The University of Southern Mississippi The University of Southern Mississippi

The Aquila Digital Community The Aquila Digital Community

Master's Theses

Summer 8-1-2021

Different Class: The Creation of the Premier League and the Different Class: The Creation of the Premier League and the

Commercialization of English Football Commercialization of English Football

Colin Damms

Follow this and additional works at: https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses

Part of the Cultural History Commons, and the European History Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Damms, Colin, "Different Class: The Creation of the Premier League and the Commercialization of English

Football" (2021).

Master's Theses

. 848.

https://aquila.usm.edu/masters_theses/848

This Masters Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by The Aquila Digital Community. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Master's Theses by an authorized administrator of The Aquila Digital Community. For

more information, please contact [email protected].

REFER TO THE DOCUMENT GUIDELINES FOR ADDITIONAL FORMATTING

INSTRUCTIONS

by

Colin Damms

A Thesis

Submitted to the Graduate School,

the College of Arts and Sciences

and the School of Humanities

at The University of Southern Mississippi

in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements

for the Degree of Master of Arts

Approved by:

Dr. Allison Abra, Committee Chair

Dr. Brian LaPierre

Dr. Kevin Greene

August 2021

COPYRIGHT BY

Colin Damms

2021

Published by the Graduate School

ii

ABSTRACT

This project examines how English football evolved from a culture of

hooliganism and poor upkeep into a popular and enterprising industry across the globe.

The Premier League and its stars marketed the English game and its culture worldwide.

Since the 1990s England has established itself as the leading club footballing nation. I

argue that through football, and the culture and economics behind it, we can see the ways

in which England attempted to change its image in the modern world. In the 1980s and

1990s Britain was confronted with its own established culture of violence, bigotry, and

nationalist pride, particularly the sport of football. English football clubs and the English

Football Association (FA) adapted in an effort to change their image and create a more

accessible and marketable product. This study examines those changes and the ways in

which they impacted the league, clubs, and fan culture in footballing communities. With

a limited and economics-focused historiography on the subject, this work will contribute

to the discussion by exploring a cultural perspective and examining the changes and

economic impact from club and fan levels. It will also place this evolution within a

broader European cultural context.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work would have been impossible without the advice and support of my

committee members, Dr. Kevin Greene, Dr. Brian LaPierre, and especially Dr. Allison

Abra, my advisor and committee chair. I would also like to thank Dr. Kyle Zelner and Dr.

Heather Stur for their support as I adjusted to working as a graduate student. Their

mentorship was crucial to my growth as a professional, and reaffirmed that my decision

to enroll in this program was the correct one. The guidance that my professors have given

me throughout graduate school and the writing process has made my progress on this

thesis possible, and I am grateful for the work they have put into this program for my

fellow students and I.

I would also like to extend thanks to all of my family and friends, a group that

continues to grow. I want to especially thank my mother and father, Jennifer and Richard,

and sisters, Rachael and Kelsey, who have been a constant support system for me

throughout my life. To my friends Adam, Keith, Matthew, Philip and Robert, thank you

for your years of support and brotherhood, and to all my new friends here in Hattiesburg,

I couldn’t have done this without you either. I also want to thank my cohort in the History

Graduate program. I especially want to thank Lucas, Hayley, and Sean, who have never

hesitated to lend a hand or share from their grad school experience. And last, but not

least, I want to thank Cody and Lindsey. I have trouble believing I am lucky enough to

have experienced this process with friends as thoughtful and devoted as you.

iv

DEDICATION

This work is dedicated to the memory of my Grandad, Michael Damms. He lived

his life with passion and humor for those he loved, and instilled in my father and myself a

love for the beautiful game. I also want to dedicate this to my friend, Philip. Through all

that he endures, he is relentless in determination and action to be the person that he wants

to be for those that mean the most to him. He continues to inspire me, and I am so

thankful for his friendship.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ABSTRACT ........................................................................................................................ ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................................................................................................. iii

DEDICATION ................................................................................................................... iv

LIST OF FIGURES ........................................................................................................... vi

LIST OF TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ................................................................... vii

CHAPTER I - INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................... 1

CHAPTER II – AN END IS A START: THE FORMATION OF THE PREMIER

LEAGUE ........................................................................................................................... 24

CHAPTER III - SAME PLACE, DIFFERENT FACES: ANTI-RACIST ACTIVISM IN

THE PREMIER LEAGUE’S FOOTBALL COMMUNITIES ......................................... 57

CHAPTER IV – NAME ON THE TROPHY: MANCHESTER UNITED AND THE

MODERN CLUB ............................................................................................................. 90

CHAPTER V – CONCLUSION ..................................................................................... 132

APPENDIX A - Figure ................................................................................................... 137

REFERENCES ............................................................................................................... 138

vi

LIST OF FIGURES

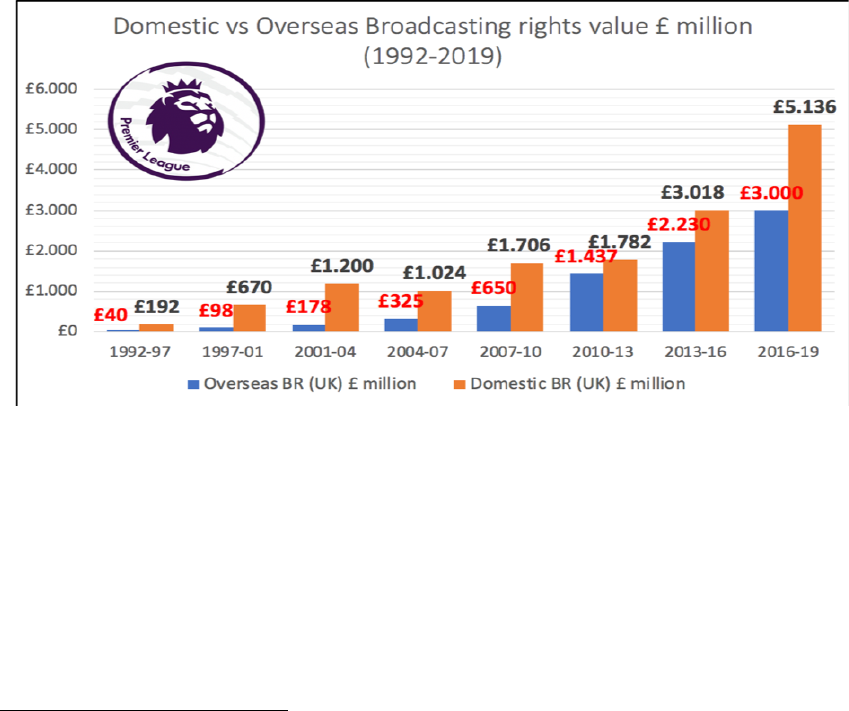

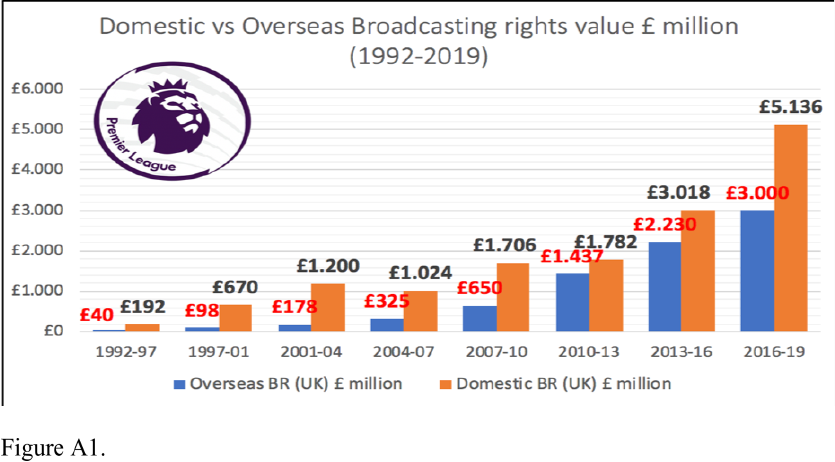

Figure 1 ............................................................................................................................. 50

Increase in value of Premier League Broadcasting rights in millions of Pounds

Sterling. ........................................................................................................................... 137

vii

LIST OF TERMS AND ABBREVIATIONS

EFL English Football League

FA English Football Association

FIFA Federation Internationale de Football

Association

UEFA Union of European Football Associations

1

CHAPTER I - INTRODUCTION

On May 13, 2012, the final day of the 2011/12 Premier League season,

Manchester United and Manchester City went into their final respective games level on

points at the top of the league table. Manchester City were battling their local rivals for

the league title for the first time since 1968, and both Manchester clubs left their London

rivals Arsenal, Tottenham Hotspurs, and Chelsea well in the dust, the closest of them

finishing nineteen points behind. Though the matches started at the same time,

Manchester United’s 1-0 victory over Sunderland finished a few minutes ahead of their

cross-town rivals, who at the time were down 1-2 to Queen’s Park Rangers with five

minutes of stoppage time to play. If the results held, United would be champions, but if

City could mount a late comeback and win, their goal difference would give them the

edge in the final league table. The Citizens had struggled to build themselves up to the

level of their much more successful neighbors, but after a financial takeover in 2008 they

began spending like champions on marquee players to put themselves on the cusp of

history.

In the first minute of stoppage time, Bosnian striker Edin Dzeko scored an

equalizer for City. Immediately the mood shifted in the stadium, and suddenly City’s

dominance late in the game felt vindicated as their efforts materialized on the scoreboard.

The season was not yet lost. QPR were well in their own goal area defending, and looked

like it was only a matter of time before they conceded. Right on cue, with seconds

remaining, Mario Balotelli exchanged passes with Sergio Aguero, who then darted into

the area and smashed the ball past QPR’s helpless goalkeeper, winning Manchester City

2

their first league title in forty-four years. It was a league title four years and over £1

billion in the making for City’s new owners, and they were just getting started.

1

Just moments after United’s match ended they believed they were champions, and

now the giants of the English game were left speechless, forced to witness the beginning

of the end of their dynasty via mobile phone updates. “I swear you’ll never see anything

like this ever again!,” cried match commentator Martin Tyler, who’d been working match

coverage for nearly as many years. “So watch it, drink it in... Two goals in added time for

Manchester City to snatch the title away from Manchester United!”

2

Over on another

channel, commentator Peter Drury voiced similar amazement. “He’s won the league with

90 seconds of stoppage time to play! Where does football go from here?”

3

The Premier

League, now broadcast globally, marketed as “The Greatest Show on Earth,” had

delivered.

The sports world was gasping for breath in its reaction, and even in the United

States, where soccer fever has taken its time to develop, the event was a hot topic. For

late night host Seth Meyers the game was reminiscent of the Boston Red Sox defeating

the New York Yankees and breaking the curse of the Bambino.

4

City played the role of

plucky underdogs who finally turned it around to beat their dynastic rivals. It was truly a

1

David Goldblatt, The Game of our Lives: The English Premier League and the Making of

Modern Britain. (New York, NY: Nation Books, 2014), 173-174.

2

Martin Tyler, “Manchester City vs. Queens Park Rangers.” Sky Sports, Manchester, England:

BSkyB, May 13, 2012.

3

Peter Drury, “Manchester City vs. Queens Park Rangers.” ITV, Manchester, England: ITV, May

13, 2012.

4

Meyers, Seth. Twitter Post. May 13, 2012, 11:00 AM.

https://twitter.com/sethmeyers/status/201703359428820994

3

remarkable turnaround for City, who only a decade earlier were fighting for promotion to

the Premier League. But were City truly underdogs?

The 2008 takeover of Manchester City by Sheikh Mansour and the Abu Dhabi

United Group for Development and Investment introduced state wealth investment,

forever changing the fortunes of the club and football.

5

Within two seasons they were

attracting top up-and-coming talents in the transfer market, offering high wages to

compete with traditionally successful clubs such as Manchester United and Arsenal. By

2012 Manchester City had won the FA Cup and Premier League respectively in

successive seasons, cementing themselves as a competitor in English Football.

6

The

power of investment was undeniably the driving force behind City’s arrival as a Premier

League power, and was indicative of how the sport had evolved in recent years. Soon

after City’s Emirati takeover, members of the Qatari royal family purchased French club

Paris Saint-Germain. In 2003 Russian Oligarch and Vladimir Putin ally Roman

Abramovich successfully purchased Chelsea Football Club. An age of new money had

well and truly begun, and was turning up results for the clubs in question. Significantly,

many of the Premier League’s newest investors were not British, indicating the new wide

reach of English football. Football attracted money for a multitude of reasons, and the

Premier League was at the forefront of a movement that made revenue focused

management the standard in football. It set the standard for lucrative television deals,

attracted the biggest stars in the game with high wages, and sent multiple star-studded

teams into Europe’s premier tournament, the UEFA Champions League.

5

“Manchester City: Timeline of a transformation since 2008 Sheikh Mansour takeover.” BBC,

August 31, 2018.

6

Goldblatt, The Game of our Lives, 175.

4

Any Manchester United loss was rare enough in the Premier League era, but

getting outdone by their local rival was a very new experience for the Red Devil faithful.

Manchester United won thirteen Premier League titles in the twenty seasons after the

inception of the Premier League in the spring of 1992. Manager Sir Alex Ferguson took

charge in 1986 and rarely looked back over his twenty-six year career with the club,

returning the club to familiar heights as one of the best football sides in the world. Not

only this, the era of dominance that Ferguson oversaw made Manchester United the most

valuable sports franchise in the world in 2012, valued at nearly $2.235 billion by Forbes.

7

Only three clubs in England truly challenged Ferguson’s sporting genius and

powerhouse club. The first, Arsenal, was another traditional power of the game which

grew into the Premier League era with grace and style. Their bold decision to bring in

French manager Arsene Wenger in 1996 led to a cultural and tactical evolution of the

club, and their success reinforced the arrival of foreign players, managers, and styles to

the English game. The other two clubs to challenge Ferguson’s United teams were the

aforementioned Manchester City and Chelsea respectively. Both were historically mid-

tier clubs whose fortunes were changed by an enormous injection of money from new,

rich owners.

8

For Chelsea it was Russian billionaire Roman Abramovich, an oil and

television mogul who aided tremendously in Vladimir Putin’s arrival in Russian politics.

For Manchester City it was Sheikh Mansour, a member of the royal family of Abu Dhabi

and Deputy Prime Minister of the United Arab Emirates. Each spent heavily on transfers

with the intent to build title winning sides as soon as possible. The fortunes of both clubs

7

“Manchester United still the world's richest football club.” BBC News, April 19, 2012,

https://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/football/17769654 (November 17, 2020)

8

Goldblatt, The Game of our Lives, 85.

5

were changed overnight by these owners, and they were not alone. Premier League

football attracted a lot of foreign investment, and the reason why was the level of

popularity, profit, and opportunity that it offered its clubs was a level unmatched in any

other league.

Money became the primary driver of modern professional sports in the late

twentieth century, and football was no exception. However, unlike American professional

sports, money was not regulated the same way in England, and before the 1990s

expanding profit was not a driving motivation for most teams. The sport was by no means

young, but the culture of it was not at the exposure level that it has since developed.

Football clubs did what they needed to stay afloat financially, remaining competitive as

best they could within those parameters. Most clubs were majority fan owned, with

perhaps one to a few wealthy businessmen acting as major financial backers. In order to

maintain the stadium experience and match-day revenue, very few games were televised

for much of the 20th century.

9

However, the upkeep of English football by the 1980s

demonstrated to club owners and executives that old methods of club management were

unsustainable. Even the best clubs had trouble maintaining stadiums and quelling fan

violence, and English football’s reputation soured quickly in the mid-1980s. A violent

incident started by Liverpool fans at the 1985 European Cup final at Heysel stadium in

Brussels, Belgium led to the ban of all English clubs from participating in European

competitions for at least six seasons.

10

In a human stampede thirty-nine people were

9

Jonathan Clegg and Joshua Robinson, The Club: How the English Premier League Became the

Wildest, Richest, Most Disruptive Force in Sports, (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing,

2018), 59-60.

10

“English Clubs Bid To Lift Bans,” Aberdeen Press and Journal, June 26, 1985.

6

killed, and hundreds more were left injured. The European Cup, rebranded as the UEFA

Champions League in 1992, was the most sought after prize in club football, and a

competition English clubs had done quite well in for previous decades. Manchester

United were the first English side to lift the cup in 1968, and from the years 1977-1984

English clubs Liverpool (four times), Nottingham Forest (two times), and Aston Villa

(once) won the competition a combined seven times. Despite a historically poor period

for the English national team at that time, the clubs were taking over the world nearly

every year.

11

The ban by UEFA ended that reign, and by the time English clubs re-

entered the competition they were undergoing seismic structural and cultural changes.

The foundation of the English Premier League was a pivotal moment in the sport.

The owners and chairmen of the most successful clubs in the country decided to take it

upon themselves to reform the top flight of the English league system, and through the

financial backing of satellite television, an alliance with the BBC, and approval from the

English FA and players union they successfully broke away from the English Football

League in 1992. They created a league that was designed for profit, expansion of

television revenue, and importantly club governance. Inspired by the National Football

League in the United States, the Premier League based its governance and business

model on the ideals of profitability and club control without many barriers of

accountability. The sport was forever changed in England, and though the football

product increased in quality, a number of issues within the game and its communites

became exposed by the spotlight.

11

“UEFA Champions League: Champions League Winners,” TransferMarkt,

https://www.transfermarkt.com/uefa-champions-league/erfolge/pokalwettbewerb/CL (November 19, 2020)

7

Football became one of England’s most celebrated national pastimes. England

was the birthplace of organized structure in the sport, and became the precedent for the

growth of the game in the nineteenth century to what it became as a global phenomenon.

The pride associated with this was complicated but undying, and the importance of the

Premier League in English culture was reflective of that. The Premier League was the

catalyst for English football’s revival at the club level after the dark decade of the 1980s,

and brought an unprecedented level of talent to England’s shores. The economics behind

the league were crucial, but posed a danger of leaving behind what made the sport

special. At the heart of this topic is a power struggle between these communities and the

club owners that took control of their clubs. Football supporters and the communities

behind players, clubs, and national teams generated a passion that fueled the game to

global conquest, and though globalization came with further complications it remained

impossible for the consumer to be ignored. Despite this, power undeniably shifted away

from the community and toward the wealthy individual owners of clubs, many of whom

were increasingly disconnected from the communities of their clubs. The football

communities are an undeniably important part of England, let alone English football, and

all of the baggage that came with that societal connection was inherently intertwined with

the sport. Their significance within the game could not be forgotten, but whether or not

they had agency within their club became an important factor in their conditional support.

In this thesis I will argue that through commercialization and the formation of the

Premier League, English football transformed economically and culturally in

unprecedented ways. Clubs attracted the best talent in football with higher wages and

elite managers, and played attractive hybrid football that blended English styles with

8

other philosophies, concepts, tactics from around the world. The embarrassment of

Heysel paired with the tragedy of the Hillsborough Disaster in 1989 created a moment of

opportunity in English football, which England’s biggest clubs took by agreeing to break

away from the Football League and form the new Premier league in 1992. The result was

a monumental, and especially profitable sporting venture that gave English clubs

unprecedented financial power through the introduction of television revenue.

Commercialization led revenue focused club and league management to become the

norm in the game of football, and this thesis will examine the ways in which the English

game was impacted by this shift. In addition to the economic effects of the Premier

League, I will study the ways in which the culture, management, and the football itself

were impacted at fan and club levels. Significantly the conditions of commercialization

and the expenses associated with it gave greater value to making football accessible.

Racism and fan violence had to be addressed for the sake of social and financial safety,

which brought England’s long history of racism and xenophobia to the surface of

governance in the sport. The expense of club management in this era also led clubs to

turn to wealthy individuals and investment groups, which in turn established greater

control over clubs independent from the input of supporters. These changes underlined

the significant reach of football culture in England, and how it reflected English society

as a whole.

Literature Review

English and European football has been a source of interest to economists,

sociologists, and historians. One of the most important football historians to this thesis is

Jonathan Wilson. Though Wilson is not a professional academic, he is well respected as a

9

historian of football, and has made major contributions to English football historiography

in recent years, particularly in his ability to tie culture to the game itself. His most

popular work Inverting the Pyramid is a thorough history of football tactics and the ways

in which philosophies of the game spread across the world, taking on new and unique

identities within specific cultural groups, nations, and clubs. This book provides thorough

historical context to the development of the modern European game, and the multiple

pan-European methods that have made their way into the English game.

12

Though the

book was not as relevant to my study of English football as it would be to a wider study,

it was helpful in providing frameworks for viewing the interaction of cultures and ideas

across borders.

Wilson’s Anatomy of Manchester United book was useful to this thesis as well.

The book is disjointed in terms of historical focus, choosing to address certain periods of

club history by focusing on specific matches and the context surrounding them. However,

it offers relevant content through its focus on club issues in the 1980s, 1990s, and twenty-

first century, and its creative writing style and use of sources.

13

The book provides

primary sources for chapter four on Manchester United, and offers insight on the club’s

commercial and cultural transformation in the 1990s and 2000s and the most recent

developments since the Glazer family takeover of the club. Though their tenure was

anything but easy-going, football writers were quick to point out the stability and laid

back approach provided by the Glazer leadership. This massively underestimated the

12

Wilson, Jonathan. Inverting the Pyramid: The History of Football Tactics, (Orion Publishing

Group: London, Limited), 2018.

13

Jonathan Wilson, The Anatomy of Manchester United: A History in Ten Matches, (Orion

Publishing Group: London, 2017),

10

inconsistency that followed on the pitch as well as the inadequate performance of their

Chief Executive Ed Woodward drew a lot of criticism.

14

Another important work of Wilson’s to this project is The Barcelona Inheritance,

a book which frames FC Barcelona’s modern history as an almost familial history.

Wilson argues that though the club has had many separate periods of success, it is unique

for its devotion to a tradition and philosophy that has become almost synonymous with

the club itself and Catalan culture. Tactically managers have changed a bit, but there is

always a focus on the system installed by Johann Cruyff. Cruyff was a star player of AFC

Ajax in Amsterdam and the Dutch national team in the 1960s and 1970s before moving

to Barcelona as a player in 1973.

15

He left in 1978, but returned in 1988 as a manager,

and installed his Dutch tiki-taka system. In addition to his tactical prowess, Cruyff

focused on building up La Masia, Barcelona’s youth academy, by identifying and

developing talent early. This academy produced many successful players, including Xavi

Hernandez, Andres Iniesta, and Lionel Messi, the latter of whom is regarded as one of the

greatest players of all time.

16

This modern history is not unlike that of English club

Manchester United, whose greatest period of success has also happened from the 1990s

to the early 2010s, and whose club structure and culture value philosophy, tradition, and

style. Both commercialization and success have complicated these values, something

14

Simon Edmonds, “Manchester United: Arguments For and Against the Glazers,” Bleacher

Report, September 6, 2012. https://bleacherreport.com/articles/1324651-manchester-united-arguments-for-

and-against-the-glazers-at-man-utd (September 1, 2020)

15

Jonathan Wilson, The Barcelona Inheritance: The Evolution of Winning Soccer Tactics from

Cruyff to Guardiola, (PublicAffairs: New York, 2018), 22-23.

16

Wilson, The Barcelona Inheritance. 58.

11

which Wilson’s perspective covers well, having witnessed much of the game’s modern

developments in his career as a journalist.

17

Wilson's club case study in The Barcelona Inheritance is a useful study of a

specific club and its fan culture over an extended period in the modern era of the sport.

Manchester United is similar to Barcelona in terms of history, success, and following,

and established a particular significance to the English game as well as world football.

My work is similar to Wilson’s in that I try to approach this history of the Premier

League with an understanding of the culture of the game in mind. The significance of

football did not rest solely in its economic value, even as commercialization drastically

increased the economy of the sport. The sport existed for over one hundred years in

England before television money injected a fortune of cash into the game, and though

money became a necessity the clubs and players still rely on supporters and football

communities for patronage and sustainability.

The undeniable influence of money in the Premier League era made economics a

necessary area of scholarship to incorporate into this project, and there was significant

work done by economists in the area which guided my research. Economist Stefan

Szymanksi took specific focus on the growth of commercialization and investment in the

sport over the past few decades. The influence of television money behind this shift

towards commercially driven management and the competitive ramifications of the

money-driven game are both compelling narratives in this thesis as well. Szymanski

identified a social hierarchy in the game, which was not absent from the discourse before

17

Wilson, The Anatomy of Manchester United, xiii.

12

the era of big-money, but was dramatically flipped on its head in the 1990s and 2000s.

Largely unrestricted investment into clubs allowed both the consolidation of power by

certain traditionally successful clubs and the rise of new powerhouses funded by oligarch

billionaires and, in some cases, state investment groups representing royal families.

Books like Money and Soccer and Soccernomics demonstrate Szymanski’s work on the

role of finances in modern football in general, and were hugely influential to this thesis.

Jonathan Clegg and Joshua Robinson’s The Club was another major contributor to

the history of the Premier League from an economic perspective. The book offered a

narrative of the financial developments in English football, unpacking the history behind

the dramatic structural transformations that took place in the early 1990s, the conditions

and tragedies in English football that led to such transformations, and the impact of

foreign and domestic investment into the English top flight. The scholarship on this

subject emphasized Heysel and Hillsborough as primary influences of change in England,

which led to the formation of the Premier League. Clegg and Robinson in particular gave

significance to this period of change as a tremendous economic opportunity for the top

English clubs, which they showed were looking for avenues of modernization and

revenue growth for some time.

18

Their work is an excellent blueprint for studying the

Premier League, but is heavily economics focused. They emphasized the influence of

figures like Rupert Murdoch, one of many financial moguls to profit from the easing of

government restrictions under Margaret Thatcher, was identified for his role, with his

company BSkyB, in deciding to gamble on television rights to the young but promising

18

Clegg and Robinson, The Club, 74.

13

Premier League.

19

The revision of the English top flight from the First Division to the

Premier League was conceived by the executives of the most historically successful clubs

in England, but led by Manchester United and Arsenal Executives, Martin Edwards and

David Dein respectively.

20

The Club also demonstrated the dramatic way in which money

impacted football discourse. This aspect of the game is crucial to its modern

developments, and I argue it is the turn that made the Premier League such an attractive

product to domestic and foreign managers, players, audiences, and financiers. The

Premier League drew some of the largest worldwide television audiences in the history of

sport, and its profit-driven approach from day 1 helped to expand its audience, attract the

best talents with higher wages than almost all continental leagues, and drive foreign

investment in its clubs by billionaires from all over the globe.

21

Clegg and Robinson, both

regular contributors to The Wall Street Journal, have a clear background in economics,

and an even clearer interest in the economics of the sport rather than the culture. Though

this thesis focuses heavily on cultural developments in the history of the Premier League,

the economic perspective and analysis of economic scholars are necessary to this project

for their telling of the history and translation of economic discourse.

Football’s profitability was a driving motivation behind a number of changes to

the league, partially spearheaded by club officials and owners, and was successful in

changing fortunes in English Football both financially and competitively. However, there

is not necessarily a direct correlation between profitability and success, something that

19

Clegg and Robinson, The Club, 31.

20

Clegg and Robinson, The Club, 74-75.

21

Clegg and Robinson, The Club, 236.

14

became far more noticeable as the commercialization of the game continued, nor was

there any longer a distinction between the two, as was believed to be the case for years

before the creation of the Premier League.

22

The issue of racism in football is particularly important to the arguments of this

thesis as well. Racism in English football was significant not only for its effect on fan

culture, but for the relationship between fans and players as football became an area of

society in which racism was actively combated. As questions of football governance

came into the spotlight, so too did the issue of racism, efforts to fight racism, and the

ways in which agents of the game participated in those efforts. Football was a cultural

arena in which England was firmly in the spotlight because of the international reach of

the Premier League and the diverse star personalities that it attracts from around the

world. Scholars like Emy Onuora and Brett Bebber showed how in the closing decades of

the twentieth century England was confronted with its own culture of violence, bigotry,

and nationalism in society and the sport of football, and that football culture became a

vessel for anti-racist activism.

23

Significantly the works of both of these scholars leads

directly into the Premier League era in question in this thesis.

24

The government, the FA,

the clubs, and even the players themselves acted against racism to varying degrees of

success in order to change the image and create a more accessible footballing product.

Works such as Laurent Dubois’ Soccer Empire and The Changing Face of

Football by Les Back, Tim Crabbe, and John Solomos also gave greater context to a

22

Stefan Szymanski, “Why is Manchester United so Successful?” Business Strategy Review. 47.

23

Onuora, Emy, Pitch Black, (London: Biteback Publishing Ltd, 2015), 23.

24

Bebber, Brett, Violence and Racism in Football, (London: Pickering & Chatto Limited, 2012),

190.

15

complex history of racism,postcolonialism, and national identity in European football.

Dubois, a historian of the French Empire, contributed to the historical scholarship in

modern football by analyzing the strong, and often tense relationship between the French

national team stars and French nationalism in politics and the press.

25

As the French team

began to more and more visibly resemble the diversity of France, so too did it endure the

unwanted attention of the National Front and racism and islamophobia. This work offers

an important parallel to my own study of the way black and foreign players dealt with

abuse and criticism in England, as well as using the English press as a source for

measuring public discourse. Dubois studied players whose experiences were unique to

France and the French public, but his discussion of the sport in regards to the legacy of

imperialism and the ties between the sport and political activism are both relevant in

England as well.

Back, Crabbe, and Solomos similarly addressed issues of national identity, race,

and football culture, but this sociological work examines cases within the English game.

26

Sources included fan articles, newspaper coverage, club songs, and official policy on

racism and hate speech at football grounds.

27

Football was almost exclusively a white-

male dominated spectacle in Britain for much of the 20th century, and as the sport

evolved attempts were made to make the environment safer for other demographics and

families. The issues of identity and expression within public rituals is crucial to the

cultural aspect of this project, and this book and other sociological studies are a useful

25

Laurent Dubois, Soccer Empire: The World Cup and the Future of France, (Oakland, CA:

University of California Press, 2010), 14.

26

Les Back, Tim Crabbe, and Jon Solomos, The Changing Face of Football: Racism, Identity,

and Multiculture in the English Game, (Oxford: Berg Publishers, 2001)

27

Back, Crabbe, and Solomos, The Changing Face of Football, 289.

16

source of data on the social arena of football. These works include surveys and statistics

on racism and abuse, as well as accounts of player and fan experiences. For a topic with a

young historiography, sociological literature was particularly helpful in establishing links

between the culture of the game and broader social issues.

Sources

The sources utilized in this thesis vary greatly, from government legislation to

match commentary, but a significant and repeated source was press reports. The common

saying “journalism is the first rough draft of history” is especially applicable to sport, and

its meticulous documentation was immensely helpful in the assembly of the history of the

Premier League and editing of timelines. Crucially, reports also helped to offer insight

into the sport and major events. This was particularly useful, especially in pieces that

reflected on events some time after the fact. Some of these reports usefully feature

supporter-written opinions and blog posts. These primary sources and the secondary

source literature make up most of the sourcebook for the project.

In addition to analysis of supporters and the press, there is a specific section of

source analysis of films produced by or in association with Manchester United. I use

these films to critically unpack the club’s conscious construction of club identity and

history. Though the films in question could be used as secondary sources, documentary

creations after the fact of the history in question, I mostly utilize them as products of the

extended period of time in question. For example, the Class of 92 documentary film

produced in 2013, tells the story of Manchester United’s most successful group of

academy graduates, including star talents Ryan Giggs, Paul Scholes, and David

17

Beckham.

28

The film featured a number of key interviews, including former Prime

Minister Tony Blair, as well as a clear expression of the club values that molded

Manchester United’s era of success. The presentation of this documentary, I argue, serves

as a useful source for understanding how the club consciously embraced a certain image

of its history and culture. The club bought into a positive, almost mythical reputation of

itself that persisted in that time period, and utilized multiple forms of media to perpetuate

said reputation as an iconic and constant power in the English game. In addition to

nation-wide and European-wide dominance, the films demonstrate how significant the

production of local talent is to the club identity. The films are conscious of a “never say

die” mentality that became synonymous with the club. It is clear that Manchester United

view their history of comeback wins in big games, late title races, and dramatic cup runs

as emblematic of their identity.

29

This image was pushed often as well, symbolically

linking itself to its history as a working class club, and even the club’s recovery after the

tragic Munich Air Disaster claimed the lives of many club officials and first team players.

Chapter Structure

In the first chapter I explore the establishment of the Premier League, the

economic changes in English league football behind the move, and the revival of English

clubs as a competitive force in European football as a whole. One of these major

economic changes was the introduction of television broadcasting. Prior to 1990 it was

highly irregular for professional football games to be televised live in England. Apart

from major finals and perhaps the English national team, most audiences were generally

28

Leo Pearlman, “The Class of 92.” DVD. Directed by Ben and Gabe Turner. (London: F73

Productions, 2013).

29

Pearlman, “The Class of 92.”

18

limited to one live game, replays, and Match of the Day, an end of the day condensed

highlights show on the BBC. This system was in place primarily to keep up the match-

day revenue that came with offering an exclusively in-person experience to fans. In 1992

the clubs in the English First Division left and formed the Premier League, with the

English FA’s backing, and signed a lucrative TV contract with Rupert Murdoch’s Sky

Sports channel on BSkyB satellite television, removing English top flight club football

from terrestrial television.

30

The deal was considered by economic historians to have

been a high risk-reward move that paid off big for BSkyB, and it led to even more

lucrative television deals domestically and internationally. I show how television revenue

guaranteed Premier League expansion to overseas markets in the age of burgeoning mass

communication. This expansion helped to boost popularity of English football, clubs, and

players and increased club revenue to unprecedented heights.

The increase in wealth within the game also persuaded more and more wealthy

individuals to bankroll team expenses as the majority owner, funding higher player

transfers and wages as the market continued to inflate. However, the increase in the

Premier League’s wealth also created an immense wealth gap in the English football

league pyramid, meaning there was more financial risk for clubs that were relegated from

the Premier League. There was also a more difficult path for promotion to the Premier

League for clubs in lower divisions. As was the case for Leeds United, the financial stress

of staying competitive at a Premier League level was too great for some clubs. Entering

30

Clegg and Robinson, The Club, 414-415.

19

administration and declaring bankruptcy led to points deductions and penalties for some

clubs, exacerbating dire situations that sent some clubs to the brink of dissolution.

Chapter two unpacks the issue of racism and xenophobia in English football,

which had an ugly reputation for fan violence, hooliganism, and white nationalism in the

twentieth century. This fostered a sour relationship between fans, players, and authority

in the game such as the government, the police, and even the clubs themselves. It became

clear that to reform the sport in Britain there would also need to be a reformation of the

spectator, something which is expressed by players themselves and members of the press.

While in the first chapter these reforms were more legal and structural, the second

chapter explores cultural changes in football communities. Some players took matters

into their own hands, kicking out against racism and xenophobia in both literal and

figurative cases, and participating in anti-racism activism and campaigns. The arrival of

foreign players and managers meant that the English game was more diverse than ever

before. I argue that these changes were an integral part of English club football’s

competitive revival in the 1990s and 2000s, and that efforts at social reform to combat

fan violence and racism were heavily motivated by the need to make the sport more

accessible to the league’s increasingly diverse players, managers, and audience. Although

the government enacted policy to combat hooliganism, this chapter shows the influence

of activism in the sport by anti-racist organizations, supporters, and footballers, as well as

the effects of multiculturalism and expanded diversity in the Premier League.

While these efforts and increased regulation of fan culture did quell fan violence,

and created a more accessible and safe football culture and stadium environment, there

were also complications with the relationship between fans and authority. With greater

20

investment into teams came the necessity of wealthy backers, and the interest of wealthy

owners did not often call for greater power to supporters’ trust and minority fan

ownership. Wealthy owners consolidated their power by conducting forceful buyouts of

minority shareholders, and the landscape of football communities has been reshaped by

the necessity of money and investment. The importance of wealth led to a shift from fan-

focused styles of ownership, which created a cultural crisis among fan groups. There

became a greater concern about the influence that supporters had in the football economy

as owners acted individually and took power away from fan ownership groups. This

development played out in various ways that are relevant to the final chapter concerning

ownership changeover in the Premier League era, and specifically the effects of such

changeover at the behemoth football club and global brand that is Manchester United

Football Club.

The final chapter shifts the focus of the study to the club level, examining the

effects of commercialization at a top flight English club. It was in fact clubs that led the

formation of the Premier League, and the richest clubs at that. For this reason I will

examine the Premier League’s clubs in general, but focus on Manchester United in

particular. Manchester United were the most successful English top flight team of all

time, and one of the biggest sports franchises in the world. With an estimated 659 million

supporters worldwide from a study conducted in 2012, their global appeal paired well

with their history as a pioneering club in English football before and after the creation of

the Premier League.

31

The most successful era in the club’s history occurred in the 1990s

31

Ed Prior, “Do Manchester United really have 659m supporters?” BBC News, February 18,

2013. https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-21478857 (November 6, 2020)

21

and 2000s under the leadership of Sir Alex Ferguson. The club built strong teams year

after year by utilizing their financial power and appeal in the transfer market to attract

stars from all over the world. Adding to their success and legacy was their world class

football academy, which developed some of the best youth talent into star professional

players. Among these talents was David Beckham, a generational English talent who

became one of the most recognizable celebrities in the world. He was a member of the

“Class of 92,” which featured 5 other United academy products that helped form the

backbone of the squad for decades, and played a hybrid style of English football that

allowed for more individual creative expression that became synonymous with the club

and culture.

32

As the Premier League marketed itself as the greatest show on earth to a global

television audience, Manchester United’s sustained success and starpower made them a

must-watch team. Though clubs like Arsenal and Chelsea achieved periods of success,

United remained a constant in the English game, winning the league title 13 times in the

first 20 years of the Premier League. However, after the retirement of Sir Alex Ferguson

the club’s performances drastically dipped, and the incompetence of the executives in

team management under the Glazer ownership became much more apparent. For this

reason the club is an excellent case study with a multi-layered modern history and

sustained relevance in the age of big money. They were a club with undeniable financial

and historical credibility, but also a club which was limited in many ways as it attempted

to form a new identity post-Sir Alex Ferguson. Manchester United became a global entity

32

Pearlman, “The Class of 92.”

22

as well as a football team, and capitalized on its historic success to much economic gain,

even as performances dipped. This brought positive and negative consequences, as the

club was able to cement itself at the highest level and maintain its high level of talent, but

at the same time complicated its cultural fabric and legacy. Fallout of club corporatization

even alienated some of United’s fans, a section of support which broke away and formed

a new football club entirely. I explore the impact of commercialization in football culture

at the fan and player levels, and examine the implications of commercialization inside

and outside of football grounds. Dramatic economic changes had a widespread impact on

the culture of the game as well as the game itself. Manchester United grew with their

success, cemented themselves as an iconic representation of their culture and maintained

an important relationship with their community and fans. I argue the Glazers takeover

upset that balance between the club and the local community, and that through protest

fans tried to maintain influence in a market they had increasingly less control over. The

fan culture in England experienced a re-working similar to the scale of the economics,

and with similar motivations as well.

Like much of British society, class was enormously influential in the development

of clubs in the early days of the organized game. Manchester United was founded by

workers of the Lancashire-Yorkshire Railway workers’ union in the late 19th century,

and maintained a strong tie to labour culture in arguably the most influential city of the

Industrial Revolution.

33

The takeover by American billionaire Malcolm Glazer in 2005

sparked protest from many local supporters, as well as debate amongst fans over the

33

Wilson, “The Anatomy of Manchester United.”

23

identity of the club and its connection, or lack thereof, to the people of Manchester. One

section of supporters broke away from the club entirely to start a new club at the bottom

of the English league system. Paired with the club’s growth of support across the world,

the modern era of commercial success was juxtaposed with an identity crisis among

supporters who suddenly questioned whether the club was still the same one they’d

supported for so long.

24

CHAPTER II – AN END IS A START: THE FORMATION OF THE PREMIER

LEAGUE

There was a dramatic power shift in the institutional control of English football in

the early 1990s. The English Football League’s First Division had lost traction with clubs

because of its restrictive measures and lack of entrepreneurship. For decades, the nation’s

top professional football clubs had been on a trajectory of strength and success in the

game itself, but this did not reflect in the financial well-being of English clubs. In this

chapter, I will demonstrate that many of England’s biggest clubs, especially Manchester

United and Arsenal, were conscious of this, and made efforts to maximize their revenue

and to influence the governing structure of English football in order to create a new top

flight division, the English Premier League. This shift among the clubs at the top of the

game laid the groundwork for transformational restructuring of the English top flight and

had a lasting impact on the sport as a whole. These changes and the people who pushed

for them were aided by club commercialization and evolving understandings of the

football economy and regulation, including the impact of severe and tragic stadium

incidents. Football governance in England became more focused on economic growth

and sustainability, and the result was a well-oiled, commercially driven football product.

The Premier League became one of the most followed sporting leagues in the

world, and took over at an advantageous time in the rise of the digital age. Mass media,

the internet, and international television broadcasting all aided the Premier League in

becoming a sporting superpower. English football clubs were not always run in such a

capitalistic way, but the structure of the English league system is quite reminiscent of a

free market hierarchy. Unlike professional leagues in the United States, teams were not

25

guaranteed a spot in the league for the next season. Teams compete for a league position

every year, and the teams that finish in the bottom three to four spots in every league

division were relegated to the division below. At the top of the league table, the top three

to four teams from the lower divisions below got promoted every season. The system is

referred to as the Football Pyramid, and was the basic structure of league football

throughout the world, with Major League Soccer in the United States being a notable

exception.

The inception of the Premier League and its replacing of the old First Division did

not dismantle the English Football Pyramid. There remains a promotion/relegation

system, which maintains a strong link between the professional and semi-professional

leagues. This link is crucial for keeping small-town football clubs alive, even if a path to

the top is not easy. The sponsorship, partnership, and television deals that the reformation

allowed for increased revenue for the leagues and clubs at an unprecedented rate.

However, as I will explore in this chapter, the reformation led to a greater wealth gap

between the Premier League and lower divisions, and created an enormous financial

advantage for clubs that stay in the Premier League safely for an extended period of time.

While the Premier League enhanced the financial stability of clubs at the top of the

pyramid the wealth did not trickle down, and the drop off of relegation came with an

even greater penalty that threatened the existence of some clubs. The clubs that benefited

most from the system were the very same that led efforts for its creation, and the shift

towards commercialism in the sport aided the consolidation of power by these clubs over

England’s top competitions and qualification spots for European tournaments.

26

The chapter will also demonstrate that although the Premier League era began

because of financial motivations by club owners and executives, the situation that

allowed for its creation was one of tragedy and social disorder. English football had a

problem with hooliganism that boiled over in multiple ugly instances, attracting the

attention of the British government. Margaret Thatcher and the Conservative Party in the

1980s were intent on addressing hooliganism, and incidents such as the Heysel Stadium

Disaster in 1985 and the Hillsborough Disaster in 1989 furthered calls for reform in

England’s national pastime. Government interference prompted mixed reception, but

created the opportunity that club executives desired to break away from the football

league and create the Premier League.

The Heysel and Hillsborough Incidents and the Transformation of English Football

There are two key events that influenced a more economic and capitalistic

approach to managing clubs and, eventually, the league as a whole. The first was the

Heysel Stadium Disaster at the 1985 European Cup Final in Brussels, Belgium. Liverpool

was the perennial champion of both England and Europe in the 1970s and 1980s, and

were set to play in yet another European Cup Final at the end of the 1984/85 season.

Their opponents in the 1985 European Cup, Italian giants Juventus, were underdogs,

expected to fall to yet another English champion. Before the match however, an

altercation broke out between sets of Liverpool and Juventus fans.

The opposing fan sections were divided only by a small chain link fence and a

thin line of Belgian police. Liverpool supporters, the instigators of the incident, began

throwing flares, rocks, and chunks of concrete that littered the deteriorating stadium.

Liverpool fans tore at the barriers as well, and eventually many of them broke through the

27

barrier and charged at the Juventus supporters.

34

A riot ensued, and many fans crushed

each other against barriers as Liverpool supporters poured into the Juventus section.

Many fans forced their way out of the stands entirely and onto the track surrounding the

football pitch, but were met by Belgian police who were waiting to attack them. The

assumption by authorities was that a pitch invasion was taking place, but a much more

troubling and violent attack exploded. A portion of the Juventus stand collapsed, and as

fans attempted to escape the chaos, many trampled or crushed each other. In total, there

were thirty-nine Italian and Belgian fans killed with hundreds more injured because of

the riot and collapse started by violent Liverpool supporters.

35

Police, stadium officials, and fans shared the blame for the disaster, but Liverpool

supporters, and English fans in general, bore the most of the blame. In total, twenty-six

Liverpool supporters faced charges for their role in starting the stadium riot.

36

The only

extraditable charge that could be levelled against them was manslaughter, but additional

charges of assault were added upon their arrival in Belgium. The court convicted fourteen

fans of charges for manslaughter and assault, and handed down three-year sentences.

37

A

handful of stadium officials were charged as well, and the poor upkeep of Heysel

Stadium started a dialogue on the serious danger that crumbling stadium infrastructure

posed to fans. Officials were well aware of the poor state of Heysel stadium, something

accentuated by the chunks of concrete littering the stands of the stadium. These were

34

Jamie Jackson, “Heysel: The Witnesses’ Stories,” The Guardian, April 3, 2005,

https://www.theguardian.com/football/2005/apr/03/newsstory.sport (October 14, 2020).

35

Jackson, “Heysel: The Witnesses’ Stories.”

36

“All 25 Liverpool Supporters Formally Charged in Connection with the Heysel Stadium

Disaster,” Liverpool Echo, September 10, 1987.

37

Jackson, “Heysel: The Witnesses’ Stories.”

28

even used as projectiles by both sets of fans, and perhaps a symbol of the dramatic decay

in the sport and culture both literally and figuratively.

Though Heysel did not happen in England, it was a full display of the problems in

English football that absolutely had to be addressed in the immediate years after. The

English government saw this, and noticed the inaction of the English FA and Football

League in the wake of this disaster. The question of government intervention was raised,

and later in 1985 Parliament voted for football fan-focused legislation, The Sporting

Events Act of 1985, which limits the sale and consumption of alcohol in football

stadiums. The act specifically addresses the consumption of alcohol within sight of the

football pitch, and states the crime is even punishable with prison time, depending on the

severity.

38

This is clear evidence of the concerns in England about football issues being a

public safety issue. The consequences of the Heysel Disaster were deemed necessary by

the Tory government especially, who through legislation demonstrated an eagerness to

prevent and punish future incidents to greater effect. Despite the effects that the clubs

knew would come, there was little doubt among directors and board members that

English football needed a culture change.

There was an established reputation amongst English football fans for

hooliganism dating back to the 1950s and 1960s.

39

Alhough there were no incidents to

the scale of Heysel, many clubs, and even the English national team, were followed by

football firms. Football firms were essentially gangs of supporters that provoked

38

Sporting Events (Control of Alcohol etc.) Act 1985

https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1985/57/contents (November 5, 2020).

39

Bebber, Brett, Violence and Racism in Football, (Pickering & Chatto Publishers: London,

2012). 14.

29

altercations with each other and the police or other stadium security/authority, all in the

name of supporting their team. Teams across Europe were followed by firms, but the

culture thrived in Britain in the second half of the 20th Century. Though some only

sought to follow the club, others were used as vessels for neo-Nazi and far-right white

nationalist demonstrations. By the 1980s the culture had gotten out of hand. Fighting

inside and outside football grounds, stabbings and gang attacks, and even rioting were

responsible for making football a public safety issue. Heysel was not the first major

incident of hooliganism in 1985, and Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher set up a

committee earlier that year for the purpose of combating hooliganism at football

grounds.

40

A riot in London after a Luton Town vs. Millwall match the same year

prompted the move by Thatcher, and this would not be the last time the government

would have to get involved in the governance of the game.

Hooliganism from British supporters of English clubs was tolerated without

significant action for some time, but the Heysel Disaster was also the last straw for

UEFA, the governing body of European football. The organization passed down a five-

year ban from European competitions to all English clubs, which remained in place until

the 1990/91 season for the UEFA Cup and European Cup Winners’ Cup, and 1991/92 for

the European Cup.

41

The European competitions ban seriously impacted the longterm

40

“Conservative Governments and Football Regulation.” Urban75.

http://www.urban75.org/football/after3.html (November 19, 2020).

41

Liverpool were league winners for the 1989/90 season, but did not participate in the 1990/91

European Cup due to an additional year added to their ban. Liverpool were the club who were deemed the

perpetrators in the Heysel Disaster, and were prevented from being the first English team to compete in the

competition again. Arsenal would compete the next season as defending league champions from the

1990/91 First Division. Aston Villa participated in the 1990/91 UEFA Cup, and Manchester United won

the 1990/91 European Cup Winners’ Cup, becoming the first English club to win a European competition

post-Heysel.

30

competitiveness of English clubs in Europe. It would be several years before English

teams would come close to replicating dominance in Europe that was on display nearly

every season in the 1970s and 1980s. From 1990 it would be nearly a decade before

Manchester United became the first English team to once again win the European Cup,

rebranded as the UEFA Champions League in 1992.

42

The second of the key stadium disasters to transform the future of English football

was the Hillsborough Disaster, a stadium collapse incident that occurred at an FA Cup

Semi-Final match between Liverpool and Nottingham Forest on April 15, 1989. The

match took place at Sheffield Wednesday’s Hillsborough Stadium in Sheffield, England,

where an overcrowded standing section of the west stand collapsed. Over three thousand

Liverpool fans were crowded into their designated section behind one of the goals. The

listed safety capacity however was around two thousand, but should have been listed

around one thousand-six hundred according to the Taylor Report.

43

South Yorkshire

Police and even Liverpool goalkeeper Bruce Grobbelaar noticed fans packed tightly

against the fenced barrier asking for help, but it was not until after the section collapse

that it became clear to police that something had happened. Many people died of

asphyxia before the stadium collapse had occurred because of the severe overcrowding

that pushed the front rows of fans forward against the fence and barriers.

44

The stampede

42

“UEFA Champions League: Champions League Winners,” TransferMarkt.

https://www.transfermarkt.com/uefa-champions-league/erfolge/pokalwettbewerb/CL (November 19, 2020).

43

“How the Hillsborough Disaster Happened,” BBC News, April 26, 2016,

https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-

19545126#:~:text=Police%20errors%20caused%20a%20dangerous,the%20stadium%20contributed%20the

%20disaster. (October 28, 2020).

44

Lord Justice Peter Taylor, “Lord Taylor's final report on the Hillsborough stadium disaster,"

London, 1989, 52.

31

that followed after the collapse caused even more deaths and injuries from crushing. Fans

poured through holes in the fencing and barricades separating them from the pitch, and

turned back to help those trapped and injured climb out of the pile however they could.

Police stopped the match and allowed fans onto the pitch when the situation became

clear, but by then much of the damage was done.

In the Hillsborough Disaster, ninety-six Liverpool fans died, prompting a

thorough investigation by football and government authorities into the causes, both

human and structural. The entire footballing community mourned the disaster and the

pain football fans suffered because of the incompetence of the South Yorkshire Police

and the misinformation campaign pushed by law enforcement and government officials

which blamed Liverpool supporters for the incident.

45

Hillsborough sent shockwaves through English football, and justifiably became a

cornerstone moment in the evolution of the sport in England. Economists Jonathan Clegg

and Joshua Robinson describe the Hillsborough Disaster well in their history of the

English Premier League, The Club. They write:

[Hillsborough] was more than the deadliest stadium catastrophe in British history.

It was a calamity that has blighted the lives of thousands; led to more than two

decades of smears, cover-ups, and outright lies by culpable authorities; and raised

45

David Conn, “ Duckenfield admitted trying to blame fans for Hillsborough, court told,” The

Guardian, October 31, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2019/oct/31/duckenfield-admitted-

trying-to-blame-fans-for-hillsborough-court-told

32

a series of deeply troubling social, political, and economic questions. To this day,

Britain is still grappling with the fallout.

46

Hillsborough impacted football in a number of ways, others of which will be discussed in

the next chapter, but one immediate impact on the footballing economy was the demand

for stadium restructuring. The Taylor Report, published in January, 1990 by Lord Justice

Peter Taylor upon his investigation into the disaster, cited a number of safety hazards that

played a role in the deaths and injuries at Hillsborough, including mismanagement by the

South Yorkshire Police and stadium structural failure.

47

New safety measures passed by Parliament, the Football Licensing Authority, and

even language from the Taylor Report began a stadium reformation era, and a transition

into all-seating stadiums. Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and the British government

took the opportunity to get involved where the FA did not, and passed sweeping

legislation addressing problems of both Heysel and Hillsborough. Even before the Heysel

disaster in 1985 there was debate in the House of Commons about quelling crowd

violence, with an emphasis on protecting police officers. One Tory MP reported the

Metropolitan Police alone had sustained 83 injuries during the 1984/85 season, with

several requiring hospitalisation.

48

Parliament passed the Football Spectators Act later in

1989, which introduced a number of legislative measures, restrictions, and definitions in

46

Jonathan Clegg and Joshua Robinson, The Club: How the English Premier League Became the

Wildest, Richest, Most Disruptive Force in Sports, (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing,

2018), 76.

47

Taylor, 95.

48

MP Giles-Shaw, “Football Hooliganism,” Hansard, 66. Volume 76: debated on Thursday,

March 28, 1985. https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1985-03-28/debates/488e0a44-2eee-405a-b103-

76a1141108b8/FootballHooliganism

33

English football. “Violence” and “Disorder” at or around a football match became a

criminal offense, which could result in a banning order and prison time, depending on the

severity of the crime. The act also gave definition to “Disorder,” which included the use

of threatening language, display of threatening language, or targeted hate against specific

groups of people, and specifically outlined “racial hatred” as an offense.

49

Police were also given power to designate a crime as a “football related offence”

if the crime occurred within twenty-four hours before or after a match, as long as there

was sufficient evidence the perpetrator was associated with a football match or football

gang.

50

Spectator violence was specifically defined as violence against “persons” or

“property,” which turned some heads when it was enacted after Hillsborough, which was

not an incident of fan violence.

51

Police notably dodged responsibility for the disaster

despite the conclusions of the Taylor report, and fed a misinformation campaign in the

press. Tabloid paper The Sun ran a story claiming sensationalist and untrue allegations of

hooliganism during the disaster. A large headline reading “The Truth,” was followed with

outrageous allegations that claimed fans “picked pockets of the victims,” “urinated on the

brave cops,” and “beat up PC giving kiss of life.”

52

The feature, published just four days

after the disaster, was later deemed false by an independent inquiry into Hillsborough, an

inquiry which ruled the police and local government had worked extensively to cover up

49

Football Spectators Act of 1989, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1989/37 (October 30,

2020).

50

Football Spectators Act of 1989.

51

Football Spectators Act of 1989.

52

“The Truth,” The Sun, April 19, 1989, 1.

34

their wrongdoing in the disaster by encouraging a smear campaign against the victims

and survivors to paint them as drunken hooligans.

53

Newspapers at the time seemed to understand the British government’s

involvement in the matter as a direct reflection of Thatcher’s interest in Britain’s image

abroad, and not an interest in improving football. Her legacy in football is associated

directly with the legacy of Hillsborough, and the ugly way in which she painted football

fans. She was hesitant to show support to the Taylor report because of the blame it placed

on police, and believed it could encourage more aggressive behavior from Liverpool fans

towards authority.

54

The Sunday Independent described her push of the Spectators’ Bill in

1989 as “duplicitous,” implying her involvement in football was a noble but misguided

attempt to combat a serious problem in the game.

55

Thatcher and Parliament’s responses

focused on the violence specifically, which showed an urgency to prevent further

displays of public hooliganism. Concerns about cultural decay in football through

hooliganism were, however, shared by administrators of the sport. Club chairmen at First

Division clubs had long sought an excuse to reform stadiums and increase matchday

revenue, and discussions had already taken place regarding sale of television rights as a

way to fund stadium renovation.

56

Leaders in the top league of the sport took the situation

53

Owen Gibson and David Conn, “New Hillsborough inquest likely after damning report,” The

Guardian, September 13, 2012. https://www.theguardian.com/football/2012/sep/12/hillsborough-disaster-

inquest-prosecutions-report

54

Paddy Shennan, “Margaret Thatcher: Her role in the aftermath of the Hillsborough disaster,”

The Liverpool Echo, May 7, 2013. https://www.liverpoolecho.co.uk/news/liverpool-news/margaret-

thatcher-role-aftermath-hillsborough-3416839

55

“Thatcher’s Folly,” The Sunday Independent. November 5, 1989. 1.

56

Clegg and Robinson, The Club, 74-75.

35

seriously, and the FA, Football League, and clubs all complied with the change in

governance.

For big, wealthy clubs like Manchester United and Arsenal, the news of new

stadium regulations and upkeep measures was in a way quite welcome. Martin Edwards,

the majority owner and club chairman of Manchester United, and David Dein, club

chairman of Arsenal, wanted to run their respective clubs with more attention to business

and free enterprise. To improve their product, they needed to create a safer, more

enjoyable stadium experience that attracted higher attendance and matchday spending.

Dein in particular was absolutely disgusted by the state of Highbury Stadium, which did

not even feature a proper bathroom.

57

All-seated stadiums did, however, require

renovation and out of pocket expenses that many lower league clubs could not afford.

This raised more questions about the responsibility of the league and football governing

bodies to aiding clubs that could not meet the new regulations while other clubs were

able to simply rebuild huge sections of their stadium, or even fund a new stadium

altogether. Lower league sides campaigned for a relaxation of the policy that allowed a

stadium transition within their budgets, and eventually the government agreed to

subsidize a portion of stadium conversions.

58

Such involvement by the government in

football was unprecedented, but the new policies were successful in preventing

overcrowding and crushing incidents. They also allowed for tighter regulation of fans

57

Clegg and Robinson, The Club. 53-54.

Stadiums in the 1980s were an abysmal place for everything other than football. Instead of a bathroom

there was often only a trough or a ditch dug in the ground. Even Wembley Stadium, the home of the

English national team and numerous FA Cup, League Cup, Playoff, and European finals, waa demolished

at the turn the century.

58

Clegg and Robinson, The Club. 75.

36

entering the stadium, sectioning for potentially disruptive and violent supporters’ groups,

and a gradual increase in ticket prices as clubs looked to maximize matchday revenue.

Heysel and Hillsborough were tragic events that rocked English football to its

core. These incidents brought a number of long-festering issues within the English game

into the spotlight, and the British government’s involvement highlighted the severity of

the situation. Historian David Goldblatt argued in his book The Game of our Lives that

the English FA was largely absent from football governance since its inception in 1863,

which resulted in a serious crisis for the survival of the game.

59

The tragedies and

hooliganism brought the mismanagement into public safety discourse, and the FA faced a

reckoning in the 1980s. The government stepped in where the FA did nothing, and after

over 100 years of being left to its own devices, Parliament began taking a serious interest

in public policy concerning football. “[The FA’s] autonomy from both political and

economic power was crumbling,” Goldblatt writes. “Hillsborough and its judicial

aftermath drew the entire football industry into an extended and now semi permanent

relationship with the state.”

60

In the late 1980s English football entered a period where