Rie's Memoirs

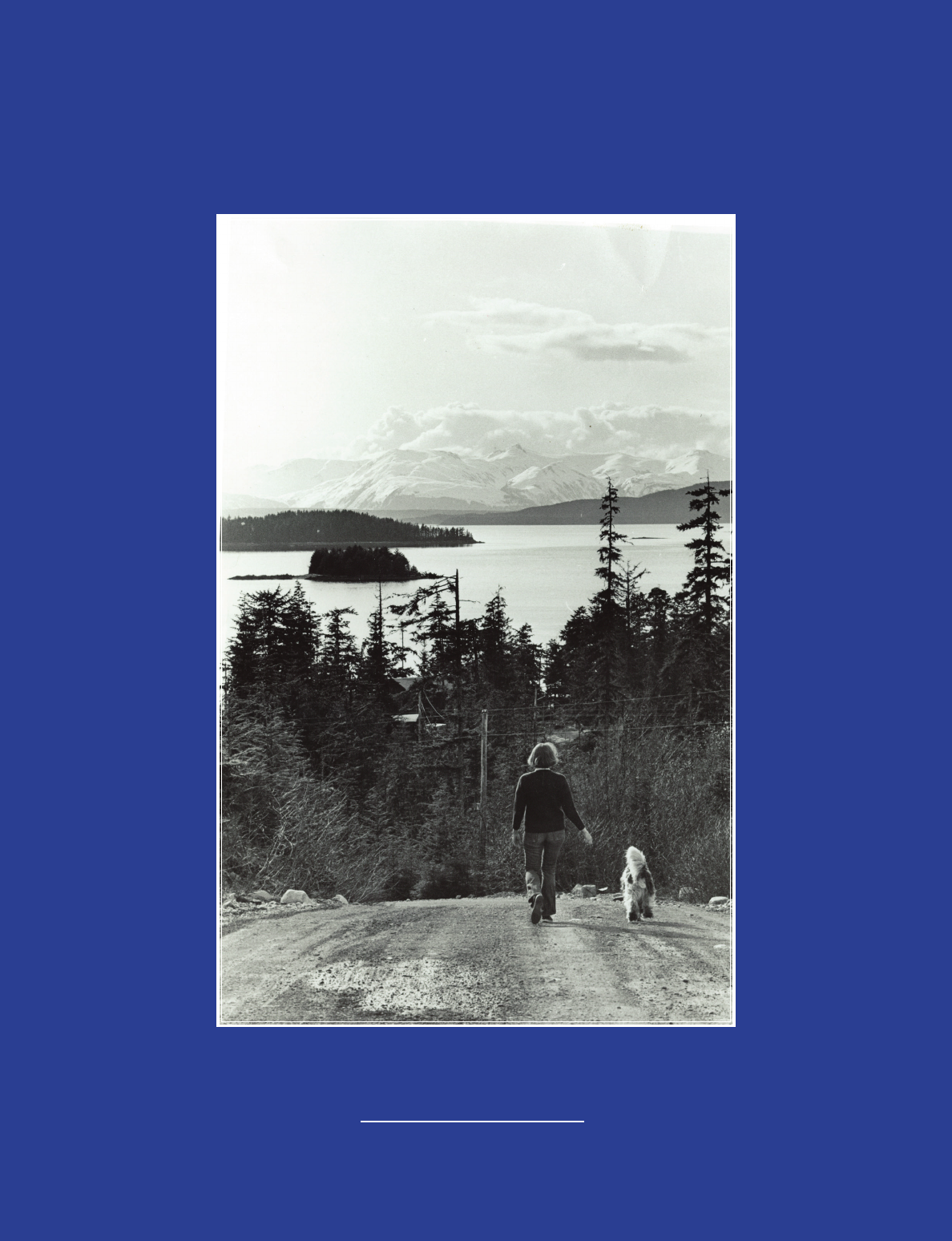

RIE MUÑOZ

8/17/1921 - 4/6/2015

Rie’sMemoirs

BY RIE MUÑOZ

I was born in Van Nuys, California on August 17, 1921, of Holland

Dutch parents. My father, Pierre Jean Jacques Mounier, and my mother,

Maria Engelina Christina Reynders Mounier, were both born in Holland. My

dad worked for a Dutch magazine and traveled often to the U.S. for extended

periods of time. My mother told me that when I was six weeks old they

carried me to Holland in a wicker basket. She also mentioned that around

that time sanitary napkins had been invented in America. So, along with me,

she brought back several boxes of Kotex. When she went through customs in

Rotterdam, the official asked her, “What are these?” She blushed so intensely

that he asked no further.

My very first memory is of Holland—being pushed through the snow by my

mother in a perambulator with runners instead of wheels. e moon shone

through the trees. Another early memory, also in Holland, is of waking up

suddenly, my mother at my bed, frantically fussing with my bedding and

calling out to my father in the living room, “ere’s a mouse running over her

face!”

I have vague memories of falling out of a neighbor’s tree and of voyages

across the Atlantic on steamships. When we were little kids we were served

our dinner meal several hours before the adults. Presumably, we were put to

bed or maybe to a playroom, supervised of course.

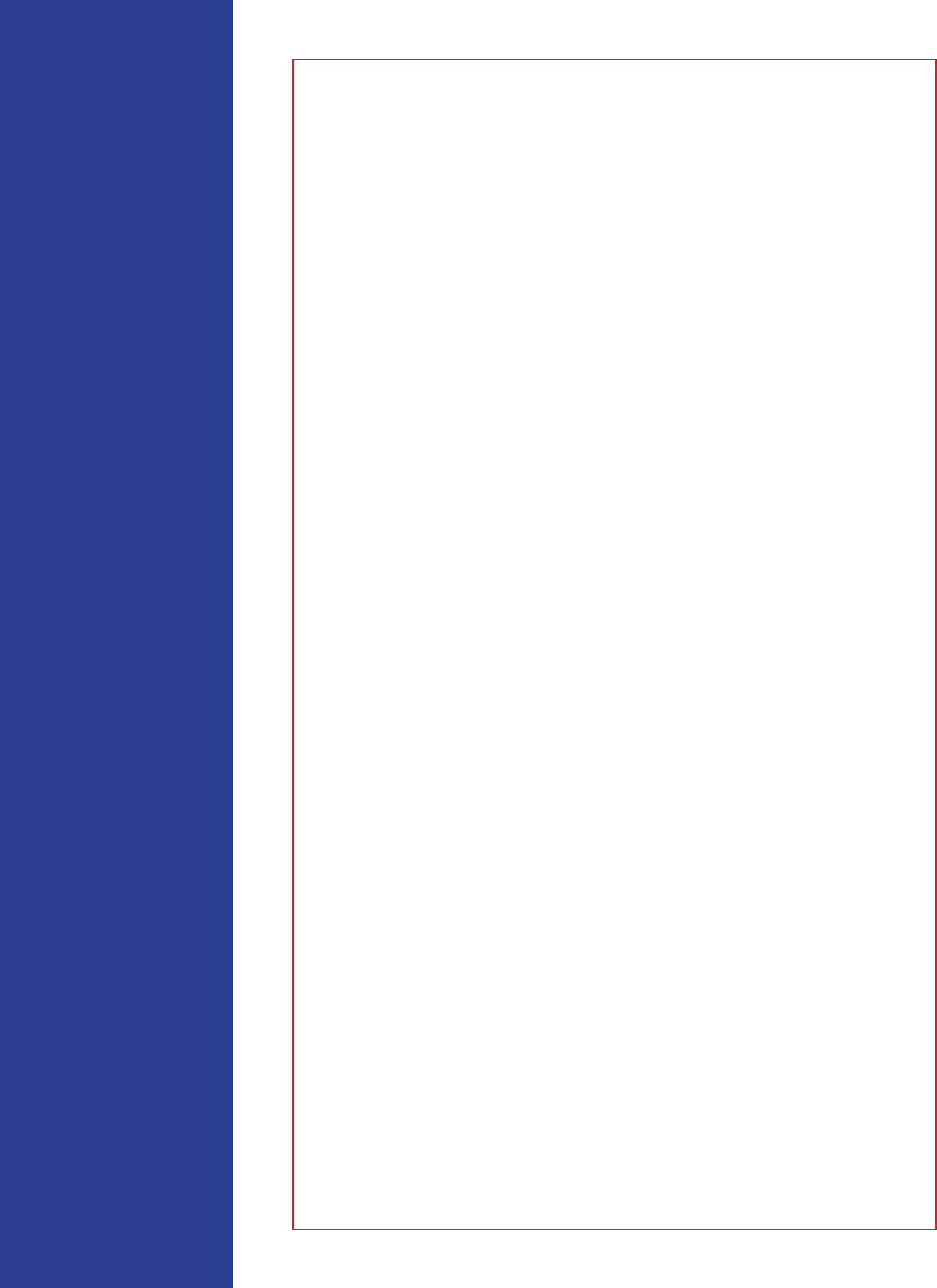

Rie with brothers Piet and Frits

2

Rie’sMemoirs

My father was a good artist, even though he never pursued it. And I

inherited his talent. Beginning in my early childhood, I liked nothing

better than drawing. Often when other kids would be outside

playing, I would be on my parents’ bedroom floor on my knees with

a sheet of paper, drawing. I drew all sorts of things, but my favorite

subjects were horses and beautiful princesses with crowns on their

heads. I must have drawn hundreds and hundreds of them. My

princesses were easier to draw than the horses, by far.

When I started first grade in Van Nuys Elementary School, we had

specific orders of subject matter to draw, and my horse and princess

period came to an end. But my drawing and painting continued. I

learned to paint with oil paints and began to give lots of my paintings

away, especially to family members, all of which would disappear

from their wall after a while or when I presented them with a new

one. It was perfectly OK with me. Frankly, I was surprised when they

hung them up in the first place. My parents were very nice people

and always encouraged me to paint.

Like me, my brothers Piet and Frits were born at home, which most

of the kids were at that time. We lived on Kitrich in Van Nuys, a

street lined with lovely cork trees. Later, we moved to another house

on Kitrich Street, where my father planted a tiny evergreen tree in

the center of the front lawn. e last time I saw the tree it was at least

50 feet tall. Is it still standing? I think so. Also, at this same address, I

met my first boyfriend. His name was Kenneth, and we spent many a

day on our tricycles going up and down the sidewalk. We also had a

fig tree in the back yard. We climbed up and sat on the high branches

of the tree and ate yummy fresh figs when they were in season.

We were always pestered by thousands of ants, which my mother

thought she was keeping under control by pouring boiling water

down the ant holes.

q

3

Rie’sMemoirs

Some Early Memories

M y father had several dozen chickens that we kept for eggs.

Periodically, he would slaughter one by laying its head and neck on

the chopping block and axing off the head. en, miracle of miracles,

the chicken would crazily run around for 10 or 20 seconds headless.

Hence the saying!

Once a year, a man with a pony would go from house to house. For a

nickel or so, children could sit on the pony so that parents could take

photos of the fun.

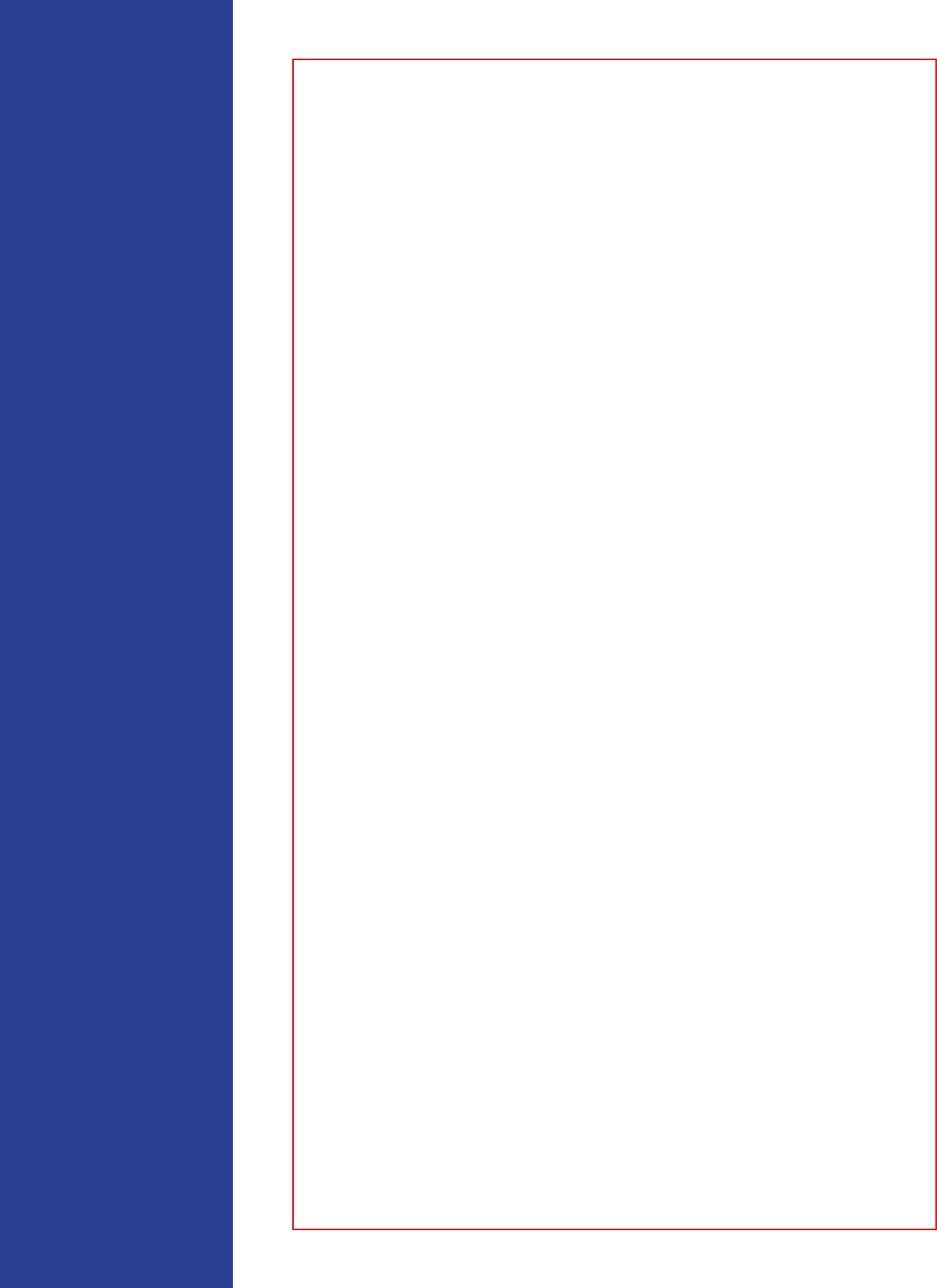

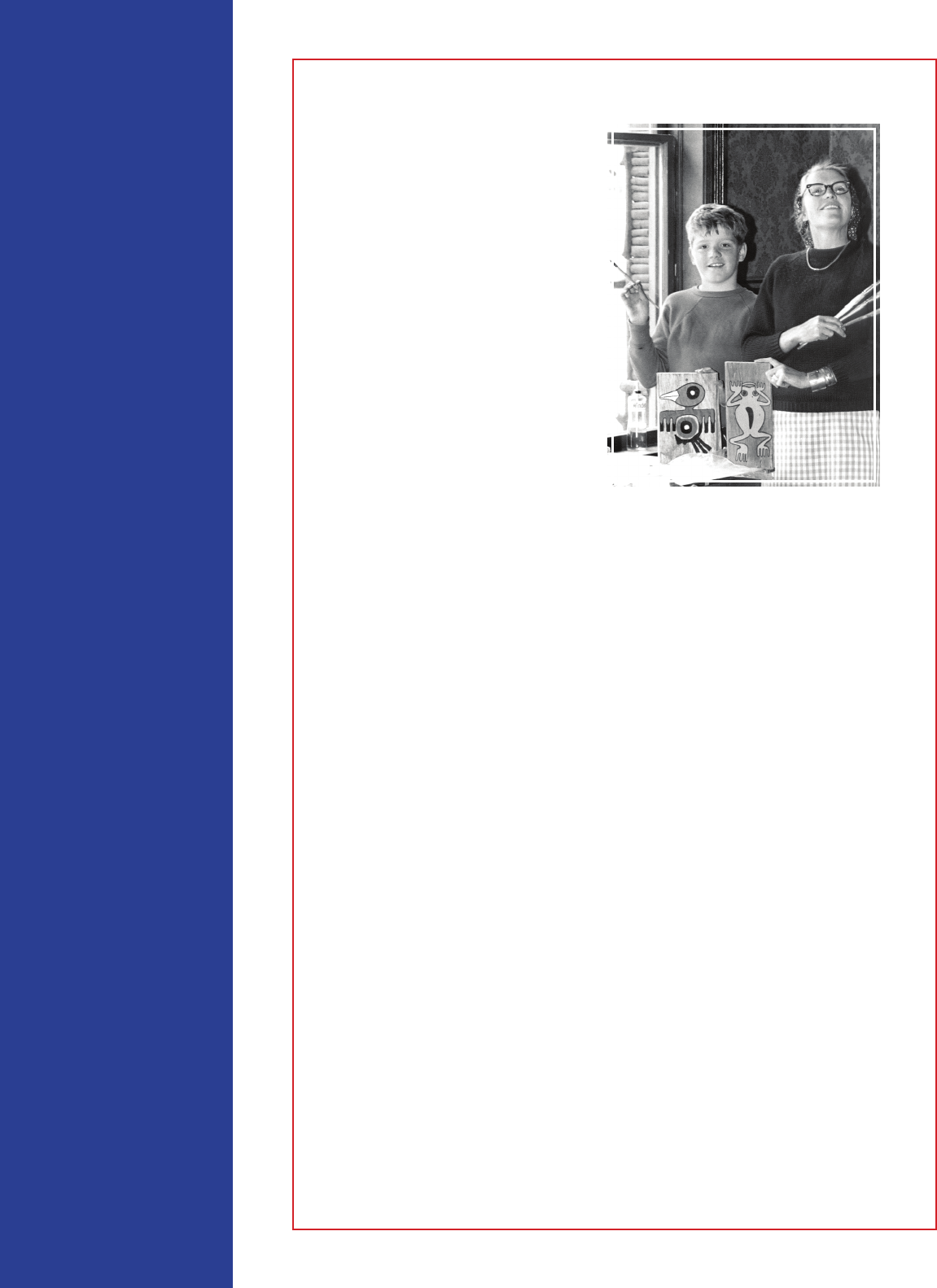

Piet and friend, 1938

“Oomi” Anton and “Tante” Akke (Dutch for aunt and uncle, even

though they technically weren’t) would visit. According to our

parents, we would always run over to them for a good hug, excitedly

asking, “When are you leaving? When are you leaving?” It was our

awkward way of asking, “How long are you staying?”

My other clear memory of that period is of my best and only

girlfriend in the neighborhood. e only girl of my age, she was

rather skinny and had a bad hand from when she had caught it in

a clothes wringer sometime before I met her. It had been badly

damaged, but her parents didn’t believe in doctors. Several times I

went with my friend to her house and no one was ever there. I never

met her parents, or her siblings, if she had any. We would go to the

kitchen and each take a slice of bread and butter. (ese were the

days before margarine.) We would add a slice of raw onion and eat it.

I have very fond memories of those sandwiches.

4

Rie’sMemoirs

I am a great admirer of dogs and have had one with me most of my

life. Once when I was young, our dog went to his reward, and my dad

came home with a new puppy. “What shall we name him?” he asked

us three children. “Bozo!” one of us piped in. Since Bozo had been

the name of our dog who had just died, it seemed appropriate. So,

“Bozo” he became. We went on to have four or five dogs, all named

“ B oz o .”

Another very

important memory

is the Crystal

Swimming Pool,

to which a large

amount of chlorine

was added to keep

the water “pure.”

is effort worked

very well; however

it did have an effect

on frequent “toe-

headed” swimmers,

like my brothers and

me. “Toe-headed,”

along with “fair

haired” and “flaxen-

haired,” used to be a

common way to refer to blonde-haired and light-skinned children.

By the time school started again in the fall, after a long hot summer

at the Crystal Pool, we toe heads had turned into light green heads,

thanks to the active qualities of chlorine. By Christmas, we had

morphed back into our old toe-headed selves.

My brother Frits tried to save my life one day at the Crystal Pool

when three “big” girls swam over to where I was floating on an inner

tube. ey asked if they could have the inner tube. I let them have it

and started to swim over to the edge of the pool. I didn’t quite make

it, and down I went several times. Frits grabbed me and, in my state

of panic, I pulled him under also. e life guard pulled us both out.

q

Rie with Bozo, 1939

5

Rie’sMemoirs

Sherman Oaks

L ater, we moved to Sherman Oaks, to a house on Willis Street,

which was about the length of three city blocks. At the dead end

there was a river that most of the year had about 18” of water in it

and ran all of the way to Ventura Boulevard—today, a busy main

highway from Hollywood to the San Fernando Valley.

When we lived on Willis Street, there were only three houses, and

we were in the middle. I seemed to recall that my Dad had the

three houses built and rented or sold the other two. Behind our

back yard was a small apricot orchard and, beyond that, a larger

walnut orchard. is far orchard butted up to Ventura Blvd. During

summers, my brothers would sometimes set up a fruit stand with an

umbrella for shade. ey would make a sign advertising their fruit

and nuts and tack it to a self-standing ladder. It was on Willis Street

that I learned how to ride a bike. My older brother, Frits, held the full

size bike as I nervously mounted. He gave me a huge push and yelled

after me, “Keep pedaling!” I did, until I approached the river, when I

simply fell off and walked the bike back home. Subsequently I learned

how to use the brakes.

While at school I learned I was a slow reader. During our reading

period, each child had to read a paragraph. I would count the

children in rows ahead of me, then I would count paragraphs and

figure out which one I would have to read. I would study it until my

turn came. Periodically, I would miscount and end up stumbling

through my turn.

One fascinating Sherman Oaks resident was known as the “King of

the Gypsies.” Annually on his birthday, gypsies would come from

far and near to honor him on the big day. My uncle, Tony Reynders

(my mother’s brother) lived in the general area and operated a gas

station. He told us the gypsy cars would be loaded with numerous

children of all ages, perhaps grandparents, and the family dog. When

it came time to pay for the gas, the driver and adult passengers would

dig through their respective pockets, handing over small coins.

ey were probably hoping Uncle Tony would grow impatient and

tell them to be on their way. But, no—Uncle Tony knew their game

and waited until the bill was properly settled. Alas, I never saw the

gypsies. Or Edgar Rice Burroughs, for that matter.

6

Rie’sMemoirs

On Sundays, we would all pile in the car and go for the customary

“Sunday drive.” Our favorite drive was to take the car over the ridge

route to Bakersfield to see the poppies, which turned the usual

brown or green hills into bright orange. One time, only a mile or less

out of Bakersfield, an old junker pulled over to the side of the road

ablaze! All of the gear, from pots and pans to boxes, mattresses and

other household items, was piled up safely several yards from the fire.

Alongside the road, members of the unfortunate family were going

from car to car as they passed, asking for money. Most sympathetic

onlookers gave.

My father explained that this family was one of many from the Dust

Bowl area. ey had lost most everything and had packed up and

found a place to resettle at Bakersfield. All they had after the fire

was the belongings on the side of the road and the money they had

received from people passing by.

Both my brothers, Frits and Piet, had paper routes at this time. Frits

went by bike to deliver the Times or Examiner and Piet by foot.

I think it was the Examiner that would give their delivery boys

free round trip tickets to Catalina Island once per year if they got a

certain amount of new subscribers. My brothers always succeeded

and were rewarded round trips for the entire family. We would go by

passenger ship, the SS Catalina or the SS Avalon, and would always

see flying fish en route. Catalina Island was owned by Mr.Wrigley of

Wrigley’s chewing gum.

I joined Piet on his paper routes periodically because I loved making

friends with the dogs. Sometimes Piet would have to wait while I

made the acquaintance of a surly dog.

e famous 1932 earthquake struck when we lived on Willis Street.

We all ran outside, as we were trained to do. Our neighbor to the

right had an Irish setter who, in his panic, crazily ran at great speed

around his house again and again. I decided to grab him and try to

soothe him as he raced by me. e frantic dog bit me on the wrist.

I still have the scars 77 years later. It was also in Sherman Oaks that

I started school in Van Nuys. I got a black eye the very first day of

school when a door knob hit me as it was being opened from the

other side.

q

7

Rie’sMemoirs

The 1932 Depression

O ne day on Willis Avenue, our father gathered us and said, “ere

is a depression on. at means we have very little money. We must

all work together to use as little money as possible. at means no

more Sunday drives.” One of us said, “We can go for walks instead,”

at which point my dad said, “Shoe leather costs money, too.” We

knew this was serious. I have no memory if my dad lost our house

or possibly all three houses. Perhaps they were sold. In any event we

shortly were packing for our train trip across country to New York,

where we boarded a Holland America Line ship and went back to

Holland.

q

Travel

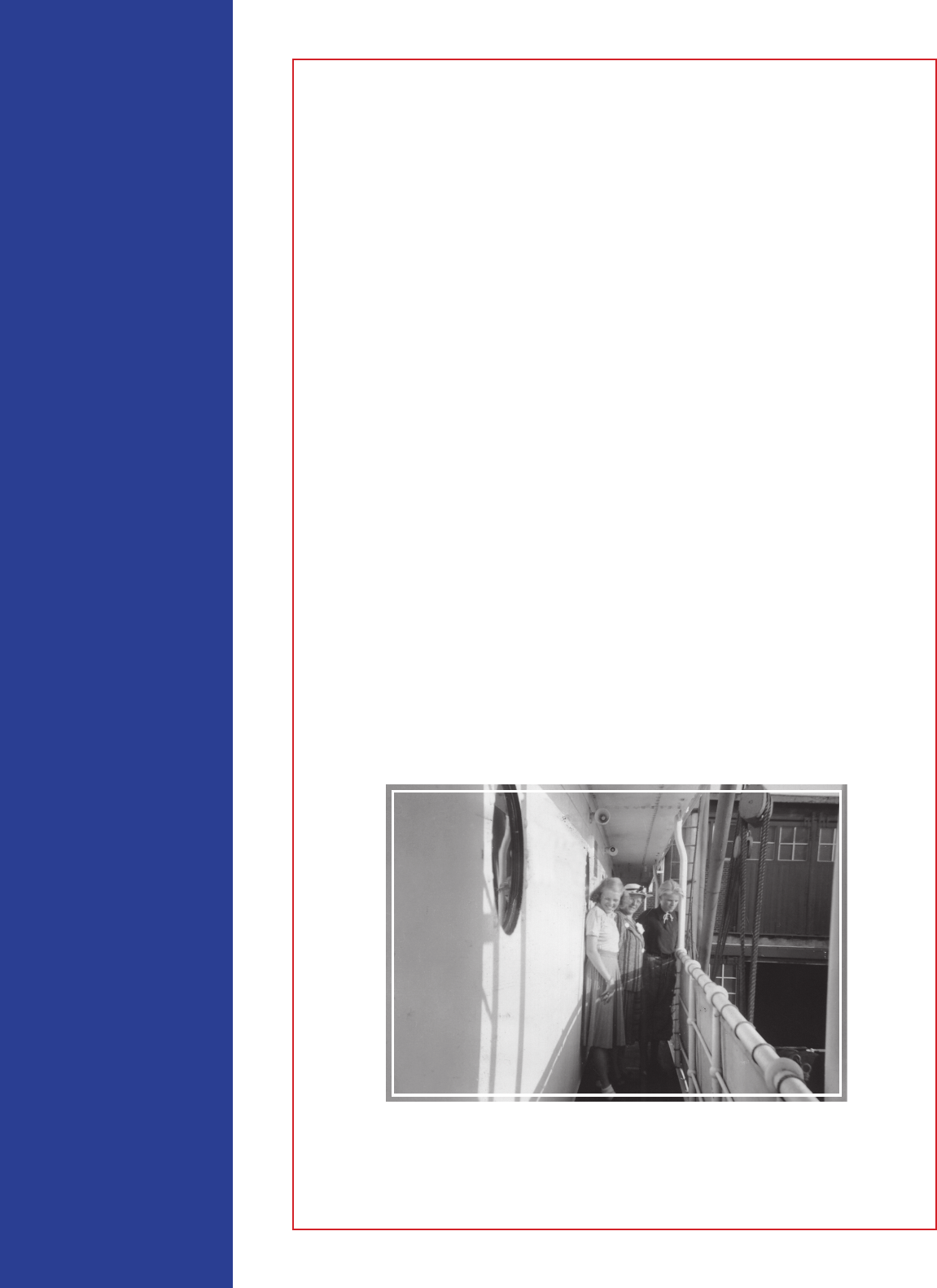

I n my young life, we

traveled to California

and Holland and back

again at least a dozen

times. e trips, of

course, were always by

steamship—most often

on the Holland America

Line, but at least once

on the English Line.

When we were all three

small, we would attend

the children’s dinner at

5:00p.m. with the other

youngsters and toddlers,

accompanied by a

parent. ereafter, the

children would be put

to bed in the stateroom,

and the adults would have

dinner at 7:00.

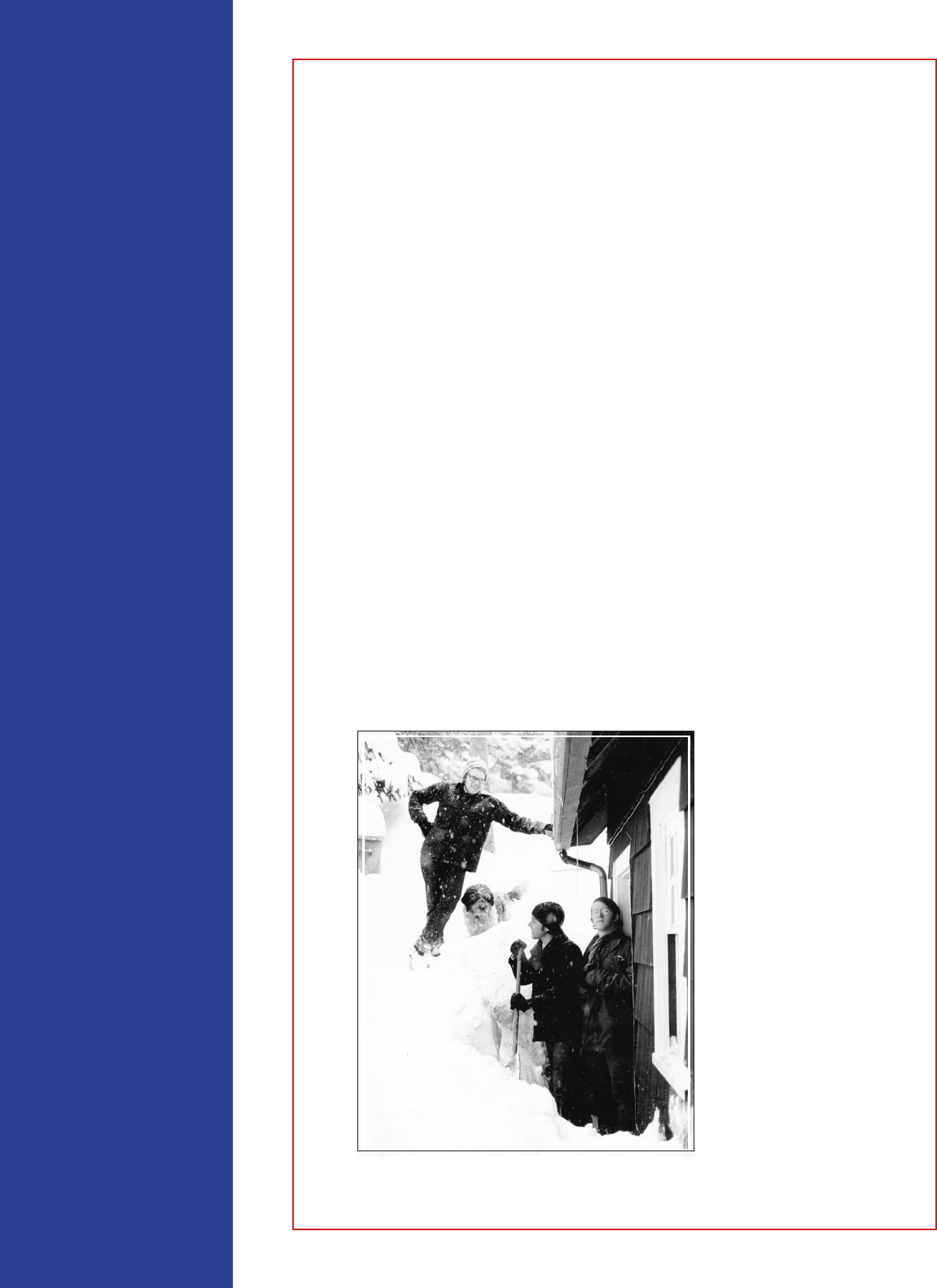

Frits, Rie and Piet with their parents,

getting ready to embark on a

freighter to the US)

8

Rie’sMemoirs

We three always loved crossing the Atlantic because the ships were

so lovely and everyone spoiled us rotten. ere were play rooms

that had slides and all sorts of toys and games. e “short” Atlantic

crossing was five days of sheer pleasure and yummy food. e

exception was when we got seasick on the rough seas. At that time,

the crew would string out lines all over the interior of the ship to

hold on to while walking down the halls.

e round dining room tables had wooden barriers in the shape of

an apple-pie cut in six serving slices to prevent dishes and everything

from sliding to one’s lap. e doors leading to the deck were kept

locked during those occasions. I was always the first one of the three

to get seasick; Piet was next and Frits hardly ever did. Neither did our

father. My mother, yes. However, after a half day or so, the sea would

calm down a bit. We would get our sea legs back, and the fun and

joy would start all over again. e ropes would come down and the

barriers removed from the dining room tables until another storm

hit.

q

Greyhound Bus

W hen our ship arrived in New York, we would take a train across

country to California. In later years, we rode a Greyhound bus,

sometimes both ways to New York or the West Coast. To keep three

young children amused or at least somewhat content, we would be

taken to the “5 & 10” store to select anything we wished for our trip.

I remember one year we all three bought Jew’s harps and played

them on the three-day cross country trip. Another year I bought a

little counter bell to ring to call a salesperson. I would amuse myself

endlessly by ringing the bell every time I saw a Texan on horseback.

Or a blue car. Or a dog. In the desert or in areas where there was

nothing worthy of bell ringing, I would ring the bell for every

telephone pole. I was totally oblivious to the feelings of other bus

passengers. Evidently, so were my parents!

When in Holland, we kids all jumped for joy when our parents

announced “We’re going to America!” To me it meant saddle shoes

and soda crackers. In America, we all jumped for joy when our

parents announced “We’re going to Holland!” Holland was our real

9

Rie’sMemoirs

home, where we had grandparents and other relatives. It had gezellig

(gemutlich in German). ere is no such English word and is hard to

translate—it refers to a kind of ambiance or convivial atmosphere.

q

Bussem

F or a while we lived in Bussem, in a new development adjacent to

the ancient walled city of Naarden. Here, farmers who lived within

the walled city had their farmland and grazing land outside the walls.

e back of our house abutted farmland where tulips were raised

commercially for export. Beyond, stood an active windmill. In the

spring, this huge acreage burst into bloom with large rectangles

of every color of tulip imaginable. Soon, itinerant workers would

come and nip off all the flowers to be tossed in very large piles. e

result, the fields themselves were green again, interspersed with what

looked like brightly colored haystacks. One would be a red stack,

next a white stack, blue stack, black, yellow, green, and so on. In the

background, the windmill would be spinning.

q

No Lady

W e had an aunt who lived nearby. One day my aunt told my

mother that once when she had returned home from doing a few

errands in town, her maid had told her someone had come by to

visit—and that the person was “no lady.” After learning who it was,

my aunt asked the maid why she had said the person was not a lady.

“Because,” the maid answered, “she was wearing brown shoes with a

black coat!”

q

10

Rie’sMemoirs

Boy Friends

K enneth was a little boy who road tricycles with me when we

were just out of toddler age, my first special friend. He grew up,

married, and moved to Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe). I had another

friend whose name I can’t recall, but I remember he was very tall and

skinny, like me. He was our neighbor when we lived on the outskirts

of Den Haag, also known as the Scheven Hague. He was probably

about 14 and I about 13. We and a bunch of other neighbor kids all

hung out together on the quiet street where we lived. One day, there

was a knock on the door and it was HIM. I said “Hi” and invited

him in, yelling over to the kitchen to my mother that it was HIM.

She came in, greeted him and invited him to a seat. I sat down, too,

but didn’t really know why he was there. He was very bashful. My

mother bravely tried to keep the conversation going. After about five

minutes, I got up, walked to my room, and started on my homework.

About 10 minutes later, I practically jumped out of my chair when

my mother barked from below…RIE! COME HERE! e long and

the short of it was that he had come to see me! Dense me, sigh.

A few days later, he asked me to go to a masquerade party that his

dancing class was giving. At that time, many children went to dance

class. I, too, attended a dance class once a week where we learned

the fox trot, waltz, tango, rumba, and, I think, the Lambeth walk.

Anyhow, I accepted his invitation—my first date, very exciting. I was

going as a “Scotch girl” or lassie. My mother made me a lovely wool

plaid kilt and, with it, I wore all the appropriate trappings. e whole

family, including myself, felt that I looked great. My date arrived as a

chimney sweeper—all in black, including a decrepit black top hat. He

had some soot on his hands and face. My father drove us to the Ball.

When we arrived, it turned out the masquerade was the following

week! Being young teenagers, we were terribly embarrassed. As we

turned to leave, everyone said, “No, stay! Dance and have fun!” We

did and had a lot of fun. at was the one and only “date” we had.

at was ok with me and, obviously, with him also.

q

11

Rie’sMemoirs

School

W e lived in Waasenaar but went to school in e Hague. We road

our bikes to school, which took us about 25 minutes. Most of the

route took us on a bike trail through the woods that separated the

two towns. Piet and Frits went to a boys’ school and I went to a girls’

school that wasn’t far from where my grandmother lived. e school,

located “downtown,” had no playground, only a cemented area in

front. Large buildings loomed on both sides of the cemented area,

and here we all walked during recess, two or three abreast in a large

oval. About halfway through recess time, the teacher would come

out and blow her whistle. At that point, we would all turn around

and walk in the other direction until recess was over. I remember

two teachers. Miss Cigar was our Home Economics teacher. I

remember her unusual name and that she had dirty fingernails. e

other teacher, whose name I don’t recall, taught history. She would

act out all the famous people of history during her lectures. One

minute she would be Napoleon directing his generals in some battle,

then she’d jump over to the generals’ side, looking back at Napoleon

and acknowledging his direction. History was lots of fun and

certainly interesting.

q

The Queen

W hile still in Holland, I remember seeing Mother Beatrix, Queen

of Holland. We caught a glimpse of her numerous times, on special

days like her birthday. Annually, when “Congress” convened, she

and her entourage of a hundred or so soldiers dressed to the hilt on

horseback would ride through the streets. e queen, in a golden

carriage pulled by eight stunning horses, waved her forearm and

hand to her cheering subjects. I was in great awe of the whole

procession.

q

12

Rie’sMemoirs

A Drunk

A lso while in Holland, I saw my first drunk. My brothers and

I were playing catch with a tennis ball on our very quiet street. I

missed catching the ball and chased after it down the street. Far in

the distance, I saw a man walking next to his bike, coming our way.

Several more times I missed the ball, and each time he was a little

closer. en I missed the ball again, and there he was staggering and

smelling something awful. We quit playing ball then and went inside.

He staggered on.

q

Scheveningen and Wassenaar

S cheveningen is a beach town near the Hague and also near

Wassenaar, where we lived. Now and again we went to the

Scheveningen beach. e beach was separated in large sections.

If you were a single female, you had to stay in that section. It was

separated in the middle for married couples with or without

children. e far section was for single men. As I recall, there were

no boundaries once in the water. One could rent wonderful rattan

beach chairs shaped somewhat like a peanut in a shell. Of course, we

always sat in the family section. Swimming was so-so. ere were no

real waves to bob up or down on. e water was just about always

cold and, worse yet, if the wind came in toward land, you had to look

out for the jelly fish that would sting badly if you came in contact

with the tentacles.

Still, we loved going to the Scheveningen. Once a year, they would

have a wonderful fireworks display on the beach. My memory of

one of those exciting evenings stays with me. I still shudder to think

about it. Our family was together in a crowded area. My mother was

holding on to my hand; the other was getting cold, so I stuck it in

my coat pocket. ere was a strangers hand in there! A big one that

instantly withdrew. Period!

q

13

Rie’sMemoirs

Oma

O ma was my father’s mother. She lived in e Hague and had

an upstairs apartment. On the main floor lived two maiden

ladies, sisters probably in their mid-fifties, who took care of my

grandmother. She had a bell that she would ring if she needed help.

ey would come upstairs immediately to do her bidding, so to

speak. We three kids liked the sisters very much, and they, us. We

visited Oma once a week and stayed for a couple of hours. She always

served us hot chocolate, teaching us first two teaspoons of sugar,

then one teaspoon of cocoa, and mix very well. Add three teaspoons

of milk and mix til it all turns shiny. en she would poor in hot milk,

and we would enjoy the most wonderful hot chocolate, with dunking

biscuits made by the downstairs ladies.

Oma, we were told, was the first person in Holland who volunteered

to study brail “typewriter”— a small gadget resembling a miniature

typewriter. is contraption could type up to four keys at a time,

HARD, and somehow punch holes in a thick piece of waxed poster

board. e opposite side of the material would be raised due to the

hole being punched, and that was the side the blind could read by

moving their fingers over it lightly. My grandmother explained that

a book never lasted very long with so many blind people’s fingers

sliding along, eventually flattening the bumps.

We always asked her to type some brail when we visited, and she was

always pleased to do so. We also played board games with her. is

was a fun visit for us and Oma as well.

q

Schiermonnikoog

O ne year, we actually went on a “summer vacation” for a month

on Schiermonnikoog, a very small island in a chain off the northern

coast of Holland. e Oostveen family (Monk, Dien and their son,

Kuno, who was a close friend) joined us. We rented a small village

house where the adults and I slept. Frits, Piet and Kuno slept outside

in a tent my dad had set up on the small lawn in the backyard. I had

14

Rie’sMemoirs

the best and the most interesting bed, built into the kitchen wall.

Two large cupboard doors opened up to the single bed. One simply

climbed in and went to sleep. I could close the cupboard doors or

keep them open.

e island of Schiermonnikoog offered little except a wonderful

beach, which we and all the other tourists walked daily. ere were

mostly farms on the island. On one, we noticed a small hand-printed

sign offering horseback riding.

We pestered our parents until one day they gave in. We were each

loaded onto the bare back of an enormous plow horses and handed

the reins. We were off to the beach on the same road everyone else

walked down. e horses, all four, were more interested in stopping

frequently to graze along the side of the road. It took us longer to get

to the beach than by walking.

q

The War Intrudes on Our Happy Life

P iet and I would be sent back to America in the late 1930s, after

Hitler’s army invaded Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, and Austria.

It was no secret that the low-lying countries like Holland would most

likely be next. My parents were eager to get the family back to the

USA before that came about. My older brother, Frits, then 18, had

just graduated from high school. As a graduation present, my parents

gave him a round trip ticket to the U.S. His best friend, Jan Kook, had

just gotten a similar gift from his parents, and the two had gone to

California. Both sets of parents wired their sons to tell them to stay

put and not return to Holland, though Jan’s parents later changed

their minds and had their son come home.

\Joy and Renee Feenstra were my closest and best friends in our

neighborhood, especially Joy. She and I were the same age, and Renee

was two years younger. After Piet and I left for the U.S., in September

of 1939, I never saw them again. We wrote each other several times,

but that eventually came to an end.

\Years later, when we were reunited with our parents, they told this

story:

15

Rie’sMemoirs

When the Germans invaded Holland, in 1940, some Dutch people

became traitors, welcoming the German troops, inviting them for

dinners, etc. e German soldiers reciprocated by giving the Dutch

traitors cigarettes, silk stockings, and other hard-to-get items. It was

quite profitable to be nice to the enemy for this reason. Also, this was

war. ese Dutch people probably figured if the Germans won the

war it could make a large positive difference for them to have been

on the German side. However, needless to say, the Dutch had blood

in their eyes for these turncoats or “Quislings,” as they were called.

(Quisling, I was told, was a famous Scandinavian turncoat.) When

the war ended and the Germans were gone, the Dutch rounded up

all the traitors. e women had their heads shaved so all could see

what they really were. I don’t recall the punishment for the men.

q

Wassenaar

I have very fond memories of the several times in Wassenaar I

faked sudden early morning tummy aches. ese usually coincided

with my being unprepared for a test at school that day. In a very soft

voice, I would tell my mother what ailed me, and she would gently

pat me on the head and tuck me in to bed and say, “No school today.

Rest.” She would then lightly close the door. Around 10 a.m., she

would quietly reappear and ask me how I was doing. In a slightly

more normal voice, I would say I thought I was improving. My

mother would recommend that I get dressed and perhaps take a walk

with her through the dunes.

Our 45-minute walk would take us through the dunes to the beach

in Scheveningen where there was a very long pier with a beautiful

ornate building at the end that housed a fine café. We would sit at an

outside table and sip delicious hot chocolate. After a while, we would

walk through the dunes and head home. Of course, my mother knew

from the start that I was faking it, but decided to make the best of it

both for her and for me. We loved it, both of us.

One morning in Wassenaar, I woke up with a real tummy ache and

got out of bed. I had the shock of my life: a blood puddle on my

sheets! I ran to my parents’ bedroom. “I’m dying, I’m dying!” I cried.

16

Rie’sMemoirs

My mother ran to my bedroom with me, and it was only then that I

learned of menstruation. I was very annoyed that my mom had not

prepared me for this. However, I didn’t show my annoyance; I was

highly relieved that I wasn’t dying after all.

Another memorable moment in Wassenaar was when I was in a

junior high Montessori School—the first in Holland. It was there that

I met Maria Montessori. It turns out she was from Italy and had had

a child out of wedlock, a real taboo in those days, especially in Italy.

Holland had always been a very liberal country, so she had moved

there with her child.

In due time, it became obvious to me that my mother dreaded

informing me, her only daughter, about the “facts of life.” Admittedly,

I was also shy and embarrassed to ask her where babies came from,

although I had a fair idea from school mates. I didn’t quite believe

all their hair-raising tales, such as “the woman had her stomach cut

open to get the baby out,” though.

When my parents brought Piet and me to the SS Bloemendam, the

Dutch freighter that returned us to the U.S. in 1939, they boarded

with us, as was the custom. After about 20 minutes, the loudspeaker

came on and announced, “All ashore that’s going ashore.” I noticed

my father taking Piet by the arm. At the same time, my mother took

me by the arm and led me around a corner. en, in less time than

it takes to write this, she blushingly told me the facts of life. My

parents turned around and both quickly descended the gang plank,

Rie on ship after hastily being told

the facts of life before casting off, 1939

17

Rie’sMemoirs

cheerfully waving goodbye from the dock below. I later asked Piet

if dad had filled him in at the same time mother talked to me. He

laughingly said, “No!”

In the late 1930s, Hitler was conquering one small country after the

other: Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland. Every Dutchman, as well

as everybody in Belgium and Luxembourg, knew it was only a matter

of time before the Germans came their way.

We would all sit by the radio and listen to Hitler giving speeches to

the German people. His speeches were amplified by loudspeakers

to huge crowds made even larger when the Nazis would empty out

factories and schools for everybody to attend. A speech would begin

in a measured and controlled voice. In a short time, Adolph Hitler’s

voice grew louder and louder until he was screaming. After each

sentence, the crowd yelled at the top of their thousands of voices

HEIL HITLER! e more the crowd yelled, the more frantic Hitler’s

voice got.

In those troubled times, Hollanders could not get visas to go to the

U.S. e only Dutchmen who could get a visa then were Dutch

parents who had minor American children in the U.S. So, in early

September of 1939, my parents booked passage for Piet and I on the

Holland America Line freighter, the S.S. Bloemendam.

q

Aboard the S.S. Bloemendam

T raditionally, freighters carry only 13 passengers. Piet and I were

two of those passengers; my memory of the other 11 totally escapes

me. Considering the times, it’s likely that a good number of them

were Dutch Jews. e first night out, I was awoken from a sound

sleep by the silence. e ships engines had been turned off. Piet woke

up, too. We quickly threw our coats over our pajamas, slipped on our

shoes, and ran out on deck to complete darkness. We went to the

railing and looked out to sea for other ships, but nothing. en we

looked straight down. A submarine! A submarine with the German

Swastika was tied up to our vessel. We looked at each other and,

without saying a word, tiptoed back to our stateroom and crawled

18

Rie’sMemoirs

into bed. We didn’t exchange a word; we just lay still in suspense.

Finally, the ship’s engines started again, we got underway, and Piet

and I fell back asleep.

e next morning, we learned that, although the Germans had not

yet declared war on Holland, they still wanted to inspect our cargo.

We had passed the inspection, and they had let us continue with our

voyage to the U.S. e ship had very little cargo, only two thousand

canaries in individual cages from the Hertz Company.

Later in the voyage, once in U.S. waters, all 13 passengers were

invited down to visit the canaries. ere was only one person in

charge of feeding and caring for the birds, and I found out why. e

captain made an announcement that hidden under all the 2,000

chattering birds was other cargo the Germans hadn’t found: the

Crown Jewels of Holland, destined for safe storage in the U.S. due to

the impending war.

As we approached New York Harbor, someone pointed out the

Statue of Liberty, which brought tears to my eyes. What a beautiful

sunny day it was. Boats of all sizes were moving about, birds flying,

horns blowing, magnificent skyscrapers. In the crowd at the dock

awaited Mr. Paul, a family friend who was to watch us until my

parents could make it over. Now that my parents had minor children

in the U.S., they could begin the lengthy process of applying for their

own visas so that they could be reunited with us.

q

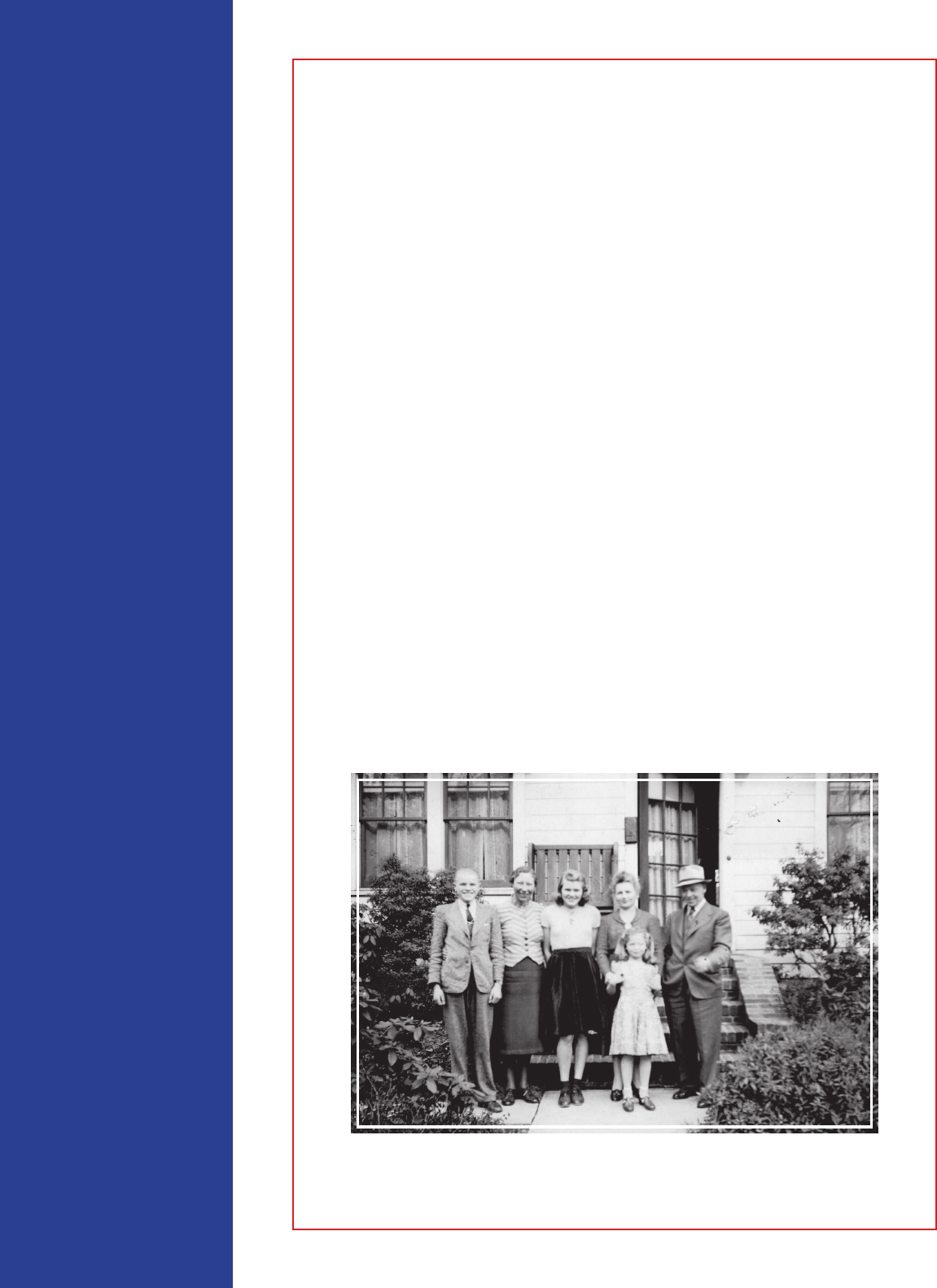

Piet, Tanta Zus, Rie, Mr. and Mrs. Paul with their child, 1940

19

Rie’sMemoirs

Plainfield, New Jersey

A lthough the Paul family (mom, dad, and three kids) was from

Holland, the stay there was neither interesting nor fun. High school

life was the same. at entire school year, I made no close friends.

I don’t think my brother Piet did either. e high school fashion

for girls at the time was a cardigan sweater and saddle shoes. I had

neither and was simply not “in the loop.”

To be honest, even if I did have a cardigan sweater and saddle shoes,

I would still probably not have been in the loop. In class, I was the

shy new girl from Holland. Our home life was also so-so. e Pauls

didn’t laugh much or even talk much for that matter. Mind you, they

treated us as well as their own kids, but, on the whole, they were kind

of dull. Saturdays, after we had done our chores, Piet and I would go

for a long walk—always following the same route through open fields

and around grazing pastures following a narrow stream. We looked

forward to our walk every week.

Our parents’ visa took much longer than we all had anticipated. And,

after the visas finally arrived, booking passage on a steamer to the

U.S. took forever. is was, after all, wartime, and the Germans had

occupied a number of European countries, with the Jews from these

countries being sent off to concentration camps and, in most cases,

death.

ousand and thousands of people were fleeing for their lives to safe

countries like America and Canada. My parents had gone through

the entire process of getting their visas and booking passage to the

U.S., which had taken years. ey were scheduled to leave from

Portugal on May 14, 1940, but, on May 10, 1940, Germany invaded

Holland and Rotterdam was bombed to near total destruction.

Holland surrendered, all in 24 hours. All plans changed. We would

not reunite with our parents until seven years later.

q

20

Rie’sMemoirs

To Hollywood

M y parents had earlier considered all contingencies in the family’s

flight to America, including what to do if the two of them couldn’t

make it out of the country. My father had stipulated to Mr. Paul

to send Piet and I to Frits in California when school ended in the

spring. Piet and I enthusiastically anticipated our trip to California

and leaving New Jersey. e Paul family also seemed excited and

had packed our bags for us. Two days after school was out, Piet and

I were on the All American Busline (cheaper than Greyhound) for

California!

Not only were we three kids together again, but we had additional

family in California. In anticipation of our arrival, Frits had rented

us a nice apartment with two bedrooms in Hollywood, three blocks

away from the famous Hollywood Boulevard. Our Aunt and Uncle,

Jetty and Tony Reynder, lived only a few miles away in Van Nuys.

ey had a daughter, Ann, who, during that general period, married

George Clark and had children: Barbara and George.

Tante (Aunt) Jetty was a native Indonesian who had never learned

to speak English—only Dutch, along with her native language. Ann

and George (mainly Ann) raised Chinchillas, which they had been

talked into by some scammer who promised they’d make a fortune.

ey didn’t. ey told me once that they had bought their brand new

house on Oxnard Street for $2,000, shortly after they were married in

the 1940s.

Frits worked in a department store in L.A. as an assistant buyer.

Piet, being 16 years old, had to continue high school, which was at

North Hollywood High. I got a job in North Hollywood decorating

windows at Woolworth Five and Dime store. I would commute to

and from work via streetcar. One of the daily commuters on the

street car was a Mexican man. I found it odd that he would usually

have a double seat to himself. Once in a while, someone would share

the double seat with him, but then take another seat at the next stop

or sooner. I wondered if this was racism, but California’s population

was almost 50% Mexican, so what was the deal? Feeling sorry for

the old geezer, I sat next to him the following day and immediately

jumped up and sat elsewhere; he reeked of garlic! Another time, a

man sitting next to me told me that when he had started commuting

many years earlier there was a sign in all the streetcars that read

“Shooting rabbits from the window is not permitted!”

21

Rie’sMemoirs

At Woolworths I made $15 a week. e employees were nice and I

enjoyed the work. At the local Bank of America I met a local teller

named Sara Barta. We became lifelong friends, although there were

times when we would be out of contact with each other.

Our lives in Hollywood as teenagers need not have worried our

parents, who remained far away back in Holland. It was much safer

in California than in war-torn Europe, although it never occurred

to ask them if they were concerned. Back in the 1930s and 1940s,

teenage life in the big city was totally innocent. By the time Piet and I

left at 18 we had never seen another teenager even smoke a cigarette.

Never, not even downtown! In Holland, I never saw a teenager with

a bottle of beer or wine, except, as is the custom, when we had wine

on the dinner table. When served, we always made a gruesome

face of one taking a spoon of medicine, but we did appreciate the

importance of the custom.

I don’t recall that we had many friends in Los Angeles at the time

except a few friends Piet had at school and I had at work. Frits

became friends with Harry Klein who worked at a print shop. In no

time he became friends with Piet and me too. One of our favorite

pastimes would be to go to the Santa Monica Beach on Sundays with

Harry. Afterwards we would go back to Hollywood for dinner at Joe’s

Eats, where the cafeteria type meals were 35 cents. Another favorite

haunt was Clifton’s, a local chain, where they not only had singing

waiters but the price was basically “whatever you can pay.” My

friend, Sara Butler, and the rest of us were pals for some years.

Sara had an interesting family. Her parents were simple people—

farmers from Bulgaria or Yugoslavia who spoke with a thick accent.

Her mother seemed quite religious and God fearing, I think. I say

“I think” because she spoke no English at all and never made an

effort to learn. All the Butler kids were born in the U.S. Sara had

an older sister who was also a bank teller as well as two brothers. I

don’t know what Sara’s dad did for a living, but, whatever it was, he

supplemented his taxable income by making ”bathtub gin,” as it was

called at the time. I think that applies to any production of illegal

liquor. Be it gin or whiskey, whatever it was, it evidentially was made

in the bathtub. Sara’s mother did not approve.

One day, according to Sara, when her mother happened to look

out the window, she saw a policeman on the beat walk by and ran

out yelling for him to stop. In her native language and in a loud and

22

Rie’sMemoirs

excited voice she told

him of her husband’s

bathtub gin goings on.

She went on to tell

the officer how bad

her husband was and

how she had told him

time and time again

to stop. Of course,

the policeman didn’t

understand a word.

Hearing the excitement,

Sara’s father calmly

walked outside and

apologized for his

wife’s behavior, alleging

she was mentally ill.

e policeman said

he understood and

continued on his beat.

Sara’s father continued

on with his sideline business.

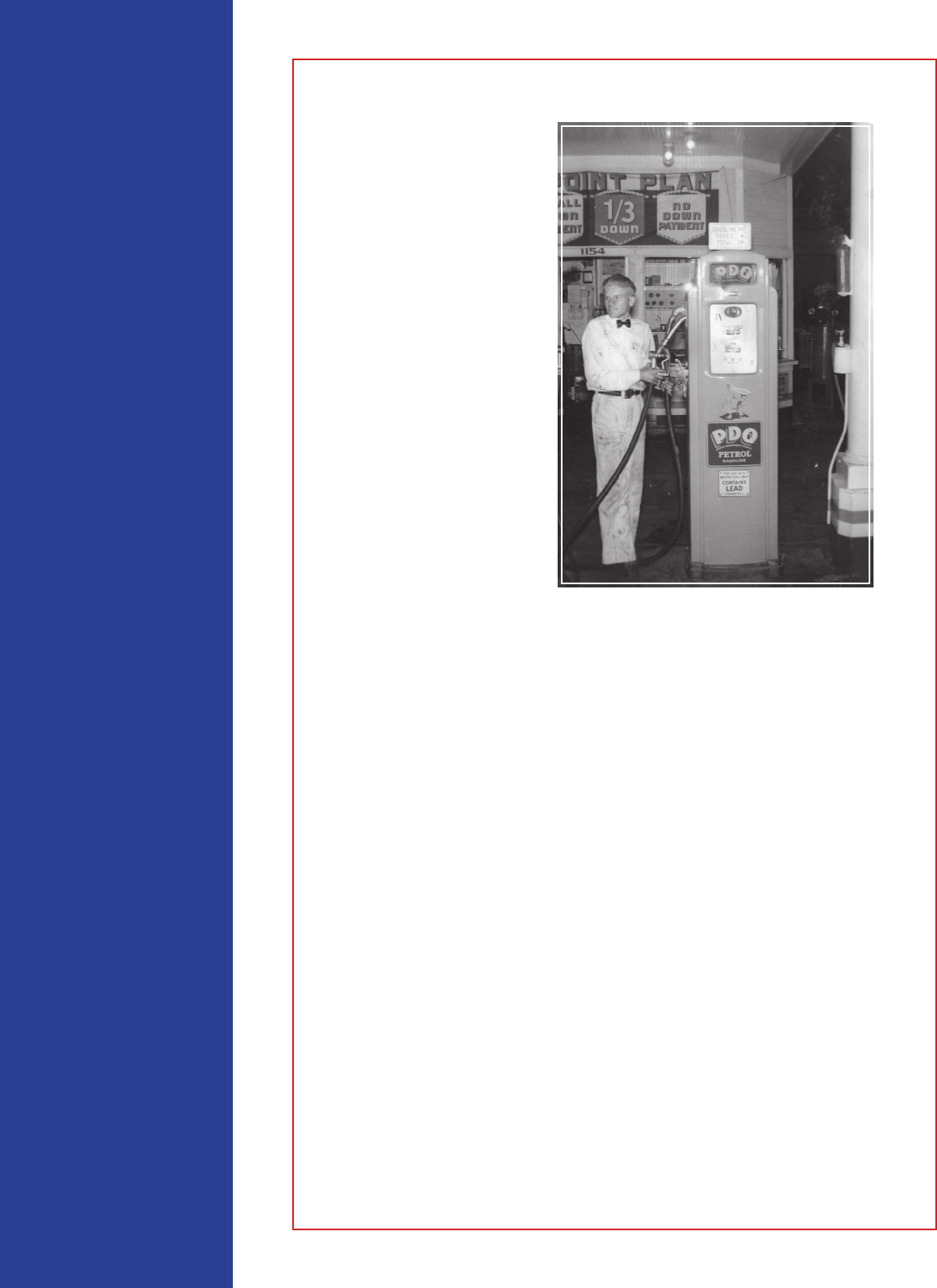

During summer vacations, Piet worked at a gas station. After

graduating, he continued working full time and eventually bought his

own gas station.

He also did repair work on cars. When war broke out, he got a night

shift job at a San Diego factory that manufactured airplanes. At

midnight he would get off work and drive back home to Hollywood,

over three hours away.

q

Hollywood Christmas Parade

E very year, the three of us and thousands of others attended

the Hollywood Christmas Parade. e parade route went along

Hollywood Boulevard, and leading the parade was always Tom Mix

on his equally famous horse, Tony.

Piet at work

23

Rie’sMemoirs

Tom Mix was a cowboy movie actor and he was followed by many

beautiful floats carrying other Hollywood stars—the exception being

the float that carried Santa Claus. is was years before stars stuck

their hands in cement and signed their names along the sidewalks of

Hollywood Boulevard.

After several years decorating windows at the Five and Dime store in

Hollywood, I decided it was time to improve my lot with bigger and

better things. I quit my job and ventured downtown to Los Angeles

city center. I went to Broadway Boulevard and started submitting

applications as an experienced window decorator. I went from

store to store and, at the last intersection, where the stores turned

from “high end” to 2

nd

and 3

rd

rate outfits, I got a job. e job paid

$19 a week in the area’s first 2

nd

rate store, Nelson’s. e store had

huge permanent new print signs that read “Giant Closing Sale 50%

off, Everything Has to Go!” I worked there for about a year and a

half. e sales ladies were nice. e main activity was to change the

clothes in the windows before they faded. It was not very creative

work.

Periodically I would go across the street during my lunch to

Broadway Department Store’s personnel office to see if they had any

openings in their display department. A year or so later, they did, and

I got the job. It was at that job where I learned that there was such a

condition among humans called homosexuality. e display staff in

this large high end department store consisted of six men and me.

All six were gay, and they treated me very nicely. We all became good

friends and would go to each other’s apartments for dinners. Since

they were all artistically inclined, they had beautifully furnished and

decorated apartments that they had done themselves. We enjoyed

operas and plays together. e job paid more than my last two and I

was working with a small congenial group. Life was good.

An interesting event happened at the Broadway shortly before I

started working there. e Los Angeles Times, actually all the local

newspapers, were devoting their front pages to an escapee from the

women’s state prison in Tehachapi. Some clues indicated that she

could be hiding in L.A. Weeks went by and she remained at large.

An employee from the Broadway Department Store began to

wonder about a specific bed on display. It appeared to have been

slept in. He alerted the night watchman and that night he caught

the escapee from Tehachapi! She told the police she would roam the

24

Rie’sMemoirs

streets during the day and then return close to closing time, and hide

somewhere in the store until all had left. She would find prepared

food, sometimes still warm for her dinner. I think she would also

select a few new clothes and perhaps a pair of sunglasses before

retiring for the night.

q

Short Engagement to Max Gorman

D uring my friendship with Sara, we would take Sunday horseback

rides. We became regulars at the stable and also the horse trails. One

of the people we met during our jaunts was Max Gorman. Max was

a rather serious, good looking young man who worked at the Bank

of America. We began dating and getting around in my car. Max not

only did not have his own car, he didn’t know how to drive. He was

the second man I dated who didn’t drive a car, which should have

been a warning to me. Anyhow, we dated for about a half year and

then decided to get married. He set a date and told all our friends

and family. Well, almost. Something told me not to write my parents

quite yet.

Everyone was very happy for us, and Sara started phoning friends

inviting them to a shower. e closer the wedding date came the

more I began to question the wisdom of the whole affair. So, one

evening after a date, as we pulled up to Max’s apartment in my 2

nd

hand Chevy, I told him I had made a big mistake and the wedding

was off. He did not take it very well. After arguing with me for

a while, he got physical. Now, in those days, the 1940s, sex was

frowned upon before marriage. I guess Max thought “Custom be

dammed. If no marriage, I’ll have some sex anyhow.” He started

struggling with me, trying to open my blouse. Max’s attempt to

overpower me was to no avail. I had been raised with two brothers—

one two years older than me and one two years younger. We wrestled

all the time together when we were growing up. Max only had one

sister. As he forcibly tried to undo my blouse buttons, I started

giggling. is made Max furious, and he got out of the car, slammed

the door, and went into his apartment.

25

Rie’sMemoirs

e only other person who was really mad at me, other than Max,

was my good friend Sara, who had just completed her elaborate

arrangements for the wedding shower.

.

q

War Work

O ne day when I was still working at the Broadway Department

Store, Sara called enthusiastically to tell me she had gotten a job

at the Lockheed Airplane Factory at $90 per month! Of course,

I immediately applied for a job and got one on the spot. Alas, it

was not in the factory, but in the small U.S. Post Office on location

there. My salary wasn’t as high as Sara’s but it was still good, given

that I did not see myself getting much higher in the window display

business. Luck came my way after we had a postal inspection. My

boss was fired when they found hundreds of undelivered letters she

had stashed in a remote cabinet that needed forwarding addresses.

I was appointed the new head of our small post office and got a big

increase in salary!

A year or so went by with both Sara and I making good money, much

of which we saved for a planned trip around the world—which we

never did take. We did, however, save enough money to go to Mexico

and across the U.S. to New York with a side trip to Quebec City. We

hoped to go to Europe after this trip.

.

q

Mexico

To really see the country, we went by train, which was very

inexpensive. Since it was inexpensive, we upgraded our tickets from

3

rd

class to 2

nd

class. e porter helped us carry our gear to our 2

nd

class seats, and we tipped him $2. We didn’t have much gear and also

carried some of it ourselves. is was our first tipping experience and

the porter saw us for what we were: two young wide-eyed naïve girls.

When he looked at the two dollar bills in his hand, he immediately

26

Rie’sMemoirs

said that it was not enough. We had seen someone else tip $2 for

much more luggage, so we bravely but nervously held our ground.

e porter said he was going to report us to “the inspector” and left.

e inspector never came, and we were on our way to Mexico City!

Second class still did not have any berths, and we were not allowed

to eat in the dining car. at turned out to be no problem as the train

stopped at all the villages in route. We would hop off the train and

enjoy the food from the small shops and stands. ey had a great

variety of hot and cold food that was peddled along side the train

stop. Hungry passengers needed only to open the window to get a

three or four course meal.

During these numerous stops, beggars would come aboard, terribly

maimed, begging for coins. New passengers would board; others

would disembark. Some carried chickens held by their legs—perhaps

a gift to a relative they were visiting. Other passengers would bring

aboard a goat or two or several sheep on leashes. Second class was

very accommodating, and we enjoyed it immensely. I walked through

third class one time. ere was considerable more livestock there.

We were happy to arrive in Mexico City despite the extra fun the

train ride had provided. We went straight to the YMCA. We figured

they would be reasonably priced and so they were. We were given a

room on the 5

th

floor and learned that there were no elevators. But

we were young, so what? Mexico City is at 5,000 ft. elevation, and

for us lowlanders from Los Angeles, which is at sea level, climbing

the five floors was more difficult than we had anticipated. e 4

th

floor had a swimming pool with benches where we always stopped

to rest and look at the swimmers before tackling our floor #5. Our

room was quite plain, just two single beds and a sink with hot and

cold water. e beds were about 2½ feet apart. Sarah became aware

that her lower limbs were becoming more and more itchy, a clue that

there might be spiders or mosquitoes? We never saw the culprits,

but Sara figured it out one morning, exclaiming in a loud voice, “Bed

bugs!!” e odd thing was that I was in the other bed, only three feet

away, and never got a bite.

I could easily say that the bull fights were my most memorable

experience in Mexico. ey took place at 3:00 sharp every Sunday.

Sara and I didn’t miss a single Sunday while we were there.

After Mexico, I went home again to Los Angeles for several years.

Piet, Frits, and I still lived together. Piet had graduated from high

school and was working at the airplane factory in San Diego. Frits

27

Rie’sMemoirs

was still working as assistant manager in a department store. He met

Vannie and they became husband and wife. Sara was still making

a large salary at Lockheed, and I was still the “postmaster” at the

Lockheed post office.

Sara and my plans for more travel soon turned to reality. Before long,

we were on the Greyhound Bus headed across country for Canada’s

Quebec City, where French was the first language. Having learned

French in school in Holland beginning in second grade, I did fairly

well. We were there for about three weeks and then traveled by train

to New York City. We liked “the City” so much we moved from a

cheap hotel to a cheap apartment on the East Side with a window

facing the East River. We still had a goodly amount of money at our

disposal, and our days and weeks were spent sightseeing.

When I think of New York, I immediately think of our door man

at the apartment. He was a scruffy elderly man in his early 70s.

We greeted him cheerfully coming and going. He took a liking to

us and invited us for a cup of coffee at his apartment, which we

accepted. His apartment was a mess, but then the whole East Side

neighborhood was also. We sat down at the kitchen table while he

made coffee and searched through his cupboard for some cups.

Finding none, he reached into the dirty dishes piled high and found

three cups plastered with molded coffee grounds. He briefly rinsed

them under cold water and poured three cups of coffee. I won’t go

into details on how Sara and I managed to get the coffee down, but

it wasn’t easy. He offered us refills, which we declined. Despite it all

we survived and enjoyed the old gentleman’s stories about early New

York.

.

q

The W ACS

O ne day while we were sightseeing on the West Side, we came to a

storefront advertising the wonderful worldwide places one could see

by joining the Woman’s Army Corp, or “WACS,” as they were called.

We enlisted, our reasoning being that now we could see the world

for free! Within weeks, we and numerous other young women were

on the train headed for Des Moines, Iowa, for basic training. Sara

28

Rie’sMemoirs

and I were separated, as we were assigned to separate companies.

We saw each other on the base several times and chatted about the

different places we might see. After six weeks of basic training, I was

transported to Rome, New York, where I had several interviews.

I took written tests to determine the type of work I would be best

suited for in the army. Another WAC I had met in Des Moines was

also sent to Rome for the same reason. She was an attractive and very

bright young woman who had been raised in Paris as the daughter

of a U.S. diplomat. It was decided that she would go to the Army

cooking school to become a mess hall cook! She was devastated to

say the least. I was first given a typing test, which I failed. During the

interviews, however, I had mentioned that I drew pictures, so the

army assigned me to the only Special Service Company in the WAC,

the Jonathan Wainwright Company, named after a famous general.

Although I was chosen because I drew pictures, they also thought

I should learn something more practical, so I became a movie

projector operator—a skill I learned in two lessons.

In Rome, I also learned to enjoy coffee; before that, I had drunk

only tea. It was wintertime in northern New York State when I

was stationed there. e walk to the mess hall was about a quarter

mile, by which time my hands were ice cold. Coffee urns were

the first thing you encountered upon entering the mess hall, and

I immediately would pour myself a cup for the sole purpose of

warming my fingers. After some time, I would take a sip and I was

soon hooked.

Before long, our company got good news. We were going to Europe

on the Queen Mary, which was serving as a troop transport ship

during World WarII. Not only could the Queen Mary carry a huge

amount of troops, it was also quite fast, so it did not need a convoy.

is was toward the end of World War II, and fewer troops were

headed to the war zone. Consequently, the Queen Mary carried only

the number of troops that it had passenger berths for.

We landed at Fauve [??] and took a troop train to Compiegne, just

outside Paris. e Compiegne camp was a staging area for troops

before being sent to their designated assignments throughout

Europe. e bunch of us spent the nights on cots outside. It was late

spring and the weather was perfect for outdoor sleeping. When we

washed our hair we used fresh lemons for a rinse. Around the same

time, we were introduced to a new invention, the first shampoo

rinse—so much for lemons. e short time our company was

29

Rie’sMemoirs

there we had no assignment, with the result that many of us made

frequent trips to Paris to see the sights. Just a 20-minute free train

ride would get us there. Of course, we visited all the well-known

tourist attractions, which were free to all military personnel. At the

bistros and restaurants in Paris we had the best meals we had ever

experienced. I did well communicating with the French. We were

in Compiegne for two weeks before getting transferred to Salzburg,

Austria.

.

q

Salzburg, Austria

S alzburg is an ancient walled city built on a hill with Hohensalz-

burg Castle on top. As I recall, we were stationed there for four or

five months. e birthplace of Bach, it was a renowned music center.

Bach’s house was a sightseeing

destination then and is now.

Being in a Special Service Com-

pany, our Captain approved the

plan created by certain mem-

bers of our company to put on

a play. Titled “is Gal’s Army,”

the performance was very well

received by the American troops

stationed there and sold out

every night for a week. After all,

what else was there to do there?

I had exactly one line, which was

“She was built like a brick house!”

It brought down the house every

time. I had no idea why it was so hilariously funny. Considering the

reaction I got, I presumed it was a very dirty joke. I was afraid to ask

and never did. I still don’t know what it means.

It was in Salzburg that I got my first proposition. I was having a cup

of coffee in a sidewalk café; at a nearby table sat an American soldier.

We said a few words to each other, and then he moved over to my

table and we chatted on. Pretty soon, he said, “What do you say we

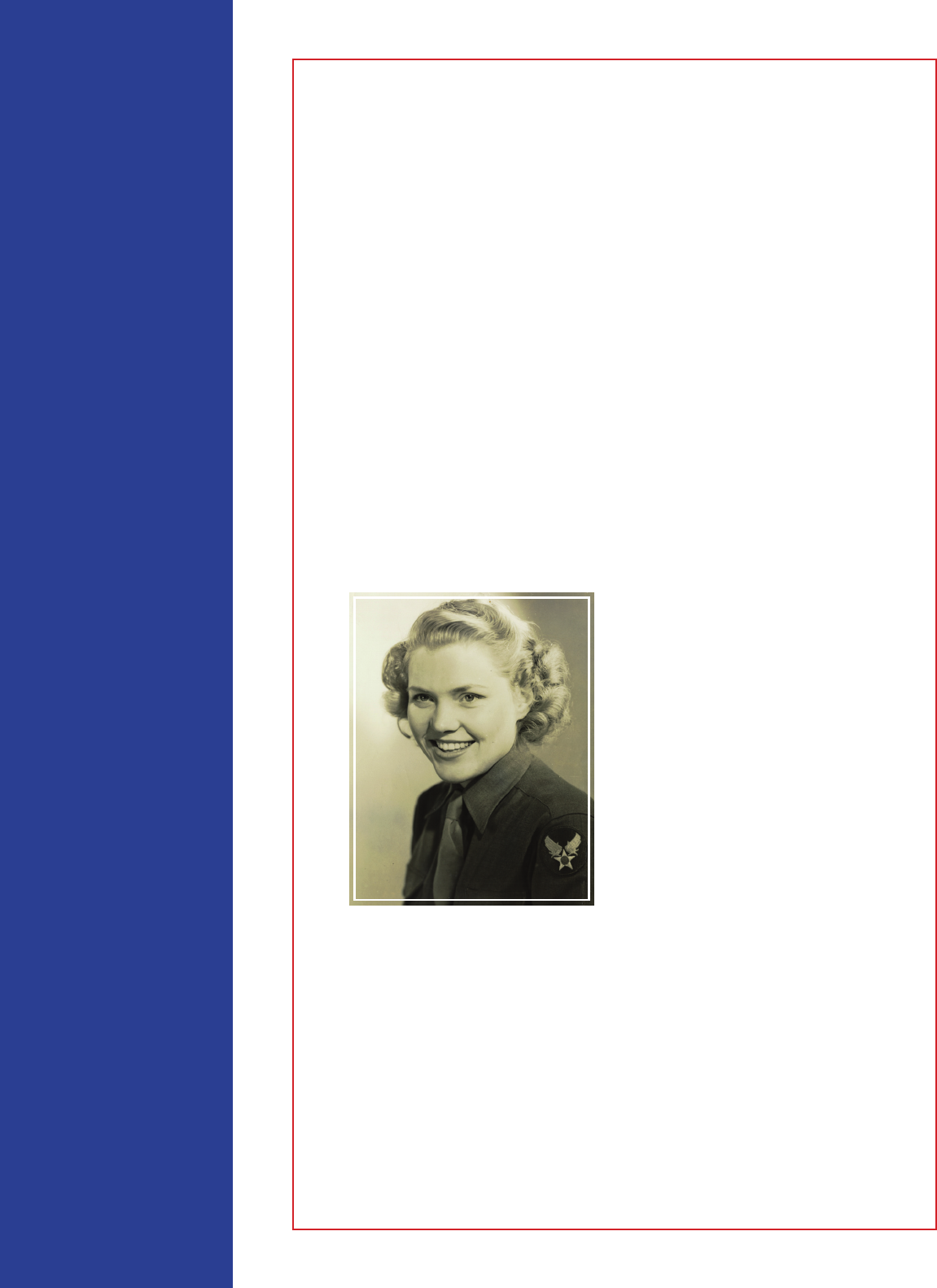

Rie in WAC uniform

30

Rie’sMemoirs

go to a hotel and have sex?” I said something like, “No thank you, but

thanks for inviting me.” We finished our coffee and chatted until we

finally went our separate ways.

.

q

Garmisch Partenkirchen

O ur Special Services Company was finally split into platoons or

smaller, and we were scattered all over Germany. At this point in

the war, the Army was designating troops to R&R (recreation and

rehabilitation) camps.

For our R&R, we were sent to our station of Garmisch Partenkirchen.

is beautiful city in southern Bavaria, Germany, is known for its

ski resorts. ere, like in all other conquered German areas where

Americans were stationed, included hotels, motels, and a huge

number of private homes that were taken over by the Americans to

house the troops. About 12 of us from our company were sent to

Garmisch Partenkirchen, where we were assigned the Opal family ski

resort home away from home. e house was large enough to easily

house all of us, and it came with the services of a cook and a maid! In

addition, we had a Jeep and driver at our disposal. Having all come

from middle to lower income families, none of us had ever lived in

such luxury.

When we went to town, every public service was free to the

conquering troops. My roommate, Fran Grave, and I were the

only two in our group to take professional ski lessons in this world

class resort. We did so practically every day for a half a year and, in

that time, became very adequate skiers. One day on the slopes, we

noticed a small group of six or seven women taking ski lessons also.

We would never see any other women skiing there, so we asked our

instructor about them, and he didn’t know either. Eventually, we

learned that the U.S. Army had decided to put on the U.S. Army Ski

Olympics. All U.S. Military could apply. About two weeks before

the event, it was ordered that women were to be included, namely

the WACS. Notices were sent out to all the camps, but not many

women stepped forward. is was in the late 1940s, and skiing had

not really caught on yet. From my recollection, there were only two

ski resorts in the U.S. at that time.

31

Rie’sMemoirs

Since no women had volunteered for the U.S. Army Ski Olympics

and time was running short, the head of the U.S. troops in Europe

ordered that they “recruit volunteers.” So these six to seven WACS,

none of whom had ever skied, were recruited for the U.S. Army

Olympics. In less time than it takes to tell, Fran and I high-tailed it

to the G.I. Olympic Committee and volunteered. We won all the

events: downhill, slalom, and cross-country.

Once in Garmisch Partenkirchen they showed a film made by the

U.S. Army advertised widely to the German citizens, who were

“ordered” to attend. Fran and I wondered if American troops could

see it, too. We decided to go and find out. ere was no fee, so we

just walked in. ere were no other G.I.s inside as we sat down and

watched the show. e film started. It was too shockingly horrible

to describe in full. One scene showed the U.S. Army advancing on

a German concentration camp. e troops encountered a large pit

with hundreds of nude bodies, both men and women, in it. e

commentator said that the prisoners had been ordered to dig the

hole and take off their clothes, and then they were shot. ose who

didn’t fall in the hole were bulldozed in after the slaughter. During the

40-minute film, you could hear a pin drop.

e Dutch and German languages are quite similar. Since I was

relatively fluent in those languages, along with English, I also had

a job as a translator. Some American officers spoke gruffly to the

Germans, but my translation was always civilized and pleasant. A

real translator is not supposed to editorialize, but I often did. In one

case, an officer remarked that a large ugly crucifix had to be removed

from a building the army had taken over. e officer made several

unflattering remarks about the object. I translated that by asking the

elderly owner if perhaps it would be a good idea to remove the large,

handsome crucifix from the wall to prevent it from getting damaged

by the many troops moving in. She readily agreed.

In Germany at this time, cigarettes were the currency of the country,

at least in Bavaria. When walking down the street smoking a

cigarette, one would surely be followed by a German a short distance

away. When the smoker tossed out his “butt,” the follower would

pounce on it, making sure it was extinguished, and put it in a little

bag. Enough of these butts would make a complete cigarette. I was

told that waiters in night clubs sometimes got no wages but were

allowed to have all the cigarette butts in the ashtrays. Americans

were allowed to purchase full cartoons of cigarettes for a dollar.

32

Rie’sMemoirs

When we would buy something from a German, they would

demand that we pay them in cigarettes, which we happily did. I had a

seamstress make me a skirt one time for the price of two packs (not

cartoons) of cigarettes.

During the height of the war, each soldier had to do 16 hours in a

bunker, with eight hours off to get a little shut eye. Although this

shift schedule was used for war, the kitchen and meals were not

on it. Marvelous meals were served to all. It only took three days,

if I remember correctly, to get across the Atlantic to visit the Firth

of Forth in Scotland. Upon arriving, we got on a train headed to

the English border. In many European towns, the trains stopped in

residential neighborhoods where children would run out of their

homes to greet the soldiers, probably hoping they would get a stick

of American chewing gum. e surprising thing was that out of each

house would come five to eight kids! Each house! We found out later

that the majority of the children were Londoners who had been sent

to Scotland for safety from the nightly bombings. During the last

days of the war, the Germans planes and rockets pummeled London

in hopes of a long-shot victory. Winston Churchill made his famous

quote regarding the British pilots; “Never have so few done so much

for so many.”

One day in Germany, a WAC in our group told us she was going

back to her home in New York. We were all surprised. How could

she want to go home? is was the life! We were living in a world

class ski resort, staying in the magnificent “Opal house,” complete

with maid and cook, free skiing, entertainment, transportation, and

good friends, both German and American.

How could she think about leaving all this glamour? e New Yorker

responded, “is is not real life, getting everything free. I’ve got to get

back to my real life some time, and that time is now.” She resigned her

commission after she had completed her minimum 18-month duty,

and off she went. e rest of us who had stayed more than a year and

a half in Garmisch Partenkirchen started to think about what our

friend had said.

My parents, who had still not managed to reserve transportation to

the U.S., were still in Holland. I hadn’t seen them in six years. About

this time, I learned that G.I.s who had parents or siblings living in

Europe could get a two-week leave of absence to visit them. I applied

and received a two-week pass, but it was for Poland, not Holland. I

33

Rie’sMemoirs

applied again, and this time they got it right and I got my two-week

pass for Holland. e only catch? ere was no transportation

provided. Passenger trains, buses, and airplanes were not running.

I asked around and got a few leads. Our jeep driver got the okay to

drive to Munich. Once there, I was told to make the rounds to the

American service clubs and find out if there were any G.I.s convoying

north. If so, I was to ask the commanding officer if I could join them.

My only luggage was a large, heavy duffle bag I’d stuffed with things

I thought my parents might need. I could hardly drag it. I lucked

out—the first service club I came to was packed with several

hundred servicemen. is was a bit unusual, since it was only 9:00

in the morning. I asked one of the men if by chance they were on a

convoy north, and he replied, “Yes, up to Cologne.” When I asked

if I could join the group, since I was headed to Holland, he went to

ask his commanding officer and returned shortly with a “Yes.” When

their break at the club was over, we all went outside where Jeeps

and service trucks pulled up. e convoy of about 2,000 troops all

loaded in the rigs. After a few hours of driving on Hitler’s Autobahn

Highway, I was beginning to wonder when we were going to stop to

go to the bathroom. I also wondered how that was going to work,

since I was the only woman with this large group of men. At a

wooded area, the entire convoy came to a halt. An order was given

at the front of the convoy and relayed down the line. I couldn’t hear

it a first, but eventually the order made its way to us: “Men to the left,

woman to the right.” All the soldiers crossed the highway, and I went

to the other side and did my business. Once we got to Cologne, I had

another stroke of luck. Dutch trains were running, and one route

came very close to the town of Amerfoort, where my parents lived. I

met a G.I. at the Cologne train station who helped me haul and load

my duffle bag onto the Dutch train. I asked the station manager how

to get to my parents’ address. Seeing my huge duffle bag, he offered

to walk me there with his bike, packing the big load on the seat.

q

34

Rie’sMemoirs

Reunited

S eeing my parents after six years was like a most happy dream.

ey had gotten a bit older and my mother had lost a few pounds,

but, of course, I had gotten a bit older as well. I opened the duffle

bag with all the gifts, and we talked late in to the night, catching

up on everything that had happened over the years. e German

occupation had made everything scarce, so the gifts were much

appreciated. What they couldn’t use themselves they could easily

trade for other needed items. We had a most wonderful reunion.

ey told me fascinating stories of their years of occupation by the

Germans. My parents had a small radio, which was not allowed, that

they carried to the road to listen to the evening news with the British

Broadcasting. ey also listened to the U.S. Army radio for news.

ey would hide the radio and go back to their living quarters.

When Germany occupied Holland, all Dutch food produced for the

country was confiscated by the Nazis for their troops. Practically

all the European countries were either still fighting or occupied by

the Germans. All these countries faced the same threat as Holland:

starvation, as occupying soldiers ate their food. Much of Holland’s

vegetables and fruits were produced in the two Dutch states of

Groningen and Freisland, the farthest northeasterly states in the

nation. Amerfoort, on the other hand, was in south central Holland.

Some Dutch women with their starving families would take a purse

full of money and start a bike ride north to Freisland and Groningen

and buy whatever food they could. ere were no cars or gas

available. e farmers would grow their regular crop on order of the

Germans to feed their troops. Of course the farmers were not paid,

so any food they could hide and sell on the black market was to their

advantage.

My dad would not go up north for food. Any able-bodied man

seen on the streets would be picked up immediately and sent off

to labor camps to build tanks, ammunition, and so on. So it was up

to my mother. My mother rode her bike up twice to buy food, as

did hundreds of other women. When they rode north to the farms,

they would sleep in fields or woods. When they returned, however,

they were laden with stuffed bags hanging from the handle bars and

usually a box of food strapped to the back of the bike. erefore, they

would sleep in the day and travel by night, so their precious cargo

35

Rie’sMemoirs

would not be taken by the Germans. My mother said it was kind of a

fun adventure, depending on the weather, and that she made friends

with a number of other women.

e German soldiers confiscated anything and everything they

wanted. One of the most popular things they wanted was men’s

bicycles. ey would stop every man on a bike and simply take it

away and ride off. en the Dutch came up with an idea that brought

the whole thing to an immediate stop. ey removed the front tire

and replaced it with a very small child’s bike tire. It made it extremely

awkward to ride—but they could bike again, since the Germans

didn’t want them. Of course, there were women’s bikes, too, but no

self-respecting German male would be caught dead or alive on a

woman’s bike.

After the two week visit with my parents, I returned to Garmisch.

e trip back was easy, because Holland had not been an enemy

country. I went to Schiphol, the main airport in Holland and was told

that an American DC3 was going to Munich.

My parents finally got passage out of Holland on a Swedish ship

in 1946. It wasn’t too long after my visit to Holland that I started

thinking of the wonderful but unreal life in Garmisch Partenkirchen.

I decided to resign from the army in 1945 and head back to the states.

I was going to Emden, a port in Northern Germany and had passage

on a confiscated small German freighter. ere were about a dozen

or so other passengers; all were German war brides. e voyage was

not that enjoyable as the German mothers did not get along with

each other. All of them liked me because I admired their adorable

little babies. One continuous problem in the lounge was some of the

mothers liked to open the window and get some fresh air. Others

complained of the draft, saying it would make the babies sick. After

a few minutes, one of the other mothers would get up and close the

window with a bang! Around and around that would go every day.

Some of the officers’ wives would try and pull rank on the wives of

privates. is went on for the entire crossing from Emden to New

York Harbor. However, when we reached the harbor, all the husbands

and family were there happily waving and cheering. I’ve thought

about these war brides now and then, hoping they persevered.

My parents had been corresponding with their close friends Oma,

Anton, and Tante Akka, who lived in Home, Washington, and

who urged my parents to move up to their small town, which was

36

Rie’sMemoirs

populated by a large number of Dutchmen. In 1950, my parents

decided they should rent a house in Home and see how they liked it.

I volunteered to drive them up. e trip would take about a week I

figured. I was working at the Broadway Department Store at the time

and getting tired of it and ready for a change. Perhaps I would visit

Alaska. I happily quit my job and the four of us prepared for the trip:

me, Father, Mother, and Buff, my one-year-old lab who I had adopted

in Garmisch.

We had a lovely trip to Tacoma, where we took the notorious

“Galloping Gertie” bridge over the Tacoma Narrows to Gig Harbor

and then on to Home. e long and short of the story is that my

parents both loved the tiny village and were delighted to see their

friends. ey met and also thoroughly enjoyed the other Dutchmen

there and decided to stay. ey were able to buy a house they were

renting and, as luck would have it, it came with a huge productive

cherry tree in the front yard. We three children would visit our

parents and climb the cherry trees, sitting in the branches for hours

eating our fill of cherries.

. q

Alaska!

I was getting more and more intrigued with visiting Alaska, and

decided to take a voyage up to Southeast. I booked passage on the

Canadian Princess line, and, toward the end of May 1950, I departed

from Victoria, Canada.

Needless to say, I had the most marvelous time on my voyage. It was

even more fun having a college class of about 30 Geology students on

board. e Princess Pat arrived in Juneau on June 1. I had gotten up

early and was already on deck by 6:00 a.m. It was a most wonderful

day. Warm, sunny, snow-covered mountain peaks on either side of

the channel. ere, nestled between Mt. Juneau and Mt. Roberts, lay

the town of Juneau, population about 7,000 people.

As we approached the dock, my mind was racing, “What a gorgeous

town, setting, mountains, sparkling ocean. What a great place to live.

Oh, if only I lived here . . . I should try!” I decided to go ashore for the

seven hours it would take the ship to go north to another town and

37

Rie’sMemoirs

return. Perhaps I could get a job and a place to live. “Maybe I’m out of