University of Florida Journal of Law & Public Policy University of Florida Journal of Law & Public Policy

Volume 33 Issue 3 Article 3

5-1-2023

You Belong with Me: The Battle for Taylor Swift's Masters and You Belong with Me: The Battle for Taylor Swift's Masters and

Artist Autonomy in the Age of Streaming Services Artist Autonomy in the Age of Streaming Services

Kylee Neeranjan

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.u;.edu/jlpp

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Neeranjan, Kylee (2023) "You Belong with Me: The Battle for Taylor Swift's Masters and Artist Autonomy

in the Age of Streaming Services,"

University of Florida Journal of Law & Public Policy

: Vol. 33: Iss. 3,

Article 3.

Available at: https://scholarship.law.u;.edu/jlpp/vol33/iss3/3

This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for

inclusion in University of Florida Journal of Law & Public Policy by an authorized editor of UF Law Scholarship

Repository. For more information, please contact rachel@law.u;.edu.

413

YOU BELONG WITH ME: THE BATTLE FOR TAYLOR SWIFT’S

MASTERS AND ARTIST AUTONOMY IN THE AGE OF

STREAMING SERVICES

Kylee Neeranjan

*

“I think artists deserve to own their work. I just feel very passionately

about that.”

1

Abstract

Taylor Swift released six chart-topping albums during the tenure of

her first recording contract with Big Machine Records, LLC. Upon expiry

of the initial contract, Swift made a new home with Republic Records and

contracted for her retained ownership of the masters for future works.

Soon after, the masters to Swift’s first six albums were sold to an

investment fund, preempting Swift from ownership. In an effort to regain

control over her life’s work, Swift launched an initiative to re-record each

of her first six albums. This note argues that copyright laws enforce a

pervasive power dynamic between musicians and record labels,

preventing artists from meaningful ownership over their creative

accomplishments. Just as the methods for music production and

consumption have evolved over time, the laws governing music

copyright should evolve accordingly.

I. I

WROTE DOWN OUR SONG: A HISTORY OF MASTER

RECORDINGS AND RELATED RIGHTS ...................................... 414

A. The History of Recorded Sounds .................................... 414

B. Music Recordings Today ................................................ 416

II. THERE’S NOTHING LIKE A MAD WOMAN: TAYLOR

SWIFT’S DECISION TO RE-RECORD HER FIRST

SIX ALBUMS ........................................................................... 417

A. The Fallout ..................................................................... 417

B. The Re-Recordings ......................................................... 420

* Kylee Neeranjan graduated cum laude from the University of Florida Levin College of

Law with her Juris Doctorate in May 2023. During law school, she was an Associate Justice on

the UF Supreme Court, the Fall 2022 President of Florida Blue Key, and inducted into the UF

Hall of Fame. She is currently an associate at Holland & Knight, LLP in Fort Lauderdale, Florida.

This note was written in the Spring of 2021, predating Taylor Swift’s Midnights album, The Eras

Tour, and re-recordings subsequent to Red (Taylor’s Version). Neeranjan thanks Professor

Sabrina Lopez, her faculty advisor, and the members of the Journal of Law and Public Policy for

their feedback and hard work. A final thank you to Neeranjan’s mentors, Samantha Schosberg

Feuer and Taylor Swift for always being there during law school. This note is dedicated to

Neeranjan’s parents because no thanks will ever be enough.

1. Interview by Robin Roberts with Taylor Swift, in New York, N.Y. (Aug. 22, 2019).

414 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

III. I PROMISE THAT YOU’LL NEVER FIND ANOTHER LIKE

ME: COPYRIGHT TERMINATION LAW ..................................... 422

A. Copyright Law Origins ................................................... 422

B. Theories of Copyright Law ............................................. 423

C. The Judiciary and Copyright Law .................................. 424

D. Copyright Termination ................................................... 425

IV. ARE YOU READY FOR IT?: MASTER RECORDING RIGHTS

DURING THE AGE OF STREAMING SERVICES ........................... 427

A. The Streaming Revolution .............................................. 427

B. The New Value of Music ................................................. 428

C. Legislative Reform .......................................................... 429

D. Judicial Interpretation .................................................... 431

V. T

HESE THINGS WILL CHANGE: RECOMMENDATIONS

FOR COPYRIGHT TERMINATION REFORM ................................ 431

A. Termination Rights Are Too Complicated

to Exercise ...................................................................... 432

B. Artists Are Unfairly Compensated and Unable

to Reap the Fruits of Their Intellectual Creativity ......... 437

C. Proposed Solutions ......................................................... 439

VI. LONG STORY SHORT, IT WAS A BAD TIME: CONCLUSION ..... 442

I.

I WROTE DOWN OUR SONG: A HISTORY OF MASTER RECORDINGS AND

RELATED RIGHTS

“What do you sing on your drive home?”

2

A. The History of Recorded Sounds

Thomas Edison, the man of a thousand patents, laid the foundation for

music recording and reproduction with the advent of the phonograph in

1877.

3

Edison wrapped tinfoil around a cylindrical, rotating drum.

4

As it

rotated, the drum made contact with a metal stylus, which moved in

response to an operator speaking into a diaphragm on the other end.

5

The

movement of the stylus on the tinfoil vibrated the diaphragm, driving air

in and out of the mouthpiece, recreating the inputted sound.

6

Though the

resulting “Mary had a little lamb” was barely audible, Edison technically

2. TAYLOR SWIFT, Mad Woman, on FOLKLORE (Republic Records 2020).

3. Roger Beardsley & Daniel Leech-Wilkinson, A Brief History of Recording to ca. 1950,

CHARM, https://charm.rhul.ac.uk/history/p20_4_1.html [https://perma.cc/KA37-BPRC].

4. Id.

5. Id.

6. Id.

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 415

managed to be the first to reproduce a recorded sound with this tinfoil

contraption.

7

Alexander Graham Bell and Charles Tainter upgraded

Edison’s tinfoil materials with a hard-wax phonograph, improving sound

quality tremendously.

8

The technology evolved over the next few decades when Emil

Berliner developed the gramophone in the late 1880s.

9

Simpler to

playback and capable of cheap mass production, the gramophone played

sound through the creation of metal discs with etched grooves, which

could be easily copied and reproduced by creating a negative version with

ridges mirroring the original grooves.

10

The first “celebrity” gramophone

recordings featured the voices of the Imperial Russian Opera at the start

of the 20th century.

11

The use of the hard-wax masters became popular

with American recording studios shortly after and remained the preferred

method until the early 1920s when two engineers at Bell Telephone Labs

developed a method for recording that used purely electronic

components.

12

This method of recording, capable of producing clearer

sound than the aforementioned mechanical varieties, enabled record

companies to capture more of the musician in the studio.

13

The age of vinyl commenced in the 1950s and dominated through the

1980s until CDs replaced vinyl LPs.

14

In the midst of this, sound

recordings first entered into copyright law in the 1970s.

15

Prior to

February 15, 1972, individual state laws dictated copyrights for sound

recordings.

16

The Copyright Act of 1976 provided the basic framework

for modern copyright laws.

17

7. Id.

8. Id.

9. Beardsley & Leech-Wilkinson, supra note 3.

10. Id.

11. Id.

12. Id.

13. Stewart Hilton, The History of Recorded Music, M

USICAL U, https://www.musical-

u.com/learn/history-of-recorded-music/ [https://perma.cc/KJV7-M9MZ] (last visited Mar. 2,

2023).

14. Id.

15. Amanda Jenkins, Copyright Breakdown: The Music Modernization Act, L

IBR. OF CONG.

BLOGS (Feb. 5, 2019), https://blogs.loc.gov/now-see-hear/2019/02/copyright-breakdown-the-

music-modernization-act/ [https://perma.cc/NH7T-Y9SA].

16. Id.

17. Copyright Law of the United States (Title 17), U.S.

COPYRIGHT OFF.,

https://www.copyright.gov/title17/ [https://perma.cc/K8M3-2TEU] (last visited Mar. 28, 2023).

416 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

B. Music Recordings Today

Today, every song has two copyrights: one for the sound recording

and one for the composition.

18

A “master recording” is a song or

performance’s official, original sound recording.

19

Music critic Dan

DeLuca opined that masters are “the most authentic superior sonic

account of the song. Everything else is a copy, and after that, in the digital

world, a copy of a copy.”

20

These master recordings are commonly

referred to as “masters” and can be played back and reproduced.

21

Ownership of an artist’s masters furnishes legal rights to license the

recordings to third parties and collect royalties on any such licensing.

22

When signing recording artists, music labels will leverage the master

rights to recordings for a finite time period with the opportunity for a full-

time career as a musician.

23

In exchange for the rights to the artist’s

master recordings, music labels will provide the artist with an advance

payment, recoupable against the royalties earned from sales.

24

The allure

of the advance, and the potential for a promising career, often

overshadow the negative and restrictive implications that come with

signing away the rights to an artist’s masters. Once under contract, artists

cannot release records with another label and forfeit ownership of the

recording made under contract to the record label.

25

Often, the

reassignment of master recording rights accompanying recording

contracts lasts perpetually.

26

Generally, a copyright grants authors the rights to reproduce the work,

prepare derivative works, distribute copies of the work, publicly perform

the work, and publicly display the work.

27

The owners of master

18. Evie Bloom, What Does It Mean to Own Your Masters?, AMUSE,

https://www.amuse.io/content/owning-your-masters?cn-reloaded=1 [https://perma.cc/SED3-7C

6D] (last visited Mar. 28, 2023).

19. Id.

20. Seraphina DiSalvo, What Is a Master Recording And Why Is Taylor Swift So Mad Hers

Just Got Sold?, P

HILA. INQUIRER, https://www.inquirer.com/entertainment/music/taylor-swift-

master-recordings-scooter-braun-20190702.html [https://perma.cc/W7ED-KF98] (last updated

July 2, 2019, 10:33 AM).

21. What Is the Difference Between Master Recordings and Music Publishing?,

S

ONGTRUST, https://help.songtrust.com/knowledge/what-is-the-difference-between-master-

recordings-and-music-publishing [https://perma.cc/CNY4-R8X2] (last visited Mar. 28, 2023).

22. Bloom, supra note 18.

23. Why Owning Your Master Recordings Means Everything, AWAL (Sept. 19, 2018),

https://www.awal.com/blog/maintaining-ownership-rights-as-an-artist [https://perma.cc/9P4A-

M964].

24. Id.

25. Id.

26. Id.

27. U.S.

COPYRIGHT OFF., HOW SONGWRITERS, COMPOSERS, AND PERFORMERS GET PAID

3 (2020), https://www.copyright.gov/music-modernization/educational-materials/musicians-

income.pdf [https://perma.cc/MC9P-TKVV]; 17 U.S.C. § 106.

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 417

recordings have no public display rights and a limited public performance

right.

28

Master recording rights are distinct and separate from the publishing

rights accompanying the musical work, including the notes, lyrics, and

melody.

29

These composition rights are vested in the songwriters,

producers, and publishers of a given song.

30

These stakeholders have the

exclusive right to control the reproduction and redistribution of the work,

as well as the right to perform the work publicly.

31

Record labels and

music publishers typically favor the master recording rights to the

detriment of the author’s publishing rights because these entities make

more money from the recordings than the publishing.

32

The copyright for a master recording cannot be used in substitution

for the copyright of the musical work.

33

Similarly, composition rights

protecting the underlying musical work cannot protect the recorded

performance of a given composition.

34

II. THERE’S NOTHING LIKE A MAD WOMAN: TAYLOR SWIFT’S DECISION

TO

RE-RECORD HER FIRST SIX ALBUMS

“He’s got my past frozen behind glass, but I’ve got me.”

35

A. The Fallout

The love story between Taylor Swift (Swift) and music executives like

Scott Borchetta of her former record label, Big Machine Records, LLC

(Big Machine), was tainted by bad blood during the summer of 2019.

36

In 2005, at the start of her career, Swift signed a contract with Big

Machine, stipulating that the record company would retain ownership of

28. U.S. COPYRIGHT OFF., supra note 27.

29. Id.; Bloom, supra note 18; Jenkins, supra note 15.

30. Lisa A. Alter, Protecting Your Musical Copyrights, W

IXEN MUSIC (2012),

https://www.wixenmusic.com/copyright/protecting-your-musical-copyrights [https://perma.cc/

M2JC-H3Z3].

31. Camille N. Anidi, The Difference Between the Underlying Composition and the Master

Recording, ANIDI L. (Nov. 16, 2020), https://www.anidilaw.com/blog/the-difference-between-

the-underlying-composition-and-the-master-recording [https://perma.cc/M77V-WZM7].

32. Music Streaming and Its Impact on Composers & Songwriters, ECSA (May 6, 2021),

https://composeralliance.org/news/2021/5/music-streaming-and-its-impact-on-composers-song

writers/ [https://perma.cc/DJ3A-FZBR].

33. Anidi, supra note 31.

34. Id.

35. T

AYLOR SWIFT, It’s Time To Go, on EVERMORE (DELUXE VERSION) (Republic Records

2020).

36. See Nicholas Hautman, Taylor Swift’s Fallout with Big Machine Records, Scooter

Braun and Scott Borchetta: Everything We Know, U.S. WEEKLY (June 23, 2021),

https://www.usmagazine.com/celebrity-news/pictures/taylor-swift-big-machine-records-fallout-

everything-we-know/ [https://perma.cc/9DNW-HB46] (explaining the conflict over the

acquisition of Swift’s master recordings).

418 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

the master recordings for the length of a thirteen-year term, an ode to

Swift’s favorite number.

37

The contract also contained an “original

production clause,” which essentially prohibited Swift from making any

future songs sound exactly like the original master recordings that Big

Machine owned.

38

The full contract remains private.

39

During her tenure with Big Machine, Swift released six studio albums:

Taylor Swift, Fearless, Speak Now, Red, 1989, and Reputation;

Swift is credited as a songwriter or co-songwriter on each album.

40

Swift

won ten Grammys and earned thirty Grammy nominations for the work

she authored and recorded during this time.

41

Upon the expiration of the thirteen-year term of the Big Machine

contract, Swift opted against renewing with Big Machine and instead

made a “new home” at Republic Records and Universal Music Group.

42

The new agreement provided that Swift would “own all of [her] master

recordings . . . from now on”

43

and reflected the shift in audience

consumption mechanisms with an intentional focus on revenues from

streaming services.

44

For example, Swift specifically negotiated for the

distribution of money to her when Spotify sells shares.

45

37. Brittany Spanos & Amy X. Wang, Taylor Swift ‘Absolutely’ Plans to Re-Record

Catalog After Big Machine Deal, R

OLLING STONE (Aug. 21, 2019), https://www.rollingstone

.com/music/music-news/taylor-swift-absolutely-plans-to-re-record-catalog-after-big-machine-

deal-874173/ [https://perma.cc/EX3M-9WRJ]; Jocelyn Vena, Taylor Swift Explains Why 13 Is

Her Lucky Number, MTV (May 7, 2009, 1:18 PM), https://www.mtv.com/news/1610839/taylor-

swift-explains-why-13-is-her-lucky-number/ [https://perma.cc/8F23-LXN4]. The article quoted

Swift, stating “[b]asically whenever a 13 comes up in [her] life, it’s a good thing.” Id. Swift

elaborated that “[e]very time [she’d] won an award [she’d] been seated in either the 13th seat, the

13th row, the 13th section[,] or row M, which is the 13th letter.” Id.

38. Starr Bowenbank, Exactly How Can Taylor Swift Rerecord All Six of Her Old Albums?,

C

OSMOPOLITAN (Nov. 12, 2021), https://www.cosmopolitan.com/entertainment/music/a3549

1914/how-taylor-swift-will-rerecord-old-albums-explained/ [https://perma.cc/B3S3-HMMN].

39. Jeffrey H. Brown, The Legal Take on the Taylor Swift Rerecording Dispute, Bᴇsᴛ Lᴀᴡ.

(Dec. 5, 2019, 8:00 AM), https://www.bestlawyers.com/article/taylor-swift-recording-contract-

controversy/2747 [https://perma.cc/M9ST-7F98].

40. Emma Nolan, Does Taylor Swift Write Her Own Songs? Full List of Her Songwriting

Credits, Nᴇᴡsᴡᴇᴇᴋ (Jan. 25, 2022), https://www.newsweek.com/does-taylor-swift-write-own-

songs-full-list-songwriting-credits-damon-albarn-1672546 [https://perma.cc/7LZQ-N3T2].

41. Taylor Swift, R

ECORDING ACAD. GRAMMY AWARDS, https://www.grammy.com/artists/

taylor-swift/15450 [https://perma.cc/8VWY-3424]

(last visited Aug. 04, 2023).

42. Taylor Swift (@taylorswift), I

NSTAGRAM (Nov. 19, 2018), https://www.instagram.com

/p/BqXgDJBlz7d/ ; Nicholas Hautman, Taylor Swift Changes Record Labels 13 Years After

Signing with Big Machine: ‘My New Home’ (Nov. 19, 2018), https://www.usmagazine.com/

entertainment/news/taylor-swift-changes-record-labels-after-13-years-my-new-home/ [https://

perma.cc/XBT5-6HQ9].

43. Hautman, supra note 42.

44. See id. (“[Swift] pushed for Universal to agree that “any sale of their Spotify shares

[will] result in a distribution of money to their artists” and it is “non-recoupable” against what

those performers owe the label.”).

45. Id.

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 419

On June 25, 2019, Big Machine notified all its shareholders of a

pending deal with Ithaca Holdings, LLC (Ithaca), an “investment holding

company focused on the media and entertainment and consumer brand

sectors” founded by music executive Scooter Braun.

46

Swift’s father,

Scott Swift, was among the shareholders of Big Machine, who met on

June 28, 2019, and ultimately approved the deal with Ithaca.

47

The sale

transferred ownership of the master recordings of Swift’s first six albums

to Ithaca and Braun.

48

The deal went public on June 30, 2019, and Swift took to Tumblr, a

blog platform she used to connect with fans (“Swifties”), to express her

immense dissatisfaction with the deal; in fact, the sale of her masters to

Braun was Swift’s “worst case scenario.”

49

A very public scuffle ensued,

and other well-known artists defended either Swift or Braun on social

media, including Cher and Justin Bieber.

50

The complications from the deal with Ithaca had only just begun.

Because Swift did not own the rights to her masters, she could not

perform a medley of her old songs as she planned to celebrate winning

the “Artist of the Decade Award” at the 2019 American Music Awards

(AMAs).

51

Swift again took to Tumblr pleading with Swifties to “let Scott

Borchetta and Scooter Braun know how [they] feel about this.”

52

Days

before the performance, the executives announced they had “come to

terms on a licensing agreement that approves their artists’ performances

46. Ithaca Holdings, CRUNCHBASE, https://www.crunchbase.com/organization/ithaca-

holdings [https://perma.cc/W7W3-S7FD] (last visited Mar. 29, 2023).

47. Scott Borchetta, So, It’s Time for Some Truth..., BIG MACH. LABEL GRP. (June 30, 2019),

https://www.bigmachinelabelgroup.com/news/so-its-time-some-truth [https://perma.cc/ 2FTQ-

5PAH]. But see Taylor Swift, T

UMBLR (June 30, 2019), https://taylorswift.tumblr.com/post/

185958366550/for-years-i-asked-pleaded-for-a-chance-to-own-my [https://perma.cc/8UXA-RJ

6A] (explaining that Swift “learned about Scooter Braun’s purchase of [her] masters as it was

announced to the world).

48. Talia Smith-Muller, 3 Lessons Taylor Swift’s Rift with Big Machine Can Teach Us

About Record Contracts, B

ERKLEE ONLINE (Dec. 20, 2019), https://online.berklee.edu/takenote/3-

lessons-taylor-swifts-rift-with-big-machine-can-teach-us-about-record-contracts/ [https://perma.

cc/3YM3-XUHP].

49. Swift, supra note 47.

50. Ellie Woodward, Here Are All the Celebs Who’ve Spoken Out in Support of Taylor Swift

After She Exposed Scott Borchetta and Scooter Braun Again, B

UZZFEED (Nov. 15, 2019),

https://www.buzzfeed.com/elliewoodward/celebs-taylor-swift-scott-borchetta-scooter-braun-

drama [https://perma.cc/U8GA-GF7P]; Madison Feller, Here Are All the Celebrities Who Have

Defended Taylor Swift and Scooter Braun so Far, E

LLE (July 1, 2019), https://www.elle.com

/culture/celebrities/a28242033/celebrities-defending-taylor-swift-scooter-braun/ [https://perma.

cc/ARY3-AYXD].

51. Taylor Swift, T

UMBLR (Nov. 14, 2019), https://taylorswift.tumblr.com/post/189

068976205/dont-know-what-else-to-do [https://perma.cc/A828-QZRS] (“I’m not allowed to

perform my old songs on television because [Scott Borchetta and Scooter Braun] claim that would

be re-recording my music before I’m allowed to next year.”).

52. Id.

420 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

to stream post-show and for re-broadcast on mutually approved

platforms,” including the AMAs.

53

Swift took the AMAs stage,

donning a white shirt etched with the titles of the six albums she did

not own the masters for.

54

B. The Re-Recordings

The terms of Swift’s original contract with Big Machine stipulated

that she could not re-record any of her first five albums until November

2020.

55

Swift’s sixth album could not be re-recorded until November

2022.

56

Swift repeatedly and publicly expressed her genuine intent to re-

record and re-release her original works once it was legal.

57

Coincidentally around October 2020, seventeen months after acquiring

them from Big Machine, Braun sold the six masters to an investment fund

for over $300 million.

58

Shortly thereafter, Swift officially announced she was “rerecording all

of [her] old music” on November 22, 2020, during a virtual acceptance

speech at the AMAs as she was declared the 2020 “Artist of the Year.”

59

However, the “original production clause” from Swift’s 2005 agreement

with Big Machine provided that the re-recordings must sound

distinguishable from the original masters.

60

On February 11, 2021, Swift announced that her “new version” of her

second album, Fearless (Taylor’s Version), was finished.

61

In the

Instagram post’s caption, Swift added that her version of the album

53. Neha Prakash, 2019 AMAs: Taylor Swift Shut Down Feud over Music Rights with

Career-Spanning Medley, G

LAMOUR (Nov. 24, 2019), https://www.glamour.com/story/taylor-

swift-performance-2019-amas [https://perma.cc/Q48U-DX3Z].

54. Id. (noting that Swifties call these coy references to other Taylor Swift works “Easter

Eggs”).

55. Smith-Muller, supra note 48.

56. Jessica Derschowitz, So...Where Are We At With the Taylor Swift Rerecordings?,

V

ULTURE, https://www.vulture.com/2023/08/taylor-swift-rerecorded-albums-which-album-is-

next.html [https://perma.cc/YM8S-BW48] (Aug. 10, 2023).

57. Spanos & Wang, supra note 37.

58. Shirley Halperin, Scooter Braun Sells Taylor Swift’s Big Machine Masters for Big

Payday, V

ARIETY (Nov. 16, 2020), https://variety.com/2020/music/news/scooter-braun-sells-

taylor-swift-big-machine-masters-1234832080/ [https://perma.cc/JD4P-ZDWV]; see Taylor

Swift (@taylorswift13), T

WITTER (Nov. 16, 2020), https://twitter.com/taylorswift13/status/

1328471874318311425 [https://perma.cc/L2PF-E887]

(discussing Swift’s negotiations with

Scooter Braun and the sale to Shamrock Holdings).

59. Sarah Curran, Taylor Swift Announces That She’s Re-Recording All of Her Old Music

While Accepting Artist of the Year at AMAs, ET C

ANADA (Nov. 22, 2020), https://etcanada.com

/news/716392/taylor-swift-fans-share-their-theories-about-her-not-a-lot-going-on-post/ [https://

perma.cc/34M5-Q7W7].

60. Bowenbank, supra note 38.

61. Taylor Swift (@taylorswift), INSTAGRAM (Feb. 11, 2021), https://www.instagram.com/

p/CLJzk9MjcCe/ [https://perma.cc/BHE7-CEU7].

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 421

included “6 never before released songs from the vault,” and she released

Love Story (Taylor’s Version) later that same night.

62

The full album,

Fearless (Taylor’s Version), dropped on April 9, 2021.

63

The release was

Swift’s third number-one album in under nine months.

64

On June 18, 2021, Swift announced that Red (Taylor’s Version) would

drop on November 12, 2021.

65

Again, Swift teased on Instagram that the

re-recording would contain never-before-released songs “from the vault,”

this time nine tracks, including a ten-minute version of All Too Well, a

song many Swifties claim as one of Swift’s best works.

66

Red (Taylor’s

Version) became Swift’s fourth number-one album in sixteen months.

67

Swift still has four original albums for which she has yet to release a

Taylor’s Version. Swifties have speculated about which release is next,

making expert utilization of the many “Easter egg” hints Swift herself has

seemingly dropped along the way.

68

Swift’s sixth studio album,

Reputation, seems the least likely for re-release as recording contracts

often require artists to wait at least five years after a project’s release date

before even beginning to re-record.

69

As such, Reputation’s November

62. Id.

63. Taylor Swift (@taylorswift), I

NSTAGRAM (Apr. 9, 2021), https://www.instagram.com/

p/CNbnuyojgrZ/ [https://perma.cc/8S9S-2N4U].

64. Ben Sisario, Taylor Swift’s Rerecorded ‘Fearless’ Is the Year’s Biggest Debut So Far,

N.Y.

TIMES (Apr. 19, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/04/19/arts/music/taylor-swift-

fearless-taylors-version-billboard-chart.html [https://perma.cc/WWW9-228B]. Swift released

albums folklore and evermore, under the new contract with Universal and Public, on July 24, 2020

and December 11, 2020, respectively. Jonathan Ponciano, Taylor Swift Announces Surprise

Release of 9th Album ‘Evermore’ on Friday, F

ORBES (Dec. 10, 2020), https://www.forbes.com/

sites/jonathanponciano/2020/12/10/taylor-swift-announces-surprise-release-of-9th-album-ever

more-on-friday/ [https://perma.cc/CL7J-8F8B]. folklore won Album of the Year at the Grammys

and evermore was nominated for the same award. Daniela Avila, Taylor Swift Celebrates

‘Evermore’ 2022 Grammy Nomination: ‘No Problems Today Just Champagne’, P

EOPLE (Nov. 23,

2021), https://people.com/music/grammys-2022-taylor-swift-celebrates-evermore-nomination/

[https://perma.cc/WYV8-FKF7].

65. Taylor Swift (@taylorswift), I

NSTAGRAM (June 18, 2021), https://www.instagram.com/

p/CQRUBXtjZXT/ [https://perma.cc/63CW-CR8G].

66. Taylor Swift (@taylorswift), INSTAGRAM (Aug. 6, 2021), https://www.instagram.com

/p/CSPEsteMmE5/ [https://perma.cc/E6BV-FX8S]; Ashley Boucher, Taylor Swift Has a 10-

Minute Version of Fan-Favorite Song 'All Too Well', P

EOPLE (Nov. 19, 2020),

https://people.com/music/taylor-swift-has-a-10-minute-version-of-fan-favorite-song-all-too-well/

[https://perma.cc/J6D2-LC5T].

67. Ben Sisario, Taylor Swift Earns Her Fourth No. 1 in 16 Months with New ‘Red’, N.Y.

TIMES (Nov. 22, 2021), https://www.nytimes.com/2021/11/22/arts/music/taylor-swift-red-taylors

-version-billboard-chart.html [https://perma.cc/8YWG-2W7B].

68. See Eliza Thompson, Which Taylor Swift Album Will Be Rerecorded Next? The Wildest

Fan Theories and Speculation, U

S WKLY., https://www.usmagazine.com/entertainment/

pictures/which-taylor-swift-album-will-be-rerecorded-next-fan-theories/1989-2-13/

[https://perma.cc/JWD4-BMDR] (Apr. 14, 2023) (providing that “fans are already thinking about

which one of her early albums she’ll rerecord next”).

69. Id.

422 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

2017 original release precluded Swift’s ability to re-record it any time

before November 2022.

III. I PROMISE THAT YOU’LL NEVER FIND ANOTHER LIKE ME:

COPYRIGHT TERMINATION LAW

“I’ve come too far to watch some namedropping sleaze tell me what are

my words worth.”

70

A. Copyright Law Origins

Copyright law has roots in the United States Constitution, specifically

in Article I, Section 8, Clause 8.

71

The Founding Fathers reserved to the

Legislature the power “[t]o promote the Progress of Science and useful

Arts, by securing for limited Times to Authors and Inventors the

exclusive Right to their respective Writings and Discoveries.”

72

Enactment of the United States’ first Copyright Act was even on the

agenda of the U.S. Congress’ first convention in 1789.

73

Accordingly, the

Copyright Act of 1790 furnished copyright protections for “maps, charts,

and books.”

74

Since 1897, the owner of a copyrighted musical composition has

retained the exclusive right “to perform the work publicly for profit.”

75

By 1914, the number of performers and performances showcasing

copyrighted music was so burdensome that, negotiation for licensed use

of the copyrighted materials was practically impossible.

76

In response,

the American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers assembled

to serve as a “‘clearing-house’ for copyright owners and users to solve

[the] problems” associated with the widespread performance of licensed

music.

77

The United States Copyright Office (USCO) provides that “[i]t is a

principle of American law that an author of a work may reap the fruits of

his or her intellectual creativity for a limited period of time.”

78

The USCO

also provides, in relevant part, that “in the case of sound recordings, [the

owner of copyright has the exclusive right] to perform the work publicly

70. TAYLOR SWIFT, The Lakes, on FOLKLORE (DELUXE VERSION) (Republic Records 2020).

71. U.S. Cᴏɴsᴛ. art. I, § 8, cl. 8.

72. Id.

73. Anandashankar Mazumdar, Historic Court Cases That Helped Shape Scope of

Copyright Protections, L

IBR. OF CONG. (Sept. 9, 2020), https://blogs.loc.gov/copyright/2020/09/

historic-court-cases-that-helped-shape-scope-of-copyright-protections/ [https://perma.cc/84VB-

WX9M].

74. Id.

75. Broad. Music, Inc. v. Columbia Broad. Sys., Inc., 441 U.S. 1, 4 (1979).

76. Id. at 4–5.

77. Id. at 5 (citing CBS v. Am. Soc’y of Composers, 400 F. Supp. 737 (S.D.N.Y. 1975)).

78. A Brief History of Copyright in the United States, U.S.

COPYRIGHT OFF.,

https://www.copyright.gov/circs/circ1a.html [https://perma.cc/VT49-FAKM].

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 423

by means of a digital audio transmission.”

79

Copyright claims are

registered, and the USCO has recorded copyright-related documents.

80

Despite the long-recognized importance of copyright protections,

protection for sound recordings under federal copyright laws was not

recognized until 1971.

81

Section 101 of the Copyright Act provides many relevant definitions

for copyright law terms.

82

Sections 102 through 105 of the Copyright Act

shed light on the subject matter of copyright.

83

Exclusive rights afforded by copyright exist under Section 106 of the

Copyright Act.

84

Specifically, this section provides the music copyright

owner with the rights to reproduction,

85

adaptation,

86

public

distribution,

87

public performance,

88

and public display.

89

B. Theories of Copyright Law

Several theories justify copyright law protections. Two, in particular,

are geared specifically toward creators and authors of works.

Incentive theory, for example, serves as a utilitarian justification for

copyright law.

90

Under incentive theory, one believes copyrights are

necessary to solve the problem of public goods.

91

Public goods are “‘non-

rivalrous’ (meaning that they can be enjoyed by an unlimited number of

people) and ‘non-excludable’ (meaning that once they are made available

to one consumer, it is challenging to prevent other consumers from

gaining access to them).”

92

Music on a streaming platform would qualify

as a non-rivalrous and non-excludable good. Incentive theory is purely

consequentialist, believing that creators must receive intellectual

79. Id.

80. Id.

81. Sound Recording Act of 1971, Pub. L. No. 92-140, 85 Stat. 391 (1971).

82. 17 U.S.C. § 101.

83. Id. §§ 102–105.

84. Id. § 106.

85. Id. § 106(1).

86. Id. § 106(2).

87. Id. § 106(3).

88. 17 U.S.C. § 106(4).

89. Id. § 106(5).

90. See J

EANNE C. FROMER & CHRISTOPHER JON SPRINGMAN, COPYRIGHT LAW CASES AND

MATERIALS 10 (Jeanne C. Fromer & Christopher Jon Springman, eds., vol. 5 2023) (stating that

the utilitarian justification for copyright provides “that copyright contributes to the ‘progress of

Science’ by maintaining adequate incentives to engage in the production of new artistic and

literary works.”).

91. See William Fisher, Copyright Theory, BERKMAN KLEIN CTR.,

https://cyber.harvard.edu/copyrightforlibrarians/Introduction [https://perma.cc/N9RM-LLZF]

(last visited Aug. 7, 2023) (explaining how copyright law incentivizes people to continue

producing works that would serve as public goods).

92. Id.

424 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

property protections to incentivize them to create their works.

93

An

incentive-minded individual would think that a potential author might not

spend all the time and money required to write a book or make a movie

if others could freely make and sell copies.

94

Personality theory, on the other hand, views creative works as

personal manifestations of an author’s personhood.

95

Under personality

theory, authors have a continuing relationship and bond to their works

and should be able to prevent any unapproved changes.

96

With this frame

of mind, “[t]he originator of ideas should then be entitled to personal and

[sic] control over their reputation and dignity under the joint forces of law

and creativity. Essentially, an individual’s personality traits are further

‘materialized’ as visual or tangible creative property.”

97

Moral rights

derive from personality theory, including “an author’s rights to be

credited for her work, to protect the integrity of her work, to determine

when to publish a work, to demand that a work be returned, to be

protected from excessive criticism[,] and to collect a fee when a work is

resold.”

98

C. The Judiciary and Copyright Law

The Supreme Court has addressed many copyright-related questions,

opining that copyright law aims to “stimulate artistic creativity for the

general public good.”

99

In 1879, the Court set forth the “Idea/Expression

Dichotomy” principle in its Baker v. Selden ruling, which provided that

copyright only protected the expression of an idea rather than an idea

itself.

100

The sentiment translates to Section 102(b) of the Copyright Act,

which states, “[i]n no case does copyright protection for an original work

of authorship extend to any idea, procedure, process, system, method of

operation, concept, principle, or discovery, regardless of the form in

93. Id.

94. See id. (“To maximize social welfare, the government must somehow create an

incentive for the novelist to write novels.”).

95. Id.

96. See F

ROMER & SPRINGMAN, supra note 90, at 15 (“[B]ased on the view that ‘to achieve

proper self-development—to be a person—an individual needs some control over resources in the

external environment.’”) (citation omitted).

97. Lily Yuan, Personality Theory and Intellectual Property, P

ERSONALITY PSYCH. (Feb.

3, 2020), https://personality-psychology.com/personality-theory-intellectual-property/ [https://

perma.cc/66ZN-F6C7].

98. Jessica Meindertsa, Theories of Copyright, O

HIO STATE UNIV, (May 9, 2014),

https://library.osu.edu/site/copyright/2014/05/09/theories-of-copyright/ [https://perma.cc/Y3V9-

6DRA].

99. Twentieth Century Music Corp. v. Aiken, 422 U.S. 151, 156 (1975).

100. Baker v. Selden, 101 U.S. 99, 107 (1879).

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 425

which it is described, explained, illustrated, or embodied in such

work.”

101

The Court clarified that a copyright’s originality level requires

independent creation and a modicum of creativity because copyrights

intend to protect “the fruits of intellectual labor.”

102

This sentiment is

reflected in Section 102(a) of the Copyright Act, stating that the

protections are for “original works of authorship.”

103

The elements of

originality, notably, do not require novelty, just that the idea originated

with the author.

104

In Eldred v. Ashcroft, the Court upheld that the constitutional

authority of Congress to “prescribe the duration of copyrights” for a

“limited time” permitted enactment of the 1998 Copyright Term

Extension Act (CTEA), which extended the term of copyrights to “life

[of the author] plus 70 years” from the previous life plus fifty years

standard.

105

D. Copyright Termination

The termination of a transferred copyright, made pre-January 1, 1978,

is governed by Section 304 of the Copyright Act.

106

The section provides

that:

[T]he exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer or license

of the renewal copyright or any right under it . . . may be

effected at any time during a period of five years beginning

at the end of fifty-six years from the date copyright was

originally secured, or beginning on January 1, 1978,

whichever is later.

107

For more modern creations, the language governing the termination

of a transferred copyright made after January 1, 1978, is found in Section

203 of the Copyright Act.

108

Section 203 of the Copyright Act provides

that:

[T]he exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer or license

of copyright or of any right under a copyright, executed by

the author . . . [may be terminated] at any time during a

101. 17 U.S.C. § 102(b).

102. In re Trade-Mark Cases, 100 U.S. 82, 94 (1879).

103. 17 U.S.C. § 102(a).

104. Trade-Mark Cases, 100 U.S. at 94.

105. Eldred v. Ashcroft, 537 U.S. 186, 193–94 (2003).

106. 17 U.S.C. § 304(c).

107. Id. § 304(c)(3).

108. Id. § 203.

426 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

period of five years beginning at the end of thirty-five years

from the date of execution of the grant.

109

Essentially, authors who assign a copyright after 1978 can reclaim the

copyright, terminating the assignment after thirty-five years have passed

since assignment. Authors have a five-year window from assignment to

do this, meaning from thirty-five to forty years after assignment. Notice

of such termination shall be executed, in writing, “not less than two or

more than ten years before” the thirty-five-year mark,

110

meaning from

twenty-five to thirty-eight years after assignment. The USCO must have

a record of the copy of notice before the effective date of termination.

111

Termination rights are not alienable, as specified in Section 203(a)(5),

which says “[t]ermination of the grant may be effected notwithstanding

any agreement to the contrary, including an agreement to make a will or

to make any future grant.”

112

Congress created a termination right for copyright law intending to

protect creators against “unremunerative transfers . . . resulting in part

from the impossibility of determining a work’s value until it has been

exploited.”

113

The right of termination empowers recording artists and

songwriters to regain control of their works by renegotiating contracted

agreements or entering into entirely new agreements.

114

Such an

opportunity effectively gives creators a second chance at a better deal.

115

109. Id. § 203(a)(3).

110. Id. § 203(a)(4)(A).

111. Id.

112. 17 U.S.C. § 203(a)(5).

113. Ray Charles Found. v. Robinson, 795 F.3d 1109, 1112 (9th Cir. 2015) (citing H.R. R

EP.

NO. 94-1476, at 124 (1976)).

114. Kenneth Abdo et al., Termination of Music Copyright Transfers: The Renegotiation

Reality, ABA, https://www.americanbar.org/groups/intellectual_property_law/publications/

landslide/2018-19/november-december/termination-music-copyright-transfers/ [https://perma.cc

/5ARH-AQ3K].

115. Brittany L. Kaplan-Peterson, Copyright Termination: A Primer, CDAS

(Jan. 18, 2017),

https://cdas.com/copyright-termination-prime/ [https://perma.cc/CGG4-QARK].

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 427

IV. ARE YOU READY FOR IT?: MASTER RECORDING RIGHTS DURING

THE

AGE OF STREAMING SERVICES

“Is it romantic how all my elegies eulogize me?”

116

A. The Streaming Revolution

Revenue from sales of recorded music increased each year from 2015

to 2021.

117

This recent growth can be attributed to a number of things,

including a rise in piracy in the 2010s as consumers moved away from

physical record consumption and the resulting popularity of streaming

services for music consumption, like Spotify and Apple Music.

118

A comparison of the statistics of Taylor Swift’s studio album sales

reflects the popularization of streaming services. Swift’s 2006 debut

album, Taylor Swift, sold 39,000 hard copies in its first week.

119

The 2008

release, Fearless, sold 592,300 hard copies.

120

Released in 2010, Speak

Now sold 1.047 million copies.

121

The 2012 album, Red, sold 1.208

million copies.

122

Reputation sold around 1.2 million copies during its

first week in 2017, and Swift kept the album off streaming services upon

its release.

123

Lover saw 679,000 album sales and 226 million streams in

its first week in 2019.

124

Fearless (Taylor’s Version) brought 179,000

116. TAYLOR SWIFT, The Lakes, on FOLKLORE (DELUXE VERSION) (Republic Records 2020).

117. See Oscar Heanue, Streaming Services Are the Future of the Music Industry, but They’re

Leaving Musicians Behind, O

N LABOR (Jan. 25, 2022), https://onlabor.org/streaming-services-

are-the-future-of-the-music-industry-but-theyre-leaving-musicians-behind/ [https://perma.cc/2V

6Q-TLPA] (outlining the resurgence of revenues from recorded music sales following decades-

long lows in the early 2010s).

118. Id.; Katie Allen, Piracy Continues to Cripple Music Industry as Sales Fall 10%,

G

UARDIAN (Jan. 21, 2010), https://www.theguardian.com/business/2010/jan/21/music-industry-

piracy-hits-sales [https://perma.cc/C8R7-9PCD].

119. Chris Harris, Taylor Swift Scores First Chart-Topping Debut with Fearless, MTV (Nov.

19, 2008), https://www.mtv.com/news/1599721/taylor-swift-scores-first-chart-topping-debut-

with-fearless/ [https://perma.cc/Q2QT-VQH8].

120. Id.

121. Ben Sisario, Taylor Swift Album Is a Sales Triumph, N.Y.

TIMES (Nov. 3, 2010),

https://www.nytimes.com/2010/11/04/arts/music/04country.html? [https://perma.cc/EK6U-GW

6U].

122. Keith Caulfield, Taylor Swift’s ‘Red’ Sells 1.21 Million; Biggest Sales Week for an

Album Since 2002, B

ILLBOARD (Oct. 30, 2012), https://www.billboard.com/music/music-

news/taylor-swifts-red-sells-121-million-biggest-sales-week-for-an-album-since-2002-474400/

[https://perma.cc/4X8H-XT9R].

123. Andrew Flanagan & Sidney Madden, First-Week Sales of Taylor Swift’s ‘Reputation’

Vary Widely, Depending Who You Ask, NPR (Nov. 21, 2017), https://www.npr.org/sections/the

record/2017/11/21/565761702/first-week-sales-of-taylor-swifts-reputation-vary-widely-depend

ing-who-you-ask [https://perma.cc/NJD6-N482].

124. Brittany Hodak, Why Taylor Swift’s First-Week ‘Lover’ Sales Total Is a Big Deal,

F

ORBES (Sept. 1, 2019), https://www.forbes.com/sites/brittanyhodak/2019/09/01/why-taylor-

428 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

pure album sales and 142.98 million on-demand streams during its first

week in 2021.

125

Swift also released Red (Taylor’s Version) in 2021,

which sold 369,000 copies and racked up 303 million streams in its first

week.

126

Globally, streaming services accumulated $13.4 billion in revenue in

2020, most of which attributes to paid monthly or annual subscriptions.

127

Spotify operates using a “freemium” business model, characterized by

two different tiers of users; the first tier allows users to consume music

on Spotify at no cost with advertisements, and the second tier requires a

paid subscription for advertisement-free streaming.

128

Spotify generates

revenue from the advertisements viewed by first-tier users and

subscription payments made by second-tier users.

129

The number of subscribers to streaming services grew by 109.5

million in 2021.

130

The ever-expanding audience of streaming services

demands a catalog that grows accordingly. To keep up with the needs of

its consumers, Spotify sees a new track uploaded to its platform every 1.4

seconds, meaning Spotify adds roughly 60,000 new tracks every day.

131

An evolving understanding of the law that governs music copyright

should mirror this robust evolution of music consumption.

B. The New Value of Music

The shift in the method of music consumption has fundamentally

changed how music is valued. While in the past, album sales were the

leading indicator of a particular album’s success, the current metrics

swifts-first-week-lover-sales-total-is-a-big-deal/?sh=3f33264b749c [https://perma.cc/JQB5-6R

SZ].

125. chart data (@chartdata), TWITTER (Apr. 18, 2021, 4:06 PM), https://twitter.com/chart

data/status/1383874683397840899 [https://perma.cc/8GNM-RX73].

126. Sisario, supra note 64.

127. Heanue, supra note 117.

128. Premium, S

POTIFY, https://www.spotify.com/us/premium/ [https://perma.cc/9BTM-

KJK4] (last visited Feb. 27, 2023).

129. See E. Jordan Teague, Saving the Spotify Revolution: Recalibrating the Power

Imbalance in Digital Copyright, C

ASE W. RESERVE J.L. TECH. & INTERNET 207, 222 (2012)

(discussing Spotify’s revenue which is funded through advertising and subscriptions).

130. Chris Willman, Streaming Music Subscriptions Grew 26% in 2021, with YouTube

Music as Fastest Growing DSP in the West, Vᴀʀɪᴇᴛʏ (Jan. 18, 2022), https://variety.com/2022/

music/news/streaming-music-growth-worldwide-youtube-spotify-apple-1235156594/ [https://

perma.cc/A4JQ-2HXV].

131. Tim Ingham, Over 60,000 Tracks Are Now Uploaded to Spotify Every Day. That’s

Nearly One Per Second, Mᴜsɪᴄ Bᴜs. Wᴏʀʟᴅᴡɪᴅᴇ (Feb. 24, 2021), https://www.musicbusiness

worldwide.com/over-60000-tracks-are-now-uploaded-to-spotify-daily-thats-nearly-one-per-

second/ [https://perma.cc/B8TX-J44D].

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 429

emphasize repeat streams or downloads to popular playlists.

132

Today, a

stream counts only when the listener has consumed the track for at least

thirty seconds, regardless of the total time duration of the track.

133

This

tracking mechanism may disadvantage genres and creators with longer

works or works with longer introductions.

134

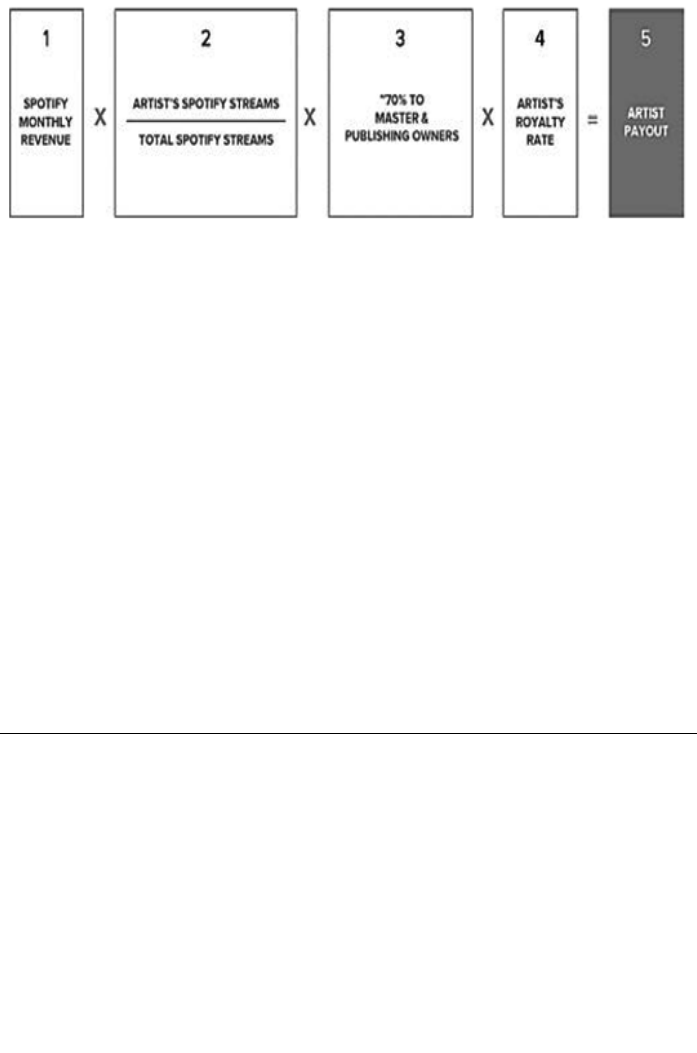

Spotify and Apple Music use a “pro rata” model for determining

monetary payout from their streaming services.

135

This model pays right-

holders according to market share—how their streams stack up against

the most popular songs in a given time period.

136

It follows, then, that the

most revenue is available for the stakeholders with the rights to the most

listened-to tracks.

137

Spotify’s Chief Economist, Will Page, notes that the

model, while perceived as “inherently objective and fair,” does not

account for “different user behaviors.”

138

While the model values each

stream in the same way, the model also provides a significant advantage

to the most popular music stars.

C. Legislative Reform

In response to the digital revolution of music, Congress has

considered over 120 proposed amendments to the Copyright Act

139

and

ultimately adopted the 1995 Digital Performance Rights in Sound

Recordings Act (DPRSRA), the 1998 Digital Millennium Copyright Act

(DMCA), and the 2018 Music Modernization Act (MMA).

The 104th Congress enacted the DPRSA as an amendment to Title 17,

the Copyright Act, that “provide[s] an exclusive right to perform sound

recordings publicly by means of digital transmissions.”

140

A great deal of

debate surrounded H.R. 2576 and S. 1421, the proposed bills from

Representatives Hughes and Berman and Senators Hatch and Feinstein,

132. David Curry, Music Streaming App Revenue and Usage Statistics (2023), BUS. OF APPS

(last updated Feb. 1, 2023), https://www.businessofapps.com/data/music-streaming-market/

[https://perma.cc/3P96-DA3Y].

133. Music Streaming and Its Impact on Composers & Songwriters, supra note 32.

134. Id.

135. Paula Mejía, The Success of Streaming Has Been Great for Some, but Is There a Better

Way?, NPR (July 22, 2019), https://www.npr.org/2019/07/22/743775196/the-success-of-

streaming-has-been-great-for-some-but-is-there-a-better-way [https://perma.cc/29AZ-VL2S].

136. Id.

137. Id.

138. Id.

139. See U.S. COPYRIGHT OFF., COPYRIGHT LEGISLATION: 109TH CONGRESS,

http://www.copyright.gov/legislation [https://perma.cc/R96L-LH9D] (listing proposed bills from

2005 to 2006); see also U.S. COPYRIGHT OFF., COPYRIGHT LEGISLATION: ARCHIVE,

http://www.copyright.gov/legislation/archive [https://perma.cc/PJ4H-PMWA] (listing proposed

bills from 1997 to 2004).

140. Digital Performance Right in Sound Recordings Act, H.R. 1506, 104th Cong. (1995).

430 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

respectively, that would later become the DPRSA.

141

In an effort to come

to an agreement, Representative Hughes hosted a roundtable with music

industry representatives for songwriters, performers, unions, performing

rights societies, music publishers, and record companies.

142

The roundtable of stakeholders drafted a consensus agreement that

prioritized the creation of “a compensation system for performance of

sounds recordings that are distributed by commercial subscription audio

services.”

143

The consensus agreement also included an exclusive right to

authorize digital performance by subscription services.

144

The DPRSRA

was formed after review of the consensus agreement, and it serves two

main purposes: to create a right to perform sound recordings publicly “by

means of a digital audio transmission”

145

and to confirm that certain

digital transmissions, known as digital phonorecord deliveries, implicate

copyrights in musical works and sound recordings and are subject to the

compulsory mechanical license.

146

Phonorecords, as defined by the

Copyright Act, are “material objects in which sounds, other than those

accompanying a motion picture or other audiovisual work, are fixed by

any method now known or later developed, and from which the sounds

can be perceived, reproduced, or otherwise communicated, either directly

or with the aid of a machine or device.”

147

President Clinton enacted the DCMA in 1998, which amended

existing copyright law to address the relationship between copyright and

the internet that was developing at the time.

148

The DMCA contained

three main updates, and most notably for music in the streaming age,

“encourage[d] copyright owners to give greater access to their works in

digital formats by providing them with legal protections against

unauthorized access to their works.”

149

In 2018, Congress signed the MMA into law in an attempt to overhaul

outdated legislation and address the modern needs of sound recording

141. Marybeth Peters, Digital Performance Right in Sound Recordings Act of 1995 (H.R.

1506), C

OPYRIGHT (June 28, 1995), https://www.copyright.gov/docs/regstat062895.html

[https://perma.cc/R7Z5-F5PM].

142. Id.

143. Id.

144. Id.

145. 17 U.S.C.A. § 106(6) (West Supp. 1996).

146. See id. § 115(1)(A) (“A person may by complying with the provisions of this section

obtain a compulsory license to make and distribute phonorecords of a nondramatic musical work,

including by means of digital phonorecord delivery.”).

147. 17 U.S.C. § 101.

148. The Digital Millennium Copyright Act, C

OPYRIGHT, https://www.copyright.gov/dmca/

[https://perma.cc/TU2R-EVJA].

149. Id.

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 431

rights.

150

The MMA addressed the impact of streaming services on

publishing royalties by creating a new collection society, the Mechanical

Licensing Collective, Inc. (MLC), which issues licenses to streaming

services, collects royalties from those services, and distributes those

royalties to artists.

151

The MLC also creates a public database that logs

information for musical works and their owners.

152

D. Judicial Interpretation

The shift to the use of streaming services has also prompted litigated

issues. In Yoakam v. Warner Music Group Corp., Warner Brothers

Records (WBR) removed Dwight Yoakam’s, a country artist’s, earliest

tracks, approaching the thirty-five-year termination benchmark, from

streaming services because they did not want to run the risk of

distributing music recordings they did not control.

153

In doing so,

Yoakam argued that WBR prevented him from earning on those tracks

because he could not partner with another label or distributor in the

meantime.

154

In his complaint, Yoakam contended that:

Every hour that Mr. Yoakam’s works are absent from the

marketplace, as a result of Mr. Yoakam’s inability to exploit

the works due to Defendants’ false ownership claim and

Defendants’ refusal to exploit Mr. Yoakam’s works, Mr.

Yoakam is financially damaged. Mr. Yoakam is unable to

earn royalties on these works, his fans are unable to listen to

these works, and his streaming count, a quantifier that

directly impacts the known value of a song, is detrimentally

impacted.

155

V. THESE THINGS WILL CHANGE: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR COPYRIGHT

TERMINATION REFORM

Holding musicians to copyright transfers, made at the conception of

their career, for decades until their statutory termination rights mature

does not advance the aim of copyright law in allowing “an author of a

150. What is the Music Modernization Act?, TUNECORE, https://support.tunecore.com/hc/en-

us/articles/360051524372-What-is-the-Music-Modernization-Act- [https://perma.cc/4YP3-DF

VU].

151. Id.; The Music Modernization Act, C

OPYRIGHT, https://www.copyright.gov/music-

modernization/ [https://perma.cc/8YDY-949T].

152. What is the Music Modernization Act?, supra note 150.

153. Second Amended Complaint & Demand for Jury Trial at 15, 92, Yoakam v. Warner

Music Grp. Corp., No. 2:21-cv-01165-SVW-MAA, 2021 WL 7907790 (C.D. Cal. July 26, 2021).

154. See id. at 17 (stating that the plaintiff was precluded from earning from his works

because WBR was essentially holding the works hostage).

155. Id. at 92.

432 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

work [to] reap the fruits of his or her intellectual creativity”;

156

especially

when the exercise of the termination rights as they exist is unduly

burdensome. Further, the payment schemes for streaming platforms like

Spotify have cheated creators and artists out of their fair share of

profits.

157

Termination rights were enacted to protect authors and their heirs

against unprofitable or inequitable agreements by allowing authors and

their heirs to share in the later economic success of their works.

158

The

rapid growth in popularity of streaming services has significantly

changed the way artists receive compensation for music consumption,

and their rights to terminate agreements entered pre-success should

change accordingly.

A. Termination Rights Are Too Complicated to Exercise

Attempting to exercise termination rights, as they currently exist,

often poses complications for musicians. The many eligibility and timing

requirements imposed by Section 203 create significant hurdles to

overcome.

159

These hurdles lead musicians to “lengthy and expensive

litigation” in pursuit of the rights to their own work.

160

A class action complaint, for example, filed in the Southern District

of New York, alleged that:

[W]hile the Copyright Act confers upon authors the valuable

“second chance” that they so often need, the authors of

sound recordings, in particular, who have attempted to avail

themselves of this important protection have encountered

not only resistance from many record labels, they have been

subjected to the stubborn and unfounded disregard of their

156. A Brief Introduction and History, U.S. COPYRIGHT OFF., https://www.copyright.gov/

circs/circ1a.html [https://perma.cc/F36X-HA9L]; see also Dylan Gilbert, It’s Time to Pull Back

the Curtain on the Termination Right, Pᴜʙ. Kɴᴏᴡʟᴇᴅɢᴇ (Dec. 5, 2019), https://publicknowledge.

org/its-time-to-pull-back-the-curtain-on-the-termination-right [https://perma.cc/ZE8U-QWKH]

(“Many artists enter into deals . . . [that] involve [them] granting or licensing the copyright in their

work to these business partners for lengthy periods of time; sometimes these transfers are legally

binding forever.”).

157. See Gabriela Tully Claymore, Spotify Explains Royalty Payments, S

TEREOGUM (Dec.

3, 2013), http://www.stereogum.com/1587932/spotify-explains-royalty-payments/news/ [https://

perma.cc/LUD9-LMQK] (explaining how Spotify distributes royalties and why some artists are

upset with this process).

158. See Gilbert, supra note 156 (“[T]he termination right offered artists and their heirs a fair

shot at ending unfair contracts by reclaiming their rights.”).

159. See generally 17 U.S.C. § 203 (detailing the conditions and effects of an author’s

termination of transfers and licenses).

160. Gilbert, supra note 156.

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 433

rights under the law and, in many instances, willful

copyright infringement.

161

The notice element required for termination under Section 203, in

particular, has prompted litigation. In Yoakam v. Warner Music Group

Corp., Dwight Yoakam (Yoakam), a successful country music singer and

songwriter, served notice of termination for several singles on his record

label, WBR, exactly thirty-five years from the date of the work’s

publication.

162

The notice was served on February 5, 2019, which proved

problematic as the earliest eligible date for termination service for the

notice mistakenly listed the singles provided by Yoakam as January 31,

2021.

163

Because Section 203(a)(4)(A) of the Copyright Act requires a

two-year minimum notice period, the service fell five days short

according to Yoakam’s own listed “effective date of termination”

provided in the notice.

164

Yoakam alleged that the error in listing the

effective termination date was “inconsequential and harmless” under the

harmless error doctrine in 37 C.F.R. § 201.10(e) as he intended effective

termination to be the correct date of February 5, 2021.

165

The District

Court for the Central District of California ultimately applied the

harmless error doctrine to the issue and excused Plaintiff’s error in

communicating the effective date in the notice of termination.

166

Artists have also encountered disputes over ambiguity in the meaning

of “work for hire” in the music industry context.

167

In Johansen v. Sony

Music Entertainment Inc., plaintiff David Johansen (Johansen) released

five albums with Sony Music Entertainment Inc. (Sony) after entering a

recording agreement on or about 1978.

168

Johansen served a notice of

termination to Sony on June 15, 2015, and two years later, on June 14,

2017, Sony sent a letter of refusal to Johansen.

169

The letter cited that:

161. Class Action First Amended Complaint & Demand for Trial by Jury at 3, Waite v. UMG

Recordings, Inc., 450 F. Supp. 3d 430 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 27, 2023) (No. 19-CV-01091 (LAK)).

162. Yoakam v. Warner Music Grp. Corp., No. 2:21-cv-01165-SVW-MAA, 2021 WL

3774225, at *1–2 (C.D. Cal. July 12, 2021).

163. Id. at *2.

164. Id.

165. Id.

166. Id. at *3.

167. See generally Kyle Jahner, Musicians Attack Sony’s Refusal of Copyright Termination

Rights (1), B

LOOMBERG L. (Feb. 6, 2019), https://news.bloomberglaw.com/ip-law/musicians-attack

-sonys-refusal-of-copyright-termination-rights-1 [https://perma.cc/72YS-5SU8] (summarizing

the class action dispute between musicians and Sony Music Entertainment Inc. for declaratory

judgment and copyright infringement).

168. Johansen v. Sony Music Ent. Inc., No. 1:19-cv-01094 (ER), 2020 WL 1529442, at *1

(S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2020).

169. Id.

434 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

(a) “the Works are works made for hire,” and thus not subject

to termination; (b) “the [n]otice does not adequately identify

the specific grant David Johansen seeks to terminate, as the

[n]otice broadly makes reference to all grants or transfers of

copyright in and to certain sound recordings ‘including,

without limitation to the grant dated in or about 1984

between the recording artist David Johansen and Blue Sky

Records/CBS, Inc.’”; (c) Sony is unaware of any grant made

in 1984, and “to the extent that any grant was made,” the

grant was made before 1978 and thus 17 U.S.C. § 203 does

not apply; and (d) to the extent there was a grant in 1984,

termination could not be effected before 2019.

170

In his demand for trial by jury, Johansen argued that the term “work

for hire” could not encompass sound recordings, citing the defined terms

of Section 101 of the Copyright Act.

171

If an artist were deemed an

employee of the music publisher, all of the rights to the work created by

the artist would be under the ownership of the employer.

172

The definition

in Section 101, according to Johansen, did not include sound recordings

as being one of the types of works that can be made for hire.

173

The

section instead defines “work made for hire” as work either:

(1) a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his

or her employment; or (2) a work specially ordered or

commissioned for use as a contribution to a collective work,

as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, as a

translation, as a supplementary work, as a compilation, as

an instructional text, as a test, as answer material for a test,

or as an atlas, if the parties expressly agree in a written

instrument signed by them that the work shall be considered

a work made for hire.

174

Music publishers have, however, argued that because Section 101 lists

compilations as one of the categories, music albums qualify

accordingly.

175

Section 101 defines a “compilation” as “a work formed

by the collection and assembling of preexisting materials or of data that

170. Id.

171. First Amended Class Action Complaint & Demand for Trial by Jury at 23(A), Johansen

v. Sony Music Ent. Inc., No. 1:19-cv-01094 (ER), 2020 WL 1529442 (S.D.N.Y. Mar. 31, 2020).

172. Jeanne Hamburg, The Real-Life Consequences of Copyright Termination, N

AT’L L.

REV. (Nov. 1, 2021), https://www.natlawreview.com/article/real-life-consequences-copyright-

termination [https://perma.cc/7J8N-A54K].

173. First Amended Class Action Complaint & Demand for Trial by Jury at 23(A), Johansen,

2020 WL 1529442.

174. 17 U.S.C. § 101.

175. Jahner, supra note 167.

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 435

are selected, coordinated, or arranged in such a way that the resulting

work as a whole constitutes an original work of authorship.”

176

The statute of limitations has also been a litigated dispute related to

copyright termination rights. In Scorpio Music (Black Scorpio) S.A. v.

Willis, Victor Willis (Willis), the lead singer of the Village People, was

challenged by his music publisher, Scorpio Music S.A. (Scorpio), after

serving Scorpio with a Notice of Termination in January of 2011 of post-

1977 grants of copyright on some of Willis’s works.

177

One of the issues that Scorpio alleged in their complaint was that

Willis’s claim to the copyright in the compositions was somehow time-

barred by the statute of limitations.

178

Nevertheless, the District Court for

the Southern District of California rejected this argument because

Scorpio failed to explain why Willis should have been time-barred from

asserting his rights under the law.

179

Contributing to the financial burden of copyright litigation, the

Supreme Court has interpreted the phrase “full costs” as it appears in

Section 505 of the Copyright Act expansively.

180

The section reads:

In any civil action under this title, the court in its discretion

may allow the recovery of full costs by or against any party

other than the United States or an officer thereof. Except as

otherwise provided by this title, the court may also award a

reasonable attorney’s fee to the prevailing party as part of

the costs.

181

In Rimini Street, Inc. v. Oracle USA, Inc., the Supreme Court found

that the best interpretation “[was] that the term ‘full costs’ meant in 1831

what it mean[t] now: the full amount of the costs specified by the

applicable costs schedule.”

182

This interpretation means that “copyright

cases will [be] longer and be more expensive to litigate” and that “it will

be more difficult for victorious litigants to recover their non-increased

costs.”

183

176. 17 U.S.C. § 101.

177. Scorpio Music (Black Scorpio) S.A. v. Willis, No. 11cv1557 BTM(RBB), 2013

WL790940 at *1 (S.D. Cal. Mar. 4, 2013).

178. Id. at *2.

179. Id. at *4.

180. See Rimini St., Inc. v. Oracle USA, Inc., 139 S. Ct. 873, 879 (2019) (holding that “full

costs” are all costs generally available under the federal costs statutes).

181. 17 U.S.C. § 505.

182. Rimini, 139 S. Ct. at 880.

183. Scott Alan Burroughs, Copyright Litigation: Now More Expensive and with More Delay

than Ever Before!, A

BOVE THE LAW (Mar. 13, 2019), https://abovethelaw.com/2019/03/copyright-

litigation-now-more-expensive-and-with-more-delay-than-ever-before/ [https://perma.cc/AM8M

-N6H4].

436 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

Another noteworthy ownership battle, similar to Swift’s, took place

between Prince and WBR, who released Prince’s first eighteen albums.

184

In 1993, in an act of defiance against WBR, as Prince began to feel he

was losing artistic control over his work, Prince changed his name “in

order to signal a fundamental severance from an identity he saw as a

wholly owned commodity of Warner.”

185

The name change ultimately

failed to make Prince’s contracts unenforceable, but Prince nevertheless

continued his very public campaign against WBR.

186

Prince especially

emphasized the power dynamics implicating his “freedom and his own

artistic agency” as a black man in a recording contract with white

executives.

187

Prince wrote “Slave” on his face in protest of his WBR

contract and is quoted to have said “[i]f you don’t own your masters, your

master owns you.”

188

In 2019, a class action suit was filed on behalf of music artists and

their estates against Universal Music Group (UMG), seeking $100

million for damages from the destruction of masters in the 2008 fire on

the Universal Studios lot.

189

This fire is often referred to as “the biggest

disaster in the history of the music business” because an estimated several

thousand master recordings burned.

190

Many master recordings of

unreleased material and outtakes were completely lost.

191

The Plaintiffs

proffered that UMG attempted to minimize their error by “concealing the

loss with false public statements.”

192

UMG defended with the notion that because the label had full

ownership over the master recordings, it had no obligation to split any of

the insurance proceeds gained from the fire with the artists whose music

184. Chris Eggertsen, What Are Masters and Why Do Taylor Swift & Other Artists Keep

Fighting for Them?, BILLBOARD (July 3, 2019), https://www.billboard.com/articles/business/

8518722/taylor-swift-masters-artists-ownership-labels-rights-prince [https://perma.cc/N6Y9-VL

KH].

185. Id.; August Brown, What Today’s Artists Learned from Prince’s Approach to the

Industry, L.A.

TIMES (Apr. 22, 2016), https://www.latimes.com/entertainment/music/posts/la-et-

ms-prince-imaginative-legacy-music-business-20160422-story.html.

186. See Eggersten, supra note 184 (“Once it became clear that his ploy wouldn’t work, the

singer-songwriter began appearing in public with the word “slave” written on his cheek.”).

187. Brown, supra note 185.

188. Eggersten, supra note 184; Kory Grow, Prince Releasing Two New Albums this Fall,

CNN (Aug. 26, 2014), https://www.cnn.com/2014/08/26/showbiz/music/prince-new-album-

rs/index.html [https://perma.cc/Y3UL-YKMM].

189. Soundgarden v. UMG Recordings, Inc., No. LA CV19-05449 JAK (JPRx), 2019 WL

10093965 (C.D. Cal. Dec. 2, 2019)

190. Jody Rosen, The Day the Music Burned, N.Y. TIMES MAG. (June 11, 2019),

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/11/magazine/universal-fire-master-recordings.html [https://

perma.cc/AF86-ZJDC].

191. Id.

192. Soundgarden, 2019 WL 10093965, at *4.

2023] YOU BELONG WITH ME 437

the fire destroyed.

193

UMG also argued that it did not breach their

contracts with artists under an alleged bailment agreement, as UMG was

not “bound to return the identical thing deposited.”

194

UMG maintained

a position that ownership of the masters provides full control over the

masters and the ability to do anything with the recordings, even destroy

them as UMG was under no “obligation to return the master

recordings.”

195

This position ultimately undermines the fact that artists

can terminate the transfer rights bestowed upon the creator of the content

after thirty-five years, as provided by the Copyright Act.

196

B. Artists Are Unfairly Compensated and Unable to Reap the Fruits of

Their Intellectual Creativity

Many aspiring artists wield much power to the will of one of the three

major American record labels: Universal Music Group, Warner Music

Group, and Sony Music Entertainment.

197

These three powerhouses made

up 62.4% of global music revenue in 2016.

198

The bargaining power

record labels have over artists at the start of their careers may rise to the

level of undue influence.

Undue influence occurs “when a fiduciary or confidential relationship

exists in which one person substitutes his own will for that of the

influenced person’s will.”

199

Undue influence typically takes place

behind closed doors with no witnesses.

200

Major record labels wield

immense power over the artists they are recruiting to sign because the

labels have the resources and expertise to bring an artist’s creative dreams

to fruition; contracting with one of these major labels increases the

193. See Defendant UMG Recordings, Inc.’s Memorandum of Points and Authorities in

Support of its Motion to Dismiss Plaintiffs’ Class Action Complaint at 2, Soundgarden, 2019 WL

10093965 (“[N]othing in the underlying contracts at issue (or Plaintiffs’ broad-brush

generalizations thereof) even remotely entitles Plaintiffs to any such proceeds.”).

194. Id.

195. Id. at 16.

196. 17 U.S.C. § 203.

197. See Paul Resnikoff, Two-Thirds of All Music Sold Comes from Just 3 Companies, D

IGIT.

MUSIC NEWS (Aug. 3, 2016), https://www.digitalmusicnews.com/2016/08/03/two-thirds-music-

sales-come-three-major-labels/ [https://perma.cc/T9ZK-CP7S] (“The three major labels—Sony

Music Entertainment, Warner Music Group, and Universal Music Group—are currently enjoying

a surge in streaming revenues from companies like Spotify and Apple Music.”).

198. Id.

199. Mary Joy Quinn, Defining Undue Influence, ABA (Feb. 1, 2014),

https://www.americanbar.org/groups/law_aging/publications/bifocal/vol_35/issue_3_feb2014/de

fining_undue_influence/ [https://perma.cc/NC69-8YP4].

200. Id.

438 UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA JOURNAL OF LAW & PUBLIC POLICY [Vol. 33

chances that an artist will become successful by helping them achieve

creative and commercial success and building a long-term career.

201

The three major record labels received partial ownership in Spotify in