Yale University Yale University

EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale

Public Health Theses School of Public Health

January 2022

Novel Applications Of Music And Digital Media In Global Health Novel Applications Of Music And Digital Media In Global Health

Intervention And Education Initiatives During The Covid-19 Intervention And Education Initiatives During The Covid-19

Pandemic: A Case Study Of Bts And Army Pandemic: A Case Study Of Bts And Army

Mariko Fujimoto Rooks

Follow this and additional works at: https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Rooks, Mariko Fujimoto, "Novel Applications Of Music And Digital Media In Global Health Intervention And

Education Initiatives During The Covid-19 Pandemic: A Case Study Of Bts And Army" (2022).

Public Health

Theses

. 2196.

https://elischolar.library.yale.edu/ysphtdl/2196

This Open Access Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Public Health at EliScholar –

A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. It has been accepted for inclusion in Public Health Theses by an

authorized administrator of EliScholar – A Digital Platform for Scholarly Publishing at Yale. For more information,

please contact [email protected].

Novel Applications of Music and Digital Media in Global Health Intervention and Education

Initiatives During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of BTS and ARMY

A Thesis Presented In Partial Fulfillments of the Requirements for a Master of Public Health in

Social and Behavioral Sciences with a Concentration in United States Health Justice

Mariko Fujimoto Rooks

May 1

st

, 2022

Advised by Professor Trace Kershaw

With Professor Grace Kao

Yale School of Public Health, Class of 2022

2

Abstract

The Korean musical group BTS (full name Bangtan Seoyeondan/방탄소년단) is one of

the world’s most commercially and artistically successful entertainment acts. BTS is primarily

known for their domination of both Western and Korean musical markets, impressive digital

media presence, major role in supporting the South Korean economy, and highly mobilized

400,000 member fandom known as ARMY. BTS and their parent company HYBE’s artistic

creation and marketing model has long focused on creating “Music and Artists for Healing,” or

using music and various forms of primarily digital content to connect with and improve health

outcomes for fans. In response, ARMY have developed significant grassroots public health

organizing to improve health of other fans and general populations. Both BTS and ARMY’s

intervention work regularly reaches global audiences of millions through primarily digital media

delivery mechanisms.

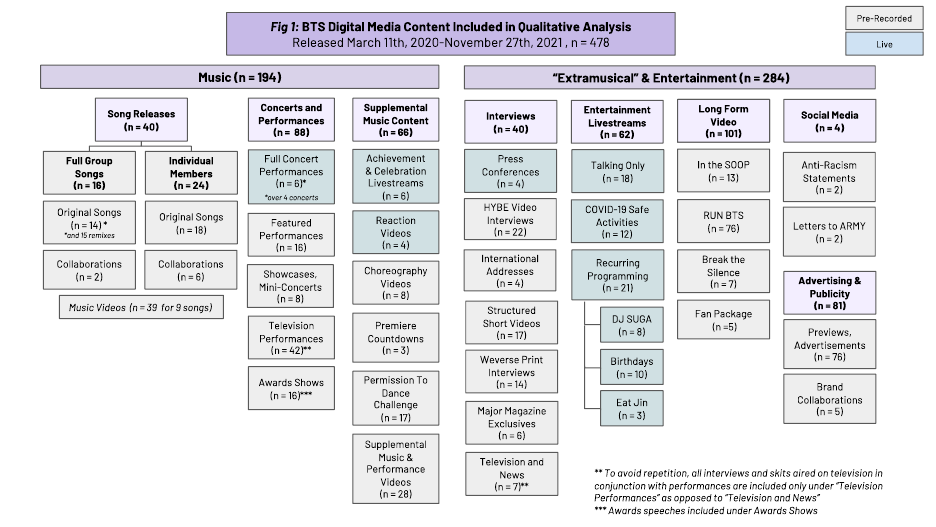

This interdisciplinary, mixed methods study uses qualitative analysis of BTS’ digital

content (n = 478) and an introductory exploration of ARMY public health organizations to

demonstrate that BTS’ music, HYBE’s digital content production and dissemination strategies,

and ARMY’s community grassroots organizing produced one of the largest-reaching public

health interventions in response to the early COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020- December

2021). Major intervention strategies included mitigating negative mental health outcomes,

distributing health information, modeling safe behaviors, and engaging in both mutual aid and

anti-racist health equity work. This exploratory research illuminates new directions in effective,

novel public health intervention and education practices and posits that critical, nuanced study of

BTS and ARMY’s impact on public health may hold important keys to re-imagining digitally

delivered health interventions and their subsequent economic profitability.

3

Acknowledgements

To paraphrase Kim Namjoon, we are only a small percentage of our overall success. While it is

yet to be determined whether this thesis is a success or not, I have many, many people to thank

for making sure it came to fruition at all. Firstly, to my advisors: Prof. Kershaw, who has been

one of my most flexible and insightful mentors since 2019 and only blinked only once when I

suggested writing my thesis about a Korean boyband, and to Prof. Kao for her eternal patience

with my Jimin-like tardiness and for always reminding me grounding my conclusions in data.

Both of you have drastically shaped this project for the better.

Further thanks must be issued to all the faculty and administration at the Yale School of

Public Health who have led me through this five-year journey to two degrees. Mary Keefe and

Prof. Marney White have both been invaluable every step of the way, and Prof. Ijeoma Opara

makes this space affirming and livable. I’m also indebted to my exemplary, kind, and brilliant

Yale College mentors: Prof. Carolyn Roberts, whose guidance and light is my backbone, Prof.

Gary Okihiro, Prof. Quan Tran, and all the ER&M faculty members. As always, Dr. Simons, Dr.

Gupta, and Mr. Foster are my origin story. A huge thanks to all the ARMY organizations I

interviewed and the ARMY academics who have “paved the way,” especially Dr. Kate Ringland

for her academic brilliance and support.임선생님, 김선생님, 한국어 수업 친구들,

감사합니다! These two semesters of Korean have truly been the best classes I’ve taken at Yale!

The people are truly the best part of this institution, and I’m so profoundly grateful for all

my friends! Biggest appreciation for all the five year mentors who came before me, with special

love to the eternally kind and wise Bri Matusovsky. I’ve been privileged to make my way

through this journey with incredible cohort members. Ruiyan, you are inimitable. Mila, the fact

that you’re literally next to me while I write these words says it all. Shannon, Georgiana, and

Jacob will forever be one of best parts of the MPH program. Abby has taught me how to be a

better friend every day and literally hauled me over the finish line. I’ve already written poems

about Lillian, Alice, Kayley, & Dean. Karen, Hanah, and Lena are the BEST mentees in the

world. Big love to the 20222 Yale Women’s Water Polo team #beepbeep and USA Water Polo.

Finally, this piece bears witness to the life-changing and life-saving experience that is

loving BTS. I wouldn’t have anything to write about, let alone wouldn’t have made it through the

last two years, without all the incredible ARMY in my life (moots and ARMY Magazine

bloggers included!). Kristin Fukushima sent me down the BTS rabbit hole and grabbed a seat

alongside me, and has in a million ways shown me the path to a better self and community for

almost ten years. My B(L)TS friends: Candice, Kari, Mayta, Yuri, Kat, and Steph have all

provided me with an incredibly important connection to HOME when I have often been so far

away. Isabelle, I purple you too, more than you know.

And, of course, to the boys. Namjoon unearths the poetry and beauty of this impermanent

world. Jin shows me how to be fearless and funny and wholeheartedly self-loving. Hobi

demonstrates that working hard to achieve iterative, gentle, and determined excellence in

everything I do is a form of love. Taehyung is my comfort on all hard days. Jungkook shows me

exactly who I want to be. Yoongi puts everything I’ve ever lived into words in ways I didn’t

know were possible. Jimin has taught me how to ask for what I need and how to give and

unapologetically receive the love we all deserve, has shown me the power in gentle growth and

vulnerability, has made me confront and re-confront every part of myself, and makes me

immensely grateful that I am alive to witness and marvel in art. To the end of the rainbow,

always: “어쩜 이 밤의 표정이 이토록 또 아름다운 건 저 어둠도 달빛도 아닌 우리

때문일 거야.”

4

Table of Contents

Abstract .......................................................................................................................................... 2

Introduction ................................................................................................................................... 5

Background ................................................................................................................................... 6

Methods .......................................................................................................................................... 9

Results .......................................................................................................................................... 11

Section 1- A Rhizomatic Intervention Model...................................................................................... 11

Section 2- Music and Artists for Healing ............................................................................................ 12

1.1 “Our Rock Bottom:” Songs About Pandemic Health Struggles................................................................... 13

1.2 Cognitive Reframing .................................................................................................................................... 14

1.3 Temporal Distancing .................................................................................................................................... 15

1.4 Joy and Comfort ........................................................................................................................................... 16

1.5 Diversity and Accessibility ........................................................................................................................... 17

Section 2- “Seven Billion Lights:” Multi-Media Connectivity and Public Health Education ........ 18

2.1 “Still With You” Through Songs for ARMY ............................................................................................... 18

2.2 “Extramusical” Content Beyond the Scene .................................................................................................. 20

Section 3- Fan to Fan Interventions: Grassroots ARMY Health Organizations ............................ 22

3.1 ARMY Help Center ...................................................................................................................................... 23

3.2 BTS ARMY Medical Union ......................................................................................................................... 24

3.3 Disabled Army Advocacy & Support Network ............................................................................................ 25

Section 4- For a Better World .............................................................................................................. 26

4.1 One (In An ARMY) For the Money: Mutual Aid and Global Fundraising ................................................. 27

4.2 Equity and Activism ..................................................................................................................................... 28

Discussion..................................................................................................................................... 31

Summary of Findings ............................................................................................................................ 31

Limitations ............................................................................................................................................. 31

Conclusions & Implications .................................................................................................................. 32

References .................................................................................................................................... 33

Bibliography........................................................................................................................................... 33

Notes ....................................................................................................................................................... 52

Table of Figures

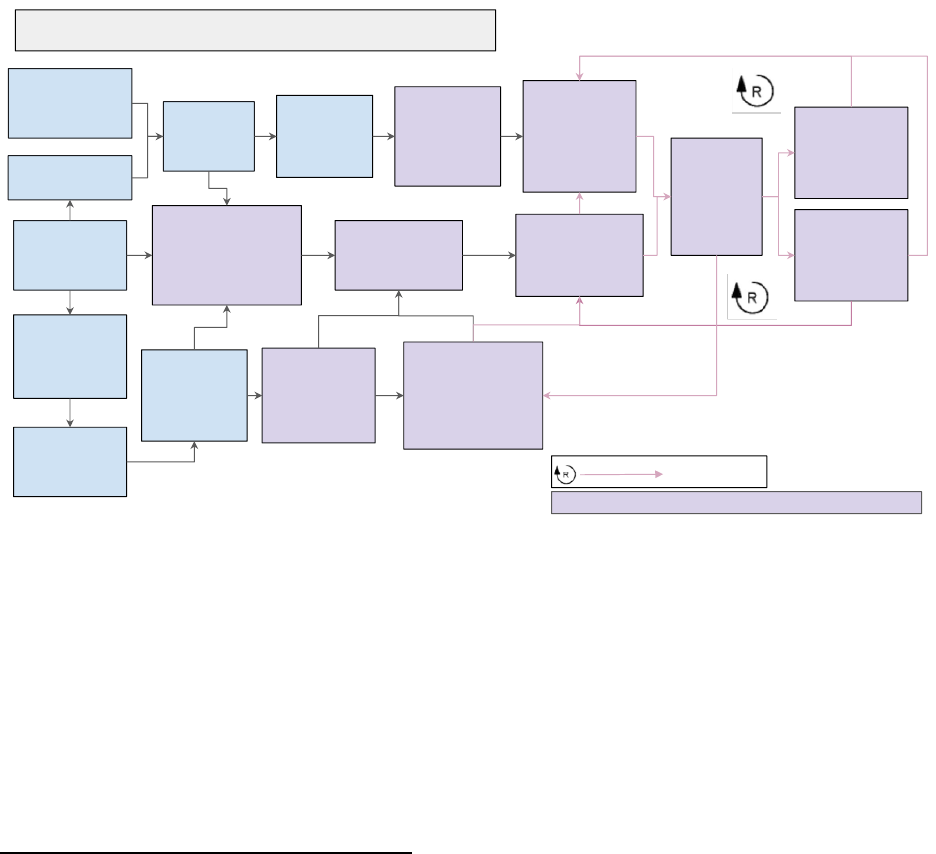

Figure 1: BTS Digital Media Content Included in Qualitative Analysis ...................................... 10

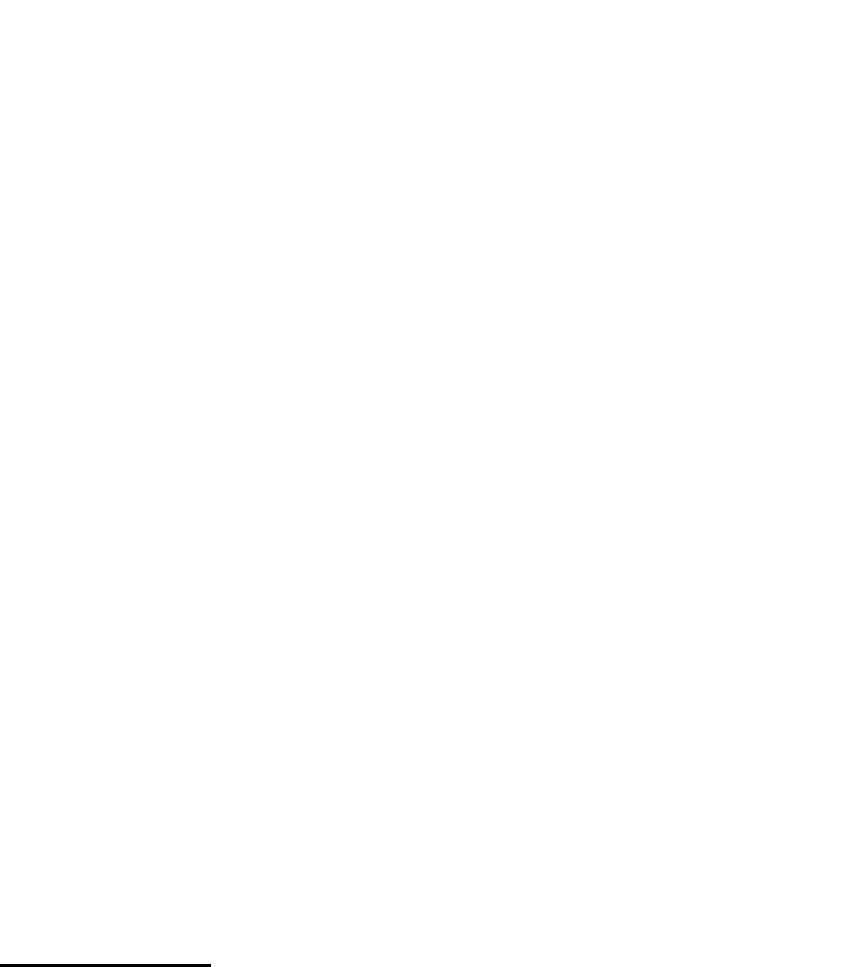

Figure 2: BTS and ARMY Health Intervention Model ................................................................ 12

5

Novel Applications of Music and Digital Media in Global Health Intervention and

Education Initiatives During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Case Study of BTS and ARMY

Introduction

Comprised of seven male members who specialize in different combinations of singing,

dancing, rapping, and acting, the Korean musical group BTS (full name Bangtan

Seoyeondan/방탄소년단) is known for their immaculate stage performances, primarily self-

written and produced lyrics discussing their personal experiences, and their incredibly dedicated

and organized fandom of over 400,000 people across the globe known as ARMY (Adorable

Representative M.C. for Youth).

1

The group’s record-breaking sold-out stadium tours, major

awards across Asian and Western markets, and stretches of #1 Hit Songs on major musical charts

are quantitatively unprecedented for any musical act. Moreover, BTS frequently breaks

language, race, and nationality barriers as the first and only Korean act to accomplish these feats.

BTS emerged from the “K-pop”/ “idol” industry, wherein Korean entertainment agencies

such as the group’s parent company HYBE, scout, train, and “debut” promising young

performers on the Korean musical market.

2

While most successful K-pop groups are produced by

large and well-known entertainment agencies, BTS was the first group developed by HYBE

(known initially as BigHit Entertainment).

3

HYBE’s innovative conceptualization, marketing,

and development of BTS and subsequent idol groups has made the entertainment conglomerate

one of the fastest growing and most profitable companies in the world.

4

Academics and professionals across a myriad of disciplines have attempted to analyze

how and why BTS is so successful. Many have noticed that BTS’ reach and popularity, along

with HYBE’s profits, skyrocketed during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic (2020-

2022). The group landed their first five Billboard Hot 100 singles, received their first two

Grammy nominations (the only ever awarded to Korean artists), and were named the world’s

best-selling artists of both 2020 and 2021 by the International Federation of the Phonographic

Industry (IFPI).

5

Meanwhile, HYBE posted an overall revenue of $1.1 Billion in 2021 after

going public on the Korean stock market in 2020.

6

BTS also seemed to acquire more fans than ever before, increasing their Twitter

following by almost 20 million users between December 2019 and December 2021.

7

As a result,

BTS holds the single largest social media engagement footprint on Twitter along with outsized

impacts on other digital media sites.

8

Any public health intervention work conducted by BTS or

members of their fandom therefore has some of the largest potential reach of any singular entity

in the world (for comparison purposes, BTS recently received 9316.77% more likes than the

World Health Organization when both platforms tweeted about the same topic on the same

date).

9

Both the group and its fans have used this shared global platform for years to discuss

mental health and critique systemic oppression facing youth around the world.

10

However, little

to no research has explored the public health implications of their work and how this level of

reach and success might impact population-level health outcomes.

This multidisciplinary study uses a public health lens to explore how BTS’ music,

HYBE’s digital content production and dissemination strategies and ARMY’s responsive

community grassroots organizing, produced one of the largest-reaching public health

interventions in response to the early COVID-19 pandemic (March 2020- December 2021). This

research represents important new directions in exploring effective, novel methods and structures

for widespread public health education and intervention dissemination with important economic,

6

socio-cultural, and population health implications. While ascertaining the impact of these

intervention strategies is beyond the scope of this study, this introductory exploration

demonstrates that a critical, nuanced study BTS and ARMY’s impact on public health may hold

important keys to re-imagining effective intervention delivery methods, target audiences, and

economic profits.

Background

Music-based public health interventions holistically improve a myriad of mental and

physical health outcomes.

11

The multi-faceted neural, social-emotional, and physiological

impacts of listening to music allow for effective primary and secondary interventions

addressing

health issues from traumatic injury and cognitive illness to depression and anxiety.

12

On the

community level, folk religious songs have been used to teach and retain health education

practices across the globe for centuries.

13

In contemporary practice, public health officials have

successfully utilized the accessibility, relatively low cost, and affective appeal of “culturally

relevant” songs to spread information about health topics ranging from HIV prevention to proper

tooth brushing techniques.

14

Moreover, artists from many oppressed communities have created and performed “protest

songs to raise awareness of health issues, advocate for social equity, and promote resilience

and

hope, with important health implications for marginalized populations.

15

Black American music

in particular has been long used to “speak truth to power,” a strategy that historically and

contemporarily has had immense success in improving a myriad of health outcomes for

marginalized populations.

16

Contemporarily, hip hop has proven effective in fighting for equity

“within and beyond national borders with the incredible urgency of now” in a variety of global

contexts.

17

More broadly, the commercial music industry mass-produced and disseminated

protest, resilience, “feel good,” and empowerment songs.

18

However, very little research has

explored commercial music as a strategy for population-wide health interventions, nor the

development of music technology in delivering music-based interventions.

19

Additionally, few

companies have developed an entire business model based on this premise, with the notable

exception of BTS’ parent company, HYBE.

In the mid-late 2000’s, HYBE’s founding CEO Bang Sihyuk theorized that developing

increased fan loyalty towards musical artists would counteract the drop in physical album sales

that wracked the late 2000’s music market.

20

After company focus groups demonstrated that

youth felt increasingly isolated and wanted to “connect with” and derive “comfort” from artists,

Bang decided that HYBE would focus on releasing music that would “help and inspire” young

people through providing sincere and emotionally resonant lyrics that were designed to make

fans’ lives better.

21

This was reflected in HYBE’s original motto: “Music and Artists for

Healing,” a marked difference from most Korean and Western record label slogans that center

around providing quality “entertainment.”

22

BTS’ subsequent focus on music as a source of health improvement thus represents a

cornerstone of a larger company’s entire guiding philosophy and business model rather than the

focus of a singular song or artist(s).

23

As HYBE’s first group, the septet initially sought to

exemplify this model through “speaking out against the bullets of oppression, stereotypes, and

prejudice facing youth (hence their Korean name 방탄소년단, which translates to “Bulletproof

Boy Scouts”).

24

Thus, BTS’ approach to improving public health through music has always been

grounded in attention to structural health (in)equities that shape health outcomes (their first three

7

albums, for example, explored the toxic mental and physical health impacts of standardized

education and late-stage capitalism in Korea).

25

This is reflected in genre as well; BTS debuted

as a hip-hop and rap group, not a pop group, and every single full-group BTS song but one has

intentionally utilized a genre built to articulate and challenge systemic marginalization

experienced by Black Americans into a South Korean context.

26

Over the course of their career, BTS has developed multiple health intervention strategies

in their music. In addition to the societal commentary discussed above, the group has actively

enacted psychotherapeutic methodologies in several songs designed to “comfort” and “heal”

fans.

27

As a result, a significant body of research has demonstrated BTS’ music has improved

listener health outcomes. Studies have noted that pre-2020 BTS songs emphasize Branden’s Six

Pillars of Self-Esteem, and that listening to BTS music predicts hope, optimism, self-esteem,

self-acceptance, self-forgiveness, perseverance, and happiness in consumers.

28

The most

comprehensive study conducted to ascertain the impact of listening to BTS music (n = 1,190)

showed that BTS music helped the study participants feel “‘safe’ and ‘understood’ during

situations that were challenging, frustrating or unfulfilling,” served as a catalyst to release

emotions that participants were unable to verbalize, and made listeners “feel more focused,

empowered, and persistent, helping them deal with real-life challenges” while still helping them

“forget about their troubles or worries. As a result, listeners found certain songs led them to

challenge their way of thinking, change their behavior, or “take concrete actions to better their

mental health,” including seeking professional treatment.

29

Through creating a musical and digital media presence that emphasizes genuine and

honest communication of emotions, experiences, and struggles between fans and artists, BTS and

ARMY have developed a mutual relationship of love, care, and respect that challenges

conceptualizations of one-sided “parasocial” celebrity-fan relationships. BTS frequently credit

ARMY with not just their professional success, but with improving the members’ own mental-

emotional health, self-esteem, and happiness.

30

The result is what Dr. Jiyoung Lee calls a

“rhizomatic” fan-artist relationship, in which no study of either is complete without examining

both constituent entities.

31

This relationship is centered in BTS’ creation of music as a source of public health

intervention.

32

Several BTS “fan songs” remind ARMY of their powerful and affirming impact

on BTS’ lives to give listeners hope and purpose.

33

In one such song, the members tell ARMY

that “you've shown me, I have reasons I should love myself…me, who used to be sad, me, who

used to be hurt” to remind listeners that community love and support (exemplified by ARMY

themselves) can be used to overcome mistakes and insecurities.

34

This process is further

employed during concerts, where audiences physically sing with both BTS and each other in an

experience that actualizes health outcomes. As one fan wrote in 2018:

“The first time hearing Epiphany [a song about self-love] live in concert was LITERALLY

life-changing. Somehow, in that stadium, him [the BTS member who sings the song]

telling me that I'm the one I should love and me singing that so loudly with a bunch of

others, internalized it and made it real and practicable. It was magical.

35

As this tweet demonstrates, concert spaces can be powerful sites of community health

intervention work that deeply impact individual attendees, though further research would be

needed to ascertain impact and efficacy.

However, BTS’ public health impact isn’t limited to producing and performing music. A

long attributed major factor in BTS’ meteoric rise to success is the scaffolding and integration of

their value-based music with innovative and accessible digital media content production,

8

particularly their utilization of social media to interact with fans and promote their work.

36

This

social media-focused strategy was in part borne simply as a result of BTS and HYBE’s relatively

marginalized position in both the Korean and Western music markets, but was also an incredibly

intentional part of HYBE’s “horizontal” leadership model wherein artists are marketed as

“relatable” rather than being “placed on a pedestal.”

37

Increasing artist social media presence and

developing a wide variety of “intellectual property” related to the “message and personality” of

their artists, e.g. graphic novels, video games, brand deals, has significantly increased fan

engagement and overall profit for the company.

38

Examples of BTS’ diverse digital media content production abound. Beyond the auditory

tracks for each of their songs, BTS has been heralded for developing “dance moves, strong visual

language in music videos and…additional content,” creating an “immersive world” of

“transmedia storytelling”

that is “dense with intertextual citations” and cross-media connections

to a wide variety of current events, literary and artistic works, and psychological practices.

39

This

complex, cross-platform content production underscores the lyrical health-centric themes

discussed in the previous section, and pre-pandemic music videos have tackled themes from

domestic violence to mental illness and suicide.

40

Additionally, BTS members and their

management are routinely active on a variety of social media platforms and consistently deliver

video, picture, and text content to ARMY.

41

As a result, BTS fans are a highly engaged and digitally activated fandom driven by

shared values of world betterment. Both researchers and public media outlets frequently examine

how ARMY uses digital media to promote BTS’ work and increase the group’s power and

influence globally.

42

In addition to streaming, viewing, and voting for BTS to support their

musical work, ARMY engage in transformative practices of “remixing” and “re-imagining”

BTS’ media content to communicate with and increase “affective bonds” with both BTS

members and other fans.

43

“Fandoms,” or “communities built around a shared enjoyment of an aspect of popular

culture,” can be generative strategies of public health interventions and campaigns.

44

Previous

research has posited that K-pop fandoms can be considered “communities of practice,” or

“group[s] of people who share a common concern, a set of problems, or an interest in a topic and

who come together to fulfill both individual and group goals.”

45

Communities of practice,

including digital communities, are well-demonstrated important and useful public health

intervention sites.

46

Because “fan engagement” can be “a site of renewal and optimism,” the

“experience of joy leads to further investments that transform one’s life and others, including the

possibility of struggling and resisting…oppressive power structures.”

47

This is evident in studies

of several other fandoms.

Successful fandom-based public health campaign models include artist-driven campaigns

to support causes such as queer rights or autonomous, fan-driven fundraising campaigns inspired

by the fandom’s subject of interest.

48

Brough and Shrestha have classified some of these

practices as “fan-activism,” or “fan-driven efforts to address civic or political issues through

engagement with and strategic deployment of popular culture content” and transformative,

participatory campaign engagement.

49

However, most fandom efforts are temporally limited

campaigns surrounding specific causes (e.g. natural disaster relief, existing fundraisers) rather

than a primary, sustained aspect of fandom involvement.

In recent years, fandom participation has been marked with high levels of media

engagement and mobilization. This is particularly prevalent in “K-pop” (Korean language pop

music) fandoms, where digital media is a primary source of artist exposure and engagement for

9

global audiences.

50

Despite sometimes toxic online fan environments, this primarily digital

participation in K-pop fanship has been shown to be a “significant predictor of…psychosocial

outcomes” including “happiness, self-esteem, and social connectedness, pointing to positive

psychosocial benefits to fandom participation.”

51

Moreover, K-pop fanship inherently challenges

the privileged position of Anglophone pop stars by creating a counter-hegemonic culture focused

on non-English, non-Western musical and artist content.

52

The rise of digital media and communication has also allowed for faster and more

expansive real-time public health organizing across national and organizational borders. The lack

of in-person health services during COVID-19 has made these digitally delivered public health

campaigns and healthcare services essential to strengthening the contemporary public health

landscape.

53

With regards to mental health specifically, quarantine and isolation protocols have

“disrupted the delivery of…services globally” during a time of heightened “psychological and

mental health responses including the spread of fear, stress, and anxiety, which also impact the

spread and containment of infectious diseases.”

54

Research studies have unanimously

demonstrated significant mental health burdens in regions affected by COVID-19 outbreaks as a

result of the pandemic, particularly in adolescents and youth.

55

Several technologically-based preventive and rehabilitative interventions have been

shown to alleviate pandemic-associated anxiety and depression and improve quality of life.

56

Additionally, providing “reliable COVID-19 information sources “may assist in

alleviating…anxiety and fear” surrounding the pandemic, as pandemic-specific “health literacy”

is associated with decreased depression and increased health-related quality of life.

57

Only one

digital intervention model reported the successful integration of music in promoting “COVID-19

prevention and control as well as hope,” though many original and re-written popular songs were

digitally disseminated to provide information about COVID-19 prevention in the early days of

the pandemic.

58

BTS’ digital media-focused content dissemination structures and value-driven musical

output thus represent a nexus of technology, art, and health that are uniquely suited to addressing

new challenges presented in delivering effective public health interventions in response to

COVID-19. Given that ARMY has one of the biggest digital media presences of all time, any

exploration of BTS and ARMY’s health intervention work also represents an important and

understudied exploration of alternative pathways to increase global health intervention

scalability.

59

Methods

To illustrate the processes by which BTS, HYBE, and ARMY sought to improve health

outcomes during the COVID-19 pandemic, a health intervention model was designed to illustrate

the complex, multi-dimensional system of intervention delivery methods and sites developed

over the course of BTS’ nine-year career. This model was then applied to BTS and ARMY’s

digital content released between March 11, 2020-November 21, 2021, the period when BTS was

unable to perform for or meet their fans in person due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Qualitative

parent-child iterative coding was used to ascertain COVID-19-specific intervention approaches

and methods found in digital media content, including songs, livestreamed and pre-recorded

video content, and interviews, produced by BTS and HYBE (n =478). Video content was

obtained using the “BTS Road Map” online database produced by ARMY digital creator Landon

10

Mark.

60

Lyric translations, when needed, were obtained from the ARMY website “doolset lyrics”

that provides both direct lyric translations and relevant Korean socio-cultural context.

Print content was limited to materials produced directly by HYBE and a small sample of

major magazine covers (TIME, Vogue, Variety, and Esquire magazines). Short social media

posts on Twitter, Weverse, TikTok, along with shorter behind the scenes and Korean culture

YouTube video series, were excluded due to volume and overall relevance. Shorter interviews

conducted by third parties and print, video, and audio advertisements aired on non-BTS or

HYBE platforms were also excluded from primary analysis due to volume and theme saturation,

as most short interviews involved answering similar questions about music releases.

Figure 1: BTS Digital Media Content Included in Qualitative Analysis

Additionally, demographic, informational, and quantitative data was solicited from three

major ARMY public health-oriented organizations that operate using primarily Twitter-based

platforms. Organizations were selected through conducting Twitter searches for the key words

“BTS” and “ARMY” combined with “health,” “public health,” “medicine,” and “global health,”

and via previously published articles in both academic and popular media. ARMY organizations

were then chosen for inclusion based on relevance of mission statement to public health

intervention work. Each organization was contacted by either Twitter direct message or email,

after which interested administrators provided information about the organization’s purpose,

reach, and strategies via email correspondence. Given the frequency with which ARMY

organization statements and testimonies are manipulated by academic researchers and popular

media, Zoom calls were also held to further explain study purpose, develop trust between

organization and researcher, and gain clarity regarding organizational purpose and history.

61

All

community organizations were given the opportunity to review this study before publication to

ensure that they were appropriately represented in the final work.

11

Results

From March 2020-December 2021, BTS and ARMY synergistically developed one of the

largest digitally delivered public health interventions in the world in response to COVID-19,

focusing primarily on mitigating negative mental health outcomes, health information

distribution, safe behavior modeling, mutual aid, and anti-racist health equity work. The

following analysis first provides readers with an overall model of BTS and ARMY’s health

intervention work that has been developed over the course of the group’s career, which serves as

the foundation for the pandemic-time analysis that comprises the greater part of this project.

“Section 2: Music and Artists for Healing” then discusses how BTS, to great commercial and

financial success, openly discussed mental health struggles, employed psychological techniques

such as reframing and temporal distancing, and increased accessibility in their original

discography during this time. The third section, “Seven Billion Lights: Multi-Media

Connectivity and Public Health Education,” discusses how BTS and ARMY used music and

digital media to form and maintain community and model best health practices during periods of

intense physical isolation. The final two sections outline how ARMY, inspired by BTS, have

built community health organizations that provide mental health assistance services, fundraising,

health advocacy and education resources, and health-based activism efforts to both fans and the

public.

As will be demonstrated across these five sections, BTS and ARMY’s synergistic

relationship drives digital media-driven health intervention efforts across languages,

nationalities, and identities, fundamentally restructuring the contemporary public health

landscape at a remarkably broad scale. This has a myriad of important implications in public and

global health, including potential solutions and strategies for subverting hegemonic power

imbalances (West/non-West, provider/recipient), economic gains, and intervention strategies that

resonate with large numbers of people.

Section 1- A Rhizomatic Intervention Model

Unlike many organizations, movements, and communities, BTS and ARMY’s digitally-

driven model of digitally delivered health intervention and education work was well-established

before the advent of COVID-19. In fact, HYBE, BTS, and ARMY developed an iterative,

rhizomatic model of “healing” based on reinforcing and reflexive digital engagement and

advocacy work over the course of 2013-2020 that provided an unusually strong springboard

upon which all three parties transitioned to the “digital only” era of early COVID-19. Previous

mixed methods systems thinking and information studies have also used modeling to understand

and conceptualize BTS’ overwhelming success; this model draws upon these studies but

provides new connections between existing variables through connecting them via a public

health lens.

62

The model below illustrates the interdisciplinary structural, economic, and creative

factors that shaped the development of both BTS and ARMY as public health interventionists,

much of which were discussed in the Background section. Highlighted purple sections represent

elements of the model that gained and/or maintained significant importance in intervention

content and delivery during COVID-19. Of particularly important note is the reinforcing

feedback loop created by BTS and ARMY wherein each party is inspired by the other to

continue improving public health.

12

Figure 2: BTS and ARMY Health Intervention Model

As demonstrated, BTS and ARMY engage in three major modalities of public health

interventions across music, digital media content, and social media interaction: (1) awareness of

mental health issues driven by personal experience-sharing, (2) actual health-based interventions

through music, and (3) societal commentary and critique of systemic injustice. In addition,

ARMY have developed both lasting public health-focused organizations and campaign efforts

aligning with these three themes. As the following sections will demonstrate, several elements of

this model were particularly useful and effective when applied to addressing health outcomes of

COVID-19 pandemic during forced isolation.

Section 2- Music and Artists for Healing

While artists of all mediums and styles generated creative work to process the COVID-19

pandemic, HYBE maintained a distinctly unique approach at the production company level that

led to impressive and unprecedented commercial results.

63

Prior to the pandemic, BTS primarily

released music using the “album cycle” strategy, releasing clusters of thematically interrelated

works over the course of multiple months or years. During the pandemic, however, HYBE and

BTS shifted their focus to releasing two types of songs in smaller, more frequent installments

that directly addressed the health effects of the pandemic: “emotionally honest songs” that

reckoned frankly with the impacts COVID-19 and “songs to give the hope and comfort needed to

overcome this moment together.”

64

The former were predominantly found on the group’s LP BE,

and the latter produced in the form of predominantly English language singles.

65

In addition to being novel intervention techniques and delivery modalities in and of

themselves, BTS’ pandemic-time discography demonstrates the unprecedented commercial

power and potential of this model. All six lead singles BTS released during the pandemic have

premiered at #1 on the Billboard Hot 100 Chart for a total of 16 weeks at #1.

66

Despite being

almost entirely in Korean with a November release date, BE was still the fifth best-selling album

Fans draw comfort,

“healing,” and joy

from all BTS content,

(also expressed on

digital media)

BTS self-produces value-

based music designed to

“block out stereotypes,

criticisms, and

expectations that aim on

adolescents like bullets.”

BTS inspired by

fans, group

feels “sense of

responsibility”

to continue

helping people

through music

BTS creates music

to improve fan

health that utilizes

psychotherapeutic

techniques

Early 2010’s:

Decreased physical

sales, low digital

presence in music

market

Development of

“Music and Artist for

Healing” model that

provides connection

and comfort to fans

via “relatable” artists

Reduced

broadcast time

and advertising

for BTS

BTS generates high

levels of artist

relatability, empathy

and authenticity

K-pop industry ruled by

“Big 3 Companies”

Mid-2000’s: Bang Si-

Hyuk creates BigHit

Music (HYBE), forms

BTS

Community-level

culture and

infrastructure to

support intensive,

global, digitally

coordinated fan

mobilization

Asian and non-English

underrepresentation in

Western music

industry

Grassroots, fan-

driven organizing

essential to

commercial

success

ARMY inspired to

develop digital

public health

intervention,

education and

advocacy

organizations and

campaigns

Bang theorizes that

increasing fan

loyalty will offset

drops in record sales

HYBE identifies

increased isolation

in digital age,

youth oppression

as customer pain

points

HYBE focuses on developing

BTS’ relationship with fans

via high volume of digital

media content &

instantaneous two-way

communication

BTS extends health

work through

partnerships with

United Nations,

UNICEF, etc. and

advocacy work

Fig. 2: BTS and ARMY Health Intervention Model

*Purple: elements explored in-depth during COVID-19 pandemic

: Reinforcing Loop

13

in the United States and topped South Korean sales at almost 3 million copies in four months (for

context, South Korea only has around 52 million people).

67

A myriad of less public health-

focused factors, including ARMY’s comprehensive buying and streaming strategies and HYBE’s

well-thought out marketing plan, contributed to the group’s overwhelming success; regardless,

the fact remains that this health-based musical model has been the key to breaking open a

notoriously xenophobic Western musical market and continuing to reign on Korean charts.

The following section discusses how BTS used their music to normalize negative health

impacts of the pandemic and incorporated joy and comfort, cognitive reframing, and temporal

distancing into lyrics and performance as helpful coping and processing mechanisms for their

audience. Additionally, BTS expanded the accessibility of their music and performance by

incorporating sign language into their single “Permission to Dance.” These themes were

underscored in BTS’ public addresses to the United Nations and UNICEF, interviews, and other

public-facing statements, and ultimately represent an unprecedented and unrecognized scale of

multi-layer COVID-19 mental health intervention delivery.

1.1 “Our Rock Bottom:” Songs About Pandemic Health Struggles

Throughout the pandemic, BTS released both group and individual songs that explicitly,

often painfully, discussed the negative impacts of the pandemic on the members’ mental health

and overall well-being. The group’s critical, reflexive articulation of ongoing, evolving,

pandemic-induced depression and anxiety provide important contributions to the normalization

of mental health struggles, with potentially important impacts on improving population health

outcomes among fans.

A large body of literature demonstrates that increased awareness and normalization of

mental health issues is crucial in reducing negative mental health outcomes, particularly among

youth.

68

Notably, “pop music artists who open up about mental health difficulties may have

potential as novel message sources in communication campaigns designed to improve mental

health outcomes among college students.”

69

In particular, songs discussing artists’ “mental

health difficulties'' are “associated with increased mental health empathy [and] mediate outcomes

including reduced mental health stigma, increased support for public mental health resources,

and increased willingness to support others struggling with their mental health.”

70

This is

supported by BTS-specific research; one study examining BTS music listeners in 2020 found

that the group’s pre-COVID-19 lyrical messages pertaining to mental health were strengthened

through the perceived authenticity of the artists’ experiences.

71

These study results have been

echoed in public statements made about BTS by several mental health professionals.

72

BTS was well-known for explicitly discussing personal mental health in their music far

before the pandemic, writing about lived experiences of depression, anxiety, and OCD.

73

In these

songs, powerful lyrics are underscored through “sonic vulnerabilities,” a composition technique

that invokes and expresses these feelings through specific key choices, tonal centers, and

melodic progression.

74

The members have explained that these songs are designed to comfort

and console fans by demonstrating that mental health challenges are “not things that need to be

hidden.”

75

By creating an environment where people “can ask for help” when they are “suffering

and lonely,” BTS has “innovated a major paradigm shift in mental health discourse” wherein

personal authenticity and vulnerability enhances public health messaging about help-seeking.

76

BTS continued to normalize the discussion of mental health and well-being

during the

pandemic, frequently talking and singing about the difficulties they experienced as artists whose

vocation and livelihood is primarily dependent on large-scale in-person performances. A handful

14

of songs explicitly address broad depression and anxiety brought upon by the pandemic, with the

goal of “making it obvious…everyone was having a hard time.”

77

Most of these songs rely

heavily on metaphor; rapper and group member SUGA references being “deserted on an island”

without escape

throughout his songs and speeches, vocalist Jin compares depression to a “deep

sea” in the song Abyss, and all of the group members compare depression and anxiety to the

colors “blue and grey” in the song of the same name.

78

These songs are supported with sonic

choices that convey these emotions to the listener. HYBE’s official magazine explained, for

example, that the song Blue & Grey uses “long melodies [with] no clear ending…distant rapping

delivered through left and right on stereo” and vocal echoes to trigger “an image of a lonely

winter night” for listeners.

79

Similarly, some of the vocals in Abyss sound almost muted to give

the listener the sensation of listening to the song underwater, as the song’s narrator compares

depression to being “submerged” in “my ocean,” unable to surface.

80

BTS further discussed these themes in their public-facing interviews and speeches, often

mentioning that they felt “hopeless,” “bewildered,” and “frustrated” about the “current

situation.”

81

During these speeches, members also acknowledged that they “were not the only

ones feeling like this,” acknowledging that the entire world needed “time to mourn for the things

that COVID-19 took away from us.”

82

Through sharing these feelings on global platforms, such

as in addresses to the UN and UNICEF, BTS served as an important ambassador for youth

mental health concerns on prominent global stages that far extend beyond the normal realm of

pop music.

1.2 Cognitive Reframing

BTS also used several clinically identified psychological techniques to re-frame feelings

of “entrapment,” helplessness, depression, and anxiety during the pandemic through re-

imagining physical space.

83

Throughout much of BTS’ pandemic-time discography, geographic

isolation is represented by the word “room,” an all-encompassing term that is understood to

represent a variety of quarantine situations. Songs, music videos, and online concerts then

reframe and reconceptualize one’s room as a communal place of exploration, adventure, and

connectivity for both fans and artists, creating an “imagined space” grounded in physical reality

where listeners and artists can process the pandemic together.

84

Clinical psychologist David A. Clark writes that cognitive reframing (referred to

cognitive restructuring in clinical settings) consists of multiple “structured, goal-directed, and

collaborative intervention strategies that focus on the exploration, evaluation, and substitution

of…maladaptive thoughts.” Through “reframing…. inflexible, closed, impermeable, and

relatively concrete” thought patterns such as “everything is hopeless” or “I am a failure” into

more balanced “schema” (e.g., “I am a person who recently experienced failure, but also has had

many successes”), patients increase coping and resilience in the face of adverse circumstances.

85

The most prominent example of cognitive re-imagination can be found in “Fly to My

Room,” the second track from BE. The song’s first verse begins with the previously discussed

normalization of pandemic-induced negative mental health outcomes, specifically widely-

experienced feeling being trapped in one’s home (“this room is all I have”).

86

In order to cope,

the song’s narrator then “generate[s] alternative[s]” and decides “well then, I'll change this room

into my world” in order to “get me outta my blues” so that “I'm feelin' brand new.”

87

Through

actively telling listeners that “you can change the way you think” (an example of “positivity

reorientation”), BTS encourages cognitive reframing of physical space and isolation.

88

15

The members then offer listeners several imaginative reframing strategies. One member

personifies the “room” as a figurative rather than purely literal support structure that can “hug

you” and “hold…happiness and sadness, all emotions.”

89

Another reimagines physical elements

of being trapped in one’s room as aspects of a trip or vacation (i.e., “the toys in my room greet

me again like people, the TV bustles like I'm out in the city”). This development of a “secure

base” relies heavily on “directed, intentional imagination,” which “is pivotal for self-regulation

in the form of escapism.”

90

Interestingly, music as the mode of intervention may also enhance

the effectiveness of this imagination-driven cognitive reframing, as “musical auditory

stimuli…induce higher vividness ratings” in directed interventions designed to alleviate anxiety

and depression.

91

These strategies were also demonstrated and amplified through the production of digital

multimedia content accompanying BE. The music videos for Dynamite and Life Goes On, for

example, demonstrate the members modeling these techniques through example: members

literally perform the lyrics in both songs that talk about using daily activities to ground oneself in

the pandemic.

92

Another particularly novel approach was the “Curated By BTS” project, a

participatory multi-media digital installation wherein the members collaboratively created a

bedroom filled with items to “comfort ARMY.”

93

Released over the course of several days in

February 2021, the project began with a simple drawing of a bedroom that could be found on

BTS’ official blog. Every day, a new member-designed “special object” was added to the room,

1

accompanied by an explanatory voice recording.

94

Users could then manually move the objects

around the “room” to create unique design configurations (which, perhaps unintentionally,

resulted in a plethora of humorously unrealistic room designs shared on Twitter).

95

Lastly, BTS’ online concerts focused on re-imagining one’s room as a concert space.

Instead of the group’s normal pre-concert announcements about safety and proper decorum, a

similarly designed animated text series tells viewers to “get comfortable” and reminds them that

“all food and drinks are allowed!” to emphasize the perks to having an at-home concert

experience.

96

During multiple concerts, the members remined the audience members that they

were connected to the artists through “each of your own rooms,” often joking that audience

members should “make some noise in your room.”

97

At the end of 2021’s Sowoozoo, members

encouraged the audience to turn on their phone flashlights and hold the light by their windows to

see if any other ARMY were watching nearby “from their own rooms,” and many ARMY

reported their success via social media.

98

Thus, BTS engages in communal cognitive reframing

that encourages both singer and listener to re-imagine the enclosed physical space of a “room”

into a space of community. Through these techniques, and many other content production

strategies, BTS co-creates and re-negotiates the new boundaries of the physical space wrought by

the pandemic as a real-time coping strategy.

1.3 Temporal Distancing

BTS prominently employed temporal distancing in song lyrics, speeches, performances,

and interviews, jointly encouraging both themselves and their audience that “life goes on” to

cope with the negative effects of the pandemic. The pandemic’s abrupt cessation of human

activity created a sensation for many that the “world stopped” or was “frozen in time,” which the

1

For example, one member added a clock to the room because “listening to the ticking of the clock when everything

is silent can…bring some calm to your mind.” The clock was set to 6:13 to represent the date of BTS’ first public

appearance (6/13/2013) so that “every time you see it, you’ll think of BTS.”

16

members discussed in multiple songs and interviews.

99

BTS knowingly and deliberately draws

heavily on “temporal distancing” in lyrics and speeches to increase psychological resilience.

Previous research has demonstrated that temporal distancing, a behavioral technique

focused on “imagining oneself in one’s future” that “can play an important role in emotional

coping with negative events” by “directing individuals’ attention to the impermanent aspects of

these events.”

100

Actively distancing through language specifically has been shown to help

improve emotional regulation.

101

Notably, some interventions featuring temporal distancing have

“decrease[d]...negative affect” driven by the COVID-19 pandemic specifically.

102

RM, BTS’

leader and one of the group’s main songwriters, learned about this technique from a

“psychological counselor” as early as 2016, and applied this technique in the lyrics in both

individual and group songs around this time.”

103

This strategy is heavily utilized in BTS’

pandemic-time music.

A key phrase through which the group enacted temporal distancing through music

appears to be “Life Goes On,” the title of the lead single for BE and the theme of their Fall 2020

UN address.

104

In addition to constant refrains of the phrase itself, the chorus of “Life Goes On”

points out that everyday activity markers such as eating, sleeping, and watching the seasons pass

demonstrate that “time goes by on its own” even though it “feels like there is no end in sight.”

105

Another song entitled “A Moment” in Korean was written to remind ARMY that “we’ll be able

to meet each other after a moment,” another attempt to linguistically reframe the pandemic’s

temporality as passing rather than permanent.

106

Lyrics in the single “My Universe,” released

almost a year later, similarly remind listeners that “these hardships are just temporary.”

107

The

pre-chorus of “Life Goes On” actually prompts the audience to partake in temporal distancing

with the singing artists, inviting the listener to “hold my hand [and] run away” to a “future

[where] the day will come back around as if nothing has happened.”

108

Similarly, the group’s

2020 UN General Assembly address ended with the members calling the audience to “dream of a

better future” and “re-imagine the world.”

109

This temporal distancing was visualized in several performances of “Life Goes On,” most

notably the Melon Music Awards 2020 performance that featured masked dancers frozen and

painted in all white who transform in a burst of color and perform everyday activities joyfully

(but still masked) at the end of the song.

110

Similarly, the song’s music video shows a transition

from the BTS members at home in pajamas to the group in concert (though sans audience).

111

Lastly, BTS members engaged in mutual temporal distancing directed towards

themselves and their fans, primarily, during concerts and speeches, by frequently envisioning a

future in which “we will all be able to meet again.” In fact, some of the lyrics for “My Universe”

were written “while picturing the day we reunite with ARMY.”

112

Members connected this

reminder of delayed gratification to engaging in “more careful” health practices and continued

motivation to “practice” and “get better” even without immediate upcoming concerts.

113

The members also encouraged ARMY to “wait” and “stay healthy” to actualize this future

reunion.

114

These statements provide important implications for the use of temporal distancing to

encourage health-positive and COVID-19-risk decreasing behavior.

1.4 Joy and Comfort

Though many of the group’s lyrics were oriented towards processing and addressing the

painful and difficult health impacts of COVID-19, BTS’ most commercially successful singles

were upbeat, cheerful songs designed to combat these health issues through providing “comfort

and joy” to listeners. Sung in English to increase international accessibility, “Dynamite”

17

(released September 2020), “Butter” (released May 2021), and “Permission To Dance” (released

July 2021) are all upbeat, pop singles released as standalone “comebacks,” the K-pop industry’s

term for new release. The simple and peppy English lyrics combined with brightly colored high-

energy performances might seem like substance-light “bubble gum” pop at first listen; however,

this attention to joy and happiness is an intentional, calculated public health intervention

designed to deliver “hope” and “strength” to those struggling in the face of the pandemic.

115

In interviews and public appearances, BTS frequently discusses that the “bright and

refreshing energy” of “Dynamite” was cultivated intentionally to “shake off the low spirits” of

summer 2020. Rather than writing a “serious and difficult song,” HYBE and BTS sought to

“cheer ARMY up as soon as possible” and provide “real, substantial hope” through a brighter,

more upbeat disco-pop track.

116

While “Butter” can be described as a more “cheeky, self-aware

tribute” to the group’s own “irresistibility” (see lyrics such as “When I look in the mirror / I’ll

melt your heart into two / I got that superstar glow”), the group’s general philosophy about

producing a “fun song” that “reach[es] out to as many people as possible” remains a consistent

theme throughout their press releases.

117

While it would be difficult to ascertain the efficacy of this strategy without more in-depth

study of song listeners, these three singles were BTS’ most wide-reaching and record-breaking

pieces of music. “Dynamite” earned the group their first solo Hot 100 #1 song, followed by both

“Butter” and “Permission to Dance,” which reigned at the top the charts for a combined eight

weeks in May-July 2021. “Butter” holds records for largest YouTube video premiere (3.9 million

viewers) and most watched video on YouTube in 24 hours (108,200,000 views), both of which

were previously held by “Dynamite”. “Dynamite” and “Butter” earned the group (and Korean

artists at large) their first two Grammy nominations and performances, along with sweeping most

major Korean and U.S.-based awards shows.

118

Spotify reported a 300% spike in new listeners

after “Dynamite” was released.

119

That these songs are historic is generally noteworthy, but that

each was developed as a pandemic-specific health intervention makes each and every award

intimately connected to advancements in and the prominence of public health as a field.

Lastly, BTS expressed at length that online concerts were designed to “be healing for

ARMY,” and that the members “hope[d] we could comfort and make you happy through…

online concerts.”

120

While the members expressed their continued frustration about a lack of in-

person concerts, they also acknowledged how lucky they were to continue performing thanks to

technology and felt that “we were comforted by this, it really feels like there is hope.”

121

BTS’

four online concerts hold worldwide records for number of attendees and virtual concert profits

that only increased over time. One showing of BangBangCon in June 2020 generated $20

million in tickets from around 756,600 viewers, “Map of the Soul: ONE”’ generated at least $43

million over two performances. 2021 MUSTER: Sowoozoo earned an estimated $71 million

over two performances thanks to 1.33 million viewers from 195 different countries, which means

that BTS attracted least one viewer from every country in the world. These metrics demonstrate

once again the unparalleled size, scope, and profitability of BTS’ health-based approach to

making and performing music.

1.5 Diversity and Accessibility

In addition to discussing and responding to health issues through their musical career,

BTS also uses their platform to actively create a more inclusive space for marginalized

populations.

122

This trend continued during the pandemic with the group’s use of sign language

and disability-inclusive imagery in their English language single “Permission To Dance.”

BTS

18

has a reputation for intricate, complex, and show-stopping dance moves; however, “Permission

to Dance” instead incorporates American and International Sign Language words for “dance”

and “enjoy” into the “beautifully simple” chorus choreography, designed so that “people of all

ages with a full range of (dis)abilities” can “learn…and participate” in the dance.

123

Deaf and disabled ARMY responded with overwhelming, but thoughtful and critical

positivity, and the entire fandom trended #DeafARMY on Twitter to commemorate the

occasion.

124

Popular media articles across multiple countries discussed the importance of BTS’

inclusivity, and the director of the WHO commended the group for their actions on Twitter,

linking the use of sign language directly to large-scale accessibility in an audio-driven field that

can be uniquely inaccessible for deaf and hard of hearing individuals.

125

HYBE and BTS also

premiered an online dance challenge that quickly accrued thousands of submissions, some of

which were included in both a YouTube compilation video and onscreen at their Los Angeles

concerts.

126

Lastly, the group performed the song at the United Nations General Assembly in

New York when the group addressed the Sustainable Development Goals Summit in October

2021.

127

Through targeting a population often excluded by the hearing-centric music market,

BTS proactively centers marginalized identities in their music making to ensure that their health-

based interventions can encompass a larger and more diverse audience.

Section 2- “Seven Billion Lights:” Multi-Media Connectivity and Public Health Education

BTS, like the rest of humanity, quickly and drastically ceased person-to-person

interactions in March 2020 due to COVID-19. As BTS are performers whose livelihood, well-

being, and financial success is greatly dependent on large-scale live performance, the members,

ARMY, and HYBE rapidly developed alternative forms of fan-artist engagement to counteract

the socio-emotional and financial impacts of this newfound separation. BTS and ARMY utilized

song lyrics, cutting-edge online concerts, and non-musical video and social media content to

ameliorate the negative physical and mental health effects of increased isolation during COVID-

19.

128

Given evidence that social isolation during the early pandemic was robustly linked with a

variety of negative physical, mental, and emotional outcomes and that “online contacts seemed

crucial in protecting mental health….when offline contacts were limited” during this time, BTS

and ARMY’s innovative uses of music and digital media to build community represent a unique,

large-scale intervention combatting social isolation.

129

2.1 “Still With You” Through Songs for ARMY

BTS unquestionably struggled with their extended separation from their fans. Lyrics in

songs such as My Universe, Still With You, Telepathy, and Stay compare their pre-COVID-19

experiences with ARMY to a “dream” that evaporates “when I open my eyes,” underscoring the

ways in which isolation challenged conceptualizations of lived reality.

130

Perhaps the most

obvious example of these sentiments was the group’s cover of I’ll Be Missing You. In this re-

imagining of Puff Daddy’s tribute to the late Tupac, the titular refrain is dedicated to BTS’ fans,

and the members changed the lyrics to COVID-19-specific sentiments such as “give anything to

see half your face.”

131

The members also frequently mentioned how much they missed and

wanted to perform for ARMY in concert speeches, with one member even breaking down in

tears at the end of the Map of the Soul ON:E online concert.

132

As a result, BTS sought to affirm connections with ARMY through their music and

digital media presence. Throughout their pandemic-time discography, BTS constantly assured

19

ARMY that “even when you’re not next to me, even when I’m not next to you, we all know

we’re together.”

133

Songs such as “Stay” and “Still With You” need little explanation beyond

their titles, while “Your Eyes Tell” promises the audience that “wherever you are I'll find you.”

The bridge of “Butter” reminds not only the group’s fans, but the entire world, that BTS “got

ARMY right behind us when we say so,” a line accompanied by YMCA-style choreography that

spells out the letters “A-R-M-Y” with the members’ bodies.

134

One of BTS’ self-stated main themes in creating pandemic-time music was “telepathy,”

or the concept that two parties can understand, empathize, and communicate with each other

without interacting face-to-face.

135

While telepathy in modern media often falls into the realm of

supernatural or magically ordained, BTS instead deliberately constructs this form of

“togetherness” through intentional acts of emotional vulnerability, empathy, and community care

across multiple digital platforms.

One such instance of vulnerability can be found in how BTS used their music to

explicitly affirm ARMY’s positive health impacts on the members’ own well-being during the

pandemic. The actual song “Telepathy” opens with the lines “In the days that feel the same, I’m

the happiest when I meet you…you are the most special person to me.”

136

The lyrics of “Snow

Flower” inform listeners that “your warmth will melt my blue and grey away,” implying that the

anxiety and depression that the members experienced during COVID-19 can be and were

alleviated through ARMY’s support.

137

Pandemic-time lyrics frequently call upon the group’s

long-used comparison of ARMY to stars in the night sky (i.e. “My night is adorned with stars of

love made of you”),

with the group extending this metaphor by referring to ARMY as “my

universe” in their song of the same name.

138

Online concerts expanded the platform through which BTS and ARMY could facilitate

pandemic-safe “togetherness” through constantly evolving real-time communication pathways.

In their first online concert in June 2020, the members were able to read live comments from

viewers, though it was difficult for the software platform to keep up in real-time. At Map of the

Soul: One in October 2020, fans entered a lottery to have their faces displayed in real time during

a portion of the concert, and live fan cheers were piped into the stadium. June 2021’s Sowoozoo

represented the pinnacle of digital audience participation: fans were placed onscreen where the

audience would normally sit for the entire duration of the show, allowing BTS members to

interact with specific audience members. ARMY could submit recordings of “fan chants”

(company-designed audience call and response cheers that accompany most K-pop songs) that

were played in real time during performance, and applause and cheering were piped in

throughout.

139

Additionally, BTS and HYBE used social media to interact with ARMY in live-streamed

concert spaces, engaging in cross-media communication to demonstrate artist engagement in fan-

created digital content. During Sowoozoo, a concert catered specifically to fans, the members

noted that “since we haven’t met in a while, we may feel like we’re further apart. But in order to

get to you…we’re continuously seeking and following your signals.”

140

The “signals” in

question were ARMY’s various hashtag events, where the fans trend a particular hashtag on

Twitter and/or Weverse for mass impact. A particularly moving example was the group’s

discussion of #SkyforNamjoon, which trended #1 worldwide on Twitter for around a day in July

2020.

141

On July 15, 2020, BTS’ leader Namjoon, stage name RM, commented on a fan’s

Weverse post of a sunset that “sky always gives us the reasons to live.”

142

Moved by the

sentiment, ARMY mass-posted pictures of skies around the world to share with RM. During

Sowoozoo, RM thanked ARMY for their participation and warmly stated that “I was so happy to

20

see so many beautiful skies.”

143

He then showed the audience his in-ear microphone monitors,

which were newly painted sky blue with clouds and his name in tribute. These cyclic, reciprocal

interactions merged digital communication with embodied reality to produce stronger bonds of

connection between BTS and ARMY both during the hashtag event and during BTS’ online

concert.

Lastly, BTS reframes COVID-19 as an event that will bring the members and ARMY

closer to each other throughout their concerts, songs, and interviews. “In a world of uncertainty,

we must cherish the importance of ‘me,’ ‘you’ and ‘us,’” because the “reason we can endure this

situation is that we are in this together,” remarked several members.

144

The members reflected

several times that the pandemic showed the group that ARMY was what was “really important,”

and frequently emphasized that they will never be able to take concerts and in-person

interactions “for granted” again.

145

In these ways, the group suggests instead that “someday the

sadness will wind us together” instead of merely keeping the artists and their fans apart.

146

Thus,

“even the darkness we see is so beautiful” because “[I’m] looking straight ahead, only at you.”

147

Through this reframing of separation, BTS helps listeners re-imagine and cope with separation

while still acknowledging the painful, difficult reality of isolation.

2.2 “Extramusical” Content Beyond the Scene

In addition to connecting with fans via music and online concerts, some of BTS’ most

novel sites of digital media-delivered health interventions can be found via what I dub the

group’s “extramusical” digital content, or that which is not explicitly produced to create,

promote, or perform the group’s discography. BTS’ extramusical content spans many formats

and platforms, from the group’s self-produced weekly variety game show that premiered in 2015

and livestreamed videos to engaging with fan posts on Twitter and HYBE’s social media

platform Weverse. During the early days of the pandemic, BTS and HYBE “gave a lot of

thoughts on how we could keep communicating with ARMYs and share emotions even though

we cannot meet in a close distance so that we can give more energy to all of you.”

148

Their

solution: developing regular, pandemic-specific extramusical content to connect to, comfort, and

communicate with ARMY during the early days of the pandemic in hopes of improving the

health of both artists and fans.

It is important to note that this content strategy did not emerge in March 2020, and is

rather the product of ten years’ worth of development courtesy of HYBE, ARMY, and BTS.

Beginning with vlogs (video logs) that expressed the members’ fears, hopes, and dreams for their

careers before the group even released their first single in 2013, HYBE and BTS have used

digital media platforms to increase artist relatability through giving ARMY structured insights

into the members’ complex internal thoughts and feelings.

149

ARMY in turn have taken to

various social media platforms to share their stories (life experiences, worries, struggles) through

posts, pictures, and videos, often expressing their gratitude to BTS for improving their lives and

overall health. BTS members then directly respond with words of encouragement, advice, and

affirmation; they have also discussed in both interviews and music that reading these posts gives

the members themselves comfort, happiness, and inspiration to continue making value-based

music.

150

BTS and HYBE also create entertainment rather than musical content, including full-

length variety show episodes and documentary series that are designed to bring joy and

happiness to viewers through showing fans a “different side” of BTS.

151

Variety show episodes,

for example, regularly feature the members playing all age-appropriate board and card games,

21

learning new sports, and completing challenges. Some members also maintain regular individual

content series, such as the food-focused “Eat Jin” mukbang show.

152

ARMY often meme,

parody, and amplify this content, which BTS members often directly respond or refer to in

subsequent posts and videos, resulting in what Ringland et. al refers to as a reciprocal “culture of

play” in digital spaces.

153

As Ringland et. al discusses, “play has real world impact and