Edith Cowan University Edith Cowan University

Research Online Research Online

Research outputs 2022 to 2026

3-1-2023

Does pain matter in the Australian royal commission into aged Does pain matter in the Australian royal commission into aged

care quality and safety? a text mining study care quality and safety? a text mining study

Mustafa Atee

Edith Cowan University

Matthew Andreotta

Rebecca Lloyd

Daniel Whiting

Marie Alford

See next page for additional authors

Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2022-2026

Part of the Medicine and Health Sciences Commons

10.1016/j.ahr.2023.100126

Atee, M., Andreotta, M., Lloyd, R., Whiting, D., Alford, M., & Morris, T. (2023). Does pain matter in the Australian royal

commission into aged care quality and safety? a text mining study. Aging and Health Research, 3(1), article

100126. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahr.2023.100126

This Journal Article is posted at Research Online.

https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks2022-2026/2746

Aging and Health Research 3 (2023) 100126

Available online 9 February 2023

2667-0321/© 2023 The Authors. Published by Elsevier B.V. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-

nc-nd/4.0/).

Does pain matter in the Australian Royal Commission into Aged Care

Quality and Safety? A text mining study

Mustafa Atee

a

,

b

,

c

,

d

,

*

, Matthew Andreotta

a

, Rebecca Lloyd

a

, Daniel Whiting

e

, Marie Alford

e

,

Thomas Morris

e

,

f

a

The Dementia Centre, HammondCare (Osborne Park, WA, Australia)

b

Curtin Medical School, Faculty of Health Sciences, Curtin University (Bentley, WA, Australia)

c

Sydney Pharmacy School, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney (Sydney, NSW, Australia)

d

School of Nursing and Midwifery, Edith Cowan University (Joondalup, WA, Australia)

e

The Dementia Centre, HammondCare (St Leonards, NSW, Australia)

f

Sydney School of Public Health, Faculty of Medicine and Health, The University of Sydney (Sydney, NSW, Australia)

ARTICLE INFO

Keywords:

Pain

Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and

Safety

Aged care

Mentions

Text mining

Term frequency analysis

ABSTRACT

Background: Pain is often poorly documented, assessed and managed in the Australian aged care sector. The

Australian Government called for the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety (RC) to investigate

the serious concerns, neglects and abuses including the inadequate pain management seen in the sector. This

study examined the degree to which the RC discussed the issue of pain in their published reports and

recommendations.

Methods: A text mining study with a computer-assisted term frequency analysis identied mentions of the word

“pain” in the text of two key reports produced by the RC: the Interim Report and the Final Report. Main outcome

measures included frequency of mentions of “pain”, cumulative percentile rank of the word “pain”, proportion of

words that were “pain”, and frequency of mentions of the word “pain” in quotes.

Results: The word “pain” was mentioned often in the Interim Report (n = 10, 0.03% of all words, 87th percentile)

and the Final Report (n = 218, 0.05% of all words, 97th percentile). However, the word “pain” was absent from

nal recommendations of the RC.

Conclusions: Although the RC discussed pain in their reports, the topic was omitted from recommendations,

reecting a lack of attention to the presented evidence. Without specic recommendations for pain management,

a disconnection may arise between targeted polices, programs and funding schemes, and the clinical practice.

Thus, older adults living in the community and residential aged care homes may remain vulnerable.

1. Introduction

In Australia, 4.2 million people (16% of the population) are aged 65

years and above [1]. In 2020, a total of 335,889 people were using

residential aged care (permanent or respite, 189,954), home care (142,

436), or transition care (3499) in Australia. Approximately 58% of

residential care recipients and 30% of those accessing home support

were over 85 years old [1]. These age groups are susceptible to frailty,

pain, and care dependence [1–3].

Recognising and managing pain is a fundamental human right for all

individuals, regardless of their age, gender, and cognitive status [4].

Older Australians, including those living in residential aged care homes

(RACHs), are particularly vulnerable to under-recognition and

under-treatment of pain, due to multiple factors, such as inadequate

pain assessment and management, comorbidities, stoicism, and cogni-

tive impairment [5]. According to the Australian Pain Society, the

estimated prevalence of pain in this group exceeds 90% [6]. This is

particularly problematic in residents who are no longer able to

self-report the presence, nature and/or intensity of pain, such as those

living with dementia or cognitive impairment. This latter group con-

stitutes at least 52% of people living in the Australian RACHs [6]. Un-

controlled pain can lead to multiple negative clinical, social, and care

Abbreviations: RACHs, residential aged care homes; RC, Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and Safety.

* Corresponding author at: Level 2, 302 Selby Street Nth, Osborne Park, WA 6017, Australia, Website: https://www.dementiacentre.com/

E-mail address: [email protected] (M. Atee).

Contents lists available at ScienceDirect

Aging and Health Research

journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ahr

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ahr.2023.100126

Received 24 February 2022; Received in revised form 10 January 2023; Accepted 7 February 2023

Aging and Health Research 3 (2023) 100126

2

outcomes, such as delirium, immobility, behavioural disturbances,

inappropriate pharmacotherapy (e.g., psychotropic polypharmacy),

caregiver distress, and reduced quality of life [3].

In Australia, some aged care services were accused of neglect and

suboptimal clinical and social care including lack of proper documen-

tation, assessment, and management practices (e.g., pain). To shed light

on the current decits of the aged care system, the Australian Govern-

ment announced the Royal Commission into Aged Care Quality and

Safety in 2018 (hereby denoted as RC). The RC held hearings across

Australia in all capital cities and some regional locations. Over the

enquiry period (8 October 2018 to 1 March 2021), the RC received a

total of 10,574 submissions, 6,800 telephone calls to an information

line, and heard 641 witnesses. The population of interest targeted by the

RC were recipients of aged care services, including those living in

RACHs.

In October 2019 (after one year of enquiry), the RC released an

Interim Report, entitled Neglect, which summarised their ndings and

drew the conclusion that the Australian aged care system failed to meet

the needs of citizens receiving aged care [7]. In February 2021, the RC

released their Final Report, Care, Dignity and Respect, which outlined a

vision of a new aged care system [8].

The RC examined key clinical issues, such as pain and pain-related

aspects, including pain assessment, pain management, and pain moni-

toring. This study aimed to examine the degree and context in which the

RC discussed pain in their reports and recommendations. We conducted

a term frequency analysis (detecting the presence of the word “pain”) of

RC reports, to examine where the topic of pain was most prevalent and

absent.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Ethical considerations

As the RC reports are publicly available, no ethics approval was

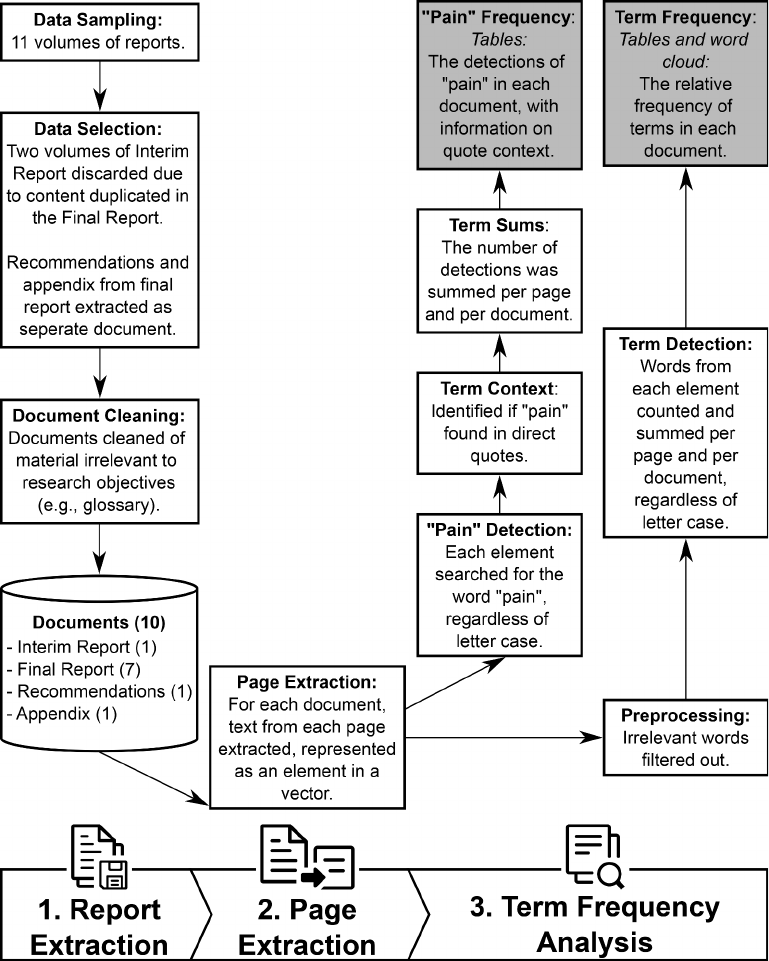

Fig. 1. Term frequency analysis to

detect the presence of “pain” in the

Royal Commission reports.

The three major steps of the analysis are

featured in the bottom-most bar. Each

square is a stage of the analysis, with

the nal output shaded in grey, and the

connecting arrows indicate the

sequence of analysis. The cylinder out-

lines data used for analysis, which we

have shared in an online repository

(https://osf.io/6kst8/). Boxes and cyl-

inders align, such that the process is

vertically above the relevant analysis

step (e.g., document cleaning is part of

report extraction).

M. Atee et al.

Aging and Health Research 3 (2023) 100126

3

required for this study. This article does not contain any personal

medical information or images.

2.2. Study design and method of analysis

We adopted a text mining approach [9] that used a three-step term

frequency analysis [10] to categorise pain-related content in the Interim

and Final Reports of the RC, as outlined in Fig. 1. A blind, independent

analysis was conducted between June and August 2021 by two re-

searchers who used similar methods to achieve identical results. Anal-

ysis was conducted using the R programming language version 4.1.0

[11]. Our analysis script is available for download at: https://osf.io/6kst

8/.

2.2.1. Steps of analysis

2.2.1.1. Step 1: report extraction. Text for analysis was obtained from

the two major reports of the RC: the Interim Report and the Final Report.

Released on 31 October 2019, the Interim Report, entitled Neglect,

consisted of three volumes. Of those areas discussed by the Report, pain

management was identied as a key issue that requires an immediate

action. The Final Report was titled Care, Dignity and Respect, and

comprised of eight volumes that covered the following: summary and

recommendations (Volume 1), current system (Volume 2), new system

(Volumes 3A and 3B), hearing overviews and case studies (Volumes 4A,

4B, 4C), and appendices (Volume 5). The RC reports were downloaded

from the RC website [7,8] and saved in Portable Document Format

(PDF).

Interim Report Volume 2 was not included in the analysis as it

contained duplicate content that also appeared in Final Report Volume

4A. Similarly, after removing duplicate content from Interim Report

Volume 3, the report consisted of lists of exhibits and of evidence pre-

sented to the commission. For this reason, this report was also not

included in the analysis.

Final Report Volume 1 contains the nal 148 recommendations

made by the RC. These recommendations, hereby referred to as ‘Rec-

ommendations’, were extracted and removed from the report and ana-

lysed separately. Lastly, Final Report Volume 5, which consisted

primarily of appendices, will be referred to as ‘Appendices’ in this paper.

Thus, ten documents were analysed: one volume of the Interim Report,

seven volumes of the Final Report, the Recommendations, and the

Appendix.

The front (i.e., cover page, contents, non-numerically numbered

pages, publishing details, blank pages) and end matter (i.e., glossaries)

were removed from each report. The rst and last lines of each page (i.e.,

headers and page numbers), and endnotes from each chapter were also

removed.

2.2.1.2. Step 2: page extraction. The text from each report was extracted

and divided into separate pages.

2.2.1.3. Step 3: term frequency analysis. To examine the degree and

context in which the RC reports discussed pain, we completed a term

frequency analysis which involved automatically detecting the word

“pain” in texts. To avoid matching words that contained pain as a subset

of their letters (e.g., “Spain”), a search restricted to complete words was

performed. For each report volume, we calculated the occurrences of the

word “pain”, the proportion of words that were “pain” (as a percentage),

and the cumulative percentile rank of the word “pain”. Additionally, we

reported occurrences of the word “pain” appearing in quotes, dened as

lines starting with nine or ten whitespaces (i.e., quotes formatted as

indented blocks of text) or text appearing in-between a single left and

single right quotation marks (i.e., inline quotes). It is worth noting that

we did not mine for the term analgesic/analgesia as the RC referred to

this as pain relief and therefore it was identied under the word “pain”.

Alongside descriptive statistics for detections of the word “pain”, we

reported a word cloud of frequent terms across reports and the top ten

most frequent words in each report, to provide context for the inter-

pretation of our ndings. Before calculating frequencies, we excluded

words with minimal meaning. This included stop words (commonly

occurring words in the English language, such as “the”), found in the

onix, smart, and snowball stop word lists available in the tidytext R

package [12]. Additionally, two members of the research team identi-

ed further words to exclude, due to the nature of the RC reports (e.g.,

locations/dates, terms such as hearing/transcript, or “commission” or

“royal”). Excluded words are presented in the supplementary material.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics of the occurrences of the

word “pain” by report and volume. Pain was mentioned a total of 245

times within the RC reports. The word “pain” was most prevalent for

Volume 4A of the Final Report (99th percentile), which concerned

hearing overviews and case studies. This is the case for both global (n =

133 occurrences) and in-quote contexts (n = 17 occurrences). Across all

volumes in the report, the use of the word “pain” was in the 87th

(Interim Report) and 97th (Final Report) percentile in word frequency

(Table 2).

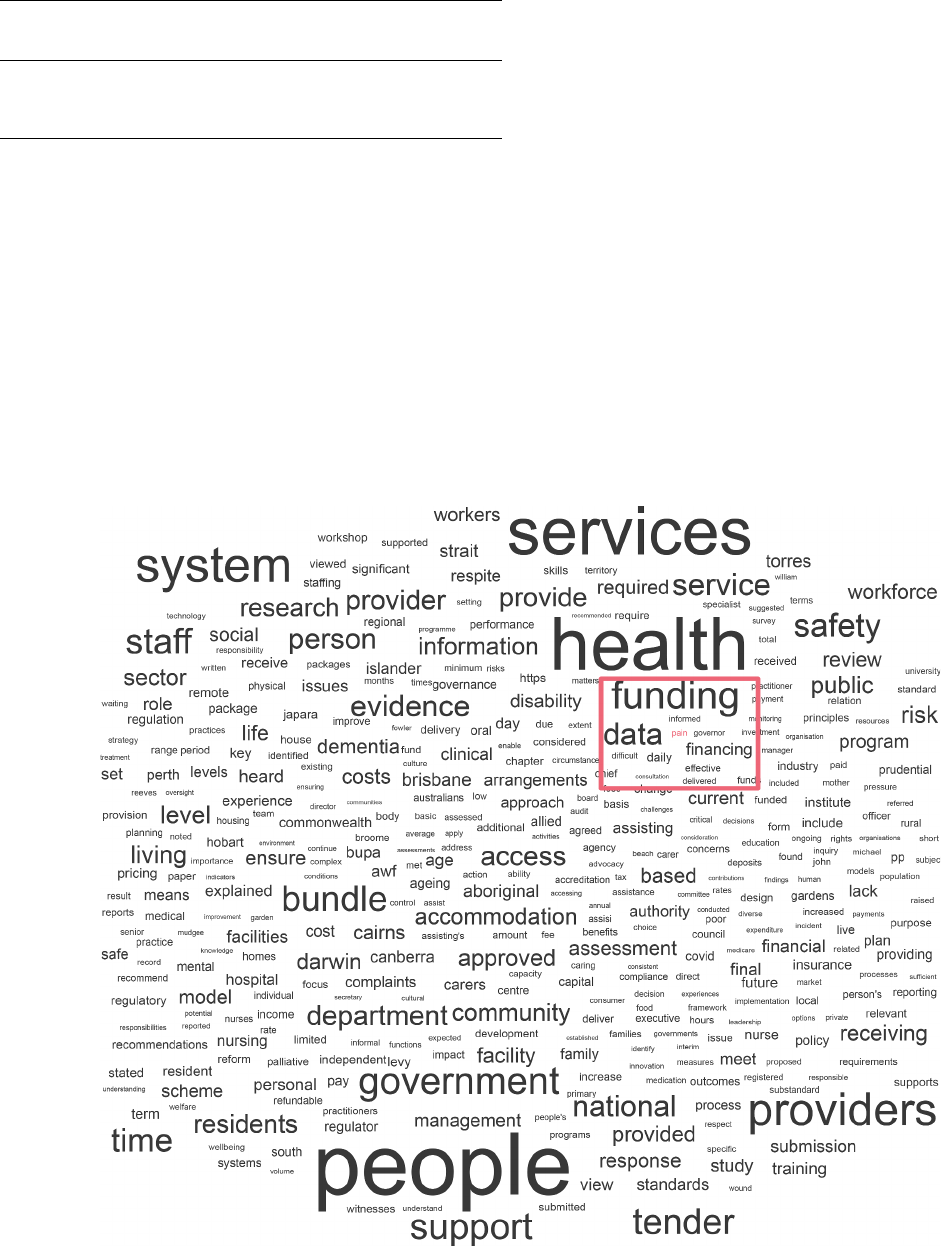

Fig. 2 presents a word cloud of common words across reports.

Relative to other words, the word ‘pain’ is very small graphically

reecting its lack of importance across all reports. Table 3 shows the top

ten most frequently occurring words in each report. Comparing the most

frequent words in the reports to the most frequent words in the nal

recommendations made by the RC, there is a degree of overlap, sug-

gesting that key terms and issues discussed in the report are reected in

the recommendations. However, the issue of pain is not directly

addressed in any of the 148 nal recommendations (n = 0 occurrences),

despite its prevalence in the Interim Report and Final Report.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to identify the frequency and context in which

“pain” was discussed in the reports of the RC, an independent public

investigation/enquiry into the serious concerns and abuses in Australian

aged care which involved holding public hearings, calling witnesses

Table 1

Detections of the word “pain” (raw count and proportion as a percentage), cu-

mulative percentile of the use of the word “pain”, and the number of instances

where the word “pain” occurred in quotes, for each volume of each Royal

Commision report.

Total detections

Volume n % Cumulative

percentile

n Detections in

quotes

Interim Report

Summary &

Recommendations

Volume 1 10 0.03 87.09 4

Final Report

Summary

Volume 1 8 0.02 83.44 0

Current System

Volume 2 37 0.08 96.26 5

New System

Volume 3A 8 0.01 78.80 3

Volume 3B 5 0.01 65.15 1

Hearing Overviews/Case

Studies

Volume 4A 133 0.25 99.17 17

Volume 4B 17 0.02 87.17 6

Volume 4C 10 0.02 80.85 4

Recommendations 0 0.00 0.00 0

Appendices 17 0.09 96.58 0

M. Atee et al.

Aging and Health Research 3 (2023) 100126

4

under oath, and generating evidence. We found discussions of pain were

most prevalent in reports of overviews on hearings and case studies. The

word “pain” was absent from the nal recommendations of the RC,

despite an otherwise large degree of congruence of words used in the

recommendations and other reports. This suggests that evidence offered

to the RC on pain was not translated into pain-specic

recommendations.

To our knowledge, this study is the rst analysis of the RC reports.

Though, two studies have analysed the transcripts from RC hearings.

First, a content analysis of concepts from a testimony revealed contex-

tual factors, such as resources and culture, can impact across myriad

domains of aged care [13]. Second, a qualitative analysis of testimony

transcripts identied the moral disengagement featured in Australian

aged care [14]. The authors drew specically on testimonies of pain to

exemplify the absence of human relatedness in routinised care and the

evidence of dehumanised and mechanistic care routines, stripping

bodies of their personal characteristics, functions, and worth. Combined

with our ndings, this small literature on the RC reports reveals that

pain characterises the experiences of those engaging with aged care

services. The impact of pain extends beyond physical suffering and

function, to include quality of life and experiences of moral injustice

[14]. As such, pain relief is one of the greatest ‘end of life’ priorities,

according to seriously ill patients, bereaved family members, physicians,

and other care providers [15].

Public policy is critical in shaping and transforming clinical practice

within the aged care sector. A good example is the United States where

legislating and implementing the 1987 Omnibus Budget Reconciliation

Act resulted in a reduction of the inappropriate use of psychotropic

medications in RACHs [16]. In Australia, aged care reforms over the last

decade introduced person-centred care and person-directed care prin-

ciples that underpin the concepts of personal dignity, autonomy, and

choice. These principles align well with the perspective “pain is whatever

the experiencing person says it is, existing whenever the experiencing person

say it does” [17 p. 8], and facilitate best-practice pain management (e.g.,

applying standardised and regular pain assessments). However, pain

remains poorly documented, assessed, and managed in Australian

RACHs [5,18–20].

Receipt of evidence-based pain care is essential for social, physical,

and emotional wellbeing. Despite the importance of pain management

to aged care recipients, pain-specic recommendations were omitted

Table 2

Overall detections of the word “pain” (raw count and proportion as a percent-

age), cumulative percentile of the use of the word “pain”, and the number of

instances where the word “pain” occurred in quotes.

Total detections

Report n % Cumulative

percentile

n Detections in

quotes

Interim 10 0.03 87.09 4

Final 218 0.05 97.44 36

Recommendations 0 0.00 0.00 0

Appendices 17 0.09 96.58 0

Fig. 2. Word cloud of the 400 most frequently occurring terms across the Royal Commission reports.

The frequency of words corresponds to their size in the word cloud. The word “pain” is coloured pink and highlighted with a pink rectangle.

M. Atee et al.

Aging and Health Research 3 (2023) 100126

5

from the Final Report of the RC. This is at odds with the ‘rights-based’ or

egalitarian approach of the RC, that recommends a “new system for aged

care should be rooted in the protection and promotion of the rights of the

people who require support and care.” [8 p. 14] General recommendations

for improving aged care are unlikely to sufciently achieve adequate

pain management for consumers, as effective pain management requires

specialised knowledge, techniques, and care culture [21]. For example,

effective and appropriate pain management is most likely in RACHs with

pain-vigilant cultures, where staff suspect the presence of pain.

Additionally, pain management for individuals living in RACHs re-

quires strategies and knowledge to identify pain in all residents

including those who are unable to communicate verbally such as those

with cognitive impairment (e.g., people living with dementia) or those

with a language barrier (e.g., people from culturally and linguistically

diverse backgrounds). This is evident in the former group (i.e., residents

with cognitive impairments), for example, where fewer, weaker and

lower-dose analgesics are often administered compared to cognitively

intact individuals [22–24]. As such, in their submission to the RC, the

Australian Pain Society provided the following recommendations:

encourage evidence-based strategies of pain management, facilitate a

government or publicly funded multidisciplinary care in RACHs, and

restructure existing aged care funding towards evidence-based multi-

disciplinary pain management [21]. These best care practices, including

the value of multidisciplinary pain management to deliver a

comprehensive, expertise-driven, person-centred and effective pain care

are supported not only in Australia, but also in other countries, such as

Japan and the Netherlands [25–28].

In response to the RC’s ndings, the federal government pledged a

historic nancial support of 17.7 billion Australian dollars reform

package in the 2021 budget. A judicious use of some of this support

should be targeted towards implementing the best practice recommen-

dations of the Australian Pain Society. Yet, as evidenced by the absence

of the word “pain”, no clear pathway to pain management-specic

outcomes was mapped. This is despite the published RC reports high-

lighting the failure of the aged care system to meet the pain care needs

and deliver safe and quality care to older Australians. The repudiation of

mentioning or listing pain in any of the RC Recommendations perhaps

result in compromising the focus on best practice pain management that

the older population rightly deserves and awaits from aged care pro-

viders. By doing so, the human right of aged care recipients to access

appropriate pain management may have been excluded or overlooked

from the rights-based approach of the RC.

Finally, our ndings suggest that government initiated public in-

quiries should consider the presented evidence to help formulate specic

and targeted recommendations to enable subsequent legislations and

policies that benet the target population.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Term frequency analysis is limited by the rigid operationalisation of

the concept of interest. Pain was operationalised as a single term

(“pain”), and therefore the text was examined through a narrow se-

mantic lens which omits other phrases used to express or refer to pain,

such as analgesia. We did not report any other clinically relevant words

featuring in the nal recommendations of the RC, as this was outside the

scope of the paper. Absent from our approach was an attempt to describe

the latent, rather than semantic, meaning of words. The emotional and

conceptual differences that can underscore each instance of the word

“pain” remains unexamined. Though, the automated detection of the

word “pain” has advantages as an efcient process which can be easily

replicated by other researchers. Further, blind independent analyses

were completed as part of the study with the same results produced by

two different researchers. Thus, our text mining technique offers a

simple, rigorous, and systematic approach to text analysis of ofcial

documents such as reports published by the government and other

stakeholders (e.g., peak body organisations).

Due to our operationalisation of pain as a single word, our analysis

does not identify recommendations that holistically address the causes

of poor pain management or foster environments that enhance pain

management. For example, the RC recommended access to specialists

via multidisciplinary outreach [8], congruent with the Australian Pain

Society’s recommendation for multidisciplinary pain management [21].

However, this specic recommendation by the RC has raised concerns,

due to the lack of operational detail by the RC [29]. This supports our

conclusion that the RC Recommendations do not sufciently describe a

roadmap for achieving satisfactory pain management outcomes for

consumers of aged care services.

5. Conclusions

Pain per se characterises the suffering experience of aged care re-

cipients, disrupting physical function, emotional wellbeing, and quality

of life. Yet, the testimonial and submitted evidence on recipients’

experience of pain obtained during the RC have not translated to clear,

actionable recommendations. The sizable population of older adults in

Australia remain vulnerable, with common pain experiences that are

often under-recognised and under-treated. Policy makers must act now

to incorporate the operational details and pain-specic changes to

funding structures and health policies in order to restore the human

right to adequate and appropriate pain management to some of

Table 3

The top ten most frequent words appearing in each Royal Commission report.

Rank Word n % Cumulative percentile

Interim Report

1 People 1025 2.57 100.00

2 Services 536 1.35 99.98

3 Health 375 0.94 99.97

4 System 297 0.75 99.95

5 Support 263 0.66 99.93

6 Community 242 0.61 99.92

7 Government 233 0.59 99.90

8 Providers 192 0.48 99.89

9 Time 192 0.48 99.89

10 Broome 191 0.48 99.85

Final Report

1 People 6174 1.50 100.00

2 Health 5104 1.24 99.99

3 Services 4616 1.12 99.99

4 Providers 3046 0.74 99.98

5 System 2995 0.73 99.97

6 Government 2433 0.59 99.97

7 Funding 2342 0.57 99.96

8 Bundle 2074 0.50 99.95

9 Tender 2065 0.50 99.94

10 Support 1933 0.47 99.94

Recommendations

1 Services 223 1.73 100.00

2 People 209 1.62 99.95

3 Health 198 1.53 99.91

4 Providers 139 1.08 99.86

5 Government 134 1.04 99.81

6 System 131 1.01 99.77

7 Provider 111 0.86 99.72

8 Receiving 99 0.77 99.67

9 Approved 95 0.74 99.62

10 Funding 95 0.74 99.62

Appendices

1 Health 257 1.38 100.00

2 People 209 1.12 99.98

3 Covid 158 0.85 99.96

4 Residents 143 0.77 99.94

5 Services 142 0.76 99.91

6 Staff 123 0.66 99.89

7 Community 116 0.62 99.87

8 Family 79 0.42 99.85

9 Facility 77 0.41 99.83

10 National 74 0.40 99.81

M. Atee et al.

Aging and Health Research 3 (2023) 100126

6

Australia’s most vulnerable citizens.

Data availability statement

All data used in this article are extracted from the publicly available,

published reports of the Australian Royal Commission into Aged Care

Quality and Safety. The code for the text mining analysis is publicly

available online on the Open Science Framework at: https://osf.io/

6kst8/.

Author contributions

Conceptualisation and study design: M Atee. Data curation and

formal analysis: M Atee, M Andreotta, R Lloyd and D Whiting. Meth-

odology: M Atee, M Andreotta, R Lloyd and D Whiting. Project admin-

istration: M Atee. Writing original draft: M Atee and M Andreotta.

Review and editing: all authors.

Consent to publish

All authors have provided the corresponding author with permission

to be named in the manuscript and consented to submit this manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare the following nancial interests/personal re-

lationships which may be considered as potential competing interests:

M Atee is one of the originators of the PainChek® instrument, which

is marketed by PainChek Ltd. (ASX: PCK). He is also a shareholder of

PainChek Ltd. He previously held the position of a Senior Research

Scientist (October 2018 - May 2020) at PainChek Ltd. and is currently

serving the position of Research and Practice Lead at The Dementia

Center. He had a granted patent titled “A pain assessment method and

system; PCT/AU2015/000501” in Australia, China, Japan, and the U.S.,

which was assigned to PainChek Ltd. M Atee is also a member of the

Australian Pain Society. Other authors declare no conict of interest.

Acknowledgements

Nil.

Funding

This research received no specic grant from any funding agency in

the public, commercial, or not-for-prot sectors.

The authors are staff members of The Dementia Centre; a research,

education, and consultancy arm of HammondCare, an independent

Christian charity which auspices the DSA programs. DSA programs are

funded by the Australian Government (Department of Health) under the

Dementia Aged Care Services (DACS) Fund since 2016. The funder had

no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management,

analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval

of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for

publication.

Supplementary materials

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in

the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.ahr.2023.100126.

References

[1] Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. People using aged care, https://www.

gen-agedcaredata.gov.au/Topics/People-using-aged-care; 2022 [accessed March 1,

2022].

[2] Thompson MQ, Theou O, Karnon J, Adams RJ, Visvanathan R. Frailty prevalence in

Australia: ndings from four pooled Australian cohort studies. Australas J Ageing

2018;37:155–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12483.

[3] Domenichiello AF, Ramsden CE. The silent epidemic of chronic pain in older

adults. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 2019;93:284–90. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.pnpbp.2019.04.006.

[4] International Pain Summit of the International Association for the Study of Pain.

Declaration of Montr

´

eal: declaration that access to pain management is a

fundamental human right. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother 2011;25:29–31.

https://doi.org/10.3109/15360288.2010.547560.

[5] Atee M, Morris T, Macfarlane S, Cunningham C. Pain in dementia: prevalence and

association with neuropsychiatric behaviors. J Pain Symptom Manage 2021;61:

1215–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2020.10.011.

[6] Goucke CR. Pain in residential aged care facilities: management strategies. 2nd ed.

Sydney: Australian Pain Society; 2018.

[7] Commonwealth of Australia. The royal commission into aged care quality and

safety: interim report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2019.

[8] Commonwealth of Australia. The royal commission into aged care quality and

safety: nal report. Canberra: Commonwealth of Australia; 2021.

[9] Tandel SS, Jamadar A, Dudugu S. A survey on text mining techniques. In: 2019 5th

International Conference of Advance Computer Communication System. IEEE;

2019. p. 1022–6. https://doi.org/10.1109/ICACCS.2019.8728547.

[10] Leskovec J, Rajaraman A, Ullman JD. Mining of massive datasets. Cambridge:

Cambridge University Press; 2020.

[11] R Core Team. R: a language and environment for statistical computing 2021.

[12] Silge J, Robinson D. tidytext: text mining and analysis using tidy data principles in

R. J Open Source Softw 2016;1:37. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00037.

[13] Pinero De Plaza MA, Conroy T, Mudd A, Kitson A. Using a complex network

methodology to track, evaluate, and transform fundamental care. Stud Health

Technol Inform 2021;284:31–5. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI210656.

[14] Austen K, Hutchinson M. An aged life has less value: a qualitative analysis of moral

disengagement and care failures evident in Royal Commission oral testimony.

J Clin Nurs 2021;30:3563–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15864.

[15] Steinhauser KE, Christakis NA, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, McIntyre L, Tulsky JA.

Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and

other care providers. JAMA 2000;284:2476–82. https://doi.org/10.1001/

jama.284.19.2476.

[16] Shorr RI, Fought RL, Ray WA. Changes in antipsychotic drug use in nursing homes

during implementation of the OBRA-87 regulations. JAMA 1994;271:358–62.

[17] McCaffrey M. Nursing management of the patient with pain. 2nd ed. Philadelphia:

Lippincott; 1979.

[18] Andrews SM, Dipnall JF, Tichawangana R, Hayes KJ, Fitzgerald JA, Siddall P, et al.

An exploration of pain documentation for people living with dementia in aged care

services. Pain Manag Nurs 2019;20:475–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

pmn.2019.01.004Get.

[19] Peisah C, Weaver J, Wong L, Strukovski J-A. Silent and suffering: a pilot study

exploring gaps between theory and practice in pain management for people with

severe dementia in residential aged care facilities. Clin Interv Aging 2014;9:

1767–74. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S64598.

[20] Veal F, Williams M, Bereznicki L, Cummings E, Winzenberg T. A retrospective

review of pain management in Tasmanian residential aged care facilities. BJGP

Open 2019;3. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgpopen18X101629.

[21] Australian Pain Society. Submission to the australian government royal

commission into aged care quality and safety. Sydney: Australian Pain Society;

2019.

[22] Bauer U, Pitzer S, Schreier MM, Osterbrink J, Alzner R, Iglseder B. Pain treatment

for nursing home residents differs according to cognitive state - a cross-sectional

study. BMC Geriatr 2016;16:124. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0295-1.

[23] Chang AK, Edwards RR, Morrison RS, Argoff C, Ata A, Holt C, et al. Disparities in

acute pain treatment by cognitive status in older adults with hip fracture.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2020;75:2003–7. https://doi.org/10.1093/gerona/

glz216.

[24] Green E, Bernoth M, Nielsen S. Do nurses in acute care settings administer PRN

analgesics equally to patients with dementia compared to patients without

dementia? Collegian 2016;23:233–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.

colegn.2015.01.003.

[25] Savvas SM, Toye CM, Beattie ERA, Gibson SJ. An evidence-based program to

improve analgesic practice and pain outcomes in residential aged care facilities.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2014;62:1583–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.12935.

[26] Savvas S, Dang C, Peck A, Vaughan M, Scherer S. Pain management guide (PMG)

toolkit for aged care. 2nd ed. Melbourne and Sydney: National Ageing Research

Institute and Australian Pain Society; 2019.

[27] Takahashi N, Takatsuki K, Kasahara S, Yabuki S. Multidisciplinary pain

management program for patients with chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan: a

cohort study. J Pain Res 2019;12:2563–76. https://doi.org/10.2147/JPR.S212205.

[28] Achterberg WP, de Ruiter CM, de Weerd-Spaetgens CMEE, Geels P, Horikx A,

Verduijn MM, et al. Multidisciplinary guideline “Recognition and treatment of

chronic pain in vulnerable elderly people. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 2012;155:

A4606.

[29] Looi JC, Kisely S, Bastiampillai T, Allison S. Psychiatric care implications of the

Aged Care Royal Commission: putting the cart before the horse. Aust N Z J

Psychiatry 2022;56:11–3. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211025700.

M. Atee et al.