/Transportation Asset Management

Accountability

Beyond

The Short Term

Transportation Asset Management For Long-Term

Sustainability, Accountability and Performance

Beyond The Short Term

Transportation Asset Management

For Long-Term Sustainability, Accountability

and Improved Performance

Butch Wlaschin

Director

Office of Asset

Management

Message from the Director,

Transportation Asset Management (TAM) has long been recognized as a sound, long-term approach to

managing infrastructure. It provides decision makers with a rational, long-term systematic process for

making difficult and complex decisions about how to achieve the highest system condition levels for the

lowest cost, over the longest term.

TAM also is evolving to help transportation officials address two new challenges. TAM provides a

sound basis for demonstrating the long-term sustainability of current infrastructure practices. By using

TAM as an over-arching framework, transportation executives can demonstrate that they are making

decisions to sustain the transportation system to the best of their ability over the long term.

Also, TAM can demonstrate accountability. TAM relies upon strategic long-term goals, the pursuit of

measureable targets and the continuous evaluation of results. In this way, TAM not only produces short-

term performance metrics but it closely resembles "quality systems" such as Six Sigma which are

widely recognized as leading to improved performance. TAM can be the foundation for performance

measurement systems which assure not only short-term performance but also long-term sustainability.

This report re-examines TAM as an approach for sustainability and as a system for greater

accountability and improved performance. It also includes advice on Change Management practices to

elevate and expand TAM practices within a department of transportation.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance i

Table of Contents

Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................... 1

Asset Management: Linking Accountability and Sustainability .............................................. 1

Leadership Driven................................................................................................................................................. 3

Performance Focused ............................................................................................................................................ 3

Transparent ........................................................................................................................................................... 4

Data-Driven .......................................................................................................................................................... 4

Formally Structured .............................................................................................................................................. 4

System Based ........................................................................................................................................................ 4

Chapter 1 Overview of Asset Management ................................................................................ 7

Asset Management Is a Strategic Approach ....................................................................................................... 11

TAM Breaks Down ‘Silos’ ................................................................................................................................ 11

Asset Management Relies on Good Information and Analytic Capabilities ....................................................... 12

Asset Management Practices Are Flexible ......................................................................................................... 12

Asset Management Works at Multiple Levels .................................................................................................... 12

People, Processes, Plans and Products ................................................................................................................ 12

Chapter 2 Key Agency Roles in Asset Management............................................................... 15

Policy, Strategy and Planning Establish Direction ............................................................................................. 15

Project Delivery Reliability is Key to Timely Asset Treatments ........................................................................ 17

The Importance of Maintenance Should Not be Overlooked in Asset Management .......................................... 18

Information and Analysis Rises in Importance in Asset Management ............................................................... 19

Leadership and Communication Link Strategy and Action in Asset Management ............................................ 19

NORTH CAROLINA DOT - A CASE STUDY IN LEADERSHIP, PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT, ACCOUNTABILITY AND

ASSET MANAGEMENT .............................................................................................................................................. 21

Setting Direction ................................................................................................................................................. 22

Review and Continuous Improvement ................................................................................................................ 22

Leadership and Communication ......................................................................................................................... 23

Clear, Simple Common Mission and Goals ........................................................................................................ 23

Restructure and Realign ...................................................................................................................................... 24

Collaboration from Cradle-to-Grave ................................................................................................................... 24

Focus Resources in Strategic Planning and Asset Management ......................................................................... 24

Office of Asset Management .............................................................................................................................. 25

The North Carolina Multimodal Investment Network (NCMIN) ....................................................................... 26

Being Strategic in Selecting Projects and Services ............................................................................................. 27

Role of Data in Quality Processes ...................................................................................................................... 27

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance ii

Data Collection and Dissemination .................................................................................................................... 28

Aging Assets, Long Term Decisions and Asset Management ............................................................................ 28

Streamlining and Instituting On-site Project Scoping for Bridge Projects.......................................................... 29

Performance Tied to Mission and Goals ............................................................................................................. 29

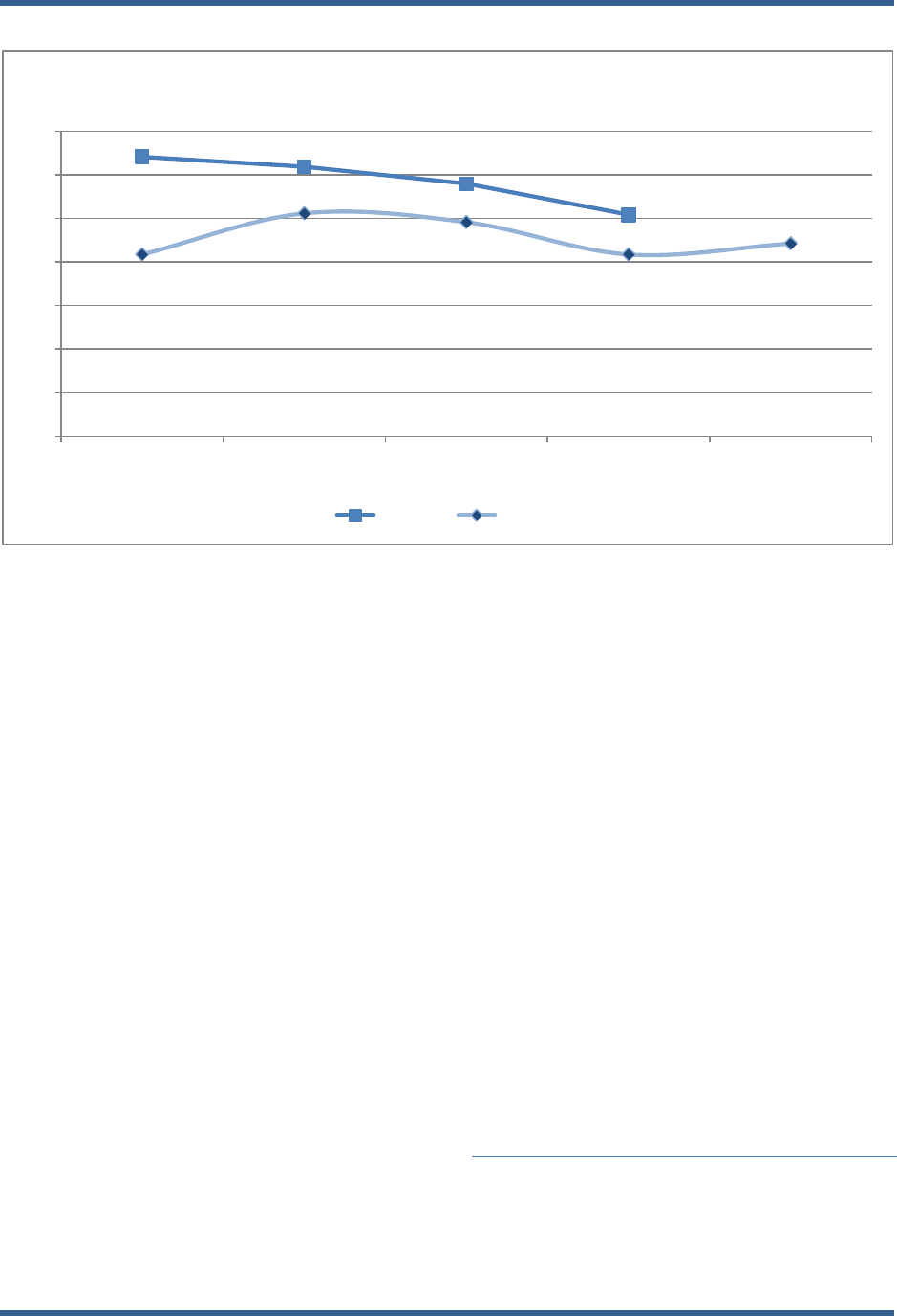

Performance Management, Accountability and Asset Management .................................................................. 31

Effectiveness of Cascading Performance Measures ........................................................................................... 31

Role of Leadership Emphasized ......................................................................................................................... 22

Improving Assets through Changes in Preservation and Maintenance Strategies .............................................. 23

Outcomes of Better Asset Information and Forecasting ..................................................................................... 24

Summary: Leadership and Accountability Contribute to Successful Management of Transportation Assets .... 24

Chapter 3: Structures and Strategies for Asset Management ................................................ 25

Structure or Process? .......................................................................................................................................... 26

The Critical Role of the Leader in Asset Management ....................................................................................... 30

Interlocking Decisions ........................................................................................................................................ 32

Resource Allocation Processes ........................................................................................................................... 33

UTAH DOT CASE STUDY - EMBRACING NEW STRUCTURES AND STRATEGIES FOR ASSET MANAGEMENT .............. 35

Utah’s Asset Management Beginnings ............................................................................................................... 35

Performance Management Linkage .................................................................................................................... 36

Creating an Asset Management Structure ........................................................................................................... 36

Lessons Learned: Engagement and Evolution .................................................................................................... 37

Strategies for Adaption ....................................................................................................................................... 39

Toward Comprehensive Asset Management ...................................................................................................... 40

LESSONS .................................................................................................................................................................. 42

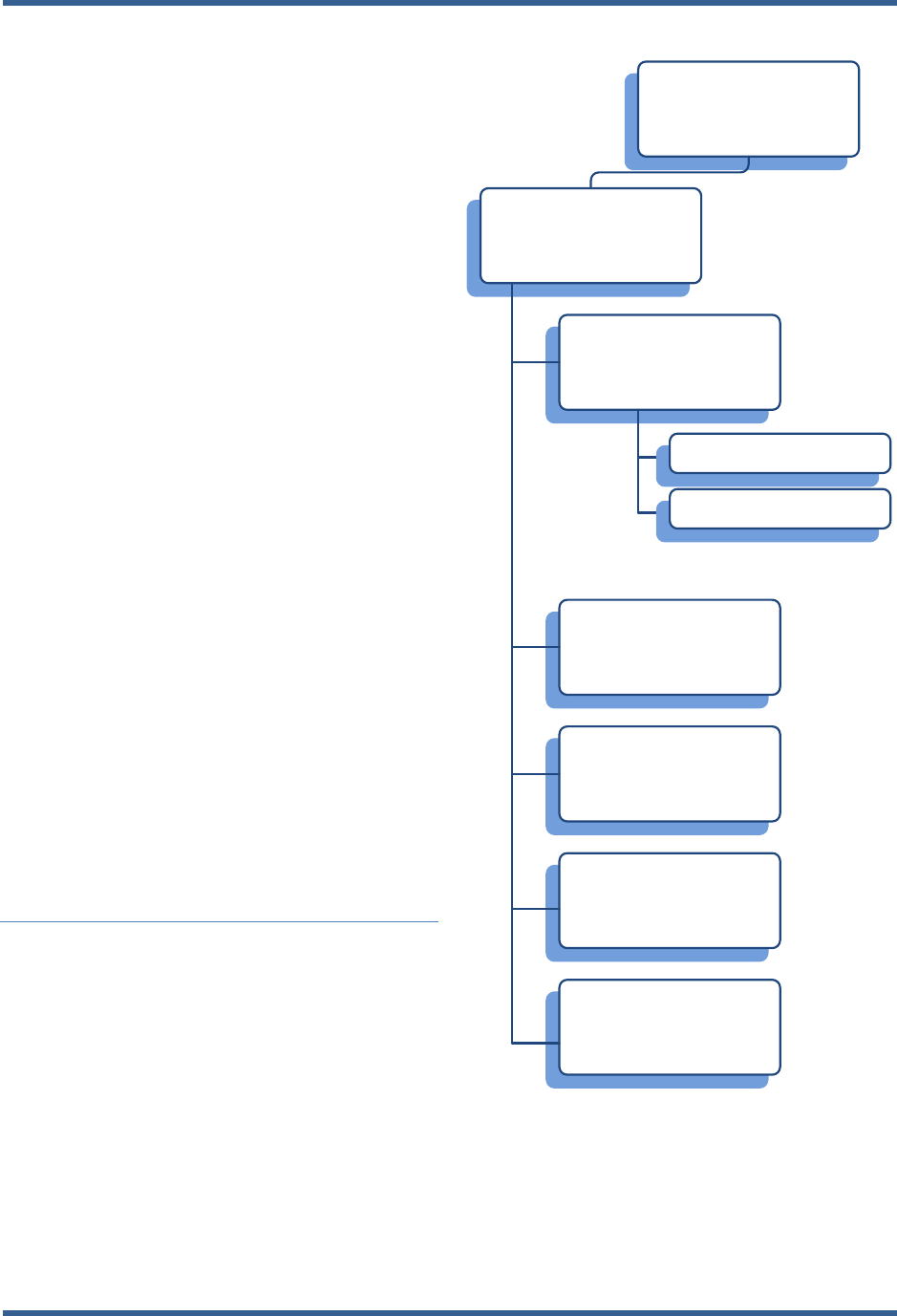

Chapter 4 Information Needs for Asset Management............................................................. 43

Organizational Direction Information ................................................................................................................. 44

Organizational Competency Information ............................................................................................................ 45

Organizational Asset Data .................................................................................................................................. 46

Analysis for Asset Management ......................................................................................................................... 47

SUMMARY OF ASSET MANAGEMENT DEVELOPMENT IN OREGON ............................................................................ 49

Achieving Organizational Direction ................................................................................................................... 49

Change Management and the Asset Management Communication Plan ............................................................ 53

Organizational Competency Information ............................................................................................................ 53

Implementation Plan to Close the Competency Gap .......................................................................................... 53

Developing Organizational Asset Data ............................................................................................................... 54

Asset Management Steering Committee ............................................................................................................. 54

Decision Support: People and Tools ................................................................................................................... 56

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance iii

A Way of Doing Business .................................................................................................................................. 56

‘Words of Wisdom’ in Developing an Asset Management Process ................................................................... 56

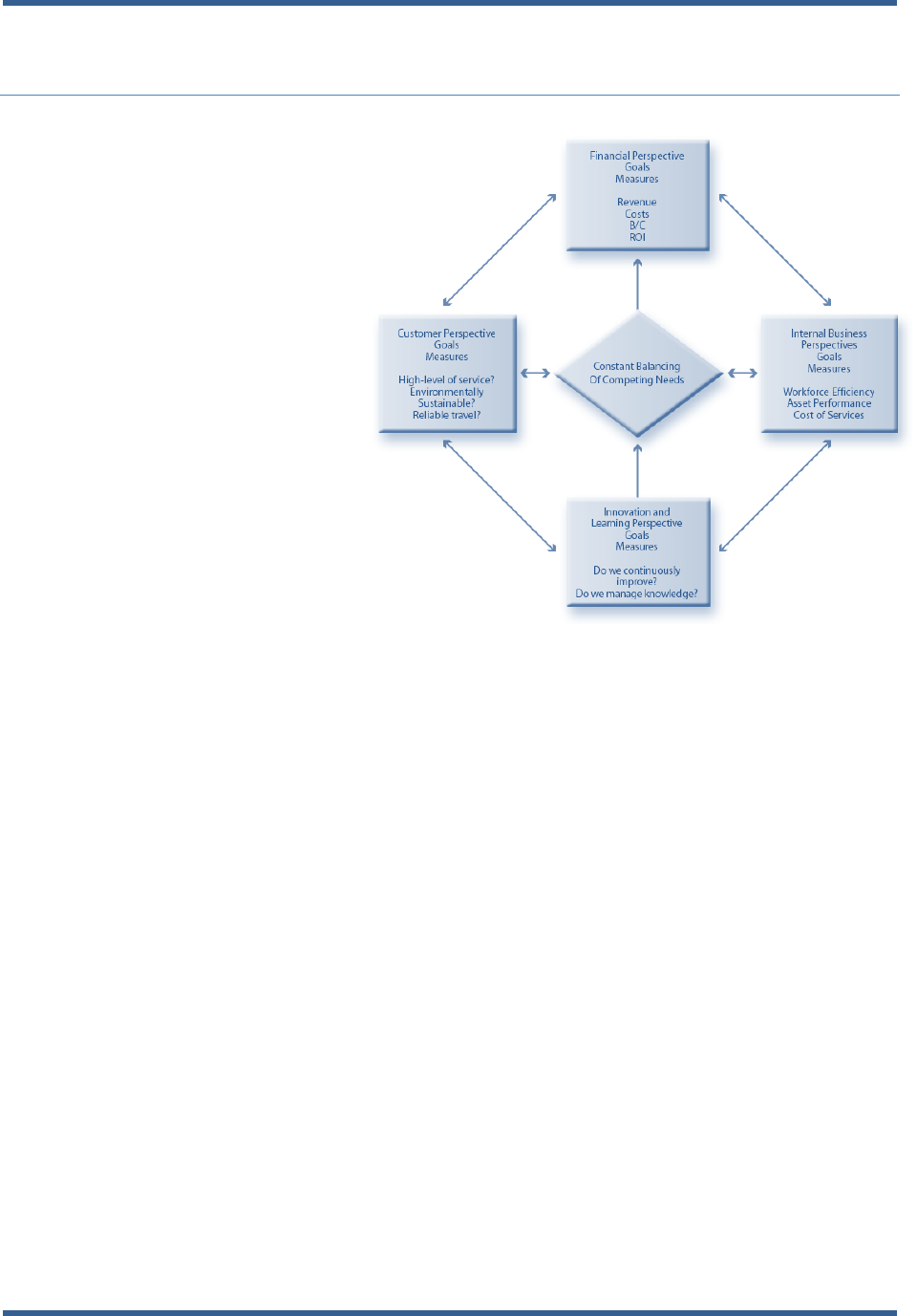

Chapter 5 Asset Management as A ‘Quality’ Framework...................................................... 57

Development of "Quality Systems" .................................................................................................................... 58

Asset Management and Other Quality Systems .................................................................................................. 59

Asset Management as a Form of Performance Management .............................................................................. 61

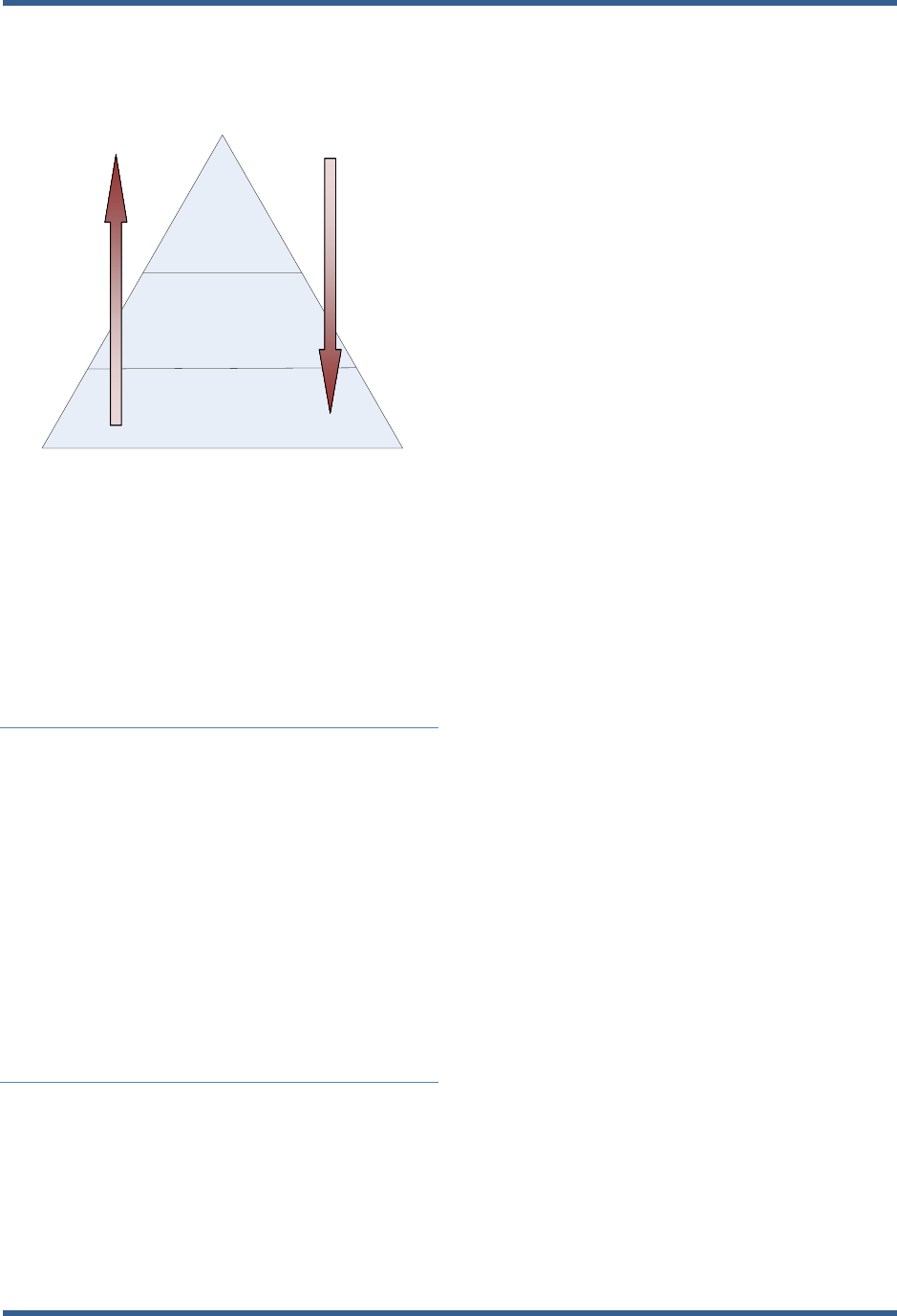

Short-Term and Long-Term Perspectives ........................................................................................................... 63

Asset Management And Similarities to the Baldrige Process ............................................................................. 65

The Balanced Scorecard Can Complement Asset Management ......................................................................... 67

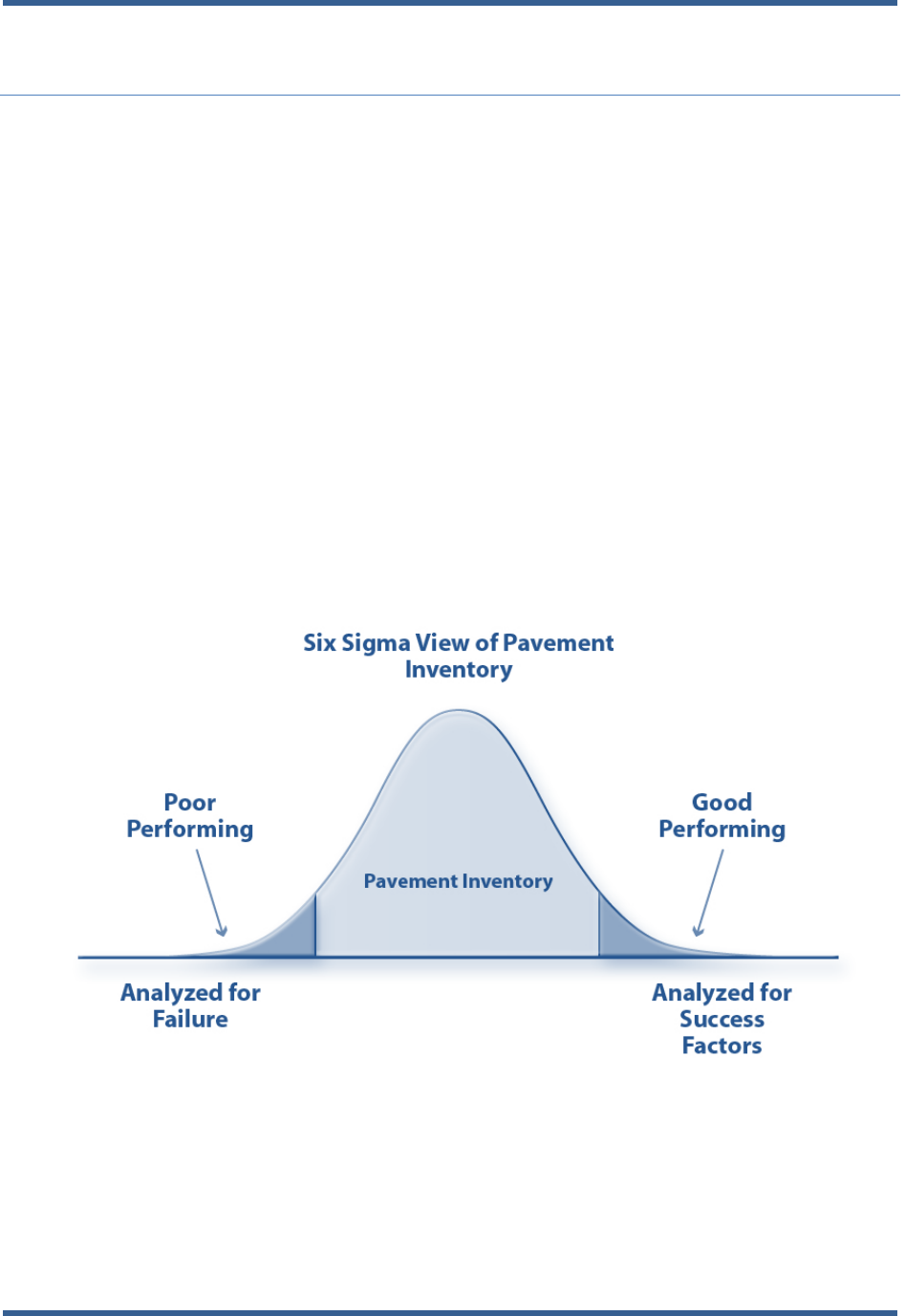

Six Sigma as a Subsystem Within Asset Management ....................................................................................... 68

ISO, International Organization for Standardization .......................................................................................... 69

Summary ............................................................................................................................................................. 70

EXAMPLES OF ASSET MANAGEMENT PRACTICES COMPLEMENTING “QUALITY” SYSTEMS IN LEADING

TRANSPORTATION AGENCIES ................................................................................................................................... 70

New Zealand ....................................................................................................................................................... 70

Swedish Road Authority ..................................................................................................................................... 71

Queensland, Australia ......................................................................................................................................... 71

New South Wales ............................................................................................................................................... 72

Florida Department of Transportation Office of Materials ................................................................................. 74

MISSOURI DOT PERFORMANCE MANAGEMENT CASE STUDY ................................................................................. 77

Complementary Systems .................................................................................................................................... 78

MoDOT's Story - Changing a Culture to Embrace Accountability .................................................................... 80

Tracking Performance ......................................................................................................................................... 80

Keeping It Simple ............................................................................................................................................... 82

Resource Optimization ....................................................................................................................................... 83

The Role of Maintenance .................................................................................................................................... 84

Increased Efficiencies as an Investment Strategy ............................................................................................... 85

Lessons Learned from MoDOT .......................................................................................................................... 85

Chapter 6 Summary and Conclusions ...................................................................................... 87

MARYLAND STATE HIGHWAY AGENCY CASE STUDY .............................................................................................. 90

Pavement Performance and the Organization ..................................................................................................... 90

Allocations and Project Selection ....................................................................................................................... 91

Performance Measures and Asset Management Results ..................................................................................... 91

Information and Analysis .................................................................................................................................... 92

Decision support: People and Tools ................................................................................................................... 92

Collaborative Decision Making and Support ...................................................................................................... 93

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance iv

Achieving Organizational Commitment ............................................................................................................. 94

Ownership and Accountability ........................................................................................................................... 94

A Way of Doing Business .................................................................................................................................. 94

Communication with Stakeholders ..................................................................................................................... 94

Future Initiatives ................................................................................................................................................. 95

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 1

Executive Summary

Asset Management: Linking Accountability and Sustainability

ransportation agencies face increasing pressures

from Congress and state legislatures to

demonstrate results, accountability and transparency

in their management of highway assets. The National

Surface Transportation Policy and Revenue Study

Commission issued a clarion call for performance

accountability in the federal transportation programs.

Senior members of Congress are examining how to tie

federal transportation spending to state accountability.

The Government Accountability Office called for

greater linkage between federal transportation

expenditures and transportation agency results.

As transportation agencies consider how to respond to

these calls for accountability and transparency, the

appeal of Transportation Asset Management (TAM)

becomes increasingly apparent. Asset Management

provides agencies with a proven framework to

demonstrate long-term accountability and

accomplishment in the management of highway

networks. As Asset Management matured in the past

decade, it became increasing clear to its practitioners

that it provides a systematic, data-driven and

continually improving framework for managing

assets. In this maturation, Asset Management has

come to closely resemble many other "quality

systems" that major corporations use to meet customer

goals, achieve performance targets and to continually

improve their products. "Quality Systems” such as

ISO, Six Sigma, the Balanced Scorecard, Baldrige,

Total Quality Management and Performance

Management all have elements which resemble Asset

Management. All of these systems rely on variants of

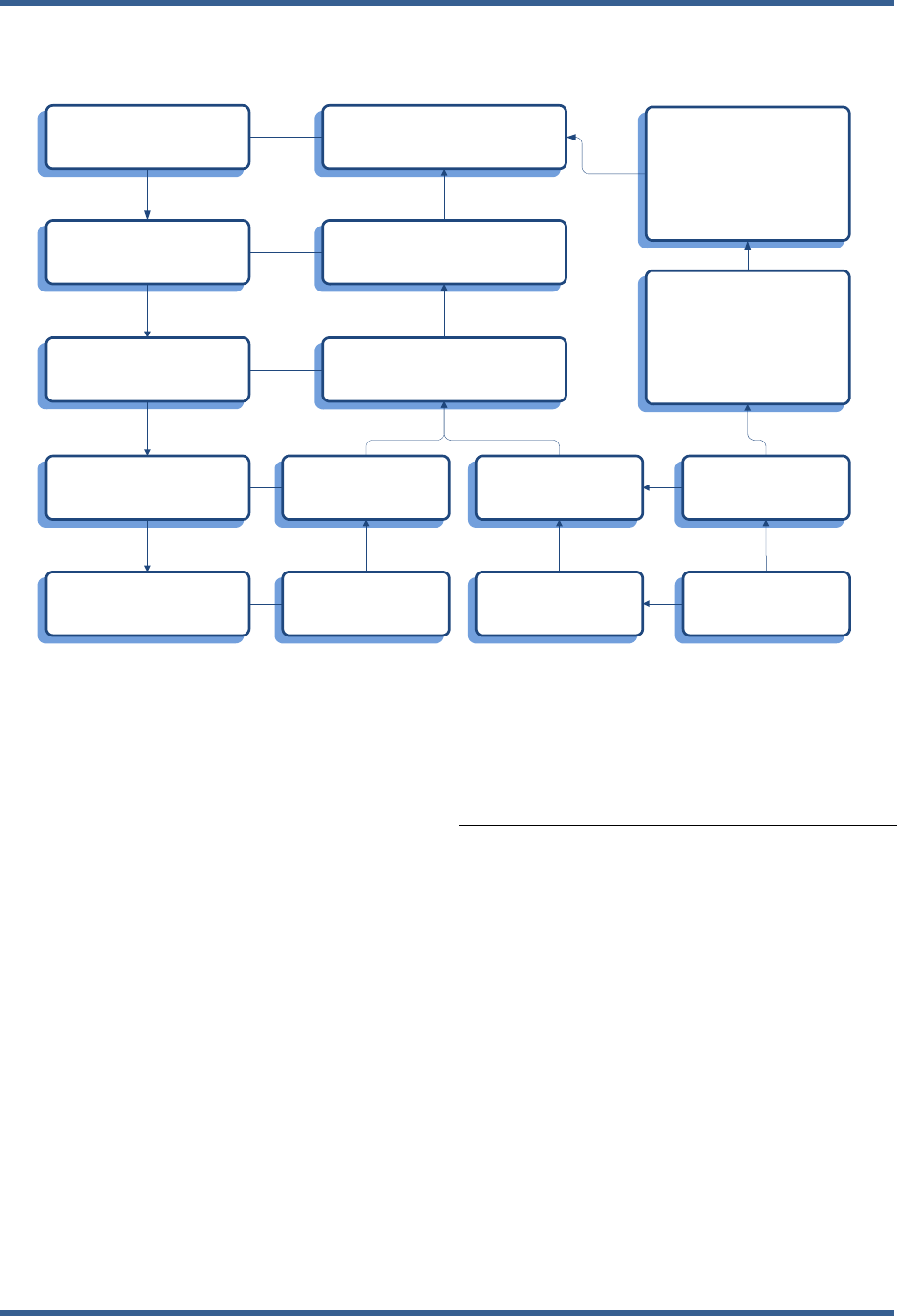

the famous “Plan, Do, Check, Act” processes first

recommended by “quality” guru W. Edwards Deming

in the 1950s and 1960s, and shown in Figure 1 on

page 3. His writings lie at the heart of most major

“quality” programs in use globally today. General

Electric uses Six Sigma to ensure the quality of its jet

engines. Award-winning hospitals rely on the Baldrige

Process to ensure high levels of patient care. More

than 17,000 ISO standards were developed to ensure

quality in technical processes. A highway agency's

embrace of Asset Management allows it to

demonstrate that strategies similar to those which

ensure the success of Fortune 500 companies ensure

T

Asset

management

provides the

linkage

between a need

to demonstrate

short-term

performance

while also

ensuring long-

term

sustainability

of highway

assets.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 2

the long-term, sustainable quality of its highway

network.

As these "quality" systems do for major corporations,

Asset Management does for transportation agencies. It

helps them manage scarce resources, articulate

rational investment policies, measure the effects of

past decisions and provide alternative scenarios to

improve future performance. Asset Management

allows highway agencies to document that their

investment of scarce resources is made within a

logical, comprehensive and systematic framework.

Agencies that use Asset Management are so data

driven, results focused and policy based, that, for

them, producing performance metrics to demonstrate

results is practically incidental. The agency officials

reviewed in the following case studies expressed little

trepidation about producing performance metrics

because their Asset Management frameworks produce

metrics as a matter of course.

This report addresses three major areas of Asset

Management.

First, it examines asset management as a framework

for demonstrating accountability - both in the short-

term management of current transportation programs

but also for the long-term sustainability of a state

highway network. In describing Asset Management as

a framework for demonstrating accountability, this

report also spends considerable time addressing

similarities and differences between Asset

Management and Performance Management. To the

uninitiated, the differences between the two

management frameworks or philosophies may not be

clear. The growing movement for accountability has

led to a significant emphasis upon Performance

Management and this report examines how it and

Asset Management complement and enhance each

other. The report also briefly compares and contrasts

Asset Management to the other highly respected

quality systems such as the Balanced Scorecard, ISO

and Six Sigma.

Second, this report examines successful organizational

structures and leadership strategies for instilling Asset

Management into transportation agencies.

Implementing Asset Management requires much more

than buying a new software package or adopting new

terminology. It involves creating new cross-cutting

collaboration between traditionally separate

disciplines within a highway agency. When a

highway agency is optimally structured or managed to

fully capitalize on Asset Management, the formerly

separate functions of planning, design, construction,

maintenance and information technology all must

work together more closely. Instead of operating

strictly within their own silos, they need to collaborate

to carefully manage assets throughout each phase of

the asset’s life. Successfully creating such cultural

and organizational change requires skills in areas such

as Change Management, Organizational Com-

munication and Organizational Theory. These fields

are seldom discussed in transportation literature but

their practice can be essential to change the approach,

the attitude and the culture of large organizations

which are trying to embrace Asset Management.

Shifting the direction of a large organization requires

consistent, sustained leadership, communication,

education and the creation of a common consensus

among the different subcultures within a large

organization.

Third, this report examines case studies of successful

Asset Management programs across the United States

and internationally. Although these transportation

agencies differ significantly in their size, political

structure, and resources, certain principles of how to

instill Asset Management within them appear to be

universal. Examples as diverse as North Carolina,

Sweden, New Zealand, Utah, Maryland, Australia

and Oregon are examined. Despite the significant

geographic, cultural and governmental differences

between these examples, their underlying strategies

for successfully ingraining Asset Management into

their organizations are strikingly similar.

Management trends come and go, creating a degree of

skepticism among some that the lasting benefits of

them may not be worth the effort to adopt them.

However, the results of Asset Management are

difficult to dispute, particularly during an era of

accountability.

• In Utah, the agency has successfully convinced its

Legislature and its Transportation Commission of

its sound stewardship by demonstrating the

systematic and comprehensive way it manages

the state’s highway assets. As a result, Governing

magazine rates it an A for infrastructure

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 3

• management and its Legislature has bestowed

unprecedented levels of funding upon the agency;

• In New Zealand, the national transportation

agency has ingrained Asset Management into

legislation. Now, it is a basic principle of

national transportation policy that assets should

be preserved at a high level, and be sustained into

the future. More than 98 percent of the New

Zealand pavements meet smoothness targets;

• In North Carolina, the Department of Trans-

portation has successfully made organizational

changes to improve and sustain the performance

and condition of its assets to meet the needs of the

21

st

century. It has aligned and assigned

ownership, roles, responsibility and

accountability for performance of the system

across business units, eliminating silos and

forcing collaboration. Accountability for system

performance is clear and transparent, starting at

the highest level and cascading down to all

employees. These approaches have been

integrated into the agency’s day-to-day operations

and are expected to continue irrespective of

changes to the leadership of the agency.

• In New South Wales, Australia, the state

transportation agency has ingrained Asset

Management into all levels of its operations. It

produces a Total Asset Management Plan which

functions like a parallel budget document to

ensure that agency expenditures and agency

efforts achieve its long-term Asset Management

targets. It has sustained 87 percent of its

pavements in good ride condition for at least a

decade, and is forecast to maintain those levels

into the future. It reports having only one load-

limited bridge in its populous and urbanized state.

• In Sweden, the nation’s Road Authority has used

Asset Management and a Balanced Scorecard

framework to keep more than 95% of major

routes above acceptable pavement targets for

more than a decade despite its harsh climate and

diminishing purchasing power.

• The Oregon DOT has developed a comprehensive

asset management process which guides decision

making while also providing legislators with

performance information to assure them of the

agency's direction.

These diverse agencies relied on several common

management tactics for deploying Asset Management

into their agencies.

Leadership Driven

In all of the examples, the use of Asset Management

has evolved from an isolated technical or planning

effort to a department-wide focus which was

embraced by senior leadership. The leadership

impetus came in different forms. In some cases, it

came from a strong individual executive who was

personally committed to Asset Management. In other

cases, strong legislative emphasis led to the embrace

of Asset Management. While there are variations

across agencies, it is clear that a strong leadership

focus underlies sustained efforts to adopt Asset

Management.

Performance Focused

Another key finding is that departments that have

successfully embraced Asset Management tend to

have a strong systems approach to managing. That is,

the department has embraced the Goal-Setting-and-

Performance-Measurement processes inherent in the

"quality systems" such as Six Sigma or ISO. In most

of these cases, the focus upon systematically

measuring and improving assets conditions was not

unique. Similar strategies were applied to other

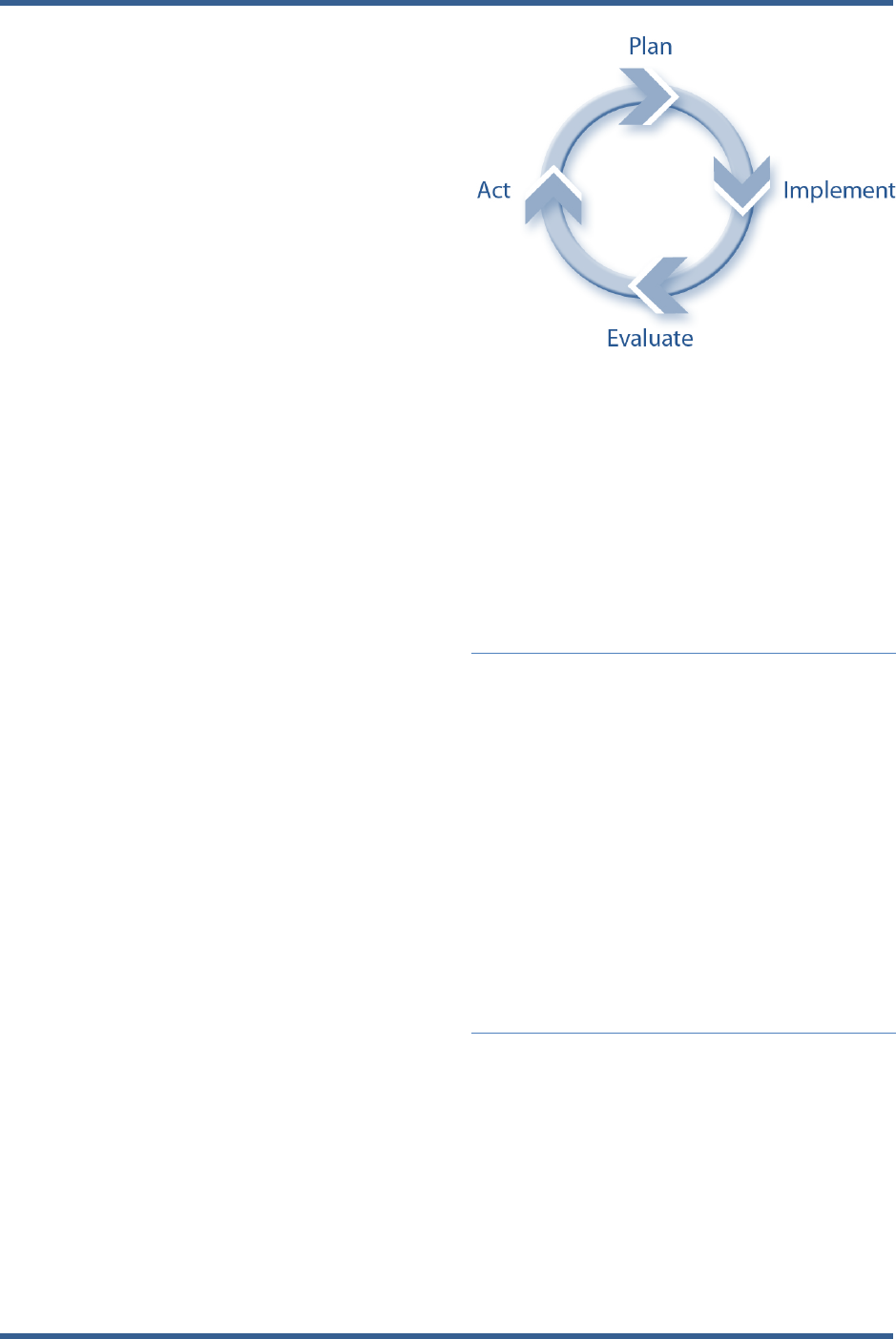

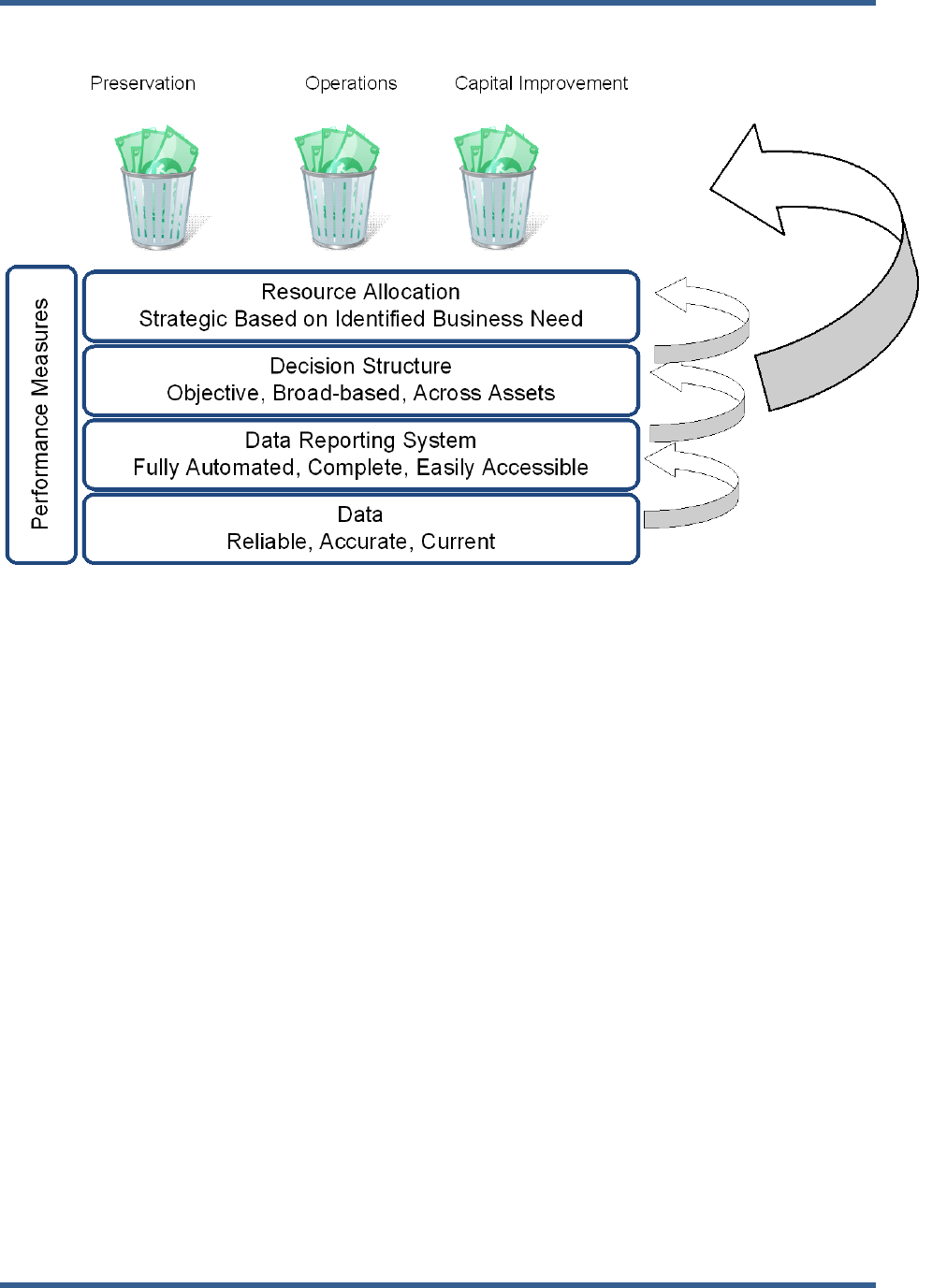

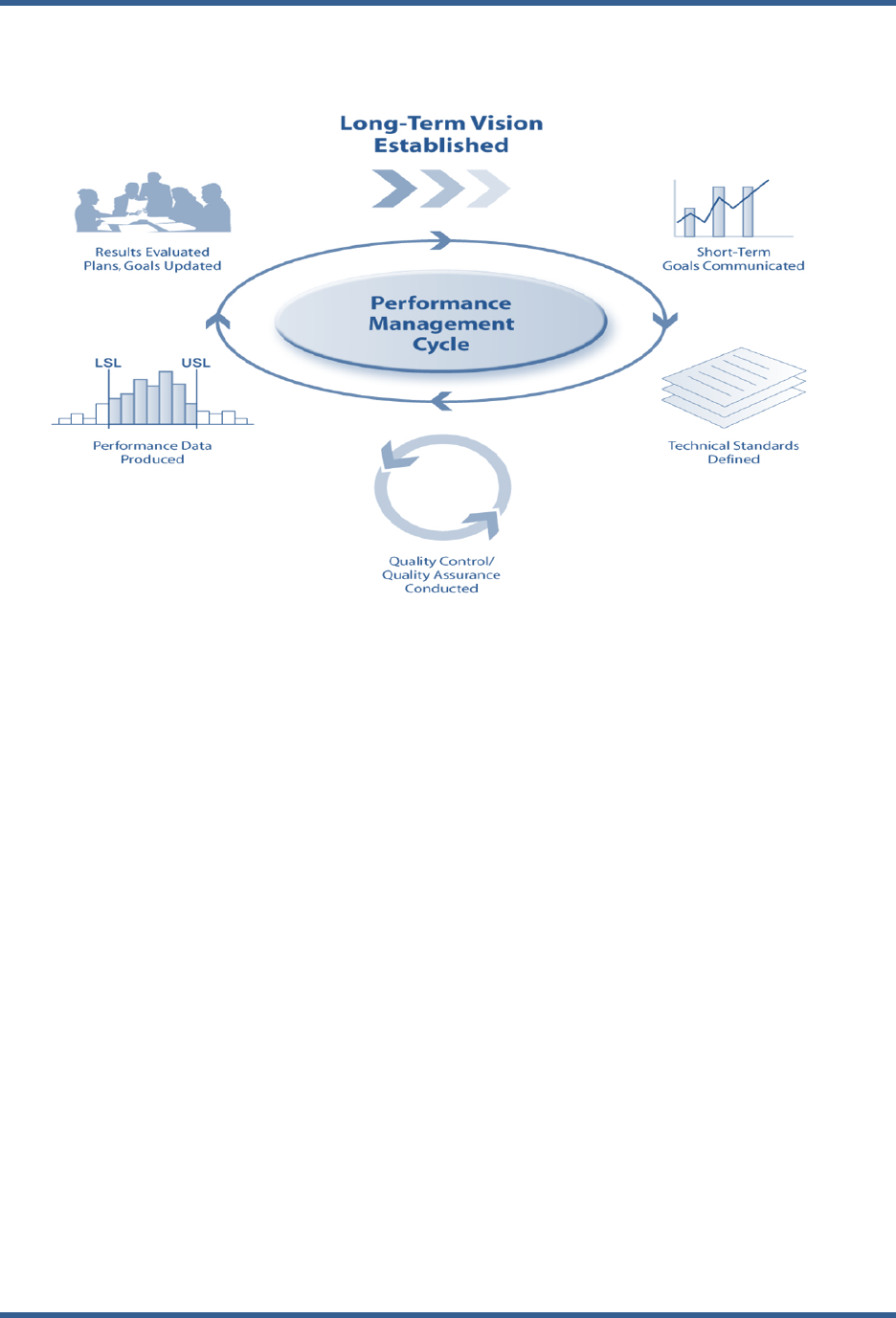

Figure 1 The "Plan, Implement, Evaluate, Act" cycle is

inherent in "quality systems" and is essential in asset

management as well.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 4

department functions such as reducing crashes,

delivering projects, or responding to customers. It

appears that once Asset Management is ingrained in

an agency, expanding a performance focus to other

agency programs becomes simpler.

Transparent

A strong sense of transparency seems to accompany

agencies that have embraced Asset Management.

These agencies were able to document to the public

and to policy makers that they have embraced a

rational, systematic, long-term approach to managing

assets, often for the lowest life-cycle costs.

Data-Driven

The journey to long-term Asset Management has led

to a steady improvement in inventory data and

forecasting tools. As the agencies become more

focused upon asset performance, they become more

data hungry and tend to improve their asset

inventories and data systems.

Formally Structured

Formality marked many Asset Management systems.

Asset Management was rooted in official policies,

ingrained into agency standards, manifested in agency

manuals and articulated in agency publications.

System Based

Although the management structures of these agencies

vary widely, they appear to have evolved similar

management strategies including the primary strategy

of adopting a systems approach to managing their

agencies. In these states and countries, the Asset

Management framework does what virtually all

management systems are supposed to do – it provides

a process, a logic, and a feedback cycle to

methodically and comprehensively get things done

with ever-improving results. By adopting Asset

Management, these agencies find themselves well

positioned to respond to the growing demands for

performance and accountability.

This report does not replicate the excellent work in the

Asset Management Guide, either the earlier 2002

guide or the current update. Nor does it seek to

supplant any technical or procedural guidance on

Pavement Management, Bridge Management or

Maintenance Management. It relies very little on

engineering but instead addresses organizational

change management, institutional communication,

organizational theory and systems approaches to

managing. It examines the management strategies, the

organizational structures and information needs of

transportation executives who seek to lead their

agencies to the next generation of Asset Management.

The Asset Management Guide and its related reports

explain the “what” of implementing Asset

Management. This report examines “how” executives

have instilled Asset Management and its related

practices within their departments. It also explains

how in an era of accountability, they can rely on Asset

Management to demonstrate their agency's efficiency,

effectiveness and transparency.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 5

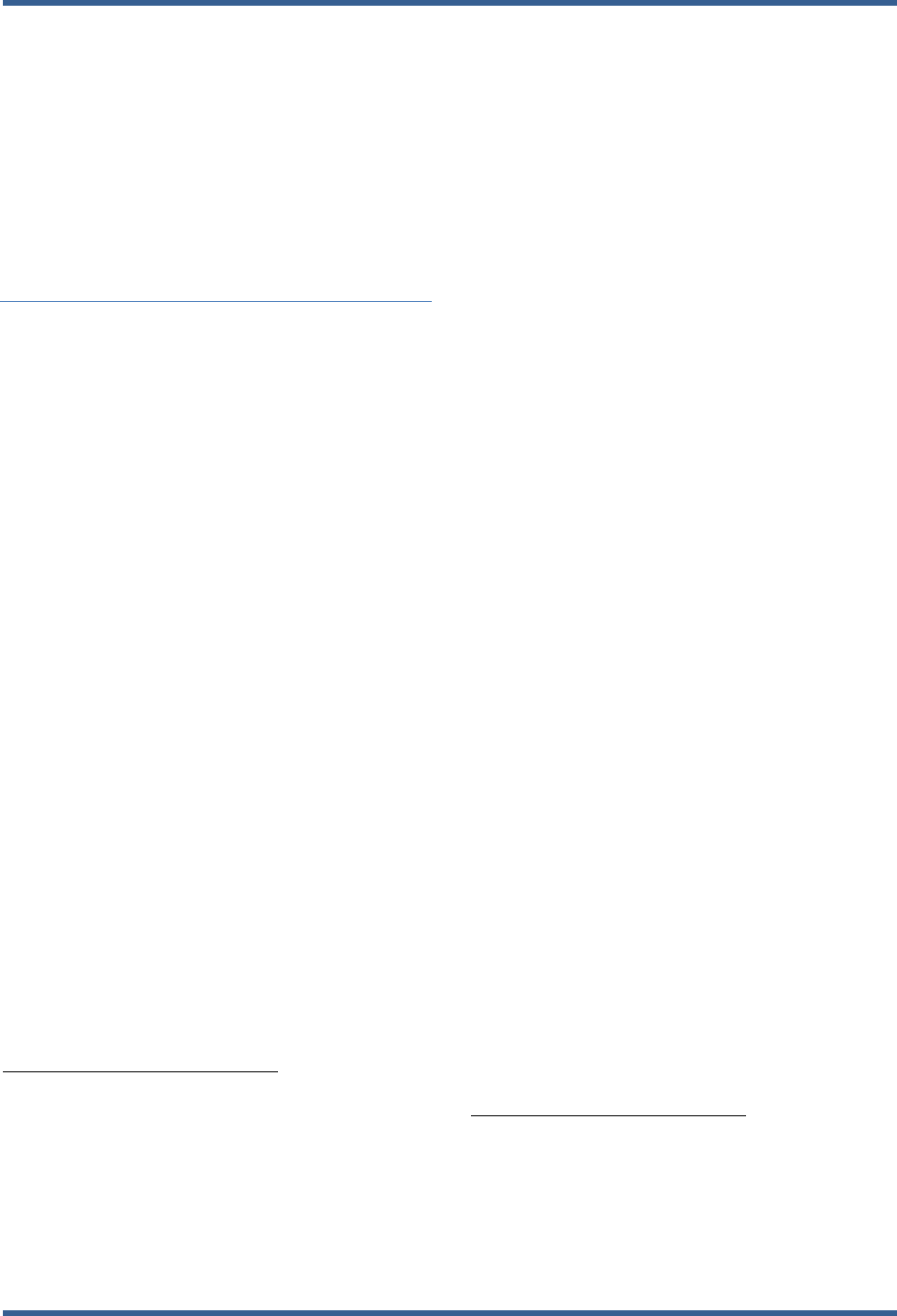

Table 1 The table provides definitions for the management systems commonly referenced in this report.

Management Frameworks Defined

Asset Management is a strategic and systematic process of operating, maintaining, upgrading and expanding

physical assets effectively throughout their lifecycle. It focuses on business and engineering practices for

resource allocation and utilization, with the objective of better decision making based upon quality information

and well defined objectives.

Pavement Management provides decision makers at all management levels with optimum strategies derived

through clearly established rational procedures. A Pavement Management System evaluates alternative

strategies over a specified analysis period on a basis of predicated values of quantifiable attributes, subject to

predetermined criteria and constraints.

Bridge Management includes the establishment of optimal investment funding levels and performance goals for

an inventory of bridges, as well as identification of the appropriate combinations of treatment scope and timing

for each individual bridge over the lifecycle.

Performance Management is an on-going process which translates strategic goals into relevant and detailed

measures which are then tracked to ensure uniform achievement of institutional goals. Performance

Management Systems include an "institutional learning" function in which the agency analyzes the root cause of

failure or success to achieve its performance targets, and disseminates the lessons of that analysis to perpetuate

continuous improvement.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 6

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 7

Chapter 1 Overview of Asset Management

To devise the best organizational structure and the best

leadership strategies for Transportation Asset

Management, it is important to first understand all the

functions which comprise this discipline. This section

summarizes the basic functions of Transportation Asset

Management as described in the Asset Management

Guide and other documents. Much of the description

relates to Pavement Management as an illustrative

example of Asset Management. However, the general

principals could apply to any asset, not just pavements.

As the Asset Management Guide notes, transportation

asset management is a strategic approach to managing

physical transportation infrastructure. It became a

focus in the 1990s after the earlier development of

Pavement Management, Bridge Management,

Maintenance Management, Fleet Management and

even Facilities Management systems. Each of these

processes applies a systems approach to managing not

only individual assets but also the entire class of assets

for the lowest, long-term, life-cycle cost.

The term Asset Management can be ambiguous to both

the uninitiated as well as those who are familiar with

these earlier management systems. To the uninitiated,

Asset Management can be vague because it is named

after two generic words, “Assets” and “Management.”

It is described in general ways which could refer to

many systematic processes. To the non-transportation

specialist, the descriptions of “good” Asset

Management sound like the description of just “Good

Management.” Both rely on effectively executing a

logical strategy to achieve the highest returns for an

organization. To the experienced transportation

practitioner, it can be difficult to differentiate Asset

Management from the earlier systems such as

Pavement Management, Maintenance Management and

Bridge Management. A comparison of the definitions

in Table 1, page 5, illustrates the similarities.

Further complicating the dialogue is the increasing

focus upon “Performance Management.” In this report,

Performance Management is defined “as an on-going

process which translates strategic goals into relevant

and detailed measures and targets which are then

tracked to ensure uniform achievement of institutional

goals.”

Performance management relies heavily on the use of

performance measures to assess whether the

Asset

management

can provide a

framework for

transportation

agencies to

manage their

resources, both

their physical

resources and

also their

human and

informational

resources.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 8

organization is achieving its goals. It also has an

“institutional learning process” built in because it

requires continuous analysis of results and root-cause

evaluation of why results were not achieved. From that

analysis, adjustments can made to improve

performance.

Performance Management for federal agencies is

required in the 1993 Government Performance and

Results Act, although the Act’s requirements did not

extend to states. Performance management was

strongly recommended for the federal transportation

program in the 2007 National Surface Transportation

Policy and Revenue Study Commission Report and it

has been an increasing focus of AASHTO. So in

addition to the original pavement and bridge

management systems and Asset Management, the

transportation community is now also coming to grips

with “Performance Management.”

In many ways description rather than definition helps

to clarify Asset Management. Transportation Asset

Management applies a “rational and comprehensive”

approach to managing pavements, bridges and other

assets.

As the Asset Management Guide says,

“At its core, asset management deals with an agency’s

decisions in resource allocation and utilization in

managing its system of transportation infrastructure.

Asset management is a way of looking at an agency’s

“way of doing business” to see if there are better ways

to reach decisions in infrastructure management – for

instance, by basing decision methods and criteria on

current policy guidance, considering a range of

alternatives, focusing on outcomes of decisions, and

applying more objective information to decisions.”

Asset Management has been defined as,

“… a strategic and systematic process of operating,

maintaining, upgrading, and expanding physical assets

effectively throughout their lifecycle. It focuses on

business and engineering practices for resource

allocation and utilization, with the objective of better

decision making based upon quality information and

well defined objectives.”

The antithesis of Asset Management is neglect of

assets until they deteriorate and require reactive

maintenance treatments to restore at least minimal

functionality without regard to long-term need or

performance. Instead, Asset Management is about

applying policies, forecasts, tradeoffs and economic

optimization to comprehensively manage an inventory

of assets. Asset Management is distinguished by being:

Policy-driven—Resource allocation decisions are

based on a well-defined set of policy goals and

objectives.

Performance-based—Policy objectives are translated

into system performance measures that are used for

both day-to-day and strategic management.

Analysis of Options and Tradeoffs—Decisions on

how to allocate funds within and across different types

of investments (e.g., preventive maintenance versus

rehabilitation, pavements versus bridges) are based on

an analysis of how different allocations will affect

achievement of relevant policy objectives.

Decisions Based on Quality Information—The

merits of different options with respect to an agency's

policy goals are evaluated using credible and current

data.

Monitoring Provides Clear Accountability and

Feedback—Performance results are monitored and

evaluated for both efficiency and effectiveness.

The general principles of asset management are

similar, whether the assets involved are pavements,

bridges, roadside features, or even facilities. By using

pavement management as an example, the following

steps illustrate the type of methodical, systematic and

cyclical steps inherent within Asset Management.

First, a target level of service or performance goal for

pavements is set. This target or goal usually is based on

customer requirements, such as the degree of

smoothness customers desire balanced against the

available budget.

Second, the inventory of pavements is developed, if

one does not already exist, and current conditions are

assessed against the desired targets.

Third, an economic-tradeoff analysis is conducted at

the program level to determine what is the estimated

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 9

optimum amount to invest in pavements to achieve the

highest economic return. Investing too little will lead to

degradation of pavement conditions which will be

more expensive in the long term to repair. Investing too

much draws essential resources from bridges, safety,

maintenance, capacity and other important needs. This

tradeoff can be conducted through a state-of-the-art

optimization software program or it can be a much

simpler straight-line forecast based off of the pavement

inventory and past expenditure levels. Either way, it

begins with a logical economic evaluation of the

amount that should be budgeted for pavements.

Fourth, once the optimum amount of pavement

spending is estimated, a rational analysis is conducted

to allocate funds among preventive maintenance,

reactive maintenance, rehabilitation and pavement

replacement categories. Preferably, each category’s

spending levels would be predicated upon a highest

Return on Investment analysis. If such a formal

analysis is not possible, engineering judgment and past

experience can be relied upon.

Fifth, once pavement sections are selected for

treatment, the actual treatment would be based upon a

rational analysis of the individual pavement to provide

it the lowest-cost treatment at the right time. The

pavement’s place on the Pavement Deterioration Curve

would be located and the appropriate preventive,

reactive, rehabilitative or replacement treatment would

be selected.

Sixth, once the pavement was brought to good

condition, a planned and rational multi-year preventive

maintenance schedule would be identified, and then

executed.

Seventh, the pavement’s performance would be

assessed annually and adjustments made in its

treatment schedule to provide the highest Remaining

Service Life.

Eighth, if the pavement fails to perform as expected, a

root cause analysis would be conducted so the agency

can learn from the poor performance and can take

corrective action so it is not repeated.

Ninth, the attributes of that pavement’s performance

and treatment costs would be fed into a Pavement

Management System to continually assess if pavement

goals were met and if adjustments need to be made to

achieve overall pavement goals, expenditures or

strategies.

In a fully developed Transportation Asset Management

environment, similar rational and comprehensive

approaches would be taken for the bridges,

maintenance items, the department’s fleet, its

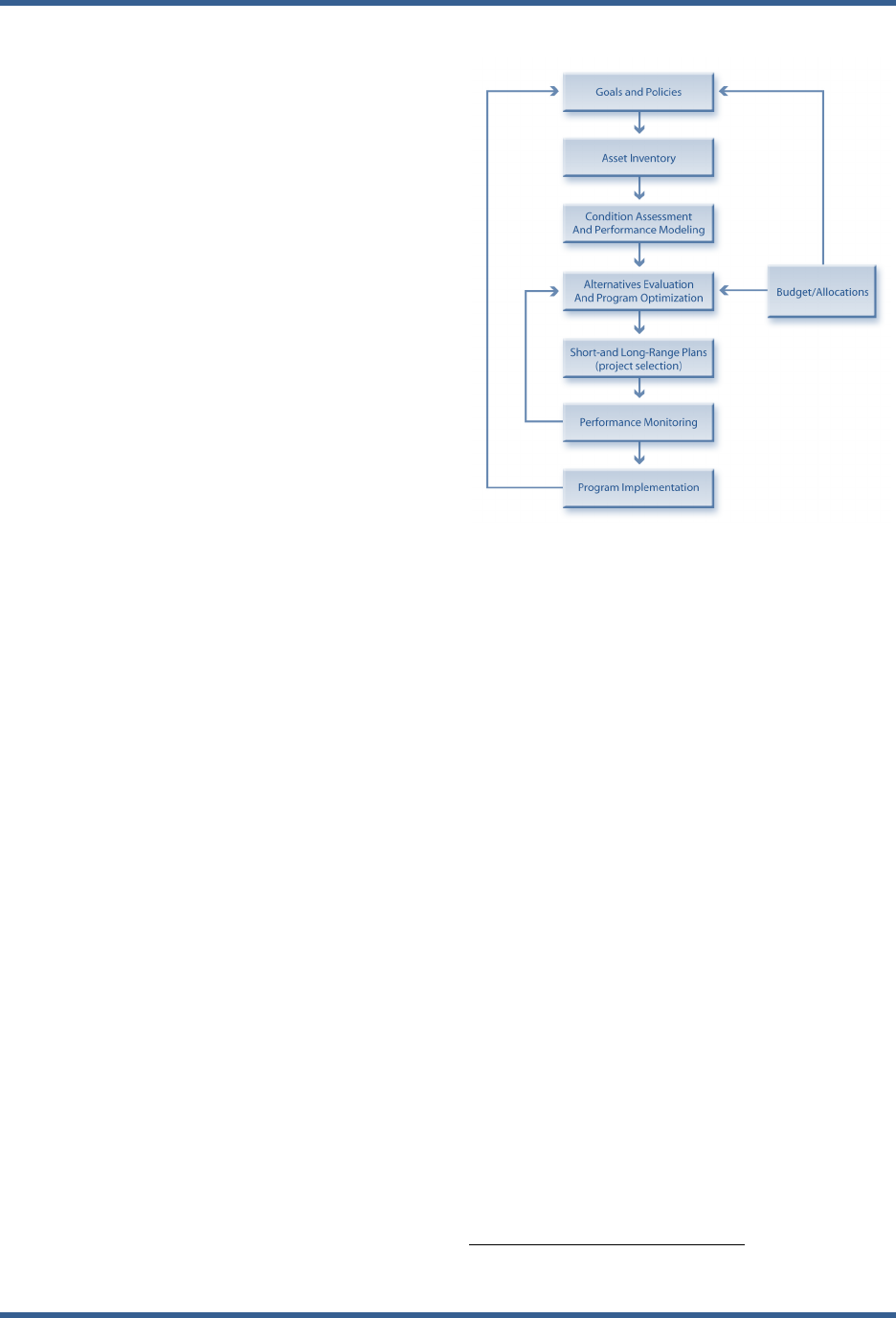

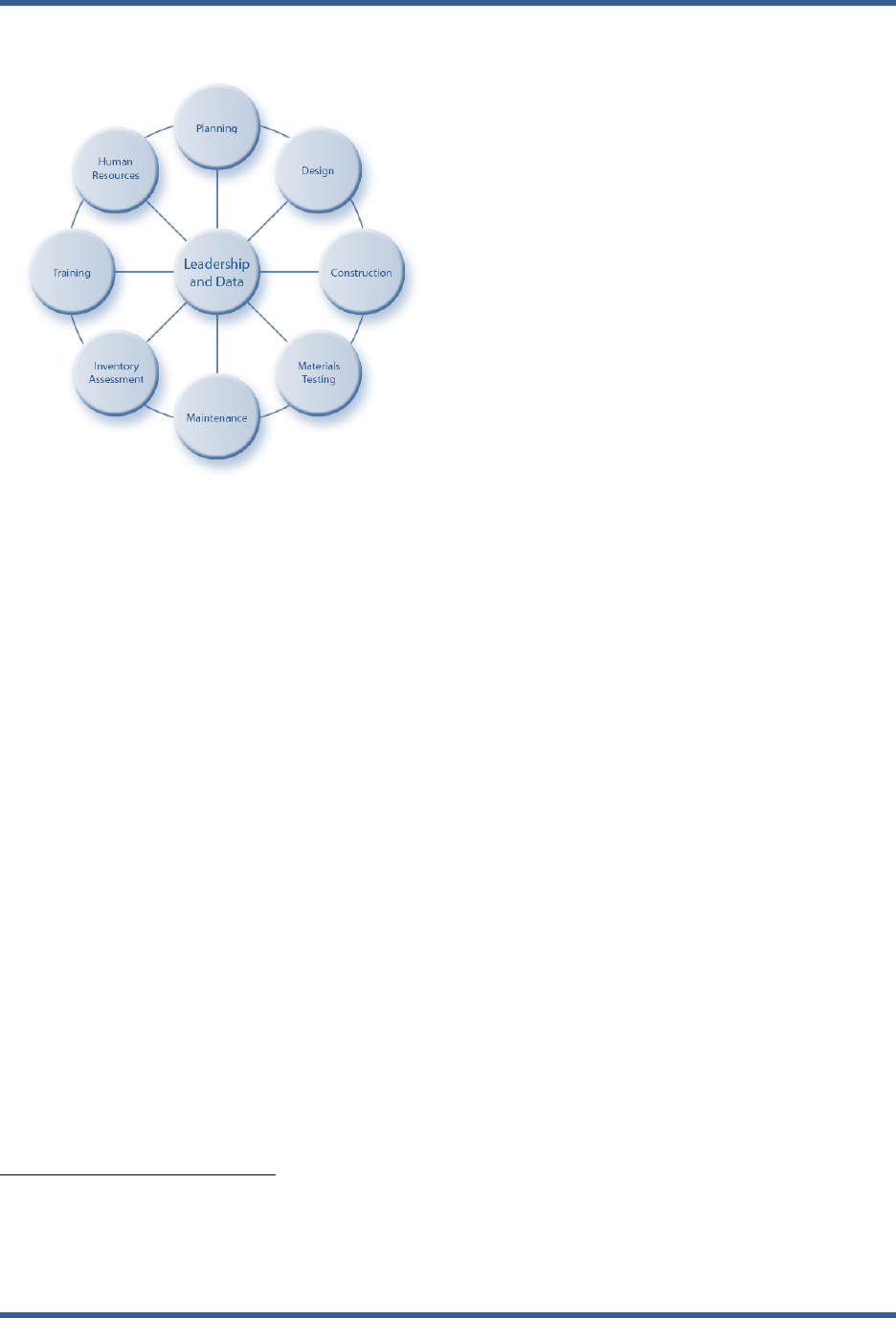

equipment, and even its human resources. Figure 2

above illustrates the basic steps within Transportation

Asset Management. Similar steps would be taken for

any individual class of assets, as well.

In short, Asset Management is a comprehensive,

rational, systems approach to managing pavements,

bridges and other transportation assets.

Haas and Hudson speak in similar terms when

describing pavement management.

1

“Good pavement management is not business as usual.

It requires an organized and systematic approach to

the way we think and in the way we do day-to-day

business. Pavement management, in its broadest

sense, includes all activities involved in the planning

1

Haas and Hudson, 1994, pg. 4.

Figure 2 The asset management process includes a

continuous and systematic setting of goals and

evaluating of results.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 10

and programming, design, construction, maintenance,

and rehabilitation of a pavement portion of a public

works program. A pavement management system

(PMS) is a set of tools or methods that assist decision

makers in finding optimum strategies for providing and

maintaining pavements in a serviceable condition over

a given period of time. The function of PMS is to

improve the efficiency of decision making, expand the

scope, provide feedback on the consequences of

decisions, facilitate the coordination of activities within

the agency, and ensure the consistency of decisions

made at different management levels within the

organization.”

Nearly 50 years ago, a renowned Yale economist

named Charles E. Lindblom wrote a famous public

sector management article in which he argued that

most public agency decisions are not based on rational

and comprehensive analysis, such as that described by

Haas or the Asset Management Guide. Lindblom

argued that instead, decisions generally are based on

narrow, incremental changes to past practice, or

“muddling through.”

2

The advent of powerful scenario-producing informa-

tion systems such as travel-demand models, pavement

management systems, HERS-ST, Pontis, and many

maintenance management systems now allow

transportation policy makers to run numerous

forecasting scenarios. They can routinely evaluate

different investment levels and different investment

mixes between programs to seek the optimum program

budgets and strategies. The “rational and

comprehensive” decision-making process that evaded

Lindblom’s peers now is available to transportation

executives for many of their most-important

infrastructure decisions.

He wrote in 1959 that the

complexities of conducting a rational, comprehensive

analysis of many alternatives was generally so difficult

and expensive that public agencies could not afford it.

Instead, they tended to make minor, incremental

changes to past practice as a means of “muddling

through” their policy-making process.

In the absence of sound Asset Management, the

2

Lindblom, Charles E., The Science Of Muddling

Through, in Public Administration Review, Vol. 19,

pp. 79-88, 1959

following conditions are likely to be found, much in

the manner described by Lindblom:

• Investment levels for various programs are based

upon outdated formulas, geographic splits,

political compromises or simple past practice;

• Bridges, pavements and maintenance assets are

not treated systemically with an optimum mix of

timely preventive and reactive treatments;

• The department lacks a clearly defined set of

goals for where it wants its system conditions to

be and it lacks strategies for how it will get there;

• Planning, design, construction, maintenance and

information technology lack adequate coordin-

ation and take a “silo” approach to their role in

managing assets;

• In other words, an agency “muddles through” its

infrastructure-management process.

Asset Management therefore relates to improving

existing agency functions such as long-range planning,

short-range programming, scheduling of maintenance

and the delivering of projects. These functions clearly

are not new. What is new in an Asset Management

approach is that they are conducted in a tightly

coordinated fashion to ensure they result in the highest-

system conditions for the lowest cost over the life of

the department’s infrastructure planning horizon.

Asset Management should not be viewed as yet another

new program, requiring another new bureaucracy.

Rather, Asset Management is a “way of doing

business.” It brings a particular perspective to how an

agency conducts its existing procedures, reaches

decisions, and applies its information technology

capabilities. It suggests principles and techniques to

apply in policymaking, planning, project selection,

program tradeoffs, program delivery, data gathering,

and management system application.

There is no one correct table of organization and no

one correct set of performance measures that will

guarantee a successful Asset Management program.

However, there are a variety of common functions

which need to occur in an Asset Management structure.

Leaders seeking to instill Asset Management in their

organizations will have to decide how best to

coordinate these functions.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 11

Asset Management Is a Strategic

Approach

Asset Management requires a strategic approach to

managing a department’s infrastructure. A strategic

perspective takes a long view of infrastructure

performance and cost, and considers options in a

comprehensive, proactive, and informed way. It is

driven by policy goals and objectives and relies on

systematic assessments of asset performance and cost

in making decisions on future actions.

An agency which practices sound Asset Management

has well-defined policies that can be related to clear

objectives and measures of performance. Management

emphasizes customer service and accountability for

system performance and cost effectiveness. Decisions

on allocating resources are policy driven and

performance-based, consider a range of alternatives,

have clear criteria for decision making, and investigate

the most cost-effective solutions through analyses of

tradeoffs.

TAM Breaks Down ‘Silos’

Asset management encompasses a number of business

processes related to infrastructure management in

DOTs, including those related to planning, program

development, design, construction, maintenance,

information technology and knowledge management.

The functions of planning, design, construction,

maintenance and information technology work through

common, coordinated processes to ensure that each

contributes to asset management, without encumbering

the other. The “sub-optimization” that can occur within

silos is prevented through effective communication and

coordination strategies. The business processes are

managed to elicit effective contributions from all levels

of the organization, and to foster communications on

Asset Management needs and accomplishments both

within and outside the agency. The organizational

roles of each unit are clear, but also clear is the shared

requirement that each unit coordinates with and

complements the other. For instance, if maintenance

has responsibility for crack sealing of pavements, it

understands that role and executes it in a timely and

appropriate manner in the pavement’s lifecycle. Design

provides plans on time to provide treatments when

needed. Information technology understands the

information needs of the other functions and provides

0.8

0.82

0.84

0.86

0.88

0.9

0.92

0.94

0.96

0.98

1

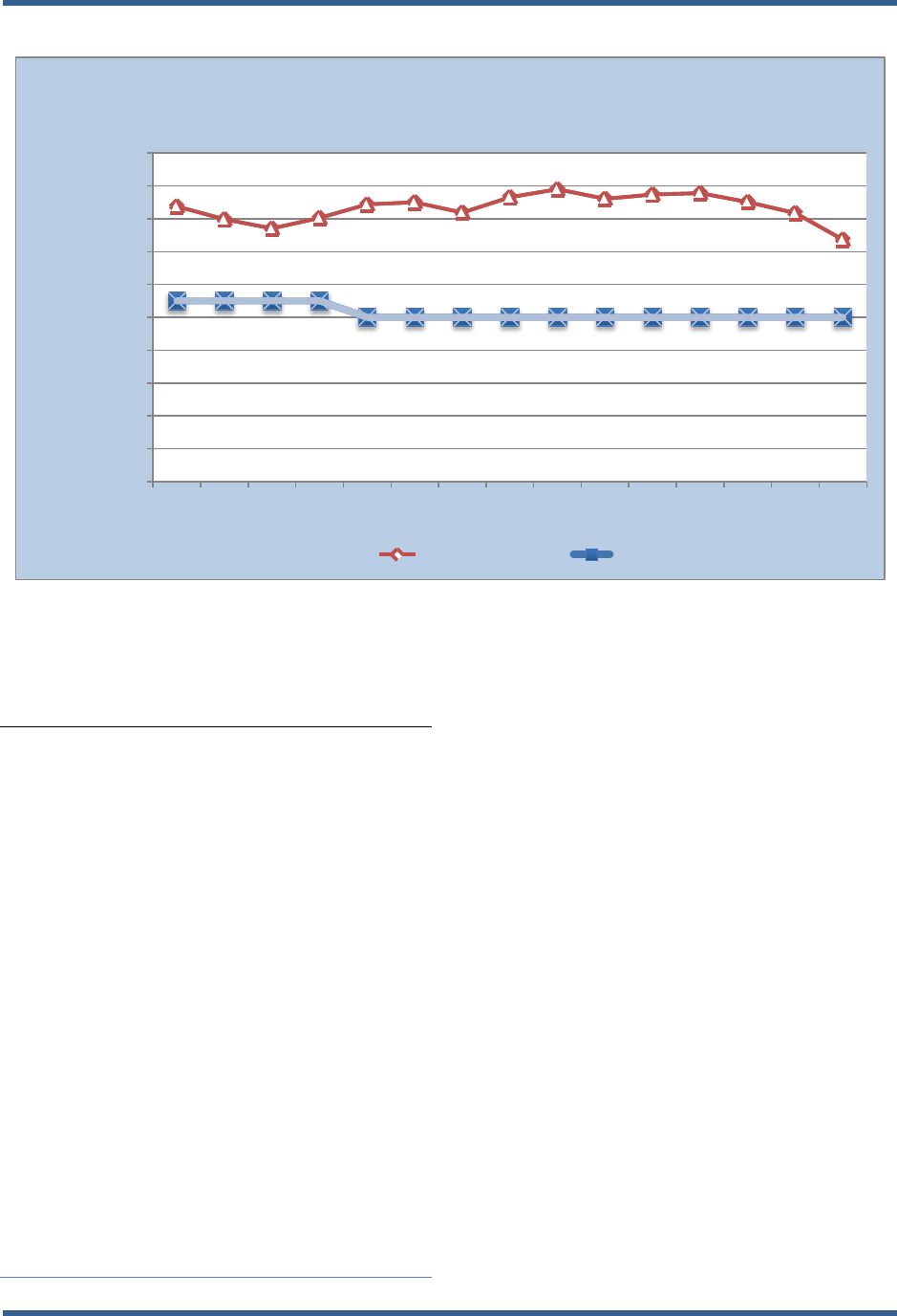

2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016

Percent of Networkk Acceptable

Pavements Trends Compared to Goal

Condition Goal

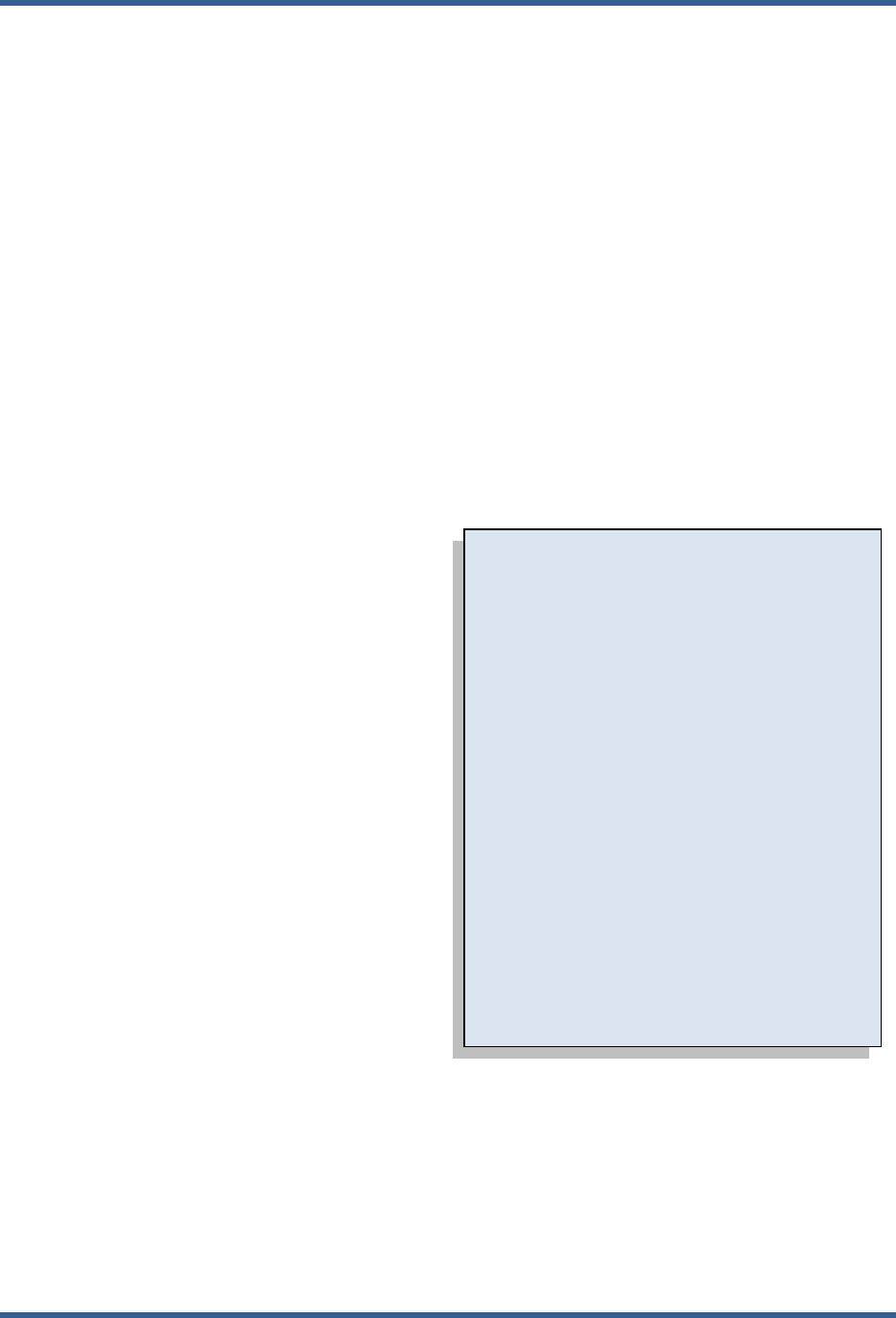

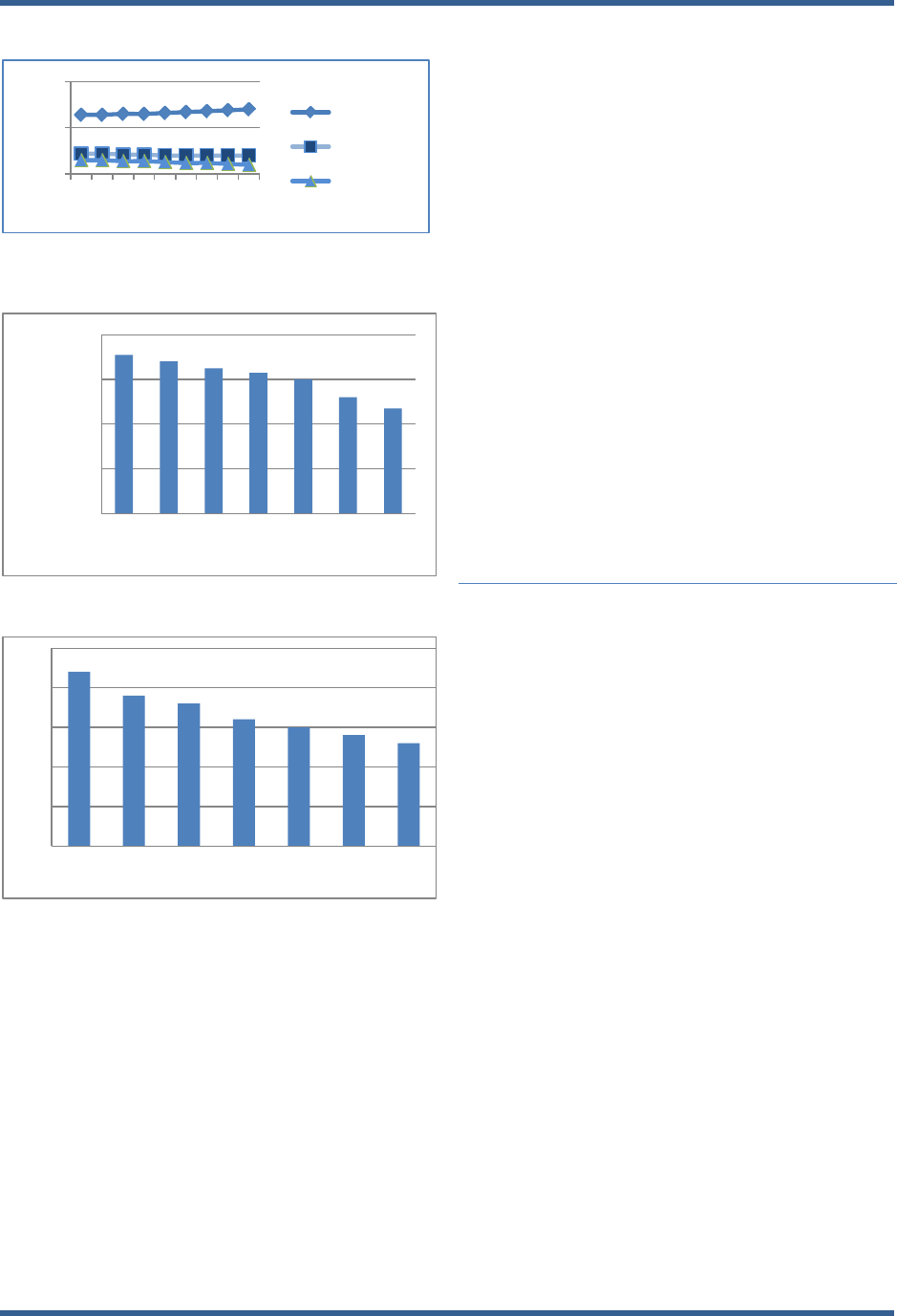

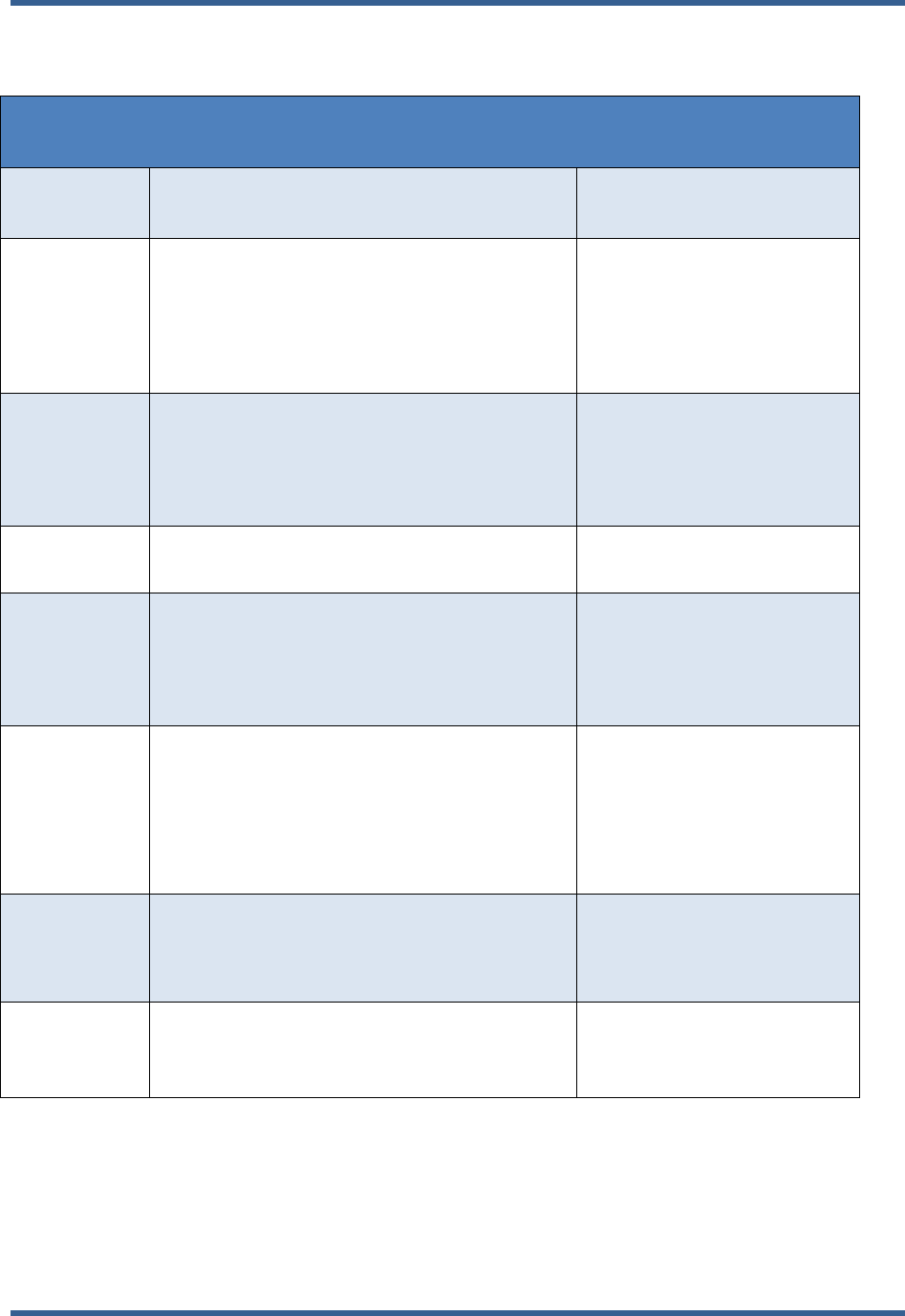

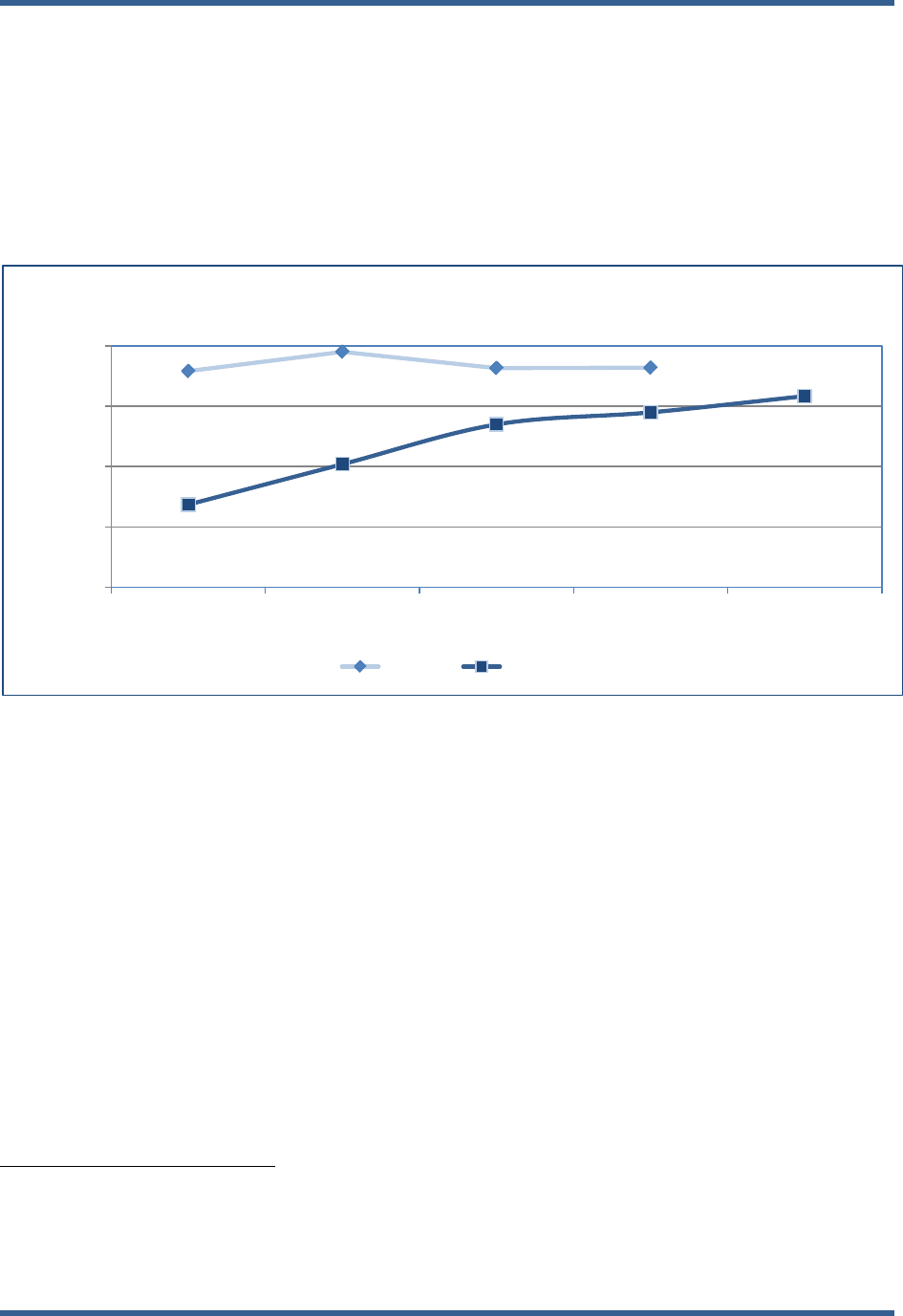

Figure 3 The ability to illustrate future trends and the results of current practices allows asset management

practitioners to demonstrate the consequences of current decisions.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 12

the data they require. In short, the units function in a

coordinated fashion to execute the thousands of

individual steps required. Management authors

sometimes refer to this as “Horizontal Alignment,”

which often does not occur in large organizations

without specific effort from the senior leadership.

Asset Management Relies on

Good Information and Analytic

Capabilities

Quality information – accurate, complete, timely – is

important at all stages of Asset Management.

Information technology is a practical necessity in

supporting Asset Management. A sound Asset

Management program relies on information regarding

past asset performance, remaining service life, the

expected performance of treatments and a forecast of

future trends. The needed trend forecasts must address

not only expected infrastructure performance but also

future resource availability. Information is needed in

standard reports for system-wide performance. Also

innumerable ad hoc reports are required for front-line

managers seeking to optimize their short-term

performance of individual assets.

Asset Management Practices Are

Flexible

Successful Asset Management practices vary

considerably across the nation because of the significant

differences between how states are organized and

governed. Asset Management performance measures,

data systems and analytical tools also vary widely

because of the disparate development of information

systems over the decades. No two states have the same

legal structure, span of responsibility or legacy

information systems. Each state and locality which

undertakes Asset Management does so in a fashion

unique unto itself.

Asset Management Works at

Multiple Levels

Asset Management provides benefits at three levels, a

policy level, an administrative level and a technical

level.

First, at the public-policy level it provides the

organization with a clear framework it can use to

explain its investment decisions and to illustrate the

investment tradeoffs that it faces, as in Figure 3 above.

If legislators ask for scenario planning to illustrate the

impacts of increased or decreased investment, the

agency can respond in a systematic fashion. The

agency can explain its infrastructure-management

philosophy and document that it is rational,

comprehensive and economical, based on the lowest-

overall life-cycle cost.

Secondly at the administrative level, Asset

Management provides the agency a means by which to

organize its disparate and widely distributed resources

in a coordinated fashion to achieve one of its key

missions – the optimization of roads, bridges and other

transportation assets. The typical department of

transportation will have essential staff distributed

across dozens of counties and regions and hundreds of

construction projects. Asset Management policies and

practices provide a unifying structure and philosophy

to coordinate these widely distributed people and the

resources they control.

Third, at the technical level, Asset Management

systems provide the information that engineers,

planners, information technology specialists and

managers need to conduct their jobs. Asset inventories

provide information on the extent and condition of

assets. Degradation rates can be used to predict assets’

future remaining service life. Information about the

performance of past materials and construction

techniques can be used to assess the adequacy of

construction standards and materials. The planned

preventive and reactive maintenance needs provide

structure to the efforts of maintenance forces. In

summary, Asset Management provides a “knowledge

management” framework which contributes to

continued organizational learning.

People, Processes, Plans and

Products

Two of the agencies examined in this report, the

Oregon and the Utah DOTs, use very similar language

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 13

in describing the major focus areas necessary to instill

asset management successfully. They describe “people,

processes, plans and products” as being essential. The

fact that four fundamental aspects of an organization

need to be engaged reflects the complexity and

comprehensiveness of Asset Management. Changing

people, changing processes, changing plans and

changing products can involve a transformative

evolution which extends to most major business areas

of a large transportation organization.

Such transformation has been experienced by leading

Asset Management practitioners, and by those

organizations which have embraced other advanced

frameworks such as ISO, Baldrige or Six Sigma. This

report will later describe those other systems and

illustrate how they compare to Asset Management. But

first, the report will describe what leadership strategies

and organizational structures have been used

successfully to ingrain these frameworks into the

people, processes, plans and products of transportation

agencies.

The Case Studies

Beginning with the next chapter, case studies follow each section. These case studies elaborate

upon and illustrate the themes from each topical section. Particularly they focus upon the common

issues that agencies confront and how they address them when they attempt major organizational

change to improve asset conditions.

All of the case study agencies stressed that they do not consider themselves to have achieved a

perfect process. All stressed that while they are pleased with their progress, they are on a long

journey and their asset management practices continue to evolve. Each agency has taken a

different approach based upon its statutes, geography, history and organizational structure. No

case study is presented as representing the definitive approach. Rather, they illustrate the rich and

innovative approaches which have been adopted. In their diversity, they illustrate that Asset

Management principles can be applied successfully in many different settings, with different

organizational structures and with differing legal frameworks. From New Zealand to North

Carolina, agencies have achieved success with asset management practices in their own ways.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 14

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 15

Chapter 2 Key Agency Roles in Asset

Management

To explain how to organize and operate an agency to

maximize Asset Management it is necessary to

elaborate on the how the traditional functions within

a department of transportation need to change. The

functions of planning, design, construction and

maintenance all need to alter or tailor their activities

in important ways to achieve the full benefits of

Asset Management. Operating in silos with a

reactive, short-term term mindset impedes Asset

Management, while a multi-disciplinary, long-term

approach enhances it.

Policy, Strategy and Planning

Establish Direction

Asset Management begins with sound strategy. It

rejects a “business-as-usual,” “muddling-through”

acceptance of past practices. Instead it embraces a

clearly articulated “rational comprehensive”

approach to planning, programming, project-delivery,

maintenance and on-going analysis. As such, a

department which wants to embrace Asset

Management must develop realistic long-term goals

for its system conditions. It needs to set clear,

numeric goals for what level of condition it wants to

achieve for its pavements, bridges, maintenance

features, fleet and facilities. These specific, numeric

goals must be realistic to be credible. They can be

based upon computerized forecasts conducted by

Creating

organizational

alignment is one of

many benefits of

adopting an asset

management

approach. TAM

provides an

overarching

framework for

decision making

which coordinates

disparate activities.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 16

models or be conducted by ad hoc analysis of past

trends and future projections. They should extend at

least a decade into the future to fully capture the

long-term effects of current practices in planning,

programming, construction and maintenance. To

understand whether today’s actions are sufficient, the

departmental leader needs to understand how today’s

actions will affect system conditions in the future.

By its very nature, Asset Management assumes a

long-term view. Therefore, a long-term strategic

approach to thinking about the department and about

organizing its activities is essential to implementing

Asset Management.

The department’s planning function must be able to

produce sound investment scenarios. The asset

planning functions reside in various units in different

agencies. Sometimes, the asset planning functions are

in the Planning Division, other times they are within

districts, or materials units, or for bridges they may

be in the structures divisions or even maintenance.

Wherever the asset planning function resides, it must

do more than fulfill the short-term mechanics of the

federal or state planning process. The planning

function must conduct strategic long-term forecasts

of system conditions and provide senior management

with alternative investment options based upon

various long-term scenarios. The scenario which best

meets the department’s policy needs, system-

condition goals and financial resource forecasts can

be selected.

An important component of the department’s

strategic, long-term approach is to meaningfully

translate the long-term objectives into short-term

performance measures which are drivers for annual

activities. If the department seeks to increase

preventive maintenance investments for greater long-

term pavement performance, the number of

preventive maintenance projects in the short-term

Transportation Improvement Program probably needs

to increase. The planning function can measure and

track the short-term annual and bi-annual pavement

project accomplishments for their conformance to the

long-term objectives.

Formerly separate functions often become linked in

an Asset Management process, therefore cross-

cutting coordination is important. The maintenance

of asset inventories is an important planning function

within an Asset Management environment. Another

important planning function is the development of

the State Transportation Improvement Program

(STIP), or the collection of capital projects and

activities to be undertaken. In an Asset-

Management framework, these two formerly separate

functions become linked in important ways. Each

year as the inventory conditions are updated, the

conditions should be assessed and compared against

the short-term condition goals which the department

had set for the year. Also, the development of the

projects in the STIP should be carefully done so that

the particular projects actually include the precise

number of preventive, reactive, rehabilitative and

replacement projects which were prescribed in order

to achieve the desired long-term system conditions.

As mentioned earlier, all the traditional departmental

functions occur in an Asset Management operation

but they often occur with more cognizance and

linkage as to their effects upon other aspects of the

department. In this case, the development of the STIP

is done with a clear objective of achieving the short-

term system-condition goals, which are one annual

component of a multi-year strategy. Also, as the

annual inventory assessments of the condition of

bridges, pavements and maintenance items occur, the

resulting overall condition levels are compared to

“field verify” whether the forecasted conditions were

actually achieved. The two formerly separate

functions of STIP development and inventory

condition updates become strategically linked in an

Asset Management planning framework.

Traditional planning and forecasting scenarios must

be clearly understood by policy makers. The planning

functions must fulfill an important forecasting role,

both internally and externally to policy makers.

Departments are always influenced by outside policy

forces, whether they be gubernatorial, legislative,

media-driven or embodied within a commission.

These forces will seek to influence project selection

and programming to whatever ends they deem most

important. The policy and planning process of an

organization can provide these influencers with clear

information on the tradeoffs to be faced and the

consequences to be expected from their decisions. To

effectively influence the investment decisions, the

forecasts need to be clear, credible and

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 17

understandable. This requires the planning function

to not only be expert in conducting forecasts but also

to be able to clearly explain them to the public and

policy makers. Important within this forecasting

function is:

• the clear estimation of available resources;

• the trends in system condition;

• the investment tradeoff scenarios which are

possible, and;

• a recommendation for how to balance these

complex, and competing needs.

These competing needs can be between asset classes

such as bridges and pavements, between important

objectives such as safety and environmental

enhancement, or between modes.

Project Delivery Reliability is

Key to Timely Asset Treatments

The coordination between the asset planning

functions and the project delivery functions is very

important in an optimized Asset Management

operation. The planning and programming functions

play an explicit role in selecting specific projects to

achieve specific system-condition goals. Outcome-

related metrics drive programming decisions, as

opposed to more general output measures such as

merely the number of miles paved or whether a

department hit a goal for the size of its construction

program. The programming and project-selection

decisions are explicitly tied to predicted asset-

deterioration cycles. The timing of preventive and

reactive maintenance projects are carefully planned

to maximize asset-condition longevity. For any one

project, predicting this time window and delivering a

treatment project accordingly is relatively simple.

When departments are managing thousands of

disparate pavement sections and thousands of

separate structures, the coordination of hundreds of

specifically scoped and specifically timed projects

becomes quite complex. Therefore, the coordination

between planning and design functions must be

sound.

For instance, by tracking structural deficiencies in

pavement sections, the pavement planning officials

can identify pavement sections appropriate for

preventive maintenance treatments. Projects for those

treatments can be scoped and timed appropriately

with the design division. The pavement planning

function also can assist design by forecasting the

cumulative effects of all programmed projects upon

meeting the department’s pavement or bridge-

condition goals. If the overall program is not

projected to achieve the desired goals for a specific

horizon year, either additional projects can be

considered or the scope of the existing projects can

be altered to achieve the asset condition goals.

Projects are reliably delivered on time and within

scope in an agency that successfully optimizes asset

management. The role of design or plan

development units is to reliably deliver the

appropriately scoped project on time so that the

lowest-lifecycle-cost treatment actually is delivered

to the asset when it is needed. If preventive or

reactive maintenance is delivered too late in an

asset’s deterioration curve, the treatment

effectiveness will be diminished. The importance of

treatment timing is particularly acute considering the

lack of adequate funding that most agencies

experience.

Agencies are seeking to stretch their assets’ useful

lives without letting them deteriorate to a stage where

they require expensive reconstruction or replacement.

This creates a treatment window in which the

appropriate low-cost treatment will improve the asset

but the same treatment delayed may be inappropriate

for that asset. For instance, a minor overlay timed

appropriately can extend a pavement’s life but a

minor overlay on a severely structurally deficient

pavement will accomplish little in the long-term.

The overall lifecycle cost assumptions of when to

treat an asset and how to treat it must be predicated

on the reliable assumption that the treatments will

occur on schedule.

Design units also must have sound cost data to

successfully support Asset Management. Asset

Management is about seeking the highest-return-on-

investment strategies for the assets over their useful

life. Assumptions about how to treat those assets

must be predicated upon sound cost information.

This cost information generally comes from a

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 18

comparison between estimated costs and actual costs.

The actual costs are derived not only from the

awarded bids, but also from all the change orders

which occur to a project during its construction. The

final, as-built costs must be tracked and translated

into useful unit costs which are fed back into the

planning forecasts. The accuracy of the unit costs

which can be escalated with realistic growth factors

is essential to investment forecasts and scenarios. To

coordinate the accuracy of planned, estimated and as-

built costs, requires coordination of the planning,

estimating and construction sectors. The accurate

data they generate must be available to the Asset

Management planners who are forecasting system

needs. In the Utah DOT case study, the Asset

Management staff noted that capturing reliable asset-

treatment unit prices was a key step in their Asset

Management development. Separating the costs of

pavement treatments from ancillary costs in projects

was important to forecasting budget levels needed to

sustain pavement conditions.

Departments have a formal, documented process for

approving significant change orders and cost

increases in an Asset Management framework.

Because funding and programming decisions have

been carefully balanced in an Asset Management

environment, a significant cost increase in one

project results in the delay or cancellation of another.

The cost change which results in a project delay or

cancellation may ripple through the carefully

balanced network analysis. The production or plan

delivery unit needs to formally report the cost

increases and coordinate that information with the

planning and programming staffs who had balanced

the program originally. Not only are project-delivery

dates carefully tracked, but adherence to project cost

and scope must also be coordinated.

The Importance of Maintenance

Should Not be Overlooked in

Asset Management

Maintenance forces can become a key partner in an

Asset Management framework. Maintenance

activities traditionally have been reactive but they

become incrementally more strategic and pro-active

when they are fully integrated into an Asset

Management framework. The daily work

maintenance forces do can be strategically focused

upon the maintenance activities which most directly

support the continued performance of assets. These

activities are unglamorous but important. They can

include:

• Systematic crack sealing;

• The application of low-cost treatments such as

chip seals;

• The cleaning of under drains;

• General drainage maintenance;

• The strengthening of shoulders which can

prevent pavement edge failures;

• The clearing of scuppers and expansion joints

on bridges;

• Bridge deck patching;

• Full-depth pavement repairs which contribute to

pavement structural integrity instead of mere

surface patching.

It has been common in recent decades for

maintenance forces to operate under , however, for

those forces to be explicitly trained as to how the

above activities can extend the life of pavements and

bridges. In a fully organized, asset management

framework the front-line maintenance forces are

viewed as an important ally in the process.

Construction’s Critical Quality-

Control Role

It is self-evident that sound construction,

inspection and materials-testing practices

are important in Asset Management. The

detailed adherence to materials and

construction specifications are always a

priority. In an Asset Management

framework, the reliance on sound

construction techniques is even heightened

because the organization is relying on the

full performance of any particular treatment

as part of its carefully choreographed and

balanced program of projects.

Asset Management for Sustainability, Accountability and Performance 19

Information and Analysis Rises

in Importance in Asset

Management

Information and analysis is probably the area of a

traditional department of transportation which most

grows in importance during the transition to a full

Asset Management environment. As departments

embark on an Asset Management effort, they quickly

consume ever-increasing amounts of information and

analysis. Legacy asset inventories such as bridge,

pavement and maintenance inventories are

increasingly relied upon as the basis for scenario and

tradeoff analysis. Management systems are often

found to be lacking in the detail and flexibility which

decision-makers soon require as they seek ever-more

complex scenario planning.

Nearly all departments have basic inventories for

their pavement, bridge and maintenance assets. In

some cases where Asset Management was not

emphasized, these inventories degraded in terms of

the accuracy and timeliness of their data. If the data

were not heavily relied upon for decision making,