Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

The Color of Wealth in Boston

A Joint Publication with Duke University and The New School

The information, analyses, and conclusions set forth are those of the individual

authors and do not necessarily indicate concurrence by the Board of Governors of

the Federal Reserve System, the Federal Reserve Banks, or members of their stas.

Federal Reserve Bank of Boston

The Color of Wealth in Boston

A Joint Publication with Duke University and The New School

Authors

Ana Patricia Muñoz

Marlene Kim

Mariko Chang

Regine O. Jackson

Darrick Hamilton

William A. Darity Jr.

Acknowledgments

is project is made possible by the generous support of the Ford Foundation’s Building

Economic Security Over a Lifetime (BESOL) initiative and the Federal Reserve Bank

of Boston. William A. Darity Jr. (Research Network on Racial and Ethnic Inequality at

the Duke Consortium on Social Equity, Duke University) and Darrick Hamilton (Mila-

no School of International Aairs, Management, and Urban Policy at e New School)

serve as primary investigators; Kilolo Kijakazi served as the Ford Foundation’s program

ocer. e National Asset Scorecard for Communities of Color–Boston project manager

is Ana Patricia Muñoz (Federal Reserve Bank of Boston).

e authors are grateful to Prabal Chakrabarti, Erin Graves, Je Fuhrer, and Anna Steiger

(Federal Reserve Bank of Boston); Ray Boshara (Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis); and

Tatjana Meschede (Brandeis University and visiting scholar at the Federal Reserve Bank

of Boston) for reviewing this report and providing valuable insights and feedback. Rebecca

Leung provided excellent research assistance. Marcin Hitczenko (Federal Reserve Bank of

Boston) and Kobi Abayomi (Columbia University) provided helpful methodological sug-

gestions. Tom M. Guterbock (University of Virginia) directed the survey collection process.

e views expressed in this report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily

represent those of the Ford Foundation, the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, or the Federal

Reserve System.

Additional talent that went into this publication:

Copyeditor:

Beth Magura

Illustrator:

Ken Dubrowski

Visit www.bostonfed.org/commdev

Summary of Findings

Introduction

Demographic Changes in the Boston MSA

Methodology

Assets, Debt, and Net Worth Estimates

The Implications of Racial Disparities

About the Authors

References

Endnotes

Appendix

..........................................................................................................1

..........................................................................................................................3

.................................................................4

........................................................................................................................8

........................................................................10

..........................................................................22

.............................................................................................................24

...........................................................................................................................25

..............................................................................................................................28

..............................................................................................................................30

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Table of Contents

1

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Abstract

e widening wealth gap in the United States is a worrisome sign that millions of families

nationwide do not have enough in assets to oer better opportunities for future genera-

tions. Wealth allows families to make investments in homes, in education, and in business

creation. On the basis of data collected using the National Asset Scorecard for Commu-

nities of Color (NASCC) survey, we report that, when analyzed by race, wealth accumula-

tion is vastly unequal. By means of the NASCC survey, researchers have collected, for the

rst time, detailed data on assets and debts among subpopulations, according to race, eth-

nicity, and country of origin—granular detail ordinarily unavailable in public datasets. In

this analysis we focus on estimates for U.S. born blacks, Caribbean blacks, Cape Verdeans,

Puerto Ricans, and Dominicans in the Boston Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA). Our

analysis shows that with respect to types and size of assets and debt held, the data collected

on white households and nonwhite households exhibit large dierences. e result is that

the net worth of whites as compared with nonwhites is staggeringly divergent.

Summary of findings

• While it has been common to lump the experiences of all blacks and all Hispanics

together, in fact, subcategories of blacks and Hispanics—for example, Puerto Ricans

and Dominicans, or U.S. blacks and Caribbean black immigrants—exhibit import-

ant dierences. e level of detail needed to dierentiate among these groups has

not been available until the implementation of the NASCC survey.

• ere exist key dierences in liquid assets, which may be thought of as representing

buers to income and expenditure shocks. e typical white household in Boston is

more likely than nonwhite households to own every type of liquid asset. For exam-

ple, close to half of Puerto Ricans and a quarter of U.S. blacks are unbanked (that is,

they do not have bank accounts) compared with only 7 percent of whites. For every

dollar, the typical white household has in liquid assets (excluding cash), U.S. blacks

have 2 cents, Caribbean blacks 14 cents, and Puerto Ricans and Dominicans less

than 1 cent.

• Whites and nonwhites also exhibit key dierences in less-liquid assets that are

primarily associated with homeownership, basic transportation, and retirement

or health savings. While most white households (56 percent) own retirement

accounts, only one-fth of U.S and Caribbean blacks have them. Only 8 per-

cent of Dominicans and 16 percent of Puerto Ricans have such accounts. Most

whites—79 percent—own a home, whereas only one-third of U.S. blacks, less

than one-fth of Dominicans and Puerto Ricans, and only half of Caribbean

blacks are homeowners.

• Although members of communities of color are less likely to own homes, among

homeowners they are more likely to have mortgage debt. Nonwhite households are

more likely than whites to have student loans and medical debt.

• us nonwhites are likely to experience far more short-term nancial disruptions

due to their lack of liquid buer assets. ey are also more likely to experience much

poorer longer-term housing and retirement outcomes as a consequence of their lack

of homeownership, housing equity, and retirement savings. e result is that the net

worth of whites as compared with nonwhites is staggeringly divergent.

2

The Color of Wealth in Boston

• Nonwhite households have only a fraction of the net worth attributed to white

households. While white households have a median wealth of $247,500, Domini-

cans and U.S. blacks have a median wealth of close to zero. Of all nonwhite groups

for which estimates could be made, Caribbean black households have the highest

median wealth with $12,000, which is only 5 percent of the wealth attributed to

white households in the Boston MSA.

• In the coming decades, a signicant rise in the share of nonwhite populations is

projected nationwide. Population growth in the Boston MSA is already driven by

the nonwhite population increase. us, the nancial well-being of communities

of color is central to ensuring the inclusive long-term growth and prosperity of the

Boston MSA. Unless net worth outcomes in communities of color improve, the

aggregate magnitude of the wealth disparity will increase. is is a rst-order public

policy problem requiring immediate attention.

3

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Introduction

e widening wealth gap in the United States is a worrisome sign that millions of families

nationwide do not have enough in assets to oer better opportunities for future generations.

Wealth (or net worth) provides a more complete picture of the disparity than the narrower

measure of income. While income is a ow that provides a snapshot of a family’s resources

at a given point in time, wealth reects the stock that a family accumulates over the long

term. Whereas income helps families cover their current needs, wealth allows them to make

investments in homes, in education, and in business creation. It provides safety during times

of family crisis or economic insecurity, such as during a stretch of unemployment or when

a family member faces a serious illness. Without being able to draw upon assets such as

savings accounts, a head of household must pay for his or her family’s nancial needs from

current or future income (that is, by borrowing)—which, for many in the United States, is

often insucient to cover large and critically important unexpected expenses.

Yet wealth accumulation is vastly unequal in the United States, with a small population

owning most of the wealth (Saez 2014). Such wealth disparities are problematic in this

country. Nationally and regionally, economic growth would be greater if wealth were dis-

persed more evenly, some economists argue (Rugaber 2013). Even Federal Reserve Chair

Janet Yellen has stated that “the extent of and continuing increase in inequality in the

United States greatly concerns” her. She has asked whether this trend of widening wealth

inequality “is compatible with values rooted in our nation’s history, among them the high

value Americans have traditionally placed on equality of opportunity” (Yellen 2014). In ad-

dition, wealth is transmitted intergenerationally—with the few who own wealth bequeath-

ing inheritances and house down payments to their progeny, which serves to perpetuate

inequality in wealth and impede social mobility for those who are not similarly advantaged.

As this report will show, accrual of wealth is vastly unequal when race is taken into account.

In part, racial dierences in net worth are derived from racially based dierences in income

because nonwhites generally earn less (Gittleman and Wol 2007). But racial dierences in

income and racial dierences in wealth are only weakly correlated. Rather, the racially based

gulf in wealth accumulation widens as income increrases (Tippett et al. 2014, see Figure 1)

and because wealth dierences reect an accumulated lifetime of income disparities, com-

pounded by asset returns (or lack thereof), the racial wealth gap is much greater than the

income dierences. Over the past 30 years, this gap has widened (McKernan et al. 2013).

Furthermore, nonwhites seem to have fewer opportunities than whites to build wealth by

means of income gains (Shapiro et al. 2013). In addition, intergenerational transmission

of wealth and the opportunities this provides are unequal when race is taken into account.

Black families who attain higher levels of income typically have greater transfer demands

from their less well-o kin networks in comparison to their white peers, further reducing

the resources earmarked for savings (Chiteji and Hamilton 2002; Hein and Pattillo 2000).

Furthermore, intergenerational transmissions of wealth and the opportunities these provide

are also unequal by race (Blau and Graham 1990; Menchik and Jianakoplos 1997; Gittle-

man and Wol 2007). Consequently, nonwhites have more limited opportunities—lacking

parents who can provide college educations, down payments, or inheritances. Wealth dis-

parity on the basis of race will persist in part because of lower rates of intergenerational

transmission of assets.

4

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Acknowledging the existence of diering levels of net worth transmission and striving to

implement policies that help to level the playing eld are of greater importance than ever,

given the rapid growth of communities of color across the nation. is report examines

racial wealth inequality in the Boston MSA and discusses its implications. Using the

NASCC survey, we have examined subpopulations by race, ethnicity and country of origin.

e NASCC survey has addressed two shortcomings of the public datasets (see Appendix

for more information) that have data on assets and debts, that is, a lack of information (1)

for small geographic areas and (2) for race, ethnicity and/or ancestral origin. Because rele-

vant geographic distinctions exist within asset markets and variations exist in racial compo-

sition across geographies, the NASCC survey was designed to collect data at the level of the

metropolitan statistical area. In addition, because nonwhite groups are not monolithic, the

NASCC survey gathered more detailed data, such as country of origin for certain groups.

1

is report provides a brief overview of the demographic changes in the Boston MSA,

revealing the growing presence of nonwhite groups. e second section summarizes the

NASCC methodology, and the third part analyzes asset and debt ownership and estimates

the wealth position of various communities of color in the Boston metro area. e last sec-

tion discusses the implication of racial disparities.

Demographic Changes in the Boston MSA

e Boston MSA, which is home to 4.6 million residents and accounts for almost one-

third of New England’s population,

2

has experienced noteworthy demographic changes

over the past decade or so. e non-Hispanic white population declined 3 percent from

2000 to 2012.

3

During the same period, the number of Asian and Hispanic residents in

the Boston MSA increased 58 percent and the number of non-Hispanic blacks increased

33 percent.

4

According to recent estimates, Hispanics accounted for 10 percent of the

total population, up four percentage points since 2000. e proportion of non-Hispanic

black residents in the Boston MSA increased from 6 to 7 percent.

5

e nationality and ethnic breakdown within these broadly dened racial and ethnic

groups is a distinctive feature of the Boston MSA. According to the 2012 U.S. Census, of

the 368,133 black residents in the metropolitan area, 34 percent (126,200) were foreign

born and 10.5 percent (38,686) were of Hispanic origin.

e origin of most Hispanics in the Northeast is also distinct from what is found in the rest

of the United States. In the country as a whole, Mexicans represented more than two-thirds

of the Hispanic population, whereas they accounted for less than 7 percent in the Boston

metro area. e two largest Hispanic groups in the Boston MSA were Puerto Ricans and

Dominicans, who represented 29 percent and 23 percent of the Hispanic population, re-

spectively.

6

e number of Dominicans grew 121 percent to 100,850 from 2000 to 2012,

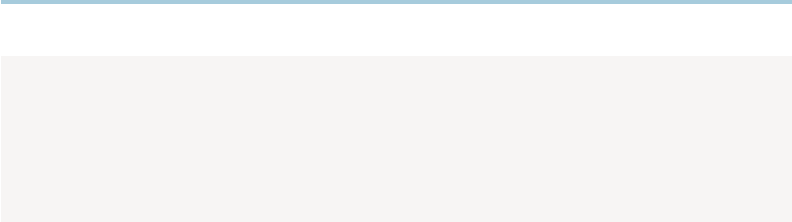

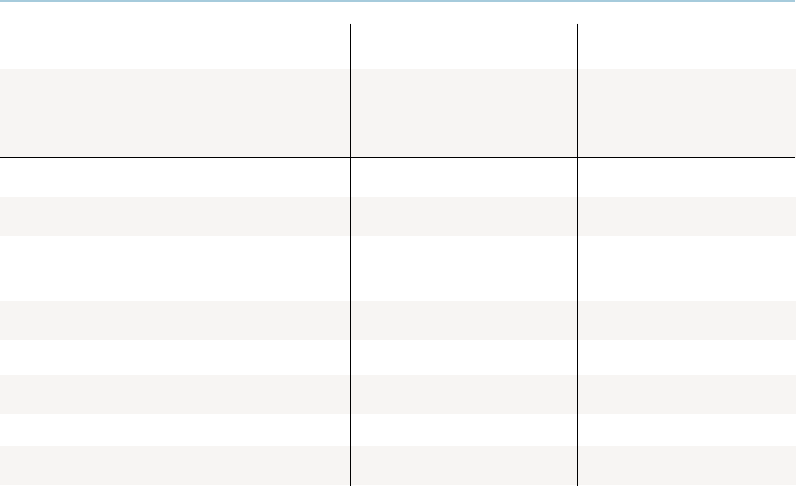

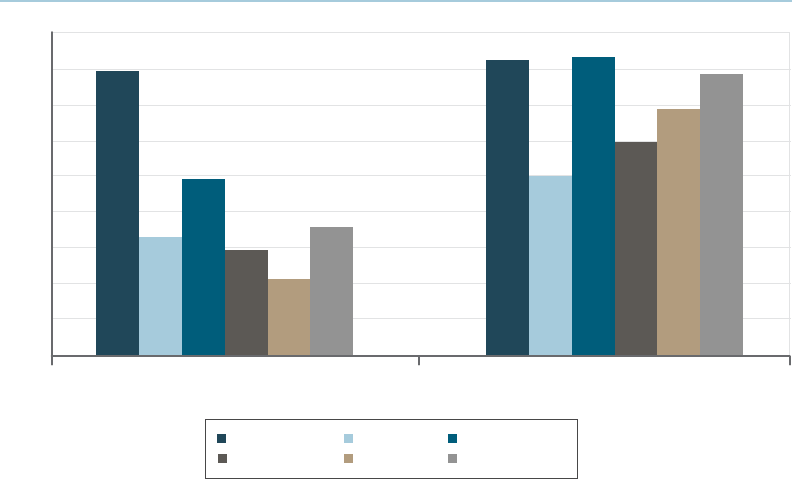

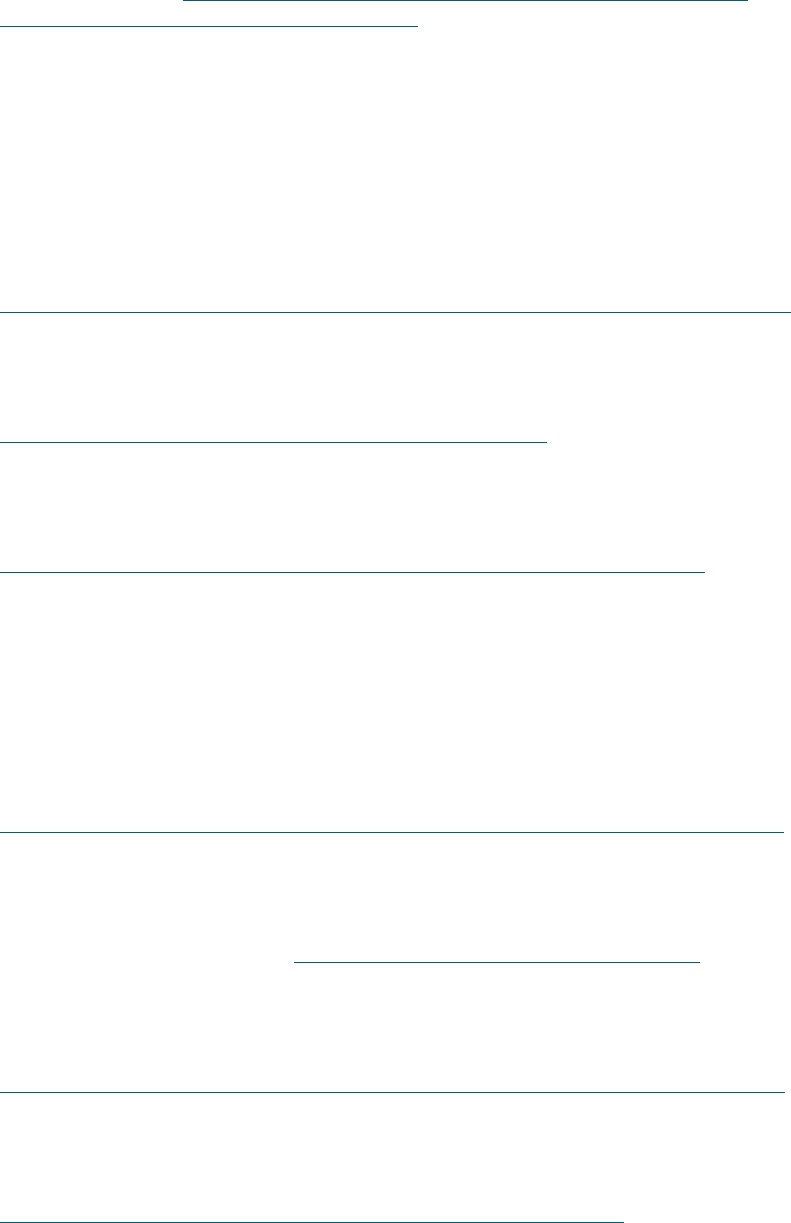

the largest percentage increase of any group in the Boston metro area (Figure 1).

Two other groups living in the Boston metropolitan area, whose numbers are on the rise,

were Haitians and Cape Verdeans. Close to 9 percent of Haitians living in the United

States—about 75,600—resided in the Boston MSA. e concentration of Cape Verdeans

was even greater, with about 45 percent of the 87,000 Cape Verdeans living in the United

States residing in the Boston metro area.

5

The Color of Wealth in Boston

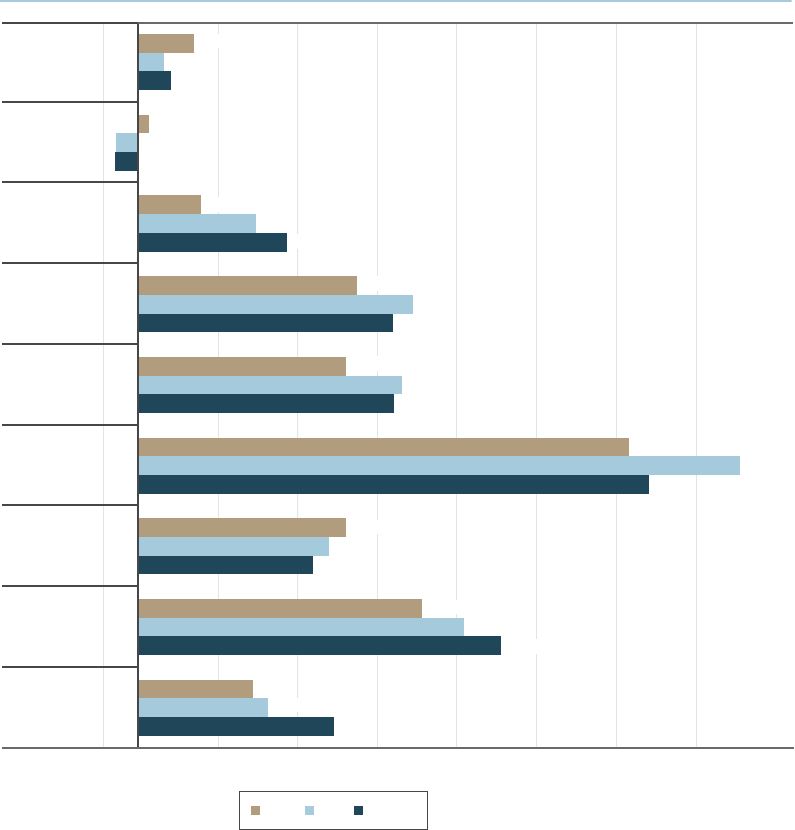

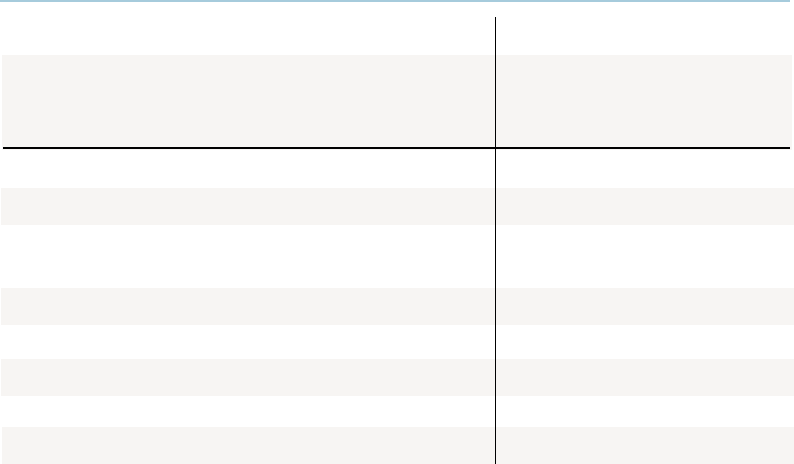

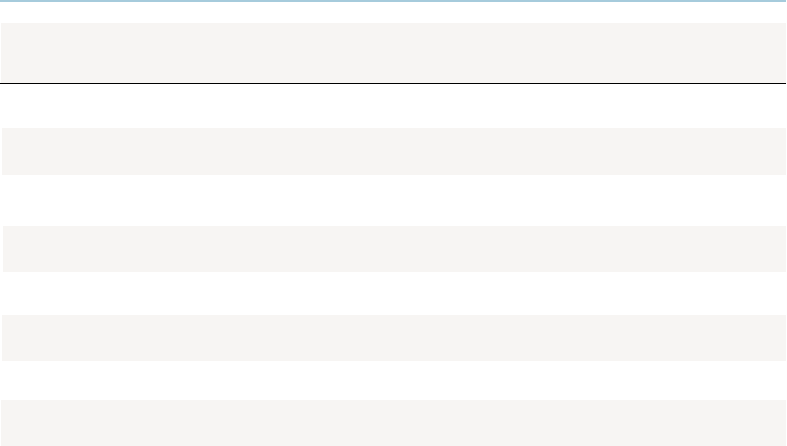

ese groups were not distributed evenly in the cities and towns of the Boston MSA. Al-

though overall the Boston metro area was 74 percent white, the city of Boston and most

gateway cities (or “working cities”)

7

in the Boston metropolitan area have high concentra-

tions of nonwhite populations. On average, only 53 percent of the population in working

cities located in the metro area was white, whereas in the city of Boston whites constituted

approximately 46 percent of the residents. e highest concentration of black residents was

found in the city of Boston; and in Brockton, more than one-third of the population was

black. e majority of the population in Chelsea (62 percent) and Lawrence (74 percent)

was Hispanic. In addition, close to 30 percent of the population in Lynn and Revere and

20 percent in Everett were Hispanic. In Lowell and Malden, Asians accounted for about

20 percent of residents (Figure 2).

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2012, 1 year estimates

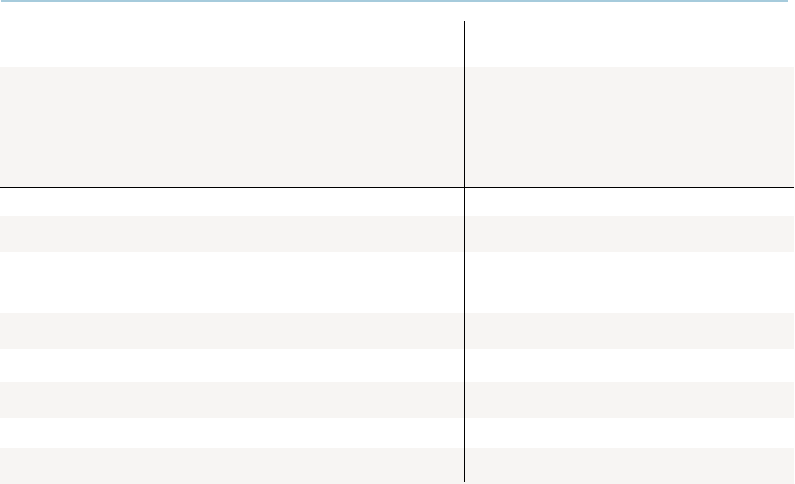

Figure 1.

Population change, 2000-2012, U.S., New England and Boston MSA

15%-5% 35% 55% 75% 95% 115% 135%

5%

6%

1%

-3%

-3%

26%

64%

58%

59%

58%

117%

149%

121%

43%

37%

76%

21%

41%

Total

White

Black

Asian

Hispanic

Dominican

Puerto

Rican

Haitian

Cape

Verdean

23%

84%

65%

46%

50%

52%

13%

12%

33%

U.S. NE Boston

6

The Color of Wealth in Boston

What’s behind the numbers?

A closer look at the population in the Boston metropolitan area revealed the distinctive

characteristics of its communities of color and their histories, which have implications for

better understanding inequality in the accrual of wealth. Our analysis conrmed that the

nonwhite population is far from homogenous.

Since the end of World War II, the region and the MSA have attracted growing numbers

of Latin American, Caribbean, Asian, and African immigrants. As of 2012, close to 17

percent of the population of the Boston MSA was foreign-born and less than 20 percent of

these immigrants came from Europe.

8

Migrants from Haiti, China, Vietnam, the Domin-

ican Republic, Cape Verde, Jamaica, Brazil, El Salvador, and Colombia have contributed

signicantly to the increase in Boston’s foreign-born population.

Compared with Asians and Latin Americans, black immigrants from the Caribbean and

Africa were still a relatively small group, accounting for less than 10 percent of 40 million

immigrants nationwide and for 15 percent of nearly 775,000 foreign-born residents in the

Boston area. But roughly one-third of blacks in the Boston MSA were immigrants, compared

with nearly 9 percent nationwide.

Violet Johnson’s book e Other Black Bostonians: West Indians in Boston, 1900–1950 focuses

on the West Indian community that began to take shape in Boston on the eve of World War

I ( Johnson 2006). is mostly black and working class migration of both men and women

(unlike the privileged mulatto men who preceded them in late 19th century) grew into a

visible presence until the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1952 (also known as the Mc-

Carran-Walter Act) denied Afro-Caribbeans the right to take advantage of the quotas set

for Great Britain. Johnson credits the United Fruit Company, headquartered in Boston, for

Somerville

Salem

Revere

Malden

Lynn

Lowell

Lawrence

Haverill

Everett

Chelsea

Brockton

Boston

80

70

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

Figure 2.

Percentage of total population by race and ethnicity, 2012, for Boston

and working cities

White Black Asian Hispanic/Latino

Source: U.S. Census Bureau, American Community Survey 2012, 1 year estimates

Percentage of population

7

The Color of Wealth in Boston

setting in motion the estimated 5,000 émigrés from the English-speaking Caribbean colo-

nies—mainly Barbados, Jamaica, and Montserrat—that eventually settled in Greater Boston.

Today 50 percent of Boston’s Caribbean population is made up of Haitian immigrants and

their descendants. e earliest wave of Haitian immigrants began to arrive in Massachusetts

as early as 1950 ( Jackson 2011). e registered population, statewide, increased twofold in

1970. By the late 1970s, pockets of Haitians could be identied in various sections of the city,

and in the early 1980s these communities began to crystallize. ere are sizeable clusters of

Haitians residing throughout the southern precincts of the City of Boston, in the suburbs

of Milton, Randolph, and Brockton, as well as in other cities in the larger metropolitan area,

such as Cambridge and Somerville. Jackson argues that the two- and three-decker homes

widely available in Dorchester for $24,000 to $26,000 in the 1970s, helped to stabilize the

Haitian community, creating a new class of homeowners and landlords that gave Haitian

renters a low-cost alternative to public housing (Jackson 2011; see also Jackson 2007).

9

African immigrants and refugees also contributed to the diversity of the black community.

Cape Verdeans are the African immigrants of longest duration in the city and the greatest in

number. e rst voluntary African emigrants to the United States, they began arriving in the

area in the 1900s to work in the whaling industry. As Gibau notes, “ere are Cape Verdeans

who came to the U.S. twenty years ago and others who have just arrived a few months ago.

Likewise, there are Cape Verdeans who were born in Boston fty years ago and others just

two years ago” (Gibau 2008, p. 263).

Unlike New Bedford, MA, or Providence, RI, there are more Cape Verdean immigrants liv-

ing in the Boston area than second- and third-generation Cape Verdean Americans. eir

numbers increased as a result of post-1965 and especially post-independence (1975) relo-

cations to the area (Ibid.). Since the 1950s, the American-born Cape Verdeans of Boston

migrated from the smaller South Shore communities of Massachusetts, such as Taunton and

New Bedford, and also from Cape Cod (Gibau 2008).

Likewise, Hispanics are not a monolithic group. Puerto Ricans arrived in the region in great

numbers after World War II. According to Hernandez (2006), as the original Hispanics,

Puerto Ricans were instrumental in laying the groundwork for the metropolitan area’s His-

panic community. As U.S. citizens, Puerto Ricans were spared problems with visas, had ac-

cess to social services, and could vote. It was not till the 1980s that diversity in the Hispanic

population of Boston became visible for the rst time (Uriarte et al. 2003) as Dominican

immigrants began to arrive. e Dominican population grew more slowly (Hernandez 2006).

Central Americans from El Salvador are the more recent arrivals.

A brief history of Boston’s heterogeneous population suggests the likelihood of a wide array

of economic positions and prospects among these diverse racial and ethnic groups in metro-

politan Boston.

8

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Methodology

A research initiative known as the National Asset Scorecard for Communities of Color

(NASCC) has embarked on the design and implementation of a pilot survey in targeted

metropolitan areas to collect data about the asset and debt positions of racial and ethnic

groups at a detailed ancestral origin level. In the past, other eorts have studied the

net worth position of broadly dened ethnic groups, such as Latinos or Asians taken

collectively. In contrast, the NASCC survey collects asset and debt information on key

subgroups within the broader categories—from such subgroups as Mexicans, Puerto

Ricans, and Cubans or Asian Indians, Chinese, Filipinos, Koreans, Vietnamese, and

Japanese. e NASCC data collection also includes information about native Americans,

disaggregated by tribal aliation, and about black Americans, disaggregated by ancestral

origin, that is, whether from the Caribbean or recently from the African continent. To

date, little had been known about the asset positions of these subgroups.

e survey was conducted in the Boston MSA and in four other metropolitan areas (Los

Angeles, CA; Miami, FL; Tulsa, OK; and Washington, DC). ese areas were chosen using

a systematic approach to ascertain the geographic and demographic national representa-

tiveness of the ethnic groups dened at the ancestral origin level. Criteria for choosing

metropolitan areas to be included in the sampling were primarily ethnic plurality and other

variables such as geographical representation, area size, and access to certain ethnic groups

that might be hard to identify in an urban context.

e survey instrument was designed primarily to gather information about a respondent’s

specic assets, liabilities, nancial resources, and personal savings and investment activity

at the household level. Net worth is estimated by subtracting debts from assets. Assets

included nancial assets (savings and checking accounts, money market funds, govern-

ment bonds, stocks, retirement accounts, business equity, life insurance) and tangible assets

(houses, vehicles, and other real estate). Debts included credit card debt, student loans,

installment loans, medical debt, mortgages, and vehicle debt.

Additional areas of inquiry included remittance behavior, that is, sending assets or other

resources abroad, and support for relatives in the United States. In addition, the survey

collects information on home ownership, foreclosure experiences, and the equity status of

homes. e survey also solicits additional information relevant to thenancial experiences

of lower wealth nonwhite individuals, such as the use of payday lenders. Core demographic

characteristics, such as age, sex, educational attainment, household composition, nativity,

income, and family background, are included in the survey.

10

e asset and debt module of the questionnaire replicates questions used in the Panel Study

of Income Dynamics (PSID), the longest running national longitudinal household survey

that collects data on employment, income, wealth, expenditures, health, marriage, educa-

tion, and numerous other topics. For the non asset and debt-based questions, the

NASCC survey replicated many questions found on the Multi-City Study of Urban In-

equality (MCSUI) survey, which in the early 1990s was a cross-sectional four-city survey

aimed at gathering socioeconomic data across ethnic and racial groups.

Various sampling techniques were used to locate and identify an ethnically plural sample

consisting of the specically dened ethnic groups. e techniques included the fol-

lowing: directory-listed landline samples targeted to census tracts where specic ethnic

9

The Color of Wealth in Boston

groups were known to reside; cell phone random digit dialing samples drawn from rate

centers that covered the targeted ethnic group ZIP codes; samples drawn from targeted

ZIP codes on the basis of billing address; and the use of surname-based lists targeting

specic national origin groups.

Race and ethnic identity for this study was based on self-identication of the family re-

spondent best qualied to discuss family nancial matters. e statistics in the sam-

ple used weights based on family characteristics in the U.S. Census Bureau’s American

Community Survey to generate results representative of specic ethnic group character-

istics in the respondent’s metropolitan area of residence. Overall, the results computed

from the unweighted NASCC sample are not dissimilar from those using the weight-

ed NASCC sample, suggesting that the specic ethnic group observations in the metro-

politan areas covered by the study were fairly representative of their populations at large.

e study was primarily designed to compare specic ethnic and racial groups within the

same metropolitan area. An advantage of this approach is the implicit control with regard

to asset and debt pricing and products, chiey housing prices, associated with particular

geographic areas.

e Boston sample targeted ve nonwhite groups: multigenerational African Americans

(referred here as U.S. blacks), Caribbean blacks (including Haitians), Cape Verdeans (both

black and white), Puerto Ricans, and Dominicans.

11

e sample also collected information

on whites. In the Boston MSA, 403 surveys were completed.

12

Table 1.

Boston Metropolitan Statistical Area sample characteristics

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean Black

Cape Verdean

Puerto Rican

54.0 55

Number of

observations

Bachelor’s

degree

or higher

Married

Median

age

Median

family

income

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

Asian

55.2

78

24.8 55

43.4

71

40.8 49

57.2

36

58.0 43

72.7

14

34.4 51

38.0

43

32.1 40

10.5

51

18.4 44

16.7

38

32.1 37

33.3

21

32.1 50

44.2

51

90,000

41,200

50,000

96,000

65,000

37,000

25,000

46,000

55,000

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race (30 respondents).

10

The Color of Wealth in Boston

As shown in Table 1, in general, white households in the sample were older, much more

educated,

13

more likely to be married,

14

and have higher income

15

than nonwhite groups in

the study.

Assets, Debt, and Net Worth Estimates

Survey respondents were asked if they owned various assets and debts and, if so, to

estimate their value. In the following analysis, we used the weighted sample and reported

the percentage of households that owned dierent types of assets and debts. We

evaluated whether the data for whites and nonwhites dier in a statistically signicant

way. Note that what we report here as statistically signicance results are considered to

be conservative.

16

Small sample sizes limit the statistical power to detect meaningful

dierences even when there is good reason to suspect that group-based dierences in

assets levels and debts exist.

In addition, even when respondents owned assets, many did not report estimated values.

e result is that asset values were often not statistically signicant when examined sep-

arately, but they were statistically signicant when combined. Finally, we use the median

rather than the mean (or average) to measure asset values because medians more accurately

represent the typical holdings of families within each racial or ethnic group.

17

Unfortunate-

ly, the sample size for Asians is too small to make any inferences.

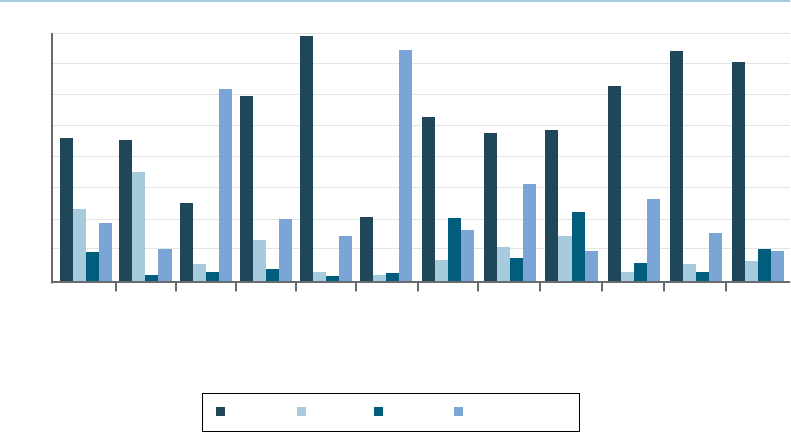

Financial Assets:

e Boston NASCC survey results show that white households were more likely to hold

assets than every other racial and ethnic group; this held true for every type of asset. e

dierences were all statistically signicant with a few exceptions (Table 2).

In general, among communities of color, Cape Verdeans, Caribbean blacks, and racial

groups not otherwise classied were the most likely to own an asset, whereas Puerto Ricans

and Dominicans were generally the most asset poor.

Liquid assets:

Liquid assets include checking accounts, savings accounts, money market funds, certi-

cates of deposit, and government bonds. Table 2 shows that nearly all whites in the Boston

area—96 percent—owned liquid assets. In comparison, the proportion of the other racial

groups was considerably lower. Eighty-three percent of blacks born in the United States

held a liquid asset, whereas the share for Caribbean blacks and Cape Verdeans was 85 per-

cent and 74 percent, respectively. e groups least likely to own a liquid asset were Puerto

Ricans, Dominicans, and other Hispanics; among those three groups, 57 percent, 63 per-

cent, and 67 percent owned any type of liquid asset, respectively.

18

Checking and savings accounts:

Being banked, or having a checking or savings account, is critical for everyday nancial

ecacy. Yet surprisingly, most Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, and other Hispanics did not

hold either type of account. Rather than using a bank for nancial transactions, many in

these populations may use alternative nancial institutions, which charge transaction fees

for cashier’s checks or money orders or for wiring money.

11

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Within these populations, only 39 percent of Puerto Ricans, 37 percent of Dominicans,

and 48 percent of other Hispanics had savings accounts. Although they were more likely to

own checking accounts, these numbers remained surprisingly low: 53 percent of Puerto Ri-

cans, 62 percent of Dominicans, and 54 percent of other Hispanics held such accounts. In

contrast, almost all whites were likely to hold checking or savings accounts (93 percent).

19

e remaining racial and ethnic groups were also signicantly less likely than whites to be

banked. Close to 75 percent of U.S. blacks and Cape Verdeans and 84 percent of Caribbean

blacks held either a checking or savings account.

20

It is possible that those who are unbanked may have more cash on hand. Research has

suggested that populations that are unbanked fail to meet the minimum amounts of cash

needed for free checking or savings accounts. Paying the higher transaction fees of alter-

native nancial services—and these are notably more expensive—may actually be more

prudent than paying even higher fees or penalties due to overdrafts at traditional banks and

savings institutions (Servon 2014).

However prudent it may seem to remain unbanked and thus pay high transaction fees,

these circumstances make it dicult to accumulate savings and begin to earn interest on

owned funds. In addition, such low rates of being banked indicate that many in these pop-

ulations are living paycheck to paycheck—unable to save enough money in their accounts

to meet the minimum banking requirements.

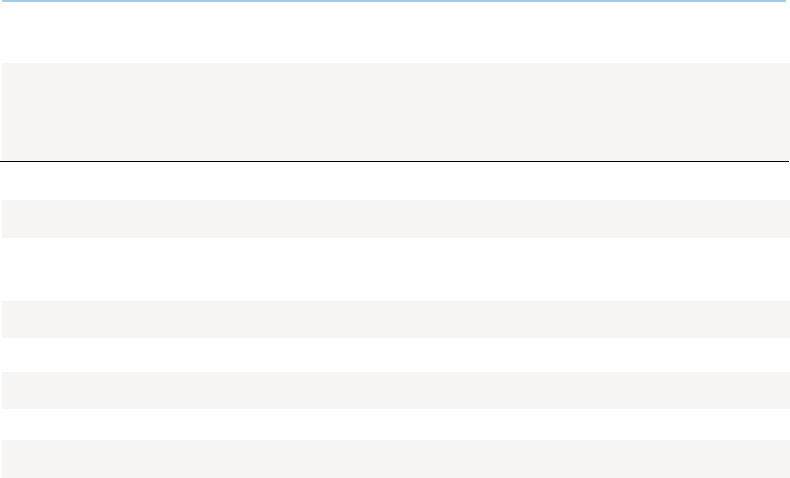

Table 2.

Comparison of percentage of white and nonwhite households owning

any type of liquid asset, a checking account, or a savings account

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean

Black

Cape Verdean

Puerto Rican

91.8 0.0

Percent

Percentage

point

dierence

from whites

Percent

Percentage

point

dierence

from whites

Percent

Percentage

point

dierence

from whites

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

Liquid Assets

Checking Account Savings Account

0.0

95.7

73.8 –18.0***–13.1***

82.6

80.0 –11.8*–1.2

94.5

54.0 –37.8***–28.2**

67.5

61.5 –30.3***–32.4***

63.3

52.9 –38.9***

–38.5***

57.2

72.8 –19.0–22.0**

73.7

82.2 –9.6*–10.9**

84.8

73.7 0.0

55.1 –18.6**

65.5 –8.2

47.6 –26.2***

37.1 –36.6***

39.0 –34.7***

65.9 –7.8

74.8 1.1

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: The dierence in the percentage of nonwhites as compared with the percentage of white households is statistically

significant at the ***99%, **95%, *90% level. The percentage of Puerto Rican households holding liquid assets as compared

with Dominican households does not dier in a statistically significant manner. Percentage of U.S. black households holding

liquid assets as compared with Caribbean black households is statistically significant for savings accounts at the 95% level.

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

12

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Other financial assets:

What is striking about ownership of other nancial assets is the general absence of owner-

ship by all nonwhite groups analyzed in this report. is indicates that most families lacked

resources for long-term investment and economic security.

Stocks, mutual funds, and investments trusts:

As Table 3 illustrates, even among white households, only 40 percent owned other types

of assets such as stocks, mutual funds, or other investments or trusts. Ownership of these

assets among other racial groups was markedly lower than among whites. Only 10 percent

of U.S. blacks, 8 percent of Caribbean blacks, and 6 percent of Cape Verdeans possessed

any of these other types of nancial assets. e percentage of Dominican, Puerto Rican,

and other Hispanic households possessing these types of nancial assets was much lower in

comparison to whites: 6 percent, 9 percent, and 19 percent, respectively.

Retirement funds:

Few families owned Individual Retirement Accounts (IRAs) or private annuities, which

is consistent with our interpretation of the data collected thus far. We speculate that most

families are spending a majority of their earnings and have little to save toward long-term

goals despite the fact that compound interest and the income tax savings or tax deferments

associated with IRAs is a key step toward building future nancial security in retirement.

is is consistent with other studies reporting that most Americans are not able to save

suciently to support themselves during retirement (Ghilarducci 2012, Sommer 2013).

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean

Black

Cape Verdean

Puerto Rican

56.2 0.0

Percentage

point

from white

households

Percentage

point

from white

households

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

Stocks IRA or Private Annuity

0.0

39.5

21.2 –34.9***–29.9***

9.6

33.8 –22.4**–9.2

30.3

28.1 –28.1***–20.1**

19.4

7.5 –48.7***–33.5***

6.0

16.2 –40***–30.1***

9.4

38.6 –17.6–33.9**

5.6

21.1 –35.1*–31.2***

8.3

Table 3.

Percentage of white and nonwhite households owning stocks,

an Individual Retirement Account (IRA) or private annuity

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: The dierence in the percentage of nonwhites as compared with the percentage of white households is statistically

significant at the ***99%, **95%, *90% level.

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

Percentage of

households

owning these

Percentage of

households

owning these

13

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Except for Cape Verdeans, the white-nonwhite disparity is greater for ownership of private

retirement assets than ownership of stocks and other nancial investment assets discussed

above. While most white households (56 percent) own either an IRA or a private annuity,

most racial and ethnic groups do not hold such retirement funds (see Table 3). Only one-

fth of U.S. and Caribbean blacks have retirement accounts. Only 8 percent of Dominicans

and 16 percent of Puerto Ricans hold such accounts.

21

ese results suggest that, if not for

the federally structured Social Security program, many households, particularly black and

Hispanic ones, would have virtually no nancial assets of their own at retirement.

22

Unsecured debt:

Unsecured debt refers to debt not backed by an underlying asset and includes credit card

debt, student loans, and medical debt.

Credit card debt:

Credit card debt is usually debt associated with consumption goods that have no invest-

ment value. Hence, credit card debt is generally considered to be less “healthy” than other

forms of debt, which, for example, may be associated with a good that could appreciate

over time. Most households in the sample had credit card debt; Cape Verdeans were least

likely to have credit card debt (27 percent). In contrast, approximately half of whites, U.S.

blacks, Caribbean blacks, and Dominican households have such debt. e dierences in the

percentage of white and nonwhite households having credit card debt did not dier in a

statistically signicant way. However, nonwhites often have credit cards with less favorable

terms, such as higher interest rates (Weller 2007), further inhibiting their ability to pay

down their credit card debt (see Table 4).

Student loans:

Since 2008, student loan debt nationwide has increased 84 percent to $1.1 trillion (Federal

Reserve Bank of New York 2014). Given the relatively lower levels of household income

among nonwhites, student loan debt may be more relevant for nonwhite college students

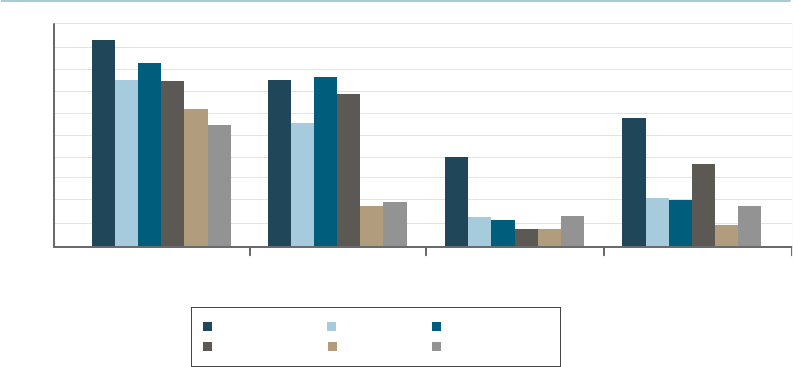

100

80

60

40

20

0

White U.S. Black Caribbean Black

Cape Verdean Dominican Puerto Rican

Checking Account Savings Account Stocks IRA or Private

Figure 3.

Percentage of households having financial assets by type of asset

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Percentage of households

90

70

50

30

10

14

The Color of Wealth in Boston

than their white peers. For example, black and Hispanic students graduate from college

with substantially higher debt than their white peers (Baum and Steele 2010). As shown

in Table 4, nonwhite households were more likely to have student loan debt than white

households with Caribbean blacks and other Hispanics almost twice as likely to have stu-

dent loan debt. Although obtaining a college degree provides greater lifetime earnings

potential than having only a high school diploma, clear disadvantages are associated with a

debt-burdened degree.

Medical debt:

While only 2 percent of Cape Verdeans reported having medical debt, most respondents

from communities of color reported similar or higher percentages of medical debt as com-

pared with whites (11 percent). However, Dominicans and other Hispanics are about twice

as likely as whites to have medical debt: 20 percent and 24 percent, respectively.

23

One

reason medical debt may be higher generally for Hispanic groups is that Hispanics are least

likely to have health insurance (Brown and Patten 2014) and, within the Hispanic popula-

tion, Puerto Ricans are more likely to have health insurance than other Hispanics (Motel

and Patten 2012). is is consistent with our ndings that Puerto Ricans were less likely to

have medical debt than Dominicans and other Hispanics. Likewise, blacks were less likely

to have health insurance than whites (Brown and Patten 2014) and were more likely to re-

port having medical debt (although the percentage dierence among households reporting

medical debt was statistically insignicant).

24

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean

Black

Cape Verdean

Puerto Rican

18.9 0.0

Percentage

of

households

having a

credit card

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

Percentage

of

households

having a

student loan

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

Percentage

of

households

having

medical debt

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

Credit Card Student Loan Medical Debt

0.0

46.5

28.0 9.15.8

52.3

28.9 10.013.6

60.1

34.4 15.5*–6.9

39.6

21.1 2.28.3

54.8

19.4 0.5–5.7

40.8

25.5 6.6–19.8

26.8

33.7 14.8*6.1

52.7

10.9 0.0

17.1 6.2

13.9 3.0

24.1 13.3*

19.8 8.9

10.6 –0.2

2.0 –8.9*

17.1 6.2

Table 4.

Percentage of households having various types of debt

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: The dierence in the percentage of nonwhites as compared with the percentage of white households is statistically

significant at the ***99%, **95%, *90% level.

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

15

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Tangible assets and secured debt:

Tangible assets include houses, vehicles, and other property households may own.

Homeownership:

Homeownership serves as the primary asset in which most Americans build and store their

wealth. e federal tax code also incentivizes homeownership by providing tax savings as-

sociated with mortgage interest deductions. Furthermore, there are other positive attributes

that owning a home, particularly in a certain neighborhood, may oer, such as access to a

good public school district and other neighborhood amenities such as convenient shops

and access to parks. Finally, the purchase of a home and regular on-time payments of a

mortgage lead to higher Fair Isaac Corporation (FICO) credit scores than for families who

regularly make on-time payments for rent.

Yet the percentage of households owning a home diers radically by race and ethnicity in

Boston. Most whites—79 percent—are homeowners, whereas most nonwhites are not. Ca-

ribbean blacks were most likely to own a home (49 percent) in Boston among the analyzed

nonwhite groups. Only one-third of U.S. blacks and other Hispanics owned their homes

25

(see Table 5).

Twenty-nine percent of Cape Verdeans owned their home, as did 21 percent of Puerto Ri-

cans. Dominicans had the lowest rate of home ownership—only 17 percent owned or were

in the process of purchasing a home.

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean

Black

Cape Verdean

Puerto Rican

83.6 0.0

Percentage

of

households

owning a

home

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

Percentage

of

households

owning a

vehicle

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

House Vehicle

0.0

79.1

50.7 –32.8***–45.3***

33.8

83.5 –0.1–36.3***

42.8

77.2 –6.3–45.1**

34.0

69.0 –14.5*–61.9***

17.3

61.1 –22.4**–57.9***

21.2

85.4 1.9–49.7**

29.4

84.1 0.5–30.4**

48.7

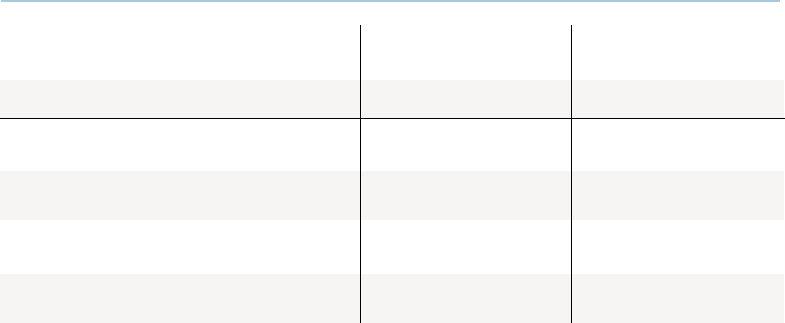

Table 5.

Percentage of households that have tangible assets by type of asset

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: The dierence in the percentage of nonwhites as compared with the percentage of white households is statistically

significant at the ***99%, **95%, *90% level.

Note: The percentage of Puerto Rican households holding tangible assets as compared with Dominican households did not

dier in a statistically significant way. The percentage of U.S. black households owning homes and vehicles diered

significantly when compared with Caribbean black households as follows: for homes, at a 90% level, and for vehicles, at a

99% level.

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

16

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Mortgages:

Across all households, whites were most likely to have mortgage debt with 47 percent of

white households reporting mortgage debt (Table 6). In contrast, only 15 percent of Do-

minicans, 18 percent of Puerto Ricans and 29 percent of U.S. blacks

26

had mortgage debt.

In regard to the percentage of households having mortgage debt, whites, Cape Verdeans,

and Caribbean blacks did not dier in a statistically signicant way.

When the sample is restricted to homeowners, white households are least likely to have

mortgage debt than the other racial and ethnic groups. To put it dierently, whites are

more likely to own their own homes outright. Although 60 percent of white homeowners

have mortgage debt, the proportion of homeowners with mortgage debt is much higher

for other groups. Close to 90 percent of U.S. blacks,

27

Caribbean blacks, and Domini-

can homeowners have a mortgage. While mortgage debt for Puerto Ricans and other

Hispanics also is higher than for white homeowners, the percentage dierence was not

statistically signicant.

Of all types of debt, mortgage debt is potentially the most benecial for long-term asset

building if the total amount is not excessive, if it is not accompanied by high interest rates,

and if home prices do not drop dramatically. Very few people can aord to become home-

owners without acquiring mortgage debt, and, if conditions are favorable, homeownership is

often a primary mechanism for building assets, especially for the middle class. However, our

analysis of the survey data suggests that racial and ethnic minorities are not beneting to the

same extent as white households from the potential wealth-enhancing eects of homeown-

ership. Why? Because racial and ethnic minorities are less likely to own homes and because,

when they do own homes, they are much more likely than whites to have mortgage debt.

40

30

20

10

0

White U.S. Black Caribbean Black

Cape Verdean Dominican Puerto Rican

House Vehicle

80

70

60

50

90

Percentage of households

Figure 4.

Percentage of households that have tangible assets by type of asset

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

17

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Vehicles:

Like homeownership, owning a vehicle has far-reaching implications. ose who own ve-

hicles have access to job opportunities beyond the zones of public transportation, and they

can work late or take unusual shifts because of having their own transportation. For this

reason, patterns of vehicle ownership analyzed on the basis of race were noteworthy. U.S.

blacks had the lowest rates—only 50 percent owned a vehicle (Table 5). Puerto Ricans and

Dominicans also had relatively low rates of ownership (61 percent and 69 percent, respec-

tively). In contrast, close to 85 percent of whites, Cape Verdeans, and Caribbean blacks

owned a vehicle.

Vehicle debt:

Compared with the percentage of white households having vehicle debt, U.S. blacks and

Puerto Ricans were less likely to be so encumbered; the dierence in the percent of other

racial groups with vehicle debt as compared with whites was not statistically dierent.

Whereas 30 percent of whites had vehicle debt, 21 percent of U.S. blacks and 16 percent

of Puerto Ricans had vehicle debt. However, as shown in Table 6, U.S. blacks and Puerto

Ricans were much less likely to own vehicles than whites. Interestingly, among households

owning vehicles, no statistically signicant dierences in vehicle debt were noted.

Among all

households

Among all

households

Among

homeowners

Among households

that own vehicles

Vehicle Debt Mortgage

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

–14.2*

–1.5

–9.1

9.5

–8.9***

0.0

–7.6

–6.2

Among all

households,

percentage

with vehicle

debt

16.1

25.8

21.2

39.9

21.4

30.3

22.7

24.1

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

–29.5***

–32.21***

–18.7

–2.8

–18.3**

0.0

–10.0

–20.5**

Among all

households,

percentage

with

mortgage

debt

17.7

15.1

28.6

44.4

28.9

47.2

37.3

26.7

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

–9.9

5.4

–1.6

11.1

5.9

0.0

–9.1

–2.2

Among

households

that own

vehicles,

percentage

with vehicle

debt

26.4

41.7

34.7

47.4

42.2

36.3

27.2

34.1

0.0

Percentage

point

dierence

from white

households

23.9

27.8**

37.3***

31.6***

25.8**

27.4**

18.7

Among

home-

owners,

percentage

with

mortgage

debt

83.6

87.5

97.0

91.3

85.5

59.7

87.1

78.4

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean

Black

Cape Verdean

Puerto Rican

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: The dierence in the percentage of nonwhites as compared with the percentage of white households was

statistically significant at the ***99%, **95%, *90% level.

Note: The dierence between the percentage of U.S. blacks having mortgages (among all households) as compared with

Caribbean blacks was statistically significant at ***99 percent. The dierence between the percentage of U.S. blacks having

mortgages (among all homeowners) as compared with Cape Verdeans was statistically significant at the 90% significance level.

The dierence between the percentage of U.S. blacks having vehicle debt (among all households) as compared with

Caribbean blacks was statistically significant at the 99% significance level.

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

Table 6.

Comparison of the percentage of white and nonwhite households having vehicle

debt or mortgage

18

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Asset, debt and net worth values:

Asset Values:

Whites own far more in assets than every other racial group, and comparisons of asset

data for racial groups exhibited statistically signicant dierences. We analyzed not only

the prevalence of these assets but also their estimated value. We looked at liquid and total

assets separately. Liquid assets, which can quickly be converted into cash, include money

in savings and checking accounts, stocks, money market, and government bonds.

28

e

median value of liquid assets for Puerto Ricans and Dominicans was only $150 and $20,

respectively. Some of these families may hold cash in hand, but most of them have no for-

mal savings. e median value of liquid assets among U.S. blacks and other Hispanics was

close to $700, whereas the median level of liquid assets in white households was $25,000.

A typical Caribbean black household has $3,500 in liquid assets. In case of an emergency,

half of members of the nonwhite groups in this analysis would be unable to weather an

unexpected expenditure shock of even $700 with their own savings.

29

We totaled the value of all assets held by each racial group, including the value of all liquid

assets, nancial assets, retirement, home and vehicle equity, and the values of all other assets

(these include life insurance policies and valuables such as jewelry). White households had

by far the highest values; the median total value of assets was $256,500. e median asset

values for communities of color were far below this threshold, at best, barely approaching

20 percent of the median asset value of white households (Table 7).

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean

Black

Cape Verdean

b

Puerto Rican

256,500 100.0

Median amount

(U.S.dollars)

Nonwhite

household

percentage of

white household

liquid assets

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

Liquid Assets Total Assets

100.0

25,000

700 0.3**2.7**

670

18,000 7.0***16.0***

4,000

15,000 5.8***2.8**

700

1,724 0.7***0.6**

150

3,020 1.2***0.1**

20

— —0.6**

150

12,000 4.7***14.0*

3,500

Table 7.

Comparison of the value of assets held by white and nonwhite households

Median amount

(U.S.dollars)

Nonwhite

household

percentage of

white household

liquid assets

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: The dierence in the percentage of nonwhites as compared with the percentage of white households was

statistically significant at the ***99%, **95%, *90% level.

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

b

Values for Cape Verdeans were not calculated because sample sizes were too small.

19

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Blacks had the lowest median asset value, $700, which is less than 0.3 percent of the median

asset value of whites. e median asset value of Puerto Ricans and Dominicans was only 1

percent of the median asset value of whites. Caribbean blacks were slightly better o, at 5

percent of the median asset value of whites. e median asset value of other Hispanics was

6 percent that of whites. All told, our analysis of these data substantiates the existence of a

staggering racial wealth gap in the Boston MSA.

30

Debt values:

Among the various racial and ethnic groups, the percentage of nonwhite group members

carrying various forms of debt diered; the groups are heterogeneous in regard to debt. Our

data analysis also revealed that the amount of debt owned by whites as compared with other

racial and ethnic groups diered only slightly (Table 8). A noteworthy exception was that

Dominicans, other Hispanics, U.S. blacks, and Caribbean blacks had signicantly lower

median mortgage debt than white households. e lower median mortgage debt is likely

a result of whites being able to purchase homes valued at higher prices (and thus having

higher mortgages).

31

In this study, the lack of statistical signicance stemming from our analysis of white and

nonwhite median debt burden should not be misconstrued as indicating equity in the bur-

den of debt for white and nonwhite households.

32

Minority households often pay more for

their debt as a result of carrying higher fees and interest rates, for example; they have higher

debt-to-income ratios; and they are more likely to be denied credit (Weller 2007).

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean Black

Cape Verdean

Puerto Rican

Median amount

(U.S. dollars)

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

2,000

3,000

4,000

5,000

2,200

300

2,200

6,000

Table 8.

Comparison of total median nonhousing debt for white and nonwhite households

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

20

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Net worth:

Net worth (or wealth), the sum of the value of total assets minus the value of debts, provides

a snapshot of household nancial well-being. Striking racial dierences are evident when

looking at total household wealth. Nonwhite households have only a fraction of the wealth

of white households. Whereas white households have a median wealth

33

of $247,500, Do-

minicans and U.S. blacks have a median wealth of close to zero (see Table 9). Of all non-

white groups for which estimates could be made, Caribbean black households had the

highest median wealth with $12,000, which represents only 5 percent as much wealth as

white households.

34

Racial and ethnic dierences in net worth demonstrate the extreme nancial vulnerabil-

ity faced by nonwhite households. Possessing less than 5 percent of the wealth of white

households, nonwhites are less likely to have the nancial resources to draw upon in times

of nancial stress. In addition, they have fewer resources to invest in their own future and

those of their children.

Racial dierences in asset ownership, particularly homeownership, contribute to vast racial

disparities in net worth. Homes—the most valuable asset owned by middle-class house-

holds—comprise the bulk of middle-class wealth. However, unequal opportunities (past

and present) to build other assets and to reduce debt are contributors to the vast racial

wealth gap substantiated in this analysis.

Table 9.

Comparison of white and nonwhite household median net worth

White

U.S. Black

Caribbean

Black

Cape Verdean

b

Puerto Rican

Amount

(U.S. dollars)

Nonwhite household

percentage of white

household median

net worth

Dominican

Other Hispanic

NEC

a

Median net worth

100.0

247,500

0.0***

8

4.8***

12,000

1.1***

2,700

0.0***

0

1.2***

3,020

—

—

4.8***

12,000

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: Dierence in findings of nonwhite household median or mean net worth values were statistically significant at the

***99 percent level.

a

The “not elsewhere classified” (NEC) category includes mainly respondents that chose more than one race.

b

Net worth values for Cape Verdeans were not calculated because sample sizes were too small.

21

The Color of Wealth in Boston

Some of the dierences observed may be driven by dierences in age or educational attain-

ment. In general, nonwhites in the survey were younger and had much lower educational

attainment rates. Unfortunately, it was not possible to provide data broken down by age

for all the groups analyzed in Boston, because the sample size was too small. So we have

focused on how whites, blacks, and Hispanics dier. Even among highly educated house-

holds, black and Hispanics were less likely than whites to be banked and to own a house.

Almost all whites with a bachelor’s degree or higher had either a savings or a checking ac-

count, whereas a quarter of Hispanics and 11 percent of blacks

35

did not have either (Table

10). Homeownership rates diered widely. Among Hispanics and blacks having bachelor’s

degrees, less than half owned a home, whereas 82 percent of comparably educated whites

were homeowners.

36

A majority of households with high educational attainment owned a

vehicle. In this regard, whites, blacks, and Hispanics did not dier in a statistically mean-

ingful way.

Age may greatly inuence a family’s assets and debts. One expects lower or negative savings

during the early years when individuals do not have enough income to save and incur debt

to buy assets or nance their education. Generally, the middle-aged working population

tends to save and prepare for retirement. In this analysis, we focused on two age brack-

ets: 31- to 50-year-olds and 51- to 65-year-olds. Interestingly, for the 31- to 50-year-old

bracket, whites and blacks had a similar percentage of banked households, at close to 90

percent. Among Hispanics in the same age category, only 60 percent had either a savings

or checking account. However, disparity in homeownership rates were considerable when

comparing groups in the same age bracket. Close to 80 percent of white households were

homeowners, compared to 45 percent of blacks and 25 percent of Hispanics. Vehicle own-

ership did not dier signicantly in the 31- to 50-year-old category. Taking into account

heads of households 51 to 65 years old, a much higher percentage of white households were

banked and owned a home and a vehicle than black households and Hispanic households.

Percentage of

banked households

Homeownership

rate

Vehicle ownership

rate

Net worth

(U.S. dollars)

74.7***

White Black Hispanic

Bachelor’s Degree

or Higher

Age: 31 to 50 Years

88.7**

98.1

49.3***47.9***

82.4

12,000*

313,500

90.679.0

84.1

Age: 51 to 65 Years

58.5

White Black Hispanic

91.7

87.5

25.7***44.7***

78.9

69.976.0

87.1

52.3***

White Black Hispanic

69.1***

95.5

32.8***45.3***

82.3

4,000***

311,000

61.8**57.9***

87.9

_b _b _b _b _b

Source: NASCC survey, authors’ calculations

Note: The dierence in the figures of nonwhites as compared with the figures of white households was statistically

significant at the ***99%, **95%, *90% level.

b

Values not calculated because sample size is too small.

Table 10.

Comparison of the percentage of banked households, homeownership, and vehicle

ownership rates, and net worth values for white and nonwhite households by

college education and age group

22

The Color of Wealth in Boston

e net worth dierences of whites and blacks were remarkable even when level of educa-

tion or age were considered. Median wealth among black households that have a bachelor’s

degree or higher ($12,000) was 4 percent of the median for white households ($313,500).

Similarly, if we look at households in the 51- to 65-year-old bracket, the typical white

household holds $311,000 in wealth, compared with only $4,000 for the typical black

household (Table 10).

The Implications of Racial Disparities

Assets are important for nancial security and have long-term implications for

communities and families. In our analysis, the data revealed disparities in both nancial

and tangible assets that are striking. e extremely low homeownership rates among

communities of color in Boston are worrisome. Most nonwhite groups do not have

enough liquid savings to serve as buers to income and expenditure shocks. Lack of

retirement and nancial savings not only implies possible hardship in the long term, it

also makes short-term disruption much more likely. Any problem—a car breaking down,

losing a job, medical needs—is likely to become a crisis. e stress experienced when

someone is unable to meet family needs, x the car, buy school supplies, or take care of

medical ailments can be long-term and debilitating (Fiscella 2004, Massey 2004).

With respect to debt, several key ndings emerged from our analysis. Although members

of communities of color are less likely to own homes, among homeowners they are more

likely to have mortgage debt. Also, data on student loans and medical debt for whites and

racial/ethnic minorities suggest that whites are often less likely to have these forms of debt.

Because households from communities of color often have higher-cost debt, have higher

debt-to-income ratios, and are more likely to be denied credit, their ability to build assets

is crippled and contributes to lower asset ownership and lower asset values when compared

with white households.

It is beyond the scope of this report to identify the major drivers of the enormous wealth

gap that exists in the Boston MSA. However, a review of the economic literature (Hamil-

ton and Chiteji 2013) demonstrates that inheritances, bequests, and intrafamily transfers

account for more of the racial wealth gap than any other demographic and socioeconomic

indicators, including education, income, and household structure (see, for example, Blau

and Graham 1990, Menchik and Jianakoplos 1997, Conley 1999, Chietji and Hamilton

2002, Charles and Hurst 2003, Gittleman and Wol 2007).

So what explains the racial dierences in resource transfers across generations?

Blacks experienced deprivation of property, especially the land of former slaves between the

period 1880 to 1910 (Darity 2008). More recently, general housing and lending discrim-

ination through restrictive covenants, redlining and other lending practices has inhibited

blacks from accumulating wealth (Lui et al. 2005, Katznelson 2005, Oliver and Shapiro

2006, Munnell et al. 1996, Hamilton and Darity 2010).

Moreover, people of color were excluded from post-Depression and World War II (1939–

1945) public policy, which was largely responsible for the asset development of an Amer-

ican middle class (for example, racially discriminatory local implementation of Federal

Housing Administration loans and G.I. Bill benets; see Lui et al. 2005, Katznelson 2005,

and Oliver and Shapiro 2006). us, explanations that attribute the lack of assets among

minority groups to a relative deciency in current savings behaviors are at the very least an

oversimplication the problem.

37

23

The Color of Wealth in Boston

e cumulative consequences of a lack of net worth exacerbate the enormous racial divide

in wealth in Boston. e staggering disparities identied in this analysis should urge us to

nd policies that can help narrow the wealth divide by: providing opportunities for asset

development; ensuring fair access to housing, credit, and nancial services; ensuring equal

opportunity to good-paying jobs regardless of race or ethnicity; strengthening retirement

incomes; promoting access to education without overburdening individuals with debt; and

providing access to healthcare while helping minimize medical debt.

38

All policies aimed at

bridging the wealth gap should also consider the wide diversity among nonwhite popula-

tions and be targeted or adapted accordingly. Policy solutions are complex and need to use

a multifaceted approach that includes input from practitioners who are familiar with the

unique needs and challenges dierent communities of color face.

Finally, this analysis highlights the importance of collecting data on assets and debts at the

local level, including disaggregated information for nonwhite groups. is is the rst time

this kind of data has been collected, and it is an important step to help shape policymakers’,

practitioners’, and foundations’ responses to the enormous challenges communities of color

experience across the country. More needs to be done to ensure that the diverse voices of

nonwhite groups are included in public debates and to understand the reasons behind the

enormous dierences uncovered in this analysis. Having a qualitative research component

is also going to be important for a deeper understanding.

24

The Color of Wealth in Boston

About the Authors

Ana Patricia Muñoz is the community development research director in the Regional and

Community Outreach department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston. She conducts

applied research on issues that impact low- and-moderate-income (LMI) families and is

interested in issues related to wealth inequality, asset building, equal access to credit, and

immigration. Muñoz holds a master’s degree in economics from the Université de Mon-

tréal, a master of public aairs from Brown University, and a B.S in economics from the

Universidad Católica del Ecuador.

Marlene Kim is a professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts, Boston. She

edited Race and Economic Opportunity in the Twenty-First Century (Routledge 2007)

and is the recipient of the rst Rhonda Williams Prize for her work on race and gender

discrimination. She is the associate editor of Feminist Economics and serves on the edito-

rial boards of Industrial Relations. She holds a Ph.D. in economics from the University of

California, Berkeley.

Mariko Chang is a former associate professor of sociology at Harvard and the author of

Shortchanged: Why Women Have Less Wealth and What Can Be Done about It. She is

also the primary author of the Insight Center report “Lifting As We Climb: Women of

Color, Wealth and America’s Future.” In addition to her work on the wealth gap, she works

as a consultant and external program evaluator to help universities diversify their faculty.

Further information can be found at www.mariko-chang.com.

Regine O. Jackson is an associate professor of sociology at Agnes Scott College. She has a

B.A. from Brown University in Providence and a Ph.D. from the University of Michigan,

Ann Arbor. She specializes in Haitian migration and diaspora studies, contemporary Ca-

ribbean and African communities in the United States, and place/urban studies. She is the

author of Boston Haitians: Navigating Race, Place and Belonging in a Majority-Minority

City (manuscript) and editor of Geographies of the Haitian Diaspora (Routledge, 2011).

Darrick Hamilton is an associate professor of economics and urban policy at the New

School, an aliate scholar at the Center for American Progress, and co-associate director

of the Diversity Initiative for Tenure in Economics Program. He serves on the board of

overseers for the General Social Survey and is the president-elect of the National Econom-

ic Association. Hamilton is a stratication economist, whose work focuses on the causes,

consequences, and remedies of intergroup inequality.

William A. (“Sandy”) Darity Jr. is the Samuel DuBois Cook Professor of Public Policy,

African and African American Studies, and Economics and the director of the Duke Con-

sortium on Social Equity at Duke University. He was the founding director of the Research

Network on Racial and Ethnic Inequality at Duke. Darity’s research focuses on inequality

by race, class, and ethnicity, stratication economics, schooling, and the racial achievement

gap. He received the Samuel Z. Westereld Award in 2012 from the National Economic

Association, the organization’s highest honor.

25

The Color of Wealth in Boston

References

Aja, Alan, Daniel Bustillo, William Darity, Jr., and Darrick Hamilton. 2014. “From a Tan-

gle of Pathology to a Race Fair America. Dissent Magazine.” pp. 38-42. Retrieved from

http://www.dissentmagazine.org/article/from-a-tangle-of-pathology-to-a-race-fair-america

Baum, Sandy, and Patricia Steele. 2010. “Who Borrows Most? Bachelor’s Degree Recipi-

ents with High Levels of Student Debt.” College Board, Trends in Higher Education Series,

2010. Retrieved from

https://trends.collegeboard.org/sites/default/les/trends-2010-who-borrows-most-brief.pdf

Blau, Francine D., and John W. Graham. 1990. “Black-White Dierences in Wealth and

Asset Composition.” Quarterly Journal of Economics, 105(2), 321-39.

Brown, Anna, and Eileen Patten. April 2014. “Statistical Portrait of Hispanics in the Unit-

ed States, 2012.” Pew Research Center’s Hispanic Trends Project, 2014.

Charles, Kerwin, and Erik Hurst. 2003. “e Correlation of Wealth across Generations.”

Journal of Political Economy, 111(6), 1155-1182.

Chiteji, Ngina, and Darrick Hamilton. 2002. “Family Connections and the Black-White

Wealth Gap Among Middle Class Families.” Review of Black Political Economy, 30(1), 9-27.

Conley, Dalton. 1999. Being Black, Living in the Red: Race, Wealth, and Social Policy in Amer-

ica. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Darity, William Jr. 2008. “Forty Acres and a Mule in the 21st Century,” Social Science Quar-

terly 89(3), 656-64.

Federal Reserve Bank of New York. August 2014. Quarterly Report on Household Debt and

Credit. Retrieved from

http://www.newyorkfed.org/householdcredit/2014-q2/data/pdf/HHDC_2014Q2.pdf

Fiscella, Kevin, and David R. Williams. 2004. “Health Disparities Based on Socioeconomic

Inequities: Implications for Urban Health Care.” Academic Medicine, 79(12), 1139-1147.

Ghilarducci, Teresa. 2012, July 21. “Our Ridiculous Approach to Retirement.” New York

Times, p. SR5.

Gibau, Gina Sanchez. 2008. “Cape Verdean Diasporic Identity Formation.” In Luís Batal-

ha and Jørgen Carling (Eds.), Transnational archipelago: Perspectives on Cape Verdean mi-

gration and diaspora (pp. 262-263). Amsterdam University Press.

Gittleman, Maury, and Edward N. Wol. 2007. “Racial and Ethnic Dierences in Wealth.”