Bates College Bates College

SCARAB SCARAB

Honors Theses Capstone Projects

5-2023

Wild9res in the US and Australia: NGO Polarization Amidst Wild9res in the US and Australia: NGO Polarization Amidst

Political Polarization and Climate Disasters Political Polarization and Climate Disasters

Kallie E. Polgrean

Bates College

Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Polgrean, Kallie E., "Wild9res in the US and Australia: NGO Polarization Amidst Political Polarization and

Climate Disasters" (2023).

Honors Theses

. 445.

https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/445

This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please

contact [email protected].

1

Wildfires in the US and Australia:

NGO Polarization Amidst Political Polarization and Climate Disasters

An Honors Thesis

Presented to

The Faculty of the Department of Political Science

In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the

Degree of Bachelor of Arts

By Kallie Polgrean

Lewiston, Maine

April 3, 2022

2

Table of Contents

Introduction......................................................................................................................................4

Chapter 1: Literature Review...........................................................................................................7

Chapter 2: Why the US and Australia?..........................................................................................27

Chapter 3: Methodology................................................................................................................ 31

Chapter 4: NGO Classifications.....................................................................................................37

Chapter 5: Analysis........................................................................................................................49

Chapter 6: Discussion.................................................................................................................... 81

Conclusion..................................................................................................................................... 89

References......................................................................................................................................92

Appendices...................................................................................................................................101

3

Acknowledgements

I want to thank the Bates College Politics Department for giving me the opportunity to work on

this project. I am so grateful to my thesis advisor, Professor James Richter, who never failed to

make himself available for the many questions and worries that came up along the way. His

support and guidance allowed me to complete this thesis through numerous setbacks surrounding

the creation of my research question and the daunting literature review.

To my friends and loved ones, thank you for being there to listen to my ideas and excitement

over this project and for always providing me with motivation and a place to relax. Mom, Dad,

Brynn, and Emma, you have all set an example of excellence for me which I hope to have at

least somewhat lived up to with the completion of this work.

This page wouldn’t be complete without a thank you to the yellow lab that has been with me

since third grade, watching me grow up and finally graduate college! I love you, Cody, thanks

for always greeting me at the door with a wagging tail when I came home to work on my thesis.

4

Introduction

As the effects of climate change loom closer each passing year, natural disasters appear to

have increased exponentially throughout the 21st century. The most recent Intergovernmental

Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report concluded that humanity is being pushed closer to the

brink of its ability to adapt to the impacts of climate change. An increase in extreme weather

events, resource scarcity, infectious diseases, displacement, infrastructure damage, and even

phenological changes are just a fraction of the dangerous factors accompanying a changing

climate.

1

In this work, I hone in on natural disasters in the form of catastrophic wildfires bringing

destruction and increased risk to the terrain and people of the United States and Australia.

According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) with the

US Department of Commerce, climate change is playing a role in more intense wildfires and the

increase in severe droughts that often cause them in the United States. In a 2021 study conducted

with support from the NOAA, it was found that climate change is the main cause of the increase

in fire weather in the Western United States.

2

The same can be said of bushfires in Australia,

where the fire season has lengthened each year as a result of increasing average temperatures on

the continent.

3

In the past decade, the acreage of land impacted by wildfires in both countries has

hit record highs, with examples including California’s 2018 Camp Fire that decimated over

150,000 acres and Australia’s 2019-2020 Black Summer Bushfire season that burned an

estimated 46 million acres across the country.

Both people and wildlife in the US and Australia are under threat from these catastrophic

mega-fires, and science supports the frightening truth that the danger is only going to increase.

When forest fires cause billions of dollars in damage and take the lives of citizens, these natural

3

Climate Council, “The Facts about Bushfires and Climate Change.”

2

NOAA, “Wildfire Climate Connection.”

1

IPCC, “Climate Change 2022.”

5

disasters become enmeshed with the politics of climate change. As the direct impacts of climate

change begin to reveal themselves, environmental politics has gained heightened attention from

policymakers in Washington and Canberra. However, the past decade has sown deep political

divisions in both countries, representing a threat to the implementation of climate mitigation,

adaptation, and resilience measures.

Coinciding with growing climate impacts is an increase in political polarization in both

the United States and Australia. Both nations have seen rises in disagreement, antagonism, and

confrontation between the two primary political parties within their respective governing bodies.

Oftentimes, climate change is at the center of these disagreements, representing a controversial

subject that can be argued from a multitude of viewpoints. For some, implementing mitigation

measures such as carbon taxes, switching to renewable energy, or banning fossil fuels is an

unacceptable way to deal with the problem, as it sacrifices economic growth for the sake of

environmental protection. Many individuals, including officeholders, doubt the legitimacy of the

science backing climate change and are therefore hesitant to agree to policies that deal with the

issue. On the other end, some people take a strong stance on the need for progressive climate

action and the dire consequences that would confront the planet in the case of inaction. These

contrasting stances on the severity of climate change and the need for action are just one

symptom of political polarization in the US and Australia.

This research seeks to further an understanding of how Australian and American forest

fires may impact non-governmental organizations’ (NGOs) advocacy. Scholars such as Hadden

(2015) and Ciplet et al. (2015) have identified a recent split over the past fifteen years among

environmental organizations falling along increasingly radical or reformative lines, indicating

6

disagreement on how to approach the issue of climate change.

4

In this work, I aim to build an

understanding of what variables may contribute to polarization within the society of NGOs

associated with forests and the environment. Have non-governmental organizations become more

radical over time? The period in question begins in the year 2007 and ends in our current year.

Utilizing the existing literature on framing and NGO operations within climate change politics, I

analyze the emotional framing positions of eight environmental and forest-associated NGOs in

the United States and Australia along a radical-reformist spectrum. I use qualitative approaches

and sentiment analysis to examine emotional framing in the form of wildfire-related press

releases, social media posts, and newsletters from these eight organizations. I find that

polarization among the eight NGOs has been increased by the dual factors of political

polarization on the issue of climate in the USA and Australia and the experience of catastrophic

wildfires.

4

Ciplet et al., Power in a Warming World, 157.; Fitzgerald and Rogers, “Radical Social Movement

Organizations,” 581; Hadden, Networks in Contention, 3.

7

Literature Review

NGOs and ENGOs

There are a wide variety of NGOs that operate domestically, internationally, and

transnationally. From business and industry non-governmental organizations (BINGOs) to

market advocacy NGOs (MANGOs), and environmental NGOs (ENGOs), there is an acronym

out there for nearly any kind of organization operating today. Many NGOs are involved directly

in monitoring and setting standards for businesses and transnational corporations.

5

We can draw

a further distinction between service-oriented and advocacy-oriented NGOs, where advocacy

NGOs lean towards social activism, information dispersal, lobbying, or networking surrounding

a perceived problem. It is the advocacy category of NGOs that I focus on in my work. Many

advocacy-based non-governmental organizations aim to change society in some way by

attempting to mobilize citizens, policymakers, and companies.

6

I have chosen to analyze non-governmental organizations because they are key actors in

the environmental movement that can pressure the public and governments for climate change

action. Climate change is a global issue, yet it requires action at local and national levels as well

as internationally. Scholars such as Princen and Finger (1994) and Henry and Sundstrom (2021)

emphasize that environmental organizations provide the necessary link between international

norms that need to be translated to national climate change norms.

7

In addition to this ability to

navigate the two levels, non-governmental organizations that exist within domestic contexts

7

Princen and Finger, Environmental NGOs in World Politics, 30.; Henry and Sundstrom, Bringing Global

Governance Home, 216.

6

Espinosa and Treich, “Moderate Versus Radical NGOs,” 1478.

5

Beer et al., “NGOs: Between Advocacy,” 6.

8

provide scientific expertise, policy recommendations, and potential technological innovation to

governments and other organizations or partnerships.

Existing NGO scholarship highlights a wide variety of avenues NGOs have gone down in

their pursuit of influence and change. Keck and Sikkink (1998) argue that NGOs use ideas,

leverage, venue shopping, arguments, and framings, while Rodela et al. (2016) emphasize the

leveraging of cognitive, material, social, and symbolic resources as the key to NGO influence.

8

Ciplet et al. (2015) also highlight resource-oriented NGO tactics as well as their level of access

to key events, actors, and other organizations.

9

Other scholars focus on advocacy, service

provision, and regulation as the key capabilities NGOs bring to the table.

10

These works envision

the physical and immaterial capacities that are available to non-governmental organizations, of

which I hone in on the intangible, ideological stances promoted by environmental organizations.

I hold that environmental NGOs in particular utilize ideological stances to a great extent in their

operations, given the contentious topic of climate change. It is vital for an

environmentally-affiliated group to establish their values, beliefs, and solutions on the topic as a

frame for their pursuant actions. If one of the goals of this kind of NGO is to mobilize public

opinion and governmental attention to climate change, beginning with an ideology that informs

the audience of how to envision the problem is the most logical place to begin.

It is clear that governments have perhaps the greatest capability to introduce climate

change mitigation and bring certain issues to the table, but the proliferation of non-governmental

organizations (NGOs) over the past few decades has brought new solutions and knowledge to the

political sphere. Non-governmental organizations are in a unique position when it comes to

10

Beer et al., “NGOs: Between Advocacy.”

9

Ciplet et al., Power in a Warming World.

8

Keck and Sikkink, “Activists Beyond Borders.”; Rodela et al., “Developing Environmental NGO

Power.”

9

environmental advocacy as they operate outside of the bounds of government. Since the 1980s,

the number of non-governmental organizations has grown sharply, attributed to many as a

response to the globalizing world.

11

Today there are thousands of NGOs operating across the

globe and in different sectors, with a recent upswing in environmental organizations over the past

decade.

12

Climate change is global in scale, yet environmental organizations must ultimately

decide how to engage with important actors and the general public that implement policies at the

national level. As the next section will address, how NGOs choose to engage with actors outside

of their organization is not uniform and it is their distinctions that comprise the bulk of my thesis.

Radical vs Reformist Approach

A multitude of discourses surrounding how to understand and respond to climate change

have proliferated across public and political domains.

13

Naturally, this means environmental

advocates will come at the issue from a wide variety of angles and personal assumptions. In

social movement scholarship, a distinction has been made between radical and reformist

organizations. This concept has worked its way into climate change activism within NGO

society. According to Tarrow and Tilly (2009), there are ‘insiders’ and ‘outsiders’ when it comes

to activism.

14

Dryzek (2022) establishes a useful way to conceptualize environmental discourses

by classifying actors as either reformist or radical.

15

‘Insider’ or reformist organizations often

operate within existing institutional structures, emphasizing a gradual, step-by-step process

where social or political change can be achieved more efficiently in the long run.

16

Radical

organizations, also known as ‘outsiders’, tend to seek a change or dismantling of existing power

16

Dzhengiz et al., “Emotional Framing of NGO Press Releases,” 2468.; Espinosa and Treich, “Moderate

Versus Radical NGOs,” 1478.

15

Dryzek, “The Politics of the Earth,” 13.

14

Tarrow and Tilly, “Contentious Politics and Social Movements,” 6.

13

Dryzek, “The Politics of the Earth,” 5.

12

Hadden, Networks in Contention, 10.

11

Hall-Jones, “The Rise and Rise of NGOs.”

10

structures, stressing the value of drastic, large changes as a more effective route to avoid the

longer time frame often found with a reformist perspective.

17

Key features of radical organizations are a non-hierarchical and anti-bureaucratic internal

structure, often combined with anti-capitalist sentiments.

18

According to Ciplet et al. (2015)

along with Fitzgerald and Rodgers (2000), radical organizations face larger barriers to effective

mobilization and influence. Oftentimes, radical groups are discredited within larger power

structures and the social movement area as a whole, meaning reformist approaches tend to be

associated with greater resources and links to power.

19

Due to the difficulty of achieving

mainstream attention and the possibility of more moderate organizations aiming to weaken

support for radical change, radicals often rely on mass action demonstrations and grassroots

organization as well as evolving and innovative forms of communication.

20

Reformist, also associated with moderate organizational stances, are conceptualized by

Yaziji and Doh (2010) as tending to be more satisfied with existing institutions, calling for small

changes to the system that will not influence their access to resource pools found within

institutional contexts.

21

Because much of their leveraging power comes from lobbying

governmental institutions, moderate or reformist NGOs tend to target corporations as the ‘bad

eggs’ in need of reform. Their tactics to pursue this aim include the utilization of dominant

institutions such as courts, legislators, and regulatory bodies.

22

Along with these potential

avenues for action, reformative NGOs seek to mobilize public opinion, similarly to radical

22

Ibid., 90.

21

Yaziji and Doh, NGOs and Corporations, 9,81.

20

Ibid., 580,585,589.; Espinosa and Treich, “Moderate Versus Radical NGOs,” 1479.

19

Ciplet et al., Power in a Warming World, 157.; Fitzgerald and Rogers, “Radical Social Movement

Organizations,” 581.

18

Fitzgerald and Rogers, “Radical Social Movement Organizations,” 574.

17

Ibid.

11

NGOs but with a greater emphasis on common-sense or widely accepted beliefs about a

subject.

23

It is vital to recognize that radical and reformative organizations are not required to

remain as such. Dzhengiz et al. (2021) along with den Hond and de Bakker (2007) argue that the

reformative-radical divide is more akin to a spectrum, where organizations can shift their stance

over time, or take some radical and some reformist actions at differing times.

24

This means as

political contexts change over time, environmental organizations may likewise fall along

different places within the radical-reformist spectrum.

NGO Polarization

I build off of the conception of an increasing rift between radical and reformist

organizations to explain what may cause shifts among radical and reformist environmental

organizations. Both Hadden (2015) and Ciplet et al. identify a fragmentation between

reformative and radical NGOs working within the domain of climate politics.

25

Ciplet et al.

conclude that three sets of NGOs have emerged from this fragmentation: professionalized NGOs

that continue to cooperate with the government for incremental change, social movement and

advocacy NGOs pushing for radical change, and those who have stayed away from participation

entirely, leaning towards grassroots action.

26

Hadden argues that a factor explaining heightened NGO polarization was the 2009

COP15 in Copenhagen. At the conference, some organizations sought to continue their work

within existing institutions, using conventional tactics and science-based framing, while the other

side moved outside of these norms, pursuing radical approaches that utilized a justice-based

26

Ciplet et al., Power in a Warming World, 157.

25

Hadden, Networks in Contention, 3.

24

Dzhengiz et al., “Emotional Framing of NGO Press Releases,” 2468.; Den Hond and De Bakker,

“Ideologically Motivated Activism,” 904.

23

Ibid.

12

framing approach.

27

Hadden attributes this divide to growing political opportunities for

organizations to mobilize on climate change around 2009, giving space for more diverse

organizations to enter the fold of climate politics and bringing new tactics and beliefs to the

network.

28

As new coalitions sprang up in the world of climate activism, many began to take

more confrontational, dramatic action such as organizing protests and demonstrations. Hadden

argues that this was a response to ease organizational frustration fueled by a belief that the NGOs

were not able to directly impact public discourse.

29

Also creating this rift were divisions in the

social network of climate change, where less coordination and overlap in membership likewise

pushed organizations apart from one another.

30

What may be the ramifications of a heightened radical-reformist divide? Fitzgerald and

Rodgers conclude that the existence of radicals within a network is generally thought to have a

somewhat beneficial effect on the moderates.

31

Drawing from Haines (1998), the extreme stances

often taken by radicals often make those of the reformists appear more reasonable to the public

and policymakers.

32

If the environmental NGO society continues to fragment along

radical-reformist lines, one could argue that moderates will find more support for their platform,

which could be seen as a potentially positive impact of heightened polarization. Taking a more

pessimistic view, Ciplet et al. and Hadden suggest that ENGO fragmentation has led to ‘limited

coordination’(Ciplet et al.) between environmental organizations, which in Hadden’s view

disrupts the environmental movement’s ability to communicate and coordinate collective

action.

33

This latter view seems reasonable. ENGOs are often praised for their capacity to bridge

33

Ciplet et al., Power in a Warming World, 157.; Hadden, Networks in Contention, 56.

32

Haines, “Black Radicalization.”

31

Fitzgerald and Rogers, “Radical Social Movement Organizations,” 574.

30

Ibid., 47.

29

Ibid., 33.

28

Ibid., 10,19.

27

Hadden, Networks in Contention, 3.

13

the gap between parties, nations, and other coalitions, but a ‘network in contention’ will be

hard-pressed to accomplish these tasks. If the environmental network becomes so polarized that

NGOs are unable to communicate solutions and unite the public under a common cause, we will

have lost a major player in the fight against climate change. I do not doubt that environmental

NGOs have shifted along the radical-reformist spectrum, but what I aim to clarify is how they

have changed over time, and what may be the factors creating these changes.

Building on the Literature

If, in fact, environmental NGOs have become more fragmented, I investigate how these

divisions have changed since the year 2007 and what may have caused this. To build an

explanation for NGO polarization, I look at conditions of political polarization in the US and

Australia along with experiences of wildfires as climate-induced disasters.

The goal of many environmental NGOs is to mobilize public support for specific issues,

and I argue that public opinion also informs the actions of NGOs. In empirical work that looks at

concrete data on public perceptions of natural disasters, personal experience emerges as a

deciding factor in how people respond to climate change. The work done by Baccini and

Leemann as well as Konisky et al. explores the effect of proximity to natural disasters and level

of concern for climate change after the event. Both of their findings indicate that the level of

concern for climate change as expressed through opinion surveys and voting patterns increases

up to a year after an experience with a natural disaster when the participant lived within a short

distance of the event.

34

Baccini and Leemann argue that natural disasters create a window of

opportunity after small and local disasters where voters are more sensitive to questions of climate

change.

35

35

Baccini and Leemann, “Do Natural Disasters Help the Environment?” 482.

34

Baccini and Leemann, “Do Natural Disasters Help the Environment?”; Konisky et al., “Extreme

Weather Events and Climate Change Concern.”

14

It is widely accepted that advocacy NGOs seek to mobilize public opinion in much of the

work that they do. Given this apparent link between the experience of a natural disaster and

concern for climate change, I argue the same trend is paralleled within NGO media. In the

months following a catastrophic wildfire in the country that the NGO operates within, I expect

increasing emotional framing, specifically negative, as a result of heightened awareness of

climate change-induced events. Konisky et al.’s study is useful in its US-centered data collection,

providing more support for the idea that natural disasters change public perceptions of climate

change. Overall, it appears that personal experience involving extreme weather plays a role in

public mobilization and participation in politics, specifically climate change politics.

One cannot separate organizations from the people they are composed of. Individuals

working or volunteering for NGOs bring their opinions into the organization, so if the public

becomes concerned about severe wildfires, the NGO will more than likely experience the same.

Given the necessity for NGOs to gain traction with public opinion and the confirmation that

natural disasters impact public concern for climate change, I conclude that increasingly

catastrophic wildfires may be one of the driving factors pushing NGOs to become more radical

and polarized. Wildfires are inherently negative events that often inspire negative sentiment, and

if the public expresses this negative sentiment, so too will NGOs affiliated with forests and the

environment.

Alongside climate-induced disasters, I argue that political polarization in the United

States and Australia has also played a role in NGO polarization. Polarization, or the division of

groups into sharply contrasting beliefs or ideologies, has been studied primarily as an American

phenomenon, yet the polarization of politics has occurred within democracies across the globe,

including in Australia.

36

I utilize Pierson and Schickler’s (2020) work to discuss political

36

Carothers and O’Donahue, Democracies Divided.

15

polarization in the United States. According to the authors, over the past two decades, America

has moved from an area of low political polarization to a system of high political polarization.

37

The increase of polarization in politics is attributed to the 1960s and 1970s, when Republicans

and Democrats increasingly aligned themselves as conservative or liberal surrounding the topic

of race.

38

Clearing up the distinctions between the parties, the decades after saw Americans

increasingly stratifying themselves and their ideologies according to a particular party. The

political parties also became more pluralized, ensuring continued disagreement both within and

outside of the party system.

39

Australian polarization has been less far-reaching than in the US,

but polarization surrounding climate change has become a central issue in the country. Tranter

(2013) argues that attitudes to climate change fall along party lines, with both the public and

policymakers themselves becoming increasingly polarized about how to deal with climate

change and, in some earlier cases, whether it even presents a threat.

40

Tranter discusses how

climate was used as a wedge issue for the conservative, Liberal, party to distance itself from

Labor and the Greens. The 2009 election of climate-denier Abbott as Prime Minister appears as

the beginning of political polarization on climate in Australia.

41

The polarization of American and Australian politics likely has a hand in influencing

NGO polarization for many of the same reasons as catastrophic climate disasters. Political

polarization is reflected in tensions within society and the polity, where deadlocks, progress

followed by backsliding, and tempestuous election cycles are reinforced by the general public

but also demonstrated within elite circles of policymaking. I argue that NGOs, specifically the

domestic NGOs I focus on in this work, must remain privy to the political atmosphere of the

41

Ibid., 400.

40

Tranter, “The Great Divide,” 398.

39

Ibid.

38

Ibid.

37

Pierson and Schickler, “Madison's Constitution Under Stress.”

16

country they operate within. When the parties are able to cooperate and pass bipartisan

legislation, NGOs can rely less on letting politics motivate their actions, while periods of

disagreement and tension, such as we have been seeing for the past fifteen or so years, call for

organizations to realign their outreach in a manner that resonates with the public. Therefore, as

political parties in Australia and America reached two extremes of ‘right and left’, so too have

NGOs shifted further apart between radicalism and reform. To measure the extent of this

polarization, I utilize the concept of emotional framing. The following sections address framing

as a theoretical concept and explain the use of emotional framing as a logical framework with

which to measure NGO polarization.

Framing Theory

Framing theory has spread throughout a multitude of disciplines, from psychology,

anthropology and linguistics, to politics.

42

Hallahan (1999) argues that framing as a rhetorical

tool addresses the creation of messages, but also connects to the psychological motivations

underpinning human analysis, judgment, and decision-making.

43

Keck and Sikkink, citing

McAdam et al. (1996) define framing as ‘conscious strategic efforts by groups of people to

fashion shared understandings of the world and of themselves that legitimate and motivate

collective action’.

44

Framing theory covers a wide lens that encompasses the attribution of

meaning within specific messages and how they are intended to influence the audience. The

creator of the frame can stratify pieces of information that are relevant or irrelevant to the frame

they are constructing, leaving out unimportant or potentially weakening viewpoints. Entman

defines framing on the individual level as ‘clusters of ideas’ that are stored within the mind to

44

Keck and Sikkink, Activists Beyond Borders, 90.

43

Hallahan, Seven Models of Framing,” 206.

42

Benford and Snow, “Framing Processes and Social Movements,” 611.

17

guide information processing.

45

This involves both the creation of a message by a messenger and

the reception of that message, along with its impact on the decisions and interpretations of the

receiver. Framing acts as a possible method of promoting an understanding of the world or of

specific issues at the individual and collective levels.

When applied to social movements or civil society, framing entails a set of beliefs or

meanings that compel the activities of a social movement organization.

46

This is referred to as

collective action framing, an activity that results in the cohesion of people’s understandings of a

problem, and who or what to blame for it.

47

In my work, the concept of collective action framing

can be applied to the tactics utilized by various environmentally-affiliated organizations. Each

group seeks to define its media and literature in a manner that compels the general public to

generate a shared understanding of the threats wildfires pose, and who or what causes them. In

the case of logging associations and wood product professional organizations, it is often natural

weather patterns or climatic variations that are to blame for increasingly severe fire seasons, if

any blame is attributed at all. In the case of progressive environmental coalitions, it tends to be

the logging industry and extractive practices that further degrade forests, assisting climate

change in worsening fire events. For the organizations I examine in this work, frames must be

carefully constructed to resonate with people and gain the most support. I choose to employ

emotional framing as a concept that allows me to measure levels of radicalism among the NGOs

studied.

Emotional Framing

Language, rhetoric, and the emotions that they evoke are a reflection of the framing

process. The tone and significance of wording within organizational press releases, social media

47

Ibid., 615.

46

Benford and Snow, “Framing Processes and Social Movements,” 614.

45

Entman, “Framing: Toward Clarification of a Fractured Paradigm,” 53.

18

posts, newsletters, etc. all carry with them an attribution of meaning. Emotional framing refers to

the process in which rhetoric or language that is intended to evoke specific kinds of emotions

results in a negative or positive attribution by the audience.

48

Framing has a psychological

element, as the introduction of new frames to the human mind may result in the creation of new

psychological connections between framed issues and an individual’s underlying values.

49

The

evocation of certain types of emotions can promote action or awareness of specific subjects.

Emotional framing is a valuable analytical tool for this work because identifying instances of

emotional evocation in NGO media allows me to attribute these sentiments to a particular

ideological stance, whether it be radical, reformist, or neutral.

To understand the role emotions play in social movements and activism, I turn to Jasper’s

(2018) five key distinctions in types of emotions. These five types are reflex emotions, urges,

moods, affective commitments, and moral commitments.

50

Reflex emotions are chosen as the set

of emotions to be analyzed within my work because they refer to relatively quick, knee-jerk

reactions to specific events or information.

51

Although they tend to subside just as quickly as

they arise, my conception of reflex emotions is that they are often the kind evoked by stimuli

such as social media posts or press releases, where small bits of information are introduced to

create an immediate impact on an audience. Jasper conceives of the negative emotion of anger as

an external motivator, where perceived injustice or wrongdoing results may result in outside

action, whereas fear causes introspection or a self-critical look at our anxieties and weaknesses.

52

Within my research, I identify instances of emotional framing where NGOs attempt to elicit

52

Ibid., 42.

51

Ibid.

50

Jasper, The Emotions of Protest, 4.

49

Anspach and Draguljić, “Effective Advocacy,” 617.

48

Baek and Yoon, “Guilt and Shame: Environmental Message Framing Effects," 441.

19

negative emotions within their publicly-oriented media, including their websites, newsletters,

and social media.

The work conducted by Giorgi (2017) in her study of emotional and cognitive resonance

is the key framework that this paper will utilize in understanding the concept of emotional

framing. Giorgi establishes the concept of resonance as a key factor in the success of framing,

defined as a bridge that connects the frame to the audience.

53

She distinguishes between two

kinds of resonance: cognitive and emotional. While cognitive resonance deals with

understanding and beliefs, emotional resonance refers to the ability of a frame to ‘move’ or

‘shake’ its listener.

54

Given the relative lack of literature regarding emotional framing, I use this

conception of emotional resonance to describe the term ‘emotional framing’. Therefore,

emotional framing involves the use of rhetoric that expresses a certain positive or negative

sentiment that affects the audience. My conception of emotional framing is that it both possesses

and promotes an emotional response to specific issues or events.

Within media conglomerates, corporations, and managerial firms, many studies have

found a link between emotional framing and increased participation, attention, or support for the

idea being framed.

55

Given the divisiveness of climate change and the difficulty of garnering

widespread support for pro-environmental causes, concerted framing has become an important

tactic for environmentalist organizations. At the level of environmental advocacy, ENGOs tend

to strategically frame their mobilization efforts to resonate psychologically with audiences.

56

Along with the concepts of efficacy and psychological proximity, ENGOs utilize emotion to

elicit a response from target audiences, meaning the inducement of sadness or anger has a

56

Anspach and Draguljić, “Effective Advocacy.”

55

Geradts et al., “Social Entrepreneurial Action.”; Raffaelli et al., “Frame Flexibility.”; Lee,

“Asset-Oriented Framing.”

54

Ibid., 721.

53

Giorgi, “The Mind and Heart of Resonance,” 712.

20

positive impact on levels of public support for the organization’s campaign.

57

A study conducted

by Anspach and Draguljić finds that using efficacy, also known as motivational frames, results in

a null effect on audience behavior and support, but evoking psychological proximity to specified

issues and resonating with emotions such as sadness and anger had tangible success in ‘garnering

political support’.

58

These studies confirm that there is a relationship between emotional framing

and bolstered support for a variety of issues, from environmental causes to corporate and

business interests. Therefore, the evocation of emotions has the potential to be an effective tactic

for NGOs to utilize.

My work adds more content to this existing analysis of emotional framing, as eight

organizations associated with forestry and the environment are analyzed according to their

emotional framing techniques, with a specific focus on positive and negative sentiment. There

are three classifications for these NGOs based on their mission statements and preferred action:

radical, reformist, and professional. I examined four NGOs from the United States: Greenpeace

USA, American Forests, National Forest Foundation, and American Loggers Council. The four

Australian NGOs are Greenpeace Australia Pacific, Greening Australia, the Australian Forest

and Climate Alliance, and Forest and Wood Products Australia.

I hypothesize that the identified radical organizations will respond to moments of

political transition and intensifying forest fires by utilizing more emotional framing that evokes

negative sentiment. Because these organizations have already displayed a willingness to take

confrontational action when it comes to the environment, I argue that these actions will be

complemented by enhanced negative framing that expresses frustration and anger with the

current state of things. In my view, negative sentiment can be paired with radicalism because the

58

Ibid., 631.

57

Ibid.

21

goals of a radical social movement are to replace existing institutions, meaning a negative

attribution of current systems must be formed. As fires worsen in both countries and climate

laggards such as Trump and Abbott are installed in office, I hypothesize that both branches of

Greenpeace will take this as an impetus for pushing forth their radical agendas, which involve

emotional framing that relies on negativity.

I hypothesize that the reformist organizations will be confronted with the dual issues of

political polarization and increasing forest fires as a motivator for increased reliance on

emotional framing. I believe that some organizations may be more willing to assume a radical

stance, whereas other reformists, such as the NFF who were chartered by Congress, will shy

away from overt negativity, but may choose to decrease their positive sentiment evocation. I

think that over time, these organizations have been forced by severe fires and political

polarization to decide whether they will continue operating within the mainstream activist

channel which relies upon existing institutions, or begin to distance themselves from their bodies

and become more radical. I say this because both of these conditions have heightened to the

extent that they cannot easily be ignored by the NGOs, specifically the increasing prominence of

forest fires in the public. For these organizations to stay relevant, they must respond to the

factors around them that are influencing public opinion.

The professional organizations are likely to be unwavering in their framing because they

are not advocacy-based, but service provisioning. Lumber and wood product organizations rely

on the cooperation of the government to allow continued harvesting of trees, so administrations

with a lack of emphasis on environmental causes will likely be met with positivity by the

professional organizations. I do not expect to see major increases in negative sentiment within

22

the American Loggers Council and Forest and Wood Products Australia because it is in their best

interest for political institutions to remain operating as they have been.

I stress here that the two variables, climate-induced wildfires and general political

polarization, influence NGO behavior in mutually constitutive ways. In some years, where fires

are not severe but political tensions run high, NGO emotional framing will be influenced,

whereas some years fraught with severe wildfires but lacking political turmoil will also see a

difference in emotional framing. Also possible is that both factors are present in one year,

creating the greatest potential for divisions in NGO framing tactics. Therefore, I argue that

political polarization and extreme wildfires reinforce each other in their impact on emotional

framing, and can thus be analyzed in isolation and as a unit, depending on whether they occur in

similar or different time periods.

The Internet and Framing

Over the past few decades, the Internet and social media have become increasingly

prominent in the framing process. The website, typically regarded to be the ‘public face’ of an

organization has become less of a dominant factor for public outreach, as social media

supplements and enhances interactivity and participation.

59

Most NGOs or professional

organizations today have created accounts across a wide range of platforms, including Facebook,

Twitter, Instagram, LinkedIn, and recently even TikTok. This wide spectrum of influence allows

for even greater framing power and information dispersal, as groups can reach ever-increasing

numbers of people on a weekly, daily, or hourly basis. The accessibility of the Internet and social

media is both a blessing and a curse for ENGOs seeking to enhance their support. With the

hundreds of NGOs online offering their own frames for interpretation and hoping to build their

following count on various platforms, competition and overwhelming amounts of viewpoints

59

Lovejoy and Saxton, “Information, Community, and Action,” 338.

23

have become the norm. At the same time, higher levels of exposure may mean higher levels of

support and action from the public. Scholars contributing to this field have fallen along both

sides of the aisle when it comes to the benefits and drawbacks of social media for framing power.

Van Laer and Van Aelst (2010) provide a conception of the internet as a benefactor for

civil society, in its creation of new tools to support their activism.

60

In essence, the Internet brings

more information to a wider range of people more quickly and efficiently. A byproduct of these

online capabilities is that much of the research on framing has shifted to the Internet, as available

data and trends have become widely accessible.

61

A simple Google search will reveal that the

vast majority of environmental groups nowadays have some form of social media presence. Even

well-established ENGOs such as the Environmental Defense Fund, created over fifty years ago,

have a strong social media presence on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and LinkedIn.

62

From the

largest organizations with millions of dollars in resources to the smallest grassroots

organizations, social media has pervaded the scene of framing and information dispersal.

At a broad level, the goal of most ENGOs is to mobilize public action by seeking media

attention, and the Internet has served to simplify this task.

63

Hestres (2015) utilizes the term

‘internet-mediated advocacy methods’ to describe this new kind of outreach.

64

What is unique

about this form of advocacy is it does not rely upon the tactics of legacy environmental groups

that have the benefits of resources and centralized staff. The Internet and social media have

created a much more level playing field for NGOs of all sizes and capabilities to disperse their

frames of interpretation and understanding.

65

A consequence of this lowered participation barrier

65

Ibid.

64

Hestres, “Climate Change Advocacy Online,” 196.

63

Luxon, “Mobilizing Environmental Sentiment Through the Media," 639.

62

Environmental Defense Fund, “Home.”

61

Güran and Özarslan, “Framing Theory in the Age of Social Media,” 449.

60

Van Laer and Van Aelst, “Internet and Social Movement Action Repertoires,” 1147.

24

is that numerous frames compete with one another for public acceptance. Cacciatore et al. (2016)

argue that this new openness to framing on a broad scale may destroy framing as a theoretical

framework as the term begins to lose its explanatory power and meld with other frameworks

such as priming, agenda setting, and persuasion.

66

What they suggest is a move toward more

specific categorizations of framing, meaning the word framing cannot exist on its own as an

explanatory theory, but requires further clarification of what type of framing is in use.

67

To

maintain the efficacy of framing as a theoretical framework, I agree that it is necessary to be as

specific as possible when it comes to defining types of framing, which has motivated me to

utilize the concept of emotional framing rather than the broader conceptualization of framing

theory.

The abundance of frames as a result of internet-mediated advocacy methods means

environmental groups vary their communication techniques to suit their audience’s

characteristics.

68

What Merry calls ‘message tailoring’ is especially important surrounding

climate change, as the public possesses varying degrees of knowledge about the issue, so ENGOs

must be conscious of the frames they use and their accessibility to wide audiences.

69

For many

environmental organizations, this may entail a process of reframing, where content creators on

social media decide which news to share above others, taking stock of current socio-cultural

leanings on the issue and framing strategically to resonate with the greatest possible audience.

70

Social media allows ENGOs to be in near-constant contact with public audiences, meaning they

can shift their tactics depending on how their messages are being received.

70

Güran and Özarslan, “Framing Theory in the Age of Social Media,” 448.

69

Ibid., 65.

68

Merry, “Environmental Groups' Communication Strategies in Multiple Media," 49-50.

67

Ibid., 20.

66

Cacciatore et al., “The End of Framing as We Know it,” 9.

25

This constant contact may have negative impacts on the ability of an audience to accept a

frame that is offered to them. The overwhelming amount of information flowing across the

Internet at any given moment may make it challenging for a person to choose what message they

will support and whether or not they will take action. As a result, there exists a certain level of

tension between different frames that seek dominance over others.

71

Competing frames may

confuse Internet users and lead to them disengaging entirely from the process of granting support

to an environmental group. Other drawbacks introduced by Van Laer and Van Aelst (2010) refer

to the digital divide that points out inequalities of access to the Internet, meaning large groups of

people are entirely left out of the process of internet-mediated advocacy.

72

An inability to create

strong activist networks as a result of a lack of established trust between various parties on the

Internet means social media tends to create weak ties among activists.

73

The ease with which

people can participate in online activism such as signing digital petitions or ‘liking’ progressive

posts may also detract from public participation in offline activism which tends to be more

effective.

74

Despite these potential drawbacks, the Internet appears to have leveled the playing

field for the participation of diverse NGOs with varying degrees of resources.

What the literature suggests is that the Internet and social media have become important

tools for non-profits and other NGOs to utilize in garnering public support. The establishment of

internet-mediated advocacy as a legitimate method for NGOs to utilize confirms that studies

such as mine that analyze these online activities can uncover framing at work in much more

accessible ways. Thus, the analysis of emotional framing via Facebook posts, online newsletters,

74

Ibid., 1162.

73

Ibid., 1163.

72

Van Laer and Van Aelst, “Internet and Social Movement Action Repertoires,” 1161.

71

Luxon, “Mobilizing Environmental Sentiment Through the Media," 640.

26

press releases, and other forms of publicly available media provides a sharper focus on how

polarization has infiltrated the operations of environmental NGOs.

27

Why the US and Australia?

I have chosen NGOs in the United States and Australia as case studies for four primary

reasons. These factors include parallels in increasingly catastrophic wildfire seasons over the

past decade and a half, similar histories with climate politics, and democratic regime types that

are open to NGOs. Also of interest is the potential difference between NGOs operating in

parliamentary or presidential systems. Although I do not anticipate major distinctions across the

countries, there is certainly a chance that regime type will impact how NGOs frame specific

issues. The time span of 2007-2022 was decided upon due to the political upheavals within this

period as well as the severity of wildfire seasons. As the analysis of climate politics in both

countries will illustrate, political polarization begins increasing during this time, along with an

increase in concern and political attention for climate change. I briefly outline each of the factors

compelling me to examine the US and Australia in greater detail below.

Democracy and Openness

The United States and Australia are both liberal democracies, governed by principles of

equality, freedom, and free and fair elections. In both countries, the general public has a certain

degree of voting power and may elect their representatives. Australia and the United States are

home to robust civil societies, where hundreds of NGOs, think tanks, and educational institutions

provide expertise and advocacy. It is a widely held belief that NGOs and civil society as a whole

have more freedom to operate within democracies as opposed to other forms of government.

75

Both the United States and Australia remain open to civil society activism and general political

participation. Choosing two democratic nations to examine ensures my results are not clouded by

one group of NGOs’ inability to operate as freely as the other group.

75

Spires, “Contingent Symbiosis and Civil Society,” 3.

28

Similar Climate Politics History

As will become clearer in my analysis of climate politics since the late 90s in both

countries, the US and Australia have experienced notably similar progress and decline in the

realm of climate politics. Because I will be delving into the specific events in two chapters, I

avoid getting too bogged down in the details here. However, in many instances across the

development of climate change legislation in both countries, there are multiple transitions from

administrations pushing for pro-climate legislation, often followed or preceded by backsliding or

inaction. Of all the possible pairings of countries in terms of their responses to climate change, I

believe the similarities between Australian and American climate policy development share the

closest material for comparison.

Parallel Worsening Fires

The US and Australia as countries with vast territories and diverse ecosystems have

always been prone to wildfire. Each summer, comprising the months of June-September in the

US and December-February in Australia, both naturally occurring fires from forces like lightning

strikes and manmade causes such as campfires, still-lit cigarettes, and even gender reveal parties

have burnt through forests. For centuries, wildfire seasons have been expected and even

appreciated for their ability to clear underbrush and reduce fuel loads within forests. However,

the past decade and a half has indicated that these once-typical fires are becoming more severe

and harder to manage. In the past, fire safety teams would often let the fires burn their way to a

close, but now, as human settlement reaches ever closer to nature, fires are becoming more

destructive. It is not just human encroachment on wild lands that has resulted in more severe

fires, but the rising of average temperatures across the world, accompanied by dryer, hotter

weather that allows fires to easily spark and spread. Therefore, each year climate change

29

worsens, wildfires are given greater opportunities to consume trees and infrastructure in

Australia and the United States. I recognize that many other countries suffer through severe

wildfire seasons, but the scale in terms of acres of destruction and climatic conditions is closely

paralleled between Australia and the US.

Different Political Systems

Given the comparative nature of this research, it is important to establish the fundamental

differences and consistencies between the political systems in Australia and the United States.

One group of scholars such as Carey argues that there are a variety of differences between the

parliamentary and presidential systems of governance. Carey holds that these differences,

including more power being concentrated in the hands of the executive in a presidential system

and less influential veto points for actors in parliamentary systems, act to differentiate the

institutional strength of the two systems.

76

Due to the separation of powers across the branches of

presidential governments, adversarial relationships between political parties and factions tend to

flourish, while the constitutional structure keeps major disagreements from being resolved.

77

These factors along with the ever-changing nature of elected politicians and executives are in

contrast to most parliamentary systems, where voters do not have the same level of power in

determining who will represent them.

78

Parliamentary systems indeed allow voters to elect the

assembly, but it is the assembly, not the people, that elects the executive. Following this line of

thinking, institutions in presidential systems are categorized as weaker and more susceptible to

instability as a result of the diffusion of power that is viewed as more extreme than the

consolidated power inherent in a parliamentary system.

79

79

Ibid., 92.

78

Ibid., 117.

77

Ibid., 94.

76

Carey, “Presidential Versus Parliamentary Government,” 116.

30

I agree with the notion that presidential systems and their institutions may be more

volatile than parliamentary systems, which may have an impact on American NGOs' willingness

to utilize negative rhetoric as opposed to Australian NGOs. However, the shorter terms of

Australian PMs may also have an influence on NGO tactics, given more common political

transitions that could be seen to inflame tensions more often than a four-year term as President

may. Therefore, I argue that both presidential and parliamentary systems appear to have

characteristics that may compel NGOs to take radical stances, meaning the data on both

countries will not be widely dissimilar.

31

Methodology

Data Collection

I conduct a sentiment analysis provided by an online software called NVivo to survey the

activities of eight NGOs. These organizations are American Forests, National Forest Foundation,

Australian Forests and Climate Alliance, Greening Australia, Greenpeace USA, Greenpeace

Australia Pacific, American Loggers, and Forest and Wood Products Australia. The first six

NGOs listed belong to an advocacy-centered organizational form, whereas the final two embody

the professional, otherwise known as BINGO type of professional organization. To maintain

symmetry in my analysis, there are four NGOs from each country, three advocacy organizations,

and one BINGO for each of Australia and the United States.

Given the examination of these organizations over time and within the context of forest

fire seasons, I begin my analysis in the year 2007, concluding in 2022. This time frame is

constrained by the available data from the eight organizations, with some more recently formed

NGOs providing data beginning in later years. Drawing on Hadden’s (2015) argument that

environmentalism’s increasing media coverage has opened the field for more NGOs to become a

part of the discussion, I believe this is why many NGOs examined here were not established until

a few years after 2007. I provide the data on forest fire seasons in the US and Australia

throughout this period, identifying the number of acres burned during each season. This data is

grouped into two distinct tables for each country (see Appendix A).

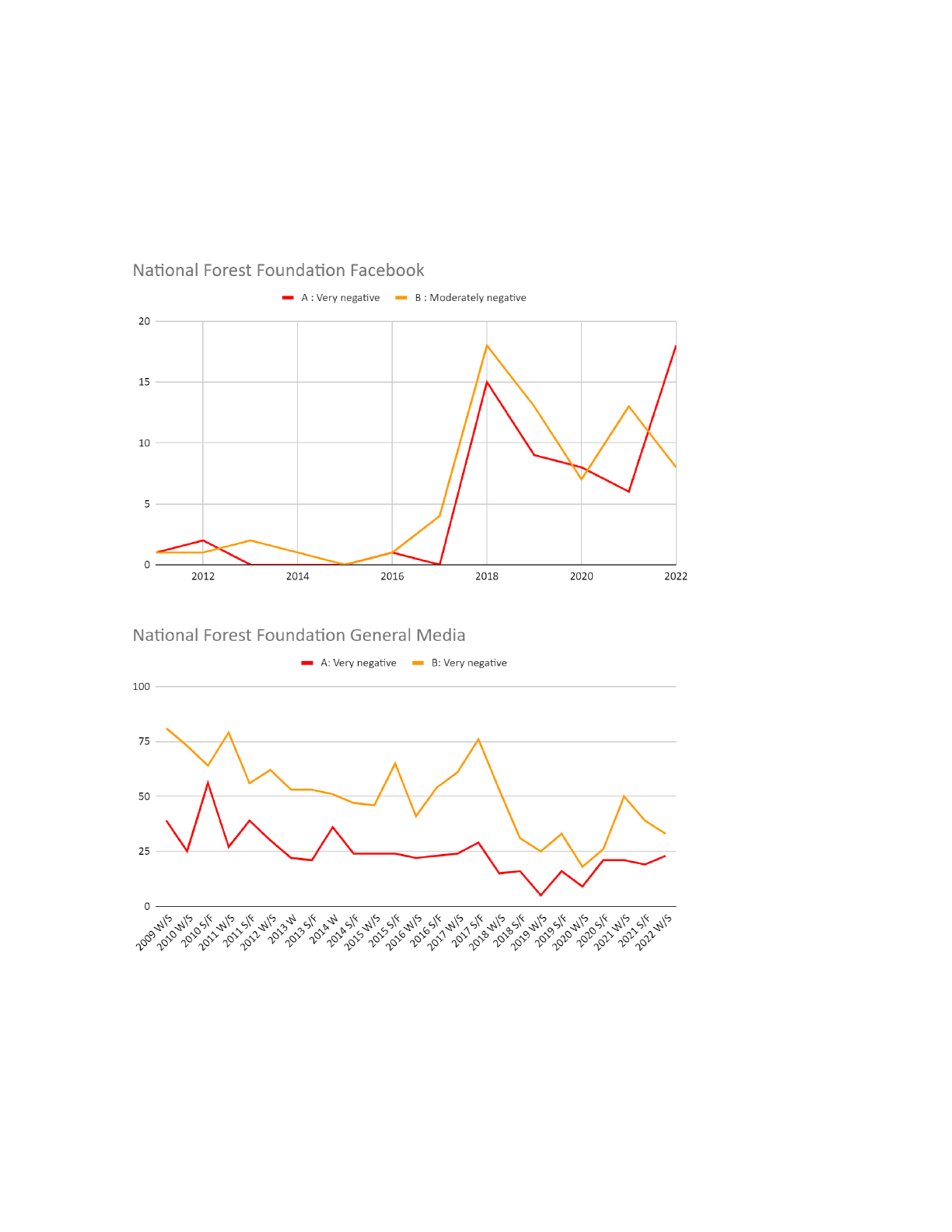

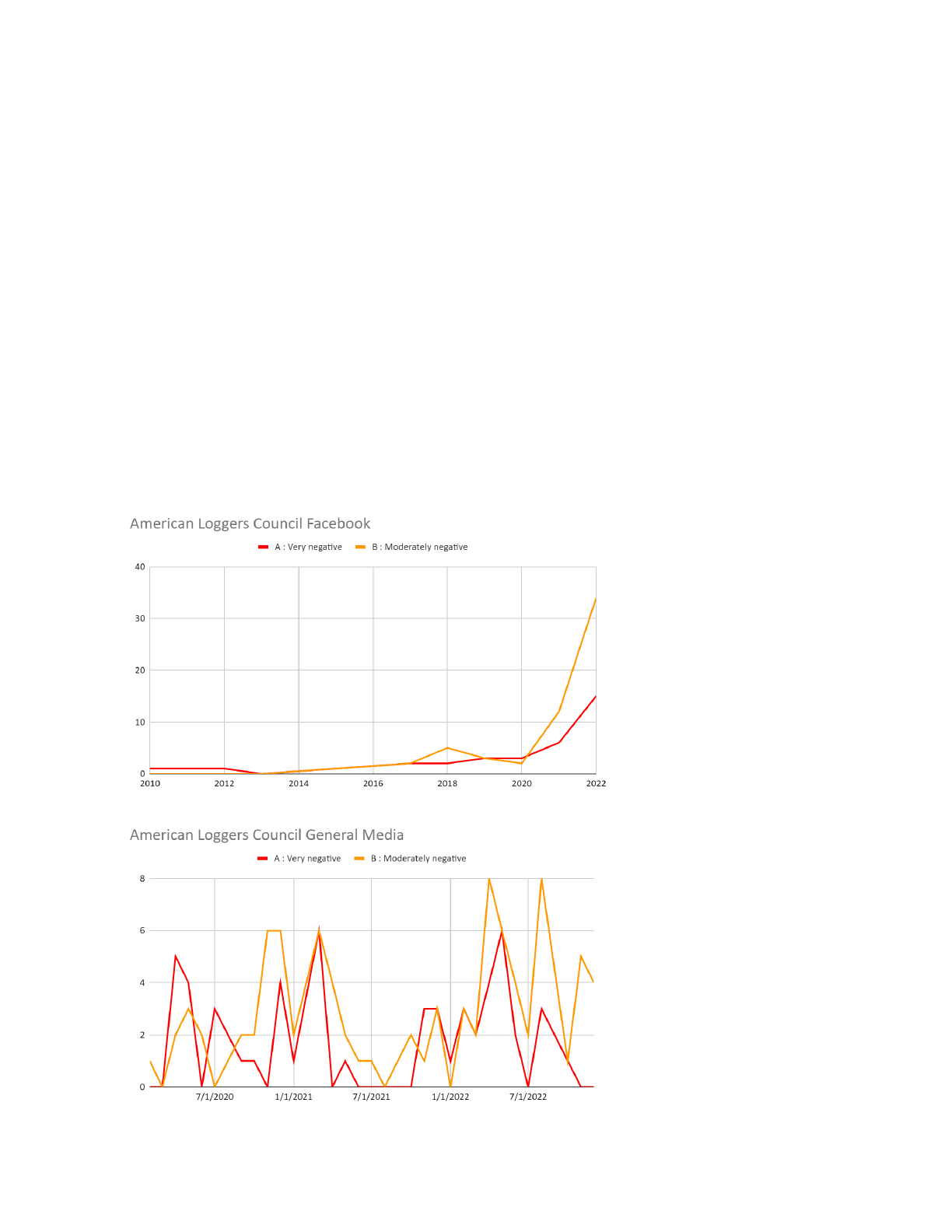

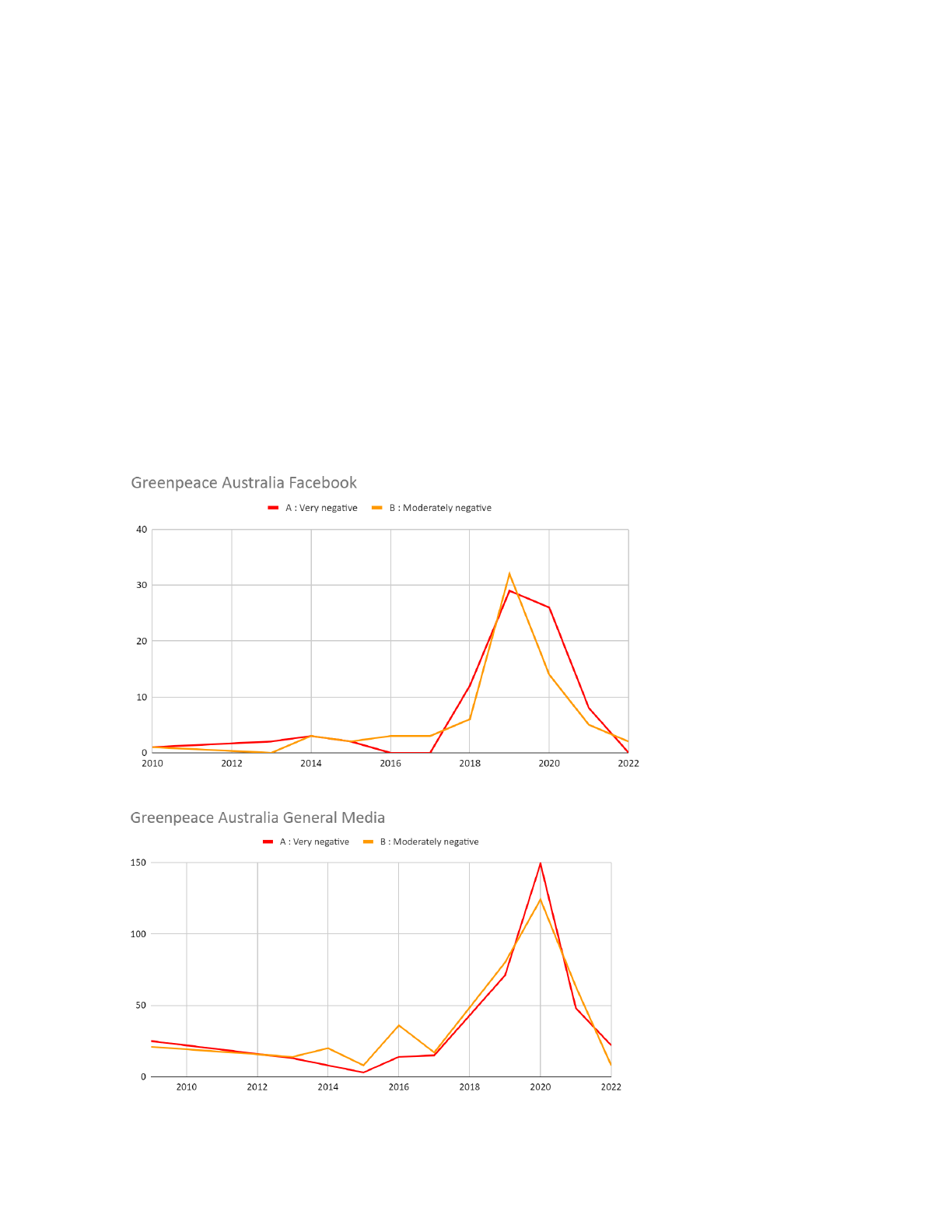

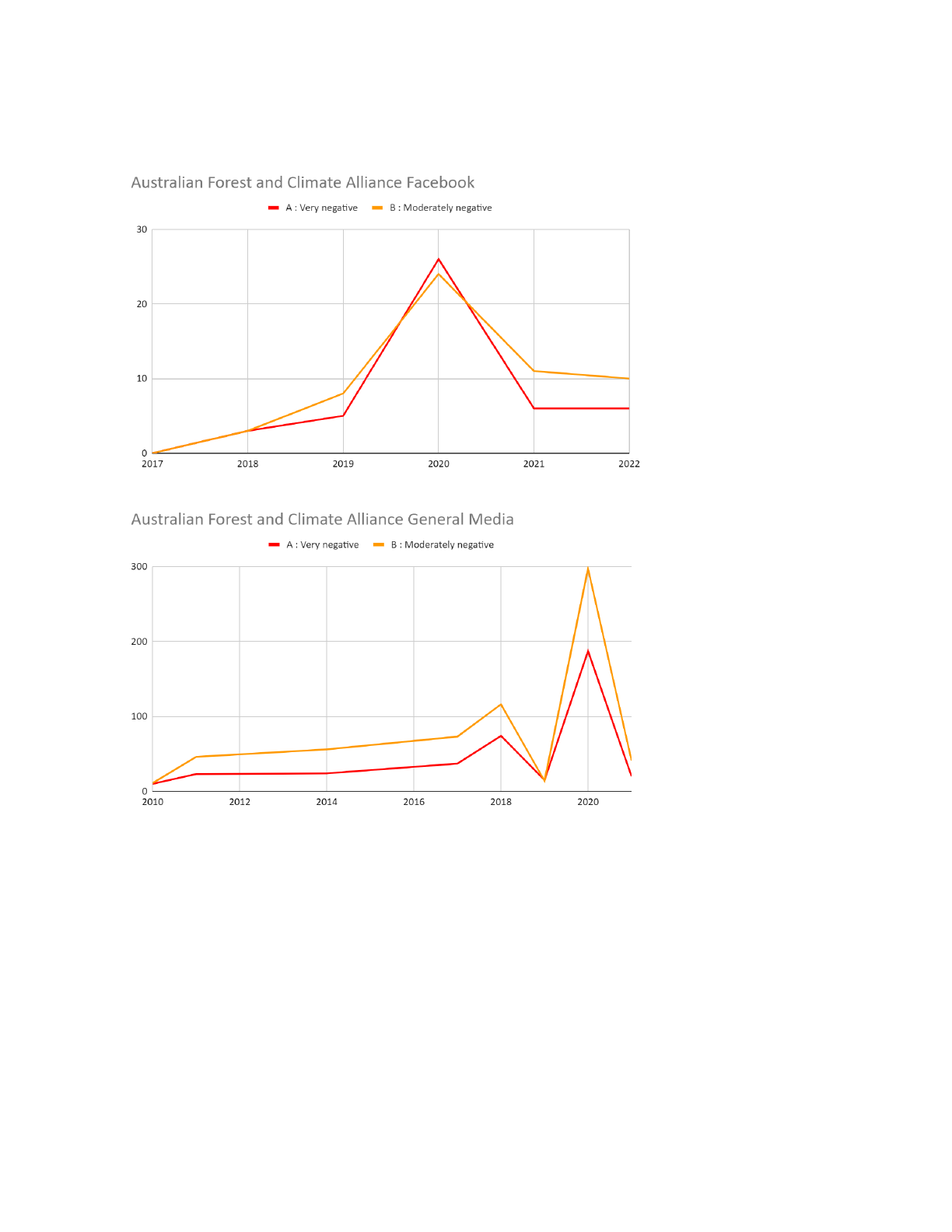

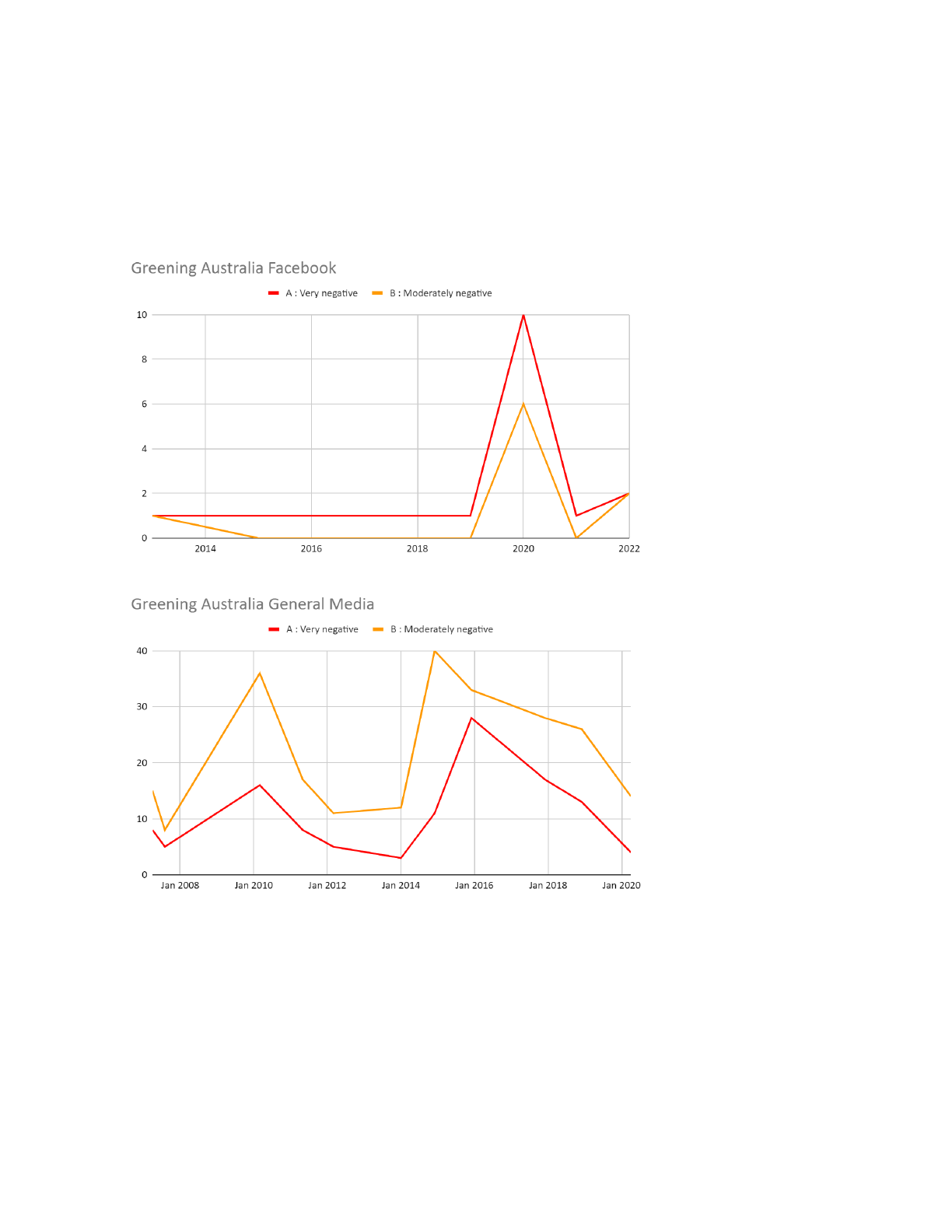

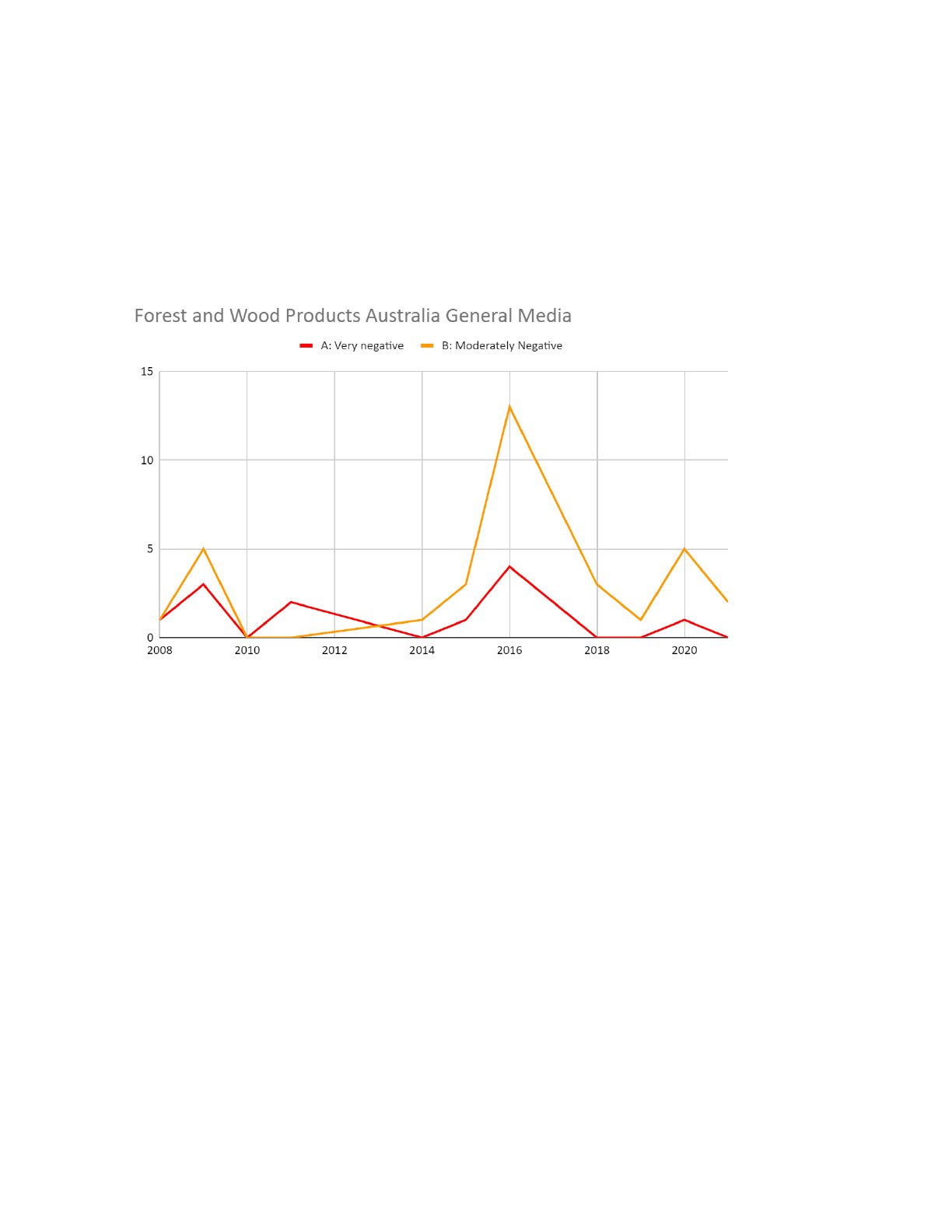

One part of the analysis of the identified eight NGOs comes from a sentiment analysis of

the publicly-available data released by these organizations. For each group, I analyze press

releases, newsletters, magazine or journal articles, and Facebook posts as they are available. It

should be noted that the early years of my analysis, essentially the years spanning 2008-2012

32

have fewer publicly-available documents for analysis, so the inclusion of social media posts is

anticipated to supplement some of these shortcomings. To conduct my analysis, I employ a

textual analysis program called NVivo. This program uses automatic coding to conduct word

search queries and identify positive and negative sentiments in a given text. I input the data

collected for each NGO, including press releases, Facebook posts, newsletters, and any other

articles concerning wildfires into the software. It is important to note that because this program

involves autocoding, a comprehensive list of negative and positive sentiment terms is not

provided by NVivo. However, each word coded is highlighted within the coding process,

allowing me to see which terms are identified with which sentiments. By looking at a sample of

the coding process and cross-referencing it with the Harvard IV-4 Sentiment Dictionary, I

confirmed that the autocoding process reliably identifies instances of positive, negative, or

neutral sentiment within sentences.

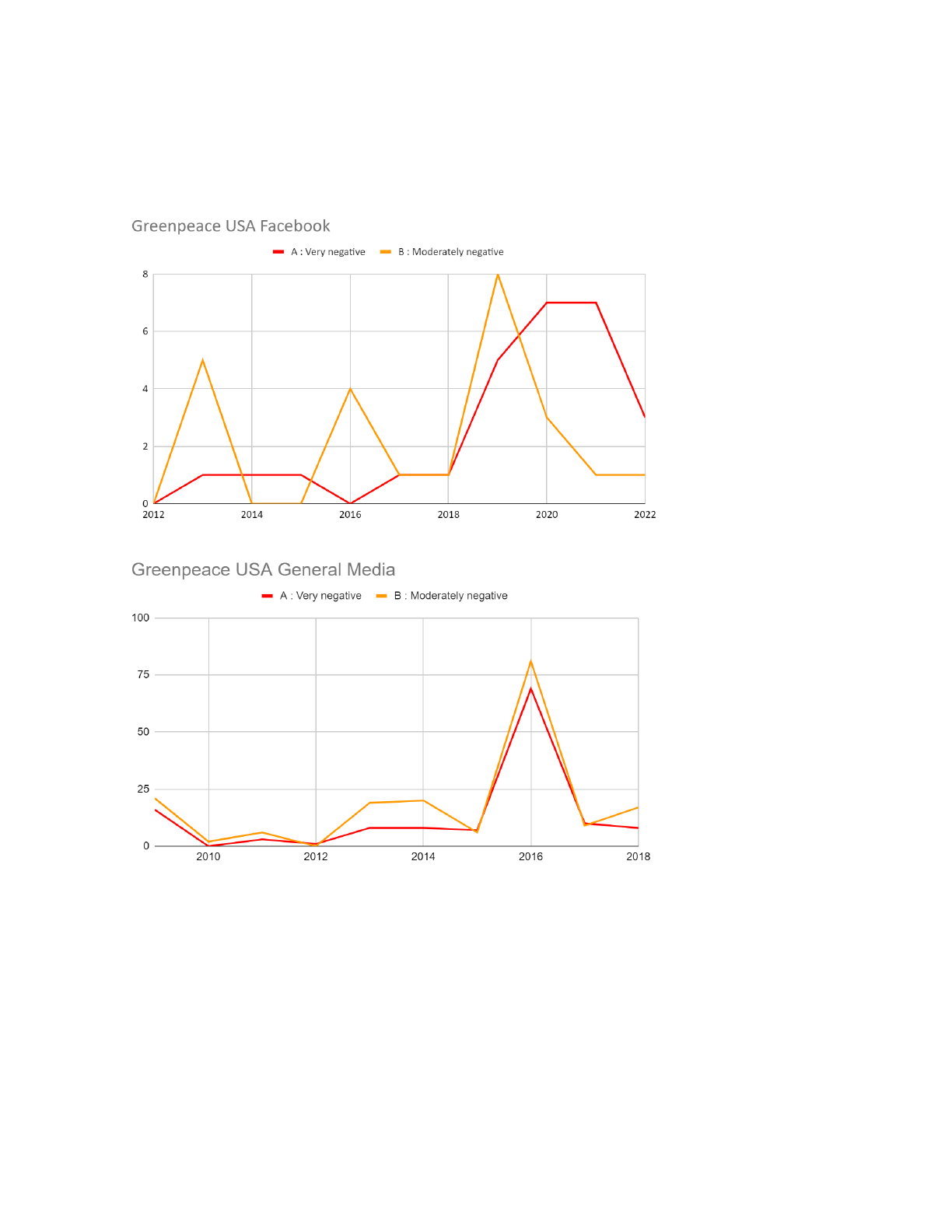

For the sentiment analysis, NVivo utilizes five classifications for each of the words it

identifies within a given text. These classifications are Very Negative, Moderately Negative,

Neutral, Moderately Positive, and Very Positive. To decide which words go with which

categories, NVivo assigns a score to each term that decides where on the scale the word belongs.

The words that fall anywhere outside of ‘neutral’ territory are then coded to determine how far

negative or positive they fall.

NVivo Explanation

A few examples of this process are provided below:

- The word safe is categorized by NVivo as moderately positive, so it is then coded as a

moderately positive term. This example is the simplest kind of analysis, where one kind

of sentiment is evoked in a sentence.

33

- The words receptive and significantly are both scored as positive, but receptive is coded

as moderately positive, whereas significantly is coded as very positive. Here, NVivo

sticks with the ‘most extreme’ term in the sentence, so this sentence would be coded as

very positive.

- The terms valuable and dangerous when used in the same sentence provide an example

of two opposing sentiments. Valuable is scored as moderately positive, while dangerous

is scored as moderately negative. In situations like this, NVivo codes the sentence as both

moderately positive and moderately negative.

- As mentioned previously, only words carrying negative or positive sentiment are coded,

so sentences holding only neutral terms are noted and included in the autocoding process.

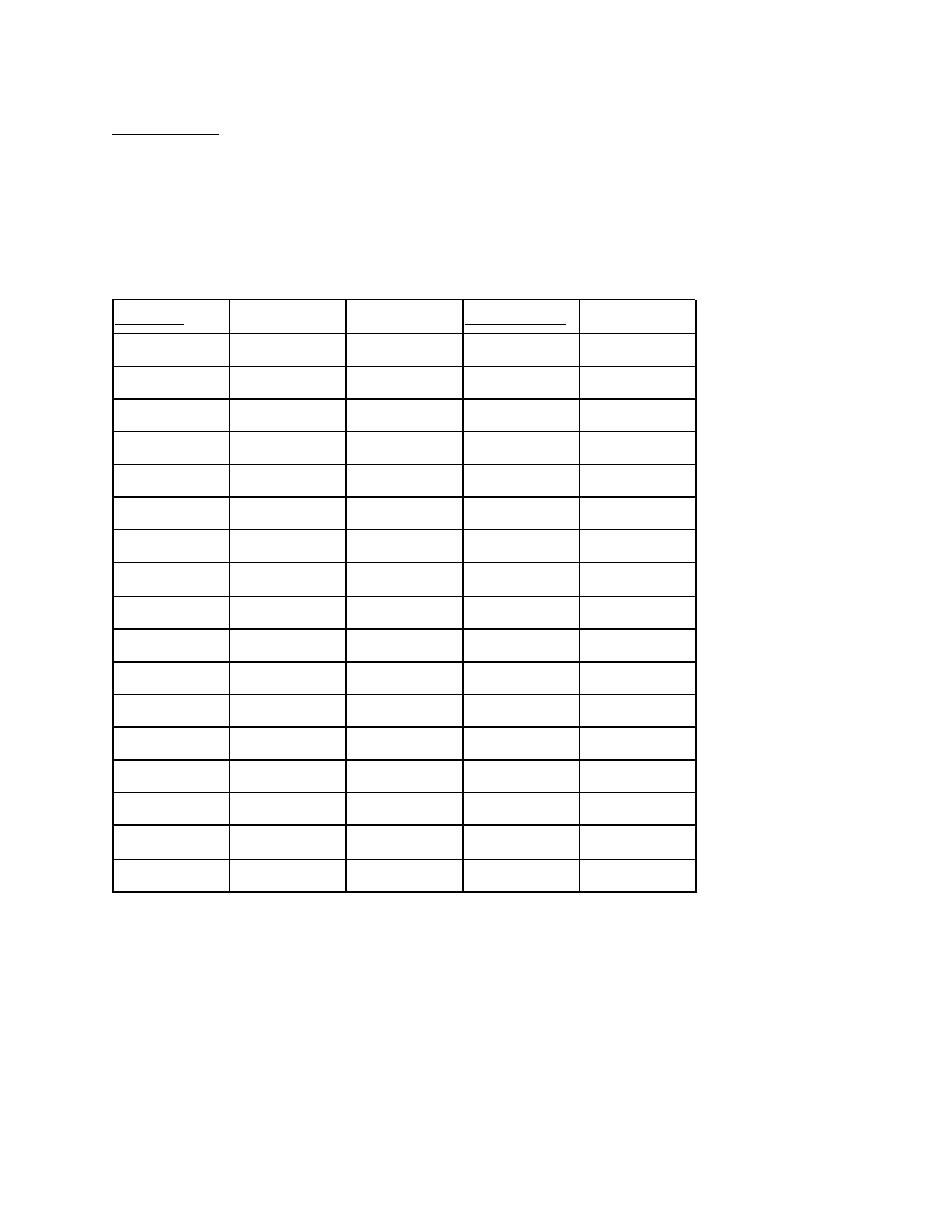

I used the autocoding process to identify sentiment within the sentences of the NGO

media imported into NVivo. The numbers within the tables indicate how many sentences

contained sentiment at each node, or each of the four coded classifications: very positive,

moderately positive, very negative, and moderately negative. From this data, I can extrapolate

trends in sentiment evocation across time and various types of media, from social media posts to

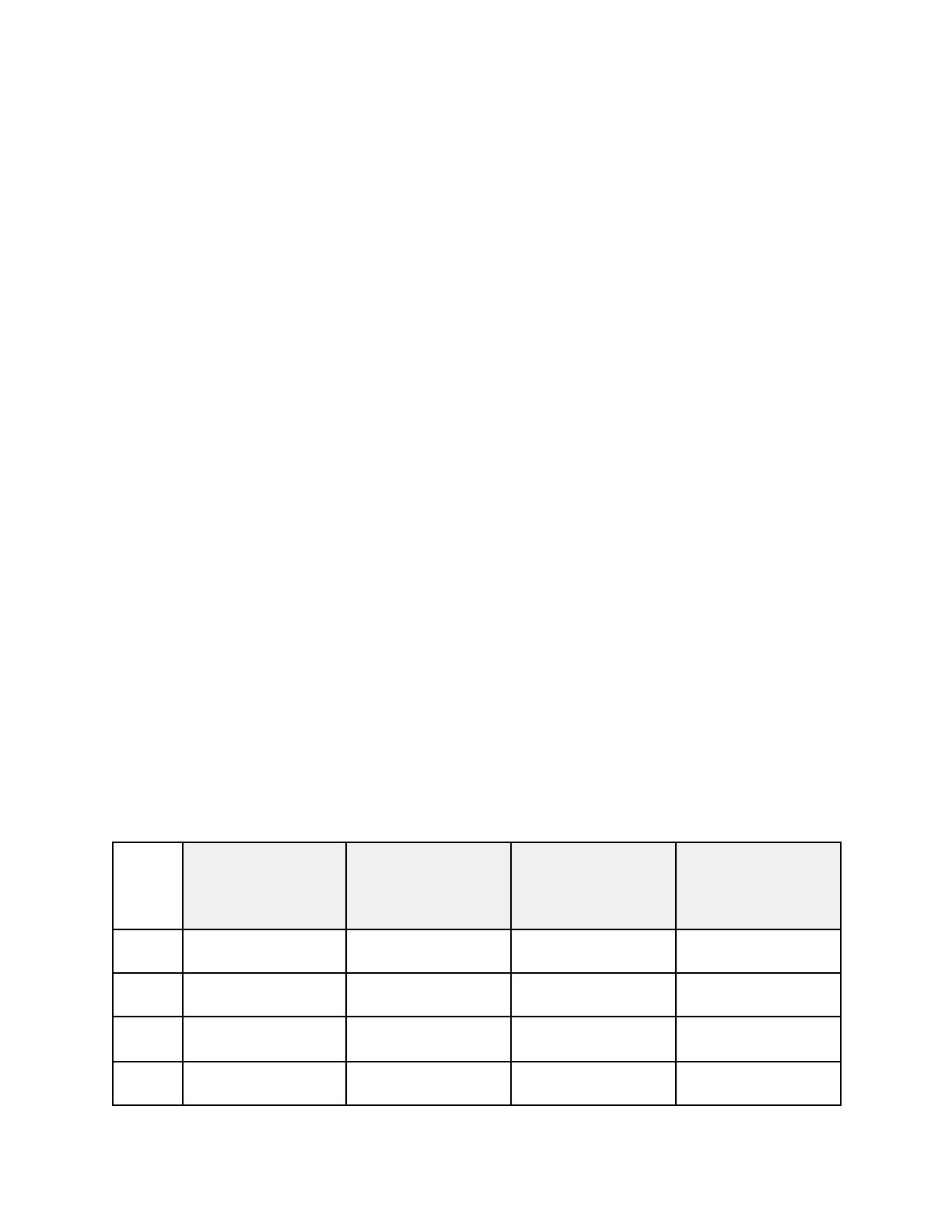

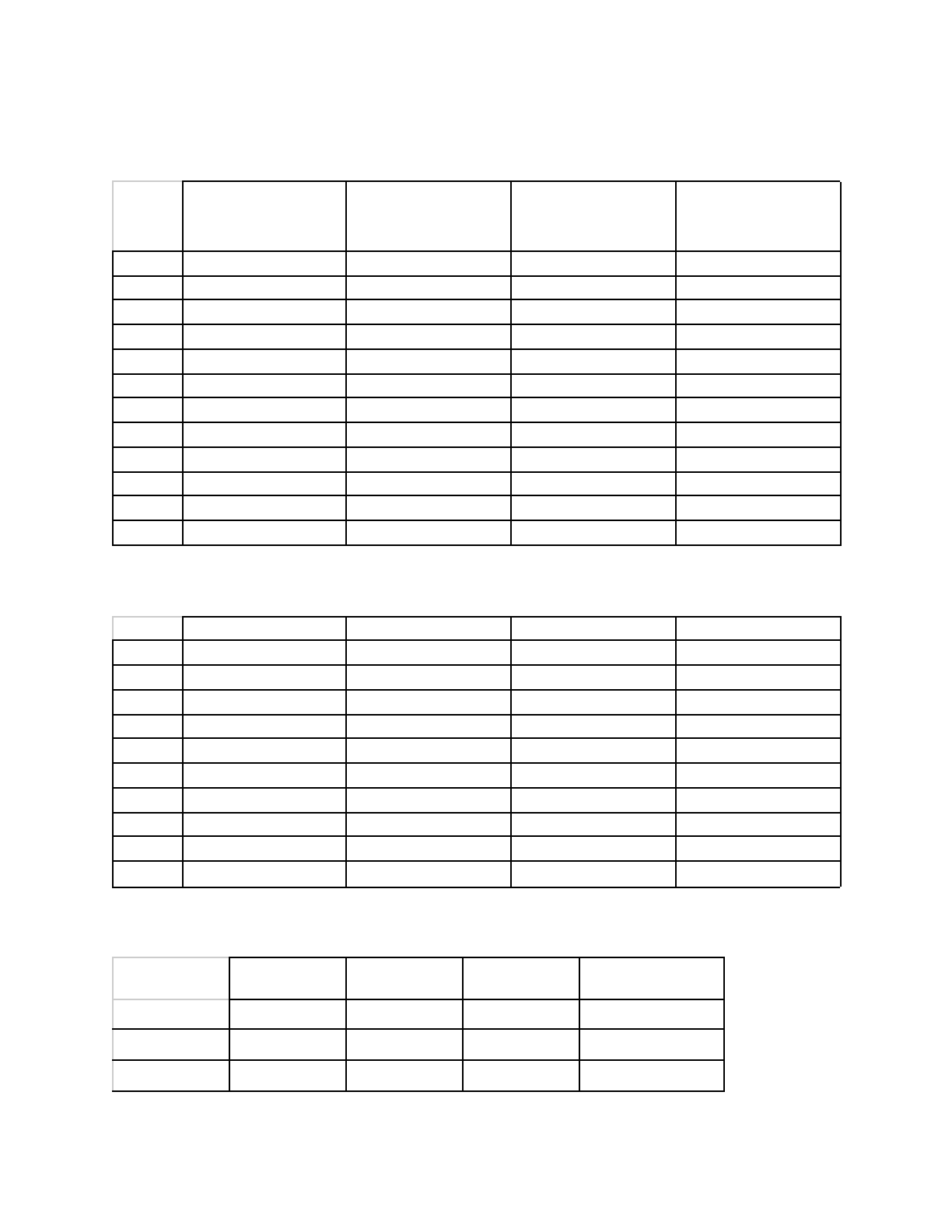

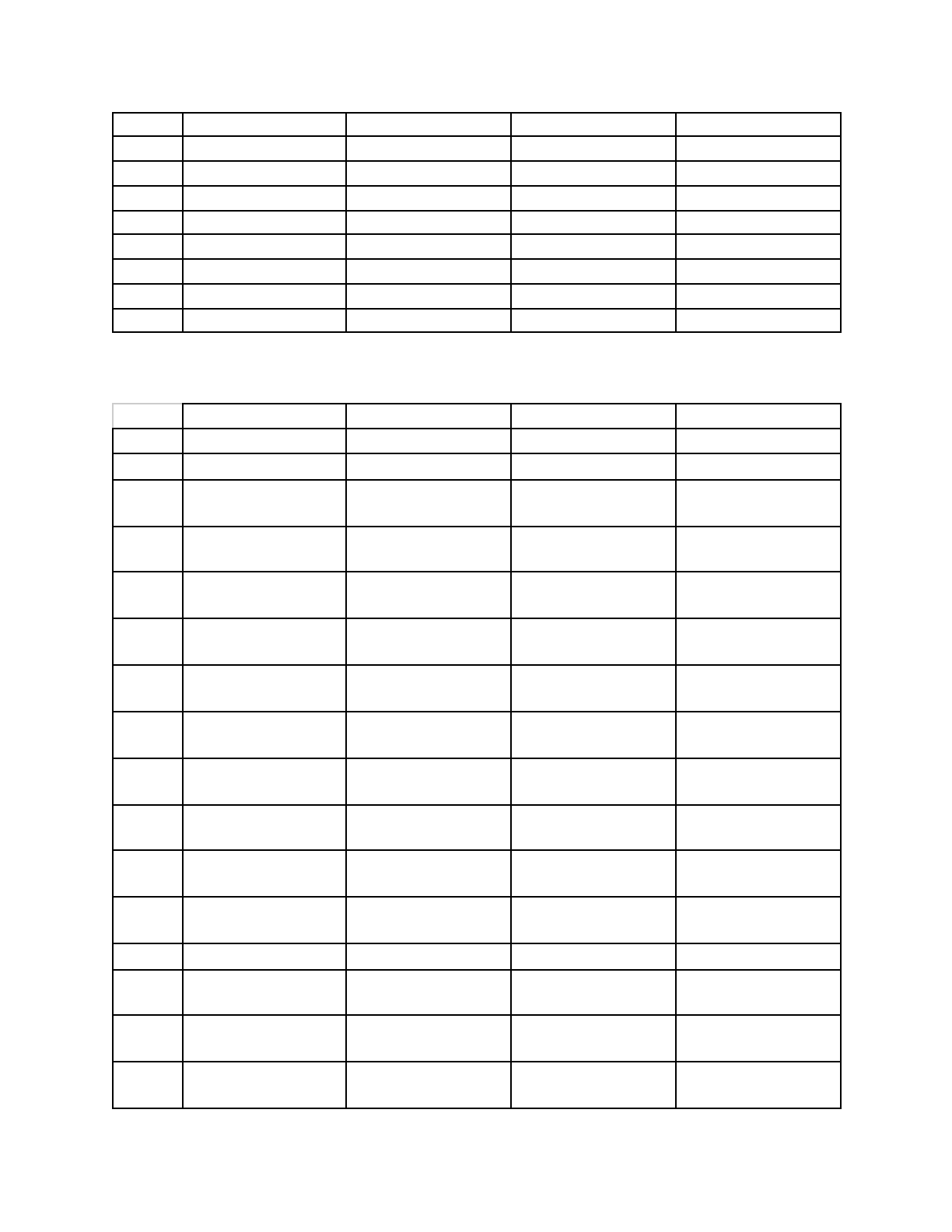

biannual newsletters. An example of the data tables used in this analysis is shown below for

clarification (see Appendix B for all raw data):

NFF

A : Very negative

B : Moderately

negative

C : Moderately

positive

D : Very positive

2011

0

1

1

1

2012

1

4

15

3

2013

4

7

12

3

2014

2

9

26

4

34

2015

10

26

50

14

2016

2

10

37

6

2017

3

4

19

4

2018

8

10

20

2

2019

8

18

55

9

2020

7

28

57

8

2021

10

13

40

5

2022

1

4

13

3

Here, the year 2013 indicates that NVivo detected four sentences in the available media where

very negative emotion was evoked. This is a smaller number compared to the 12 or 7 sentences

in the same year that were coded as moderately negative and positive, so the lighter blue color is

utilized to make this distinction clearer.

Because emotional framing involves the attribution of positive or negative meaning,

negative sentiment is associated with a more radical approach, while positive and neutral

sentiment is affiliated with reformist and professional NGOs. My decision to use negative and

positive sentiments comes from the idea that radical ideologies tend to express dissatisfaction

with the current order, often calling for change or the dismantling of existing institutions.

Positive and neutral emotions are associated with reformist ideologies because they often call for

continued operation within existing institutions and would be far less likely to evoke the same

level of negativity or pessimism as a radical group. Within my analysis, I focus primarily on the

negative sentiment data because negativity can be more telling than positivity. I hold that where

positivity is often associated with positive outcomes, it can also be used when conditions are

35

remaining consistent and are thus deemed to be positive. Negative sentiment is more useful to

examine here because it is often evoked in response to specific undesirable events or outcomes,

variables that parallel those with which I am interested. Fires and political transitions are not

protected events, but moments in time that evoke the kind of ‘reflex’ emotions described by

Jasper (2018). Thus, focusing more on the negative sentiment data may provide a better

explanation for how events are immediately responded to.

Qualitative Analysis

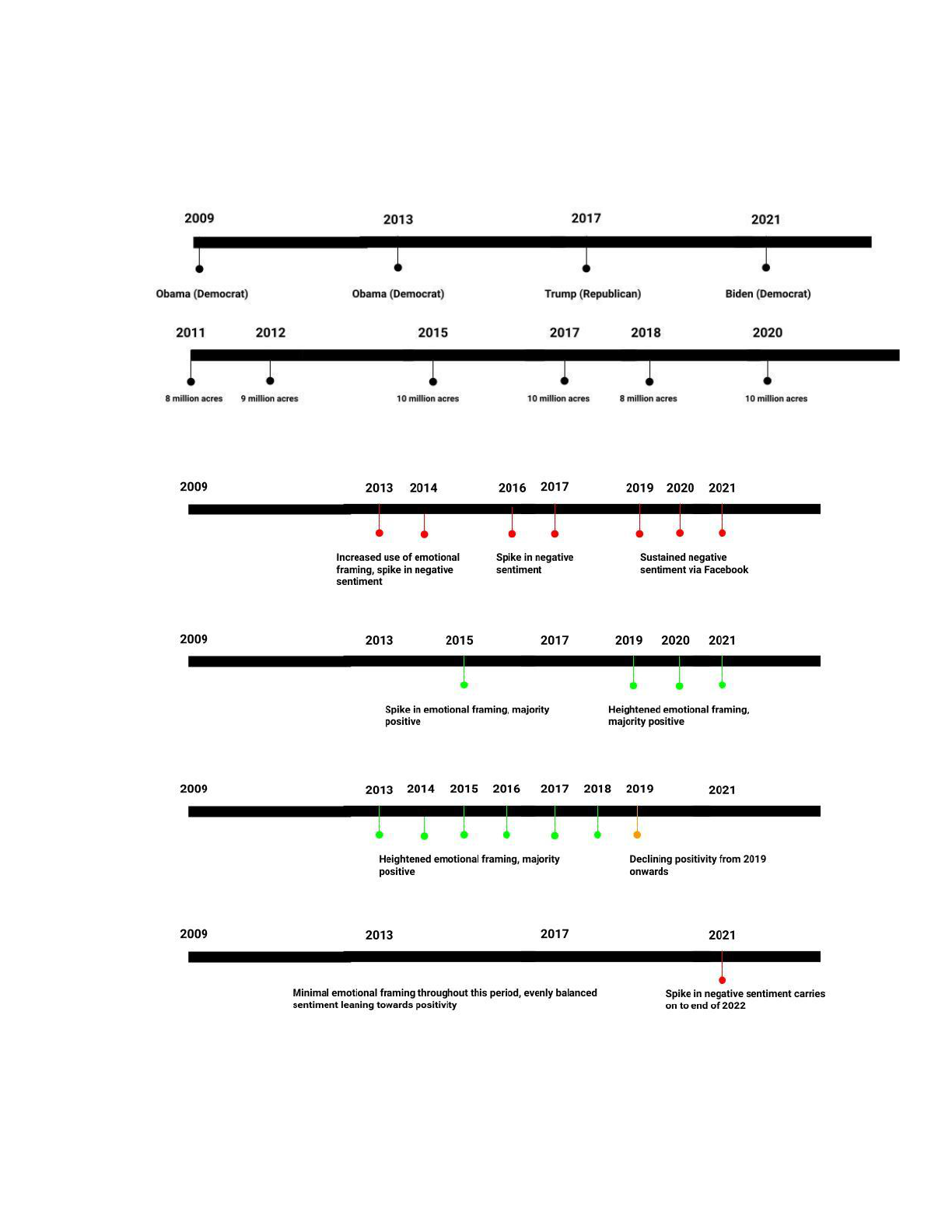

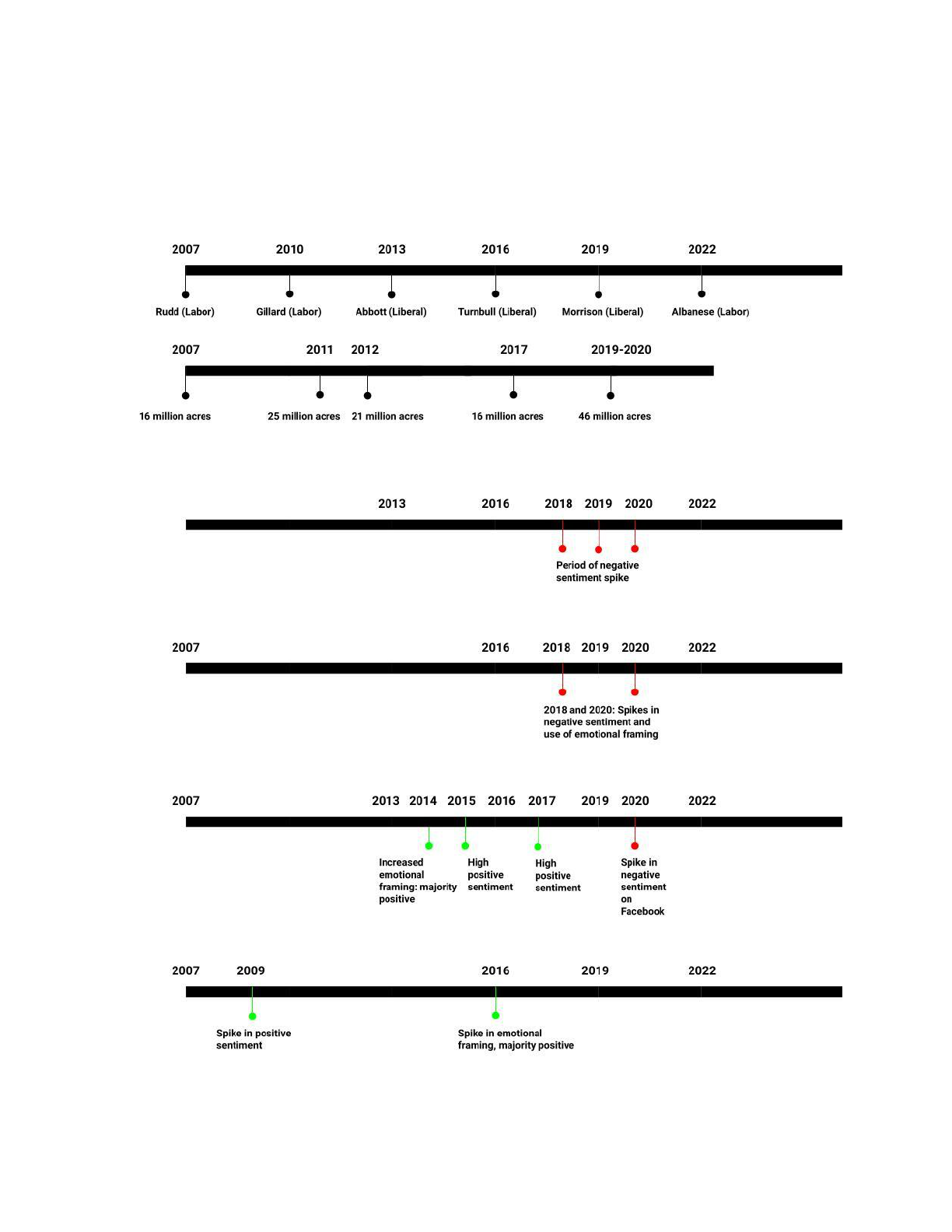

For my qualitative analysis, I analyze the history of climate politics in the United States

and Australia from the late 1990s to 2022. I focus on large political developments in terms of

environmental legislation and cooperation with international agreements, paired with moments

of political transition. The analysis paints a picture of polarization over the past fifteen years in

both countries, and I take an impressionistic account of political events to identify key years in

which political transitions occur in the form of parliamentary and presidential elections. Below

the political timelines are fire season timelines. In the United States, fires that burned 8 million

or more acres since 2007 are included, while larger acreage burned in Australia means fires that

burned 15 million or more acres are included on the timeline. I chose these values because they

are less frequently found in the data and they represent severe fire events rather than average fire

seasons. Climate-induced disaster is one of the two variables I examine to determine what

influences NGO polarization, so larger spikes in acreage burned are intended to embody these

catastrophes. These events are organized as four distinct timelines from which I compare the data

and assess the relationship between the sentiment analysis figures and years of heightened

political polarization. Below these timelines illustrating the two independent variables, each

36

organization receives a timeline to assist the reader in visualizing the data and its relationship to

the independent variables. I include these timelines at the end of the analysis chapter.

Using the data provided by NVivo, what I know about the missions of the eight NGOs,

and key moments of polarization, I can deduce how their emotional framing of wildfires has

changed over time. I hypothesize that NGO media for the eight identified organizations will

become more negative for radical groups, positive or neutral for the professional organizations,

and a split between the reformist organizations becoming more negatively oriented and thus

radical, or maintaining their rhetoric as-is. I believe these changes can be attributed to growing

political polarization surrounding proper governmental responses to climate change. In addition,

I argue that experiencing the consequences of climate change in the form of increasingly severe

wildfires in the United States and Australia has also played a role in pushing some organizations

to the more radical end of the spectrum. Before I delve into the sentiment analysis and climate

politics of both countries, I provide a brief summary of each of the eight organizations,

classifying them as radical, reformist, or professional organizations.

37

NGO Classifications

American Forests

80

American Forests has been acting to conserve and protect forests across the United States

since its creation in 1875. The organization has gone through various names and leaders, but its

mission has remained to preserve forests and their landscapes in urban and rural spaces through

innovation, broad partnerships, and movement building. The nonprofit organization views forests

as a vital resource for slowing down climate change, filtering water, and providing habitats for a

wide array of species. Throughout their nearly 150 years of operation, American Forests has

lobbied the US government and policymakers to get conservation and forestry bills passed or

added to agendas. They have published numerous scientific studies and made climate data

available to the public. A recent development they had a hand in shaping was the improvement

of funding for the United States Forest Service (USFS) budget in a bid to improve forest

conservation and protection from threats like wildfires. The organization emphasizes its

acceptance of diverse viewpoints and experiences, while focusing on the most pressing issues of

the day, which in these times has come to be embodied by climate change and social equity.

A few of the many corporate partnerships forged by American Forests include American

Express, Eddie Bauer, Microsoft, Timberland, and Bank of America. The organization receives

funding from many of these corporations as well as donations from public and private sources.

American Forests is also involved in seven coalitions with climate and forestry themes: 1t.org

US Chapter, United States Climate Alliance, Forest-Climate Working Group, U.S.

Nature4Climate, Smart Surfaces Coalition, Trees for Community Recovery, and Sustainable

Urban Forests Coalition.

80

American Forests, “Homepage.”

38

I classify this NGO as a reformist organization after an analysis of its policies and

mission. American Forests focuses primarily on lobbying in US politics to gain traction for their

ideas. They have worked towards helping pass bipartisan legislation and government programs

that champion forest conservation and protection under the USFS and played a part in adding 8

billion dollars in the 2021 Infrastructure Bill to support forests. While American Forests engages

in scientific research, coalition building, and public information sharing via social media and its

website, the organization is operating within existing American political institutions. This can be

referred to as a reformist approach, where the NGO seeks influence within legislative avenues

and attempts to amend or introduce new policies for politicians to enact. American Forests has a

mission to conserve US forests and advance notions of social equity, but this goal has been

pursued through a reformist stance that does not challenge existing political structures in the

country.

National Forest Foundation

81

The National Forest Foundation (NFF) was chartered by the US Congress in 1992 with

the primary goal of uniting people together to restore and conserve national forests and

grasslands. The NFF believes in the power of community to protect and restore public lands and

keep them for generations to come. This organization has five core values that guide its

practices: unite, restore, engage, sustain, and add value. Uniting means overcoming the conflict

that has infiltrated the political sphere and small communities as well as improving people’s

relationships with the US Forest Service. Restoration is evoked in many of the community-based

projects the NFF has organized across the country, from the grasslands to wildfire-impacted

forests in California. These initiatives often involve trail maintenance, tree planting, fire dam

building, and occasionally tree thinning to reduce fuel levels in forests. Engagement refers once

81

National Forest Foundation, “Who We Are.”

39

again to the importance of community engagement with public lands and the idea that if people

can form a bond with nature, they may be more inclined to protect and take care of it.

The National Forest Foundation combined regional programs, grants, and collaboration

on projects with blogging and a National Forests Magazine that issues biannual publications on

the organization’s projects and ongoing issues within forests. The group has a few kinds of

corporate partnerships, from ‘custom’ partnerships, to tree planting partnerships, and ski

conservation funding partnerships. They also have regional programs in most regions of the

country, spanning the Northern Rockies, California, the Southwest, Pacific Northwest, and

Alaska. Given the community-oriented nature of its mission, NFF offers a variety of ways to get

involved in conservation such as volunteer tree planting, trail maintenance, youth engagement

activities, and donations.

Like American Forests, I also classify NFF as a reformist organization, although their

approach focuses less on political mobilization and more on grassroots engagement. All the

same, the National Forest Foundation’s background as a congressionally chartered organization

places it in an interesting position as an NGO that may have less freedom to operate outside of

established institutions in the US. Their focus on the public may be the NFF’s way of exiting the

political sphere entirely and focusing on community-based outreach and engagement. Due to the

lack of emphasis on alternative order building or turning away from cooperation with US

political institutions, the NFF is regarded as a reformist organization in this study.

Australian Forests and Climate Alliance

82

The Australian Forests and Climate Alliance (AFCA) is a younger organization than the

two American NGOs discussed previously, with the first evidence of its operation coming around

2010. The AFCA focuses on ending the logging of native forests, mitigating climate change, and

82

Australian Forest and Climate Alliance, “All About AFCA.”

40

protecting biodiversity as well as the natural ecosystems of Australia. To achieve this mission,

the AFCA aims to educate the public and government about the threats native logging causes to

wildlife and the climate as well as offer them ways of assisting the organization in their hope to

preserve Australian forests. Alongside educational outreach, the AFCA campaigns for the

immediate end of native logging, restoration of forests and ecosystems, the reduction of

emissions from fossil fuels and industrial practices, ending the Regional Forests Agreements that

encourage logging, and convincing the Australian government to take a leadership role in climate

and forest protection. They campaign against practices of land conversion to plantations,

deforestation and landscape degradation, carbon credits on wood products, and forms of biomass

or biofuel coming from native forests. Guiding this work are three main values that include

ecologically sustainable development, integrity and ethics, as well as intergenerational equity

when it comes to the environment.

The AFCA has publications for each of the six states and two territories of the country,

including information on bushfire risk, threats caused by logging, and admonitions of the

government for allowing coal and lumber industries to detract from thoughtful climate action.

The organization seeks to provide a national network for forest and climate campaigners as well

as create alliances with other like-minded organizations. Along with publishing up-to-date

scientific information and organizing campaigns and public events, the AFCA submits

information and recommendations to Australian policymakers and government agencies. They

also utilize social media and email to communicate campaign actions to the public.

The AFCA is a reformist organization, but it lies in a slightly more radical position than

the two NGOs described above. I say this because the AFCA demands a radical change in the

logging practices that the Australian government has allowed to go widely unchecked for many

41