The Rodney L. White Center for Financial Research

The Long-term Returns on the Original

S&P 500 Firms

Jeremy J. Siegel

Jeremy D. Schwartz

29-04

1

The Long-term Returns on the Original

S&P 500 Firms

by

Jeremy J. Siegel and Jeremy D. Schwartz

Jeremy J. Siegel is the Russell E. Palmer Professor of Finance at the

Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania Jeremy D.

Schwartz is a 2003 graduate of the Wharton School and Assistant

Director of Research at Index Development Partners, Inc.

Draft December 5, 2004

Do note quote without permission.

2

Abstract

The S&P 500 Index, first compiled in March, 1957, is the most widely-used benchmark for

measuring the performance of large capitalization, US-based stocks. The index of 500 stocks is

continually updated, adding approximately 20 new firms each year that meet Standard and Poor’s

criteria for market value, earnings, and liquidity while deleting an equal number that fall below these

standards or are eliminated by mergers or other corporate changes.

We calculated the return of all 500 of the original S&P 500 firms and the new firms that have been

subsequently added to the index. Contrary to earlier studies, we found that the buy-and-hold returns

of the 500 original firms have outperformed the returns on the continually updated S&P 500 index

and have done so with lower risk. The new firms added to the S&P 500 Index since 1957 have

underperformed the original firms in nine of the ten industrial GICS sectors.

We also found that less than one-third of a sector’s return from 1957 through 2003 can be attributed

to the expansion and contraction of the sector’s market value relative to the S&P 500 Index. Sector

differences in dividend yields, capitalizations, and the number of firms admitted to the sector

accounted for more two-third of the changes in market share.

The underperformance of the continually updated S&P 500 Index is due to the overvaluation of

newly admitted firms, which have been caused by the cyclical fluctuations in investor sentiment and

price pressures exerted by indexers. Relative to the updated S&P 500 index, the portfolios of

original firms became heavily weighted with price-to-earnings stocks, particularly large oil

producers that have outperformed growth stocks since 1957.

3

The Long-term Returns on the Original S&P 500 Firms

by

Jeremy J. Siegel and Jeremy D. Schwartz

Introduction

The S&P 500 Index is the most widely-used benchmark for measuring the performance of large

capitalization, US-based stocks. Covering almost all of the 500 largest companies ranked by market

value, the S&P 500 Index comprised about 83% of the market capitalization of all regularly traded

stocks on the New York, American, and Nasdaq stock exchanges.

1

The index of 500 stocks, first compiled in March, 1957 is continually updated by adding new firms

that meet Standard and Poor’s criteria for market value, earnings, and liquidity while deleting an

equal number that fall below these standards or are eliminated by mergers or other corporate

changes.

2

S&P states that the purpose of updating is to maintain a representative index that includes

500 “leading companies in leading industries of the economy.”

3

It is well documented that over time

the S&P 500 index has outperformed the vast majority of active money mangers and mutual funds.

4

Since the S&P 500 was formulated, more than 900 new firms have been added and a like number

deleted from the index.

Joseph Schumpeter called the process by which new firms enter the market, challenge, and

eventually destroy the older firms, “creative destruction.”

5

Indeed, many of the giant firms in the

original index, such as US and Bethlehem Steel, Union Carbide, and Eastman Kodak have declined

while new firms, such as Intel, Microsoft, and Wal-Mart have taken their place. In fact, the market

value of the S&P 500 firms that have survived from the original 1957 list is only 31% of the 2003

year end S&P 500’s market value.

Many financial advisors counsel clients to continually upgrade their portfolio, claiming that new

firms offer investors higher returns than the older, dying companies. These recommendations were

supported by the research of Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan from McKinsey & Co who reported

that the new companies added to the S&P 500 Index have generated higher returns than the original

1

Market value based on the Wilshire 5000 Total Market Index valued at the end of October 2004.

2

A list of the selection criteria can be found on S&P’s website, www2.standardandpoors.com/spf/pdf/index/

500factsheet.pdf.

3

This quotation is found on S&P’s website, see above.

4

See “The Case for Indexing,” The Vanguard Group, September 2003, Siegel, Stocks for the Long Run, 3

rd

edition,

2002, McGraw Hill, Chapter 20, and Malkiel, B., A Random Walk Down Wall Street, 2003 edition.

5

Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Freedom, and Democracy, Harper and Bros, New York, NY, 1942

4

firms. They stated “without these new firms, the performance of the [S&P 500] index would have

been considerably less.”

6

Our research calculated the return of all 500 of the original S&P 500 firms and the new firms that

have been subsequently added to the index. Contrary to Foster and Kaplan’s results, we found that

the buy-and-hold returns of the 500 firms that were chosen for the original index in March 1957

have outperformed the returns on the continually updated S&P 500 index used by investment

professionals to benchmark their performance and have done so with lower risk. Underperformance

of the new firms added to the index were found in virtually all industries: in nine of the ten industrial

GICS sectors, the returns of the new firms added to the index fell short of the performance of the

original firms.

We also found that industry sectors that have gained market share over time have not always

translated into higher stockholder returns, while returns in shrinking sectors often beat the averages.

Specifically, less than one-third of a sector’s return can be attributed to the expansion and

contraction of the sector’s relative market value, while the remainder is due to differences in

dividends and the addition of new firms. These findings argue that updating the S&P 500 Index to

include new firms, while it may increase diversification, is not essential to achieve good returns.

History and Transformation of the S&P 500 Index

Standard & Poor’s Corporation first developed industry-wide stock price indices in 1923 and three

years later formulated the Composite Index containing 90 stocks.

7

The Composite Index was

expanded to 500 stocks on March 1, 1957 and renamed the S&P 500 Index. At that time, the firms in

the S&P 500 Index had a market value of $173 billion, comprising about 85 percent of the value of

all NYSE-listed stocks.

The Index originally contained exactly 425 industrials, 25 railroad, and 50 utility firms. In 1976, 40

financial stocks were added, and the industrial, transportation and utility groups were reduced to

400, 20, and 40, respectively.

8

In 1988 Standard and Poor’s eliminated fixed sectors with the goal of

achieving a diversified and representative portfolio of all stocks trading in US markets. In July 2002

all foreign-based companies, which comprised 1.3% of the market capitalization of the index at that

time, were eliminated and replaced by US-based firms.

9

6

Creative Destruction: Why Companies That Are Built to Last Underperform the Market – and How to Successfully

Transform Them, by Richard Foster and Sarah Kaplan, Random House, New York, 2001. p. 28.

7

See Standard and Poor’s Security Price Index Record, 2002 Edition, pg. I

8

The only financial stocks in the index in 1957 were consumer finance companies, such as Household International,

Beneficial Corp, and CIT Financial. Banks were not added to the Index until 1976. One of the reasons given for the

early exclusion of bank stocks was that most banks were trading on the over-the-counter exchange (which became

Nasdaq in 1971) and timely price data were not available.

9

In 2002, S&P eliminated Royal Dutch Petroleum, Unilever NV, and the Canadian firms Inco Ltd., Alcan Inc., Nortel

Networks, Barrick Gold and Placer Dome.

5

Updating the Index

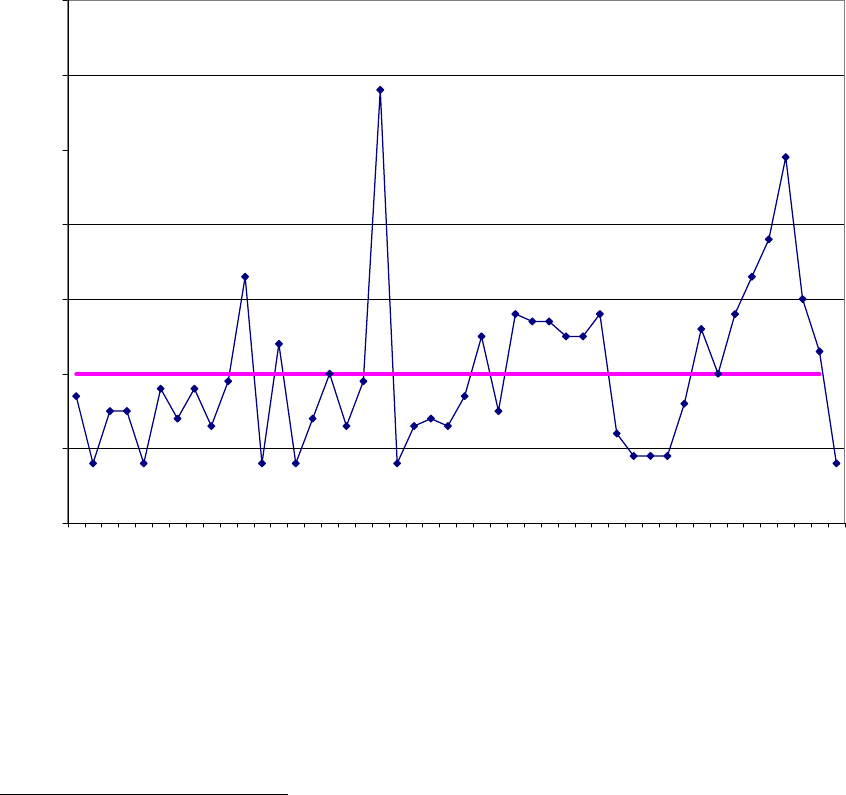

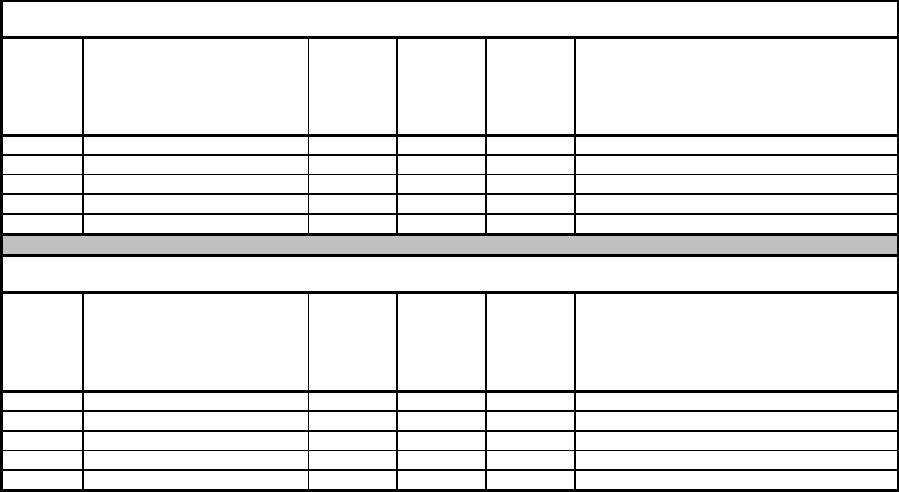

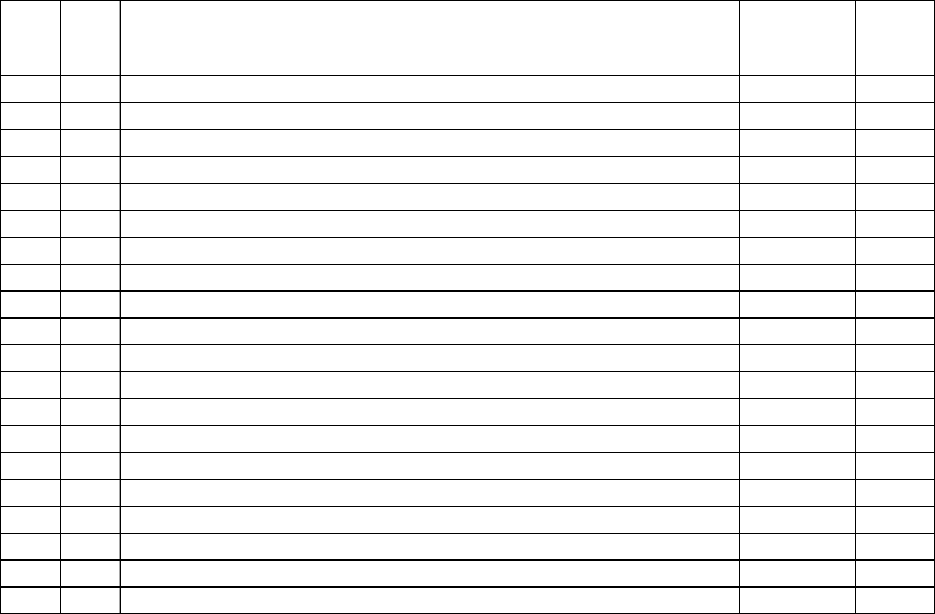

The total number of new firms added to the S&P 500 Index from its inception in 1957 through 2003

is 917, an average of 20 per year.

10

The number added each year is shown in Figure 1. The highest

number of new firms added to the index occurred in 1976, when the S&P added 60 firms, 40 of

which, as noted above, were financial. These new companies comprised 10.4% of the market value

of the index at the time.

11

Avg = 20

Total = 917

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

1958

1959

1960

1961

1962

1963

1964

1965

1966

1967

1968

1969

1970

1971

1972

1973

1974

1975

1976

1977

1978

1979

1980

1981

1982

1983

1984

1985

1986

1987

1988

1989

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

Number of Companies

Figure 1: Number of Firms added to the S&P 500 Index

10

This number may be lower than found on the S&P website since we did not consider a merger of two S&P companies

an addition to the index.

11

The addition and deletion of firms are not the only changes that have been made to the index. In order to match the

performance of the S&P 500 Index requires that indexers buy and sell shares when existing firms issue or repurchase

shares or change their capitalization in some other way. From 1993 through 2002, these capitalization changes have

averaged 1.56% of the market value of the index, a figure that rose to 2.49% during the technology boom in 2000.

Transactions related to capitalization changes have comprised about 30% of all the transactions that the S&P 500

indexers must undertake, the other 70% are related to the deletion and addition of firms to the index.

6

In recent years, annual additions have averaged slightly more than more than 5% of the market value

of the index. The percentage was higher during the late 1990s due to addition of new, high-

capitalization technology firms. In 2003, the number of new firms added to the index fell to a record-

tying low of 8, a level last reached in 1977.

Holding Period Returns to the Original Portfolio of S&P 500 Stocks

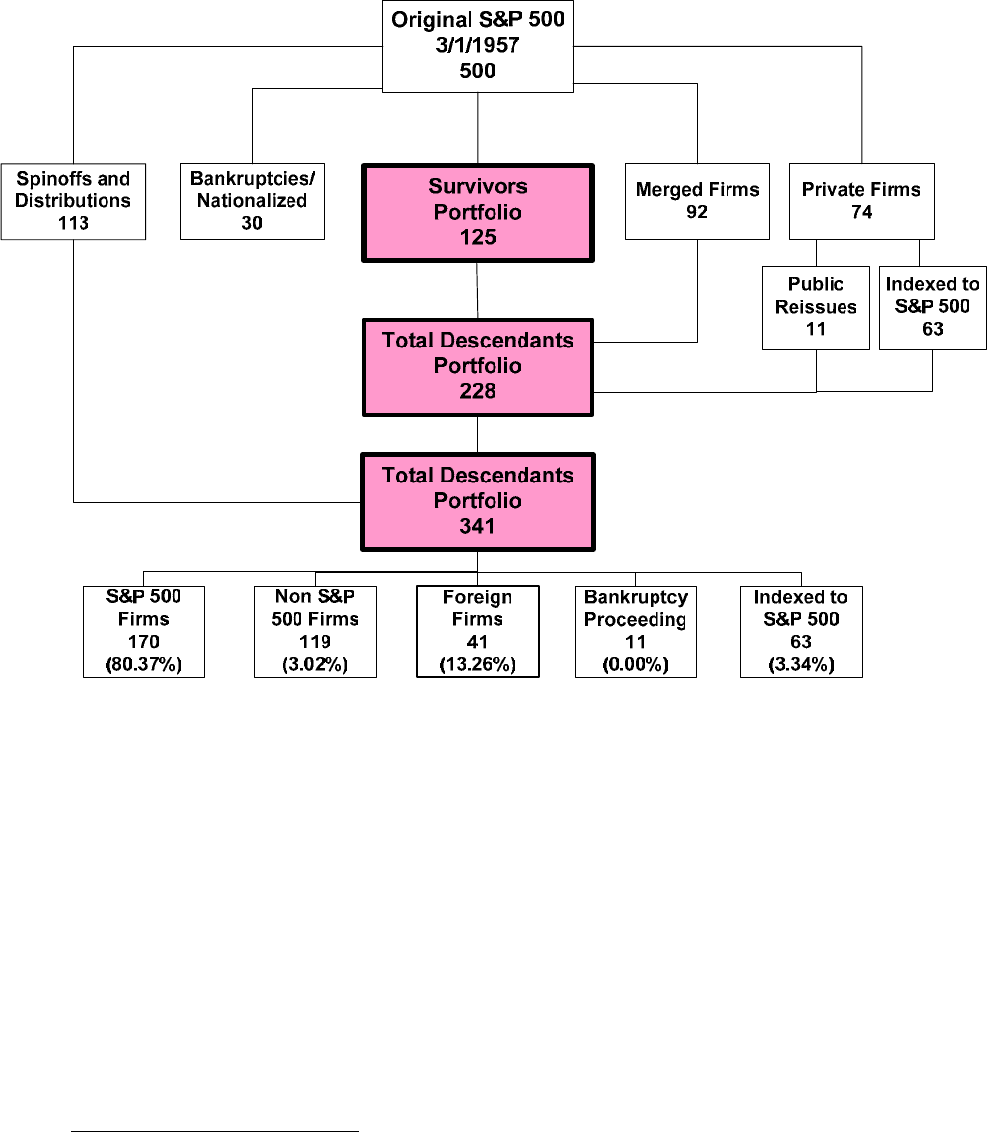

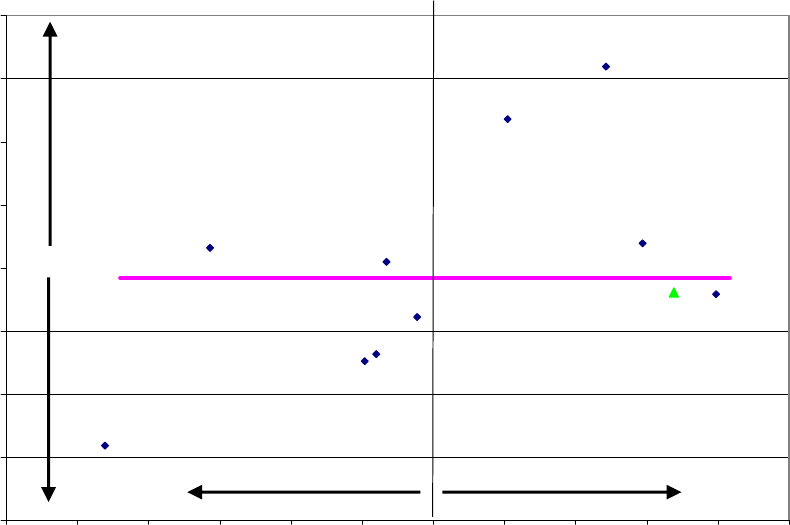

To calculate the performance of the original S&P 500 firms, we formed three portfolios. Over time

the three portfolios evolve differently depending on the assumptions we make about what investors

do with their shares received from a spin-off or when an original firm is merged into another firm or

went private. Figure 2 displays the evolution of these portfolios through time.

The first portfolio we analyze is called the Survivors’ Portfolio (SP). The survivor portfolio

consists only of shares of the original S&P 500 firms. Shares of other firms received through

mergers are immediately sold and the proceeds invested in the remaining survivor firms in

proportion to their market value. For example, when Mobil Oil was merged into Exxon in 1999,

shareholders of Mobil are assumed to sell the shares they received from Exxon-Mobil and invest the

proceeds in the remaining survivor firms. The surviving firm is identified as the company whose

identifier in the CRSP (Center for Research in Security Prices) “PERMNO” remains unchanged. All

spinoffs are immediately sold and the proceeds reinvested in the parent firm. Funds received from

privatizations are sold and the proceeds re-invested in the original surviving firms in proportion to

their market value.

It is important to note that the evolution of the survivors’ portfolio does not assume advance

knowledge of which firms survived Firms are deleted over time when they are privatized or merged

into other firms. As a result, there is no presumption that the returns on these firms would

outperform the benchmark index and there is no “survivorship bias.”

At year end 2003, the Survivors’ Portfolio consisted of 125 original firms that have remained intact

(except possibly for a name change) from 1957 to the present. Ninety-four of the surviving firms are

still in the S&P 500 index, 26 are publicly traded companies not in the index, and five are in

bankruptcy proceedings.

The second portfolio is called the Direct Descendants’ Portfolio (DDP), which consists of the shares

of firms in the survivors’ portfolio plus the shares issued by firms acquiring an original S&P 500

firm. In the case of the Mobil-Exxon merger discussed above, we assume that shareholders of Mobil

Oil hold the shares of Exxon that were issued in the merger.

If an original firm was taken private, we assume that the cash distributed from the privatization was

invested in an indexed portfolio whose returns matched the standard S&P 500 Index.

12

If a firm that

was taken private is subsequently reissued to the public again, we assume the portfolio repurchases

shares in the reissued company with the funds that had been invested in the index at the time the firm

12

In some cases, bonds or preferred shares were distributed in a privatization and we assumed that these funds were sold

and invested to match the index.

7

went private. Seventy-four original S&P 500 firms were privatized.

13

As before, spinoffs are

immediately sold and the proceeds reinvested in the parent.

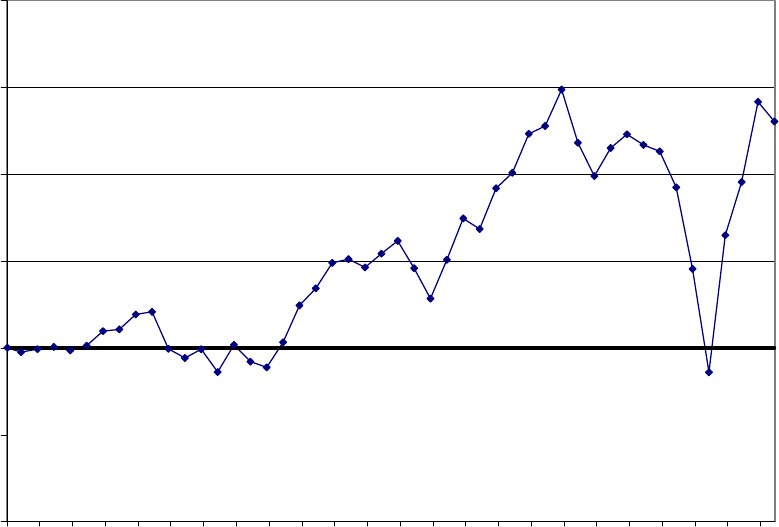

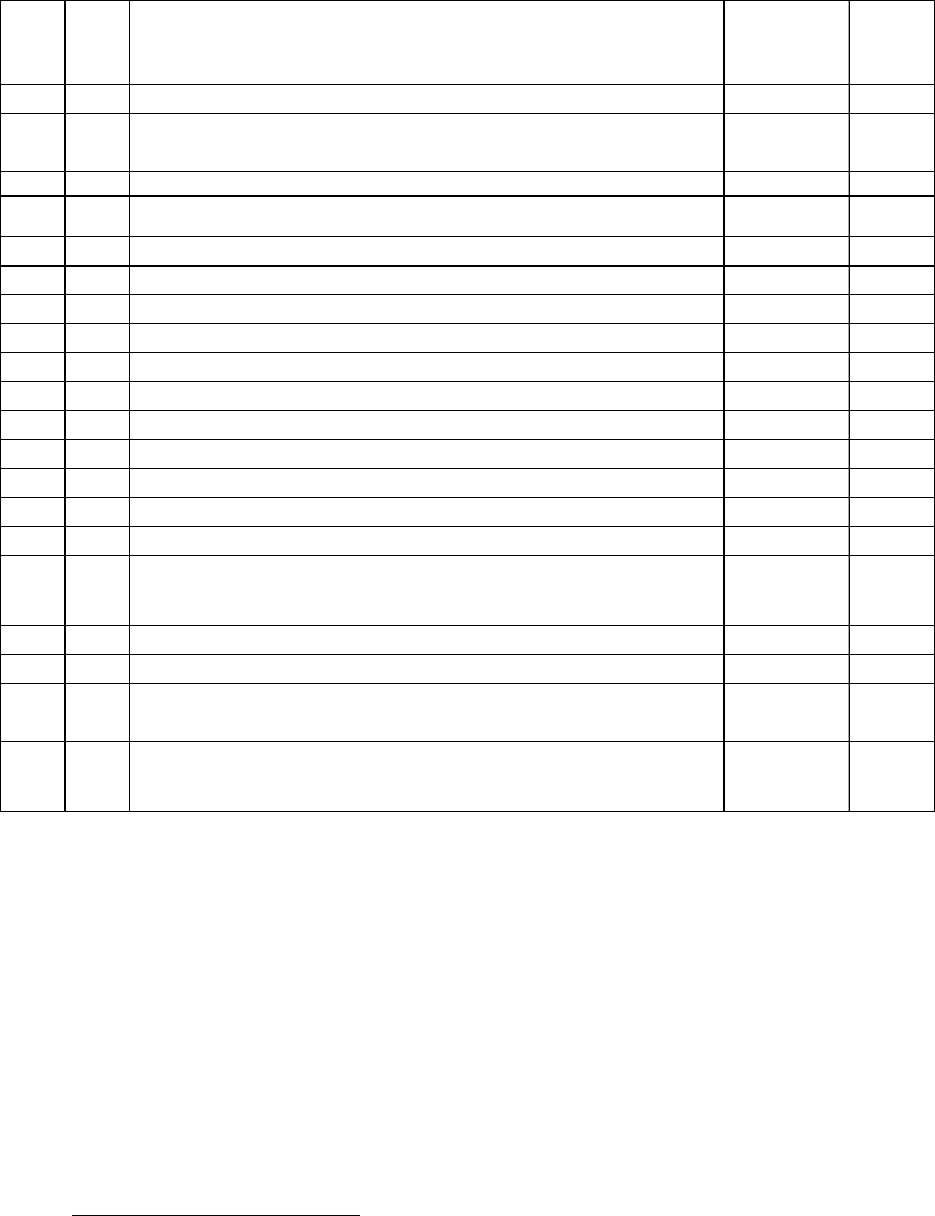

Figure 2: Composition of Original S&P 500 firms on December 31, 2003.

The third portfolio is called the Total Descendants’ Portfolio (TDP) and includes all firms in the

DDP plus all the spinoffs and other stock distributions issued by the firms in the Direct Descendants’

Portfolio. The only difference between the TDP and the DDP is that the TDP holds all the spinoffs

rather than sell them and reinvest in the proceeds in the parent firm.

The TDP is identical to the portfolio of a totally passive investor who holds all the spinoffs and

shares issued from mergers and never sells any stock. For example, when American Telegraph and

Telephone distributed its baby bells in 1983 following the government-mandated breakup of the

13

For example, when RJR Nabisco was taken private by KKR in 1989, investors in the TDP are assumed to invest the

money received for their shares in an S&P 500 index fund. Two years later when KKR reissued Nabisco Holdings,

shares were repurchased with the accumulation in the index fund.

8

monopoly, all the shares of the regional bell companies were held by investors in the TDP. Table 1

shows how the returns are calculated for each of the portfolios.

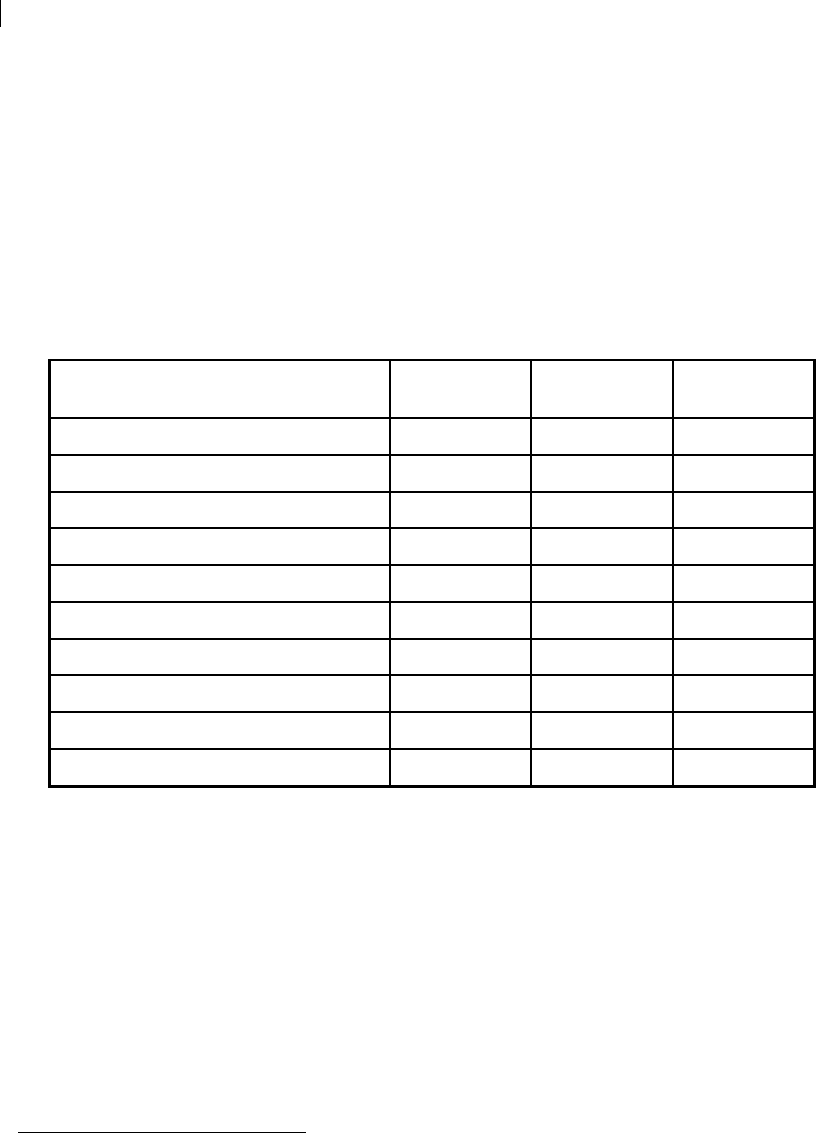

Portfolio Return Assumptions

Firms

Survivor Merged Distributions Privatized

Survivor

Held

Sold and Proceeeds

Reinvested in Remaining

Survivor Firms

Reinvested in

Parent

Sold and Proceeeds

Reinvested in Remaining

Survivor Firms

Direct Descendants

Held Held

Reinvested in

Parent

Matched to S&P

500*

Total Descendants

Held Held Held

Matched to S&P

500*

* If privatized firm subsequently re-issued, stock purchased with funds that were matched to S&P 500.

Portfolio

Table 1: Portfolio Return Assumptions

It should be noted that the return data compiled in the CRSP data bases assume that spinoffs are

immediately sold and the proceeds reinvested in the parent firm, as we have done for the direct

descendants’ portfolio.

14

But many investors do hold the spun-off firms and doing so is often both

tax and transaction-cost efficient. It is for this reason that we have also computed the returns of the

Total Descendants’ Portfolio

Figure 2 shows that through mergers, bankruptcies, nationalizations and privatizations, the original

500 firms have been reduced to 339 on December 31, 2003. Of these, 168 are still in the S&P 500

Index and these firms comprise 80.4% of the market value of the final accumulation of the TDP.

One hundred nineteen firms, comprising just under 3% of the final accumulations of the TDP are

US-based firms not currently in the S&P 500 Index; 41 firms, comprising 13.3% of the final

accumulation are foreign and headquartered outside the US, and 11 firms are in bankruptcy

proceedings. The firms privatized and not reissued constitute approximately 3% of the market value

of the portfolio.

The returns on Spin-offs versus the Parent

Although there was not a significant difference in the overall returns of the DDP and TDP portfolios,

Table 2 shows that for individual companies there were some significant differences between the

return of the parent firms and the returns of the spinoffs.

By far the most important spinoffs from the original S&P 500 firms belonged to American

Telephone and Telegraph, the largest and most widely held stock when the index was founded.

Investors who held all of AT&T’s spinoffs received a return of 10.50% per year, only 35 bps behind

the performance of the S&P 500 Index since 1957, while the return on parent company was only

7.85%, far below the market average.

14

See description of “Return” calculation in Data Description Guide for the CRSP US Stock Database and the CRSP US

Indices Database, Version CA276.200303.2, pg 184.

9

Spinoffs whose Return Exceed Parent

Company

Annual

Return w/

Spinoffs

Ann. Ret w/

Spinoffs

Reinvested

Gain in

Annual

Return

Spinoffs

1 AT&T 10.50% 7.85% 2.64% Baby Bells

2 Sears, Roebuck 11.32% 10.01% 1.31% Morgan Stanley, Allstate

3 Olin Corp. 10.88% 8.58% 2.30% Squibb Beechnut

4 Ford 11.64% 11.25% 0.39% Associates First Capital

5 American Brands 14.55% 14.42% 0.13% Gallaher Group

Spinoffs whose Return Fell Short of Parent

Company

Annual

Return w/

Spinoffs

Ann. Ret w/

Spinoffs

Reinvested

Loss in

Annual

Return

Spinoffs

1 Atchison, Topeka, Santa Fe 11.36% 13.42% -2.05% Catellus, Santa Fe Energy, Santa Fe Gold

2 Union Carbide 9.98% 10.51% -0.53% Praxair

3 Southern Co. 11.03% 12.17% -1.14% Mirant Corp

4 General Motors 8.28% 8.45% -0.17% Raytheon, Delphi

5 Du Pont 8.30% 8.40% -0.11% General Motors

Table 2: Effect of spinoffs on returns on specific companies

But spinoffs do not always outperform the parent. Praxair, a natural gas producer, underperformed

its parent Union Carbide and Mirant Corp., a provider of energy products and services and spun-off

by Southern Co. in 2001, declared bankruptcy in 2003.. Similarly, investors who held the rail stocks

were generally hurt by the relatively poor returns of the spinoffs of oil, gas, and other real properties.

Calculation of the Returns on the original S&P 500 portfolios

The returns from each of these three portfolios are analyzed from two initial allocations of the

original S&P 500 firms: value-weighted and equally-weighted. There is no rebalancing in any

portfolio after this initial allocation is made.

Table 3 shows the returns, standard deviation, and Sharpe ratios of all the portfolios and compares

them to the standard S&P 500 Index. All six of the portfolios of the original S&P 500 stocks

outperformed the S&P 500 benchmark and all had higher Sharpe ratios.

From March 1, 1957 through December 31, 2003, the S&P 500 Index registered a 10.85%

annualized compound return. The compound return on the value-weighted and equally-weighted

TDP was 11.40% and 12.14% per year respectively, beating the updated Index by 55 and 129 basis

points annually over the past 47 years.

10

Portfolio

Initial Weighting

Geometric

Return

Arithmetic

Return

Standard

Deviation

Sharpe

Ratio

Value

11.31% 12.38% 15.72% 0.4343

Equal

12.28% 13.75% 18.45% 0.4446

Value

11.35% 12.45% 15.93% 0.4331

Equal

12.18% 13.67% 18.55% 0.4375

Value

11.40% 12.53% 16.09% 0.4337

Equal

12.14% 13.63% 18.53% 0.4357

S&P 500 Value

10.85% 12.14% 17.02% 0.3871

Survivors Portfolio

Total Descendants

Direct Descendants

Table 3: Performance of Portfolios of Original S&P 500 Firms

The superior performance of the TDP is noteworthy since, as noted above, it is the most transaction-

cost and tax-efficient strategy of accumulating wealth from the original S&P 500 stocks. The TDP

involves fewer transactions than required of a standard S&P 500 index fund since no shares are ever

sold in the open market, and the only shares purchased arise from dividends or reissues of privatized

companies. Furthermore the TDP is the most tax-efficient strategy since, with very few exceptions,

no capital gains are realized as no shares are ever sold.

15

These results mean that these 500 firms chosen by Standard and Poor’s in 1957 have, on average,

outperformed the nearly one thousand new firms that had been added to the index over the

subsequent half century.

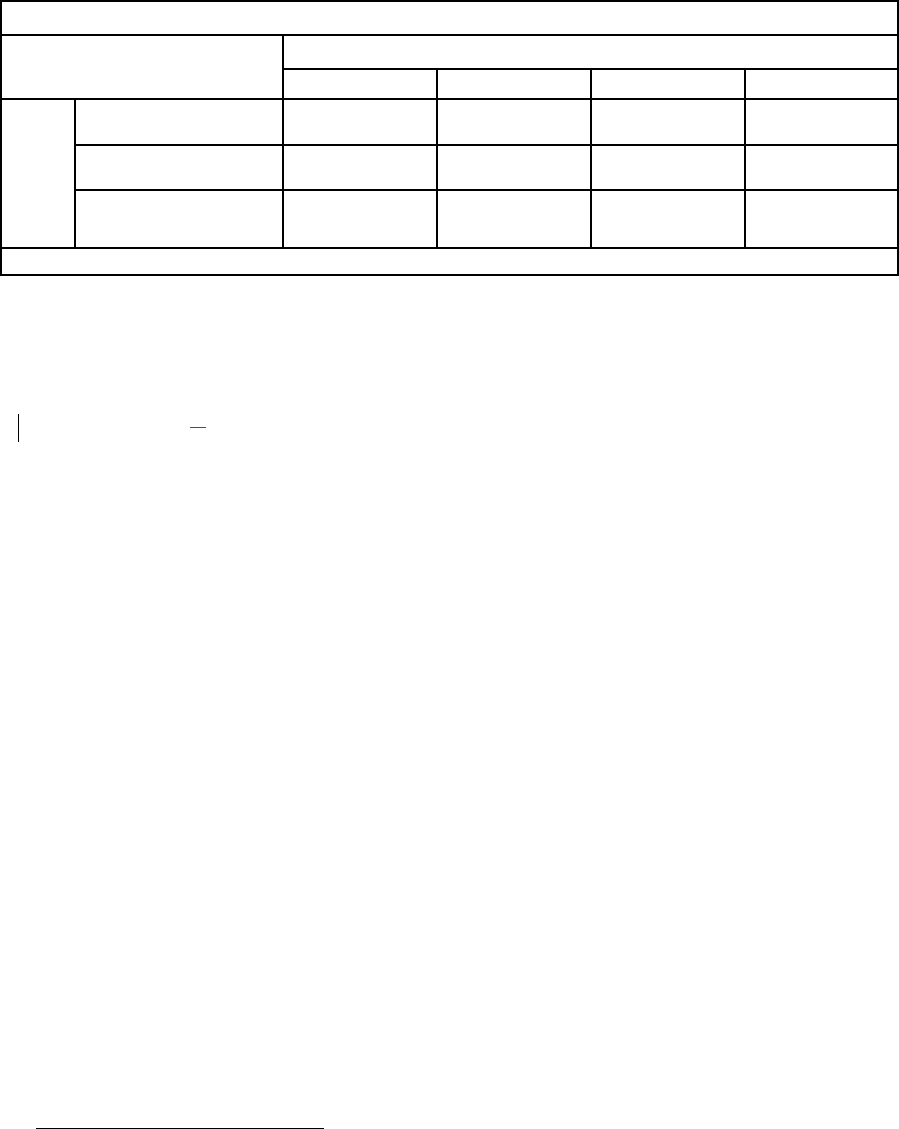

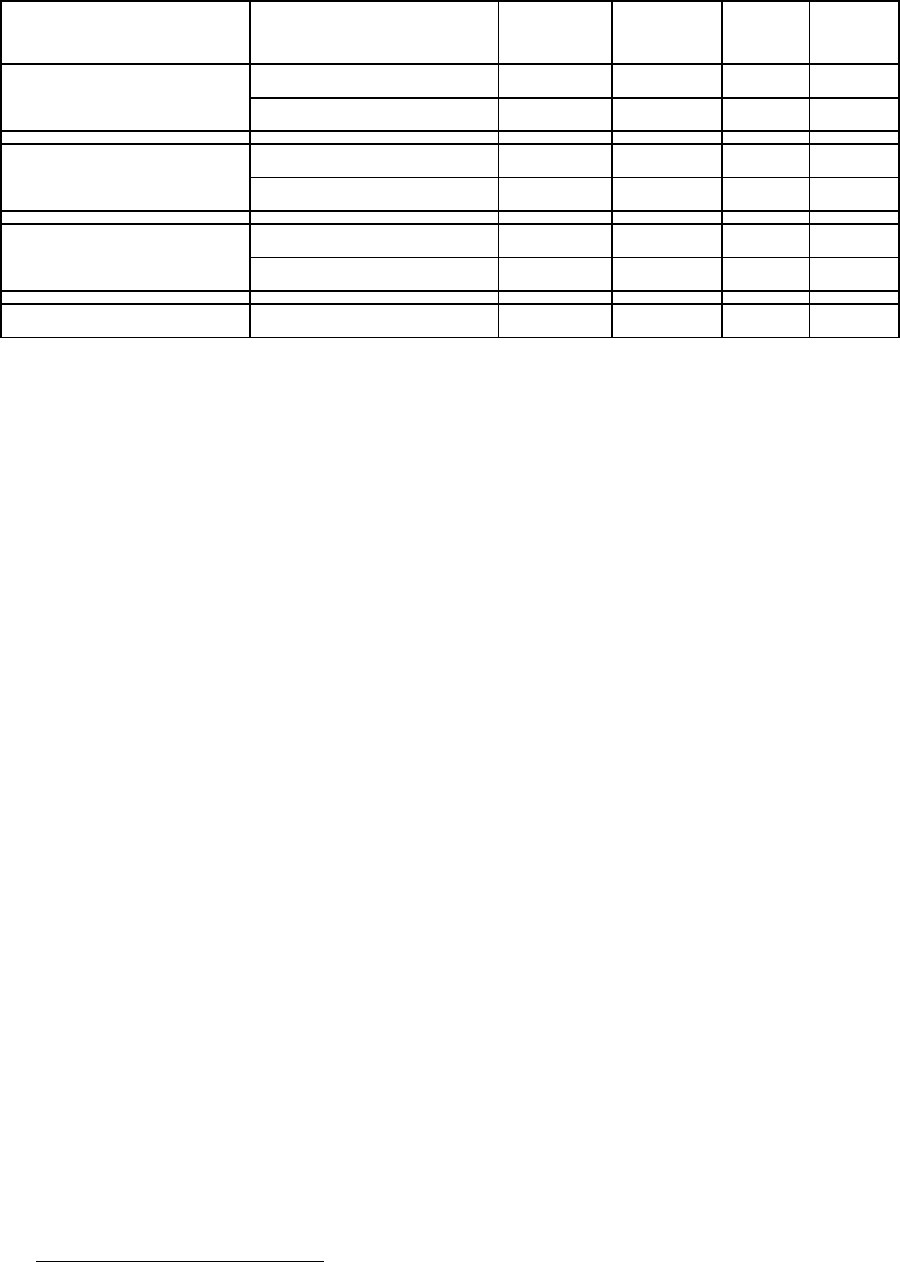

Figure 3 shows a yearly relative comparison of the cumulative return on the value-weighted TDP to

the S&P 500 Index from 1957 through 2003. The two returns are nearly coincident in the early

years because the two portfolios were nearly identical. In the late 1980s the cumulative return on the

TDP rose to a high of 30% above the S&P 500 Index. During the 1990s the relative performance of

the TDP declines, and at the end of 1999 the cumulative return on the TDP temporarily falls behind

the S&P 500 Index. This decline is due to the technology bubble which vastly inflated the returns to

the new technology entrants in the updated S&P 500 index while the TDP had a very small

technology weighting. When technology shares fell, the TDP again outperformed the standard,

updated S&P 500 Index.

15

There are a few cases where a stock distribution is not considered a non-taxable event by the IRS.

11

0.80

0.90

1.00

1.10

1.20

1.30

1.40

1957

1959

1961

1963

1965

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

Cumulative Return of TDP / S&P 500

Figure 3: Cumulative performance of value-weighted Total Dependents Portfolio relative to

S&P 500

Difference Between Changes in Market Value and Investor Return

The market value of the updated S&P 500 Index firms has risen at a 9.13% annual rate since the

index was founded, increasing from $172 billion in 1957 to $10.3 trillion by December 31, 2003. In

contrast, the market value of the Survivors’ Portfolio has grown at only a 6.44% annual rate,

reaching $3.2 trillion by the end of 2003. Yet the return on the survivor’s portfolio was greater than

the return on the S&P 500 index.

Investor return is a per share concept while market value records prices times aggregate number of

shares. Return to investors include reinvested dividends that are absent from market value data.

Furthermore, market value data are impacted by changes in the capitalization of individual firms, the

issuance of new shares, spinoffs, or by new, higher-valued firms replacing lower-valued, deleted

firms in the index. It was the confusion between market value and investor returns that led Foster

and Kaplan to their erroneous conclusions.

12

Long-term Returns of the Original S&P 500 firms.

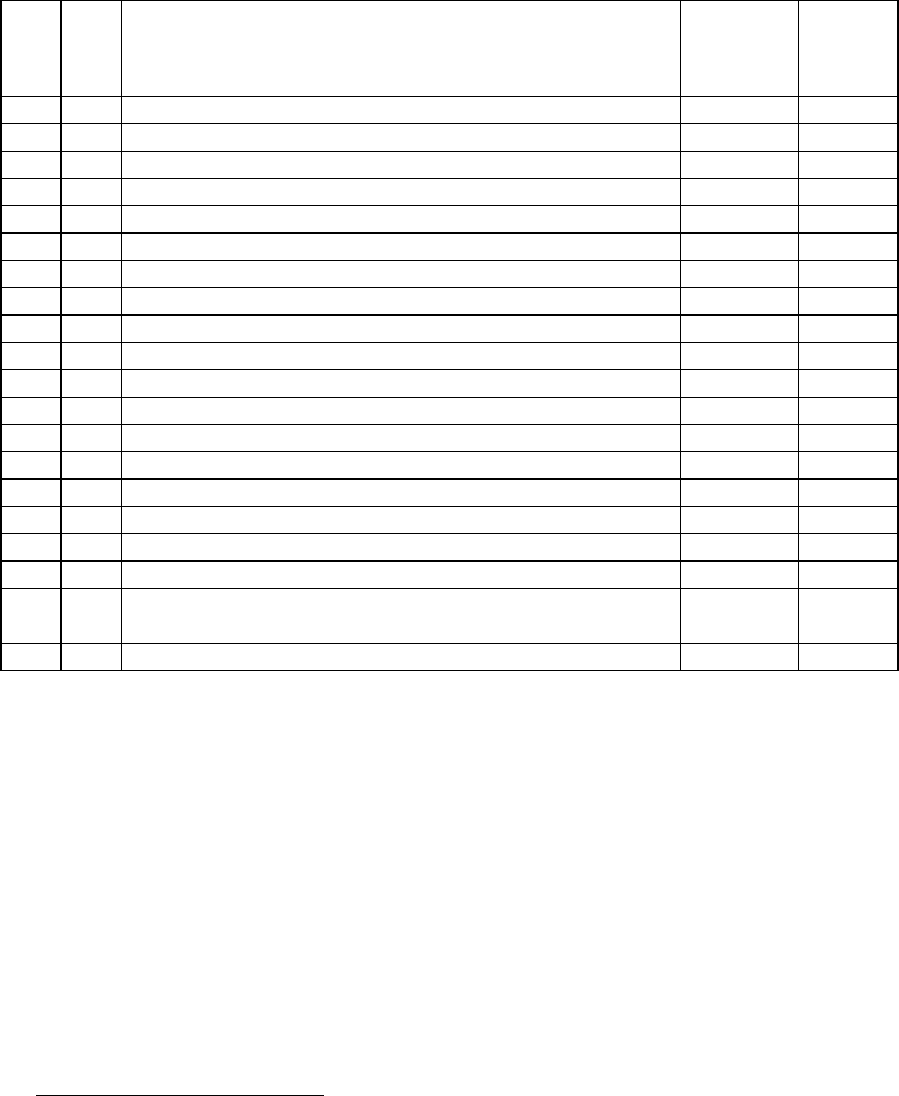

Table 4 shows the annualized returns from March 1, 1957 through December 31, 2003 of the twenty

largest market-value firms on March 1, 1957, Table 5 displays the twenty best-performing survivor

firms, and Table 6 records the twenty best-performing firms from the Total Descendants’ Portfolio.

16

Rank

Return

Rank

Market

Cap

1957

Original Name → 2003 Name (→ = Merger ► = Name Change )

Total

Accumulation

of $1

(including

s

p

inoffs

)

Annual

Return

112

Royal Dutch Petroleum

398.84 13.64%

214

Shell Oil → Royal Dutch Petroleum (1985)

323.96 13.14%

313

Socony Mobil Oil ► Mobil (1966) → Exxon-Mobil (1999)

322.41 13.13%

416

Standard Oil of Indiana ► Amoco (1985) → BP Amoco (1998)

285.31 12.83%

52

Standard Oil of New Jersey ► Exxon (1972) ► Exxon-Mobil (1999)

254.00 12.55%

65

General Electric

220.04 12.21%

76

Gulf Oil ► Gulf Corp. → Chevron (1984) ► Chevron-Texaco (2001)

214.12 12.14%

811

International Business Machines

196.50 11.94%

910

Standard Oil of California ► Chevron (1984) ► Chevron-Texaco (2001)

172.29 11.62%

10 15

Sears Roebuck

151.51 11.32%

11 8

Texas Co ► Texaco (1959) → Chevron-Texaco (2001)

128.63 10.93%

12 20

Phillips Petroleum ► ConocoPhillips (2002)

119.61 10.76%

13 1

American Telephone & Telegraph ► AT&T (1994)

107.16 10.50%

14 7

Union Carbide & Carbon ► Union Carbide (1957) → Dow Chemical (2001)

86.20 9.98%

15 4

Du Pont E I De Nemours & Co

41.82 8.30%

16 3

General Motors

41.47 8.28%

17 17

Aluminun Company of America ► Alcoa (1999)

37.74 8.06%

18 19

Eastman Kodak

35.33 7.91%

19 9

U S Steel ► USX Corp (1986) ► USX Marathon (1991) ► Marathon Oil

(2000)

8.25 4.61%

20 18

Bethlehem Steel

0.00 -13.54%

Table 4: Returns of the Largest 20 Companies from the Original S&P 500

Of the twenty largest firms in 1957, nine were oil firms and the five best performers – Royal Dutch

Petroleum, Shell Oil, Socony Mobil, Standard Oil of Indiana (now BP Amoco), and Standard Oil of

New Jersey (now Exxon-Mobil) were also oil companies. Each of these firms outperformed the

S&P 500 Index by between 2% and 3% per year over the 46 year period.

Of the four remaining oil companies, Gulf Oil, now part of Chevron Texaco, Standard Oil of

California, which changed its name to Chevron, and Texaco also outperformed the S&P 500 Index,

while Phillips Petroleum (now Conoco-Phillips) just fell short of the index’s performance.

The material and manufacturing stocks, such as Union Carbide (now part of Dow Chemical),

DuPont, General Motors, and Alcoa lagged the market significantly. US Steel would have given

16

Data on the returns of each firm of the original S&P 500 is available from the authors.

13

investors an even lower return had it not purchased and then sold Marathon Oil. Bethlehem Steel,

once the second largest steel manufacturer in the world behind US Steel, went bankrupt in 2001 and

is the only one of the twenty largest stocks to lose money for investors.

Despite the losers, an equal investment placed in each of the 20 largest S&P 500 firms when the

index was founded would have generated a 11.40% return for investors, 55 basis point greater than

the S&P 500. Interestingly, this return is exactly equal to the return received in the value-weighted

total descendants portfolio.

17

Table 5 lists the twenty top performing stocks for the survivors of the 500 original S&P 500 firms.

Many of these firms, such as Merck, Abbott Labs, Pfizer, Coca-Cola, Colgate-Palmolive, PepsiCo,

Wrigley, Heinz, outperformed the market by large margins over the past half century.

The single best performing firm of the original S&P 500 Index is Philip Morris, recently renamed

the Altria Group. Philip Morris yielded an annual return of 19.75% and beat the S&P 500 Index by

almost 9% per year since the index’s inception. $1,000 placed in an S&P 500 Index fund on

February 28, 1957 would have grown, with reinvested dividends, to almost $125,000 by December

31, 2003. But $1,000 put in Phillip Morris would have grown to almost $4.6 million.

It is of note that 18 of the twenty best-performing firms are from the pharmaceutical and consumer

staples industries. All these firms have strong consumer brand names and are marketed on an

international basis.

Table 6 lists the 20 top performing firms from the Total Descendants’ Portfolio. These include the

original S&P 500 firms that were merged into other firms as well as those survivor firms. Many of

the top-performing firms rode on the coattails of other successful firms: Through mergers the

shareholders of Thatcher Glass, General Foods, California Packing, National Dairy Products, and

Standard Brands all became shareholders of Philip Morris and shared in its success.

17

The superior performance of the original portfolios analyzed in the previous section is not solely due to the better

performance of the oil sector. Excluding the oil firms, the value-weighted TDP still beat the S&P 500 Index by 23 basis

points a year, and the return on the equally-weighted total portfolio actually rises if we exclude the oil sector.

14

Rank

Return

Rank

Market

Cap

1957

Original Name → 2003 Name (→ = Merger ► = Name Change )

Total Accum-

ulation

Annual

Return

1 215 Philip Morris ► Altria (2003) 4,626.40 19.75%

2 197 Abbot Labs 1,281.33 16.51%

3 299 Bristol Myers ► Bristol Myers Squibb (1989) 1,209.44 16.36%

4 487 Sweets Co. ► Tootsie Roll Industries (1966) 1,090.96 16.11%

5 143 Pfizer Inc. 1,054.82 16.03%

6 83 Coca-Cola 1,051.65 16.02%

7 117 Merck 1,032.64 15.97%

8 216 Pepsico 866.07 15.54%

9 239 Colgate-Palmolive 761.16 15.22%

10 275 Crane Co. 736.80 15.14%

11 277 Heinz 635.99 14.78%

12 188 Wrigley 603.88 14.65%

13 72 American Tobacco ► American Brands (1969) ► Fortune Brands (1997) 580.03 14.55%

14 180 Kroger Co. 546.79 14.41%

15 255 Schering Corp → Schering Plough (1971) 537.05 14.36%

16 31 Procter & Gamble 513.75 14.26%

17 227 Hershey Foods 507.00 14.22%

18 76 American Home Products ► Wyeth (2002) 461.19 13.99%

19 198 General Mills 420.49 13.77%

20 12 Royal Dutch Petroleum 398.84 13.64%

Table 5: Returns of the 20 top “Survivors”

15

Rank

Return

Rank

Market

Cap

1957

Original Name → 2003 Name (→ = Merger ► = Name Change )

Total

Accumulation

Annual

Return

1 215 Philip Morris ► Altria (2003) 4,626.40 19.75%

2473

Thatcher Glass → Rexall Drug (1966) ► Dart Industries (1969) → Dart &

Kraft (1980) ► Kraft (1986) → Philip Morris (1988)

2,742.27 18.42%

3 447 National Can → Triangle Industries (1985) → Pechiney SA (1989) 2,628.72 18.31%

4485

Dr. Pepper → Private (1984) → Dr. Pepper Seven Up (1993) → Cadbury

Schweppes

(

1995

)

2,392.22 18.07%

5 458 Lane Bryant → Limited Stores (1982) ► Limited Inc. (1982) 1,997.87 17.62%

6 65 General Foods → Philip Morris (1985) 1,467.10 16.85%

7 197 Abbot Labs 1,281.33 16.51%

8 234 Warner-Lambert → Pfizer (2000) 1,225.25 16.40%

9 259 Celanese Corp. → Hoechast AG (1987) → Aventis (1999) 1,220.16 16.39%

10 299 Bristol Myers ► Bristol Myers Squibb (1989) 1,209.44 16.36%

11 433 Columbia Pictures → Coca-Cola (1982) 1,154.27 16.25%

12 487 Sweets Co. ► Tootsie Roll Industries (1966) 1,090.96 16.11%

13 274 American Chicle → Warner-Lambert (1962) → Pfizer (2000) 1,069.50 16.06%

14 143 Pfizer Inc. 1,054.82 16.03%

15 83 Coca-Cola 1,051.65 16.02%

16 267

California Packing Corp → Del Monte (1978) → Reynolds RJ Industries

(1979) → Private (1989) → RJR Nabisco Holdings (1991) → Philip Morris

(2000)

1,050.10 16.01%

17 117 Merck 1,032.64 15.97%

18 348 Lorillard → Loew's Theatres (1968) ► Loew's Corp (1971) 1,026.20 15.96%

19 66

National Dairy Products → Dart & Kraft (1980) ► Kraft (1986) → Philip

Morris (1988)

1,011.39 15.92%

20 218

Standard Brands → Nabisco Brands (1981) → Reynolds RJ Industries

(1985) ►RJR Nabisco (1986) → Private (1989) → RJR Nabisco Holdings

(1991) → Philip Morris (2000)

1,002.98 15.90%

Table 6. Returns on 20 top-performing Stocks from Total Descendants’ Portfolio

GICS Sector Returns

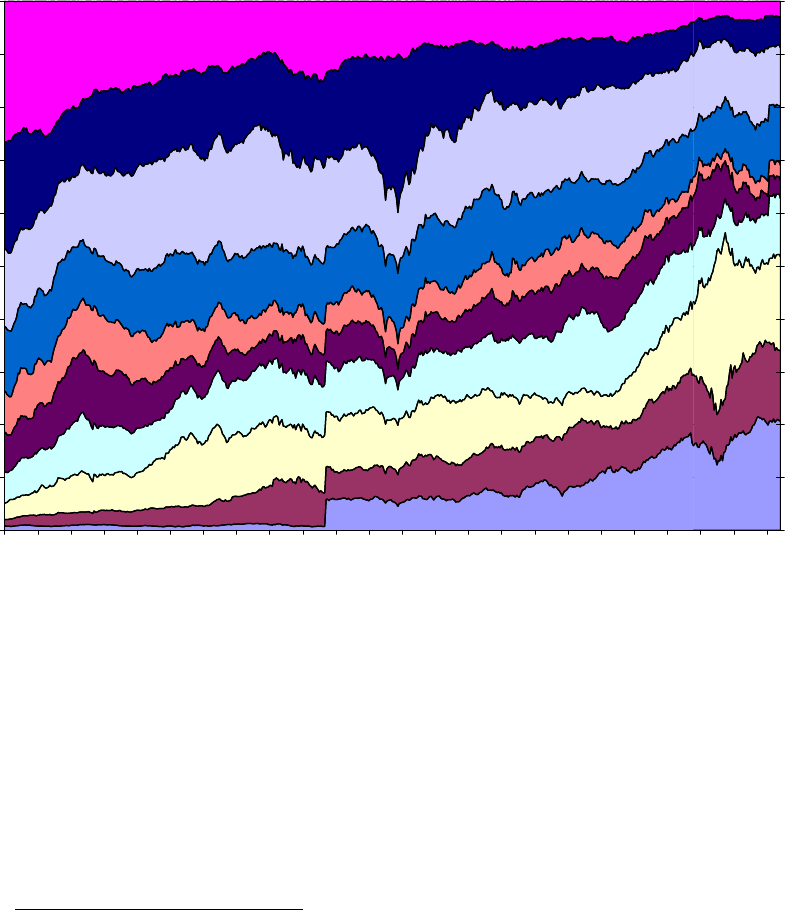

Figure 4 shows the share of the market value of the major sectors of the original S&P 500 Index in

1957 and the sector weights today.

18

The upward jump in the financial sector’s share in 1976 occurred

when Standard and Poor’s added 40 financial firms to the index.

Through the addition of new firms and the transformation of old firms, there has been a profound

change in the industry over the past half century. The three smallest sectors in 1957 (Financials,

18

While Standard & Poor’s developed the current GICS (Global Industry Classification Standard) definitions in 2001,

we were able to map firms into the sectors by using SIC (Standard Industry Classification) codes as well as S&P’s

Security Price Index Record which contains the complete company history of S&P industry groups.

16

Health Care, and Information Technology) became the three largest sectors by the end of 2003.

Financials grew from less than one percent of the market value of the S&P 500 Index to over 20%,

Health Care grew from 1.2% to 13.3%, and information technology grew from 3.1% to 17.7%.

On the other hand, the two largest sectors in 1957, materials and energy, have shrunk dramatically.

The Materials sector includes firms engaged in commodity-related manufacturing, such as

chemicals, steels, paper, etc. These firms comprised over one-quarter of the market’s value in 1957

but have become the second smallest sector in the index today. The energy sector has also shrunk

dramatically – from 20% of the market to only 6% today.

Financials

Health Care

Information Tech

Consumer Staples

Telecom Svc

Utilities

Industrials

Consumer Discretionary

Energy

Materials

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

1957

1959

1961

1963

1965

1967

1969

1971

1973

1975

1977

1979

1981

1983

1985

1987

1989

1991

1993

1995

1997

1999

2001

2003

0%

10%

20%

30%

40%

50%

60%

70%

80%

90%

100%

Figure 4 Market Sector Share, 1957-2003

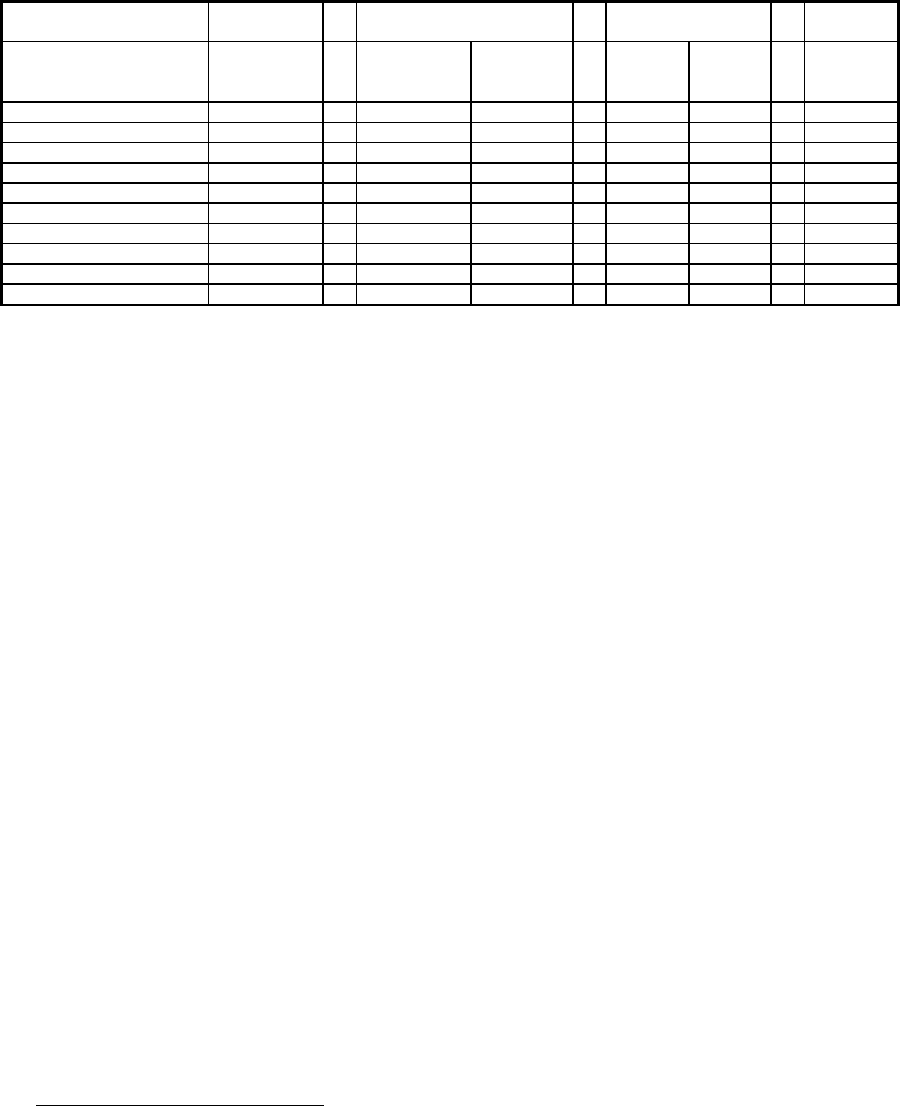

Table 7 lists the sector returns of the original and continually updated S&P 500 Index. The sector

returns based on the original firms in the index outpaced the sector returns based on the updated

S&P 500 Index in every sector except consumer discretionary.

19

This means that the outperformance

of the original firms in the S&P 500 Index was not concentrated in one sector, but present in all the

sectors of the economy.

19

As noted in footnote 7 above, the current GIC classification was begun in 1999. Prior to that date we matched firms to

the current classifications.

17

Original S&P

500

Total Descendants

Portfolio

Sector

Market Cap

1957

Market Cap

2003

Annual

Return

Market

Cap Final

Annual

Return

Difference

Consumer Discretionar

y

14.58% 6.86% 9.80% 11.30% 11.09% -1.29%

Consumer Staples 5.75% 20.19% 14.43% 10.98% 13.36% 1.07%

Energ

y

21.57% 31.82% 12.32% 5.80% 11.32% 1.01%

Financials 0.77% 1.12% 12.44% 20.64% 10.58% 1.86%

Health Care 1.17% 6.07% 15.01% 13.31% 14.19% 0.82%

Industrials 12.03% 10.33% 11.17% 10.90% 10.22% 0.95%

Information Tech 3.03% 3.10% 11.42% 17.74% 11.39% 0.03%

Materials 26.10% 10.33% 9.41% 3.04% 8.18% 1.23%

Telecom Svc 7.45% 5.94% 10.47% 3.45% 9.63% 0.84%

Utilities 7.56% 4.25% 9.97% 2.84% 9.52% 0.45%

Actual S&P 500

Table 7: Sector Returns on Total Descendants Portfolio and S&P 500 Index

The original firms in the consumer discretionary sector underperformed the updated sector for two

reasons. First, General Motors, which comprised over 43% of the sector’s market value in 1957,

realized a poor return of only 8.28%, far below the 11.09% return to the entire sector.

20

Secondly,

Wal-Mart, one of the best performing stocks in market history, was classified in the consumer

discretionary sector until 2003, when S&P switched it to the consumer staples sector. The

underperformance of General Motors and the superior performance of Wal-Mart are the reasons the

original firms in the consumer discretionary sector could not outperform the new firms added.

Sector Shifts and Sector Returns

Changes in the relative market value of a sector correlate only weakly with returns in that sector.

Investors often ignore stocks in declining market sectors, such as energy, and the low prices for their

stocks results in superior investor returns. On the other hand, expanding sectors frequently become

overvalued, attracting new firms that result in overexpansion, excess capacity, and a sharp

subsequent decline in share prices.

20

Without GM, the original sector’s return would be 79 basis points higher, whereas the updated sector would have only

been 43 basis points higher.

18

Consumer

Discr

Consumer Staples

Energy

Financials

Health Care

Industrials

Technology

Materials

Telecom

Utilities

S&P 500

Technology

Ex-IBM

7%

8%

9%

10%

11%

12%

13%

14%

15%

-30% -25% -20% -15% -10% -5% 0% 5% 10% 15% 20% 25%

Return

Shifts in GICS Sector Weighting

Expanding SectorContracting Sector

Inferior Returns Superior Returns

Figure 5: Relation between Change in Market Value and Return in each Sector

Figure 5 plots the return of each sector against the change in the weighting of the sector from 1957

through 2003. Energy and Consumer Discretionary had above-average returns despite contracting

sectors, while Financials had below average returns and Information Technology had slightly above

average returns, but without IBM, which dominated the index in the 1950s and 1960s, technology

would have also had below average returns. Eq. (1) below is a regression of the sectors’ returns, y

t

,

on the charge in the market share of the GIC sector, x

t

.

(1) y

t

= 0.1095 + .0753x

t

+ ε

t

; R

2

= 0.3187.

(t = 1.934)

Where, y

t

, is the sector’s return and x

t

is

the change of its share of market value. An R

2

of 0.31

indicates that less than one-third of the excess returns is associated with the change in the sector

weight. The other two-thirds of the return is due to the addition of new firms or changes in the

capitalization of existing firms.

Reasons for Underperformance of New Stocks

Our finding that the new firms added to the index since 1957 on average have actually reduced the

return to investors should not reflect poorly on Standard and Poor’s Index Committee or the firms

19

selected by this committee. In fact, S&P wisely resisted adding a number of technology and internet

firms in the late 1999s into the index although they attained huge market values.

21

Cyclical Overvaluation of New Firms

Despite S&P’s restrained, there is pressure to add firms of high market value when there is a

vacancy in the index. Therefore, when investor demand for a particular sector is high, such as for the

oil service stocks in the 1978-80 energy bubble or the technology and telecommunications stocks in

the 1998-2000 bubble, these stocks become candidates for admission to the index. Their high price

relative to fundamentals leads to a downward bias to future returns.

22

For example, the underperformance of the updated energy sector is due primarily to the oil and gas

extractors, many of which were added during the energy boom of the early 1980s. In fact, 12 of the

13 energy stocks that were added during the 1980s, such Texas Oil and Gas, McDermott

International, Pennzoil, Rowan, Baker Hughes, Helmerich & Payne, underperformed the index.

The telecommunications sectors also experienced a boom that resulted in the addition of overpriced

stocks that dragged down the performance of the sector. This sector added virtually no new firms

from 1957 through the early 1990s. But in the late 1990s, new firms, such as WorldCom, Global

Crossing, and Qwest entered the index and subsequently underperformed the average by a large

margin. In June of 1999 WorldCom constituted over 16% of sector’s market value, but subsequently

lost 97.9% of its value by the time it was deleted from the index in May 2002. Qwest lost over 65%

of its value since it was admitted, while Global Crossing lost over 98% of its value before it was

deleted in October 2001.

The technology sector, despite a few very successful firms, has been hurt by firms that have been

added when the public’s demand for technology stocks is high. Thirty six of the 125 technology

firms that have been added to this sector since its founding occurred in 1999 and 2000, and two-

thirds of these have underperformed the sector’s return since their admittance. Firms admitted in

1999 underperformed the sector by 4% per year and those admitted in 2000 subsequently

underperformed the sector by 12% annually. Despite the huge success of firms such as Intel,

Microsoft, Cisco, and Dell, the drag from the addition of overpriced technology firms significantly

hurt the performance of this important sector.

Price Pressure from Indexing

Another reason for superior performance of the original firms relates to the overvaluation of new

firms caused by price pressure exerted on new stocks by indexers that must buy shares of the firms

added to this popular benchmark. Standard and Poor’s Corporation published a study in September

2000 that noted that from the announcement date to the effective date of admission in the S&P 500

21

During the internet boom, S&P only admitted AOL, in January 1999 and Yahoo in December, 1999.

22

Ritter, Jay, ’Hot Issue’ Market of 1980, Journal of Business, 1984 (vol. 57, no. 2), pp 215-240 documents a similar

phenomena in the poor performance of initial public offerings during hot issue markets.

20

stock index, that over the previous decade shares rose by an average of 8.49%.

23

A more recent

study indicates that these price jumps have been reduced in recent years, but this may be due to

speculators who purchase firms that are candidates for admission, in turn pushing their price upward

before the announcement.

24

Value Bias of Original Portfolios

One of the reasons for the superior performance of the original portfolios is that the Total

Descendants’ Portfolio had a higher weights in sectors that outperformed over time and tended to

have lower price-to earnings ratios. Table 8 shows the sector weights of the Total Descendants’

portfolio on December 31, 2003 and compares this to the weights in the S&P 500 Index. Investors

in the TDP are significantly overweight in the energy sector and moderately overweight in the

consumer staples sector. Both of these sectors outperformed the S&P 500 Index. On the other hand,

investors in the TDP are underweight in the health care, financials and information technology

sectors.

Energy 34.82% 5.80% 29.02%

Consumer Staples 19.27% 10.98% 8.29%

Industrials 12.01% 10.90% 1.11%

Health Care 6.67% 13.31% -6.65%

Materials 6.78% 3.04% 3.74%

Consumer Discretionary 6.54% 11.30% -4.76%

Telecom Services 4.72% 3.45% 1.27%

Utilities 4.04% 2.84% 1.20%

Financials 2.67% 20.64% -17.98%

Information Technology 2.50% 17.74% -15.24%

Sector

Total

Descendants

S&P 500 Difference

Table 8: Composition of Total Descendants and S&P 500 portfolios on December 31, 2003.

Because the original portfolios became underweight in technology firms and overweight in energy

firms, they took on a significant “value” bias over time. On December 31, 2003, the average price to

earnings ratio, based on the last 12 months of reported earnings, was 15 on the TDP compared to 22

for the S&P 500 Index. Since the performance of “value” stocks has exceeded those of “growth”

23

Roger Bos, “Event Study: Quantifying the Effect of Being Added to an S&P Index,” Standard and Poor’s, September

2000.

24

See Srikant Das, “Index Effect Redux,” Standard and Poor’s, September 8, 2004

21

stocks from 1957 through 2003,

25

this explains some of the out performance of the original

portfolios.

Summary

Many in the financial community believe that the active updating of firms in the S&P 500 Index is

essential to obtain the high returns that this index has recorded over the past half century. This study

shows that this is not the case. We find that a portfolio of the original 500 stocks chosen by

Standard and Poor’s to formulate their index in 1957 have outperformed the standard, updated S&P

500 Index over the subsequent 46 year-period and with lower risk. Furthermore, the original firms in

nine of the ten GICS industry sectors have outperformed the new firms added to these sectors.

This study also shows that there is a weak relation between returns to a sector and the relative

change in aggregate market value of the sector. Some sectors that have outperformed the S&P 500

index have shrunk dramatically, such as energy, while others that have expanded greatly, such as

financials and information technology, have mediocre or below average returns. Less than one third

of a sector’s excess return over the S&P 500 Index is associated with the expansion or contraction of

a sector.

There are several reasons for the underperformance of the new firms added to the S&P 500 Index.

Temporary overvaluation of a firm’s stock, due to fluctuations in investor sentiment unrelated to

firm fundamentals, may push a firm’s valuation high enough to qualify for admittance to the index.

This overvaluation will result in a downward bias in future returns. Another source of overvaluation

is the price pressures exerted by indexers who must buy the stock when a new firm is admitted to the

index. Finally, the original portfolios had higher weights in value stocks with low prices relative to

fundamentals, such as energy and they were underweight in technology stocks.

25

Among the recent studies documenting superior performance of low P-E stocks are, Ibbotson Associates, Stocks,

Bonds, Bills, Inflation 2004 Yearbook and James O’Shaughnessy, What Works on Wall Street, Revised Edition,

McGraw-Hill, 1998. Important historical studies of the outperformance of low P-E stocks are ; S. F. Nicholson, “Price-

Earnings Ratios,” Financial Analysts Journal, July/August 1960, pp. 43–50; 2) S. Basu, “Investment Performance of

Common Stocks in Relation to their Price-Earnings Ratio: A Test of the Efficient Market Hypothesis,” Journal of

Finance, 32 (June 1977), pp. 663–82..

22

Bibliography

S. Basu, “Investment Performance of Common Stocks in Relation to their Price-Earnings

Ratio: A Test of the Efficient Market Hypothesis,” Journal of Finance, 32 (June 1977), pp.

663–82..

Bos, Roger. Event Study: Quantifying the Effect of Being Added to an S&P Index, Standard

and Poor’s, September 2000.

Srikant Das, “Index Effect Redux,” Standard and Poor’s, September 2004

Foster, Richard and Sarah Kaplan, Creative Destruction: Why Companies That Are Built to

Last Underperform the Market – and How to Successfully Transform Them. Random House,

New York, 2001.

Ibbotson Associates, Stocks, Bonds, Bills, Inflation 2004 Yearbook

Malkiel, Burton. A Random Walk Down Wall Street, W.W. Norton & Company, 2003

S. F. Nicholson, “Price-Earnings Ratios,” Financial Analysts Journal, July/August 1960, pp.

43–50; 2)

O’Shaughnessy, James, What Works on Wall Street, Revised Edition, McGraw-Hill, 1998

Ritter, Jay, ’Hot Issue’ Market of 1980, Journal of Business, 1984 (vol. 57, no. 2), pp 215-

240

Joseph Schumpeter, Capitalism, Freedom, and Democracy, Harper and Bros, New York,

1942.

Siegel, Jeremy. Stocks for the Long Run, 3

rd

edition, McGraw Hill, New York, 2002.

Standard and Poor’s Security Price Index Record, 2002 Edition

The Vanguard Group, The Case for Indexing, October 2003.

The Rodney L. White Center for Financial Research

The Wharton School

University of Pennsylvania

3254 Steinberg Hall-Dietrich Hall

3620 Locust Walk

Philadelphia, PA 19104-6367

(215) 898-7616

(215) 573-8084 Fax

http://finance.wharton.upenn.edu/~rlwctr

The Rodney L. White Center for Financial Research is one of the oldest financial research centers in the

country. It was founded in 1969 through a grant from Oppenheimer & Company in honor of its late

partner, Rodney L. White. The Center receives support from its endowment and from annual

contributions from its Members.

The Center sponsors a wide range of financial research. It publishes a working paper series and a reprint

series. It holds an annual seminar, which for the last several years has focused on household financial

decision making.

The Members of the Center gain the opportunity to participate in innovative research to break new ground

in the field of finance. Through their membership, they also gain access to the Wharton School’s faculty

and enjoy other special benefits.

Members of the Center

2004 – 2005

Directing Members

Geewax, Terker & Company

Goldman, Sachs & Co.

Hirtle, Callaghan & Co.

Morgan Stanley

Merrill Lynch

The Nasdaq Educational Foundation

The New York Stock Exchange, Inc.

Members

Aronson + Johnson + Ortiz, LP

Twin Capital

Founding Members

Ford Motor Company Fund

Merrill Lynch, Pierce, Fenner & Smith, Inc.

Oppenheimer & Company

Philadelphia National Bank

Salomon Brothers

Weiss, Peck and Greer