University of Arkansas, Fayetteville University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

ScholarWorks@UARK ScholarWorks@UARK

Communication Undergraduate Honors Theses Communication

5-2015

The quirky princess and the ice-olated queen: an analysis of The quirky princess and the ice-olated queen: an analysis of

Disney's Frozen Disney's Frozen

Juniper Patel

University of Arkansas, Fayetteville

Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uark.edu/commuht

Citation Citation

Patel, J. (2015). The quirky princess and the ice-olated queen: an analysis of Disney's Frozen.

Communication Undergraduate Honors Theses

Retrieved from https://scholarworks.uark.edu/

commuht/1

This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication at ScholarWorks@UARK. It has been

accepted for inclusion in Communication Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of

ScholarWorks@UARK. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected].

The Quirky Princess and the Ice-olated Queen:

An Analysis of Disney’s Frozen

An Honors Thesis submitted in fulfillment of the requirements for Honors Studies in

Communication

By

Juniper Patel

2015

Communication

J. William Fulbright College of Arts and Sciences

The University of Arkansas

ii

Acknowledgements

This thesis would not have been possible without the support of Dr. Stephanie Schulte,

Assistant Professor and my thesis mentor. I would like to express my sincerest gratitude

for her unwavering support, expertise, insight, and thesis assistance. Many thanks for her

support in attaining the Student Undergraduate Research Fellowship (SURF) award and

travel grant to present my paper at the Popular Culture Association and America Culture

Association National Conference in New Orleans.

I would like to thank Dr. David A. Jolliffe, Professor and Brown Chair of English

Literacy and Dr. Lauren DeCarvalho, Assistant Professor, for their recommendations for

the SURF grant application. In addition, I would like to thank them and Dr. Fiona

Davidson, Associate Professor and Director of European Studies, for being on my Honors

Thesis Committee.

I would like to thank the Honors College and the Arkansas Department of Higher

Education for funding my research and for funding my travel to present my paper. It was

an invaluable experience to present my paper and to see other presentations.

I would like to thank Hershel Hartford, Administrative Support Supervisor of

Communication, for assisting me with my conference travel. Additionally, I would like to

thank Pat Turner, Grant Specialist at Research and Sponsored Programs, for her SURF

grant assistance.

Finally, I would like to thank my family for their support through this process and their

belief in me. In addition, I am grateful for the supportiveness of my friends.

iii

Table of Contents

Acknowledgement ……………………………………………….… ii

Introduction …………………………………………………….…. 1

Summary of the Film ………………………………...……. 4

Princess Films: A Historical Generic Comparison ….…... 9

Chapter 1: Anna, the Quirky Princess …………………………..14

Comparison of Anna to Disney Princesses ………………14

Classic Disney …………………………………...…14

Renaissance Disney ………………………………...18

Revival Disney …………………………………….. 19

Anna’s Story Arc ………………………………………….20

Anna Seeks Love ……………………………………21

Personal Boundaries and Agency …………………..22

Anna Transformed ………………………………….24

Chapter 2: Elsa, The Ice-olated Queen ………………………......27

Villain-like Elsa …………………………………………... 27

Comparison to Disney Princesses………………………... 29

Classic Disney ……………………………………....30

Renaissance Disney………………………………....31

Revival Disney ………………………………….…..32

Elsa and the Depiction of Anxiety and Depression ….…..35

Childhood Trauma ……………………………….....35

Elsa’s Coping Mechanisms ………………………... 39

Elsa Transformed ……………………………….…..41

Love is the Answer ……………………………….....42

Conclusion ……………………………………………………...….44

Works Cited ………………………………………………….…...54

Patel 1

Introduction

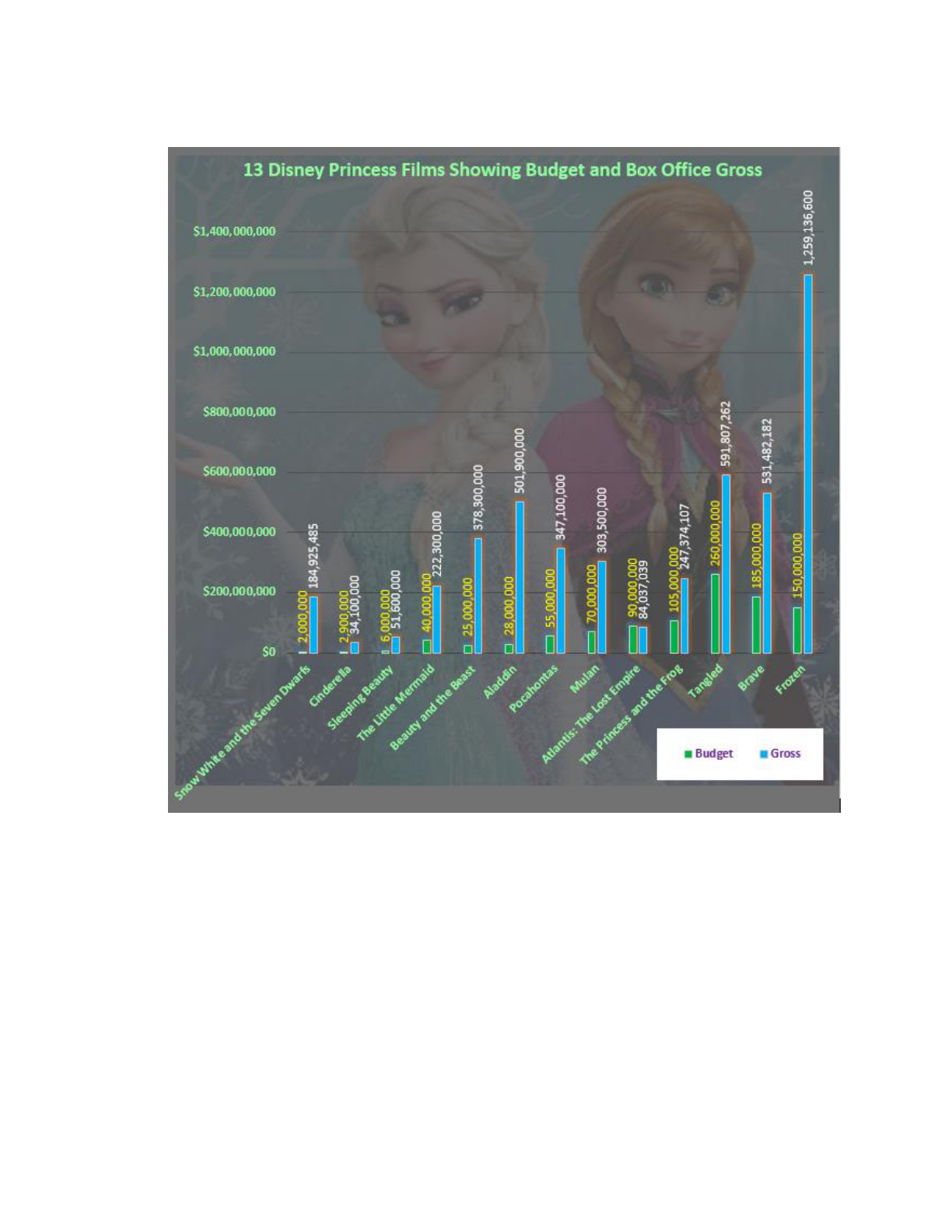

In June 2014, The New Yorker magazine reported that the film Frozen had “taken

over the world” (Konnikova). The blockbuster, Frozen, is one of the most highly

successful films, receiving both financial and critical acclaim. It is the fifth highest

grossing film of all time, earning over a billion dollars at the box office (“Frozen

Becomes”). The film won a British Academy of Film and Television Arts Award

(BAFTA), a Golden Globe, as well as two Academy Awards in 2013, including Best

Animated Feature Film and Best Original Song for “Let It Go” (Gioia). The outstanding

original music is a key element in this film’s success and popularity. “Let It Go” still

receives airplay nearly a year after hitting number five on the Billboard Hot 100 singles

in the week of May 3, 2014 (“The Hot 100”). It became the first Disney movie song to hit

the Top 10 since 1995 when the song “Colors of the Wind” from Pocahontas (“Vanessa

Williams”) enjoyed this recognition. “Let It Go” stands to become a classic along the

lines of “Zipadeedoodah” or “Hakuna Matata.” Countless translations and covers have

been performed of this song. A Google video search for “let it go cover” shows 86.5

million results, including an animated male vocal version featuring Nate Smith (Jess the

Dragoon). The Walt Disney Animation Studios YouTube channel clip of “Disney's

Frozen ‘Let It Go’ Sequence Performed by Idina Menzel” has received over 400 million

views so far. The complete Frozen soundtrack was the number one album on the

Billboard 200 chart for 13 non-consecutive weeks (Caulfield,“‘Now 50’”) making it the

longest selling number one animated soundtrack by surpassing Lion King’s 19 year claim

to this honor (Caulfield, “‘Frozen’ Earns”).

Patel 2

Frozen’s appeal continues to garner tremendous media and popular culture

attention with high demand merchandise, numerous articles and countless memes.

Tourism trips to Norway, the country which inspired the film’s settings, has risen notably

since Frozen’s release. In the first quarter of 2014 alone, the country reported a 37%

increase in hotel bookings (Stampler). Frozen’s continuing popularity and success define

it as a cultural product that has struck a resounding chord with audiences and critics alike.

Investigations into key films such as Frozen offer a deep look into the underlying values

of American culture. The continuities and discontinuities between it and previous Disney

films illustrate Frozen’s historical importance. Films are not merely reflective objects;

they also have formative power. Indeed, as media scholar Douglas Kellner argues,

“products of media culture provide materials about which we forge our very identities”

(9). A film such as Frozen can have deep impacts at an individual level. Therefore, this

film analysis hopes to offer insight into both American culture and American audiences.

Because this film is so new, there is little scholarship on Frozen. With this thesis,

I hope to begin building critical scholarship on this important film. My primary objective

is to provide an in depth analysis of Frozen’s main characters, the sister princesses Anna

and Elsa. I focus on plots and themes from their story versus previous princess films to

show how and where Frozen deviates from the long standing traditions of fairy tale films.

My first chapter compares Anna’s characteristics and storyline to previous Disney

Princesses and Disney Princess movies. In particular, I discuss how Anna’s romantic

storyline deviates from earlier Disney Princess films. In the second chapter, I focus on

Elsa, detailing the manner in which she resembles combined aspects of both Disney

villains and princesses. I delve into Elsa as a misunderstood protagonist and not as the

Patel 3

villain of the “Snow Queen” fairy tale from which her character is derived. In addition, I

explore how her mental disability links with her self-actualization. This reading takes into

account not only the film itself, but also Frozen’s acclaimed soundtrack and the

importance of what each sister vocalizes in song. I also consider the stylistic choices

made for the animated characters including: wardrobe, body posture and movement,

facial expressions, and voices.

Finally, I conclude by outlining the implications of my findings, including what

this film might indicate about American contemporary culture and viewers. I engage

feminist media studies scholarship as a lens through which to critique the film. I discuss

how women and women’s bodies serve as commodified objects. To do this, I compare

the sisters’ journey to Sarah Banet-Weiser’s idea of the commodification of authenticity,

where authenticity is utilized for branding purposes (Jacobson 673). I explore this

concept in relation to the characters Anna and Elsa. Some critics view Frozen as a pro-

feminist, progressive film. For instance, Todd McCarthy’s review for the Hollywood

Reporter noted that Frozen contains “contemporary attitudes and female-empowerment.”

Frozen is the first Disney film that has a woman co-director, with screenwriter Jennifer

Lee at the helm, which suggests a progressive representation of women. Having women

in prominent positions behind the camera has been shown to statistically improve and

increase the representation of women on screen (Lauzen). In fact, Frozen is receiving

backlash from the Christian right for having too rebellious motifs and being seen as

advocating “a gay agenda” (Skaggs) that will “indoctrinate” children to be lesbians

(“Disney’s ‘Frozen’”). The LGBTQA community also views Frozen as an allegory for

coming out but in a much more positive light (Diaz). I explore the notion that Frozen is a

Patel 4

feminist film and gauge the progressiveness of the movie in the context of its depiction of

the female leads, showing how Frozen represents women as multi-dimensional

characters, and importantly, as driving their own stories.

Summary of the Film

Because my film analysis relies on understanding nuanced character development

and complicated plot shifts, I have included a rather extensive summary of the film for

ease of reference. This summary lays the groundwork for understanding the greater

context behind subtle character relationships and interactions. In addition, this summary

also makes this analysis legible to readers who have not recently screened the film.

Frozen is about two sister princesses of Norwegian styled Arendelle: Elsa and

Anna. Elsa is the elder, in line to be queen, and possesses ice magic powers. The

importance of music in this film is immediately emphasized as Norwegian styled

chanting plays behind the brief opening credits and transforms into a deep-voiced, hearty

work song of men cutting ice. In the mountains, a young boy frolics with his reindeer calf

and emulates the ice cutters. The scene shifts to the Castle of Arendelle where the two

princesses are young girls. Little Anna wakes Elsa and convinces her to sneak into the

ballroom to play with Elsa’s ice magic. Things go awry when Anna enthusiastically

jumps off a large pile of snow faster than Elsa can produce a soft landing for her; Elsa

accidentally hits her sister in the head with an icy blast of magic. As Elsa reacts with fear,

her fun magic changes to a brief, wild-spreading freeze through the floor and walls. Their

parents rush in and take them to the rock trolls, magical creatures of the forest and

mountains. The young boy with the reindeer follows the royal family without being

noticed by them and observes what happens next. The leader of the trolls, Grand Pabbie,

Patel 5

cures Anna and takes away her memories of Elsa’s magic, implying that hiding the magic

is necessary. Grand Pabbie warns that Elsa’s magic will grow stronger and needs to be

controlled. He adds that fear is Elsa’s greatest enemy.

The King overreacts, exhibiting the very fear Grand Pabbie just warned him

about, and though the Queen appears calmer, she tacitly goes along with her husband’s

wishes. Elsa’s father orders the castle closed, and teaches Elsa to “conceal, don’t feel,”

imploring her to hide her powers (Frozen). Elsa becomes afraid of harming anyone else

and is isolated to ensure that everyone is safe. Thus, Elsa begins her estrangement from

her sister and the external world and Anna ends up lonely, missing her sister’s

companionship. Meanwhile, the young boy is adopted by the rock trolls.

A montage in which Anna sings “Do You Wanna Build a Snowman?” depicts

Elsa and Anna growing up separately, both feeling sad and alone. When Elsa is eighteen

and Anna fifteen, their parents leave for a journey overseas that ends with the ship

capsizing, drowning the King and Queen. Elsa and Anna are orphaned, separated from

one another, and isolated from Arendelle at large.

Three years pass and it is Elsa’s official coronation day now that she is twenty-

one. Arendelle is happily preparing. The visiting foreign dignitaries that are featured are

only men. The excitable Duke of Weselton, a small hyperactive man, is accompanied by

two hulking henchmen. Hans, a Prince of the Southern Isles, is mentioned as having

twelve older brothers. Anna wakes and sings “For the First Time in Forever,” excited at

the prospect of finally opening the palace for the ceremony, meeting new people, and

possibly making a romantic connection. In contrast, Elsa is dreading the audience and

afraid the secret of her magic will be exposed. Anna’s dreams are realized when she

Patel 6

literally bumps into the horse of a potential love interest, Prince Hans, just before the

coronation. Elsa dons gloves to assist in keeping her magic under control, and her best

hopes are realized when she handles her coronation without revealing her magic. Elsa

even happily connects with Anna at the ball following the ceremony. However, their

fragile connection is swiftly broken when Elsa emphatically tells Anna they cannot

continue to have visitors and refuses to explain further. Anna excuses herself, trips, and

Hans catches her. In her innocence, Anna proceeds to sing “Love is an Open Door,” a

declaration of love, with Hans. After the song ends, the two become engaged.

Anna and Hans return to the ball to ask Elsa to bless their union. However, Elsa

refuses to do so, stating “you can’t marry a man you just met” (Frozen). She and Anna

argue, and Elsa declares the ball over and begins to leave. Anna continues to harangue

Elsa and pulls off one of Elsa’s gloves. Elsa becomes angry and accidentally casts icicles

at the crowd. She then becomes scared about having revealed her secret. The Duke of

Weselton shouts out that she is a monster. Her magic bursting out of control, Elsa runs

away from the castle inadvertently leaving a huge snowstorm that engulfs Arendelle in

her wake. Once free from Arendelle, Elsa sings the hit “Let It Go” about finding freedom

to practice her magic and be herself now that she is alone beyond the bounds of society.

She creates an ice castle on a mountaintop as her new home.

Anna decides to find her sister, bring her home, and convince her to end the deep

freeze that has paralyzed Arendelle. She leaves Hans in charge of Arendelle. Seeking

warmth and supplies at a trade shop in the woods, Anna meets Kristoff. He, at first,

seems gruff but is revealed to be the grownup young boy, now a good-natured ice

salesman. Kristoff questions Anna’s judgement when he learns of her rapid engagement,

Patel 7

and cautiously does not tell her what he saw as a boy, but does agree to help find Elsa.

Anna, Kristoff, and Sven the reindeer are chased by wolves, escape, and befriend Olaf, a

plucky animate snowman inadvertently created by Elsa’s magic. The four of them reach

Elsa’s ice castle where Anna approaches Elsa. Their conversation turns into the song “For

the First Time in Forever (reprise).” Elsa becomes upset, her fear sets off the wild magic,

and she accidently hits Anna in the chest with it. Elsa, not realizing she has fatally injured

her sister, creates a giant snow monster to chase Anna and her companions away. Anna’s

hair develops streaks of white as a result of Elsa’s magic blast. This troubles Kristoff, and

he takes her to see the rock trolls who might be able to help with their magic.

Meanwhile, Hans leaves Arendelle with a party of men to find Anna whose horse

has returned riderless. The search party finds Elsa’s ice castle after Anna and her

companions have left. The Duke of Weselton’s henchmen attempt to kill Elsa. She

defends herself but is knocked out by a falling ice chandelier. She wakes up chained in a

prison cell in her Arendelle castle; Hans tells her Anna has not returned.

Deep in the mountains, the rock trolls perform an elaborate musical number,

“Fixer Upper,” in an attempt to kindle romance between Anna and Kristoff; Anna

collapses as the song ends. Grand Pabbie diagnoses Anna as having a Frozen Heart that

can only be cured by an act of true love. Thinking Hans must be her true love, Anna and

Kristoff rush back to Arendelle.

At the castle, just as he is about to kiss her, Hans pulls away and reveals his true

evil nature. After telling her she should have known a thirteenth son would only be after

her kingdom, Hans leaves the weakening Anna in a locked room to die. To the courtiers

Patel 8

and visiting dignitaries, Hans declares Anna dead as a result of Elsa’s magic, but not

before they said their marriage vows. As King, he sentences Queen Elsa to death.

Elsa escapes the prison using her magic, which conjures an even more intense ice

storm than before. Kristoff is returning to the mountains when he sees the new storm and

realizes that he might be Anna’s true love. Snowman Olaf rescues Anna from the locked

room motivated in part by seeing Kristoff and Sven racing towards the castle. Though

Anna is becoming more frozen by the minute, she and Olaf escape toward Kristoff for a

second potential true love’s kiss.

In the storm, Hans catches up with Elsa and lies to her that Anna is dead. Elsa

collapses in despair and the wild snowstorm pauses, every snowflake suspended

motionless. Before reaching Kristoff, Anna spots Elsa as Hans draws a sword to strike

her. With her last strength, Anna runs in front of Elsa and becomes completely frozen just

as Hans strikes. The blade shatters, Anna has saved Elsa.

Elsa is devastated and clasps her ice sculpture sister while she cries. Happily,

Anna unfreezes. By saving her sister, Anna’s act of true love also saves herself. Elsa

realizes the way to control and direct her magic is with love. Arendelle is relieved of the

deep freeze. Once unfrozen, Anna punches Hans in the face and sends him back to the

Southern Isles to face the judgement of his brothers. The Duke of Weselton is sent away

with all trade relations ended. Kristoff asks Anna if he can kiss her and she says yes. Elsa

is reinstated as Queen, gives Olaf his own personal snowstorm to keep him from melting,

and creates a rink for an ice skating party for the whole kingdom.

Patel 9

Princess Films: A Brief Historical Generic Comparison

Now that the film’s plot is clear, the next step is to contextualize the film within

the genre in which it appeared, to understand the film as part of a well-established

collection of Disney Princess films. This section of my thesis relies on generic criticism

as a method to analyze Frozen, investigating how the princess genre has changed over

time. Generic criticism allows the researcher to understand the larger connection of

media to society because categories used in the process reflect society’s beliefs, attitudes,

and values. Sonja Foss defines rhetorical generic criticism as an “attempt to understand

rhetorical practices in different time periods and in different places by discerning the

similarities in rhetorical situations and the rhetoric constructed in response to them” (Foss

233). The rhetorical situation behind the princess film genre is the role of women in

society in general and the role of love and men in the lives of women in specific. In this

project, I use a variant of generic criticism called “generic application,” defined by Foss

as a method for analyzing the content and form of a genre to compare the artifact to those

generic requirements for evaluative and/or interpretive purposes. While I do discuss the

central organizing plot structures of the films and individual motivations of the

characters, I do not separate out the characteristics of the princess film genre or the film

itself into “substantive” and “stylistic” categories, as Foss suggests, as it is difficult to

separate out content and form in cinema. Rather, I view them as overlapping constructs

that are often best discussed simultaneously. Therefore, this section first historicizes the

princess genre and then briefly details how Frozen both conforms to and breaks with

those historical generic conventions, thereby previewing the arguments made in more

detail in the subsequent film analysis.

Patel 10

Frozen is clearly a princess film: it features a princess. Frozen’s plot begins with

standard princess film conventions but, by the end, it has twisted these conventions into

new forms. First, princess films are traditionally centered on romantic love, meaning the

plots revolve around a princess finding love and the plot is resolved when the princess

finds the love, usually a prince. While Frozen’s plot still includes romantic love, audience

expectations about romance in princess films lead them to expect Hans to be the prince

charming. He is, conversely, the villain. An additional innovation is that the film’s plot

centers on familial love, specifically the relationship between the two sister princesses.

Though the sisters are separated by their parents’ misguided attempt to shield Anna from

Elsa’s powers, their love for each other abides and ultimately resolves the plot conflict.

There is no standard way of dividing up Disney’s animated feature films across

time. However, scholars do generally categorize them into three time periods: “the earlier

movies, the middle movies, and the most current film[s]” (England, Descartes, and

Collier-Meek 555). For the purpose of my study, and in keeping with popular culture, I

will call these three film periods: Classic Disney, Renaissance Disney, and Revival

Disney.

The Classic Disney era contains three princess films that Walt Disney worked on

himself: Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty. These films

are typified by heroines who are “innocent, naïve, passive, beautiful, domestic, and

submissive” (Wasko 116). The Classic princesses are “good, simple, and kind” (Davis

19) and only perform prosocial actions (Hoerrner 221).

Next, the Renaissance Disney era has five popular princess films made while

Michael Eisner was CEO of Disney: The Little Mermaid, Beauty and the Beast, Aladdin,

Patel 11

Pocahontas, and Mulan. The heroines of these films have increased agency but are still

highly complicit participants of patriarchal societies (Wasko 116). They are more

complex characters than Classic princesses; they take mostly prosocial actions and some

antisocial actions (Hoerrner 224-225).

The third era, Revival Disney, refers to Disney’s most recent animated films

under Bob Iger as CEO and with John Lasseter as Chief Creative Officer of Pixar

Animation Studios and Disney Animation Studios. So far, Revival films featuring

princesses are The Princess and the Frog, Tangled, Brave, and perhaps, Frozen. Revival

Disney princesses are depicted as having greater agency, actually achieving the goals

they set outside of marriage, and not necessarily needing a love interest at all (Rome

177). Anna and Elsa may be categorized as Revival princesses or may be categorized as

the beginning of a new era of Disney Princesses since they depict departures from

previous Disney films.

Throughout these eras, music is a key element. Disney songs mark important

character definitions and plot developments (Wasko 115). Princesses and supporting cast

members express their feelings, their life circumstances, as well as their dreams of future

accomplishments in song (Sells 183; Hoerrner 217; Henke, Umble, and Smith 235).

According to Don Hahn, Disney producer, songs “express the major turning points in the

story” (13). Frozen follows suit with the traditions of the musical genre, the soundtrack

emphasizes key transitions and evokes important emotional states.

Feminist media scholars have long studied the Disney Princess genre and they

agree overwhelmingly that Disney tends to frame “women’s lives through a male

discourse” (Zipes 89). In other words, the desires and actions of the female protagonists

Patel 12

are set within the parameters of a patriarchal society. Thus, women have less agency than

men. While this may be true of Classic and Renaissance Disney, these accounts do not

thoroughly consider Revival Disney princess films. The lead female characters in these

films show that Disney has shifted away from the previous princess tropes. Renaissance

era films begin this shift but do not entirely relinquish patriarchal traditions. For instance,

The Little Mermaid is more about disobeying a father than challenging a patriarchy. Yet,

although Ariel is primarily a rebellious mermaid princess, she still conforms to

patriarchal values by shaping her life around gaining the love, and hand in marriage, of

Prince Eric.

As I demonstrate below in more detail, Anna conforms closely with the typical

Disney Princess of any given era. Despite years of being shunned by her sister and being

overshadowed by the deaths of their parents, Anna still manages to be an optimist.

Optimism is a perennial Disney Princess characteristic, but Anna is developed beyond

this tradition. Anna is the most klutzy Disney Princess, which highlights her plucky

character and actually gives her some appeal. Rapunzel in Tangled premiers this

portrayal of more klutzy princesses, but Anna embodies klutziness at a new level

throughout Frozen. Perhaps the most interesting nuance of Anna is her love story.

Frozen’s plot is unique in that Anna’s initial love interest turns out to be a villain. These

aspects make Anna not just a readily acceptable protagonist and innovative character, but

also an interesting foil to Elsa.

While Frozen is defined as a princess film by featuring Anna as the protagonist,

the depiction of Elsa as an additional princess, and later queen, makes the film unique for

Patel 13

Disney. All previous films have only one leading princess, or a leading lady.

1

In fact,

Frozen’s greatest departure from Disney Classics is Elsa’s complex character, not just her

presence in the cast. Elsa often seems more similar to Disney villains than princesses, in

large part because she suffers from mental illness. Rather than following the typical

character tropes for a princess from any era, Elsa is portrayed as a misunderstood

character. Mental illness often appears in Disney Princess films. One study found eighty-

five percent of Disney films contain references to characters as mentally ill (Lawson &

Fouts 312). Characters are referred to as “crazy,” “mad,” or “nutty” in order to alienate

them (Lawson & Fouts 312). Characters that are mentally ill are usually portrayed as

objects of “derision, amusement, or fear” (Lawson & Fouts 313). While mental illness is

common in the princess genre, the princesses themselves are not mentally ill despite the

hardships they may endure. New in Frozen, Elsa suffers from depression and anxiety and

is ostracized from society. Below, I explore in more detail to what extent Elsa’s character

stigmatizes or destigmatizes mental illness and how she may appear to be villainous in

her attempts to be virtuous.

1

Mulan is listed here as a “leading lady” because she is technically not a princess,

although she is a part of the official Disney Princess franchise (Orenstein).

Patel 14

Chapter 1: Anna, the Quirky Princess

Comparison of Anna to Disney Princesses

Understanding the periodization of the Disney Princess film genre is essential to

understanding Frozen, its aesthetics, its representations, and its role as a market object

and a potential social actor. In this chapter, I focus in depth on Anna, referring to princess

portrayals from the different eras and the plot summary above. I compare her character

traits, her relationships with other characters, as well as the way she is drawn and

animated, to other Disney Princesses.

Anna’s personality and mannerisms are in keeping with the Disney Princess trend

to depict increasingly capable and proactive princesses, seen most recently in The

Princess and the Frog (Tiana), Tangled (Rapunzel), and Brave (Merida). The princesses

of these Revival Disney films all demonstrate increased agency in their stories. Anna, in

many ways, reflects and embodies recent Disney Princesses while advancing their

portrayals to an even higher level of empowerment. Few Disney Princesses have siblings,

but unlike Ariel and Merida, Anna has only one. Anna is not engaged or married by the

end of her film, only Pocahontas, Mulan, and Merida share this characteristic. Anna is

also one of the few Disney Princesses to save herself, a feat that not even the strongly

enabled Rapunzel managed. Uniquely, Anna is the only Disney Princess to have her

prince turn out to be evil in that he is willing to let her die and attempts to kill her sister.

Classic Disney

As mentioned in the periodization, the Classic Disney princesses are relatively

simple characters (Wasko 116). Physically, they appear beautiful, young and graceful.

Elizabeth Bell, Associate Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences at the University of

Patel 15

Southern Florida and Gender Studies Scholar, notes that artists sketched the Classic

Disney princesses based on “popular images of feminine beauty and youth” (109).

Cinderella looks “cultured and stately even in her work clothes,” following Disney’s

edict to his animators that princesses must look pretty in all circumstances (Bell 109).

Many Disney Princess proportions are exaggerated. For example, Jasmine from Aladdin

has eyes “bigger than her waist” (Dill 135). Sociology Professor, Philip Cohen, notes that

either of Anna’s eyes is bigger than her wrist, stating that “large eyes and small wrists”

are often part of the Disney femininity. Despite advances in overall characterization, the

princesses of Frozen still depict a definition of beauty unattainable in reality.

To argue that Disney Princesses are physically pretty and graceful is not to argue

that their bodies are weak. The tradition of drawing princess bodies based on ballerinas

continues in Frozen and thus, they all have strong posture and muscle tone. Bell notes

that Disney Princesses “have back-bone” (112), even when their personalities do not,

which strengthens their overall character.

Anna’s posture is strong and erect, yet she is klutzy, contradicting the Classic

Disney princesses who are shown to be “at the idealized height of puberty’s graceful

promenade,” following Disney’s animation edict that princesses must look pretty (Bell

108). Though she runs into things, trips, and falls throughout the film, she does recover

smoothly from her clumsiest moves. She exhibits excellent aim throwing whatever is at

hand at the wolves and the ice monster, and coldcocks Hans squarely on the jaw.

Although Anna’s body shape is in keeping with previous princess models, her

movements do not always reflect the strong body postures or grace of ballerinas. For

example, she almost falls while dancing at the ball. When searching for her sister, she

Patel 16

knocks into a tree, causing snow to fall on her, tumbles downhill and plunges into an icy

river. She even slips on the ice rink at the end. Despite her often awkward and stumbling

movements, Anna has her fair share of strong physical actions. She unwaveringly fights

off wolves alongside Kristoff. Anna attempts to climb the steep rocks to reach Elsa’s ice

castle, albeit her feet keep slipping. She has great difficulty in accomplishing this task

and is saved from the grueling climb by Olaf, who discovers an icy staircase. She

demonstrates her coordination when she hits Marshmallow with a snowball. During the

falling action, she angrily punches Hans in the face for almost killing her and her sister,

let alone betraying her feelings for him.

While she is beautiful in many of the same “ballerina” ways as her predecessors,

it is important to note that Anna is shown as a drooling mess with unruly hair on the

morning of the coronation. This scene is a marked deviation from Disney precedents in

which princesses almost always look lovely (Wasko 111). Even though it is brief, Disney

decided to depict a princess as less than beautiful, like an average person, thus increasing

sympathy for her character. Granted this is when Anna has just woken up, when most

people do not look their best, but it may open the door to other depictions of positive

female characters shown as less than perfect in appearance. Thus, Anna’s physicality is

complicated. She is both physically similar and dissimilar from Classic Disney

princesses, both beautiful and klutzy, graceful and not.

In keeping with her physical clumsiness, Anna is often shown as anxious or

awkward in her interactions with other people. For example, when she encounters Hans

for the first time she stumbles not just into his horse, but also over her words. She is even

nervous when speaking to her sister at the Coronation Ball. When she alternately entreats

Patel 17

and commands Kristoff to help her find Elsa, her arms are awkwardly placed, matching

her awkward speech. Given Anna’s relative isolation growing up, her fumbling behavior

and uncertainty are understandable. However, Anna also has her confident, undaunted

moments in the film. When she confronts her sister in the ice castle, and when she

confronts Hans near the end of the film, she is direct and eloquent in her manner. She

does not trip over her words and has a dignified posture as she sings to Elsa in the castle

and later to Hans as she saves the day. Despite her power to have Hans executed, she

shows a noble rationality and grace by having him sent back to his brothers instead.

Similarly, her personality also demonstrates both continuity and discontinuity

with her predecessors. She is innocent and lacking in experience outside of the castle. Her

naïveté is evident in her quick trust of Hans and her rushed engagement. However,

despite her youth and inexperience, Anna is quite capable of independent action and of

driving the plot through her own desires. She decides to leave Arendelle to search for her

sister and no one tells her to stay in the castle like a good little princess. She valiantly

helps Kristoff fend off the wolves and throws a snowball at Marshmallow, the giant snow

monster, despite Kristoff’s protests in both events. In contrast, Cinderella’s agency is

extremely restricted; what happens to her is a result of circumstances rather than her own

actions. After her father dies, Cinderella is at the beck and call of her stepmother and

stepsisters. In addition, Cinderella is unable to attend the ball without the help of her

animal friends and Fairy Godmother. While Anna is good and kind, she is not simple.

She proves throughout the film that she is intelligent. Anna uses her complex thinking

skills in her steadfast determination to save her sister and the kingdom from perpetual

Patel 18

winter. Anna seeks appropriate tools from the shop that she happens upon. She drives the

plot, enlisting the help of Kristoff, Sven, and Olaf in her search for Elsa.

Renaissance Disney

Anna’s behavior resembles that of the Renaissance Disney princesses: Ariel,

Belle, Jasmine, Pocahontas, and Mulan. Renaissance Disney princesses are more

intelligent and independent than Classic Disney princesses, however, their lives are still

determined by men (Wasko 116). Renaissance Disney princess story plots are largely

dictated by the pursuit of love and marriage to a prince.

In addition to the stylized poise of Classic Disney princesses, Renaissance Disney

heroines incorporate teasing, burlesque style body movements (Bell 114). For instance, in

The Little Mermaid during the “Under the Sea” song sequence, Ariel makes sultry moves

when several fish swim close by. Although Anna does not move as suggestively as Ariel,

she does move with considerable fluidity, despite her tendency to bump into things.

During a moment in the song “For the First Time in Forever,” her movement is clearly

seductive when she leans against the wall covered in a window drape. However, her

sexuality is undermined when she whaps herself in the face with the curtain cord. A

similar moment follows when she coyly flutters her fan and immediately greedily stuffs

chocolate in her mouth.

While the Renaissance Disney princesses are stronger characters than Classic

Disney princesses, they still lack in agency. Despite grandiose dreams, they ultimately

find happiness in marriage. Although Belle, from Beauty and the Beast, initially sings of

seeing the world, she abandons that goal to become a princess and wife (Murphy 133;

Patel 19

Henke, Umble, and Smith 246). Similarly, Ariel, from The Little Mermaid, initially

dreams of exploring the fascinating and relatively unknown human world. However,

Ariel’s desire quickly becomes focused on her love, Prince Eric, rather than the human

world in general (Sells 176). Yet, this is not true for the titular characters of Pocahontas

and Mulan; their culturally diverse backgrounds seem to provide them with greater

agency, and both save the day. Their films depict cultural issues of female representation

within male dominated societies. Both characters are based on real people and historic

events, and this may explain their more direct guidance of their stories (Henke, Umble,

and Smith 247). Ariel and Belle, despite being less crucial in their own salvations, do at

least save their respective princes at least once within their films (Davis 9). That said, the

men must fight the ultimate battles: the Beast saves Belle from the wolves, and Eric saves

Ariel from Ursula.

On the one hand, men determine the shape of Anna’s life in many ways. Her

father allows a male rock troll to erase her memory. Hans takes power over Arendelle for

much of the film, although he is ultimately thwarted. On the other hand, Anna shapes the

lives of men around her. Kristoff mostly defers to Anna. Kristoff tells Anna that he will

fend off the wolf pack but Anna pitches in. It is clear that Kristoff has no control over

Anna’s actions. For example, when he tells her not to upset Marshmallow by throwing a

snowball at him, she does it anyway. Kristoff even steps aside at Anna’s prompting to

allow her to deal with Hans on her own at the end.

Revival Disney

Anna is most akin to Rapunzel, from Tangled, in that despite spending much of

her time alone, she remains optimistic, friendly, and inherently trusting. Rapunzel is

Patel 20

clumsy, although Anna is much more so. This clumsy image helps the audience relate to

Anna more easily than to the unattainably perfect Disney Princess standard. Anna is also

similar to Merida in that she ultimately saves the day and is the central driver of her story

(Rome 178). Anna’s love plot is like Rapunzel’s in that both show the men assisting the

women towards destinations chosen by the women. Unlike Anna, Rapunzel is engaged by

the end of her film and has an additional short film, Tangled Ever After (2012) that

depicts her marriage. Dissimilar to Rapunzel, Anna is betrayed by her initial love interest.

Thus, Anna continues the recent traditions of Revival Disney but takes the movement to

another level.

Anna’s Story Arc

Frozen’s story arc upsets the typical woman vs. woman dynamic of many Disney

Princess films. Previous Disney Princess films of all periods rarely show women

supporting women. Instead, a woman is in opposition to another woman and/or a woman

is almost completely surrounded by men. For example, Snow White and the Seven

Dwarfs, Cinderella, and Sleeping Beauty all have young female protagonists targeted by

older woman. In Mulan, Mulan spends the majority of the movie with male companions

and is not seen as having relationships with women outside her family. This pattern also

extends to male-male interactions, meaning the male villains are often seeking power in

opposition to other males. In Aladdin, Jafar is trying to take power from the Sultan, and

in Mulan, Shan-Yu is trying to bring down the Emperor. Female same-sex collaboration

does not often occur in these films. However, in Frozen, instead of fighting over power

and beauty, Elsa and Anna contend over what is best for each other and Arendelle. Anna

is constantly trying to show support for her sister which her sister consistently rejects on

Patel 21

the basis of trying to protect her. Thus, Frozen is a story of two women who, despite their

arguments, ultimately work together in support of each other.

Anna Seeks Love

Many of Anna’s personal characteristics—including her klutziness and her naïve

optimism—are revealed through song. For example, one scene depicts the townspeople

being excited about the coronation and seeing the princesses. A man says, “I’ll bet they

are absolutely lovely” (Frozen), referring to the princesses. Humorously, the film cuts to

Anna looking very messy as she wakes. This is the lead-in to the song “For the First Time

in Forever” which features a montage sequence of a now beautified Anna running and

jumping all around the castle with joy, exuberance, and a little klutziness. She is not the

perfectly-poised Cinderella, a depiction likely designed to induce kinship with the

character and endear her to the audience. This musical number invites the audience to

think of their own quirky and klutzy moments, to share in Anna’s joy at an opening

world, to feel anticipation along with a girl who longs for company. From the lyrics, we

hear her tremendous excitement about having guests for the first time that she can really

remember. By watching her movements, we also learn she was so bored for years that she

actually memorized the poses in each painting within the castle. She sings about “the

one,” the love interest fantasy shared by most Disney Princesses in their songs. This song

establishes who Anna is three years after her parents’ death. The song also sets up the

audience to expect a love interest, playing up the genre tradition of having a leading

“prince charming” to match the “princess charming.” Without this priming, the audience

might be more skeptical of Hans, who Anna meets at the end of the song when she comes

face to face with him right as she sings the lyric: “Nothing is in my way” (Frozen). Hans

Patel 22

is physically in her way, playing on the lyric, but this also subtly foreshadows that he will

actually be in her way as the plot thickens.

The song “Love is an Open Door” exhibits Anna’s impulsiveness and naïveté, but

it simultaneously leads the audience to further trust Hans. This song centers on the

compatibility between Anna and Hans. Hans sings, “We finish each other’s…”

“Sandwiches,” Anna pipes in. Hans’ eyebrows briefly go up in surprise, but he states

“that’s what I was gonna say” (Frozen). His blatant willingness to be so agreeable at this

point in the film could be read as indicative of their status as soul mates or indicative that

Hans has his own agenda. Because of the genre conventions and because audiences are

primed from the previous song, “First Time in Forever,” the audience is likely to accept

Hans as authentic and a soul mate. With subsequent viewings, however, viewers will note

the ways this song foreshadows Hans’ villainy, including a moment when he sneaks up

and grabs her from behind. At the end of the song, Hans proposes to Anna. She naively

and impulsively agrees to marry a man that she has just met.

Personal Boundaries and Agency

Kristoff is Anna’s second love interest, which is unique for the princess genre.

2

When Kristoff first appears as an adult, his face is obscured, and he is covered in snow

from head to toe. He behaves in a gruff manner that makes him seem intimidating and

villainous. However, it quickly becomes clear his behavior is mostly bravado. He is not a

prince and has been raised by the rock trolls. His character is down to earth, exemplified

by his close connection to his reindeer, Sven. His earthiness is also depicted in the weird

2

This has only occurred in one other instance in the Disney world. In the film, Enchanted

(2007), Giselle has two love interests, but neither are evil in nature.

Patel 23

bodily jokes made about him, like his propensity to pee in the woods—pointed out by a

rock troll—and his body odor—which he notes himself in song.

Kristoff is initially presented as unfriendly and verbally confrontational. Though

he does not seem to like people, demonstrated most clearly by his song “Reindeer(s) are

Better Than People,” he is willing to help Anna. Like Elsa, Kristoff questions Anna’s

decision to marry Hans so soon after meeting him. Importantly, Kristoff is portrayed as

being respectful of Anna’s physical space. When Anna complains about feeling cold, he

makes a move to put his arm around her, thinks better of it, and instead finds a warm

steam vent they can stand over. He listens to Anna when she says she can deal with Hans

herself. Very significantly, he asks Anna’s permission to kiss her. These actions are in

keeping with a respect for bodily autonomy. Hans, the villain, does not observe these

behaviors, most noticeably by acting duplicitously when he leans forward to kiss Anna.

Anti-Bullying Program Director, James Utt, cites the importance of masculinity

transformation over the patriarchal dominated traditions to promote pro-feminism

ideology. Kristoff demonstrates the masculinity transformation with his respect for

Anna’s agency and is actually a good role model for young boys to emulate.

However, the song “Fixer Upper” actually violates many of these respectful

behaviors. The trolls have no regard for honoring engagements, let alone Anna’s or

Kristoff’s opinions on a potential relationship between the two of them. This can be seen

as the musical number sets up a wedding ceremony for the two without asking consent.

Also, the trolls seem to care more about trying to unite the couple than listening to

Kristoff’s story about Anna having been hit by ice magic. Although the song functions as

comedic relief and a sort of love song between Kristoff and Anna, it may be viewed as

Patel 24

foreshadowing the conclusion of the movie as it speaks to “love” helping those who are

“mad or scared or stressed” which is how Elsa is presently feeling (Frozen).

Anna Transformed

Anna changes and grows throughout the movie. In many ways Anna’s story arc

provides Anna with experiences that mirror Elsa’s, leading Anna toward a better

understanding and more empathy for Elsa. At the beginning, while Anna definitely feels

lonely and isolated, it does not cause her severe anxiety or depression. Anna grows up

similarly to Elsa, however she has more freedom than Elsa to move about the castle.

Later, when Anna is betrayed by Hans, she is finally given a taste of what Elsa has felt

for years. Anna is physically imprisoned in a room, her hopes crushed, much like Elsa is

physically imprisoned in the dungeon. Anna is unable to act because she is slowly

freezing to death. Anna must be feeling abandoned by Elsa, who refused to come home

with her from the ice castle, unaware that Anna’s heart is unintentionally and slowly

freezing. The camera angle emphasizes Anna looking forlorn sitting on the floor, which

mimics a scene earlier in the film of a younger Elsa sitting sadly against the door of her

room after hearing about their parents’ death. Frost covers the room and wisps of

snowflake float in the air; younger Anna sits on the other side of the door looking equally

upset. Now, as the action of the climax begins, Olaf unlocks the door with the carrot nose

Anna gave him, kindles a fire and bolsters Anna’s hope with the realization of Kristoff’s

love for her. When Olaf saves Anna from freezing, it is almost as if Elsa is indirectly

saving her since Olaf is an extension of Elsa’s magic, but the carrot nose given by Anna

becomes the actual key.

Patel 25

Anna freezing can be best described as a representation of the trauma caused by

her family suppressing Elsa’s magic. Anna’s physical state embodies Elsa’s emotional

state. Interestingly, when Anna is first hit in the head as a child by Elsa’s powers, Grand

Pabbie states “that the head can be persuaded” (Frozen). This is significant as the head is

the seat of human logic and reason. Thus, the head can be persuaded because as long as

one is using logic and reason, one is apt to be swayed by a rational and logical argument.

Grand Pabbie goes on to warn that “the heart is not so easily changed” (Frozen). The

heart is symbolic of human emotion. It is much harder to persuade someone on a subject

when they have deeply held feelings about political or religious beliefs and values. Only

actions and reasoning based on strong and true emotions can change how someone

deeply feels. Elsa tries hard to repress her feelings throughout the film, in contrast to

Anna who is emotionally open and expressive. For their characters to grow, Elsa needs to

learn to let her feelings flow and Anna needs to learn to be reserved. By being cursed

with a frozen heart, Anna is able to understand better what it was like for Elsa growing

up. Through Anna rescuing her, Elsa realizes she needs to express and share love in order

to control her magic. An act of true love is an incredibly persuasive emotional argument

to sway Elsa as Anna freezes and closes to the world, Elsa thaws and opens up.

Not only does having her heart frozen give Anna an inkling of what it is like to be

Elsa, it also provides the vehicle to a major twist on the classic role of a Disney prince.

Every prince, starting with Snow White’s Prince Charming all the way through

Rapunzel’s Eugene Fitzherbert aka Flynn Rider, heroically defeats the story’s villain.

However, in Frozen, the prince does not defeat the villain; the prince is the villain. Hans’

turn to evil is sudden and largely unexpected, due to the audience genre expectations and

Patel 26

only subtle foreshadowing. Previous heroes—such as the Beast in Beauty and the Beast—

behave poorly, a plot device that creates conflict. However, the Beast is redeemed by

Belle’s love and turns out to be a handsome prince who is generally charming. In

previous princess stories, a woman’s love makes a man a good person. Hans, in contrast,

has no avenue for redemption, regardless of whether he receives a woman’s love. Frozen,

unlike Beauty and the Beast, suggests that not only does love not always contain

redemptive power, but also that love may be untrue or disingenuously offered. False

professions of love may be a strategy for manipulation.

In summary, although Anna begins her story as innocent and naïve, she is not

pristine and perfect. Her slim, feminine ballerina figure, so similar to all previous

princesses, is mitigated by her perpetual clumsiness and the uniquely slovenly glimpse of

her waking up. Anna is not weak, passive, submissive, pristine, or incapable of

independent action. She is a natural leader who is willing to take risks to reach her

desired goal. Her character gains experience primarily through her own initiative. She

prioritizes her sister and family issues over her search for a man. She shows character

growth by taking her relationship with Kristoff slowly and in her decisive, fair-minded

handling of Hans. She shows compassion when Hans is banished instead of sentenced to

death. In these complex representations, Anna draws on Classic, Renaissance, and

Revival princess traditions while also expanding them into new territories. Indeed, the

film provides one of its most interesting plot twists by tapping audience expectations of

princess films, in particular the expectation that prince charming will save the day.

Patel 27

Chapter 2: Elsa, The Ice-olated Queen

Villain-like Elsa

While Elsa shares some commonalities with previous Disney Princesses, she also

has commonalities with past female Disney villains. Through Elsa, Frozen depicts the

greatest departure to date from the Classic Disney films. In an interview with Metro

Newspaper, co-director and writer, Jennifer Lee stated: “Originally, Elsa was a villain”

(Ivan-Zadeh). Her character’s origins stem from the Hans Christian Anderson fairy tale in

which the Snow Queen is an embodiment of evil and is not a member of the royal family.

Elsa has powerful magic, a villainous trait established by the Evil Queen in the

very first Disney feature, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and propagated throughout

the Disney eras by Cinderella’s Lady Tremaine, Sleeping Beauty’s Maleficent, The Little

Mermaid’s Ursula, and Tangled’s Mother Gothel. Elsa separates her sister from her love

interest, Hans, a type of action reflected by several Disney villains. In addition, Elsa

curses “the entire society from which [she] is excluded” (Bell 117; Henke, Umble, and

Smith 244). However, unlike a villain, Elsa performs these actions without malice. Elsa

has the Classic Disney villain privilege of being the only character in a given film to

directly address the camera; this type of shot usually ends with a close up of the villains

eyes as the screen fades to black (Bell 116). However, Elsa’s direct facial shot at the end

of “Let It Go” does not fade. In fact, the scene ends showing Elsa’s impressively

conjured ice castle rather than her. In this way, Elsa is shown as similar to a traditional

Disney villain but not completely visually equated with one. She also does not meet an

untimely “literal or social death” as female Disney villains traditionally do for using their

power (Henke, Umble, and Smith 244). Thus, though Elsa is somewhat villainously

Patel 28

stylized, she joins the Beast and Flynn Rider (Rapunzel) as the character type of a

misunderstood protagonist. She is the first woman so portrayed in a Disney Princess

movie.

Elsa is similar to a villain in that she hides her true self and her powers, like the

Evil Queen who disguises herself to visit Snow White. Elsa exhibits traits that Disney

feminist scholar Elizabeth Bell describes as the femme fatale characteristics of Disney

female villains (115-118). Bell quotes Mary Anna Doane as summarizing a femme fatale

as never being “‘what she seems to be’” and as threatening in a way that is not “‘legible,

predictable, or manageable’” (115). Bell states that Disney femme fatales are “beautiful

and shapely” women with “power and authority,” wearing “clinging black dresses,” and

“thinking only for themselves” (Bell 115-116). Internalized sexism can occur with femme

fatales because they are “regularly looked at [and] evaluated on the basis of their

appearance” by society (Bearman, Korobov, and Thorne 16). She is subject to the male

gaze as femme fatales purposely are. The male gaze is when women in film “connote [a]

to-be-looked-at-ness” which objectifies them and often freezes “the flow of action”

(Mulvey 62).

Femme fatales are often, but not always, villains in the wide pantheon of Disney

films. One example of a non-villain femme fatale is Jessica Rabbit in Who Framed Roger

Rabbit. However, in Disney Princess films, the femme fatale character has always been a

villain, which scholars have argued indicates internalized sexism. In this model, Steve

Bearman, Neill Korobov, and Avril Thorne argue that in the:

omnipresence of media images of women, and through the direct gazes of men,

women are immersed in social environments in which they and other women are

… treated as if their bodies and looks represent something essential about their

personhood (16).

Patel 29

Disney female villains’ “excess of sexuality and agency is drawn as evil” (Bell 117).

Thus, a traditional link between sexualized beauty and malice is broken by Frozen. Elsa

becomes a femme fatale villain in appearance, but not intention. When Elsa embraces her

magical power during the song “Let It Go,” her appearance transforms into the sexualized

femme fatale style that female Disney villains often sport (Do Rozario 43). Elsa’s

subdued dress becomes sparkly and sexy, and her light make-up becomes heavier. Elsa

subverts Disney’s femme fatale villain because she embodies many traits of the femme

fatale, but does not act intentionally evil. Although Elsa’s character type of the

misunderstood protagonist is not necessarily new, the context in which she is placed is

different for the princess film genre. Disney villains are usually very black and white,

both in the colors used to draw them and their character depth. In contrast, Elsa is a much

more colorful character in inks, personality, and motivations. Elsa is depicted as an

extremely sympathetic, engaging, and complex character.

Comparison to Disney Princesses

Elsa stands out from most Disney Princesses in part because she has much in

common with past Disney villains. She is also one of the only princesses whom we see

crowned queen.

3

Even Disney Princesses who become implied queens, like Cinderella

and Snow White, have to be married to royalty in order to become a queen. Lacking an

axis of power themselves, previous Disney Princesses entice a prince to marry them to

gain full royal authority.

3

The only other princess that has a similar story is Kida from Atlantis: The Lost Empire.

Patel 30

Classic Disney

Elsa is not as naïve as most Disney Princesses, especially those of the Classic era.

While she does live a sequestered life much like Snow White, Cinderella, and Sleeping

Beauty, she does not share their inherent belief in the goodness of the world (Wasko

117). Instead, Elsa fears her secret being revealed, which leads her to be cold and distant,

but polite. Her worst fears are realized when the people learn of her magic and are afraid

of her. She reacts to their fear by running away as a means to protect her people from her

power. In her behavior, she is a far cry from the warm, sometimes domestic, figures of

the Classic Disney princesses (Wasko 117). She and Anna are never once shown

cooking, cleaning, or in peasant clothes as both Snow White and Cinderella are depicted.

Elsa is unique among princesses in the way she suffers emotional problems

stemming from an inability to control her physical powers. Elsa continues to seclude

herself after her parents’ death and seems to agree with them that she should stay away

from Anna and others. Since Elsa is a child when this decision is made, it is difficult to

correlate that the isolation is truly her own choice even in adulthood. She internalizes the

fears her parents emphatically express. According to scholars Jill Birnie Henke, Diane

Umble, and Nancy J. Smith, Cinderella exhibits clear signs of “external and internalized

oppression” in that “she only reacts to those around her” and “does not act” on her own

(236). Similarly, Elsa runs away partially in reaction to being called a monster. Unlike

Cinderella, Elsa does not remain “the perfect girl” despite her oppression (Henke, Umble,

and Smith 236). Instead of secluding Elsa, her parents could have handled the situation in

a different manner. After all, Grand Pabbie explicitly warned against fear and called for

learning to control the magic. The King and Queen could have sought advice to help Elsa

Patel 31

master her magic so that she could safely play with her sibling and find constructive ways

to use her power. Obviously, this would have removed the central conflict of the story so

we have to accept it as a plot device and a simple lesson for the audience. In Arendelle,

magic is not condemned, but dangerous magic is feared. As young children, Anna and

Elsa sneak off to play with her magic, which is presented as fun and enjoyable. There is

no indication they have been expressly forbidden to do so. The rock trolls practice magic

and Elsa’s parents believe them to be beneficent and wise. However, Grand Pabbie

expresses grave concerns regarding Elsa’s ice magic that are strongly conveyed to her

parents. In addition, after Elsa uses her powers in public, everyone appears shocked, if

not horrified, by its potential danger. Although clearly present, magic is not shown as a

prominent feature of Arendelle society. A lack of understanding influences Elsa’s

decision to flee the kingdom along with her fear of hurting others. Given Elsa’s long

separation from others and the internalization of her parent’s wishes, Elsa’s freedom to

use her powers once she leaves Arendelle feels liberating, a sentiment that bursts forth in

the song “Let It Go.” Classic princesses shift the opposite way in their story arcs, from

marginalization or containment to public participation. It is in joining (or leading) society

that the Classic princess finds resolution. Of course, Elsa finds social acceptance and

inclusion in the end, but her initial self-actualization occurs when she discovers freedom

and safety in the private expressions of her power. Also, unlike Classic princesses Elsa

does not need a man to bring her back into society.

Renaissance Disney

As noted earlier, Renaissance Disney princesses often move with a burlesque

style, which aligns with Elsa’s somewhat more sexualized transformation of appearance

Patel 32

(Bell 114). Elsa is also similar to Renaissance princesses in that she has greater agency

than Classic princesses. She demonstrates this when she retracts her winter storm and

saves Arendelle. However, she does not learn to control her magic without the help of

Anna’s unconditional love. Not only does Anna save Elsa’s life from Hans, but she also

inspires her sister’s realization that love is the force which can channel her magic in a

positive direction. Elsa’s experience is similar to The Little Mermaid’s, Ariel, when she

tries to assist Prince Eric who is wrestling her father’s trident from Ursula, the evil Sea

Witch, but is thwarted. She does help keep Eric afloat but Ursula grows giant-sized and

separates them. Ultimately, Eric plays a much bigger role than Ariel in that he is the one

who kills Ursula while Ariel helplessly watches. In contrast, Mulan has greater ability to

control her situation than Ariel and is not at the mercy of her assailant. Mulan saves

herself and her country with her own creative planning and skillful action to destroy her

nemesis, Shan-Yu. In some ways, Elsa’s depiction is not as progressive as Mulan’s, but is

advanced beyond Ariel’s. In the end, both Elsa and Mulan are strong agents in their own

stories and have autonomy in their actions. Yet, Elsa is nearly killed by Hans and does

require Anna’s assistance. Deviating most directly from almost all princess genre films,

neither Anna nor Elsa is saved by a man.

Revival Disney

Elsa’s character is in keeping with the Revival line of self-empowered Disney

Princesses. Like Tiana, Rapunzel, and Merida, Elsa has strong self-agency throughout

Frozen (Rome 177). Initially, her parents heavily influence her and she internalizes their

instruction to shelter others by remaining apart even after reaching adulthood. Despite

Anna and others offering advice, Elsa decides for herself what she deems best. Although

Patel 33

fear triggers her unintentionally dangerous magic, she acts without ill intentions. Her

continued isolation deepens the damage her father inadvertently inflicted upon her psyche

by instructing her to hide her power and her person.

By running away, Elsa hopes to create a new, authentic self, similar to what

Merida does in Brave (Rome 178). Merida determinedly fights the constructs of her

traditional patriarchy by refusing to marry or to stop being a tomboy (Rome 178).

Similarly, Elsa is subject to male power at the start of the film. The King controls her

actions in his mistaken reaction to the advice from Grand Pabbie. The facial reactions of

the Queen suggest her mother disagrees with her father’s actions, but her mother appears

subject to the same male domination and does not speak. To say that her father controls

Elsa and her mother is not to say that he wishes them ill will. On the contrary, he wishes

the best for them but fear is clouding his judgement. The fact remains that the King does

not ask the Queen what she thinks would be best for Elsa. It is not implied that the

Queen’s opinions are even expressed off screen. Although Elsa is initially subject to male

power, she does not remain so. Arendelle is prepared to crown her queen without a king,

and even immediately accepts Anna’s rule when Elsa runs away. Suitors from the other

kingdoms are emphasized as guests at her Coronation Ball, but the Classic Disney

wedding is not required for Elsa to claim power. This emphasizes that Elsa is not

dependent on a man to give her status and power or reinstate her into society. She

possesses these traits by her own rights as recognized by all supporting characters; there

is no question of her as a leader just because she is female as often seen in our society.

Whereas Frozen’s central conflict focuses on two sisters, Brave focuses on a

mother versus daughter conflict. In both movies, the women attempt to reach an

Patel 34

understanding rather than tear each other down. This is important because in previous

Disney films when there is conflict between two female characters, they are diametrically

opposed. Prime examples include Snow White and the Evil Queen, Maleficent and

Aurora, The Wicked Stepmother and Cinderella, all directly at odds with each other.

Before Revival Disney, more than one prominent woman rarely appeared in a film. If

they did, the plot generally kept the women separate. Feminist media critiques often focus

on “how women are ‘spoken for’ or ‘spoken about’” (Gallagher 25). For example, the

Bechdel Test evaluates bias in media (Scheiner-Fisher & Russell 222). The test

determines if a movie has two named female characters who talk to each other about

topics other than men (Bechdel). The percentage of films that pass this test indicates the

cultural trending between films in which men dominate narratives, even those

purportedly about women, and reveals films that emphasize thoroughly developed female

characters. Classic and Renaissance Disney princess films rate low in this test because

they depict, at best, basic female friendship, and something to do with a prince is

predominantly the crux of the relationship. Beauty and power under a patriarchal system

are the defining sources of conflict between the sets of princesses and their female

oppressors. However, Frozen rates highly on the Bechdel Test, a testimony to progress

made.

In another breakthrough, Elsa is shown to suffer from anxiety and depression

stemming from her forced isolation. No other princesses show these mental health

problems. Even Rapunzel from Tangled, who is more cut-off from society than Elsa, has

a chipper, outgoing personality. Rapunzel does have her chameleon friend, Pascal, for

emotional support, but the only other human she even glimpses for eighteen years is

Patel 35

Mother Gothel. Even though Mother Gothel is manipulative and cares more about

Rapunzel’s hair than Rapunzel, she does provide Rapunzel with some sense of being

cared for. Elsa, especially after her parents’ deaths, has no one that she feels is safe for

her to come in contact with. She believes she must keep everyone at arm’s length,

including her only sibling, for fear she will hurt them. This is the only way she knows to

express her care and it prevents her from directly experiencing care from others. Growing

up, she probably only has brief contact with castle servants and administrators at best. In

contrast, in The Princess and the Frog, Tiana has friends and family that love her very

much and give her a much greater sense of belonging than Elsa initially has. At the

beginning of Brave, Merida feels emotionally isolated from her mother who invalidates

her free spirited nature and her wish to remain single. Merida’s mother insists that Merida

must marry. Despite her mother, Merida is unafraid to chart her own destiny. Elsa,

however, is drawn into an opportunity for self-discovery by her sister’s actions rather

than creating her own chance to learn.

Elsa and the Depiction of Anxiety and Depression

Childhood Trauma

Scholars point out that Disney films predominantly depict mentally ill characters

as violent and unstable, like the villain Jafar from Aladdin, or as Belle’s isolated and

othered father, Maurice, in Beauty and the Beast (Lawson & Fouts 312-313; Stuart 102;

Stout, Villegas, and Jennings 552). Othering is a term coined to mean what happens to a

person or a group of people who are “treated in exclusionary ways” by society because

they do not fit the dominant values held in that society (Andersen & Hill Collins 8). This

scholarship argues that media depictions of mental illness affects viewers, especially

Patel 36

young viewers, who have little or no experience with people who are actually mentally ill

(Lawson & Founts 311; Stuart 102; Stout, Villegas, and Jennings 553). Frozen contains

verbal references to mental illness. For example, Olaf calls Kristoff “crazy” when

Kristoff introduces his troll family, who just look like rocks at first. Kristoff’s sanity is

further mocked because his best friend is the reindeer Sven. He even does an answering

voice for Sven when he talks to him. Anna and Kristoff are labeled “crazy” for going out

in the snowstorm by Oaken, the owner of the trade shop. However, neither Anna nor

Kristoff exhibit true mental disorders as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical

Manual of Mental Disorders: DSM-5. The Disney characters from any movie that are

called crazy, insane, or nutty would not be classified as actually having diagnosable

mental disorders found in the DSM-5. These characters are often eventually deemed

rational in the resolution of their films.

The trauma of isolation stemming from her powers and the erasure of Anna’s

memories causes Elsa’s mental illness. As the film starts, Elsa seems to be happy and

content in her life. We do not know the origin of Elsa’s ice magic, but do know her

parents and sister do not have it. At this point, her gift has not been demonized and she is

in control of it. Then, Elsa is frightened by accidentally blasting her sister. Elsa’s parents

do not cope well and hide behind fear of Elsa’s ice powers instead of helping her work

through it. They decide that controlling her ice magic means suppressing it. Her parents

severely invalidate their daughter by not only telling her to hide her talents, but also by

dangerously isolating her. Her parents admonish her to remember to “Conceal it … don’t

let it show” (Frozen). One of the most heartbreaking moments of the film depicts Elsa

telling her parents to stay away from her because she is afraid of hurting them with her

Patel 37

power. Elsa’s love and concern for their well-being further isolates her. Elsa believes

isolating herself is the best way to protect others from her ice magic.

Elsa follows her parents’ wishes by keeping her powers concealed and by

isolating herself until the day of her Coronation Ball. Rachel Simmons, Director of the

Girl’s Leadership Institute and Rhodes Scholar, notes that the good girl goal promoted in

princess films of “being absolutely kind and selfless is impossible” (6). Simmons

continues that focusing on being a good girl diminishes the ability to cope with stress (6).

Thus, the good girl stereotype is not a healthy one to emulate and may lead to depression.

Elsa’s imperative need for isolation and the resulting withdrawal are classic symptoms of

depression (DSM-IV).

Although Elsa’s mental illness is readily apparent, it is never explicitly talked

about in the film. In a response to a twitter comment, Jennifer Lee, the co-director of

Frozen, tweeted Elsa’s characterization “was intentional to show anxiety and

depression.” Therefore, it is not a stretch to say she deals with the mental disorders of

anxiety and depression, largely brought on by her parents’ unintentional emotional abuse.

In this case, Elsa’s father is the key player as Elsa’s mother silently stands by and

watches. Her father’s role in shaping Elsa’s identity is similar to the influence of many

previous Disney fathers. After Mulan has failed at the matchmaker’s test, her father

sagely tells Mulan that the flower that blooms late, is the most beautiful (Rome 179).

Thus, Mulan is shaped by her father’s advice in a more positive way than Elsa. Yet,

Elsa’s father remains idealized given his prominence in imagery during “First Time in

Forever” as Elsa stands before his coronation portrait as she sings and practices holding

the scepter and orb prior to her Coronation Ball. Frozen’s depiction of mental disorder is

Patel 38

ultimately mixed as Anna does show support for her sister despite Elsa’s anxiety and this

demonstrates a positive view of mental disorders (Stout, Villegas, and Jennings 553). On

the other hand, Elsa is also depicted as isolated, unstable, wild, and dangerous with

uncontrolled magic, exemplified when she throws icicles at the ball guests and

accidentally freezes a fountain as she flees the palace. The lack of control of her emotions

and powers is also seen both times Elsa accidentally harms Anna.

While Elsa’s emotional problems are not necessarily a result of the genetic wiring

of her brain, Elsa has been under the stress of fear for most of her life. In reality, this

would cause her biology to react and create chemical imbalances. Elsa’s recovery in

reality would take longer because correcting long-standing imbalances takes some time.

Thus, Elsa’s mental illness is oversimplified compared to the reality of depression and

anxiety. Unlike typical recoveries from depression, Elsa recovers exceedingly quickly at

the end of the movie when she achieves control of her powers with love. However, with

strong support from her family and community, Elsa is not shown to struggle with

lingering anxiety and fear issues.

Truthfully, mental disorders are often a lifelong struggle though they can be

managed. Despite the oversimplification, I believe it is a good message to convey to