Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 1 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

MATTHIESEN, WICKERT & LEHRER, S.C.

Hartford, WI ❖ New Orleans, LA ❖ Orange County, CA

❖ Austin, TX ❖ Jacksonville, FL ❖ Boston, MA

Phone: (800) 637-9176

gwickert@mwl-law.com

www.mwl-law.com

LAWS ON RECORDING CONVERSATIONS IN ALL 50 STATES

Individuals, businesses, and the government often have a need to record telephone conversations that relate to their business, customers, or

business dealings. The U.S. Congress and most states’ legislatures have passed telephone call recording statutes and regulations that may

require the person wanting to record the conversation to provide notice and obtain consent before doing so. Most states require one-party

consent, which can come from the person recording if present on the call. However, some states require that all parties to a call consent to

recording.

Laws governing telephone call recording are typically found within state criminal statutes and codes because most states frame call recording

as eavesdropping, wiretapping, or as a type of intercepted communication. State laws may not explicitly mention telephone call recording

because of these technical definitions. Accordingly, counsel may need to infer when and under what circumstances a state permits telephone

call recording by reviewing prohibited actions.

The big issue when it comes to recording someone is whether the jurisdiction you are in requires that you get the consent of the person or

persons being recorded. This begs the question of which jurisdiction governs when you are talking to a person in another state. Some states

require the consent of all parties to the conversation, while others require only the consent of one party. It is not always clear whether federal

or state law applies, and if state law applies which of the two (or more) relevant state laws controls. A good rule of thumb is that the law of the

jurisdiction in which the recording device is located will apply. Some jurisdictions, however, take a different approach when addressing this

issue and apply the law of the state in which the person being recorded is located. Therefore, when recording a call with parties in multiple

states, it is best to comply with the strictest laws that may apply or get the consent of all parties. It is generally legal to record a conversation

where all the parties to it consent.

One-Party Consent

If the consent of one party is required, you can record a conversation if you’re a party to the conversation. If you’re not a party to the

conversation, you can record a conversation or phone call provided one party consents to it after having full knowledge and notice that the

conversation will be recorded. Under Federal law, 18 U.S.C. § 2511(2)(d) requires only that one party give consent. In addition to this Federal

statute, thirty-eight (38) states and the District of Columbia have adopted a “one-party” consent requirement. Nevada has a one-party

consent law, but Nevada’s Supreme Court has interpreted it as an all-party consent law.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 2 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

All-Party Consent

Eleven (11) states require the consent of everybody involved in a conversation or phone call before the conversation can be recorded. Those

states are: California, Delaware, Florida, Illinois, Maryland, Massachusetts, Montana, Nevada, New Hampshire, Pennsylvania and Washington.

These laws are sometimes referred to as “two-party” consent laws but, technically, require that all parties to a conversation must give consent

before the conversation can be recorded.

Wiretapping vs. Eavesdropping

Electronic “eavesdropping” means to overhear, record, amplify, or transmit any part of the private communication of others without the

consent of at least one of the persons engaged in the communication. It may involve the placement of a “bug” inside private premises to

secretly record conversations, or the use of a “wired” government informant to record conversations that occur within the informant’s

earshot. At common law, “eavesdroppers, or such as listen under walls or windows, or the eaves of a house, to hearken after discourse, and

thereupon to frame slanderous and mischievous tales, are a common nuisance and presentable at the court-leet; or are indictable at the

sessions, and punishable by fine and finding of sureties for [their] good behavior,” 4 Blackstone, Commentaries on the Laws of England, 169

(1769).

“Wiretapping” involves the use of covert means to intercept, monitor, and record telephone conversations of individuals. It is an unauthorized

physical connection with a communication system at a point between the sender and receiver of a message. However, where a message is

overheard by a third person during its transmission and there has been no disturbance of the physical integrity of the communication system,

it is less clear that an illegal “interception” has taken place. Wiretapping is a form of electronic eavesdropping accomplished by seizing or

overhearing communications by means of a concealed recording or listening device connected to the transmission line. In the infamous

Olmstead v. United States decision, the court held that the Fourth Amendment’s search and seizure commands did not apply to government

wiretapping accomplished without a trespass onto private property. Olmstead v. U.S., 277 U.S. 43 (1928). This decision stood for 40 years.

“Intercepted communication” generally means the aural acquisition of the contents of any wire, electronic, or oral communication through

the use of any electronic, mechanical, or other device.

Consent

What constitutes “consent” is also an issue of contention when you are considering recording a conversation. In some states, “consent” is

given if the parties to the call are clearly notified that the conversation will be recorded, and they engage in the conversation anyway. Their

consent is implied. For example, we have all experienced calling a customer service department only to hear a recorded voice warning, “This

call may be recorded for quality assurance or training purposes.” It is usually a good practice for practitioners to let the witness know they are

recording the conversation to accurately recall and commemorate the testimony being given – such as during the taking of a witness’

statement.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 3 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

Exceptions

Nearly all states include an extensive list of exceptions to their consent requirements. Common exceptions found in a majority of states’ laws

include recordings captured by police, court order, communication service providers, emergency services, etc. Generally, it is permissible to

record conversations if all parties to the conversation are aware and consent to the interception of the communication. There are certain

limited exceptions to the general prohibition against electronic surveillance. For example, so-called “providers of wire or electronic

communication service” (e.g., telephone companies and the like) and law enforcement in the furtherance of criminal investigative activities

have certain abilities to eavesdrop.

Interstate/Multi-State Phone Calls

Telephone calls are routinely originated in one state and participated in by residents of another state. In conference call settings, multiple

states (and even countries) could be participating in a telephone call which is subject to being recorded by one or more parties to the call. This

presents some rather challenging legal scenarios when trying to evaluate whether a call may legally be recorded. A call from Pennsylvania to a

person in New York involves the laws of both states. Which state’s laws apply and/or whether the law of each state must be adhered to are

questions parties to a call are routinely faced with.

In the New York Supreme Court case of Michael Krauss v. Globe International, Inc., No. 18008-92 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Sept. 11, 1995), reporters for

The Globe recorded a telephone conversation between a prostitute in Pennsylvania and Krauss, the former husband of television personality

Joan Lunden, who was in New York. Pennsylvania law requires two-party consent to record a telephone conversation, while New York law

requires only one-party consent. The court noted that in cases where New York law is in conflict with the laws of other states, New York courts

usually apply the law of the place of the tort, or more specifically, the place where the injury occurred. The Court held that under such

circumstances the New York wiretap law should apply, because any injury that was suffered by Krauss occurred in New York. Therefore, the

Court found that Krauss did not have a claim under New York law because the prostitute consented to having the phone conversation

recorded.

In Kearney v. Salomon Smith Barney, Inc., 137 P.3d 914 (Cal. 2006), the California Supreme Court applied California wiretap law to a company

located in Georgia that routinely recorded business phone calls with its clients in California. California law requires all party consent to record

any telephone calls, while Georgia law requires only one-party consent. Applying California choice-of-law rules, the Court reasoned that the

failure to apply California law would “impair California’s interest in protecting the degree of privacy afforded to California residents by

California law more severely than the application of California law would impair any interests of the State of Georgia.”

When a telephone conversation is between parties who are in different states, it also increases the chance that federal law might apply.

Federal Law

In most cases, both state and federal laws may apply. State laws are enforced by your local police department and the state’s attorney office.

Federal wiretapping laws are enforced by the FBI and U.S. Attorney’s office. It is a federal crime to wiretap or to use a machine to capture the

communications of others without court approval, unless one of the parties has given their prior consent. It is likewise a federal crime to use

or disclose any information acquired by illegal wiretapping or electronic eavesdropping. Violations can result in imprisonment for not more

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 4 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

than five years; fines up to $250,000 (up to $500,000 for organizations); in civil liability for damages, attorney’s fees and possibly punitive

damages; in disciplinary action against any attorneys involved; and in suppression of any derivative evidence. Congress has created separate,

but comparable, protective schemes for electronic mail (e-mail) and against the surreptitious use of telephone call monitoring practices such

as pen registers and trap and trace devices.

The Federal Communications Act of 1934 (47 U.S.C.A. §§ 151, et seq.) provides that no person “not being authorized by the sender shall

intercept any communication and divulge or publish the existence, contents, substance, purport, effect or meaning of such intercepted

communication to any person.” 47 U.S.C.A. § 605. In Nardone v. United States, 308 U.S. 338 (1939), it was held that this section prohibits

divulging such communications in federal criminal prosecutions and prohibits the use of information thus obtained in such prosecutions (the

“fruits of the poisonous tree” doctrine).

Evidence obtained by wiretapping in violation of § 605, is rendered inadmissible in a state court solely because its admission in evidence would

also constitute a violation of 47 U.S.C.A. § 605. Lee v. State of Fla., 392 U.S. 378 (1968). The mere interception of a telephone communication

by an unauthorized person does not in and of itself constitute a violation of § 605. Only where the interception is followed by the divulging of

the communication, as by introducing it into evidence, would there be a violation of § 605.

The Federal Wiretap Act, found at 18 U.S.C. § 2520, protects individual privacy in communications with other people by imposing civil and

criminal liability for intentionally intercepting communications using a device, unless that interception falls within one of the exceptions in the

statute. Although the Federal Wiretap Act originally covered only wire and oral conversations (e.g., using a device to listen in on telephone

conversations), it was amended in 1986 to cover electronic communications as well (e.g., emails or other messages sent via the Internet).

The Electronic Communications Privacy Act of 1986 (ECPA) is found at 8 U.S.C. § 2510 et seq. It prohibits the intentional actual or attempted

interception, use, disclosure, or “procure[ment] [of] any other person to intercept or endeavor to intercept any wire, oral, or electronic

communication.” The ECPA allows employers to listen to “job-related” conversations. It protects the privacy of wire, oral, and electronic

communications including telephone conversations (18 U.S.C. §§ 2510 to 2522). The ECPA gives employers almost total freedom to listen to

any phone conversation, since it can be argued that it takes a few minutes to decide if a call is personal or job-related. However, this exception

applies only to the employer, not the employee. This law only permits telephone call recording if at least one-party consents. However, call

recording is unlawful if the party consents with the intent to use the recording to commit a criminal or tortious act.

Exceptions to the Federal Wiretap Act’s one-party consent requirement include call recordings captured by:

• Law enforcement;

• Communication service providers, if the recording is necessary to deliver service, or protect property or rights;

• Federal Communications Commission (FCC) personnel for enforcement purposes;

• Surveillance activities under the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (50 U.S.C. §§ 1801 to1813);

• Individuals, if they record telephone calls to identify the source of harmful radio or other electronic interference with lawful

telephone calls or electronic equipment; or

• Court order.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 5 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

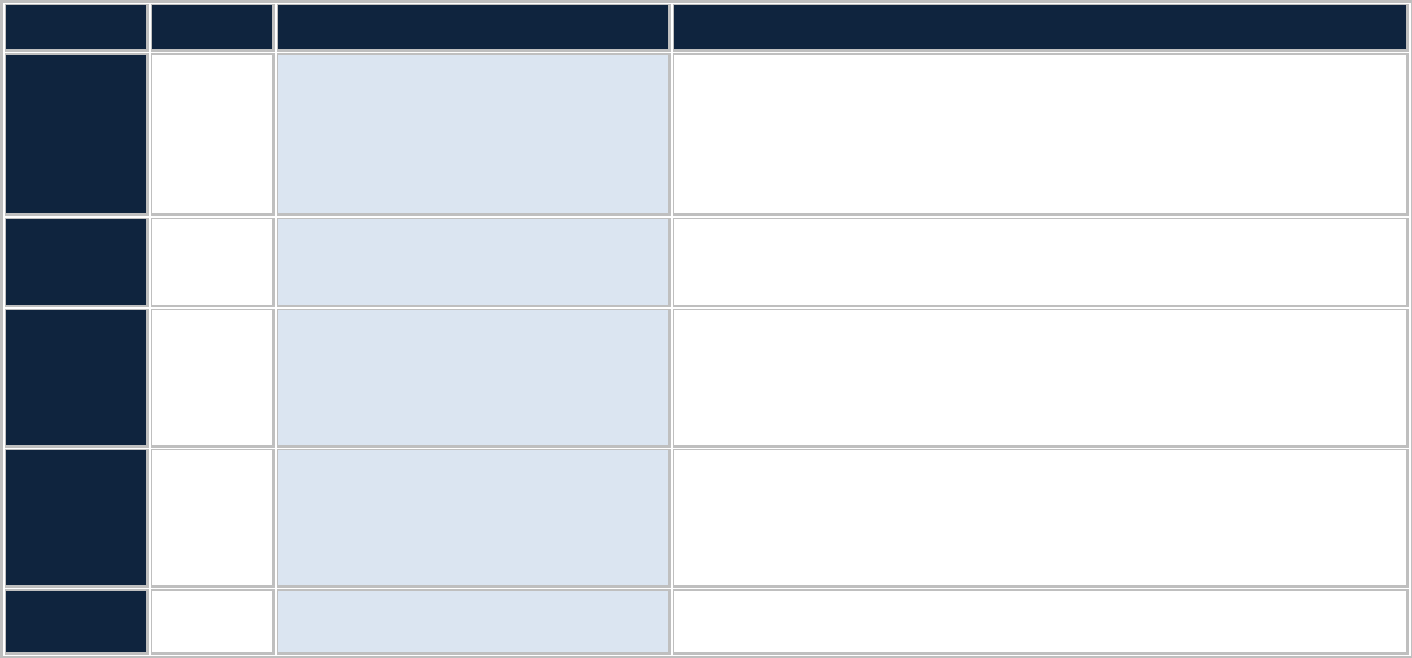

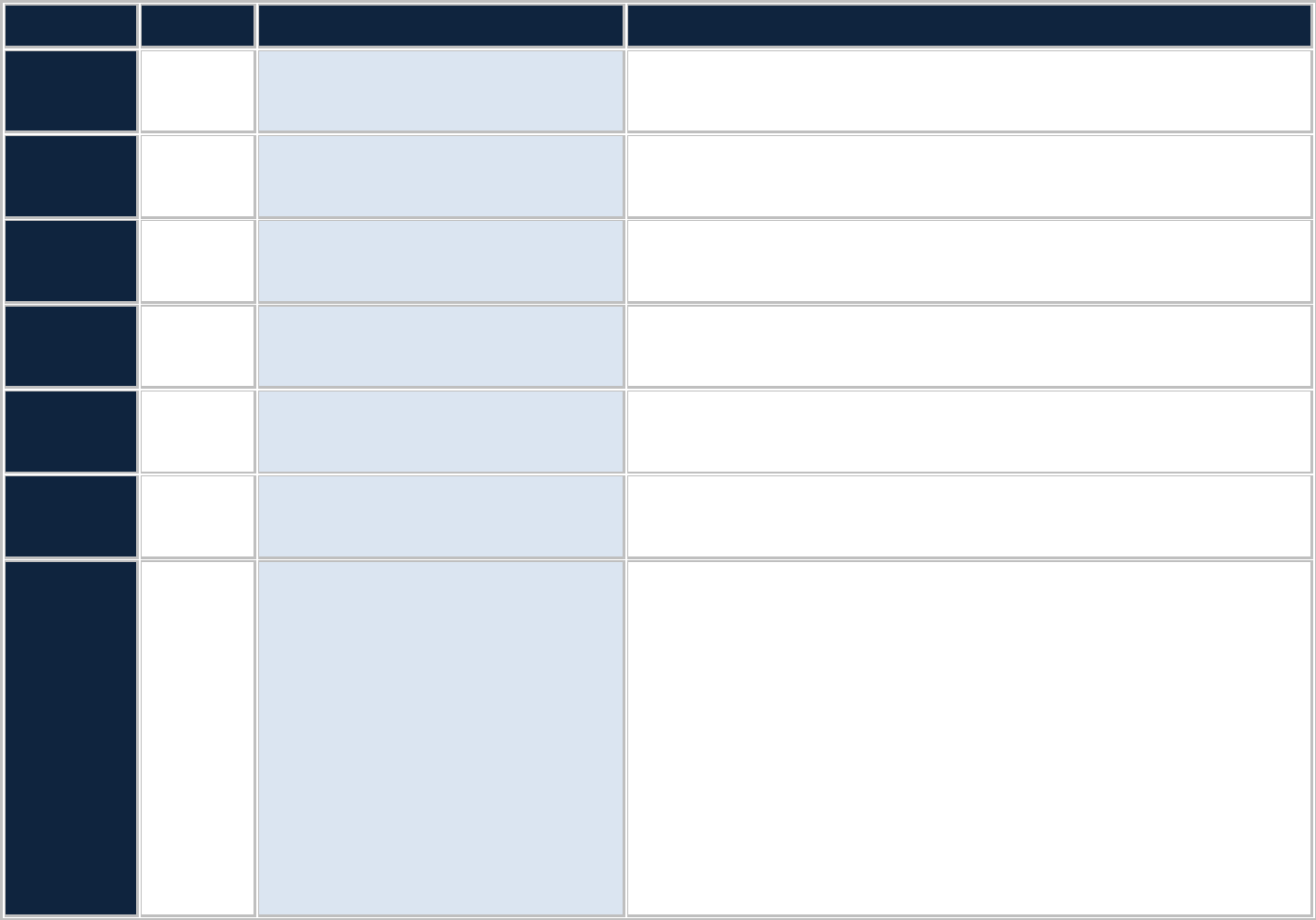

The chart below sets forth the various wiretapping/electronic surveillance statutes and case decisions, for all 50 states. It does not address the

specifics of federal law.

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Federal

One Party

18 USC § 2511(2)(d)

Electronic Communications Privacy Act

“It shall not be unlawful under this chapter for a person not acting under color of law to

intercept a wire, oral, or electronic communication where such person is a party to the

communication or where one of the parties to the communication has given prior

consent to such interception unless such communication is intercepted to commit any

criminal or tortious act in violation of the Constitution or laws of the U.S. or of any

State.”

Alabama

One Party

Ala. Code § 13A-11-30(1) and § 13A-11-31

Alabama statute defines eavesdropping as to “overhear, record, amplify or transmit any

part of the private communication of others without the consent of at least one of the

persons engaged in the communication.”

Alaska

One Party

Alaska Stat. Ann. § 42.20.300(a); Alaska Stat.

Ann. § 42.20.310(a)(1); Palmer v. Alaska, 604

P.2d 1106 (Alaska 1979).

Alaska law prohibits the use of an electronic device to hear or records private

conversations without the consent of at least one party to the conversation. Alaska’s

highest court has held that the eavesdropping statute was intended to prohibit third-

party inception of communications only; does not apply to participants in a

conversation.

Arizona

One Party

Ariz. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 13-3012(9);

§ 13-3012(5)(c)

An individual not involved in or present during a communication must have the consent

of at least one party to record an electronic or oral communication. Arizona also

permits a telephone “subscriber” (the person who orders the phone service and whose

name is on the bill) to tape (intercept) calls without being a party to the conversation

and without requiring any notification to any parties to the call.

Arkansas

One Party

Ark. Code Ann. § 5-60-120

An individual must have the consent of at least one party to a conversation, whether it

is in person or electronic.

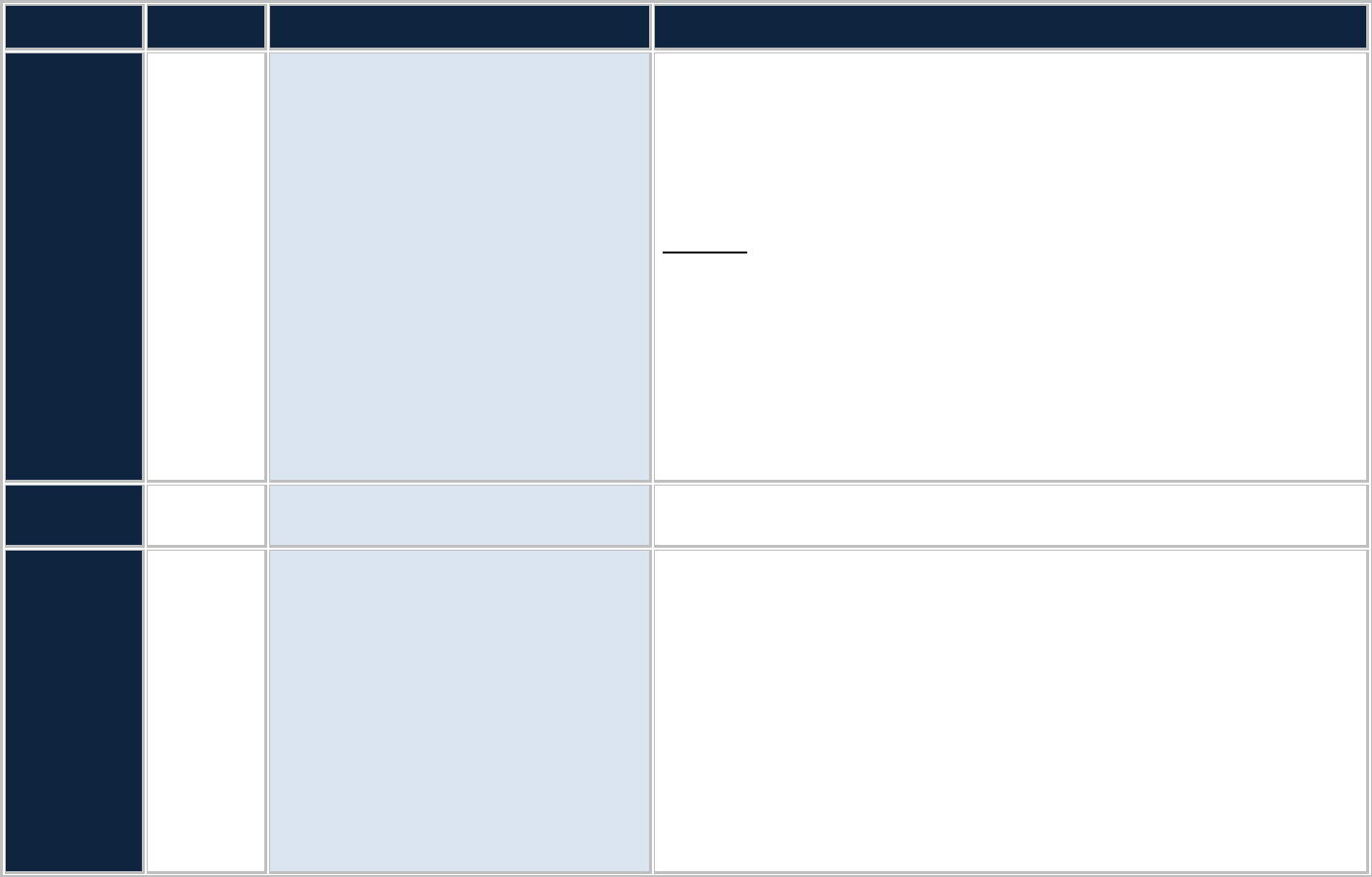

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 6 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

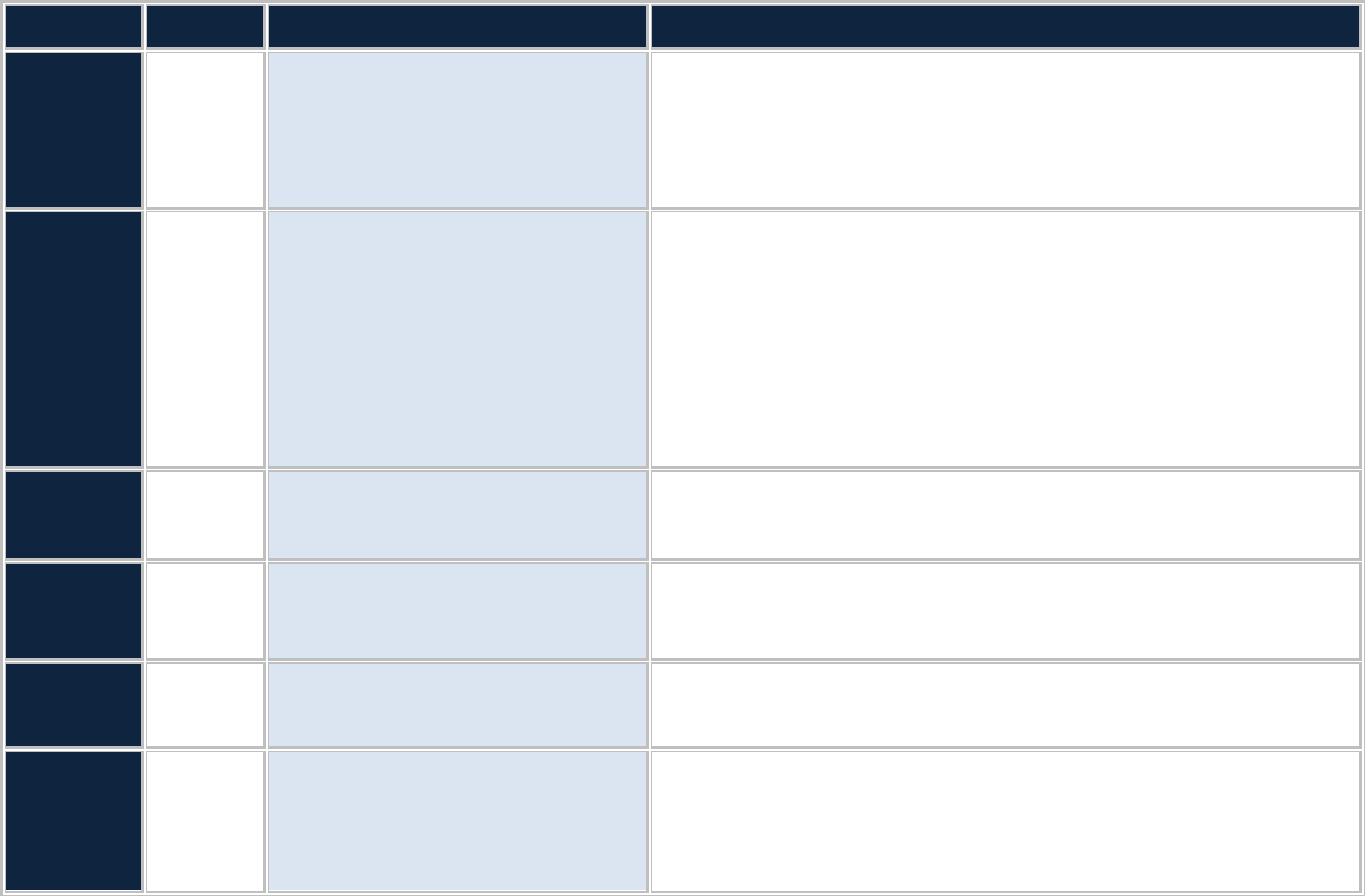

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

California

All Parties

Cal. Penal Code §§ 632(a)-(e); 633.5, 633.6(a),

633.8(b); Kearney v. Salomon Smith Barney

Inc., 39 Cal.4

th

95 (Cal. 2006); Kight v.

CashCall, Inc., 200 Cal. App. 4

th

1377 (2011);

Cal. Pub. Util. Code Gen. Order 107-B(II)(A);

Air Transp. Ass’n of Am. v. Pub. Utilities

Comm’n of State of Cal., 833 F.2d 200 (9

th

Cir.

1987).

California has very specific laws regulating the recording of oral and electronic

communications. All parties must give their consent to be recorded. However, The

California Supreme Court has ruled that if a caller in a one-party state records a

conversation with someone in California, that one-party state caller is subject to the

stricter of the laws and must have consent from all callers. Although California is a two-

party state, it is also legal to record a conversation if an audible beep is included on the

recorder and for the parties to hear.

Exceptions (one-party consent required): (1) where there is no expectation of privacy,

(2) recording within government proceedings that are open to the public, (3) recording

certain crimes or communications regarding such crimes (for the purpose of obtaining

evidence), (4) a victim of domestic violence recording a communication made to

him/her by the perpetrator (for the purpose of obtaining a restraining order or

evidence that the perpetrator violated an existing restraining order), and (5) a peace

officer recording a communication within a location in response to an emergency

hostage situation.

California also has a wiretapping law making it illegal to make a recording with no

authorization. Cal. Penal Code § 632.

Colorado

Mixed

Colo. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 18-9-303 (1)

An individual not involved in or present during a communication must have the consent

of at least one party to record an electronic or oral communication.

Connecticut

Mixed:

One Party:

In-Person

All Parties:

Telephone

C.G.S.A. §§ 53a-187, -89;

C.G.S.A. § 52-570d

Connecticut is “mixed” in part because criminally, under Connecticut General Statutes §

53a-187, it’s a one-party consent state. It is against the law to record a telephone

communication or a communication made by a person other than a sender or receiver,

without the consent of either the sender or receiver. For civil cases, however, it is not a

one-party consent state. There are also different rules for in-person recording vs.

recording telephone conversations. Pursuant to C.G.S.A. § 52-570d, you are not allowed

to record an oral private telephone conversation without consent from all parties to the

conversation. So, it’s impermissible in a civil context, meaning there’s civil, not criminal,

liability. You can also get attorneys’ fees from the eavesdropper. To record a call you

must: (1) get consent of all parties in writing before the recording; (2) Recording must

include verbal notification which is recorded at the beginning of recording, and (3) You

must use automatic tone warning during the call. However, only one person's consent is

needed for recording in-person conversations. C.G.S.A. § 53a-187-189.

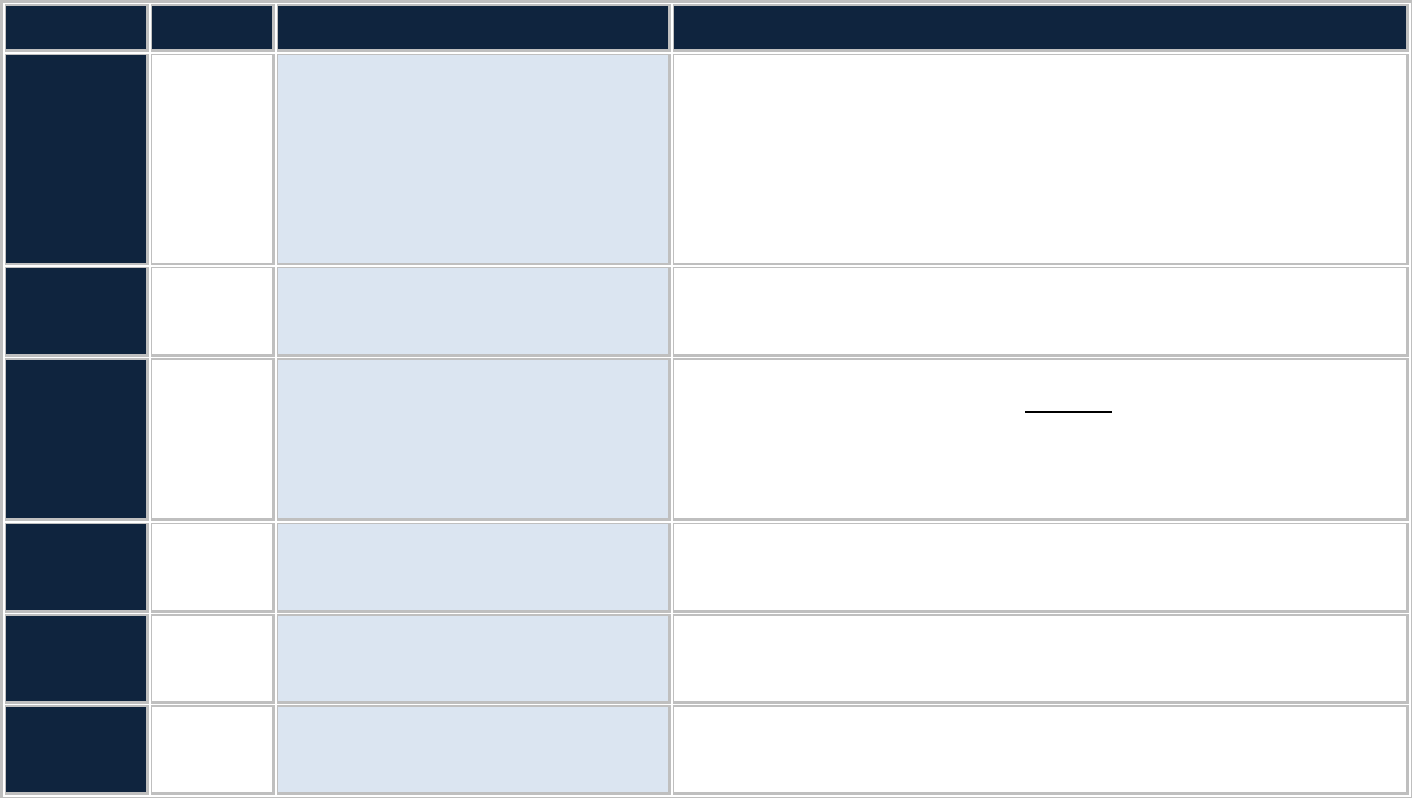

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 7 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

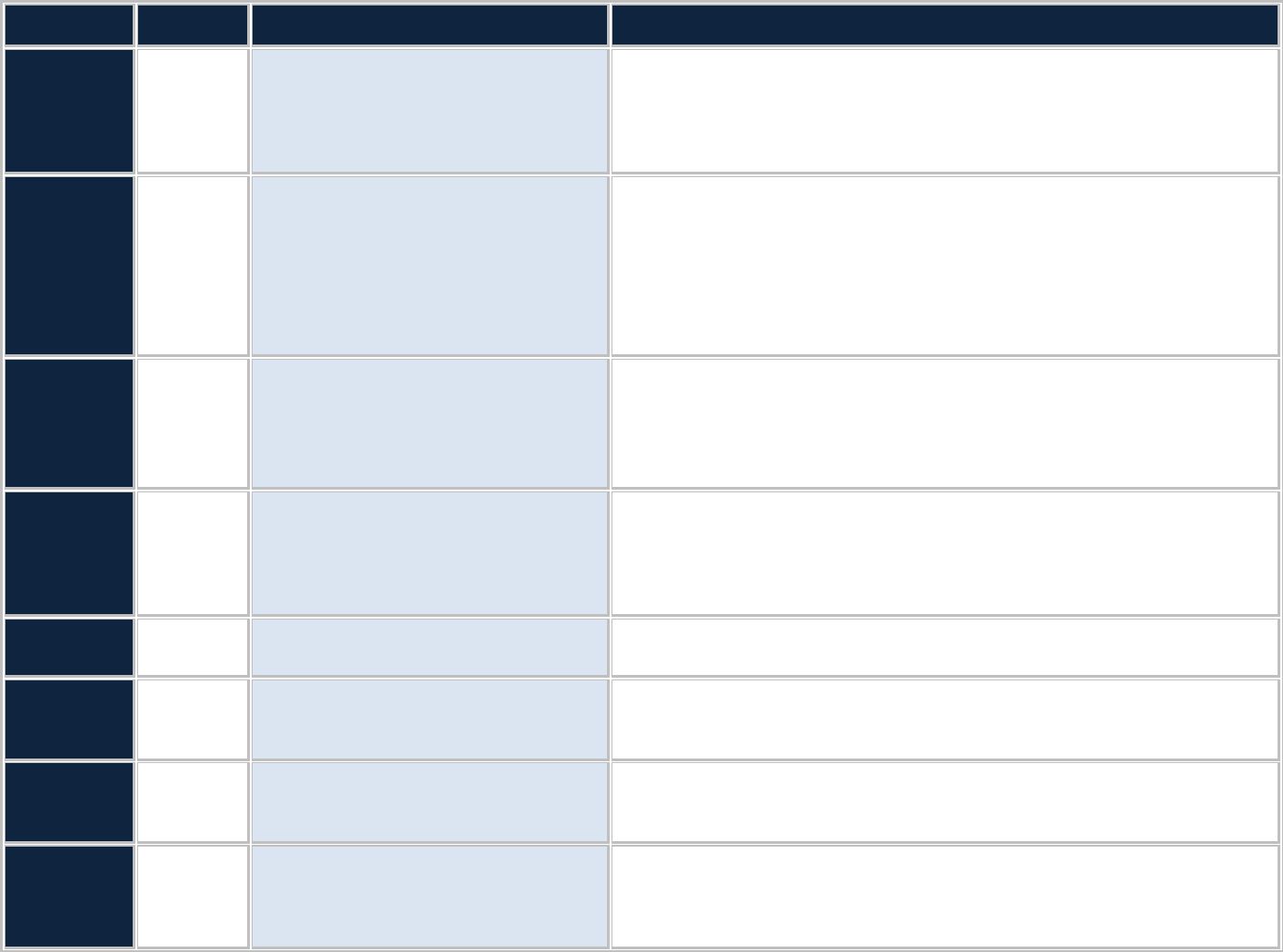

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Delaware

All Parties

Del. Code Ann. tit. 11, § 2402(c)(4)

Del. Code Ann. tit. 11, § 1335(a)(4);

U.S. v. Vespe, 389 F. Supp. 1359 (1975).

State privacy laws state that all parties must consent to the recording of oral or

electronic conversations. U.S. v. Vespe holds that even under the privacy laws an

individual has the right to record their own conversations. Section 1335 says it is a class

G felony to intercept without the consent of all parties thereto a message by telephone

or other means of communication, except as authorized by law. Section 2402 provides

that it is “authorized by law” for a person communication where the person is a party to

the communication or where one of the parties to the communication has given prior

consent, unless the communication is intercepted for the purpose of a criminal act.

District of

Columbia

One Party

D.C. Code § 23-542(b)(3)

An individual may record or disclose the contents of an electronic or oral

communication if they are a party to said communication or it they have received prior

consent from one of the parties.

Florida

All Parties

Fla. Stat. Ann. § 934.03(3)(d), (2)(k)

All parties must consent to the recording and or disclosure of the contents of and

electronic, oral or wire communication. Exceptions: (one-party consent required) (1)

where there is no reasonable expectation of privacy, and (2) a child under 18 years of

age who is a party to the communication recording a statement by another party that

the other party intends to commit, is committing, or has committed an unlawful sexual

act or an unlawful act of physical force or violence against the child.

Georgia

One Party

Ga. Code Ann. § 16-11-66(a);

Ga. Code Ann. § 16-11-62

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an electronic, oral or

wire communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given prior

consent to the recording of said communications.

Hawaii

One Party

Haw. Rev. Stat. § 803-42(3)(A)

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an electronic, oral or

wire communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given prior

consent to the recording of said communications.

Idaho

One Party

Idaho Code Ann. § 18-6702(2)(d)

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an electronic, oral or

wire communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given prior

consent to the recording of said communications.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 8 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

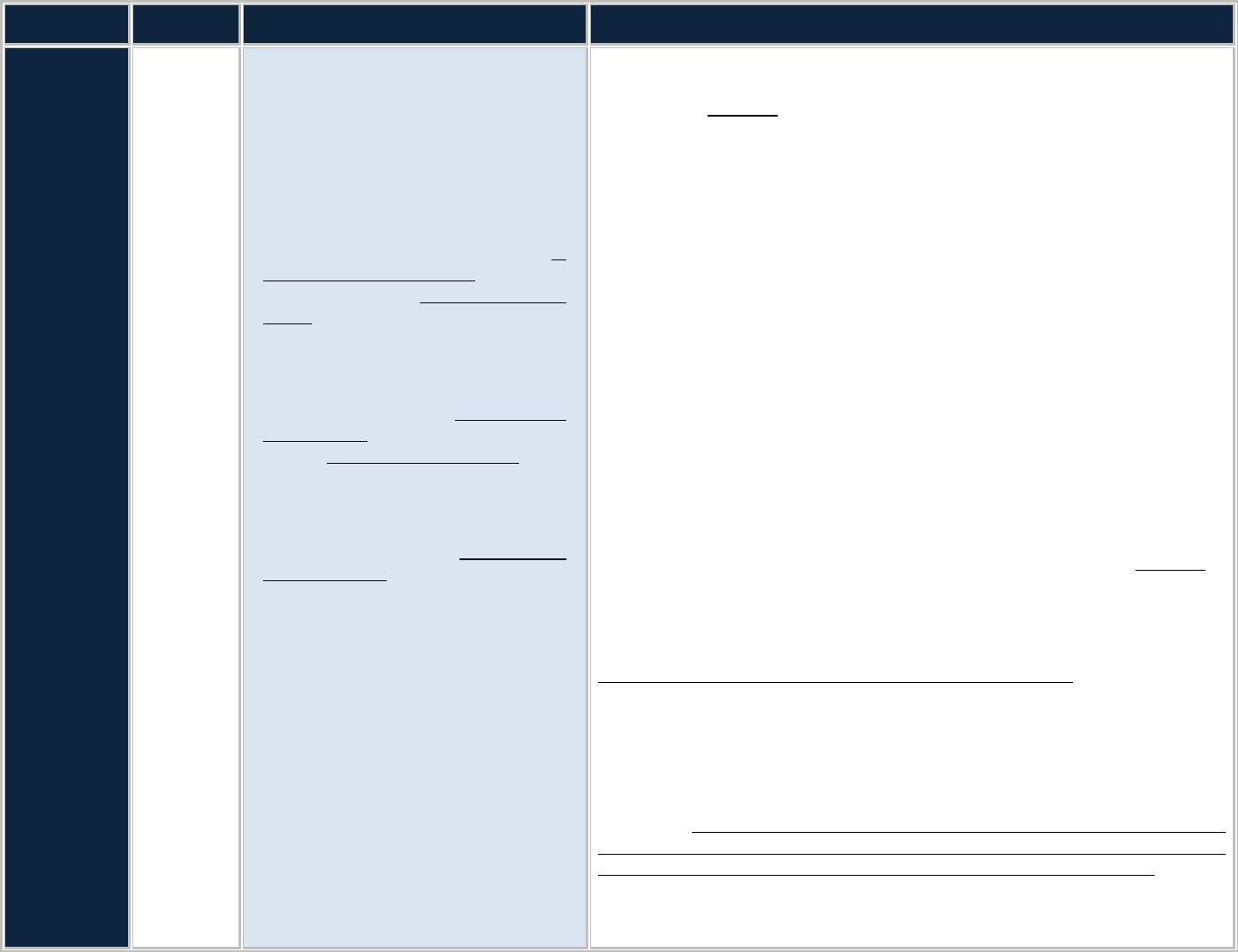

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Illinois

All Parties

(One-Party

for “private

electronic

communicat

ions”)

720 I.L.C.S. § 5/14-2(a) (Illinois Eavesdropping

Law); People v. Beardsley, 503 N.E.2d 346 (Ill.

1986); People v. Clark, 6 N.E.3d 154 (Ill. 2014).

Section 5/14-2(a)(1)(2) was amended in 2014

to make “eavesdropping” a felony if a person:

(1) Uses an eavesdropping device, in a

surreptitious manner, for the purpose of

overhearing, transmitting, or recording all

or any part of any private conversation to

which he or she is not a party unless he or

she does so with the consent of all of the

parties to the private conversation; or

(2) Uses an eavesdropping device, in a

surreptitious manner, for the purpose of

transmitting or recording all or any part of

any private conversation to which he or

she is a party unless he or she does so

with the consent of all other parties to the

private conversation.

(3) Intercepts, records, or transcribes, in a

surreptitious manner, any private

electronic communication to which he or

she is not a party unless he or she does so

with the consent of all parties to the

private electronic communication;

Section 5/14-1 defines “eavesdropping” (a

felony) as using any device capable hearing or

recording oral conversation or intercept or

transcribe electronic communications

whether such conversation or electronic

communication is conducted in person, by

telephone, or by any other means.

The use of an eavesdropping device is

surreptitious if it is done with stealth,

deception, secrecy, or concealment.

Therefore, it permits recording of

conversations in public places, such as

courtrooms, that no person could expect to

be private.

The law in Illinois is confusing and in flux. For years, § 5/14-2(a) made it a crime to use

an “eavesdropping device” to overhear or record a phone call or conversation without

the consent of all parties to the conversation, regardless of whether the parties had an

expectation of privacy. Illinois courts have ruled that “eavesdropping” only applied to

conversations that the party otherwise would not have been able to hear, thereby

effectively making it a one-party consent state. However, there still appears to be

confusion and debate over the law. The statute had repeatedly and controversially

been used to arrest people who have video-taped police. In People v. Clark, 6 N.E.3d

154 (Ill. 2014) and People v. Melongo, 6 N.E.3d 120 (Ill. 2014), the Supreme Court held

that § 5/14-2 made it a crime to knowingly and intentionally use eavesdropping devices

to hear or record all or any part of any conversation, unless done with consent of all

parties to conversation or authorized by court order, was unconstitutionally overbroad

on its face, declaring it unconstitutional.

On December 30, 2014, the statute was amended to permit recording of conversations

in public places, such as in courtrooms, where no person reasonably would expect it to

be private. The new statute draws a distinction between a “private” conversation and

other public communications. The new statute includes language indicating that in

order to commit a criminal offense, a person must be recording “in a surreptitious

manner.” It addressed a number of circumstances where there were no legitimate

privacy interests. The statute provides no guidelines or factors with regard to when an

expectation of privacy is reasonable. While the statute leaves open to debate whether a

particular “private conversation” falls within the purview of the revised law, some

argue that the new statute leaves no doubt that Illinois remains firmly within the

minority of “all-party” consent states. The amended statute requires that all parties to

an oral communication consent to the use of an eavesdropping device for that use to be

lawful.

On the other hand, by negative implication, the amended statute also appears to

establish a “one-party” consent rule for private electronic communications, by

prohibiting only someone who is not a party to a conversation from surreptitiously

using an eavesdropping device to intercept, record or transcribe such a communication

(e.g., telephone, video conference, etc.). A private electronic communication is defined

as “any transfer of signs, signals, writing, images, sounds, data, or intelligence ...

transmitted in whole or part by a wire, radio, pager, computer, electromagnetic, photo

or optical system, when the sending or receiving party intends the electronic

communication to be private under circumstances reasonably justifying that

expectation. Therefore, by negative implication, the revised statute appears to permit

someone who is a party to a telephone or a video conference to electronically record

the call without notifying any other party to the call or obtaining their consent.

A first offense is a Class 3 felony (maximum 2-5 years and $25,000 fine) and a

subsequent offense is a Class 2 felony (maximum 3-7 years and $25,000 fine).

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 9 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

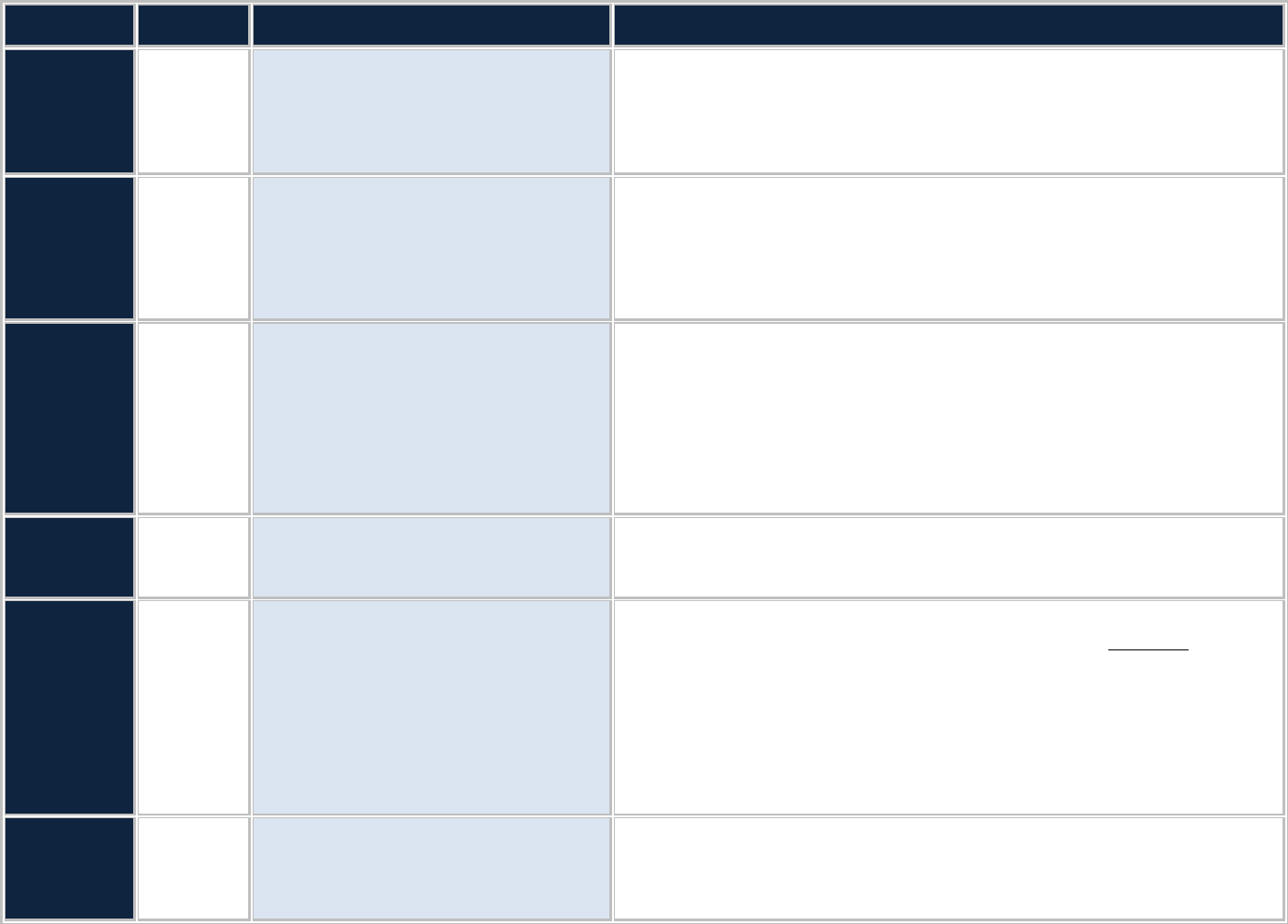

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Indiana

One Party

Ind. Code Ann. § 35-31.5-2-176

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an electronic or

telephonic communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given

prior consent to the recording of said communications.

Iowa

One Party

Iowa Code Ann. § 808B.2 (2)(c);

Iowa Code Ann. § 727.8

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an oral, electronic or

telephonic communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given

prior consent to the recording of said communications.

Kansas

One Party

Kan. Stat. Ann. § 21-6101(1);

Kan. Stat. Ann. § 21-6101(4)

Kansas law bars the interception, recording and or disclosure of any oral or telephonic

communication by the means of an electronic recording device without the consent of

at least one party or if they are a party to said communication.

Kentucky

One Party

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 526.020;

Ky. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 526.010

Kentucky law bars the interception, recording and or disclosure of any oral or

telephonic communication by the means of an electronic recording device without the

consent of at least one party or if they are a party to said communication.

Louisiana

One Party

La. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 15:1303(c)(4)

The Electric Surveillance Act bars the inception, recording or disclosure of and oral or

telephonic communication by the means of an electronic recording device without the

consent of at least one party or if they are a party to said communication.

Maine

One Party

Me. Rev. Stat. Ann. tit. 15, § 710

Maine law bars the interception, recording and or disclosure of any oral or telephonic

communication by the means of an electronic recording device without the consent of

at least one party or if they are a party to said communication.

Maryland

All Parties

Md. Code Ann., Cts. & Jud. Proc. § 10-402

(c)(3)

The Wiretapping and Electronic Surveillance Act holds that it is unlawful to:

(1) Willfully intercept, endeavor to intercept, or procure any other person to intercept

or endeavor to intercept, any wire, oral, or electronic communication;

(2) Willfully disclose, or endeavor to disclose, to any other person the contents of any

wire, oral, or electronic communication, knowing or having reason to know that the

information was obtained through the interception of a wire, oral, or electronic

communication in violation of this subtitle; or

(3) Willfully use, or endeavor to use, the contents of any wire, oral, or electronic

communication, knowing or having reason to know that the information was obtained

through the interception of a wire, oral, or electronic communication in violation of this

subtitle.

However, it is lawful to intercept a wire, oral, or electronic communication where the

person is a party to the communication and where all of the parties to the

communication have given prior consent.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 10 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Massachusetts

All Parties

Mass. Gen. Laws Ann. ch. 272, § 99(B)(4);

Mass. Gen. Ann. Laws ch. 272, § 99(C)(1)

The recording, interception, use or disclosure of any conversation, whether in person or

via wire or telephone, without the consent of all the parties is prohibited. However,

telephone equipment, which is furnished to a phone company subscriber and used in

the ordinary course of business, as well as office intercommunication systems used in

the ordinary course of business, is excluded from the definition of unlawful interception

devices.

Michigan

One Party**

Mich. Comp. Laws Ann. § 750.539(c); Sullivan

v. Gray, 117 Mich. App. 476, 324 N.W.2d 58

(1982).

The recording, interception, use or disclosure of any conversation, whether in person or

electronic or computer-based system, without the consent of all the parties is

prohibited.

**This looks like an “all party consent” law, but one Michigan court has ruled that a

participant in a private conversation may record it without violating the statute because

the statutory term “eavesdrop” refers only to overhearing or recording the private

conversations of others. The Michigan Court of Appeals interpreted that the

eavesdropping statute only applied to third-party inception of a conversation; a

participant in a communication does have the right to record the same. Michigan law is

often misinterpreted as requiring the consent of all parties to a conversation.

Minnesota

One Party

Minn. Stat. Ann. § 626A.02(d)

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an oral, electronic or

telephonic communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given

prior consent to the recording of said communications.

Mississippi

One Party

Miss. Code. Ann. § 41-29-531(e)

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an oral, telephonic, or

other communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given prior

consent to the recording of said communications.

Missouri

One Party

Mo. Ann. Stat. § 542.402(2)(3)

An individual has the right to record or disclose the contents of an oral or electronic

communication that they are a party to or if one of the parties has given prior consent

to the recording of said communications.

Montana

All Parties

Mont. Code Ann. § 45-8-213

It is unlawful to record an in person or electronic communication without the consent

of all parties except under certain circumstances namely elected or appointed public

officials or public employees when the recording occurs in the performance of an

official duty; individuals speaking at public meetings; and individuals given warning of or

consenting to the recording.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 11 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Nebraska

One Party

Neb. Rev. Stat. § 86-290(2)(c);

Neb. Rev. Stat. § 86-276

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act. It is also lawful for an individual to record electronic communications

that are accessible to the general public.

Nevada

Mixed

One Party:

Oral

All Party:

Wire/Phone

Nev. Rev. Stat. § 200.620

Nev. Rev. Stat. § 200.650

Lane v. Allstate Ins. Co., 114 Nev. 1176, 969

P.2d 938 (1998).

It is unlawful to surreptitiously record any private in-person communication without the

consent of one of the parties to the conversation.

The consent of all parties is required to record or disclose the content of a telephonic

communication. Exception: emergency situation where a court order is not possible.

The Nevada Supreme Court held in Lane v. Allstate that an individual must have the

consent of all parties in order to lawful record a telephonic communication even if they

are a party to said communication.

New

Hampshire

All Parties

N.H. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 570-A:2(I-a); New

Hampshire v. Locke, 761 A.2d 376 (N.H.

1999).

It is unlawful to record or disclose the contents of any electronic or in-person

communication without the consent of all parties.

The New Hampshire Supreme Court held that an individual efficaciously consented to

the recording of a communication when surrounding circumstances demonstrate that

they knew said communication was being recorded.

New Jersey

One Party

N.J. Stat. Ann. § 2A:156A-4(d);

N.J. Stat. Ann. § 2A:156A-2

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act. It is also lawful for an individual to record electronic communications

that are accessible to the general public.

New Mexico

One Party

N.M. Stat. Ann. § 30-12-1(C)

The reading, interrupting, taking or copying of any message, communication or report is

unlawful without the consent of one of the parties to said communication.

New York

One Party

N.Y. Penal Law § 250.00(1);

N.Y. Penal Law § 250.05

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication.

North Carolina

One Party

N.C. Gen. Stat. Ann. § 15A-287(a)

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication.

North Dakota

One Party

N.D. Cent. Code § 12.1-15-02

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 12 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Ohio

One Party

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2933.52(B)(4);

Ohio Rev. Code Ann. § 2933.51

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act.

Oklahoma

One Party

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, § 176.4;

Okla. Stat. Ann. tit. 13, § 176.2

Pursuant to the Security of Communications Act, it is not unlawful for an individual who

is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-person or electronic communication to

record and or disclose the content of said communication unless the person is doing so

for the purpose of committing a tortious or criminal act.

Oregon

Mixed

Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 165.540;

Or. Rev. Stat. Ann. § 165.535

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an

electronic communication to record or disclose the contents of said communication. It

is unlawful to record an in-person communication without the consent of all parties

involved.

Pennsylvania

All Parties

18 Pa. Cons. Stat. § 5702 to § 5704;

Com. v. Smith, 136 A.3d 170, 171 (Pa. Super.

2016); Com. v. Spence, 91 A.3d 44, 44–45 (Pa.

2014).

It is unlawful to record an electronic or in-person communication without the consent

of all parties. However, “interception” of or mere listening in to a call using a telephone

is not prohibited because the term “electronic, mechanical or other device” does not

include a telephone. Using a cell phone’s “voice memo” application would be

considered a “device” and would be prohibited.

Rhode Island

One Party

R.I. Gen. Laws Ann. § 11-35-21;

R.I. Gen. Laws Ann. § 12-5.1-1

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act. An individual may also disclose the content of any electronic or in-

person communication that is common knowledge or public information.

South Carolina

One Party

S.C. Code Ann. § 17-30-30;

S.C. Code Ann. § 17-30-15

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication.

South Dakota

One Party

S.D. Codified Laws § 23A-35A-20;

S.D. Codified Laws § 23A-35A-1

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication.

Tennessee

One Party

Tenn. Code Ann. § 39-13-601;

Tenn. Code Ann. § 39-13-604;

Tenn. Code Ann. § 40-6-303

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act. An individual may also disclose the content of any electronic

communication that is readily accessible to the general public.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 13 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Texas

One Party

Tex. Penal Code Ann. § 16.02;

Tex. Code Crim. Proc. Ann. art. 18.20

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act. An individual may also disclose the content of any electronic

communication that is readily accessible to the general public.

Utah

One Party

Utah Code Ann. § 77-23a-4;

Utah Code Ann. § 77-23a-3

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act. An individual may also disclose the content of any electronic

communication that is readily accessible to the general public.

Vermont

No Statute

or Definitive

Case Law

Vermont v. Geraw, 795 A.2d 1219 (Vt. 2002);

Vermont v. Brooks, 601 A.2d 963 (Vt. 1991).

There is no state statute that regulates the interception of telephone conversations.

The case law is also lacking in this area and there has been no clear indication as to if

Vermont is a one-party or all-party consent state. The state’s highest court has held that

surreptitious electronic monitoring of communications in a person’s home is an

unlawful invasion of privacy. Vermont v. Geraw, 795 A.2d 1219 (Vt. 2002). On the other

hand, the state’s highest court also has refused to find the overhearing of a

conversation in a parking lot unlawful because that conversation was “subject to the

eyes and ears of passersby.” Vermont v. Brooks, 601 A.2d 963 (Vt. 1991).

Virginia

One Party

Va. Code Ann. § 19.2-62

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication.

Washington

All Parties

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 9.73.030

Wash. Rev. Code Ann. § 9A.44.115(2)(a)

Lewis v. Washington, 139 P.3d 1078 (Wash.

2006).

It is unlawful for an individual to record and or disclose the content of any electronic of

in-person communication without the consent of all parties. Exceptions (one-party

consent required): (1) where there is no expectation of privacy, (2) recording

conversations of an emergency nature, such as the reporting of a fire, medical

emergency, crime or disaster, (3) recording communications that convey threats of

extortion, blackmail, bodily harm, or other unlawful requests or demands, (4) recording

communications which occur anonymously or repeatedly or at an extremely

inconvenient hour, or (5) recording communications which relate to communications by

a hostage holder.

West Virginia

One Party

W. Va. Code Ann. § 62-1D-3

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act.

Work Product of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. 14 LAST UPDATED 2/14/22

STATE

CONSENT

AUTHORITY

EXPLANATION/ADDITIONAL INFORMATION

Wisconsin

One Party**

Wis. Stat. Ann. § 968.31;

Wis. Stat. Ann. § 968.27;

**Wis. Stat. Ann. § 885.365(1)

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act.

**Evidence obtained as the result of the recording a communication is “totally

inadmissible” in civil cases, except when the party is informed that the conversation is

being recorded and that evidence from said recording may be used in a court of law.

Wyoming

One Party

Wyo. Stat. Ann. § 7-3-702

It is not unlawful for an individual who is a party to or has consent from a party of an in-

person or electronic communication to record and or disclose the content of said

communication unless the person is doing so for the purpose of committing a tortious

or criminal act.

These materials and other materials promulgated by Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. may become outdated or superseded as time goes by. If you should have questions regarding the

current applicability of any topics contained in this publication or any of the publications distributed by Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C., please contact Gary Wickert at gwickert@mwl-

law.com. This publication is intended for the clients and friends of Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. This information should not be construed as legal advice concerning any factual

situation and representation of insurance companies and\or individuals by Matthiesen, Wickert & Lehrer, S.C. on specific facts disclosed within the attorney\client relationship. These

materials should not be used in lieu thereof in anyway.