their theology

and their mission in an eort to right the relationship between

their church and Aboriginal peoples.

Many former students also expressed gratitude for the edu-

cation they received, and spoke of the long-lasting relations

that had developed between some teachers and students,

and especially among the students themselves, who became

family away from home.

e Commission also heard about the fun that children

had in school. In the presence of a dedicated teacher, some

children experienced the pleasure of learning. While tradi-

tional Aboriginal games were undermined, many told of how

they survived through their participation in sports or the arts.

In some cases, particularly in more recent years, parents had

sent them to school to learn the skills needed to make a con-

tribution on behalf of their people. e Commission heard

about how these students made, and are continuing to make,

those contributions.

Survivors described what happened after they left the

schools. People no longer felt connected to their parents or

their families. In some cases, they said they felt ashamed of

themselves, their parents, and their culture. e Commission

heard from children who found it dicult to forgive their par-

ents for sending them to residential school. Parents told the

Commission of the heartbreak of having to send their children

away, and of the diculties that emerged while they were

away and when they returned.

Some said they felt useless in their community. Still others

compared themselves to lost souls, unable to go forward,

unable to go back. Many people lost years of their lives to

alcohol, to drugs, or to the streets as they sought a way to dull

the pain of not belonging anywhere. Deprived of their own

sense of self-worth, people told us, they had spent decades

wandering in despair. People spoke of the former students

who met violent ends: in accidents, at the hands of others, or,

all too often, at their own hands.

Some people still nd themselves reliving the moments of

their victimization. For them, residential schools are not part

of the past, but vivid elements of their daily life. Sights, sounds,

foods, and even individuals can trigger painful memories.

People spoke of how the residential school left them hard-

ened. People were determined not to cry or show emotion,

not to react to discipline. People said that the prospect of

going to jail had been of little consequence to them because

they had already been through hard times at residential

school and were familiar with the feeling of being locked up

and isolated.

e government broke up families by sending children to

residential school. e people who left the schools said they

had not been given the skills needed to keep their families

together. ey had diculty in showing love. Having known

only harsh discipline, they treated their children harshly.

People spoke of incredible anger, the damage it did to them

and caused them to inict on others. e abused often became

abusers: husbands, wives, parents, children all fell victim.

People and communities have been left with the burden of

pain and the responsibility of healing. It was left to the former

students and their families to regain their voice. ousands

of them have launched what they so often refer to as healing

journeys.

e Commission heard from proud people, people who

asserted they were survivors. ey had survived mental

abuse, sexual abuse, physical abuse, and spiritual abuse. ey

were still standing. Many have reclaimed their culture, are

relearning language, and are practising traditional spirituality.

In other cases, they have remained Christians, while infusing

their beliefs with a renewed sense of Aboriginal spirituality.

People who were not able to show their children love spoke

of nding a way to love their grandchildren, and to make

amends with their grandchildren.

It is clear from the presentations that the people who have

been damaged by the residential schools—the former stu-

dents and their families—have been left to heal themselves.

It is also the former students who have led the way to recon-

ciliation, and they continue to lead the way. By regaining their

voice, they have instigated an important national conversa-

tion. All Canadians need to engage in this work.

People also came with requests.

ey want justice. People spoke about the diculties •

they have experienced in claiming compensation under

the Settlement Agreement. ey spoke of how missing

school records prevent them from being compensated.

ey spoke countless times of schools and residences

that they believe should be included in the Settlement

Agreement. ey also said that, in addition to missing

records, school-imposed variations in their names or

spellings of their names have prevented them from

being compensated for all their years at school.

ey want support for the work they have begun in •

healing. For too long, communities were left to shoulder

this burden on their own. In many of the remote com-

munities that are home to former students, health ser-

vices of any kind are scarce, and there are virtually no

mental health services available.

Interim Report | 7

R

4) e Commission recommends that each provincial

and territorial government undertake a review of the

curriculum materials currently in use in public schools

to assess what, if anything, they teach about residential

schools.

5) e Commission recommends that provincial and

territorial departments of education work in concert

with the Commission to develop age-appropriate

educational materials about residential schools for use

in public schools.

6) e Commission recommends that each provincial

and territorial government work with the Commission

to develop public-education campaigns to inform

the general public about the history and impact of

residential schools in their respective jurisdiction.

Languages and Traditional Knowledge

Residential schools suppressed Aboriginal language and

culture, contributing to the loss of culture, language, and tra-

ditional knowledge. Even when those direct attacks came to a

stop, culture remained devalued. ere is a need for the rec-

ognition of the continuing value to communities and society

of Aboriginal traditional knowledge, including spiritual, cul-

tural, and linguistic knowledge. is will require long-term

nancial investments in measures for the reclaiming and

relearning and sharing of this knowledge. e resources spent

on this should be commensurate to the monies and eorts

previously spent to destroy such knowledge.

R

7) e Commission recommends that the Government

of Canada and churches establish an ongoing cultural

revival fund designed to fund projects that promote the

traditional spiritual, cultural, and linguistic heritages of

the Aboriginal peoples of Canada.

Parenting Skills

It is clear that one of the greatest impacts of residential

schools is the breakdown of family relationships. Children

were deprived of the positive family environment necessary

for the transmission of parenting knowledge and skills. at

impact continues to be seen to this day; it is evidenced in high

rates of child apprehensions and youth involvement in crime.

e disruption of family relationships exacerbates the impact

of high mortality rates and high birth rates in the Aboriginal

community. ere is a need for the development and provi-

ey want support to allow them to improve par-•

enting skills. In particular, people asked for support in

regaining and teaching traditional parenting practices

and values.

ey want control over the way their children and •

grandchildren are educated. Reconciliation will come

through the education system.

ey want respect. People are angry at being told they •

should simply “get over it.” For them, the memories

remain, the pain remains. ey have started on their

healing journey—usually with no help and no support.

ey told the Commission they will be the ones to deter-

mine when they have reached their destination.

ey want their languages and their traditions. With •

tremendous eort, people have sought out traditional

teachings and practices, and worked at preserving

endangered languages. ey want the institutions that

invested so much over many decades in undermining

their cultures to invest now in restoring them.

ey want the full history of residential schools and •

Aboriginal peoples taught to all students in Canada at

all levels of study and to all teachers, and given promi-

nence in Canadian history texts.

As Commissioners, we have been moved, strengthened,

softened by what we have heard. We were reminded afresh

that all this happened to little children who had no control

over their lives and whose parents found themselves power-

less to prevent their children from being taken from them.

People came to the Commission in openness and honesty,

seeking to be faithful to what had happened to them. For many

people, it was an act of tremendous courage even to appear

before the Commission. Some people were so overwhelmed

by grief and emotion that they could not complete their state-

ments. In other cases, the pain was so intense that it was nec-

essary to halt the proceedings and simply hold hands. ese

Canadians have been carrying a tremendous burden of pain

for years. Finally, they are starting to be heard. eir messages

will play a crucial role in shaping the Truth and Reconciliation

Commission’s nal report.

Some issues presented to the Commission have been so

clear, urgent, important, and persistent that the Commission

is making recommendations about them in this report.

Education

ere is a need to increase public awareness and under-

standing of the history of residential schools. is will require

comprehensive public-awareness eorts by the federal gov-

ernment and in-school educational eorts by provincial and

territorial governments and educational institutions.

8 | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

sion of workshops aimed at reintroducing wise practices for

healthy families, and to compensate for the loss of parenting

knowledge experienced by generations of children raised in

institutional settings.

R

8) e Commission recommends that all levels of

government develop culturally appropriate early

childhood and parenting programs to assist young

parents and families aected by the impact of residential

schools and historic policies of cultural oppression in

the development of parental understanding and skills.

Extension and Enhancement of

Health Support Services

Survivors have told the Commission repeatedly of their

urgent need for specialized health supports available near

where they live. is need is especially acute in the northern

and more isolated regions of Canada. In those regions, the

per-capita number of residential school survivors and the

critical need for health support are higher than in the rest of

the country. In many cases, a single mental-health nurse in

the North is expected to service a region that is the geographic

size of an entire province. ey do this without the benet of

road transportation or colleagues. In some communities, there

may be no such nurse at all. e suicide rates in Aboriginal

communities are epidemic in some regions of the country.

Many survivors increasingly are angry and outspoken about

the need for more long-term help for themselves and their

children, including the creation of a specialized treatment

centre in the North.

rough its work supporting the Commission’s commu-

nity hearings, Health Canada has been able to assess and

rene its approach to providing mental-health support in

keeping with its obligations under the Settlement Agreement.

Ideally, Aboriginal health professionals who can combine

their Western medical training with knowledge of their own

healing traditions and culture should be found to do this work.

However, given the lack of sucient numbers of such profes-

sionals, the current ideal formula appears to be a balanced

team approach: specially trained cultural supports and tradi-

tional knowledge keepers from within the respective Aborig-

inal communities, working together with academically trained

health specialists from the non-Aboriginal community.

e loss of knowledge about, and access to, traditional

spiritual practices, language, and culture are among the most

frequently named abuses experienced by students at the

residential schools. For this reason, many former students

take greater comfort and strength from those health support

workers who come from within their own culture and com-

munity, and who can help them through the use of traditional

cultural methods or languages that value that part of their lost

identity.

Long-term eorts will be needed to address the deep and

prolonged community impacts of government policies that

sent generations of Aboriginal people to residential schools.

e Commission believes in the value of investing in the long-

term capacity of Aboriginal communities. is will support

their eorts to provide more of their own internal healing

resources and to continue their healing work, following

the completion of the Commission’s work and other activi-

ties associated with the implementation of the Settlement

Agreement.

R

9) e Commission recommends that the Government

of Canada, and the federal Minister of Health, in

consultation with northern leadership in Nunavut and

the Northwest Territories, take urgent action to develop

plans and allocate priority resources for a sustainable,

northern, mental health and wellness healing centre,

with specialization in childhood trauma and long-term

grief, as critically needed by residential school survivors

and their families and communities.

10) e Commission recommends that the Government

of Canada, through Health Canada, immediately

begin work with provincial and territorial government

health and/or education agencies to establish means

to formally recognize and accredit the knowledge,

skills, and on-the-job training of Health Canada’s

community cultural and traditional knowledge

healing team members, as demonstrated through

their intensive practical work in support of the Truth

and Reconciliation Commission and other Settlement

Agreement provisions.

11) e Commission recommends that the Government

of Canada develop a program to establish health and

wellness centres specializing in trauma and grief

counselling and treatment appropriate to the cultures

and experiences of multi-generational residential school

survivors.

Exclusions from Indian Residential

Schools Settlement Agreement

Compensation under the Indian Residential Schools

Settlement Agreement is restricted to the former students or

residents of schools listed in the Settlement Agreement or

Interim Report | 9

those schools that have been added to the list under specic

criteria.

Former students who attended schools or residences

not included in the Settlement Agreement have told us they

underwent the same deprivation of language and culture,

imposition of religious practices, and physical and sexual mis-

conduct by teachers and boarding-home parents or supervi-

sors as experienced by students covered by the Settlement

Agreement. Because the schools they attended are not on the

list, they are not eligible for compensation under the Settle-

ment Agreement. ey say that, once again, they are being

abused, injured, or traumatized because they have been left

out and isolated.

In particular, the Commission has heard such concerns of

exclusion from specic groups of former students:

e Inuit and Innu of Labrador. None of the boarding •

schools in Labrador were included in the Settlement

Agreement.

Students who attended the same schools by day as stu-•

dents living in the residences, but who lived in home

settings. In many cases, these ‘day scholars’ did not stay

in their own homes with their own families, but in bil-

leted accommodation.

Hostel students in the northern territories. Community •

hostels provided housing for students whose parents

were away making a traditional living o the land. Some

hostels are included in the Agreement; others are not.

ere is no clearly understood reason why.

Students who attended boarding schools where the •

federal government did not have responsibility for the

operation of the residence and the care of the children

resident there.

Students who attended non-residential schools, as •

directed by the federal government, but who also were

subjected to cultural denial, and harsh emotional and

physical treatment.

e exclusion of these students is a serious roadblock to

meaningful and sincere reconciliation.

R

12) e Commission recommends that the parties to the

Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement,

with the involvement of other provincial or territorial

governments as necessary, identify and implement

the earliest possible means to address legitimate

concerns of former students who feel unfairly left out

of the Settlement Agreement, in order to diminish

obstacles to healing within Aboriginal communities and

reconciliation within Canadian society.

Impact and Reach of Apology from Canada

On June 8, 2008, the Prime Minister of Canada issued a

“Statement of Apology to Former Students of Indian Residen-

tial Schools.” While not all survivors accept the apology, many

have told the Commission that hearing the government’s

apology has been very important to their healing.

Many of the people who have addressed the Commission

have made reference to the Commission’s commitment to act

“For the Child Taken; For the Parent Left Behind.” Often, they

have mentioned their own parents, noting that no one had

ever apologized to them. For their part, some parents have

said they felt they had been left out of the apology.

e apology does talk about the impacts of the residential

schools, not just on the students, but also on their families and

communities. However, there appears to be limited awareness

of its actual wording.

e Commission continues to face huge challenges in

raising awareness, among non-Aboriginal Canadians, of the

residential school history and legacy. is presents an enor-

mous limitation to the possibility of long-term understanding

and meaningful reconciliation. e Commission believes the

Canadian school system has a major role to play in re-edu-

cating the country about this part of our long-term, shared

history, with its present-day implications. Making the apology

available to all Canadian students in their schools would be a

positive step in this direction.

R

13) e Commission recommends that, to ensure that

survivors and their families receive as much healing

benet as the apology may bring them, the Government

of Canada distribute individual copies of the “Statement

of Apology to Former Students of Indian Residential

Schools” to all known residential school survivors.

14) e Commission recommends the Government of

Canada distribute to every secondary school in Canada

a framed copy of the “Statement of Apology to Former

Students of Indian Residential Schools” for prominent

public display and ongoing educational purposes.

Establishing a Framework for Reconciliation

ere is a need for analysis, by governments at all levels

and by churches, of the United Nations Declaration on the

Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP), in order to deepen

understanding of, and appreciation for, the value of the Decla-

ration as a framework for working towards ongoing reconcili-

ation between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal Canadians.

10 | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

R

15) e Commission recommends that federal, provincial,

and territorial governments, and all parties to the

Settlement Agreement, undertake to meet and explore

the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of

Indigenous Peoples, as a framework for working towards

ongoing reconciliation between Aboriginal and non-

Aboriginal Canadians.

e Aboriginal Healing Foundation

In response to the Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peo-

ples, Canada created a healing fund, administered primarily

by Aboriginal peoples, that would specically address the

residential school legacy and assist former students who were

physically and sexually abused. e Aboriginal Healing Foun-

dation (AHF), established for this purpose in 1998, delivers a

wide array of programs while conducting innovative research

on the eects of the residential system on Aboriginal peoples.

Its directors convinced the federal government to expand its

mandate to include not only those who attended the schools

but also those who were aected intergenerationally (the

parents and descendants of the students) as well. In 2010

the federal government discontinued funding for the AHF,

thus depriving former students and their families of a highly

valued and eective resource. e closing of the Aboriginal

Health Foundation will make Canada’s reconciliation journey

even more challenging in the years to come.

R

16) e Commission recommends that the Government of

Canada meet immediately with the Aboriginal Healing

Foundation to develop a plan to restore funding for

healing initiatives to the Foundation within the next

scal year.

e International Context

e Commissioners determined early on that the work of

the Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada has an

international importance. is was underscored when the

United Nations proclaimed 2009 as the International Year of

Reconciliation. Over the past two decades, more than forty

truth and reconciliation commissions have been struck fol-

lowing civil conicts in countries such as South Africa, Peru,

Colombia, and Sierra Leone. Canada’s TRC is unique in that

it is the rst commission to address human-rights violations

that span over a century and focus on the treatment of Indig-

enous children.

e Commissioners also recognize it is important to place

Canada’s residential school system within the international

context, particularly now that the world community, including

Canada, has endorsed the United Nations Declaration on the

Rights of Indigenous Peoples. e residential school system

was not unique to Canada. Governments and missionary

agencies in many countries around the world established

boarding schools as part of the colonial process. e systems

varied from time to time and place to place, but they shared

many common elements and left a common legacy. For these

reasons, the Commission has participated in international

activities. Representatives from other countries that have a

history of residential schooling for Indigenous children, or

similar abuses of Indigenous peoples, also have travelled to

Canada to observe Commission events.

In April 2010, Justice Murray Sinclair made a presentation to

the Ninth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on

Indigenous Issues in New York on the work of Canada’s Truth

and Reconciliation Commission. In 2010 the United Nations

Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues recognized the Truth

and Reconciliation Commission of Canada as a model of best

practices and an inspiration for other countries.

In September 2010, Commissioner Wilton Littlechild

addressed the United Nations Human Rights Council’s f-

teenth session in Geneva, Switzerland, on the value that truth

commissions bring to global reconciliation eorts. ere,

he expressed the Commission’s support for an international

experts’ seminar on truth and reconciliation processes. Such

commissions can play an important role in resolving con-

ict and improving relations between states and Indigenous

peoples.

In September 2010, Commissioners Littlechild and Wilson

presented at the sixth gathering of Healing Our Spirit World-

wide, an international forum and healing initiative that

focuses on health, governance, and drug and alcohol issues

and programs in Indigenous communities across the globe.

Many former residential school students from Canada partici-

pated in this event.

In October 2010, the Commissioners co-hosted a youth

retreat in British Columbia with the International Center for

Transitional Justice. is initiative brought together Aborig-

inal and non-Aboriginal youth to learn about social justice,

the role of truth and memory projects, and the specic history

and purpose of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

of Canada, and to identify opportunities for youth to design

and participate in truth and reconciliation activities here in

Canada.

In March 2010, the Commission participated in the Inter-

national Expert Group meeting on Indigenous Children and

Youth in Detention, Custody, Adoption and Foster Care in

Interim Report | 11

Vancouver. Commissioners Littlechild and Wilson attended

a special forum on the Native American boarding schools in

the United States that was held in Boulder, Colorado. Com-

missioner Wilson met with representatives of the Shoah

Foundation in Los Angeles to gain insight into the recording,

preservation, and educational usage of oral histories of Holo-

caust survivors. In May 2011, there was follow-up work at the

Tenth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on

Indigenous Issues in an international experts’ seminar on

truth and reconciliation processes.

In conclusion, the Commission has established relations

with international organizations that enable it to learn from

the work of other commissions, and to make contributions

from its own experiences.

12

Commission Activities

e Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement

sets out an extensive mandate for the Truth and Reconcilia-

tion Commission. It ranges from research and report writing,

holding national and community events, collecting statements

from Canadians about their residential schools experience,

and collecting documents from the parties to the Settlement

Agreement, to educating the public through commemorative

events. e work of the Commission to date is summarized

best under the following headings:

Statement Gathering•

Document Collection•

Research and Report Preparation•

A National Research Centre •

Commemoration•

National Events•

Community Events•

Statement Gathering: Truth Sharing

Until now, the voices of those who were directly involved

in the day-to-day life of the schools, particularly the former

students, largely have been missing from the historical record.

e Commission is committed to providing every former resi-

dential student—and every person whose life was aected by

the residential school system—with the opportunity to create

a record of that experience.

e work of other truth and reconciliation commissions

has conrmed the particular importance of the statement-

giving process as a means to restore dignity and identity to

those who have suered grievous harms. Statement gath-

ering is a central element in the Commission mandate, and

statement giving is voluntary. Since there are estimated to

be at least 80,000 living former students, the magnitude and

complexity of the Commission’s commitment are signicant.

e statements gathered will be used by the Commission in

the preparation of its report, and eventually will be housed in

the National Research Centre (NRC, to be established by the

Commission, and discussed in a following section).

Statement gathering has occurred at National Events,

community events, and at events coordinated by the Com-

mission’s regional liaisons. Trained statement gatherers now

are present in most regions across the country, with more

resources being added continually.

Statement gathering involves recording the biographies

of those providing statements to the Commission. Statement

providers are encouraged to talk about any and all aspects

of their lives they feel are important, including times before,

during, and after attending a residential school. e family

members of survivors, former sta, and others aected by

the residential schools also are encouraged to share their

experiences.

e Commission recognizes that providing a statement

to the Commission is often very emotional and extremely

dicult for individuals. For this reason, statement providers

are given the option of having a health support worker, a cul-

tural support worker, or a professional therapist attend their

session. ese health supports ensure statement providers

are able to talk to someone who can assist them if necessary

before and after providing a statement.

Individuals are given the option of having an audio or

video recording made of their experiences. If they wish, they

are given a copy of their statement immediately at the end of

the interview. ey may choose to provide their statement

in writing or over the phone if proper health supports are in

place.

Privacy considerations surrounding statement gathering

are extremely important to the Commission. All persons who

make statements to the Commission do so voluntarily.

Interim Report | 13

e Commission provides opportunities to give statements

in a number of dierent ways. ese include:

at public Sharing Circles at national and community •

events

at Commission hearings at scheduled locations across •

the country, including National Events

at private statement-gathering sessions where only •

a trained statement gatherer and health worker are

present.

At Sharing Circles and Commission hearings, statements

are made in a public setting. People who make their statement

in a private setting can choose from two levels of privacy pro-

tection. e rst option ensures full privacy according to the

standards of the federal Privacy Act. e second option allows

the statement provider to waive certain rights to privacy in the

interests of having their experiences known to, and shared

with, the greater public.

People who waive those rights are giving consent to the

Commission and to the National Research Centre to use their

statement for public education purposes or to disclose their

statement to third parties for public education purposes in

a respectful and dignied manner (such as for third-party

documentary lms). e Commission and National Research

Centre have the authority to decide whether to provide such

access.

ese options are explained carefully to the statement pro-

vider before a private statement-gathering session. To date,

over half the statement providers have chosen to have their

statements recorded for public education purposes.

e Commission also ensures that all digital information

is transmitted and protected carefully during trips in and out

of the eld.

e Commission has made it a high priority to gather state-

ments from the elderly or ill, as well as from particularly vul-

nerable and marginalized former students who are at risk. It

has undertaken a number of innovative measures, including

a day-long event facilitated by Métis Calgary Family Services

at the downtown branch of the Calgary Public Library that

focused on collecting statements from homeless individuals.

Projects designed to reach those survivors in jails also are

underway.

By the end of June 2011, the Commission had collected

1157 individual statements. An additional 649 statements

had been given in Sharing Circles and at public hearings.

One hundred and fteen material and artistic submissions

had been received. e Commission now has in place both

the mechanisms and process to ensure it is able to meet its

statement-gathering goals. Regional liaisons play a role in

coordinating and organizing a series of specic and targeted

visits to communities across the country. Future Commission

National Events and the community hearings held in conjunc-

tion with those events will continue to play a signicant role

in statement gathering. Private statement-gathering options

and Sharing Circles will be extended to communities and

individuals in ever-increasing numbers in the coming year,

with advance notice circulated to communities well before

the planned visits.

Document Collection

e Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement

commits the parties to the Agreement to providing the Com-

mission with all relevant documents in their possession or

control. is is to be done subject to the legislated privacy

interests of an individual, and in compliance with privacy and

access-to-information legislation. Exceptions are to be made

in cases where solicitor-client privilege applies.

In keeping with that Agreement, documents from the Inde-

pendent Assessment Process (IAP) established by the Indian

Residential Schools Settlement Agreement, existing resolved

litigation, and federal government dispute-resolution

processes (all processes dealing with claims of abuse at the

schools) are being sought by the Commission, to become part

of the documents collected.

In February 2011, the Commission retained a consulting

rm to assist in collecting all relevant documents from church

and government holdings. e Commission is in the process

of developing a fully functional and secure database, a team

of historical researchers to review and audit the holdings of

the various parties to the Settlement Agreement, and the tech-

nical resources to digitize the entire collection.

Each of the three main activities in document collection—

developing the database, the digitization, and research—are

extremely complex projects. e database will provide the

Commission with state-of-the-art backup and secure storage,

while delivering sophisticated search-and-report functions,

and multi-media capacity. Researchers will identify, review,

provide meta-data tagging, and report on all relevant docu-

ments. Digitization will involve the electronic conversion of

material that currently exists in a host of formats, including

photographs, glass-plate negatives, lm, video, onionskin

paper, cut-sheet paper, and microlm.

is eort will involve the records of at least eighty-eight

church archives and as many as thirty or more government

institutions. In addition, the creation of a full record also would

require the collection of relevant records held by organiza-

tions and individuals other than Canada and the churches,

such as museums, provincial and university archives, and

cultural and Aboriginal research centres.

14 | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

Yellowknife

Inuvik

Dawson

Whitehorse

Prince Albert

Fredericton

Charlottetown

Brandon

Iqaluit

Prince George

St. John's

Edmonton

Red Deer

Kamloops

Vancouver

Kelowna

Calgary

Saskatoon

Victoria

Lethbridge

Medicine Hat

Regina

Halifax

Winnipeg

Québec

Thunder Bay

Sherbrooke

Montréal

Sudbury

Ottawa

Sault Ste. Marie

Kingston

Peterborough

Barrie

Toronto

Guelph

Hamilton

London

Windsor

London

London

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

London

London

London

Toronto

Toronto

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Guelph

Sudbury

Ottawa

Ottawa

Montréal

Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa

Montréal

Montréal

Montréal

Montréal

Halifax

Lethbridge

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Vancouver

Kamloops

Red Deer

Red Deer

Vancouver

Vancouver

Brandon

Brandon

Sudbury

Sudbury

Vancouver

Winnipeg

Saskatoon

Edmonton

Dawson

Inuvik

Sudbury

Sudbury

Sudbury

Sudbury

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Vancouver

Red Deer

Red Deer

Red Deer

Charlottetown

Edmonton

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Fredericton

Fredericton

Québec

Thunder Bay

Thunder Bay

Sault Ste. Marie

Sault Ste. Marie

Calgary

Calgary

Vancouver

Vancouver

Vancouver

Victoria

Victoria

Edmonton

Edmonton

Regina

Regina

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa

Halifax

Halifax

Halifax

Yellowknife

Whitehorse

Whitehorse

Iqaluit

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Lethbridge

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Prince Albert

Prince Albert

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Fredericton

Fredericton

Québec

Statement gathering events

Outreach events

Statement gathering and outreach events

From 2009-2011, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

of Canada took part in more than 400 outreach and statement

gathering initiatives. This map illustrates the communities that

were visited during that time period.

TRC in the Community

(Map 1)

ATLANTIC OCEAN

ARCTIC OCEAN

PACIFIC OCEAN

Hudson Bay

YUKON

SASKATCHEWAN

QUEBEC

CANADA

P.E.I.

ONTARIO

NUNAVUT

NOVA SCOTIA

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR

NEW

BRUNSWICK

MANITOBA

BRITISH COLUMBIA

ALBERTA

Interim Report | 15

Yellowknife

Inuvik

Dawson

Whitehorse

Prince Albert

Fredericton

Charlottetown

Brandon

Iqaluit

Prince George

St. John's

Edmonton

Red Deer

Kamloops

Vancouver

Kelowna

Calgary

Saskatoon

Victoria

Lethbridge

Medicine Hat

Regina

Halifax

Winnipeg

Québec

Thunder Bay

Sherbrooke

Montréal

Sudbury

Ottawa

Sault Ste. Marie

Kingston

Peterborough

Barrie

Toronto

Guelph

Hamilton

London

Windsor

London

London

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

London

London

London

Toronto

Toronto

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Hamilton

Guelph

Sudbury

Ottawa

Ottawa

Montréal

Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa

Montréal

Montréal

Montréal

Montréal

Halifax

Lethbridge

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Vancouver

Kamloops

Red Deer

Red Deer

Vancouver

Vancouver

Brandon

Brandon

Sudbury

Sudbury

Vancouver

Winnipeg

Saskatoon

Edmonton

Dawson

Inuvik

Sudbury

Sudbury

Sudbury

Sudbury

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Vancouver

Red Deer

Red Deer

Red Deer

Charlottetown

Edmonton

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Fredericton

Fredericton

Québec

Thunder Bay

Thunder Bay

Sault Ste. Marie

Sault Ste. Marie

Calgary

Calgary

Vancouver

Vancouver

Vancouver

Victoria

Victoria

Edmonton

Edmonton

Regina

Regina

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Winnipeg

Ottawa

Ottawa

Ottawa

Halifax

Halifax

Halifax

Yellowknife

Whitehorse

Whitehorse

Iqaluit

Saskatoon

Saskatoon

Lethbridge

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Edmonton

Prince Albert

Prince Albert

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Brandon

Fredericton

Fredericton

Québec

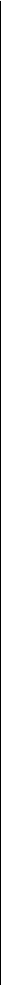

Statement gathering events

Outreach events

Statement gathering and outreach events

From 2009-2011, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission

of Canada took part in more than 400 outreach and statement

gathering initiatives. This map illustrates the communities that

were visited during that time period.

TRC in the Community

(Map 1)

ATLANTIC OCEAN

ARCTIC OCEAN

PACIFIC OCEAN

Hudson Bay

YUKON

SASKATCHEWAN

QUEBEC

CANADA

P.E.I.

ONTARIO

NUNAVUT

NOVA SCOTIA

NORTHWEST TERRITORIES

NEWFOUNDLAND AND LABRADOR

NEW

BRUNSWICK

MANITOBA

BRITISH COLUMBIA

ALBERTA

16 | Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada

e document-collection process has been placed at risk

by two factors: the lack of federal government and church

cooperation, and cost-related issues.

Lack of Cooperation

e federal government has been aware of its need to

provide all relevant documents since the signing of the 2005

agreement-in-principle that preceded the nal Settlement

Agreement. Despite this, the federal government

has provided the Commission with only a very limited •

portion of the relevant documents in its possession

has taken the position that it has no obligation to iden-•

tify and provide relevant historical documents held by

Library and Archives Canada to the Commission. Under

this approach, departments would have to search and

produce records only from active and recent les. is is

inappropriate in dealing with matters dating back over

a century.

has informed the Commission that, despite the Com-•

mission’s request, it has not agreed to provide the Com-

mission with the Settlement Agreement and Dispute

Resolution (SADRE) database, which contains all the

residential school research les of Aboriginal Aairs

and Northern Development Canada.

has yet to provide the Commission with appropriate •

levels of access to federal archives—an issue that

compromises both document collection and report

preparation.

In addition, the federal government has taken the posi-

tion that it cannot disclose records in its possession if those

records were provided to it by the churches in response to

specic residential schools court cases. It maintains this posi-

tion even for records created by the federal government but

that contain information rst obtained from church records.

e federal government asserts that since it obtained the

church records and information through the litigation pro-

cess, it is subject to an implied undertaking to use or disclose

those records only in relation to the specic court decisions

to which the records relate. e federal government asserts

that the fact that the government and the churches settled

such court cases through the Settlement Agreement, which

includes an express obligation that Canada and the churches

would disclose all relevant records in their possession, does

not constitute a waiver of those implied undertakings. In the

case of a conict between the implied undertakings and the

express obligation in the Settlement Agreement to produce all

records in its possession to the Commission, the government

maintains it must give preference to the implied undertak-

ings. e Commission nds this position unacceptable.

In addition, while the Commission has received helpful

cooperation from most of the churches and archivists it has

dealt with, individual church archivists have sought to impose

conditions before they will produce records to the Commis-

sion. Such conditions include:

instructions as to how the Commission should caption •

photographs in its reports

limitations on the Commission’s use of photographs to •

a “one-time only” use

distinctions between their “internal” and “external” and •

“restricted” and “unrestricted” records

restrictions as to how the Commission can use records •

in dierent categories.

Some archivists insist that the Commission acknowledge

that the churches own copyright in the records located in their

archives. With respect to such claims, the churches make no

copyright distinctions based on who created the records or

when, and do not explain what copyright interests they are

seeking to protect.

All these issues have caused and continue to cause con-

siderable delay for the Commission in its attempt to meet its

mandated obligation and enforce compliance of the parties’

obligations to produce relevant records. It is unlikely that the

document-collection process will be completed without a sig-

nicant shift in attitude on the part of Canada and those par-

ties who have been reluctant to cooperate.

Cost-related issues

e Settlement Agreement states that Canada and the

churches must compile and produce all relevant documents

and must bear the cost of producing those documents. Where

only original documents are involved, the parties, once they