1

THE WEST VIRGINIA PUBLIC EMPLOYEES GRIEVANCE BOARD

CARENA ROUSE, et al.,

Grievants,

v. Docket No. 2017-0308-CONS

BOONE COUNTY BOARD OF EDUCATION,

Respondent.

DECISION

Grievants

1

are employed by or retired from Respondent, Boone County Board of

Education, and are or were employed in various positions. Between August 2, 2016, and

August 24, 2016, the Grievance Board received numerous grievance forms filed by

representatives or counsel for members of three different unions and some pro se

Grievants. A representative grievance statement, which addresses the allegations made

by Grievants in total stated as follows:

“Pursuant to West Virginia Code § 6C-2-3(e)(2)

2

, Grievant

grieves on behalf of herself and similarly situated employees

(including both professional personnel/teachers and service

personnel) the unlawful elimination and/or reduction of the

county salary supplement and optical and dental insurance for

current and/or retired employees by Respondent Boone

County Board of Education which violates, inter alia,

Grievant’s rights pursuant to the Excess Levy passed on

November 4, 2014 and which is still in effect; the federal and

state constitution due process provisions regarding property

rights; as well as the constitutional provisions of the requiring

Respondent to provide a thorough and efficient education;

and the statutory and regulatory scheme governing education

law in general and teacher and service personnel

constitutional and statutory rights specifically. Moreover,

1

There are four hundred fifteen Grievants whose names are incorporated herein

by reference.

2

“Class actions are not permitted. However, a grievance may be filed by one or

more employees on behalf of a group of similarly situated employees. Any similarly

situated employee shall complete a grievance form stating his or her intent to join the

group of similarly situated employees.”

2

Grievant contends that Respondent’s actions in unlawfully

eliminating the salary supplement and optical and dental

insurance are not authorized by West Virginia Code §§ 18A-

4-5a and 5b.

The representative statement sought the following as relief: “To have the salary

supplement and dental and optical insurance restored; to receive any back pay with

interest or reimbursement with interest due to loss of ensuing coverage; and any other

appropriate relief.”

By email dated August 23, 2016, Respondent, by counsel, announced its intention

to identify and dismiss at level one those grievances filed by retirees, although no such

order was ever received by the Grievance Board. On August 26, 2016 and August 31,

2016, the parties submitted agreed motions to waive the matter to level three of the

greivance process. Throughout the next three months, the Grievance Board had

numerous communications with the parties in an attempt to determine the status of all

Grievants, as some filing information was incomplete, a number of duplicative grievances

had been received, including some in which the same Grievants were purported to be

represented by two different unions, and the retiree dismissal orders were not received.

A scheduling conference was held by telephone on December 21, 2016, in which the

parties agreed to submit stipulations of fact and it was determined that no pro se Grievants

remained. On January 6, 2017, a Consolidation and Scheduling Order was entered,

consolidating all existing grievances, ordering the agreed finalized stipulations be filed by

close of business February 13, 2017, informing parties of the ability to request a second

conference if further procedural issues occurred, and stating that a date would be

selected for level three hearing via conference call following the submission of the

stipulated facts.

3

By email dated February 7, 2017, the parties requested, by agreement, to extend

the deadline to submit the finalized stipulations by two weeks. This request was granted

and parties were given until February 27, 2017, to submit the finalized stipulations. The

parties failed to submit the agreed stipulations. Between March 2017 and October 2017,

Grievance Board staff requested numerous status updates from the parties regarding the

failure to submit the agreed stipulations and the undersigned granted the parties’ requests

to extend the deadline to submit agreed stipulations. The unsigned Parties’ Joint

Stipulation of Fact was filed on December 5, 2017, nine months after the initial deadline

for filing set in the Grievance Board’s January 6, 2017 order.

Following review of the Parties’ Joint Stipulation of Fact, the undersigned

determined a second scheduling conference would be necessary. Due to scheduling

conflicts among the parties, the conference could not be held until February 21, 2018.

During the conference, the parties asserted that a level three evidentiary hearing would

still be required in addition to the joint stipulated facts and that they were uncertain how

many Grievants intended to appear in person at the hearing. As the Grievance Board’s

facilities could only accommodate approximately fifty people for a hearing, counsel for

Grievants were directed to confer with Grievants to determine the number of people who

would participate in the hearing. In addition, counsel for Grievants agreed that, except

for the final decision, Grievants agreed to receive communications from the Grievance

Board electronically rather than by mail. After being informed that the number of

Grievants who intended to appear personally at the hearing could not be accommodated

by the Grievance Board facility, by letter dated March 16, 2018, the undersigned

requested the agreement of the parties to conduct the hearing in an auditorium or similar

4

room in one of Respondent’s facilities. The parties were directed to confer and provide

an answer by April 6, 2018. The parties agreed that the hearing could be held at

Respondent’s Operations Complex but could not agree to dates upon which the hearing

could be scheduled despite numerous communications over the course of several

months. The undersigned convened a third scheduling conference on July 2, 2018,

during which the undersigned determined, given the number of Grievants counsel had

previously informed would be in attendance, that the hearing must be held before the

beginning of the school term or it would seriously impair or completely prevent the

operation of the Boone County school system for the two days of hearing. With that

consideration, the undersigned scheduled the level three hearing for two of the original

proposed dates over the objection of certain counsel.

The level three hearing was held on August 2, 2018 and August 3, 2018, before

the undersigned at the Boone County Schools Operations Complex in Foster, West

Virginia. Thirty-five Grievants appeared in person on day one of the hearing and eighteen

Grievants appeared in person on day two of the hearing. Grievants were represented by

Jeffrey G. Blaydes, Carbone & Blaydes, Andrew J. Katz, General Counsel, WV Education

Association, and George B. Morrone III, WV School Service Personnel Association

3

.

Respondent appeared by Superintendent Jeffrey Huffman. Respondent was represented

by counsel, Howard E. Seufer, Jr. and Canon B. Hill, Bowles Rice LLP.

4

Due to the

unusual nature of the grievance and to ensure that all questions of law were addressed

as thoroughly as possible, in addition to the statutorily-allowed submission of written

3

Mr. Morrone substituted as counsel for Joe Spradling, Esq., who substituted as

counsel for John Roush, Esq.

4

Mr. Seufer substituted as counsel for Richard Boothby, Esq.

5

Proposed Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law (“PFFCL”), the parties were permitted,

by agreement, to file briefs in reply to the PFFCL. Therefore, this matter became mature

for decision on December 20, 2018, upon final receipt of the parties’ PFFCL and reply

briefs.

Synopsis

Grievants are or were employed by Respondent in various positions, both

professional and service. An unspecified number of Grievants are retirees of

Respondent. The Grievance Board lacks jurisdiction to hear the claims of the retirees in

this matter. Grievants proved Respondent failed to spend all excess levy funds for the

purposes they were raised. Grievants failed to prove Respondent was not permitted to

reduce the county salary supplement to below the 1990 level if it did not have enough

excess levy collections to fund the county salary supplement. Grievants failed to prove

Respondent was required to provide them notice and opportunity to be heard before

termination of their vision and dental insurance when Respondent was acting on the order

of the State Superintendent or that they were otherwise entitled to continuation of their

vision and dental insurance. Accordingly, the grievance is granted, in part, and denied,

in part.

Findings of Fact

The following are a combination of agreed findings of fact as submitted by the

parties in the Parties Joint Stipulation of Fact

5

and findings of fact made by the

5

The parties confirmed the unsigned Parties’ Joint Stipulation of Fact represented

the agreement of the parties. The findings have been revised to remove references to

attachments, to correct errors, to provide clarity and brevity, and to remove reference to

evidence the parties stated in the Parties’ Joint Stipulation of Fact would be moved into

evidence at the level three hearing that was not so moved.

6

administrative law judge based upon a complete and thorough review of the record

created in this grievance

1. Grievants are or were employed by Respondent in various positions, both

professional and service. An unspecified number of Grievants are retirees of

Respondent.

2. The American Federation of Teachers – West Virginia, AFL-CIO represents

the interests of approximately 200 public school teachers as well as service personnel in

Boone County, and as such, has standing to represent these teachers and service

personnel. Christine J. Campbell is the duly elected president of the American Federation

of Teachers – West Virginia, AFL-CIO.

3. West Virginia Education Association (WVEA) is an employee association.

For the relevant purposes here, the membership of the WVEA is made up of public school

teachers, service personnel and administrators. The WVEA has a very large group of

members in Boone County, virtually all of whom have been affected by the legal issues

set forth below.

4. The West Virginia School Service Personnel Association (WVSSPA) is an

employee association. For the relevant purposes here, membership of the WVSSPA is

made up of public school service personnel. The WVSSPA has a large group of members

in Boone County, virtually all of whom have been affected by the legal issues set forth

below. These members belong to the Boone County School Service Personnel

Association, which is the county affiliate of the WVSSPA.

5. The Boone County Board of Education is a county board of education and

exists by virtue of West Virginia Code § 18-5-1 et seq. and is required to perform its duties

7

in compliance therewith and with other statutory provisions.

6. John Hudson served as the Superintendent of Boone County Schools from

July 1, 2009 through June 30, 2016. Superintendent Hudson left the employment of

Respondent when he accepted employment from the Putnam County Board of Education

to serve as its superintendent.

7. Jeffrey Huffman became Superintendent of Boone County Schools effective

July 1, 2016, and continues to serve as its superintendent.

8. Mark E. Sumpter, at all relevant times, was the President of the Boone

County Board of Education.

9. Charles Chapman served as the Treasurer of Boone County Schools from

October 1993 through January 2018.

10. Samuel Pauley became the Treasurer of Boone County Schools in March

2018 and continues to serve as it treasurer. Prior to his employment as Treasurer, Mr.

Pauley was employed by the State Department of Education within the Office of School

Finance where he performed budget reviews of county boards of education, including the

Boone County Board of Education.

11. County boards of education are required to provide students with 180 days

of instruction and to provide employees with 200 days of employment.

12. Respondent is funded, in part, by the regular levy of taxes and an excess

levy of taxes.

13. Consecutive excess levies have been in place in Boone County since at

least 1984.

14. The voters of Boone County were presented with the opportunity to renew

8

the excess levy for education on November 4, 2014. The official Ballot stated as follows:

OFFICIAL BALLOT

The Board of Education of the County of Boone

Election to Authorize Renewal

of Additional Levies

Special election to authorize additional levies for

the fiscal years beginning July 1, 2015, July 1, 2016, July

1, 2017, July 1, 2018, and July 1, 2019, in the total amount

of $11,656,290.00 annually for the purpose of the payment

of the general current expenses of the Board of Education

of the County of Boone, (hereinafter “the Board”)

including, but not limited to, payment of salaries of

teachers and other employees who are paid exclusively

from local Board funds, fixed employee costs, and

supplemental salaries and benefits; provision of

optical/dental insurance for retirees of the Board; the

repair, maintenance, and operation of school buildings

and equipment; the purchase of textbooks, library books,

and instructional supplies and equipment; the provision

of capital improvements of existing schools and /or

athletic facilities; the purchase of new technology,

replacement of dated technology, as well as the

expansion of technology infrastructure in the schools;

support of the provision of free meals for all students; the

provision of three (3) School Resource Officers/school

security improvements; and the provision of school

buses and the transportation of pupils including

transport to extra-curricular activities all according to the

order of The Board entered on the 4

th

day of August, 2014.

The approximate annual amount considered necessary for each purpose is as follows:

Employee salaries that are paid

exclusively from local funds, $7,500,000.00

Fixed employee costs and benefits,

including county salary supplements $1,606,290.00

Support the provision of free meals for all students $125,000.00

Instructional supplies and equipment $400,000.00

Textbooks $200,000.00

9

Optical/dental insurance for retirees $75,000.00

Support the purchase of school buses and transportation

of students $100,000.00

Transport of teams to athletic contests and other

extra-curricular activities $75,000.00

Provision of three (3) School Resource Officers/school

security improvements $125,000.00

Building operation, repair and maintenance $650,000.00

Capital Improvements to existing schools

and/or athletic facilities $375,000.00

New Technology, replacement of dated technology,

and expansion of technology infrastructure $400,000.00

TOTAL $11,656,290.00

6

15. The excess school levy was renewed by the voters of Boone County, West

Virginia on November 4, 2014.

16. The Official Ballot for the excess school levy does not indicate that

Respondent shall have discretion to determine which of the above-listed items on the levy

call will be funded. Instead, the Official Ballot indicates that twelve line items will be

funded in the approximate amounts as listed above.

17. The total amount for the items listed in the levy language is $11,656,290.00.

18. Two line items, line item one and line item two, are at issue in this grievance.

19. The total amount earmarked for line item one, “Employee salaries that are

paid exclusively from local funds,” is $7,500,000.00, or 64.3% of the levy funds.

20. The total amount earmarked for line item two, “Fixed employee costs and

6

Stipulated Ex. 1 at 69-73.

10

benefits including salary supplements,” is $1,606,290, or 13.7% of the levy funds.

21. No amount was earmarked for optical and dental insurance for current

employees.

22. Respondent’s total tax collections began to decline in 2014 and 2015,

resulting in a decrease of total tax collections for fiscal year end 2015, although excess

levy collections were still above what would be required to support the excess levy at

issue in this case that began with fiscal year beginning 2015.

23. On February 26, 2015, the Board made numerous cuts to regular and

extracurricular professional and service personnel contracts in order to address its

decreasing financial resources.

24. On April 6, 2015, five coal companies with operations in Boone County

declared bankruptcy.

25. On August 3, 2015, two more coal companies with operations in Boone

County, including Alpha Natural Resources, LLC, which wholly owns eight coal

companies with operations in Boone County, declared bankruptcy.

26. As a result of the bankruptcies, tax collections for the fall of 2015 were $4

million short of projections.

27. On December 1, 2015, the Board voted to close three schools at the end of

the 2015-2016 school year: Wharton Elementary School, Nellis Elementary School, and

Jeffrey-Spencer Elementary School.

28. On February 26, 2016, the Board made numerous cuts to regular and

extracurricular professional and service personnel contracts for the following school year

in order to address its decreasing financial resources.

11

29. By the spring of 2016, Respondent could not meet its payroll obligations

and was forced to seek a special legislative appropriation of $2.1 million to continue

operations, which required Respondent to repay the appropriation once the delinquent

tax collections were received.

30. For fiscal year end 2016, of the budgeted excess levy amount of

$11,656,290.00, the Sheriff of Boone County collected net taxes of only $8,029,574.24,

had total revenues and receipts of $8,059,060.99, and disbursed $7,481,920.99.

1

31. Each year county boards of education are required to submit its proposed

budget for the next year for review by the Office of School Finance. The budget of a

county board of education must be approved by the State Board of Finance.

32. After thorough review of Respondent’s proposed budget for fiscal year

ending 2017, Dr. Michael J. Martirano, the State Superintendent of Schools, in a letter

dated June 29, 2016, citing Respondent’s suddenly-reduced financial resources and

apparent inability to fully fund its operations for the 2016-2017 school year ordered

Respondent to enact certain cuts to most of its employees’ salaries, certain employee

benefits, and a few employees’ contract days.

33. On June 30, 2016, Respondent voted unanimously not to comply with the

June 29, 2016 order.

34. In a letter dated July 1, 2016, the State Superintendent of Schools again

1

G. Ex. 2 at 13, line number 374, “School Levy Fund,” Sheriff’s Settlement for fiscal

year 2016. Treasurer Pauley’s later accounting of the excess levy budget showed the

excess levy collection for fiscal year 2016 was $7,700,597.00. No evidence was offered

interpreting the settlement statement and no party appeared to question why

Respondent’s excess levy budget showed a different amount than the Sheriff’s

Settlement.

12

ordered the Respondent to make certain cuts to most of its employees’ salaries, certain

employee benefits, and a few employees’ contract days. and gave the Respondent a

deadline of July 8, 2016, to comply.

35. On July 7, 2016, Respondent again voted unanimously not to comply with

the order of the State Superintendent of Schools dated July 1, 2016.

36. In a letter dated July 7, 2016, the State Superintendent of Schools, for the

third time, ordered the Respondent to enact certain cuts to most of its employees’ salaries,

certain employee benefits, and a few employees’ contract days. These cuts were slightly

different from the cuts previously ordered by the State Superintendent of Schools. Those

cuts eliminated the salary supplement for teachers and school service personnel for the

2016-2017 school year and the provision of dental and optical insurance for all

employees.

37. On July 14, 2016, the State Board of Education voted to intervene in and

take control of the operation of the school system in Boone County unless the Respondent

voted by July 18, 2016, to comply with the written order of the State Superintendent of

Schools dated July 7, 2016.

38. On July 18, 2016, Respondent voted to comply with the July 7, 2016 order

of the State Superintendent of Schools.

39. On or about July 26, 2016, Superintendent Huffman sent notice to all

employees regarding the impact of the budget revisions required by the State

Superintendent of Schools, specifically the cuts being made to employees’ salaries and

benefits. Specifically, on or about July 26, 2016, Respondent mailed to its employees

notice that it was reducing the “county pay supplement” that it has for many years paid to

13

its employees by virtue of West Virginia Code Section 18A-4-5a. The cuts eliminated the

salary supplement for teachers and school service personnel for the 2016-2017 school

year and the provision of dental and optical insurance to all employees effective August

31, 2016.

40. Between July 1, 2016 and July 22, 2016, employees with a 240-day or 261-

day contract received the salary supplement collected for the 2016-2017 school year.

Other than these employees, none of the excess levy money collected for the 2016-17

school year was utilized for county salary supplements as set forth in the language of the

excess levy.

41. On or about August 3, 2016, Superintendent Huffman sent notice to all

retirees of the Board that the Board would no longer be able to pay for their optical and

dental insurance after August 31, 2016.

42. Optical and dental insurance for retirees was paid for through August 31,

2016 using excess levy money collected for the 2015-2016

7

school year.

43. Employees were not afforded notice and opportunity to be heard regarding

these changes to their pay and benefits.

44. Boone County Schools’ total tax collections for the relevant time period were

as follows:

8

7

The Parties Joint Stipulation of Fact Stated the 2016-2017 school year but that

appears to have been a typographical error.

8

The Parties Joint Stipulation of Fact included the following: “The projected excess

gross tax collections for Boone County has declined as follows: FYE 6/30/14

$13,992.718, FYE 6/30/15 $12,520,182, FYE 6/30/16 $11,090,686.” As it is unclear

from where this information originated and it is unclear why the projected excess gross

tax collections would be relevant when the actual tax collection information was entered

into evidence, this information has not been included in the findings of fact. The tax

collection information appears in Stipulated Ex. 1 at 242.

14

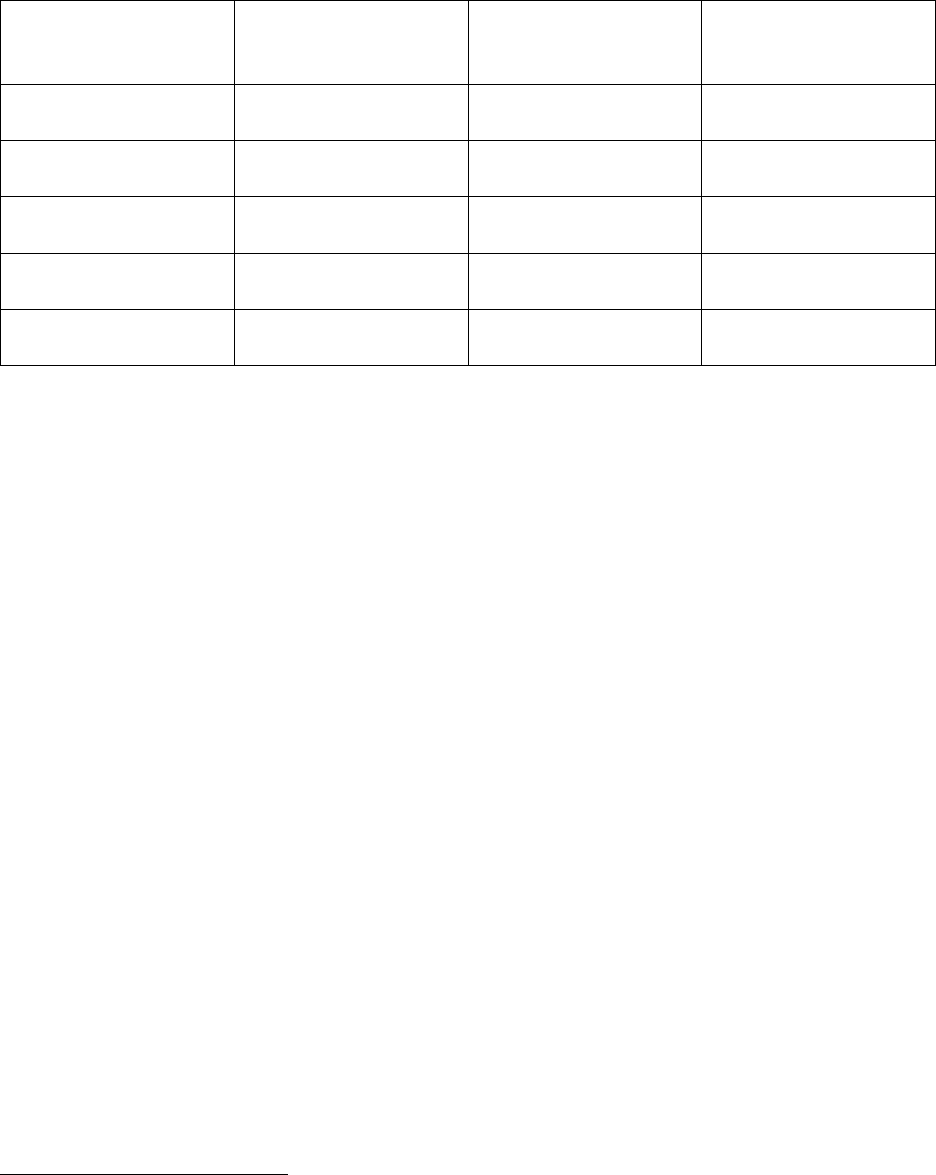

Regular Levy

Excess Levy

Total

FY ‘13

11,327,449.92

13,660,485.22

24,987,935.14

FY ‘14

11,412,657.79

13,772,691.42

25,185,349.21

FY ‘15

10,103,424.95

12,226,069.36

22,329,494.31

FY ‘16

6,606,913.50

8,059,0606.99

14,665,974.49

FY ‘17

3,020,696.64

3,624,940.39

6,645,637.03

45. Between fiscal years 2013 and 2014 the Board’s tax revenue from regular

and excess levies increased $197,414.07 or 0.08%.

46. Between fiscal years 2014 and 2015 the Board’s tax revenue from regular

and excess levies decreased $2,855,854.90 or 11.33%.

47. Between fiscal years 2015 and 2016 the Board’s tax revenue from regular

and excess levies decreased $7,663,519.82 or 34.32%.

48. Between fiscal years 2016 and 2017 the Board’s tax revenue from regular

and excess levies decreased $8,020,337.46 or 45.31%.

49. Respondent’s unrestricted fund balance

9

without OPEB liability

10

or

encumbrances (“fund balance”) peaked on or about fiscal year ending (FYE) June 30,

2010. It began declining the following year, and declined every year at least since 2012.

The fund balance has declined as follows:

FYE 6/30/12: $8,510,759

9

The unrestricted fund balance is the carryover balance after all obligations are

paid from the previous budget year, essentially, a surplus.

10

“Other Post Employment Benefits,” the liability associated with providing health

insurance to retirees.

15

FYE 6/30/13 $5,163.142

FYE 6/30/14 $4,036.028

FYE 6/30/15 $1,631,512

11

50. The state Office of Finance recommends a county board of education have

an unrestricted fund balance of between three and five percent of its budget. Some

national organizations recommend maintaining an unrestricted fund balance of sixteen to

twenty percent.

51. If a county falls below the state recommended amount, they are considered

at risk and are put on a watch list. Although Respondent began to spend down its

unrestricted fund balance in 2012, it was not considered at risk until after the crisis in

2015.

52. Throughout the pertinent time period, Respondent maintained a large

number of positions that were not eligible for state funding as follows: FYE 2012, 115;

FYE 2013, 130; FYE 2014, 131; FYE 2015, 138; and FYE 2016, 110.

12

53. Sometime in 2018, Treasurer Pauley prepared a document entitled Excess

Levy Budget which purports to account for the excess levy funds, including projected

amounts for the years remaining in the five-year levy.

13

54. Treasurer Pauley’s Excess Levy Budget is an accounting not of the

expenditure of the excess levy collections, as it should be, but is an accounting of the

total spending on the categories that were included in the excess levy, regardless of their

funding source.

11

G. Ex. 4.

12

G. Ex. 3.

13

R. Ex. 4.

16

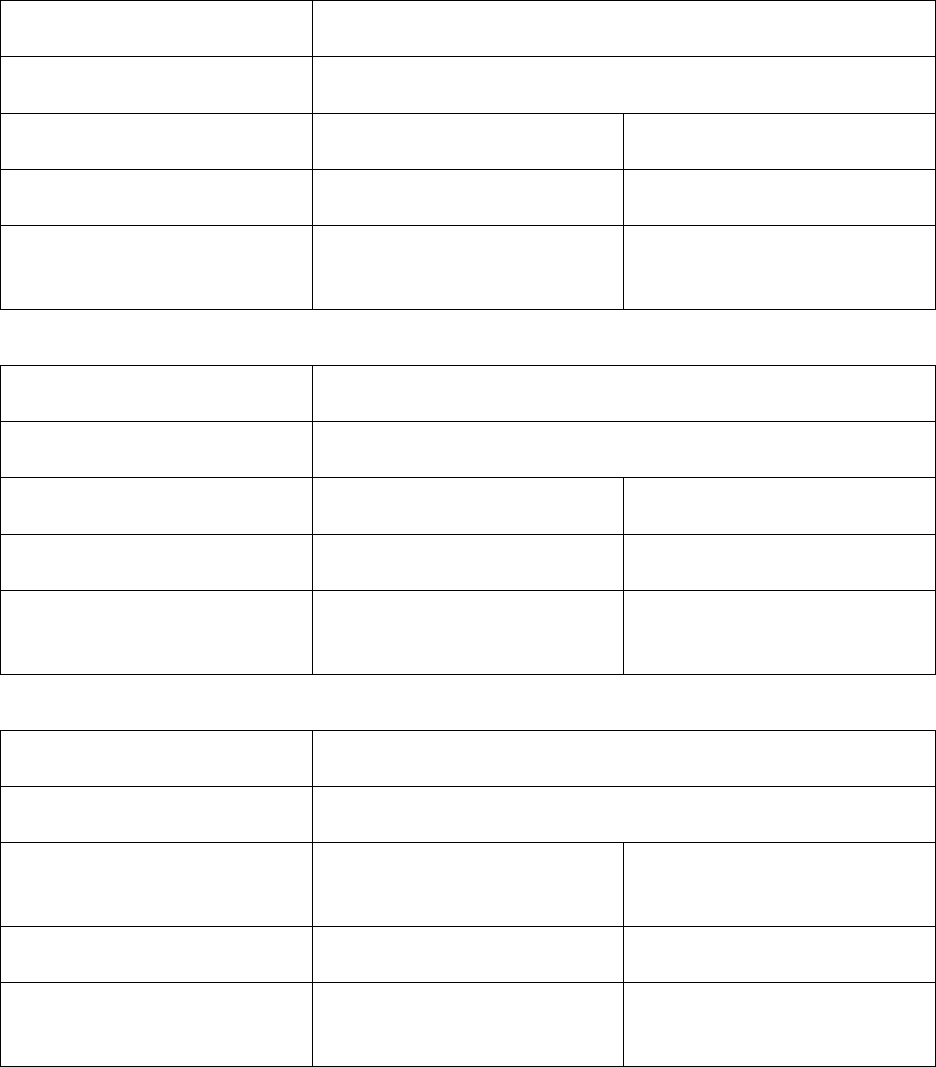

55. The Excess Levy Budget reads in pertinent part as follows:

Levy Line

2016

Revenue

$7,700,597.00

Budget to Stay at

Proportions Per Levy Call

Actual Excess Levy

Expenditures

1. Employee salaries paid

exclusively from local funds

$4,954,790.72

$10,510,066.00

2. Fixed employee costs

and benefits, including

county salary supplements

$1,061,177.44

$2,337,7122.90

Levy Line

2017

Revenue

$8,565,997.00

Budget to Stay at

Proportions Per Levy Call

Actual Excess Levy

Expenditures

1. Employee salaries paid

exclusively from local funds

$5,511,614.54

$4,161,812.00

2. Fixed employee costs

and benefits, including

county salary supplements

$1,180,433.51

$888,783.11

Levy Line

2018

Revenue

$8,565,997.00

Budget to Stay at

Proportions Per Levy Call

Actual Excess Levy

Expenditures YTD plus

encumbrances 4/30/18

1. Employee salaries paid

exclusively from local funds

$5,719,026.59

$4,200,000.00

2. Fixed employee costs

and benefits, including

county salary supplements

$1,224,855.36

$850,000.00

56. There are two types of supplements for school employees: the state

supplement and the county supplement. These supplements are not the same; they are

addressed in separate statutes with distinct purposes and are funded differently. County

17

supplements are optional and are funded wholly by the county. The state supplement is

mandatory and is funded by the State unless certain circumstances are present which

require the county to fund all or a portion of the state supplement.

57. Respondent is a county that is required to fund all or part of the state

supplement amount. Respondent paid its share of the state supplement amount under

line one of the excess levy, “Employee salaries paid exclusively from local funds.” Under

line two, “Fixed employee costs and benefits, including county salary supplements,”

Respondent paid fixed costs and benefits such as Social Security, Medicare, retirement,

and workers’ compensation.

58. Respondent paid no county supplement amount from the levy.

59. From fiscal year 2016 through fiscal year 2018, Respondent collected $25.1

million in excess levy funds but only spent an alleged $19.6 million of that money for the

excess levy purposes. Respondent actually spent less than that amount for proper

excess levy purposes.

14

60. Respondent spent the full excess levy amount collected in fiscal year ending

2016.

15

61. The full excess levy collections were not spent on the levy call in fiscal years

ending 2017 and 2018. Respondent failed to spend more than $5.5 million excess levy

funds on excess levy purposes in those years. As some of the funds spent were not for

proper excess levy purposes, the number is greater than the $5.5 million shown in

Respondent’s accounting.

16

14

R. Ex. 4.

15

Id.

16

Id.

18

62. Under West Virginia Code Sections 18A-2-2 and 18A-2-6, virtually all full-

time and half-time regular public school employees who have been employed by

Respondent for more than three consecutive years with a 200-day contract have obtained

“continuing contract” status.

17

63. School employee contracts typically run from July 1

st

through June 30

th

of

the following year.

64. School employees have contracts with county boards of education that

include a certain number of days in an employment term; a certain rate of pay (that may

include a salary supplement); and other benefits that are funded by a special levy or other

sources.

65. Regular service employees experienced a loss of income as a result of the

elimination of the county supplement.

18

66. Teachers and other professional personnel employed by the Board

experienced a loss of income as a result of the elimination of the county salary

supplement. The loss of income for each employee would be the product of their

employment term multiplied by the difference in their pay rate for their particular pay grade

and years of service from the pay scale for the 2015-2016 school year and their pay rate

17

The Parties’ Joint Stipulation of Fact stated: “Evidence regarding those grievants

who did not, at the relevant time, hold a continuing contract will be submitted by the

parties. All grievants other than those referenced in the last sentence will be presumed

by the parties to have held a continuing contract at the relevant time.” No such evidence

was presented at the level three hearing.

18

The Parties’ Joint Stipulation of Fact stated: “Pay scales for the relevant school

years will be appended as Attachments and are hereby incorporated by reference as if

fully and textually setout herein.” No such pay scales were attached or presented as

evidence at the level three hearing.

19

for their particular pay grade and years of service from the pay scale for the 2016-2017

and 2017-2018 school years.

19

67. To the extent that they performed substitute work for the Board after the

elimination of the county salary supplement, substitute teachers and other substitute

professional personnel experienced a reduction in pay. The reduced pay experienced by

each professional substitute would be the product of the days that the professional

worked as a substitute after the elimination of the county salary supplement multiplied by

the difference in his/her pay rate (which rate is based on the relevant pay grade and

his/her years of experience) for the 2015-2016 school year and his/her pay rate for the

2016-2017 and 2017-2018 school years.

68. As a result of the budget revisions ordered by the State Superintendent of

Schools, all Boone County school employees had a reduction for the 2016-2017 school

year.

69. In April 2018, Respondent received delinquent tax proceeds from Alpha

Natural Resources, LLC and repaid the 2016 special legislative appropriation.

70. On July 1, 2018, Respondent reinstated a county supplement for

professional and service personnel of $1,150.

71. At the time of the level three hearing, Respondent had an approximate $7

million unrestricted fund balance.

Discussion

As this grievance does not involve a disciplinary matter, Grievants have the burden

of proving their grievance by a preponderance of the evidence. W. VA. CODE ST. R. §

19

Id.

20

156-1-3 (2018). “The preponderance standard generally requires proof that a reasonable

person would accept as sufficient that a contested fact is more likely true than not.”

Leichliter v. Dep't of Health & Human Res., Docket No. 92-HHR-486 (May 17, 1993), aff’d,

Pleasants Cnty. Cir. Ct. Civil Action No. 93-APC-1 (Dec. 2, 1994). Where the evidence

equally supports both sides, the burden has not been met. Id.

As a preliminary matter, an unspecified number of Grievants are retirees of

Respondent. Although Respondent did not specifically move to dismiss those Grievants,

the Grievance Board cannot render a decision on a matter for which it lacks jurisdiction.

“Administrative agencies and their executive officers are creatures of statute and

delegates of the Legislature. Their power is dependent upon statutes, so that they must

find within the statute warrant for the exercise of any authority which they claim. They

have no general or common-law powers but only such as have been conferred upon them

by law expressly or by implication." Syl. Pt. 4, McDaniel v. W. Va. Div. of Labor, 214 W.

Va. 719, 591 S.E.2d 277 (2003) (citing Syl. Pt. 3, Mountaineer Disposal Service, Inc. v.

Dyer, 156 W. Va. 766, 197 S.E.2d 111 (1973)). “The purpose of [the grievance statute]

is to provide a procedure for the resolution of employment grievances raised by the public

employees of the State of West Virginia, except as otherwise excluded in this article.” W.

VA. CODE § 6C-2-1(a). “‘Employee’ means any person hired for permanent employment

by an employer for a probationary, full- or part-time position.” W. VA. CODE § 6C-2-2(e)(1).

“‘Employer’ means a state agency, department, board, commission, college, university,

institution, State Board of Education, Department of Education, county board of

education, regional educational service agency or multicounty vocational center, or agent

thereof, using the services of an employee as defined in this section.” W. VA. CODE § 6C-

21

2-2(g).

The grievance process is not available to the retirees in this matter. Although it

could be argued that the retirees meet the definition of “employee” in that they were

previously hired by Respondent, Respondent is clearly not now their “employer” under

the statute as Respondent is not “using the services” of the retirees. Therefore,

arguments presented by Grievants regarding Respondent’s elimination of vision and

dental benefits for retirees will not be further addressed.

The West Virginia constitution mandates a “thorough and efficient system of free

schools.” W. VA. CONST. art. XII, § 1. To that end, county boards of education are required

to provide students with 180 days of instruction and to provide employees with 200 days

of employment. W. VA. CODE § 18-5-45(c) (2018). County boards accomplish this

mandate primarily using a combination of state and county, also referred to as local,

funding, although county boards also receive some limited federal funding. “Our State

school aid formula is composed of four basic components: (1) an amount raised from

local levy on real and personal property; (2) the State foundation aid, which is money the

State pays out of general revenue funds to the counties based on a formula composed of

seven components; (3) State supplemental benefits; and (4) amounts raised locally by

special levies by vote of the people in the county.” Pauley v. Kelly, 162 W. Va. 672, 708-

09, 255 S.E.2d 859, 878-79 (1979). Funding for county boards is dynamic as it relies on

factors that vary year to year such as the number of students enrolled, the assessed value

of property, and the actual amount collected of taxes due.

In this case, Respondent receives local funding from both the general and a

special, or excess, levy of taxes. For fiscal year ending 2016, an unprecedented shortfall

22

in tax collections occurred in Boone County due to the closure or bankruptcy of numerous

coal companies. For the 2016 – 17 school year, Respondent’s budget was based on only

70% of the general and excess levy of taxes that had been projected. Respondent did

not have enough money in reserve to make up the shortfall, leaving Respondent with a

four-million-dollar deficit. As a result, Respondent did not formulate a budget that satisfied

its mandate to provide the specified number of instructional and employment days. The

State Board of School Finance determined in its review of the budget submitted by

Respondent that Respondent would run out of money by the spring and not be able to

pay its employees or operate its schools. To correct this failure of the budget, the State

Superintendent ordered Respondent to make certain cuts to the budget on three separate

occasions, which Respondent refused to do. Only when the state board declared it would

take over the county did Respondent make the cuts previously ordered by the State

Superintendent.

At issue in this case are two actions Respondent took in complying with the orders

of the State Superintendent: the elimination or reduction of the county salary supplement

and vision and dental benefits for Respondent’s regular employees. Grievants argue that

Respondent was required to continue to pay the salary supplement under the terms of

the special levy and the requirements of state code. Grievants argue no authority that

the Respondent was required to provide vision and dental insurance for active employees

but argues that Respondent failed to observe the notice and opportunity to be heard

provisions of statute before removing those benefits. Respondent asserts it was required

to comply with the State Superintendent’s orders and that it did not violate the levy terms

or any state code provision.

23

State Superintendent Orders

Respondent first argues that, as the changes to the budget were ordered by the

State Superintendent, the changes were beyond Respondent’s control and, seemingly

argues, therefore, not Respondent’s responsibility. County boards of education are

required to prepare and submit yearly budgets for review and approval by the State Board

of Finance

20

. W.VA. CODE § 18-9B-6.

If the board of finance finds that the proposed budget for a

county will not maintain the proposed educational program as

well as other financial obligations of their county board of

education, it may require that the budget be revised, but in no

case shall permit the reduction of the instructional term

pursuant to the provisions contained in section fifteen [§ 18-

5-15], article five of this chapter nor the employment term

below two hundred days. Any required revision in the budget

for this purpose may be made in the following order:

(1) Postpone expenditures for permanent

improvements and capital outlays except from the

permanent improvement fund;

(2) Reduce the amount budgeted for maintenance

exclusive of service personnel so as to guarantee the

payment of salaries for the employment term; or

(3) Adjust amounts budgeted in any other way so as to

assure the required employment term of two hundred

days and the required instructional term of one

hundred eighty days under the applicable provisions of

law.

W. VA. CODE § 18-9B-8 (2018). In this case, the State Superintendent found

Respondent’s budget did not comply as above and ordered certain cuts be made to the

20

The State Board of School Finance “consist[s] of the State Superintendent of

Free Schools [State Superintendent of Schools], as chairman, the state Tax

Commissioner, and the Director of the Budget as secretary.” W. VA. CODE § 18-9B-3

(2018). However, [n]otwithstanding any and all references to the Board of School Finance

as found in article nine-b [§§ 18-9B-1 et seq.] of this chapter, the West Virginia Board of

Education, through its chief executive officer, shall direct and carry out all provisions of

said article nine-b.” W. VA. CODE § 18-9A-17 (2018). Thus, essentially, the State

Superintendent may act as the Board of Finance, which he did in this instance.

24

budget. “A county board of education and a county superintendent shall comply with the

instructions of the State Board of School Finance and shall perform the duties required of

them in accordance with the provisions of this article.” W. VA. CODE § 18-9B-17 (2018).

“The board may issue orders to county boards of education requiring specific compliance

with its instructions. If a county board fails or refuses to comply, the board may proceed

to enforce its order by any appropriate remedy in any court of competent jurisdiction.” W.

VA. CODE § 18-9B-18 (2018). “The board of finance may withhold payment of state aid

from a county board that fails or refuses to comply with the provisions of this article or the

requirements of the state board made in accordance therewith.” W. VA. CODE § 18-9B-

19 (2018). The state board of education may also intervene in the operation of a county

school system. W. VA. CODE § 18-2E-5n (2018).

In support of its argument that it had no choice but to comply with the State

Superintendent’s orders

21

, Respondent further cites a case in which the State

Superintendent ordered a county school board to cut contract days without complying

with the notice and opportunity for hearing provided for by statute. See Yatauro, et al. v.

Calhoun Cty. Bd. of Educ. and Calhoun Cty. Bd. of Educ. v. Hickman, Nos. 15-0650, 15-

0651, 15-0652, 15-0653, 15-0654, 15-0922, and 15-0903, 6 (W.Va. Supreme Court, Sept.

16, 2016) (memorandum decision). In Yatauro, the West Virginia Supreme Court of

Appeals determined “the Legislature intended to confer broad fiscal powers to the State

Board of Education” and “the Legislature did not intend to limit the State Board of

21

Notwithstanding that Respondent did, in fact, refuse to comply with the State

Superintendent’s order not once but twice and only voted to comply with the State

Superintendent’s order after the state board of education issued its Declaration of

Intervention announcing its intention to take over the operation of Boone County Schools

unless Respondent complied with the State Superintendent’s order.

25

Education’s authority under West Virginia Code §§ 18-9B-1 through -21.” Yatauro, et al.

v. Calhoun Cty. Bd. of Educ. and Calhoun Cty. Bd. of Educ. v. Hickman, Nos. 15-0650,

15-0651, 15-0652, 15-0653, 15-0654, 15-0922, and 15-0903, 6 (W.Va. Supreme Court,

Sept. 16, 2016) (memorandum decision).

Although Yatauro recognized the State Superintendent’s broad fiscal powers,

Yatauro is a memorandum opinion that only specifically discusses the notice and

opportunity to be heard provisions of chapter 18A.

22

Further, chapter 18 also contains

the following provision that was not specifically discussed in Yatauro:

If . . . a county board fails or refuses to provide for the support

of the standard school term, to adhere to the budget and the

expenditure schedule, or to comply with other provisions of

this article, the board of finance may require such action on

the part of the county board, not in violation of law, as the

board of finance may find to be best calculated to restore the

financial affairs of the county board to a proper and lawful

basis. [emphasis added].

W. VA. CODE § 18-9B-4 (2018). Thus, while the State Superintendent has broad authority,

that authority is limited to ordering actions “not in violation of law.” The Code specifically

prohibits a county board of education from reducing the county salary supplement below

the 1990 level unless one of three specific circumstances exist. W. VA. CODE §§ 18-4-5a-

5b (2018). If one of those circumstances does not exist, the State Superintendent cannot

order a county board to reduce the supplement because that would be in violation of law.

Excess levy funds must be used for their stated purpose, under pain of both civil and

criminal penalty for misappropriation of funds. W. VA. CODE §§ 11-8-25, 29, 31 (2018).

22

“While memorandum decisions may be cited as legal authority, and are legal

precedent, their value as precedent is necessarily more limited. . . .” Syl. Pt. 5, State v.

McKinley, 234 W. Va. 143, 146, 764 S.E.2d 303, 306 (2014). Memorandum decisions

are used when the is “no substantial question of law. . . ” W. VA. R. APP. P. 21(c).

26

The State Superintendent cannot order those funds to be used for another purpose

because that would be in violation of law. When the State Board of Education directed a

county board to apply excess levy funds improperly, the county board was not absolved

of liability. See Thomas v. Bd. of Educ., 164 W. Va. 84, 261 S.E.2d 66 (1979); Thomas v.

Bd. of Educ., 167 W. Va. 911, 280 S.E.2d 816 (1981). Therefore, that these actions were

ordered by the State Superintendent does not insulate Respondent from review of its

actions or liability if the State Superintendent’s order was not lawful.

The Excess Levy

Grievants argue Respondent did not comply with the levy call because it did not

pay the county supplement. Respondent asserts it did comply with the levy call because

it will have spent all of the levy money by the end of the five-year levy term ending in 2020

and that it had discretion to apply the levy moneys as it did.

“Except as otherwise provided in this article, boards or officers expending funds

derived from the levying of taxes shall expend the funds only for the purposes for which

they were raised.” W. VA. CODE § 11-8-25 (2018). “Funds derived from a special levy

may be expended only for the purpose for which they are approved. W. Va. Code §§ 11-

8-25-26.” Syl. Pt. 2, Thomas v. Bd. of Educ., 164 W. Va. 84, 261 S.E.2d 66 (1979); Byrd

v. Bd. of Educ., Syl. Pt. 2, 196 W. Va. 1, 467 S.E.2d 142 (1995).

There is no power or authority in the county court or any other

tribunal to apply a fund to a purpose other than that for which

it was ordained and created by a vote of the people. As to the

application of such a fund the will of the electors is supreme.

Without their consent no debt can be imposed upon them, no

liability assumed and no money raised or appropriated by the

county tax levying bodies beyond the limitation prescribed by

law. With the levies when made in a lawful manner, for

ordinary and legitimate purposes, the taxpayer can not

interfere. But when he has consented to be taxed beyond that

27

limit, and empowered his public agent to collect and expend a

fund for the accomplishment of an object not within the power

of such agency without his express authorization, the fund,

when raised, can not be appropriated and expended

otherwise than as ordained by him. . . .

Jarrell v. Bd. of Educ., 131 W. Va. 702, 708, 50 S.E.2d 442, 445 (1948).

In support of its assertion that it will have complied with the excess levy call by the

end of the five-year levy term Respondent offered the Excess Levy Budget

23

prepared by

current Treasurer Pauley. This document, combined with Treasurer Pauley’s testimony,

reveals how Respondent viewed the excess levy funds, at least in hindsight, as the

document was prepared two years after the beginning of the levy and after the tax shortfall

had occurred.

For many years, Respondent was in the enviable position to have enjoyed

generous funding. As a result, Respondent was able to pay its obligations without regard

to the source of the funding. Because of this, the line items in the excess levy, from the

beginning of the levy term, cost more than what the excess levy would fund. Clearly,

Respondent had planned to use other funding to fully fund those items beyond what the

excess levy would pay. Further, Respondent, as multiple witnesses testified, did not

account for the excess levy funds separately from its other revenue.

Then, in 2015, the bottom dropped out. Respondent’s fall tax collection for the

excess levy was $4 million dollars short of expectations. For fiscal year ending 2016,

Respondent had budgeted for $11 million of excess levy money and the collection

received was only $7.7 million

24

. However, even though the budget for the excess levy

23

R. Ex. 4.

24

As stated above, the actual amount of excess levy funds received is unclear

considering the sheriff’s settlement statement.

28

was $11 million and collections were $4 million less than expected, Respondent still spent

$14.9 million on all levy categories combined, twice as much as the actual excess levy

collection. Thus, Respondent spent the entirety of the excess levy funds, plus $7.2 million

of other unspecified funds on the excess levy categories. In terms of Respondent’s total

budget, Respondent had overspent on those categories, but in terms of the excess levy

budget, Respondent had simply spent all the excess levy funds.

For fiscal year ending 2017, the excess levy collection was $8.6 million.

Respondent spent only $5.9 million of the excess levy collection on the levy categories,

$2.6 million less than was collected. Again, for fiscal year ending 2018

25

, Respondent

failed to spend all the excess levy money on the excess levy categories. Respondent

collected $8.8 million from the excess levy and spent only $6 million on the excess levy

categories, $2.8 less than was collected.

Respondent’s Excess Levy Budget was prepared by Treasurer Pauley in 2018,

two years after the crisis, and presents a fundamental misunderstanding of the

requirements of excess levy expenditure. By his testimony, Treasurer Pauley clearly did

not understand the restraints placed on Respondent by law regarding the expenditure of

excess levy funds and the reduction of county salary supplements. Thus, Treasurer

Pauley’s Excess Levy Budget is an accounting not of the expenditure of the excess levy

collections, as it should be, but is an accounting of the total spending on the categories

that were included in the excess levy, regardless of their funding source.

The excess levy budget should have had a zero balance going into fiscal year

ending 2017, because all the excess levy funds were spent in 2016. Instead, Treasurer

25

Based on expenditures through April 30, 2018.

29

Pauley included in the budget the amount of money spent on the excess levy categories

from other funding sources, creating an illusory deficit in the balance of the excess levy

funding. This is, frankly, as Grievants aptly stated, a shell game. Whether intentional or

not, it conceals that the full excess levy collections were not spent on the levy call in 2017

and 2018. When the improper inclusion of the $7.2 million dollars of other funding that

was spent on the excess levy categories is removed, it reveals that over those three

years, Respondent collected $25.1 million in excess levy funds but only spent $19.6

million of that money for alleged excess levy purposes.

26

In 2017 and 2018 Respondent

failed to spend more than $5.5 million excess levy funds on excess levy purposes.

27

As to the specific levy call at issue in this grievance, the county salary supplement,

Respondent asserts it did pay a reduced amount of the county supplement, the 1984

county supplement level, out of line 1 of the excess levy. To analyze whether this action

complied with the levy call, one must first determine what is meant by “the 1984 county

supplement level.”

County boards of education must pay school employees a minimum salary that is

calculated using a formula mandated by statute. W.VA. CODE §§ 18A-4-2, 8a (2018).

School employees also receive a State supplement amount designed to provide equity

among salaries around the state. W.VA. CODE §18A-4-5. If a county chooses to adopt a

26

As will be more fully discussed below, some of the funds Respondent alleges

were spent for excess levy purposes were not spent for excess levy purposes, so the

amount of excess levy funds Respondent spent on excess levy purposes is actually less

than Respondent’s accounting shows. Additionally, the numbers are based on

Respondent’s assertion that the levy collections received for fiscal year ending 2016 were

$7.7 million.

27

Again, because Respondent spent some excess levy funds on improper

purposes, the actual amount Respondent failed to spend on levy purposes cannot be

calculated from the accounting provided.

30

salary schedule higher than the minimum salary schedule, then those employees also

receive a county supplement. W.VA. CODE §18A-4-5a-5b. The funding scheme for these

three types of pay is complicated. The State provides funding for schools, including for

the provision of minimum salaries, using a complex formula that considers the relative

contribution of the county and the state.

28

The State will only pay for a certain number of

employee positions as prescribed by the formula. W.VA. CODE §18-9A-4-5 (2018). If a

county wishes to employ more positions, commonly referred to as “over formula,” the

county must pay for those positions fully through local funds. In addition, although one

may think that the state supplement would be paid for by state funds given its name, the

State’s obligation to pay the state supplement for a county is reduced by the amount of

28

The West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals explained as follows:

Very broadly, the operation of the formula may be described

as follows. First, a county's estimated level of need, or "basic

foundation program," is determined. The basic foundation

program is the total sum required for each of seven categories

of need. viz., professional educators, service personnel, fixed

costs, transportation costs, administrative costs, other current

expenses and substitute employees, and improvement of

instructional programs. W.Va. Code, 18-9A-12.

Second, the county's "local share" must be computed. W.Va.

Code, 18-9A-11(a). Local share is the amount of tax revenue

which will be produced by levies, at specified rates, on all real

property situate in the county. Local share thus represents the

county's contribution to education costs on the basis of the

value of its real property. State funding is provided to the

county in an amount equal to the difference between the basic

foundation program and the local share. W.Va. Code, 18-9A-

12.

Bd. of Educ. of the Kanawha v. W. Va. Bd. of Educ., 219 W. Va. 801, 804, 639 S.E.2d

893, 896 (2006) (citing State ex rel. Boards of Educ. v. Chafin, 180 W.Va. 219, 221-222,

376 S.E.2d 113, 115-116 (1988) (footnote omitted)).

31

any county salary supplement that was in place on January 1, 1984, in that county. W.VA.

CODE §18A-4-5(d) (2018).

In this case, “the 1984 supplement level” refers to the county offset amount of the

state supplement as Boone County had an excess levy in place in 1984 to pay a county

salary supplement.

29

Therefore, the 1984 supplement level is simply the portion of the

state supplement that Respondent is required to pay. While the requirement to fund the

state supplement through local funds was based on the existence of a county supplement

provided for by an excess levy, Respondent’s payment of its portion of the state

supplement is not payment of the county supplement as those supplements are separate

by statute. See W.VA. CODE §18A-4-5-5b (2018). The legislature’s apportionment of

funding for the state supplement amount does not change the requirement to spend levy

funds for the purposes they are raised. (See Thomas v. Bd. of Educ., 164 W. Va. 84, 261

S.E.2d 66 (1979) (County school board could not use excess levy funds raised for

supplemental payments to pay state minimum salary even when the Board of School

Finance included excess levy funds in computing the county’s local share of financing.)

Respondent argues it has discretion to pay the supplement for all employees under

line one stating:

Where the voters by their approval of a special levy do not

require that each employee of the county board of education

is to receive a designated amount of supplemental salary, the

board of education may annually exercise sound discretion in

allocating the special levy funds as salary supplements

among its employees. A court may not interfere with such

exercise of discretion, unless there is a clear showing of fraud,

collusion or palpable abuse of discretion, or unless there is a

clear showing of a violation of W. Va. Code, 18A-4-8, as

amended, or its current statutory replacement, with respect to

29

Hearing Transcript Vol. 1 at 76, lines 4-1; at 115, lines 22-24; at 116, lines 1-20.

32

its uniformity provisions or its provisions on the nonreduction

of local funds in the aggregate.

Bane v. Bd. of Educ., 178 W. Va. 749, 751, 364 S.E.2d 540, 542 (1987). Respondent

argues that, because the voters approved only approximate annual amounts and not

specific dollar amounts that it had discretion under Bane to allocate the funds however it

chooses.

Respondent’s interpretation is not supported by the language of the levy. “The

true interpretation of the language of a special levy proposal is the meaning given to it by

the voters of the county, who, by their approval of the special levy, consent to be taxed

more heavily to provide the necessary funds.” Syl. Pt. 1, Thomas v. Board of Educ., 164

W. Va. 84, 261 S.E.2d 66 (1979); Syl. Pt. 1, Byrd v. Bd. of Educ., 196 W. Va. 1, 467

S.E.2d 142, (1995). Unlike Bane, in which there was only a general statement of levy

purpose, this levy lists specific separate categories and an approximate amount to be

spent on each category. Unlike the statutory language regarding the state supplement

that defines it as part of the minimum salary, which allows Respondent to use levy money

under line one for over-formula employees, no such language was added to the code

sections regarding the county supplement, which still states that the county supplement

supplements the state minimum salary. W.VA. CODE §18A-4-5a-5b. The county

supplement was specifically listed in line item two. Obviously, that is the line from which

a voter would expect the county supplement to be paid, and that is from where it must be

paid.

Having determined that some use of the excess levy funds was improper and that

there were, in fact, excess levy funds that were not spent that must be spent, the

33

determination now turns to how Respondent may spend the excess levy funds in

compliance with this decision.

Regardless of Respondent’s dire financial situation, the excess levy funds must be

spent only on the purposes stated in the excess levy. As the West Virginia Supreme

Court of Appeals has noted, “That the board is faced with a difficult problem, due to a

condition created by causes beyond its control, is of course unfortunate, but that

regrettable situation can not justify the expenditure of the fund in a manner which the law

does not authorize or permit.” Jarrell v. Bd. of Educ., 131 W. Va. 702, 711, 50 S.E.2d

442, 447 (1948). Under line one of the excess levy Respondent was to pay “employee

salaries paid exclusively from local funds” and under line two Respondent was to pay

“employee fixed costs and benefits including the county supplement.” As discussed

above, what Respondent termed to be the county supplement was actually the state

supplement and it was paid out of line one. Ordinarily, salary would mean salary and

supplement would mean supplement, which is what the West Virginia Supreme Court of

Appeals found in Smith v. Bd. of Educ., 192 W. Va. 321, 325, 452 S.E.2d 412, 416 (1994).

However, in 2012, the legislature revised the Code to state that the state supplement

amount is considered part of the state minimum salary. W.VA. CODE §18A-4-2(d), 8a(f)

(2018). Thus, Respondent did properly pay the state supplement amount for over formula

employees under line one as the state supplement is now considered part of the basic

salary by statute and line one of the levy provides for “employee salaries paid exclusively

from local funds.” However, Respondent is not permitted to pay for its portion of the state

supplement for formula-funded employees with the excess levy money out of line one

because line one applies only to over-formula employees. Respondent cannot pay any

34

of the state supplement amount under line two because line two includes only the county

supplement.

Bane does allow Respondent the discretion to allocate funds for the purposes

listed within each line item as it sees fit, in accordance with the limitations stated in Bane.

As line two is for “employee fixed costs and benefits including the county supplement”

Respondent can pay all the other fixed costs and benefits first, before paying the county

supplement but if there is excess levy money available from the payment of the other

fixed costs and benefits, the remainder must be paid as a county supplement.

W.VA. CODE 18A-4-5a-5b

A county board of education operates under two constraints when it has adopted

a county supplement level funded in any part through an excess levy: if it collects enough

money through the excess levy it must pay the county supplement and if it does not collect

enough money through the excess levy to pay the county supplement and if it had a

county supplement in place on January 1, 1990 it cannot reduce that supplement level

unless faced with one of three specific listed circumstances per under West Virginia Code

18A-4-5a-5b.

[N]o county shall reduce local funds allocated for salaries in

effect on January 1, 1990, and used in supplementing the

state minimum salaries as provided for in this article, unless

forced to do so by defeat of a special levy, or a loss in

assessed values or events over which it has no control and

for which the county board has received approval from the

state board prior to making such reduction.

W. VA. CODE §§ 18A-4-5a-5b (2018).

Neither party provided as evidence the amount of the January 1, 1990 county

supplement. Nevertheless, as the parties have continued to pursue this issue, it must be

35

assumed that the reduction of the supplement down to the 1984 level did reduce the

county supplement below the 1990 level.

30

Respondent argues it was justified in reducing

the county supplement due to “events over which it has no control” due to the

unprecedented tax collection shortfall. Grievants argue Respondent knew, or should

have known, years before that time that its budget could not be supported, as evidenced

by the yearly decline of Respondent unrestricted fund balance.

In 2012 and prior, Respondent had a healthy funding surplus. Consequently,

Respondent was able to maintain one of the highest over-formula employee and county

supplement amounts in the state. Beginning in 2012, Respondent’s regular budget began

to run at a deficit and each year it used money from its unrestricted fund balance to pay

its obligations. Each year, Respondent spent down its unrestricted fund balance while

continuing to maintain a large number of over-formula positions, despite a decline in

enrollment and state funding. At fiscal year end 2012, Respondent’s unrestricted fund

balance was $8,510,759. By fiscal year end 2015, Respondent’s unrestricted fund

balance was only $1,631,512. Thus, when the crisis occurred in the fall of 2015,

Respondent was caught flat-footed. It is clear that, after the failure of the tax collection in

2015, Respondent had no choice but to cut everything it could because it did not have

enough money to meet payroll and, in fact, had to seek a special legislative appropriation

to meet payroll. The question is: was this circumstance truly not under Respondent’s

control given Respondent’s choice to spend down its unrestricted fund balance rather

30

If Respondent collected enough excess levy funds to fund the county

supplement above the 1990 level, this issue is moot. However, since Respondent’s

accounting of the excess levy funds was improper, it is not possible to tell from the

evidence presented what amount of county supplement should have been paid.

36

than make cuts to its budget beginning in 2012, which would have preserved its

unrestricted fund balance allowing Respondent to weather the crisis without making such

draconian cuts?

As Justice Neely noted,

“Events over which it has no control” is indeed a nebulous

phrase which has received little attention in the case law.

Appellants contend that it applies only to “acts of God,”

although they point to no authority for this assertion. In

reality, it seems that this clause was included to allow for any

unforeseeable event which may destroy a rational budget.

Newcome v. Bd. of Educ., 164 W. Va. 1, 4, 260 S.E.2d 462, 464 (1979). In that case, the

Court determined,

Where a county has a property tax base which does not

increase in assessed value at a rate commensurate with

inflation so that there is a decline in revenue relative to

expenses and a local school board is forced to choose

between eliminating a local pay supplement for teachers or

curtailing its educational programs for children, the local board

is confronted, in that event, with "events over which it has no

control" within the contemplation of W. Va. Code, 18A-4-5

[1969] and may cancel the teacher supplement.

Syl. Newcome v. Bd. of Educ., 164 W. Va. 1, 2, 260 S.E.2d 462, 462 (1979). In construing

a statute that allows a county superintendent to “act in case of emergency,” the Court

found that an “emergency” is a condition that is “unforeseen or unanticipated.” Syl. Pt. 3,

Randolph Cty. Bd. of Educ. v. Scalia, 182 W. Va. 289, 387 S.E.2d 524 (1989). The Court

further found:

A fiscal emergency may arise because adequate provision

was not made in a budget, even though the purpose for which

the funds are needed was foreseeable when the budget was

adopted. In such a case, before an emergency can be found,

it must be shown that the amount placed in the budget was

reasonable in light of all of the attendant circumstances,

including prior budgetary experience.

37

Randolph Cty. Bd. of Educ. v. Scalia, 182 W. Va. 289, 290, 387 S.E.2d 524, 526 (1989).

In applying this standard, the Court determined the county board of education’s budget

was not reasonable because it had consistently underestimated expenses and, therefore,

there was no emergency justifying action.

Faced with a similar elimination of the county salary supplement as this grievance,

the Grievance Board, in light of the above cases, determined that a county board of

education that had operated at a deficit for multiple years without any significant effort to

reduce the deficit was not faced with events outside its control that would justify the

elimination of a county salary supplement. Goff, et al. v. Calhoun County Bd. of Educ.,

Docket No. 2015-0049-CONS (Mar. 10, 2015), aff’d, Yatauro, et al. v. Calhoun Cty. Bd.

of Educ. and Calhoun Cty. Bd. of Educ. v. Hickman, Nos. 15-0650, 15-0651, 15-0652,

15-0653, 15-0654, 15-0922, and 15-0903, 6 (W.Va. Supreme Court, Sept. 16, 2016)

(memorandum decision).

This grievance is factually different than Goff in that Respondent was not operating

at an actual deficit but had spent down its unrestricted fund balance such that it was

unable to balance its budget after an unprecedented and sudden shortfall of tax

collections. In layman’s terms, the unrestricted fund balance is a surplus: the money left

over after all expenses are paid. The State Board of Finance recommends a county have

an unrestricted fund balance of between three and five percent of its budget. Some

national organizations recommend maintaining an unrestricted fund balance of sixteen to

twenty percent. If a county falls below the state recommended amount, they are

considered at risk and are put on a watch list. In 2012, Respondent had an unrestricted

fund balance much higher than the recommended three to five percent. Therefore,

38

although it continued to spend down the unrestricted fund balance, it was not considered

at risk until after the crisis in 2015.

The failure to collect $4 million of taxes in the fall of 2015 was certainly unforeseen.

Although Grievants appear to argue that this should have been anticipated based on the

general decline of the coal industry and the economy, that decline was not enough for

anyone to anticipate the sudden $4 million shortfall of taxes at once due to the bankruptcy

of numerous coal companies within a five-month span.

Once the crisis occurred, Respondent cut all non-personnel costs that could be

cut, but, as personnel costs accounted for eighty to eighty-five percent of the budget,

personnel costs had to be cut drastically. Respondent’s only choice was whether to

eliminate positions or reduce the supplement.

31

In hindsight, it is easy to say that

Respondent should have cut its over-formula positions years before it did. However, one

must consider the information Respondent had at the time and the required timing for

reduction in force. Respondent does not know its total tax collections until the end of the

fiscal year, June 30. Respondent must make personnel decisions for the following year

in March. Thus, the positions it had over formula for fiscal year 2013 are based on the

personnel decisions made in 2012, which were based on the financial information from

fiscal year 2011 and projections about the 2012 fiscal year end collections. Therefore,

Respondent’s higher over-formula number in 2015 looks less unreasonable when one

considers that the tax collection numbers were good in fiscal years ending 2013 and 2014

31

As discussed above, Respondent could only cut the county supplement if it

had not collected enough funds from the excess levy, which is unknown given the

nature of Respondent’s accounting.

39

and had actually increased between 2013 and 2014. Tax collections only decreased in

2015 and no drastic problem with tax collections occurred until fiscal year ending 2016.

This situation is further distinguished from Goff in that Respondent did take steps

to correct the situation. In February 2015, considering the lesser projected tax collections,

Respondent did reduce the number of over-formula positions for fiscal year 2016 from

138 to 110. After the crisis in the fall of 2015, Respondent closed three schools in

December 2015 and further reduced over-formula positions in February 2016. However,

this was simply not enough to make up the difference. Between 2015 and 2016,

Respondent lost $7.7 million in total tax revenue between the general and excess levies.

Respondent had also experienced a $269,867,240 or 18.4 percent loss of assessed value

from fiscal year 2015 to fiscal year 2017. That could not have been anticipated. While

Respondent had a large number of over formula positions, counties typically do employ

personnel in excess of the formula. In fact, there are certain positions that are required

that are not funded by the formula, such as the treasurer and physical therapists, so a

school system must employ a certain number of employees over formula. No testimony

was offered to explain how far from the average Respondent was for employing personnel

over formula. Given this lack of evidence regarding the over formula positions and

considering the information available to Respondent at the time the personnel decisions

were made, it is not clear that the decision to retain the positions over formula was fiscally

irresponsible at the time.

While it is true that Respondent continued to spend down its unrestricted fund

balance, it did not go below the recommended three and five percent until after the crisis.

Respondent did take steps to reduce its costs once information about its tax collections

40

become known. The dramatic shortfall in the fall of 2015 was unforeseen. Respondent

did experience a loss of assessed value. Therefore, looking at the situation in total,

Respondent met the circumstances required by West Virginia Code 18A-4-5a-5b and was

permitted to reduce the county salary supplement to below the 1990 level if it did not have

enough excess levy collections to fund the county salary supplement.

Vision and Dental Insurance

Grievants primarily argued that the elimination of vision and dental insurance was

in violation of the excess levy terms, which is not applicable to the remaining active

employee Grievants as the excess levy only provided vision and dental insurance for

retirees, who cannot be addressed in this grievance as discussed above. Grievants cited

no authority that required Respondent to provide vision and dental insurance for active

employees.

Grievants argue only additionally that Respondent failed to provide notice and

opportunity to be heard under West Virginia Code §§ 18A-2-2, 18A-2-2, and 18A-4-8(m).

This issue was specifically addressed by the West Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals in

Yatauro, in which the Court rejected the argument stating, “West Virginia Code §§ 18-9B-

1 through -21 is broad and there is no indication that its application is limited to only those

situations where the appropriate notice and hearing opportunities are provided to

aggrieved employees.” Id. at 5

Conclusion

The Grievance Board lacks jurisdiction to hear the claims of the retirees in this

matter. An order of the State Superintendent does not insulate Respondent from review

of its actions or liability if the actions taken were not lawful. Respondent spent some

41

excess levy funds improperly when it paid its portion of the state supplement amount for

formula employees from the portion of the excess levy for over-formula employees.

Respondent further failed to spend all excess levy funds collected for excess levy