1

China Residential

When will the party end?

Alpha Watch

January 2014

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

2

Executive summary

Many have raised concerns that China’s housing market is in a

bubble, given the strong sales transactions, price increases and

large vacant and pipeline inventory. However, we do not expect a

national or devastating bubble burst in the China property market

although some smaller markets may correct due to oversupply and

weak demand. China is a large country with a wide degree of

variance among different geographic areas. In the Tier 1 and 2 cities,

prices are high due to strong demand and constraint in supply.

Home ownership rate is lower than in the rural areas and there is

upgrading desire with many households in poor and cramped

conditions. In many Tier 3 and 4 cities, oversupply is the main

problem as local governments have been selling land to developers

to fund new projects and infrastructure to drive their economies.

Long-term housing demand drivers remain intact, but the momentum

of growth is expected to ease after coming up from a low base in the

past few decades. China’s economic growth rate is slowing down as

it undergoes restructuring, the population will be peaking in a few

years’ time with less moving into the marriageable age group and

the rate of urbanisation will be more moderate after hitting over 52%

in 2012. Capital controls will be slowly eased under the financial

reforms, which are likely to divert more funds to overseas properties.

Tier 1 and 2 cities will however continue to see strong housing

demand from the continuous influx of migrants, and upgrading and

investment demand. Nevertheless price increases are expected to

be more moderate from 2013 rates, given the slower economic

growth, housing curbs, high price levels and increasing supply of

affordable housing. For smaller cities with oversupply, some could

see a fall in prices with weak demand but most are likely to see flat

prices. Coastal Tier 3 and 4 cities are in a better position to resolve

their oversupply over time, as they have stronger economic drivers

to attract migrants from inland areas, aided by the recent relaxation

to make it easier for migrants to obtain hukou registration.

With the property sector contributing a significant proportion to GDP

growth, it is in the interest of the government to see a stabilised

market. The new government has shifted focus to increasing social

welfare supply instead of curbing housing demand and price

increase nationwide. The major risk for the housing market is a

significant economic slowdown as a result of drastic reforms or

another global crisis. However, it is likely that the Chinese

government will step in with some stimulus as it had done during the

global financial crisis and last year’s slowdown. As the housing

market in China is a diverse mix and coming to a new era of slower

growth momentum, investors/developers will have to carefully

consider each city’s economic growth drivers and housing demand

and supply situation.

Contents

Executive summary 2

Introduction 3

Is there a price bubble? 4

Is there oversupply? 7

Will demand slow down? 11

Impact of tightening credit 14

Impact of government

policies 16

Outlook 18

Author

Chua Chor Hoon

Director, Research

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

3

Introduction

Housing prices in China have risen for more than a decade, driven by strong

growth in disposable income and urbanisation. 470 million people have moved

from rural to urban areas over the past three decades. The share of the urban

population has increased from about 17.8% in 1978 to about 52.6% in 2012.

The increased demand for urban housing has helped to push home prices

higher in these areas. Income has grown faster than home prices, providing

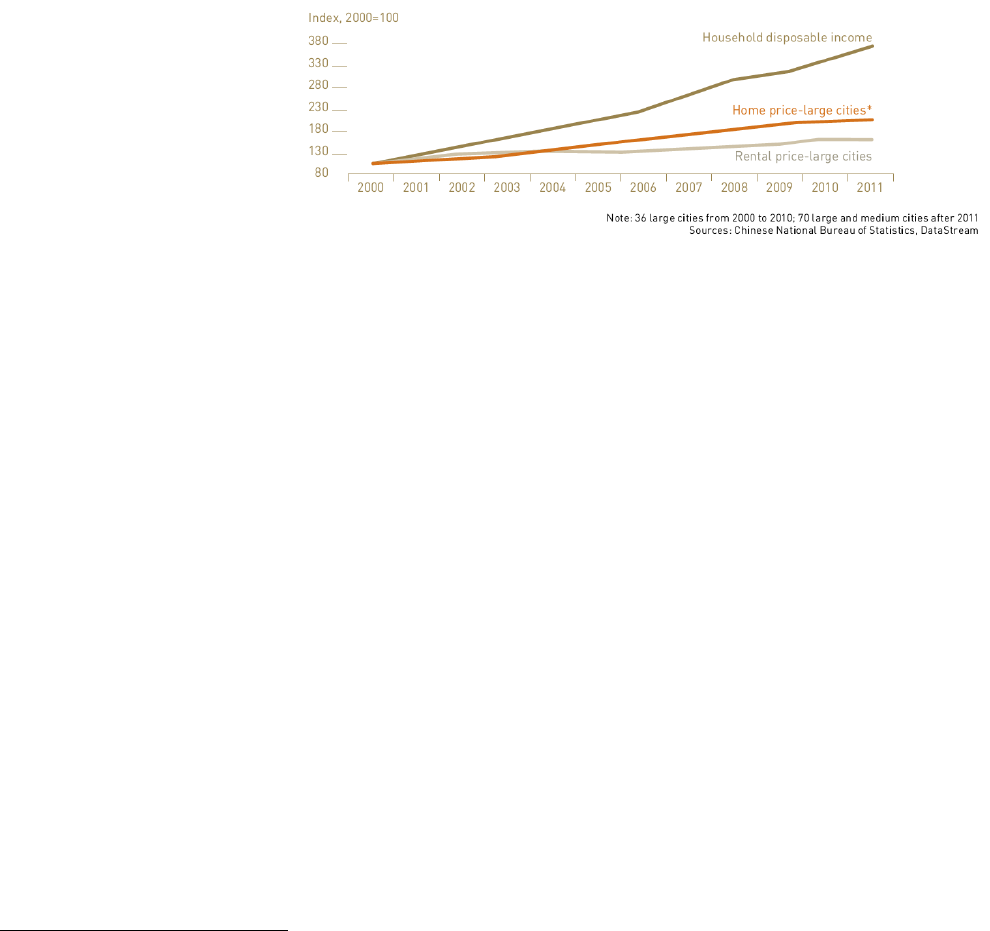

fundamental support to prices (Fig 1).

Figure 1: Disposable income grows faster than home prices

Despite three years of government measures to curb demand and price

growth, new home sales volume and prices in 2013 continued to rise. Sales

volume rose 18% to 1.2 billion sqm. New home prices among 70 large and

medium-sized cities rose an average of 9.7%, led by Tier 1 cities which saw

increases exceeding 20%

1

. The total value of new home sales in 2013 rose

27% to RMB 6.8 trillion, exceeding USD 1 trillion for the first time. This is

comparable to the total value of new and existing home sales in the US,

estimated to be around USD 1.1 trillion, including USD149 billion of new

homes

2

.

Many have raised concerns that China’s housing market is in a bubble, given

the strong sales transactions, price increases and large vacant and pipeline

inventory. The purpose of this paper is to examine the following points of

inquiry:

Is there a price bubble?

Is there oversupply?

Will demand slow down?

Will credit tightening kill the market or trigger a financial crisis similar

to what happened in the US?

What is the government policy intention?

What is the outlook and investment strategy to be taken?

1

National Bureau of Statistics

2

Cushman & Wakefield

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

4

Is there a price bubble?

The price-to-income and affordability ratios, commonly used indicators

to analyse housing market exuberance, showed that China’s nationwide

average ratios are much higher than most other countries.

However there is a degree of variance among different areas. The ratios

are much higher in the Tier 1 and 2 cities where price increases have

taken on a faster pace. Tier 3 cities have ratios that are comparable to

other countries.

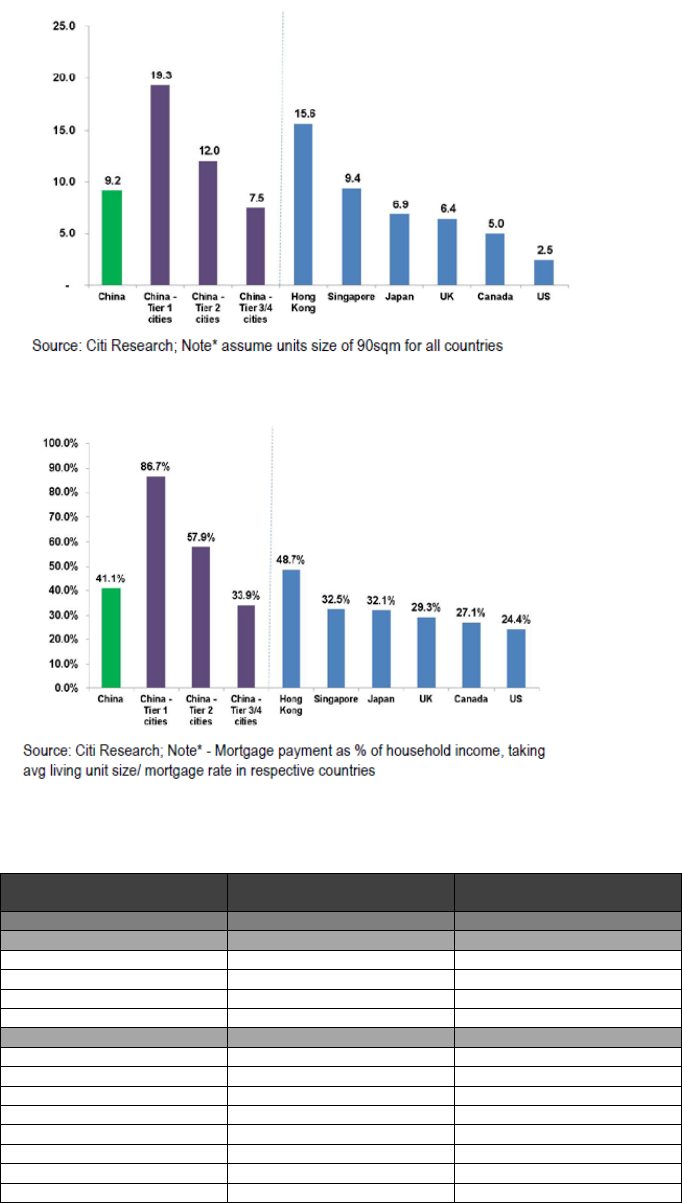

According to Citi Research

3

, the price-to-income ratio in China is 9.2, higher

than in most other countries with the exception of Hong Kong (15.6) and just

below Singapore (9.4) (Fig 2). Similarly, the affordability ratio (monthly

mortgage payment for mainstream unit size versus average household

income) in China at 41.1% is higher than in most other countries except for

Hong Kong (48.7%) (Fig 3). This is due to the higher mortgage rates in China,

besides the high property prices.

However, these do not reflect a nationwide bubble. The ratios are higher in

Tier 1 and 2 cities, while Tier 3 cities exhibit ratios comparable to other

countries. The ratios in Beijing and Shanghai are among the highest in the

world, given their fast rates of price growth which have outpaced growth in

disposable income. Price-to-income ratio and affordability ratio have reached

22.4x/95% for Beijing and 17x/78% for Shanghai (Table 1).

The root causes for the high ratios in the Tier 1 and 2 cities are ample liquidity

and supply shortage. Property has become a popular vehicle to park the

wealth of the rapidly growing affluent group and preserve value against

inflation amidst a lack of other investment channels. The better job prospects

attract a continuous growing population, including new graduates,

businessmen and migrant workers. However, land resources are getting

limited as these cities grow, exerting pressure on housing prices.

3

Citi Research: China Property, Ghost Towns and Property Bubbles, December 2013

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

5

Figure 2: Price-to-income Ratio

Figure 3: Affordability Ratio

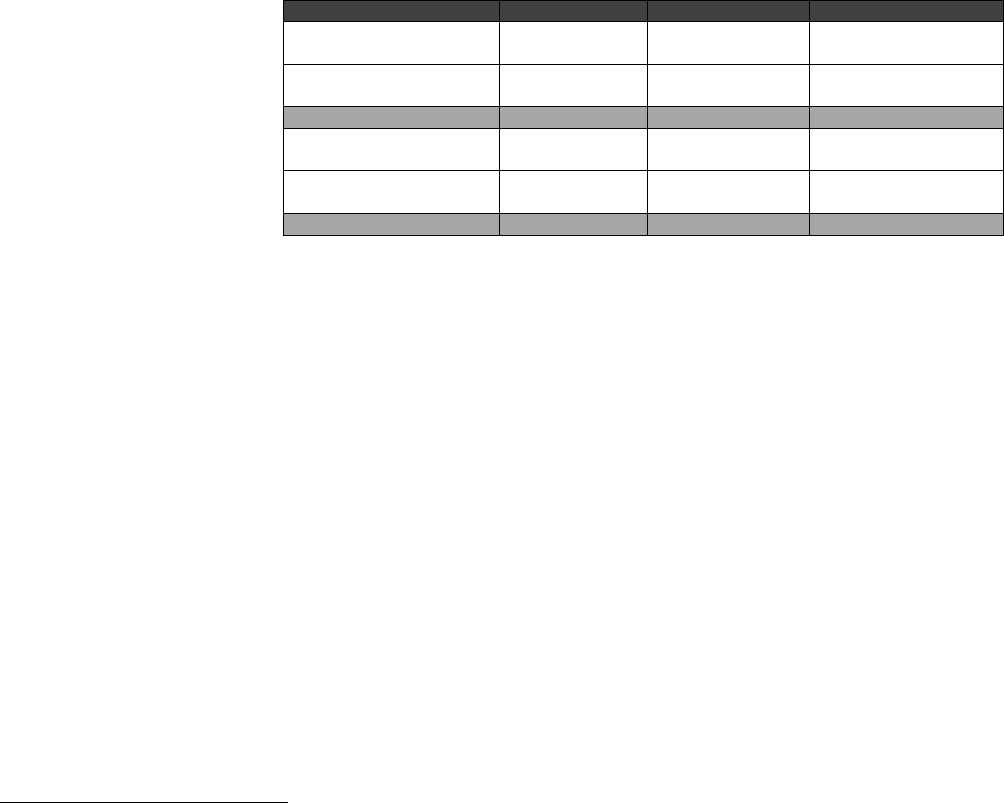

Table 1: Price-to-income and affordability ratios of Tier 1 and selected

Tier 2 cities

Price-to-Income Ratio

Affordability

(Mortgage as % of Income)

National

9.2

41.1

Tier 1 Cities

19.3

86.7

Beijing

22.4

95.4

Shenzhen

23.0

92.7

Shanghai

17.0

91.2

Guangzhou

15.6

69.4

Tier 2 Cities

12.0

57.9

Hangzhou

18.4

84.9

Tianjin

13.3

65.8

Xiamen

17.0

62.3

Chengdu

12.4

60.3

Nanjing

13.1

58.9

Chongqing

10.3

48.2

Shenyang

11.2

47.8

Wuhan

12.6

41.9

Source: Soufun, CEIC, Citi Research

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

6

While the high prices in Tier 1 and 2 cities have a part to play in the high

price-to-income ratio and affordability ratio, the huge wealth gap and

under-reporting of income have also caused these ratios to be

disproportionately higher.

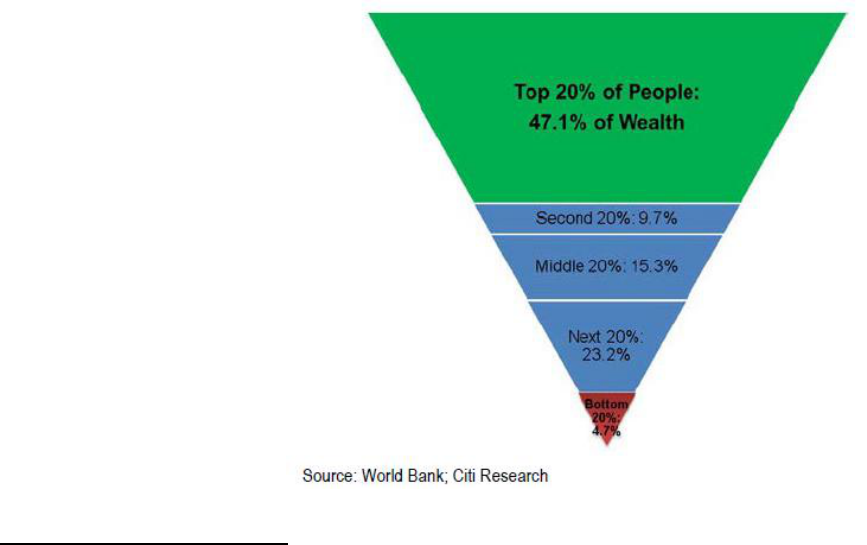

The effective home buyers come from the affluent group which controls the

majority of assets and wealth. According to a 2009 World Bank report, the top

20% of wealthy people in China controlled around 47% of assets, while the

bottom 20% owned only 4.7% (Fig 4). Based on National Statistics Bureau

(NBS) 2012 figures, the disposable income of the top 10% urban population is

about 7.8x that of the bottom 10%

4

. Unofficial estimates said that the top 20% of

earners potentially under-report incomes by 60-70%

5

. Furthermore, “grey

income” is sizeable and concentrated in top-earner groups while the low-income

population usually do not have “grey income”. Factoring these in, the disposable

income at the high end could be above10x more than the lowest income level.

Hence affordability is less of an issue for the higher income groups. The

greater constraints for them are the credit tightening for second

properties and ban on third property purchases.

Notwithstanding the flaws in the computation of the ratios, the rising

prices in the Tier 1 and 2 cities have made housing less affordable for the

lower income worker, resulting in pent-up demand in the lower end

segment. In Beijing where a new type of affordable housing product for self-use

with sale price 30% below surrounding properties was introduced in Oct 2013,

the first project of 2,000 units attracted 148,000 applicant households.

Figure 4: China Distribution of Wealth, 2009

4

NBS: Basic Conditions of Urban Households by Income Percentile (2012)

5

Savills China: Residential Chart Book 2013

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

7

Is there oversupply?

The amount of new land supplied for residential property development hit

a record high of 138,200 hectares in 2013, up 25% from the previous year.

Looking at the amount of pipeline residential space nationwide, there

appears to be more than sufficient supply to accommodate housing

demand.

Simply by looking at the incremental supply from residential land under

construction and social welfare supply for the next four years, the number is

already higher than our projections of incremental demand based on migration

and marriage needs (Table 2). We have not added in estimates of supply from

land held by developers and the possibility of some vacant units held by

multiple-home owners being put back into the market due to lack of transparent

information. These would make the supply figures look even larger.

Table 2: China’s incremental residential supply and demand

GFA (sqm)

Units

No. of people

1

Under construction by

developers

4.863 billion

2

51 million

147 million

Planned social welfare

units (2014 -2017)

28 million

3

80 million

Supply

227 million

Migration (2014 to

2017)

4

72 million

Marriages (2014 to

2017)

5

104 million

Demand

176 million

Source: National Bureau of Statistics

1 Assumes urban building space per capita of 32.9sqm and average household size of 2.86

based on NBS Population Census 2010

2 Source: NBS 2013

3 36 million or 7.2 million p.a. social welfare housing units were planned under the 12

th

Five-Year

Plan (2011-2015). We assume a similar rate of 7 million to be built p.a. thereafter.

4 Migration 18 million p.a based on average of historical and future urbanisation growth rate

6

5 Marriages 13 million p.a.

7

based on 2013 actual (Source: NBS)

6

UNDP China and Institute for Urban and Environmental Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: China National Human

Development Report 2013

7

NBS

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

8

However, we caution against jumping to the conclusion that there is an

oversupply because:

1) Supply is inflated

Some construction may stop due to weak developers’ financial

difficulties.

The land held by developers may not be built on anytime soon.

Old stock that will be demolished or abandoned is not accounted for

due to lack of data. Many old homes are self-built and of poor living

standards. In the bigger cities, many old buildings have to be

demolished to make way for new developments. Pre-reform welfare

housing transferred to individuals in 1998 accounted for over 40% of

residential stock in China

8

. Out of the 36 million social welfare housing

units to be built the 12

th

Five-Year Plan (2011-2015), 41% will be for

recently displaced individuals from demolished shanty towns rather

than development for new migrants

9

.

It is hard to define and measure vacant units. A wide range of

estimates have been reported but it is hard to verify their basis. Du

Meng, chairman of the China Enterprise Capital Alliance, claimed that

there were 68 million vacant houses but many think it is too high.

David Li, Professor of Freeman Chair in Economics, the School of

Economics and Management, Tsinghua University, has estimated 50

million. Yang Hongxu, an analyst at Shanghai E-House Real Estate

Research Institute, estimated that the nation's vacancy rate is around

5% out of the total house stock of 22 billion sqm, equivalent to about

11 million vacant houses.

We cannot assume that all vacant units can be put back into the

market as some will be genuinely kept as second homes in other cities

for self-use. In addition, there will always be some vacancy due to

time needed to find new tenants (although the rental market is small in

China) and to be fitted out for habitation as many units are delivered

bare.

2) Demand is under-estimated

Many homes comprise more than one household and more than one

generation. 11.67% of households in China comprised three- or more

generations

10

. As they become wealthier, these households can split

and occupy more than one unit. This is on top of what we have

accounted for in marriages.

8

Savills China: Residential Chart Book 2013

9

Ministry of Housing and Urban-Rural Development, Samsun Securities

10

NBS

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

9

As the older stock of homes are small and of poor quality, there is

desire to upgrade if wealth permits. Although upgrading means letting

go of the original unit to someone else and therefore there is no net

increase in demand, in reality there is at least a few years of overlap if

one buys an uncompleted unit.

We cannot simply assume that each household requires only one unit

of accommodation with China being so big geographically. Although

we have assumed migrants would require additional accommodation

on top of what they have before migration, there are others who need

second homes in other cities for business, education, leisure and

other purposes.

There is a constant flow of new rich who will want to buy a second

property.

Foreigners working in China require housing too.

What is clear is that the oversupply situation is not evenly distributed. In

the developed Tier 1 cities, land is more scarce and old buildings

especially in the prime city centres are torn down to make way for new

developments. Table 3 below shows that Tier 3 and 4 cities have a higher rate

of increase in residential GFA being commenced, constructed and completed

between 2008-2012, resulting in a higher inventory digestion period.

The smaller cities bear the brunt due to the large supply of land sold by

local governments vis-à-vis take-up. Massive advance town planning which

over-forecasted demand, and local governments’ strategies of building

infrastructure and selling land for housing construction to achieve their GDP-

driven KPIs have resulted in excess supply in many cities. Oversupply exists

not only in the units that have been completed or are under construction; it also

lies in the massive landbank held by developers following the local governments’

aggressive selling in the past. To make matters worse, many smaller cities do

not enjoy high sustainable housing demand. As a result, a number of cities have

been labeled as “ghost towns” by the media given the low occupancy of the

newly completed homes.

However, not all “ghost towns” deserve the label. According to Citi

Research

11

, Ordos, Yingkou and Tangshan deserve the label given the

massive cumulative oversupply that has been built up, virtually no rental

market, resources-driven economies which have been hit by overcapacity,

wide income disparity which means many locals cannot afford to buy

these new homes, and declining or slow population growth.

11

Citi Research: China Property, Ghost Towns and Property Bubbles, December 2013

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

10

Public perception of ghost towns usually comes from the impression of

low occupancy such as no lights at night or little activity in the town.

However there are some peculiarities in the China housing market that

takes a newly completed building a longer time to reach high occupancy.

The primary market is still dominant with bare-shell units and young couples

tend to buy first and move in upon marriage. The physical key handover can

come after 18 months or more from purchase day while often taking another

two years for decoration

12

. Hence in general, it can take 3-4 years for

homebuyers from buying to moving in. From Citi Research’s ground checks,

they noticed many projects can indeed record around 50% occupancy in around

two years’ time, and over 70% after 3-4 years.

Hence for the other “ghost towns”, Citi Research felt that they do not

deserve such labels as their oversupply is less, have more diversified

economic bases and higher proportion of transient population. Their

oversupply can be cleared, although it will be slow and take a number of

years.

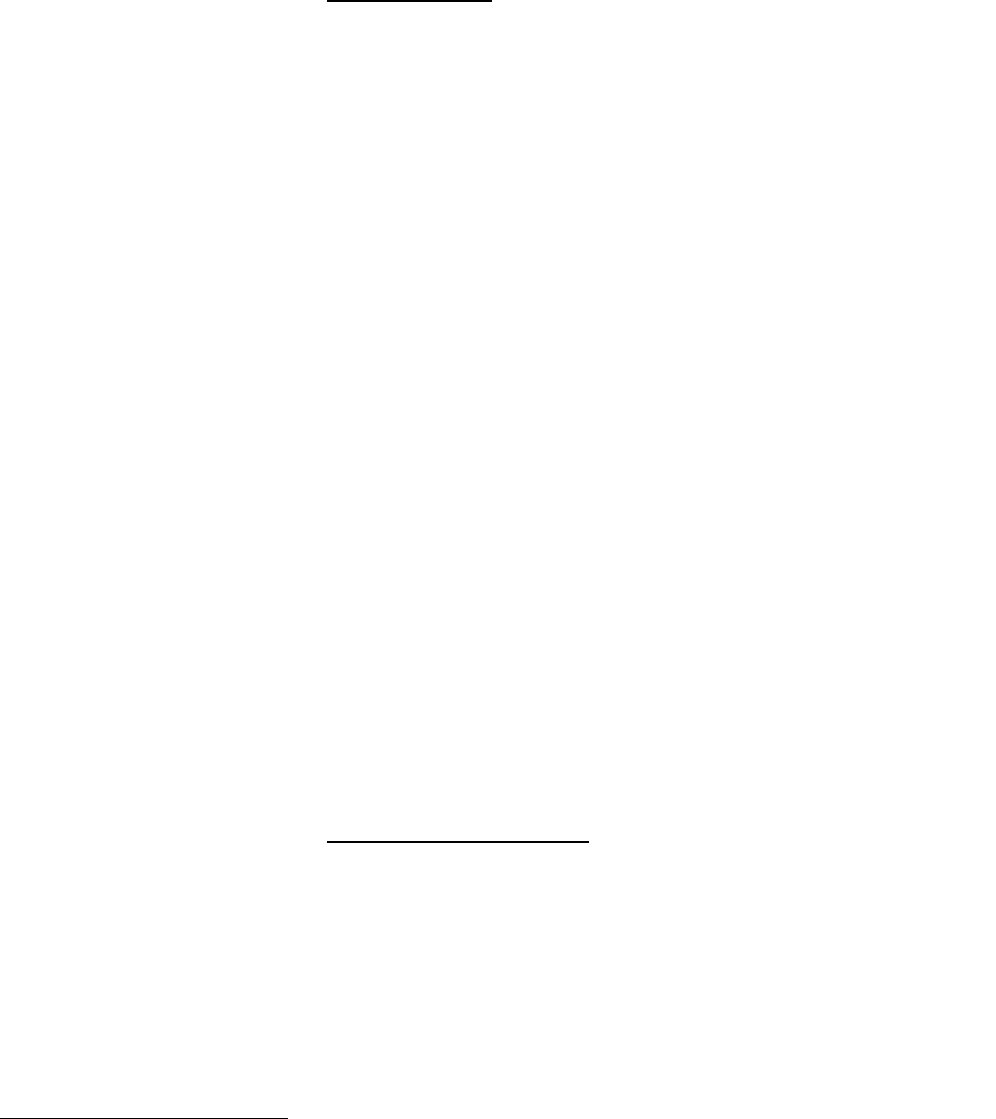

Table 3: China Property – Key Statistics by City Tier

5-year CAGR (2008 – 2012)

Tier 1

Tier 2

Tier 3/4

National

Demographic and Economic

Population

3.4%

1.9%

0.1%

0.5%

Disposable income

9.2%

12.0%

11.5%

11.0%

Real GDP growth

10.3%

13.3%

11.7%

9.3%

GDP per capita

7.7%

11.8%

13.6%

11.7%

Property Market

Residential property sales

value

6.2%

15.4%

18.7%

16.1%

Average selling price

12.4%

10.7%

7.9%

8.8%

Residential GFA started

1.3%

10.1%

15.8%

13.1%

GFA starts/GFA sold

110.8%

119.6%

160.1%

132.0%

Residential GFA completed

-0.4%

11.9%

16.5%

13.4%

Residential GFA under

construction

6.2%

15.6%

22.6%

18.6%

Inventory digestion (months)

10.4

14.9

20.7

17.8

Land Market

Land sales value

0.9%

12.5%

23.2%

17.6%

Land price

16.9%

12.3%

7.5%

14.9%

Land sold in GFA/GFA sold

77.6%

135.2%

175.2%

151.0%

Source: CEIC, Soufun, Citi Research (November 2013)

12

Citi Research: China Property, Ghost Towns and Property Bubbles, December 2013

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

11

Will demand slow down?

China’s housing market in the last two decades has been driven by various

factors – high GDP growth resulting in greater wealth, urbanisation which

created new demand in the cities and lack of investment alternatives which

have driven many to park their money in homes. It has been estimated that

about 15% - 20% own more than one housing unit in China.

While the long-term drivers of housing remain intact, going forward we

expect a slower rate of growth in housing demand given that the market

has come up from a low base in the last 20 years and as the government

rolls out more reforms:

1) Slowdown in economic growth: The economy has slowed down to

7.7% last year. With more reforms being implemented to restructure the

economy, there will continue to be some pain and impact on growth. Many

authorities have been reported to have lowered their GDP projections for 2014,

ahead of the central government’s announcement in March of its 2014 target.

Bloomberg consensus forecast

13

is a slower growth rate of 7.5% for 2014 and

7.2% for 2015.

2) Slowdown in urbanisation rate: It grew at an annual average of 1.37

percentage points between 2005 (43.0%) and 2012 (52.6%) with an annual

increase of about 21 million

14

in urban population. The urbanisation rate is

predicted to increase to 70% by 2030, at a slower annual average of 0.97

percentage point. Between 2010 and 2030, the urban population is expected to

rise by another 310 million, an annual average increase of 15.5 million

15

. Some

of the urbanisation may also not lead to a direct increase in housing demand, as

some areas may simply be re-designated from rural to urban, and people who

have already been living there already owned houses. Urbanisation does not

simply involve people from rural areas to the cities. China’s urbanisation is

focusing on the development of big city-clusters – each cluster with bigger cities

(like Tier-2 and Tier-3 cities) linking with smaller cities and towns (like Tier-4

cities and institutionalised towns) via modern infrastructure (including

transportation and information networks).

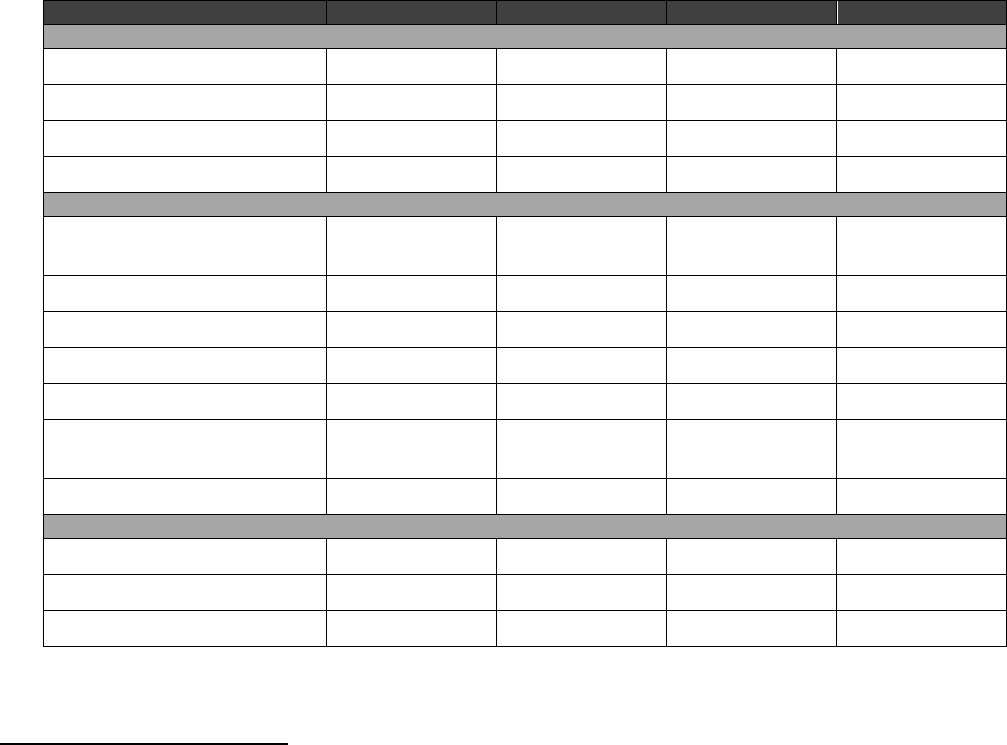

3) Slowdown in marriages: New demand from newly/soon-to-be married

couples could slow down as the population ages. The main homebuyers in

China tend to be in their late 20s, when couples are getting married. While in

the next five years we might expect this age range to grow, after that point there

is expected to be a protracted decline in new demand. The number of Chinese

in the marriageable ages of 20-34 years will fall from 325 million in 2010 to 219

million in 2030 (Fig 5). It will be another 20 years before the recent easing of the

one-child policy can boost the number of marriages. At the same time, lifestyle

is changing. Young people are marrying at an older age as more take up higher

education, and they prefer spending on entertainment and travel, or other

personal interests/projects.

13

Median of several economists’ forecast

14

UNDP China and Institute for Urban and Environmental Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences: China National Human

Development Report 2013

15

Based on projection by UNDP for China’s population in 2026

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

12

4) Increase in overseas and alternative investments: More Chinese

are expected to divert funds to purchase properties overseas as they become

more familiar with the external environment and as capital controls are gradually

relaxed under the government’s financial reforms. There could also be a loss of

capital in the physical real estate market if more alternative investments are

introduced.

5) Increase in government supplied affordable housing: The

government is addressing social inequality issues by supplying more affordable

housing which will have some effect on the lower end segment of the private

market eventually. In Beijing, 70,000 self-use units with prices capped at 30%

below market price are being put on the market (20,000 in 2013 and 50,000 in

2014) which is similar to the total number of units sold in Beijing in 11M2013

16

.

6) Increase in holding costs: There is currently little holding cost in

keeping a unit empty. Should holding costs increase significantly as a result of

property taxation or other taxes, investors will be more inclined to rent out units

or change investment class.

7) Government regulations: It has been reported that the government’s

anti-corruption campaign has caused officials to be more discreet in purchasing

multiple homes and some have been divesting. It is uncertain how long and

deep this campaign will last. A nationwide property database that has been

proposed will increase transparency in ownership and further deter multiple

home buyers.

Figure 5: Age structure of China in 2010 and 2030 (Unit: millions of people)

Source: UNDP China and Institute for Urban and Environmental Studies, Chinese Academy of Social Sciences

16

CBRE Marketview November 2013

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

13

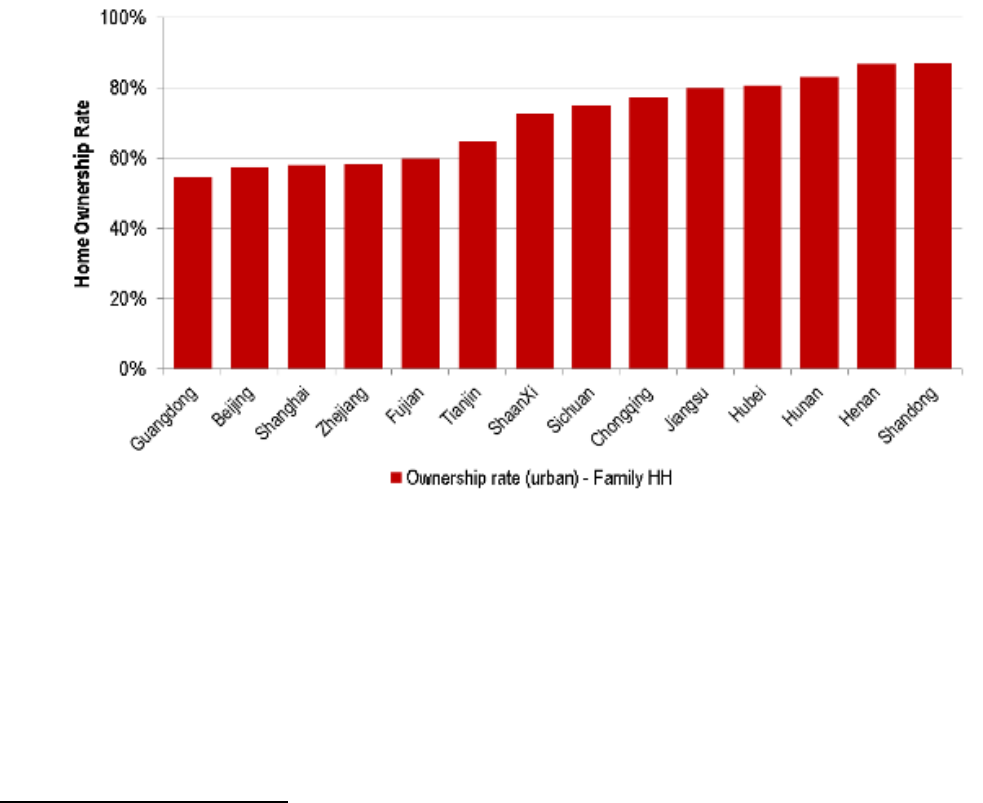

The demand is assessed to be higher in the Tier 1 cities where

homeownership rate is estimated to be below 60% given their higher

number of migrants (Fig 6). This is below the nationwide homeownership rate

of 85%

17

, as close to 50% of the households surveyed lived in the rural area,

whose close-to-100% home ownership (95% of which are self-built housing)

skewed the overall number significantly

18

.

Figure 6: Home Ownership Rate (Urban), Select Provinces, 2010

Source: NBS 2010 Population Census, JLL

17

Based on National Bureau of Statistics, Census Population 2010. Peking University's Institute of Social Sciences survey in mid-2013

showed that 87.4% of Chinese families either fully or partially own their homes. In another survey by PBOC, China Household Finance

Survey, the national homeownership rate was found to be 89.68%; cities have a lower rate of 85.39%. In a December 2013 report by Citi

Research, it estimated homeownership rate to be around 65% after adjusting for multiple home ownership as it believed that the national

statistics were based on the number of homes that are owned rather than number of households which owned homes. Milken Institute, a

non-profit, non-partisan think tank based in the US, also noted the same view on the definition. However, we have not been able to verify it

from the NBS website.

18

Jones Lang LaSalle

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

14

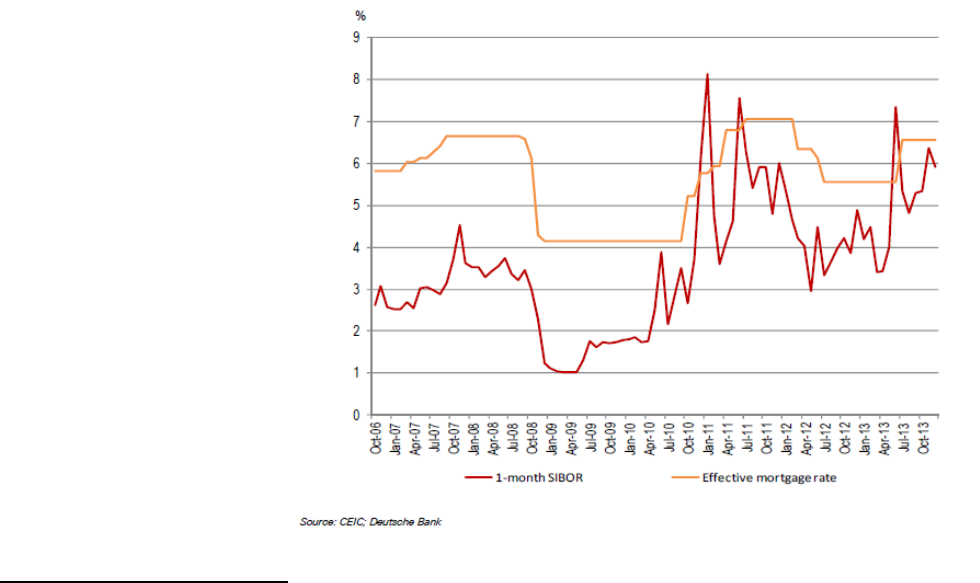

Impact of tightening credit

China experienced two credit crunches last year, a strong sign that the

central bank is keen to wean banks off cheap credit. JP Morgan

19

calls it

credit tapering, and not tightening. Credit growth still outpaced nominal GDP

growth as the government does not want to trigger a forced deleveraging. Credit

slowing is accompanied by an effort to shift credit components – credit that

supports real activity (medium and long term loans) continues to grow at a

stable pace, but parts of shadow banking activities more likely to be involved in

speculative financial activities are contained. The aim is to mitigate the negative

impact on the real economy. The continued credit tapering has nevertheless

caused liquidity tightening – interbank rates and long-term bond yields have

risen. Interest rates on home mortgages have increased by over two

percentage points from 2009 to 2013 (Fig 7).

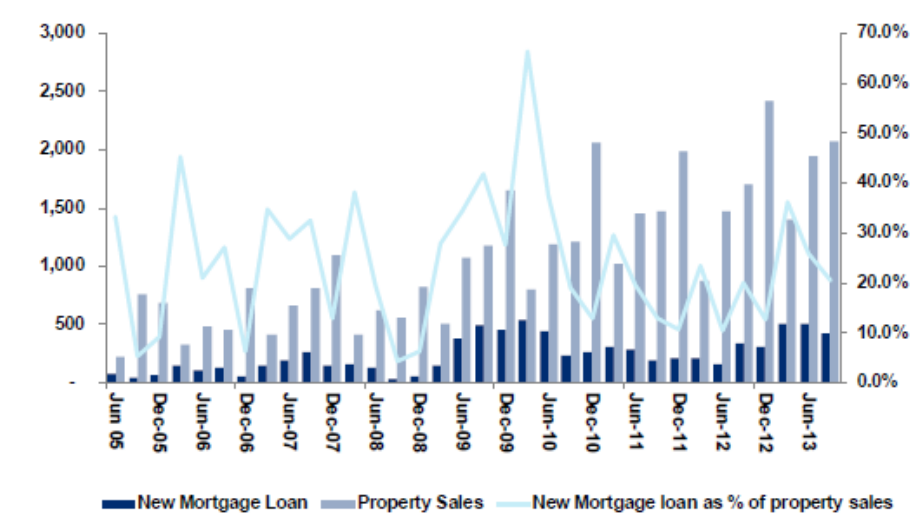

However, mortgage rate adjustments in China have less of an impact on

the housing market than restricting credit availability and prohibiting

purchases. The property market has very low levels of leverage (Fig 8); down-

payment rates are high for second properties and no mortgage is allowed for

third properties. Many buyers pay in cash or do not leverage the full amount,

especially in the smaller cities. In the larger cities where prices are higher and

there is a greater need to borrow, it is the credit availability rather than

mortgage rates that is hindering purchases. In addition to banks, employees

can apply for loans from Housing Provident Funds (HPF) at significantly lower

rates and better terms.

Figure 7: 1-month SIBOR

20

versus effective mortgage rate in China

19

JP Morgan, Ten Questions about China, December 2013

20

SIBOR refers to Shanghai Interbank Offered Rate

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

15

Figure 8: China new mortgage loans versus transaction value

Source: CEIC, Citi Research

Due to the extent of informal or shadow banking for which no reliable

statistics are available, another concern is the impact on the property

market and banking sector should some developers become insolvent.

We think the impact will be limited and not spread nationwide. China has

accumulated a large cushion against the possibility of a housing crash. The

government debt level, although rising in recent years, is still fairly low at

approximately 40% of GDP compared with 92% in the United States, 80% in

Germany and 220% in Japan. Furthermore, China has $3 trillion in foreign

exchange reserves, and the People’s Bank of China holds nearly $700 billion in

required reserves. Chinese banks depend on deposits as a major source of

funding. Consequently, they are less vulnerable to a liquidity crunch than U.S.

banks, which are more reliant on short-term borrowed funds.

Demand and supply conditions in each city and segment are still the main

drivers.

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

16

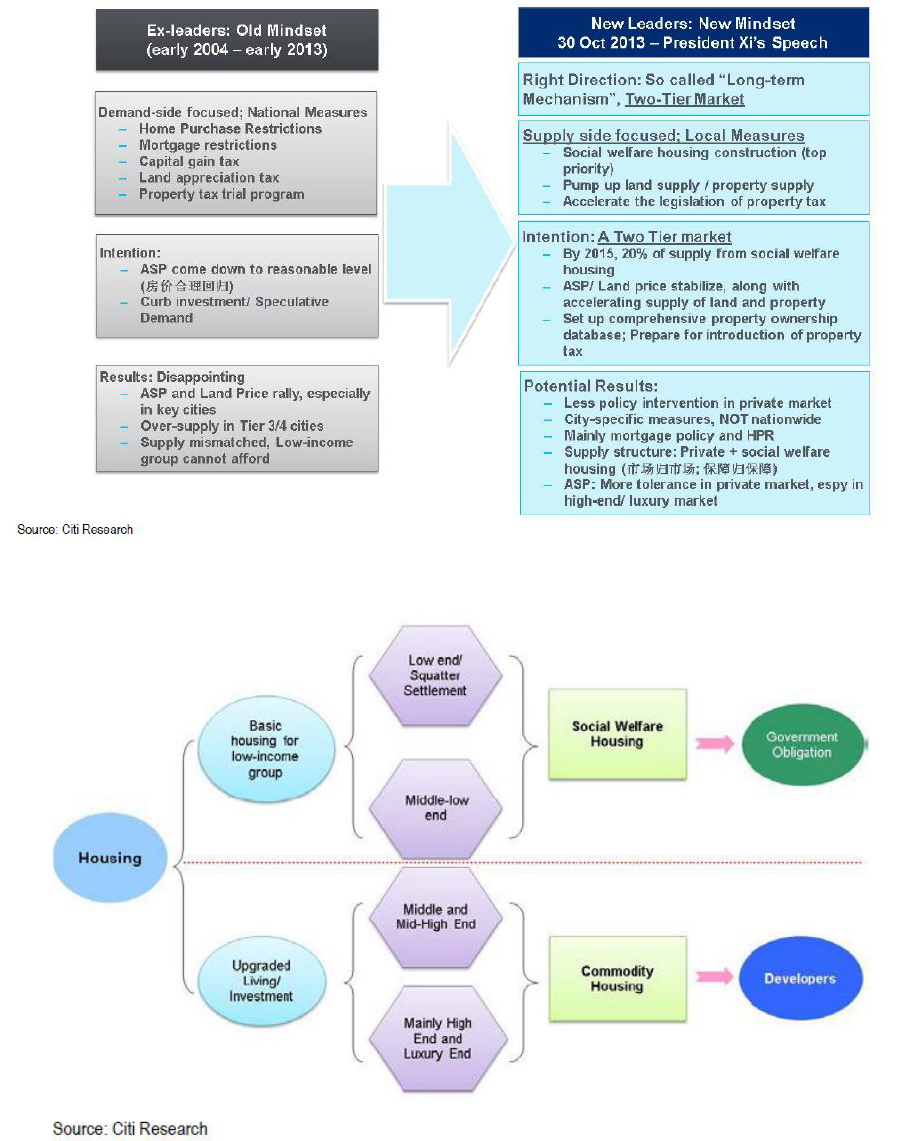

Implications of government policies

The new government’s speech in the Third Plenum last year underscored

that its policy is for stabilization in the property market, given the

significant contribution of the sector to the economy and the impact to

domestic consumption (which the government is encouraging as an

engine of growth) if asset wealth is eroded. In the past five years, the real

estate sector’s direct and indirect contribution to China’s total GDP is estimated

to be about 20-25%

21

.

Instead of focusing on curbing demand and price increase, it has shifted

focus to increasing the supply of land and social welfare housing to 20%

by 2015 (Figs 9 & 10). This may imply more tolerance for the upper-end

segment in future but for now, existing policies such as the Home

Purchase Restriction (HPR) are likely to continue. China's housing minister

said in December that the government would maintain controls on the property

market in 2014 while increasing land and housing supply in cities facing big

home-price increases. At least 17 major cities have introduced further cooling

measures in the last quarter of 2013, mainly focusing on further tightening HPR

for non-locals, raising down-payment ratio for second-home buyers and

increasing land supply in the coming year

22

.

For the lower mid-end private segment, there will be competition from the

new self-use commodity housing that will be priced 30% below market

price. There could be more land supply constraint in the higher end

segment in future as more land will be used for social welfare housing.

This would squeeze profit margins with purchase restrictions still in place

or tightened.

Property tax trials may be extended into several new cities and a

nationwide property registry database is proposed to be set up. With the

registry, the government can grasp and understand better the current

state of the market and adopt more effective measures if necessary. This

may lead to multiple homeowners reducing their property holdings if the

tax rates are high enough to make it painful to keep vacant units, or if they

do not wish to show up too often in the registry database. Progress is

however uncertain given strong objections.

21

Citi Research: China Property, Ghost Towns and Property Bubbles, December 2013. Direct contribution 8-10% and indirect contribution

is 13-18%.

22

CBRE China Residential Monthly Index November 2013

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

17

Figure 9: Property Policy – New Leaders, New Mindset

Figure 10: “Two-Tier”Market – Private + Social Welfare Housing

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

18

Outlook

We do not expect a national or devastating bubble burst in the China property

market although some smaller markets may correct due to oversupply and

weak demand. Among 70 large and medium-sized cities tracked by the National

Bureau of Statistics, Wenzhou registered a fall in prices last year.

The pace of price increase in Tier 1 and 2 cities is forecast to moderate from the

2013 levels, given the slower economic growth, high price levels, and curbs on

property purchase. The strong land sales in 2013 and increased supply of

affordable housing could also translate into a surge in home supply this year

and slow down home price gains.

For the Tier 3 and 4 cities with oversupply, some could see a fall in prices with

weak demand. However, prices could generally remain flattish as developers

hold back on construction and sale. Those at the eastern coast will fare better

than inland cities as they have stronger economic drivers to draw migrants from

the western and central regions. The relaxation of hukou registration for

migrants as announced in the Third Plenum, which will start with smaller cities,

will help to draw more migrants to the coastal Tier 3 and 4 cities. Coupled with

less housing purchase curbs than in the Tier 1 and 2 cities, the non-local

population can bring significant incremental demand for housing and help to

resolve the oversupply gradually.

A major risk for the entire Chinese housing market is a significant slowdown in

the economy as a result of drastic reforms or another global crisis. This could

lead to a loss of confidence in the property market. However, the Chinese

government had stepped in with a major stimulus in the aftermath of the global

financial crisis and a mini one in 2013 when economic growth waned. History is

likely to repeat itself.

As the housing market in China is a diverse mix and China is coming to a new

era of slower growth momentum, investors/developers would have to consider

each city’s economic growth drivers, and housing demand and supply situation.

China Residential

When will the party end? January 2014

_________________________________________________________________________________________

19

Alpha

Investment

Partners

Alpha Investment Partners (AIP) is a real estate investment

advisory firm managed by a team of established

professionals with proven fiduciary experience.

We aim to achieve superior performance by capitalizing on

our uniqueness and pertinent insights into the region’s

property markets, offering investors the competitive

advantage akin to a local player.

Disclaimer:

This report is published solely for informational purposes. No representation or warranty, either express or implied, is

provided in relation to the accuracy, completeness or reliability of the information contained herein, nor is it intended to be a

complete statement or summary of the securities, markets or developments referred to in the report. The report should not

be regarded by recipients as a substitute for the exercise of their own judgement. Any opinions expressed in this report are

subject to change without notice and may differ or be contrary to opinions expressed by other business areas as a result of

using different assumptions and criteria. Alpha Investment Partners Limited (“AIP”) is under no obligation to update or keep

current the information contained herein.

www.alphaipartners.com