Fondazione Eni Enrico Maei Working Papers

9-8-2010

Copenhagen and Beyond: Reections on China’s

Stance and Responses

ZhongXiang Zhang

Senior Fellow Research Program East-West Center, zxz@fudan.edu.cn

Follow this and additional works at: hp://services.bepress.com/feem

is working paper site is hosted by bepress. Copyright © 2010 by the author(s).

Recommended Citation

Zhang, ZhongXiang, "Copenhagen and Beyond: Reections on China’s Stance and Responses" (September 08, 2010). Fondazione Eni

Enrico Maei Working Papers. Paper 480.

hp://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

This version: March 2010

Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Responses

1

ZhongXiang Zhang, Ph.D in Economics

张中祥 美国东西方中心研究部资深研究员、经济学博士

Senior Fellow

Research Program

East-West Center

1601 East-West Road

Honolulu, HI 96848-1601

United States

Tel: +1-808-944 7265

Fax: +1-808-944 7298

Email: ZhangZ@EastWestCenter.org

Abstract

China had been singled out by Western politicians and media for dragging its feet on

international climate negotiations at Copenhagen, the accusations previously always

targeted on the U.S. To put such a criticism into perspective, this paper provides some

reflections on China’s stance and reactions at Copenhagen. While China’s reactions are

generally well rooted because of realities at home, some reactions could have been

handled more effectively for a better image of China. The paper also addresses the

reliability of China’s statistics on energy and GDP, the issue crucial to the reliability of

China’s carbon intensity commitments. The paper discusses flaws in current international

climate negotiations and close with my suggestion that international climate negotiations

need to focus on 2030 as the targeted date.

.

JEL classification: Q41; Q43; Q48; Q52; Q54; Q58; O53

Keywords: Copenhagen climate negotiations; Emissions reductions; Carbon intensity

target; Binding emissions caps; Statistics on energy and GDP; Coal and energy

consumption; China; USA

1

Invited luncheon speech at the International Workshop on Climate Change Polices,

Presidency of Complutense University, Madrid, Spain, February 18-19, 2010. It appears

in Emilio Cerdá and Xavier Labandeira (Editors), Climate Change Policies: Global

Challenges and Future Prospects, Edward Elgar.

1

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

2

1. INTRODUCTION

Under the Kyoto Protocol, developed countries had specific obligations to control their

greenhouse gas emissions, but developing countries did not. The Copenhagen Accord

ends this distinction. For the first time, all the major economies at Copenhagen pledged to

take specific individual responsibilities, with Annex I (developed) countries invited to

submit their targets for emissions reductions and non-Annex I (developing) countries to

submit their intended mitigation actions. By 31 January 2010 all had submitted their

pledges to cut or limit their greenhouse gas emissions by 2020 to the United Nations

Framework Convention on Climate Change, the deadline set by the Copenhagen Accord.

This has never happened before.

No doubt, Copenhagen was disappointing to many, particularly given that U.S.

President Obama pledge’s “yes, we can” had raised high expectations for this meeting.

However, as argued in Zhang (2009a), international climate negotiations for an

immediate post-2012 climate regime should not attempt unrealistic goals. With not all of

the factors discussed in Zhang (2009a) met for a legally binding global agreement, the

Copenhagen Accord is probably the best that could be achieved. The situation could be

worse because the negotiations could have completely collapsed. While falling far short

of the legally binding global agreement, the Accord reflects a political consensus on the

main elements of the future framework among the major emitters and representatives of

the main negotiating groups.

Also for the first time, China was blamed for dragging its feet on international

climate negotiations, previously the accusations always targeted on U.S. French President

Nicolas Sarkozy publicly criticized China, saying that China was impeding progress in

climate talks (Watts 2009). British Energy and Climate Change Secretary Ed Miliband

(2009) even wrote in The Guardian that China led a group of countries that “hijacked”

the climate negotiations which had at times presented “a farcical picture to the public”.

In the run up to and at Copenhagen, China took the initiative to ally with India and other

major developing countries, took full advantage of being the world’s largest carbon

emitter, and attempted to secure a deal to its advantage. It is widely reported that China

walked away “happy”. But that did not come without a high price tag. Whether to admit

2

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

3

or not, China angered allies, abandoned principles that it stuck during two weeks of talks,

and is likely to stoke anti-China sentiment in Western nations. The too early appearance

of this sentiment does not do any good to China because it still has to evolve from a large

country to a country that is truly strong in e.g., science, technology, innovation, economy,

etc. Officially China was backed by allies like India and Brazil, but they admitted in

private that this was mainly China’s battle (Graham-Harrison 2009).

Against this background, in this paper, I will first share my thoughts on China’s

stance and reactions at Copenhagen. Some reactions are well rooted because of realities

in China. Some reactions could have been handled more effectively for a better image of

China, provided that there were good preparations and deliberations. I then address the

reliability of China’s statistics on energy and GDP, an issue crucial to the reliability of

China’s carbon intensity commitments. Finally, I discuss flaws in current international

climate negotiations and close with my suggestion that international climate negotiations

need to focus on 2030 as the targeted date.

2. REFLECTIONS ON CHINA’S STANCE AND RESPONSES

Let me start with the widely reported episode of China rejecting unilateral greenhouse

gas emissions cut by industrialized countries. In my view, this is one area that China

could have handled more effectively in Copenhagen.

Miliband (2009) wrote in The Guardian that “We did not get an agreement on 50

per cent reductions in global emissions by 2050 or on 80 per cent reductions by

developed countries. Both were vetoed by China, despite the support of a coalition of

developed and the vast majority of developing countries”. A furious Angela Merkel,

German Chancellor, demanded that “Why can’t we even mention our own targets?”.

Kevin Rudd, Australia’s Prime Minister, was annoyed enough to bang his microphone.

Brazil’s representative also pointed out how illogical China’s position was (Lynas 2009).

Being asked in the early hours of 19 December 2009 why a pledge that applied only to

rich nations and to which all those nations seemed to agree would have vanished from the

final document, the point person for the Swedish government that was serving the EU

3

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

4

Presidency at that time gave the flat reply after the seconds of what-can-I-say silence:

“China didn’t like numbers.” (The Economist 2010).

It is not so hard to understand why China rejected the aforementioned two

numbers. Needing to cut both global greenhouse gas emissions by 50 percent and that of

industrialized countries by 80 percent by 2050 means that emissions in developing

countries are only allowed to increase by 15 percent by 2050 relative to their 1990 levels.

Given their very low levels in 1990, China considers this unacceptable. There could be a

misinterpretation here. Some may interpret that a 15 percent increase by 2050 would

mean that the developing country’s emissions are allowed to only increase by 15 percent

in any specific year from now on to 2050. This is not correct. Emissions in developing

countries can be much higher than the level allowed by a 15 percent increase prior to

2050 and then come down to that proposed allowable level by 2050. Indeed, under the

450 parts per million of CO

2

equivalent scenario, CO

2

emissions in China are projected to

go from 2.2 GtCO

2

in 1990 and 6.1 GtCO

2

in 2007 to 8.4 GtCO

2

in 2020, while the

corresponding figures for India are estimated to go from 0.6 GtCO

2

in 1990 and 1.3

GtCO

2

in 2007 to 1.9 GtCO

2

in 2020 (IEA 2009). Relative to their levels in 1990 and

2007, CO

2

emissions in 2020 increase by 282 percent and 37 percent for China and by

117 percent and 46 percent for India, respectively. More importantly, rejecting a long-

standing, widely reported proposal without putting forward alternatives cast China in a

very bad light. It led to the impression that rich countries should not even announce their

unilateral cut, which was at least reported by the Western media.

As suggested in Zhang (2009c), China should insist on at least 80 percent

emissions reduction by the developed countries, and in the meantime demand that per

capita greenhouse gas emissions for all major countries by 2050 should be no more than

the world’s average at that time.

There are reasons that explain why China took a tough position at Copenhagen.

First, China’s CO

2

emissions have increased beyond expectations. The U.S. Energy

Information Administration (EIA 2004) estimated that China’s CO

2

emissions were not

expected to catch up with the U.S., the world’s largest carbon emitter until 2030.

However, China’s energy use has surged since the turn of this century, almost doubling

between 2000 and 2007. Despite similar rates of economic growth, the rate of growth in

4

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

5

China’s energy use during this period (9.74 percent per year) has been more than twice

that of the last two decades in the past century (4.25 percent per year) (National Bureau

of Statistics of China 2009). As a result, China became already the world’s largest carbon

emitter in 2007, instead of “until 2030” as estimated as late as 2004. This is partly

because China failed to keep the expansion of inefficient and highly polluting industries

under control and to implement its own industrial restructuring and sustainable

development policies, and but because China is still on a course of rapid industrialization

and urbanization. This in turn requires the consumption of energy to produce energy-

intensive steels, cement, glasses etc for cars, buildings, houses and public infrastructure

because China as a large country can not depend entirely on imports as a small country

can do. Moreover, small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) are key to employment

for each country. This is particularly important for China to address its employment

issues and the maintenance of social stability, because of its huge surplus labor force in

the world’s most populous country and its not well developed social safety net. SMEs in

China employ 80 percent of the total working population and produce 60 percent of the

economic output. They have served as a driving force for China’s economic success over

the past three decades. Largely dictated by the current level of development in China,

however, these SMEs use much more, sometimes even more than 100 percent energy to

produce the same unit of output as their state-owned, large and modern counterparts.

While China should take the main responsibilities for this, the U.S. had also

played a role here. At Kyoto, the U.S. had made legally binding greenhouse gas

emissions commitments. The Kyoto target was seen as not high enough but yet not

unreasonable given that the U.S. economy would not be disrupted unreasonably. This

might provide the U.S. some “moral” grounds on which to argue that developing countries

should take meaningful mitigation action (Zhang 2000). The U.S. commitments at Kyoto

and the diplomatic and public pressure on China put China in a very uncomfortable

position. It looked like China would be pressured to take on commitments at much earlier

date than what China wished (Zhang 2009a).

This situation changed once the U.S. withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol. The U.S.

withdrawal from the Kyoto Protocol in 2001 not only led current U.S. emissions to be

well above their 1990 levels but the world also lost eight years of concerted efforts

5

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

6

towards climate change mitigation and adaptation, and it also removed international

pressure on China to take climate change mitigation actions at a time when the Chinese

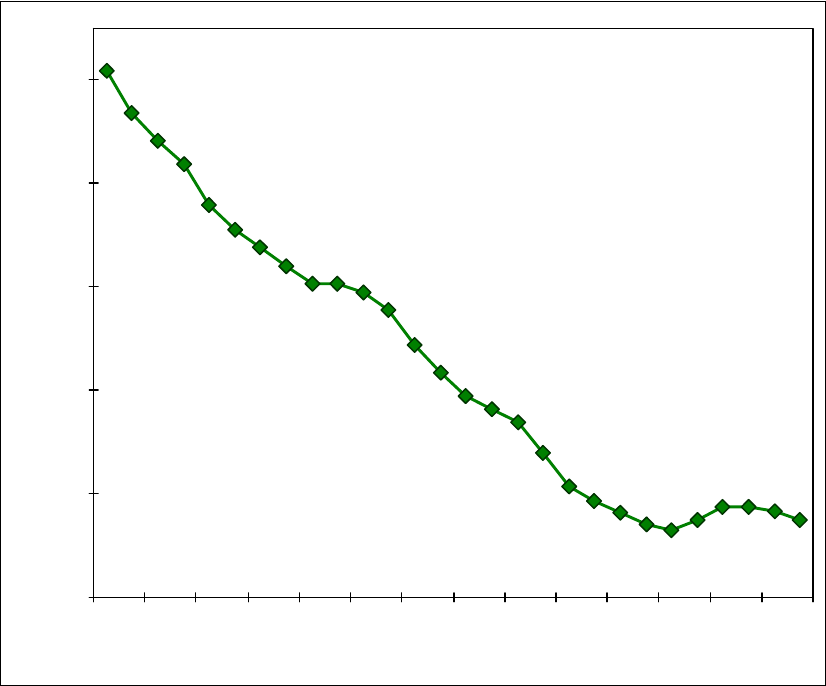

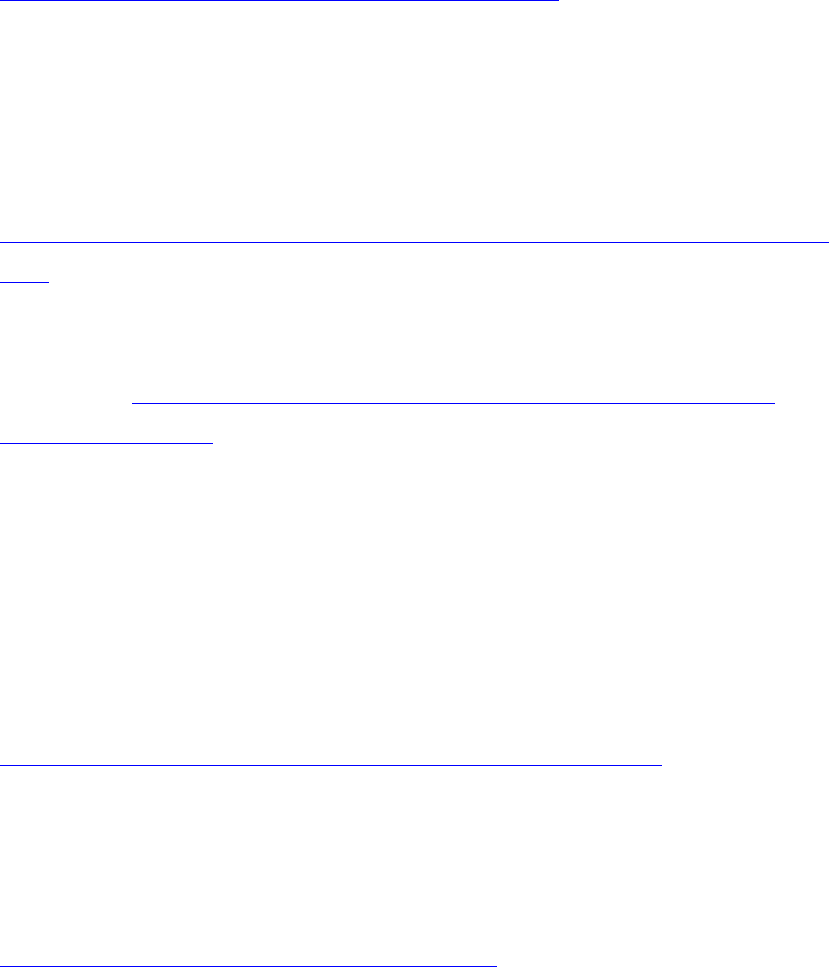

economy was growing rapidly. Coincidentally, beginning 2002 that China reversed a

declining trend in its energy intensity experienced over the last two decades in the past

century, experiencing faster energy consumption growth than economic growth (see

Figure 1). It would be inappropriate to blame this on the U.S., but if the U.S. did not

withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol, for its own concerns for competiveness the U.S.

would have kept pressuring on China as it did immediately after Kyoto and is doing again,

China would be constantly alert about its greenhouse gas emissions. As a result, China’s

actual greenhouse gas emissions would be much lower than their current levels.

Figure 1 Energy use per unit of GDP in China, 1990-2007 (tons of coal equivalent per

US$ 1000 in 1980 prices)

Source: Drawn based on China Statistical Yearbook, various years.

6

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

7

0.30

0.50

0.70

0.90

1.10

1.30

1980 1982 1984 1986 1988 1990 1992 1994 1996 1998 2000 2002 2004 2006

Ye ar

tce/1980 US$'000 of GDP

Adding the rapidly growing CO

2

emissions, China has realized increasing

difficulty in controlling its CO

2

emissions. China has incorporated for the first time in its

five-year economic plan an input indicator as a constraint – requiring that energy use per

unit of GDP cut by 20 percent during the five-year period running from 2006 to 2010

(namely, 4.4 percent cut per year). Clearly, the Chinese government was not aware of

how difficult meeting this energy saving target would be at the time the plan was set,

because China cut its energy use per unit of GDP by about three quarters between 1980

and 2000 (Zhang, 2003). The Chinese government may have thought that this trend of the

1980s and the 1990s would continue.

However, in 2006, the first year of this energy efficiency drive, while China

reversed a rise in its energy intensity in the first half of that year, the energy intensity

only declined by 1.79 percent over the entire year. Although this decline is a first since

7

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

8

2003, it was far short of the targeted 4 percent. Among the 31 Chinese provinces or

equivalent, only Beijing met that energy-saving goal in 2006, cutting its energy use per

unit of GDP by 5.25 percent, followed by Tianjin with the energy intensity reduction of

3.98 percent, Shanghai by 3.71 percent, Zhejiang by 3.52 percent and Jiangsu by 3.50

percent (NBS et al. 2007).

2

In 2007, despite concerted efforts towards energy saving, the

country cut its energy intensity by 4.04 percent (NBS et al. 2009). There are still big

variations in energy-saving performance among the 31 Chinese provinces or equivalent.

Beijing still took the lead, cutting its energy intensity by 6 percent, followed by Tianjin

by 4.9 percent and Shanghai by 4.66 percent (NBS et al., 2008). This clearly indicated

Beijing’s commitments to the 2008 Green Olympic Games. In the meantime, however,

there were seven provinces whose energy-saving performances were below the national

average. 2008 was the first year in which China exceeded the overall annualized target

(4.4 percent) for energy saving, cutting its energy intensity by 4.59 percent (NBS et al.

2009) or 5.2 percent if the upward GDP revision was factored into consideration. This

was due partly to the economic crisis that reduced the overall demand, in particular the

demand for energy-intensive products. Overall, China’s energy intensity was cut by 10.1

percent in the first three years of the plan relative to its 2005 levels. This suggests that the

country needs to achieve almost the same overall performance in the remaining two years

as it did in the first three years in order to meet that national energy intensity target. It

will certainly not be easy to achieve that goal.

These reductions in China’s energy intensity have already factored in the

revisions of China’s official GDP data from the second nationwide economic census, part

of the government’s continuing efforts to improve the quality of its statistics, whose

accuracy has been questioned by both the general public inside of China and many

analysts both inside and outside of China. Such revisions show that China’s economy

grew faster and shifted more towards services than the previously estimated, thus

benefiting the energy intensity indicator. Even so, it is still not easy for China to achieve

its own set energy-saving goal. If there were no upward revisions of GDP data, it would

2

Beijing is the first provincial region in China to establish in 2006 the bulletin system to

release data on energy use and water use per unit of GDP, quarterly releasing these and

other indicators by county. See Zhang (2007b,c) for detailed discussion on why Beijing

met but the country missed the energy-saving goals.

8

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

9

be impossible at all to meet that target. I will return to the statistical issues later when

taking about verification, the issue that is of greatest concern to the U.S. and other

industrialized countries at Copenhagen.

Thirdly, there are profound implications of government decentralization. Over the

past three decades, China has decentralized with respect to allocation and responsibility

and has shifted control over resources and decision-making to local governments. This

devolution of decision-making to local levels has placed environmental stewardship in

the hands of local officials who typically are more concerned with economic growth than

the environment (Zhang 2007a and 2008). As is often the case, what the center wants is

not necessarily what the center gets, as in the old Chinese saying, “The mountains are

high, and the emperor is far away”.

In addition to the distorted evaluation criterion for officials on which local

officials typically have been promoted based on how fast they expand their local

economies, objectively speaking, the current fiscal system in China plays a part in driving

local governments to seek higher GDP growth at the expense of the environment. This is

because that tax-sharing system makes it hard to reconcile the interests of the central and

local governments (Zhang 2008 and 2009b). Since the tax-sharing system was adopted in

China in 1994, taxes are grouped into taxes collected by the central government, taxes

collected by local governments, and taxes shared between the central and local

governments. All those taxes that have steady sources and broad bases and are easily

collected, such as the consumption tax, tariffs, vehicle purchase tax, are assigned to the

central government. VAT and income tax are split between the central and local

governments, with 75 percent of VAT and 60 percent of income tax going to the central

government. As a result, the central government revenue increased by 200 percent in

1994 relative to its 1993 level. This led the share of the central government in the total

government revenue to go up to 55.7 percent in 1994 from 22.0 percent in the previous

year (see Table 1). In the meantime, the share of the central government in the total

government expenditure just rose by 2 percent. By 2008, local governments only

accounted for 46.7 percent of the total government revenue, but their expenditure

accounted for 78.7 percent of the total government expenditure in China. To enable to

pay their expenditure for culture and education, supporting agricultural production, social

9

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

10

security subsidiary, etc., local governments have little choice but to focus on local

development and GDP. That will in turn enable them to enlarge their tax revenue by

collecting urban maintenance and development tax, contract tax, arable land occupation

tax, urban land use tax, etc.

Table 1 Shares of the central and local governments in the total government revenue and

expenditure in China, 1993-2008

Government revenue Government expenditure

Central

Government

(%)

Local

Governments

(%)

Central

Government

(%)

Local

Governments

(%)

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

22.0

55.7

52.2

49.4

48.9

49.5

51.1

52.2

52.4

55.0

54.6

54.9

52.3

52.8

54.1

53.3

78.0

44.3

47.8

50.6

51.1

50.5

48.9

47.8

47.6

45.0

45.4

45.1

47.7

47.2

45.9

46.7

28.3

30.3

29.2

27.1

27.4

28.9

31.5

34.7

30.5

30.7

30.1

27.7

25.9

24.7

23.0

21.3

71.7

69.7

70.8

72.9

72.6

71.1

68.5

65.3

69.5

69.3

69.9

72.3

74.1

75.3

77.0

78.7

Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China (2009).

10

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

11

The factors described are far from comprehensive, but they are sufficient enough

to illustrate great challenges ahead for China and constraints on its development and

climate commitments. Of course, the above discussion does not justify no further action

by China. Rather, given the fact that China is already the world’s largest carbon emitter

and its emissions will continue to rise rapidly as it is approaching becoming the world’s

largest economy, China is seen to have greater capacity, capability and responsibility. The

country is facing great pressure both inside and outside international climate negotiations

to exhibit greater ambition in limiting its greenhouse gas emissions. Moreover, China will

continue to be confronted with the threats of trade measures, as long as it does not signal

well ahead the time when it will take on the emissions caps (Zhang 2009c,d).

Indeed, there are many things that China can do to reduce its own carbon footprint.

To that end, just prior to the Copenhagen climate summit, China pledged to cut its carbon

intensity by 40-45 percent by 2020 relative its 2005 level. A lot of discussion has since

focused on whether such a pledge is ambitious or just represents business as usual. China

considers it very ambitious, whereas Western scholars view it just business as usual.

Objectively speaking, it is somewhere in between. It would not be seen as ambitious as

China argues. Zhang (2009c) suggests that China should aim a 45-50 percent cut in its

carbon intensity over the period 2006-2020. But it is certainly not just representing

business as usual. Based on the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s

top economic planning agency, China had cut its energy intensity by 14.38 percent in the

first four years (2006-2009) of the 11

th

five-year plan relative to its 2005 levels. As

discussed above, it has been challenging for China to have achieved this to date, and

China is facing great difficulty meeting its own set 20 percent energy-saving goal by

2010. The new carbon intensity target set for 2020 requires additional 20-25 percent on

top of the existing target. It poses an additional challenge for China. But for me, while the

level of China’s commitments is crucial in affecting the level and ambition of

commitments from other countries, most important is whether the claimed carbon

emissions reductions are real. This raises reliability issues concerning China’s statistics

on energy and GDP.

11

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

12

3. MEETING CHINA’S CARBON INTENSITY: THE RELIABILITY ISSUE OF

CHINA’S STATISTICS ON ENERGY AND GDP

China is not known for the reliability of its statistics (e.g., Rawski 2001). China’s refusal

to budge on U.S. and other industrialized country’s demands for greater transparency and

checks at Copenhagen was cited by negotiator after negotiator as a key block to reaching

a deal. As long as China’s pledges are in the form of carbon intensity, the reliability of

both emissions and GDP data matters.

Assuming the fixed CO

2

emissions coefficients that convert consumption of fossil

fuels into CO

2

emissions, the reliability of emissions data depends very much on energy

consumption data. Unlike the energy data in the industrial product tables in the China

Statistical Yearbook, the statistics on the primary energy production and consumption are

usually revised in the year after their first appearance. As would be expected, the

adjustments made to production statistics are far smaller than those made to consumption

statistics, because it is usually easier to collect information on a small number of energy

producers than a large number of energy consumers. Table 2 shows the preliminary and

final values for total primary energy consumption and coal consumption in China

between 1990 and 2008. Until 1996 revisions of total energy use figures were several

times smaller than in the late 1990s and early 2000s. The preliminary figures for total

energy use in 1999-2001 were revised upwards by 8-10 percent. In all three years, these

adjustments were driven by the upward revisions of 8-13 percent made to the coal

consumption figures to reflect the unreported coal production mainly from small,

inefficient and highly polluting coal mines that were ordered to shut down through a

widely-publicized nationwide campaign beginning in 1998 but many of which had

reopened because in many cases localities had backtracked to preserve local jobs and

generate tax revenues as well as personal payoffs. In recent years, preliminary figures for

energy use are almost the same as the final reported ones.

12

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

13

Table 2 Preliminary and final values for total primary energy consumption and coal

consumption in China, 1990-2008

Total primary energy consumption Total coal consumption

Year

Preliminary

value

(Mtce)

Final

value

(Mtce)

Adjustment

(%)

Preliminary

value

(Mtce)

Final

value

(Mtce)

Adjustment

(%)

1990

1991

1992

1993

1994

1995

1996

1997

1998

1999

2000

2001

2002

2003

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

980.00

1023.00

1089.00

1117.68

1227.37

1290.00

1388.11

1420.00

1360.00

1220.00

1280.00

1320.00

1480.00

1678.00

1970.00

2233.19

2462.70

2655.83

2850.00

*

987.03

1037.83

1091.70

1159.93

1227.37

1311.76

1389.48

1377.98

1322.14

1338.31

1385.53

1431.99

1517.97

1749.90

2032.27

2246.82

2462.70

2655.83

0.7

1.4

0.2

3.8

0.0

1.7

0.1

-3.0

-2.8

9.7

8.2

8.5

2.6

4.3

3.2

0.6

0.0

0.0

740.88

777.48

815.66

813.67

920.53

967.50

1041.08

1043.70

973.76

818.62

857.60

884.40

978.28

1125.94

1333.69

1538.67

1709.11

1845.80

1957.95

*

752.12

789.79

826.42

866.47

920.53

978.57

1037.94

988.01

920.21

924.77

939.39

955.14

1006.41

1196.93

1381.94

1552.55

1709.11

1845.80

1.5

1.6

1.3

6.5

0.0

1.1

-0.3

-5.3

-5.5

13.0

9.5

8.0

2.9

6.3

3.6

0.9

0.0

0.0

Notes: Mtce (million tons of coal equivalent).

*

Data on energy and coal consumption in 2008 are preliminary value.

Source: Based on China Statistical Yearbook, various years.

13

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

14

Similarly, China first releases its preliminary GDP figures and then revises them.

These revised GDP figures for the years 2005-2008 are further verified based on the

second agricultural census released in February 2008 and the second nationwide

economic census released in December 2009. With upward revisions of both GDP and

the share of services, there is a wide variation between the preliminary value for China’s

energy intensity and the final reported one. As shown in Table 3, such revisions lead to a

differential between preliminary and final values as large as 45.5 percent for the energy

intensity in 2006. With the government’s continuing efforts to improve the quality of

China’s statistics, there is a downward trend of such a differential as a result of the

revisions.

Table 3 A reduction in China’s energy intensity: preliminary value versus final value

a

Year Preliminary value

(%)

Revised value (%) Final value (%) Differential

between

preliminary

and final

values (%)

2006

2007

2008

2009

1.23 (March 2007)

3.27 (March 2008)

4.59 (30 June 2009)

3.98

c

(March 2010)

1.33 (12 July 2007)

3.66 (14 July 2008)

5.2

b

(25 December 2009)

1.79 (14 July 2008)

4.04 (30 June 2009)

45.5

23.5

13.3

Notes:

a

The dates when the corresponding data were released are in parentheses.

b

Based on China’s revised 2008 GDP from the second nationwide economic census,

which raised the growth rate of GDP to 9.6 percent from the previously reported 9

percent for that year and the share of services in GDP.

c

Own calculation based on the National Development and Reform Commission’s

reporting that China’s energy intensity was cut by 14.38 percent in the first four years of

the 11

th

five-year plan relative to its 2005 levels.

14

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

15

From the preceding discussion, it thus follows that GDP figures are even more

crucial to the impacts on the energy or carbon intensity than energy consumption and

emissions data. At Copenhagen, China eventually compromised to agree to open

emission data to international consultation and analysis. The EU has identified building a

robust and transparent emissions and performance accounting framework as a key

element of implementing the Copenhagen Accord (European Commission 2010). How all

this will be worked out remains to be seen. China has not agreed on opening its GDP

figures to international consultation and analysis. But as long as China’s commitments

are in the form of carbon intensity, establishing a robust and transparent emissions and

performance accounting framework is helpful, but not enough to remove international

concern about the reliability of China’s commitments. The aforementioned revisions of

China’s GDP figures reflect part of the government’s continuing efforts to improve the

accuracy and reliability of China’s statistics on economic activity. They have nothing to

do with the energy intensity indicator, and are certainly not calculated to make that

indicator look good to the government’s advantage, although practically they benefit the

energy intensity indicator. But such revisions have huge implications for meeting China’s

existing energy-saving goal in 2010 and its proposed carbon intensity target in 2020.

4. A WAY FORWARD

Now let us see how to go from here. For me, the U.S. Congress passing a climate bill to

cap U.S. greenhouse gas emissions has more impact on the future levels of greenhouse

gas emissions than China’s current stance. As long as commitments from the world’s two

largest greenhouse gas emitters differ in form, the U.S. Senate seems unlikely to pass a

bill to cap its emissions without imposing strict carbon tariffs, and China is constantly

confronted with the threats of trade measures whenever the U.S. Senate is shaping its

climate bill (Zhang 2009d).

15

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

16

This dilemma is partly attributed to flaws in current international climate

negotiations, which have been focused on commitments on the two targeted dates: 2020

and 2050 (Zhang 2009d). However, with the commitment period only up to 2020, there is

a very little room left for the U.S. and China, although for reasons very different from

each other.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) calls for cutting global

greenhouse gas emissions at least in half by 2050. To achieve that goal, the IPCC fourth

assessment report recommends that global greenhouse gas emissions should peak by

2020 at the latest and then turn downward in order to avoid dangerous climate change

consequences, calling for developed countries to cut their greenhouse gas emissions by

25-40 percent by 2020 relative to their 1990 levels. This recommendation was

incorporated into the Bali Roadmap at the United Nations Climate Summit in 2007. This

seems a logical choice. Once the long-term goal (namely target for 2050) is set, one

needs a mid-term goal to help facilitate the long-term one. From then, the negotiations on

industrialized countries’ commitments have been on what emissions reduction targets

would be in 2020. However, the problem with this date is that it does not accommodate

well the world’s two largest greenhouse gas emitters, namely the U.S. and China.

Because the U.S. withdrew from the Kyoto Protocol, it has not made any substantial

preparations to cut emissions as other Kyoto-constrained industrialized countries have

done over the past decade. Whether you like it or not, this is a political reality. It is very

hard for a unprepared country like the U.S. to take on a substantial emissions cut in 2020

as developing countries have demanded.

In the meantime, China overtook the U.S. to become the world’s largest

greenhouse gas emitter in 2007, at least twenty years earlier than what was estimated as

late as 2004. IEA (2009) estimates that about half of the growth of global energy-related

CO

2

emissions until 2030 will come from China. Combined with huge trade deficit with

China, the U.S. has pushed for China to take on emissions caps as early as 2020.

Otherwise, the goods from China to U.S. markets will be subject to carbon tariffs.

However, as argued in Zhang (2009c,d), the year 2020 is not a realistic date for China to

take the absolute emissions cap.

16

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

17

Meanwhile, taking on something for 2050 seems too far away for politicians. In

my view, if the commitment period were extended to 2030, it would really open up the

possibility for the U.S. and China to make the commitments that each wants from the

other in the same form, although the scale of reductions would differ from each other. By

2030, the U.S. will be able to commit to much deeper emission cuts that China and other

developing countries have demanded, while, as argued in Zhang (2009c,d), China would

have approached the threshold to take on the absolute emission cap that the U.S. and

other industrialized countries have long asked for. Being aware of his proposed

provisional target in 2020 well below what is internationally expected from the U.S.,

President Obama announced a provisional target of a 42 percent reduction below 2005

levels in 2030 to demonstrate the U.S. continuing commitments and leadership to find a

global solution to the threat of climate change. While the U.S. proposed level of emission

reductions for 2030 is still not ambitious enough, President Obama inadvertently points

to the right direction of international climate negotiations. They need to look at the

targeted date of 2030. If international negotiations could lead to much deeper emission

cuts for developed countries as well as the absolute emission caps for major developing

countries in 2030, that would significantly reduce the legitimacy of the U.S. proposed

carbon tariffs and, if implemented, their prospect for withstanding a challenge before

WTO. That will also alleviate concern about when China’s greenhouse gas emissions

peak and what China is going to do in what format.

REFERENCES

EIA (2004), International Energy Outlook 2004, U.S. Energy Information Administration

(EIA), Washington, DC.

European Commission (2010), International Climate Policy post-Copenhagen: Acting

Now to Reinvigorate Global Action on Climate Change, COM(2010) 86 final, Brussels, 9

March, Available at: http://ec.europa.eu/environment/climat/pdf/com_2010_86.pdf

.

17

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

18

Graham-Harrison, E. (2009), Snap Analysis: China Happy with Climate Deal, Image

Dented, 18 December, Reuters, Available at:

http://www.reuters.com/article/idUSTRE5BI0DH20091219

.

IEA (2009), World Energy Outlook 2009, International Energy Agency (IEA), Paris.

Lynas, M. (2009), How Do I know China Wrecked the Copenhagen Deal? I Was in the

Room, The Guardian, 23 December, Available at:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2009/dec/22/copenhagen-climate-change-mark-

lynas.

Miliband, E. (2009), The Road from Copenhagen, The Guardian, 20 December,

Available at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2009/dec/20/copenhagen-

climate-change-accord.

National Bureau of Statistics of China (2009), China Statistical Yearbook 2009, China

Statistics Press, Beijing.

National Bureau of Statistic (NBS), National Development and Reform Commission and

National Energy Administration (2008), Bulletin on Energy Use per Unit of GDP and

other Indicators by Region, Beijing, 14 July, Available at:

http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjgb/qttjgb/qgqttjgb/t20080714_402491870.htm

.

National Bureau of Statistic (NBS), National Development and Reform Commission and

Office of The National Energy Leading Group (2007), Bulletin on Energy Use per Unit of

GDP and other Indicators by Region, Beijing, 12 July, Available at:

http://hzs.ndrc.gov.cn/newjn/t20070809_152873.htm

.

National Bureau of Statistic (NBS), National Development and Reform Commission and

National Energy Administration (2009), Bulletin on Energy Use per Unit of GDP and

other Indicators by Region, Beijing, 30 June, Available at:

18

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480

19

http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjgb/qttjgb/qgqttjgb/t20090630_402568721.htm.

Rawski, T.G. (2001), What Is Happening to China’s GDP Statistics?, China Economic

Review, Vol. 12, No. 4, pp. 347-354.

The Economist (2010), Climate Change after Copenhagen: China’s Thing about Numbers,

2 January, pp. 43-44.

Watts, J. (2009), China ‘Will Honour Commitments’ Regardless of Copenhagen Outcome,

18 December, The Guardian, Available at:

http://www.guardian.co.uk/environment/2009/dec/18/china-wen-jiabao-copenhagen

.

Zhang, Z.X. (2000), Can China Afford to Commit itself an Emissions Cap? An Economic

and Political Analysis, Energy Economics, Vol. 22, No. 6, pp. 587-614.

Zhang, Z.X. (2003), Why Did the Energy Intensity Fall in China’s Industrial Sector in the

1990s?, The Relative Importance of Structural Change and Intensity Change, Energy

Economics, Vol. 25, No. 6, pp. 625-638.

Zhang, Z.X. (2007a), China’s Reds Embrace Green, Far Eastern Economic Review, Vol.

170, No. 5, pp. 33-37.

Zhang, Z.X. (2007b), Greening China: Can Hu and Wen Turn a Test of their Leadership

into a Legacy?, Presented at the Plenary Session on Sustainable Development at the first

ever Harvard College China-India Development and Relations Symposium, New York

City, 30 March – 2 April.

Zhang, Z.X. (2007c), Energy and Environmental Policy in Mainland China, The Keynote

Address at the Cross-Straits Conference on Energy Economics and Policy, Organized by

the Chinese Association for Energy Economics, Taipei, 7-8 November.

19

Zhang: Copenhagen and Beyond: Reflections on China’s Stance and Res

Published by Berkeley Electronic Press Services, 2010

20

Zhang, Z.X. (2008), Asian Energy and Environmental Policy: Promoting Growth While

Preserving the Environment, Energy Policy, Vol. 36, pp. 3905-3924.

Zhang, Z.X. (2009a), How Far Can Developing Country Commitments Go in an

Immediate Post-2012 Climate Regime?, Energy Policy, Vol. 37, pp. 1753-1757.

Zhang, Z.X. (2009b), Is It Fair to Treat China as a Christmas Tree to Hang Everybody’s

Complaints? Putting its Own Energy Saving into Perspective, Energy Economics,

doi:10.1016/j.eneco.2009.03.012

.

Zhang, Z.X. (2009c), In What Format and under What Timeframe Would China Take on

Climate Commitments? A Roadmap to 2050, International Environmental Agreements:

Politics, Law and Economics, forthcoming, Available at:

http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1415123

.

Zhang, Z.X. (2009d), The U.S. Proposed Carbon Tariffs, WTO Scrutiny and China’s

Responses, International Economics and Economic Policy, forthcoming, Available at:

http://www.eastwestcenter.org/fileadmin/stored/pdfs//econwp106.pdf

.

20

Fondazione Eni Enrico Mattei Working Papers, Art. 480 [2010]

http://services.bepress.com/feem/paper480