Department of Economics and International Development, University of Bath, Bath,

†

BA2 7AY, UK, Tel: 44 (0)1225 383074, Email: [email protected]

Nottingham Trent University

††

IASE/NAASE Working Paper Series, Paper No. 08-09

The Influence of Social Pressure and Nationality on Individual

Decisions: Evidence from the Behaviour of Referees

Peter Dawson and Stephen Dobson

†††

August 2008

Abstract

This study considers the influences on agents’ decisions in an international context.

Using data from five seasons of European cup matches it is found that football referees favour

home teams when awarding yellow and red cards. Previous research on referee decisions in

national leagues has identified social pressure as a key reason for favouritism. While social

pressure is also found to be an important influence in this study, the international context reveals

that referee decisions are also influenced by the nationality of the referee and club, and the

reputation of the league.

JEL Classification Codes: D81, L83

Keywords: social pressure, decision-making, referee behaviour, home bias, football

The Influence of Social Pressure and Nationality on Individual Decisions: Evidence from

the Behaviour of Referees

1. Introduction

Team sports are (almost) unique in that the final stage of production (contest between two

teams) is observed. This feature presents numerous opportunities for studying the behaviour of

agents in sporting contests. One aspect that has received attention is managerial decision making

in the form of team selection, substitutions or interchanges (Clement and McCormick, 1989).

Another area of interest is the testing of economic hypotheses concerning strategic behaviour by

players. In the case of penalty-kicks in football (soccer) for example, a number of studies have

found evidence that goalkeepers and penalty-takers adopt mixed strategies (Chiappori et al. 2002;

Palacios-Huerta, 2003; Coloma, 2007).

Attention has also focused on the behaviour of match officials (referees). Referees are

assigned the task of implementing the laws of the game and ensuring that players abide by the

regulations. Research based on match analysis from the European Football Championship in

2000 suggests that a top official makes 137 observable interventions on average during a game,

including awarding free-kicks, penalties, corners, throw-ins, and halting play for serious injury

(Helsen and Bultynck, 2004). In the case of free-kicks and penalties, the referee has the discretion

to decide whether a foul merits a caution, in the form of a yellow or red card. Since some of this

decision making is guided by subjective judgment, football referees are often accused of being

inconsistent and biased in their decision making (Dawson et al., 2007, Buraimo et al., 2007,

Boyko et al., 2007).

Studies of referee decision making in football tend to focus on two decisions: the decision

to add on time at the end of matches and/or the decision to award red and yellow cards. Research

on a number of domestic European leagues suggests a home team bias in referee decision making

2

and identifies social pressure (influence of the crowd) as one of the main reasons for the bias. In

contrast, research on North American sports has recently focused on (racial) discrimination in

decision making by match officials (see, for example, Price and Wolfers, 2007).

Though referee behaviour has received attention from academics in recent years, little is

known about the influences on decisions in an international context

1

. This paper seeks to fill this

gap by analysing the decision to award yellow and red cards in European cup football (UEFA

Cup and UEFA Champions League). In particular, the study addresses the extent to which social

pressure influences the award of red and yellow cards (incidence of disciplinary sanction). In

doing this, the roles played by absolute and relative size of the crowd, and the architecture of the

stadium (in terms of running tracks and fencing) are considered. The study’s international

dimension is also exploited by examining the role of nationality in the incidence of disciplinary

sanction. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to examine the influence of

nationality on individual decisions.

The reminder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 reviews the previous

academic literature. Section 3 describes the data and considers the empirical methodology.

Section 4 provides the results and Section 5 concludes.

2. Literature Review

Evidence of inconsistency and bias in decision making by referees has been found in a

number of European domestic leagues. Garicano et al. (2005), using Spanish data, find a

tendency for referees to add on more time at the end of matches when the home team is trailing

by one goal compared to when the home team is leading, particularly when contests are close.

1

In a study of the FIFA World Cup, Torgler (2004) observes that a team’s probability of winning is increased when

a referee is from the same (football) region. However, the impact is only marginally significant and appears to be

non-robust.

3

Similar findings have been demonstrated for the German premier league (1

st

Bundesliga) by

Sutter and Kocher (2004) and Dohmen (2008), and for the Italian league by Scoppa (2007).

One potential source of bias by referees is social pressure (influence of the crowd).

Dohmen (2008) finds that architectural conditions play a key role in the refereeing bias observed,

namely: the size of the crowd (absolute size), the attendance-to-capacity ratio (relative size) and

the proximity of supporters to the pitch (the presence of a running track). He finds that there is

more added time in close matches when the crowd is physically close to the field of play. Also,

home teams are significantly more likely to be awarded a disputed penalty, with the physical

distance between the crowd and the playing field important to this decision. Petersson-Lidbom

and Priks (2007) find similar results for Italian football following the Italian government’s

decision to enforce clubs with sub-standard stadiums to play home games behind closed doors.

Buraimo et al. (2007) and Dawson et al. (2007) consider the impact of social pressure on

disciplinary sanction. Buraimo et al. (2007) find the size of the stadium has no statistically

significant effect on sanctions awarded to either the home or away team in the English Premier

League or in the German Bundesliga. In contrast, Dawson et al. (2007) show that home teams

playing in front of larger crowds incur more disciplinary sanctions. Buraimo et al. (2007), in the

context of the German Bundesliga, find the presence of a running track increases the number of

yellow and red cards awarded to the home team. Neither study, however, considers the impact of

relative crowd size.

In a laboratory style setting, Nevill et al. (2002) showed videotapes of tackles to referees

who, having been told the identities of the home and away teams, were asked to classify the

tackles as legal or illegal. One group of referees viewed the tape with the soundtrack (including

the crowd’s reaction) switched on, while a second group viewed silently. The first group was

4

more likely to rule in favour of the home team (calling, on average, 15.5% fewer fouls). The first

group’s decisions were also more in line with those of the original match referee.

Recent research also suggests that match officials respond to incentives. Rickman and

Witt (2008) apply a natural experiment to assess the introduction of professional referees in the

English Premier League. They find that home team bias in adding on time at the end of matches

essentially disappears following the introduction of professionalism. This is explained in terms of

the higher remuneration associated with professional status, which, together with increased

monitoring, acts as a disincentive to show (implicit) favouritism.

A popular notion of refereeing inconsistency is the same offence being treated differently

by different referees. The fact this occurs suggests officials use prior information to inform the

decisions they make. Research has found this to be important both prior to contests taking place

and as contests unfold. Plessner and Betsch (2001) observe that officials are less likely to award a

penalty to a team if they have previously awarded the same team a penalty but are more likely to

award a penalty if they have awarded a penalty to the opposing team. Jones et al. (2002) suggest

that a player’s aggressive reputation can influence the number of red and yellow cards awarded.

For example, on observing a bad challenge by a player with an aggressive reputation, the referee

may be more inclined to dismiss that player because he interprets the challenge as a deliberate

attempt to injure an opponent. In contrast, a similar challenge made by a player with little or no

aggressive reputation may only lead to a caution because the referee believes in this instance, and

based on prior knowledge of the player, the tackle was mis-timed rather than intentional

2

.

2

The reputation of athletes has also been found to influence the behaviour of judges in individual sports such as

boxing (Balmer et al., 2005), ice skating (Findlay and Ste-Marie, 2004) and gymnastics (Ste-Marie and Valiquette,

1996).

5

3. Data and Empirical Methodology

The empirical analysis relates to matches played in the UEFA Champions League and the

UEFA Cup over the period 2002-03 to 2006-07

3

. Match data on home (away) club name, home

(away) club nationality, number of yellow and red cards, referee name, referee nationality, date

and time of contest, and attendance was provided by UEFA and the UEFA Documentation

Center. Data was also gathered for the construction of team rankings (details of which are

described below)

4

and for stadium information pertaining to ground capacity and architecture

5

.

In the analysis, all matches played at neutral venues (including finals) are excluded

6

. Following

the removal of missing values, there are 1,720 useable observations.

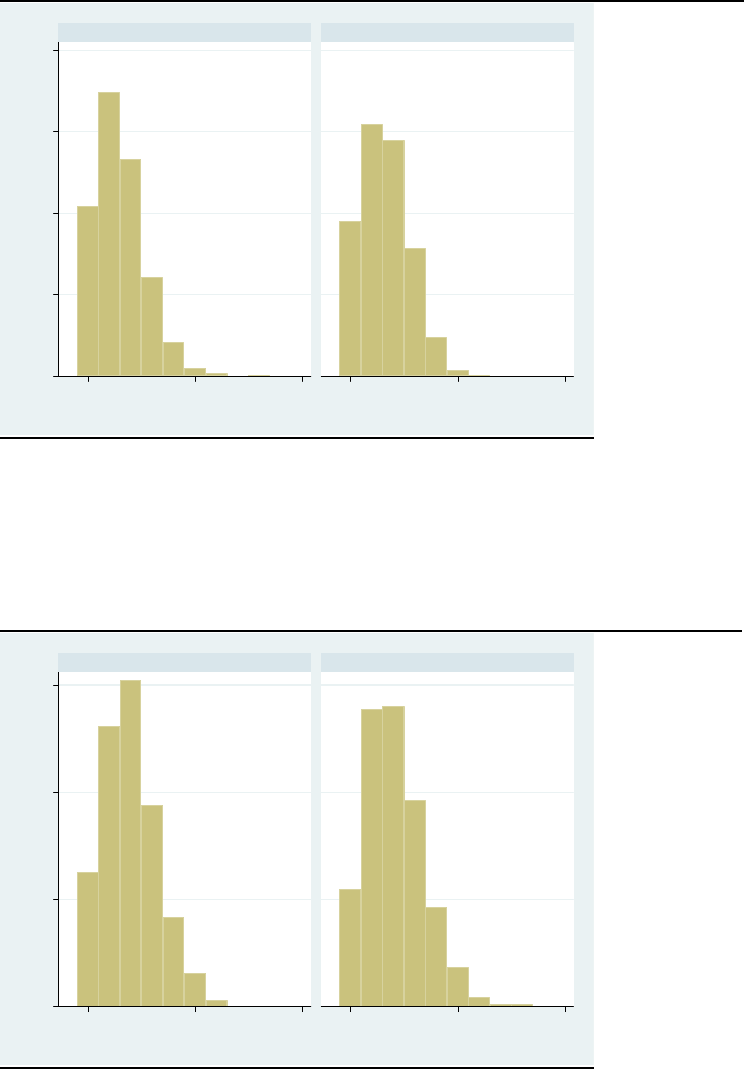

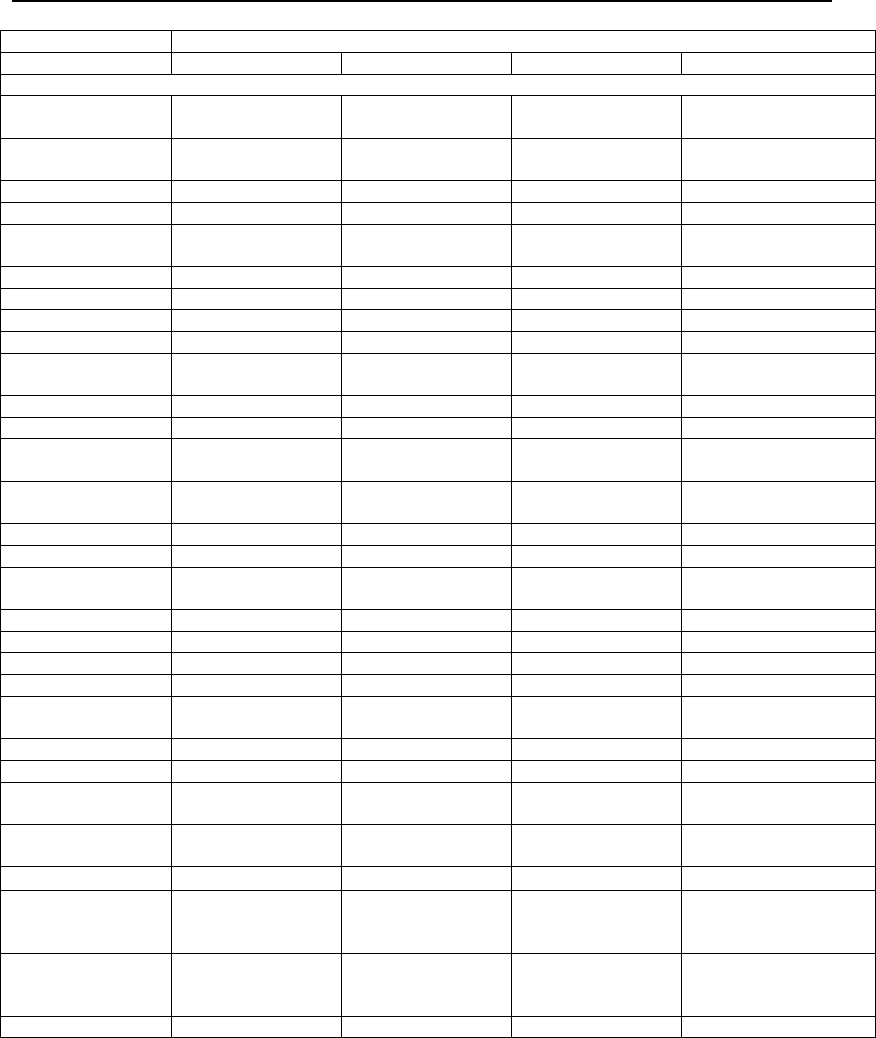

Figures 1 and 2 present frequency graphs of the number of yellow cards incurred by the

home and away team by competition. The distributions show that away teams are less likely to

incur zero yellow cards compared to home teams and are more likely to incur three or more

yellow cards. The pattern is similar across both competitions.

Figures 1 and 2 about here

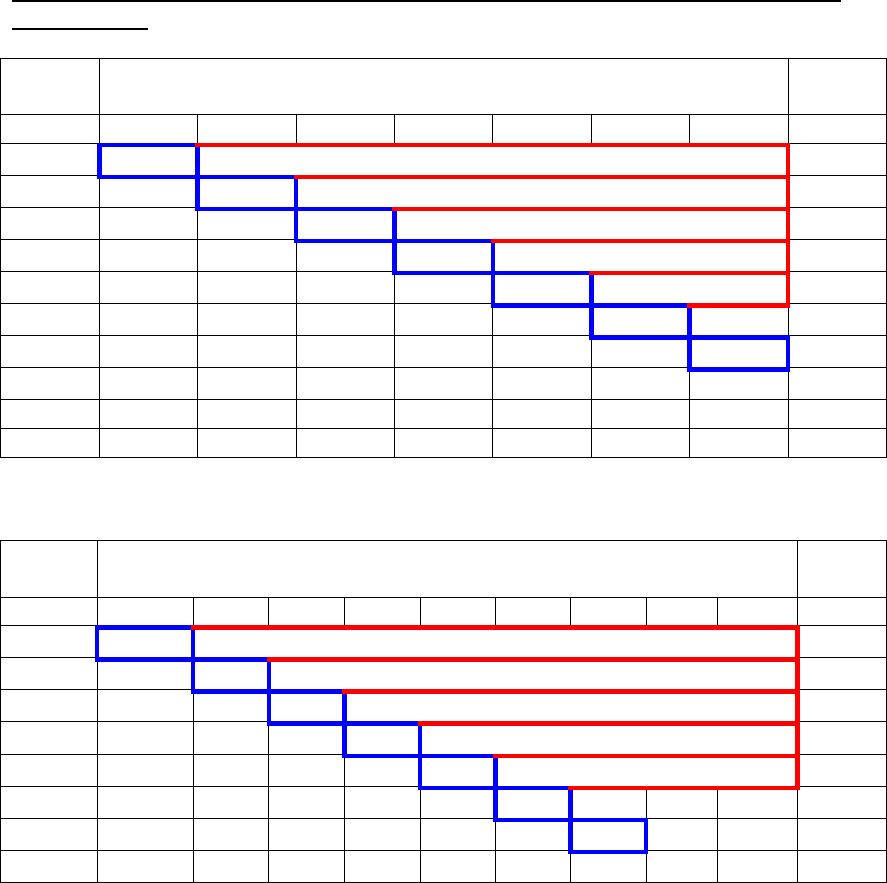

Tables 1 and 2 show the distribution of yellow and red cards by home and away team. In

only 4.63% of Champions League matches and 3.78% of UEFA Cup matches were no yellow

cards issued to either team. More significantly, in only 24.3% of Champions League and 26.67%

3

Both tournaments have undergone a number of format changes in recent times. Currently, both competitions adopt

a mix of elimination rounds and round-robin group stage matches, with both using a seeding system to protect the

stronger teams from being eliminated in earlier rounds. The total number of teams and the total number of matches

played in these competitions has also grown considerably. Prior to 1992, 32 teams competed and a total of 73

matches were played in the European Cup (former name of the Champions League). The corresponding figures for

the UEFA Cup were 64 and 126, respectively. By the start of the 2006-07 season, the number of teams competing in

the Champions League had more than doubled (to 76 teams) and the total number of games nearly trebled (to 213

games). The number of teams (157) competing and the number of matches played (353) in the UEFA Cup has also

increased, although part of this increase is the result of the amalgamation of the UEFA Cup with the European Cup

Winners’ Cup in 1999.

4

http://www.xs4all.nl/~kassiesa/bert/uefa/data

5

http://www.worldstadiums.com/europe/maps/europe.shtml

6

Examples of matches played at neutral venues include a number of matches involving Israeli teams in 2002-03 and

2006-07. A number of other matches were played in empty stadiums as punishment for crowd trouble. These

matches remain in the sample.

6

of UEFA Cup matches did the home team incur more yellow cards than the away team. It is also

notable that the number of yellow cards tends to be higher in the UEFA Cup. Red cards, in

contrast, are observed less frequently: less than 20% of matches in either competition generated

one or more red card.

Tables 1 and 2 about here

Measurement of the dependent variable follows the approach of Dawson et al. (2007). In

the estimations below, the dependent variables are the total numbers of disciplinary “points”

incurred by the home and away teams in each match, calculated by awarding one point for a

yellow card and two points for a red card. Two points are also awarded when a player is

dismissed as a result of two cautionable (yellow card) offences in the same match.

In order to establish whether there is systematic bias in either the distribution or incidence

of disciplinary sanction, it is necessary to control for relative team quality. In this study, a team

quality measure is constructed using historical match data and follows the method of UEFA in

the seeding and drawing procedures of the two cup competitions. A team coefficient is calculated

as the sum of the number of points of each individual team plus 33% of the country coefficient

7

.

The average coefficient (hereafter referred to as the coefficient index) from the previous five

years is used as a measure of team quality.

One weakness of this method is that it does not weight performance according to

competition. Further, it is less sophisticated than forecasting models, including ones based on

betting data (e.g. Buraimo et al. 2007). Whilst a detailed evaluation of forecasting models is

7

For details on the precise calculations can be found at http://www.xs4all.nl/~kassiesa/bert/uefa/.

7

beyond the scope of this study, preliminary analysis found that the team coefficient index does a

reasonably good job at predicting match outcomes

8

.

In addition to team quality, a variety of other controls are also included, based on the

discussion in Sections 1 and 2. These include variables relating to crowd size, crowd density

(attendance to capacity ratio) and stadium architecture (i.e. presence of a running track and/or

fencing), competition (Champions League or UEFA Cup) and stage of competition. The

nationality of the referee and the nationality of the club are also used as controls. Definitions of

the variables used in this study are provided in the Appendix.

The number of disciplinary points per match takes the form of count data, which suggests

the use of a count data regression model

9

. However, it is also possible to model count data using

discrete choice methods that recognise the sequential nature of the data (Cameron and Trivedi,

2005). One such candidate is the ordered probit model, hence:

aaa

hhh

y

y

εβX

εβX

+

′

=

+

′

=

*

*

(1)

Where the subscripts “h” and “a” refer to the home team and away team, respectively.

are constructed according to the following criteria:

**

and

ah

yy

8

Binary probit and ordered probit models were constructed with the team coefficient index as the explanatory

variable. In the majority of cases it was found that a one unit increase in rank difference is predicted to increase the

probability of a home win by approximately 2%, which seems intuitively plausible. Also, with the exception of

Dawson et al. (2007) and Buraimo et al. (2007), previous studies have used relatively simple measures to capture

team quality.

9

For example, Dawson et al. (2007) use zero-inflated Poisson and negative binomial regression models.

8

(2)

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎧

≥

=

=

=

=

=

=

5 if 5

4 if 4

3 if 3

2 if 2

1 if 1

0 if 0

*

*

*

*

*

*

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎩

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎪

⎨

⎧

≥

=

=

=

=

=

=

5 if 5

4 if 4

3 if 3

2 if 2

1 if 1

0 if 0

*

*

*

*

*

*

a

a

a

a

a

a

a

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

Each endogenous discrete variable is associated with X exogenous variables and coefficients β

h

β

a

as described above. If ε

h

and ε

a

are assumed to be independent and normally distributed, (1)

can be estimated using a univariate ordered probit model. A bivariate ordered probit model is

required if ε

h

and ε

a

are assumed to be joint normal

10

and

ρ

ε

ε

=

),( Cov

ah

. Thus, the univariate

model can be considered a special case of the bivariate model, where ρ=0. Both univariate and

bivariate models are estimated using the method of maximum likelihood.

4. Results

Table 3 presents results for the determinants of disciplinary points based on univariate

and bivariate ordered probit models. In the univariate model, the home team equation shows that

the difference in the team coefficient index (home coefficient index minus away coefficient

index) is negative and statistically significant. This implies that a strong home team will incur

fewer disciplinary points. For the away team, the coefficient is correctly signed (positive) but is

not statistically significant. In both the home and away equations it appears that, on average and

10

1)(Var)Var( ,0)()(

=

===

ahah

EE

ε

ε

ε

ε

9

other things unchanged, the number of disciplinary points is lower in the Champions League.

However, there is also evidence, for both teams, that the number of disciplinary points increases

as the competitions enter the final phases. In terms of the influence of the crowd and the

architecture of the stadium, it appears that relative size of the crowd matters more than the

absolute size: the away team is likely to incur more disciplinary points the closer the stadium is to

capacity. The presence of a running track has the effect of increasing the number of disciplinary

points awarded to the home team.

Table 3 about here

The findings associated with the impact of the crowd and the architecture of the stadium

are consistent with previous research. The presence of a running track increases the distance

between the pitch and the crowd. This works to increase the number of disciplinary points

awarded to the home team, implying less implicit favouritism towards the home team when the

influence of social pressure is weaker. On the other hand, the relative size of the crowd appears to

work in the opposite way, by increasing the number of disciplinary points awarded to the away

team. The absolute size of the crowd and the presence of fencing have no impact.

One criticism of the univariate approach is that it assumes no correlation between the

home and away team equations. Buraimo et al. (2007), in their study of the German Bundesliga

and the English Premier League, find that a yellow card previously awarded to the home (away)

team increases the probability of the away (home) team receiving a similar sanction. As the

authors suggest, this could reflect retaliation by players or the tendency for referees to “even-up”

decisions. To allow for this possibility, a bivariate ordered probit model is also estimated. The

significance of the ρ statistic and the LR test of independent equations provide strong evidence

10

that the error terms in the two equations are correlated, and justifies the use of a bivariate model.

However, the coefficients are virtually indistinguishable.

A unique feature of this study is the opportunity to test for the influence of nationality on

decisions. In European cup football, referees are assigned to matches according to Article 19.02

of the Regulations of the Champions League and UEFA Cup

11

. Generally, referees cannot be

from the same football association as the two teams competing in the contest. Given this, home

nation bias should be of limited concern. However, this does not preclude the possibility of

variation in referee behaviour by nationality. Nor does it preclude the possibility that referees

form judgements about teams and nations

12

.

Table 4 reports bivariate ordered probit estimates under a variety of different

specifications. Model (1) includes club nationality fixed effects alongside referee nationality

effects. The inclusion of club nationality results in the team coefficient index becoming

insignificant, so it appears that club effects are capturing some (most) of the impact of team

quality. The stage of the competition becomes insignificant in the home team equation and less

significant in the away team equation. Champions League matches (home equation and away

equation), the presence of a running track (home equation only), and the relative size of the

crowd (away equation only) remain important determinants of the incidence of disciplinary

sanction.

11

The Referees Committee, in cooperation with the UEFA administration, appoints a referee, two assistant referees

and a fourth official for each match. Only referees whose names appear on the official FIFA list of referees are

eligible. The fourth official and assistant referees are, in principle, proposed by the national association of the

referee, in accordance with criteria established by the Referees Committee.

12

In the 2006 World Cup Finals there were numerous complaints and allegations of referee bias in favour of the

larger, well-established teams. During the 2002 tournament, held jointly by South Korea (Korea Republic) and

Japan, there were allegations of favouritism towards the host nations - specifically when South Korea played, and

subsequently defeated, Italy in the Second Round. During the European 2004 Championship the Portuguese media

criticised the appointment of the German referee Merkus Merk for a game involving Portugal and Greece, claiming

that he would favour Greece because they were coached by a German national. The Romanian Football Association

has also claimed discrimination against their national team (and other Eastern European countries) when involved in

games against teams from more established associations.

11

In Model (2) club nationality fixed effects are replaced with variables denoting whether

the home or away teams (or both) is from one of the “big five” leagues (England, Italy, Germany,

Spain and France). This is designed to capture possible “league reputation” effects, whereby a

team from one of the big five leagues is likely to incur fewer disciplinary points. As expected, a

home team from the “big five” incurs fewer disciplinary points if playing a team from outside the

“big five” but the coefficient is not statistically significant. The effect is significant for an away

team from one of the big five leagues. Also, more disciplinary points are awarded to the home

team and away team if they are both drawn from one of the big five leagues. It would appear

therefore that these variables are also capturing the quality of the teams involved in the contest.

Table 4 about here

A dummy variable, capturing whether the referee officiated at the 2004 European

Championships (defined here as an “elite” referee), is included in Model (3). A positive impact is

found in both the home and away team equations (Models (3) and (4)) but there is no significant

difference. A possible interpretation is that elite referees compensate for inherent (implicit)

favouritism by issuing more disciplinary sanctions to the home team, though this conclusion must

be tentative as there may be problems associated with sample selection effects.

A sensitivity analysis, in the form of a separate analysis for yellow cards, is provided in

Table 5. In general, the coefficients are less significant compared to the disciplinary points

models. However, it is possible to control for an additional feature in these specifications, namely

the extent to which red card offences relate to yellow card offences. Here evidence is found of

simultaneity between the award of red cards and yellow cards: teams that are punished for red

card offences also tend to incur more yellow cards.

Table 5 also provides a further sensitivity test through the inclusion of within game

parameters for Champions League matches only. A series of variables are included relating to

12

possession, shots on goal and number of fouls committed. With the exception of number of fouls,

none of these factors are significant. Moreover, previous variables remain reasonably robust to

the inclusion of these additional variables.

Table 5 about here

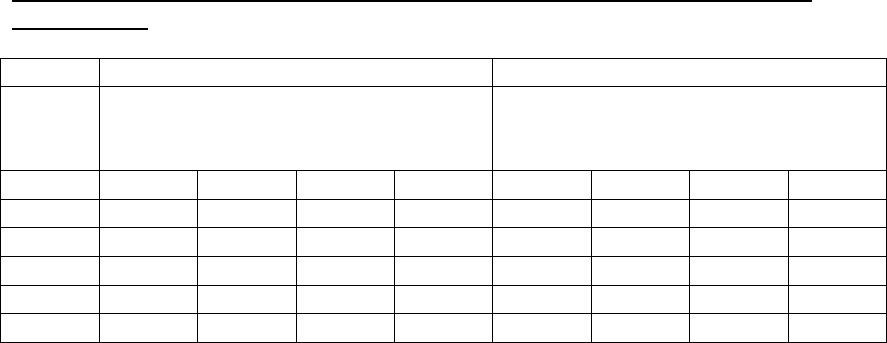

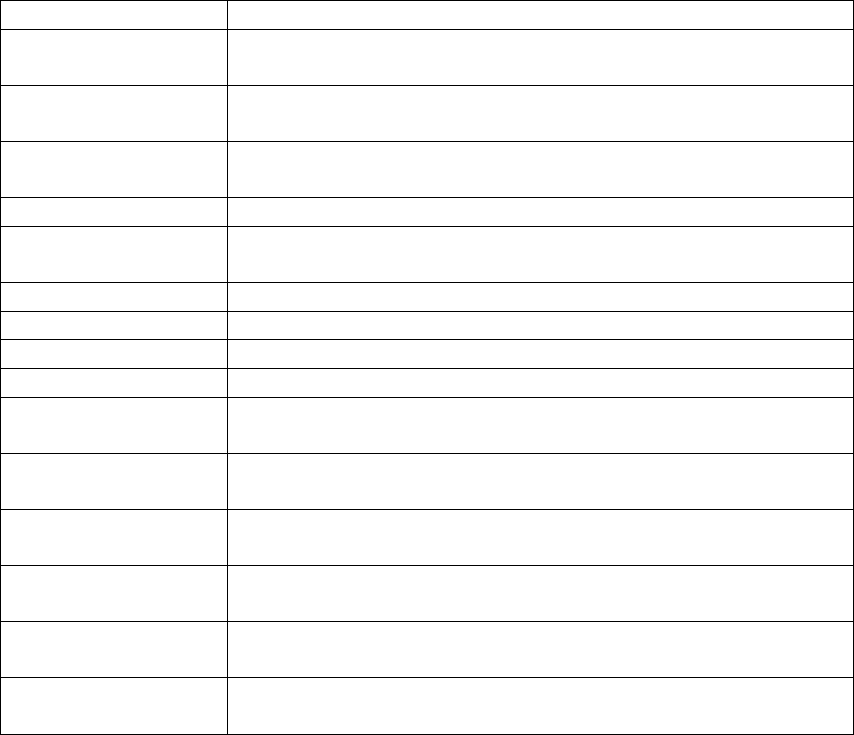

Finally, the marginal effect of referee nationality is presented in Table 6. A priori, and

given the above discussions, it might be expected that referees from the more prominent

associations (England, France, Germany, Italy and Spain) will be less prone to implicit

favouritism compared to referees from other associations. There appears to be some evidence to

support this since officials from Belgium, Holland, Norway, Russia and Sweden tend to award

fewer disciplinary points to the home team. However, Belgian, Dutch, Russian and Swedish

referees also tend to issue fewer disciplinary points to the away team. There are also some

interesting anomalies in the data. Portuguese officials issue more disciplinary points to the away

team. On the other hand, Greek officials tend to issue more sanctions (to both the home and away

teams) compared to anyone else.

Table 6 about here

The precise role of nationality in influencing referee decisions is difficult to identify not

least because of the interplay between referee and team nationality, and team reputation. Akerlof

(1997) and Akerlof and Kranton (2000) suggest that individual decisions are influenced by one’s

own identity and the perception of others. This notion seems particularly relevant in the present

context since football referees, much like officials in many other sports, are required to make

split-second decisions under uncertainty. Faced with a key (and possibly contentious) decision,

the results of this study suggest a referee is likely to be influenced not only by the crowd but also

by his perception of the quality, and nationality, of the teams involved in the contest.

13

5. Conclusion

This study has considered the influences on agents’ decisions in an international context.

Using data from European cup matches, it is found that football referees tend to favour home

teams when disciplining players. Consistent with previous work, social pressure is an important

influence on behaviour, with crowd density and stadium architecture playing important roles. The

incidence of disciplinary sanction is also influenced by the type and stage of the competition. The

international context for this study allows a further dimension to referee decisions to be

investigated, namely the role played by nationality. Of particular interest is the finding that

nationality influences individual decisions.

Referees are required to make split-second decisions. Faced with significant time

pressure, individuals tend to focus on salient cues in forming a decision. Dohmen (2008) and

Sutter and Kocher (2004) argue that in the case of football referees, crowd noise is the salient

cue. This analysis confirms that crowd noise is important but also suggests that in an international

context decisions are also influenced by referee nationality, team nationality and league

reputation.

14

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge UEFA and the UEFA Documentation Center in particular for

providing the data. The views expressed here represent the views of the authors and not the views

of UEFA or any of its employees. We would also like to thank Christos Papahristodoulou for

providing the match-play statistics from the Champions League tournament and the research

assistance of Joseph Birch. The usual disclaimer applies.

15

References

Akerlof, G.A (1997). Social distance and social decisions. Econometrica 65, 1005-1027.

Akerlof, G.A. and Kranton, R. (2000). Economics and identity. Quarterly Journal of Economics

115, 715-753.

Balmer, N.J., Nevill, A.M. and Lane, A.M. (2005). Do judges enhance home advantage in

European Championship Boxing? Journal of Sports Sciences 23, 409-416.

Boyko, R.H., Boyko, A.R. and Boyko, M.G. (2007). Referee bias contributes to home advantage

in English Premiership football. Journal of Sports Sciences 25, 1185-1194.

Buraimo, B., Forrest, D. and Simmons, R. (2007). The twelfth man? Refereeing bias in England

and German soccer. International Association of Sports Economists Working Paper 0707.

Cameron, A.C. and Trivedi, P.K. (2005). Microeconometrics: Methods and Applications.

Cambridge University Press, New York.

Chiappori, P.-A., Levitt, S., and Groseclose, T. (2002). Testing mixed-strategy equilibria when

players are heterogeneous: The case of penalty kicks in soccer. American Economic Review 92,

1138-1151.

Clement, R.C. and McCormick, R.E. (1989). Coaching team production. Economic Inquiry 27,

287-304.

16

Coloma, G. (2007). Penalty kicks in soccer. An alternative methodology for testing mixed-

strategy equilibria. Journal of Sports Economics 8, 530-545.

Dawson, P., Dobson, S., Goddard, J. and Wilson, J. (2007). Are football referees really biased

and inconsistent? Evidence from the English Premier League. Journal of the Royal Statistical

Society, Series A 170, 231-250.

Dohmen, T.J. (2008). The influence of social forces: Evidence from the behavior of football

referees. Forthcoming in Economic Inquiry. Published online January 2008.

Findlay, L.C. and Ste-Marie, D.M. (2004). A reputation bias in figure skating judging. Journal of

Sport and Exercise Psychology 26, 154-166.

Garicano, L., I. Palacios-Huerta, and C. Prendergast (2005). Favoritism under social pressure.

Review of Economics and Statistics 87, 208-216.

Helsen, W., & Bultynck, J. B. (2004). Physical and perceptual cognitive demands of top-class

refereeing in association football. Journal of Sports Sciences 22, 179-189.

Jones, M.V., Paull, G.C. and Erskine, J. (2002). The impact of a team’s aggressive reputation on

the decisions of association football referees. Journal of Sports Sciences 20, 991-1000.

17

Nevill, A.M., Balmer, N.J. and Williams, A.M. (2002). The influence of crowd noise and

experience upon refereeing decisions in football. Psychology of Sport and Exercise 3, 261-272.

Palacios-Huerta, I. (2003). Professionals play minimax. Review of Economic Studies 70, 395-415.

Pettersson-Lidbom, P. and Priks, M. (2007). Behavior under social pressure: empty Italian

stadiums and referee bias. CESifo Working Paper 1960.

Plessner, H. and Betsch, T. (2001). Sequential effects in important referee decisions: the case of

penalties in soccer. Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 23, 254-259.

Price, J. and Wolfers, J. (2007). Racial discrimination among NBA referees. National Bureau of

Economic Research, Working Paper No.13206.

Rickman, N. and Witt, R. (2008). Favouritism and financial incentives: a natural experiment.

Economica 75, 296-309.

Scoppa (2007). Are subjective evaluations biased by social factors or connections? An

econometric analysis of soccer referee decisions. Empirical Economics (forthcoming). Published

online June 2007.

Ste-Marie, D.M., & Valiquette, S.M. (1996). Enduring memory-induced biases in gymnastic

judging. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition 22, 1498-1502.

18

Sutter, M. and Kocher, M.G. (2004). Favoritism of agents – the case of referees’ home bias.

Journal of Economic Psychology 25, 461-469.

Torgler, B. (2004). The economics of the FIFA football World Cup. Kyklos 57, 287-300.

19

Figure 1: Frequency Distribution of Home Yellow Cards by Competition

Champions League

403020100

0 5 10 0 5

UEFA Cup

Frequency Percentage

Number of Yellow Cards (Home Team)

10

Figure 2: Frequency Distribution of Away Yellow Cards by Competition

Champions League

3020100

0 5 10 0 5

UEFA Cup

Frequency Percentage

Number of Yellow Cards (Away Team)

10

20

Table 1: Cross-Tabulation of Yellow Cards Issued to Home and Away Teams (by

Competition)

Home

Yellow

Away Yellow

Total

0 1 2 3 4 5 6

0 4.63 6.52 5.67 2.27 0.95 0.76 0

20.79

1 3.59 9.64 11.15 6.52 3.31 0.38 0.19

34.78

2 2.46 6.43 8.98 5.48 1.98 1.13 0.09

26.65

3 1.23 2.74 3.12 3.40 1.13 0.38 0.09

12.10

4 0.66 0.76 0.95 0.95 0.57 0.19 0

4.16

5 0 0.09 0.38 0.09 0.19 0.28 0

1.04

6 0 0 0.19 0 0.19 0 0

0.38

7 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

0

8 0 0 0 0.09 0 0 0

0.09

Total 12.57 26.18 30.43 18.81 8.32 3.12 0.57 100.00

Panel (a): Champions League

Home

Yellow

Away Yellow

Total

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8

0 3.78 6.10 5.35 2.52 0.94 0.25 0.06 0 0

19.01

1 3.84 9.88 7.17 5.98 2.83 0.88 0.13 0.06 0.06

30.84

2 2.45 7.05 8.75 6.23 2.83 1.13 0.31 0.06 0.06

28.89

3 0.63 3.65 4.47 3.52 2.14 0.94 0.19 0.06 0.06

15.67

4 0.25 0.76 1.83 0.88 0.44 0.38 0.19 0 0

4.72

5 0 0.25 0.25 0.13 0.06 0.06 0 0 0

0.76

6 0 0 0.13 0 0 0 0 0 0

0.13

Total 10.95 27.69 27.94 19.26 9.25 3.65 0.88 0.19 0.19 100.00

Panel (b): UEFA Cup

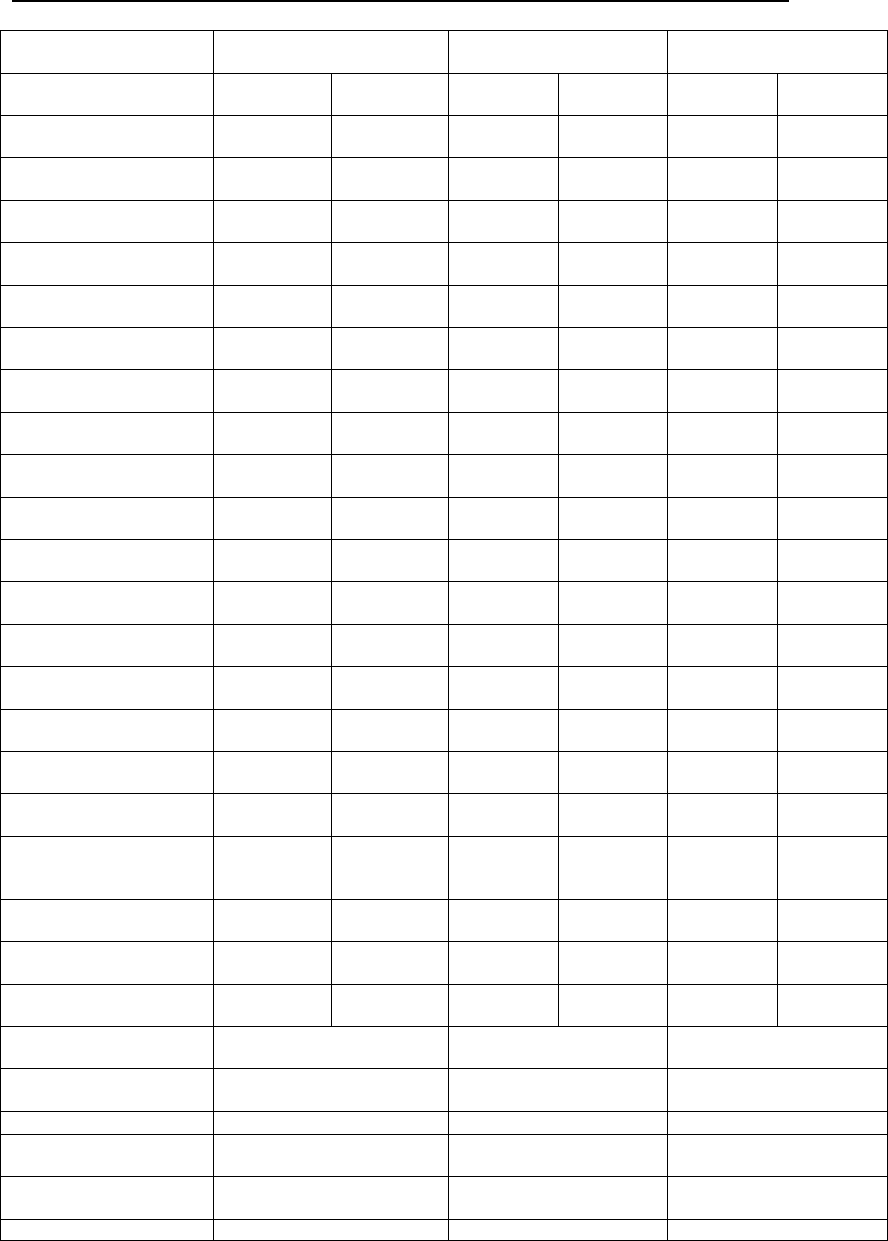

Table 2: Cross-Tabulation of Red Cards Issued to Home and Away Teams (by

Competition)

Champions League UEFA Cup

Red

Card

Home

Red Card Away Red Card Away

0 1 2

Total

0 1 2

Total

0 82.89 9.74 0.95

93.57

81.31 9.13 0.82

91.25

1 5.10 0.85 0

5.95

6.54 1.57 0.13

8.24

2 0.19 0.28 0

0.47

0.13 0.25 0.06

0.44

3 0 0 0

0

0.06 0 0

0.06

Total 88.19 10.87 0.95 100.00 88.04 10.95 1.01 100.00

22

Table 3: Univariate and Bivariate Ordered Probit Estimates

Univariate Ordered Probit Bivariate Ordered Probit

Home Team Away Team Home Team Away Team

Variables

Difference in

Team Coefficient

Index

-0.008** (0.003) 0.002 (0.003) -0.008** (0.003) 0.002 (0.003)

Stage of

Competition

0.113* (0.060) 0.150** (0.060) 0.114* (0.060) 0.149** (0.060)

Champions

League

-0.199*** (0.069) -0.187*** (0.068) -0.199*** (0.069) -0.188*** (0.068)

Attendance / 1000 0.0003 (0.002) 0.002 (0.002) 0.0003 (0.002) 0.002 (0.002)

Attendance to

Capacity Ratio

0.072 (0.093) 0.232** (0.093) 0.073 (0.093) 0.231** (0.093)

Track 0.185*** (0.059) 0.019 (0.059) 0.185*** (0.059) 0.019 (0.059)

Fence 0.101 (0.066) -0.013 (0.065) 0.101 (0.066) -0.012 (0.065)

Referee

Nationality Fixed

Effects

INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED

Rho (ρ)

0.241*** (0.025)

Thresholds

Cut1 -0.924*** (0.077) -1.174*** (0.079) -0.924*** (0.077) -1.176*** (0.079)

Cut2 -0.031 (0.075) -0.316*** (0.075) -0.028 (0.075) -0.314*** (0.075)

Cut3 0.727*** (0.076) 0.384*** (0.075) 0.728*** (0.076) 0.388*** (0.075)

Cut4 1.366*** (0.081) 0.963*** (0.077) 1.363*** (0.081) 0.964*** (0.077)

Cut5 1.847*** (0.090) 1.484*** (0.081) 1.840*** (0.090) 1.481*** (0.081)

Pseudo-R

2

0.013 0.013

LR test (joint

significance of

covariates)

69.68 75.63 69.57

LR test

(independent

equations)

87.34

N 1720 1720 1720

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. ***, **, *, significant at 1%, 5% and 10% levels, respectively (two-

tailed tests.

23

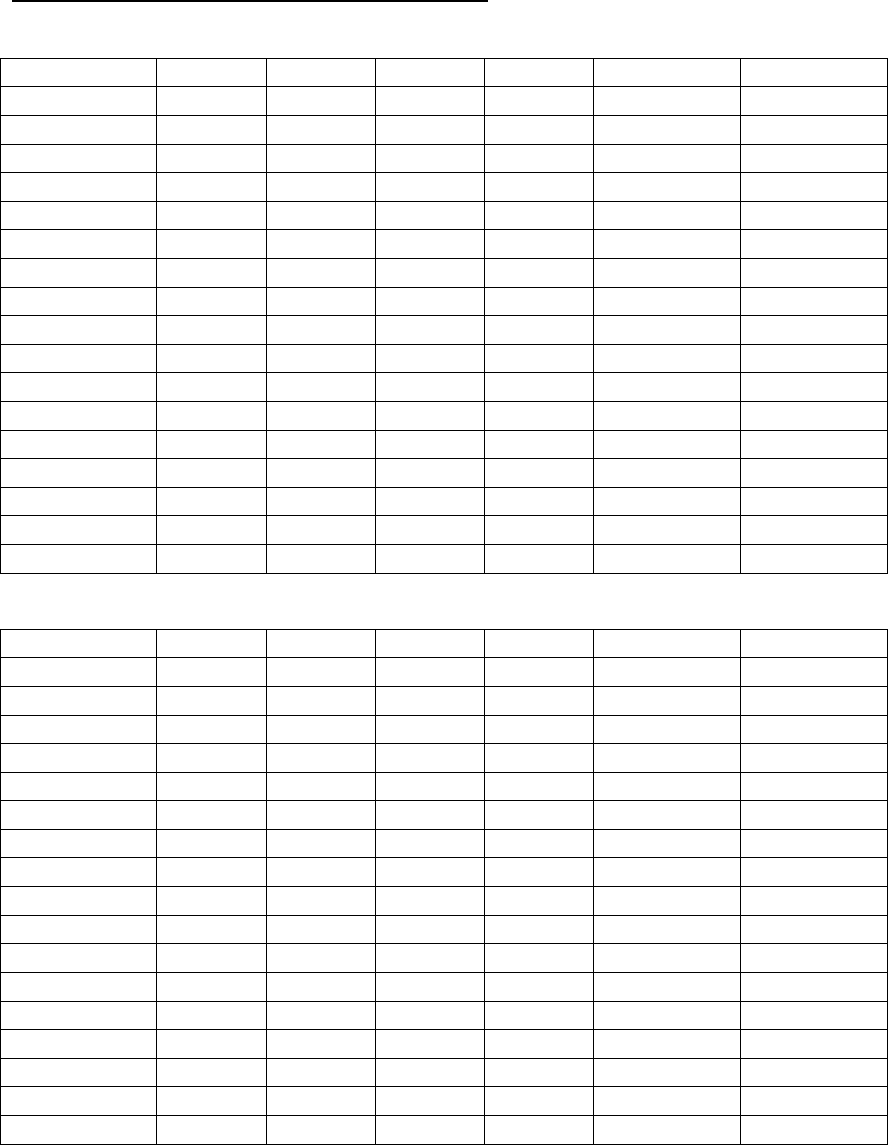

Table 4: Referee Nationality, Club Nationality and “League Reputation” Effects

Bivariate Ordered Probit Estimates

Variables

(1) (2) (3) (4)

Home Team

Difference in Team

Coefficient Index

0.0002 (0.004) -0.0001 (0.003) 0.001 (0.004) 0.0005 (0.004)

Stage of

Competition

0.080 (0.065) 0.098 (0.063) 0.062 (0.066) 0.047 (0.066)

Champions League -0.217*** (0.074) -0.213*** (0.070) -0.259** (0.076) -0.272*** (0.076)

Attendance / 1000 0.0002 (0.002) 0.001 (0.002) -0.0002 (0.002) -0.0002 (0.002)

Attendance to

Capacity Ratio

0.150 (0.100) 0.040 (0.094) 0.158 (0.10) 0.166* (0.100)

Track 0.142** (0.065) 0.177*** (0.059) 0.145*** (0.065) 0.143** (0.065)

Fence 0.022 (0.072) 0.096 (0.066) 0.021 (0.072) 0.022 (0.072)

Big Five Home -0.322*** (0.075) -0.258** (0.122)

Big Five Away 0.089 (0.074) 0.314*** (0.120)

Big Five Home x

Big Five Away

0.296*** (0.103) 0.290*** (0.105)

Elite Referee 0.190** (0.087) 0.173** (0.087)

Away Team

Difference in Team

Coefficient Index

0.0013 (0.004) 0.0001 (0.003) 0.002 (0.004) 0.001 (0.004)

Stage of

Competition

0.121* (0.064) 0.138** (0.063) 0.110* (0.065) 0.097 (0.065)

Champions League -0.207*** (0.073) -0.198*** (0.069) -0.233*** (0.075) -0.244*** (0.075)

Attendance / 1000 0.003 (0.002) 0.002 (0.002) 0.002 (0.002) 0.002 (0.002)

Attendance to

Capacity Ratio

0.273*** (0.099) 0.251*** (0.093) 0.278*** (0.099) 0.285*** (0.099)

Track 0.064 (0.064) 0.017 (0.059) 0.066 (0.064) 0.064 (0.064)

Fence 0.022 (0.071) -0.007 (0.066) 0.021 (0.071) 0.022 (0.071)

Big Five Home -0.053 (0.074) -0.053 (0.121)

Big Five Away -0.169** (0.074) -0.012 (0.120)

Big Five Home x

Big Five Away

0.255** (0.102) 0.272*** (0.104)

Elite Referee 0.116 (0.086) 0.100 (0.086)

Referee Nationality

Fixed Effects

INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED

Team Nationality

Fixed Effects

INCLUDED NOT INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED

Rho (ρ)

0.254*** (0.025) 0.244*** (0.025) 0.252*** (0.025) 0.249*** (0.025)

LR test (joint

significance of

covariates)

167.30 102.67 171.88 179.30

LR test

(independent

equations)

96.40 89.92 95.31 92.84

N 1720 1720 1720 1720

Notes: As Table 3.

24

Table 5: Sensitivity Analysis – Yellow Cards and “Within-Game” Dynamics

Model 1: Yellow Cards

Only

Model 2: “Within Game”

Dynamics

Model 3: “Within Game”

Dynamics

Variables

Home

Equation

Away

Equation

Home

Equation

Away

Equation

Home

Equation

Away

Equation

Difference in Team

Coefficient Index

-0.0004

(0.004)

0.002

(0.004)

0.006

(0.006)

0.007

(0.006)

0.009

(0.006)

0.004

(0.006)

Stage of Competition 0.031

(0.066)

0.099

(0.065)

-0.083

(0.115)

0.010

(0.114)

-0.143

(0.116)

-0.037

(0.115)

Champions League -0.252***

(0.077)

-0.220***

(0.076)

Attendance / 1000 -0.00002

(0.002)

0.002

(0.002)

-0.002

(0.003)

-0.005

(0.003)

-0.003

(0.003)

-0.005

(0.003)

Attendance to Capacity

Ratio

0.142

(0.100)

0.241**

(0.099)

0.370

(0.337)

0.919***

(0.337)

0.281

(0.342)

1.095***

(0.343)

Track 0.100

(0.065)

0.070

(0.065)

0.113

(0.125)

0.223*

(0.125)

0.124

(0.127)

0.194

(0.127)

Fence 0.039

(0.072)

0.008

(0.072)

0.085

(0.130)

-0.190

(0.129)

-0.003

(0.133)

-0.114

(0.132)

Big Five Home -0.298**

(0.123)

-0.034

(0.121)

-0.202

(0.217)

-0.266

(0.216)

-0.154

(0.222)

-0.289

(0.221)

Big Five Away 0.060

(0.113)

-0.366***

(0.112)

0.384*

(0.216)

0.530**

(0.216)

0.292

(0.221)

0.563**

(0.221)

Big Five Home x Big

Five Away

0.339***

(0.106)

0.299***

(0.104)

0.541***

(0.185)

0.195

(0.183)

0.529***

(0.188)

0.085

(0.185)

Elite Referee 0.093

(0.088)

0.058

(0.087)

0.213**

(0.106)

0.185*

(0.106)

0.142

(0.108)

0.840

(0.107)

Home Red 0.317**

(0.128)

0.314**

(0.127)

Away Red 0.040

(0.103)

0.145

(0.102)

Home Red / Yellow -0.135

(0.128)

0.264**

(0.127)

Away Red / Yellow 0.299***

(0.104)

-0.107

(0.103)

Home shots on goal -0.049

(0.055)

0.032

(0.055)

Away shots on goal 0.039*

(0.020)

0.004

(0.020)

Ratio of home possession

to away possession

(HPAP)

0.079

(0.369)

0.153

(0.368)

HPAP x Home shots on

goal

0.029

(0.045)

-0.007

(0.045)

Home fouls 0.086***

(0.010)

0.015

(0.010)

Away fouls 0.017**

(0.009)

0.080***

(0.009)

Referee Nationality Fixed

Effects

INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED

Club Nationality Fixed

Effects

INCLUDED INCLUDED INCLUDED

Rho (ρ)

0.222*** (0.025) 0.239*** (0.042) 0.207*** (0.043)

LR test (joint significance

of covariates)

171.89 89.64 172.84

LR test (independent

equations)

72.40 29.77 21.40

N 1720

Notes: Models 2 and 3 based on Champions League data only.

25

Table 6: Referee Nationality: Marginal Effects

Panel (a): Home Team Equation

Nationality 0 1 2 3 4 5

Austrian N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Belgian 0.100 0.036 -0.045 -0.050 -0.024 -0.016

Danish N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

English N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

French N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

German N/S 0.024 N/S -0.028 -0.014 -0.010

Greek -0.065 -0.051 0.018 0.045 0.028 N/S

Italian N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Dutch 0.081 0.032 -0.036 -0.042 -0.020 -0.014

Norwegian 0.105 0.037 -0.047 -0.053 -0.024 -0.017

Portuguese N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Russian 0.082 0.032 N/S -0.043 -0.021 -0.014

Scottish 0.095 0.035 -0.043 -0.048 -0.023 -0.016

Slovakian N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Spanish N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Swedish 0.086 0.033 -0.038 -0.044 -0.021 -0.015

Swiss N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Panel (b): Away Team Equation

Nationality 0 1 2 3 4 5

Austrian N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Belgian 0.073 0.065 N/S -0.047 -0.042 -0.041

Danish N/S 0.045 N/S N/S -0.029 -0.030

English N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

French N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

German N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Greek -0.042 -0.065 N/S 0.029 0.041 0.058

Italian N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Dutch 0.063 0.058 N/S -0.041 -0.037 -0.037

Norwegian N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Portuguese -0.044 -0.065 N/S 0.029 0.041 0.058

Russian 0.091 0.075 N/S -0.057 -0.049 -0.047

Scottish N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Slovakian N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Spanish 0.047 0.046 N/S -0.031 -0.030 -0.031

Swedish N/S 0.047 N/S -0.032 -0.030 -0.031

Swiss N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S N/S

Note: Estimates are significantly different from zero at the 10% level or better. N/S = not significant.

Columns represent the probability of awarding 0,1,2,3,4,5 disciplinary points. For example, the third cell of

column 2 (Panel (a)) indicates that Belgian referees are 10% more likely to issue zero disciplinary points to

the home team. Estimates based on Model 4 (Table 4).

26

Appendix: Variable Definitions

Variables Definition

Difference in Team

Coefficient Index

Team Coefficient Index of Home Team Minus Team

Coefficient Index of the Away Team.

Stage of

Competition

= 1 if Round of 32 onwards (Round of 16 in the case of the

Champions League), 0 otherwise

Champions League = 1 if Champions League Match, 0 otherwise (i.e. UEFA Cup

match)

Attendance / 1000 Attendance scaled by 1000

Attendance to

Capacity Ratio

Attendance divided by stadium capacity

Track = 1 if stadium has a running track, 0 otherwise

Fence = 1 if stadium has fencing, 0 otherwise

Home Cards Total disciplinary “points” issued to the home team

Away Cards Total disciplinary “points” issued to the away team

Referee Nationality Dummy Variables which represent referee nationalities

(minimum of 70 observations required for inclusion).

Home Club

Nationality

Dummy Variables which represent home club nationality

(minimum of 70 observations required for inclusion).

Away Club

Nationality

Dummy Variables which represent the away club nationality

(minimum of 70 observations required for inclusion).

‘Big Five’ Home =1 if home club from one of the “big five” leagues

a

, 0

otherwise

‘Big Five’ Away =1 if away club from one of the “big five” leagues

a

, 0

otherwise.

Elite Referee =1 if match official officiated at the 2004 European

Championship, 0 otherwise.

Notes:

a

Club from England, France, Germany, Italy or Spain.

27