The 2009 Economic Landscape

The Sand States: Anatomy of a Perfect Housing-

Market Storm

The historic boom and subsequent decline in the nation’s

housing market has been a defining feature of the current

recession. The housing downturn has been most acute in

four states—Arizona, California, Florida, and Nevada—

that had experienced some of the highest rates of home

price appreciation in the first half of the decade. While

these states are not all contiguously located, their similar

housing cycles and abundance of either beaches or deserts

have led some analysts to label them “Sand States.” This

article discusses the factors that led to an expanding

housing sector in these states and the market imbalances

that culminated in a sharp correction in home prices.

The article also explores the ripple effects that the hous-

ing downturn has had on the local economies.

Rapid Population Growth in the Sand States

Propelled Housing Markets

For many years, rapid population growth in the Sand

States spurred higher than average rates of home

construction. Favorable weather and relatively afford-

able housing are two factors that attracted retirees as

well as younger families to these states. In the 1980s

and 1990s, population growth rates in Arizona, Florida,

and Nevada were between two and four times the

national rate. Certain parts of California, such as the

Riverside–San Bernardino metropolitan area, experi-

enced similarly high rates of population growth. Rapid

population growth continued into the early years of this

decade. From 2004 to 2007, Arizona and Nevada

ranked as the two fastest growing states in the nation,

followed closely by Florida, which ranked ninth.

1

The influx of new residents into Arizona, Florida, and

Nevada also contributed to strong employment growth.

Job creation in these states frequently outpaced the rest of

the nation during the past few decades. From 2000 to

2006, these states repeatedly ranked among the top ten

for job growth, far exceeding the national average.

California generally reported job growth similar to the

national average during this period, although the state was

hit hard by the dot-com recession from mid-2001 to 2003.

1

U.S. Census Bureau.

Affordability Mortgages Contributed to

Housing Imbalances

During this decade, strong demand for housing,

supported by a growing population and an expanding

economy, contributed to growing housing market

imbalances across the Sand States. Perhaps the best

measure of the imbalances that accumulated in boom-

ing housing markets during this decade was the rela-

tionship between home prices and incomes. In the years

leading up to the housing downturn, escalating home

prices far outpaced income growth. For example, in

2003, housing in Nevada was considered relatively

affordable, both in absolute terms and as compared to

other states. According to one analysis, a family earning

the median income in Nevada in 2003 could afford a

home that was priced approximately 20 percent above

the median house price in the state using traditional

mortgage financing.

2

However, by late 2005, home

prices had risen so much that a family earning the

median income could only afford a home priced at

24 percent below the state’s median price.

A combination of factors drove the housing sector

imbalances in the Sand States to unprecedented levels.

Under normal market conditions, strained affordability

tends to limit housing demand because fewer house-

holds can purchase a home using traditional mortgage

financing. However, in this cycle, new mortgage “afford-

ability” products were commonly used to finance home

purchases. Besides traditional adjustable-rate mortgages

(ARMs), affordability products included hybrid ARMs,

which have a low, fixed interest rate for several years

followed by a market rate that is frequently much

higher. Affordability products also comprised the

so-called nontraditional mortgage products, which

included interest-only loans, where amortization of prin-

cipal was not required during the first few years of the

2

Moody’s Economy.com Affordability Index. The calculation assumes

a 30-year maturity and a down payment of 20 percent. It also assumes

that the monthly principal and interest payments do not exceed 25

percent of the median family income. To interpret the indices, a value

of 100 means that the family earning the median income can afford

only 100 percent of the traditional mortgage payment of the median-

priced home, taking into consideration the 20 percent down payment.

FDIC QU A R T E R L Y 30 2009, VO L U M E 3, NO. 1

2009 Economic Landscape

loan; negative-amortization loans that offered initial

payments well below the amount required to cover

interest and amortize principal; and balloon payment

loans, which typically required a large lump-sum

payment at the end of the loan. Unlike subprime mort-

gage products that were designed for home buyers with

limited or weaker credit histories, these nontraditional

mortgages were marketed broadly and often used by

first-time home buyers and investors who did not

provide a down payment. In addition, originators of

these products frequently did not require buyers to verify

that their income could support the mortgage payments.

By 2006, nearly half of total U.S. originations of privately

securitized affordability mortgages were made in the four

Sand States alone. Moreover, the proportion of these

mortgages originated in these states, including nontradi-

tional mortgages, rose as home prices escalated. During

2002, these products accounted for roughly half of the

privately securitized mortgage originations in each of the

Sand States, comparable to the rest of the nation. By 2006,

however, the proportion of these products had increased to

80 percent of privately securitized mortgage originations.

Nationwide, the percentage was about 70 percent.

3

The increased presence of speculators or investors in the

Sand States also contributed to growing imbalances in

the housing sector. Data from mortgage servicers indicate

that nonowner, investor, and second-home mortgage

originations increased noticeably in Arizona, Florida, and

Nevada between 2000 and 2005.

4

Investor and second-

home purchases tended to be more heavily concentrated

in major metropolitan areas in these states, such as

Las Vegas, West Palm Beach, Miami, and Phoenix.

Strong housing demand coupled with escalating home

prices served as a dual incentive for builders to increase

the supply of homes, arguably at a rate that exceeded

short-term demand. New home construction started to

accelerate in 2002, and, over the next three years,

housing starts in these four states increased an average

of 11 percent annually, or about twice the rate of

increase elsewhere in the nation. Housing construction

in the Sand States far outpaced annual growth in the

number of households, which peaked at 1.6 percent in

2004 and 2005.

3

Data are from Loan Performance. Affordability mortgage products

include ARM loans, interest-only loans, negative amortization mortgages,

balloon loans, and hybrid ARMs. Affordability originations are measured

as a percentage of privately securitized origination, first liens only.

4

In contrast, California had less investor activity during the period,

likely because the median home price in the state was relatively high,

resulting in a less attractive rate of return for potential investors.

Labor market imbalances also arose as job growth became

skewed toward the housing sector. During the height of

the boom, construction employment grew 10 percent per

year in these states, far outpacing growth in other indus-

try sectors. During this time, construction jobs accounted

for a disproportionate 25 percent share of new jobs, while

representing less than 10 percent of total employment.

Tipping Point: Imbalances Lead to Housing Collapse

Ultimately, the housing boom in the Sand States

proved to be mostly a mirage. The first signs of trouble

came in the form of sharply decelerating rates of home

price appreciation. Between 2003 and 2006, annual

home price appreciation rates in these states had consis-

tently exceeded the national average. Year-over-year

house price appreciation in Nevada peaked in 2004 at

37 percent. In Arizona and Florida, appreciation peaked

in 2005 at rates more than twice the national average.

Since then, average home prices in the four states have

declined between 27 and 38 percent from their peak.

5

Price declines have been most severe in metropolitan

markets such as Phoenix and Las Vegas, which regis-

tered the largest percentage declines in the nation at

34 percent and 33 percent, respectively, during 2008.

6

As home prices slumped, foreclosure activity rose at a

startling pace. While this phenomenon was occurring

across the nation, it was most pronounced in the Sand

States. According to the Mortgage Bankers Associa-

tion, the Sand States accounted for more than 40

percent of all mortgage foreclosures started in 2008,

which is nearly double the share of mortgages held by

borrowers in these four states (see Table 1). This

disproportionate share of troubled mortgages in the

Sand States was most acute among ARMs. In 2008,

these states held 46 percent of the prime ARMs

outstanding nationwide and 64 percent of foreclosures

started within this mortgage category.

In fourth quarter 2008, foreclosure resales accounted for

more than 55 percent of all California resale activity,

almost three times the level of a year ago. Foreclosure

resales were also prevalent in Las Vegas and Phoenix,

where this type of transaction accounted for about 71

and 65 percent, respectively, of house and condominium

resales.

7

5

Federal Housing Finance Agency, purchase-only index data through

fourth quarter 2008.

6

S&P/Case-Shiller Home Price Index, data as of December 2008.

7

Data Quick Information Systems through www.dqnews.com.

Las Vegas and Phoenix data are for February 2009.

FDIC QU A R T E R L Y 31 2009, VO L U M E 3, NO. 1

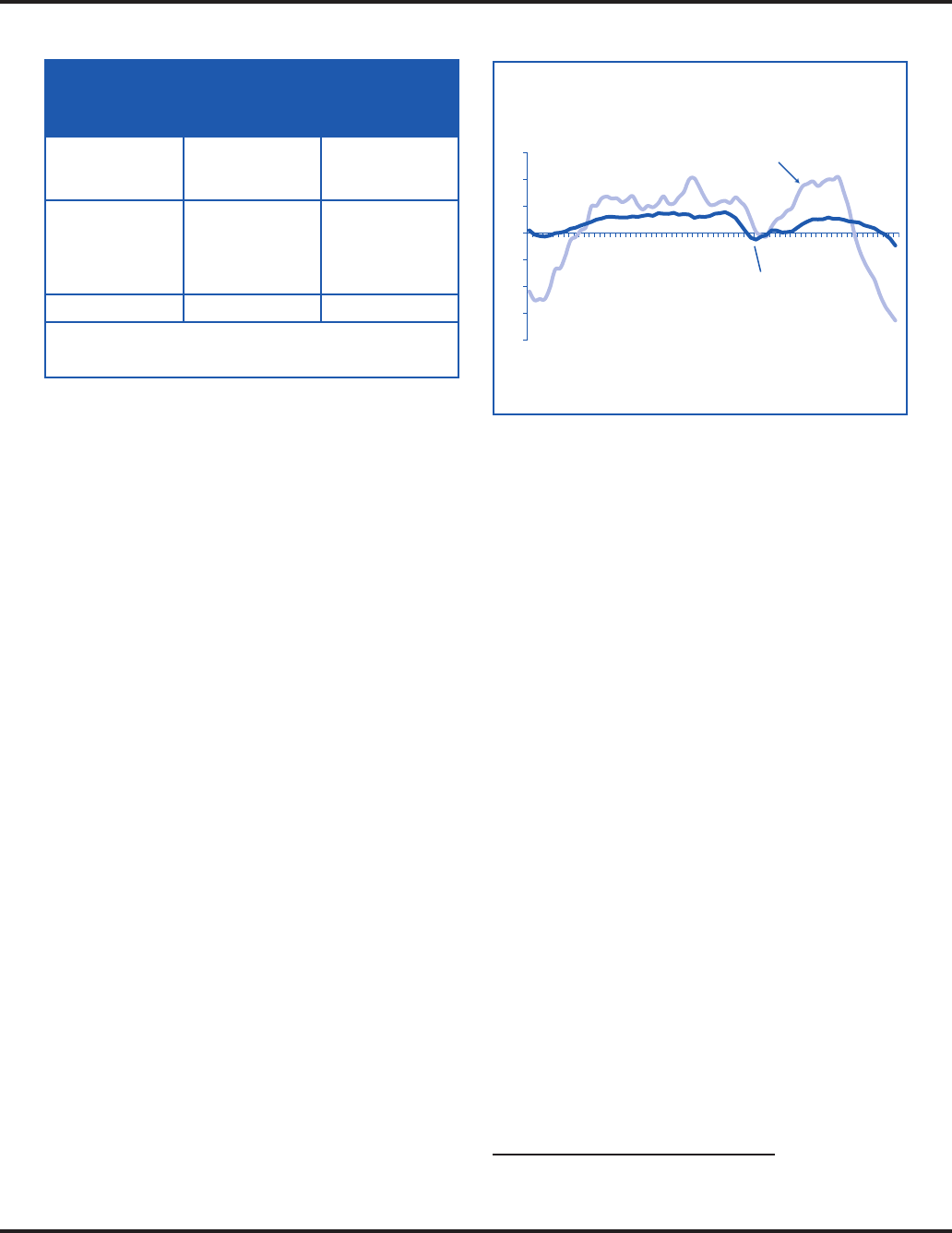

Table 1

Chart 1

The Sand States Account for a

Disproportionately High Share of

Foreclosure Activity

National Share of

Foreclosures

Started

National Share of

Mortgages

Serviced

California

Florida

Arizona

Nevada

19.2%

16.2%

4.4%

2.7%

12.9%

7.8%

2.7%

1.2%

Sand States Total: 42.5% 24.6%

Source: Mortgage Bankers Association.

Note: Data from first quarter 2008 through fourth quarter 2008. “Sand States” is the

aggregate of California, Florida, Arizona, and Nevada.

-20

-15

-10

-5

0

5

10

15

91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 02 03 04 05 06 07 08

Year-over-Year Change in Sand State Nonfarm Employment

Percent

The Construction Sector in the Sand States

Has Been an Important Driver of Job Growth

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics (Haver Analytics).

Note: “Sand States” is the aggregate of California, Florida, Arizona, and Nevada. “All Other

Sectors” is the state aggregate nonfarm employment minus the construction sector.

All Other Sectors

Job Growth

Construction Sector

Job Growth

Economic Conditions Remain Fragile as the Effects

of the Housing Collapse Spread

Compounding the housing-sector problems in the Sand

States, and elsewhere, has been the virtual shutdown of

private mortgage-backed securities (MBS) issuance

since 2007. MBS issuance had largely financed the

subprime and nontraditional lending that fueled the

boom. Total issuance of private MBS, which had

topped $1 trillion annually in both 2005 and 2006, fell

precipitously thereafter, totaling just over $50 billion in

2008. Meanwhile, the difficulties that market partici-

pants have had in valuing complex mortgage securities

and the derivatives based on them have contributed to

wider risk aversion in financial markets, which has

reached historic proportions. For housing markets,

particularly in the credit-fueled boom markets of these

four states, these financial market disruptions are

compounding what would in any case have been a steep

and extended housing market downturn.

The housing market downturn in the Sand States is

now having serious ripple effects on other parts of the

local economy. Each of the Sand States lost jobs in

2008. The losses have been most pronounced in the

construction sector, which has shed more than 450,000

jobs, or about 24 percent, between fourth quarter 2006

and fourth quarter 2008 (see Chart 1). In addition, job

losses have spread to the financial services and retail

trade sectors. Retail sales also have declined, particu-

larly for home improvement, furniture, and electronics

store sales, contributing to additional layoffs.

Although the Sand States entered this downturn with

relatively low rates of unemployment, joblessness

increased during 2008 to levels not seen since the 2001

recession. The unemployment rates for California,

Florida, and Nevada ranked among the top ten in the

nation as of fourth quarter 2008. While Arizona’s

unemployment rate remained slightly below the

national average as of fourth quarter 2008, it too rose

markedly during the year. These rising unemployment

rates are due primarily to widespread job losses and, to a

lesser degree, to additional people entering the labor

force in search of employment, including college gradu-

ates and retirees.

8

Also, rising unemployment claims are

putting more pressure on already strained state budgets.

Nonetheless, a few positive, albeit very preliminary,

signs may be emerging. The volume of home sales in

Arizona, California, and Nevada improved during

2008 relative to year-ago levels. The increase in fore-

closures sales is likely contributing to some renewal in

sales activity. In addition, while a sharp decline in

housing starts is eliminating construction jobs in the

near term, it should eventually facilitate the return to

a more stable housing landscape. Seasonally adjusted

housing starts in the Sand States dropped 40 percent

in 2007 and again in 2008. Also, despite the weakened

housing and labor markets, population growth in

Arizona, California, and Nevada was estimated to be

above the national rate in 2008.

9

This continued

growth will be an important source of long-term hous-

ing demand that will eventually help bring a measure

of stability to these troubled housing markets.

Authors: Shayna M. Olesiuk, Regional Manager

Kathy R. Kalser, Assistant Director

8

California Employment Development Department.

9

U.S. Census estimates of state-level population growth between

July 1, 2007, and July 1, 2008, the latest data available.

FDIC QU A R T E R L Y 32 2009, VO L U M E 3, NO. 1