Corresponding Author: Rebecca L Stearns, Rebecc[email protected]

Original Publication Date: June 2, 2020 1

Return to Sports and Exercise during the COVID-

19 Pandemic: Guidance for High School and

Collegiate Athletic Programs

Contributing Authors

Rebecca L. Stearns, PhD, ATC, Korey Stringer Institute, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Samantha E. Scarneo-Miller, PhD, ATC, Korey Stringer Institute, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Robert A. Huggins, PhD, ATC, Korey Stringer Institute, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Lindsay B. Baker, PhD, Gatorade Sports Science Institute, PepsiCo R&D, Barrington, IL

Tony Caterisano, PhD, CSCS*D, Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association, Furman University,

Greenville, SC

George Chiampas, DO, Chief Medical Officer United States Soccer Federation, Northwestern University Feinberg School

of Medicine, Chicago, IL

Don Decker, MS, CSCS, SCCC, Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association, New Mexico State University,

Las Cruces, NM

Jonathan A. Drezner, MD, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

John F. Jardine, MD, Korey Stringer Institute, University of Connecticut, Storrs, CT

Michael C. Koester, MD, National Federation of State High School Associations, Slocum Center for Orthopedics and Sports

Medicine, Eugene, OR

Kristen L. Kucera, PhD, MSPH, ATC, National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research, University of North

Carolina, Chapel Hill, NC

Eric McMahon, M.Ed, CSCS, RSCC*D, National Strength and Conditioning Association, Colorado Springs, CO

Neha P. Raukar, MD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN

Jennifer D. Rheeling, MS, ATC, National Athletic Trainers’ Association, Washington DC Public Schools, Washington DC

Chuck Stiggins, Ed.D, SCCC, Collegiate Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association, Provo, UT

Brady L. Tripp, PhD, ATC, National Athletic Trainers’ Association, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL

The following organizations endorsed this document: American College of Sports Medicine (ACSM), Collegiate

Strength and Conditioning Coaches Association (CSCCa), Gatorade Sports Science Institute (GSSI), Korey Stringer

Institute (KSI), National Athletic Trainers’ Association (NATA), National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research

(NCCSIR), National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS), National Strength and Conditioning

Association (NSCA).

he COVID-19 pandemic has sparked dramatic

changes across all aspects of our daily lives. The

combination of lifestyle modifications and potential

comorbidities associated with COVID-19 also presents

important, athlete specific, health and safety risks as return

to sport plans emerge. While it is clear that transition periods

have a higher risk for catastrophic sport injury,1–6 some of the

factors that place athletes at higher risk during these periods

may be amplified as a result of social distancing measures.

These risk factors may also be amplified at various levels –

so even athletes within the same team may have a spectrum

of risk profiles. As plans for a return to organized sport begin,

and over 10 million high school and college athletes emerge

from this unprecedented period,7,8 healthcare providers and

administrators must give greater consideration for how to

reduce risk while re-introducing sport.

The purpose of this document is to create an overarching

consensus statement across high school and collegiate

athletics to address return to physical activity considerations

during or immediately following physical distancing. This

document is meant to serve as a resource, providing a

streamlined approach that sport organizations and those

involved in high school and college sport programs (i.e.

athletes, coaches, strength and conditioning coaches, athletic

trainers, athletic directors, and physicians) may use. It is

important to remember that organizations must always refer

to federal and state authorities, departments of public health,

and sport specific organizational governing bodies when

considering health and safety policies and procedures. The

recommendations provided in this document are based on

published best practices and hold value for prioritizing

athlete health and safety. However, in the absence of this

evidence, expert opinion is utilized. It is acknowledged that

resources across and between high school and collegiate

programs differ, therefore the application of these

recommendations must be considered within the context of

T

2

the sport setting, compliance and individual school

resources. It should also be noted that some of these

recommendations may be accomplished over a timeline and

not at the immediate resumption of sport activity. Similarly,

these recommendations are written to apply across all sport

seasons and are not limited to only fall athletes.

The specific objectives of this document are as follows:

1. Discuss how and why physical distancing presents

added and unique risk to athletes.

2. Identify various risk profiles.

3. Identify how to mitigate risk with tools and resources

already available.

4. Discuss considerations for interruptions to normal

seasons, and when this document may be

implemented.

5. Specifically address the following topics:

• Pre-participations evaluations

• Return to physical activity/conditioning

• Heat acclimatization

• Injury prevention (preventative training programs)

• Education for related items

This document is not intended to:

1. Provide a recovery plan specific for COVID-19

patients.

2. Discuss administrative considerations and practices.

3. Discuss cleaning procedures or personal protection

practices.

4. Provide detailed discussion of screening, testing,

isolating and contact tracing for sport programs.

Preparticipation Physical Evaluation

Physical Evaluations

The preparticipation physical evaluation (PPEval) is

considered best practice for identifying potentially serious

medical conditions which may lead to injury or illness during

athletic competition. The National Federation of State High

School Associations (NFHS) and National Collegiate

Athletic Association (NCAA) recommend a history and

physical evaluation prior to athletic participation. All state

high school athletic associations require a PPEval, but the

scope, medical providers approved to conduct the exam, and

required time interval between exams vary.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, many healthcare offices

have significantly scaled back or canceled routine well care

visits, including PPEval appointments. As healthcare offices

slowly re-open in the coming months, there is a concern that

the demand for regular routine care and maintenance of

chronic medical conditions may overburden healthcare

offices, making it difficult, or impossible, for athletes to

obtain a PPEval in a timely manner. Given the unprecedented

loss of employment nationwide, many young athletes may

also lose health insurance benefits and see delays in primary

care provider assignment when or if they enroll in a state

Medicaid program.

While the recommendations below are in agreement with

the NFHS Statement on PPE’s and Athletics Participation

(released in April 2020),9 the recommendations are also

generalizable to the college setting across all levels (Junior

College, NCAA DIII, DII, DI, and NAIA).

As such, we recommend the following minimum

recommendations for both high school and collegiate

athletes:

1) Be familiar with state and local laws as well as

organizational policy requirements for PPEvals.

2) Discuss with local health departments and state medical

associations prior to making a final decision on how best

to approach this issue.

3) If needed, and absent indications to the contrary, a one-

year extension should be considered for any student who

has a PPEval that “expires” before or during the 2020-21

academic year.

4) Access to the PPEval should be assessed at a local level

as much as is organizationally possible. When the

opportunity for an in-office encounter is unavailable, an

interim history update and a review of any chronic

medical conditions with an athletic trainer or a

telemedicine visit with a primary care provider should be

strongly encouraged.

5) Athletes who have not had a PPEval, such as incoming

freshmen and students who are first time participants in

athletics, or athletes who did not have a PPEval during

the 2019-2020 academic year, should still be required to

have a PPEval prior to athletic participation. Therefore,

athletes, parents and guardians should be informed of the

need to obtain a PPEval prior to the start of the 2020-21

academic year and should schedule the appointment with

their primary care provider as soon as possible.

Past Medical History

Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-

CoV-2), the novel coronavirus that causes COVID-19,

presents unique health issues that should be considered prior

to a return to sports and exercise. While the vast majority of

young persons afflicted with the coronavirus have mild

symptoms or remain asymptomatic, rarely the infection can

cause direct injury or inflammation to the heart or kidneys.

Concerns for cardiac complications from COVID-19 arise

from data in the sickest of hospitalized patients, and evidence

on the prevalence and risks of myocardial injury during more

mild illness remains limited. Likewise, acute kidney injury

has been seen in critically ill patients, affecting nearly one-

third of patients requiring intensive care. Nonetheless, the

sports medicine community believes that patients with prior

COVID-19 should undergo a medical assessment before

returning to exercise.

3

1) We recommend that every student-athlete with a prior

diagnosis of COVID-19, symptoms suggestive of

COVID-19, or a “close exposure” to someone with

COVID-19 should contact their medical provider to

determine if further evaluation is warranted prior to

returning to sports. A close exposure is defined as having

a household member with COVID-19, prolonged

exposure (>10 minutes) within 6 feet of an individual

with confirmed COVID-19, direct exposure to infectious

secretions (e.g., being coughed on) or direct physical

contact during sports from an individual with COVID-

19.

2) A medical evaluation is strongly recommended for

student-athletes with a confirmed diagnosis of COVID-

19.

3) Those at greater risk for developing severe COVID-19

disease or complications should undergo an informed

decision-making process with their medical provider

before a return to sports as exposure to teammates and

opponents may increase their risk of becoming infected.

Individuals at higher risk of severe COVID-19 include

those with a serious heart condition, uncontrolled or

moderate to severe asthma, chronic lung disease,

diabetes, obesity, pre-existing kidney disease, or a

weakened immune system.

a) Although the Centers for Disease Control and

Prevention states that patients with these conditions

may be at greater risk for more severe disease, there

are limited published data in young athletes to

support this determination at this time.

4) All athletes with prior COVID-19 should be screened for

ongoing symptoms of chest pain/pressure with exercise,

difficulty breathing or dizziness with exercise, or

decreased exercise tolerance.

5) Additional cardiac testing, such as an electrocardiogram

(ECG), cardiac biomarkers (i.e. hs-troponin), and an

echocardiogram may be indicated depending on the

severity of past COVID-19 illness, ongoing symptoms,

or clinical suspicion. Specific medical guidance can be

found from a publication by Baggish et al.10

6) Tests to evaluate kidney function (i.e. urinalysis, serum

creatinine) should be considered to evaluate kidney

function after recovery from COVID-19.

7) Athletes with ongoing respiratory symptoms associated

with COVID-19 should undergo cardiac and pulmonary

testing as guided by a physician.

8) Secondary schools and collegiate athletic programs

should consider a supplemental questionnaire addressing

COVID-19 specific medical issues (see Appendix A).

Positive responses from this questionnaire should trigger

an evaluation by a medical provider prior to participation

in sports.

PPEval Resources:

1. NFHS Statement on PPE and Athletic Participation:

Ramifications of the COVID-19 Pandemic

2. American Academy of Pediatrics Preparticipation

Physical Evaluation (PPE)

3. National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position

Statement: Preparticipation Physical Examinations and

Disqualifying Conditions

4. AMSSM Position Statement on Cardiovascular

Preparticipation Screening in Athletes: Current

evidence, knowledge gaps, recommendations and future

directions

5. The resurgence of sport in the wake of COVID-19:

cardiac considerations in competitive athletes

Return to Physical Activity

Exercise Adaptations

The COVID-19 crisis and physical distancing policies have

resulted in high school and college athletes being separated

from their normal training facilities and workout routines for

several months. Because of this crisis, athletes will be

returning with a variety of conditioning levels, creating the

potential for “a perfect storm” of detrained athletes returning

to shorter training preparation time.

In June 2019, a joint position paper was published in the

Strength and Conditioning Journal entitled “CSCCa and

NSCA Joint Consensus Guidelines for Transition Periods:

Safe Return to Training Following Inactivity.”11 These

guidelines apply to those athletes with any period of

inactivity of two weeks or greater. If a two-week break or

longer occurs after the resumption of training, the

recommendation is to re-start the guidelines in the 2019

consensus document, which may even need to be done

multiple times. While these recommendations were written

specifically for the collegiate athlete, many of these

recommendations should be considered for the high school

athlete when possible. It is recommended that coordination

occurs between the coach, strength and conditioning staff

and athletic trainer to be sure that training is developmentally

appropriate and not superfluous or excessive.

As such, we recommend the following:

1) Register your written training programs with athletics

administrators.

a) Prior to restarting training workouts, coaches should

record a written strength and conditioning program.

This record should adhere to established

recommendations of training protocols within the

field of strength and conditioning by organizations

such as the Collegiate Strength and Conditioning

Coaches Association (CSCCa), the National

Strength and Conditioning Association (NSCA), the

NFHS, the individual state high school athletic

association, and the NCAA, and a copy of the

conditioning program should be held on file by an

appropriate member of the athletics administration.

b) This program should reflect the upper limit for

exercise intensity and volume. The “upper limit”

4

workout would be the highest level of intensity and

volume an athlete would be able to tolerate when in

peak condition. This workout will be utilized to

determine the maximum allowable limits using the

50/30/20/10 and F.I.T. (Frequency, Intensity, Time

of Weight Training) rules.

2) Follow the 50/30/20/10 Rule11

a) The 50/30/20/10 Rule for athletes is a testing

protocol, and a daily and weekly conditioning

protocol.

b) College Student-Athletes

i) It is recommended that weekly conditioning

volume be reduced by 50% from the uppermost

volume on file in week 1 with a 1:4 or greater

Work to Rest Ratio (W:R) and 30% in week 2

with a 1:3 or greater W:R. Based on the protocol,

the returning athletes can then return to normal

training volumes and intensities based upon the

professional judgment of the coach. For athletes

who are new to the program, it is recommended

that a minimum of a 20%, and 10% reduction

takes place in weeks 3 and 4, respectively.

ii) If conditioning testing is completed for returning

athletes, then the workload (whether through

intensity, volume, rest time, or a combination)

should be reduced by 20% in the first week and

10% in the second week. Because of the

reduction in workload, there is no mandate to

change the W:R for these testing sessions.

iii) For new athletes, conditioning testing must be

completed on the first day of return to training

and should be performed at 50% of the standard

volume of the test on file with the administrator,

using 1:4 or greater W:R. Although not

mandatory, testing may be repeated, but should

follow the rule for conditioning activities, with a

30/20/10% weekly reduction in volume at

standard intensities and rest times.

c) High School Student-Athletes

i) High school programs might use training

regimens that are different from collegiate

programs, but the recommendation is being

made that a reduction be applied to exercise

programs in order to create a phased re-

introduction of physical activity. Because a

consensus statement on transition periods for

high school athletes has not been published, the

50/30/20/10 rule provides the best

recommendations available to guide exercise

modifications within the high school setting.

These recommendations would allow the re-

introduction of exercise over the first 4 weeks

based on reductions from the normal exercise

load/plan: Week 1 a 50% reduction, Week 2 a

30% reduction, Week 3 a 20% reduction and

Week 4 a 10% reduction in conditioning

volume.

ii) For that reason, the recommendation is that in

week one of training, if a conditioning test is

done, a reduction of 50% should be applied to

the chosen measuring tool with a W:R of 1:4 or

greater. This should remain consistent , and the

same is true for all daily and weekly

conditioning programs. This is a recommended

“ceiling”. If at any time prior to achieving the

50% volume prescribed athletes begin to

struggle, they should be removed from the drill.

In Week 2 the volume, whether for testing or

general conditioning, is reduced by 30% with a

1:3 W:R or greater; Week 3 by 20% with no

added accommodation for work rest; and week

4 by 10% with no added accommodations for

work rest.

iii) Athletes involved in multiple sports should

consider not participating in multiple sport

practices or conditioning sessions during the

pre-season or should reduce the workload in

each of the sports practices or conditioning

sessions by at least 50%.

3) Follow The F.I.T. Rule (Frequency, Intensity, Time of

Weight Training)11

a) The F.I.T. Rule provides guidance for phasing in

weight training and should be used following a

period of active rest or periods of minimal training

(See Appendix B).

b) The F.I.T. Rule has been described in the Joint

Consensus Document for collegiate athletics.

Because a consensus statement on transition periods

for high school athletes has not been published, the

F.I.T. Rule provides the best recommendations

available to guide weight training modifications

within the high school setting.

c) The F.I.T. rule is designed to ensure that frequency,

intensity relative volume (IRV), and time of rest

interval are appropriately administered to minimize

the chance of severe muscle damage during weight

training.

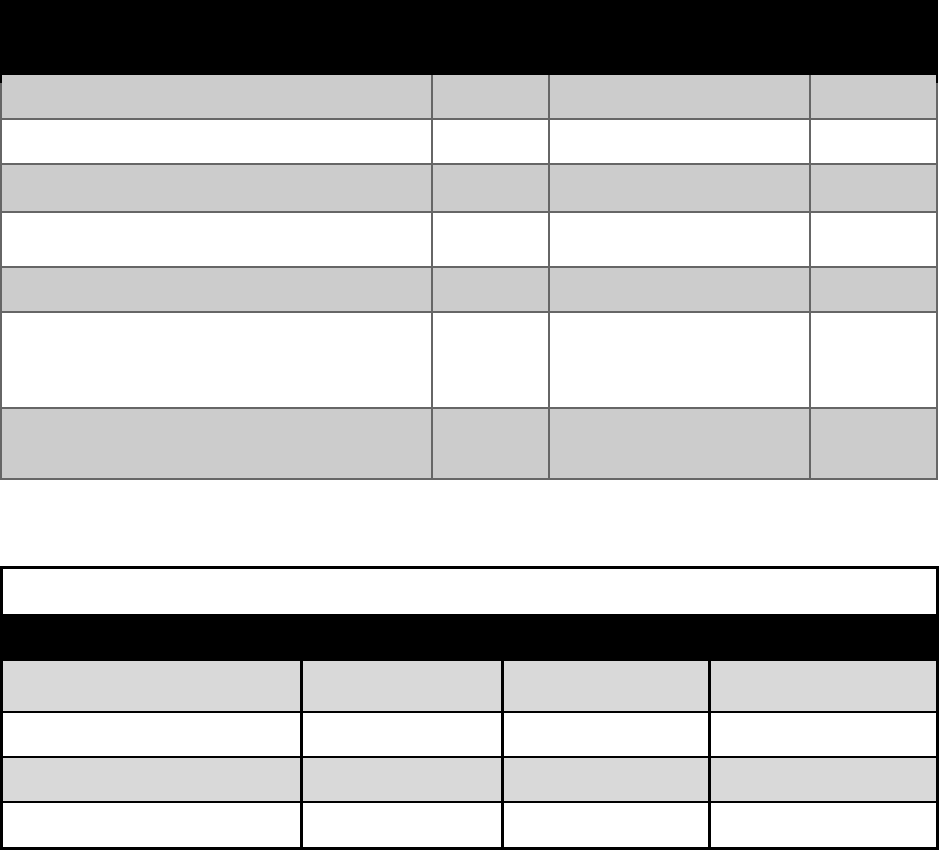

d) Frequency is defined as the number of training

sessions completed per week for a specific muscle

group or movement type. For example, the student-

athlete might train a total of 5 days in the week, but

only train the lower body for 3 days, so the frequency

for lower-body movements equals 3. Following a

period of inactivity, it is recommended that

frequency not exceed 3 days in the first week and no

more than 4 days in the second week. IRV is a

derivation of volume load that includes the %1RM

(one repetition maximum) and is calculated with the

following equation: Sets x Reps x % of 1RM (as a

decimal) = IRV

5

i) Example: 3 sets x 10 reps x 0.50 (which would

be 50% 1RM) = 15 IRV

e) The recommendation is to keep IRV between 11 –

30 with a W:R of 1:4 or greater the first week and

1:3 or greater the second week. IRVs of greater than

30 are contraindicated in the first 2 weeks following

a period of inactivity in addition to coaches’ own

professional judgment regarding limitations on the

return to training program.

f) Examples and specific usage of the F.I.T. principle

can be found within the 2019 CSCCa and NSCA

Joint Consensus Guidelines for Transition Periods:

Safe Return to Training Following Inactivity.11

Exercise Adaptations Resources:

1. CSCCa and NSCA Joint Consensus Guidelines for

Transition Periods: Safe Return to Training Following

Inactivity

2. National Athletic Trainers’ Association – Key Facts

about Detraining

Heat Acclimatization

Exercising in the heat imposes significant strain on the

cardiovascular system to simultaneously support

thermoregulatory and metabolic demands, thus presenting a

serious challenge to body core temperature regulation.

Routine exposure to exercise in the heat elicits physiological

adaptations that gradually improve exercise heat tolerance.

As such, a proper heat acclimatization program is essential

to reduce the risk of exertional heat illness, death from

exertional heatstroke, and death from other causes such as

sudden cardiac and exertional sickling that are exacerbated

by heat intolerance. Established heat acclimatization

guidelines are clearly outlined and take into account summer

and pre-season scheduling, however the timing of a return to

activity during or following social distancing may alter the

feasibility of these guidelines.

Thus, consider the following to properly heat acclimatize

athletes:

1) Time course of adaptations

a) An important consideration is that fitness

acclimatization may overlap and even

enhance/jumpstart the heat acclimatization process.

b) Once physical fitness is established (see exercise

adaptations section), gradually increase the duration

and intensity of exercise in the heat over a minimum

of 7 days, with full adaptations occurring at 10-14

days (see Appendix C). Repeated maximal physical

efforts over a prolonged period and competitive play

should be avoided until both fitness and heat

acclimatization are achieved.

c) While some adaptations can be obtained from

exposure to hot environments without exercise as

well as from exercise without heat exposure, these

approaches do not maximize the adaptations.

d) Organizations should consider modifying regular

season start dates and/or shortening the length of the

regular season to allow sufficient time for heat

acclimatization to occur.

e) If training is paused for more than 5-7 days due to

“stay at home orders” or due to individual/team

quarantines, schools should consider restarting or

extending the heat acclimatization process prior to

the resumption of activity.

2) Hydration considerations

a) Hydration plays an important role in maintenance of

thermoregulatory function and can influence the risk

of exertional heat illness. Therefore, it is critical to

allow for frequent and open access to cool, palatable

fluids to promote proper hydration in hot weather.12–

14

b) Hydration status should be monitored daily via pre-

practice body mass, urine concentration, and thirst.

See GSSI Sport Science Exchange: Hydration

Assessment of Athletes or NATA Position

Statement: Fluid Replacement15 for the Physically

Active for more information.

c) To reduce the risk of viral transmission, the sharing

of bottles and water sources should be avoided. All

efforts should be made to have individualized and

labeled bottles for each athlete. Good hygiene

practices (e.g., hand washing) and personal

protective equipment (i.e. gloves, masks) should be

used when filling bottles for athletes. Heightened

awareness should be taken to support access to

individualized fluids containers.

d) Other means of fluid delivery besides individual

bottles/containers (like hoses, PVC pipes, mass

drinking stations etc.) should not be utilized as

individual drinking stations.

e) If proper access to fluids during exercise in the heat

is not possible due to COVID-19 transmission

concerns, sessions should be modified or cancelled.

3) Modifying exercise based on environmental conditions

a) During and after the heat acclimatization period,

modification or cancellation of physical activity

(consistent with organizational, state, and regional

policies) based on routine measurements of

environmental conditions (ideally via wet-bulb

globe temperature per best practices) is strongly

recommended.4,16

b) As environmental heat stress increases,

modifications, such as the removal of unnecessary

equipment or clothing, increased frequency of rest

breaks, and access to hydration, or rescheduling the

session to an earlier/later (i.e., cooler) time of the day

should be implemented.4,16–18

6

Heat Acclimatization Resources:

1. 2013-2014 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook

2. Korey Stringer Institute Heat and Hydration

3. National Athletic Trainers’ Association: Preseason

Heat Acclimatization Guidelines for Secondary

School Athletics

4. National Athletic Trainers’ Association – Heat

Acclimatization

5. National Federation of State High School

Associations – Heat Acclimatization and Heat

Illness Prevention Position Statement

6. GSSI Sport Science Exchange: Hydration

Assessment of Athletes

7. NATA Position Statement: Fluid Replacement for

the Physically Active

Injury Prevention

There is an increased risk of musculoskeletal injury

following a prolonged period of physical inactivity. Given

lower extremity injuries make up approximately 66% of all

sports injuries, preventative training programs (also known

as injury prevention programs, multicomponent training

programs) may reduce the likelihood of these injuries during

sport.19 Preventative training programs that require more

than 1 type of exercise (e.g., strength, balance, agility,

flexibility, plyometrics) are more effective at reducing

injuries.

The following guidelines are recommended to reduce lower

extremity injuries:

1) Preventative training programs:

a) Should include exercises in at least 3 of the

following categories: strength, balance, plyometrics,

agility, and flexibility.19

b) Should be performed at least 2-3 times per week

throughout the pre-season and in-season.19

c) Are easily implemented to replace, or in conjunction

with, a team’s warm-up program or strength and

conditioning program. The programs are typically

10-15 minutes and dynamic in nature.19

2) It is important to note that the pre-participation physical

evaluation may also assist with injury prevention (See

Preparticipation Physical Evaluation section).

Injury Prevention Resources:

1. National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position

Statement: Prevention of Anterior Cruciate

Ligament Injury

2. Stanford Orthopedics Sports Medicine

Education

It is important to remember that it is the responsibility of

sport organizations to interpret these recommendations and

apply what is relevant and feasible to their setting.

Additionally, an educational plan should be in place to

ensure a timely, streamlined communication of the policies

and procedures that should be in place.

The following considerations are recommended to achieve

this:

1) Education of all entities involved. This may include (but

not limited to): coaches, athletes, administrators,

parents/guardians, healthcare team, maintenance staff,

etc.

2) Designate a point person to disseminate information

pertaining to policies/procedures that should be

disseminated/implemented.

3) Define targets/audience for the dissemination of this

information.

4) Determine mode of information dissemination (email,

conference call, video conference, etc.).

5) Determine timing of this information and future updates.

6) Recommendations and guidelines may be subject to

change in response to an increased viral burden or other

evolving situations.

7) Re-education and policy re-evaluation given developing

circumstances.

Disclaimer

This document is intended to provide relevant practice

parameters for high school and collegiate sport programs to

use when performing their responsibilities in providing

services to athletes or other participants. The

recommendations presented here are based on published

scientific studies, position statements, inter-association task

force documents, personal communications, and a

consensus of expert views available based on the time of

publication. However, this information is not a substitute

for individualized judgment or independent professional

advice.

Neither the Korey Stringer Institute/The University of

Connecticut, nor the contributors to this project assume any

duty owed to third parties by those reading, interpreting, or

implementing this information. When rendering services to

third parties, these recommendations cannot be adopted for

use with all participants without exercising independent

judgment and decision making.

Sport programs using this information are encouraged to

seek and obtain advice from licensed healthcare

professionals responsible for the health and safety of their

programs (e.g. athletic trainer, team physician, school nurse

etc).

References:

1. Casa DJ, Anderson SA, Baker L, et al. The Inter-

Association Task Force for Preventing Sudden Death

in Collegiate Conditioning Sessions. Strength and

Conditioning Journal. 2015;37(6):113–116.

2. Yau RK, Kucera KL, Thomas LC, Price H, Cantu RC.

Catastrophic Sports Injury Research Thirty-Fifth

7

Annual Report: Fall 1982 – Spring 2017. National

Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Reearch at the

University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2018.

3. Kay MC, Register-Mihalik JK, Gray AD, Djoko A,

Dompier TP, Kerr ZY. The Epidemiology of Severe

Injuries Sustained by National Collegiate Athletic

Association Student-Athletes, 2009–2010 Through

2014–2015. Journal of Athletic Training.

2017;52(2):117-128. doi:10.4085/1062-6050-52.1.01

4. Casa DJ, Guskiewicz KM, Anderson SA, et al.

National athletic trainers’ association position

statement: preventing sudden death in sports. Journal

of Athletic Training. 2012;47(1):96–118.

5. Parsons JT, Anderson SA, Casa DJ, Hainline B.

Preventing catastrophic injury and death in collegiate

athletes: interassociation recommendations endorsed

by 13 medical and sports medicine organisations. Br J

Sports Med. 2020;54(4):208-215.

doi:10.1136/bjsports-2019-101090

6. Casa DJ, Almquist J, Anderson SA, et al. The inter-

association task force for preventing sudden death in

secondary school athletics programs: best-practices

recommendations. Journal of Athletic Training.

2013;48(4):546–553.

7. National Federation of State High School

Associations. 2018-2019 High School Athletics

Participation Survey Results. Published online 2019.

8. Irick E. NCAA Sports Sponsorship and Participation

Rates Report: 1981-82 - 2018-19. National Collegiate

Athletic Association; 2019.

9. Statement on PPE and Athletic Participation:

Ramifications of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Published

online April 2020.

10. Baggish A, Drezner JA, Kim JH, Martinez M, Prutkin

JM. The resurgence of sport in the wake of COVID-

19: cardiac considerations in competitive athletes.

Blog British Journal of Sports Medicine. Published

April 24, 2020. Accessed May 27, 2020.

https://blogs.bmj.com/bjsm/2020/04/24/the-

resurgence-of-sport-in-the-wake-of-covid-19-cardiac-

considerations-in-competitive-athletes/

11. Caterisano A, Decker D, Snyder B, et al. CSCCa and

NSCA Joint Consensus Guidelines for Transition

Periods: Safe Return to Training Following Inactivity.

Strength and Conditioning Journal. 2019;41(3):23.

12. Armstrong LE, Maresh CM. The induction and decay

of heat acclimatisation in trained athletes.

1991;12(5):302–312.

13. Sawka MN, Leon LR, Montain SJ, Sonna LA.

Integrated physiological mechanisms of exercise

performance, adaptation, and maladaptation to heat

stress. Compr Physiol. 2011;1(4):1883-1928.

doi:10.1002/cphy.c100082

14. Pandolf KB. Time course of heat acclimation and its

decay. Int J Sports Med. 1998;19 Suppl 2:S157-160.

doi:10.1055/s-2007-971985

15. McDermott BP, Anderson SA, Armstrong LE, et al.

National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position

Statement: Fluid Replacement for the Physically

Active. J Athl Train. 2017;52(9):877-895.

doi:10.4085/1062-6050-52.9.02

16. Casa DJ, DeMartini JK, Bergeron MF, et al. National

Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement:

Exertional Heat Illnesses. Journal of Athletic

Training. 2015;50(9):986–1000.

17. Cooper ER, Ferrara MS, Broglio SP. Exertional heat

illness and environmental conditions during a single

football season in the southeast. Journal of Athletic

Training. 2006;41(3):332–336.

18. Cooper ER, Ferrara MS, Casa DJ, et al. Exertional

Heat Illness in American Football Players: When Is

the Risk Greatest? Journal of Athletic Training.

2016;51(8):593–600.

19. Padua DA, DiStefano LJ, Hewett TE, et al. National

Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement:

Prevention of Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury.

Journal of Athletic Training. 2018;53(1):5-19.

doi:10.4085/1062-6050-99-16

8

Summary Points

• While it is clear that transition periods have a higher risk for catastrophic sport injury,1–3 some of the

factors that place athletes at higher risk during these periods may be amplified as a result of social

distancing measures.

• PPEs may be difficult to coordinate or obtain, and flexibility may be called for, such as a one-year

extension for any student who has a PPEval that "expires" before or during the 2020-21 academic

year.

o Every student-athlete with a prior diagnosis of COVID-19, symptoms suggestive of COVID-19, or a

“close exposure” to someone with COVID-19 should contact their medical provider to determine if

further evaluation is warranted prior to returning to sports.

• Exercise programs will need to be modified upon returning from any period of inactivity of two weeks

or greater. The 50/30/20/10 rule and F.I.T. rule are the best guidelines for achieving this.

• Once physical fitness is established, gradually increase the duration and intensity of exercise in the

heat over a minimum of 7 days to establish heat acclimatization.

• Preventative Training Programs should include three of the following: strength, balance, plyometrics,

agility, and flexibility,19 and be performed at least 2-3 times per week19 and last ~ 10-15 minutes.

9

Additional Resources

1) Pre-Participation Exam:

i) NFHS Statement on PPE and Athletic Participation: Ramifications of the COVID-19 Pandemic

ii) American Academy of Pediatrics Preparticipation Physical Evaluation (PPE)

iii) National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Preparticipation Physical

Examinations and Disqualifying Conditions

iv) AMSSM Position Statement on Cardiovascular Preparticipation Screening in Athletes: Current

evidence, knowledge gaps, recommendations and future directions

v) The resurgence of sport in the wake of COVID-19: cardiac considerations in competitive

athletes

2) Exercise Adaptations:

i) CSCCa and NSCA Joint Consensus Guidelines for Transition Periods: Safe Return to Training

Following Inactivity

ii) NSCA Strength and Conditioning Professional Standards and Guidelines

iii) National Athletic Trainers’ Association – Key Facts about Detraining

3) Heat Acclimatization:

i) National Athletic Trainers’ Association: Preseason Heat Acclimatization Guidelines for

Secondary School Athletics

ii) National Athletic Trainers’ Association – Heat Acclimatization

iii) 2013-2014 NCAA Sports Medicine Handbook

iv) KSI: Heat and Hydration

v) National Federation of State High School Associations – Heat Acclimatization and Heat Illness

Prevention Position Statement

vi) GSSI Sport Science Exchange: Hydration Assessment of Athletes

vii) National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Fluid Replacement for Athletes

4) Injury Prevention Resources:

i) National Athletic Trainers’ Association Position Statement: Prevention of Anterior Cruciate

Ligament Injury

ii) Stanford Orthopedics Sports Medicine

5) Additional Resources:

i) NFHS Guidance for Opening Up High School Athletics and Activities

ii) USOPC Youth Sport Return to Play Report (Aspen Project Play.org)

iii) Preventing catastrophic injury and death in collegiate athletes: interassociation recommendations

endorsed by 13 medical and sports medicine organizations

iv) The Inter-Association Task Force for Preventing Sudden Death in Secondary School Athletics

Programs: Best-Practices Recommendations

v) The Inter-Association Task Force for Preventing Sudden Death in Collegiate Conditioning

Sessions: Best Practices Recommendations

vi) Association of Chief Executives for Sport (ACES): Return to Play

vii) NSCA COVID-19 Return to Training – Guidance on Safe Return to Training for Athletes

viii) National Center for Catastrophic Sport Injury Research (NCCSIR)

ix) U.S. Soccer “PLAY ON”

x) World Health Organization. Considerations for sports federations/sports event organizers when

planning recommendations for Mass Gatherings in the

context of COVID-19: interim guidance.

xi) World Health Organization. Guidance for the use of the WHO Mass Gatherings Sports:

addendum: risk assessment tools in the context of COVID-19.

10

Appendix A

COVID-19 Supplemental Questionnaire

1. Have you had any of the following symptoms in the past 2 weeks?

a. Fever

b. Cough

c. Shortness of breath or difficulty breathing

d. Shaking chills

e. Chest pain, pressure, or tightness

f. Fatigue or difficulty with exercise

g. Loss of taste or smell

h. Persistent muscle aches or pains

i. Sore throat

j. Nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea

2. Do you have a family or household member with current or past COVID-19?

3. Do you have moderate to severe asthma, a heart condition, diabetes, pre-existing kidney

disease, or a weakened immune system?

4. Have you been diagnosed or tested positive for COVID-19 infection?

5. If you had COVID-19:

a. During the infection did you suffer from chest pain, pressure, tightness or

heaviness, or experience difficulty breathing or unusual shortness of breath?

b. Since the infection, have you had new chest pain or pressure with exercise, new

shortness of breath with exercise, or decreased exercise tolerance?

11

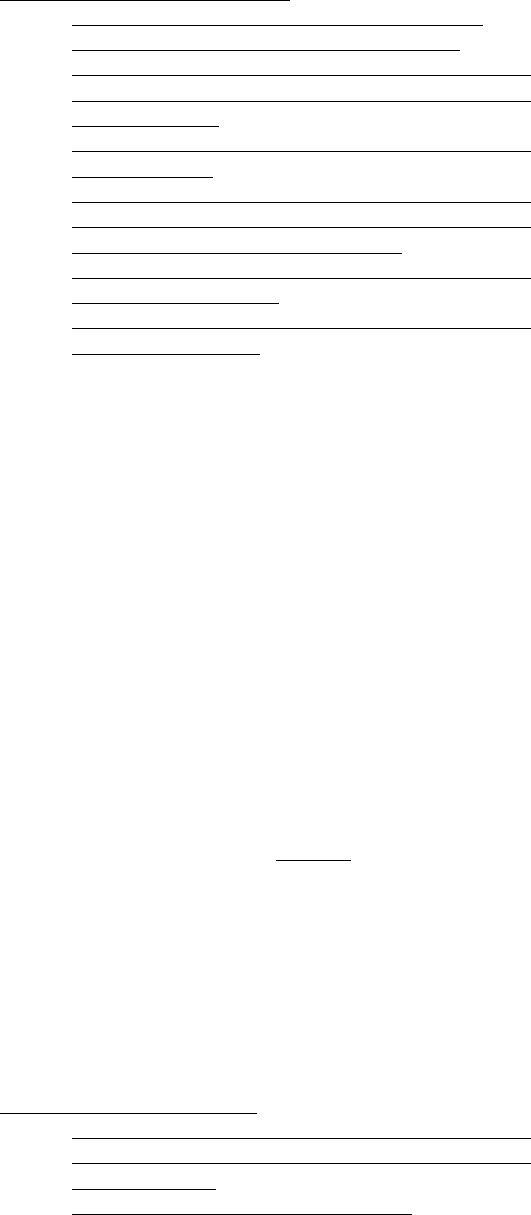

Appendix B

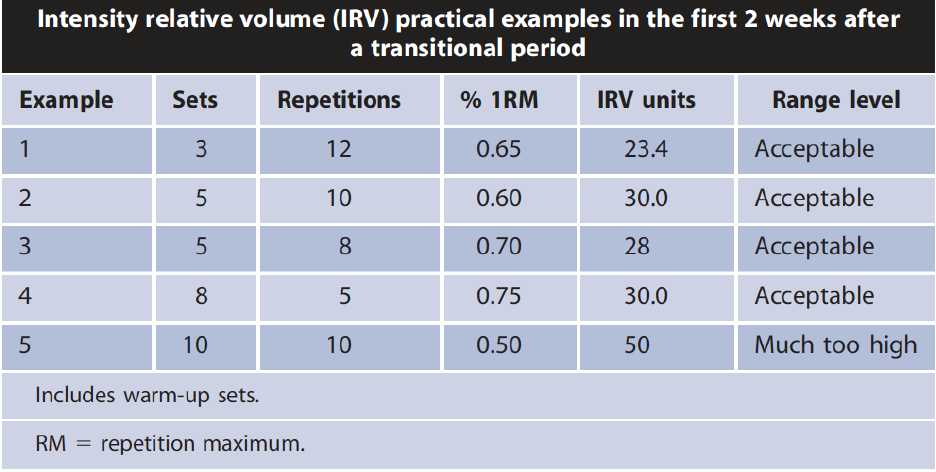

Examples of Frequently Used High School Football Conditioning Drills (a),

Example Application of 50/30/20/10 Rule (b) and F.I.T. Rule (c)

Table 1a. Sampling of High School Football Conditioning Drills

(Collected from personal communication with various high school football strength & conditioning

coaches within Arkansas, Kansas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, Texas)

Drill

Reps

Time in Seconds

(Skill/Power/Linemen)

Rest

110's Drill

16

16/18/21

45

Staggered 110/100/90 Drill

16

16

45

Half Gasser Drill (Over & Back)

14

17/18/21

45

300 yd. Shuttles (25 yds.)

3

65/70/75

2:30

300 yd. Shuttles (50 yds.)

3

59/66/70

2:30

300 yd. Shuttles

(50&Back/40&Back/30&Back/20&Back

/10&Back

3

62/68/73

2:30

50 (25&Back)/40 (20&Back)/30

(15&Back) Drill

20

8/7/6

35/30/25

Table 1b. Example of the Application of 50/30/20/10 to the 110 Drill

New Athletes - 110 Drill

Reduction

Reps

Time

Rest

Week 1 - 50%

50% = 8

16/18/20

64/72/80

Week 2 - 30%

30% = 11

16/18/20

48/54/60

Week 3 - 20%

20% = 13

16/18/20

45

Week 4 - 10%

10% = 14

16/18/20

45

12

Table 1c. Example Application of the F.I.T. Rule

Reprinted with permission from: Caterisano A, Decker D, Snyder B, et al. CSCCa and NSCA Joint

Consensus Guidelines for Transition Periods: Safe Return to Training Following Inactivity. Strength and

Conditioning Journal. 2019;41(3):23.

13

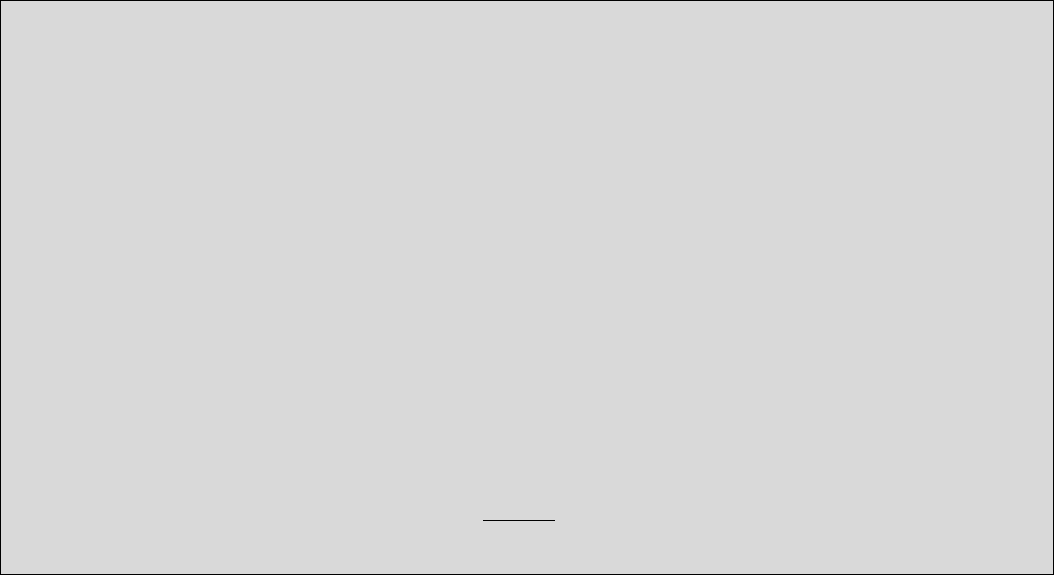

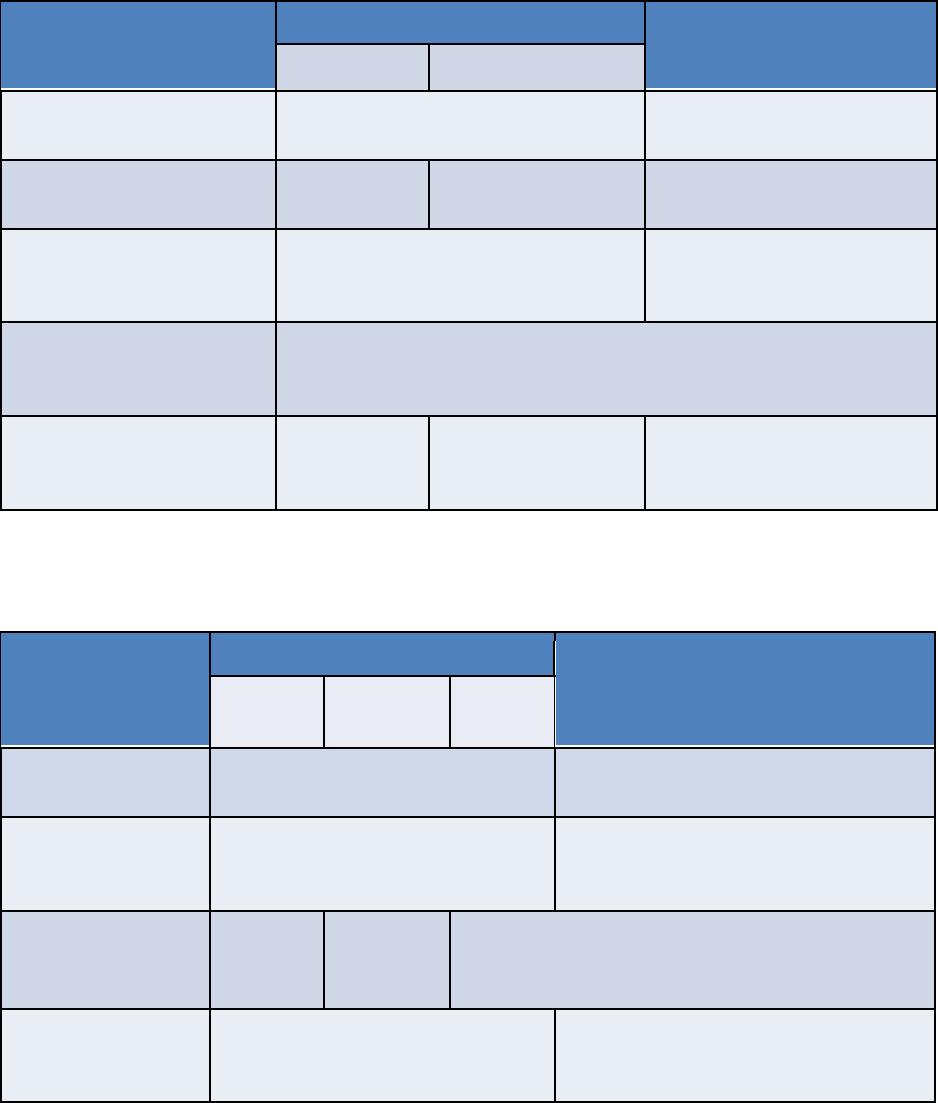

Appendix C

High School (a) and NCAA (b) Preseason Heat Acclimatization Guidelines

Table 2a. High School Preseason Heat Acclimatization Guidelines

Area of Practice

Modification

Practices 1-5

Practices 6-14

Practices 1-2

Practices 3-5

# of Practices Permitted Per

Day

1

2, only every other day

Equipment

Helmets only

Helmets & Shoulder

Pads

Full Equipment

Maximum Duration of

Single Practice Session

3 hours

3 hours (a total maximum of

5 hours on double session

days)

Permitted Walk Through

Time (not included as

practice time)

1 hour (but must be separated from practice for 3 continuous hours)

Contact

No Contact

Contact only with

blocking

sleds/dummies

Full, 100% live contact drills

NOTE: warm-up, stretching, cool-down, conditioning, and weight-room activities are Included as part of

practice time

Table 2b. NCAA Football Preseason Heat Acclimatization Guidelines

Area of Practice

Modification

Practices 1-5

Practices 6+

Practices

1-2

Practices

3-4

Practice

5

# of Practices

Permitted Per Day

1

>1, if not consecutive days with

multiple practices

Maximum Duration

of Single Practice

Session

3 hours

3 hours on days with 1 practice

Equipment*

Helmets

only

Helmets &

Shoulder

Pads

Full Pads

Full Equipment

Double Practice

Days

None

No more than 5 total hours of on-field

practice permitted - with at least 3

continuous hours between practices