Airport Management

C. Daniel Prather, Ph.D., A.A.E., CAM

Airport Management

C. Daniel Prather, Ph.D., A.A.E., CAM

Aviation Supplies & Academics, Inc.

Newcastle, Washington

Airport Management

by C. Daniel Prather, Ph.D., A.A.E., CAM

Aviation Supplies & Academics, Inc.

7005 132nd Place SE

Newcastle, Washington 98059-3153

asa@asa2fly.com | www.asa2fly.com

See the ASA website at www.asa2fly.com/reader/ai rptmgt for the “Reader Resources”

page containing additional information and updates relating to this book.

Resources for instructors using this textbook in their courses are available at

www.asa2fly.com/instructor/airptmgt.

©2015 Aviation Supplies & Academics, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval

system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopy,

recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder.

While every precaution has been taken in the preparation of this book, the publisher and

C. Daniel Prather assume no responsibility for damages resulting from the use of the

information contained herein.

None of the material in this book supersedes any operational documents or procedures

issued by the Federal Aviation Administration, aircraft and avionics manufacturers, flight

schools, or the operators of aircraft.

ASA-A IR PT-MGT-PD

ISBN 978-1-61954-211-2

Photography © C. Daniel Prather unless otherwise noted.

Cover photos: Bottom image courtesy of Louisville Regional Airport Authority.

Top image ©iStock.com/jxfzsy.

The airport photo used as a background for the chapter beginnings is courtesy of

Hillsborough County Aviation Authority.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Prather, C. Daniel

Airport management / by C. Daniel Prather, Ph.D., A.A.E., CAM.

pages cm

Includes index.

“ASA-A IR PT-MGT.”

ISBN 978-1-61954-209-9 (trade paper) – ISBN 1-61954-209-9 (trade paper)

1. Airports–United States—Management–Textbooks. I. Title.

TL725.3.M2P73 2015

387.7’36068–dc23

2014041887

v

Contents

Foreword ............................................................................................................. xi

Acknowledgments ............................................................................................ xiv

About the Author ............................................................................................. xvi

Introduction ........................................................................................................1

CHAPTER 1 Historical Overview .................................................................. 6

Introduction ..................................................................................................9

The Beginning of an Industry ...................................................................10

World War I ................................................................................................ 14

Post World War I ........................................................................................ 15

World War II ............................................................................................... 19

Post World War II ....................................................................................... 20

Pre-Deregulation .........................................................................................21

Deregulation ...............................................................................................24

Post-Deregulation .......................................................................................24

9/11 ..............................................................................................................33

Post 9/11 ......................................................................................................33

Contemporary and Future Period ..............................................................40

Concluding Thoughts ................................................................................41

Chapter Summary ......................................................................................42

Review Questions .......................................................................................45

Scenarios ......................................................................................................46

References and Resources for Further Study .............................................46

CHAPTER 2 Structure of Airports ..............................................................50

Introduction ................................................................................................53

Categories of Airports .................................................................................53

Ownership of Airports ...............................................................................63

Organizational Structure ............................................................................ 75

Major Airport Departments .......................................................................78

Airport Training Programs ........................................................................89

Career Advancement ..................................................................................90

Concluding Thoughts ................................................................................92

Chapter Summary ......................................................................................93

Review Questions .......................................................................................94

Scenarios ......................................................................................................95

References and Resources for Further Study .............................................96

vi AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

CHAPTER 3 Air Traffic, Capacity, and Delay ..........................................98

Introduction .............................................................................................. 101

ATC System Overview .............................................................................101

Signage and Markings ..............................................................................121

Radio Communications ...........................................................................130

Federal Contract Tower Program.............................................................134

NextGen ....................................................................................................135

Airfield Capacity .......................................................................................137

Airfield Delay ............................................................................................143

Demand Management .............................................................................. 145

Concluding Thoughts .............................................................................. 149

Chapter Summary .................................................................................... 149

Review Questions ..................................................................................... 151

Scenarios .................................................................................................... 152

References and Resources for Further Study ........................................... 153

CHAPTER 4 Planning ................................................................................ 154

Introduction .............................................................................................. 157

NPIAS ....................................................................................................... 157

Regional Aviation System Plans ............................................................... 159

State Aviation System Plans ...................................................................... 159

Metropolitan Aviation System Plans ........................................................ 160

Airport Master Plans and Airport Layout Plans ..................................... 161

Strategic Plans ...........................................................................................171

Business Plans ...........................................................................................175

Aviation Activity Forecasts ...................................................................... 176

Concluding Thoughts ..............................................................................182

Chapter Summary .................................................................................... 183

Review Questions ..................................................................................... 185

Scenarios ....................................................................................................186

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................187

CHAPTER 5 Design and Construction................................................... 188

Introduction .............................................................................................. 191

Construction Standards ............................................................................ 191

Design Standards ..................................................................................... 200

Airspace and Approach Standards ...........................................................221

Selection Process ...................................................................................... 226

International Practice................................................................................229

Concluding Thoughts ..............................................................................229

Chapter Summary ................................................................................... 230

Review Questions .....................................................................................233

Scenarios ................................................................................................... 234

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................235

Contents vii

CHAPTER 6 Environmental ...................................................................... 236

Environmental Regulations ...................................................................... 239

Environmental Management System .......................................................239

Compliance and Enforcement ................................................................ 240

Impacts ......................................................................................................241

Noise ..........................................................................................................243

Compatible Land Use ............................................................................... 251

Zoning ....................................................................................................... 252

Easements .................................................................................................. 253

Water Quality ...........................................................................................254

Air Quality ................................................................................................ 259

Hazardous Waste ......................................................................................261

Sustainable Environmental Stewardship .................................................265

Concluding Thoughts ............................................................................. 268

Chapter Summary ................................................................................... 268

Review Questions .....................................................................................271

Scenarios ....................................................................................................272

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................273

CHAPTER 7 Operations .............................................................................274

Introduction ............................................................................................. 277

Title 14 CFR Part 139 ............................................................................. 277

Airport Communications ........................................................................ 306

Wildlife Hazard Management ................................................................ 308

New Generation Aircraft .......................................................................... 312

Concluding Thoughts .............................................................................. 314

Chapter Summary .................................................................................... 314

Review Questions ..................................................................................... 317

Scenarios .................................................................................................... 318

References and Resources for Further Study ........................................... 319

CHAPTER 8 Maintenance ........................................................................ 320

Introduction ..............................................................................................323

Inspections ................................................................................................323

Preventive Maintenance ...........................................................................323

Maintenance Equipment ..........................................................................324

Recordkeeping ..........................................................................................324

Airside Maintenance ................................................................................. 325

Landside Maintenance .............................................................................337

Concluding Thoughts ............................................................................. 340

Chapter Summary ....................................................................................341

Review Questions .................................................................................... 343

Scenarios ................................................................................................... 344

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................345

viii AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

CHAPTER 9 Safety and Security ............................................................ 346

Safety .........................................................................................................349

Security ......................................................................................................367

Concluding Thoughts ..............................................................................383

Chapter Summary ................................................................................... 384

Review Questions .....................................................................................387

Scenarios ....................................................................................................388

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................389

CHAPTER 10 Marketing ............................................................................ 390

Purpose of Marketing ...............................................................................393

Marketing Basics ....................................................................................... 394

Developing a Marketing Plan ..................................................................395

Variables ................................................................................................... 408

Implementing the Plan .............................................................................410

Characteristics of an Effective Marketing Plan ....................................... 411

Air Service Development .......................................................................... 412

Concluding Thoughts .............................................................................. 417

Chapter Summary .................................................................................... 417

Review Questions ..................................................................................... 419

Scenarios ................................................................................................... 420

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................421

CHAPTER 11 Governmental, Legal, and Public Relations ................ 422

Governmental Relations ...........................................................................425

Industry Relations .................................................................................... 444

Public Relations ....................................................................................... 448

Concluding Thoughts .............................................................................. 452

Chapter Summary .................................................................................... 453

Review Questions .....................................................................................457

Scenarios ....................................................................................................458

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................459

CHAPTER 12 Properties, Contracts, and

Commercial Development ....................................................................... 460

Agreements ................................................................................................463

Interacting with Tenants ..........................................................................478

Commercial Development .......................................................................479

Disadvantaged Business Enterprise ..........................................................483

Information Systems .................................................................................483

Concluding Thoughts ............................................................................. 484

Chapter Summary ....................................................................................485

Review Questions .................................................................................... 487

Scenarios ................................................................................................... 488

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................489

Contents ix

CHAPTER 13 Financial Management .................................................... 490

Budgeting Overview .................................................................................493

Budget Development ................................................................................493

Revenues .................................................................................................... 498

Expenses ....................................................................................................508

Financial Statements .................................................................................509

Establishing Fees, Rates and Charges ...................................................... 524

Risk Management ..................................................................................... 526

Concluding Thoughts ..............................................................................528

Chapter Summary ....................................................................................529

Review Questions ..................................................................................... 531

Scenarios ....................................................................................................532

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................533

CHAPTER 14 Funding and Financial Impacts ..................................... 534

Introduction ..............................................................................................537

Sources of Capital Development Funding ..............................................537

Economic Impact of Airports ..................................................................549

Impacts of Airline Bankruptcies on Airports ..........................................549

Performance Management and Benchmarking ....................................... 551

Concluding Thoughts .............................................................................. 553

Chapter Summary .................................................................................... 553

Review Questions ..................................................................................... 555

Scenarios ....................................................................................................556

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................557

CHAPTER 15 Future Challenges and Opportunities .......................... 558

Introduction ..............................................................................................561

Airline Bankruptcies and Mergers ...........................................................561

New Large Aircraft ...................................................................................562

Capital Development Funding ................................................................. 563

Unfunded Federal Mandates................................................................... 564

Passenger Leakage ..................................................................................... 565

Customer Service ..................................................................................... 566

Sustainability Initiatives ...........................................................................567

Airside Congestion ...................................................................................568

Unmanned Aircraft Systems ....................................................................569

Concluding Thoughts ..............................................................................570

Chapter Summary ....................................................................................571

Review Questions .....................................................................................572

Scenarios ....................................................................................................573

References and Resources for Further Study ...........................................573

APPENDIX A Case Studies ........................................................................574

APPENDIX B Grant Assurances .............................................................. 602

Index ................................................................................................................625

xi

Foreword

I consider it an honor to be asked to write the foreword for Airport Manage-

ment. This textbook’s author, Dr. C. Daniel Prather, A.A.E., CAM, has been

my mentor since I entered this dynamic and fast-paced community of airports.

Dr. Prather has extensive airport experience from his tenure as an Assistant

Director of Operations at Tampa International Airport, and is now a key player

in education program development and in the training of hundreds of airport

professionals nationally and internationally. He is an accredited member of the

American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE), and recently developed

and implemented the first aviation program at California Baptist University in

Riverside, California.

Dr. Prather’s objective in all of his educational development and presen-

tations is to provide airport professionals with practical, industry-focused

information. You will find this as the baseline throughout all chapters of Air-

port Management. This textbook covers the exciting areas that other airport

professionals and I are involved with on a daily basis, including airport plan-

ning, design, and construction; air traffic and capacity delay; environmental

issues; regulatory compliance; airport operations and maintenance; safety and

security; and much more. The chapter scenarios and case studies are designed

to allow readers to apply knowledge gained in the text to solving real-world

airport challenges.

Some of the more specific topics on the minds of airport professionals

include the integration of the National Incident Management System (NIMS),

Incident Command System (ICS) into airport emergency plans, and the train-

ing and exercise of personnel for use during incidents and events; operational

safety on airports during construction, as most airports are always in some

phase of construction; addressing FAA Runway Safety Action Team (RSAT)

action items; implementation of safety management systems (SMS); measurable

metrics; and airport sustainability, just to name a few.

I personally began my aviation career in the United States Marine Corps

as an avionics technician on CH-46E Sea Knight helicopters, and quickly

progressed through the enlisted ranks as well as becoming a qualified Aerial

Observer/Door Gunner, Quality Assurance Inspector, and working on other

helicopter and fixed-wing aircraft platforms. While traveling and serving in the

United States Marine Corps, I was fortunate to have the opportunity to com-

plete my undergraduate degree from Southern Illinois University, Carbondale,

where I got my first taste of aviation industry business management from an

academic perspective.

xii AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

At the end of my second enlistment in the United States Marine Corps, my

family and I decided to take the leap from the military and I began my civilian

aviation career as an Airport Operations—Communications Center Dispatcher

at Tampa International Airport in Tampa, Florida. This position was ideal for

someone new to an airport. I was able to experience the full spectrum of daily

operations at an airport, ranging from response coordination to small incidents

such as broken plumbing pipes in a terminal, to higher-level incidents such as

security breaches, people jumping from parking structures to commit suicide,

and aircraft alerts. Since that first position as a dispatcher, I have again been

very fortunate to hold several positions within airport operations departments

at Tampa International Airport (TPA), Burbank Bob Hope Airport (BUR), and

now at Los Angeles International Airport (LAX). I have held positions ranging

from my initial position as a dispatcher, to Airside and Landside Operations

Manager, to my current position as a Chief of Operations I at LAX.

My current job responsibilities include working some shifts as the Air-

port Duty Manager, and serving as the LAX Department Operations Center

(DOC) Director during large-scale events. In this position, I was on duty for

the Asiana Airlines Flight 214 accident at San Francisco Airport in which we

received multiple flight diversions; utility disruptions affecting multiple termi-

nals and other facilities; and one of the most challenging incidents our airport

has experienced in the past ten years involving an active shooter at Terminal 3

in which three of our nine terminals were evacuated, and Terminal 3 remained

closed for 28 hours.

If this is your first exposure to the airport community, airports are often

referred to as “cities within cities.” Airports have several components, regula-

tions, and political pressures similar to a city. Depending on the size of an

airport, it may have components similar to a city, such as a municipal fire

station or its own fire department; a police, security, and/or public safety

department; emergency medical personnel; administrative and financial ser-

vices; and a maintenance department similar to city public works. Unlike a city,

however, hazards at airports can pose unique challenges since the operation of

aircraft traffic, vehicle traffic, pedestrian traffic, baggage, and cargo through-

put must continue to flow, or be restored promptly, to sustain commerce and

e-commerce.

In addition, airports have multiple federal agencies, private entities, con-

tractors, and airport personnel that all operate within the same few acres of

airport property to provide safe and secure services to the traveling public. In

addition to these departments and divisions that are similar to those of a city,

Foreword xiii

airports will also have an airport operations department. The personnel in

this department conduct inspections of the airside, terminals, and landside to

identify and report any irregular conditions that impact operations, and coor-

dinate the response by emergency services, maintenance personnel, and others

to resolve these issues. Airport operations, along with public safety, agency, and

stakeholder partners, also responds to emergencies such as aircraft accidents,

security breaches, structure fires, hazmat spills, property damage incidents,

utility disruptions, etc., with the primary objective of coordinating the flow of

the airport’s operation around the incident, and then becoming the incident

commander during the recovery phase of an accident or incident.

The best phrases, words, and guidance that I have learned from fellow

employees and leaders in airports include: exciting, high consequence, and polit-

ical; operations revolve around local, state, and federal regulatory compliance;

airports must partner, train, and build solid relationships with stakeholders and

mutual aid responders to ensure efficient response plans and procedures have a

common operational picture; the only thing constant at an airport is change;

your customers include the traveling public, airport tenants, contractors, and

your own airport employees; and the most critical asset at an airport are the

employees that keep it operating, so keep them involved.

In conclusion, you will find this textbook and the aviation professionals you

meet to be valuable resources as you progress through your career. Anyone who

intends to work and succeed in this exciting and challenging field must master

a thorough understanding of the rules, regulations, and standards that affect

airports, and be able to apply critical thinking skills to continue to progress.

Airport Management will prove to be an excellent resource for current and future

airport professionals.

Richard N. Steele, C. M., MCA

Chief of Operations I

Los Angeles International Airport (LAX)

Los Angeles World Airports (LAWA)

xiv AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

Acknowledgments

The development of this book would not have been possible without the sig-

nificant level of support provided by colleagues in the industry. My experiences

have been enriched because of others. I would like to thank Mr. Robert Burr,

Mr. Grant Young, and Mr. Ed Cooley for believing in me. These gentlemen

provided me with ten outstanding years of experience in airport operations at

Tampa International Airport (TPA). Ms. Marilyn Gauthier, a coworker at TPA,

was a friend from day one and continues to be to this day. I would also like to

thank collegiate aviation faculty everywhere who are members of the University

Aviation Association (UAA), as well as Mrs. Carolyn Williamson, former UAA

Executive Director. Collegiate aviation faculty are a small group of devoted pro-

fessionals, and I have learned from and with them extensively over the years.

These professionals have supported me in many ways as I transitioned from the

airport industry to being a faculty member at a collegiate aviation program. I

especially benefitted from the annual UAA Fall Education Conferences and the

Collegiate Aviation Review. I would like to particularly thank Dr. Julie Speakes

for providing me an opportunity to teach online as an adjunct faculty member

in the Delta State University Master of Commercial Aviation degree program

and being a close friend. Dr. Alexander Wells graciously provided me the first

opportunity to author a book, by asking me to revise his General Aviation Mar-

keting and Management textbook. Mr. Dave Boelio and Ms. Nicole Sgueglia both

encouraged me to write this Airport Management text, while Mr. Fred Boyns and

Ms. Jackie Spanitz enthusiastically asked me to write this text for ASA.

I would like to thank Dr. Paul Craig for giving me my first position as a

faculty member at Middle Tennessee State University. California Baptist Uni-

versity (CBU) President Dr. Ronald Ellis, former Provost Dr. Jonathan Parker,

and College of Arts and Sciences Dean Dr. Gayne Anacker believed in me and

trusted that I was the right person to develop the nation’s newest collegiate avia-

tion program at their fine institution. I am humbled by this opportunity and

would like to express my heartfelt gratitude for their tremendous support. This

has been by far the greatest professional challenge and thrill of my life. Mrs.

Kim Roper and Mrs. Maria LeBlanc have been instrumental in my success at

CBU, as have our wonderful team of faculty and flight instructors.

I would also like to thank the staff of the American Association of Airport

Executives, specifically Mr. James Johnson, A.A.E. (now retired), Ms. Starla

Bryant, Mr. Kevin Miller, C.M., ACE (now with the Boca Raton Airport

Authority) and Mr. Scott Boeser, C.M., ACE for trusting me to revise the Air-

port Certified Employee (ACE)—Operations modules and subsequently train

airport professionals across the country in Part 139. I would also like to thank

Acknowledgments xv

Mr. Jay Evans and Mrs. Sarah Wolf of the National Business Aviation Associa-

tion for allowing me the opportunity to serve on the Professional Development

Program (PDP) Review Committee and provide professional training to business

aviation professionals nationwide. I would also like to thank Ms. Anne Nevel

of the Helicopter Association International for allowing me the opportunity to

provide professional training to helicopter aviation professionals nationwide.

My past and current students have provided me significant insight and

allowed me the opportunity to improve my teaching abilities. I am proud of

each and every one of you who have graduated and are now making significant

contributions to the industry. Your success keeps me motivated.

I am indebted to the following individuals who have provided me the

greatest direct support in the development of this text, through their research,

photographs and case studies:

Mr. Jordan Biegler, A.A.E.

Mr. Lee Brown, C.M., ACE

Ms. Patricia Burke

Mr. Brett Fay, C.M.

Ms. Diana Fernandez, ACE

Ms. Robin Gardner, C.M., ACE

Mr. Peter Lubbers, ACE

Mr. Adam Lunn, C.M., ACE

Mr. Kevin Miller, C.M., ACE

Ms. Lacey Schimming

Ms. Amanda Snodgrass

Mr. Richard Steele, C.M.

Ms. Laura Walker

Additionally, I must recognize Mr. David Nicewinter (TPA) and Mr. John

Padgett (Nashville International Airport), both of whom spent a number of

hours with me allowing me to tour their respective airfields to obtain photos.

I would like to express my love and gratitude to my family, who supported

me throughout this project. My wife, Grace, my daughter, Savannah, and my

son, Layton, are the joys of my life and I would not be the man I am today if

not for you guys. Thanks for being such an awesome family.

My dad, Mr. Louis Prather, and my mom, Dr. Barbara Corry, provided me

the opportunity to take flying lessons with Mr. Langley Nelson at Hawkins

Field in Jackson, Mississippi, while I was still in high school. These lessons

fueled my passion for the aviation industry, which led me to Delta State Univer-

sity for a Bachelor of Commercial Aviation degree, Southern Illinois University

for a Master of Public Administration degree, and ultimately to Tampa Interna-

tional Airport, which allowed me the experiences necessary to be able to write

this textbook. Thanks Mom and Dad!

Finally, my Lord and Savior Jesus Christ daily provides me the strength and

wisdom to accomplish and succeed to bring Him glory. My life verse is found

in Philippians 4:13, “I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me.”

This book would not be possible without the breath He alone provides me.

xvi AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

About the Author

Serving as Assistant Director of Operations

at Tampa International Airport (TPA) from

1998 to 2006, and Associate Professor of

Aerospace at Middle Tennessee State Uni-

versity (MTSU) from 2006 to 2012, Dr.

C. Daniel Prather, A.A.E., CAM, has been

serving as professor and founding chair of

the Department of Aviation Science at

California Baptist University (CBU) since

July 2012. In this position, Dr. Prather has

been responsible for developing curriculum

and recruiting students and faculty to the

nation’s newest collegiate aviation program.

Active with the University Aviation

Association (UAA), the American Association of Airport Executives (AAAE),

and the National Business Aviation Association (NBAA), Dr. Prather is an

Accredited Airport Executive through AAAE, a Certified Aviation Manager

through the NBAA, and an instrument-rated private pilot. He is also an active

aviation industry consultant, often busy on projects with the Airport Coopera-

tive Research Program (ACRP) of the Transportation Research Board (TRB).

He holds a Doctor of Philosophy degree from the University of Nebraska at

Lincoln, a Master of Public Administration degree from Southern Illinois Uni-

versity at Carbondale, and a Bachelor of Commercial Aviation degree from

Delta State University.

In addition to this textbook, Dr. Prather is author of General Aviation Mar-

keting and Management: Operating, Marketing and Managing an FBO. He is

also the designated Airport Certified Employee (ACE) – Operations trainer

for AAAE, and a leadership trainer for NBAA and the Helicopter Association

International (HAI).

Not counting his one year as a flight coordinator intern at FedEx Express

while in college, or flight training he undertook while in high school, Dr.

Prather entered the aviation industry in 1996 and has never looked back. Visit

Dr. Prather at www.dprather.com.

1

Introduction

As a collegiate aviation professor with ten years of airport managerial experi-

ence, I have always endeavored to teach courses in airport management from a

practical, real-world perspective. However, the available textbooks on this topic

are lacking in practical application. For me, this was not significant, because I

could easily supplement the text I was using with real-world examples from my

ten years of experience at Tampa International Airport. However, I began to

meet other faculty members across the country who were being asked to teach

courses in airport management, but had no professional airport industry experi-

ence from which to draw when teaching these courses. As a result, students in

these courses learned less practical application than is necessary to be prepared

for positions in the airport industry.

It was this realization that led me to begin writing this practical book

on airport management. Of course, I soon learned that writing a book was a

tremendous undertaking. Writing this book soon became a labor of love that

required a significant investment. While working on the manuscript each day,

I thought of all the current students who would become airport professionals

in the future. This book has been written for your benefit. My goal has been

to provide practical insight into the airport management business, and I trust

this first edition will accomplish that.

The book has been designed to cover all areas of airports, to give a future

airport manager a thorough understanding of the many aspects of the airport

business. Key terms are identified at the beginning of each chapter and set in

bold within the text. Features throughout the chapters shine the spotlight on

specific airlines, airports, and other entities. Each chapter ends with scenarios

designed to allow readers to apply knowledge gained from studying the chapter

to solving real-world airport issues. The book also includes comprehensive case

studies that allow readers to dive even deeper into the topics. Helpful review

questions are provided for each chapter to prompt reflection and focus atten-

tion on the most important concepts. As these questions are meant to stimulate

thought, discussion with your instructor, and classroom conversation, specific

answers are not provided. Additional resources and information related to air-

port management can be found on the Reader Resources webpage for this book

at www.asa2fly.com/reader/airptmgt.

Chapter 1, Historical Overview, presents a historical perspective of both

the airport and airline industry, including important pieces of legislation that

played an integral role in the safe development of both. The funding of airports

2 AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

is also discussed to allow the reader to better understand the role of federal

funding in airport development. This chapter is important to the reader to gain

a full understanding of the airport industry; we must understand from where

we came to better prepare for future challenges.

Chapter 2, Structure of Airports, presents the organizational structure

of airports, including types and the nature of ownership. It covers the major

departments common at larger airports, as well as available airport training and

career opportunities. This chapter is important in understanding the breadth of

airports in this country, including how they are organized and owned.

Chapter 3, Air Traffic, Capacity and Delay, introduces the capacity and

delay issue that airports must confront. In addition, it presents classes and types

of airspace; NAVAIDs; airport lighting, signage, and markings; radio commu-

nications; the federal contract tower program; and NextGen. This chapter is

full of information that introduces readers to the airspace in which airports are

located, as well as the facilities and equipment in place to provide guidance to

pilots and ground vehicle operators on the airfield.

Chapter 4, Planning, presents the need for airport planning, from the

national level to the local airport-specific level. Airports are always planning

for the future, and specific processes are in place to carry out this planning. To

effectively plan, however, forecasting must take place, and this chapter covers

the types and uses of forecasting in airport planning. This chapter is important

for the reader in understanding the nature of and need for airport planning to

prepare for future demand.

Chapter 5, Design and Construction, is a lengthy chapter that explains the

nature of design and construction, from pre-bid to project completion. Airport

construction projects can require many months or even years from start to

finish, and there are specific procedures to be followed in designing a project,

selecting a contractor, and maintaining safety on the airfield during construc-

tion. This is especially true of projects funded by the FAA. This chapter is

important for the reader in understanding the design and construction side

of airport management, which can oftentimes appear too technical for non-

engineers. However, even the smallest airports have need for the occasional

construction project, which makes the information in this chapter important

to understand.

Chapter 6, Environmental, presents the many environmental impacts of

an airport, and the regulations and requirements necessary to ensure environ-

mental compliance. This chapter addresses noise, compatible land use, zoning,

easements, water quality, air quality, and hazardous materials. For airports to

Introduction 3

be good neighbors and operate within regulations, it is imperative that airport

management understand various environmental impacts and implement pro-

cedures to ensure environmental compliance (from both the airport and all

tenants). Sustainable environmental stewardship is the ultimate goal, and this

chapter is important in leading readers to that goal.

Chapter 7, Operations, focuses on the actual operation of the airport with a

specific emphasis on airfield operations. Specifically, 14 CFR Part 139, Airport

Certification, provides the foundation for this chapter. This is the regulation to

which air carrier airports must comply to maintain an airport operating certifi-

cate and is, as a result, an important regulation to understand. Topics addressed

in this chapter include snow and ice control, emergency response, aircraft rescue

and firefighting, wildlife, and NOTAMs. This chapter is important for all

future airport professionals because of the extreme importance placed on Part

139 compliance at air carrier airports. Lack of Part 139 compliance could result

in the airport losing its operating certificate (in extreme cases), which would

prohibit air carrier operations at that airport.

Chapter 8, Maintenance, is to some degree the flip side of Chapter 7. Oper-

ations personnel rely heavily on support of maintenance personnel to maintain

the airfield in peak condition and within Part 139 requirements. Specifically,

this chapter addresses airport pavements and airside and landside maintenance,

including the use of contracted maintenance providers. This chapter is impor-

tant for readers to understand because maintenance is integral to maintaining

a safe and efficient airport.

Chapter 9, Safety and Security, addresses the need to ensure a safe and

secure airport. This chapter addresses the protection of the public, employees

and tenants; fire hazards; driving on the movement area; safety management

systems; emergency preparedness; aircraft accidents and incidents; media rela-

tions; security; etc. This chapter is valuable for the reader in understanding the

role of safety and security in maintaining a top-notch airport.

Chapter 10, Marketing, focuses on the importance of effectively marketing

airports to ensure a competitive position to minimize the leakage of passengers

and ensure positive publicity in the community. Topics include the basics of

marketing; goals and objectives; SWOT analysis; promotional mix; marketing

plans; and air service development. This chapter is important for the reader in

understanding the role of marketing in airport management, which includes

much more than securing additional air service or building a website.

Chapter 11, Governmental, Legal, and Public Relations, presents a valuable

overview of the politically active climate in which airports always operate, and

4 AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

covers national, state, and local governmental relations. This chapter examines

the manner in which FAA regulations and advisory circulars are revised, and

describes Robert’s Rules of Order to enable the reader to understand formal pro-

cedures typically in use during city council meetings, airport board meetings,

and other formal meetings. Regulatory agencies and industry trade associations

are also presented within the chapter. This chapter is important for the reader to

gain an understanding of the political nature of airports and the concepts to be

adhered to in managing an airport facility in this environment. The politically

naïve airport manager (with no knowledge of the concepts presented in this

chapter) will likely encounter more of a challenge on the job than is necessary.

Chapter 12, Properties, Contracts, and Commercial Development, is the

first of the “money” chapters. Without an understanding of airport property,

the nature of contracts, and the common ways in which to develop airport

property to increase revenues (and create jobs), an airport will effectively lose

money annually from lost opportunities in the form of commercial develop-

ment of property. The chapter presents aeronautical lease agreements, airline

operating agreements, land lease agreements, rate-making methodologies, con-

cessionaires, FBOs, minimum standards, rules and regulations, MOUs/LOAs,

self-fueling, etc. This chapter is important for the reader in understanding the

myriad of ways in which airports earn revenue through various tenants, ven-

dors, and others and the legal agreements that must be in place to define these

relationships.

Chapter 13, Financial Management, is the second of the “money” chapters

and presents operating and capital budgets, including budgeting techniques;

financial ratios; fees, rates, and charges; and risk management. This chapter is

important for the reader in understanding how to budget properly and manage

the budget to track revenues and expenditures, as well as assets and liabilities.

Although the chapter presents common financial management terminology,

airports have unique budgeting requirements that airport managers must fully

understand. Otherwise, the knowledge gained in chapter 12, even if applied

properly, will be less successful.

Chapter 14, Funding and Financial Impacts, continues the “money” discus-

sion with a focus on capital development funding, including matching funds,

bonds, PFCs, internally generated funds, state and local sources, and AIP. This

chapter covers grant assurances, which airports must comply with once federal

funds are accepted, as well as methods to determine the economic impact of

Introduction 5

airports, the impact of airline bankruptcies, and benchmarking. This chapter is

important for the reader in understanding the methods available to airports in

funding large capital projects, as well as the role airports play in the economy.

Chapter 15, Future Challenges and Opportunities, wraps up the book by

presenting the expected challenges airports will face in the future, as well as

the opportunities that may be grasped. Specifically, airline bankruptcies and

mergers, new large aircraft (such as the A380), capital development funding,

unfunded federal mandates, passenger leakage, customer service, sustainable

initiatives, airside congestion, and unmanned aircraft systems are presented.

This chapter provides a few last thoughts on future challenges to be faced by

airport managers.

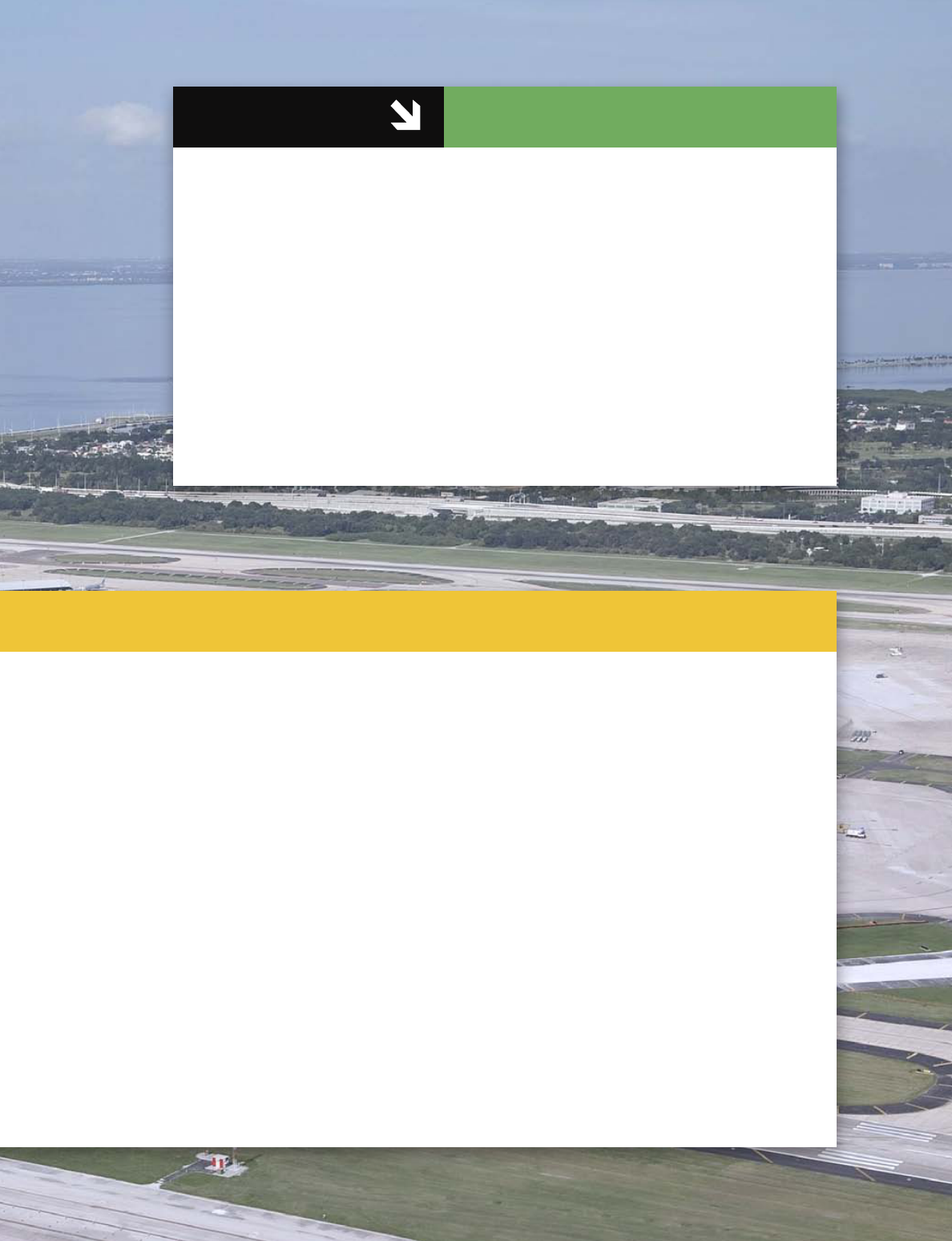

Tampa International Airport, with main terminal complex and satellite terminals connected by

automated people movers shown. (Hillsborough County Aviation Authority)

6 AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

14 CFR Part 139, Certification of Airports

AIP Temporary Extension Act

Air Cargo Deregulation Act of 1976

Air Commerce Act of 1926

Airline Deregulation Act of 1978

Airport and Airway Development Act of 1970

Airport and Airway Improvement Act of 1982

Airport and Airway Revenue Act of 1970

Airport and Airway Safety and Capacity Expansion

Act of 1987

Airport and Airway Safety, Capacity, Noise

Improvement, and Intermodal Transportation

Act of 1992

Airport and Airway Trust Fund

Airport Development Aid Program (ADAP)

Airport Improvement Program (AIP)

Airways Modernization Act

Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990

Aviation and Transportation Security Act (ATSA)

of 2001

Aviation Investment and Reform Act for the 21st

Century (AIR-21)

Aviation Safety and Capacity Expansion Act of

1990

Aviation Safety and Noise Abatement Act of 1979

Aviation Security Improvement Act of 1990

cargo revenue ton miles

Civil Aeronautics Act of 1938

Civil Aeronautics Administration (CAA)

Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA)

Civil Aeronautics Board (CAB)

Civil Works Administration (CWA)

Clean Air Act

continuing resolution

Contract Air Mail Act of 1925

Contract Air Mail (CAM) routes

Department of Transportation Act of 1966

Development of Landing Areas for National

Defense (DLAND)

Emergency Relief Appropriation Act of 1935

Historical Overview

Chapter 1

Key Terms

CHAPTER 1 Historical Overview 7

Objectives

Upon completion of this chapter, you should:

•Understand the historical events and important pieces of legislation affecting the

development of airlines.

•Understand the historical events and important pieces of legislation affecting the

development of airports.

•Understand the historical funding of airport development.

•Understand the pre- and post-deregulation periods.

•Understand the significance of the events of 9/11 on the aviation industry.

•Be able to discuss contemporary issues and future challenges confronting the airport

industry.

Essential Air Service (EAS)

Federal Aid to Airports Program

Federal Airport Act of 1946

Federal Aviation Act of 1958

Federal Aviation Administration Authorization Act

of 1994

Federal Aviation Agency (FAA)

Federal Aviation Reauthorization Act of 1996

Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA)

Federal Water Pollution Control Act

general aviation (GA) airports

Homeland Security Act of 2002

hub and spoke

Implementing Recommendations of the 9/11

Commission Act of 2007

Kelly Act

load factors

low-cost airlines

Military Airport Program (MAP)

National Airport Plan

National Civil Aviation Review Commission

National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon

the United States

National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB)

oligopolistic

omnibus spending bill

passenger facility charge (PFC)

Planning Grant Program (PGP)

revenue passenger miles

Security Guidelines for General Aviation Airports

spending bill

State Block Grant Program

Transportation Security Administration (TSA)

Vision 100—Century of Aviation Reauthorization

Act of 2003

Works Progress Administration (WPA)

World War I

World War II

In Chapter 1

Introduction ............................................. 9

The Beginning of an Industry ....................10

World War I ............................................14

Post World War I .....................................15

World War II ...........................................19

Post World War II ................................... 20

Pre-Deregulation .................................... 21

Deregulation .......................................... 24

Post-Deregulation ................................... 24

9 / 11 ..................................................... 33

Post 9/11 .............................................. 33

Contemporary and Future Period .............. 40

Concluding Thoughts ...............................41

Chapter Summary .................................. 42

Review Questions ................................... 45

Scenarios .............................................. 46

References and Resources

for Further Study ................................. 46

FEATURES

The Role of Federal Express

in the Air Cargo Industry ........ 25

Federal Express played an integral

role in establishing the air cargo

industry and the subsequent

deregulation of that industry.

The Rise and Fall of

People’s Express ................... 27

A low-cost airline that attained great

success, but eventually went out of

business due to competition from

other airlines during the deregulated

era.

8

CHAPTER 1 Historical Overview 9

Introduction

Airports are an integral part of the aviation industry. In this industry, billions

of passengers and billions of tons of cargo have been moved from point to point

since it began, which could not have occurred without airports. The industry is

a little more than 100 years old and yet responsible for more than $1 trillion per

year in economic activity and almost 10 million jobs. Consider the U.S. airlines

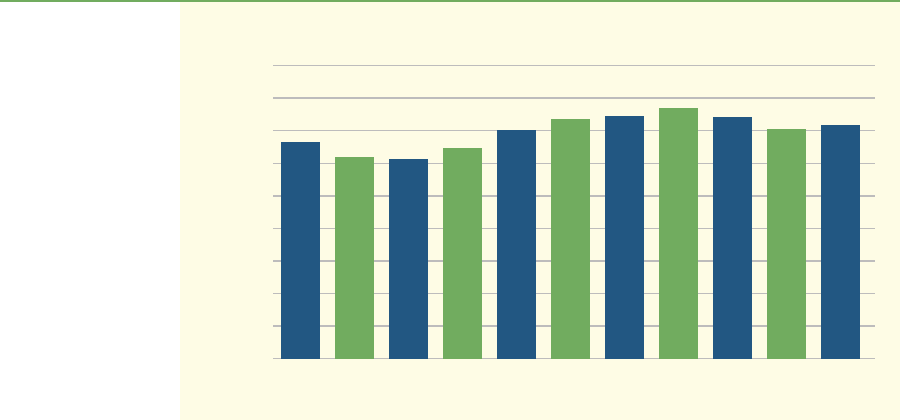

(Figure 1-1). Although down from a ten-year high of 769.6 million enplaned

passengers in 2007, U.S. airlines enplaned 720.5 million passengers, which

equates to 798 billion revenue passenger miles, in 2010. Additionally, airlines

generated more than 27 billion cargo revenue ton miles and generated more

than 10 million departures during the year (Air Transport Association, 2011).

Each of these departures, passengers, and pounds of cargo were accommo-

dated at an airport. Whether large or small, public or private, airports serve as

an interface between ground and air transportation (Figure 1-2). As an industry,

they directly serve the needs of pilots, passengers, and meeters and greeters,

and provide employment to hundreds of thousands of employees nationwide.

Indirectly, they serve the communities in which they are located by providing

facilities to support emergency medical transport, law enforcement services,

and the movement of goods and services. Even general aviation (GA) airports

provide beneficial economic impacts to the local community. Airports in the

United States have a significant impact on local, state, regional, and national

economies. As part of an industry that provides 10 million jobs, $396 billion

in wages, and an impact of $1.3 trillion to the economy, airports clearly play a

crucial role in the aviation industry (Federal Aviation Administration, n.d.). In

sum, airports serve a unique and substantial need throughout the world, and

have an interesting history in the United States—the birthplace of aviation.

Figure 1-1.

Number of enplaned

passengers, U.S.

airlines, 2000–2010

900

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

2000

100

0

2001 2002

Enplaned passengers

2003 2004

Year

Number of enplaned passengers (millions)

2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010

10 AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

The Beginning of an Industry

The history of the aviation industry in the United States began on December

17, 1903. It was on this day that Orville Wright first flew the now-famous

Wright Flyer I in a controlled flight lasting 12 seconds (see Figure 1-3). How-

ever, aviation did not immediately succeed. After these first flights at Kitty

Hawk, North Carolina, the Wright brothers faced quite a challenge in promot-

ing their aircraft to a willing buyer. In fact, five years passed before they were

able to convince the U.S. government to test a much improved version.

Figure 1-2.

Airports are

transportation

lifelines, often serving

airline passengers

and cargo carriers,

flight training and

general aviation

pilots, with beneficial

economic impacts felt

locally, regionally, and

nationally.

(jlye/Bigstock.com)

CHAPTER 1 Historical Overview 11

Although the four flights flown by the Wright brothers on that day marked

the beginning of controlled, powered, and sustained heavier-than-air human

flight, the first scheduled commercial airline flight using heavier-than-air air-

craft did not occur until eleven years later, when on January 1, 1914, Tony

Jannus piloted the Benoist XIV flying boat biplane across Tampa Bay (Florida)

on an historic 23-minute flight (see Figure 1-4). This inaugural flight also

carried the mayor of St. Petersburg, Florida—Mr. Abram C. Pheil. At a fare

of five dollars per passenger, this was the first time in history that tickets were

sold to the general public for point-to-point scheduled air travel. Known as the

St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line, the airline offered service six days per week

with two roundtrip flights daily until ceasing service on March 31, 1914, which

was five weeks after the termination of a three-month contract that had been

signed with the St. Petersburg Board of Trade. This service greatly improved

travel between the two cities, as travel by steamship took 2 hours, rail between

4 and 12 hours, and automobile around 20 hours (Bluffield, 2010).

Although the early days of

aviation did not start and end at

airports as we know them, these

airfields did serve as the first air-

ports. Whether in the form of a

grassy field, sand dune, body of

water, or other flat place, these

first airfields served the unique

needs of the early aviators. As

more aircraft were built and the

aviation industry began growing,

the need for landing areas grew.

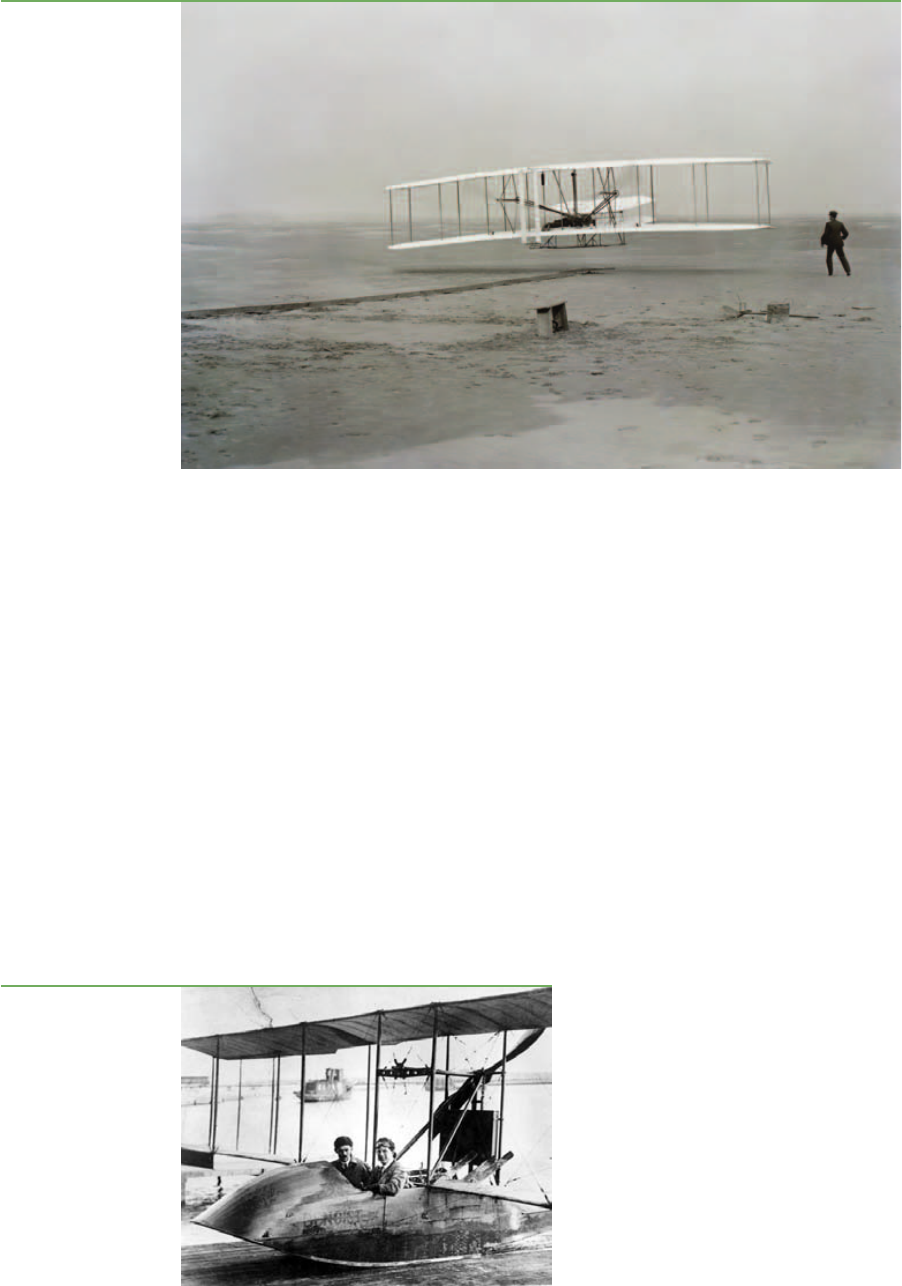

Figure 1-3.

The first flight of

Orville Wright

(1871–1948) at

Kill Devil Hills, Kitty

Hawk, North Carolina,

on December 17,

1903 (120 feet in 12

seconds). His brother

Wilbur Wright (1867–

1912) is standing on

the right.

(Wikimedia Commons;

see credit on page 623)

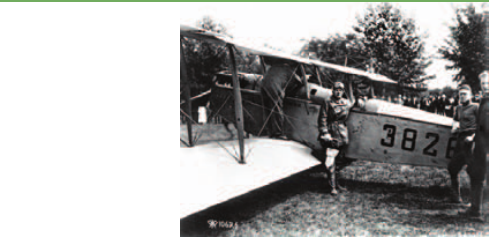

Figure 1-4.

The historic departure

of Jannus and Pheil.

(Wikimedia Commons;

see credit on page 623)

12 AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

Providing dedicated airfields was seen as the best solution to this need. One way

in which to do this was to develop dirt-only fields (see Figure 1-5). This option

improved aircraft performance on takeoff roll, due to an elimination of the

drag produced by grass. As can be imagined, however, these dirt landing sites

were only usable in dry conditions. Muddy landing sites were, in fact, worse

than the old grass landing sites. Often, race tracks, golf courses, or fairgrounds

doubled as landing sites.

A significant boost in the quality of airfields came about with the addition

of concrete landing areas. Portland cement, which had been invented in 1824 by

English inventor Joseph Aspdin, was the preferred material. However, macadam

or cinders were also used. Macadam was a type of road construction pioneered

by Scotsman John Loudon McAdam around 1820. Single-sized aggregate layers

of stone with a coating of binder as a cementing agent were mixed in an open-

structured macadam. Cinder, on the other hand, is a small type of volcanic rock

that has many uses, including material for road construction and decorative

rock for landscaping, especially in the southwest U.S.

Possibly the first use of the term “airport” was by a Brazilian airship inven-

tor, Mr. Alberto Santos-Dumont. According to the April 11, 1902 edition of

The New York Times, Mr. Santos-Dumont explained his expectation that the

city of New York would be “the principal ‘airport’ of the world in less than a

score of years” (The New York Times, 1902). However, the nation’s first munici-

pal airport was built in 1908 in Albany, New York. Located on a former polo

field, the airport was moved to Westerlo Island after one year due to the unsuit-

ability of the former polo field. Deemed an ideal location, Westerloo Island

had long, level stretches of land bordering the Hudson River. During its early

years, the airport welcomed such famous aviators as Glenn Curtis, Charles

Lindbergh, Amelia Earhart, and James Doolittle. The mayor of Albany at the

time, Mr. John Boyd Thacher II, once said, “A city without the foresight to

build an airport for the new traffic may soon be left behind in the race for

Figure 1-5.

Early landing strip.

(©iStock.com/andipantz)

CHAPTER 1 Historical Overview 13

competition.” So, in 1928, a new modern airport was built. The new airport

originally consisted of 249 acres and contained two brick hangars and a brick

administration building. As part of airport construction, three runways were

built—the first was 2,200 feet long, the second 2,350 feet long, and the third

measured 2,500 feet long. Two of the runways were paved with macadam and

one with cinders. By 1930, Albany was known as the “aerial crossroads of the

great Northeast.” Although the airport was closed for a brief period by the Civil

Aeronautics Administration (CAA), it remains in operation to this day, overseen

by the Albany County Airport Authority (Hakes, n.d.).

Although Albany Airport was initially funded by the City of Albany, its

operation and upkeep during the first eight years was financed through a spe-

cial fund established by the Albany Chamber of Commerce. Even in those

early years, airports required financial resources for maintenance and operation.

Airport maintenance during this time involved grading to maintain the level

runway, mowing grass, and keeping the runway free of obstructions. In January

1939, however, the newly formed Civil Aeronautics Authority (CAA) closed

the new airport to commercial flights declaring it unsuitable for use. This

action was taken by the CAA following a long dispute between the city and

federal officials over who should be responsible for paying for needed improve-

ments to the airport. Mayor Thacher believed the city should not have to pay for

improvements that would benefit national defense and commerce. The CAA

disagreed and as a result, eventually closed the field to all air traffic. The city

then initiated a Works Progress Administration (WPA) project to make the

necessary improvements at the airport, resulting in the CAA allowing day-

light operations to begin once again in December 1940. On January 21, 1942,

the CAA, recognizing the improvements to the airport, allowed the airport to

reopen for nighttime use. Except for wartime restriction, the airport has had

uninterrupted flight service since that time (Hakes, n.d.).

The College Park Airport in Maryland was established by Wilbur Wright

in 1909, one year after the Albany Airport. It claims the distinction of being the

“World’s Oldest Continually Operating Airport.” It is indeed an airport with

a long history. In 1909, after the U.S government agreed to purchase a Wright

Flyer, the aircraft was officially accepted by the U.S government. However, the

contract required the Wrights to teach two army officers to fly the plane. A

field in the small town of College Park, Maryland, was selected for this flight

instruction and the College Park airfield was established. Operating strictly as a

general aviation facility, in 1977 the airport was added to the National Register

of Historic Places (College Park Aviation Museum, n.d.).

Even so, very few airports were built during these early years of aviation.

Rather than focus on areas at which to land aircraft, efforts were focused on

improving the design of aircraft. In fact, by 1912, only 20 landing facilities

were thought to exist in the U.S. Although this seems like a small number,

this network of landing facilities was sufficient to meet the needs of aviation at

that time. It is interesting to note that all of these landing facilities, including

Albany and College Park, grew from fields or country clubs. They had not been

designed as airports, per se (Mola, n.d.).

14 AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

World War I

However, the environment soon changed as World War I (WWI) began in

1914, triggered by the assassination on June 28 of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

of Austria, the heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary. Thousands of aircraft

were subsequently produced to serve in WWI, most of which were produced

and utilized in France, Germany, and England (Figure 1-6). Of course, hun-

dreds of pilots were needed to fly these aircraft and numerous landing facilities

were needed to accommodate their operation. Although the U.S. Army had

established three military airfields by the time WWI began, an additional 67

military airfields were established during the war to meet this need. These

airfields provided facilities for fueling, maintenance, and aircraft parking. At

the time, the military envisioned returning these airfields to grassland upon

the war’s conclusion.

By the end of WWI in 1918, the U.S. Army listed no less than 980 official

landing fields. However, many of these fields were unsuitable for regular air-

craft operations. For instance, pilots may have had to avoid flags, sand traps,

and water hazards while landing on a golf course. Additionally, racetracks were

generally sufficient for landing aircraft, but too short to allow for takeoffs.

Some, however, worked quite well—including dry lakebeds in Nevada or long

stretches of country roads. During this time, “aerial garages” were being built

to accommodate aircraft storage and maintenance needs. These forerunners

to contemporary hangars and maintenance shops were oftentimes built out of

whatever materials were on hand, including the packing crates used for new

aircraft delivery (Mola, n.d.).

Figure 1-6.

Aviation in use during

World War I.

(©iStock.com/igs942)

CHAPTER 1 Historical Overview 15

Post World War I

Upon the conclusion of WWI, there were a large number of aircraft and

skilled pilots that desired to utilize their talents. Conveniently, in 1918, the

U.S. Congress appropriated $100,000 for the first regularly scheduled airmail

service. This route, between Washington, DC, and New York, was to be flown

roundtrip once daily by U.S. Army Service pilots (Figure 1-7). Major Reuben

H. Fleet was picked by Army Colonel E.A. Deeds to manage the first regular

airmail flights. Although Assistant Postmaster General Otto Praeger and Fleet

disagreed about landing fields, pilots, and the date airmail service would begin,

the inaugural airmail flight occurred on schedule on May 15, 1918.

Interestingly, the two pilots selected for these inaugural airmail flights were

not chosen for their experience or abilities; rather, they were the sons of politi-

cally important men. Lt. George Boyle was to fly from the Potomac Park Polo

Grounds in Washington, DC, to a relay handover point in Philadelphia. Simul-

taneously, Lt. James Edgerton was to fly from Hazelhurst Field on Long Island,

New York, to the same relay handover point in Philadelphia. Lt. Boyle’s flight

was a failure. He was inexperienced, encountered low visibility due to thick fog,

flew a poorly equipped airplane in the form of an open cockpit Curtiss Jenny,

and followed the wrong railroad tracks to Philadelphia. He quickly became lost,

flying for only 24 miles before landing

in a field and flipping over. Although he

was not injured, the mail he was carry-

ing (3,300 letters weighing 140 pounds)

had to be offloaded and placed on a train

to Philadelphia. Lt. Edgerton’s flight,

however, was a success, leading the news-

papers to declare this inaugural airmail

service a success (Mola, n.d.).

Two months later, pilot Leon Smith

refused to fly his route of New York to

Washington, DC, due to rain, clouds,

and 200 feet visibility. Praeger ordered him to make the trip regardless of the

weather. Smith and his fellow pilot, E. Hamilton “Ham” Lee refused to fly

in those weather conditions. As a result, they were both fired, which then led

to a strike by all pilots in the airmail system. After three days of talks, it was

agreed that field managers would make a flight check in bad weather. If the

field managers were not pilots, they would sit in the mail bin in front of the

pilot to visually verify the weather. Flights would then continue only if the field

manager gave the go-ahead (U.S. Centennial of Flight Commission, n.d.[c]).

Over the following three months, pilots flying these airmail routes were

heartily challenged. With only a simple magnetic compass and maps with no

elevations or landmarks, these pilots were pressured to maintain a six day per

week schedule regardless of weather. In less than three months, the army had

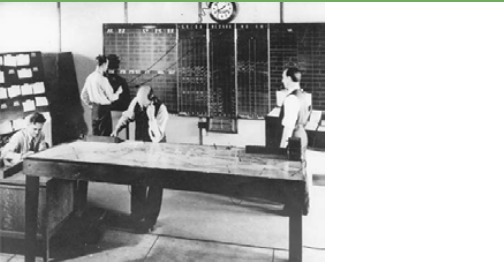

Figure 1-7.

Early days of airmail

in the United States.

(Wikimedia Commons;

see credit on page 623)

16 AIRPORT MANAGEMENT

made 270 flights and carried 40,500 pounds of mail. Although several pilots

had been injured, none had been killed. However, the Post Office felt that the

army had not sufficiently met the schedule and had been uncooperative. As a

result, the army contract was cancelled and the Post Office began carrying the

mail on August 12, 1918 (Mola, n.d.).

As the airmail system grew, so did the country’s airports. Indeed, many

communities began constructing airports to allow them a connection to the rest

of the world. Early airfields built by the Post Office typically had a 2,000-foot

by 2,000-foot square to allow for takeoffs and landings in any direction. Land-

ing surfaces were generally of gravel or cinders, as they allowed for adequate

drainage. Airfields generally ranged in size from 70 to 100 acres and consisted

of a hangar, storage of gasoline and oil, a wind indicator, a telephone connec-

tion, and a location marker. By the end of 1920, there were 145 airports owned

and operated by municipalities. Clearly, a national network of airports was

being established (Mola, n.d.).

The first permanent, hard-surfaced runway in the United States, at 1,600

feet long, is thought to have been constructed at Newark, New Jersey, in 1928.

Some airports were being developed by airlines. For instance, Pan American

Airways, flying a Miami–Key West–Havana route twice daily, constructed the

first U.S. land-based international airport: Pan American Field.

Yet as airmail began crossing the country successfully in the mid-1920s, the

owners of various railroads expressed their frustration with the government’s

sponsorship of the airmail system. They felt that railroad profits were being

negatively impacted due to the carriage of mail by air. Congressman Clyde

Kelly of Pennsylvania, chairman of the House Post Office Committee, was a

friend of the railroad industry and on February 2, 1925, sponsored H.R. 7064:

the Contract Air Mail Bill, which, upon enactment, became the Contract Air

Mail Act of 1925, also known as the Kelly Act. The act elevated airmail to

another level by allowing the postmaster general to contract for domestic air-

mail service with commercial air carriers. It also set airmail rates and the level

of cash subsidies to be paid to companies that carried the mail. The Act was

successful in expanding airmail service without undue burden on the taxpay-

ers. Routes created as part of the Act were known as Contract Air Mail routes

or CAM routes (see Figure 1-8). Initial routes were flown between cities such

as New York and Boston, Detroit and Cleveland, and Atlanta and Jackson-

ville. Eventually, a transcontinental route was established. In essence, this Act

effectively established the commercial aviation industry. Indeed, several airlines

that existed well into the twentieth century (such as Trans World Airlines,

Northwest Airlines, and United Airlines) were formed during this time (U.S.

Centennial of Flight Commission, n.d.[a]).

To financially support the airmail service, 80 percent of the airmail stamp