Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=tsfi20

Download by: [Camille Smith] Date: 05 October 2016, At: 02:42

Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment

ISSN: 2043-0795 (Print) 2043-0809 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tsfi20

ESG factors and risk-adjusted performance: a new

quantitative model

N. C. Ashwin Kumar, Camille Smith, Leïla Badis, Nan Wang, Paz Ambrosy &

Rodrigo Tavares

To cite this article: N. C. Ashwin Kumar, Camille Smith, Leïla Badis, Nan Wang, Paz Ambrosy &

Rodrigo Tavares (2016): ESG factors and risk-adjusted performance: a new quantitative model,

Journal of Sustainable Finance & Investment, DOI: 10.1080/20430795.2016.1234909

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2016.1234909

Published online: 04 Oct 2016.

Submit your article to this journal

View related articles

View Crossmark data

ESG factors and risk-adjusted performance: a new quantitative

model

N. C. Ashwin Kumar

a

, Camille Smith

a

, Leïla Badis

a

, Nan Wang

a

, Paz Ambrosy

a

and

Rodrigo Tavares

b

a

IE Business School, Madrid, Spain;

b

Granito & Partners

ABSTRACT

Conventional finance wisdom indicates that less risk leads to

lower returns. Against this belief, new mathematical analysis,

introduced in this article, demonstrates that companies that

incorpora te Environmental, Social and Fair Governance (ESG)

factors show lower volatility in their s tock perfor mances than

thei r peers in the same industry, that each industry is affected

differently by ESG factors, and that ESG companies generate

higher retu rns. The study assessed, for a period of 2 y ears, 157

companies list ed on the Dow Jones Sustainability Index and 809

that are not.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 13 June 2016

Accepted 7 September 2016

KEYWORDS

Corporate responsibility; ESG;

responsible investment;

social finance

1. Introduction

It is commonsense that the integration of Environmental, Social and Fair Governance

(ESG) practices makes a company less vulnerable to reputation, political and regulatory

risk and thus leading to lower volatility of cash flows and profitability. Doing the right

things means you are less exposed in the long run.

In recent years we saw a flurry of publications demonstrating the positive financial per-

formance of sustainable investments – those that generate social or environmental impacts

alongside financial returns. Although this is positive progress, more work is necessary on

the primary link between ESG and risk. Is there a difference in the average of the standard

deviation of stocks prices of ESG positive companies vis-à-vis non-ESG stocks? Is it poss-

ible to quantitatively demonstrate this difference, and establish that ESG firms bear less

risk compared to non-ESG stocks? And, critically, since lower risk has traditionally

meant lower financial returns, how can ESG investment really be a viable investment

strategy?

This article aims to demonstrate the importance of ESG factors to investors by using a

new quantitative model to show evidence of the link between ESG factors and investment

risk-adjusted performance. In the long term, we hope this paper drives more research to

this topic, which will promote better overall investment decisions in addition to increased

attention and efforts to build a better ESG society.

© 2016 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

CONTACT Rodrigo Tavares [email protected]

JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE FINANCE & INVESTMENT, 2016

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/20430795.2016.1234909

2. Literature review

Recent studies on the financial performance of sustainable investments (Deutsche Bank

2012; Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim 2012; Borgers et al. 2013; Allianz Global Investors

2015; Cambridge Associates and the Global Impact Investing Network 2015; Mercer

and LGT Capital Partners 2015; Morgan Stanley 2015; Eccles, Verheyden, and Feiner

2016; Khan, Serafeim, and Yoon 2015) somehow overlook the issue of risk. They

matter-of-factly take the nexus ‘high ESG-less risk’ as granted and leapfrog to demonstrate

improved financial, portfolio and stock performance where ESG factors are analytically

applied. Interestingly, some of them actually underline that ignorance of ESG criteria

could violate pension funds’ fiduciary risk management duties. But by focusing on the

idea that ESG principles can help deliver what everyone wants: superior, risk-adjusted per-

formance over the long term, they overlook the importance of dissecting the impact of

ESG on risk, even if, as the Cambridge Associates and GIIN report claims, ‘Credible

data on risk and return can help both existing and future impact investors better identify

strategies that best suit their desired social, environmental and financial criteria’ (our

italics).

The only exceptions are Morgan Stanley ( 2015) – that finds that sustainable mutual

funds had equal or higher median returns and equal or lower median volatility for 64%

of the periods examined over the last 7 years compared to their traditional counterparts

– and Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim (2012) that concluded that the portfolio of companies

that have adopted a substantial number of environmental and social policies for a signifi-

cant number of years exhibits lower volatility (1.43% and 1.72% on a value-weighted and

equal-weighted base) than a non-ESG portfolio (1.72% and 1.79%, respectively).

Yet, for the sustainable investing ecosystem to mature and go mainstream, investment

analysts will likely demand more quantitative work on ESG and standard deviation of

stocks returns. This is what encouraged professors and MBA graduates from the IE

Business School in Madrid to collaborate with Granito & Partners (G&P), an impact

business consulting firm, to develop the ESG risk-premium model. An endeavor that

started as a study conducted within the framework of the MBA program with support

from G&P, it gradually incorporated additional IE and G&P’s resources.

3. Data and methodology

3.1. ESG risk-premium model

This new quantitative model is designed to establish the correlation between ESG per-

formance and volatility of stock returns. We relied upon the Dow Jones Sustainability

Index [DJSI], one of the oldest and most recognized indices in the field of ESG, to identify

157 companies that have good ESG performance. To contrast, and in order to bring

statistical significance to the results, we randomly selected a greater number of companies –

809 of them – that are not listed on the DJSI. These companies can be considered repre-

sentative of average market performance. The larger population of reference stocks

ensures that the average returns and standard deviations of the stocks are skewed

towards the average in the market, even if there are a few stocks with high ESG perform-

ance within the population. The populations are of different sizes because the use of a

2 N. C. ASHWIN KUMA R ET AL.

smaller reference portfolio for the market average would make this skew difficult to ident-

ify. Additionally, there are limited stocks with trackrecords on the DJSI.

Our ESG Population of stocks is really the top of the top when it comes to ESG prac-

tices; in other words, they are the ‘best-in-class’. The DJSI selects index companies

through an independent research firm, RobecoSAM, who conducts its Corporate Sustain-

ability Assessment. This assessment is based upon primary evidence and is rules-based.

To be included on the index, RobecoSAM invites companies across the world to be ana-

lyzed. From these invitations, companies will agree to be analyzed either from completing

a questionnaire of RobecoSAM or from publically available information. RobecoSAM

then selects the very top ESG performers compared to the company’s industry bench-

mark. As a further check, a company is only eligible for selection if its score is at least

40% of the highest score within the respective index universe and if it is within the

10% best companies per industry. Thus, if a company is good enough to be on the

DJSI, it is the very top of ESG performers relative to peers. So, even if a non-DJSI

company has good ESG practices and is in our reference portfolio, our results would

not be negatively affected because companies listed on the DJSI are indicative of the

best in terms of ESG performance.

As the materiality of the ESG factors is highly related to the industry in which the firm

operates, we grouped equity stocks into 12 industries. The industry-specific sustainability

portfolios were built by equally weighting all stocks within each index to eliminate bias

caused by any single stock with large market capitalization. Similarly, equally weighted

reference portfolios were built using randomly weighted stocks.

As long-term performance tends to be skewed by a number of factors outside of ESG

factors, thus making it difficult to prove that our hypothesis is due to only ESG factors

from long-term performance indicators, we chose short-term indicators: weekly stock

returns and volatility as they are most relevant to the study. A key distinction of our

model is that it is a market-based approach, based upon real, historical stock price

returns. It removes subjectivity, as it is not reliant upon any significant assumptions on

future performance of the stocks. In other words, there is minimal human input or inte-

gration in this analysis.

For each industry, companies are chosen from the sustainability index considering the

geographic location and level of market development: developed versus emerging. We

have analyzed the annualized weekly returns and the annualized volatility of the weekly

returns over a period of 2 years from 1 January 2014 to 31 December 2015 to provide stat-

istically significant data points.

4. Results and discussion

4.1. ESG companies show lower volatility in their stock performances than their

peers in the same industry

In our model the different degrees of risk in the equity stocks are reflected through the

volatilities (annualized) of their stock returns. In all 12 industries studied, the group of

ESG listed companies show lower stock return volatility in comparison to the reference

companies – on average by 28.67% less (see Figure 1). This lower volatility means that

companies that perform better in ESG factors exhibit less risk than the rest of companies

JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE FINANCE & INVESTMENT 3

in the same industry. Among all the industries studied, it seems that ESG factors have

stronger impact in the industries of materials, banking, energy and technology. The differ-

ence ranges from 6.10% (for food and beverage) to as much as 50.75% (in the case of the

energy industry). This difference of percentage is a risk premium that the other (reference

or non-ESG) companies face and that investors should take into consideration when

making investment decisions. Equity investments in non-ESG companies in these indus-

tries could bear as much as 28% or more risk on an annual basis than investments in ESG

companies of the same industry on average.

4.2. Each industry is affected differently by ESG factors

We now know that industry results change with and without ESG practices. Examining

even closer, we can also determine that ESG factors affect various industries to a

greater or lesser degree as well. Further, the differences in volatilities among the 12 indus-

tries studied are much more pronounced in the group of non-ESG companies than in the

ESG ones. Combining this all together, we can say that positive ESG practices could help

companies reduce risk, although in varied amounts, based upon the characteristics or par-

ticularities of the industry itself (Figure 1).

For example, in the reference group, we can see that the difference between the most

volatile industry (Energy) and the least volatile one (Insurance) is very significant

(approximately 47%). However, if we look at these same two industries in the ESG

group, we find that the volatility of the two industries is much more similar (difference

of only 11% compared to 47%). So, considering ESG factors when investing in Energy

could help reduce significant potential risk in this industry. Therefore, different industries

Figure 1. Annualized volatility comparison between ESG and reference companies.

4 N. C. ASHWIN KUMA R ET AL.

are affected differently by ESG factors and the degree to which they are impacted could

serve as stronger guidance in industries for which ESG factors have greater bearing.

4.3. Lower risk, but higher return

In contrast to conventional thinking in which lower risk means lower return, our model

showed that even with a lower risk, the investment could achieve a higher equity return.

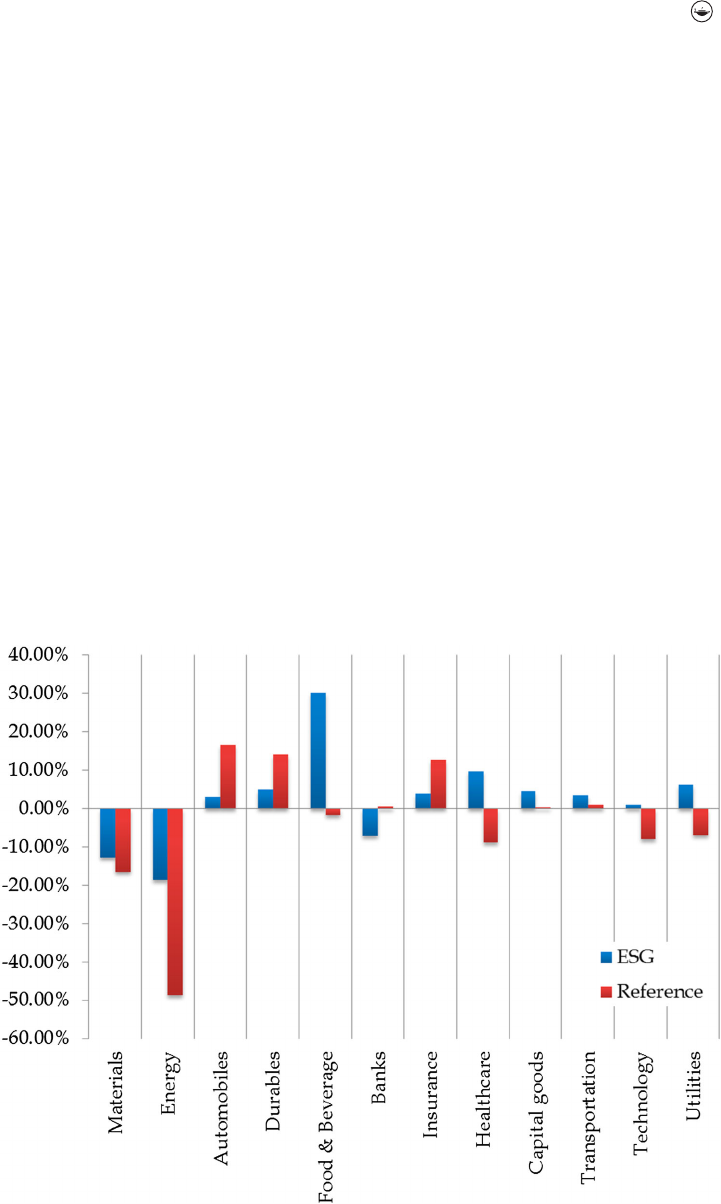

The majority of the industries that we studied (8 out of 12) resulted in better returns for

ESG companies than their peers – ranging from 2.25% to 31.84% higher (see Figure 2).

Across all 12 industries, the positive effect on equity return is 6.12% higher for ESG com-

panies, on average. And, if we only look at the eight industries with clearly higher ESG

returns, this difference jumps to an average 14.08% for ESG companies compared with

their peers. The industries of energy, food & beverage and healthcare show the highest

advantage regarding the positive impact of good ESG practices on the stock return

(lower risk and higher return). However, negative impact of ESG factors on return is

found in automobiles, durables, banking and insurance industries. A possible explanation

for the energy industry can be the existence of the oil and gas energy. Most oil and gas

companies do not operate in an environmentally sustainable fashion. However, this sort

of operation is currently prominent and is often rewarded with superior cash flows. A

similar analysis can be made for banks, as companies in the banking industry have

Figure 2. Annualized return comparison between ESG and reference companies.

JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE FINANCE & INVESTMENT 5

been known for operating in a socially unsustainable fashion; these practices can often

generate short-term rewards.

Combining the two sides of investing – risk and return – we found that the relationship

between the two may not actually reflect traditional market thinking. The lower risk

brought by better ESG practices may actually improve the risk-adjusted return of the

investments in these companies. In today’s world, just as a business can no longer excel

in isolation from a thick web of stakeholders, so too investors must think in a more com-

prehensive fashion. The original equation of higher risk – higher return has not considered

those constant internal and external interactions. Our Risk-Premium model does include

these interactions and uncovers hidden value of ESG investments.

The argument is not about lower risk–lower returns, but rather about lower risk for

the same or higher returns: a higher risk-adjusted return. A popular measure for compar-

ing risk-adjusted returns is the ‘Sharpe ratio’, calculated as the expected return per unit

volatility (risk) – higher the Sharpe ratio, the greater the efficiency of the investment.

An analysis of the stock returns and volatility during January 2014 to December 2015,

reveals that integration of ESG factors can significantly improve the efficiency of invest-

ment decisions.

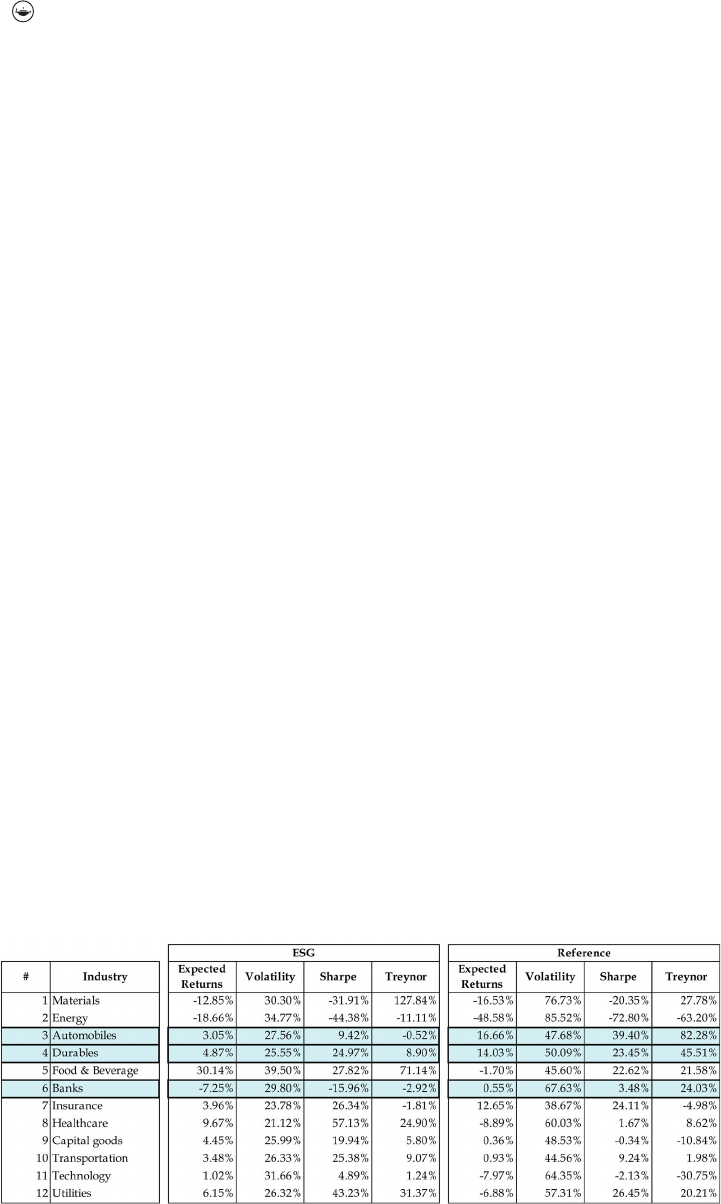

As can be seen from Figure 3, the Sharpe ratio for ESG stocks in every industry, with the

exceptions of the materials, energy and banking industries, is greater than those of the

reference stocks in the respective industries – on average by 7.67%. Essentially, investors

would have been able to earn higher than average return for each unit of risk taken on their

investment if they had invested in ESG stocks. For example, an investor wanting to limit

the annual volatility of investments to 50% would have earned an annualized return of

1.05% investing in Transportation companies from the reference companies list. Alterna-

tively the investor would have earned 6.61% investing in ESG companies in the same

sector. These higher Sharpe ratios are indicative of similar results that could be achieved

by specifically investing in stocks with good ESG performance.

Another common measure of risk-adjusted return is the Treynor ratio. This measure

compares the return earned on a stock against the beta or market risk of a stock as an

alternative risk measure to standard deviation. Accordingly, stocks are selected from

various geographies to compute the Betas for each stock. An example index is the

MSCI world index, which covers 23 different geographic markets.

Figure 3. Summary of detailed model results.

6 N. C. ASHWIN KUMA R ET AL.

Similar results from our risk-premium model are noted in the case of the Treynor ratio

measure as well. ESG stocks exhibit superior Treynor ratios over their reference counter-

parts in 9 out of 12 industries. The difference, on average, of Treynor ratios for ESG com-

panies and reference Companies are 11.81% (Figure 3). The three exception industries are

two of the same from the Sharpe ratio Analysis – automobile and banking. Additionally,

the durables industry is an exception to our results.

Even in the case of the both Sharpe and Treynor ratio exceptions (Automobiles, Dur-

ables and Banking), our analysis exhibits that ESG stocks are still less volatile by 20.12%,

24.54% and 37.83%, on average. Therefore, ESG stocks tend to be less risky and more effi-

cient vehicles for investments.

5. Conclusions and further research

Our model shows evidence that stock performance is closely linked with ESG factors. ESG

factors bring lower volatility and therefore lower risk, and consequently higher risk-

adjusted returns.

With the recent volatility in global stock markets, low-volatility investments are

increasingly relevant. Although traditional analysis assumes that lower volatility translates

into lower returns, integrating ESG factors into the investment decision can provide

superior risk-adjusted returns and is specifically relevant for improving efficiency of

low-risk investment strategies such as those followed by pension funds.

The study of ESG factors and their relevance to performance of investments is a rela-

tively recent phenomenon and requires further research. Most studies that exist focus

upon how to define and evaluate ESG factors and their impact on stock returns and

tend to overlook the impact of ESG factors on the volatility of stocks. Also, they are cen-

tered on complex investment vehicles such as private equity funds or mutual funds. The

two studies highlighted earlier, which also integrate a risk analysis, similarly indicate a

positive correlation between ESG and lower volatility. But our methodology is fairly differ-

ent. In a positive way, the Morgan Stanley study addresses long time horizons but it

assesses only mutual funds and Separately Managed Accounts and solely in the United

States, whereas we assessed directly publicly listed equity stocks. And it seemed more

apposite in our view to use the DJSI as an ESG benchmark rather than MSCI 400 KLD

Social Index given its worldwide coverage. In addition, neither Morgan Stanley (2015)

nor Eccles, Ioannou, and Serafeim (2012) dissected the particularities of different indus-

tries. As we have shown, industries react different to ESG integration and it is not necess-

arily wise to treat them by the same token.

Our study research attempts to evidence that efficient investment strategies can be

developed around listed equity stocks that perform well in terms of ESG factors. By ana-

lyzing stocks industry-wise this research can be of use to retail as well institutional inves-

tors. Our further work will expand the current model to include even longer time horizons,

control for the size and geography of companies, and account for other ESG performance

benchmarks beyond the DJSI. It would also be important to delve deeper into the robust-

ness of the model by performing quartile and percentile analyses on the existing dataset, to

ensure the results are applicable across the selected population. Even so, with the basic

relationship between ESG factors and risk-adjusted returns established, we are one step

JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE FINANCE & INVESTMENT 7

closer to developing investment strategies that provide superior returns and promote

investment in sustainable assets.

Notes on contributors

N. C. Ashwin Kumar has dev eloped his career in management and finance with Deloitte and is cur-

rently working with the research and analytics firm, Tracxn Technologies, both in India. He holds a

Fellow Chartered Accountants (FCA) from the Insti tute of Chartered Accountants of India and also

has an MBA from the IE Business School, Madrid.

Camille Smith is the owner and founder of reVive Consulting+, a boutique profitability and growth

advisory firm. She has over eight years of investment management experience, and holds an MBA

from the IE Busi ness School in Madrid, Spain, where she was awarded the Dean’s List Merit for

finishing as Top 5% of the graduating class.

Leïla Badis has over a decade of international experience in developmental aid policy. She holds an

MBA from the IE Business School, a Master in International Relations from Sciences-Po Paris, as

well as a Master in History of Art from University Paris 1 Panthéon-Sorbonne.

Nan Wang has significant professional experience in the finance sector. She worked several years in

Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria (BBVA), in Spain and Hong Kong, dealing with analysis and

project management. She currently works in Commonwealth Bank of Australia, in Shanghai, as

a project manager. She holds a Master in Economics from the University of Castile-La Mancha

and an MBA from the IE Business School.

Paz Ambrosy is both a Professor of Private Equity and the Corporate Partners Director at the IE

Business School. She also se rves as the Managing Partner and Founder of Global Institutional Inves-

tors (GII). Graduated in Law by the Autónoma University in Madrid, she received her MBA from

the IE Business School.

Rodrigo Tavares is the Founder and CEO of Granito & Partners, an impact business international

consulting firm. He holds over 15 years of experience in government and international organiz-

ations working with foreign affairs and economic cooperation. His academic path includes the uni-

versities of Harvard (Senior Research Fellow), Columbia (Research Fellow on a postdoc grant),

Gothenburg (Ph.D.) and California, Berkeley (Visiting Research Fellow).

References

Allianz Global Investors. 2015. “ESG in Equities. Research Analysis into the Materiality of

Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance Factors for Equity Portfolios.” http://www.

risklab.com/files/20150518_agi_gs_risklab_esg_in_equities.pdf.

Borgers, Arian, Jeroen Derwall, Kees Koedijk, and Jenke ter Horst. 2013. “Stakeholder Relations and

Stock Returns: On Errors in Investors’ Expectations and Learning.” Journal of Empirical Finance

22: 159–175.

Cambridge Associates and the Global Impact Investing Network. 2015. “Introducing the Impact

Investing Benchmark.” https://thegiin.org/assets/documents/pub/Introducing_the_Impact_

Investing_Benchmark.pdf.

Deutsche Bank. 2012. “Sustainable Investing: Establishing Long-term Value and Performance.”

https://www.db.com/cr/en/docs/Sustainable_Investing_2012.pdf.

Eccles, Robert G., Ioannis Ioannou, and George Serafeim. 2012. “The Impact of Corporate

Sustainability on Organizational Processes and Performance.” NBER Working Paper No. 17950.

Eccles, Robert G., Tim Verheyden, and Andreas Feiner. 2016. “ESG for All? The Impact of ESG

Screening on Return, Risk, and Diversifi cation.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 28 (2):

47–55.

8 N. C. ASHWIN KUMA R ET AL.

Khan, Mozaffar N., George Serafeim, and Aaron Yoon. March 2015. “Corporate Sustainability: First

Evidence on Materiality.” Harvard Business School Working Paper, No. 15-073. https://dash.

harvard.edu/bitstream/handle/1/14369106/15-073.pdf?sequence=1.

Mercer and LGT Capital Partners. 2015. “Global Insights on ESG in Alternative Investing.” http://

www.mercer.com/content/dam/mercer/attachments/global/investments/responsible-investment/

lobal-Insights-ESG-in-Alternative-Investing-2015-Mercer-LGT.pdf.

Morgan Stanley. 2015. “Sustainable Reality: Understanding the Performance of Sustainable

Investment Strategies.” https://www.morganstanley.com/sustainableinvesting/pdf/sustainable-

reality.pdf.

JOURNAL OF SUSTAINABLE FINANCE & INVESTMENT 9