203

American Fisheries Society Symposium 66:203–221, 2009

© 2009 by the American Fisheries Society

Harvest of Paddlefi sh in North America

JEFFREY W. QUINN*

Arkansas Game and Fish Commission

2 Natural Resources Drive, Little Rock, Arkansas 72205, USA

Abstract.—Paddlefi sh Polyodon spathula have been intensively harvested

in both sport and commercial fi sheries. Recent harvests (2000–2006) were

surveyed from state agencies and compared to historical harvests (1965–

1975). Seven major sport fi sheries had recent annual harvests greater than

1,000 fi sh, and most large sport fi sheries appeared to have sustainable har-

vests due to intensive management. Recent commercial harvest was greater

than sport harvest across the species’ range. Most of the commercial harvest

was from Arkansas, Kentucky, and Tennessee. Annual commercial harvest

from the Ohio River increased from 6,000 to 196,000 kg from 1965–1975 to

2000–2006. Annual harvest remained substantial from the Arkansas River

(37,000 kg), the lower Tennessee River (121,000 kg), and the Mississippi River

(103,000 kg). Harvests of paddlefi sh (sport and commercial) compiled from

the literature were highly variable and ranged between 0.01 and 5.06 fi sh/

ha and 0.04–43.43 kg/ha (median = 0.12 fi sh/ha, 1.73 kg/ha). Stock depres-

sion has been associated with a fi rst-year harvest as low as 1.46 kg/ha, and

harvests greater than 5 kg/ha were usually associated with overfi shing

or opening a previously closed fi shery. Case histories from the Tennessee

and Ohio River systems documented that paddlefi sh were susceptible to

overharvest in lentic waters and river reservoirs, but the threat posed by

commercial harvest from large rivers will remain unresolved until more

fi sheries-independent data becomes available. Anthropogenic alterations

to habitat, overreliance on harvest data, and lack of fi sheries-independent

data limit our historical understanding of the degree of threat that harvest

is to paddlefi sh populations.

* Corresponding author: [email protected].us

Introduction

Harvest is a threat to paddlefi sh Polyodon

spathula populations throughout the spe-

cies’ range because they are harvested for

recreation or commercially for the roe or

fl esh. Overfi shing is a global problem for

marine (Sissenwine and Rosenberg 1993)

and freshwater fi sheries (Allen et al. 2005).

Early paddlefi sh researchers documented

high susceptibility of paddlefi sh to commer-

cial seines in oxbow lakes, and these fi sher-

ies were often depleted by overharvest (e.g.,

Stockard 1907; Coker 1923; Larimore 1950).

Multiple commercial fi sheries have been

overexploited to the extent that they were

no longer commercially viable (e.g., Norris

Lake, Lake Cumberland, and Old Hickory

Reservoir; Pasch and Alexander 1986).

Global harvest of paddlefi sh and sturgeon

has been reported to have declined since

1960 due to the collapse of Caspian Sea stur-

geon fi sheries (Pikitch et al. 2005), and sev-

eral closely related sturgeon species are now

rare or endangered (Birstein et al. 1997).

204 QUINN

The goal of this chapter is to review

harvest of paddlefi sh in North America.

The specifi c objectives were to (1) survey

recent (2000–2006) commercial and sport

harvests and compare the results with past

surveys (1965–1975; Carlson and Bonis-

lawsky 1981), (2) compare harvests with

density and biomass estimates to better

understand the limits of paddlefi sh har-

vest, (3) and review select commercial fi sh-

ing case-history studies. My intent was to

improve understanding of what may con-

stitute a sustainable harvest while limiting

the amount of information repeated from

previous reviews (e.g., Carlson and Bonis-

lawsky 1981; Gengerke 1986; Pasch and Al-

exander 1986; Graham 1997; Mosher 1998;

Todd 1998; CITIES 2000; Jennings and

Zigler 2000; Williamson 2003; McDougal

2005; Pikitch et al. 2005).

Commercial Fisheries

Modern commercial paddlefi sh fi sher-

ies used large-mesh gill and trammel nets

(127–152 mm bar mesh) to selectively tar-

get gravid female paddlefi sh for the roe

due to its high value. As of 2006, only six

states allowed commercial harvest of pad-

dlefi sh (Arkansas, Illinois, Indiana, Ken-

tucky, Missouri, and Tennessee). Missis-

sippi recently allowed commercial harvest

with restrictions designed to prevent roe

harvest (i.e., season was open from May 1

to October 31), but 2006 was the last year

Mississippi allowed harvest during the

summer months. Sport and commercial

harvest data were unavailable from Missis-

sippi (D. Riecke, Mississippi Department

of Wildlife, Fisheries, and Parks, personal

communication).

From 1894 to 1975, paddlefi sh com-

mercial harvest declined in the Missis-

sippi, Missouri, Ohio, and Red rivers and

increased in the impounded Tennessee,

Arkansas, and Cumberland rivers (Carlson

and Bonislawsky 1981). Peak harvest from

the Mississippi River was estimated at

853,000 kg during 1899 (Carlson and Bon-

islawsky 1981), which refl ects the massive

seining operations for fl esh harvest that

depleted numerous oxbow lakes (Stockard

1907; Hussakof 1911; Coker 1923; Larimore

1950). Sedimentation of aquatic habitats

was likely related to declining commercial

catches of paddlefi sh for the Missouri Riv-

er (Funk and Robinson 1974).

Commercial Harvest Survey

Methods

Commercial harvest data were surveyed

from appropriate state agencies from 2000

to 2006. Data reporting standards were not

consistent among states with commercial

harvests (Scholten 2009, this volume). Ma-

jor reporting issues included (1) reporting

period was not standard among states, (2)

some states did not collect either number

(e.g., Illinois) or weight of fi sh landed (e.g.,

Arkansas), and (3) weight of fi sh and roe

harvested was reported as processed (e.g.,

dressed fl esh, screened roe) or unpro-

cessed weights (whole fi sh and egg sack

weights).

The effect of nonstandardized report-

ing period was minimized by organizing

data so that large spring harvests were

synchronized for each year. Missouri and

Illinois reported harvest by calendar year

(January 1 to December 31), Kentucky by

license year (March 1 to February 28), and

Arkansas, Indiana, and Tennessee report-

ed by harvest season. Arkansas considered

harvest from the 2000–2001 roe season

(November to April) to be the 2001 har-

vest year, whereas Tennessee considered

it the 2000 harvest year. For this paper, the

harvest year was standardized as July 1 to

June 31, and the year designation followed

the Arkansas convention of the year being

assigned the later date of the harvest year.

Thus, harvest from July 1, 2005 to June 30,

2006 was designated the 2006 harvest year

and had spring harvests that were com-

205HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

parable with

those from the 2006 calendar

year. Monthly harvest data were obtained

from Kentucky, and harvest was compiled

so that harvest year was reported in this

paper instead of license year.

Mean weight was used to calculate ei-

ther harvest by weight (Arkansas) or by

number (Illinois, Kentucky, and Missouri)

because of inconsistent reporting stan-

dards. Appropriate mean weights were

obtained from state agency biologists.

Mean weight for the Arkansas River was

13.6 kg (Quinn et al. 2009, this volume).

Mean weight of paddlefi sh harvested from

the Ohio River in Indiana (7.3 kg; T. Stefa-

navage, Indiana Department of Natural

Resources, personal communication) was

used to calculate fi sh harvested from Ken-

tucky because most of Kentucky’s harvest

came from the Ohio River. Mean weight of

paddlefi sh harvested from Illinois (11.4 kg)

was applied to Missouri data because both

states have harvests that were largely from

the Mississippi River. Harvest by number

(and calculated weight) for Arkansas was

likely underestimated but did refl ect all the

gravid females harvested.

States with commercial harvest gen-

erally reported whole fl esh weights (e.g.,

Illinois, Indiana, Kentucky, and Missouri)

of fi sh landed, but Tennessee collected

dressed weight of fi sh harvested. Esti-

mates of whole fl esh weights landed from

Tennessee were obtained by summing

the estimated weight of each harvested

fi sh (G. Scholten, Tennessee Wildlife Re-

sources Agency, personal communication).

Weight was estimated from the reported

eye-to-fork length (EFL) using an observed

length–weight relationship for Kentucky

Lake (Scholten and Bettoli 2005). Most

states reported processed roe weights (e.g.,

Arkansas, Illinois, and Tennessee), but Ken-

tucky and Indiana reported unprocessed

roe weights. Conversion data were not

available for the Ohio River, so the conver-

sion for the Yellowstone/Sakakawea stock

was used (processed roe weight was 62%

of the unprocessed roe weight; V. Riggs,

Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife, and

Parks, unpublished data).

Commercial Harvest Results

Mean annual commercial fl esh harvest of

paddlefi sh in North America was 487,600

kg from 2000 to 2006 (Table 1), and the

annual mean number of paddlefi sh com-

mercially harvested was 47,400 fi sh (Table

2). Estimated mean annual processed roe

harvest from North America was 25,380 kg

from 2000 to 2006 (Table 3).

Mean annual commercial harvest from

2000 to 2006 was much higher than reports

from 1965 to 1975 (260,000 kg; Carlson

and Bonislawsky 1981) and 1992 (223,000–

269,000 kg; Graham 1997). Although the re-

cent (2000–2006) average was only 44% of

peak fl esh harvest from 1899 (1,105,000 kg;

Carlson and Bonislawsky 1981), recent har-

vest appeared substantial because (1) only

six states were open and reported harvest

(compared to 11 states in 1984; Gengerke

1986), (2) some waters were closed in states

open to commercial fi shing (e.g., Red River,

Arkansas), (3) several states had roe fi sher-

ies skewed towards gravid females (e.g.,

Arkansas, Tennessee), (4) and large com-

mercial seining operations were no longer

a commonly used harvest method. Recent

(2000–2006) mean commercial harvest was

104% of the 1894 harvest, 77% of the 1922

harvest, and 113% of the 1931 and 1975

harvests from Carlson and Bonislawsky

(1981).

The majority of the commercial paddle-

fi sh harvest came from the states of Arkan-

sas, Kentucky, and Tennessee (Tables 1–3).

Arkansas and Tennessee led the nation in

annual processed roe harvested at slightly

greater than 8,000 kg. Tennessee’s harvest

came primarily from Kentucky Lake (Ten-

nessee River; 80%) and the Mississippi Riv-

er (17%). Eighty-three percent of the harvest

206 QUINN

Table 1. Commercial fl esh harvests (kg whole weight) of paddlefi sh in six states with an

open season from 2000 to 2006. Year was based on (1) calendar year for Illinois and Mis-

souri, and (2) harvest season for other states (e.g., July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2001 is de-

fi ned as the 2001 year). Harvests were unavailable for Mississippi.

State 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Mean

Arkansas

a

– – 62,500 60,800 106,950 111,600 118,300 99,400

Illinois 16,700 19,600 29,900 25,300 31,600 30,000 – 25,500

Indiana 13,900 8,900 28,700 25,700 23,500 26,500 31,100 22,600

Kentucky 118,600 165,300 279,100 199,900 166,100 240,100 219,900 198,400

Missouri 6,100 8,500 9,500 6,900 7,400 4,500 – 7,200

Tennessee 148,700 181,500 157,400 118,700 92,100 104,200 139,000 134,500

Total 487,600

a

Estimated using a 13.6-kg mean weight of fi sh harvested; data from 2002 from an incomplete

season.

Table 2. Estimated number of paddlefi sh harvested in six states with an open commercial

fi shing season from 2000 to 2006. Year was based on (1) calendar year for Illinois and

Missouri, and (2) harvest season for other states (e.g., July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2001 is

defi ned as the 2001 year). Harvest data were unavailable for Mississippi.

State 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Mean

Arkansas – – 4,600 4,500 7,800 8,200 8,700 7,300

Illinois

a

1,500 1,700 2,600 2,200 2,800 2,600 – 2,600

Indiana 2,400 1,500 4,300 2,700 2,400 3,100 3,500 2,900

Kentucky

b

14,500 20,200 34,100 24,400 20,300 29,300 26,900 24,300

Missouri

a

500 800 800 600 700 400 – 600

Tennessee 11,000 13,500 11,800 8,300 6,800 7,400 8,900 9,700

Total 47,400

a

Estimated using a 11.4-kg mean weight of fi sh harvested.

b

Estimated using a 7.3-kg mean weight of fi sh harvested.

Table 3. Estimated commercial harvest of processed paddlefi sh roe (kg) in six states from

2000 to 2006. Year was based on (1) calendar year for Illinois and Missouri, and (2) har-

vest season for other states (e.g., July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2001 is defi ned as the 2001

year). Harvest data were unavailable from Mississippi, but they were closed for the major-

ity of the roe season.

State 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Mean

Arkansas – – 6,120 6,760 6,640 8,330 11,380 8,280

Illinois 1,040 280 2,550 1,460 1,820 3,110 1,900 1,740

Indiana 1,580 960 2,590 1,830 1,250 2,020 2,870 1,650

Kentucky 4,760 4,330 6,930 4,500 4,000 6,950 6,930 4,810

Missouri – – – 790 810 610 – 740

Tennessee – – – 6,330 5,220 8,150 12,900 8,160

Total 23,380

207HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

in Arkansas harvest came from the Arkan-

sas (40%), Mississippi (22%), and White

(21%) rivers. Kentucky led the nation in

total commercial paddlefi sh fl esh harvest,

with the majority of the fl esh harvest com-

ing from the Ohio River (87%). The fl esh

harvest from Kentucky was higher than

any other state because year-round fi shing

was legal without size limits. Missouri had

the least commercial harvest because the

only open water body was the Mississippi

River and use of unattended entanglement

gear was illegal. Illinois and Indiana had

intermediate harvests.

Annual commercial harvest from the

Ohio River increased from 6,000 to 196,000

kg from 1965–1975 to 2000–2006 (Table 4).

Thomas et al. (2005) documented increased

paddlefi sh abundance in lock chambers of

the Ohio River from 1957 to 2001, which

coincided with improved water quality

(increased dissolved oxygen and pH). Har-

vest declined for the Missouri and Red riv-

ers because they were closed to commercial

paddlefi sh harvest. Annual fl esh harvest

from the Mississippi River remained sub-

stantial (1965–1975 average: 41,000 kg;

2000–2006 average: 103,000) despite com-

mercial closures in Iowa and Louisiana

(Graham 1997) and a partial closure in Illi-

nois (Quist et al. 2009, this volume). Recent

mean annual harvest of 19,000 kg from the

White River was similar to historical Ar-

kansas Game and Fish Commission mean

annual harvest estimates (SD) of 38,000

61,000 kg (1950–1989; N = 26 years).

Commercial harvest data from Mis-

souri were obtained to evaluate harvest

trends from 1945 to 2006 because they have

a complete and continuous harvest record.

Missouri’s harvest regulations remained

relatively stable over time. The Missouri

and St. Francis rivers were closed to har-

vest during 1989. A 610-mm-EFL minimum

length limit was enacted during 1991, but

it was unlikely that this length limit highly

infl uenced harvest because fi sh less than

610 mm were not recruited to large mesh

gill nets (e.g., Paukert and Fisher 1999).

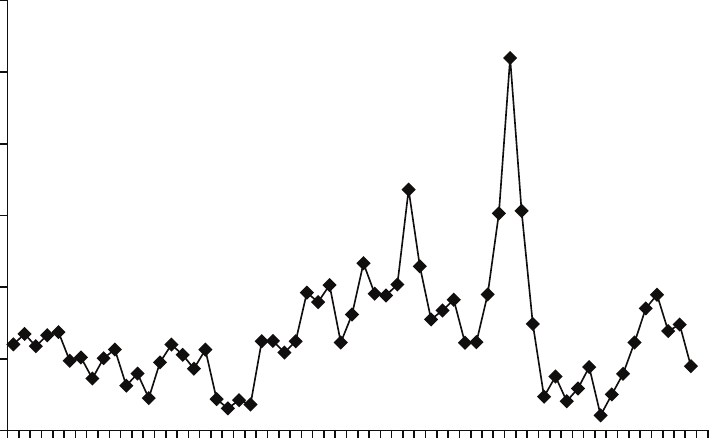

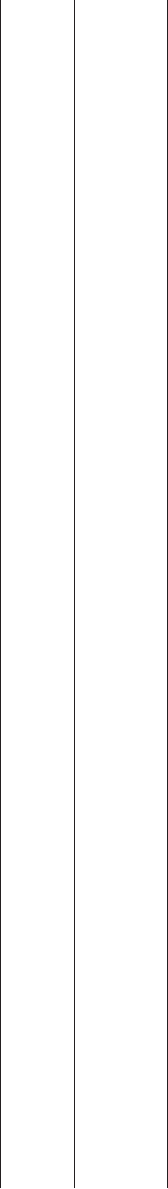

Harvest time-series data from Missouri

were highly variable (Figure 1), and mean

annual fl esh harvest (SD) was 6,800

4,200 kg. Similar to Quist et al. (2009, this

volume), harvest appeared low during

the early to mid-1960s and appeared to be

sustained at relatively high levels for most

Table 4. Estimated commercial fl esh harvest (metric tons) of paddlefi sh in the major rivers

of North America from 2000 to 2006. Year was based on (1) calendar year for Illinois and

Missouri, and (2) harvest season for other states (e.g., July 1, 2000 to June 30, 2001 is

defi ned as the 2001 year). Harvest data were unavailable from Mississippi. One metric ton

is equivalent to 1,000 kg.

River 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Mean

Ohio 112 164 286 185 160 247 218 196

Tennessee

a

149 168 126 114 84 88 119 121

Mississippi

a

– – 75 79 149 106 – 103

Arkansas

b

– – – 25 31 38 57 37

White

a

– – 18 14 16 45 4 19

Cumberland

c

12 10 23 15 12 14 30 17

Ouachita

a

– – – 3 3 4 6 4

Illinois 2 1 7 6 1 1 – 3

Black

a

– – – 1 2 3 3 2

a

Estimated using a 11.4-kg average weight.

b

Estimated using a 13.6-kg average weight.

c

Estimates from Tennessee were based on calculating a mean weight from each fi sh harvested

from the Kentucky Lake length–weight relationship.

208 QUINN

0

5,000

10,000

15,000

20,000

25,000

30,000

1945

1950

1955

1960

1965

1970

1975

1980

1985

1990

1995

2000

2005

Year

Harvest (kg)

Figure 1. Harvest of paddlefi sh from Missouri from 1945 to 2006. Data were obtained from

Vince Travnichek, Missouri Department of Conservation. The Missouri River and St. Fran-

cis River were closed to harvest during 1989, and during 1991, a 610-mm-EFL minimum

length limit was enacted.

of the 1970s. Two major harvest peaks oc-

curred during 1980 (16,800 kg) and 1989

(26,000 kg; Figure 1). During 1980, large

harvests were also observed for the Ten-

nessee and Cumberland rivers (340,000

kg dressed weight; Pasch and Alexander

1986). Missouri commercial harvest was

comparatively low from 1992 to 1997 (Fig-

ure 1), and Todd (1998) and Williamson

(2003) suggested that harvest declined

from 1990 to 1997 for Illinois, Missouri, and

Tennessee. From 1993 to 1998, national har-

vest was likely infl uenced by the February

16 through April 15 closed season regula-

tion in Tennessee (Williamson 2003).

Sport Fisheries

Blind snagging was the primary method

sport fi shers use to capture paddlefi sh,

and

archery was a lesser-used harvest method

(Mestl et al. 2005; Scarnecchia et al. 2007).

Recreational fi shing with snagging had

low-size selectivity (Gengerke 1978; Con-

over and Grady 2000; Scarnecchia et al.

2007), and harvest of juvenile paddlefi sh

may occur where permitted. The distribu-

tion of paddlefi sh sport fi sheries were re-

viewed by Carlson and Bonislawsky (1981),

Gengerke (1986), and Graham (1997). Ma-

jor recreational sport fi sheries tend to ex-

ist where paddlefi sh make spawning runs,

especially in tailwaters below dams. The

Lake Sakakawea/Yellowstone River snag

fi shery was unique because donated sport-

harvested roe was processed and sold and

the proceeds were applied toward paddle-

fi sh management in North Dakota and

Montana (Scarnecchia et al. 2007).

Carlson and Bonislawsky (1981) sug-

209HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

gested that sport harvest was greater than

commercial harvest in the Mississippi Riv-

er basin, and they reported harvest for 11

major sport fi sheries. They reported that

maximum sport harvest was at Kentucky

Dam, Kentucky, where anglers snagged

102,800 fi sh during 1978 with average size

of only 3 kg. However, this was an ex-

treme harvest outlier. Sport harvest from

the Kentucky Dam tailwater was 15,050,

1,000, and 1,790 fi sh in 1979, 1994, and 2006

(Carlson and Bonislawsky 1981; Timmons

and Hughbanks 2000; P. Rister, Kentucky

Department of Fish and Wildlife Resourc-

es, personal communication). Carlson and

Bonislawsky (1981) reported that the aver-

age weight of paddlefi sh harvested in snag

fi sheries varied from 3 to 28 kg.

Sport harvest data were surveyed from

appropriate state agency and university per-

sonnel. The number of fi sh harvested was

reported for all sport fi sheries, but mean

weight data were generally unavailable.

Mean annual sport harvest in North

America was estimated as 12,700 fi sh from

2000 to 2006 (Table 5). Sport harvest data

were not available for the major Lake of

the Ozarks, Truman Lake, and Osage River

fi sheries in Missouri, which were expected

to add roughly 2,000–5,000 fi sh to the total

harvest (Graham 1997). Sport harvest data

for most of the Arkansas, Ohio, and upper

Mississippi River tailwater fi sheries were

not available (Graham 1997; Williamson

2003), but cumulative harvest from these

waters may be important. For example, the

Markland tailwater, Ohio River, had a har-

vest of 500 paddlefi sh during 1997 (Henley

et al. 2001a), and 1,320 paddlefi sh were har-

vested from the Mississippi River at Lock

and Dam 12 in Iowa during 1976 (Carlson

and Bonislawsky 1981). Thus, the estimate

of 12,700 fi sh was very conservative, and a

more accurate range-wide sport harvest es-

timate may reasonably be expected to be be-

tween 15,000 and 20,000 fi sh. Overall, seven

major sport fi sheries had harvests greater

than 1,000 fi sh annually, including the Lake

of the Ozarks and Truman Lake fi sheries.

Comparing Harvest to

Population Estimates

Mean paddlefi sh population density among

12 select waters was 2.7 fi sh/ha (95% confi -

dence interval; 0.1–5.3; median = 0.9; Table

Table 5. Number of paddlefi sh harvested from major paddlefi sh sport fi sheries from 2000

to 2006. Data were unavailable for the Lake of the Ozarks and Truman Lake fi sheries in

Missouri.

Fishery State 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 Mean

Grand Lake/

Neosho River OK – – – 2,930 2,700 – – 2,810

Yellowstone/Missouri/

Sakakawea ND, MT 2,870 1,930 2,570 2,100 1,300 2,420 2,250 2,210

Kentucky Dam tailwater KY – – – – – – 1,790 1,790

Missouri River/

Gavins Point NE, SD 940 1,030 730 1,200 2,090 1,950 1,940 1,410

Table Rock Lake MO – 1,260 1,370 – – – – 1,310

Missouri River/

Fort Peck MT – – 540 870 790 1,030 1,290 900

Barkley Dam tailwater KY 810 – – – – – – 810

Ozark Lake/

Pool 13 tailwater AR – – – – 600 – – 600

Neosho River,

Chetopa Dam KS 100 – 480 1,590 510 380 440 510

Fort Gibson/Grand River OK – – – – – 320 – 320

210 QUINN

6), and maximum reported density was 13.1

paddlefi sh/ha for Sibley Lake, an oxbow of

the Alabama River (Hoxmeier and DeVries

1997). Biomass estimates for paddlefi sh in

natural waters typically ranged between 11

and 22 kg/ha (Onders et al. 2001), but max-

imum biomass exceeded 40 kg/ha (Jenkins

et al. 1982). A rotenone evaluation of Bar-

kley Lake, Kentucky estimated biomass at

6.8 kg/ha (Aggus et al. 1979), and biomass

ranged from 0 to 10.5 kg/ha among seven

Louisiana oxbow lakes (Lambou 1959).

Mean biomass estimates for paddlefi sh at

four long-term (>25 years; SD) Arkansas

River rotenone sites were 0, 0, 21.7 10.3,

and 25.6 11.2 kg/ha (Quinn and Limbird

2008).

Harvests of paddlefi sh compiled from

the literature were highly variable and

ranged between less than 0.01 and 5.06

fi sh/ha and less than 1 and 43 kg/ha (me-

dian = 0.12 fi sh/ha, 1.73 kg/ha; Appendix

1). Maximum reported harvest for a large

water body (>2,000 acres) was 42 kg/ha

from Wilson Reservoir, Tennessee River,

Alabama (Tarzwell and Bryan 1945). This

harvest is realistic because biomass esti-

mates of paddlefi sh greater than 914 mm

EFL ranged from 32 to 87 kg/ha for Ozark

Lake, Arkansas River (Quinn et al. 2006).

Also, Jenkins et al. (1982) reported harvests

of 32.6 and 43.4 kg/ha for Energy and

Bards Lakes, which are 150- and 129-ha

subimpoundments of Lake Barkley.

The highest sustainable harvest rates

found in the literature were 1.9–3.5 kg/ha

for the Neosho/Grand Lake sport fi shery,

with an associated exploitation rate of 15–

17% and population density of 1.02–1.38

fi sh/ha (Combs 1982). Based on the liter-

ature, harvests less than 1 kg/ha did not

appear to be problematic. However, stock

depression for Norris Reservoir occurred

at a relatively modest 1.5 kg/ha (0.06 fi sh/

ha), and after the fi shery recovered, this

reservoir had a biomass of 11.2 kg/ha (0.64

fi sh/ha; Alexander and Peterson 1982). Us-

ing the suggested 15% maximum exploi-

tation rate (Combs 1982) and an expected

biomass range of 11–22 kg/ha (Onders et

al. 2001), harvests greater than 3.3 kg/ha

should raise management concerns for pro-

ductive waters. Harvests greater than 5 kg/

ha reported in the literature were usually

related to opening a previously closed fi sh-

ery or overharvest (Appendix 1). Compar-

ing harvests to population density and bio-

mass estimates is useful for understanding

sustainability of harvests, but it should not

replace understanding of site-specifi c fi sh-

eries characteristics and demographic rates

(e.g., mortality, growth, recruitment).

Table 6. Paddlefi sh density estimates (fi sh/ha) for select waters in North America. CI =

confi dence interval.

Area Density

Water (ha) fi sh/ha (95% CI) Citation

Barkley Lake, KY 23,400 1.2 Aggus et al. 1979

Grand Lake, OK 22,000 1.14 (0.86–1.45) Combs 1982

Keystone Reservoir, OK 10,600 0.81 (0.37–1.25) Paukert and Fisher 2001

Lake Cumberland, KY 20,336 0.64 Hageman et al. 1986

Lake Francis Case, SD 33,994 0.79 Unkenholtz 1979

Lake Sakakawea, MT 156,000 0.21 Ryckman 2003

Norris Reservoir, TN 13,695 0.64 (0.34–1.35) Alexander and Peterson 1982

Ozark Lake, AR 4,249 3.53 (0.87–6.19) Quinn et al. 2004

Mississippi River, IA 10,918 0.99 (0.40–2.47) Gengerke 1978

Sibley Lake, AL 32 13.10 Hoxmeier and DeVries 1997

South Cross Creek R., KY 192 8.79 (8.12–9.47) Boone and Timmons 1995

Watts Bar, TN 15,783 0.22 (0.14–0.42) Alexander et al. 1985

211HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

Case Histories for Commercial

Fisheries

Kentucky Lake

Kentucky Lake was the best studied com-

mercial paddlefi sh fi shery and it provided

a valuable case history for understanding

the effects of harvest (Bronte and John-

son 1983, 1984, 1985; Hoffnagle and Tim-

mons 1989; Timmons and Hughbanks

2000; Scholten and Bettoli 2005; Bettoli et

al. 2007). This large main-stem Tennes-

see River reservoir was 296 km long and

64,800 ha and had a residence time of 14 d

(Voigtlander and Poppe 1989). The riverine

portion fl ows through Tennessee, and the

Kentucky portion was primarily reservoir

habitat. Paddlefi sh segregated in this river

reservoir, with juvenile paddlefi sh remain-

ing in the downstream, lacustrine portion

of the lake (Scholten and Bettoli 2005).

Kentucky Lake was reopened to com-

mercial entanglement gear during 1979

after being closed for 3 years (Bronte and

Johnson 1983). Based on fi sh observed from

commercial landings, Bronte and Johnson

(1985) estimated that total annual mortal-

ity for fi sh greater than age 6 was 44% and

maximum age was 14 during 1980–1981.

Gravid females were greater than age 9

and ranged from 930 to 1,002 mm EFL and

16.8–22.7 kg. Age at recruitment into the

fi shery was 6–7 years and length at recruit-

ment was 700 mm EFL. Bronte and John-

son (1985) concluded that fi sh growth was

rapid to large sizes, and fi sh recruited into

the fi shery before contributing to repro-

duction.

Hoffnagle and Timmons (1989) indi-

cated that Kentucky Lake was overfi shed

during 1985–1986 after a period of heavy

exploitation from 1984 to 1985. They ob-

served 702 paddlefi sh captured by com-

mercial fi shers. The sex ratio was 1:1, but

only 2% were gravid females. Total annual

mortality from catch curve was 69%, and

maximum age was 16 years. Mean length

and weight of the catch was only 691 mm

EFL and 5.7 kg.

From 1991 to 1994, Timmons and

Hughbanks (2000) found 14% exploitation

and 22% total annual mortality for ages

9–15, and they concluded that the paddle-

fi sh stock of Kentucky Lake was recover-

ing. Sex ratio was 0.64:1 males:females.

Mean length of paddlefi sh was 857 mm

EFL (range: 690–1,220 mm EFL), where-

as mean length was 691 mm EFL during

1985–1986 (Hoffnagle and Timmons 1989).

Mean length, weight, and maximum age in-

creased by 166 mm EFL, 5.8 kg, and 5 years

(16–21) since 1985–1986. Todd (1998) noted

that commercial harvest of paddlefi sh de-

clined in Tennessee waters from 221,000 to

29,000 kg between 1990 and 1996.

Scholten and Bettoli (2005) found

very high total annual mortality (68%) for

paddlefi sh in Kentucky Lake during 2003.

They found that harvest was positively re-

lated to the number of fi shable days when

mean discharge was less than 850 m

3

/s

because fi shers could not deploy nets dur-

ing high fl ows. They found evidence that

no mature females were protected by the

864-mm-EFL minimum length limit, and

recruitment overfi shing likely occurred

during low-fl ow years. They suggested a

1,016-mm-EFL minimum length limit was

needed to maintain spawning potential ra-

tios greater than 20% at high exploitation

rates (62%).

Tennessee River, Alabama

The Tennessee River commercial paddle-

fi sh fi shery in Alabama provides a classic

paddlefi sh stock-depression, overfi shing

example. Pasch and Alexander (1986) re-

viewed harvests for the Tennessee River

snag fi sheries (i.e., Guntersville, Wheeler,

Wilson, and Pickwick lakes; total area =

56,000 ha) and found major declines in

commercial harvest from 1942 to 1952

(293,000–43,500 kg; 5.23–0.77 kg/ha). This

fi shery apparently recovered during the

212 QUINN

late 1950s and 1960s (Tarzwell and Bryan

1945; Bryan and White 1958). From 1948 to

1973, harvest ranged from 21,800 kg (1956)

to 281,700 kg (1964), with a secondary har-

vest peak of 175,900 kg in 1973 (Pasch et

al. 1978). Paddlefi sh harvest increased in

the late 1970s and reached 150,000 kg (2.68

kg/ha) by 1980 due to increased roe prices

(Gengerke 1986). Hoxmeier and DeVries

(1996) failed to fi nd paddlefi sh in the Ala-

bama portion of the Tennessee River dur-

ing 1993–1994 after the fi shery was closed

during 1988, although their efforts were

not extensive. Fisheries biologists from

Alabama, based upon fi eld sampling and

creel reports, concluded that the paddle-

fi sh population in the Alabama portion of

the Tennessee River has not recovered as

of 2006 (S. Cook, Alabama Wildlife and

Freshwater Fisheries Division, personal

communication). Additional evidence that

Guntersville Lake has not recovered is

that opening of the Tennessee portion be-

low Nickajack Lake produced a very small

commercial harvest (Appendix 1). The

Tennessee River and Kentucky Lake case

histories provided evidence (e.g., Pasch

and Alexander 1986) that river reservoirs

are susceptible to overfi shing.

Ohio River

The Ohio River commercial fi shery (Ken-

tucky, Indiana, and Illinois) has been inten-

sively fi shed from 1999 to 2006 and shows

signs of heavy exploitation (Henley et al.

2001a). Estimated average size and age at

harvest was only 5.45 kg, 710 mm EFL,

and 8.5 years (Henley et al. 2001a). Dur-

ing 1995–2001, total annual mortality esti-

mates ranged from 47% to 68% (Henley et

al. 2001b), and length-frequency distribu-

tions were truncated at 850 mm EFL. The

Ohio River management team tracked the

percentage of fi sh age 10 and older and

found that it peaked in 127-mm bar mesh

gill nets at 71% during 1997 and declined

to a low of 46% during 2001 after a period

of intensive fi shing. The Ohio River case

history indicated that intensive commer-

cial harvest resulted in a small size distri-

bution and a relatively young population

with high annual mortality.

Discussion

Anthropogenic alterations to habitat, over-

reliance on harvest data, and lack of fi sh-

eries-independent data limit our historical

understanding of the degree of threat that

harvest is to paddlefi sh populations. Hu-

man-alteration of large North American

rivers (e.g., Barnickol and Starrett 1951;

Sheehan and Rasmussen 1999) occurred

at the same time that commercial harvests

of paddlefi sh reportedly declined (Carl-

son and Bonislawsky 1981; Gengerke 1986;

Pikitch et al. 2005). Factors that increased

uncertainty with the quality of harvest data

included lack of data collection standards,

lack of quality control in several states, and

inconsistent reporting by fi shers. Draw-

ing inferences about historical popula-

tion trends from commercial harvest data

should be done with caution because (1)

fi shing effort, habitat, and harvest regu-

lations varied over time, and some states

closed commercial fi shing (Graham 1997);

(2) data collection formats were often not

thoroughly documented; (3) many fi sher-

ies shifted from fl esh to roe harvest; and (4)

harvest data only represent minimal catch

estimates (Carlson and Bonislawsky 1981).

Thankfully, fi sheries-independent stock

surveys have increased in recent decades

since the development of the Mississippi

Interstate Cooperative Resource Associa-

tion (Grady et al. 2005).

The magnitude of recent commercial

harvest estimates (Tables 1 and 2) indicates

that previous comments and analyses sug-

gesting range-wide population declines

and depletion of paddlefi sh stocks may

have been overstated (e.g., Gengerke 1986;

Graham 1997; Pikitch et al. 2005). Pikitch

213HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

et al. (2005) described a steeply declining

paddlefi sh harvest trend over time, and

their results refl ected (1) that states such

as Arkansas stopped collecting paddlefi sh

harvest data after National Marine Fisher-

ies Service eliminated funding in the late

1980s, and (2) several states closed paddle-

fi sh harvest (e.g., Iowa, Louisiana). Graham

(1997) stated that paddlefi sh have declined

dramatically in most areas during the past

100 years; however, state-by-state status re-

views suggested that paddlefi sh were com-

mon throughout much of the species range

where habitats were not severely altered

(Gengerke 1986; Graham 1997).

Market conditions and fi shing effort

were primary factors infl uencing harvest

of paddlefi sh (Gengerke 1986; Quist et al.

2009; Scholten 2009). Increased demand

and effort occurred when Caspian Sea

sturgeon caviar imports were banned or

reduced. Major peaks in effort occurred

during the 1940s associated with World

War II (Bryan and White 1958), during the

embargo on Iranian caviar in the late 1970s

through the 1980s (Alexander and Peterson

1982), and from 2005 to present associated

with limited Caspian Sea quotas (Colombo

et al. 2007).

A growing body of evidence suggested

commercial harvest was a threat to paddle-

fi sh in lentic waters, including impounded

rivers such as the Arkansas, Ohio, and Ten-

nessee rivers (Leone et al. 2005; Scholten

and Bettoli 2005). Stockard (1907) noted

depletion of paddlefi sh from oxbow lakes

from seining operations. Paddlefi sh typi-

cally grow faster in reservoirs (Paukert

and Fisher 2001) and become susceptible to

commercial harvest before reaching sexual

maturity (Pasch and Alexander 1986; Schol-

ten and Bettoli 2005). Main-stem reservoirs

on large rivers, with abundant lentic habi-

tats, such as those on the Tennessee River

and Arkansas River, had high commer-

cial harvests and appeared susceptible to

overharvest without adequate regulation

(Pasch and Alexander 1986; Scholten and

Bettoli 2005). The degree of threat posed

by harvest of paddlefi sh from large open

rivers such as the Mississippi and lower

White River, Arkansas, will remain unre-

solved until fi sheries independent data be-

comes available.

Commercial fi shing has the potential

to quickly reduce the abundance of large,

old fi sh in a population (e.g., Hoffnagle

and Timmons 1989; Henley et al. 2001b),

and maximum age usually declined with

increasing harvest. Maximum age for Ken-

tucky Lake was 7.2, 14, and 21 years when

total annual mortality was 68%, 44%, and

14%, respectively (Bronte and Johnson 1984;

Timmons and Hughbanks 2000; Scholten

and Bettoli 2005). Three Arkansas River

pools appeared to follow the pattern of de-

clining maximum age with increased har-

vest, and maximum ages were 16, 15, and

13 years for pools with 51%, 56%, and 66%

total annual mortality (F. Leone, Arkansas

Game and Fish Commission, unpublished

data). Francis et al. (2007) suggested that

maintaining old fi sh in fi sh populations

was one of the key tenants of ecosystem-

based fi sheries science because old fi sh

often had higher spawning success. Scar-

necchia et al. (2007) suggested that harvest

regulations should be developed to protect

a range of ages of mature fi sh, including

middle-aged and old spawning females.

Published population modeling stud-

ies indicated that paddlefi sh are suscep-

tible to recruitment overfi shing (Boreman

1997; Scholten and Bettoli 2005), and fi eld

studies confi rmed that recruitment was

depressed for some paddlefi sh popula-

tions by the harvesting of adult spawners

(Alexander and McDonough 1983). Alex-

ander and McDonough (1983) noted a se-

vere decline in age-0 paddlefi sh at the Gal-

latin Steam Electric Plant on Old Hickory

Lake, Tennessee after heavy exploitation

during the late 1970s. Hilborn and Walters

(1992) noted that studies often fail to relate

214 QUINN

recruitment to stock size, but when fi sher-

ies are fi shed extensively, recruitment will

eventually decline.

The functions used to describe stock–

recruitment relationships can provide

greatly different results in population

models (e.g., Rieman and Beamesderfer

1990). Population modeling indicated that

some gill-net fi sheries may not experience

recruitment or growth overfi shing with ad-

equate minimum length limits if bycatch

mortality of undersized fi sh is low (Schol-

ten and Bettoli 2005; Leone et al. 2005). By-

catch mortality of undersized fi sh may be

a threat for maintaining sustainable com-

mercial paddlefi sh fi sheries (Barnickol and

Starrett 1951; Bettoli and Scholten 2006).

Increased management by state agen-

cies has reduced the threat of harvest to

paddlefi sh over the species range. Rec-

reational harvests were often intensively

managed through complex harvest regu-

lations, and harvest quotas were used to

create sustainable fi sheries (e.g., Ryck-

man 2003; Mestl et al. 2005). Commercial

harvest was closed for much of the range

of paddlefi sh (e.g., Alabama, Iowa, Loui-

siana, Minnesota, Nebraska, New York,

North Dakota, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania,

South Dakota, Ohio, Texas, West Virginia,

and Wisconsin). Management of commer-

cial fi sheries in Arkansas and Tennessee

has focused on protecting sexually imma-

ture paddlefi sh to commercial exploitation

through high minimum length limits, and

harvest seasons were set to limit bycatch

mortality (Scholten 2009). Several states

open to commercial fi shing for paddlefi sh

had some rivers or river sections that were

closed to provide a refuge (e.g., Arkansas,

Illinois). However, management for sus-

tainable paddlefi sh fi sheries has faced nu-

merous political challenges (Bettoli et al.

2007).

A major challenge for fi sheries manag-

ers is characterizing what is a sustainable

harvest. Recent freshwater commercial

fi sheries management has focused on

maintaining spawning potential ratios

(SPR; Goodyear 2003) greater than 20–30%

to prevent recruitment overfi shing (e.g.,

Slipke et al. 2002; Goodyear 2003; Schol-

ten and Bettoli 2005; Leone et al. 2005;

Maceina and Pereira 2007). Slipke et al.

(2002) reviewed recruitment overfi shing

in freshwater fi sheries and demonstrated

the utility of SPR for freshwater fi sher-

ies management. Traditional commercial

fi sheries stock assessments and biological

reference points (e.g., FMSY, F0.1) used

to assess growth overfi shing for marine

fi sheries (Hilborn and Walters 1992) have

not been applied to paddlefi sh roe fi sher-

ies. During the next decade, paddlefi sh

managers will likely fi eld test the utility

of SPR targets for preventing recruitment

overfi shing.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank all the biologists who

provided information and harvest data that

contributed to this review, including Doug

Henley (Kentucky Department of Fish and

Wildlife Resources), Rob Maher (Illinois

Department of Natural Resources), Gerald

Mestl, Tom Mosher (Kansas Wildlife and

Parks), Bill Posey (Arkansas Game and

Fish Commission), Vic Riggs (Montana

Department of Fish, Wildlife, and Parks),

Paul Rister (Kentucky Department of Fish

and Wildlife Resources), Fred Ryckman

(North Dakota Game and Fish Depart-

ment), George Scholten (Tennessee Wildlife

Resources Agency), Tom Stefanavage (In-

diana Department of Natural Resources),

Vince Travnichek (Missouri Department of

Conservation), and Trish Yasger (Missouri

Department of Conservation). This manu-

script was improved by discussions I have

had with Arkansas commercial fi shers, and

constructive reviews by Jason Olive, Frank

Leone, George Scholten, Craig Paukert,

and two anonymous reviewers.

215HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

References

Aggus, L. R., D. C. Carver, L. L. Olmsted, L. L.

Rider, and G. L. Summers. 1979. Evalua-

tion of standing crops of fi shes in Crooked

Creek Bay, Barkley Lake, Kentucky. Pro-

ceedings of the Annual Conference South-

eastern Association of Fish and Wildlife

Agencies 33:710–722.

Allen, J. D., R. Abell, Z. Hogan, C. Revenga, B.

W. Taylor, R. L. Welcomme, and K. Wine-

miller. 2005. Overfi shing of inland waters.

BioScience 55:1041–1051.

Alexander, C. M., and D. C. Peterson. 1982. Fea-

sibility of a commercial paddlefi sh harvest

from Norris Reservoir, Tennessee. Proceed-

ings of the Annual Conference Southeast-

ern Association of Fish and Wildlife Agen-

cies 36:202–212.

Alexander, C. M., and T. A. McDonough. 1983.

Effects of water conditions during spawn-

ing on paddlefi sh year-class strength in

Old Hickory Reservoir, Tennessee. Tennes-

see Valley Authority, Knoxville.

Alexander, C. M., A. I. Myhr, III, and J. L. Wil-

son. 1985. Harvest potential of paddlefi sh

stocks in Watts Bar Reservoir, Tennessee.

Proceedings of the Annual Conference

Southeastern Association of Fish and Wild-

life Agencies 39:45–55.

Barnickol, P. G., and W. C. Starrett. 1951. Com-

mercial and sport fi shes of the Mississippi

River between Caruthersville, Missouri,

and Dubuque, Iowa. Bulletin of the Illinois

Natural History Survey 25:267–350.

Bettoli, P. W., and G. D. Scholten. 2006. Bycatch

rates and initial mortality of paddlefi sh in

a commercial gillnet fi shery. Fisheries Re-

search 77:343–347.

Bettoli, P. W., G. D. Scholten, and W. C. Reeves.

2007. Protecting paddlefi sh from overfi sh-

ing: a case history of the research and regu-

latory process. Fisheries 32(8):390–397.

Birstein, V. J., W. E. Bemis, and J. R. Waldman.

1997. The threatened status of acipenseri-

form species: a summary. Environmental

Biology of Fishes 48:427–435.

Boreman, J. 1997. Sensitivity of North Ameri-

can sturgeons and paddlefi sh to fi shing

mortality. Environmental Biology of Fishes

48:399–405.

Boone, E. A., Jr., and T. J. Timmons. 1995. Den-

sity and natural mortality of paddlefi sh,

Polyodon spathula, in an unfi shed Cumber-

land River subimpoundment, South Cross

Creek Reservoir, Tennessee. Journal of

Freshwater Ecology 10:421–431.

Bronte, C. R., and D. W. Johnson. 1983. Occur-

rence of sport fi sh in a commercial net fi sh-

ery. North American Journal of Fisheries

Management 3:239–242.

Bronte, C. R., and D. W. Johnson. 1984. Evalu-

ation of the commercial entanglement-

gear fi shery in Lake Barkley and Kentucky

Lake, Kentucky. North American Journal of

Fisheries Management 4:75–83.

Bronte, C. R., and D. W. Johnson. 1985. Growth

of paddlefi sh in two mainstream reser-

voirs with reference to commercial harvest.

Transactions of the Kentucky Academy of

Science 46:28–31.

Bryan, P., and C. E. White, Jr. 1958. An economic

evaluation of the commercial fi shing in-

dustry in the T.V.A. lakes of Alabama dur-

ing 1956. Proceedings of the Annual Con-

ference Southeastern Association of Game

and Fish Commissioners 12:128–132.

Carlson, D. M., and P. S. Bonislawsky. 1981. The

paddlefi sh (Polyodon spathula) fi sheries of

the Midwestern United States. Fisheries

6(2):17–27.

Carrol, B. B., G. E. Hall, and R. D. Bishop. 1963.

Three seasons of rough fi sh removal at Nor-

ris Reservoir, Tennessee. Transactions of the

American Fisheries Society 92:356–364.

CITES (Convention on International Trade in

Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and

Flora). 2000. Acipenseriformes. Document

AC. 16.7.2. Sixteenth meeting of the CITES

animals committee. Convention on Inter-

national Trade in Endangered Species of

Wild Fauna and Flora, Shepardstown, West

Virginia.

Coker, R. E. 1923. Methuselah of the Mississip-

pi. Scientifi c Monthly 16:89–103.

Colombo, R. E., J. E. Garvey, N. D. Jackson,

R. Brooks, D. P. Herzog, R. A. Hrabik,

and T. W. Spier. 2007. Harvest of Missis-

sippi River sturgeon drives abundance

and reproductive success: a harbinger of

collapse? Journal of Applied Ichthyology

23:444–451.

Combs, D. L. 1982. Angler exploitation of pad-

dlefi sh in the Neosho River, Oklahoma.

216 QUINN

North American Journal of Fisheries Man-

agement 4:334–342.

Conover, G. A., and J. M. Grady. 2000. Mis-

sissippi River basin paddlefi sh research

coded-wire tagging project 1998 annual

report. Mississippi Interstate Cooperative

Resource Association, Bettendorf, Iowa.

Filipek, S. 1990. Arkansas paddlefi sh investiga-

tions. Arkansas Game and Fish Commis-

sion, Little Rock.

Francis, R. C., M. A. Hixon, M. E. Clarke, S. A.

Murawski, and S. Ralston. 2007. Ten com-

mandments for ecosystem-based fi sheries

scientists. Fisheries 32:217–233.

Funk, J. L., and J. W. Robinson. 1974. Changes

in the channel of the lower Missouri River

and effects on fi sh and wildlife. Missouri

Department of Conservation, Aquatic Se-

ries Number 11, Jefferson City.

Gengerke, T. W. 1978. Paddlefi sh investigations.

Iowa Conservation Commission, Project

2–255-R, Des Moines.

Gengerke, T. W. 1986. Distribution and abun-

dance. Pages 22–35 in J. G. Dillard, L. K.

Graham, and T. R. Russell, editors. The

paddlefi sh: status, management, and prop-

agation. American Fisheries Society, North

Central Division, Special Publication 7,

Bethesda, Maryland.

Goodyear, C. P. 2003. Spawning stock biomass

per recruit in fi sheries management: foun-

dation and current use. Pages 67–81 in S.

J. Smith, J. J. Hunt, and D. Rivard, editors.

Risk evaluation and biological reference

points for fi sheries management. Canadian

Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquat-

ic Sciences 120.

Grady, J., N. Utrup, and C. Bergthold. 2005. A

summary of the national paddlefi sh stock

assessment project 1995–2004. U.S. Fish

and Wildlife Service, Columbia, Missouri.

Graham, K. 1997. Contemporary status of the

North American paddlefi sh, Polyodon

spathula. Environmental Biology of Fishes

48:279–289.

Graham, K. 1988. Paddlefi sh management

plan. Missouri Department of Conserva-

tion, Columbia.

Hageman, J. R., D. C. Timpe, and R. D. Hoyt.

1986. The biology of the paddlefi sh in Lake

Cumberland, Kentucky. Proceedings of the

Annual Conference of the Southeastern

Association of Fish and Wildlife Agencies

40:237–248.

Henley, D., L. Frankland, S. Hale, C. O’Bara,

and T. Stefanavage. 2001a. The case for

multi-jurisdictional management of Ohio

River paddlefi sh. Proceedings of the An-

nual Conference Southeastern Association

of Fish and Wildlife Agencies 55:243–256.

Henley, D., L. Frankland, S. Hale, C. O’Bara,

and T. Stefanavage. 2001b. Paddlefi sh in

the Ohio River sub-basin: current status

and strategic plan for management. Ohio

River Fisheries Management Team, Final

Report 2001.1, Columbus.

Hilborn, R., and C. J. Walters. 1992. Quantita-

tive fi sheries stock assessment: choice,

dynamics, and uncertainty. Chapman and

Hall, New York.

Hoffnagle, T. L., and T. J. Timmons. 1989. Age,

growth, and catch analysis of the com-

mercially exploited paddlefi sh population

in Kentucky, Lake, Kentucky–Tennessee.

North American Journal of Fisheries Man-

agement 9:316–326.

Houser, A. 1965. Growth of paddlefi sh in Fort

Gibson Reservoir, Oklahoma. Transactions

of the American Fisheries Society 94:91–93.

Hoxmeier, R. J. H., and D. R. DeVries. 1996. Sta-

tus of paddlefi sh in the Alabama waters of

the Tennessee River. North American Jour-

nal of Fisheries Management 16:935–938.

Hoxmeier, R. J. H., and D. R. DeVries. 1997.

Habitat use, diet, and population struc-

ture of adult and juvenile paddlefi sh in the

lower Alabama River. Transactions of the

American Fisheries Society 126:288–301.

Hussakof, L. 1911. The spoonbill fi shery of

the lower Mississippi. Transactions of the

American Fisheries Society 40:245–248.

Jenkins, G., T. Forsythe, J. Conder, and C. Bronte.

1982. Size selectivity and effects on game-

fi sh populations of entanglement gear in

Lake Barkley, Energy Lake and Bard’s Lake.

Pages 80–90 in T. Crawford, M. Freeze, and

S. H. Newton, editors. Proceedings of the

11th Annual Meeting Inland Commercial

Fisheries Association. Inland Commercial

Fisheries Association, North Little Rock,

Arkansas.

Jennings, C. A., and S. J. Zigler. 2000. Ecology

and biology of paddlefi sh in North Ameri-

ca: historical perspectives, management ap-

217HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

proaches, and research priorities. Reviews

in Fish Biology and Fisheries 10:167–181.

Lambou, V. W. 1959. Fish populations of back-

water lakes in Louisiana. Transactions of

the American Fisheries Society 88:7–15.

Larimore, R. W. 1950. Gametogenesis of Polyo-

don spathula (Walbaum): a basis for regula-

tion of the fi shery. Copeia 116–124.

Leone, F. J., J. Stoeckel, and J. W. Quinn. 2005.

Population characteristics of paddlefi sh in

the Arkansas River, Arkansas: implications

for the management of an exploited fi sh-

ery. Arkansas Game and Fish Commission,

Little Rock.

Maceina, M. J. and D. L. Pereira. 2007. Recruit-

ment. Pages 121–185 in C. S. Guy and M.

L. Brown, editors. Analysis and interpreta-

tion of freshwater fi sheries data. American

Fisheries Society, Bethesda, Maryland.

McDougal, P. T. 2005. Commercially wild-

caught sturgeons and paddlefi sh: United

States and Caspian Sea regions. Monterey

Bay Aquarium, Seafood Watch, Monterey,

California.

Mestl, G., K., K. Kopf, J. Grady, J. Sorenson,

L. Miller, T. Yasger, and T. Mosher. 2005.

Paddlefi sh in the lower Missouri River

sub-basin, South Dakota, Nebraska, Iowa,

Kansas, and Missouri. Mississippi Inter-

state Cooperative Resource Association,

Lower Missouri River Management Team,

Marion, Illinois.

Mosher, T. D. 1998. Sturgeon and paddlefi sh

sportfi shing in North America. Pages 42–50

in D. G. Williamson, G. W. Benz, and C. M.

Hoover, editors. Proceedings of the sym-

posium on the harvest, trade, and conser-

vation of North American paddlefi sh and

sturgeon. TRAFFIC North America, Wash-

ington, D.C.

Onders, R. J., S. D. Mims, C. Wang, and W. D.

Pearson. 2001. Reservoir ranching of pad-

dlefi sh. North American Journal of Aqua-

culture 63:179–190.

Pasch, R. W., P. A. Hackney, and J. A. Holbrook

II. 1978. Ecology of paddlefi sh, Polyodon

spathula (Walbaum), in Old Hickory Reser-

voir, Tennessee, with emphasis on fi rst year

life history and the effects of impingement

at Gallatin Steam Plant on the population.

Tennessee Valley Authority, Norris.

Pasch, R. W., P. A. Hackney, and J. A. Holbrook,

I. I. 1980. Ecology of paddlefi sh in Old Hick-

ory Reservoir, Tennessee, with emphasis

on fi rst-year life history. Transactions of the

American Fisheries Society 109:157–167.

Pasch, R. W., and C. M. Alexander. 1986. Pages

46–53 in J. G. Dillard, L. K. Graham, and T.

R. Russell, editors. The paddlefi sh: status,

management and propagation. American

Fisheries Society, North Central Division,

Special Publication 7, Bethesda, Maryland.

Paukert, C. P., and W. L. Fisher. 1999. Evalua-

tion of paddlefi sh length distributions and

catch rates in three mesh sizes of gill nets.

North American Journal of Fisheries Man-

agement 19:599–603.

Paukert, C. P., and W. L. Fisher. 2001. Charac-

teristics of paddlefi sh in a southwestern

U.S. reservoir, with comparisons of lentic

and lotic populations. Transactions of the

American Fisheries Society 130:634–643.

Pikitch, E. K., P. Doukakis, L. Lauck, P.

Chakrabarty, and D. E. Erickson. 2005. Sta-

tus, trends, and management of sturgeon

and paddlefi sh fi sheries. Fish and Fisheries

6:233–265.

Posey B., 2006. A report of the commercial roe

harvest in Arkansas: November 2005–May

2006. Arkansas Game and Fish Commis-

sion, unpublished report, Little Rock.

Purkett, C. A. 1963. The paddlefi sh fi shery of

the Osage River and the Lake of the Ozarks,

Missouri Transactions of the American

Fisheries Society 92:239–244.

Quinn, J. W., R. L. Limbird, F. J. Leone, G. Krae-

mers, T. R. Bly, and C. A. Perrin. 2006.

Ozark Pool paddlefi sh population evalua-

tion: 2004 report. Arkansas Game and Fish

Commission, Little Rock.

Quinn, J. W. and R. L. Limbird. 2008. Trends

over time for the Arkansas River fi shery:

a case history. Pages 169–191 in M. S. Al-

len, S. Sammons, and M. J. Maceina, edi-

tors. Balancing fi sheries management and

water uses for impounded river systems.

American Fisheries Society Symposium 62,

Bethesda, Maryland.

Quinn, J. W., W. R. Posey, F. J. Leone, and R. L.

Limbird. 2009. Management of the Arkan-

sas River commercial paddlefi sh fi

shery

with check stations and special seasons.

Pages 261–275 in C. Paukert and G. D.

Scholten, editors. Paddlefi sh management,

218 QUINN

propagation, and conservation in the 21st

century: building from 20 years of research

and management. American Fisheries Soci-

ety, Symposium 66, Bethesda, Maryland.

Quist, M. C., M. J. Steuck, and M. M. Marron.

2009. Commercial harvest of paddlefi sh in

the upper Mississippi River. Pages 345–355

in C. Paukert and G. D. Scholten, editors.

Paddlefi sh management, propagation, and

conservation in the 21st century: building

from 20 years of research and management.

American Fisheries Society, Symposium 66,

Bethesda, Maryland.

Rieman, B. E., and R. C. Beamesderfer. 1990.

White sturgeon in the lower Columbia

River: is the stock overexploited? North

American Journal of Fisheries Manage-

ment 10:388–396.

Rosen, R. A., D. C. Hales, and D. G. Unkenholz.

1982. Biology and exploitation of paddle-

fi sh in the Missouri River below Gavins

Point Dam. Transactions of the American

Fisheries Society 111:216–222.

Ryckman, F. 2003. New rules: adjusting to a de-

clining paddlefi sh population. North Da-

kota Outdoors (April–May ):7–8.

Scarnecchia, D. L., L. F. Ryckman, Y. Lim, G. J.

Power, B. J. Schmitz, and J. A. Firehammer.

2007. Life history and the costs of reproduc-

tion in northern Great Plains paddlefi sh

(Polyodon spathula) as a potential frame-

work for other Acipenseriform fi shes. Re-

views in Fisheries Science 15:211–263.

Scholten, G. D., and P. W. Bettoli. 2005. Popu-

lation characteristics and assessment of

overfi shing for an exploited paddlefi sh

population in the lower Tennessee River.

Transactions of the American Fisheries So-

ciety 134:1285–1298.

Scholten, G. D. 2009. Management of com-

mercial paddlefi sh fi sheries in the United

States. Pages 291–306 in C. Paukert and G.

D. Scholten, editors. Paddlefi sh manage-

ment, propagation, and conservation in

the 21st century: building from 20 years

of research and management. American

Fisheries Society, Symposium 66, Bethesda,

Maryland.

Sheehan, R. J., and J. L. Rasmussen. 1999. Large

Rivers. Pages 529–559 in C. C. Kohler and

W. A. Hubert, editors. Inland fi sheries

management in North America, 2nd edi-

tion. American Fisheries Society, Bethesda,

Maryland.

Sissenwine, M. P., and A. A. Rosenberg. 1993.

Marine fi sheries at a critical juncture. Fish-

eries 18:6–14.

Slipke, J. W., A. D. Martin, J. Pitlo, Jr., and M.

J. Maceina. 2002. Use of the spawning po-

tential ratio for the upper Mississippi River

channel catfi sh fi shery. North American

Journal of Fisheries Management 22:1295–

1300.

Stockard, C. R. 1907. Observations on the natu-

ral history of Polyodon spathula. American

Naturalist 12:753–766.

Tarzwell, C. M., and P. Bryan. 1945. Changes in

the commercial fi shery on the Tennessee

River. Journal of the Tennessee Academy of

Science 20:49–54.

Thomas, J. A., E. B. Emery, and F. H. McCor-

mick. 2005. Detection of temporal trends

in Ohio River fi sh assemblages based on

lockchamber surveys (1957–2001). Pages

431–449 in J. N. Rinne, R. M. Hughes, and

B. Calamusso, editors. Historical changes

in large river fi sh assemblages of the Amer-

icas. American Fisheries Society, Sympo-

sium 45, Bethesda, Maryland.

Timmons, T. J., and T. A. Hughbanks. 2000. Ex-

ploitation and mortality of paddlefi sh in

the lower Tennessee River and Cumber-

land rivers. Transactions of the American

Fisheries Society 129:1171–1180.

Todd, R. M. 1998. Sturgeon and paddlefi sh com-

mercial fi shery in North America. Pages

42–50 in D. G. Williamson, G. W. Benz, and

C. M. Hoover, editors. Proceedings of the

symposium on the harvest, trade, and con-

servation of North American paddlefi sh

and sturgeon. TRAFFIC North America,

Washington, D.C.

Voigtlander, C. W., and W. L. Poppe. 1989. The

Tennessee River. Pages 372–384 in D. P.

Dodge, editor. Proceedings of the Interna-

tional Large River Symposium. Canadian

Special Publication of Fisheries and Aquat-

ic Sciences 106.

Williamson, D. F. 2003. Caviar and conservation.

Status, management, and trade of North

American sturgeon and paddlefi sh. TRAF-

FIC North America, Washington, D.C.

219HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

Appendix 1. Harvest, exploitation (u), and roe harvest of paddlefi sh from select sport and commercial fi sheries in North American

waterbodies. Mean harvest is provided where multiple years are listed. Type of fi shery included commercial (C) and sport (S).

Mean Roe

Drainage and Area Harvest Harvest weight Harvest Harvest harvest

Waterbody or state Years(s) Type (ha) (fi sh) (kg) (kg) (fi sh/ha) (kg/ha) u (kg)

Arkansas River

Ozark Lake

1

* 2004 C 4,291 1,075 15,910 14.8 0.25 3.71 19% 1,473

Ozark Lake (5 d)

1

* 2006 C 4,291 1,065 16,934 15.9 0.25 3.95 25% 2,048

Ozark Lake (150 d)

1

* 2006 C 4,291 2,260 35,934 15.9 0.53 8.37 4,326

Pool 13

1

* 2003 C 2,308 1,588 23,026 14.5 0.69 9.98 714

Pool 13

1

* 2006 C 2,308 2,453 35,569 14.5 1.06 15.40 35% 2,030

Lake Dardanelle

2

2003–2006 C 13,887 1,041 15,615** 0.07 1.12 3,365

Neosho River

3

1979–1980 S 22,000 3,008 57,011 19.0 0.14 2.71 17%

Fort Gibson Lake

4

1957–1960 C 8,900 370 0.04

Clinch River

Norris Reservoir

5

*** 1959 C 13,840 781 20,256 25.9 0.06 1.46

Norris Reservoir

5

1960 C 13,840 233 5,684 24.0 0.02 0.41

Norris Reservoir

5

1961 C 13,840 63 1,038 22.2 0.01 0.08

Norris Reservoir

5

1959–1961 C 13,840 359 8,993 22.2 0.03 0.65

Cumberland River

Bards Lake

6

*** 1980 C 129 653 5,602 8.5 5.06 43.43 0

Old Hickory Reservoir

7

1977 C 9,100 630 2,835 4.5 0.07 0.31

Old Hickory Reservoir

8

1999–2006 C 9,100 66 0.01 8

Cheatham Reservoir

8

1999–2006 C 3,015 174 0.06

Energy Lake

6

*** 1980 C 150 495 4,883 9.9 4.07 32.55 0

Lake Cumberland

9

1983–84 C 20,336 3,566 37,764 10.5 0.18 1.86 ~12%

Barkley Lake, KY

10

1979 C 18,960 7,015 62,000 8.8 0.37 3.27

Barkley Lake, KY

10

1980 C 18,960 3,685 21,500 5.8 0.19 1.13

Barkley Lake KY, TN

11

1991–1994 B 23,400 3,597** 37,764 10.5 0.18 1.61 14%

Barkley Lake, TN

8

1999–2006 C 7,407 150 0.02

Barkley Dam

tailwater

12

1979 S 2,276 6,828 3.0

Mississippi River

AR

2

2003–2006 C 40,740 2,143 24,430** 0.05 0.60 1,656

IL

13

1999–01 C 1,914** 21,828 503

KY

13

1999–01 C 270** 3,080 779

MO

13

1999–01 C 543** 6,195

MO, open river

14

2003–2005 C ~55,000 465 5,305 0.01 0.10 647

Pool 13, IA

12

1976 S 10,918 1,320 7,920 6 0.12 0.73

220 QUINN

Appendix 1. Continued.

Mean Roe

Drainage and Area Harvest Harvest weight Harvest Harvest harvest

Waterbody or state Year(s) Type (ha) (fi sh) (kg) (kg) (fi sh/ha) (kg/ha) u (kg)

Pool 13, IA

15

1975–1977 C 10,918 760** 8,812 0.81 4–12%

Pool 24, MO

14

2003–2005 C 4,472 102 1,163** 0.02 0.26 3

Pool 26, MO

14

2003–2005 C 6,490 849 9,679** 0.13 1.49 85

TN

8

1999–2006 C 40,150 1,504 0.04 2,948

Reelfoot Lake

8

2002–2006 C 4,220 56 0.01

Missouri River

Unchannelized

reach

16, 12

1972–1974 B 3,294 19,764** 6 7%

Yellowstone/Missouri

17

1973–1974 S 156,000 4,452 42,000 18 0.03 0.27 8%

Ohio River

KY, IL, IN

18, 19

1999 C 67,178 11,711 63,827 5.5 0.174 0.95 2,733

KY, IL, IN

18, 19

2000 C 67,178 29,194 159,109 5.5 0.582 2.37 10,071

Osage River

Lake of the Ozarks

20

1958–61 S 22,275 5,822 79,569 14.0 0.26 3.57 19%

Lake of the Ozarks

21

1978–1988 S 22,275 2,809 48,315 17.2 0.13 2.17

Harry S. Truman

Lake

22

1992 S 22,000 4,041 0.18

Ouachita River, AR

2

2003–06 C 3,225 325 3,705** 0.10 1.15 486

Tennessee River

Wilson Reservoir

23

*** 1942 C 6,475 324,000 42.03

AL

23

*** 1942–52 C 80,664 267,302 3.31

Cherokee

8

1999–2002 C 12,262 98 0.01

Chickamauga

8

2000–2006 C 13,962 356 0.03 300

Guntersville

8

2003–2006 C 468 8 0.02

Kentucky Lake

8

1999–2006 C 43,784 7,460 0.17 4,593

Kentucky Dam

tailwater

12

1978 S ~1,450 102,837 308,511 3.0 70.9 212.8

Kentucky Dam

tailwater

12

1979 S ~1,450 15,050 45,150 3.0 10.4 10.4

Kentucky Dam

tailwater

8

2006 S ~1,450 1,788 1.2

Pickwick Lake

8

1999–2006 C 2,492 35 0.02 11

Watts Bar

8

2001–2006 C 15,783 63 <0.01 46

White River

221HARVEST OF PADDLEFISH

Appendix 1. Continued.

Mean Roe

Drainage and Area Harvest Harvest weight Harvest Harvest harvest

Waterbody or state Years(s) Type (ha) (fi sh) (kg) (kg) (fi sh/ha) (kg/ha) u (kg)

Black River, AR

2

2003–06 C 162 234

Table Rock Lake

21

1990 S 17,400 350 0.02

Lower White River

24

1987–1988 C ~8,148 108,818 13.3 19–31% Lower

White River

2

2003–06 C ~8,148 1,743 19,870 0.21 2.4 1,642

1

Quinn et al. 2009;

2

Posey 2006;

3

Combs 1982;

4

Houser 1965 ;

5

Carrol et al. 1963;

6

Jenkins et al. 1982;

7

Pasch et al. 1980;

8

Tennes-

see Wildlife Resources Agency, unpublished data;

9

Hageman et al. 1986;

10

Alexander and Peterson 1982;

11

Timmons and Hughbanks

2000;

12

Carlson and Bonislawsky 1981;

13

Williamson 2003;

14

Missouri Department of Conservation, unpublished data;

15

Gengerke 1978, Pool

12 tailwater;

16

Rosen et al. 1982, reach below Gavins Point Dam;

17

Rehwinkle 1978, Lake Sakakawea stock;

18

Henley et al. 2001b;

19

Henley

et al. 2001a;

20

Purkett 1963;

21

Graham 1988;

22

Graham 1997;

23

Guntersville, Pickwick, and Wheeler reservoirs, Pasch and Alexander 1986;

24

Robison and Buchanan 1988, Filipek 1990; *First year harvest after the fi shery was closed; **Estimated using an assumed mean weight;

***Documented overharvest.