TECHNICAL REPORT

www.ecdc.europa.eu

Guide to revision of

national pandemic influenza

preparedness plans

Lessons learned from the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic

ECDC TECHNICAL REPORT

Guide to revision of national pandemic

influenza preparedness plans

Lessons learned from the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic

ii

This report of the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC) and the WHO Regional Office for

Europe was developed by experts in pandemic preparedness planning from 11 European Union Member States and

staff members of the following organisations: WHO Regional Office for Europe, the European Commission, the

WHO Collaborating Centre for Pandemic Influenza and Research (University of Nottingham), the US Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention, and ECDC.

It was coordinated and compiled by Caroline Brown (WHO), Massimo Ciotti (ECDC), Michala Hegermann-

Lindencrone (WHO), Pasi Penttinen (ECDC), René Snacken (ECDC) and Angus Nicoll (ECDC).

Contributing authors

Theodor Ziegler, Florence Allot, Joan O Donnell, Ehud Kaliner, André Jacobi, Radu Cojocaru, Kosim Kuirbonov,

Nicholas Phin, Jonathan Nguyen Van Tam (WHO Collaborating Centre for Pandemic Influenza and Research, Helmut

Walerius (European Commission) and Adrienne Rashford (WHO Regional Office for Europe).

We acknowledge the valuable input from public health experts from all EU Member States and all countries of the

WHO European Region.

Suggested citation: European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control. Guide to revision of national pandemic

influenza preparedness plans - Lessons learned from the 2009 A(H1N1) pandemic. Stockholm: ECDC; 2017.

Stockholm, November 2017

Print

ISBN 978-92-9498-090-8

doi: 10.2900/466319

TQ-04-17-829-EN-C

PDF

ISBN 978-92-9498-091-5

doi: 10.2900/096346

TQ-04-17-829-EN-N

Cover picture: © Government of Alberta, image licensed under a Creative Commons attribution 2.0 generic license

(CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

© European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control, 2017

Reproduction is authorised, provided the source is acknowledged.

For any use or reproduction of photos or other material that is not under the EU copyright, permission must be

sought directly from the copyright holders.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

iii

Contents

Abbreviations ............................................................................................................................................... iv

Introduction .................................................................................................................................................. 1

Twelve key areas of pandemic preparedness .................................................................................................... 4

Key area 1: Framework for pandemic planning ............................................................................................ 4

Key area 2: Pandemic planning and response based on risk assessment ........................................................ 5

Key area 3: Coordination, command and control .......................................................................................... 7

Key area 4: Risk communication................................................................................................................. 8

Key area 5: Pandemic vaccines .................................................................................................................. 9

Key area 6: Antivirals and other essential medicines .................................................................................. 10

Key area 7: Healthcare services preparedness ........................................................................................... 11

Key area 8: Non-pharmaceutical public health measures ............................................................................ 13

Key area 9: Essential services and business continuity................................................................................ 14

Key area 10: Special groups and settings .................................................................................................. 15

Key area 11: After the pandemic – recovery and transition phase ............................................................... 15

Key area 12: International cooperation, coordination and interoperability..................................................... 16

References and resources ............................................................................................................................. 17

General references .................................................................................................................................. 17

Key area 1: Framework for pandemic planning .......................................................................................... 17

Key area 2: Pandemic planning and response based on risk assessment ...................................................... 17

Key area 3: Coordination, command and control ........................................................................................ 18

Key area 4: Risk communication............................................................................................................... 18

Key area 5: Pandemic vaccines ................................................................................................................ 18

Key area 6: Antivirals and other essential medicines .................................................................................. 19

Key area 7: Healthcare services preparedness ........................................................................................... 19

Key area 8: Non-pharmaceutical public health measures ............................................................................ 19

Key area 9: Essential services and business continuity................................................................................ 20

Key area 10: Special groups and settings .................................................................................................. 20

Key area 11: After the pandemic: Recovery and transition phase ................................................................ 20

Key area 12: International cooperation, coordination and interoperability..................................................... 20

Figures

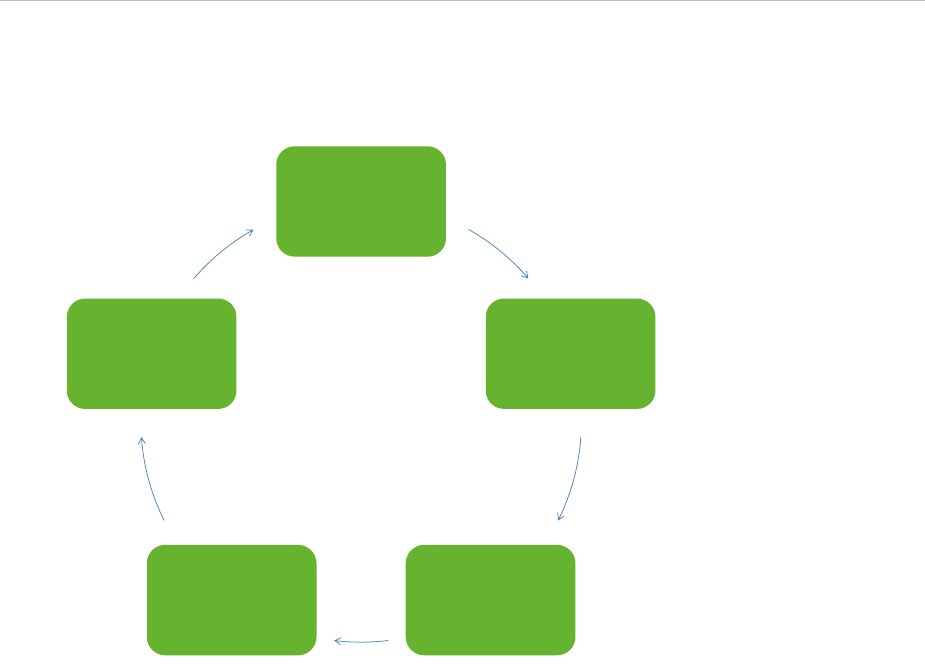

Figure 1. Key elements of the pandemic preparedness planning cycle ................................................................. 2

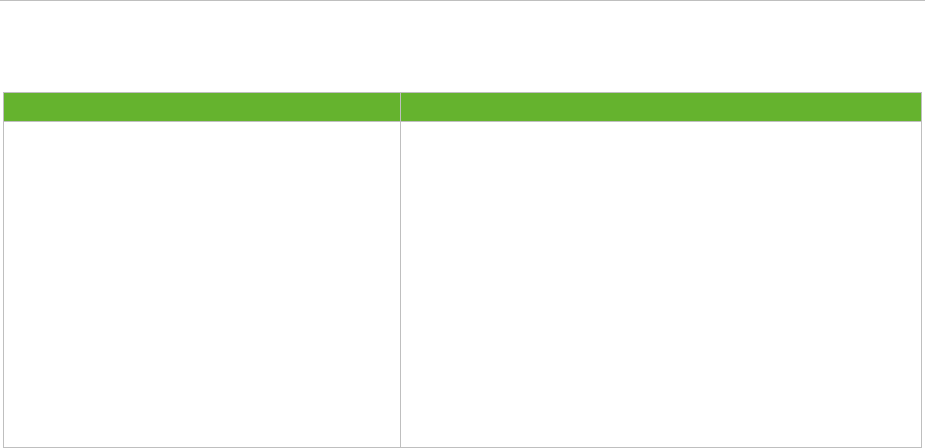

Figure 2. The continuum of pandemic phases ................................................................................................... 6

Table

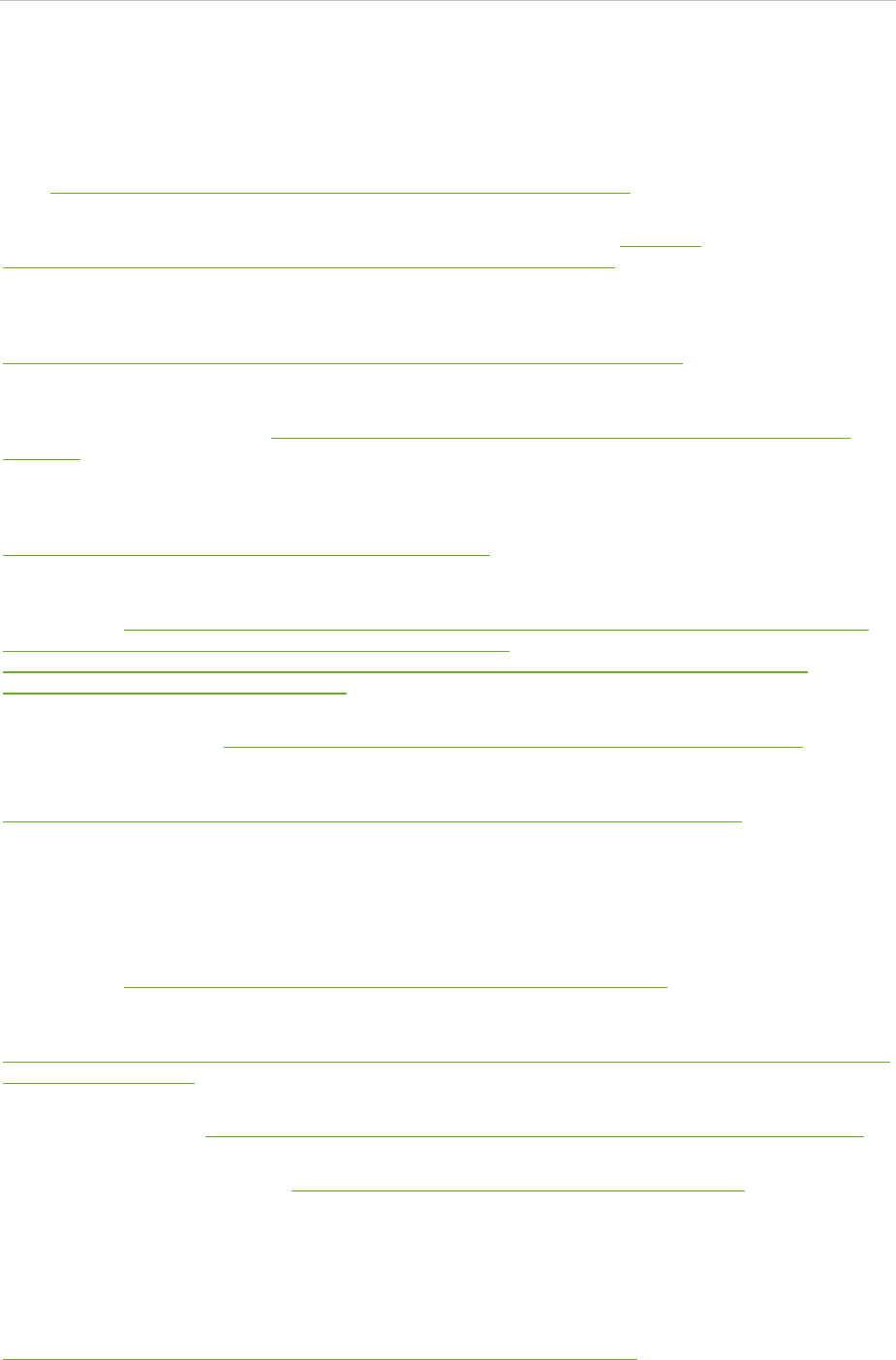

Table 1. Example of stakeholder-representation in the national pandemic preparedness planning committee ......... 5

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

iv

Abbreviations

AEFI Adverse events after immunization

ARI Acute respiratory infection

AV Antiviral drugs

BCP Business continuity plan

CDC US Centres for Disease Control and Prevention

EC European Commission

ECDC European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control

ECMO Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation

EEA European Economic Area

EMA European Medicines Agency

EU European Union

EuroFlu WHO Regional Office for Europe, influenza surveillance bulletin

EWRS Early Warning and Response System

GISRS Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System

HCW Healthcare worker

ICU Intensive care unit

I-MOVE Influenza Monitoring Vaccine Effectiveness

NIC National influenza centre

NITAG National Immunisation Technical Advisory Group

NPI Non-pharmaceutical intervention

NRA National regulatory authority

SAGE Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation

UN United Nations

VAESCO Vaccine Adverse Event Surveillance and Communication

WHO World Health Organization

WHOCC WHO Collaborating Centre for Reference and Research on Influenza

WHO/Europe WHO Regional Office for Europe

WISO ECDC Weekly Influenza Surveillance Overview

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

1

Introduction

During the past decade, the 53 Member States of the WHO European Region, 31 of which are part of the European

Union/European Economic Area, invested considerably in pandemic preparedness. This came in the wake of global

threats posed by (re-)emerging diseases such as avian influenza A(H5N1) and A(H7N9), the SARS outbreak of

2003, and the outbreak of MERS (Middle East respiratory syndrome) which began in 2012. Adequate preparedness

is also a national obligation under the International Health Regulations (2005) and the EU Decision on serious

cross-border threats to health (No 1082/2013/EU).

The first pandemic since 1968 occurred in 2009, caused by a new strain of influenza A(H1N1) of swine origin. The

virus spread rapidly around the globe and caused only mild disease in the majority of cases. However, severe

disease and deaths occurred in a significant number of people, mostly in the same groups that are at risk of

complications due to seasonal influenza infection, but also in other risk groups and even in previously healthy

individuals. It has been estimated that in the first year of the pandemic between 151 000 and 475 000 deaths

worldwide were attributable to influenza. Healthcare services, particularly critical care units, were often stretched

to their limits, and early recognition and treatment of severe disease could be life-saving.

The 2009 pandemic tested national plans, and in the aftermath many countries and international organisations

evaluated their preparedness and response activities. European countries, particularly in the western part of the

Region, were generally better prepared for the 2009 pandemic than most countries. But when confronted with a

milder pandemic than was expected, even the better prepared countries experienced gaps in their surveillance and

healthcare systems. Their planning assumptions were not flexible enough, they faced difficult communications and

logistics issues with respect to pandemic vaccines, and often failed to establish effective communication lines with

front-line healthcare responders.

An evaluation performed by the WHO Regional Office for Europe in collaboration with the WHO Collaborating

Centre for Pandemic Influenza and Research, University of Nottingham, United Kingdom, showed that pandemic

preparedness activities undertaken prior to the 2009 pandemic were useful in the response to the pandemic, and

guidance from WHO and ECDC was critical in the preparedness phase. However, a global review of the functioning

of the International Health Regulations and the response to the pandemic by both countries and WHO came to the

conclusion that the ‘world is ill-prepared to respond to a severe influenza pandemic or to any similarly global,

sustained and threatening public-health emergency.’ The recommendations of this review have been only partially

implemented, and the world has since been confronted with the failure to respond rapidly – and on the scale

needed – to prevent the largest outbreak of Ebola ever recorded. As a result, the 69th World Health Assembly

agreed to reform the WHO emergency response arrangements. It also agreed that the full implementation of the

IHR core capacities by all Member States must be accelerated. In 2016, the new WHO Health Emergencies

Programme was established (http://www.who.int/topics/emergencies/en/).

A future influenza pandemic is inevitable, although it cannot be predicted when it will happen nor how severe it will

be. Since the stress on the non-healthcare sectors was limited during the 2009 pandemic, only limited experience

has been gained in multisectoral coordination. Business continuity which will be crucial in a more severe pandemic.

Earlier findings from European assessments and exercises show that there are still weaknesses in those areas.

Since 2009, only thirteen countries in the WHO European Region have published revised pandemic preparedness

plans (as of July 2017). This document therefore takes into account:

the need for all countries to review and revise as necessary their pandemic plans based on the lessons

learned from the 2009 pandemic and WHO guidance on pandemic influenza risk management (see:

http://www.who.int/influenza/preparedness/pandemic/influenza_risk_management_update2017/en/);

the need for continuous integration of pandemic preparedness with preparedness for other public health

emergencies, in line with the International Health Regulations, Decision No. 1082/2013/EU, and in light of

shrinking resources;

the need to develop plans for different scenarios of severity with more emphasis on national risk

assessment to inform pandemic response; and

the need to revise the ‘WHO/Europe and ECDC Joint European Pandemic Preparedness Self-Assessment

Indicators’ and develop a planning document that is useful to all Member States.

Why is pandemic preparedness planning important?

Influenza pandemics, whether mild, moderate or severe, affect a large proportion of the population and require a

multisectoral response over several months or even years. For this reason, countries develop plans describing their

strategies for responding to a pandemic supported by operational plans at national and subnational levels.

Preparing for an influenza pandemic is a continuous process of planning, exercising, revising and translating into

action national and subnational pandemic preparedness and response plans. A pandemic plan is thus a living

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

2

document which is reviewed at intervals and revised if there is a change in global guidance or evidence-base;

lessons learned from a pandemic, an exercise, or other relevant outbreak; or changes to national or international

legislation related to communicable disease prevention and control (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Key elements of the pandemic preparedness planning cycle

Strategic

planning

Operational

planning

Exercises,

reviews

Implementation

Evaluation

Pandemic preparedness is most effective if it is built on general principles that guide preparedness planning for any

acute threat to public health. This includes the following:

Pandemic preparedness, response and evaluation should be built on generic preparedness platforms,

structures, mechanisms and plans for crisis and emergency management.

To the extent possible, pandemic preparedness should aim to strengthen existing systems rather than

developing new ones, in particular components of national seasonal influenza prevention and control

programmes.

New systems that will be implemented during a pandemic should be tested during the inter-pandemic

period.

Adequate resources must be allocated for all aspects of pandemic preparedness and response.

The planning process, implementing what is planned, testing and revising the plan in order for key

stakeholders to familiarise themselves with the issues at hand, may be even more important than the

pandemic plan itself.

Pandemic response requires that business continuity plans and surge capacity plans be developed for the

health sector and all other sectors that could be affected by a pandemic to ensure sustained capacity during

a pandemic.

The response to a pandemic must be evidence-based where this is available and commensurate with the

threat, in accordance with the IHR. Planning should be based on pandemics of differing severity while the

response is based on the actual situation determined by national and global risk assessments.

Not all countries will be in a position to contribute to global risk assessment, nor conduct evaluations such

as pandemic vaccine effectiveness. They must all have the capacity to access and interpret data for risk

assessment provided by WHO, ECDC, and from other countries or sources.

Target audience, purpose and use of the guide

This guide is intended for use by those involved in pandemic preparedness planning, generic preparedness and

implementation of IHR core capacities in European countries. The document describes good practice for pandemic

preparedness planning based on lessons learned from the 2009 pandemic. It can be used to identify gaps in

pandemic preparedness, improve plans, and advocate for and prioritise resources to close those gaps. It can be

used to guide requests for support to ECDC, the WHO Regional Office for Europe, or other agencies and donors.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

3

Description of the guide

Pandemic planning can be divided into 12 key areas. For each key area, the rationale and a list of good practice

requirements for effective pandemic preparedness are provided.

For each key area, or requirement under a key area, countries may:

add requirements, indicators or outcomes for determining if a key area or requirement has been covered or

implemented, or if progress has been made;

indicate changes that have been made to their pandemic plans after the 2009 pandemic;

provide to the WHO Regional Office for Europe and ECDC examples of good practice which may be shared

with other countries; and

include questions to be addressed for each key area.

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

4

Twelve key areas of pandemic preparedness

Key area 1: Framework for pandemic planning

Rationale

The purpose of developing national pandemic preparedness plans is to define, organise and coordinate the wide

range of activities that are necessary to respond to a pandemic. A national pandemic plan is a strategy or

framework that guides subnational and operational planning in the health and non-health sectors by identifying the

areas that need to be addressed in pandemic preparedness. National pandemic plans vary from being a legal act or

law in some countries to an internal planning document by the ministry of health in others.

Strategic planning at the national level is needed to identify and involve key stakeholders from all sectors and

administrative levels and to lay out key components of the national response to a pandemic, informed by a range

of realistic, risk-based planning assumptions which take into account that it is not possible beforehand to predict

the severity or impact of a future pandemic. In order to maximise the flexibility, national responses should be

based on national risk-assessments guided by global and European risk assessments which will allow different

response measures to be implemented in different parts of the country at different stages of a pandemic.

At the time of the 2009 pandemic, although there were well-advanced national pandemic plans in many countries,

operational plans were lacking at the subnational level or within different domains of the health sector, thus

slowing down and weakening the initial responses. Since much of the operational response to a pandemic in a

country takes place at the subnational level, well-developed pandemic preparedness plans at the subnational level

and local operational plans – down to the facility/organisation level – are crucial. Border regions may also benefit

from exchanging and coordinating pandemic plans.

Good practice for strategic planning

Political commitment and dedicated, sustained government funding for the development, endorsement and

publication of the pandemic plan and its subsequent implementation.

A national pandemic plan based on clear planning assumptions that serves as a strategic framework and

guidance for national and subnational operational planning.

A national planning committee representing relevant stakeholders from the health and non-health sectors

(Table 1 provides a sample list of stakeholders) established by the government which meets regularly to

develop and update the national pandemic preparedness plan, coordinates the strategic and operational

planning process and ensures there are working links between the pandemic preparedness plan and generic

preparedness or civil protection plans.

Realistic and coordinated national and subnational pandemic plans that were produced by involving

subnational representatives in national planning (and national representatives in subnational planning), and

a mechanism to maintain regular communication between national and subnational level planners.

National and subnational plans that define the roles and responsibilities of relevant stakeholders that would

be involved in the pandemic response (authorities, nongovernmental organisations, private sector

participants, experts to provide advice, etc.).

Pandemic plans that include planning assumptions based on a range of possible scenarios that consider

different response measures that can be tailored to the actual situation during a pandemic and that provide

triggers for the activation/de-escalation of specific measures.

Pandemic plans that include methodologies and protocols to evaluate the response to a pandemic

(assessment of the measures applied to mitigate the effects of the pandemic, coordination, etc).

There is a legal framework for the deployment of pandemic response measures, e.g. regulatory approval

and procurement of pandemic vaccines and other pharmaceutical countermeasures, social distancing

measures, emergency release of budget.

Pandemic plans that take into account ethical aspects, such as prioritisation of clinical treatment or vaccine,

provision of pandemic vaccine to healthcare workers, handling of conflicts of interest, possible infringement

of basic human rights in pandemic response, extent of medical professionals’ duty of care.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

5

Table 1. Example of stakeholder-representation in the national pandemic preparedness planning

committee

Healthcare sector

Other sectors

National and regional health authorities

(includes public health)

National influenza centre and its epidemiological

counterpart

National expert advisory group

National immunisation technical advisory group

National drug regulatory agency

Medical professional associations representing

doctors and nurses, e.g. ICU physicians,

paediatricians, gynaecologists, etc.

Representatives from the association of

healthcare workers and general practitioners

Pharmacists

Scientists

Pharmaceutical/vaccine manufactures

Subnational level representatives

Department or ministry responsible for civil emergency response

Social services administration

Ministry responsible for education

Representatives from water and power plant associations

Representatives from the transport sector

Media relations experts/risk communication specialists

Representatives from the business and financial sectors

Nongovernmental and community-based organisations, e.g. Red

Cross, Red Crescent, health charities

Ministry of agriculture and the veterinary sector

Local government bodies

Good practice for effective operational planning and implementation

of pandemic plans

Operational planning at subnational and local levels (operational plans) based on national strategies and

planning assumptions that serve as a framework, guidance and unifying basis.

Operational plans based on templates provided by the national level that include performance criteria

allowing peer reviews or audits of subnational plans against the national pandemic plan, especially to

ensure multisectoral and vertical interoperability of plans.

Operational plans that have a number of components, for example healthcare facility plans, business

continuity plans for the health and non-health sectors, communication strategies, vaccination plans, and

logistics plans.

Operational plans that clearly define responsibilities in pandemic response at subnational and local levels

and are developed with input from healthcare facilities and essential businesses in the geographical area

covered.

Operational plans that are coordinated with those of neighbouring regions or municipalities.

Operational plans whose implementation includes communicating the plan to responders and other

stakeholders at national and subnational levels, conducting pandemic simulation exercises to test strategic

and operational responses, also with neighbouring countries, training staff etc.

Communication channels between operational planners at national, subnational and local levels.

Key area 2: Pandemic planning and response based on risk

assessment

Rationale

Pandemic plans describe the actions and measures that would be implemented during a pandemic to reduce

morbidity and mortality. The data and information that are needed to determine which measures should be

implemented and when will be obtained by assessing the overall risk of the pandemic by assessing severity and

groups at risk of severe disease, as well as overall impact on the population, health services and other essential

services.

One of the main lessons learned from the 2009 pandemic was that the six global WHO phases were inadequate as

triggers for national response actions due to the different timing of the pandemic in different parts of the world and

different severity in different countries. In addition, many pandemic plans based the response on a single scenario

which was more severe than the 2009 pandemic, and response strategies had to be adjusted. In particular,

countries that changed their pandemic vaccine strategies (e.g. from total population coverage to vaccinating risk

groups only) encountered difficulties in rapidly implementing new deployment strategies. Pandemic plans that were

triggered in this way by the WHO phases were considered to be inflexible.

The 2017 WHO guide on pandemic influenza risk management takes this into account: there are four phases which

are not linked to specific actions at the country level (Figure 2), and countries are encouraged to conduct their own

risk assessment.

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

6

Figure 2. The continuum of pandemic phases

Source: 2017 WHO guide on pandemic influenza risk management

The four phases are the interpandemic phase (the period between influenza pandemics), the alert phase (when

influenza caused by a new subtype has been identified in humans [see reference to WHO case definitions on page

18, last entry under key area 2], e.g. the emergence of avian influenza A(H7N9) in 2013), the pandemic phase (the

period of global spread of human influenza caused by a new subtype) and the transition phase (when the global

risk drops and reductions in response activities may be appropriate, see key area 11). Global risk assessments will

determine in which phase we are, based on virological, epidemiological and clinical data. Depending on the risk

assessment, WHO may convene an Emergency Committee under the IHR, which may issue temporary

recommendations to Member States. The Director General of WHO can declare a Public Health Emergency of

International Concern (PHEIC) under Article 12 of the IHR.

Good practice for an effective risk assessment-based approach to

pandemic planning

Countries conduct mapping of all (potential) threats in order to prioritise resources for pandemic

preparedness.

Pandemic plans based on planning assumptions, i.e. different scenarios of intensity, severity and impact

based on expected clinical attack rate, infectiousness, number of children and adults requiring primary,

hospital and higher-level (intensive) care per unit of population, death rate, and the peak percentage of the

workforce unavailable to work. WHO is developing a pandemic influenza severity assessment methodology

which can be used for this severity and impact assessment.

Pandemic plans that include options for response but allow for the planned response measures to be

implemented in a flexible way. Measures can be implemented at different times (depending on local

differences in the timing, spread and peak of the pandemic), can be adjusted, can be postponed, or can be

cancelled. Unplanned response measures can be implemented, depending on the actual severity and impact

of the pandemic.

Risk assessments are conducted throughout the pandemic and integrated with communication plans and

the decision-making process for the pandemic response.

Risk assessments consider – apart from the public health risks – the social and economic risks and weigh

the consequences of action versus non-action. This includes interpretation of data from the countries that

were affected first and that will inform the response as well as national data collection needs.

Risk assessments consider impact (on risk groups, healthcare capacities and essential public services) and

effectiveness of countermeasures, both medical (e.g. influenza-specific antivirals, antibiotics and pandemic

vaccines) and non-pharmaceutical public health measures (e.g. social distancing, personal protective

equipment, hygiene measures).

Mathematical modelling to determine the basic reproductive number R

0

, serial interval, estimated case

fatality rates and other parameters as needed in countries that have the capacity to do so.

Good practice for effective risk assessment and surveillance during a

pandemic

Investigating individual cases and clusters early in the response

Early warning systems and event-based surveillance (national epidemic intelligence capacity) to detect and

assess the risk of a pandemic coupled with the capacity to communicate this to experts and decision makers

in a timely fashion.

Outbreak response teams, procedures and laboratory capacities in place to swiftly conduct investigations.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

7

A system to rapidly implement the national notification of cases in order to detect the first cases in a

country.

Investigation of the first cases and their contacts, especially in the countries that are affected first;

investigation should focus on determining transmission characteristics, basic reproduction number, clinical

symptoms, severity, and characteristics of the virus. These factors differ from pandemic to pandemic and

determine operational decisions, e.g. the use of antiviral stockpiles among groups experiencing the most

transmission and the most severe disease.

Investigation includes seroepidemiology in countries that have this capacity.

National influenza centres share influenza viruses with WHO Collaborating Centres for Reference and

Research on Influenza throughout a pandemic, but particularly in the early stages (for risk assessment

purposes and timely vaccine development). This is part of their obligations to the Pandemic Influenza

Preparedness (PIP) framework and the WHO Global Influenza Surveillance and Response System (GISRS).

Surveillance when a pandemic becomes widespread

There are routine influenza surveillance systems based in primary healthcare facilities (acute respiratory

infections and influenza-like illness) and hospitals (severe acute respiratory infections, laboratory-confirmed

influenza cases) that provide information on trends and patterns of disease, namely the spread, affected

age groups, risk factors, virus characteristics, magnitude, and severity of the epidemic compared with

previous seasons pandemics.

Countries that do not have a surveillance system for severe/hospitalised cases have developed and tested a

plan for rapid implementation during a pandemic or rely on data from other countries.

Countries that will establish alternative systems, such as telephone or web-based surveillance, have tested

them beforehand.

Surveillance units have discussed beforehand with decision makers the information that should be provided

and have been allocated adequate resources and manpower to do so during a pandemic. Reporting of

surveillance data to WHO and ECDC is sustained throughout the pandemic.

Off-the-shelf research protocols with prior ethical and review board approvals implemented in order to

study severity of disease, transmission patterns, effectiveness of pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical

countermeasures, etc.

Laboratory testing

National influenza centres (NICs) have the capacity to rapidly implement assays for emerging influenza

viruses to be able to detect early cases in a pandemic and conduct risk assessments. The current gold

standard for influenza detection is RT-PCR.

The influenza laboratory network in a country may consist of public health and/or clinical laboratories that

can, supported by the NIC, quickly establish testing of the new virus in a pandemic.

A system to transport samples to the NIC in a timely and safe fashion.

Defined roles and responsibilities of the laboratory network for the different stages of a pandemic with

respect to testing for surveillance purposes versus clinical diagnosis of patients.

Once infections with the pandemic virus become widespread, laboratory surveillance focuses on testing of

sentinel samples, monitoring the antigenic and genetic properties of viruses, and antiviral susceptibility by

characterising a representative sample of viruses.

Countries may opt to confirm a subset of cases for surveillance purposes, e.g. all deaths due to pandemic

influenza, or a subset thereof.

Key area 3: Coordination, command and control

Rationale

An influenza pandemic is a complex emergency of uncertain severity and long duration. It involves health and non-

health sectors at all administrative levels, and it impacts the entire society and different actors at different stages.

For example, the animal health sector will be involved during the alert phase if a new influenza virus is detected in

animals but will have less of a role if the virus gains the ability to transmit efficiently among humans. Therefore, in

a pandemic as well as in other major health crises, it is important that a structure for coordination and chain of

command exists.

Good practice for effective coordination, command and control in a

pandemic

A robust and operational crisis management structure with adequate health emergency operations/crisis

management infrastructure including IT and telecommunications equipment and software.

A business continuity plan for the crisis management structure.

Standard operating procedures to ensure implementation of response actions.

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

8

Committed representation of the relevant ministries and departments/agencies in the crisis management

structure which is linked to technical and decision-making levels.

Lines of command and control are based on existing structures and mechanisms and are described in the

pandemic plan. The plan anticipates how these may change during the response according to the actual

severity and impact of the pandemic.

All those that will be involved in the response are aware of their tasks and responsibilities, familiar with

each other and with the pandemic plan, and have received training where necessary.

The pandemic plan defines coordination between sectors and different administrative levels.

Lines of communication within the crisis management structure and with relevant outside stakeholders and

sectors have been practiced to ensure a coordinated response.

Information and data requirements for decision-making have been defined in advance, based on the data

that are expected to be available (see key area 2).

Mechanisms are in place for the regular monitoring of capacities in the healthcare sector (primary,

secondary and higher level care), stockpiles, use and distribution of medical countermeasures (antivirals,

vaccines, antibiotics, equipment for mechanical ventilation and oxygenation) and other supplies.

Two-way communication channels are in place from the national to local level and vice versa in order to

disseminate information effectively and for the crisis management structure to receive feedback which

resources are available and where support is needed.

Key area 4: Risk communication

Rationale

Risk communication is a key public health tool in pandemic planning and in the response to a pandemic because it

aims to establish public and professional confidence and trust. Lessons learned during the 2009 pandemic

highlighted difficulties that public health authorities had in communicating scientific uncertainty and special

attention needs. Risk communication is targeted to the public but also to key stakeholders and responders like

health workers, to continuously update them about the evolving situation as well as about interventions, in

particular the pandemic vaccine.

Good practice for effective risk communication in a pandemic

A communication strategy describing how communication will be conducted in a pandemic, i.e. how to

disseminate information rapidly during a pandemic and which information should be disseminated when and

by whom.

The communication strategy is tailored to different groups (stakeholders in different sectors and

administrative levels, the public, healthcare workers, media, etc.) and addresses the type of messages

needed at different stages of a pandemic. For example, after the first reports of an emerging pandemic

virus, the following may be communicated: a first assessment of severity, reports about the first cases in

the country, reports when infections become widespread, information on which groups are affected most,

reports on the first deaths in a country, or a declaration of a Public Health Emergency of International

Concern by WHO.

The communication strategy takes into account behavioural aspects of how people react and act on advice

and information received, both from authorities but also from other sources (mass and social media).

Risk communication during a pandemic is informed by evidence that is consistent from different authorities,

across sectors, and at different organisational levels.

The mass media are informed about the communication strategy and there are regular press conferences

planned during the response phase in order to channel the information disseminated by the media to the

general public.

A spokesperson within the ministry in charge of the response has been appointed to conduct regular press

conferences during a pandemic. An alternate spokesperson is available should the lead ministry change.

Communication materials and distribution channels that have been tested in the interpandemic period (e.g.

information about pandemic vs. seasonal influenza, personal protective measures, etc.).

Methods (such as population surveys, focus groups) for regularly monitoring the perception and opinions of

the public and healthcare workers during a pandemic in order to enhance interpretation and understanding

of the messages and to guide the risk communication efforts.

The communication cycle will include situational awareness, achieved with epidemic intelligence using

media monitoring techniques and targeted communications for public health professionals.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

9

Key area 5: Pandemic vaccines

Rationale

During a pandemic, countries will endeavour to vaccinate a large number of people within a short time period.

Using current technology for producing inactivated egg-based or culture-based influenza vaccines, it will take about

six months from the start of a pandemic to develop, manufacture and deliver the first batches of a vaccine, which

then has to be delivered and distributed to vaccination sites. These sites may be the same sites as for seasonal

influenza vaccination or sites set up for mass vaccination. How the pandemic vaccine is delivered will be partly

determined by whether countries decide to offer the vaccine to the whole population, to risk groups only (which

may differ from those for seasonal influenza), health workers and/or other essential workers, and how delivery to

these target groups is prioritised.

Good practice for effective use of pandemic vaccines

Pandemic vaccine deployment plan

Seasonal influenza vaccination programmes are a framework upon which pandemic vaccination strategies

are based. This includes the role of national regulatory authorities (NRA) and national immunisation

technical advisory groups (NITAGs) that determine risk groups, cost effectiveness and vaccine effectiveness,

regulatory issues, communication strategies, monitoring and reporting of adverse events.

A pandemic vaccine deployment plan that includes a strategy, or strategies, for procurement, distribution,

storage and policy for use of pandemic vaccines during a pandemic. This plan should have been rehearsed

through simulation exercises.

The strategy considers destruction of remaining pandemic vaccine stocks when the pandemic is over.

The strategy is flexible in that it considers different options for pandemic vaccination (whole population, risk

groups only, essential workers only) which will be implemented or adjusted according to the actual severity

of the pandemic. It also considers what to do if excess vaccine becomes available, e.g. donation to WHO

and/or countries in need.

The strategy takes into account ethical and equity issues: safety (risk–benefit), priority groups (vaccinating

non-health sector essential services staff versus healthcare workers versus risk groups), prioritisation within

priority groups when supplies are low, mandatory vaccination for healthcare workers, etc.

The actual number of doses, the communication strategies and the mode of delivery (mass vaccination

campaign versus using existing mechanisms for seasonal influenza vaccination) are determined by the

severity of the pandemic.

Authorities have considered how groups not normally vaccinated during seasonal influenza will be offered

the vaccine, e.g. universal vaccination of children and first responders.

The process of making decisions on the procurement and delivery of pandemic vaccines, using different

scenarios, has been rehearsed, e.g. by an exercise involving the ministry of health and other ministries,

departments and stakeholders such as the NRA, NITAG, vaccine manufacturers, and the authority

responsible for adverse event monitoring.

Countries that have advanced purchase agreements with vaccine manufacturers have considered the timing

of activation of the contract which will rely on the national as well as the global risk assessment.

Contracts may be developed as part of a coordinated approach involving multiple countries, e.g. the joint

procurement of medical countermeasures for EU countries described in Decision No 1082/2013/EU.

The pandemic vaccine strategy takes into account that the vaccine will probably be available in smaller

batches initially, and that prioritisation within the groups that are going to be targeted for vaccination –

based on a risk assessment – is necessary.

As part of the pandemic vaccination campaign and to generate confidence/acceptance in the newly

developed vaccine, risk communication will be carried out among target groups (in particular among those

groups that are not normally targeted for seasonal influenza vaccination).

Staff that will administer the vaccine have been identified and trained, taking into account different

scenarios, e.g. a mass vaccination campaign has different training requirements compared to targeting risk

groups, in which case it may be possible to employ the same mechanism used to vaccinate against seasonal

influenza.

Regulations and monitoring

Countries improve the process behind vaccination choices and decisions by strengthening NRAs and NITAGs

and ensure they have access to rapid scientific and expert advice for evidence-based strategic decisions.

Expert panels have been identified and members have public declarations of interest to avoid jeopardising

the integrity of the advisory bodies they are supporting.

Countries expecting to be eligible to receive vaccine donations (e.g. from another country or through WHO)

have considered the regulatory issues beforehand to not delay the donation.

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

10

Countries are aware of the rapid authorisation pathway available in the EU, which is designed specifically for

pandemic vaccines to minimise the administrative delay of introducing a new vaccine, namely the pre-

approval by the European Medicines Agency (EMA) of vaccines based on a mock-up model of H5N1 vaccine

to be rapidly adapted to a newly emerging pandemic strain.

There is reciprocal approval between countries in an emergency, e.g. the national regulatory authority

(NRA) of a country outside the EU may adopt EMA approval, which is valid in all EU Member States, or the

NRA of a country may adopt approval bilaterally.

If vaccination is to be provided by staff that do not normally do so (e.g. nurses), the required competencies

have been defined and training has been provided.

A system for monitoring vaccine uptake and adverse events following immunisation (AEFIs), e.g. VAESCO.

Mechanisms for monitoring the effectiveness of pandemic vaccines. Currently, the I-MOVE project monitors

seasonal influenza vaccine effectiveness in Europe.

Communication and information

Communication strategies tailored to different target groups, e.g. professionals (healthcare workers) and

the public, that address questions about vaccine effectiveness and adverse events, some of which have

been predicted and prepared beforehand.

Attitudes and beliefs are monitored during a pandemic.

The use of social media to deliver messages related to pandemic vaccines.

Communication strategies have been tested by conducting an exercise based on an unforeseen crisis, e.g.

rehearse the communication aspects of a scenario whereby serious side effects are encountered.

Communication strategies utilise information from WHO (e.g. SAGE recommendations on risk groups for

vaccination), ECDC, the EMA (e.g. information on pharmacovigilance data), and other Member States

through the IHR, EWRS or other regional platforms.

Key area 6: Antivirals and other essential medicines

Rationale

During a pandemic, it is expected that the number of both severe and mild cases of influenza will increase

compared with seasonal influenza. This may lead to shortages of influenza-specific antiviral drugs (AV), specifically

neuraminidase inhibitors. The use of AV complements other medical and non-medical measures that may be

implemented and for which it is necessary to stockpile supplies. Examples include infection control materials,

antibiotics and other essential medicines. There is no set formula for the size of stockpile required as this depends

on the strategy adopted by the country and the market availability of supplies. This in turn depends production

capacity and the extent to which there is regular use of AV during seasonal influenza. During the 2009 pandemic,

antiviral manufacturers were able to increase production, and thus the necessity for using the AV stockpiles was

less critical.

Good practice for effective use of antivirals and other essential

medicines in a pandemic

Planning

A strategy for the procurement, storage, distribution and policy for the use (including paediatric use) of AV

during a pandemic.

The AV strategy is flexible in that it describes different options for use in accordance with different scenarios

of severity of a pandemic; it is understood by all stakeholders that the strategy may be adjusted during a

pandemic in accordance with a national risk assessment.

The strategy includes a provisional priority list for the choice of AV, or combination AV, and prioritisation

during different stages of a pandemic in accordance with different scenarios of severity.

The strategy considers the establishment of a stockpile of AV for use in a pandemic. The most effective

stockpile is a rolling stockpile, i.e. one that is used routinely during seasonal influenza and replenished. AV

use in a pandemic will be under government control, e.g. by prescription from general practitioners,

pharmacies, or at collection points.

The strategy includes how to deal with AV stockpiles that are unused after a pandemic, by describing use

during seasonal influenza, or possible extension of the expiry date and later destruction of unused

stockpiles.

The increased need for other medicines or techniques, notably antibiotics and ECMO, are included in the

plan (see also key area 7).

Countries that may be eligible to receive donations of AV and/or other essential medicines from other

countries or organisations have developed an essential medicines list and addressed regulatory issues in

order not to delay the donation.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

11

AV may be purchased through contracts developed as part of a coordinated approach involving multiple

countries, e.g. the joint procurement of medical countermeasures for EU countries described in Decision No

1082/2013/EU.

An alternative therapeutic strategy in case of reduced susceptibility to neuraminidase inhibitors.

Prioritisation and use of AV

AV are stockpiled centrally or have been distributed to local stocks across a country before a pandemic.

Mechanisms are in place to distribute AV rapidly when a pandemic is declared, and this has been tested by

an exercise.

For countries whose AV supplies or stockpile are insufficient to treat all cases of pandemic influenza, the

first priority is to treat persons with severe disease.

Use of AV to delay spread or reduce transmission and peak sickness rates, or for long-term prophylaxis for

healthcare workers, has been considered if the pandemic is severe and/or during the early stages of a

pandemic when vaccines are not yet available.

AV guidelines recommend initiation of treatment as early as possible and preferably within 48 hours of

symptom onset, based on clinical judgement alone. There is no case for delaying treatment pending

laboratory confirmation. Initiation of treatment of severe cases is also considered after 48 hours from

symptom onset.

The use of AV does not replace other basic life-saving strategies, such as monitoring for vital signs and

supportive therapy, particularly oxygen.

Monitoring AV use and surveillance for AV resistance

A mechanism for monitoring the national AV stockpile.

Countries that plan to use AV in a pandemic have mechanisms to rapidly detect and monitor signals

indicating adverse events or side effects associated with their use.

Surveillance to rapidly detect and assess signals indicating the emergence and spread of antiviral resistant

pandemic influenza viruses, or rapid shipment of viruses to a Collaborating Centre for Reference and

Research on Influenza (WHO CC) is in place.

Key area 7: Healthcare services preparedness

Rationale

The aim of preparing the healthcare services for a pandemic is to ensure the continuation of regular and

emergency services while providing appropriate clinical care for cases of pandemic influenza, whether these

present to primary healthcare, are hospitalised or admitted to critical or intensive care units (ICUs). Appropriate

clinical treatment will reduce morbidity and mortality and thus mitigate the effects of the pandemic.

During a pandemic, primary and secondary healthcare facilities will experience a significant increase in the number

of respiratory patients (in addition to the usual number of ill persons) while healthcare workers will also become ill

and so be absent from work. There will be an excess demand for healthcare services with potentially fewer

healthcare workers to deliver these services. In addition to limited staff, other resources will be stretched, including

beds, medicines and mechanical ventilators, and this may last for several months. Hospitals may face a situation

where it is necessary to discharge non-critical patients (pandemic and non-pandemic) to free up resources for

severely ill patients and to cancel planned non-urgent treatments.

The 2009 pandemic showed that even during a relatively mild pandemic, healthcare services may easily be

overwhelmed. Hence, health services preparedness planning is vital regardless of the severity of the pandemic in

order to be able to continue services when capacities are exceeded.

Good practice for effective healthcare system response in a pandemic

Planning

Healthcare services planning should be based on national assumptions as to the estimated numbers of

deaths and the number of cases requiring primary, secondary and higher level care – in relation to local

demographics and in accordance with different scenarios of severity.

Plans that include provisions on how to increase critical care capacity/respiratory support.

Plans that take into account the need for cross-referral between healthcare facilities in the country or

region.

Local plans that encompass all health and social care services, both public and private, e.g. conventional,

long-term, acute care, and care by community-based organisations. This should ensure that there is

harmonised care and coordinated transfer of patients.

Healthcare services response planning that involves representatives of professional organisations (covering

family doctors, hospital and ICU physicians, occupational health, social care workers, etc.).

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

12

Health system preparedness exercises performed at the geographical level, i.e. covering the area that a

health authority or facility serves, that address large numbers of people seeking care with potentially

increased numbers needing higher levels of care than normal.

All healthcare professionals are briefed with respect to pandemic preparedness arrangements in their

facility, their obligations, responsibilities and rights.

Business continuity plans are available for key healthcare providers and public health stakeholders.

Financial issues related to the referral of patients (ambulance, testing, care provided, etc.) have been

considered and the necessary arrangements made.

Surge capacity and monitoring of resources

As part of general healthcare services management, countries have an inventory of existing capacities,

including both public and private healthcare facilities, number of hospital beds, ICU beds, equipment and

medicines for the treatment of severe cases, staffing and options for surge capacity (e.g. retirees, medical

students, etc.).

Plans for surge capacity that estimate the capacities required to deal with pandemics of different severities

and thus numbers of severe cases. There are indicators for filling or exceeding existing capacity and for

triggering arrangements to increase capacity at the local/healthcare facility level.

Plans for surge capacity based on different scenarios of severity

and

local differences in the timing of the

pandemic which may peak at different times compared with the national level.

Plans that include the care of non-influenza acute/chronic patients and provisions for cancellation of elective

surgery.

Provisions to ensure that clinical diagnostic laboratory services (for haematology, biochemistry, immunology

etc.) are maintained for pandemic cases and other priority patients.

Adequate plans for handling larger numbers of deaths than usual.

In addition to healthcare authorities, individual healthcare facilities have plans to manage surges of patients

for a sustained period of time, taking into account the 2009 experience of some patients requiring longer

periods of care (for example patients with acute respiratory distress syndrome).

The legal and financial requirements to recruit a reserve workforce, e.g. retirees, students, nurses

performing additional tasks normally allocated to clinicians, and to pay existing staff overtime, have been

planned for.

There is a national (electronic) system to monitor in real-time healthcare capacities and resources. As a

minimum, health authorities have planned to have regular contact with the healthcare services to monitor

the situation and needs throughout a pandemic, e.g. by means of weekly teleconferences.

Clinical management of patients

Guidelines for the clinical management and infection control aspects of severe acute respiratory infections –

associated with influenza (seasonal, zoonotic, or pandemic) or other respiratory infections – developed by

health authorities in collaboration with relevant professional organisations.

There is a mechanism to review and adjust these guidelines during a pandemic, according to the

characteristics of the new influenza virus, severity of illness, and the groups at risk of severe disease. They

include triage, the use and prioritisation of AV in patients, and AV prophylaxis for healthcare workers in

different settings (e.g. ICUs).

The clinical management guidelines can be made rapidly available to all staff in all healthcare facilities

during a pandemic.

Treatment of patients is on the basis of clinical assessment alone rather than awaiting laboratory

confirmation for pandemic influenza. This is particularly important when considering the use of AV (see also

key area 6).

The administration of AV to patients is informed by surveillance that monitors for the emergence of AV

resistance in the pandemic virus.

Off-the-shelf research (including clinical trial) protocols with prior ethical and review board approvals

implemented in order to study severity of disease, transmission patterns, effectiveness of pharmaceutical

and non-pharmaceutical countermeasures, etc.

Protection of healthcare workers

Plans at healthcare facilities include modifications to standard infection prevention and control procedures

that may be required in a pandemic, according to the severity and transmission characteristics of the virus.

Plans at healthcare facilities include provisions for personal protective equipment, a plan for providing

healthcare workers (HCW) with AV, and prioritisation of HCW for receiving pandemic vaccine.

Healthcare facilities have policies and procedures in place should HCW get sick or need to care for sick

family members. HCW who are reluctant to come to work during a pandemic will be encouraged to do so by

providing proper protective measures, by making arrangements to allow them to care for sick family

members, etc. The ethical aspects of staff refusing to work will be discussed with HCW as part of pandemic

preparedness planning.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

13

The psychological well-being of HCW has been considered and the needs for support during a pandemic

have been planned for. HCW know beforehand where they can obtain information and support during a

pandemic.

Laboratory testing for clinical purposes

In the early stages of a pandemic it is desirable to test all cases for both risk assessment and clinical

management purposes.

When infections are widespread, testing of a subset of mild and severe cases should suffice for risk

assessment and surveillance purposes, but throughout the pandemic – depending on resources – countries

may strive to laboratory-confirm all fatal cases and possibly also severe cases, e.g. those requiring critical

care. The results of testing performed for clinical purposes can also contribute to risk assessment and

surveillance and should, where possible, be coordinated by the NIC.

The treatment of patients with symptoms of respiratory illness, whether mild or severe, is initiated based on

clinical judgement alone, without waiting for laboratory test results. This includes supportive treatment,

such as the administration of oxygen, as well as AV.

Clinicians request testing of all patients that do not react to AV to determine if the cause is a pathogen

other than pandemic influenza or if resistance to the AV has developed.

Testing is performed for infection control purposes if needed to ensure that infected patients are placed in

the correct section of a healthcare facility.

Testing for clinical management purposes and for secondary bacterial infections is performed in situ, i.e. by

the hospital laboratory. If this is not possible, arrangements are in place with another laboratory.

All laboratories that test clinical specimens from patients suspected of infection with the pandemic virus

have established appropriate biosafety procedures in accordance with their own risk assessment and refer

to national and WHO guidelines.

Communication with clinicians, information sharing among clinicians

During the preparedness phase, medical professional groups and HCW have been informed how information

will be provided in a pandemic, e.g. through a dedicated website, professional medical associations etc.

Mechanisms have been tested to rapidly inform medical professional groups and HCW about the situation,

risk groups for severe disease as soon as they are known, and up-to-date guidance and/or practice notes

for the clinical management of patients.

This communication channel includes information on decisions taken at national or subnational levels on

measures to be implemented and on any changes in the response, e.g. whether confirmed cases are

notifiable, where patients should seek care, updates to guidelines for clinical care, laboratory testing, etc.

Communication channels have been tested and a range of decisions has been exercised before a pandemic

to determine the feasibility of implementation of the proposed measures and increase the likelihood of

timely implementation of measures in an actual pandemic.

A network or platform for frequent and rapid exchange of information and experience among clinicians,

nurses, public health laboratories, public health authorities, and healthcare services authorities on the

clinical management of severe cases and on healthcare facility needs when resources are stretched. Such

networks can also be utilised during a severe seasonal influenza epidemic.

Key area 8: Non-pharmaceutical public health measures

Rationale

Non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPIs) may help reduce transmission of the pandemic virus and may be

especially important in the first months of a pandemic when there is no pandemic vaccine available and in

countries with limited antiviral stockpiles or critical care capacities. Implementation of any public health measure

requires planning and proper communication and often this involves multiple sectors. Countries should consider the

recommendations provided by WHO and EU authorities in the event of a pandemic and the measures implemented

should be commensurate with the IHR (2005), and, for EU Member States, coordinated under the provisions of

Decision No 1082/2013/EU, whether they pertain to international travel and trade, personal protection or social

distancing. It should be noted that the evidence-base for the effectiveness of many NPIs is weak. This, as well as

acceptability, feasibility and legal framework for implementation differs between countries and should be taken into

account in national planning.

Good practice for effective public health measures in a pandemic

A national list of NPIs based on evidence, international guidance and best practice – all likely to be effective

and feasible for the setting/country – are included in the pandemic plan. Their implementation and timing

depends on the actual situation and severity in a pandemic. The main goals of NPIs are to delay and reduce

the number of cases and severe or fatal outcomes.

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

14

As a minimum, the public will be informed about the measures they can take to protect themselves and

others from getting ill, i.e. by applying universal hygiene measures, such as frequent handwashing and

cough etiquette. Such information is part of seasonal influenza campaigns and is re-emphasised in a

pandemic.

Social distancing measures, including closure of schools, pre-schools and other educational institutions,

banning of mass gatherings, adjusted working patterns, or advising contacts of cases to reduce their social

interactions, are considered.

Advice for travellers is given.

There are mechanisms for communicating with those who will implement the measures and those that will

be affected, e.g. parents and teachers by school closures, and both the mechanisms and messages have

been tested.

The benefit–cost ratio and feasibility of NPIs has been calculated and assessed in advance.

The legal and ethical ramifications and effects of NPIs have been taken into account in planning and

appropriate risk mitigation strategies have been considered.

The scientific evidence for the effects has been weighed against socio-political considerations and their

negative impact.

The pandemic plan identifies triggers that determine when a particular measure will be implemented and

terminated.

Mechanisms for monitoring the effects/effectiveness of NPIs have been identified.

Off-the-shelf research protocols with prior ethical and review board approvals implemented in order to

study the effectiveness and response to non-pharmaceutical countermeasures.

Key area 9: Essential services and business continuity

Rationale

A severe pandemic has the potential to affect all sectors due to a significant number of people in the population

falling ill or dying or simply being too worried to come to work. Even a pandemic of mild severity may affect other

sectors than health. High workplace absenteeism will affect the functioning of businesses and services. Some

businesses or services are essential for society (e.g. water supply, electricity production, waste management, law

enforcement), and it needs to be ensured that these services continue to function during a pandemic. Therefore,

relevant authorities need to ensure that essential services develop operational business continuity plans, which also

cover an influenza pandemic. This planning requires guidance and support from national and regional levels.

Business continuity planning is important for many emergencies and should not be seen in isolation from other

resilience planning, but pandemics differ from other hazards as they may last for many months and therefore

specific planning for business continuity during pandemics is necessary.

Good practice for effective business continuity planning in a pandemic

Business continuity management requires interministerial and multisectoral coordination, e.g. for workers’

rights and obligations, and has been considered by all sectors.

Business continuity is particularly important for the ministry of health, key public health agencies and major

health facilities, as well as other essential public and private services, public authorities and corporations,

private sector stakeholders and community-based organisations.

Business continuity planning is supported by including a list of essential public and private services in the

national pandemic preparedness plan that has been agreed across government. These services have been

prioritised through a sectoral risk and impact assessment, national ethics committees, and relevant

stakeholders.

Guidance and formal frameworks for business continuity plans (BCPs), evaluations and audits, have been

provided by the government. All BCPs are guided by the nationally adopted planning assumptions and

strategies (pharmaceutical and non-pharmaceutical interventions, etc.).

BCPs developed by the identified essential services include roles and coordination mechanisms among

sectors and have been tested. This will ensure that there is appropriate interoperability across public and

private sectors and services.

Business continuity planning for essential public and private services and private businesses occurs both at

local and international levels and BCPs interlink with national plans.

The identified essential services, and first and foremost the healthcare sector, are prioritised in the national

pandemic planning process to be among the first to benefit from medical interventions and NPIs in order to

protect the adequate functioning of these services during a pandemic.

BCPs prepare for a long-term crisis (especially for human resources), make provisions for staff to have time

off during the response, and make sure there is continuation of usual tasks by some staff.

TECHNICAL REPORT Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans

15

BCPs consider the legal frameworks and insurance issues surrounding business continuity, e.g. compulsory

measures to reduce infection.

BCPs consider the role of community-based groups in, for example, awareness raising and surge capacity

and identify methodologies for non-profit organisations to support vulnerable groups during a pandemic.

Key area 10: Special groups and settings

Rationale

There are some groups in society that require special attention and consideration in preparedness planning as they

have specific needs in terms of language or means of communication. These groups need to be identified and their

particular needs should be determined during the preparedness planning process. Groups, facilities and institutions

include:

Prisons

Schools for children with learning or other disabilities

Psychiatric patients

Residential homes

Migrants and persons in transit

Asylum seekers

Homeless people

Community-based organisations

Others as appropriate

Good practice for effective inclusion of special groups in pandemic

preparedness

Prioritisation and inclusions of special groups have been broadly discussed at the national level as part of

the planning process. These discussions should include ethical considerations.

Consider if special strategies or response measures need to be developed for certain groups in society, e.g.

if information material in a minority language needs to be developed.

Test the strategies or measures on the specific groups, as part of the pandemic planning cycle.

Key area 11: After the pandemic – recovery and transition

phase

Rationale

Pandemics do not end overnight. A pandemic virus may cause several waves of severe epidemics worldwide over

the following years before continuing to circulate as seasonal influenza. The first post-pandemic winter season may

be worse than the actual pandemic. This happened in some European countries in 1968–70 and 2009–2011. The

workload for responders and stakeholders can remain high after the first epidemic wave, due to evaluation of the

response, recovery, and scientific and administrative assessment procedures. The decision on when a pandemic is

over is likely to be just as complex as the decision to announce a pandemic.

Good practice for effective recovery and transition

The pandemic plan incorporates recovery and transition activities to facilitate the return to ‘normal’ seasonal

influenza activities after a pandemic.

Recovery and transition includes replenishment of stockpiles (medicines, equipment, etc.)

The effectiveness of all implemented response measures should be evaluated, as should the overall

response. Results from evaluations should be used to revise the national pandemic plan.

The need for human resources mobilised during the pandemic as included in BCPs should be assessed (in

terms of psychosocial impact and core functions) and its return to normal business appropriately timed.

Awareness of the pandemic is utilised to promote precautionary measures for seasonal influenza and other

respiratory infections.

Risk-based triggers to identify the end of the pandemic at national and possibly subnational levels are

included in the pandemic plan.

Operational plans include mechanisms to de-escalate response measures, e.g. triggers for retrieving and

storing pandemic vaccine stocks, returning to normal procedures in healthcare facilities, etc.

Guide to revision of national pandemic influenza preparedness plans TECHNICAL REPORT

16

Key area 12: International cooperation, coordination and

interoperability

Rationale

A pandemic, by definition, affects many regions and countries of the world. Global populations move freely across

borders, and this is particularly so for citizens within internal EU borders. Citizens often obtain healthcare across

borders, and in the case of the EU, this is an entitlement.

However, Member States are responsible for preparedness for their citizens and residents only within the sovereign

national borders. Therefore, in order to enhance coordination of pandemic planning and response, intercountry

cooperation during the pandemic planning process, plans based on commonly agreed scenarios of severity, and

plans that take into account cross-border issues (such as migrant workers, cross-border healthcare, etc.) will all

enhance the interoperability of pandemic preparedness and response. As it is provided by EU legislation (Decision

No 1082/2013/EU), exchange of national pandemic plans between countries and necessity for creating

interoperability of pandemic plans between countries offers confidence in a coherent and consistent response and

is highly valuable in terms of professional support during national planning processes.

A coherent and consistent response to a pandemic across countries can only be achieved if public health

authorities rapidly share information on pandemic developments. Particular focus should be on the experience of

the first affected countries in Europe to address the ‘known unknowns’ of pandemics. There is a tendency to think

internally in countries during a pandemic, especially as work pressure increases. It is important to think about

national findings and experiences that might be useful to other countries. Providing information to WHO and the

EU during a pandemic is required under the IHR and EU legislation but its utility will be enhanced if it happens

based on prior thought and planning.

Good practice for effective international cooperation, coordination

and interoperability

Planning

National pandemic plans based on WHO and EU pandemic guidance.

Coordinated UN agency approaches to support national pandemic preparedness in countries.

National and local pandemic plans consider interoperability aspects of plans of neighbouring countries –

including migrants and citizens of other countries, migrant workers – and access to cross-border healthcare.

Neighbouring countries conduct cross-border simulation exercises as a platform to exchange information on

national pandemic plans, test responses, and highlight areas for improvement.

Member States participate in international activities facilitated by WHO and ECDC; topics include pandemic

planning, exercises and information exchange.