ODYSSEY 2012

14

asl/english

bimodal

bilingual program

During the past few years, the teachers and staff at Kendall Demonstration

Elementary School (KDES) have reviewed research to identify factors that

positively impact language development for deaf and hard of hearing

children, and established language and communication practices to reflect

what we have learned. Based on the research, which details the advantages of

early accessible visual language (Baker, 2011) and documents the variations

in spoken language outcomes regardless of the use of hearing aids and

cochlear implants (Yoshinaga-Itano, 2006), we have examined how an

American Sign Language (ASL)/English bilingual program can be designed

to benefit children with a wide range of characteristics—from children who

have minimal access to spoken language through hearing aids and cochlear

implants to those who benefit greatly from these technologies. We refer to

this as an ASL/English bimodal bilingual approach, which includes

establishment of language foundations and access to learning through two

modalities, e.g., auditory and visual, and two languages, e.g., ASL and

English (Berent, 2004; Bishop, 2006; Emmorey, Bornstein, & Thompson,

2005). Through our experience in establishing a bimodal bilingual program

at KDES and through our consultations with schools and programs

throughout the United States, we are finding that with purposeful planning

this multisensory approach can be implemented to effectively support the

overall development of deaf and hard of hearing children.

Photos by John T. Consoli

Debra Berlin

Nussbaum, MA, is

coordinator of the

C

ochlear Implant

Education

Center (CIEC)

at the Laurent

Clerc National

Deaf Education

Center at Gallaudet

University. She earned her

master’s degree in

audiology from George

Washington University

and has worked at the

Clerc Center since 1977,

first as a pediatric

audiologist and since

2000 as coordinator of the

CIEC. She has

spearheaded national

efforts to address how

spoken language and

signed language can be

included in the education

of children who are deaf or

hard of hearing. She has

also developed numerous

resource materials and

professional training

workshops; she speaks

nationally and

internationally on this

topic.

Susanne Scott, MS,

is a cochlear

implant/bilingual

specialist at the Laurent

Clerc National Deaf

Education Center at

Gallaudet University.

With a degree in

audiology from

Gallaudet

University, she has

worked at Gallaudet

University and the

Clerc Center since 1980,

first as an educational

audiologist and then as a

By Debra Berlin Nussbaum, Susanne Scott, and Laurene E. Simms

T H E “ W H Y ” A N D “ H O W ” O F A N

2012 ODYSSEY

15

clinical educator in the

Department of Hearing,

S

peech and Language

Sciences. In 2003 Scott

joined the Cochlear

Implant Education

Center, where she provides

expertise in cochlear

implants and ASL/English

bilingual programming

for professionals, students,

and families at the Clerc

Center and throughout

the nation.

Laurene E. Simms,

PhD, is a professor in the

Department of Education

at Gallaudet University.

After graduating from the

Indiana School for the

Deaf, she earned her

bachelor’s and

master’s degrees

in elementary

education from

the University of

Nebraska, Lincoln

and Western

Maryland College (now

McDaniel College),

respectively. She received

her doctorate in language,

reading, and culture from

the University of Arizona.

An acknowledged expert

in ASL/English

instruction, Simms has

implemented

bilingual/multicultural

educational environments

for diverse deaf and hard

of hearing children.

The authors welcome

questions and comments

about this article at

Debra.Nussbaum@gallaudet

.edu, Susanne.Scott@

gallaudet.edu,and Laurene.

respectively.

Research Support for a

Bimodal Bilingual Approach

For children who are deaf or hard of hearing

and cannot fully access linguistic meaning

through audition, the use of ASL has been

documented to promote linguistic,

communication, cognitive, academic, and

literacy development as well as social-

emotional growth and identity formation

(Baker, 2011; Cummins, 2006; Grosjean,

2008; Morford & Mayberry, 2000; Yoshinaga-

Itano, 2006). Evidence also indicates that there

is a risk of language delay if an accessible

language is not used as early as possible, even

for children who have some level of access to

spoken language through a hearing aid or

cochlear implant (Mayberry, 1993, 2007;

Mayberry & Eichen, 1991; Mayberry, Lock, &

Kazmi, 2002; Schick, de Villiers, de Villiers, &

Hoffmeister, 2007). The brain has the capacity

to acquire both a visual and a spoken language

without detriment to the development of

either (Kovelman et al., 2009; Petitto et al.,

2001; Petitto & Kovelman, 2003), and there is

no documented evidence demonstrating that

ASL inhibits the development of spoken

English (Marschark & Hauser, 2012). An

ASL/English bimodal bilingual approach has

the characteristics to be advantageous to

language acquisition and learning. The child

ODYSSEY 2012

acquires language through his or her

intact visual modality while developing

spoken English to the maximum extent

possible. This approach is “additive”; it

builds upon a child’s strength in one

language while adding a second

language (Baker, 2006).

Evolution of an ASL/English

Bimodal Bilingual Approach

Use of a bilingual approach, which

addresses the acquisition and use of both

ASL and English, emerged during the

1980s. Referred to as the

bilingual/bicultural (“Bi-Bi”) approach,

this model reflects the importance of

including the language accessibility

needs as well as the cultural and identity

needs of deaf learners. ASL is

recommended as a first language and

major medium of communication, with

English addressed primarily through

reading and writing (Nover, 1995;

Nover, Christensen, & Cheng, 1998;

Reynolds & Titus, 1991; Vernon &

Daigle, 1994). A framework later

emerged emphasizing the development

of ASL and English, including the

development of spoken English

commensurate with a child’s potential

for oral/aural development (Garate,

2011; Nover, Christensen, & Cheng,

1998). As growing numbers of children

demonstrate the potential to access

language and learning through audition

via improved digital hearing aids and

cochlear implants, increasing numbers of

educational programs have moved

towards designing and implementing an

ASL/English bilingual program that is

also bimodal.

Planning and Implementing a

Bimodal Bilingual Program

The key to designing and implementing

a successful bimodal bilingual program

is planning (Knight & Swanwick, 2002;

Nover, 2004). Regardless of whether

this approach is implemented in schools

for deaf students or in public or private

school settings, three components are

integral: school-wide planning,

individualized planning, and teacher

implementation planning.

School-wide planning is the first

step. It is critical that the school

administration define and share with

the school community the school’s

philosophy and guiding principles

surrounding the development and use of

ASL and spoken and written English

(Muhlke, 2000). (See sidebar on

“Guiding Principles for Bilingual

Planning at the Clerc Center.”) An

effective planning process should

include teachers, staff, and families. A

strategic plan to identify resources for

ongoing professional development and

family education and a system to

monitor program effectiveness is also an

important part of the process. From our

experience, it has been beneficial to have

a designated person(s) responsible for

oversight of the school-wide planning

and implementation process.

Individualized planning, the

development of a language and

communication plan for each child, is

the second key component. The

individualized plan should include the

child’s profile (based on informal and

formal assessment) and his or her

functioning in both ASL and spoken

English (Easterbrooks & Baker, 2002); it

should also include recommendations for

individual goals to facilitate

development and use of each language

and a system to monitor each child’s

progress. (See sidebar on “Planning to

Implementation: A Look at Tommy’s

Day.”) The plan can be tailored to reflect

the needs of children who:

•

Are from families that are culturally

deaf

•

Have additional disabilities

•

Are in the early language

development stages

•

Are beyond the early language

development years

•

Use and benefit from hearing aids or

cochlear implants

•

Do not use or benefit from hearing

aids or cochlear implants

As part of the individualized planning

process, the Clerc Center has developed

and is utilizing a Language and

Communication Profile. This profile

includes a variety of tools we have

chosen to document a child’s language

and communication characteristics and

reflects a child’s use of language in

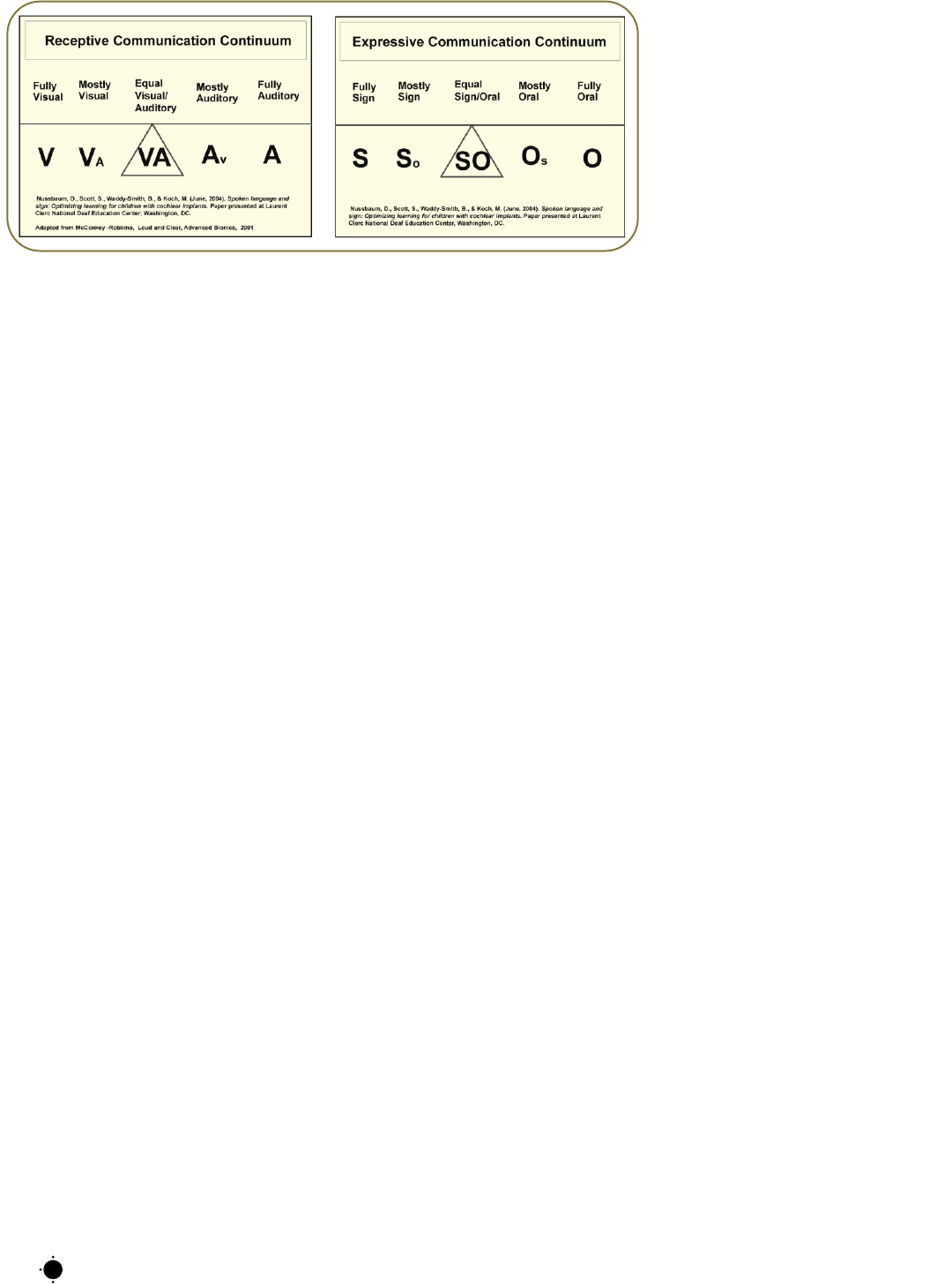

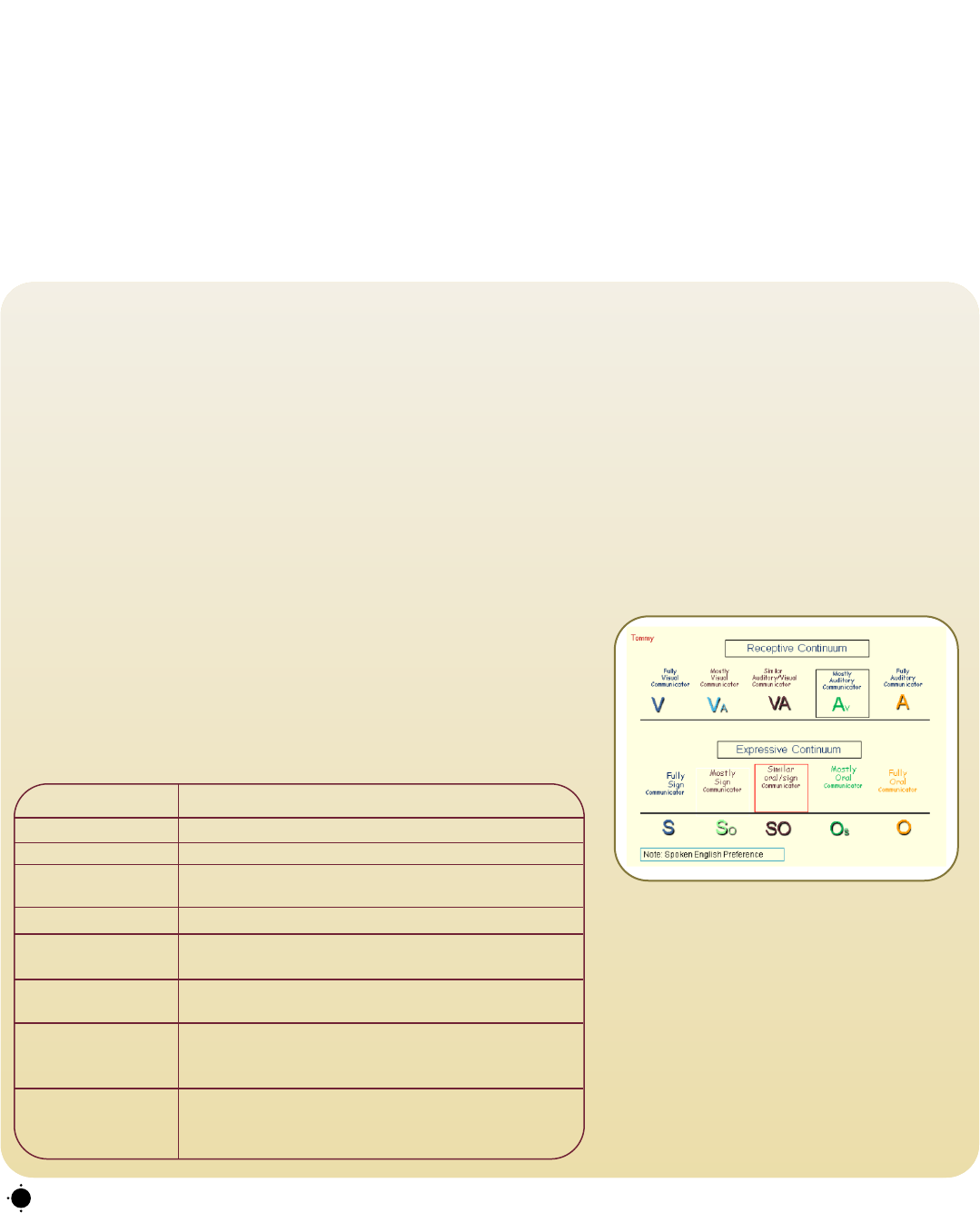

varied environments. One part of the

profile includes a description of the

child’s functioning along two

continuums (see Figure 1): a receptive

continuum for how a child accesses

language—visually, aurally, or

somewhere in between; and an

expressive continuum for how a child

expresses language—signed, spoken, or

somewhere in between (Nussbaum &

Scott, 2011). As placements within

these continuums are incorporated into

developing an individualized plan, it is

important to emphasize the following:

•

How a child functions on either

continuum may differ in varied

settings (e.g., social settings, large

classrooms, small groups, 1-1

situations, noisy environments,

complicated fast-paced language

situations). Language use decisions

should reflect a child’s needs in each

of these settings.

•

How a child functions in

understanding ASL and spoken

language may differ from how he or

she functions in generating either

language. For example, a child may

be able to readily understand

spoken language or ASL; however,

16

Figure 1: Continuums used at the Clerc

Center to document receptive and expressive

communication as part of the individualized

language planning process

2012 ODYSSEY

he or she may not demonstrate the

ability to express him- or herself at

t

he same level through either

language.

Regardless of which assessment tools

or documentation system a school uses,

the individualized plan should be

developed by a team of professionals

working with the child, including his or

her teacher, speech language specialist,

audiologist, ASL specialist, etc.

Gathering family input related to a

child’s use of language and

communication in the home, as well as

family goals related to the development

and use of each language, is an integral

part of developing the individualized

plan. If professionals or specialists

outside of the school are involved with

the child, they should also be included

in the planning process.

Teacher implementation planning,

the third step in the process, should be

coordinated by the child’s teacher and

include feedback from other support

professionals and the family. It should

reflect language use for each activity

throughout the day, identify who will

use each language to facilitate the

activity, and determine how to group

children with similar language and

communication characteristics and goals

(Swanwick & Tsverik, 2007; Garate,

2011). Part of the plan can also include

recommendations for families regarding

how and when to use each language in

the home.

At KDES, two of the practices used

for implementing individual language

and communication plans are language

immersion and classroom integration:

•

Language immersion is the targeted

use of either ASL or spoken English

for a dedicated period of time

guided by the activity, the person

facilitating the activity, and/or the

place of the activity. This practice

provides an opportunity for children

to acquire and experience a distinct

separation between ASL and spoken

English (Baker, 2006). Language

use during immersion activities is

purposeful, meaningful, and

developmentally appropriate,

allowing language acquisition to

proceed in a way that is natural and

incidental. For example, in a

preschool classroom, an art activity

may be facilitated through spoken

English in one area of the classroom

and through ASL in another area of

the classroom. Other immersion

opportunities we have implemented

include lunchtime, facilitated in

ASL or spoken English at separate

tables, and read-aloud stories,

facilitated either in ASL or spoken

English. For children in

kindergarten through eighth grade,

ASL immersion occurs via a

dedicated ASL language arts class.

•

Classroom integration is the use of ASL

and English within a lesson, activity,

or interaction to facilitate

development of skills in ASL and

spoken English. Classroom

integration provides structured

opportunities to address each child’s

individual language and

communication goals. For example,

while working on curriculum

content in class, one group of

children may be with a speech-

language specialist and/or teacher to

develop spoken English skills and

17

Guiding Principles for Bilingual

Planning at the Clerc Center

B

ELIEF STATEMENT ON LANGUAGE:

We believe that early access to and acquisition of linguistic proficiency

i

n ASL and English are integral to a deaf or hard of hearing

student’s overall development.

GUIDING PRINCIPLES:

•

Early, unrestricted access to language is critical to linguistic and cognitive

development.

•

Bilingual development of ASL and English is critical to deaf and hard of

hearing children establishing early communication with their parents,

developing their cognitive abilities, acquiring world knowledge,

communicating fully with the surrounding world, and acculturating into the

world of the hearing and of the deaf. (Grosjean, 2008)

•

Accessible and consistent ASL and English adult and peer language models are

integral to fostering language acquisition and learning.

•

Use of visual language, including ASL and a rich English print environment,

is critical for access, acquisition, and development of both languages.

•

Spoken English is valued, encouraged, and incorporated specific to an

individual child’s characteristics and goals.

•

Family involvement and competence in facilitating early accessible language

and communication is critical to a child’s cognitive and social-emotional

development.

a

nother group of children may be

with an ASL specialist and/or teacher

to develop ASL skills. Skill

development in each language can

also be integrated through use of

learning centers (Garate, 2011).

During both immersion and

integration opportunities, bilingual

strategies can be used to link ASL and

spoken English, including:

•

Sandwiching—Saying it-signing it-

s

aying it, or signing it-saying it-

signing it

•

Chaining—Signing it-fingerspelling

it-using picture support-saying it

While research exists to support the

bimodal bilingual approach, research has

not yet formally documented student

outcomes. However, at KDES we have

witnessed positive outcomes in both ASL

and spoken English for our students. We

have also experienced the benefit to our

s

chool community, families, and students

of using a language planning process that

is reflective of research and driven by

individualized student assessment. While

a bimodal bilingual program requires

dedicated planning and coordination, we

are optimistic that its potential to

positively impact the development of

linguistic competence of deaf and hard of

hearing children will offer strong

motivation for educational settings to

implement this approach.

ODYSSEY 201218

Planning to Implementation: A Look at Tommy’s Day

B

ACKGROUND:

Tommy is 5 years old and enrolled in an ASL/English bilingual kindergarten class. He is one of 12 students with varying

degrees of hearing levels, varied use and benefit from listening technologies (e.g., hearing aids, cochlear implants), and varied skills in ASL and

spoken English. He has a teacher who is hearing and bilingual in ASL and English as well as an instructional aide who is a native ASL user.

Tommy has a bilateral, moderate to severe sensorineural hearing loss that was identified via newborn hearing screening. Tommy’s

parents are hearing and he has a 2-year-old sister who is also hearing. He started receiving early intervention services at 4 months of age.

At that time he was fitted with digital hearing aids that he uses consistently, and his parents started learning and using ASL. The

primary language of the home is spoken English; however, the family also uses ASL. Based on the results of formal and informal

assessments, Tommy’s language and communication functioning is as follows:

•

ASL: Tommy understands simple, familiar information when language is context embedded and predictable. He demonstrates the

emerging potential to understand and use ASL for increasingly complex new information in one-on-one or small group settings.

His signing is generally understood by family members, teachers, and peers.

•

SPOKEN ENGLISH: Tommy receives significant benefit from his hearing aids

and is able to understand and use spoken English for complex new

information in a variety of settings. He has few articulation errors, and his

speech is generally understood by family members, teachers, and peers.

Communication Continuum:

Tommy’s primary language for communication in

most situations is spoken English; however, he is

comfortable using ASL with his peers and for

specific class activities. On the receptive

continuum Tommy is rated “Av,” indicating that

he primarily accesses information through

listening but benefits from visual clarification

through signs in noisy situations or when content

is unfamiliar. Expressively he is rated “SO,”

suggesting that he has equal ability to use spoken

language and ASL.

Below: A description of Tommy’s individualized plan to address how and when to use ASL

and spoken English.

ACTIVITY IMPLEMENTATION PLAN

Arrival/Breakfast Daily hearing aid check

Morning Meeting ASL used for full class

Language Arts Spoken English used to facilitate activities; Tommy grouped

with peers having similar access and skills for spoken English

Math ASL used for full class

Lunch Spoken English used at lunch table; Tommy grouped with

peers having similar access and skills for spoken English

ASL Language Arts ASL immersion*

*ASL taught as a content class

Social Studies/Science ASL integration*: 2x a week

Spoken English integration*: 2x a week

*Skill development in each language using classroom content

Additional Supports Spoken language habilitation services: 2x a week for 30

minutes. Family ASL class once a week

Development of a family plan for language use in the home

References

B

aker, C. (2006). Foundations of bilingual education and bilingualism

(4th ed.). Clevedon, England: Multilingual Matters.

Baker, S. (2011). Advantages of early visual language. Available from

the Visual Language & Visual Learning website,

http://vl2.gallaudet.edu/assets/section7/document104.pdf

Berent, G. P. (2004). Sign language-spoken language bilingualism:

Code mixing and mode mixing by ASL-English bilinguals. In W. C.

Ritchie & T. K. Bhatia (Eds.), The handbook of bilingualism (pp. 312-

335). San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

Bishop, M. (2006). Bimodal bilingualism in hearing, native users of

American Sign Language. Unpublished dissertation, Gallaudet

University, Washington, D.C.

Cummins, J. (2006). The relationship between American Sign Language

proficiency and English academic development: A review of the research.

Unpublished paper for the Ontario Association of the Deaf, Toronto,

Ontario, Canada.

Easterbrooks, S., & Baker, S. (2002). Language learning in children who

are deaf and hard of hearing: Multiple pathways. Boston: Allyn and

Bacon.

Emmorey, K., Bornstein, H. B., & Thompson, R. (2005). Bimodal

bilingualism: Code-blending between spoken English and American

Sign Language. In J. Cohen, K. T. McAlister, K. Rolstad, & J.

MacSwan (Eds.), ISB4: Proceedings of the 4th international symposium on

bilingualism (pp. 663-673). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Garate, M. (2011). Educating children with cochlear implants in an

ASL/English bilingual classroom. In R. Paludneviciene & I. Leigh

(Eds.), Cochlear implants evolving perspectives (pp. 206-228).

Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Grosjean, F. (2008). Studying bilinguals. New York: Oxford University

Press.

Knight, P., & Swanwick, R. (2002). Working with deaf pupils: Sign

bilingual policy into practice. London: David Fulton.

Kovelman, I., Shalinsky, M. H., White, K. S., Schmitt, S. N.,

Berens, M. S., Paymer, N., et al. (2009). Dual language use in sign-

speech bimodal bilinguals: fNIRS brain-imaging evidence. Brain &

Language, 109, 112-123. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2008.09.008

Marschark, M., & Hauser, P. (2012). How deaf children learn: What

parents and teachers need to know. New York: Oxford University Press.

Mayberry, R. I. (1993). First-language acquisition after childhood

differs from second-language acquisition: The case of American Sign

Language. Journal of Speech & Hearing Research, 36(6), 1258-1270.

Mayberry, R. I. (2007). When timing is everything: Age of first-

language acquisition effects on second-language learning. Applied

Psycholinguistics, 28(3), 537-549. doi: 10.1017/S0142716407070294

Mayberry, R. I., & Eichen, E. B. (1991). The long-lasting advantage

of learning sign language in childhood: Another look at the critical

period for language acquisition. Journal of Memory and Language,

30(4), 486-512. doi: 10.1016/0749-596X(91)90018-F

M

ayberry, R. I., Lock, E., & Kazmi, H. (2002). Linguistic ability and

early language exposure. Nature, 417(6884), 38.

doi:10.1038/417038a

Morford, J. P., & Mayberry, R. I. (2000). A reexamination of “early

exposure” and its implications for language acquisition by eye. In C.

C

hamberlain, J. Morford, & R. Mayberry (Eds.), Language acquisition

by eye (pp. 111-127). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Muhlke, M. (2000, Winter). The right to language and linguistic

development: Deafness from a human rights perspective. Virginia

Journal of International Law, 40, 705-760.

Nover, S. (1995). Politics and language: American Sign Language

and English in deaf education. In C. Lucas (Ed.), Sociolinguistics in deaf

communities (pp. 109-163). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University

Press.

Nover, S. M. (2004). A theoretical framework for language planning in

ASL/English bilingual education. Manuscript in preparation.

Nover, S. M., Christensen, K. M., & Cheng, L. L. (1998).

Development of ASL and English competence for learners who are

deaf. Topics in Language Disorders, 18(4), 61-72.

Nussbaum, D., & Scott, S. (2011). The Cochlear Implant Education

Center: Perspectives on effective educational practices. In R.

Paludneviciene & I. Leigh (Eds.), Cochlear implants evolving perspectives

(pp.175-205). Washington, DC: Gallaudet University Press.

Petitto, L. A., Katerelos, M., Levy, B. G., Gauna, K., Tetreault, K., &

Ferraro, V. (2001). Bilingual signed and spoken language acquisition

from birth: Implications for the mechanisms underlying early

bilingual language acquisition. Journal of Child Language, 28, 453-

496.

Petitto, L. A., & Kovelman, I. (2003). The bilingual paradox: How

signing-speaking bilingual children help us resolve bilingual issues

and teach us about the brain’s mechanisms underlying all language

acquisition. Learning Languages, 8, 5-18.

Reynolds, D., & Titus, A. (1991). Bilingual/bicultural education:

Constructing a model for change. Paper presented at the 55th Biennium

Meeting of the Convention of American Instructors of the Deaf, New

Orleans, Louisiana.

Schick, B., de Villiers, J., de Villiers, P., & Hoffmeister, R. (2007).

Language and theory of mind: A study of deaf children. Child

Development, 78(2), 376-396.

Swanwick, R., & Tsverik, I. (2007). The role of sign language for

deaf children with cochlear implants: Good practice in sign bilingual

settings. Deafness and Education International, 9(4), 214-231.

Vernon, M., & Daigle, B. (1994). Bilingual and bicultural education.

In M. Garretson (Ed.), Deaf American monograph, 44 (pp. 121-126).

Silver Spring, MD: National Association of the Deaf.

Yoshinaga-Itano, C. (2006). Early identification, communication

modality, and the development of speech and spoken language skills:

Patterns and considerations. In P. E. Spencer & M. Marschark (Eds.),

Advances in the spoken language development of deaf and hard-of-hearing

children (pp. 298-327). New York: Oxford University Press.

2012 ODYSSEY

19