1

S

ome decades ago, the Inuit people of Greenland were noted

to have a low rate of cardiovascular disease,

1

and this was

attributed to their high intake of oily fish. Early trials testing

this hypothesis found a beneficial effect of fish oil on mortal-

ity,

2,3

with subsequent recommendations developed for the use

of omega 3 fatty acids (ω-3 FA) for the primary and secondary

prevention of cardiovascular disease. More recent trials have,

however, failed to replicate these initial positive results, with

several large studies reporting null effects. Systematic reviews

of the accumulating data

4–8

done during the last decade have

also delivered variable findings. In part, this is because more

recent overviews have included new data from large neutral tri-

als,

9,10

and in part it is because different overviews have sought

to address particular questions for specific patient groups.

4,7,8

This is the first overview to include all recent trials, systemati-

cally address the effects on all-important outcomes, and fully

explore the potentially different effects achieved with particu-

lar interventions in major patient subgroups and in primary and

secondary prevention. With several large trials completed in

the past 18 months, we sought to more precisely and reliably

define the effects of ω-3 FA on a broad range of clinical out-

comes, overall and in major patient subsets.

Methods

Data Sources and Searches

The study was undertaken according to the PRISMA statement

11

for

overviews of intervention studies. Randomized, controlled trials were

identified without language restriction by searching Medline via Ovid

(from 1946 to March 2011), EMBASE (from 1966 through March

2011), and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (until

March 2011). Reference lists of relevant trials and review articles

were also hand searched. The MeSH terms used were the following:

fish oils, omega fatty acids, omega 3, fatty acids, α linolenic acid,

docosahexaenoic acids, eicosapentaenoic acid, cardiovascular

disease, heart failure, cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction,

revascularization, stroke, coronary disease, arrhythmia, sudden

death, cardiovascular outcome, mortality, chronic kidney failure,

renal insufficiency, kidney failure, kidney disease, renal failure, renal

outcome, albuminuria, serum creatinine, exp creatinine, and cancer.

All terms were not used in every database, but all spellings of the

terms were used as needed. Subject headings were exploded and

truncated where necessary.

Background—Early trials evaluating the effect of omega 3 fatty acids (ω-3 FA) reported benefits for mortality and

cardiovascular events but recent larger studies trials have variable findings. We assessed the effects of ω-3 FA on

cardiovascular and other important clinical outcomes.

Methods and Results—We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, and the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials for

all randomized studies using dietary supplements, dietary interventions, or both. The primary outcome was a composite

of cardiovascular events (mostly myocardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death). Secondary outcomes were

arrhythmia, cerebrovascular events, hemorrhagic stroke, ischemic stroke, coronary revascularization, heart failure,

total mortality, nonvascular mortality, and end-stage kidney disease. Twenty studies including 63 030 participants were

included. There was no overall effect of ω-3 FA on composite cardiovascular events (relative risk [RR]=0.96; 95%

confidence interval [CI], 0.90–1.03; P=0.24) or on total mortality (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.86–1.04; P=0.28). ω-3 FA did

protect against vascular death (RR=0.86; 95% CI, 0.75–0.99; P=0.03) but not coronary events (RR=0.86; 95% CI, 0.67–

1.11; P=0.24). There was no effect on arrhythmia (RR=0.99; 95% CI, 0.85–1.16; P=0.92) or cerebrovascular events

(RR=1.03; 95% CI, 0.92–1.16; P=0.59). Adverse events were more common in the treatment group than the placebo

group (RR=1.18, 95% CI, 1.02–1.37; P=0.03), predominantly because of an excess of gastrointestinal side effects.

Conclusions—ω-3 FA may protect against vascular disease, but the evidence is not clear-cut, and any benefits are almost

certainly not as great as previously believed. (Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2012;5:00-00.)

Key Words: cardiac outcomes

◼

cardiovascular disease

◼

fatty acids

◼

meta-analysis

◼

systematic review

© 2012 American Heart Association, Inc.

Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes is available at http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org DOI: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966168

Received August 22, 2011; accepted September 18, 2012.

From the George Institute for Global Health, University of Sydney, Sydney, Australia (S.K., M.J., V.P., B.N.); and University of Sydney, Sydney,

Australia (D.S.).

The online-only Data Supplement is available at http://circoutcomes.ahajournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.112.966168/-/

DC1.

Correspondence to Sradha Kotwal, BHB, MBChB, FRACP, the George Institute for Global Health, University of Sydney, PO Box M201, Missenden Rd,

Sydney, NSW 2050, Australia. E-mail [email protected]g.au

Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Outcomes

Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Sradha Kotwal, BHB, MBChB, FRACP; Min Jun, BSc (Hons), MSc; David Sullivan, MBBS, FRACP, FRCPA;

Vlado Perkovic, MBBS, PhD, FRACP; Bruce Neal, MBChB, PhD, FRACP

Original Article

2 Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes November 2012

Study Inclusion Criteria

Studies were included if they were done in adults, were randomized

or quasirandomized (trials using methods not completely random for

patient allocation, eg, sequential allocation, etc), reported effects on 1

or more of the primary or secondary outcomes, included a comparison

between ω-3 FA (delivered as either a dietary supplement or as dietary

modification) and control, and recorded ≥100 patient years or more of

follow-up per randomized group. Trials with a crossover design were

excluded, as were trials done in pregnant women or children.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

Two investigators (S.K. and M.J.) reviewed all abstracts independent-

ly for eligibility according to the prespecified inclusion criteria. A

third investigator (V.P.) resolved any discrepancies. For selected stud-

ies, the full text articles were reviewed and data were extracted from

each qualifying study into a standard form by 2 independent investi-

gators, with discrepancies resolved by reviewing the original data or

with the assistance of a third investigator as necessary. Data extracted

included the baseline characteristics of the trial participants (age, sex,

history of hypertension, history of diabetes mellitus, history of prior

cardiovascular disease, mean systolic and diastolic blood pressure

levels, baseline and end trial lipid levels, smoking status, body mass

index, and medication use), type of ω-3 FA supplementation used,

dose of ω-3 FA, nature of intervention (dietary change or supplemen-

tation), follow-up duration, outcome events, compliance, and adverse

events. The quality of the studies was assessed by the application of a

modified version of the Jadad criteria, which is a quality assessment

tool to assess the methodological quality of clinical trials

12

with ad-

ditional recording of the use of intention-to-treat analysis methods. A

higher Jadad score indicates higher methodological quality.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was a composite of cardiovascular events (myo-

cardial infarction, stroke, and cardiovascular death, or, as defined by

the authors of the contributing trials) (Table 1). Secondary outcomes

were vascular death (death from myocardial infarction, stroke, sud-

den death), myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular events (recorded

separately for hemorrhagic and ischemic stroke where reported),

coronary revascularization (percutaneous coronary interventions and

coronary artery bypass grafting), arrhythmia (atrial fibrillation, ven-

tricular fibrillation, or ventricular tachycardia), total mortality, non-

vascular mortality, and end-stage kidney disease. Wherever reported,

medication adherence rates and total adverse events (which mostly

comprised gastrointestinal side effects) were recorded.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Overall estimates of effect were estimated using random effects

models to calculate relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence inter-

vals (CIs). In each case, the numerator was the number of patients

with an event and the denominator the total number of patients ran-

domized. Where there were no events recorded in 1 randomized

group in a trial, 0.5 was added to the numerator and denominator to

enable the trial to be included in the analysis.

13

The I

2

statistic was

used to quantify heterogeneity in the results of studies contributing

to each overview analysis, with sensitivity analyses excluding indi-

vidual trials done to explore the heterogeneity. Subgroup analyses

and univariate meta-regressions were used to explore the association

between the primary outcome and study characteristics, including

median age of patients, proportion with hypertension, proportion

with diabetes mellitus, mean baseline lipid levels (triglycerides, low-

density lipoprotein, high-density lipoprotein, and total cholesterol),

proportion using lipid lowering agents, dietary modification versus

supplementation, dose of free fatty acids (high versus low dose), me-

dian follow-up time, every 5-year increase in publication year, study

size, trial setting, and Jadad score. The presence of publication bias

was investigated and quantified using Egger test and Begg funnel

plots of the natural log of the RR versus its standard error

14

for com-

posite cardiovascular outcomes and all cause mortality. P<0.05 was

considered unlikely to have arisen by chance, and all analyses were

done using Stata version 11.1 (Stata, College Station, TX).

Results

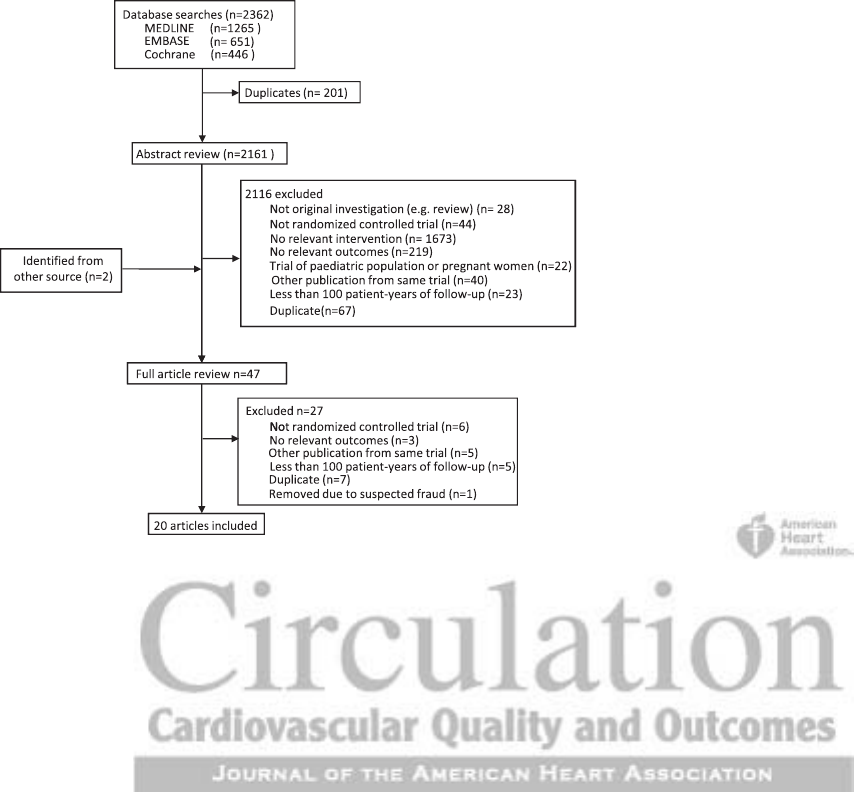

Search Results

Initial search identified 2362 possibly eligible studies, of

which 201 were duplicates, leaving 2161 abstracts that were

reviewed by the 2 investigators. Two thousand, one hundred

sixteen were excluded on the basis that they did not evaluate

an intervention of interest, did not report an outcome of

interest, were nonrandomized studies, were trials done in a

pediatric or pregnant population, included <100 patient years

of follow-up per arm, were repeat publications from the same

trial or were crossover designs. Full text reports were obtained

for the 47 remaining studies, and on further review another 27

were excluded. One study was excluded subsequently on the

basis of strong suspicion of fraud.

15

The recent ORIGIN trial

16

has also been included yielding a total of 20 studies being

included for the meta-analysis (Figure 1).

Characteristics of Included Studies

The 20 studies randomized a total of 62 851 patients with

31 456 assigned to active treatment and 31 395 to control

(Table 1). The total sample size of contributing trials ranged

from 106 to 18 645 participants, and the follow-up duration

from 6 months to 6 years. The median age of the participants

was 61 years, and 50% of the participants were male despite

several studies being conducted exclusively in men.

2,17,18

Sev-

enteen were multicenter trials,

2,3,9,10,16–28

and 2 were exclusively

studies of primary prevention.

18,19

The trials were variously

conducted in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe,

and Japan.

Three trials assessed the effect of dietary advice

2,17,24

and the

remainder, the effects of fish oil supplements.

3,9,10,16,18–23,25–31

Fourteen used supplements comprising a combination of eicos-

apentaenoic acid and docosahexaenoic acid,

3,10,16,18,20–23,25,27–30

WHAT IS KNOWN

• On the basis of the positive results of early trials, var-

ious clinical guidelines recommend the use of omega

3 fatty acid supplements to reduce mortality and car-

diovascular risk.

• Several recent large trials have reported no benefit of

omega 3 acids on cardiovascular outcomes; however,

the recommendations for their use remain.

WHAT THIS ARTICLE ADDS

• This meta-analysis, which includes 20 trials and

>60 000 patients, summarizes the entire body of evi-

dence on this subject including all the recent trials.

• The results of this meta-analysis report that omega

3 fatty acids protect against vascular death, but there

is no clear effect on total mortality, sudden death,

stroke, or arrhythmia.

• The beneficial effects of omega 3 fatty acids are not

as large as previously implied and recommendations

for widespread use should be tempered.

Kotwal et al Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Outcomes 3

Table 1. Baseline Characteristics of Included Studies

Study Inclusion Criteria

Treatment

Group Placebo

Design/

Country of

Origin

Mean

Follow-Up,

y

No. of

Patients

Mean

Age, y

Male,

%

Hypertension,

%

Diabetes

mellitus,

%

Primary or

Secondary

Prevention

No. of

Composite

CV Events

No. of All

Cause

Mortality

No. of

Coronary

Events

DART study (1989)

2

Men<70 post acute AMI Dietary

advice

No dietary

advice

Randomized,

UK

2 2033 56.55 100 24 NR Secondary 276 224 NR

Lyon Diet heart

Study (1994)

24

Men and women <70 post

AMI within past 6 mo

Dietary

advice

No dietary

advice

Randomized,

France

1.25 605 53.5 91 NR NR Secondary NR 28 22

IgA nephropathy (1994)

20

Biopsy proven IgA nephropathy,

urinary protein excretion of

≥1 g/d, serum Cr≤3.0 mg/dL

and survival >2 y

EPA/DHA

1680/970

Placebo Randomized,

US

3 106 37 91 58 NR Secondary NR NR NR

CART study (1999)

29

Patients for elective coronary

angioplasty

EPA/DHA

900/780

Corn oil

as Placebo

Randomised,

Norway

0.5 500 59.7 77.6 34 8.6 Secondary NR 4 NR

GISSI-Prevenzione (1999)

3

Patients with recent AMI EPA/DHA

850/882

Placebo Randomized,

Italy

3.5 5664 59.4 85 35 15 Secondary 584 529 NR

Effect of Dietary Omega-3

fatty acids on coronary

atherosclerosis (1999)

31

Patients hospitalised for

coronary angiography

Fish oil,

1650–3300

mg

Placebo Randomized,

Germany

2 223 52.35 80 49 NR Secondary 9 NR 4

High dose n-3 fatty acids

introduced early after

AMI (2001)

30

Patients post AMI EPA/DHA

1700/1764

Corn oil

as Placebo

Randomized,

Norway

1.5 300 64 79 24 10 Secondary 78 46 NR

Dietary advice to men with

angina (2003)

17

Men<70 with angina Dietary

advice

Sensible

eating

Randomized,

UK

6 1528 61.1 100 49 12 Secondary NR 250 NR

Fish oil Supplementation

and risk of VT and VF

in patients with implantable

defibrillators (2005)

25

Patients receiving ICD for

VT/VF not because of AMI

Fish oil, EPA/

DHA 756/540

Placebo Randomized,

US

1.97 200 62.5 86 51 24 Secondary NR 14 4

FAATI (2005)

26

Patients with ICD at high risk

for fatal ventricular arrhythmias

EPA 2600 mg Placebo Randomized,

US

1 402 65.5 83 NR NR Secondary NR 25 NR

SOFA trial (2006)

27

Men and women with 1 true

spontaneous VT or VF in past

3 mo and either had or were

receiving ICD

Fish oil EPA/

DHA 464/335

Placebo Randomized,

Europe

0.9753 546 61.5 84 51 16 Secondary NR 22 4

OPACH study group

(2006)

21

Patients with CVD and

stablished on HD for 6 mo

EPA/DHA

765/638

Placebo Randomized,

Denmark

1.53 206 67 65 78 24 Secondary 121 64 17

JELIS trial (2007)

19

Patients with

hypercholesterolemia

EPA 1800 mg

and statin

Placebo

and statin

Randomized,

Japan

4.6

18645

61

31

35

16

Primary

and

secondary

586

551

145

(Continued)

AQ13

4 Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes November 2012

Table 1. (Continued)

Study Inclusion Criteria

Treatment

Group Placebo

Design/

Country of

Origin

Mean

Follow-Up,

y

No. of

Patients

Mean

Age, y

Male,

%

Hypertension,

%

Diabetes

mellitus,

%

Primary or

Secondary

Prevention

No. of

Composite

CV Events

No. of All

Cause

Mortality

No. of

Coronary

Events

GISSI-Prevenzione HF

(2008)

22

Men and women >18 with

clinical evidence of heart

failure

EPA/DHA

850–882 mg

Placebo Randomized,

Italy

3.9 7046 67 78 54 28 Secondary 3322 1969 236

Omega (2010)

10

Men and women >18 with

acute STEMI or NSTEMI

EPA/DHA

460/380

Placebo Randomized,

Germany

1 3851 64 74 66 27 Secondary 331 158 NR

Efficacy and safety of

prescription N-3 FA for

the prevention of recurrent

symptomatic AF (2010)

28

Patients>18 with persistent

or paroxysmal AF

EPA/DHA

1860/1500

Placebo Randomized,

US

0.5 663 60.5 56 NR NR Secondary NR 2 NR

Alpha Omega (2010)

9

Men and women, 60–80 y

of age, with MI in past 10 y

EPA/DHA/ALA ALA and

Placebo

Randomized,

Netherlands

3.4 4837 69 78 90 21 Secondary 671 NR NR

SU.FOL.OM3 (2010)

23

Men and women aged

45–80 y who had an acute

coronary or cerebral ischemic

events within last 12 mo

EPA/DHA

1200/600

Placebo Randomized,

France

4.7 2501 60.9 79 NR NR Secondary 157 117 60

Diet and Omega 3

Intervention trial (2010)

18

Survivors from a population of

healthy men with

hypercholesterolemia from

the OSLO Diet & Antismoking

study

EPA/DHA

1176/840

Placebo Randomized,

Norway

3 563 70.1 100 28 14 Primary 68 38 NR

n-3 Fatty Acids and Cardio-

vascular Outcomes in Patients

with Dysglycemia (2012)

16

Patients with impaired fasting

glucose, impaired glucose

tolerance or diabetes mellitus

EPA/DHA

465/375

Olive oil as

placebo

Randomized,

International

6.2 12611 63.5 65 79 100 Primary

and

secondary

2051 1915 660

EPA indicates eicosapentaenoic acid, DHA, docosahexaenoic acid.

Kotwal et al Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Outcomes 5

with the daily doses of eicosapentaenoic acid/docosahexae-

noic acid ranging between 464 to 1860 mg and 335 to 1500 mg,

respectively,

27,28

compared with recommended dietary intakes

of 250 to 2000 mg/d for each.

32

The placebo composition

varied and included control,

19,21–23,31

corn oil,

18,28–30

and olive

oil.

10,16,25,26

The reporting of trial methodology was variable (Table 2),

with the earlier studies reporting less information about their

methods of randomization, allocation concealment, and com-

pleteness of follow-up. Nine studies scored 4 on the Jadad

scale,

9,16,18,21,23,25,27,28,31

5 studies scored 3,

19,20,22,24,26

3 studies

scored 2,

3,10,30

1 study scored 1,

2

and 2 studies scored zero.

17,29

Effects of ω-3 Fatty Acids on Clinical Outcomes

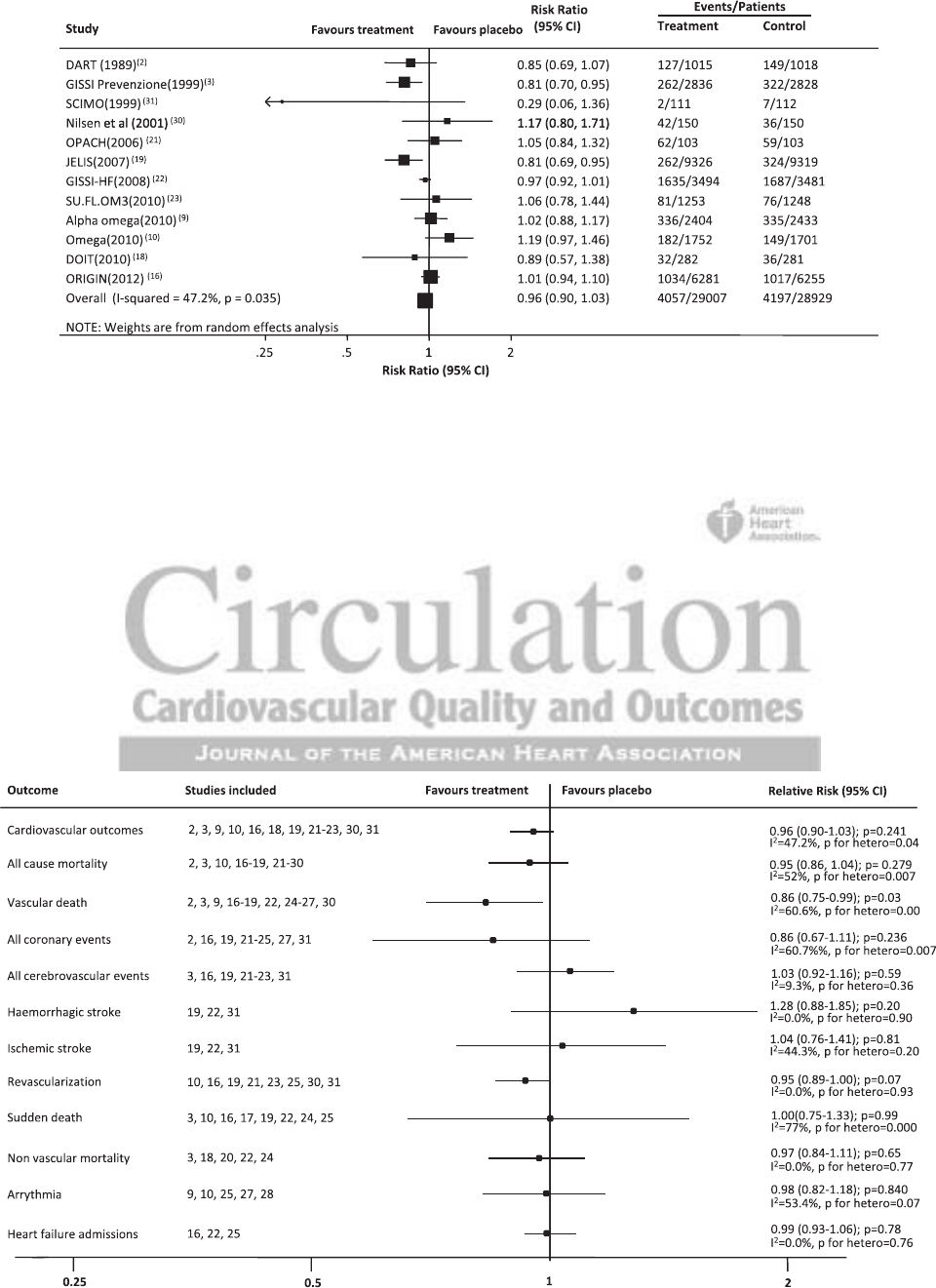

Composite Cardiovascular Outcome

For the primary composite cardiovascular outcome, 12 stud-

ies involving 57 936 participants

2,3,9,10,16,18,19,21–23,30,31

recorded

8254 events (Figure 2). There was no clear effect of ω-3 FA

(RR=0.96; 95% CI, 0.90–1.03; P=0.24) on this outcome.

There was, however, moderate heterogeneity in the effects

of treatment across the included studies (I

2

=47.2%; P=0.04).

Sequentially excluding individual studies as part of a sensitiv-

ity analysis did not identify a single trial responsible for the

heterogeneity. The definition of the composite cardiovascular

outcome differed somewhat between studies with the majority

comprising cardiovascular death, myocardial infarction, and

sudden death but not all including stroke outcomes.

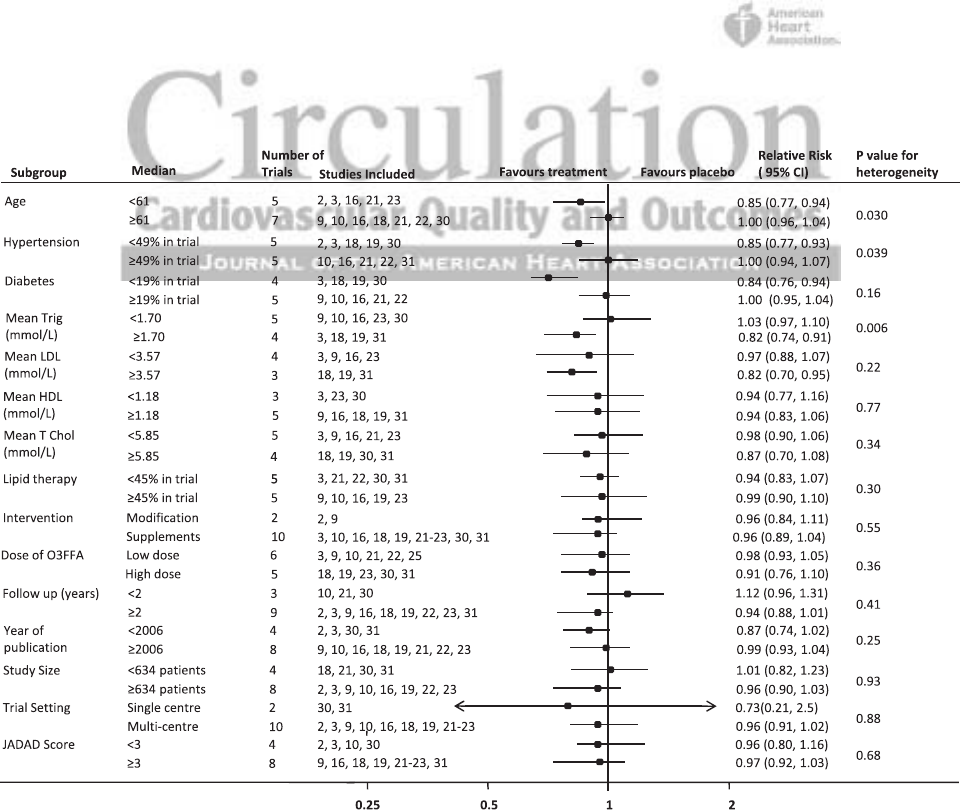

Vascular Death and Sudden Death

Thirteen studies reported 3776 heart disease deaths, stroke

deaths, or sudden deaths that occurred among 54 834

randomized participants.

2,3,9,16–19,22,24–27,30

Of these stud-

ies, 8 separately reported 1496 sudden deaths among

49 971 participants.

3,10,16,17,19,22,24,25

Treatment with ω-3 FA

protected against vascular death (Figure 3; RR=0.86; 95% CI,

0.75–0.99; P=0.03) but not against sudden death (RR=1.00;

95% CI, 0.75–1.33; P=0.99). There was substantial heteroge-

neity (I

2

=60.7%, P=0.001) across the results of the 12 trials

contributing to the analysis of vascular death and across the 8

trials that evaluated sudden death (I

2

=77.0%, P<0.0001). No

individual trial was able to explain a substantial proportion of

the heterogeneity for the vascular death or the sudden death

outcome.

Total Mortality and Nonvascular Mortality

Seventeen studies done in 57 671 participants

2,3,10,16–19,21–30

reported 5956 deaths from any cause, and 5 studies reported

723 deaths of nonvascular origin that occurred among 13 913

individuals.

3,18,20,22,24

There was no evidence that ω-3 FA

reduced total mortality (Figure 3; RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.86–

1.04; P=0.28) or nonvascular mortality (RR=0.97; 95% CI,

0.84–1.11; P=0.65). The heterogeneity across the individual

trial results for total mortality (I

2

=52.1%; P=0.007) was sig-

nificant but once again it was hard to identify specific trials

that caused this.

Coronary Events and Revascularization

One thousand, two hundred thirty-four coronary events were

reported by 10 studies among 44 470 participants

2,16,19,21–25,27,31

and 3537 occurrences of cardiac revascularization in 8 studies

and 38 429 participants.

10,16,19,21,23,25,30,31

There was no evidence

of benefit for coronary events (Figure 3; RR=0.86; 95% CI,

0.67–1.11, P=0.24) and no significant benefit for revascular-

ization (RR=0.95; 95% CI, 0.89–1.00; P=0.07). There was

moderate heterogeneity for the coronary outcome (I

2

=60.6%,

P=0.07).

Cerebrovascular Events

Only 7 studies done among 46 750 participants

3,16,19,21–23,31

reported on stroke outcomes. There were a total of 1369

Figure 1. Flow of papers.

6 Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes November 2012

Table 2. Quality Assessment of Trials Included in the Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis

Study

Randomization

Process

Described

Randomization

Process

Achieved

Allocation

Concealment

Described

Allocation

Concealment

Adequately

Achieved

Similarity

of Baseline

Characteristics

Eligibility

Criteria

Described

Double-

Blinding

Described

Completeness

of Follow-Up/

Loss to Follow-Up

Described

Intention-

To-Treat

Described

Completion Rate

(Treatment/

Placebo)

Jadad

Score

DART study (1989)

2

No Yes No NR Yes Yes No Yes Yes 6.8/6.9 1

Lyon Diet heart Study (1994)

24

No Yes No NR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes NR 3

IgA nephropathy (1994)

20

No Yes No NR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 71% 3

CART study (1999)

29

Yes Yes Yes NR Yes Yes No Yes No 78% 0

GISSI-Prevenzione (1999)

3

Yes Yes No NR Yes Yes No No Yes Reported 2

Effect of Dietary Omega-3

fatty acids on coronary

atherosclerosis (1999)

31

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes NR 4

High dose n-3 fatty acids introduced

early after AMI (2001)

30

No NR No NR Yes Yes Yes No Yes NR 2

Dietary advice to men with

angina (2003)

17

No No No NR No Yes No No Yes NR 0

Fish oil Supplementation

and risk of VT and VF in patients

with implantable defibrillators (2005)

25

Yes Yes No NR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 98%/94% 4

FAATI (2005)

26

Yes Yes No NR Yes Yes No Yes Yes 86% 3

SOFA trial (2006)

(27)

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 89%/91% 4

OPACH study group (2006)

21

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 74%/78% 4

JELIS trial (2007)

19

Yes Yes Yes NR Yes Yes No Yes Yes 71%/73% 3

GISSI-Prevenzione HF (2008)

22

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No 99%/99% 3

Omega (2010)

10

No Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No No NR 2

Efficacy and safety of prescription

n-3 FA for the prevention of recurrent

symptomatic AF (2010)

28

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes No 88% 4

Alpha Omega (2010)

9

Yes Yes No NR Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 90%/92% 4

SU.FOL.OM3 (2010)

23

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 90%/90% 4

Diet and Omega 3 Intervention

trial (2010)

18

Yes No Yes Yes No Yes Yes Yes Yes 94% 4

ORIGIN Trial

16

Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes Yes 88% 4

Kotwal et al Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Outcomes 7

events. Of these 6 studies, 3 provided a further subclassifi-

cation into strokes of ischemic and hemorrhagic origin.

19,22,31

Overall, there was no clear effect of ω-3 FA on all cerebrovas-

cular events (Figure 3; RR=1.03; 95% CI, 0.92–1.16; P=0.59),

although the point estimate of effect was just to the right side

of unity. The trend toward harm was stronger for hemorrhagic

stroke (RR=1.28; 95% CI, 0.88–1.85; P=0.20) than ischemic

stroke (RR=1.04; 95% CI, 0.76–1.41; P=0.80).

Arrhythmia

This outcome was reported in 5 studies involving 10 097 par-

ticipants

9,10,25,27,28

and recorded 758 events with no treatment

effect identified overall (Figure 3; RR=0.98; 95% CI, 0.82–

1.18; P=0.84) or for the subset of 3 trials that included patients

with a confirmed prior history of atrial fibrillation, ventricular

tachycardia, or ventricular fibrillation.

25,27,28

There was evidence

of moderate heterogeneity across the included trials (I

2

=53.5%;

P=0.07) but no 1 trial was clearly responsible for this.

Other Outcomes

Two thousand, six hundred fifty heart failure admissions were

reported by 3 studies of 19 711 participants.

16,22,25

The overall

estimate of effect was a RR of 0.99 (Figure 3; 95% CI, 0.93–

1.06; P= 0.78). Renal outcomes were reported by 1 study

20

of

106 participants with IgA nephropathy, in which the use of

fish oil protected renal function. A further longer-term follow-

up of these same patients confirmed this result,

33

although the

long-term data were not included in our meta-analysis.

Figure 2. Effect of ω-3 fatty acids on composite cardiovascular outcomes. CI indicates confidence interval.

Figure 3. Effect of ω-3 fatty acids on all outcomes. CI indicates confidence interval.

8 Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes November 2012

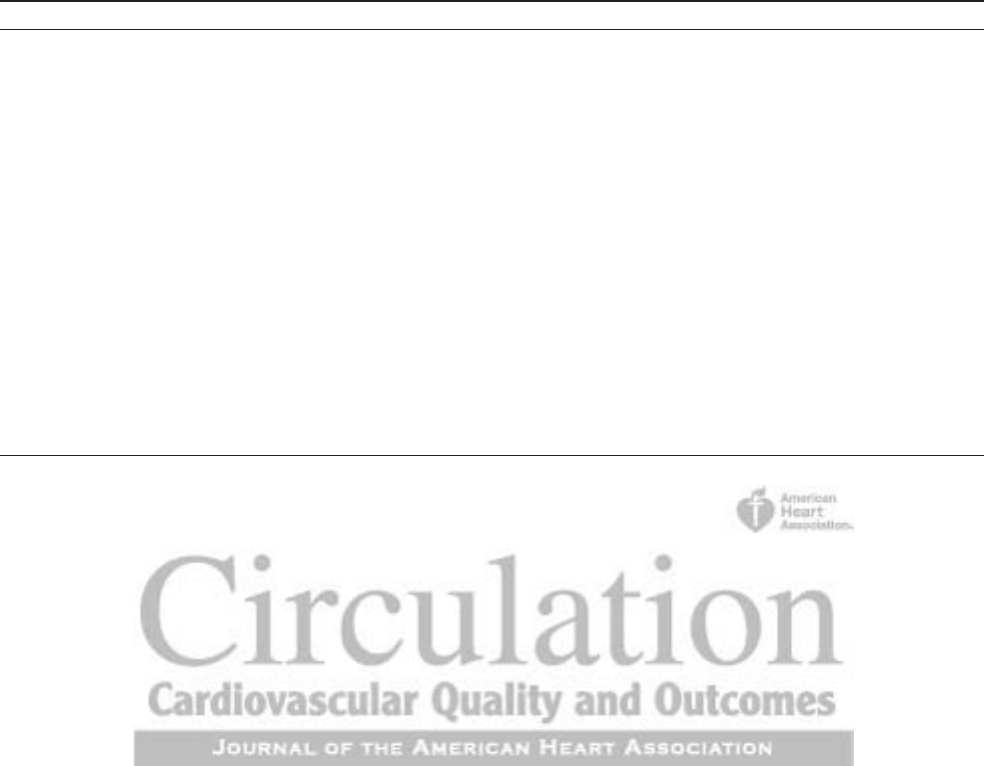

Subgroup Analysis

We undertook a large number of subgroup analyses accord-

ing to the baseline characteristics of patients and design fea-

tures of the trials (Figure 4). These analyses identified greater

protection against the composite cardiovascular outcomes in

trials of younger patients, in trials with fewer hypertensive

patients, and in trials in which patients had higher baseline

triglyceride levels. There was no difference in effect based on

era of publication, study size, or trial setting or when trials

were separated into those that used dietary advice compared

with those that used dietary supplementation. Univariate

meta-regression, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, achieved

cholesterol reduction, year of publication, and Jadad score

were associated with the likelihood of benefit from ω-3 FA

(Table 3) with these variables being well distributed to allow

us to estimate the change in proportional risk.

Side Effects

Thirteen studies reported adverse effects among a total of

52 213 participants.

9,10,16,18,19,21–23,25,27–29,31

The use of ω-3 sup-

plements compared with placebo showed an increased risk

of side effects (RR=1.18; 95% CI, 1.02–1.37; P=0.03). The

majority were gastrointestinal and comprised nausea, diar-

rhea, and other mild gastrointestinal disturbances. Eight stud-

ies

9,10,18,19,22,23,25,27

also reported rates of malignancies during

the study period with no significant association between the

use of ω-3 FA and the incidence of cancer detected (RR=1.10,

95% CI 0.98–1.23, P=0.10).

Publication Bias

We found evidence of publication bias (online only Data Sup-

plement Figures I and II) as our funnel plots show an asym-

metrical distribution of data. The majority of the studies are

located at the base of the plots.

Discussion

The findings of this large systematic review, that includes

data from 20 trials, >60 000 individuals and >6000 major

cardiovascular events raises important questions about

the use of fish oil for the prevention of cardiovascular

disease. Recommendations for the use of fish oil supple-

ments are included in a number of guidelines,

34,35

but the

neutral outcomes of recent large trials

9,10,16

have served to

weaken rather than strengthen the evidence base. Although

it remains possible that fish oil supplements will produce

health benefits through the prevention of vascular compli-

cations, the size of these gains are probably smaller than

previously believed, and both physician and patient expec-

tations may need to be reset.

A key strength of this overview is the attempt to extract

data on all commonly reported vascular outcomes from all

trials and to systematically report the summary estimates of

effect in each case. The impact of this approach has been

to move the focus of attention from the positive or nega-

tive findings for particular outcomes identified in individual

studies or overviews, to the overall estimates of effect across

Figure 4. Subgroup analysis for the effect of ω-3 free fatty acids on cardiovascular outcomes. CI indicates confidence interval.

Kotwal et al Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Outcomes 9

the entire body of evidence. This attempt to apply greater

objectivity to the analysis of the data has not, however, been

without its challenges. In part because the reporting of out-

comes across studies is inconsistent and in part because

there is significant heterogeneity between the trials’ results

for several of the outcomes studied. This heterogeneity may

also contribute to the absence of positive findings in this

meta-analysis.

The heterogeneity in results between trials was large for

several analyses and is unlikely to simply reflect the play

of chance. Although not easy to explain in every case, the

analyses of trial subgroups suggest a number of explanations

based on plausible biological phenomena and correlations

in the data. Greater average effects on the primary outcome

were observed in the studies that used higher doses of ω-3

FA

3,18,19,22,23,30,31

and trials done in patients with higher base-

line levels of triglycerides.

3,19,31

These findings are similar to

those reported for fibrates, which is notable given that both

classes of agents have similar effects on lipid profiles, and

especially on triglyceride levels.

36

We also observed greater

average effects in those with younger average ages,

3,23,31

and

in trials with lower proportions of hypertensives

2,3,18,19,30

and

lower proportions of diabetes mellitus.

3,18,19,30

These differ-

ences between subgroups are difficult to explain on the basis

of physiology, although there are also animal data that sug-

gest a mechanism of action for lesser effects in patients with

diabetes mellitus.

37

The subgroup findings also seem to be

heavily influenced by the characteristics and results of a few

large trials. The GISSI-Prevenzione trial,

3

for example, stud-

ied mostly younger individuals who were nonhypertensive,

and was reported before the year 2000. As a major contributor

of events to all 3 of these subgroup analyses, it is easy to see

how the heterogeneity of effects by these trial characteristics

arises even if it is not entirely explained. The neutral find-

ings of the more recent trials might also be associated with

underlying levels of marine oil intake, but with background

consumption data reported by only 7 trials

3,9,10,17,24,29,30

that

used very different definitions this was difficult to robustly

investigate. Variation in the composition of the placebo com-

pound may also contribute to the neutrality of the findings,

although a subgroup analysis based on the use of an inactive

control compared with corn oil or olive oil identified signifi-

cant heterogeneity.

Vascular death was the only outcome for which a signifi-

cant benefit was observed. This result does not seem to have

been driven by an effect on sudden death or arrhythmia, both

of which had more moderate and nonsignificant estimates of

effect. The JELIS trial

19

as well as the GISSI-Prevenzione

trial

3

however, found a reduction in major cardiovascular

events. The absence of benefit in the more recent trials raises

the possibility that the effects of ω-3 FA are determined by

some as yet unquantified external factor.

The overview identified no effect of fish oil on the over-

all risk of stroke, although there was a trend toward harm for

intracerebral hemorrhage. This is an effect that might be antic-

ipated on the basis of the known effects of ω-3 FA on bleeding

time and platelet aggregation.

38–40

The conduct of the analyses on tabular data extracted from

the original trial reports was a limitation of our study design.

Access to the original trial datasets would likely uncover

additional outcome events from trials that did not publish data

on each of the outcomes we studied. This would increase the

power of the analyses by raising the number of events avail-

able as well as permitting analyses based on more directly

comparable definitions than has been possible here. Analyses

done on individual participant data would also allow for

much more sophisticated exploration of the effects in dif-

ferent patient subgroups, and provide a better understand-

ing of the sources of heterogeneity in the trial findings. A

notable deficit in the current data are the systematic reporting

Table 3. Univariate Meta-Regression

Variable Scale RR 95% CI No. of Studies

Age Every 5 y 1.08 0.90 1.26 12

Male, % Every 10% increase 0.99 0.92 1.06 12

HTN Every 10% increase 1.09 1.04 1.13 10

DM Every 10% increase 1.07 1.05 1.08 8

Mean baseline TRIG Every 1 mmol/L increase 0.50 −0.56 1.55 6

Mean baseline LDL Every 1 mmol/L increase 0.76 0.51 1.02 5

Mean baseline HDL Every 1 mmol/L increase 1.00 0.98 1.03 6

Mean baseline cholesterol Every 1 mmol/L increase 0.84 18.00 19.68 7

TRIG difference: TX1 vs TX2 Every 0.1 mmol/L difference 0.89 0.62 1.17 3

HDL difference: TX1 vs TX2 Every 0.02 mmol/L reduction 1.04 0.88 1.20 3

CHOL difference: TX1 vs TX2 Every 0.1 mmol/L increase 0.93 0.92 0.95 3

Drug dose (composite cv outcomes) Every 200 mg increase 0.97 0.92 1.02 11

Follow-up (y) Every 1 y 1.04 0.97 1.11 12

Year of publication Every 5 y 1.09 1.01 1.18 12

Study size Every 100 participants 1.00 1.00 1.00 12

Jadad score Every 1 point increase 1.12 1.02 1.23 12

HTN indicates hypertension; RR, risk ratio, CI, confidence interval, DM, diabetes mellitus; TRIG, triglycerides; LDL, low-density lipoprotein, HDL, high-density lipo-

protein; and CHOL, cholesterol.

10 Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes November 2012

of side effects. Total adverse events, although mostly fairly

benign, were clearly higher with fish oil, and if the benefits

are smaller than previously believed the risk-benefit trade-off

will require more careful evaluation. Therapies that amelio-

rate cardiovascular risk, such as antihypertensives, statins,

and antiplatelet agents have become prevalent and potent

over time and, therefore, trials, such as the ORIGIN trial that

include patients with moderate cardiovascular risk at base-

line, are likely to comprise patients that are on these thera-

pies. This might further dilute the detectable effect of ω-3

FA. Finally, the generalizability of the overview findings may

be questioned, given that aside from a handful of trials,

18,19

the data derive entirely from the secondary prevention setting

and white populations.

In conclusion, these results raise further uncertainty about

the net effects of ω-3 fish oil therapy and reinforce the

importance of the forthcoming ASCEND

41

and R&P

42

trials.

Although it is probably reasonable for patients with exist-

ing vascular disease who are currently using fish oil to con-

tinue to do so, better evidence is required to support the more

widespread promulgation of this strategy, particularly among

lower risk patients. Individuals with high triglyceride levels

or IgA nephropathy may be especially worthy of investiga-

tion, and higher rather than lower doses seem more likely to

produce benefit. Further research in the primary prevention

setting would be welcome given the potential implications of

evidence about fish oil intake to dietary advice about fish con-

sumption in the general population.

Acknowledgments

S. Kotwal, M. Jun, D. Sullivan, V. Perkovic, and B. Neal were respon-

sible for the design of the study. S. Kotwal and M. Jun were respon-

sible for data collection and analysis. All authors were responsible for

interpretation and manuscript preparation. All authors contributed to

data interpretation and critical revision of the publication. S. Kotwal

had full access to all data in the study and takes responsibility for the

integrity of the data and accuracy of the analysis.

Sources of Funding

M. Jun was supported by an Australian Postgraduate Award and

the Australasian Kidney Trials Network, Dr Perkovic by a New

South Wales Cardiovascular Research Network/Australian Heart

Foundation Career Development Award, and Dr Neal by an Australian

Research Council Future Fellowship.

Disclosures

D. Sullivan reports educational and advisory consultancy to

Pfizer, Merck Schering Plough, AstraZeneca, Abbott, Amgen, and

Roche, as well as research projects involving Pfizer (2007), Merck

Schering Plough (2010), Abbott (2005), Sanofi-Aventis (2010),

and AstraZeneca (2009). V. Perkovic reports his employer has re-

ceived grants for clinical trials from Baxter, Johnson and Johnson,

Novartis, Roche, and Servier; lecture fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca,

Roche, and Servier; serving on a grant review panel for Baxter

and on a steering Committee for Abbott. B. Neal reports receiv-

ing consulting fees from Pfizer, Roche, and Takeda; grant support

from Johnson and Johnson, Merck Schering Plough, Servier, and

United Healthcare Group; lecture fees and travel reimbursements

from Amgen, AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Pfizer, Roche, Sanofi-

Aventis, Servier, and Tanabe; and being a member of advisory boards

for Pfizer and Roche. The other authors report no conflicts.

References

1. Dyerberg J, Bang HO, Hjorne N. Fatty acid composition of the plasma

lipids in Greenland Eskimos. Am J Clin Nutr. 1975;28:958–966.

2. Burr ML, Fehily AM, Gilbert JF, Rogers S, Holliday RM, Sweetnam

PM, Elwood PC, Deadman NM. Effects of changes in fat, fish, and fibre

intakes on death and myocardial reinfarction: diet and reinfarction trial

(DART). Lancet. 1989;2:757–761.

3. GISSI-Prevenzione Investigators. Dietary supplementation with n-3 poly-

unsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results

of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della So-

pravvivenza nell’Infarto miocardico. Lancet. 1999;354:447–455.

4. Filion KB, El Khoury F, Bielinski M, Schiller I, Dendukuri N, Brophy

JM. Omega-3 fatty acids in high-risk cardiovascular patients: a meta-

analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2010;

10:24.

5. Mozaffarian D, Rimm EB. Fish intake, contaminants, and human health:

evaluating the risks and the benefits. JAMA. 2006;296:1885–1899.

6. Wang C, Harris WS, Chung M, Lichtenstein AH, Balk EM, Kupelnick B,

Jordan HS, Lau J. n-3 Fatty acids from fish or fish-oil supplements, but

not alpha-linolenic acid, benefit cardiovascular disease outcomes in pri-

mary- and secondary-prevention studies: a systematic review. Am J Clin

Nutr. 2006;84:5–17.

7. León H, Shibata MC, Sivakumaran S, Dorgan M, Chatterley T, Tsuyuki

RT. Effect of fish oil on arrhythmias and mortality: systematic review.

BMJ. 2008;337:a2931.

8. Kwak SM, Myung SK, Lee YJ, Seo HG; Korean Meta-analysis Study

Group. Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (eicosapentaenoic acid

and docosahexaenoic acid) in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular

disease: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled

trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:686–694.

9. Kromhout D, Giltay EJ, Geleijnse JM; Alpha Omega Trial Group. n-3

fatty acids and cardiovascular events after myocardial infarction. N Engl J

Med. 2010;363:2015–2026.

10. Kwak SM, Myung SK, Lee YJ, Seo HG; Korean Meta-analysis Study

Group. Efficacy of omega-3 fatty acid supplements (eicosapentaenoic acid

and docosahexaenoic acid) in the secondary prevention of cardiovascular

disease: a meta-analysis of randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled

trials. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:686–694.

11. PRISMA. PRISMA: Transparent reporting of systematic reviews and meta-

analysis. 2009 [cited 2011]. Available at: http://www.prisma-statement.org/.

Accessed March 1, 2011.

12. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis

detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634.

13. Woodward M. Epidemiology: Design and Data Analysis. 2nd ed . Boca

Raton, FL: Chapman and Hall/CRC Press; 2005.

14. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis

detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315:629–634.

15. Singh RB, Niaz MA, Sharma JP, Kumar R, Rastogi V, Moshiri M. Ran-

domized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of fish oil and mus-

tard oil in patients with suspected acute myocardial infarction: the

Indian experiment of infarct survival–4. Cardiovasc Drugs Ther. 1997;11:

485–491.

16. The ORIGIN Trial Investigators. n-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular out-

comes in patients with dysglycemia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:309–318.

17. Burr ML, Ashfield-Watt PA, Dunstan FD, Fehily AM, Breay P, Ashton

T, Zotos PC, Haboubi NA, Elwood PC. Lack of benefit of dietary ad-

vice to men with angina: results of a controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr.

2003;57:193–200.

18. Einvik G, Klemsdal TO, Sandvik L, Hjerkinn EM. A randomized clini-

cal trial on n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids supplementation and all-cause

mortality in elderly men at high cardiovascular risk. Eur J Cardiovasc

Prev Rehabil. 2010;17:588–592.

19. Yokoyama M, Origasa H, Matsuzaki M, Matsuzawa Y, Saito Y, Ishikawa

Y, Oikawa S, Sasaki J, Hishida H, Itakura H, Kita T, Kitabatake A,

Nakaya N, Sakata T, Shimada K, Shirato K; Japan EPA lipid intervention

study (JELIS) Investigators. Effects of eicosapentaenoic acid on major

coronary events in hypercholesterolaemic patients (JELIS): a randomised

open-label, blinded endpoint analysis. Lancet. 2007;369:1090–1098.

20. Donadio JV Jr, Bergstralh EJ, Offord KP, Spencer DC, Holley KE. A con-

trolled trial of fish oil in IgA nephropathy. Mayo Nephrology Collabora-

tive Group. N Engl J Med. 1994;331:1194–1199.

21. Svensson M, Schmidt EB, Jørgensen KA, Christensen JH; OPACH Study

Group. N-3 fatty acids as secondary prevention against cardiovascular

Kotwal et al Omega 3 Fatty Acids and Cardiovascular Outcomes 11

events in patients who undergo chronic hemodialysis: a randomized,

placebo-controlled intervention trial. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2006;1:

780–786.

22. Gissi HFI, Tavazzi L, Maggioni AP, Marchioli R, Barlera S, Franzosi MG,

Latini R, Lucci D, Nicolosi GL, Porcu M, Tognoni G. Effect of n-3 poly-

unsaturated fatty acids in patients with chronic heart failure (the GISSI-

HF trial): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet.

2008;372:1223–1230.

23. Galan P, Kesse-Guyot E, Czernichow S, Briancon S, Blacher J, Hercberg

S; SU.FOL.OM3 Collaborative Group. Effects of B vitamins and omega

3 fatty acids on cardiovascular diseases: a randomised placebo controlled

trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c6273.

24. de Lorgeril M, Renaud S, Mamelle N, Salen P, Martin JL, Monjaud I,

Guidollet J, Touboul P, Delaye J. Mediterranean alpha-linolenic acid-

rich diet in secondary prevention of coronary heart disease. Lancet.

1994;343:1454–1459.

25. Raitt MH, Connor WE, Morris C, Kron J, Halperin B, Chugh SS, Mc-

Clelland J, Cook J, MacMurdy K, Swenson R, Connor SL, Gerhard G,

Kraemer DF, Oseran D, Marchant C, Calhoun D, Shnider R, McAnulty J.

Fish oil supplementation and risk of ventricular tachycardia and ventricu-

lar fibrillation in patients with implantable defibrillators: a randomized

controlled trial. JAMA. 2005;293:2884–2891.

26. Leaf A, Albert CM, Josephson M, Steinhaus D, Kluger J, Kang JX, Cox

B, Zhang H, Schoenfeld D; Fatty Acid Antiarrhythmia Trial Investigators.

Prevention of fatal arrhythmias in high-risk subjects by fish oil n-3 fatty

acid intake. Circulation. 2005;112:2762–2768.

27. Brouwer IA, Zock PL, Camm AJ, Böcker D, Hauer RN, Wever EF, Dulle-

meijer C, Ronden JE, Katan MB, Lubinski A, Buschler H, Schouten EG;

SOFA Study Group. Effect of fish oil on ventricular tachyarrhythmia and

death in patients with implantable cardioverter defibrillators: the Study

on Omega-3 Fatty Acids and Ventricular Arrhythmia (SOFA) randomized

trial. JAMA. 2006;295:2613–2619.

28. Kowey PR, Reiffel JA, Ellenbogen KA, Naccarelli GV, Pratt CM. Efficacy

and safety of prescription omega-3 fatty acids for the prevention of recur-

rent symptomatic atrial fibrillation: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA.

2010;304:2363–2372.

29. Johansen O, Brekke M, Seljeflot I, Abdelnoor M, Arnesen H. N-3 fatty

acids do not prevent restenosis after coronary angioplasty: results from the

CART study. Coronary Angioplasty Restenosis Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol.

1999;33:1619–1626.

30. Nilsen DW, Albrektsen G, Landmark K, Moen S, Aarsland T, Woie L. Ef-

fects of a high-dose concentrate of n-3 fatty acids or corn oil introduced

early after an acute myocardial infarction on serum triacylglycerol and

HDL cholesterol. Am J Clin Nutr. 2001;74:50–56.

31. von Schacky C, Angerer P, Kothny W, Theisen K, Mudra H. The ef-

fect of dietary omega-3 fatty acids on coronary atherosclerosis. A ran-

domized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med.

1999;130:554–562.

32. FAO/WHO. Fats and fatty acids in human nutrition. Proceedings of the

Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation. November 10–14, 2008. Geneva,

Switzerland. Ann Nutr Metab. 2009;55:5–300.

33. Donadio JV Jr, Grande JP, Bergstralh EJ, Dart RA, Larson TS, Spencer

DC. The long-term outcome of patients with IgA nephropathy treated with

fish oil in a controlled trial. Mayo Nephrology Collaborative Group. J Am

Soc Nephrol. 1999;10:1772–1777.

34. Kris-Etherton PM, Harris WS, Appel LJ; AHA Nutrition Committee.

American Heart Association. Omega-3 fatty acids and cardiovascular dis-

ease: new recommendations from the American Heart Association. Arte-

rioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2003;23:151–152.

35. National Heart Foundation of Australia, Cardiac Society of Australia

and New Zealand. Lipid management guidelines--2008. Med J Aust.

2008;75:S57–S85.

36. Jun M, Foote C, Lv J, Neal B, Patel A, Nicholls SJ, Grobbee DE, Cass A,

Chalmers J, Perkovic V. Effects of fibrates on cardiovascular outcomes: a

systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1875–1884.

37. Sullivan DR, Yue DK, Capogreco C, McLennan S, Nicks J, Cooney G,

Caterson I, Turtle JR, Hensley WJ. The effects of dietary n - 3 fatty acid

in animal models of type 1 and type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract.

1990;9:225–230.

38. Agren JJ, Väisänen S, Hänninen O, Muller AD, Hornstra G. Hemostatic

factors and platelet aggregation after a fish-enriched diet or fish oil or doc-

osahexaenoic acid supplementation. Prostaglandins Leukot Essent Fatty

Acids. 1997;57:419–421.

39. Mori TA, Beilin LJ, Burke V, Morris J, Ritchie J. Interactions between di-

etary fat, fish, and fish oils and their effects on platelet function in men at risk

of cardiovascular disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:279–286.

40. De Caterina R. n-3 fatty acids in cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med.

2011;364:2439–2450.

41. ASCEND : A Study of Cardiovascular Events iN Diabetes 2011. Available

at: http://www.ctsu.ox.ac.uk/ascend/. Accessed July 1, 2011.

42. Rischio and Prevenzione Investigators. Efficacy of n-3 polyunsaturated

fatty acids and feasibility of optimizing preventive strategies in patients

at high cardiovascular risk: rationale, design and baseline characteristics

of the Rischio and Prevenzione study, a large randomised trial in general

practice. Trials. 2010;11:68.