AGILE

P L A Y B O O K

1

INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................4

Who should use this playbook? ................................................................................6

How should you use this playbook? .........................................................................6

Agile Playbook v2.1—What’s new? ...........................................................................6

How and where can you contribute to this playbook?.............................................7

MEET YOUR GUIDES ...................................................................................................8

AN AGILE DELIVERY MODEL ....................................................................................10

GETTING STARTED.....................................................................................................12

THE PLAYS ...................................................................................................................14

Delivery ......................................................................................................................15

Play: Start with Scrum ...........................................................................................15

Play: Seeing success but need more exibility? Move on to Scrumban ............17

Play: If you are ready to kick o the training wheels, try Kanban .......................18

Value ......................................................................................................................19

Play: Share a vision inside and outside your team ..............................................19

Play: Backlogs—Turn vision into action .............................................................. 20

Play: Build for and get feedback from real users ................................................ 22

Teams ..................................................................................................................... 25

Play: Organize as Scrum teams ........................................................................... 25

Play: Expand to a value team when one Product Owner isn’t enough .............. 30

Play: Scale to multiple delivery teams and value teams when needed ............. 30

Play: Invite security into the team ........................................................................31

Play: Build a cohesive team ..................................................................................31

TABLE OF CONTENTS

2

Craftsmanship ...........................................................................................................35

Play: Build in quality ..............................................................................................35

Play: Build in quality and check again ................................................................. 40

Play: Automate as much as you can ....................................................................43

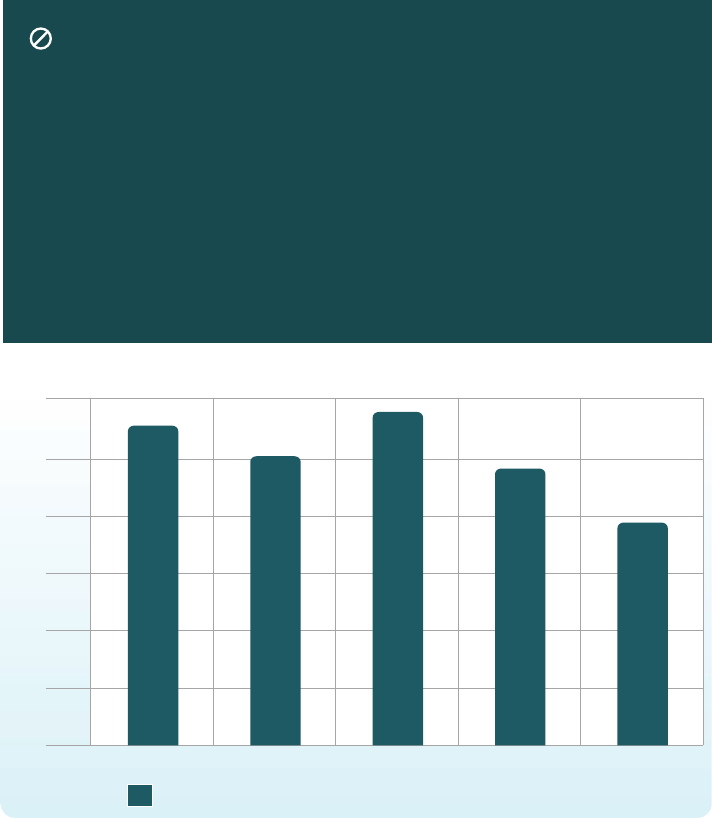

Measurement ............................................................................................................47

Play: Make educated guesses about the size of your work .................................47

Play: Use data to drive decisions and make improvements .............................. 49

Play: Radiate valuable data to the greatest extent possible ............................... 50

Play: Working software as the primary measure of progress .............................53

Management .............................................................................................................55

Play: Manager as facilitator ...................................................................................55

Play: Manager as servant leader .......................................................................... 56

Play: Manager as coach .........................................................................................57

Adaptation ................................................................................................................ 58

Play: Reect on how the team works together ................................................... 58

Play: Take an empirical view................................................................................. 58

Meetings ....................................................................................................................59

Play: Have valuable meetings ...............................................................................59

Agile at scale ............................................................................................................. 60

Play: Train management to be agile .....................................................................61

Play: Decentralize decision-making ......................................................................61

Play: Make work and plans visible ....................................................................... 62

Play: Plan for uncertainty in a large organization ............................................... 62

Play: Where appropriate, use a known framework for agile at scale................. 62

STORIES FROM THE GROUND ............................................................................... 63

U.S. Army Training Program: An Agile Success Story .........................................67

PARTING THOUGHTS ............................................................................................... 68

ABOUT BOOZ ALLEN ................................................................................................ 69

About Booz Allen Digital Solutions ........................................................................ 69

About Booz Allen’s agile practice and experience ................................................. 69

REFERENCES AND RECOMMENDED READING LIST ...........................................70

3

4

Lead Engineer Thuy Hoang sits

working in our Charleston Digital Hub

INTRODUCTION

Agile is the de facto way of delivering software today.

Compared to waterfall development,

agile projects are far more likely to deliver

on time, on budget, and having met the

customer’s need. Despite this broad

adoption, industry standards remain

elusive due to the nature of agility—

there is no single set of best practices.

The purpose of this playbook is to

educate new adopters of the agile

mindset by curating many of the good

practices that we’ve found work for teams

at Booz Allen. As we oer our perspective

on implementing agile in your context, we

present many “plays”—use cases of agile

practices that may work for you, and

which together can help weave an overall

approach for tighter delivery and more

satised customers.

Core to our perspective are the following

themes, which reverberate throughout

this playbook.

We’ve come to these themes as software

practitioners living in the trenches and

delivering software on teams using

increasingly modern methods, and in

support of dozens of customers across

the U.S. Government and the

international commercial market.

+ Agile is a mindset. We view agile as a

mindset—dened by values, guided

by principles, and manifested through

emergent practices—and actively

encourage industry to embrace this

denition. Indeed, agile should not

simply equate to delivering software

in sprints or a handful of best practices

you can read in a book. Rather, agile

represents a way of thinking that

embraces change, regular feedback,

value-driven delivery, full-team

collaboration, learning through

discovery, and continuous improvement.

Agile techniques cannot magically

eliminate the challenges intrinsic to

high-discovery software development.

But, by focusing on continuous delivery

of incremental value and shorter

feedback cycles, they do expose these

challenges as early as possible, while

there is still time to correct for them.

As agile practitioners, we embrace

the innate mutability of software and

harness that exibility for the benet of

our customers and users. As you start

a new project, or have an opportunity

to retool an existing one, we urge you

to lean to agile for its reduced risk

and higher customer satisfaction.

+ Flexibility as the standard, with

discipline and intention. Booz Allen

Digital Solutions uses a number of

frameworks across projects, depending

on client preferences and what ts

best. We use Scrum, Kanban, waterfall,

spiral, and the Scaled Agile Framework

(SAFe), as well as hybrid approaches.

But we embrace agile as our default

approach, and Scrum specically as

our foundational method, if it ts the

scope and nature of the work.

+ One team, multiple focuses.

Throughout this playbook, we explicitly

acknowledge the symbiotic relationship

between delivery (responsible for the

“how”) and value (responsible for the

5

Senior Consultant Anastasia Bono, Lead

Associat Joe Out, and Senior Lead Engineer

Kelly Vannoy solve problems at our oce in

San Antonio, TX.

“what”), and we use terms like “delivery

team” and “value team” to help us

understand what each team member’s

focus may be. However, it’s crucial to

consider that, together, we are still one

team, with one goal, and we seek a

common path to reach that goal.

+ Work is done by teams. Teams are

made of humans. A team is the core

of any agile organization. In a project

of 2 people or 200, the work happens

in teams. And at the core of teams

are humans. Just as we seek to build

products that delight the humans

who use them, we seek to be happier,

more connected, more productive

humans at work.

+ As we move faster, we cannot sacrice

security. According to the U.S. Digital

Service, nearly 25% of visits to

government websites are for nefarious

purposes. As we lean toward rapid

delivery and modern practice, we must

stay security-minded. Security cannot

be a phase-gate or an afterthought;

we must bring that perspective into our

whole team, our technology choices,

and our engineering approach.

6

Consultant Leila Aliev, Associate

Joanne Hayashi, Engineer Tim Byers,

and Lee Stewart work together at our

oce in Honolulu, HI.

WHO SHOULD USE THIS PLAYBOOK?

This playbook was written primarily

for new adopters of agile practices, and

it is intended to speak to managers,

practitioners, and teams.

While initially written as a guide solely

for Booz Allen digital professionals, it

is our hope that the community will

also nd value in our experience. We

have deliberately minimized Booz Allen

specic “inside baseball” language

wherever possible.

A Booz Allen internal addendum is also

available for Booz Allen sta, with links

and information only relevant for them.

This is not because it is full of “secret

sauce” proprietary information; rather,

it is to keep the community version

accessible and broadly valuable.

HOW SHOULD YOU USE THIS

PLAYBOOK?

This playbook is not intended to be read

as a narrative document. It is organized,

at a high level, as follows:

1. Agile Playbook context. This is what

you are reading now. We introduce

the playbook, provide a high-level

“Agile Model.”

2. The plays. The plays are the meat of

the playbook and are intended to be

used as references. Plays describe

valuable patterns that we believe agile

teams should broadly consider—they

are “the what.” Within many plays, we

describe techniques for putting them

into practice. Plays are grouped into

nine categories: Delivery, Value, Teams,

Craftsmanship, Measurement,

Management, Adaptation, Meetings,

and Agile at scale.

AGILE PLAYBOOK V2.1—WHAT’S NEW?

This is version 2.1 of our Agile Playbook.

The rst edition was published in 2013

and aided many practitioners in adopting

and maturing their agile practice across

our client deliveries and internal eorts.

In June 2016, we created version 2.0,

expanding that content, especially

around agile at scale and DevOps,

and transforming what was an internal

playbook into an external publication—

open source and publicly available.

This version is primarily a visual refresh

with minor content adjustments.

OUR DIGITAL HUBS

Over the last 4 years, our digital business

and footprint has grown by leaps and

bounds, in part through our acquisitions

of the software services unit SPARC in

Charleston, South Carolina and the

digital services rm Aquilent in Laurel,

Maryland. These digital hubs are part of

our Digital Solutions Network, where

integrated teams of digital professionals

collaborate to solve our clients’ toughest

problems. Within this virtual network,

we’re able to help our clients in more

places, and with more expertise. Our

hubs create a tight-knit community for

our technologists and innovators to

exchange ideas and combine their

expertise in cloud, mobile, advanced

analytics, social, and IoT with modern

techniques, including user-centered

design, agile, DevOps, and open source.

7

REMINDER: BEST

LEARNING

PRACTICES

The rst playbook referred to itself as a

collection of best practices, but we want

to clarify that. In most cases these are

best learning practices. If you need a

place to start or you want to understand

something in context, we hope this

playbook serves as a valuable guide

and helps you keep walking toward high

performance as a team or program. But,

just as guitar virtuosos or Olympic skiers

have moved past the form and rules they

learned in their rst few weeks of practice,

we expect our delivery teams to learn

the values here, start with the learning

practices, and eventually innovate their

way toward even higher performance

methods that are unique to them.

HOW AND WHERE CAN YOU

CONTRIBUTE TO THIS PLAYBOOK?

We want to build this playbook as

a community.

If you have ideas or experiences (or nd a

typo or broken link) you wish to share, we

would love to hear about it. Contributions

can be sent in one of two ways:

+ Pull requests—This playbook is

maintained and kept up to date

continuously through GitHub at

https://github.com/booz-allen-

hamilton/agileplaybook. We

welcome your contributions

through pull requests.

+ Email us at [email protected]

We welcome feedback on the entire

playbook, but we are looking for

contributions in a few specic areas:

+ New play or practice descriptions

+ Reports or articles from the ground,

completely attributed to you

+ Favorite tools and software for

inclusion in our tools compendium

+ Additional references or further reading

Please be sure to take a look at our style

guide before submitting feedback.

“Agile organizations view change

as an opportunity, not a threat.”

-JIM HIGHSMITH

8

Luke Lackrone

@lackrone

Lauren McLean

@SPARCedge

Marianne Rogers

@SPARCedge

Timothy Meyers

@timothymeyers

Doug James

@SPARCedge

Stephanie Sharpe

@Sharpneverdull

Hallie Krauer

@SPARCedge

Noah McDaniel

@SPARCedge

Claire Atwell

@twellLady

Kim Cumbie

@kimnc328

MEET YOUR GUIDES

The bulk of this content was developed by the following

practitioners, coaches, and software developers from

Booz Allen Hamilton.

9

Lead Associate Stan Hawk, Lead Associate

Henry Lee, Alumna Ashley Fagan, Consultant

Maggie Joyce, Lead Associate Darren Withers,

and Senior Consultant Hallie Miller talk

during a meeting in Chantilly, VA.

We would like to also thank all of our reviewers,

editors, contributors, and supporters:

Gary Labovich, Je Fossum, Dan Tucker,

Kileen Harrison, Keith Tayloe, Elizabeth

Buske, Joe Dodson, Emily Leung, Jennifer

Attanasi, James Cyphers, Merland Halisky,

Bob Williams, Gina Fisher, Aaron Bagby,

and Elaine (Laney) Hass.

And, we would like to acknowledge the

champions, contributors, and reviewers

of the rst version of this Agile Playbook:

Philipp Albrecht, Tony Alletag, Maxim

Aronin, Benjamin Bjorge, Wyatt Chaee,

Patrice Clark, Bill Faucette, Shawn Faunce,

Allan Hering, Amit Kohli, Raisa Koshkin,

Paul Margolin, Debbie McCoy, Erica

McDowell, Johnny Mohseni, Robert

Newcomb, Jimmy Pham, Rose Popovich,

Melissa Reilly, Haluk Saker, Li Lian Smith,

Alexander Stein, Tim Taylor, Loree

Thompson, Elizabeth Wakeeld, Gary

Kent, Amy Dagliano, Alex Lyman, Alicia

White, Kevin Schaa, and Joshua Sullivan

10

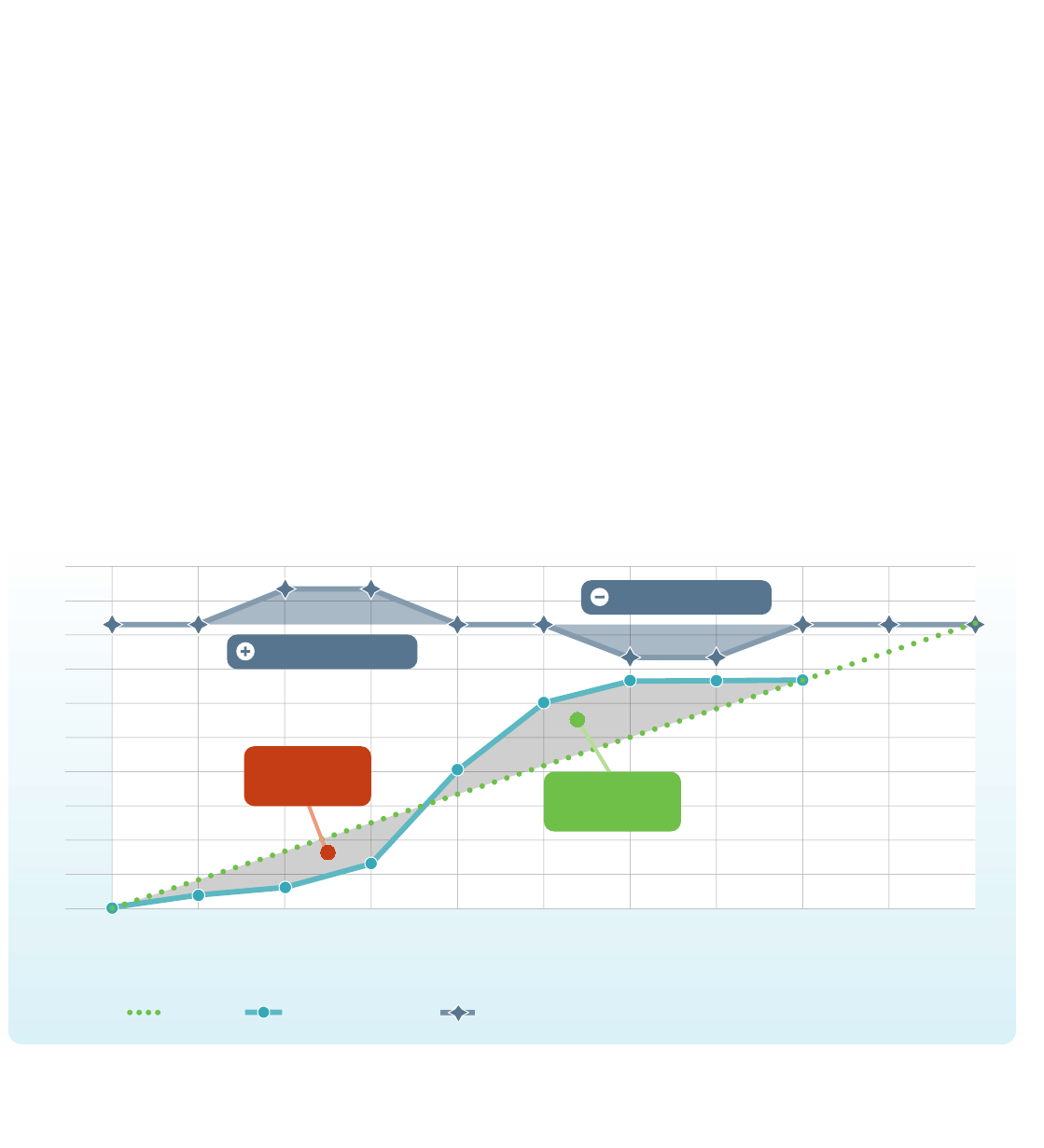

Like most models, it is not perfect, but

we believe it is useful. It illustrates the

focus areas that a team may have over

time—often simultaneously—and

provides context for the plays and

practices described in the rest of this

playbook. Our intentions are to show that

delivery is majority of our work and that

successful delivery is built on a foundation

of alignment and preparation.

To truly put this model into action, refer

to the plays and practices.

We’ll describe these focus areas in broad

strokes. To truly put this model into action,

refer to the details captured in the plays

and practices.

AN AGILE DELIVERY MODEL

Here we introduce the agile delivery model that we use to drive

delivery across our business.

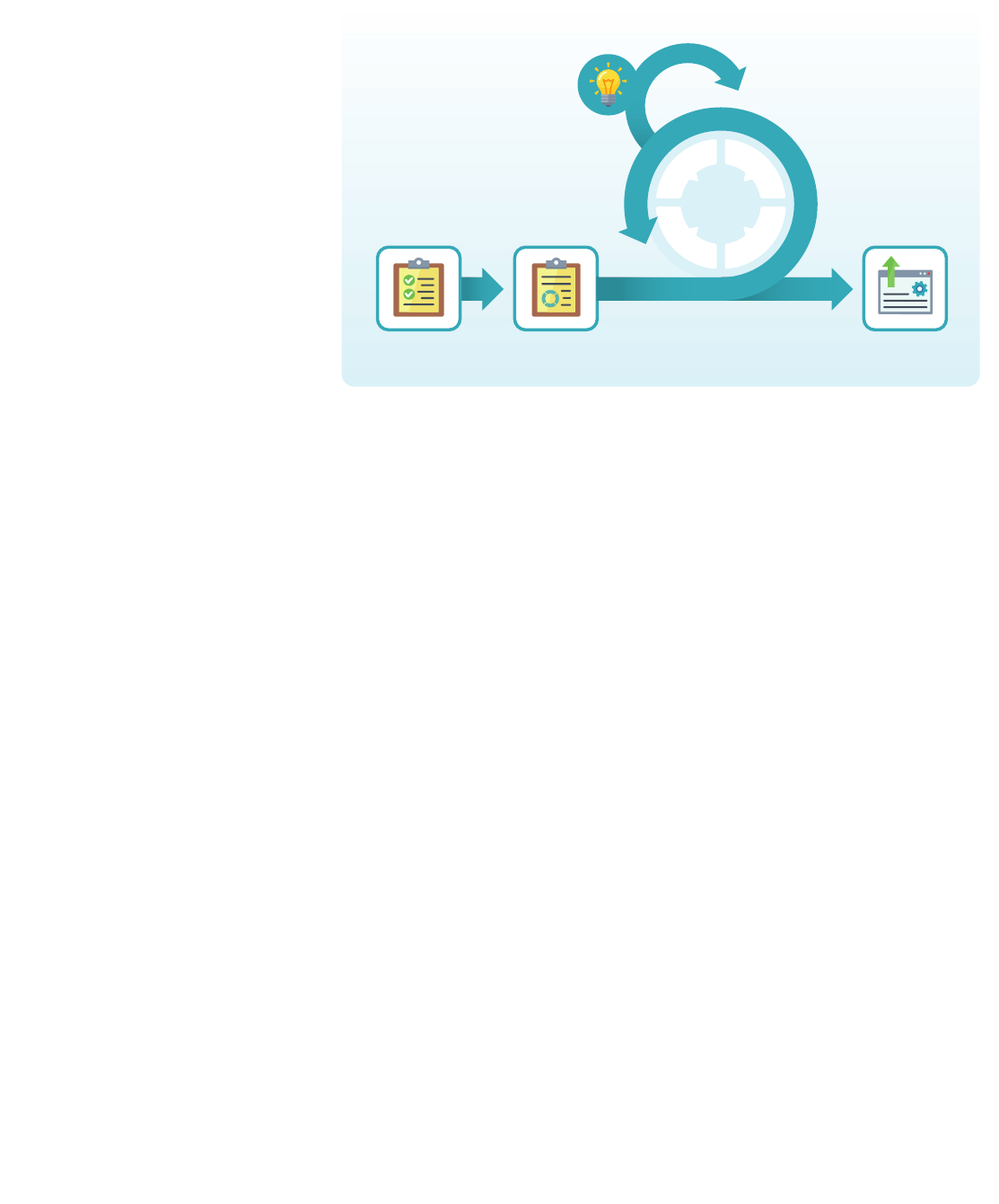

Figure 1: Our agile delivery model

PREPARE

Estimate &

Prioritize Work

Create Initial

Infrastructure

Product Plan

& Backlog

Plan Initial

Sprint

Review Demo

Deploy

Software

Short-Term

Plan

DEL IV E R

Check

Retrospective

Stop

Start

More

Less

Build Working Software

Scrum • Scrumban • Kanban

D

E

S

I

G

N

C

O

D

E

T

E

S

T

B

U

I

L

D

Do

Plan

Set Technical

Expectations

Determine

Vision & Goal

Form & Charter

the Team

ALIGN

Create Working

Agreements

Act

Act

08.031.17_01

Booz Allen Hamilton

11

ALIGN

We must have a clear understanding of who

we are and what we’re trying to build.

With this focus, we cultivate relationships

with our stakeholders and users. Together,

we build a shared understanding of

the project vision, goals, values, and

expectations. We often employ

chartering sessions to build product

roadmaps and user personas, and to

capture strategic themes.

We also create our team working

agreements—how we will work together.

These identify how we’ll communicate,

resolve conict, and have fun, among

other things, and we’ll establish technical

expectations, such as coding standards

and our denitions of done.

This is a dominant focus area during a

project’s rst several days (but no more!

We want to align quickly and get to

delivering as quickly as possible). While

our teams begin with this focus, we

realize that this is not only important

during project startup. Teams may

need to realign throughout the life of a

project when signicant change occurs.

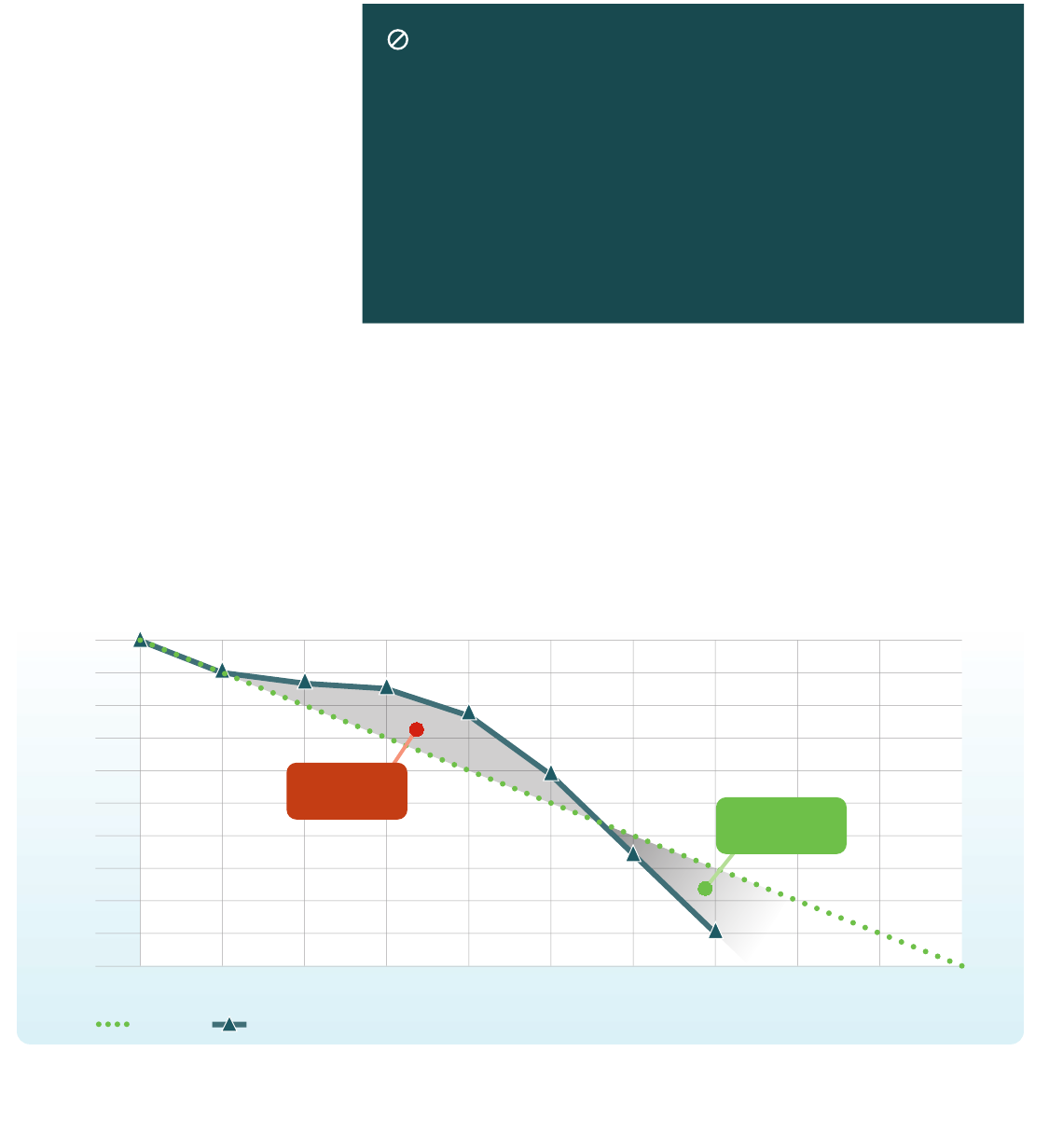

PREPARE

Once we are clear on who we are and what

we’re here to do, the team needs to come

together to get a look ahead, and prepare

enough to get started.

With this focus, we build, estimate, and

groom our product backlog. We put some

thought into architecture. We sketch out a

few sprints’ worth of work—3 months or

so. Here, we’re trying to understand the

things we will do soon. We accept that we

are fuzzy on things we’ll be doing a few

months from now, and that time spent

planning these things now is possibly

waste. Because software development is

primarily highly creative knowledge work,

we have to do it to understand it. We

continually discover. It is dicult to pull

together a 12-month master schedule—

if we did, it would probably be wrong in a

matter of days. We embrace this truth

instead of ghting it.

In addition to doing just-enough planning,

we generally invest some time in our

infrastructure and tooling. We want to

make sure we can get from a commit

to a build quickly. Let’s smooth our

deployment process so it’s not a pain

when time is tight.

DELIVER

This is where the rubber meets the road,

so to speak.

With this focus, we transform the needs

of users into valuable, tested, potentially

shippable software. Generally, we follow

small Plan-Do-Check-Act cycles. In the

Delivery section of this playbook, we

expand on several popular agile delivery

frameworks, and when we use them.

When we are delivering, we build; we test;

we keep designing; we keep talking to

users. We inspect and adapt. We do this

as much as we need to, until we are done.

Any team members who are not actively

delivering something for the current

sprint are helping the team get ready

for the next sprint.

12

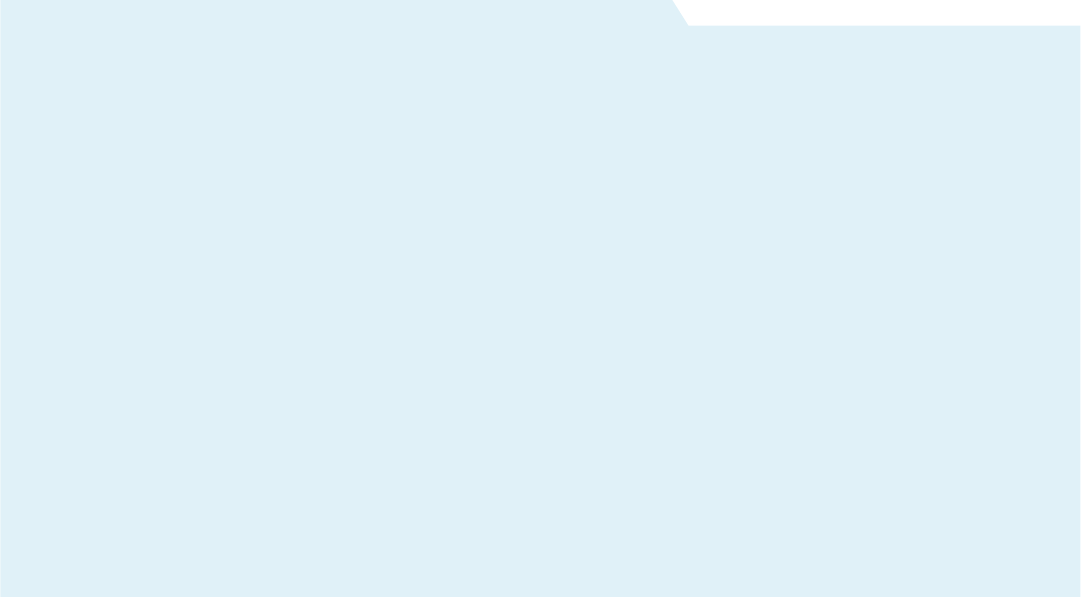

GETTING STARTED

So you’ve never been an agile team before. How to get started?

This guide gives a quick frame for getting started, tying together concepts you’ll nd

more detail about in other areas of this playbook. Not all the terms are explained, so

you’ll want to reference the rest of the playbook to nd more context and advice.

Keep in mind, it’s not practical to totally change everything about how you work

overnight. Start here; try these ideas and improve as you go.

08.031.17_02

Booz Allen Hamilton

2 WEEKS

Sprint 1

• Prioritize product backlog

and plan the sprint

• Hold daily standups

• Write code, test, and get

user stories “done”

• Hold a demo with whatever

you have

• Hold a retrospective and

make changes to improve

2 WEEKS

Sprint 2

• Hold daily standups

• Reprioritize the backlog

with new items

• Hold sprint planning;

establish the Sprint backlog

• Write code, test, and get

user stories and demo for

user feedback “done”

• Measure, reflect, and

improve

TO COMPLETION

Sprint 3+

• Keep going—Inspect and

adapt

2–4 WEEKS

Sprint 0

• Identify your Scrum Master

and Product Owner

• Have a team chartering

session

• Prepare the physical and

virtual team space with

information radiators

• Set up your development

environment

• Get a few user stories into

the backlog

13

SPRINT 0

This period does not have to be strictly

timeboxed; you want to get things in place

so that you’re ready to begin delivery as an

agile team. Don’t linger though—we want

to be delivering!

LIKELY ACTIVITIES

+ Identify your Scrum Master and

Product Owner

+ Identify the users and stakeholders

+ Have a team chartering session

+ Identify, dene, and commit to an

initial set of coding standards

+ Identify initial architecture approach

+ Identify some likely technologies

+ Prepare the physical team space with

information radiators

+ Setup your development environment

+ Set up your build infrastructure

+ Set up a basic automated test

environment

+ Get a few user stories into the backlog

+ Communicate the output of Sprint 0 to

the teams and stakeholders

SPRINT 1

LIKELY ACTIVITIES

+ Hold daily standups

+ Prioritize product backlog

+ Estimate top user stories

+ Establish a sprint backlog

+ Write code; test; get user stories “done”

+ Hold a demo with whatever you have

+ Hold a retrospective and make changes

to improve

SPRINT 2

LIKELY ACTIVITIES

+ Hold daily standups

+ Reprioritize the backlog with new items

+ Hold sprint planning, establish the

sprint backlog

+ Write code; test; get user stories “done”

+ Hold a demo; gather user feedback

+ Measure your velocity

+ Reect and identify improvements

SPRINT 3+

LIKELY ACTIVITIES

+ Keep going —inspect and adapt!

“In my experience, there’s no such

thing as luck.”

- OBI-WAN KENOBI

14

Consultant Candice Moses and Sta Engineer

Perry Spyropoulos work together in our

Charleston Digital Hub.

THE PLAYS

Plays describe valuable patterns that we believe agile teams

should broadly consider.

These plays and practices are intended to be used as reference. Within many plays, we

describe practices that teams can do to turn the plays into action.

“If, on your team, everyone’s input

is not encouraged, valued, and

welcome, why call it a team?”

- WOODY WILLIAMS

DELIVERY

This section describes how agile teams

work together to produce value that

satises their stakeholders.

VALUE

This section describes how agile teams can

understand the value of the work they do.

TEAMS

Agile teams are where the work gets done.

Team members care about each other,

their work, and their stakeholders. And

agile teams are constantly stretching,

reaching for high performance. This

section describes plays for team

formation, organization, and cohesion.

CRAFTSMANSHIP

This section walks through practical

ways to inject technical health into

your solutions.

MEASUREMENT

Measurement aects the entire team.

It is an essential aspect of planning,

committing, communicating, improving,

and, most importantly, delivering.

MANAGEMENT

Where is the manager on an agile team?

This section explores how the manager

leads in an agile organization.

ADAPTATION

This section looks at ways to regularly

examine and nd ways to improve the

team and product.

MEETINGS

This section describes common meetings

for agile teams, and how to eectively use

your time together.

AGILE AT SCALE

This section describes some of our initial

thoughts on scaling agility.

Antipatterns

Antipatterns are consistently observed behaviors that can impede a team’s

agility. Throughout this guide, examples of antipatterns are given in boxes

like this one.

15

DELIVERY

Agile teams are biased to action and are

constantly seeking ways to deliver more

product and more often.

PLAY: START WITH SCRUM

Start with Scrum for agile delivery, but with

an eye for “agility.”

Scrum is the most popular delivery

framework for agile teams to use, by

far; so much so that it’s often confused

for “agile” itself. Scrum is a powerful,

lightweight product delivery framework

that has existed for 25 years. The denitive

description of the framework is maintained

by its creators in the Scrum Guides

[Sutherland and Schwaber 2013].

Because the Scrum Guides are such

well-maintained and well-used resources,

we won’t try to explain everything about

Scrum here.

Scrum was developed to rapidly deliver

value while accommodating the changes

that are inevitable in product delivery.

It’s also meant to create a predictable

pace for the team.

Traditionally, a product is designed, then

developed, then demonstrated or released

to the customer. This occurs mostly as a

sequence and over long stretches of time.

Often, the customer is unhappy with the

result and wants changes. Since we are so

late in development, changes found after

release are typically very costly. Scrum,

however, incorporates frequent demos and

feedback to mitigate surprise requirement

changes. All the project work gets cut

into short development iterations known

as sprints. Scrum emphasizes that work

planned in sprints must be small, well

understood, and prioritized.

Each sprint is typically 1–4 weeks long (and

stays consistent for a given team). During

a sprint, the delivery team chooses the

high-value work it can complete; the team

focuses on just that work for the sprint’s

duration. At the end of each sprint, the

team demonstrates the working software

it produced. During the demo, the team

gathers feedback that helps shape the

direction of the product going forward.

Practically, this means that design

decisions are not made way ahead of time,

but rather right before or even during

active development. Instead of having

heavy, top-down design, design emerges

and evolves over several iterations:

develop, demo, gather feedback,

incorporate feedback, develop, demo…

THIS SECTION DESCRIBES HOW AGILE

TEAMS WORK TOGETHER TO PRODUCE VALUE

THAT SATISFIES THEIR STAKEHOLDERS:

“Deliver working software

frequently, from a couple of

weeks to a couple of months,

with a preference to the

shorter timescale.”

“Agile processes promote

sustainable development.

The sponsors, developers,

and users should be able to

maintain a constant pace

indenitely.”

“Simplicity—the art of

maximizing the amount

of work not done —is essential.”

Figure 3: The Scrum framework

D

E

S

I

G

N

C

O

D

E

T

E

S

T

B

U

I

L

D

WEEKS

2

-

4

Daily Standup

Meeting

Potentially

Shippable

Product

Product Backlog Sprint Backlog

HOURS

24

08.031.17_03

Booz Allen Hamilton

16

Over the course of several sprints, a

picture of progress and direction emerges.

Customers and management are kept

informed through progress charts (see

Measurement section) and end-of-sprint

demos. It becomes easy to keep everyone

informed while avoiding many pitfalls of

micromanagement.

If Scrum is followed, many of the traditional

problems associated with complex projects

are avoided. The frequent feedback prevents

projects from spending too much time

going in the wrong direction. Furthermore,

because of Scrum’s iterative nature,

projects can be terminated early (by choice

or circumstance) and deliver value to the

end user.

Iteration—trying something and looking

at it—is core to how Scrum operates.

A variety of development teams use Scrum,

from those working on highly complex

systems with an unknown end, through

operations and maintenance patching.

The key to using this method is ensuring

the maintenance of a groomed backlog

and allowing for the exibility needed in

this short learning cycle.

SCRUM IS BUILT ON THREE PILLARS: TRANSPARENCY, INSPECTION, AND ADAPTATION

TRANSPARENCY

Many of the challenges teams face boil down to communication issues. Scrum values keeping communication

and progress out in the open; doing things as a team; being transparent. The fact that Scrum’s ceremonies

(Sprint Planning, Daily Standup, Sprint Review, and Retrospective) are intended for the whole team speaks to the

importance of transparency.

INSPECTION

Inspecting things is how we know if they’re working. Everything on a Scrum team is open to inspection, from the

product to our process.

ADAPTATION

As we inspect things, if we think we would benet from doing it dierently, let’s try it! We can always adjust again

later. Notably, Scrum’s Sprint Review ceremony gives us an explicit, regular opportunity to adapt based on how

the product is coming along; the Retrospective ceremony does the same for how our team is working. Scrum is

built on three pillars: transparency, inspection, and adaptation

17

P L AY: S E E I N G S U C C E S S B U T

N E E D M O R E F L E X I B I L I T Y ?

MOVE ON TO SCRUMBAN

If Scrum is too restrictive or there are too

many changing priorities within a sprint,

consider Scrumban to provide the structure

of ceremonies with the exibility of delivery.

Scrumban is derived from Scrum and

Kanban (described below, in the next play)

as the name would suggest. It keeps the

underlying Scrum ceremonies while

introducing the ow theory of Kanban.

Scrumban was developed in 2010 by Corey

Ladas to move teams from Scrum which

is a good starting point in agile, to

Kanban, which enables ow for delivery

on demand [Ladas 2010]. Kanban focuses

on ow, but it does not have prescribed

meetings and roles—so we borrow those

from Scrum in this Scrumban model.

The primary dierence versus Scrum is

that the sprint timebox no longer applies

to delivery in Scrumban.

Instead, the team is constantly prioritizing

and nishing things as soon as possible.

In Scrumban, we keep Scrum’s cadence

just to have our ceremonies so we don’t

miss out on planning together, showing

our work, and having a time for reection.

A strict work-in-progress limit (WIP limit)

is set to enable team members to pull

work on demand, but not so many things

that they have trouble nishing the work

at hand. Scrumban has evolved some of

its own practices.

Examples of unique practices to Scrumban

include the following:

+ Bucket-size planning was developed to

enable long-term planning where a

work item goes from the idea bucket, to

a goal bucket, then to the story bucket.

The story bucket holds items ready to

be considered during an on-demand

planning session.

+ On-demand planning moves away from

planning on a regular cadence, instead

only holding planning sessions when

more work is needed. Items to be

pulled into the Kanban board are

prioritized, nalized, and added to

the Kanban board.

Scrumban is useful for teams who are very

familiar with their technical domain and

may have constantly changing priorities

(e.g., a team working on the same product

for an extended amount of time). The

exibility of Scrumban allows for the

backlog to be re-prioritized quickly and

release the product on demand.

< No process >

In environments where we are used to doing work in our own swim lane,

or a single person possesses most the knowledge, it’s easy to skip dening

processes. The team needs to nd ways to work together which often take

the form of a process. Repeatable well-understood processes for regularly

occurring tasks help the team move faster, reduce stress, and integrate

new team members. A process needs to be understood by the entire team

and perhaps documented for it to work. The repeatable tasks are often

dened during team chartering and revisited at retrospectives. Some

common processes to reect on: Who checks our work? When and how

do we deploy our software? How do we avoid becoming single threaded

on a capability? How do we track our work? Do we need a tool? What is

our defect tracking process?

18

P L AY: I F Y O U A R E R E A DY T O K I C K

OFF THE TRAINING WHEELS,

TRY KANBAN

Try Kanban on only the most disciplined

teams and when throughput is paramount.

Kanban is a framework adopted from

industrial engineering. It was developed to

be mindful of organizational change

management, which is apparent in the four

original principles:

+ Start with existing process.

+ Agree to pursue incremental,

evolutionary change.

+ Respect the current process, roles,

responsibilities and title.

+ Leadership at all levels.

So, in Kanban, you will not (inherently)

be receiving a bunch of new titles, or

using much new vocabulary.

In 2010 David Anderson elaborated with

four “Open Kanban” practices tailored

for software delivery:

+ Visualize the workow.

+ Limit WIP.

+ Manage ow.

+ Make process policies explicit.

+ Improve collaboratively (using models

and the scientic method).

In Kanban, you fundamentally want to

make all of your work visible, continuously

prioritize it, and always ow things to

“done.” This is great for a software team

that issues several new releases per week,

or per day. A pitfall, however, is that if

priorities are allowed to change too often,

no work will ever get done. So, be mindful

about nishing things and not starting

too many things.

Kanban is appropriate for teams ready

to self-regulate, rather than rely on

timeboxes. The practices require

discipline to enable ow. An operations

and maintenance team with a small

backlog could benet from Kanban, as it

would enable delivery of small items as

needed and ensure all issues are getting

to a done state. In addition, mature agile

teams with a highly automated pipeline

could use Kanban as a way to enable

quick ow of value to production.

19

PRACTICE: PRODUCT BOX

The product box is another way to try to

crack into the product’s vision. You might

try this exercise as an alternative to working

with the Vision Board. The product box is

a great way to engage a whole team in the

conversation around the vision and value

of the project at hand, and to have some

fun together while doing so. While there

are many versions of this idea, Innovation

Games is a well-known one. As described

there, “[Ask your stakeholders] to imagine

that they’re selling your product at a

tradeshow, retail outlet, or public market.

Give them a few cardboard boxes and ask

them to literally design a product box

that they would buy. The box should have

the key marketing slogans that they nd

interesting” [Innovation Games 2015]. We

have also seen this work nicely by imagining

that your product is appearing in the App

Store; what would the description, icon,

screenshots, and reviews look like?

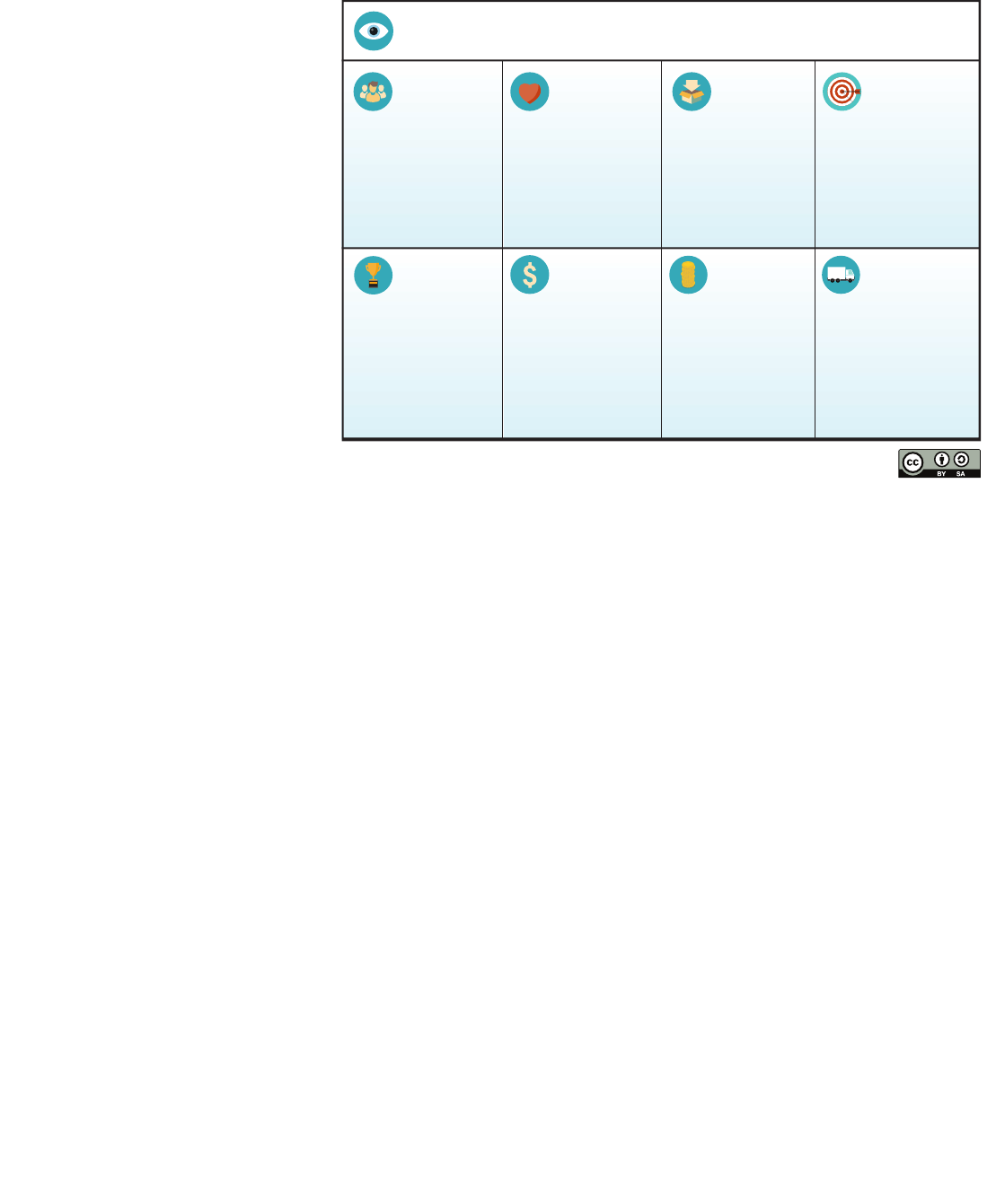

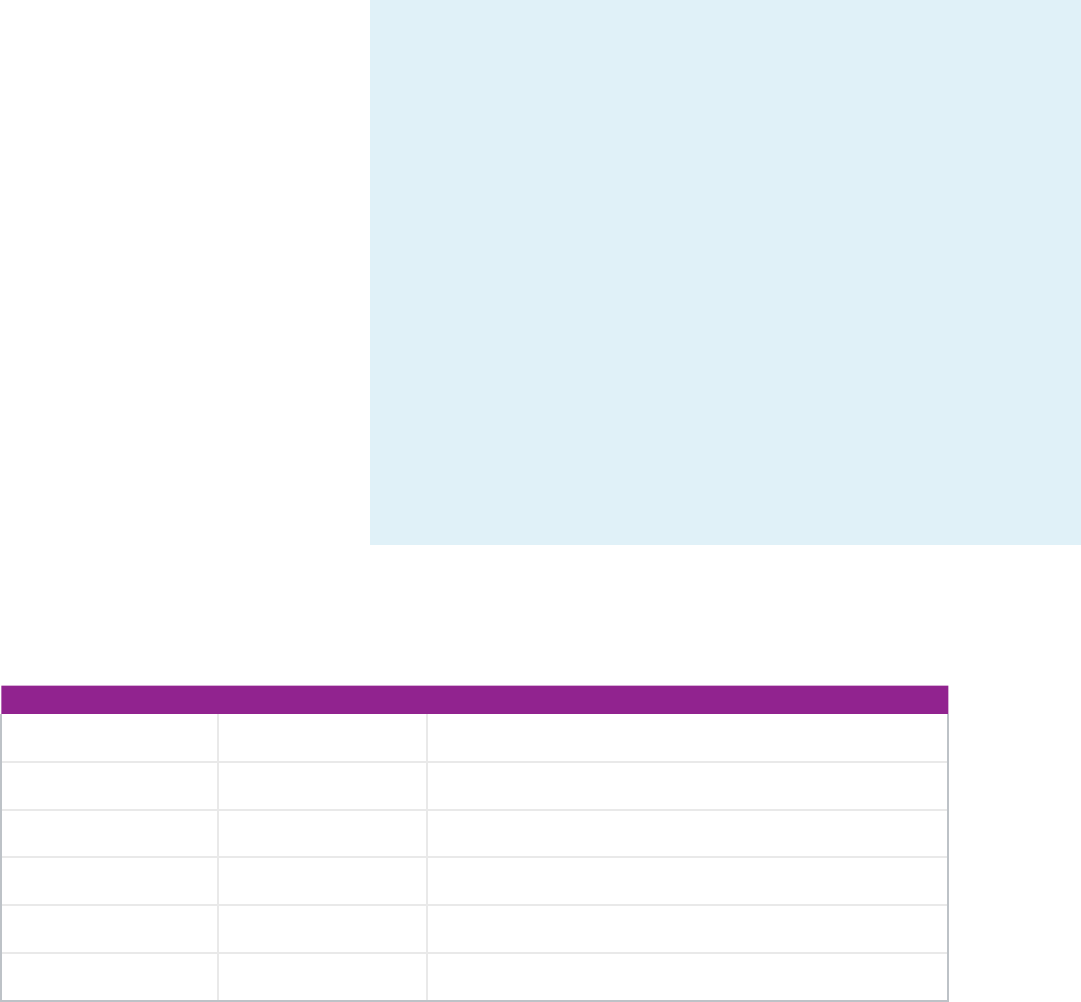

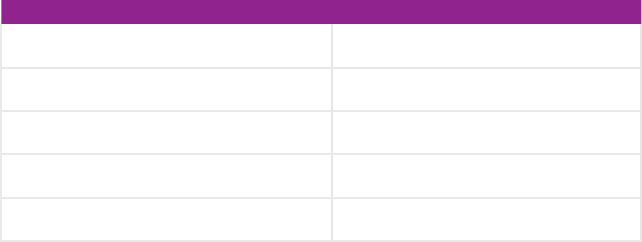

Figure 4: Product Vision Board by Roman

Pichler [Pichler Consulting 2016]

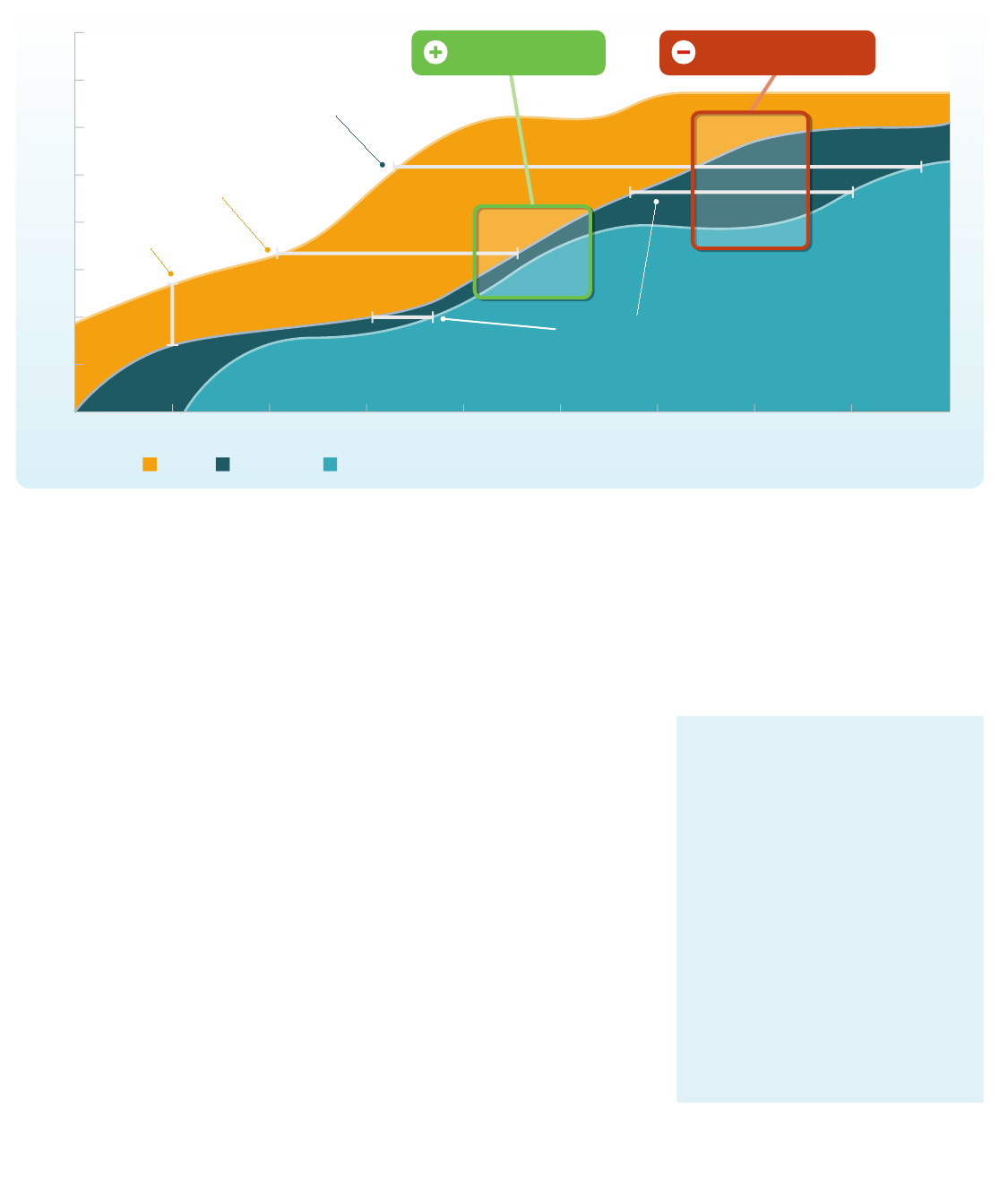

VALUE

Most software has more features

than necessary.

Agile teams emphasize prioritizing features

by the value they bring to real users and

stakeholders. Considering the value of

things is just as important as delivering

working software, since time spent on

non-valuable features is wasted time.

P L AY: S H A R E A V I S I O N I N S I D E

AND OUTSIDE YOUR TEAM

The vision is the foundation upon which

product decisions are made. When at

critical junctures, turn to the vision to help

determine which direction will help the

vision become a material reality. At the

team and individual levels, the vision

provides a common mission to rally

around and helps understand the long-

term goals, as well as incremental goals.

PRACTICE: PRODUCT VISION

STATEMENT

The vision for the project should be

encapsulated in a product vision statement

created by the Product Owner. Akin to

an “elevator pitch” or quick summary, the

goal of the product vision statement is to

communicate the value that the software

will add to the organization. It should be

clear and direct enough to be understood

by every level of the eort, including

project stakeholders. The Vision Board

by Roman Pichler is a nice, simple

template for forming this statement

[Pichler Consulting 2016].

Once you have your vision board, work with

the Product Owner and key stakeholders to

test the vision with the target group to see

how well it resonates with eventual users.

What is your vision, your overarching goal for creating the product?

www.romanpichler.com

Which market segment

does the product address?

Who are the target users

and customers?

How will you market and

sell the product to the

customers?

Do the channels exist

today?

What are the main cost

factors to develop, market,

sell, and service the

product?

What resources and

activities incur the highest

cost?

How can you monetise

your product and generate

revenue?

What does it take to open

up the revenue sources?

Who are the product’s

main competitors?

What are their strengths

and weaknesses?

How is the product going

to benefit the company?

What are the business

goals?

Which one is most

important?

What product is it?

What makes it desirable

and special?

Is it feasible to develop the

product?

How does the product

create value for its users?

What problem does it

solve?

Which benefit does it

provide?

Vision

Needs

Channels

Cost

Factors

Revenue

Sources

Competitors

Business

Goals

Product

Target

Group

“Business people and developers

must work together daily

throughout the project.”

20

Sta Engineer Peter Bingel with Lead Technologists Lakeshia Winchester, Sebastian Steadman,

Amy Longworth, and Sta Engineer Peter Bingel work together to solve problems in Charleston, SC.

Once you have your product box, use focus

groups or hallway testing with your target

group to discover how well the vision

resonates with target users and to under-

stand their expectations for what’s inside.

PRACTICE: PRODUCT ROADMAP

Most teams need a product roadmap to

understand high-level objectives and

direction for the project. We think of this

as the project’s North Star. If we’ve

deviated distinctly from it, we should have

a good reason, and we probably need to

update the roadmap. Be sure to include

the ultimate project goals in the roadmap,

keeping in mind their value added and the

desired outcomes from the customer’s

point of view. The roadmap should loosely

encapsulate the overall vision and give a

sense for when capabilities will be

delivered or intersecting milestones are

going to occur. The roadmap should

probably cover the next 6–12 months, and

only in broad strokes. On the roadmap,

releases contain less detail the farther they

are into the future. Your team will have to

talk through rough sizing of work and

prioritization during the creation process.

You’re not building a schedule; you’re

trying to paint a plausible picture. Be sure

to build this together as a team, or at least

review and revise it together. Too many

roadmaps are built by leadership and

never have buy-in from the team.

PRACTICE: RELEASE PLAN

Once the roadmap is complete, a release

plan may be created for the rst release.

Each release should begin with the

creation of a release plan specic to the

goals and priorities for that release. This

plan ensures that the value being added

to the project is consistently reviewed and,

if necessary, realigned to maximize the

overall value and eciency of development.

Like the product roadmap, the release plan

should include a high-level timeline of the

progression of development, specic to

the priorities for that release only. The

highest value items should be released

rst, allowing the stakeholders visibility

into the progression of the work.

User engagement is often overlooked when

developing release plans. We nd that the

best roadmaps and release plans include user

communication and engagement strategies,

such as training and rollout.

PLAY: BACKLOGS—TURN VISION

INTO ACTION

Once we have and share our vision, we

understand the big stu, but we have to

turn this to action quickly. A core practice

for agile teams is to have a backlog of work.

In this context, a backlog is a prioritized

set of all the desired work (that we know

about) we want to do on the project.

BACKLOG BASICS

Treat your backlog as a “catch all”; any

item that moves the team ahead to a nal

product or project goal can be added to

your backlog. New features, defects,

abandoned refactoring, meetings, and

other work are all game to be placed

there. Additionally, keep in mind that your

backlog will evolve in detail and priority

through engagement with the end user.

Your backlog should be a living, breathing

testament to your product, as you will

iteratively rene your backlog as your build

your product. Product backlog items are

added and rened until all valuable

features of that product are delivered,

which may occur through multiple releases

during the project lifecycle.

21

BACKLOG CREATION

A backlog is made of epics and user

stories. User stories are simply something

a user wants, and they’re sized such that

we understand them well; epics are bigger

than that and we need to break them down

further so the team can actually execute.

Generally, anyone can add something to

the backlog, but the Product Owner

“owns” that backlog overall—setting the

priority of things and deciding what we

really should be working on next.

We dive further into both epics and user

stories in the following play.

PRACTICE: PRODUCT AND

SPRINT BACKLOGS

A product backlog is a prioritized list of

product requirements (probably called

user stories), regularly maintained,

prioritized, and estimated using a scale

based on story points. It represents all

of the work we may want to do for the

project, and it changes often. We have

not committed to deliver the full scope

captured in the product backlog.

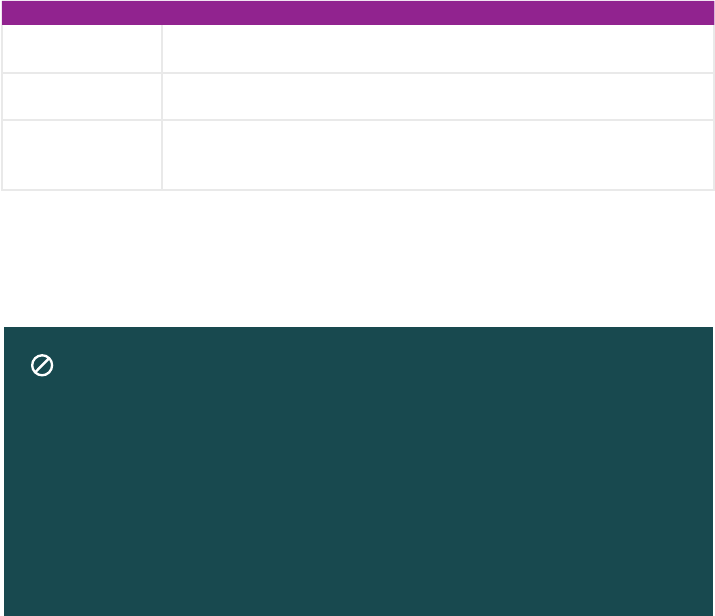

GOOD BACKLOGS FOLLOW THE ACRONYM DEEP

DETAILED

The backlog should be detailed enough so that everyone

understands the need (not just the person who wrote it).

ESTIMATED

The user story should be sucient for the delivery team to

provide an estimated eort for implementing it. (Stories near

the top of the product backlog can be estimated more accurately

than those near the bottom.)

EMERGENT

The product backlog should contain those stories that are

considered emergent—reecting current, pressing, or

realistic needs.

PRIORITIZED

The product backlog should be prioritized so everyone

understands which stories are most important now and

require implementation soon.

“Welcome changing requirements, even late in development. Agile

processes harness change for the customer’s competitive advantage.”

22

Figure 5: A persona template

P L AY: B U I L D F O R A N D G E T

FEEDBACK FROM REAL USERS

PRACTICE: DEFINE PERSONAS

Personas are ctitious people who

represent the needs of your users, and

they help us understand if our work is

going to be valuable for the people

we’re trying to reach. They can be very

useful at the start of the requirements

gathering process, but typically remain

important throughout.

Each persona should capture the user

and their individual needs. Create a

template with an area to draw a picture

of the user and separate spaces to

describe the user personally, but also

describe their desired goals, use cases,

and desires for the software.

PRACTICE: TALK WITH USERS ABOUT

NEEDS, NOT SOLUTIONS

Consider the dierence between “I want

the software to have one button for each

department in my business” and “I need

to be able to access each department in

my business from the software.”

Users often think they know exactly what

they want to see, but we nd it can be

much more eective if we understand

the needs and then exercise creativity in

how to provide a delightful experience

that satises that need.

A sprint backlog is a detailed list of all the

work we’ve committed to doing in the

current sprint—just a few weeks of work.

Once we set it up in sprint planning, it

remains locked for the duration of the

sprint. No new (surprise!) work should be

added. The whole team should keep it up

to date by (at least daily), and items should

be marked complete based on the team’s

agreed denition of done.

CUSTOMER NAME:

Picture (Yes, draw it!) Description

Goals & Needs

Age:

Gender:

Occupation:

Tech Usage (web savvy, desktop, laptop,

tablet, smart phone, favorite sites/apps...)

“Our highest priority is to

satisfy the customer through

early and continuous delivery

of valuable software.”

23

As you can, guide your users into

conversations of value and need, and

let the delivery team work through

the solution.

PRACTICE: EPICS AND USER STORIES

User stories

User stories are the agile response to

requirements, and you can call them

requirements if you like.

They often look like this:

+ As a solo traveler

+ I want to safely discover other travelers

who are traveling alone

- So I can meet possible companions

on my next trip.

There are a few things that are

dierent about user stories versus

typical requirements.

+ They are communicated in terms of

value, from the user perspective.

+ They might look a little lightweight at

rst. We agree we need to tell stories—

we know there are details that can only

be sussed out through collaborating

with our users and stakeholders. We

understand that what is written down

is imperfect. What we want to do is

capture enough to get started!

A TEMPLATE FOR USER STORIES AND EPICS

Epics and user stories are described below, but both share a typical template:

+ Title (short)

+ Value statement

- Outlines and communicates the work to be completed and what value

delivering this epic or story will bring to a specic persona/user

- Format: As a (user role/persona) I need (some capability), so that

(some value)

+ Acceptance criteria

- An outlined list of granular criteria that must be met in order for the story

or epic to be fully delivered and adequately tested and veried. This helps

inform development and understanding of when the story is ready to

demonstrate or test further

THE THREE Cs

CARD

This is the description of the user story itself, written on a card or in a tracking tool.

The card should give us enough detail to get started and know whom to talk to.

CONVERSATION

We acknowledge that anyone implementing needs to—and should—speak

with some of the players involved in the value that story will deliver. So they

need to go have a conversation and record anything that needs to be preserved

from that conversation.

CONFIRMATION

Once implemented, every user story needs to be veried. We call this the

Conrmation. And we should record in the user story how we intend to verify

it. This could be the list of acceptance criteria, test plans, and so on. Important

now and require implementation soon.

24

The Product Owner collaborates with

the delivery team to develop user stories

that will mold the product’s functionality.

User stories are identied and prepared

throughout the project’s lifecycle.

There are two devices we typically use to

describe good user stories: the three Cs

and INVEST.

Epics

Epics are broad functionalities we want

our product to deliver. They are larger

than user stories. Epics would typically

take multiple sprints to deliver, and

would ultimately be broken down into

many user stories. You can still write

epics like user stories, and the guidelines

above typically apply, with the exception

of Small and Estimable.

INVEST

A way to see if your user stories are pretty good is to consider the INVEST acronym.

INDEPENDENT

Stories should be as independent as possible, so they can be implemented out

of order.

NEGOTIABLE

We should be able to discuss the details of the user story, nd the optimal

solution, and not treat the initial writing as gospel.

VALUABLE

A story must deliver value to the user or customer when complete.

ESTIMABLE

Stories should be such that we can estimate their eort.

SMALL

User stories should be small enough to prioritize, work on, and test. For teams

using sprints, user stories should be able to be completed inside one sprint.

TESTABLE

We should know how to verify and test the story.

STRONG USER STORIES ARE… WEAK USER STORIES ARE…

ü Developed and prioritized by the Product Owner û Created with limited Product Owner involvement

ü Written from the user’s perspective û Developed without designating the specic user or user group

that will receive value from the story

ü Simple and concise, with clear alignment to business value û Missing a description of the business value

ü Entry points to a conversation on how the implementation

activities can be decomposed

û Technical specications that don’t link to the user’s point of view

ü Written with easy-to-understand acceptance criteria û Open ended with no means to validate acceptance

Table 1: Strong vs. weak user stories

STRONG VS. WEAK USER STORIES

25

TEAM

AGI LE

08.031.17_06

Booz Allen Hamilton

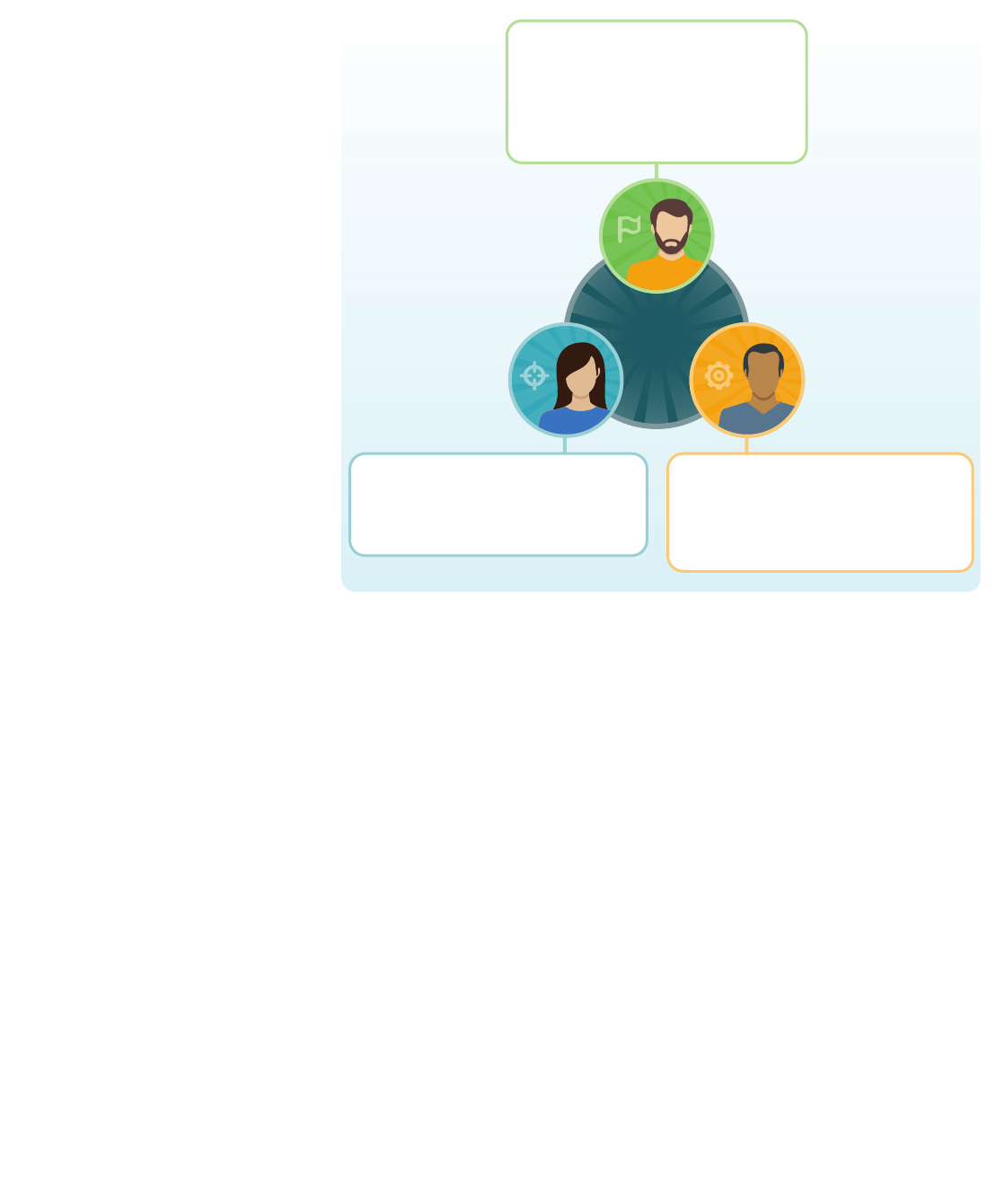

Scrum Master

• Removes impediments and keeps the

team on track

• Facilitates ceremonies; helps the team

reflect and stretch themselves

Product Owner

• Helps the team know what to build

• Owns the backlog and works directly with

the delivery team

Team Members

• Do whatever it takes to create value and

meet the sprint commitments

• Figure out how to build it

• Develop, design, test, ask questions,

and hold each other accountable

TEAMS

Agile teams are where the works gets done.

Team members care about each other,

their work, and their stakeholders. And

agile teams are constantly stretching,

reaching for high performance.

Build projects around motivated

individuals. Give them the environment

and support they need, and trust them

to get the job done.

The most ecient and eective

method of conveying information to

and within a development team is

face-to-face conversation.

PLAY: ORGANIZE AS SCRUM TEAMS

Agile teams are cross-functional in nature

and work together to analyze, design,

and build the solution their customers

need. Agile team members, together, can

understand the business or mission needs

and create an eective solution that meets

those needs.

We use one particular set of vocabulary

here for this playbook, which is reective

of some of the most common terms found

across government and industry; but,

individual client environments may dictate

dierent names for things. We stress that

the jobs and structures mentioned here are

helpful in any context, and we urge teams

to strive for the greatest agility possible,

then seek to continuously improve through

small changes.

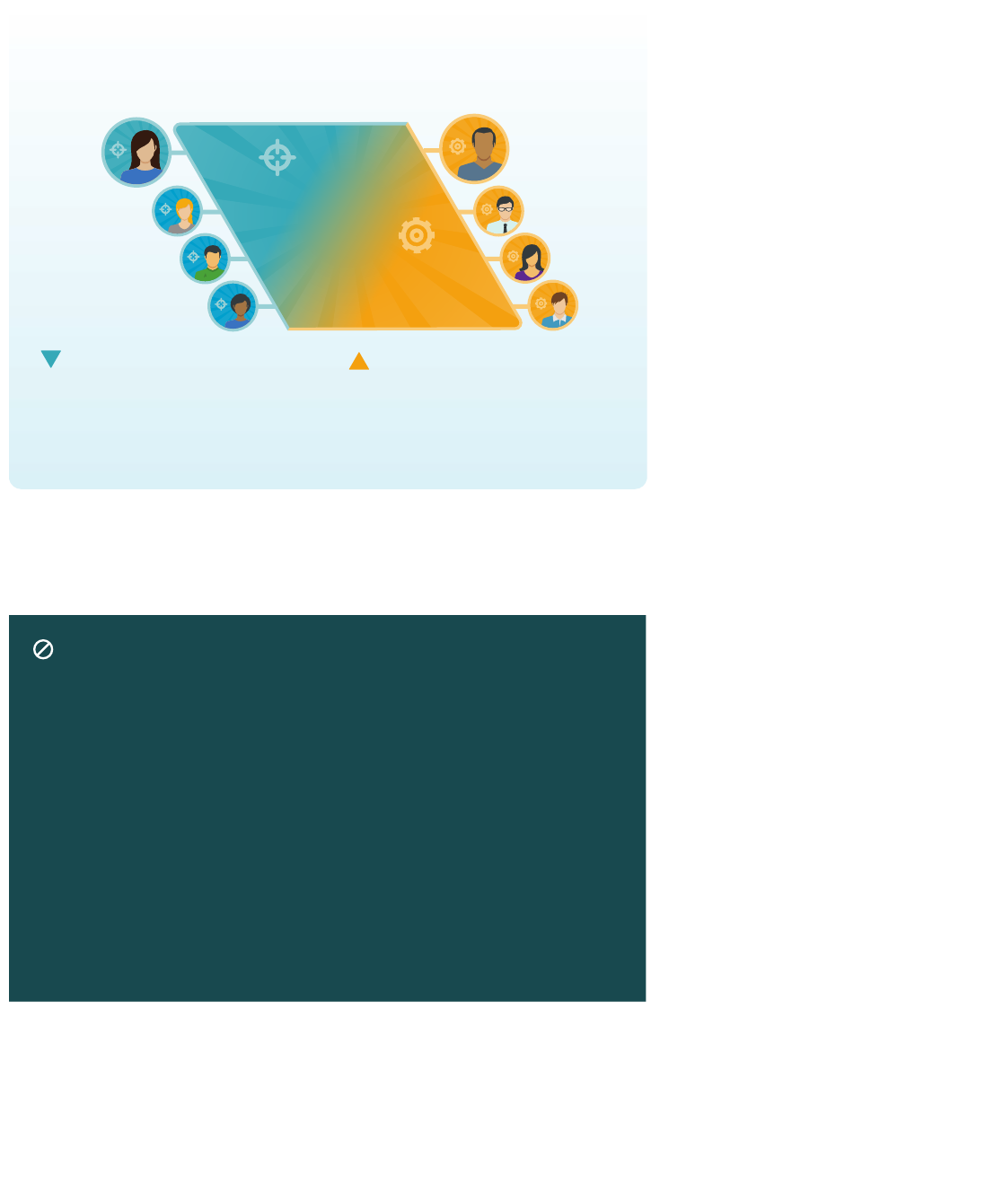

Figure 6: An agile team

PRACTICE: BUILD THE SCRUM TEAM

Scrum gives us a simple model for a team,

and we believe this is a valuable frame for

most agile teams. Scrum suggests just

three roles:

+ Scrum Master

+ Product Owner

+ Team Member

26

Although Scrum is a specic agile

framework, (explained more in the

Delivery section), the notion of a delivery

team facilitator in an agile team is so

common and so eective, we feel it’s

simplest to refer to this person as a

Scrum Master—even for a non-Scrum

team—given it is the most common

term for that role.

Growing Scrum Masters

We routinely encounter clients and

teams who place more stock in entry-

level certications, like Certied Scrum

Master, than is truly warranted. While this

certication and others like it provide a

great overview of the Scrum framework,

it does not magically make someone an

eective Scrum Master. Because of this,

we recommend the following learning

plan for our Scrum Masters:

The Scrum Master

The Scrum Master is an experienced

agilist, responsible for upholding agile

values and principles for the delivery

eort. The Scrum Master helps the team

execute its agreed-upon delivery process

and typically facilitates common team

ceremonies, like daily standup meetings,

planning meetings, demos, retrospectives,

and so on. The Scrum Master biases

the team toward action and delivery

and stretches the team to continuously

improve, hold each other accountable,

and take ownership of the way the

process works.

Table 2: Scrum Master learning plan

CORE OR ELECTIVE CERTIFICATION DESCRIPTION

Core ICP ICAgile Certied Professional

Core PSM I Professional Scrum Master I

Core ICP-ATF ICAgile Certied Professional in Agile Team Facilitation

Elective PMI-ACP PMI-Agile Certied Practitioner

Elective ICP-ACC ICAgile Certied Professional in Agile Coaching

Elective SA SAFe Agilist

27

The Product Owner

The Product Owner is the person who

most considers the mission or business

value of the solution being developed. They

are responsible for maximizing the return

on investment for the development eort,

and they speak for the interests of the users.

They could be from the client organization;

if they are from the Booz Allen team, they

represent the client’s perspective. They

interact regularly with the delivery team,

clarifying needs and providing feedback

on designs, prototypes, and iterations

of the solution.

Growing Product Owners

We use the following learning plan

to grow Product Owners and agile

business analysts:

PRODUCT OWNERS TYPICALLY:

1. Create and maintain the product backlog

2. Prioritize and sequence the backlog according to business value

3. Assist with elaboration of epics into user stories that are granular enough

to be completed soon (like a single sprint)

4. Convey the vision and goals for the project, for every release, and for

every sprint

5. Represent and engage the customer

6. Participate in regular team ceremonies (like standups, planning, reviews,

retrospectives)

7. Inspect progress every sprint, accept or reject work, and explain why

8. Steer the team’s direction at sprint boundaries

9. Communicate status externally

10. Terminate a sprint when drastic change is required

Table 3: Product Owner and agile business

analyst learning plan

CORE OR ELECTIVE CERTIFICATION DESCRIPTION

Core ICP ICAgile Certied Professional

Core PSPO I Professional Scrum Product Owner I

Core ICP-BVA ICAgile Certied Professional in Business Value Analysis

Elective PMI-ACP PMI-Agile Certied Practitioner

Elective ICP-ATF ICAgile Certied Professional in Agile Team Facilitation

Elective SPM/PO SAFe Product Manager/Product Owner

28

The team member

Team members are, of course, the other

members of the team, such as testers,

developers, and designers. They are the

people who, collectively, work together to

deliver value on the project. They carry a

diverse set of skills and expertise, but they

are happy to help out in areas that are not

their specialty. Team members, together,

take collective responsibility for the total

solution, rather than having a “just my job”

outlook. Team members do whatever they

can to help the team meet its sprint goal

and build a successful product.

On functional roles and T-shaped people

On agile teams, there should be less

emphasis on being a “tester” or a

“business analyst” or a “developer”; we

should be working together, sharing the

load, collectively getting to the goal. That

said, we still value the specialties and

disciplines our team members bring to

the project. Agile teams are ideally made

of generalizing specialists, sometimes

referred to as T-shaped people, who

collaborate across skill sets but bring

valuable depth in a useful specialty to

the project. This means that while a team

member may have deep knowledge in a

particular area, known as a specialist,

they also need to build knowledge broadly,

known as a generalist.

The “T” in T-shaped is made up of a

vertical line representing the deep

knowledge of a specialist and a horizontal

line representing the broad knowledge of

a generalist. Specialists who are deep

but not broad can only accomplish work

in a particular area and can become a

bottleneck when they are the only team

member who can accomplish the work.

Conversely, generalists who have broad

but not deep knowledge can become a

bottleneck when the work requires a deeper

understanding or greater skill set. Teams

of generalizing specialists build trust in one

another by collectively committing to goals,

sharing knowledge, actively mentoring,

and delivering solutions.

On bigger teams, it’s reasonable that

people may live in their specialty more than

on a smaller team. Team composition is

heavily inuenced by nancial feasibility.

Teams working for a client under contract

often have constraints related to a labor

category and hourly rate. This is the perfect

opportunity to bring junior members

along and encourage learning skills outside

the specialty as needed. For example, a

junior developer may benet from learning

test automation, which is adjacent to

development. Constraints on skill sets

or level are the perfect opportunity to

emphasize the need for teams with

T-shaped members. Ultimately this is a

balance that the team, with all its local

context, should talk about and adapt

through inspection and conversation.

< Assuming a class is enough >

While agile education is a core piece of the adoption puzzle, sending a

few people (or worse, a single would-be Scrum Master) to a 2- or 3-day

certication course is not a recipe for success. In many ways, agile

represents a paradigm shift for individuals, teams, and leadership. These

entry-level agile certications simply introduce this new way of thinking

and some of the popular frameworks or practices. They do not equip an

individual with the essential change management skills required to achieve

sustainable agility. We employ a team of certied and experienced agile

coaches to partner with teams on their journeys towards agility and

high-performance. Read more about creating a coaching capability from

Lyssa Adkins [Adkins 2015].

29

On team size

Our experience shows that a cross-

functional team of less than 10 is the

preferred team size. This is supported by

the Project Management Institute and

generally follows the Scrum Guides.

This size would include a dedicated

Scrum Master and a Product Owner.

As the project size scales beyond 10,

the eectiveness of the team per person

declines, and signicantly more time is

spent coordinating work. If the scale of the

work requires a large team, we need to

think about how that can be divided into

multiple cross-functional teams that are

tightly coordinated but loosely coupled.

More thoughts on scale can be found in

the Agile at Scale section.

Team structure patterns

In its simplest frame, agile teams have

people who focus on the value of things—

what needs to be built—and other folks

focused on the delivery of things—how we

will build it, what’s possible. Though they

operate as a single team with one goal and

one purpose, you can also consider that

there are two virtual, smaller teams here:

a value team and a delivery team. There

are a few patterns we see work well, so

we explain those in the next three plays.

< Assuming delivery or maintenance are

someone else’s problem >

So we’re back to throwing things over the fence in a “that’s not my job”

mentality (see generalizing specialist). Not only does this cause tension

between teams but it also leads to poor quality and just plain “bad stu.”

When we don’t take responsibility for delivering valuable, quality solutions

as a team in the larger sense of the word, we short change our customer.

< Scrum Master is also the Product Owner >

The Product Owner naturally wants as much value completed in the

shortest time to market. The Scrum Master is there to facilitate the

team, help unblock impediments, and stay attuned to the team needs.

The natural tension that exists with the Scrum Master’s and Product

Owner’s goals helps the team nd balance. If they are combined into

one person, you lose the benets of each role. Either the Product Owner

no longer pushes the team to get the most, based on their Scrum Master

persona; or the Scrum Master no longer cares about the team’s pulse

and pushes as the Product Owner. The team needs both roles.

30

Figure 7: An agile project team

PL AY: E XPAN D T O A VA L U E T E A M

WHEN ONE PRODUCT OWNER

ISN’T ENOUGH

If the mission needs are suciently

complex or there are complicated

relationships with multiple client

stakeholders, it might be impossible to

have just one Product Owner. In that case,

we recommend thinking of a larger value

team. This team might grow to around

10 people and would typically include

representatives like business analysts,

compliance interests, end users, and so on.

In this case, there can still be a Product

Owner, but that person is now the value

team’s facilitator, bringing together all

those perspectives and creating a common

voice, and typically would not be able to

trump the other stakeholders. In this

setting, the jobs of the Scrum Master and

Product Owner become more dicult—

trying to coordinate all the interests at

play—but they can still be very successful.

P L AY: S C A L E T O M U LT I P L E

DELIVERY TEAMS AND VALUE

TEAMS WHEN NEEDED

If the overall solution scope is very large,

the expertise required is suciently diverse,

or the timeline is constrained such that a

single team is insucient to produce the

solution, then you’ll have to scale up to

multiple delivery teams, each with its own

Product Owner/value team. There are a

few frameworks that help in scaling agile,

which we discuss later in this playbook.

Additional roles are likely required,

like architects to keep the technology

suciently robust and coordinated.

Project Teams

AG IL E

Value Team

Communicates and represents client

needs by defining priorities and

acknowledging acceptance

Delivery Team

Cross-functional group that does

whatever it takes to produce a

valuable, working product

Delivery

Team

Value

Team

Product

Owner

Developers

Tes ter s

Architect/

Tec h L ead

Scrum

Master

Business

Analysts

Program

Managers

Compliance

08.031.17_07

Booz Allen Hamilton

< Scrum Master is also the Project Manager >

The Scrum Master is there to support the team and uphold their process,

whereas the Project Manager is there as an interface with the client and

keep the project on the rails. Much like the Product Owner, the Project

Manager should be in a natural tension with the Scrum Master. Managing

the work often means tracking resources, budget, risk, tasking, and cross

team dependencies, and ensuring delivery on the work committed.

The Scrum Master focuses on the team needs. By combining these roles,

you make both less eective. The Project Manager taking the Scrum

Master stance will put the team rst, being less likely to push the team

on delivery. The Scrum Master taking the Project Manager stance would

be less likely to protect the team from the outside pressures, and impose

less favorable team atmosphere.

31

skills and passions are. How do you like

to have fun? How do you like to

communicate? What makes you happy?

What makes you frustrated? You’ll likely

want a good facilitator to pull this

chartering meeting together. Teams nd

it has lasting eects on the sense of

community, empathy for each other,

and overall eectiveness.

PRACTICE: CHARTERING

At the beginning of a project, or after

signicant change on a project (in scope

or in team makeup), we recommend team

chartering. This is a meeting, ideally in

person, together—even for a team that’s

otherwise distributed. And the real focus

of this meeting is: Who are we, and what

are we doing? We recommend working

through activities to get to know each

other and nd out what each member’s

P L AY: I N V I T E S E C U R I T Y I N T O

THE TEAM

The security perspective needs to be ever

present in the process, not just an after

thought. From establishing requirements,

through designing the system and

implementing features, to operations

and sustainment, security needs to be

considered and baked in. In a modern

team, it is everyone’s responsibility to

think about, address, and implement

secure practices. Security should be

embedded in the culture; it isn’t just a

step at the end, or “that other team”

down the hall. It will typically make sense

for security-focused professionals to nd

their home in the value team, when we

think about how the software may need

to attain a certain accreditation or

certication. But, security-mindedness

is essential for the delivery team as well,

because we want those practices and

habits that build secure software to be

part of the routine work.

PLAY: BUILD A COHESIVE TEAM

We strongly believe in keeping the team

together. And the simplest team is under

10 people, has a dedicated single Product

Owner, and has a dedicated single Scrum

Master. This team is committed to just

one project at a time and can plan and

estimate together. The longer a team is

together, it tends to be more predictable,

has great potential for high-performance,

and really enjoys working together.

< People are rewarded for non-agile,

non-collaborative behavior >

The hero approach is often applauded by organizations because it shows

immediate results and it’s easy to identify the reason for success. In the

long run, it diminishes the importance of tackling issues as a team.

When each team member strives to take on everything alone, they risk

burnout, becoming a bottleneck for the team, and stunting growth of

team members. When team members are rewarded for collaborative

behavior, they build trust, grow skill sets, exchange knowledge, mentor

one another, and share responsibility in success and failure.

< Moving people to work, rather than work to teams >

Management made switches to resources on an organization chart, so

the work is dispersed and assigned to the new project. Managers should

consider how to foster high-performing teams. Teams that work together

for a stretch of time begin to nd their stride and form an identity.

When a team member is moved to “put out res” on another project,

the team members left behind must reform. They must establish velocity,

revisit working agreements, and begin to normalize around their new

composition. This disruption ends up being costly since the receiving

team must do the same with the addition of the new team member.

When the project needs to increase capacity, the additional stories should

be prioritized into the team’s backlog instead of moving individuals.

32

TEAM CHARTER

TEAM MEMBERS

+ Who are the team members? Names and preferred

contact info (email, call, text, etc.)

+ Who will be acting as the Product Owner (or

representative) and Scrum Master?

COLLABORATION LOCATIONS

+ Team area location

+ Conference call/video chat info

+ Agile board name & URL

+ Wiki URL

WORKING TOGETHER

+ What does our team value? What do we stand for?

+ Working agreement: How will we get work done and

stay happy along the way? (e.g., How will absences be

communicated? How will we hold ourselves accountable

for tasks/action items?)

+ How will our team handle conict?

+ Core working hours: Do you have core hours when team

members will be available/reachable

PRODUCT OWNER

+ Who is the Product Owner?

+ Who are our stakeholders and how do they coordinate

with the Product Owner?

+ Product Owner availability: When is the Product Owner

available/unavailable? Does the Product Owner sit with

the team? Which ceremonies does the Product Owner

lead/attend?

+ What do we do when the Product Owner is unavailable

for agile ceremonies?

SPRINT CADENCE

+ What day does our sprint begin and end? (recommend

not Monday or Friday)

+ Sprint planning: time/day/location

+ Daily standup: time/location

+ Sprint retrospective: time/day/location

+ Backlog renement/grooming: time/day/location

+ Who is invited to each ceremony? (list attendees)

+ Important known milestones: Are there any dates or

deliveries that we know of already? Begin to build out our

team roadmap (in Conuence or some other accessible

place) using those known milestones

COORDINATING WITH OTHER TEAMS/VENDORS

+ Do we ever need to coordinate across teams?

+ How will our team handle this situation?

+ How will we proactively manage dependencies/

blockers/etc.?

+ How will you collaborate? Who will facilitate the

coordination?

DEFINITIONS

+ Denition of done: How will we dene done on our team?

Getting on the same page about this and having the

discussion up front and being able to refer back to it will

save the team later. Revisit what done means to you once

in a while to make sure you update it as things change

(e.g., passed unit tests, documentation done, peer

reviewed, code checked in…)

+ Denition of ready: How can we make sure something