A guide to detecting cognitive impairment during the Medicare

Annual Wellness Visit

COGNITIVE

ASSESSMENT TOOLKIT

800.272.3900

|

alz.org®

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Overview 3

Medicare Annual Wellness Visit Algorithm for

Assessment of Cognition 4

General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) 5

Mini-Cog™ © 8

Short Form of the Informant Questionnaire on

Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (Short IQCODE) 10

Eight-Item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging

and Dementia (AD8) 12

Alzheimer’s Association Recommendations for Operationalizing

the Detection of Cognitive Impairment During the

Medical Annual Wellness Visit in a Primary Care Setting 15

800.272.3900

|

alz.org®

The Alzheimer’s Association®, the leading voluntary health organization in Alzheimer’s care, support and research, is

dedicated to driving early detection and diagnosis of dementia. To help, the Association has created an easy-to-implement

process to assess cognition during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit. Developed by a group of clinical dementia experts,

the recommended process outlined on Page 4 allows you to efficiently identify patients with probable cognitive impairment

while giving you the flexibility to choose a cognitive assessment tool that works best for you and your patients.

This Cognitive Assessment Toolkit contains:

• The Medicare Annual Wellness Visit Algorithm for Assessment of Cognition, incorporating patient history,

clinician observations, and concerns expressed by the patient, family or caregiver

• Two validated patient assessment tools: the General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) and

the Mini-Cog™©. Both tools:

› Can be administered in five minutes or less

› Are equal or superior to the Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE) for detecting dementia

› Are easily administered by medical staff who are not physicians

› Are relatively free from educational, language and/or cultural bias

• Three validated informant assessment of patient tools: the Short Form of the Informant Questionnaire

on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (Short IQCODE), the Eight-Item Informant Interview to Differentiate

Aging and Dementia (AD8) and the GPCOG

• The “Alzheimer’s Association Recommendations for Operationalizing the Detection of Cognitive Impairment

During the Medical Annual Wellness Visit in a Primary Care Setting,” as published in Alzheimer’s & Dementia®:

The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association

For more information on the detection, diagnosis and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease, as well as direct access to patient

and caregiver resources, please visit our Health Systems and Clinicians Center at alz.org/hcps.

1. 3

3

Overview

800.272.3900

|

alz.org®

4

Alzheimer’s Association®

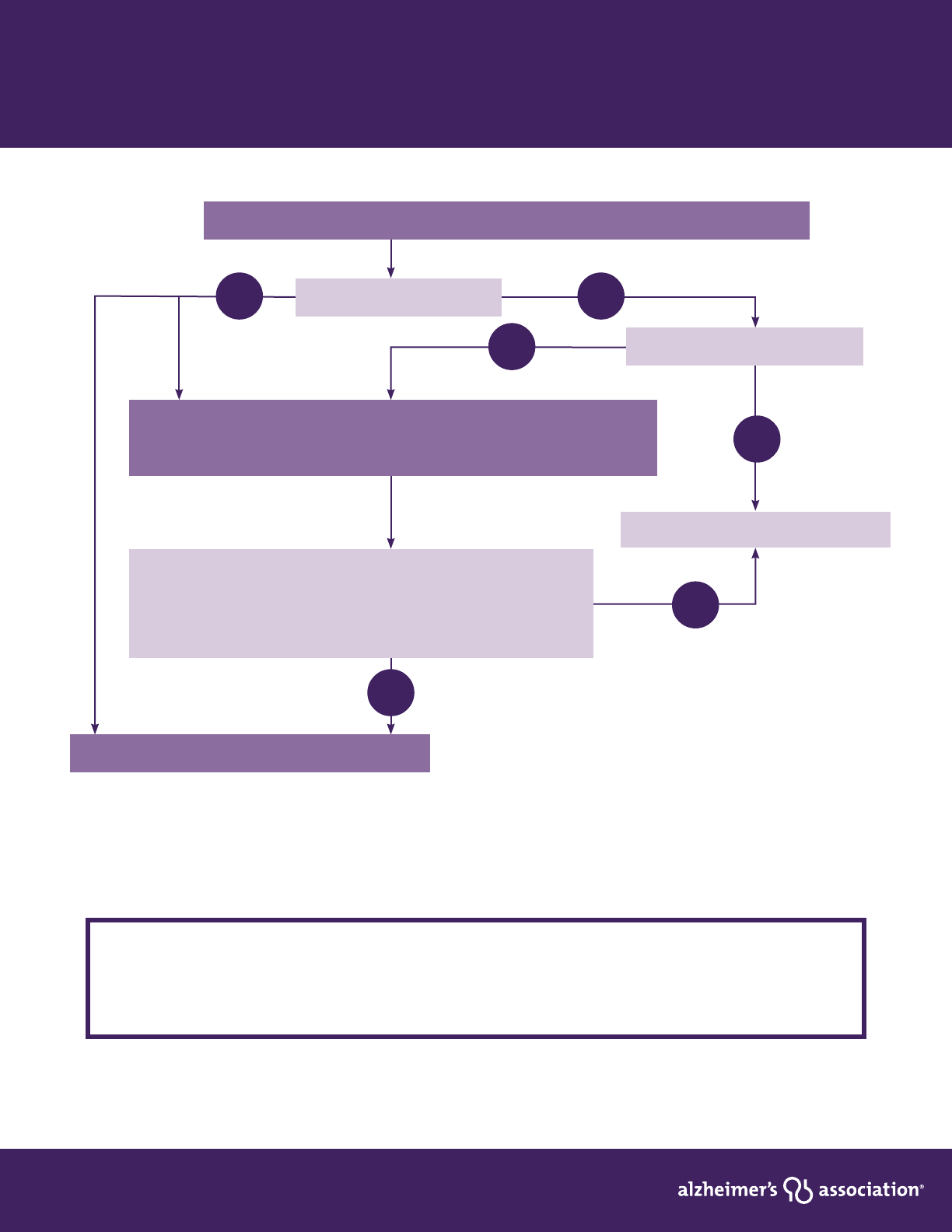

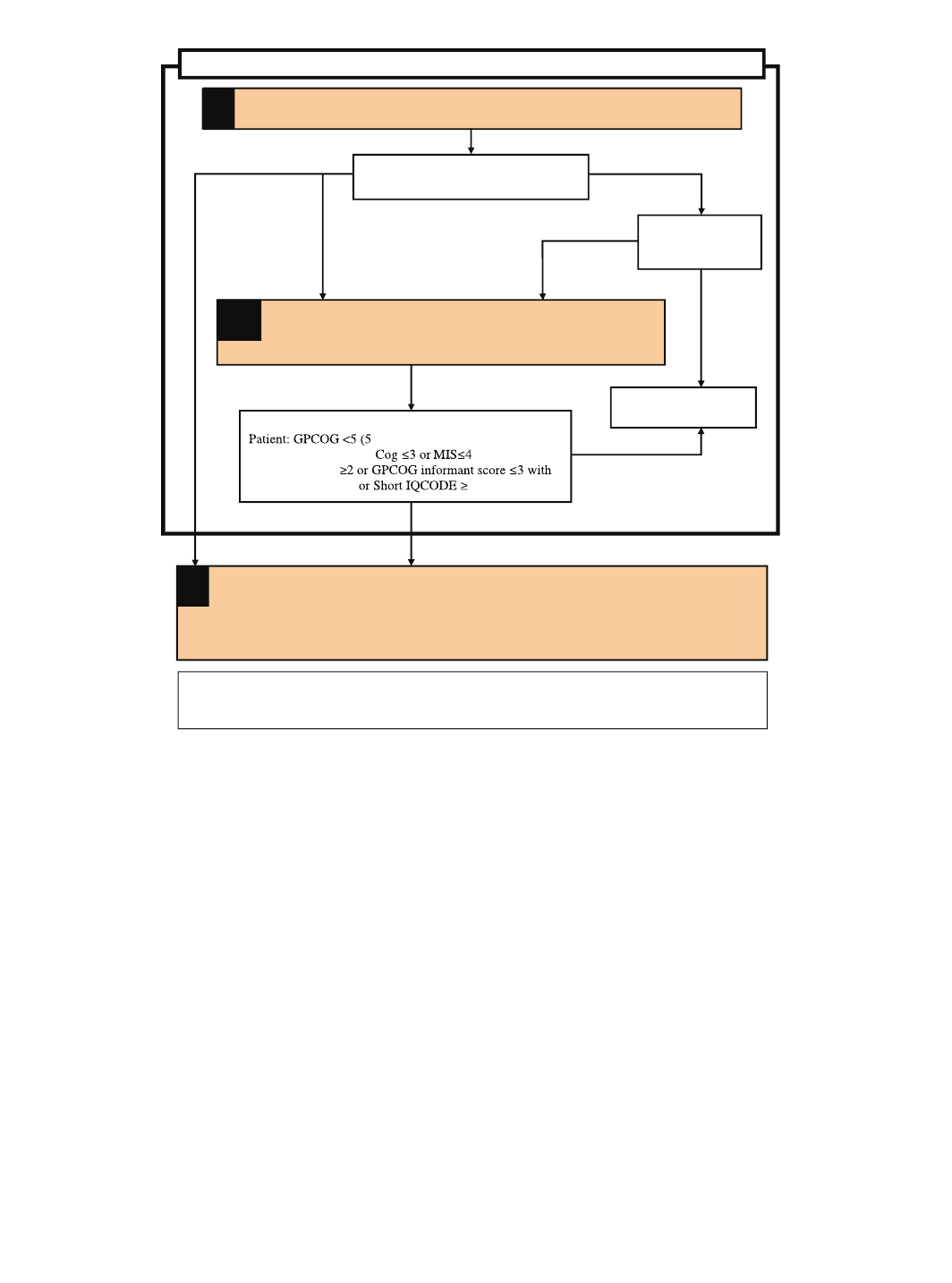

Medicare Annual Wellness Visit Algorithm for Assessment of Cognition

Cordell CB, Borson S, Boustani M, Chodosh J, Reuben D, Verghese J, et al. Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing

the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual Wellness Visit in a primary care setting. Alzheimers Dement. 2013;9(2):141-150.

Available at https://alz-journals.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/journal/15525279

1. 4

YES

YES

YES

NO

NO

NO

C. Refer OR conduct full dementia evaluation

A. Review HRA, clinician observation, self-reported concerns, responses to queries

B.* Conduct brief structured assessment

• Patient assessment: Mini-Cog or GPCOG

• Informant assessment of patient: Short IQCODE, AD8 or GPCOG

Signs/symptoms present

Informant available to confirm

Follow-up during subsequent AWV

Brief assesment(s) triggers concerns: Patient: Mini-Cog ≤3

or GPCOG <5 (5-8 score is indeterminate without informant)

or Informant: Short IQCODE ≥ 3.38 or AD8 ≥ 2 or GPCOG

informant score ≤3 with patient score <8

* No one tool is recognized as the best brief assessment to determine if a full dementia

evaluation is needed. Some providers repeat patient assessment with an alternate tool

(e.g., SLUMS, or MoCA) to confirm initial findings before referral or initiation of full

dementia evaluation.

AD8 = Eight-Item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia; AWV = Annual Wellness

Visit; GPCOG = General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition; HRA = Health Risk Assessment;

MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SLUMS = St. Louis University Mental Status Exam;

Short IQCODE = Short Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly

1. 5

5

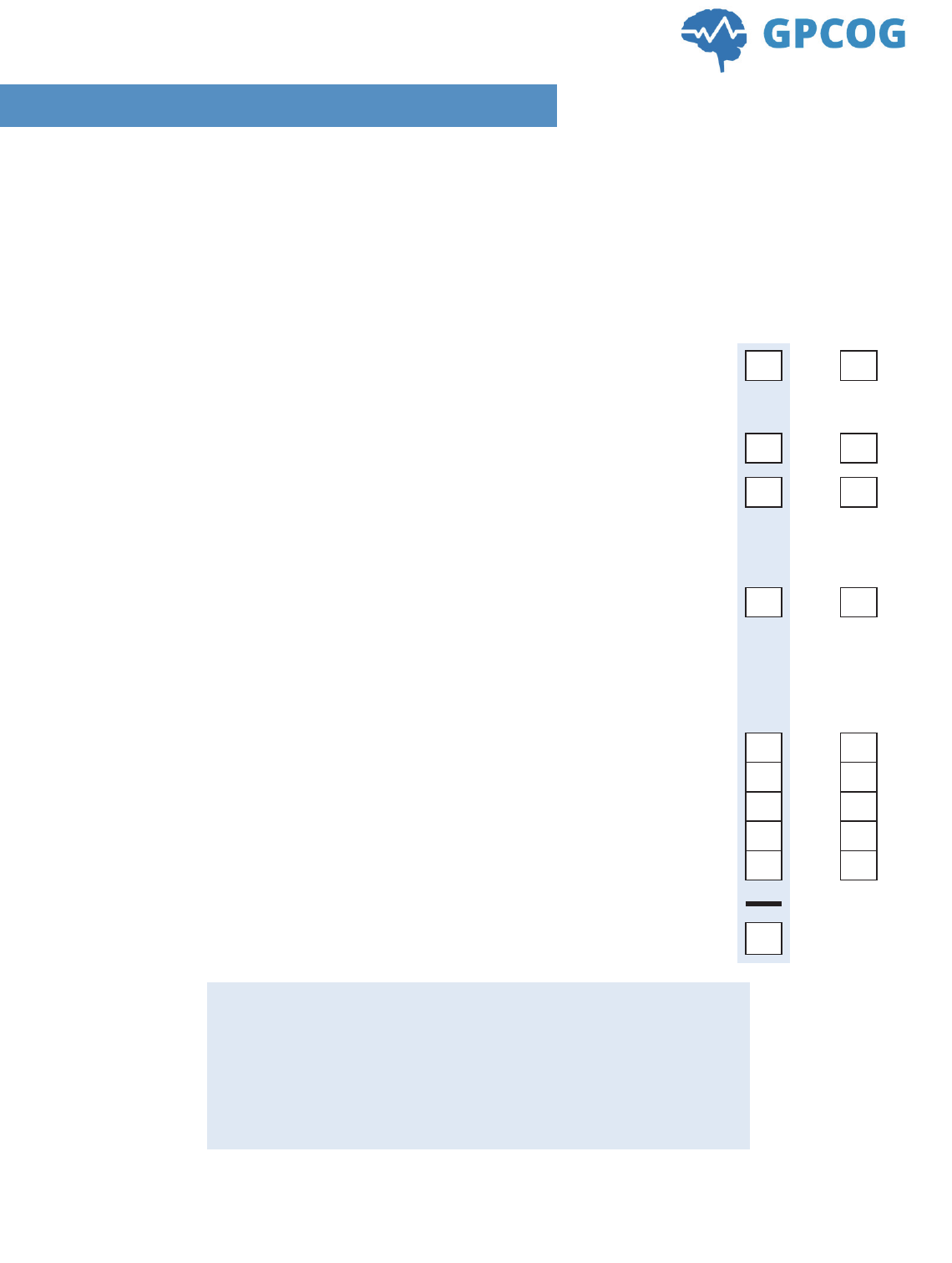

GENERAL PRACTITIONER ASSESSMENT

OF COGNITION (GPCOG)

A web-based GPCOG and downloadable paper-and-pencil versions of the

GPCOG (in many languages) are available at gpcog.com.au. Both ask the

same questions, the only difference being the web-based GPCOG

automatically scores the test.

Preparation & Training

Before you administer GPCOG for the rst time, please review the following:

1. Make sure you have read the instructions (on the rst page of the test)

2. Watch the training video (approx. 5 minutes)

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=If7nv2_B89M

Patient name: _________________________

Testing date: _________________________

© University of New South Wales as represented by the Dementia Collaborative Research Centre – Assessment and Better Care;

Brodaty et al, JAGS 2002; 50:530-534

STEP 1 – PATIENT EXAMINATION

Unless specified, each question should only be asked once.

Name and address for subsequent recall test

I am going to give you a name and address. After I have said it, I want you to repeat it.

Remember this name and address because I am going to ask you to tell it to me again in a

few minutes: John Brown, 42 West Street, Kensington. (Allow a maximum of 4 attempts.)

Time orientation Correct Incorrect

1. What is the date? (exact only)

Clock drawing (use blank page)

2. Please mark in all the numbers to indicate

the hours of a clock. (correct spacing required)

3. Please mark in hands to show 10 minutes past

eleven o’clock. (11.10)

Information

4. Can you tell me something that happened in the news recently?

(Recently = in the last week. If a general answer is given, e.g.

“war”, “lot of rain”, ask for details. Only specific answer scores.)

Recall

5. What was the name and address I asked you to remember?

John

Brown

42

West (St)

Kensington

Add the number of items answered correctly: Total score: out of 9

9

No significant cognitive impairment

Further testing is not necessary

5 – 8

More information required

Proceed with informant interview in step 2 on next page

0 – 4

Cognitive impairment is indicated

Conduct standard investigations

/

9

1. 6

Patient name: _________________________

Testing date: _________________________

© University of New South Wales as represented by the Dementia Collaborative Research Centre – Assessment and Better Care;

Brodaty et al, JAGS 2002; 50:530-534

STEP 1 – PATIENT EXAMINATION

Unless specified, each question should only be asked once.

Name and address for subsequent recall test

I am going to give you a name and address. After I have said it, I want you to repeat it.

Remember this name and address because I am going to ask you to tell it to me again in a

few minutes: John Brown, 42 West Street, Kensington. (Allow a maximum of 4 attempts.)

Time orientation Correct Incorrect

1. What is the date? (exact only)

Clock drawing (use blank page)

2. Please mark in all the numbers to indicate

the hours of a clock. (correct spacing required)

3. Please mark in hands to show 10 minutes past

eleven o’clock. (11.10)

Information

4. Can you tell me something that happened in the news recently?

(Recently = in the last week. If a general answer is given, e.g.

“war”, “lot of rain”, ask for details. Only specific answer scores.)

Recall

5. What was the name and address I asked you to remember?

John

Brown

42

West (St)

Kensington

Add the number of items answered correctly: Total score: out of 9

9

No significant cognitive impairment

Further testing is not necessary

5 – 8

More information required

Proceed with informant interview in step 2 on next page

0 – 4

Cognitive impairment is indicated

Conduct standard investigations

/

9

6

1. 7

Patient name: _________________________

Testing date: _________________________

© University of New South Wales as represented by the Dementia Collaborative Research Centre – Assessment and Better Care;

Brodaty et al, JAGS 2002; 50:530-534

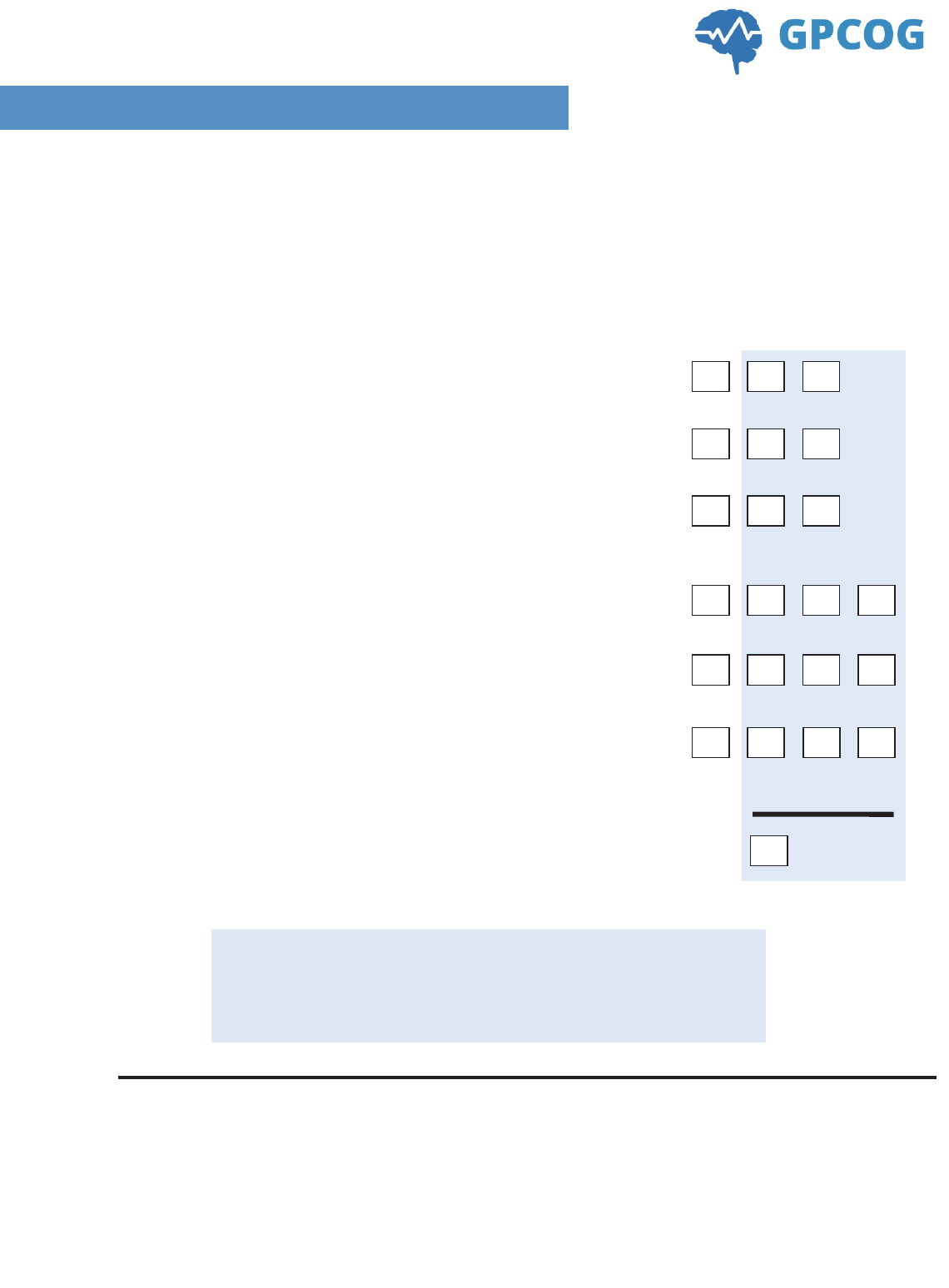

STEP 2: INFORMANT INTERVIEW

Informant name: _______________________

Relationship to patient, i.e. informant is the patient’s: _________________________

Ask the informant:

Compared to 5–10 years ago,

1. Does the patient have more trouble remembering things

that have happened recently than s/he used to?

2. Does s/he have more trouble recalling conversations

a few days later?

3. When speaking, does s/he have more difficulty in

finding the right word or tend to use the wrong words

more often?

4. Is s/he less able to manage money and financial

affairs (e.g. paying bills and budgeting)?

5. Is s/he less able to manage his or her medication

independently?

6. Does s/he need more assistance with transport

(either private or public)?

(If the patient has difficulties only due to physical

problems, e.g. bad leg, tick ‘no’.)

Add the number of items answered Total score: out of 6

with ‘NO’, ‘Don’t know’ or ‘N/A’:

4 – 6

No significant cognitive impairment

Further testing is not necessary

0 – 3

Cognitive impairment is indicated

Conduct standard investigations

When referring to a specialist, mention the individual scores for the two GPCOG test steps:

STEP 1 Patient examination: __ / 9

STEP 2 Informant interview: __ / 6 or N/A

YES NO

Don’t

know

N/A

7

8

Mini-Cog™

Instructions for Administration & Scoring

Step 1: Three Word Registration

Step 2: Clock Drawing

Step 3: Three Word Recall

Scoring

Look directly at person and say, “Please listen carefully. I am going to say three words that I want you to repeat back

to me now and try to remember. The words are [select a list of words from the versions below]. Please say them for

me now.” If the person is unable to repeat the words after three attempts, move on to Step 2 (clock drawing).

The following and other word lists have been used in one or more clinical studies.

1-3

For repeated administrations,

use of an alternative word list is recommended.

Say: “Next, I want you to draw a clock for me. First, put in all of the numbers where they go.” When that is completed,

say: “Now, set the hands to 10 past 11.”

Use preprinted circle (see next page) for this exercise. Repeat instructions as needed as this is not a memory test.

Move to Step 3 if the clock is not complete within three minutes.

Ask the person to recall the three words you stated in Step 1. Say: “What were the three words I asked you to

remember?” Record the word list version number and the person’s answers below.

Word List Version: _____ Person’s Answers: ___________________ ___________________ ___________________

Version 1

Banana

Sunrise

Chair

Version 4

River

Nation

Finger

Version 2

Leader

Season

Table

Version 5

Captain

Garden

Picture

Version 3

Village

Kitchen

Baby

Version 6

Daughter

Heaven

Mountain

Word Recall: ______ (0-3 points) 1 point for each word spontaneously recalled without cueing.

Clock Draw: ______ (0 or 2 points)

Normal clock = 2 points. A normal clock has all numbers placed in the correct

sequence and approximately correct position (e.g., 12, 3, 6 and 9 are in anchor

positions) with no missing or duplicate numbers. Hands are pointing to the 11

and 2 (11:10). Hand length is not scored.

Inability or refusal to draw a clock (abnormal) = 0 points.

Total Score: ______ (0-5 points)

Total score = Word Recall score + Clock Draw score.

A cut point of <3 on the Mini-Cog™ has been validated for dementia screening,

but many individuals with clinically meaningful cognitive impairment will score

higher. When greater sensitivity is desired, a cut point of <4 is recommended as

it may indicate a need for further evaluation of cognitive status.

Mini-Cog™ © S. Borson. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of the author solely for clinical and educational purposes.

May not be modified or used for commercial, marketing, or research purposes without permission of the author (soob@uw.edu).

v. 01.19.16

ID: ______________ Date: ________________________

9

1. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen PJ et al. The Mini-Cog as a screen for dementia: Validation in a population-based

sample. J Am Geriatr Soc 2003;51:1451–1454.

2. Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J et al. Improving identification of cognitive impairment in primary care. Int J

Geriatr Psychiatry 2006;21: 349–355.

3. Lessig M, Scanlan J et al. Time that tells: Critical clock-drawing errors for dementia screening. Int

Psychogeriatr. 2008 June; 20(3): 459–470.

4. Tsoi K, Chan J et al. Cognitive tests to detect dementia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Intern

Med. 2015; E1-E9.

5. McCarten J, Anderson P et al. Screening for cognitive impairment in an elderly veteran population:

Acceptability and results using different versions of the Mini-Cog. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011; 59: 309-213.

6. McCarten J, Anderson P et al. Finding dementia in primary care: The results of a clinical demonstration

project. J Am Geriatr Soc 2012; 60: 210-217.

7. Scanlan J & Borson S. The Mini-Cog: Receiver operating characteristics with the expert and naive raters. Int J

Geriatr Psychiatry 2001; 16: 216-222.

References

Clock Drawing

ID: ______________ Date: ________________________

Mini-Cog™ © S. Borson. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission of the author solely for clinical and educational purposes.

May not be modified or used for commercial, marketing, or research purposes without permission of the author (soob@uw.edu).

v. 01.19.16

10

Short Form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline

in the Elderly (Short IQCODE)

1

by A. F. Jorm

Centre for Mental Health Research

The Australian National University

Canberra, Australia

There is no copyright on the Short IQCODE. However, the author appreciates

being kept informed of research projects which make use of it.

Note: As used in published studies, the IQCODE was preceded by questions to the

informant on the subject’s sociodemographic characteristics and physical health.

11

Now we want you to remember what your friend or relative was like 10 years ago and to compare it with what he/she is

like now. 10 years ago was in 20__.* Below are situations where this person has to use his/her memory or intelligence and

we want you to indicate whether this has improved, stayed the same or got worse in that situation over the past 10 years.

Note the importance of comparing his/her present performance with 10 years ago. So if 10 years ago this person always

forgot where he/she had left things, and he/she still does, then this would be considered “Hasn’t changed much”. Please

indicate the changes you have observed by circling the appropriate answer.

Compared with 10 years ago how is this person at:

1 2 3 4 5

1. Remembering things about family and friends

e.g. occupations, birthdays, addresses

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

2. Remembering things that have happened

recently

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

3. Recalling conversations a few days later

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

4. Remembering his/her address and telephone

number

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

5. Remembering what day and month it is

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

6. Remembering where things are usually kept

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

7. Remembering where to find things which have

been put in a different place from usual

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

8. Knowing how to work familiar machines

around the house

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

9. Learning to use a new gadget or machine

around the house

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

10. Learning new things in general

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

11. Following a story in a book or on TV

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

12. Making decisions on everyday matters

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

13. Handling money for shopping

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

14. Handling financial matters e.g. the pension,

dealing with the bank

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

15. Handling other everyday arithmetic problems

e.g. knowing how much food to buy, knowing

how long between visits from family or friends

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

16. Using his/her intelligence to understand what’s

going on and to reason things through

Much

improved

A bit

improved

Not much

change

A bit

worse

Much

worse

*The original tool was published in 1994.

The Alzheimer’s Association updated the year 19__ as published in the original tool to 20__ .

Tool Reference: Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the

Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation. Psychol Med 1994; 24: 145–153.

12

AD8®DementiaScreeningInterview

PatientID#:

CSID#:

Date:

Remember,“Yes,achange”indicatesthat

therehasbeenachangeinthelastseveral

yearscausedbycognitive(thinkingand

memory)problems.

YES

,

NO

,

N/A

,

A

change

No

change

Don’

t

kno

w

1. P

r

o

blems

wi

t

h

judgmen

t

(e.g.,

p

r

o

blems

makingdecision s,badfinancial

decisions,problemswiththinking)

2. Less

in

t

e

r

es

t

in

h

o

bbies/ac

t

i

v

i

t

ies

3. Repea

t

s

t

he

same

t

hings

o

v

e

r

and

o

v

e

r

(questions,stories,orstatements)

4. T

r

o

uble

lea

r

ning

h

o

w

t

o

use

a

t

o

o

l,

appliance,orgadget(e.g.,VCR,

computer,microwave , remotecontrol)

5. F

o

r

ge

t

s

c

o

r

r

ec

t

m

o

n

t

h

o

r

yea

r

6. T

r

o

uble

handling

c

o

mplica

t

ed

f

inancial

affairs(e.g.,balancingcheckbook,income

taxes,payingbills)

7. T

r

o

uble

r

emembe

r

ing

app

o

in

t

men

t

s

8. Daily

p

r

o

blems

wi

t

h

t

hinking

and/

o

r

memory

TOTAL

AD8

SCORE

AdaptedfromGalvinJEetal,TheAD8,abriefinformantinterviewtodetectdementia,Neurology2005:65:559‐564.

Copyright©2005 by Washington University in St. Louis, MO.

AllRightsReserved.

13

TheAD8®AdministrationandScoringGuidelines

Aspontaneo usself‐correctionisallowedforallresponseswithoutcountingasanerror.

Thequestionsaregiventotherespondentonaclipboardforself–administrationorcanbe

readaloudtotherespondenteitherinpersonoroverthephone.Itispreferableto

administertheAD8toaninformant,ifavailable.Ifaninformantisnotavailable,theAD8

maybeadministeredtothepatient.

Whenadministeredtoaninformant,specificallyasktherespondenttoratechange

inthepatient.

Whenadministeredtothepatient,specificallyaskthepatienttora techangesinhis/her

abilityforeachoftheitems,withoutattributingcausality.

Ifreadaloudtotherespondent,itisimportantfort hecliniciantocarefullyreadthephrase

aswordedandgiveemphasistonotechangesduetocognitiveproblems(notphysical

problems).Th ereshouldbeaoneseconddelaybetweenindividualitems.

Notimefr ameforchangeisrequire d.

Thefinalscoreisasumof thenumberitemsmarked“Yes,Achange”.

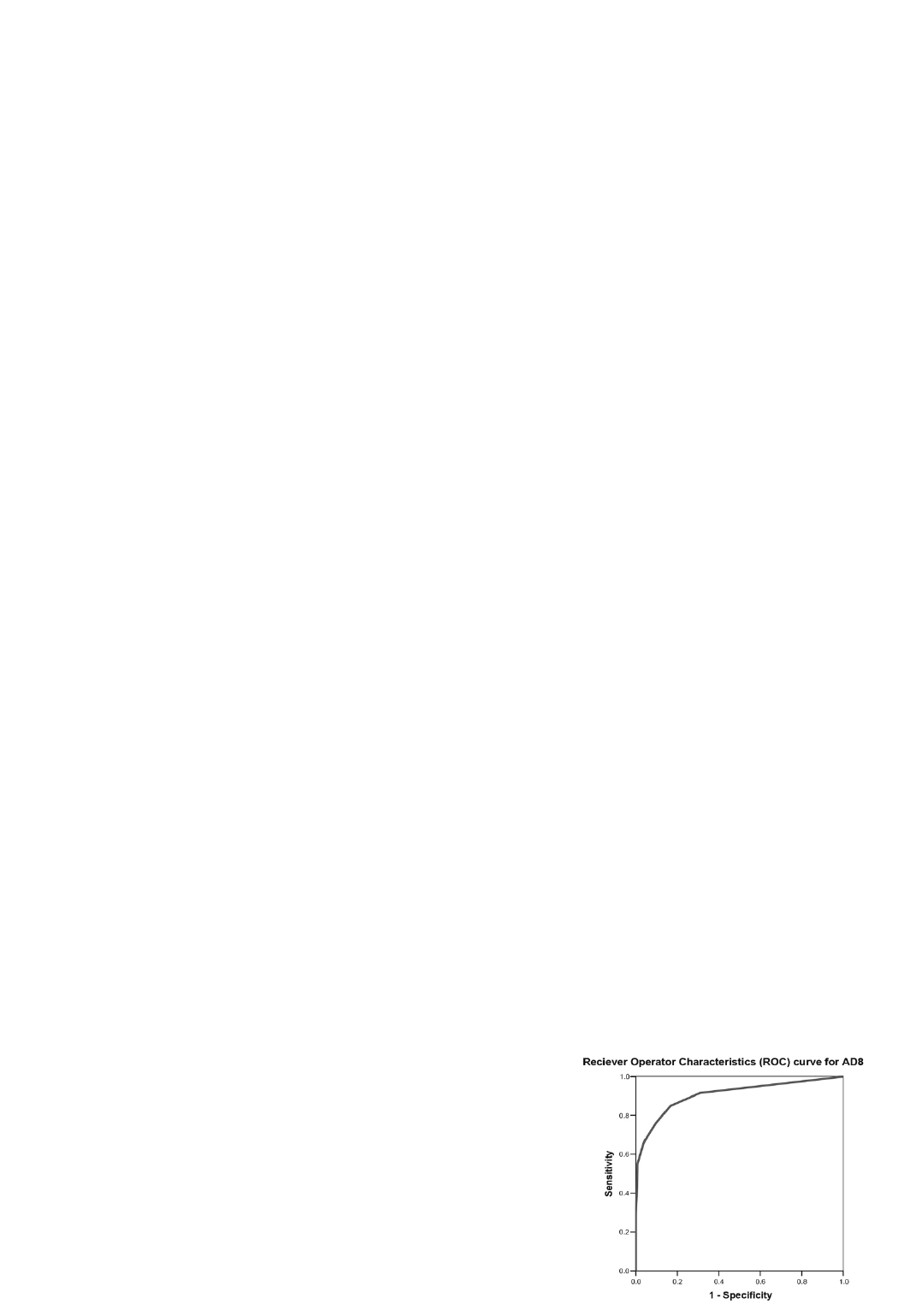

InterpretationoftheAD8

(AdaptedfromGalvinJEetal,TheAD8,abriefinformantinterv iewtodetect

dementia,Neurology2005:65:559‐564)

Ascreeningtestinitselfisinsufficienttodiagnoseadementingdisorder.TheAD8is,

however,quitesensitivetodetectingearlycognitivechan gesassociatedmanycommon

dementingillnessincludingAlzheimerdisease,vasculardementia,Lewybodydementiaand

frontotemporaldementia.

Scoresintheimpairedrange(seebelow)indicateaneedforfurtherassessment.Scoresin

the“normal”rangesuggestthatadementingdisorderisunlikely,butaveryearlydisease

processcannotberuledout.Moreadvancedassessmentmaybewarrantedincaseswhere

otherobjective evidenceofimpairmentexists.

Basedonclinicalresearchfindin gsfrom995individualsincludedinthedevelopment

andvalidation samples,thefollowingcutpointsareprovided:

0–1:Normalcognition

2orgreater:Cognitiveimpairmentislikelyto

bepresent

Administeredtoeithertheinformant(preferable)orthe

patient,theAD8hasthefollowingproperties:

Sensitivity>84%

Specificity>80%

PositivePredictiveValue>85%

NegativePredi ctiveValue>70%

AreaundertheCurve:0.908;95%CI:0.888‐0 .925

Copyright ©2005 Washington University,

St. Louis, Missouri. All Rights Reserved.

14

PermissionStatement

WashingtonUniversitygrantspermissiontouseandreproducetheEight‐itemInformantInterviewto

DifferentiateAgingandDementiaexactlyasitappearsinthePDFavailableherewithoutmodification

oreditingofanykindsolelyforenduseruseininvestigatingdementiainclinicalcareorin non-profit

research(the“Purpose”).Fortheavoidanceofdoubt,thePurposedoesnotincludethe(i) use or

distribution of the Eight-item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia in a clinical trial

sponsored in whole or in part by a commercial entity; (ii)sale,distributionortransferof theEight‐item

InformantInterviewtoDifferentiateAgingandDementiaorcopiesthereofforany c on s id er a ti on or

commercialvalue;(iii)thecreationofanyderivativeworks,includingtranslations;(iv)useoftheEight‐

itemInformantInterviewtoDifferentiateAgingandDementiaasamarketingtoolforthesaleofanydrug;

and/or (v) use of the Eight-item Informant Interview to Differentiate Aging and Dementia with any

electronic medical health records sytem or electronic registry.

AllcopiesoftheAD8®shallincludethefollowingnotice:“Copyright© 2005 Washington University, St.

Louis, Missouri.AllRightsReserved.”Pleasecontact[email protected]for a commercial license, for

permission to make modifications, orfor anyother intendedpurpose.

Copyright ©2005 Washington University,

St. Louis, Missouri. All Rights Reserved.

15

Alzheimer’s Association recommendations for operationalizing

the detection of cognitive impairment during the Medicare Annual

Wellness Visit in a primary care setting

Cyndy B. Cordell

a,

*

, Soo Borson

b,c

, Malaz Boustani

d,e,f

, Joshua Chodosh

g,h

, David Reuben

h

,

Joe Verghese

i

, William Thies

a

, Leslie B. Fried

j,k

; for the Medicare Detection

of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup

a

Alzheimer’s Association, Chicago, IL, USA

b

Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA

c

Memory Disorders Clinic and Dementia Health Services, University of Washington School of Medicine, Seattle, WA, USA

d

Indiana University Center for Aging Research, Indianapolis, IN, USA

e

Regenstrief Institute, Inc., Indianapolis, IN, USA

f

Department of Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN, USA

g

Veterans Administration Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, Los Angeles, CA, USA

h

Division of Geriatrics, David Geffen School of Medicine, University of California Los Angeles, Los Angeles, CA, USA

i

Department of Neurology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY, USA

j

American Bar Association, Washington, DC, USA

k

Alzheimer’s Association Medicare Advocacy Project, Washington, DC, USA

Abstract The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act added a new Medicare benefit, the Annual

Wellness Visit (AWV), effective January 1, 2011. The AWV requires an assessment to detect cog-

nitive impairment. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) elected not to recom-

mend a specific assessment tool because there is no single, universally accepted screen that

satisfies all needs in the detection of cognitive impairment. To provide primary care physicians

with guidance on cognitive assessment during the AWV, and when referral or further testing is

needed, the Alzheimer’s Association convened a group of experts to develop recommendations.

The resulting Alzheimer’s Association Medicare Annual Wellness Visit Algorithm for Assessment

of Cognition includes review of patient Health Risk Assessment (HRA) information, patient ob-

servation, unstructured queries during the AWV, and use of structured cognitive assessment tools

for both patients and informants. Widespread implementation of this algorithm could be the first

step in reducing the prevalence of missed or delayed dementia diagnosis, thus allowing for better

healthcare management and more favorable outcomes for affected patients and their families and

caregivers.

2013 The Alzheimer’s Association. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Annual Wellness Visit; AWV; Cognitive impairment; Assessment; Screen; Dementia; Alzheimer’s disease;

Medicare; Algorithm; Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act

1. Introduction

The Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010

added a new Medicare benefit , the Annual Wellness Visit

(AWV), effective January 1, 2011. The AWV includes

routine measurements such as height, weight, and blood

pressure; a review of medical and family history; an assess-

ment to detect cognitive impairment; and establishment of

a list of current medical providers, medications, and sched -

ule for future preventive services. In addition, during the first

AWVonly, beneficiaries are to be screened for depression (if

*Corresponding author. Tel.: 312-335-5867. Fax: 866-699-1246.

1552-5260/$ - see front matter 2013 The Alzheimer’s Association. All rights reserved.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jalz.2012.09.011

Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

16

not completed under a separate Medicare benefit) and for

functional difficulties using nationally recognized appropri-

ate screening questions or standardized questionnaires. Al-

though the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)

in 2003 concluded that there was insufficient published evi-

dence of better clinical outcomes as a result of routine

screening for cognitive impairment in older adults, the

Task Force recognized that the use of cognitive assessment

tools can increase the detection of cognitive impairment

[1]. As per the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services

(CMS) regulation, the AWV requires detection of cognitive

impairment by “. assessment of an individual’s cognitive

function by direct observation, with due consideration of in-

formation obtained by way of patient report, concerns raised

by family members, friends, caretakers, or others” [2]. Dur-

ing the public comment period, several organizations, in-

cluding the Alzheimer’s Association, noted that the use of

a standardized tool for assessment of cognitive function

should be part of the AWV.

These comments are supported by a number of studies

showing that cognitive impairment is unrecognized in

27%–81% of affected patients in primary care [3–7]. The

use of a brief, structured cognitive assessment tool

correctly classifies patients with dementia or mild

cognitive impairment (MCI) more often than spontaneous

detection by the patients’ own primary care physicians

(83% vs 59%, respectively) [8].

In response to concerns submitted during public comment,

CMS elected not to recommend a specific tool for the final

AWV benefit because “There is no nationally recognized

screening tool for the detection of cognitive impairments at

the present time.” [9]. However, CMS recognizes that with-

out clarification, the full intended benefits of the AWV cogni-

tive assessment may not be realized [10]. CMS is working

with other governmental agencies (e.g., National Institutes

on Aging) on recommendations for use of specific tools.

Understanding that, under the present regulation, each

healthcare provider who conducts an AWV would have to

determine how best to “detect cognitive impairment,” the

Alzheimer’s Association convened the Medicare Detection

of Cognitive Impairment Workgroup to develop recommen-

dations for operationalizing the cognitive assessment com-

ponent in primary care settings. This workgroup was

comprised o f geographically dispersed USA experts with

published works in the field of detecting cognitive impair-

ment during primary care visits. The focus on primary care

was deliberate, as most Medicare beneficiaries will receive

their AWV in this setting.

2. Guiding principles for recommendations

2.1. Consensus on general principles

Based on their expertise, the workgroup agreed on the fol-

lowing general principles to guide the development of rec-

ommendations for cognitive assessment:

Detection of cognitive impairment is a stepwise, itera -

tive process.

Informal observation alone by a physician is not suffi-

cient (i.e., observation without a specific cognitive

evaluation).

Detection of cognitive impairment can be enhanced by

specifically asking about changes in memory, lan-

guage, and the ability to complete routine tasks.

Although no single tool is recognized as the “gold stan-

dard” for detection of cognitive impairment, an initial

structured assessment should provide either a baseline

for cognitive surveillance or a trigger for further eval-

uation.

Clinical staff can offer valuable observations of cogni-

tive and functional changes in patients who are seen

over time.

Counseling before and after cognitive assessment is an

essential component of any cognitive evaluation.

Informants (family member, caregiver, etc.) can pro-

vide valuable information about the presence of

a change in cognition.

2.2. Principles specific to the AWV

The AWV requires the completion of a Health Risk As-

sessment (HRA) by the patient either before or during

the visit. The HRA should be reviewed for any reported

signs and symptoms indicative of possible dementia.

The AWV will likely occur in a primary care setting.

Tools for initial cognitive assessments should be brief

(,5 min), appropriately validated, easily administered

by non-physician clinical staff, and available free of

charge for use in a clinical setting.

If further evaluation is indicated based on the results of

the AWV, a more detailed evaluation of cognition

should be scheduled for a follow-up visit in primary

care or through referral to a specialist.

3. Review of available brief tools for use during the AWV

3.1. Workgroup review process

Although there is no single cognition assessment tool that

is considered to be the gold standard, there is a plethora of

tools in the literature. A MEDLINE (PubMed) search con-

ducted in October 2011, using the key words “screening or

detection of dementia or cognitive impairment,” yielded

over 500 publications. To narrow the search to tools more

applicable to the AWV, the workgroup sought to determine

whether the literature offered a consensus regarding brief

cognitive assessment during time-limited primary care visits.

The workgroup focused on systematic evidence review

(SER) studies publishe d since 2000 resulting in four studies

by Lorentz et al, Brodaty et al, Holsinger et al, and Milne et al

[11–14]. Although each SER had a similar objective—to

determine which tools were best for administration during

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

17

primary care visits—different comparison criteria to select

the tools were applied (Table 1 ). Two other studies were

also considered relevant to the development of the work-

group recommendations: Ismail et al [15] conducted a litera-

ture review designed to identify widely used and most

promising newer brief cognitive tools being used in primary

care and geriatrics, and an SER by Kansagara and Freeman

[16] of six brief cognitive assessment tools that could serve

as possible alternatives to the Mini-Mental State Examina-

tion (MMSE) for use by the U.S. Department of Veterans

Affairs (VA). Neither study was designed to determine which

brief tool is the “best,” but both provided evidence related to

primary care use and performance characteristics of brief

assessments of cognition (Table 1).

3.2. Workgroup review results

Of the five publications that focused specifically on

identifying brief cognitive assess ments most suitable or

most us ed in primary care settings [11–15], all selected

the Memory Impairment Screen (MIS), and four of these

publications [11,12 ,14,15] also selected the General

Practitioner Assessment of Cognition (GPCOG) and the

Mini-Cog (Table 2).

The following attributes of the GPCOG, Mini-Cog, and

the MIS contributed to their selection as most suited for rou-

tine use in primary care:

Requires 5 minutes or less to administer.

Is validated in a primary care or community setting.

Is easily administered by medical staff members who

are not physicians.

Has good to excellent psychometric properties.

Is relatively free from educational, language, and/or

culture bias.

Can be used by clinicians in a clinical setting without

payment for copyrights.

Charging a fee for clini cal use of brief cognitive assess-

ment tool has become an issue because of increas ed enforce-

ment of the MMSE copyright. First published in 1975 [17],

the MMSE copyright is now held by Psychological Assess-

ment Resources, Inc., which charges a fee for each use (for

exact fees see www.parinc.com). The comparative SER

within the VA [16] evaluated alternatives to the proprietary

MMSE, including the GPCOG and the Mini-Cog, along

with four other brief tools (Table 2). The Mini-Cog and

MIS are copyrighted, but the owners, Soo Borson, MD,

and Albert Einstein College of Medicine, respectively, allow

free use by clinicians as clinical tools with distribution re-

strictions for other entities (e.g., commercial companies).

The GPCOG has similar use rules.

3.3. Patient structured cognitive assessment tools

recommended for AWV

In alignment with the workgroup’s guiding principles

and supported by data in the six selected SERs/reviews,

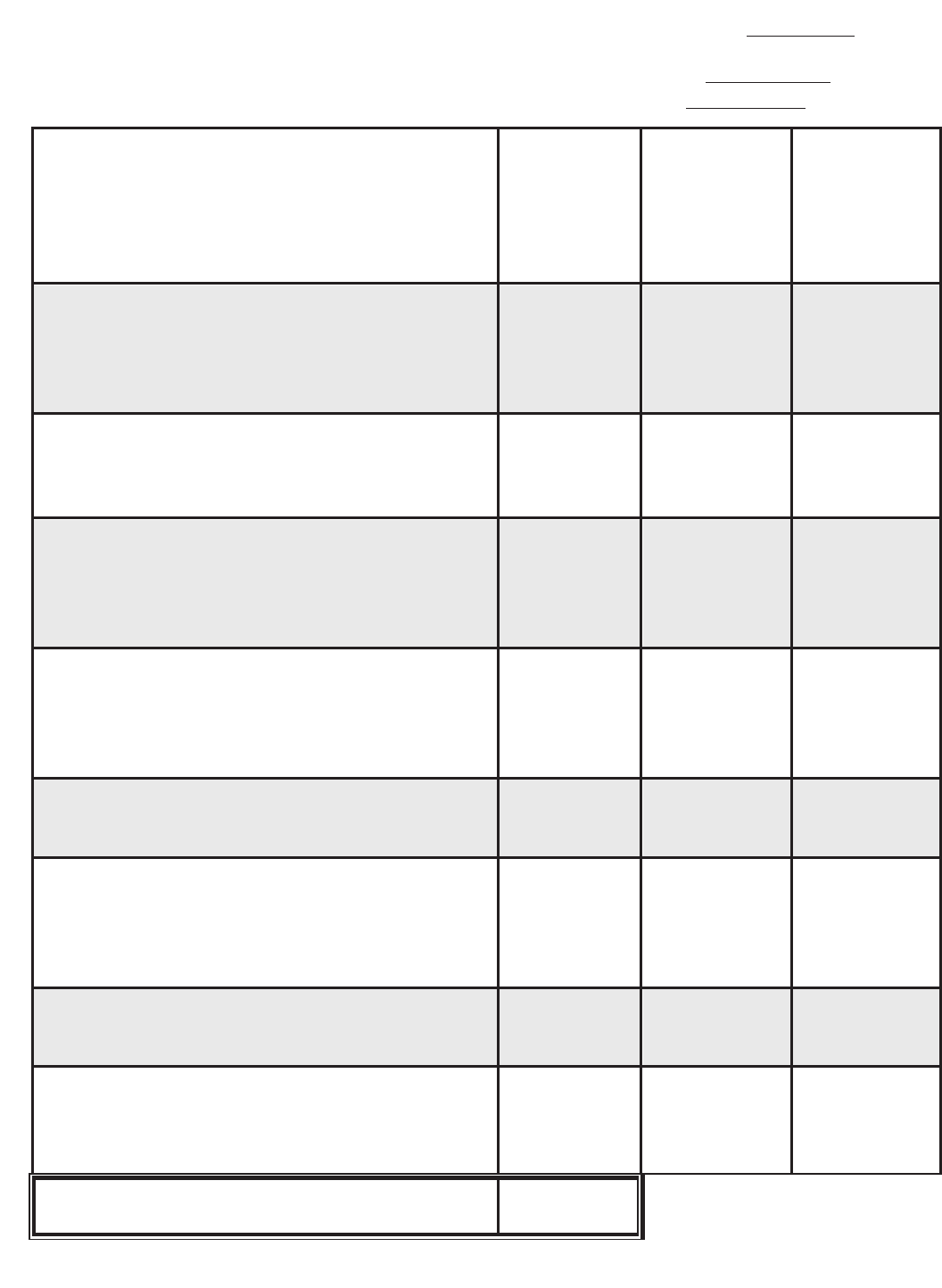

Table 1

Review articles of brief cognitive assessment tools—select inclusion and comparison criteria

Lorentz et al, 2002 [11] Brodaty et al, 2006 [12] Holsinger et al, 2007 [13] Milne et al, 2008 [14] Ismail et al, 2010 [15] Kansagara and Freeman, 2010 [16]

Inclusion

criteria

Admin 10 min

Performance characteristics

evaluated in 1 community

or clinical setting

Admin 5 min and simple

Validated in community or PC

Misclassification rate

MMSE

NPV MMSE

Studied in patients

60 years

Criterion to diagnose

dementia acceptable

Admin time suitable for

PC in UK

Geriatric PC screens for

cognitive change

Tools most frequently

used in PC

Tools recommended or

newly used in PC

Tools identified by the VA as

alternatives to the MMSE

Comparison

criteria

Face validity, sensitivity, and

specificity

Sociodemographic biases

Comparison with MMSE

Acceptability

Ease of use by nonspecialists

Study validity

Applicability to PC

Psychometric properties

Administration characteristics

Admin time

Study quality

Likelihood ratios

Domains tested

Utility in special

situations

Practicality

Feasibility

Applicability

Psychometric proper-

ties

Summ

ary of other

studies and strength/

weaknesses of tools

Newer tools that ad-

dress weaknesses

Relevance of study to the VA

setting

Admin time

Sensitivity

Specificity

Cost

Abbreviations: MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; NPV, negative predictive value; PC, primary care; UK, United Kingdom; VA, US Department of Vet eran Affairs.

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

18

the GPCOG, Mini-Cog, and MIS are brief structured

tools that are suitable for assessment of cognitive func-

tion during the AWV. Each tool has unique benefits.

The GPCOG has patient and informant components

that can be used alone or together to increase specificity

and sensitivity [18]. The Mini-Cog has been validated in

population-based studies and in community-dwelling

older adults heterogeneous with respect to language, cul-

ture, and education [19–22]. The MIS i s a verbally

administered word-recall task that tests encoding as

well as retrieval [23], and is an option for patients who

have motor impairments that prevent use of paper and

pencil.

3.4. Structured cognitive assessment tools for use with

informants

Cognitive assessment combined with informant-

reported data improves t he accuracy of assessment

[24–27]. If an informant is present during the AWV,

use of a structured informant tool is recommended.

Similar to cognitive assessment tools for use with

patients, there is no single “gold standard” informant

tool; however, relatively few brief informant tools

have been validated in community and/or primary care

settings. Brief tools appropriately validated include the

Short IQCODE [25], the AD8 [28], which can be ad-

ministered in-person o r by telephone, and the aforemen-

tioned GPCOG [18], which has both patient and

informant components.

4. Recommended algorithm for detection of cognitive

impairment during the AWV

4.1. Incorporating assessment of cognition during the

AWV

The Alzheimer’s Association Medicare Annual Wellness

Visit Algorithm for Assessment of Cognition for consistency

(Figure 1) illustrates a stepwise process. The process is in-

tended to detect patients with a high likelihood of having de-

mentia. The AWV algorithm includes both structured

assessments discussed previously and other less structured

patient- and informant-based evaluations. By assessing and

documenting cognitive status on an annual basis during the

AWV, clinicians can more easily determine gradual cogni-

tive decline over time in an individual patient—a key crite-

rion for diagnosing dementia due to Alzheimer’s disease and

other progressive conditions affecting cognition.

For patients with a previous diagnosis of MCI or demen-

tia, this should be documented and included in their AWV

list of health risk factors. Annual unstructured and structured

cognitive assessments could be used to monitor significant

changes in cognition and potentially lead to a new diagnosis

of dementia for those with MCI or new care recommenda-

tions for those with dementia.

4.2. Detection of cognitive impairment during the AWV—

initial HRA review, conversations, and obser vations

The first step in detection of cognitive impairment during

the AWV (Fig. 1, Step A), involves a conversation between

Table 2

Brief cognitive assessment tools evaluated in multiple review articles

Assessment Tool

Lorentz et al,

2002 [11]

Brodaty et al,

2006 [12]

Holsinger et al,

2007 [13]

Milne et al,

2008 [14]

Ismail et al,

2010 [15]

Kansagara and

Freeman, 2010* [16]

7-Minute Screener X X X X

AMT X X X X

CAMCOG X Suited

y

CDT X X Suited

z

XX

GPCOG Most suited Most suited X Most suited Most suited X

Mini-Cog Most suited Most suited X Most suited Most suited X

MIS Most suited Most suited Suited

z

Most suited Most suited

MMSE X X Suited

x

XX

MoCA Suited

y

XX

RUDAS X X

SAS-SI X X X

SBT (BOMC, 6-CIT) X X X X X

SPMSQ X X

STMS X X X X

T&C X X

Abbreviations: 6-CIT, 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test; AMT, Abbreviated Mental Test; BOMC, 6-item Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test;

CAMCOG, Cambridge Cognitive Examination; CDT, Clock Drawing Test; GPCOG, General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition; MIS, Memory Impairment

Screen; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; RUDAS, Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment; SAS-SI, Short

and Sweet Screening Instrument; SBT, Short Blessed Test; SLUMS, St Louis Mental Status; SPMSQ, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire; STMS, Short

Test of Mental Status; T&C, Time and Change Test.

X 5 assessment reviewed, but not identified as most suited for general use in primary care.

Suited 5 tool appropriate for the following clinical issue: y available time is not limited; z available time is limited; and x cognitive impairment is at least

moderate. Most suited 5 tool identified as most suited for routine use in primary care.

*Kansagara and Freeman evaluated six tools, including the SLUMS, which was not evaluated in any other review.

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

19

a clinician and the patient and, if present, any family member

or other person who can provide collateral information. This

introduces the purpose and content of the AWV, which in-

cludes: a review of the HRA; observations by clinicians

(medical and associated staff); acknowledgment of any self-

reported or informant-reported concerns; and conversational

queries about cognition directed toward the patient and others

present. If any concerns are noted, or if an informant is not

present to provide confirmatory information, further evalua-

tion of cognition with a structured tool should be performed.

Patient completion of an HRA is a required element of the

AWVand can be accomplished with the help of a family mem-

ber or other knowledgeable informants, including a profes-

sional caregiver. Published CMS guidance offers healthcare

professionals flexibility as to the specific format, questions,

and delivery methods that can be used for an AWV HRA

[29]. The following questions may be suitable for the AWV

HRA and have been tested and evaluated in the general popu-

lation through the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System

or presented as HRA example questions:

1. During the past 12 months, have you experienced con-

fusion or memory loss that is happening more often or

is getting worse [30]?

2. During the past 7 days, did you need help with others

to perform everyday activities such as eating, getting

dressed, grooming, bathing, walking, or using the toi-

let [29]?

3. During the past 7 days, did you need help from others

to take care of things such as laundry and housekeep-

ing, banking, shopping, using the telephone, food

preparation, transportation, or taking your own medi-

cations [29]?

A noted deficit in activities of daily living (ADLs) (e.g.,

eating and dressing) or instrumental activities of daily living

(IADLs) (e.g., shopping and cooking) that cannot be

Conduct brief structured assessment

Patient Assessment: GPCOG or Mini-Cog or MIS

Informant assessment of patient: AD8 or GPCOG or Short IQCODE

Refer for full dementia evaluation or

Conduct full dementia evaluation

If informant is

available during AWV can follow- up same day as AWV and bill for E/M service with

CPT codes 99201-99215. If not, schedule new visit for evaluation and request presence of

family/companion to facilitate assessment.

Follow-up during

subsequent AWV

Brief assessment(s) triggers concerns:

-8 score is indeterminate without

informant) or Mini-

Informant: AD8

patient score <8 3.38

AWV = Annual Wellness Visit; GPCOG = General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition; HRA = Health Risk Assessment;

MIS = Memory Impairment Screen; MMSE = Mini Mental Status Exam; MoCA = Montreal Cognitive Assessment; SLUMS =

St. Louis University Mental Status Exam; Short IQCODE = short Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly

Review HRA (especially reports of functional deficits), clinician observations, and self-

reported concerns; and query patient and, if available, informant

A

B

*

C

*

No one tool is recognized as the best brief assessment to determine if a full dementia evaluation is

needed. Alternate tools (eg, MMSE, SLUMS, or MoCA) can be used at the discretion of the clinician.

Some providers use multiple brief tools prior to referral or initiation of a full dementia evaluation.

Signs/symptoms of cognitive

impairment present

Medicare Annual Wellness Visit (HCPCS codes G0438 or G0439)

Yes

No

Informant

available to

confirm

Yes

No

No

Yes

Fig. 1. Alzheimer’s Association Medicare Annual Wellness Visit Algorithm for Assessment of Cognition.

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

20

attributed to physical limitations should prompt concern, as

there is a strong correlation between decline in function and

decline in cognitive status across the full spectrum of demen-

tia [31]. In addition to clinically observed concerns, any pa-

tient- or informant-reported concerns should trigger further

evaluation [13]. Positive responses to conversational

queries, such as “Have you noticed any change in your mem-

ory or ability to complete routine tasks, such as paying bills

or preparing a meal?” should be followed up with a struc-

tured assessment of cognition.

Upon realizing the time constraints of a typical primary

care visit, if no cognitive concerns surface during the initial

evaluation and this information is corroborated by an infor-

mant, the clinician may elect not to perform a structured cog-

nitive assessment and assume that the patient is not currently

demented. This approach is supported by studies in popula-

tions with low rates of dementia that suggest the absence of

memory difficulties reported by informants and patients re-

duces the likelihood that dementia is present [32,33].

4.3. Structured cognitive assessment tools for use with

patients and informants during the AWV

The second step in detection of cognitive impairment dur-

ing the AWV (Figure 1, Step B) requires cognitive assess-

ment using a structured tool. Based on synthesis of data

from the six review articles previously discussed, patient

tools suitable for the initial structured assessment are the

GPCOG, Mini-Cog, and MIS.

Recognizing that there is no single optimal tool to detect

cognitive impairment for all patient populations and set-

tings, clinicians may select other brief tools to use in their

clinical practice, such as those listed in Table 3. The 15 brief

tools listed were evaluated in multipl e review articles

(passed through at least two review search criteria for tools

possibly suited for prima ry care) or are used in the VA. Tools

listed in Table 3 are subject to the inclusion/exclusion crite-

ria of each review and do not represent the entire listing of

the .100 brief cognitive assessment tools that may be suit-

able for primary care practices .

If an informant is present, defined as someone who can

attest to a patient’s change in memory, language, or function

over time, it is suitable to use the AD8, the informant com-

ponent of the GPCOG, or the Short IQCODE, during the

AWV.

4.4. Primary care workflow considerations

According to the algorithm, any patient who does not

have an informant present should be assessed with a struc-

tured tool. For such patients (and for practices that imple-

ment structured assessments during all AWVs), completion

of this structured assessment can be administered by trained

medical staff as the first step for cognitive impairment detec-

tion. This could improve office efficiency. To increase ac-

ceptance of a structured assessment, the reason provided to

the patient can be normalized with a statement such as,

“This is something I do for all of my older patients as part

of their annual visit.” When the initial assessment prompts

further evaluation, explanation of results should be deferred

until a more comprehensive evaluation has been completed.

“There are many reasons for not getting every answer cor-

rect. More evaluation will help us determine that,” is an ex-

ample statement that may encourage patients to pursue

further testing.

5. Full dementia evaluation

Patients with assessments that indicate cognitive im-

pairment during the AWV should be further evaluated to

determine appropriate diagnosis (e.g., MCI, Alzheimer’s

disease) or to identify other causes. As reflected in the algo-

rithm (Figure 1, Step C), initiation of a full dementia evalu-

ation is outside the scope of the AWV, but can occur in

a separate visit either on the same day, during a newly sched-

uled visit, or through referral to a specialist. Specialists who

have expertise in diagnosing dementia include geriatricians,

geriatric psychiatrists, neurologists, and neuropsychologists.

The two-visit approach has been cited as a time-effective

process to evaluate suspected dementia in primary care

[34] and is consistent with the two-step approach widely

used in epidemiologic research on dementia. Regardless of

the timing and setting, clinicians are encouraged to counsel

patients to include an informant in the diagnostic process.

Components of a full dementia evaluation can vary de-

pending on the presentation and include tests to rule in or

out the various causes of cognitive impairment and est ablish

its severity. Diagnostic evaluations include a complete med-

ical history; assessment of multiple cognitive domains, in-

cluding episodic memory, executive function, attention,

language, and visuospatial skills; neurologic exam (gait, mo-

tor function, reflexes); ADL and IADL functioning; assess-

ment for depression; and review for medications that may

adversely affect cognition. Standard laboratory tests include

thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH), complete blood count

(CBC), serum B

12

, folate, complete metabolic panel, and,

if the patient is at risk, testing for sexually transmitted dis-

eases (human immunodeficiency virus, syphilis). Structural

brain imaging, including magnetic resonance imaging

(MRI) or computed tomogr aphy (CT), is a supplemental

aid in the differential diagnosis of dementia, especially if

neurologic physical exam findings are noted. An MRI or

CT can be especially informative in the following cases: de-

mentia that is of recent onset and is rapidly progressing;

younger onset dementia (,65 years of age); history of

head trauma; or neurologic symptoms suggesting focal

disease.

6. Discussion

Unfortunately, up to 81% of patients who meet the crite-

ria for dementia have never received a documented diagnosis

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

21

Table 3

Key advantages and limitations of brief cognitive assessment tools evaluated in multiple reviews and/or for use in the VA

Assessment* Time (wmin) Advantages Limitations

7-Minute Screener [48] 7–12 Little or no education bias

Validated in primary care

Difficult to administer

Complex logarithmic scoring

AMT [49] 5–7 Easy to administer

Verbal memory test (no writing/drawing)

Education/language/culture bias

Limited use in US (mostly used in Europe)

Does not test executive function or visuospatial

skills

CAMCOG [50] 20 Tests many separate domains (7) Difficult to administer

Long administration time

CDT [51] 1 Very brief administration time

Minimal education bias

Lacks standards for administration and scoring

GPCOG

y

[18]

Patient 2–5 Developed for and validated in primary care

Informant component useful when initial

complaint is informant-based

Little or no education bias

Multiple languages accessible at www.gpcog.

com.au

Patient component scoring has an indeterminate

range that requires an informant score to assess as

pass or fail

Informant component alone has low specificity

Lacks data on any language/culture biases

Informant 1–3

Mini-Cog

y

[8, 19] 2–4 Developed for and validated in primary care

and multiple languages/cultures

Little or no education/language/race bias

Short administration time

Use of different word lists may affect failure rates

Some study results based on longer tests with the

Mini-Cog elements reviewed independently

MIS [23,52] 4 Verbal memory test (no writing/drawing)

Little or no education bias

Does not test executive function or visuospatial

skills

MMSE [17] 7–10 Most widely used and studied worldwide

Often used as reference for comparative eval-

uations of other assessments

Required for some drug insurance reimburse-

ments

Education/age/language/culture bias

Ceiling effect (highly educated impaired subjects

pass)

Proprietary—unless used from memory, test needs

to be purchased at www.parinc.com

Best performance for at least moderate cognitive

impairment

MoCA

y

[53] 10–15 Designed to test for mild cognitive impairment

Multiple languages accessible at www.

mocatest.org

Tests many separate domains (7)

Lacks studies in general practice settings

Education bias (12 years)

Limited use and evidence due to published data

relatively new (2005)

Admin time 10 min

RUDAS [54] 10 Designed for multicultural populations

Little or no education/language bias

Validated in Australian community

Limited use and evidence due to published data

relatively new (2004)

SAS-SI [55] 10 Detected dementia better than neuropsycho-

logic testing in a community population

Does not test memory

Lacks data on any education/language/culture

biases

SBT (BOMC

y

and

6-CIT) [56,57]

4–6 Verbal test (no writing/drawing) Education/language/cultural/race bias

Scoring can be cumbersome

Does not test executive function

SLUMS

y

[58] 7 No education bias

Tests many separate domains (7)

Available at: http://aging.slu.edu/pdfsurveys/

mentalstatus.pdf

Limited use and evidence due to published data

relatively new (2006)

Studied in VA geriatric clinic (predominantly white

males)

SPMSQ [59] 3–4 Verbal test (no writing/drawing) Scoring can be cumbersome

Does not test short-term memory

STMS

y

[60] 5 Validated in primary care

Tests many separate domains (7)

Education/language/race bias

Studied in relatively educated subjects, may not be

applicable to general population

T&C [61] 1 Very brief administration time

Little or no education bias

Strong language/cultural bias

Abbreviations: 6-CIT, 6-Item Cognitive Impairment Test; AMT, Abbreviated Mental Test; BOMC, 6-item Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test;

CAMCOG, Cambridge Cognitive Examination; CDT, Clock Drawing Test; GPCOG, General Practitioner Assessment of Cognition; MIS, Memory Impairment

Screen; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; MoCA, Montreal Cognitive Assessment; RUDAS, Rowland Universal Dementia Assessment; SAS-SI, Short

and Sweet Screening Instrument; SBT, Short Blessed Test; SLUMS, St Louis University Mental Status; SPMSQ, Short Portable Mental Status Questionnaire;

STMS, Short Test of Mental Status; T&C, Time and Change Test.

*References provide descriptions of assessments.

y

Brief tools used in the VA healthcare system reviewed by Kansagara and Freeman.

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

22

[35]. Delayed or missed diagnosis deprives affected individ-

uals of available treatments, care plans, and services that can

improve their symptoms and help maintain independence.

Studies show that interventions tailored to patients with de-

mentia can improve quality of care, reduce unfavorable

dementia-related behaviors, increase access to community

services for both the patient and their caregivers, and result

in less caregiver stress and depression [36–42]. Early

diagnosis of dementia also provides families and patients

an opportunity to plan for the future while the affected

individual is still able to participate in the decision-making

processes.

Early detection and medical record documentation may

improve medical care. The medical record could inform

all clinicians, including those who may be managing comor-

bidities on a sporadic basis, that treatment and care shoul d be

adjusted to accommodate cognitive impairment. According

to a 2004 Medicare beneficiary survey, among patients

with dementia, 26% had coronary heart disease, 23% had di-

abetes, and 13% had cancer [43].

It is important to note that the unstructured and structured

cognitive assessments being recommended for the AWV are

only the first steps in diagnosing dementia, and cognitive as-

sessment is best as an iterative process. For example, clini-

cians concerned with HRA information about decline in

function may proceed directly to a structured assessment

or continue to query the patient for additional information;

a self-reported memory concern coupled with a failed struc-

tured cognitive assessment should always result in a full de-

mentia evaluation.

Not all who are referred for further assessment will ul-

timately receive a dementia diagnosis. In a USA primary

care population aged 65 years ( N 5 3340), 13% failed

a brief screen for cognitive impairment and approxi-

mately half (n 5 227) agreed to be further evaluated

for dementia [7]. Among the 107 patients ultimately di-

agnosed with dementia, 81% were newly diagnosed

based on the absence of any medical record of dementia,

thus facilitating appropriate medical and psychosocial in-

terventions [7].

Despite the many advantages of early dementia diagno-

sis, several barriers to diagnosis still exist. These include

physician concerns of the time burden resu lting from testing

and counseling [35] and stigma concerns among physicians,

patients, and caregivers [35,44,45]. Despite thes e barriers,

successful widespread implementation of a brief cognitive

assessment has been reported. McCarten et al [22] evaluated

the Mini-Cog for routine cognitive assessment of veterans

presenting for primary care. Of the 8342 veterans ap-

proached, .96% agreed to be assessed and those that failed

the brief assessment exhibited no serious reactions upon dis-

closure of test results.

The AWV provides an unprecedented opportunity to

overcome current barriers and initiate discussions about cog-

nitive function among the growing population most at risk

for Alzheimer’s disease. Detec tion of cognitive impairment

during the AWV is further supported by previously pub-

lished quality indicators that state all vulnerable elders (de-

fined as persons 65 years who are at risk for death or

functional decline) should be evaluated annually for cogni-

tive and functional status [46].

There are limitations to these recommendations. They

are based on assessment of recommendations from review

articles and on expert opinion, not on a new, comprehensive

review of original research to define the optimal approach

to detection of cognitive impairment or review of emerging

technologies that could assist in testing (e.g., use of online

or electronic tablet applications). Further complicating

SERs of brief cognitive assessment tools is that sensitivity

and specificity will vary depending on the dementia preva-

lence of the study population, the tool(s) used, and the cut

score selected for each tool. Brodaty et al [12] recognized

that published research concerning cognitive impairment

screening tools is uneven in quantity and quality. The liter-

ature also is lacking in comparative validity of brief cogni-

tive assessment tools in low-education or illiterate

populations.

The Alzheimer’s Association Medicare Annual Wellness

Visit Algorithm for Assessment of Cognition is based

on current validated tools and commonly used rule-out

assessments. The use of biomarkers (e.g., CSF tau and

beta amyloid prot eins, amyloid tracer positron emission

tomography scans) was not considered as these measures

are not currently approved or widely available for clinical

use.

In 2011, greater than two million Medicare beneficiaries

received their AWV preventive service [47]. There are no

data available as to what methods were used to detect cogni-

tive impairment or how many beneficiaries were assessed

as having cognitive impairment. For future AWVs, the

Alzheimer’s Association Medicare Annual Wellness Visit

Algorithm for Assessment of Cognition provides guidance

to primary care practices on a process to operationalize

this required AWV element. With widespread implementa-

tion of the algorithm, the AWV could be the first step in re-

ducing the prevalence of missed or delayed dementia

diagnoses, thus allowing for better healthcare management

and more favorable outcomes for affected patients and their

families and caregivers.

7. Author Disclosures

Soo Borson is the developer of the Mini-Cog and is the

owner of its copyrights.

Over the past 5 years, Malaz Boustani has received re-

search suppor t for investigator- initiated projects from Forest

Pharmaceutical and Novartis; honoraria from Norvartis and

Pfizer, Inc.; and research support for investigator-initiated

projects from the NIH and AHRQ. Dr Boustani was a mem-

ber of the US Preventive Services Task Force that published

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

23

the systematic evidence review, Dementia Screening, for the

AHRQ in 2003.

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT

1. Systematic review: Our research included com paring

five systematic evidence reviews (SER) of brief de-

mentia screening tools published since 2000 and

a 2010 literature review of newer brief assessments

of cognition. Our research focused on determining

if there was a consensus among the published SERs

as to which tool is most suited for primary care and

if there were any common results across the publica-

tions.

2. Interpretation: Our research concluded there is a con-

sensus in the literature concerning suitable tools for

screening for dementia in primary care. We also reaf-

firmed that many validated tools are availabl e, and

that screening for dementia should not be solely

based on a tool, but should be a stepwise process to

include other assessments.

3. Future directions: Further validation of existing and

emerging screening tools (e.g., iPad applications,

gait monitoring) may result in newer tools being rec-

ognized more suitable and practical for primary care

settings.

References

[1] Boustani M, Peterson B, Harris R, Lux L, Krasnov C, Sutton S, et al.

Screening for dementia. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Re-

search and Quality. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/

NBK42773/; 2003. Accessed September 3, 2011.

[2] Anonymous. Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act of 2010, 42

CFR. x410.15(a). 2010. Available at: http://ecfr.gpoaccess.gov/cgi/t/

text/text-idx?c5ecfr&sid56b50669da0f96db4eea346533db23747&

rgn5div8&view5text&node542:2.0.1.2.10.2.35.4&idno542.

[3] Chodosh J, Petitti DB, Elliott M, Hays RD, Crooks VC,

Reuben DB, et al. Physician recognition of cognitive impairment:

evaluating the need for improvement. J Am Geriatr Soc 2004;

52:1051–9.

[4] Camicioli R, Willert P, Lear J, Grossmann S, Kaye J, Butterfield P.

Dementia in rural primary care practices in Lake County, Oregon.

J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol 2000;13:87–92.

[5] Callahan CM, Hendrie HC, Tierney WM. Documentation and evalua-

tion of cognitive impairment in elderly primary care patients. Ann In-

tern Med 1995;122:422–9.

[6] Valcour VG, Masaki KH, Curb JD, Blanchette PL. The detection of

dementia in the primary care setting. Arch Intern Med 2000;

160:2964–8.

[7] Boustani M, Callahan CM, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG,

Perkins AJ, Fultz BA, et al. Implementing a screening and diagnosis

program for dementia in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2005;

20:572–7.

[8] Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, Tu S-P, Lessig M. Improving iden-

tification of cognitive impairment in primary care. Int J Geriatr Psychi-

atry 2006;21:349–55.

[9] Anonymous. Medicare coverage of Annual Wellness Visit providing

a personalized prevention plan. Fed Regist 2010;75:73401.

[10] US Department of Health and Human Services. Advisory Council on

Alzheimer’s research, care, and services: opportunities and gaps. 2011.

Available at: http://aspe.hhs.gov/daltcp/napa/092711/Mtg1-Slides3.

pdf. Accessed October 14, 2011.

[11] Lorentz WJ, Scanlan JM, Borson S. Brief screening tests for dementia.

Can J Psychiatry 2002;47:723–33.

[12] Brodaty H, Low L-F, Gibson L, Burns K. What is the best dementia

screening instrument for general practitioners to use? Am J Geriatr

Psychiatry 2006;14:391–400.

[13] Holsinger T, Deveau J, Boustani M, Williams JW Jr. Does this patient

have dementia? JAMA 2007;297:2391–404.

[14] Milne A, Culverwell A, Guss R, Tuppen J, Whelton R. Screening for

dementia in primary care: a review of the use, efficacy and quality of

measures. Int Psychogeriatr 2008;20:911–26.

[15] Ismail Z, Rajji TK, Shulman KI. Brief cognitive screening instru-

ments: an update. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2010;25:111–20.

[16] KansagaraD, Freeman M. A systematic evidence review of the signs and

symptoms of dementia and brief cognitive tests. Available at: http://

www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/21155200. Accessed June 7, 2011.

[17] Folstein MF, Folstein SE, McHugh PR. “Mini-mental state.” A practi-

cal method for grading the cognitive state of patients for the clinician.

J Psychiatr Res 1975;12:189–98.

[18] Brodaty H, Pond D, Kemp NM, Luscombe G, Harding L, Berman K,

et al. The GPCOG: a new screening test for dementia designed for gen-

eral practice. J Am Geriatr Soc 2002;50:530–4.

[19] Borson S, Scanlan J, Brush M, Vitaliano P, Dokmak A. The Mini-Cog:

a cognitive “vital signs” measure for dementia screening in multi-

lingual elderly. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2000;15:1021–7.

[20] Borson S, Scanlan JM, Watanabe J, Tu S-P, Lessig M. Simplifying de-

tection of cognitive impairment: comparison of the Mini-Cog and

Mini-Mental State Examination in a multiethnic sample. J Am Geriatr

Soc 2005;53:871–4.

[21] Borson S, Scanlan JM, Chen P, Ganguli M. The Mini-Cog as a screen

for dementia: validation in a population-based sample. J Am Geriatr

Soc 2003;51:1451–4.

[22] McCarten JR, Anderson P, Kuskowski MA, McPherson SE, Borson S.

Screening for cognitive impairment in an elderly veteran population:

acceptability and results using different versions of the Mini-Cog.

J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:309–13.

[23] Buschke H, Kuslansky G, Katz M, Stewart WF, Sliwinski MJ,

Eckholdt HM, et al. Screening for dementia with the memory impair-

ment screen. Neurology 1999;52:231–8.

[24] Mackinnon A, Mulligan R. Combining cognitive testing and informant

report to increase accuracy in screening for dementia. Am J Psychiatry

1998;155:1529–35.

[25] Jorm AF. A short form of the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive

Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE): development and cross-validation.

Psychol Med 1994;24:145–53.

[26] Ayalon L. The IQCODE versus a single-item informant measure to

discriminate between cognitively intact individuals and individuals

with dementia or cognitive impairment. J Geriatr Psychiatry Neurol

2011;24:168–73.

[27] Galvin JE, Roe CM, Morris JC. Evaluation of cognitive impairment in

older adults: combining brief informant and performance measures.

Arch Neurol 2007;64:718–24.

[28] Galvin JE, Roe CM, Xiong C, Morris JC. Validity and reliability

of the AD8 informant interview in dementia. Neurology 2006;

67:1942–8.

[29] Goetzel R, Staley P, Ogden L, Strange P, Fox J, Spangler J, et al. A

framework for patient-centered health risk assessments—providing

health promotion and disease prevention services to Medicare benefi-

ciaries. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services,

C.B. Cordell et al. / Alzheimer’s & Dementia 9 (2013) 141–150

24

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Available at: http://www.

cdc.gov/policy/opth/hra/; 2011.

[30] Anonymous. Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Survey

Questionnaire. Bethesda, MD: Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/brfss/questionnaires/

pdf-ques/2011brfss.pdf; 2011. Accessed January 10, 2012.

[31] Njegovan V, Hing MM, Mitchell SL, Molnar FJ. The hierarchy of

functional loss associated with cognitive decline in older persons.

J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M638–43.

[32] Carr DB, Gray S, Baty J, Morris JC. The value of informant versus in-

dividual’s complaints of memory impairment in early dementia. Neu-

rology 2000;55:1724–6.

[33] Tobiansky R, Blizard R, Livingston G, Mann A. The Gospel Oak Study

stage IV: the clinical relevance of subjective memory impairment in

older people. Psychol Med 1995;25:779–86.

[34] Simmons BB, Hartmann B, Dejoseph D. Evaluation of suspected de-

mentia. Am Fam Physician 2011;84:895–902.

[35] Bradford A, Kunik ME, Schulz P, Williams SP, Singh H. Missed and

delayed diagnosis of dementia in primary care: prevalence and contrib-

uting factors. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord 2009;23:306–14.

[36] Bass DM, Clark PA, Looman WJ, McCarthy CA, Eckert S. The Cleve-

land Alzheimer’s managed care demonstration: outcomes after 12

months of implementation. Gerontologist 2003;43:73–85.

[37] Callahan CM, Boustani MA, Unverzagt FW, Austrom MG,

Damush TM, Perkins AJ, et al. Effectiveness of collaborative care

for older adults with Alzheimer disease in primary care: a randomized

controlled trial. JAMA 2006;295:2148–57.

[38] Fortinsky RH, Unson CG, Garcia RI. Helping family caregivers by

linking primary care physicians with community-based dementia

care services: the Alzheimer’s Service Coordination Program. Demen-

tia 2002;1:227–40.

[39] Reuben DB, Roth CP, Frank JC, Hirsch SH, Katz D, McCreath H, et al.

Assessing care of vulnerable elders—Alzheimer’s disease: a pilot

study of a practice redesign intervention to improve the quality of de-

mentia care. J Am Geriatr Soc 2010;58:324–9.

[40] Vickrey BG, Mittman BS, Connor KI, Pearson ML, Della Penna RD,

Ganiats TG, et al. The effect of a disease management intervention on

quality and outcomes of dementia care: a randomized, controlled trial.

Ann Intern Med 2006;145:713–26.

[41] Olazar

�

an J, Reisberg B, Clare L, Cruz I, Pe

~

na-Casanova J, Del Ser T,

et al. Nonpharmacological therapies in Alzheimer’s disease: a system-

atic review of efficacy. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord 2010;30:161–78.

[42] Auclair U, Epstein C, Mittelman M. Couples counseling in Alz-

heimer’s disease: additional clinical cindings from a novel intervention

study. Clin Gerontol 2009;32:130–46.

[43] Thies W, Bleiler L. 2011 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. Alz-

heimers Dement 2011;7:208–44.

[44] Justiss MD, Boustani M, Fox C, Katona C, Perkins AJ, Healey PJ, et al.

Patients’ attitudes of dementia screening across the Atlantic. Int J Ger-

iatr Psychiatry 2009;24:632–7.

[45] Boustani MA, Justiss MD, Frame A, Austrom MG, Perkins AJ,

Cai X, et al. Caregiver and noncaregiver attitudes toward dementia

screening. J Am Geriatr Soc 2011;59:681–6.

[46] Feil DG, MacLean C, Sultzer D. Quality indicators for the care of de-

mentia in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55(Suppl

2):S293–301.