Rapid evidence

assessment of

the research

literature on the

buy-to-let housing

market sector

Rapid evidence

assessment of

the research

literature on the

buy-to-let housing

market sector

February 2008

Priestley House

12-26 Albert Street

Birmingham

B4 7UD

United Kingdom

T 0121 616 3600

F 0121 616 3699

www.ecotec.com

ECOTEC is an international provider of research, consulting and management services.

Our aim is to deliver real benefit to society through the work we do. For more than twenty years

we have worked with clients in the public, private and not for profit sectors. Our housing research

and consultancy team specialises on housing research and intelligence, housing policy analysis,

supporting regional and sub-regional planning and housing market renewal.

5

Contents

Executive summary 7

Characteristics of investors and investment motives 7

Housing quality and voids 8

Investors and the wider housing market 8

Future prospects 9

Conclusions 9

1. Introduction 11

1.1 A growing sector 11

1.2 Research questions 13

1.3 Methodology: the rapid evidence assessment 14

1.4 Quantity and strength of evidence 15

2. Characteristics of investors and investment motives 19

2.1 Investors seeking a financial return 19

2.2 Amateurs investing for retirement 20

2.3 Speculative investors in new-build 22

2.4 Professional landlords living on rental income 26

2.5 Regional variation found 27

2.6 Summary of key findings 28

3. Housing quality and voids 29

3.1 Improvement to property conditions 29

3.2 Consistent level of voids 31

3.3 Summary of key evidence 32

4. Investors and the wider housing market 33

4.1 Financing purchases with BTL mortgages 33

4.2 Some effect on property prices 34

4.3 Competition with first-time buyers? 35

4.4 Summary of key findings 37

5. Future prospects 38

5.1 Buoyant investment for the medium to long term 38

5.2 Interest rates and personal finance affect landlord behaviour 39

5.3 Importance of demand for private renting 40

5.4 Summary of key findings 40

6

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

6. Conclusions 42

6.1 The growth of BTL 42

6.2 Stability and risks for amateur investors 42

6.3 Speculators can spur and unsettle the market 42

6.4 Professional landlords ride the storm 43

6.5 Cyclical behaviour from landlords 43

6.6 Property conditions are improving 43

6.7 The housing market is complex 43

6.8 Future research is needed 44

7. Bibliography 46

Annex 1: Search strategy 50

Search strategy 50

Annex 2: Review template 51

Buy-to-let literature review template 51

List of figures

Figure 1.1 Number of dwelling in the private rental sector (thousands) 11

Figure 1.2 Private sector rental properties with and without a buy-to-let mortgage 12

Figure 2.1 Yields on housing, gilts and equities 19

Figure 2.2 Distribution of private rented stock by size of landlord’s portfolio 21

Figure 2.3 Location of private non-owner occupiers in Merseyside sample 25

Figure 3.1 Property condition and returns for landlords 31

List of tables

Table 2.1 Who buys new homes in London? 23

Table 3.1 Rate of unfitness by tenure in England, 1991 to 2001 (% of households) 29

Table 3.2 Privately renting households living in non-decent housing in England 29

7

Executive summary

This report reviews evidence on the buy-to-let (BTL) market on behalf of the National Housing

and Planning Advice Unit. It focuses on the supply side of the private rented market, particularly

looking at investor characteristics and their motives for investing. It also considers the interplay

between BTL, house prices and first-time buyers.

We have used a rapid evidence assessment to review literature on the BTL market. This is a

methodology for assessing evidence, particularly published literature, to guide public policy

research and evaluation. It aims to find out what is already known in a quick and efficient but

critical way.

Using a broad definition of BTL – buying property with the intention of letting out – we have

generated a wider pool of evidence. We have found most evidence on the particular

characteristics of investors or the housing markets they invest in and the future prospects for the

sector. Evidence has been most lacking around the supply and quality of BTL housing stock,

vacancy rates and international evidence.

The private rented sector is today bigger in size and proportion of the housing market than in the

late-1980s, currently housing some 2.5 million households and representing 12% of all stock.

BTL mortgages make up just over a quarter of the whole PRS stock, although some of this

investment represents remortgages rather than additional purchases.

Characteristics of investors and investment motives

The overriding motive for private landlords is to receive a financial return, with returns in residential

property outperforming other forms of investment in recent times. Yet landlords have different

motives for investing. The biggest group of BTL investors are small-scale and amateur, investing

for retirement. These are most likely to expect to continue letting property over the medium- to

long-term.

Speculative investors form a second group, though much smaller in size. They are seeking short-

term gain through capital growth and are concentrated in new-build apartments. There is also

overlap between this group and the ‘buy-to-leave’ phenomenon, with properties bought as an

investment but with no intention of letting out. A concern for both groups is that there appears to

be a saturation of the PRS in some markets which could lead to a fall in prices. Another worry is

that such investment has encouraged developers to build small apartments, although there may

not be sufficient household demand for such units.

The third key group of landlord is those who own large portfolios. These investors are more

focussed on generating a positive cash flow from rental income and less preoccupied with short-

term capital growth. Understandably, this group of investors is also more professional and

knowledgeable about housing tax and finance.

8

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

Housing quality and voids

The private rented sector has consistently held the highest level of unfitness among all tenures,

although fitness appears to have increased dramatically over the decade. Improvement to

property condition appears to happen more with new stock entering the market than by the active

modification by landlords.

Some BTL investors are happy to hold on to poor-quality stock and obtain high rental yield,

though have little interest in long-term capital growth. These landlords have been called ‘rent

maximisers’, though may face higher voids. Another group of landlords often buys good-quality

stock and invest to maintain this high standard or buys poor quality stock but improves it. These

investors will receive better capital growth but reduced net rental yield, because of higher

management and maintenance costs.

Evidence on vacancy periods and void rates is patchy but generally consistent. Some 6%–7% of

landlords’ properties appear to be vacant at any one time, and the duration of voids is about one

month per year. These figures are probably currently for BTL investors, but there would be a

public policy concern if demand dropped or the BTL market became saturated with supply.

Investors and the wider housing market

The lending industry and some academics view BTL mortgages as a positive contribution to how

investors operate. Some state that gearing (that is the relationship between invested equity and

debt) is low in the PRS, and see much potential for investors to improve their returns if they

borrower further. For the lending industry, BTL borrowers are currently proving to be a safer bet

than others, as BTL borrowers have lower levels of arrears.

Few of the studies provide empirical evidence on a direct relationship between BTL investment

and house prices, and none has shown that BTL alone has increased prices. Instead, a number

of studies conclude that the housing market is more complex, with no single element precipitating

rapid house growth. There is stronger evidence that private landlords are attracted to low value

properties, therefore making an association between BTL and property prices.

There is also concern that investors have priced out first-time buyers. Yet the evidence is

ambiguous. A number of studies state that rather than pricing out first-time buyers, BTL is

providing a demand-led alternative at a time when attitudes to homeownership have changed.

Other studies point to a different interplay between BTL investment and first-time buyers.

Alternative reasons for the rise in property prices include weak housing supply, new demand as a

result of in-migration, low rates of property transactions, rising incomes at a time of low interest

rates and the deregulation of mortgage markets. The strongest case for BTL investors pricing out

potential owner occupiers is found in the competition for small new-build apartments and city

centre or waterside developments. However, more rigorous research is required.

9

Executive summary

Future prospects

Most studies found that the majority of landlords regarded their investments as medium-to-long-

term and that landlords plan to maintain the size of their portfolio. But more landlords, particularly

BTL borrowers, intend to buy properties than sell them, showing confidence in the market.

One in-depth survey of BTL borrowers found that stable or low interest rates, stable or rising

house prices and very good rental yields were seen as primary reasons for increasing one’s

investment portfolio; rising interest rates and insufficient rental income to cover mortgage

payments were identified as primary reasons for decreasing holdings. This is used to show that

landlords’ behaviour is cyclical rather than counter-cyclical.

A number of studies conclude that the risks are greatest for new investors. These are most likely

to be inexperienced in the letting process, have higher financial risks and experience slower

capital growth. If these landlords have to sell up, this would be unsettling if they are concentrated

in particular property ‘hot-spots’ and would be painful for these investors.

There is considerable uncertainty over the likely future demand for private renting. But on balance,

it appears that demand will increase because of affordability problems in owner occupation and

quite large changes to the population structure from new migrants. So long as supply has not

become saturated, BTL will have a place; but where an over-supply has already occurred, a short-

term contraction may take place.

Conclusions

Our key conclusions are:

• The PRS is today bigger in both number and as a share of all households than its lowest

point in the late-1980s, and is growing rapidly.

• But there are different motivations for buying and letting property, mostly driven by a

desire for a financial return. The biggest group of investors are small-scale and amateur

landlords, seeking a return for their retirement. A small proportion of BTL investors have made

speculative investments for short-term capital growth. A third group of BTL investors is

professional landlords living on rental income.

• Landlord behaviour appears to be cyclical rather than counter-cyclical. However,

landlords’ predicted behaviour and their actual behaviour might not be the same, and that

new entrants may not behave as their predecessors did.

• House prices are driven by a complex interplay of factors. BTL investment will be one of

these but not the sole or even necessarily the major factor. The evidence shows the strongest

direct relationship between BTL and new-build apartments. The low price of old terraced

stock in housing market renewal areas has been an incentive for BTL investment.

• The most rapidly changing part of the English housing market is the part we currently know

least about.

10

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

We suggest that future research on BTL should therefore look at:

• the extent to which BTL investment has ‘priced out’ first-time buyers, and how this interacts

with the local housing market;

• the motivation to invest in property maintenance by newer landlords and their use of

managing agents;

• demand for private renting among new groups, particularly A8 migrants;

• geographical gaps, particularly in cities with large student populations and in coastal areas,

where private renting is higher;

• local authority-level systems to monitor developments and trends in the PRS, to ensure that

they understand the changing market – these should also use a common methodology to

compare across regions; and

• updating old evidence.

11

1. Introduction

This report reviews evidence on the buy-to-let (BTL) market on behalf of the National

Housing and Planning Advice Unit. It has been carried out by ECOTEC with support from

Professor Ian Cole at the Centre for Regional Economic and Social Research at Sheffield

Hallam University. This section focuses on the context of BTL, the methodology we have

used, and the strength of evidence reviewed.

Throughout this project we have used a broad definition of BTL: buying property with the

intention of letting it out, not just with a BTL mortgage. This takes into account properties

that have been bought outright and those bought using other means (eg mortgages on

other properties, business loans). A key concern, though, is whether new investment

(often with BTL mortgages) is affecting the established market, which is considered in this

report. Where we consider investment with BTL mortgages (the narrow definition), we talk

about ‘BTL borrowers’ or ‘BTL mortgages’.

1.1 A growing sector

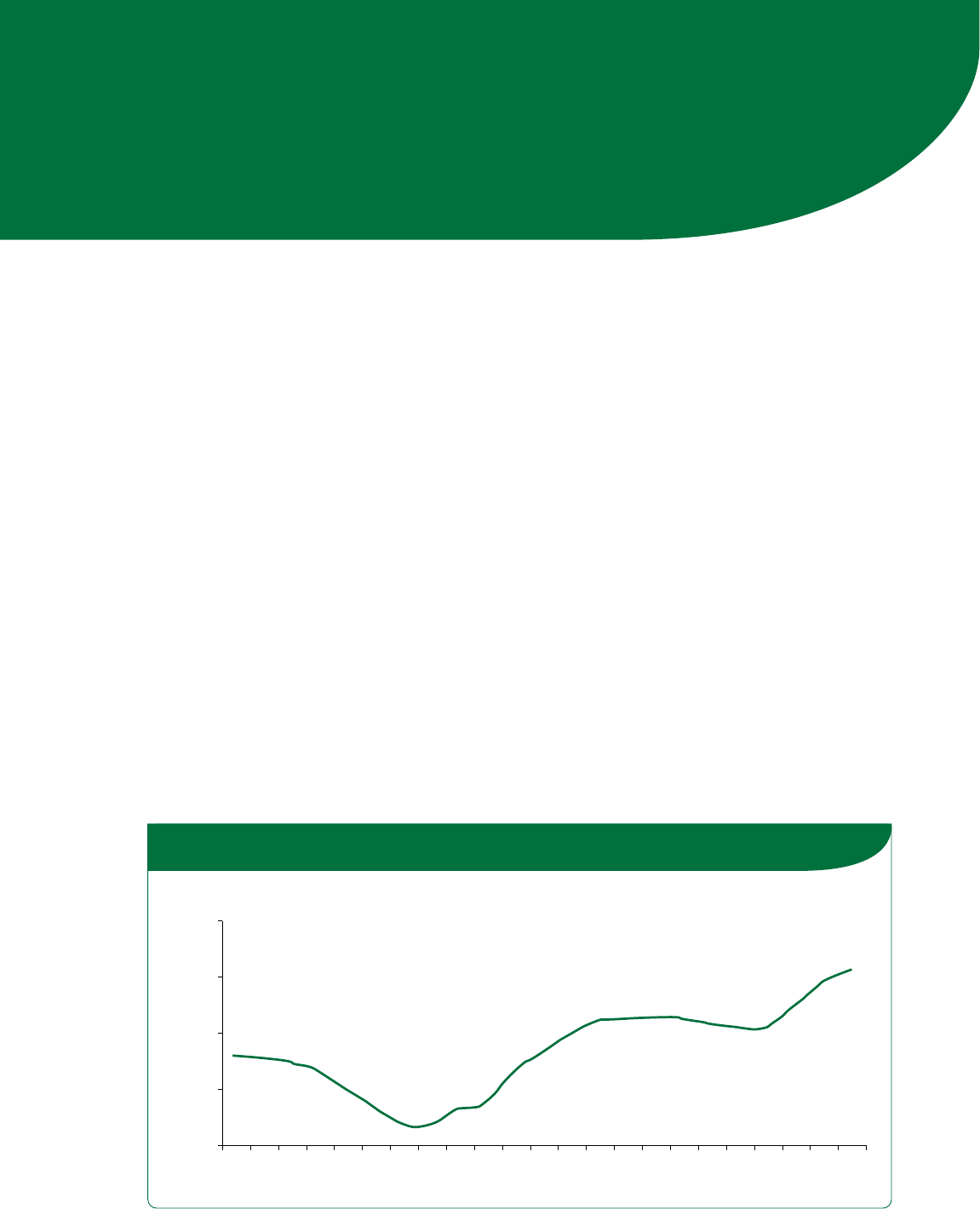

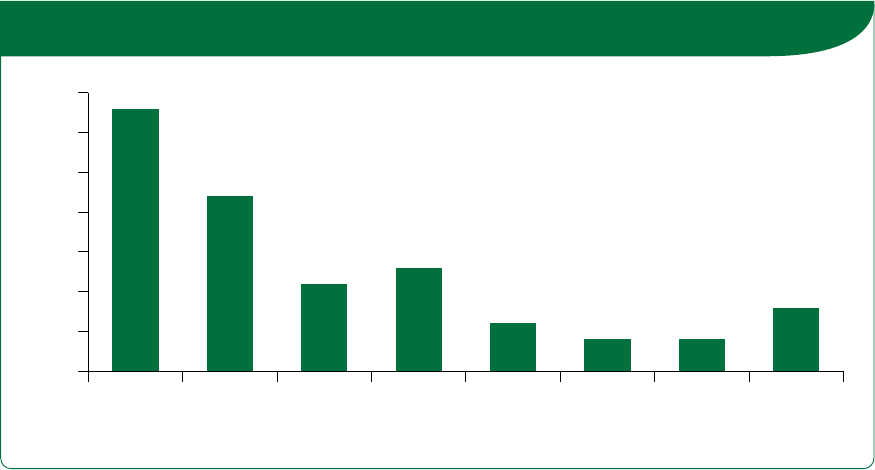

The size of the private rented sector (PRS) at large was in steady decline throughout

most of the twentieth century. Its lowest point in England was in the late-1980s, when the

sector dropped to just over 2 million properties, representing just 10% of all stock

(Thomas, 2006b). But there has been clear growth since then. Today the sector is bigger

in size and proportion of the housing market (Figure 1.1), housing some 2.5 million

households and representing 12% of all stock (CLG, 2007). Although the tenure is still

dwarfed by owner occupation (accounting for around 70% of stock), the absolute and

relative increase in properties is significant.

Figure 1.1 Number of dwelling in the private rental sector (thousands)

Source: Thomas (2006b) using ODPM figures

2,800

2,600

2,400

2,200

2,000

1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992

Number

1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004

12

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

The development of the sector has not taken place evenly across the country as some

local markets have experienced higher levels of PRS growth than others. For example,

ECOTEC (2007) estimated the PRS in the NewHeartlands housing market renewal

pathfinder area to have grown from 19% to 26% of stock in the five years to 2006. This is

a very steep rise and demonstrates the very quick change in property ownership, coupled

with new supply, in some neighbourhoods. Other local level studies have underlined this.

For example, Gibb and Nygaard (2005) estimated that the entire PRS had grown in

Glasgow from under 7.7% to 9%–10% in the three years to 2004. Unsworth (2007) shows

the scale of this potential growth, with some 19,000 units in the planning pipeline in

Leeds. Even if all these do not come to fruition, it will take some time to stem the flow.

1.1.1 BTL mortgage market is also increasing

BTL mortgages were first introduced by the Association of Residential Letting Agents

(ARLA) in 1996, as a means of allowing investors to borrow specifically to invest in

residential property. The home loans were first offered by a select panel of providers but

today have grown to form an important segment of the mortgage lending market.

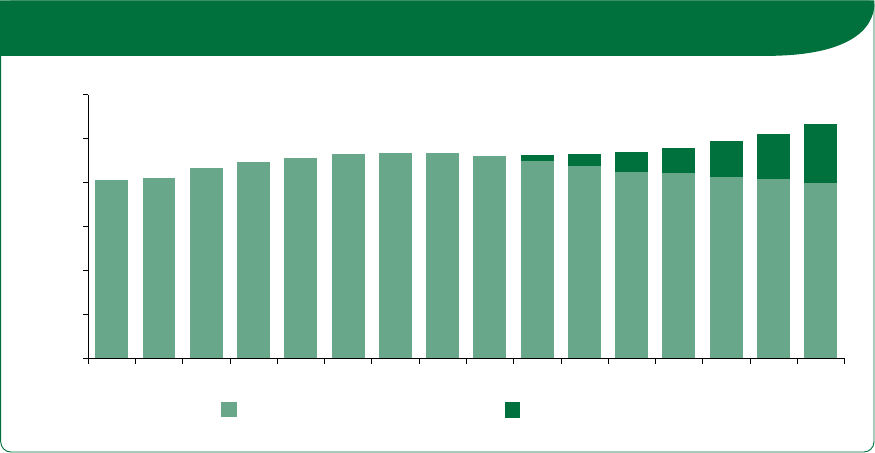

Figure 1.2 shows recent evidence from the Council of Mortgage Lenders (CML), with BTL

mortgages making up just over a quarter of the whole PRS stock. The industry is quick to

boast the huge numbers involved. For example, Thomas (2006b) stresses that the BTL

(mortgage) part of the wider PRS has grown from 1% to 20% in just six years. He goes on

to say: “By mid-2006, there were over 750,000 buy-to-let loans outstanding with a total

value of £84 billion.” (Thomas, 2006b, p1; echoed in Ball, 2004, 2006).

Figure 1.2 Private sector rental properties with and without a buy-to-let mortgage

Source: CML (2007)

3,000

2,500

2,000

1,500

1,000

500

0

1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005

Thousands

Private rental without BTL mortgage Private rental with BTL mortgage

13

1. Introduction

The growing importance of BTL mortgages is clear. But properties bought with such

mortgages are not all new stock to the sector. Lenders say that a large share of BTL loans

are remortgages of existing investment properties. Data for 2004 states that 37% of BTL

mortgages in that year were remortgages (Scanlon and Whitehead, 2005). As the take-up

of BTL mortgages is often – but wrongly – assumed to indicate new PRS stock, this

creates a false impression. The trend is therefore not as straightforward as often assumed.

1.2 Research questions

The BTL market has clearly grown in importance within the PRS at large. It has prompted

much media attention, especially as it is believed by some to have had an adverse effect

on the wider housing market, and has provoked intense political and policy interests as a

result. To investigate these concerns surrounding BTL the NHPAU set nine research

questions to be answered by this project:

1 To what extent (if any) has BTL increased house prices?

2 What specific factors attract buy-to-let investment into a particular local housing

market and to certain types of property, and what are the characteristics of investors?

3 Has property speculation in BTL priced out prospective first-time buyers?

4 What is the impact of BTL on private rental provision?

5 Has there been any improvement in the supply and quality of the housing stock as a

result of BTL?

6 What are the vacancy rates of BTL properties?

7 Is there any international evidence that can be drawn upon?

8 What are the future prospects for the BTL sector?

9 Are there any gaps in the evidence base in relation to the above questions?

The focus of this project has been on the supply side of the housing market, with little

evidence specifically reviewed on demand for private renting. Although the sector would

not function without both supply and demand, the latter has not been the impetus for this

project and so is not covered in any depth in this report. Because the sector changes so

rapidly, some phenomena are too recent to be captured in already published research

evidence. An example is investment clubs, which are used to pool capital to buy

properties to let. Such aspects of the market are understandably beyond the scope of a

rapid evidence assessment, though no doubt are having an increasing influence on the

market.

14

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

1.3 Methodology: the rapid evidence assessment

1.3.1 Rapid evidence assessment explained

We have used a rapid evidence assessment to review literature on the BTL market. This is

a methodology for assessing evidence, particularly published literature, to guide public

policy research and evaluation. It aims to find out what is already known in a quick and

efficient but critical way. The approach is more critical than a literature review and closer to

a systematic review.

The government’s Magenta Book (Davies, 2003) explains the rapid evidence assessment.

In systematic reviews, all evidence on a subject (eg effects of pharmaceutical drugs) is

brought together to find consistencies and explain variation between studies. Unlike other

types of research synthesis, systematic reviews are more methodical and rigorous in the

way they search existing evidence, with explicit and transparent criteria for appraising

evidence and explicit ways of comparing different studies. This way of synthesising

evidence is clearly more critical than a standard literature review.

A rapid evidence assessment is one step back from a full systematic review, as it seeks to

critically appraise the evidence but quickly. It therefore relies on evidence that is readily

available, identified by keyword searches of electronic databases and websites; hand

searches of journals and reviewing ‘grey’ literature (unpublished studies or work in

progress) are not necessary. The main purpose is to establish what is already known to

determine if any further, detailed research is needed. However, the critical manner of

appraising evidence is still evident and a transparent approach remains important.

1.3.2 Our approach

Our approach to the rapid evidence assessment has therefore stressed that the search

criteria and process are transparent (Annex 1 contains further details of our search

strategy), that evidence has been appraised in a clear and open way (Annex 2 contains

our review template) and that gaps in the evidence have been identified.

For the assessment we have gathered literature from a variety of sources, including:

central, regional and local government; academic sources; industry representatives; and

private consultancies. We have gone beyond the normal scope of a rapid evidence

assessment by contacting all nine regional assemblies (and the Greater London

Assembly). We are grateful for their help in providing the most recently published literature

on BTL, which has offered some wider stakeholder consultation and allowed us to use the

most up-to-date evidence.

We have appraised all literature using a standard template, probing the methodologies

used in the studies, their limitations and bias. Putting all these factors together, we graded

each item of literature as low, medium or high quality for the particular research question.

This review has been summarised in each mini report on the six research questions that

we have answered separately. The limitations of literature mainly referred to the

transparency of the methodology, the use of primary evidence and sample sizes (though a

15

1. Introduction

full list is included in Annex 2). Rather than exclude literature, we have included anything

that matched the primary research questions or secondary issues (outlined in Annex 1).

Where a study had only limited relevance, we have included it in the review but usually

given it a low or medium grade.

1.4 Quantity and strength of evidence

For a rapid evidence assessment to go beyond a traditional literature review it must

assess the quality and strength of evidence. Overall there has been only limited evidence

looking at the BTL market in its narrow sense, that of purchasing property with a BTL

mortgage. But this project has used a broader definition: buying property with the

intention of letting out. This wider definition has generated a wider pool of evidence, with

studies looking at the PRS more broadly. Some of the evidence we have reviewed has

been generic (eg Ball, 2004, 2006; ODPM, 2003, 2006), while other studies have had a

much narrower remit (eg Crook, 2002) or somewhat limited relevance to this project (eg

Holmans, 2005).

1.4.1 Some research topics covered well

In our review, we have found most evidence on the particular characteristics of investors

or the housing markets they invest in (research question 2) and the future prospects for

the sector (Q8). This is mainly due to three reasons. First, a large share of the evidence

has been commissioned by public or publicly accountable agencies trying to plan and

operate in local housing markets. Second, much of the work has been empirical to

understand investors in the market, either personal characteristics (eg age, location) or

property characteristics (eg type of dwelling, portfolio size). Third, the interest in the future

prospects of the sector is driven by a concern for the wider housing market and an

interest in how public policy can anticipate the direction of development in order to

respond effectively to it.

We have found less evidence looking at the impact of BTL on house prices (Q1), first-time

buyers (Q3) and private rental provision (Q4). The wider research material on house prices

and first-time buyers has been more interested in the owner occupier market (eg

Holmans, 2005; Wilcox, 2005, 2006). We have found a lack of academic investigation into

the relationship between the owner-occupier market and the investment market. Equally,

evidence on private rental provision has been included in some of the studies we have

reviewed but often in conjunction with other research aims.

Evidence has been most lacking around the supply and quality of BTL housing stock (Q5),

vacancy rates (Q6) and international evidence (Q7). Although the quality of PRS stock has

consistently been identified as poorer than in other tenures, the means of improving this

stock are less well understood. There has been much greater policy momentum to bring

social rented housing up to the decency standard, so there has been more emphasis and

research on this issue. Vacancy rates, meanwhile, are sometimes alluded to in broader

research findings but they do not feature as the subject of stand-alone studies. Lastly,

international evidence on housing issues tends to be provided by academic literature and

although there is some evidence on BTL available, this is very limited (eg Montezuma,

16

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

2006; Mandicˇ, 2000). The inherent difficulties of developing a comparative understanding

of housing markets, given their unique characteristics and histories have limited the

amount of such evidence. It is therefore highly problematic to offer superficial comparisons

between the English housing market and markets in other countries.

1.4.2 Varied affiliation to the subject

When looking at the evidence reviewed by affiliation to the subject, there are five distinct

groups. They are described here in order of amount of evidence produced:

• Academic literature: A large share of the evidence has be commissioned by the

Joseph Rowntree Foundation or published in academic journals and books. Such

studies have almost all had strong and transparent methodologies and generally

looked at the PRS nationally. Academics have also worked on research commissioned

by other organisations outlined below.

• Local, sub-regional and regional level agencies: The second most common type

of evidence has been commissioned by local authorities and sub-regional or regional

bodies. These have been produced by private consultancies as well as academics.

They have been particularly common in towns and cities working on housing market

renewal, in South East England (including London) and where there are large student

populations. Much evidence in this group has also been of high quality, though some

studies have relied on relatively small samples and therefore contained high margins of

error.

• The lending and letting industries: There have been a few studies by and on behalf

of the lending and letting industries, particularly for the CML and ARLA. These have

often drawn on industry data that would otherwise not be published and are often

up-to-date, so a valuable contribution to the literature. They are weak, however, by

reporting much opinion; they are closer to promotional material than solid and

transparent research evidence.

• Other national level organisations: Some research has been commissioned by

other organisations with a particular interest in BTL. The best example is Kemp (2004),

commissioned by the Chartered Institute of Housing, which provides one of the most

in-depth understandings of the PRS, though no primary evidence is included. Another

example is Ball (2004), commissioned by the Social Market Foundation to stimulate

discussion on the performance of markets and the social framework. A third is Birch

(2007), an article written for Roof, the magazine of housing rights charity Shelter. The

article provides new evidence on housing affordability but is selective in presenting data.

• Central government: Just a few of the studies reviewed have been commissioned

directly by central government. The two national surveys of private landlords (ODPM,

2003, 2006) are strong empirical datasets and provide a good overview of the broad

BTL market. Surprisingly few other studies (before this project by the NHPAU) have

been commissioned by central government that look in particular at BTL, although the

evaluation of the housing benefit reforms (eg DWP, 2005, 2006) has provided some

useful comparative evidence along the way.

17

1.4.3 Mostly national or local authority geographic scopes

Those commissioning work have generally determined the geographic scope of studies.

This has resulted in a fair amount of evidence at national level but a patchwork of studies

at a lower spatial level.

The two surveys of private landlords carried out alongside the English House Condition

Surveys (ODPM, 2003, 2006) are good examples of national level studies providing much

empirical data on a range of investor and property issues. Their shared limitation is that

even such large samples are too small to break down to regional or local authority level.

Both reports acknowledge this drawback, though, and do not attempt to break down the

samples spatially.

Most of the studies carried out by academics are also at a national level. This is often

because they have been commissioned by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation or bodies

with a national interest (eg ARLA, CML, Social Market Foundation). The benefit of such

studies is their scale and broad remit in terms of understanding the working of the housing

market at large. Their weakness is a lack of detailed understanding of particular housing

markets or sub-markets.

This drawback is allayed by studies that have considered the BTL and the PRS at a

regional or sub-regional level. These include ECOTEC (2007), Green et al (2007), Hickman

et al (2007), London Development Research Ltd (2006), Pendle Borough Council (2007)

and Savills Research (2007). The advantage of such studies is being able to concentrate

on links and interactions between the BTL and the rest of the PRS, and between different

tenures, on more localised phenomena and providing much larger samples at a local level.

For example, Green et al include a survey of 576 landlords, almost the same sample size

as one of the national surveys (ODPM, 2003). These studies are particularly useful for

shaping regional policy making.

We have also found some evidence on BTL collected at a local authority level. In particular

these are: CSR Partnership (2004), CRESR (2007), ECOTEC and SURF (2006), Gibb and

Nygaard (2005), Knight Frank Residential Research (2007) and Unsworth (2007). These

have the added benefit of understanding change at an even smaller level, sometimes

down to parts of towns or cities (eg west Glasgow) and even down to neighbourhood

level (eg Nottingham’s Lace Market area). However, some of these studies are weakened

by relying on small samples (eg 24 landlords in Glasgow and 14 agents and developers in

Nottingham).

At an even more localised level, when looking specifically at neighbourhoods, we have found

much less evidence. Although there will undoubtedly be less research at this level, some

studies will exist that have been beyond the scope of our search strategy. Yet property

investors are often attracted to particular streets or neighbourhoods, not just towns or cities,

so such localised research is important. The Leeds Beeston Hill case study in Hickman et al

(2007) is an exception in the literature, although it was purposely included in their research

as a distinct case study and not just studied because of a local public policy concern.

1. Introduction

18

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

1.4.4 Methodologies focused on housing market analysis

Many types of methodologies have been used in the studies we have reviewed. Some

research has relied exclusively on empirical data collected from surveys (eg ODPM, 2003,

2006). Most projects, though, have combined methods for collecting data, often using

qualitative and quantitative approaches (eg ECOTEC, 2007; Green et al, 2007; Hickman et

al, 2007). Most techniques have appeared adequate for collection and analysis, although

some studies have used seemingly inappropriate methods (eg collecting mainly statistical

evidence using interviews rather than paper questionnaires in Gibb and Nygaard, 2005) or

relied on weak statistical associations (eg Crook, 2002, although these were

acknowledged).

We have also included a few studies that have exclusively used secondary evidence (Ball,

2004; Kemp, 2004). Although these would not normally be included in rapid evidence

assessments, we have done so because they have been large-scale and offered depth to

the topics covered. We have, however, been cautious not to double-count such evidence

when reviewing the primary sources, too.

By research discipline, most evidence comes from the applied and eclectic ‘housing

studies’ sector, with a direct interest in housing market analysis. In contrast, we have

reviewed less evidence from an overtly economistic perspective, although some studies

have been included (eg Hughes, 1999; Meen, 2006; Scanlon and Whitehead, 2005; but

also Ball, 2004, 2006).

1.4.5 Some very new literature, but some dated

A rapid evidence assessment benefits from using a methodical search strategy. Because

we contacted regional and local agencies in our search we have been able to review the

newest evidence available, some even before publication. This means that our overall

review has included the most up-to-date evidence available as well as solid studies from

over the last 10 years.

We do suggest some caution, though, when looking at the date of studies. Housing

markets change all the time; property prices and housing supply both fluctuate and public

policy instruments are continually implemented and refined. The BTL market can change

more quickly, as witnessed by the sudden rise in investors in housing market renewal

areas. This means that evidence published as recently as 2002 can be considered out of

date in some areas, and offer little insight into contemporary issues and pressures in those

local housing markets, especially in the BTL sector.

19

2. Characteristics of investors

and investment motives

We have found most evidence on the characteristics of investors and their investment

motives. This section looks at these issues, first their overriding motives and then looking

at three particular investor types.

2.1 Investors seeking a financial return

Most studies point to the fact that many individuals have decided to become landlords.

But what are their motives for doing so? There are many reasons people invest in

property. The overriding motive for private landlords is to receive a financial return, either

through rental income, capital gain or both. This financial motive is also increasing, up

from 59% in 1994 and 1998 to 68% in the 2001 national survey (ODPM, 2003) to 72%

among private individual landlords in the 2003 survey (ODPM, 2006).

BTL mortgages have given investors the means to borrow easily and at competitive rates.

But the BTL phenomenon has done more by making it more socially acceptable to invest

in property (Ball, 2004) or even socially desirable (ECOTEC and SURF, 2006). At a

financial level, investment in rental property has also been attractive, especially when

compared with other forms of investment. The index constructed by Rhodes and Kemp

(2002) found total returns for residential property investors at almost 14% in 2000. Yet

this was higher than the total return of 10% for all types of commercial property, minus

6% for equities, 9% for gilts and 6% for cash (Rhodes and Kemp, 2002, Table 4.1).

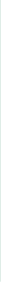

Data from the CML reinforces the strong return from property investment when compared

with gilts and equities (Figure 2.1). This shows how net rental yield has been

outperforming UK share dividend yield since 1992 and surpassed the 30-year gilt yield in

1998. By 2004, however, net rental yield was clearly moving downwards, making it a less

attractive investment proposition in terms of rental income. This indicates that expected

capital gains alone have driven the most recent wave of investment in the sector.

Figure 2.1 Yields on housing, gilts and equities

Source: CML (2006)

16%

14%

12%

10%

8%

6%

4%

2%

0%

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004

30-year gilt yield UK all share dividend yield Net rental yield

20

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

The comparison with other forms of investment is apt, as falling stock markets and

companies closing final salary pension schemes have been suggested in the literature as

two drivers for people to invest in residential property (eg Rhodes and Bevan, 2003). Ball

(2004) suggests that this has given people greater confidence in managing their own long-

term investment affairs rather than rely on financial market specialists, hence the rise in

BTL investment. Landlords themselves see their investment as medium- to long-term. For

example, the ARLA survey of landlords shows that over 2004 to 2007 most landlords

expected their property investment to last over 16 years (ARLA, 2007). However, such

intentions are bound to be adaptable to market pressures and changes, not just in

property but in other assets as well.

We must also acknowledge, though, that some people become private landlords for other,

non-financial reasons. For example, the evidence shows a rising trend of landlords

acquiring property with the intention of living in it. In addition, some landlords buy

properties to let to friends or family, sometimes rent-free, while organisational investors

buy bought property to let to employees as part of a remuneration package. These last

two types of landlord have little interest in the investment return of their properties and

more concern for the use of their properties. There is also a small proportion of people

who have inherited property (eg 14% of respondents in the Bridging NewcastleGateshead

survey: Green et al, 2007). Although the letting can then result in financial gain, this is not

the main reason they have acquired it.

The evidence suggests the following distinct groups of investors:

• small-scale, amateur landlords investing for their retirement;

• speculative investors seeking short-term capital growth, often in new-build

apartments; and

• professional landlords living on rental income.

We outline these groups in more depth below.

2.2 Amateurs investing for retirement

The BTL phenomenon, helped by BTL mortgages, has encouraged a generation to invest

in residential property. Yet much of this new investment is small-scale but long-term.

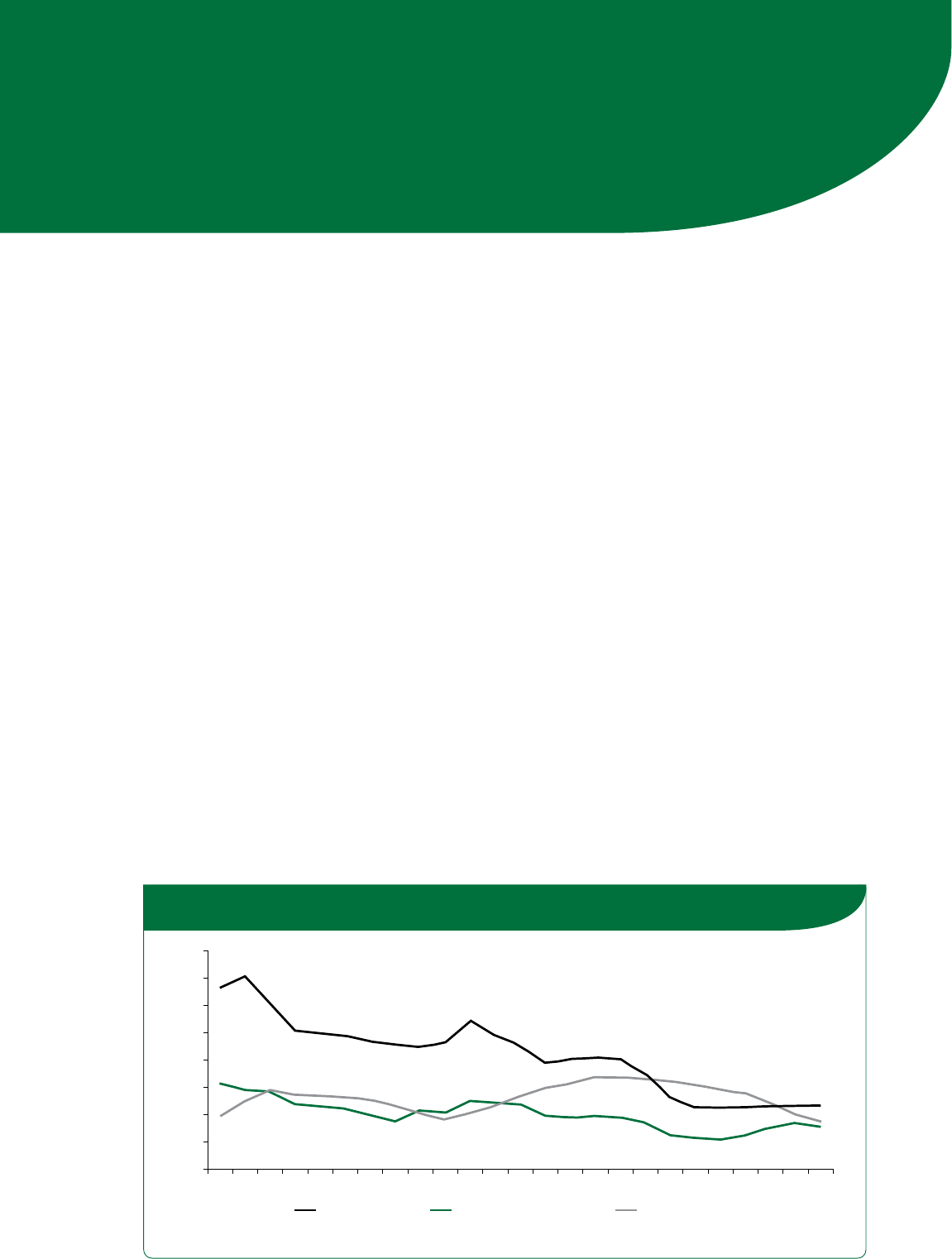

Figure 2.2 shows the distribution of stock across the entire PRS by landlord’s portfolio

size. This clearly shows that the majority of stock (55%) is owned by landlords who own

fewer than 5 properties. In contrast, 12% of stock is owned by large-scale investors with

100+ properties.

21

2. Characteristics of investors and investment motives

Evidence of these small portfolios is also found in other surveys. For example, Scanlon

and Whitehead (2004) found that most non-professionals with BTL mortgages owned one

or two properties, and 69% of all these landlords owned less that six properties. Also, the

survey of private landlords in the Bridging NewcastleGateshead housing market renewal

area (Green et al, 2007) found that 57% of landlords owned 4 properties or less.

In addition to the small-scale nature of this investment, there has been a move away from

institutional investors to private individuals owning PRS property. The last national survey

showed that two-thirds (67%) of landlords were private individuals or couples (ODPM,

2006). This is mirrored elsewhere, for instance 81% of landlords letting to people on

housing benefit described themselves as private individuals or couples (DWP, 2006).

Furthermore, with such small portfolios, these landlords can fairly be described as

‘amateur’. For example, the survey of BTL landlords (Scanlon and Whitehead, 2004)

revealed that 68% had another full-time job and managed their investment in their spare

time.

Rather than seeking short-term gain or rental income, this group of BTL investors are

much more interested in long-term retirement planning (Rhodes and Bevan, 2003; Gibb

and Nygaard, 2005). Many of these landlords plan to keep their investments and live on

the rental income during retirement. Green et al (2007) also found that most landlords said

they were in it “for the long haul”, while the survey of BTL borrowers revealed that over

60% of landlords expected to stay in the residential market for at least 10 years (Scanlon

and Whitehead, 2004).

Figure 2.2 Distribution of private rented stock by size of landlord’s portfolio

Source: CLG (2008)

Landlord’s portfolio size

% of PRS stock

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

250+100-24950-9925-4910-245-92-41

22

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

2.3 Speculative investors in new-build

In sharp contrast to the long-term retirement planning of the above group, another group

of BTL investors seeks to gain through short-term capital appreciation. Due to high levels

of media attention this group is often most strongly identified with the rise of the BTL

phenomenon. While this group of property owners is undoubtedly distinct, most studies

show that speculative investors account for just a small proportion of the overall private

rental market. They are, however, significantly concentrated in new-build apartments in city

centres.

The ARLA survey of landlords showed that over 2004 to 2007 an average of just over 3%

had bought for short-term capital gains (of less than five years) (ARLA, 2007). The national

survey of landlords by the ODPM (2006) found that among new landlords nearly a third of

properties would not be relet if they became vacant. This suggests that they too are short-

term investors, potentially seeking rapid capital appreciation, though it could also indicate

short-term investment for other reasons. Ball (2004) points out that investors in recent

years will have seen significant year on year capital appreciation, unlike in previous and

shorter boom-bust cycles. He suggests this will have been an incentive for those investors

seeking short-term gains.

There has clearly been an attraction to certain types of property by these investors.

Unsworth (2007), for example, found that the city centre market in Leeds between 2001

and 2004 was driven by speculative investors looking for short-term capital gain. Most

apartments were bought off-plan with little regard for the quality of the product or the

location. This type of investment is also reported in studies elsewhere in Yorkshire and

Humber (Hickman et al, 2007), in Stoke-on-Trent (ECOTEC and SURF, 2006), Manchester

and Sheffield (Allen and Blandy, 2004) and Glasgow (Gibb and Nygaard, 2005). The 2003

national survey of landlords supports this, finding that ownership of modern properties

(build after 1964) and purpose-built flats was more common under new landlords than

under longer-term ones (ODPM, 2006).

According to the analysis of the central Nottingham housing market (Knight Frank

Residential Research, 2007), investors were more inclined to buy an unfinished product

than owner occupiers and were further attracted to new-builds due to their lower

maintenance, the potential for discounts for buying off-plan (up to 10% off), building

warranties, the potential for more efficient management if several units were bought within

one scheme and the ability to furnish and immediately rent a unit rather than have to

invest time and money renovating an older property.

23

2. Characteristics of investors and investment motives

This type of investment is sometimes labelled ‘buy to leave’, with properties bought as an

investment but with no intention of letting out. While this is going beyond the scope of our

project (as there is no intention of letting out), the evidence revealed the existence of this

sector. For example, the study of new-build homes in London (London Development

Research, 2006) found that 16% of purchases were to the ‘buy to sell’ group (Table 2.1).

But even in this study, the ‘buy to let’ group is three times as big, and expands further (to

58%) by the time of completion, as the majority of ‘buy to sell’ properties are sold-on to

‘buy to let’ investors. Yet the ‘buy to leave’ sector is an inherently unstable part of the

market as decisions about the future of properties may be taken quickly if market

conditions change.

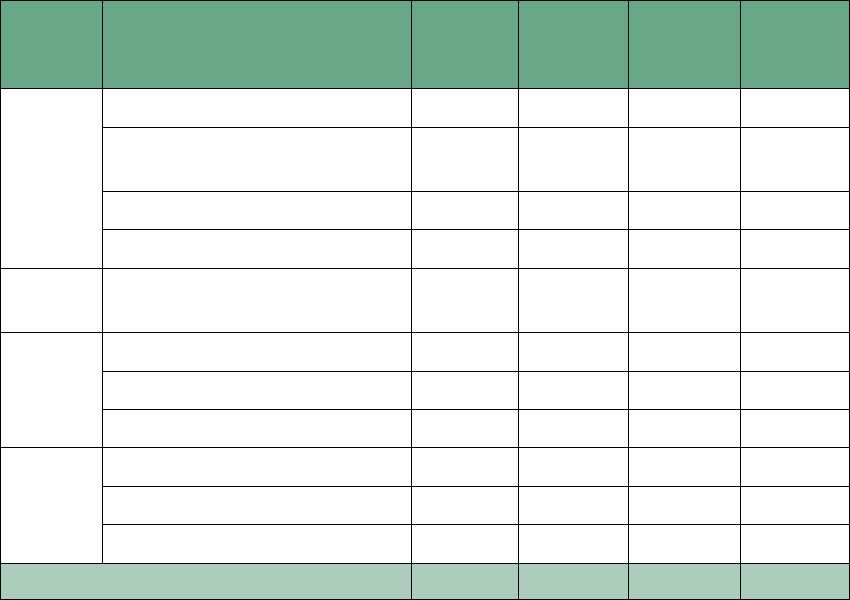

Table 2.1 Who buys new homes in London?

Category Sub-category Number of

buyers in

London

Number of

purchases

(2005)

Number of

purchases

per buyer

% of total

purchases

Buy to

Let

Private individuals with <3 homes 3,000 4,500 1.5 28%

Private individuals: larger

portfolios

200 2,000 10.0 13%

Investment funds 15 750 50.0 5%

Total buy to let 3,215 7,250 2.3 45%

Buy to

Sell

Total buy to sell 50 2,500 50.0 16%

Build to

let

Developers 30 1,000 33.3 6%

RSLs 10 500 50.0 3%

Total build to let 40 1,500 37.5 9%

Owner

occupiers

First home 4,250 4,250 1.0 27%

Second home 500 500 1.0 3%

Total owner occupiers 4,750 4,750 1.0 30%

Total London 8,055 16,000 2.0 100%

Source: London Development Research (2006)

24

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

This sort of investment in new-build properties, more common among newer investors,

will inevitably lead to property price inflation providing that investors can sell at a profit.

However, there may be saturation of the PRS in some markets which could lead to a fall in

prices. According to Unsworth (2007), who was examining the development of the ‘urban

living’ phenomenon in Leeds, the market has changed since 2004 – with higher interest

rates, over-supply and declining yields – resulting in a tailing off of investor interest in this

market. This is an issue that needs to be monitored closely.

The London Development Research (2006) study also points to high levels of activity from

overseas investors in the capital. Quoting figures provided by Hampton International

covering some 1,000 home sales in recent developments, 56% of investors were found to

be from the UK and 44% from abroad, with the Middle East, South Africa, Western

Europe and Ireland well represented among foreign investors. Foreign investors were

found to be attracted to the UK market by the prevailing conditions of legal and political

stability and by the strength of sterling. For Irish investors a regulation change concerning

pension funds in Ireland was also a driver (Fox and Unsworth, 2005). This illustrates how

the far removed from the housing market some of the pressures driving investment can be.

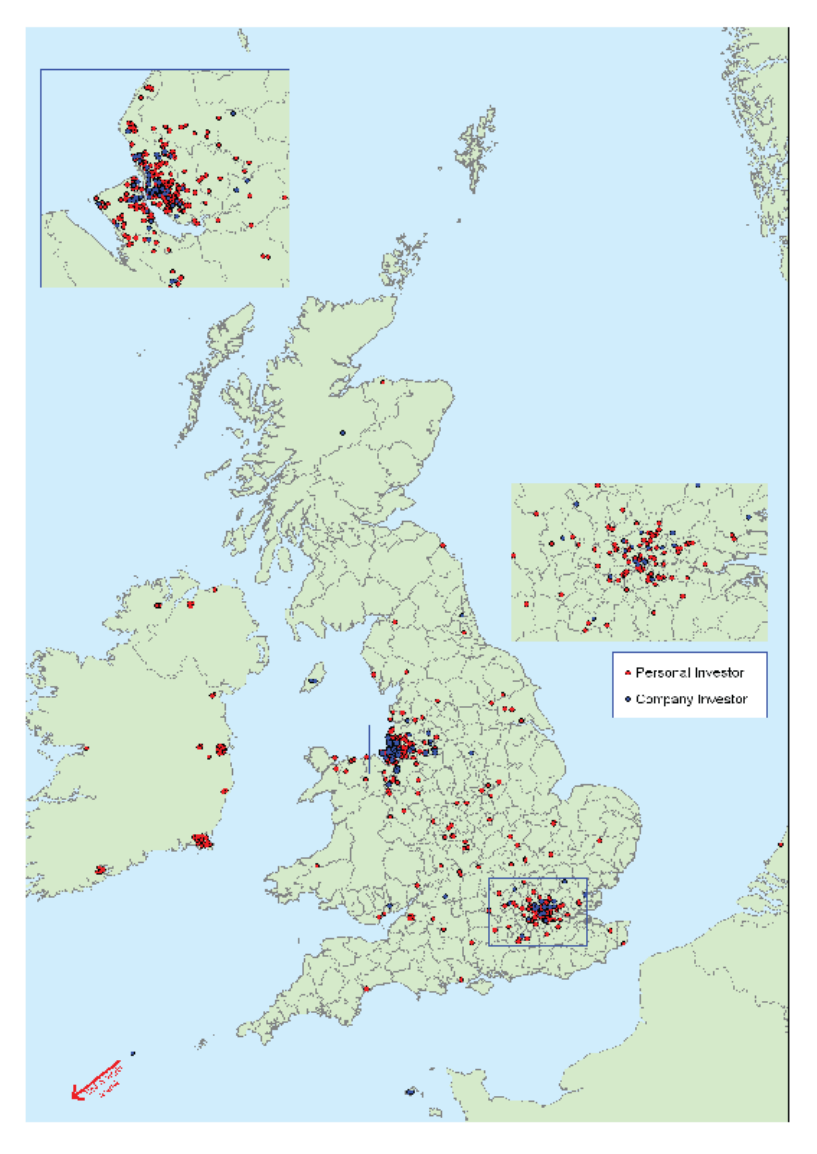

Another local study (ECOTEC, 2007), this time of Merseyside, also found significant levels

of international investment in private rental property. Figure 2.3 shows the home or

company address of investors of a sample of property in the NewHeartlands pathfinder.

There are a significant number of personal investors from Ireland (particularly Wexford,

Dublin and Cork) and company investors from off-shore tax havens (Guernsey, the Isle of

Man and the British Virgin Islands). However, the study also shows that the largest

concentrations of investors were from within Merseyside and in Greater London. However,

the two studies quoted here may not be representative of the market as a whole.

25

2. Characteristics of investors and investment motives

Figure 2.3 Location of private non-owner occupiers in Merseyside sample

Source: Land Registry data of property sales in NewHeartlands Apr 01 to Mar 06 in ECOTEC (2007)

26

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

This BTL or buy-to-leave investment in new-build properties has had positive and negative

consequences. It has financed much new-build development, contributing to an increase

in housing supply (Rowlands et al, 2006) and greater choice for those who want to rent.

But there are also disadvantages of such activity. First, there is evidence of owner

occupiers being priced out of new-build developments, reducing the level of choice

available to them (Allen and Blandy, 2004). Second, BTL investment has spurred

developers to construct smaller, studio apartments (Knight Frank Residential Research,

2007; Rowlands et al, 2006). This is only a problem if people do not want them, which it

would seem they do not (Unsworth, 2007). This is because rental yields can be higher in

these units (Allen and Blandy, 2004) and because investors are also facing rising prices,

so want properties they can afford.

2.4 Professional landlords living on rental income

The third key group of BTL investors is professional landlords seeking rental income.

Scanlon and Whitehead found that almost a third (31%) of landlords owning more than

20 properties were acting under a company structure or as part of a partnership. These

property owners are therefore closer to being letting agents – many in fact do operate as

letting agencies – than private individuals.

The business model of those with large portfolios tends to be more focussed on

generating a positive cash flow from rental income and is less preoccupied with short-

term capital growth (Rhodes and Bevan, 2003; Scanlon and Whitehead, 2004). The 2003

national landlord survey found that over 60% of full-time landlords sought only rental yield

from their investment, the highest of any type of investor (ODPM, 2006). The study of BTL

borrowers by Rhodes and Bevan (2003) reiterated this and stated that for some of these

landlords capital growth was an irrelevance.

Understandably, this group of investors is also more professional and knowledgeable

about their work. For example, the CML survey (Scanlon and Whitehead, 2004) found that

‘professional landlords’ were generally more active in making changes to their portfolios

than non-professional landlords. This is backed up by Rhodes and Bevan (2003) who

found that full-time landlords were more commercially-focussed in disposing of

underperforming stock and maximising the yield of their portfolios. More experienced

landlords were generally felt to be in a stronger position to be able to weather short- or

medium-term market fluctuations.

27

2. Characteristics of investors and investment motives

2.5 Regional variation found

The evidence suggests some regional variation in BTL investment levels, although the

geographic coverage of the evidence is patchy. The CML-commissioned survey (Scanlon

and Whitehead, 2004) found the amount of BTL activity in London, the South East and

the South West regions to be disproportionate in relation to the population of these areas.

Activity was found to be considerably less prevalent in the East of England, the Midlands,

the North East and Yorkshire & Humber. However it should be noted that this survey

sample was not strictly representative due to the self-selection of the 12 lenders who took

part. This survey also revealed that a quarter of those landlords owning more than one

dwelling had properties in more than one region.

Some studies have suggested a link between investment in a certain area and the type of

stock available. New-build apartments have often been developed in city or town centres,

part of the urban renaissance drive. The studies back up the generally held view that BTL

investment (as well as buy-to-leave) has been prevalent in these developments. This is

clearly evidenced in the study of London (London Development Research, 2006),

particularly in east London where prices were lower, in Nottingham (Knight Frank

Residential Research, 2007), Leeds (Fox and Unsworth, 2005; Unsworth, 2007),

Manchester and Sheffield (Allen and Blandy, 2004), Liverpool (ECOTEC, 2007) and

Glasgow (Gibb and Nygaard, 2005).

Housing market renewal areas and other lower-value areas with poor property conditions

have developed a different BTL segment. According to Sprigings (2007, but echoed in

CSR Partnership, 2004; Knight-Markiegi, 2006) much of the BTL activity in pathfinder

areas concerned cheaper houses, especially in areas dominated by older terraced

housing. This finding is also reported by Hickman et al (2007) in the case of Beeston Hill,

an inner-city neighbourhood of Leeds with a high PRS and mainly pre-1919 terraced

stock, in the study of Hull (CRESR, 2007) and of the Merseyside pathfinder (ECOTEC,

2007). This last one found a large concentration in low-value terraced housing, making up

some three-quarters of private rented stock. Most of these properties in Merseyside are

small, lack space, have no garden and are overcrowded. Because of its old age, much is

likely to need repairs or improvements and offer poor thermal insulation.

While the above section discussed foreign investment into BTL, and numerous studies

have talked about ‘flush’ investors from London buying elsewhere in the UK, many

landlords still buy property in their local area. Rhodes and Bevan (2003) found that most

landlords preferred to invest close to home, firstly because local knowledge was seen to

be important in making shrewd investment decisions, and secondly because this made

management and maintenance easier. A predominance of local landlords was also found

in the studies of Yorkshire and the Humber (Hickman et al, 2007), Merseyside (ECOTEC,

2007), Newcastle and Gateshead (Green et al, 2007), East Lancashire (Pendle Borough

Council, 2007), Stoke-on-Trent (ECOTEC and SURF, 2006) and Glasgow (Gibb and

Nygaard, 2005). This last study also found that these local landlords, who were often

small-scale, were generally committed to the market for the longer term.

28

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

2.6 Summary of key findings

The overriding motive for private landlords is to receive a financial return, with returns in

residential property outperforming other forms of investment in recent times. Yet landlords

have different motives for investing. The biggest group of BTL investors are small-scale

and amateur, investing for retirement. These are most likely to expect to continue letting

property over the medium- to long-term.

Speculative investors form a second group, though much smaller in size. They are seeking

short-term gain through capital growth and are concentrated in new-build apartments.

There is also overlap between this group and the ‘buy-to-leave’ phenomenon, with

properties bought as an investment but with no intention of letting out. A concern for both

groups is that there appears to be a saturation of the PRS in some markets which could

lead to a fall in prices. Another worry is that such investment has encouraged developers

to build small apartments, although there may not be sufficient household demand for

such units.

The third key group of landlords are those who own large portfolios. These investors

are more focussed on generating a positive cash flow from rental income and less

preoccupied with short-term capital growth. Understandably, this group of investors

is also more professional and knowledgeable about housing tax and finance.

29

3. Housing quality and voids

Going beyond the characteristics of investors and attraction to particular types of dwelling,

this section considers the condition of properties in the BTL market and void levels.

3.1 Improvement to property conditions

Table 3.1 shows the rates of unfitness across all tenures from 1991 to 2001 (Kemp,

2004). This clearly shows that private renting has consistently held the highest level of

unfitness (also found in ODPM, 2006), although fitness has increased dramatically over

the decade, which coincides with the expansion of the sector. When broken down, the

highest levels of unfitness are found in terraced houses and converted flats.

Table 3.1 Rate of unfitness by tenure in England, 1991 to 2001

(% of households)

Tenure 1991 1996 2001

Owner occupation 5.4 5.4 2.9

RSL rented 7.1 3.8 3.0

Council rented 6.8 6.8 4.1

Private rented 24.7 17.9 10.3

Source: Kemp (2004) Table 6.7

When looking at the alternative definition of housing quality, the decency standard, private

rented properties again perform badly (Kemp, 2004). Breaking down the sector by sub-

sector (Table 3.2), regulated tenants fare worst, with 74% living in non-decent housing.

This is due to three reasons. First, the old age of many of the dwellings, with therefore

more use and in need of more work. Second, the long history of rent controls has made

it uneconomical for landlords to repair or maintain properties. Third, many of the tenants

will be classed as vulnerable (in receipt of housing benefit and elderly) and will have weak

bargaining power.

Table 3.2 Privately renting households living in non-decent

housing in England

PRS sub-sector % living in non-decent housing

Regulated 74

Non-regulated 49

Not accessible to public 37

All private tenants 49

Source: Kemp (2004) Table 6.8

Looking at the regional picture, it appears that property repair condition is poorer the

further away it is from London and the South East (Crook, 2002). Urban and city centre

properties along with rural dwellings in village centres and in non-residential locations are

also in relatively poor repair. However, much of the data used for this study relates to the

time before BTL mortgages, so must be treated with caution.

30

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

In terms of the link between landlord type and property condition the 2003 national survey

(ODPM, 2006) noted that companies tend to own a higher proportion of older dwellings

than other landlord types, and lower rates of decency. In contrast, dwellings acquired

since 1999 – a fifth of dwellings – tend to be in better condition than dwellings already in

the sector. Together, these suggest that the quality of properties in the PRS improves

most with the replacement of poor-quality stock by dwellings in better condition rather

than the active modification by landlords.

Crook (2002) found that the likelihood of work being undertaken and of the amount spent

on the work also relate to the character and motivation of the landlord. He showed that

addresses in the worst conditions were more likely to be owned by landlords who regard

them as investments whereas those in the best conditions were more like to be owned by

those who do not have investment motives.

One local level study, of Stoke-on-Trent (ECOTEC and SURF, 2006), found that there had

been three distinct drivers of stock improvement for student landlords. First, Staffordshire

University registration scheme initially set minimum standards but raised these standards

each year. Second, the action of a few landlords had improved the condition of student

rentals. One landlord was renowned for the quality of his stock and for raising the

standard of student houses more widely. He had purposely positioned himself as a

landlord of good quality stock, buying properties in a bad state but investing to improve

them (also seen in Knight-Markiegi, 2006). This had the effect of encouraging other

landlords to improve their stock. Third, Stoke-on-Trent City Council’s landlord accreditation

scheme had promoted membership by offering 50% property improvement grants to

members. This action increased membership and got landlords to invest in the fabric of

their properties sooner than they would have otherwise done.

The statistical study by Crook (2002) also looked particularly at the issue of stock quality

and its relationship to rental income and property price. He found that returns, not rents,

were related to property condition. The best condition properties tended to be better

maintained than those in poorer condition. So annual spending on maintenance and minor

repair was greater for properties in better condition, thus reducing the level of return. But

vacant possession market values were higher among the better condition than the poorer

condition properties. This means that some landlords will be interested in maintaining

already good-quality homes, seeking capital growth and hoping for longer-term tenants,

while others will be happy to receive rental income from poor-quality properties (Knight-

Markiegi, 2006). Rhodes and Bevan (2003) labelled these two groups as “turnover

minimisers” and “rent maximisers” respectively.

Knight-Markiegi (2006) summarised three distinct pathways for landlords and property

conditions, which sums up much of this evidence (Figure 3.1). Although related to a low-

value housing market, his findings appear transferable to other areas. One group of

investors is interested in buying good-quality properties for higher prices, receiving a lower

rental yield but hoping for capital gain. This group is closely aligned to the group of

amateur but long-term landlords. A second group is interested in buying cheap properties

31

3. Housing quality and voids

but investing in them to minimise turnover by tenants and again seeking capital gain. The

third group is happy to buy poor-quality properties and keep them so, receiving higher

rents but also facing higher turnover, so higher management costs. This last group shares

a short-term focus as the speculative, ‘buy-to-leave’ investors but is investing in poor-

quality, rather than new and good-quality, properties.

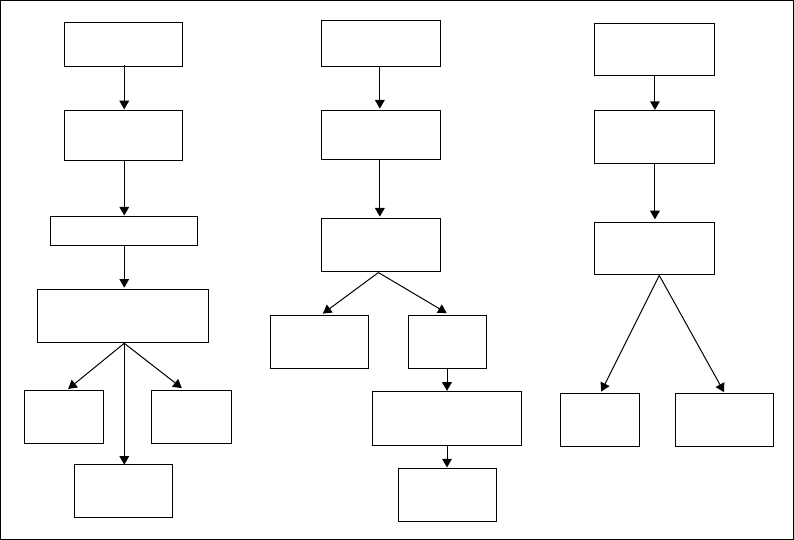

Figure 3.1 Property condition and returns for landlords

Poor-quality

properties

Poor-quality

properties

Good-quality

properties

Low property

prices

Low property

prices

High property

prices

Rent lower

than mortgage

Capital remaining

Properties improved

by landlords

Properties left

in poor state

Low rental

yield

High rental

yield

Low rental

yield

Lower rental

yield

Capital

growth

Capital

growth

Low

turnover

High

turnover

High management

cost

Source: Adapted from Knight-Markiegi (2006)

3.2 Consistent level of voids

Evidence on vacancy periods and void rates is patchy but generally consistent. Two large-

scale surveys of landlords (ODPM, 2006; DWP, 2005) found that at the time of interview

some 6%–7% of landlords’ properties were vacant. When looking at the duration of voids,

most studies show that the average void rate in market renting (so ignoring ‘buy-to-leave’)

is about one month per year (ARLA, 2007; Ball, 2004, which includes evidence from a

variety of sources; Scanlon and Whitehead, 2005).

32

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

Ball relates this level of voids to the mobility of tenants. Evidence from ARLA (2007) shows

that the average length of tenure for private tenants is some 15–17 months, which leads

to continual churn in the sector. But this is partly what the PRS is about: providing quick

and easy access to – and exit from – housing.

The 2003 national survey of landlords (ODPM, 2006) found that over half of vacant

properties were non-decent, higher than all other properties let for less than six years.

A study in one housing market renewal pathfinder (Green et al, 2007) found that landlords

with city centre or waterfront apartments were most likely to report that some of their

properties were empty, followed by landlords who owned a house converted into self-

contained flats or into bedsits. When looking at regional differences, the evidence is very

slight. Only ARLA (2007) covers this to some degree, showing that void rates were higher

in ‘prime central London’ than ‘elsewhere in the South East’ and ‘rest of the UK’ from late

2003 (when the survey began) to late 2006; since then, though, rates had equalised

between the areas covered.

While the level of voids is relatively consistent, empty properties of course cost landlords

in lost rent. Scanlon and Whitehead (2005) found that among BTL borrowers the most

common means of covering mortgage payments during void periods was to use savings.

Surplus rents from other properties, and from the same property, were also significant.

Providing that vacant properties are occupied in a relatively short time, there is little fear

of BTL borrowers defaulting on their mortgage payments on a large scale. In fact, the level

of arrears among BTL borrowers is lower than across the mortgage market as a whole

(Thomas, 2006). But there would be a public policy concern if demand dropped or there

was an oversupply in the BTL market.

3.3 Summary of key evidence

The private renting has consistently held the highest level of unfitness among all tenures,

although fitness has increased dramatically over the decade. Improvement to property

condition appears to happen more with new stock entering the market than by the active

modification by landlords.

Some BTL investors are happy to hold on to poor-quality stock and obtain high rental

yield, though have little interested in long-term capital growth. These landlords have been

called ‘rent maximisers’, though may face higher voids. Another group of landlords often

buys good-quality stock and invest to maintain this high standard or buys poor quality

stock but improves it. These investors will receive better capital growth but reduced net

rental yield, because of higher management and maintenance costs.

Evidence on vacancy periods and void rates is patchy but generally consistent. Some

6%–7% of landlords’ properties appear to be vacant at any one time, and the duration

of voids is about one month per year. These figures are probably affordable for BTL

investors, but there would be a public policy concern if demand dropped or the BTL

market became saturated with supply.

33

4. Investors and the wider

housing market

BTL investment has made a significant impact on the PRS at large, now accounting for at

least a fifth of the entire sector. But how have investors used BTL mortgages and what

affect has all this had on property prices and homeowners? These issues are considered

in this section.

4.1 Financing purchases with BTL mortgages

In assessing the proportion of the PRS with BTL mortgages, much of the literature has

looked at the use of mortgages and other types of loan. ODPM (2006) states that almost

half (46%) of landlords bought property using mortgages, though this rises to 54% for

private individuals and even further to 64% for new landlords (those involved in renting for

up to three years). This is in clear contrast to the situation in 1998, when three-quarters of

PRS properties were bought with cash (ODPM, 2003). Investors are clearly attracted to

borrowing, particularly BTL mortgages, to finance their purchases.

Scanlon and Whitehead (2005) provide further evidence about investors’ use of BTL

mortgages. They find that at least half of landlords had mortgages on all their properties,

but many had unmortgaged property in their portfolio. Variable interest rates, particularly

trackers, were the most common type, with most loan-to-value ratios between 26% and

75%; the maximum allowed by providers is now 85%. The vast majority of landlords had

interest-only mortgages, which minimise the monthly cost. Another reason is that

mortgage interest payments are tax deductible for landlords, while payments of principal

are not. Their research also found that large landlords were more likely than small ones to

have interest-only mortgages, suggesting a greater awareness of housing tax and finance.

Both the lending industry (eg Thomas, 2006) and some academics (particularly Ball,

2004, 2006) view BTL mortgages as a positive contribution to how investors operate.

They particularly stress the optimal use of gearing, which is the relationship between

invested equity and debt. In this sense, gearing in the property market is about reducing

personal capital in investments in order to gain greater return. Using evidence from ARLA,

Ball (2004) states that the total return for residential investors could double if 75% of the

initial capital costs were borrowed instead of by paying cash for an outright sale.

Ball (2004, 2006) states that gearing is low in the PRS, and sees much potential for

investors to improve their returns. He concludes that this demonstrates the lack of

financial sophistication in the market. If there was more gearing, BTL mortgage lending

could grow significantly in future, Ball believes, and the “private rental sector could

operate on lower gross returns, if potential gearing and associated tax effects were

adopted more effectively” (Ball, 2004, p34). While this latter point could well be true, it is

dependent on investors being financially astute and changing their financial behaviour

accordingly. This will be the case for some investors (as demonstrated in Hickman et al,

2007), but Ball himself labels many investors as “still relatively financially unsophisticated”

(Ball, 2004, p34) and having “limited understanding of the benefits of borrowing linked to

gearing and taxation” (Ball, 2006, p14). So, some investors will not use BTL finance to

their full benefit.

34

Rapid evidence assessment of the research literature on the buy-to-let housing market sector

For the lending industry, BTL borrowers are currently proving to be safer investors than

across the whole mortgage market. This is demonstrated by lower levels of arrears. At the

end of June 2006 the proportion of BTL mortgages in arrears of three months was 0.73%,

compared with 0.96% for the wider mortgage market (Thomas, 2006b). As such – and no

doubt due to the reduced numbers of first-time buyer mortgages – BTL lenders have

recently relaxed their lending criteria. The typical maximum loan-to-value ratio has risen to

85% and minimum interest cover ratio falling to 125% (Thomas, 2006b); previously it was

80% and 130% respectively (Ball, 2004).

4.2 Some effect on property prices

Few of the studies provide empirical evidence on a direct relationship between BTL

investment and house prices, and none has shown that BTL alone has increased prices.

One local level study of Glasgow found that one in three landlords explicitly attributed the

rental market investment to contributing to higher house prices, though a minority said it

had no impact on prices (Gibb and Nygaard, 2005). But this is just anecdotal evidence

from a small number of investors. A second local level study also includes similar

anecdotal evidence: that the buoyancy of the PRS of Burngreave in Sheffield had

contributed to house price inflation (Hickman et al, 2007).

However, Hickman et al (2007) also concluded that no single element had precipitated

rapid house growth in the four case study areas they assessed. They call for a better

understanding on the type of local housing market before pronouncing on the effects of

BTL. Instead, what we have witnessed across England has been the parallel rise in

property prices and growth of the PRS, particularly around BTL activity. Alternative

reasons for the rise in property prices include weak housing supply, new demand as a

result of in-migration, low rates of property transactions, rising incomes at a time of low

interest rates and the deregulation of mortgage markets (Birch, 2007; Meen, 2006). On

this basis, BTL investors are as much affected by rising property prices as they affect

them.

There is stronger evidence that private landlords are attracted to low value properties,

therefore making an association between BTL and property prices. ODPM (2006) found

that areas with higher than average concentrations of private renting were most frequently

found in areas where the housing market was healthy but house prices were modest. This

association is further demonstrated by evidence from lenders that BTL investors bought

properties cheaper than average prices, £78,000 compared to more than £100,000

(Pannell and Heron, 2001). This study also suggested that 80% of rented properties held

by residential landlords was made up of flats and terraced houses. Gibb and Nygaard

(2005) found consensus among stakeholders that BTL activity targeted one- and two-

bedroom properties at the lower end of valuations. Taken together, this evidence suggests

that a group of investors choose to buy relatively cheap property (as seen in the above

section on property condition). Apart from being more affordable, cheaper property can

lead to higher returns.

35

4. Investors and the wider housing market

4.3 Competition with first-time buyers?

A big question for policy makers is the effect, if any, of BTL investment on owner

occupiers. There is concern that investors have priced out first-time buyers. The evidence

we reviewed is ambiguous. A number of the studies point to a more complex situation in

the housing market. For example, a study into understanding housing demand (Hickman

et al, 2007) concludes that there was no single ingredient that had precipitated rapid

house growth in the case study areas. From the mortgage lending perspective, Thomas