RESEARCH & ANALYSIS

Economic Well-Being of

U.S. Households in 2022

May 2023

BOARD OF GOVERNORS OF THE

FEDERAL RESERVE SYSTEM

The Federal Reserve System is the central

bank of the United States. It performs five key

functions to promote the effective operation

of the U.S. economy and, more generally, the

public interest.

The Federal Reserve

■ conducts the nation’s monetary policy to promote maximum employment

and stable prices in the U.S. economy;

■ promotes the stability of the financial system and seeks to minimize

and contain systemic risks through active monitoring and engagement in

the U.S. and abroad;

■ promotes the safety and soundness of individual financial institutions

and monitors their impact on the financial system as a whole;

■ fosters payment and settlement system safety and efficiency through

services to the banking industry and U.S. government that facilitate

U.S.-dollar transactions and payments; and

■ promotes consumer protection and community development through

consumer-focused supervision and examination, research and analysis of

emerging consumer issues and trends, community economic development

activities, and administration of consumer laws and regulations.

To learn more about us, visit www.federalreserve.gov/aboutthefed.htm.

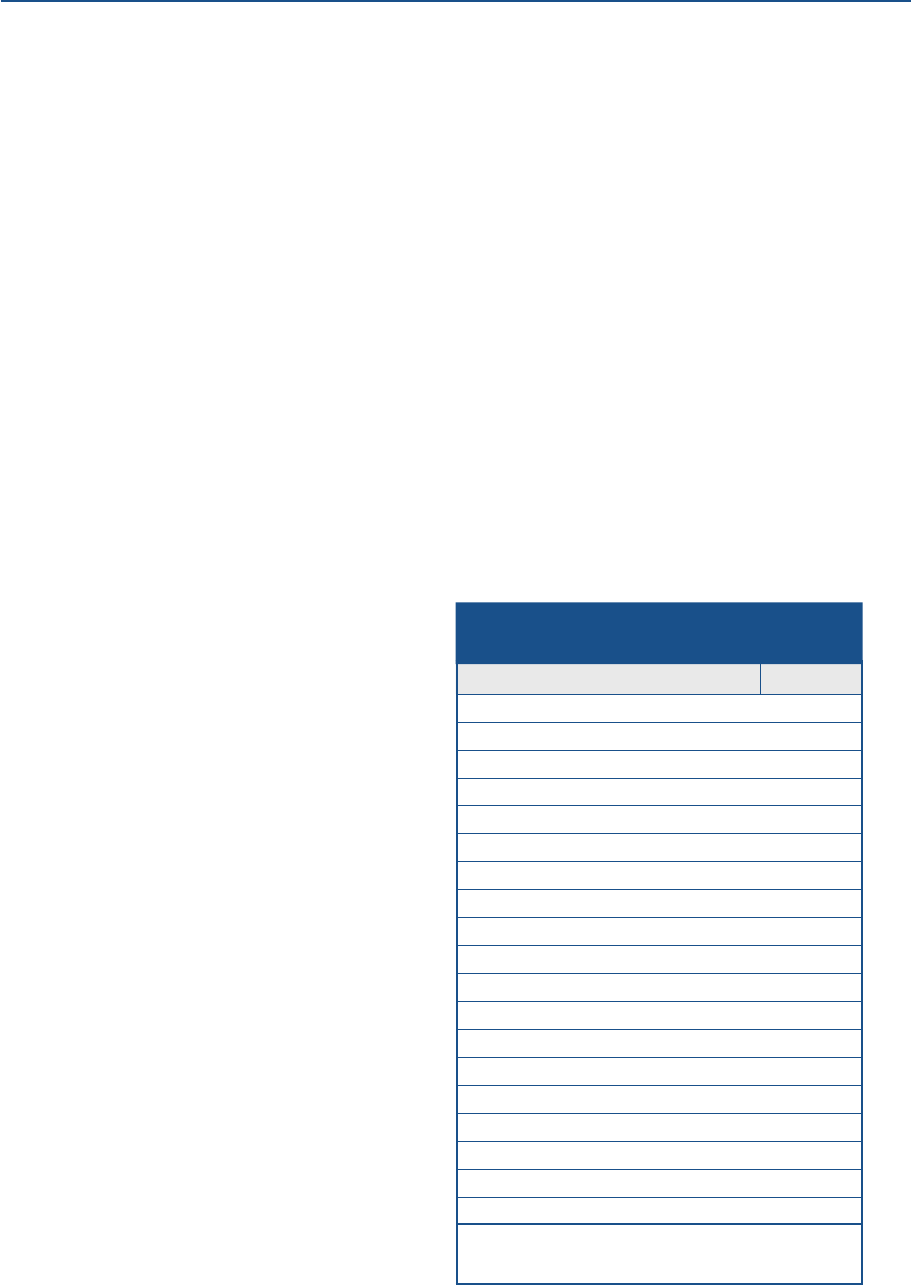

Contents

Executive Summary

......................................................................................................... 1

Overall Financial Well-Being ................................................................................................ 2

Income ............................................................................................................................. 2

Employment ...................................................................................................................... 2

Expenses .......................................................................................................................... 2

Banking and Credit ............................................................................................................ 3

Housing ............................................................................................................................ 3

Higher Education and Student Loans ................................................................................... 3

Retirement and Investments ............................................................................................... 3

Overall Financial Well-Being

.......................................................................................... 5

Current Financial Situation ................................................................................................. 5

Changes in Financial Situation over Time ............................................................................. 9

Main Financial Challenges ................................................................................................ 10

Local and National Economic Conditions ............................................................................ 12

Income

............................................................................................................................. 15

Level and Source of Income .............................................................................................. 15

Changes in Income and Spending ..................................................................................... 16

Income Variability ............................................................................................................. 18

Employment

.................................................................................................................... 21

Working from Home .......................................................................................................... 21

Job Searching and Advancement ....................................................................................... 23

Work Arrangements and Autonomy at Work ........................................................................ 24

Reasons for Not Working .................................................................................................. 25

The Gig Economy ............................................................................................................. 26

Expenses

......................................................................................................................... 29

Bills and Regular Expenses ............................................................................................... 29

Unexpected Expenses ...................................................................................................... 31

Health-Care Expenses ...................................................................................................... 34

Hardships from Natural Disasters ..................................................................................... 35

Banking and Credit

........................................................................................................ 39

Bank Account Ownership .................................................................................................. 39

Nonbank Check Cashing and Money Orders ....................................................................... 40

Cryptocurrency ................................................................................................................. 41

Credit Outcomes and Perceptions ..................................................................................... 43

Credit Cards .................................................................................................................... 44

Buy Now, Pay Later ........................................................................................................... 45

Payday, Pawn, Auto Title, and Refund Anticipation Loans ..................................................... 47

Housing

............................................................................................................................ 49

Living Arrangements ......................................................................................................... 49

Homeownership and Mortgages ........................................................................................ 50

i

Renters ........................................................................................................................... 51

Renter Experiences .......................................................................................................... 51

Challenges with Rental Payments ...................................................................................... 53

Higher Education and Student Loans

......................................................................... 55

Educational Attainment .................................................................................................... 55

Overall Value of Higher Education ...................................................................................... 56

Look Back on Education Decisions .................................................................................... 57

Incidence and Types of Education Debt .............................................................................. 59

Student Loan Payment Status ........................................................................................... 61

Retirement and Investments

....................................................................................... 65

Current Retirees .............................................................................................................. 65

Retirement Savings among Non-Retirees ........................................................................... 67

Financial Literacy and Experience with Financial Decisions .................................................. 70

Description of the Survey

............................................................................................. 73

Survey Participation ......................................................................................................... 73

Targeted Outreach and Incentives ...................................................................................... 73

Survey Questionnaire ....................................................................................................... 74

Survey Mode ................................................................................................................... 74

Sampling and Weighting ................................................................................................... 75

Item Non-response and Imputation .................................................................................... 76

Acknowledgements

....................................................................................................... 79

Corrections

..................................................................................................................... 81

ii Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

Executive Summary

Results from the 2022 Survey of Household Economics and Decisionmaking (SHED) indicate a

decline in peoples’ financial well-being over the previous year.

1

The survey, which was fielded in

October 2022, found that self-reported financial well-being fell sharply and was among the lowest

observed since 2016. Similarly, the share of adults who said that they spent less than their

income in the month before the survey fell in 2022 from the prior year, while the share who said

that their credit card debt increased rose. Among adults who were not retired, the survey also

showed a decline in the share who felt that their retirement savings plan was on track, suggesting

that individuals had concerns about their future financial security. The declines in financial well-

being across these measures provide an indication of how families were affected by broader eco-

nomic conditions in 2022, such as inflation and stock market declines.

While people expressed concerns about rising prices and their ability to build savings, the survey

results indicated continued labor market strength in late 2022. The share of adults who voluntarily

quit, asked for a raise, or received a raise increased slightly over the prior year’s survey, reflecting

the strong labor market. The survey found that the share of prime-age adults not working because

of difficulty finding work remained low.

Experiences at work differed, however, based on the amount of education that workers had. Those

with a bachelor’s degree were more likely than those with less education to be in jobs where they

control their schedules, have autonomy over their work activities, or have the ability to telework.

The report also provides insights into other areas that are central to individuals’ financial circum-

stances, including emergency savings, returns to education, housing situations, and retirement

savings. Across these topics, the results provide a window into how individuals’ financial well-

being has changed in recent years. In doing so, it illustrates the diversity of people’s financial

1

The Federal Reserve has fielded the SHED annually in the fourth quarter of each year since 2013. The latest survey was

fielded from October 21 until November 1, 2022. Since over 99.5 percent of respondents completed the survey in

October, this report describes the field period as October 2022. The anonymized data, as well as appendixes containing

the complete SHED questionnaire and responses to all questions in the order asked, are also available at https://

www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/shed.htm.

Self-reported financial well-being fell sharply and

was among the lowest observed since 2016.

1

experiences. This includes notable differences by income, education, race, and ethnicity. Key find-

ings across each of the topics covered in the report include the following:

Overall Financial Well-Being

•

Overall financial well-being declined markedly over the prior year. Seventy-three percent of adults

were doing at least okay financially in 2022, down 5 percentage points from 2021.

•

The share of adults who said they were worse off financially than a year earlier rose to 35 per-

cent, the highest level since the question was first asked in 2014.

Income

•

More adults experienced spending increases than income increases. Forty percent of adults

said their family’s monthly spending increased in 2022 compared with the prior year, while

33 percent said their monthly income increased. While some adults saw both their spending

and their income increase, 23 percent of adults said that their spending had increased but their

income had not.

•

The share of adults who said they spent less than their income in the month before the survey

fell in 2022 to below the level it had been before the pandemic.

Employment

•

As an indication of workers’ strong labor market options, one-third of adults received a raise or

promotion in 2022 and 13 percent of adults asked for a raise or promotion. This compares with

30 percent who received a raise and 9 percent who asked for one in the 2021 survey. Among

those who asked for a raise in 2022, 70 percent also said that they received one.

•

Among those working from home at least some of the time, survey results indicate that a

requirement to work in person full-time would have similar effects on retention as a 2 to 3 per-

cent pay cut.

Expenses

•

Consistent with declines in overall financial well-being, 63 percent of adults said they would

cover a hypothetical $400 emergency expense exclusively using cash or its equivalent, down

from a high of 68 percent in 2021.

•

When asked for the largest expense they could cover using only savings, rather than how they

would pay a small emergency expense, 18 percent said the largest expense they could cover

with savings was under $100 and an additional 14 percent said the largest expense they could

cover was between $100 and $499.

•

Inflation affected people’s spending and saving choices in several different ways. Nearly two-

thirds of adults stopped using a product or used less because of inflation, 64 percent switched

2 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

to a cheaper product, and just over one-half (51 percent) reduced their savings in response to

higher prices.

Banking and Credit

•

Access to financial services from banks and credit unions, which can be important for people’s

financial well-being, remained high. In 2022, 94 percent of adults had a bank account although

notable gaps remain by income, age, race, ethnicity, and disability status.

•

Use of relatively new financial services like cryptocurrency for transactions and Buy Now, Pay

Later (BNPL) remained low compared with traditional payment and credit methods. Three per-

cent of adults used cryptocurrency for financial transactions and 12 percent used BNPL in the

prior year. That said, while still low overall, use tended to be higher among Black and His-

panic adults.

Housing

•

While some people chose to rent for convenience, the survey found that financial constraints

were often a reason why people rent. Nearly two-thirds of renters said that their inability to

afford a down payment to buy a home was a reason they rent. This is consistent with levels

seen before the pandemic.

•

Some renters indicated they had difficulty keeping up with their rent payments. Seventeen per-

cent of renters were behind on their rent at some point in the prior year.

Higher Education and Student Loans

•

Education was seen as a path to higher income and greater financial well-being in 2022. More

than two-thirds of adults with a bachelor’s degree or more said the financial benefits of their

education exceeded the cost. However, a lower 3 in 10 of those who started but did not com-

plete at least an associate degree shared this view.

•

People’s difficulty handling student loans varied by the level of education they completed. Con-

sistent with their greater earnings potential, those who completed at least a bachelor’s degree

were less likely to have fallen behind on payments.

Retirement and Investments

•

Progress toward retirement savings goals declined in 2022. Thirty-one percent of non-retirees

thought their retirement savings plan was on track, down from 40 percent in 2021.

•

Building retirement savings can have implications for financial well-being later in life. Seventy-

nine percent of retirees said they were doing at least okay financially. However, retirees who

received income from sources such as wages, pensions, or investments were much more likely

to be doing at least okay financially than those who had no private income.

Executive Summary 3

Overall Financial Well-Being

The share of adults doing at least okay financially fell sharply in 2022 and was among the lowest

observed since 2016.

2

This decline in financial well-being occurred broadly across the population.

Notably, it was the first time since the survey began that adults with at least a bachelor’s degree

saw a decline in well-being. Even so, existing gaps by education and by race and ethnicity

remained large.

Current Financial Situation

At the end of 2022, 73 percent of adults were doing at least okay financially, meaning they

reported either “doing okay” financially (39 percent) or “living comfortably” (34 percent). The rest

reported either “just getting by” (19 percent) or “finding it difficult to get by” (8 percent).

The 73 percent of adults doing at least okay financially in 2022 was down 5 percentage points

from 2021 and was among the lowest observed since 2016 (figure 1). As further evidence of

declining financial well-being in 2022, the share of adults who said they were living comfortably fell

2

The survey was fielded in October 2022, and results reflect financial situations at that time. Results typically capture

financial experiences at the time of the survey or in the 12-month period before the survey rather than the precise cal-

endar year. Results discussing the period shortly after the onset of the pandemic are based on the two supplemental

surveys were fielded during the pandemic in April 2020 and July 2020.

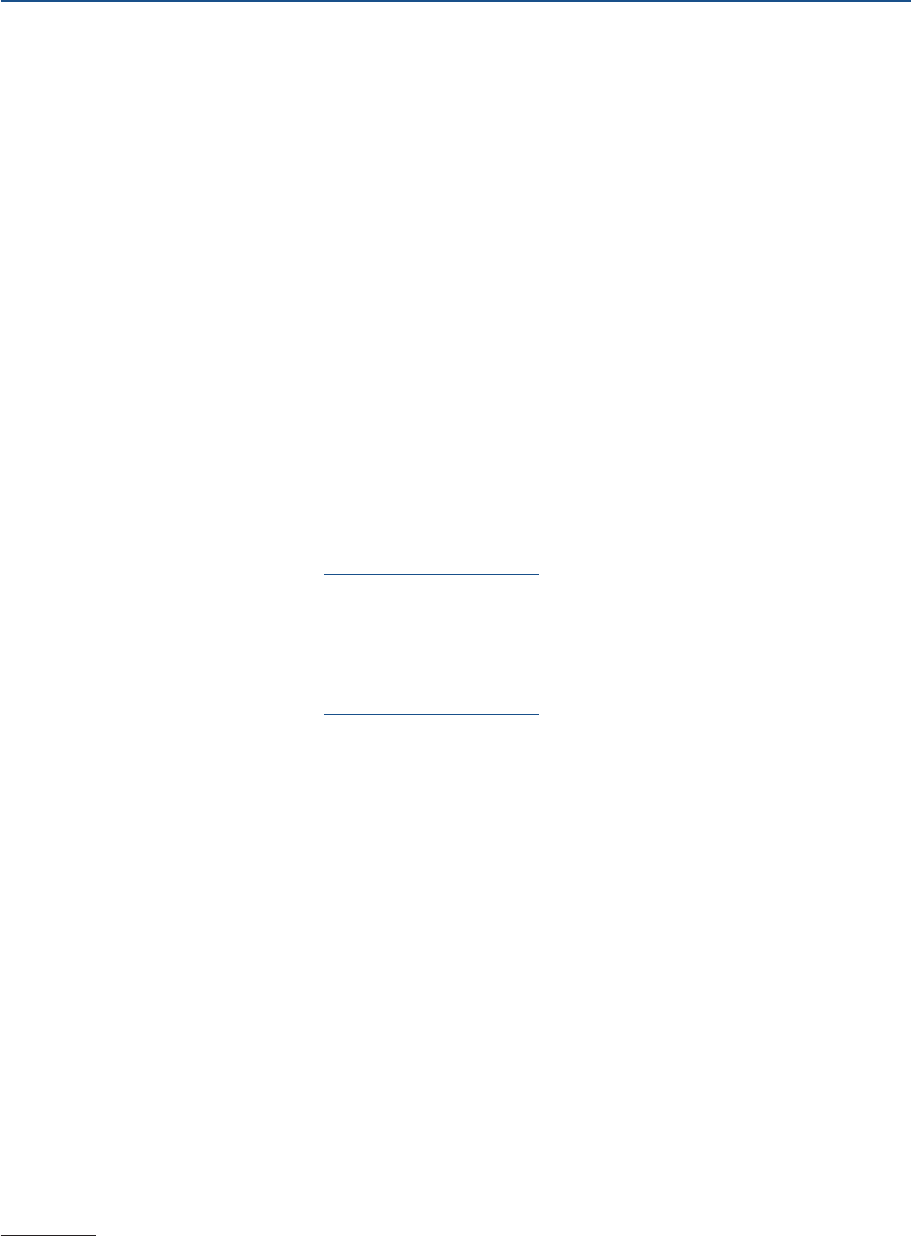

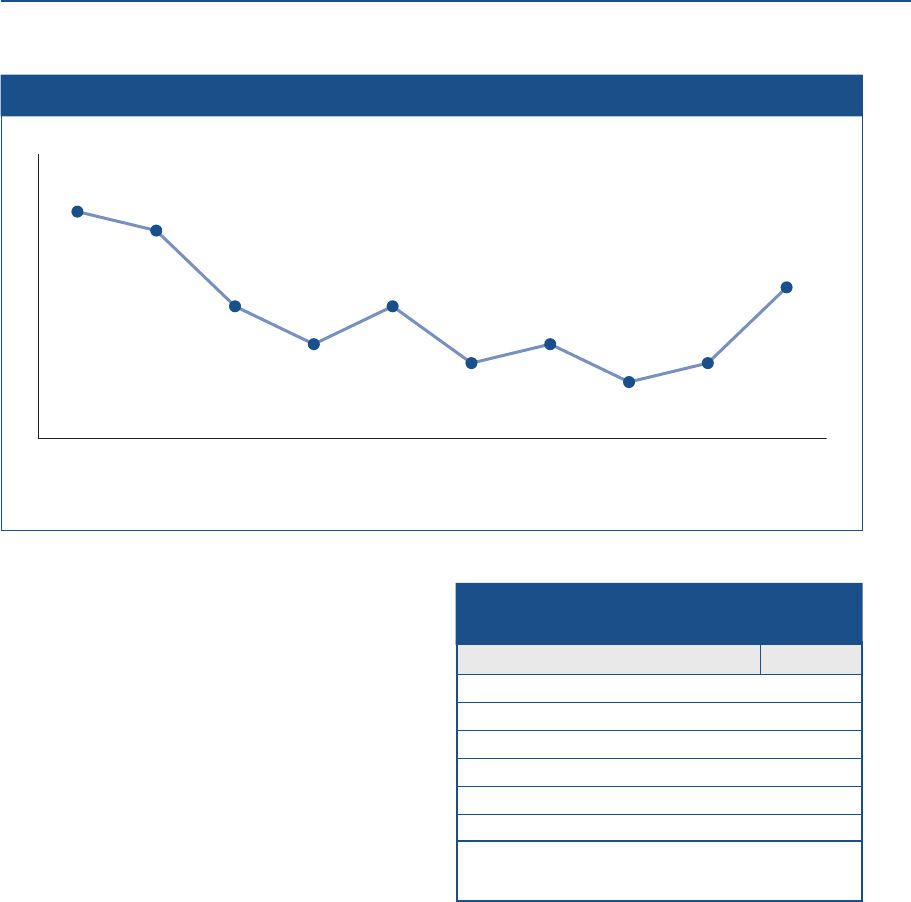

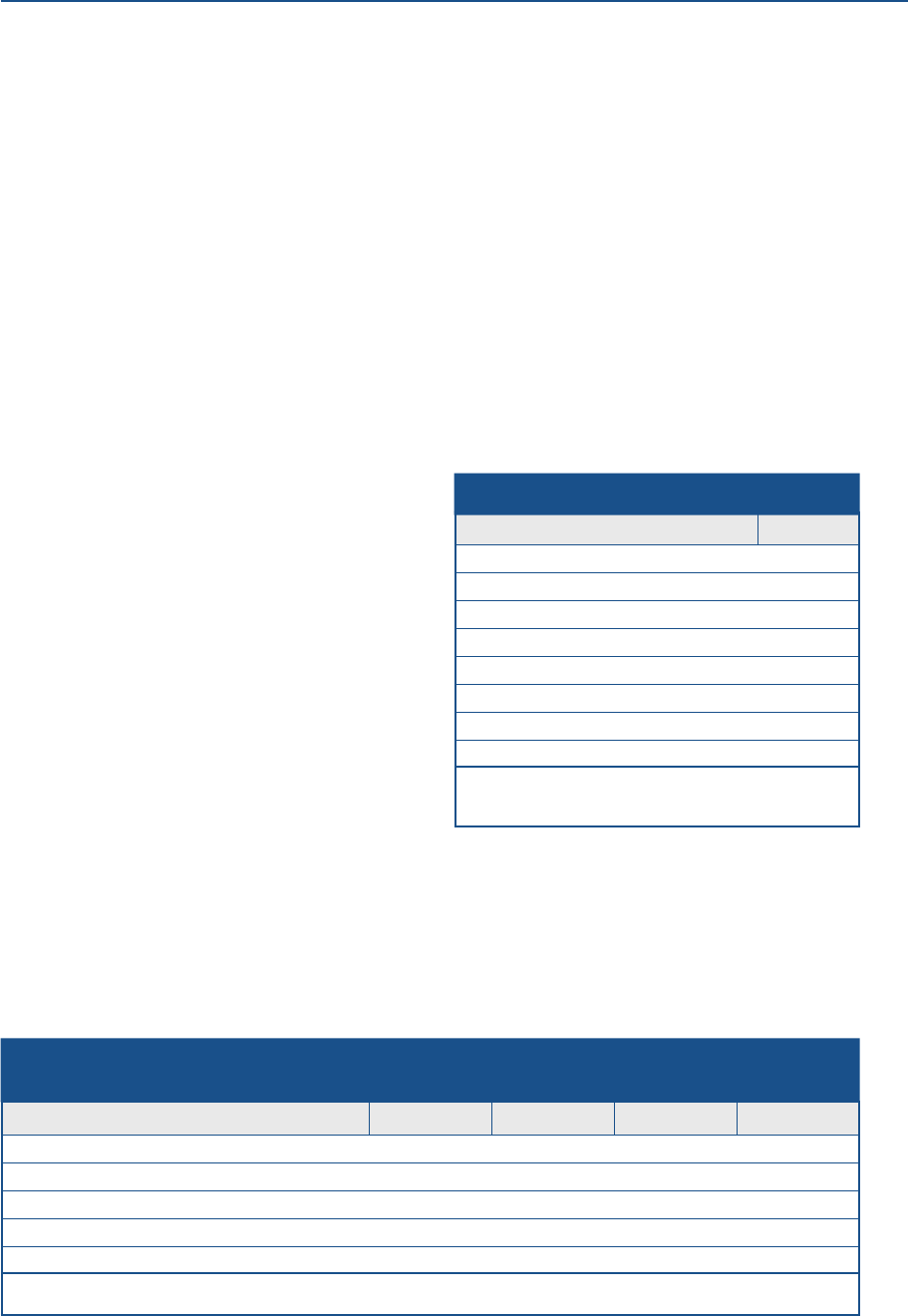

Figure 1. At least doing okay financially (by year)

62

65

69

70

74

75 75

72

77

75

78

73

Percent

Oct.

2022

Oct.

2021

Oct.

2020

July 2020

Apr. 2020

Oct.

2019

Oct.

2018

Oct.

2017

Oct.

2016

Oct.

2015

Oct.

2014

Oct.

2013

Note: Among all adults.

5

5 percentage points. This decline in well-being may reflect the broader economic conditions in

2022, such as inflation and stock market declines. It also occurred despite a strong labor market.

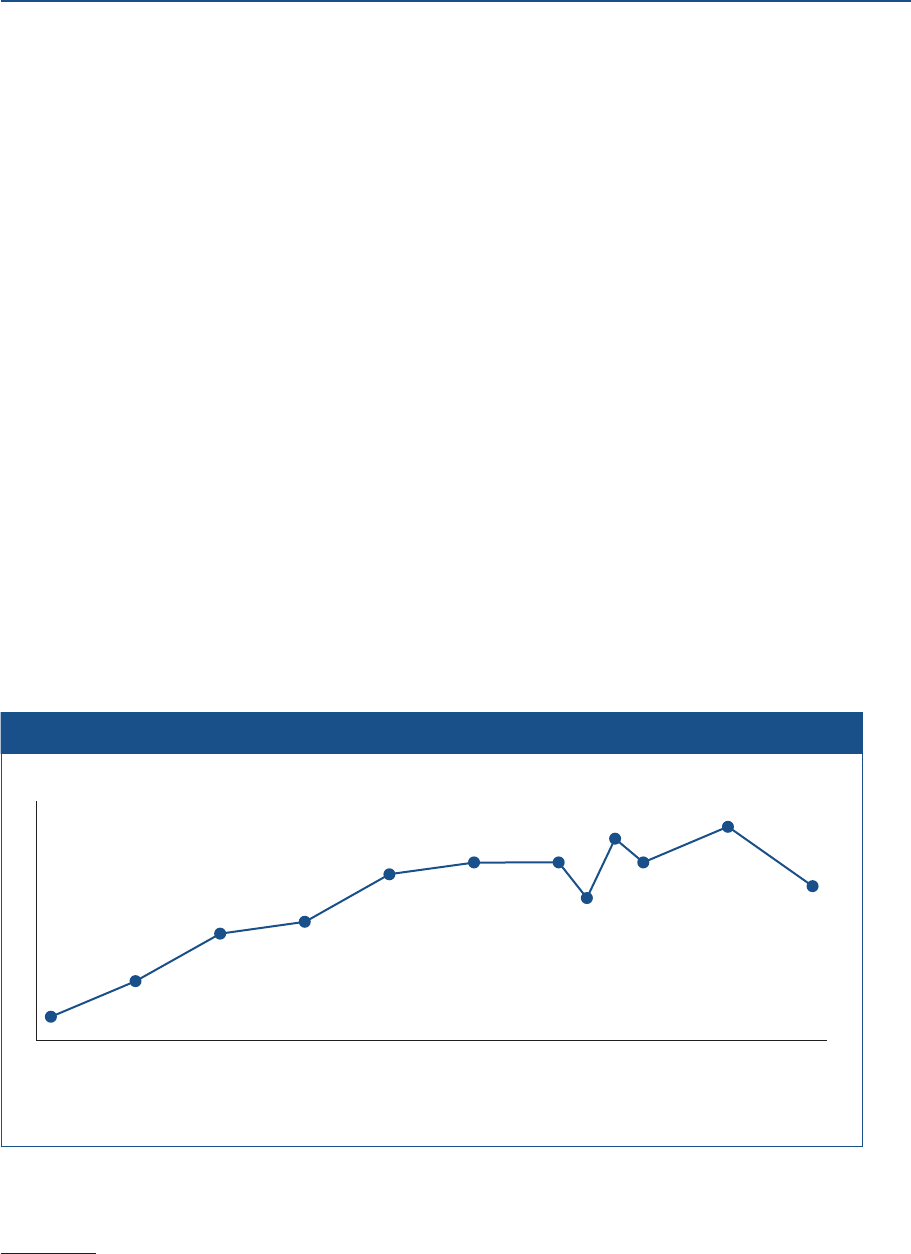

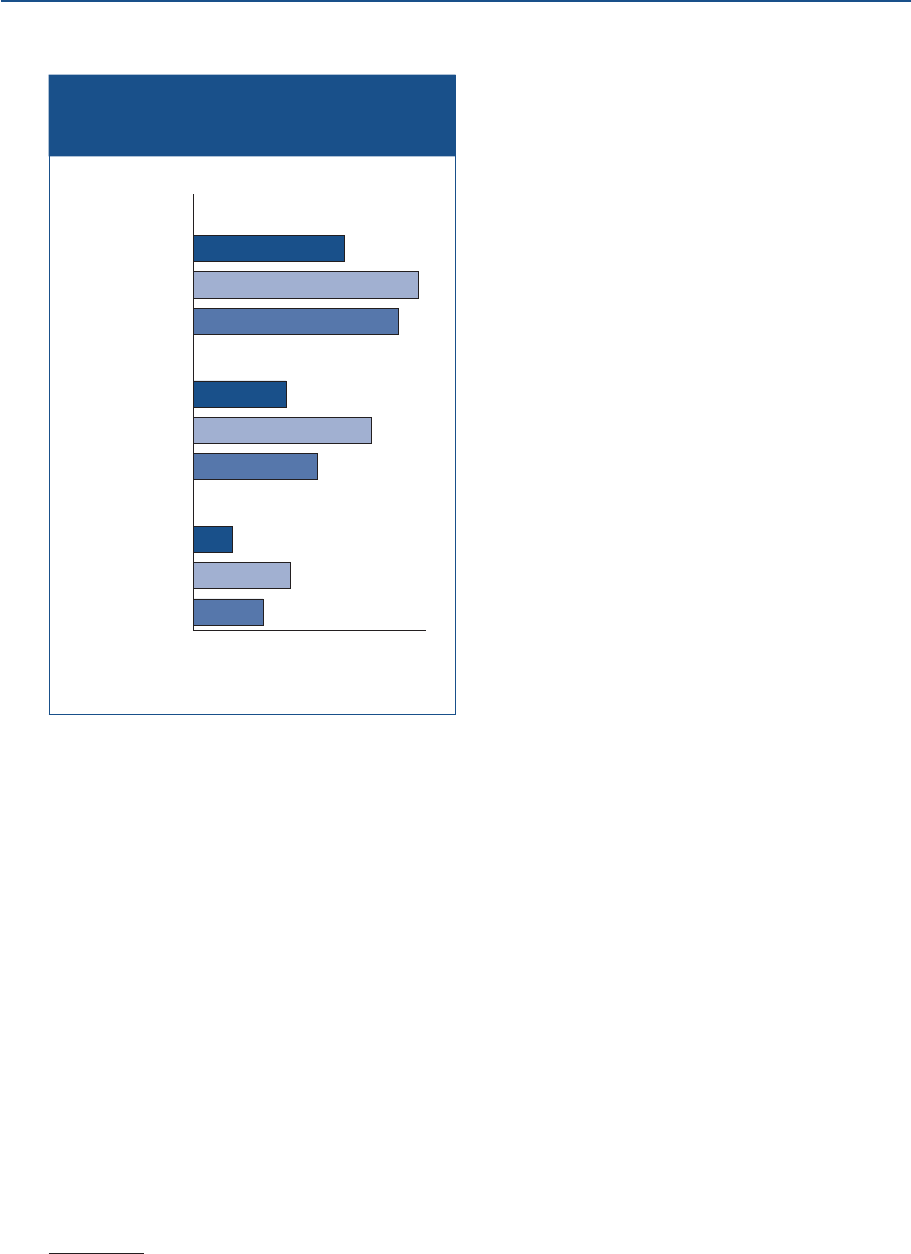

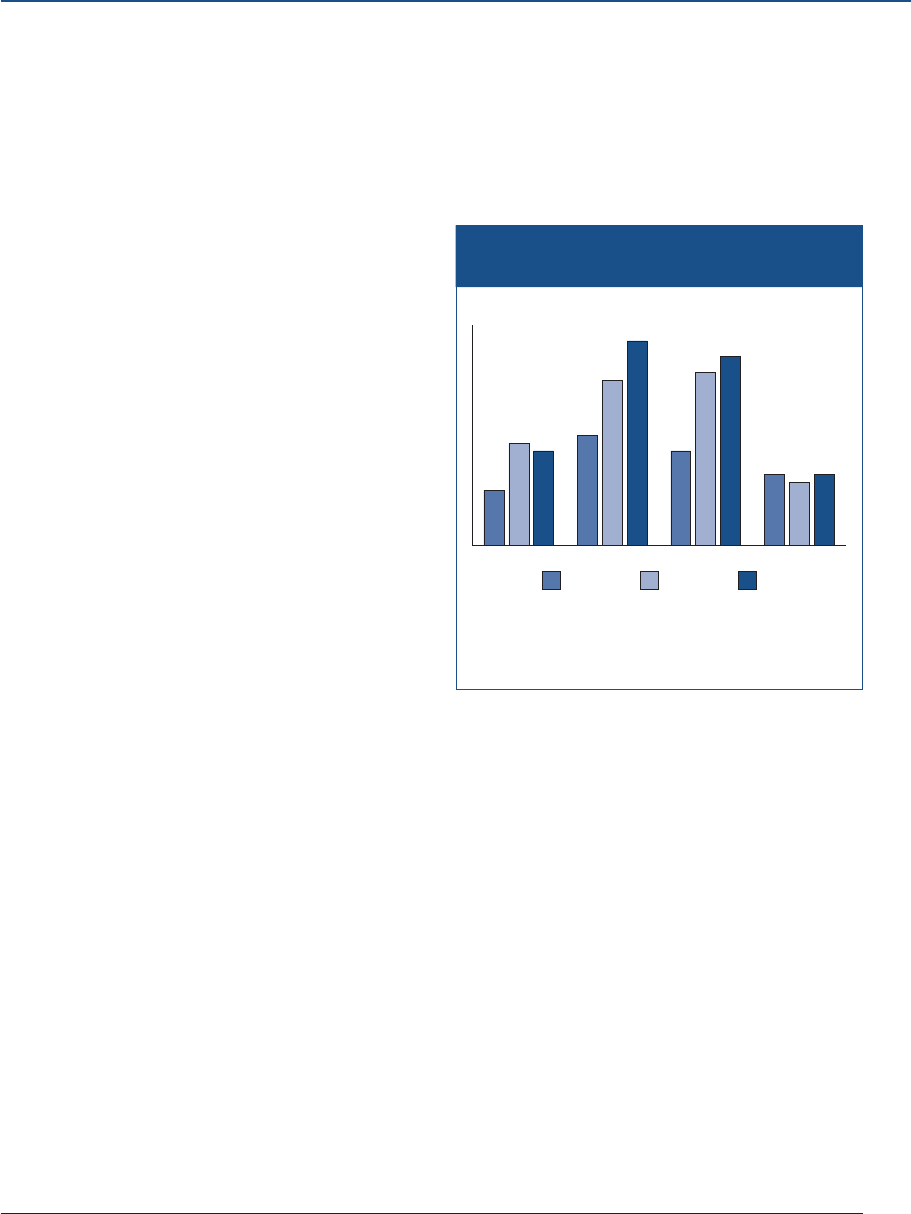

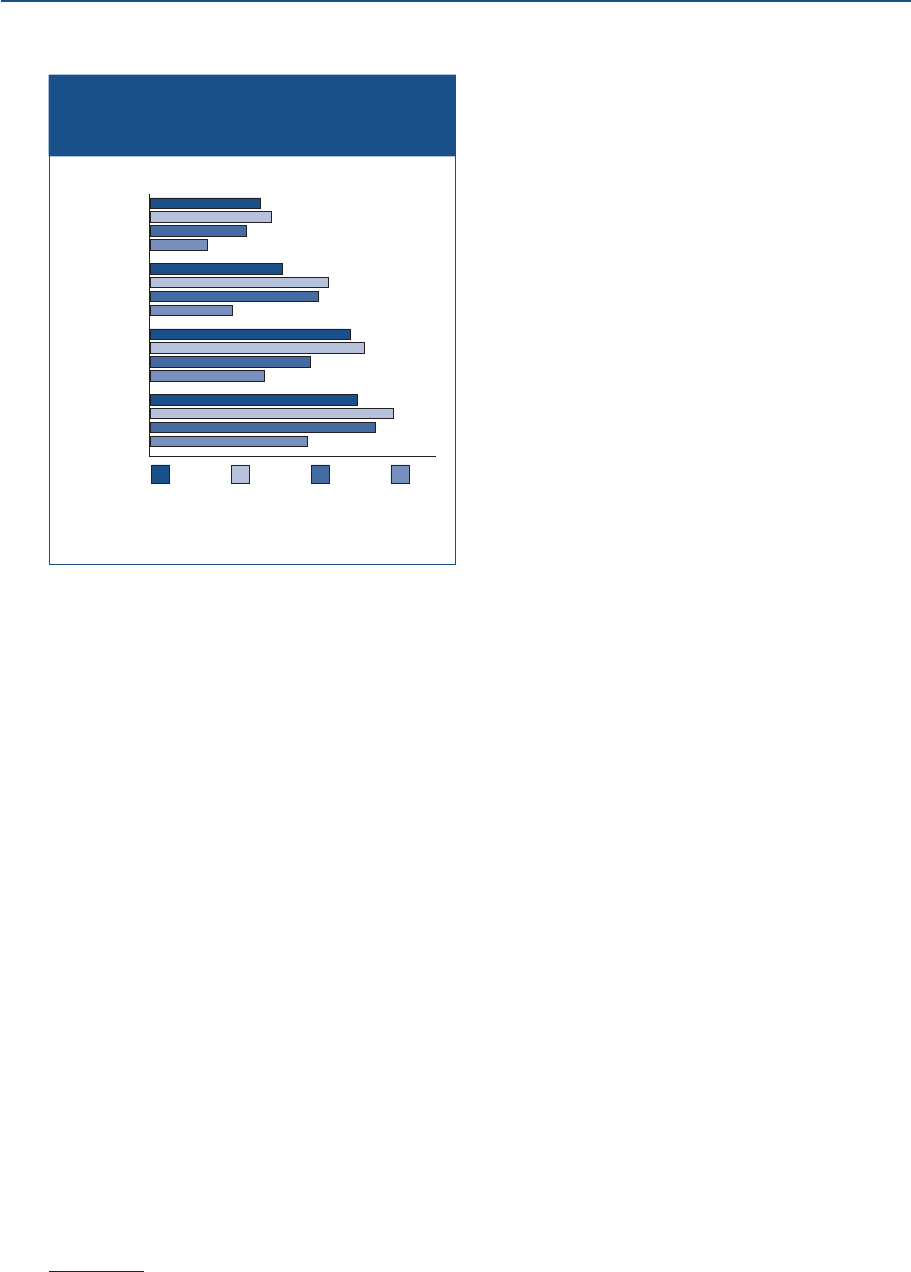

As in past years, adults with at least a bachelor’s degree were much more likely to be doing at

least okay financially (88 percent) than those with less than a high school degree (49 percent).

That said, the gap in well-being between these groups has declined 6 percentage points since

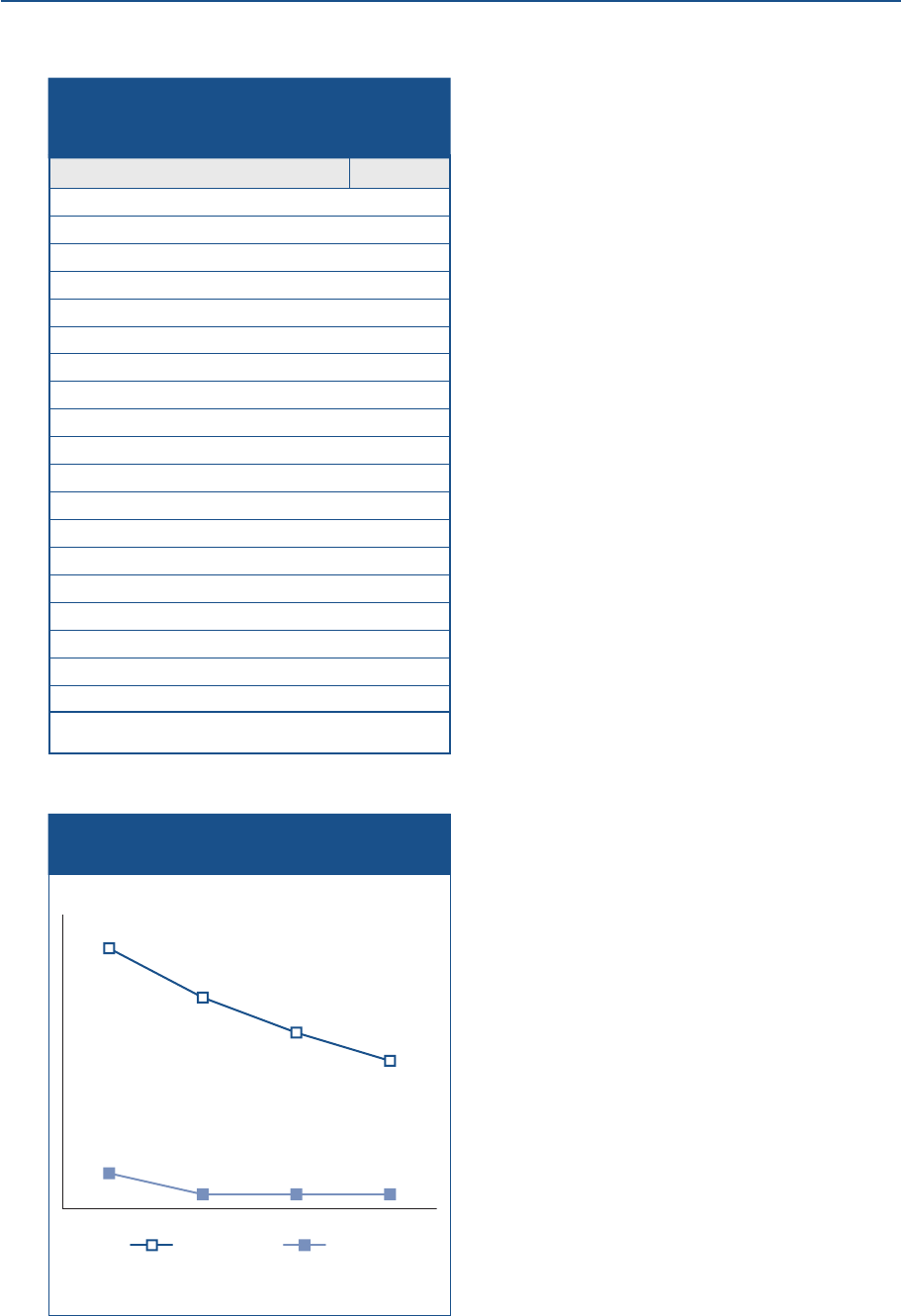

2020 (figure 2).

The shrinking education gap in well-being marks a change from recent years and largely reflects a

decline in well-being among those with at least a bachelor’s degree. In fact, for the first time since

the survey began in 2013, well-being fell among adults with at least a bachelor’s degree, down

from 91 percent doing at least okay in 2021. In contrast, well-being among those with less than a

high school degree has generally remained flat in recent years.

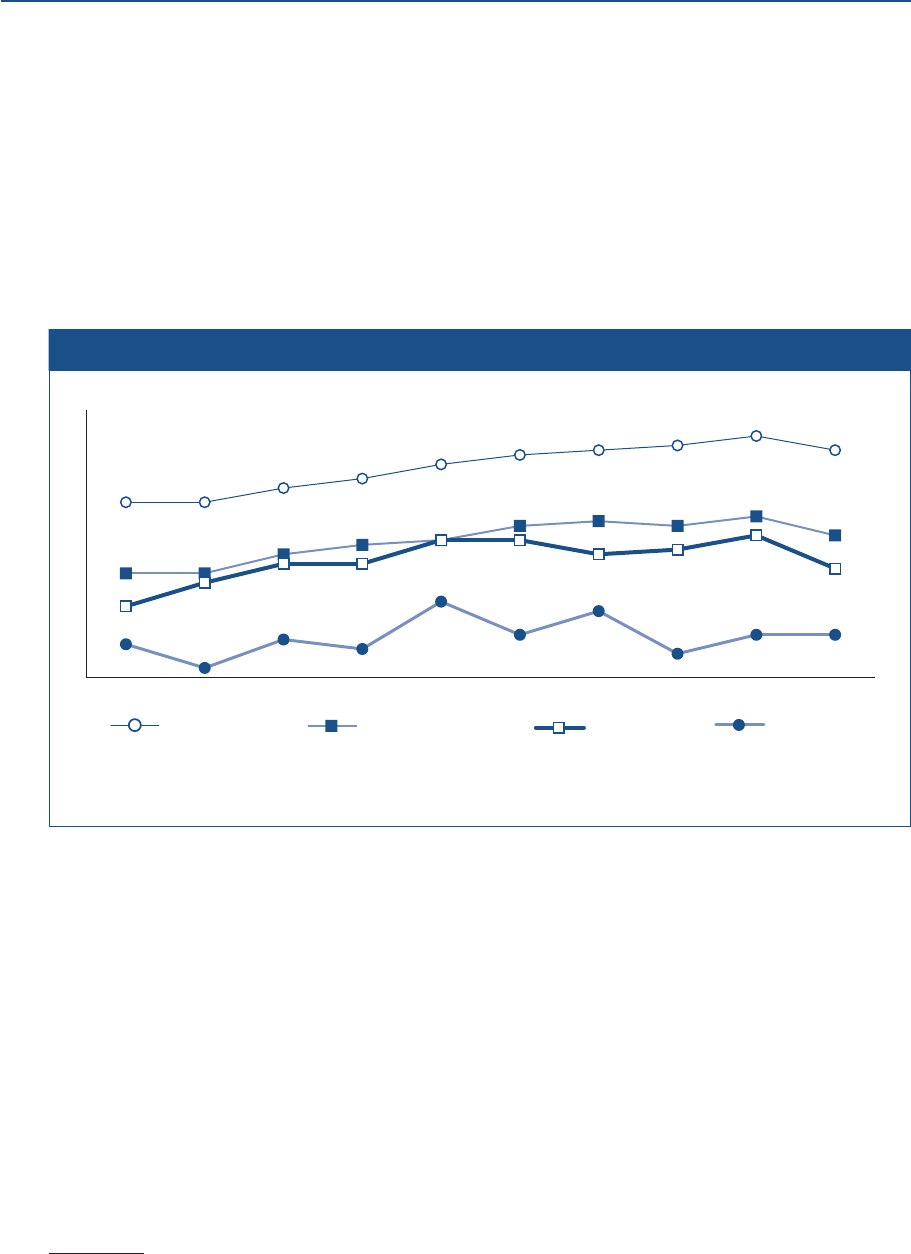

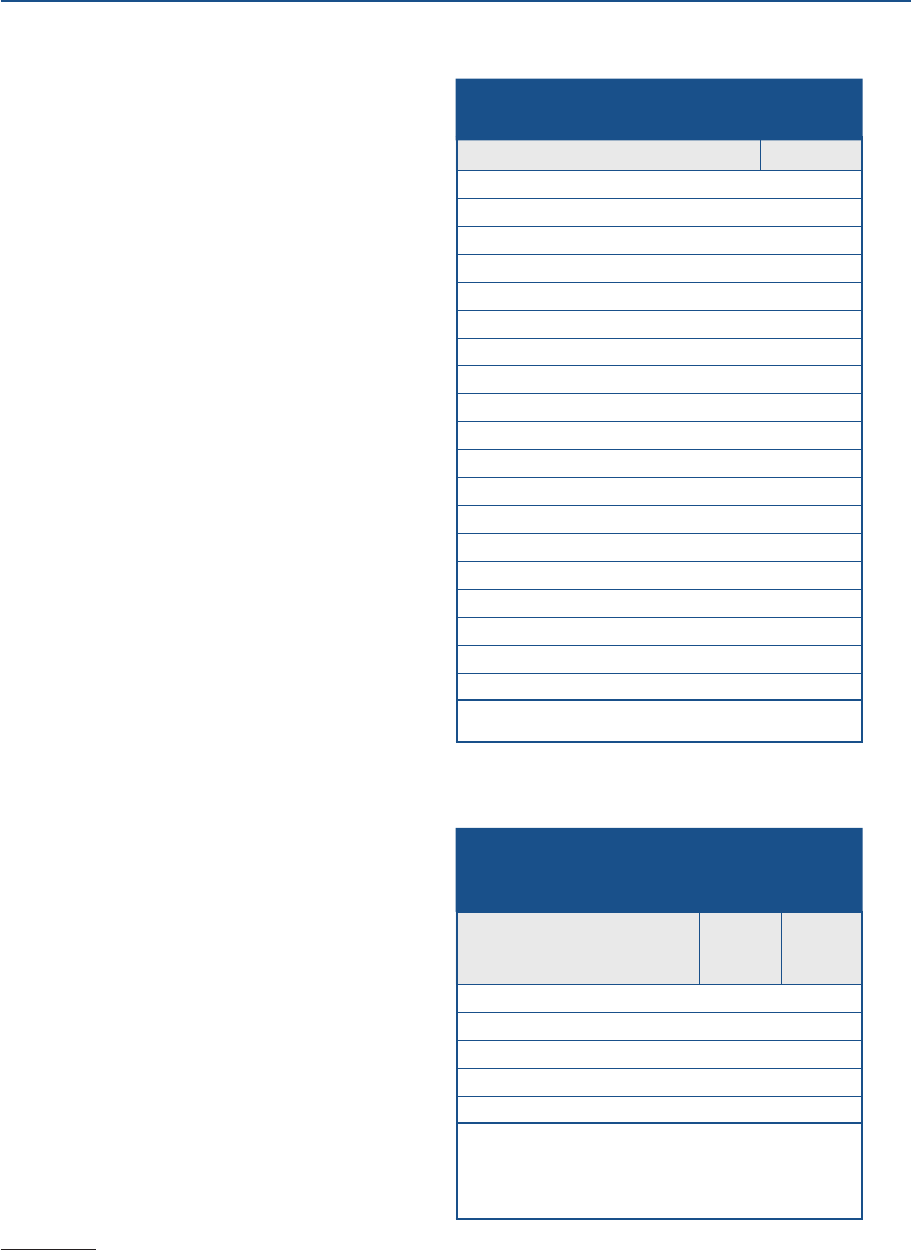

Differences in financial well-being across racial and ethnic groups persisted in 2022. Eighty-

four percent of Asian adults were doing at least okay financially, followed by 77 percent of White

adults, and 64 percent of both Hispanic and Black adults (figure 3).

3

3

The reported categorizations reflect the largest statistical groupings but are neither exhaustive nor the only distinctions

important to understand. Sample sizes for other racial and ethnic groups and subpopulations are not large enough to

produce reliable estimates. Additionally, results for Asian adults are sometimes excluded when the sample size is insuf-

ficient to provide a reliable estimate.

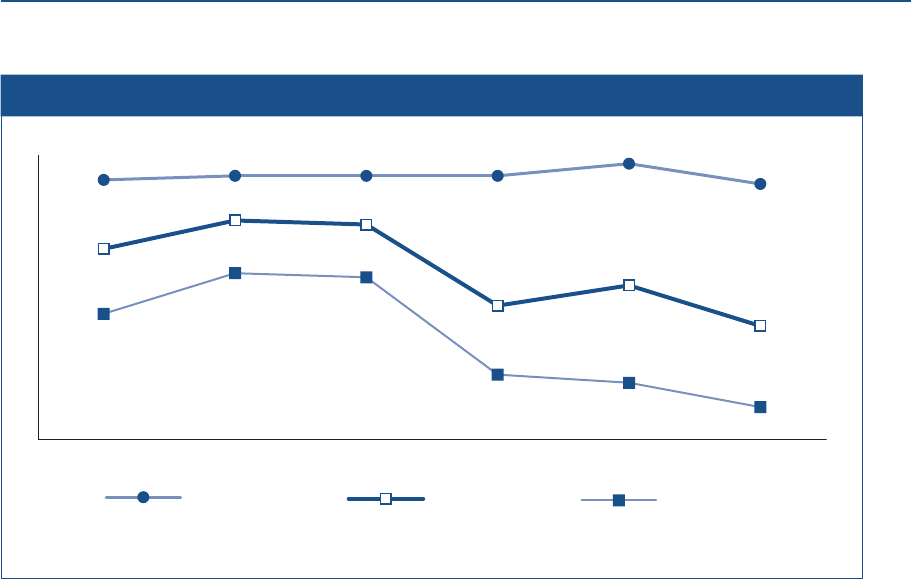

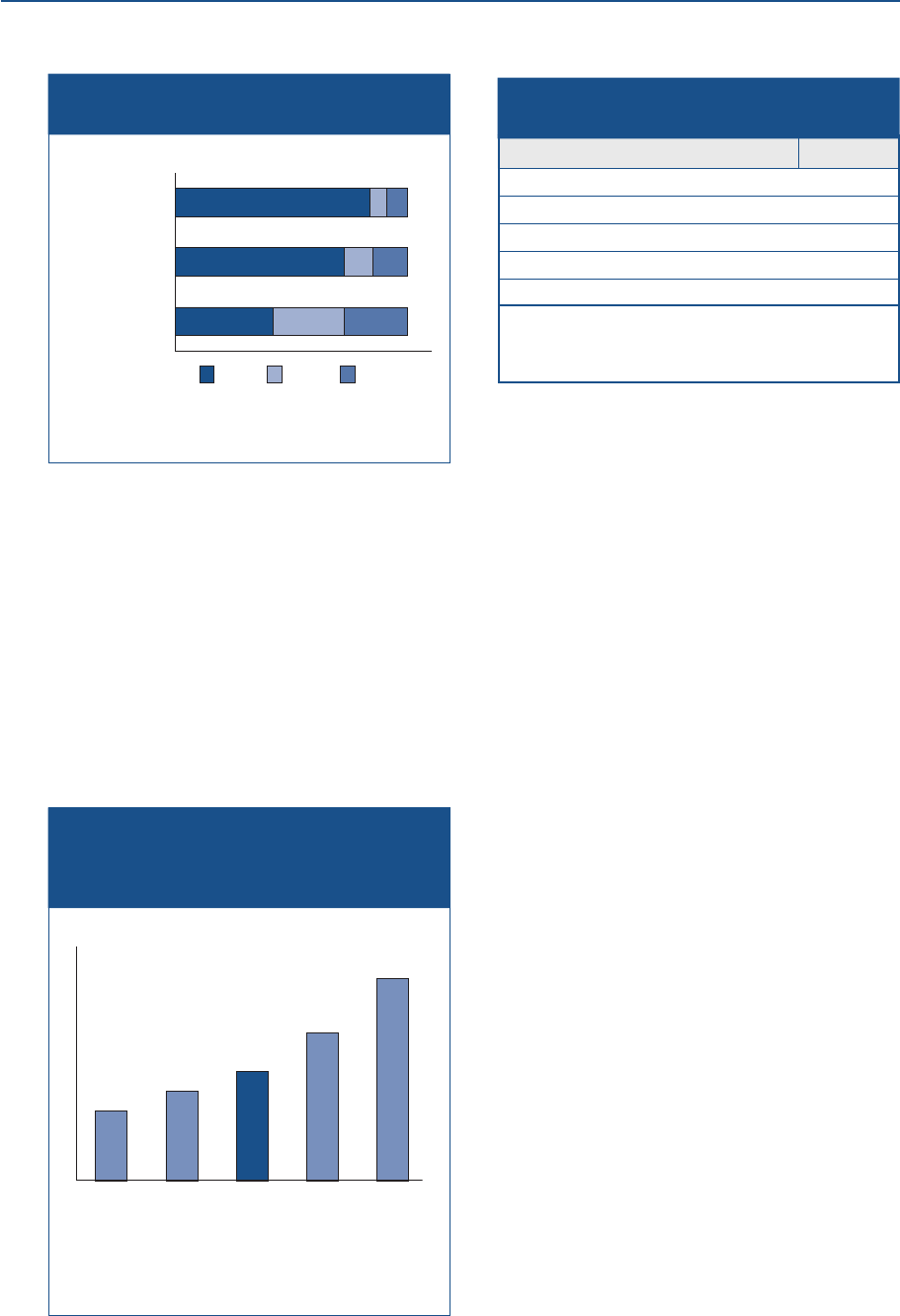

Figure 2. At least doing okay financially (by year and education)

Bachelor’s degree

or more

Some college/technical

or associate degree

High school

degree or GED

Less than a high

school degree

Percent

47

55

62

42

60

62

48

64

66

46

64

68

56

69

69

49

69

72

54

66

73

45

67

72

49

70

74

49

63

70

77 77

80

82

85

87

88

89

91

88

2022202120202019201820172016201520142013

Note: Among all adults. Results for 2017 to 2019 differ slightly from previous reports because of adjustments in

education coding for consistency.

6 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

All racial and ethnic groups measured in the survey saw a decline in financial well-being over the

prior year. Well-being among Asian, Hispanic, and Black adults returned to the same level as in fall

2020, during the first year of the pandemic. Notably, well-being among White adults fell for the first

time since the survey began, down 4 percentage points to 77 percent.

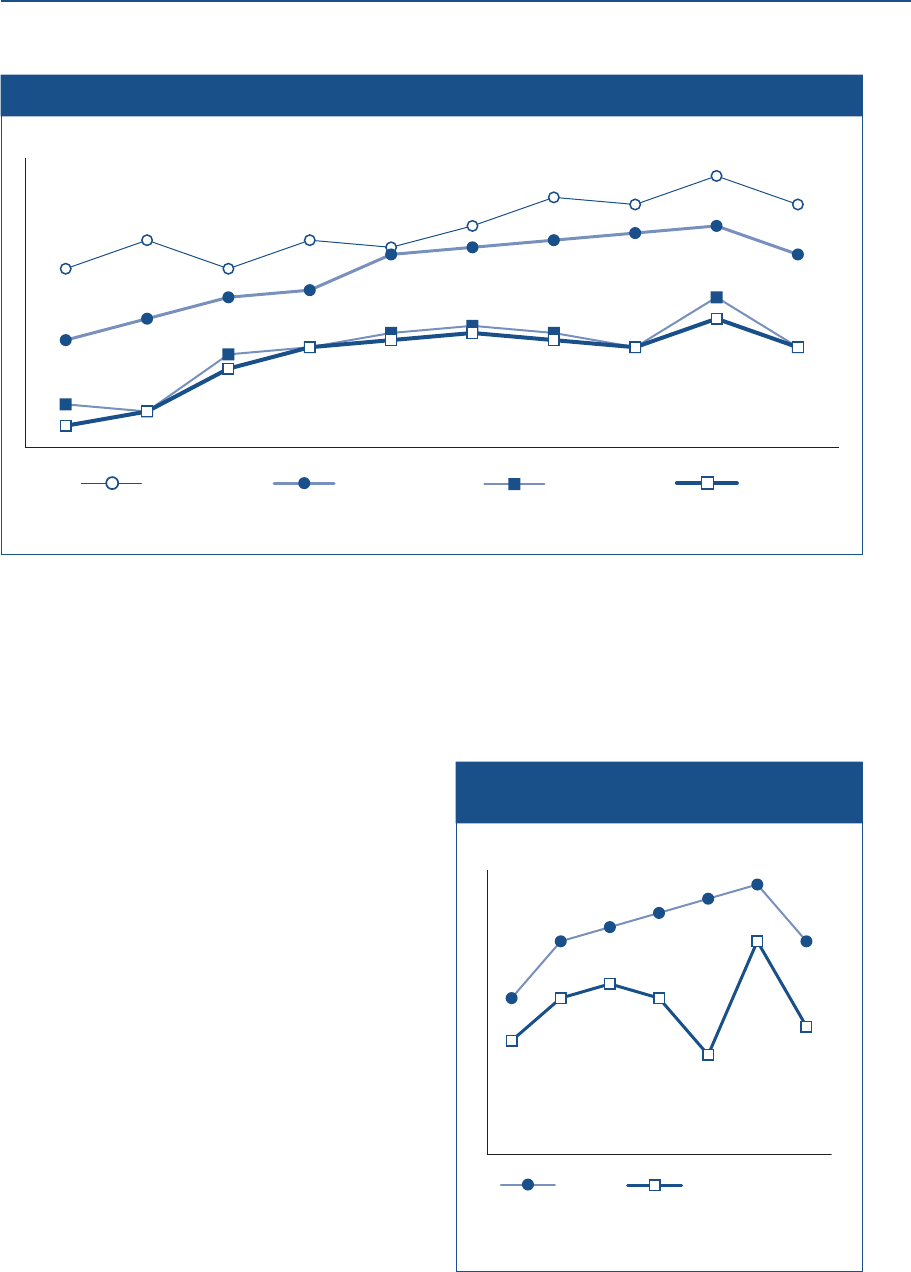

Parents are one group that has seen large

swings in well-being in recent years, falling

sharply after the onset of the pandemic,

rebounding in 2021, and falling again over the

prior year. The share of parents doing at least

okay financially fell to 69 percent in 2022,

down from its peak of 75 percent in 2021

(figure 4). For additional discussion of this

decline in parents’ financial well-being in

2022, see the “Expenses” section of

this report.

Financial well-being continued to differ by

income, LGBTQ+ status, disability status, met-

ropolitan status, and neighborhood income

Figure 3. At least doing okay financially (by year and race/ethnicity)

Asian Hispanic

Black

White

Percent

65

53

56

75

68

55

55

79

71

61

63

75

72

64

64

79

77

65

66

78

78

66

67

81

79

65

66

85

80

64

64

84

81

68

71

88

77

64

64

84

2022202120202019201820172016201520142013

Note: Among all adults.

Figure 4. At least doing okay financially (by

year and parental status)

Parents (living with own

children under age 18)

All other

adults

71

68

75

71

76

72

77

71

78

67

79

75

75

69

Percent

2022202120202019201820172016

Note: Among all adults.

Overall Financial Well-Being 7

(table 1).

4

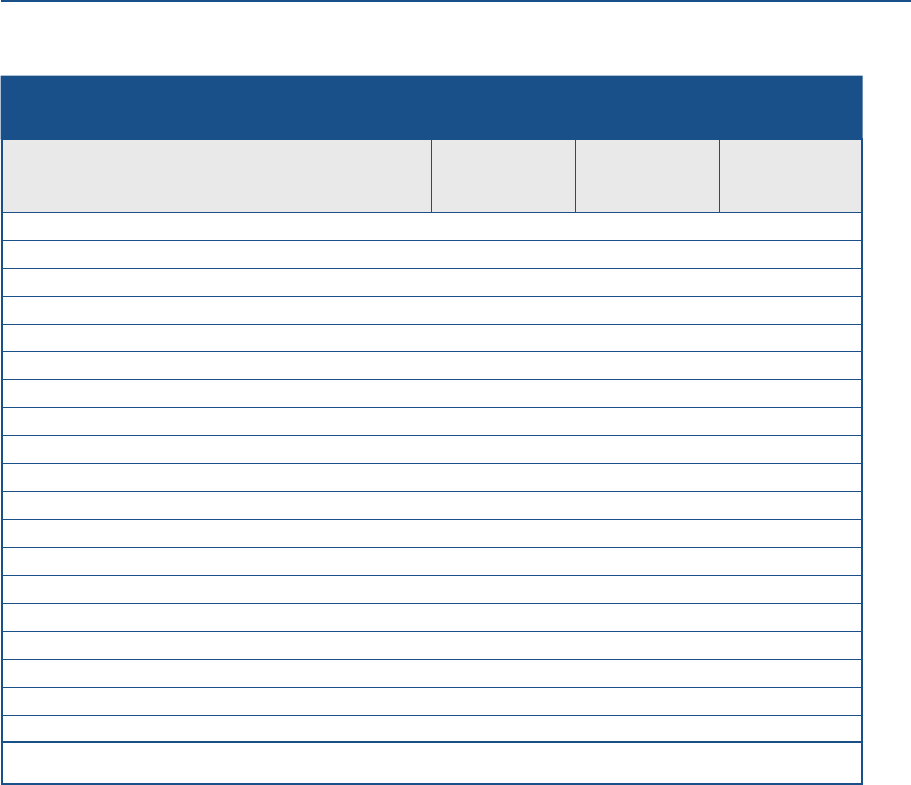

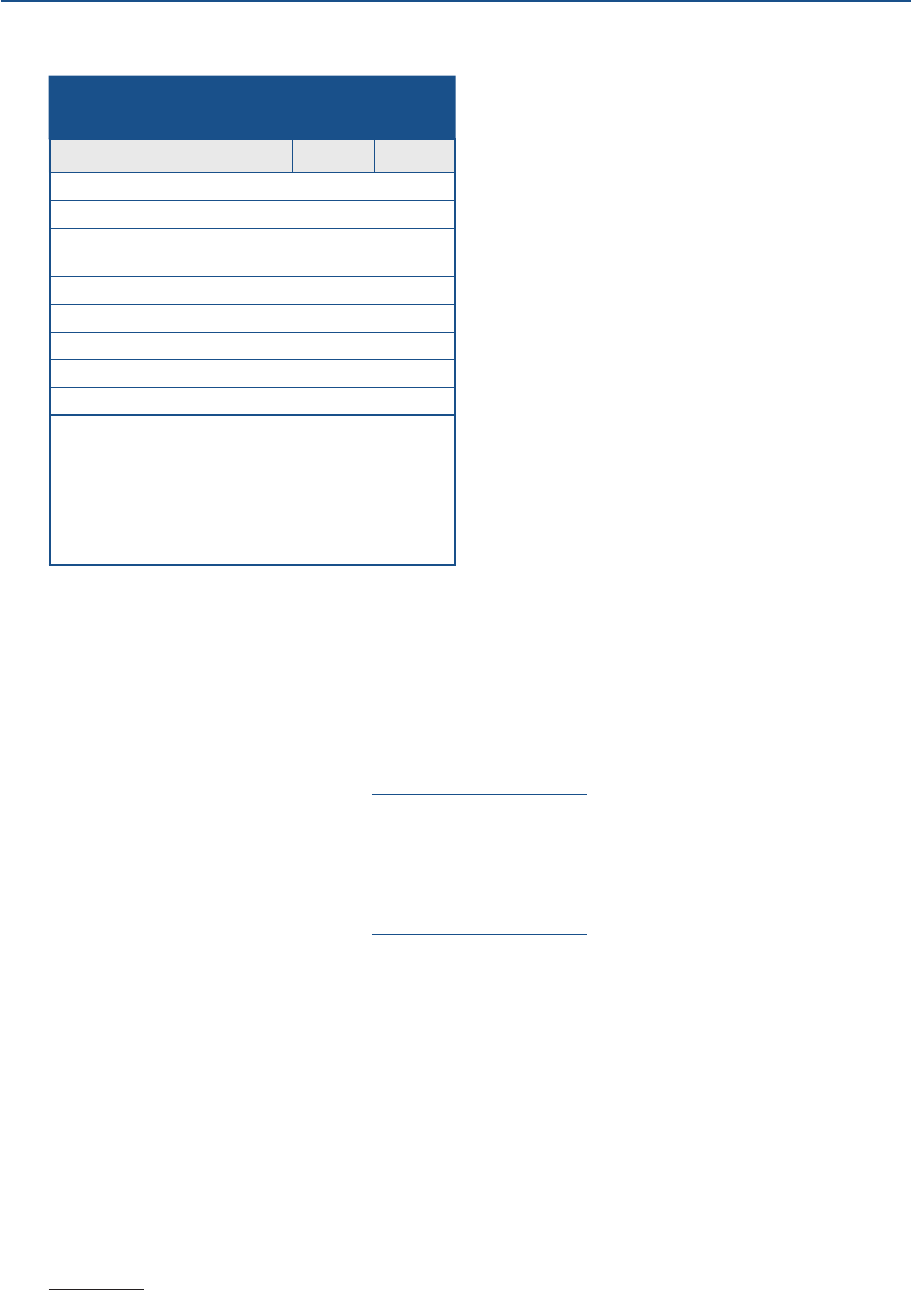

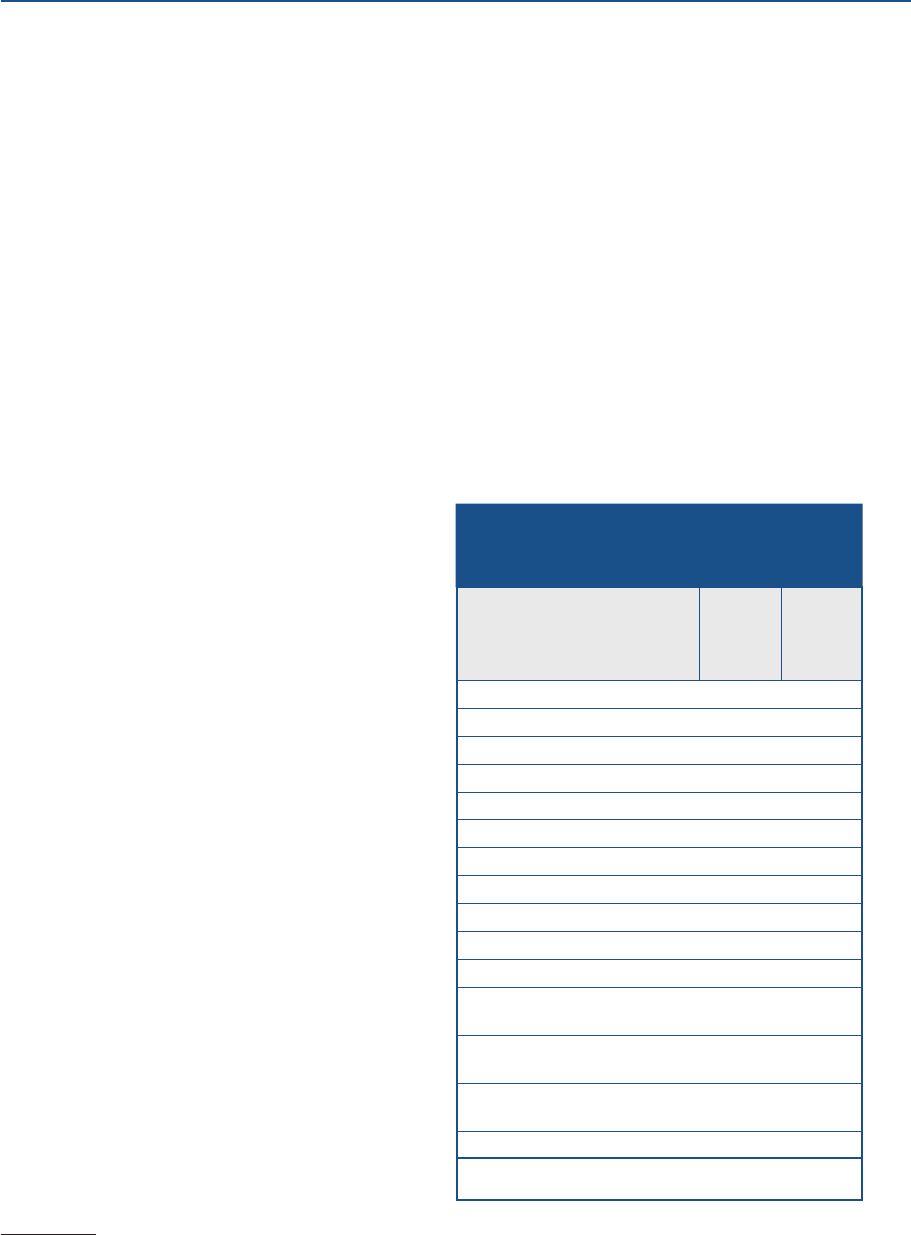

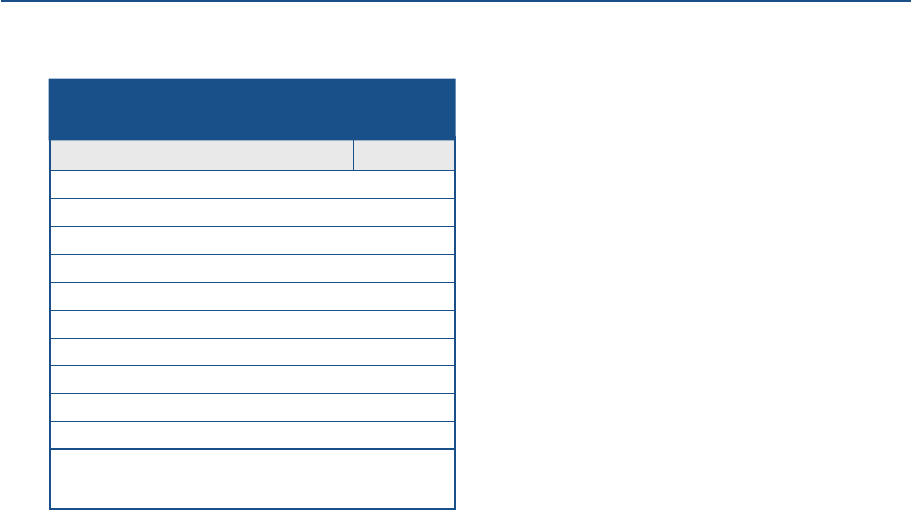

Fifty-four percent of adults with

family income less than $25,000 were doing

at least okay financially, compared with

93 percent of adults with family income

greater than $100,000. While all income

groups saw declines in well-being, those with

family income between $25,000 and $99,999

saw the largest declines.

Earlier research has shown that LGBTQ+

adults were more likely to face economic inse-

curity, suggesting LGBTQ+ status may be

associated with financial well-being.

5

Consis-

tent with this evidence, the 2022 SHED found

that 65 percent of adults identifying as

LGBTQ+ were doing at least okay financially,

compared with 75 percent of those not identi-

fying as LGBTQ+.

6

Moreover, an even lower

55 percent of transgender or nonbinary adults

were doing at least okay financially.

Finally, 56 percent of adults with a disability

were doing at least okay financially, markedly

lower than adults without a disability.

7

4

Neighborhood income is defined using the Community Reinvestment Act definition. Under this definition, low- and

moderate-income refers to communities that have a median family income of less than 80 percent of the area median

income. For details on the definition, see Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, “Community Reinvestment

Act (CRA) Resources,” https://www.federalreserve.gov/consumerscommunities/cra_resources.htm.

5

For example, see Thom File and Joey Marshall, “Household Pulse Survey Shows LGBT Adults More Likely to Report

Living in Households with Food and Economic Insecurity than Non-LGBT Respondents,” America Counts: Stories Behind

the Numbers (Suitland, MD: U.S. Census Bureau, August 11, 2021), https://www.census.gov/library/stories/2021/08/

lgbt-community-harder-hit-by-economic-impact-of-pandemic.html.

6

Survey respondents could report their sexual orientation and gender identity on a demographic profile survey previously

conducted by the survey vendor. Respondents are classified as LGBTQ+ based on responses to these questions. Differ-

ences in financial well-being between adults identifying as LGBTQ+ and other adults were present even after controlling

for age.

7

Disability status is defined based on a five-question functional limitation sequence that asks about hearing, vision,

ambulatory, self-care, and independent living difficulties. This approach for determining disability status is similar to the

six-question sequence used for the American Community Survey (see U.S. Census Bureau, “How Disability Data Are Col-

lected from the American Community Survey,” https://www.census.gov/topics/health/disability/guidance/data-

collection-acs.html).

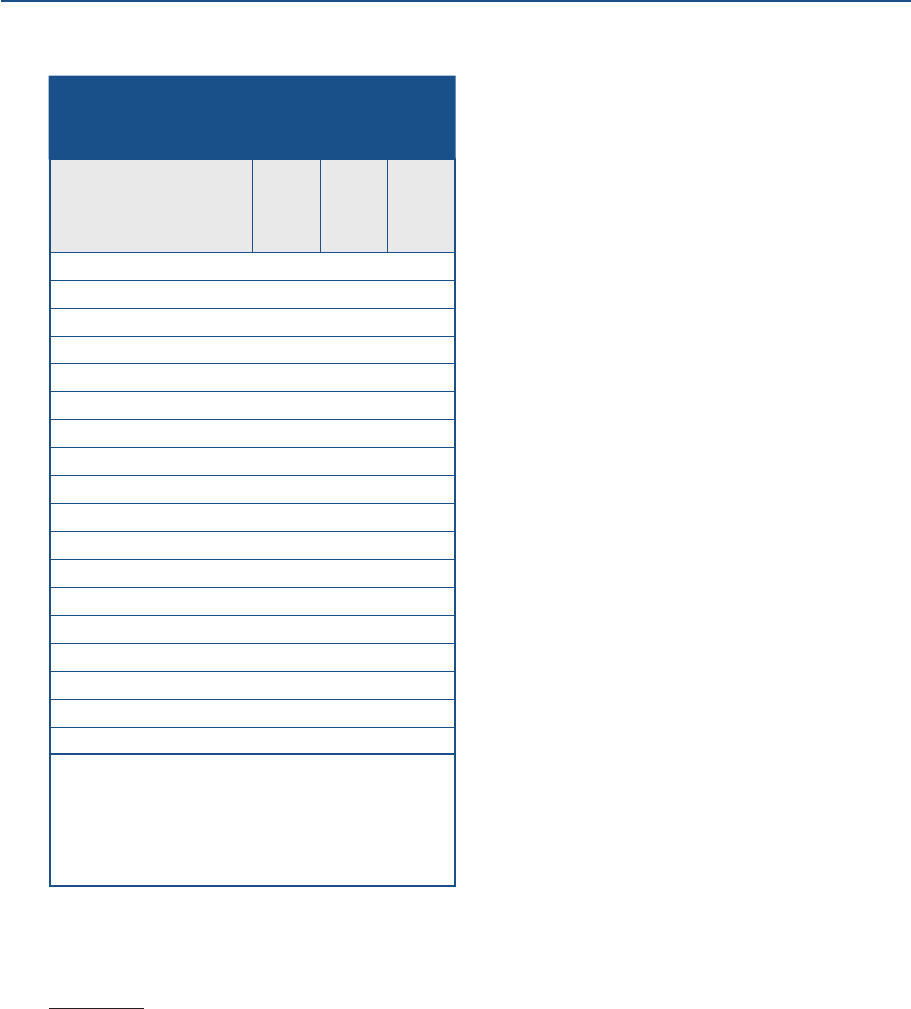

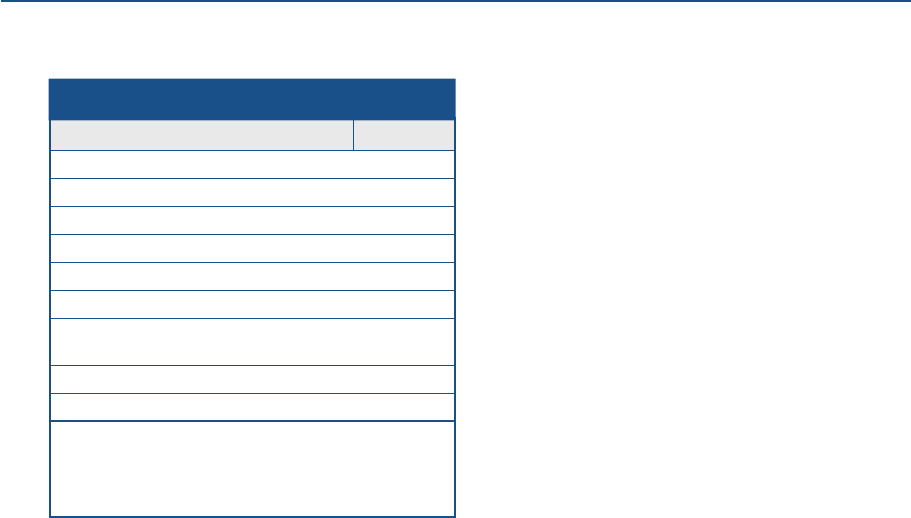

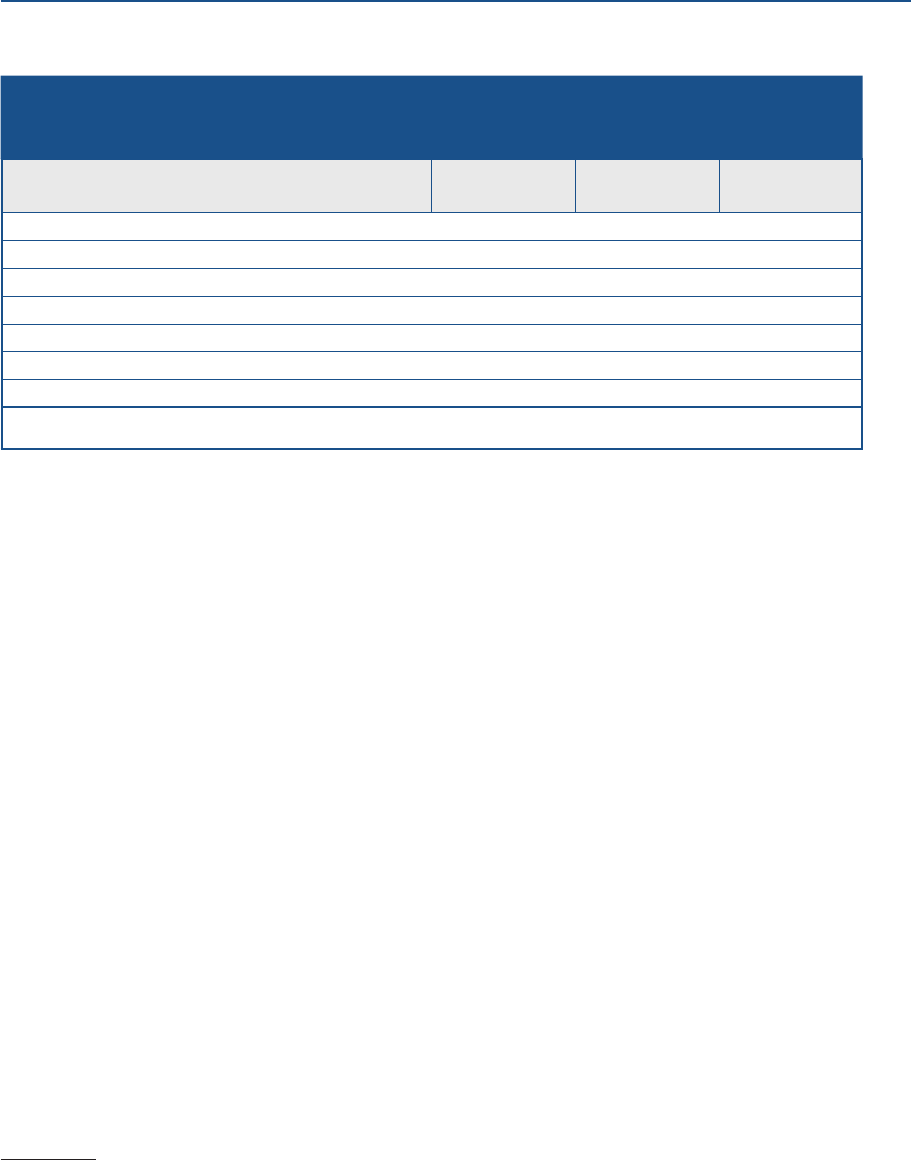

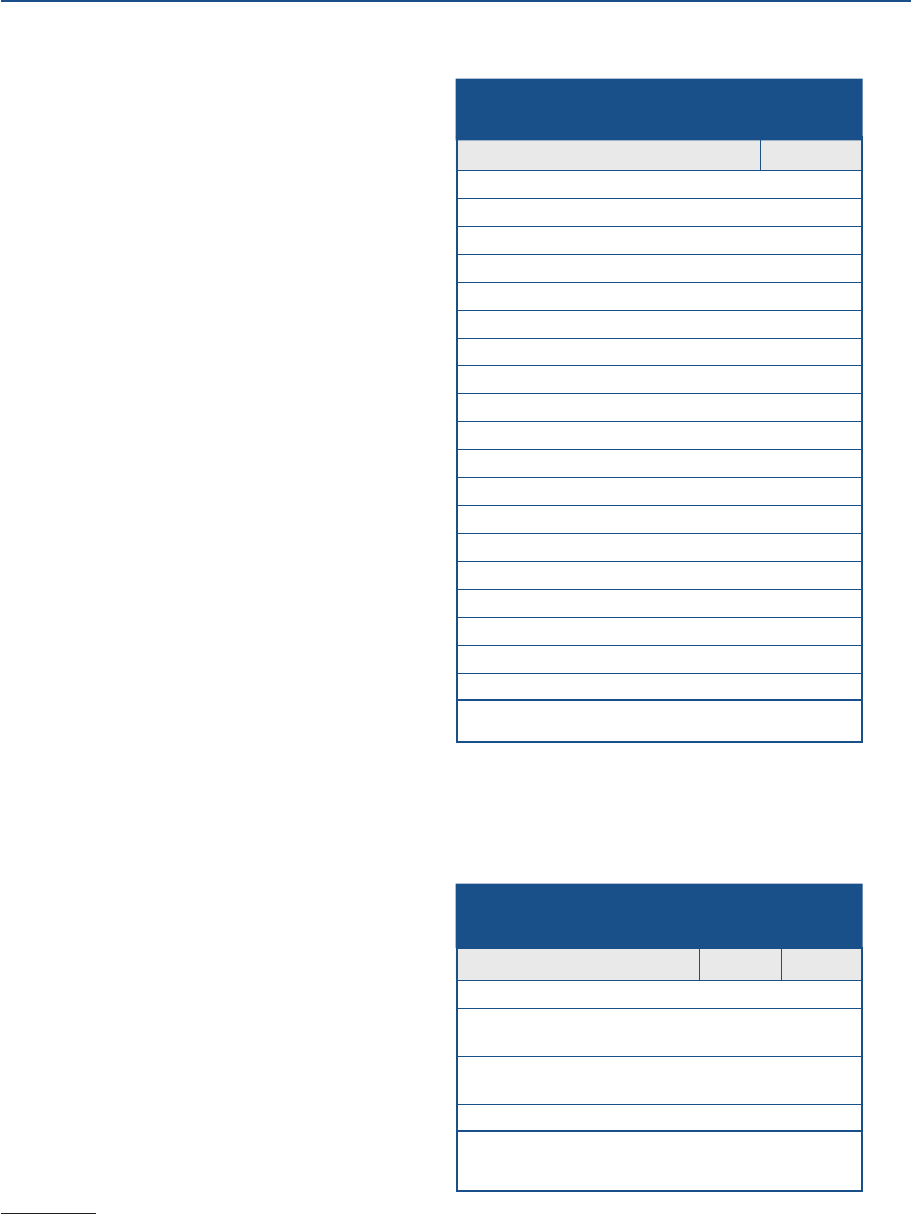

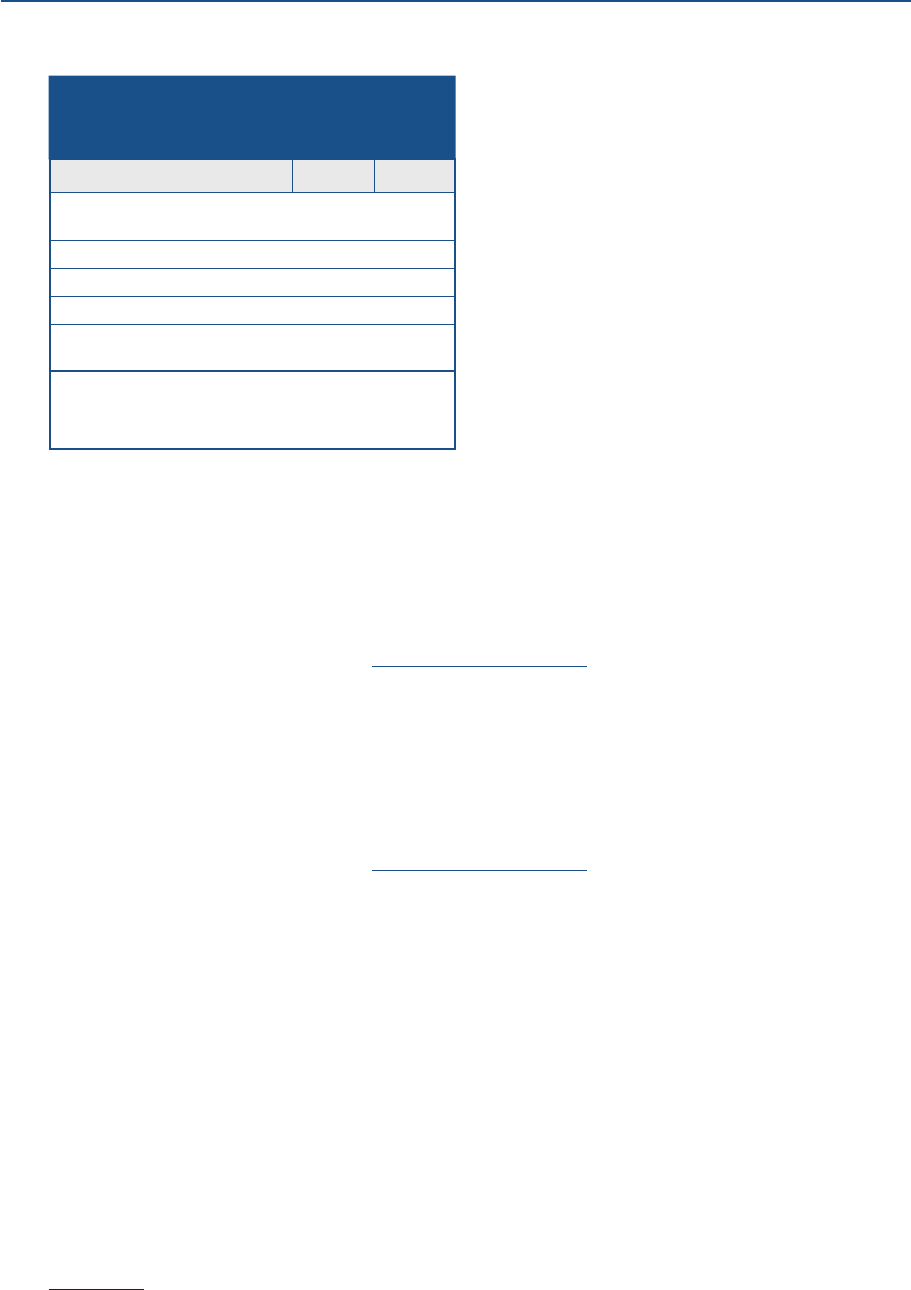

Table 1. At least doing okay financially (by

demographic characteristics)

Percent

Characteristic 2022

1-year

change

(since

2021)

3-year

change

(since

2019)

Family income

Less than $25,000 54 −1 3

$25,000–$49,999 61 −5 −5

$50,000–$99,999 78 −7 −6

$100,000 or more 93 −3 −2

Disability status

Disability 56 −4 n/a

No disability 77 −4 n/a

LGBTQ+ status

Identifies as LGBTQ+ 65 −2 1

Does not identify as LGBTQ+ 75 −5 −2

Metropolitan status

Metro area 74 −4 −2

Non-metro area 67 −5 −5

Neighborhood income

Low or moderate income 63 −3 0

Middle or upper income 77 −5 −3

Overall 73 −5 −2

Note: Among all adults. Low- or moderate-income neighbor-

hoods are defined here using the definition from the Community

Reinvestment Act. Disability status was first identifiable in the

2021 survey. Here and in subsequent tables and figures, per-

centages may not sum to 100 because of rounding.

n/a Not applicable.

8 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

Changes in Financial Situation over Time

The survey also measures overall financial well-being by asking respondents whether they are

better or worse off financially than they were 12 months earlier. Measuring well-being in this way

helps track changes in perceived well-being over time, as some individuals may have felt worse off

financially than they were a year earlier, for instance, even if they felt they were still doing okay

overall (or that their financial well-being was improving even if they were still struggling overall).

The share of adults who said they were worse

off financially than a year earlier increased

sharply from 20 percent in 2021 to 35 per-

cent in 2022, the highest level since the ques-

tion was first asked in 2014 (figure 5). The

share doing about the same as a year earlier

fell 8 percentage points to 46 percent, while

the share who said they were better off fell

6 percentage points to 19 percent.

The spike in those doing worse off financially

occurred across demographic groups, though

adults with higher levels of education saw the

largest change. Thirty-one percent of those

with at least a bachelor’s degree said they

were worse off financially than a year ago, up

from 13 percent in 2021 and 10 percent in

2019, before the pandemic. This pattern may

reflect the fact that those with bachelor’s degrees not only faced rising prices but, because they

are more likely to have exposure to the stock market, may have also been more affected by stock

market declines.

8

That said, those with lower levels of education continued to be the most likely to say they were

doing worse off than a year ago. In 2022, 40 percent of adults with less than a high school degree

reported doing worse off financially. The share was up from 33 percent in 2021 and was more

than double the 18 percent seen in 2019, before the pandemic.

To get a longer-term perspective, individuals were also asked to compare their current financial cir-

cumstances to how they perceived their parents’ financial situation at the same age. Looking

across generations shows evidence of economic progress over time, despite financial setbacks

8

For example, adults with over $1 million in savings or investable assets had a far larger increase in their likelihood of

saying they were worse off than was seen among those with under $50,000 of assets.

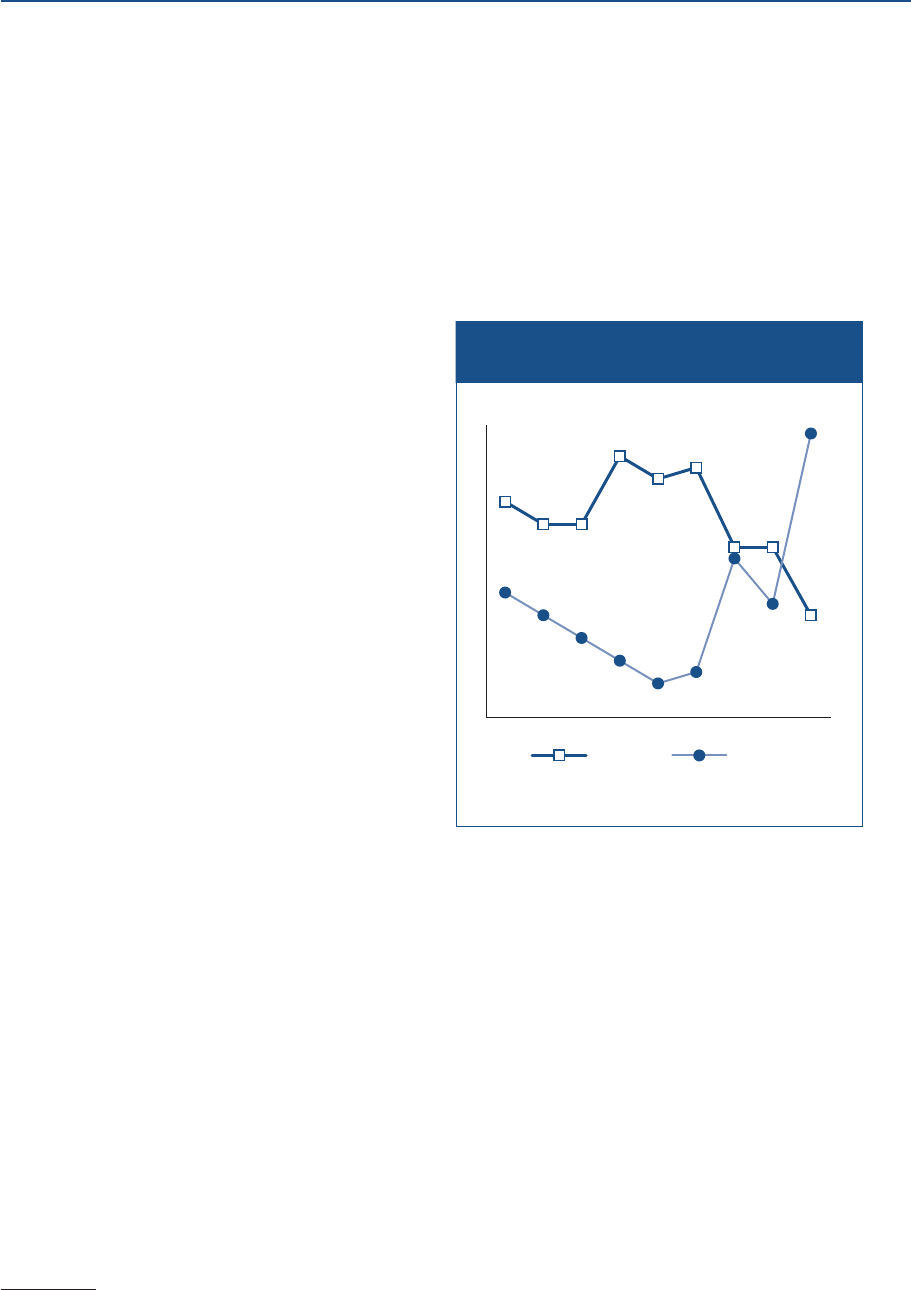

Figure 5. Financial situation compared with

12 months prior (by year)

Better off

Worse off

21

29

19

27

27

17

15

33

13

31

14

32

24

25

20

25

35

19

202220212020201920182017201620152014

Percent

Note: Among all adults.

Overall Financial Well-Being 9

during the pandemic. A majority of adults (54 percent) thought they were better off financially than

their parents had been. This compares with the 57 percent who thought so both in 2021 and in

2019, before the onset of the pandemic. Nearly one-fourth thought they were worse off than their

parents were at the same age in 2022.

People holding at least a bachelor’s degree were more likely to experience upward economic

mobility, relative to those with less education. This was particularly true among first-generation col-

lege graduates—those who completed a bachelor’s degree and whose parents did not—among

whom 69 percent thought they were better off financially than their parents were.

Main Financial Challenges

The survey further explored financial well-being by posing an open-ended question asking people

about their main financial challenges or concerns.

9

The responses were classified into broad cat-

egories based on keywords or phrases.

10

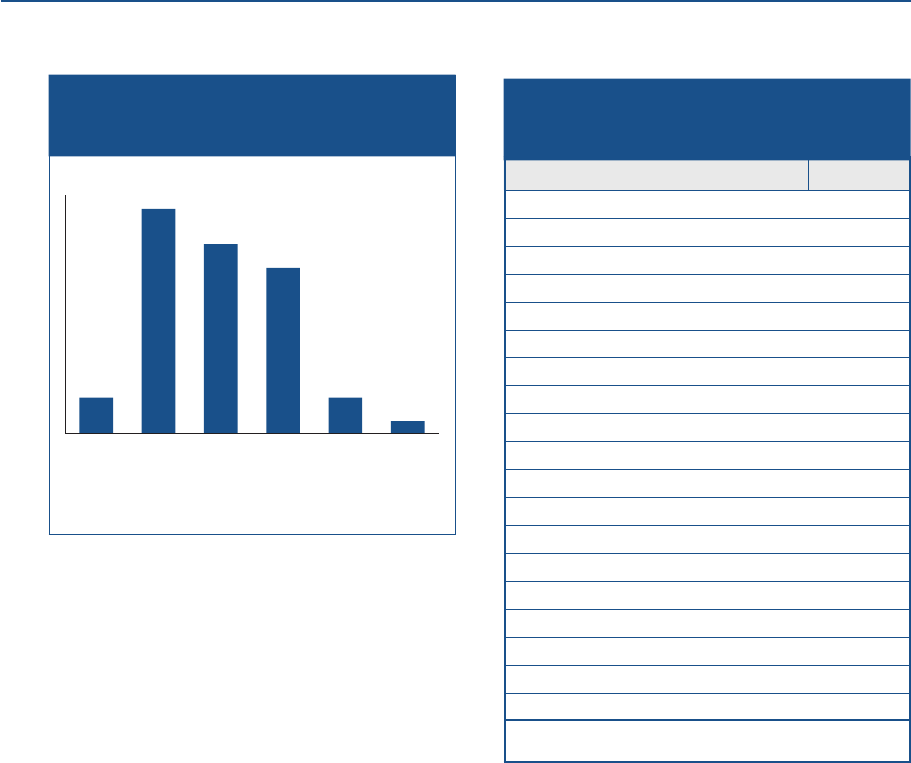

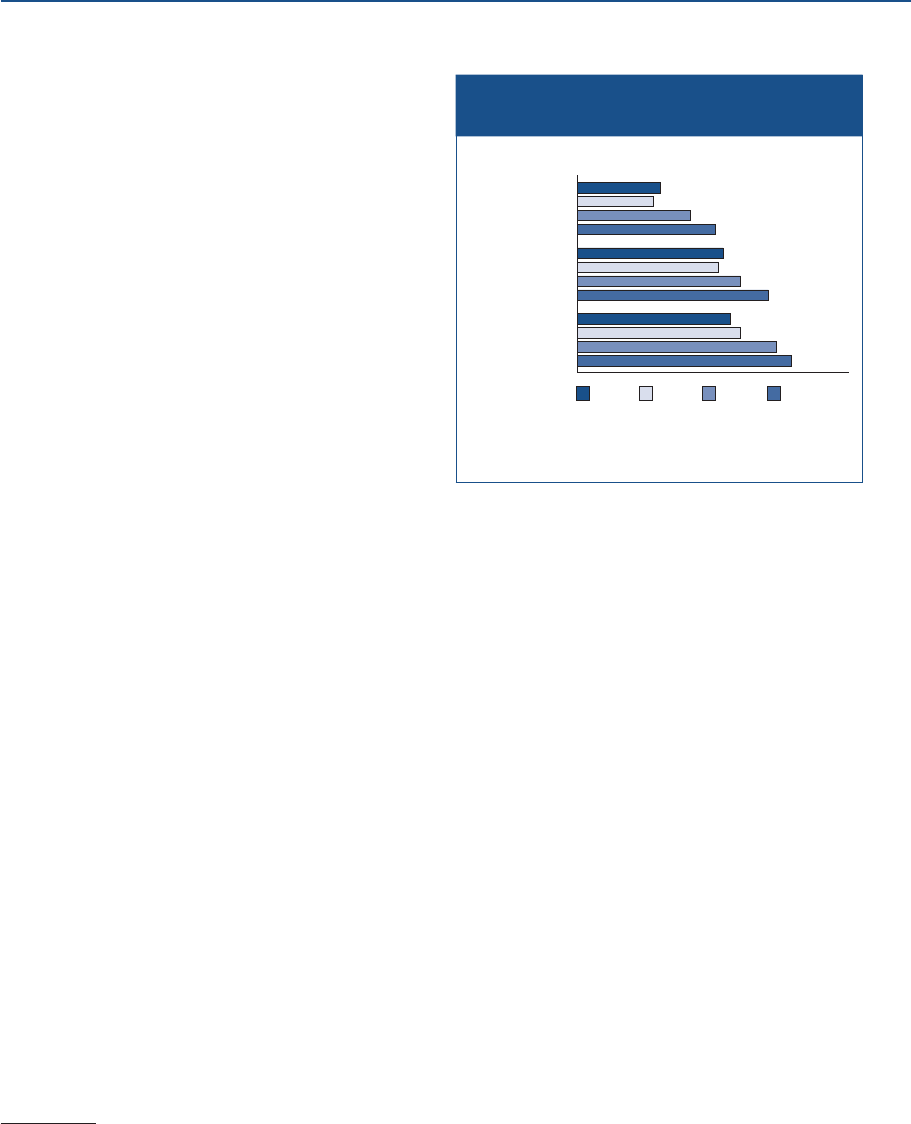

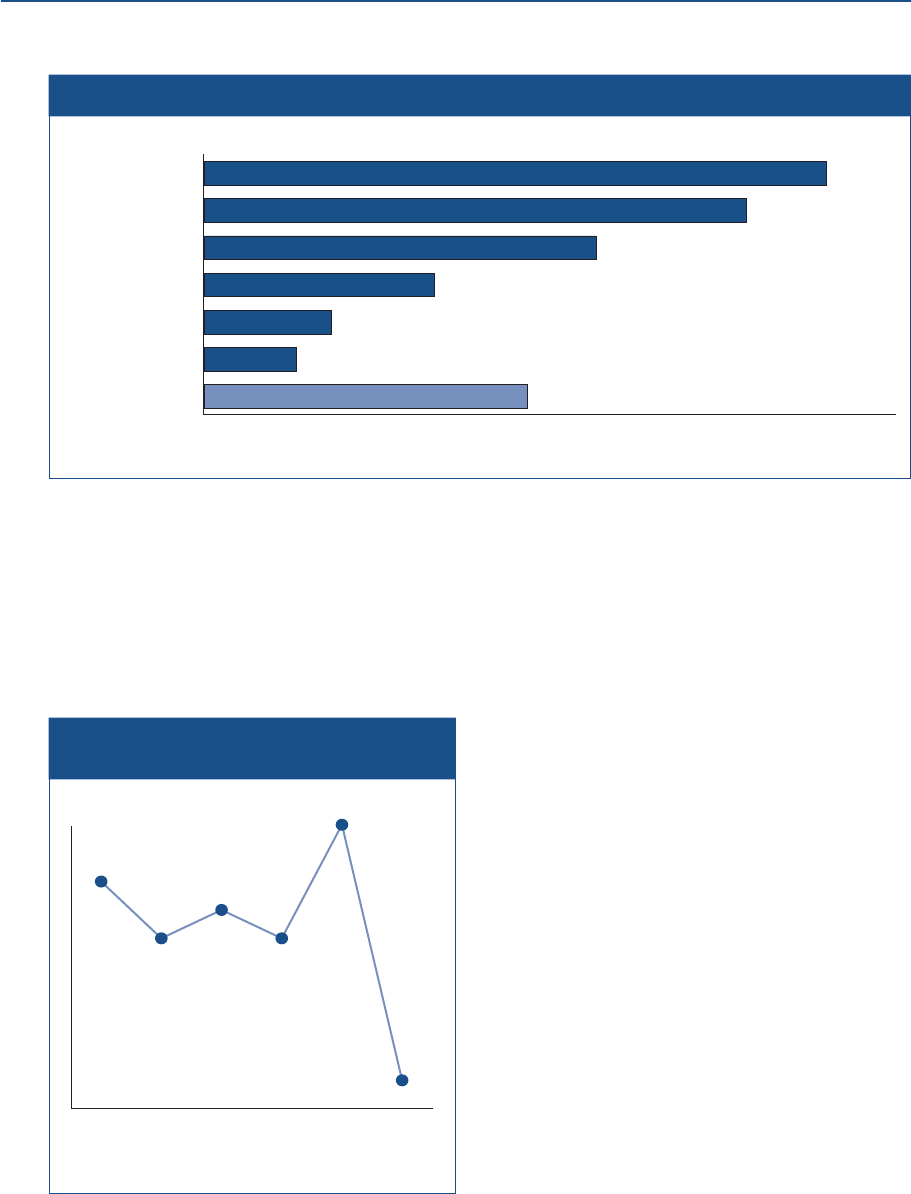

Inflation was the most common challenge, with one-third

classified into that category, followed by general needs, retirement and savings, and housing

(figure 6). Twenty-eight percent said they did not have any financial challenges or concerns.

When describing challenges related to inflation, many people mentioned the cost of food, gas, and

utilities. For example, one respondent stated that “energy costs, grocery costs, gasoline: every-

thing we buy now has increased drastically.”

Others noted that, while prices have increased, wages have often not kept up. This sentiment was

expressed by one respondent who said that “prices [are] going up but our paychecks don’t. [It is]

hard to afford what we need and our kids need.” This concern is consistent with those adults who

said their spending had increased, but their income had not (see the “Income” section of

this report).

9

The question text is as follows: “In a couple of words, please describe the main financial challenges or concerns facing

you or your family. If none please click the “None” box.” Seventy-one percent of respondents provided a text response to

the question, and 27 percent selected “None.” The remaining 2 percent of respondents who did not provide a text

response and did not check the “None” box were excluded from the analysis.

10

Text entries were categorized based on words or word stems included in the response. “Inflation” includes responses

with inflat, cost, pay more, paying more, increas, expensive, price, pricing, higher, rising, skyrocket, sky rocket, going up,

gone up. Those with bill, util, electric, heat, everything, necessities, basic needs, essential, can’t afford, not enough, get

by, getting by, surviv, struggl, no money, challenge, living expense, or food were categorized as “general needs;” those

with retire, 401k, stock, market, portfolio, pension, old age, Medicare, SSI, IRA, 401(k), Social Security, save, saving, or

fund were categorized as “retirement and savings;” those with hous, rent, home, or mortgage were categorized as

“housing;” those that mentioned work, job, wage, employ, raise, paycheck, pay check, salary, laid off, part time, hours,

full time, overtime, skills, or unemp were categorized as “employment;” those with medical, medicine, health, Medicaid,

Medicare, dental, dentist, cancer, sick, ill, doctor, hospital, or prescription were categorized as “medical;” those with

credit, loan, debt, or owe were categorized as “debt;” those that mentioned college, school, education, tuition, degree,

university, or student were categorized as “education.” Responses may be included in multiple categories or no catego-

ries, as the categories are neither exhaustive nor mutually exclusive.

10 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

People also expressed concerns about saving for retirement. For example, one respondent said,

“Not able to save enough for retirement. My 401K and IRA have lost a significant amount of

money. I won’t be able to retire as initially planned.” Concerns about retirement savings are con-

sistent with the finding that just 31 percent of non-retirees think that their retirement savings are

on track, as discussed in the “Retirement and Investments” section of this report.

The 2016 survey also included the same open-ended question about financial challenges, allowing

for comparison of people’s main financial challenges over time (figure 6). In 2016, 53 percent of

adults said they did not have any financial challenges or concerns, much higher than the 28 per-

cent who said so in 2022. People were much less likely to mention challenges related to inflation

in 2016, consistent with macroeconomic trends at that time.

11

They also were less likely to men-

tion general needs. Incidence for most of the other categories was generally similar in 2016

and 2022.

12

Inflation was the most common challenge among people of all income levels in 2022, suggesting

a widespread effect of higher prices across the population (figure 7).

13

The prevalence of other

challenges varied by income. For example, higher-income adults were more likely than lower-

income adults to mention financial challenges related to retirement—and this was the case

11

In 2016, no respondents directly mentioned the word “inflation” as a financial challenge, instead mentioning things like

an increasing cost of living or rising prices.

12

The specific challenges and concerns within the broader categories may have changed from 2016 to 2022.

13

In part, the lower share reporting inflation concerns among the lowest income group may reflect the different terms

people use to describe their finances—as evidenced by the higher share citing general needs. It also partially reflects

somewhat more respondents in that income group selecting “none,” which may be a form of non-response to the open-

text question.

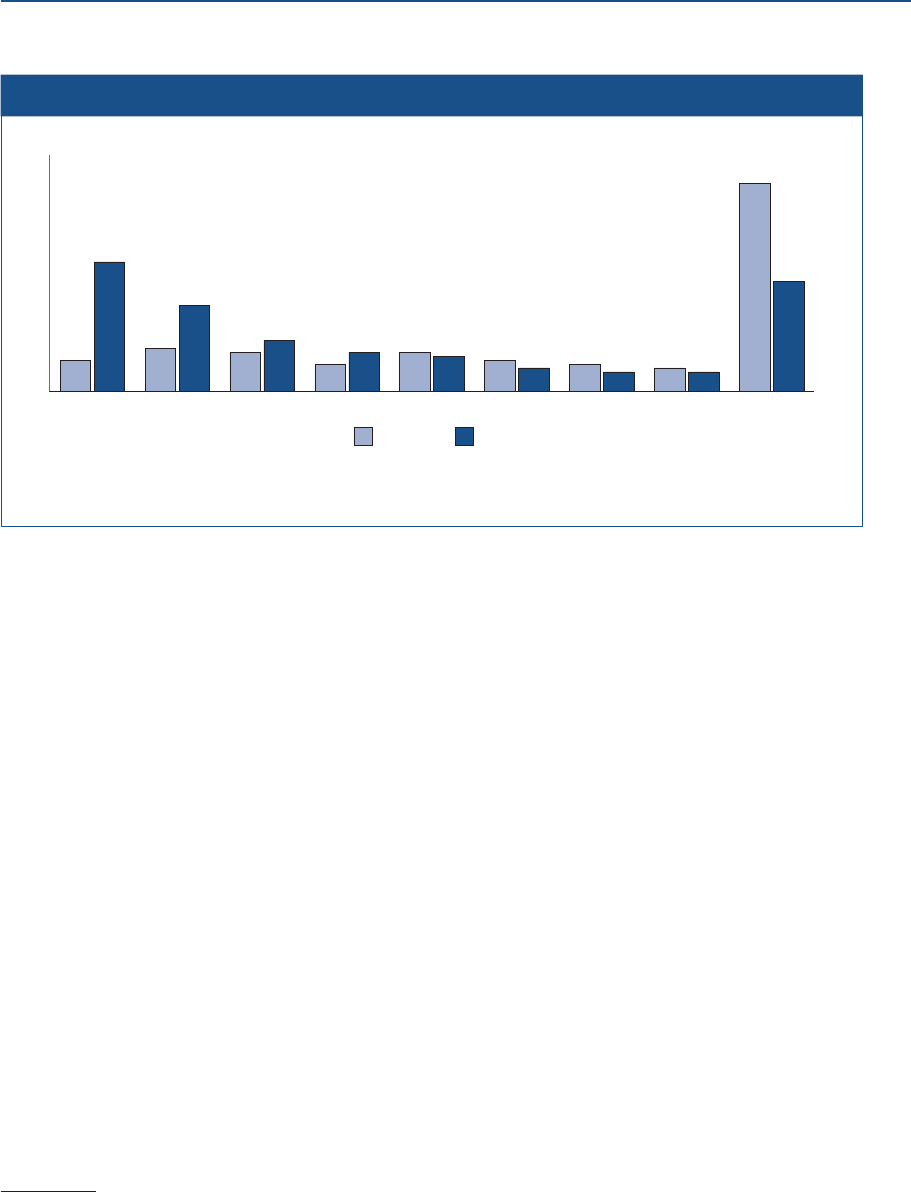

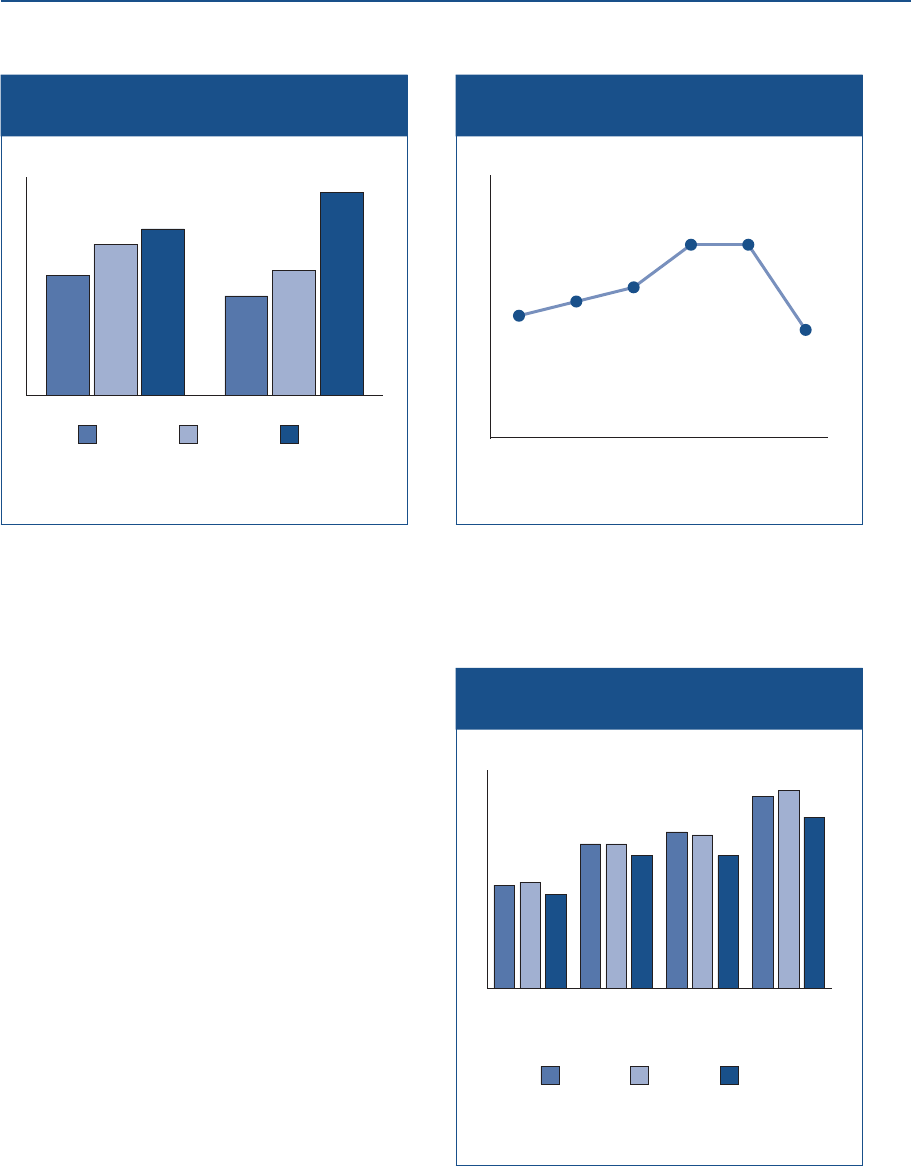

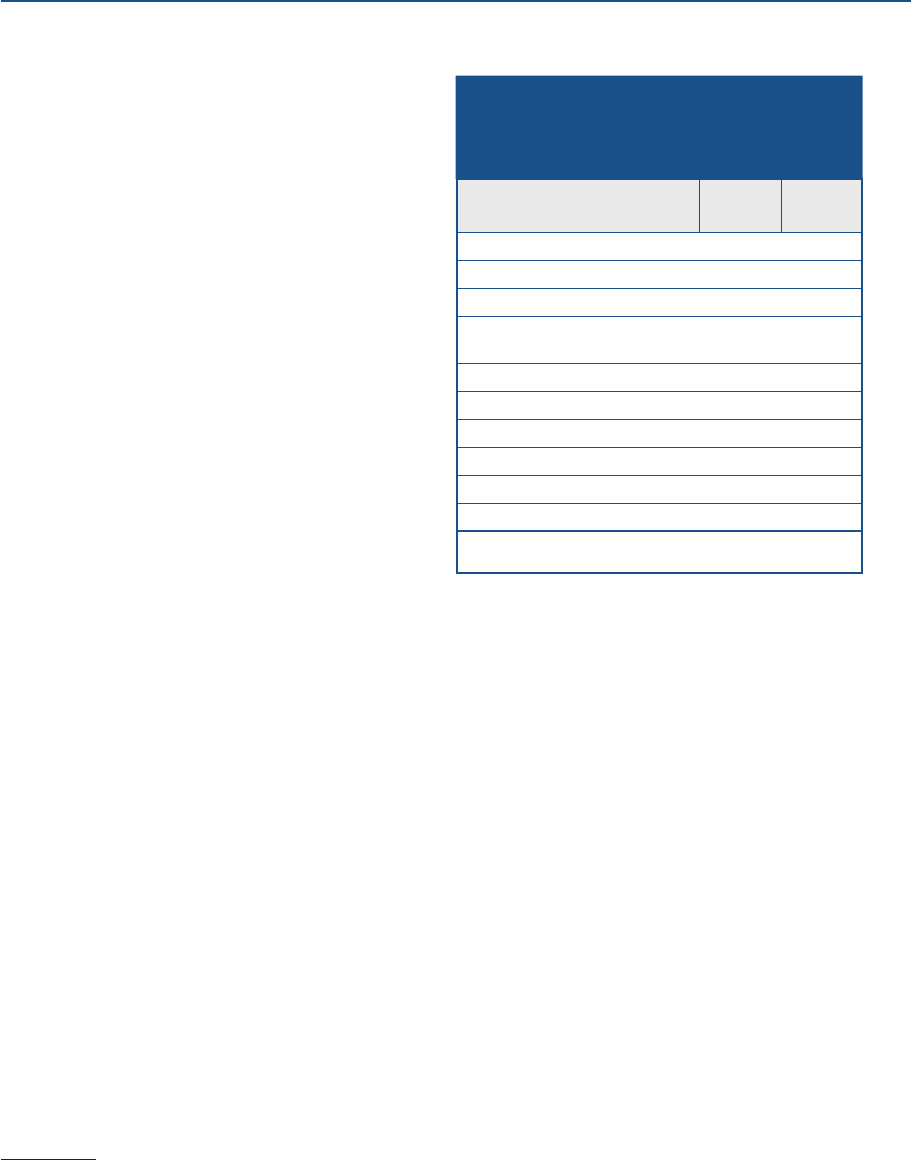

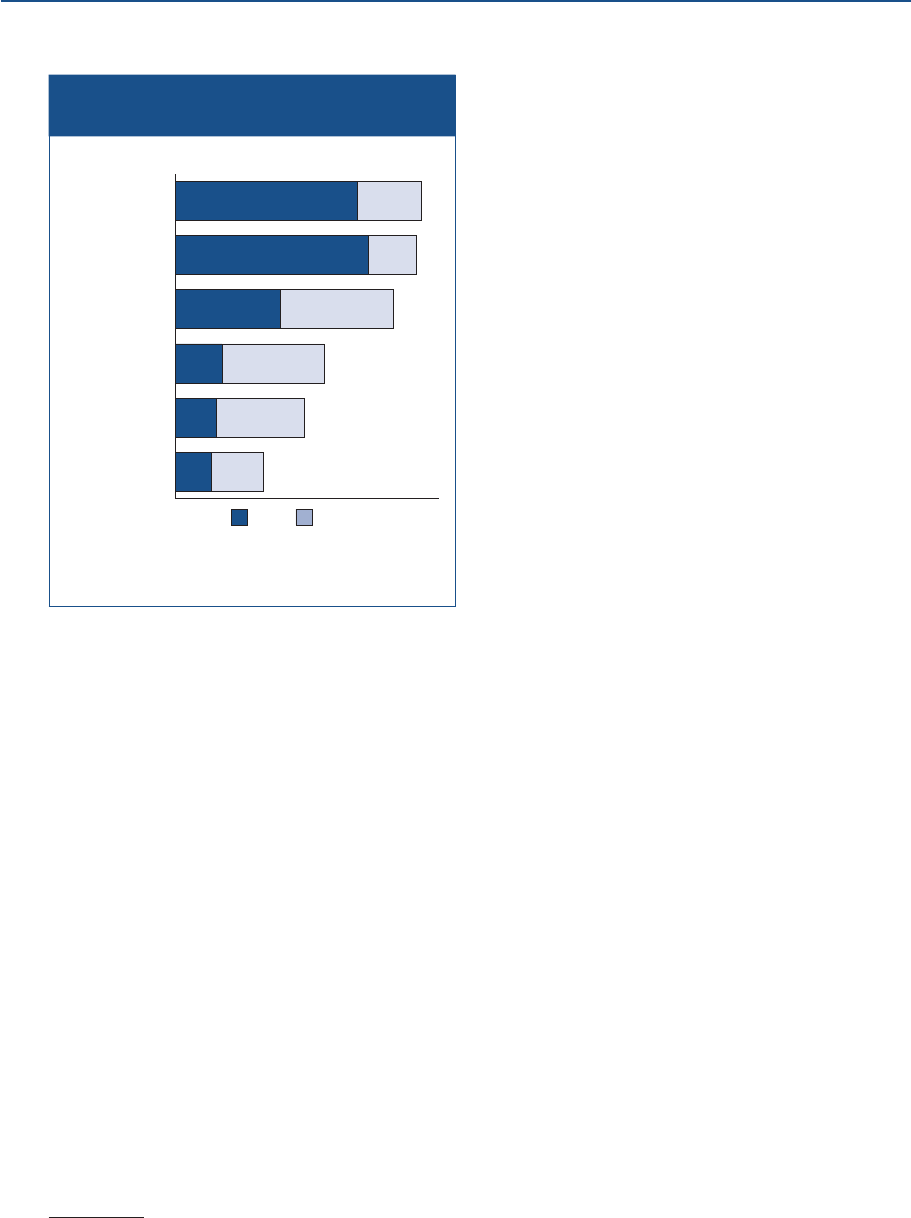

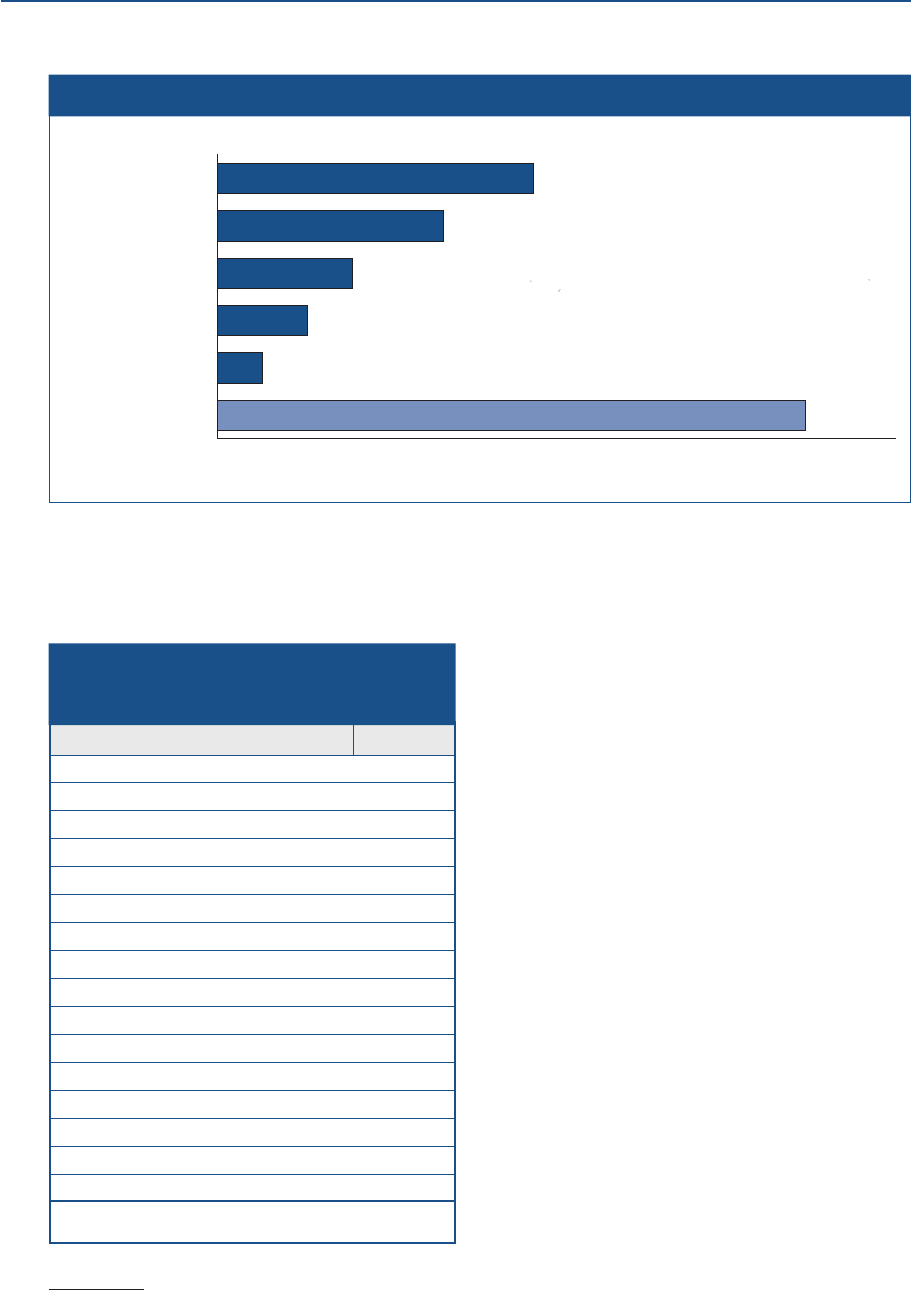

Figure 6. Categories of self-reported main financial challenges, 2016 and 2022

2022

2016

Percent

8

33

11

22

10

13

7

10 10

9

8

6

7

5

6

5

53

28

NoneEducationDebtMedicalEmploymentHousingRetirement

and savings

General

needs

Inflation

Note: Among respondents who provided a text response or selected the “none” box. Key identifies bars in order from

left to right.

Overall Financial Well-Being 11

regardless of age—while lower-income adults were more likely than higher-income adults to men-

tion general needs and employment.

Local and National Economic Conditions

Along with questions about their own financial

circumstances, people were asked to rate

their local economy and the national economy

as “excellent,” “good,” “only fair,” or “poor.”

Thirty-eight percent of adults rated their local

economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2022,

down from 48 percent in 2021, and well below

the 63 percent of adults who rated their local

economy as “good” or “excellent” in 2019,

before the pandemic.

Declines in people’s perceptions about their

local economy occurred across census region

and metropolitan status (table 2).

Figure 7. Categories of self-reported main financial challenges (by family income)

Percent

NoneEducationDebtMedicalEmploymentHousingRetirement

and savings

General

needs

Inflation

Less than $50,000 $50,000-$99,999

$100,000 or more

31

25

29

6

6

66

7

7

4

4

44

11

1111

8

9

8

14

19

28

23

13

34

40

29

Note: Among respondents who provided a text response or selected the “none” box. Key identifies bars in order from

left to right.

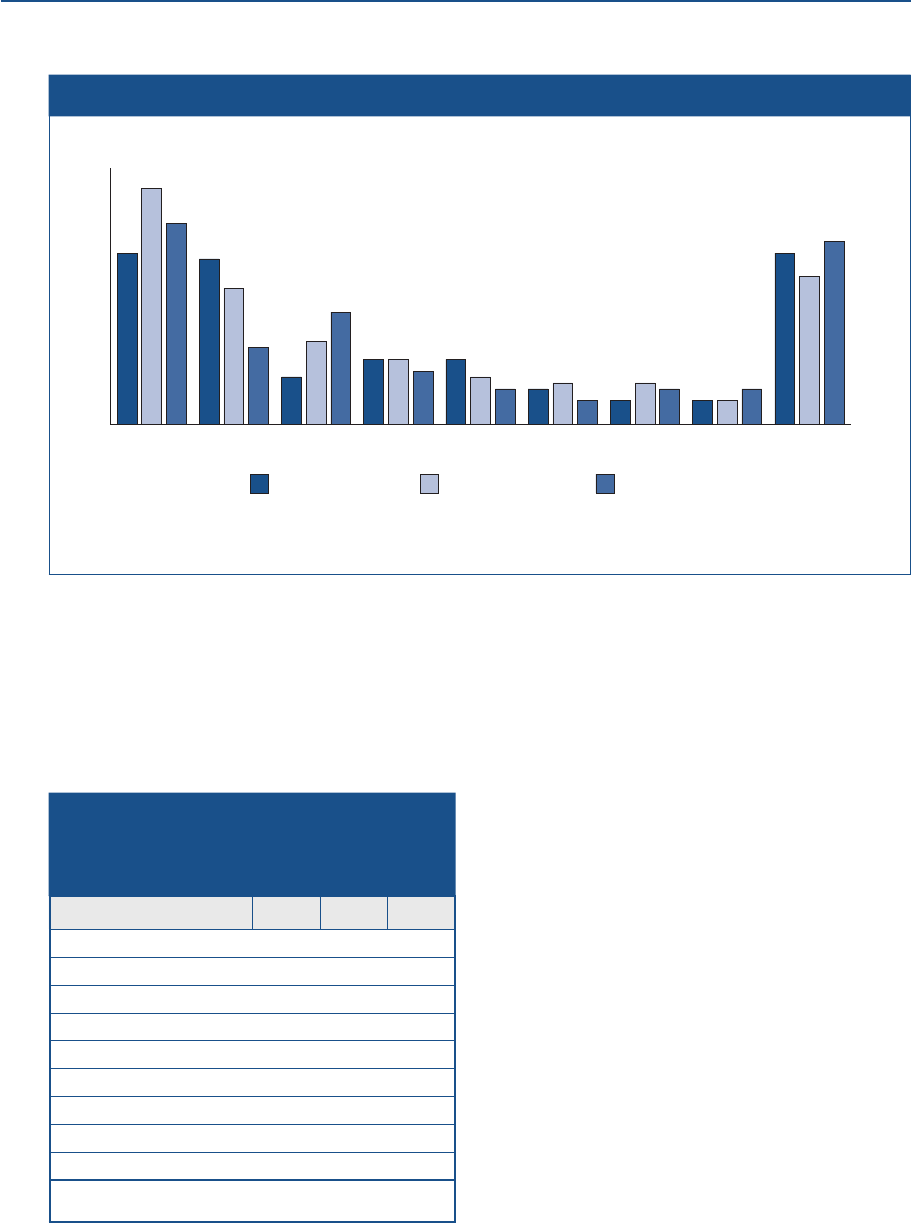

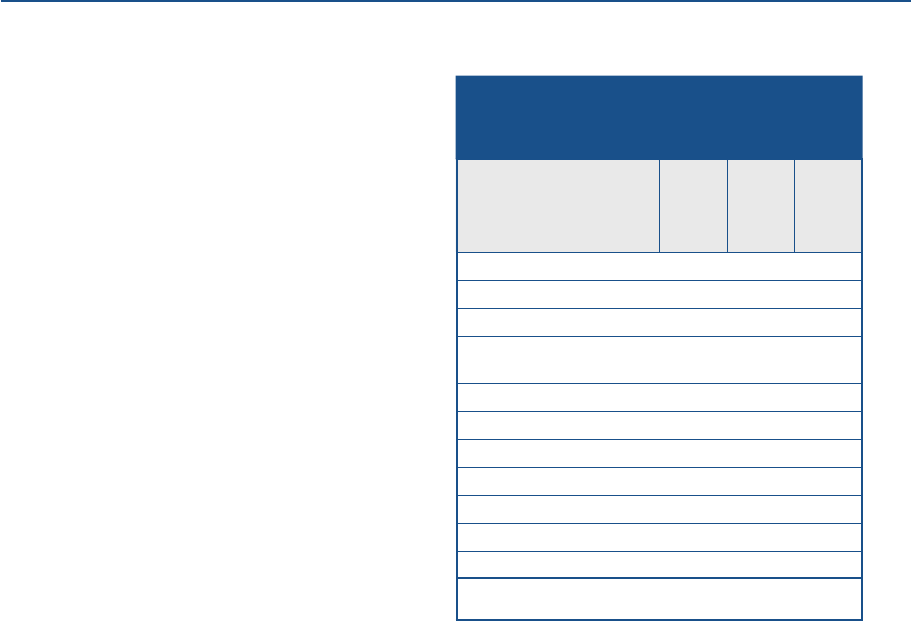

Table 2. Self-assessment of local economy as

good or excellent (by census region and

metropolitan status)

Percent

Characteristic 2019 2021 2022

Census region

Northeast 63 48 38

Midwest 64 49 40

South 64 49 40

West 61 46 35

Metropolitan status

Metro area 65 50 40

Non-metro area 53 34 30

Overall 63 48 38

Note: Among all adults.

12 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

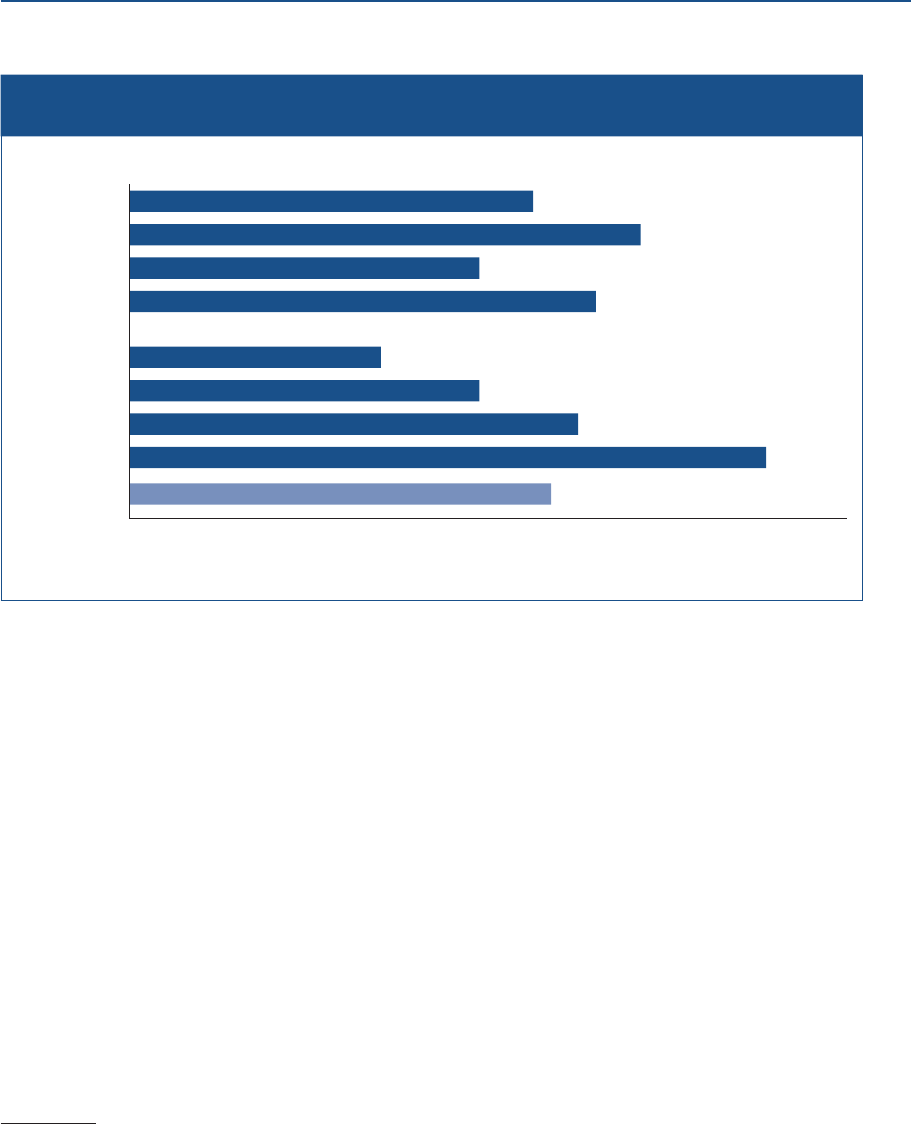

People’s perception of the national economy continued to decline. The share rating the national

economy as “good” or “excellent” fell to 18 percent in 2022, the lowest share since the survey

began asking this question in 2017. Moreover, this share has fallen a substantial 32 percentage

points since before the pandemic in 2019, when one-half of adults rated the national economy as

“good” or “excellent” (figure 8).

In contrast, people’s perception of their own financial well-being was down 2 percentage points

since 2019. As a result, the gap between people’s perceptions of their own financial well-being

and their perception of the national economy has more than doubled in recent years, widening

from 26 percentage points in 2019 to 55 percentage points in 2022.

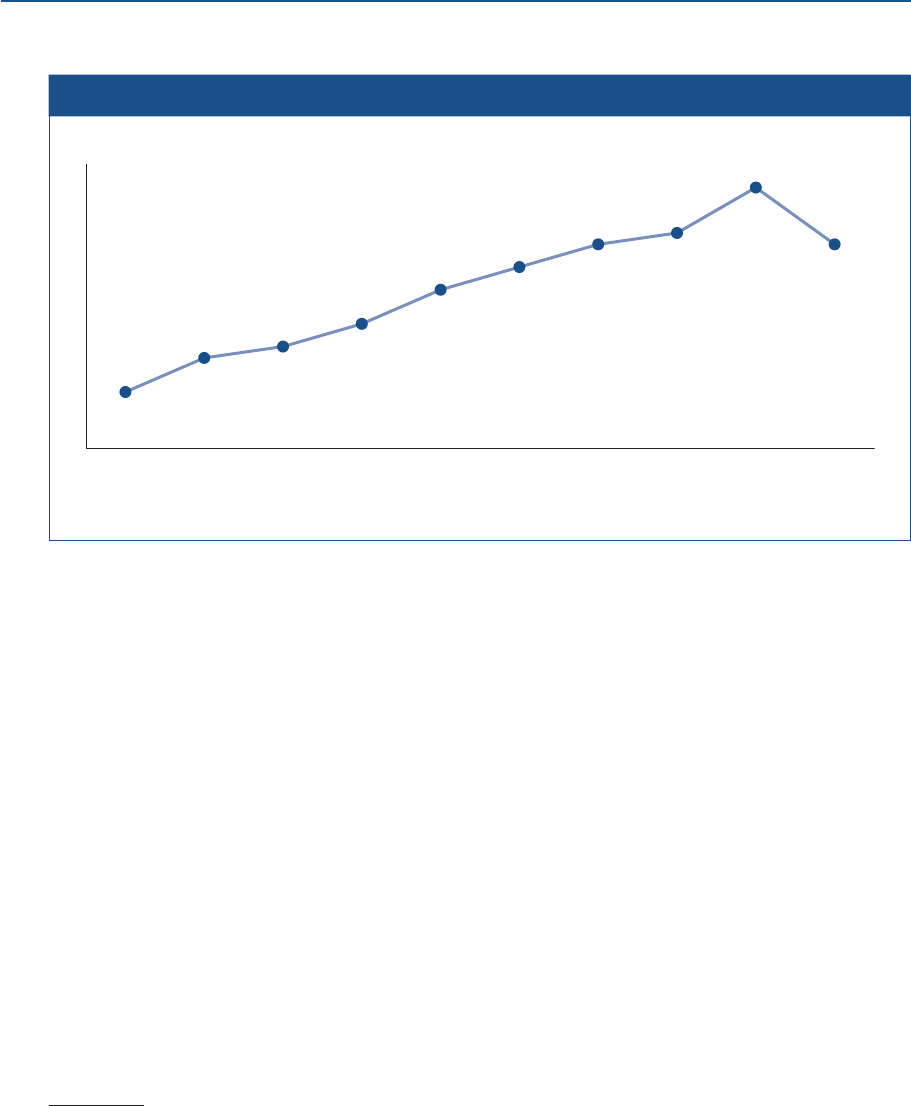

Figure 8. Assessment of own financial well-being, local economy, and national economy (by year)

202220212020201920182017

74

75 75

57

41

64

51

63

50

75

43

26

78

73

48

38

24

18

Percent

National economy

(good or excellent)

Local economy

(good or excellent)

Own finances

(doing at least okay)

Note: Among all adults.

Overall Financial Well-Being 13

Income

A sizeable share of adults said their family’s monthly income increased in 2022 compared with a

year earlier. However, the share of adults who said their spending increased from the prior year

was even greater. Consistent with these changes in income and spending, fewer adults appear to

have margin in their family budgets. The share of adults who said they spent less than their

income in the month before the survey fell below the level it had been before the pandemic.

Level and Source of Income

In this report, family income is defined as the

cash income from all sources, prior to taxes

and deductions, that respondents and their

spouse or partner received during the pre-

vious year. Thirty percent of adults had a

family income below $25,000, and 32 percent

had a family income of $100,000 or more

(figure 9).

14

Labor earnings were the most common source

of income, but many people had other sources

of income. Nearly two-thirds of adults and

their spouse or partner received wages, sala-

ries, or self-employment income (collectively

referred to here as labor income) (table 3). Fifty-three percent of all adults received non-labor

income in 2022.

15

Some adults received both types of income: 48 percent of those with a labor

income also had some form of non-labor income. Additionally, as discussed in the “Retirement

and Investments” section of the report, receipt of non-labor income was more common among

retirees.

14

In the 2022 SHED, respondents were asked to provide the amount of their income in dollars, with a follow-up question

using income ranges for those who did not give a response. The income distribution in the 2022 SHED is broadly similar

to that from the 2022 March Current Population Survey. However, the SHED has a slightly higher share with incomes

less than $25,000 or over $100,000 but fewer with incomes between $25,000 and $99,999. These deviations in the

estimates may result from differences between the surveys in how income questions are asked.

15

Non-labor or nonwage income is defined as income from interest, dividends, or rental income; Social Security (including

Old-Age and Disability Insurance (DI)); Supplemental Security Income (SSI), Temporary Assistance for Needy Families

(TANF), or cash assistance from a welfare program; unemployment income; or income from a pension. Non-labor income

does not include tax credits such as the Earned Income Tax Credit or in-kind benefits. It also does not include the small

number of respondents who reported receiving income but did not specify the source.

Figure 9. Family income

$100,000

or more

$50,000–

$99,999

$25,000–

$49,999

Less than

$25,000

30

15

23

32

Percent

Note: Among all adults.

15

While people received most forms of income

at similar rates as in 2021, receipt of unem-

ployment assistance dropped markedly. In

2022, the share of all adults receiving unem-

ployment income returned to the pre-pandemic

level of 2 percent, dropping from the elevated

levels of 14 percent in 2020 and 9 percent in

2021. This decline in the receipt of unemploy-

ment assistance reflects both the lower rate

of unemployment in 2022 and the termination

of enhanced unemployment assistance pro-

grams that were put into place during the

pandemic.

In addition to the income sources discussed

above, some adults relied on cash or in-kind

assistance from nonprofits and private sources—including financial support from a friend or family

member living outside of their home. Fifteen percent of adults received at least one type of assis-

tance from private or nonprofit sources in 2022. Specifically, 9 percent of all adults received free

groceries or meals through a food pantry, religious organization, or community organization, 2 per-

cent received financial assistance from a religious or community organization, and 8 percent

received financial assistance from friends or family not living with them. These rates are nearly

identical to those reported in 2021.

The likelihood of receiving financial support varied by age, with young adults being more likely than

older adults to receive assistance. For those age 18 to 29, 15 percent received financial assis-

tance from friends or family—over twice as high as the share of those age 30 and older who

received this type of financial assistance (7 percent).

Changes in Income and Spending

Many people experienced a change in their family’s monthly income and spending from a year ear-

lier. Thirty-three percent of adults said their family’s monthly income increased in 2022 compared

with the prior year, while 40 percent increased their monthly spending (figure 10). This share of

adults who reported an increase in monthly spending was 14 percentage points higher than the

share who reported this in 2021. While some adults saw both their spending and their income

increase, 23 percent of adults said that their spending had increased but their income had not.

In October 2022, just under half of adults reported spending less than their income in the past

month, down from highs reached in 2020 and 2021, and below the pre-pandemic levels in 2017

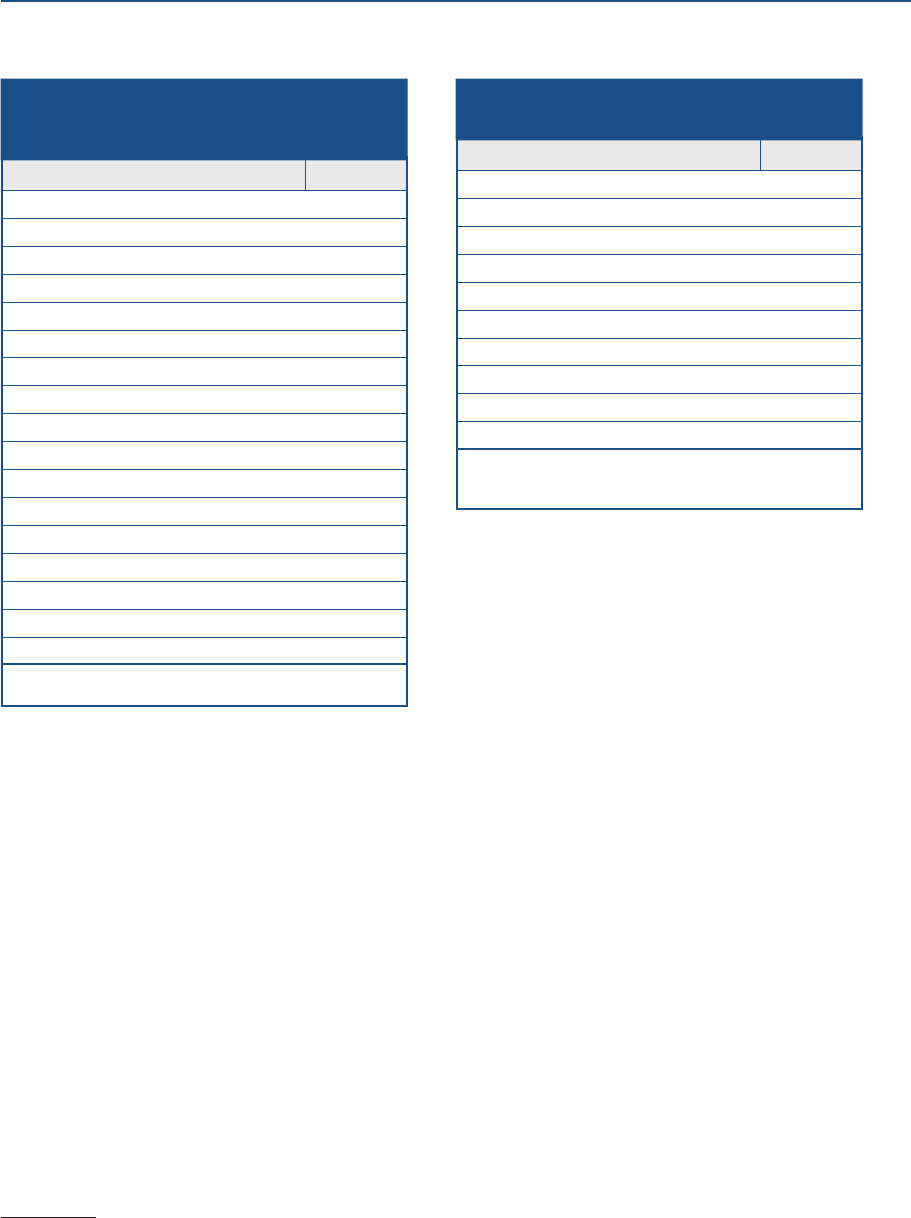

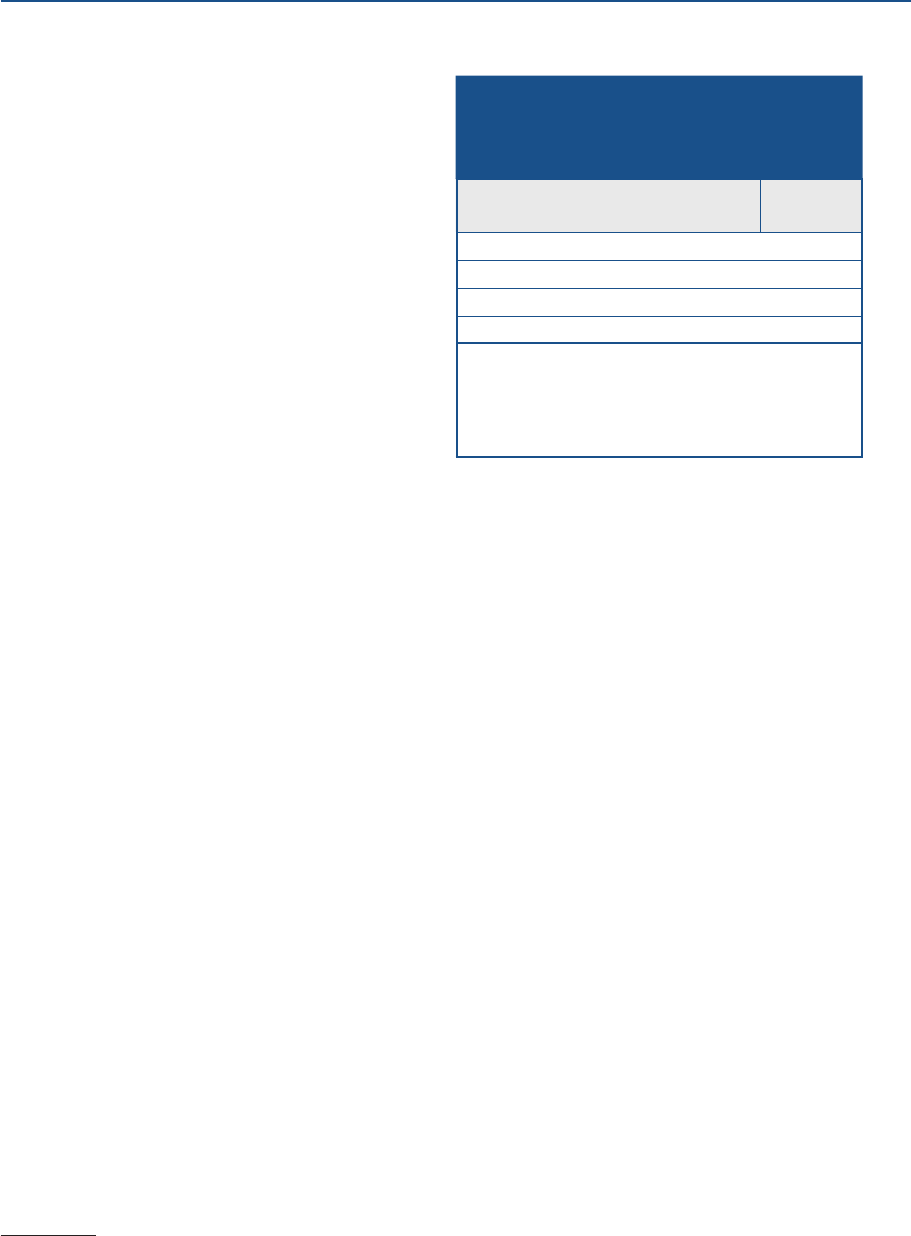

Table 3. Sources of income

Source Percent

Labor income

Wages, salaries, or self-employment 66

Non-labor income

Interest, dividends, or rental income 31

Social Security (including Old-Age and DI) 27

Pension 18

SSI, TANF, or cash assistance from a welfare

program 6

Unemployment income 2

Any non-labor income 53

Note: Among all adults. Respondents could select multiple

answers. Sources of income include the income of a spouse or

partner. DI is Disability Insurance; SSI is Supplemental Security

Income; and TANF is Temporary Assistance for Needy Families.

16 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

to 2019 (figure 11). Nineteen percent said their spending exceeded their income, while the

remainder (32 percent) said their spending and income were about the same.

Pullbacks in spending in the early part of the

pandemic, coupled with fiscal support that

many families received in 2020 and 2021,

may have given some households more

margin in their budgets over this period. In

2022, price increases affected family budgets

for many adults and may have contributed to

the decline in the share of adults who spent

less than their income in the prior month.

(See the “Expenses” section of this report for

more on the effect of price increases.)

Likely reflecting their higher income and

stronger financial circumstances generally,

adults with more education were more likely to

say they spent less than their income in the

past month. Thirty-two percent of adults with

less than a high school degree said their

spending was less than their income, compared with 58 percent of adults with a bachelor’s degree

or more (figure 12). However, adults with more education also saw a larger drop between 2021

and 2022 in the share spending less than their income.

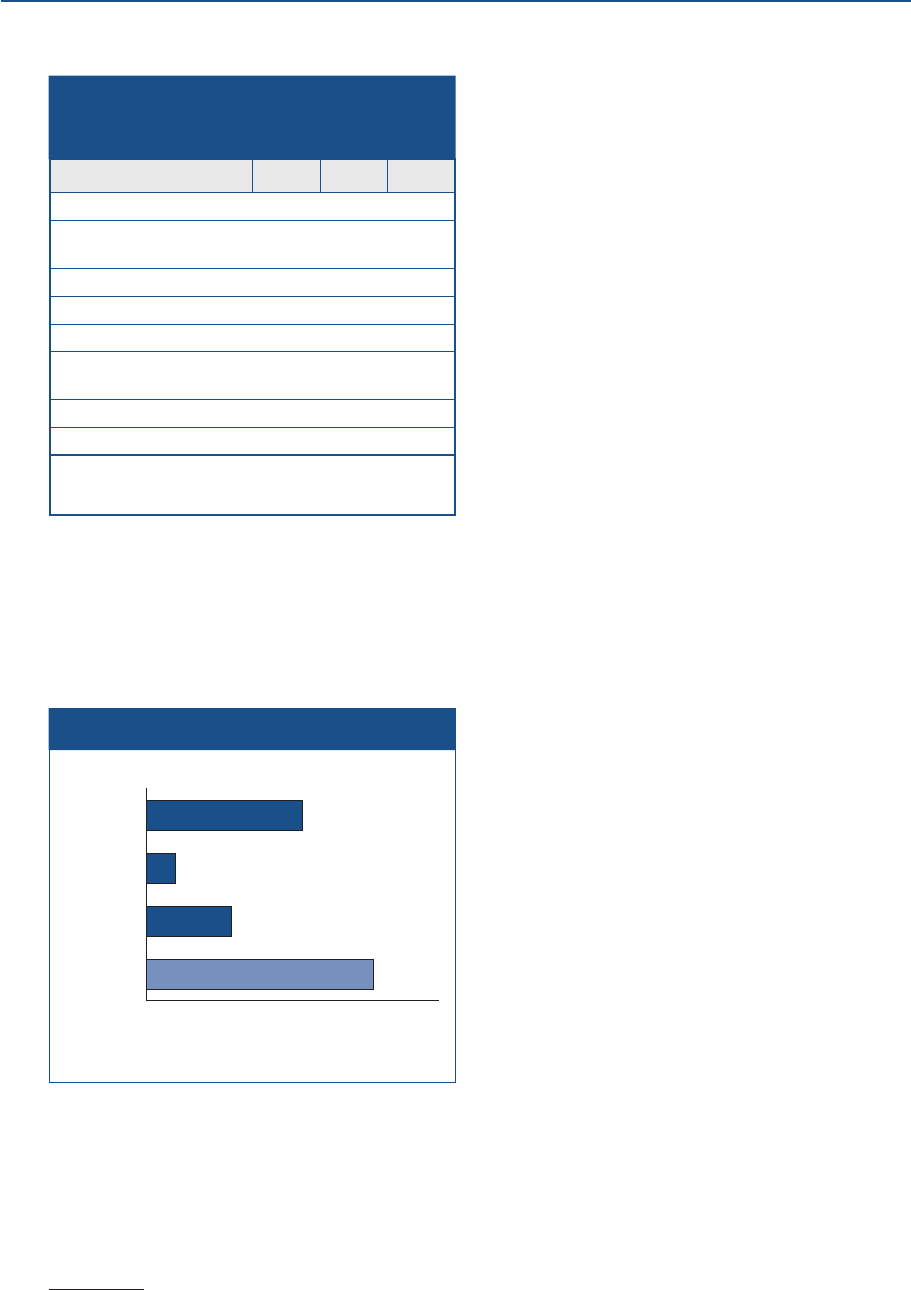

Figure 10. Increase in monthly income and

spending from 12 months earlier (by year)

Monthly spending increasedMonthly income increased

202220212020

24

30

33

20

25

40Percent

Note: Among all adults. Key identifies bars in order of

left to right.

Figure 11. Total spending less than income in

the prior month (by year)

202220212020201920182017

50

51

52

55 55

49

Percent

Note: Among all adults.

Figure 12. Total spending less than income in

the prior month (by year and education)

20222021

2020

35

49

53

65

36

49

52

67

32

45 45

58

Bachelor’s

degree

or more

Some college/

technical or

associate

degree

High school

degree

or GED

Less than a

high school

degree

Percent

Note: Among all adults. Key identities bars in order of

left to right.

Income 17

Income Variability

The total level of yearly income may mask changes in income from month to month, and mis-

matches between the timing of income and expenses can lead to financial challenges.

16

In 2022,

most adults had income that was roughly the same each month, but nearly 3 in 10 had income

that varied from month to month, similar to previous years.

Income variability was related to the type of income people received. Adults who received only

wages or other sources of labor income were more likely to report their income varied from month

to month (33 percent), compared with those with only non-labor income (13 percent).

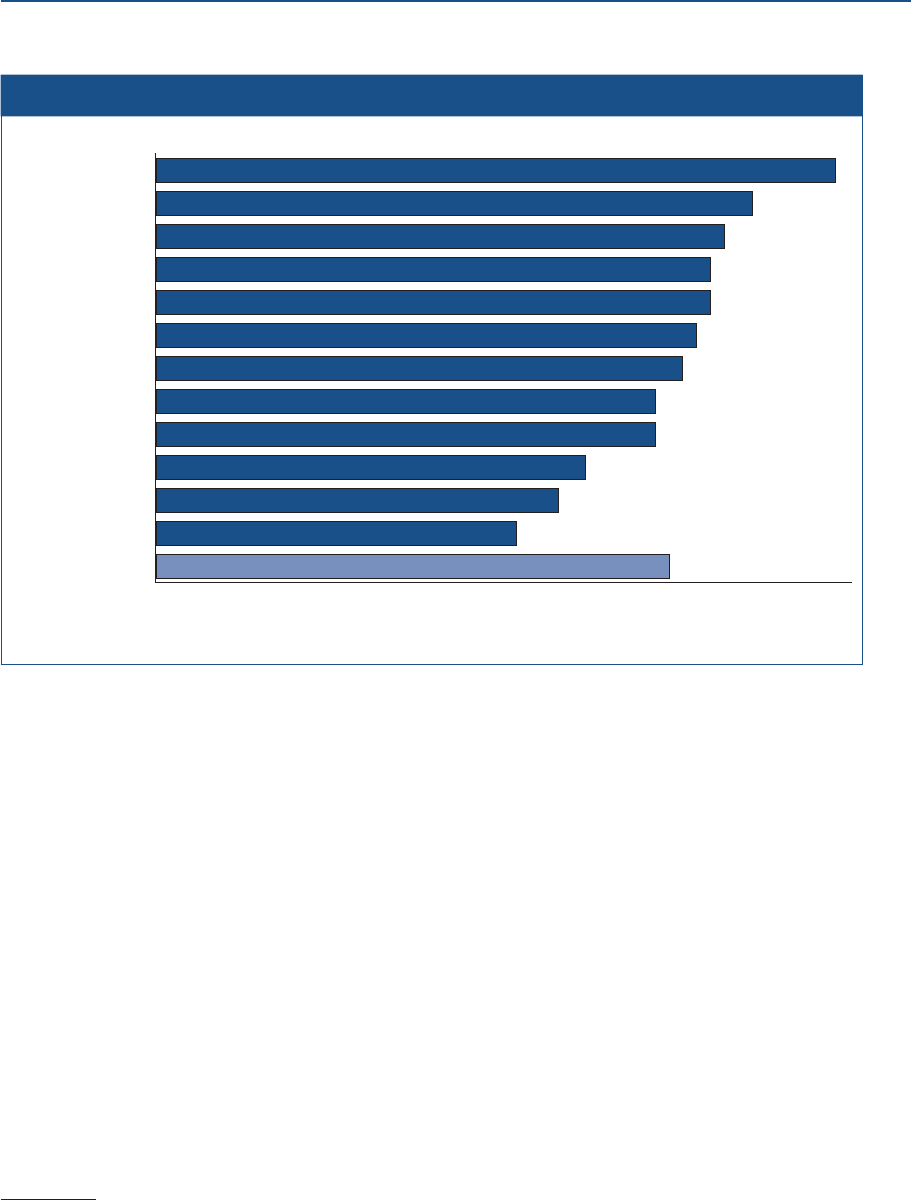

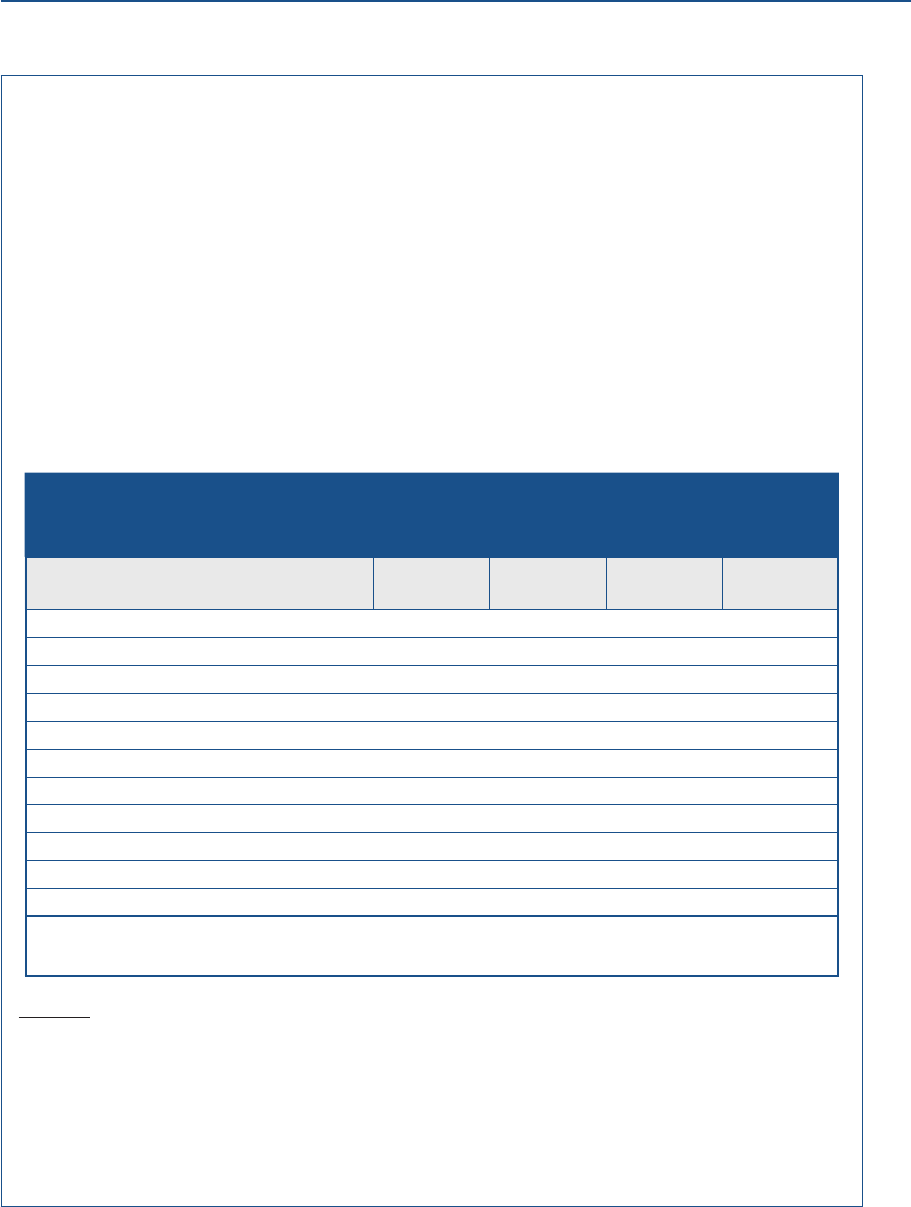

Income variability continued to differ greatly by industry in 2022.

17

Workers in the leisure and hos-

pitality industry were the most likely to have varying monthly income (figure 13). The high rate of

income variability for leisure and hospitality workers has occurred since before the pandemic.

Monthly variations in income may cause financial hardship for some families. In 2022, 10 percent

of adults reported they struggled to pay their bills in the past 12 months because their income

varied, up from 9 percent in 2021.

16

For additional information on monthly income variability, see Jonathan Morduch and Julie Siwicki, “In and Out of Poverty:

Episodic Poverty and Income Volatility,” Social Service Review 91, no. 3 (2017): 390–421.

17

This variability can come from any aspect of household income, however, and is not necessarily related to the person’s

income from the industry they work in.

Figure 13. Income varied at least occasionally from month to month (by industry)

Armed Forces

Professional and Business Services

Public Administration

Information

Manufacturing

Financial Activities

Education and Health Services

Natural Resources and Mining

Transportation and Utilities

Wholesale and Retail Trade

Other Services

Construction

Leisure and Hospitality

Percent

44

41

41

39

38

37

30

28

28

24

24

23

11

Note: Among adults who reported industry of employment.

18 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

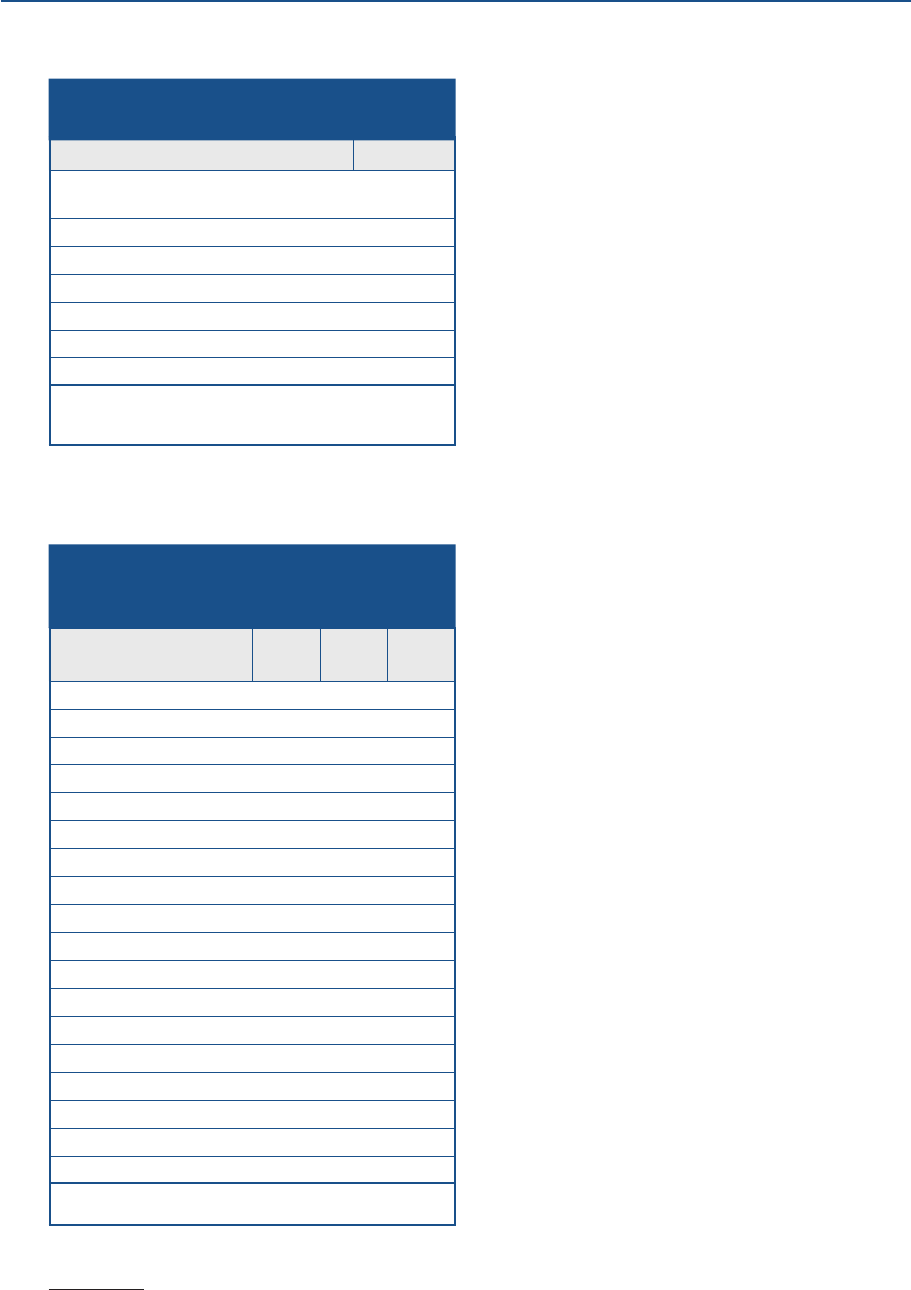

The likelihood of experiencing income vari-

ability and related hardship differed by educa-

tion, race, and ethnicity. Adults with less edu-

cation were more likely to experience hardship

from varying income. Twenty-one percent of

adults with less than a high school degree

said they had difficulty paying bills in the past

year because their income varied, compared

with 5 percent of adults with a bachelor’s

degree or more (table 4). Black and Hispanic

adults also were more likely to experience

income variability and related hardship, com-

pared with White and Asian adults.

Table 4. Varying income and related hardship

(by education and race/ethnicity)

Percent

Characteristic

Varying

income,

causes

hardship

Varying

income,

no hard-

ship

Varying

income,

overall

Education

Less than a high school degree 21 16 38

High school degree or GED 13 17 30

Some college/technical or

associate’s degree 12 20 32

Bachelor’s degree or more 5 18 23

Race/ethnicity

White 8 18 26

Black 14 19 34

Hispanic 16 20 36

Asian 7 15 22

Overall 10 19 29

Note: Among all adults.

Income 19

Employment

Workers’ relationships with their employers vary substantially. For example, workers with at least a

bachelor’s degree were more likely than those with less education to telework, control their sched-

ules, and have autonomy over their work activities.

That said, measures of workers’ opportunities in the job market, such as the share asking for or

receiving a raise, increased over the prior year, and this was the case among those with and

without a bachelor’s degree.

Working from Home

A major change in many people’s work lives since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic was the

increased prevalence of working from home, also known as remote work. In October 2022, 19 per-

cent of adults who worked for someone else (“employees”) worked entirely from home in the week

before the survey and 20 percent did so some of the time. The share working entirely from home

was down from 29 percent in 2020 and 22 percent in 2021, but well above the 7 percent who

worked mostly from home in 2019, before the pandemic.

18

Job type, employer rules, and personal preferences influenced whether people worked from home.

Just under half (48 percent) of employees said they had a job that could not be done from home.

Eleven percent of employees felt that their job could be done from home and that they would

prefer to do so, but their employer would not allow it. A smaller 3 percent said that they could

work from home but chose not to.

Employees who completed more education continued to be more likely to work from home. Twenty-

seven percent of employees with at least a bachelor’s degree worked entirely from home com-

pared with 9 percent of those with a high school degree or less (figure 14).

One explanation for the differences by education is that employees with more education were

more likely to have a job where they could work from home. Three-fourths of employees with at

least a bachelor’s degree either worked from home or said that they could if their employer would

let them, compared with 25 percent among employees with a high school degree or less.

18

The question asked in 2019 was different from later years. The 2019 survey asked where people worked in their main

jobs most of the time.

21

Common reasons for preferring to work from home were spending less time commuting, work-life

balance, and increased productivity (table 5). Concerns about COVID-19 were less frequently cited.

Additionally, the share of those working from home who cited COVID-19 concerns as a reason for

their preference declined substantially in 2022 from that seen in the previous survey—falling from

56 percent to 40 percent.

In addition to asking about why employees preferred to work from home, the survey also asked

those who worked from home about the likeli-

hood of actively looking for another job or

leaving their job if their employer required

them to work in person each day. To provide

context on these results, respondents were

also asked if they would actively look for work

if their employer froze their pay or cut their pay

by different amounts.

Nearly 3 in 10 employees (28 percent) who

worked from home at least some of the time

said they would be very likely to actively look

for another job if their employer required them

to work in person each workday (figure 15).

Employees viewed a hypothetical in-person

work requirement similarly to a hypothetical

small decrease in pay. Of employees currently

Table 5. Reasons employees prefer to work

from home

Reason Percent

Work-life balance 88

Less time commuting 87

More productive working at home 73

Able to live in a different area 48

Concerns about COVID-19 40

Note: Among adults who worked for someone else and worked

from home at least some of the time. Respondents could select

multiple answers.

Figure 15. Very likely to actively look for

another job or leave their job if employer

changes pay or requires in person work (by pay

cuts and exclusive in person work)

Percent

18

23

28

38

52

Lower

pay

by 10%

Lower

pay

by 5%

Report

in person

Lower

pay

by 1%

Freeze

pay

Note: Among adults who worked for someone else and

worked from home at least some of the time.

Figure 14. Amount of work done from home

(by education)

AllSomeNone

Bachelor’s degree

or more

Some college/

technical or

associate degree

High school

degree or less

84

7 9

15

27

12

31

73

42

Percent

Note: Among adults who worked for someone else.

Key identifies bars in order from left to right.

22 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

working from home at least some of the time, 18 percent would be very likely to look for another

job if their employer froze their pay, while 52 percent would look for another job if their employer

cut their pay by 10 percent (figure 15). For those currently working from home, the likelihood of

looking for another job after a full-time in-person work requirement is consistent with that expected

from a 2 to 3 percent pay cut.

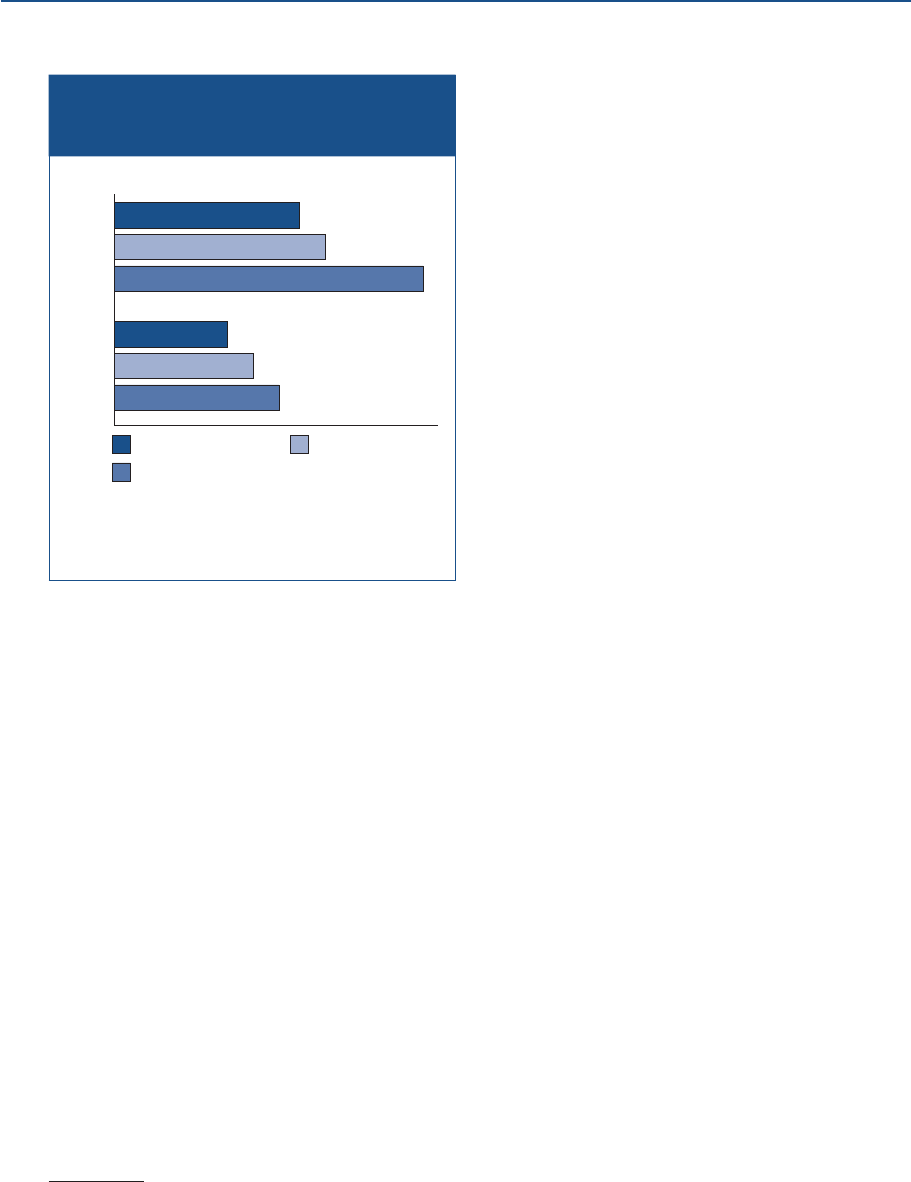

Job Searching and Advancement

Indicators of workers’ opportunities for new

positions and pay advancement strengthened

compared with 2021, as the share who

received a raise, asked for a raise, or volun-

tarily left a job increased, while the share who

lost a job decreased. Thirty-three percent of

adults said they received a raise or a promo-

tion in the prior 12 months, up slightly from

2021.

19

A higher share also said they asked

for a raise or promotion in 2022 than during

2021 (figure 16). Five percent of adults lost a

job during the prior year, down from 7 percent

in 2021.

Adults with more education were more likely to

ask for or receive a raise than those with less

education. They also were more likely to have

applied to a new job, started a new job, or vol-

untarily left a job in the prior year. For

example, 26 percent of adults with at least a bachelor’s degree applied for a new job in the prior

year and 17 percent started a new job. Among those with a high-school degree or less, a lower

19

Restricting the sample to just those who are working, the likelihood of asking for or receiving a raise is higher. Among

those who were working in the month of the survey, 21 percent asked for a raise and 54 percent received one.

For those currently working from home, the

likelihood of looking for another job after a

full-time in-person work requirement is consistent

with that expected from a 2 to 3 percent pay cut.

Figure 16. Job actions taken in prior 12

months (by year)

20222021

Got laid off or

lost a job

Voluntarily

left a job

Started

a new job

Applied for

a new job

Asked for a raise

or a promotion

Received a raise

or a promotion

30

33

9

13

20

23

13

15

9

11

7

5

Percent

Note: Among all adults. Respondents could select

multiple answers. Key identifies bars in order from top

to bottom.

Employment 23

18 percent applied for a new job and 11 percent started one. These indicators of how workers are

faring in the job market were either similar to or above that seen in the prior year for each educa-

tion group.

Most people who asked for a raise received one. Among those who asked for a raise in 2022,

70 percent also said that they received a raise. This share was similar in 2021 and was up 4 per-

centage points from 2019, before the pandemic.

Those who searched for a job also frequently found new work. Among people who applied for a

new job, 52 percent reported starting a new job in 2022, up 3 percentage points from 2021 and

up 7 percentage points from 2019.

Work Arrangements and Autonomy at Work

In addition to pay, other important dimensions of job quality are the duration of jobs, job schedules

and autonomy. Seven percent of working adults (4 percent of all adults) said their main job was a

temporary position. These temporary positions were most frequent among young workers and

older workers. Nine percent of workers under age 30, and 11 percent of those age 60 or older,

indicated that they had a temporary position, compared with 5 percent of workers between ages

30 and 59.

Although many people have regular work schedules, this is not the case for all workers. More than

one-fourth (27 percent) of employees had irregular work schedules in 2022. This includes 16 per-

cent who had a work schedule that varied based on their employer’s needs, and 11 percent whose

schedule varied at their own request.

Employees were also asked about how much choice they had to decide what tasks to work on and

how to do those tasks. In general, employees were more likely to have control over how to com-

plete tasks than which tasks they worked on. Nearly 6 in 10 employees said they often or always

chose how to complete tasks, compared with 37 percent who said they often or always chose

which tasks to work on.

Employees with at least a bachelor’s degree reported higher levels of autonomy at work than

those with lower levels of education (table 6). Forty-four percent of employees with at least a bach-

elor’s degree said they often or always chose what tasks to work on, and more than two-thirds said

they chose how to complete tasks. In contrast, around one-third (32 percent) of employees without

24 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

a bachelor’s degree often or always chose

what tasks to work on and one-half chose how

to complete tasks.

20

Autonomy at work also differed by race and

ethnicity, though these differences were

smaller than those by education (table 6).

About one-third of both Black and Hispanic

employees said they often or always chose

what tasks to work on, compared with 39 per-

cent of White employees. Black and Hispanic

employees were also less likely to report that

they chose how to complete tasks.

Reasons for Not Working

Twenty-three percent of prime-age adults (ages

25 to 54) were not working in the month

before the survey, matching the share who were not working in 2021. This share is less than the

26 percent who were not working in 2020 during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic but is

greater than the 21 percent not working in 2019, before the pandemic.

21

Health limitations or disability, as well as family or personal obligations besides childcare, were

the most commonly cited reasons for not working, followed by an inability to find work. Consistent

with the continued strength of the labor market, the 6 percent of prime-age adults said that they

were not working because they could not find work was similar to the share of adults who cited

this reason in 2021 (5 percent), and in late 2019, before the pandemic (5 percent).

Notable differences existed in prime-age employment rates by gender. Twenty-eight percent of

prime-age women were not working, compared with 18 percent of prime-age men.

This difference may reflect greater family and childcare responsibilities held by women. Prime-age

women were more likely than men to cite both childcare and other family or personal obligations

20

The different types of jobs people work in based on their level of education is likely a contributing factor for these differ-

ences in levels of autonomy by education. For example, 40 percent of business and professional services workers—

most of whom have a bachelor’s degree—say that they often or always chose what tasks to work on, while a lower

26 percent of transportation and utilities workers—most of whom have less than a bachelor’s degree—say they have

this level of control over their work.

21

Despite differences in question wording, this pattern is consistent with that observed by the Bureau of Labor Statistics,

which reported 20 percent of prime-age adults not working in October 2022, down from 24 percent not working at the

time of the survey in 2020, and similar to the percent in October 2019. See U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics, “(Seas)

Employment-Population Ratio—25–54 yrs.,” https://data.bls.gov/timeseries/LNS12300060.

Table 6. Share who often or always choose

what tasks to work on and how to complete

tasks (by education and race/ethnicity)

Percent

Characteristic

What tasks

to work on

How to com-

plete tasks

Education

Less than a high school degree 35 49

High school degree or GED 31 49

Some college/technical or

associate degree 32 51

Bachelor’s degree or more 44 68

Race/ethnicity

White 39 61

Black 32 52

Hispanic 34 54

Asian 35 61

Note: Among adults who worked for someone else.

Employment 25

as a reason for not working (table 7). More-

over, among prime-age adults living with their

children under age 18, one-third of women

were not working in October 2022, compared

with 12 percent of men. Prime-age men and

women who did not live with their children

under age 18 had similar rates of not working

to each other.

The Gig Economy

Individuals who perform gig work or other gig

activities may be contributing to the economy

in ways not observed through traditional

employment measures. Gig activities in this

report include selling items at places such as

flea markets and garage sales or through online marketplaces, short-term rentals of items or prop-

erty, and freelance gig work such as ridesharing or other roles where people are paid for specific

tasks and generally have flexibility about when and how to work.

Overall, 16 percent of adults performed gig

activities over the prior month, matching the

share in 2021. This includes 11 percent who

sold things, 2 percent who offered short-term

rentals, and 6 percent doing other freelance or

gig work (with some people performing more

than one type of gig activity) (figure 17).

Gig activities were typically not full-time jobs.

Twenty-nine percent of adults who performed

gig activities (5 percent of all adults) said they

spent more than 20 hours doing so over the

prior month. Fifty-three percent of gig workers

(8 percent of all adults) also had another job

working for someone else.

22

22

Gig questions were asked separately from the standard employment questions. One percent of all adults said that they

were both not employed and spending at least 20 hours on gig activities in the prior month.

Table 7. Reasons for not working among

prime-age adults (by gender)

Percent

Reason Overall Male Female

Health limitations or disability 8 8 8

Family and personal obligations

besides childcare 7 5 10

Could not find work 6 6 6

Childcare 4 1 7

Concerned about COVID-19 4 3 5

Would lose access to

government benefits 3 3 3

School or training 2 2 2

Retired 2 2 2

Note: Among adults ages 25 to 54. Respondents could select

multiple answers.

Figure 17. Gig activities performed

Any gig

activity

Freelance or

gig work

Offering

short-term

rentals

Selling items

11

2

6

16

Percent

Note: Among all adults. Respondents could select

multiple answers.

26 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

Consistent with their part-time nature, gig activities were rarely people’s main source of income.

Only 12 percent of gig workers (2 percent of all adults) said they earned more than half of their

income from gigs over the prior month. An even lower 6 percent of gig workers (1 percent of all

adults) said that they earned at least 90 percent of their income from gig activities.

Employment 27

Expenses

The share of adults who would cover a relatively small emergency expense using cash or its

equivalent dropped back down to the level in 2019, before the pandemic. The share of adults who

said they were able to pay all their bills in full also declined to the level last seen in 2018. Most

adults said that the prices they paid had increased over the prior year and a majority adjusted

their spending in response to higher prices.

Bills and Regular Expenses

To understand how people were handling their regular household expenses, the survey asked

about their ability to pay their monthly bills. As of October 2022, 82 percent of adults said they

expected to be able to pay all their bills in full that month—down 4 percentage points from 2021,

and near the level last seen in 2018.

Lower-income adults were less likely to be able to pay all their bills. In the month of the survey,

67 percent of adults with a family income less than $25,000 expected to pay all their bills in full,

compared with 94 percent of adults with a family income of $100,000 or more (table 8). In addi-

tion, Black and Hispanic adults were less likely than White or Asian adults to be able to pay all

their bills in full in October 2022.

The most common type of bill people did not

expect to pay in full was a credit card bill.

Nine percent of adults said they did not

expect to pay a credit card bill in full that

month. Other bills, such as a water, gas or

electric bill (6 percent) or a phone or cable bill

(6 percent), were somewhat less common

responses.

Price increases can make it more difficult to

keep up with bills and expenses. In

October 2022, nearly all adults said the prices

they paid had increased at least somewhat in

the prior 12 months on one or more types of

purchases. Over 90 percent of adults said

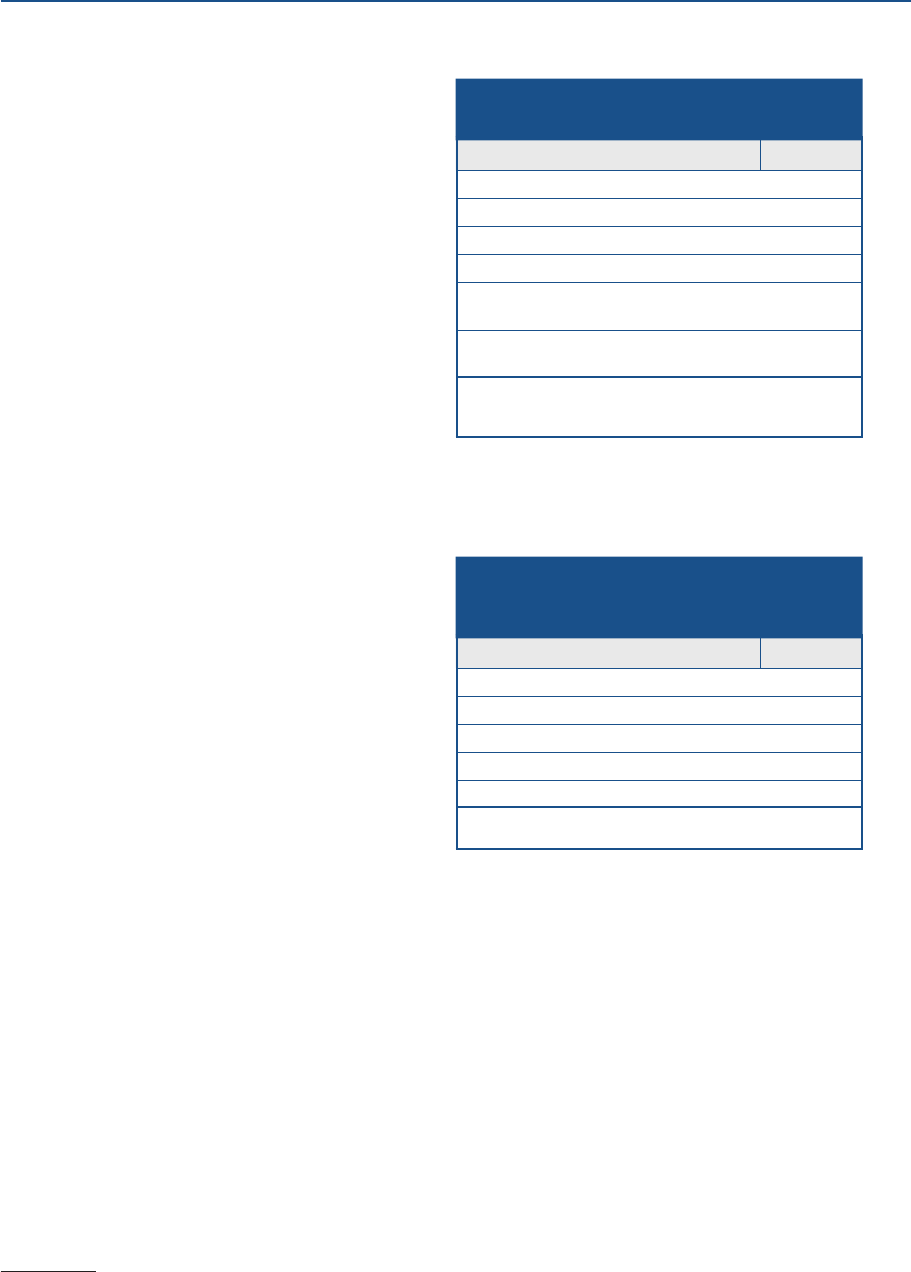

Table 8. Able to pay current month’s bills in full

(by family income and race/ethnicity)

Characteristic Percent

Family income

Less than $25,000 67

$25,000–$49,999 78

$50,000–$99,999 86

$100,000 or more 94

Race/ethnicity

White 86

Black 70

Hispanic 73

Asian 88

Overall 82

Note: Among all adults.

29

that the prices they had paid for food and

gasoline had increased, and 85 percent said

prices for utilities had increased (figure 18).

23

Although fewer people said their rent or mort-

gage increased than said they experienced

rising prices for other expenses, the preva-

lence of housing cost increases differed sub-

stantially by homeownership status. Renters

were more likely than homeowners to say that

these housing costs had gone up. Sixty-

four percent of renters said their rent had

increased over the prior 12 months, including

30 percent who said it had increased a lot. In

contrast, 22 percent of homeowners said their

mortgage had increased in the past year, with

7 percent saying it had increased a lot.

Consistent with the widespread experience of higher prices over the prior year, most adults said

that their family budgets had been affected by price increases. Eighty-five percent of adults said

their family budgets had been affected at least somewhat by price increases, including 54 percent

of adults who said their budgets had been affected a lot by price increases on at least one type of

expense. Adults with income under $100,000 were more likely to say that their family budget was

affected a lot by rising prices, compared with higher-income adults (table 9). Parents living with

children under age 18, Black and Hispanic adults, and those with a disability were also more likely

to say their budget had been affected a lot by higher prices.

Most people took some action in response to higher prices. The most common actions were

spending changes, including using less of a product or stopping using it (66 percent), switching to

a cheaper product (64 percent), or delaying a major purchase (49 percent) (table 10). Just over

one-half of adults reported they reduced savings (51 percent). Increasing borrowing was less

common, as were activities to generate additional income, such as working more or asking for

a raise.

23

Consumer Price Index (CPI) data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed that in October 2022, gasoline costs were

up by 17.5 percent year-over-year and food costs were up by 10.9 percentage points (see U.S. Bureau of Labor Statis-

tics, “Consumer Price Index–October 2022,” news release, November 10, 2022, https://www.bls.gov/news.release/

archives/cpi_11102022.pdf). A difference between the CPI and the SHED results reported here is that the SHED

focuses on the share of people who say they experienced increases in prices rather than the specific amount of

increases.

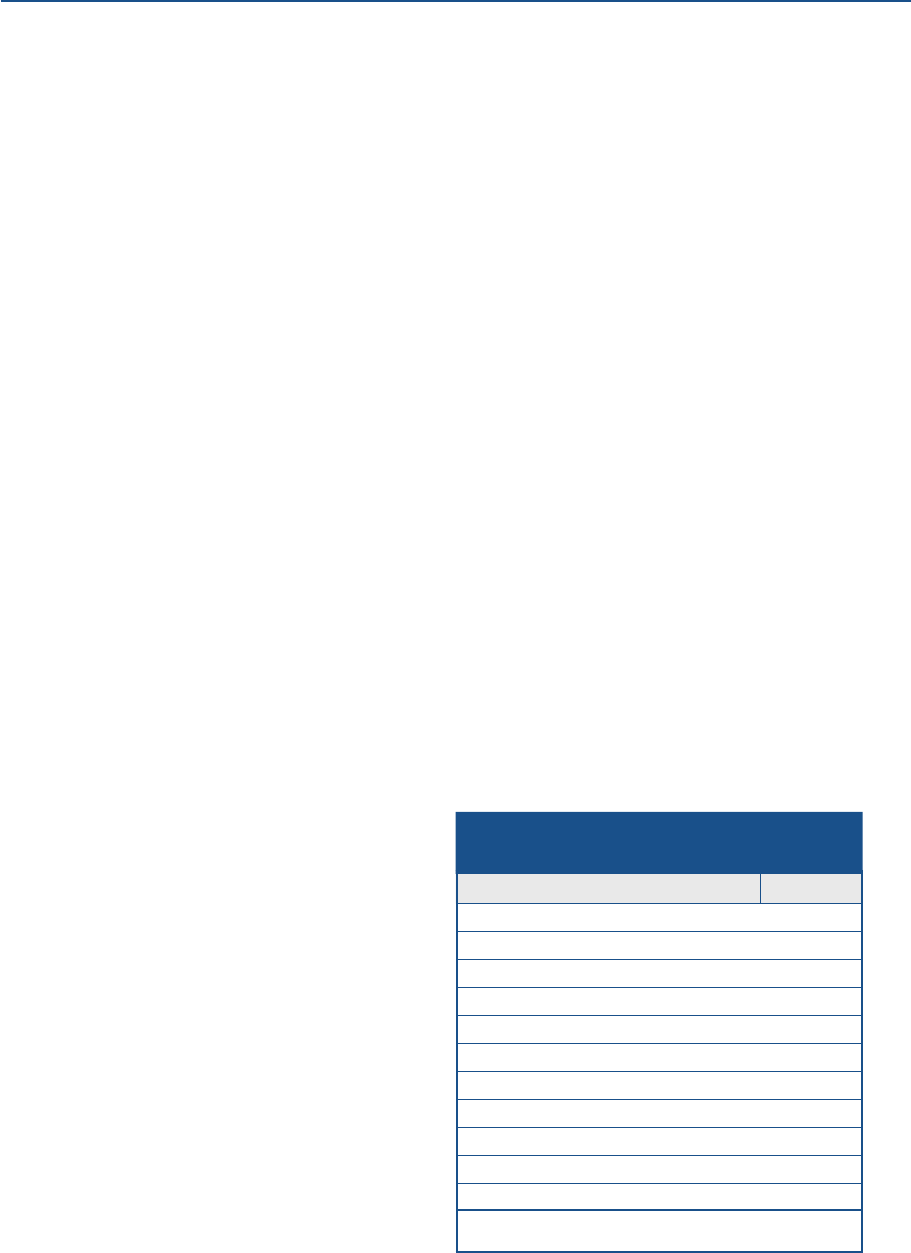

Figure 18. Prices paid increased in prior 12

months (by product type)

Percent

Rent or

mortgage

Medical care,

medication, or

health insurance

Home or auto

insurance

Utilities (electricity,

heating fuel, etc.)

Gasoline and

other motor fuels

Food

Somewhat

A lot

71 25

19

44

75

41

40

18

34

16

20

97

94

85

58

50

34

14

Note: Among all adults. Key identifies bars in order

from left to right.

30 Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2022

Adults who had less margin between their

spending and their income appeared more

likely to take action in response to higher

prices. Among adults who said their spending

exceeded their income in the month before

the survey, 93 percent took at least one

action in response to higher prices. Among

those whose spending was less than their income, a lower 76 percent took at least one action.

Unexpected Expenses

Relatively small, unexpected expenses, such as a car repair or a modest medical bill, can be a

hardship for many families. When faced with a hypothetical expense of $400, 63 percent of all

adults in 2022 said they would have covered it exclusively using cash, savings, or a credit card

paid off at the next statement (referred to, altogether, as “cash or its equivalent”). The remainder

said they would have paid by borrowing or selling something, or said they would not have been

able to cover the expense.

The share who would pay using cash or its equivalent was down 5 percentage points from 68 per-

cent in 2021, and back at the level in 2019 (figure 19).

24

This decrease may reflect some reduc-

24

Since 2013, when this question was first asked, and the 2022 survey, median household incomes increased as did con-

sumer prices. To check how changes in price levels affect responses to this question, the 2022 survey asked one-fifth

of respondents how they would handle a $500 expense instead. Changing the threshold only altered the share who

would pay in cash by 0.5 percentage points, suggesting that shifts in the price level have not materially affected the

trend in this series. The discussion in this section only includes those respondents who are asked the question with the

$400 threshold.

Table 9. Family budget affected a lot by price

increases in the prior 12 months (by demo-

graphic characteristics)

Characteristic Percent

Family income

Less than $25,000 60

$25,000–$49,999 64

$50,000–$99,999 59

$100,000 or more 41

Race/ethnicity

White 52

Black 57

Hispanic 62

Asian 48

Disability status

Disability 66

No disability 51