2

SECOND OF TWO BRIEFS

WhatWorks

Winter 2006

L E A R N I N G F R O M T H E F O U N D A T I O N C O N S O R T I U M

F O R C A L I F O R N I A ’ S C H I L D R E N & Y O U T H :

Foundation-Government

Partnerships

B Y J U D I T H K . C H Y N O W E T H

E D I T E D B Y M I C H A E L K R E S S N E R

The Foundation Consortium for California’s Children &

Youth is closing after fourteen years. This brave experiment,

unlike any other in the nation, served California from

1991–2005, left behind many accomplishments and birthed

three new entities. This policy brief is the second in a two-part

series that explores the Consortium’s experience. The first brief,

“Foundation Collaboration in Action” is intended as a guide

for those interested in starting and sustaining foundation

collaborations. It discusses the Consortium as a foundation

collaboration and focuses on critical success factors as well

as the reasons for its eventual demise.

This brief examines the Consortium’s primary strategy,

foundation-government partnership. It is written primarily for

a foundation audience, but public sector officials will find it

informative. It begins with the story of the Consortium, then

goes on to describe the benefits of foundation-government

partnerships, discuss evaluation challenges, and identify factors

associated with success. The heart of the brief presents key

lessons. It closes with some pointers on starting a partnership.

P O L I C Y B R I E F

The Foundation Consortium would

like to thank everyone who has

helped us over the years improve

outcomes for California’s children

and youth. Individually and in new

groups, we will continue to work for

positive change in our communities

and hope you will do the same.

Trim Line Does Not Print.

Trim Line Does Not Print.

Dear Friends of the Foundation Consortium for

California’s Children & Youth,

As most of you know by now, the Foundation Consortium will close

its doors after over 14 years of successful work on December 23, 2005.

That means you are now reading our last What Works Policy Brief. If

we counted right, this is brief number fourteen. What began with a

grant from The California Wellness Foundation for a series of four such

publications in 1998 became the Consortium’s primary print publication,

always focusing on what we care about most: good policies and their

implementation. We would like to thank all of the authors and review

teams for their fine work and you, the readers, for your loyalty and

support throughout the past seven years.

While the Foundation Consortium will end, many of its members

will continue to work together in different ways to help California’s

children be safe, healthy and learning each day. The ending of the

Consortium is in no way a reflection of diminished member

commitment to their own priorities and many of those the

Consortium has adopted, e.g. After-School, Child Welfare and

Family Support.

The Consortium’s website will stay alive until June 2006. Here

you can find information on our program areas (e.g., go-to places),

and the whereabouts and contact information of our staff. All of

our policy briefs are available for download as well. Please visit

www.foundationconsortium.org.

Last, but not least, I would like to thank the Board of Directors, our

partners, consultants and staff for their ongoing support and work.

Without you, the Foundation Consortium, would not have been able

to be one the most successful and longest-lasting foundation-governed

pooled funds in the country.

Judith K. Chynoweth

Executive Director

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

partnership

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

2

What Are the Benefits of

Foundation-Government

Partnership?

Leverage of Foundation Funds

Foundation-government partnerships have

a number of benefits for foundations, for

government and for the individuals, families or

communities the partnership seeks to help. For

foundations, the most alluring (and challenging)

benefit is the ability to leverage public

resources toward a desired policy goal.

Through the Healthy Start partnership,

Consortium member foundations encouraged

the expenditure of $10 million public dollars

(SB620) for a statewide program strategy they

themselves were supporting on a small scale.

Furthermore, a Consortium expenditure of less

than a million yielded hundreds of millions of

federal dollars for expanded children’s services

through the LEA MediCal Billing Option. In

the Child Welfare Partnership, Consortium

members leveraged $3.2 million in targeted grants

from the Marguerite Casey Foundation and the

California Endowment into approximately $6.5

million for a capacity-building process to help 40

counties implement a new response to families

reported to the child abuse hotline. In 2005,

AB2496 was passed to institutionalize the ability

of foundations to grant money to government to

match federal dollars for specific and allowable

purposes. This would not have happened

without a foundation-government partnership.

Quality Policy Implementation

Through partnerships, foundations and

governments can ensure quality implementation

of policies they support. The California

After School Partnership of the Foundation

Consortium and the California Department

of Education created a brand new approach

to building quality programs at the local level.

Instead of supporting a centralized office to

develop and deliver periodic trainings to diverse

sites throughout the state, the partnership

developed a decentralized system of field

support. This system brought hands-on coaching

to program sites — a “guide by the side.” In 11

regions in the state, it funded “leads” who are

accountable for program quality, broker local

training and provide technical assistance and peer

support. It designated and funded regional learning

centers that model quality programs and serve the

other sites in their region as peer learning centers.

Foundation-government partnerships can help

foundations and their government partners

learn to implement challenging policies.

Proposition 10 required local commissions to

include diverse groups in their planning and

decision-making and to be accountable for results.

Through partnering with The Foundation

Consortium, four First 5 county commissions

developed processes that included a highly diverse

group of community residents and providers. They

also developed accountability systems for their

grantees that focused on participant results and

program performance measures.

Improved Public Systems

A third benefit is improvement of public

systems. The Foundation Consortium partnered

with the California Department of Social Services

to support proposed improvements in the child

welfare system. Through this partnership 40

counties began implementation of differential

response,

1

a more individualized response to

families reported to the child welfare system. Local

inter-disciplinary, inter-agency teams around the

state are working to improve outcomes of youth

transitioning out of foster care. Partnerships

between county welfare agencies and community-

based agencies are taking joint action to provide

families with the help they need before abuse and

neglect occurs. Finally, proactive and positive

communications about child welfare activities are

being developed and coordinated at the state and

county level.

advocacy

What Works Policy Brief Foundation-Government Partnerships

Winter 2006

3

Prevention

Finally, foundation-government partnerships

enable government to stretch their prevention

dollars. Publicly funded services are generally

for individuals and families with the most severe,

chronic or complicated challenges. The Public-

Private Family Support Funders Group built the

capacity of community-based neighborhood family

centers to strengthen and sustain their programs.

This effort could not have been funded without

the resources and technical expertise of the

Consortium and its members.

Government partners have highly valued the

Consortium for its comprehensive policy

perspective, consistent push for accountability,

and willingness to spend time and money to solve

implementation challenges.

There are times, however, when a foundation-

government partnership does not make sense.

Partnerships break down when foundations

advocate for a policy not supported by their

government partners. For example, towards

the end of the Healthy Start partnership,

the Foundation Consortium pushed for the

accomplishment of the third partnership objective:

a system of comprehensive, integrated school-

linked services. The government partners were

not really interested in this policy objective, and

the more the Consortium reminded their partners

that this objective was a part of the partnership

agreement, the more uncomfortable and less

productive the overall partnership became.

Foundation-government partnerships are not

indicated as a strategy when either party wishes

to exercise a high level of control over activities

or when either party is in a hurry. Partnerships

take time to develop even when both sides

have partnership experience. Rushing to action

undermines the long-term success of partnerships.

Policy and Program Integration

Partnerships promote policy and program

integration across department and discipline

lines. The Consortium Policy Academies supported

19 county inter-agency teams to develop more

comprehensive child and family policy. The Child

Welfare Partnership formed a state interagency

team (SIT) at the deputy level to improve

outcomes for shared populations of children

and families. The SIT develops and implements

integrated state-level policy across multiple

agencies including social services, alcohol

and drug abuse prevention, physical and mental

health, education, employment and training,

developmental services and the Attorney General.

Additional Resources

For government, the most compelling benefit is

securing resources for critical activities that

have not been publicly funded. For example,

the California Department of Education did not

receive adequate funds from the state to support

technical assistance for local after school programs

when the After School Education and Safety Act

passed. Public funds for administering the Act also

were scant. Foundation resources helped with both

of these shortfalls as well as provided considerable

strategic advice and expertise. The California

Department of Social Services had no state

resources to support county capacity building

for differential response. The partnership enabled

private foundation dollars to be used as a match

for federal title IVE funds to support the

Breakthrough Series Collaborative that provided

technical support to counties.

Advocacy

A second but equally powerful benefit to

government is the voice of outsiders —

the foundations — pushing for policy

implementation and accountability already

desired by government administrators. The

Child Welfare Partnership helped to transition the

child welfare redesign recommendations from a

Democrat to a Republican administration. The

Partnership provided much needed focus and

continuity during the transition and persistently

reminded public partners of their longer-term

strategic goals.

opportunity

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

4

T H E F O U N D A T I O N C O N S O R T I U M F O R C A L I F O R N I A ’ S C H I L D R E N & Y O U T H

— A S T O R Y O F A C C O M P L I S H M E N T S

In January 1992, the Chief Executive Officers of

eight California foundations signed an Agreement in

Principle with Governor Pete Wilson and the State

Superintendent of Public Instruction, William Honig.

The agreement was a public-private partnership to

support and influence public policy for children and

families. Specifically, the partnership was designed

to support the implementation of Healthy Start

(SB620), a discretionary grant for school districts

to build comprehensive, integrated, school-

linked services in elementary schools throughout

California. The first objective of the partnership was

to support the development and implementation

of Healthy Start. The second was to identify and

secure a source of ongoing funding for Healthy

Start sites once the three-year state grant period

expired. The third and most difficult objective was

to develop a statewide system of comprehensive,

integrated support services for children and their

families. The state contribution to the partnership

included administration, training for program

development and grants to local districts — a total

expense of about $10 million a year. The Foundation

Consortium contributed $1.7 million per year for

three years to support a statewide evaluation and

to develop the Local Education Agency MediCal

Billing Option, a local match for the federal Medicaid

funding stream.

Many lessons in public-private collaboration

were learned in this first partnership. The results

were well worth the risks to both partners.

Healthy Start

2

has a proven track record in

improving outcomes for children and their families

in California. Though Healthy Start state funding

has been eliminated, many Healthy Start programs

remain strong and vibrant in their communities,

supported by a combination of funds from school

districts, counties and foundations. The Consortium

is proud to be part of that success. For more

information on Healthy Start please visit the

Web site of the California Department of Education

(www.cde.ca.gov/ls/pf/hs).

The Consortium was the first ever pooled fund

governed by the state’s leading foundations. By

2005, Consortium membership had grown from

eight foundations to 19, with 23 member foundations

at its peak. The Consortium’s mission was to bring

philanthropy together with community, schools and

government to improve public policy and practice.

What held the Consortium’s members together was

a commitment to improving public policy and a set

of values. Staff and board were acting on the basis

of these values before they were even articulated.

However, articulation of these values reinforced the

Consortium’s vision and enabled it to communicate

that vision more effectively to government partners

and foundation boards. In brief, these values were:

■ Focus on the whole child within the context of

the family and community. Children and families

experience life’s challenges as an interrelated

whole, not as a series of categorical problems.

■ Be inclusive. Policy decisions must involve those

who are impacted, including service providers,

youth, families and community residents.

■ Be accountable for results. Funders must focus

primarily on community results, and programs

on participant outcomes.

■ Fund smart. Learn what works or what shows

promise. Gather and analyze data to learn what

works and stop funding what doesn’t.

Throughout its fourteen years the Consortium faced

many barriers to effective policy for children and

their families. The Consortium sought champions

within government who wanted to build capacity for

quality in local programs, create sensible financing

structures and get input from those typically left out

of legislative and administrative policy development.

accomplishments

What Works Policy Brief Foundation-Government Partnerships

Winter 2006

5

The work was all done through foundation-

government partnerships:

■ The Consortium provided technical support

to legislative staff working to develop AB1741,

known as the Youth Pilot Project. The legislation

authorized the Health and Human Services Agency

to offer selected counties the flexibility to blend

state dollars from selected programs to provide

more comprehensive, preventive services to

children and youth. In partnership with the Health

and Human Services Agency, the Consortium

designed, funded and directed a county policy

academy with the goal of helping nine counties

prepare for AB1741 selection. The academy was so

successful the Consortium funded a second round

involving an additional 11 counties. The academies

augmented the capacity of county inter-disciplinary

teams to collaboratively develop and implement

more integrated child and family policy at the

county level.

■ The California After School Partnership built

a decentralized system that redesigned the way

the California Department of Education supported

program quality at the local district level. After

School “regional leads” in 11 regions throughout

the state are responsible for supporting quality

after school programs through fund development,

local partnerships

3

, training and technical

assistance. Designated “regional learning centers”

— one or more per region — demonstrate

exemplary after school programs and are peer-

learning centers for other programs throughout

the region. Regional leads and learning centers

work together with individual sites to increase

program effectiveness and sustainability. In

addition, the Partnership laid the groundwork

for a statewide after school network, an inclusive

group of after school stakeholders that will

advocate for appropriate policy and advise a

legislatively mandated after school advisory

committee that reports to the governor and

the state superintendent.

■ The California Child Welfare Partnership

accomplished numerous objectives and spawned

additional collaborations. It launched the State

Interagency Team to integrate policy across

departments and agencies and to break down

barriers to effective policy implementation,

including increasing financing flexibility. It

established the Breakthrough Series Collaborative,

a major effort involving over 40 counties, whose

mission is to improve county and community

collaboration to assist families reported to the

child abuse hotline.

4

It coordinated the first major

strategic effort among state and county child

welfare agencies to proactively communicate

the positive results — grounded in data — of

improved child welfare policy and practice. This

included four major publications used as primary

reference by private and public funders alike.

5

And, the California Child Welfare Partnership

established a mechanism, authorized by the

legislature, to enable private funders to match

public dollars for improving the outcomes of

children and youth who are in foster care.

■ The Public-Private Family Support Funders

Group has taken a highly diverse, fragmented,

under-funded, under-developed field — the

family support field — and organized it into a

new association: the California Family Resource

Association. It has breathed new life into programs

by designing and testing a high quality curriculum

on sustaining quality family support programs.

The Consortium held four statewide conferences

entitled Pilots to Policy to emphasize the need

to replace pilot projects that come and go with

state policy that ensures consistent results for

children and families. It also urged three California

Policymaker Institutes to focus on results

accountability, particularly in the improvement of

child welfare and health. The Consortium published

thirteen policy briefs in total on how to strengthen

policy and practice for improved results. $30 million

over 14 years: Quite an investment and worth

every penny.

success

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

6

What Does Success Look Like

for a Foundation-Government

Partnership?

How do you know a successful foundation-

government partnership when you see one? This

has been a tremendously challenging question for

both the members and the staff of the Foundation

Consortium. There are so many possible measures

of success. First, there are results for people,

programs and systems. Are the beneficiaries of

the partnership work any better off? Have agencies

changed the way they conduct business? Are systems

more comprehensive, integrated, preventive?

Second, did the partnership achieve its objectives?

Third, it is important to look at the process of the

partnership itself. Is communication among partners

frequent, direct and honest? Are partnership

decisions transparent to each partner and to

others with whom they work?

Then there is the issue of attribution versus

contribution. Did the partnership make a critical

difference or did it merely take credit for an

accomplishment of some other entity or force?

How can we know if partnership work contributed

to an accomplishment? Can the level of contribution

be measured?

The Foundation Consortium has spent considerable

sums on and experimented with many different

evaluation methods throughout its history. Here

are some of the approaches that have been tried:

A $1.5 million evaluation of Healthy Start

programs conducted by Stanford Research

Associates (SRI) produced data that were

used repeatedly in support of continued

program funding.

An outside evaluation of county capacity building

for system change (County Policy Academy)

conducted by Brizius and Foster confirmed the

value of the academy process in helping county

departments and agencies work together to plan

more comprehensively for children and families.

ß

ß

An assessment of county programmatic and

administrative changes to make services more

comprehensive, integrated and flexible for

families. Through surveys and key informant

interviews Philliber Research Associates defined

these systems changes, but could not attribute

the change to Consortium activities.

A summary analysis of California local after

school evaluations and state evaluation data

prepared by U.C. Irvine documented improved

outcomes for participating students as a result of

the program and made the difference in building

legislative support for continued funding.

Applied Survey Research evaluated the Results

for Children Initiative, a partnership between the

Consortium and four county First 5 commissions.

The outside evaluation of the Child Welfare

Partnership by the National Health Foundation

documented the importance of the partnership in

maintaining focus on child welfare improvements

during an administrative transition.

The Consortium director’s report on work plan

performance measures informed the board of

accomplishments and trouble spots needing

course correction.

Despite their utility, these various efforts of

measuring results still left most Consortium

members (and staff) dissatisfied. Though each

evaluation demonstrated positive results, none

could demonstrate overwhelming success.

Furthermore, the Consortium could not prove its

contribution really made the difference. Separately

or together, the evaluation results did not tell a

powerful story that helped the collaborating

foundations communicate to their constituencies

“Wow! This partnership is really worth the effort.”

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

measurement

What Works Policy Brief Foundation-Government Partnerships

Winter 2006

7

Measurement as a Learning Tool

In spite of these challenges, the Consortium

learned a lot from the evaluations it conducted:

Legislatively mandated initiatives that do

not specify desired results have a hard time

demonstrating their success. For example, was

Healthy Start about meeting children’s health

needs, meeting basic family needs, improving

children’s academic achievement or increasing

family involvement in the schools?

Outcomes of comprehensive initiatives (such as

Healthy Start) are very challenging to measure.

Statewide evaluations of local programs (such

as Healthy Start) are expensive and challenging

to design in a way that responds flexibly to

local needs and circumstances while yielding

comparable data across programs or counties.

A partnership’s ultimate outcome can be complex

and quite distant in time. Interim accomplishments

frequently are process measures and do not

generate the kind of excitement sometimes

needed to keep partners motivated. In addition,

the relationship between partnership activities

(interventions) and desired results may not

be direct.

Systems change is difficult to measure and

very difficult to attribute to any single entity

or group of interventions.

California legislators hold state agencies

accountable for results, but often do not allocate

resources to support rigorous evaluation. As

a result evaluation data from local programs

can sometimes sit in cardboard boxes for

extended periods of time because the agency

is unable to analyze the data or use it for

continued program improvement.

One can better measure the success of capacity-

building initiatives if baseline information is first

gathered on what participants know and can

do at the beginning of an initiative and is later

compared to what participants know and have

done at the end. Such an approach really informs

future efforts.

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

An outsider’s evaluation of the foundation-

government process is extremely helpful

to the partnership — especially during a

partner transition.

Should foundations give up on evaluating

partnerships? Absolutely not. At a minimum,

it is important to know if you accomplished

what you set out to and if the “customers” of

your effort were satisfied. For example, in the

First 5 Partnership, the Consortium was successful

in helping four county commissions build more

inclusive planning and governance processes and

in helping the commissions learn how to hold

their grantees accountable for results. However,

it was less successful in helping the commissions

hold themselves accountable for results. The

Consortium learned that it did not offer enough

technical advice on implementation of results-

based accountability. This finding led the

Consortium to develop the Guide to Results

Oriented Community Change.

2

An internal performance measurement system

for the partnership, accompanied by honest self-

appraisal, can produce very valuable information.

This requires the partnership to develop a work

plan with performance measures for each specific

activity it engages in. Partnership staff can design

data collection processes for the performance

measures and review progress quarterly. At the

end of each year, performance against expectations

is summarized and accomplishments are reported.

The remaining question is both relatively

straightforward and tremendously important:

What convinces the members of a foundation-

government partnership that its results justify the

costs? Consortium experience shows that in the

absence of definitive data, a good story will do.

More and more evaluators understand that data

and stories are best for convincing funders — both

public and private. The Consortium “story” is at

the beginning of this brief.

ß

six lessons

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

8

Six Lessons for Foundations that

Wish to Partner with Government

Lesson 1: Be humble. Know yourself and

your partner.

It takes humility to be a good partner. Just

accepting that you cannot dance alone takes some

humility. Once the partnership gets underway,

however, it is easy for both partners to lose

perspective and to think: “I deserve to lead this

dance. My partner should just follow my lead.”

This type of thinking creates serious challenges for

foundation-government partnerships — especially

if one partner does not know or understand the

context of the other. Here are five points that

foundation partners need to remember:

The policymaking process is chaotic and

uncontrollable. Protect your interests but be

flexible — learn to live with bumps and sudden

changes of direction (and administration).

Understand how public policy issues arise, turn

into policy proposals that ultimately pass (or fail)

and become implemented and how this cycle

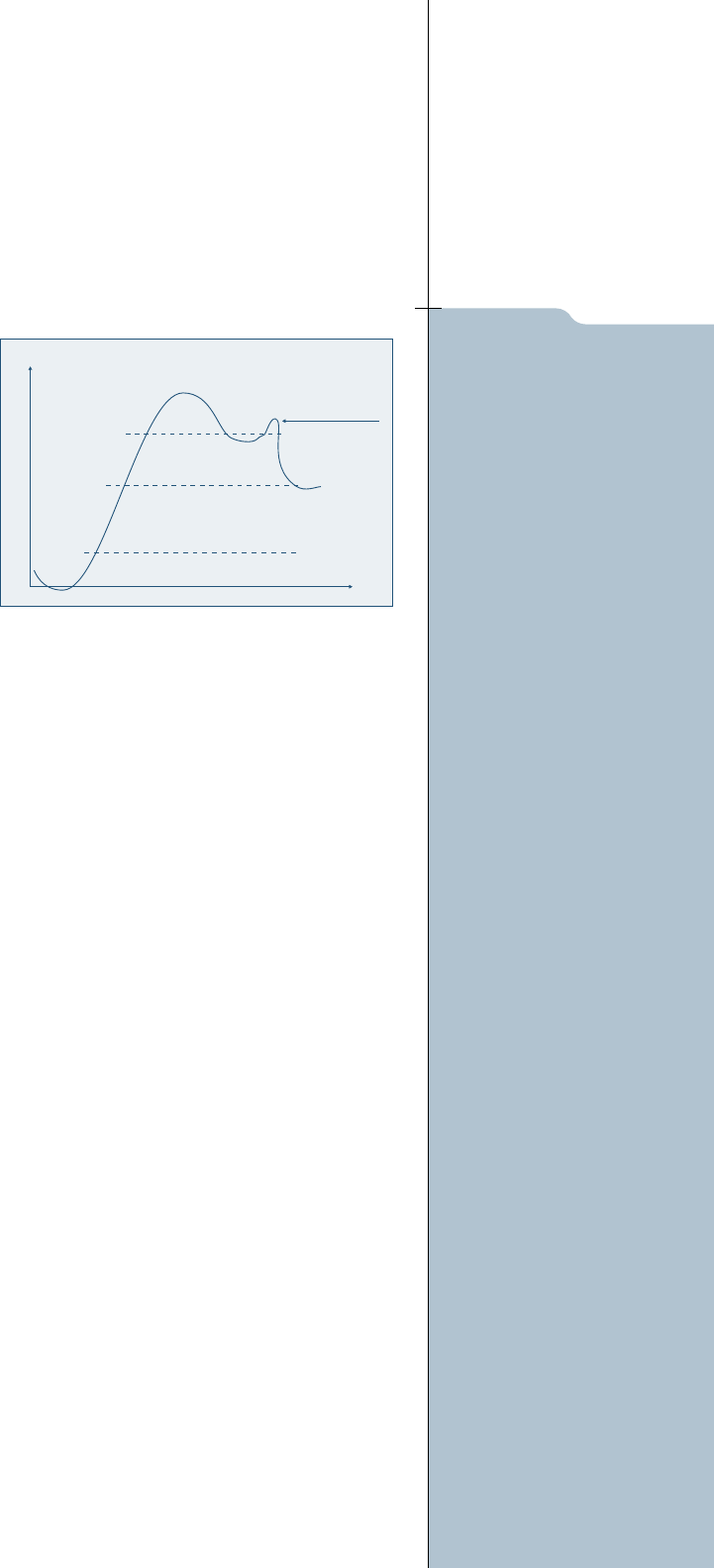

relates to public attention. Take a look at the chart

on page 13 and ask yourselves, “Where on this

chart is the issue we want to partner on? Given

where the issue is, what activities should we be

helping our government partners to accomplish?

What activities should we be anticipating?

Don’t expect government to be accountable in

the same ways foundations are. The public sector

has a much wider range of constituencies and

needs than you do. In government, accountability

rests with the voters and those who get the votes.

As a foundation, don’t expect to drive partnership

accountability. You didn’t get any votes.

No matter how much you know, no matter how

non-partisan you think you are, no matter if you

wear the “good government” hat, among some

people in government, you are still just another

special interest.

No matter how big your foundation endowment,

your partnership contribution is just a rounding

error in a big public budget. You are a flea on the

elephant’s back.

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

Once upon a time there was a flea who lived

on the right ear of a big, powerful elephant

that worked in a forested region in India.

The elephant spent all day doing many

important jobs in the forest and for the

people in the villages on the edge of the

forest. He pulled up trees for building huts

and for firewood. He helped to make roads

and build houses.

Now, while elephants are smart, they need

to be managed. This elephant had a mahout

who sat upon his back and told the elephant

where to go and what to do. The mahout

got the elephant started in the morning, gave

him instructions all day, and in the evening

he led him to a forest river to bathe and cool

off. Without the mahout to direct him, the

elephant sometimes got confused or decided

to go off on his own. This could be quite

a disaster for the forest and the villagers.

One time he ran amuck through the town

ripping huts apart, wrecking the marketplace

entirely and even accidentally crushing a few

innocent bystanders.

The flea remained calm no matter what the

elephant did except, of course, when the

elephant splashed in the river and got him

wet. He sat very high up on the elephant and

from his vantage point he learned a lot about

the forest and the villages. He could see what

the villagers had and what they needed. But,

while he knew a lot, he was a bit of a foolish

flea. Somehow, he got the idea that he could

actually influence the elephant to do what he

thought was best for the villagers. He began

hollering directions into the elephant’s ear.

As long has the flea’s directions matched the

mahout’s directions things went well.

T H E S T O R Y O F T H E F L E A

A N D T H E E L E P H A N T

persistence

What Works Policy Brief Foundation-Government Partnerships

Winter 2006

9

The flea began to feel like he was telling the

elephant what to do:

“Turn left here, Elephant.”

“Take this wood to that family who

needs to build a house.”

“Don’t muddy the river right now,

Elephant, the women need to wash

their clothes.”

When the elephant did what he said the flea

puffed out his chest and felt very proud. “I

am a fine fellow,” he thought. “I have much

more power than an ordinary flea.” He knew

a lot and he had good intentions, but, as I

said, he was a foolish flea.

One day, the elephant was involved in build

-

ing school huts in the villages on the edge of

the forest. The huts were places the children

could go near the school when they needed

help or to just to relax and have fun when

their lessons were over. The elephant built

huts in two villages and the flea could see

that the children really liked the huts. The

flea was excited and spent hours offering his

wisdom and directions, which he mistakenly

thought the elephant was really listening to.

He was looking forward to school huts in

every village, full of happy, playing children.

But one morning, as he was waking up and

stretching all his many legs and yawning his

proboscis, he noticed that his Elephant was

not walking to the next village to build a

school hut. Instead, the Elephant was helping

other elephants build a new road in the

forest far away from the village that needed

the school hut. This was very upsetting

to the flea. He knew the children in the

remaining villages needed school huts.

What was he going to do?

He thought to himself: “Maybe my friend the

Elephant forgot what he is supposed to be

doing.” He crawled close to the elephant’s

ear opening and shouted as loud as he

could: “GO BACK TO THE VILLAGE AND

BUILD THE NEXT SCHOOL HUT.” But the

elephant kept right on pulling logs onto the

dirt road. So the flea jumped right into the

elephant’s ear and bit him as hard as he could

on the softest place he could find. “That will

make him listen up,” he thought. “I know

what is best for the children in the villages.”

Well, the elephant trumpeted loudly. He

shook his big head from side to side. He

flapped his right ear again and again. “What

is wrong with you today?” asked the mahout

in a soothing voice to the elephant. I must

calm you down or soon you will run amuck.”

So he leaned forward and lifted up the

elephant’s ear and peered in. “Oh,” he said,

“There is a flea on your ear right on this

tender spot.” And he put his thumb and fore

-

finger together picked off the flea and threw

it on the ground.

The flea was indignant and for just a moment

thought of fighting back. Then he saw the

elephant’s very big feet about to crush him.

“I’d better get to a safe place,” he thought

and he ran under a log as quick as ever he

could. “I guess I’m just a tiny flea compared

to this big elephant,” he thought. But when

the elephant (and the mahout) weren’t

looking he jumped back on the elephant’s

leg and began the long climb up. “Hum,” the

flea thought as he climbed. “I guess I’ll have

to think of a different way of getting the

elephant’s attention.

Moral: Don’t think you have more

power than you do. Strategic direction

and persistence work better than bravado.

realistic

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

10

You cannot leverage a boulder with a toothpick.

The Consortium once held a meeting with six

counties to discuss systems change for children and

families. Near the end of the meeting one county

administrator raised his hand and said, “This is

all very well and good, but what you have outlined

will take about 20 years.” He was trying hard

to be polite and not laugh at us. It turns out he

underestimated the job. At the end of 14 years of

existence, the Consortium still hasn’t accomplished

all the “system changes” it envisioned.

Building comprehensive solutions is harder than

anyone thought. It is easier to think than to act

comprehensively and probably more important.

Over time, Consortium objectives became more

specific and realistic:

A statewide system of comprehensive, integrated

school-linked services became a statewide

association of community-based, neighborhood

family centers.

Comprehensive school-based programs for

children and

families became after school

programs that focus on mentoring, homework

assistance and youth development.

Countywide systems change for families

and children became county-community

partnerships to provide a more individualized,

preventive response to families who have been

reported to the child abuse hotline.

Here are two important lessons:

Spend time on the front end of the partnership,

defining very specifically what goals and objectives

mean to each party. Your understanding of them

will change over the life of the partnership and

differences will arise. At least you will know that

you did have common ground at one point. That

can help you through the rough times as you

refine your objectives.

ß

ß

ß

ß

It also helps for foundations to share with their

government partner some things about their

culture. For example:

Philanthropy works hard to be smart. Foundations

invest heavily in knowledge development and are

eager to share what they know.

Philanthropy can be nimble and flexible in

getting resources, executing contracts,

responding to needs, changing directions.

Philanthropy is devoted to doing “right.”

Compromise is not a well-honed skill and

in some foundations not even valued.

Foundations have resources, particularly for

things government cannot fund, like capacity

building, research, evaluation and demonstration

projects. Foundations will go a long way to

leverage their resources with public dollars.

Funders do not like to be told to “leave their

money on the stump and walk away.” Many

want to be involved in building a solution.

Government cannot make foundations do

anything. It cannot starve them or mandate any

specific action. Foundations are stubborn. They

last. They will be around when a politician loses

the next election or gets “termed out.”

Lesson 2: Be realistic about what you want

and can accomplish.

Clear objectives are a must for any partnership.

Written agreements are necessary but not sufficient.

The memorandum of understanding between the

Foundation Consortium and the Governor and

State Superintendent had three clear objectives.

The problem was nobody really knew what the

third objective -“Create a statewide system of

school-linked services” — meant. The lack of

agreement on the meaning of this objective was

the death knell of the Healthy Start foundation-

government partnership.

You may be clear on your objective — for example,

make county systems that serve children and

families more comprehensive, integrated and

preventive — but your expectations can be out

of sync with your resources or your time line.

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

communicate

What Works Policy Brief Foundation-Government Partnerships

Winter 2006

11

Match expectations to resources. See the big

picture. Think comprehensively. But, focus,

focus, focus. Do what you have the ability and

resources to do and celebrate that. If you share a

vision, others will pick up where you left off. A

well-articulated vision also can draw other resources

to support additional parts of the implementation.

Lesson 3: Communicate, communicate,

communicate.

Over the Consortium’s history, communications —

telling stories well — became a key feature in

partnerships with government. The first partnership,

Healthy Start, had no communications component

at all. The After School Partnership developed a

name and logo and included several press events.

The Child Welfare Partnership had a strategic

communications plan with state, county welfare

and consortium partners, press kits, fact sheets, and

op-ed pieces. The Consortium invested heavily in

communications expertise for the new California

Family Resource Association.

One of the most important lessons the Consortium

has learned in partnering with government is

that foundation partners must be prepared to

communicate their policy agenda in terms that

make sense to both elected and appointed officials.

The truth is most elected officials are interested

in what their constituents want — at least those

who vote. Foundations do not vote. They cannot

contribute to campaigns. Public officials must pay

attention to what their bosses — the governor

or state superintendent — want. Foundations

must be able to tell a story about people, what

they need and want, what will help them, and

how a foundation-government partnership can

make a difference.

Most foundations do not have communications

expertise on staff. Furthermore, most foundation

trustees are reluctant to make communications

grants. Communications expertise in a foundation-

government partnership is essential. It is not

a luxury.

ß

Lesson 4: When partners change, adjust.

Expect change in a partnership. In general, change

happens more frequently in government than in the

foundation environment. Throughout its govern-

ment partnerships the Consortium experienced:

Three governors.

Three state superintendents.

Four Secretaries of Health and Human Services.

Numerous department directors, deputy

directors and other administrative changes.

Yet partnerships depend upon personal relation-

ships. Here are several lessons the Consortium

has learned about changing partners in a

foundation-government partnership:

Be aggressive about meeting with the new partner.

No matter how busy the new appointee is, no

matter how many pressing priorities they have,

contact them right away and schedule a face-to-

face meeting.

Prior to a meeting prepare written communication

that briefly describes the history of the partnership

and its accomplishments to date.

Be direct with your new partner about:

the goals of the partnership

what you need from them for the partnership

to remain successful

what parts of the agreements with the

previous partners must remain in place

for the partnership to be viable for you

what parts you can be flexible about

Be willing to let go. If after a few face-to-face

meetings you still get signals that the new

partner does not understand or put a priority on

the partnership, request a face-to-face meeting to

politely but formally end the partnership. You

don’t need to threaten. It is not personal. Just let go.

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

change

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

12

Lesson 5: Watch where you are going — it

will change over time.

Foundation-government partnerships change.

Even if the strategic goal of a partnership is well

defined and agreed upon by all partners, shifts in

direction are inevitable. The California After

School Partnership wanted after school programs

to achieve results such as improved academic

achievement and more positive choices by

participating youth. The Consortium knew that

it took well-funded, quality programs to achieve

those results, but our under- standing of how to

achieve quality changed. Over time it became clear

that program staff learned quality by being coached

and mentored, not just by being “trained.” It made

a difference for program staff to visit an exemplary

program site to see, touch and feel — not just hear

about — “quality.” Furthermore, after school

program leaders needed to define quality for

themselves and not have indicators picked for

them by funders. The partnership discovered that

the road to quality was a lot more complicated

than we thought.

As previously mentioned, partners change. The

new partner wants to remain in the partnership

but change the goal — perhaps focus on a

particular aspect of the original goal. The Child

Welfare Partnership with the Davis administration

was focused on Child Welfare Redesign — broad

changes in how child welfare services were

delivered, including partnerships with community

agencies to prevent child abuse and neglect from

occurring. The Schwarzenegger administration

narrowed its focus to three child welfare system

reforms: child safety, differential response to

families reported to the child abuse hotline and

permanency and improved outcomes for children

in the system and youth transitioning out of it.

They wanted to remain in a partnership with the

Foundation Consortium and continue the work

on interagency coordination and communications,

but prevention was not a priority for them. The

partnership redefined its goals and continued.

Watch where you are going in a foundation-

government partnership:

Be strategic: never loose sight of your ultimate

goal.

ß

Be tactical: understand your environment and

how changes impact your ability to achieve your

strategic goals.

Remember, purpose is no substitute for process.

You have to be able to negotiate obstacles in your

path. This takes all the process skills that myriad

publications about partnership cite over and over:

leadership, open and honest communication,

mutual respect, highly skilled meeting facilitation,

governance that defines conflict management,

inclusive planning and patience.

Lesson 6: Be persistent. But be willing

to let go.

The longest foundation-government partnership

the Consortium participated in was five years: The

California After School Partnership. By the end,

we were just hanging on to each other, all our

energy and enthusiasm drained. We had no

common direction because we had difficulty even

communicating. Obviously, persistence was not

enough. The Consortium made a decision, with

its partners, to end the partnership. We left as

we started — in good faith. Because of that the

Consortium has been able to continue its after

school work even though the California After

School Partnership ended.

Here are four important signs that the partnership

is in trouble:

Your partner is saying one thing to you and

doing another.

Decisions are not being made in a timely

manner or there is no follow-through.

Meetings are tough to schedule and decision-

makers do not attend.

You realize that you and your partners no longer

have shared goals.

If you make several efforts to address these issues

with no improvement, it is time to end the

partnership. Be up-front with your concerns.

Take a measured pace. It took the Consortium

and the California Department of Education

almost nine months to end the partnership.

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

intention

P O L I C Y L I F E C Y C L E

First Evaluation Results

Re-Authorization

On-Going Implementation

Phase One Implementation

Enactment/Program

Development

Education

Building Support

Awareness

R E S P O N S E I N T E N S I T Y

T I M E

What Works Policy Brief Foundation-Government Partnerships

Winter 2006

13

Ready… Set… Go!

Getting Started

The Consortium hopes that many more foundation-

government partnerships get started. Such partnerships

achieve results, can leverage millions in public funds

and make government more effective. On top of that

they are exciting and rewarding.

Get Ready: Ask Yourself Four Questions

What is your purpose? If you want to influence

policy and its implementation you need to

understand the policy cycle.

Are you trying to build public awareness of a

problem or a public policy solution to that problem?

Are you educating others about general solutions or

providing technical advice on a specific solution

such as legislation or a county executive order?

Perhaps you are interested in making sure that a

specific policy solution actually achieves the results

intended. Are you trying to re-awaken the public to

the fact that a problem was not actually solved?

Ride the policy wave. In its Healthy Start

and After School Partnerships the Foundation

Consortium rode the rising crest of policy cycle.

We offered technical advice to legislators, conducted

general policy education and provided support for

quality implementation of passed legislation for

three and five years respectively. In child welfare, a

California Policymaker Institute called attention to

an emerging problem and helped move stakeholders

to action. The Consortium created the Child Welfare

Partnership during the developing phase of the policy

cycle and continued through policy implementation.

The Public-Private Family Support Funders group

worked at the emerging end of the policy wave,

building the capacity of neighborhood family

centers to raise public awareness about problems

facing families — particularly poor and immigrant

families — and advocate for neighborhood family

centers as a solution.

What is your intention? Intention is different

than purpose; it is subtler. Be clear about your

motivations. Do you want just to share information

or powerfully influence a government course of

action? Are you open to joint discovery of the right

approach or do you know it all? Don’t imagine you

can manipulate government. Be transparent about

your motivations.

What do you need to make the partnership work

for you? As a foundation, you are accountable to

your Board of Trustees. Foundation boards differ

greatly. Before you build your partnership, be clear

about what your board needs to know to feel

successful in this partnership. Make sure you can

get this in the partnership. If a potential public

partner is not willing to help you get it, the

partnership is doomed from the start.

What are you offering? How much money can you

put on the table? Is it sufficient to be attractive to

public partners? Is your money the only way they

can accomplish an activity they are committed to?

Perhaps your potential government partner wants

technical expertise or information you can access or

develop for them. Sometimes, potential government

partners want to build internal support for a policy

approach and they want to use your knowledge and

expertise to convince key policymakers. It helps to

know about the motivating factors of potential

government partners, but be clear about what you

yourself are offering.

relationships

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth

14

Get Set

Approach your potential partner. Relationships

make or break a partnership. At the start of every

Consortium partnership somebody in a foundation

knew somebody in government. It can be a

legislator, senior public official, county supervisor

or agency head. If you do not have a relationship,

start one. Ask for an appointment with a public

official. Go to the appointment with someone who

already has a relationship with that official. Invite a

policymaker to meet with your board. Focus your

interaction on discovering what goals you might

have in common. Gather information on your

potential partner’s way of operating. If you are

going to play a lead role in the partnership, what

does your “gut” tell you about how you will get

along with a potential partner? Pay attention to

what your gut says. A solid relationship between

individuals can carry a partnership through some

unexpected rough spots in the dance.

Make “the ask.” Here are three examples based on

Consortium experience:

“We see that you are charged with implementing an

after school program with very little administrative

dollars and no funds for technical assistance. We

would like to work with you to provide support

for quality programming and support to build

the policy voice of the new after school field.

Are you interested?”

“The Consortium is really interested in community

partnerships between county agencies and community

organizations to improve outcomes for children and

families. We noticed that community partnership is

a key component of your proposed Child Welfare

Redesign. Could we work together to support

implementation of the Redesign in a way that would

ensure community participation and partnerships?”

“We see that you spend a considerable amount of

public dollars on family support programs around

the state. Would you be interested in working with

several private foundations that are also interested

in family support programs? We would like to

see if public and private funders have some

common interests around strengthening the

field of family support.”

The final design of each partnership looked different

than what we had imagined at the time we asked

the question. In each case, however, the question set

the stage for a very satisfying (and productive) dance.

Sign. A formal signed partnership agreement

or joint work plan is a must — especially if the

partnership is going to last for more than six

months. The partnership may not stick with the

formal agreement or work plan. The contents

may change over time. However, a signed, joint

agreement or work plan yields several benefits:

The process of developing the agreement helps

the partners to clarify their goals and objectives.

It uncovers each partner’s real intentions (if you

listen carefully). It builds relationships because

during the process disagreement is bound to

occur. The emerging partnership can test its

approach to dealing with conflict.

The written agreement creates a common history.

If the partnership drifts or if individual members

change, the agreement recalls the original purpose.

It forms the basis for communication with others

about the partnership.

The agreement or work plan reinforces

accountability within the partnership.

Commitments of dollars and other resources

are on the record. Partnership policy and

procedures are clear.

Common components to a partnership agreement

or work plan include:

The purpose, goals and objectives of the partnership.

Joint activities and a timetable.

The commitments each partner makes to

each major activity: dollars, staffing, and

technical expertise.

Governance process, including conflict resolution.

Major partnership policies such as

communication with the public or media.

Now, you are ready. You are set. All you have left to

do is expect unpredictability, be flexible, work hard,

have fun and don’t take it personally.

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

ß

The Consortium wants California’s children to be safe,

healthy and learning each day.

Established in 1991, the Foundation Consortium for California’s

Children & Youth is a non-partisan resource bringing philanthropy

together with community, schools and government to improve

public policy and practice. The Consortium is a pooled fund of

21 of California’s leading foundations. Foundation members are

independent, yet they share common goals and the strategy of

public-private partnerships.

Judith K. Chynoweth, Executive Director

Michael Kressner, Communications Director

About the Author

Judy K. Chynoweth has been the Executive Director for the

Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth since it

was established in 1991. Ms. Chynoweth is a nationally recognized

expert in strategic policy development, collaborative planning,

foundation-government partnerships, and public policy affecting

children and families. She now is working as a consultant from her

home in Chester, California. She can be reached at 530.258.2354.

Acknowledgements

The Foundation Consortium gratefully acknowledges the

contribution of the following individuals who assisted in

the process of writing and editing this brief: Miryam Choca,

Susan Brutchy, Ruth Holton, Marianne Kugler, Margaret Laws,

Kathy Lewis, Rita Saenz, Jay Scheniver, Gary Yates, and

Deanna Zachary.

Members of Foundation

Consortium for California’s

Children & Youth

The California Endowment

The California Wellness Foundation

Casey Family Programs

The Annie E. Casey Foundation

S. H. Cowell Foundation

The East Bay Community Foundation

Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation

Evelyn and Walter Haas Jr. Fund

William and Flora Hewlett Foundation

The James Irvine Foundation

Marin Community Foundation

Orfalea Family Foundation

The David and Lucile Packard

Foundation

Lucile Packard Foundation for

Children’s Health

Peninsula Community Foundation

The San Francisco Foundation

Santa Barbara Foundation

Charles and Helen Schwab Foundation

Sierra Health Foundation

Y & H Soda Foundation

Stuart Foundation

Sources of More Information:

Collaborative Philanthropies: What Groups of Foundation Can Do That Individual Funders Cannot, Elwood Hopkins, Lexington Books, 2005

Child Welfare System Improvements in California, 2003–2005: Early Implementation of Key Reforms. December 2005

The Foundation Consortium for California’s Children & Youth: Foundation Collaboration in Action. By Judith K. Chynoweth. December 2005

After School Public-Private Partnerships. By Marianne Russell Kugler. Ph.D. December 2005

Choosing the Path Less Traveled: Strengthening California Families Through Differential Response. By Patricia Shene, Ph.D. and Stuart Oppenheim.

Edited by Cathy Senderling. July 2004

Mutual Assistance: Galvanizing the Spirit of Reciprocity in Communities. By Yoland Trevino and Roland Trevino. November 2004

Getting the Job Done: Effectively Preparing Foster Youth for Employment. By Linda Lewis. October 2004

The Child Welfare System Improvement and Accountability Act (AB 636): Improving Results for Children and Youth in California. By Barbara Needell

and Ken Patterson. August 2004

Community Partnerships: The Living Legacy of Healthy Start. By Lisa Villarreal with Joanne Bookmyer. April 2004

Smart Cuts or Dumb Cuts: Family Support Programs in Tight Budget Times. By Sid Gardner. March 2003

Inclusive Governance: A Call to Action. By Hedy Nai-Lin Chang and Judy Chynoweth. September 2000

Reforming Finance/Financing Reform. By Mark Freidman, Fiscal Policies Studies Institute. January 2000

Making a Difference for Children and Families: The Community Approach. By Tia Melaville. November 1999

Getting to Results: Data-Driven Decision-Making for Children, Youth, Families and Communities. By Jacqueline McCroskey. March 1999

Citizens Making Decisions: Local Governance Making Change. By Frank Farrow and Sid Gardner. March 1999

F O O T N O T E S

1

Choosing the Path Less Traveled: Strengthening California Families Through Differential Response. By Patricia Shene, Ph.D. and Stuart Oppenheim.

Edited by Cathy Senderling. July 2004

2

Community Partnerships: The Living Legacy of Healthy Start. By Lisa Villarreal with Joanne Bookmyer. April 2004

3

The Guide to Results Oriented Community Change will be available on the Consortium’s Web site (www.foundationconsortium.org) from

1/3/2006-6/30/2006 and subsequently located on the Web site of the California Family Resource Association. (www.californiafamilyresource.org)

What Works

P O L I C Y B R I E F

www.foundationconsortium.org

www.promisingpractices.net

Prsrt Std

U.S. Postage

PAID

Permit No. 333

Sacramento, CA