The Professional Counselor

From the National Board for Certied Counselors, Inc. and Aliates

Volume 5, Issue 2

The refereed,

online, open-source

journal promong

scholarship and

academic inquiry

within the profession of

counseling

Special Issue: Counseling Children With Special Needs and Circumstances

National Board for Certied Counselors

3 Terrace Way

Greensboro, NC 27403-3660

Susan A. Adams

Walter P. Anderson, Jr.

Janine M. Bernard

Kathleen Brown-Rice

Matthew R. Buckley

Rebekah Byrd

Keith A. Cates

Rebecca G. Cowan

Jamie Crockett

Stephanie Crockett

Joel F. Diambra

Peggy A. Dupey

Judith C. Durham

Mark Eades

Bradley T. Erford

Syntia Santos Figueroa

Courtney E. Gasser

Edwin R. Gerler, Jr.

Gary G. Gintner

Samuel T. Gladding

Barry Glick

Yuh-Jen Martin Guo

W. Bryce Hagedorn

Lynn K. Hall

George E. Harrington

Stephen Hebard

Tanya Johnson

Laura K. Jones

Joseph P. Jordan

Michael Alan Keim

Budd L. Kendrick

Branis Knezevic

Joel A. Lane

Jeffrey S. Lawley

Sonya Lorelle

Amie A. Manis

Mary-Catherine McClain

Matthew J. Mims

Keith Morgen

Adele Logan O’Keefe

Jay Ostrowski

Fidan Korkut Owen

Richard L. Percy

J. Dwaine Phifer

Verl T. Pope

Theodore P. Remley, Jr.

James P. Sampson, Jr.

Stephen R. Sharp

Ann K. Thomas

Alwin E. Wagener

Jeffrey M. Warren

Editorial Staff

Thomas W. Clawson, Publisher

J. Scott Hinkle, Editor

Traci P. Collins, Managing Editor

Verl T. Pope, Associate Editor

Michelle Gross, Associate Editor

Carie McElveen, Editorial Assistant

Jay Ostrowski, Technical Editor

About

The Professional Counselor

The Professional Counselor

(TPC) is the ofcial, peer-

reviewed, open-access

electronic journal of the

National Board for Certied

Counselors, Inc. and Afliates

(NBCC), dedicated to

research and commentary

on empirical and theoretical

topics relevant to professional

counseling and related areas.

TPC publishes original

manuscripts relating to the

following topics: mental and

behavioral health counseling;

school counseling; career

counseling; couple, marriage

and family counseling;

counseling supervision;

theory development;

ethical issues; international

counseling issues; program

applications; and integrative

reviews of counseling and

related elds. The intended

audience for TPC includes

National Certied Counselors,

counselor educators, mental

health practitioners, graduate

students, researchers,

supervisors, human services

professionals and the general

public.

Editorial Board 2015

The Professional Counselor

© 2015 NBCC, Inc. and Afliates

Volume 5, Issue 1

Table of Contents

Volume 5, Issue 2

Table of Contents

195

Children With Special Needs and Circumstances: Conceptualization Through a

Complex Trauma Lens

Edward Franc Hudspeth

200

Addressing the Needs of Students Experiencing Homelessness: School Counselor

Preparation

Stacey Havlik, Julia Bryan

217

The School Counselor and Special Education: Aligning Training With Practice

Jennifer Geddes Hall

225

Trauma and Treatment in Early Childhood: A Review of the Historical and

Emerging Literature for Counselors

Kristen E. Buss, Jeffrey M. Warren, Evette Horton

238

All Foreign-Born Adoptees Are Not the Same: What Counselors and Parents Need

to Know

Yanhong Liu, Richard J. Hazler

248

Parent–Child Interaction Therapy for Children With Special Needs

Carl Sheperis, Donna Sheperis, Alex Monceaux, R. J. Davis, Belinda Lopez

261

Advancements in Addressing Children’s Fears: A Review and Recommendations

Monica Leppma, Judit Szente, Matthew J. Brosch

273

Professional Counseling for Children With Sensory Processing Disorder

Emily Goodman-Scott, Simone F. Lambert

293

Counseling Children With Cystic Fibrosis: Recommendations for Practice and

Counselor Self-Care

Cassandra A. Storlie, Eric R. Baltrinic

304

Because “Mama” Said So: A Counselor–Parent Commentary on Counseling

Children With Disabilities

Sherry Richmond-Frank

Special Issue: Counseling Children With Special Needs and Circumstances

Guest Editor: Edward Franc Hudspeth, NCC

195

The Professional Counselor

Volume 5, Issue 2, Pages 195–199

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

© 2015 NBCC, Inc. and Affiliates

doi:10.15241/efh.5.2.195

Edward Franc Hudspeth, NCC, is an Assistant Professor of Counselor Education at Henderson State University and served as the guest

editor for the special issue of The Professional Counselor on children with special needs and circumstances. Correspondence can

be addressed to Edward Franc Hudspeth, Department of Counselor Education, Henderson State University, 1100 Henderson Street,

Arkadelphia, AR 71999, [email protected].

Edward Franc Hudspeth

Children With Special Needs and

Circumstances: Conceptualization

Through a Complex Trauma Lens

When conceptualizing this special issue, we had a basic idea of what might be included; however, as submissions

arrived, it was evident that our basic denition of special needs was limited and could include much more when

broadened. Therefore, the issue was reconceptualized as “Children with Special Needs and Circumstances.” It is

my hope that when practitioners, researchers and faculty read this issue, each begins to see that the term special

needs encompasses more than we think, because anything that hinders the optimal growth and development of a

child constitutes a special need. In this issue, readers will nd articles concerning fears, trauma, sensory processing

disorder, foreign adoption, cystic brosis, spina bida, homelessness, special education and parent–child interaction

therapy.

Keywords: counseling, children, special needs, complex trauma

To set the stage for this special issue, to provide a foundation for understanding and to link the various

articles, I encourage readers to conceptualize the impact of a special need through a complex trauma or

developmental lens. Over the past 15 years, countless articles have reported and described the impact of

chronic stress and adverse childhood experiences (Anda et al., 2006; Edwards et al., 2005) and the subsequent

development of complex trauma.

Complex and Developmental Trauma

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (n.d.-a) has dened complex trauma as a series of traumatic

experiences that are usually interpersonal in nature and lead to numerous long-term adverse effects on health

and well-being. Similarly, van der Kolk, Roth, Pelcovitz, Sunday and Spinazzola (2005) described experiencing

repeated traumatic events during childhood as developmental trauma. The duration and intensity of the

traumatic experiences, as well as the age of onset of these experiences, can determine the outcome of both

complex trauma and developmental trauma. Neuroscience research provides ample evidence of neurochemical

and brain structural changes caused by complex trauma that result in affective and behavioral dysregulation

(Lanius, Bluhm, & Frewen, 2011).

Though the terms developmental trauma and complex trauma were originally used to represent repeated

abuse or an accumulation of traumatic experiences, recent neuroscience research has extended these terms

to other conditions and experiences. Copeland, Keeler, Angold, and Costello (2007) noted that a long-term

physical illness may lead to complex trauma, while D’Andrea, Ford, Stolbach, Spinazzola, and van der Kolk

(2012) and Finkelhor, Ormrod, and Turner (2007) reported that bullying also may lead to similar outcomes.

196

Courtois (n.d.), as well as Ford and Courtois (2009), Vogt, King, and King (2007), and the National Child

Traumatic Stress Network (n.d.-b), offered a more descriptive explanation and extensive list when they stated

the following:

Cumulative adversities faced by many persons, communities, ethno-cultural, religious, political, and

sexual minority groups, and societies around the globe can also constitute forms of complex trauma.

Some occur over the life course beginning in childhood and have some of the same developmental

impacts described above. Others, occurring later in life, are often traumatic or potentially traumatic and

can worsen the impact of early life complex trauma and cause the development of complex traumatic

stress reactions. These adversities can include but are not limited to:

• Poverty and ongoing economic challenge and lack of essentials or other resources

• Community violence and the inability to escape/relocate

• Homelessness

• Disenfranchised ethno-racial, religious, and/or sexual minority status and repercussions

• Incarceration and residential placement and ongoing threat and assault

• Ongoing sexual and physical re-victimization and re-traumatization in the family or other contexts,

including prostitution and sexual slavery

• Human rights violations including political repression, genocide/“ethnic cleansing,” and torture

• Displacement, refugee status, and relocation

• War and combat involvement or exposure

• Developmental, intellectual, physical health, mental health/psychiatric, and age-related limitations,

impairments, and challenges

• Exposure to death, dying, and the grotesque in emergency response work (para. 7)

Cook et al. (2005) stated that as a result of complex trauma, individuals experience impairments in (a)

attachment, (b) affect regulation, (c) behavioral control, (d) cognition, (e) self-concept, and (f) sensory and

motor development. Treatment recommendations include (a) being developmentally sensitive, (b) building on

the safety and security of caregivers and community (e.g., teachers), and (c) addressing affective and behavioral

dysregulation.

Special Issue: Children with Special Needs and Circumstances

The articles in this special issue provide implications for counselors and ways that specic special needs and

circumstances may be addressed with individuals, families, schools and communities.

In order to support the educational and emotional development of children and youth experiencing

homelessness, Havlik and Bryan indicate that school counselors must rst identify which students are

experiencing homelessness in their school and then determine their specic needs. Some of these needs, to name

a few, include violence, abuse, neglect, mental and physical health issues, and mobility issues. The authors

note that once homeless children and their individual needs are identied, school counselors should engage the

students within their schools and assist with collaborative efforts between school and community resources.

Havlik and Bryan challenge schools counselors to seek out and participate in professional development

regarding the policies related to individual needs of homeless students.

Geddes Hall states that less than half of school counselor preparation programs include content related

to special education in their training. Geddes Hall encourages school counselors to have a comprehensive

knowledge of the specic needs of those receiving special education services, and she offers precise

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

197

recommendations for how counselor educators can infuse special education content throughout a school

counseling curriculum. She reects that it is in the best interest of future school counselors, as well as the special

students they will serve, to receive support and supervision during such experiences as they complete their

programs.

Buss, Warren, and Horton provide in-depth coverage of the short- and long-term impact of trauma on the

physical, mental, emotional and social development of traumatized children that includes associated trajectories

to adult mental and physical health conditions. The authors indicate that early intervention and treatment can

minimize the social and emotional impact of a child’s exposure to a traumatic event. The authors also discuss the

advantages of numerous evidence-based treatment strategies as well as the realistic limitations of these strategies.

Across treatment methods, factors such as safety and attachment are paramount.

Liu and Hazler delineate differences noted among adoptees from various countries. These differences include

behavioral, social and emotional characteristics, as well as the adoptees’ proclivity to form an attachment with

a primary caregiver. The authors demonstrate that pre-adoption characteristics are associated with smooth

transitions during the adoption process as well as post-adoption integration. Liu and Hazler discuss ways that

counselors may emphasize adoptee–parent relationships in which trust is a fundamental element. They provide

specic recommendations for counselors and adoptive parents that ease the transition and support successful

attachment.

Sheperis and colleagues acknowledge that counselors, whether working with children who have disruptive

behavior or providing parenting training to families, should be knowledgeable of the application of various

behavioral techniques in order to utilize them effectively and to teach them to parents. In their article, the authors

review a wealth of research information related to one evidence-based method and demonstrate how this method

may be useful when working with children with special needs. Sheperis and colleagues describe a session-

by-session application of this model as well as report contemporary research about the model’s application to

working with children with special needs.

Leppma, Szente, and Brosch provide an overview of the current landscape of children’s fears to help delineate

a contemporary, adaptive and holistic approach to treatment. The authors convey an image of fear and anxiety

development that can be physically and mentally paralyzing for individuals who experience these states. In their

treatment section, the authors outline an approach that addresses affect regulation and development of positive

emotions, as well as inoculating the client against stress and supporting the development of resilience. They

report on several studies that demonstrate the value of play in the development of self-efcacy, optimism and

positive affect.

Despite the fact that few within the world of counseling have written about the subject, Goodman-Scott and

Lambert pull together many resources to conceptualize the special needs of children with sensory processing

disorder (SPD). The authors provide a detailed description of the disorder and its subtypes and describe in detail

appropriate assessment of the disorder. Goodman-Scott and Lambert recommend that counselors collaborate with

occupational therapists in order to address the unique needs of children with SPD. They report that counselors

can provide individual, group and family counseling modalities using solution-focused and cognitive-behavioral

techniques to address children’s mental health needs and co-occurring disorders.

Storlie and Baltrinic’s article illuminates the impact of a chronic disease on the individual, the caregivers and

the counselors working with the family. They indicate that counselors working with children and families affected

by cystic brosis (CF) should consider the physical and psychosocial challenges facing this special-needs

population. The authors encourage counselors to be knowledgeable about CF so that they will be sensitive to the

198

traumatic impact of this life-shortening disease on the child or adolescent with CF and caregivers. Storlie and

Baltrinic offer suggestions for compassionate counseling as well as for avoiding compassion fatigue.

In a personal account of rearing a child with spina bida, Richmond-Frank expresses both the successes

and shortcomings that she has experienced over nearly 3 decades. The author provides a thorough account of

her experience as a parent of a child with special needs, as well as what she has to teach others who may be

working with a child with special needs. As a professional counselor, as well as a parent of a special-needs

child, Richmond-Frank provides readers with specic and realistic suggestions. She shares that a systemic,

strengths-based counseling model respects the inherent worth of the child with a disability by not presuming

that he or she is the identied patient.

Conclusion

From the special issue editor’s point of view, issues that are prolonged, intense and cumulative, and

vary over developmental periods should be conceptualized through lenses that address the complexity of

intermingled systems. By failing to see this complexity and all of its aspects, we fail to fully address the

complexity of children with special needs and circumstances.

Conict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The author reported no conict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

Anda, R. F., Felitti, V. J., Walker, J., Whiteld, C. L., Bremner, J. D., Perry, B. D., . . . Giles, W. H. (2006). The enduring

effects of abuse and related adverse experiences in childhood: A convergence of evidence from neurobiology and

epidemiology. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 256, 174–186. doi:10.1007/s00406-

005-06244

Cook, A., Spinazzola, J., Ford, J., Lanktree, C., Blaustein, M., Cloitre, M., . . . van der Kolk, B. (2005). Complex trauma

in children and adolescents. Psychiatric Annals, 35, 390–398.

Copeland, W., Keeler, G., Angold, A., & Costello, J. (2007). Traumatic events and posttraumatic stress in childhood.

Archives of General Psychiatry, 64, 577–584.

Courtois, C. A. (n.d.). Understanding complex trauma, complex reactions, and treatment approaches. Retrieved from

http://www.giftfromwithin.org/html/cptsd-understanding-treatment.html

D’Andrea, W. D., Ford, J., Stolbach, B., Spinazzola, J., & van der Kolk, B. A. (2012). Understanding interpersonal trauma

in children: Why we need a developmentally appropriate trauma diagnosis. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry,

82, 187–200. doi:10.1111/j.1939-0025.2012.01154.x

Edwards, V. J., Anda, R. F., Dube, S. R., Dong, M., Chapman, D. F., & Felitti, V. J. (2005). The wide-ranging health

consequences of adverse childhood experiences. In K. A. Kendall-Tackett & S. M. Giacomoni (Eds.), Child

victimization: Maltreatment, bullying, and dating violence prevention and intervention (pp. 8-1–8-12). Kingston,

NJ: Civic Research Institute.

Finkelhor, D., Ormrod, R. K., & Turner, H. A. (2007). Poly-victimization: A neglect component in child victimization.

Child Abuse and Neglect, 31, 7–26. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.06.008

Ford, J. D., & Courtois, C. A. (2009). Dening and understanding complex trauma and complex traumatic stress

disorders. In C. A. Courtois & J. D. Ford (Eds.), Treating complex traumatic stress disorders: An evidence-based

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

199

guide (pp.13–30). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Lanius, R. A., Bluhm, R. L., & Frewen, P. A. (2011). How understanding the neurobiology of complex post-traumatic

stress disorder can inform clinical practice. A social cognitive and affective neuroscience approach. Acta

Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 124, 331–348. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01755.x

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.-a). Complex trauma. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/trauma-

types/complex-trauma

The National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (n.d.-b). Types of traumatic stress. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/

trauma-types#q2

van der Kolk, B. A., Roth, S., Pelcovitz, D., Sunday, S., & Spinazzola, J. (2005). Disorders of extreme stress: The

empirical foundation of a complex adaptation to trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 18, 389–399.

Vogt, D. S., King, D. W., & King, L. A. (2007). Risk pathways for PTSD: Making sense of the literature. In M. J.

Friedman, T. M. Keane, & P. A. Resick (Eds.), Handbook of PTSD: Science and practice (pp. 99–115). New York,

NY: Guilford Press.

200

Stacey Havlik is an Assistant Professor at Villanova University. Julia Bryan is an Assistant Professor at Pennsylvania State

University. Correspondence can be addressed to Stacey Havlik, 800 East Lancaster Avenue SAC 356, Villanova, PA 19085,

stacey[email protected].

Stacey Havlik

Julia Bryan

Addressing the Needs of Students Experiencing

Homelessness: School Counselor Preparation

This study of 207 school counselors revealed signicant relationships between types of counselors’ training, number

of students in counselors’ schools experiencing homelessness, and counselors’ perceived knowledge and provision

of services regarding students experiencing homelessness. In-service training and professional development, but

not graduate training, were related to counselors’ knowledge of the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act

and their advocacy for and provision of services to students experiencing homelessness. Differences also existed by

school level and school setting. Implications of these ndings are discussed.

Keywords: school counselors, homelessness, McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act, advocacy, professional

development

Homeless, although a difcult term to clearly dene, refers to those who “lack a xed, regular, and adequate

nighttime residence” (U.S. Department of Education, 2004, p. 2). Families with children are the fastest

growing homeless population in the United States, comprising one third of the homeless population (National

Coalition for the Homeless, 2009). Twenty-two percent of all sheltered persons experiencing homelessness are

under the age of 18, with over half of this group under the age of 6 (U.S. Department of Housing and Urban

Development, 2010). Some live doubled-up with other families, in transitional housing such as shelters or

in inhumane conditions (U.S. Department of Education, 2004). In 2012, the National Center for Homeless

Education (NCHE) reported that 1,065,794 children in schools experienced homelessness, an increase of

over 50% since 2007. The rapidly increasing gures, due in part to the economic recession in the United

States, are cause for grave concern because homelessness is detrimental to the emotional, social and cognitive

development and well-being of children (Coker et al., 2009; Grothaus, Lorelle, Anderson, & Knight, 2011).

Families who experience homelessness are more likely to experience separation from each other, violence

and serious health conditions (National Center on Family Homelessness, 2011). Children experiencing

homelessness may face high rates of abuse, neglect and mental health issues, as well as barriers that make it

nearly impossible for them to succeed academically and emotionally without additional systemic supports

(Buckner, Bassuk, Weinreb, & Brooks, 1999; Gewirtz, Hart-Shegos, & Medhanie, 2008; Swick, 2008;

U.S. Department of Education, 2004). Due to the challenges of homelessness, students can be worse off

academically and socially than their middle-class peers (Obradović et al., 2009; Shinn et al., 2008). Unlike

most of their peers, they may lack supports such as before- and after-school services, mentors, transportation

to and from school, and attendance support (Hicks-Coolick, Burnside-Eaton, & Peters, 2003; Miller, 2009;

U.S. Department of Education, 2004). Higher levels of mobility and absenteeism make it difcult for homeless

students to acquire a consistent education (Hicks-Coolick et al., 2003; Miller, 2009; Rafferty, Shinn, &

Weitzman, 2004; U.S. Department of Education, 2004). Students experiencing homelessness, and those who

The Professional Counselor

Volume 5, Issue 2, Pages 200–216

http://tpcjournal.nbcc.org

© 2015 NBCC, Inc. and Affiliates

doi:10.15241/sh.5.2.200

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

201

are highly mobile, have lower reading and math scores from second through seventh grade than students living

in poverty (Obradović et al., 2009). Further, relative to their peers, students experiencing homelessness are less

likely to aspire to postsecondary education (Rafferty et al., 2004).

In response to the growing crisis among children experiencing homelessness, policymakers designed

the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act (U.S. Department of Education, 2004) to provide access to

education and remove barriers in order to ensure that schools address the unique needs of students experiencing

homelessness. The provisions of the act require that school districts provide transportation to and from the

school of origin for students experiencing homelessness, even when the students relocate to an area outside

of their home school. Further, the act allows students to enroll in school immediately without the required

paperwork (e.g., immunization records, educational records, lease or deed), assigns a homeless liaison to

schools to ensure that provisions under McKinney-Vento are being met, and assigns a State Coordinator to

coordinate services for students experiencing homelessness.

School counselors, teachers and administrators can help support students experiencing homelessness at the

school level and ensure that the provisions of the McKinney-Vento Act are met. In their roles, they provide

supportive services that address the academic, personal, social and career planning needs of all students

(American School Counselor Association [ASCA], 2012). Interventions and services provided by school

counselors include individual and group counseling, classroom guidance, academic advisement and planning,

consultation with teachers and staff, collaboration with outside services, and parental support (ASCA, 2012).

According to ASCA (2010), an important role of school counselors is to promote awareness and understanding

of the McKinney-Vento Act and the rights of students experiencing homelessness. School counselors collaborate

with other service providers in children’s education to address the academic, career planning and personal/

social needs of students experiencing homelessness (ASCA, 2010; Baggerly & Borkowski, 2004; Daniels,

1992, 1995; Grothaus et al., 2011). They should be knowledgeable about the issues faced by children and

youth experiencing homelessness and be equipped to provide appropriate services to these students (Grothaus

et al., 2011; Walsh & Buckley, 1994). In particular, school counselors must be aware of the McKinney-Vento

program requirements (Baggerly & Borkowski, 2004) and understand how to advocate for their effective

implementation. However, without knowledge of the policies that impact students experiencing homelessness

and the interventions necessary to help them, school counselors may nd it difcult to serve this population.

In order to develop comprehensive school counseling programs that systemically address the needs of children

and youth experiencing homelessness, school counselors need awareness of the policies that pertain to these

students, and the emotional and educational issues they face.

To date, limited research exists concerning school counselors’ knowledge of the McKinney-Vento Act,

knowledge about the educational and emotional issues that homeless students face, and service provision for

these students (Gaenzle, 2012). Also, limited research exists on whether school counselors receive training

regarding homelessness and the source of that training, whether graduate training, in-service training or

professional development. Further, little is known about the size of school counselors’ caseloads of students

experiencing homelessness and whether these caseloads differ in some locations (e.g., urban schools, high

schools). Given that 77% of the homeless population is found in urban areas (Henry & Sermons, 2010), perhaps

school counselors in urban schools face larger caseloads and greater demands for services from students

experiencing homelessness. Exploring school counselors’ knowledge, service provision and experiences

regarding students experiencing homelessness would help to better focus service delivery at the school level to

this student population. To this end, this exploratory study attempts to investigate school counselors’ knowledge

and service provision regarding students experiencing homelessness and to examine related variables (e.g.,

school level, school setting, years of experience, training received). The results of this study may help to guide

202

future research and improve counselor preparation and interventions regarding homelessness. The following

questions guided this research:

1. What is school counselors’ knowledge about

• the McKinney-Vento Homeless Assistance Act?

• the emotional and educational needs of students experiencing homelessness?

2. What services and interventions are school counselors providing for students experiencing

homelessness?

3. What are the relationships of demographic and other variables (e.g., school type, school setting, school

level, number of students in the school who are homeless, years of experience as a school counselor,

type of training received and knowledge of location of homeless shelters) to school counselors’

knowledge and provision of services related to students experiencing homelessness?

Methods

Participants

Participants included 207 respondents from a random sample of 1,000 school counselors who were listed

in the ASCA member directory. Of the participants, 72 (36.4%) worked in elementary schools, 35 (17.6%) in

middle schools, 86 (43.4%) in high schools and 5 (2.5%) in both middle and high schools. Fifty-nine (29.6%)

of the participants worked in urban settings, 55 (27.6%) in rural settings and 85 (42.7%) in suburban school

settings. Most respondents (185 or 93%) worked in public schools while 7 (3.5%) worked in private schools and

7 (3.5%) worked in parochial schools.

Instrumentation

The survey (see Appendix) was developed by the rst author to assess school counselors’ perceived

knowledge of the McKinney-Vento Act and the needs of students experiencing homelessness as well

as counselors’ provision of services to these students (Baggerly & Borkowski, 2004; Strawser, Markos,

Yamaguchi, & Higgins, 2000; Walsh & Buckley, 1994). The survey was piloted on 12 second-year master’s-

level school counseling students at a large East Coast university who were completing their internships at

the time. After students completed a paper version of the survey, they provided feedback on the clarity and

comprehensibility of the survey items. Minor adjustments were made to improve clarity on several items.

Demographic items. Three items assessed school setting (urban, rural, suburban), school level (elementary,

middle, high) and years of experience as a school counselor. Years of experience was reported as a continuous

variable with a mean of 9.35 years (SD = 7.25) and a range from 1–31.

Training. Two items assessed training. The rst item assessed the extent of training in work with students

experiencing homelessness and was rated on a scale from 1 (no training) to 3 (extensive training). The second

item assessed type of training (i.e., in graduate school, in-service training at their school, required professional

development outside of school, voluntary professional development outside of school, two or more sources of

training, and no training).

Number of students experiencing homelessness. One item measured the number of students experiencing

homelessness that counselors reported as enrolled at their schools. Participants were asked to select a category

that best t the amount. The categories were 0, 1–5, 6–10, 11–15, 16–25, 26–35, 36–45, 46–55 or over 55

students.

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

203

Perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento and emotional and educational issues. Seven Likert scale

items were written specically to assess school counselors’ perceived knowledge of the McKinney-Vento Act

and the emotional and educational issues of students experiencing homelessness. Participants were instructed

to rate their knowledge on a scale from 1 (no knowledge) to 5 (extensive knowledge). Items were designed to

measure school counselors’ perceptions of their knowledge on specic requirements under the McKinney-Vento

Act, as well as their knowledge on general emotional and educational issues affecting students experiencing

homelessness.

Provision of services. Two items focused on the services and interventions that participants reported

implementing with students experiencing homelessness. One item prompted participants to report the frequency

of their engagement in these interventions on a scale from 1 (not at all) to 5 (always), where interventions

signied nine specic services to students experiencing homelessness. The second item required school

counselors to indicate any of 25 interventions provided to students experiencing homelessness, including the

option I have not provided any services or interventions. The services and interventions were selected based on

the McKinney-Vento requirements and the literature on education and homelessness.

Procedures

Using Survey Monkey (www.surveymonkey.com), the survey was e-mailed to 1,000 randomly selected

ASCA members selected via the ASCA member directory (www.schoolcounselor.org). Of the 1,000 surveys

sent, 80 e-mails bounced back or were invalid, while 713 recipients did not reply and 207 responded. The total

response rate was 22.5%, with 19.8% (N = 182) completing all sections of the survey. Completing the survey in

its entirety included lling out one qualitative section (for results see Havlik, Brady, & Gavin, 2014). Several

participants did not complete this section.

Data Analysis

Descriptive analyses. To answer research questions one and two, we examined frequencies and means of

school counselors’ responses to survey items.

Analyses of variance (ANOVAs). To answer question 3, we conducted four one-way ANOVAS: (1) one

to examine whether elementary, middle and high school counselors differed in the extent of training they

received for working with students experiencing homelessness; (2) a second to examine whether urban, rural

and suburban school counselors differed in the extent of training they received for working with students

experiencing homelessness; (3) a third to examine whether elementary, middle and high school counselors

differed in the number of students experiencing homelessness at their school; and (4) a fourth to examine

whether urban, rural and suburban school counselors differed in the number of students experiencing

homelessness at their school.

Regression analyses. To answer the fourth research question, we conducted simultaneous multiple

regression analyses to examine the relationships among the demographic variables (e.g., school setting, school

level, number of students experiencing homelessness at school, years of experience as a school counselor,

type of training received) and school counselors’ knowledge and provision of services related to students

experiencing homelessness.

Factor analysis. Prior to conducting the multiple regression analyses, we conducted a principal component

analysis (PCA) of the seven items assessing counselors’ perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento and students’

emotional and educational needs, and the nine items assessing the extent to which counselors provided nine

specic services for students experiencing homelessness (see Tables 1 and 2). The PCA with varimax rotation

was conducted as a data reduction method (Costello & Osborne, 2005) to determine how participants’ responses

204

were structured. The components or factors derived from the PCA comprised the dependent variables in the

study. Decisions to retain the factors were based on (a) the scree test, (b) eigenvalues greater than one (Kaiser

criterion) and (c) the conceptual meaning of each item.

Post hoc analyses. One-way ANOVAs and Crosstabs analyses were used to take a closer look at any

interesting ndings from the multiple regression analyses.

Results

Descriptive Analyses

In Table 1, we present the means and standard deviations for the 16 items used to assess school counselors’

knowledge and provision of services regarding students experiencing homelessness.

Question 1a: Perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento. The average response to the ve items that

assessed school counselors’ knowledge of McKinney-Vento was 2.90 (SD = 1.38), slightly below the midpoint

of 3 on the 5-point scale (1 = no knowledge to 5 = extensive knowledge). More specically, school counselors

reported about average knowledge of the McKinney-Vento Act (M = 2.86, SD = 1.47). They also reported lower

levels of knowledge of the role of the State Coordinator (M = 2.04, SD = 1.19), but slightly above average

knowledge of the role of the homeless liaison (M = 3.19, SD = 1.45). Counselors reported above average

knowledge of registration policies for students experiencing homelessness (M = 3.45, SD = 1.25), and about

average levels of knowledge of transportation requirements (M = 2.97, SD = 1.53).

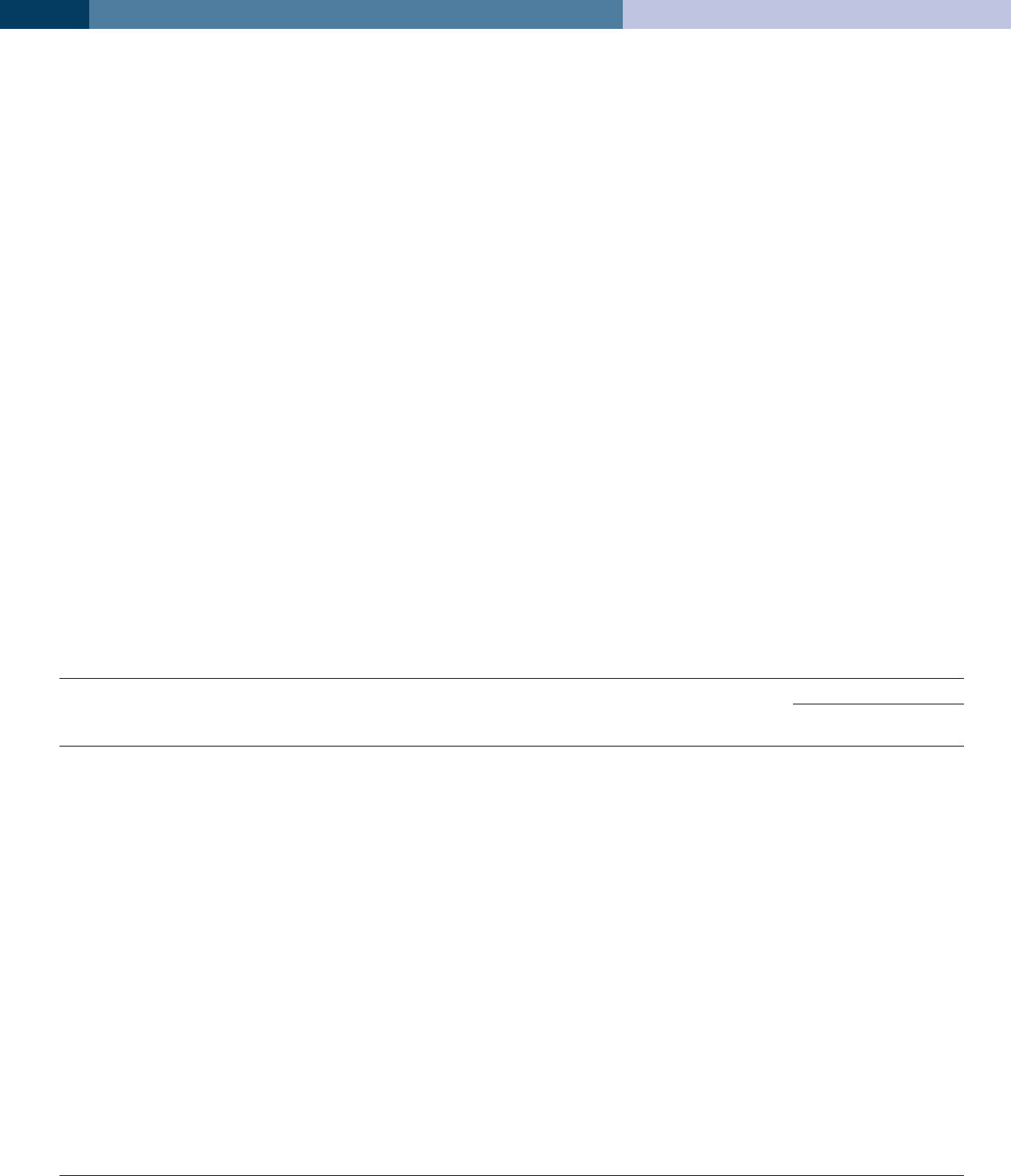

Table 1

Means, Standard Deviations and Factor Loadings of Knowledge and Provision of Services

Factor loadings

Component

Item

M SD

1 2 3

Knowledge of McKinney-Vento

a

2.86 1.47

.83

.16 .25

I review the McKinney-Vento Act policies to ensure homeless students’ needs are

being met

b

2.77 1.54

.80

.35 .12

Knowledge of transportation requirements under McKinney-Vento

a

2.97 1.53

.76

.16 .30

Knowledge of role of the State Coordinator

a

2.04 1.19

.67

.26 .23

I have contact with my school’s homeless liaison

b

3.48 1.66

.59

.21 .40

Knowledge of the role of the homeless liaison

a

3.19 1.45

.58

.15 .59

Knowledge of registration policies for homeless students

a

3.45 1.25

.51

.24 .52

I assess the emotional needs of homeless students

b

3.86 1.21 .08

.81

.33

I make contact with homeless families

b

3.42 1.32 .20

.71

.33

I ensure that homeless students with whom I work have equal opportunities

compared to their non-homeless peers

b

4.31 1.00 .07

.68

.40

I assist with the registration of homeless students

b

3.45 1.25 .26

.64

-.01

I ensure that homeless students have transportation to attend before- or after-school

programs

b

3.01 1.57 .35

.62

.12

I provide mentorship programs for homeless students at my school

b

2.43 1.34 .15

.57

.08

I visit shelters where homeless students at my school live

b

1.44 .88 .41

.46

-.11

Knowledge of emotional/social issues

a

3.85 .97 .23 .16

.87

Knowledge of educational issues

a

3.87 .96 .29 .25

.83

a

On these items the scale ranged from 1 = no knowledge at all to 5 = extensive knowledge.

b

On these items the scale ranged from 1 = not at all to 5 = always.

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

205

Question 1b: Perceived knowledge of emotional and educational issues. The average response to the two

items written to assess school counselors’ knowledge of emotional and educational issues faced by homeless

students was 3.86 (SD = 0.97), above the midpoint of 3 on the 5-point scale used (1 = no knowledge to 5 =

extensive knowledge). School counselors reported above average knowledge of emotional issues (M = 3.85,

SD =. 97) and knowledge of educational issues (M = 3.87, SD = .955), suggesting that counselors may perceive

themselves as fairly knowledgeable about the emotional and educational issues faced by students experiencing

homelessness.

Question 2: Provision of services and advocacy. The average response to the nine items written to assess

school counselors’ provision of services was 3.10 (SD = 1.35), slightly above the midpoint of 3 on the 5-point

scale used (1 = not at all to 5 = always). School counselors provided responses close to average regarding their

frequency of assisting with registration (M = 3.20, SD = 1.58). Their responses were above average for their

frequency of assessing the emotional needs of students experiencing homelessness (M = 3.86, SD = 1.21).

However, most school counselors reported infrequently conducting shelter visits (M = 1.44, SD = .88) or

providing mentorship programs (M = 2.43, SD = 1.34). The highest average was of school counselors’ reports

on the extent to which they ensured equal opportunities for students experiencing homelessness (M = 4.31, SD =

1.04).

Types of interventions. In response to the item that requested for participants to report on their engagement

in 25 types of interventions provided to students experiencing homelessness, nearly 70% of all participants

reported making referrals to community resources (69.5%) and providing individual counseling (68.0%). Other

frequent interventions reported included providing academic support (57.9%), teacher consultation (52.8%),

parent consultation (50.3%) and advocating for homeless students (43.7%). Interventions infrequently reported

included parent education workshops (6.6%), workshops/training for teachers (7.1%), behavioral skills training

(13.7%), mentor programs (16.2%), communicating with shelter staff (17.8%), after-school programs (20.3%),

college planning (21.8%), small group counseling (22.8%) and IEP (Individualized Education Program)

planning (23.9%). Only 3% of counselors reported conducting shelter visits, while 13.2% of school counselors

reported not providing any services at all to students experiencing homelessness.

ANOVAs

Question 3a: Training received for working with students experiencing homelessness. No signicant

differences existed among school counselors by school level or school setting in the extent of training received

for working with students experiencing homelessness.

Question 3b: Number of students experiencing homelessness at their school. No signicant differences

existed among elementary, middle and high school counselors in the number of students experiencing

homelessness at their schools. However, signicant differences existed among urban, rural and suburban school

counselors in the number of students at their schools experiencing homelessness, F(2, 196) = 7.14, p = .001,

with a very small effect size, η

2

= .07. Urban school counselors had signicantly higher numbers of students

experiencing homelessness (M = 3.09, SD = 2.34) than rural (M = 1.98, SD = 1.82) and suburban (M = 1.89,

SD = 1.72) school counselors. A rating of 3 is equivalent to 11–15 students, a rating of 2 is equivalent to 6–10

students, and a rating of 1 is equivalent to 1–5 students experiencing homelessness.

Principal Component Analysis

A PCA of the 16 items resulted in three components or factors, which were the dependent variables in

subsequent regression analyses. A four-factor model was initially considered; however, the three-factor model

was selected based on the scree test and eigenvalues greater than one. The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of

206

sampling adequacy was .88, indicating that factor analysis of these variables was appropriate. Barlett’s Test

of Sphericity was signicant, indicating that the items were excellent candidates for PCA. The factor loadings

of each factor are presented in Table 1. Factor 1, perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento, comprised seven

items with factor loadings ranging from .83–.51 with 24.2% of the variance explained and a Cronbach’s alpha

of .91. Items loading on this factor measured school counselors’ perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento

and the policies that schools must implement under McKinney-Vento. Factor 2, advocacy and provision of

services, comprised seven items with factor loadings from .45–.81 with 21.19% of the variance explained and

a Cronbach’s alpha of .81. Items on this factor described services and forms of advocacy that school counselors

provided for students experiencing homelessness. Factor 3, perceived emotional and educational issues,

comprised two items with loadings of .87 and .83 with 17.78% of variance explained and a Cronbach’s alpha

of .96. Factor scores were created for each factor using the regression method approach so that participants

had a score on each factor. The factor score is a linear combination of the items that load on that factor and is

a standardized score. Therefore, the three factors used in the following regression analyses were standardized

variables, each with a mean of zero and a standard deviation of one.

Multiple Regression Analyses

Following the PCA, we conducted three simultaneous multiple regression analyses with each factor serving

as a dependent variable in each regression. The B coefcients and standard errors for each regression analysis

appear in Table 2.

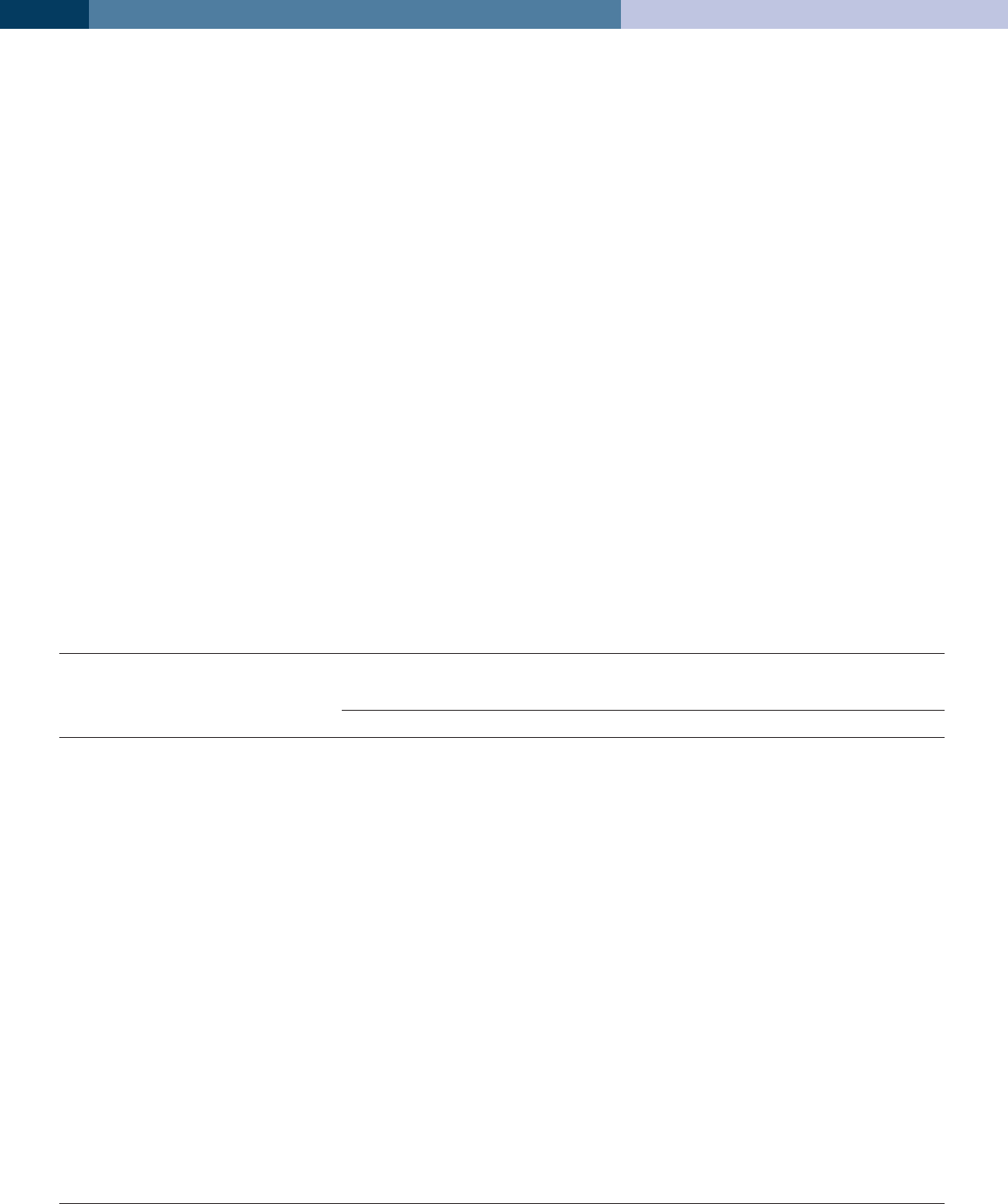

Table 2

Regression Analyses of Variables Related to School Counselors’ Knowledge and Service Provision Regarding

Students Experiencing Homelessness

Variables

Perceived knowledge of

McKinney-Vento

Knowledge of emotional

and educational needs

Advocacy and provision

of services

B SEB B SEB B SEB

Intercept -1.83

***

.33 -1.44

***

.30 -1.99

***

.36

Elementary .32

*

.15 .22 .15 .15 .16

Middle .19 .18 .10 .19 .21 .20

High (reference category)

Public .38 .30 .50 .29 .70

**

.32

Private/parochial (reference category)

Urban -.12 .16 -.12 .16 -.23 .17

Rural .13 .16 -.21 .16 .26 .18

Suburban (reference category)

Years of experience .01 .01 .01 .01 .00 .01

1–25 homeless students .58

*

.26 .52

**

.24 .80

**

.27

26–55 homeless students .61 .34 .72

**

.34 .87

**

.36

55+ homeless students 1.08

**

.40 1.13

**

.37 1.37

**

.40

No homeless (ref)

Graduate training .28 .25 .66

**

.26 .58

*

.28

In-service training 1.16

***

.17 .83

***

.18 .65

**

.19

Professional development .93

***

.19 .54

**

.19 .65

**

.21

Two or more sources 1.11

***

.20 .96

***

.21 .82

***

.23

No training (ref)

R

2

(adj. R

2

)

.45

***

(.41)

.28

***

(.23)

.28

***

(.23)

***p < .001. **p <. 01. *p < .05.

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

207

Perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento. The independent variables explained 47% of the variability in

school counselors’ perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento, R

2

= .45, Adjusted R

2

= .43, F(23, 146) = 10.87, p

= .000. Participant grade levels, β = .15, t = 2.18, p = .003, numbers of students experiencing homelessness and

training predicted knowledge of McKinney-Vento. Relative to school counselors who had received no training,

responses of having received in-service training, β = .54, t = 7.32, p = .000, professional development outside

of school, β = .39, t = 5.65, p = .000, and two or more sources of training, β = .43, t = 6.03, p = .000, predicted

perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento. However, no relationship with perceived knowledge of McKinney-

Vento existed among those who received their training in their graduate program and those who had no training.

Perceived knowledge of emotional and educational issues. The independent variables explained 30%

of the variability in school counselors’ perceived knowledge of emotional and educational issues, R

2

= .28,

Adjusted R

2

= .23, F(12, 175) = 6.24, p = .000. Number of students experiencing homelessness predicted

participants’ perceived knowledge of emotional and educational issues in schools with 1–25 students, β = .32, t

= 3.50, p = .001, in schools with 26–55 students, β = .22, t = 2.62, p = .010, and in schools with more than 55

students, β = .32, t = 4.00, p = .000. Type of training received also predicted perceived knowledge of emotional

and educational issues in participants who received their training in their graduate program, β = .14, t = 2.11, p

= .000, as well as those who received in-service training, β = .39, t = 5.13, p = .000, professional development

outside of school, β = .27, t = 3.74, p = .000, and two or more sources of training, β = .36, t = 4.92, p = .000.

Advocacy and provision of services. The independent variables explained 30% of the variability in school

counselors’ reported advocacy and provision of services, R

2

= .28, Adjusted R

2

= .23, F(12, 151) = 5.31, p =

.000. Number of students experiencing homelessness in the school and type of training received both predicted

school counselors’ reported advocacy and provision of services. As expected, when compared to participants

who reported having no students experiencing homelessness, the number of homeless students at each school

predicted advocacy and provision of services from participants who reported having 1–25 students experiencing

homelessness, β = .39, t = 3.72, p = .000, 26–55 students, β = .24, t = 2.47, p = .014, and 55 or more students,

β = .36, t = 4.02, p = .000. Type of training received also predicted advocacy and provision of services.

Compared to participants who had received no training on homelessness, training responses that included in-

service training, β = .31, t = 3.69, p = .000, professional development outside of school, β = .29, t = 3.61,

p = .000, and two or more sources of training, β = .43, t = 4.06, p = .000, predicted advocacy and provision

of services. However, no relationship was reported in advocacy and provision of services among those who

received their training in their graduate program and those who had no training on homelessness.

Post Hoc Analyses

To take a closer look at the signicant differences between elementary, middle and high school counselors

on perceived knowledge of McKinney-Vento, we conducted a one-way ANOVA, F(2, 157) = 6.44, p = .002, η

2

= .07. Elementary school counselors fell signicantly above the mean on perceived knowledge of McKinney-

Vento (M = .33, SD = .91), while high school counselors fell signicantly below the mean (M = -.27, SD =

.97). Middle school counselors (M = -.10, SD = 1.06) also fell below the mean, although the difference was not

signicant. To shed further light on this relationship, we conducted a crosstabs analysis with school level and

source of training. Although the previous ANOVA (see research question 3a) revealed no signicant differences

in extent of training by school level or setting, a post hoc examination of the frequencies regarding source of

training revealed that elementary school counselors (59.3%) were more likely than high school counselors

(29.6%) or middle school counselors (11.1%) to receive training from two or more sources (i.e., from some

combination of graduate school, professional development outside of school and in-service training). High

school counselors (52.9%) were more likely to report that they had received no training from any source than

were elementary school counselors (28.6%).

208

Discussion and Implications

This national study explored school counselors’ perceived knowledge of the McKinney-Vento Act,

perceived knowledge of the emotional and educational needs of students experiencing homelessness, and

perceived involvement in advocacy and provision of counseling services. In general, school counselors

in the current study appear to view themselves as less knowledgeable about the McKinney-Vento Act and

its requirements, but more knowledgeable about the general emotional and educational issues of students

experiencing homelessness. However, due to the general nature of the questions, reporting greater knowledge

of emotional and educational issues may be a result of self-report bias, since specic knowledge was not

solicited. A lower level of knowledge about McKinney-Vento is not surprising given that about 40% of school

counselors in the study reported never having received training related to working with students experiencing

homelessness. In addition, whether they had no or some training, school counselors reported working in various

ways with students experiencing homelessness, including enrolling them in school and assessing their needs.

However, regarding more collaborative services such as visiting shelters and involving students in mentoring

programs, school counselors reported less involvement. As recommended in the school counseling literature

on homelessness (Baggerly & Borkowski, 2004; Strawser et al., 2000; Walsh & Buckley, 1994), these school

counselors appear to provide more services such as referrals, individual counseling and teacher consultation

to students experiencing homelessness. Yet, Miller (2009, 2011) emphasized the importance of school

personnel’s collaboration with families and community stakeholders and building bridges to connect homeless

students to after-school programs and community services to improve their academic and emotional outcomes.

Previous research suggests that training specically related to building partnerships is a prerequisite of school–

community collaboration and that 40% of school counselors lack this type of training (Bryan & Grifn, 2010).

Overall, while 90% of school counselors in the current study appear to work with students experiencing

homelessness, school counselors in urban settings appear to face larger caseloads of homeless students than

counselors in rural and suburban schools. Yet, no differences exist between the surveyed urban, rural and

suburban school counselors’ levels of knowledge about McKinney-Vento and about emotional and educational

issues or advocacy and provision of services. Given the increasingly large number of families experiencing

homelessness in urban areas (Henry & Sermons, 2010), though a variable not investigated in this study, one

might expect that with larger caseloads, urban school counselors would report higher levels of advocacy and

provision of services. Provision of services and levels of advocacy are related to training. Without adequate

training, counselors in urban schools may nd themselves ill-equipped to perform the boundary-spanning

role that is integral to providing these students with adequate support—that is, linking them to information,

resources and programs (Miller, 2009, 2011). Note that the numbers related to participants’ school location

should be interpreted with caution due to the lack of specic percentages of students experiencing homelessness

on their caseloads available for this study.

In general, elementary, middle and secondary school counselors appear to face similar situations regarding

the numbers of students experiencing homelessness and their perceived training for working with this

population. However, elementary school counselors reported above average knowledge of the McKinney-Vento

provisions, signicantly higher than high school counselors, although these groups do not differ in the perceived

extent of training received. The ndings suggest that their knowledge of McKinney-Vento may be attributed

to the source or type of training they are receiving. Also, this difference may reect the fact that most school

counseling publications on students experiencing homelessness, although few, have focused on elementary

school counselors (e.g., Baggerly & Borkowski, 2004; Daniels, 1992, 1995; Strawser et al., 2000).

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

209

According to the results of this study, training on homelessness is positively related to school counselors’

knowledge of McKinney-Vento, knowledge of emotional and educational issues, and advocacy and provision

of services. Overall, school counselors with no training regarding students experiencing homelessness

reported less knowledge of McKinney-Vento and of their emotional and educational issues, and less advocacy

and provision of services compared to counselors who with some training (with the exception of those who

received their training in graduate programs). For the participants in this study, graduate program training

regarding homelessness is only indicative of higher knowledge of emotional and educational issues of students

experiencing homelessness when compared to counselors with no training. These ndings suggest the need for

an intentional focus in counseling graduate programs on the McKinney-Vento Act and its provisions as well as

on specic practices for advocating and implementing service delivery to students experiencing homelessness.

Graduate students in school counseling programs and related degree programs in education would benet from

specic training that helps them develop skills as effective boundary spanners and information brokers who

function within and across the contexts of families and children experiencing homelessness (Miller, 2009,

2011).

Taken together, the relationships between the number of students experiencing homelessness, school

counselor training, and advocacy and provision of services are particularly interesting. These ndings suggest

that school counselors’ exposure to issues related to homelessness, through both training and direct contact

with students experiencing homelessness, may compel them to learn about homelessness and to advocate

for and provide recommended services to these students. Indeed, as their caseloads of students experiencing

homelessness increase, school counselors may feel compelled to nd resources and supports for these students.

More importantly, for counselors who have caseloads with only a few students experiencing homelessness,

these ndings highlight the value of training and its implications for services. Perhaps these ndings hint at

the need to couple school counselor training on homelessness with direct exposure to students experiencing

homelessness—that is, with immersion experiences. Intentional and coherent integration of service learning

experiences with families and children experiencing homelessness into counselor education programs

can provide school counseling trainees with appropriate and invaluable real-world learning experiences

for developing the requisite skills for working with students experiencing homelessness (Baggerly, 2006;

Constantine, Hage, Kindaichi, & Bryant, 2007).

Implications for School Counselor Practice

The ndings of this study have several implications for the practice of school counselors. We recommend

that school counselors (a) seek professional development to enhance their knowledge of the policies and

needs related to students experiencing homelessness, (b) build relationships with the students experiencing

homelessness in their schools, and (c) build partnerships with families experiencing homelessness, homeless

liaisons, homeless shelters, and community organizations in order to better advocate for and provide services to

students experiencing homelessness.

Professional development on homelessness. School counselors are required to promote awareness and

understanding of McKinney-Vento and the rights of students experiencing homelessness and provide services

aligned to meet their needs (ASCA, 2010). Based on the results of this study, school counselors who do not

receive training regarding students experiencing homelessness may lack knowledge of McKinney-Vento.

Without knowledge of policies that impact students experiencing homelessness and the interventions necessary

to work with them, counselors may provide students with ineffective support.

School counselors must take the initiative to seek training on the McKinney-Vento Act and the specic needs

and challenges faced by students experiencing homelessness. They may seek this knowledge by attending state,

regional or national conferences on homelessness, and should advocate for the topic to be included at state,

210

regional and national conferences of counseling associations. In the absence of these opportunities, school

counselors may arrange to meet with the local homeless liaison to discuss the provisions of the McKinney-

Vento Act and the needs of students experiencing homelessness and to explore available services in the school

district.

Build relationships with students experiencing homelessness. In order to support the educational

and emotional development of children and youth experiencing homelessness, school counselors must rst

identify which students are experiencing homelessness in their school and then determine their specic needs

(Daniels, 1992). Identifying students experiencing homelessness requires that all stakeholders, including

teachers, know the variety of denitions that qualify students as experiencing homelessness (U.S. Department

of Education, 2004; Zerger, Strehlow, & Gundlapalli, 2008). Educating all teachers and staff on the denitions

of homelessness will allow them to quickly and condentially report if they suspect a student is experiencing

homelessness and recognize issues that may arise due to their housing status. When students and families are

identied as experiencing homelessness, school counselors may then plan interventions accordingly to support

their educational and developmental needs.

Build partnerships with stakeholders. One critical way in which school counselors can support the needs

of students experiencing homelessness is by building collaborative relationships with partners in the community

(ASCA, 2010; Grothaus et al., 2011). Determining student needs may require visiting shelters to nd ways to

connect with families and children. Given that shelters offer families a variety of resources that may or may

not adequately meet their needs (Shillington, Bousman, & Clapp, 2011), it is important for school counselors

to know what services local shelters provide in order to understand what additional supports are needed. For

instance, determining what educational support is available at the shelter (e.g., whether there is allotted space

for students to study) may help counselors determine what academic enrichment and support programs (e.g.,

tutoring, computer access, homework help) are needed at the school level.

As previously mentioned, McKinney-Vento requires that every local educational agency has a designated

local homeless liaison. This person ensures that students experiencing homelessness are identied and have

equal opportunities to be successful. Therefore, when coordinating services and planning interventions for

students, counselors should collaborate with the assigned homeless liaison at their school (Grothaus et al.,

2011; Strawser et al., 2000). Counselors and homeless liaisons can collaborate to plan appropriate interventions

for meeting the identied needs of students experiencing homelessness. They also may partner to educate

staff members about the emotional and educational challenges that homeless students face. In some cases,

school counselors may be assigned as the local homeless liaison, which requires them to better understand the

requirements of McKinney-Vento and initiate partnerships between all stakeholders.

School counselors also might partner with teachers and community stakeholders to provide supportive

services for students experiencing homelessness. They may collaborate to coordinate tutoring or mentoring

programs and to develop safe classroom and school environments for students (Bryan, 2005). They also can

plan culturally sensitive classroom guidance units that relate to the personal and social issues faced by students

experiencing homelessness. For example, a classroom lesson on the topic of developing social skills might be

particularly benecial for all students, including those experiencing homelessness (Baggerly & Borkowski,

2004).

Limitations and Future Research

The limitations of this study include self-report bias, sample bias, low response rate, and the validity and

reliability of the survey itself. The survey measures participants’ perceptions of their knowledge rather than

their actual knowledge, which may have led to self-report bias in reporting levels of knowledge. Further, the

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

211

low response rate might render these ndings ungeneralizable to all school counselors. The response rate may

be due to the e-mail-only method of sending out the survey, which has been shown to generate lower response

rates than mailing surveys (Dillman et al., 2009; Kaplowitz, Hadlock, & Levine, 2004; Kongsved, Basnov,

Holm-Christensen, & Hjollund, 2007; Shih & Fan, 2009). For instance, one study suggested that e-mail surveys

have a response rate approximately 20% lower than that of mail surveys (Shih & Fan, 2009). However, the

response rate also may suggest that the counselors who chose not to participate in the survey did so because

they did not have or were not aware of any students experiencing homelessness on their caseloads. Another

limitation concerns the selection of respondents exclusively among ASCA members. Thus, this sample may

not be representative of all counselors in the United States. As a caveat, the results of this study should not be

interpreted in causal terms because the ndings suggest relationships between variables, not specic causality.

Finally, since the survey is newly developed, its reliability and validity should be considered with caution.

Though there are several limitations, due to the exploratory nature of this study, the results provide insight into

school counselors’ work with students experiencing homelessness and guide future research on this important

subject.

This exploratory study is one of only two studies (e.g., Gaenzle, 2012) to examine the relationship between

counselor demographics and their knowledge, advocacy and provision of services for students experiencing

homelessness. This initial information lays the foundation for further research on the topic. It is possible that

other variables, such as actual (rather than perceived) knowledge, may predict school counselor advocacy

and provision of services. The omission of certain variables may explain the low R squares (e.g., R

2

< .30)

in some of the regression models. Future research should use a larger sample to explore school counselors’

knowledge about and advocacy for students experiencing homelessness as well as examine additional variables

that may inuence school counselors’ and other service providers’ advocacy and service provision for students

experiencing homelessness. Further, this study suggests a need for future research that examines the efcacy of

current school counseling programs with students experiencing homelessness.

Conict of Interest and Funding Disclosure

The authors reported no conict of

interest or funding contributions for

the development of this manuscript.

References

American School Counselor Association. (2010). The professional school counselor and children experiencing

homelessness. Retrieved from http://www.schoolcounselor.org/asca/media/asca/PositionStatements/

PositionStatements.pdf

American School Counselor Association. (2012). The American School Counselor Association national model: A

framework for school counseling programs (3rd ed.). Alexandria, VA: Author.

Baggerly, J. (2006). Service learning with children affected by poverty: Facilitating multicultural competence

in counseling education students. Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development, 34, 244–255.

doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2006.tb00043.x

Baggerly, J., & Borkowski, T. (2004). Applying the ASCA national model to elementary school students who are

homeless: A case study. Professional School Counseling, 8, 116–123.

Bryan, J. (2005). Fostering educational resilience and achievement in urban schools through school-family-community

partnerships. Professional School Counseling, 8, 219–227.

212

Bryan, J. A., & Grifn, D. (2010). A multidimensional study of school-family-community partnership involvement:

School, school counselor, and training factors. Professional School Counseling, 14, 75–86.

Buckner, J. C., Bassuk, E. L., Weinreb, L. F., & Brooks, M. G. (1999). Homelessness and its relation to the mental health

and behavior of low-income school-age children. Developmental Psychology, 35, 246–257.

doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.1.246

Coker, T. R., Elliott, M. N., Kanouse, D. E., Grunbaum, J. A., Gilliland, M. J., Tortolero, S. R., . . . Schuster, M. A. (2009).

Prevalence, characteristics, and associated health and health care of family homelessness among fth-grade

students. American Journal of Public Health, 99, 1446–1452.

Constantine, M. G., Hage, S. M., Kindaichi, M. M., & Bryant, R. M. (2007). Social justice and multicultural issues:

Implications for the practice and training of counselors and counseling psychologists. Journal of Counseling and

Development, 85, 24–29. doi:10.1002/j.1556-6678.2007.tb00440.x

Costello, A. B., & Osborne, J. W. (2005). Best practices in exploratory factor analysis: Four recommendations for getting

the most from your analysis. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 10. Retrieved from http://pareonline.

net/getvn.asp?v=10&n=7

Daniels, J. (1992). Empowering homeless children through school counseling. Elementary School Guidance &

Counseling, 27, 104–112.

Daniels, J. (1995). Homeless students: Recommendations to school counselors based on semistructured interviews. School

Counselor, 42, 346–352.

Dillman, D. A., Phelps, G., Tortora, R., Swift, K., Kohrell, J., Berck, J., & Messer, B. L. (2009). Response rate and

measurement differences in mixed-mode surveys using mail, telephone, interactive voice response (IVR) and the

Internet. Social Science Research, 38, 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2008.03.007

Gaenzle, S. A. (2012). An investigation of school counselors’ efforts to serve students who are homeless: The role

of perceived knowledge, preparation, advocacy role, and self-efcacy to their involvement in recommended

interventions and partnership practices (Doctoral dissertation). Available from ProQuest Dissertations and Theses

database. (UMI No. 3543452)

Gewirtz, A., Hart-Shegos, E., & Medhanie, A. (2008). Psychosocial status of homeless children and youth in family

supportive housing. American Behavioral Scientist, 51, 810–823. doi:10.1177/0002764207311989

Grothaus, T., Lorelle, S., Anderson, K., & Knight, J. (2011). Answering the call: Facilitating responsive services for

students experiencing homelessness. Professional School Counseling, 14, 191–201.

Havlik, S. A., Brady, J., & Gavin, K. (2014). Exploring the needs of students experiencing homelessness from school

counselors’ perspectives. Journal of School Counseling, 12(20). Retrieved from http://jsc.montana.edu/articles/

v12n20.pdf

Henry, M., & Sermons, M. W. (2010). Geography of homelessness. Washington, DC: The Homeless Research Institute

at the National Alliance to End Homelessness. Retrieved from http://b.3cdn.net/naeh/3953e7051f30801dc6_

iim6banq3.pdf

Hicks-Coolick, A., Burnside-Eaton, P., & Peters, A. (2003). Homeless children: Needs and services. Child & Youth Care

Forum, 32, 197–210.

Kaplowitz, M. D., Hadlock, T. D., & Levine, R. (2004). A comparison of web and mail survey response rates. Public

Opinion Quarterly, 68, 94–101. doi:10.1093/poq/nfh006

Kongsved, S. M., Basnov, M., Holm-Christensen, K., & Hjollund, N. H. (2007). Response rate and completeness of

questionnaires: A randomized study of Internet versus paper-and-pencil versions. Journal of Medical Internet

Research, 9, e:25.

Miller, P. M. (2009). Boundary spanning in homeless children’s education: Notes from an emergent faculty role in

Pittsburgh. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45, 616–630. doi:10.1177/0013161X09333622

Miller, P. M. (2011). Homeless families’ education networks: An examination of access and mobilization. Educational

Administration Quarterly, 47, 543–581. doi:10.1177/0013161X11401615

National Center for Homeless Education. (2012, June). Education for homeless children and youths program: Data

collection summary. Retrieved from http://center.serve.org/nche/downloads/data_comp_0909-1011.pdf

National Center on Family Homelessness. (2011). The characteristics and needs of families experiencing homelessness.

Retrieved from http://www.familyhomelessness.org/media/306.pdf

National Coalition for the Homeless. (2009, July). Homeless families with children. Retrieved from http://www.

nationalhomeless.org/factsheets/families.html

The Professional Counselor/Volume 5, Issue 2

213

Obradović, J., Long, J. D., Cutuli, J. J., Chan, C.-K., Hinz, E., Heistad, D., & Masten, A. S. (2009). Academic

achievement of homeless and highly mobile children in an urban school district: Longitudinal evidence on risk,

growth, and resilience. Development and Psychopathology, 21, 493–518. doi:10.1017/S0954579409000273

Rafferty, Y., Shinn, M., & Weitzman, B. C. (2004). Academic achievement among formerly homeless adolescents and

their continuously housed peers. Journal of School Psychology, 42, 179–199. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2004.02.002

Shih, T.-H. & Fan, X. (2009). Comparing response rates in e-mail and paper surveys: A meta-analysis. Educational

Research Review, 4, 26–40. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2008.01.003

Shillington, A. M., Bousman, C. A., & Clapp, J. D. (2011). Characteristics of homeless youth attending two different

youth drop-in centers. Youth & Society, 43, 28–43. doi:10.1177/0044118X09351277

Shinn, M., Schteingart, J. S., Williams, N. C., Carlin-Mathis, J., Bialo-Karagis, N., Becker-Klein, R., & Weitzman, B. C.

(2008). Long-term associations of homelessness with children’s well-being. American Behavioral Scientist, 51,

789–809. doi:10.1177/0002764207311988

Strawser, S., Markos, P. A., Yamaguchi, B. J., & Higgins, K. (2000). A new challenge for school counselors: Children who

are homeless. Professional School Counseling, 3, 162–172.

Swick, K. J. (2008). The dynamics of violence and homelessness among young families. Early Childhood Education

Journal, 36, 81–85. doi:10.1007/s10643-007-0220-5

U.S. Department of Education. (2004, July). Education for homeless children and youth program: Title VII-B of the

McKinney-Vento homeless assistance act. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from www.ed.gov/programs/

homeless/guidance.pdf

U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Ofce of Community Planning and Development. (2010, June).

The 2009 annual homeless assessment report to congress. Retrieved from http://www.hudhre.info/documents/5th

HomelessAssessmentReport.pdf

Walsh, M. E., & Buckley, M. A. (1994). Children’s experiences of homelessness: Implications for school counselors.

Elementary School Guidance and Counseling, 29, 4–15.

Zerger, S., Strehlow, A. J., & Gundlapalli, A. V. (2008). Homeless young adults and behavioral health: An

overview. American Behavioral Scientist, 51, 824–841. doi:10.1177/0002764207311990

214

Appendix

Knowledge and Skills with Homeless Students Survey

Self-Administered Questionnaire