The Certificate IV in Assessment

and Workplace Training:

Understanding learners and

learning

Support document

M

ICHELE SIMONS, ROGER HARRIS AND ERICA SMITH

This document was produced by the authors based on their

research for the report The Certificate IV in Assessment and

Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning, and is an

added resource for further information. The report is

available on NCVER’s website:

<http://www.ncver.edu.au>

The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author(s) and

do not necessarily reflect the views of the Australian Government, state and

territory governments or NCVER. Any errors and omissions are the responsibility

of the author(s).

© Australian Government, 2006

This work has been produced by the National Centre for Vocational Education

Research (NCVER) on behalf of the Australian Government and state and

territory governments with funding provided through the Australian Department

of Education, Science and Training. Apart from any use permitted under the

CopyrightAct 1968, no part of this publication may be reproduced by any process

without written permission. Requests should be made to NCVER.

SUPPORT DOCUMENT

2 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

Contents

Tables and figures 3

Literature review 4

Introduction 4

Conceptions of learning 5

Characteristics of learners 9

Learners and learning in the VET context 13

Competency standards and qualifications for VET teachers and

trainers 16

Conclusion 18

Research design and method 19

Design of the study 19

The research process 19

The respondents 21

Limitations 22

Interview protocols 23

References 28

Simons, Harris & Smith 3

Tables and figures

Table 1: Theories of learning 7

Table 2: Distribution of case studies by state and number of

respondents 21

4 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

Literature Review

Introduction

The current National Strategy for Vocational Education and Training (VET) acknowledges the

vital role that VET professionals need to play to ensure the provision of quality learning

opportunities for individuals, enterprises and industries (ANTA 2003, p. 10). Since the earliest

training reforms of the 1990s, the role of those working in public and private training providers

has changed dramatically in response to successive demands for a more client-driven, responsive

and innovative training system. The VET system has expanded and now includes over 3000

private training organisations as well as TAFE providers (Harris, Simons & Clayton, 2005).

Enterprises are increasingly engaging in the process of providing learning opportunities for their

staff, both within and outside of the national VET framework. Many of those now engaged in the

process of facilitating learning in the VET sector are drawn from a wide range of occupations.

These persons may hold a variety of qualifications (for example, specific trade, human resource

development/management, adult education and other professional qualifications) and working

under a variety of non-teaching awards and conditions (ACIRRT 1998, p. 8).

This increasing diversity in the VET teacher and trainer workforce poses considerable challenges

for those concerned with the quality of VET teaching and training. On the one hand, efforts

need to ensure that all teachers and trainers, regardless of their context, are provided with

relevant and effective training for their role. On the other hand, this effort needs to reflect the

reality that, for many people, training often only comprises a proportion of their work role and is

increasingly being undertaken by a growing cohort of part-time, casual or contract workers who

often may work for more than one registered training organisation (Harris et al. 2005). What can

reasonably be expected of these people in relation to investment in training for their role has

been an ongoing source of debate. These debates have shaped what has been made available for

the initial and on-going development of VET teachers and trainers and the research activities to

underpin these developments.

A large proportion of the VET literature on professional development for teachers and trainers

has been descriptive in nature, focussing on the development and outcomes of a wide range of

professional development initiatives at both state and national levels (for example, Mitchell 2000;

Mitchell, Young, McKenna & Hampton 2002; Mitchell & Wood 2001; Mitchell & Young 2001).

A smaller body of work has examined the nature and extent of initial and on-going professional

development undertaken by VET teachers and trainers at a general level (Harris, Simons, Hill,

Smith, Pearce, Blakeley, Choy & Snewin, 2001) or in relation to particular aspects of national

training reforms such as competency-based training (Lowrie, Smith & Hill 1999; Simons 2002) or

on-line learning (Brennan, McFadden & Law 2001; Harper, Hedberg, Bennett & Lockyer 2000;

Kemshal-Bell 2001). Studies have also addressed perceived gaps in knowledge, skills and

attributes of specific groups of VET practitioners and some of the barriers staff face in accessing

appropriate and timely professional development (Harris et al. 2001; Western Australia

Department of Training/David Rumsey & Associates 2002). However, there has been little

critical analysis of the curricula (or learning pathways) used to inform initial VET teacher /

Simons, Harris and Smith 5

trainer development programs, particularly those that lead to the Certificate IV in Assessment

and Workplace Training.

The vocational education and training (VET) sector has aspirations to embrace the learning needs

of a wide range of learners and to promote learning across diverse contexts (institutions,

workplaces, virtual learning environments). The sector is also concerned with promoting lifelong

learning. Part of ensuring quality education and training in the sector relates to understanding

how these aspirations are played out in the practice – specifically for this project, through the

implementation of the Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training. Completion of this

certificate is viewed as a means by which teachers, trainers and all those concerned with

promoting learning within the VET sector are equipped with the necessary knowledge, skills and

attributes to undertake their roles. Part of this process inevitably includes developing knowledge

of how learning takes place and particular characteristics of learners. The ideas around learners

and learning are critically important as they frame the actions of teachers and trainers in the

sector. They gives rise to assumptions about the ways in which learner ‘needs’ might be addressed

and what constitutes quality teaching / training in the sector.

The starting point for this literature review is an overview of understandings of learning, the

process of learning and the characteristics of adult learners from the wider education literature.

Focus then turns to the VET sector and recent literature exploring the nature of teaching and

learning required of the sector in order to meet the established goals for the sector. The final

section of this review focuses on the content of the units of competency that comprise the

current Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training and the recently released Certificate

IV in Training and Assessment with particular reference to the content of the units in relation to

issues relating learners and learning.

Conceptions of learning

Learning within the VET sector is concerned with developing competence in workplace

performance, although what this looks like and how it might be achieved is a highly contested

issue (see for example, Stevenson 1996). Within the sector, learning is largely undertaken by

persons who see themselves as adult. Further, the learning is a form of facilitated learning – that

is learning that is the end point of ‘an educational process that is directed and facilitated by

others’ (Moore, Willis & Crotty n.d. p. 17). Learning is sponsored and facilitated within a

particular context (workplace, private training provider, TAFE College) and, as such, is located

within a specific culture.

The concept of learning can be understood in a variety of ways. Most ‘commonsense’

understandings contain some blending of the idea that learning is something that a person does –

it is a process - and learning results in achievement of some kind – a product (Merriam & Caffarella

1999 p. 250; Tight 2002, p. 23). Hager (2004) argues that despite significant arguments in

educational literature to the contrary,

…much educational policy and practice, including policies and practices that directly

impact on the emerging interest in learning at work, are clearly rooted in the learning-as-

product view (Hager 2004, p. 5).

Illustrative of this notion are expressions such ‘attaining competencies and/or

generic/employability skills’ and so forth. These ideas suggest that discrete entities such as skills

and competencies can be accumulated and unproblematically transferred from site to site as

needed (Hager 2004, p. 4). Knowledge is viewed as lying outside of the learner, waiting to be

apprehended and accumulated, usually with the assistance of a teacher. In other words, a

positivist view of learning is emphasised (Candy 1991, p.430).

6 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

As Hager (2004, p. 6) and Tight (2002, p. 26) note there are several problems when this view of

learning is unquestioningly accepted. Firstly, learning is viewed as able to be apprehended and

described fully in order for it to be then codified in ways that can be replicated by learners.

Secondly, it usually emphasises an individualised notion of learning. Thirdly, these ideas contrast

sharply with what is known about the social nature of learning (Jarvis 1987) and the work of

researchers such as Lave and Wenger (1991) where understandings of learning and work

intimately involve learning in the company of others as part of ‘communities of practice’. This

view is also questioned by the work of researchers such as Schön (1983) who has showed that

practitioners do not merely ‘apply’ what they have learned but rather ‘reflect in action’, acting to

create ways of working and that arise out of this process – in other words, emphasising learning

as a process.

Jarvis offers five other definitions of learning:

• any more or less permanent change in behaviour as a result of experience;

• a relatively permanent change in behaviour which occurs as a result of practice;

• the process whereby knowledge is created through the transformation of

experience;

• the processes of transforming experience into knowledge, skills and attitudes; and

• memorizing information (Jarvis cited in Tight 2002, p. 25).

In these definitions learning results in some form of change, is grounded in experience and

possible outcomes from the process include changes to knowledge, skills and attitudes. The fifth

definition carries with it the notion of learning as a continual accumulation of facts and

information. It has a strong connotation of the ‘product’ of learning being the internalisation of

the ‘correct information’.

Beyond these fairly straight forward understandings of learning, there are a wide range of

explanations (theories) of learning. These theories attempt to answer, in various ways and to

varying degrees, four central questions:

• who are the subjects of learning?

• why do they learn?;

• what do they learn; and

• how do they learn? (Engeström 2001, p.133).

There are a variety of ways of classifying this wide range of theories. Most classifications offer

some schema using the basic orientations of behaviourist, cognitivist and humanistic

understandings of learning. By way of summarising this vast literature, the following table

(adapted from Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p. 264) summarises these orientations, including their

understandings of the learning process and key proponents of these theories.

Simons, Harris and Smith 7

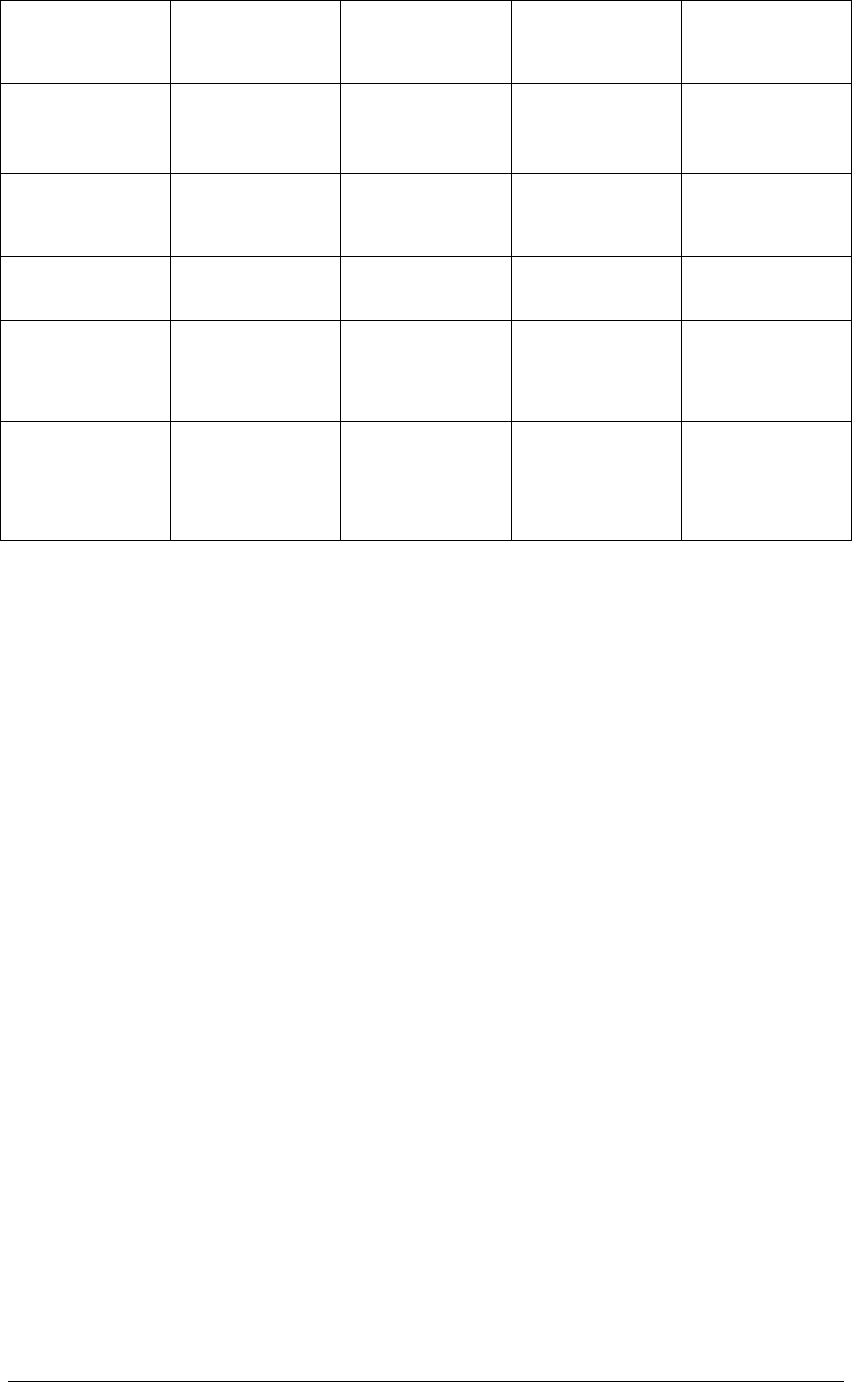

Table 1: Theories of Learning

Understandings of

the learning process

Focal point for

learning

Key theorists Example of

educational

practices which draw

on this orientation

Behaviourist Learning focuses on

bringing about

change in behaviour

Stimulus from the

environment

(outside the learner)

Pavlov, Skinner,

Thorndike, Watson

Competency-based

training

Skill development

and training

Cognitivist Learning focuses on

internal mental

processes

Internal cognitive

structures of the

individual

Ausubel, Bruner,

Gagnè, Lewin,

Piaget

Cognitive

development,

Intelligence, learning

how to learn

Humanistic Learning focuses on

attaining personal

fulfilment

Affective and

cognitive needs

Rogers, Maslow Andragogy, self-

directed learning

Social Learning Learning focuses on

interaction with and

observation of

others in a social

context

Interaction between

person, behaviour

and environment

Bandura, Rotter Mentoring

Constructivist Learning focuses on

constructing learning

from experience

Internal construction

of reality by

individual

Candy, Dewy, Lave

Piaget, Rogoff,

Vygotsky

Experiential

learning, self-

directed learning,

perspective

transformation,

reflective practice

Adapted from Merriam and Caffarella (1999, p. 264)

Behaviourist orientations are concerned with changes to observable behaviour as the products

of learning. These theories emphasise the role that the environment plays in shaping learning and

the value of appropriately timed reinforcement to shaping the outcomes from learning.

Behaviourist notions of learning are widely acknowledged in VET as they underpin educational

practices associated with competency-based training including identification of behavioural

outcomes and modularised instruction.

Cognitivist theories emphasise the role of the mind and internal mental processes in learning. As

Rogers (2002, p.10) notes:

[cognitive theories]…stress the processes involved in creating responses, the organisation

of perceptions, the development of insights. In order to learn, understanding is

necessary…

Humanistic understandings of learning emphasise growth and personal development in

learning. Theorists place great importance on the activities of individuals in creating learning,

intrinsic motivation, the drives of personality, the active search for meaning and personal self

fulfilment. Humanistic orientations also emphasise ‘that perceptions are centred in experience’

(Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p.256) and have played a significant role in shaping the tenets of

self-directed learning and the value of experience in the learning process. These concepts are

central to many adult educators’ understandings of learning which have been shaped by the work

of Malcolm Knowles and his work on andragogy (see below).

Social learning theories emphasise the role of interaction with others in the learning process.

These explanations of the learning process draw on behaviourist and cognitive orientations

(Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p. 258) and the process of observation (see, for example, the work

of Bandura 1976) and the importance of the social situation.

Constructivist understandings of learning

8 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

…maintain[s] that learning is a process of constructing meaning; it is how people make

sense of their experience (Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p.261).

Generally, two subsets of understandings of learning can be deduced in writers adopting a

constructivist orientation – personal and social constructivism (Driver cited in Merriam &

Caffarella 1999, p.261). Piaget for example, focuses on meaning making by the individual. The

social constructivist view of learning, on the other hand, suggests that knowledge is developed by

way of interactions with others. Candy (1991, p.275) argues that

…[learning] involves acquiring the symbolic meaning structures appropriate to one’s

society, and, since knowledge is socially constructed, individual members of society may be

able to add to or change the general pool of knowledge. Teaching and learning, especially

for adults, is a process of negotiation, involving the construction and exchange of

personally relevant and viable meanings.

Current understandings of workplace learning such as those associated with situated learning,

cognitive apprenticeship and communities of practice draw from constructivist understandings of

learning. These perspectives of learning also sit well understandings of learning particularly

associated with adult learning – namely andragogy, self-directed learning and experiential learning.

One of the distinguishing features of learning in adult education more generally, and in VET

specifically, is an emphasis on the nature of learners as ‘adult’. As such, ideas which emphasise or

distinguish the nature of adult learning from that connected to children have received widespread

attention. Perhaps the most dominant of these views are those associated with the work of

Malcolm Knowles who articulated his model of andragogy.

Knowles’ model of andragogy, which evolved over a period of several decades, rests on six

assumptions:

• Adults need to be able to make sense of the reasons for their learning and be able

to make sense of how useful the learning will be for them

• Adults have a strong self concept and need to be self directing which needs to be

acknowledged in learning situations

• Adults bring a wide range of experiences to any learning situation which can have

both positive and negative impacts on learning situations

• Adults’ readiness to learn is connected to their need to be able to cope effectively

with their ‘real life situations’

• Adults adopt a task-centred / problem-centred orientation to their learning

• Adults’ motivation for learning is largely derived from intrinsic sources (Knowles

1990, pp. 57-63).

In his writing Knowles does not explicitly define learning although Pratt (1993) deduced that

andragogy views learning as resting on two beliefs, namely that ‘knowledge is assumed to be

actively constructed by the learner’ and ‘learning is an interactive process of interpretation,

integration and transformation of one’s experiential world (Pratt 1993, p. 17). These ideas

however, do not take account contemporary explanations of learning which acknowledge the

situated nature of learning. Andragogy has also been discredited as providing a uniquely adult–

focussed explanation of learning (Merriam 1993; Tight 2002) and for its overly individualistic

focus (Pratt 1993). Questions have also been raised in relation to the lack of empirical evidence to

justify the notion that self direction and a problem-based orientation to learning are is a peculiarly

adult traits, an apparent preference for learning attached to social roles rather than reflective or

personal ends (Tight 2002, p.113) and the unresolved tension between the autonomy of adult

learners and the providers of education (this is a particularly salient issue in an industry-led VET

system). While the critiques on the concept of andragogy have been widespread and sustained

over time, it still retains its place as one of the most influential pieces of thinking on adult

Simons, Harris and Smith 9

education practice (Pratt 1993, p. 21). From the perspective of contemporary VET practitioners,

it is best perhaps understood, not as a theory of adult learning which provides the one

overarching and persuasive answer to questions relating to how learning might be best facilitated

for VET clients, but as providing some valuable starting points for guiding thinking about

teaching and learning.

A related field of thinking in adult learning is that of self-directed learning. Three related ideas are

usually associated with the concept of self-directed learning:

• …a self initiated process of learning that stresses the ability of individuals to plan

and manage their own learning;

• an attribute or characteristic of learners with personal autonomy as its hallmark;

and

• a way of organising instruction in formal settings that allows greater learner

control (Caffarella 1993, pp.25-26).

Self-directed learning has drawn attention to the ways in which adults might go about the process

of learning and the role that a ‘teacher’ might (or might not) play in this process. Rather than

‘teacher’, terms such as ‘facilitator’, ‘lecturer’ and trainer are more widely used. These terms

emphasise the ‘helping’ role ascribed to those working with adults, with the role seen as:

…[involving] negotiation, recognition of experience and a… degree of partnership

between the learner and teacher…(Tight 2002, p. 29).

One final concept that is also central to adult learning is the concept of experiential learning. The

act of reflection on experience is central to understanding how experience is transformed into

knowledge. This is perhaps best exemplified by the work of Kolb and his experiential learning

cycle (1984) which has been the catalyst for a body of work on learning styles or preferences.

This literature has reinforced strongly held beliefs in relation to the role of the teacher / trainer in

addressing the range of learning styles that will always necessarily be present in any group of adult

learners by way of adopting a wide range of teaching activities, albeit that this may not be feasible

or desirable. The concept of experiential learning is also closely linked to the notion of

recognition of prior learning (RPL) which acknowledges that many adult have prior knowledge,

understandings and skills which should be recognised in a formal sense (Tight 2002, p. 107).

In addition to understandings of learning, facilitating learning has also been informed by a body

of knowledge which has examined the characteristics of adult learners.

Characteristics of learners

Describing the nature of adult learners in any depth is an exhaustive task as many characteristics

could be chosen. Cranton (1992, p.20) divides a number of characteristics into two groups. Firstly

there are those characteristics which are relatively stable themselves, but are likely to impact on

the process of learning. Characteristics such as personality type, culture, philosophy, experience

and developmental phase are included in this group. Secondly there are those characteristics

which themselves are influenced by, but also influence the learning process. These include

learning style, autonomy, values, experience, developmental stage and self-directedness (Cranton

1992, p. 21). Those characteristics that are likely to affect the learning process are more likely to

be the focus of efforts to guide teachers and trainers, since these can have ‘flow-on’ effects for

other learner traits such as motivation (Wlodkowski 1999) or persistence (Mackinnon-Slaney

1994).

Characteristics such as values, autonomy, personal experiences, culture and philosophy are

important underlying constructs that influence the learning process, but are not as easily

measured or studied systematically as characteristics such as personality type, learning style or

10 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

developmental stages or phases (Cranton 1992, p. 56). This collection of characteristics,

nonetheless, do influence the learning process and as such

…the best that an educator can hope to do is have an awareness and understanding of

[these constructs] which explain and influence learner behaviour (Cranton 1992, p. 56).

Experiences (personal work-related, spiritual etc) can be used as a way of learning (see Dewy) or

as a resource for learning (see Knowles) (Cranton 1992, p. 57). Reflection on experience with its

potential to generate new perspectives is a central tenant of adult education practice (Boud,

Keogh and Walker 1985; Mezirow 1990) and is foundational to the learning process. Experience

can facilitate or act as a barrier to learning and as such ‘it is impossible to ignore’ (Cranton 1992,

p. 58). Working to understand the experiences that adult learners bring with them is integral to

facilitating learning.

Philosophy deals with the theory, principles and ideas that underpin a person’s behaviour can

include fundamental belief systems as well as ideas around the acceptance of stated socio-cultural

norms or those that derive from childhood and family of origin experiences. For example, how a

person views learning (as a process or a product) will influence the ways in which a learner might

chose to interact in the learning environment. Cranton offers the contrast between one group of

learners who want the ‘correct answers’ with another group that seek to challenge and critically

examine every detail (Cranton 1992, p. 59).

Closely related to an individual’s philosophic framework are their values. Brundage and

Mackeracher (1980, p.69) alert us to the importance of raising the awareness of a learner’s values

system and the ways in which they influence the choices that they may make. Further they place

great emphasis on educators respecting and valuing the feelings of learners and providing learners

with feedback that indicates this valuing is genuine and transparent. Conversely, as Cranton

(1992, p. 61) notes, sometimes it is the educator’s role to challenge these values and the context

in which the learning takes places is significant in weighing the importance of particular values

and their appropriateness (or lack thereof) to the learning process.

Autonomy relates to an individual’s ability to act independently. It is shaped by social and

political factors and brings into sharp relief issues relating to the empowerment of learners

(Cranton 1992, p.62). For educators, some learners are able to act autonomously and view their

learning as a means of promoting their freedom to choose. It may open potential pathways that

might not otherwise be available to them (for example learning in VET to attain recognised

qualifications can open up new career directions, thus providing greater choices for individuals).

Conversely, individuals who are mandated to attend training have an entirely different experience

as they may feel that their autonomy has been restricted in some way. This can, in turn, impact on

their expectations of the training and the ways in which they might engage with the learning

process.

As noted above, there are some characteristics of learners that have been subject to systematic

study and these are discussed in further detail in the next sections of this review.

Personality type

Personality type has been shown to have a ‘clear and powerful influence on learning preference’

(Cranton 1992, p. 28). This concept was introduced by Jung but is more popularly known

through the work of Isabel Myers and Katharine Briggs and the Myer-Briggs Type Indicator

(MBTI).

The basis of the theory rests on the assumption that every person uses four basic mental

functions – sensing, intuition, thinking and feeling (Myers & McCaulley (1993, p. 12). These

functions are shaped by the priorities an individual gives to these functions and the attitudes of

introversion and extroversion ‘in which [people] typically use each function’ (Myers & McCaulley

Simons, Harris and Smith 11

1993, p. 12). Two further functions – judging and perception – which centre on an individual’s

behaviour towards the outside world - were further developed in the work of Myers and Briggs

(Myers & McCaulley 1993, p. 13). Combinations of these functions give rise to sixteen ‘types’

which, in terms of features of the learning process, can be mapped along four dimensions:

! Extroversion – Introversion

" Extraverts prefer outside stimulation and interaction in order to engage in learning. They

like to dialogue with others and work on activities with a group focus.

" Introverts show a preference for solitary thought and reflection. They value ideas, forming

theories and developing an overall view. They like to work alone.

! Sensing – Intuition

" Sensing learners like details and facts. They work systematically and observe closely.

" Intuitive learners like to come up with conceptual models. They are more concerned with

the overall picture than with the details.

! Thinking – Feeling

" Thinking learners are objective decision makers. They prefer clear instructions and action

plans.

" Feeling learners are concerned with human values and are considerate of others. They

need appreciation social harmony.

! Judging – Perception

" Judging learners are decisive and are only concerned with the essentials and like to bring

events to closure.

" Perceptive learners are spontaneous and value openness and possibilities. They start many

tasks and are easily sidetracked.

Personality theory has been used to explore a number of educational concepts including aptitude

(for example training for particular types of occupations, types of work), application and interest

(Myers & McCaulley 1992, p. 95). The extension of this understanding has been a growing

literature of how teachers might respond to different personality preferences in order to better

facilitate learning (see for example, Lawrence 1989).

Developmental phases and stages

The developmental phases that a learner passed through over the life cycle change in relation to

age and external events in a person’s life (Cranton 1992, p.35). These changes can impact on

adults’ motivation to participate in adult learning (Aslanian & Brickell 1980). Brundage and

Mackeracher (1980, p. 52) refer to a developmental phase as ‘based largely on age related issues in

physical, social and psychological areas’.

There is a vast literature examining adult development. Merriam and Caffarella (1999) categorise

this literature into three groups. Firstly there is the literature that examines adult development

from a biological perspective. Emphasis is placed on the impact of physical ageing as well as the

impact of environment, health habits and disease on the learning process (Merriam & Caffarella

1999, p. 90).

Secondly there is a body of knowledge examining psychological perspectives on adult

development. Adult development is conceptualised as not being age related but as an unfolding

process occurring across different stages in a person’s life. There are a range of models that

examine adult development in terms of a sequence of events and their resultant impact on

learning (for example, Erikson 1982; Levinson 1986; Kohlberg 1973). Life events and transitions

(such as birth, marriage) and relational models (which view relationships as central to

development) provide alternative frameworks for understanding adult development. Much of this

latter literature is grounded in studies on women’s development (Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p.

110).

12 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

The concept of developmental stages forms another sub-section of psychological perspectives on

adult learning and addresses the movement from child-like understandings of the world to more

complex understandings which also embrace a deeper understanding of self. These stages of

growth in an individual have been addressed through the work of authors such as Rogers (1969)

who explored the notion of self-actualisation, Jung (1970) who examined the concepts of

individuation and Loevinger (1976) who examined ego development.

Thirdly, there is more recent literature which, rather than taking an individual focus on adult

development, focus on socio-cultural understandings of development. That is, it examines the

‘work’ done by the world around us to ‘define who [we are] and what we ought to do as adults’

based on race, ethnicity, gender and culture (Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p.118).

An understanding of development phases and stages helps to focus attention on motivations and

the rationale for learning held by individuals. Different types of developmental needs and stages

give rise to different learning needs and interests and also alert us the ‘multiple explanations of

what adulthood is all about (Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p.136) which necessarily impact of the

work of facilitating learning for vocational purposes.

Learning styles

Learning style theory has evolved from the earlier research of psychologists who were interested

in the relationship between personality and perception and mental processes including learning

(Cronbach & Snow 1977; Guildford 1956; Hudson 1966; Witkin, Ottman, Raskin & Karp 1971).

This work has largely been reported in the literature on cognitive styles. In essence learning styles

describe individuals’ approaches to learning in terms of those educational conditions under which

they are most likely to learn (Knaak 1983, p. 14).

Although different definitions and terms are used to describe learning styles, some basic

generalisations can be made from the literature. Most conceptualisations of learning styles are

established as sets of dichotomous approaches to learning – for example empirical – conceptual;

field-dependent – field independent; or wholist – serialist. Attempts to develop different

categories of learning styles are usually accompanied by inventories or scales which attempt to

quantify these preferences. These various approaches attempt to differentiate and categorise

methods of processing information (Kolb 1985, Honey & Mumford 1986, Grecorc 1979),

personal differences, motivational factors (Vermunt 1994) and general neuro-physiological

tendencies (Riding, Glass & Douglas 1993). Specific inventories or scales have their own

descriptive categories for learning styles.

Most writers on adult education are quick to acknowledge the value of learning styles (see for

example Cranton 1992, p.45; Merriam & Caffarella 1999, p.210) in assisting teachers, trainers and

learners appreciate the different ways in which individuals approach learning and how learning

might be best facilitated for them. However, they also caution against their uncritical application.

There have been arguments put that the concept of learning style is culturally based (see for

example Brookfield 1990) which can sometimes suggest a hierarchy of learning styles or the

existence of ‘better’ approaches to learning. While this need not mean the rejection of learning

styles, what is needed is caution in their application and interpretation because as James and

Blank (1993, p.55) have observed

…although various authors claim strong reliability and validity for their instruments, a solid

research base for many of these claims does not exist.

Self-directness

The notion of self-direction as a characteristic of adult learners is widely accepted, largely as a

result of the work of Alan Tough (1971) and Malcolm Knowles (1990). Knowles’ work to

develop the concept of andragogy has been particularly influential in respect of promoting self-

Simons, Harris and Smith 13

direction as an outcome of education, not solely as characteristic of adult learners. This latter idea is

often misunderstood by educators (Cranton 1992, p. 50). As a characteristic of adult learners,

self-direction needs to be understood like other characteristics of adult learners that have been

explored thus far and taken into account by teachers and trainers in their planning and delivery.

However the concept of self-direction is problematic on a number of fronts. There is no

universally accepted definition of the concept. To date, there has been no research which verifies

self-directedness as a constant trait of adult learners. The notion that self-direction is an inherent

characteristic of adults has been challenged particularly in relation to the extent to which adults

choose to display this characteristic in all learning situations and the notion that that adults move

towards self-directedness in a variety of ways (see for example Brockett and Hiemstra 1991).

Arguably there are also issues related to the relevance of the concept of self-direction across

different cultures, and as Caffarella (1993, p. 32) notes ‘we should not idealise self-directed

learning as the true marker of a mature adult learner’. It is also arguable that any learning can be

entirely ‘self-directed’ since learning can never be autonomous of the environment in which it

occurs (Cranton 1992, p. 53). Cranton notes that adult learners may be more or less capable of

undertaking a self-directed learning process and that this process does not necessarily preclude

the involvement of others including teachers and trainers who have a role to play in encouraging

and facilitating the self-directed learning process (Cranton 1992, pp. 54-55).

In summary, the adult learner brings with them a complex array of characteristics which have the

potential to influence and be influenced by the learning process. While is not possible to fully

understand the impact of all these characteristics on the learners who engage in VET, awareness

of the potential ways in which learners might be different would seem to be a critical foundation

in the development of sound approaches to teaching and learning However, the broader field of

education and adult education serves to provide the backdrop to the practice of teachers and

trainers in the VET sector. Within the context of VET, the nature of the learning and decisions

that have been taken in relation to the ways in education and training might be organised,

planned and accredited place particular demands on teachers and trainers in relation to their

practice.

Learners and learning in the VET context

The training reforms that have unfolded over the past decade in Australia flowed from three core

beliefs (Hawke 1998). Firstly, the system of vocational education and training that existed prior to

the mid-1980s was ill-equipped to deliver the type of education and training needed to ensure

that Australia had a flexible, highly skilled workforce that would enable the country to compete

successfully on a global stage. Secondly, the nature of the skills, knowledge and attributes

required by the Australian workforce would continue to undergo rapid change where workplace

competence would best be developed in authentic learning environments that fostered greater

linkages between working and learning. Thirdly, the nature and extent of the cost of increasing

the skills and expertise of the Australian workforce to meet these demands was going to be high.

In order to contain these costs ways needed to be found to encourage enterprises to invest in

training in the workforce in order that the effort and cost for the development of the workforce

be more equitably spread between individuals, their workplaces and the government.

The training reforms where predicated on the assumption that system wide change were required

to bring about the scale of change required to meet the goals of increasing both the adequacy and

standard of vocational education and training. As such, the reform process that was embarked

upon in the early 1990s was a multi-dimensional phenomenon which required substantial change

to the ways in which vocational education and training was designed, implemented and assessed.

Widespread pressure was brought to bear on the vocational education and training sector, with

concomitant implications for teachers and trainers involved in the process of facilitating learning

and assessment within the sector.

14 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

Initial reforms in the sector introduced a competency-based framework as the defining

organisational framework for teaching, learning and assessment in the VET sector. The adoption

of competency-based training was intended to affect a number of elements of the program

design, implementation and assessment including the developing of curricula, the forms of

teaching methods adopted, the materials developed to support learning and the assessment

approaches and strategies. Competency-based approaches to education and training, as

conceptualised within the reforms, have continuously ‘framed’ the development of curricula by

defining the purpose of education and training and have thus provided a schema for integrating

key aspects of the curriculum such as content, delivery, assessment and outcomes. The result of

this framing is a ‘particular pattern of curricula organisation’ that has become an integral part of

vocational education and training (Carter 1995, p. 37).

Competency-based education and training, it is argued, can embrace understandings of learning

drawn from behaviourist and cognitive perspectives (Harris, Guthrie, Hobart & Lundberg 1995,

p. 135). Further since competency-based training is concerned with outcomes, rather than

process, Harris et al. argue that this provides greater freedom for the teacher / facilitator to

customise learning strategies to meet particular learning styles or preferences of students (Harris

et al. 1995, p.136).

Other reforms such as a national regulatory framework for providers of VET and the

introduction of policies such as User Choice and the development of the open training market has

resulted in VET being undertaken in a wide range of settings including schools, workplaces, adult

and community education providers using a range of delivery modes including the use of distance

and on-line technologies. VET teachers and trainers are now working in a system characterised

by increasing diversity, both in terms of the contexts in which they work and the students and

clients they work with (Curtain 2000). The growth and change in information technologies has

altered the temporal and spatial organisation of VET teachers’ and trainers’ work as well as their

professional identities, particularly for those VET practitioners located in public TAFE

institutions (Chappell 2001). This emergent environment has also had a concomitant impact on

the understandings attached to learning - central to the core of VET work – and learners – the

object of VET teachers’ and trainers’ labour.

Learning in pre-reform times, was arguably mostly associated with institutional environments and

led by teachers and trainers. Curricula were driven by processes which codified ‘acceptable’

knowledge and skills which were then delivered to learners using pre-defined set of teaching

methods. Where learning in the workplace was undertaken it was not connected in any significant

way to the learning that took place in institutional settings. Emphasis was placed on the

attainment of identified skills and a body of specialist technical knowledge associated with a

chosen occupational area.

As Chappell, Hawke, Rhodes and Solomon (2003) note, however, there has been a significant

shift is what is valued and understood as learning in VET contexts, the importance of learning as

a process and what should be the intended outcomes from learning within the sector.

Increasingly learning is been viewed as occurring across both on and off-job learning sites and the

current VET system aims to particularly recognise learning from across both contexts.

Integration of learning – in both the institutional sense and as a personal act for learners (Harris,

Willis, Simons & Underwood 1998) is increasingly being viewed as important. Further learning, is

no longer viewed as taking place in environments separate from the world of work. Learning is

viewed as co-terminus with work (Van der Krogt 1998, Poell, Van der Krogt & Wildereersch

1998). Learning is increasingly being linked to organisational processes including human resource

development (Chappell et al. 2003, p.16-17) and facilitated by attention to the way in the structure

and process of work is managed, and the ways in which workplace relationships and culture are

attended to (Harris, Simons & Bone 2000). Curricula are not content driven, but work-driven and

linked to the immediate needs and concerns of the workplace (Chappell et al. 2003, p. vi). The

facilitation of learning is no longer the sole providence of designated trainers or teachers.

Simons, Harris and Smith 15

Increasingly learning from one’s work colleagues is more likely. Learners are also workers and

potentially undertaking various roles (worker, learner, facilitator of learning – both of one’s own

learning and that of others), sometimes simultaneously.

In addition to these identified shifts which give greater priority to authentic learning

environments and a stronger focus on the process of learning rather than training, there have also

been shifts in thinking in relation to the outcomes that VET should seek to attain. Employers are

increasingly stating a preference for the attainment of generic or employability skills as well as

occupational specific skills (ACCI/BCA 2002). Teaching and learning that fosters the

development of these attributes necessarily takes on a different character those approaches, for

example that focus only on the development of technical skills.

These changes to understandings of learning and the outcomes required from VET therefore

require new approaches to facilitating learning which represents a significant shift from current

notions of learning as product and the transmission model of learning that underlies this

conception (Chappell et al. 2003, p. 15). Rather constructivist understandings of learning, which

promote ‘experiential, problem-based and project-based learning’ are deemed to be more

appropriate (Chappell et al. 2003, p. vii). This however

…does not mean that teacher-centred pedagogies are no longer useful or relevant, rather

they are one category of a much larger available pedagogical repertoire (Chappell et al.

2003, p. viii).

Rather it requires

…[VET] practitioners who have a sophisticated appreciation of the pedagogical choices

that are not only available to them but which are consistent with the contexts, clients and

learning sites that make up the arena in which they work (Chappell et al. 2003, p.13).

Constructivist notions of learning promote a particular understanding of the role of VET

teachers and trainers:

The vocational teacher’s role is not to set tasks but to organise experiences that allow

learners to develop their own knowledge and understanding (Kerka 1997, p.3).

These shifts in thinking about teaching and learning in VET have been emphasised in other

recent research. A scoping study examining teaching and learning practices associated with the

implementation of Training Packages (CURVE & University of Ballarat 2003) found that quality

teaching and learning practices exhibit particular characteristics. Firstly, they display a learner-

centred approach with the teacher / trainer acting as a facilitator. Secondly, teaching and learning

practices have a strong workplace focus with an emphasis on the application of learning

experiences to the workplace regardless of the context in which learning takes place. Thirdly there

is an emphasis on flexibility and innovation which enables the development of learning strategies

which are characterised by customisation and a holistic understanding of the learning and

assessment processes (CURVE & University of Ballarat 2003, p.50).

The imperative for new thinking around teaching and learning in VET has implications for the

view one might take about understanding the work of VET teachers and trainers. Rather than

promoting the view that VET teachers and trainers act as ‘technicians’ who deliver and maintain

training services, teachers and trainers are viewed as ‘professionals’ in the sense that they are

reflexive, critical and act to create (and recreate) learning systems through their work (Simons

2001, p. 196). This view is in keeping with understandings of professional work that emphasises

the interrelationship between theory and practice, where practitioners are ‘practical theorists’

(Foley 2000, p. 8) who work in complex environments where they are engaged in making

decisions, reflecting-in-action and thus theorising about their practice:

16 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

…[practitioners] theorise…to attempt to make connections between variables, to explain

outcomes…theorising involves the application of concepts…Theorising is something that

we inevitably do and it is inevitably selective…(Foley 2000, p. 9).

Theories or explanations of learning and the characteristics of learners form part of the

frameworks that VET teachers and trainers draw from and use to inform their practice. They can

be formal (that is codified in the literature) or informal (drawn from personal experience). Formal

theories can challenge the everyday understandings that form the basis of teaches and trainers’

practice (Foley 2000, p. 12):

Theorising is not just an abstract, impractical activity, engaged in by

intellectuals…removed from the ‘real world’ but is something that we do all the time. We

can come to understand more clearly how we theorise ….formal theory ceases to be seen

as something external to us that we have to master and apply, and becomes something that

we can take into our existing understanding, and which can illuminate both our implicit,

informal knowledge and our practice (Foley 2000, p.16).

Arguably, this literature points to the importance of quality teaching and learning practices if

VET is to deliver its promised outcomes. Implications for how we understand the role and

function of VET teachers and trainers flow from this goal.

Competency standards and qualifications for VET teachers

and trainers

As part of the implementation of the training reforms, policy makers were keen to ensure that

learners within workplaces should have access to support from suitably qualified trainers. One of

the first set of competency standards to be developed was for workplace trainers (CSB-Assessor

and Workplace Trainers 1994). The purpose for the development of these standards was

essentially practical, focussing on assisting those responsible for hiring and training workplace

trainers (Garrick and McDonald 1992) and addressing the needs of trainers located in workplace

environments (NAWT, 2001, p. 23).

These initial standards were designed to address the work functions of two different groups of

workplace trainers:

…people providing training in the workplace but for whom the training function is not a

major part of their job…[and]… people for whom training is a large part of the their job

(Workplace Trainers Ltd, 1992 cited in NAWT 2001, p. 23; CSB Endorsement submission

to NTB 1992 cited in NAWT 2001, p. 23).

Standards for the first group were designated ‘Category 1’ standards and ‘Category 2’ for the

second. They included seven units of competency encompassing identifying needs for training,

designing and developing training, organising training resources, delivering and evaluating

training, assessing training, promoting and managing training (NAWT 2001, p.23). Units of

competency for the ‘Category 2’ trainers were distinguished by more elements of competency and

different performance criteria across the seven units.

Competency standards for assessors were subsequently developed and endorsed in 1993. These

standards were directed to ‘all persons who carry out an assessment role either in a workplace or

institutional setting’ (NAWTB 1993, cited in NAWT 2001, p. 24). They consisted of three units

of competency: ‘plan assessment, carry out assessment and record assessment results and review

the procedure’ (NAWT 2001, p. 24).

The workplace trainer and assessor standards were revised in 1994 and 1995 respectively with the

outcome maintaining two ‘categories’ of trainer but providing greater distinction between the two

Simons, Harris and Smith 17

roles. The Category 1 Workplace Trainer Standards consisted of three units of competency –

Prepare for Training, Deliver Training and Review Training. In the context of this project, it is

interesting to note that the word ‘learn’ or ‘learning’ only appears four times in these units – once

in the unit focussing on reviewing training with the remaining three mentions occurring in the

unit entitled Deliver Training (CSB-Assessors and Workplace Trainers 1994, p. 4). The

overwhelming emphasis is on training. One element of competency refers to the need to revise

and modify instruction processes to meeting trainees’ ‘learning needs’. The other instances refer

to the use of feedback to help trainees to ‘learn from their mistakes’ and providing practice

‘according to the specific learning situation’. Trainee characteristics are acknowledged as a key

factor to consider when selecting training methods (CSB-Assessors and Workplace Trainers

1994, p. 2-4). In keeping with the framework for presenting competency standards in use at the

time, the absence of any range of variables statements and evidence guides precluded any

significant elaboration of the process of learning and understanding learners. The units of

competency arguably emphasise a transmission mode of learning where trainees are ‘instructed’

using a ‘systematic approach’ with reference to processes such as ‘explanation, demonstration,

review, trainee explanation, trainee demonstration and feedback (CSB-Assessors and Workplace

Trainers 1994, p. 4). Emphasis is also placed on learning by doing with an emphasis on practice

and feedback. The view of learning as a product is also emphasised by way of reference to

trainees discussing ‘their ability to apply their learning outcomes’ (CSB-Assessors and Workplace

Trainers 1994, p. 6).

The revised Category 2 standards consisted of four units of competency – prepare for training,

deliver training, assess training, review and promote training. By way of contrast to the Category

1 units of competency units in this group place greater attention (by using frequent references) to

the importance of attending to barriers to learning and characteristics of learners (CSB-Assessors

and Workplace Trainers 1994, p. 10). The use of learning outcomes (in keeping within a

framework where national curricula were in use at that time) and emphasis on a variety of

learning processes (teacher-directed, individual and group-based) were singled out for particular

attention (CSB-Assessors and Workplace Trainers 1994, pp.14-15). This suggests that these units

of competency recognised that learning can occur in a variety of contexts.

The next iteration of the competency standards for Assessment and Workplace Training were

developed after the advent of Training Packages:

Two fundamental shifts occurred with development of the Training Package – the two

categories of Workplace Trainer disappeared and the units were packaged into designated

qualifications… a Certificate IV… and a Diploma (NAWT 2001, p. 26).

The new Certificate IV represented a combining and significant revision of the units of

competency that previously comprised the Category 1 and Category 2 qualifications. These units

of competency, in keeping with current ANTA requirements relating to the format of industry

standards included the addition of Range of Variable statements, expanded Evidence Guides and

the inclusion of the Mayer Key competencies. The certificate now comprised eight units of

competency. The content of the unit BSZ404A Train Small Groups was drawn from the Category

1 units of competency and, as such, continued to reflect a strong preoccupation with training as

opposed to learning, with the term ‘learning’ only occurring three times in the unit – twice in

relation to issues relating to the learning process and once in reference to experiential learning as

an example of ‘training delivery methods and opportunities for practice’ (NAWT 1999, pp.53-54).

The characteristics of ‘training participants’ were noted as a significant variable which needed to

be taken into account in the training process. These characteristics included ‘language, literacy

and numeracy needs, cultural, language and educational background, gender, physical ability, level

of confidence, nervousness or anxiety, age, previous experience with the topic and experience in

training and assessment’ (NAWT 1999, p.55).

18 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

Other units related to planning and delivery of training BSZ405A Plan and Promote a Training

Program, BSZ 406A Plan a Series of Training Sessions and BSZ 407A Deliver Training Sessions make

specific reference to ‘principles of adult learning’ as required knowledge and skills, but in keeping

with the minimalist revisions undertaken as part of the development process (NAWT 2001, p.27),

few direct references to the process of learning are evident in these units. Arguably, a strong

emphasis on training remains along with a strong teacher / trainer led focus on these activities.

However, the emphasis on the various contexts in which training might take place and the

importance of acknowledging various characteristics of participants (noted above) are also

featured in these units.

The review of the current Training Package (NAWT 2001) undertaken to develop the new

Training and Assessment (TAA) Training Package has taken up a number of issues relating to

how learners and learning are depicted in the previous Training Package. These include

recommendations for:

• broadening the focus of the units of competency to embrace a wider range of delivery

approaches and models (including mentoring, coaching, action learning, flexible

delivery); and

• separating out group facilitation as a unit of competency rather than embedding these

competencies in a unit covering the delivery of training and providing a clearer focus on

work-based learning

The review also acknowledged that existing units of competency also contained gaps in relation

to adult learning principles/theory, reflective practice amongst other issues (NAWT 2001, p. 86).

Conclusion

The development and refinement of the competency standards used in successive iterations of

the Training Package are important as they provide ‘information that informs the content of

vocational education and training programs’ (Chappell et al. 2003, pp.19-20). Thus, while some

inferences can be made about the understandings attached to the concepts of learners and

learning by way of analysing the standards, it is the choices made by people engaged in the

delivery and assessment of certificate IV programs that more fully reveals these understandings.

This is notwithstanding the critiques of the implicit assumptions contained in Training Packages

which suggest that by their very structure they promote a transmission understanding of learning

and miss contemporary understandings that view competence as conceptually bounded, not

residing in individuals but in the collective (the interaction between people at work) (Chappell et

al. 2003, p.20-21). The issue that is of relevance particularly to this research study is the extent to

which the competency standards and the overall Training Package are able to convey the

emerging understandings of what is required of persons engaged in supporting learning within

the VET sector and that the Training Package is used as a way of promoting high quality teaching

and learning in VET to those most intimately concerned with this outcome – namely the teachers

and trainers.

Simons, Harris and Smith 19

Research design and method

Design of the study

The purpose of the study was to explore how the concepts of learners and learning are embedded

in the intended curriculum, the delivered curriculum and the received curriculum (Glatthorn cited in

Print 1993, pp. 3-4). Different perspectives – including those of the teachers and trainers

implementing the course and graduates from the various courses – were required. The study

therefore relied on a subjective world view where phenomena are best studied using methods that

permit the researcher to ‘get inside them’ (Simons 2001, p.56). The study required an in-depth

analysis of instances of a particular unit – in this case, registered training organisations and their

Certificate IV courses. The purpose of this approach was to ‘probe deeply and to analyse

intensively the multifarious phenomena that constitute the life cycle of the unit’ (Cohen &

Manion 1994, p. 106).

A case study approach enabled the researchers to focus on particular aspects of the Certificate IV

courses that were of central interest to the study (that is how learners and learning are

understood) and to analyse and describe these aspects in detail within the context of the courses

which were delivered by particular teachers and trainers to specific groups of students.

The research process

The research process was designed to comprise three interrelated stages:

Stage 1: Planning and preparation

Stage 2: Data gathering and analysis

Stage 3 Cross case analysis and report writing

Stage 1: Planning and preparation

Following a preliminary reading of the literature in the areas related to the research questions,

potential sites for the case studies were sought. In the first instance, an audit of all registered

training organisations offering the Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training was

undertaken using the National Training Information Service (NTIS). From this data base, a list of

seventeen potential sites was generated. These sites were selected to ensure that the various

different types of public and private registered training providers were represented in the sample.

The sites also included higher education institutions which were registered training organisations

and where the Certificate IV was offered either as a ‘stand alone’ course or embedded in degree

programs. These sites were located in five different states/territories. Fourteen were based solely

in the VET sector (four in Queensland, four in New South Wales, four in Victoria and two in

South Australia) and three were higher education institutions (one in each of New South Wales,

Victoria and an Australian Territory).

Parallel to this process the case study protocol was developed. Information derived from the

literature review was used to inform the development process. For each site (case), interviews

were to be conducted with at least one teacher and/or trainer involved in the delivery of

Certificate IV programs and two recent graduates from their courses. As the training package, at

least in part, established the intended curriculum for the Certificate IV qualification, the protocols

20 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

were designed to collect data on the delivered curriculum from a number of Certificate IV courses

(through the experiences of teachers and trainers who offer the course) and the received curriculum

– what graduates from the Certificate IV courses report as their learning from participating in the

courses. The protocols were circulated amongst the research team for comment and were tested

with a small number of potential respondents. Minor amendments were made to the protocols as

a result of these processes.

The final part of the preparation process involved attention to processes relating to the ethical

issues associated with the conduct of the study. Ethical approval for the study was sought from

the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of South Australia and the New South

Wales Department of Education and Training for those case studies which were to take place in

TAFE institutes in that state.

Stage 2: Data gathering and analysis

Where possible, visits were made to each of the sites selected for the study. Each visit took

between one and two days and was sometimes supplemented with follow up telephone calls for

interviews with participants where they were not able to be scheduled within the timeframe of the

visits. Where face-to-face interviews were not possible, telephone interviews were conducted. The

interviews were audio-taped and later transcribed. Individual case studies were then developed by

members of the research team using a format that was agreed by the team and returned to key

personnel at each site for verification.

In total, sixteen case studies were conducted for the study. One case study was not able to be

completed during the time that the field work for the study was undertaken. Table 1 provides

details of the distribution of the organisations by state and the number of interviews that were

conducted at each site. A total of 18 interviews were conducted with teachers and trainers who

deliver the Certificate IV course and 27 interviews were conducted with graduates. In some

instances the number of interviews fell short of the targeted numbers. This was largely due to the

challenges inherent in attempting to follow up graduates from courses.

Stage 3: Cross case analysis and report writing

Once each individual case study had been completed, analysis of the data was undertaken in a

number of discrete stages. In the first instance each case study was analysed using the research

questions to guide the process. The second stage involved a cross case analysis to synthesise key

themes and issues. Particular attention was paid to the ways in which the various data supported

and/or contradicted each other. This was done by bringing together the data for each individual

teacher/trainer and graduate, and then returning to further scrutiny of the data within their

respective cases. The final stage of the data analysis process focused on drawing conclusions,

elaborating meanings and verifying the findings in the light of the available data. This was aided

by a return to the research objectives which had guided the study and their use in formulating a

series of tentative conclusions which were then passed through several iterations becoming

increasingly grounded and explicit with each iteration. A verification process which required

extensive reference back to the literature and the original data was undertaken to provide

extended arguments to support the conclusions drawn from the data.

Simons, Harris and Smith 21

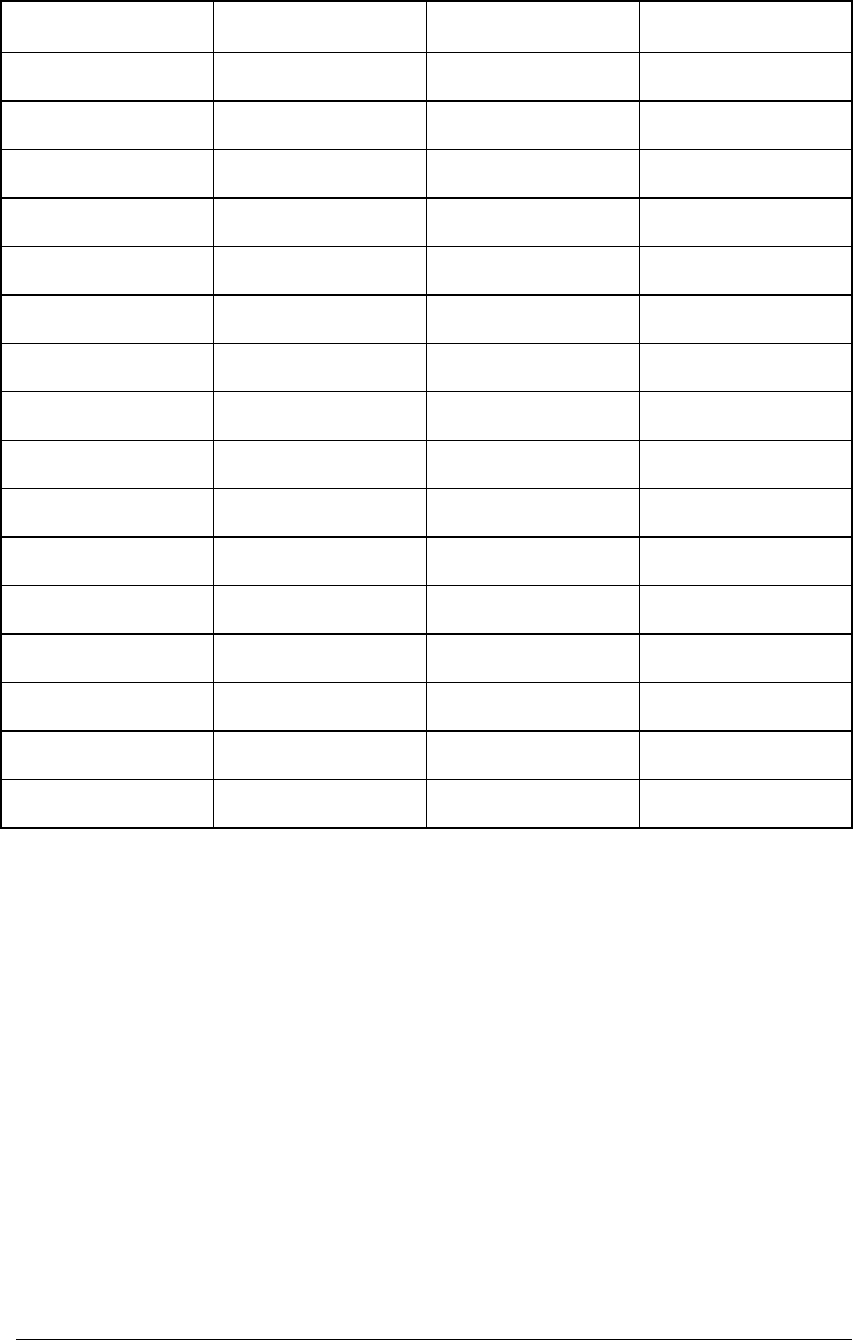

Table 2: Distribution of case studies by state and number of respondents at each site

State

Location RTO Type Number of interviews

at site

South Australia City Private – community-

based

1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

City Public 1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

New South Wales Regional Public 2 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

City Public 1 Teacher and 1

graduate

Regional Private – community-

based

2 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

City Private – Enterprise

based

1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

City Private – government -

other

I Teacher and 1

graduate

Queensland Regional Private – commercial 1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

Regional Public 1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

City Public 1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

City Private – community

based

1 Teacher and 1

graduate

Victoria City Private commercial 1 Teacher and 1

graduate

City Public 1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

Regional Public 1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

City Private – enterprise 1 Teacher / Trainer and

2 Graduates

Regional Private – other –

government

1 Teacher and 1

graduate

The respondents

Persons delivering the Certificate IV (teachers and trainers)

The persons who were offering the Certificate IV were a highly qualified and experienced group

of educators. With the exception of one participant who was currently completing an

undergraduate degree in adult and vocational education, all held a combination of graduate and

post graduate qualifications in education. Over half the group held secondary teaching

qualifications and/or specific qualifications in adult and vocational education. Three participants

were currently undertaking studies at Masters Level and another person was undertaking

certificate level studies in on-line learning from an institution in the United Kingdom. In addition

to their qualifications in education and training, eight participants specifically referred to their

industry experience and vocational qualifications which they held in addition to their educational

qualifications. Nine respondents also cited that they held more than ten years experience as a

teacher.

22 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

The Certificate IV graduates

The graduates from the Certificate IV programs were a diverse group, both in terms of their

educational backgrounds and their current work roles. This latter characteristic particularly

highlights the wide range of occupations for which the Certificate IV may hold some relevancy.

Just under one quarter of graduates (six in total) were currently employed in public vocational

education and training providers. Two of this group were employed as teachers, one as a VET

coordinator, one as a support officer for teachers working in flexible delivery, one as a short

course administrator and one as an internal auditor.

Five graduates were employed in teaching/tutoring roles in community based organisations while

a further two had undertaken the Certificate IV as part time employees in an enterprise (their

employment being undertaken while they were studying at university).

The remaining graduates occupied a range of work roles including

! Marketing coordinator

! Educational officer for a state department

! Consultant in a nursing agency

! Manager of interior design business

! Trainer for an educational publisher

! Quality, risk and safety officer in a hospital

! Manager of wards in a hospital

! National sales development manager

! Trainer / assessor for enterprise

! Private dog trainer /Coordinator of respite centre

! Volunteer coordinator

! Workplace learning coordinator

! OHSW officer in enterprise

! Trainer of apprentices in an enterprise.

Just over 40% of the Certificate IV graduates held graduate and post graduate level qualifications.

A further 40% held vocational qualifications and almost all listed a diverse range of occupational

experience.

Limitations

The case study method adopted for this study is not without its limitations. Since the purpose of

the study was primarily interpretive, the findings from this study are not able to be generalised to

all registered training organisations offering the Certificate IV qualification. However, since the

purpose of the study was to illuminate practices and experiences, generalisability can be gauged

with respect to the use of a sample of registered training organisations that is diverse enough to

allow assertions of broader applicability. While every effort was taken to ensure that respondents

were encouraged to express their views about the Certificate IV programs in which they were

participants in an open and frank manner, the absence of observation of the actual programs

necessarily limited the verification of findings from the study. The data relied solely on the

reports and recollections of the teachers, trainers and participants from the programs.

Simons, Harris and Smith 23

Interview protocols

Interview with staff responsible for delivering the

Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training

Please note: For the purposes of this interview when we refer to learners and learning we are

referring to the ways in which learners are represented and spoken about in the course of the

delivery of your Certificate IV program. When we refer to learning we are referring to the ways in

which the process of learning is represented and spoken about during the delivery of the

program. In other words, we are interested in focusing on what you tell participants in the

Certificate IV program about learners and learning.

Introduction

Some information about your RTO

! How long has your organisation been an RTO?

! In addition to the Certificate IV what other Training Packages are you registered to deliver

from?

! Do you offer all qualifications from these Training Packages or only some? Do you offer any

additional courses that are not part of Training Packages?

! How many teaching / training staff are employed in your organisation? What percentage of

staff are part-time or casual? What percentage are full time staff members?

! Does your organisation offer

" Full fee paying courses?

" Courses for international students coming to Australia?

" Courses in other countries (if yes, where)?

Some information about your RTO and the delivery of the Cert IV

! How did your organisation become involved in the delivery of the Certificate IV? Who

initiated this?

! Why is your organisation currently involved in the delivery of the Certificate IV?

! How long has your organisation been offering the current Certificate IV? Did you

organisation offer the previous workplace trainer qualifications (Category I and II)?

! Where do most of your students for the Certificate IV come from?

! How many graduates have you had from your Certificate IV program in the past 12 months?

! How many of these graduates gained the Certificate IV through a) partial or b) full RPL?

Some information about yourself

! Can you tell me a little bit about yourself?

" Your background

" Qualifications

" How long you have been working in this RTO

" Your history of involvement in the delivery of the Certificate IV

24 The Certificate IV in Assessment and Workplace Training: Understanding learners and learning

Positioning the interview

! What sort of learning do you think is promoted and valued in the VET sector?

! Is this the same sort of learning that is valued and promoted in your RTO?

! How is it similar / different?

! So what does learning in the VET sector mean for you?

Context

! Can you please ‘walk me through program that you use to deliver the Certificate IV starting

with the first session? (include details of the content and processes that you use throughout

the program).

Learning

In this research we are interested in how you talk about and represent learners and learning in the

course that you deliver and how the participants are assisted to understand learning and the