Appendix S: Curatorial Care of Objects Made From

Leather and Skin Products

Page

A. Overview ................................................................................................................................................S:1

What information will I find in this appendix?.........................................................................................S:1

Why is it important for me to practice preventive conservation with these objects? ............................S:1

How can I find the latest information on care of these types of materials? ..........................................S:1

B. The Nature of Leather and Skin Products.........................................................................................S:2

What is the structure of skin?.................................................................................................................S:2

How is animal skin processed?..............................................................................................................S:3

How do I recognize different species?...................................................................................................S:3

C. Agents of Deterioration .......................................................................................................................S:7

What is the threat of biological infestation? ...........................................................................................S:7

How do I prevent pest problems? ..........................................................................................................S:8

What about the loss of hair and fur?......................................................................................................S:8

How can I stop hair and fur loss?...........................................................................................................S:9

What is the threat of thermal reaction?..................................................................................................S:9

How can I minimize the threat of thermal reactions? ............................................................................S:9

What about water and moisture damage?.............................................................................................S:10

What are the measures for limiting water and moisture damage? .......................................................S:10

What is the threat of prolonged exposure to oxygen?...........................................................................S:11

How can I minimize these oxidation reactions? ....................................................................................S:11

What about pollutants?...........................................................................................................................S:11

How can I minimize the effects of pollutants? .......................................................................................S:11

What harm can light cause?...................................................................................................................S:11

How can I minimize the effects of light? ................................................................................................S:12

D. Preventive Conservation: Guidelines for Leather and Skin Object

Care, Handling, and Storage...............................................................................................................S:12

How do I provide a stable and appropriate humidity? ...........................................................................S:13

How do I monitor the condition of objects?............................................................................................S:13

How do I clean

objects? .........................................................................................................................S:13

How do I handle skin and hide materials?.............................................................................................S:14

What about catalog labeling?.................................................................................................................S:14

How do I provide adequate physical support for objects? ....................................................................S:16

How do I store objects properly?............................................................................................................S:16

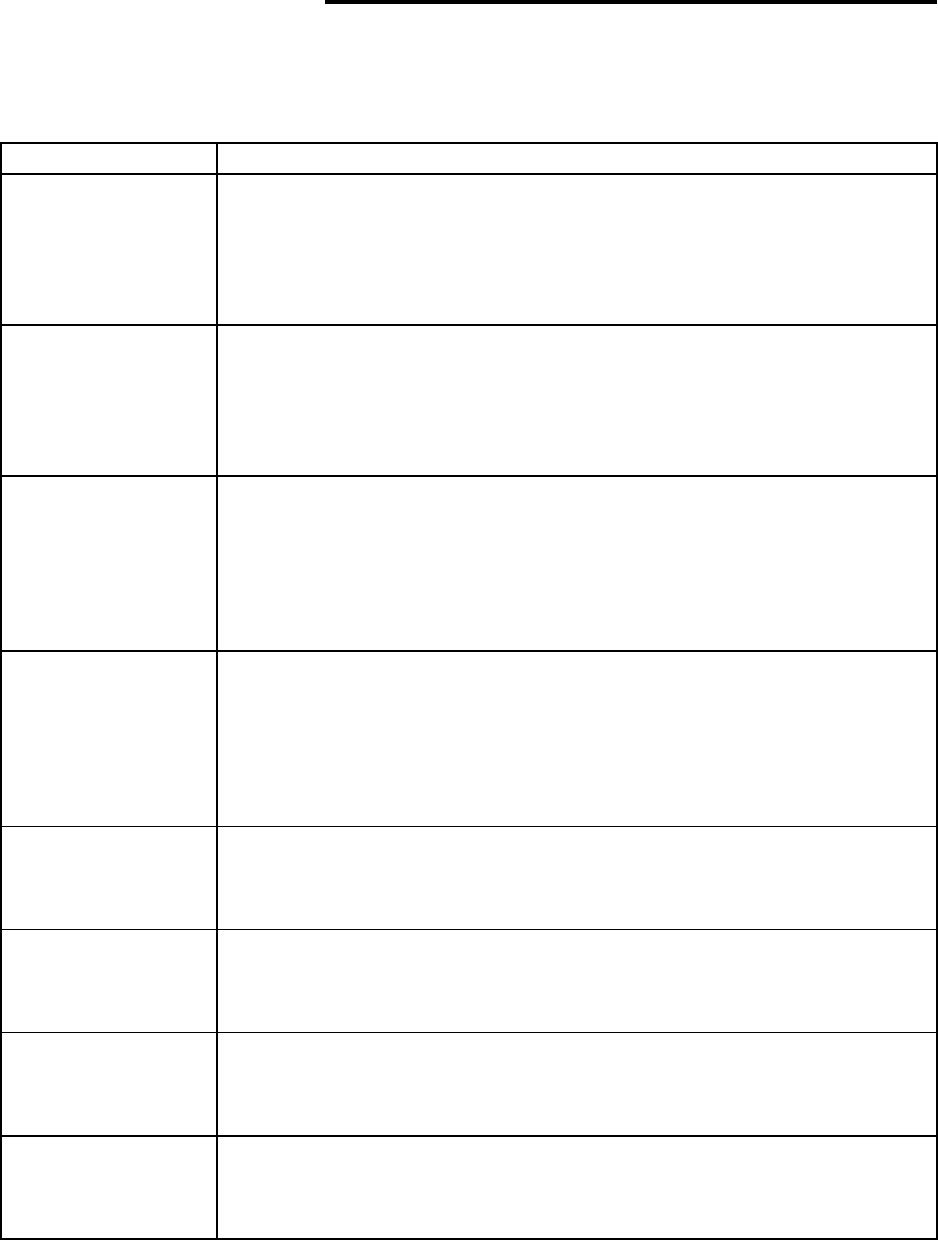

E. Summary: Leather and Skin Product Deterioration and Preventive Care...................................S:19

F. Conservation Treatment Issues .........................................................................................................S:20

What are the perils of saddle soap? ......................................................................................................S:20

What are the drawbacks of leather dressings? .....................................................................................S:20

What about neutralization of acids?.......................................................................................................S:21

G. Selected Bibliography..........................................................................................................................S:22

List of Figures

Figure S.1 The Structure of Skin...........................................................................................................S:2

Figure S.2 Degrees and Types of Tannage .........................................................................................S:3

3

4

5

6

7

Figure S. Characteristics of Leather and Skin Products ....................................................................S:4

Figure S. Thickness of Skins and Hides.............................................................................................S:5

Figure S. Cleaning Techniques for Leather and Skin Objects in Good Condition............................S:15

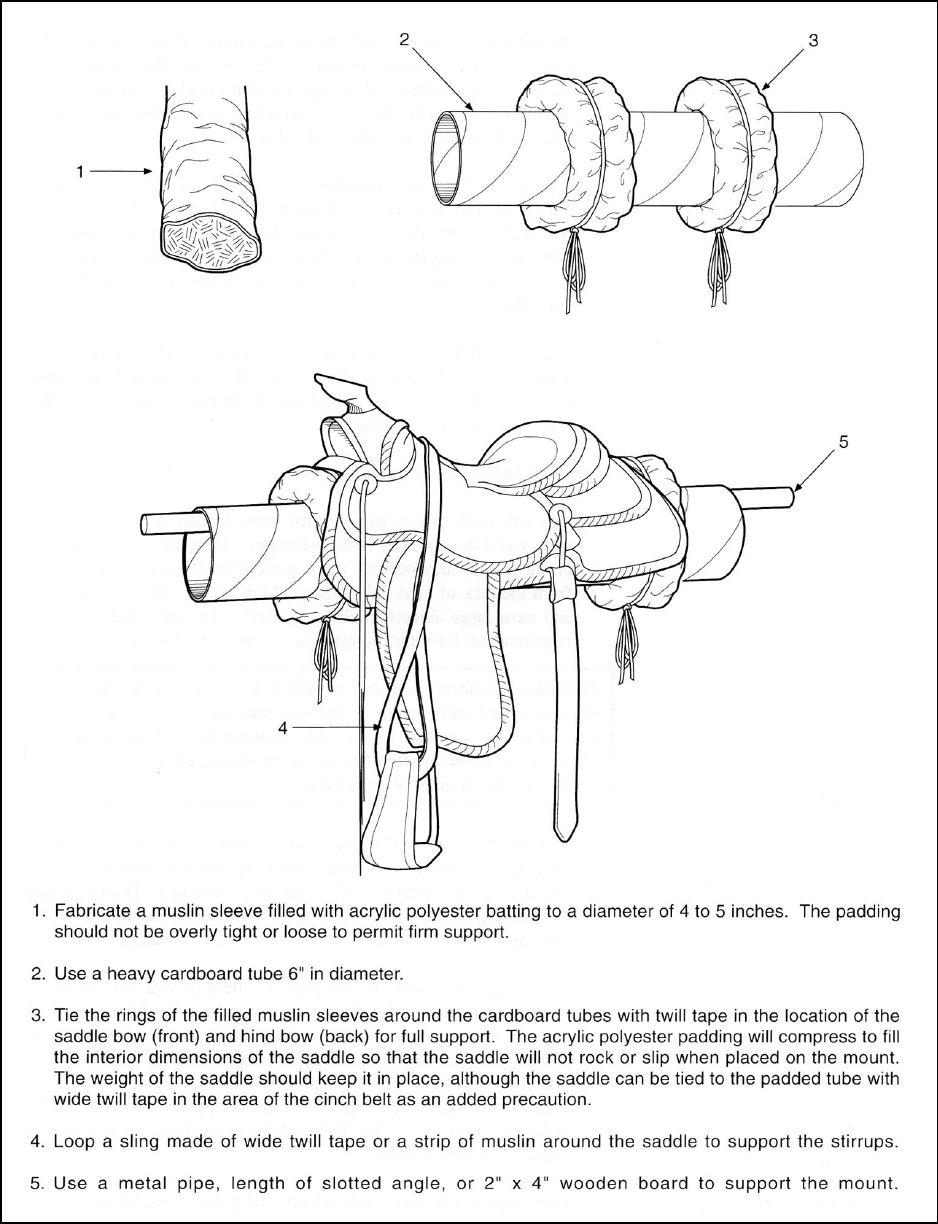

Figure S. Constructing a Saddlemount...............................................................................................S:18

Figure S. Leather and Skin Product Deterioration and Preventive Care...........................................S:19

A. APPENDIX S: CURATORIAL CARE OF OBJECTS MADE FROM LEATHER AND SKIN

PRODUCTS

B. Overview

1. What information will I find

in this appendix?

2. Why is it important for me to

practice preventive

conservation with these

objects?

You will find the National Park Service's present understanding of objects

made of leather and skin products. You also will learn about preventive

care for these objects including:

• agents of deterioration posing the greatest threat to these objects

• measures for preventing or minimizing the impact of these agents

• techniques for handling, marking, and cleaning these objects

• methods and techniques for improving storage and exhibit conditions

• methods for monitoring the condition of these objects

Advancements in the treatment of leather and skin products have not kept

pace with the progress made in conserving other kinds of museum objects.

The conservation field only can offer limited solutions to the problems

facing objects made of leather and skin. Conservators and the scientific

community have begun to focus more specifically on developing new

treatment strategies for the preservation of leather and skin. While new

information is provided as it becomes available, you need to practice sound

preventive conservation now because:

• preventive measures stabilize objects and leave opportunity for

appropriate future interventive treatments

• conservators can only offer limited treatment solutions

Conservators discourage traditional interventive treatments, such as the

application of saddle soaps and dressings. Avoid interventive conservation

treatment of leather and skin objects whenever possible.

See NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (MH-I), Chapter 3, Museum

Objects Preservation: Getting Started, for a discussion of preventive

conservation and conservation treatment.

3. How can I find the latest Refer to the following sources for new information and techniques:

information on care of these

types of materials?

• NPS Conserve O Gram series

• e-mail NPS Museum Management Newsletter

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:1

C. The Nature of Leather and

Skin Products

The skins and hides from vertebrates constitute the class of natural materials

called skin products. Leather is one type of skin product that is produced by

a particular tanning process. Processed and unprocessed animal skins have

supplied the basic fabric for making utilitarian and decorative objects since

prehistoric times. You will often find these materials in art, history,

ethnology, and science collections.

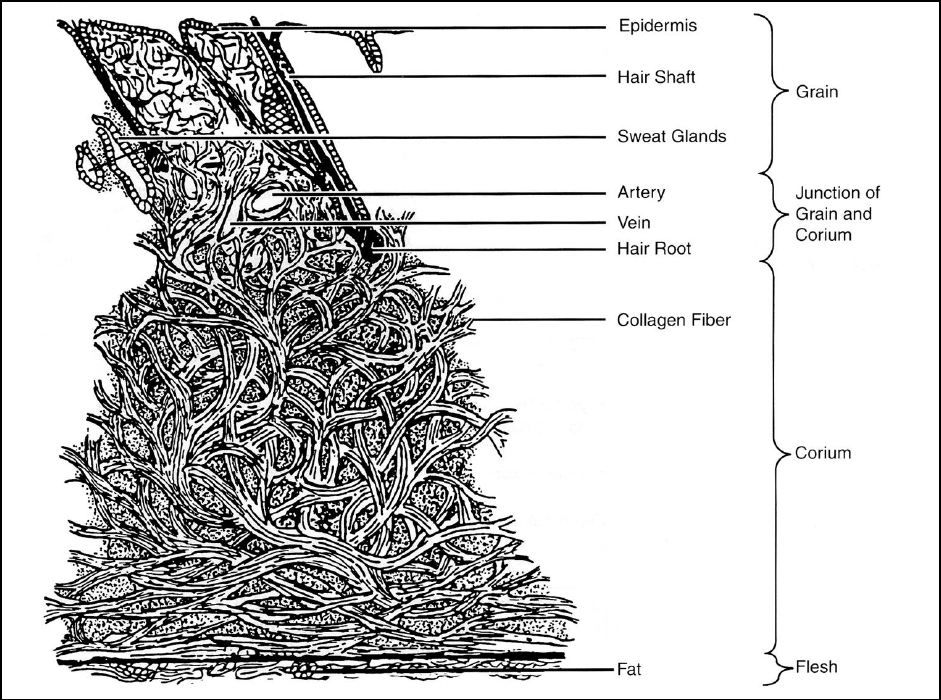

1. What is the structure of Animal skin is a fibrous layer of living tissue that protects an organism from

skin? the elements. Figure S.1 illustrates its structure.

Figure S.1. The Structure of Skin

Once removed, an unadulterated skin is a proteinaceous sheet containing

hair, sweat glands, fat and blood vessels, as well as its basic constituent

of collagen fibers. These protein fibers are composed of coil-like

molecules built of tiny fibrous strands that are twisted together, then

aligned side by side overlapping one another, much like cotton fibers are

arranged in a textile yarn. (To prevent separation of the cotton fibers the

yarn is twisted during manufacture to produce a strong and usable

thread.)

2. How is animal skin Animal skin can be tanned and untanned. Examples of untanned skin

S:2 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

processed? include rawhide, parchment, and vellum. Stable skin is processed by

chemically binding fibers together, commonly referred to as tanning. The

amount and type of bonding that occurs within a skin establishes its

"degree of tannage." The term "leather" refers technically only to the

fully tanned skin products. Figure S.2 describes degrees and types of

tannage of most skin and leather objects in park collections.

Un-tanned Semi-tanned Native-tanned Fully-tanned

rawhide oil tannage smoke tannage vegetable tannage

parchment alum tannage brain tannage mineral tannage

vellum

oil tannage combination

tannage

3. How do I recognize different

species?

Figure S.2. Degrees and Types of Tannage

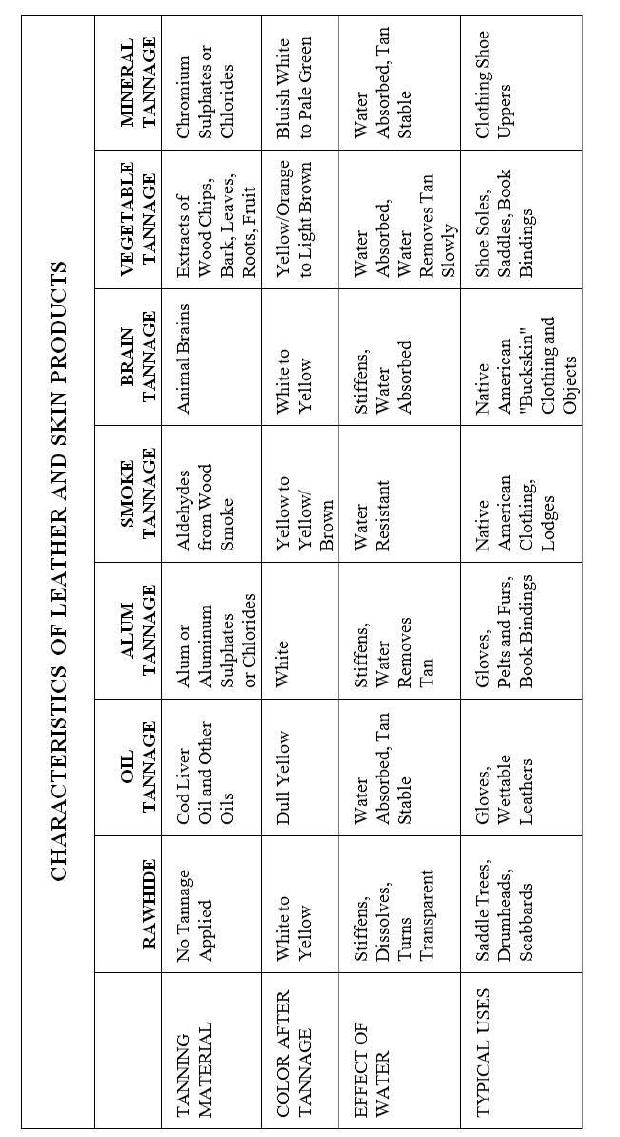

People have preserved or “tanned” skin products in many ways to render

them strong, insoluble, and more resistant to temperature and moisture.

Nearly all of the methods of skin processing techniques used by skin and

leather workers throughout the ages achieve some degree of tannage. Many

of these procedures rely on mechanical properties more heavily than

chemical tanning, such as the softening that results from introducing oils.

Unfortunately, determining an object's original manufacture requires

considerable study. While laboratory treatments vary for different types of

skins and leathers, preventive conservation procedures are similar for most

of these materials. Your familiarity with the general skin processing

categories can be very useful since these methods are responsible for many

of the object's functional characteristics. See Figure S.3 for physical

characteristics of these products.

The skin or hide of each animal species is recognizable by its physical

characteristics. The principle variations among animal types are the size,

density, and distribution of the animal’s hair, which gives rise to a

distinctive grain pattern.

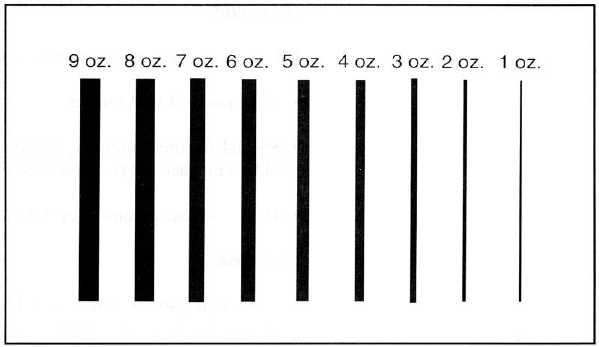

The relative thickness of hide and skin products is traditionally measured in

“ounces.” Each ounce represents 1/64 of an inch. The black solid lines in

Figure S.4. represent the thickness of leather being measured.

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:3

Figure S.3. Characteristics of Leather and Skin Products

S:4 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

C

HARA

CTERISTICS OF

LE

A

THER

AND SKIN

PR

O

DU

CTS

O

IL

ALUM

SM

OKE

BRAIN

VE

G

ETABLE

MINERAL

RAWHIDE

T

ANN

AGE

T

AN

N

AG

E T

AN

NA

GE

TANN

A

GE

TANN

AG

E T

ANNAG

E

TANNING No Tannage

CodLiver

Alumor

Aldehydes Animal Brains Extracts

of

Chromium

MATERIAL Applied Oil

and

Other Aluminum

fromWood

WoodChips, Sulphates

or

Oils Sulphates Smoke Bark, Leaves, Chlorides

or

Chlorides Roots,

Fruit

COLORAFTER

White to

Dull Yellow

White

Yellowto

Whiteto

Yellow/Orange

Bluish

White

TANNAGE

Yellow Yellow/ Yellow

to

Light Brown

to

Pale

Green

Brown

EFFECTOF

Stiffens,

Water

Stiffens, Water Stiffens, Water Water

WATER Dissolves, Absorbed,

Tan

Water Resistant

Water

Absorbed, Absorbe,d, Tan

Turns Stable Removes Absorbed Water Stable

Transparent

Tan

RemovesTan

Slowly

TYPICAL USES

Saddle Trees, Gloves, Gloves,

Native

Native Shoe Soles, Clothing Shoe

Drumheads, Wettable

Pelts

and

Furs, American American Saddles, Book Uppers

Scabbards Leathers Book Bindings Clothing, "Buckskin" Bindings

Lodges Clothing and

Objects

Figure S.4. Thickness of Skins and Hides

The characteristics and uses of common animal skins and hides are listed

below.

Cow Hide

• Grain/hair pattern: pebbly, pronounced with large, equidistant hair

spacing

• Thickness: 2 to 20 ounces

• Processing note: often split into several pieces

• Special feature: very durable, excellent for tooling and carving

• Uses: shoe soles, belting, trunks, clothing

Calf Skin

• Grain/hair pattern: same as cowhide only smaller

• Thickness: 1.5 to 4 ounces

• Special feature: greater uniformity and fineness than cowhide

• Uses: upholstery, shoe uppers, clothing, bookbindings

Bison Hide

• Grain/hair pattern: similar but less uniform than cattle

• Thickness: 5 to 20 ounces

• Special feature: loose-knit fibers on flesh side; very large hide size; stiff

hump between shoulders

• Uses: 19th century boots, sleigh blankets, Native American shields,

robes, clothing, tipis

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:5

Horse Hide

• Grain/hair pattern: resembles cow hide but less dense

• Thickness: 3 to 7 ounces

• Special feature: strength, texture and thickness are inferior to cow hide;

compact fibers, especially in butt region

• Uses: whips, aprons, base for enameled leathers, trunks

Deer Skin

• Grain/hair pattern: large follicles form definite single rows; closely

spaced fine hairs are similar to goat skin

• Thickness: 2 to 9 ounces

• Processing note: hairs are sometimes left on

• Special feature: loose structure (like sheep) results in a very stretchy

leather

• Uses: parchment, gloves, clothing; Native American clothing,

moccasins, containers

Sheep Skin

• Grain/hair pattern: linear groupings of large and small groups

• Thickness: 1.5 to 3 ounces

• Special feature: weaker, less durable skin (loose interweave of fibers);

loosened texture (fibers run parallel to skin surface)

• Uses: suede leathers, bookbindings, jackets, gloves, chamois

Goat Skin

• Grain/hair pattern: groupings of three coarser hair follicles with closely

spaced fine hair follicles

• Thickness: 2 to 3 ounces

• Special feature: close-knit collagen fibers; more durable and stronger

than sheep skin

• Uses: linings, billfolds, shoe uppers

Pig Skin

• Grain/hair pattern: very coarse hairs are sparsely distributed in groups of

three

• Thickness: 3 to 4 ounces

S:6 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

• Special feature: high fat cell content produces tough but spongy leather;

very rough surface; limited water resistance

• Uses: shoes, bags, gloves, pants

Exotic Leathers

Reptile

• Special feature: surface patterns distinguish reptile type: crocodile,

alligator, snake, or lizard

• Special feature: light, thin, grainless leathers often are made from bellies

Fish

• Special feature: structure is different from mammals but scales are

comparable to hair on mammals

Seal

• Special feature: proportionally stronger than other leather materials; fur

is left on for coats, fur is removed from base for enameled leather

D. Agents of Deterioration

The ways that skin products deteriorate can be identified and categorized.

The interdependency of these mechanisms cannot be overstated. For

example, temperature changes directly affect a skin or hide's moisture

content, the rate at which chemical deterioration proceeds, and the object's

susceptibility to biological infestation.

1. What is the threat of A great variety of biological organisms are attracted to skin and hide

biological infestation? products making these materials subject to quick and irreversible damage or

total destruction. For example, insects are frequently attracted to the oils

present in skin products as well as surface soils. Also, poorly cleaned

materials are particularly attractive as a nutrient material for insects and

microorganisms, as are all items made from rawhide.

Most insects prefer skin products made from fur and unborn animal skins.

The most frequent infestations involve dermestid beetles and clothes moths,

but other beetles and moths also attack skin and fur on occasion, as do

silverfish and cockroaches.

Insect development usually relies on higher levels of humidity and

temperature.

Since skin products are acidic in nature, microbic deterioration of skin

products is generally limited to molds and occasionally bacteria. This

deterioration is primarily due to environmental factors such as high

humidity (above 65% RH) and a wide temperature range (in most cases

10-40C [50-104F]). These organisms produce organic acids and

enzymes that bleach and stain the skin. Fungal growths are often

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:7

characterized by a white, gray, or green fuzzy appearance. These growths

occur most commonly on objects made from rawhide and on those skin

products that have become heavily soiled.

2. How do I prevent pest Here are some measures to prevent or minimize biological infestation:

problems?

• Monitor all areas of the museum continually and systematically to

identify insect and microbial problems at an early stage. Use insect

monitoring traps and routinely inspect objects for frass, nesting

materials and damage. See MH-I, Chapter 5, Biological Infestations,

for guidance on developing a museum Integrated Pest Management

(IPM) Program.

• Identify dead or living pests that you suspect of attacking skin objects.

• Develop a pest control program that includes a designated staff

coordinator, with guidelines for preventive and emergency measures.

Its focus should be pest control through good housekeeping and

modifying the environment.

• Minimize microbiological attack of skin products by keeping relative

humidity below 65% and by keeping areas clean.

• Never apply insecticides and fungicides directly to hide artifacts

because they can damage the objects, complicate long term

preservation, and contaminate the material for future handling and

study.

• Gaseous fumigation methods available for skin and hide materials are

few and require coordination by a conservator. In addition, contact the

park, center, or your IPM coordinator prior to pesticide use.

Technology is constantly changing and the coordinator will have access

to the latest and most appropriate solutions. Your IPM coordinator

must authorize and approve all pesticide use before application.

3. What about the loss of hair

and fur?

Non-toxic means of extermination such as freezing are preferable. See

NPS Conserve O Gram 3/6, An Insect Pest Control Procedure: The

Freezing Process, for guidance on the technique of freezing for

controlling pest infestations.

The loss of hair and fur from skins and hides not only devalues an object,

but also can destroy its potential usefulness. The causes of hair or fur loss

are complex and usually depend on the form and structure of the animal, the

hide's original processing techniques, and the environmental conditions to

which it has been subjected.

There are numerous types of hair loss:

• Epidermal slippage: hair is lost as the epidermal layer separates from

the dermal layer.

• Deterioration of the individual hair follicles: hair roots become loose

and hair falls out.

S:8 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

4. How can I stop hair and fur

loss?

5. What is the threat of thermal

reaction?

6. How can I minimize the

threat of thermal reactions?

• Hair shaft breakage: mechanical damage weakens the hair and it

breaks at its base.

• Biological attack: insects feed on the hair itself or epidermal layer,

resulting in the hair being severed.

You can't do much about hair loss that is due to insufficient fixing during

processing, but you can control many of the other causes, such as high

temperatures, low relative humidity, photochemical degradation, and insect

damage.

To limit the loss of hair and fur:

• Minimize the exposure of fur or hair products to lighting; illuminate

only to the minimum level necessary to see the object. Recommended

levels are 50 lux (5 footcandles) or less.

• Minimize handling.

• Stabilize the relative humidity and temperature to which hides with hair

and fur are exposed. Don't expose them to rapid changes of either

temperature or humidity and protect them from desiccation.

• Routinely inspect hair and fur products for insect damage. Remove

loose or broken hair by brushing and vacuuming, and store materials in

insect-proof containers such as metal museum storage cabinets with

door gaskets.

Skin and leather products are thermosensitive. Skin tissue has a heating

threshold, or point of thermal contraction, which is referred to as its

shrinkage temperature. For newly processed skins and hides, this point is

frequently between 60-75C (140-167F). However, the shrinkage

temperature of degraded hides of aged objects can be considerably lower.

Heating dries out, embrittles, and deforms skin and leather objects.

Changes in temperature also can destabilize relative humidity levels.

Exhibit lighting, direct sunlight, and proximity to heating registers and

radiators can easily damage leather and skin objects, which also become

more sensitive to heat as they age.

Elevated temperatures cause eventual damage not only by speeding up the

chemical deterioration processes, but by causing unstable fats and oils to

come to the surface where they often deposit as unsightly spews. Spews

(also spelled spues) are surface deposits of solidified fats and oils that exude

from the interior of the leather/skin material. They appear as a white

crystalline deposit or as a whitish bloom. Desiccation can also result from

over-heating.

Try these preventive measures to minimize thermal reaction:

• Safeguard skins from exposure to warm, moist air. The acceptable

minimum and maximum temperature levels are from just above

freezing to 20C (70F).

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:9

7. What about water and

moisture damage?

8. What are the measures for

limiting water and moisture

damage?

• Reduce the damaging effect of heat cycling by placing objects away

from external building walls, exterior doors and windows, exposed

pipes, heating and air conditioning vents, direct sunlight, exhibit

lighting sources, and locations such as hot attic spaces.

While skin materials have a great affinity for water, inappropriate levels of

atmospheric moisture or direct wetting usually cause serious damage. The

direct wetting of skin products initiates deterioration because these

materials have only a limited degree of water resistance. Rawhide,

parchment and vellum are most prone to damage. Aged objects made of

full-tanned leather are also highly susceptible to stiffening and darkening

from wetting.

All animal materials readily absorb moisture from the air. Excessive

moisture (levels above 65% RH) causes swelling of the skin's fibers and

encourages biological infestation. Excessive dehydration (humidity levels

below 22% RH) forces the skin to give up moisture permanently, which

results in shrinkage and deformity.

Dehydration reduces the skin's ability to take up and hold moisture, thus

weakening it and dramatically decreasing its flexibility. Repeated exposure

to moist and dry cycles will, eventually, physically stress the hide's fibers

enough to induce mechanical damage and increase its susceptibility to

chemical deterioration. The hide's soluble components are frequently

displaced, leached, or deposited on the surface resulting in the alteration of

physical characteristics.

When skin material is subjected to either excessive moisture or high

humidity in conjunction with heat and acid conditions, its chemical

structure is attacked, causing shrinkage and embrittlement. If allowed to

continue, the skin will lose its structure and become gelatinous. The boiling

of skin to produce gelatin or hide glue is an example of this process.

To minimize water and moisture damage:

• Keep hide materials dry by protecting them from wetting and exposure

to relative humidity levels above 65%. House objects in water-resistant

containers, such as storage cabinets and exhibit cases. Whenever

possible, include moisture absorbing materials to buffer enclosed

spaces against extreme fluctuation of RH. These materials may include

commercially-available buffers such as cotton or linen cloth, acid-free

paper products, or silica gel. See MH-I, Appendix I, Curatorial Care of

Archeological Objects, for a discussion of the use of silica gel.

• Control the relative humidity to conform to the recommended levels

suitable for the collection's circumstances. Stabilize humidity

fluctuation to the recommended range of 40-60% RH. Normally, you

will regulate humidity through the central air-handling system, but you

also can use localized and portable sources of humidification/

dehumidification to protect objects from unnecessary damage.

• If you discover mold on objects made of leather or skin, consult a

conservator regarding vacuum cleaning and disinfectant procedures.

S:10 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

9. What is the threat of

prolonged exposure to

oxygen?

10. How can I minimize these

oxidation reactions?

11. What about pollutants?

12. How can I minimize the

effects of pollutants?

13. What harm can light cause?

For organically-based materials like skin products, prolonged exposure to

oxygen is one of the more serious and avoidable chemical factors that

causes deterioration and is responsible for altering both the skin's chemical

structure and many of its tanning compounds.

Its long-term effects include the hardening of skin and hide material,

embrittlement, cracking and crazing of the skin surface and overall

yellowing or darkening as well as a number of serious internal structural

changes. Oxidative degradation is caused by high temperatures and

humidities and exposure to light radiation.

By taking the following preventive measures:

• While it is impractical to keep most of these materials from being

exposed to oxygen, if an object is extremely rare, consult with a

conservator about storage and display in a hermetically sealed container

filled with inert gas (such as nitrogen or helium).

• Don't expose hide materials to excessive humidity or heat. Use air

conditioning, storage design and exhibit design to eliminate the

detrimental effects of these environmental stimulants of oxidation.

• Reduce the level of visible light to the minimum required and eliminate

exposure to ultraviolet light.

The threatening forms of pollutants to skin products are particulate and

gaseous pollutants. Particulates are solids that are suspended in air and

range in composition from inorganic to organic. Because skin has such a

porous and absorbent surface, these solid foreign materials easily work their

way into the fibrous network of skin products causing soiling, staining, and

eventual stiffness.

Little data is available regarding the effect of gaseous pollutants on skin but

it is probable that oxidant, acidic and sulphating gases play some role in the

deterioration process. Native-tanned and semi-tanned materials seem

relatively more resistant than do commercial, vegetable-tanned leathers. It

is likely that pollutants promote oxidation, hydrolysis and overall

discoloration.

To minimize their effects:

• Modify the building's central air conditioning and filtering system.

Various filters can trap different size particles, and effectively remove

gaseous contaminates.

• Exhibit and store your objects in tightly sealed enclosures constructed

of the highest quality inert materials. Install specialized pollutant

absorbers with individual storage cabinets.

Light is an important factor in the process that degrades skin products. Its

damage is cumulative and irreversible.

Certain wavelengths break down polymeric bonds and are detrimental to all

skin materials. The ultraviolet range of light is one of the most dangerous

wavelengths for skin products; however, visible light also causes structural

damage and color change.

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:11

Light can act as a catalyst when oxygen, water vapor and various pollutants

in the atmosphere combine to increase the rate of deterioration. The rate of

degradation is generally related to the intensity and length of light exposure.

Fading of smoked and pigmented hides is a particular problem where

prolonged light exposure is involved.

14. How can I minimize the Take these preventive measures:

effects of light?

• Minimize the exposure of skin materials to visible light; illuminate only

to the minimum level necessary to see the object. Recommended

maximum levels are 150 lux (15 footcandles) for most materials and 50

lux (5 footcandles) for painted skins and hides with fur.

• Eliminate ultraviolet (UV) radiation through the use of UV absorbing

filters installed between the light source and the artifact or on the light

source itself. Select lighting systems with low proportions of UV

radiation. The maximum acceptable proportion of UV radiation is 75

microwatts per lumen.

• Maintain stored objects in darkness. Ensure that unfiltered light does

not reach stored skin and hide materials.

• Monitor and adjust lighting fixture locations and light bulb wattage

individually. Use timers and dimmers for controlling light in exhibits.

E. Preventive Conservation:

Guidelines for Leather

and Skin Object Care,

Handling, and Storage

See MH-I, Chapter 4, The Museum Environment, for general guidance

on temperature, relative humidity, light, and pollution.

The most successful method of preserving leather and skin products is a

good preventive conservation program. This program needs to include

systematic collection care, handling and storage practices, and regular

inspection and condition evaluation. This approach replaces the traditional

practices and remedies of the past that have been found to be detrimental to

museum objects.

For longer life of skin and leather objects follow these general guidelines:

• Identify the general category of the skin product correctly.

• Understand the product's basic characteristics, as well as its

deterioration features.

• Upgrade the general environment that includes controlling climatic

conditions, minimizing light exposure, providing physical support, and

protecting from mishandling, soil accumulation, and pest infestation.

S:12 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

1. How do I provide a stable

and appropriate humidity?

2. How do I monitor the

condition of objects?

3. How do I clean objects?

• Inspect, evaluate, monitor, and document an object's condition,

periodically; record the urgency for conservation treatment.

• Provide specialist care for those objects requiring complex or

considerable conservation treatment.

And follow these specific guidelines:

Use enclosures such as exhibit cases or storage cabinets to stabilize

humidity and reduce handling, soil accumulation, and attack from

microorganisms and insects.

Set relative humidity to an acceptable range: less than 5% RH change

within a 24-hour period and an annual change of no more than ±8%

fluctuation from the set point.

Humidity parameters are frequently 40%-60% RH; however, the specific

set points will vary according to:

• climatic considerations

• an object's state of deterioration

• your facility's air handling capability

• requirements of any composite and associated materials present

• the relative humidity with which the object has reached equilibrium

Inspect objects for deterioration regularly. If you do not regularly evaluate

and document their state of degradation, deterioration of leather and skin

objects can go undetected and unchecked. Evaluate the condition of objects

thoroughly when they are acquired. Then, inspect the objects periodically

to identify progressive damage, such as lengthening of tears, increases in

surface or pigment loss, and evidence of biological attack. Finally, use a

conservator to assist in periodic surveying of significant objects in order to

establish conservation treatment needs. See MH-I, Chapter 3, Museum

Objects Preservation: Getting/Started, for guidance on Collection

Condition Surveys.

The degree to which each soiled object can be cleaned is a function of the

nature of the soil and the sensitivity of the object. Clean an object only as

necessary to remove airborne soil accumulation.

Don't directly apply chemical reagents such as cleaners, dressings,

waxes, and coatings: they are not beneficial and will complicate future

conservation treatment.

You can't remove some surface soils by simple cleaning methods, and other

soils are not removable at all. Highly deteriorated objects cannot be cleaned

by routine procedures so degraded surfaces should be noted and protected

so that cleaning will be avoided.

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:13

When decorative elements on an object are extensive and very delicate,

refer cleaning to a professional conservator. Surfaces that have specialized

finishes also may require exemption from cleaning. Figure S.5 describes

cleaning techniques that can be considered for objects in good condition.

4. How do I handle skin and Much of the damage caused to leather and skin products is due to improper

hide materials? handling. Therefore, you need to train staff in proper handling techniques.

See MH-I, Chapter 6, Handling, Packing, and Shipping Museum Objects,

for general handling rules.

In addition to the general rules there are a few essential rules for the safe

handling of these objects:

• Be prepared before handling these objects by having a clean area ready

to receive the object. Arrange for assistance from others when

necessary.

• Consider the weight of the entire object before lifting; aged and

deteriorated fibers cannot tolerate much physical stress. Avoid

suspending, creasing, and folding items.

• Move leather and skin artifacts on a tray support, in a drawer, or in a

box; if direct handling is necessary, use both hands and support the

object from underneath, not from original handles and straps.

• Accommodate the special handling requirements of appendages and

decorative elements such as beadwork and dangles.

• Handle skin and hide materials only while wearing clean, cotton

gloves; if hand contact is required, wash hands just before handling.

See MH-I, Appendix I, Curatorial Care of Archeological Objects, for a

discussion of support trays for objects.

5. What about catalog Marking and labeling leather and skin artifacts for cataloging purposes can

labeling? present a number of preservation problems:

• The porous, absorbent nature of all skin products can cause labeling

inks, paints and varnishes to be absorbed into the skin tissue causing

irreversible staining and stiffening.

• The adhesives associated with commercial labeling tapes have poor

long-term stability.

• Pressure sensitive tapes and embossed plastic tapes tend to fall off in

time, and their adhesives are generally not removable from the skin.

• Any type of metal tag (including aluminum) or metal ringed tag can

cause corrosion. Aluminum in contact with skin and hide materials

causes dark spots on the surface of the object.

S:14 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

Cleaning Techniques

Tools

Caution

VACUUMING - This is the safest

cleaning method, if carefully

executed.

Use fine plastic screening and a

vacuum cleaner with adjustable

suction or a rheostat and a small

standard nozzle attachment.

Screening between the leather and

the nozzle protects the leather, but

movement of the screen can also

cause abrasion. Flaking surfaces

and loose parts may be accidentally

removed.

DUSTING - This is the most

Use camel hair brushes.

Dust acts as an abrasive; each time

frequently used technique. It can

a material is brushed, surface

be combined with vacuuming.

material may be removed.

Brushing also increases the danger

of knocking off delicate pieces.

FORCED AIR - Compressed air

cleaning must be done outside the

collection area or dust will simply

be redistributed.

Use a compressor, air hose, and

broad compressed air nozzle.

Loose or fragile pieces can be

blown off if too great a pressure is

used; 40 pounds/square inch is

maximum.

ARTIST'S ERASER - This method

Use artist's block or powder eraser.

This technique is not useful on

can occasionally remove stubborn

(Testing has shown "Magic Rub"

deteriorated surfaces or where skin

surface deposits from the grain side

block and "Scum X" powder to be

or decorative layers may be

of firm, intact leathers and skins.

the least damaging.)

susceptible to flaking. Remnants of

the eraser may become deposited in

textured surfaces and require

vacuuming.

Figure S.5. Cleaning Techniques for Leather and Skin

Objects in Good Condition

You can determine the specific labeling technique you will need by

considering the individual object. Maintain consistency throughout the

collection and use the least damaging method. Consider both indirect and

direct labeling.

• Indirect labeling allows you to avoid irreversibly damaging the hide

material with ink. The two recommended methods of indirect labeling

are tie-on tags and fabric labels.

− Make tie-on tags from high quality, acid-free paper products or

inert plastic materials. Corners should not be sharp. Attach tags in

a manner that does not cause undue stress, such as to an orifice,

strap or handle. Use soft cotton string or a non-abrasive plastic

loop for attachment.

− If you can't label an object with a tie-on tag, use a fabric label,

such as those made from cotton twill tape or non-woven spun-

bonded polyester; these can be sewn to soft skin products using a

beading needle and single strand, white cotton thread. You can

usually attach these labels without passing completely through the

skin, and you can limit stitches to the upper edge of the label.

Attach at a seam or inconspicuous area of the skin or hide material,

or loop to a permanent strap.

• Direct labeling on skin products can be recommended only for firm

leathers and rawhide. You can apply a barrier coating or ground of

clear Acryloid B-72 resin to a small, inconspicuous area

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:15

(approximately 1 cm x 3 cm in size). When dry, apply the catalog

number directly. The ink should have different solubility than that of

the ground resin, so it may be changed if necessary.

6. How do I provide adequate

physical support for

objects?

7. How do I store objects

properly?

See NPS Conserve O Gram 1/4, Use of Acryloid B-72 Lacquer for

Labeling Museum Objects and the Museum Handbook, Part II, Chapter

3, Cataloging. In addition to normal health precautions, exercise

additional caution when using solvents around leather and skin products

because excessive amounts can cause deterioration.

Label the object neatly in the most inconspicuous place possible. Your

labels should be small yet clearly readable from a distance of one foot. Use

a high quality and iron-free ink, such as India ink.

Most organic materials lose their structural integrity as they age. Collapsed,

creased, or folded materials will develop local weaknesses and damage if

not protected by custom mounts and supports.

Use high quality, non-reactive materials:

• rigid acrylic sheeting

• acid-free matboard and unbuffered paper tissues

• washed and undyed cotton and linen fabrics

• polyester batting

• polyethylene foam products

Attached components can cause deterioration when in contact with other

materials (such as metal parts). Separate components by a barrier of

polyethylene sheeting or layers of acid-free tissue.

Store skin and leather objects in a space that is dedicated to the storage of

museum collections, where climate control and security can be adequately

controlled. Although storage requirements vary somewhat for individual

leather and skin materials, basic conservation principles recommend that

you provide a spacious and secure storage area, appropriate cabinets and

containers, an area that is as free as possible from environmental threats,

and individual storage supports. See MH-I, Chapter 7, Museum Collections

Storage, for guidance on storage of museum collections.

The storage needs of tanned and untanned materials can be discussed at two

levels. The first level addresses the overall collections storage facility with

its system of shelving, cabinets, drawers, and trays. The second level

focuses on individualized object supports. The following discussion

provides more guidance based on these basic principles.

• Provide Appropriate Cabinets and Containers

− Protect objects made of skin products within cabinets or on

shelving with dust covers. Items should not be piled, folded,

squashed or leaned. Use cabinets and storage furniture made of

S:16 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

metal with a baked enamel finish. Don't use wooden cabinets and

shelving, because wood products emit damaging vapors.

− Use storage trays and containers to house and support individual

objects as well as to reduce stress and damage during handling.

Any material that directly contacts the specimen, such as boxes,

tubes and tissue papers, must be of acid-free unbuffered paper.

Limit your use of plastics to pure polyethylene, acrylic and

polyester products.

− Vacuum and dust your storage areas regularly. Dust is acidic,

abrasive and damaging to these materials. Routine and systematic

housekeeping also lessens the chance of insect problems that can

harm leather and skin objects.

• Provide Individual Storage Supports

− You will need custom supports for many leather and skin artifacts

just as you do for other sensitive organic materials. As skin

products age, they become more susceptible to damage resulting

from the lack of physical support. Many three-dimensional objects

and most large objects (such as saddles) have additional

requirements for either internal or external reinforcement.

Individual supports shouldn't constrict or interfere with the

expansion and contraction of the skin materials, restrict the gain

and release of moisture as the hide responds to environmental

changes, be permanently attached to be object, or provide

harborage for damaging insect pests.

− Use supports to provide specific reinforcement to all vulnerable

areas that are prone to damage under the object's own weight or

because of the limitations of the storage container. Disfigurement

and folding of skin materials frequently leads to permanent

deformity, the straining of fibers and eventual cracking.

− The design and materials (see page 16, item 6) you will use in your

supports depends on the shape, weight and needs of the individual

object. For instance, you can roll flat hides and robes around large

diameter (minimum of 6" diameter) tubes. Store garments flat and

stuffed with a light weight support to eliminate creasing. Place

saddles on a rigid saddle tree or dummy support if fenders are

likely to become deformed. See Figure S.6 for an illustration of

how to construct a saddle mount.

− Hide objects can deteriorate because of poorly selected and

inappropriate support materials. Harmful materials are those that

emit damaging vapors and organic compounds.

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:17

Figure S.6. Constructing a Saddlemount

S:18 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

2

1-

5

1.

Fabricate a muslin sleeve filled with acrylic polyester batting to a diameter of 4 to 5 inches. The padding

should not be overly tight

or

loase to permit firm support.

2. Use a heavy cardboard tube 6" in diameter.

3. Tie the rings

of

the filled muslin sleeves around the cardboard tubes with twill tape

in

the location of the

saddle bow (front) and hind bow (back) for ful! support. The acrylic polyester padding will compress to fil!

the interior dimensions

of

the saddle so that the saddle will not rock or slip when placed on the mount.

The weight of the saddle should keep it in place, although the saddle can be tied to the padded tube with

wide twill tape in the area

of

the cinch belt as an added precaution.

4.

Loop a sling made

of

wide

tw

ill tape

or

a strip of muslin around the saddle to support the stirrups.

5.

Use

a

metal

pipe

, l

ength

of

slotted

angle,

or

2"

x 4"

wooden

boa

rd

to

support

the

mount.

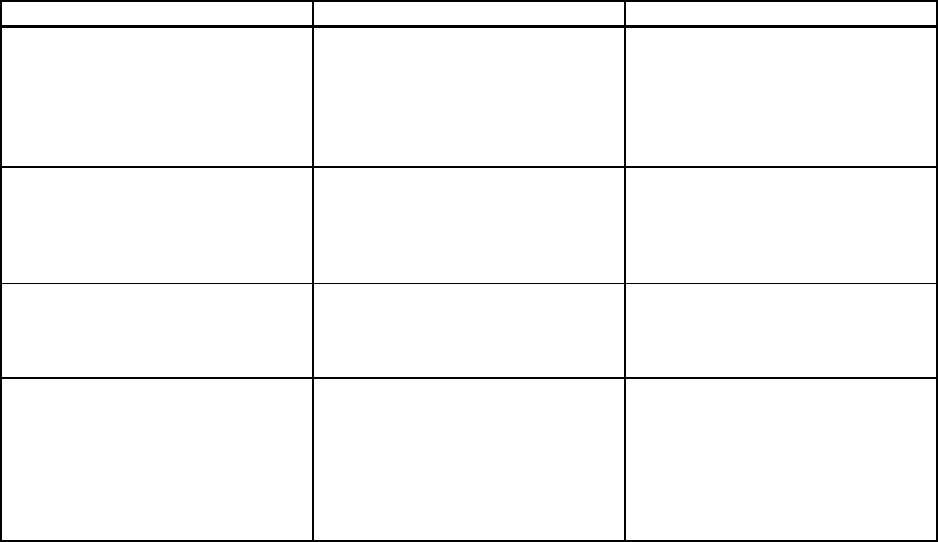

F. Summary: Leather and

Skin Product

Deterioration and The previous two sections discussed deterioration, the causes of

Preventive Care deterioration, and ways to limit deterioration through preventive

conservation efforts. Figure S.7 summarizes some of this information.

CONDITION PROBABLE CAUSE PREVENTIVE ACTION

Deformation

(contraction, cockling, cupping,

shrinkage)

Physical alteration during

use, storage or exhibition ..................................................... Support in unconfined space

Desiccation............................................................................... Raise & stabilize ambient RH

Alternate wetting or drying.......... .............................................Use container to protect against humidity extremes

Excessive heating.....................................................................Lower ambient temperature

Photochemical reaction ............................................................Filter UV radiation, lower visible light

Embrittlement

Disuse, absence of flexing .......................................................None available

(rigid, inflexible, brittle)

Desiccation................................................................................Raise and stabilize ambient RH

Soil impregnation ......................................................................Use container, filter air

Deterioration, loss of fat............................................................Filter UV radiation, lower visible light

Detanning..................................................................................Use container

Photochemical reaction ............................................................Filter UV radiation, lower visible light

Low cohesive strength

(weakened, powdering,

separating, fibrous)

Poor manufacture .....................................................................None available

Mechanical abuse.....................................................................Use container, eliminate handling

Chemical air pollution ...............................................................Use container, filter air

High acidity................................................................................Use container, filter air, stabilize ambient RH

Oxidation ...................................................................................None available

Loss of fat or water content ......................................................Stabilize ambient RH

Photochemical reaction ............................................................Filter UV radiation, lower visible light

Physical Damage

(abrasion, tearing, splitting,

holes, missing parts, disjoined

section)

Historic usage ...........................................................................Support, limit handling

Inherent stress ..........................................................................Support, limit handling

Dimensional movement............................................................Stabilize ambient RH

Handling ....................................................................................Use container, limit handling

Stitching failure..........................................................................Use container, limit handling

Adhesive failure.........................................................................Use container, limit handling

Biological attack ........................................................................Inspect, initiate control program

Soil or stain

Use during historical period......................................................Document, identify using remaining characteristics

accumulation

Improper handling.....................................................................Instruct staff in proper handling, limit handling

(oiliness, water staining)

Unprotected storage or display ................................................Use container, filter air

Unstable fat spew formation.....................................................Stabilize ambient temperature

Discoloration

Soiling or staining......................................................................Use container, filter air

(fading, darkening, lightening)

Excessive fat content................................................................None available

Acid deterioration......................................................................Use container, filter air

Photochemical reaction ............................................................Filter UV radiation, lower visible light

Loss of grain layer or

Morphological feature of skin ...................................................Use container, limit handling

exterior surface

Poor manufacture .....................................................................Use container, limit handling

Mechanical abuse.....................................................................Limit handling

Uneven consolidation ...............................................................None available

Loss of fur or hair

Morphological feature of hair....................................................Use container, limit handling

(slippage, breakage)

Poor manufacture .....................................................................Use container, limit handling

Desiccation................................................................................Stabilize RH

Insect attack ..............................................................................Initiate periodic inspection and control program

Figure S.7. Leather and Skin Product Deterioration and Preventive Care

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:19

G. Conservation Treatment

Issues

Curators, collectors, and conservators alike have been guilty of relying on

old treatments to preserve skin materials, and far too frequently they

accepted the promotions of commercial products designed for contemporary

leathers. This history of haphazard treatment and unsystematic evaluation

of skin products has resulted in considerable damage and loss. Common

criticisms of past treatments of skin and leather products are that

preservation attempts have not differentiated among the distinct categories

of skin materials and have relied too heavily on the application of

"preservatives."

The traditional remedies and reagents once routinely used in museum

collections are now being carefully scrutinized by museum conservators.

With the aid of scientific investigation and the assessment of the results of

past treatment, several important new directions are being taken. The

findings on past treatments have not been encouraging.

The routine application of preservatives (such as saddle soaps and

leather dressings) is discouraged.

1. What are the perils of

saddle soap?

2. What are the drawbacks of

leather dressings?

There are many problems associated with the use of "saddle soap" on

historic and artistic objects made from animal skin products. With the best

of intentions, this commercial product has been inappropriately applied to

just about every form of skin material in the past.

"Saddle soap" was not developed as a cleaner, but as a 19th century leather

conditioner. Its basic components of neatsfoot oil and cod or sperm oil

were emulsified with soap in water to produce an emulsion fat-liquor

introduced during early tanning. As a conditioner, saddle soap is

considered obsolete by tanners today.

Its application has caused considerable permanent damage to skin and

leather objects since its components cannot be easily rinsed out and

adequately removed (as manufacturer instructions often suggest). Saddle

soap effectively softens and emulsifies surface oil and dirt, however it

usually distributes them deeper into the material. The mixture's high

moisture content presents a hazard to aged skin materials that should not be

wetted, as well as light colored vegetable and/or alum tanned leathers.

Commercial formulations of saddle soap differ in their ingredients, some

containing abrasives and even colorants. Saddle soap quality fluctuates

greatly among manufacturers.

Perhaps most importantly, conservators now suspect that the surface

cracking on many older skin and leather objects may well be due to past

"saddle soap" application. Avoid it.

The care of skin and leather goods has traditionally involved the routine use

of leather dressings, solutions of fats and oils that lubricate skin products to

increase flexibility. Modern research has shown, however, that the

haphazard use of dressings has been the cause of considerable deterioration

within museum collections.

S:20 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

3. What about neutralization of

acids?

These solutions should never be applied to Native-tanned materials or

objects comprised of untanned or semi-tanned skin products. Avoid the

use of leather dressings on museum objects.

Numerous drawbacks are associated with dressing of skin products. For

example, dressings frequently:

• darken lighter colored leathers

• encourage biological attack

• form fatty spews at the surface

• oxidize over time and stiffen the material

• wick into surrounding materials

• soften original finishes and decoration

• cause dust to accumulate

• impede future conservation treatment

• contaminate the material for future analysis

The chemical decay and disintegration of leather resulting from exposure to

acids is a well-known problem and its solution for older leathers remains

unresolved. Vegetable-tanned leathers produced since the mid-19th century

frequently exhibit a condition of internal fiber degradation known as "red

rot." The color of the leather actually reddens as the deterioration

progresses. In its advanced state, affected leather will disintegrate into a

powdery form.

This condition is most always associated with sulfuric acid, introduced

either during the tanning process or from atmospheric contact with the

contaminant sulphur dioxide. (Leather readily absorbs acid from the air.)

Sulphur dioxide, when absorbed, becomes sulphur trioxide, which unites

with water to form sulfuric acid, resulting in a devastating effect on

collagen fibers. Certain vegetable tannages (the ones categorized as

condensed tannins) have been identified as being much more susceptible to

this mechanism of deterioration.

Modern leathers are fortified against acid formation by incorporating

buffering salts that repress acid formation and action. Some of the museum

preservation literature during the last decade recommended that older

leathers be treated with similar buffering salts, such as potassium lactate

and potassium citrate, to protect them from acid attack.

The problem that museum curators face is that there is no easy and safe

method for long-term neutralization of acids that are present in historic

leather objects. There are three drawbacks associated with the treatment of

leather with standard buffering salt solutions:

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:21

• The salts must be introduced in an aqueous solution yet water can be

very damaging to historic leather causing stiffening, color change and

disruption of applied finishes.

• Salt solutions are meant only for vegetable-tanned leather and will de-

tan and damage mineral-tanned materials; the applicator must,

therefore, be able to distinguish between them, which is not an easy

task.

• The addition of buffering salts will do nothing for leathers that have

already begun to deteriorate from acid exposure.

The conservation field is looking at other methods of deacidifying leathers;

vapor phase reagents and non-aqueous chemicals are being investigated.

The importance of this conservation issue is clear to those involved, and

acceptable procedures should be available to museum staffs in the near

future.

H. Selected Bibliography

Canadian Conservation Institute. Leather Skin and Fur, CCI-ICC Notes, No. 1-4 (Notes on Curatorial Care).

Ottawa, Canada: Canadian Conservation Institute, 1986.

Fogle, Sonja, Toby Raphael and Katherine Singley. Recent Advances in Leather Conservation. Washington,

DC: Foundation of the American Institute for Conservation, 1985.

Haines, Betty. The Conservation of Bookbinding Leather, A Report by the British Leather Manufactures'

Research Association for the British Library. The British Library, Great Russell Street, London, England

WC1B 3DG, 1984.

__________. Monograph Series on Leather. The Leather Conservation Center Ltd., 34 Guildhall Road,

Northampton, England NM1 1EW, 1991.

Krahn, Ann Howatt. “Conservation: Skin and Native-Tanned Leather.” American Indian Art Magazine

(Spring), 1987.

Nathanson, David, and Diane Vogt-O'Connor. “Care and Security of Rare Books.” Conserve O Gram 19/2.

Washington, DC: National Park Service, Curatorial Services Division, 1993.

Raphael, Toby, and Ellen McCrady. “Leather Dressing: To Dress or Not To Dress.” Conserve O Gram 9/1.

Washington, DC: National Park Service, Curatorial Services Division, 1993.

__________. Ethnographic Skin and Leather Products: A Call for Conservative Treatment. Published

Proceedings of Symposium '86: The Care and Preservation of Ethnological Materials. Ottawa, Canada:

Canadian Conservation Institute, 1986.

Raphael, Toby. “Preventive Conservation Recommendations for Organic Objects.” Conserve O Gram 1/3.

Washington, DC: National Park Service, Curatorial Services Division, 1993.

__________. “An Insect Pest Control Procedure: The Freezing Process.” Conserve O Gram 3/6. Washington,

DC: National Park Service, Curatorial Services Division, 1994.

Reed, R. Ancient Skins, Parchments and Leathers. London: Seminar Press, 1972.

S:22 NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996)

Stambolov, T. Manufacture, Deterioration and Preservation of Leather: A Literature Survey of Theoretical

Aspects and Ancient Techniques. ICOM, Amsterdam: Central Research Laboratory, 1969.

Storch, Paul (Editor). Leather Conservation News, Objects Conservation Laboratory, Minnesota History

Center, 345 Kellogg Boulevard, West St. Paul, MN 55102-1906.

Sullivan, Brigid and Donald R. Cumberland, Jr. “Use of Acryloid B-72 for Labeling Museum Objects.”

Conserve O Gram 1/4. Washington, DC: National Park Service, Curatorial Services Division, 1993.

Waterer, John. A Guide to the Conservation and Restoration of Objects Made Wholly or in Part of Leather.

New York, NY: Drake Publishers Inc., 1972.

NPS Museum Handbook, Part I (1996) S:23