PHOTO BY LINDA DAVIS

!

!

!

!

!

!

!

KIMBERLY!SWEENEY!|!JUNE!2017!

The Death of Sunday

School and the Future of

Faith Formation

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

2

Contents!

Message from the Author .................................................................................................. 3!

Executive Summary .......................................................................................................... 4!

The Death of Sunday School ............................................................................................ 5!

The Future of Faith Formation ........................................................................................ 15!

What Have We Learned? ................................................................................................ 21!

References ...................................................................................................................... 26!

Appendix A: Impacts of a Family Ministry Focus on Current Roles ................................ 29!

Appendix B: Sample Job Description for Coordinator of Family Ministry ........................ 31!

Appendix C: Sample Job Description for Director of Family Ministry .............................. 32!

Appendix D: Examples of Roles for Family Ministry Volunteers or Teams ..................... 34!

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

3

Message from the Author

This was an extremely challenging piece to write. While my experiences as a parent,

religious educator, and member of the Unitarian Universalist Association’s

Congregational Life staff have affirmed the observations and ideas herein, it was still

difficult to lay them all out on paper. At times it felt risky. Often it was overwhelming.

You may experience the tone of this writing to be bold or blunt, and that is with reason.

Religious professionals have been talking about the challenges of Sunday school for

close to a decade, yet talking about it and acknowledging that things need to change has

not made a measurable difference. The conversations remain more or less the same

year after year. Thus, it felt prudent to be as straightforward as possible.

I imagine that for some of you, reading this will affirm your own observations and

experiences. Some of you may feel awash in grief and despair. Others might feel

defensive. You might call to mind the mentors, parents, ministers, and teachers who

spent countless hours building and supporting Sunday school programs. A few will say

that your Sunday school program is thriving. I expect all of these reactions.

This is holy work. Our ancestors and pioneers in religious education dedicated their lives

to this call and have gifted us with an enormous history and legacy. For that we are

grateful and continue to honor their contributions, selflessness, and dedication to our

children and youth. A paper cannot erase that work or the impact they had. This paper

was not written to diminish the work that has come before in any way.

This paper was written because while the structures of our past met the needs of

families in that time and place, they are not meeting the needs of our families today. We

don’t build programs or develop strategies with the intention that they will live forever.

We implement these programs and use these strategies for as long as they are effective

and useful. While our programs and strategies should and will change over time, the

purpose of our work remains the same: to bring the love and grace of Unitarian

Universalism to our families’ lives.

At the end of the day, I wrote this paper because the stakes felt too high to give in to my

own fears. We are in rapidly evolving times, and it is mission critical that we empower

one another to face this truth head on. It will be a whole lot easier if we face it together.

In faith and with tremendous appreciation,

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

4

Executive Summary

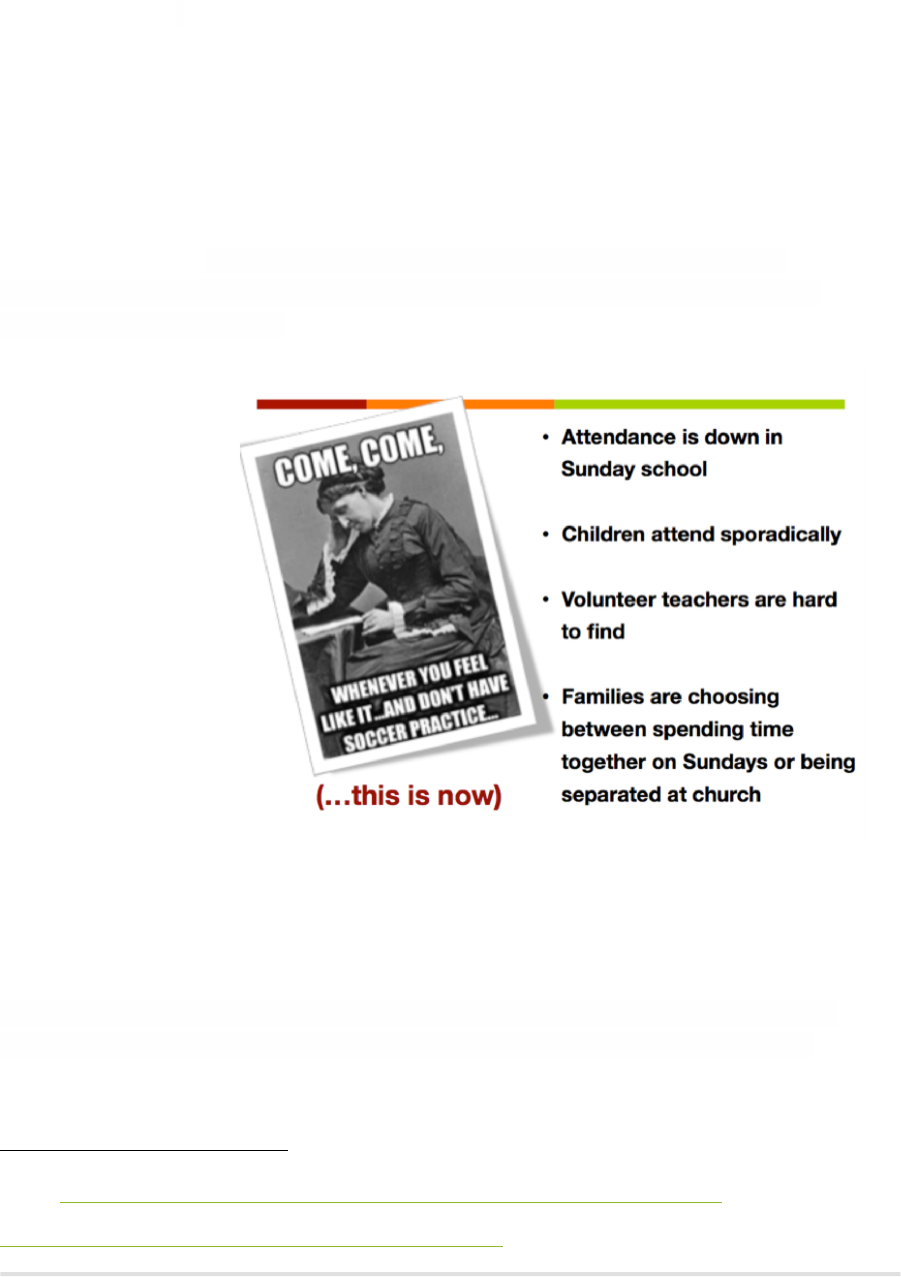

The Sunday school model of religious education has been much beloved in our Unitarian

Universalist tradition. Half a century ago, and at the time of its inception, Sunday school

was a significant draw for children and families and was popular in dominant culture.

Over the past two decades, religious professionals and lay leaders have been

questioning the effectiveness of this model. Working harder, moving things around, and

investing more money in Sunday school has not increased its effectiveness. These

strategies have not worked in part because we have failed to convey that the way we

have always done things is no longer serving our Unitarian Universalist congregations.

While we have been applying a multitude of technical fixes to this adaptive challenge, we

have failed a generation of young Unitarian Universalists.

Changes in demographics, family structures, societal norms, and the role of the church

in US life have evolved drastically over time. Yet the Sunday school model that came out

of the twentieth century has remained relatively unchanged. Families report having to

choose between spending time together or going to church and being separated.

Participation in religious communities should not require families to have to sacrifice their

time with one another by being shuffled in opposite directions once they enter the door.

Competing priorities, generational shifts, cultural attitudes, and norms about church—

coupled with local demographic shifts—have resulted in congregations in New England

having the lowest percentage of Sunday school attendance in the country.

It is past time to return to our roots by engaging, inviting, and expecting our families to

worship together. It is past time to return to the ministry of preparing parents and

caregivers to be the primary religious educators for their children. It is past time to bury

Sunday school, a model that has not been adapted to contemporary times. The future of

faith formation resides in family ministry.

Ending Sunday school is not tantamount to ending faith formation. To the contrary, faith

formation is a foundational ethos of our Unitarian Universalist ministries. Paying attention

to the shifting needs of our families and children, releasing ourselves from the structures

of our past, and boldly experimenting to contribute to the evolution of faith formation may

just be the spiritual task of our time. The future of Unitarian Universalist faith formation in

New England depends on it.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

5

The Death of Sunday School

The Sunday school model of religious education died in New England two decades ago.

Many leaders had a sense that its death was coming, but the passing was subtle and

slow. While we have been taking our time moving in out of the stages of grief,

sometimes lingering in or returning to denial, we have failed a generation of young

Unitarian Universalists. We have been unable to part ways with Sunday school and have

done everything we could think of to resuscitate it, to the detriment of our youth and their

families. We have a responsibility to bury Sunday school and move forward before we

lose another generation. It is imperative to the future of our faith.

For the majority of the history of religion in the United States, faith formation has

occurred outside of a classroom. Several centuries ago, when the nation housed far less

religious diversity, children were most often raised in the shared faith tradition of their

family. Families recognized the Sabbath or Shabbat together. “Seventeenth-century New

England Puritans took the Sabbath very seriously, enacting harsh measures, known as

Blue Laws, to punish the impious. Starting in the mid-1600s, any Sunday activity that

took away from worship—shopping, laundry, consumption of alcohol, “unseemly”

walking—was strictly forbidden”.

1

Aspects of these Blue Laws remained in effect for

centuries, leaving household responsibilities and worship as the only options for Sunday

activities. Families prayed together, celebrated the traditions of their faith together, and

worshipped together. This was faith formation. For Indigenous peoples, faith formation

was interwoven and imbued in all aspects of living. Sunday school did not exist. In fact,

the earliest public schools in the United States were not academically focused, but

instead taught morality and virtues, focusing on family, religion, and community. It wasn’t

until the mid–nineteenth century that public education shifted its focus to academics, and

even then classes were mostly multi-aged.

The American Unitarian Association embraced graded curriculum—lessons designed for

different age levels, a progressive innovation—in 1909 with its "Beacon Series." But by

the 1930s, Unitarianism was in crisis. Membership had dropped to 50,228 in 1935. The

Christian Register reported widespread dissatisfaction with Unitarian Sunday school

programs in 1930.

2

Educational theorists (e.g., Dewey, Piaget, and Erikson) and educational reform were

responsible for the current academically focused, age-segregated model of public

1

“Blue Laws in New England,” Ancestry.com, accessed May 24, 2017,

https://www.ancestry.com/contextux/historicalinsights/new-england-blue-laws.

2

Christopher L. Walton, “Sophia Lyon Fahs, Revolutionary Educator,” UU World Magazine, March/April

2003, http://www.uuworld.org/articles/sophia-lyon-fahs-revolutionary-educator.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

6

education in the United States. It wasn’t until the 1940s and 1950s that the Sunday

school model we recognize today came to life. Church and religion still played a

significant role in US culture. Sunday school mimicked the structure of public schools,

providing age-segregated classes for children to receive religious instruction and lessons.

Weekly attendance was the norm, and perfect attendance awards were not uncommon.

In New England, these programs were often run by the minister’s spouse or by another

parent in the congregation. It was decades before program administrators (or Directors

of Religious Education) were compensated for their work.

The 1960s and 1970s ushered in an anti-establishment culture with Baby Boomers

rebelling against institutions, including church.

We rebelled by dropping out: 2/3rds of my generation dropped out of church. In

the late 1970’s/early 1980’s, innovative pastors and congregations of all sizes

and denominations looked for ways to draw Boomers back to church. They

began to create worship experiences based on the unique “personality” of the

Boomer generation. These churches went “contemporary,” “seeker,” and/or

“seeker-friendly.” Because these were the primary parenting years for Boomers,

these congregations recognized the need to not only provide Boomer-friendly

worship experiences for adults, but the need to create dynamic experiences for

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

7

their children as well, knowing that if the kids wanted to come back, the parents

were more likely to come back.

3

Thus began the shift from families worshipping together to creative and attractive

Sunday school programs for kids, offered at the same time as the worship service.

Suddenly, in Unitarian Universalist spaces, children and adults were having drastically

different Sunday morning experiences in isolation from each other. These programs

eventually moved to a cooperative model where parents volunteered to run the Sunday

school program and teach the classes as well. Some churches would exclude children

from the worship experience, expecting Sunday school to engage them and meet their

needs until such time as they became recognized as adults. Many still do.

The pendulum swung from one direction where congregations gathered as a single body

(mixing), to the other direction where people were gathering by age or cohort (huddling).

The long-term and unintended consequence of this strategy was a generation of young

people who had no connection to their faith or congregation outside of Sunday school.

The implicit message of this divergent approach was that what happened in the

sanctuary was for adults; it was framed as being boring and unappealing for children.

Young people spent their childhood and adolescence segregated from the adult

congregation. In our Unitarian Universalist tradition, bridging out of the youth ministry

program essentially meant bridging out of the church. The only connection of youth to

the church was through their peers, who were also moving on.

Changes in demographics, family structures, societal norms, and the role of the church

in dominant white US culture have evolved drastically over time.

4

Yet the Sunday school

model that came out of the twentieth century has remained relatively unchanged.

For the past century Christian churches have structured their faith formation

programs for children around a classroom model. This approach brings together

teachers and children for regular, planned teaching and learning, in settings

where significant relationships take shape. Many churches still structure their

children’s program around the “traditional” classroom model, which looks and

feels the same as it did decades ago. The books and materials have been

updated, but the basic model remains. This model served churches in previous

3

Tim Wright, “Sunday Schooling Our Kids out of Church,” Patheos, August 5, 2014,

http://sixseeds.patheos.com/timwright/2014/08/sunday-schooling-our-kids-out-of-church.

4

In families and communities of color, the church has generally played a much more significant role as

compared with the dominant white culture in the United States.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

8

generations, but changes in families, society, and churches have accentuated its

limitations.

5

When Baby Boomers were in their prime parenting years, the current structure of age-

segregated Sunday school classes was born. Finding volunteers wasn’t much of a

challenge for a generation of roughly eighty million at a time when many two-parent

households had only one parent working outside the home. But today’s generation of

parents, Generation X, is roughly half the size of the Baby Boomer generation, with

intense expectations and requirements for volunteerism. The number of volunteers

needed to staff these programs has not changed, but the number of adults in this

generation has decreased by 50 percent.

6

Add in the decrease of religious identity in

each successive generation, changes in family structure, the economic reality that

necessitates more parents working outside the home, and the culture of intense

overscheduling

affecting people of

all ages in our

society, and there

just isn’t the

capacity to replace

the Baby Boomer

volunteer base.

Religious educators

report, “Teacher

recruitment time is

one of the most

demoralizing times

of my job for me,”

and,

I need teachers and childcare providers. Thus far, all recruiting has been futile, even for

paid positions.” This structure essentially sets up our religious educators for failure.

It has long been recognized that parents and families play a significant and vital role in

the faith development of children and youth. Sociological and demographic changes

have made a substantial impact on twenty-first-century family structures and even the

numerous ways the concept of family is named or defined. Families are often pulled in a

5

John Roberto and Katie Pfiffner, “Best Practices in Children’s Faith Formation,” Lifelong Faith 1.3 (2007):

39–46, http://www.lifelongfaith.com/uploads/5/1/6/4/5164069/lifelong_faith_journal_1.3.pdf.

6

Mike Allen and Renee Allen, “Generational Differences Chart,” accessed May 24, 2017,

http://www.wmfc.org/uploads/GenerationalDifferencesChart.pdf.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

9

variety of directions and experience no shortage of competition for their time. For many

families, Sunday is often the only time of the week when they are all at home at the

same time.

Unfortunately many congregations have contributed to the situation by over-

emphasizing age-segregated programming, which further divides families, and

over-programming family members. Oftentimes there is little to no programming

that engages the entire family as a family, or that empowers and equips parents

for their task as the primary religious teachers of their children and teens. Sadly,

many churches blame parents for the situation or have given up on families,

“because they don’t come to Sunday worship or the programs we offer, so why

bother.”

7

Families report having to choose between spending time together or going to church and

being separated. Participation in religious communities should not require families to

have to sacrifice their time with one another by being shuffled in opposite directions once

they enter the door.

These observations and cultural realities explain, in part, religious educators reporting a

sharp decline in Sunday school attendance for the past many years. Competing priorities,

generational shifts, and cultural attitudes and norms about church, coupled with local

demographic shifts, have led to congregations in New England having the lowest

percentage of Sunday school attendance in the country.

8

New England has seen a sharp increase in the turnover of UU Directors of Religious

Education in the past five years, an increase in positions that go unfilled, and a decrease

in the number of applicants overall. At the time of this writing, New England UU

congregations were experiencing twenty-five staff transitions in religious education. By

the end of May 2017, only six of those positions had been filled, four of which were filled

by applicants new to the field. The remaining nineteen positions range from full time to

three hours a week, and have received minimal interest from applicants regardless of

their background or training. The average number of staff transitions for religious

educators in New England was thirty-three annually from 2015 to 2017. Newer religious

educators are less inclined to apply for positions steeped in the traditional Sunday school

7

John Roberto, “Best Practices in Family Faith Formation,” Lifelong Faith 1.3 (2007): 21–35,

http://www.lifelongfaith.com/uploads/5/1/6/4/5164069/lifelong_faith_journal_1.3.pdf.

8

Joseph V. Crockett, Teaching and Learning in American Congregations (Hartford, CT: Hartford Institute for

Religion Research, 2016),

http://www.faithcommunitiestoday.org/sites/default/files/Teaching_and_Learning_in_American_

Congregations_0.pdf.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

10

model. Even with the offer of fair compensation and benefits, religious educators are

increasingly wary of maintaining declining religious education programs.

It bears noting that there is no prescribed pathway to a career as a Unitarian Universalist

religious educator. Our religious educators are hired from a wide and varied spectrum of

experiences, education, and backgrounds. Some have previously served as volunteers

in religious education, while others come with backgrounds in education, art, music,

social work, and many other fields. Unlike ordained clergy who have attended seminary,

there is no single training, experience, or course that our religious educators can be

expected to have completed before coming to this work. Their professional development

often happens while they are serving, not during their preparation for the work, and the

education they receive varies greatly depending on the needs, interests, and financial

commitment of the congregation. Religious educators wishing to be credentialed through

the Unitarian Universalist Association are only able to begin the process after they have

been in the work for some time.

In New England, the majority of religious educator positions are half-time or less, with

many congregations increasingly reducing the hours of these positions. Quarter-time

positions maintain the disconnection between children and the rest of the congregation

because there is simply no staff time to align the religious education program with the

rest of the church. In effect, the congregation is paying a person to keep young people

busy and separate from the rest of the congregation.

In actuality, Generation X is the most highly educated generation, graduated from school

with the highest rate of student debt, and is the first generation in modern US history that

will earn less than their parents. Part-time, low-paying or stipend positions without

benefits that require no educational background are not attractive, sustainable, or

realistic for this generation. Unitarian Universalism is stuck between a model that worked

successfully two generations ago and a model that we have yet to fully imagine or

articulate. We have inherited a Sunday school model that depends on unpaid or

underpaid leadership, despite decades of tremendous dedication and sacrifice. We are

in a time when that is simply not an option for our current workforce.

An interfaith poll of US congregations found that only 16 percent of all Sunday school

programs are run by religious educators. Over 70 percent of these programs are

managed by clergy or volunteers.

9

With the majority of Sunday school programs being

9

Overall, by a 2:1 ratio (51 percent), clergy, rabbis, imams, and priests outnumber all other categories of the

“organizers” of congregational teaching and learning ministries. The next largest group is lay volunteers (22

percent). Together, more than 70 percent of congregational educational leaders either have multiple

congregational responsibilities or, as lay volunteers, may not have had professional training in religious

education. Crockett, Teaching and Learning in American Congregations.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

11

organized peripherally by clergy or by impassioned and untrained lay volunteers, it is no

wonder that we continue to maintain this structure. We haven’t had the time or capacity

to make way for something new. The culture shift required to be the relevant faith

communities our children and families need today is considerable.

There are six key facts that feel particularly relevant to this conversation of how the

Unitarian Universalist model of religious education must change, and why culture shift is

called for instead of more superficial solutions.

1. As stewards of our Unitarian Universalist faith, it is our responsibility to adapt

our approaches to faith formation to these contemporary times.

New England is seeing significant demographic shifts as the Baby Boomer generation

continues to age. Connecticut, Maine, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont are

among the nine states in the country with the oldest populations, with New Hampshire,

Maine, and Vermont being the top three.

By 2020, the US Census predicts that 20 percent of New Hampshire’s 1.3 million

residents will be sixty-five or older, up from 13.5 percent in 2010.

10

Public school

enrollment in New Hampshire has fallen more than 10 percent over the past decade, and

population projections forecast that decline to continue through the coming decade. In

Vermont, the number of births has been on a steady decline for the past 15 years, a

major factor contributing to Vermont’s population stagnation and to the declining number

of students in its schools. A 2016 headline read, “Number of VT Births Lowest since

before Civil War.”

11

The result of these trends is that there are fewer children and youth living in New

England than in previous generations.

12

For example, a UU congregation in Maine offers

a Sunday morning religious education program for infants through high school–age

youth, yet the only public school in town has only between three and eight students

enrolled at each grade level. Dozens of other New England congregations frequently

report needing to combine classes or operate with a one-room-schoolhouse model on

Sunday mornings due to minimal attendance numbers.

10

Gretchen M. Grosky, “The Changing Face of NH: What It Means to Have the 2nd Oldest Population in the

Nation,” New Hampshire Union Leader, August 13, 2016, http://www.unionleader.com/The-changing-face-of-

NH:-What-it-means-to-have-the-2nd-oldest-population-in-the-nation.

11

Art Woolf, “Number of VT Births Lowest since before Civil War,” Burlington Free Press, June 23, 2016,

http://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/news/2016/06/23/number-vt-births-lowest-since-before-civil-

war/86204456.

12

Daniel Barrick, School Consolidation in New Hampshire (Concord, NH: New Hampshire Center for Public

Policy Studies, 2015), http://www.nhpolicy.org/UploadedFiles/Reports/school_consol_forweb.pdf.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

12

Elders will make up the overwhelming majority of the membership of UU churches for

decades to come, and there is no reason to believe that attendance numbers for children

and youth in Sunday school programs will rise. Sunday school in New England is dead.

We don’t have the children, the time, the volunteers, or the staff to maintain this outdated

structure of faith formation.

13

Religious leaders have been talking about these demographic shifts for two decades.

John Roberto got religious professionals talking about it in 2010 with the research in his

book, Faith Formation 2020.

14

Despite much talking, and learning, and tweaking

programs, for the most part the systems and structures remain unchanged.

Even at the end of her long career, revolutionary Unitarian religious educator Sophia

Lyon Fahs continued to put forth questions about the nature of religious truths and the

adequacy of church school structures in passing on religion.

15

For nearly a decade,

religious professionals and lay leaders alike have been asking questions too, such as:

• “How can we attract more children and families to our church?

• “What can we do in religious education to make kids want to come on Sunday?”

• “How can we invite more people to volunteer to staff the religious education

program?”

• “Where can we find a religious educator who can bring our program back to life?”

Despite the demographic shifts discussed above, many congregations throughout New

England feel that they are not “doing church right” without a religious education program,

even in towns where there are hardly any children.

2. Finding a different religious educator is not the key.

The most skilled, talented, and experienced religious educators out there are as unable

to change demographic shifts as anyone else. Hiring a religious educator to maintain or

reinvigorate a religious education program using an outdated structure will not yield

different results. Ask yourself, “If the structure of the program remains roughly

unchanged, and none of the religious educators in the past ten years have been able to

‘reinvigorate’ the program, might it be possible that the structure is no longer working?”

13

While uncommon in New England, there are a small number of congregations reporting growing religious

education programs that use a Sunday school model. These are rare exceptions to the rule and are not

representative of the majority of experiences reported by New England UU congregations of all sizes.

14

John Roberto, Faith Formation 2020: Designing the Future of Faith Formation (Naugatuck, CT:

LifelongFaith Associates, 2010).

15

Edith F. Hunter, Sophia Lyon Fahs: A Biography (Boston: Beacon Press, 1966).

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

13

3. Increasing staffing to minister to specific subsets of young people maintains

age segregation.

Part-time positions that minister to five or ten kids each Sunday implicitly suggest that a

congregation would prefer to pay someone to manage, entertain, or teach its children

than engage in religious community with them.

4. As Baby Boomers move into retirement and Gen X moves into leadership and

lay positions, the size of the volunteer pool is cut nearly in half.

Combine the smaller volunteer pool with adults who want to be in worship and families

that want to stay together on Sunday morning, and there simply are not enough adults

left to staff the volunteer-heavy Sunday school model of yesterday.

5. A curriculum will not save the day.

There is no curriculum out there that will bring a religious education program back to the

levels of participation seen twenty or thirty years ago. There is no curriculum waiting to

be written that will do that either. Curriculum is not the issue. A curriculum does not

determine whether or not a family will participate on Sunday morning.

6. Adults need just as much faith formation as children and youth.

Roughly 88 percent of adult members come to Unitarian Universalism from other faith

traditions or from no tradition at all.

16

The lack of faith development for UU adults is a

serious problem, resulting in a high percentage of adults with a tenuous connection to or

understanding of Unitarian Universalism. Parents and other adults within a congregation

cannot be the guides our children need until they have developed their own spiritual

capacity.

Dr. Diana Butler Bass, author, speaker, and independent scholar specializing in US

religion and culture, relates this story:

A few years ago, I attended a rapidly growing congregation in California. Most of

the newcomers fit one of two categories. They were either returning baby-

boomers or spiritual seekers. Most returnees had grown up in a mainline tradition

but quit church in their teens or early twenties. They had lots of emotional and

spiritual baggage regarding the Bible, theology, and Christian tradition. Many of

the seekers, often Gen Xers, had rarely been inside a church.

16

Richard Higgins, “Three in a Thousand Identify as Unitarians,” UU World Magazine, June 2, 2008,

http://www.uuworld.org/articles/three-in-thousand-identify-as-unitarians.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

14

Those of us in congregational leadership quickly realized that we had a set of

problems. How to honor the life experience and practical wisdom of the returnees

while helping them to theological maturity? And how, at the same time, to

introduce unchurched people to the fullness of life in [religious] community?

Our problem was not evangelism. People were coming to the church. Our

problem was adult education.

And, still worse news: no single curriculum or program could help us. We needed

to fashion an introduction to church that worked in our setting. Adult formation

would be a process, not a program. We needed to understand our own identity

and communicate our vision of faith and vocation to the new members.

17

Herein lies the opportunity to consider what Unitarian Universalist congregations can

contribute to the evolution of faith formation in a way that is relevant spiritually and

contextually and is mindful of the contemporary realities of the day. Congregations can

meet the needs of twenty-first-century families—we have evidence that this is true.

It is past time to return to our roots of engaging, inviting, and expecting our families to

worship together. It is past time to return to the ministry of preparing parents and

caregivers to be the primary religious educators for their children. It is past time to bury

Sunday school, a model that has not been adapted to contemporary times.

17

Diana Butler Bass, Process Not Program: Adult Faith Formation for Vital Congregations (Indianapolis, IN:

Congregational Resource Guide, 2010.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

15

The Future of Faith Formation

Today’s reformation calls for the centering of faith formation in the mission of our

communities of faith. The reformation called for within Unitarian Universalism asks

religious educators to lead in a new way. Religious educators are being invited to

engage the entire congregation in faith formation, bringing certitude to the words of UU

leader Connie Goodbread, “Faith development is all we do. Unitarian Universalism is the

faith we teach. The congregation is the curriculum.”

Today’s reformation calls for the decentering of dominant ways of doing things and

dominant experiences of the world. It calls for the decentering of the older adult

experience, the decentering of whiteness, the decentering of upper-class norms, all in

service of our vision for a multicultural, multiracial and multigenerational Unitarian

Universalism. As the Rev. Dr. Mark Morrison-Reed has put it, we are moved to do this

because we “see the richness in human diversity and [are] excited by its possibility.”

Given the cultural context in which we now find ourselves, this is where Unitarian

Universalism’s deepest theological principles and religious values draw us. Religious

liberalism has always been marked by its ability to engage and respond to the

circumstances of its own time and place. This is what has kept our UU theology

intellectually credible and socially relevant. If we fail to respond to our new multicultural

reality—if we choose to stand rather than to move—we will not only fail to honor this core

principle of liberal theology, we also will simply become irrelevant.

18

The future of faith formation resides in family ministry. The concept of family ministry isn’t

new. Our evolving definitions of family may change, but the call to support faith formation

at both church and home remains true. Reggie Joiner, founder and president of the

reThink Group, frames it this way:

The church realizes it can’t be effective alone and needs the home. As family

ministry expands, it’s also evolving. Just being family-friendly no longer counts.

The old approach of keeping people of all ages busy with lots of family-specific

programming is missing the mark. All the “random acts of ministry” that churches

line up for families overload church and family schedules, ultimately “competing

with the very families you’re trying to help.”

19

18

Paul Rasor, “Can Unitarian Universalism Change?” UU World Magazine, February 22, 2010,

http://www.uuworld.org/articles/can-uu-change.

19

Stephanie Martin, “THIS Is Family Ministry: The Experts Speak,” Children's Ministry Magazine, November

3, 2016, http://childrensministry.com/articles/this-is-family-ministry.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

16

Churches have been focused on resourcing faith formation that happens within their

walls, and have failed to focus adequate time, attention, and resources to equip families

to do the work of faith formation at home. Being contemporarily relevant will challenge us

to move away from an educational and entertaining model of religious education in

service of intentionally working to meet the faith formation needs of families today.

There are many ways in which congregations can partner with parents and caregivers to

bring faith formation out of the church and into the home. One effort to bridge the gap

between Sunday school and home is the “taking it home” segment of Tapestry of Faith

curricula.

20

While the goal was commendable, most of those “taking it home” sheets are

left behind during coffee hour or crumpled up in the back seat of the car on the drive

home (and if you didn’t attend the religious education class on Sunday, you didn’t

receive the handout).

A more inspiring effort was “Full Week Faith,” an approach offered by Karen Bellavance-

Grace that served as a bridge between church and home.

21

Full Week Faith tried to

redefine faith formation as something we do in more than just one hour a week. Knowing

that we are in the middle of a seismic shift in the landscape of religious life, it offered a

transitional model for forming faith without certainty of what the new paradigm would be,

citing family ministry as one of its core pillars.

Family ministry aims to support families of all configurations by modeling how to bring

our faith home. Often times, Unitarian Universalists simply need to be reminded or

shown that there are ways to do just that. From stories and songs to spiritual practices

and social justice opportunities, from ethical eating and voting as a person of faith to

celebrating Lent or Advent in affirming ways, there are numerous ways in which to model

bringing our faith out of the sanctuary and into our lives.

Mike Clear, family life pastor at Discovery Church in Simi Valley, California, reinforces

the importance of intentionality. “Family ministry needs to be about churches intentionally

influencing parents to be the spiritual leader for their kids,” he says. A child might attend

church some fifty hours per year, but a parent or caregiver has more like three thousand

hours per year “to impact the heart of their child”—an influence that is lifelong. “As good

as we might think we are as a church and as electrifying and relevant as our ministries

20

“Tapestry of Faith Curricula,” Unitarian Universalist Association, accessed May 24, 2017,

http://www.uua.org/re/tapestry.

21

Karen Bellavance-Grace, Full Week Faith: Rethinking Religious Education and Faith Formation Ministries

for Twenty-First Century Unitarian Universalists (Chicago: The Fahs Collaborative, 2013),

http://fullweekfaith.weebly.com/uploads/1/2/2/9/12293877/finalto_web.fahs_fellowship_paper_copy.pdf.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

17

might be, we still don’t have the potential to influence children the way parents do,” Clear

says.

22

The purpose of faith formation programs is to bring the love and grace of Unitarian

Universalism to our families’ lives. A compelling and supported path to disciplined

spiritual maturity is central to congregational life. While the majority of UU congregations’

focus has been on providing faith formation opportunities for children and youth, most

parents still expect congregational life to support them in forming their children into

spiritual beings. How can this happen if the parent or caregiver is not also engaging in

faith formation? Faith formation is a lifelong process. If we are to bring the love and

grace of this faith to our families’ lives, we must intentionally support the faith formation

of both our children and our adults.

Considering the pendulum swung from mixing to huddling, it’s now time to land

somewhere in between, offering opportunities for people of all ages to be in community

together (mixing), as well as opportunities to gather with peers in similar ages or stages

of life (huddling). Intentional family ministry provides adults with opportunities to dig

deeper into their own beliefs, strengthening their ability to discuss the values and history

of Unitarian Universalism with their children. Parents and caregivers have space to talk

about the spiritual aspects of parenting, or learn how to support their teenagers as they

go through Our Whole Lives. With intentional family ministry, faith formation is no longer

seen as just for children. In fact, it is structured in a way that encourages participation

from the entire congregation.

Some congregations offer just such opportunities each Sunday after a traditional worship

service in their second-hour religious education program, including the UU Church of

Chattanooga, Tennessee; the UU Congregation of Duluth, Minnesota; Emerson UU

Chapel in the greater St. Louis, Missouri, area; the UU Church of Annapolis, Maryland;

and the UU Church of Ogden. Some of these opportunities are age-specific (e.g., Our

Whole Lives, Spirit Play, Tapestry of Faith) and some are specific to life stages (e.g.,

parenting, emerging adults, retirement) or interests (e.g., small group ministry, particular

spiritual practices). Family ministry varies greatly depending on the specific needs of any

congregation.

Intentional family ministry welcomes the whole congregation to worship together on

Sunday morning. Gone are the days of families going in opposite directions upon arriving

at church, under this model. Children have the opportunity to witness and be a part of

the traditions of worship. Congregations can come together as a singular community for

that one hour each week, instead of being fragmented by worship, children’s classes,

and youth group. While whole-congregation worship may be countercultural within

22

Martin, “THIS Is Family Ministry.”

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

18

Unitarian Universalism today, it is much more welcoming and conscious of the beloved

community we aim to be.

For most UU congregations, moving to whole congregation worship would be a

substantial shift. In many of our congregations there might be some reluctance or anxiety

in even considering it. Unitarian Universalism is one of the few denominations in the

United States that assumes that children cannot and should not be in weekly worship

with adults for an hour. The Unitarian Universalist Association’s 2005 Commission on

Appraisal report found that “the way UUs raise our children seems to prepare them for

something completely different than what Unitarian Universalism actually offers. This

suggests that UUs should change one or the other (or both).”

23

Without experiencing

worship with the whole congregation, UU children and youth cannot learn how to be in a

sanctuary, let alone benefit from the spiritual practice of congregational worship. They

cannot see adults modeling moments of silence or stewardship, caring deeply for one

another with expressions of joy and sorrow, singing the songs of our faith, or sharing in

the ministry of worship.

If the above alone is not enough, here are twelve more reasons to welcome children in

church:

24

1. Children are people too: When we welcome kids in church, we acknowledge that

they are important humans and community members in the present, not just in

the future.

2. A kid-friendly church is a parent-friendly church: When we welcome children, we

are making their caregivers feel welcome too.

3. Children learn by participating: When we welcome kids, we invite them to

experience the sacred in community with adults.

4. Kids can handle sermons: When we involve children in church, we expose them

to deep, important ideas.

5. It’s good for everyone: When we include kids in church, we all get to practice

being more generous with each other.

6. It makes services better: When we plan for children to be involved, we plan better,

richer services.

7. Kids have lots to offer: When we welcome children, they are able to contribute

their time and skills.

23

The Commission on Appraisal of the Unitarian Universalist Association, Engaging Our Theological

Diversity (Boston: Unitarian Universalist Association, 2005), http://www.uua.org/sites/live-

new.uua.org/files/documents/coa/engagingourtheodiversity.pdf.

24

Slightly adapted from Thalia Kehoe Rowden, “12 Reasons to Welcome Kids in Church + Tips for Actually

Doing It,” Sacraparental, June 11, 2016, http://sacraparental.com/2016/06/11/12-reasons-welcome-kids-

church-tips-actually.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

19

8. It makes us stronger: When we welcome kids in church, we strengthen

relationships across generations.

9. It can improve preaching: When we include children in church, our preachers are

prompted to do a better job for everyone and make sermons more accessible to

all.

10. Adults don’t miss out: When kids are part of the church service, adults don’t have

to choose between worshipping and leading or attending kids’ programs.

11. It helps young people bridge the gap: When we include people in services from a

young age, they have a less jolting transition in adolescence.

12. It models welcome: When we welcome kids in church, we demonstrate how

welcome everyone is.

Research shows that “involvement in all-church worship during high school is more

consistently linked with mature faith in both high school and college than any other form

of church participation.”

25

What is the best way to prepare high school–aged youth for

attending worship? Establishing it as a practice in childhood.

Knowing and being known by people of all generations needs to be an expectation of

congregational life. There is clear evidence that young people benefit from multiple,

sustained relationships outside of their immediate family. To grow up healthy, our youth

need to be supported and known by at least five adults in addition to their parents or

caregivers who are willing to invest time with them personally and spiritually.

26

Very often

Unitarian Universalist congregants report wanting more multigenerational experiences,

yet they aren’t being given such opportunities with the young people in our

congregations. “Effective religious socialization comes about through embedded

practices; that is, through specific, deliberate religious activities that are firmly intertwined

with the daily habits of family routines . . . and of being part of a community.”

27

We are more age-segregated as a society now than perhaps ever before. Younger

generations of adults are transient and mobile. Older generations have moved out of

their neighborhoods, sometimes into retirement communities or assisted living facilities,

which are often not in the same town or state as their children or families. Children are

further segregated in schools, with typically only a few grades housed within the same

building. We need multigenerational connections, but mainstream culture conspires to

25

Kara Powell, Brad Griffin, and Cheryl Crawford, “The Church Sticking Together,” Sticky Faith, October 17,

2011, http://stickyfaith.org/articles/the-church-sticking-together.

26

Eugene C. Roehlkepartain, Building Assets, Strengthening Faith: An Intergenerational Survey for

Congregations (Minneapolis: Search Institute, 2003).

27

Robert Wuthnow, Growing up Religious: Christians and Jews and Their Journeys of Faith (Boston:

Beacon Press, 2000).

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

20

keep the generations apart and isolate them from each other. Our congregations are one

of the last places in our society where people of all ages can come together.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

21

What Have We Learned?

Religious educators, ministers, and lay leaders have been talking in varying degrees

about the need for the reformation of religious education programs and faith formation

practices for decades. Collegial conversations, common reads, and shared trainings

alone have not been effective strategies for ushering in change of this magnitude.

Numerous technical approaches have been initiated to no avail.

We have learned of the tremendous impact collaborative shared ministry can have when

ministers and religious educators are able to work together in service of one whole

congregation. The most vital and thriving congregations practice covenantal shared

ministry among their staff and lay leaders. Perhaps the 2013 Excellence in Shared

Ministry report said it best:

The best we can hope for our religion is that the future we co-create is rooted in

our heretical heritage. We stand on the shoulders of people who, against

mandates of their day, promoted counter-cultural ideas. “Freedom, reason, and

tolerance,” resounded from their lips and their living, though their world was

steeped in proscription and intolerance. Still, we must acknowledge that while

this is our foundation, it is not our current battle. Tolerance and freedom are

touted widely in popular culture. Quests of the individual (See me. Accept me.

Make room for me.) fail to address the desperate isolation in which we all live.

Our faith currently offers a vital alternative. Without the dictates of dogma, we are

freed to create the substantive covenantal communities in which people can

recover a sense of connection to self, others and spirit. Ours is the religion that

binds us first to the other and in doing so to all that is holy or life itself. We can

hold each other. We can love each other because of who we are not in spite of

who we are. We can love each other into being more.

That lofty, but attainable goal, requires living into reality the notion that our

religion is at its core about transformation. Engagement with this faith, true

engagement, means that we will be changed by it. Thus, our religious

professionals are agents of transformation. As such, we are called upon to be

modelers and guides of the spirits, rather than technicians of separate aspects of

our religion. We are called to lead and to do so in relationship. We are called to

model covenantal living and shared empowerment.

28

28

Karen Bauman et al.,LREDA/UUMA/UUMN Task Force for Excellence in Shared Ministry: Preliminary

Report (Huntington Beach, CA: Liberal Religious Educators Association, 2013),

http://www.lreda.org/assets/docs/excellence-in-shared-ministry-report.pdf.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

22

We have learned that the future of faith formation requires adaptive leadership. It also

requires the attention and engagement of the congregation as a whole. Culture shift,

embracing new norms, and bold experimentation is too much for a single person to

establish alone. Unitarian Universalists have done this work before. Those who came

before us saw the need to attend to the religious education of children in ways they had

never seen before. Unitarian Universalists can do this work again.

In her book Salsa, Soul, and Spirit, Juana Bordas writes about how incorporating

leadership models of communities of color can strengthen the whole: “Leaders in

communities of color . . . are the link between the past, present, and future. They

promote a sense of continuity and wholeness.”

29

The Honorable Anna Escobedo Cabral,

former Treasurer of the United States, observes:

Leaders in our community have a really good sense of the past and how it relates

to the present. However, they know that in the end, they have to address the

challenges the community is facing today, and be concerned with the impact on

the future. Our past guides us. It is important to know the struggles our

community has faced, but we cannot live in the past. The challenge is to make

sure the community is evolving and creating a better future.

30

We know that leaders must engage the whole of our communities if we are to evolve.

What leaders invite people to talk, think, and pray about determines the path they will

follow into the future. Leaders have the power of agenda: determining what a

congregation should focus on by devoting time and attention to that conversation.

In his book Doing the Math of Mission, Gil Rendle describes three types of leadership

conversations: maintenance, preferential, and missional.

31

Congregations engaging in maintenance conversations will find themselves focused on

preserving who they are and what they usually do. This might show up as maintaining a

declining Sunday school program for those who show up.

Congregations engaging in preferential conversations will find themselves focused on

satisfying the people who are already in the congregation. They will also be searching for

ways to keep people happy and unchanged. This might look like a Sunday school model

that bases their programming on what people who show up say they want. For example,

29

Juana Bordas, Salsa, Soul, and Spirit: Leadership for a Multicultural Age, 2nd ed. (San Francisco: Berrett-

Koehler, 2012).

30

Ibid.!

31

Gilbert R. Rendle, Doing the Math of Mission: Fruits, Faithfulness, and Metrics (Lanham, MD: Rowman &

Littlefield, 2014).

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

23

learning about world religions, more time spent outside, or building a house out of

cardboard like we did with the haunted house curricula forty-two years ago! Trying to

keep each person happy is never possible, and negates the possibility of planning

strategically.

Congregations able to have missional conversations will focus on purpose and the

possibility of the future. Missional conversations where people truly say “yes!” create the

possibility for the evolution of a church’s relevance, and—in this case—its approach to

faith formation.

Unitarian Universalist congregations that have had these missional conversations and

have moved beyond the Sunday school model have offered these pieces of advice:

1. Communicate early, often, and in every conceivable way. Preach from the pulpit,

include articles in the newsletter, host conversations. People need to feel heard.

It can be important to have intentional conversations with stakeholders,

especially those you anticipate will be upset or most resistant.

2. Remember: people aren’t afraid of change; they are afraid of loss. There may be

hesitation or resistance in releasing ourselves from the current model, especially

if it is the model we grew up with, taught in, volunteered for, or watched children

be a part of. This may be the only model the majority of a congregation has ever

been exposed to or can imagine. Many congregations have experienced a sense

of shame or failure when their Sunday school programs have dwindled or ended.

3. Don’t be surprised if you experience an initial drop off in numbers. Some people

won’t have the patience or interest in being part of change or an experiment.

Many will come back once the kinks are worked out, or once they see that it

“works.”

4. Make a commitment to this journey for several years. Evaluate and make small

adjustments as you move along, but don’t make any major changes to your

approach for at least two years.

We are in rapidly evolving times, and it is mission critical that we empower one another

to face this truth head on. The future of our faith is hanging in the balance. Our faith is

asking us to move into a space of not knowing. An evolution of faith formation is the

faithful response. We may not be able to fully imagine or visualize the future of faith

formation. We may be confronted with experiments that do not go as planned. It is okay

to experiment and not succeed. Our power of expertise is gone. Commitment, courage,

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

24

and the ingenuity of the congregation are all needed now, during the spiritual moment of

our time.

We are searching for new words and new thoughts. Indeed, we stand aquiver on

the threshold of a new day; none sees clearly what is in the distance beyond our

present experience. The possibilities are as yet untried. But there is a thrill and a

glowing hope in being part of a young movement, even though it be small and

may long be unpopular.

32

Ending Sunday school is not tantamount to ending faith formation. To the contrary, faith

formation is a foundational ethos of Unitarian Universalist ministries. Paying attention to

the shifting needs of our families and children, releasing ourselves from the rigid

structures of our past, and boldly experimenting to contribute to the evolution of faith

formation may just be the spiritual task of our time. The future of faith formation in New

England depends on it. It will be a whole lot easier if we face it together.

32

Sophia Lyon Fahs, It Matters What We Believe (Boston: Beacon Press, 1952).

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

25

Benediction

In the words of Sophia Lyon Fahs:

“Let us all worship together. Let us venture together into the future of faith, determined to

keep faith alive because our humanity is only complete when our believing selves are

strong and healthy.”

33

“A Power at Work in the Universe”

34

by Tom Schade

My friends,

There is a power at work in the universe.

It works through human hands,

but it was not made by human hands.

It is a creative, sustaining, and transforming power

and we can trust that power with our lives

[and with our ministries].

It will sustain us whenever we take a stand on the side of love;

whenever we take a stand for peace and justice;

whenever we take a risk.

Trust in that power.

We are, together, held by that power.

33

Sophia Lyon Fahs, Today’s Children and Yesterday’s Heritage: A Philosophy of Creative Religious

Development (Boston: Beacon Press, 1967).

34

Tom Schade, “A Power at Work in the Universe,” Unitarian Universalist Association, accessed May 24,

2017, http://www.uua.org/worship/words/benediction/power-at-work.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

26

References

Allen, Mike, and Renee Allen. “Generational Differences Chart.” Accessed May 24, 2017.

http://www.wmfc.org/uploads/GenerationalDifferencesChart.pdf.

Barrick, Daniel. School Consolidation in New Hampshire. Concord, NH: New Hampshire

Center for Public Policy Studies, 2015.

Bass, Diana Butler. Process Not Program: Adult Faith Formation for Vital Congregations.

Indianapolis, IN: Congregational Resource Guide, 2010.

Bauman, Karen, Gail Carey, Evan Keeley, Anne Principe, Annie Scott, and Wendy

Williams. LREDA/UUMA/UUMN Task Force for Excellence in Shared Ministry:

Preliminary Report. Huntington Beach, CA: Liberal Religious Educators

Association, 2013. http://www.lreda.org/assets/docs/excellence-in-shared-

ministry-report.pdf.!

Bellavance-Grace, Karen. Full Week Faith: Rethinking Religious Education and Faith

Formation Ministries for Twenty-First Century Unitarian Universalists. Chicago:

The Fahs Collaborative, 2013. http://fullweekfaith.weebly.com/uploads/1/2/2/9/

12293877/finalto_web.fahs_fellowship_paper_copy.pdf.

“Blue Laws in New England." Ancestry.com. Accessed May 24, 2017.

https://www.ancestry.com/contextux/historicalinsights/new-england-blue-laws.

Bordas, Juana. Salsa, Soul, and Spirit: Leadership for a Multicultural Age, 2nd ed. San

Francisco: Berrett-Koehler, 2012.

Commission on Appraisal of the Unitarian Universalist Association, The. Engaging Our

Theological Diversity. Boston: Unitarian Universalist Association, 2005.

Crockett, Joseph V. Teaching and Learning in American Congregations. Hartford, CT:

Hartford Institute for Religion Research, 2016.

http://www.faithcommunitiestoday.org/sites/default/files/Teaching_and_Learning_

in_American_Congregations_0.pdf.

Fahs, Sophia Lyon. It Matters What We Believe. Boston: Beacon Press, 1952.

Fahs, Sophia Lyon. Today’s Children and Yesterday’s Heritage; a Philosophy of

Creative Religious Development. Boston: Beacon Press, 1967.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

27

Grosky, Gretchen M. “The Changing Face of NH: What It Means to Have the 2nd Oldest

Population in the Nation.” New Hampshire Union Leader. August 13, 2016.

http://www.unionleader.com/The-changing-face-of-NH:-What-it-means-to-have-

the-2nd-oldest-population-in-the-nation.

Higgins, Richard. “Three in a Thousand Identify as Unitarians.” UU World Magazine.

June 2, 2008. http://www.uuworld.org/articles/three-in-thousand-identify-as-

unitarians.

Hunter, Edith F. Sophia Lyon Fahs: A Biography. Boston: Beacon Press, 1966.

Martin, Stephanie. “THIS Is Family Ministry: The Experts Speak.” Children's Ministry

Magazine. November 3, 2016. http://childrensministry.com/articles/this-is-family-

ministry.

Powell, Kara, Brad Griffin, and Cheryl Crawford. “The Church Sticking Together.” Sticky

Faith. October 17, 2011. http://stickyfaith.org/articles/the-church-sticking-together.

Rasor, Paul. “Can Unitarian Universalism Change?” UU World Magazine. February 22,

2010. http://www.uuworld.org/articles/can-uu-change.

Rendle, Gilbert R. Doing the Math of Mission: Fruits, Faithfulness, and Metrics. Lanham,

MD: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014.

Roberto, John. “Best Practices in Family Faith Formation.” Lifelong Faith 1.3 (2007): 21–

35. http://www.lifelongfaith.com/uploads/5/1/6/4/5164069/lifelong_faith_journal_

1.3.pdf.

Roberto, John. Faith Formation 2020: Designing the Future of Faith Formation.

Naugatuck, CT: LifelongFaith Associates, 2010.

Roberto, John, and Katie Pfiffner. “Best Practices in Children’s Faith Formation.” Lifelong

Faith 1.3 (2007): 39–46. http://www.lifelongfaith.com/uploads/5/1/6/4/5164069/

lifelong_faith_journal_1.3.pdf.

Roehlkepartain, Eugene C. Building Assets, Strengthening Faith: An Intergenerational

Survey for Congregations. Minneapolis: Search Institute, 2003.

Rowden, Thalia Kehoe. “12 Reasons to Welcome Kids in Church + Tips for Actually

Doing It.” Sacraparental. June 11, 2016. http://sacraparental.com/2016/06/11/12-

reasons-welcome-kids-church-tips-actually.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

28

Schade, Tom. “A Power at Work in the Universe.” Unitarian Universalist Association.

Accessed May 24, 2017. http://www.uua.org/worship/words/benediction/power-

at-work.

Strybis, Erin. “See How Children Experience Church through This ‘Pray-Ground.’” Living

Lutheran. June 7, 2016. https://www.livinglutheran.org/2016/06/see-children-

experience-church-pray-ground.

“Tapestry of Faith Curricula.” Unitarian Universalist Association. Accessed May 24, 2017.

http://www.uua.org/re/tapestry.

Walton, Christopher L. “Sophia Lyon Fahs, Revolutionary Educator.” UU World

Magazine, March/April 2003. http://www.uuworld.org/articles/sophia-lyon-fahs-

revolutionary-educator.

Woolf, Art. “Number of VT Births Lowest since before Civil War.” Burlington Free Press,

June 23, 2016. http://www.burlingtonfreepress.com/story/news/2016/06/23/

number-vt-births-lowest-since-before-civil-war/86204456.

Wright, Tim. “Sunday Schooling Our Kids out of Church.” Patheos, August 5, 2014.

http://sixseeds.patheos.com/timwright/2014/08/sunday-schooling-our-kids-out-of-

church.

Wuthnow, Robert. Growing up Religious: Christians and Jews and Their Journeys of

Faith. Boston, MA: Beacon Press, 2000.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

29

Appendix A

Impacts of a Family Ministry Focus on Current Roles

How might focusing on family ministry impact a congregation’s...

Governing

Board

Devote time and attention to missional conversations. Integrate

spiritual practice and reflection into board work as a part of faith

formation.

Minister

Engage in truly collaborative shared ministry with Director of Family

Ministry, to develop goals, strategies, and resources for meeting the

spiritual needs of congregants at every age and stage of spiritual

development.

Director of

Religious

Education

Become a Director of Family Ministry, developing strategies to meet

the faith formation needs of people of all ages and at every stage of

spiritual development, recognizing that unchurched adults or adults

coming from other faith traditions will need as much if not more

orientation to Unitarian Universalism as children and youth.

Music Director

Prepare for additional choir members or musicians available to

contribute to music ministry as children and teachers are in worship

each week and are available to participate.

Membership

Professional

Welcoming visitors and guests will no longer necessitate separating

families at the door; they will be encouraged to explore the

congregation and participate together.

Administrator

May have more space requests on Sunday mornings. Solicit family

friendly resources and articles for newsletter.

Worship

Assess the physical space of worship more regularly (e.g., whether

to include rocking chairs at the back of the sanctuary for adults

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

30

Committee

rocking children or for worshippers who need to move, or “pray

space”

35

for children and toddlers). Prepare for a wider cross section

of people who can participate in the roles of worship.

Religious

Education

Committee

Become the Family Ministry Team. May include representatives

from other congregational committees to ensure that families are

considered when planning for social justice activities, stewardship,

small group ministry, etc.

Children and

Youth

Welcome into whole congregation worship; offer ways in which to

participate through greeting, ushering, readings, music, and even

worship planning. Opportunities for age-based gathering may

happen before or after Sunday morning worship.

Parents

Able to experience and model worshipping with their children. Able

to have opportunities to attend to their own faith formation needs

while their children are experiencing age-based gatherings before or

after Sunday morning worship (e.g., classes in UU theology, UU

identity, small group ministry for parents, mentoring, etc.).

Other Adults

Able to have a variety of opportunities to learn, share, and grow in

their own faith formation. May lead or attend classes and

conversations after worship. May be more inclined to minister to

children and youth without having to sacrifice worshipping on

Sunday morning.

Entire

Congregation

Able to know and be known by members of all ages. Will exercise

patience, understanding, and empathy as they grow into one single

congregation. Increased recognition that each person plays a role as

both teacher and student, and that we all impact one another’s faith

formation.

35

Erin Strybis, “See How Children Experience Church through This ‘Pray-Ground,’” Living Lutheran, June 7,

2016, https://www.livinglutheran.org/2016/06/see-children-experience-church-pray-ground.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

31

Appendix B

Sample Job Description for Coordinator of Family Ministry (part time)

(Adapted from the Messiah Lutheran Church in Springfield, Missouri)

36

Summary of Position

The Coordinator of Family Ministry works to ensure that family members are provided

with opportunities to grow in their relationship to Unitarian Universalism and respond to

that relationship faithfully in the church and the wider world. Primarily an administrative

role, the coordinator will work independently on clearly defined tasks, as well as working

closely with ministerial and lay leadership.

Spiritual Gifts and Qualifications

• Strong interpersonal relationship skills, with the ability to relate to and motivate

people of all ages and backgrounds

• Leadership skills, including the ability to recruit and nurture volunteers and

delegate tasks

• Strong verbal and written communication skills, with the ability to speak

comfortably before a congregation or other large groups

• Proven commitment to being a positive role model and witness of the Unitarian

Universalist faith

• Strong organizational and administrative skills with interest in expanding own

knowledge, skills, and abilities

Responsibilities

• Recruit and support volunteers (often with assistance from others)

• Communicate with families

• Provide tools for parents and caregivers that equip them in their role as primary

spiritual caregivers of their children

• Coordinate the involvement of committees and teams that participate in

supporting youth and family activities

• Seek to invite worship visitors, new members, or members not engaged in youth

and family ministries to specific events

36

“Messiah Lutheran Church Coordinator of Youth and Family Ministry,” Messiah Lutheran Church, May 22,

2016, http://www.messiahmo.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/YouthandFamilyMinister-Revised-52216-

docx.pdf.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

32

Appendix C

Sample Job Description for Director of Family Ministry

(Adapted from the United Methodist Church)

37

Summary of Position

The Director of Family Ministry develops and nurtures a ministry for all types of families,

striving to guide, nurture, and support all people as they grow in the Unitarian

Universalist faith. The Director must pay attention to family circumstance, understand the

home as a setting for spiritual formation, and provide relevant and intentional ministry for

people of all ages through the church and in the community. All ministry must address

basic human needs as well as provide opportunities for faith formation, service, and

witness. The Director will work to provide family members with opportunities to grow in

their relationship to Unitarian Universalism and respond to that relationship faithfully in

the church and the wider world.

Spiritual Gifts and Qualifications

• One or more of these spiritual gifts: teaching, encouragement, leadership,

administration, helping, and/or companioning

• Prior leadership experience

Strong communication skills, including the ability to listen to and communicate

with people of all ages

• Ability to work with other ministry leaders, delegate responsibility, and follow up

to complete tasks

• Knowledge and respect for Unitarian Universalism and its history, principles, and

theology

A passion for family ministry, including genuine interest in responding to the

hopes and concerns of all families in the community and affirming all family units

(single and multiple people)

Responsibilities

• Maintain a healthy and growing spiritual life and lead other teachers and leaders

in doing the same

37

“Family Ministries Coordinator,” Discipleship Ministries, accessed May 24, 2017,

https://www.umcdiscipleship.org/resources/family-ministries-coordinator.

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

33

• Be attentive to the hopes, concerns, and needs of families of all configurations in

the community to determine how the congregation might serve them and how

they might serve one another as Unitarian Universalists

• Be familiar with the congregation’s overall goals and how they are achieved

through the congregation’s ministry with families

• Encourage extending the goals of the congregation to include all types of families

• Advocate for all kinds of families, educating the congregation and community

about the forms of family life in the twenty-first century and providing families with

resources for living their faith

• Work with others to plan and carry out ministry with families in a varied and wide-

ranging program that includes worship, study, fellowship, service opportunities,

and more

• Build networks with community organizations and people to connect the

congregation with the surrounding community for a strong program, including

looking for new ministry opportunities

• Encourage other congregational ministry leaders to understand and make all

ministries applicable and relevant to varying types of family units

New England Region of the Unitarian Universalist Association | Kimberly Sweeney

34

Appendix D

Examples of Roles for Family Ministry Volunteers or Teams

(will vary widely depending on a congregation’s particular context and capacity)

Welcome and Connection: Ensure that new attendees are warmly welcomed and

enthusiastically connected with the congregation, from first impression to ongoing

connection through family ministry opportunities.

Second-Hour Religious Education Teacher or Workshop Leader: Teach or assist in

weekly classes held after Sunday worship and/or facilitate a learning opportunity or

series of sessions aligned with the mission of the congregation.

Small Group Ministry Facilitator: Facilitate weekly or monthly lay-led small groups that

provide opportunities for deeper relationships and spiritual exploration.

Faith at Home: Equip members to establish spiritual practices, routines, and reminders

of our Unitarian Universalist faith throughout the week.

Events Coordinator: Plan and oversee no more than three family ministry events per

year, to occur outside of Sunday morning. Bonus points if they get on the calendar six

months in advance.

Sports Outreach: Mobilize members to connect with children and adults in the

surrounding community through sports, fitness, and recreational activities, providing

opportunities to mentor youth, promote wellness, and engage with people who do not

know about Unitarian Universalism.

Mobilization: Motivate and equip members to engage their passions and gifts through

volunteer ministry—serving within the church and in the wider community as an

expression of the UU faith.