1

School of Mechanical

Department of Aeronautical Engineering

UNIT- I – AVIATION MANAGEMENT - SAE1403

2

1.1 Introduction

The term aviation was coined by a French pioneer named Guillaume Joseph Gabriel de La Landelle

in 1863. It originates from the Latin word avis that literally means bird. Aviation means all the

activities related to flying the aircraft.Aviation management involves managing the workflow of

airline, airport, or other businesses pertaining to aviation or aerospace industry by carrying out the

day-to-day operations of an airport or an airline.The Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) of

Government of India is responsible to formulate policies and programs to develop and regulate

civil aviation, and to implement the schemes for expanding civil air transport. It also oversees

airport facilities, air traffic services, and air carriage of passengers and goods. An Indian regulatory

body for civil aviation named The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) is under the

MoCA. This directorate investigates aviation accidents and incidents.

The following are some most important factors that drive civil aviation:

• The Low Cost Carriers (LCCs), modern airports

• Emphasis on regional connectivity

• Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) in domestic airlines

• Advanced information technology (IT) interventions

In May 2016, domestic air passenger traffic rose 21.63 per cent from 7.13 million to 8.67 million

as compared to the traffic in May, 2015. In March 2016, total numbers of flights at all Indian

airports are recorded as 160,830; which is 14.9 per cent higher than the flights of March

2015.According to the reports of the Centre for Asia Pacific Aviation (CAPA), by FY2017, Indian

domestic air traffic is expected to cross 100 million passengers compared to 81 million passengers

in 2015. According to CRISIL’s reports, the airlines of India are expected to record a collective

profit of INR 8,100 crore (US$ 1.29 billion) in year 2016.

Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL), a government-owned corporation based at Bangalore,

Karnataka, is an Indian giant that is governed by Ministry of Defence (MoD). It is involved in

manufacturing and assembly of aircraft, navigation, and allied communication equipment. It also

governs airports operations.HAL works in collaboration with numerous international aerospace

agencies such as Airbus, Boeing, Sukhoi Aviation Corporation, Israel Aircraft Industries, RSK

MiG, Rolls- Royce, Dassault Aviation, Indian Aeronautical Development Agency, and the Indian

Space Research Organization (ISRO).

Airline includes its equipment, routes, operating personnel, and their management. Airline

provides a regular service of air transport on various routes. It is responsible for booking the tickets

for the prospective passengers, taking care of the passengers and their luggage during transit, and

transporting them safely to their destination. As the types of duties required to be done are

multifold, the airline business is always working round the clock.

An organization that owns and operates many aircrafts, which are used for carrying passengers

and cargo to different places.The world’s first airline named DELAG established on 16th

November, 1909. An airline business can be of various sizes and the ownership also varies. For

3

example, it can be privately owned, jointly owned, or publicly owned. It also can be as small as a

Domestic or as large as an International airline.

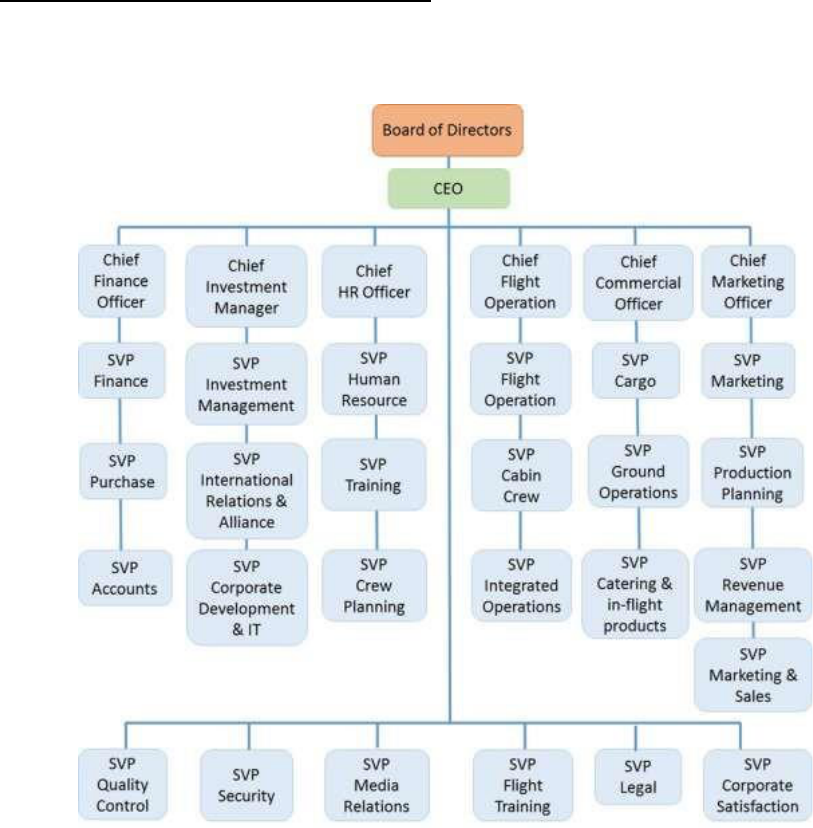

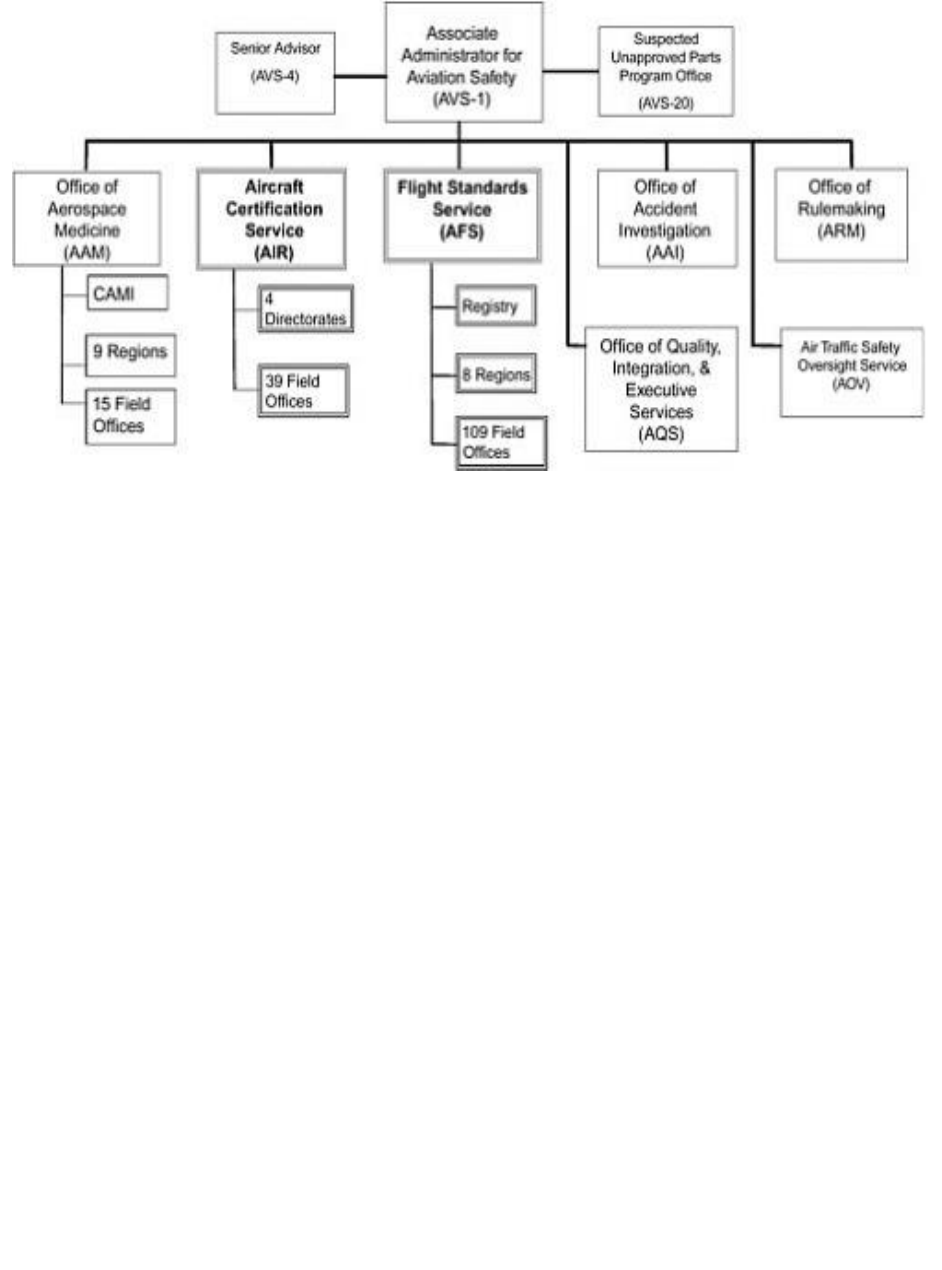

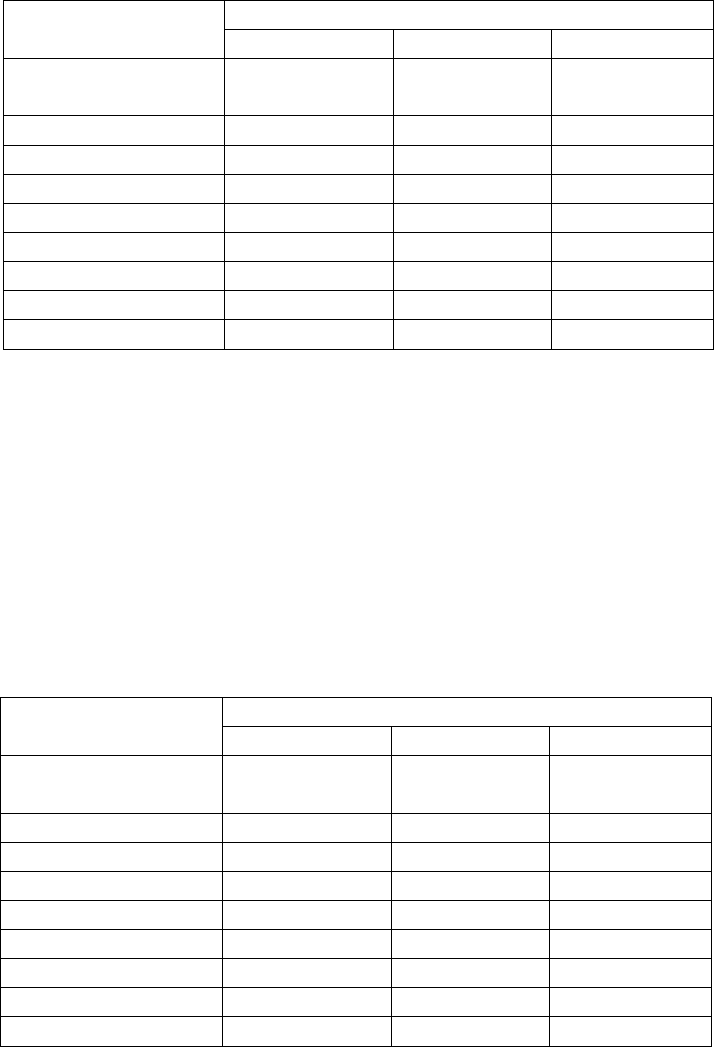

1.2 Organizational Structure of an Airline

Airline, as any other business calls for teamwork from its personnel. As we see in the diagram

given below, there are various responsibilities the airline staff needs to carry out and the structure

is indeed like that of a big elephant.

Fig1.1 Organizational Structure of an Airline

1.2.1 Cockpit Positions in Flight

o

Pilot: The highest ranking member of the aircrew, designated as Pilot-in- Command.

o

First Officer: He is a pilot who is not the chief pilot.

o

Second Officer: He works as a relief pilot and also performs selected duties.

o

Flight Engineer: He is responsible for flight systems and fuel. Today, the position is

diminished and his position is typically crewed by a dual-licensed Pilot and Flight Engineer.

o

Airborne Sensor Operator: He gathers information from airborne platforms.

1.2.2 Cabin Positions in Flight

•

In-Flight Service Manager: This manager is a team lead of the rest of the cabin crew.

•

Flight Attendant: They are responsible for assisting the passengers and their safety.

4

•

Flight Medic: A Para-medic officer employed on flying ambulance.

•

Loadmaster: For cargo aircrafts, he is responsible to load the goods and check the weight and

balance before and after the loading.

1.3 INDIAN AVIATION SECTOR

The Indian aviation sector can be broadly divided into the following main categories:

1. Scheduled air transport service: It is an air transport service undertaken between two or more

places & operated according to a published timetable. It includes: Domestic & International

Airlines.

Air Deccan,

Spice Jet,

Kingfisher Airline &

Indigo

2. Non-scheduled air transport service: It is an air transport service other than the scheduled

one & may be on charter basis. The operator is not permitted to publish time schedule & issue

tickets to passengers.

3. Air cargo services: It is an air transportation of cargo & mail. It may be on scheduled or non-

scheduled basis. These operations are to destinations within India. For operation outside India,

the operator has to take specific permission of Directorate General of Civil Aviation

demonstrating his capacity for conducting such an operation.

4. Apart from this, the players in aviation industry can be categorized in three groups:

Public players : Air India, Indian Airlines

Private players : Jet Airways, Air Sahara, Kingfisher Airlines, Spice Jet, Air Deccan

Start up players: Omega Air, Magic Air, Premier Star Air & MDLR Airlines.

1.4 Airport Authority of India(AAI)

The Airport Authority of India (AAI) is a public authority that provides Air Navigation Service

(ANS) at the airports. It works under the Ministry of Civil Aviation (MoCA) to build, upgrade,

maintain, and manage civil aviation infrastructure in India.

The Indian government formed this organization in April 1995 by merging two organizations:

One, International Airports Authority of India (IAAI) that was founded in 1972 to manage the

nation's international airports and two, the National Airports Authority (NAA) that was formed in

1986 to look after domestic airports.

The major roles of AAI include:

•

To provide communication, navigation, and surveillance systems (CNS).

•

To provide Air Traffic Management (ATM) service in Indian airspace and

adjoining oceans.

•

To manage all the Indian airports.

•

To ensure the safety of the airports and aircrafts.

•

To provide calibration of navigational aids in the flights of Indian Air Force,

Indian Navy, Indian Coast Guard, and private airfields in India.

•

To provide passenger facilities and information system at the passenger

terminals at airports.

5

1.4.1. Airports in India

Airports in India are managed by the Airports Authority of India (AAI) under the Ministry of Civil

Aviation is responsible for creating, upgrading, maintaining and managing civil aviation

infrastructure in India. It provides Air traffic management(ATM) services over Indian airspace and

adjoining oceanic areas.

1.4.2. Category of Airport:

• Total 125 Airports

• 18 International Airports,

• 7 Customs Airports,

• 78 Domestic Airports and

• 26 Civil enclaves at Military Airfields

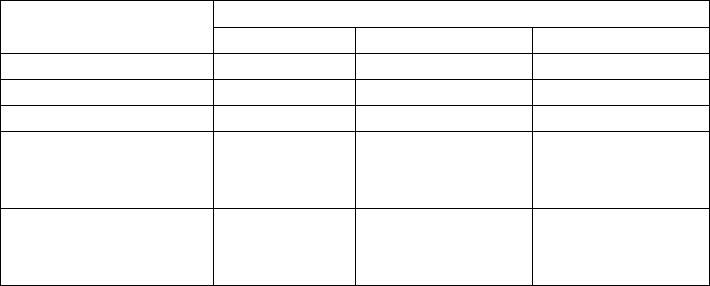

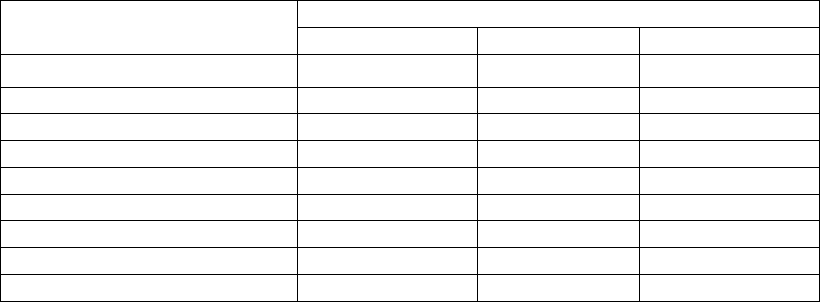

Table 1 List of Some Important Airport:

No

STATE

CITY

AIRPORT NAME

1.

Andaman & Nicobar

Islands

Port Blair

Veer Savarkar International Airport

2.

Andhra Pradesh

Visakhapatnam

Visakhapatnam International Airport

3.

Assam

Guwahati

Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi

International Airport

4.

Bihar

Gaya

Gaya International Airport

5.

Delhi

New Delhi

Indira Gandhi International Airport

6.

Goa

Goa/td

Goa International Airport/Dabolim

Airport

7.

Gujarat

Ahmedabad

Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel International

Airport

8.

Jammu & Kashmir

Srinagar

Srinagar Airport

9.

Karnataka

Bengaluru

Kempegowda International Airport

10.

Karnataka

Mangalore

Mangalore International Airport

11.

Kerala

Kochi

Cochin International Airport

12.

Kerala

Kozhikode

Calicut International Airport

13.

Kerala

Thiruvananthapuram

Trivandrum International Airport

14.

Madhya Pradesh

Bhopal

Raja Bhoj International Airport

15.

Maharashtra

Mumbai

Chhatrapati Shivaji International

Airport

16.

Maharashtra

Nagpur

Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar International

Airport

17.

Manipur

Imphal

Tulihal International Airport

18.

Odisha

Bhubaneswar

Biju Patnaik International Airport

19.

Punjab

Amritsar

Sri Guru Ram Dass Jee International

Airport

20.

Rajasthan

Jaipur

Jaipur International Airport

21.

Tamil Nadu

Chennai

Chennai International Airport

22.

Tamil Nadu

Coimbatore

Coimbatore International Airport

6

23.

Tamil Nadu

Madurai

Madurai Airport

24.

Tamil Nadu

Tiruchirapalli

Tiruchirapalli International Airport

25.

Telangana

Hyderabad

Rajiv Gandhi International Airport

26.

Uttar Pradesh

Lucknow

Chaudhary Charan Singh International

Airport

27.

Uttar Pradesh

Varanasi

Lal Bahadur Shastri Airport

28.

West Bengal

Kolkata

Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose

International Airport

1.5 THE DGCA

The Directorate General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) is the Indian governmental regulatory body

for civil aviation under the Ministry of Civil Aviation. This directorate investigates aviation

accidents and incidents.

1.5.1 RESPONSIBILITES & FUNCTIONS OF DGCA

1. Statutory authority responsible for laying down standards and their implementation

covering:

• Airworthiness,

• Safety and operation of aircraft,

• Flight crew standards & training,

• Air transport operations.

2. Licensing of flight crew, aircraft engineers and civil aerodromes.

3. Certification of aircraft operators.

4. Investigation into incidents and minor accidents.

5. Regulation and control of air transport operations.

6. Formulation of aviation legislation.

7. Research and development activities in the field of civil aviation

8. Handling of matters relating to ICAO.

1.5.2. DIRECTORATE OF AIRWORTHINESS (INSPECTION)

• Exercising of airworthiness regulatory control of civil aircraft registered in the country.

• Laying down airworthiness standards.

• Licensing of aircraft maintenance engineers.

• Issue of certificate of registration of civil aircraft.

• Issue and revalidation of certificate of airworthiness of aircraft.

• Approval of firms dealing with manufacture, maintenance and overhaul of aircraft and

components.

• Approval and monitoring of quality control standards and procedures of aircraft

maintenance.

• Surveillance and spot check on the engineering activities of operators, manufacturers,

storage facilities and approved firms.

• Investigation of major defects.

• Airworthiness control of VVIP aircraft.

7

• Anti sabotage checks and fuel quality control check for VVIP flights.

• Review of service bulletins and airworthiness directives and their compliance.

1.5.3 DIRECTORATE OF AIRWORTHINESS (EXAMINATION)

1. To conduct examinations for issue and endorsement of aircraft maintenance engineers’

license, glider maintenance engineers license and basic aircraft maintenance engineers’

certificate.

2. To conduct technical examinations for pilots and flight engineers.

1.5.4. TRAINING WING (ENGINEERING)

To impart specialized training to the officers of DGCA in technical fields, to arrange refresher

courses for the DGCA officers and to arrange frequent meetings between DGCA officers, pilots,

engineers and air traffic control officers to achieve proper coordination and understanding of each

others functions and responsibilities.

1.5.5. DIRECTORATE OF TRAINING & LICENSING

• Training of pilots at flying and gliding clubs/institutions/schools including flying

subsidy allotment to flying clubs.

• To conduct examinations for various categories of pilot licenses.

• To review medical examination reports of pilots.

• To issue and renew pilots licenses of various categories.

1.5.6. DIRECTORATE OF FLIGHT INSPECTION

• Approval of check pilots, instructors and examiners on various types of aircraft for

carrying out periodic proficiency checks of pilots.

• To carry out standardization checks of check pilots/instructors/examiners.

• To conduct random proficiency checks of pilots and monitor their skill.

• Approval of training simulators, flying training programmes, key operational personnel

and operations manual.

• Surveillance of various operational aspects of the airlines and operators.

1.5.7. DIRECTORATE OF REGULATIONS AND INFORMATION

• Review and implementation of air services agreements with foreign governments.

• Clearance of schedules of foreign airlines.

• Examination and ratification of international conventions.

• Drafting of bills to implement international convention.

• Rendering of aeronautical information service through issuance of aeronautical

information circulars, NOTAMS, AIP and other regulatory publications.

• Amendment of aircraft rules.

• Issuance of various permits under aircraft rules (for example aerial photography,

carriage of dangerous goods, dropping of flowers from aircraft etc.).

• Examination of ICAO recommendations.

8

1.5.8. DIRECTORATE OF AERDROME STANDARDS

• Licensing and inspection of civil airports, civil enclaves, private and state govt.

Airfields used for air transport operations.

• To check serviceability of Various Navigational, communication and

Landing Facilities, safety services and Proper Maintenance of

aerodromes.

1.5.9. DIRECTORATE OF AIR SAFETY

• Investigation of civil aircraft incidents and minor accidents.

• To provide technical experience to courts/committees of inquiry.

• To associate with the investigation of incidents/accidents to Indian registered aircraft

abroad.

• To monitor implementation of recommendations made by various courts and

committees investigating aircraft incidents.

• Periodic inspection of aerodromes and facilities therein.

• To coordinate implementation of measures to prevent bird strikes to aircraft at all civil

airports.

• To monitor action taken reports on safety audits carried out on airlines and aviation

agencies.

• To issue air safety circulars, bulletins, posters and publication of annual civil aircraft

accident summary.

1.5.10. DIRECTORATE OF RESEARCH & DEVELOPMENT

• Type certification of civil aircraft, engines and components.

• Approval of repairs and modifications of aircraft and components.

• Design and development of prototype light aircraft, gliders and glider launching

winches.

• Indigenous development and standardization of aircraft equipment and materials.

• Laboratory investigation of failed components.

• Economic evaluation of civil aircraft.

• Monitoring of air transport data for implementation of laid down requirements.

• Quality control test of aviation fuel.

• Study of aircraft noise and other operational problems.

1.5.11. DIRECTORATE OF AIR TRANSPORT

• Issue and renewal of scheduled and non- scheduled operators permit including

agricultural operators.

• Clearance of non-scheduled flights, charter tourist and cargo flights.

• Approval of flight schedules of Indian operators.

• Publication of Indian air transport statistics.

9

• Study of IATA fare and tariff structure.

• Scrutiny of tariff schedules of carriers for transportation to and from India.

1.5.12. DIRECTORATE OF ADMINISTRATION

• All establishment work of DGCA including creation of posts, filling up of posts,

transfers etc.

• Vigilance and disciplinary cases.

• Security arrangements of department.

• Welfare of the employees of the department.

• Budget work.

• Parliament work.

1.6. AIR TRAFFIC MANAGEMENT

The term "air traffic management" (ATM) is generally accepted as covering all the activities

involved in ensuring the safe and orderly flow of air traffic. It comprises three main services:

• Air traffic control (ATC), the principal purpose of which is to maintain sufficient

separation between aircraft and obstructions on the ground to avoid collisions. However,

this safety objective must not impede the flow of traffic and must therefore meet the needs

of users. Appendix 2 describes how this service is provided in practice, and the division of

responsibilities between the various parties involved.

• Air traffic flow management (ATFM), the primary objective of which is, again on safety

grounds, to regulate the flow of aircraft as efficiently as possible in order to avoid the

congestion of certain control sectors. The ways and means used are increasingly directed

towards ensuring the best possible match between supply and demand by staggering the

demand over time and space; and also by ensuring better planning of the control capacities

to be deployed to meet the demand. The Commission communication on congestion and

crisis in air traffic is described how this service is performed.

• Airspace management (ASM), the purpose of which is to manage airspace -a scarce

resource - as efficiently as possible in order to satisfy its many users, both civil and military.

This service concerns both the way airspace is allocated to its various users (by means of

routes, zones, flight levels, etc.) and the way in which it is structured in order to provide

air traffic control services.

1.6.1. The basic ATM functions

Air traffic management comprises two distinct, basic functions - one "regulatory, in a broad sense;

and the other "operational". The first of these functions involves setting broad objectives in terms

of the safety, quantity, quality and price of the .services to be provided and taking steps to ensure

that they are met. It also involves the allocation of airspace to its various users including military

users, and all the measures needed to meet a wide range of other policy objectives to do with such

issues as environmental protection, town and country planning, national defense and meeting

international commitments. The second function is the 'actual provision of services, for reward,

10

within the regulatory framework provided by the first function. This is a quasi-commercial activity,

the safety aspect of which is of course essential.

1.6.2. The participants

These services and functions are the responsibilities of individual countries, which have put in

place the necessary organizations and infrastructure by their own. In few cases, two or more

countries have used regional organizations to provide some of the corresponding services ' and

functions jointly on their behalf ' in Europe EURO CONTROL' s control centre at Maastricht

provides air traffic control for the upper airspace of the Benelux countries and Northern Germany

under specific agreements between the Agency and the States concerned. EURO CONTROL has

also been given responsibility for setting up and implementing a Central Flow Management Unit

(CFMU) to provide ATFM over nearly all of Europe. The regulatory framework in which the

operational function is provided nevertheless always remains a national prerogative, except when

exist "ICAO Standards, which are binding international commitments, or "EUROCONTROL

Standards made mandatory by the Community. As a consequence, each State .is almost entirely

free to decide the level of service to be provided and the means to be employed for this purpose,

with the result that the technology used and the results achieved vary very widely from one country

to another, making the overall system less efficient than it should be. To overcome this problem,

if only in part, most countries in the world have felt it necessary to develop their international

cooperation. They have done so on the basis of the principle of "full and exclusive sovereignty of

each country over its own territory, as established in the Chicago convention of.1944 which laid

the foundation of the, global system of international air transport.In this context, the International

Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) was set up to define and adopt the common rules - the "ICAO

standards” - needed to make the system interoperable so that anyone aircraft could travel anywhere

in the world. This organization, which has 184 member countries around the globe, is also

responsible for ensuring that the services correspond as closely as possible to the needs of the users

by adopting and amending from time to time Regional Air Navigation Plans, including the

European Regional Air Navigation Plan. It may, consequently, give certain States responsibility

for supplying such services to aircraft crossing international waters.

It is nevertheless a relatively flexible framework, within which it is possible to notify differences

from the common rules, while the undertakings given in the Regional Plans are not legally binding.

Groups of States have also chosen to cooperate more closely at regional level and, in some cases,

to consider actually integrating their national services. It was for this reason that EURO

CONTROL was set up in 1960 by an international convention, to provide air traffic control for the

entire upper airspace of its Member States. This however, represented too great a transfer of

sovereignty for some of the first of its member countries: even before the Convention entered into

force, France and the United Kingdom reclaimed control of the whole of their own. airspace, and

Germany later largely followed suit. Consequently, EURO CONTROL was given essentially a

coordinating role in planning and research, and its Convention was supplemented by a multilateral

agreement under which it was given responsibility for collecting route charges.

11

In parallel' with these developments, and, in, view of the lessons learned from overambitious

attempts at integration, ICAO reinforced the existing. mechanisms for cooperation at regional level

by setting up the EANPG, 4 which meets once or twice a year as necessary and works more or less

continuously on updating and monitoring the European Regional Air Navigation Plan. At a more

political level the European Civil Aviation Administrations have established, under the aegis of

the Council of Europe, the European Civil Aviation Conference (ECAC)S where they can discuss

and co-ordinate their various policies. Up until now, despite the existence and continuing

development of its competence in aviation, the Community has no formal status in any of these

organizations. It is only involved as an observer, in certain aspects of their work.

1.7. International Air Transport Association (IATA)

Private organization promoting cooperation among the world's scheduled airlines to ensure safe,

secure, reliable, and economical air services. Through IATA, local airlines have combined their

individual ticketing and reservation networks into a global system that overcomes differences in

currencies, customs, languages, and laws. Founded in Hague in 1919 as International Air Traffic

Association, it was given the current name in 1945 in Havana and now includes 280 airlines from

130 countries which handle over 95 percent of the world's scheduled air traffic. IATA accredits

the travel agents all over the world, except the US where a local organization (Airline Reporting

Corporation) provides accreditation. IATA's headquarters are in Montreal, Canada and the

executive offices are in Geneva, Switzerland. Not to be confused with International Civil Aviation

Organization (ICAO) this is a governmental organization.

During World War II, the air transport industry has been affected very badly at the world level, in

general and, in the USA, UK, Germany, India, France and Canada, in particular. As a non-

governmental organization, it derived its legal existence from a special Act passed by the Canadian

Parliament in December 1945. The IATA closely resembles with the International Civil Aviation

Organization in terms of its activities and organizational structure.

1.7.1. IATA Objectives:

As per the Articles of Association of IATA, the main objectives are:

1. To promote safe, regular and economical air transport for the benefit of the people of the world,

to foster air commerce and, to study the problems connected therewith;

2. To provide means for collaboration among the air transport enterprises engaged directly or

indirectly in international air transport services;

3. To cooperate with the International Civil Aviation Organization and other international

organizations;

4. To provide a common platform for travel agencies/tour operators

5. To promote and develop international tourism.

1.7.2. The Organizational Structure of IATA is given below:

• Each air transport enterprise, irrespective of its size, and operation, has a single vote in the

12

IATA council. Thus, the main source of authority in IATA is its annual general meeting,

in which all active members have an equal vote.

• Year-round policy direction is provided by an elected Executive Committee which is

subsequently carried out by its Financial, Legal, Technical, Traffic Advisory and Medical

Committees.

• Negotiations of fares and rates agreement are carried out through the IATA Traffic

Conferences, with separate conferences as regards passenger and cargo matters.

• Members of various IATA Committees are nominated by individual airlines, but these

serve as experts in the interests of the entire industry. In the Traffic Conference(s),

however, delegates act as representatives of their individual companies.

• While the Executive Committee fixes the terms of reference of these conferences, their

decisions are subject only to the review of governments and cannot be altered by any other

part of IATA. The organizational structure of IATA is the formal network of performing

various types of activities and powers/duties associated with each role in this network

• IATA administration and management is carried out under a Director General who is

supported by other executive officers like Treasurer and Financial Director, Secretary,

Technical Director, and Traffic Director.

• The main IATA headquarter is in Montreal while Administrative Headquarters of the

IATA Traffic Conferences and IATA Clearing House are located in Geneva. The IATA

Enforcement Office is in New York and the Regional Technical Offices in London,

Singapore, Kenya, USA, and Belgium.

• IATA activities are closely related with operation of the airlines, the airlines charges to the

public and the airlines desire to ensure maximum possible convenience and safety to the

passengers.

• Every year constant and progressive efforts are taken to simplify and standardize devices,

procedures and documentations, within the airlines themselves, and by IATA to streamline

growth and progress of airlines business.

1.7.3. Three Broadly Classified Membership of IATA

The membership of the association is classified as under:

1. Active Members:

Any air transport enterprise which has been licensed to operate a scheduled air service under proper

authority in the transport of passengers, mail or cargo between the territories of two nations, is

eligible to become an active member of the association.

These members have various rights, duties and responsibilities prescribed in the articles of

association. Presently, there are more than 275 air transportation companies from 200 countries on

the membership register in this category.

2. Associate Members:

• Associate membership is open, to any organization/enterprise operating in Air transport

under the Flag of the state and eligible to qualify as member of ICAO is eligible to become

associate member of IATA.

• After a period of ninety days, any associate member comes to be qualified for active

13

membership. However, its associate membership shall be automatically terminated, unless

during such period it shall apply to the Executive Committee for transfer to active

membership.

• Any member desirous of terminating its membership may do so by giving notice to the

Director General. Further, the membership of a member may be terminated by the

Executive Committee on following counts but only after due substantiation:

i. A breach by the member concerned of one or more articles of the association or

any regulation;

ii. Failure by the member concerned to comply with any procedures of the

association.

iii. Adoption of unprofessional and illegal practices.

3. Allied Members:

Allied members are those who after membership can deal with airlines tickets and can use IATA

Logo for all purposes. These types of membership are open to travel agencies/ tour operators and

those who are selling airline tickets to the general public on behalf of airlines.

Application for the membership in the association must be submitted in prescribed form for the

consideration and action of the executive committee and all such applicants can become active,

associate or allied members, only after approval of IATA.

However, any organization whose membership application is rejected by the Executive Committee

has every right to appear in the next General Meeting of members and the action taken thereat is

deemed to be final.

1.7.4. Rules and Conditions, Required to Become IATA Approved Travel Agency / Tour

Operator

1. An application for recognition shall be addressed to the Director, Agency Investigation

Panel IATA.

2. The application for grant of approval shall be in the prescribed form. The objective of

recognition is to promote and develop air transport and tourism industry at global, regional

and national level.

3. Travel agency has to be in the business for the last two to three years.

4. The travel/tour company must have professional staff members, qualified from IATA

approved institutions.

5. The agency must have financial credibility.

6. The location of the agency must be freely accessible and clearly identified to the tourists.

7. Security for the control of airlines tickets block/stock.

8. Ability to generate business.

9. The travel/tour company granted approval shall be entitled to such rights and privileges

as may be granted by the Association from time to time and shall abide by the several terms

and conditions of recognition as prescribed by the Association from time to time.

10. The agency must attach audited annual reports with the application form.

14

11. The agency must attach the statement of International Sales with the application form.

12. The decision of the IATA in the matter of recognition shall be final. The association

may refuse to recognize any Travel/Tour company without assigning any reason.

13. The association reserves the right to withdraw at any time, the recognition already

granted, without assigning any reason.

14. The recognition granted by the IATA shall not automatically entitle the Travel Agency/

Tour Operator to be approved by any other organization/association.

1.7.5. IATA FACT SHEETS

IATA fact sheets present up-to-date key facts and figures related to Air Transport Industry issues

such as.

• IATA Agency Program

• IATA Financial Services

1. Industry Statistics

• Fuel

• Economic and Social Benefits of Air Transport

• Industry Facts and Statistics

• Aviation Charges, Fuel Fees and Taxes

2. Safety & Security

• Safety

• Security

• IATA Safety Audit Programs (IOSA / ISSA / ISAGO)

• Cargo Security

• Cyber Security

• Lithium Batteries

• Remotely Piloted Aircraft Systems (RPAS)

• Public Health Preparedness

• Volcanic Ash

3. Environment

• Climate Change

• Green Taxation

• Alternative Fuels

• Technology Roadmap

• Night flights

4. Policy

• European Airspace Strategies

• Unruly passengers

• Wildlife

• MC99

• Airport Privatization

• Smarter Regulation

15

• Airport Slots

5. Innovation

• New Distribution Capability (NDC)

• ONE Order

• ONE Record

• ONE iD

• Fast Travel

• e-freight and the e-Air Waybill

• RFID & Bag Tag Initiative

1.7.6. IATA Committee’s

1.7.6.1. CARGO COMMITTEE

The Cargo Committee shall act as advisor to the Board of Governors, the Director General, IATA

management and other relevant IATA bodies on all air cargo industry policy issues and develop,

enhance and prioritize policies/guidelines/positions/action plans to resolve such issues. Areas of

activity include:

(i) Cargo Security and Safety

(ii) Cargo technology and automation

(iii) Cargo handling

(iv) Cargo trade facilitation

(v) Cargo-related regulatory development

(vi) Cargo Distribution/CASS

(vii) Agent / carrier relations

1.7.6.2.ENVIRONMENT COMMITTEE

The Environment Committee shall act as advisor to the Board of Governors, the Director General,

and other relevant IATA bodies on environmental matters and act as the focal point in IATA on

environmental issues. Specifically, the Environment Committee shall:

(i) Monitor, assess and respond to environmental developments, policies and regulations of

concern to IATA Member airlines

(ii) Develop and recommend common industry positions on environmental issues

(iii) Advise and, as necessary, implement strategies to promote IATA positions with regulatory

bodies and stakeholders

(iv) Develop and adopt non-binding best practices on environmental issues.

1.7.6.3.FINANCIAL COMMITTEE

The Financial Committee shall act as advisor to the Board of Governors, the Director General,

and other relevant IATA bodies on IATA’s industry financial services and activities connected

with international air transport. The Financial Committee shall advise IATA management on

development of industry financial positions, IATA priorities, strategy, objectives, and policy

implementation for industry financial matters, and promote campaigning, particularly in the

following areas:

16

(i) Industry Financial Strategy: Industry challenges and trends impacting the airline financial

community

(ii) Industry Financial Services and Settlement Systems

(iii) Industry Financial Standards and Services that support airlines’ financial

processes

(iv) Industry External Charges and Cost Management

(v) Industry risk management

1.7.6.4.INDUSTRY AFFAIRS COMMITTEE

The Industry Affairs Committee shall act as advisor to the Board of Governors, the Director

General, and other relevant IATA bodies on all industry affairs and aero-political matters

connected with international air transport. It should identify future trends that could have a

significant impact on our industry and recommend IATA establishes necessary work programs

related to identified risks and opportunities.

The Industry Affairs Committee shall develop industry positions, supervise policy

implementation, and promote campaigning, particularly in the following areas:

(i) Customer service, including passenger and airport services

(ii) Facilitation

(iii) Governmental, intergovernmental and other air transport policy including taxation

(iv) Distribution

(v) Slots and related Infrastructure issues

(vi) Multilateral interlining

(vii) Promotion and enhancement of competition within the aviation industry and of its overall

competitiveness

1.7.6.5.LEGAL COMMITTEE

The Legal Committee shall act as advisor to the Board of Governors, the Director General, the

General Counsel and other IATA bodies on legal and compliance matters affecting member

airlines or IATA. The Committee shall:

(i) identify opportunities for IATA to act as an advocate for the air transport industry by

participating in judicial, regulatory, and legislative proceedings;

(ii) remain apprised of IATA’s strategic objectives and Board-monitored activities and seek

opportunities to advance them through the tools available to lawyers;

(iii) provide advice to, or coordinate with, IATA Legal Services in obtaining from outside legal

resources advice on legal and regulatory issues of interest to the air transport industry;

(iv) liaise with member airlines’ in-house counsel, other IATA Industry Committees, and other

industry associations on matters relating to the air transport industry;

(v) identify, recommend and approve to the General Counsel, based on one or more of the

following criteria, which issues should be litigated, or where IATA should intervene before

courts, tribunals, or regulatory bodies, on an industry wide basis or through a smaller group of

airlines.

(vi) in conjunction with the General Counsel, advise which law firm(s) should be representing the

interests of IATA in industry or regional matters;

(vii) provide recommendations for the following year’s Industry Litigation

budget for approval by the Board of Governors and review periodically the development of the

Industry Litigation budget for any necessary changes or adjustments as the case may be;

17

(viii) advise on the legal and compliance aspects of IATA Conference issues and services operated

by IATA on behalf of the industry;

(ix) develop best practices and templates for legal and compliance issues affecting the industry;

(x) advise IATA on matters related to the development of international law; and

(xi) take any other action relating to industry legal affairs which is considered necessary and

appropriate.

1.7.6.6.OPERATIONS COMMITTEE

The Operations Committee shall act as advisor to the Board of Governors, the Director General,

and other relevant IATA bodies on all matters that relate to the improvement of safety, security

and efficiency of civil air transport. This will include, but not be limited to matters that relate to:

(i) airline safety

(ii) flight operations, ground operations, and global air traffic management

(iii) engineering and maintenance

(iv) security

(v) aviation infrastructure

1.8. INDIAN AVIATION SECTOR

Indian aviation sector is growing at an accelerating rate and the country is getting the

benefits of its improved connectivity. Since its inception the sector has seen many changes. The

vast geographical coverage of the country and its industrial growth makes the aviation sector more

meaningful. The rising working group and economic improvement of Indian middle class is also

expected to boost the growth of the sector further. As a result of this growing demand the

Government of India is planning to increase the number of airports to 250 by 2030.This

improvement in infrastructure has happened to be as a result of improved business and leisure

travel. The major requirement of the aviation sector is development of ground infrastructure. The

Government of India has planned to invest approximately US$12.1 billion, out of these private

investment is in the tune of US$9.3 billion.

Private investment is one of the important components to develop the ground infrastructure.

It is not possible for the government to develop a robust nature like this without the help of private

players. More importantly the private players have the expertise to develop a technology enabled

airport which is the need of the hour. Another area which now a days the government is also

focusing is to create green airport to reduce the environmental impact. To improve the participation

of private players, the government has decided to increase the FDI upto 49% through automatic

route in case of air transport. Thus, the sector which was mainly dominated by the government

agencies now is going hand in hand along with the private players. The increased competition in

the market helps to improve the on air as well as ground services

Growth of Indian aviation sector Indian aviation sector has a long history and moved from

private sectors to government sector then again in the hand of both government and private sectors.

With every passing year, the sector witnessed significant improvement in the movement of traffic

in both the passenger and cargo segment. According to India Brand Equity Survey Report, 2017

India stands at 9th position in terms of market size. During the financial year 2017, the country

18

witnessed 21.5% improvement in domestic passenger traffic. If this is the growth rate, the sector

is expected to become 3rd largest aviation market in the world by 2020.

With the increase in standard of living and introduction of economy class the passenger’s

preference also changed dramatically. Earlier airlines being used by class people only. Now a days

the trends changed and now the mass people also able to travel in airlines. This is being reflected

with the number of increase of passenger’s volume. In 2015-16 the domestic passengers were

85.20 million and in 2016-17 it becomes 103.75 million. In case of international passengers also

increased from 49.78 million in 2015-16 to 54.68 million in 2016-17. The top players are Indigo

with 38% market share, followed by 15.9% share by Jet airways. Similarly Spice jet with market

share of 14%, Indian airlines with 13.2% and Go air with 8%.

1.9. AIRLINE INDUSTRY OF INDIA AIR INDIA CASE STUDY

Overview India is the 9th largest aviation market in the world with a size of around US$ 16 billion

and is poised to be the 3rd biggest by 2020. India aviation industry promises huge growth potential

due to large and growing middle class population, rapid economic growth, higher disposable

incomes, rising aspirations of the middle class and overall low penetration levels.. The Indian

airports have a combined capacity to cater to 220.04 million passengers and 4.63 million tones

cargo per annum and handled 168.92 million passengers and 2.28 million tones cargo in 2013-14.

As per estimates, passenger traffic at Indian Airports is expected to increase to 450 million by

2020 from 159.3 million in 2012- 2013. History Civil Aviation in India traces back to 18 February

1911, when the first commercial civil aviation flight took off from Allahabad for Naini over a

distance of 6 miles (9.7 km). During the Allahabad Exhibition Henri Piquet, a French aviator,

carried 6,500 pieces of mail on a Humber-Sommer biplane from the exhibition to the receiving

office at Allahabad, marking the world's first official airmail service. FDI up to 49% allowed in

domestic airlines by the foreign carriers. Foreign equity up to 100% allowed in airport

development. Domestic and international passenger traffic expected to grow at annual average rate

of 12% and 8% in next five years. Annual average rate of growth of domestic and international

cargo estimated to be 12% and 10% during next five years. MRO industry to triple in size from

INR 2250 crore in 2010 to INR 7000 crore by 2020. Around 3,50,000 new employees are essential

to facilitate growth in the next decade Market Opportunities

1.9.1. Market Opportunities

• An investment of over US$ 12 billion required during the Twelfth Five Year Plan

• Airlines are expected to operate about 1000 aircraft's by 2020, up from the present 450

• Investment to the tune of US $4 billion required for General Aviation aircrafts by 2017

• Air Navigation Services entails investment worth US$ 7 billion in Twelfth Five Year Plan

The civil aviation market in India is all set to become the world's third largest by 2020. Total

passenger traffic stood at a 190.1 million in FY15, registering an increase of 12.47 per cent. By

2020, passenger traffic at Indian airports is expected to increase to 421 million from 190.1 million

19

in 2015. Domestic passenger traffic expanded at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 11.8

per cent over FY06–15. It is expected to touch 209 million by FY17. International passenger traffic

posted a CAGR of 9.5 per cent over FY06-15 and is set to touch 60 million by FY17.

1.9.2.Major Carriers of India

• Air India

• Air India Express

• Jet Airways

• Air Asia

• IndiGo

• Spice Jet

• Vistara

• Go Air

1.10. Air India

The history of civil aviation in India began in December 1912, with the opening of the first

domestic air route between Karachi and Delhi. This was by the Indian state Air services in

collaboration with the imperial Airways, UK. Three years later, the first Indian airline, Tata Sons

Ltd., started a regular airmail service between Karachi and Madras without any patronage from

the government. At the time of independence, the number of air transport companies, which were

operating within and beyond the frontiers of the company, carrying both air cargo and passengers,

was nine. It was reduced to eight, with Orient Airways shifting to Pakistan.

Tata Services became Tata Airlines and then Air- India and spread its wings as Air-India

International. The domestic aviation scene, however, was chaotic. When the American Tenth Air

Force in India disposed of its plane sat throwaway prices, 11 domestic airlines sprang up,

scrambling for traffic that could sustain only two or three. In 1953, the government nationalized

the airlines, merged them, and created Indian Airlines. For the next 25 years JRD Tata remained

the chairman of Air-India and a director on the board of Indian Airlines . After JRD left, voracious

unions mushroomed, spawned on the pork barrel jobs created by politicians

• Headquarters in Mumbai:

The Air India Building is a 23-storey commercial tower on Marine Drive in Nariman Point,

Mumbai, India. The building served as the corporate headquarters for the Indian national airline,

Air India, up to 2013. There are at least 10,800 square feet (1,000 m2) of space on each floor of

the building. In February 2013, Air India officially vacated the building as part of its asset-

monetization plan, and shifted its corporate office to New Delhi. The Indian Airlines House was

chosen as the airline's new headquarters.

Statistics (Rupees in Million)

• Revenue in 2013-14 : 190934.9

• Expenses in 2013-14: 264201.9 Net loss for the current year (62796.0)

Problems

• Over – Employment of employees

• Increased fuel prices result to decline of air traffic

20

• Increasing competition in the market

• Over Staffing

• Large no of staff not required that they had

Solutions

• Must have that staff that is required in operating a plane

• Operating expenses cutting/ cost cutting

• Must have good marketing policies

• Good knowledge about market competitors

• Better management policies

School of Mechanical

Department of Aeronautical Engineering

UNIT- II – AVIATION MANAGEMENT - SAE1403

21

2.1. International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO)

ICAO consists of an Assembly of representatives from the contracting states, a Council of

governing bodies out of various subordinate bodies, and a Secretariat. The chief officers are the

President of the Council and the Secretary General. ICAO conducts meeting every three years to

discuss about the work and to set future policies.

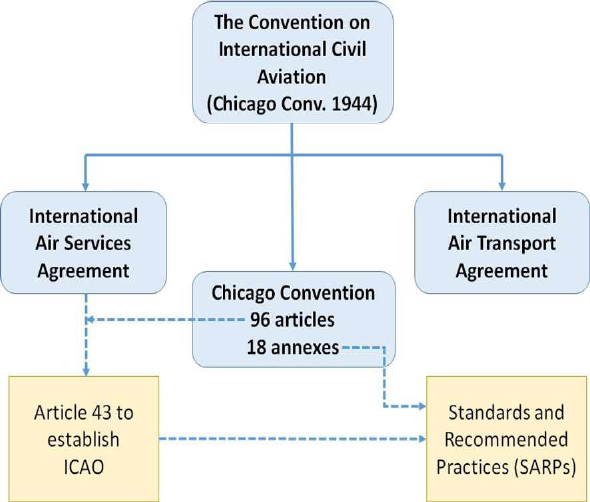

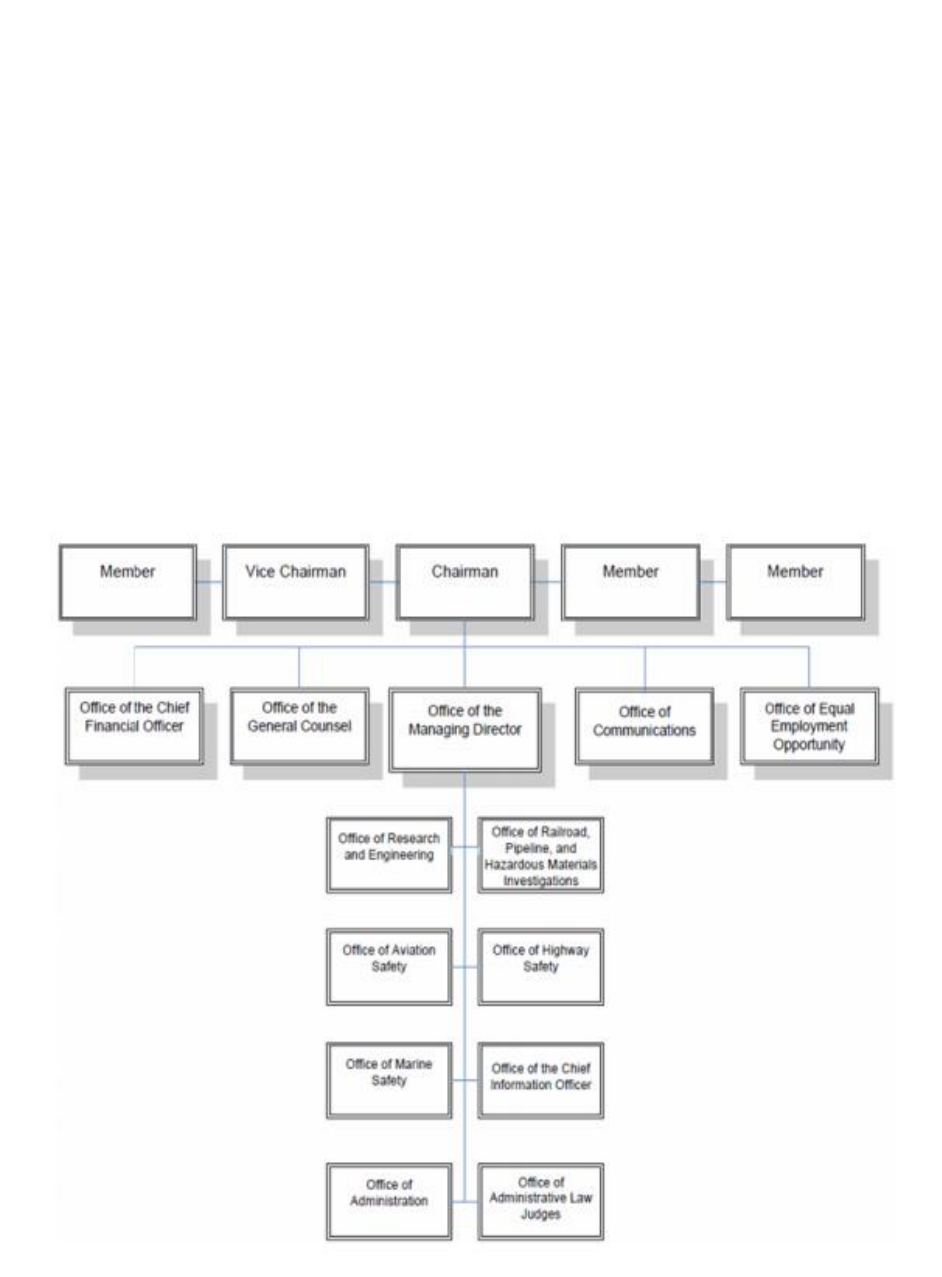

Fig2.1 ICAO

The suggestions, standards, and recommendations are amended by the convention. ICAO

identifies nine separate geographical regions to plan the provision of air navigation facilities and

on-ground services the aircrafts require for flying in these regions.

ICAO's objectives, are to foster the planning and development of international air transport so as

22

to ensure the safe and orderly growth of international civil aviation throughout the world;

encourage the arts of aircraft design and operation for peaceful purposes; encourage the

development of airways, airports, and air navigation facilities for international civil aviation; meet

the needs of the peoples of the world for safe, regular, efficient, and economical air transport;

prevent economic waste caused by unreasonable competition; ensure that the rights of contracting

states are fully respected and that every contracting state has a fair opportunity to operate

international airlines; avoid discrimination between contracting states; promote safety of flight in

international air navigation; and promote generally the development of all aspects of international

civil aeronautics.

The International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) is a specialized agency and an aviation

technical body of the United Nations. Its headquarters is located in Montreal, Canada. It was

created after the Chicago Convention on International Civil Aviation of which was signed by 52

countries in 1944 and was ratified and founded in 1947. ICAO’s primary role is to provide a set of

standards which will help regulate aviation across the world. It classifies the principles and

techniques of international air navigation, as well as the planning and development of international

air transport to ensure safety and security. It also oversees the US Government’s International

Group on International Aviation (IGIA). The international aviation standards were provided to the

191 member states of ICAO around the globe through a global forum in which the member states

are expected to adopt and implement these standards. However, the International Civil Aviation

Organization (ICAO) only provides the fundamental guidelines or SARPs (Standards and

Recommended Practices). It is possible for each member states/countries to modify and adjust

these regulations when necessary under ICAO’s approval. Despite slight variations from different

countries based on the actual implementation in national regulations, civil aviation standards and

regulations are still harmonized all over the world. These local differences are then reported back

to ICAO and published.

2.2. FEDERAL AVIATION ADMINISTRATION (FAA)

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) or formerly “Federal Aviation Agency” is a national

aviation authority of the United States formed in 1958. The FAA is primarily responsible for the

advancement, safety, security and regulation of civil aviation. FAA ensures that every aircraft pilot

is perfectly adequate to their role as air navigators, and that all aircraft in operation follows a strict

set of guidelines in order to ensure safety and minimize danger. To accomplish these things, FAA

created an effective set of aviation regulations known as the Federal Aviation Regulations.

The Federal Aviation Regulations or FAR is a document which consists of tens of thousands of

sections covering every details of aviation. It gives detailed instructions such as aircraft

maintenance, pilot requirements, hot-air ballooning and model rocket launches, covering almost

everything that is needed in order to understand how, when and what to fly. Aircraft pilots and air

carriers are very much required to be familiar with the rules and regulations outlined in the FARs.

23

Aside from its regulatory role, the FAA is also responsible for research and development of

aviation related systems and technologies, air traffic control system, maintenance of air navigation

facilities infrastructure, airspace and development of commercial space travel.

2.3. Primary roles of ICAO and FAA

Some of the major roles of ICAO and FAA in aviation are already mentioned above. One of their

primary roles is of course to ensure security and safety by regulating all aspects of civil aviation

which includes the construction and operation of airports, the management of air traffic, the

certification of personnel and aircraft, enforcing rules and regulations for obstruction lighting,

aeronautical charts, search and rescue standards and many more aspects pertaining to air

navigation.

We may sometimes think that there are too many laws, rules and regulations in the world today.

We may somehow think that they steal away our freedom and hinder us on what we want to do.

But remember that these laws, rules and regulations are made for our protection. We may not

appreciate them now, but once something bad or unnecessary happens, maybe we will.

2.4. Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association (AOPA)

The Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association is a Frederick, Maryland-based American non-profit

political organization that advocates for general aviation. The organization started at Wings Field

in Blue Bell, Pennsylvania. On 24 April 1932, The Philadelphia Aviation Country Club was

founded at Wings Field.AOPA has several programs.

2.4.1 AOPA Foundation, is AOPA’s 501(c)(3) charitable organization. The foundation's four

goals are to improve general aviation safety (under the auspices of its Air Safety Institute), grow

pilot population, preserve and improve community airports, and provide a positive image of

general aviation.

2.4.2 AOPA Political Action Committee is just for AOPA members. Through lobbying, it

represents the interests of general aviation to Congress, the Executive Branch, and state and local

governments. The AOPA PAC campaigns in favor of federal, state and local candidates that

support their policies and oppose those who do not through advertising and membership grassroots

campaigns.

2.4.3. GA Serves America was created to promote general aviation to the public.Legal Services

Plan/Pilot Protection Services, provides AOPA members with legal defense against alleged FAA

enforcement charges as well as assistance obtaining an FAA flight medical. Enrollment in Pilot

Protection Services is only open to AOPA members and requires an additional payment above

dues. The Legal Services Plan was combined with the former medical program in May 2012 under

the name Pilot Protection Services. The Legal Services Plan was created in June 1983.

24

2.4.4 Air Safety Institute (formerly the Air Safety Foundation) is a separate nonprofit, tax

exempt organization promoting safety and pilot proficiency in general aviation through quality

training, education, research, analysis, and the dissemination of information.

2.5 Aviation Management Consulting Group

AMCG has been promoting general aviation management excellence through the provision of

trusted aviation management consulting services, support, and resources for over 20 years.

AMCG’s clients consist of airports, aviation businesses, agencies, associations, and other industry

stakeholders (e.g., aircraft owners and/or operators; airport property lessees and/or developers;

industry vendors; financial institutions; law firms; architectural, engineering, and planning firms;

etc.). AMCG is composed of a unique blend of talented and respected aviation industry

professionals who have strong credentials, proven track records, and over 125 years of combined

aviation industry experience. Together, these individuals have first-hand aviation, aviation

business, and airport planning, development, operations, management, leadership, and consulting

experience and each of the firm’s principals, consultants, and project analysts are pilots. As a

result, AMCG has the unique ability to view any project and any issue that may arise from a multi-

dimensional (airport, aviation business, and aircraft operator) perspective. This team of highly

qualified, knowledgeable, and results-oriented professionals works collaboratively to maintain a

company culture focused on meeting the needs and exceeding the expectations of the client.

Airport services include:

- Strategic Planning / Business Planning

- Primary Management and Compliance Documents (Rules and Regulations, Leasing

Policy, Rents and Fees Policy, Minimum Standards, Development Standards)

- Rent Study (wholesale and retail - land, hangar, office, shop, cargo, etc.)

- Fee Study (landing, based aircraft, fuel flowage, etc.)

- Appraisal (fee simple estate, leasehold interest, and leased fee estate)

- Valuation (business, stock, and asset)

- Transaction Services (acquisition, divestiture, and due diligence)

- RFP Development and Proposal Evaluation

- Agreement Development and Negotiation (Lease, Use, Operating, Through-The-Fence, etc.)

- Assessments and Feasibility Studies (including FBO Options Analysis)

25

- Operational, Managerial, and Financial Assessments

- Land Use, Site Planning, and Facility Programming

- Marketing and Business Development

- Litigation Support and Expert Testimony

These services are provided with the goal of:

- Improving relationships

- Enhancing the range, level, and quality of products, services, and facilities

- Maximizing efficiency and productivity

- Increasing revenues and decreasing costs/expenses

- Capitalizing on opportunities

- Minimizing risk

- Creating value

With AMCG, you can be assured that we put our clients first and you will get straight answers,

objective advice, accurate and timely information, and only the highest quality services, support,

and resource

2.6. IAAE

In the early 1990s, major global barriers around the world were dissolving. To effectively address

the challenges of managing airports in a global economy, there was a need for advanced airport

management education and professional development around the world. To respond to that need,

AAAE’s commitment to professional excellence and the AAAE accreditation program went

international through the creation of the International Association of Airport Executives (IAAE)

in 1992.

The International Association of Airport Executives provides international access to the benefits

of AAAE. IAAE members are eligible to apply for the Certified Member (C.M.) and Accredited

Airport Executive (A.A.E.) programs.

There are three categories of IAAE members:

• IAAE Affiliate – Any individual with responsibility for the management or staff functions

of a public airport.

• IAAE Associate – Any individual not otherwise qualified for membership, who has a

business or professional interest in airports and aviation.

• IAAE Corporate – Public or private companies and corporations, engaged in activities

related to aviation.

IAAE members enjoy a wide range of member benefits and rewards, including:

• Networking Opportunities

• Career Development Opportunities

• Vital Industry Information

• Training Opportunities

• Membership Rewards

Join your IAAE below:

26

2.6.1.IAAE Affiliate Member - Open to any individual who has active full time responsibility for

the management, administration, or staff functions of a public airport. Affiliate members become

eligible to enter the Accreditation program after a minimum of one year in airport management.

2.6.2. International Associate Member - Open to individuals who have an interest in airports and

aviation and do not fall into any of the other specified membership categories.

2.6.3. International Corporate - Open to public or private companies and corporations, who are

engaged in activities related to aviation, or who offer a product or service of interest to airport

management and wish to further their contacts within the aviation industry. IAAE and AAAE

airport executive members are encouraged to buy products and services from IAAE corporate

members and these members also receive substantial savings on marketing and promotional

opportunities for their products or services.

2.6.4. Central European - Open to individuals who work in the countries of Central Europe.

2.7. FAIRS

FAIRS is a management information system operated by GSA to collect, maintain, analyze, and

report information on Federal aircraft inventories and cost and usage of Federal aircraft and

Commercial Aviation Services (CAS) aircraft and related aviation services. Executive agencies of

the United States Government must report to FAIRS if they own, bail, borrow, loan, lease, rent,

charter, contract for, or obtain by ISSA Government aircraft.

• Inventory data on Federal aircraft, including Unmanned Aircraft Systems (UAS),

• Cost and utilization (flight hours) data on Federal aircraft, including Unmanned Aircraft

Systems (UAS),

• Cost and utilization data on Commercial Aviation Services (CAS) aircraft and related

aviation services,

The Capital Asset Planning (CAP) Tool section of FAIRS is an OMB approved substitute for the

Exhibit 300 process for Aviation that can be used to meet the capital asset planning requirements

of OMB Circular A-11.

2.8. Federal Aviation Administration (FAA)

The Federal Aviation Administration (FAA) is the agency of the United States Department of

Transportation responsible for the regulation and oversight of civil aviation within the U.S., as

well as operation and development of the National Airspace System. Its primary mission is to

ensure safety of civil aviation.

The responsibilities of the FAA include:

• Regulating civil aviation to promote safety within the U.S. and abroad;

• Encouraging and developing civil aeronautics, including new aviation technology;

• Developing and operating a system of air traffic control and navigation for both civil and

military aircraft;

27

• Researching and developing the National Airspace System and civil aeronautics;

• Developing and carrying out programs to control aircraft noise and other environmental

effects of civil aviation;

• Regulating U.S. commercial space transportation. The FAA licenses commercial space

launch facilities and private launches of space payloads on expendable launch vehicles.

Investigation of aviation incidents, accidents and disasters is conducted by the National

Transportation Safety Board (NTSB), an independent US government agency.

Along with the European Aviation Safety Agency (EASA) the FAA is one of the two main

agencies world-wide responsible for the certification of aircraft.

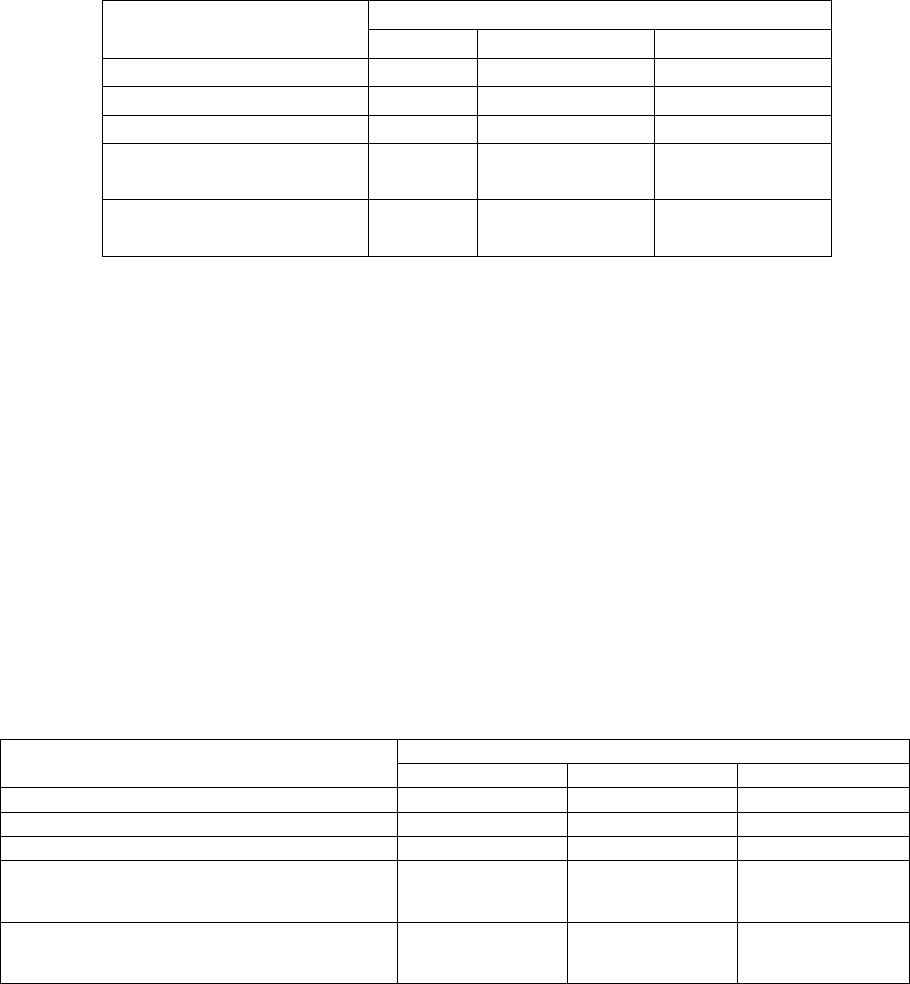

2.8.1. Organisation of the FAA

• FAA is managed by an Administrator, assisted by a Deputy Administrator. Five Associate

Administrators report to the Administrator and direct the line-of-business organisations

that carry out the agency's principle functions.

• The Chief Counsel and nine Assistant Administrators also report to the Administrator. The

Assistant Administrators oversee other key programs such as Human Resources, Budget,

and System Safety.

• FAA also has nine geographical regions and two major centers, the Mike Monroney

Aeronautical Center and the William J. Hughes Technical Center.

2.8.2. Key Activities

The FAA’s key activities may be summarized as:

• Safety Regulation

Issuing and enforcing regulations and minimum standards covering manufacturing, operating, and

maintaining aircraft. Certification of airmen and airports that serve air carriers.

• Airspace and Air Traffic Management

The safe and efficient use of navigable airspace is one of the FAA’s primary objectives. The

Administration operates a network of airport towers, air route traffic control centers, and flight

service stations, as well as developing air traffic rules, assignment of the use of airspace, and the

control of air traffic.

• Air Navigation Facilities

The FAA builds/installs visual and electronic aids to air navigation, maintains, operates and

assures the quality of these facilities as well as sustains other systems to support air navigation and

air traffic control, including voice and data communications equipment, radar facilities, computer

systems, and visual display equipment at flight service stations.

• Civil Aviation Abroad

The FAA promotes aviation safety and encourage civil aviation abroad. It exchanges aeronautical

information with foreign authorities, certifies foreign repair shops, airmen, and mechanics,

provides technical aid and training, negotiates bilateral airworthiness agreements with other

countries and takes part in international conferences.

• Commercial Space Transportation

28

The FAA regulates and encourages the U.S. commercial space transportation industry, including

licensing commercial space launch facilities and private launches of space payloads on expendable

launch vehicles.

• Research, Engineering, and Development

The FAA undertakes research on, and development of, the systems and procedures needed for a

safe and efficient system of air navigation and air traffic control. The Administration helps develop

better aircraft, engines, and equipment and tests/ evaluates aviation systems, devices, materials,

and procedures. It also undertakes aeromedical research.

2.8.2. The FAA’s Role in ATM

The FAA has a complex set of responsibilities in the ATM field. It provides the vast majority of

tower-based ATM, including all major airport facilities. It is the sole provider of en-route ATM

services in the US. The FAA’s service-provision tasks are undertaken by the Air Traffic

Organisation (ATO), which has been established as a functionally separate entity within the FAA’s

organisational structure.

At the same time, the FAA is responsible for the safety regulation of all US aviation activities,

including ATM. For this purpose, an ATM Safety Oversight organisation has been established

within the regulatory division of the FAA with responsibility for oversight of the safety of the

ATO’s operations and activities.

2.8.3. The History of ICAO and the Chicago Convention

• The Convention on International Civil Aviation, drafted in 1944 by 54 nations, was established

to promote cooperation and “create and preserve friendship and understanding among the

nations and peoples of the world.”

• Known more commonly today as the ‘Chicago Convention’, this landmark agreement

established the core principles permitting international transport by air, and led to the creation

of the specialized agency which has overseen it ever since – the International Civil Aviation

Organization (ICAO).

• The Second World War was a powerful catalyst for the technical development of the

aeroplane. A vast network of passenger and freight carriage was set up during this period, but

there were many obstacles, both political and technical, to evolving these facilities and routes

to their new civilian purposes.

• Subsequent to several studies initiated by the United States, as well as various consultations it

undertook with its Major Allies, the U.S. government extended an invitation to 55 States to

attend an International Civil Aviation Conference in Chicago in 1944.

• These delegates met at a very dark time in human history and travelled to Chicago at great

personal risk. Many of the countries they represented were still occupied. In the end, 54 of the

55 States invited attended the Chicago Conference, and by its conclusion on 7 December, 1944,

52 of them had signed the new Convention on International Civil Aviation which had been

realized.

29

• Known then and today more commonly as the ‘Chicago Convention’, this landmark agreement

laid the foundation for the standards and procedures for peaceful global air navigation. It set

out as its prime objective the development of international civil aviation “…in a safe and

orderly manner”, and such that air transport services would be established “on the basis of

equality of opportunity and operated soundly and economically.”

• The Chicago Convention also formalized the expectation that a specialized International Civil

Aviation Organization (ICAO) would be established, in order to organize and support the

intensive international co-operation which the fledgling global air transport network would

require.

• ICAO’s core mandate, then as today, was to help States to achieve the highest possible

degree of uniformity in civil aviation regulations, standards, procedures, and organization.

• Because of the usual delays expected in ratifying the Convention, the Chicago Conference

presciently signed an Interim Agreement which foresaw the creation of a Provisional ICAO

(PICAO) to serve as a temporary advisory and coordinating body.

• The PICAO consisted of an Interim Council and an Interim Assembly, and from June 1945 the

Interim Council met continuously in Montreal, Canada, and consisted of representatives from

21 Member States. The first Interim Assembly of the PICAO, the precursor to ICAO’s triennial

Assemblies in the modern era, was also held in Montreal in June of 1946.

• On 4 April 1947, upon sufficient ratifications to the Chicago Convention, the provisional

aspects of the PICAO were no longer relevant and it officially became known as ICAO. The

first official ICAO Assembly was held in Montreal in May of that year.

• During this march to the modern air transport era, the Convention’s Annexes have increased

in number and evolved such that they now include more than 12,000 international standards

and recommended practices (SARPs), all of which have been agreed by consensus by ICAO’s

now 192 Member States.

• These SARPs, alongside the tremendous technological progress and contributions in the

intervening decades on behalf of air transport operators and manufacturers, have enabled the

realization of what can now be recognized as a critical driver of socio-economic development

and one of humanity’s greatest cooperative achievements – the modern international air

transport network.

2,9 INTERAGENCY COMMITTEE FOR AVIATION POLICY (ICAP)

GSA established the Interagency Committee for Aviation Policy (ICAP) to promote

sound policy and foster the highest aviation standards.

GSA provides a leadership role by chairing the committee, providing programs to support aviation

activities, and collecting and reporting data related to Federal aviation management.

2.9.1 Members of ICAP

Department of Agriculture • Department of Commerce • Department of Defense • Department of

Energy • Department of Health and Human Services • Department of Homeland Security •

Department of Interior • Department of Justice • Department of State • Department of the Treasury

30

• Department of Transportation • Department of Veterans Affairs • Environmental Protection

Agency • General Services Administration • National Aeronautics and Space Administration •

National Science Foundation • Office of Management and Budget • Tennessee Valley Authority

2.9.2. Aircraft Engineers International

The Aircraft Engineers International ( AEI ) is an international umbrella organization of trade

unions of aircraft technicians. In the Netherlands, the union The Union with its aircraft technicians

is a member of this international organization. Around 41 organizations worldwide are members

of the AEI.

2.9.3. Objective

The objective of the AEI is to promote aviation safety by striving to ensure that skilled and well-

trained technicians work in a safe working environment and under good working conditions and

with sufficient independence in their actions to ensure that safety is beyond direct financial gain.

School of Mechanical

Department of Aeronautical Engineering

UNIT- III– AVIATION MANAGEMENT - SAE1403

31

3. AIR LAW

• Aviation Law is one of the specialty fields in Studies of Law. Air Law is a general viewpoint

that covers the special characteristics and demands of aviation field. There is no governing

body with the right to frame the air laws governing all states in the legal sense or there is not

any international law. But the phrase Air Law is used to describe a system of implicit and

explicit agreements that the nations together. These agreements are known as conventions.

There are numerous conventions such as Chicago, Rome, Tokyo, Geneva, and few more.

• It is a branch of law that is concerned with air transport operations, and all the associated legal

and business concerns. This is a series of rules that governs the use of airspace for aviation,

and its benefits for the general public and the nations of the world.

• The first attempt to set the air law was made around 1910, when German air balloons

repeatedly trespassed over French territory. The French government wanted both the

governments to come together to form an agreement to resolve the problem. The Paris

Conference of 1910 was in favor of the sovereignty of states in the space above their territories.

• It started developing further when after the World War I, the first scheduled flight from Paris

to London took its first flight in 1909.

3.1. Public International Air Law: Chicago Convention

32

A Convention on International Civil Aviation was signed at Chicago on 7th December, 1944. It

established specific principles in order to develop international civil aviation in a safe and orderly

manner. It also ensures that international air transport services are established on the basis of fair

opportunity for participating countries.The convention formed the International Civil Aviation

Organization (ICAO), the Canada-based agency of the United Nations. It sets the principles of

international air navigation and works to:

• Ensure a well-ordered growth of international civil aviation throughout the world.

• Encourage aircraft design and operation for peaceful and constructive purposes.

• Promote the development of airways, airports, and air navigation facilities for international

civil aviation.

• Meet the safety, regularity, efficiency, and economical air transport needs of the people

around the world.

• Prevent unplanned economic decisions and in turn waste.

• Ensure that each Contracting State has an opportunity to operate international airlines.

• Encourage flight safety in international air transport.

• Foster the development of all aspects of international civil aviation.

3.2 Air Law in European Union

The laws are regarding the following:

Sovereignty: It is the right of a state to impose its national law on users of its airspace.

Territory: It is the airspace over and within the territorial borders of a state. Territorial airspace

has no vertical limit. For the states with sea boundaries, territorial airspace extends beyond the

land. This limit is internationally agreed limit of the territorial waters.

3.3. International Air Laws

The three International Air Laws are as follows:

• Public International Law

It refers to the process which binds the states and international organizations to agreements