Report to Congressional Requesters

United States General Accountin

g

Office

GA

O

December 2003

PRESCRIPTION

DRUGS

OxyContin Abuse and

Diversion and Efforts

to Address the

Problem

GAO-04-110

www.gao.gov/cgi-bin/getrpt?GAO-04-110.

To view the full product, including the scope

and methodology, click on the link above.

For more information, contact Marcia Crosse

at (202) 512-7119.

Highlights of GAO-04-110, a report to

congressional requesters

December 2003

PRESCRIPTION DRUGS

OxyContin Abuse and Diversion and

Efforts to Address the Problem

Purdue conducted an extensive campaign to market and promote OxyContin

using an expanded sales force to encourage physicians, including primary

care specialists, to prescribe OxyContin not only for cancer pain but also as

an initial opioid treatment for moderate-to-severe noncancer pain.

OxyContin prescriptions, particularly those for noncancer pain, grew

rapidly, and by 2003 nearly half of all OxyContin prescribers were primary

care physicians. The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has

expressed concern that Purdue’s aggressive marketing of OxyContin focused

on promoting the drug to treat a wide range of conditions to physicians who

may not have been adequately trained in pain management. FDA has taken

two actions against Purdue for OxyContin advertising violations. Further,

Purdue did not submit an OxyContin promotional video for FDA review

upon its initial use in 1998, as required by FDA regulations.

Several factors may have contributed to the abuse and diversion of

OxyContin. The active ingredient in OxyContin is twice as potent as

morphine, which may have made it an attractive target for misuse. Further,

the original label’s safety warning advising patients not to crush the tablets

because of the possible rapid release of a potentially toxic amount of

oxycodone may have inadvertently alerted abusers to methods for abuse.

Moreover, the significant increase in OxyContin’s availability in the

marketplace may have increased opportunities to obtain the drug illicitly in

some states. Finally, the history of abuse and diversion of prescription

drugs, including opioids, in some states may have predisposed certain areas

to problems with OxyContin. However, GAO could not assess the

relationship between the increased availability of OxyContin and locations

of abuse and diversion because the data on abuse and diversion are not

reliable, comprehensive, or timely.

Federal and state agencies and Purdue have taken actions to address the

abuse and diversion of OxyContin. FDA approved a stronger safety warning

on OxyContin’s label. In addition, FDA and Purdue collaborated on a risk

management plan to help detect and prevent OxyContin abuse and diversion,

an approach that was not used at the time OxyContin was approved. FDA

plans to provide guidance to the pharmaceutical industry by September 2004

on risk management plans, which are an optional feature of new drug

applications. DEA has established a national action plan to prevent abuse

and diversion of OxyContin. State agencies have investigated reports of

abuse and diversion. In addition to developing a risk management plan,

Purdue has initiated several OxyContin-related educational programs, taken

disciplinary action against sales representatives who improperly promoted

OxyContin, and referred physicians suspected of improper prescribing

practices to the authorities.

Amid heightened awareness that

many patients with cancer and

other chronic diseases suffer from

undertreated pain, the Food and

Drug Administration (FDA)

approved Purdue Pharma’s

controlled-release pain reliever

OxyContin in 1995. Sales grew

rapidly, and by 2001 OxyContin had

become the most prescribed brand-

name narcotic medication for

treating moderate-to-severe pain.

In early 2000, reports began to

surface about abuse and diversion

for illicit use of OxyContin, which

contains the opioid oxycodone.

GAO was asked to examine

concerns about these issues.

Specifically, GAO reviewed (1) how

OxyContin was marketed and

promoted, (2) what factors

contributed to the abuse and

diversion of OxyContin, and

(3) what actions have been taken to

address OxyContin abuse and

diversion.

To improve efforts to prevent or

identify abuse and diversion of

controlled substances such as

OxyContin, FDA’s risk

management plan guidance should

encourage pharmaceutical

manufacturers with new drug

applications to submit plans that

contain a strategy for identifying

potential problems with abuse and

diversion. FDA concurred with

GAO’s recommendation. DEA

agreed that such risk management

plans are important, and Purdue

stated that the report appeared to

be fair and balanced.

Page i GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

Letter 1

Results in Brief 4

Background 7

Purdue Conducted an Extensive Campaign to Market and Promote

OxyContin 16

Several Factors May Have Contributed to OxyContin Abuse and

Diversion, but Relationship to Availability Cannot Be Assessed 29

Federal and State Agencies and Purdue Have Taken Actions to

Prevent Abuse and Diversion of OxyContin 34

Conclusions 41

Recommendation for Executive Action 42

Agency and Purdue Comments and Our Evaluation 43

Appendix I Scope and Methodology 46

Appendix II Summary of FDA Changes to the Original Approved

OxyContin Label 48

Appendix III Databases Used to Monitor Abuse and Diversion of

OxyContin and Its Active Ingredient Oxycodone 51

DAWN Data 51

NFLIS Data 51

STRIDE Data 52

National Survey on Drug Use and Health Data 52

Monitoring the Future Survey Data 52

Appendix IV Comments from the Food and Drug Administration 53

Appendix V Comments from the Drug Enforcement

Administration 56

Contents

Page ii GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

Tables

Table 1: Sales Representative Positions Available for OxyContin

Promotion, 1996 through 2002 19

Table 2: Total OxyContin Sales and Prescriptions for 1996 through

2002 with Percentage Increases from Year to Year 31

Table 3: Selected Language Approved by FDA in Warning Sections

of OxyContin Labels, 1995 and 2001 35

Table 4: Selected Language Approved by FDA in the Indication

Sections of OxyContin Labels, 1995 and 2001 35

Table 5: FDA Changes to the Original OxyContin Label Made from

June 1996 through July 2001 48

Figure

Figure 1: Promotional Spending for Three Opioid Analgesics in

First 6 Years of Sales 22

Page iii GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

Abbreviations

DAWN Drug Abuse Warning Network

DEA Drug Enforcement Administration

FDA Food and Drug Administration

FD&C Act Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act

HHS Department of Health and Human Services

HIDTA High Intensity Drug Trafficking Area

JCAHO Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare

Organizations

NFLIS National Forensic Laboratory Information System

ONDCP Office of National Drug Control Policy

PDUFA Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992

PhRMA Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America

RADARS Researched Abuse, Diversion, and Addiction-Related

Surveillance

SAMHSA Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services

Administration

STRIDE System to Retrieve Information from Drug Evidence

WHO World Health Organization

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in the

United States. It may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without further

permission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images or

other material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish to

reproduce this material separately.

Page 1 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

December 23, 2003

The Honorable Frank R. Wolf

Chairman

Subcommittee on Commerce, Justice, State, and the Judiciary,

and Related Agencies

Committee on Appropriations

House of Representatives

The Honorable James C. Greenwood

Chairman

Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations

Committee on Energy and Commerce

House of Representatives

The Honorable Harold Rogers

House of Representatives

Patients with cancer may suffer from fairly constant pain for months or

years. Patients with other diseases or conditions, such as rheumatoid

arthritis, osteoarthritis, chronic back pain, or sickle cell anemia, may also

suffer from pain that lasts for extended periods of time. Since 1986, the

World Health Organization (WHO) and others have reported that the

inadequate treatment of cancer and noncancer pain is a serious public

health concern. To address this concern, efforts have been made to better

educate health care professionals on the need to improve the treatment of

both cancer and noncancer pain, including the appropriate role of

prescription drugs.

Amid the heightened awareness that many people were suffering from

undertreated pain, in 1995 the Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

approved the new drug OxyContin, a controlled-release semisynthetic

opioid analgesic manufactured by Purdue Pharma L.P.,

1

for the treatment

of moderate-to-severe pain lasting more than a few days.

2

According to

1

OxyContin is an opioid analgesic—a narcotic substance that relieves a person’s pain

without causing the loss of consciousness. Hereafter, we refer to the company as Purdue.

2

As discussed later in this report, FDA approved the revised OxyContin label in July 2001 to

describe the time frame as “when a continuous around-the-clock analgesic is needed for an

extended period of time.”

United States General Accounting Office

Washington, DC 20548

Page 2 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

Purdue, OxyContin provides patients with continuous relief from pain

over a 12-hour period, reduces pain fluctuations, requires fewer daily

doses to help patients adhere to their prescribed regimen more easily,

allows them to sleep through the night, and allows a physician to increase

the OxyContin dose for a patient as needed to relieve pain.

3

Sales of the

drug increased rapidly following its introduction to the marketplace in

1996. By 2001, sales had exceeded $1 billion annually, and OxyContin had

become the most frequently prescribed brand-name narcotic medication

for treating moderate-to-severe pain in the United States.

In early 2000, media reports began to surface in several states that

OxyContin was being abused—that is, used for nontherapeutic purposes

or for purposes other than those for which it was prescribed—and illegally

diverted.

4

According to FDA and the Drug Enforcement Administration

(DEA), the abuse of OxyContin is associated with serious consequences,

including addiction, overdose, and death.

5

When OxyContin was approved,

the federal government classified it as a schedule II controlled substance

under the Controlled Substances Act because it has a high potential for

abuse and may lead to severe psychological or physical dependence.

6

DEA

has characterized the pharmacological effects of OxyContin, and its active

ingredient oxycodone, as similar to those of heroin. Media reports

indicated that abusers were crushing OxyContin tablets and snorting the

powder or dissolving it in water and injecting it to defeat the intended

controlled-release effect of the drug and attain a “rush” or “high” through

3

According to FDA, there is no known limit to the amount of oxycodone, the active

ingredient in OxyContin, that can be used to treat pain.

4

Prescription drug diversion can involve such activities as “doctor shopping” by individuals

who visit numerous physicians to obtain multiple prescriptions, prescription forgery, and

pharmacy theft. Diversion can also involve illegal sales of prescription drugs by physicians,

patients, or pharmacists, as well as obtaining controlled substances from Internet

pharmacies without a valid prescription.

5

According to the National Institute on Drug Abuse, addiction is a chronic, relapsing

disease, characterized by compulsive drug seeking and use and by neurochemical and

molecular changes in the brain, whereas physical dependence is an adaptive physiological

state that can occur with regular drug use and results in withdrawal symptoms when drug

use is discontinued.

6

Under the Controlled Substances Act, which was enacted in 1970, drugs are classified as

controlled substances and placed into one of five schedules based on their medicinal value,

potential for abuse, and safety or dependence liability. Schedule I drugs have no medicinal

value; have not been approved by FDA; and along with schedule II drugs, have the highest

potential for abuse. Schedule II drugs have the highest potential for abuse of any approved

drugs.

Page 3 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

the body’s rapid absorption of oxycodone. During a December 2001

congressional hearing, witnesses from DEA and other law enforcement

officials from Kentucky, Virginia, and West Virginia described the growing

problem of abuse and diversion of OxyContin.

7

Questions were raised

about what factors may have caused the abuse and diversion, including

whether Purdue’s efforts to market the drug may have contributed to the

problem. In February 2002, another congressional hearing was conducted

on federal, state, and local efforts to decrease the abuse and diversion of

OxyContin.

8

Because of your concerns about these issues, you asked us to examine the

marketing and promotion of OxyContin and its abuse and diversion.

Specifically, we addressed the following questions:

1. How has Purdue marketed and promoted OxyContin?

2. What factors contributed to the abuse and diversion of OxyContin?

3. What actions have been taken to address OxyContin abuse and

diversion?

To identify how Purdue marketed and promoted OxyContin, we

interviewed Purdue officials and analyzed company documents and data.

We also interviewed selected Purdue sales representatives who were high

and midrange sales performers during 2001 and physicians who were

among the highest prescribers of OxyContin. To determine how Purdue’s

marketing and promotion of OxyContin compared to that of other drugs,

we examined the promotional materials and information related to FDA

actions and interviewed officials from companies that manufacture and

market three other opioid drugs, Avinza, Kadian, and Oramorph SR, that

like OxyContin are classified as schedule II controlled substances.

9

Because of their concern about the proprietary nature of the information,

7

OxyContin, Hearings of the Subcommittee on the Departments of Commerce, Justice, and

State, the Judiciary, and Related Agencies, House Committee on Appropriations, 107th

Cong. Part 10 (Dec. 11, 2001).

8

OxyContin: Balancing Risks and Benefits, Hearing of the Senate Committee on Health,

Education, Labor, and Pensions, 107th Cong. 287 (Feb. 12, 2002).

9

Avinza was approved by FDA in 2002 and is marketed by Ligand Pharmaceuticals; Kadian

was approved in 1996 and is marketed by Alpharma-US Human Pharmaceuticals; and

Oramorph SR was approved in 1991 and is now owned by Élan Corporation, which told us

it is not currently marketing the drug.

Page 4 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

the three companies that market these drugs did not provide us with the

same level of detail about the marketing and promotion of their drugs as

did Purdue. We also examined data from DEA on promotional

expenditures for OxyContin and two other schedule II controlled

substances. To examine what factors may have contributed to the abuse

and diversion of OxyContin, we interviewed officials from DEA, FDA, and

Purdue and physicians who prescribe OxyContin. We also analyzed IMS

Health data on sales of OxyContin nationwide and Purdue’s distribution of

sales representatives, as part of an effort to compare the areas with large

sales growth and more sales representatives per capita with the areas

where abuse and diversion problems were identified. However, limitations

on the abuse and diversion data prevented an assessment of the

relationship between the availability of OxyContin and areas where the

drug was abused or diverted. To determine what actions have been taken

to address OxyContin abuse and diversion, we interviewed FDA officials

and examined FDA information regarding the drug’s approval and

marketing and promotion. We also interviewed DEA officials and

examined how DEA determined the prevalence of OxyContin abuse and

diversion nationally. In addition, we examined state efforts to identify

those involved in the abuse and diversion of OxyContin. We also reviewed

actions taken by Purdue to address this problem. (See app. I for a detailed

discussion of our methodology.)

We performed our work from August 2002 through October 2003, in

accordance with generally accepted government auditing standards.

Purdue conducted an extensive campaign to market and promote

OxyContin using an expanded sales force and multiple promotional

approaches to encourage physicians, including primary care specialists, to

prescribe OxyContin as an initial opioid treatment for noncancer pain.

OxyContin sales and prescriptions grew rapidly following its market

introduction in 1996, with the growth in prescriptions for noncancer pain

outpacing the growth in prescriptions for cancer pain from 1997 through

2002. By 2003, nearly half of all OxyContin prescribers were primary care

physicians. DEA has expressed concern that Purdue’s aggressive

marketing of OxyContin focused on promoting the drug to treat a wide

range of conditions to physicians who may not have been adequately

trained in pain management. Purdue has been cited twice by FDA for using

potentially false or misleading medical journal advertisements for

OxyContin that violated the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act (FD&C

Act), including one advertisement that failed to include warnings about the

potentially fatal risks associated with OxyContin use. Further, Purdue did

Results in Brief

Page 5 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

not submit an OxyContin promotional video for FDA review at the time of

its initial distribution in 1998, as required by FDA regulations. Therefore,

FDA did not have the opportunity to review the video at the time of its

distribution to ensure that the information it contained was truthful,

balanced, and accurately communicated. FDA reviewed a similar video in

2002 and told us that the video appeared to have made unsubstantiated

claims about OxyContin and minimized its risks.

Several factors may have contributed to OxyContin’s abuse and diversion.

OxyContin’s controlled-release formulation, which made the drug

beneficial for the relief of moderate-to-severe pain over an extended

period of time, enabled the drug to contain more of the active ingredient

oxycodone than other, non-controlled-release oxycodone-containing

drugs. This feature may have made OxyContin an attractive target for

abuse and diversion, according to DEA. OxyContin’s controlled-release

formulation, which delayed the drug’s absorption, also led FDA to include

language in the original label stating that OxyContin had a lower potential

for abuse than other oxycodone products. FDA officials thought that the

controlled-release feature would make the drug less attractive to abusers.

However, FDA did not recognize that the drug could be dissolved in water

and injected, which disrupted the controlled-release characteristics and

created an immediate rush or high, thereby increasing the potential for

abuse. In addition, the safety warning on the label that advised patients

not to crush the tablets because a rapid release of a potentially toxic

amount of the drug could result—a customary precaution for controlled-

release medications—may have inadvertently alerted abusers to a possible

method for misusing the drug. The rapid growth in OxyContin sales, which

increased the drug’s availability in the marketplace, may have made it

easier for abusers to obtain the drug for illicit purposes. Further, some

geographic areas have been shown to have a history of prescription drug

abuse and diversion that may have predisposed some states to the abuse

and diversion of OxyContin. However, we could not assess the

relationship between the increased availability of OxyContin and locations

where it is being abused and diverted because the data on abuse and

diversion are not reliable, comprehensive, or timely.

Since 2000, federal and state agencies and Purdue have taken several

actions to try to address abuse and diversion of OxyContin. In July 2001,

FDA approved a revised OxyContin label adding the highest level of safety

warning that FDA can place on an approved drug product. The agency also

collaborated with Purdue to develop and implement a risk management

plan to help detect and prevent abuse and diversion of OxyContin. Risk

management plans were not used at the time OxyContin was approved.

Page 6 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

The plans are an optional feature of new drug applications that are

intended to decrease product risks by using one or more interventions or

tools beyond the approved product labeling. FDA plans to provide

guidance on risk management plans to the pharmaceutical industry by

September 2004. Also at the federal level, DEA initiated 257 OxyContin-

related abuse and diversion cases in fiscal years 2001 and 2002, which

resulted in 302 arrests and about $1 million in fines. At the state level,

Medicaid fraud control units have investigated OxyContin abuse and

diversion; however, they do not maintain precise data on the number of

investigations and enforcement actions completed. Similarly, state medical

licensure boards have investigated complaints about physicians who were

suspected of abuse and diversion of controlled substances, but they could

not provide data on the number of investigations involving OxyContin.

Purdue has initiated education programs and other activities for

physicians, pharmacists, and the public to address OxyContin abuse and

diversion. Purdue has also taken disciplinary action against its sales

representatives who improperly promoted OxyContin and has referred

physicians who were suspected of misprescribing OxyContin to the

appropriate authorities. Although Purdue has used very specific

information on physician prescribing practices to market and promote

OxyContin since its approval, it was not until October 2002 that Purdue

began to use this information and other indicators to identify patterns of

prescribing that could point to possible improper sales representative

promotion or physician abuse and diversion of OxyContin.

To improve efforts to prevent or identify the abuse and diversion of

schedule II controlled substances such as oxycodone, we recommend that

FDA’s risk management plan guidance encourage the pharmaceutical

manufacturers that submit new drug applications for these substances to

include plans that contain a strategy for monitoring the use of these drugs

and identifying potential abuse and diversion problems.

We received comments on a draft of this report from FDA, DEA, and

Purdue. FDA agreed with our recommendation that risk management

plans for schedule II controlled substances contain a strategy for

monitoring and identifying potential abuse and diversion problems. DEA

reiterated its statement that Purdue’s aggressive marketing of OxyContin

exacerbated the abuse and diversion problems and noted that it is

essential that risk management plans be put in place prior to the

introduction of controlled substances into the marketplace. Purdue said

the report appeared to be fair and balanced, but that we should add the

media as one of the factors contributing to abuse and diversion problems

Page 7 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

with OxyContin. We incorporated their technical comments where

appropriate.

Ensuring that pharmaceuticals are available for those with legitimate

medical need while combating the abuse and diversion of prescription

drugs involves the efforts of both federal and state government agencies.

Under the FD&C Act, FDA is responsible for ensuring that drugs are safe

and effective before they are available in the marketplace. The Controlled

Substances Act,

10

which is administered by DEA, provides the legal

framework for the federal government’s oversight of the manufacture and

wholesale distribution of controlled substances, that is, drugs and other

chemicals that have a potential for abuse. The states address certain issues

involving controlled substances through their own controlled substances

acts and their regulation of the practice of medicine and pharmacy. In

response to concerns about the influence of pharmaceutical marketing

and promotional activities on physician prescribing practices, both the

pharmaceutical industry and the Department of Health and Human

Services’s (HHS) Office of Inspector General have issued voluntary

guidelines on appropriate marketing and promotion of prescription drugs.

As the incidence and prevalence of painful diseases have grown along with

the aging of the population, there has been a growing acknowledgment of

the importance of providing effective pain relief. Pain can be characterized

in terms of intensity—mild to severe—and duration—acute (sudden onset)

or chronic (long term). The appropriate medical treatment varies

according to these two dimensions.

In 1986, WHO determined that cancer pain could be relieved in most if not

all patients, and it encouraged physicians to prescribe opioid analgesics.

WHO developed a three-step analgesic ladder as a practice guideline to

provide a sequential use of different drugs for cancer pain management.

For the first pain step, treatment with nonopioid analgesics, such as

aspirin or ibuprofen, is recommended. If pain is not relieved, then an

opioid such as codeine should be used for mild-to-moderate pain as the

second step. For the third step—moderate-to-severe pain—opioids such as

morphine should be used.

10

Title II of the Comprehensive Drug Abuse Prevention and Control Act of 1970 (Pub. L. No.

91-513, §§100 et seq., 84 Stat. 1236, 1242 et seq.).

Background

Medical Treatment of Pain

Page 8 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

Beginning in the mid-1990s, various national pain-related organizations

issued pain treatment and management guidelines, which included the use

of opioid analgesics in treating both cancer and noncancer pain. In 1995,

the American Pain Society recommended that pain should be treated as

the fifth vital sign

11

to ensure that it would become common practice for

health care providers to ask about pain when conducting patient

evaluations. The practice guidelines issued by the Agency for Health Care

Policy and Research provided physicians and other health care

professionals with information on the management of acute pain in 1992

and cancer pain in 1994, respectively.

12

Health care providers and hospitals

were further required to ensure that their patients received appropriate

pain treatment when the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare

Organizations (JCAHO), a national health care facility standards-setting

and accrediting body, implemented its pain standards for hospital

accreditation in 2001.

OxyContin, a schedule II drug manufactured by Purdue Pharma L.P., was

approved by FDA in 1995 for the treatment of moderate-to-severe pain

lasting more than a few days, as indicated in the original label.

13

OxyContin

followed Purdue’s older product, MS Contin, a morphine-based product

that was approved in 1984 for a similar intensity and duration of pain and

during its early years of marketing was promoted for the treatment of

cancer pain. The active ingredient in OxyContin tablets is oxycodone, a

compound that is similar to morphine and is also found in oxycodone-

combination pain relief drugs such as Percocet, Percodan, and Tylox.

Because of its controlled-release property, OxyContin contains more

active ingredient and needs to be taken less often (twice a day) than these

11

The other four vital signs physicians use to assess patients are pulse, blood pressure, core

temperature, and respiration.

12

In 1999, the name of the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research was changed to the

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The agency, which is part of HHS, is

responsible for supporting research designed to improve the quality of health care, reduce

its costs, and broaden access to essential services.

13

When we refer to OxyContin’s label we are also referring to the drug’s package insert that

contains the same information about the product.

OxyContin

Page 9 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

other oxycodone-containing drugs.

14

The OxyContin label originally

approved by FDA indicated that the controlled-release characteristics of

OxyContin were believed to reduce its potential for abuse. The label also

contained a warning that OxyContin tablets were to be swallowed whole,

and were not to be broken, chewed, or crushed because this could lead to

the rapid release and absorption of a potentially toxic dose of oxycodone.

Such a safety warning is customary for schedule II controlled-release

medications. FDA first approved the marketing and use of OxyContin in

10-, 20-, and 40-milligram controlled-release tablets. FDA later approved

80- and 160-milligram controlled-release tablets for use by patients who

were already taking opioids.

15

In July 2001, FDA approved the revised label

to state that the drug is approved for the treatment of moderate-to-severe

pain in patients who require “a continuous around-the-clock analgesic for

an extended period of time.” (See app. II for a summary of the changes

that were made by FDA to the original OxyContin label.)

OxyContin sales and prescriptions grew rapidly following its market

introduction in 1996. Fortuitous timing may have contributed to this

growth, as the launching of the drug occurred during the national focus on

the inadequacy of patient pain treatment and management. In 1997,

OxyContin’s sales and prescriptions began increasing significantly, and

they continued to increase through 2002. In both 2001 and 2002,

OxyContin’s sales exceeded $1 billion, and prescriptions were over 7

million. The drug became Purdue’s main product, accounting for 90

percent of the company’s total prescription sales by 2001.

Media reports of OxyContin abuse and diversion began to surface in 2000.

These reports first appeared in rural areas of some states, generally in the

Appalachian region, and continued to spread to other rural areas and

larger cities in several states. Rural communities in Maine, Kentucky, Ohio,

Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia were reportedly being devastated

by the abuse and diversion of OxyContin. For example, media reports told

of persons and communities that had been adversely affected by the rise of

addiction and deaths related to OxyContin. One report noted that drug

14

For example, according to Purdue’s comparable dose guide a patient taking one Percodan

4.5-milligram tablet or one Tylox 5-milligram tablet every 6 hours can be converted to

either a 10- or a 20-milligram OxyContin tablet to be taken every 12 hours. For a 12-hour

dosing period, one OxyContin tablet replaces two Percodan or Tylox tablets, and one

OxyContin tablet contains twice as much oxycodone as one of the other tablets.

15

In April 2001, Purdue discontinued distribution of the 160-milligram tablets because of

OxyContin abuse and diversion concerns.

Page 10 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

treatment centers and emergency rooms in a particular area were

receiving new patients who were addicted to OxyContin as early as 1999.

Pain patients, teens, and recreational drug users who had abused

OxyContin reportedly entered drug treatment centers sweating and

vomiting from withdrawal. In West Virginia, as many as one-half of the

approximately 300 patients admitted to a drug treatment clinic in 2000

were treated for OxyContin addiction. The media also reported on deaths

due to OxyContin. For example, a newspaper’s investigation of autopsy

reports involving oxycodone-related deaths found that OxyContin had

been involved in over 200 overdose deaths in Florida since 2000.

16

In

another case, a forensic toxicologist commented that he had reviewed a

number of fatal overdose cases in which individuals took a large dose of

OxyContin, in combination with alcohol or other drugs.

After learning about the initial reports of abuse and diversion of

OxyContin in Maine in 2000, Purdue formed a response team made up of

its top executives and physicians to initiate meetings with federal and

state officials in Maine to gain an understanding of the scope of the

problem and to devise strategies for preventing abuse and diversion. After

these meetings, Purdue distributed brochures to health care professionals

that described several steps that could be taken to prevent prescription

drug abuse and diversion. In response to the abuse and diversion reports,

DEA analyzed data collected from medical examiner autopsy reports and

crime scene investigation reports. The most recent data available from

DEA show that as of February 2002, the agency had verified 146 deaths

nationally involving OxyContin in 2000 and 2001.

According to Purdue, as of early October 2003, over 300 lawsuits

concerning OxyContin were pending against Purdue, and 50 additional

lawsuits had been dismissed. The cases involve many allegations,

including, for example, that Purdue used improper sales tactics and

overpromoted OxyContin causing the drug to be inappropriately

prescribed by physicians, and that Purdue took inadequate actions to

prevent addiction, abuse, and diversion of the drug. The lawsuits have

been brought in 25 states and the District of Columbia in both federal and

state courts.

16

Doris Bloodsworth, “Pain Pill Leaves Death Trail: A Nine-Month Investigation Raises

Many Questions about Purdue Pharma’s Powerful Drug OxyContin,” Orlando Sentinel,

Oct. 19, 2003.

Page 11 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

The Controlled Substances Act established a classification structure for

drugs and chemicals used in the manufacture of drugs that are designated

as controlled substances.

17

Controlled substances are classified by DEA

into five schedules on the basis of their medicinal value, potential for

abuse, and safety or dependence liability. Schedule I drugs—including

heroin, marijuana, and LSD—have a high potential for abuse and no

currently accepted medical use. Schedule II drugs—which include opioids

such as morphine and oxycodone, the primary ingredient in OxyContin—

have a high potential for abuse among drugs with an accepted medical use

and may lead to severe psychological or physical dependence. Drugs on

schedules III through V have medical uses and successively lower

potentials for abuse and dependence. Schedule III drugs include anabolic

steroids, codeine, hydrocodone in combination with aspirin or

acetaminophen, and some barbiturates. Schedule IV contains such drugs

as the antianxiety drugs diazepam (Valium) and alprazolam (Xanax).

Schedule V includes preparations such as cough syrups with codeine. All

scheduled drugs except those in schedule I are legally available to the

public with a prescription.

18

Under the FD&C Act and implementing regulations, FDA is responsible for

ensuring that all new drugs are safe and effective. FDA reviews scientific

and clinical data to decide whether to approve drugs based on their

intended use, effectiveness, and the risks and benefits for the intended

population, and also monitors drugs for continued safety after they are in

use.

FDA also regulates the advertising and promotion of prescription drugs

under the FD&C Act. FDA carries out this responsibility by ensuring that

prescription drug advertising and promotion is truthful, balanced, and

accurately communicated.

19

The FD&C Act makes no distinction between

17

Section 201, classified to 21 U.S.C. § 811.

18

Some schedule V drugs that contain limited quantities of certain narcotic and stimulant

drugs are available over the counter, without a prescription.

19

FDA regulations require that promotional labeling and advertisements be submitted to

FDA at the time of initial dissemination (for labeling) and initial publication (for

advertisements). The FD&C Act defines labeling to include all labels and other written,

printed, or graphic matter accompanying an article. For example, promotional materials

commonly shown or given to physicians, such as sales aids and branded promotional items,

are regulated as promotional labeling. FDA may also regulate promotion by sales

representatives on computer programs, through fax machines, or on electronic bulletin

boards.

Controlled Substances Act

FDA’s Regulation of

Prescription Drugs

Page 12 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

controlled substances and other prescription drugs in the oversight of

promotional activities. FDA told us that the agency takes a risk-based

approach to enforcement, whereby drugs with more serious risks, such as

opioids, are given closer scrutiny in monitoring promotional messages and

activities, but the agency has no specific guidance or policy on this

approach. The FD&C Act and its implementing regulations require that all

promotional materials for prescription drugs be submitted to FDA at the

time the materials are first disseminated or used, but it generally is not

required that these materials be approved by FDA before their use. As a

result, FDA’s actions to address violations occur after the materials have

already appeared in public. In fiscal year 2002, FDA had 39 staff positions

dedicated to oversight of drug advertising and promotion of all

pharmaceuticals distributed in the United States. According to FDA, most

of the staff focuses on the oversight of promotional communications to

physicians. FDA officials told us that in 2001 it received approximately

34,000 pieces of promotional material, including consumer advertisements

and promotions to physicians, and received and reviewed 230 complaints

about allegedly misleading advertisements, including materials directed at

health professionals.

20

FDA issues two types of letters to address violations of the FD&C Act:

untitled letters and warning letters. Untitled letters are issued for

violations such as overstating the effectiveness of the drug, suggesting a

broader range of indicated uses than the drug has been approved for, and

making misleading claims because of inadequate context or lack of

balanced information. Warning letters are issued for more serious

violations, such as those involving safety or health risks, or for continued

violations of the act. Warning letters generally advise a pharmaceutical

manufacturer that FDA may take further enforcement actions, such as

seeking judicial remediation, without notifying the company and may ask

the manufacturer to conduct a new advertising campaign to correct

inaccurate impressions left by the advertisements.

Under the Controlled Substances Act, FDA notifies DEA if FDA is

reviewing a new drug application for a drug that has a stimulant,

depressant, or hallucinogenic effect on the central nervous system and has

abuse potential. FDA performs a medical and scientific assessment as

20

For details on FDA’s oversight of drug advertising see U.S. General Accounting Office,

Prescription Drugs: FDA Oversight of Direct-to-Consumer Advertising Has Limitations,

GAO-03-177 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 28, 2002).

Page 13 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

required by the Controlled Substances Act, and recommends to DEA an

initial schedule level to be assigned to a new controlled substance.

FDA plans to provide guidance to the pharmaceutical industry on the

development, implementation, and evaluation of risk management plans as

a result of the reauthorization of the Prescription Drug User Fee Act of

1992 (PDUFA).

21

FDA expects to issue this guidance by September 30,

2004. FDA defines a risk management program as a strategic safety

program that is designed to decrease product risks by using one or more

interventions or tools beyond the approved product labeling. Interventions

used in risk management plans may include postmarketing surveillance,

education and outreach programs to health professionals or consumers,

informed consent agreements for patients, limitations on the supply or

refills of products, and restrictions on individuals who may prescribe and

dispense drug products. All drug manufacturers have the option to develop

and submit risk management plans to FDA as part of their new drug

applications.

DEA is the primary federal agency responsible for enforcing the

Controlled Substances Act. DEA has the authority to regulate transactions

involving the sale and distribution of controlled substances at the

manufacturer and wholesale distributor levels. DEA registers legitimate

handlers of controlled substances—including manufacturers, distributors,

hospitals, pharmacies, practitioners, and researchers—who must comply

with regulations relating to drug security and accountability through the

maintenance of inventories and records. All registrants, including

pharmacies, are required to maintain records of controlled substances that

have been manufactured, purchased, and sold. Manufacturers and

distributors are also required to report their annual inventories of

controlled substances to DEA. The data provided to DEA are available for

use in monitoring the distribution of controlled substances throughout the

United States and identifying retail-level registrants that received unusual

quantities of controlled substances. DEA regulations for schedule II

prescription drugs, unlike those for other prescription drugs, require that

each prescription must be written and signed by the physician and may

not be telephoned in to the pharmacy except in an emergency. Also, a

21

The Prescription Drug User Fee Act of 1992, Pub. L. No. 102-571, title I, 106 Stat. 4491, was

reauthorized by the Food and Drug Modernization Act of 1997, Pub. L. No. 105-115, 111

Stat. 2296, and, most recently, by the Prescription Drug User Fee Amendments of 2002,

Pub. L. No. 107-188, title V, subtitle A, 116 Stat. 594, 687.

DEA’s Regulation of

Controlled Substances

Page 14 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

prescription for a schedule II drug may not be refilled. A physician is

required to provide a new prescription each time a patient obtains more of

the drug. DEA also sets limits on the quantity of schedule II controlled

substances that may be produced in the United States in any given year.

Specifically, DEA sets aggregate production quotas that limit the

production of bulk raw materials used in the manufacture of controlled

substances. DEA determines these quotas based on a variety of data

including sales, production, inventories, and exports. Individual

companies must apply to DEA for manufacturing or procurement quotas

for specific pharmaceutical products. For example, Purdue has a

procurement quota for oxycodone, the principle ingredient in OxyContin,

that allows the company to purchase specified quantities of oxycodone

from bulk manufacturers.

State laws govern the prescribing and dispensing of prescription drugs by

licensed health care professionals. Each state requires that physicians

practicing in the state be licensed, and state medical practice laws

generally outline standards for the practice of medicine and delegate the

responsibility of regulating physicians to state medical boards. States also

require pharmacists and pharmacies to be licensed. The regulation of the

practice of pharmacy is based on state pharmacy practice acts and

regulations enforced by the state boards of pharmacy. According to the

National Association of Boards of Pharmacy, all state pharmacy laws

require that records of prescription drugs dispensed to patients be

maintained and that state pharmacy boards have access to the prescription

records. State regulatory boards face new challenges with the advent of

Internet pharmacies, because they enable pharmacies and physicians to

anonymously reach across state borders to prescribe, sell, and dispense

prescription drugs without complying with state requirements.

22

In some

cases, consumers can purchase prescription drugs, including controlled

substances, such as OxyContin, from Internet pharmacies without a valid

prescription.

22

For more details on Internet pharmacies, see U.S. General Accounting Office, Internet

Pharmacies: Adding Disclosure Requirements Would Aid State and Federal Oversight,

GAO-01-69 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 19, 2000).

States’ Regulation of the

Practice of Medicine and

Pharmacy and Role in

Monitoring Illegal Use and

Diversion of Prescription

Drugs

Page 15 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

In addition to these regulatory boards, 15 states operate prescription drug

monitoring programs as a means to control the illegal diversion of

prescription drugs that are controlled substances. Prescription drug

monitoring programs are designed to facilitate the collection, analysis, and

reporting of information on the prescribing, dispensing, and use of

controlled substances within a state. They provide data and analysis to

state law enforcement and regulatory agencies to assist in identifying and

investigating activities potentially related to the illegal prescribing,

dispensing, and procuring of controlled substances. For example,

physicians in Kentucky can use the program to check a patient’s

prescription drug history to determine if the individual may be “doctor

shopping” to seek multiple controlled substance prescriptions. An

overriding goal of prescription drug monitoring programs is to support

both the state laws ensuring access to appropriate pharmaceutical care by

citizens and the state laws deterring diversion. As we have reported, state

prescription drug monitoring programs offer state regulators an efficient

means of detecting and deterring illegal diversion. However, few states

proactively analyze prescription data to identify individuals, physicians, or

pharmacies that have unusual use, prescribing, or dispensing patterns that

may suggest potential drug diversion or abuse. Although three states can

respond to requests for information within 3 to 4 hours, providing

information on suspected illegal prescribing, dispensing, or doctor

shopping at the time a prescription is written or sold would require states

to improve computer capabilities. In addition, state prescription drug

monitoring programs may require additional legal authority to analyze data

proactively.

23

At the time that OxyContin was first marketed, there were no industry or

federal guidelines for the promotion of prescription drugs. Voluntary

guidelines regarding how drug companies should market and promote

their drugs to health care professionals were issued in July 2002 by the

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA). In

April 2003, HHS’s Office of Inspector General issued voluntary guidelines

for how drug companies should market and promote their products to

federal health care programs. Neither set of guidelines distinguishes

between controlled and noncontrolled substances.

23

For more details on these programs, see U.S. General Accounting Office, Prescription

Drugs: State Monitoring Programs Provide Useful Tool to Reduce Diversion, GAO-02-634

(Washington, D.C.: May 17, 2002).

Guidelines for Marketing

Drugs to Health Care

Professionals

Page 16 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

PhRMA’s voluntary code of conduct for sales representatives states that

interactions with health care professionals should be to inform these

professionals about products, to provide scientific and educational

information, and to support medical research and education.

24

The

question-and-answer section of the code addresses companies’ use of

branded promotional items, stating, for example, that golf balls and sports

bags should not be distributed because they are not primarily for the

benefit of patients, but that speaker training programs held at golf resorts

may be acceptable if participants are receiving extensive training. Purdue

adopted the code.

In April 2003, HHS’s Office of Inspector General issued final voluntary

guidance for drug companies’ interactions with health care professionals

in connection with federal health care programs, including Medicare and

Medicaid. Among the guidelines were cautions for companies against

offering inappropriate travel, meals, and gifts to influence the prescribing

of drugs; making excessive payments to physicians for consulting and

research services; and paying physicians to switch their patients from

competitors’ drugs.

Purdue conducted an extensive campaign to market and promote

OxyContin that focused on encouraging physicians, including those in

primary care specialties, to prescribe the drug for noncancer as well as

cancer pain. To implement its OxyContin campaign, Purdue significantly

increased its sales force and used multiple promotional approaches.

OxyContin sales and prescriptions grew rapidly following its market

introduction, with the growth in prescriptions for noncancer pain

outpacing the growth in prescriptions for cancer pain. DEA has expressed

concern that Purdue marketed OxyContin for a wide variety of conditions

to physicians who may not have been adequately trained in pain

management. Purdue has been cited twice by FDA for OxyContin

advertisements in medical journals that violated the FD&C Act. FDA has

also taken similar actions against manufacturers of two of the three

comparable schedule II controlled substances we examined, to ensure that

24

In addition, the American Medical Association, a professional association for physicians,

issued guidelines in 1990 regarding gifts given to physicians by drug industry

representatives. For example, physicians may accept individual gifts of nominal value that

are related to their work, such as notepads and pens, and may attend conferences

sponsored by drug companies that are educational and for which appropriate disclosure of

financial support or conflicts of interest is made.

Purdue Conducted an

Extensive Campaign

to Market and

Promote OxyContin

Page 17 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

their marketing and promotion were truthful, balanced, and accurately

communicated. In addition, Purdue provided two promotional videos to

physicians that, according to FDA appear to have made unsubstantiated

claims and minimized the risks of OxyContin. The first video was available

for about 3 years without being submitted to FDA for review.

From the outset of the OxyContin marketing campaign, Purdue promoted

the drug to physicians for noncancer pain conditions that can be caused

by arthritis, injuries, and chronic diseases, in addition to cancer pain.

Purdue directed its sales representatives to focus on the physicians in

their sales territories who were high opioid prescribers. This group

included cancer and pain specialists, primary care physicians, and

physicians who were high prescribers of Purdue’s older product, MS

Contin. One of Purdue’s goals was to identify primary care physicians who

would expand the company’s OxyContin prescribing base. Sales

representatives were also directed to call on oncology nurses, consultant

pharmacists, hospices, hospitals, and nursing homes.

From OxyContin’s launch until its July 2001 label change, Purdue used two

key promotional messages for primary care physicians and other high

prescribers. The first was that physicians should prescribe OxyContin for

their pain patients both as the drug “to start with and to stay with.” The

second contrasted dosing with other opioid pain relievers with OxyContin

dosing as “the hard way versus the easy way” to dose because OxyContin’s

twice-a-day dosing was more convenient for patients.

25

Purdue’s sales

representatives promoted OxyContin to physicians as an initial opioid

treatment for moderate-to-severe pain lasting more than a few days, to be

prescribed instead of other single-entity opioid analgesics or short-acting

combination opioid pain relievers. Purdue has stated that by 2003 primary

care physicians had grown to constitute nearly half of all OxyContin

prescribers, based on data from IMS Health, an information service

providing pharmaceutical market research. DEA’s analysis of physicians

prescribing OxyContin found that the scope of medical specialties was

wider for OxyContin than five other controlled-release, schedule II

narcotic analgesics. DEA expressed concern that this resulted in

25

Following OxyContin’s July 2001 label change, Purdue modified its promotional messages

but continued to focus on encouraging physicians to prescribe OxyContin for patients

taking pain relievers every 4 to 6 hours. In 2003, Purdue began using the promotional claim

“there can be life with relief” in OxyContin promotion.

Purdue Focused on

Promoting OxyContin for

Treatment of Noncancer

Pain

Page 18 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

OxyContin’s being promoted to physicians who were not adequately

trained in pain management.

Purdue’s promotion of OxyContin for the treatment of noncancer pain

contributed to a greater increase in prescriptions for noncancer pain than

for cancer pain from 1997 through 2002.

26

According to IMS Health data,

the annual number of OxyContin prescriptions for noncancer pain

increased nearly tenfold, from about 670,000 in 1997 to about 6.2 million in

2002.

27

In contrast, during the same 6 years, the annual number of

OxyContin prescriptions for cancer pain increased about fourfold, from

about 250,000 in 1997 to just over 1 million in 2002. The noncancer

prescriptions therefore increased from about 73 percent of total

OxyContin prescriptions to about 85 percent during that period, while the

cancer prescriptions decreased from about 27 percent of the total to about

15 percent. IMS Health data indicated that prescriptions for other schedule

II opioid drugs, such as Duragesic

28

and morphine products, for noncancer

pain also increased during this period. Duragesic prescriptions for

noncancer pain were about 46 percent of its total prescriptions in 1997,

and increased to about 72 percent of its total in 2002. Morphine products,

including, for example, Purdue’s MS Contin, also experienced an increase

in their noncancer prescriptions during the same period. Their noncancer

prescriptions were about 42 percent of total prescriptions in 1997, and

increased to about 65 percent in 2002. DEA has cited Purdue’s focus on

promoting OxyContin for treating a wide range of conditions as one of the

reasons the agency considered Purdue’s marketing of OxyContin to be

overly aggressive.

26

IMS Health reported noncancer prescriptions written for the following types of pain

conditions: surgical aftercare; musculoskeletal disorders including back and neck

disorders, arthritis conditions, and injuries and trauma including bone fractures; central

nervous system disorders including headache conditions such as migraines; genitourinary

disorders including kidney stones; and other types of general pain.

27

The IMS Health data included information from the National Disease and Therapeutics

Index and the National Prescription Audit. The National Disease and Therapeutics Index

does not capture data from anesthesiologists and dental specialties. The National

Prescription Audit data include retail pharmacy, long-term-care, and mail-order

prescriptions.

28

Duragesic is a skin patch used to deliver the opioid pain reliever fentanyl over a 72-hour

period.

Page 19 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

Purdue significantly increased its sales force to market and promote

OxyContin to physicians and other health care practitioners. In 1996,

Purdue began promoting OxyContin with a sales force of approximately

300 representatives in its Prescription Sales Division.

29

Through a 1996

copromotion agreement, Abbott Laboratories provided at least another

300 representatives, doubling the total OxyContin sales force.

30

By 2000,

Purdue had more than doubled its own internal sales force to 671. The

expanded sales force included sales representatives from the Hospital

Specialty Division, which was created in 2000 to increase promotional

visits on physicians located in hospitals. (See table 1.)

Table 1: Sales Representative Positions Available for OxyContin Promotion, 1996

through 2002

Positions available

a

1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002

Purdue Prescription Sales Division 318 319 377 471 562 641 641

Purdue Hospital Specialty Division 0 0 0 0 109 125 126

Subtotal—All Purdue sales

representatives

318 319 377 471 671 766 767

Abbott Laboratories sales

representatives

b

300 300 300 300 300 300 300

Total 618 619 677 771 971 1,066 1,067

Source: GAO analysis of Purdue data.

a

All positions were not necessarily filled in a given year.

b

Under the OxyContin copromotion agreement, Abbott Laboratories provided at least 300 sales

representatives each year.

The manufacturers of two of the three comparable schedule II drugs have

smaller sales forces than Purdue. Currently, the manufacturer of Kadian

has about 100 sales representatives and is considering entering into a

copromotion agreement. Elan, the current owner of Oramorph SR, has

approximately 300 representatives, but told us that it is not currently

marketing Oramorph SR. The manufacturer of Avinza had approximately

50 representatives at its product launch. In early 2003, Avinza’s

manufacturer announced that more than 700 additional sales

29

These sales representatives were also responsible for promoting other Purdue products.

30

Abbott Laboratories sales representatives’ promotion of OxyContin is limited to hospital-

based anesthesiologists and surgeons and major hospitals, medical centers, and

freestanding pain clinics.

Purdue Significantly

Increased Its Sales Force

to Market and Promote

OxyContin

Page 20 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

representatives would be promoting the drug under its copromotion

agreement with the pharmaceutical manufacturer Organon—for a total of

more than 800 representatives.

By more than doubling its total sales representatives, Purdue significantly

increased the number of physicians to whom it was promoting OxyContin.

Each Purdue sales representative has a specific sales territory and is

responsible for developing a list of about 105 to 140 physicians to call on

who already prescribe opioids or who are candidates for prescribing

opioids. In 1996, the 300-plus Purdue sales representatives had a total

physician call list of approximately 33,400 to 44,500. By 2000, the nearly

700 representatives had a total call list of approximately 70,500 to 94,000

physicians. Each Purdue sales representative is expected to make about 35

physician calls per week and typically calls on each physician every 3 to 4

weeks. Each hospital sales representative is expected to make about 50

calls per week and typically calls on each facility every 4 weeks.

Purdue stated it offered a “better than industry average” salary and sales

bonuses to attract top sales representatives and provide incentives to

boost OxyContin sales as it had done for MS Contin. Although the sales

representatives were primarily focused on OxyContin promotion, the

amount of the bonus depended on whether a representative met the sales

quotas in his or her sales territory for all company products. As

OxyContin’s sales increased, Purdue’s growth-based portion of the bonus

formula increased the OxyContin sales quotas necessary to earn the same

base sales bonus amounts. The amount of total bonuses that Purdue

estimated were tied to OxyContin sales increased significantly from about

$1 million in 1996, when OxyContin was first marketed, to about $40

million in 2001. Beginning in 2000, when the newly created hospital

specialty representatives began promoting OxyContin, their estimated

total bonuses were approximately $6 million annually. In 2001, the average

annual salary for a Purdue sales representative was $55,000, and the

average annual bonus was $71,500. During the same year, the highest

annual sales bonus was nearly $240,000, and the lowest was nearly

$15,000. In 2001, Purdue decided to limit the sales bonus a representative

could earn based on the growth in prescribing of a single physician after a

meeting with the U.S. Attorney for the Western District of Virginia at

which the company was informed of the possibility that a bonus could be

based on the prescribing of one physician.

Page 21 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

In addition to expanding its sales force, Purdue used multiple approaches

to market and promote OxyContin. These approaches included expanding

its physician speaker bureau and conducting speaker training conferences,

sponsoring pain-related educational programs, issuing OxyContin starter

coupons for patients’ initial prescriptions, sponsoring pain-related Web

sites, advertising OxyContin in medical journals, and distributing

OxyContin marketing items to health care professionals.

In our report on direct-to-consumer advertising, we found that most

promotional spending is targeted to physicians.

31

For example, in 2001, 29

percent of spending on pharmaceutical promotional activities was related

to activities of pharmaceutical sales representatives directed to

physicians, and 2 percent was for journal advertising—both activities

Purdue uses for its OxyContin promotion. The remaining 69 percent of

pharmaceutical promotional spending involved sampling (55 percent),

which is the practice of providing drug samples during sales visits to

physician offices, and direct-to-consumer advertising (14 percent)—both

activities that Purdue has stated it does not use for OxyContin.

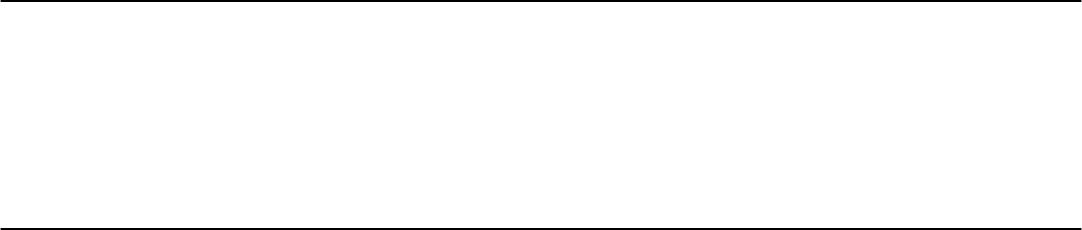

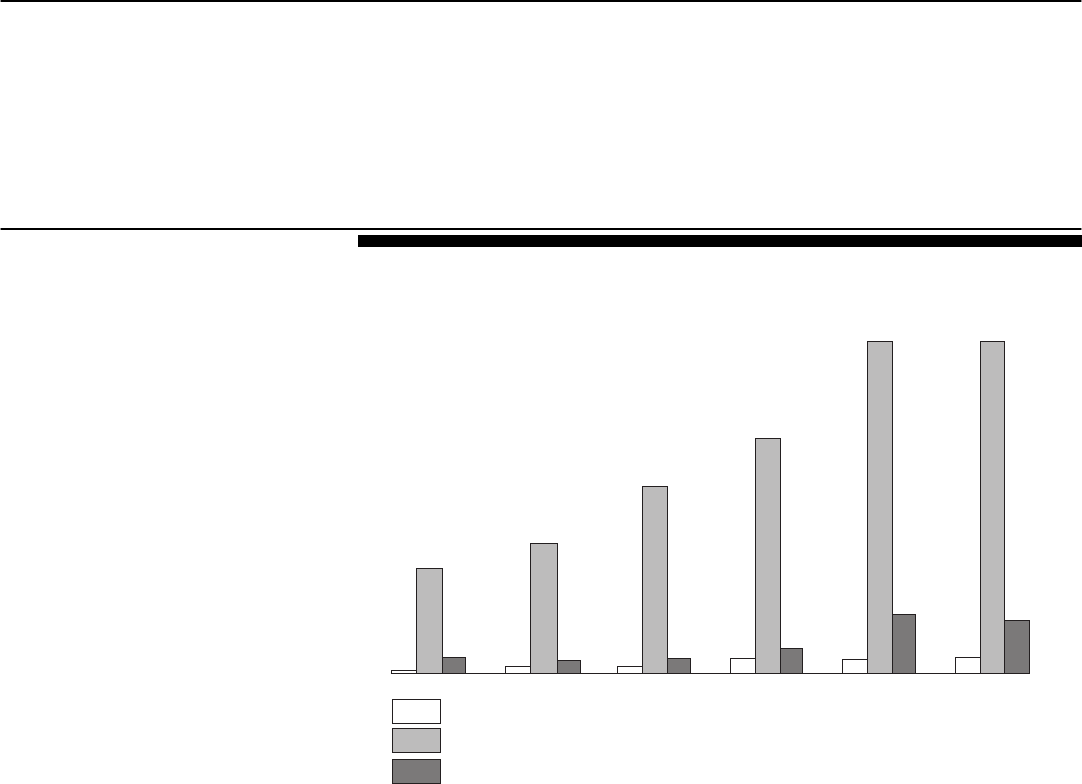

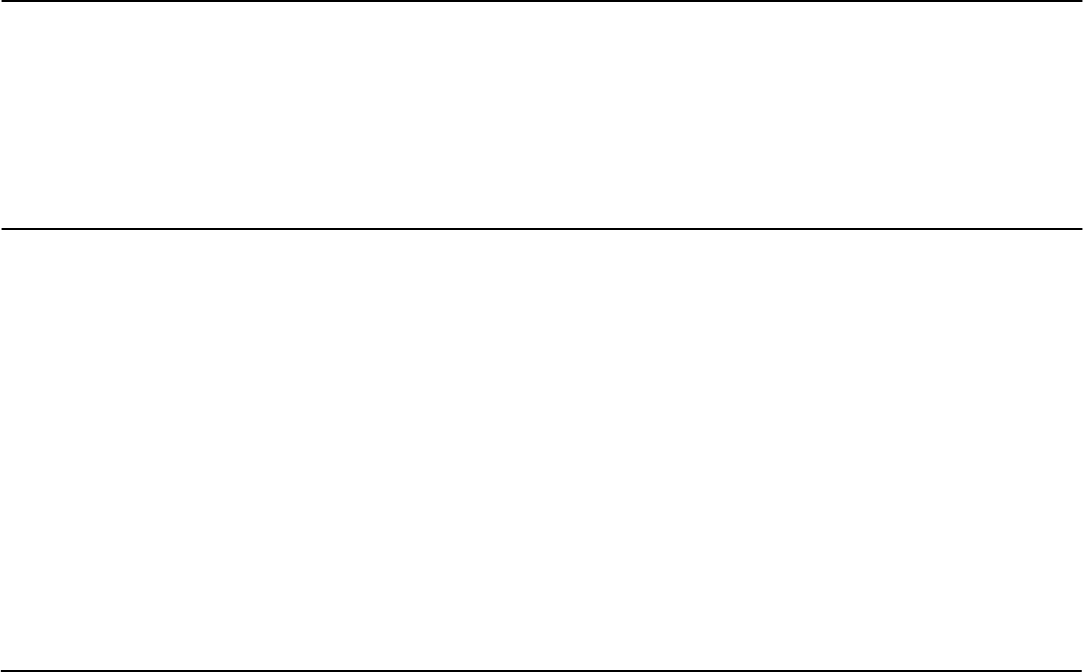

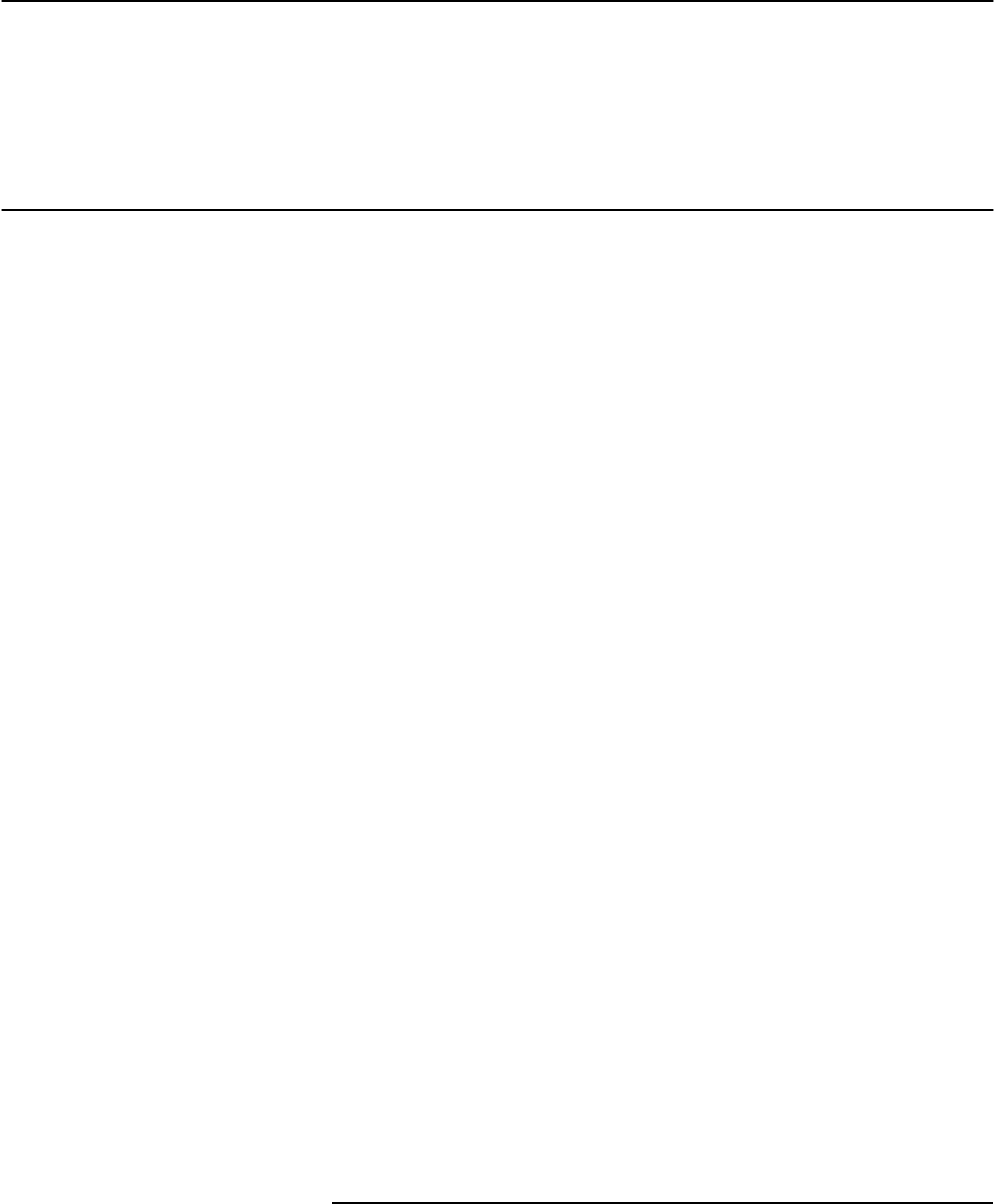

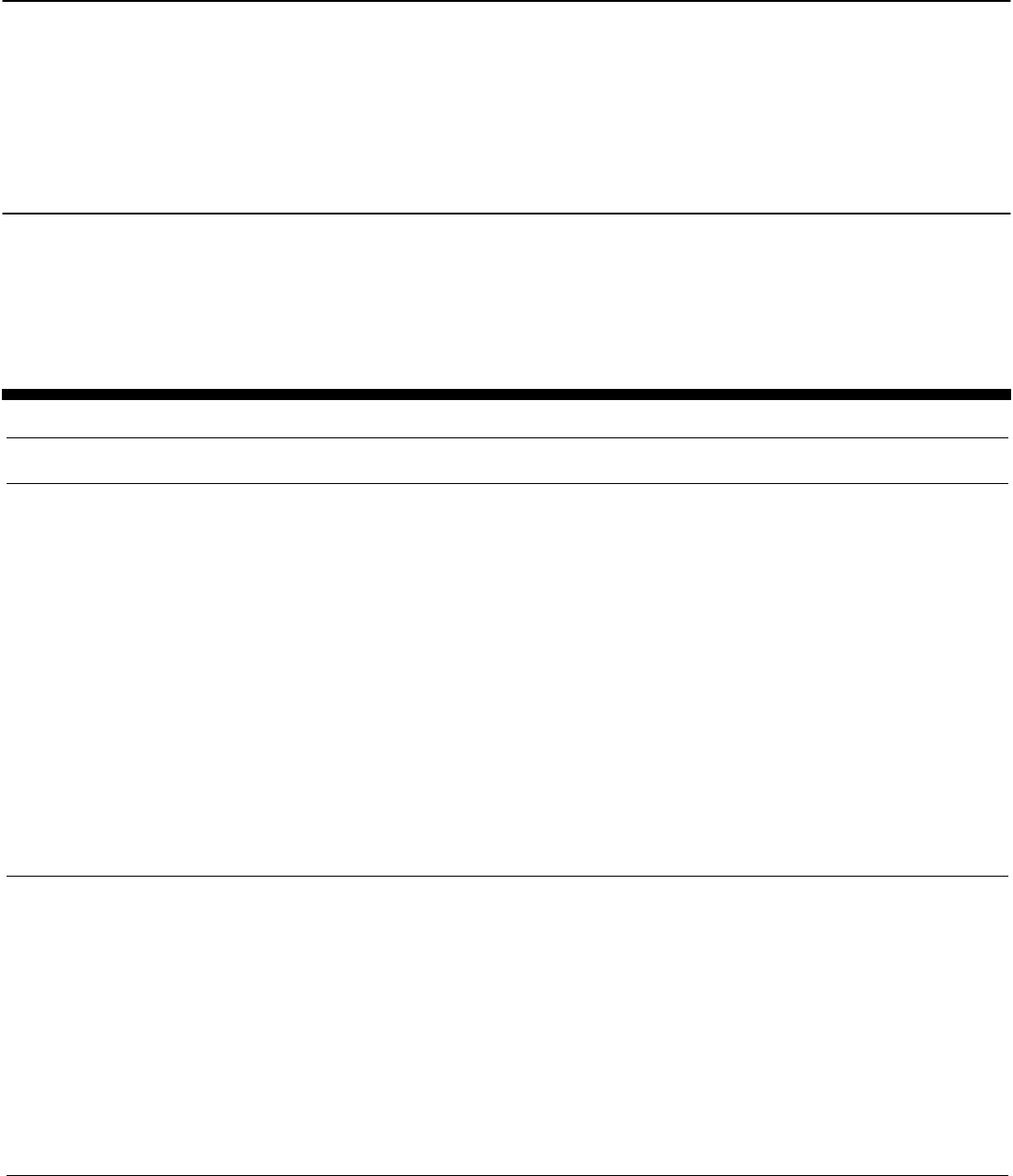

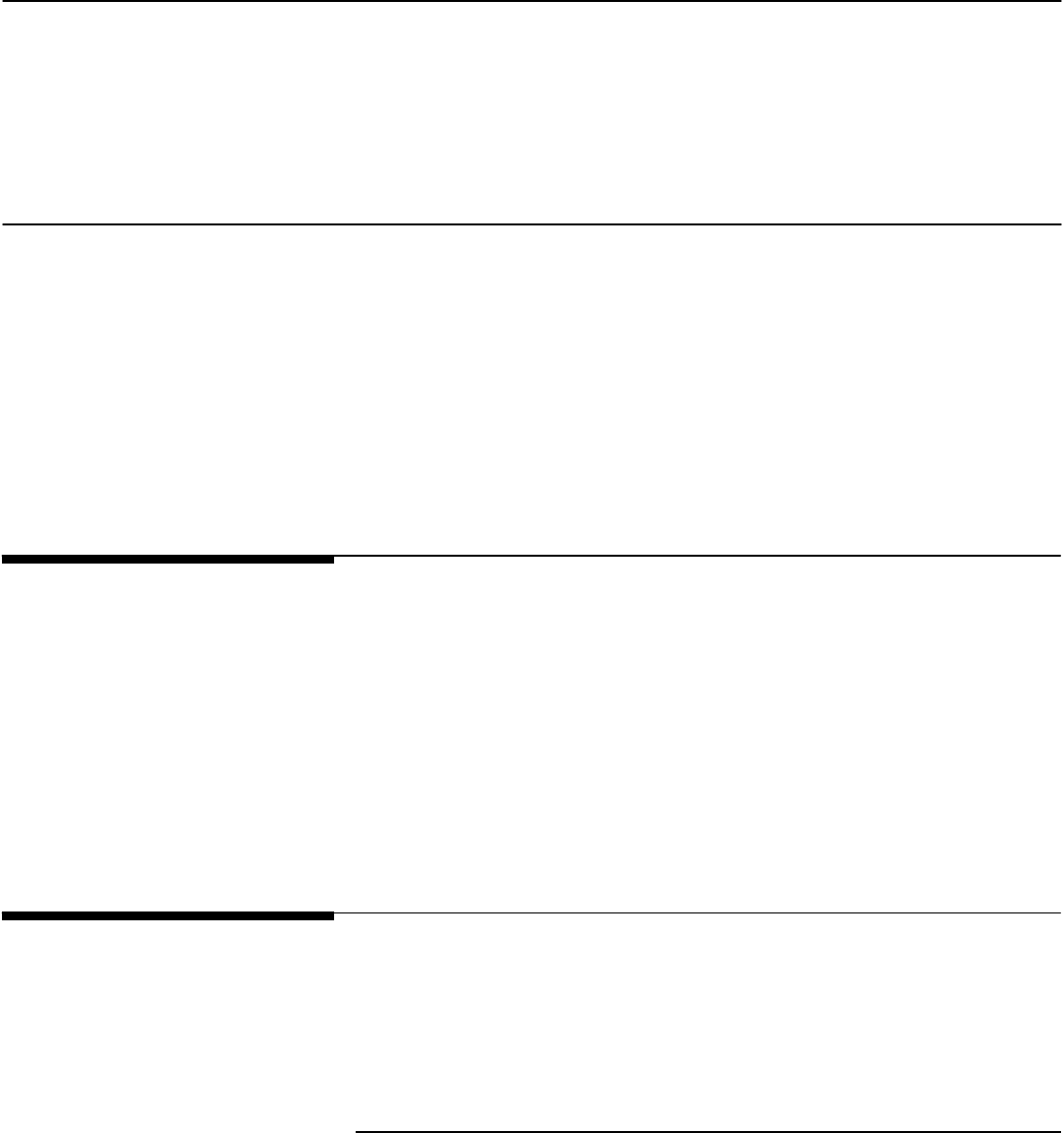

According to DEA’s analysis of IMS Health data, Purdue spent

approximately 6 to 12 times more on promotional efforts during

OxyContin’s first 6 years on the market than it had spent on its older

product, MS Contin, during its first 6 years, or than had been spent by

Janssen Pharmaceutical Products, L.P., for one of OxyContin’s drug

competitors, Duragesic. (See fig. 1.)

31

U.S. General Accounting Office, Prescription Drugs: FDA Oversight of Direct-to-

Consumer Advertising Has Limitations, GAO-03-177 (Washington, D.C.: Oct. 28, 2002).

Purdue Employed Multiple

Approaches to Market and

Promote OxyContin

Page 22 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

Figure 1: Promotional Spending for Three Opioid Analgesics in First 6 Years of

Sales

Note: Dollars are 2002 adjusted.

During the first 5 years that OxyContin was marketed, Purdue conducted

over 40 national pain management and speaker training conferences,

usually in resort locations such as Boca Raton, Florida, and Scottsdale,

Arizona, to recruit and train health care practitioners for its national

speaker bureau. The trained speakers were then made available to speak

about the appropriate use of opioids, including oxycodone, the active

ingredient in OxyContin, to their colleagues in various settings, such as

local medical conferences and grand round presentations in hospitals

involving physicians, residents, and interns. Over the 5 years, these

conferences were attended by more than 5,000 physicians, pharmacists,

and nurses, whose travel, lodging, and meal costs were paid by the

company. Purdue told us that less than 1 percent annually of the

physicians called on by Purdue sales representatives attended these

conferences. Purdue told us it discontinued conducting these conferences

in fall 2000. Purdue’s speaker bureau list from 1996 through mid-2002

included nearly 2,500 physicians, of whom over 1,000 were active

participants. Purdue has paid participants a fee for speaking based on the

physician’s qualifications; the type of program and time commitment

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

MS Contin: 1984-1989

OxyContin: 1996-2001

Duragesic: 1991-1996

Year 1 Year 2 Year 3 Year 4 Year 5 Year 6

Source: DEA and IMS Health, Integrated Promotional Service Audit.

Absolute dollars in millions

Page 23 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

involved; and expenses such as airfare, hotel, and food. The company

currently marketing the comparable drug Avinza has a physician speaker

bureau, but does not sponsor speaker training and conferences at resort

locations. Kadian’s current company does not have a physician speaker

bureau and has not held any conferences.

From 1996, when OxyContin was introduced to the market, to July 2002,

Purdue has funded over 20,000 pain-related educational programs through

direct sponsorship or financial grants. These grants included support for

programs to provide physicians with opportunities to earn required

continuing medical education credits, such as grand round presentations

at hospitals and medical education seminars at state and local medical

conferences. During 2001 and 2002, Purdue funded a series of nine

programs throughout the country to educate hospital physicians and staff

on how to comply with JCAHO’s pain standards for hospitals and to

discuss postoperative pain treatment. Purdue was one of only two drug

companies that provided funding for JCAHO’s pain management

educational programs.

32

Under an agreement with JCAHO, Purdue was the

only drug company allowed to distribute certain educational videos and a

book about pain management; these materials were also available for

purchase from JCAHO’s Web site. Purdue’s participation in these activities

with JCAHO may have facilitated its access to hospitals to promote

OxyContin.

For the first time in marketing any of its products, Purdue used a patient

starter coupon program for OxyContin to provide patients with a free

limited-time prescription. Unlike patient assistance programs, which

provide free prescriptions to patients in financial need, a coupon program

is intended to enable a patient to try a new drug through a one-time free

prescription. A sales representative distributes coupons to a physician,

who decides whether to offer one to a patient, and then the patient

redeems it for a free prescription through a participating pharmacy. The

program began in 1998 and ran intermittently for 4 years. In 1998 and 1999,

each sales representative had 25 coupons that were redeemable for a free

30-day supply. In 2000 each representative had 90 coupons for a 7-day

supply, and in 2001 each had 10 coupons for a 7-day supply.

Approximately 34,000 coupons had been redeemed nationally when the

32

During 2000 through 2002, JCAHO sponsored a series of educational programs on pain

management standards with various cosponsors, including pain-related groups such as the

American Pain Society and the American Academy of Pain Medicine.

Page 24 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

program was terminated following the July 2001 OxyContin label change.

The manufacturers of two of the comparable drugs we examined—Avinza

and Kadian—used coupon programs to introduce patients to their

products. Avinza’s coupon program requires patients to make a copayment

to cover part of the drug’s cost.

Purdue has also used Web sites to provide pain-related information to

consumers and others. In addition to its corporate Web site, which

provides product information, Purdue established the “Partners Against

Pain” Web site in 1997 to provide consumers with information about pain

management and pain treatment options. According to FDA, the Web site

also contained information about OxyContin. Separate sections provide

information for patients and caregivers, medical professionals, and

institutions. The Web site includes a “Find a Doctor” feature to enable

consumers to find physicians who treat pain in their geographic area.

33

As

of July 2002, over 33,000 physicians were included. Ligand, which markets

Avinza, one of the comparable drugs, has also used a corporate Web site to

provide product information. Purdue has also funded Web sites, such as

FamilyPractice.com, that provide physicians with free continuing medical

educational programs on pain management.

34

Purdue has also provided

funding for Web site development and support for health care groups such

as the American Chronic Pain Association and the American Academy of

Pain Medicine. In addition, Purdue is one of 28 corporate donors—which

include all three comparable drug companies—listed on the Web site of

the American Pain Society, the mission of which is to improve pain-related

education, treatment, and professional practice. Purdue also sponsors

painfullyobvious.com, which it describes as a youth-focused “message

campaign designed to provide information—and stimulate open

discussions—on the dangers of abusing prescription drugs.”

Purdue also provided its sales representatives with 14,000 copies of a

promotional video in 1999 to distribute to physicians. Entitled From One

Pain Patient to Another: Advice from Patients Who Have Found Relief,

the video was to encourage patients to report their pain and to alleviate

patients’ concerns about taking opioids. Purdue stated that the video was

to be used “in physician waiting rooms, as a ‘check out’ item for an office’s

33

The “Find a Doctor” feature is a physician listing service provided by the National

Physicians DataSource, LLC.

34

Purdue has also helped to fund the Dannemiller Memorial Education Foundation and the

American Academy of Physician Assistants Web sites.

Page 25 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

patient education library, or as an educational tool for office or hospital

staff to utilize with patients and their families.” Copies of the video were

also available for ordering on the “Partners Against Pain” Web site from

June 2000 through July 2001. The video did not need to be submitted to

FDA for its review because it did not contain any information about

OxyContin. However, the video included a statement that opioid

analgesics have been shown to cause addiction in less than 1 percent of

patients. According to FDA, this statement has not been substantiated.

As part of its marketing campaign, Purdue distributed several types of

branded promotional items to health care practitioners. Among these

items were OxyContin fishing hats, stuffed plush toys, coffee mugs with

heat-activated messages, music compact discs, luggage tags, and pens

containing a pullout conversion chart showing physicians how to calculate

the dosage to convert a patient to OxyContin from other opioid pain

relievers.

35

In May 2002, in anticipation of PhRMA’s voluntary guidance for

sales representatives’ interactions with health care professionals, Purdue

instructed its sales force to destroy any remaining inventory of non-health-

related promotional items, such as stuffed toys or golf balls. In early 2003,

Purdue began distributing an OxyContin branded goniometer—a range

and motion measurement guide. According to DEA, Purdue’s use of

branded promotional items to market OxyContin was unprecedented

among schedule II opioids, and was an indicator of Purdue’s aggressive

and inappropriate marketing of OxyContin.

Another approach Purdue used to promote OxyContin was to place

advertisements in medical journals. Purdue’s annual spending for

OxyContin advertisements increased from about $700,000 in 1996 to about

$4.6 million in 2001. All three companies that marketed the comparable

drugs have also used medical journal advertisements to promote their

products.

Purdue has been cited twice by FDA for using advertisements in

professional medical journals that violated the FD&C Act. In May 2000,

FDA issued an untitled letter to Purdue regarding a professional medical

35

It is common drug industry practice for companies to provide conversion tables for sales

representatives to distribute to health care practitioners. Purdue used a similar pen for its

older product, MS Contin.

OxyContin Advertisements

Violated the FD&C Act

Page 26 GAO-04-110 OxyContin Abuse and Diversion

journal advertisement for OxyContin.

36

FDA noted that among other

problems, the advertisement implied that OxyContin had been studied for

all types of arthritis pain when it had been studied only in patients with

moderate-to-severe osteoarthritis pain, the advertisement suggested

OxyContin could be used as an initial therapy for the treatment of

osteoarthritis pain without substantial evidence to support this claim, and

the advertisement promoted OxyContin in a selected class of patients—

the elderly—without presenting risk information applicable to that class of

patients.

37