MAY/JUNE 2001 71Photo, this page: Michael Pekovich

’ve never seen the virtues of building a

table with drawers in the traditional

way—with a double-tenoned stretcher

below the drawer and a dovetailed top rail.

It just seems like unnecessary work. I’ve

developed methods for building a table

with drawers that are faster and, to my

mind, stronger. It’s the same approach I

use when building a chest of drawers. I

build frames to go over and under the

drawers, then simply attach them to pre-

assembled ends. This approach makes the

entire project more manageable and all but

guarantees a smooth and square glue-up.

This library table is adapted from various

Stickley catalogs from the turn of the 20th

century. It would work well as a writing

desk or as a reading table. My approach to

the construction of this traditional Arts and

Crafts piece is straightforward. I used quar-

tersawn stock, hand-hammered hardware

and a slightly lighter finish than is custom-

ary for this style.

The best boards go on top

For this project, I ordered 100 bd. ft. of oak,

then riffled through to choose boards for

specific parts. Once all of the boards had

been surfaced, I designated the best of the

lot for the tabletop, which I typically glue

An Arts and Crafts

Library Table

A nontraditional approach

to building a desk with drawers

BY ERIC KEIL

I

72 FINE WOODWORKING

Drawings: Bob La Pointe

up first so that I know what I’m working to-

ward. I also sorted all of the other lumber,

denoted which pieces will be used where

and milled them to their finished thickness.

The less-attractive lumber was designat-

ed for interior parts, such as the two

frames. These frames are identical to face

frames on an ordinary plywood cabinet,

but they have a very different use. Just as

on a chest of drawers, the frames span the

two ends, and drawers are housed be-

tween them. I built the frames using biscuit

joinery, but mortise-and-tenon joinery

would work, too. Once installed, the

frames will be joined in so many ways that

the chance of their failing is negligible, if

not impossible. I left the frames slightly

oversized to be squared up later.

Assemble the ends

Building the ends was the first big task of

this job. I started with the legs. To ensure

figured surfaces on all four sides, I ripped

four matching quartersawn boards 2

1

⁄4 in.

wide, then mitered the edges at 45°. The

easiest way to make the legs was to miter

the four faces first, see that they fit together

square, then cut a solid core. The solid core

helps keep the assembly square during

glue-up and supports and strengthens the

mortise-and-tenon joinery of the apron. I

cut the core piece slightly undersized (a

small

1

⁄32 in. or so) to ensure that all of the

joints would close up and to avoid failure

of the leg joints during seasonal expansion.

I placed the mitered faces side by side

and taped up the corners, making sure that

there were no gaps between the pieces.

Then I flipped over the assembly, spread

Table-end glue-up

LEGS WITH QUARTERSAWN FIGURE ON FOUR SIDES

Four mitered pieces are required for each

leg. Choose quartersawn stock with matching

fleck patterns, then miter both edges.

Strips of masking tape act as clamps. Set

the mitered edges of the legs tightly against

each other, then tape them together.

Wrap up the leg. Spread glue on all of the in-

terior surfaces, including the core. Then wrap

the four mitered sections around the core and

secure the assembly with additional tape.

Fill-in strip,

5

⁄8 in. thick by

3

⁄4 in. wide

Distance

between

slats,

7

⁄8 in.

Tenon at

back of table

is mitered.

Side apron,

5

1

⁄8 in. wide by

21

3

⁄4 in. long,

shoulder to

shoulder

Tenon,

1

⁄2 in.

thick by 3 in.

wide by 1

1

⁄2 in.

deep

Tenon,

3

⁄8 in.

thick by 3 in.

wide by

1 in. deep

Tenon,

1

⁄2 in. thick

by 2

1

⁄2 in. wide by

2

1

⁄2 in. deep

Leg, 2

1

⁄4 in. square

by 29 in. long

Leg is assembled

from

5

⁄8-in.-thick

mitered stock

wrapped around

a solid core.

Slat,

5

⁄8 in. thick

by 3

3

⁄4 in. wide

by 16

1

⁄4 in. long,

shoulder to

shoulder

Through-mortise,

1

⁄2 in. wide by 7 in.

long

Lower rail, 3 in. wide

by 21

3

⁄4 in. long,

shoulder to shoulder

MAY/JUNE 2001 73

Photos, except where noted: Matthew Teague; this page (top right): Michael Pekovich

glue in the V-grooves and on the inside

faces. I simply set the core in place, rolled

up the entire thing and bound the last cor-

ner with tape. If the joinery is cut with care,

the pieces should close up without any

trouble. Slight gaps can be coerced shut

with the use of a clamp or two.

I allowed the legs to cure overnight, then

cut all of the leg mortises with a

1

⁄2-in.

straight bit mounted in a plunge router out-

fitted with an edge guide. Even the

through-mortises can be cut this way. To

handle the through-mortises on the thick

legs, though, I plunged from each side of

the leg rather than all the way through the

leg from one side.

The rest of the end assembly was fairly

simple. All of the mortises were cut with a

router and squared up with a chisel.

I cut the tenons on the tablesaw. First I es-

tablished the shoulder cuts with the board

held horizontally and then the trimmed the

cheeks with the workpiece held upright.

For efficiency, I cut all of the mortises and

tenons for the entire table at the same time.

I then angled the blade to 45° and cham-

fered the ends of the through-tenons.

Attach the frames and shelf

I scratched my head for some time trying

to figure out how to handle the rear apron

of this table. I wanted the corbels to be a

full 1 in. thick, but that meant they would

be flush with the rear apron, which neither

mimicked the drawer fronts nor provided a

necessary shadow line between the apron

and corbel. In the end, I decided to build

out the top and bottom of the rear apron to

Assemble the ends.

First fit the slats to the

apron and lower rail,

then set the assembly

into the mortises on

the legs.

Biscuits make for

foolproof alignment.

After the insides of the

ends are blocked out

flush with the legs, bis-

cuit slots are cut to ac-

cept the frames.

Rout the mortises. Using an edge guide on a

plunge router, drop the bit a little at a time un-

til you reach the desired depth.

74 FINE WOODWORKING

echo the top and bottom frames on the

front of the desk.

After cutting the tenons on the rear

apron, I ran a rabbet

3

⁄4 in. wide and

1

⁄4 in.

deep along the outside edges. After assem-

bly,

1

⁄2-in.-thick strips will be added to cre-

ate raised areas that mimic the front and

provide a necessary change in thickness

where the corbel abuts the leg and apron.

Because the frames were to be biscuited

to the ends, I added fill-in strips to the in-

side of the apron at top and bottom, mak-

ing sure that the strips were flush with the

front and rear legs. The strips can be at-

tached with glue or with glue and screws.

Once the fill-in strips were in place, I

squared up the frames using a large sled

at the tablesaw, using the length of the

rear apron as a reference. I then drilled

holes for the tabletop. While I could have

let the drawer dividers into sliding dove-

tails, I simply cut them to size, set them in

place at the front and back of the frames

and doweled them from above and below.

Once the drawer glides are installed, the

dividers will be locked in place by about

five different joints.

I used #20 biscuits to join the frames to

the two ends and to the rear apron. To ac-

commodate the corbels, I cut #10 biscuit

Frames are

biscuited to rear

apron before they

are joined to ends.

Tabletop,

1 in. thick by

28 in. deep by

54 in. wide

Strip,

1

⁄2 in. thick by

1 in. wide, set into

1

⁄4-in.-deep rabbet

on rear apron.

#20 biscuits

join frames to

assembled

ends.

Dividers,

3

⁄4 in.

thick by 3

5

⁄8 in.

wide by 3 in. tall,

are doweled to

upper and lower

frames.

Frames, 24

1

⁄4 in.

deep by 45

7

⁄16 in.

long, are biscuited

and assembled using

3

⁄4-in.-thick by 3-in.-

wide stock.

Shelf, 1 in. thick

by 8 in. wide by

46

3

⁄4 in. long,

shoulder to shoulder

Corbel is attached

to leg and frame

with #10 biscuits.

Shelf tenon,

1

⁄2 in.

thick by 7 in. wide

by 1

3

⁄8 in. deep,

protrudes from

mortise

3

⁄8 in.

Shelf and drawer assembly join the two ends

54 in.

30 in.

50 in. 26

1

⁄4 in.

4

1

⁄2 in.

28 in.

MAY/JUNE 2001 75

slots underneath the frame and along the

inside of the legs.

I dry-fit the assembly to be sure that the

shelf and the frames fit onto the ends and

closed up squarely. Once I was confident

there wouldn’t be any surprises, I glued the

rear apron to the frames, making sure that

the ends of the apron aligned exactly with

the ends of the frames. Then I was finally

ready for the entire assembly to go

Frames are the starting

point. The author constructs

two frames that will go

above and below the draw-

ers. The frames are simply

biscuited together.

The rear apron is biscuit-

ed to the frame assembly.

Note that the drawer di-

viders are already in place.

Bring it all together. The through-tenoned shelf, the biscuited frames and the ends are all

assembled in one operation. The glue-up proceeds easily when it is done with the table up-

side down on a flat surface.

13

1

⁄4 in.

2

9

⁄16 in.

CORBEL

76 FINE WOODWORKING

together. It was easiest to glue up the table

upside down on a flat surface. One nice

thing about using preassembled frames is

that, at glue-up, it took only a few clamps

to pull everything closed.

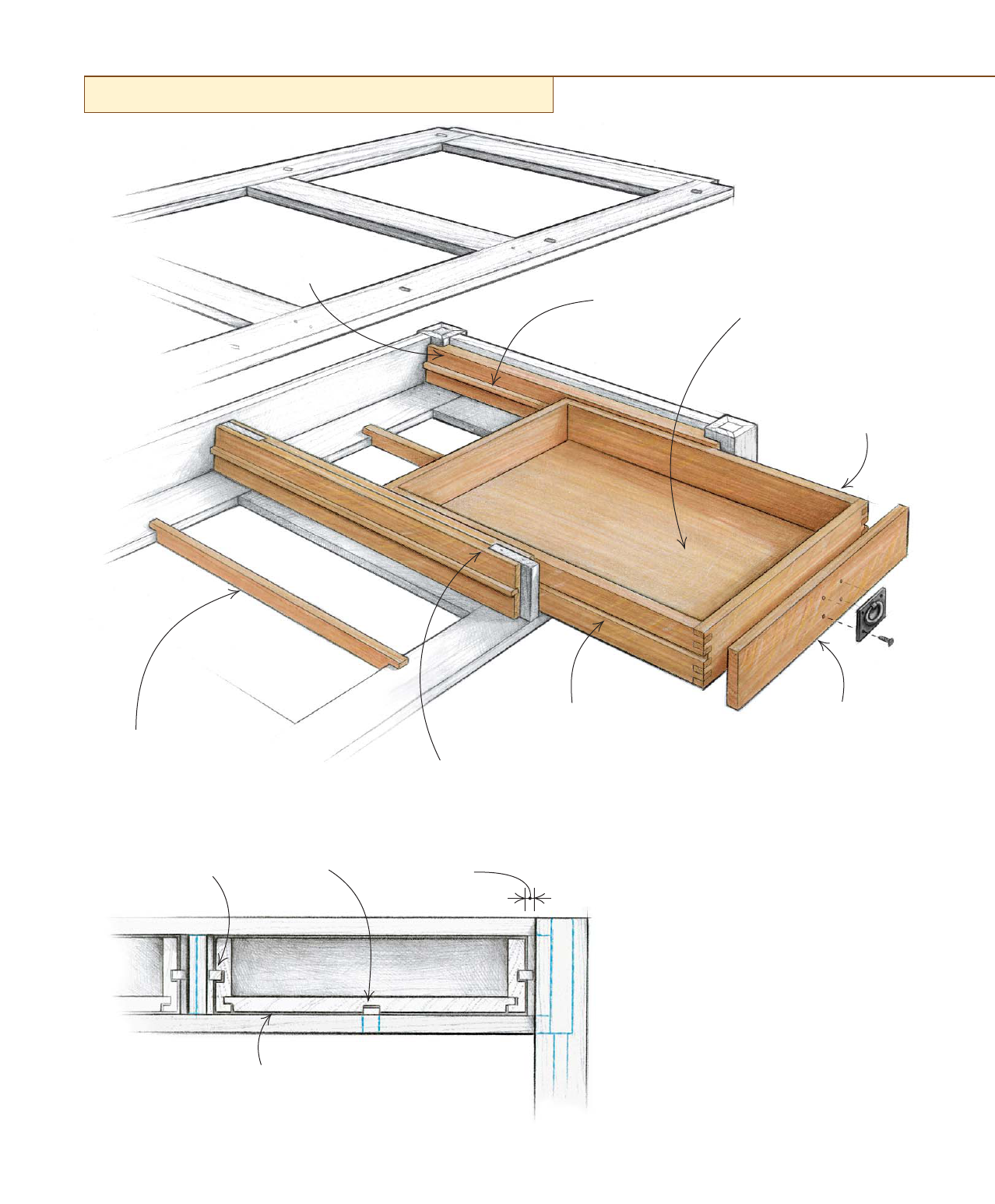

Install the drawer glides

I know that secondary woods and ply-

wood drawer bottoms might be acceptable

when building furniture, but I can’t help

myself—I love the sound and feel of a

heavy oak drawer seating itself smoothly

into place. And, as I mentioned before, I

ordered the lumber in bulk, so using oak as

the secondary wood allowed me to use up

some of the less-desirable pieces.

The method I use for building and in-

stalling drawers is one I’ve relied on many

times. While I could have let the drawers

Install drawer blocking and glides last

Side filler board,

15

⁄16 in. thick by

23

1

⁄8 in. long

Center glide,

3

⁄4 in.

thick by 1

1

⁄8 in. wide

by 23

1

⁄8 in. long, is

half-lapped onto

frame.

Groove,

3

⁄8 in. by

3

⁄8 in., accepts

glide.

Drawer front,

3

1

⁄2 in. wide by

14

1

⁄2 in. long,

conceals filler

boards and glides.

Drawer is

constructed from

3

⁄4-in.-thick stock

and finger-jointed

at corners.

Side glide,

3

⁄8 in.

thick by

3

⁄4 in. wide,

is let into groove

on filler board.

Drawer bottom is

3

⁄4 in.

thick to allow for center

glide.

Drawer is

supported by

side glides.

Filler board

extends

3

⁄8 in. into

drawer opening.

Drawer is

suspended

1

⁄16 in. above

frame.

Drawer bottom

is grooved for

center glide.

Center filler board,

3

⁄4 in. thick by 23

1

⁄8 in. long,

straddles drawer divider.

MAY/JUNE 2001 77

ride on the frames alone, I prefer drawers

that have a bottom glide and are side-

hung. Using three wooden glides, it is sim-

ple to make small adjustments to the fit and

to the drawer reveal, even before anything

is installed.

My first step was to make the drawers

themselves. I used a box-joint sled on a

tablesaw (see FWW #148, pp. 60-63) to

construct simple finger-jointed boxes that

will receive false fronts once installed. I left

the drawers about 1 in. shy of full length

(from front apron to rear apron) to accom-

modate the drawer fronts and to allow

some room for adjustments.

Once the drawers were glued up—and it

is essential that there be no twist in the

drawer—I used a dado setup on the table-

saw to plow grooves in the two sides and

along the center of the

3

⁄4-in.-thick drawer

bottom. After that, it was time to install the

glides. Essentially, I was simply blocking

out the ends and the voids between the di-

viders, then setting glides into grooves.

The glides can be sized and adjusted to fit

the drawers before any glue has been ap-

plied, but it’s important to get a perfect

fit before securing them permanently. A

few small screws or brads are all it takes to

attach the glides. Once everything is in

place, the grooved drawers should ride

smoothly along the glides. Then it was a

simple matter of gluing the drawer fronts

to the drawer boxes.

Because I use a spray setup for finishing,

I sprayed the top and base separately, be-

cause it’s easier to spray the base when

you don’t have to work into corners or

worry about overspray. I coated the piece

with a mix of Minwax stains and let it sit

for a week. I then sprayed on two coats of

flat lacquer.

The tabletop itself was screwed directly

to the frames. It was fixed at the center with

screws, and then the front and back were

screwed into elongated holes—which al-

low for seasonal movement—through the

upper frame. The drawer fronts, likewise,

were simply attached with screws.

A final touch was the hand-hammered

copper pulls (see the back cover) from

Gerald Rucks. With the solid drawers,

smooth-running glides and the authentic

pulls, the desk is a pleasure to use.

Eric Keil builds custom furniture and cabinetry in

Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

Block out the ends. The ends of the table are blocked out with a board grooved to accept the

drawer glides.

Glides span the dividers. Center dividers

are sandwiched between two filler boards that

house the drawer glides.

Insert the drawer glides and install the

center glide. Glue the drawer glides in place

and mount the center glide on the lower draw-

er frame. The center glide ensures that the

drawer tracks correctly.