DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT B: STRUCTURAL AND COHESION POLICIES

AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT

COMPARISON OF FARMERS’ INCOMES

IN THE EU MEMBER STATES

STUDY

This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Agriculture and

Rural Development.

AUTHORS

1

University of London: Professor Berkeley Hill, Emeritus Professor of Policy Analysis

Agra CEAS Consulting: Dr B. Dylan Bradley

RESPONSIBLE ADMINISTRATOR

Albert Massot

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

European Parliament

B-1047 Brussels

E-mail: poldep-cohesi[email protected].eu

EDITORIAL ASSISTANCE

Catherine Morvan

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to its monthly newsletter please write to:

poldep-cohesion@europarl.europa.eu

Manuscript completed in June, 2015.

© European Union, 2015.

This document is available on the Internet at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/studies

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the author and do

not necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorized, provided the

source is acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy.

1

Acknowledgements: Most of our analysis has made use of public databases. However, the authors gratefully

acknowledge the assistance provided by the DG AGRI EU-FADN unit which provided special analysis where

access to raw data was needed and for the construction of maps. The authors also gratefully acknowledge the

input of Professor Sophia Davidova, University of Kent.

DIRECTORATE-GENERAL FOR INTERNAL POLICIES

POLICY DEPARTMENT B: STRUCTURAL AND COHESION POLICIES

AGRICULTURE AND RURAL DEVELOPMENT

COMPARISON OF FARMERS’ INCOMES

IN THE EU MEMBER STATES

STUDY

Abstract

With the main stated objectives of the CAP in mind, relevant comparisons

that involve the incomes of farmers are made. EU official data sources

are used to describe income differences between holdings of different

sizes and types and between Member States. Comparisons between the

incomes of farmer household and other groups in society have to rely on

ad hoc information. Recommendations relate to the support of small

farms, actions to mitigate instability and to fill the important gap in farm

household income information.

IP/B/AGRI/IC/2014-68 June 2015

PE 540.374 EN

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

3

CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 5

LIST OF TABLES 7

LIST OF MAPS 7

LIST OF FIGURES 7

LIST OF BOXES 9

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 11

1. INTRODUCTION 17

1.1. The economic function of profit from farming 18

1.2. Characteristics of incomes in agriculture 18

1.3. Accounting systems and agricultural incomes 21

1.4. Policy aims and appropriate measures of income 24

2. DATA SOURCES AND METHODOLOGICAL EXPLANATION 29

2.1. Data sources on the incomes of agricultural households 30

2.2. Data sources on the rewards from agricultural production 31

3. OVERVIEW OF THE INCOME DEVELOPMENT OF EU AGRICULTURE 35

3.1. Incomes of farm households 36

3.2. Incomes from agricultural activity 40

4. THE DYNAMICS OF FARM INCOMES AND THE KEY DRIVERS 65

4.1. Farm household income 66

4.2. Income from agricultural activity 67

5. DIFFERENCES BETWEEN MEMBER STATES 83

5.1. Differences in income levels 84

5.2. Differences in direction of change 88

5.3. Comparisons between Member State incomes for each main farm type

(FADN data) 91

5.4. Comparisons between Member States of farms by economic size group 94

5.5. Agricultural wages in Member States 96

6. RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FUTURE INCOME SUPPORT UNDER THE

CAP 101

6.1. The need for reliable statistics on agricultural household incomes 101

6.2. Statistics based on people rather than production 104

6.3. Income stabilisation 105

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

4

6.4. Support for small farms 108

6.5. Balance between support and market orientation 109

REFERENCES 111

LEGAL REFERENCES 115

ANNEX : Data sources on the rewards from Agricultural production 117

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

5

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

ARMS

AWU

Agricultural Resource Management Survey

Agricultural work unit

CAP

Common Agricultural Policy

CMO

Common market organisation

DG AGRI

Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development

EAA

Economic Accounts for Agriculture

ECA

European Court of Auditors

ECU

European Currency Unit

ERS

Economic Research Service (of the United States Department of

Agriculture)

ESA

European System of Accounts

EU

European Union

EU-15

Grouping of Austria, Belgium, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany,

Greece, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Netherlands, Portugal, Spain,

Sweden and the UK.

EU-27

Grouping of the EU-15, EU-N10 and EU-N2

EU-28

Grouping of the EU-15, EU-N10, EU-N2 and Croatia

EU-N2

Grouping of Bulgaria and Romania

EU-N10

Grouping of Cyprus, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia,

Lithuania, Malta, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia

EU-SILC

European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions

FADN

Farm Accountancy Data Network

FAO

Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

6

FFI

Farm Family Income

FNVA

Farm Net Value Added

FSS

Farm Structural Survey

FWU

Family Work Unit

GATT

General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade

IAHS

Income of the Agricultural Households Sector

JRC

Joint Reserarch Centre (of the European Commission)

LFA

Less Favoured Area

LKAU

Local Kind of Activity Unit

NVA

Net Value Added

OECD

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

OGA

Other Gainful Activity

SFS

Small Farmers Scheme

SNA

System of National Accounts

SO

Standard Output

TFEU

Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union

UN

United Nations

UK

United Kingdom

US(A)

United States (of America)

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

7

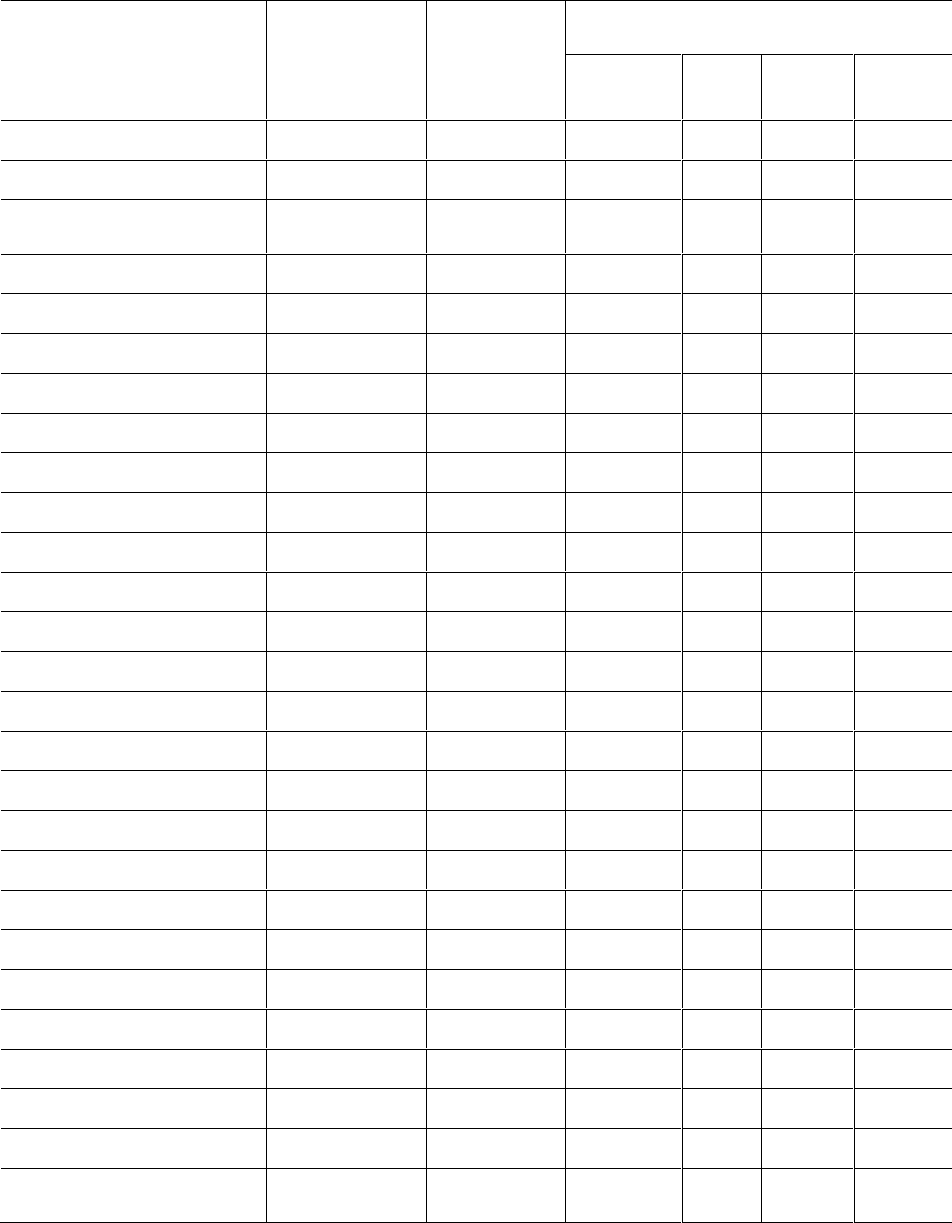

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1:

Economic Accounts for Agriculture: current transactions accounts from 1999 118

Table 2:

FADN field of observation 121

LIST OF MAPS

Map 1:

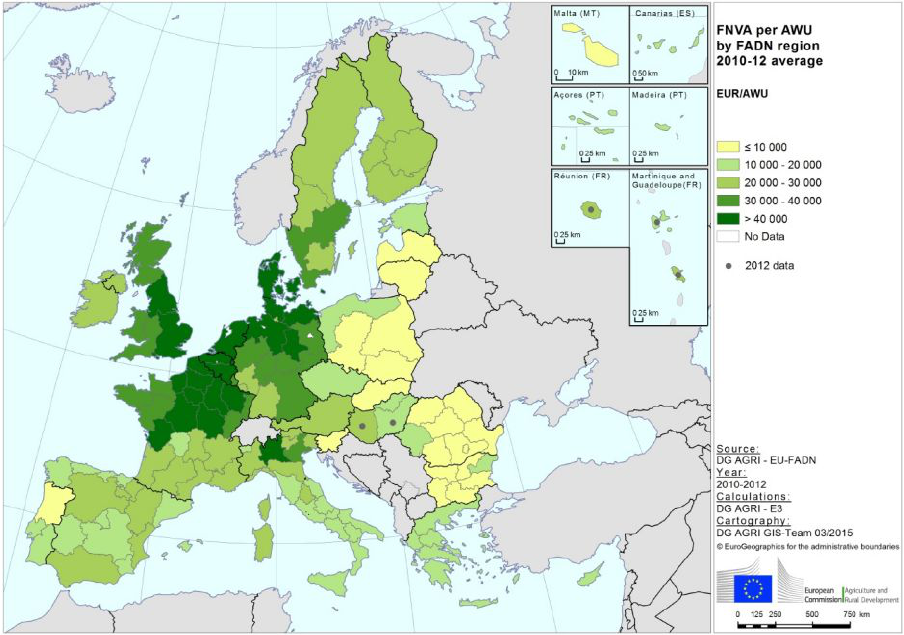

FNVA in Euro per AWU by FADN region, 2010-2012 average 87

Map 2:

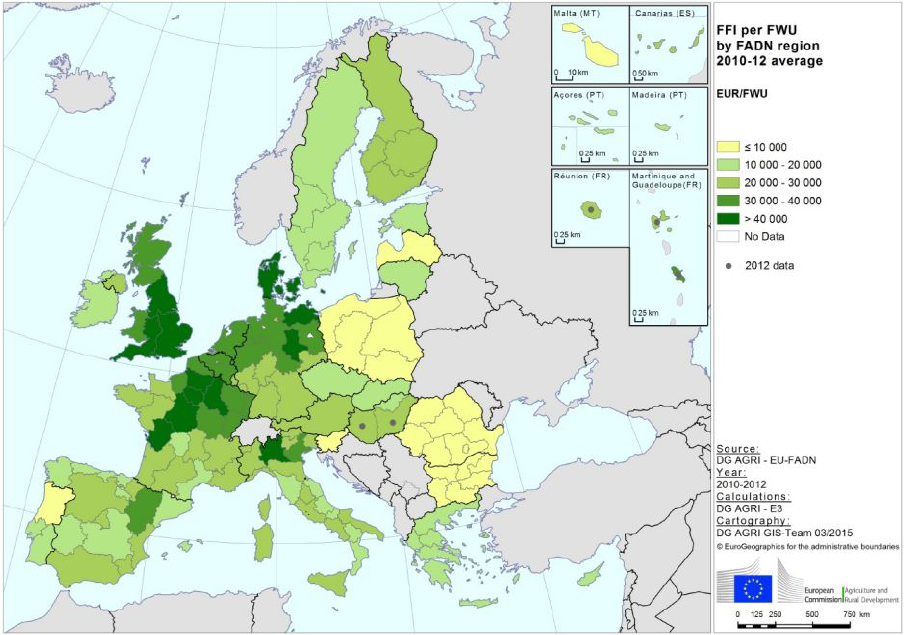

FFI in Euro per FWU by FADN region, 2010-2012 average 88

Map 3:

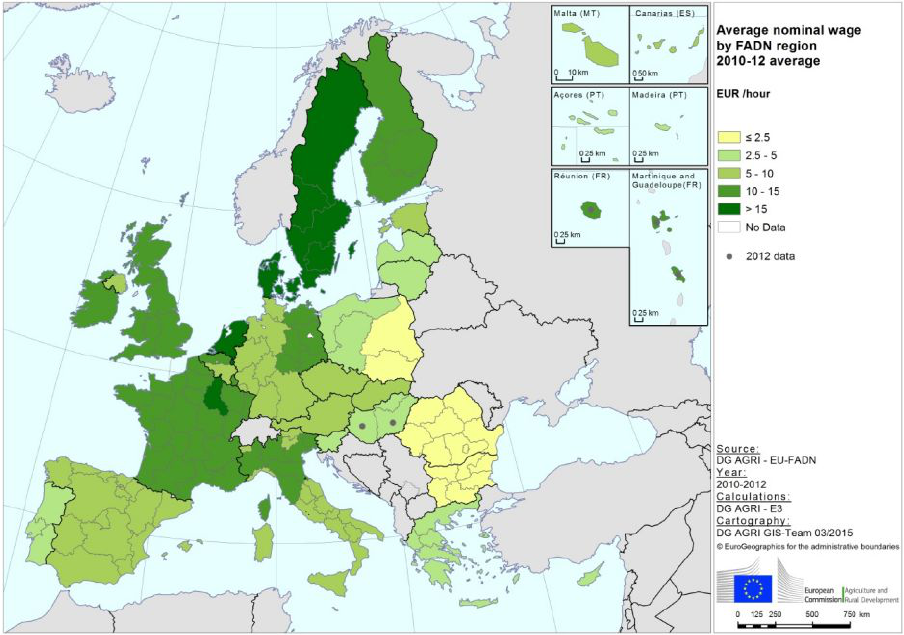

Average nominal wages paid by FADN region, 2010-12 average 98

LIST OF FIGURES

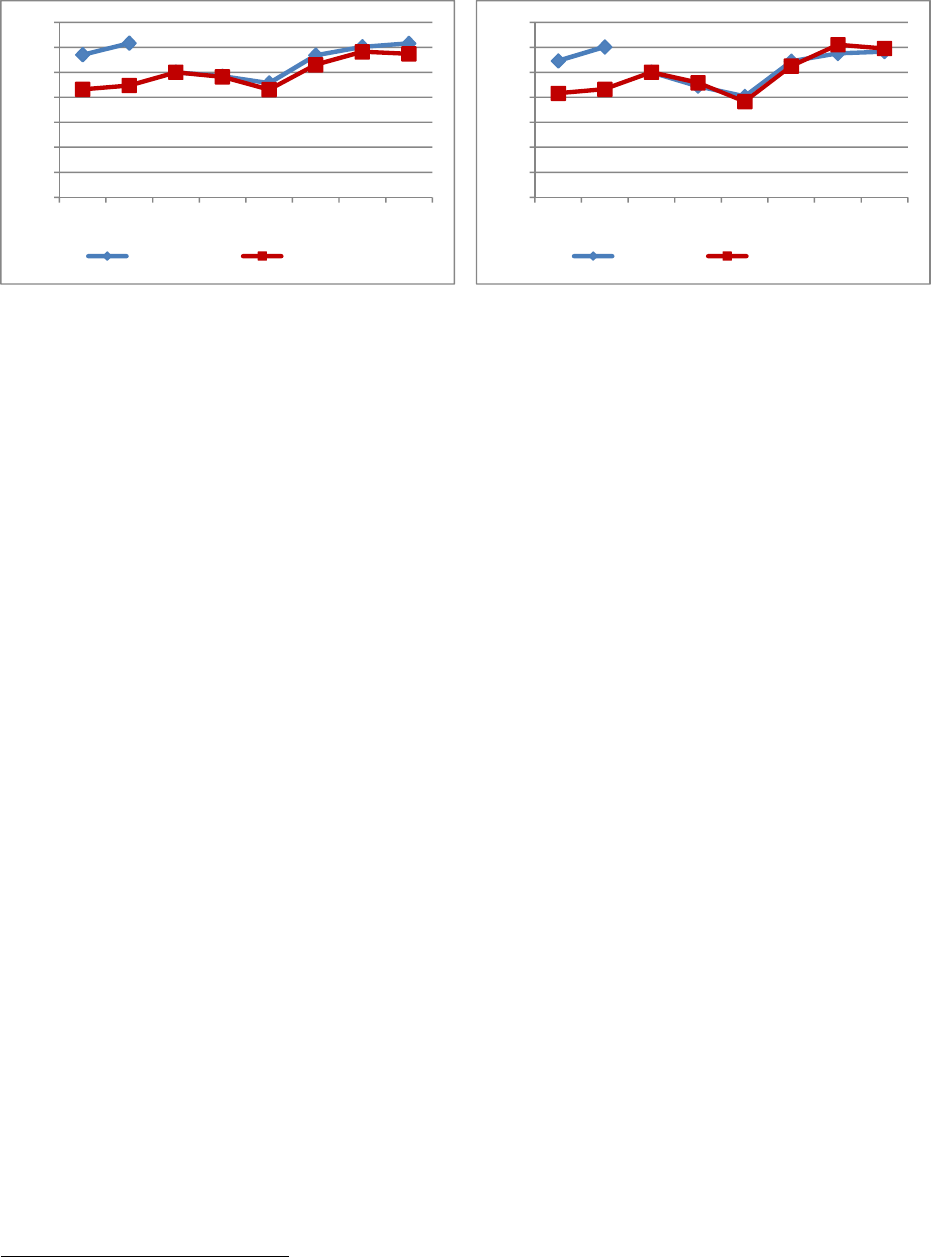

Figure 1:

The relationship between agricultural activity and the institutional units that generate it 23

Figure 2:

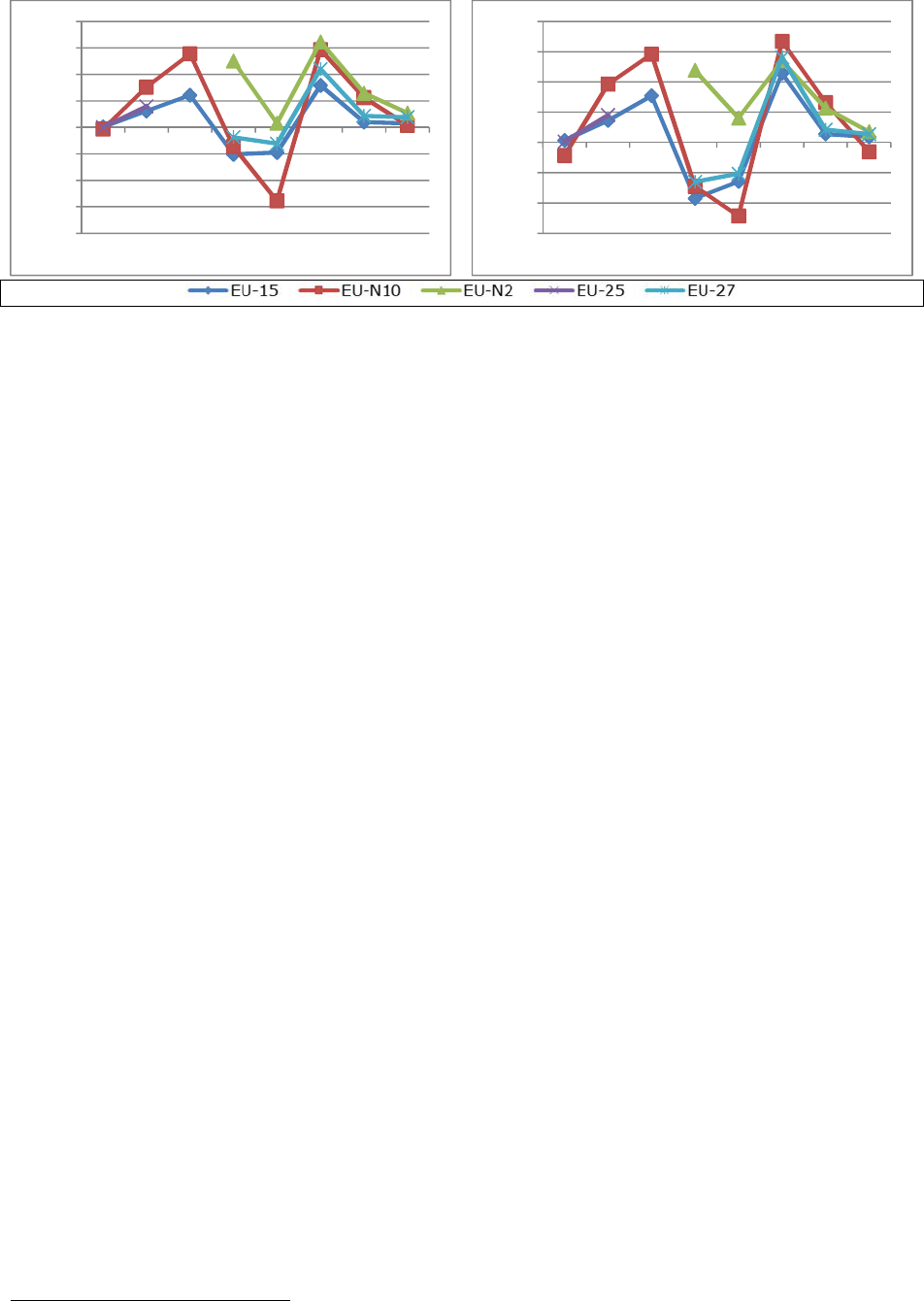

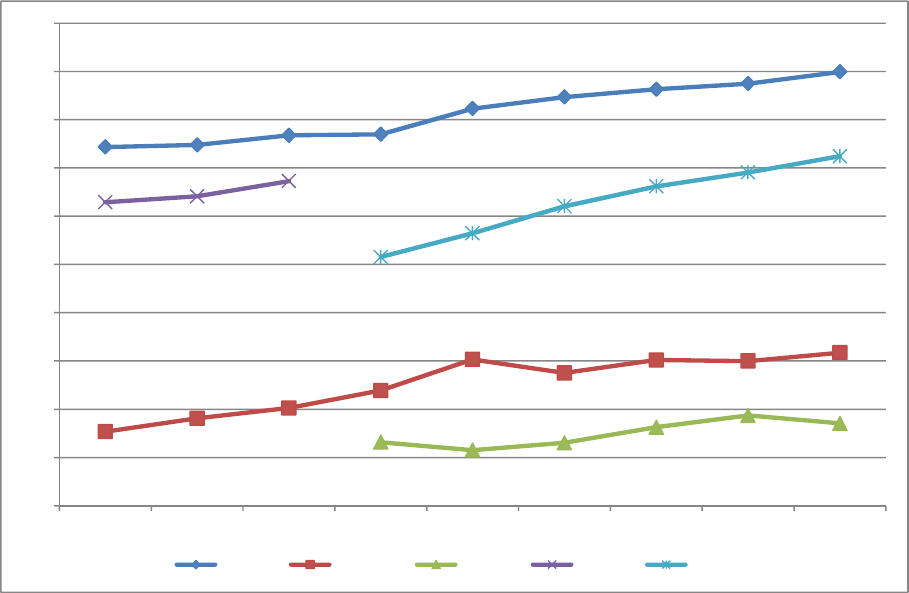

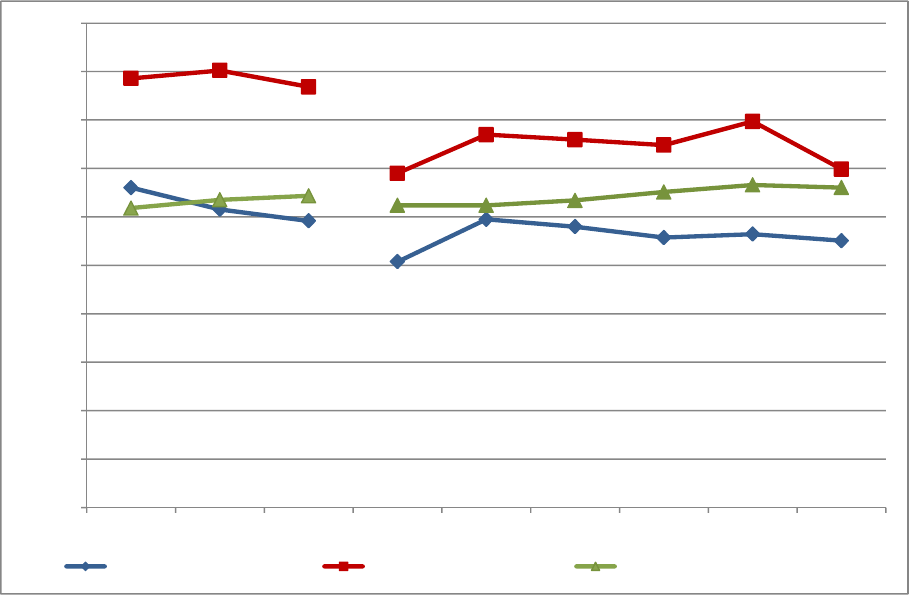

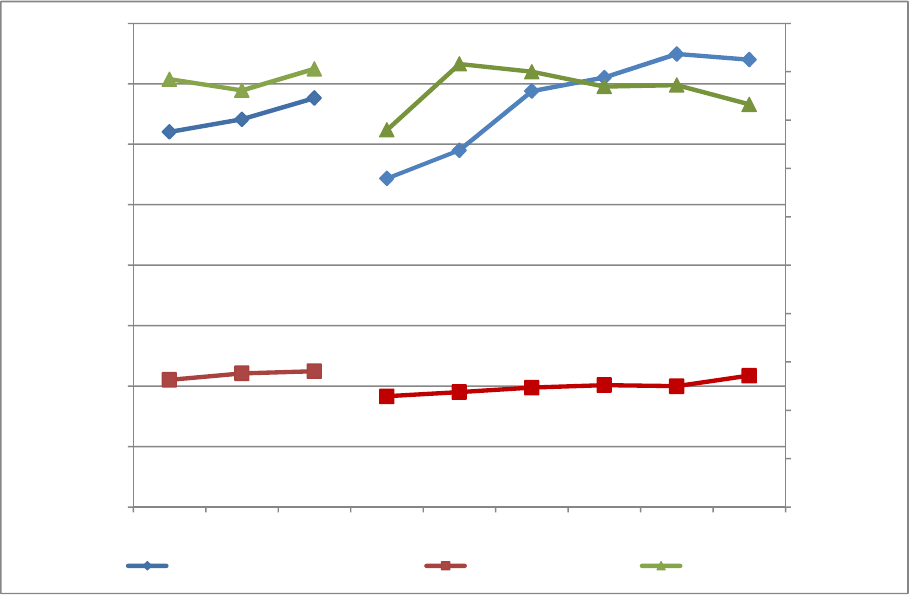

Evolution of index of real income of factors in agricultural activity per annual work unit

(Eurostat Indicator A) and index of real net agricultural entrepreneurial income per

unpaid work unit (Eurostat Indicator B) (2005=100) 41

Figure 3:

Comparison of FADN FNVA/AWU against Eurostat Indicator A and FFI/FWU against

Eurostat Indicator B, EU-25/EU-27 (2007=100, real terms) 42

Figure 4:

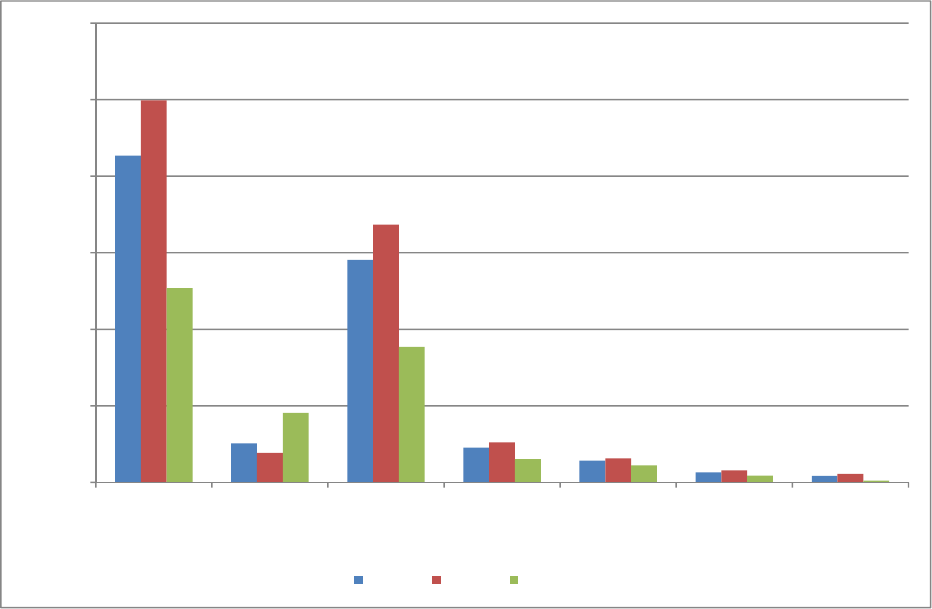

Distribution of farm size by farm type in the FADN sample, 2010-2012 average 44

Figure 5:

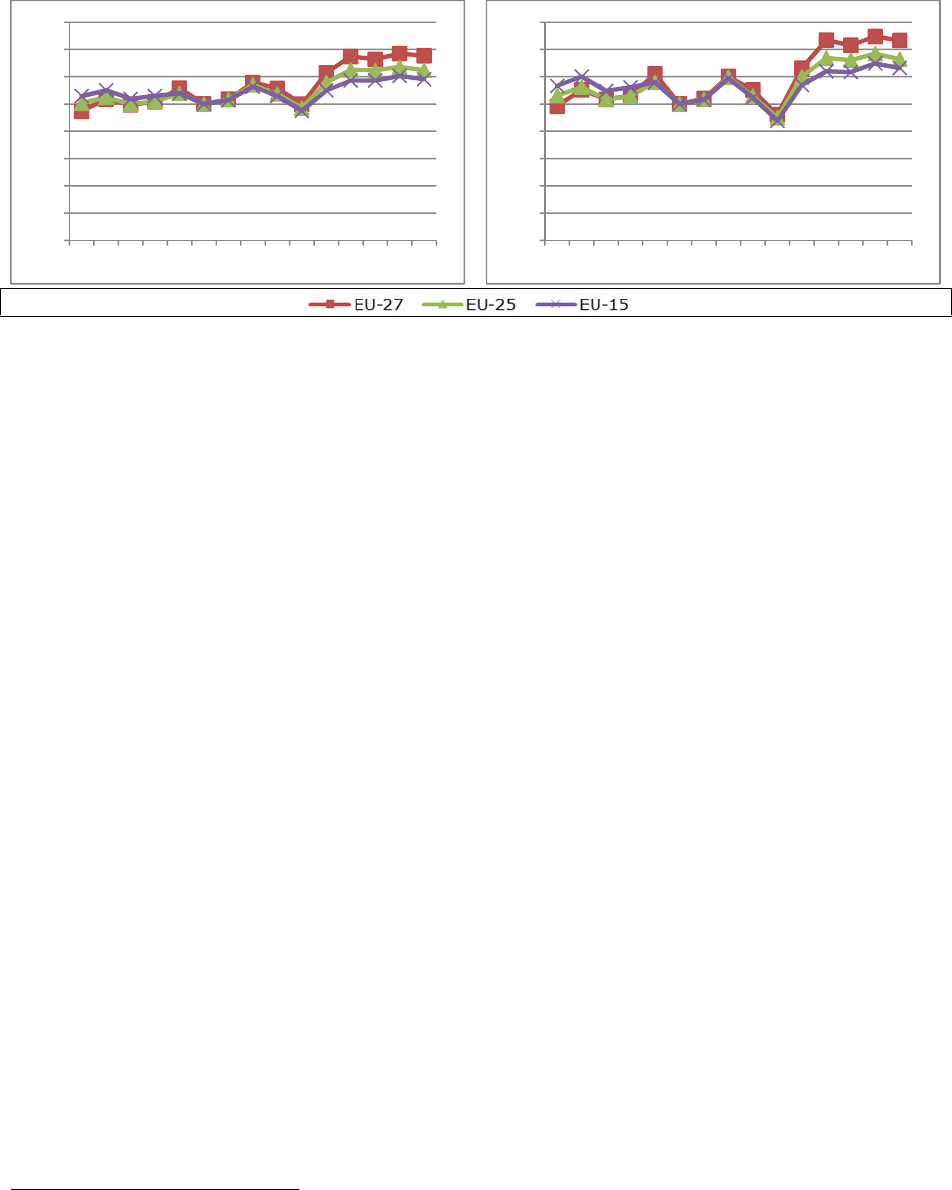

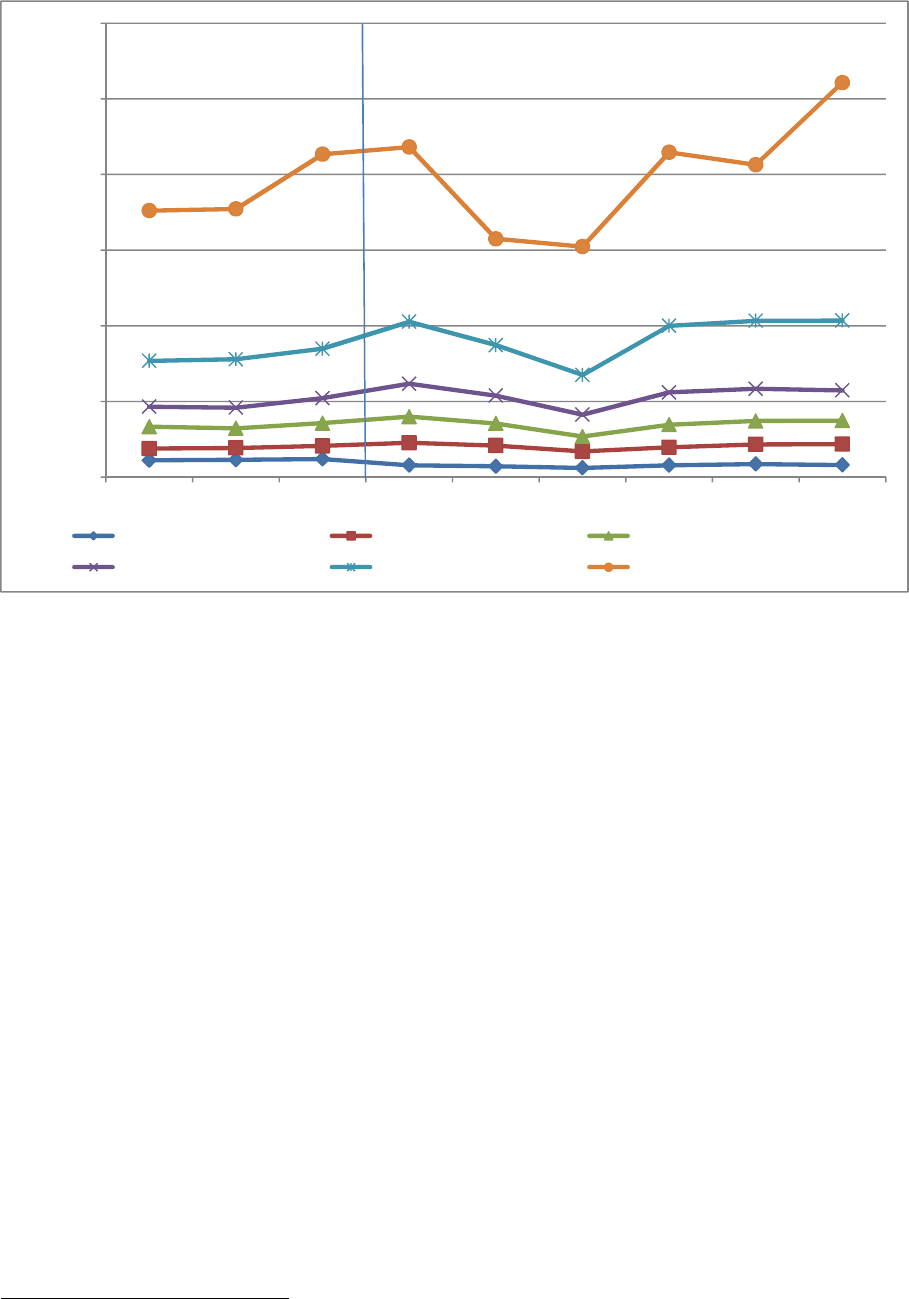

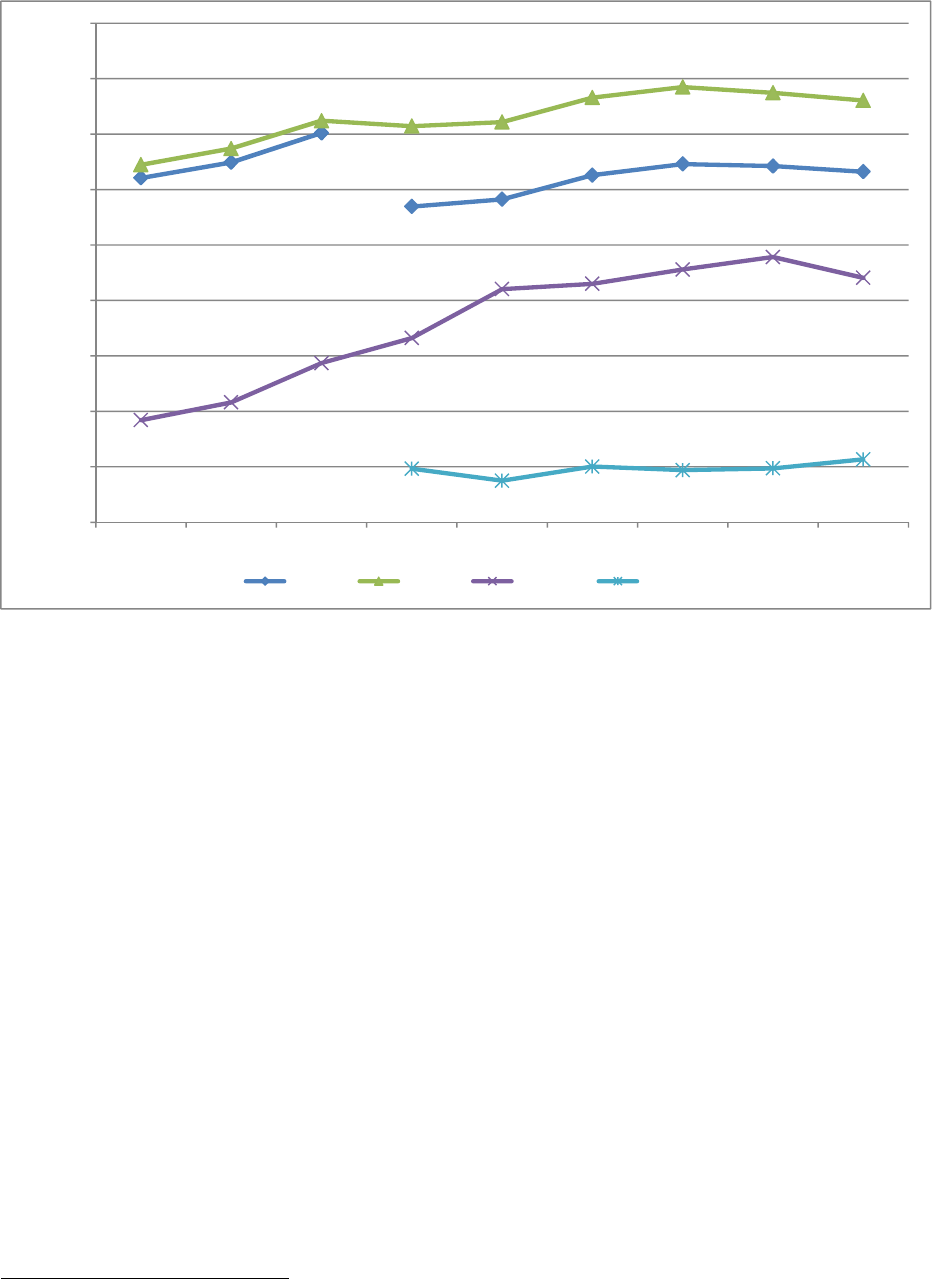

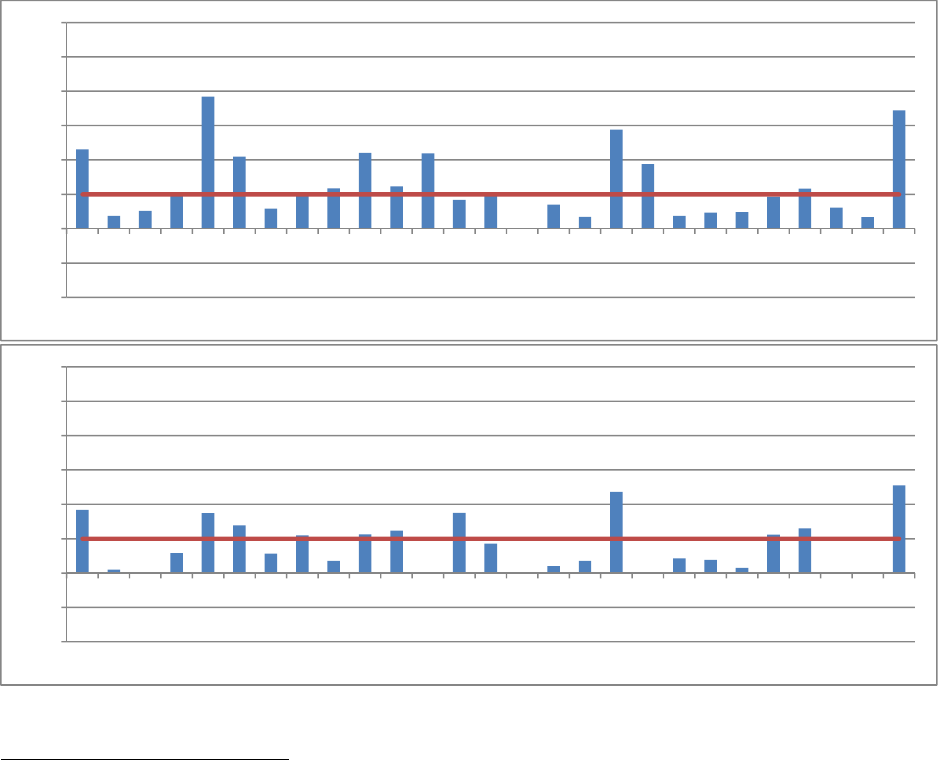

Indicators of farm income, EU-25 2000-06, EU-27 2007-12, 2004-2012 45

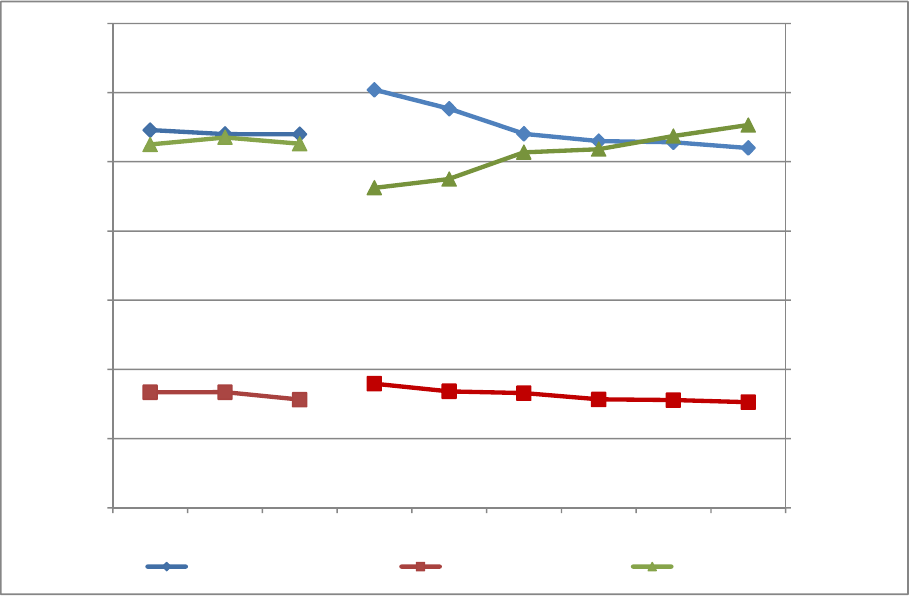

Figure 6:

Evolution of FFI/FWU by EU groupings, 2004-12 46

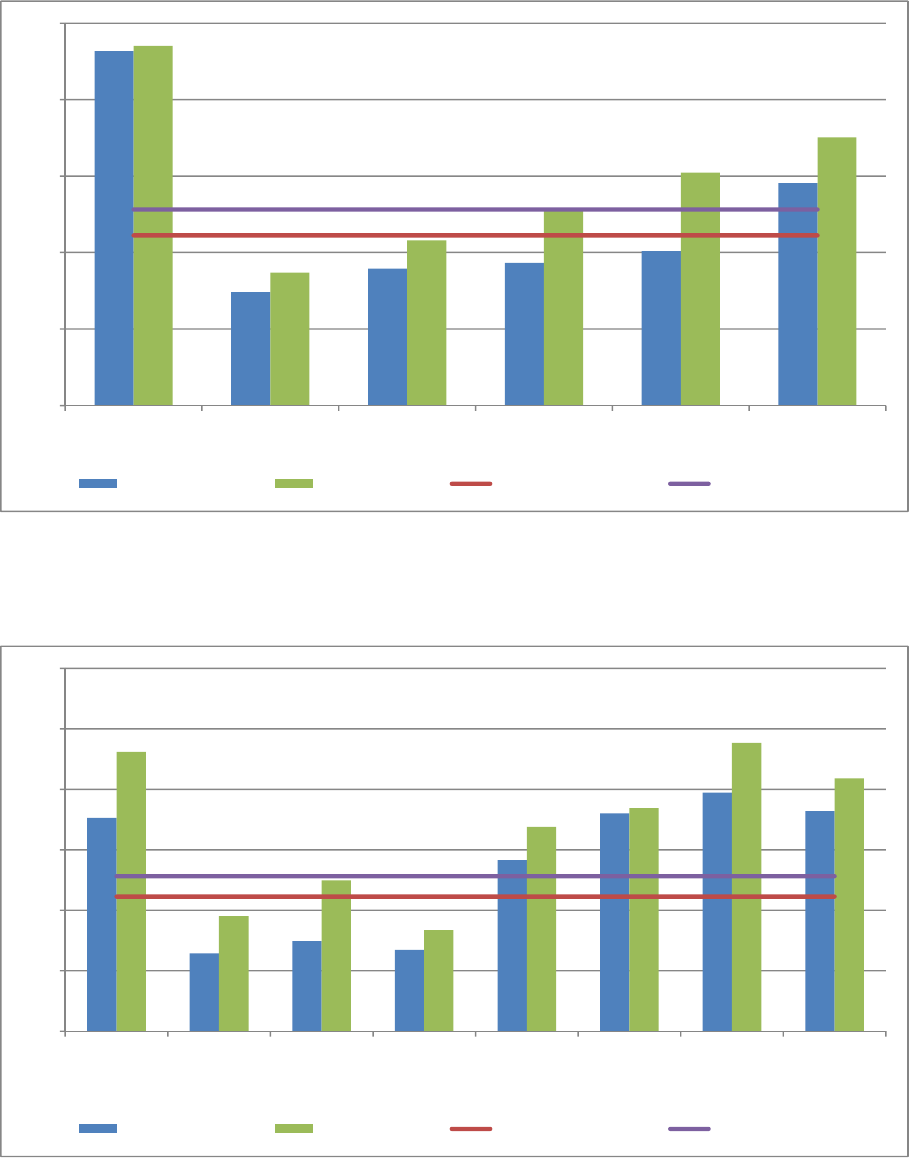

Figure 7:

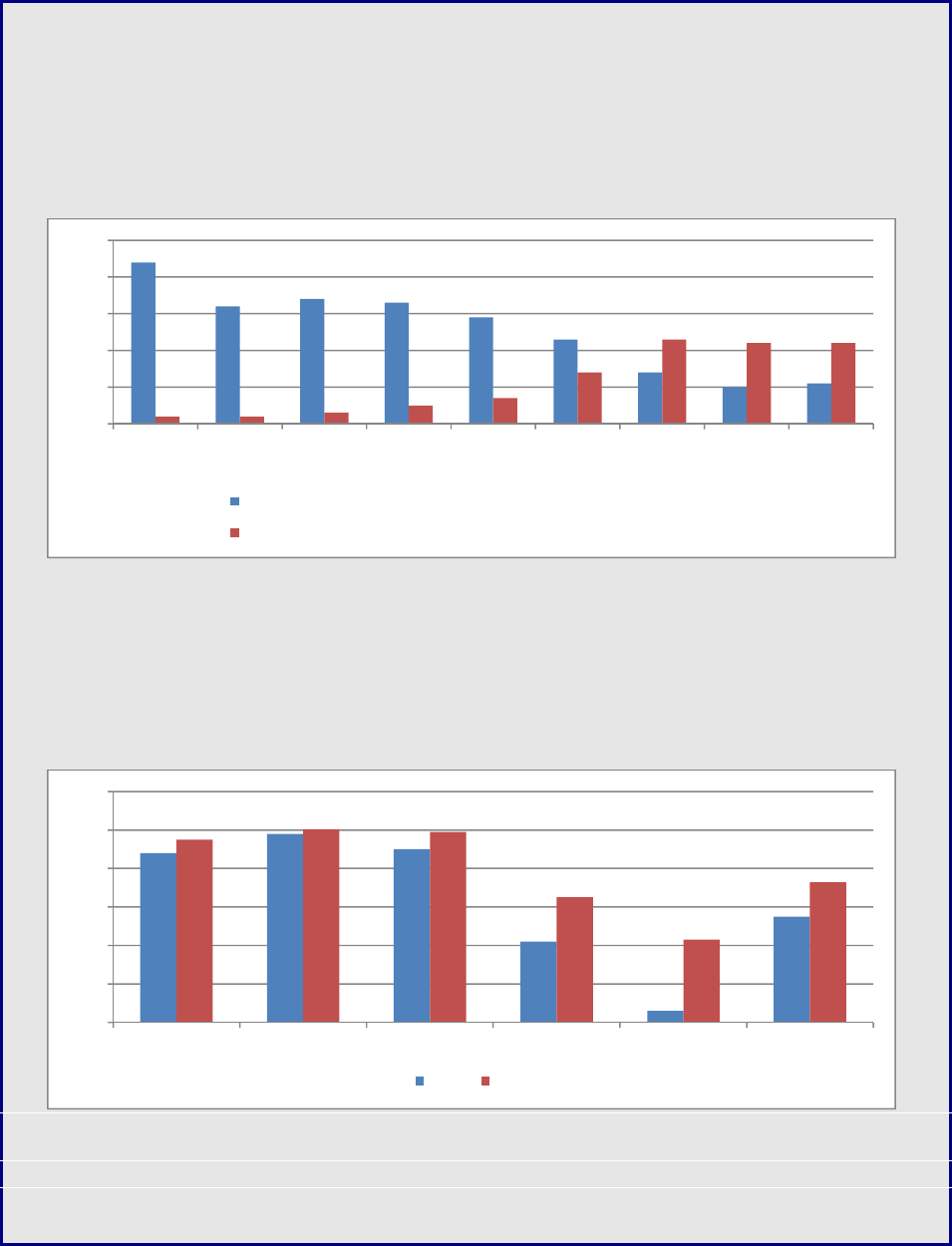

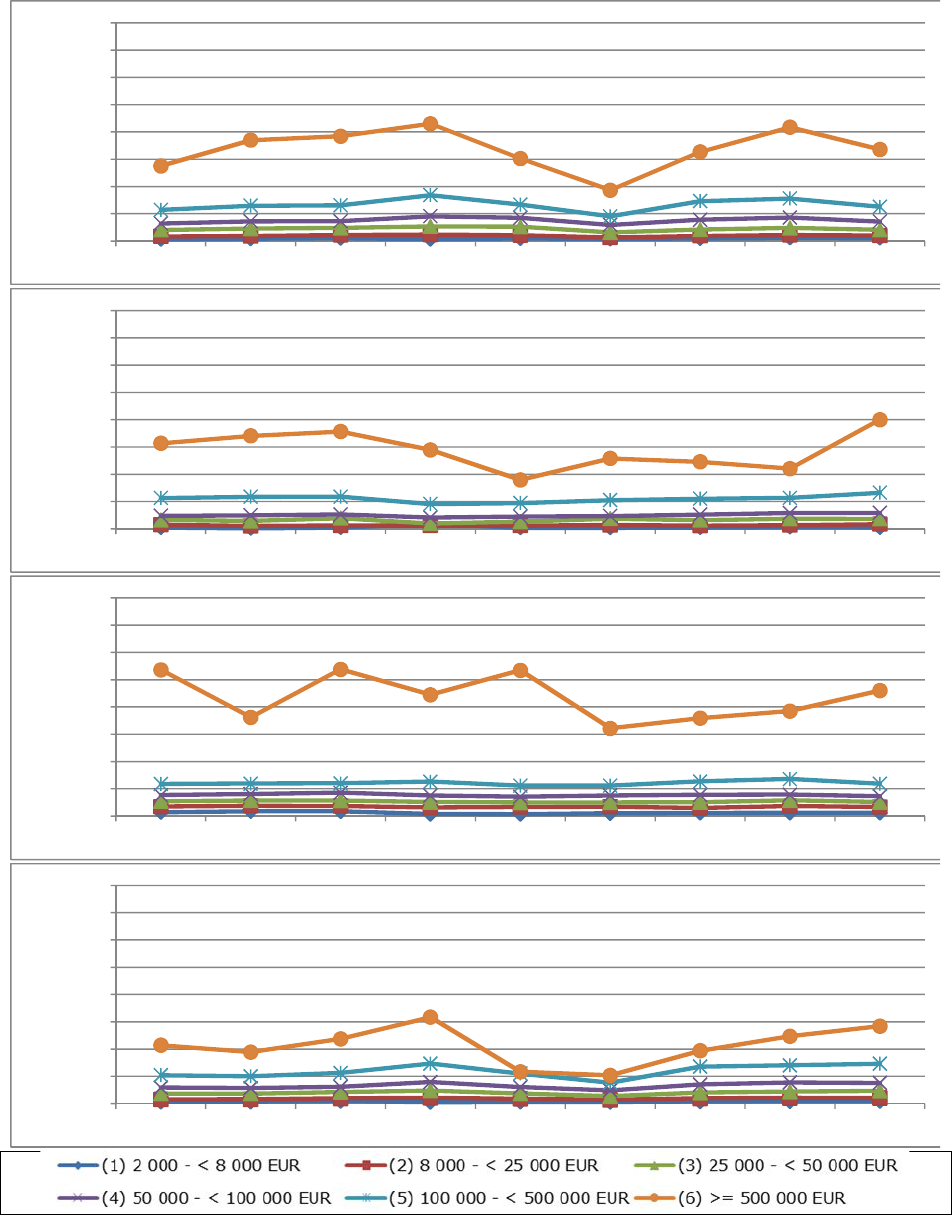

Indicators of farm income by farm size, 2010-2012 average 47

Figure 8:

Evolution of FFI/FWU by farm size, 2004-2012 48

Figure 9:

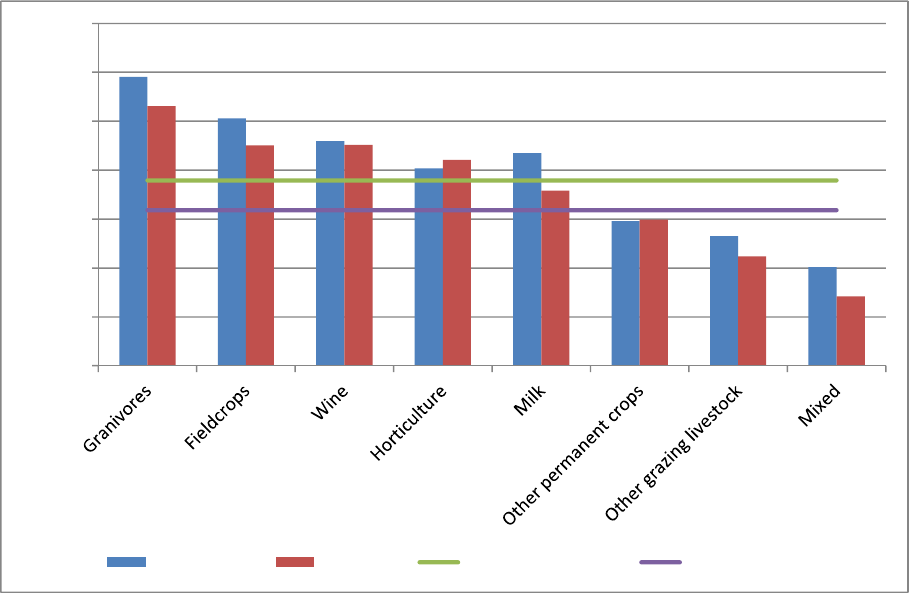

Indicators of farm income by farm type, 2010-2012 average 49

Figure 10:

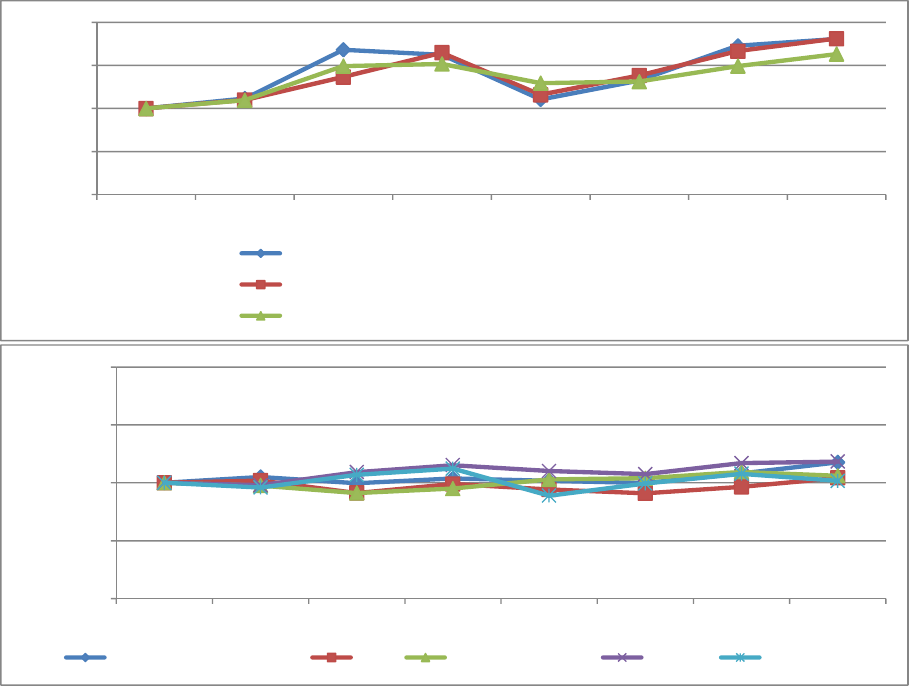

Evolution of FFI/FWU by farm type, 2004-2012 50

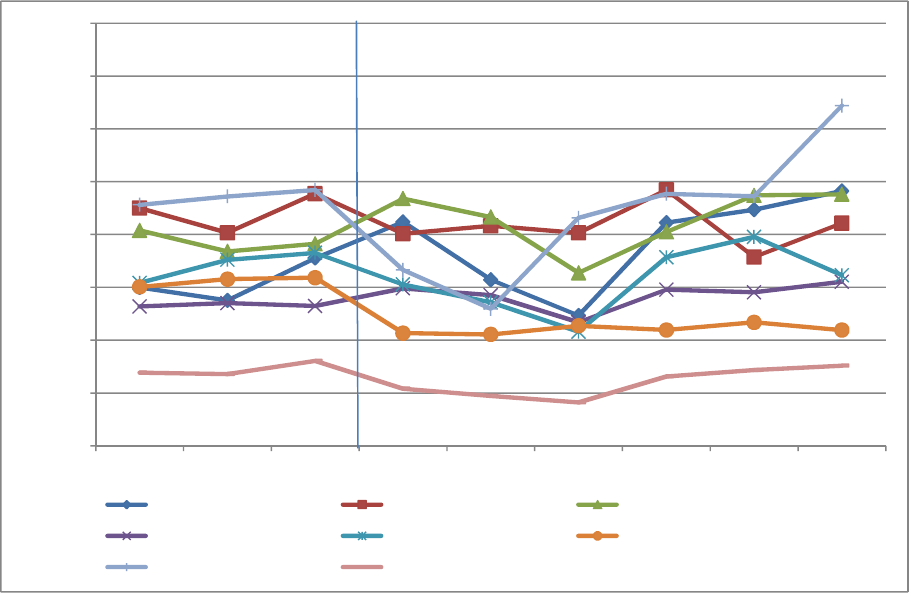

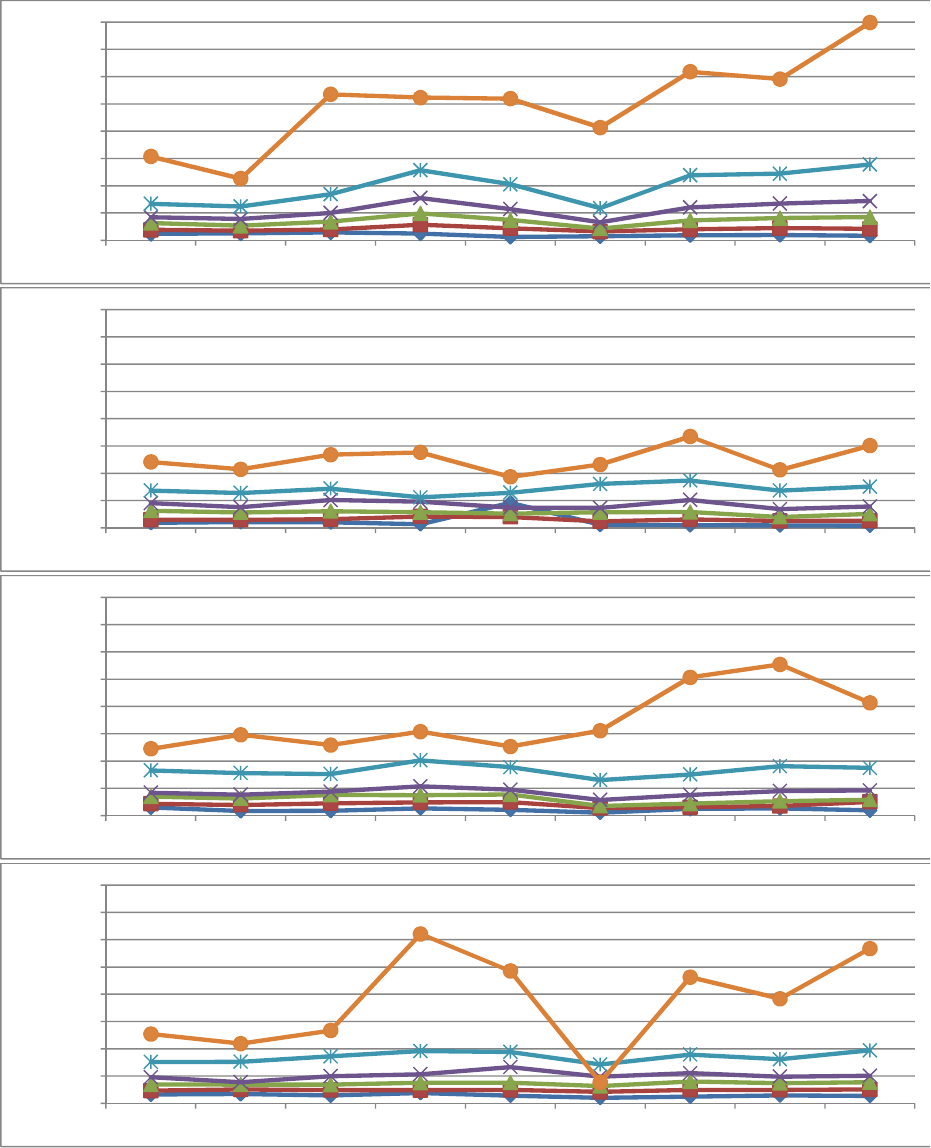

Figure 11:

FFI/FWU by type of farm and size class, 2004-2012 51

Figure 12:

Indicators of farm income by age, EU-27 2010-2012 53

Figure 13:

Indicators of farm income by ownership structure and EU sub-group, 2010-2012 average 54

Figure 14:

Indicators of farm income by Less Favoured Area status, EU-27 2010-2012 55

Figure 15:

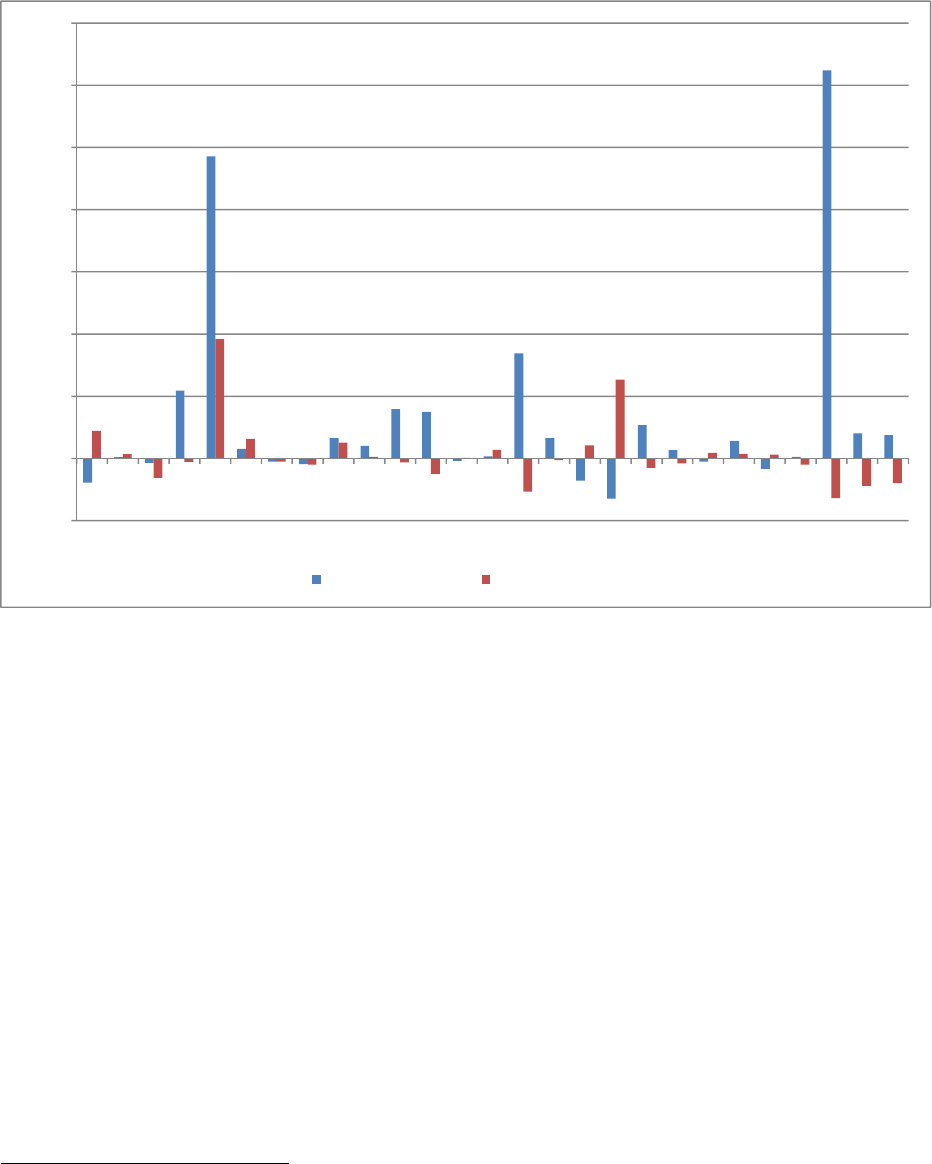

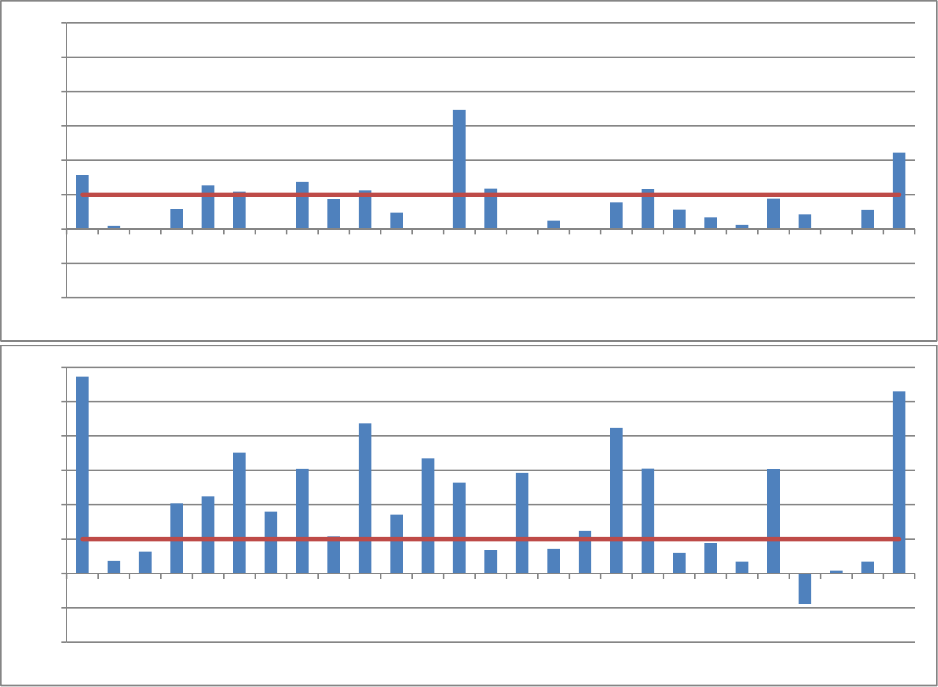

Annual year-on-year change in farm income indicators 56

Figure 16:

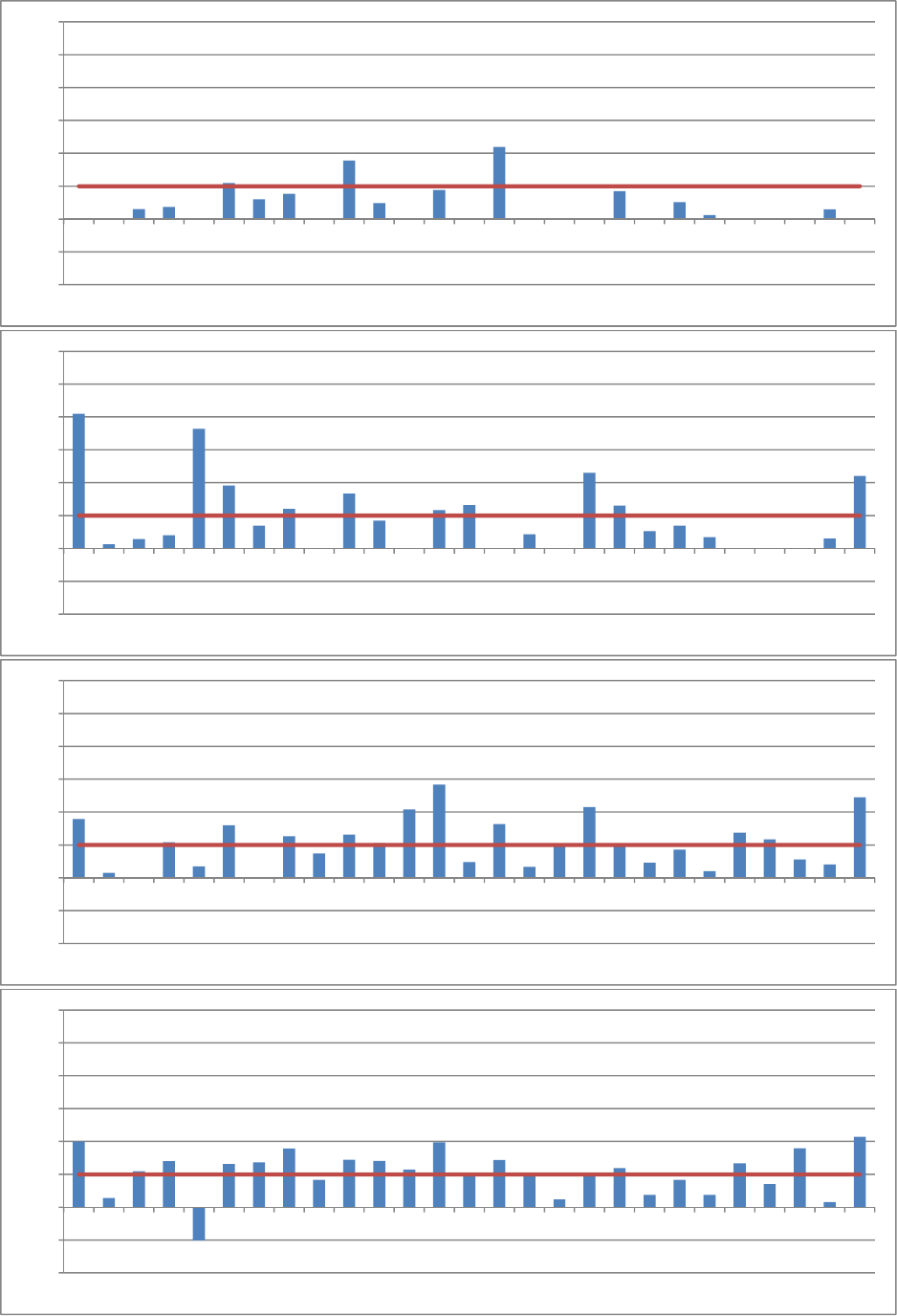

Coefficient of variation of income indicators by farm size, 2004-2012 57

Figure 17:

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

8

Coefficient of variation by farm type, 2004-2012 57

Figure 18:

Farm level volatility, 1998-2007 58

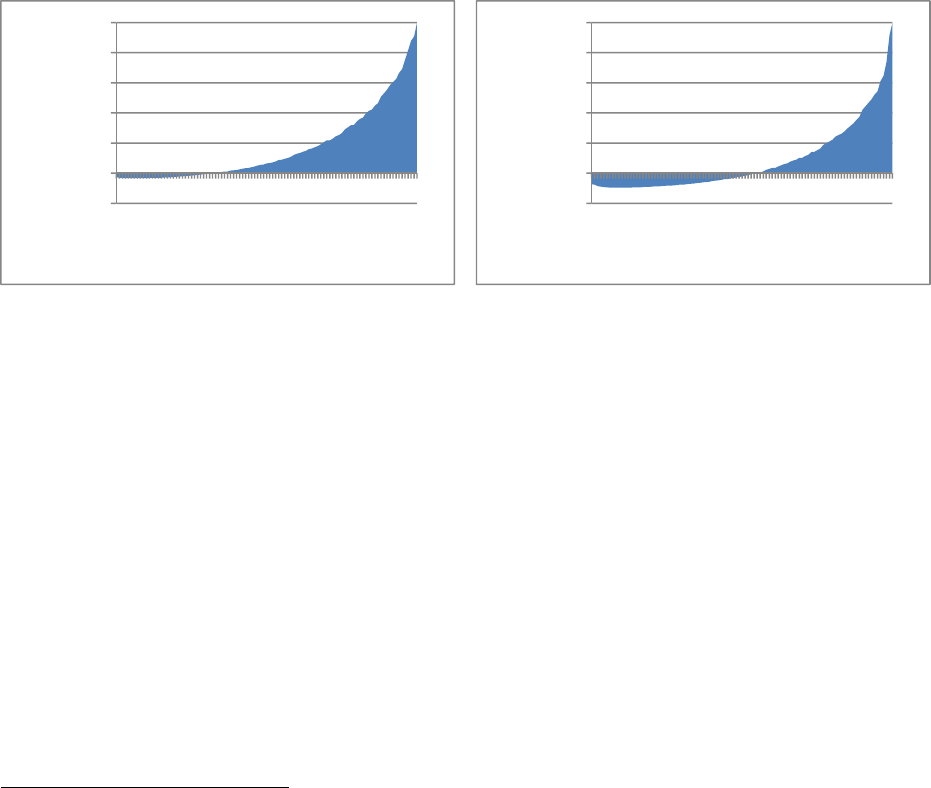

Figure 19:

Lorenz curve of the distribution of FNVA and FFI, EU-27, 2010-2012 average 59

Figure 20:

Development of the Gini coefficient of FNVA per AWU 60

Figure 21:

Paid labour (

€/hour), 2004

-2012 61

Figure 22:

Paid labour (

€/hour) by farm type, 2010

-2012 average 62

Figure 23:

Annual year-on-year change in paid agricultural wages per hour 63

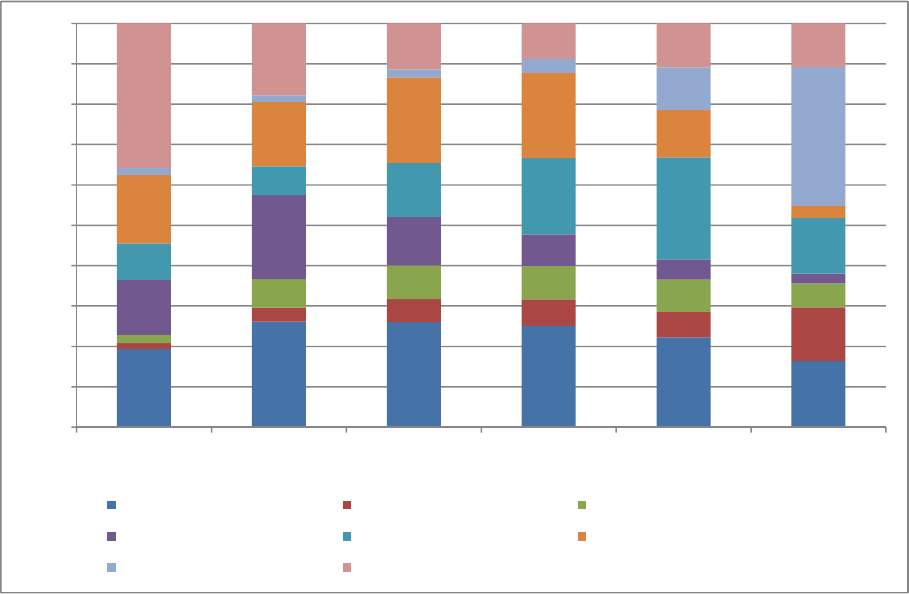

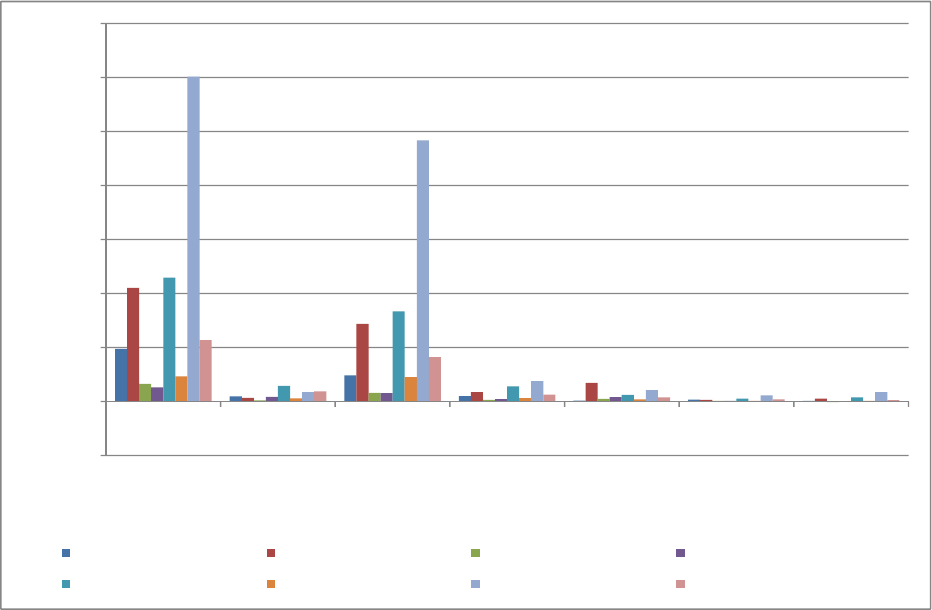

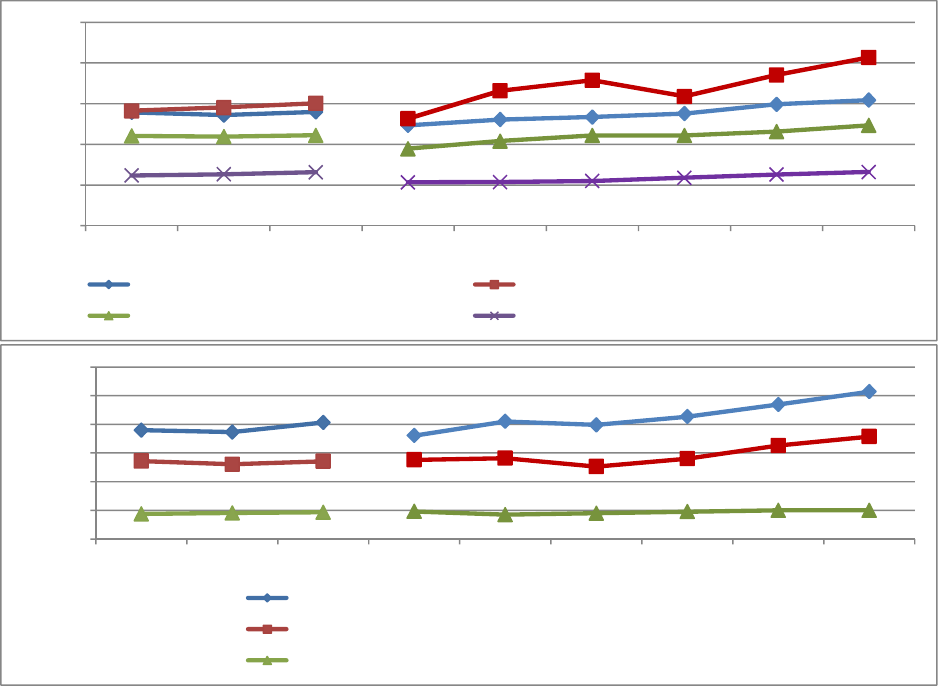

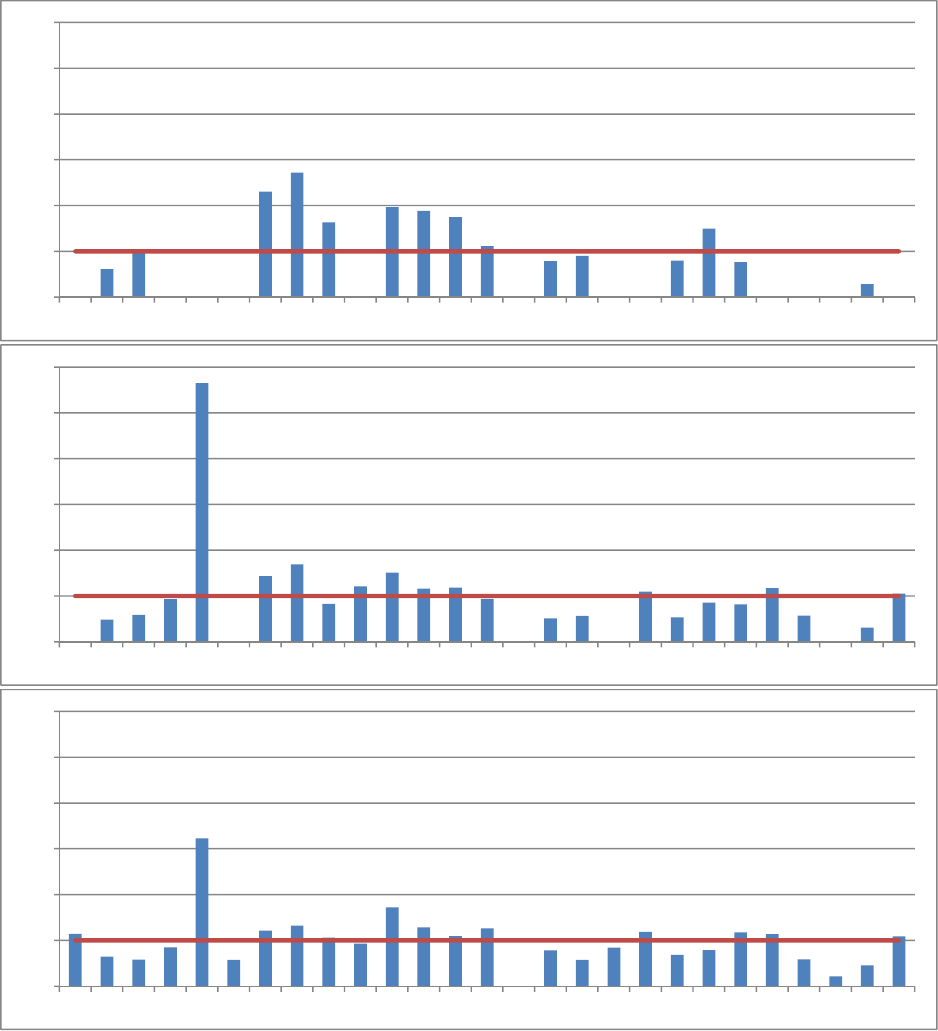

Figure 24:

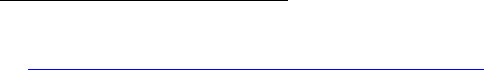

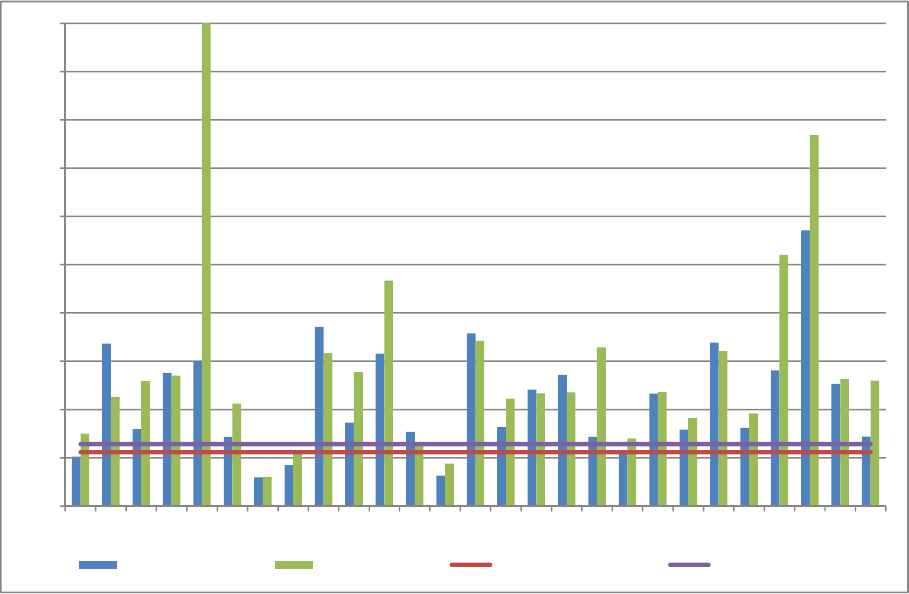

Income components per farm by EU group, 2010-12 average 68

Figure 25:

Income components per farm by EU farm type, 2010-12 average 70

Figure 26:

Income components per farm by economic size, 2010-12 average 71

Figure 27:

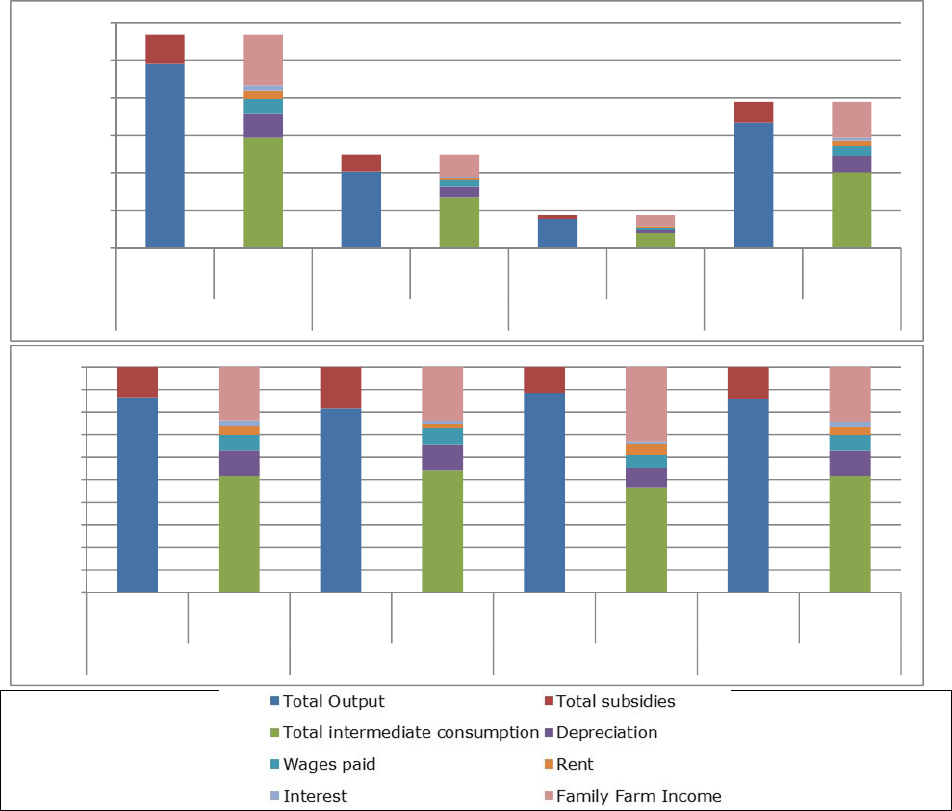

Change in value of income components 2004-06 average compared to 2010-12 average

by EU sub-group 72

Figure 28:

Change in value of income components 2004-06 average compared to 2010-12 average

by farm type 73

Figure 29:

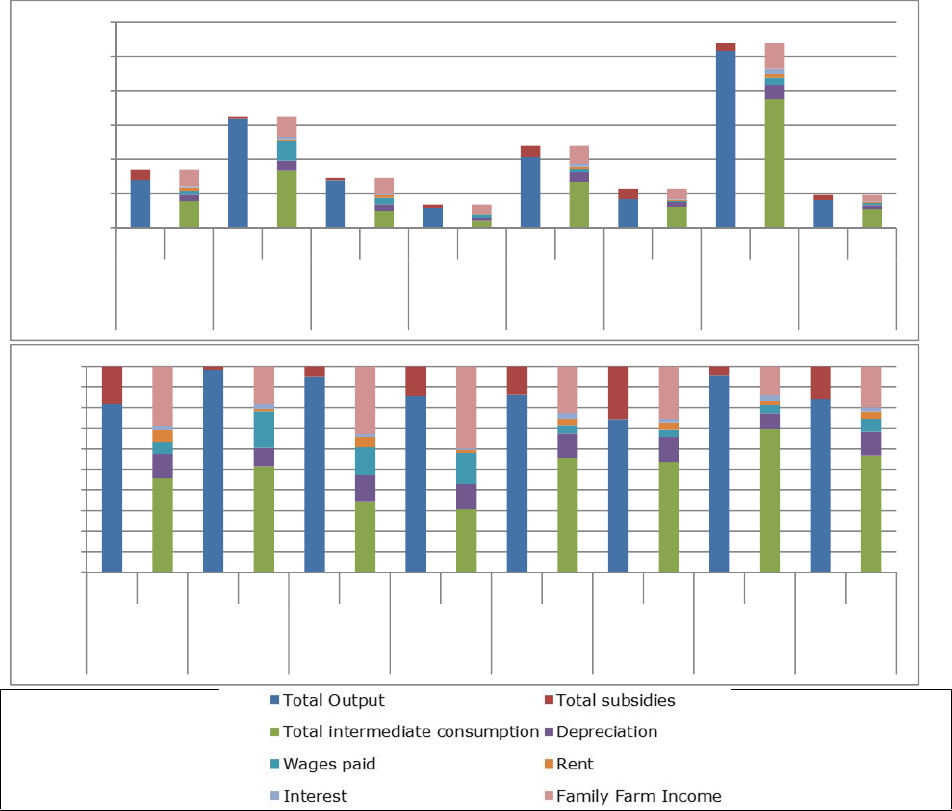

Evolution of the components of Total Output per farm, EU-25 2004-2006, EU-27 2007-

2012 74

Figure 30:

Evolution of crop and livestock prices, EU-27, 2005 = 100 75

Figure 31:

Evolution of yield per unit of output, EU-25 2004-06, EU-27 2007-12 76

Figure 32:

Evolution of subsidies, EU-25 2004-06, EU-27 2007-12 77

Figure 33:

Evolution of specific crop and livestock costs and total farming overheads, EU-25 2004-

16, EU27 2007-12 78

Figure 34:

Evolution of specific crop and livestock costs per farm, EU-25 2004-06, EU-27 2007-12 79

Figure 35:

Evolution of the elements of total farm overheads, EU-25 2004-06, EU-27 2007-12 80

Figure 36:

Evolution of value of outstanding loans and annual interest per farm, EU-25 2004-2006,

EU-27 2007-2012 81

Figure 37:

Evolution of labour use and wages paid per farm, EU-25 2004-2006, EU-27 2007-2012 82

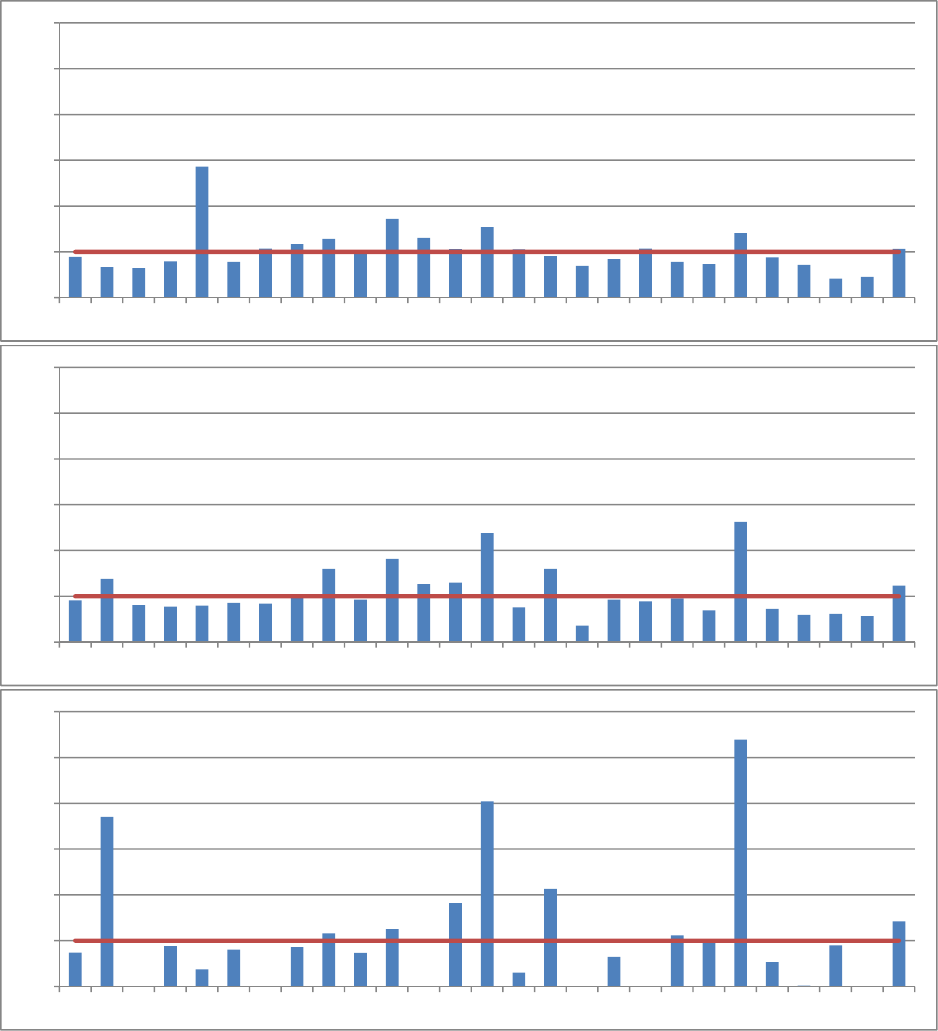

Figure 38:

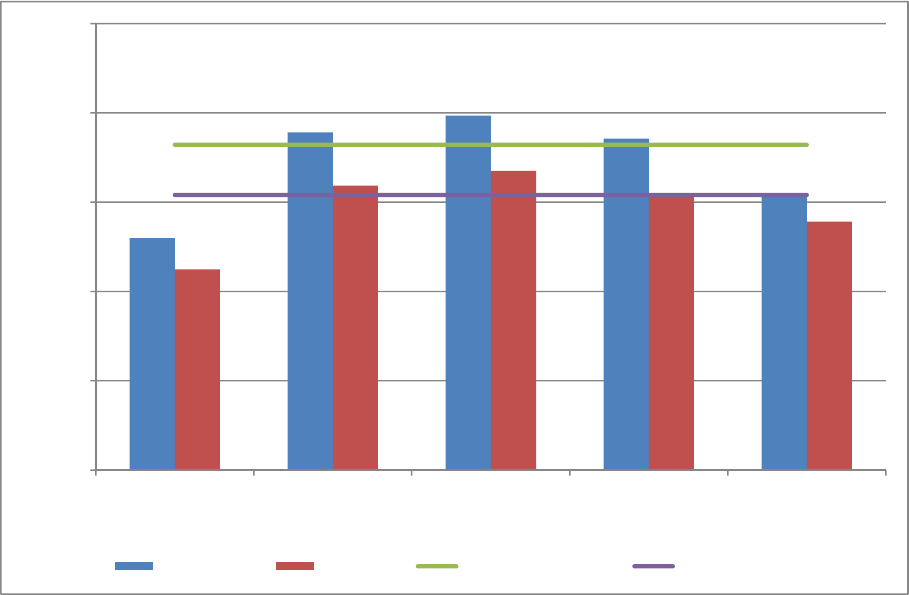

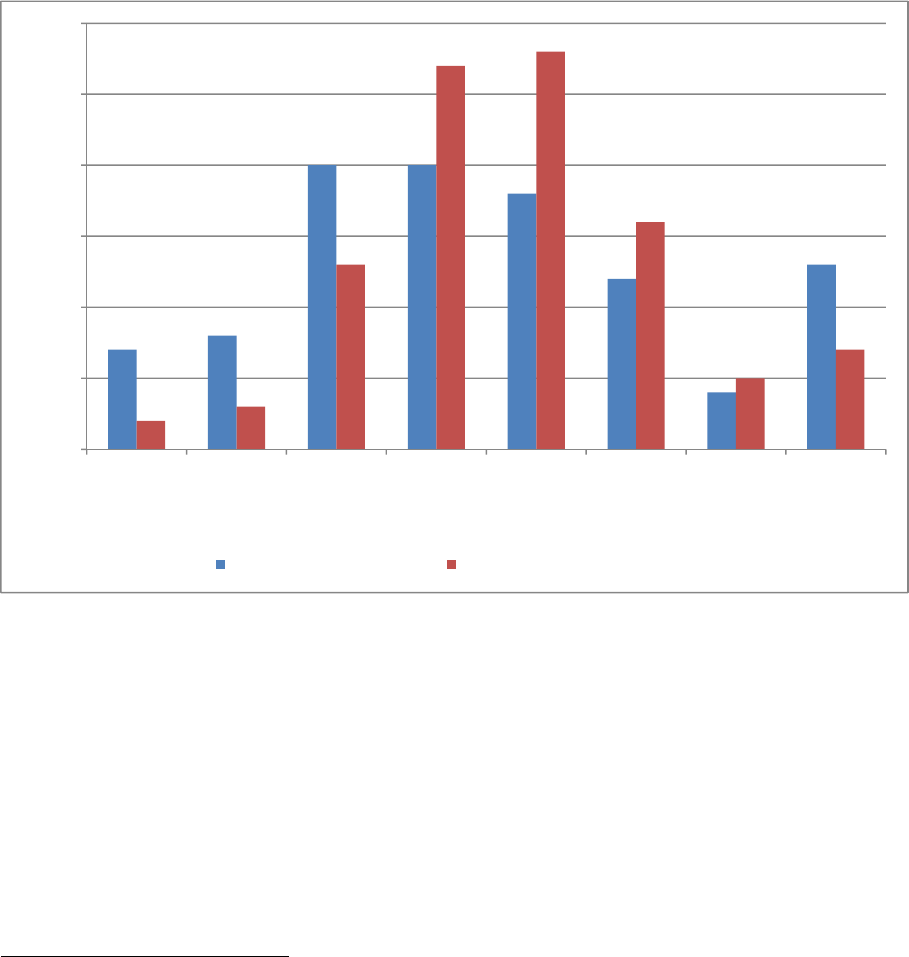

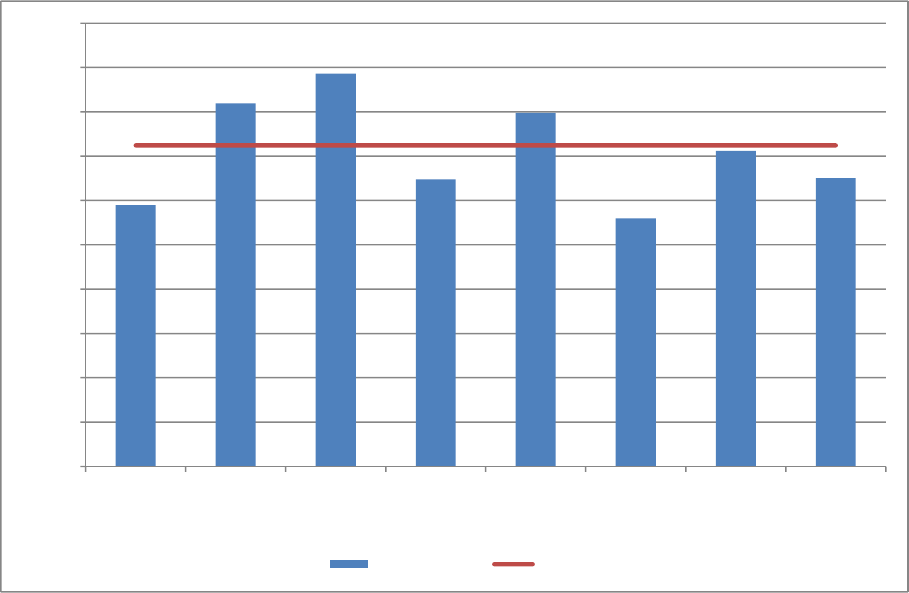

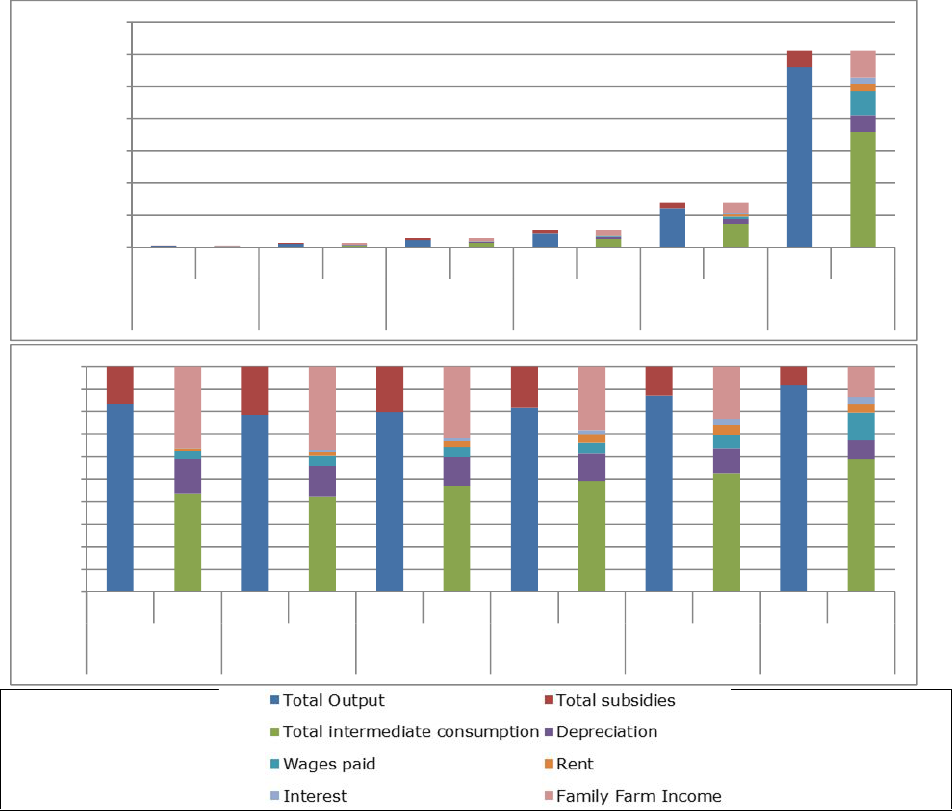

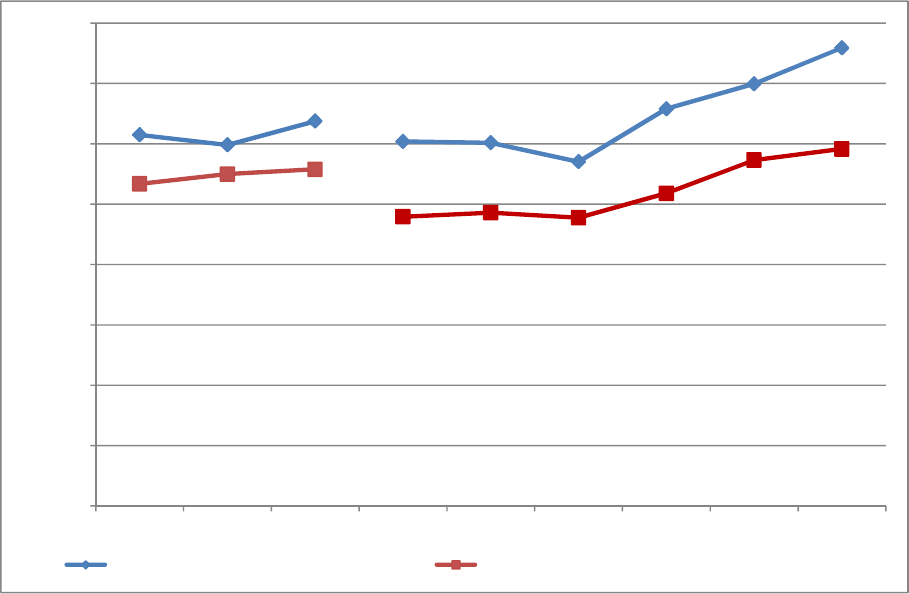

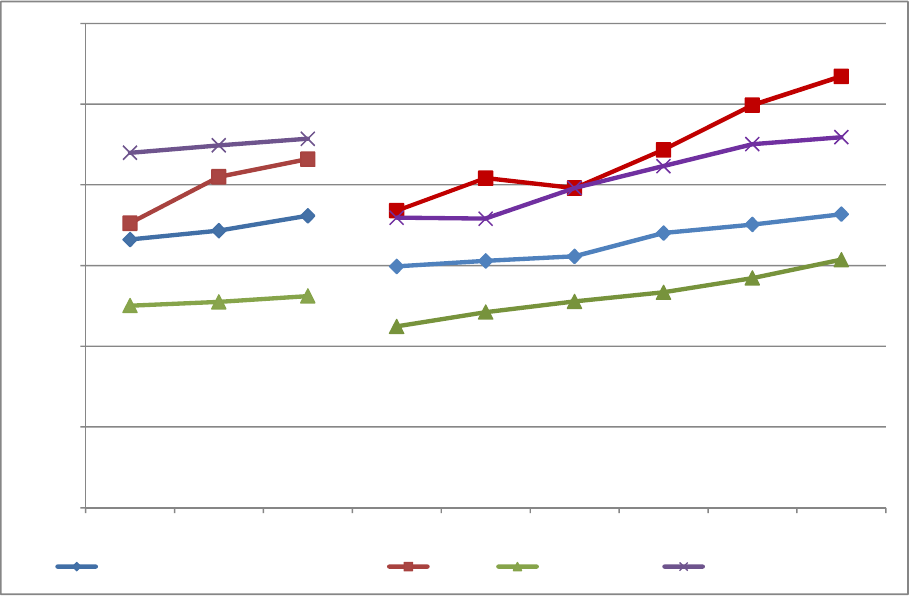

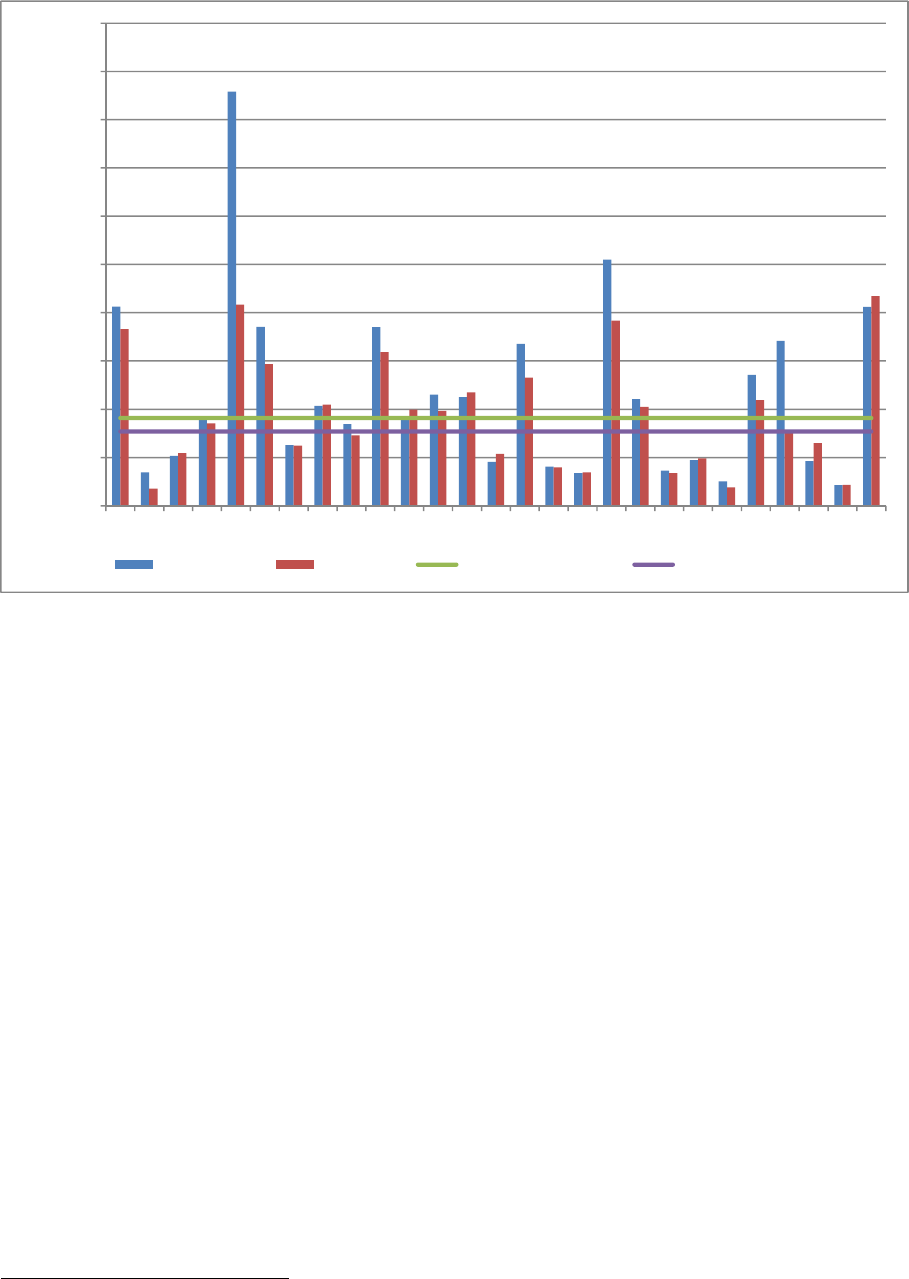

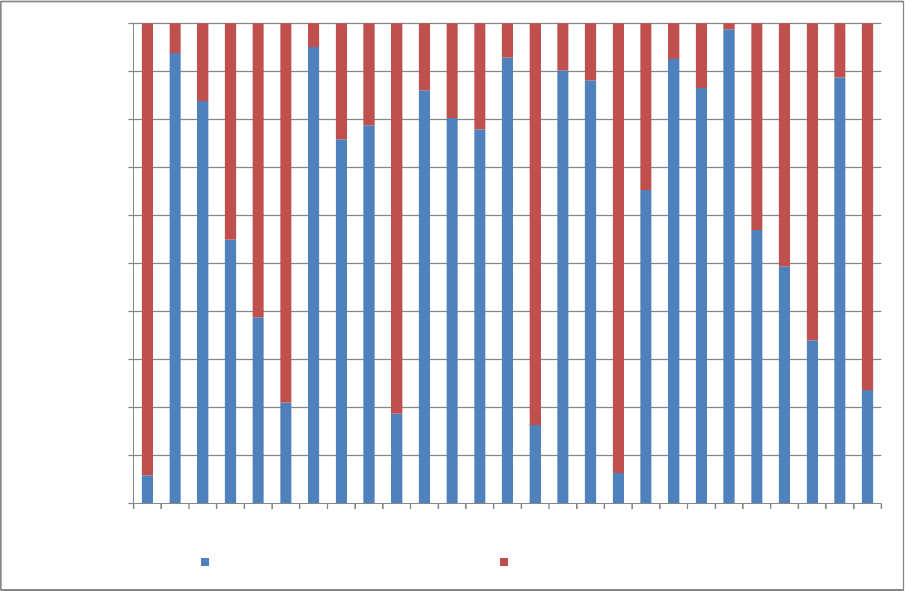

FNVA/AWU and FFI/FWU by Member State (2010-2012 average) 85

Figure 39:

FADN coverage of economic farm size (ES) by Member State, 2010-2012 86

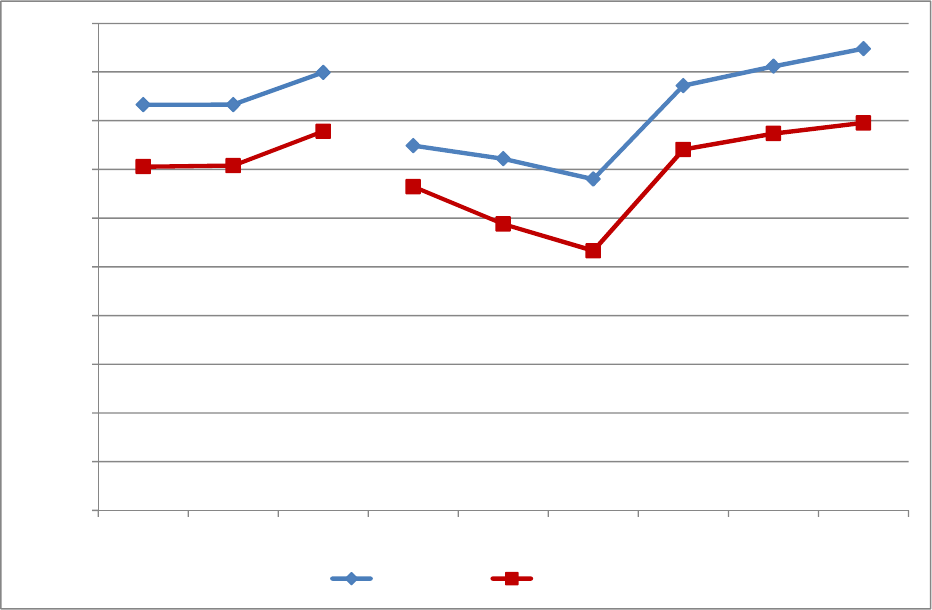

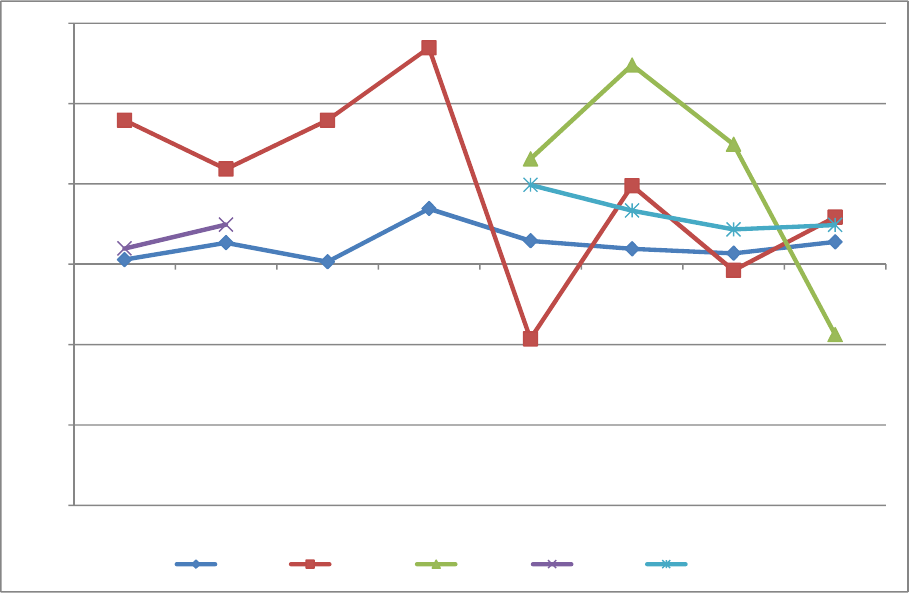

Figure 40:

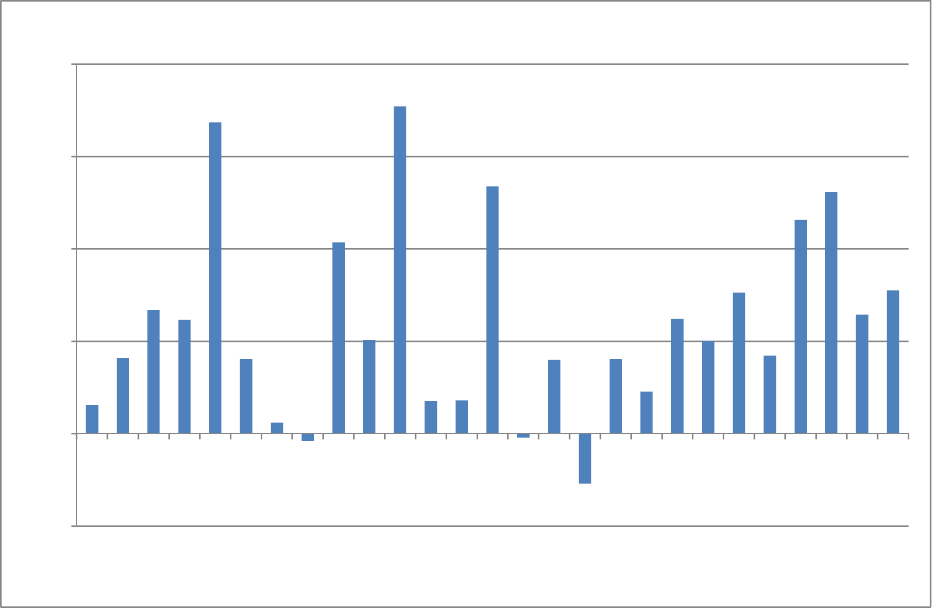

Change in FFI/FWU, average 2010-2012 vs average 2004-2006 89

Figure 41:

Annual change in FFI/FWU, 2010-11 and 2011-12 90

Figure 42:

Coefficient of variation of farm income indicators by Member State, 2004-12 91

Figure 43:

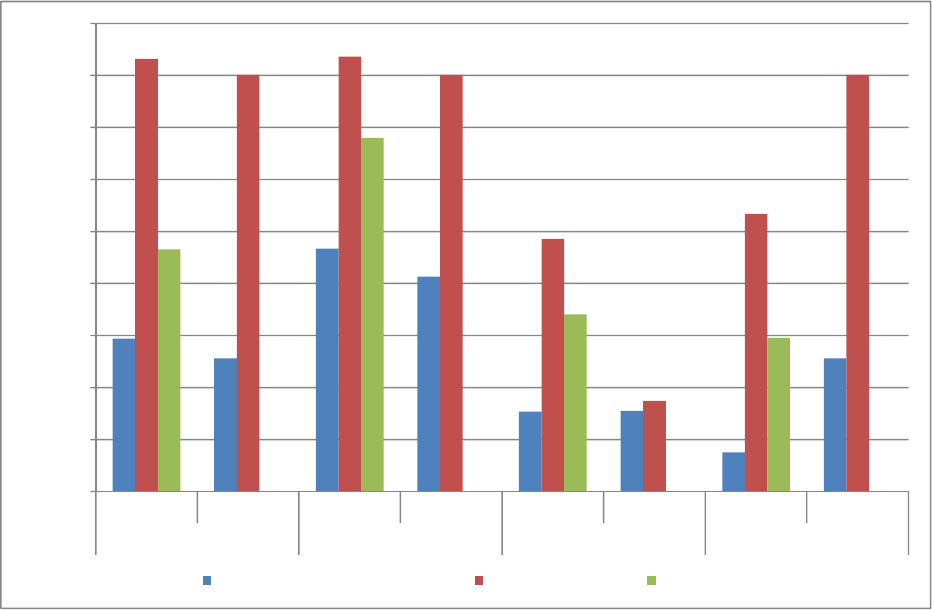

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

9

FFI/FWU by farm type and Member State, 2010-2012 average, EU-27 = 100 92

Figure 44:

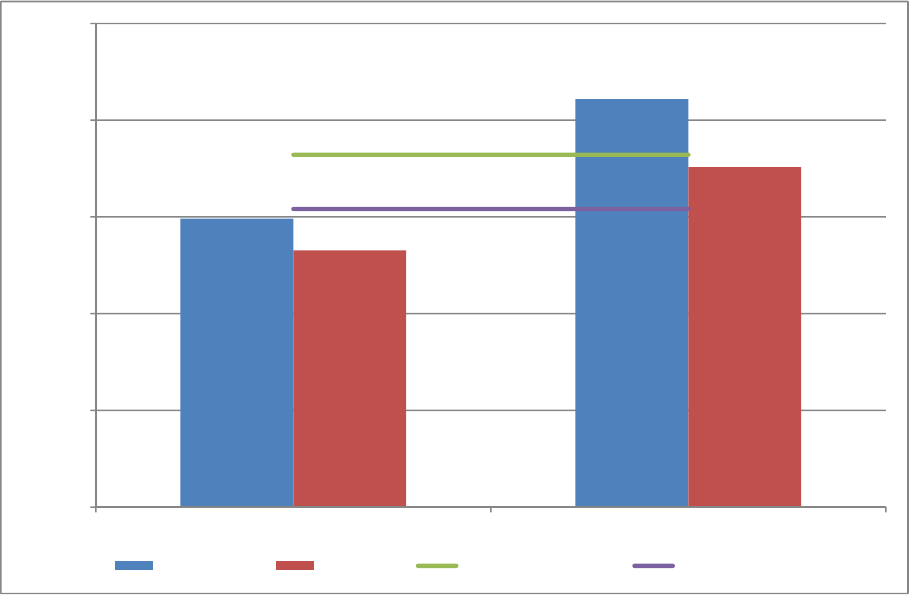

FFI/FWU by Economic Size and Member State, 2010-2012 average, EU-27 = 100 95

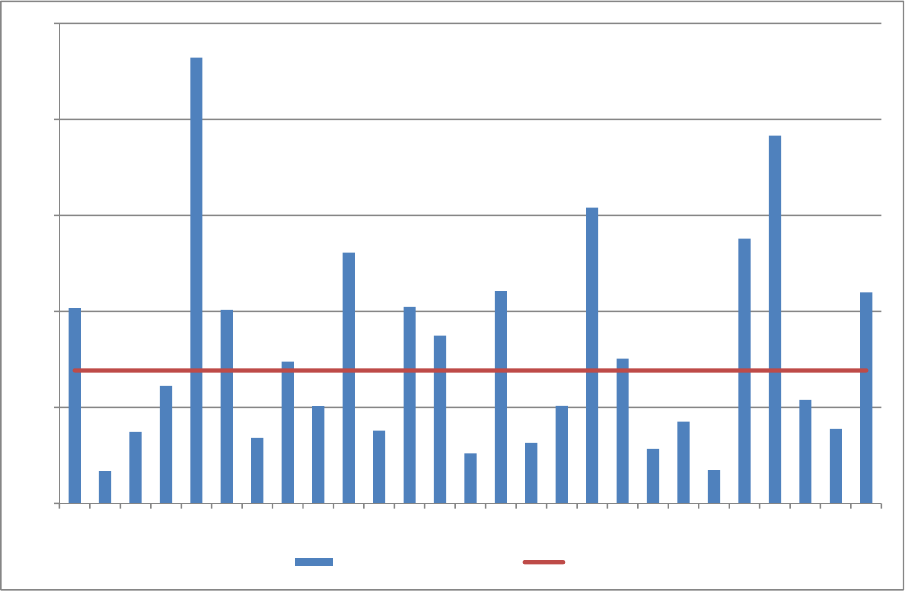

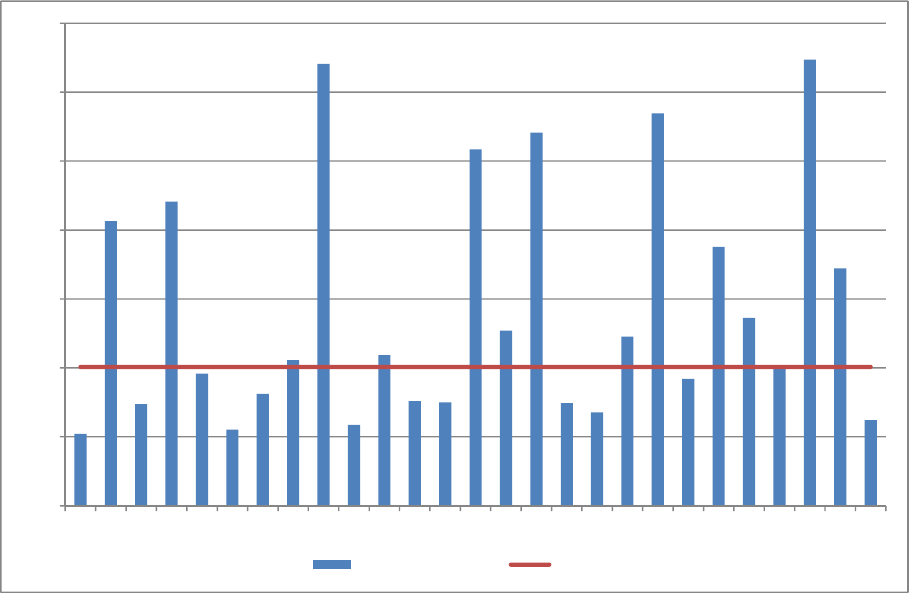

Figure 45:

Paid wages per hour (2010-12 average) 97

Figure 46:

Coefficient of variation in paid wages by Member State, 2004-2012 99

Figure 47:

The calculation of Economic Indicators in the FADN 124

LIST OF BOXES

Box 1:

The economic functions of profit 18

Box 2:

The Treaty statement of the objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy 24

Box 3:

CAP aims as articulated in Agenda 2000 (European Commission, 1997) 25

Box 4:

Reasons for non-adoption of household statistics 27

Box 5:

Definition of indicators used in the Economic Accounts for Agriculture 32

Box 6:

Definition of indicators used in the Farm Accountancy Data Network 33

Box 7:

Statements by the Commission on the relative position of incomes in agriculture 37

Box 8:

Pluriactive farm operators in the EU-27 39

Box 9:

Safety net for farm households (based on Gundersen et al., 2000) 103

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

10

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

11

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

Introduction

The purpose of this study for the European Parliament, as set out in the Terms of

Reference, is to:

Provide an overview of the income developments of EU agriculture.

Examine the different dynamics of farming incomes (changes, amplitudes of

movements, stability) and their main drivers.

Analyse the disparities across Member States and aggregates.

Provide recommendations in order to adjust the CAP income support and national

policies to counteract current trends.

This purpose has to be achieved within the context of what the Terms of Reference describe

as the central aim of the Common Agricultural Policy ‘to ensure a fair standard of living for

the agricultural community, in particular by increasing the individual earnings of persons

engaged in agriculture’.

The Terms of Reference also make it clear that data sources and methodologies for making

the comparative analysis are the responsibility of the authors of the briefing note. With that

in mind, the chosen staring point is a review of the incomes of agricultural households and

in particular the incomes they receive from independent activity in agriculture (their self-

employment income from farming).

The profit from running a business (which may be called entrepreneurial income) has a

number of economic functions which make it a very important concept in the context of

farmers and agriculture. In particular, it represents both funds generated within the farm

that can be used for consumption, investment and saving and the rewards to the resources

owned by the farmer (including the unpaid labour on the farm).

Profits from agriculture in developed countries such as those of the EU generally suffer from

a long-term downward pressure that help explain structural change and from shorter-term

instability. Furthermore, there are geographical and circumstantial differences between

groups within agriculture.

There are two alternative approaches to measuring entrepreneurial incomes in agriculture:

aggregate accounting as used by the Economic Accounts for Agriculture (EAA) drawn

up by Eurostat and microeconomic accounting as used by the EU’s Farm Accountancy

Data Network (FADN). Both have important limitations, and there are also

methodological differences between them that have relevance for their use in the context of

this brief.

However, profit from agriculture is only part of the income picture for many farm

households and a focus on their returns from agriculture will therefore present only a

partial picture of the farm household’s income, which is a main determinant of the farmer’s

standard of living.

Data sources and methodological explanations

Literature has been drawn on to establish the main types of comparison relevant to this

study. This has been followed by an in-depth analysis of the statistical systems that

generate income data in the EU, and a detailed and independent analysis of what the data

show (presented in Chapters 3 to 5).

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

12

For statistics on the incomes of agricultural households key definitions for use in the

monitoring and guidance of agricultural policy have been worked out by Eurostat and at

international level by the FAO. The most appropriate indicator is considered to be the net

disposable income of households (covering income from farming and other gainful

activities, from property, pensions and other transfers, and after the deduction of personal

taxes and other non-optional payments). Possible data sources to furnish these statistics

are considered; these vary between Member States.

For income that arises from agricultural activity indicators based on the Economic Accounts

for Agriculture are calculated by Eurostat, but these are only available at the national level.

However, the Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) calculates indicators at the level of

the farm business and these can be used to illustrate detailed patterns in the agricultural

industry.

Two FADN indicators are appropriate in the present context. Farm Net Value Added

(FNVA) represents the rewards to all the fixed factors used in the farm business,

irrespective of their ownership. Farm Family Income (FFI) is after the further deduction

of the costs of hired labour, interest paid and rent paid and is the return to the farmer for

the use of his own labour, own land and own capital; it represents the amount generated

by the farm business that is available for consumption, investment and saving.

FFI expressed per business or per work unit of family (unpaid) labour (FFI/FWU) is the

preferred income concept for this analysis because it corresponds most closely to the

concept of the profit from farming that is available to support the living standards of

farmers. Because incomes are subject to much short-term instability, where possible,

averages are taken across three adjacent years; the main study period is 2010-2012.

Overview of the income development of EU agriculture

There is currently no working statistical system at EU level for agricultural household

incomes. Structural statistics for EU agriculture make it clear that many farmers (at least a

third, and more if other members of their household are included) also have other gainful

activities. National results where available show that other incomes not only raise the

household income levels of farm families, but also add to its stability.

Furthermore, the evidence points to farmers NOT being a particularly low-income sector of

society in most Member States judged on the basis of their household disposable incomes.

This is of obvious importance to the CAP’s aim to ensure a fair standard of living of the

agricultural community.

In terms of incomes from agricultural activity, the focus of this report, it is clear that the

income indicators at aggregate level (Eurostat) and farm level (FADN), where they share

similar concepts, tend to move in similar fashion. The two FADN indicators (FNVA/AWU

and FFI/FWU) are also closely aligned in their directions of change over time.

Among the various groups of Member States in common usage, in absolute terms FFI/FWU

is highest in the EU-15, then the EU-N10 and lowest in the EU-N2. FFI/FWU increased over

the 2004 to 2012 period with a substantial decline between 2007 and 2009 in all groupings

with the exception of EU-N2.

For the EU-27, a strong relationship exists between the economic size of farm business and

the average levels of income generated. This applies not only to FFI per farm (as might be

expected) but, more importantly, income per unit of family labour (FFI/FWU). Care has to

be exercised in interpreting results for small farms because only some Member States are

represented because of the application of different thresholds for inclusion in FADN; only

for size classes with Standard Output of

€25

,000 and over are all countries represented.

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

13

That said, in each farming type the smallest farms have the lowest incomes, and absolute

incomes per FWU increase with farm size.

Incomes differ between the various types of farming, granivores having the highest

incomes, and mixed farms the lowest. Granivores also tend to dominate in the largest size

groups.

This relationship between farm size and income levels permeates other differences, such as

between farms of different legal status and age of farmer, with the observed patterns

largely explainable by differences in farm size.

Incomes of farms in Less Favoured Areas were lower than those in non-Less Favoured

Areas, even after including the special payments that the former receive.

It is clear that the variability of income over time in FADN results at the group level is much

greater in the smallest size class of farms, though it should be recalled that this omits data

from many Member States because of the differing size thresholds applied. Beyond that,

variation increases with farm size.

‘Granivore’ and ‘Fieldcrop’ farms have the greatest volatility of income. The most stable

incomes are found in the ‘Horticulture’ and ‘Other permanent crops’ sectors.

When income volatility is measured at the level of the individual farm 55% of large farms

and 38% of small farms experienced income volatility of ±30% from the previous three

year average.

The distribution of income at the farm level is very unequal; 20% of the labour force

generates 78% of the FFI. Furthermore, incomes averaged over three years 2010-2012

were negative for large parts of the farm labour force, suggesting that additional factors,

such as income from other gainful activities, is important in explaining the ability of such

farms to survive.

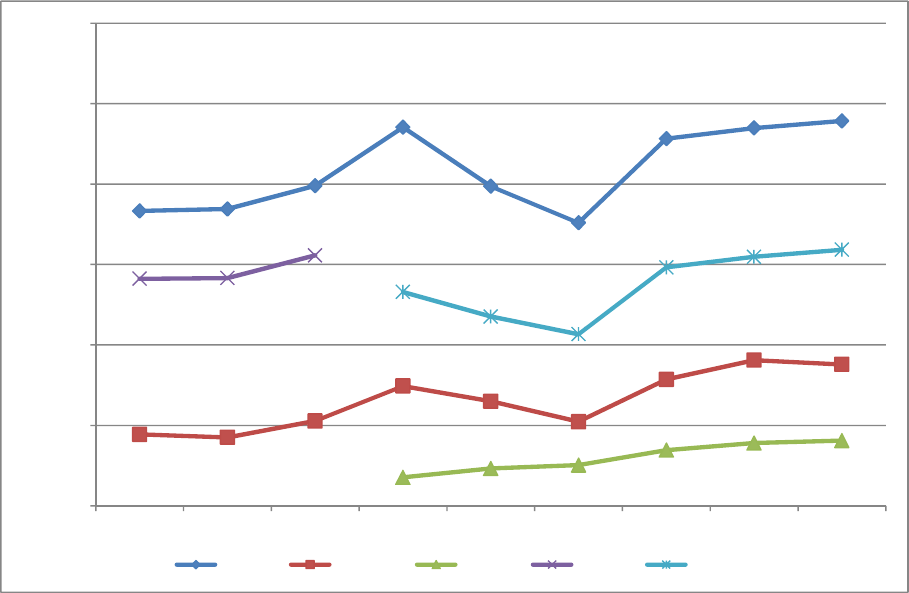

For the dependent (paid) section of the labour force, agricultural worker income (wages)

increased steadily (in nominal terms) over the 2004-12 period with only the EU-N2 group

experiencing a decline in 2008 and the EU-N10 one in 2009. The pay of agricultural

workers in the EU-N10 converged with that in the EU-15 over the period, but pay in the EU-

N2 did not. Agricultural wages per hour differ across farming type, being highest in the

wine sector and lowest in ‘Other grazing livestock’ and ‘Fieldcrops’ farm types.

The dynamics of farm incomes and the key drivers

For agricultural households with income from other gainful activities, earnings from

property and/or pensions and transfers, the drivers of this non-farm income are largely

those that shape the general economy. Some 12% of EU-27 farms also draw income from

on-farm diversified activities, and these increase with farm scale; this income is also driven

by general economic factors, although some will be related to the agricultural economy.

The most important component of agricultural revenue is returns from the market

which account for 86% of FADN Total Output for the EU-27.

Market returns are driven by quantity of output and price. Yields have been relatively

stable, but prices, especially for crops, have fluctuated considerably over the 2005 to 2012

period.

Subsidies make up the balance of Total Output; there is no suggestion that changes in

subsidies have played a major role in the evolution of income.

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

14

The most important cost element is total intermediate consumption which accounts for two-

thirds of total expenses for the EU-27. Depreciation accounts for 15% of total costs, wages

paid 9%, rent 5% and interest payments 3%.

Total intermediate consumption is made up of total specific costs (crop and livestock) and

overheads (machinery and building costs, energy, contract work and direct inputs). These

elements of intermediate consumption have all increased between 2004 and 2012, but

specific crop costs have increased the least. Within specific crop costs, fertiliser cost is the

most volatile element. Within overheads, energy costs have been the most volatile and

showed the sharpest absolute increase.

Although the use of paid labour has declined, wages paid per farm increased steadily

between 2007 and 2012.

The importance of these income components differs by farm type. Subsidies account for

a quarter of the value of total output in ‘Other grazing livestock’ farms, but less than 5% in

the horticulture, granivore and wine sectors. There is less difference in the relative

importance of costs by farm type, although paid wages are more important in the

horticulture and wine sectors.

Analysis by farm size shows that the relative importance of subsidies decreases as farm

size increases.

Differences between Member States

A Common Agricultural Policy does not appear to result in a common absolute level of

income for the average farm in different Member States. Belgium, Denmark, Germany,

France, Luxembourg, the Netherlands and the UK stand out as having high farm incomes.

Amongst the EU-N10 Member States, only in the Czech Republic, Estonia and Hungary do

farm income indicators exceed or come close to the EU-27 average.

The main reason for this is the economic size of farms; the mix of farm types also plays a

role. However, when farms of the same size and type are compared, performance is often

equivalent throughout the EU-28 and sometimes higher in the EU-N10 and EU-N2 than it is

in the EU-15.

The influence of farm structure is also important at the regional level with farm incomes

varying widely within Member States. This regional variation is especially noticeable in

France and Germany.

In terms of the growth in farm incomes between figures averaged for the 2004-06 and

2010-12 periods, EU-N10 Member States have outperformed EU-15 Member States as a

result of higher market prices, access to the single market and increased public support.

The increase in farm income per unit of labour in these Member States also reflects

decreases in total labour use. Despite these increases, farm income in the EU-N10 and

especially the EU-N2 lags behind that in the EU-15.

Within this overall trend, farm incomes are highly variable from year to year, but farm

incomes in different Member States move in different directions and by different

magnitudes, partly the result of structural difference in farm type.

Some Member States have higher levels of income variation than others. Again this is

partly structural with income in the granivore and fieldcrop sectors relatively unstable while

income in horticulture and permanent crops is relatively stable. The relatively low variability

in farm income seen in Greece, Spain and Italy reflects the substantial proportion of other

permanent crop farm types in these Member States.

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

15

There is a tendency for EU-N12 Member States to have higher coefficients of variation than

EU-15 Member States, but this is partly the result of the general upward trend in farm

incomes that these Member States have experienced.

Farm income levels differ between Member States within farm type, although this is partly

the result of the structure of farms within FADN. A key factor in differences between

Member States by farm type is actually farm size within the FADN sample.

As economic size increases, it becomes more common for farms from the EU-N10 to show

higher FFI/FWU than farms in the EU-15. For the largest size group, only farms in Italy and

the UK from the EU-15 have farm income higher than the EU-27 average.

Agricultural wages differ markedly between Member States. In Denmark, the Netherlands

and Sweden wage levels average more than

€15 per hour while in Bulgaria, Greece, Latvia,

Lithuania, Poland and Romania the average is €3 or less.

Agricultural wages vary little within Member States, although there are some exceptions

with wages higher in Champagne than in the rest of France and higher in the east of

Germany where the wages of company farm managers and administrators are included in

the figures.

Recommendations for future income support under the CAP

Based on our analysis the recommendations to the European Parliament are that:

Further consideration is given to the re-establishment of EU statistics on the

incomes of agricultural households, since they are needed to assess the extent to

which the CAP is achieving this core objective of a fair standard of living.

Data sources that relate to the entire economic activities of the households (and

other institutional units) that operate farms should be encouraged.

A study be undertaken to assess the relative attributes of a safety net for the

incomes of farm households for the EU, including its costs, and the necessary

technical conditions that would be required for it to operate successfully.

When considering the need for support of incomes, the wealth of agricultural

holdings should be taken into account.

Suitable caveats should be used when FADN data are reported to make clear the

impact of the field of observation on the results.

Consideration should be given to the need to represent people (the operators of

farm holdings) rather than production. A suitable balance needs to be struck

between the current production/land use focus of FADN and the social impact of the

CAP.

Attention should be diverted away from interventions that attempt to combat

instability directly at the farm level and towards risk management schemes that

prepare farm operators to better anticipate and cope with instability. This could

involve further studies.

Consideration should be given as to how the occupiers of small farms can enhance

their economic prospects by building their skills and other forms of human capital.

We recommend that policies that increase market participation and ease the

adjustment of farm businesses and households should be further supported and that

current impediments to access be examined.

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

16

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

17

1. INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this detailed briefing note for the European Parliament, as set out in the

Terms of Reference, is to:

Provide an overview of the income developments of EU agriculture.

Examine the different dynamics of farming incomes (changes, amplitudes of

movements, stability) and their main drivers.

Analyse the disparities across Member States and aggregates.

Provide recommendations in order to adjust the CAP income support and national

policies to counteract current trends.

This purpose has to be achieved within the context of what the Terms of Reference describe

as the central aim of the Common Agricultural Policy ‘to ensure a fair standard of living for

the agricultural community, in particular by increasing the individual earnings of persons

engaged in agriculture’.

The Terms of Reference also make it clear that data sources and methodologies for making

the comparative analysis are the responsibility of the authors of the briefing note.

KEY FINDINGS

Entrepreneurial income (less formally called ‘business profit’) has a number of

economic functions which make it a very important concept in the context of

farmers and agriculture.

Profits from agriculture are generally suffering from long-term downward pressure

and shorter-term instability and there are geographical and circumstantial

differences between groups within agriculture.

However, profit from agriculture is only part of the income picture for many

farm households and a focus on returns from agriculture will therefore present only

a partial picture of farm household income.

There are two possible approaches to measuring entrepreneurial incomes in

agriculture: aggregate accounting as used by the Economic Accounts for

Agriculture (EAA), drawn up by Eurostat, and microeconomic accounting as used

by the EU’s Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN). Both have important

methodological limitations and there are also methodological differences between

them that have relevance for their use. Neither at present is capable of describing

the overall income situations of the households that operate farms, which represents

a major gap in the information needed to assess the performance of the CAP in

relation to its stated objectives.

The evidence on ‘Comparison of Farmers’ Incomes in the EU Member States’ and its

accompanying analysis presented in this Report needs to be put in context. This section

does so by presenting the functions of income (for farmers the essential component of

which is profits from their agricultural activity), the characteristics of incomes in

agriculture, the approaches taken to incomes within accounting systems, and the

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

18

relationship between policy aims and measurements of income. Further contextual

information is provided in Hill (2012), FAO (2011) and UN (2008).

1.1. The economic function of profit from farming

The large majority of EU farms are arranged as independent units (businesses operated by

households or corporations) and thus farmers receive their rewards from agriculture in the

form of entrepreneurial income, or less formally, business profit. For household firms

entrepreneurial income is a hybrid, in the sense that it is a mix of rewards for the unpaid

labour provided by the family, for using its own land and capital, and for the risk-taking

and management function. Ways in which this income is defined and measured will be

considered later, but at the outset it is worth noting why there is interest for purposes

related to the CAP in observing changes and differences in entrepreneurial incomes

(various forms of comparisons over time and place and circumstance).

In the EU’s modern competitive market economy profit performs important economic

functions as shown in the Box below.

Box 1: The economic functions of profit

Profit is the reward from production, and is the residual remaining to the operators

of businesses (including farms) once the costs of inputs, wages paid to hired labour,

rent paid to landowners, interest paid on loans and an estimate of depreciation have

been deducted from the value of sales and other forms of revenue. Profit reflects the

risks that the farmer is taking and the use of his/her own factors of production

including labour.

Profits signal to producers where expansion or contraction of production should take

place as they reflect changes in market prices (driven by changes in demand) and

costs.

Profits enable the most efficient firms to expand.

Profits provide the incentive for innovation.

Profits are therefore key to explaining structural change, although it should be

noted that income from non-agricultural activities is also a factor here.

In addition to its economic functions, the business structure of EU agriculture, with the

numerical dominance of the small family farms

2

, means that profits from farming form an

important component of the personal incomes of most farmers’ households, though they

often also have other income sources (see below).

1.2. Characteristics of incomes in agriculture

The literature shows that agriculture is characterised by a number of features that have to

be understood if income comparisons over time and place and circumstance are to be

understood.

The long-term downward pressure on incomes (comparison over time).

Historical evidence shows that agriculture in economically developed countries is

caught in a cost-price squeeze. On the one hand, the prices that farmers receive for

their output is in long-run decline because the supply of farm products has

2

According to the 2010 Farm Structure Survey there were 12 million farms in the EU-28, 97% of which were

single holder operations.

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

19

expanded faster than the demand for them. Technological advances in production

processes (new varieties of crops, improved livestock, more and better machinery

and fertilisers, etc.), which it is in the interest of the individual farmer to adopt,

have led to greater volumes of production, whereas in contrast factors that affect

demand (such as the size of the market and willingness of people to spend more on

food) have changed much less. The outcome has been a fall in the real value of the

net margin between costs and revenues remaining to the sector as a whole, and

thus a fall in the relative position of average rewards to productive resources (in

particular labour) in agriculture compared with those available in the rest of the

economy. This in turn has led to structural change (such as the migration of labour

out of agriculture, the reduction in numbers of smaller farms and the absorption of

their land by larger ones). This downward pressure on incomes in agriculture is a

result of the basic economics of supply and demand and shows the competitive

market economy performing its normal role in bringing about change.

Shorter-term income instability (comparisons over time). Superimposed on

the long-term trend are shorter-term movements in income which, mostly, reflect

the market doing its job in better matching shorter-term supply and demand. There

are medium-term diversions from the long-term trend, resulting, for example, from

natural disasters or political events that interrupt supply or demand. There will be

inter-seasonal variations caused by good or poor growing conditions that lead to

temporary over or under-supply. There are also regular seasonal price variations

and random market ones. Thus farmers face an inherently unstable income

situation. Farmers are expected to manage most of these risk factors as part of their

normal operation.

The heterogeneous nature of agriculture (comparisons over space and

circumstance). Farms differ greatly in terms of the types of production taking

place on them (their farming type), their size (measured in terms of land area or

economic size), the diversity of natural conditions they face (climate, soil, slope,

altitude, etc.), labour force (numbers of workers and composition), and region. Even

within one type/size/region group there will be differences in income brought about

by differences in management ability, the age profile and experiences of farmers,

etc. It is worth noting that the Commission has drawn a distinction between income

disparities, income dispersion, and income distribution (CEC, 1985b). Disparities

refer to the differences in average incomes between groups (such as between

Member States or types of farming); a specific type of disparity which is of

significance to achieving the official aims of the CAP is the relative incomes of

farmers and those of the rest of the EU population. Income dispersion refers to

the deviations of the individual figures within a given group from the average for the

group. Income distribution refers to the breakdown of farmers (and/or other units

of labour) according to income classes. This in-depth analysis deals with all three,

within the constraints of available data.

Observation of the documentation, discussion and practice of policy suggests that farmers

and their households are caught up in income problems that are widespread and

characterise the agriculture industry. These income problems are as follows:

The particularly low incomes in certain regions or sizes of farm (the poverty issue).

At the same time the occupiers of other farms may have high incomes, so that the

heterogeneity of the income situation presents a problem in describing the (income)

poverty issue in agriculture as a whole and in designing policy to address it.

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

20

The variations of income experienced by the individual farm over time (the

instability issue). Again this may vary between region, type and size of farm.

However, it is readily shown that instability as measured by group averages greatly

understates the degree of instability experienced at the level of the individual farm

business (for a review of this evidence see Hill (2012), Chapter 4). An implication is

that the measurement of income in a single year is unlikely to be a reliable indicator

of the income of a farm over a run of years; empirical evidence suggests that an

average over three years is preferable and this is the approach we take in this

report where possible. While incomes from agricultural activity are inherently

unstable, the presence of other income may dampen the impact on total farm

household income; this appears to be usually the situation. This means that farm

household income is usually more stable than agricultural income.

The general levels of rewards of those engaged in farming compared with earnings

in other sectors (the parity issue). This is often expressed in terms of the incomes

of people working in agriculture compared with those in other groups in society or

the national average. However, for self-employed farmers these incomes are a mix

of rewards to labour, capital and land and the issue of parity includes the return to

investments in land and capital assets as well as to labour. A major factor in

explaining the apparently low reward to land is that its value is determined in a

market, typically very small in relation to the total stock that is often dominated, on

the demand side, by existing farmers trying to expand to reap the benefits of

spreading fixed costs and technical advances that require larger-scale production.

However, expanding farmers typically bid up land prices to levels that are

determined by their margins over variable costs, not by total costs, and thus land

appears very expensive in relation to average profits.

Partly as a result of this last point, and because in market economies public support

of farm incomes tends to be capitalised into higher land prices

3

, income problems

are often seen among farm occupiers that are often also owners of substantial

amounts of wealth. Wealth is even more unequally distributed than are incomes,

and farmers who own land are likely to have a markedly different economic status

from those who are tenants or where land rights are poorly defined. It is worth

noting that the wealth of farm households is usually ignored when discussing the

need for policy intervention to tackle income problems.

The first three of these points are the same trio of central components of ‘the farm

problem’ that have been identified in the United States and summarised by Gardner

(1992).

Parity and poverty are concerned essentially with the welfare of farmers and their

dependants. Instability is somewhat different. A low farm income in a single year may not

immediately throw the recipients into the poverty category. Reserves will be drawn on or

borrowings made to maintain living standards through times of temporary financial

setback. Thus in industrialised countries it is important to distinguish between those farm

households that have to contend with occasional periods of low income and those that

suffer hardship from incomes that are persistently low. However, when year-to-year

fluctuations are anticipated, the level of consumption by farmers and their households may

have to be curtailed in order to set aside reserves for years of low incomes or to pay for

past borrowing in lean years. Farmers may have to be content with generating a safer but

3

See, for example, European Parliament (2013b); Swinnen, et al. (2008); and the Framework 7 project Factor

Markets, Grant agreement N°: 245123-FP7-KBBE-2009-3 http://www.factormarkets.eu/content/rural-land-

market

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

21

lower income, with consequences both for consumption possibilities and the potential for

the business to grow.

A further characteristic of agriculture in the EU that must be borne in mind is the business

structure of farms. As noted above, the large majority of EU farms, in terms of numbers,

are arranged as unincorporated businesses that are operated by households (the relevance

of this for income accounting is covered below). In EU structural statistics these are

returned as farms operated by ‘natural persons’, in contrast with farms arranged as

companies or similar forms which have their own legal status (‘legal persons’). In practice

this means that:

On farms operated by households no clear distinction can be drawn between the

business income and assets of the farm and the personal income and wealth of the

farmer and his immediate household. This is of importance when assessing the sums

that are available to support the living standards of the farm household.

Because many farm households have additional sources beyond what they receive

from farming, the income obtained from farming activity is not a reliable guide to

the total or disposable income of the household, usually taken as an important

determinant of potential consumption spending and thus of the standard of living of

the household.

Because in international accounting systems households are seen as being engaged

in both consumption and (as in agriculture) production activities, great care has to

be taken not to confuse and misuse indicators of one function for the other. As will

be seen below, in reality indicators of the rewards from farm production have often

been used as proxies for household disposable income, leading to importance

misunderstandings of the need for and effectiveness of spending under the

CAP.

1.3. Accounting systems and agricultural incomes

Accounting systems allow for the possibility of basing the measurement of incomes on

institutional units (e.g. family farms) or activities (e.g. agricultural production). Within this

structure, each approach can be taken at the level of the aggregate (industry/sector) or of

the individual unit (farm or household). Within the EU’s statistical system aggregate

accounting is represented by the Economic Accounts for Agriculture (EAA) (based in

national accounts) which are drawn up by Eurostat for the EU and Member States.

Microeconomic accounting, built up from individual units, is used to produce the EU’s

Farm Accountancy Data Network (EU-FADN) and household accounts, such as in the

EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC). For historic reasons,

accounting systems and income measurement in agriculture have been based on farming

activities and not the more appropriate farm household unit (when measuring incomes that

relate to the standards of living). This has resulted in misunderstandings and potentially

inappropriate policies.

The UN’s System of National Accounts (SNA) is probably the most universally accepted

set of international accounting conventions and is the basis of the European System of

Accounts (ESA). With roots going back some fifty years, the SNA has formed the basis of

much of the economic statistics that already exist for agriculture in countries at all levels of

economic development. The SNA, though aggregate in nature, also commonly acts as a

benchmark for micro-economic accounting.

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

22

Two main approaches towards accounting for agriculture can be found within the SNA

accounting framework:

accounts for the activity of producing commodities (goods and services) deemed

to be agricultural according to agreed international classification, together with their

residual ‘income’ concepts;

accounts for institutional units that engage in agricultural production; these

form three main types:

households, in their role as units of production (household-firms), and for

which agricultural activity is one (possibly the only) form of independent activity

(self-employment) that the household members engage in. The household may

also engage in dependent activity (its members work as employees) and may

also receive resources in other ways (for example, from welfare transfers,

property income, etc.). The independent agricultural activity may account for

various shares of the total resources available to the household;

corporations, at least part of whose activity involves agricultural production;

and,

other types (including government and Non-Profit Institutions).

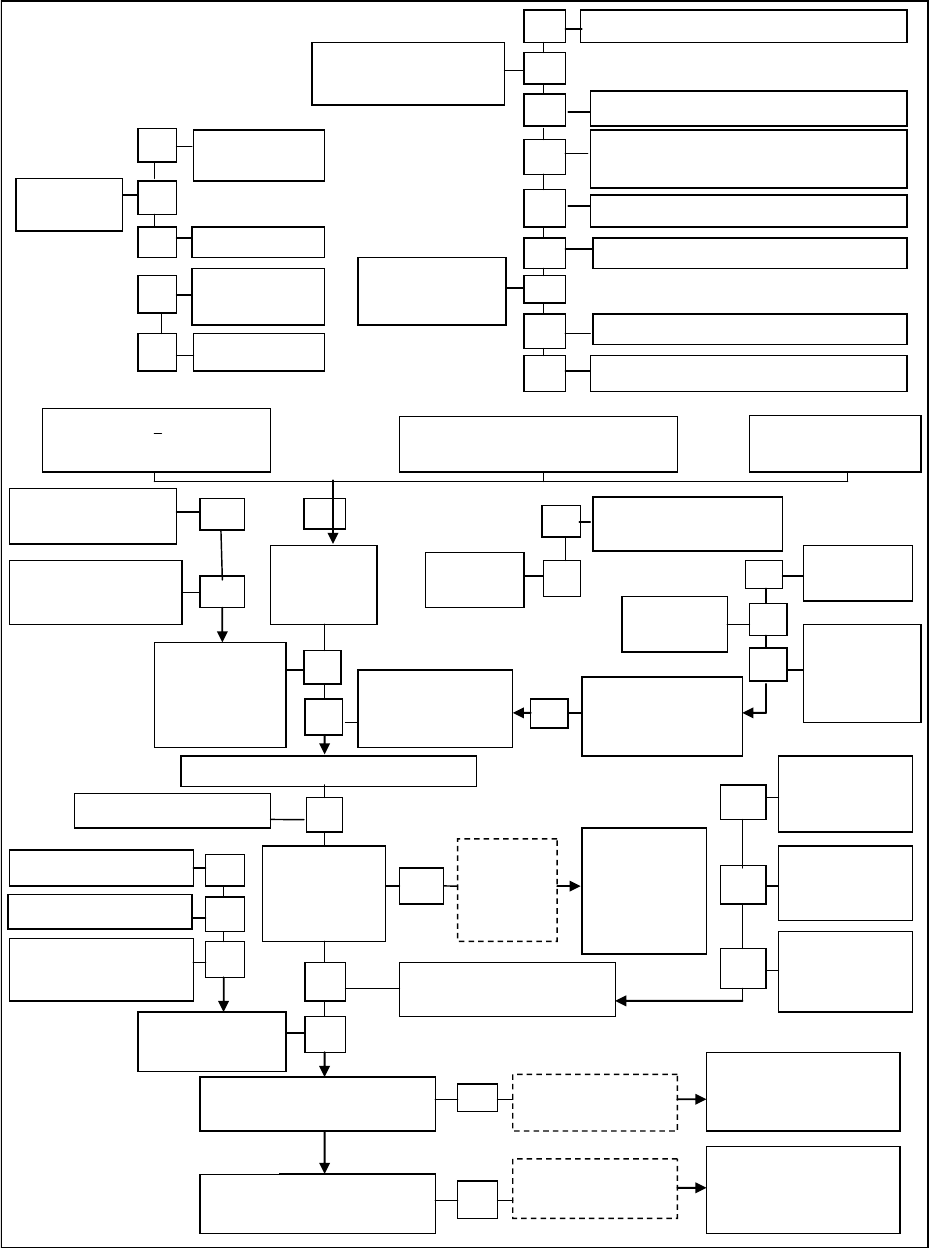

Of course, as these are part of a single system, they relate to each other (see Hill, 2003).

Figure 1 illustrates this relationship in an agricultural context. It shows that agricultural

activity is divided between the various types of institutional units that are involved

in entrepreneurial activity.

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

23

Figure 1: The relationship between agricultural activity and the institutional units

that generate it

4

REAL INSTITUTIONAL UNITS

Mixed income

(Operating

surplus of

agricultural Local

Kind of Activity

Units (LKAUs)

HOUSEHOLDS-AGRICULTURAL

OTHER

HOUSEHOLDS

CORPORATIONS

OTHER

Entrepreneurial income from

agricultural

activity

Other income

from independent

and dependent

activity transfers

etc.

Other

EI

Kitchen

gardens

Source: Hill (2003).

Activity accounts which cover the value of production of agricultural commodities and the

associated costs can only, strictly, be taken to the level of Operating Surplus (value

added minus the cost of paid labour). To go further to estimate Entrepreneurial Income by

the further deduction of interest and rent payments means attributing these to specific

activities. This requires assumptions about the extent to which the farm household is

involved in other (non-agricultural) activities and how these payments should be allocated.

For example, the extent to which any of the interest payment relate to non-farming

activities or consumption goods. However, such assumptions are often made by the array

of indicators commonly in use. Both aggregate income indicators developed by Eurostat

from the EAA and microeconomic indicators within FADN make such assumptions.

The nature of what constitutes an agricultural household (or an agricultural corporation)

is critical to the generation of statistics and can affect both the numbers of households and

the income levels and compositions relating to them. The concept of a household (which

may take a variety of forms) and the basis used to classify them as agricultural or non-

agricultural (for which several possibilities exist) is discussed in Chapter 3.1.

4

Also used in Hill and Platt (2003) and FAO (2011). An agricultural Local Kind of Activity Unit (LKAU) is the

fictional basic statistical unit concerned with agricultural production and for which accounting for output,

intermediate consumption, etc. is possible. It may form part of an institutional unit (such as a farm business

operated by a household), but does not include any non-agricultural activities in which the farm may engage

other than those that are inseparable in the data sources (such as minor farm-gate sales). See Eurostat

(2000).

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

24

1.4. Policy aims and appropriate measures of income

A major issue that has to be confronted when reviewing the information on incomes in EU

agriculture is that there is a mismatch between the declared aims of the CAP and the

indicators that are available to monitor the policy’s performance. As will become clear, in

reality accounts drawn up on the basis of institutions (such as farm households) are

relatively poorly developed, whether at sector or microeconomic levels. In contrast,

accounts for the activity of agricultural production are well established at both levels

and the indicators are in common use.

One source of the aims of policy is what appears in official statements. On the one hand,

the Treaty is clear that a central concern is with the living standards of the agricultural

community, though Hill (2012) points out that this rather general objective has not been

articulated in a more precise and testable form. First seen in the 1957 Treaty of Rome

(Article 39), the wording has been carried forward into subsequent Treaties, including the

2012 Consolidated Version of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (Official

Journal of the European Union, C326, 26 October, 2012). The implication is that the 1957

wording has been the basis of giving legal validity to any proposed policy measures since

the start of the CAP and continues to do so.

Box 2: The Treaty statement of the objectives of the Common Agricultural Policy

5

The Treaty states that ‘The common agricultural policy shall have as its objectives:

a) To increase agricultural productivity by promoting technical progress and by

ensuring the rational development of agricultural production and the optimum

utilisation of the factors of production, in particular labour.

b) Thus to ensure a fair standard of living for the agricultural community, in

particular by the increasing of the individual earnings of persons engaged

in agriculture [emphasis added].

c) To stabilise markets.

d) To assure the availability of supplies.

e) To ensure that supplies reach consumers at reasonable prices.’

The Agenda 2000 agreement, though lacking the full authority of a Treaty, also

articulated the CAP’s aims, carrying over the ‘fair standard of living’ phrase but also adding

an assurance of promoting income stability and of expanding on how farmers might be

assisted by providing alternative sources of livelihood.

5

Official Journal of the European Union, C326/47, Article 39, pp62-63.

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

25

Box 3: CAP aims as articulated in Agenda 2000 (European Commission, 1997)

[To] 'increase competitiveness internally and externally in order to ensure that

Union producers take full advantage of positive world market developments.

Food safety and food quality, which are both fundamental obligations towards

consumers.

Ensuring a fair standard of living for the agricultural community and contributing

to the stability of farm incomes [emphasis added].

The integration of environmental goals into the CAP.

Promotion of sustainable agriculture.

The creation of alternative job and income opportunities for farmers and

their families [emphasis added].

Simplification of Union legislation'.

To ensure that supplies reach consumers at reasonable prices.’

Another indication of the persistence of the CAP aim of ‘ensuring a fair standard of living of

the agricultural community’ is that these words are incorporated into the Regulations that

give the legal basis for spending on agriculture from the EU budget. For example,

Regulation (EC) No 1308/2013 establishing a common organisation of the markets in

agricultural products uses these same words, following a convention demonstrated in the

superseded legislation. When referring to support of particular commodities, the aim of

ensuring the living standards of growers concerned is also mentioned. The apparent

requirement for this aim to be stated in Regulations, linking back to the fundamental

Treaties, should be noted, even if what the phrase means is far from transparent.

The need for income information relevant to the standard of living of farmers, as a major

component of the agricultural community however defined, is supported by a number of EU

and other international organisations. It was the basis of Eurostat’s establishment of its

Income of the Agricultural Households Sector (IAHS) statistics in the late 1980s (see

Eurostat 1996, 2002), was commented on by the European Court of Auditors as something

that the Commission should monitor

6

(ECA, 2004), was the subject of studies and a policy

brief by the OECD (OECD 2002, 2003, 2004), and was the driver for the drafting of a

Handbook covering statistics on agricultural households (in two editions, UNECE 2007 and

FAO 2011) under the auspices of the UNECE, FAO, OECD, the World Bank and Eurostat.

Agra CEAS Consulting (2007) investigated the feasibility of reintroducing a rebased IAHS

for Eurostat, although this has not been acted upon. There are many other commentators

and researchers who also interpret the income situation of farmer households as at the

centre of the purpose of the CAP (reviewed in Hill 2012).

Given that there would appear to be an obvious need to know about the standard of living

of the agricultural community for policy purposes, statisticians are faced with the task of

turning the concepts of ‘standard of living’ and ‘agricultural community’ into operational

entities (indicators) before the process of actual measurement by data collection can take

place. Indicators should be closely aligned with the policy impact that is required and be

sensitive to the extent of that impact. When attempting to devise practical indicators for

the standard of living it is conventional to use disposable income of the household or the

average per household member, as this represents their potential command over the

consumption of goods and services, though it has to be acknowledged that some factors

which may be important to farm families (such as their independence and work

6

The ECA (2004) noted that ‘Although this is only one of the five objectives of agricultural policy expressly stated

in the EC Treaty, the income of the agricultural community runs like a leitmotif through the CAP’.

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

26

environment) are not captured. Farm families are typically asset-rich, and there are ways

in which the wealth of farm households can be taken into account; wealth itself provides a

potential command over goods and services, and estimates of ‘economic status’ combine

current income with an annuitized value of net worth, though this indicator has not so far

taken a significant part in EU agricultural statistics.

The agricultural community is similarly a concept that has to be made operational.

Again, alternatives approaches are possible (see Hill, 1990). The consensus is that (a) this

is made up of households, rather than individuals; (b) it is made up of the households

where income from independent activity in agriculture (that is, entrepreneurial income) is

part of the household’s total income, though various criteria can be used to, for example,

separate those households where farming is the main source of income from those where it

is a minor part. It should be noted that hired workers on farms are not treated as part of

the agricultural community according to this approach as their incomes are not residual

profits; this is not considered satisfactory in some countries where agriculture is dominated

by large corporate (and similar) units, and even where farms in other countries are

arranged as private companies; to answer such problems Eurostat proposed a series of

‘add-ons’ to the strict coverage.

As has been noted above, despite the apparent need for income statistics to be available

that relate to agricultural households and to agricultural activity, in practice there is no

working system for agricultural household income statistics in the EU. Eurostat’s

IAHS statistics, which was a pioneer in this area when it started in the late 1980s, was

terminated in 2002 for reasons that included problems with quality (especially in Member

States using national accounting methodology), lack of comparability across Member

States, low priority given to developing these statistics at a time of declining resources,

and, in some administrations, concerns with the results that showed farmers as a group to

have household incomes broadly comparable with the rest of society (with some

exceptions). Instead, indicators taken from activity accounts are dominant, though they are

incapable of answering central questions on the income of agricultural households that are

crucial to illuminating the living standards of farmers.

UNECE 2007 offers some suggestions as to why (taken from Hill, 2000), which can be

adapted to the present circumstances (see Box 4).

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

27

Box 4: Reasons for non-adoption of household statistics

Lack of political demand. Politicians have not requested this information, perhaps

because of a too-simple perception of the agricultural industry, or a fear of the electoral

consequences of drawing attention to results that suggest that farmers are in a

relatively favourable income position.

Historical precedent. Activity accounts, at both aggregate and farm levels, and their

related “income” indicators are long-established, having been set up when there were

stronger grounds for assuming that the only source of incomes of farm households was

from farming. In the EU, the EAA adopted the ‘Branch’ concept at its outset in 1964; as

did the FADN basic legislation of 1965.

Operational requirement. The fact is that the CAP has operated apparently

successfully for many years in many countries without information on the incomes of

agricultural households. The administration of income support systems has rarely if ever

required the data (though some tests of eligibility have been applied within individual

structural schemes).

‘Rational ignorance’ among many users. There is a tendency among users,

especially non-specialists, to adopt satisficing behaviour. That is, they take the first

available indicator that appears to meet their needs, so that measure of the income

from agricultural activity may be assumed to show the income of farmers. Among some

users there may be a suspicion that the information revealed by household-firm data

could be against their political and/or bureaucratic interests.

Self-interest of bureaucracies. Government departments for agriculture have often

taken a pro-farmer stance and might therefore not wish to draw attention to anything

that might lead to a reduction in support for the industry, as might be revealed by

statistics on household income. There is also an understandable aim of wishing to

maintain continuity with long-established systems of activity accounting.

Data availability. Lack of basic data of suitable quality in some countries is a major

constraint in the development of statistics on the complete activities of farm businesses

and their households. In countries where it has not been conventional to ask questions

on non-farm income, agencies that collect data have been reluctant to ask new

questions about non-farm income for fear of harming response rates.

The importance of knowing about the income situation of farm households does not remove

the importance of knowing what is happening to the rewards from the activity of

agricultural production. For example, these would be helpful in understanding changes in

the supply of farm commodities, in explaining why farmers diversify and take steps to

reduce risk, and why structural change occurs in the industry. The indicators of the rewards

from agricultural production, though superficially more agreed upon among statisticians in

EU Member States than those relating to agricultural households, in fact are based on

concepts that are by no means self-evident. Principle among these are the following:

In both the aggregate Economic Accounts for Agriculture and microeconomic FADN

the basic unit is not the complete farm business. Rather it is only the

agricultural activities taking place on farms and excludes (with small exceptions) any

other gainful activities in which the farm may engage. This may involve

misattribution of the costs of inputs where these are used by both the agricultural

and other activities (such as energy usage). These other activities (which may take

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

28

place on or off the farm) may well be important in explaining the overall

performance and viability of the farm business as an economic unit

7

.

The main indicator at both levels (Net Value Added per Annual Work Unit, in

absolute or index form), though usually labelled as income, is a concept distinctly

different from that of business profit and even further from personal or household

income. It represents the reward to all the ‘fixed’ factors of production (all the land

and all the capital irrespective of whether or not owned by the farm operator, and all

the labour whether hired or part of the farmer’s family). When looking at changes

over time the practice of dividing the NVA factor reward by the size of the factor

base has some logic, but taking account of changes in only one fixed factor (labour)

can be objected to on both theoretical grounds (such as attributing any productivity

gains to labour whereas increases in capital may be partly responsible) and practical

ones (at least in some countries statisticians have reservations about the quality of

data on labour input where most of this consists of the contribution of the self-

employed farmer and spouse) (Hill, 1991).

While the EAA Entrepreneurial Income and FADN Family Farm Income

8

(both of

which involve removing the costs of paid labour, paid interest and paid rent) are

reasonable approximations of profit from agricultural production, indicators that go

further and attempt to remove costs for the farmer’s owned land, owned capital and

family (unpaid) labour, singly or together, are on weak ground because of the

difficulty of agreeing on imputed values. This was proposed by the Commission

(CEC, 1982) but soon abandoned. Nevertheless, attempts to use the same dubious

process have been repeatedly made, most recently in 2014

9

.

7

This problem has been behind suggestions that agricultural income statistics at both macroeconomic and

microeconomic levels should be re-engineered and based on real institutional units (in effect, households and

companies). While this would represent a hiatus in agricultural statistics, it would place agriculture on a similar

footing as other industries.

8

The term Farm Net Income (FNI) is used for farms that are arranged as legal entities (such as companies)

within FADN.

9

In EU farm economics overview (European Commission, 2014a) two indicators involving imputation are used.

The concept of ‘Remuneration of family labour’ involves imputing a charge for owned capital and land. The

concept of ‘Return on assets’ involves imputing a cost for family (unpaid) labour.

Comparison of farmers’ incomes in the EU Member States

____________________________________________________________________________________________

29

2. DATA SOURCES AND METHODOLOGICAL

EXPLANATION

KEY FINDINGS

For statistics on the incomes of agricultural households key definitions for use in

the monitoring and guidance of agricultural policy have been worked out by Eurostat

and at international level by the FAO. The most appropriate indicator is considered

to be the net disposable income of households (covering income from farming

and other gainful activities, from property, pensions and other transfers, and after

the deduction of personal taxes and other non-optional payments). Possible data

sources to furnish these statistics are considered; these vary between Member

States.

For income that arises from agricultural activity the Economic Accounts for

Agriculture calculated by Eurostat are only available at the national level. However,

the Farm Accountancy Data Network (FADN) calculates indicators at the level of the

farm business and can be used to illustrate detailed patterns in the agricultural

industry.

Two indicators are appropriate in the present context. Farm Net Value Added

(FNVA) represents the rewards to all the fixed factors used in the farm business,

irrespective of their ownership. Farm Family Income (FFI) is after the deduction of

the costs of hired labour, interest paid and rent paid and is the return to the farmer

for the use of his own labour, own land and own capital.

FFI expressed per business or per work unit of family (unpaid) labour (FFI/FWU) is

the preferred income concept for this analysis because it corresponds most closely

to the concept of the profit from farming that is available to support the living

standards of farmers.

The evidence on the comparisons required in this report has comprised three main

components. First there was a literature review to establish the nature of the comparisons

of incomes that can be expected to be of concern to policy makers (which will include those

that have featured in regular and occasional reports by the services of the European

Commission). This has been followed by an in-depth analysis of the methodology used by

the statistical systems that generate data about EU agriculture (especially those of the

Commission). Thirdly, and potentially of greatest concern to the European Parliament,

there has been a fresh and independent analysis of the data on the incomes from farming

in the EU and a presentation of results with a commentary on the findings. This means

that, with a few exceptions, our results are not dependent on what is found in

existing publications from the European Commission.

In the light of the objectives of the CAP that appear in the Treaty on the Functioning of the

European Union (TFEU, 2012), attention is given first to data on the incomes of

agricultural households before moving to the rewards from agricultural activity.

Data are not the same as information; information implies the analysis and interpretation

of data in the context of some problem. However, data form an integral part of the

information required for agricultural policy directed at achieving the objects set. As has

already been noted, a major aim of the CAP is directed at the living standards of the

agricultural community, though there are reasons why there is also interest in the levels of

production of agricultural commodities and the way in which these are changing.

Policy Department B: Structural and Cohesion Policies

____________________________________________________________________________________________

30

2.1. Data sources on the incomes of agricultural households

As explained above, there is currently no EU statistical system that is capable of

providing information on the living standards of the agricultural community, either

directly or through the conventional proxy of the disposable income of agricultural

households. Despite this, a substantial amount of national information exists, much of

which is relevant to understanding the income problems faced by farmers and their

responses to policy interventions. Data come from three main types of source, each of

which has drawbacks:

National surveys of farm accounts that contribute to FADN (see below) where

these collect information beyond the narrow requirements of FADN and extend to

questions relating to the household (such as income from other gainful activities

and from property and social transfers). However, in many Member States such

surveys do not collect this sort of data.

Taxation and administration records where persons that are members of

agricultural households can be distinguished from those in other socio-professional

groups. Problems with this source are that, in many Member States, some or all

farmers are not taxed according to their personal incomes as shown in accounts

but by various flat rate systems (per hectare, etc.). Operators of farms arranged

as companies may escape coverage (as their directors may not have income from

self-employment in agriculture).

National surveys of households. There are EU-wide networks of household

surveys of expenditure and income and the EU Statistics on Incomes and Living

Conditions (EU-SILC); each of these is capable of providing data on the household

incomes of agricultural households. The main limitations for both are the small

number of cases of farmer households (sometimes very small) that are found

within these surveys at national level and, for countries where numbers are

adequate, issues over the quality of the income data relating to self-employment.

Sometimes these sources are used in combination (for example, France which periodically

combines FADN and tax records, and Ireland which uses farm accounts surveys in

association with its household survey). The situation in each EU-27 Member State is

described in detail in Hill (2012), Chapter 5 and in the online edition of the Wye Group

Handbook

10

.

Though within a single data source the income of agricultural households will generally be

assessed in a consistent way compared with those of other households, care has to be

taken in interpreting results for consistency between sources and between Member

States in three key methodological issues:

Definition of a household. The main alternatives are the single dwelling unit