DRAFT

Sustainability: Delivering Agility’s Promise

Jutta Eckstein

Email: [email protected]

Claudia de O. Melo

Email: [email protected]

Abstract—Sustainability is a promise by agile development, as

it is part of both the Agile Alliance’s and the Scrum Alliance’s

vision. Thus far, not much has been delivered on this promise.

This paper explores the Agile Manifesto and points out how

agility could contribute to sustainability in its three dimensions

– social, economic, and environmental. Additionally, this paper

provides some sample cases of companies focusing on both

sustainability (partially or holistically) and agile development.

I. INTRODUCTION

The two major agile organisations, the Agile Alliance and

the Scrum Alliance, both promise in their vision statements

that sustainability is one of their core goals:

Agile Alliance is a nonprofit organisation committed

to supporting people who explore and apply

Agile values, principles, and practices to make

building software solutions more effective,

humane, and sustainable [1].

Scrum Alliance®is a nonprofit organisation that is

guiding and inspiring individuals, leaders, and

organisations with agile practices, principles, and

values to help create workplaces that are joyful,

prosperous, and sustainable [2].

If we want to support building software solutions to be more

effective, humane, and sustainable or to help create workplaces

that are joyful, prosperous, and sustainable we have to aim

(among other things) for sustainability. However, thus far not

much has been done for approaching this aim.

In this paper, we are going to provide a new lens in order

to understand the Agile Manifesto under the premise the agile

approach wants to fulfil its promise for sustainability and we

will provide various case studies of companies attempting to

use agile development to contribute to sustainability.

The paper is structured as follows: we will at first

examine the various definitions of sustainability and explore

both how the business and Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT) approach and classify sustainability. We

will then take a close look at the principles defined by the

Agile Manifesto in order to find out how they can support

sustainable development [3]. Next, we present various case

studies of companies either addressing sustainability partially

or holistically by leveraging it with an agile approach. In

the conclusion, we will take a critical look at sustainability

initiatives before we will provide an outlook on the (hopefully)

not so far future.

II. SUSTAINABILITY

There are several definitions for sustainability and

nuances across the spectrum of sustainable use, sustainable

development and sustainability [4]. The most famous and

frequently definition adopted to frame discussions around

sustainability is provided by the Brundtland report [5]:

“Sustainable development is development that meets

the needs of the present without compromising the

ability of future generations to meet their own needs.

It contains within it two key concepts: the concept

of ’needs’, in particular the essential needs of the

world’s poor, to which overriding priority should

be given; and the idea of limitations imposed by

the state of technology and social organisation on

the environment’s ability to meet present and future

needs”.

The Brundtland report suggests how economic and social

development should be defined and calls all countries to action:

Thus the goals of economic and social development

must be defined in terms of sustainability in all

countries - developed or developing, market-oriented

or centrally planned. Interpretations will vary, but

must share certain general features and must flow

from a consensus on the basic concept of sustainable

development and on a broad strategic framework for

achieving it.

Finally, the report describes how a path towards

sustainability should look like, bringing the concept of

physical sustainability (related to living under the laws of

nature and minimising the impact on the physical environment)

and its connection to intra- and inter- generational social

equity:

“Development involves a progressive

transformation of economy and society. A

development path that is sustainable in a physical

sense could theoretically be pursued even in a

rigid social and political setting. But physical

sustainability cannot be secured unless development

policies pay attention to such considerations

as changes in access to resources and in the

distribution of costs and benefits. Even the narrow

notion of physical sustainability implies a concern

for social equity between generations, a concern

that must logically be extended to equity within

each generation”.

arXiv:2103.05520v1 [cs.SE] 9 Mar 2021

DRAFT

According to the these definitions, sustainability is about

taking long-term responsibility for your action and reaches

further than energy consumption and pollution as it is often

casually understood.

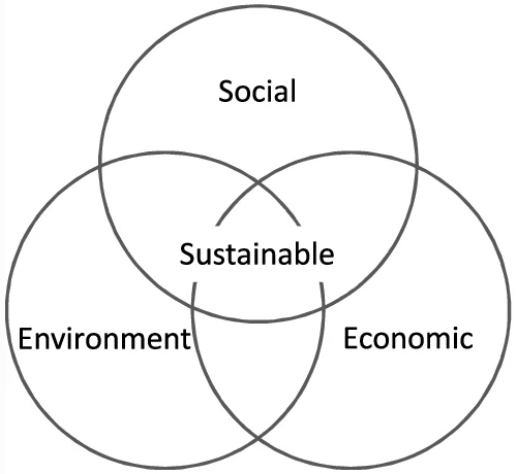

Other important concepts that seek to explain sustainability

are: the three-pillar model and the triple bottom line. The

three-pillar model depicts sustainability by synthesising

social, economic, and environmental concerns. It is the model

most widely used, for example, it is the definition given

by Wikipedia and also used on the 2005 World Summit on

Social Development [6], [7]. However, as explained in [8], “the

conceptual foundations of this model are far from clear and

there appears to be no singular source from which it derives”.

The triple bottom line is an accounting framework that

seeks to broadening the notion of a company bottom line by

introducing a full cost accounting. A single bottom line is the

company’s profit (if negative, loss) in an accounting period. A

triple bottom line adds social and environmental (ecological)

concerns to the accounting. If a corporation has a monetary

profit, but it causes thousands of deaths or pollutes a river, and

the government ends up spending taxpayer money on health

care and river clean-up, the triple bottom line needs to account

for these cost-benefit analysis too.

The triple bottom line is also known by the phrase “people,

planet, and profit” and was coined by John Elkington in

1994 while at SustainAbility (a British consultancy). A triple

bottom line company seeks to gauge a corporation’s level of

commitment to corporate social responsibility and its impact

on the environment over time [9].

Another important framework that also articulates

sustainability is the United Nations 2030 Agenda and

the 17 Sustainable Development Goals: “The Sustainable

Development Goals are a universal call to action to end

poverty, protect the planet and improve the lives and

prospects of everyone, everywhere” [10].

Also these sustainable development goals are founded

in the three pillar model: social (the aim of ending

poverty), environmental (protecting the planet), and economic

(improving the lives and prospects of everyone, everywhere).

Therefore, throughout this article we will use the three-pillar

model as the definition for sustainability, as illustrated by

Figure 1.

Even with the definition of the three pillars, it has always to

be understood that sustainability is highly interconnected that

any elaboration on sustainability requires a holistic perspective

because all actions are interdependent [11]:

“All definitions of sustainable development require

that we see the world as a system—a system that

connects space; and a system that connects time.

When you think of the world as a system over

space, you grow to understand that air pollution

from North America affects air quality in Asia,

and that pesticides sprayed in Argentina could harm

fish stocks off the coast of Australia. And when

you think of the world as a system over time, you

start to realise that the decisions our grandparents

Fig. 1. The three dimensions of sustainability [8]

made about how to farm the land continue to

affect agricultural practice today; and the economic

policies we endorse today will have an impact on

urban poverty when our children are adults”.

A. Business and Sustainability

According to the dictionary [12], “Business pertains broadly

to commercial, financial, and industrial activity, and more

narrowly to specific fields or firms engaging in this activity”.

However, also the business and its self-conception is

changing. In particular, this became visible, by the Business

Roundtable, an association of chief executive officers of

leading companies in the USA, refining its statement on the

purpose of a corporation in 2019. This refined statement

made a shift from the focus on satisfying shareholders by

making money to a more holistic understanding and aiming for

satisfying customers, employees, communities, suppliers, and

shareholders equally. This shift comprehends an understanding

that financial success is not the sole purpose of business.

For example, the statement says [13]:

“...when it comes to addressing difficult

economic, environmental and societal challenges,

these companies are starting in their own backyards

– partnering with communities to provide the

investment and innovative solutions needed to

revitalize local economies and improve lives.

These investments and initiatives aren’t just

about doing good; they’re about doing good business

and creating a thriving economy with greater

opportunity for all.”

Although, when talking about sustainability, the Business

Roundtable refers only to energy and environment, they show

DRAFT

an understanding of sustainability as it is defined by the

Brundtland report [5], [14] by pointing out the importance and

interdependence of the economic, environmental, and societal

challenges.

At the organisational level, there are concrete movements

aiming to answer the question of how an organisation can

be more balanced across the three sustainability pillars. They

recognise that capitalism, as it’s currently practised, is starting

to run into fundamental structural problems.

In the US, B Lab [15] has worked to create a

certification of “social and environmental performance” to

evaluate for-profit companies. B Lab certification requires

companies to meet social sustainability and environmental

performance, and accountability standards, as well as being

transparent to the public according to the score they receive

on the assessment. Later on, they also developed the

concept of “benefit corporations”, companies that legally

commit themselves to honour moral values, while pursuing

the standard capitalist goal of maximising profits. A few

examples of well-known benefit corporations include Method,

Kickstarter, Plum Organics, King Arthur Flour, Patagonia,

Solberg Manufacturing, Laureate Education, and Altschool.

In Europe, Economy for the Common Good (ECG)

[16] has similar goals. ECG is an economic model, which

makes the Common Good, a good life for everyone on a

healthy planet, its primary goal and purpose. The Economy

for the Common Good (ECG) was initiated in 2010 by

economic reformist and author Christian Felber, together

with a group of Austrian pioneer enterprises. ECG is an

ethical model for society and the economy with the goal of

reorienting the free market economy through a democratic

process towards common good values. According to Felber,

it seeks to address a capitalist system that “creates a number

of serious problems: unemployment, inequality, poverty,

exclusion, hunger, environmental degradation and climate

change”. The solution is an economic system that “places

human beings and all living entities at the centre of economic

activity”.

At the heart of ECG lies the idea that values-driven

businesses are mindful of and committed to: 1) Human

Dignity; 2) Solidarity and Social Justice; 3) Environmental

Sustainability, and 4) Transparency and Co-Determination.

ECG is currently supported by more than 1800 enterprises

in 40 countries such as Sparda-Bank Munich, VAUDE,

Sonnentor, and taz (German newspaper), about 250 have

created a Common Good Balance Sheet. This balance sheet

is a scorecard that measures companies based on their

preservation of those 4 fundamental values, considering 5

key stakeholders: Suppliers; Owners/Equity/Financial Service

Providers; Employees/Co-worker employers; Customers/Other

Companies; and Social Environment.

B. ICT/Technology and Sustainability

The idea of using Information and Communication

Technologies (ICT) to address sustainability issues has

been investigated in a number of interdisciplinary fields

that combine ICT with Environmental and/or Social

sciences. Amongst these are Environmental informatics,

Computational sustainability, Sustainable Human-Computer

Interaction, Green IT/ICT, or ICT for Sustainability [4].

The contributions of these fields are manifold:

monitoring the environment; understanding complex systems;

data-sharing, and consensus-building; decision support for the

management of natural resources; reducing the environmental

impact of ICT hardware and software; enabling sustainable

patterns of production and consumption; and understanding

and using ICT as a transformational technology.

For these different areas, there is a common understanding

that ICT can be used to reduce its own footprint and to support

sustainable patterns [4]:

• Sustainability in ICT (also referred as Green in ICT):

Making ICT goods and services more sustainable over

their whole life cycle, mainly by reducing the energy and

material flows they invoke.

• Sustainability by ICT (also referred as Green by ICT):

Creating, enabling, and encouraging sustainable patterns

of production and consumption

The problem with this differentiation is that often

sustainability in and by ICT are intertwined. When analysing

the impact of certain technology, looking for a final positive

or negative conclusion, it is not possible to assess it in isolated

contexts to make a decision. A positive positive occurs when

the effect of a sustainable activity on the social fabric of the

community causes well-being of the individuals and families

considering the three pillars [17]. Thus, assessing the ICT

impact needs to consider that [4]:

“Sustainable development [...] is defined on a global

level, which implies that any analysis or assessment

must ultimately take a macro-level perspective.

Isolated actions cannot be considered part of the

problem, nor part of the potential solution, unless

there is a procedure in place for systematically

assessing the macrolevel impacts”.

Therefore, the assessment of specific technology impact

on sustainable development must consider its nuances and

inter-dependencies on multiple levels, that might be on both

spaces of “in” and “by”. A good example is provided in [18],

p 284:

“[...] history of technology has shown that increased

energy efficiency does not automatically contribute

to sustainable development. Only with targeted

efforts on the part of politics, industry and

consumers will it be possible to unleash the true

potential of ICT to create a more sustainable

society”.

III. AGILE AND SUSTAINABILITY

If agile is really aiming for sustainability, as it is suggested

by the vision of both the Agile Alliance and the Scrum

Alliance, then we should take a look at the principles of

the Agile Manifesto to understand how these principles can

DRAFT

contribute to or guide sustainability [3]. Sustainability requires

a much broader view to integrate the environmental, economic,

and social perspectives.

A. Our highest priority is to satisfy the customer through early

and continuous delivery of valuable software.

At the core of this very first principle is continuous

learning by focusing constantly on the customer. Only

through continuous delivery you will be able to keep

adjusting the system to the customer’s satisfaction. Broadening

the perspective, and looking at this principle through a

sustainability lens, that is taking also the environmental

and social aspect into account, shifts also the meaning of

“valuable” software. The value is not only defined by the

economic benefit for the customer but also by the social and

environmental improvements.

Moreover, by broadening the perspective, we’ll find that it

will become even harder to come up with a perfect solution

right away. For example, measuring the carbon footprint

of the system you’re building will teach you what aspects

you need to adapt, rethink, and redo. Thus, adding two

more dimensions (environmental and social) increases the

complexity of development and thus, continuous learning is

even more important to uncover emergent practices [19].

B. Welcome changing requirements, even late in development.

Agile processes harness change for the customer’s competitive

advantage.

This second principle addresses sustainability by ICT, by

focusing on the customer (like the principle before). At first

sight, the “customer’s competitive advantage” sounds like it

can only aim for economical success. Yet, the advantage

can also be built by a reputation of the product as being

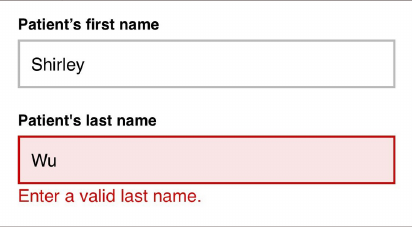

environmental and social friendly. As a counter example, the

authors have seen websites that require the specification of

the first and last name of the user (Figure 2

1

). However, both

need to be at least three characters long. If the developers

would have been socially aware they would have understood

that there are many people (especially in Asia) whose names

are only two characters long. This is only a minor example

but still shows how broadening the view can make a difference

for the customer - by gaining a good or bad reputation.

Fig. 2. Application requiring two characters for last name

1

https://twitter.com/shirleyywu/status/1300628412466298881?s=20

To provide the customer this kind of competitive advantage,

we have to answer:

• How is the product that we’re creating helping the world?

• How is it part of a wider sustainable solution?

• How can we ensure the product is inclusive?

• How can the product even improve the environment?

• How can we ensure the product itself is environment

friendly?

C. Deliver working software frequently, from a couple of

weeks to a couple of months, with a preference to the shorter

timescale.

Similar to the first principle, also this one focuses on

continuous learning. The difference is that this third principle

asks to establish a regular cadence for feedback. The shorter

the feedback cycle, the better, because then we can keep

the focus on the learning about the changes in the system

by the last delivery. This principle is important for tackling

sustainability because the knowledge, wisdom, and experience

is steadily increasing in all three dimensions (economical,

social, and environmental) and this learning has to be reflected

in the system.

For example, although we might have designed the system

to be highly accessible, only by getting the feedback from the

people who are in the need of the accessibility will we know

how well the system performs. Similarly, we can learn from

the real carbon footprint of the system only when we know

how it performs in reality.

To continuously learn from the delivery you should

regularly ask yourself questions as [20]:

• Does the system work for people with disabilities?

• Does the system work for people using older devices?

• Does the system provide the best possible performance

with the least amount of resources across devices and

platforms?

D. Business people and developers must work together daily

throughout the project.

This is the fourth principle of the Agile Manifesto and

points out the importance of collaboration between the ones

creating the product or service (developers) and the ones

who want to offer that product or service to the market.

Continuous collaboration enables self-organisation around the

system created and this allows to discover and actually meet

the market needs.

The collaboration between business people and developers

is not market focused only (anymore), but keeps the

wider perspective of addressing all three dimensions of

sustainability. This includes a reflection on the market

we serve, disrupt, and/or create. For example, in the last

decades car manufacturers did create a market for heavy

and environmental unfriendly cars (the sport Utility Vehicles,

SUVs) and hesitated on the other hand to create a market for

electric cars with the argument that this market does not exist

[21].

DRAFT

Thus, this principle is a continuous reminder to consider all

aspects of sustainability in our daily work.

E. Build projects around motivated individuals. Give them the

environment and support they need, and trust them to get the

job done.

This is the principle number five and directly mentions the

environment. First of all, this principle is a call to action

for sustainability in ICT. At first sight, the social pillar is

emphasising the importance of supporting the individuals for

example, by paying them fair (also despite any difference

in i.e., race, gender, religion, location, etc.). Providing an

environment that helps the individuals to self-organise for

getting their job done includes the technical tools yet, also

the safety of the environment: the individuals are not put at

risk by e.g. a polluted or toxic work-space (think of asbestos,

colours, or carpets that evaporate toxic emissions).

Moreover, the environment can also contribute, neutralise,

or reduce the carbon footprint. For example, by the energy

that is used, the availability of natural light, the existence of

natural plants, or the commute that is required. Finally, from

an economic point of view, this principle also requests that

the environment allows every individual in the same way to

prosper and grow by offering life-long learning.

F. The most efficient and effective method of conveying

information to and within a development team is face-to-face

conversation.

This sixth principle puts direct conversation at the core.

Face-to-face conversation provides transparency particularly

from the social and economic point of view. If the system you

are building should support for example, (individual) growth

and development or / and inclusiveness, then you will get

qualitatively better feedback from the users if talking to them

directly. Direct observation, eye contact, mimic, and gesture

provide additional information how well the system is serving

the users.

This principle invites as well to build a community with

everyone involved in making the product sustainable. The

community reflects in the process and in the product it is an

interdependent relationship.

G. Working software is the primary measure of progress.

This principle aims for transparency. Certainly, it is

important to think ideas through however, you will only know

if they keep their promises when hitting reality. This includes

to regularly examine the system for unintended consequences

(also known as the precautionary principle [22]). Therefore,

it is also the responsibility of an agile team to prevent and

monitor for any unintended consequences in order to address

them [23].

Therefore, never underestimate the importance of feedback

for example, on energy consumption on the running system,

theory and reality do not always show the same results. From

the social perspective, regularly examine the working system

guided by questions as:

• Does the system work in the same way for everyone

independent if i.e., the gender differs or it is used by

people from different races or ethnicity?

• Would a domestic abuser find possibilities to do harm to

the system but more so to other people?

• Can the system be used by a government to oppress?

We suggest to take a look at other questions, for example the

ones offered by the Ethical Explorer toolkit [24].

H. Agile processes promote sustainable development. The

sponsors, developers, and users should be able to maintain

a constant pace indefinitely.

This is the eighths of twelve principles and the only one

that calls for sustainable development explicitly. It focuses

foremost on sustainability in ICT. Thus far, this principle has

mainly been understood from the social aspect for example,

calls for the ’40 hour week’ have been argued with the

reference to this principle [25].

Using the lens of sustainability, it asks that developers

learn continuously about all three pillars and take the learning

into account: environment, social, and economic. Therefore,

having a constant pace in mind, developing the product or

service should not lead to burnout of the developers (social),

to reduction of resources (environment), or to overspending

financially (economic). For example, the features developed

should take the diversity and the abilities of the users into

account, the energy used creating the product should be

renewable, and the so-called feature-creep should be avoided.

Feature-creep, the inclusion of unnecessary features and the

development of features that do not adhere to the intended

design and architecture leads to inefficiency of the overall

system. Moreover, the utilised capacity of the CPU in idle

mode or the demand for storage are reasons for software

getting slower.

Therefore, sustainable development has to be taken into

account by the developers and the sponsors to ensure that, for

example, the user is not required to invest in a new hardware

regularly. Modularity and allowing the user to determine which

modules to buy, install, and use take into account that not every

user will need every possible innovation (at least not on every

device).

I. Continuous attention to technical excellence and good

design enhances agility.

Developments in sustainability are progressing fast - from

new understandings of algorithm bias (social aspect), or of

where most energy is used and how it could be reduced

i.e. by storing data locally and reducing network traffic

(environmental aspect) to better ways for finding out which

features are actually used and so - to ensure that money is not

wasted by feature-creep.

Thus, this ninth principle, is a call for continuous learning

and for keeping technologically up-to-date and taking into

account new learning and development that enable good

design: now good in the sense of sustainability. This ensures

the principle supports sustainability in ICT.

DRAFT

J. Simplicity–the art of maximising the amount of work not

done–is essential.

The tenth principle often requires a second read before

it is understood. In general, it addresses the feature-creep

mentioned above. So, when developing software, we need

to pay attention to what is really needed in the product.

Looking through a sustainability lens at this principle,

we need to examine for example, how does this new

feature fit in the system without increasing the energy

consumption? Using Scrum as an example, sustainability or

rather energy consumption needs to be considered during

backlog refinement, sprint planning, by the definition of done,

as well as monitored through tests.

The German Federal Environment Office created and

published in 2020 a label (or certificate) “Blauer Engel” for

resources and energy-efficient software stand-alone products,

based on a criteria catalogue jointly developed by the

university of Trier and Zurich [26], [27]. The label focuses

on energy-efficiency, conservative resource consumption, and

transparent interfaces. The plan is to develop a similar label

for cloud-based software. However, already today, the criteria

catalogue can guide a team to develop a sustainable system.

For example, the following questions should be regularly

discussed [27]:

• How much electricity does the hardware consume when

the software product is used to execute a standard usage

scenario?

• Does the software product use only those hardware

capacities required for running the functions demanded

by the individual user? Does the software product provide

sufficient support when users adapt it to their needs?

• Can the software product (including all programs, data,

and documentation including manuals) be purchased,

installed, and operated without transporting physical

storage media (including paper) or other materials goods

(including packaging)?

• To what extent does the software product contribute to

efficient management of the resources it uses during

operation?

Thus, this principle requires transparency for features that are

needed (and used) and those that are not.

K. The best architectures, requirements, and designs emerge

from self-organising teams.

The eleventh principle points out the benefits of

self-organising teams. This includes that every team member

is invited to speak up and make their contribution to the

architecture, requirements, and design - independent of other

characteristics of that team member (social perspective).

Similarly, all team members will get the same fair chance to

progress on the their career by getting equal support through

training, mentoring, or coaching (economic perspective).

L. At regular intervals, the team reflects on how to

become more effective, then tunes and adjusts its behaviour

accordingly.

The twelfth and final principle asks teams to run regular

retrospectives. Both the reflection and behavioural adjustments

should take (also) sustainability aspects into account: how

can the team tune and adjust its behaviour to become more

effective regarding the three pillars - environmental, social,

and economical? Dedicating time regularly for reflecting on

sustainability will lead to continuous improvements. This last

principle combines the quest for teams to self-organise in order

to learn continuously by making their effectiveness with the

focus on the customer transparent.

M. Summary of the Agile Manifesto’s Perspective on

Sustainability

Implementing sustainable development goals requires

approaching wicked problems, i.e. complex, non-linear,

dynamic challenges in situations of insufficient resources,

incomplete information, emerging risks and threats, and fast

changing environments [28]. Examining the principles of

the Agile Manifesto shows how an agile approach indeed

promotes (or can promote) sustainable development. It might

be surprising how much guidance the principles can provide

although they have been defined originally with the focus on

software development only.

Concentrating continuously on inspect and adapt allows

sustainable systems to emerge. An agile, cross-functional

team integrates different perspectives on the emerging system

and has this way the possibility to design solutions for

sustainability. The disciplined approach provided by agile

development enables the team to permanently learn from their

delivery, to measure the outcome according its environmental,

social, and economic impact and take according actions for

adjustments.

However, taking all three dimensions of sustainability into

account leads to higher complexity, so an agile approach also

comes in handy for addressing this complexity by breaking

down the problems and using an inspect and adapt approach

for making them simpler.

The role of Agility is not to save the world, but to provide

a value system based on transparency, constant customer

focus, self-organisation, and continuous learning that leads

into sustainable thinking and offers an approach that supports

putting this sustainable thinking into action.

IV. CASE STUDIES: LEVERAGING AGILITY FOR

SUSTAINABILITY

Although the Agile Manifesto [3] originates in 2001 and

the Brundtland report [5] in 1987, the combination of agility

and sustainability is just in its beginnings. There are some

sample companies being conscious of one of the three pillars

and even fewer sample companies taking a holistic approach

on combining sustainability and agility. In this section we will

provide some sample case studies for both attempts - agility

DRAFT

and one of the three pillars as well as company-wide agility

and sustainability using a holistic approach.

We want to point out that for the following case studies,

as for other examples, there is no such thing as a “perfect”

company, neither in terms of sustainability nor in terms of

agility. However, these case studies still can serve as examples

of possible steps to take in order to leverage agility for

sustainability.

A. Agility and Partial Sustainability

In this section, we explore different examples from

companies applying agility on one of the three pillars - social,

environmental, and economical - individually. The examples

show that being conscious about sustainability can be guided

by an agile approach.

1) The Social Pillar: Often, we act as if our responsibility

would end by delivering the value to the customer. An agile

team typically aims to deliver regularly high value for the

customer’s advantage. After the (or rather after each) delivery,

the team’s job is completed (except for maintenance and

further development). However, if the team takes the full

responsibility of their products, then they are also interested in

the usage of the product and consider its impact to the world.

For example, some developers working for CHEF (a

company providing a configuration management tool with

the same name) were also interested in how their customers

are using the product and how this is supporting the social

good. In this case, these developers learned that one of their

customers, the Customs and Border Protection or Immigration

and Customs Enforcement (ICE), uses the product at the

border between Mexico and the United States of America

for running detention centres, ensuring deportation, and for

implementing the family separation policy. In this case, the

developers took the Brundtland definition (sustainability is

about taking long-term responsibility for your action) and the

social aim of ending poverty by heart and decided that the

usage of their product does not confirm with their ethical

values and has an unintended social impact.

In the beginning, the developers brought their ethical

interest to the attention of CHEF’s management. However,

the management at first referred to the long-standing contract

and to the fact that the product has been used by ICE for

many years (and nobody complained). The developers kept

trying to convince the management that due to the change

in politics also the usage of the product has shifted to the

worse. However, the developers could only make a difference

once one of the developers decided to delete all the code he

contributed to the (Open Source) software. As a consequence,

the product was not usable anymore for two weeks which

created enough pressure for the management to decide on not

renewing the contract [29].

It is important to understand that delivering value and

satisfying the customer with your product is not an agile

teams’ sole responsibility. An agile team is also responsible

for the social impact of the product it is creating. This means

for a truly agile team, to stay in touch with the customer for

recognising any differences in the usage of the product. This

ongoing connection can be supported by automation such as

monitoring, logging, and having tests that observe the usage

of the product.

2) The Environmental Pillar: The environmental pillar is

mostly connected with the resources consumed. The global

e-waste monitor reports that in 2016, 44.7 million metric tons

of e-waste were generated – most often because the hardware

gets (seemingly) too soon outdated [30]. Additionally, as

Nicola Jones reports, by 2030 information technology might

exceed 21% of the global energy consumption [31].

Thus, it gets more and more important to consider the

energy consumption of the products we are creating. Often

it is assumed that hardware is cheap and thus, there is no

need to pay much attention to performance, because if the

software is not performing well enough we request that the

hardware is getting faster. This proves Wirth’s law from 1995

[32]: “Software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware

becomes faster”. As elaborated by Gr

¨

oger and Herterich, one

of the reasons for this effect is the feature-creep where features

are developed for a product that are unnecessary (not used) and

don’t fit the intended software architecture [33].

The Mozilla foundation argues for the importance of

examining cloud-based software in particular. In their 2018

Internet Health Report, they concluded that data centres have

a similar carbon footprint as global air traffic with the latter

being 2% of all greenhouse gas emissions [34].

However, while some companies ignore the problem despite

the protests of their employees (see Amazon [35]), others

address it by shifting toward renewable energy for their

data centres (see Google [36]). This means for an agile

organisation when deciding on a cloud infrastructure that it

is essential to also consider the carbon footprint of that data

centre. Therefore, it is the responsibility of an agile team to

bring not only any technical information but also information

about energy consumption and the carbon footprint of the

infrastructure under question to the attention when the decision

is up.

Another example is Mightybytes, a company focusing on

developing digital strategies to create the design and user

experience for their clients [20]. By doing so, they pay

particularly attention to how much energy is consumed by

the designs they are creating and decide, for example, against

including videos with high energy consumption. Additionally,

they also take care of the environment the developers are in by

ensuring the carpets are not toxic, there is enough space for

everyone, natural light and plants, plus the offices are powered

with renewable energy. Finally, other examples of initiatives

that explore energy aspects in ICT can be found in [37], Part

II.

3) The Economical Pillar: The economic dimension is

often understood as the economic balance, e.g. that no nation

(or company) grows economically at the cost of another one.

Thus, topics like fair trade or paying fairly are often discussed

along these lines. While this can be a topic also in (agile)

software development, according to our experience this is

DRAFT

seldom the case because, agile developers are still benefiting

from good payments globally (however, this statement is not

based on any research). Yet, there is another economic impact

for organisations, because as the Cone Communications

CSR study revealed, a company’s reputation regarding their

sustainability efforts will have an effect on both their market

share and their search for talent [38]. For example, as reported

in this study:

“Nearly nine-in-10 Americans (89%) would switch

brands to one that is associated with a good cause,

given similar price and quality, compared with 66

percent in 1993. And whenever possible, a majority

(79%) continue to seek out products that are socially

or environmentally responsible”.

An economic impact can also be made by organisations

and teams through sharing learning. One example is Munich

Re, one of the world’s leading re-insurers, who got concerned

about climate change already in the 70’s. At that time,

they began collecting and publishing research data about

climate change. Protecting the research data for a competitive

advantage was never considered by Munich Re because they

realised that transparency allows them to learn from others and

to improve the data. Transparency, they decided will increase

both the general societal awareness of climate change and their

own resilience [39]. This insight provided a great foundation

for Munich Re’s further effort in combining also the other

two pillars (environmental and social) with a general agile

approach [40], [41].

Transparency is also key for all the lessons learned in the

near future on how to make the software we are creating

more sustainable – only if we make those learning transparent

right away, we can make a huge difference for everyone,

everywhere.

B. Company-wide Agility and Holistic Sustainability

Implementing agility company-wide comes with a

responsibility. Professionals as well as companies who claim

to be agile are expected to also “take actions based on the best

interests of society, public safety, and the environment” [2].

Similarly, are corporate Agile Alliance members expected to

“to help make the software industry humane, productive, and

sustainable” [1]. This means agile companies are expected to

have a systemic view and understand the impact of the own

actions and products created. This means, an organisation

implementing company-wide agility has to have a wider

perspective than one that is aiming at business agility only,

as defined by the Business Agility Institute [42]:

“Business agility is the capacity and willingness of

an organisation to adapt to, create, and leverage

change for their customer’s benefit!”

Thus, business agility focuses on the customer only whereas

agile organisations aim for humanity and sustainability while

having the society and the environment in mind. In this section

we will explore companies that made quite some progress in

implementing company-wide agility in that sense by having a

holistic perspective on all three pillars, thus acting with social,

environmental, and economical outcomes in mind.

1) Patagonia: Patagonia, Inc. is an American clothing

company that markets and sells outdoor clothing since 1973.

The company has become recognised as a leading industry

innovator through its environmental and social initiatives, and

the brand is now considered synonymous with conscious

business and high-quality outdoor wear. In 2019, Patagonia

received the 2019 Champions of the Earth award from the

United Nations [43], being recognised as an organisation that

has sustainability at the very core of its successful business

model.

Patagonia’s mission statement is “We’re in business to save

our home planet”. They implement it by accomplishing a

number of initiatives that inspires all levels of the organisation,

as donating profits from their Black Friday sales (millions

of dollars) to the environment through grassroots movements

[44], or creating their new office space by restoring condemned

building using recycled materials. The company states its

benefits as: 1% for the Planet; Build the Best Product

with No Unnecessary Harm; Conduct Operations Causing

No Unnecessary Harm; Sharing Best Practices with Other

Companies; Transparency; and Providing a Supportive Work

Environment.

Patagonia has been cited as an example for Agile

Organisations, not only because it has agile teams, but

because they embody a north star across the organisation

that recognises the abundance of opportunities and resources

available, reducing the mindset of competition and scarcity

and moving towards co-creating value with and for all of our

stakeholders [45].

Other examples of their practices that demonstrate their

concern about the three pillars are: encouraging consumers

to think twice before making premature replacements, or

over-consuming; designing durable textile yarns from recycled

fabric; upholding a commitment to 100% organic cotton

sourced from over 100 regenerative small farms; sharing its

best practices through the Sustainable Apparel Coalition’s

Higg Index; paying back an “environmental tax” to the earth

by founding and supporting One Percent For The Planet;

donating its $10 million federal tax cut to fund environmental

organisations addressing the root causes of climate change.

As an example of social impact, Patagonia invests on

improving the supply chain to alleviate poverty. They

screen their partners, as factories and more recently farms,

using Patagonia staff, selected third-party auditors and NGO

certifiers. They recognise a number of challenges, specially in

the farm level [46], pp. 30:

“There can be land management and animal

issues, as well as child labour, forced labour, pay

irregularities, discrimination, and unsound health

and safety conditions. These are often more difficult

to resolve because of the complexities that extreme

poverty, illiteracy and exploitation bring to this level

of the supply chain.

When it comes to land management, we’re most

DRAFT

concerned with a farm’s use of chemicals and the

impact its operations have on water, soil, biodiversity

and carbon sequestration. For animal welfare, we

look at humane treatment and slaughter. And when

it comes to labour, we want to see safe and healthy

working conditions, personal freedom, fair wages

and honest payrolls.”

More recently, the company has started to support

regenerative agriculture, establishing a goal of sourcing 100%

of their cotton and hemp from regenerative farming by 2030.

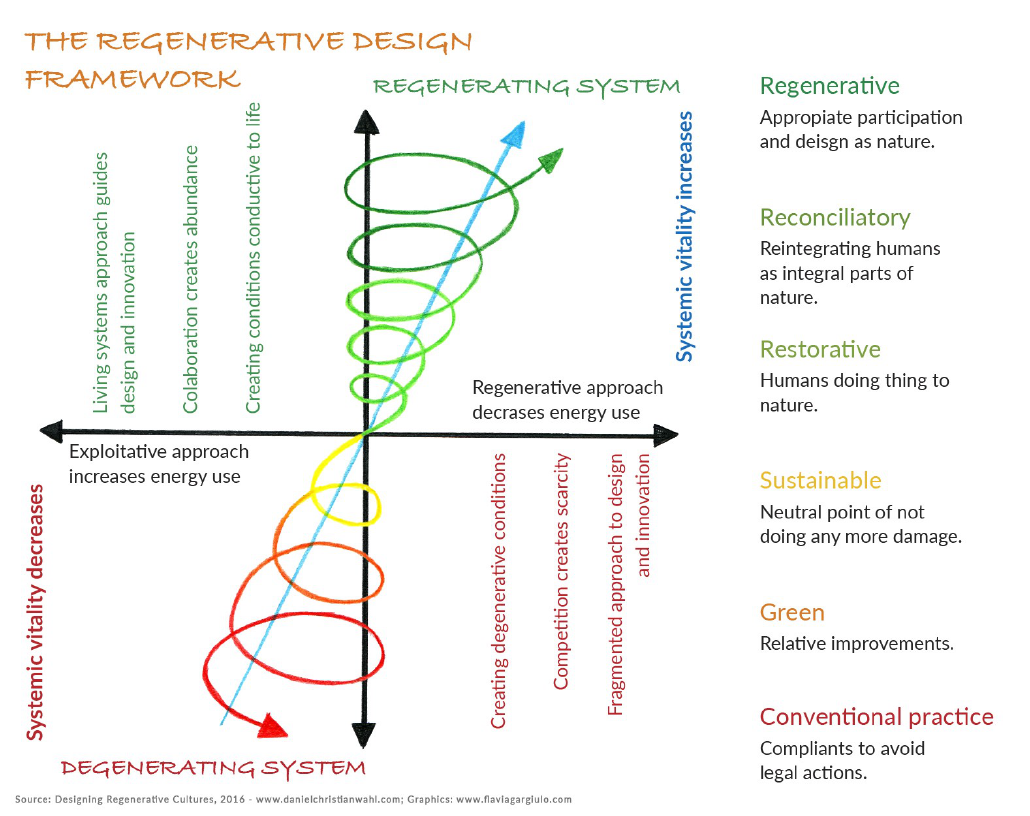

It is important to stress how relevant this initiative is by

introducing the meaning of regenerative. While the concept

of sustainable refers to a neutral point of not harming or

damaging, the regenerative concept goes beyond, stating that

Humans are not only doing the right things to nature, but

actually are an integral part of it, learning how to design as

nature does [47]. This means we can reverse the damage we’ve

already done. Figure 3 illustrates the continuum between 1)

the conventional practices our society adopts in many areas,

2) sustainable practices, and 3) regenerative practices.

Patagonia is a founding member of the Regenerative

Organic Alliance

2

, alongside Dr. Bronner’s, Compassion in

World Farming, Demeter and the Fair World Project and

others. They created a certification that showcases whether a

product has been made using processes to regenerate the land

or not.

Thus, supporting regenerative agriculture is a bold step

Patagonia is taking that helps to reverse damage and create

abundance. The reason is that agricultural practices are a

huge contributor to climate change, accountable for around

25% of global carbon emissions. Regenerative agriculture has

the intention to restore highly degraded soil, enhancing the

quality of water, vegetation and land-productivity altogether. It

makes possible not only to increase the amount of soil organic

carbon in existing soils, but to build new soil [48]. If more

companies follow this example, we will see more ecosystems

being restored and communities being benefited.

2) DSM-Niaga: DSM-Niaga is a joint venture of the startup

Niaga and the multinational firm Royal DSM. DSM-Niaga’s

vision is to design for circularity of everyday products. They

started off with carpets and mattresses with the idea to stop

these -most often toxic- products to go into land-fills but

instead to decouple the material and use the very same material

to go into the next production cycle. To guide this idea, they

defined three design principles [49], illustrated by Figure 4:

1) Keep it simple: Use the lowest possible diversity of

materials.

2) Clean materials only: Only use materials that have

been tested for their impact on our health and the

environment.

3) Use reversible connections: Connect different materials

only in ways that allow them to be disconnected after

use.

2

https://regenorganic.org/

For ensuring clean materials only and also proving it,

they developed for example, a digital passport for every

carpet based on blockchain technology. With the focus on

the customer, this passport makes the complete value chain

transparent. DSM-Niaga is also sharing their learning and

pushing the industry to design for circularity:

“Moving forward, we will continue to focus our

efforts and push boundaries to drive transparency

and accountability across value chains. Indeed, with

designers, producers and recyclers all needing to

know what’s in a product in order to recycle it, it’s

only a matter of time before digital product passports

are in demand everywhere”.

DSM-Niaga is focusing on both sustainability and

company-wide agility. The firm is actually a teal organisation,

that is a company defined by self-organisation where for

example, employees are guided by the organisation’s purpose

and not by orders [50]. According to Rhea Ong Yiu, an Agile

Coach at DSM-Niaga, the mother company (Royal DSM) is

constantly learning from DSM-Niaga. Under the leadership of

Feike Sijbesma, CEO and Chairman of the Managing Board,

Royal DSM sold its entire petrochemical business. This has

also been recognised. As a consequence, Feike Sijbesma has

been appointed as Global Climate Leader for the World Bank

Group, Co-Chair of the Carbon Pricing Leadership Coalition,

and as Co-Chair of the Impact Committee of the World

Economic Forum where he is one of the originators of the

“Stakeholder Principles in the COVID Era”. The latter states

among other things [51]:

“we must continue our sustainability efforts

unabated, to bring our world closer to achieving

shared goals, including the Paris climate agreement

and the United Nations Sustainable Development

Agenda”.

Worth mentioning that the business strategy of Royal DSM

(and as such as well of DSM-Niaga) is based on the United

Nations Sustainable Development Goals. The sustainable

development goals that are in particular focus for DSM-Niaga

are [52]:

• Good health and well-being (Goal 3): Ensuring healthy

lives and promoting well-being for all at all ages.

• Responsible consumption and production (Goal 12):

Ensuring sustainable consumption and production

patterns.

• Climate action (Goal 13): Taking urgent action to combat

climate change and its impact.

3) Sparda-Bank Munich: Sparda-Bank is the largest

cooperative bank in Bavaria, with more than 300,000

members. The bank maintains on its website a comprehensive

description on how they implement all Economy for the

Common Good (ECG) values, as well as their Common Good

Balance Sheets and the certificate. Sparda was part of the first

companies that agreed on ECG goals, back in 2010, being the

first - and so far only - bank that operates according to the

principles of the common good economy.

DRAFT

Fig. 3. Continuum between Conventional, Sustainable and Regenerative practices [47].

At the same time, the company keeps looking for innovation

and agility [53]. So the organisation needs and it is opened to

technological solutions. Due to its own values, it would have

to carefully examine the need for and impact of the tools that

it adopts. In fact, Sparda does have agile coaches and digitised

solutions for their clients. They have also regularly had formats

such as “World-Caf

´

e” or smaller events with a “marketplace

character” that are carried out in order to obtain the opinion of

as many participants as possible and to initiate a dialogue. The

design thinking method is adopted to support their product and

projects solutioning.

The company claims on its website [54] that they are climate

neutral and provides an annual CO2 balance. They reduce

greenhouse gas emissions to the extent to what is technically

and economically possible, or otherwise by purchasing climate

certificates (or permits) in accordance with the Kyoto Protocol,

which [55]:

“operationalizes the United Nations Framework

Convention on Climate Change by committing

industrialized countries and economies in transition

to limit and reduce greenhouse gases (GHG)

emissions in accordance with agreed individual

targets [...]

One important element of the Kyoto Protocol was

the establishment of flexible market mechanisms,

which are based on the trade of emissions permits”.

Sparda-Bank has other initiatives that cover different aspects

of the common good matrix. For instance, planting a tree for

every new member or agreements to provide green electricity

with special tariff for their clients. When financing an electric

or hybrid car or an e-bike, Sparda-Bank Munich customers

receive a reduced interest rate. They also state having no

customer relationships with or investments in companies

whose core business is in the armaments sector, as well as

many other restrictions published on their website [56].

There are other examples related to suppliers and

DRAFT

Fig. 4. Design Principles of DSM-Niaga

employees: they buy dishes and towels from works for the

blind and disabled; they work to reduce the difference between

the lowest salary and the highest salary (CEO)(which is

currently published as 1:13.7 ratio); and finally they don’t pay

commissions or establish individual goals related to salary,

only goals at a team level.

V. CONCLUSION

This paper examined that agility can contribute to

sustainability. As we have seen, the Agile Manifesto in general

and the principles in particular can provide guidance to

sustainability [3]. We have presented some achievements of the

companies combining agility and sustainability. We explored

examples of companies focusing on one of the dimensions

only, as well as companies taking all three pillars into account.

Certainly, if an agile company takes sustainability seriously,

then it has to take an holistic view and look at all three

dimensions at once - at people (social), planet (environmental),

and profit (economic).

We have seen that most of these sample companies in the

case studies are concentrating on using agile development and

sustainability yet, without the focus on leveraging the one

with the other. Especially the companies following a holistic

approach implement sustainability by ICT. Using an agile

approach for implementing sustainability in ICT seems to be

a relatively new field.

A. Criticism

Sustainability became a trend and a symbol for progressive

individuals, movements, and organisations, which sometimes

leads to the so-called green-washing. It happens when it seems

to be important to have a reputation of being sustainable

yet, not everyone who claims to live up to it really does it.

Often this is supported by advertising for ones own sustainable

reputation as [20] exemplifies:

“One hosting provider even claims in its marketing

materials that it plants a tree for every new account,

which is wonderful, but doesn’t move us closer to

an Internet powered by renewable energy”.

Sustainability and its deeper implications are still not

well-understood by society, despite more diffused, in particular

because of the UN 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development.

Initiatives on many sectors, from business to NGOs and

universities can easily distort or simplify it, intentionally or

not. Taking the example of companies, we illustrated agile

organisations that aim at balancing the 3 pillars in section

IV-B, considering BCorps and ECG certified companies. It is

important to be aware of the criticism (or limitations) around

these models.

The main critique to BCorps and similar movements is that

these models still rely on capitalism as the core mechanism -

and world view - for our economy, “ignoring the possibility

that capitalism itself, as it is largely practised today, might be

at least one cause of the problems we are seeking to solve”

[57]. This analysis is also supported by Nobel Prize winning

economist Joseph Stiglitz [58]:

“Like the dieter who would rather do anything to

lose weight than actually eat less, this business

elite would save the world through social-impact

investing, entrepreneurship, sustainable capitalism,

philanthro-capitalism, artificial intelligence,

market-driven solutions. They would fund a

million of these buzzwordy programs rather than

fundamentally question the rules of the game— or

even alter their own behavior to reduce the harm of

the existing distorted, inefficient and unfair rules”.

High expectations are on digitalisation for sustainability by

ICT. One example is that it is the replacement for paper, but, all

digital products (thus, also the paper replacements) consume

energy. Moreover, as Lorenz M. Hilty points out in [33]:

DRAFT

“So far, neither in the case of air travel nor in

the case of lifespan of household goods has the

hope been fulfilled that due to digitalization the

material and energy intensity of our activities would

be reduced. It rather became evident in the digital

age that providers turned the principle of intangible

value creation through software into its opposite by

stimulating or even forcing material consumption

through software”.

One reason is Wirth’s law (Software is getting slower more

rapidly than hardware becomes faster) that an update in

software often requires the exchange of hardware [32].

Another reason is the rebound effect: the effect that

environmental friendliness is a selling point that leads to

overall higher consumption than before. And a third reason

(related to the rebound effect) is, that the environmental

friendly product is often used in addition - and not instead

- to the environmental unfriendly product. An example for

the latter are many car sharing offerings that are not used for

substituting private cars but, instead, for substituting travelling

by (local) public transport [33]. Thus, the rebound effect is

the main controversy for all achievements of digitalisation

regarding sustainability.

B. Outlook

Although agile development promises sustainability for a

long time, it has not been addressed sincerely thus far.

However, there are some promising developments and also

concrete ideas for delivering on agility’s promise. Most

importantly, we have to increase the awareness of the impact

of agility so that at least agile teams can make conscious

decisions on effecting the social, environmental, or economical

dimension of sustainability.

An agile team can for example, consider the energy

consumption in their definition of done as well as via

respective tests and monitoring. Individual teams and

companies might discover ways to improve their own and

their ecosystem’s sustainability. Yet, only if these learning are

shared and the effort improving sustainability is a collaborative

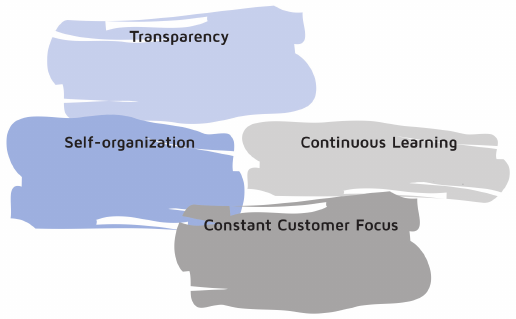

one, can we really make a difference. As pointed out by

Eckstein & Buck, a company claiming to be agile also has

to aim for sustainability and as such needs to live up to the

following values [59] p. 196, also illustrated by Figure 5:

• Self-organisation: An agile company should understand

itself as a part of an ecosystem, belonging to itself, other

companies, and the whole society.

• Transparency: An agile company makes its learning and

doing transparent for the greater benefit for all.

• Constant customer focus: An agile company understands

all aspects of its ecosystem – be it social, environmental,

or economic – as its customer.

• Continuous learning: An agile company learns

continuously from and with its ecosystem to make

the whole world a better place.

Fundamental for agile companies that are

sustainability-aware is the need for a connected perspective

Fig. 5. Four values guiding agile companies [59]

[59], p. 198: “This connected perspective incorporates the

surrounding environment (economic, ecologic, societal, and

social) in which companies operate.” Thus, companies have

to fulfil their role as active members of the society. One

way for doing so, is by joining networks that focus on

improving the economic, social, and environmental aspects of

the society. Sample networks are: transparency international,

global compact, fair labour association, or the climate group

[60]–[63].

Sustainability is not only important for (agile) companies

because it’s part of the Agile’s vision [1], [2]. It is also

important because it will be the key factor that decides on

the survival of companies both in terms of finding talent and

clients. This is the reason why some companies have already

a sustainability officer in place who ensures sustainability in

its many domains - environmental, economic, and social. It is

the agile community’s task to support the people in this role

in making sustainability real.

With digitalisation becoming more momentum and the core

competency of agile in software development more needs to be

investigated in how agile development can make an important

-positive- contribution for achieving higher sustainability.

Because, as stated by the Karlskrona Manifesto [64]:

“Software in particular plays a central role in

sustainability. It can push us towards growing

consumption of resources, growing inequality in

society, and lack of individual self- worth. But it

can also create communities and enable thriving

of individual freedom, democratic processes, and

resource conservation”.

REFERENCES

[1] Agile Alliance, “Agile alliance vision,” https://www.agilealliance.org/

the-alliance/, 2020.

[2] Scrum Alliance, “Scrum Alliance Vision,” https://www.scrumalliance.

org/, 2020.

[3] K. Beck, M. Beedle, A. van Bennekum, A. Cockburn, W. Cunningham,

M. Fowler, J. Grenning, J. Highsmith, A. Hunt, R. Jeffries, J. Kern,

B. Marick, R. C. Martin, S. Mellor, K. Schwaber, J. Sutherland,

and D. Thomas, “Manifesto for agile software development,”

http://www.agilemanifesto.org/, 2001.

DRAFT

[4] L. M. Hilty and B. Aebischer, “ICT for Sustainability: An Emerging

Research Field,” in ICT Innovations for Sustainability, L. M. Hilty and

B. Aebischer, Eds. Springer International Publishing, 2015, pp. 3–36.

[5] WCED, Our Common Future. Oxford University Press, 1987.

[6] Wikipedia, “Wikipedia Sustainability,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Sustainability, 2004.

[7] World Summit, “World Summit on Social Development,” https://en.

wikipedia.org/wiki/2005 World Summit, 2005.

[8] B. Purvis, Y. Mao, and D. Robinson, “Three pillars of sustainability: in

search of conceptual origins,” Sustainability Science, vol. 14, no. 3, pp.

681–695, 2019.

[9] Investopedia, “Triple bottom line,” https://www.investopedia.com/terms/

t/triple-bottom-line.asp, 2020.

[10] United Nations General Assembly, “Transforming our world: The 2030

agenda for sustainable development,” un.org/ga/search/view doc.asp?

symbol=A/RES/70/1&Lang=E, United Nations, Tech. Rep., 2015.

[11] P. Borowski and I. Patuk, “Selected aspects of sustainable development

in agriculture.” in Proceedings: 2nd International Conference on Food

and Agricultural Economics. ICFAEC, 2018, pp. 154–160.

[12] The American Heritage Dictionary, “Definition of business,”

https://ahdictionary.com/word/search.html?q=business, 2020.

[13] Business Roundtable, “Our commitment to our employees and

communities,” https://opportunity.businessroundtable.org/, 2020.

[14] ——, “Embracing sustainability challenge,” https : / / www .

businessroundtable . org / policy-perspectives / energy-environment /

sustainability, 2020.

[15] Benefit Corporation, “General questions,” https://benefitcorp.net/faq,

2020.

[16] Economy for the Common Good, “What is ECG,” https://www.ecogood.

org/what-is-ecg/, 2020.

[17] Sousa, Thiago C. and Melo, Claudia de O., Encyclopedia of the UN

Sustainable Development Goals: Industry, Innovation and Infrastructure

(SDG9). Springer International Publishing, 2019, ch. Sustainable

Infrastructure, Industrial Ecology and Eco-innovation: Positive Impact

on Society, pp. 1–10.

[18] L. M. Hilty, B. Aebischer, G. Andersson, and W. Lohmann, Eds.,

Proceedings of the First International Conference on Information

and Communication Technologies for Sustainability. ETH Zurich,

University of Zurich and Empa, Swiss Federal Laboratories for Materials

Science and Technology, 2013.

[19] C. F. Kurtz and D. J. Snowden, “The new dynamics of strategy:

Sense-making in a complex and complicated world,” IBM Systems

Journal, vol. 42, no. 3, pp. 462–483, 2003.

[20] T. Frick, Designing for Sustainability: A Guide to Building Greener

Digital Products and Services. O’Reilly Media, 2016.

[21] H. Mortsiefer, “The market doesn’t want electric

cars.” https : / / www . tagesspiegel . de / wirtschaft /

auto-der-zukunft-der-markt-will-elektroautos-nicht / 19634320 . html,

2017.

[22] T. O’Riordan and J. Cameron, Interpreting the Precautionary Principle.

Taylor & Francis, 2013.

[23] E. Tenner, Why Things Bite Back: Technology and the Revenge Effect.

Fourth Estate, 1997.

[24] Omidyar Network, “Ethical explorer,” https://ethicalexplorer.org, 2020.

[25] K. Beck, Extreme Programming Explained. Embrace Change. Reading,

Mass., USA: Addison Welsey, 2000.

[26] Blauer Engel, “Ressourcen- und energieeffiziente softwareprodukte,”

2020. [Online]. Available: https:// www.blauer-engel.de/de/get/

productcategory/171/ressourcen-und-energieeffiziente-softwareprodukte

[27] E. Kern, L. M. Hilty, A. Guldner, Y. V. Maksimov, A. Filler, J. Gr

¨

oger,

and S. Naumann, “Sustainable software products - towards assessment

criteria for resource and energy efficiency,” Future Generation Computer

Systems, vol. 86, pp. 199–210, 2018.

[28] Melo, Claudia de O., “Another purpose for agility: Sustainability,” in

Agile Methods: 10th Brazilian Workshop, WBMA 2019, P. Meirelles,

M. A. Nelson, and C. Rocha, Eds. Springer International Publishing,

2019, pp. 3–7.

[29] T. Chappellet-Lanier, “After protest, open source software company

Chef will let ICE contract expire,” https : / / www. fedscoop . com /

protest-open-source-software-company-chef-will-let-ice-contract-expire,

September 2019.

[30] ITU, “E-waste monitor,” https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Climate-Change/

Pages/Global-E-waste-Monitor-2017.aspx, 2017.

[31] N. Jones, “How to stop data centres from gobbling up the world’s

electricity,” Nature, vol. 561, pp. 163–166, 09 2018.

[32] N. Wirth, “A plea for lean software,” Computer, vol. 28, no. 2, pp.

64–68, 1995.

[33] J. Gr

¨

oger and M. Herterich, “Obsolete by software. how to keep

digital hardware longer alive.” in What connects bits and trees: making

digitization sustainable, A. H

¨

ofner and V. Frick, Eds. Munich,

Germany: oekom, jul 2019, pp. 58–60.

[34] Internet Health Report, “The Internet uses more electricity than. . . ,”

April 2018. [Online]. Available: https://internethealthreport.org/2018/

the-internet-uses-more-electricity-than

[35] L. Matsakis, “Amazon employees will walk out

over the company’s climate change inaction,”

https://www.wired.com/story/amazon-walkout-climate-change, 09

2019.

[36] Google, “Moving toward 24x7 carbon-free energy at

google data centers: Progress and insights,” https : / /

storage . googleapis . com / gweb-sustainability . appspot . com / pdf /

24x7-carbon-free-energy-data-centers . pdf, Google, Tech. Rep.,

2018.

[37] L. Hilty and B. Aebischer, ICT Innovations for Sustainability, 01 2015,

vol. 310.

[38] Cone Communications, “Cone communications csr study,”

https : / / www . conecomm . com / news-blog / 2017 / 5 / 15 /

americans-willing-to-buy-or-boycott-companies-based-on-corporate-values-according-to-new-research-by-cone-communications,

2017.

[39] Wikipedia, “Munich re,” https://en . wikipedia . org/ wiki / Munich Re,

2020.

[40] Munich-RE, “Corporate responsibility report,” https://www.munichre.

com / content / dam / munichre / global / content-pieces / documents /

cr-report-2019.pdf/ jcr content/renditions/original./cr-report-2019.pdf,

2019.

[41] I. Jacobson, “Munich Re Transforms Application Development with

Lean and Agile Practices,” https://www.ivarjacobson.com/sites/default/

files/field iji file/article/munich re case study.pdf.

[42] Business Agility Institute, “Business Agility Institute,” https : / /

businessagility.institute/, 2020.

[43] UN Environment, “Champions of the earth 2019,” https : / / www.

unenvironment . org / championsofearth / laureates ? title = &field award

year value=2019&field award category target id=All, 2019.

[44] CNN Money, “Patagonia’s black friday sales hit $10 million – and

will donate it all,” https://money. cnn.com/ 2016/11/29/technology/

patagonia-black-friday-donation-10-million/index.html, 2016.

[45] McKinsey, “The five trademarks of agile organisations,” https :

/ / www. mckinsey. com / business-functions / organization / our-insights /

the-five-trademarks-of-agile-organizations, 2019.

[46] Patagonia, “Environmental + social initiatives,” https : / / issuu . com /

thecleanestline / docs / patagonia-enviro-2016-europe-eng ? e = 1043061 /

44692562, 2016.

[47] D. C. Wahl, “Why sustainability is no longer

enough, yet still very important on the road to

regeneration,” https : / / medium . com / age-of-awareness /

sustainability-is-no-longer-enough-yet-still-very-important-on-the-road-to-regeneration-57f5a37e05a,

2018.

[48] C. J. Rhodes, “The imperative for regenerative agriculture,” Science

Progress, vol. 100, no. 1, pp. 80–129, 2017.

[49] DSM-Niaga, “Design out waste. Design for circularity,” https://www.

dsm-niaga.com/design.html, 2020.

[50] F. Laloux, Reinventing Organizations: A Guide to Creating

Organizations Inspired by the Next Stage in Human Consciousness.

Nelson Parker, 2014.

[51] World Economic Forum, “Stakeholder Principles in the COVID Era,”

http://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF Stakeholder Principles COVID

Era.pdf, April 2020.

[52] DSM-Niaga, “Design for circularity with Niaga,” https :

/ / www . dsm . com / corporate / solutions / resources-circularity /

design-for-circularity-with-niaga.html, 2020.

[53] S. Marquard, “What the Sparda Bank learns from Silicon

Valley,” https : / / www . stuttgarter-nachrichten . de / inhalt .

digitalisierung-in-der-bankenwelt-wie-die-sparda-bank-selbst-kunden-in-malaysia-hilft.

0a532acf-fc61-40a0-9c70-34db83e0f7b8.html, 2018.

[54] Sparda-Bank, “We are pioneers in climate protection,” https://www.

sparda-m.de/genossenschaftsbank-umwelt-und-klimaschutz, 2020.

DRAFT

[55] UNFCC, “What is the kyoto protocol?” https: / / unfccc .int / kyoto

protocol, 2020.

[56] Sparda-Bank, “Transparency in own investments,” https : / / www .

sparda-m.de/gemeinwohl-oekonomie-eigenanlagen/#innernav, 2020.

[57] J. C. Gilbert, “Are B Corps An Elite Charade For Changing

The World?” https : / / www . forbes . com / sites / jaycoengilbert / 2018 /

08 / 30 / are-b-corps-an-elite-charade-for-changing-the-world-part-1 /

#67395ea97151, 2018.

[58] J. E. Stiglitz, “Review of the book ”winners take all: The elite charade

of changing the world”,” https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/20/books/

review/winners-take-all-anand-giridharadas.html, 2018.

[59] J. Eckstein and J. Buck, Company-wide Agility with Beyond Budgeting,

Open Space & Sociocracy: Survive & Thrive on Disruption.

Braunschweig, Germany: Jutta Eckstein, 2020.

[60] Transparency International, https://www.transparency.org.

[61] United Nations Global Compact, https://www.unglobalcompact.org.

[62] Fair Labor Association, https://www.fairlabor.org.

[63] The Climate Group, https://www.theclimategroup.org.

[64] C. Becker, R. Chitchyan, L. Duboc, S. Easterbrook, M. Mahaux,

B. Penzenstadler, G. Rodr

´

ıguez-Navas, C. Salinesi, N. Seyff, C. C.

Venters, C. Calero, S. A. Koc¸ak, and S. Betz, “The karlskrona manifesto

for sustainability design,” CoRR, 2014.