SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

Formulations, Recommendations, and Resources for the Pharmacist

PRACTICAL INFORMATION FOR TODAY’S PHARMACIST®

®

The Role of Nutraceuticals: What

Pharmacists Need to Know in 2020

Melatonin: Considerations for Use

in Patients With Sleep Disorders

To D or Not to D:

That Is the Question

Omega-3 Recommendations:

Counseling Points for Pharmacists

Prenatal and Postnatal

Supplementation: What Do

Pharmacists Need to Know?

Identification and Communication

Approaches to Drug and Dietary

Supplement Interactions

APRIL 2020

VITAMINS & SUPPLEMENTS

GUIDE FOR PHARMACISTS

Sign up today!

www.PharmacyTimes.com

Access resources through multiple communication platforms

Receive Current

Pharmacy News and

Continuing Education

Updates Daily!

l

Market Trends

l

Clinical Information

l

Product Reports

l Expert Videos

®

VITAMINS & SUPPLEMENTS

GUIDE FOR PHARMACISTS

Special Report: Formulations, Recommendations, and Resources

APRIL 2020

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

Formulations, Recommendations, and Resources for the Pharmacist

PRACTICAL INFORMATION FOR TODAY’S PHARMACIST®

®

COVER STORY

The Role of Nutraceuticals: What Pharmacists Need to Know

in 2020

LUMA MUNJY, PHARMD

FEATURES

Melatonin: Considerations for Use in Patients With

Sleep Disorders

RASHI C. WAGHEL, PHARMD, BCACP; AND JENNIFER A. WILSON, PHARMD, BCACP

To D or Not to D: That Is the Question

CHELSEA RENFRO, PHARMD, CHSE; AND ALEX STANLEY, PHARMD CANDIDATE

Omega-3 Recommendations: Counseling Points for Pharmacists

BRADY COLE, RPH

Prenatal and Postnatal Supplementation: What Do Pharmacists

Need to Know?

CORTNEY MOSPAN, PHARMD, BCACP, BCGP

Identification and Communication Approaches to Drug and

Dietary Supplement Interactions

JAY HIGHLAND, PHARMD

2

6

9

11

13

16

Opinions expressed by authors, contributors, and advertisers are their own and not necessarily those of Pharmacy & Healthcare Communications, LLC, the

editorial staff, or any member of the editorial advisory board. Pharmacy & Healthcare Communications, LLC, is not responsible for accuracy of dosages

given in articles printed herein. The appearance of advertisements in this journal is not a warranty, endorsement, or approval of the products or services

advertised or of their effectiveness, quality, or safety. Pharmacy & Healthcare Communications, LLC, disclaims responsibility for any injury to persons or

property resulting from any ideas or products referred to in the articles or advertisements.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Troy Trygstad, PharmD, PhD, MBA

EDITORIAL & PRODUCTION

EXECUTIVE EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Colleen Hall

ASSOCIATE EDITORIAL DIRECTOR Davy James

MANAGING EDITOR Caitlin Mollison

MANAGING EDITOR Kristen Crossley, MA

ASSISTANT EDITOR Jill Murphy

ASSISTANT EDITOR Aislinn Antrim

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT Jeff Prescott, PharmD, RPh

ASSISTANT DIRECTOR, CONTENT SERVICES

Angelia Szwed

SCIENTIFIC DIRECTORS Darria Zangari, PharmD, BCPS,

BCGP, Danielle Jamison, PharmD, MS

MEDICAL WRITERS Amber Schilling, Valerie Sjoberg

SENIOR CLINICAL PROJECT MANAGERS

Ida Delmendo, Danielle Mroz, MA

CLINICAL PROJECT MANAGERS Ted Pigeon,

Lauren Burawski

ASSOCIATE EDITORS Jillian Pastor, Hayley Fahey,

Amanda Thomas

COPY CHIEF Jennifer Potash

COPY SUPERVISOR Paul Silverman

MEDICAL & SCIENTIFIC QUALITY REVIEW EDITOR

Stacey Abels, PhD

COPY EDITORS Rachelle Laliberte, Kirsty Mackay,

Amy Oravec, and Holly Poulos

CREATIVE DIRECTOR, PUBLISHING Melissa Feinen

SENIOR ART DIRECTOR Marie Maresco

PHARMACY TIMES

CONTINUING EDUCATION™ STAFF

PRESIDENT Jim Palatine, RPh, MBA

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, PHARMACY

ADVOCACY Ed Cohen, PharmD, FAPhA

PUBLISHING

VICE PRESIDENT, PHARMACY & HEALTHCARE

COMMUNICATIONS John Hydrusko

ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR,

PARTNERSHIPS & PROGRAMS Grace Rhee

SALES & MARKETING COORDINATOR Marissa Silvestri

ADVERTISING REPRESENTATIVES

Anthony Costella; [email protected]

Madeline Garrigan; mgarrigan@pharmacytimes.com

Molly Higgins; mhiggins@pharmacytimes.com

Matt Miniconzi; mminiconzi@pharmacytimes.com

Kelly Walsh; kw[email protected]

MAIN NUMBER: 609-716-7777

OPERATIONS & FINANCE

CIRCULATION DIRECTOR

Jon Severn; [email protected]

VICE PRESIDENT, FINANCE Leah Babitz, CPA

CONTROLLER Katherine Wyckoff

CORPORATE

CHAIRMAN & FOUNDER Mike Hennessy Sr

VICE CHAIRMAN Jack Lepping

PRESIDENT & CEO Mike Hennessy Jr

CHIEF FINANCIAL OFFICER Neil Glasser, CPA/CFE

EXECUTIVE VICE PRESIDENT, OPERATIONS Tom Tolvé

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, CONTENT Silas Inman

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

OFFICER John Moricone

SENIOR VICE PRESIDENT, AUDIENCE GENERATION &

PRODUCT FULFILLMENT Joy Puzzo

VICE PRESIDENT, HUMAN RESOURCES AND

ADMINISTRATION Shari Lundenberg

VICE PRESIDENT, BUSINESS INTELLIGENCE Chris Hennessy

VICE PRESIDENT, MARKETING Amy Erdman

EXECUTIVE CREATIVE DIRECTOR Jeff Brown

PUBLISHING STAFF

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

2

WHAT ARE NUTRACEUTICALS?

Nutraceuticals are commonly defined as any

substance that is a food or part of a food which

provides medicinal or health benefits, including

the prevention and treatment of disease.

1

This

term includes a broad array of agents such as

dietary supplements, isolated nutrients, herbal

supplements, and specific food products.

2

It is

estimated that 77% of Americans use dietary sup-

plements, including more than 70% of adults who

are aged more than 60 years.

3,4

With an increase

in use and variety of nutraceuticals, it is essential

that pharmacists are made aware of the potential

benefits and risks of the products that are available

for consumer use.

MONITORING OF NUTRACEUTICAL

PRODUCTS IN THE UNITED STATES

Monitoring of nutraceutical products differs from

that of prescription drugs. Nutraceuticals are

broadly regulated under the Federal Food, Drug

and Cosmetic Act, with more specific regulation

for dietary supplements, vitamins, and minerals,

falling under the Dietary Supplement Health and

Education Act of 1994 (DSHEA). Although the

FDA oversees the manufacturing and distributing

process of supplements, rigorous clinical trials

and investigations of safety and efficacy are not

required to market such products. Nutraceuticals

are not intended, according to FDA standards, to

prevent, treat, or cure disease.

5-7

According to the DSHEA, manufacturers and

distributors of dietary and herbal supplements must

ensure the safety and accurate labeling of their

products, to guarantee that they are not adulterated

or misbranded.

7

If adulteration or misbranding

is identified, the FDA is responsible for taking

action to ensure safety and remove products from

consumer use. For example, in March 2019, the

FDA took action against foreign and domestic

companies stating false claims for more than

50 supplement products alleging to prevent, cure,

or treat Alzheimer disease.

8,9

To learn about the

latest warnings and alerts regarding the safety of

such products, pharmacists can refer to the FDA

Dietary Supplement and Advisory List available on

the FDA’s website.

10

In addition to FDA oversight, the official

United States Pharmacopeia (USP) and the official

National Formulary are considered national com-

pendia in the United States, accepted as sources

to provide official guidance. The USP sets qual-

ity standards for drug substances, drug products,

excipients, and dietary supplements under fed-

eral law in the United States, and USP standards

are considered binding under the Federal Food,

Drug, and Cosmetic Act for any manufacturer

claiming USP approval.

11-13

The 4 P’s of quali-

ty that the USP provides are: Positive identity,

Potency, Purity, and Performance of ingredients

in a product.

14

Positive identity ensures the listed

ingredients are present in the supplement and that

The Role of Nutraceuticals: What Pharmacists

Need to Know in 2020

BY LUMA MUNJY, PHARMD

LUMA MUNJY, PHARMD

COVER STORY

© IRYNA / ADOBE STOCK

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

APRIL

3

rigorous testing and auditing have been conducted for verifica-

tion. Assessment of potency guarantees the listed ingredients

are present in the stated amounts. Purity safeguards against

harmful excipients and/or contaminants such as pesticides, mold,

and active pharmaceutical agents, to name a few. Performance

ensures the formulation will break down and release the appro-

priate ingredients, allowing absorption via the labeled route

of administration.

14

USP also provides standards for food ingredients under the

umbrella of nutraceutical products. Pharmacists can refer to the

Food Chemicals Codex monographs for references regarding

assessment of food chemicals and additives.

12

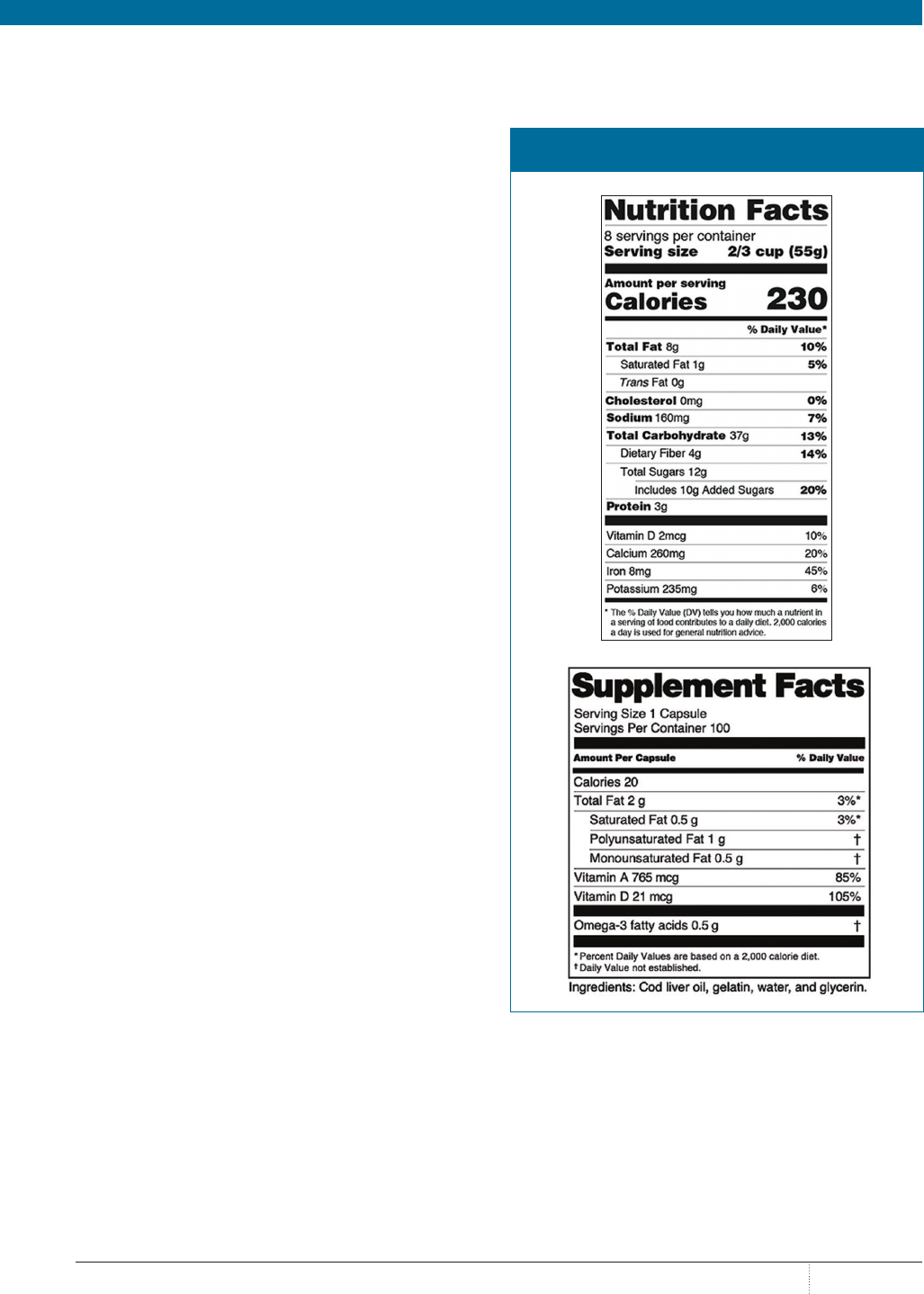

UNDERSTANDING NUTRACEUTICAL LABELS

Because the term nutraceuticals refers to both dietary supple-

ments and food products, understanding label information is

essential for providing appropriate consultations and preven-

tion of potential harm to patients. Supplement labels provide

information regarding suggested use, serving size, percent daily

value of the active ingredients, and a list of inactive ingredients,

as well as cautions and warnings. The manufacturer’s address,

lot number, and notice of potential allergens should also be

present. It is important to note that only the potency of the active

ingredients is listed on the product label. Inactive ingredients

are not tested for strength or potency in the supplement but are

verified only as being present in the product.

15

Food product labels that fall under the category of nutraceu-

ticals must abide by labeling requirements under the FDA’s

Nutrition Facts Labeling Guidance as well. These are also regu-

lated under the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act. Labeling

for food products requires Nutrition Facts labeling, whereas

dietary supplements require Supplement Facts labeling. A nota-

ble difference in Nutrition Facts compared with Supplement

Facts includes the requirement to list “zero” amounts of nutrients

in the Nutrition Facts label. Additionally, sources of dietary

ingredients and ingredients without a daily reference intake or

daily recommended value cannot be listed in the Nutrition Facts

panel for foods.

16

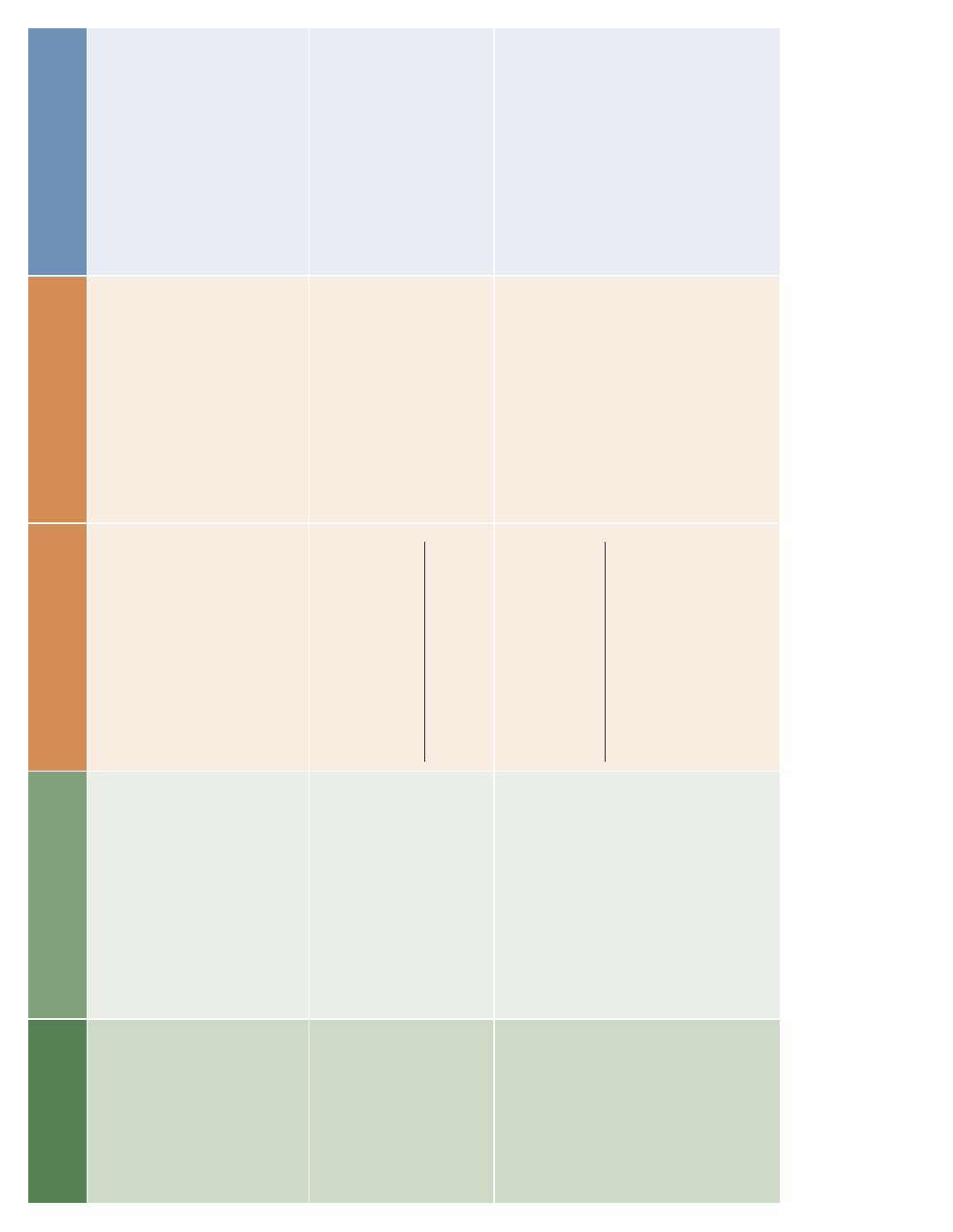

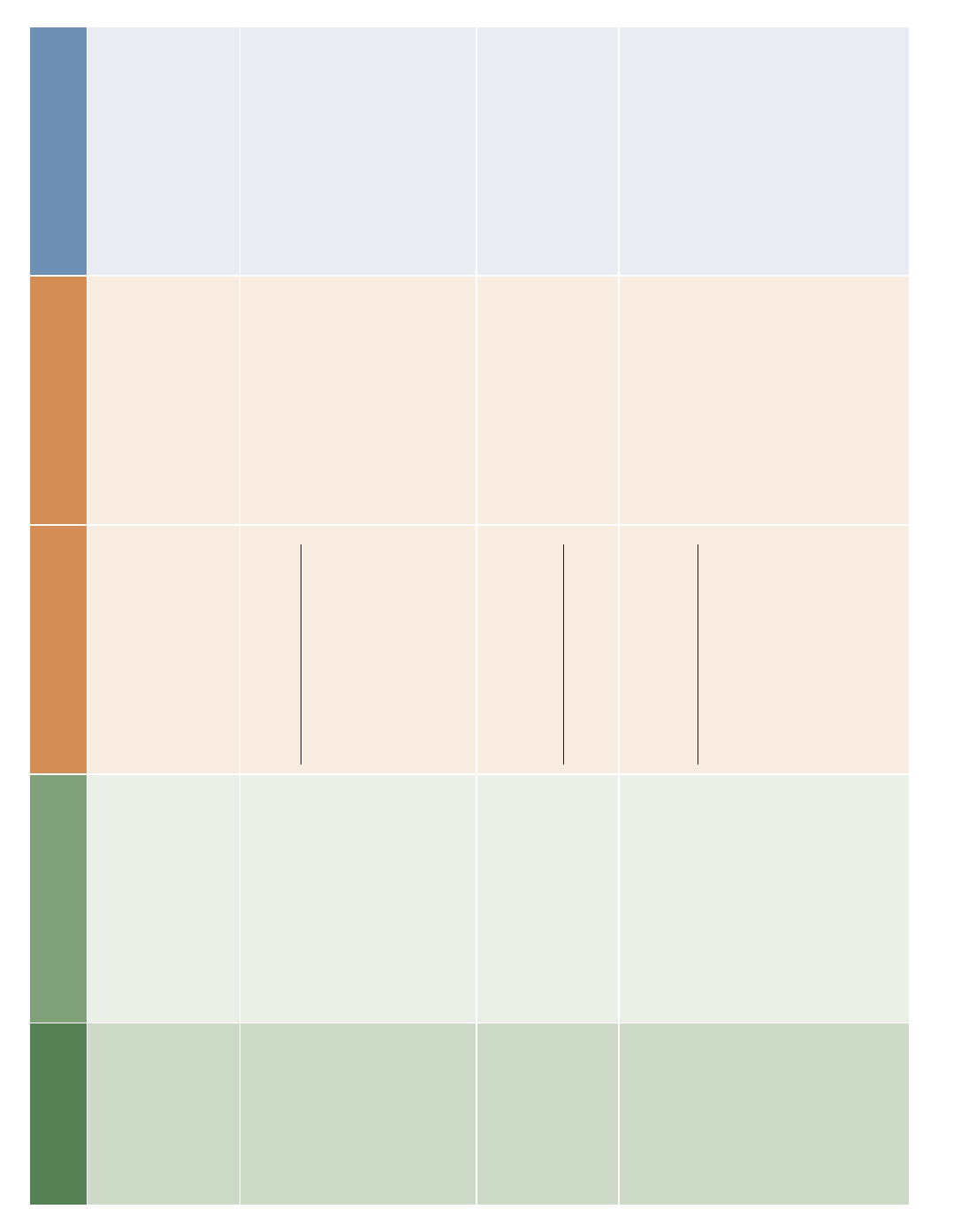

The images in the

figure depict the differences between a

Nutrition Facts and a Supplement Facts label.

16

USE OF NUTRACEUTICALS IN THE UNITED STATES

As previously stated, the Council on Responsible Nutrition

reported that dietary supplement usage has been at an all-time

high in recent years, with approximately 77% of Americans

reporting using supplements in 2017, and rates have been

steadily rising.

3

It is estimated that 9 of 10 Americans have some

form of nutritional deficiency and 8 of 10 physicians recom-

mend supplements for patient use.

3

Additionally, an increased

number of millennials adhere to specialized eating plans, such

as gluten-free, vegan, vegetarian, and dairy-free diets; this

makes their need for nutritional supplementation potentially

higher, to ensure that they consume essential nutrients.

14,17

Overall, nutraceuticals are used for numerous health purposes.

An overview of some common nutraceutical products and their

use follows.

FIGURE. NUTRITION FACTS VERSUS SUPPLEMENT

FACTS LABEL

Reprinted with permission from US Department of Health and Human Services, FDA,

Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition. fda.gov/media/134505/download.

Published January 2020. Accessed March 9, 2020.

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

4

DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS AND THE COMMON COLD

Zinc, Echinacea purpurea, nasal saline, honey (buckwheat),

geranium extract, and garlic have all been marketed as dietary

supplements used for the common cold. Meta-analyses assess-

ing the effectiveness of zinc for reducing symptoms of the

common cold have concluded that zinc lozenges shortened the

duration of nasal discharge, nasal congestion, sneezing, sore

throat, cough, and muscle aches, with minimal adverse effects

(AEs) noted.

18

Evidence has demonstrated that the use of buck-

wheat honey showed improvement over placebo for decreasing

the frequency of cough and improving the quality of sleep in

pediatric patients.

19

Echinacea purpurea, nasal saline, gerani-

um extract, and garlic have provided inconsistent results and

require improved trials to demonstrate their effectiveness for

use in the common cold.

20

DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS AND DEPRESSION

Marketing for the use of dietary supplements in the manage-

ment of depression is widespread; the most common supple-

ments include omega-3 fatty acids, St John’s wort, SAMe,

and inositol. Of these therapies, meta-analyses have provided

evidence that St John’s wort may have effectiveness in the

treatment of mild to moderate depression in comparison with

placebo; however, well-controlled trials are needed to con-

firm its place in therapy.

21

It should also be noted that several

drug–drug interactions exist with the use of St John’s wort,

and pharmacists should be diligent in assessing all medica-

tions for interactions before recommending use of the product.

Omega-3 fatty acids, SAMe, and inositol have inconclusive

evidence and require further assessment before recommenda-

tions can be made.

22

DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS AND SPECIAL POPULATIONS

Special populations—eg, those who are pregnant and/or nurs-

ing; older adults—may be at greater risk for AEs, and caution

should be taken when recommending nutraceutical products

in these populations. During pregnancy, for example, levels

of essential vitamins and minerals such as iron, calcium, and

folic acid may decline, but they are required for proper growth

and development of the fetus.

23

Although prenatal vitamins

are readily available without prescription, pharmacists should

recommend that patients who are pregnant be assessed by their

obstetrician prior to the use of supplements or nutritional prod-

ucts.

24

In geriatric populations, the use of nutraceuticals should

be monitored because of the increased risk for drug, supple-

ment, and food interactions that may lead to AEs.

4

The National

Institute on Aging recommends a balanced diet including a

variety of healthy foods and fortified food products to maintain

adequate nutrition in geriatric patients; however, individuals

with malabsorption of nutrients due to disease- or drug-induced

nutrient depletions should be assessed by a health care provider

to determine need for supplementation.

25

For further informa-

tion, pharmacists can access the US Department of Agriculture

Dietary Reference Intake calculator to assess specific nutrient

needs in various populations.

26

HERBAL SUPPLEMENTS

Herbal supplements are a subset of dietary supplements that

contain 1 or more herbs. They are also referred to as botanicals

and are made from plants, fungi and/or algae, or a combination

of these substances. Herbal products are often sold as teas,

extracts, tablets, capsules, or powders.

27

Common herbal sup-

plements include green tea, valerian root, cinnamon, Ginkgo

biloba, evening primrose oil, black cohosh, and chamomile,

to name a few. An ample number of herbal supplements exist,

and pharmacists can consult the National Institute of Health’s

National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health for

current research and recommendations regarding their use.

28

PROBIOTICS

Probiotics are also under the umbrella of nutraceutical prod-

ucts. Probiotics generally consist of live microorganisms that

can be placed in dietary supplements and fermented foods and

in topically applied products including cosmetics. Probiotics

may contain a variety of diverse bacteria; the most common

include Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium Yeast, too, such

as Saccharomyces boulardii, may be included in probiotic

supplements. Probiotics have demonstrated some effectiveness

in specific health conditions, such as preventing antibiot-

ic-associated diarrhea, preventing necrotizing enterocolitis in

premature infants, treating periodontal disease, and supporting

remission of ulcerative colitis. Probiotic use shows promising

results; however, studies with consistent formulations and

amounts of each culture are needed to establish guidance

regarding products. Probiotics are generally safe but should

be used cautiously in patients who are immunocompromised

and/or critically ill to prevent new infections or worsen

current ones.

29

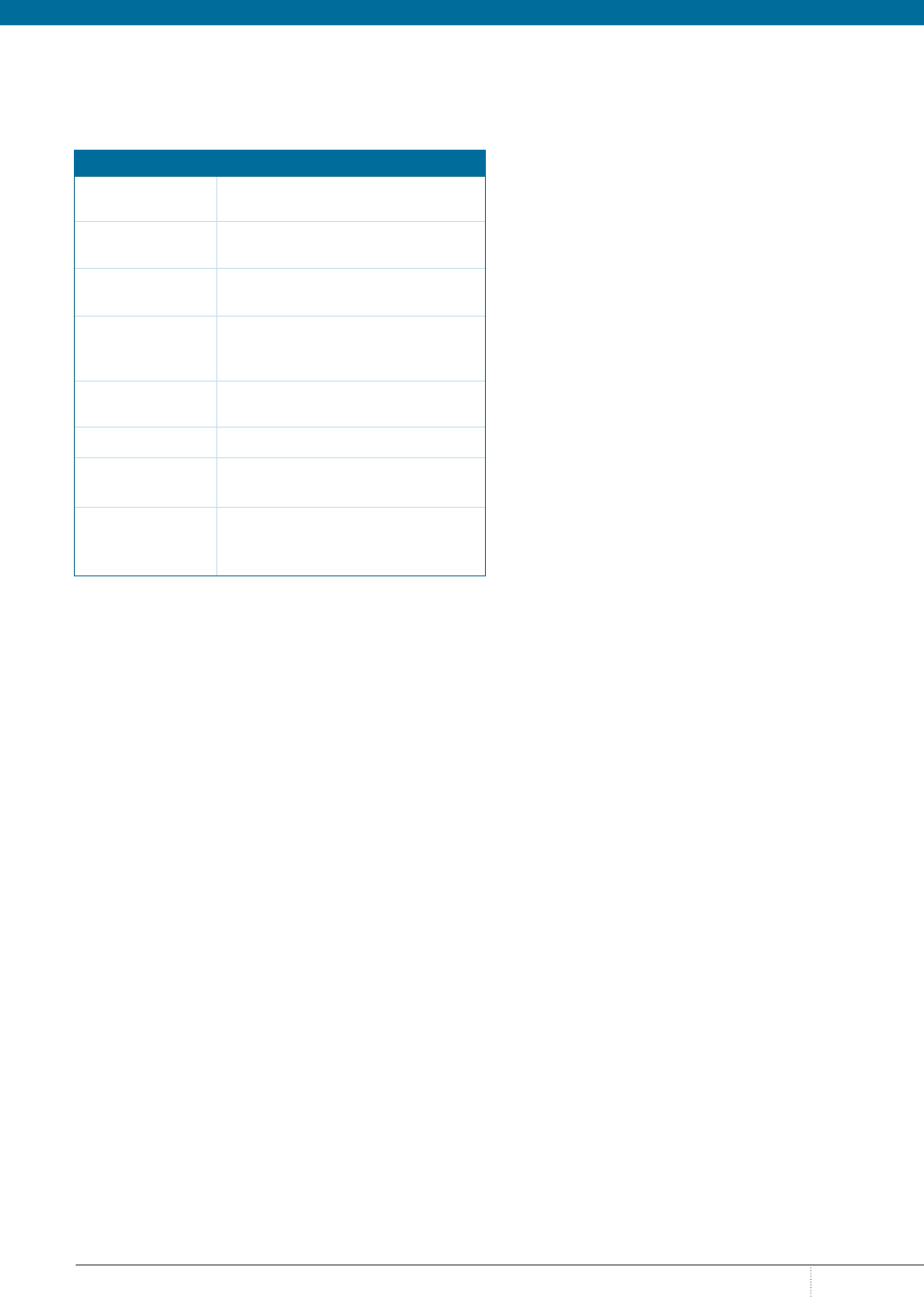

DRUG-INDUCED NUTRIENT DEPLETIONS

Drug-induced nutrient depletions pose an additional area for

pharmacist consultation regarding use of nutraceutical products.

Drug-induced depletions may be mild to moderate in nature and

can be corrected through use of nonprescription products. For

example, use of histamine-2 receptor blockers has been associated

with calcium depletion; therefore, calcium supplementation may

be needed, especially in older adults who are at a higher risk of

bone fractures and osteoporosis. More severe depletions require

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

APRIL

5

evaluation by a health care professional to establish replacement

needs, as in the case of the depletion of such electrolytes as potas-

sium and magnesium in the presence of thiazide and loop diuret-

ics. Pharmacists should be aware of common drug-induced

nutrient depletions and educate patients regarding the need for

nutrient replacement and/or referral for evaluation. The

table

highlights some common nutrient–drug interactions.

30

CONCLUSIONS

Nutraceutical use across the United States is increasing, and

this provides an opportunity for pharmacists to counsel patients

on the appropriate use of available products. As the number of

nutraceuticals increases, it is essential for pharmacists to remain

informed on the latest recommendations for their use and safety.

Pharmacists can refer to the FDA website for current informa-

tion regarding the purity, safety, efficacy, and use of nutraceuti-

cal products. Product selection should be based on verification

of authenticity through national compendia such as the official

USP. Only products with a USP label ensure the purity, poten-

cy, performance, and presence of the listed ingredients on the

label. The need for supplementation is highly patient-specific:

It ranges from broad use of multivitamins to specific replace-

ment of nutrients due to drug-induced nutrient depletions and

conditional replacement during pregnancy and lactation. A

detailed patient history, assessment of current medications, and

determination of risk and benefit should guide pharmacists’

recommendations of nutraceutical products. ®

REFERENCES

1. Andlauer W, Furst P. Nutraceuticals: a piece of history, present status and out-

look. Food Res Int. 2002;35(2-3):171-176. doi: 10.1016/s0963-9969(01)00179-x.

2. Food labeling & nutrition. FDA website. fda.gov/food/food-labeling-nutrition.

Updated February 20, 2020. Accessed March 9, 2020.

3. Dietary supplement use reaches all time high. Council on Responsible

Nutrition website. crnusa.org/newsroom/dietary-supplement-use-reaches-all-

time-high-available-purchase-consumer-survey-reaffirms. Published September

30, 2019. Accessed March 26, 2020.

4. Gahche JJ, Bailey RL, Potischman N, Dwyer JT. Dietary supplement use

was very high among older adults in the United States in 2011-2014. J Nutr.

2017;147(10):1968-1976. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.255984.

5. Dietary supplements. FDA website. fda.gov/food/dietary-supplements.

Updated August 16, 2018. Accessed March 9, 2020.

6. Dietary supplement products and ingredients. FDA website. fda.gov/food/

dietary-supplements/dietary-supplement-products-ingredients. Updated August

16, 2019. Accessed March 9, 2020.

7. Dietary supplements guidance documents & regulatory information. FDA web-

site. fda.gov/food/guidance-documents-regulatory-information-topic-food-and-di-

etary-supplements/dietary-supplements-guidance-documents-regulatory-informa-

tion#healthclaims. Updated September 5, 2019. Accessed March 9, 2020.

8. Watch out for false promises about so-called Alzheimer’s cures. FDA website.

fda.gov/consumers/consumer-updates/watch-out-false-promises-about-so-called-

alzheimers-cures-0. Updated March 28, 2019. Accessed March 9, 2020.

9. Unproven Alzheimer’s disease products. FDA website. fda.gov/consumers/

health-fraud-scams/unproven-alzheimers-disease-products. Updated December

22, 2018. Accessed March 9, 2020.

10. Dietary supplement ingredient advisory list. FDA website. fda.gov/food/

dietary-supplement-products-ingredients/dietary-supplement-ingredient-adviso-

ry-list. Updated December 16, 2019. Accessed March 9, 2020.

11. USP and FDA working together to protect public health. United States

Pharmacopeia website. usp.org/about/public-policy/usp-fda-roles. Accessed

March 9, 2020.

12. Legal recognition – standards categories. United States Pharmacopeia website.

usp.org/about/legal-recognition/standard-categories. Accessed March 9, 2020.

13. Dietary Supplements Verification Program. United States Pharmacopeia

website. usp.org/verification-services/dietary-supplements-verification-program.

Accessed March 9, 2020.

14. Choose a quality supplement. United States Pharmacopeia website. quality-

matters.usp.org/sites/default/files/user-uploaded-files/when-food-is-not-enough-

download_0.pdf. Accessed March 9, 2020.

15. How to read a supplement label. United States Pharmacopeia website.

qualitymatters.usp.org/how-read-supplement-label. Published August 26, 2016.

Accessed March 9, 2020.

16. Small Entity Compliance Guide: revision of the Nutrition Facts and Supplement

Facts Labels. FDA website. fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guid-

ance-documents/small-entity-compliance-guide-revision-nutrition-and-supple-

ment-facts-labels. Updated February 3, 2020. Accessed March 9, 2020.

17. Gahche JJ, Bailey RL, Potischman N, et al. Federal monitoring of dietary

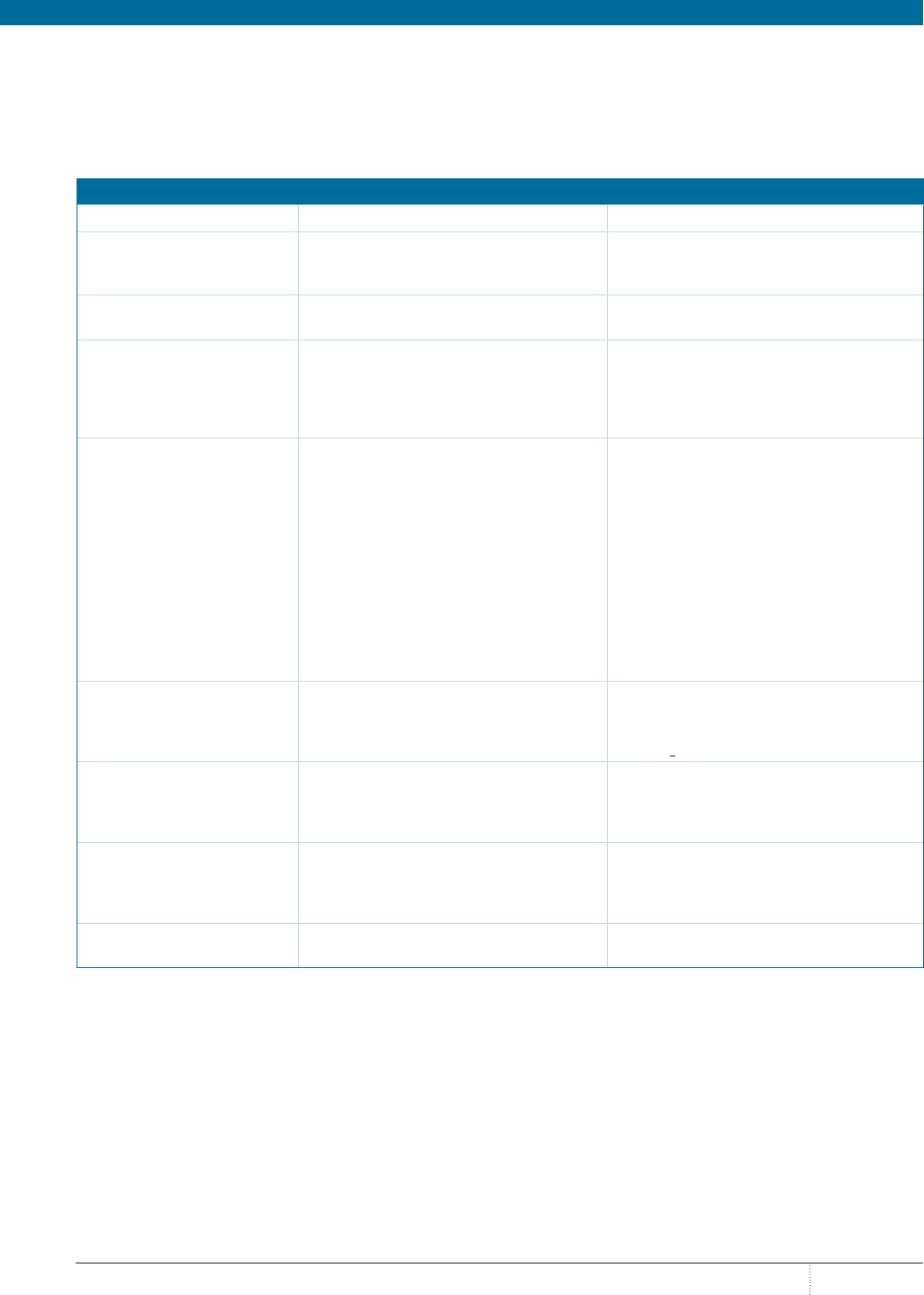

TABLE. COMMON NUTRIENTDRUG INTERACTIONS

Nutrient

Depleted

Associated Drugs/Drug Classes

Calcium Corticosteroids, loop diuretics, H

2

RAs,

benzodiazepines, digoxin, SSRIs

Vitamin D Corticosteroids, bile acid sequestrants,

H

2

RAs, SSRIs

Folic acid Oral contraceptives, pancreatic

enzymes, hormone replacement

therapy

Vitamin B

12

Metformin, H

2

RAs, PPIs, hormone

replacement therapy

Vitamins A and K Bile acid sequestrants

Potassium Loop diuretics, thiazide diuretics,

corticosteroids, digoxin

Magnesium Oral contraceptives, loop diuretics,

thiazide diuretics, PPIs, H

2

RAs,

digoxin, hormone replacement therapy

H

2

RA indicates histamine-2 receptor antagonist; PPI, proton pump inhibitor; SSRI,

selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

page 18

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

6

M

elatonin, an endogenous, or natural,

hormone mainly produced by the pineal

gland in the brain, regulates several

body processes, including circadian rhythm and

sleep patterns.

1,2

Darkness stimulates melatonin

release, whereas light, especially blue light emitted

by screens, suppresses release.

2

Secretion of mela-

tonin varies by age, with highest secretion in those

aged approximately 1 to 3 years and lowest secre-

tion in young infants (<1 year) and elderly adults

aged at least 65 years.

3,4

Melatonin can be given exogenously, such as in

the form of a synthetically produced supplement,

and has been investigated for various medical con-

ditions, most commonly sleep disorders, including

jet lag, insomnia, shift-work disorder, and other

circadian rhythm disorders (eg, delayed sleep phase

syndrome or non–24-hour sleep–wake disorder).

1,2

When given exogenously, melatonin is

proposed to improve sleep onset latency (time to

fall asleep) rather than cause drowsiness to induce

sleep.

2,3

Doses of 1 mg to 5 mg of melatonin taken

at night can produce 10 to 100 times higher

nighttime peaks within an hour when compared

with endogenous peaks.

3

Metabolism of melatonin

occurs in the liver, resulting in a relatively short

half-life of 30 minutes to 60 minutes.

3

Most exog-

enous melatonin is synthetically produced.

2

Less

often, it is produced from animal pineal gland;

bovine derivations should be avoided because of

possible bacterial contamination.

2

SAFETY OF MELATONIN SUPPLEMENTS

Melatonin appears to be safe for short-term use

in the general population as an 8-mg dose per day

for up to 6 months. Even with larger doses (up to

10 mg, which is safe to use for up to 2 months),

only mild adverse effects (AEs) such as dizziness,

headache, nausea, and drowsiness were general-

ly reported. Some patients may be able to take

melatonin safely for up to 2 years.

1

Long-term

studies of the use of melatonin for up to 2 years in

children have shown similar AEs as those in short-

term studies; however, because these studies are

limited, long-term use of melatonin should occur

under health care provider supervision, regardless

of age.

1,5

There is a lack of evidence in pregnant women

regarding safety, and so melatonin should be

avoided in this population. Higher doses (75-300

mg/day) have been associated with inhibition of

ovulation, and so patients desiring to become

pregnant should avoid high or frequent doses.

1,5

Few data are available regarding use in lactation,

and so women who are breastfeeding should be

counseled to avoid use.

1,5

In children, melatonin may be safe when used

short term in low doses. Dosing should be limited

to 3 mg daily for infants (aged >6 months) and

children. Melatonin use in adolescents may poten-

tially affect sexual hormones and development, so

doses should not exceed 5 mg daily if medically

needed. Otherwise, it should be avoided for healthy

children.

1,5

Elderly patients may be more suscepti-

ble to AEs such as daytime drowsiness because of

decreased clearance of the drug in this population.

5

Melatonin is specifically not recommended in

elderly patients with dementia who have irregular

sleep–wake rhythm disorder.

6

EFFICACY OF MELATONIN SUPPLEMENTS

Melatonin has been studied in a variety of sleep

disorders, but evidence is often weak or conflict-

ing because of smaller or lower-quality studies.

Most evidence supports its use in delayed sleep

phase syndrome, non–24-hour sleep–wake dis-

order in the blind, and primary insomnia.

1,6

It

is often used for occasional insomnia, although

evidence and dosage is less certain.

2

In chronic

insomnia, there is evidence of a slight reduction

Melatonin: Considerations for Use in Patients

With Sleep Disorders

BY RASHI C. WAGHEL, PHARMD, BCACP; AND JENNIFER A. WILSON, PHARMD, BCACP

FEATURE

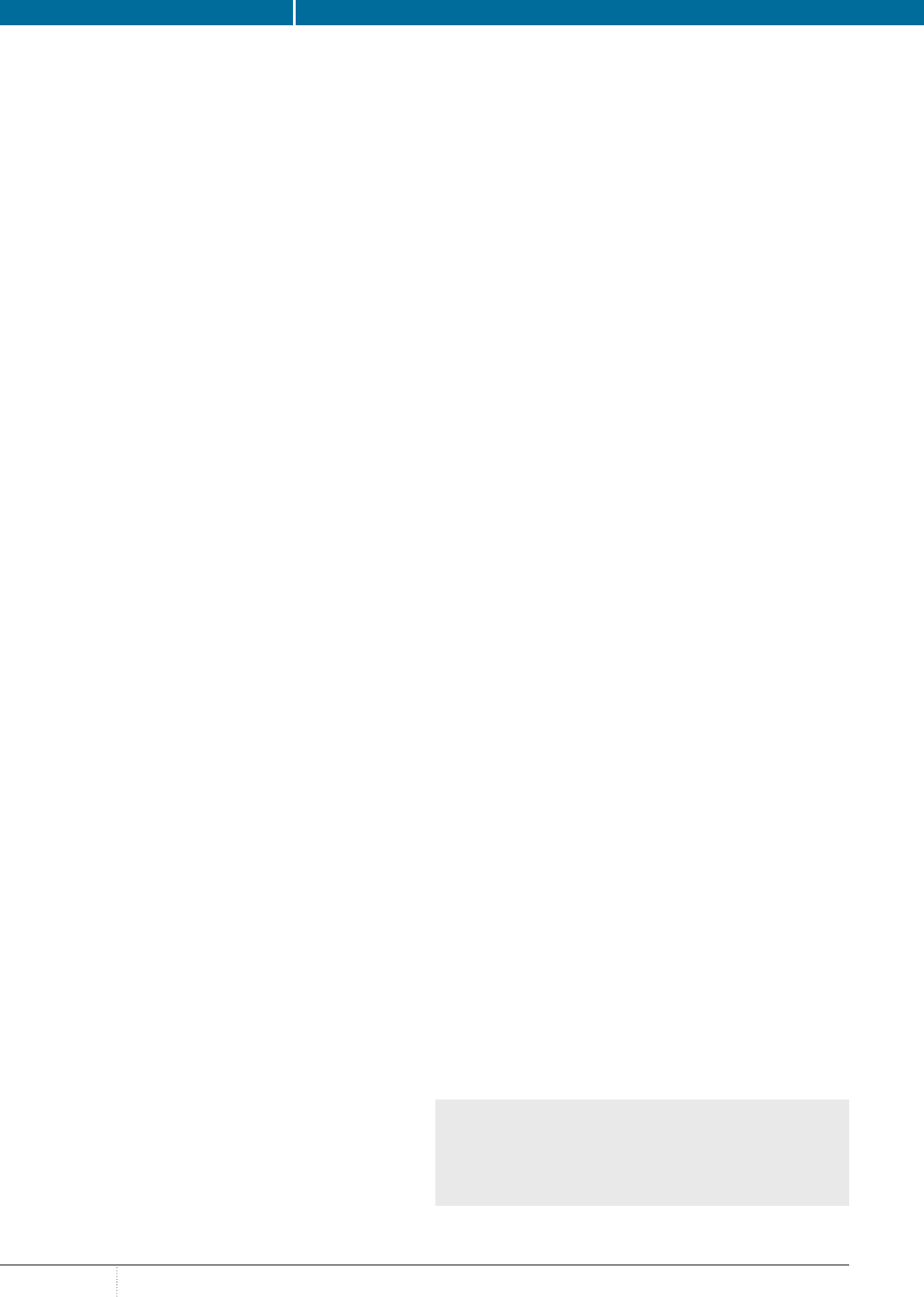

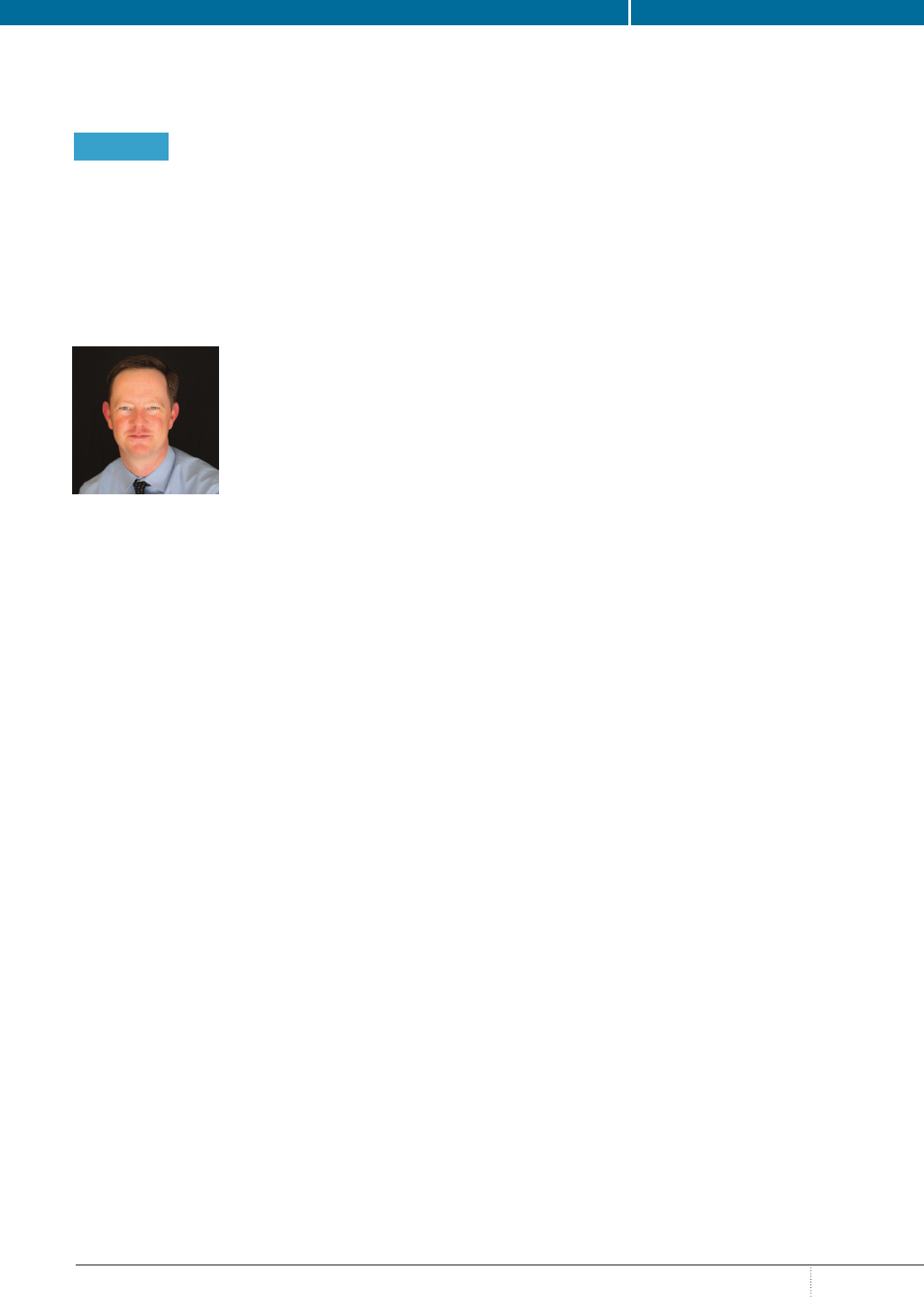

RASHI C. WAGHEL,

PHARMD, BCACP

JENNIFER A. WILSON,

PHARMD, BCACP

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

APRIL

7

in sleep onset latency (about 7-12 minutes) compared with

placebo and a small improvement in subjective sleep quality.

1,7,8

However, the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and the

American College of Pharmacy both state that sufficient evi-

dence is lacking to recommend use of melatonin in the general

population for chronic insomnia.

7,8

Despite the lack of evidence,

guidelines recognize that an informed patient would be more

likely to use melatonin over no treatment.

8

An overview of mel-

atonin efficacy in insomnia, along with other sleep disorders,

can be found in the

table.

1,2,6-14

COUNSELING POINTS

Pharmacists can counsel patients on selecting products to ensure

that they choose the intended product strength (eg, melatonin

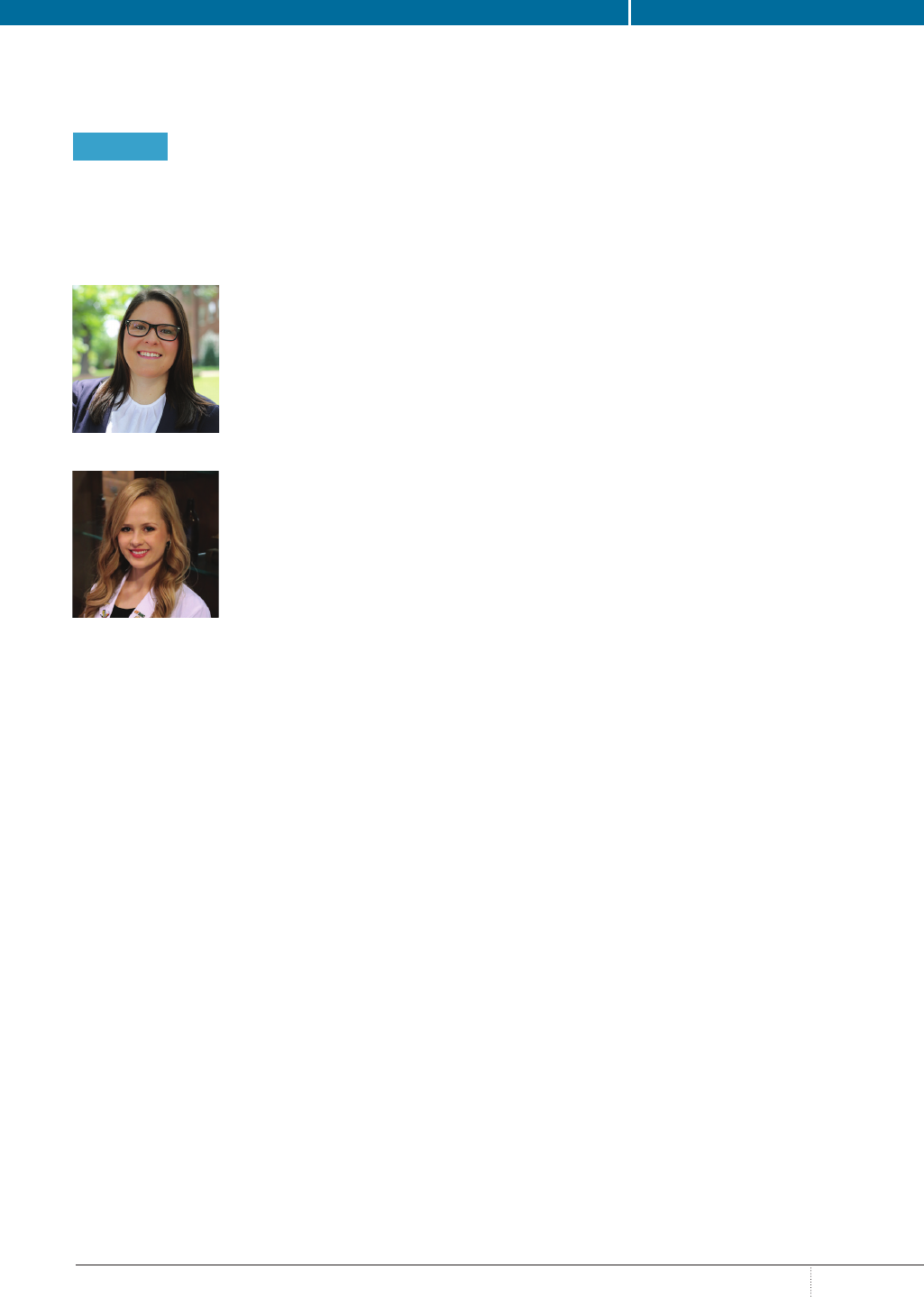

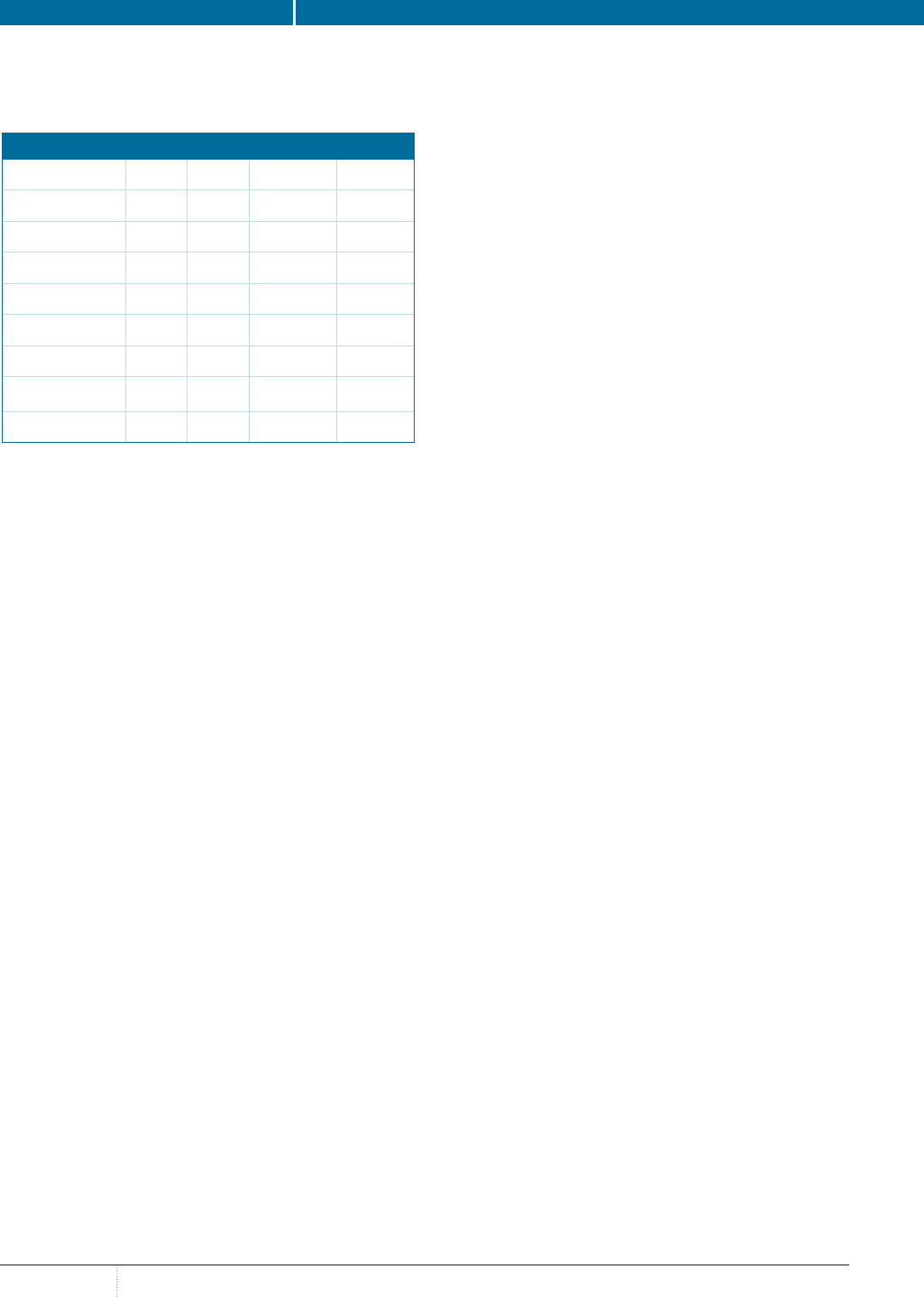

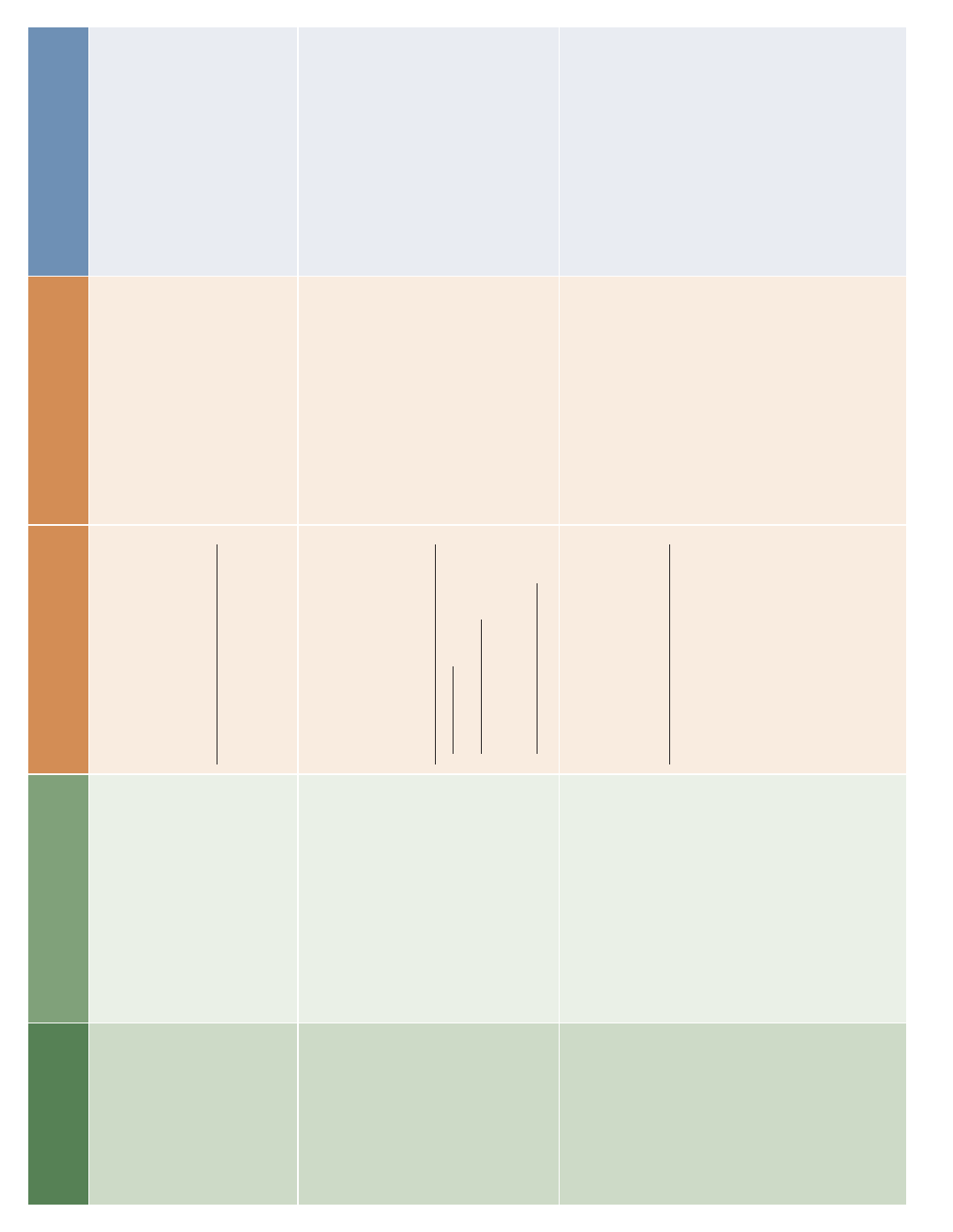

TABLE. MELATONIN USE FOR SLEEP DISORDERS SUMMARY

,,

Condition Studied

a

Doses Studied Results

DSPS - likely effective

1,5,6

0.3-5.0 mg daily up to 4 weeks Improves sleep onset latency; improves QOL

(eg, mental health, vitality, bodily pain) in

young adults with DSPS

Non–24-hour sleep–wake

disorder - likely effective

1,5,6

0.5-10 mg daily in adults and 0.5-4.0 mg daily

in children for up to 6 years

Improves circadian rhythm sleep disorders

in adults and children who are blind

Beta blocker–induced insomnia

- possibly effective

1

2.5-5.0 mg at night (eg, 1 hour before bed and

after taking the beta blocker)

May improve sleep latency, total wake time,

wakefulness after sleep onset, and/or

increase total sleep time to counter proposed

decrease in endogenous melatonin with beta

blocker use

Insomnia -

possibly effective

1,2,6,7,8,9

0.3-5.0 mg in adults nightly

typically for ≥21 days

5 mg in children for 28 days

(0.05-0.15 mg/kg for 7 days in 1 trial)

Short-term use may improve sleep-onset

latency, increase total sleep time, and improve

sleep quality; more benefit may be seen in

elderly individuals (due to melatonin defi-

ciency); more benefit seen with insomnia with

certain comorbidities (depression, schizophre-

nia, bipolar disorder, epilepsy, asthma, cystic

fibrosis, tuberous sclerosis, autism spectrum

disorders, and developmental disabilities),

whereas conflicting results have been seen

with other conditions (Alzheimer disease,

dementia, Parkinson disease, traumatic brain

injury, substance use disorder, and dialysis)

Jet lag - possibly effective

1,2,10,11

0.5-5.0 mg (preferably 2.0-3.0 mg)

at local bedtime on day of arrival and

for 2-5 nights thereafter

May improve alertness, jet lag, psychomotor

performance, daytime sleepiness, and fatigue;

may be most effective when traveling eastward

through >5 time zones

Preoperative anxiety and

sedation - possibly effective

1,12

3.0-14.0 mg orally or 0.05-0.2 mg/kg

sublingually in adults

0.05-0.4 mg/kg in children

Studies show conflicting efficacy; may

improve sedation and reduce preoperative

anxiety similar to taking midazolam, cloni-

dine, or gabapentin as a preanesthetic agent

Shift-work disorder -

possibly ineffective

1,2,11,13

1.0-10.0 mg after night shift Does not significantly improve sleep latency,

sleep efficiency, or adjustment to rotating shift

work; may slightly increase total sleep time

and/or overall sleep quality

REM sleep behavior disorder -

insufficient evidence

1,6

3.0 mg nightly for 4 weeks May increase likelihood of appropriate muscle

paralysis during REM sleep

DSPS indicates delayed sleep phase syndrome; QOL, quality of life; REM, rapid eye movement.

a

Ratings (likely effective, possibly effective, possibly ineffective, insufficient evidence) based on the Natural Medicines Comprehensive Database rating system.

1

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

8

can be dosed in both milligrams and micrograms: 0.3 mg or

equivalently, 300 mcg). A 300-mcg dose of exogenous mela-

tonin produces higher-than-normal physiologic concentrations,

and so high doses are not usually necessary.

2

Lower doses may

also minimize potential AEs such as dizziness, headache, nau-

sea, and sleepiness, but no study results support this.

5

Patients

should be counseled on appropriate timing of dose and length

of use depending on indication (eg, 30-60 minutes before

bedtime for insomnia).

2

Additional details can be found in the

Table.

1,2,6-14

Regardless of whether a patient chooses to use

melatonin for sleep disorders, patients should be counseled on

appropriate sleep hygiene, such as establishing a regular sleep

pattern, avoiding daytime naps, and avoiding use of electronics

before bed.

15

CONCLUSIONS

Strong evidence from long-term clinical trials evaluating the

use of melatonin for sleep disorders is lacking. Although some

evidence shows modest benefit in reducing sleep onset latency

and improving sleep quality, the overall clinical impact may be

limited. However, melatonin is generally regarded as safe in

the general population, with only mild AEs reported. As such,

despite the lack of strong evidence, patients may opt to try mel-

atonin to help with sleep disorders such as insomnia or jet lag. ®

REFERENCES

1. Melatonin. Natural Medicines website. naturalmedicines.therapeuticresearch.

com/databases/food,-herbs-supplements/professional.aspx?productid=940.

Updated February 19, 2020. Accessed February 28, 2020.

2. McQueen CE, Orr KK. Natural products. In: Krinsky DL, Ferreri SP,

Hemstreet BA, et al. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs: An Interactive

Approach to Self-Care. 19th ed. Washington, DC: American Pharmacists

Association; 2017:957-994.

3. Wassmer E, Whitehouse WP. Melatonin and sleep in children with neurodevel-

opmental disabilities and sleep disorders. Curr Paediatrics. 2006;16(2):132-138.

doi: 10.1016/j.cupe.2006.01.001.

4. Mishima K, Okawa M, Shimizu T, Hishikawa Y. Diminished melatonin

secretion in the elderly caused by insufficient environmental illumination. J Clin

Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86(1):129-134. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.1.7097.

5. Andersen LP, Gögenur I, Rosenberg J, Reiter RJ. The safety of melatonin

in humans. Clin Drug Investig. 2016;36(3):169-175. doi: 10.1007/s40261-015-

0368-5.

6. Auger RR, Burgess HJ, Emens JS, Deriy LV, Thomas SM, Sharkey KM.

Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of intrinsic circadian rhythm

sleep-wake disorders: advanced sleep-wake phase disorder (ASWPD), delayed

sleep-wake phase disorder (DSWPD), non-24-hour sleep-wake rhythm disorder

(N24SWD), and irregular sleep-wake rhythm disorder (ISWRD). an update for

2015: an American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin

Sleep Med. 2015;11(10):1199-1236. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5100.

7. Auld F, Maschauer EL, Morrison I, Skene DJ, Riha RL. Evidence for the

efficacy of melatonin in the treatment of primary adult sleep disorders. Sleep Med

Rev. 2017;34:10-22. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.06.005.

8. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, Cooke M, Denberg TD; Clinical

Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Management

of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the

American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(2):125-133. doi:

10.7326/M15-2175.

9. Sateia MJ, Buysse DJ, Krystal AD, Neubauer DN, Heald JL. Clinical practice

guideline for the pharmacologic treatment of chronic insomnia in adults: an

American Academy of Sleep Medicine clinical practice guideline. J Clin Sleep

Med. 2017;13(2):307-349. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.6470.

10. Ferracioli-Oda E, Qawasmi A, Bloch MH. Meta-analysis: melatonin for the

treatment of primary sleep disorders. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63773. doi: 10.1371/

journal.pone.0063773.

11. Herxheimer A. Jet lag. BMJ Clin Evid. 2014;2014.

12. Costello RB, Lentino CV, Boyd CC, et al. The effectiveness of melatonin for

promoting healthy sleep: a rapid evidence assessment of the literature. Nutr J.

2014;13:106. doi: 10.1186/1475-2891-13-106.

13. Hansen MV, Halladin NL, Rosenberg J, Gögenur I, Møller AM. Melatonin

for pre- and postoperative anxiety in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2015;(4):CD009861. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009861.pub2.

14. Liira J, Verbeek JH, Costa G, et al. Pharmacological interventions for sleep-

iness and sleep disturbances caused by shift work. Cochrane Database Syst Rev.

2014;(8):CD009776. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD009776.pub2.

15. Melton ST, Kirkwood CK. Insomnia, drowsiness, and fatigue. In: Krinsky

DL, Ferreri SP, Hemstreet B, et al. Handbook of Nonprescription Drugs:

An Interactive Approach to Self-Care. 19th ed. Washington, DC: American

Pharmacists Association; 2017:855-871.

ABOUT THE AUTHORS

RASHI C. WAGHEL, PHARMD, BCACP, is an associate professor of pharmacy at

Wingate University in Charlotte, North Carolina.

JENNIFER A. WILSON, PHARMD, BCACP, is an associate professor of pharmacy at

Wingate University.

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

APRIL

9

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

V

itamin D encompasses a group of fat-

soluble secosterols that are found in

certain foods and supplements and can

also be produced when synthesis of vitamin D

is triggered after the sun’s ultraviolet rays touch

skin. It is required for bone growth and

remodeling,and when paired with calcium, it

can help to prevent osteoporosis. Low levels of

vitamin D have been linked with poorer health

and with disease.

1

Although the importance of

vitamin D in regard to bone health has been

established, its importance in other areas, such

as skin pigmentation, pregnancy, cancer, and

immune function, is unclear and not supported

by clinical evidence.

1,2

WHO NEEDS VITAMIN D

Because few foods naturally contain vitamin D,

supplementation is commonly used to avoid risk

of vitamin D deficiency (

table).

1

Herein are

described 4 populations of patients who may

benefit from vitamin D supplementation.

Breastfed Infants

The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

recommends that infants who are breastfed receive

vitamin D supplementation. Although most infant

formulas contain vitamin D, the AAP still rec-

ommends that infants who are receiving less than

1 L of formula per day also receive supplemen-

tation, in addition to those who are exclusively

breastfed.

3

The results of a 2010 study of data

from the Infant Feeding Practices Study II, in

which mothers of both breastfed and formula-fed

infants responded to mailed questionnaires on

a variety of topics, including dietary intake,

found that 44% to 58% of infants met the 2003

recommended amount of 5 mcg per day of vitamin

D. When the AAP recommendation increased to

10 mcg per day in 2008, less than a quarter

of infants would have met the recommenda-

tion.

4

Mothers who responded to the question

gave a variety of reasons for not supplementing

their infants with vitamin D, including lack of

knowledge about supplementation, misinforma-

tion about vitamins in formula and breast milk,

inconvenience of administering supplements, and

infant’s dislike of them. Common phrases repeat-

ed by the mothers were, “I didn’t know I should,”

“Baby formula has all that is needed and recom-

mended,” and “It causes [the baby] to spit up.”

5

Of the mothers who responded to the question-

naire who were breastfeeding, most (88.4%) pre-

ferred to take a vitamin D supplement themselves

rather than directly administer it to their infant. The

benefits of maternal supplementation with vitamin

D include ease of administration, both mother and

infant receiving vitamin D, and decreased risk

of infant toxicity due to dosing errors. Maternal

supplementation at 100 mcg to 162.5 mcg per day,

or a single monthly dose of 3750 mcg, can suffi-

ciently enrich breast milk with enough vitamin D

to meet an infant’s needs without causing toxicity.

If mothers choose to give their infants vitamin D

supplementation directly, the infant should receive

10 mcg per day through drops administered by

mouth or in the bottle.

5

Older Adults

The results of a study conducted between 2011

and 2014 found that vitamin D supplementation

use has increased in the United States, with 26%

of older adults (≥60 years) taking a vitamin D

supplement.

6

As people grow older, their skin

becomes thinner and they cannot absorb and

process vitamin D as efficiently.

1

Further, renal

decline can occur in older adults. This affects

vitamin D levels because the kidneys are needed

to convert vitamin D in the body.

1

When levels of vitamin D in the body are inad-

equate, bones can become thin, fragile, and mis-

shapen, and the risk of osteoporosis is increased.

2

Therefore, the National Osteoporosis Foundation

recommends that women and men aged under

50 years receive 10 mcg to 20 mcg of vitamin D

per day, and that those 50 years and older receive

To D or Not to D: That Is the Question

BY CHELSEA RENFRO, PHARMD, CHSE; AND ALEX STANLEY, PHARMD CANDIDATE

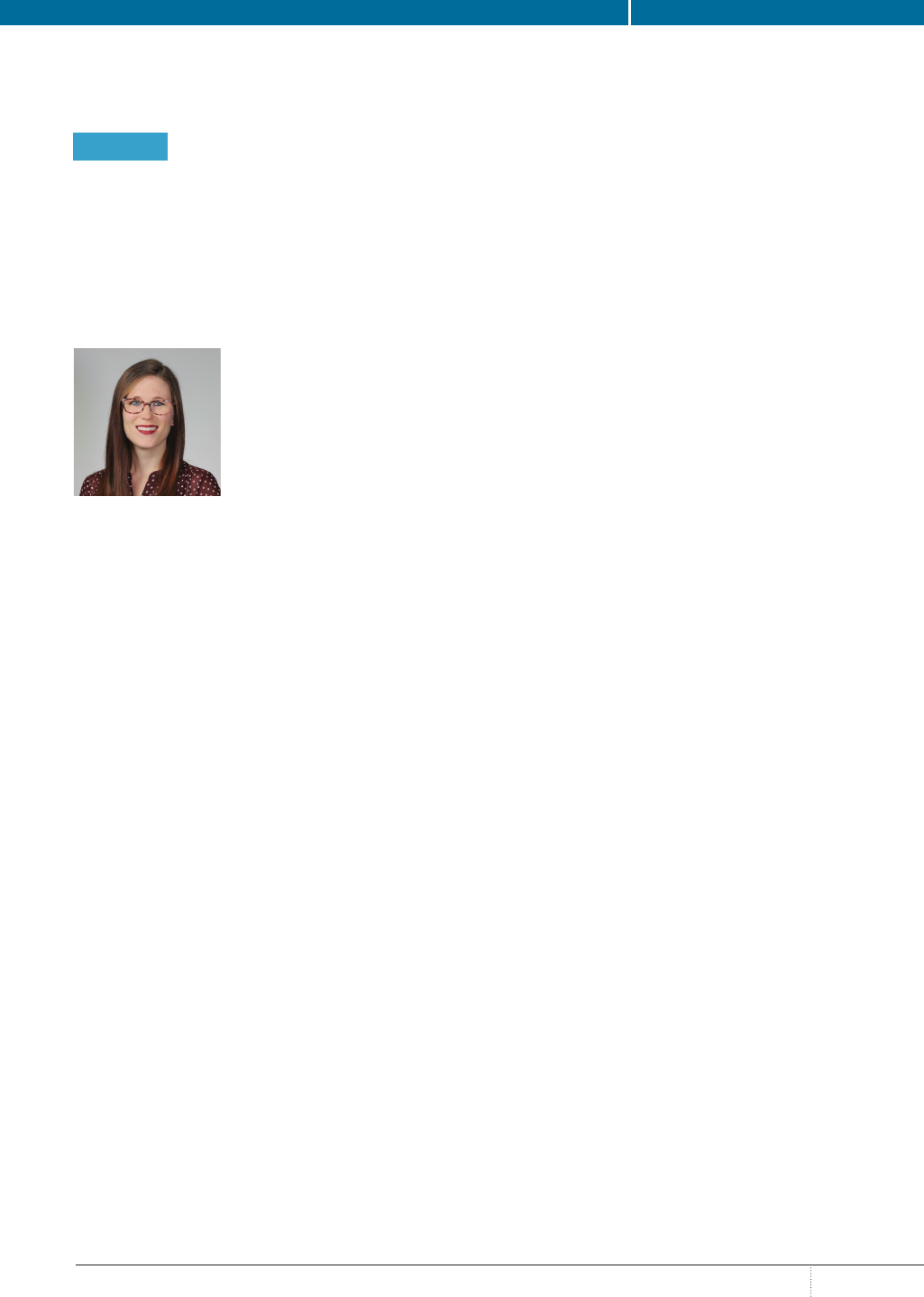

CHELSEA RENFRO, PHARMD, CHSE

FEATURE

ALEX STANLEY,

PHARMD CANDIDATE

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

10

20 mcg to 25 mcg of vitamin D per day.

7

Increasing vitamin D levels is also a modifiable risk factor

to potentially reduce falls and fractures in older adults if taken

daily. Sanders and colleagues sought to determine whether a high

annual dose of vitamin D, instead of daily doses, would reduce

the risk of falls and fractures. They conducted a study in 2010

on community-dwelling women 70 years and older and found

that annual administration of 12,500 mcg of vitamin D increased

the risk of falls and fractures, with the highest risk being within

the first 3 months after administration.

8

Based on these findings,

daily dosing for older adults is preferred. It is recommended that

adults younger than 70 years receive 15 mcg of vitamin D per

day, and those 70 years and older receive 20 mcg per day.

2

Individuals Who Have Undergone Bariatric Surgery

Obesity, which is prevalent in the United States, poses many

health risks, and an increasing number of adults are undergo-

ing weight loss (bariatric) surgery.

9

Although bariatric surgery

decreases the risk of disease and other complications related to

obesity, it also decreases the body’s ability to absorb vitamins

and other nutrients.

10

According to the American Society for

Metabolic and Bariatric Surgery, vitamin D deficiency occurs in

up to 100% of patients who have undergone surgery for weight

loss. To this end, they recommend vitamin D

3

supplementation

for these patients at daily doses of 75 mcg.

11

Individuals With Diabetes

Vitamin D deficiency also has been linked with hypertension,

kidney disease, and diabetes.

12

Beta cells in the pancreas, where

insulin is secreted, have vitamin D receptors, and it is speculat-

ed that vitamin D may improve insulin sensitivity and secretion,

as well as glomerular filtration rate.

13

Study results related

to this effect have been inconclusive, however, and research

on the effect of vitamin D supplementation in patients with

diabetes continues.

14

Regardless, supplementing with 15 mcg of

vitamin D per day in people younger than 70 years, and 20 mcg

per day in those 70 years and older, to ensure that each patient

meets the recommended daily value, has many health benefits

and may later prove to be beneficial in patients with type 1 and

type 2 diabetes.

2

WHAT PHARMACISTS AND THEIR PATIENTS NEED

TO KNOW

Although in some instances quantities that are higher than the

recommended dietary allowance are indicated, overaggressive

supplementation of vitamin D, or any nutrient, may result

in adverse reactions.

1

Inform patients that evidence supports

the benefit of vitamin D to bone health but that its use is

unclear in areas previously discussed, such as skin pigmenta-

tion, pregnancy, cancer, and immune function. For the average,

healthy adult patient, the recommended dietary allowance

of 15 mcg per day—and 20 mcg per day for those aged

over 70 years—is appropriate. ®

REFERENCES

1. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee to Review Dietary Reference Intakes for

Vitamin D and Calcium; Ross AC, Taylor CL, Yaktine AL, Del Valle HB, eds.

Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D. Washington, DC: National

Academies Press; 2011.

2. Vitamin D: fact sheet for health professionals. NIH Office of Dietary Supplements

website. ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminD-HealthProfessional/#ref. Updated

August 7, 2019. Accessed March 7, 2020.

3. Vitamin D supplementation for infants. American Academy of Pediatrics web-

site. aap.org/en-us/about-the-aap/aap-press-room/pages/vitamin-d-supplementa-

tion-for-infants.aspx. Published March 22, 2010. Accessed March 6, 2020.

4. Perrine CG, Sharma AJ, Jefferds ME, Serdula MK, Scanlon KS. Adherence to

vitamin D recommendations among US infants. Pediatrics. 2010;125(4):627-632.

doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2571.

5. Umaretiya PJ, Oberhelman SS, Cozine EW, Maxson JA, Quigg SM, Thacher

TD. Maternal preferences for vitamin D supplementation in breastfed infants. Ann

Fam Med. 2017;15(1):68-70. doi: 10.1370/afm.2016.

6. Gahche JJ, Bailey RL, Potischman N, Dwyer JT. Dietary supplement use

was very high among older adults in the United States in 2011-2014. J Nutri.

2017;174(10):1968-1976. doi: 10.3945/jn.117.255984.

7. Calcium and vitamin D. National Osteoporosis Foundation website. nof.org/

patients/treatment/calciumvitamin-d/. Updated February 26, 2018. Accessed

March 8, 2020.

8. Sanders KM, Stuart AL, Williamson EJ, et al. Annual high-dose oral vitamin

D and falls and fractures in older women: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA.

2010;303(18):1815-1822. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.594.

9. Adult obesity facts. CDC website. cdc.gov/obesity/data/adult.html. Updated

February 27, 2020. Accessed March 13, 2020.

10. Lupoli R, Lembo E, Saldalamacchia G, Avola CK, Angrisani L, Capaldo

B. Bariatric surgery and long-term nutritional issues. World J Diabetes.

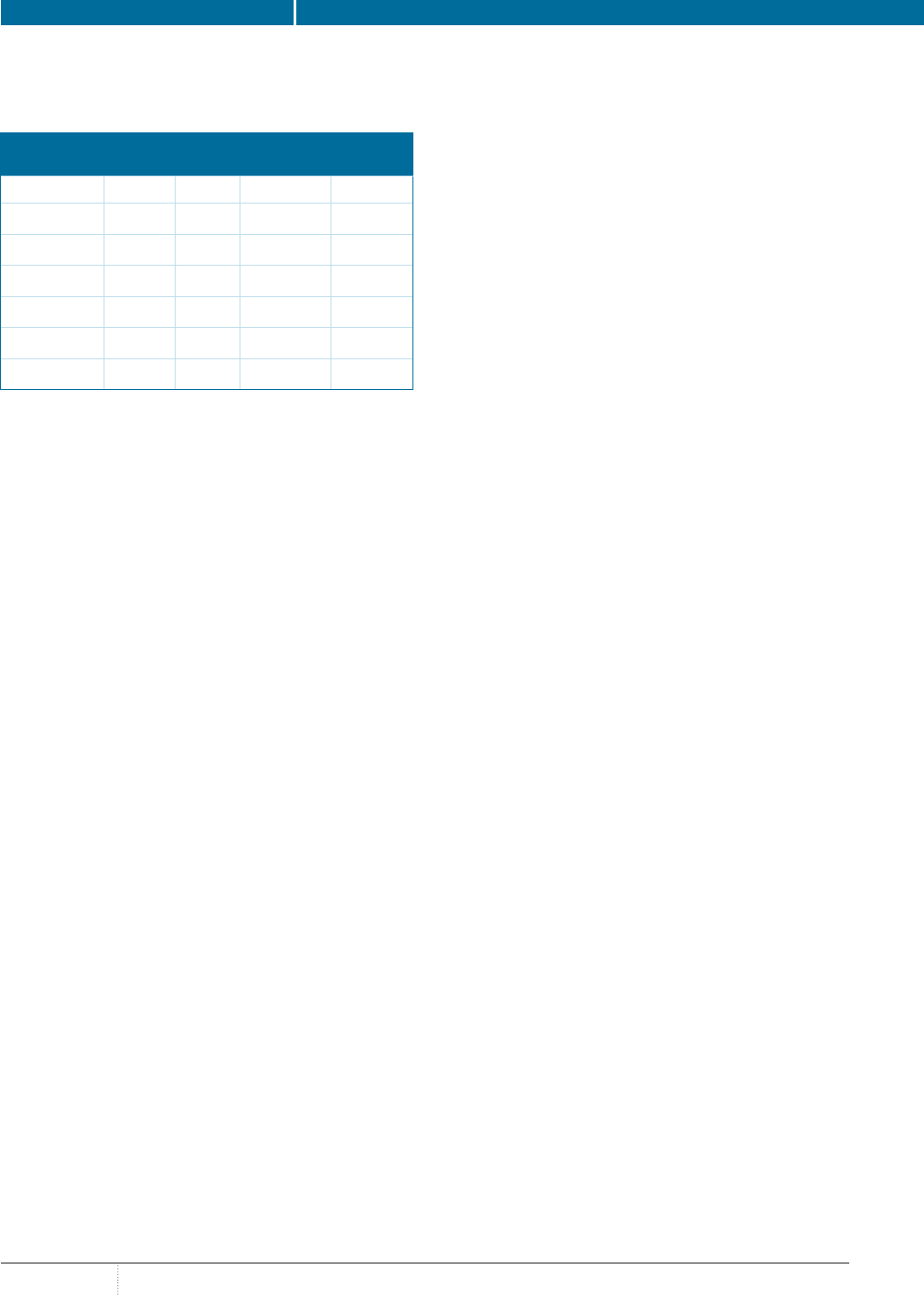

TABLE. RECOMMENDED DIETARY ALLOWANCES

OF VITAMIN D

a

Age Male Female Pregnancy Lactation

0-12 months 10 mcg 10 mcg - -

1-13 years 15 mcg 15 mcg - -

14-18 years 15 mcg 15 mcg 15 mcg 15 mcg

19-50 years 15 mcg 15 mcg 15 mcg 15 mcg

51-70 years 15 mcg 15 mcg - -

>70 years 20 mcg 20 mcg - -

a

Adequate intake.

Adapted with permission: Dietary Reference Intakes for Calcium and Vitamin D.

Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2011.

page 18

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

APRIL

11

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

O

mega-3 fatty acids (omega-3s) have

received much publicity and advertising

attention over the last few years stating

that they are an essential supplement many peo-

ple should consider taking. As a pharmacist, it is

important to know which patients may benefit from

omega-3 supplements the most, the supplements’

proper dosage, and the benefits that can be expect-

ed. It is also important to know which health claims

about omega-3s have the most validity.

OMEGA-3 COMPONENTS AND SOURCES

Omega-3 fatty acids have 2 main components

that are beneficial in humans: eicosapentaenoic

acid (EPA) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA).

DHA levels are highest in the retina and brain.

Omega-3s can also be used to form eicosa-

noids, which have activity in the cardiovascular,

pulmonary, immune, and endocrine systems.

A third component of omega-3s, alpha-linolenic

acid (ALA), is not active in the body, but it can be

converted to EPA and DHA.

1,2

The primary vehicle for EPA and DHA to

enter the body is through the consumption of

fish and other seafood, so the American Heart

Association recommends consuming 2 servings

of fish per week, particularly fatty fish such as

tuna, salmon, herring, or sardines, which have

high levels of omega-3s.

1,3

For patients who do

not get enough omega-3s through their diet or who

require a higher level than what their diet pro-

vides, OTC and prescription dietary supplements of

omega-3s may help to meet their daily needs.

FISH OIL SUPPLEMENTS

Fish oil supplements are a common source of

DHA and EPA. For individuals who cannot tol-

erate fish oil, or do not wish to take it, omega-3s

are also contained in krill, cod liver, and algal

oil supplements.

Fish oil supplements come in various dos-

age forms or combinations. A target dose of

around 1 g of omega-3s is a good place to start.

4

When taking fish oil supplements, patients may

experience an unpleasant “fishy” taste; how-

ever, the use of higher-quality products with a

United States Pharmacopeia seal may alleviate this

problem, as these products may be less likely

to have the unpleasant taste or smell.

5

Patients

may also be advised to store the capsules in the

refrigerator or to take them at bedtime to avoid the

unpleasant taste.

Krill oil, sourced from tiny crustaceans called

krill, can be an alternative for patients who cannot

tolerate the fishy smell or taste that can be associat-

ed with fish oil supplements. Krill oil is more stable

than fish oil, which may mean it is absorbed better,

and because it is not sourced from fish, it may be

less likely to cause a fishy aftertaste. The use of

krill oil has not been studied as extensively as that

of fish oil, however, and probably should remain as

a secondary recommendation until further research

reinforces its safety and effectiveness. The rec-

ommended dosage from the manufacturer will be

included on the krill oil product that is selected.

6

For those patients who follow a vegetarian or

vegan diet, pharmacists may recommend an algal

oil supplement to add omega-3s to their diet. Algal

oil is derived from algae and may be a good source

of EPA and DHA; however, studies on algal oil

have not been extensive.

7,8

Recommendations of

these products may need to be limited to only

those patients who cannot tolerate fish oil or those

patients who do not consume any fish products

because of dietary preferences or needs.

Pharmaceutical-grade omega-3 products are also

available and are prescribed in dosages as high

as 4 g per day. These products are indicated

for patients with very high triglyceride levels.

9

Patients should be advised to not take dosages

BRADY COLE, RPH

FEATURE

Omega-3 Recommendations: Counseling

Points for Pharmacists

BY BRADY COLE, RPH

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

12

in this range through OTC products without the advice of

their physician.

BENEFITS OF OMEGA-3s

The efficacy of omega-3s in various conditions has been

researched extensively, sometimes with conflicting results.

Several trials have been conducted researching the link between

a diet rich in omega-3s and a decreased risk of cardiovascular

disease.

9

Although these data vary across studies, the FDA

states that there is supportive (but not conclusive) research

indicating that consumption of EPA and DHA may reduce the

risk of coronary heart disease.

9

DHA is important for fetal growth and is found in high concen-

trations in the cellular membranes of the brain and the retina, and

so many prenatal vitamins and infant formulas are fortified with

DHA. Omega-3s have anti-inflammatory properties, and their use

may provide some relief from mild inflammation or joint pain

as well as help to reduce patients’ reliance on nonsteroidal anti-

inflammatory drugs for inflammation.

10

Many other benefits claimed for omega-3s have been studied

but have been proved inconclusive. These include potential

benefits studied in patients with dementia, depression, and

attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, as well as cancer

prevention.

9

Continued research is needed to try to uncover

additional benefits or to confirm the validity of other perceived

advantages of a diet rich in omega-3s.

RECOMMENDED DOSES

According to Dietary Guidelines for Americans 2015-2020,

the goal for most Americans should be to consume 8 oz of

seafood per week, which is about 250 mg of EPA and DHA per

day.

11

For those patients who are looking for more advanced

benefits from omega-3s, pharmacists may recommend a total

dose of 1 g per day via supplements.

4

Patients with very high

levels of triglycerides can be prescribed doses as high as

4 g per day while under supervision of a physician.

9

The Institute of Medicine published a guideline in 2005 for

intake of total omega-3s for infants and of ALA for children and

adults, which is still used by the National Institutes of Health

today (see

table).

2

CONCLUSIONS

The use of omega-3 supplements may be beneficial for some

patients; however, the most effective way to add omega-3s to

the diet is by consuming them through food. Pharmacists may

recommend 2 servings of fatty fish per week to patients as a

starting point, which will not only introduce the beneficial EPA

and DHA components into the diet but may also replace foods

or meals that are not as healthy. For patients who are unwilling

or unable to eat fish every week, other foods that are rich in

omega-3s, such as flaxseeds, walnuts, Brussels sprouts, soy-

beans, or seaweed, can be recommended. Omega-3 supplements

such as fish oil, krill oil, or algal oil are the next alternative

for patients who cannot consume enough omega-3s from their

diet. Pharmacists should be prepared to answer questions about

omega-3 supplementation and know which types of patients

could benefit from them the most. Educating patients on the

reasoning for a recommendation and encouraging them to dis-

cuss recommendations with their physician will go a long way

in ensuring positive outcomes. ®

REFERENCES

1. Harris WS. Omega-3 fatty acids. In: Coates PM, Betz JM, Blackman MR, et

al, eds. Encyclopedia of Dietary Supplements. 2nd ed. London and New York:

Informa Healthcare; 2010:577-586.

2. Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate,

Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press; 2005. doi: 10.17226/10490.

3. Fish and omega-3 fatty acids. American Heart Association website. heart.

org/en/healthy-living/healthy-eating/eat-smart/fats/fish-and-omega-3-fatty-acids.

Updated March 23, 2017. Accessed March 4, 2020.

4. Should you be taking an omega-3 supplement? Harvard Health Publishing

website. health.harvard.edu/staying-healthy/should-you-be-taking-an-omega-3-

supplement. Published April 2019. Accessed March 2, 2020.

5. Fish oil. Mayo Clinic website. mayoclinic.org/drugs-supplements-fish-oil/art-

20364810. Published October 24, 2017. Accessed March 13, 2020.

6. Krill oil vs fish oil: what’s the difference between them?. Drugs.com website.

drugs.com/medical-answers/krill-oil-vs-fish-oil-difference-3040407. Updated

April 12, 2019. Accessed March 4, 2020.

7. Sasso S, Pohnert G, Lohr M, Mittag M, Hertweck C. Microalgae in the post-

TABLE. ADEQUATE INTAKES FOR OMEGAs

Age Male Female Pregnancy Lactation

Birth to 6 months

a

0.5 g 0.5 g - -

7-12 months

a

0.5 g 0.5 g - -

1-3 years

b

0.7 g 0.7 g - -

4-8 years

b

0.9 g 0.9 g - -

9-13 years

b

1.2 g 1.0 g - -

14-18 years

b

1.6 g 1.1 g 1.4 g 1.3 g

19-50 years

b

1.6 g 1.1 g 1.4 g 1.3 g

51+ years

b

1.6 g 1.1 g - -

a

As total omega-3s.

b

As alpha-linolenic acid.

Reprinted with permission from: Institute of Medicine. Dietary Reference Intakes for

Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids.

Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2005.

page 18

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

APRIL

13

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

P

renatal vitamins are designed to support both

the health of the mother and the development

of the baby during pregnancy. Pregnancy is

difficult to predict; it may take a woman 1 month,

1 year, or longer of trying to conceive before

she becomes pregnant. Additionally, many crit-

ical fetal developments occur before a woman

even knows that she is pregnant.

1

The results of a

2016 study found that in 2011, nearly half (45%)

of pregnancies were unplanned, with a rate of

unintended pregnancy among women of

reproductive age of 4.5%.

2

WHEN SHOULD A PRENATAL VITAMIN

BE STARTED?

Because of the prevalence of unintended

pregnancy as well as the uncertainty of how

quickly or slowly conception will occur, pre-

natal vitamins should be started 3 months prior

to attempted conception.

1

This is to ensure that

any potential nutritional deficiencies have been

corrected, or increased needs supplied, prior to

conception.

1

If prenatal vitamins cannot be started

3 months in advance, folic acid supplementation

should be initiated at least 1 month before trying

to get pregnant. This is crucial because folic acid

aids in growth and development and because the

neural tube, which later develops into the baby’s

spinal cord, spine, brain, and skull, forms between

week 4 and week 6 of gestation, before most

women know they are pregnant. This can help

reduce the risk of neural tube defects.

3,4

Prenatal

vitamins should be continued throughout the

entire pregnancy.

4

The results of a 2017 survey by the March

of Dimes found that only 34% of women aged

18 to 45 years who took a prenatal vitamin during

their current or last pregnancy started the prenatal

vitamin before they knew that they were pregnant.

Although 97% took a prenatal vitamin, these may

have not been started by the optimal time to prevent

birth defects, which have an annual prevalence

in the United States of 120,000, or 3% of births

per year. Use of prenatal vitamins prior to the

knowledge of pregnancy was lower in minority

populations, with just 10% of African American

and 27% of Hispanic patients taking them before

they knew they were pregnant.

5

WHAT VITAMINS SHOULD PREGNANT

PATIENTS TAKE?

The American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends that all

female patients of childbearing potential “be

screened regarding their diet and vitamin sup-

plements to ensure they are meeting recom-

mended daily allowances for calcium, iron, vita-

min A, vitamin B

6

[pyridoxine], vitamin B

12

[cobalamin], vitamin D, and other nutrients.”

6

Folic acid supplementation should be encouraged

for these patients as well regardless of dietary

intake of folic acid, to reduce the risk of neural

tube defects.

7

Despite being recommended in 1998 by the

National Academy of Medicine as an essential

nutrient,

8

the role of choline in maternal and

fetal development remains underrecognized. Of

the top 25 prenatal vitamins, none contained the

450-mg recommended daily allowance, often

providing only 0 mg to 55 mg per day.

9-11

Lack

of sufficient levels provided in prenatal vitamins

could be of consequence because only 25% of

women of childbearing potential from high-in-

come countries such as the United States obtain

enough choline from their diets.

10-13

Choline is

emerging as a nutrient of important consequence

during pregnancy because it plays an import-

ant role in neural tube development, memory

development, stem cell proliferation, and apop-

tosis.

9

Choline is thought to have an impact on

Prenatal and Postnatal Supplementation:

What Do Pharmacists Need to Know?

BY CORTNEY MOSPAN, PHARMD, BCACP, BCGP

CORTNEY MOSPAN,

PHARMD, BCACP, BCGP

FEATURE

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

14

the risk of development of neural tube defects independent of

folic acid intake.

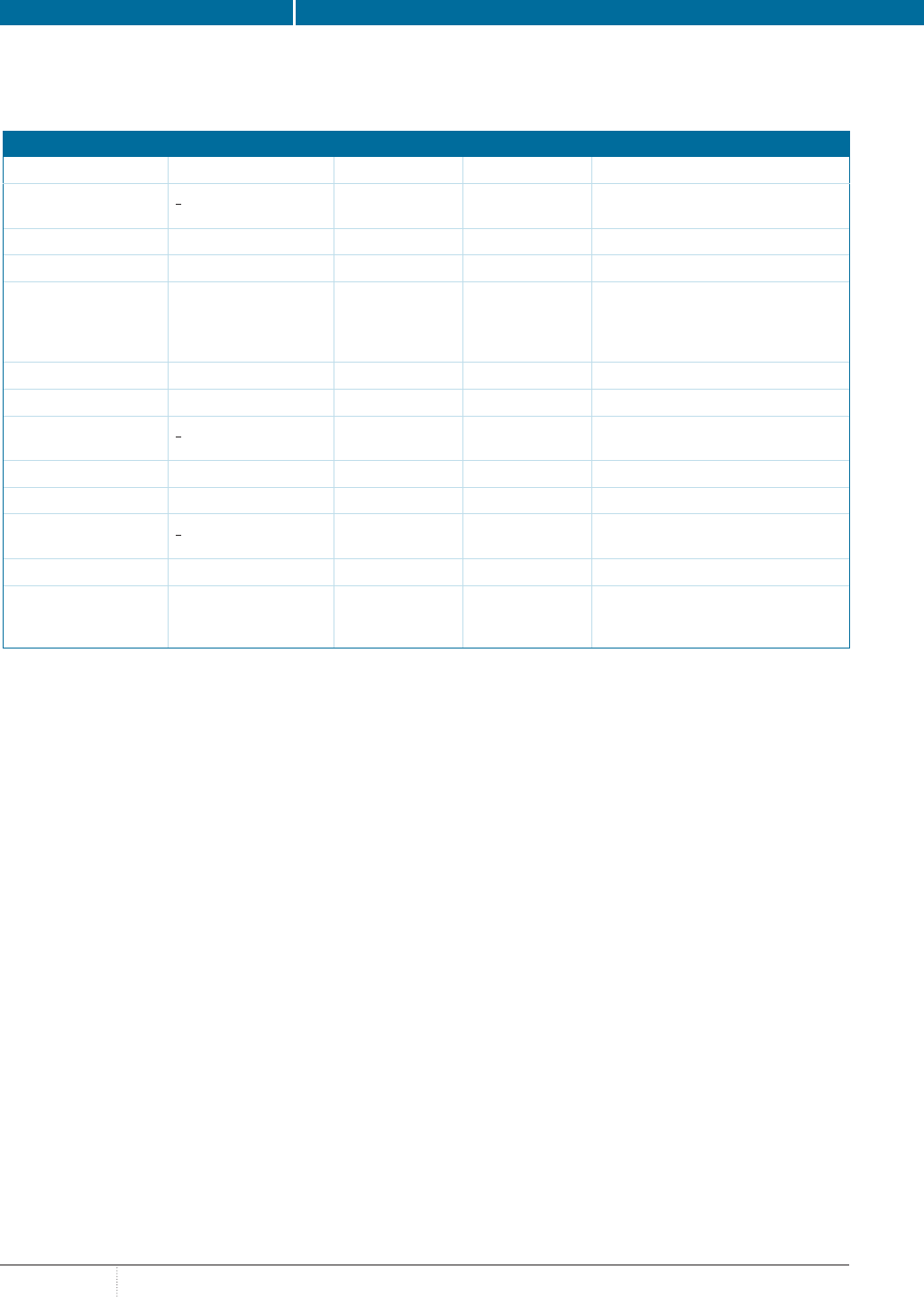

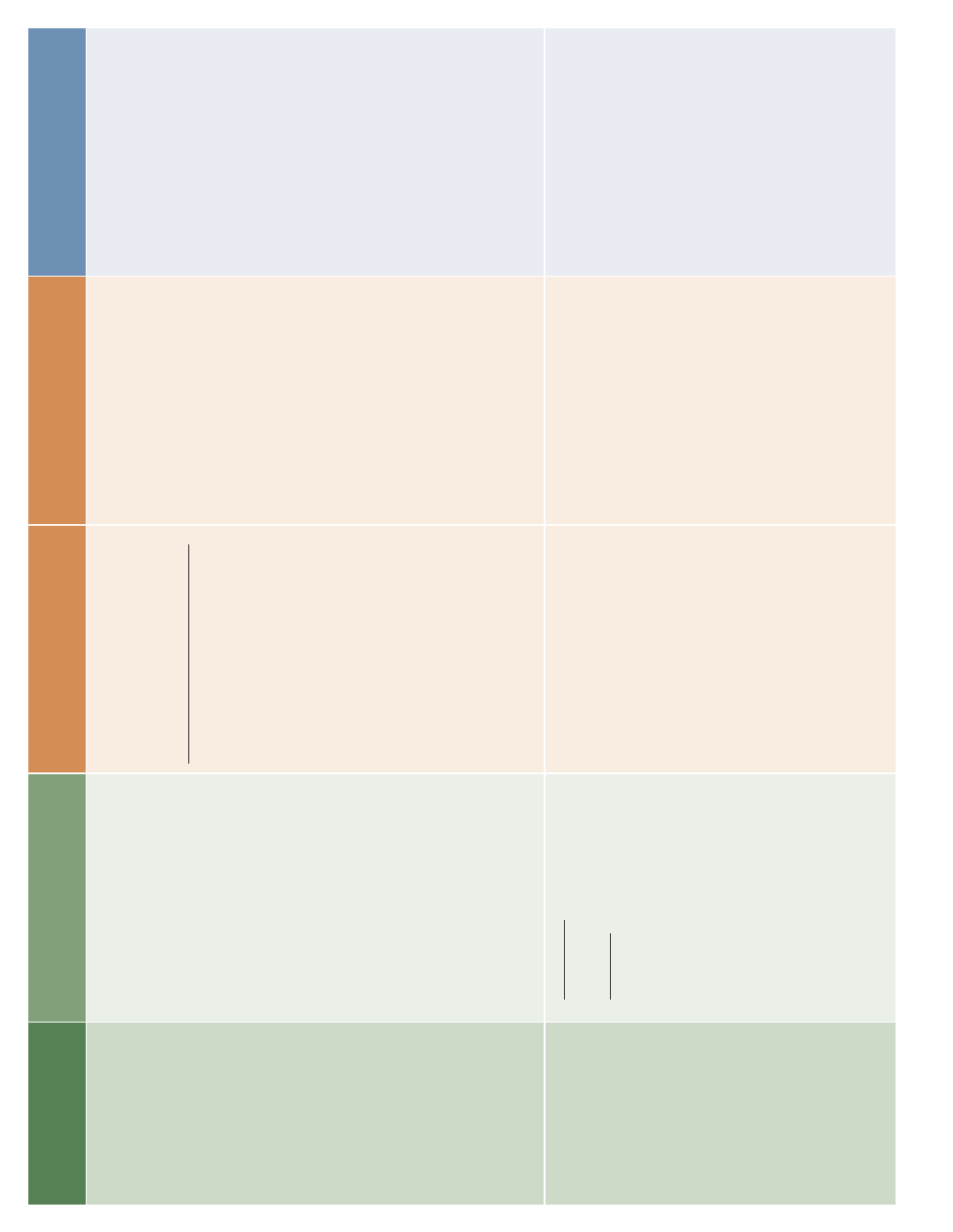

The

table includes information from ACOG, CDC, FDA,

and the World Health Organization (WHO) regarding the

recommended vitamins and minerals a woman should take

during pregnancy.

7,14-19

WHEN CAN A PRENATAL VITAMIN BE STOPPED?

Patients who are pregnant may struggle with long-term adher-

ence to their prenatal vitamin because of undesirable effects

such as a fishy aftertaste

20

due to docosahexaenoic acid (DHA),

constipation from iron or calcium, or general nausea from tak-

ing the prenatal vitamin on an empty stomach. Thus, there is a

delicate balance between advising women of proper duration of

use for health benefits for the mother and baby and preventing

unnecessary supplementation due to adverse effects that can

affect patients’ quality of life.

21

Breastfeeding is well established as the best nutrition option

for infants if mothers are able to breastfeed. One of the values

of breastfeeding is provision of essential vitamins and nutrients

in breast milk. However, it is debated whether simply following

a well-balanced diet may be sufficient to provide these valuable

nutrients to infants.

22,23

The CDC recommends continuation of

nutrient supplementation in mothers who breastfeed only if they

follow restrictive diets (eg, vegetarian diets). They do state that

nutritional supplementation may also offer benefit in women who

breastfeed who consume balanced diets.

22,23

Supplementation

likely provides the greatest benefit to meet increased iodine

needs.

22

No leading organization provides any clear or specific

vitamin or nutrition supplement recommendations in lactation.

Most women will continue the same prenatal vitamin used

throughout pregnancy during lactation, but there are differ-

ent and unique nutritional needs during pregnancy.

23

ACOG

makes no definitive recommendation on how long prenatal

supplements should be continued during the postnatal period

or which vitamins should be supplemented and at what dose.

24

Supplementation with DHA, vitamin D, folic acid, or iodine

has been shown to improve the infant’s visual acuity, hand/eye

coordination, attention, problem solving, and information pro-

cessing.

25

The WHO recommends continuation of prenatal vita-

TABLE. RECOMMENDED DAILY INTAKE OF VITAMINS AND MINERALS DURING PREGNANCY

,

ACOG CDC FDA

a

WHO

Calcium (elemental)

>19 years: 1000 mg

14-18 years: 1300 mg

N/A 1300 mg 1500-2000 mg

b

Choline N/A N/A 550 mg N/A

DHA N/A N/A N/A N/A

Folic acid (vitamin B

3

) 400 mcg before

pregnancy

600 mcg during

pregnancy

400 mcg 600 mcg 400 mcg

Iodine 200 mcg 220 mcg 290 mcg N/A

Iron (elemental) 27 mg N/A 27 mg 30-60 mg

Vitamin A

>19 years: 770 mcg

14-18 years: 750 mcg

10,000 IU 1300 mcg Only recommended in areas with

severe vitamin A deficiency

Vitamin B

6

1.9 mg N/A 2 mg Not recommended

Vitamin B

12

2.6 mcg N/A 2.8 mcg N/A

Vitamin C

>19 years: 85 mg

14-18 years: 80 mg

N/A 120 mg Not recommended

Vitamin D 15 mcg N/A 15 mcg Not recommended

Vitamin E Not recommended

unless needed to

prevent deficiency

N/A 19 mg Not recommended

ACOG indicates American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists; DHA, docosahexaenoic acid; N/A, no recommendation available; WHO, World Health Organization.

a

Recommended intake during pregnancy.

b

Recommended intake during pregnancy with low dietary intake of calcium.

Reprinted and updated with permission from Segal K, Cieri-Hutcherson NE, Lampkin S. Recommending prenatal vitamins: a pharmacist’s guide. Pharmacy Times® website.

pharmacytimes.com/resource-centers/omega-3/recommending-prenatal-vitamins-a-pharmacists-guide. Published October 4, 2018. Accessed March 20, 2020.

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

APRIL

15

mins for at least 3 months in the postpartum period in geographic

regions with a high incidence (> 40%) of anemia in pregnancy.

26

It is recommended to increase choline intake to 550 mg daily

during lactation.

12

Continuation of prenatal supplements until the

mother has completed breastfeeding may be worthwhile if the

supplement is tolerable and affordable for the mother in light of

these data.

KEY POINTS FOR PHARMACISTS

Pharmacists can play a key role in ensuring that patients are tak-

ing appropriate prenatal and postnatal supplements—including

ensuring that patients are taking formulations that include the

vitamins and nutrients recommended by leading organizations

at appropriate dosages. Pharmacists can screen both women

using contraception and women who are actively planning to try

to get pregnant for potential supplementation needs by asking,

“Are you planning to become pregnant in the next 12 months?”

This allows prepregnancy planning to occur to ensure that

patients can try to prevent adverse health outcomes associated

with pregnancy and potential birth defects before they occur. At

a minimum, all female patients of reproductive potential should

be advised to take folic acid, even if adherent to contraception,

to reduce the risk of neural tube defects.

Selecting a prenatal vitamin can be an overwhelming task

for patients, as nutrient contents vary greatly from one prenatal

vitamin to the next and especially because there are no nutrient

standards or requirements that must be adhered to for a product

to be labeled a prenatal vitamin. Prenatal vitamins that contain

appropriate appointments of folic acid, iron, and iodine should

be targeted, and these will often contain adequate amounts of

other important nutrients such as B vitamins, calcium, copper,

DHA, vitamin A, vitamin D, vitamin E, and zinc.

27

In their 2018

study, DeSalvo and colleagues found that of the 163 OTC and

88 prescription prenatal vitamins included in the study, more

than 80% were able to correct vitamin and mineral deficiencies

in the average pregnant woman who could not get those vita-

mins and minerals from dietary intake alone.

28

Generally, these

vitamins contained recommended daily allowances for most

vitamins and minerals; however, choline, magnesium, and vita-

min D were often not provided in sufficient levels.

28

Pharmacists

should pay attention to the selection of prenatal vitamins and

ensure that they include the recommended daily allowance for

these vitamins and minerals. Alternatively, they may need to

recommend supplementation with an additional supplement to

meet these levels. ®

REFERENCES

1. When should you start taking prenatal vitamins? consider the 3-month

rule. Ritual website. ritual.com/articles/1-when-to-start-taking-prenatal-vitamins.

Accessed March 5, 2020.

2. Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States,

2008-2011. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(9):843-852. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1506575.

3. Folic acid now. CDC website. cdc.gov/Images_-_Video_and_Audio/Images/

Folic_Acid/QandAfactfolic.pdf. Published June 2003. Accessed March 5, 2020.

4. What are prenatal vitamins? Planned Parenthood website. plannedparenthood.

org/learn/pregnancy/pre-pregnancy-health/what-are-prenatal-vitamins. Accessed

March 5, 2020.

5. Fewer than half of U.S. women take recommended vitamins prior to pregnan-

cy, according to March of Dimes new prenatal health & nutritional survey. March

of Dimes website. marchofdimes.org/news/fewer-than-half-of-u-s-women-take-

recommended-vitamins-prior-to-pregnancy-according-to-march-of-dimes-new-

prenatal-health-nutrition-survey.aspx#. Published September 19, 2017. Accessed

March 5, 2020.

6. ACOG Committee opinion no. 762: prepregnancy counseling. Obstet Gynecol.

2019;133(1):e78-e89. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000003013.

7. Nutrition during pregnancy. American College of Obstetricians and

Gynecologists website. acog.org/patient-resources/faqs/pregnancy/nutri-

tion-during-pregnancy. Published February 2018. Accessed March 5, 2020.

8. Institute of Medicine (US) Standing Committee on the Scientific Evaluation

of Dietary Reference Intakes and its Panel on Folate, Other B Vitamins, and

Choline. Dietary reference intakes for thiamin, riboflavin, niacin, vitamin B6,

folate, vitamin B12, pantothenic acid, biotin, and choline. The National Academies

Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. Washington, DC:

National Academies Press; 1998.

9. Berg S. AMA backs global health experts in calling infertility a disease.

American Medical Association website. ama-assn.org/delivering-care/pub-

lic-health/ama-backs-global-health-experts-calling-infertility-disease. Published

June 13, 2017. Accessed March 5, 2020.

10. Bell CC, Aujla J. Prenatal vitamins deficient in recommended choline intake

for pregnant women. J Fam Med Dis Prev. 2016;2(4):048.

11. Mun JG, Legett LL, Ikonte CJ, Mitmesser SH. Choline and DHA in maternal

and infant nutrition: synergistic implications in brain and eye health. Nutrients.

2019;11(5). pii: E1125. doi: 10.3390/nu11051125.

12. Zeisel SH, da Costa KA. Choline: an essential nutrient for public health. Nutr

Rev. 2009;67(11):615-623. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2009.00246.x.

13. Zeisel SH. Nutrition in pregnancy: the argument for including a source of

choline. Int J Womens Health. 2013;5:193-199. doi: 10.2147/IJWH.S36610.

14. American Academy of Pediatrics’ Committee on Fetus and Newborn (author);

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ Committee on Obstetric

Practice (editor). Guidelines for Perinatal Care. 7th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL, and

Washington, DC: American Academy of Pediatrics and The American College of

Obstetricians and Gynecologists; 2012.

15. Folic acid for the prevention of neural tube defects: preventive medication. US

Preventive Services Task Force website. uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/

Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/folic-acid-for-the-prevention-of-neu-

ral-tube-defects-preventive-medication. Updated January 10, 2017. Accessed

March 5, 2020.

16. Food labeling: revision of the Nutrition and Supplement Facts Labels:

guidance for industry – small entity compliance guide. FDA website. fda.gov/

media/134505/download. Updated February 3, 2020. Accessed March 23, 2020.

page 19

SPECIAL REPORT: NUTRACEUTICALS

APRIL

PHARMACYTIMES.COM

16

D

ietary supplement use is common among

adults in the United States. According

to the results of the 2019 Council for

Responsible Nutrition Consumer Survey on

Dietary Supplements, 77% of Americans reported

consuming dietary supplements.

1

Data on pre-

scription drug use from the National Center for

Health Statistics (2013-2016) indicated that about

48% of Americans have used at least 1 prescription

medication in the past 30 days, and research has

shown that approximately one-third of American

adults have reported taking dietary supplements

while using prescription medications.

2,3

Although

drug interactions exist among many prescription

medications and dietary supplements, certain

nutrients may be beneficial for patients, particularly

while taking certain medications, and as frontline

providers, pharmacists are ideally positioned to

educate patients on which supplements to take with

their medications.

1,4

The following patient cases provide examples

of potential dietary supplement and medication

interactions along with counseling approaches

and suggested supplements that could be used in

such scenarios.

Case Study #1

An Adult Woman Picks Up Birth Control

Medication and Would Like to Purchase

a St John’s Wort Supplement

A 35-year-old woman arrived at the pharmacy

window to pick up her birth control medica-

tion (norethindrone acetate + ethinyl estradiol +

ferrous fumarate). She also brought a bottle of

St John’s wort to the window to add to her

purchase. After prompting from the pharmacist,

the patient stated she was taking the St John’s

wort for mild depression and stress support.

What concerns might exist regarding her current

birth control medication and this supplement?

PHARMACY PROCEDURES

The pharmacy technician who helped the woman

with her medication pickup knew to notify the

pharmacist of any other medications or supple-

ments the patient was taking. The pharmacist then

confirmed with the patient that she was not taking

any other dietary supplements. He then completed

an updated drug utilization review (DUR) with the

new information provided.

The pharmacist was then able to counsel the

patient on the potential for drug–supplement inter-

actions. He explained that St John’s wort can

interact with the birth control medication the

patient is currently prescribed, decreasing the birth

control medication’s effectiveness by increasing its