Experiential Gifts Foster Stronger Social

Relationships than Material Gifts

CINDY CHAN

CASSIE MOGILNER

Interpersonal relationships are essential to well-being, and gifts are often given to

cultivate these relationships. To inform gift givers of what to give and to gain in-

sight into the connecting function of gifts, this research investigates what type of

gift is better at strengthening relationships according to gift recipients—material

gifts (objects for recipients to keep) or experiential gifts (events for recipients to

live through). Experiments examining actual gift exchanges in real-life relation-

ships reveal that experiential gifts produce greater improvements in relationship

strength than material gifts, regardless of whether the gift giver and recipient con-

sume the gift together. The relationship improvements that recipients derive from

experiential gifts stem from the intensity of emotion that is evoked when they con-

sume the gifts, rather than when the gifts are received. Giving experiential gifts is

thus identified as a highly effective form of prosocial spending.

Keywords: gift giving, experiential purchases, material purchases, emotion,

relationships

E

ach year is replete with occasions to give gifts. From

birthdays to religious holidays, Valentine’s Day to

Father’s Day, these occasions are fraught with the ques-

tion: What to give?! Should you give your dad a designer

tie or golf lessons? Would giving your spouse a watch or

concert tickets spark greater affection? Would a set of

wine glasses or a wine tasting better cement your friend-

ship with your favorite colleague? And, ultimately, why

would one of these gifts strengthen the relationship more

than the other?

With the average American household spending almost

2% of its annual income on gifts (US Bureau of Labor

Statistics 2013), and with gift-giving occasions serving as

great opportunities (and liabilities) for relationship build-

ing, these are surprisingly consequential decisions. Indeed,

interpersonal relationships are essential to well-being

(Baumeister and Leary 1995; Clark and Lemay 2010;

Mogilner 2010; Reis, Collins, and Berscheid 2000), and

gifts serve as a means to foster these important connections

(Algoe, Haidt, and Gable 2008; Dunn et al. 2008b; Ruth,

Otnes, and Brunel 1999; Sherry 1983). To help inform gift

givers of what to give and to gain insight into the interper-

sonal benefits of gifts, this research adopts the gift recipi-

ents’ perspective and experimentally investigates which

type of gift is more effective at strengthening their relation-

ship with their gift giver—material gifts (objects for the re-

cipients to keep) or experiential gifts (events for the

recipients to live through). And why?

MATERIAL VERSUS EXPERIENTIAL GIFTS

Borrowing Van Boven and Gilovich’s (2003) definition

of material and experiential purchases, we define material

marketing at the UTSC Department of Management and the Rotman

School of Management, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON M1C 1A4.

Cassie Mogilner (cassie.holmes@anderson.ucla.edu) is an associate

professor of marketing at the UCLA Anderson School of Management,

University of California, Los Angeles, CA 90024. This article is based on

a portion of the first author’s dissertation. The authors greatly appreciate

the support and facilities provided by the Wharton Behavioral Lab and the

financial support provided by Wharton’s Dean’s Research Fund, as well

as the research assistance provided by Christina Gizzo and Karishma

Antia. The authors are also grateful to have enjoyed the connecting power

of experiential gifts in their own relationships, particularly with their hus-

bands, Tom and Rob.

Ann McGill and Darren Dahl served as editors for this article. Darren

Dahl also served as associate editor.

Advance Access publication December 11, 2016

V

C

The Author 2016. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Journal of Consumer Research, Inc.

DOI: 10.1093/jcr/ucw067

1

Journal of Consumer Research Advance Access published December 29, 2016

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

gifts as objects to be kept in the recipient’s possession

(e.g., jewelry or electronic gadgets) and experiential gifts

as an event that the recipient lives through (e.g., concert

tickets or a photography lesson).

The research comparing material and experiential pur-

chases to date has focused on the effects of making these

purchases for oneself, finding that buying an experience is

typically more personally beneficial than buying a material

good (Gilovich, Kumar, and Jampol 2015). Compared to

possessions, experiences lead to greater satisfaction (Carter

and Gilovich 2010), less regret (Rosenzweig and Gilovich

2012), and greater happiness (Van Boven and Gilovich

2003), especially when the outcome of the experience is

positive (Nicolao, Irwin, and Goodman 2009). The benefits

of acquiring an experience over a possession stem from the

fact that experiences are more likely to be shared with

others (Caprariello and Reis 2013), contribute more to

one’s sense of self (Carter and Gilovich 2012), are more

unique (Rosenzweig and Gilovich 2012), and are harder to

compare against alternatives (Carter and Gilovich 2010).

Although prior research offers guidance on whether to buy

experiences or material goods to improve one’s own well-

being, the question of what to buy to strengthen one’s rela-

tionships with others remains unanswered. Would giving

something to do or something to keep forge a stronger so-

cial bond?

It turns out that people are more inclined to give material

gifts. In a survey we conducted among 219 gift givers

(66% female; ages 18–74, M ¼ 34.68), 78% reported hav-

ing most recently given a gift that was material. This ten-

dency is consistent with the argument that giving a gift that

is durable will leave a lasting impression (Ariely 2011).

A pilot study we conducted around Father’s Day, how-

ever, hints that this tendency to give material gifts might

be misguided. Recipients of Father’s Day gifts (N ¼ 42;

ages 48–75; M ¼ 55.05) participated in a two-part survey:

one completed the week before Father’s Day and one the

week after. Both before and after Father’s Day, dads rated

the strength of their relationship with their child (1 ¼ feel

extremely distant and disconnected, 9 ¼ feel extremely

close and connected); any change would reflect the impact

of receiving the gift on the relationship. Dads also rated to

what extent the gift they received was material (1 ¼ not at

all, 7 ¼ completely) and experiential (1 ¼ not at all, 7 ¼

completely). A multiple regression analysis predicting

change in relationship strength showed that gifts that were

more experiential strengthened dads’ relationships with

their children (b ¼ 0.16, SE ¼ 0.07, t(39) ¼ 2.21, p ¼ .03,

d ¼ .71), whereas the material nature of the gift did not

(b ¼ –0.03, SE ¼ 0.07, t(39) ¼ –0.39, p ¼ .70, d ¼ .12). It

was not that experiential gifts were more likely to be given

in initially stronger relationships, since the material and ex-

periential gift ratings were unrelated to relationship

strength before Father’s Day (p’s

> .43). These results

were corroborated by a second pilot study conducted

following Mother’s Day among moms who had received a

gift from their child (N ¼ 99; ages 38–64, M ¼ 51.9; 11

unspecified). In this study, moms first reported the rela-

tional impact of their gift on a subjective change scale (1 ¼

felt more distant and less connected, 9 ¼ felt closer and

more connected), and then rated the experiential versus

material nature of the gift on a bipolar scale (1 ¼ purely

material, 9 ¼ purely experiential; Van Boven and Gilovich

2003). Like dads, moms who received gifts that were more

experiential reported having a stronger relationship with

their child as a result of receiving the gift (b ¼ 0.21,

SE ¼ 0.07, t(97) ¼ 2.96, p ¼ .004, d ¼ .60). Although these

results are correlational and based on small samples, they

provide preliminary evidence to suggest that experiential

gifts are more effective than material gifts at strengthening

relationships between gift recipients and their gift givers.

RELATIONSHIPS AND THE ROLE OF

EMOTION

Recent experimental research on gift giving has made

great strides in understanding how recipients evaluate dif-

ferent types of gifts (Flynn and Adams 2009; Gino and

Flynn 2011; Waldfogel 1993; Zhang and Epley 2012);

however, less is known about how giver-recipient relation-

ships are best cultivated through different types of gifts

(Aknin and Human 2015). That is, much of the work on

gift giving has focused on how much recipients appreciate,

value, or like particular gifts, rather than the impact of

these gifts on the relationship. For instance, prior gift-

giving experiments have shown that despite gift givers’ be-

liefs that expensive gifts will be more appreciated, recipi-

ents appreciate expensive and inexpensive gifts alike

(Flynn and Adams 2009) and put a lower monetary value

on a gift than its actual cost (Waldfogel 1993). And al-

though gift givers think that unsolicited gifts convey

greater thoughtfulness and serve as a stronger signal of re-

lationship value, recipients prefer receiving cash or gifts

that they had explicitly requested (Gino and Flynn 2011;

Ward and Broniarczyk 2015). Additionally, when buying

for multiple recipients, gift givers select overly

individuated gifts in an attempt to be thoughtful and under-

standing of each unique recipient, but recipients unfortu-

nately tend not to recognize the thought put into gifts they

like (Zhang and Epley 2012), and gift givers’ efforts to

convey thoughtfulness can even result in selecting gifts

that recipients like less (Steffel and LeBoeuf 2014). Even

the most well-intentioned gifts can go awry, as givers also

tend to mispredict how much recipients will appreciate so-

cially responsible gifts, such as charitable donations given

on their behalf (Cavanaugh, Gino, and Fitzsimons 2015).

In light of these findings that gift givers are poor predictors

of what recipients will like, it is fortunate that recipients

2 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

can regift their gifts without offending the giver

(Adams, Flynn, and Norton 2012)!

Our research adopts a different approach to assess a

gift’s value. Namely, we measure the gift’s influence on re-

lationship strength from the recipient’s perspective, rather

than how much the recipient likes the gift. We looked to

the literature on close relationships to define relationship

strength. Although there is substantial variation among re-

lationship types (i.e., friendships, romantic partners, and

family members) with respect to what constitutes a strong

relationship, there are principle indicators of relationship

strength that span across personal relationships: the extent

to which partners feel close to each other (Algoe et al.

2008; Aron, Aron, and Smollan 1992; Dibble, Levine, and

Park 2012; Kok et al. 2013; Kok and Fredrickson 2010)

and connected to each other (Algoe et al. 2008; Dibble

et al. 2012; Hutcherson, Seppala, and Gross 2008), as well

as how satisfied they are with their relationship (Rusbult,

Martz, and Agnew 1998). Across our studies, we adopt

these indicators of relationship strength to measure how

much the gift changes the gift recipient’s perception of the

strength of his or her relationship with the gift giver from

before to after receiving the gift.

This perspective on the success of a gift is similar to that

taken in earlier qualitative research exploring how gift ex-

changes produce relationship change. A series of depth

interviews and surveys offer rich insights into how the con-

text, rituals, meaning, and emotions that surround a gift ex-

change can lead to different relational outcomes ranging

from relationship strengthening to rare cases of relationship

severing (Ruth et al. 1999; Ruth, Brunel, and Otnes 2004).

For instance, Ruth et al. (1999) observed that gift ex-

changes that involve highly personalized rituals can imbue

the gift with shared meaning and often lead to relationship

strengthening. More recently, experimental work has iden-

tified that gifts reflecting the giver can promote relation-

ship closeness (Aknin and Human 2015). The current work

builds on these insights by specifically testing the rela-

tional impact of particular types of gifts—those that are

material versus experiential. It further examines why ex-

periential and material gifts may differ in their ability to

forge a stronger relationship between gift recipients and

givers.

A distinction between experiential and material pur-

chases that has yet to be explored is how much emotion

they evoke during consumption. Prior research has focused

on the happiness elicited by experiences and material pos-

sessions (Van Boven and Gilovich 2003; Weidman and

Dunn 2016), but it is important to note that experiences

can stimulate a wide range of emotions (Bhattacharjee and

Mogilner 2014; Chan et al. 2014; Derbaix and Pham 1991;

Halvena and Holbrook 1986; Mogilner, Aaker, and

Kamvar 2012; Mogilner, Kamvar, and Aaker 2011;

Richins 1997). For instance, a safari adventure can elicit

feelings of awe and fear; a rock concert can fuel

excitement; a spa package can promote calmness; and an

opera may move one to tears. Given the diversity of dis-

crete emotions that consuming both experiences and mater-

ial goods can evoke, we focus our investigation on the

overall intensity of emotion felt during gift consumption,

and propose that the emotion felt by recipients when con-

suming an experiential gift will be more intense than when

consuming a material gift.

Research on relationships highlights emotion as a key

feature in relationship development and maintenance.

Emotions expressed and experienced within the context of

a relationship yield positive interpersonal effects (Clark

and Finkel 2004; Graham et al. 2008; Kubacka et al. 2011;

Laurenceau, Barrett, and Pietromonaco 1998; Slatcher and

Pennebaker 2006). For instance, disclosing one’s emotions

(vs. facts and information) makes people feel closer

(Laurenceau et al. 1998), positive emotions such as grati-

tude promote relationship maintenance behaviors

(Kubacka et al. 2011), and sharing negative emotions pro-

motes bonding (Graham et al. 2008). The relationship-

strengthening effect of emotions extends to situations in

which the emotions are not shared. Prior research has

shown that partners who write about their feelings within a

relationship are

more likely to stay together, even when

they don’t share what they wrote (Slatcher and Pennebaker

2006). More generally, greater emotional intensity has

been found to reduce perceived psychological distance

(Van Boven et al. 2010). Taking these findings together,

we assert that a gift that evokes greater emotion should be

more effective at strengthening relationships than a gift

that elicits a weaker emotional response, and thus experien-

tial gifts should foster stronger relationships than material

gifts. Furthermore, in the case of gifts, the mere fact that

the experience was given by the relationship partner psy-

chologically places the experience and the resulting emo-

tion within the context of the relationship. We therefore

propose that the experiential gift need not be shared be-

tween the gift giver and recipient for it to evoke greater

emotion and thereby improve the relationship.

Notably, the emotion evoked during the gift consump-

tion is distinct from the emotion evoked during the gift ex-

change. In his theoretical model delineating the impact of

gifts on relationships, Sherry (1983) highlights the import-

ance of focusing beyond the gift exchange to the consump-

tion of the gift, during which “the gift becomes the vehicle

by which the relationship of the donor and the recipient is

realigned” (165). Indeed, it is the emotion evoked while

the recipient is consuming the gift that we propose drives

the difference between experiential and material gifts on

relationship change. Whereas material and experiential

gifts are both likely to elicit emotion during a gift exchange

(e.g., a recipient could feel grateful whether given a wallet

or tickets to a comedy show), experiential gifts should

elicit more intense emotion during gift consumption as the

recipient lives through an event (e.g., a recipient may feel

CHAN AND MOGILNER 3

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

mild enjoyment while using a wallet, yet will likely feel in-

tensely amused and delighted while attending a comedy

show; Weidman and Dunn 2016). Additionally, although

Ruth et al. (1999, 2004) found that the valence of the emo-

tion during a gift exchange mattered more than the inten-

sity of emotion in predicting changes in the relationship

(perhaps because the gift giver is likely the source and tar-

get of the emotions evoked during a gift exchange), we

propose that it is the intensity of emotion evoked during

gift consumption that is responsible for the greater power

of experiential gifts to strengthen relationships.

Altogether, we predict that experiential gifts will im-

prove relationships more than material gifts, and that this is

driven by the greater emotional intensity evoked from con-

suming an experience rather than a possession. More for-

mally, we predict:

H1: From the recipient’s perspective, experiential gifts

strengthen relationships more than material gifts, irrespect-

ive of whether the gift is consumed with the gift giver.

H2: Consuming experiential gifts evokes more intense emo-

tion than consuming material gifts, and this greater emotion-

ality drives the effect of gift type on change in relationship

strength.

To test these hypotheses, we conducted experiments

involving actual gift exchanges in the context of existing

personal relationships. In study 1, gift givers were provided

with $15 to purchase either an experiential or material gift

to give to someone they know; in study 2, gift givers were

provided with a coffee mug, framed as experiential or not,

to give to someone they know; and in studies 3 and 4, par-

ticipants recalled experiential or material gifts they had

received from someone they know. Across the studies, the

experiential versus material nature of the gift was manipu-

lated to test how gift type influenced relationship strength

from the recipient’s perspective. To examine the underly-

ing role of emotion, study 3 measured and study 4 manipu-

lated the emotion evoked during gift consumption.

Together, these studies seek to contribute a better under-

standing of how the type of gift received can differentially

affect relationships. Across all four studies, sample size

was determined prior to each study with an effort to collect

as many participants as resources would permit in the allot-

ted timeframe, and all data exclusions and experimental

conditions are reported.

STUDY 1: A $15 GIFT

Study 1 used a two-part design measuring gift recipients’

reports of pre- and post-gift relationship strength to test our

primary hypothesis that experiential gifts strengthen rela-

tionships more than material gifts. Participants were re-

cruited with a friend, and in each participant pair, one was

randomly assigned to be the gift giver and the other to be

the gift recipient. Gift givers were provided with $15 and

instructed to purchase either an experiential gift or material

gift for their friend, which they were not to consume with

their friend. We specifically examined gifts that were not

consumed together to counter the explanation that experi-

ential gifts strengthen relationships solely because sharing

in the experience involves the giver and recipient spending

more time together (Bhattacharjee and Mogilner 2014;

Hershfield, Mogilner, and Barnea 2016; Mogilner and

Aaker 2009).

Method

Fifty-nine pairs of friends (118 participants; 57% fe-

male, 1% unspecified; ages 18–27; M ¼ 20.63) were re-

cruited through a university laboratory to participate in a

gift-giving study in exchange for $10. Upon arriving to the

laboratory, participants in each friend pair were randomly

assigned to the role of gift giver or recipient. Gift givers

were provided with an additional $15 along with instruc-

tions for how to spend this money.

Gift Type Manipulation. Gift givers were randomly as-

signed to purchase either an experiential or material gift

for their friend using definitions adapted from Van Boven

and Gilovich (2003). Gift givers in the experiential gift

condition were instructed, “Purchase a gift that is an ex-

perience ... Experiential gifts are experiences intended for

the recipient to do or live through.” Gift givers in the ma-

terial condition were instructed, “Purchase a gift that is a

material good ... Material gifts are tangible items for the

recipient to have and keep for him/herself.” All gift givers

were further instructed to give a gift that their friend would

consume without them and within the next week, to spend

as close to the $15 as possible on the gift, to give their

friend the gift within the next three days, and not to tell

their friend our instructions regarding the type of gift they

were to purchase. Gift givers left the laboratory with the

$15 and a printout of the gift instructions corresponding to

their assigned condition.

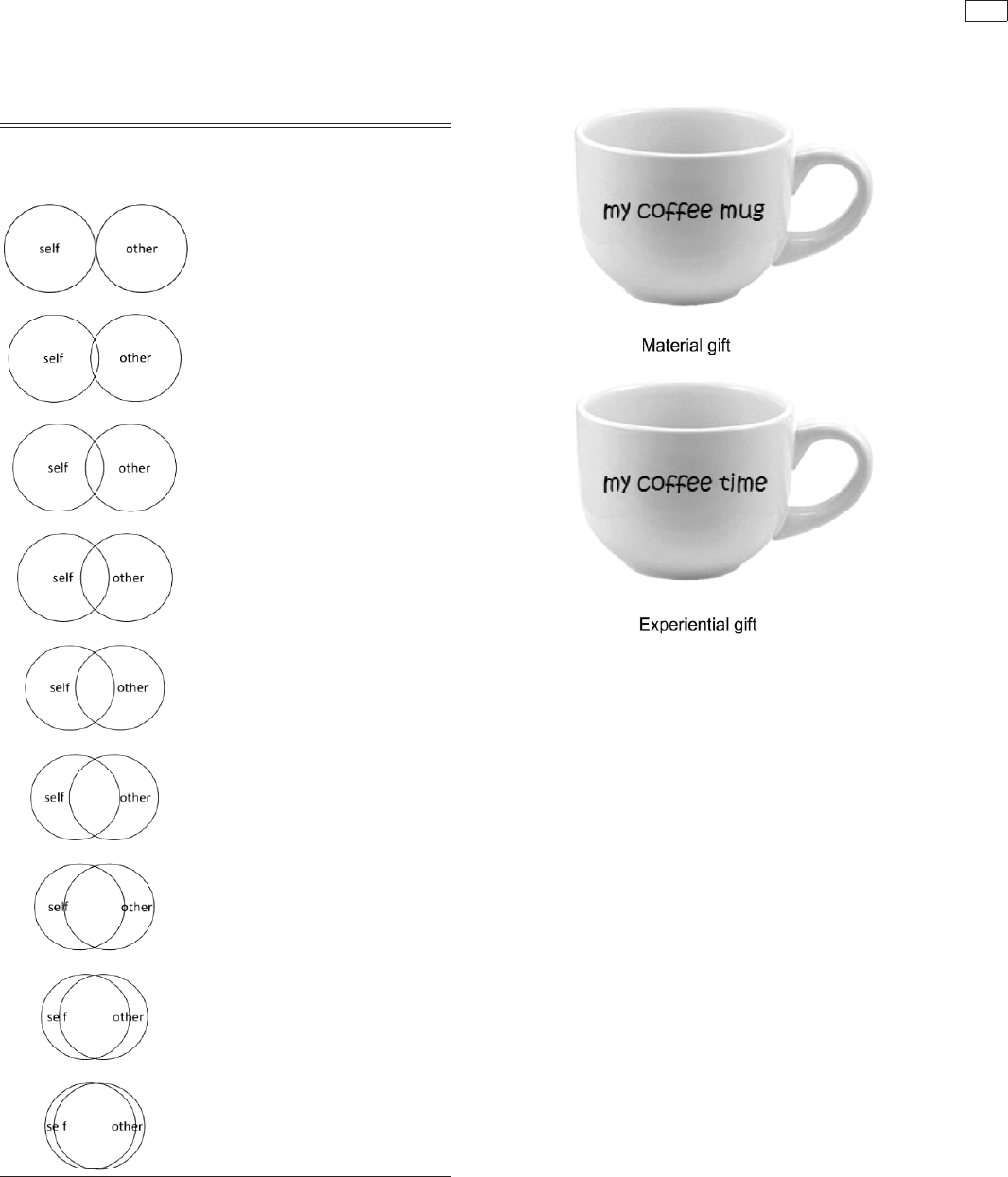

Change in Relationship Strength. To serve as the base-

line measure of relationship strength, gift recipients rated

their relationship with their friend on four items. The first

measure was the inclusion of other in self (IOS) scale

adapted from Aron et al. (1992). Prior research has effect-

ively visually portrayed and measured the sense of inter-

connection central to relationship strength through the

degree of overlap between two circles that represent each

partner’s self-concept (Aknin and Human 2015; Aron et al.

1991; Aron et al. 1992; Brown et al. 2009). We therefore

presented gift recipients with a set of nine circle pairs, in

which one of the circles was labeled “self” and the other

circle was labeled “other.” These pairs ranged in their de-

gree of overlap to represent the strength of the recipient’s

relationship with the gift giver. Gift recipients were asked

4 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

to choose the set of circles that best described their rela-

tionship with their gift giver (see appendix A). Next, re-

cipients were asked to rate their relationship with their

friend on three Likert scales measuring closeness (1 ¼ ex-

tremely distant, 9 ¼ extremely close), connection (1 ¼ ex-

tremely disconnected, 9 ¼ extremely connected), and

relationship strength (1 ¼ extremely weak, 9 ¼ extremely

strong). The average of these four items served as our

measure for pre-gift relationship strength (a ¼ .84).

Recipients were then told that they would be receiving a

gift from their friend within the next three days and a link

to an online follow-up survey from us in one week. They

were instructed to consume the gift they receive once

within the next week (before completing the follow-up sur-

vey), and to not consume the gift with their friend.

Recipients left the laboratory with a printout of their gift

instructions.

One week later, gift recipients received an email inviting

them to complete the online follow-up survey in exchange

for a $5 Amazon.com gift card. Forty-four gift recipients

responded (n

experiential

¼ 20, n

material

¼ 24; 57% female;

ages 18–25, M ¼ 20.5). After describing the gift they had

received, recipients reported the strength of their relation-

ship with their friend using the same four items as before.

These responses were averaged to serve as the post-gift re-

lationship strength measure (a ¼ .93). The post-gift rela-

tionship strength score was subtracted from the pre-gift

score for our measure of change in relationship strength.

One extreme outlier was excluded from further analyses

(greater than three standard deviations from the mean, stu-

dentized residual ¼ 4.72, Cook’s D ¼ 0.59).

Thoughtfulness and Liking. Because much of the ex-

perimental research on gift giving has focused on how

much recipients like the gift and how thoughtful they per-

ceive the gift to be (Flynn and Adams 2009; Gino and

Flynn 2011), we also measured thoughtfulness and liking

to assess whether material and experiential gifts differ on

these dimensions. Recipients rated the thoughtfulness of

their gift on four items adapted from Flynn and Adams

(2009) and Gino and Flynn (2011): the extent to which the

gift was thoughtful, considerate, took their needs into ac-

count, and took what they really wanted into account (1 ¼

not at all, 7 ¼ to a great extent; a ¼ .86). Recipients rated

how much they liked the gift on three items: how much

they liked the gift, how satisfied they were with the gift,

and cost aside, how desirable the gift would be to an aver-

age other person (third item adapted from Rosenzweig

and Gilovich 2012;1¼ not at all, 7 ¼ to a great extent;

a ¼ .85).

Manipulation Checks. As a check for whether gift giv-

ers had followed their instructions, we asked recipients to

1) rate to what extent the gift they received was material or

experiential (1 ¼ purely material, 5 ¼ equally material and

experiential, 9 ¼ purely experiential), 2) report whether

they had shared in the consumption of their gift with their

gift giver, and 3) estimate the price of the gift. Participants

also reported how much time they had spent with their gift

giver during the gift exchange and how much time they

had spent consuming the gift.

Results and Discussion

Gifts Received. Experiential gifts included a pass to a

barre class and movie tickets. Material gifts included a

shirt, a poster, and a wine aerator. The manipulation

check confirmed that recipients in the experiential gift

condition received gifts that were more experiential

(M ¼ 4.89, SD ¼ 2.38) than those in the material gift

condition (M ¼ 3.17, SD ¼ 2.24; t(41) ¼ 2.45, p ¼ .02,

d ¼ .71). Also, the majority of recipients (86%) had not

consumed their gift with their gift giver, there was no

significant difference in estimated price between recipi-

ents of experiential gifts (M ¼ $14.01, SD ¼ 4.19)

and material gifts (M ¼ $13.10, SD ¼ 5.53; t(41) ¼ 0.59,

p ¼ .56, d ¼ .18), and there were no significant differ-

ences in how much time recipients had spent with their

gift giver during the gift exchange (p > .99) or how

much time they had spent consuming their gift (p ¼ .17).

Change in Relationship Strength. The pre-gift relation-

ship measures confirmed that there were no differences in

baseline levels of relationship strength among participants

in the experiential condition (M ¼ 6.71, SD ¼ 2.12) and

material condition (M ¼ 7.10, SD ¼ 2.12; t(41) ¼ 0.95,

p ¼ .35, d ¼ .29). In support of our first hypothesis, the re-

lationship change measure revealed that recipients of an

experiential gift (M ¼ 0.08, SD ¼ 0.79) showed a more

positive change in relationship strength than recipients of a

material gift (M ¼

–0.54, SD ¼ 1.10; t(41) ¼ 2.06, p ¼ .05,

d ¼ .61).

Because som

e participants rated their pre-gift relation-

ship using the extreme ends of the scales, we conducted a

robustness check by trimming the data of any participants

who reported a pre-gift relationship score greater than 8

(n ¼ 11) or less than 2 (n ¼ 0). Omitting these participants

strengthened the effect of gift type on relationship change,

with recipients of experiential gifts reporting greater rela-

tionship improvements than recipients of material gifts

(t(32) ¼ 2.41, p ¼ .02, d ¼ .78).

Thoughtfulness and Liking. Although experiential gifts

were directionally perceived as more thoughtful and better

liked, the effects were not significant (thoughtfulness: M

exp

¼ 5.49, SD ¼ 2.32 vs. M

mat

¼ 5.07, SD ¼ 2.32; t(41) ¼

0.94, p ¼ .35, d ¼ .29; liking: M

exp

¼ 5.68, SD ¼ 0.96 vs.

M

mat

¼ 5.07, SD ¼ 1.43; t(41) ¼ 1.61, p ¼ .12, d ¼ .43).

Therefore, the ability of experiential gifts to strengthen re-

lationships does not appear to be driven by perceived

thoughtfulness or liking.

CHAN AND MOGILNER 5

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

The results of study 1 showed that receiving an experi-

ential gift improves the strength of recipients’ relationships

with their gift giver, compared to receiving a material gift.

Study 2 tests whether highlighting the experiential aspect

of a material gift can similarly improve relationship

strength.

STUDY 2: A COFFEE MUG GIFT

Across a variety of gifts that were individually selected

by each gift giver, study 1 demonstrated the relationship-

strengthening benefits of experiential gifts over material

gifts. This next study provided an even more rigorous test

for the connecting power of experiential gifts by holding

the gift itself constant and varying only the experiential

versus material framing of that gift. Indeed, many material

gifts have experiential components. For example, a stereo

is a material object that is kept in one’s possession for

years, yet it also provides the experience of listening to

music. Similarly, a bottle of wine has a tangible, physical

presence that can contribute to a collection, but it can also

provide a very pleasurable multisensory experience when

consumed with a perfectly paired cheese. Study 2 took ad-

vantage of the malleable distinction between material and

experiential gifts and tested whether a material gift (a cof-

fee mug) could be framed as more experiential (by high-

lighting the experience of drinking coffee) to further

strengthen gift givers’ and recipients’ relationships.

Method

Gift Type Manipulation. Two hundred gift givers were

recruited through a university laboratory (57% female;

ages 18–39, M ¼ 20.6) and provided with a gift-wrapped

coffee mug to give as a gift to someone they know.

Participants were randomly assigned to either give a mug

that highlighted the experience of drinking coffee (with the

words “my coffee time” inscribed on it) or give a mug

identified as a material possession (with the words “my

coffee mug” inscribed on it; see appendix B). A between-

subjects pre-test validated the manipulation: participants

(N ¼ 68; 56% female; ages 18–29, M ¼ 20.94) were pre-

sented with one of the two mugs and asked to rate the mug

on a nine-point scale (1 ¼ purely material, 9 ¼ purely ex-

periential). Participants rated the “my coffee time” mug as

more experiential (M ¼ 3.69, SD ¼ 2.20) than the “my cof-

fee mug” mug (M ¼ 2.63, SD ¼ 1.83; t(67) ¼ 2.13, p ¼

.04, d ¼ .50). The mugs did not differ in rated desirability,

positivity, or favorability (a ¼ .90; t(67) ¼ 0.06, p ¼ .95,

d ¼ .01).

Change in Relationship Strength. A survey link was

provided on a voucher that was inside the gift-wrapped

coffee mug. The voucher was for $5 at a local coffee shop,

and it would become valid if the gift recipient completed a

brief online survey. Each mug condition had a separate sur-

vey link, allowing us to know the type of mug received.

One hundred nine recipients completed the survey (64%

female; ages 16–58, M ¼ 21.5; n

material

¼ 64; n

experiential

¼

45). The survey asked gift recipients to rate how receiving

the gift changed the strength of their relationship with the

person who gave them the gift (1 ¼ felt more disconnected,

9 ¼ felt more connected), and how much they liked the gift

(1 ¼ hate it, 9 ¼ love it).

Results and Discussion

Recipients of the more experiential gift (M ¼ 7.47,

SD ¼ 1.50) reported greater strengthening of their relation-

ship with their gift giver than recipients of the more mater-

ial gift (M ¼ 6.92, SD ¼ 1.34; t(107) ¼ 1.99, p ¼ .05, d ¼

.37). Again, this effect appears to be independent of how

much recipients liked the gift, because recipients reported

no difference in how much they liked their mug (M

exp

¼

7.33, SD ¼ 1.41 vs. M

mat

¼ 7.25, SD ¼ 1.50; t(107) ¼

0.29, p ¼ .77, d ¼ .06).

Study 2 provided additional support for our main hy-

pothesis (hypothesis 1) using a highly conservative and

controlled test for the effect of gift type on change in rela-

tionship strength. Holding all features of the gift constant

except for the extent to which the giving of an experience

was highlighted, this study showed that receiving a more

experiential gift is better at strengthening relationships

than receiving a more material gift. Indeed, even a material

gift (a coffee mug) could be made more connecting by re-

minding the recipient of the experience it offers (the time

spent drinking coffee). Many gifts have both experiential

and material elements, and these results demonstrate that

gift givers can enjoy

AQ1

some of the relational benefit of ex-

periential gifts by merely highlighting the experience the

gift provides. The next study explored a mechanism for the

effect, testing the underlying role of emotion from gift

consumption.

STUDY 3: THE MEDIATING ROLE OF

EMOTION FROM GIFT CONSUMPTION

Studies 1 and 2 provided evidence for experiential gifts

being more effective at strengthening relationships than

material gifts. In this next study, we explored the underly-

ing role of emotion. Participants in study 3 were asked to

recall either an experiential or material gift they had

received and then to rate how the gift impacted their rela-

tionship with the gift giver. To examine the mechanism,

this study additionally measured the intensity of the emo-

tion evoked from gift consumption separately from the

emotion evoked from the gift exchange. Qualitative re-

search observed that a gift exchange can be highly emo-

tional, and the combination of negative and positive

emotions felt during a gift exchange, as well as the

6 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

recipient’s reaction to the emotions expressed by the gift

giver, contribute to relationship change (Belk and Coon

1993; Ruth et al. 1999, 2004). We predict that while a gift

exchange can be highly emotional for both material and ex-

periential gifts, consuming an experiential gift will elicit a

more intense emotional response than consuming a mater-

ial gift (Weidman and Dunn 2016). For example, attend-

ing a theatre performance or going on a vacation is likely

to be more emotional than wearing a new pair of boots or

driving a car. Furthermore, it is this emotion evoked from

consuming experiential gifts that we propose is respon-

sible for their positive impact on relationship strength

(hypothesis 2).

Though study 1 showed the more positive effect of

receiving an experiential gift versus a material gift even

when participants were instructed to not consume the gift

together, this study further examined the role of sharing the

gift through a 2 (gift type: material vs. experiential) 2

(consumption: shared vs. nonshared) between-subjects

design.

Method

Gift Type Manipulation. Six hundred adults were re-

cruited through Amazon Mechanical Turk to participate in

this study in exchange for $0.75. Participants were ran-

domly assigned to recall a particular type of gift they had

received: shared experiential gift, nonshared experiential

gift, shared material gift, or nonshared material gift.

Participants in the experiential gift conditions were in-

structed, “Please recall and describe an experiential gift

that you have received at some point in your life from an-

other person.” Participants in the material gift conditions

were instructed, “Please recall and describe a material gift

that you have received at some point in your life from an-

other person.” Participants were provided with a definition

of material or experiential gifts adapted from Van Boven

and Gilovich (2003). Those in the shared consumption con-

ditions were further instructed, “This should be [a material/

an experiential] gift that you consumed with the person

who gave it to you (i.e., you shared the gift with your gift

giver).” Those in the nonshared consumption conditions

were further instructed, “This should be [a material/an ex-

periential] gift that you consumed on your own (i.e., you

did not share the gift with your gift giver).”

Participants who could not recall a gift (n ¼ 7), did not

complete the survey (n ¼ 41), or did not follow the gift re-

call instructions (i.e., described a gift they had given, n ¼

1; described a gift received from multiple people, n ¼ 15;

described a gift of cash, n ¼ 1; described multiple gifts, n

¼ 1) were eliminated from the analysis. This left 534 gift

recipients in the analyzed dataset (59% female; ages 18–

78, M ¼ 33.1).

Change in Relationship Strength. Using the measures

from study 1, participants rated the strength of their rela-

tionship to the gift giver before and after receiving the gift.

Participants first chose two pairs of overlapping circles:

one to represent their relationship before receiving the gift

and one to represent their relationship after receiving the

gift (see appendix A; adapted from Aron et al. 1992).

Participants also rated their relationship both before (a ¼

.92) and after (a ¼ .91) receiving the gift in terms of close-

ness (1 ¼ extremely distant, 9 ¼ extremely close), connec-

tion (1 ¼ extremely disconnected, 9 ¼ extremely

connected), and relationship strength (1 ¼ extremely weak,

9 ¼ extremely strong). The difference between each of the

before and after ratings on the four relationship measures

was calculated, and these values were averaged to form an

overall indicator of change in relationship strength.

Emotion. Recipients reported how emotional they felt

from the gift exchange separately from how emotional they

felt during gift consumption. They were specifically in-

structed, “Think about the emotions you felt from receiving

the gift. Focus on the moment when you felt the most emo-

tional from receiving the gift, and rate how intensely you

felt that emotion” (1 ¼ did not feel emotional at all from

receiving the gift, 7 ¼ felt extremely emotional from

receiving the gift); and “Think about the emotions you felt

from consuming the gift. Focus on the moment when you

felt the most emotional from consuming the gift, and rate

how intensely you felt that emotion” (1 ¼ did not feel emo-

tional at all from consuming the gift, 7 ¼

felt extremely

emotional from

consuming the gift). We asked participants

to focus on the moment they felt most emotional to remove

the influence of hedonic adaptation that is more likely to

have occurred for the more durable material gifts (Nicolao

et al. 2009). To account for this difference in durability, we

also asked participants to estimate the total amount of time

they had spent consuming the gift.

To explore the specific emotions evoked by their gifts,

we then asked participants to select one primary emotion

from a list of 30 randomly ordered discrete emotions that

they were feeling at the moment they felt most emotional

(see appendix C). This list was followed by a text box, in

case the emotion they felt was not provided. The listed

emotions were drawn from the Positive and Negative

Affective Schedule—Expanded Form (PANAS-X; Watson

and Clark 1994), including the two general dimension

scales (10 positive and 10 negative emotions), along with

eight additional basic emotions (four positive and four

negative). Given our interest in the social aspects of a gift

exchange and consumption, we also added two emotions

(embarrassed and grateful) that serve important social

functions (Fischer and Manstead 2008; Tooby and

Cosmides 2008).

CHAN AND MOGILNER 7

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

Thoughtfulness and Liking. Thoughtfulness and liking

of the gift were measured using the same items as in study

1. Perceived thoughtfulness was measured using four

items (a ¼ .84), and liking was measured using three items

(a ¼ .73).

Other Features of the Gift. To account for the likely

variation among the gifts received, we asked recipients to

estimate the price of the gift, to report when they had

received the gift, and to indicate how they were related to

their gift giver (spouse or significant other, child or grand-

child, parent, another family member, close friend, ac-

quaintance, colleague, or other).

Lastly, participants responded to manipulation checks

by rating the extent to which the gift they received was ma-

terial or experiential (1 ¼ purely material, 5 ¼ equally ma-

terial and experiential, 9 ¼ purely experiential), and by

indicating whether they had consumed the gift with their

gift giver (yes, no).

Results

Gifts Received. Shared experiential gifts included vac-

ations, meals, and tickets to concerts or sporting events.

Nonshared experiential gifts included music or dance les-

sons, spa services, vacations, meals, and tickets for events

that were not attended with the gift giver. Shared material

gifts included coffee makers, game consoles, televisions,

tablet computers, and cars; and nonshared material gifts

included jewelry, clothing, computers, portable music

players, and digital cameras. Manipulation checks con-

firmed that participants in the experiential gift conditions

recalled gifts that were more experiential (M ¼ 7.55,

SE ¼ 0.13) than participants in the material gift conditions

(M ¼ 2.90, SE ¼ 0.13; t(532) ¼ 25.49, p < .001, d ¼ 1.48);

and most participants in the shared gift conditions (93%)

consumed their gifts with their gift giver (vs. 3% in the

nonshared gift conditions; v

2

(1) ¼ 435.96, p < .001).

Participants in the experiential gift conditions also con-

sumed their gift over a shorter period of time (M ¼ 3.41

days, SE ¼ 12.56) than participants in the material gift con-

ditions (M ¼ 118.98 days, SE ¼ 12.24; t(532) ¼ 6.59, p <

.001, d ¼ .55), consistent with the more durable nature of

material gifts.

The estimated price of the gifts ranged from $1 (a mag-

net) to $19,000 (a car). The majority of gifts (60%) were

received within the past year, but the oldest gift was

received in 1969. Most gifts were received from a spouse

or significant other (37%), parent (19%), another family

member (16%), or a close friend (19%).

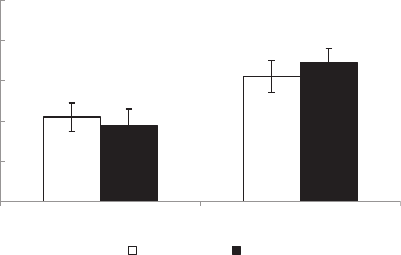

Change in Relationship Strength. A2 2 ANOVA

conducted on change in relationship strength revealed only

a main effect of gift type, with experiential gifts (M ¼

0.66, SE ¼ 0.05) strengthening relationships more than

material gifts (M ¼ 0.40, SE ¼ 0.05; F(1, 530) ¼ 11.81,

p < .001, d ¼ .30; see figure 1). Neither the shared con-

sumption main effect (p ¼ .50) nor the gift type by shared

consumption interaction (p ¼ .81) was significant, suggest-

ing that the relationship-strengthening effect of receiving

an experiential gift occurred regardless of whether recipi-

ents consumed the gift with their gift giver (see web

appendix A for robustness check).

Given the wide range of gifts, we also conducted a 2

(gift type) 2 (shared) ANCOVA on change in relation-

ship strength, controlling for estimated price, date of re-

ceipt, and how the recipient was related to the gift giver

(dummy coded). Results again showed that receiving an

experiential gift strengthened relationships more than

receiving a material gift (F(1, 520) ¼ 6.83, p ¼ .009, d ¼

.23). Including the covariates did not affect the significance

levels of the shared consumption main effect (p ¼ .72) or

the interaction effect (p ¼ .32).

Emotion from Consumption. To examine the role of

emotion, we first conducted a 2 (gift type) 2 (shared)

ANOVA

on the extent to which consuming the gift made

recipients feel emotional. The results revealed only a main

effect of gift type, with experiential gifts (M ¼ 5.14,

SE ¼ 0.09) evoking greater emotion than material gifts (M

¼ 4.70, SE ¼ 0.09; F(1, 530) ¼ 11.08, p < .001, d ¼ .29).

There was a nonsignificant effect of sharing (p ¼ .14) and

a nonsignificant interaction effect (p ¼ .50).

These effects held when the covariates were included in

the analysis. The results again revealed only a main effect

of gift type, with experiential gifts evoking greater emotion

than material gifts (F(1, 520) ¼ 15.55, p < .001, d ¼ .34),

and a nonsignificant effect of sharing (p ¼ .92) and inter-

action effect (p ¼ .90). Accounting for factors such as the

type of relationship and the time that has passed since the

gift exchange, these results suggest that consuming an ex-

periential gift evokes greater emotion than consuming a

material gift, regardless of whether recipients consume the

gift with their gift giver. The vast majority of the specific

FIGURE 1

STUDY 3: RELATIONSHIPS IMPROVED MORE AMONG

RECIPIENTS OF EXPERIENTIAL (VS. MATERIAL) GIFTS

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

Material Experiential

Relationship change

Nonshared Shared

8 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

emotions participants felt most intensely while consuming

the gift were positive (97.6%; see table 1).

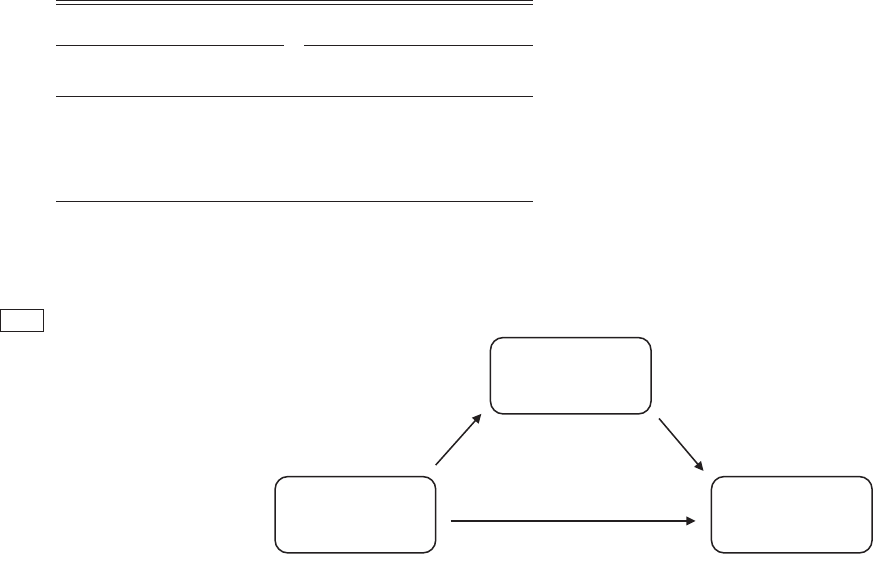

We next conducted a mediation analysis to test our the-

ory that the positive effect of receiving an experiential gift

(vs. material gift) on relationship strength is driven by the

greater emotion evoked during gift consumption. We

entered recipients’ ratings of how emotional consuming

the gift was as the mediator, controlling for estimated

price, date of receipt, and how the recipient was related to

the gift giver. As our previous analyses showed, experien-

tial gifts strengthened relationships more than material

gifts (b ¼ 0.10, SE ¼ 0.04, t(522) ¼ 2.70, p ¼ .007, d ¼

.23). In addition, gifts that were more emotional were more

effective at improving relationship strength (b ¼ 0.14,

SE ¼ 0.02, t(522) ¼ 33.95, p < .001, d ¼ .49). When both

gift type and emotion were entered into the model predict-

ing change in relationship strength, the effect of consump-

tion emotion remained significant (b ¼ 0.13, SE ¼ 0.02,

t(521) ¼ 5.44, p < .001, d ¼ .46), whereas the effect of

gift type was no longer significant (b ¼ 0.07, SE ¼ 0.04,

t(521) ¼ 1.80, p ¼ .07, d ¼ .15). Corroborating evidence

was obtained in a bootstrap analysis, which generated a

confidence interval of the indirect effect that did not cross

zero (95% CI ¼ [.03, .12]; Hayes 2012; Zhao, Lynch, and

Chen 2010; see figure 2). In sum, experiential gifts tend to

be more emotional to consume, and gifts that are more

emotional to consume lead recipients to have a stronger re-

lationship with their gift giver, thus supporting our hypoth-

esis that experiential gifts strengthen relationships more

than material gifts because they evoke greater emotional

intensity during consumption (hypothesis 2).

Emotion from Gift Exchange. Having identified the

significant role of the emotion evoked during gift con-

sumption, we next examined the emotion evoked during

the gift exchange. A 2 2 ANOVA conducted on how

emotional recipients felt upon receiving the gift showed a

nonsignificant main effect of gift type. Material and ex-

periential gifts did not differ in how emotional it was to re-

ceive the gift (p ¼ .88). The main effect of shared

consumption (p > .99) and

the gift type shared inter-

action (p ¼ .63) were also not significant. Like the emo-

tions evoked during gift consumption, the vast majority of

the specific emotions participants felt most during the gift

exchange were positive (96.8%; see table 1). These find-

ings are consistent with our theorizing that experiential and

material gifts are similarly emotional when received, and

thus it is the emotion felt from gift consumption, rather

than the gift exchange, that is responsible for the greater re-

lationship-strengthening effect of experiential gifts.

TABLE 1

STUDY 2: EMOTIONS FELT MOST INTENSELY

DURING GIFT CONSUMPTION AND GIFT RECEIPT

(FIVE MOST COMMONLY REPORTED)

Gift consumption Gift receipt

Emotion

%of

participants

Emotion

%of

participants

Happy 29.0% Grateful 20.0%

Delighted/cheerful 15.9% Delighted/cheerful 17.6%

Grateful 13.1% Excited 17.4%

Excited 10.3% Happy 13.7%

Enthusiastic 6.9% Surprised 13.5%

FIGURE 2

AQ6

STUDY 3: EXPERIENTIAL GIFTS WERE MORE EMOTIONAL TO CONSUME AND THEREFORE MORE CONNECTING

Note: ** p < .01, *** p < .001, two-tailed test. Parameter estimates are listed with standard

errors in parentheses, with estimated price of gift, date of gift receipt, and how the recipient

was related to the

g

ift

g

iver

(

dumm

y

coded

)

as model covariates.

Experiential gift

vs.

material gift

Emotion from gift

consumption

Relationship

change

a = .26(.07)*** b = .13(.02)***

c = .10(.04)**

c' = .07(.04)

CHAN AND MOGILNER 9

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

Thoughtfulness and Liking. We again found no differ-

ences in thoughtfulness and liking across conditions. A 2

2 ANOVA predicting perceived thoughtfulness of the gift

revealed no significant effects for gift type (p ¼ .77),

shared consumption (p ¼ .16), or the interaction (p ¼ .08).

Similarly, a 2 2 ANOVA predicting liking of the gift re-

vealed no significant effects for gift type (p ¼ .19), shared

consumption (p ¼ .42), or the interaction (p ¼ .75).

Discussion

Examining a wide range of real-world gifts across a var-

iety of relationships, this study provided robust evidence

that experiential gifts strengthen relationships more than

material gifts, regardless of whether gift recipients and giv-

ers consume the gift together (hypothesis 1). Furthermore,

the mechanism underlying this effect is the intensity of

emotion evoked during gift consumption, which is distinct

from the emotion evoked during the gift exchange.

Specifically, consuming experiential gifts evokes greater

emotion than consuming material gifts, and it is this emo-

tional intensity that strengthens recipients’ relationships

with their gift givers (hypothesis 2).

Because the vast majority of participants in study 3 re-

ported the emotion they felt most intensely while consum-

ing their gift to be positive, there was not sufficient data to

assess whether the effect of emotion on relationship

strength would generalize to negative emotions felt during

gift consumption. For example, would an intense feeling of

sadness while watching a performance of Madame

Butterfly or an intense feeling of fear while watching

Silence of the Lambs strengthen the giver-recipient rela-

tionship? To explore the role of emotional valence, we

conducted a similar study in which we asked participants

(N ¼ 523; 46% female, three unspecified; ages 18–66, M

¼ 32.0, one unspecified) to recall a significant material or

experiential gift they had received. Participants rated how

much their relationship with the gift giver had strengthened

as a result of the gift, as well as how intensely they felt

each of 30 discrete emotions while consuming their gift

(15 positive emotions and 15 negative emotions; see ap-

pendix C). Ratings for all 30 emotions were averaged to

create an index of overall emotion. In addition, the ratings

for the positive and the negative emotions were averaged

separately. The results showed that recipients of experien-

tial (vs. material) gifts felt more emotional overall (M

exp

¼

3.29, SE ¼ 0.07 vs. M

mat

¼ 3.02, SE ¼ 0.07; F(1, 510) ¼

20.02, p < .001, d ¼ .39), and this effect held for purely

positive emotions (M

exp

¼ 3.73, SE ¼ 0.06 vs. M

mat

¼

3.52, SE ¼ 0.07; F (1, 510) ¼ 12.96, p < .001, d ¼ .30),

and purely negative emotions (M

exp

¼ 2.22, SE ¼ 0.07 vs.

M

mat

¼ 2.08, SE ¼ 0.07; F(1, 510) ¼ 5.09, p ¼ .03, d ¼

.20). Furthermore, significant indirect effects were

observed when we used the average of all 30 discrete emo-

tions (95% CI ¼ [.05, .15]), as well as just the 15 positive

emotions (95% CI ¼ [.04, .14]), and just the 15 negative

emotions (95% CI ¼ [.003, .08]) as mediators for the effect

of gift type on change in relationship strength. This offers

preliminary evidence suggesting that strong negative emo-

tions evoked through gift consumption can also strengthen

giver-recipient relationships.

STUDY 4: THE MODERATING ROLE OF

EMOTION FROM GIFT CONSUMPTION

Building on the mediation evidence from study 3, study

4 sought further evidence for the underlying role of emo-

tion from gift consumption through a test of moderation.

This study followed a 2 (gift type: material vs. experien-

tial) 2 (emotion: control vs. emotion) between-subjects

design. Participants were asked to recall either an experien-

tial gift or material gift they had received, and half were

more specifically instructed to recall a gift that had evoked

intense emotion during consumption.

Additionally, this study design allowed us to identify a

boundary condition for the benefit of receiving experiential

gifts over material gifts. Although we argue that consum-

ing experiential gifts tends to evoke greater emotion than

consuming material gifts, there surely are some material

gifts that elicit a great deal of emotion when consumed.

For example, wearing one’s engagement ring hopefully

makes one feel incredibly loved and loving, and looking at

a photograph that captures a meaningful moment should

stir emotion. Because we argue that experiential gifts

strengthen giver-recipient relationships by eliciting more

intense emotion during consumption, material gifts that

evoke intense emotion should similarly strengthen

relationships.

Method

One thousand forty-two participants were recruited

through Amazon Mechanical Turk to participate in this

study in exchange for $0.50. Participants who did not com-

plete the survey (n ¼ 26) or wrote that they could not fol-

low the instructions or could not think of a gift (n ¼ 21)

were eliminated from the analysis. This left 995 partici-

pants in the analyzed dataset (45% female, two unspeci-

fied; ages 18–77, M ¼ 33.2).

Gift Manipulations. Participants were randomly as-

signed to one of the four conditions comprising the 2 (gift

type: material vs. experiential) 2 (emotion: control vs.

emotion) design. Participants in the control conditions

were asked to “Please recall and describe [a material/an ex-

periential] gift you’ve received.” Participants in the emo-

tion conditions were asked to “Please recall and describe [a

material/an experiential] gift you’ve received that makes or

made you feel emotional while consuming it.” Participants

were provided with the definition of material or

10 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

experiential gifts from studies 1 and 3. All participants

were also instructed that the gift should be one they

received from someone they know and one they did not

consume with the gift giver.

Change in Relationship Strength. This study used yet

another measure for change in relationship strength, which

was adapted from the Relationship Satisfaction Level

index of Rusbult et al.’s (1998) Investment Model Scale.

Participants rated their agreement (1 ¼ don’t agree at all, 5

¼ somewhat agree, 9 ¼ agree completely) with five state-

ments (a ¼ .95): “I feel more satisfied with our relation-

ship as a result of the gift”; “Our relationship is closer to

ideal as a result of the gift”; “Our relationship is much bet-

ter than others’ relationships as a result of the gift”; “Our

relationship makes me very happy as a result of the gift”;

and “Our relationship does a good job of fulfilling my

needs for intimacy, companionship, etc. as a result of the

gift.”

Thoughtfulness and Liking. Thoughtfulness and liking

of the gift were measured using the same items as in stud-

ies 1 and 3. Again, perceived thoughtfulness of the gift was

measured using four items (a ¼ .78), and liking was meas-

ured using three items (a ¼ .56).

Other Features of the Gift. To account for the variation

among the gifts received, we asked recipients to estimate

the price of the gift, to report when they had received the

gift, and to indicate how they were related to their gift

giver (spouse or significant other, child or grandchild, par-

ent, another family member, close friend, acquaintance,

colleague, or other) and for what occasion they had

received the gift (birthday, wedding, anniversary,

Christmas, Valentine’s Day, Mother’s Day, Father’s Day,

graduation, for no special occasion, or other).

Lastly, participants responded to manipulation checks

by rating the extent to which the gift they received was ma-

terial or experiential (1 ¼ purely material, 5 ¼ equally ma-

terial and experiential, 9 ¼ purely experiential), and how

emotional they had felt while consuming the gift (1 ¼ did

not feel emotional at all from consuming the gift, 9 ¼ felt

extremely emotional from consuming the gift).

Results

Gifts Received. As in study 3, the experiential gifts re-

called included vacation, meals, and tickets to perform-

ances and events. The recalled material gifts included

clothing, electronics, musical instruments, and jewelry.

A2 2 ANOVA conducted on the material-experiential

manipulation check confirmed a main effect of gift type

(F(1, 991) ¼ 1157.74, p < .001, d ¼ 1.45), along with

a main effect of emotion condition (F(1, 991) ¼ 11.72,

p < .001, d ¼ .15) and an interaction (F(1, 991) ¼ 34.88,

p < .001, d ¼ .25). The experiential gifts were rated as

more experiential than the material gifts in the control

conditions (M

exp

¼ 7.72, SE ¼ .13 vs. M

mat

¼ 2.42, SE ¼

.13; t(991) ¼ 28.85, p < .001, d ¼ 1.70) and emotion con-

ditions (M

exp

¼ 7.39, SE ¼ .13 vs. M

mat

¼ 3.66, SE ¼ .14;

t(991) ¼ 19.48, p < .001, d ¼ 1.19).

A2 2 ANOVA conducted on the emotion manipula-

tion check confirmed a main effect of emotion condition

(F(1, 991) ¼ 105.91, p < .001, d ¼ .62), as well as a main

effect of gift type (F(1, 991) ¼ 11.83, p < .001, d ¼ .21),

and an interaction (F(1, 991) ¼ 12.84, p < .001, d ¼ .22).

The recalled emotional gifts were rated as more emotional

than the control gifts in the experiential conditions (M

emot

¼ 5.63, SE ¼ .09 vs. M

cont

¼ 5.02, SE ¼ .09; t(991) ¼

4.84, p < .001, d ¼ .40) and material conditions (M

emot

¼

5.64, SE ¼ .10 vs. M

cont

¼ 4.38, SE ¼ .09; t(991) ¼ 9.62,

p < .001, d ¼ .83). Consistent with our theorizing that ex-

periential gifts tend to evoke more intense emotion during

consumption than material gifts, these results show that in

the control conditions, experiential gifts were more emo-

tional than the material gifts (M

exp

¼ 5.02, SE ¼ .09 vs.

M

mat

¼ 4.38, SE ¼ .09; t(991) ¼ 5.07, p < .001, d ¼ .42).

Employing yet another approach to check the emotion

manipulation, we conducted a textual analysis on partici-

pants’ written description of their gift using the Linguistic

Inquiry and Word Count (LIWC; Pennebaker, Booth, and

Francis 2007), which is an effective measure of the amount

of emotion expressed (Kahn et al. 2007). The LIWC enum-

erated the percentage of emotion words written by each

participant. This additional check confirmed that, overall,

participants in the emotion conditions expressed greater

emotion when writing about their gift, and that within the

control conditions, participants in the experiential condi-

tion also expressed greater emotion when writing about

their gift. Specifically, participants in the experiential emo-

tion (M ¼ 6.89, SE ¼ 0.31), material emotion (M ¼ 6.42,

SE ¼ 0.33), and experiential control (M ¼ 5.08, SE ¼ 0.31)

conditions each wrote a significantly higher percentage of

emotion words than did participants in the material control

condition (M ¼ 3.83, SE ¼ 0.31; p’s < .005). Again, this is

consistent with our theorizing that experiential gifts tend to

evoke greater emotion than material gifts.

The estimated price of the gifts ranged from $0 (e.g., a

handed-down shirt) to $25,000 (a wedding ring). Fifty per-

cent of gifts were received within the past year, and the

oldest gift was received in 1960. Most gifts were received

from a spouse or significant other (32%), parent (24%), an-

other family member (17%), or a close friend (18%), and

were received for a birthday (34%), Christmas (25%), or

no special occasion (26%). Wedding and anniversary gifts

combined constituted less than 6% of the gifts.

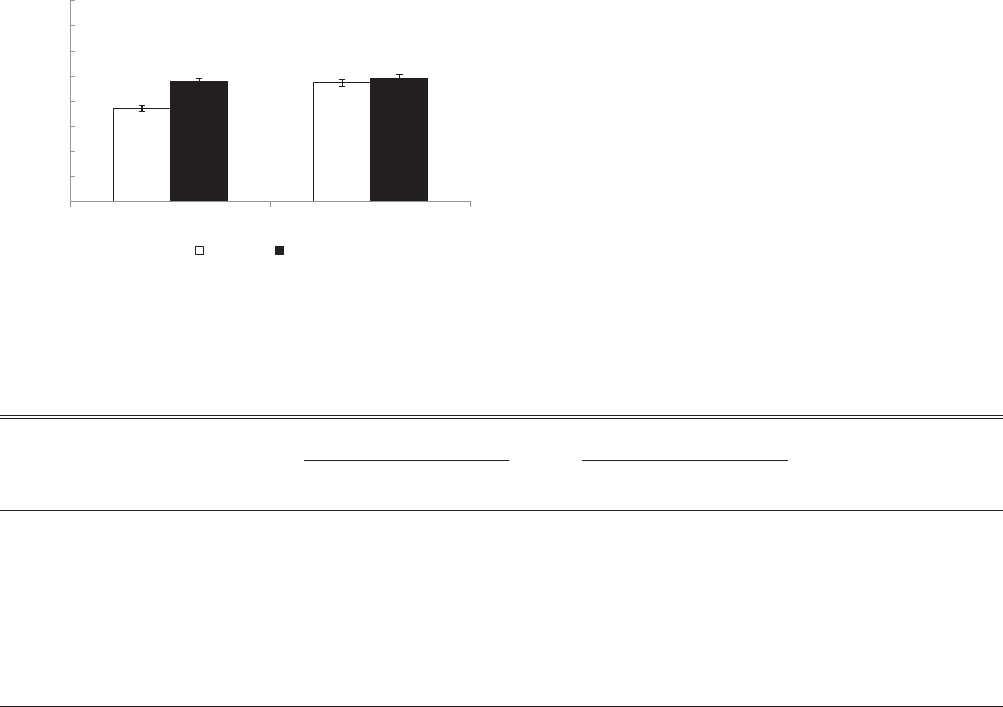

Change in Relationship Strength. A 2 (gift type) 2

(emotion) ANOVA conducted on change in relationship

strength revealed a main effect of gift type (F(1, 991) ¼

21.33, p < .001, d ¼ .29), a main effect of emotion

(F(1, 991) ¼ 17.81, p < .001, d ¼ .26), and the predicted

CHAN AND MOGILNER 11

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

interaction (F(1, 991) ¼ 10.62, p ¼ .001, d ¼ .21).

Consistent with our previous findings, in the control condi-

tions, experiential gifts (M ¼ 5.78, SE ¼ 0.13) resulted in

greater improvements in relationship strength than material

gifts (M ¼ 4.71, SE ¼ 0.13; t(991) ¼ 5.69, p < .001, d ¼

.49). Furthermore, in support of our proposed underlying

role of emotion, material gifts that evoked intense emotion

during consumption (M ¼ 5.73, SE ¼ 0.15) resulted in

similar improvements in relationship strength as experien-

tial gifts that evoked emotion (M ¼ 5.92, SE ¼ 0.13; t(991)

¼ 0.94, p ¼ .35, d ¼ .08; figure 3). Controlling for the esti-

mated price of the gift, date of receipt, how the recipient

was related to the gift giver (dummy coded), and the gift

occasion (dummy coded) did not affect the significance of

the main effect of gift type (F(1, 972) ¼ 15.72, p < .001,

d ¼ .26), emotion (F(1, 972) ¼ 15.20, p < .001, d ¼ .24),

or their interaction (F(1, 972) ¼ 10.10, p ¼ .002, d ¼ .20).

We observed that many of the emotional material gifts

were pieces of jewelry commemorating a meaningful life

event (e.g., engagement or wedding, birth of a child, gradu-

ation) or passed down as heirlooms. Others included photo-

graphs and religious items (e.g., bible, rosary). Though the

predicted effects of gift type and emotion on change in re-

lationship held when we controlled for gift occasion and

other features of the gifts (i.e., price, date of receipt, and re-

lationship to the gift giver), it is still possible that the emo-

tion manipulation elicited gifts in participants’ minds that

differed in ways other than their material or experiential

distinction. To assess this, we asked two research assistants

who were blind to study conditions and hypotheses to cat-

egorize the gifts participants had received. First, the re-

search assistants jointly determined purchase categories

that encompassed the full range of gifts (e.g., travel; food

and drink; clothing, shoes, and accessories). The research

assistants then independently assigned each gift to one of

the 10 purchase categories (84% agreement, and disagree-

ments were resolved through discussion). An examination

of the coded gifts revealed some differences among the

material gifts between the control and emotion conditions

(see table 2). For example, jewelry was more likely to be

mentioned as an emotional material gift, and though elec-

tronics were also frequently mentioned as an emotional

material gift, they were more likely to be mentioned in the

control condition. More importantly, however, the pur-

chase category of the gifts received did not affect the pri-

mary outcome of relationship change. Controlling for

purchase category (dummy coded), a 2 (gift type) 2

(emotion) ANCOVA conducted on change in relationship

strength still revealed a main effect of gift type (F(1, 959)

¼ 3.89, p < .05, d ¼ .20), a main effect of emotion

FIGURE 3

STUDY 4: RELATIONSHIPS IMPROVED MORE AMONG

RECIPIENTS WHO RECEIVED EXPERIENTIAL (VS. MATERIAL)

GIFTS OR GIFTS THAT WERE EMOTIONAL TO CONSUME

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

Control Emotion

Relationship change

Material Experiential

TABLE 2

STUDY 4: PERCENTAGE OF GIFTS RECEIVED (BY CONDITION) AND MEAN CHANGE IN RELATIONSHIP STRENGTH IN EACH

PURCHASE CATEGORY

Material Experiential Mean change in

relationship strength

Control Emotion Control Emotion

(n ¼ 259) (n ¼ 220) (n ¼ 258) (n ¼ 258)

Travel 0% 0.9% 24.4%* 16.3%* 6.18

Recreation and leisure 1.5% 2.7% 21.3% 16.7% 6.10

Food and drink 0%* 2.3%* 19.4% 19.4% 5.67

Beauty and wellness 2.7% 2.3% 8.1% 6.2% 5.60

Arts, music, and literature 5.8% 9.6% 20.9% 25.2% 5.58

Jewelry 10.8%* 19.6%* 0% 1.6% 5.54

Electronics and technology 36.7%* 19.6%* 0%* 4.3%* 5.27

Home and garden 8.1% 13.2% 0% 0.8% 5.21

Other 7.0%* 12.7%* 3.9% 5.4% 5.19

Clothing, shoes, and accessories 27.4%* 17.3%* 1.2% 4.3% 4.86

Note: Within each material or experiential gift condition, * represents a statistical difference between the control and emotion conditions for each purchase

category at p < .05.

12 JOURNAL OF CONSUMER RESEARCH

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

(F(1, 959) ¼ 19.39, p < .001, d ¼ .28), and the predicted

interaction (F(1, 959) ¼ 8.42, p ¼ .004, d ¼ .18); the effect

of purchase category was not significant (F(1, 959) ¼ 1.43,

p ¼ .17, d ¼ .22), and none of the individual purchase cate-

gories significantly predicted the change in relationship

strength. This suggests that the specific purchases gener-

ated in each condition cannot explain the effect of con-

sumption emotion on relationship strength for experiential

versus material gifts. Moreover, an examination of the

average change in relationship strength across the various

purchase categories reflects a pattern consistent with the

primary hypothesis: recipients of gifts in more experiential

categories reported greater improvements in relationship

strength than those who received gifts in more material cat-

egories (see table 2).

Thoughtfulness and Liking. A2 2 ANOVA predict-

ing thoughtfulness revealed only a main effect of emotion,

with emotional gifts (M ¼ 6.23, SE ¼ .04) being con-

sidered more thoughtful than control gifts (M ¼ 6.12,

SE ¼ 0.04; F(1, 991) ¼ 3.85, p ¼ .05, d ¼ .12). The effects

of gift type and the interaction were not significant (p’s >

.16). A 2 2 ANOVA predicting liking revealed a main

effect for gift type, with experiential gifts (M ¼ 6.18, SE ¼

.04) being better liked than material gifts (M ¼ 6.04,

SE ¼ 0.04; F(1, 991) ¼ 6.31, p ¼ .01, d ¼ .16). The effects

of the emotion manipulation and the interaction were not

significant (p

’s > .50). When thoughtfulness and liking

were included as covariates in the analysis of change in re-

lationship strength, the results held: we still observed a

main effect of gift type (F(1, 989) ¼ 19.71, p < .001, d ¼

.27), of emotion (F(1, 989) ¼ 15.68, p < .001, d ¼ .24),

and their interaction (F(1, 989) ¼ 10.20, p < .001, d ¼

.19). Again, this suggests that perceived thoughtfulness

and liking of the gift are not responsible for the greater

ability of experiential gifts to strengthen relationships.

Discussion

Using yet another measure of change in relationship

strength, the control conditions in study 4 replicated the

beneficial effect of receiving experiential gifts over mater-

ial gifts observed in the previous studies. This effect was

robust even when we controlled for many other features of

the gift. Moreover, this study used a test of moderation to

provide additional evidence for the underlying role of con-

sumption emotion and to identify an important boundary

condition for the effect: material gifts that made recipients

feel emotional while consuming them were as effective at

strengthening the relationship as experiential gifts.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Consumers spend a lot of money on others (Americans

spend approximately $130 billion on gifts per year; Unity

Marketing 2015), and spending money on others has been

proven to increase one’s own happiness (Dunn, Aknin, and

Norton 2008a). The current research explores the more far-

reaching effect on relationships between people, finding

that not all prosocial expenditures are equally beneficial.

Despite gift givers’ tendencies to give material posses-

sions, our findings show that material gifts are less effect-

ive than experiential gifts at strengthening

AQ2

relationships

between gift givers and their recipients.

This research provides guidance for gift givers on what

to give and offers insight into the relational function of

gifts. Taking the recipients’ perspective to assess the suc-

cess of gifts, we conducted experiments involving a variety

of real-life gift exchanges and ways of measuring relation-

ship change, and we consistently found that experiential

gifts strengthen relationships more than material gifts

(studies 1–4). This effect also emerged when the very same

gift was framed as being relatively more experiential

(study 2). A driving factor underlying this effect is the

greater level of emotion elicited when recipients consume

experiential gifts versus material gifts, which we identified

through tests of mediation (study 3) and moderation (study

4). Even though there was no difference in the intensity of

emotion recipients felt upon receiving experiential and ma-

terial gifts, recipients felt more emotional when consuming

experiential (vs. material) gifts, which served to strengthen

their relationship with the gift giver. From this, we learn

that gift givers seeking to foster closer relationships with

their recipients are likely to achieve greater success by giv-

ing experiential gifts, rather than material gifts.

Theoretical Contributions

To build on the now-established body of work that has

demonstrated that purchasing experiences (vs. material

goods) for oneself positively affects one’s personal well-

being (Carter and Gilovich 2010; Gilovich et al. 2015;

Nicolao et al. 2009; Rosenzweig and Gilovich 2012; Van

Boven and Gilovich 2003), research has begun investigat-

ing factors that precede experiential and material purchas-

ing (Dai, Chan, and Mogilner 2016; Kumar and Gilovich

2016; Kumar, Killingsworth, and Gilovich 2014; Tully,

Hershfield, and Meyvis 2015). Findings suggest that the

benefit of acquiring experiences for the purchaser can be

largely explained by the typically more social nature of ex-

periences (Bhattacharjee and Mogilner 2014; Caprariello

and Reis 2013). Our findings further contribute to this bur-

geoning stream of research by being the first to show the

interpersonal consequences of experiential versus material

purchases. In addition, we identify a novel advantage of

experiential purchases: consuming an experience evokes

greater emotion than consuming a material possession.

Our finding that the emotion felt during gift consump-

tion is responsible for strengthening relationships is con-

sistent with past work on interpersonal relationships that

CHAN AND MOGILNER 13

by guest on January 9, 2017http://jcr.oxfordjournals.org/Downloaded from

has highlighted the importance of emotion in close rela-

tionships (Aron et al. 2000; Bazzini et al. 2007; Clark and

Finkel 2004; Laurenceau et al. 1998; Nummenmaa et al.

2012; Peters and Kashima 2007; Raghunathan and

Corfman 2006; Ramanathan and McGill 2007; Slatcher

and Pennebaker 2006). Our research builds on this litera-

ture by showing that the gift of an emotional experience

can strengthen relationships, even when relationship part-

ners do not consume the gift together.

Our research also contributes to gift-giving research by

testing how different types of gifts impact relationships

and by examining the emotion evoked from gift consump-

tion. The bulk of the existing experimental work examining

recipients’ responses to gifts has focused on identifying

gifts that are better liked and appreciated (Flynn and

Adams 2009; Gino and Flynn 2011), rather than on under-

standing how gifts can change the relationship between the

gift giver and recipient (Aknin and Human 2015).

Although our findings indicate that the extent to which the

recipient likes the gift is positively related to change in re-