Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=rurb20

Urban Geography

ISSN: 0272-3638 (Print) 1938-2847 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/rurb20

Seeing ghosts: parsing China’s “ghost city”

controversy

Max D. Woodworth & Jeremy L. Wallace

To cite this article: Max D. Woodworth & Jeremy L. Wallace (2017) Seeing ghosts:

parsing China’s “ghost city” controversy, Urban Geography, 38:8, 1270-1281, DOI:

10.1080/02723638.2017.1288009

To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1288009

Published online: 14 Feb 2017.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 1704

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Citing articles: 19 View citing articles

URBAN PULSE

Seeing ghosts: parsing China’s “ghost city” controversy

Max D. Woodworth

a

and Jeremy L. Wallace

b

a

Department of Geography, Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA;

b

Department of Government,

Cornell University, Ithaca, NY, USA

ABSTRACT

Controversy has arisen in recent years over the creation of so-

called “ghost cities” across China. The ghost city term tends to

describe large-scale urban areas, sometimes planned as new

towns, featuring an abundance of new built space and appearing

to also have extremely low tenancy. This article examines key

questions related to the ghost city phenomenon, such as: what

is a ghost city? Are ghost cities driven by a tendency toward over-

supply in housing? How are local-level political incentives aligned

to foster the production of ghost cities? Are ghost cities temporary

anomalies or structural features of China’s urban-led economic

growth model? We discuss recent scholarly research into ghost

cities and present original findings to show how an excess of

urban space may plague certain Chinese cities.

ARTICLE HISTORY

Received 30 June 2016

Accepted 23 January 2017

KEYWORDS

China; ghost city; new town;

housing; land development

1. Introduction

In recent years, considerable controversy has arisen over the existence of so-called

“ghost cities” in China. Driving the controversy is a proliferation of monumentally

scaled urban developments, even entire new cities featuring skyscrapers and enormous

public spaces, all built at breakneck pace but with scant population (see Shepard, 2015;

Sorace Hurst, 2016). Widely circulating photographic exposés of these ghost cities have

generated troubling impressions of severely imbalanced and unsustainable urban

development.

1

And yet, while evocative, the term ghost city is shrouded in ambiguity

over what counts under this appellation. More specifically, questions linger over

whether ghost cities refer to specific places or types of places, or whether the term

merely describes an extreme expression of a more general trend toward a surfeit of built

urban space and especially over-supply in housing and other forms of real property in

China.

The purpose of this entry in “Urban Pulse” is to assess conceptual issues and data-

collection challenges surrounding the ghost city controversy, review some of the emer-

ging research touching upon this phenomenon, and hopefully provide some clarity to

help guide research efforts in this area of China’s urbanization. Our intent is not to lay

down a strict definition of ghost city, nor is it to dismiss the concept as merely a

journalistic cliché. Indeed, much excellent reporting on the topic has supplied impor-

tant and timely insights (see especially Shepard, 2015), and, moreover, sufficient data

CONTACT Max D. Woodworth [email protected]

URBAN GEOGRAPHY, 2017

VOL. 38, NO. 8, 1270–1281

https://doi.org/10.1080/02723638.2017.1288009

© 2017 Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group

exists to draw some reliable conclusions about trends in urban growth that support

concerns connected with the ghost city controversy. We also highlight some of the

theoretical challenges that this phenomenon presents for the study of Chinese urbani-

zation and for global urbanism more broadly. In this latter sense, the discussion here

responds to Parnell and Robinson’ s (2012) call in this journal for scholars to focus

theory-building efforts on experiences in the Global South, with particular emphasis on

better understanding the nature of the state and governance at the city scale, where

much of the action in development is occurring today around the world. China’s ghost

city phenomenon points in particular toward the importance – as well as the potential

pitfalls – of entrepreneurial urban strategies engaged by empowered local-state autho-

rities. Moreover, as increasing numbers of urban projects around the world are being

labeled ghost cities, including most notably Masdar Eco City in the United Arab

Emirates and Songdo in South Korea, China’s experience potentially holds wide

relevance.

2. Background

It deserves mention at the outset that the current ghost city terminology is a media

invention. Its origins in China are traceable to two news reports, one by Al-Jazeera

2

and

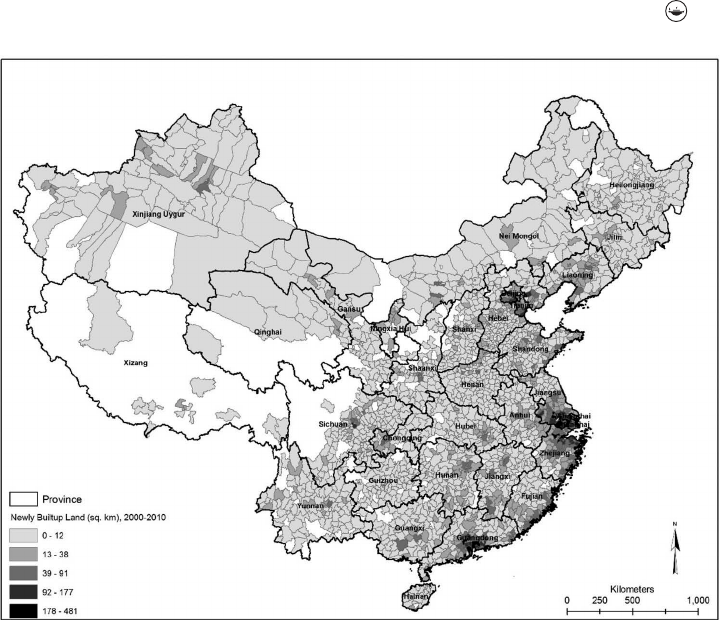

Figure 1. Newly built-up land, 2000–2010. Source: World Bank’s East Asia’s changing urban land-

scape 2015 using MODIS and other satellite imagery. Source: World Bank, East Asia’s changing urban

landscape 2015.

URBAN GEOGRAPHY 1271

the other by Time magazine (Powell, 2010). Both reports focused on the Kangbashi

New District, a new-town project undertaken by Ordos Municipality, a coal-mining

boomtown in China’s Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region. The municipality initiated

the project in 2004 and by 2009 the town’s basic infrastructure was completed along

with municipal agency buildings, landmark civic institutions, and a significant amount

of commercial property. The rapid pace of construction, driven by speculative invest-

ment amid a massive regional mining boom, led to extremely low residential density in

the new town and produced jarring landscapes composed of huge new city spaces

seemingly devoid of people (Woodworth, 2015). While overheating and low tenancy in

the property market had been recurring features of China’s urbanization since the

1990s, Kangbashi’s barren cityscapes suggested the inflation of property bubbles on

an altogether new scale and seemed to lend credence to arguments that the country

faced potential crisis originating in the real estate sector. Kangbashi’s location on the

arid fringes of the Gobi desert also made for dramatic imagery that doubtless helped to

inspire the “ghost city” theme.

In the wake of reports about Kangbashi, China’s leading domestic media outlets and

global news organizations filed a continuous stream of reports on the topic of “ghost

cities.”

3

Quite suddenly, ghost cities were being found throughout the country. Projects

such as the Chenggong New District, Dongtan eco-city, Zhengdong New District, and

the former 2010 World Expo site in Shanghai, are just some of the projects that have

been reported under this heading.

4

The sudden currency of the ghost town terminology

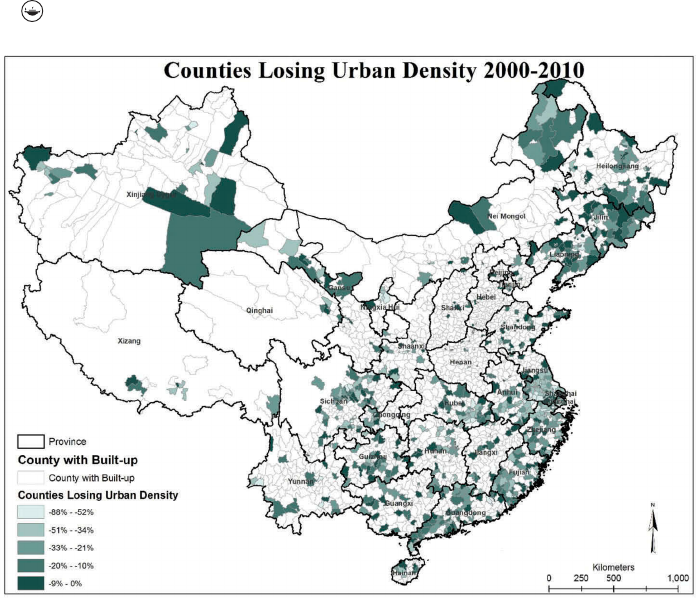

Figure 2. Counties losing urban density, 2000–2010. Urban density calculated using 2000 and 2010

urban population census data. Source: World Bank, East Asia’s changing urban landscape 2015.

1272 M. D. WOODWORTH AND J. L. WALLACE

and its application to a diverse array of urban projects supplied a charged new

metaphor through which to report on China’s property sector and to understand the

central function of urban land development in driving economic growth in the 2000s.

The cementing of the ghost town metaphor in popular discourse also coincided with

mounting concerns among the political leadership over urban housing policy in the

2000s. A widely read policy memo produced in 2012 by the research branch of the State

Council, for example, revealed high-level alarm over what the author called “urban

sicknesses” (Ch. chengshi bing) to refer to an interwoven set of structural problems

fueling “irrational” urban development (cited in Sorace & Hurst, 2016). In particular,

the paper underscored the perverse incentives – short appointed terms in office,

emphasis on GDP in assessing officials’ performance, the constitutionally defined

state monopoly over the primary land market – that lead urban officials to promote

city growth without regard to functionality, cost, accessibility, or long-term sustain-

ability (Development Research Center of the State Council [DRCSC], 2012). Prominent

scholars and policymakers have voiced similar concerns with increasing urgency in

recent years, and the central state has responded by issuing prohibitions against the

construction of new city halls (2013), new towns without State Council approval (2014),

and “weird” architecture (2016) all in attempts to temper the enthusiasm of city

governments for monumental construction projects. The ghost city metaphor therefore

has been taken up within broader urban policy debates and has become an emerging

topic of scholarly research (see He, Mol, & Lu, 2016; Shih, Li, & Bo, 2014; Yu, 2014).

The central government has also assimilated the ghost city terminology. Since 2014, the

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development has instituted a measure by which

ghost cities are to be defined. Specifically, any urban area with a population density

below 5,000 residents per square kilometer can be thusly categorized. Such a definition,

however, fails to differentiate between low density attributable to urban shrinkage, as in

a city such as Yumen (Gansu Province), and cities where spatial growth outpaces

demographic growth, as with new towns. Most reporting on ghost cities and the

attendant controversies have focused on the latter type of city.

In the following sections, we approach the problem of China’s ghost cities from three

key perspectives: property market dynamics, new-town projects, and land-use change.

Our discussion draws upon extant literatures in this field and brings original data from

our own research.

3. Three views upon ghost cities

3.1. Property market dynamics

The ghost city phenomenon is closely tied to the rapid pace of growth in China’s

property

sector. China’s real estate market has been a prime driver of economic growth

in the 2000s. Averaging across China’s provinces and municipalities, real estate devel-

opment has grown to nearly 15% of GDP by 2014 since the turn of the millennium,

when the country experienced a renewed phase of accelerating investment-driven

growth in the wake of the 1997/98 Asian financial crisis.

5

The construction sector’s

share of GDP has exceeded 5.4% every year since 2000 and was measured at a reform-

era high in 2013 at 6.9%.

6

Such levels are quite high whether one compares such data

URBAN GEOGRAPHY 1273

with advanced economies or emerging ones and is higher than Japan’s during its bubble

years of the 1980s. The centrality of urban land and property development in the

Chinese urban economy is made dramatically visible by the vertical and horizontal

growth of cities in recent years. Indeed, the Council on Tall Buildings and Urban

Habitat noted that by 2016 half the world’s skyscrapers would be in China, while few

such buildings existed at the outset of economic reforms in 1978 (Wood, 2014).

Property sector growth on this scale raises important questions about the drivers of

expansions and whether and how it might contribute to an oversupply of housing and

other types of property.

It must be noted first that growth in the real estate sector has been driven by robust

demand. By the end of the 1990s, the central government formally abandoned the

system of employer-provided housing, which was in fact already much reduced in scope

by that time. Households were encouraged to purchase their employer-provided homes,

often at deep discounts, or to purchase in the open market. Response was enthusiastic,

as evidenced by the rapid increase in urban homeownership rates; in Shanghai, for

example, homeownership rose from 36% in 1997 to 82% by 2005 (Arora, 2005). Rapid

urbanization of the population is also driving housing demand, as tens of millions of

households cement their status as new urban residents through home purchases. In the

context of such strong demand, home prices nationally have risen by an average of 10%

per annum since 2004. Crucially, the steady rise in prices was not fed by supply

pressure. In most cities, demand has been met through rapid increases in floor space

and units. A study by Jing, Gyourko, and Deng (2015), for example, found that total

completed floor space had increased by 50% within their study sample of major cities

since 2009.

The specific geography of property market dynamics is essential to understanding

the problem of oversupply and imbalances in the sector, as well as the emergence of

urban spaces with ghost-town traits. In major cities, such as Beijing and Shanghai, rapid

in-migration and rates of economic growth consistently above national averages have

supported high levels of demand and rapid increases in the stock of property. Quite

contrary to the “ghost city” trope, recent evidence points to a supply shortage in these

largest markets. Yet the so-called “tier-one” cities account for only about 10% of total

floor space sold across urban China. The rest is fairly evenly divided among the far

larger subset of lower-tier cities (Chivakul, Lam, Liu, Maliszewski, & Schipke, 2015: 4).

It is among these lower-tier cities where we find weaker growth in home prices and land

price appreciation, despite central government support for the development of small

and medium-sized cities (Wallace, 2014). Driving this trend toward weaker property

markets in lower-tier cities have been comparatively rapid rates of growth in the

amounts of completed property as well as rates of increase in housing supply that

vastly outpace the growth in numbers of new households. In combination, these forces

raise the prospect of oversupply with potential to last for many years to come.

Recent studies have shown remarkable heterogeneity in the expansion of supply

and inventory among second-tier and lower cities since the implementation of a 4-

trillion RMB stimulus program rolled out in 2009, which concentrated investment

in real estate.

7

For example, exceptionally large additions of floor space have been

recorded in Xian, Chengdu, and Tianjin (Jing et al., 2015: 5). Using datasets from

the National Bureau of Statistics and local housing bureaus, Chivakul et al. (2015)

1274 M. D. WOODWORTH AND J. L. WALLACE

have found a substantial increase in developers’ inventory (the total of unsold

completed properties) of residential real estate across second-tier and third-tier

cities. Indee d, between 2010 a nd 2013, they calculate a nearly 200% increase in

floor space inventory in second-tier and third-tier cities and note distinct regional

patterns: regions they categorize as “less developed” and “industrial northeast” have

registered the most pronounced rises in inventory (Chivakul et al., 2015:8).The

expansion of inventory translates i nto significant pressure on developers and, by

extension, local economies, as excess supply may take years to absorb. For example,

as of 2014, the calculated time required to clear existing supply was 6 years in Inner

Mongolia and 5 years in Shanxi, Liaoning, Jilin, and Ningxia. Inventory on this

scale–often cluster ed in new d evelopments –represents the presence of massive

amounts of unsold property, leaving visibly desolate landscapes readily chara cter-

ized as “ghost cities.”

Yet, even before the emergence of substantial inventory since 2009, the surge in real

estate demand over the past decade or more was also driven by households’ financial

strategies, which were not necessarily connected to the use of purchased properties. As

numerous studies have noted, real estate serves as an essential financial asset in an

environment with immature capital markets, benchmark bank interest rates near zero,

underdeveloped pension systems, and capital controls (Ong, 2014; Sorace & Hurst,

2016). Rapid price appreciation coupled with nearly as rapid increases in household

income have tended to justify property purchases as a household financial strategy, even

in spite onerous price-to-income ratios at the time of purchase. Assuming that income

increases maintain recent trends, heavy financial burdens at signing stand to be

significantly lightened over the amortization period of mortgages. These factors help

to explain why even lower-income households have rushed to participate in the housing

market. They also point to the significant risk posed by any sharp reduction in

economic growth, as households face the risk of heavy financial burdens extending

over far longer periods than anticipated. However, down payments of 30–40%, as well

as the use of purchased homes as collateral, effectively shield banks from risk exposure

and lower the likelihood of a financial crisis originating in the mortgage market.

8

Robust demand for property as a financial asset is a key factor in the under-

utilization in property. It is widely known, for example, that households commonly

own multiple homes as a reflection of family growth outlooks and investment portfo-

lios. Units purchased for these purposes are often left empty since there is no property

tax in China and therefore no holding cost on property. And yet, the amount of

property sitting empty across China is unknown, as statistics on such indicators are

not currently collected. The National Bureau of Statistics has only recently begun to

produce regular statistical reports on the category of property labeled “awaiting sale”

(Ch. daishou) but has no capacity to reliably assess properties that are uninhabited or

unused. Additionally, using mortgage data to track second-home purchases likely

understates the amount of such homes given the tendency of higher-income households

to pay cash for properties (Koss, 2015 ). There exists, then, no official measure of actual

vacancy; sporadic efforts to gauge vacancy in major cities using proxy measures have

produced results ranging from nearly 20% to 7% (see Jing et al., 2015: 6). The current

lack of reliable data measuring vacancy across Chinese cities underscores the challenges

URBAN GEOGRAPHY 1275

in assessing the scope of the ghost city phenomenon if it is tied to over-supply and

under-utilization of built space.

3.2. New-town

projects

The ghost city controversy has also focused attention on the proliferation of new-town

projects

being built throughout China under the labels of new districts (Ch. xinqu), eco-

cities (Ch. xingtai cheng), new towns (Ch. xincheng), and university towns (Ch. daxue

cheng) (see Chien, 2013; Li, Li, & Wang, 2014; Wu, 2015). The recent trend in new-

town development comes on the heels of China’s “zone fever” of the 1980s and 1990s,

which entailed the establishment of thousands of industrial parks throughout the

country, many of which were commercial failures (Cartier, 2001). Like their industrial

park predecessors, today’s new towns have similarly struggled, and many are featured in

reporting on “ghost cities.”

Though the planning themes of recent new-town projects differ from one another,

they share a number of important features that contribute to their characterization as

“ghost cities.” First, such projects are planned, city-scale mega-projects, with first-phase

urban construction areas of 30 km

2

or more, and sometimes considerably larger. One of

Nanjing’s three planned university towns (Xianling), for example, has a planned area of

70 km

2

(Chien, 2013: 183). New district projects are often much larger still, reaching

461 km

2

in the case of Chenggong New District (Yunnan Province) and 806 km

2

in

Lanzhou New District (Gansu Province). To accommodate such massive area, new-

town projects are most often undertaken in peri-urban areas either adjoining the city or

at some distance from the originating city. Second, given officials’ short terms in office

(on average about 3 years) and the bureaucratic assessment system focused on meeting

various growth-oriented targets, city leaders are keen to commence construction on

large-scale developments as quickly as possible. The rapid pace of construction is

designed to maximize city leaders’ immediate benefits from the economic growth

generated by construction and the additional fiscal income obtainable by putting

huge parcels of cheaply acquired peri-urban rural land onto primary urban land

markets. Given the rapid tempo of project initiation and construction, however, the

supply of built space tends to outpace in-migration, leaving much space under-utilized.

Third, China’s new-town projects are notable for featuring an abundance of monu-

mental public infrastructures, such as museums, theaters, libraries, convention centers,

city halls, and gigantic public plazas and parks. These occupy prime central spaces but

see little day-to-day use. These three core features of new-town projects have meant that

they achieve immense scale and visual extravagance from the outset but often take years

to gain significant population. In the interim, such spaces lack the vitality of the

downtown spaces in the adjacent old population centers. Jarring contrasts between

the crowded and bustling streets of Zhengzhou and its capacious and less-crowded

new-town project, Zhengdong, for example, make the latter town decidedly ghostly

(Xue, Wang, & Tsai, 2013).

Recent research exploring the political–economic and territorial logics of China’s

project-led urban growth strategies provides additional insight into the causal factors

driving new-town projects and suggests why many appear to struggle commercially and

become ghost cities. At one level, the establishment of new towns represents a territorial

1276 M. D. WOODWORTH AND J. L. WALLACE

dynamic driven by various state actors’ struggles for control over cities’ key fiscal

resource: land (for example, see Lin & Yi, 2011; Hsing, 2006; Chien, 2008; Hsing,

2010; Wu, 2015) Municipalities that successfully initiate mega-projects such as new

towns gain control over vast areas, often doubling the size of the original city and

greatly increasing the amount of developable land. As You-tien Hsing (2006) has

argued, acquiring land and building on it is essential to the territorial strategies of

municipal authorities, who rely on control of land for fiscal revenue and to cement their

political legitimacy through effective and visually striking construction projects.

At another level, large-scale land development supplies cash-strapped city adminis-

trations with vital fiscal resources through leases and rents. Incentives to expand land

development are strong, as income from land transactions is categorized as “extra-

budgetary revenue” and, therefore, is exempt from tax sharing with the central govern-

ment (see Song & Ding, 2007). Initiating land development is also a crucial mechanism

to mobilize development capital wherever capital is scarce, as acquired land parcels can

be used as collateral for bank loans applied toward various urban development projects

(Lin & Yi, 2011). In this sense, the forces of demographic and industrial expansion

propelling urban growth are given additional thrust by municipal-level politics, which

have a profound impact on the pace and scale of city growth.

The rapid growth of city-scale new-town projects has thus made for striking images

of barely inhabited cities. It is unclear, however, which of these will gradually gain

population and become more city-like, and which will earn reputations as white

elephants. As Shepard notes in Ghost Cities of China: “Rome wasn’t built in a day;

neither are new cities in China” (2015: Chapter 9). It may still be too early to judge the

outcomes for these cities-in-waiting.

3.3. Land-use

approaches

Another way to investigate the ghost city phenomenon is to consider land uses in order

to

discern patterns that reveal a surge in built space relative to population. At the

national scale, the category of urban construction land, which refers to land that can be

used for the range of urban functions, has expanded at nearly double the rate of

demographic urbanization (Figures 1 & 2). In short, land is being urbanized at a faster

rate than the population. Official statistics show built-up land area more than doubling

from 22,439 km

2

in 2000 to 47,108 km

2

in 2013, while urban population increases only

at half that rate, from 459,060,000 in 2000 to 731,000,000 in 2013.

9

At this national

scale, the data points toward massive sprawl of urban built-up areas into adjacent land

and a remarkable increase in per-capita urban space.

Assessing this trend at more local scales reveals important differences suggestive of

regional trends in the over-production of urban space since 2000. Using World Bank

data for county-level administrative units, for example, we find considerable hetero-

geneity in changes in urban density (see World Bank, 2015). Urban areas in coastal

regions have seen more population growth in absolute terms and have expanded urban

construction land significantly through lateral sprawl. By contrast, similarly large

physical expansions of urban construction land in the absence of comparable increases

in population more easily code as empty in our findings. These results echo reporting

on ghost cities that locate such sites in interior regions, where rapid urbanization of

URBAN GEOGRAPHY 1277

land has preceded the presence of populations and produced spaces of remarkably low

urban population density.

The lack of official data on urban tenancy and vacancy, however, makes it difficult to

develop a more granular analysis of density and ghost town development. Some recent

research efforts have attempted an end run around official data limitations, however, by

taking advantage of Internet and wireless communication-based “big data” in a GIS

environment. Using location data from cell phones accessing Baidu for internet

searches in combination with mapped locations of buildings, Chi, Liu, Zhengwei, and

Haishan (2015) identify locations consistent with ghostly emptiness. As their study

acknowledges, however, the employed data-generation process contains a number of

selection biases, most notably the equation of location-aware Baidu searches with

tenancy and the exclusion from the study of populations with alternative Internet use

patterns or lack of Internet access. Yet despite data shortcomings, their study’s results

turn up a number of usual suspects in reporting on ghost cities, including Kangbashi

and Tianjin’s Binhai New District. Results such as these provide further evidence of

trends in city building that produce spaces widely referred to as ghost cities.

4. Prospects

There is currently no consensus on what constitutes a ghost city in China. At the heart

of this definitional and conceptual quandary is confusion over the significance of

emptiness and tenancy in urban spaces, a confusion based in no small part on an

absence of data. But also, more conceptually, what level of tenancy qualifies as proble-

matic? To what point is strong demand for real estate an effect of distortions caused by

a remarkable accumulation of capital with insufficient productive outlets? These chal-

lenges make it difficult to assess where ghost cities exist, how large they me be, their

originating causes and for how long they may lack population.

Nonetheless, recent research into property oversupply and ghost cities has stimulated

useful debates about China’s urbanization. This work has brought to light problems at

the heart of our empirical grasp of the country’s urban transformations as well as

shortcomings in our conceptual language used to understand this process. Is a city a

city if there are no people? What are the connections in China’s peculiar setting

between industrialization, capital accumulation, and city growth? Given the strong

role played by local states in pushing urban expansion, to what degree are demographic

growth and industrialization the drivers of China’s urbanization? Relatedly, how are use

and exchange values connected in China’s drive to urbanize? How might the relation-

ships among these forces alter longstanding urban theory that has tended to see

urbanization as a capital-driven process linked to industrialization?

The China case clearly demonstrates the vital interplay among city-level political

forces, the urban land tenure regime, and national-level economic forces in shaping the

country’s dramatic urbanization. Strong economic growth alone does not account for

the production of urban spaces that have come to be referred to as “ghost cities.”

Neither does the decantation of the countryside fully explain the particular spatial

patterns of urban sprawl and housing over-supply. Indeed, a recent review by the

cabinet-level National Development and Reform Commission found 3,500 urban pro-

jects currently on the books in China with potential to house 3.4 billion people (Xinhua,

1278 M. D. WOODWORTH AND J. L. WALLACE

2016). Such findings highlight anew the relevance of the ghost town terminology and

hold alarming implications for the economic and social viability of cities. In short, they

point to a gigantic absorption of capital in urban built space and reveal that a major

output of China’s economy in the 2000s has simply been cities.

Notes

1. For exa mples of photographic e ssays, see http://content.time.com/time/photogallery/

0,29307,1975397,00.html (Time magazine), http://www.thebohemianblog.com/2014/02/wel

come-to-ordos-world-largest-ghost-city-china.html (Bohemian blog), http://www.raphaeloli

vier.com/china/architecture/photographer/ordos/failed-utopia/ (Rafael Olivier). All sites

accessed 25 June 2016.

2. See http://www.aljazeera.com/news/asia-pacific/2009/11/2009111061722672521.html

3. To illustrate the volume of reporting on China’s

ghost cities, a search on Google news for

“China ‘ghost city’” returns 1,720 results as of June 2016.

4. We note that in the years since the emergence of China’s

ghost city controversy, other sites

around the world, such as Masdar in Dubai and Songdo in South Korea, have also been

labeled “ghost cities” in various reports. See Shapiro (2015) and (Goldenberg, 2016).

5. National Bureau of Statistics. www.stats.gov.cn and

CEIC.

6. National Bureau of Statistics. www.stats.gov.cn

7. The four trillion RMB estimate comes from the fiscal

side, yet harder to measure but likely

even larger in size was financial stimulus in the form of loans from state-owned policy and

commercial banks. See (Naughton, 2009).

8. Property-related debt on corporate balance sheets, on the other hand, are a major source of

macro-economic

concern. See, e.g. Kroeber (2016).

9. National Bureau of Statistics. www.stats.gov.cn

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Jeremy L. Wallace

http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7152-8481

References

Arora, Raksha. (2005). Homeownership Soars in China. Gallup. March 1. http://www.gallup.com/

poll/15082/homeownership-soars-china.aspx (accessed January 31, 2017).

Bank, World. (2015). East Asia’s changing urban landscape: Measuring a decade of spatial

growth. http://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/21159 (accessed June 27, 2016)

Cartier, Carolyn. (2001). Zone Fever”, the Arable land debate, and real estate speculation: China’s

evolving land use regime and its geographical contradictions. Journal of Contemporary China,

10(28), 445–469.

Chi, Guanghua, Liu, Yu, Zhengwei, Wu, & Haishan, Wu. (2015). “Ghost Cities” Analysis based

on positioning data in China. Arxiv Preprint, arXiv, 1510.08505.

Chien, Shiuh-Shen. (2008). The isomorphism of local development policy: a case study of the

formation and transformation of national development zones in post-mao jiangsu. China.

Urban Studies, 45(2), 273-294.

URBAN GEOGRAPHY 1279

Chien, Shiuh-Shen. (2013). Chinese eco-cities: A perspective of land-speculation-oriented local

entrepreneurialism. China Information, 27(2), 173–196.

Chivakul, Mali, Lam, Raphael W., Liu, Xiaoguang, Maliszewski, Wojciech, & Schipke, Alfred.

(2015). Understanding residential real estate in China (Vol. WP/15/84). Washington, DC:

International Monetary Fund.

DRCSC (Development Rese arch Center of the State Council) (2012). An analysis of the

systemic causes of china’surbanpathologies[我国城市病的体制性成 因分析], Report

Number 67, 1–13.

Fang, Hanming, Quanlin, Gu, Xiong, Wei, & Zhou, Li-an (2015). Demystifying the Chinese

housing boom, Working Paper 21112, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge,

MA.

Goldenberg, Suzanne. (2016, February 16). Masdar’s cero-carbon dream could become world’s

first green ghost town. The Guardian. (accessed June 29, 2016)., https://www.theguardian.

com/environment/2016/feb/16/masdars-zero-carbon-dream-could-become-worlds-first-

green-ghost-town

He, Guizhen, Mol, Arthur PJ, & Lu, Yonglong. (2016). Wasted cities in urbanizing China.

Environmental Development, 18,2–13.

Hsing, You-tien. (2006). Land and territorial politics in urban china. The China Quarterly, 187,

575-591.

Hsing, You-tien. (2010). The great urban transformation: politics of land and property in china.

Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Jing, Wu, Gyourko, Joseph, & Deng, Yongheng (2015). Evaluating the risk of chinese housing

markets: What we know and what we need to know, Working Paper 21346, National Bureau

of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA.

Koss, Richard (2015). How significant is housing risk in China? Paper presented at the

International Symposium on Housing and Financial Stability in China, Shenzhen, December

18-19.

Kroeber, A. R. (2016). China’s economy: What everyone needs to know. New York, NY: Oxford

University Press.

Li,

Zhigang, Li, Xun, & Wang, Lei. (2014). Speculative urbanism and the making of university

towns in China: A case of guangzhou university town. Habitat International, 44, 422–431.

Lin, George C.S., & Fangxin, Yi. (2011). Urbanization of capital or capitalization on urban land?

Land development and local public finance in urbanizing China. Urban Geography, 32 (1), 50–

79.

Naughton, B. (2009). Understanding the Chinese stimulus package. China Leadership Monitor,

28. (accessed June 27, 2016) http://www.hoover.org/sites/default/files/uploads/documents/

CLM28BN.pdf

Ong, Lynette H. (2014). State-led urbanization in China: Skyscrapers, land revenue and “con-

centrated villages”. The China Quarterly, 217, 162–179.

Powell, Bill. (2010, April 5). Inside China’s run-away building boom. Time. (accessed June 27,

2016)., http://www.time.com/time/magazine/article/0,9171,1975336,00.html

Shapiro, Ari (2015). A South Korean city designed for the future takes on a life of its own,

national public ra dio, October 15. http://www.npr.org/ sections/parallels/2015/10 /01/

444749534/a-south-korean-city-designed-for-the-future-takes-on-a-life-of-its-own (accessed

June 29, 2016).

Shepard, Wade. (2015). Ghost cities of China: The story of cities without people in the world’s most

populated country. London: Zed Books.

Shih, Yu-Nien, Li, Hao-Chuan, & Bo, Qin. (2014). Housing price bubbles and inter-provincial

spillover: Evidence from China. Habitat International, 43, 142–151.

Song, Yan, & Ding, Chengri. (2007). Urbanization in China: Critical issues in an era of rapid

growth. Cambridge, MA: Lincoln Institute of Land Policy.

Sorace, Christian, & Hurst, William. (2016). China’s phantom urbanisation and the pathology of

ghost cities. Journal of Contemporary Asia, 46(2), 304–322.

1280 M. D. WOODWORTH AND J. L. WALLACE

Wallace, Jeremy. (2014). Cities and stability: Urbanization, redistribution, and regime survival in

China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wood, Anthony. (2014). Best tall buildings: An overview of 2013 skyscrapers. London: Routledge.

Woodworth, Max D. (2015). Ordos municipality: A market-era resource boomtown. Cities, 43,

115–132.

Wu, Fulong. (2015). Planning for growth: Urban and regional planning in China. London:

Routledge.

Xue, Charlie Q.L., Wang, Ying, & Tsai, Luther. (2013). Building new towns in China – A case

study of Zhengdong new district. Cities, 30, 223–232.

Xinhua. (2016). Guihua 3500 ge xincheng rongna 34 yi renkou, shei lai zhu? (3,500 new towns

are planned with space for 3.4 billion, who will live there?). Beijing, 13 July. http://news.

xinhuanet.com/politics/2016-07/13/c_1119214482.htm (accessed January 31, 2017).

Yu, Hong. (2015). China’s “Ghost Cities”. East Asian Policy, 6(2), 33–43.

URBAN GEOGRAPHY 1281