TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction 3

About the Book 4

A Biography of Dr. Seuss

a.k.a Theodor Geisel 7

The Making of an Animated Classic 11

Bringing the Story to Life 13

How to Watch a Show 15

Now That You’ve Seen the Show 16

Appendix: Lesson Plans 17

• Point of View 17

• Creating Your Own Poetry 18

• Political Cartoons 19

National Standards for Arts Education as developed by the Consortium for National

Arts Education Associations (under the guidance of the National Committee for

Standards in the Arts), please visit:

https://artsedge.kennedy-center.org/educators/standards

To read the New York State Learning Standards for the Arts as developed by the New

York State Academy for Teaching and Learning, please visit:

http://www.p12.nysed.gov/ciai/arts/artstand/home.html

To read the New York City Theater Blueprint for Teaching and Learning in the Arts

developed by educators and representatives from the arts and cultural community of

New York City, please visit:

http://schools.nyc.gov/offices/teachlearn/arts/Blueprints/Theaterbp2007.pdf

INTRODUCTION

This guide, designed to easily implement in the weeks before you attend the

performance, provides jumping off points for discussion and suggested activities

that you can adapt to the needs of your class. We have also included exercises to use

after seeing the show to help you bring together all your class discussions from prior

to the performance. Arts Education benefits every student by cultivating the whole

person. In developing literacy, intuition, reasoning, and imagination into unique forms

of expression and communication, students learn to see education and learning as

fun and interesting throughout their lives. Founded in 1960, Group Sales Box Office is

New York’s leading theatre ticket company dedicated to serving your needs. Not only

can we obtain the best price, we also have the best grasp of the needs of your group

and your teaching goals. We hope this guide enhances your teaching experience and

your students’ enjoyment of DR. SEUSS’ HOW THE GRINCH STOLE CHRISTMAS! THE

MUSICAL.

3

© 2010 Grinch Company. Photo by: PAPARAZZIBYAPPOINTMENT.COM

ABOUT THE BOOK

The book How the Grinch Stole Christmas was published in 1957 and was an

immediate success. It consists of rhyming couplets and has black and white

illustrations by the author, who uses only red and pink as accent colors.

In the story a grumpy creature with a heart “two sizes too small” is disgusted by the

Christmas celebrations in the town below him. He decides to keep Christmas from

coming to the Whos in Who-ville by dressing up as Santa Claus - with his dog, Max,

as a reindeer - and during the night pilfering every bit of Christmas from their homes.

All the decorations, presents, and food are stuffed into his sleigh leaving the town

barren. The next morning, Christmas arrives anyway and he realizes the holiday “does

not come from a store.”

4

ACTIVITIES AND DISCUSSIONS

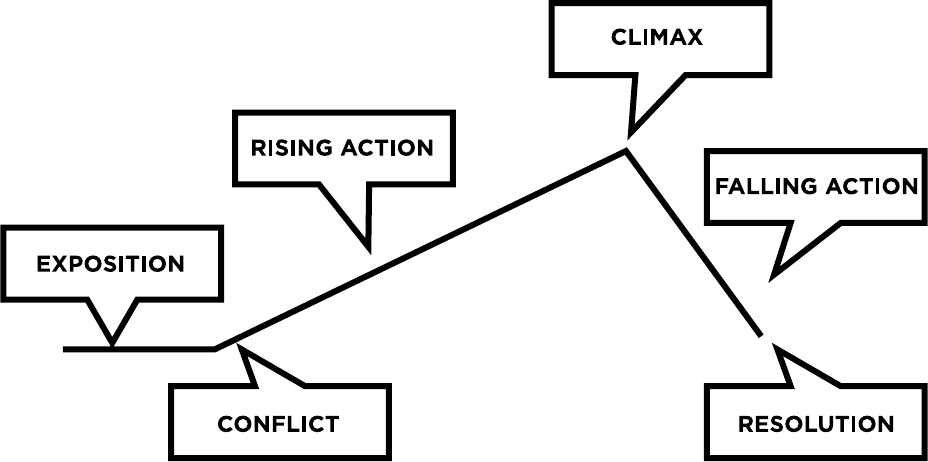

• Diagram the plot. The plot is the easiest way to talk about a story;

it is how the story unfolds. If the story is what happens, the plot

is how the story happens. A good plot should be logical, with no

unjustified turns and no deliberately misleading information.

It should also have some level of suspense to keep the audience

interested and make them wonder what will happen next.

The Plot itself is made up of 6 pieces:

Exposition - the information the audience needs to know in order to

understand the story (time and place or what happened before

the audience joined the story)

Conflict - the problem the main character must overcome. We learn

about the characters’ inner selves through their actions and decisions

made in response to the conflict.

Rising action - the complications that may change the

course of the story

Climax - a turning point within the play

Falling action - the tying up of loose ends

Resolution - the ending when problems are solved

After reading the book, define each of these parts of the story and draw

a diagram of the action.

5

ADDITIONAL ACTIVITIES

• Define the Characters. Make a list of all the characters that appear in the book.

What do you know about each of the characters and how do you know it? Examples

include a character’s words, thoughts, actions, and the impact each has on other

characters. List some words that describe each character.

• Writing Assignment. Have you ever hated something the way the Grinch hates

Christmas? Do you still hate it or did you come around the way he did? Write about

your experience including why you felt so strongly and what you learned about

yourself or the situation.

• Who-Feast. We learn that the Whos serve Who-hash and Who Roast Beast at

their Christmas Dinner. What fun foods would you serve at your Who-Feast? Create

a menu of imaginary foods (from all the food groups) to serve your guests. Choose

one and write a recipe card listing the ingredients and the steps involved in preparing

your invented dish. You could also draw pictures of each dish or of a dinner table

spread with all your fantastic foods.

• Ted Geisel (aka Dr. Seuss) once received a letter from two brothers with the last

name “Grinch.” They were being teased by friends and asked him to change the

Grinch’s name. Ted replied that the Grinch was actually the Hero of Christmas. “He

starts out as the villain, but it’s not how you start out that counts.” What do you think

he means and do you agree?

• Discuss an illustration from the book or any photo from a theatre performance:

What’s going on in it? What feelings are conveyed and how? Who are the characters

and how do you know? What do the surroundings tell you? Give a copy of the picture

to small groups and ask them to create a new story about the picture. Discuss how

the groups’ stories are the same and different from each other and from the book.

• Create Group Stories. Divide the class into small groups and give each a picture

from the book with the text covered. (You could also use a photo from any theatre

production.) Ask each group to write the opening lines of a story told based on what

is happening in the picture. Each group then passes their paragraph (but not the

picture) to the next group, who then adds another paragraph. Each story is passed

from group to group, with each group adding and finally completing the story. When

the first group gets its story back, they read it to the class and share the original

photo.

6

A BIOGRAPHY OF DR. SEUSS A.K.A. THEODOR GEISEL

(Excerpted from the biography on www.seussville.com. More information on Theodor Geisel can be

found at the Dr. Seuss National Memorial website -www.catinthehat.org)

Childhood

Theodor (“Ted”) Seuss Geisel was born on March 2, 1904, in Springfield,

Massachusetts. His father, Theodor Robert, and grandfather were brewmasters and

enjoyed great financial success for many years. Coupling the continual threats of

Prohibition and World War I, the German-immigrant Geisels were targets for many

slurs, particularly with regard to their heritage and livelihoods. In response, they were

active participants in the pro-America campaign of World War I. Thus, Ted and his

sister Marnie overcame such ridicule and became popular teenagers involved in many

different activities.

Dartmouth College

Ted attended Dartmouth College and by all accounts was a typical, mischievous

college student. He worked hard to become the editor in chief of Jack-O-Lantern,

Dartmouth’s humor magazine. His reign as editor came to an abrupt end when Ted

and his friends were caught throwing a party that did not coincide with school policy.

Geisel continued to contribute to Jack-O-Lantern, merely signing his work as “Seuss.”

This is the first record of his use of the pseudonym Seuss, which was both his middle

name and his mother’s maiden name. It was a perfectly ingenious pseudonym; it

squeaked Ted’s work past unsuspecting college officials, yet clearly identified him as

the creator.

Oxford

In 1925, with graduation approaching, Ted’s father asked the question all college

students dread: what was Ted going to do after college? Ted claimed to have been

awarded a fellowship to Oxford University and the elder Geisel reported the news to

the Springfield paper, where it was published the following day. Ted confessed the

truth - Oxford had denied his fellowship application - and Mr. Geisel, who had a great

deal of family pride, managed to scrape together funds to send him anyway. Ted left

for Oxford intending to become a professor. (He couldn’t think of anything else to do

with an Oxford education.)

Early Career

After leaving Oxford, Dr. Seuss returned to New York in 1927. He decided that he

could make a living as a cartoonist and was thrilled when one of his submissions was

published in The Saturday Evening Post. His work caught the eye of the editor for

Judge, a New York weekly, and Ted was offered a staff position. Standard Oil also

recognized Ted’s talent and offered him a job in their advertising department. In all,

Ted spent over 15 years in advertising, primarily with Standard. His advertising work

insured him enough income that in 1927 he married Helen Palmer, a classmate at

Oxford University. It was Helen who first suggested that Ted draw for a living.

7

In 1931, an editor at Viking Press offered him a contract to illustrate a collection

of children’s sayings called Boners. While the book received bland reviews, Ted’s

illustrations were championed; he considered the opportunity his first official “big

break” in children’s literature.

While traveling on a luxury liner, Ted became bothered by the rhythm of its engines.

At his wife’s urging, he applied the incessant rhythm to his first children’s book, And

to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Publishers in 1937 were not receptive; in

fact, Ted presented his manuscript to 27 publishing houses and received 27 rejections.

Discouraged, Ted literally bumped into an old Dartmouth friend who happened to

work at Vanguard Press, a division of Houghton Mifflin. His friend offered to show the

manuscript and illustrations to key decision-makers. Vanguard wound up publishing

Mulberry Street, which was well received by librarians and reviewers.

WWII

While Ted was not an advocate of war, he knew that war against Japan and Germany

was imminent. Ted contributed anywhere from 3-5 urgent political cartoons each

week to PM Magazine, considered by many to be a liberal publication. Despite the

steady work from PM, however, Ted wanted to contribute more to the war effort. In

1942, at age 38, Ted was too old for the draft, so he sought a commission with naval

intelligence. Instead, he wound up serving in filmmaker Frank Capra’s Signal Corps

(U.S. Army) making movies relevant to the war effort. He was introduced to the art of

animation and developed a series of animated training films, which featured a trainee

called Private Snafu. At first, many balked at the idea of a “cartoon” training series,

but the younger recruits really responded to them.

Publishing Success

He continued writing during this time since children’s books were one of the few

side activities allowed under his advertising contract. Three of his books received

Caldecott Honor Awards: McElligot’s Pool (1947), Bartholomew and the Oobleck

(1949), and If I Ran the Zoo (1950). He also received an Oscar for Gerald McBoing-

Boing (Best Cartoon, 1951). In 1955, Ted received an honorary Doctorate of Humane

Letters from his alma mater, Dartmouth. He received an additional six other honorary

doctorates during his lifetime. An influential book titled Why Johnny Can’t Read was

published in 1955. It said children were being held back by boring books. An article

under the same name in Life magazine called for more imaginative illustration, and

named Dr. Seuss as a good example of what could be done. So Ted was asked to

write a children’s primer using 220 new-reader vocabulary words; the end result

was The Cat in the Hat, published in 1957. While schools were hesitant to adopt it

as an official primer, children and parents swarmed for copies. The Cat in the Hat

catapulted Ted from pioneer in children’s literature to definitive children’s book

author-illustrator.

8

In 1960, friend and publisher Bennett Cerf wagered that Ted couldn’t write a book

using 50 words or less, prompting Ted to write Green Eggs and Ham.

How the Grinch Stole Christmas! aired during the 1966 holiday season and it still ranks

high in viewer ratings so many years later.

Helen Palmer Geisel - an author in her own right and a tremendous support

editorially, artistically, and administratively during much of his career - suffered from

frail health, including cancer. She died on October 23, 1967. He later married long time

friend Audrey Stone. A former nurse, she brought order and stability to his life at a

time when Ted’s popularity was pulling him in various directions.

Ted was concerned about the environment and wanted manufacturers, businesses,

and individuals to take responsibility for their actions. The Lorax, published in 1971,

weaves a familiar tale of a good thing gone wrong.

In 1980, the American Library Association (the same organization responsible for the

prestigious Newbery and Caldecott Awards) honored Ted with a Laura Ingalls Wilder

Award. This special award is given to an author or illustrator whose books - having

been published in the United States - have made a substantial contribution and

lasting impact to children’s literature.

The Butter Battle Book, published in 1984 and perhaps the most controversial of all

his books, was written in response to the arms buildup and nuclear war threat during

the Reagan administration. For the first time in decades, editors and art directors

questioned Dr. Seuss - the cover, the ending, the verb tenses, even the title itself went

through several changes. Ultimately, few changes were made. For six months, Butter

Battle remained on The New York Times’ Bestseller List - for adults.

In 1984, Ted received a Pulitzer Prize and in 1986 he was awarded a New York Library

Literary Lion. That same year, the San Diego Museum of Art, under the watchful eye

of Ted himself, featured a retrospective dedicated to his life and work. Several of his

paintings and early sketches were included in the mix. The show was well-received by

the public and traveled to many locations throughout the United States.

Legacy

Theodor Seuss Geisel passed away on September 24, 1991, at the age of 87.

In 1993, Ted’s widow Audrey founded Dr. Seuss Enterprises (DSE) to protect and

monitor the use of Dr. Seuss’s characters for licensing purposes. To date, many DSE-

endorsed projects include a theme park, a board game, interactive CD-ROMs, and

affiliations with Hallmark and Espirit. Mrs. Geisel oversees the selection process of

each project, always considering Ted’s wishes and dreams.

9

Additional Resources:

A video interview (and transcript) with Audrey Geisel is available at:

http://www.readingrockets.org/books/interviews/seuss

The Mandeville Special Collections Library at UC San Diego has an online library of

Dr. Seuss’ political cartoons and advertising artwork. It can be reached at:

http://libraries.ucsd.edu/collections/sca/collections/the-dr-seuss-collection.html

Activities and Discussion:

• What other Dr. Seuss books have you read?

How are they similar and different to Grinch?

• Write your own story or poem in a rhyming-style similar

to Dr. Seuss’. Here’s one example to help inspire you

Seal up the Chimney

Nail Down the Tree

Stash the Stockings

Scrap the Jubilee

Camouflage the Presents

Keep the Wreath in your Sights

Arm the Toy Soldiers

And Unplug the Lights

Beware of Green Santas

Don’t give ‘em an Inch

Stay up past your bedtime

And Catch the Grinch!

10

The Making of an Animated Classic

In 1966, nine years after the book was published, Ted received a call from his old

friend Chuck Jones, a successful animator who had created Bugs Bunny,

Wile E. Coyote, the Roadrunner, and many others. The two had worked together

during World War II while creating military training films and had remained friends for

life. Jones convinced Ted to adapt How The Grinch Stole Christmas! for television.

It was a painstaking task, as Jones used the full animation technique that had been

popular at Disney. The idea behind full animation is that one could follow the story,

with or without the benefit of narration. With full animation, a half-hour television

program would require approximately 25,000 drawings-over 12 times as many

drawings as most animations of equal length.

The length of the story, the color of the Grinch, and the development of a script that

did not end on a trite or overly religious note also had to be addressed.

Ted was always very particular about colors, and it took some convincing by Jones

for Ted to concede to paint the Grinch green with evil red eyes. The songs were

a collaborative effort between Ted and composer, Albert Hague. To resolve Ted’s

concern that the story end in a way that was not trite or overly religious, the script

called for a star to rise to the heavens (rather than drop from the sky) to emphasis

the power of the heart.

The voices of the characters in the film were very important. The voice of the Grinch

(and the narrator of the film) was provided by Boris Karloff who was best known

for his roles in monster movies such as Frankenstein’s monster in the 1931 film. The

song “You’re a Mean One, Mister Grinch” was sung by Thurl Ravenscroft, whose rich

baritone was also used for Tony the Tiger’s “grrrrrrreat” for Kellogg’s Frosted Flakes.

At last, How the Grinch Stole Christmas! aired in time for the 1966 holiday season and

it still ranks high in viewer ratings. In 1971, it won a Peabody award in combination

with an animated version of another Dr. Seuss classic, Horton Hears a Who!

Activities and Discussion:

• What other books do you know that have been made into movies? How did you

feel about the transition? What differences did you notice?

• Chuck Jones is considered to have helped usher in the “Golden Age of American

Animation.” Research his contributions and characters

• Make a flip book. Draw the outline of a face and make many copies on a copy

machine. On the first page draw eyes and on subsequent pages, draw them getting

larger or looking in the other direction. You could also show changes to the nose,

mouth or hair (getting larger, opening into a grin, or standing on end.) Making sure

each picture is only slightly different from the previous one. Put the previous drawing

under the next to help you keep the features in the right place each time. When all

your drawings are done, reverse the order so the last is on top. Than staple the top

and flip through them from bottom to top. Your drawings could also be a moving

animal or vehicle.

11

• Create a storyboard. A storyboard looks similar to a comic strip in that it is a series

of pictures with explanations of the action and dialogue. They help a director plan

a film and its camera shots and angles. Make a storyboard of your favorite Dr. Seuss

book. The quality of your drawings is less important than the way you express your

view of the story.

• The animated TV show added some songs to help express the feelings of the

characters. In musical theatre, songs are added to help express a character’s inner

feelings. In small groups, make a list of other moments in the story where songs could

be logically added. Compile a list of songs that you like which could be used to help

advance the story or share the feelings of a character.

• Create a Venn diagram comparing what student like about the book version and

what they like about the animated special. Older students might prefer comparing

how a story is told in print as compared to how it is told on film. Things to include

might be the amount of imagination used for each, the visual and aural components,

and point of view. After you have seen the live stage performance, add a third circle

showing the similarities and differences among the three forms of storytelling.

• Research what was involved in animation when the special was made in 1966. How

has the art form evolved and what were some of the key examples of the changes?

What is involved in making animated specials today? Create your own animated

version of another Dr. Seuss book.

• Before you see the stage production, discuss how you think certain scenes will be

done on stage. What part of the story do you think will be the most difficult to

recreate in front of an audience? What are you looking forward to the most?

Additional resources:

National Public Radio has an article on the creation of the animated special with

video and song clips and a link to an interview with Chuck Jones at:

http://ipad.npr.org/programs/morning/features/patc/grinch/index.html

12

Bringing the Story to Life

Dr. Seuss’ How the Grinch Stole Christmas! The Musical was originally commissioned

by and produced at The Children’s Theater Company in Minneapolis, Minnesota,

a theater recognized as North America’s flagship theatre for your people and

families. The Grinch made his debut on the CTC stage in November of 1994, after

special arrangements had been made with the Dr. Seuss estate to exclusively adapt

and perform the book. The original production was an enormous success and was

remounted again in 1995 and 1998 playing to sold-out houses every time.

The director and choreographer of CTC’s production, Matthew Howe, said, “We’re

trying to emulate what Dr. Seuss gave us in his book, to capture the true spirit of

his story.” Howe worked with the actors to develop a rich understanding of the

characters. “The script allows for a very full exploration of the Whos, the Grinch, Max

and their relationships.”

San Diego’s Old Globe Theatre, one of the most critically acclaimed regional theaters

in the country, launched its own production of The Grinch in November 1998. It has

played to critical acclaim and sold-out houses there for the past eight years.

In bringing this show to Broadway, the New York producers had to overcome several

problems. One was the size of the Hilton Theatre – much larger than the Old Globe.

Everything needed to be adjusted to fit in a much larger space. Another problem was

keeping the show as close to the story as possible. “Everyone on the creative and

production team is very intent on keeping the tale true to the heart and spirit of the

original work just as the Seuss Estate wishes. Dr. Seuss wrote a story about the

Grinch’s realization of the true meaning of the holidays and that is what we want

to tell in the theatre,” said Kathryn Schwarz of Running Subway Productions, the

producers of the New York show. When Ted Geisel died, his widow became the

head of Dr. Seuss Enterprises and it is very important to her that the integrity of her

husband’s work be preserved.

The stage production is different from the book and animated movie in that it is

narrated by Max the Dog, but it does include the songs “You’re a Mean One Mr.

Grinch” and “Welcome Christmas,” which were created specifically for the animated

TV show.

Activities and Discussion:

• When developing the animated special, Chuck Jones said that,“Max

represents all of us. He is very honest, very decent, and a very put-upon

dog.” Dr. Seuss described him as “Everydog--all love and limpness and loyalty.”

Do you agree with these views? How do you think he will be as a narrator?

Why?

• Research the history of one of the production elements (sets, sound,

costumes, lighting). How did it develop? How is technology used today? What

are today’s trends in the industry?

• How can a costume designer let the audience know about the character

wearing it? What can the set tell you about the story? How can lighting

and sound convey mood?

13

• Who is involved in creating theatre? As a member of the audience, you only

see the actors on stage and maybe an usher who shows you to your

seat. What you don’t see are all the other people who contributed to the

production. As an art and as a business, a theatre production is a huge

effort with a number of areas to cover. Some of these include:

• The Playwright who writes the script

• The Producer who provides the money for the production

• The Director who coordinates all the actors and design elements

• The Designers of Sound, Scenery, Costumes & Lighting

• The Builders and Technicians to make the designers ideas come to life

• The Composer and Lyricist who write the music and the lyrics for the

songs

• The Musical Director and Orchestra who play the music

• The Choreographer who creates the dance number

• The Understudies who go on when an actor is unable to perform

• The Stage Manager who coordinates the backstage activity

• The House Manager and Ushers who get people to their seats

• The Marketing and Public Relations Managers who get the word out to

the public about the show

• The Box Office Manager and Staff who sell the tickets

Sometimes one person may take on several of these roles; sometimes not all of these

roles need to be filled. Research one of “behind the scenes” positions and determine

the education or training level required for entry-level employment, the number of job

openings in that area, three post-secondary programs offering advanced training, and

entrepreneurial possibilities.

Additional resources:

The Center for Arts Education’s Career Development Program publishes a series of

handbooks with lessons and activities to help prepare students for careers in the arts.

To download these, visit:

http://www.cae-nyc.org/pages/career-resources

14

Now That You’ve Seen The Show

• What if you could interview someone involved with the show? Start with your

playbill to research someone involved with the production and then create a list of

questions you would ask.

• Design or create a television commercial to bring in others to see the show. What

parts of the show would you highlight? What would you want to leave as a surprise?

• Write a review of the show. Consider the show’s environmental aspects and their

effectiveness. Consider the choices the actors made. What made the experience real

for you? Discuss how different audience members interpreted different choices.

• What happens next? Write additional scenes that could happen after the story ends

or write letters from one character to another.

• Create your own Who costume. What sorts of qualities did the costumes have? Did

the shapes seem very square and sharp or round and curvy? Were they made of

things that were soft and fluffy or hard and stiff? Draw a Who costume on paper or

find pictures of things that remind you of the costumes. Perhaps you can make a

costume out of clothing you have at home.

• Write a newspaper article (or film a news story) about the Grinch and his actions.

Or create a whole Who-ville newspaper/newscast with articles and viewpoints for

all the characters in the show. You could include stories, reviews, comics, horoscopes

and ads from local Who-businesses.

15

© 2010 Grinch Company. Photo by: PAPARAZZIBYAPPOINTMENT.COM

How to Watch a Show

The usher shows you to your seat and hands you a playbill. The lights go down on

you and up on stage. Now what?

Watching a play with live actors in front of you can be a wonderful experience. The

actors have rehearsed for months and are committed to making you believe every

moment on stage. In return there are things as an audience member that you should

do to show the same respect for their work.

• Arrive on time. If the show has started before you arrive, you may be asked to wait

in the lobby and then you will miss the opening number.

• Stay in your seat during the performance. Use the restroom before the performance

starts or during the intermission. If you must get up, be polite to the people around

you.

• Don’t talk on your cell phone or send text messages. Turn off any electronic devices

that make noise or shed light.

• If you did not hear something, keep listening. You will probably understand what is

happening even if you missed on a line. Don’t talk to your friends around you; there

will be time afterwards to talk about what you loved.

• While you are allowed to eat during the performance, please do so quietly and

unwrap candy and snacks prior to the start of the show.

• Show your appreciation of the work the actors are doing. It is customary to applaud

at the end, but if something make you laugh during the show - then laugh!

Just because you are sitting in the dark does not mean you are alone. Remember

that the actors can hear you. What you do can motivate them to give you more or it

can distract them from giving a good performance. Ask any actor and he or she can

probably tell you a story about an audience member who fell asleep or laughed like a

donkey.

Also keep in mind the other audience members in the theatre. They paid for their

tickets too, and deserve a good time just like you. They want to concentrate on the

conversations on stage and not be distracted by what is going on behind them.

Activities and Discussion:

• Who has been to a live theatre performance before? What did each notice about

the

experience? How did people behave?

• What makes a good audience or a bad audience? What does an audience member

need to contribute to make the experience a good one?

• How is attending a play different from watching a movie in a theatre or in your

home? How is it different from attending a live sports event? How are they the same?

16

Resources:

• Additional information about Dr. Seuss’ political cartoons can be found in the

“Issues/Opinions/Inspirations” section of his biography on:

http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dswenttowar/#issues

• A catalog of his political cartoons can be found at the Mandeville Special

Collections Library at the University of California, San Diego:

http://libraries.ucsd.edu/speccoll/dswenttowar/#intro

• The PBS show, Independent Lens broadcasts an award winning documentary

entitles “The Political Dr. Seuss” about his political cartoons and perceived social

subtext of his books. More information about this film - plus lesson plans, sample

cartoons, additional resources and a history of political cartooning - can be found at:

http://www.pbs.org/independentlens/politicaldrseuss/

17

Lesson Plan - Point of View

Objective: Students will write a creative story from a different character’s

point of view.

Stories are not reflections of reality but are selective versions of it, told from a

particular perspective. “Point of View” is how one person perceives a story or series

of events. The facts are given from his or her perception. In Dr. Seuss’ story, we see

the events of the day from the view of an outsider standing with the Grinch. Who

else appears in the story? - the dog, Max; Cindy-Lou Who coming upon the Grinch

mid-theft; the rest of the Whos who wake up to find their gifts and decorations gone.

Each of them sees the day the Grinch stole Christmas in a different way.

A. Consider everyday objects from their point of view. What does a piece of

chalk think about as it writes on a chalkboard? Is it sad to think about

how it will be erased soon, or is it happy to give itself up to helping children

learn? How does a football feel as it flies across a field after a kick? Does

a shoe enjoy the view from the ground or does it hate the smell of feet?

Ask students to write a riddle or essay from the point of view of an inanimate

object (perhaps a tree ornament or candy cane) and share them with the class.

B. As a class, create a chart comparing how the Grinch views Christmas to how

the Whos of Who-ville do. While the narrator says the Grinch has no known

reason to hate Christmas (perhaps his head, or his shoes, or the size of

his heart), the Grinch refers to the noise of the toys, the sharing of a feast, and

the sounds of the singing. The Whos demonstrate that their feelings about

Christmas are not based on the gifts or the food, but rather the feeling

expressed by joining hands with others and singing.

C. Ask each student to write a letter to a friend (or a journal entry or a news

interview) as if he or she were a character in the story. How does Max feel

about being dressed as a reindeer and being forced to pull the overstuffed

sleigh? Does Cindy-Lou Who fall asleep when she gets back to bed, or

does she lie awake wondering why Santa looked green? Is their

another Who living in the town who wakes to find a favorite food gone

and doe not immediately respond in a Christmas spirit? How does he or she

come around?

D. Have the students share their letters with the class. Did any similar

characteristics show up in the letters?

18

Lesson Plan - Creating Your Own Poetry

Objective: Students will understand basic elements of a rhyming poem and

create their own.

A. Give students a copy of How the Grinch Stole Christmas to read or read it aloud

to them.

B. List the following words on the board: throat, coat, trick, nick, around, found,

said, instead, thread, head. Students will likely think they are from the story when the

Grinch decides to dress as Santa Claus. Discuss the concept of initial and final

sounds to a word (“thr” and “c” vs. “oat” for “throat” and “coat”), pointing out

that the difference in rhyming words is in the initial sounds. Choose one of the

words on the board and give the students one minute to list as many words as

they can think of that rhyme with it. Try several rounds. Since Dr. Seuss was

known for making up his own words, ask students to make-up words that rhyme

with a word on the initial list. After asking each to share his or her most

nonsensical word, ask the students to create a definition for one of their made-up

words.

C. Put the letter “A” next to the word “throat” and ask students to identify other

words on the board that rhyme with it. Continue labeling each pair of rhymes

with a different letter. Since you have now identified the rhyme scheme of

AABBCCDDEE you can explain how this format can vary in other poems. Next,

have students count the number of syllables in each rhyming line of the story. Is

there a pattern?

D. Show students the word “onomatopoeia” and ask them what they think to

means. Give them the definition (a word whose sound imitates the actual sound of

the think the word refers to) and some examples such as “The buzzing of

innumerable bees” where the “zz” and “mm” sounds in these words imitate the

actual sounds of bees. Looking at just the pictures in the book (or in this teacher’s

guide), have students come up with a sound or sounds to represent what is

happening in each picture. For example, if there is a picture of the Grinch stuffing a

tree up the chimney, what sounds could students make that could signify that:

grunting, the swishing of pine needles, or jangling ornaments, for instance.

E. Alliteration is the repetition of the same letter or sound within nearby words.

Most often, repeated initial consonants. Tongue twisters are excellent examples of

alliteration. Have students create their own tongue twisters by selecting a letter of

the alphabet. Then select two nouns and a verb that begin with that letter, such as

“The Grinch gave gifts” for the letter “G”. Then ask students to fill out the

sentence with additional related words: The gregarious green Grinch gave

gorgeous gifts of grapes.

F. Have students create their own story-poem in a style similar to Dr. Seuss’,

including made up words. If time allows, allow them to illustrate their stories and

share the final product with the class.

19

Lesson Plan - Political Cartoons

Objective: After examining some of Dr. Seuss’ early political works, students will

create their own.

In 1941, Ted Geisel, then working as an advertising cartoonist, drew a cartoon about

Mussolini, the dictator of Italy from 1922 to 1943. The liberal New York newspaper

PM liked it and ended up printing his cartoons for two years. His cartoons satirized

the isolationists who did not believe the US should get involved in a world war that

was seen as “foreign.” Other cartoons of his were about the Japanese attack on Pearl

Harbor, Hitler, and wartime prejudice.

A. Choose a few of Dr. Seuss’ political cartoons to discuss with the class. (See the

following list of resources for web pages with his work.) Some good examples are

“What this country needs is a good mental insecticide,” (about racism), “All Aboard…

if you insist! But if you want to help the Army, stay home.” (about rationing during

WWII) or “Put your finger here, pal” (about anti-Semitism). Discuss qualities of the

drawings that are similar to the illustrations in his children’s books. What do students

see as the objective of each cartoon and why? Are these cartoons effective in their

opinions?

B. A political cartoon is based around the use of a symbol used as a visual cue to get

an idea across quickly. Examples commonly used in political cartoons are a donkey

for the Democratic Party, an elephant for the Republican Party, and the Statue of

Liberty or an eagle used to represent the United States. Choose a current political

cartoon from a newspaper or from the Professional Cartoonist Index

http://www.cagle.com/ (which also has teachers’ guides of daily lesson plans).

What are the messages conveyed in these examples? What symbols are used and

why are they effective? Why would someone draw a cartoon rather than write an

opinion piece for a newspaper?

C. Ask each student (or in teams) to choose a topic that is important to her or him.

It could be a current event, a social issue or simply a topic getting lots of media

attention. Next, students should consider and list icons which could be used to

help symbolize the topic - people, locations, or images - that would make people

immediately think of the topic. How can these symbols be used to convey your

opinion about your topic? Finally, each student should draw the cartoon (or combine

photographs to create the image) and write is or her topic/opinion on the back.

D. Display these for the class and allow time for everyone to view them all. Then

gather back together to discuss or write about the effectiveness of different pieces

and why.

20