P E A C E C O R P S

Classroom

Management

IDEA BOOK

Information Collection and Exchange

Publication No. M0088

ii Peace Corps

Information Collection and Exchange

The Peace Corps Information Collection and Exchange (ICE), a

unit of the Oce of Overseas Programming and Training Support

(OPATS), makes available the strategies and technologies developed

by Peace Corps Volunteers, their co-workers, and their counterparts

to development organizations and workers who might nd them

useful. ICE works with Peace Corps technical and training specialists

to identify and develop information of all kinds to support

Volunteers and overseas sta. ICE also collects and disseminates

training guides, curricula, lesson plans, project reports, manuals,

and other Peace Corps-generated materials developed in the eld.

Some materials are reprinted “as is”; others provide a source of eld-

based information for the production of manuals or for research in

particular program areas. Materials that you submit to ICE become

part of the Peace Corps’ larger contribution to development.

This publication was produced by Peace Corps OPATS. It is

distributed through the ICE unit. For further information about ICE

materials (periodicals, books, videos, etc.) and information services,

or for additional copies of this manual, please contact ICE and refer to

the ICE catalog number that appears on the publication.

Peace Corps

Oce of Overseas Programming and Training Support

Information Collection and Exchange

1111 20

th

Street, NW, Sixth Floor

Washington, DC 20526

Tel: 202.692.2640 | Fax: 202.692.2641

Abridged Dewey Decimal Classication (DDC) Number: 371.102

Share your experience!

Add your experience to the ICE Resource Center. Send your

materials to us so we can share them with other development

workers. Your technical insights serve as the basis for the

generation of ICE materials, reprints, and training materials. They

also ensure that ICE is providing the most up-to-date innovative

problem-solving techniques and information available to you and

your fellow development workers.

Peace Corps iii

C O N T E N T S

Introduction .......................................................................... 1

Chapter

1: Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student

Learning: An Overview .......................................................... 3

What Do You Think? .......................................................................... 3

Key Ideas in This Chapter ................................................................ 4

Positive Expectations of Student Success ................................... 4

Classroom Management Skills ....................................................... 6

What does a well-managed classroom look like? ..................... 7

How to support student learning ................................................... 7

Instruction Skills ............................................................................... 9

Eective teachers ................................................................................. 9

Lesson planning ..................................................................................12

Examples and Tools ........................................................................14

Sample Graphic Organizers ..........................................................14

Chapter 2: Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context ................ 17

What Do You Think? ........................................................................17

Key Ideas in This Chapter ..............................................................18

Examine Your Own Culture ........................................................... 19

What is your cultural intelligence? ...............................................19

Cultural values .....................................................................................20

Cultural norms .....................................................................................23

Examine a New Culture .................................................................24

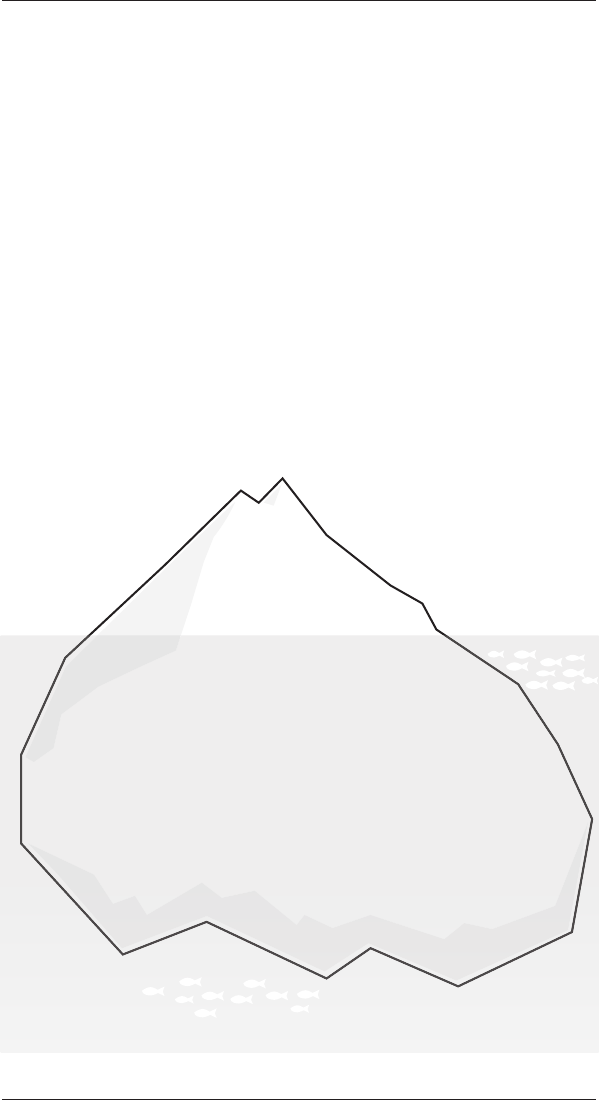

School culture as an iceberg ..........................................................24

Six activities to gain insight into the host school culture ....26

Introducing Change .......................................................................31

Change and cultural implications ................................................33

Planning to overcome resistance .................................................36

Examples and Tools ........................................................................39

Sample Overcoming Resistance to Change Chart .................39

Sample Force Field Analysis Chart ...............................................40

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

iv Peace Corps

Chapter 3: Strategies for Classroom Management ............. 41

What Do You Think? ........................................................................41

Key Ideas in This Chapter ..............................................................42

Eight Strategies for Classroom Management ...........................42

Strategy 1: Create an eective learning environment ..........42

Strategy 2: Establish classroom procedures .............................47

Strategy 3: Create a motivational environment .....................49

Strategy 4: Make every minute count .........................................52

Strategy 5: Keep everyone engaged ...........................................53

Strategy 6: Teach life skills and good learning habits ...........56

Strategy 7: Be creative ......................................................................60

Strategy 8: Use project design and management

techniques ...........................................................................................61

Examples and Tools ........................................................................62

Sample Classroom Procedures Planning Guide ......................62

Sample Classroom Management Planning Guide .................63

Sample Classroom Report Card ....................................................66

Chapter 4: Managing Disruptive Behavior ......................... 67

What Do You Think? ........................................................................67

Key Ideas in This Chapter ..............................................................68

Teaching Expected Behaviors .....................................................68

Why Do Students Misbehave? ......................................................71

Student behavior often reects cultural norms ......................72

Implementing Discipline ..............................................................75

Consequences and/or Punishment ............................................76

Discipline ideas ..................................................................................78

Considerations for dierent types of punishments ...............81

Corporal Punishment ..................................................................... 84

What can Volunteers do to reduce corporal punishment

incidents? ............................................................................................85

Examples and Tools ........................................................................91

Sample Consequences Worksheet ..............................................91

Peace Corps v

Chapter 5: Assessment, Grading, and Cheating .................. 93

What Do You Think? ........................................................................93

Key Ideas in This Chapter ..............................................................94

Discover Your School’s Assessment Culture ..............................95

Formative Assessment ...................................................................96

Assessment tools and strategies ...................................................97

Using feedback from ongoing assessment............................ 101

Grading ...........................................................................................102

Student-friendly grading practices ........................................... 104

Time-saving grading tips .............................................................. 106

Cheating .........................................................................................106

Ideas to prevent cheating ............................................................ 110

Consequences for cheating ......................................................... 113

Examples and Tools ......................................................................115

Sample Rubrics ................................................................................. 115

Chapter 6: Checking Your Progress ...................................119

Appendices ........................................................................ 123

Culture and the Ideal Teacher/Classroom ...............................123

Don’t Hit and Don’t Shout ...........................................................126

Resources .......................................................................... 129

Contents

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

vi Peace Corps

Peace Corps 1

I N T R O D U C T I O N

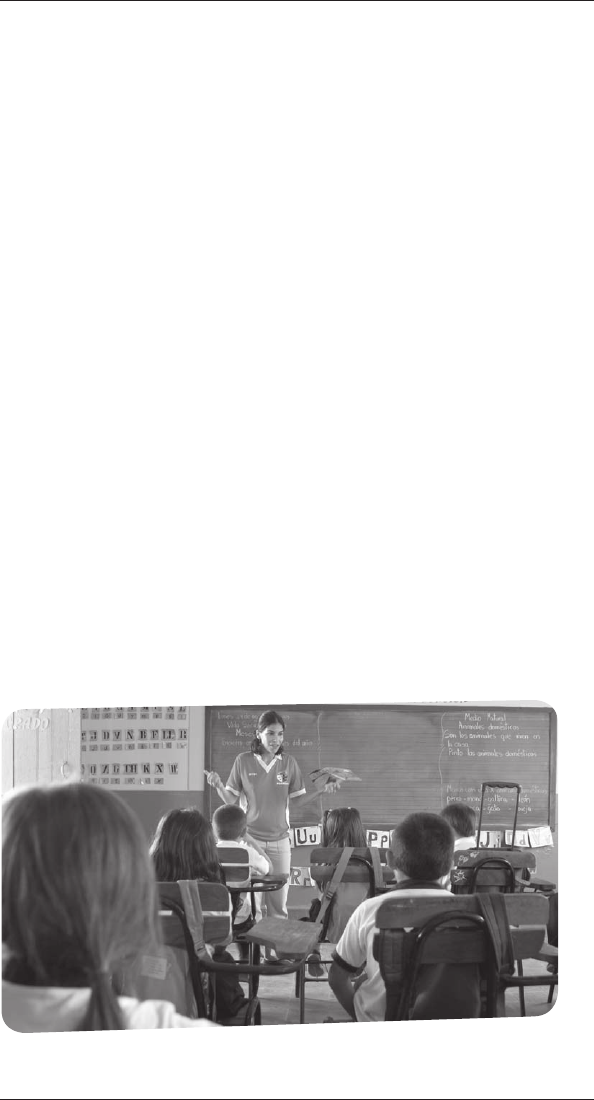

As a Peace Corps Volunteer teacher, you are in a unique situation.

Not only do you have the opportunity to learn and observe a new

culture and introduce your own culture to others, you will also

create—together with your students—a whole new classroom

culture. This is exciting and inspiring! Whether or not you have

previous teaching experience, teaching in a new culture requires

thoughtful planning and adjustment. This Idea Book will help

you approach your new classroom in a culturally sensitive and

appropriate manner.

This book was written in response to feedback from Volunteer

teachers. They report that managing a classroom in a new cultural

environment is a primary challenge. Many feel that the time spent

dealing with classroom management issues detracts from the

time spent actually teaching content. Sensitive and complicated

questions, such as how to teach in a school that condones corporal

punishment, surfaced frequently.

Volunteers and sta members from around the world were

asked to submit ideas and suggestions. Here you will nd

practical strategies for dealing with the most commonly reported

challenges. Suggestions range from how to develop useful

classroom routines to more complex topics, such as assessing

students fairly and eectively.

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

2 Peace Corps

It would be helpful to read this book before you start teaching,

but it will be equally helpful once you are teaching. When you

run into situations that you did not expect, this book will give

you some strategies to begin to understand them. It will help you

think about the classroom, your students, and your colleagues

from new perspectives so you can adapt to a new teaching

environment. There are exercises that ask you to exchange

information with your host colleagues. Take the opportunity to

learn as much as you can from your teaching colleagues, your

students, and Peace Corps sta.

Finally, do not forget to assess your own learning! In Chapter 6,

you will nd a progress checklist so you can chart your growth as

a classroom manager as the year unfolds. Above all, enjoy your

teaching (and learning) experience and come back to this book

often. With each review, you will nd another idea that you can

read about today and implement tomorrow.

Peace Corps 3

C H A P T E R 1

Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student

Learning: An Overview

What Do You Think?

Reect back on all the classes and classrooms in which

you were a student, teacher, or observer—including

those in your host country. With these thoughts in mind,

complete the exercise below.

Imagine your ideal classroom. You are in your host country

classroom. Look around.

What does your room look like?

What is in it?

What are the students doing?

What are you doing?

Close your eyes and try to imagine the scene. Write about some of

your images in the space below.

●

●

●

●

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

4 Peace Corps

You may have a vision of your perfect classroom, but what

do teachers actually do to make it a reality? This is a common

question; generations of teachers have looked for ways to ensure

an ideal learning environment. In this chapter, you will nd time-

tested ideas gathered from education research, host country

teachers, and Volunteer teachers. Keep in mind that not every idea

will work in all situations: teachers need to be exible and have a

variety of tools to suit the context in which they nd themselves.

Often, a strategy that works with one group of students in the

morning will not work with a similar but dierent group of

students in the afternoon!

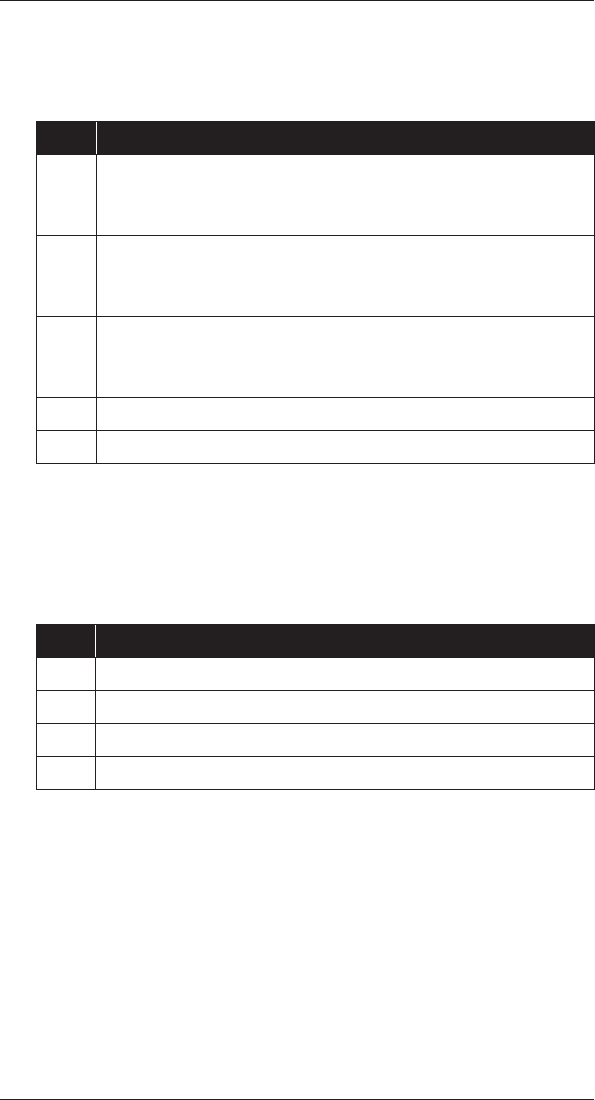

Key Ideas in This Chapter

Three teacher characteristics are essential to support

student learning.

1

Eective teachers

• have positive expectations for student success;

• are good classroom managers; and

• know how to provide good instruction.

Positive Expectations of Student Success

Students tend to live up to the expectations teachers set for

them. Set your expectations realistically high and consistently

communicate positive expectations during instruction and your

students will rise to meet those expectations.

❝

Be positive with your students! Let them know you believe

in them and that they can do it! Encourage and praise

student attempts (e.g., “You got the rst part right, keep

trying! You’ll get it!”).

❞

—Peace Corps/The Gambia

1 Adapted from Thomas L. Good and Jere E. Brophy. Looking in Classrooms, 9th ed.

Boston: Allyn and Bacon, 2002.

Peace Corps 5

Look for opportunities to communicate positive expectations to

your students.

Meet them at the classroom door with a smile and greeting

that says, “I am glad you are here today to learn.”

Set challenging but achievable learning objectives and allow

adequate time for students to accomplish the objectives.

Acknowledge past learning achievements and predict future

success. “Yesterday we learned adjectives to describe physical

characteristics. Now we are ready to brainstorm adjectives to

describe someone’s personality.”

Provide students with an assist, hint, or prompt. For example:

“Remember the formula for the area of a rectangle? How

might that relate to the formula for the area of a triangle?”

Ask follow-up questions that make students think. For

example: “That is an interesting position. What thought

process led you to it?”

Give lower-achieving and higher-achieving students (and

girls as well as boys) equal attention and structure learning

activities to ensure their success.

Prepare core activities for everyone and extension activities

for those who nish rst. One option: ask students who nish

quickly to assist peers who may have questions.

Follow up on work that you assign to students. When

teachers assign work and do not follow up on it, students

begin to lose motivation.

Reaction to Positive Expectations of Student Success

“I walk in my classroom. I’m a few minutes late. The teacher smiles

at me. I go to my desk and start working. I don’t quite nish when

the teacher asks for volunteers to check our work. I raise my hand

for the rst problem and the teacher calls on me. I say my answer,

and the teacher says, ‘Good try! Thanks for taking a chance!’ I

know my answer is wrong, but I feel good anyway. The teacher

tells us that it’s more important that we try than to always get the

answer right. The teacher calls us ‘risk takers.’ After I hear the right

answer and she explains it, I change mine so I’ll remember it.”

—a student from the South Pacic

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student Learning: An Overview

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

6 Peace Corps

Demonstrating your positive expectations of student success

motivates students, helps ensure their cooperation, and builds

productive student-teacher relationships. Your expectations

become a self-fullling prophecy.

The Star Strategy

“At the end of each class, I recognize at least one student

for something she or he did that day that deserves

recognition. On a star-shaped piece of paper that I will

pin to a bulletin board, I write the student’s name, the

date, and what he or she did. Once a student has three

stars, he or she can choose a prize from the treasure

chest. If I forget to give the star, my students frantically

call, ‘Miss! The star!’”

—Peace Corps/Kiribati primary teacher

Changing Negative Words to Positive Phrases

During a workshop, Bolivian teachers generated a list of negative

Spanish words or commands that might be used with students

and then developed more positive, encouraging terms to use

instead. For example, instead of saying “You are lazy,” say, “You

are capable of doing your homework”; instead of “Be quiet!” say,

“Keep calm, please.”

Collect more ideas to communicate positive expectations of

student success that t the host country’s culture from your teacher

counterpart, other teachers, Peace Corps sta, and students.

Classroom Management Skills

Classroom management refers to teacher behaviors that facilitate

learning. A well-managed classroom increases learning because

students spend more time on task. Chapter 3: “Strategies for

Classroom Management” probes deeper into the topic and

includes many ideas. Following are a few thoughts to jumpstart

thinking about classroom management.

Peace Corps 7

What does a well-managed classroom look like?

Students are deeply involved with their work. The climate of the

classroom is work-oriented, but relaxed and pleasant.

|

Peace Corps Volunteers in Bulgaria recommend “classroom

structure before instruction.”

How to support student learning

Establish classroom rules and procedures during the rst days

of school and consistently and fairly enforce them throughout

the school year. Be consistent.

Establish a positive professional relationship with students—

the teacher is both in charge and cooperative. You will never

have enough techniques to get students to behave and learn if

you do not rst create positive relationships.

Give understandable instructions so students know exactly

what they are expected to do. (Cultural Hint: Do not ask,

“Does everyone understand?” In many cultures, students

would not dare say “No” because that would indicate the

teacher did not do his or her job well.)

Use nonverbal signals rather than words. Silent cues are less

disruptive.

Delegate, delegate, delegate! Students learn skills and

responsibility, while saving the teacher time. But, teach

students how to accomplish the delegated task or this time

saver can turn into a time waster.

Move around the classroom. Move closer to problem

spots in the classroom. This tactic tends to prevent or stop

inappropriate behaviors.

Have a back-up plan if the lesson is not going well or runs short.

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student Learning: An Overview

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

8 Peace Corps

Discuss the classroom management teacher

behaviors described on the previous pages with

your counterpart teacher. Ask if they are culturally

appropriate and inquire about classroom

management norms at your host school.

❝

Classroom management will not make your students hate

you. On the contrary, students will respect you more and

be more enthusiastic about learning when they see you are

serious about education.

❞

—Peace Corps/Romania

Using sign language or nonverbal cues encourages a person

to look at the speaker. Some students who do not do as well

academically excel in reading sign language or nonverbal cues.

“As much as I want my students to take the content knowledge

from my class, I also want to teach life skills, like manners. For

a student who has done something for me, such as turning o

the lights at the end of the day, I sign or cue, ‘Thank you.’ During

assemblies, I often catch the eye of a student whose mind is

wandering and sign or cue, ‘Pay attention, please.’

“There are some basic words that I use over and over. I created

signs or cues for these. In time, the students become involved and

create signs of their own. They even made up signs for ‘give me

ve.’ Many of my students are kinesthetic learners.”

—Volunteer teacher in Latin America

“Values are caught, not taught.” Teachers who are courteous,

enthusiastic, in control, patient, and organized provide examples

for their students through their actions. For example, if the class

is getting too loud, don’t shout to be heard, speak at a normal

volume so the class has to be quiet to hear you.

Peace Corps 9

Instruction Skills

Instruction is what most people think of as teaching. In addition to

content knowledge, teachers need the skills to design and deliver

engaging lessons, and the skills to monitor learning progress.

Cultural note: Using a teaching method that produces

good results in one culture does not mean it will work in

a different culture. The method may need to be culturally

adapted or it may not be appropriate. For example, a

straightforward, fact-based, logical instructional approach

is effective in training some teachers, while others prefer

stories from which they can deduce information. There

is more about culture and how it influences education in

Chapter 2: “Teaching in a Cross-cultural Context.”

Both instruction and learning are easier in a well-managed classroom

where students are expected to succeed. But when instruction fails to

actively involve students in their learning, they become restless and

classroom management becomes increasingly dicult.

Eective teachers

Understand students’ level of knowledge and design lessons

to t students’ abilities.

Clearly state the learning objective for the lesson. When

students are told the objective, they know what they are

responsible for learning.

Break concepts and skills into small digestible learning

chunks—no more than two or three new ideas per lesson.

Structure lessons so students experience a variety of

instruction methods and to accommodate dierent learning

styles and maintain students’ interest. Change the type of

activity during the lesson to help students concentrate more

eectively on each task.

Pace instructions to allow students the time they need to

achieve learning objectives.

●

●

●

●

●

Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student Learning: An Overview

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

10 Peace Corps

Incorporate students’ interests into lessons. Use examples from

students’ daily lives to make lessons relevant. (Community

Content-based Instruction (CCBI) Volunteer Workbook [ICE No.

M0073] is a great resource.)

Use visuals (graphic organizers, maps, word webs, drawings,

pictures). Students may understand visuals better than

words, especially when the teacher and student have

dierent rst languages. See sample graphic organizers at

the end of the chapter.

Use silent signals to give directions, such as a nger on the lips

to mean don’t speak, or a hand behind your ear to mean listen.

Engage students physically and mentally in lessons

(manipulatives, role-plays, drama, pantomime, games, or

artwork).

Assess learning to determine if learning objectives were

achieved. If not, adjust instruction to enable students to learn

the concepts and/or skills.

Teach to dierent learning modalities—auditory, visual,

kinesthetic; right brained, left brained; multiple intelligences;

learning styles. (See chart on the next page and Nonformal

Education Manual [ICE No. M0042] Pages 48-49 for more

information on learning styles.)

❝

Use common factors that all teenagers are interested in

to grab their immediate attention, such as music, sports,

television and lm. Incorporate these interests into your

lesson plans and real learning will occur.

❞

—Peace Corps/Bulgaria

●

●

●

●

●

●

Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student Learning: An Overview

Peace Corps 11

❝

Not an artist? Simple stick gures suce. Copy clip art

illustrations. Enlist students to provide the visuals—let

students with artistic talent shine.

❞

—Peace Corps/Tonga

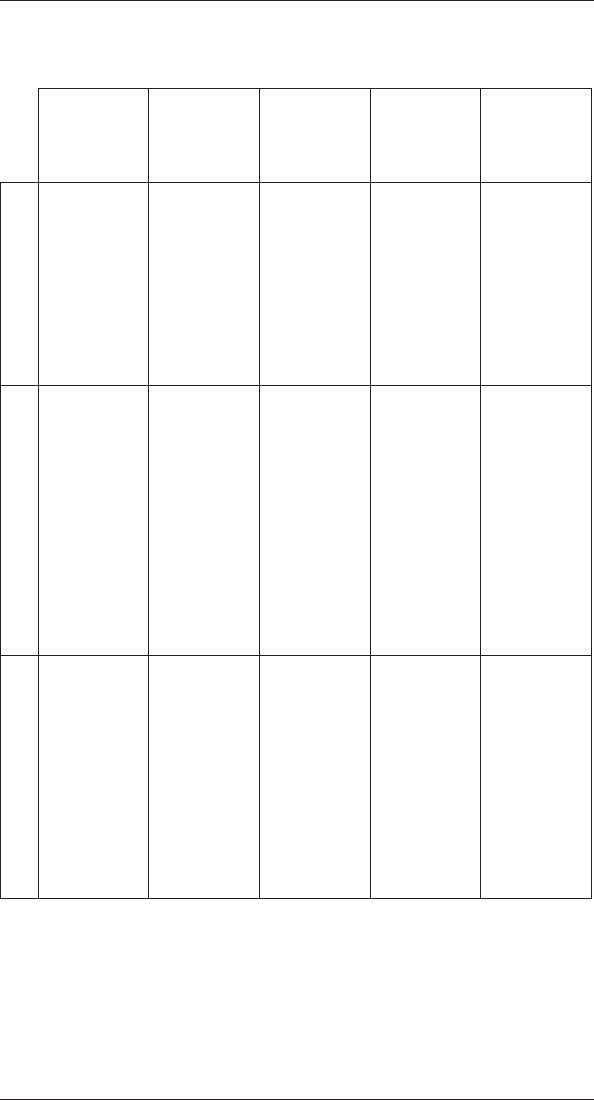

Learning from Feeling

(Concrete Experience)

• Learning from specic experiences

• Relating to people

• Sensitivity to feelings and people

Learning

by Doing

(Active

Experimentation)

Ability to get

things done

Risk taking

Inuencing people and

events through action

•

•

•

Learning by Thinking

(Abstract Conceptualization)

• Logical Analysis of ideas

• Systematic planning

• Acting on an intellectual understanding of a situation

Learning

by Watching

and Listening

(Reective

Observation)

Careful observation

before making a

judgment

Viewing things from

dierent perspectives

Looking for the

meaning of things

•

•

•

HOW WE PROCESS

H

O

W

W

E

E

R

C

E

I

V

E

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

12 Peace Corps

Lesson planning

Well developed lesson plans help ensure eective instruction

techniques are incorporated into your lessons. As a rule of thumb,

it takes about twice as long to develop an eective lesson plan as

it does to teach the lesson in the classroom. Talk to your supervisor

or Peace Corps sta to learn about approved lesson plan formats

for your host school.

|

Regardless of teaching styles, traditions and cultures, all high-

quality teaching has a common goal—student learning.

Thoughts on Instruction from a Peace Corps/Nepal Volunteer Teacher

One reason Volunteers might feel that their classes are “falling apart”

may be because they are teaching to only one type of learner. For

example, lecturing day in and day out may leave many students in the

class lost or bored, which may result in acting out, chatting too much,

or even missing class.

Even with few teaching materials and obligations to teach specic

content, it is possible to be creative and appeal to visual, tactile, and

auditory learners. Also remember that some students learn well from each

other in a more social way; they will need to work in pairs and groups.

Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student Learning: An Overview

Peace Corps 13

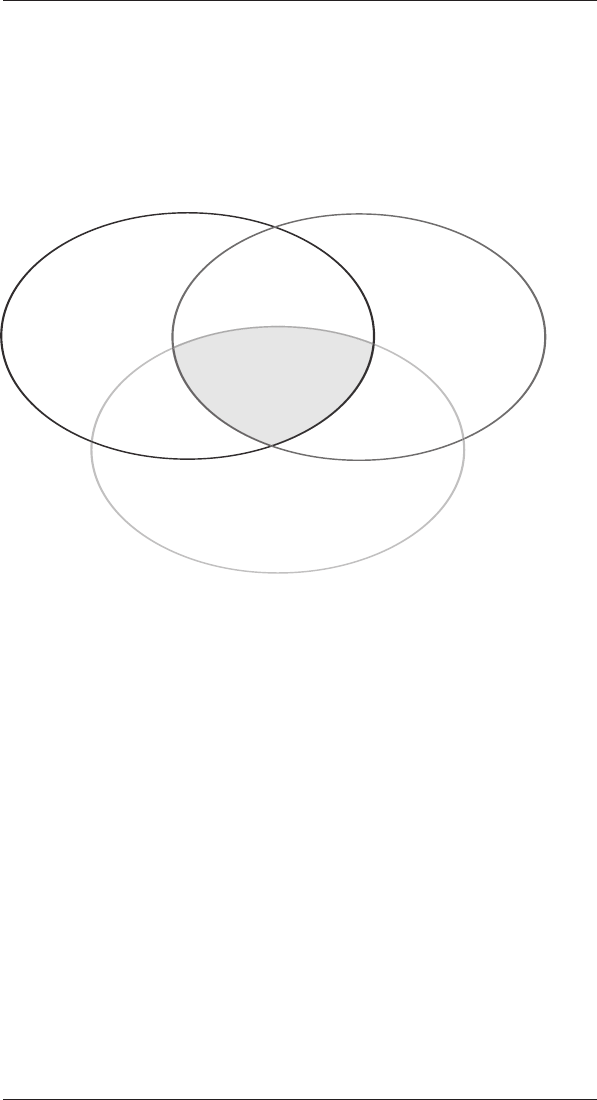

Summary

This chapter has described three key skill sets teachers need to

develop in order to support student learning. When all three skills

sets are present, you provide a positive classroom environment for

student success.

As you read the rest of this book, you will have opportunities to

test ideas against host country cultural norms—including dierent

value systems. These norms may produce dierent expectations

of the roles and behaviors of students and teachers. Keep an open

mind and continually try and imagine what will work for you and

your students in your new teaching context. Discuss your ideas

with Peace Corps sta, counterpart teachers, and experienced

Volunteers to see if they will succeed in your school.

❝

The way to get good ideas is to get lots of ideas and throw

the bad ones away.

❞

—Dr. Linus Pauling

Additional instruction resources:

Community Content-based Instruction (CCBI) Volunteer Workbook. Washington, DC:

Peace Corps, 2005. [ICE No. M0073]

Nonformal Education Manual. Washington, DC: Peace Corps, 2004. [ICE No. M0046]

Teaching English as a Foreign Language to Large Multilevel Classes. Washington, DC:

Peace Corps, 1992. [ICE No. M0046]

Teacher has

excellent

classroom

management

skills

Teacher

has good

instruction

skills

Positive

learning

environment

Teacher has

positive expectations

of student success

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

14 Peace Corps

Examples and Tools

Sample Graphic Organizers

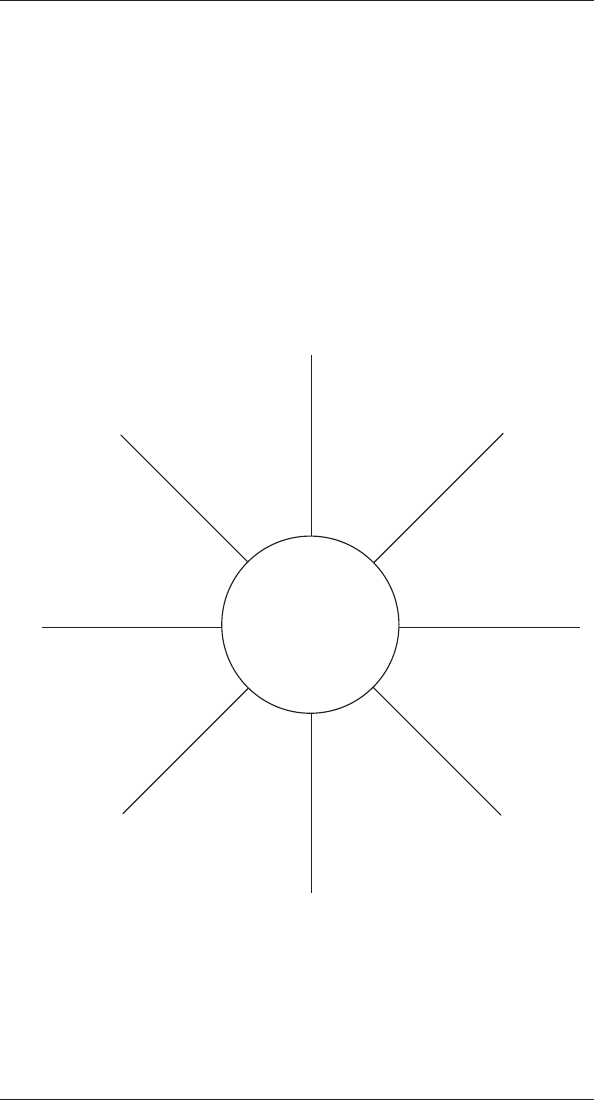

Word web

The word web (or cluster map) is used to describe a central idea: a

thing, a process, a concept, a proposition. The map can be used to

check students’ level of understanding before planning a lesson,

as a warm-up or transition, or as a quick assessment. The key

questions are: What is the central idea? What does this central idea

make you think about or remember?

TOPIC/

CONCEPT/

THEME

Fact/

Information

Managing Classrooms to Maximize Student Learning: An Overview

Peace Corps 15

For example, before starting a unit on a particular period of

history, brainstorm what students know (or think they know)

about it. Refer to the web as you teach the unit to help students

make connections in their thinking, to reinforce what they know,

or to clarify misconceptions. Or, use the web as a warm-up in a

mathematics class. Put a number in the middle and ask students

to think of as many ways as they can to add or subtract to get that

number. (So, with “5” in the middle, you would get “4+1”, “7-2”,

“3+2”, etc., radiating from the middle.)

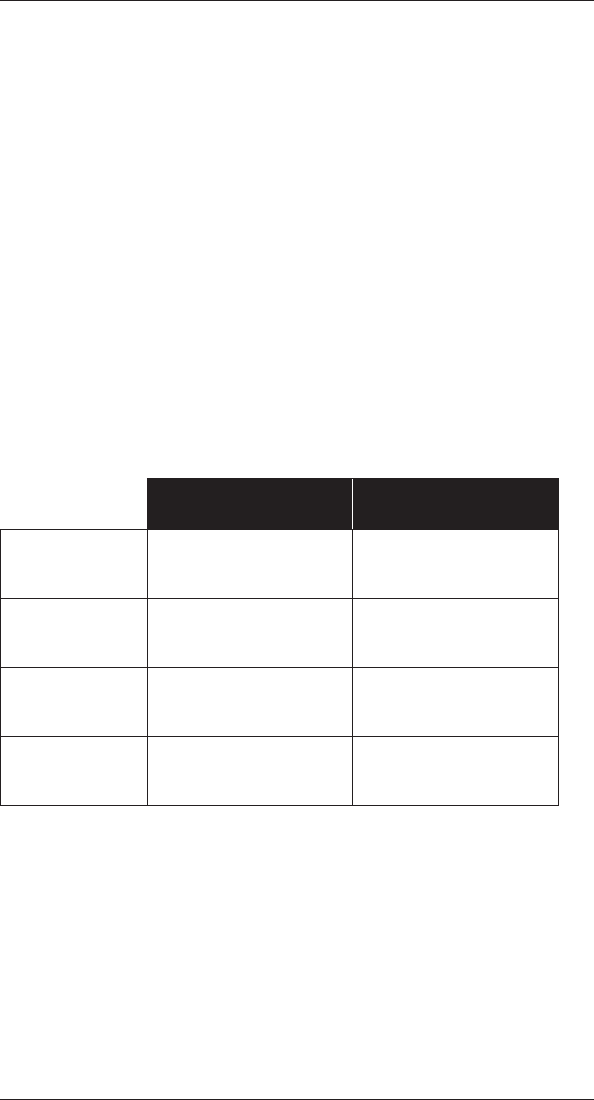

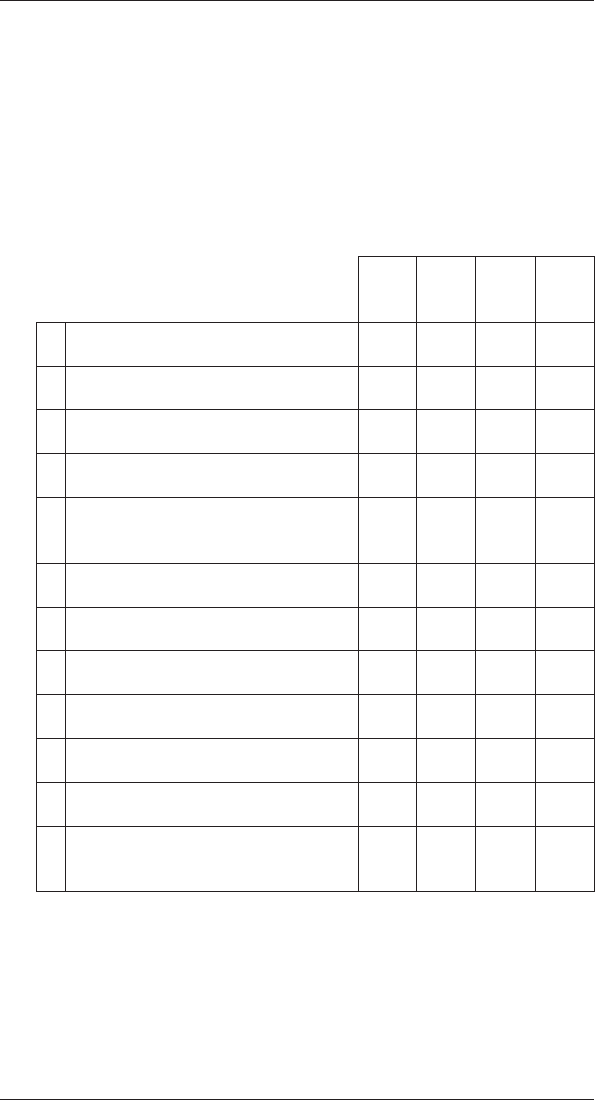

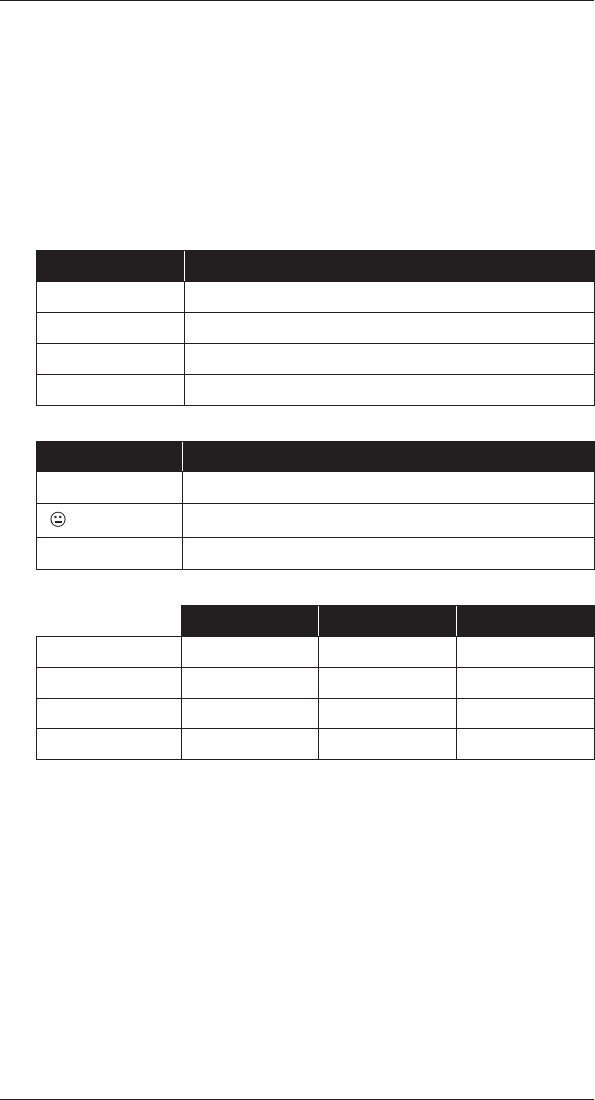

Compare/contrast chart

This chart can be used to compare and contrast two or more items,

characters in a story, proposals, etc. List each item to be compared

along the top, and list the characteristics of the items you want to

compare along the side.

Example:

Proposal A Proposal B

Cost

Time to completion

Skills/assets needed

Overall end result

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

16 Peace Corps

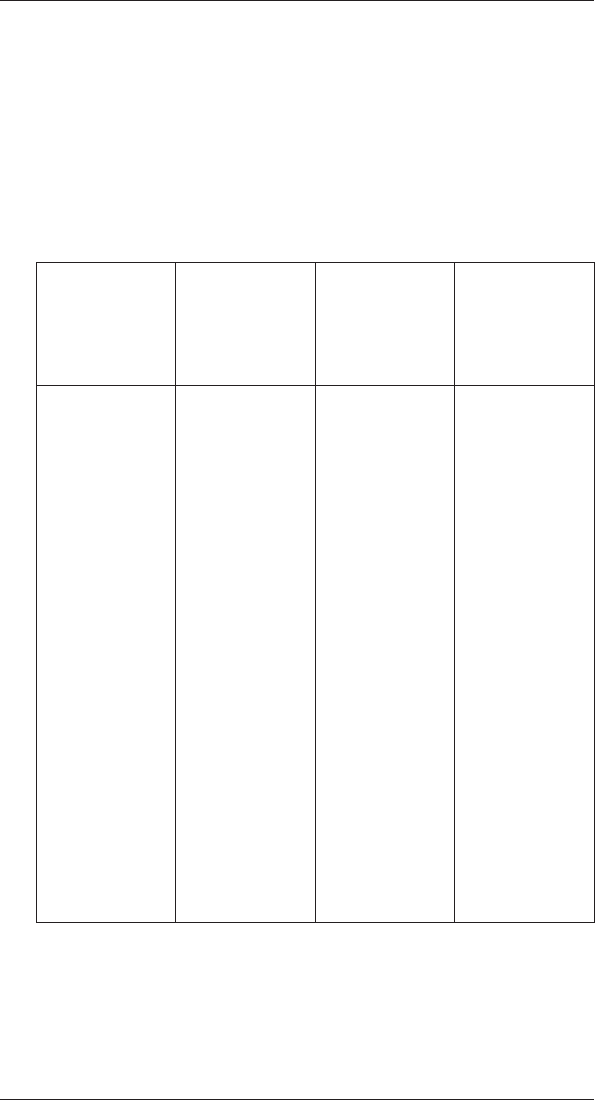

Problem-solving organizer

Use this organizer to help students map out their problem-solving

thinking in any content area. The key questions are: What is the

problem? What are the possible solutions? Which solution is best?

How will you implement this solution?

The problem: ______________________________________________

Possible

Solutions

Consequences

What will happen

if this solution is

adopted?

Pro

or

Con?

Value

How important is

the consequence?

Why?

The best solution is: _________________________________________

Peace Corps 17

C H A P T E R 2

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

What Do You Think?

Before reading this chapter, think back to an experience

you had with a foreign teacher or trainer. Perhaps you had

a college professor or a teaching assistant from another

country. You can also reect on host country teachers or

trainers you have had while in Peace Corps training.

Here are some questions to guide your thoughts.

1. How was their dress, body language, tone of voice, or level of

formality dierent from American teachers?

2. How did this teacher aect your learning, both positively and

negatively?

3. Did this teacher bring new perspectives to the topic or present

material using techniques you had not encountered before?

4. Were you always able to understand what the teacher said?

5. Did the examples this teacher use seem relevant to your life?

6. Were this teacher’s expectations of student behavior and/

or academic standards similar to your previous classroom

experiences?

7. Can you remember an instance when you had trouble talking

to or explaining something to the teacher? If so, why do you

think it was dicult?

8. If given the opportunity, would you choose to have this

teacher/trainer again? Why or why not?

Reecting on your experience of being taught by someone from a

dierent culture might provide insight into how your behavior might

be perceived by your students. Having a foreign teacher can be

enriching and frustrating. Much depends on cultural understanding

and how teaching is adapted to accommodate cultural dierences.

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

18 Peace Corps

This chapter explores the question of why cultural awareness is

important when planning and conducting day-to-day teaching

and learning activities.

Key Ideas in This Chapter

1. Culture matters—it inuences day-to-day

classroom activities.

2. To understand others, you must rst understand yourself.

3. To understand the cultural environment of your school

and classroom requires ongoing eort.

4. Introduce new ideas or changes in a culturally sensitive manner.

What can you do to ensure your students have a positive learning

experience with their foreign teacher? Start by seeing your

“cultural” self in the school setting. Then learn as much as you can

about the host country’s values and assumptions that inuence

how your school is run and how the students and teachers

behave. This will be an ongoing process your entire Volunteer

service! Every time something causes you to say, “I didn’t expect

that!” or “What did he or she mean by that?” you are trying to

gure out another cross-cultural experience. If you determine

that introducing change would benet students, this chapter

oers some considerations for introducing new ideas or change.

|

Simple denitions of commonly used terms in this book

Culture: “The way we do things around here.”

Values: Principles a group believes are good or right.

Norms: Typical behaviors of group members.

Peace Corps 19

Examine Your Own Culture

❝

The essence of cross-cultural understanding is knowing how

your own culture is both similar to and dierent from the

local or ‘target culture.’ For this reason, those who pursue

cross-cultural knowledge must, sooner or later, turn their

gaze on themselves.

❞

—Culture Matters: The Peace Corps

Cross-Cultural Workbook, Page 37

What is your cultural intelligence?

“Cultural intelligence” is the sum of the knowledge, skills, and

attitudes that enable a Volunteer teacher to work successfully

with students, fellow teachers, administrators, and parents at a

host school. You are not born with cultural intelligence, nor is it

acquired overnight.

Remember the three aspects of cultural intelligence with three

questions: What? Why? How?

1

What? Knowledge about cultures

Why? Awareness of yourself and others

How? Specic skills

Knowledge

about Cultures

(facts and

cultural traits)

+

Awareness

(of yourself

and others)

+

Specic

Skills

(behaviors)

=

Cultural

Intelligence

1 Peterson, Brooks. Cultural Intelligence: A Guide to Working with People from Other

Cultures. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press, Inc., 2004. Page 13.

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

20 Peace Corps

How do you gain cultural intelligence?

First: Increase your awareness of your own cultural values, beliefs,

traditions, and norms and how they aect your behavior.

Next: Appreciatively observe everyday school life and ask

nonjudgmental questions. Make tentative assumptions about

the culture and check your assumptions through additional

observations and/or discussions with individuals familiar with the

culture. Learn from your mistakes. Study and practice the language.

Finally: Adapt some behaviors that enable you to function in the

culture, while maintaining your own values and beliefs.

Volunteers who have developed cultural intelligence recognize

cultures have evolved to meet the needs of their people. There are

valid, but perhaps not obvious, reasons why a culture is how it is.

Having a reaction to or questions about another culture is natural,

but it is important to respect the host country’s cultural beliefs,

values, or traditions. It is their culture and it works for them.

In addition to working with your counterpart and colleagues, you

might want to nd your own personal “cultural coach.” Respectful and

successful expatriates who have lived in the country for many years may

be more attuned to the cultural dierences than host country nationals.

They may nd it easier to explain cultural dierences than your host

colleagues. Be sure, though, to check the information you get from an

expatriate with host country coaches, just to be sure it is accurate!

Cultural values

Because cultures are complex, we use models to help understand

them. The ve culture scales described by Brooks Peterson also

illustrates the dierences between low-context and high-context

cultures.

2

Keeping these generalizations in mind may oer

insight into behavior patterns and relationships you observe

in your school and community. A simplied model of low

context (informal) and high context (formal) is shown below as a

continuum. The ends of the continuum are denitions. People’s

styles and values may fall all along the continuum.

2 Peterson, Brooks. Cultural Intelligence: A Guide to Working with People from Other

Cultures. Yarmouth, ME: Intercultural Press, Inc., 2004. Page 61.

Peace Corps 21

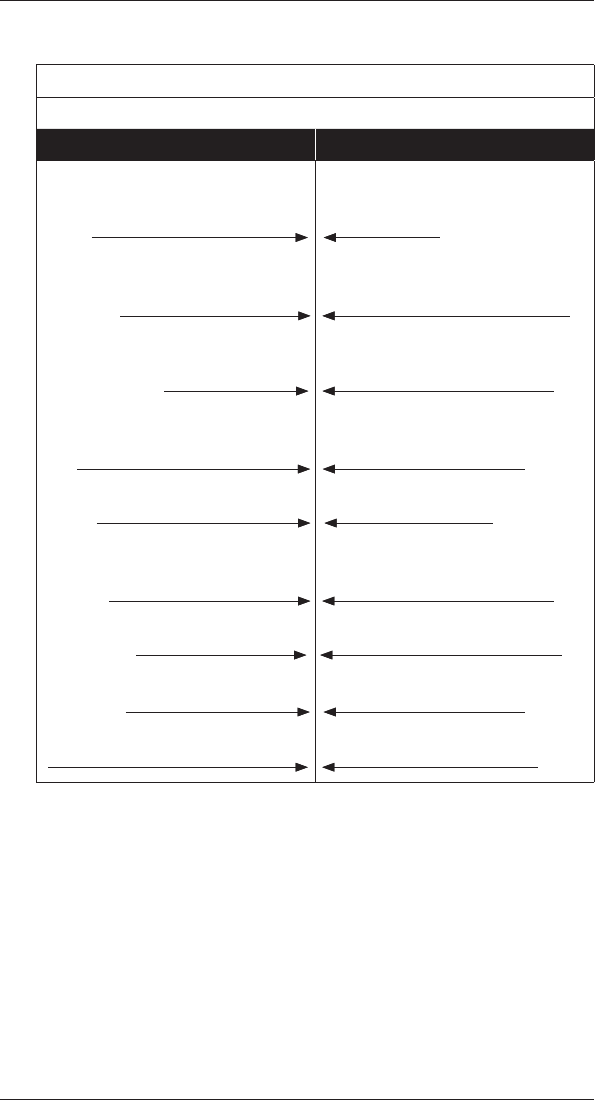

Low Context (Informal) High Context (Formal)

Equality (low

power distance)

________________________________________

Hierarchy

(high power

distance)

Direct

communication

________________________________________

Indirect

communication

Individual is

important

________________________________________

Group is

important

Task focus ________________________________________

Relationship

focus

Risk taking ________________________________________ Cautious

Context refers to the circumstances in which a particular event or

action occurs. In reference to culture, context refers to the often

unwritten rules or norms that have evolved and become part of a

group’s expected behavior in various situations.

A high-context, or formal, culture evolves when people live

together for many generations. Because there is so much general

understanding and shared knowledge, people do not need to

explain many things to each other; the context gives the clues. For

example, the form of communication may vary by age. A young

person speaking to someone older

may use specic verb forms (honoric

titles) and/or may look/not look at

the person, stand or stay seated,

bow slightly or deeply, etc. All of

these things are done automatically,

without much conscious thought.

Everything matters in high-context

cultures: how you dress, how you

greet each other, who you consider

your “family,” and so on. Members of the culture understand

behavioral expectations from the context. Outsiders nd

behaviors puzzling because they cannot see the context. People in

high-context cultures are cautious of change because they often

have long traditions of how things are done.

Typical

U.S. Citizen

Most of the rest

of the world

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

22 Peace Corps

Low-context, or informal, cultures are relatively young societies

and often include mixed ethnic groups. Because people do not

come from generations of living together and knowing everyone,

they have less shared context on which to base their interactions.

They tend to ask more direct questions to learn about each other,

and get to know people for what they do rather than from whom

they are related. Dress codes may be relaxed and people may

address each other in a casual manner even across age groups—

the use of rst names is common.

People focus more on doing things,

rather than spending time nurturing

relationships. Change is more readily

accepted as the norm, generally with

a belief that the future will be better.

Most Peace Corps Volunteers come

from the low-context U.S. culture,

unless their family belongs to one

of the high-context subcultures in

the U.S. In most of the rest of the world cultures are higher context.

It is important to remember, however, that this is a model. There is

diversity within every culture. Also, each individual may nd him/

herself in a dierent place on the continuum depending on the

situation or context, such as at work, at home with family, etc.

Based on the diagram and description about low- and high-

context cultures, what are ve specic dierences you would

expect if your school is in a high-context culture and you come

from a low-context culture?

1. __________________________________________________

2. __________________________________________________

3. __________________________________________________

4. __________________________________________________

5. __________________________________________________

To learn more about American cultural values read Pages 37–57 and complete

the exercise “Fundamentals of Culture: Comparing American and Host Country

Views” on Pages 179–182 in Culture Matters: The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural

Workbook [ICE No. T0087].

Peace Corps 23

Cultural norms

Cultural norms are often so strongly ingrained in an individual’s

daily life that the individual is unaware of certain behaviors. Until

these behaviors are seen in the context of a dierent culture with

dierent values, the individual may have diculty recognizing and

changing or adapting them.

Think-Pair-Share Activity

When we look at a situation, we interpret what

is happening through the lter of what our

culture tells us is happening. Read the following

description of a classroom in a developing

country written by an American observer.

Teachers’ frequent use of corporal punishment discourages

students from actively participating in the classroom. Students

are expected to sit rigidly in their seats and speak only when

spoken to. Conditioned in that way, it is not surprising they don’t

feel free to speak out in the classroom; their shyness, however,

should not be mistaken for lack of interest.

Think about what you just read. What conclusions

(judgments) were made about learning conditions in this

classroom? How did cultural values and beliefs inuence the

writer’s conclusions?

Pair with a host country teacher who has also read and

thought about the classroom description by the American

observer.

Share your thoughts with each other and discuss how cultural

values and beliefs aect how teachers manage their classrooms.

—Activity adapted from a Peace Corps/Tonga pre-service training exercise.

Classroom description is from Culture Matters: The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural

Workbook, Page 8.

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

24 Peace Corps

Examine a New Culture

Schools are a microcosm of community culture. They reect the

community’s cultural values and take an active role in passing both

visible and hidden cultural elements to the next generation. Cross-

cultural experts use the analogy of an iceberg to help explain the

visible and hidden components at play in a culture. The iceberg

is used because culture, like an iceberg, is nearly 90 percent

underwater or invisible. The invisible or hidden parts to culture are

beliefs, values, and assumptions—the reasons people behave the

way they do. The visible aspects of culture are things you might

photograph or observe.

Let’s examine some of the cultural elements that are in, or

inuence, the formal educational setting.

School culture as an iceberg

•What school stakeholders want students to become as adults (the

desired outcome of education)•How the individual ts into society•Beliefs

about human nature•Beliefs about the role of religion in education•Beliefs about

the value of the individual•Importance of work or study•Motivations for academic

achievement•Tolerance for change•Importance of “saving face,” i.e., maintaining appearances

and dignity •Communications styles (direct or indirect)•Attitudes about the roles of men and

women•Attitude toward authority•Sense of what is fair in assigning grades and discipline

•Attitude about ownership (individual ownership or group ownership)•Attitude toward doing

your own work or getting help from others•Attitude toward oering money to school ocials to

gain entrance to the school or to assure a favorable grade•Others?

Hidden

culture/values,

beliefs, and

attitudes

•Behaviors of

students, teachers,

administrators•Dress

•Materials on the walls •Furniture

arrangements•Types of books and materials

•Discipline methods•Classroom activities

•Student/teacher relationship

Tip of the iceberg/

observable culture

Peace Corps 25

Some examples of how the hidden culture may aect behaviors in

host schools.

Teachers and friends do what they can to help a strong math

student gain admission to higher education, even though he

or she cannot get a high enough score in a language class.

Child-rearing and religious values are reected in school

discipline practices.

Grades may be inuenced by the status of the student’s family

or a “gift” to a teacher or school ocial.

Students stand when a teacher enters the classroom.

Good students sit in front and bad students sit in the back of

the classroom.

An education leader from the Caucasus, during a speech on

university academic standards, noted that people had always

accepted bribery for university entrance. They thought it was just

part of their culture, and they had never even considered that other

countries had merit-based systems rmly in place.

An educational leader from the South Pacic said, “Our students

need a good education so they can go overseas to New Zealand,

Australia, or the United States and send money home to their

families.” In Tonga there is a strong cultural duty for young people

to maintain the nancial well-being of their families.

By observing visible culture (the tip of the iceberg), and

understanding low- and high-context culture generalizations, you

can make some reasonable guesses concerning the hidden values

of the host school’s culture.

●

●

●

●

●

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

26 Peace Corps

Six activities to gain insight into the host school culture

➊

A host teacher shadowing activity

This activity allows you to observe the tip of the iceberg.

Find a teacher at the host school who will let you accompany

him or her for several hours a day.

Watch and listen to what is going on around you and record

what you observe. Note the dierences between what you see

here and what you would expect to see if you were following a

teacher in a U.S. school.

Keep this checklist and the points in mind during the rst

school semester. It will take time and knowledge of the host

language to understand some of these things. You may want

to revisit the checklist over the course of the year. As your

language skills improve and your cultural knowledge deepens,

you will notice more subtle nuances of the culture.

Adapted from Culture Matters: The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural Workbook

Pages 131-133.

Nonverbal Communication

How do people dress?

How do they greet each other?

Do people maintain eye contact when

they talk?

How far apart do people stand?

Power Distance Behaviors

How do teachers treat school administrators?

How do school administrators treat teachers?

How do teachers treat students?

How do students treat teachers?

Do you see evidence of administrators

delegating authority?

Do you see evidence of teachers

taking initiative?

With whom do people eat lunch or have tea?

Do they eat only with their peers, or is there

mixing of the ranks? Does everyone share food?

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

Communication Styles

How do people make suggestions,

propose ideas?

How are disagreements expressed?

Are people generally direct or indirect in

their conversation?

Does this appear to be a high- or low-

context workplace?

Other Workplace Norms

When people interact, do they get to the

task right away or talk more generally rst?

Are women treated dierently than men? If

so, in what way?

What does the prevailing attitude seem to

be about rules and procedures and the need

to follow them?

Do teachers come to work on time and do

meetings start on time?

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

What major dierences do you see between the host school and schools you are familiar with in the U.S.?

Peace Corps 27

➋

A values and norms clarication exercise

Use this activity to identify similarities and dierences in your

education values and norms and those of your host school.

Instructions: This is a forced choice exercise where you must choose either answer a or answer b.

Sometimes it will be hard to decide. The purpose is to prepare for a discussion of these topics. There is

not necessarily one right answer.

Trainees/Volunteers answer the questions to clarify their own education values.

Invite as many host country education stakeholders (ministry of education ocials, school

administrators, teachers, parents, community members, and/or students) as possible to answer the

same questions.

Volunteer and host country stakeholder answers might vary. Insights into the cultural values behind

answers may be gained by discussing why each individual chose particular answers.

Answer each of the following, circling only one choice:

1. Students should

be spontaneous and

talk out when they

have something to say.

a. raise their hands

and participate in an

orderly way.

b.

2. Homework should be given

sparingly and only

when needed.

a. every night.b.

3. The classroom should be

student-centered.a. teacher-centered.b.

4. Teachers should be

friendly and

spontaneous.

a. reserved and formal.b.

5. Teachers should

create their own

curriculum based on

student needs.

a. follow a set

curriculum.

b.

6. In group work

the process is

important.

a. the product is

important.

b.

7. Class assignments are most

useful when they are

done in a group.a. done individually.b.

8. The classroom should be

open with students

free to move around.

a. closed and orderly.b.

9. Students are mostly motivated by

internal rewards.a. external rewards.b.

10. Male and female students

should be held to the

same standards.

a. should be held to

dierent standards.

b.

11. Evaluation should be

informal.a. formal.b.

12. It is more important to

change values.a. change behavior.b.

1.

2.

3.

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

28 Peace Corps

13. The curriculum should be

directed toward

local community needs.a. national examinations.b.

14. Grades are

a deterrent to

developing self-

motivation.

a. an eective

mechanism for

motivating students.

b.

15. It is important to cover

certain content in depth.a. all pre-set curriculum.b.

16. Standards for discipline should

be determined by

the individual teacher.a. school policy and

tradition.

b.

17. Class time should

include nontopic-

related discussions.

a. be spent on task.b.

18. Students should be tracked by

ability.a. age.b.

19. In school, it is most important to

learn how to learn.a. learn facts.b.

20. Teachers

should have all the

answers.

a. are allowed to say, “I

don’t know.”

b.

21. Teachers and students should

suppress their

emotions.

a. be free to show their

emotions.

b.

22. Students should expect

teachers to show them

the way.

a. to be taught how to

nd their own way.

b.

—Adapted from Peace Corps/Mauritania

➌

A cultural interview activity

Encourage students or teachers to think about school

culture and share their thoughts with the Volunteer teacher

with this activity.

Student Activity: Cultural Interviews

When teaching within a new cultural context, reaching students can be dicult at rst

because you lack an understanding of your students’ culture and how to relate to them. This

activity helps bridge that gap.

Note: Because it is often easier to say what others think, in this activity students are asked

about their friends’ opinions rather than their own. This would also be a valuable activity to

conduct with your teaching colleagues by changing “your friends” to “your fellow teachers.”

As mentioned earlier in this chapter, cultural norms are often so strongly ingrained in an

individual’s daily life that the individual may be unaware of certain behaviors. It is usually

dicult for people to describe their own culture. By asking indirect questions, you allow

Peace Corps 29

people to describe in broad terms how they think their culture is perceived by more than just

one person. These indirect questions can be asked of students individually, in pairs, or in small

groups. After students have written their answers, they present them, and a class discussion

is held. This activity gives students an opportunity to reect on their school’s culture and the

teacher an opportunity to learn what students are thinking.

What would your friends tell a new student about this school?

What is the one thing your friends would most like to change about this school?

Who is a hero at this school? Why?

What is your friends’ favorite thing about this school?

What do your friends think a new teacher should know about this school?

➍

Compare parents’ aspirations for their children to learn

about cultural values

This exercise requires a few host country nationals who have

children (they can be your trainers, teaching colleagues, or

community members) and a few Americans. You will need a

blackboard or chart paper.

1. Ask small groups to make a list of the characteristics/values/behaviors they hope

their children will develop. Items might include ‘successful,’ ‘good students,’ ‘parents,’

‘independent,’ ‘loyal to family,’ etc.

2. Have groups share lists, explaining or clarifying what the items mean. For example,

what does “successful” mean? It might mean owning a farm or marrying and having

a family or getting a well-paying job. Once everyone understands both lists, you

probably will see some dierences. Perhaps there are some items on one chart that are

not reected on the other.

3. For each item on each chart, discuss what the parents would do to raise their

children to have those characteristics. For example, if the children are expected to be

independent as adults, they may be given opportunities to make some of their own

decisions (like getting an allowance and being able to spend it the way they want or

choosing what they want to eat in a restaurant). If children are expected to grow up to

be closely connected to the family, they may spend most of their free time with family

members and receive money they need for activities from their parents.

4. Generally what will emerge is that the children are raised to carry the values of the

culture; dierent values will lead to dierent child-raising activities. Learning more

about your host culture’s values in this way may help you understand why schools are

run the way they are and why students are expected to behave the way they do.

•

•

•

•

•

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

30 Peace Corps

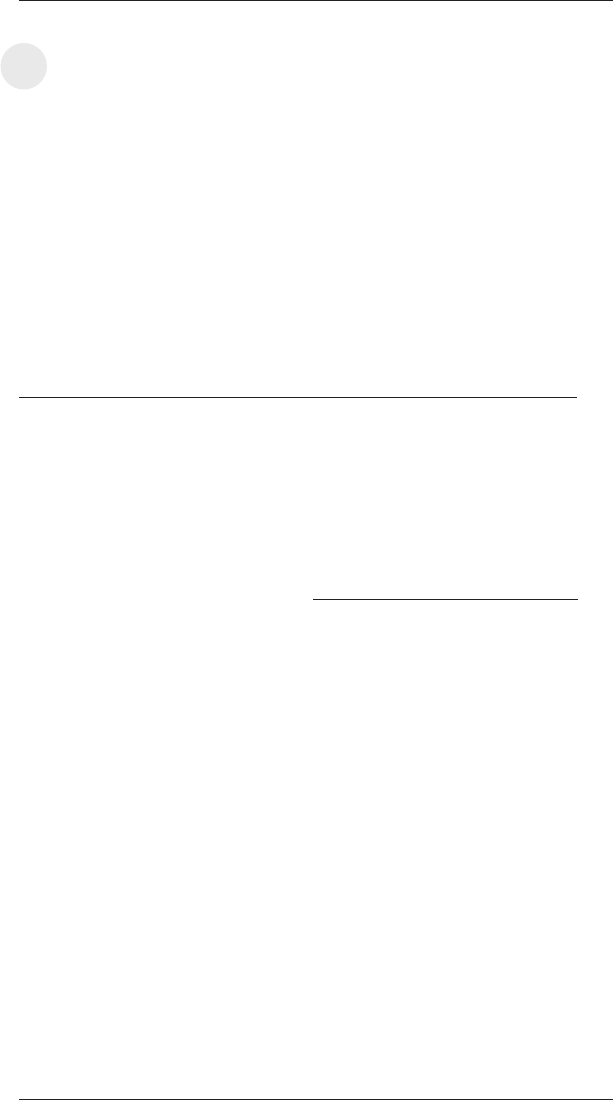

➎

Use participatory analysis for community action (PACA)

activities to explore the host school’s culture

Participatory analysis for community action (PACA) tools are

useful in discovering more about your students, your fellow

teachers, and your community. Here are some examples of

how the dierent tools can be used to teach skills while they

provide you with important information about your students

and the community.

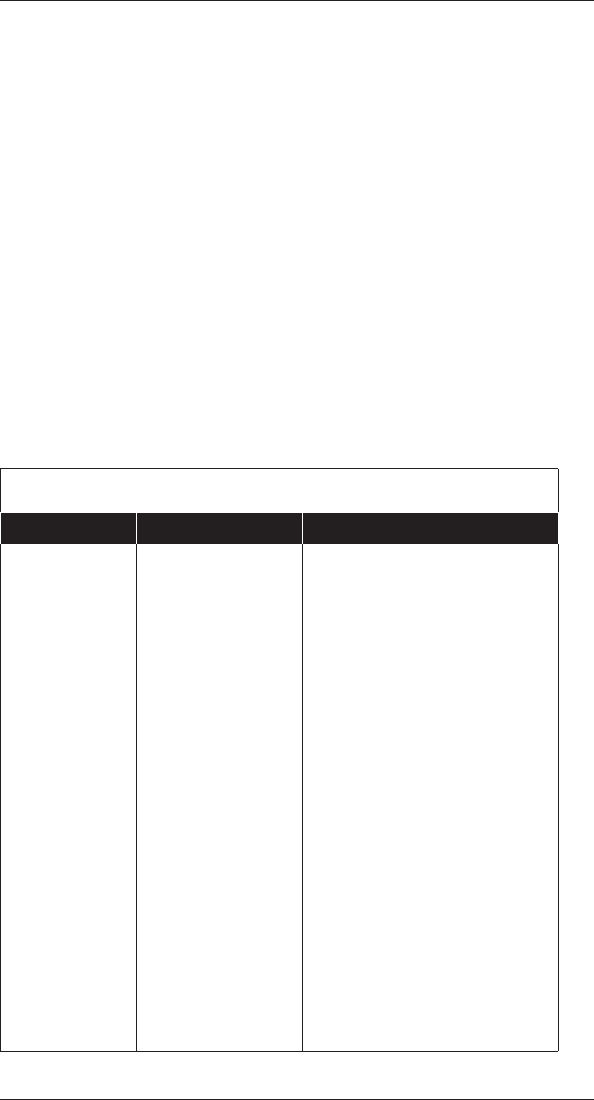

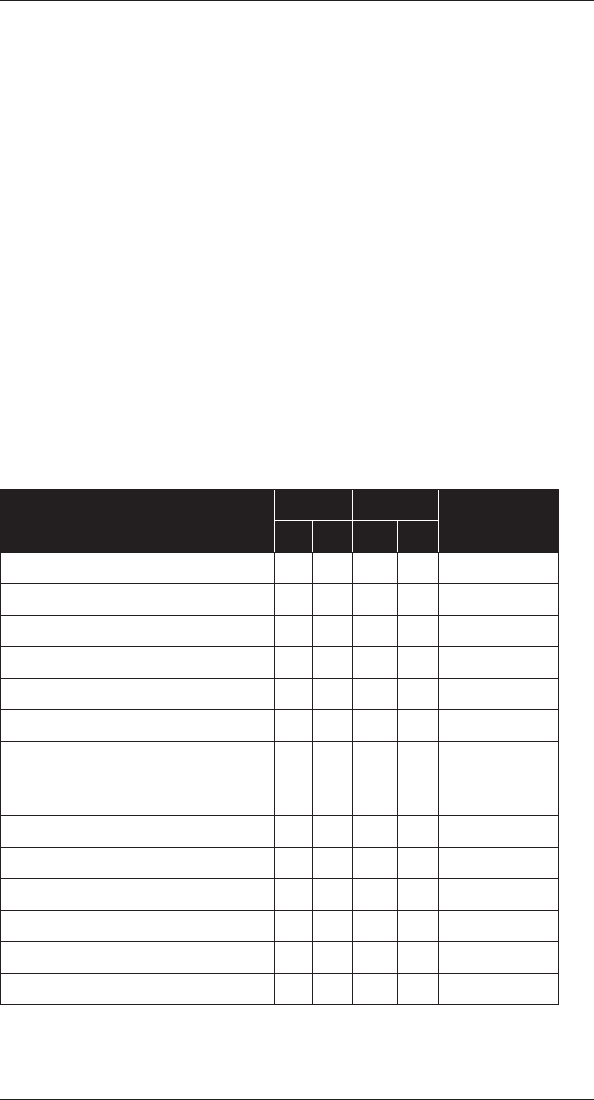

PACA Tool Students learn Volunteer teachers learn

Assign students to create

daily activity schedules

Sequencing and

writing skills

The time students have

available for studying,

homework, after school

activities such as clubs,

and tutoring sessions

Have small groups

of male and female

students separately draw

community maps

Group and

mapmaking skills

Dierent perceptions of

boys and girls

Boys’ and girls’ interests

and concerns; their

perceptions of the

community

Teach students priority

ranking techniques

and use them to select

classroom rules and/or

consequences

Ranking skills

How to participate in

group decision making

Critical thinking skills

Responsibility

Students’ expectations

for classroom behavior,

and students’ sense of fair

consequences

Have small groups of male

and female students make

and present seasonal

calendars

Group, organizational,

and presentation skills

Seasonal dierences

in terms of activities,

health, and out of school

obligations; opportune

periods to schedule

dierent lesson activities

during the school year

Also, consider inviting your counterpart or team teacher to

do a daily activity schedule to identify possible times for co-

planning and to gain a better understanding of their non-school

responsibilities. Consider ways the other tools might be useful at

the school, such as the seasonal calendar.

For more ideas, see PACA: Using Participatory Analysis for Community Action Idea

Book. Washington, DC: Peace Corps, 2005. [ICE No. M0086]

Peace Corps 31

➏

Attend workshops or faculty meetings in the host country

Look for opportunities to hear experienced host country

teachers discuss teaching issues, techniques, and classroom

management. Ask your program manager if there are local or

regional meetings or workshops that you can attend.

Introducing Change

By now, you have developed some cultural awareness and have

adjusted some behaviors to accommodate living with people

from a dierent culture. You realize changes are necessary when

working in a new culture.

Are there changes you want to make in your

behavior as a professional teacher, your

teaching methods, and/or how you promote

educational change? Below are a few ideas to

help you t in with the host school’s culture.

Use culturally appropriate behaviors to establish

professional credibility.

Learn the language. Of course, learning the language

facilitates communication. It also shows respect for the culture

and a desire to understand the host school’s culture.

Dress and groom yourself for your role as a professional

teacher: use host country teachers as models.

Behave appropriately when meeting colleagues for the

rst time. (Find out: Do you introduce yourself or is it more

appropriate for someone else to introduce you? Do you shake

hands? What should you say—should you talk about your

family rst or your education and experience?)

Observe the correct protocol for meeting with the school

administrator. (Find out: Do you schedule the appointment

or does the administrator? How should the administrator be

addressed? Do you talk about generalities or get right down to

business? What questions are appropriate to ask? How do you

know when it is time to leave?)

●

●

●

●

❝

Give respect to

get respect.

❞

—Peace Corps/Mozambique

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

32 Peace Corps

Behave appropriately when rst meeting your students. (Is it

better to do it alone or have the school head or a team teacher

introduce you? How should you ask students to address you?

What should you tell students about your background and

expectations?)

Learn how you are expected to interact with parents. (When

and where should you meet them? Do you visit their homes?

During regularly scheduled meetings? Only when there is

a problem with their son or daughter? How do you address

parents and how should they address you?)

Learn what community involvement is expected of a teacher.

(In what types of community activities do teachers participate?

Are there expectations about their dress and/or behaviors

even when not at school?)

Will some of these require you to change what you might do at

home in the U.S.?

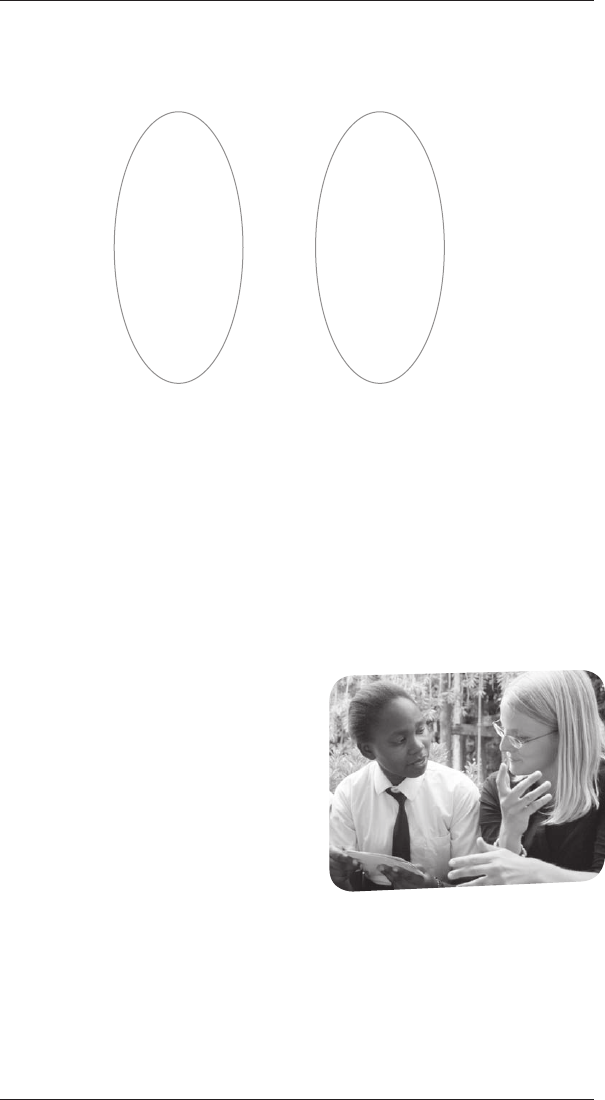

Volunteer-Counterpart Activity

This activity could also be used with students or

community members.

Complete the drawing on the next page. Consider

that the adult in the drawing is you as a teacher.

Add to the drawing details of dress, statements, and thoughts that

would reect a respected teacher at a school in the U.S. Provide the

student gure with indications that the student respects YOU.

Invite your counterpart to complete a similar drawing.

Share your drawings and reections. Explore together what is

expected of teachers and students.

—Adapted from Fulbright Teacher Exchange Orientation

3

3 Blohm, Judee and Sandra Fowler. Fulbright Teacher Exchange Program

Orientation. Washington, DC. August, 2000.

●

●

●

Peace Corps 33

How do teachers and students show respect?

See the appendix for a training session similar to this activity from Working with

Supervisors and Counterparts, Washington, DC: Peace Corps, 2002. Pages 70-71.

[ICE No. T0121]

Change and cultural implications

Before you decide to initiate change, consider your options.

A. You inquire about behaviors you don’t understand, determine

the beliefs and values behind them, and learn to accept their

cultural rules.

B. You weigh the benets of doing something “their way” even

though you are slightly uncomfortable with it because it really

isn’t all that important.

C. You take time to analyze the things you are thinking about

changing, pick out one or two you believe are critical, and

work carefully to make changes in those things.

What

he/she

says

My own

behavior,

dress,

thoughts,

speech

A student’s

behavior, dress,

thoughts,

speech in

relation to me

What

he/she is

thinking

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

34 Peace Corps

Think 1-2-3 when considering change in the classroom:

1. How would a change improve student learning? How will

you know?

2. Are you the one that needs to change? Look within yourself

before you look at others. It is often best for foreign teachers to

change the way they act or their attitude to t in with the host

school’s culture.

3. Do you have a strong feeling that if others change there would

be an overall improvement in student learning? If you do, then

nd ways to involve students, administrators, and parents from

the very beginning of the change process.

Read the stories of three foreign teachers below. Would the stories

be dierent if they had thought 1-2-3? Why or why not?

“The rst month or two in class I was always saying, ‘Look at me

when I talk to you,’ and the kids simply wouldn’t do it. They would

always look at their hands, or the blackboard, or anywhere except

looking me in the face. And nally one of the other teachers told

me it was a cultural thing.”

—Tony Hillerman from Skinwalkers in Culture Matters:

The Peace Corps Cross-cultural Workbook, Page 109.

One teacher felt that talking in class was the number one problem

in dealing with classroom management. “Before you become too

frustrated and disheartened, keep in mind that in Bulgaria, it is not

unusual for a teacher to continue with a lesson while his or her

students chat in the meantime. The students are also accustomed

to this, so having a silent classroom is not very realistic.”

—Peace Corps/Bulgaria

When I entered the classroom, all the students automatically stood

up until I gave them a signal to sit. I was uncomfortable with this

deferential behavior and told my students they need not stand

when I entered the room. Two weeks later, the headmaster asked

to speak with me. He informed me the other teachers had heard

my students were not standing when I entered the room and they

were upset. They regarded this behavior as a sign of disrespect,

which they feared might spread to their classrooms. They worried

Peace Corps 35

that I deliberately might be trying to blur the distinction between

teacher and student. If students put themselves on the same level

as teachers, chaos would result. It didn’t occur to me that this small

change in my classroom would cause problems.

—Adapted from “Upstanding Students” in Culture Matters:

The Peace Corps Cross-cultural Workbook, Page 124.

A Volunteer teacher in the Czech Republic had diculty

communicating with her supervisor. The following change

beneted both the supervisor and Volunteer: Each Friday the

Volunteer wrote a short English note to her supervisor, explaining

what she had done during the week and asking any questions

she had. When the Volunteer and supervisor met on Monday

the supervisor had translated the note into Czech to give to the

Volunteer and was prepared to discuss the Volunteer’s questions.

One area where Volunteer teachers will need to modify their

classroom behavior is when (and if) they speak English. Some

modications that help ensure understanding:

Speak slowly and clearly, but not loudly.

Keep it simple; use short sentences.

Avoid idiomatic expressions, such as “Am I in the ballpark?”

Use open-ended questions. Close-ended questions prompt

students to respond as they think you want.

Write key points on the board; students often understand

better when they see the words.

Use examples to which the students can relate.

Use clear, culturally appropriate gestures.

Give and seek feedback to check understanding.

Fostering change requires good communication skills. Proceed

respectfully and slowly.

While Americans usually view change as a positive and inevitable

force and are relatively quick to make changes, people in high-

context cultures often value traditions and may rarely contemplate

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

❏

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

36 Peace Corps

change. Risk-taking outside the cultural norms might be unheard of.

This high-context cultural tendency suggests it is best to go slowly,

do not rush through the change process, and be sure to involve

other teachers, school administrators, parents, and perhaps students.

A Volunteer advisor to an educational nongovernmental

organization in central Europe became exasperated with the long

discussions of what seemed to her to be rather trivial matters. A

young sta member responded to the Volunteer’s frustration by

pointing out a key dierence: “You Americans decide quickly and

if it doesn’t work you try something else. We know we can’t aord

to make mistakes.”

If you decide to be a change agent, rst nd a committed local

partner and start with positive advice; move on to more cautionary

words later. Know that sustainable change will only occur if local

people adopt the change as their own and institutionalize it (make

it part of school norms).

Explain the rationale for change—communicate frequently

and clearly.

Provide a clear vision.

Seek opportunities to involve people.

Make sure people have the know-how.

Track behavior and measure results.

Beware of bureaucracy.

Expect resistance.

Get resistance out in the open. (See the useful tools

“Overcoming Resistance to Change” and “Force Field Analysis”

on the next pages.)

Planning to overcome resistance

When Volunteer teachers and counterparts or team teachers are

considering changes in instruction or classroom management

techniques, the table on the following page is a useful model to

identify proposed changes, reasons for resistance, and strategies

for overcoming resistance.

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

●

Peace Corps 37

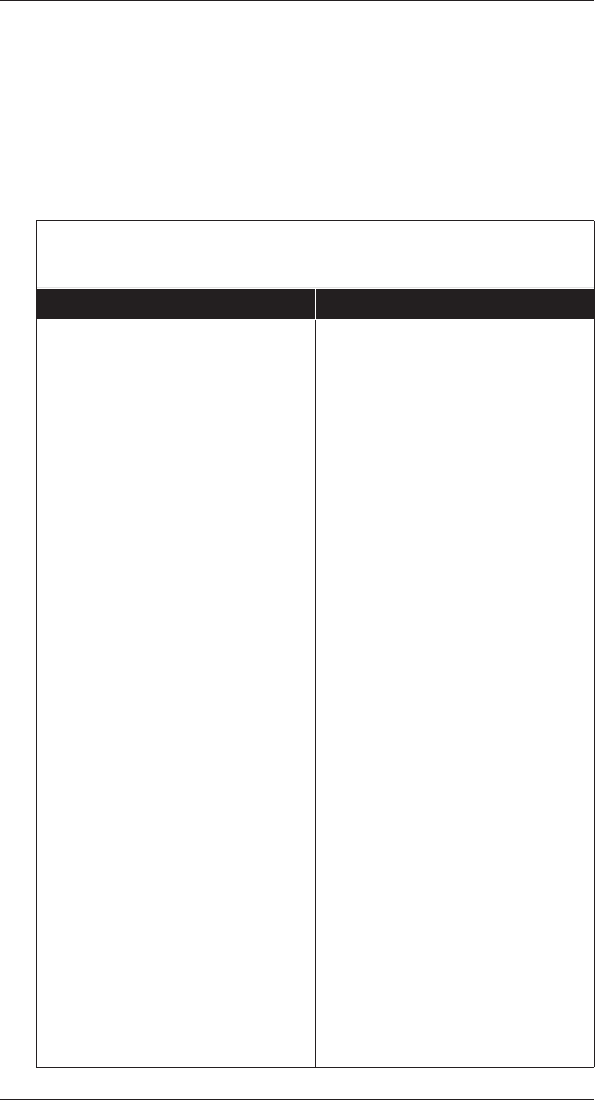

Overcoming Resistance to Change

Peace Corps/South Africa

Areas of Resistance Reasons for Resistance Strategies for Overcoming Resistance

Using cooperative

learning strategies

• Fear of losing control

of class

• No previous experience

as a learner

• Not sure how to organize

learner groups

• Not sure how to give

individual grades for

group activities

• Explain how using cooperative groups can

help the teacher manage the class

• Observe others who can model

cooperative learning activities

• Start with pair work activities

• Use two grades: a group grade (all

members receive identical grades) and an

individual grade (based on an assessment

of a student’s learning)

There is a blank template of this chart at the end of this chapter.

Force Field Analysis is a useful tool in preparing for and working with

resistance to change. Do the force eld analysis with a representative

group of people who would be involved in the change.

1. Propose a change.

2. Brainstorm driving forces, as well as restraining forces in

its implementation.

3. Evaluate both forces in terms of strength. (This is a group

subjective judgment.)

4. Develop strategies to remove or decrease restraining forces,

starting with the easily changed ones.

5. Develop strategies to strengthen driving forces, striving for

win/win solutions.

6. Translate these strategies into action plans: Why? What? When?

Where? How?

7. Develop a plan to evaluate the eectiveness of your action

plan, once implemented.

Teaching in a Cross-Cultural Context

Classroom Management | IDEA BOOK

38 Peace Corps

Force Field Analysis Example

Proposed change: Incorporate student-centered learning into classroom instruction

Favoring (driving) forces Restraining (opposing) forces

Students learn to take responsibility

for their own learning and thus gain

the skills to become lifelong learners.

It is the teacher’s job to

make students learn.

Through experiential and discovery

learning students acquire

problem-solving skills as they learn.

Experiential and discovery lessons take students

longer; they will not be able to cover all the

required material during the school year.

Students are actively involved

in learning; consequently,

more learning takes place.

Only the bright students will learn. Slower

students will not be able to gure out what they

are supposed to learn and become frustrated.

Student-centered learning allows students

more exibility in adapting their learning

methods to t their individual learning styles

Playing games and group activities

seem like play; students will not take

schoolwork seriously.

When students enjoy the learning

process they are less likely to misbehave.

Teachers will lose face if they are

not the purveyors of knowledge.

Students acquire planning and

decision-making skills as they

participate in student-centered learning.

The national syllabus prescribes what

students must learn. Students might not

choose to learn what is listed in the syllabus.

Students tend to help each

other and learn to work together.

Our school does not have the materials needed

to implement student-centered activities.

Student-centered learning puts the

focus on the student and learning.

Teachers have not been taught how to

teach and use student-centered methods.

Student-centered learning better accommodates

students who are at dierent levels of understanding.

Assigning grades is more dicult when

all students are not doing the same thing.

There is a blank template of this chart at the end of this chapter.

Change is possible

Although change is sometime slow and dicult, it is possible. Some

Volunteers found that with the support of their host countries’

ministry of education, change was welcomed and encouraged.

In the Dominican Republic and in Kiribati, ministries of education

are actively supporting new and innovative teaching techniques

in their schools. Volunteers in the Dominican Republic work with

teachers to implement Quantum Learning techniques—the use

Peace Corps 39

of neurocognitive strategies to maximize memory retention by

capturing students’ interest and attention, sharing a common

experience, and linking new learning with prior knowledge.

Volunteers in Kiribati model “learner centered” activities. A student

(or learner)-centered approach empowers students (learners)

to take responsibility for their own learning. Teachers facilitate

learning by developing activities and materials relevant to the

students’ needs and interests. This kind of support is especially

important in cultures where authority is highly regarded.

Examples and Tools

Sample Overcoming Resistance to Change Chart

Use this template to reveal areas of resistance and determine

strategies for overcoming the resistance.

Overcoming Resistance to Change