This report summarizes the ndings and recommendations of the

Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force. With the support of the Hogg Foundation

for Mental Health, child welfare experts, stakeholders, advocates and consumers came together to

address the variety of mental health issues facing children and youth in the child welfare system. Membership

was comprised of physical and mental health care practitioners, judges, social workers, psychologists and state agency

personnel.

Texas CASA wanted to ensure that the urgent mental health needs of the children remained a constant focus of the Task Force’s work. Therefore, a

vision was developed to guide their work and advocacy:

We envision a system of care that:

• respects the needs of traumatized children and youth in substitute care;

•places the utmost importance on ensuring they have access to the best mental health services and systems of support; and

• provides them with a real opportunity to heal from their traumatic experiences and grow into successful adults.

Task Force members were charged with:

• identifying problems facing children and youth in state custody in regards to their mental health;

• developing actionable solutions (recommendations) that will improve the well-being of children and youth in foster care; and

• advocating for those solutions.

This report represents the Task Force’s recommendations around three major issue areas identied by Task Force members as the most impactful issues affecting mental health outcomes of children and youth in foster care in Texas:

Diagn o s is an d tre atm e n t o f m e n tal h e alth is s ue s in ch ild re n an d yo u th in s u bs titute ca re

:

an accurate and appropriate m ental health diagnoses for children and y outh in substitute care. Furtherm ore, w hen diagnoses are assigned, accurate or

unclear w hether therapeutic or non-pharm acological strategies or m odels are av ailable and/ or used appropriately .

in norm alcy activities. These obstacles can prev en t y oung people in care from engaging in norm al adolescent experiences and building social and life

skills. This struggle can be made more difcult depending on how restrictive a child’s placement is and depending on their cultural and spiritual identity and/or what special needs they may have.

supported to successfully care for children and youth struggling w ith sy m ptom s of traum a. This challenge is one of m any existing obstacles in attem pts

The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force also recognized a number of barriers to achieving needed system and care improvements. Predictably, the most prominent barriers recognized by the Task Force are the same as those recognized by many mental health

stakeholders and advocacy groups:

Medicaid reimbursements are too low and discourage well-trained and specialty practitioners from choosing to become Medicaid providers.

There is a lack of providers overall, especially those who are well-trained in treating trauma and specically trained to treat trauma experienced by children.

To research and create recommendations around these challenges, Task Force members were divided into sub-committees around the three major issue areas. These sub-committees met many times over the course of one and a half years and worked with the larger

Task Force to produce the recommendations found in this report.

RESPECTING THE NEEDS OF CHILDREN AND

YOUTH IN TEXAS FOSTER CARE:

ACKNOWLEDGING TRAUMA AND PROMOTING POSITIVE MENTAL

HEALTH THROUGHOUT THE SYSTEM

RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE

TEXAS CASA MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE

Acknowledgements

This report was prepared by Stephanie LeBleu and Sarah Crockett, with

generous support from Cristina Masters, Andy Homer, Elizabeth Krog and

Jemila Lea. It would not have been possible without the input of the experts

who served on the Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force and volunteered

their time to think critically about how to improve the lives and experiences

of children and youth in foster care in Texas. This endeavor was facilitated

by Texas CASA under the leadership of its CEO, Vicki Spriggs.

This project was made possible through a generous grant from the

Hogg Foundation for Mental Health at the University of Texas.

Texas CASA Mental Health

Task Force Members

Tymothy Belseth

Texas Department of Family

and Protective Services

Gail Biro

DePelchin Children’s Center

Duncan Cormie

Texas Network of Youth

Services

Sheila Craig

Center for Elimination of

Disproportionality and

Disparities

Texas Health and Human

Services Commission

Cheryl Fisher

Cenpatico

Michael Greenwood, MSSW

Giocosa Foundation

William Holmes, MD

Cenpatico

Andy Homer

Texas CASA

Richard Lavallo, JD

Disability Rights Texas

Jemila Lea, JD

Hogg Foundation for Mental

Health

Molly Lopez, PhD

Texas Institute for Excellence in

Mental Health

Jon Olson, MSSW

Center for Elimination of

Disproportionality and

Disparities

Texas Health and Human

Services Commission

Anu Partap, MD

Foster Care Clinic

Children’s Medical Center

Dallas

Courtney McElhaney Peebles

Center for Elimination of

Disproportionality and

Disparities

Texas Health and Human

Services Commission

Karyn Purvis, PhD

Institute of Child Development

Texas Christian University

Cindy Rains

CASA of the Permian Basin

Area, Inc.

Debbie Sapp

CASA of Walker County, Texas

Kristopher Sharp

Texas Foster Care Alumni

Andrea Sparks

Texas Regional Ofce

National Center for Missing

and Exploited Children

Yolanda Valenzuela

Child Advocates of San Antonio

Dianna Velasquez

Governor’s Ofce of Budget,

Planning and Policy

Ofce of Texas Governor Rick

Perry

Sara Wood, RN, PMHNP,

APRN-BC,

Ex Ofcio Members

Debra Emerson

Child Protective Services

Texas Department of Family

and Protective Services

Judge John Hathaway

Travis County, Texas

Monica Thyssen

Medicaid and Chip Division

Texas Department of Health

and Human Services

Jennifer Sims

Department of Family and

Protective Services

Kristi Taylor, JD

Texas Children’s Commission

Technical Assistance

Dan Capouch

Texas Department of Family

and Protective Services

Shannon Ramsey

Texas Department of Family

and Protective Services

Kathy Teutsch

Texas Department of Family

and Protective Services

RESPECTING THE NEEDS OF CHILDREN AND

YOUTH IN TEXAS FOSTER CARE:

ACKNOWLEDGING TRAUMA AND PROMOTING POSITIVE

MENTAL HEALTH THROUGHOUT THE SYSTEM

RECOMMENDATIONS OF THE

TEXAS CASA MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE

December 2014

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Introduction..................................................................................................6

Executive Summary.......................................................................................8

Section 1: Diagnosis and treatment of mental health issues

in children and youth in substitute care.......................................14

Integrated care is the standard, not the reality........................................................................18

The term “non-pharmacological interventions” is not well-dened or

understood..............................................................................................................................21

Medical and mental health providers serving this population are not

beholden to American Academy of Pediatrics standards and the current

Medicaid reimbursement rates in Texas deter providers...........................................................22

Limited information is available regarding the array of mental health

services available under STAR Health and understanding of how to

utilize the Medicaid appeals process and other legal options is limited....................................23

Texas youth who aged out of care are not auto-enrolled in Medicaid and

youth who aged out in other states are not extended coverage in Texas...................................24

Section 2: Empowerment and normalization of youth in

substitute care............................................................................26

The current system inhibits caregivers’ ability to make decisions about

a child’s participation in normalcy activities and experiences...................................................28

Service plans can be too prescriptive and unwittingly block a young

person from participating in an activity or experience and caregivers can

be discouraged from allowing for participation in normalcy activities.......................................30

Youth are not empowered to address concerns within their placements

or to report abuse and are not aware of their individual rights or what

recourse is available to them when rights are violated.............................................................32

Section 3: Appropriate caregiving environments for children

and youth in substitute care.......................................................35

Caregivers are not adequately trauma-informed and efforts to establish

a trauma-informed care system are slow, disconnected, and vary in how

they are dened......................................................................................................................36

Current practice does not include an assessment for adult attachment

for alternate caregivers...........................................................................................................40

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 6

INTRODUCTION

This report summarizes the ndings and recommendations of the Texas CASA Mental Health Task

Force. Child welfare experts, stakeholders, advocates and former foster youth came together to address

the variety of mental health issues facing children and youth in the child welfare system. Membership

was comprised of physical and mental health care practitioners, judges, social workers, psychologists,

attorneys and state agency personnel.

Texas CASA wanted to ensure that the urgent mental health needs of the children remained a constant

focus of the Task Force’s work. Therefore, the following vision was developed to guide their work and

advocacy:

We envision a system of care that:

• Respects the needs of traumatized children and youth in substitute care;

• Places the utmost importance on ensuring they have access to the best mental health

services and systems of support; and

• Provides them with a real opportunity to heal from their traumatic experiences and grow

into successful adults.

Task Force members were charged with:

• Identifying problems facing children and youth in state custody in regards to their mental

health;

• Developing actionable solutions (recommendations) that will improve the well-being of children

and youth in foster care; and

• Advocating for those solutions.

This report represents the Task Force’s recommendations around three major issue areas identied by

Task Force members as the most impactful issues affecting mental health outcomes of children and

youth in foster care in Texas:

1. Diagnosis and treatment of mental health issues in children and youth in substitute care:

There is currently a lack of emphasis on achieving an accurate and appropriate

mental health diagnoses for children and youth in substitute care. Furthermore,

when diagnoses are assigned, accurate or not, it is unclear whether therapeutic

or non-pharmacological strategies or models are available and/or used

appropriately.

2. Empowerment and normalization of youth in substitute care:

Systemic obstacles exist for young people in care who wish to participate in

normalcy activities. These obstacles can prevent young people in care from

engaging in normal adolescent experiences and building social and life skills.

This struggle can be made more difcult depending on how restrictive a child’s

placement is and depending on the child’s cultural and spiritual identity and/or

what special needs he or she may have.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 7

3. Appropriate caregiving environments for children and youth in substitute care:

Currently, caregivers in Texas are not effectively recruited,

screened, prepared or supported to successfully care for children

and youth struggling with symptoms of trauma. This challenge

is one of many existing obstacles in attempts to achieve a truly

trauma-informed system of child welfare.

The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force also recognized a number of barriers to

achieving needed system and care improvements. Predictably, the most prominent barriers

recognized by the Task Force are the same as those recognized by many mental health

stakeholders and advocacy groups:

• Medicaid reimbursements are too low and discourage well-trained and specialty

practitioners from choosing to become Medicaid providers.

• There is a lack of providers overall, especially those who are well-trained in treating

trauma and specically trained to treat trauma experienced by children.

To research and create recommendations around these challenges, Task Force members

were divided into sub-committees around the three major issue areas. These sub-

committees met individually numerous times over the course of one-and-a-half years and

worked as a part of the larger Task Force to produce the recommendations found in this

report.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Mental health has found its way to center stage over the last few years in our country. Tragic incidents

have occurred across the nation that have forced states and communities to look at issues of mental

health and gure out more effective ways to care for people who need help and support.

Texas engaged in this effort as well. Last legislative session Texas appropriated $2.6 billion toward

providing mental and behavioral health services for its residents (approximately a 15% increase from

the 2012-2013 budget).

1

The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force believes that the same emphasis

and imperative placed on addressing general mental health should be placed on addressing the

unique mental health needs of children and youth in the child welfare system. While it remains to be

seen how or if this infusion of funding will impact the children and youth in the Texas child welfare

system, research has shown that their need for mental health care and services is great and based

on a unique set of needs and complex circumstances.

Children in foster care experience mental illness at a rate almost 30% greater than the average

population of children.

2

Children and youth in care are also less likely to receive adequate treatment

and services for their mental health needs.

3

Given these facts, it is no surprise that children in care

experience negative outcomes at a much higher rate as well.

Child welfare advocates have learned that unresolved trauma plays an enormous role in driving

these negative outcomes. Trauma can cause both long and short-term problems for children.

“Consequences of trauma include difculties with learning, ongoing behavior problems, impaired

relationships and poor social and emotional competence. Children and youth exposed to trauma,

especially violence, experience more learning and academic difculties and behavioral and mood-

related problems.”

4

This means that children who experience trauma may still struggle to attach

to caregivers or regulate their emotions and behaviors, even if they are placed in an ideal home,

where loving and consistent care is available to them.

The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force believes that these complex physical and behavioral

health needs have been poorly addressed or not addressed at all for children and youth in Texas.

There are a number of reasons why children in foster care may not get the care or support they need.

These include:

• Frequently changing providers due to placement moves

• Lack of physical and mental health providers who accept Medicaid

• Lack of providers well-trained in trauma, grief and loss

1 Ligon, Katharine. Sizing Up the 2014-15 Texas Budget: Mental Health. Rep. Center for Public Policy Priorities, Sept. 2013. Web. 15 Dec.

2014. <http://forabettertexas.org/images/2013_10__PP_Budget_MentalHealth.pdf>.

2 Texas Medicaid Managed Care and Children’s Health Insurance Program: EQRO Summary of Activities and Trends in Healthcare Quality.

Rep. Institute for Child Health Policy at the University of Florida Texas External Quality Review Organization, 28 Mar. 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2014. <http://

www.hhsc.state.tx.us/reports/2014/EQRO-Summary.pdf>.

3 Carrillo, Sarah, and Elisa Ashton. Improving Care Coordination for Foster Children: An Update on California’s Audacious Goal. Rep.

California Ofce for Health Information Integrity, 20 Jan. 2013. Web. 15 Dec. 2014.

4 Cooper, Janice L. “Facts about Trauma for Policymakers: Children’s Mental Health.” National Center for Children in Poverty. Columbia

University Mailman School of Public Health Department of Health Policy & Management, July 2007. Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 9

• Lack of providers who are specically trained to treat children

• Lack of understanding of the root cause of a child’s behavior

• Overburdened caseworkers and other parties in the case

• Systemic resistance to using non-pharmacological interventions other than therapy

• Systemic inability to make decisions about a child’s outcomes based on their emotional and

mental health needs

• Lack of access to normal life experiences that contribute to positive mental health outcomes

The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force decided to focus its efforts on three major areas of

concern and make recommendations about issues within those three areas. A summary of the issues

and recommendations are as follows:

I. DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES IN CHILDREN AND

YOUTH IN SUBSTITUTE CARE

Issue 1: Integrated care is the standard, not the reality

Recommendations:

1. The Health and Human Services Commission should activate and publicize Medicaid

billing codes that will allow providers to bill for collaborative consultation, which

allows practitioners to bill for “peer consults” between primary care physicians

(PCPs) and other PCPs; PCPs and Psychiatrists; and PCPs and other mental health

practitioners.

2. Ensure the Health Passport is being utilized and includes updated information on the

child’s medical history, mental health, developmental and psychosocial functioning—

any information pertinent to any course of care for the child.

Issue 2: The term “non-pharmacological interventions” is not well dened or

understood

Recommendation:

1. Adoption of the following denition of “non-pharmacological interventions” by the

judicial system, medical care providers, insurers, CASA, CPS and others:

• “Non-pharmacological interventions” is terminology meant to represent an

array of strategies, supports and interventions intended to help children recover

and heal from trauma, build resilience and meet developmental milestones.

Non-pharmacological interventions must be used in lieu of or concurrently with

psychotropic medications and should be informed by accurate and continuous

assessment and/or diagnosis. Non-pharmacological interventions include both

evidence-based interventions, promising practices and those interventions

proven effective by peer-reviewed research.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 10

Issue 3: Medical and mental health providers serving this population are

not beholden to American Academy of Pediatrics standards and the current

Medicaid reimbursement rates in Texas deter providers

Recommendations:

1. Implement, require and train on American Academy of Pediatrics standards for

physicians treating children in substitute care on health screenings in foster care.

2. Provide equivalent reimbursement rates for all licensed professionals who provide

Medicaid mental health services to children in foster care.

Issue 4: Limited information is available regarding the array of mental

health services available under STAR Health and understanding of how to

utilize the Medicaid appeals process and other legal options is limited

Recommendations:

1. Revise STAR Health Member Handbook to include:

• Information on trauma and trauma-informed care

• Information on behavioral health services, including a list of covered services,

denition of services, and information on how to access services and who can

provide services

• A simpler explanation of the Medicaid appeals process

2. Train consumers, attorneys, judges, CASA volunteers, medical consenters and

youth (especially those 16 and older) on:

• What behavioral health services are available through STAR Health, including

denitions of services, how to access services and who can provide services

• The Medicaid appeals process, including how to appeal when a requested

medically necessary service is denied

3. Train attorneys, CASA volunteers, judges, medical consenters and youth on how to

petition the court for an order related to the medical care for a foster child. This is not

a formal Medicaid appeal but the use of the exclusive jurisdiction of the court could

help to ensure that foster children receive appropriate medical care, including mental

health and behavioral health services.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 11

Issue 5: Texas youth who aged out of care are not auto-enrolled in Medicaid

and youth who aged out in other states are not extended coverage in Texas

Recommendations:

1. Create automatic enrollment transfers from STAR Health to STAR when a child turns

21, assuring that former foster children will have Medicaid coverage until age 26

regardless of reapplication.

2. Extend Medicaid eligibility to former foster youth from any state until age 26.

II. EMPOWERMENT AND NORMALIZATION OF YOUTH IN SUBSTITUTE CARE

Issue 1: The current system inhibits caregivers’ ability to make decisions

about a child’s participation in normalcy activities and experiences

Recommendations:

1. Dene the Reasonable and Prudent Parenting Standard and include what to consider

when caregivers are making decisions.

2. Require DFPS to verify that private contracted agencies promote and protect

the ability of a child to participate in normalcy activities by requiring that private

agencies have the same provisions of “reasonable and prudent parenting standards”

as foster caregivers.

Issue 2: Service plans can be too prescriptive and unwittingly block a young

person from participating in an activity or experience and caregivers can be

discouraged from allowing for participation in normalcy activities

Recommendations:

1. Address service plan limitations by listing normalcy activities and/or experiences the

child has/is participating in rather than listing activities as a limited list of activities in

which a child can participate.

2. Mandate that the foster parent and/or the associated child placing agency shall not be

held responsible for potentially negative outcomes beyond their reasonable control as

a result of the child’s participation in an age-appropriate normalcy activity, provided

the activity is approved by the foster parent using the reasonable and prudent parent

standard.

3. Require training for residential staff, child placing agency staff, foster parents, kinship

providers and residential child care licensing staff. This training should include

instruction on decision-making as a “reasonable and prudent parent”, appropriate

and trauma-informed ways to deal with a child or youth’s misbehavior, the importance

of a child’s participation in normal adolescent activities and experiences, and the

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 12

benets of such participation to a child’s social, emotional and developmental growth,

well-being and mental health.

Issue 3: Youth are not empowered to address concerns within their

placements or to report abuse and are not aware of their individual rights or

what recourse is available to them when rights are violated

Recommendations:

1. Establish an independent Ombudsman ofce or establish autonomy within the OCA,

ensuring that the Department of Family and Protective Services shall have no authority

to:

• Create or change the policy and practice of the Ofce of Consumer Affairs;

• Determine the budget of the Ofce of Consumer Affairs; or

• Make decisions regarding personnel of the Ofce of Consumer Affairs

2. Caseworkers and CPA personnel should provide foster children and youth with better

access to the Children’s Bill of Rights by making copies available at court hearings

and at site visits and provide ongoing education around these rights in order to fully

empower them.

3. Require Child Placing Agencies and foster care placements to provide access to the

OCA or independent Ombudsman’s ofce contact information in private spaces, such

as bathrooms or on the back of bedroom doors.

4. Require the OCA or independent Ombudsman’s ofce to establish a written policy on

foster youth’s provisions and protections from retaliation by a caregiver, including a

procedure of investigation of such retaliation and consequences for caregivers who are

found to have engaged in retaliation against a child or youth in foster care.

5. Require the OCA to establish a secure form of communication with the child or youth

in order to ensure that he or she is made aware of the investigation including the

substantiation of any complaints that are brought to the attention of or determined by

the OCA.

6. Require the OCA to establish specic procedures for working with youth in foster care

who call to make an inquiry or complaint.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 13

III. APPROPRIATE CAREGIVING ENVIRONMENTS FOR CHILDREN AND YOUTH

IN SUBSTITUTE CARE

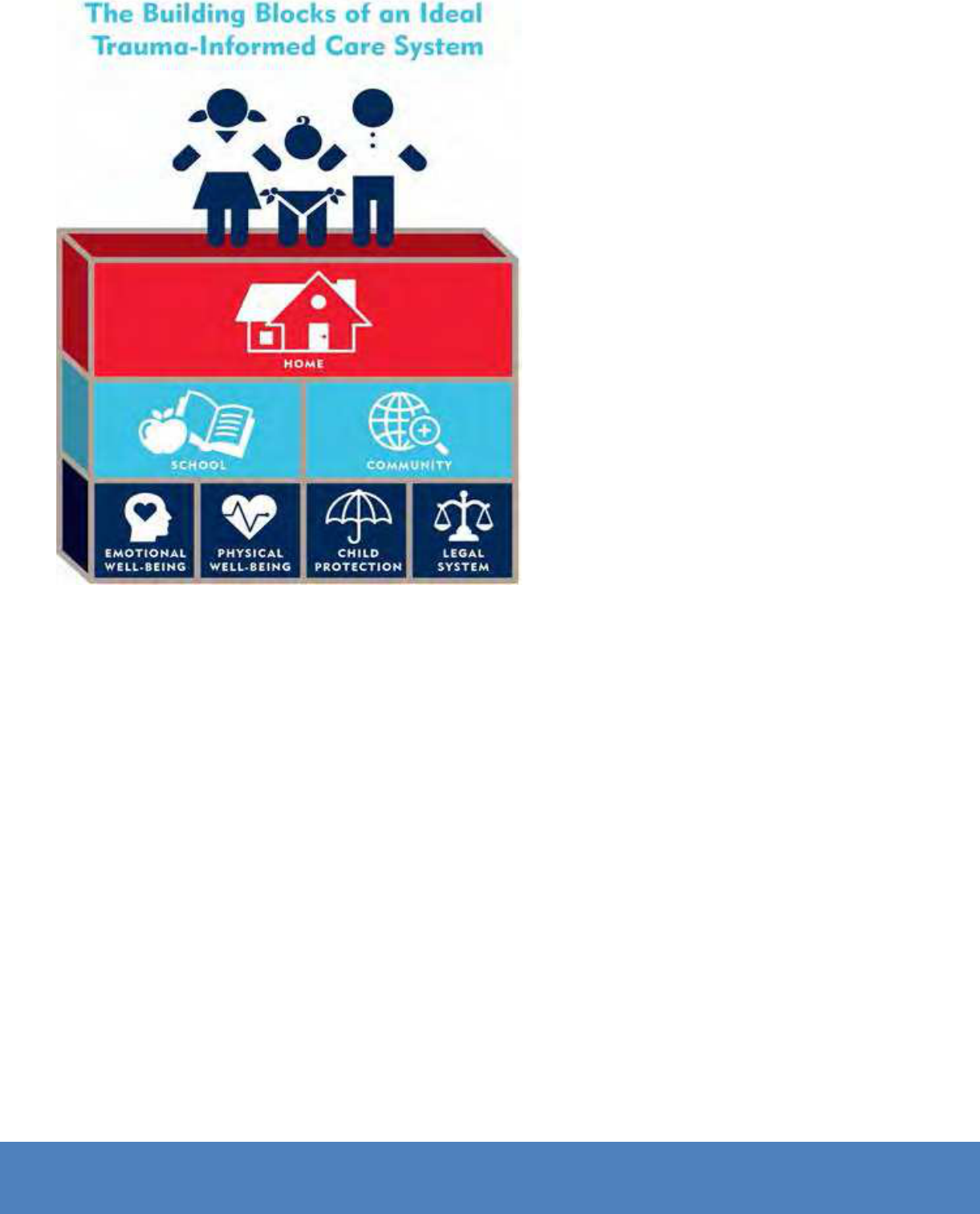

Issue 1: Caregivers are not adequately trauma-informed and efforts to establish

a trauma-informed care system are slow, disconnected, and vary in how they

are dened

Recommendations:

1. Dene trauma-informed care for caregivers within Minimum Standards.

2. Require all residential child care administrators and staff to complete trauma-informed

care training, as dened by the Department of Family and Protective Services.

3. Incentivize Child Placing Agencies (CPAs) to incorporate trauma-informed care into

their assessments, training and support of caregivers of children with increased

reimbursement rates.

4. Evaluate the utilization and effectiveness of implementing trauma-informed care models,

as dened by the Department of Family and Protective Services, within the eligible CPAs.

Issue 2: Current practice does not include an assessment for adult attachment

for alternate caregivers

Recommendations:

1. Require all agencies that screen potential caregivers to include an attachment screening

as a component of the overall assessment to better understand that caregiver’s

ability to form meaningful and trust-promoting relationships with children who have

experienced trauma. There are several free attachment screening options and the Task

Force recommends that the Department of Family and Protective Services create a

standardized list of tools for agencies to utilize for these screenings.

2. Train Child Placing Agency staff to screen potential caregivers using attachment

screening and ensure they have the proper assessment tools, as dened by the

Department of Family and Protective Services.

3. Require a set of standardized assessments of prospective caregivers, dened by the

Department of Family and Protective Services, across child placing agencies.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 14

I. DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT OF

MENTAL HEALTH ISSUES IN CHILDREN AND YOUTH

IN SUBSTITUTE CARE

Background

Children in care more likely to experience poor mental and physical health

Children and youth in the child welfare system have a higher prevalence of physical, developmental,

dental and behavioral health conditions than any other group of children.

1

Physical trauma, such as

a blow to the head or body or violent shaking, can result in negative effects on physical development.

Neglect, such as inadequate nutrition, lack of adequate stimulation or withholding of medical treatment,

can also negatively impact physical development. Additionally, maltreatment in the rst few years of

life can negatively affect brain development and have repercussions into adolescence and adulthood.

2

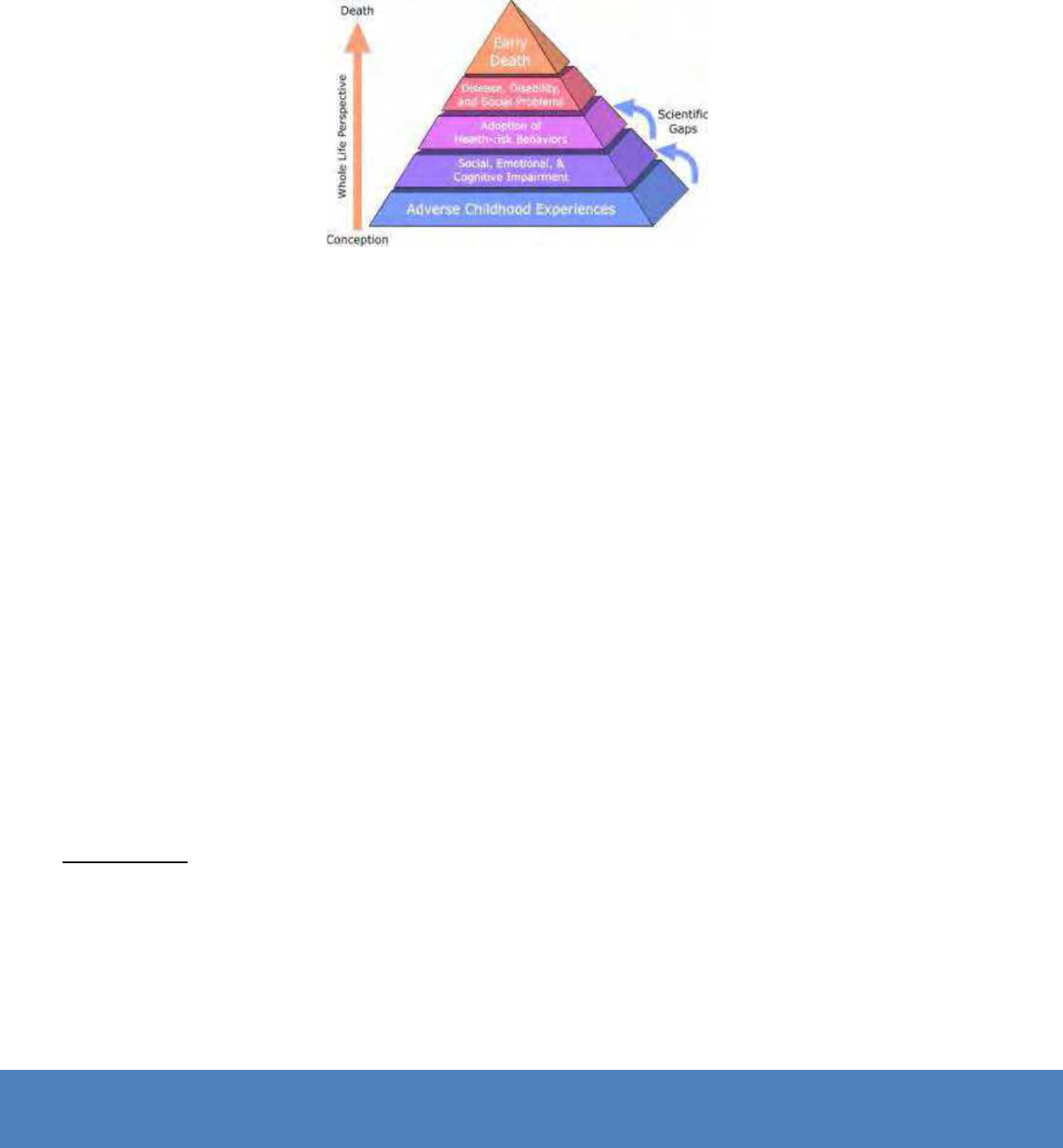

There is also a great body of research, especially the Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study,

that documents the conversion of traumatic experiences in childhood into organic disease later in life,

including all of the major causes of adult mortality in the United States.

3

The Task Force on Health Care

for Children explains the issue this way:

“Children and adolescents in foster care are a group with special health care needs. They

are a uniquely disadvantaged group. Prior to foster care, the vast majority lived with families

devastated by substance abuse, mental health disorders, poor education, unemployment,

violence, lack of parenting skills, and involvement with the criminal justice system. High

rates of premature birth, prenatal drug and alcohol exposure, and postnatal abuse and

neglect contribute to the extremely poor health status of children and adolescents entering

foster care. In addition, health care prior to foster care placement often is inadequate,

meaning that children and adolescents entering foster care have multiple unmet health

care needs, far exceeding even those of other children who are poor.”

4

These challenges are reected in the statistics on this issue, especially when one compares the

differences between the three major health insurance programs that serve low-income children: STAR

(typical Medicaid), CHIP (the Children’s Health Insurance Program, which is for families with incomes

slightly higher than what Medicaid allows), and STAR Health (the Medicaid program exclusively for

children in the child welfare system). According to the FY 2012 STAR Health Caregiver Survey, it

served a considerably higher percentage of child MSHCN (members with special health care needs)

than other programs (48 percent). This was more than double the rates observed in STAR (18

percent) or CHIP (20 percent). In STAR Health, more than one-third of recipients were prescribed

1 “Fostering Health: Health Care for Children and Adolescents in Foster Care.” Task Force on Health Care for Children 2 (2005): n. pag. Http://

www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Documents/FosteringHealthBook.pdf. 2005. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

2 Health and Mental Health. Child Welfare Information Gateway, n.d. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. <https://www.childwelfare.gov/can/impact/longterm/

health.cfm>.

3 Felitti, Vincent J. “The Relationship of Adverse Childhood Experiences to Adult Health: Turning Gold into Lead.”Z Psychsom Med Psychother 48.4

(2002): 359-69. Web. 9 Dec. 2014. <http://www.acestudy.org/les/Gold_into_Lead-_Germany1-02_c_Graphs.pdf>.

4 “Fostering Health: Health Care for Children and Adolescents in Foster Care.” Task Force on Health Care for Children 2 (2005): n. pag. Http://

www.aap.org/en-us/advocacy-and-policy/aap-health-initiatives/healthy-foster-care-america/Documents/FosteringHealthBook.pdf. 2005. Web. 9 Dec. 2014.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 15

medications for mental illness (35 percent) or had problems that required mental health treatment

or counseling (36 percent). More than a quarter of STAR Health recipients also need more medical

care, mental health or educational services than is typical for children (29 percent). The percentage of

STAR Health recipients who had functional/ability limitations or needed special therapies in 2012 was

16 percent and 14 percent, respectively.

5

Children in Substitute Care Exist Within Complex Systems

Children in state custody are served simultaneously by many systems, including the child welfare system,

the judicial system, the education system, the medical system and mental health systems. All of these

systems are structured and function differently. It is difcult to imagine how a child could experience

positive outcomes within all of these systems when few people, including those who work with and

advocate for these children, understand the intricacies of each of them. This labyrinth of systems,

processes and services and the general lack of knowledge about how to navigate them can create

signicant barriers to children receiving the services they need.

Task Force members found this complexity difcult as they set out to identify specic issues regarding

how children in state custody receive mental health diagnoses and how they receive treatment for those

issues. The Task Force sought to ensure that each child in the system is receiving an accurate and

appropriate mental health diagnosis based on that child’s individual needs. However, what Task Force

members found was that because of the extremely complex nature of the systems that touch the lives

of these children, they would rst have to gain a better understanding of how these systems interact.

Due to limited time and resources, Task Force members decided to focus solely on the system of mental

health care established to treat children in substitute care, its interaction with the child welfare system

and how the functioning of these two systems can discourage appropriate and accurate diagnosis and

treatment for individual children in care. Current functioning and interaction between these systems

limits the possibility for every child to be accurately and appropriately diagnosed based on their

individualized needs.

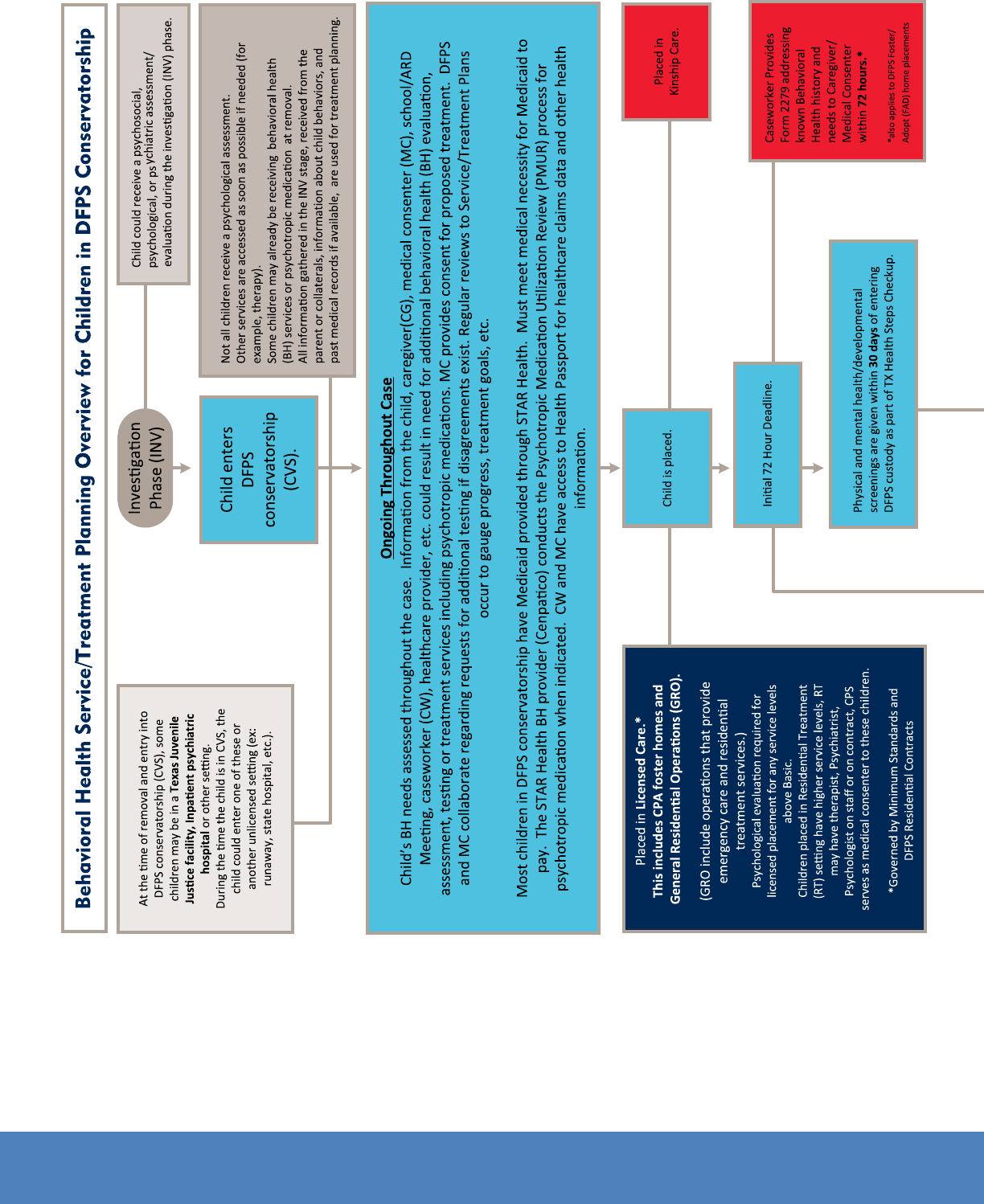

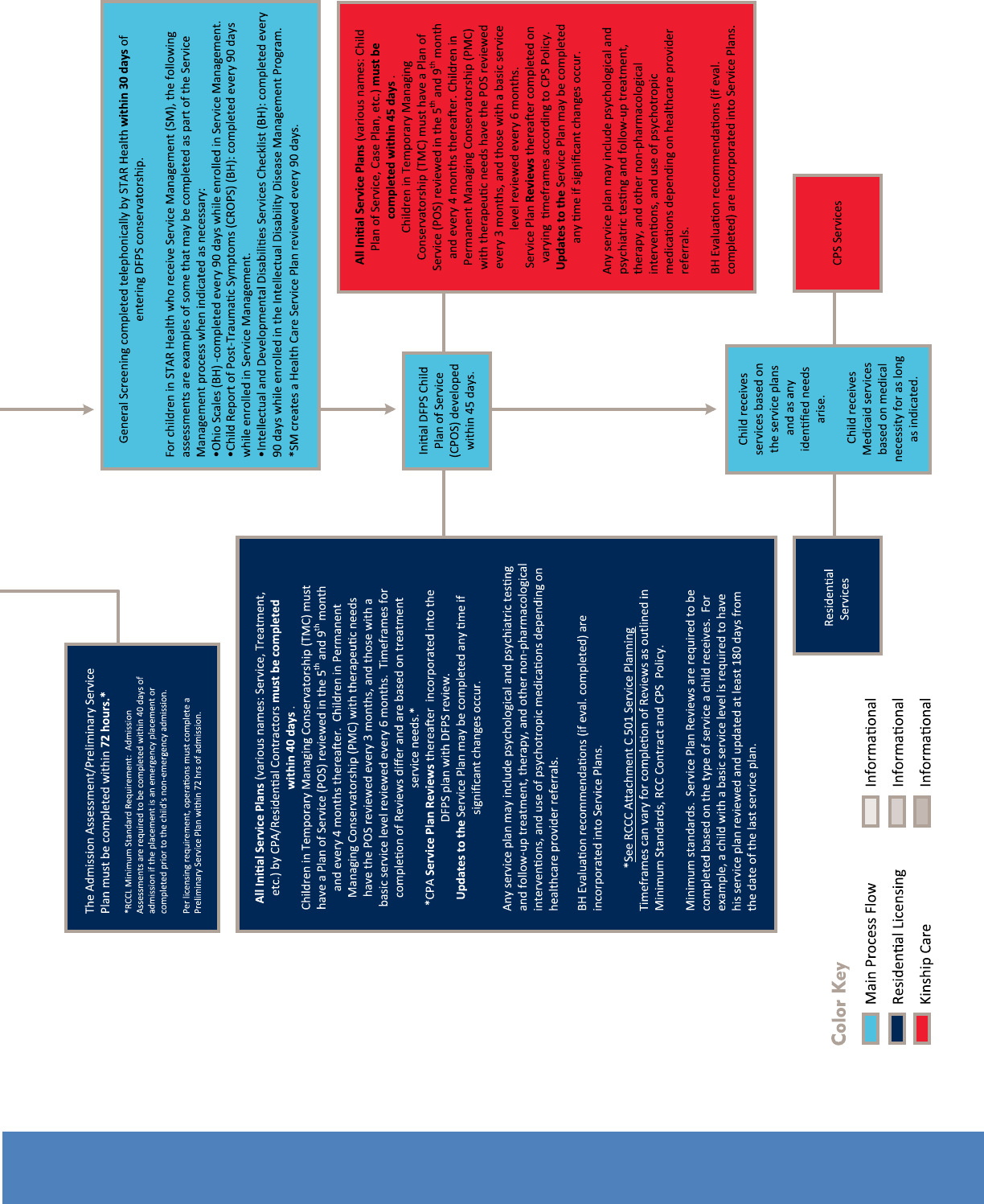

In order to gain a better understanding of how the mental health care system and child welfare system

interact, Task Force members worked with Pamela Baker, Well-Being Specialist, and other Department

of Family and Protective Services staff to create a guide to demonstrate the systems’ interactions and

to identify keys points in the systems where a child receives mental health-related services. Figure 1a

demonstrates the process of how a child in CPS custody is assessed, diagnosed and treated through the

mental health system.

5 Texas Medicaid Managed Care and Children’s Health Insurance Program: EQRO Summary of Activities and Trends in Healthcare Quality. Rep.

Institute for Child Health Policy at the University of Florida Texas External Quality Review Organization, 28 Mar. 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2014. <http://www.hhsc.

state.tx.us/reports/2014/EQRO-Summary.pdf>.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 16

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 17

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 18

As is demonstrated by Figure 1a, navigating the interwoven systems of mental health care and child

welfare can be difcult. The complexity raises the question: How do we know that the best mental

health decisions are being made for our state’s most vulnerable children?

The Texas child welfare system houses our state’s most vulnerable children. Members of the Task Force

believe these children face great challenges and deserve the best care. They deserve to heal from

the pain and trauma of being abused or neglected. They deserve to grow up feeling normal and safe.

They deserve to nish high school and get a college degree. They deserve to grow into healthy adults.

Therefore, they deserve the best system and services that exist in order to help them achieve these

things.

The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force believes that the current system that provides medical and

mental health care for the children in state custody can greatly improve its services and delivery.

KEY ISSUES

Issue 1: Integrated Care is the standard, not the reality

A major concern that Task Force members identied is that children in state custody often do not

receive accurate or appropriate diagnoses. This has been an ongoing concern for Texas and a number

of efforts have been employed to address this issue. While those efforts have mostly been benecial,

Texas must not stop short of realizing a system that works effectively for children in care. If Texas

wishes to ensure accurate and appropriate diagnoses for children and youth in foster care then it

needs to create a truly integrated, collaborative system that is staffed with well-trained, trauma-

informed medical and mental health professionals.

The mental health care, medical care and child welfare systems may be independently helping children,

however, the situations of children in state custody are extremely complex and thus require a smarter,

more exible, and collaborative integrated system of care.

Current System

STAR Health is the Medicaid program that covers medical and behavioral health care for children

in substitute care. Superior Health is the managed care organization for STAR Health. Cenpatico

manages the behavioral health benets for STAR Health. According to STAR Health, their coverage

offers each child in their network an “integrated medical home where each foster care child has access

to primary care physicians, behavioral health clinicians, specialists, dentists, vision services and more”.

6

Integrated care is dened as:

“The care a patient experiences as a result of a team of primary care and behavioral health

clinicians, working together with patients and families, using a systematic and cost-effec-

tive approach to provide patient-centered care for a dened population. This care may

address mental health and substance abuse conditions, health behaviors (including their

contribution to chronic medical illnesses), life stressors and crises, stress-related physical

symptoms, and ineffective patterns of health care utilization.”

7

6 Welcome to STAR Health. Superior Health Plan, 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.fostercaretx.com/welcome-to-star-health/>.

7 “What Is Integrated Behavioral Health Care?” Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services,

2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://integrationacademy.ahrq.gov/atlas/What%20Is%20Integrated%20Behavioral%20Health%20Care>.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 19

The Texas Department of State Health Services (DSHS) denes a medical home as:

“A partnership between a child, the child’s family, and the place where the child gets

primary health care. At a medical home, the child’s family and health care experts are a

team. They work together to nd and get all the services the child and family need, even

if they are not medical services.”

8

DSHS continues its denition, suggesting a medical home offers “health care that is accessible, family-

centered, continuous, comprehensive, coordinated, compassionate, [and] culturally competent”.

9

While these are lofty and strong denitions about the current system, the Task Force believes that this

is not how the system actually functions. CASA volunteers and staff around the state, as well as other

child welfare advocates and professionals on the Task Force, have expressed concern over the ability of

the current medical and mental health care system to provide truly integrated, quality care to children

based on the child’s specic needs and with the goal of healing as the focus. Concerns raised regarding

the integration of mental and physical health care of children include:

• Moving between placements and changing providers interrupts continuity of care. Additionally,

new providers may add new diagnoses on top of an already inappropriate diagnosis or they may

not appropriately treat or even be made aware of chronic issues.

• Children’s medical histories are often non-existent, unknown or not properly acquired by either

caseworkers or the medical and mental health professionals treating the child. Therefore, their

histories may not be used to inform the process of continued treatment for the child.

• Children’s medical care information, while shared with caseworkers and courts, is not required

to be shared with medical or mental health providers treating the child.

• The Health Passport, while benecial in some ways, has not historically contained the most

important health information, nor does it organize information in a way that is efcient for

providers to access and use. It is often under-utilized and not updated, so it can lack in-depth

information about the child’s medical history, mental health, developmental and psychosocial

functioning—information pertinent to any course of care for the child.

If health conditions, medications and medical events are not recorded, maintained, and delivered to the

child’s provider as the child moves between different providers and living situations, the consequences

may include missed diagnoses, inappropriate treatment, duplications in therapy and more. “Such com-

plications can lead to signicant adverse health outcomes and poor quality of life for the child, as well

as increased healthcare costs for the state.”

10

The statistics about this issue reect the concerns that

the Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force laid out above. In fact, on average, children in care experi-

ence eleven placements in a three-year period.

11

8 Every Child Deserves a Medical Home. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, 14 May 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.dshs.

state.tx.us/layouts/contentpage.aspx?pageid=29472&id=2019&terms=%22medical+home%22+and+%22denition%22>.

9 Every Child Deserves a Medical Home. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services, 14 May 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014. <http://www.dshs.

state.tx.us/layouts/contentpage.aspx?pageid=29472&id=2019&terms=%22medical+home%22+and+%22denition%22>.

10 Carrillo, Sarah, and Elisa Ashton. Improving Care Coordination for Foster Children: An Update on California’s Audacious Goal. Rep. California

Ofce for Health Information Integerity, 20 Jan. 2013. Web. 18 Dec. 2014.

11

Ramshaw, Emily. “Lawsuit Can’t Cover All Kids in Long-Term Foster Care.” The Texas Tribune. N.p., 23 Mar. 2012. Web. 07 Aug. 2014. <https://

www.texastribune.org/2012/03/23/lawsuit-texas-failing-foster-children/>.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 20

Given the amount of upheaval and the rapid nature in which transitions to new placements must be

made, it is often difcult to transfer medical and mental health records or to ensure that providers

are communicating the needs of each child to new care providers, especially when those placements

are in different cities, counties or states.

Another indication that Texas’ integrated system of health care is not functioning as is intended can be

seen in the high number of potentially preventable readmissions (PPRs) of children enrolled in STAR

Health. These types of readmissions result from “poor coordination of services at time of discharge…

or deciencies in the process of care and treatment, including actions taken or omitted during the

initial hospital stay”.

1

Children enrolled in STAR Health had PPRs at a rate over ten percentage points

higher (15.5%) than children enrolled in CHIP (5.1%).

2

A truly integrated, coordinated system of care

should not experience this high a rate of PPRs, nor should the children in state care be subjected to

repeat hospital visits when proper care coordination could have prevented them.

One of the most challenging components of achieving positive outcomes for children in state custody

is the ability of the state to create stability and establish continuity across systems as children shufe

through homes, courts, medical and mental health providers and caseworkers. So much is lost for

these children along the way, including the rapport and trust they have potentially built with a provider,

as well as information regarding their needs, what treatments

may have been employed and the success of those treatment options.

The Collaborative Care Model

It is the responsibility of the Department of Family and Protective Services, STAR Health and its

managed care organizations to provide care that is thoughtful, continuous, well-coordinated,

collaborative, trauma informed and sensitive to the child’s experiences and unique needs. Given the

problems that were outlined above, this kind of care is not consistently available in the current system

in Texas.

While STAR Health is supposed to be an integrated system, there is a lack of consideration for the

role that the Department should play in integration efforts. To be a truly integrated care model

serving this population, integration must include not only physical and mental health care but also

care within the child welfare system. This means doctors and mental health professionals need to

collaborate better with each other and they must collaborate with key care partners within the child

welfare system such as the CPS caseworker, the judge and the CASA.

The Task Force recommends that Texas consider adopting the Collaborative Care model. Collaborative

Care is dened as:

“Ongoing working relationships between clinicians, rather than a specic product of

service. Providers combine perspectives and skills to understand and identify problems

1 Texas Medicaid Managed Care and Children’s Health Insurance Program: EQRO Summary of Activities and Trends in Healthcare Quality. Rep.

Institute for Child Health Policy at the University of Florida Texas External Quality Review Organization, 28 Mar. 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2014. <http://www.

hhsc.state.tx.us/reports/2014/EQRO-Summary.pdf>.

2 Texas Medicaid Managed Care and Children’s Health Insurance Program: EQRO Summary of Activities and Trends in Healthcare Quality. Rep.

Institute for Child Health Policy at the University of Florida Texas External Quality Review Organization, 28 Mar. 2014. Web. 15 Dec. 2014. <http://www.

hhsc.state.tx.us/reports/2014/EQRO-Summary.pdf>.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 21

and treatments, continually revising as needed to hit goals.”

3

Establishing a truly integrated, well-coordinated, collaborative system with a medical home could lead

to more positive and healthy outcomes for children. Research suggests that “collaborative care has

consistently demonstrated higher effectiveness than usual care”.

4

“Studies have shown that integrated

health care approaches, such as the Collaborative Care model are more effective than usual care for

depression, anxiety disorders and more serious conditions such as bipolar disorder and

schizophrenia.”

5

Because of the often mobile nature of a child’s life in state care, an integrated method of health care

should include a collaborative element. As a child moves from one provider to the next, past providers

should speak with new providers and share all pertinent information about his or her care. Caseworkers,

CASA volunteers and court systems should also contribute to this collaborative approach by assisting

in the timely transfer of medical and insurance information so that the child’s care is seamless as they

transition.

By establishing an integrated, collaborative system, Texas can be sure that a child’s social, behavioral,

psychological and medical histories can travel along with them. When practitioners have a fuller

understanding of what is going on for a child, they are more likely to make an accurate diagnosis

and suggest more useful treatment options. Integrated, collaborative and holistic systems of health

care mean all practitioners (medical care providers, mental health professionals, psychiatrists, etc.)

are communicating, frequently assessing the progress of the child’s care, regularly re-evaluating the

treatment plan and referring to outside, community-based services that may also be useful to the child.

Recommendations:

1. The Health and Human Services Commission should activate and publicize Medicaid billing codes

that will allow providers to bill for collaborative consultation, which allows practitioners to bill for

“peer consults” between primary care physicians (PCPs) and other PCPs; PCPs and Psychiatrists, and

PCPs to other mental health practitioners.

2. Ensure the Health Passport is being utilized and includes updated information on the child’s medical

history, mental health, developmental and psychosocial functioning—any information pertinent to any

course of care for the child.

Issue 2: The term “non-pharmacological interventions” is not well dened or

understood

The 83

rd

Texas Legislature passed House Bill 915, establishing added protections from the overuse of

psychotropic medications for children and youth in state custody. The new law states that the Depart-

ment of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) and judges are now responsible for ensuring non-phar-

3 Peek, C.J. Lexicon for Behavioral Health and Primary Care Integration: Concepts and Denitions Developed by Expert Consensus. Rep. Agency for

Healthcare Research and Quality, Apr. 2013. Web. 18 Dec. 2014.

4 Unutzer, J., Harbin, H., Schoenbaum, M., and Druss, B., The Collaborative Care Model: An Approach for Integrating Physical and Mental Health

Care in Medicaid Health Homes. 2013. http://www.medicaid.gov/State-Resource-Center/Medicaid-State-Technical-Assistance/Health-Homes-Technical-

Assistance/Downloads/HH-IRC-Collaborative-5-13.pdf.

5 Ybarra, Rick. “Our Journey Through Integrated Health Care and What We Have Learned.” Web log post. Hogg Blog. Hogg Foundation for Mental

Health, 5 Aug. 2014. Web. 18 Dec. 2014.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 22

macological interventions are considered in lieu of or along with psychotropic medications. Shortly after

this bill became law, questions arose regarding the denition of “non-pharmacological interventions”.

The purpose of this law was to ensure that children and youth in state custody are only treated with

psychotropic medications when absolutely necessary and that other methods of mental health inter-

vention be employed to assist a child in coping with symptoms of mental health conditions and trauma.

Yet, there is no broad understanding between DFPS, the courts, caregivers, stakeholders, practitioners

or advocates about what “non-pharmacological interventions” means.

The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force set out to establish a denition for “non-pharmacological

interventions” to provide clarity to those working within the child welfare system and to ensure that

children and youth in substitute care have access to a wide array of services that have proven benets

for their mental health outcomes. In developing a denition, the Task Force demanded that space be

made for both what professional mental health providers refer to as “evidence-based practices” and for

other interventions that have been proven through research to have a positive effect on mental health

outcomes.

Recommendation:

1. Adoption of the following denition of “non-pharmacological interventions” by the judicial system,

medical care providers, insurers, CASA, CPS and others:

• “Non-pharmacological interventions” is terminology meant to represent an array of strategies,

supports and interventions intended to help children recover and heal from trauma, build

resilience and meet developmental milestones. Non-pharmacological interventions must be used

in lieu of or concurrently with psychotropic medications and should be informed by accurate

and continuous assessment and/or diagnosis. Non-pharmacological interventions include both

evidence-based interventions, promising practices and those interventions proven effective by

peer-reviewed research.

Issue 3: Medical and mental health providers serving this population are

not beholden to American Academy of Pediatrics standards and the current

Medicaid reimbursement rates in Texas deter providers

Not only does the current functioning and interplay between the child welfare, mental health care and

medical care systems raise questions regarding coordination of services for children, there are also

challenges around the quality of and access to services.

Like many other states, Texas struggles to host quality medical and mental health providers and that

struggle is further complicated as fewer providers choose to serve Medicaid clients. In fact, in 2011,

less than 33 percent of Texas’ practicing doctors accepted Medicaid patients.

6

There are a number

of reasons why providers choose not to become a Medicaid provider, including the huge amount of

paperwork involved and inadequate reimbursement rates for services. In Texas, licensed clinical social

workers and licensed professional counselors are reimbursed at only 70 percent of the rate paid to

licensed psychologists and psychiatrists, even though they are providing the majority of the Medicaid

mental health services to children and youth in foster care.

7

Since Texas is already struggling to recruit

6 Crisis Point: Mental Health Workforce Shortages in Texas. Rep. Hogg Foundation for Mental Health and Methodist Healthcare Ministries, Mar.

2011. Web. 19 Dec. 2014. <http://www.hogg.utexas.edu/uploads/documents/Mental_Health_Crisis_nal_032111.pdf>.

7 “Texas Medicaid Fee-For-Service Reimbursement.” Texas Medicaid Provider Procedures Manual 1 (2014): 2-1--11. American Medical Association,

Dec. 2014. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 23

and maintain quality Medicaid mental health providers, it should not create additional challenges for

providers by not reimbursing all licensed professionals at the same rates for the same services.

The Task Force members also believe that mental health and medical providers who care for children

in the child welfare system should be expected to adhere to the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

standards and recommendations on Health Screenings in Foster Care. The AAP requirements for health

screenings in foster care detail information about how to conduct a comprehensive evaluation, how

to create a medical home, the importance of preventative health care for this population and how

to properly maintain medical records for children and youth in foster care.

8

In order to meet these

standards, physicians need to spend more time with each patient. Allowing more time with the children

is imperative because they will be better able to develop a trusting relationship with the child and should

(if they adhere to AAP standards) be eliciting important medical and mental health related information

from the child throughout their time in state care.

9

Training on national standards, including the

American Academy of Pediatrics standards, is not widely available or required for physicians in Texas,

even if they are providing care for the vulnerable children and youth in the foster care system.

Recommendations:

1. Implement, require and train on American Academy of Pediatrics standards for

physicians treating children in substitute care on health screenings in foster care.

2. Provide equivalent reimbursement rates for all licensed professionals who provide

Medicaid mental health services to children in foster care.

Issue 4: Limited information is available regarding the array of mental health

services available under STAR Health and understanding of how to utilize the

Medicaid appeals process and other legal options is limited

Task Force members experienced difculty in attempting to nd a comprehensive list of services covered

by STAR Health and had further challenges dening the services that are covered. Despite their best

efforts, Task Force members were unsuccessful at compiling a list of covered services, and it was even

unclear to members what the services entail as there are no easily available denitions of services.

Given the difculty seasoned advocates experienced nding a comprehensive list of mental health

services and their denitions, how can caregivers, consenting youth or other medical consenters be

expected to understand the variety of options available to the children they care for?

Additionally, Task Force members found that the complexity of the Medicaid appeals process and other

legal avenues to challenge denial of services present signicant, unnecessary challenges for stakeholders

and caregivers in Texas. The basic appeals process overseen by Superior Health Plan is available to

all enrollees in STAR Health but it can be difcult to access and to navigate for consumers without

experience in the process. The appeals process is important for caregivers to understand because it

allows them to seek coverage for services not explicitly covered by STAR Health, as long as the services

are deemed medically necessary by the child’s physician. Additionally, currently provided services must

continue to be provided during an appeal if the appeal is requested in a timely manner. STAR Health

8 “Requirements for Health Screenings in Foster Care.” Healthy Children. The American Academy of Pediatrics, 03 Oct. 2013. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

<http://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/family-dynamics/adoption-and-foster-care/Pages/Requirements-for-Health-Screenings-in-Foster-Care.

aspx>.

9 “Requirements for Health Screenings in Foster Care.” Healthy Children. The American Academy of Pediatrics, 03 Oct. 2013. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

<http://www.healthychildren.org/English/family-life/family-dynamics/adoption-and-foster-care/Pages/Requirements-for-Health-Screenings-in-Foster-Care.

aspx>.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 24

members also have the right to initiate a fair hearing appeal process that is separate from the fair

hearing appeals process and adjudicated by the Health and Human Services Commission, rather than

Superior Health Plan.

Gaining a better understanding of what services are available under STAR Health and knowledge about

how to navigate the Medicaid fair hearing appeals process would allow those making medical decisions

for children in care to advocate appropriately for the individual needs of the children they are caring for

and promote better health outcomes.

Recommendations:

1. Revise STAR Health Member Handbook to include:

• Information on trauma and trauma-informed care

• Information on behavioral health services, including a list of covered services, denition of

services, and information on how to access services and who can provide services

• A simpler explanation of the Medicaid appeals process

2. Train consumers, attorneys, judges, CASA volunteers, medical consenters and youth (especially

those 16 and older) on:

• What behavioral health services are available through STAR Health, including denitions of ser-

vices, how to access services and who can provide services

• The Medicaid appeals process, including how to appeal when a requested medically necessary

service is denied

3. Train attorneys, CASA volunteers, judges, medical consenters and youth on how to petition the

court for an order related to the medical care for a foster child. This is not a formal Medicaid appeal

but the use of the exclusive jurisdiction of the court could help to ensure that foster children receive

appropriate medical care, including mental health and behavioral health services.

Issue 5: Texas youth who aged out of care not auto-enrolled in Medicaid and

youth who aged out in other states are not extended coverage in Texas

With the passage of The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA), states are now required

to provide Medicaid coverage to individuals under the age of 26 who were in foster care and receiving

Medicaid at the time of aging out of care.

10

According to the Texas Department of Family and Protec-

tive Services (DFPS), the changes set forth by the ACA have expanded the Former Foster Care Children

Program. So, depending a child’s age, the child will have Medicaid coverage until the age of 26 in

Texas. DFPS has altered the structure of the program and has laid out how this Medicaid expansion

will be accessible to foster youth.

11

While the expansion is well-needed, concern exists regarding the

implementation of these changes. The Texas CASA Mental Health Task Force identied two potential

barriers that youth might experience when they try to access this program.

10 Deckinga, Audrey. “Former Foster Care Children Program-Medicaid Healthcare Coverage for Former Foster Youth Ages 18 through 25.”

Memorandum to CPS Regional Directors. 18 Nov. 2013. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. 1-6. Print.

11

Deckinga, Audrey. “Former Foster Care Children Program-Medicaid Healthcare Coverage for Former Foster Youth Ages 18 through 25.”

Memorandum to CPS Regional Directors. 18 Nov. 2013. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. 1-6. Print.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 25

Foster youth face immense challenges when they age out of foster care, including lack of family and/

or social support, poverty, potential unemployment, inadequate living arrangements and little or no

coordination of their physical and mental health services. In spite of the fact that they are supposed

to be enrolled in Medicaid services, foster youth are likely to face untreated medical and mental health

problems.

12

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, children who have aged out of state care

lack access to health and mental health services, which are critically important and have a signicant

impact on the child’s transition into adulthood.

13

Under current Texas statute, former foster youth in the initial Medicaid coverage plan, STAR health,

are covered until age 21. At that time, the former foster youth must request and apply to be enrolled

into the second coverage plan, STAR, extending coverage to age 26. This is Texas’ approach to com-

pliance with the Affordable Care Act requirements. The Task Force views the fact that foster youth

must reapply for Medicaid benets at age 21 as a signicant barrier that prevents many foster youth

from obtaining critical physical and mental medical care. The Task Force recommends changing this

practice to include seamless and automatic enrollment transfers from STAR Health to STAR when the

child turns 21, assuring that former foster children will have Medicaid coverage until age 26 regardless

of reapplication.

Another barrier for foster youth that the Task Force identied is the lack of Medicaid coverage for for-

mer foster youth who relocate to Texas after they age out of care. DFPS’s recent statutory changes

include a provision that alters the eligibility of the Medicaid Transitioning Foster Care Youth (MTFCY)

program from including former foster care children from any state to only those who aged out in Texas.

14

This leaves a gap of coverage for former foster youth from other states who newly reside in Texas. For

example, if a former foster care youth moves to Texas (to reunite with family, seek employment or pur-

sue educational opportunities), the eligibility change will roll back coverage for the youth. This means

that youths in this situation were covered until age 21 in the original program and now they are only

covered until age 18.

This change prevents former foster youth from accessing the resources necessary to lead healthy lives

and could potentially impact their overall life outcomes.

Recommendations:

1. Create automatic enrollment transfers from STAR Health to STAR when a child turns 21, assuring

that former foster children will have Medicaid coverage until age 26 regardless of reapplication.

2. Extend Medicaid eligibility to former foster youth from any state until age 26.

12 “Health Care of Youth Aging Out of Foster Care.” Pediatrics 130.6 (2012): 1170-173. Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care and

Committee on Early Childhood. American Academy of Pediatrics, 26 Nov. 2012. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

13

“Health Care of Youth Aging Out of Foster Care.” Pediatrics 130.6 (2012): 1170-173. Council on Foster Care, Adoption, and Kinship Care and

Committee on Early Childhood. American Academy of Pediatrics, 26 Nov. 2012. Web. 19 Dec. 2014.

14 Deckinga, Audrey. “Former Foster Care Children Program-Medicaid Healthcare Coverage for Former Foster Youth Ages 18 through 25.”

Memorandum to CPS Regional Directors. 18 Nov. 2013. Texas Department of Family and Protective Services. 1-6. Print.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 26

II. EMPOWERMENT AND NORMALIZATION OF

YOUTH IN SUBSTITUTE CARE

Background

Normalcy shapes children and youth in the state’s care

As children develop into adolescence and then adulthood, their growth is marked by experiences that

contribute to their autonomy and their social functioning, shaping who they will become as adults and

how successful they may be in life and relationships. These experiences can include things from spending

the night at a friend’s house, volunteering in the community, having an after school job, playing sports,

running for student government, to going on a rst date or attending senior prom. The list of activities a

young person may experience during their adolescence is extensive. All of these experiences help shape

the person this youth will ultimately become.

These types of activities are referred to as “normalcy” activities and are dened as “the opportunity

for children and youth to participate in and experience age and culturally appropriate activities,

responsibilities, and life skills that promote normal growth and development”.

1

The Texas Department

of Family and Protective Services has made efforts to ensure that all children/youth in its care have

access to normalcy activities. These guidelines are laid out in communication from the agency, within

their minimum standards and residential contracts.

Empowerment and normalcy activities are key to mental health and healthy

development

Access to normalcy activities and opportunities for empowering young people in substitute care can

improve mental health outcomes. Simple experiences such as having friends and spending time with them

can vastly improve a young person’s disposition. Friendship and socialization are essential in maintaining

health and psychological well-being.

2

Positive relationships are correlated with happiness, quality of

life, resilience and cognitive capacity.

3

Friendships are essential for foster youths and friendships with

peers outside of the foster care program are especially important. Research has shown these friendships

may act as a deterrent against victimization, promote social skills and increase emotional health.

4

The types of experiences offered through friendships are sometimes taken for granted, but it is important

to understand that establishing, maintaining and enjoying friendships is not something easily achieved

by our young people in foster care. Youth in substitute care move often, change schools frequently and

are sometimes housed in isolated facilities. Even in stable placements, youth face prohibitions on simple

1 “Normalcy Recommendations: Improving Well-Being by Addressing Normalcy for Foster Youth.” The National Foster Care Youth & Alumni Policy

Council. N.p., 16 Apr. 2013. Web. 16 Dec. 2014.

2 Blieszner, R. The Worth of Friendship: Can Friends Keep Us Happy and Healthy? Journal of the American Society on Aging. Spring 2014 Vol. 38.

No. 1

3 Fowler, J.H., Christakis, N.A., Dynamic spread of happiness in a large social network: longitudinal analysis over 20 years in the Framingham Heart

Study. Dec. 2008.

4 Skrzypiec, G., Slee P., Askel-Williams, H. and Lawson, M. Associations between types of involvement in bullying, friendships and mental health

status. Emotional and Behavioral Difculties

Vol. 17, Nos. 3–4, September–December 2012, 259–272.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 27

things like staying the night with friends or having friends stay the night at their home.

In addition to building relationships with friends, young people’s mental health is greatly beneted

by participating in recreational activities. Age-appropriate recreational activities can promote positive

emotions, increase relationship skills and advance mental and physical health. Part of the positive

benet of physical activity on mental health occurs through the socialization that happens when young

people engage in physical activities with their peers.

5

Other social activities such as band, religious

involvement, drama club and others contribute to a young person’s self-esteem, moral and cognitive

development.

6

These social activities help foster youth create and maintain relationships and help

them develop important life skills and coping strategies. Recreational activities that involve play and

playfulness have also been shown to reduce defensiveness, enhance well-being and foster maturation

in children.

7

While normalcy and access to age-appropriate activities are important for foster children in general,

they are even more critical for foster youth with poor mental health. Due to the stigma associated with

mental health issues, many foster youth create coping strategies outside of professional mental health

interventions, including many of the normalcy activities described above. Mental health professionals

have drastically underestimated the importance of therapeutic lifestyle interventions, including self-help

and coping mechanisms. Unlike what occurs in sometimes rigid and highly structured mental health

therapies, these activities are free of stigma and have profound effects on self-esteem and quality of

life.

8

Normalcy activities are essential for the mental health of foster youth. In fact, these activities may

lessen the need for professional intervention in the mental health of children in state care, providing

nancial incentive for DFPS and foster care providers to help children and youth access normalcy

activities.

The current status of foster youth decision-making and normalcy activities in Texas Department of

Family and Protective Services is troubling. In depth-interviews conducted with former Texas foster youth

conrm the need of normalcy activities in foster youth lives. This report, entitled Voices of Experiences,

identied many alarming facts regarding the mental health of children in substitute care in Texas.

More than one third of the youth who aged out of care in Texas reported they had no input on their

mental health diagnoses or mental health services. Many of the youth also reported they had negative

experiences with mental health services while in state custody. Youth in Texas also indicated a desire

to have a gradual increase of responsibilities and liberties as their age and maturity increased.

They

reported that they believe the child welfare system kept them “isolated from the real world”.

9

Similar

information was revealed in the youth surveys conducted by Texas Department of Family and Protective

Services. Some youth felt they were not given chances to make decisions about their lives as they

prepared for adulthood.

10

5 VanKim N., Nelson T. Vigorous Physical Activity, Mental Health, Perceived Stress, and Socializing Among College Students. American Journal of

Health Promotion. September/October 2013, Vol. 28, No. 1

6 Alexander, C.N. & Langer, E. (1990). Higher stages of human development: Perspectives on adult growth. New York, NY: Oxford University Press

7 Walsh, Roger. “Lifestyle and Mental Health.” American Psychologist 66.7 (2011): 579-92. Web. 16 Dec. 2014.

8 Walsh, Roger. “Lifestyle and Mental Health.” American Psychologist 66.7 (2011): 579-92. Web. 16 Dec. 2014.

9 Gendron, Christine. Voices of Experience: Improving Mental Health Supports for Homeless & Transitioning Youth. Rep. Texas Network of Youth

Services, 2011. Web. 16 Dec. 2014.

10 Improving the Quality of Services to Youth in Substitute Care: A Report on Surveyed Youth in Foster Care FY 2007. Rep. Texas Department of

Family and Protective Services, Sept. 2008. Web. 16 Dec. 2014.

MENTAL HEALTH TASK FORCE REPORT | PAGE 28

A recurring challenge in helping children in foster care achieve a sense of normalcy is the lack of

consistency in their lives. Numerous personal narratives and testimonies of children shine light on

the traumatizing feelings associated with moving from placement to placement. In 2007, focus group

studies were conducted in order to examine the mental health of foster youth dealing with the ongoing

stresses of substitute care. According to the study, youth interviewed noted the importance of routine

and control over life situations:

“[They have a] need for normalcy related to feelings of lack of control and confusion as

a result of constant life changes. These feelings affected the informants’ self-esteem,

security, and identity. The foster children described the desire for foster care professionals

to allow them to participate in decisions about home placements”.

11

Foster children have desire for autonomy and involvement in decisions inuencing their lives and well-

being. They have repeatedly emphasized their wish to be involved in their own mental health decisions.

12

Foster children also expressed a desire to have autonomy over other important decisions, such as

placement options and the type of preparation they need for aging out of state custody.

Examining testimonies of former foster children led the Task Force to the conclusion that foster youth

may be reluctant to participate in mental health resources or therapy.

13

Youth in state custody often have

resentment about being forced to receive therapy before they feel they are ready for such services.

14

Due to negative experiences in the child welfare and mental health systems, foster youth may distrust

mental health professionals, which further elevates the importance of normalcy activities and decision-

making for children in care. Children in state custody should be allowed to be actively involved in

normalcy activities and have more autonomy to make decisions regarding their care, leading to better

mental and physical health outcomes.

The challenge is that access to these activities is difcult to achieve for many young people who are

cared for by a system. The system wants youth to be able to participate in normalcy activities but it is

set up to discourage such participation.

KEY ISSUES

Issue 1: The current system inhibits caregivers’ ability to make decisions

about a child’s participation in normalcy activities and experiences

In the Department of Family and Protective Services (DFPS) literature, normalcy activities are guaranteed

to foster youth through a Bill of Rights. This Bill of Rights states “I have the right to attend my choice